Federal Court of Australia

Rakman International Pty Limited v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 464

Table of Corrections | |

The medium neutral citation has been amended from “Rakman International Pty Limited v Trafalgar Group Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 464” to “Rakman International Pty Limited v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 464”. |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in agreed draft orders or, if agreement cannot be reached, competing draft orders, giving effect to these reasons and providing for the further conduct of this proceeding, by 4.00 pm on 10 May 2022.

2. The parties liaise with the Associate to Yates J to list the proceeding for further case management and the making of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 641 of 2019 | ||

BETWEEN: | BOSS FIRE & SAFETY PTY LTD Applicant | |

AND: | TRAFALGAR GROUP PTY LTD Respondent | |

order made by: | YATES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 April 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in agreed draft orders or, if agreement cannot be reached, competing draft orders, giving effect to these reasons, by 4.00 pm on 10 May 2022.

2. The parties liaise with the Associate to Yates J to list the proceeding for the making of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

ORDERS

NSD 1242 of 2019 | ||

BETWEEN: | TRAFALGAR GROUP PTY LTD Applicant | |

AND: | BOSS FIRE & SAFETY PTY LTD Respondent | |

order made by: | YATES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 APRIL 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in agreed draft orders or, if agreement cannot be reached, competing draft orders, giving effect to these reasons, by 4.00 pm on 10 May 2022.

2. The parties liaise with the Associate to Yates J to list the proceeding for the making of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

[1] | |

[13] | |

[13] | |

[28] | |

[33] | |

[33] | |

[54] | |

[55] | |

[70] | |

[89] | |

[90] | |

[108] | |

[115] | |

[121] | |

[126] | |

[126] | |

[128] | |

[151] | |

[173] | |

[242] | |

[274] | |

[284] | |

[332] | |

[332] | |

[346] | |

[353] | |

The disclosures in the Firestopit PDS and the presence or lack of innovative steps | [391] |

[412] | |

[425] | |

[435] | |

[436] | |

[436] | |

[441] | |

[447] | |

[449] | |

[453] | |

[471] | |

[501] | |

[501] | |

[518] | |

[519] | |

[541] | |

[550] | |

[554] | |

[555] | |

[556] | |

[573] | |

[582] | |

[590] | |

[598] | |

[640] | |

[653] | |

[668] | |

[675] | |

[688] |

YATES J:

1 There are three proceedings before the Court involving common parties, which have been heard concurrently.

2 In the first proceeding (NSD 1589 of 2018), Rakman International Pty Limited (Rakman) and Trafalgar Group Pty Ltd (Trafalgar) sue Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd (Boss) and its sole director, Mark Prior, for infringement of Patent No. 2017101778 (the patent), in reliance on s 117(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Patents Act). Rakman is the patentee, and Trafalgar claims to be the exclusive licensee, of the patent.

3 The respondents deny infringement. Boss has cross-claimed, seeking revocation of all the claims. Boss has also cross-claimed against Trafalgar seeking relief pursuant to s 128(1) of the Patents Act for unjustifiable threats, and for relief on the basis that Trafalgar has contravened s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (the ACL). The claims for relief under s 128(1) of the Patents Act, and the claims for relief based on contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL, concern a letter which Trafalgar sent to a number of firms and others engaged in the building industry, in which Trafalgar made a number of statements concerning Boss’s conduct and the fact that it (Trafalgar) had commenced proceedings against Boss for patent infringement.

4 The second proceeding (NSD 641 of 2019) is an appeal by Boss from a decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks in opposition proceedings relating to Trade Mark Application No. 1736748 for the word FIREBOX (the 748 application). The applicant for the mark is Trafalgar whose registered corporate name, at the time of application, was Fire Containment Pty Ltd (Fire Containment). The delegate found that Boss had failed to establish the grounds of opposition on which it relied, and directed that the mark proceed to registration.

5 The third proceeding (NSD 1242 of 2019) is an appeal by Trafalgar from a decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks in opposition proceedings relating to Trade Mark Application No. 1812214 for a composite mark which includes the word FYREBOX in stylised form and a stylised flame device (the 214 application). The applicant for the mark is Trafalgar whose registered corporate name, at the time of the application, was, once again, Fire Containment Pty Ltd. The delegate found that Boss had made out its opposition and refused to register the mark.

6 Rakman is, primarily, a holding company for various assets including intellectual property rights. It does not trade, other than to offer consulting services under the name “J-RAK Consulting”.

7 Fire Containment acquired certain assets of the business of Trafalgar Building Products Pty Ltd in May 2009. It then traded under the name “Trafalgar Fire Containment Solutions”, manufacturing and supplying fire containment products and systems. Fire Containment has since changed its name to Trafalgar Group Pty Ltd.

8 For ease of reference, it is convenient to refer to Rakman, Fire Containment, and Trafalgar as, simply, Trafalgar, unless it is necessary to distinguish between them. Similarly, it is convenient to refer to Boss and Mr Prior as, simply, Boss, unless it is necessary to distinguish between them.

9 For the reasons that follow, I have found that all claims of the patent are invalid. Claims 1, 2, 3, and 4 are invalid on the ground that the invention, as claimed in each claim, is not novel. Claim 5 is invalid on the ground that the invention, as claimed in that claim, does not involve an innovative step. Had I not found that the invention as claimed in claim 3 is not novel, I would have found that the invention, as so claimed, does not involve an innovative step.

10 It follows that Trafalgar’s claim of infringement against Boss under s 117(1) of the Patents Act is not, and cannot be, established. Had the claims of the patent not been invalid, Trafalgar’s case of infringement against Boss would have succeeded. However, its case against Mr Prior for infringement would not have succeeded.

11 I am not satisfied that Boss has established that Trafalgar made unjustifiable threats within the meaning of s 128(1) of the Patents Act. However, I am satisfied that Trafalgar contravened s 18(1) of the ACL by sending the letter to which I have referred.

12 As to the trade mark appeals, I have concluded that the appeal in NSD 641 of 2019 should be allowed. In light of that conclusion, and subject to hearing further from the parties, I have reached the provisional conclusion that the appeal in NSD 1242 of 2019 should be dismissed.

13 In its patent case, Trafalgar adduced evidence from Mr Rakic, who is the director and company secretary of the applicants. It also adduced evidence from Mr Todd, who is Trafalgar’s Director of Innovation, and Mr Vickery, who is Trafalgar’s Chief Financial Officer and General Manager. Mr Rakic and Mr Todd were cross-examined. Evidence of a formal nature was also adduced from Ms Currey, a solicitor employed in the firm of solicitors acting for Trafalgar in the three proceedings. Ms Currey was not cross-examined.

14 In answer, Boss adduced evidence from Mr Prior, who is the director and company secretary of Boss. It also adduced evidence from Mr Bacon, the National Sales Manager of Boss; Mr Visser, the former Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer of Speedpanel Australia Pty Ltd; Mr Atkinson, the former Managing Director and Chairman of the United Kingdom company FSi Ltd; and Mr Ramunddal, the Chief Executive Officer of the Norwegian company Seltor Gruppen AS. These witnesses were cross-examined. Evidence of a formal nature was also adduced from Ms Sanders, a partner in the firm of solicitors acting for Boss, and from Mr Warzecha, a solicitor employed in that firm. Ms Sanders and Mr Warzecha were not cross-examined.

15 As I have noted, the patent case and the trade mark appeals have been heard concurrently. Mr Rakic and Mr Prior, for example, each gave evidence that was directed to all three proceedings. Because of the overlapping nature of the evidence, evidence in one proceeding was taken to be evidence in each other proceeding as well.

16 Evidence specifically directed to the trade mark appeals was adduced not only from Mr Rakic and Mr Prior but also, for Trafalgar, from Mr Wax, a Project Manager employed by Paladin Group and, for Boss, from Mr Falkiner, a former Passive Fire Services Manager at Wormald International; Mr Halliday, one of the founders and Managing Directors of Airport Consultancy Group Pty Ltd; Mr Talbot, the founder and Managing Director of Verified Pty Ltd; and Mr Bradley, a Construction Manager employed by Paladin Group.

17 In closing submissions, the parties made various criticisms of (some of) each other’s witnesses. With one exception, it is not necessary for me to recount these criticisms in this part of the reasons. I have considered and reflected on these criticisms in my assessment of the evidence. Where I have considered it necessary to make specific comment, I have done so in my discussion of that evidence.

18 The exception is Mr Prior’s evidence. Trafalgar made a sustained attack on Mr Prior’s credit. It submitted that Mr Prior’s evidence should not be accepted on any issue adverse to Trafalgar’s case, “unless corroborated by a genuine contemporaneous document”.

19 Trafalgar put the matter that way because it contended that Mr Prior had been involved in the creation of a number of documents adduced in evidence which, it claimed, were not created on the dates asserted by him. Trafalgar contended that Mr Prior’s creation of “highly significant documents … casts doubts about the veracity of his evidence and is illustrative of the steps he is willing to take to advance Boss’ interests in the proceeding”. This is really an allegation that Mr Prior falsified and fabricated evidence in aid of Boss’s case.

20 None of these claims were made good by Trafalgar. What is more, Trafalgar’s allegations of falsification and fabrication extended to documents which were, in fact, documents whose contents emanated from third parties for which Mr Prior could not have been responsible—for example, the Firestopit PDS prepared by Mr Atkinson, a digital image taken at FSi, and a digital image taken by Mr Ramunddal, all of which are discussed below. To the extent that these claims were advanced in cross-examination—and not all such claims were advanced in the cross-examination of relevant witnesses—they failed. I raise these matters, primarily, in fairness to Mr Prior and to make clear that I do not accept the submission which Trafalgar advanced in this regard.

21 This, however, was not the end of Trafalgar’s criticisms of Mr Prior’s evidence. Based on identified passages from Mr Prior’s cross-examination, Trafalgar submitted that the Court should have “serious doubts about the accuracy and reliability of [Mr Prior’s] recollection in circumstances where he was unable to recall basic matters during the same period which did not suit his case”. Trafalgar also submitted that Mr Prior presented as “a witness whose recollection of matters occurring in 2014 and 2015 was not as clear as he presented it to be in his affidavit and whose ability to recall matters occurring many years later was dictated solely by his self-interest in the proceeding”.

22 Trafalgar also submitted that the Court should conclude that aspects of Mr Prior’s affidavit evidence were implausible. This submission was coupled with the submission that the Court should find that Mr Prior gave deliberately false evidence concerning the fact that he had lost certain documents relating to the time that he said that Boss commenced using FYREBOX for certain products supplied by Abesco, and that he could not recall the name of the consulting company that he requested to recover emails and documents.

23 I do not accept these submissions. In particular, I do not accept that Mr Prior gave deliberately false evidence on the topic of lost documents and the steps that Boss had taken to recover documents. Further, I do not have particular concerns about Mr Prior’s ability to recall events. In that regard, I have exercised caution in accepting Mr Prior’s recollection of events that occurred some years ago, in the same way as I have exercised caution in accepting other witnesses’ recollections of such events.

24 There are, however, some aspects of Mr Prior’s evidence which have caused me concern. In the trade mark opposition proceeding below in relation to the 748 application, Mr Prior made a declaration in which he deposed to the total sales revenue received by Boss, in a particular period, from the sale of products bearing, or promoted by reference to, the FYREBOX trade mark. Leaving aside the question of whether the products did bear, or were promoted by reference to, the FYREBOX trade mark, Mr Prior accepted, in cross-examination, that the revenue recorded in the declaration for the products (to which he was referring) was grossly different to the revenue recorded in Boss’s sales records. When asked to explain this discrepancy, Mr Prior said:

No. I can’t give clarity on exactly how that happened. As I said a few minutes ago, I don’t recall writing this. I accept that it came from me; it was authorised by me. And certainly, in the declaration, there was a less level of detail and focus as there was in court proceedings. So I very much accept they’re different. I can see that. It’s in front of me.

25 Mr Prior accepted that, at the time he made his declaration for the purposes of the opposition proceeding, the declaration would be used to advance Boss’s interests over Trafalgar’s interests. When asked whether, by his answers in cross-examination, he was suggesting that the declaration had not been prepared with the degree of care that he (Mr Prior) thought the declaration should have been prepared, Mr Prior said:

I’m not sure I would put it like that. However, I would say that for Federal Court proceedings, there was considerably more and intensive research that went into this case than there was into a declaration, and evidenced by having different legal representation as well, with a considerably different focus on the depth of data they had to dig into. I don’t recall the legal advice I had in the preparation of the declaration; much of a discussion at all.

26 Relatedly, Trafalgar submitted that Mr Prior was being less than frank in his declaration, and also in his affidavits in the present proceedings, by giving the impression that significant sales of products had been made by Boss since 2013 using the FYREBOX trade mark when, in fact, on careful consideration, the evidence did not show this to be the case.

27 These criticisms of Mr Prior’s evidence are justified. They have led me to scrutinise Mr Prior’s evidence with some care. Having said that, my impression of Mr Prior in cross-examination was that he was careful, and responded directly and truthfully, in the answers he gave. As will become apparent, on a number of critical matters, Mr Prior’s evidence was, in fact, corroborated by other evidence, which I consider to be reliable.

28 Trafalgar adduced evidence from a number of experts in its patent case. It adduced evidence from Mr Harriman, who is a building and fire regulation consultant, and from Mr Hunter, who is a mechanical engineer. It also adduced evidence from Mr van de Weijgert, a fire safety engineer, whose evidence was directed to the standards applicable to fire protection devices in the United Kingdom and Europe.

29 Trafalgar also called evidence from Mr McKemmish, an expert in computer forensics. Mr McKemmish addressed the metadata recorded in electronic copies of documents that had been produced on discovery by Boss. Mr McKemmish was cross-examined.

30 For its part, Boss adduced evidence from Mr Page, who has expertise in the field of passive fire safety based on various roles he has had working with suppliers and manufacturers of passive fire safety equipment, subcontractors responsible for the installation of passive fire safety products, laboratories involved in the testing of passive fire safety products, and consultants to the building and fire safety industry. His experience has been gained predominantly in the United Kingdom and New Zealand.

31 Four joint expert reports were provided. These were designated Part A (Mr Harriman, Mr Hunter and Mr Page); Part B (Mr Hunter and Mr Page); Part C (Mr Harriman and Mr Page); and Part D (Mr Harriman, Mr van de Weijgert, and Mr Page).

32 Mr Harriman and Mr Page were separately cross-examined. There were also a number of concurrent evidence sessions over Days 9 and 10 of the hearing: Mr Harriman, Mr Hunter, and Mr Page; Mr Harriman and Mr Page; Mr Hunter and Mr Page; Mr Harriman, Mr van de Weijgert and Mr Page; and a further session involving Mr Hunter and Mr Page.

33 The title of the complete specification of the patent (the specification) is: A Firestopping Device and Associated Method. The application for the patent was filed on 21 December 2017 as a divisional application of Patent Application 2016208262. The priority date of the claims is 12 February 2016 (the date of filing Provisional Application No 2016900475).

34 The specification describes the invention as relating to the field of passive fire protection, with embodiments of the invention finding application in the construction of buildings, such as residential apartment buildings and the like.

35 In essence, the claimed invention is a method of constructing a barrier (typically, a wall) and routing services (electrical cables, water pipes, and the like) through the wall deploying an element referred to in the specification as a “firestopping device”, but commonly referred to as a transit (or fire transit). The firestopping device is fastened to an external object (typically, but not necessarily, a soffit) and the barrier is constructed around the device. It is this feature which is said to distinguish the method of the invention from prior art methods.

36 In describing the prior art methods, the specification states:

In a typical prior art method for constructing a residential apartment building the walls are constructed prior to installation of the services such as electrical cables, water pipes, etc. In this prior art method, a hole is made in the wall for each of the services, which typically must be separated by a standard separation distance, such as 200 mm for example. This separation distance requires significantly larger overall areas for services, which severely limits the design options for construction. Additionally, the typical prior art method often requires ladders and the like to be set up and moved repeatedly. Each of the individual holes through which the services extend must then be separately sealed in a fire rated fashion, which can be time consuming and expensive.

37 The specification explains that an object of the invention is to overcome, or substantially ameliorate, one or more of these disadvantages, or to provide a useful alternative.

38 The specification continues by providing consistory statements for claims 1, 2, and 3 of the patent. It is convenient, at this stage, to quote all the claims, noting that Trafalgar alleges that Boss has infringed claims 1, 2, 3, and 5, and that Boss alleges (as I have noted) that all the claims are invalid:

1. A method of constructing a barrier having at least one service routed there through, the method including the steps of:

providing a firestopping device including: a first portion formed from a metallic material or a thermally insulative material having formations for fastening of the first portion to an external object; and a second portion formed from a metallic material or a thermally insulative material being separable from the first portion and being mateable to the first portion such that the first and second portions, when mated together, define the firestopping device; wherein the firestopping device has a first opening at a first end, a second opening at a second end and an internal volume intermediate the first and second ends, the internal volume and each of the openings being sized such that at least one service may extend through the firestopping device, and wherein an intumescent material is housed within the internal volume, the intumescent material being responsive to heat so as to swell within the internal volume;

fastening the first portion to an external object at a position that straddles the proposed positioning of the barrier;

positioning at least one service such that it is adjacent to, or in alignment with, the first portion;

positioning the second portion around the at least one service;

mating the first and second portions to each other such that the at least one service extends through the firestopping device; and

constructing the barrier around the firestopping device.

2. A method according to claim 1 wherein the first and second portions of the firestopping device are mateable to each other by at least one mechanical fastener without the use of any tools.

3. A method according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the first portion of the firestopping device is a planar panel defining a pair of opposite sides each having a side wall extending therefrom.

4. A method according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the second portion of the firestopping device is U-shaped so as to define a base connected to a pair of opposed side walls.

5. A method according to any one of the preceding claims further including the step of marking a line on the external object so as to depict the proposed centre line of the barrier.

39 As will be clear, all the claims are method claims, and claims 2 to 5 are each dependent, directly or indirectly, on claim 1.

40 The specification describes non-limiting embodiments of the invention. In order to summarise the invention as described, I will focus on the first embodiment, which receives the greatest treatment in the specification.

41 In the first embodiment, the firestopping device is comprised of two separate portions which are mated. Consistently with the claims, these portions are referred to as, simply, the first portion and the second portion. The separability of the two portions allows the firestopping device to be used in the method that is claimed.

42 The first portion is a planar panel with a pair of opposing side walls. The first portion is provided with holes to facilitate the fastening of this portion to an external object. The specification explains:

… In typical implementations the object to which the first portion 2 is likely to be fastened is an overhead concrete slab, although other possibilities include wooden frame structures, walls, floors, service shafts, etc. Fasteners, in the form of bolts, screws, or the like, extend through the holes 3 so as to fasten into the concrete slab, thereby securing the first portion 2 in place.

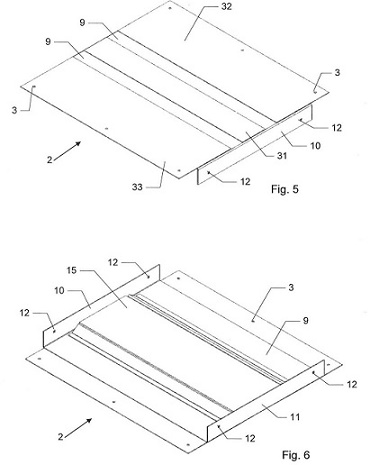

43 The first portion is illustrated in Figures 5 and 6. Figure 5 is an upper perspective view, and Figure 6 is a lower perspective view, of the first portion:

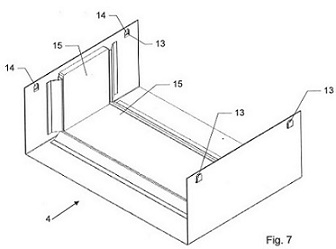

44 The second portion is described as U-shaped, so as to define a base with a pair of opposing side walls. The second portion is illustrated in Figure 7, which is an upper perspective view of that portion:

45 The specification describes features of the first portion and the second portion that provide means by which the two portions can be mated to provide the firestopping device. It is not necessary to dwell on these particular features. They do not feature prominently in the claims. Claim 2, for example, merely requires that the two portions are “mateable” to each other by at least one mechanical fastener, without the use of tools.

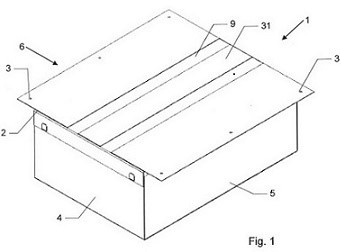

46 The first embodiment of the firestopping device is illustrated by Figure 1, which is an upper perspective view of the device:

47 The specification states that, in this particular embodiment, the second portion forms the base and “the majority” of the side walls of the firestopping device. This statement acknowledges that, in this particular embodiment, the side walls of the first portion also define, in part, the side walls of the device. Indeed, as I have noted, the first portion is described as a planar panel with a pair of opposing side walls. Figure 6 shows the opposing side walls by indices 10 and 11.

48 The specification continues:

... in other embodiments the second portion mates with the first portion so as to form one of the sides and/or the top of the firestopping device.

49 This statement discloses that, in other embodiments, the opposing side walls of the first portion provide the side walls of the firestopping device, with the second portion providing one wall of the device, including by acting as a “top” for the device.

50 The specification continues by explaining that, in the described embodiment, the firestopping device has openings (shown by indices 5 and 6 in Figure 1) and an intermediate, internal volume through which at least one service (not illustrated) extends.

51 The specification describes the placement of intumescent material within and outside the device to resist the passage of fire and smoke.

52 The specification then describes a method of constructing a barrier:

Either of the above-described embodiments of the firestopping device 1 or 19 may be used in a method of construction of a barrier having at least one service routed there through. For the sake of providing an example, we shall assume that the barrier is a wall. The method commences with the marking of a line 27 on the concrete ceiling 28, which depicts the proposed centre line of the wall. The installer then fastens the first portion 2 to the ceiling 28 at a position that straddles the proposed positioning of the wall. More specifically, the first portion 2 is bolted onto the ceiling such that its intumescent material 15 is centred over, and extends parallel to, the centre line of the proposed wall, as shown in figure 13. Hence the positioning of the first portion 2 on the ceiling 28 provides a visual guide as to where the services are to penetrate through the proposed wall.

Next the installer positions the services (not illustrated) such that they are adjacent to, or in alignment with, the first portion 2. More specifically, the services are typically suspended by fastening devices such as clips, clamps, etc., approximately 50 mm below the ceiling so as to extend below the first portion 2 and generally perpendicular to the intumescent material 15 of the first portion 2. Typically, the installer will be supported by a lifting mechanism, such as a scissor lift or the like, whilst running the services. This process doesn't require the threading of the services through a prior art style of firestopping device, which helps ease of running the services and minimises the potential for the services to be damaged by the firestopping device. It is also time efficient and therefore has the potential to yield cost savings for the construction of the building. It also has the potential to assist project managers to coordinate the activities of various tradesmen and sub-contractors.

The reduction in required space for the firestopping of these services allows for significantly more flexibility in design, and the application of a multi-service firestopping device provides an "all-in-one" solution, allowing easier certification and compliance procedures.

Once the services have been run, the second portion 4 is positioned around the services. That is, the side walls 7 and 8 of the second portion 4 are positioned on either side of the services, with the base 17 of the second portion 4 below the services. The second portion 4 is then slid upwards so as to mate the first and second portions 2 and 4 to each other as shown in figure 14. Hence, the services now extend through the firestopping device 1.

It is now possible to construct the wall 30, as illustrated in figure 15, around the firestopping device 1 using standard barrier building techniques. For example, the wall installer may now attach wall engaging formations, in the form of a head track, to the ceiling 28 and to the exterior of the second portion 4, to which a barrier material, such as plaster board for example, may be attached. Additionally, or alternatively, wooden frame work may be constructed, to which a barrier material, such as plaster board for example, may be attached. Alternatively, formwork may be positioned to allow the pouring of a concrete wall. These processes may be assisted with the use of the second embodiment of the firestopping device 19, as illustrated in figures 16 to 19, to which the wall engaging formations in the form of channels 20 are pre-installed.

The resulting wall 30 has the firestopping device 1, and the services (not illustrated), extending there through. A number of services may extend together through the firestopping device without requiring the approx. 200 mm separation between each of them that is applicable to some prior art techniques.

53 The specification describes the application of sealant around the inner perimeters of the first and second openings, and the placement of graphite impregnated foam and, optionally, thermally insulative wrap around the services, externally to the device.

54 There are two questions of construction. The first is the meaning of “around” as used in claim 1 to describe the positioning of the second portion when forming the fire stopping device. The second question is the meaning of “thermally insulative” as used in claim 1 to describe the material from which the first and second portions can be made.

55 Claim 1 defines a method in which, after the first portion of the fire stopping device is fastened to an external object, and after at least one service is positioned adjacent to or in alignment with that portion, the second portion is positioned “around” at least one service. The parties described this as integer 1.11.

56 The question that arises is: what does it mean to say that the second portion is positioned “around” the (at least one) service, bearing in mind that: (a) the specification describes an embodiment in which the second portion is U-shaped, but also refers to other embodiments in which the second portion forms one wall and/or the “top” of the device; and (b) in claim 1, the second portion is not expressly defined as having any particular shape or configuration.

57 The issue that divides the parties is this:

(a) Boss submitted that where, for example, the second portion is a planar portion and/or is the “top” of the fire stopping device (in other words, it has no side walls), positioning this portion, in the sequence described, cannot be positioning it “around” the (at least one) service because this portion can only form one side of the device.

(b) Trafalgar submitted that positioning this portion in the sequence described is positioning it “around” the (at least one) service because it would partially surround the service(s).

58 The parties advanced their competing constructions through the expert evidence of Mr Hunter (for Trafalgar) and Mr Page (for Boss). Both witnesses used as their starting point a dictionary meaning of “around”—namely, to “surround”. They reasoned that, as used in integer 1.11, “around” could not have this meaning. It must mean something less than surround. They agreed that if the second portion had the U-shaped configuration of the first embodiment, then it would be appropriate to speak of this portion being positioned “around” the (at least one) service in the step preceding the mating of the two portions to form the firestopping device. However, Mr Hunter went further. He contended that if the second portion was planar, and could thus only provide one side of the device, it would still be appropriate to speak of it being positioned “around” the (at least one) service.

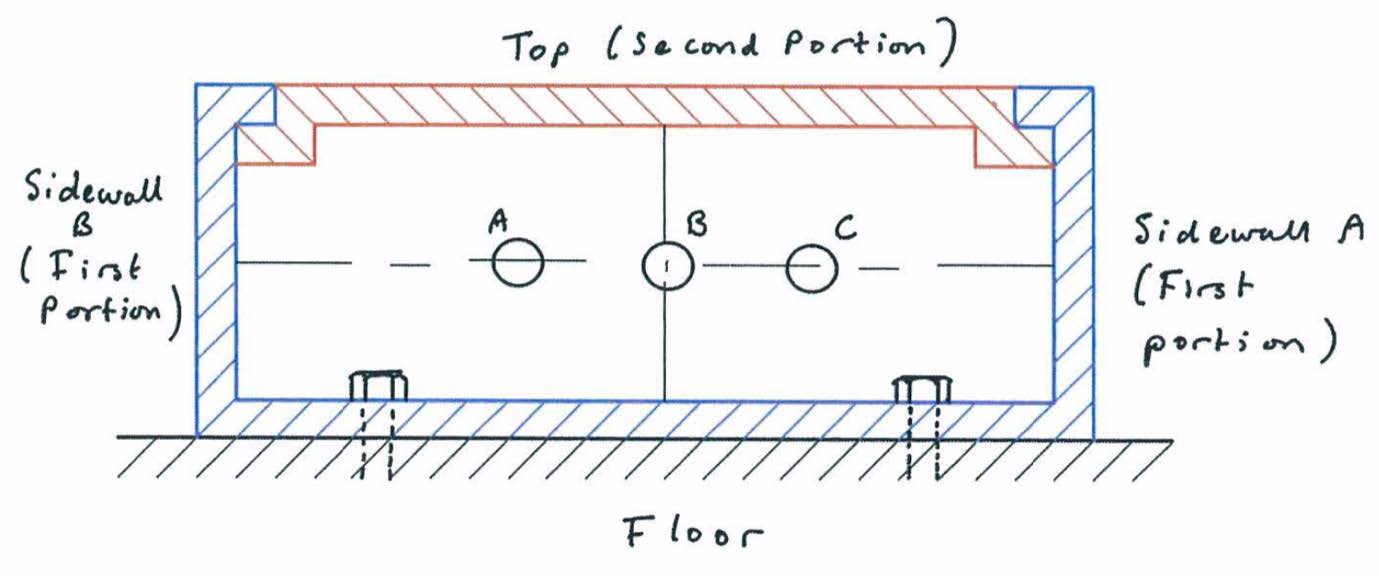

59 Mr Hunter illustrated his view by the following diagram:

60 The effect of Boss’s submission is that by using the word “around” in integer 1.11, claim 1 confines the shape and configuration of the second portion to exclude a one-sided or substantially planar element, even though earlier integers in the claim do not do so. In developing its submissions on this question, Boss submitted that, even though the specification refers to other embodiments of the invention, in which the second portion forms but one side and/or the top of the device, these embodiments are disclaimed in claim 1 by the presence of integer 1.11. On occasion, Boss’s submissions went so far as to suggest that integer 1.11 effectively required the second portion to be a three-sided element.

61 The parties agreed that “around” is not used in claim 1 as a technical term or a term of art. They accepted that, as the question of construction is one for the Court to decide, the evidence given by Mr Hunter and Mr Page on this score is of limited assistance.

62 I think it is perfectly clear what claim 1 means when it uses the word “around” in integer 1.11, as I will now explain.

63 Claim 1 defines the firestopping device by reference to two “mateable” portions which, when mated, have an opening at one end, an opening at the other end, and an internal volume that is intermediate the two ends. The internal volume and the two ends are of a size that permits at least one service to extend through the device. The internal volume also houses the intumescent material.

64 Other than providing for these features, the method claimed in claim 1 is agnostic as to the shape or configuration of the firestopping device. The claimed method is also agnostic as to the shape or configuration of each, separate portion making up the device.

65 According to claim 1, the firestopping device is provided by: fastening the first portion to an external object in a particular position (straddling the position of the proposed barrier); positioning the (at least one) service adjacent to or in alignment with the first portion; positioning the second portion “around” the (at least one) service; and then mating the two portions so that the (at least one) service extends through the device.

66 When these sequential steps of claim 1 are recognised—appreciating that neither the firestopping device nor its two separate and “mateable” portions are required to be of any particular shape or configuration—the step of positioning the second portion “around” the (at least one) service means no more than positioning the second portion in relation to the (at least one) service (which is already adjacent to or in alignment with the first portion) so that, when the second portion is mated with the first portion to create the first and second openings at respective ends of the device and the intermediate internal volume, the (at least one) service is accommodated within the device.

67 In short, the word “around” does not function as a limitation on the shape or configuration of the second portion, so as to require the second portion to be something other than a one-sided or substantially planar element. It is simply referring to the positioning of the second portion so that the (at least one) service is accommodated within the device.

68 Boss submitted that its construction is supported by the further integer of claim 1—referred to by the parties as integer 1.13—“constructing the barrier around the firestopping device”. The gist of this argument is that integer 1.13 cannot mean constructing the barrier on one side of the firestopping device; it must mean constructing the barrier so as to surround the device on three sides. Therefore, the word “around” in integer 1.11 should be construed conformably with the word “around” in integer 1.13.

69 I am not persuaded that the use of “around” in integer 1.13 dictates the meaning of “around” in integer 1.11. “Around” in integer 1.13 is used in a different context to “around” in integer 1.11. The two integers speak to different relationships.

70 The contest about the meaning of “thermally insulative” arises from a subsidiary argument concerning integer 1.11 that was advanced through Mr Hunter with reference to Boss’s FyreBox device. Trafalgar contends that the supply of this device is an infringement of the patent because its use in accordance with Boss’s installation instructions would infringe claims 1, 2, 3, and 5 of the patent: s 117(1) of the Patents Act, read with s 117(2)(c). Alternatively, Trafalgar contends that the supply of this device is an infringement of the patent because Boss has reason to believe that it would be put to use in a way that would infringe claims 1, 2, 3, and 5 of the patent: s 117(1) of the Patents Act, read with s 117(2)(b).

71 The meaning of “thermally insulative” is also relevant to Boss’s challenge to the validity of the patent based on the ground of lack of utility.

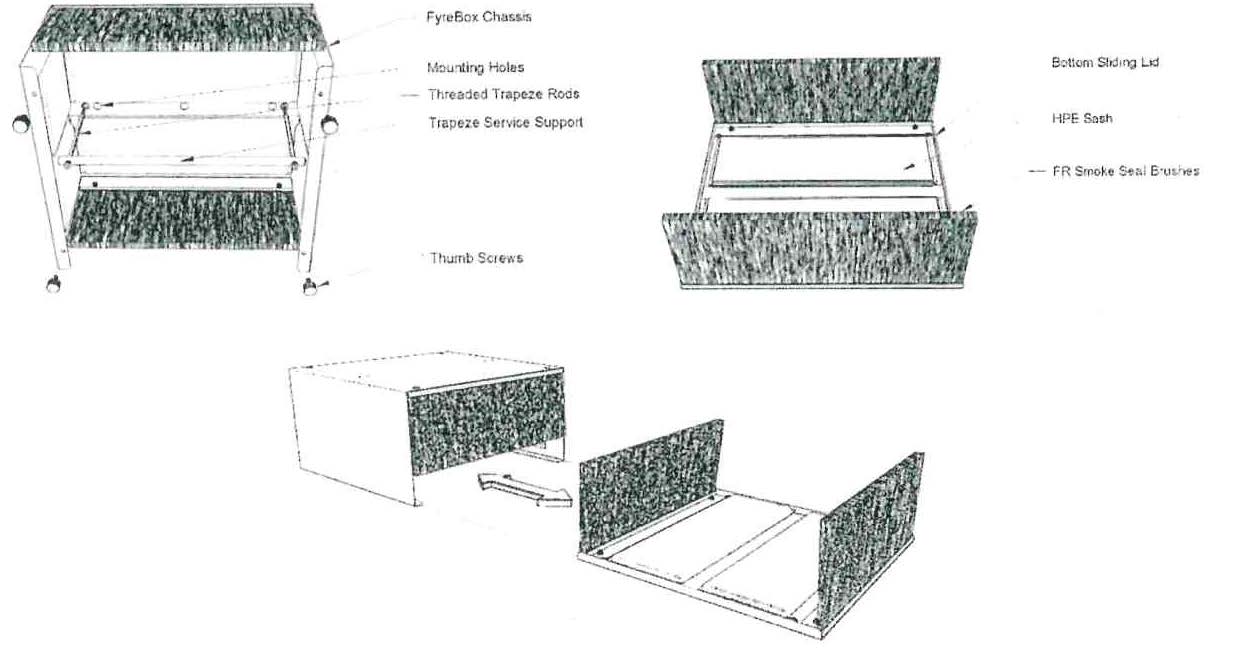

72 The FyreBox device has two, separable portions which can be mated. One portion is a three-sided chassis. The second portion is described as a “bottom sliding lid”. The bottom sliding lid engages with the chassis. The two portions are held in place by four thumbscrews. The instructions direct that the bottom sliding lid be removed from the chassis by removing the four thumbscrews, and that the chassis then be mounted on the underside of a soffit or slab using mounting holes provided in the chassis.

73 It will be necessary to return to these instructions when considering the question of infringement. Of present importance is the fact that the bottom sliding lid is a substantially planar metal element that is fitted with smoke brushes at each of two opposing ends of the lid. The brushes are disposed perpendicularly. They are referred to in the instructions as “FR Smoke Seal Brushes”. Mr Hunter and Mr Page understood the letters “FR” to mean “Fire Resistant”.

74 The instructions direct that, after the services are installed, the lid be installed by resting it on flanges provided in the chassis, and sliding it into place. The instructions continue:

The Smoke Brushes will shape themselves around the penetrating services and when closed, the Smoke Brushes can easily be tucked into place by hand. Secure the lid using the four thumb screws provided ...

75 The subsidiary argument advanced through Mr Hunter is that the lid is one component comprising the substantially planar metal element and the smoke brushes attached to it, and that the step of sliding the lid into engagement with the chassis constitutes the step of “positioning the second portion around the at least one service”, within the meaning of integer 1.11.

76 This argument seeks to accommodate integer 1.11 in two ways. First, if the word “around”, as used in integer 1.11, has the literal meaning of “surround”—an argument which both expert witnesses rejected—then the smoke brushes “surround” the (at least one) service. Secondly, if only a second portion configured with at least three sides can be positioned “around” the (at least one) service, then that feature of claim 1 is satisfied by the lid of the FyreBox device because the planar metal element and the smoke brushes form a three-sided second portion.

77 This last-mentioned argument provoked more arguments—namely, (a) whether the lid (the planar element and smoke brushes) is formed from a metallic material or a thermally insulative material, as required for the second portion referred to in clam 1, and (b) whether the smoke brushes are, truly, “around” the (at least one) service if they are not “around” the (at least one service) for the entire length of the service as it extends through the device.

78 In light of my finding about the meaning of “around” in integer 1.11, it is not necessary for me reach a view on these arguments for that purpose. As a matter of substance, they add nothing to the construction I have found. Nevertheless, the first argument has a continuing relevance to Boss’s challenge to validity based on lack of utility. I will state my conclusions on both arguments as briefly as I can.

79 First, I do not accept that the smoke brushes are positioned “around” the (at least one) service for the purposes of integer 1.11. As I have explained, the word “around” in integer 1.11 means positioning the second portion of the firestopping device in relation to the (at least one) service so that, when the second portion is mated with the first portion of the device, the mated portions create the first and second openings at respective ends of the device, and the intermediate internal volume through which the (at least one) service is accommodated. The smoke brushes might, literally, “surround” the (at least one) service at each end of the completed Fyrebox, but it is the planar element of the FyreBox lid that is positioned “around” the (at least one service) so that, in combination with the chassis, it creates the openings for the device and the internal, intermediate volume through which the services extend and are accommodated.

80 Secondly, the fact that the smoke brushes happen to be attached to the “bottom sliding lid” of the FyreBox device is neither here nor there. I do not regard them as comprising part of the first portion or the second portion of the firestopping device that is described in the specification and defined in the claims.

81 Thirdly, claim 1 requires the first and second portions of the firestopping device to be formed from a metallic material or a thermally insulative material. It is silent on the composition of other elements that, in practice, might happen to be part of the firestopping device, but which are extraneous to the definition of the firestopping device in the claims. Whether the “fire resistance” of the brushes, which are extraneous to the claims, equates with them being formed from “thermally insulative” material is not a question that need be pursued.

82 Fourthly, Boss’s case on the meaning of this integer was advanced through Mr Page’s evidence. In a Joint Report prepared by Mr Page, Mr Harriman, and Mr Hunter, which was signed by them on 16 April 2020 (Joint Report Part A), Mr Harriman said that “thermally insulative” means “to restrict the passage of heat in a fire”. Mr Hunter agreed.

83 Mr Page said that his understanding of “thermally insulative” was similar to Mr Harriman’s view, but added that:

… the term referred to the ability of the device to restrict the passage of heat across it, including in fire situations where there could be 1200°C on one side of a barrier for an extended period (rerf 30 minutes), and there was requirement for the temperature to be kept to less than 180°C on the other side of the barrier.

84 Mr Harriman disagreed. He included the following section in Joint Report Part A:

Mr Harriman made the point that in his view the Patent did not specify that the invention needed to work solely in the case of a 1200°C fire. He added that another exemplary fire could be a smouldering fire of less than 200°C, or a sprinkler-protected fire of ~ 200°C. Mr Harriman noted that for such lower temperature fires, the foam would be important as it is the initial barrier which restricts the passage of heat and hot smoke across the device before the intumescent material is triggered (which occurs in the range 200-300°C). Mr Harriman added that in some of these lower temperature fires, the intumescent material may not be triggered at all. Mr Harriman stated that the example of the foam pads shows that ‘thermally insulative’ is therefore not limited solely to materials which can retain their integrity up to 1200°C (which he considers to be a ‘worst case’ fire). Mr Harriman stated that some materials used in firestopping devices (for example powder coat paints) are thermally insulative, but burn off well below 1200°C.

85 In Joint Report Part A, Mr Page agreed that the “invention” can be exposed to lower temperature fires. He said, however, that:

… the primary intent of the patent was to solve the problem of multiple services with a fire stopping device this term [sic] in itself suggests that the device must work at least equal to the external object which is being fitted around it.

86 I do not accept that the expression “thermally insulative” as used in the specification and claims has the qualified meaning given by Mr Page. The firestopping device defined in the claimed method is not one limited to use in fires of any particular temperature. I accept Mr Harriman’s evidence in that regard.

87 It is also to be understood that it is the intumescent material within the firestopping device that operates to “stop” the fire, not the first and second portions formed from a metallic material or thermally insulative material. The first and second portions are made from this material to retard the transmission of heat to enable the intumescent material to respond to the heat by swelling within the internal volume of the firestopping device to resist the passage of fire and smoke through the device. The evidence before me is that, in practice, the intumescent material, inside the device, will swell when the ambient temperature reaches 230°C.

88 I accept that, as used in the specification and claims, the expression “thermally insulative” has the meaning of “to restrict the passage of heat in a fire”.

Patent Validity: Legal principles

89 Boss challenges the validity of the claims of the patent on a number of discrete grounds.

90 First, Boss alleges that the invention, as claimed in each claim of the patent, is not novel in light of the public disclosure of certain documents, and in light of the public disclosure of certain firestopping devices in circumstances where, according to Boss, the manner of their installation was explained in terms which disclosed each and every step of the method claimed in claims 1 to 5 of the patent. All the disclosures involve fire transits manufactured by FSi Limited (formerly called Firestopit Limited), a United Kingdom company.

91 For the purposes of the Patents Act, an invention is to be taken to be novel, when compared with the prior art base, unless it is not novel in light of certain kinds of information, including (a) prior art information made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act; and (b) prior art information made publicly available in two or more related documents or through doing two or more related acts, if the relationship between the two or more documents or two or more acts is such that a person skilled in the art would treat them as a single source of information: ss 7(1)(a) and (b).

92 When dealing with prior publication in a document or documents, the plurality in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99; 226 FCR 324 (AstraZeneca v Apotex) at 293, said that the touchstone for determining whether the prior publication discloses (anticipates) a claimed invention is stated in General Tire & Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Company Ltd (1971) 1A IPR 121 (General Tire) at 138:

When the prior inventor's publication and the patentee's claim have respectively been construed by the court in the light of all properly admissible evidence to technical matters, the meaning of words and expressions used in the art and so forth, the question whether the patentee's claim is new for the purposes of s 32(1)(e) falls to be decided as a question of fact. If the prior inventor's publication contains a clear description of, or clear instructions to do or make, something that would infringe the patentee's claim if carried out after the grant of the patentee's patent, the patentee's claim will have been shown to lack the necessary novelty, that is to say, it will have been anticipated. The prior inventor, however, and the patentee may have approached the same device from different starting points and may for this reason, or it may be for other reasons, have so described their devices that it cannot be immediately discerned from a reading of the language which they have respectively used that they have discovered in truth the same device; but if carrying out the directions contained in the prior inventor's publication will inevitably result in something being made or done which, if the patentee's patent were valid, would constitute an infringement of the patentee's claim, this circumstance demonstrates that the patentee's claim has in fact been anticipated.

If, on the other hand, the prior publication contains a direction which is capable of being carried out in a manner which would infringe the patentee's claim, but would be at least as likely to be carried out in a way which would not do so, the patentee's claim will not have been anticipated, although it may fail on the ground of obviousness. To anticipate the patentee's claim the prior publication must contain clear and unmistakable directions to do what the patentee claims to have invented: Flour Oxidising Co Ltd v Carr & Co Ltd (1908) 25 RPC 428 at 457, line 34, approved in BTH Co Ltd v Metropolitan Vickers Electrical Co Ltd (1928) 45 RPC 1 at 24, line 1. A signpost, however clear, upon the road to the patentee's invention will not suffice. The prior inventor must be clearly shown to have planted his flag at the precise destination before the patentee.

93 After referring to that passage, the plurality in AstraZeneca v Apotex said (at [294]):

294 The metaphor of planting the flag has been taken up in this Court. For example, in ICI Chemicals, the Full Court at [51], after noting the metaphor, remarked that, in that case, the appellant’s argument involved the skilled addressee rummaging through a “flag locker“ to find a flag which the prior art document possessed and could have planted. In Apotex Pty Ltd and Another v Sanofi-Aventis and Another (2008) 78 IPR 485 …, Gyles J at [91] adopted a different metaphor, remarking that “anticipation is deadly but requires the accuracy of a sniper, not the firing of a 12 gauge shotgun“. Each metaphor underlines the importance of the specificity required in order for a prior art document to anticipate an invention as claimed.

94 In order to be novelty-destroying, a prior documentary disclosure must provide information that is equal to the invention that is claimed: Hill v Evans (1862) 1A IPR 1 at 7; Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc [2011] FCAFC 156; 217 FCR 238 at [127]. In Mylan Health Pty Ltd v Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 116; 279 FCR 354, the Full Court noted (at [82]) that:

82 … equality in this context refers to both the specificity of the information and its completeness. Unless these twin qualities are present, the prior disclosure will not be sufficient to deprive the invention of novelty.

(Emphasis in original.)

95 The same approach applies to public disclosure by an act or acts. Where, however, the prior art information is said to have been made publicly available by an act or acts, caution must be exercised in relying on the memory of witnesses in recounting the act or acts that are said to be anticipatory, given the fallibility of memory and the risk of reconstruction: Commonwealth Industrial Gases Ltd v MWA Holdings Pty Ltd (1970) 180 CLR 160 (CIG) at 165 – 166. As Besanko J observed in Aspirating IP Ltd v Vision Systems Ltd [2010] FCA 1061; 88 IPR 52 at [200], the correct principle is that a prior public use must be strictly proved, and evidence which is not corroborated must be scrutinised with care, particularly where it is evidence of events which occurred many years ago.

96 This is even more so where the evidence of the prior acts is constituted by recollections of the features of, and/or the manner of use of, equipment that is not in evidence before the Court. For example, in Old Digger Pty Ltd v Azuko Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 676; 51 IPR 43 (Old Digger) Von Doussa J said (at [156]):

156 The onus of proof is on the respondents to establish a clear case of invalidity: see Montecatini Edison SpA v Eastman Kodak Co (1971) 45 ALJR 593 at 595-596 per Gibbs J. The evidence adduced by the respondents as to the prior use of the invention is the oral evidence of witnesses to the alleged use based on their recollections of events years beforehand. The alleged use is said to have taken place in the course of trialling reverse circulation percussive hammers incorporating prototype face sampling drill bit assemblies. The particular assemblies have not been produced in evidence. Oral evidence led in these circumstances must be viewed with particular caution, partly for the reason that the memory of the witnesses is likely to have been influenced by other products seen in the meantime, and to reflect reconstruction on the basis of these later observations: see Commonwealth Industrial Gases Ltd v MWA Holdings Pty Ltd (1970) 180 CLR 160 at 165-166, and Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd & Others v Martin Engineering Co & Another (1990) 91 ALR 513 at 525 per Gummow J.

97 A further example is provided by Fieldturf Tarkett Inc v Tigerturf International Ltd [2014] FCA 647; 317 ALR 153 (Fieldturf). There, the case on lack of novelty was based on prior art information comprising both acts and documents. The acts concerned four installations of synthetic turf. The primary evidence was the recollections of a witness who was involved, one way or another, in each installation. The installation was carried out 25 or more years before the evidence was given. The claims were directed to a synthetic surface. A large number of claims were in issue. The claims specified features of the alleged invention in some detail. The claims in issue are quoted at [12] of the reasons for judgment. To illustrate the particular evidential difficulties in Fieldturf, it will suffice to quote claims 1 to 4:

1. A synthetic surface comprising a flexible backing member, parallel rows of synthetic ribbons, representing blades of grass, projecting upwardly from the backing member, the rows of ribbons spaced apart from each other from between 5/8 inch (1.588 cm) and 2 ¼ inches (5.715 cm), and the length of the ribbons, extending upwardly from the backing member, is at least twice the dimension of the spacing between the rows of ribbons, whereby the synthetic surface can receive an infill of particular [sic] material to approximately 2/3 the height of the ribbons such that a free length of ribbon extending above such infill can overlap with a corresponding free length of ribbon from adjacent rows to encapsulate such infill.

2. A synthetic surface for a sports playing field comprising a flexible backing member, parallel rows of synthetic ribbons, representing blades of grass, projecting upwardly from the backing member, the rows of ribbons spaced apart from each other, whereby the relationship of the length of the ribbons and the spacing between the rows is 2A ≤ L such that the length of the ribbons is at least twice the spacing; where A is the spacing between the rows, and L is the length of the ribbon measured from the flexible backing, whereby the synthetic surface can receive an infill of particulate material to approximately 2/3 the height of the ribbons such that a free length of ribbon extending above such infill can overlap with a corresponding free length of ribbon from adjacent rows to encapsulate such infill.

3. A synthetic surface having a flexible backing member, parallel rows of synthetic ribbons, representing blades of grass, projecting upwardly from the backing member, the rows of ribbons spaced apart from each other from between 5/8 inch (1.588 cm) and 2 ¼ inches (5.715 cm), and the length of the ribbons, extending upwardly from the backing member, is at least twice the dimension of the spacing between the rows of ribbons, the surface including a layer of particulate material on the backing member supporting the ribbons in a relatively upright position relative to the backing member 2A ≤ L such that the length of the ribbons is at least twice the spacing; and the particulate material having a thickness, T, which is substantially equal to 2/3 the length, L, of the ribbons, where A is the spacing between the rows, L is the length of the ribbon measured from the flexible backing and T is the thickness of the layer of particulate material.

4. A synthetic surface for a sports playing field wherein the synthetic surface comprises a flexible backing member, parallel rows of synthetic ribbons, representing blades of grass, projecting upwardly from the backing member, the rows of ribbons spaced apart from each other, the surface including a relatively thick layer of particulate material on the backing member supporting the ribbons in a relatively upright position relative to the backing member, whereby the relationship of the length of the ribbons and the spacing between the rows is 2A ≤ L such that the length of the ribbons is at least twice the spacing; and the particulate material having a thickness, T, which is substantially equal to 2/3 the length, L, of the ribbons, where A is the spacing between the rows, L is the length of the ribbon measured from the flexible backing and T is the thickness of the layer of particulate material.

98 The evidence of prior use, given by this witness, was described by Jagot J (at [95]) as a form of “self-reinforcing tapestry”. Her Honour noted (at [96]) the significant length of time that had elapsed since the installations were undertaken. She said (at [95]) that it was apparent that the witness had added, to his recollection, information which had been made available to him “over the past ten years”. She noted, further (at [97]), that the witness’s evidence was given with full knowledge of the claimed invention. At [98], she also remarked on the fact that the witness’s evidence changed over time, saying:

98 … It tends to reinforce the overall impression of reconstruction and forcing new information to fit within a framework first identified in 2004.

99 As I will later explain, I do not think that the particular difficulties illustrated in Old Digger and Fieldturf are present in the instant case, or at least present to the same extent.

100 It is convenient at this point to turn to the notions of inevitable result and implicit disclosure, and their role in determining whether an invention, as claimed, is not novel. These are aspects of the specificity and completeness which a prior documentary publication must have before it will be novelty-destroying.

101 As is made clear in General Tire, if a prior documentary publication contains clear instructions which, if followed, will inevitably constitute an infringement of the invention as claimed (assuming the claim to be valid), then the prior publication will be novelty-destroying. However, if the prior publication gives a direction which could be carried out in a way that would infringe the claim, but could also be carried out in a way that would not infringe the claim, the prior publication will not be novelty-destroying. In short, the “flag” will not have been “planted”.

102 Turning to implicit disclosure, it is trite that a prior documentary publication, which is alleged to be novelty-destroying, must be read through the eyes of the person skilled in the art. If an essential feature of the invention, as claimed, is not explicitly disclosed, the publication may still be novelty-destroying if the person skilled in the art would infer the presence of the feature from the document itself.

103 The decision in C Van der Lely N.V. v Bamfords Limited [1963] RPC 61 provides an example. In that case, the claimed invention was a hay rake having a combination of features, including a number of rake wheels arranged to be rotated by contact between the ground and consecutive teeth disposed on the circumference of the wheels. The question was whether the invention was anticipated by certain photographs of a prior art hay rake, even though the ground contact feature was not visible in the photographs. It was held that the invention was anticipated because the person skilled in the art would infer the presence of the ground contact feature from the photographs themselves.

104 There are limits to which this notion can be applied. As Jacob J cautioned in Hoechst Celanese Corp v BP Chemicals Ltd [1998] FSR 586 at 600 – 601:

… if what is said to be implicit in a document is given too much scope you will be blurring the distinction between lack of novelty and obviousness. On the other hand it must be right to read the prior document with the eyes of the skilled man. So if he would find a teaching implicit, it is indeed taught. The prior document is novelty-destroying if it explicitly teaches something within the claim or, as a practical matter, that is what the skilled man would see it is teaching him.

105 This caution was also emphasised by the Full Court in Ramset Fasteners (Aust) Pty Ltd v Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 898; 164 ALR 239 (Ramset). In that case, the invention was a method of using a quick release hoisting attachment (a ring clutch) for tilt-up walls. The method included remotely operating the lever arm of the ring clutch by means of a release cable (rope) attached to the distal end of that arm. The invention was alleged to have been anticipated by three advertisements. One advertisement depicted the hoisting attachment with a lever arm which had a hole at one end to which something could be attached. However, no release cable or release rope was illustrated. The appellant argued that the rope release method would be inferred by the person skilled in the art on reading the advertisements. The Full Court disagreed and held that the advertisements were not novelty-destroying.

106 At [25], the Full Court said:

25 In the present case, it is clear that the “pull rope” is an essential integer of the combination described in the patent. It is claimed as such in the claims by the words “a release cable attached to the distal end of the lever arm to remotely operate the lever arm by rotating it outwardly and downwardly to a predetermined degree relative to the wall section to rotate the bolt to the released condition and disconnect the ring clutch from the anchor”. This aspect of the combination is fundamental to the invention claimed, which aims at speedy and safe release of the clutch. Whether or not a skilled worker might deduce the desirability of adding such a feature, it cannot be said that any of the pictures in the advertisements, or anything said in them, infers that the device to which they relate involved the presence of this feature. The appellant argued that the alleged invention makes no “difference in substance from that which was known”, presumably by virtue of these advertisements. But this way of putting the matter, which departs from an investigation as to whether the essential integers of the combination were revealed, risks a coalescence between considerations of novelty and obviousness so as to create an amorphous test on which the modern law of patents has turned its back. In a case in which any allegation of obviousness has been deliberately abandoned, both fairness and clarity of thought require the Court to concentrate on the doctrine of novelty as posing a distinct test. The appellant's argument would reintroduce the confusion of the issues of novelty and obviousness which, earlier in this litigation, was introduced by the attack on the patent as not involving a new manner of manufacture. The sole question raised by the issue of novelty is whether the device to be seen by the skilled viewer as being depicted and in part described in the advertisements anticipated the Burke patent. That depends on whether all the essential integers were revealed in any one of those publications. It is not to be disposed of by a kind of confession and avoidance that acknowledges an integer is missing, but treats it as unimportant because, as the appellant asserts, it could easily have been worked out by a very small application of thought and experimentation. Any argument along those lines is inadmissible in principle, and betrays what seems to be the lingering influence of the approach the High Court has rejected. Considerations of the value, that is, of the magnitude or paucity, of the insight inherent in the advance made by the invention are considerations belonging to obviousness and not to novelty. So far as novelty is concerned, the attack on the patent must be rejected; whether or not the idea was brilliantly inventive, the respondents’ system did involve a new feature, claimed as such, which was essential to its safe and effective operation.

107 Thus, in a challenge to validity based on lack of novelty, it is not sufficient to say that, on reading the prior documentary publication, the person skilled in the art would see that the need for a claimed feature, which is not explicitly referred to or illustrated, is obvious. The question is whether the claimed feature would be (is) revealed to the person skilled in the art, implicitly, by the disclosure itself, based on that person’s understanding of the disclosure. This is a nuanced, but important, distinction. The plurality in AstraZeneca v Apotex said (at [311]):

311 Section 7(1) of the Act sets the precise boundaries of the information that is to be taken into account when assessing novelty. Common general knowledge, as a notionally organised body of information possessed by the person skilled in the art, does not fall within these boundaries.

108 Secondly, Boss alleges that the invention, as claimed in each claim of the patent, does not involve an innovative step.

109 For the purposes of the Patents Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an innovative step, when compared with the prior art base, unless the invention would, to a person skilled in the relevant art, in light of the common general knowledge before the priority date, only vary from certain kinds of information, in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention: s 7(4).

110 The kinds of information are (a) prior art information made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act; and (b) prior art information made publicly available in two or more related documents or through doing two or more related acts, if the relationship between the two or more documents or two or more acts is such that a person skilled in the art would treat them as a single source of information: ss 7(5)(a) and (b). Each kind of information must be considered separately.

111 The approach to determining whether an innovative step is present was discussed by Gyles J in Delnorth Pty Ltd v Dura-Post (Aust) Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1225; 78 IPR 463. At [52] – [53], his Honour said:

52 There is no need to search for some particular advance in the art to be described as an innovative step which governs the consideration of each claim. The first step is to compare the invention as claimed in each claim with the prior art base and determine the difference or differences. The next step is to look at those differences through the eyes of a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of common general knowledge as it existed in Australia before the priority date of the relevant claim and ask whether the invention as claimed only varies from the kinds of information set out in s 7(5) in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention. It may be that there is a feature of each claim which differs from the prior art base and that could be described as the main difference in each case but that need not be so. Section 7(4), in effect, deems a difference between the invention as claimed and the prior art base as an innovative step unless the conclusion which is set out can be reached. If there is no difference between the claimed invention and the prior art base then, of course, the claimed invention is not novel.

53 The phrase “no substantial contribution to the working of the invention” involves quite a different kind of judgment from that involved in determining whether there is an inventive step. Obviousness does not come into the issue. The idea behind it seems to be that a claim which avoids a finding of no novelty because of an integer which makes no substantial contribution to the working of the claimed invention should not receive protection but that, where the point of differentiation does contribute to the working of the invention, then it is entitled to protection, whether or not (even if), it is obvious. Indeed, the proper consideration of s 7(4) is liable to be impeded by traditional thinking about obviousness.

112 At [54], his Honour turned to consider the proper meaning of “substantial” as used in s 7(4): did it mean “great” or “weighty”, or did it mean “more than insubstantial” or “of substance”? After considering certain secondary materials, and earlier case law dealing with the expanded view of novelty expressed in Griffin v Isaacs (1938) 1B IPR 619—which is the provenance of the expression “make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention” as used in s 7(4)—Gyles J held (at [61]):

61 In my view the provenance of the phrase “make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention” indicates that “substantial” in this context means “real” or “of substance” as contrasted with distinctions without a real difference. That confirms my impression from construction of the words of the section itself.

113 Gyles J’s construction of s 7(4) was not disturbed on appeal: Dura-Post (Aust) Pty Ltd v Delnorth Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 81; 177 FCR 239 at [73] – [79] and [91]. As the plurality in the Full Court pointed out (at [73]):

73 Section 7(4) requires a comparison to be made between the invention as claimed in each claim with the information s 7(5) describes. That is, s 7(5) identifies the kinds of information to which the invention as claimed in each claim is to be compared. This information is particular kinds of prior disclosures. Section 7(6) requires that each such prior disclosure be considered separately. That is, the invention as claimed in each claim must be compared separately with each relevant prior disclosure.

114 In undertaking a claim by claim comparison with the prior art information, it should not be forgotten that a dependent claim includes the features that define the invention in the claim from which the dependency derives: Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Consulting Group Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 395; 101 IPR 496 at [222] – [223]. It is not the case that, in assessing the validity of a dependent claim, the innovative step must be found in the features added to the definition of the invention by that claim.

115 Thirdly, Boss alleges that the complete specification does not comply with the requirements of s 40(3) of the Patents Act in that the claims are not “supported by matter disclosed in the specification”.

116 This requirement of s 40(3) cannot be considered in isolation from s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act, having regard to the explanation given by Burley J in Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation v Wyeth LLC (No 3) [2020] FCA 1477; 155 IPR 1 (Merck v Wyeth) at [502] – [547] as to the operation of these provisions following the amendments to the Patents Act introduced by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (the RTB Act). The parties were at one that this aspect of Boss’s challenge to validity should be considered in light of that explanation.

117 Section 40(2)(a) provides that a complete specification must disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art. This requirement is directed to the sufficiency of the description of the invention given in the specification. In Merck v Wyeth, Burley J surveyed the United Kingdom law in relation to the concepts termed “classical insufficiency” and “Biogen insufficiency”. It is not necessary for me to repeat his Honour’s careful analysis. It is sufficient for me to note that “classical insufficiency” concerns the disclosure obligation of a patent specification under s 14(3) of the Patents Act 1977 (UK) (the UK Act) (the language of which is substantially reflected in s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act) and “Biogen insufficiency” concerns the claim support obligation of a patent specification under s 14(5)(c) of the UK Act (the language of which is substantially reflected in s 40(3) of the Patents Act).

118 The disclosure obligation under s 14(3) of the UK Act has been interpreted to require the teaching of the specification to enable the skilled addressee to perform the invention to the full extent of the claims—conveniently referred to as an “enabling disclosure”. The requirement for claim support in s 14(5)(c) of the UK Act is directed to claim breadth, but it interacts with the s 14(3) requirement that the claims should, essentially, correspond to the scope of the invention, in the sense of not exceeding the scope of the invention, disclosed in the description given by the specification. In other words, the breadth of a claim must be supported (or justified) by the “technical contribution to the art” (meaning, the enabling disclosure of the specification).

119 In Merck v Wyeth, Burley J explained (at [527] – [529]):

527 “Classical insufficiency” is to be distinguished from “Biogen insufficiency” which is also considered under United Kingdom law to form part of the disclosure obligation. That overlap may be considered to be confusing at first, because Biogen insufficiency draws on the law of support, identified in s 14(5)(c) of the UK Act. However, as the cases in that jurisdiction explain, the reason for this is because the UK Act contains a “logical gap” arising from its drafting, in that whilst s 14(5)(c) imposes the claim support obligation as a statutory requirement for the grant of a patent, there is no concomitant provision whereby a granted patent that fails to satisfy the claim support obligation may be revoked. That gap was plugged when the House of Lords resolved that the claim support obligation fell under the umbrella of the requirement that the patent specification contain an enabling disclosure: Biogen Inc v Medeva Plc [1996] 10 WLUK 486; [1997] RPC 1 at 47 (Lord Hoffman, with whose reasons the other members of the House of Lords agreed). Accordingly, in the context of revocation actions, the UK courts sometimes (but not always) refer to a distinction between classical insufficiency and Biogen insufficiency, the former arising from s 14(3) and the latter arising from s 14(5)(c), but both falling within the unifying requirement that there be an enabling disclosure, and both being available as a ground of invalidity within s 14(3).

528 The main difference between the two is that the disclosure obligation under s 14(3) relates to the specification as a whole whereas the claim support obligation under s 14(5)(c) relates to the claims which define the invention: Generics UK (HL)at [19]. As Walker LJ said in Generics (UK) at [20]:

Ss 14(3) and (5)(c) operate together, as EPC Arts 83 and 84 operate together, to spell out the need for an “enabling disclosure”, which is central to the law of patents …The disclosure must be such as to enable the invention to be performed (that is, to be carried out if it is a process, or to be made if it is a product) to the full extent of the claims. The question whether there is sufficient enabling disclosure often interacts with a question of construction as to the extent of the claims …

529 In Terrell the learned editors summarised the distinction between classical sufficiency and Biogen sufficiency in the following terms at page 403:

The self-standing objection that a claim is broader than the technical contribution of the patent, even when it can be performed, is sometimes referred to as “Biogen insufficiency”. It is to be contrasted with “classical insufficiency” which is concerned with whether or not embodiments within the claim can be performed. Thus peculiarly under English law it is said that at patent can be insufficient even if it is possible to make everything within the scope of the claim, if the scope of the claims exceed the technical contribution.

120 Later, his Honour said with respect to the Patents Act (at [544] – [545]):

544 It is apparent from the language adopted in the sections and also from the Second Reading Speech and the Explanatory Memorandum that the intention of parliament in amending s 40(2)(a) and s 40(3) of the Patents Act was to align the law in relation to these requirements with that of the United Kingdom and Europe. That is not to say that all aspects of the approach adopted in the United Kingdom are to be adopted here. In particular, there is no warrant provided in the language of s 40(2)(a) to incorporate within the disclosure obligation a separate claim support obligation, in addition to the one within s 40(3). Nor is there any need to do so: failure to comply with either ss 40(2)(a) or 40(3) provides a basis upon which a granted patent may be revoked: s 138(3)(f). There is no gap in the Patents Act akin to the one in the UK Act referred above, and each ground is to be considered separately. Nevertheless, the law as it has developed in the United Kingdom and Europe in relation to the support obligation, when disentangled from classical insufficiency, provides guidance as to how s 40(3) should be approached.