Federal Court of Australia

Illinois Tool Works Inc v Airco Fasteners Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 495

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | AIRCO FASTENERS PTY LTD (ACN 068 705 699) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 May 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and, within 14 days of these orders, submit to the Associate to Justice Rofe an agreed minute of orders giving effect to these reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 711 of 2021 | ||

BETWEEN: | AIRCO FASTENERS PTY LTD (ACN 068 705 699) Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS First Respondent ILLINOIS TOOL WORKS INC Second Respondent | |

order made by: | ROFE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 May 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 716 of 2021 | ||

BETWEEN: | AIRCO FASTENERS PTY LTD (ACN 068 705 699) Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS First Respondent ILLINOIS TOOL WORKS INC Second Respondent | |

order made by: | Rofe J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 May 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROFE J:

Introduction

1 ITW is the patentee of Australian Patent No. 2005232970 entitled “In-can fuel cell metering valve” (the Patent). The Patent relates to fuel cells for use in combustion tools (eg, construction nail guns), wherein the “metering valve” (a valve which causes a metered or measured dose of fuel to be released into the combustion chamber of the tool) is located within the housing of the fuel cell. The Patent claims a priority date of 19 April 2004 (Priority Date).

2 In the primary proceeding, VID 593 of 2020 (Infringement Proceeding), ITW seeks injunctive, monetary and declaratory relief against the Respondent (Airco) for infringement of claims 1, 2, 3, 17 and 20 of the Patent (Asserted Claims).

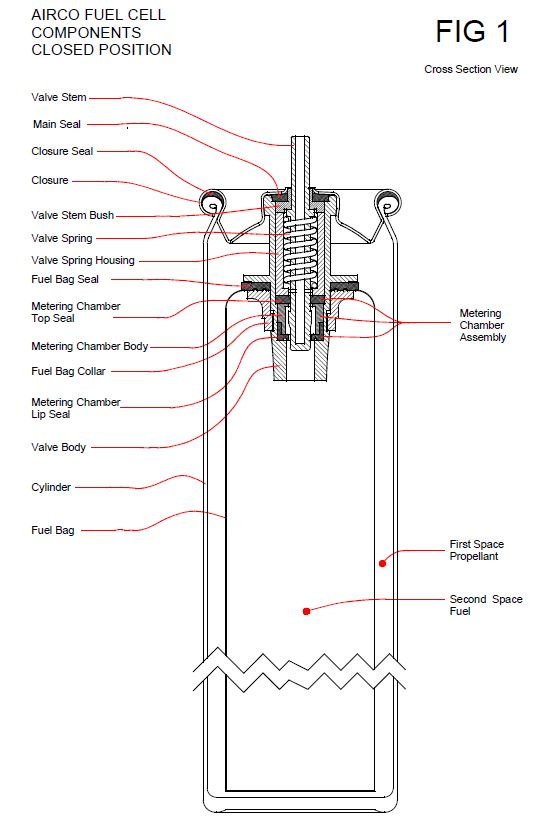

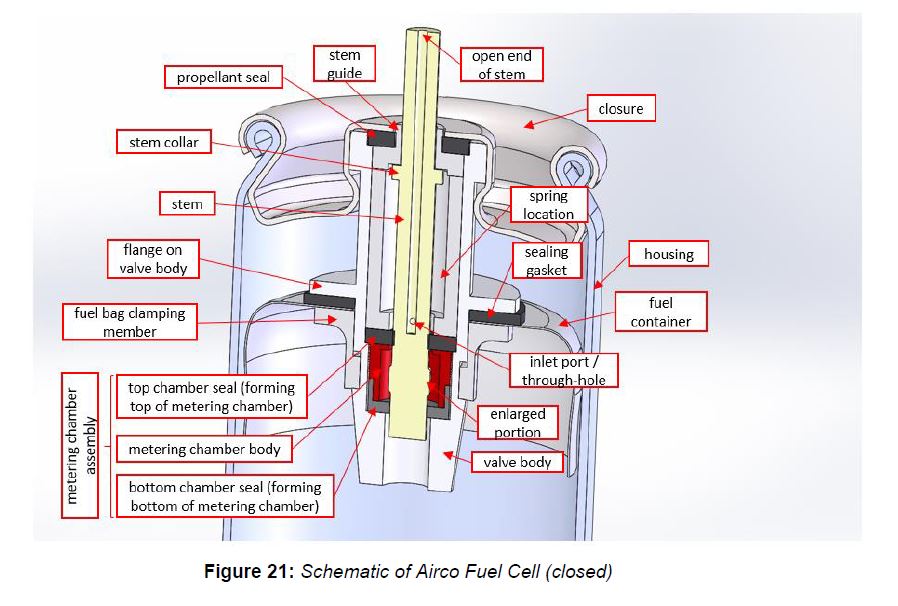

3 Airco admits that it imports, supplies and sells combustion tool fuel cells bearing the names “Senco”, “Senco Pack” or “Airco Procell” (Airco Fuel Cell).

4 Airco has admitted that the Airco Fuel Cell comprises nearly all of the features of the Asserted Claims. However, Airco denies that the Airco Fuel Cell takes all of the essential integers of any of the asserted claims, for three reasons:

(a) integer 1: the fuel metering chamber in the Airco Fuel Cell is not “disposed in close proximity to said closure”, as required by claim 1 (and all dependent claims);

(b) integer 7: the fuel metering valve of the Airco Fuel Cell does not have “a valve body having a second end opposite said fuel metering chamber located within said container”, as required by claim 1 (and all dependent claims); and

(c) integer 10 (claim 3): the Airco Full Cell does not have “a first end of said valve body [which] engages said closure”, as required by claim 3 when dependent on claim 1 (and all claims dependent on claim 3).

5 Airco commenced two separate proceedings (the Airco Proceedings) in the week prior to the hearing of the Infringement Proceeding. In these proceedings, brought against the Commissioner of Patents (Commissioner), Airco seeks to set aside various amendments to the Patent made on 21 April 2020, including new claims 17, 20 and 21. Otherwise there is no challenge to the validity of the claims of the Patent.

6 The parties (including the Commissioner) agreed to have the Airco Proceedings heard and determined at the same time as the Infringement Proceedings.

7 In the first of these proceedings, VID 711 of 2021 (the First Airco Proceeding), Airco seeks an extension of time:

(a) under r 31.02 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) to lodge an application for an order of review pursuant to ss 5 and 16 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act); and

(b) under r 34.25 of the Rules to file a notice of appeal (intellectual property).

8 In the second proceeding, VID 716 of 2021 (the Second Airco Proceeding), Airco seeks relief under s 39 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (Judiciary Act), on the basis that the Commissioner did not have jurisdiction to allow the amendments as they were not allowable under s 102(2) and therefore the decision to allow the amendments was beyond the authority of the Commissioner by reason of s 104(5) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act).

9 In summary, for the reasons that follow I find that:

(a) the Airco Fuel Cell infringes the Asserted Claims of the Patent; and

(b) based on my construction of claim 17 of the Patent, it is unnecessary to determine the Airco Proceedings.

The Patent

10 The Patent is entitled “In-can fuel cell metering valve”.

11 Broadly, the invention described in the Patent is a fuel cell for use with a combustion tool (for example a nail gun), which includes an internally mounted metering valve arranged such that a measured dose of fuel is dispensed each time the stem is pressed into the “open” position.

Background and prior art

12 The background to the invention is discussed in the first eight paragraphs of the Patent.

13 That section of the Patent first states that the invention relates generally to improvements in fuel cell delivery arrangements for use in combustion tools, and more specifically to metering valves used with such fuel cells for delivering the appropriate amount of fuel for use by a combustion tool during the driving of fasteners. It also explains that while the Patent focusses on fuel cells in combustion tools, the invention may also be applied to other pressurised containers using stem valves, such as those used in relation to cosmetics and pharmaceutical products.

14 The Patent refers to four US prior art patent specifications, each of which are said to be incorporated by reference into the Patent. One of these, US patent No 5,115,944, is later in the specification said to disclose the general construction of fuel cells. The prior art specifications disclose the use of mechanical or electronic valve assemblies designed to be able to control the amount of fuel that is dispensed from the fuel cell into the tool during each operation.

15 The Patent lists a number of “design criteria” it says are relevant to the design of fuel cells containing separate compartments of pressurised fuel and propellant.

16 First, the Patent refers to the prevention or minimisation of leakage of fuel and/or propellant. In particular, a stated objective is to prevent or minimise leakage of fuel and/or propellant after production and before use, also known as shelf life, and during periods when the fuel cell is installed in the tool but the tool is stored or otherwise not in use. The Patent notes that as with other aerosol or fuel canisters, a certain amount of leakage occurs over time. However, there is a concern that gradual leakage over a prolonged shelf life may result in reduced performance of the fuel cell due to insufficient propellant and/or fuel remaining for expected performance needs.

17 A second stated objective of the Patent is that only a desired amount of fuel should be emitted by the fuel cell for each combustion event.

18 The Patent refers to two further US patent specifications: US patent no 5,263,439, which discloses an internal-tool metering valve (where the metering valve is located internal to the tool housing and external to the fuel cell); and US patent no 6,307,297, which discloses an external metering valve (where the metering valve is “attached to the fuel cell” prior to the fuel cell being inserted into the tool housing). These metering valves are designed to control the amount of fuel emitted each time, for example, a nail gun is fired. These two additional specifications are also said to be incorporated by reference into the Patent.

19 The Patent emphasises that regardless of where the fuel metering valve is located, fuel leakage has remained a design consideration. In this context, it states that internal tool fuel metering valves have the disadvantage of requiring an excessive number of seal locations, which, in turn, provides more opportunities for fuel leaks. In order to facilitate disposability of external fuel cell metering valves, inexpensive materials are used. However, the aggressive nature of the fuel constituents may in some cases cause premature failure of the valve seals or the valve housing itself.

20 Another design consideration is said to be to avoid the duplication of components associated with external fuel cell metering valves, in that a first valve controls the flow of fuel from the cell, and a second valve controls a metered dose of fuel for delivery to the tool for a single combustion event. A related concern is the shipping of external fuel cell metering valves. The valves are shipped in an inoperative position and must be activated by the user by moving the valve into position. Fuel leakage from improper installation of the metering valve is a problem.

21 A further design consideration associated with cell-mounted metering valves is said to be that once the valve is operationally installed, the main cell stem valve is continuously open. The nature of the seal formed by the main fuel cell valve stem seal changes from a face seal to a radial seal about the valve stem, a more relaxed seal which proves less effective sealing and increases the potential for leakage.

Summary of the invention

22 The “background” section is followed by a “brief summary of the invention”. This section describes the invention in a broad or general form, as opposed to providing a detailed description of a preferred embodiment. A discussion of the preferred embodiment, including by reference to figures, is found later in the specification.

23 Against the above background, including the incorporated prior art specifications, the invention disclosed in the Patent provides a fuel cell for use with a combustion tool which includes an internal metering valve, arranged such that a measured dose of fuel is dispensed each time the stem is depressed into the “open” position.

24 The invention disclosed in the Patent facilitates one or more of the fuel seals in the previously known internal-tool or external metering valves (which may have contributed to the total amount of leakage from the device) to be “designed out”. This has been done by structurally changing the device so that the metering valve is located within the fuel cell housing, which in turn reduces the number of component connections and streamlines the flow of the fuel between the fuel cell housing and the tool. The fuel travels through fewer components, resulting in fewer leakage paths.

25 Further, by locating the metering valve inside the fuel cell, the invention combines in a single unit the functions of two valves in the prior art fuel cells, and thereby reduces duplication of components. The invention only requires one valve body, one biasing element (eg a spring), and one stem; and reduces the overall number of required seals compared to the prior art discussed in the Patent. This configuration is said to reduce cost, increase reliability and also make the invention more user friendly.

26 Descriptions of exemplary embodiments of the above invention are provided in paragraphs [8a] to [8n] and [9] of the Patent. The first aspect of the invention described at [8a] reflects the broadest form of the invention claimed in claim 1.

27 Paragraph [9] goes on to provide a description of a preferred embodiment featuring a metering valve internally mounted in the fuel cell, defined by a one-piece valve body, one end of which is located inside the inner fuel container located within the fuel cell. In the context of this example, the Patent explains that it is by locating the metering valve inside the fuel cell housing (or can) that the valve usefully combines in a single unit the functions of the Prior Art standard fuel cell “check valve” and separate “external metering valve”.

Detailed description and preferred embodiments

28 Under the heading “Detailed Description of the Invention”, commencing at [19], the Patent describes the features and operation of certain further preferred embodiments of the invention, including with reference to Figures 1 to 7.

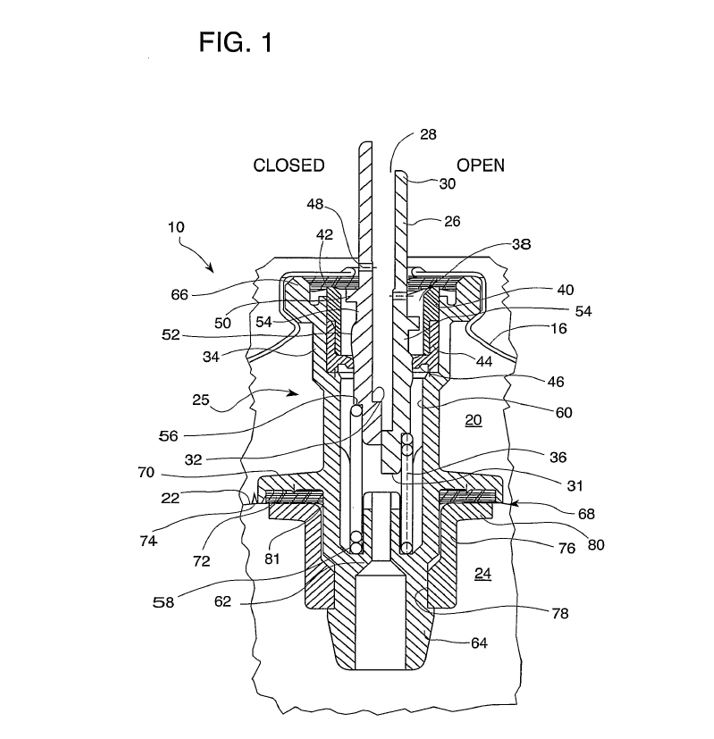

29 Fig 1 is as follows:

30 In the brief summary section, the Patent explains that the function of the fuel metering chamber (38) is to facilitate the storage and subsequent dispensation of a measured amount of fuel through the outlet of the fuel cell. In the preferred embodiment depicted in Fig 1, the fuel metering chamber engages an outlet seal, which is adjacent to the closure (16) of the fuel cell. However, the Patent explains that the fuel metering chamber may be located within the housing and is preferably located within the valve body (34) and in close proximity to the closure. Locations external of the valve body (34) are also expressly contemplated.

31 Both parties’ submissions referred to paragraphs [20], [22], [25], and [27] from the Detailed Description to support their constructions of “opposite” in claim 1. It is useful to set those paragraphs out in full here. The parts on which the parties’ focussed their submissions are bolded below. The numbers correspond to the numbers in Figure 1 above.

[20] A main valve stem 26 is configured for emitting fuel from the container 22 and as such as an outlet 28 at a first end 30 projecting from the housing, and a second end 31 opposite the first end. The valve stem 26 is in fluid communication with the source of fuel, preferably the container 22, which is preferably flexible or compressible to accommodate pressure exerted by the propellant as fuel is consumed and the volume of the container accordingly reduced. The first and second ends 30, 31 are separated from each other, preferably by a passageway 32. To emit fuel, the main valve stem 26 reciprocates relative to the housing 12 within a valve body 34 under a biasing force, preferably exerted by a biasing element 36 such as a spring, between a closed position (shown on the left half of FIG. 1) and an open position (shown on the right half of FIG. 1). In the closed position, the main valve stem 26 is biased by the biasing element 36 to an extended condition. In the open position, the main valve stem 26 is pushed back or retracted in a way that overcomes the biasing force of the element 36.

…

[22] In the embodiment of FIGs. 1 and 2, the fuel metering valve 25 includes a fuel metering chamber 38 located within the housing 12. This configuration is intended to reduce components and/or to reduce unwanted leakage or emission of fuel, which are design issues with current fuel cells. Preferably, the fuel metering chamber 38 is located within the valve body 34, and more preferably in close proximity to the closure 16, however locations externally of the valve body are also contemplated. By incorporating the metering valve 25 so that the valve body 34 is located permanently inside the fuel cell 10, potential leakage areas at the engagement point of an external valve to the prior art main valve stem are eliminated. Also, potential dosage changes due to environmentally or hydrocarbon exposure-caused changes in external metering valve dimensions are also eliminated.

…

[25] In the closed position, the inlet 48 is no longer located within the fuel metering chamber 38, and is preferably external of the seal 42. Thus, in this position, fuel cannot enter the main valve stem 26. The at least one stop member 50 is positioned on the main valve stem 26 so that it engages the outlet seal 42 and prevents further movement of the valve stem past the closure 16. Another feature of the main valve stem 26 is a generally radially enlarged portion 52. The enlarged portion 52 is of sufficient diameter to sealingly engage the lip seal 46 and prevent the passage of fuel into or out of the entry of fuel relative to the fuel metering chamber 38. A standard or relatively narrow diameter portion 54 of the main valve stem 26 is located between the stop 50 and the enlarged portion 52. At the opposite end, the generally enlarged portion 52 gradually reduces in diameter to form a seat 56 for the biasing element 36. An opposite end of the biasing element 36 engages an end of a body cavity 60 in the main valve body 34 in which reciprocates the main valve stem 26.

…

[27] To facilitate the delivery of fuel to the metering chamber 38, the valve body 34 is secured to the container 22, preferably such that the valve body has a first end 66 engaging the closure 16, such as by being crimped, and the second end 62 having the nipple portion located within the container. It will be seen that the biasing element 36 is located in the valve body 34 between the second end 62 and the first end 66, the latter providing the location for the fuel metering chamber 38, which is opposite the second end 62. It is contemplated that variations of this disposition of the valve body 34 are suitable for achieving the goal of secure mounting of the valve body relative to the fuel cell 10 for support and for consistent fuel metering during tool operation.

32 The Patent also contemplates that the location and construction of the fuel metering chamber are such that the dimensions of the chamber body may be changed to alter fuel dosage volume to suit different application conditions. The alteration of the dosage volume is contemplated as being performed by the manufacturer not the user.

33 Fuel enters the fuel metering chamber, when the main valve is in the closed position, through the body cavity which is said to be in fluid communication with a second end defining a nipple portion of the valve body. Fuel flows from the fuel container and enters the nipple portion of the valve body, the body cavity and the fuel metering chamber prior to being emitted from the outlet.

The claims

34 The Patent expressly notes that the person skilled in the art will appreciate that the claimed invention is not limited to the preferred embodiments of the fuel metering valve and associated combustion tool shown and described.

35 There are 22 claims. Claim 1 of the Patent claims:

A fuel cell for use with a combustion tool, comprising:

a housing defining an open end enclosed by a closure;

a main valve stem having an outlet, disposed in operational relationship to said open end and reciprocable relative to said housing at least between a closed position wherein said stem is relatively extended, and an open position wherein said stem is relatively retracted;

a fuel metering valve associated with said main valve stem, including a fuel metering chamber disposed in close proximity to said closure and configured so that when said stem is in said open position only a measured amount of fuel is dispensed through said outlet;

said housing including a separate fuel container,

wherein said fuel metering valve is located within said housing and includes a valve body having a second end opposite said fuel metering chamber located within said container, and wherein the flow of fluid out the outlet of the fuel cell is solely from said separate fuel container.

36 The presence or absence of the two italicised integers set out above in the Airco Fuel Cell is the issue remaining in dispute in claim 1. Key to that dispute is the construction of the bolded terms above.

37 Claim 2 provides:

The said fuel cell of claim 1, wherein said main valve stem has a radially enlarged portion, and said fuel metering chamber is provided with a lip seal constructed and arranged to engage said enlarged portion in said open position, but defining a fuel passage therebetween in said closed position.

38 There is one further integer (italicised below) in dispute in claim 3 (and any claim dependent on claim 3):

The fuel cell of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein a first end of said valve body engages said closure.

39 Claims 17 to 22 were introduced via the amendments challenged in the Airco Proceedings. Claim 17 provides:

A fuel cell according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the fuel metering chamber is disposed in said close proximity to said closure such that the metering chamber is located closer to the open end of the housing than an end of the housing opposing said open end.

40 Claim 20 provides:

A fuel cell according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the main valve stem is biased toward the closed position by a biasing element, and wherein the biasing element is located outside the metering chamber.

41 Claim 21 provides:

A fuel cell according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the biasing element is located in the main valve body between the metering chamber and a lower end portion of the valve body that extends to the separate fuel container.

42 Claim 22 is an omnibus claim which claims a fuel cell for use with a combustion tool substantially as hereinbefore described with reference to the drawings.

Evidence in Infringement Proceeding

43 ITW relied on the evidence of Dr Allan Wallace. Dr Wallace has a PhD in fluid mechanics from the University of Adelaide. He is a mechanical engineer with over 40 years’ experience in the fields of mechanical engineering and fluid mechanics, including designing valves, manufacturing prototypes of valves, specifying types of valves for commercial production, and investigating the operation of and problems associated with a vast number of different types of valves and other components associated with fluid flow. Dr Wallace made two affidavits dated 30 July 2021 and 13 September 2021.

44 Airco relied on evidence from Mr Graham MacDonald. Mr MacDonald has a Bachelor of Applied Science in Industrial Design from the University of Canberra. He has more than 40 years’ experience in industrial design including product design and detailing for mass production, 3D computer modelling and rendering, computer and hand illustration, graphic design, model making, and technical writing and illustration. Mr MacDonald prepared three reports dated 21 May 2021 (the Airco Fuel Cell product description), 2 August 2021, and 15 September 2021.

45 Prior to the hearing the joint experts prepared a joint report for the Court in which they gave their responses to 11 questions posed by the parties, and indicated where they agreed or disagreed in their response (the JER). The two experts gave concurrent oral evidence at the hearing, appearing by Microsoft Teams.

46 Dr Wallace provided the following background information about valves and seals.

(a) A “metering valve” relates to a valving system that allows a metered, fixed or particular amount of fluid to be dispensed from the valve assembly upon actuation.

(b) Valves commonly include one or more seals. Seals are designed to stop the flow of fluid or prevent fluid or particulate leakage between components of a device. They may be made from a variety of materials, including soft plastics or metal. Seals may be “static” (reliant on a clamping pressure setup during installation), or “dynamic” (activated predominantly by the action of the applied fluid pressure).

(c) Generally, a seal will act as a “face seal” where the compression forces acting on the seal are parallel to the axis of the seal (for this reason, face seals can also be known as axial seals).

(d) Generally, a seal will act as a “radial seal” where the compression forces acting on the seal act in a radial or outward fashion.

47 Dr Wallace reviewed the prior art specifications incorporated by reference into the specification. He gave particular attention to US patent no 5,263,439 (US 439) and US patent no 6,302,297 (US 297), which the Patent described as prior attempts to achieve the design criterion that only a designated amount of fuel be emitted by the fuel cell for each combustion event. In US 439, the fuel metering valve is located in the tool, separate from the fuel cell. In US 297, the fuel metering valve is external to, but attached to, the fuel cell.

48 The invention in US 439 is stated to be concerned with providing an improved system for controlling combustible fuel entering the combustion chamber of a combustion power tool. This objective is stated to be achieved by including in the tool a means (e.g. a fuel injector) for controlling the time during which fuel is able to enter the tool’s combustion chamber. In preferred embodiments, the time interval may be varied in response to variations in ambient temperature and pressure.

49 The invention described in US 439 relates to a fuel system for a combustion-powered, fastener driving tool having a switch that must be closed to enable ignition of a combustible fuel in a combustion chamber of the tool, whereby the fuel is permitted to flow from a source into the combustion chamber for a time interval after the switch is actuated. The fuel delivery comprises a fuel injector mounted in a cavity of the tool, which is arranged for injecting the fuel into the combustion chamber for a predetermined time interval to control the amount of fuel injected. Fuel is dispensed into the combustion chamber in a time-controlled manner, rather than in a volume controlled manner and mechanical force is not required to dispense the fuel. Dr Wallace understood that the valving system described in US 439 would require at least six seals.

50 The invention described in US 297 relates to improvements in an external metering valve for use with a fuel cell, aerosol can or dispenser for dispensable fluid

51 The object of the invention described in US 297 is said to be the provision of an improved external metering valve that is able to address the problems associated with the “prior art” external metering valves, through the use of a valve that is mounted to the fuel cell in a shipping position without a shipping cap and which can more easily be moved into an operational position. A preferred embodiment valve in US 297 comprises two legs shaped to allow the valve to easily move from the shipping to the operational position.

52 In the embodiment depicted in Figure 4 of US 297, the external metering valve contains a fuel metering chamber. Fuel flows out of the fuel cell and into the external metering valve attached to the fuel cell. Fuel is dispensed from the external fuel metering valve perpendicular to the fuel cell. Dr Wallace noted that Figure 4 exemplified one of the problems with the prior art, the duplication of components. Figure 4 depicts the invention as having two valves (each with valve stems and springs etc), a tubular “check” valve for controlling the flow of fuel from the fuel cell, and the external metering valve for metering the dose of fuel injected into the tool for a single combustion event. Dr Wallace considered that the valving system described in US 297 would require at least 6 different sealing locations

53 Dr Wallace noted that as the valve arrangements of the prior art specifications were located external to the fuel cell they required the use of two different valves, one for controlling the flow of fuel from the fuel cell (a “check valve”) and another, separate external fuel cell metering valve, for delivering a metered dose of fuel to the tool for a single combustion event.

54 Mr MacDonald agreed with Dr Wallace’s description of what was disclosed by the prior art specifications and the advances over that prior art identified in the Patent, although in cross-examination he acknowledged that he was not familiar with every detail of the prior art.

55 In their JER, the experts agreed that the objectives of the invention described in the Patent over the prior art, as summarised in paragraphs [1] to [9] are:

(1) to prevent or minimise leakage of fuel and propellant, both during the shelf life, and in-service;

(2) to enable emission of only a desired amount of fuel at each combustion event;

(3) to reduce the number of sealing locations and accordingly the potential for fuel or propellant leaks;

(4) to reduce the "periodic loading" on the valve stem, by which we understand that a main seal against the stem is arranged to use a face seal rather than a radial seal for most of the time;

(5) [to] reduce the number of components and therefore cost; and

(6) to make the device more user friendly.

56 The experts agreed that fuel cells can come in different shapes and sizes – big, small, long, thin, short, and wide. The Patent contemplates that the invention can be applied to pressurised containers of different sizes and dimensions from the outset. In addition to fuel cells in combustion tools, applications in other pressurised containers using stem valves such as, but not limited to, cosmetic and pharmaceutical products are contemplated.

Principles of construction

57 The principles of construction are well settled. Both parties highlighted particular principles including:

(a) Proper construction of the specification is a matter of law: Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86 at [67] (Jupiters);

(b) In the absence of an express reference in the claim itself, it is not legitimate to import into a claim features of the preferred embodiment. The preferred embodiment cannot properly be used to introduce into the definite words of a claim an additional definition or qualification of the patentee’s invention: Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd v Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd (2019) 145 IPR 39 at [94] (Globaltech); Rehm Pty Ltd v Websters Security Systems (International) Pty Ltd (1988) 11 IPR 289 at 298 (Rehm);

(c) A claim is to be construed from the perspective of a person skilled in the relevant art as to how such a person, who is neither particularly imaginative nor particularly inventive (or innovative), would have understood the patentee to be using the words of the claim in the context in which they appear. A claim is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge before the priority date: Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC (2015) 116 IPR 54 at [35] (Kenny and Beach JJ) (Blue Gentian);

(d) The complete specification is not to be read in the abstract; it is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date. The Court is to place itself in the position of someone acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24] (Kimberly-Clark); Globaltech at [95];

(e) Claims should be construed in the context of the specification, even where there is no ambiguity: Blue Gentian at [37]; quoted in ESCO Corporation v Ronneby Road Pty Ltd (2018) 131 IPR 1 at [144] (ESCO);

(f) In Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrell (1961) 106 CLR 588 (Welch Perrin), the Court said at 610:

…It is, however, fitting that we remind ourselves of the criterion to be applied when it is said that a specification is ambiguous. For, as the Chief Justice pointed out in Martin v Scribal, referring to Lord Parker’s remarks in National Colour Kinematograph Co Ltd v Bioschemes Ltd, we are not construing a written instrument operating inter partes, but a public instrument which must, if it is to be valid, define a monopoly in such a way that it is not reasonably capable of being misunderstood.

(g) A claim should be given a purposive construction. Words should be read in their proper context. Further, a too technical or narrow construction should be avoided. A “purposive rather than a purely literal construction” is to be given: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 21 at [41] (Greenwood and Nicholas JJ); Blue Gentian at [39];

(h) The integers of a claim should not be considered individually and in isolation: Blue Gentian at [39];

(i) A construction according to which the invention will work is to be preferred to one in which it may not: Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co (2005) 68 IPR 1 at [250]; Blue Gentian at [39];

(j) The claims in a patent are not to be narrowed by reference to the preferred embodiment. The preferred embodiment cannot properly be used to introduce into the definite words of a claim an additional definition or qualification of the patentee’s invention. A proper analysis of the specification may show that references to a particular embodiment are by way of “illustration and explanation of the invention” rather than a “definition of it”: Welch Perrin at 612;

(k) Moreover, reading each claim as a whole, as the hypothetical skilled addressee is expected to do, is more likely to give such an addressee an appreciation of what is really meant by the words used rather than some literal and grammatically parsed construction devoid of practicality and context: Blue Gentian at [26]; and

(l) The specified objects may be useful in construing a claim in context, however, they are not controlling in terms of construing a claim: Blue Gentian at [38].

58 It was accepted by both parties, and the experts, that the key terms in issue (“close proximity and “opposite”) would not be understood to have a particular technical meaning unless the specification itself ascribes a particular meaning to them. As the terms in dispute are not specifically defined in the Patent, and are words of ordinary English meaning, the construction of the terms is a matter for the Court.

59 Accordingly, the proper role of the experts was primarily to assist the Court in understanding the technical background to the invention, including the prior art which is incorporated into the specification and which the invention is said to be an improvement upon. Nevertheless, much of the expert evidence, including the joint report and the joint session was taken up by the experts providing their opinion as to the meaning of “close proximity” and “opposite” in the context of the claims.

Person skilled in the art

60 The skilled addressee comes to a reading of the specification with the common general knowledge of persons skilled in the relevant art, and they read it in a common sense and practical manner knowing that its purpose is to describe and demarcate an invention and not to be a textbook in the relevant field: Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd (2004) 64 IPR 444; [2004] UKHL 46 at [33] (Lord Hoffman).

61 The applicant submitted, based on the evidence of Dr Wallace, that the Patent is addressed to a mechanical engineer with experience in fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, combustion technology, materials science, stress analysis and/or manufacturing mechanical devices. Dr Wallace said in his first affidavit:

The relevant person would, for example, ideally need to have the necessary skills to allow them to determine:

(a) the optimal dimensions of the relevant fuel cell components, having regard to product (e.g. shelf life), manufacturing and cost constraints and requirements; and

(b) which materials are to be used, including, for example, ensuring the relevant materials are compatible with the chosen propellant and/or fuel.

62 Dr Wallace has practiced as a consulting mechanical engineer for over 40 years. He has extensive experience designing valves, manufacturing prototypes of valves, specifying types of valves for commercial production, and testing the operation of and investigating problems associated with a vast number of different types of valves and other components associated with fluid flow. Dr Wallace’s experience with valves includes the design of a prototype of the valve for dispensing wine from a cask; and the design and production of prototypes of a pump and associated valves for dispensing laundry detergents into industrial washing machines.

63 Dr Wallace provided evidence as to his understanding of the Patent and the terms used in the claims prior to being given any samples of the Airco Fuel Cell.

64 Mr MacDonald is a very experienced industrial designer, but he holds no qualifications in engineering and accepted he had no relevant experience in designing the components of combustion tools or fuel cells.

65 Mr MacDonald’s evidence was that he had not read the prior art specifications referred to and incorporated into the Patent. He agreed that the prior art specifications were technical documents which contained a considerable amount of detail on the mechanical arrangements and components that make up the fuel metering valves in the prior art.

66 Mr MacDonald’s evidence as to the construction of the terms in dispute was heavily dependent upon the description of the preferred embodiment and the depiction of the invention in Figure 1 of the Patent. This in part may have arisen from the way in which Mr MacDonald became involved in the matter.

67 Mr MacDonald’s introduction to the matter was when he was asked to prepare a product description of the Airco Fuel Cell pursuant to orders of Moshinsky J dated 19 April 2021. According to the order, the product description was to identify the features of the Airco Fuel Cell and be sufficiently detailed so as to properly address the allegations pleaded by ITW.

68 For the purposes of preparing the product description Mr MacDonald was provided with a copy of the Patent, samples of the Airco Fuel Cell, and copies of the statement of claim and defence filed in the proceeding. From reading those court documents, Mr MacDonald was aware of Airco’s contentions that the fuel metering chamber of the Airco Fuel Cell was not in close proximity to the closure, and that the fuel metering chamber was not opposite the second end of the valve body.

69 After completing the product description, Mr MacDonald was then asked to review the integers of the claims of the Patent and opine on whether or not each of the integers were present in the Airco Fuel Cell. It was accepted by Mr MacDonald that he was aware of the contentions that Airco was making in the proceedings and the features of the Airco Fuel Cell when he prepared his evidence as to his understanding of the integers of the Patent, and that he took the features of the Airco Fuel Cell into account in forming the views that he expressed about his understanding of the terms used in the claims of the Patent.

70 Mr MacDonald’s consideration of the integers in dispute was heavily reliant upon the description of the preferred embodiment as depicted in Figure 1 of the Patent. He used Figure 1 (and the description of the preferred embodiment which it depicted) to justify why he had adopted particular constructions of the terms in the Patent, including limitations which he gleaned from those sources, and repeatedly returned to Figure 1 and the description in his explanations.

71 Mr MacDonald relied on a side by side comparison of his drawing of the Airco Fuel Cell with a simplified version of Figure 1 of the Patent to show how the Airco Fuel Cell differed from the fuel cell in Figure 1 in his infringement analysis.

72 To the extent that the experts’ opinions can inform the determination of the issues before the Court, Dr Wallace’s opinion on technical matters should be preferred.

Construction

73 The claims of the Patent are directed to a fuel cell with various physical components which functionally interact to ensure the flow of fuel from the fuel container into the fuel metering chamber and then, upon actuation, for a consistent metered dose of fuel to be dispensed to the outlet of the fuel cell (and ultimately to a combustion tool), with minimal fuel leakage along the way. The claims should be purposively construed in that functional context and cognisant of the background of the objectives over the prior art.

“Close proximity”

74 As noted earlier, it was common ground that the phrase “close proximity” had no specialised technical meaning, nor any meaning defined in the specification, and that the words had their ordinary English meaning.

75 Airco submits that:

Taken together, the ordinary meaning of “close proximity” requires the fuel metering chamber to be located next, nearest and/or closely adjacent to the closure.

76 ITW submits that “close proximity” should be construed as the fuel metering chamber and the closure being nearby or close to each other in the context of the relative locations of each within the fuel cell as a whole.

77 Both parties relied upon the definitions of “close” and “proximity” from the third edition of the Macquarie Dictionary:

Close: 27. having the parts near together: a close texture… 29. Near, or near together, in space, time, or relation: in close contact

Proximity: noun nearness in place, time or relation.

78 Airco also relied on the definition of “proximate” from the same edition of the Macquarie Dictionary:

Proximate: adjective 1. next; nearest. 2. closely adjacent; very near…

79 Airco submitted that the expression is a tautology. Whilst the phrase “in close proximity” may be tautologous, it is a commonly used phrase. In common usage it is used to describe things which are near to each other. For example, one might say “the house is located in close proximity to schools and shops”. In this example, the house is not next to or adjacent to the schools or shops, a short walk or drive may be involved.

80 In the JER, Dr Wallace referred to common-usage examples of “close proximity” where the concept of proximity is related to the scale of the object, such as close proximity to an airport, house, golf-hole or insect. In cross-examination, Dr Wallace elaborated that “close proximity” in relation to an airport could be a kilometre or two; while “close proximity” to a house (in relation to a shed or similar) might be 10 or 20 metres.

81 The Merriam-Webster dictionary lists the phrase “close proximity” as an idiom: an expression that cannot be understood from the meanings of its separate words but that has a separate meaning of its own.

82 The phrase must be construed in the context of the specification as a whole and not just in the particular integer of interest.

83 The use of the phrase “close proximity” imports a concept of relativity into the location of the fuel metering chamber with respect to its disposition in relation to the closure. The definitions of both words above refer to nearness in space or relation.

84 The phrase “disposed in said close proximity” in claim 1 calls for an assessment of the relative nearness of the fuel metering chamber and the closure within the context of the fuel cell as a whole, and bearing in mind the express functional objectives of the invention.

85 Claim 1 defines a fuel cell for use with a combustion tool. It is a product or apparatus that comprises a combination of features as set out in the following parts of the claim. Thus, the starting point is that the fuel cell as a whole provides the context for assessing the relationship of those features to each other. As the experts agreed, fuel cells may come in different shapes and sizes.

86 The phrase “close proximity” is used to describe the disposition of the fuel metering chamber relative to the closure in the context of the fuel metering valve in which the fuel metering chamber is located. Claim 1 defines a “fuel metering valve” which is associated with the said main valve stem, and which includes “a fuel metering chamber disposed in close proximity to said closure”. The claim identifies the two components which are said to be disposed in “close proximity”, being: (1) the fuel metering chamber; and (2) the closure of the fuel cell housing (as earlier defined in the claim). These two components (and the fuel cell and housing) are defined before any reference to a valve body.

87 The “said closure” is located at the open end of the housing, through which the main valve stem protrudes. From a functional perspective the fuel metering chamber needs to be sufficiently close to the closure to allow the same measured dose of fuel to be efficiently and safely metered by the valve and dispensed through the outlet in the stem for each combustion event. In other words, it needs to be sufficiently close to the closure to allow the fuel cell, including the fuel metering valve, to function effectively and meet the objectives of the Patent. This is consistent with the functional language that follows the integer “and configured so that when the stem is in said open position only a measured amount of fuel is dispensed through said outlet.” This is also consistent with the evidence of both experts.

88 Mr MacDonald accepted that the role of the requirement of the “close proximity” feature was to ensure that the fuel metering chamber was sufficiently proximate to the closure to allow the fuel metering valve and fuel cell to function effectively.

89 In order for the fuel metering chamber to function effectively, it needs to be configured to receive delivery of a designated amount of fuel in the closed position and to allow a measured amount of fuel to be dispensed each time the valve is actuated. The fuel metering chamber does not need to be positioned adjacent to, or as close as possible to, the closure in order for the internal valve fuel cell of the invention to be configured in a manner that operates more efficiently and effectively than the fuel cells described in the prior art incorporated by reference into the Patent. The words “in close proximity” do not require this.

90 Claim 1 does not impose any limitation on the location of the fuel metering valve or valve body within the housing of the fuel cell. This is apparent from the language of the claim and was accepted by the experts. Mr MacDonald’s understanding of the phrase in the JER was that the fuel metering chamber was positioned at the end of the fuel metering valve that is crimped to the closure. However, Mr MacDonald accepted in his oral evidence that claim 1 does not require that there is an end of the fuel metering valve that is adjacent to, or engages the closure.

91 The claim does not require that the valve body, or any part of it such as the fuel metering chamber, be adjacent to the closure, or that the valve body have a “first end” which engages the closure. Requirements of that kind are introduced in later claims. In claim 1, however, it is the requirement that the fuel metering chamber be “disposed in close proximity to said closure” that performs the function of ensuring that the fuel metering chamber is sufficiently close to the closure to allow the fuel cell to function effectively. Mr MacDonald agreed that the valve body could be located away from the closure to some degree.

92 Subsequent claims 3 and 7, which are ultimately dependent upon claim 1, support the “relative” construction. Claims 3 and 7 add limitations which provide for a fixed relationship between components.

93 Claim 3 introduces a “first end” of the valve body and provides “wherein a first end of said valve body engages said closure”. This emphasises that no such requirement appears in claim 1. So, in claim 1, subject to the requirement that the fuel metering chamber be in “close proximity” to the closure, the fuel metering valve itself may be located anywhere along the length of the fuel cell.

94 “Engaging” is used in claim 7 in relation to the position of the fuel metering chamber. Claim 7 provides that the fuel metering chamber “includes a first end engaging a main seal”. This provides a specific requirement as to the location of an end of the fuel metering chamber, including that it engages a main seal in the fuel metering valve. Again, this emphasises that no such requirement as to the positioning of the fuel metering chamber appears in claim 1.

95 The omnibus claim, claim 22, expressly incorporates the features of the preferred embodiment described by reference to Fig 1. This underscores the fact that, consistent with general principle, the broader language of claim 1 is not so limited.

96 Finally, this construction of the claim is consistent with the description as a whole, including the description of the preferred embodiment by reference to the figures. The preferred embodiment is a specific, preferred example of a fuel cell that falls within the scope of claim 1, but does not impose a limitation on the more general language of the claim.

97 Consistent with a reading of the specification as a whole including the stated objectives over the prior art, the requirement that the fuel metering chamber be disposed in “close proximity” to the closure is to be determined by assessing the relative locations of the fuel metering chamber and the closure within the context of the fuel cell as a whole, with the two components being sufficiently nearby or close to each other in that context such that the same measured dose of fuel is dispensed for each combustion event.

98 Airco’s construction of “close proximity” must be rejected.

99 As noted earlier, the construction of “close proximity” is derived from the definition of “proximate” rather than “proximity”. I have extracted the definition of “proximate” from the Macquarie Dictionary above.

100 “Proximate” and “proximity” have different meanings. Comparing the Macquarie Dictionary definitions shows that “proximity” imports considerations of relationship or relativity, whereas proximate does not.

101 Airco substitutes the meaning of “proximity” with that of “proximate”; and uses that conflated definition for the purposes of construing the claim. Proximity has a different meaning to "proximate" which is defined in the Macquarie dictionary as "next; nearest", or "closely adjacent; very near". The phrase in the Patent is not “closely proximate” which is, in effect, the definition that Airco propounds. Airco elides the definition of proximate and proximity together to propound its construction. It is by this sleight of hand that Airco achieves a construction incorporating concepts of next and “adjacent”.

102 By the time Airco came to its submissions on non-infringement, the common, ordinary meaning of the term “in close proximity” it propounded had evolved to “next, nearest or closely adjacent, very near” to the closure.

103 Airco also referred to the absence of any dimensions for the fuel cell in the specification and claims, in particular the length of the housing, to support its construction.

104 The absence of dimensions in the Patent is consistent with the evidence of both experts that fuel cells may come in all shapes and sizes. The use of a relative term such as "close proximity" avoids placing arbitrary numerical limits on the relative locations of the components in question, so as to ensure that the claim caters for the full range of shapes and dimensions of fuel cells.

105 The use of relative terms in patent claims, rather than arbitrary fixed dimensions, is common in patent claim drafting. Claiming by reference to arbitrary dimensions would allow potential infringers to avoid infringement by making a fuel cell marginally longer or wider than the dimensions claimed.

106 There was no challenge to the validity of the Patent on the basis of clarity, utility, lack of best method or any other ground of invalidity.

107 Patent language which uses terms expressing approximation or requiring assessment according to circumstances does necessarily not mean that the impugned claim lacks clarity. Exact expressions are not always essential: see Stena Rederi Aktiebolag v Austal Ships Sales Pty Ltd (2007) 73 IPR 257 at [21] (Stena Rederi).

108 A patentee’s use of relative terms rather than precise dimensions is consistent with Dixon CJ’s observation that a patentee does not have to express their claim with a precision that implies an arbitrary restriction on the inherent variability of a feature which is part of the invention: Martin v Scribal Pty Ltd (1954) 92 CLR 17 at 60; see also Stena Rederi at [22].

109 At [22]–[23] of Stena Rederi, Tamberlin J said:

In Leonardis v Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd; Olympic Products Pty Ltd t/as Remax (1996) 67 FCR 126 at 134; 35 IPR 23 at 32, the Full Court stated that it is not inadmissible to use an imprecise word in a claim where, in an appropriate context, it conveys the necessary meaning. The court there referred to the use in patent claims of imprecise expressions such as “relatively small”, “a minor amount”, “substantial effect” and “substantially above” as terminology which does not necessarily invalidate a patent. Relative expressions which require the exercise of judgment can be used but they must be understood in a practical commonsense manner…

In Melbourne v Terry Fluid Controls Pty Ltd (1993) 26 IPR 292, Jenkinson J decided that the words “substantial portion” used in a claim to describe a sleeve of a mechanical assembly did not apply to a situation where the portion was less than 50% of the total length. In that case it was 48%. In reaching this conclusion his Honour had regard to context of the complete specification and to the expert evidence concerning the functions which the sleeve was intended to perform in operation of the device.

110 In Stena Rederi, which also involved the construction of “substantial portion”, Tamberlin J concluded at [38]:

In my view, the evidence indicates that it is not necessary to have numerical parameters to ascertain the meaning of “substantial portion”. Having regard to the proposed practical operation of the vessels, and read in the context of the specification as a whole, I prefer the construction of Mr Soars to that of Mr Quigley. The meaning of the expression can be more closely defined when assessing the circumstances and objectives of the particular design of a vessel in the particular conditions in which it is expected to operate. The specification allows for a range of forms which will differ according to these variables. Accordingly, I do not consider that the expression is obscure or uncertain or otherwise inappropriate, regardless of whether considered in isolation from or in context of the other requirements in the specification.

111 Here, the experts agreed, and the Patent contemplated, that the fuel cells could be of varied dimensions. In order to sensibly claim the invention in all fuel cells in which it might be expected to operate, the claims of the Patent use relative terms, rather than fixed dimensions. Further, it is not just the dimensions of the fuel cell housing that may vary, none of the other components such as the valve stem or the valve body are defined by reference in claim 1 to a specific size or dimension. The components may also vary in dimension and still fall within the claims.

112 Airco also relied on paragraph [22] of the Patent as support for its construction. This is the only passage of the Patent, other than the abstract, consistory clauses, and claims, which makes any use of the phrase "in close proximity". That paragraph simply states that the fuel metering chamber is preferably located in a valve body, whilst in the same paragraph acknowledging that it may be located externally to the valve body, and more preferably in close proximity to the closure. The paragraph does not, and does not attempt to, set the limits of the relative term “close proximity”. Nor does it require the fuel metering chamber to be adjacent or “as close as possible” to the closure.

113 Airco also refers to Figures 1 and 2, which depict the fuel metering valve as being immediately under and adjacent to, the closure as further support for its construction. Figure 2 is described in the Patent as being a split vertical cross-section of the fuel cell in Figure 1. Thus both Figures 1 and 2 depict the same preferred embodiment of the invention. Even if the Figures depicted different preferred embodiments, the presence of two depictions of preferred embodiments which have the fuel metering chamber in a particular position, does not support the importation of a limitation of such a position into the claims. Especially when, as in the Patent, the patentee expressly notes that the person skilled in the art will appreciate that changes and modifications can be made without departing from the invention.

114 Airco also submitted that there was no support in the specification for a construction of “in close proximity” which encompassed a fuel metering chamber being located in a part of the valve body that is remote from the closure. ITW did not advocate for a construction of “close proximity” that encompassed a fuel metering chamber that was remote from the closure. It is possible to reject Airco’s “next, nearest and/or closely adjacent to” construction without adopting an alternative construction that encompasses the fuel metering chamber being remote from the closure. The relative construction that I have adopted above, does not encompass the fuel metering chamber being remote from the closure.

115 Airco also relied on Mr MacDonald’s construction as set out in the JER, that he understood “disposed in close proximity” to mean positioned at the end of the fuel metering valve that is crimped to the closure. Mr MacDonald did not adhere to this construction in his oral evidence.

116 Mr MacDonald’s evidence on the construction of “close proximity” was infected by both his knowledge of Airco’s contentions of non-infringement, and the preferred embodiment described in the Patent.

117 Mr MacDonald accepted that he was aware of Airco’s contentions as to why the Airco Fuel Cell did not infringe the claims of the Patent, and had those matters in mind when he prepared his evidence on construction. He also accepted that he took into account the features of the Airco Fuel Cell in forming his understanding of the phrase “close proximity”.

118 Mr MacDonald also accepted that his construction of the phrase “close proximity” was influenced by Figure 1 and the description of the preferred embodiment. Many of his written and oral explanations of his understanding of the claim integers were similarly influenced. In his non-infringement analysis, Mr MacDonald said in relation to “close proximity”:

Noting that the patentee’s explanation is that it is preferable for the fuel metering chamber to be “within the valve body” and then, even more preferably, “in close proximity to the closure”. I regard positioning the fuel metering chamber near the end of the valve body that is most distant from the closure as not positioning it in close proximity to the closure.

119 In his oral evidence, his response was based on the preferred embodiment as depicted in Figure 1:

In the 970 patent, the preferred design, the fuel metering chamber must be disposed in close proximity to the closure, in fact, in very close proximity because the two inlet holes only travel a very short distance from the outside of the housing to the inside of the fuel metering camber. If the fuel metering chamber of the 970 patent is located further from the top of the closure and the distance that the valve stem travels when depressed in normal operation of the combustion… then it doesn’t work…

… [T]his is why the words “in close proximity” are used because it is this close proximity that allows the 970 patent to use the main seal as both a seal for the valve stem and as the part that closes the top fuel metering chamber. The Airco Fuel Cell is configured completely differently…

120 In relation to infringement, Mr MacDonald agreed to the proposition that the comparison he was giving was between the Airco Fuel Cell and what he understood to be a preferred embodiment in the Patent as shown in Figure 1.

121 Mr MacDonald also accepted in cross-examination that there may be arrangements in which the valve body did not engage the closure that would fall within claim 1.

122 Mr MacDonald also accepted that the role of “close proximity” in claim 1, having regard to the fact that claim 1 doesn’t place any requirement as to the positioning of the fuel metering valve or the valve body, is to ensure that the fuel metering chamber is sufficiently proximate to the closure to allow the fuel metering valve and fuel cell to function effectively.

123 Mr MacDonald accepted that the assessment of “close proximity” does not involve a consideration of whether there are any intervening components. The only relevant measure is the distance between the fuel metering chamber and the closure.

124 For the reasons above, I consider that the requirement that the fuel metering chamber be disposed in “close proximity” to the closure is to be determined by assessing the relative locations of the fuel metering chamber and the closure within the context of the fuel cell as a whole, with the two components being sufficiently nearby or close to each other in that context such that the same measured dose of fuel is dispensed for each combustion event.

Claim 17

125 Claim 17 provides:

A fuel cell according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the fuel metering chamber is disposed in said close proximity to said closure such that the metering chamber is located closer to the open end of the housing than an end of the housing opposing said open end.

126 ITW submits that claim 17 is dependent upon, and narrower than claim 1.

127 Mr MacDonald considered that claim 17 provided a definition of the term “close proximity”. He considered that, according to the definition in claim 17, a fuel metering chamber that was one millimetre closer to the closure than the midpoint along the total length of the fuel cell would be “within close proximity” to the closure. I have discussed above my concerns as to the limitations of Mr MacDonald’s evidence as to the construction of “close proximity”.

128 Airco submits that claim 17 has a bearing on the proper construction of “close proximity” in claim 1. Airco submitted, in accordance with Mr MacDonald’s evidence, that the wording of claim 17 in effect supplies a definition for “close proximity” in claim 1, and that ITW sought to deploy claim 17 to expand the meaning of “in close proximity” in claim 1

129 Airco also relied upon the bolded part of Dr Wallace’s answer to question 11 in the JER. That question asked:

In the context of the [unamended] Patent as a whole, would a fuel metering chamber located “closer to the open end of the housing than an end of the housing opposing said open end” be “disposed in close proximity to said closure” within the meaning of Claim 1?

Dr Wallace answered:

The [unamended] Patent provides no dimensional information. The answer would be influenced by the relative proportions of the closure and the housing. The first phrase calls on consideration of the size of the housing, while the second calls on consideration of the size of the closure. The two metrics are not directly related to each other. It is apparent that “close proximity to said closure” would mostly satisfy “closer to the open end…” but not necessarily the other way round.

[Emphasis added.]

130 When cross-examined on this point, Dr Wallace said:

There are two different metrics there. … They’re not directly related to each other. … The overlap makes them consistent with each other in one sense and inconsistent or a conflict in the other sense.

131 Airco relied on Dr Wallace’s responses to submit that it was “common ground” between the experts that claims 17, 20 and 21 extended beyond the scope of the claims in the Patent before amendment.

132 Airco submits that the amendment to add claim 17 was a broadening amendment in contravention of s 102 of the Act. If correct, that contention founds Airco’s applications for review, and s 104(7) appeal in the Airco Proceedings.

133 Claim 17 is dependent upon, and adds a further requirement to claim 1 as to the location of the fuel metering chamber. It does not provide a definition of “close proximity” for the purposes of claim 1. The amendment to include claim 17 was not a broadening amendment contrary to s 102.

134 The experts agreed that fuel cells came in different shapes and sizes. Depending on the configuration of the particular fuel cell under consideration, it would be possible to have an arrangement in which the fuel metering chamber is located anywhere within the half of the housing closer to the open end and at the same time is disposed in close proximity to the closure. Such an arrangement would fall within claim 17. Not all fuel metering valves located within the half of the housing closer to the open end will be within close proximity to the closure. It will depend on the shape and dimensions of the particular fuel cell being considered.

135 There was no “common ground” between the experts as contended by Airco. At the outset of their response to question 11, the experts noted that they disagreed. Airco misconstrues Dr Wallace’s evidence on this topic. Whilst Dr Wallace agreed that there might be fuel cell configurations in which the fuel metering valve satisfied the requirement that it be “located closer to the open end of the housing than an end of the housing opposing said open end”, but which were not in close proximity to the closure, he did not agree that such a configuration would fall within claim 1 (or claim 17).

“Opposite”

136 The second construction issue relates to the meaning of “opposite” in the following integer from claim 1:

wherein said fuel metering valve is located within said housing and includes a valve body having a second end opposite said fuel metering chamber located within said container, and wherein the low of fluid out the outlet of the fuel cell is solely from said separate fuel container.

(Emphasis added.)

137 Airco submits that the meaning of the word “opposite” in the above integer is to be assessed by determining whether the fuel metering chamber is located closer to the identified “first” end of the valve body, being a fixed location, in other words, at the end other end of the valve body to the first end.

138 ITW submits that the meaning of the word “opposite” in the above integer is to be assessed by determining whether the second end of the valve body is “opposite” the fuel metering chamber in the sense of “facing” or “across from it”, which involves a spatial relationship between the two identified objects.

139 For the reasons that follow, I prefer the construction propounded by ITW.

140 It was common ground that the second end of the valve body referred to in the claim is the end of the valve body that is located in the separate fuel container (or bag). The claim makes no mention of a “first end”, a reference to which, as noted above, first appears in claim 3.

141 The Macquarie Dictionary defines “opposite” as:

Opposite: adjective 1. placed or lying against something else or each other, or in a corresponding position from an intervening line, space or thing: opposite ends of a room; opposite to our house. 2. contrary or diametrically different, as in nature, qualities, direction, result or significance... preposition 8. facing: she sat opposite me… adverb 10. on opposite sides.

142 In the JER, Dr Wallace considered that there were two “equally valid” meanings of opposite as used in this integer:

(a) “At the other end” of the valve body (Mr MacDonald’s preferred construction); and

(b) “Facing” or “across something”, such as a gap.

143 In cross-examination, Mr MacDonald accepted that “facing” and “across from” are established meanings of the word “opposite”. This is consistent with the Macquarie Dictionary definition above. It is not an unusual or counterintuitive meaning.

144 “Opposite” occurs in several places in the specification other than in the consistory clause. Opposite is found in the detailed description of the invention at paragraphs [20], [25] and [27], each of which is set out above in the discussion of the Patent. “Opposite” also appears in paragraph [33].

145 In a discussion of the main valve stem at [20], the specification refers to the “second end 31 opposite the first end”. In this context “opposite” is being used to describe two ends of the same component, the main valve stem, not two separate components. The two ends of the one component are also facing each other along the axis of the stem. Both meanings of “opposite” are apposite in this context.

146 At [25] of the specification “opposite” is used twice. First, in relation to the main valve stem; and second, in relation to the biasing element (or spring). In both cases the description is used to describe the other end of one component which has two ends, not the positioning of two separate components. Given the use of the phrase “opposite end”, “opposite” in these instances refers to the different ends of the relevant components.

147 At [27] a preferred embodiment of the invention is described in which the fuel metering chamber is located at the first end: “the [first end] providing the location for the fuel metering chamber 38, which is opposite the second end 62”. Immediately after that description of a preferred embodiment of the valve body of the invention, the specification continues:

It is contemplated that variations of this disposition of the valve body 34 are suitable for achieving the goal of secure mounting of the valve body relative to the fuel cell 10 for support and for consistent fuel metering during tool operation.

148 Paragraph [33] of the specification relates to Figure 5, and describes an inline actuator, in particular an actuator arm which is said to “pivot about a pivot point 104 and at an opposite end is moved by at least one of the linkage 96 or the workpiece contact element 94”. Opposite is used here in relation to one component, the actuator arm, and the opposite ends of that component.

149 When used in the specification in relation to two ends of one component, “opposite” is used to indicate the other end of that component by reference to “opposite end”. That is not the context in which it is used in claim 1.

150 Airco appeared to go further than the experts, submitting that the Patent repeatedly and consistently uses “opposite” to refer to the “farthermost parts or extremities of various components of the invention”. Such an extreme view of “opposite” is inconsistent with its submission that the “second end” is not “right at the very end” which it based on the depiction of the preferred embodiment in Figure 1, in which the second end is marked as a region at the end of the valve body, rather than being the end face. Airco also criticised Dr Wallace’s view that the end face of the valve body end in the fuel container was the second end of the claim, saying that it was “incontrovertible that the second end is not the end face of the valve body, but is rather a region towards the bottom of the valve body”.

151 In the context of its non-infringement analysis, Airco submitted that the “only sensible construction” of “second end opposite” in the claim, is “at the other end” of the valve body to the first end. It submits that this avoids the redundancy that would arise if “opposite” was given a meaning that would render all other components of a fuel cell “opposite” (ie facing or across from) the second end. Mr MacDonald’s explanation of the redundancy was based on the preferred embodiment in Figure 1, and an assumption that all the internal components are arranged co-axially. Whilst this is the case for the invention as depicted in Fig 1, there is no requirement in the claim for such an arrangement, other than the word “opposite”.

152 On ITW’s propounded construction “opposite” is not redundant; rather, it assists in distinguishing the invention from the fuel cells of the prior art by indicating that in addition to being in “close proximity” to the closure, the fuel metering chamber is also facing or across from the second end (and not, for example, at right angles as in the prior art).

153 Airco’s proposed construction of the word “opposite” doesn’t add anything to the description, because the skilled reader already knows that the fuel metering chamber is in “close proximity” to the closure. It is Airco’s construction that renders “opposite” redundant.

154 The word “opposite” in the context of claim 1 is used in relation to two separate and different components: the second end of the valve body and the fuel metering chamber, not two ends of the one component. This usage is in contrast to other uses in the specification where two ends of the same component, such as the valve stem are being discussed.

155 The word “opposite” as used in the claim integer is a preposition. It defines a spatial relationship between these two separate components, being a second end of a valve body and a fuel metering chamber. In that context, it requires that a second end of a valve body be “facing” or “across from” a fuel metering chamber, with the two components being across from each other on the same axis (or, having a co-axial relationship with each other).

156 The fuel metering chamber and second end of the valve body identified in claim 1 are two separate components. The use of “opposite” in this context is not the same as the use to describe two ends of the same component. It is wrong to suggest that a word used more than once in the Patent must be construed consistently regardless of the context in which that word is used. Where the context of use indicates that a different meaning is appropriate for that context, that meaning should be adopted.

157 Thus, the claim requires that the “second end” of the valve body be “opposite” the “fuel metering chamber”. It does not refer to “the opposite end” of the valve body. The claim does not define the relationship of the fuel metering chamber with reference to any other component, including any other “end” of the valve body. The only end of the valve body identified in claim 1 is the “second end” of this feature.

158 In this integer, the claim imposes the requirement that there is a relationship between the second end, which is the end of the valve body in the separate fuel container where the fuel is going to come from, and the fuel metering chamber, which is where the fuel must flow in order for the invention for work. Fuel flows from the container into the second end of the valve body, the cavity and the metering chamber prior to being emitted from the outlet of the valve stem.

159 Paragraph [26] describes the path of the fuel from the fuel container to the fuel metering chamber. It relevantly states:

Fuel enters the chamber 38 through the body cavity 60 which, in turn is in fluid communication with a second end 62 defining a nipple portion of the valve body 34. A receiving end 64 of the nipple portion of the valve body 34 is located within, and is in fluid communication with the second space 24, which preferably contains the fuel.

[Emphasis added.]

160 Consistent with this discussion of the fuel flow path and various components being “in fluid communication”, Dr Wallace discusses his understanding of “opposite” in the context of fluid flow — fuel flows across from a second end to a metering chamber. In his opinion, Figure 1 shows a second end vertically spaced across from, and on the same axis as, the metering chamber. Fuel flows from a fuel container via a second end of the valve body and into a fuel metering chamber.

161 In the context of the Patent, Dr Wallace considers that “opposite” as used in claim 1 means that two components are “facing or across from one another in a co-axial fashion”. Co-axial indicates that the components are on the same axis.

162 Dr Wallace observed that the Patent describes just one fluid flow path (or the fuel path), which is necessary and important for the claimed invention to work efficiently. This feature goes some way to achieving the objective of fuel efficiency and minimising loss of fuel in contrast to the prior art.

163 The requirement in the claim that the second end of the valve body be “opposite” the fuel metering chamber imposes the functional requirement that those two components be facing or across from each other, so that fuel will flow directly from the second end, (in the separate fuel container), to the fuel metering chamber. From there, upon actuation, it will follow the pathway that has already been defined earlier in the claim via the main valve stem, through the outlet and into the combustion tool. This is the context in which the word “opposite” is used in the claim.

164 This is different to the other references to “opposite end” in the specification. In each of those cases there is one component being discussed, and it is the other end of that component to which “opposite” is directed. Airco takes this further to submit that it is the “furthermost extremity” of the various components mentioned. In the integer, the “end” is the second end of the valve body, and “opposite” is used in relation to another component, not the other end of the valve body.

165 This is consistent with the functional language of claim 1, which requires that the fuel flow from the fuel bag to the metering chamber so as to release a measured amount of fuel through the outlet when the stem is in an open position, and the latter requirements of this integer.

166 It is not a natural or ordinary meaning of “opposite” to mean “at the other end” or “at the furthermost extremity” when the term is used to describe the relationship between two different components and not, for example, to describe or distinguish two ends of the same object such as a valve stem, valve body or a biasing element. This is the manner in which “opposite” is used in paragraphs [20] and [25]. Opposite when used to define the relationship between two separate objects plainly does not mean or convey that those objects are as far away from each other as is possible. For example, saying “I am sitting opposite X at the table” would not carry such a meaning.

167 The facing or across from construction of “opposite” is supported by the Figure 1 embodiment of the invention. Such a construction does not render the use of “opposite” entirely redundant in claim 1.

168 The location of the fuel metering chamber relative to other parts of the fuel cell is informed by the “close proximity” requirement rather than “opposite”.

169 Airco’s expert Mr MacDonald focussed on the valve body and the ends of that component to require the fuel metering chamber to be at the extremity of the first end of the valve body.

170 Mr MacDonald’s understanding of the meaning of “opposite” in claim 1 effectively rewrote the claim to require a consideration of the “first end” of the valve body, an element which is not expressly referred to in claim 1. In cross-examination, he agreed that in his view, “claim 1 required the fuel metering chamber to be at the first end of the valve body”.