Federal Court of Australia

Neptune Hospitality Pty Ltd v Ozmen Entertainment Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCA 427

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent KANKI SEA TOURISM HOSPITALITY & ENTERTAINMENT PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 26 APRIL 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory application filed by the respondents on 21 March 2022 (Interlocutory Application) is dismissed.

2. Subject to Order 3 below, by 3 May 2022 the parties are to provide the Associate to Markovic J with proposed consent orders concerning the costs of the Interlocutory Application.

3. In the event that the parties are unable to agree on the question of costs of the Interlocutory Application:

(a) by 10 May 2022 the appellant is to file and serve submissions on the question of costs, not exceeding two pages in length;

(b) the respondents are to file and serve their submissions on the question of costs, not exceeding two pages in length, by 17 May 2022; and

(c) the proceeding will be listed on a mutually convenient date in order to resolve the question of the costs of the Interlocutory Application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 On 11 March 2022 by consent between the appellant, Neptune Hospitality Pty Ltd, and the first and second respondents, Ozmen Entertainment Pty Ltd (in liq) and Kanki Sea Tourism Hospitality & Entertainment Pty Limited (in liq) (collectively respondents), the Court made the following orders:

1. The Appellant pay $190,000 towards the Respondents’ costs of the appeal.

2. The total sum payable by the Respondents to the Appellant pursuant to Order 2 of the Orders of 3 March 2022 is $0.

3. $170,000 of the funds held in Court is released to the Respondents within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable.

4. $30,000 of the funds held in Court is released to the Appellant within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable.

5. Of the $381.43 interest accrued on the sums that were held in Court, $329.40 be paid to the Respondents and $52.03 be paid to the Appellants within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable.

6. The $2,000 paid to the court for security for the costs of any taxation of the bill be repaid to the Appellant.

7. The taxation is otherwise vacated.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

8. Pursuant to Order 5 of the Orders of Rares J of 17 December 2020 in matter NSD1424/2017, $20,000 of the $220,000 that was held in Court as security for the Respondents’ costs of the appeal has been set aside to pay the Respondents’ (Applicants in matter NSD1424/2017) share of security for the costs of the Referee in those proceedings.

(11 March Orders).

2 By interlocutory application filed on 21 March 2022 the respondents seek an order pursuant to r 39.05(h) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) setting aside the 11 March Orders.

background

3 This proceeding has a lengthy history. It is not necessary to describe it in full as the application which is now before the Court for resolution concerns only some aspects of its history which I set out below.

4 On 19 March 2020 a Full Court of this Court made an order dismissing an appeal brought by Neptune and requiring the parties to file submissions on the question of costs of the appeal: see Neptune Hospitality Pty Ltd v Ozmen Entertainment Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 47; 375 ALR 489.

5 On 29 April 2020 the Full Court made orders that Neptune pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal on a party party basis, to be assessed if not agreed: see Neptune Hospitability Pty Ltd v Ozmen Entertainment Pty Ltd.

6 The effect of the order dismissing the appeal was that the proceeding resumed before the trial judge for the determination of quantum. The parties informed me at the hearing of the respondents’ interlocutory application that questions of quantum have been referred by the trial judge to a referee for determination and that orders were made for the parties to pay security for the referee’s costs in equal shares (Referee’s Security). I understand that the notation at [8] of the 11 March Orders (which I will refer to in these reasons as Notation 8) reflects the effect of an earlier order made by the trial judge namely that the respondents’ share of the Referee’s Security was to be satisfied by allocating $20,000 of the amount paid into Court by Neptune for security of the respondents’ costs of the appeal to the former.

7 In the meantime, in the absence of agreement about the quantum of the respondents’ costs of the appeal, the parties proceeded to a taxation which was listed for hearing before Registrar Segal on 8, 10, 11, 14 and 15 March 2022.

8 My-Linh Dang, the managing director of Metis Law, is the solicitor for the respondents. Ms Dang was and is assisted by David Kerr, a solicitor at Metis Law, and other members of her team in relation to the matter, including the taxation.

The events of 11 March 2022

9 On 11 March 2022, the third day of the taxation, Ms Dang was logged into Microsoft Teams as were Neptune’s costs consultant, Suzanne Ward, and the respondents’ costs consultant, Roslyn Walker. Just prior to the time that the taxation was scheduled to commence Ms Ward and Ms Dang had a conversation to the following effect:

Ms Walker: I have been informed that my client has made an offer of settlement to your client.

Ms Dang: I’m not aware of this.

Ms Ward: I have just got off the phone with Mr Leather and I understand he has or is just about to email you.

10 At about 10.12 am Ms Dang received an email from Neptune’s solicitor, Greg Leather, a partner in the firm Barringer Leather Lawyers, in which Mr Leather stated:

We are instructed to make a further offer of $185,000 in full and final settlement of the costs order, based on where we are tracking to date in the taxation. For an abundance of clarity, this offer is made on the basis that each party bear their own costs of the taxation to date, is made as a Calderbank offer and remains open until 2pm today.

We look forward to hearing from you once you have obtained instructions.

11 After reading Mr Leather’s email Ms Dang and Ms Ward had a further conversation to the following effect:

Ms Dang: Leaving aside the quantum that has been offered, the problem with your client’s offer is that it doesn't include the condition that our clients require, which is, that any settlement funds are to be fully and finally released to them. This has been canvassed in previous correspondence with your client and they have refused to agree to that.

Ms Ward: Would you like me to get instructions?

Ms Dang answered Ms Ward’s query in the affirmative at which point Ms Ward turned off her video and muted herself. Shortly after Ms Ward returned, turning on her video and unmuting herself, and said words to the following effect:

I have spoken to my client. I’ve just noticed that the recording of the proceedings has commenced. Ms Dang, would you like to discuss it over the phone?

12 Ms Dang and Ms Ward then had a telephone conversation to the following effect:

Ms Ward: My client agrees to the condition to release the funds in full to your client.

Ms Dang: On that basis, I will need to get instructions from my clients in relation to the new offer. Can you inform the Court that we will need about 15 minutes?

13 Ms Dang called her clients to obtain instructions. According to Ms Dang, on the basis that Neptune had ostensibly agreed to release any settlement sum that was agreed, she was instructed by her clients to engage in negotiations with its solicitor. Thereafter, Ms Dang had a series of conversations with Mr Leather. At about 11.24 am Ms Dang telephoned Mr Leather and said words to the following effect:

My clients agree to $190,000. I will send you the offer in writing.

14 At about 11.56 am Ms Dang caused a without prejudice letter to be sent to Mr Leather which provided:

We refer to your email of even date at 10:12am and the writer’s telephone correspondences with you. We are instructed to respond as follows.

1. By way of compromise and in full and final settlement of the dispute relating to the costs of the appeal and the taxation, our client makes the following counteroffer to your client:

(a) The total costs payable to our clients is $190,000.

(b) This settlement sum includes any amount that would have been payable by the Respondents in respect of order 2 of the orders of 3 March 2022 (in relation to the Appellant’s costs of the security for costs application for the taxation).

(c) Any interest accrued on the funds that have been held in the interest-bearing account by the Court is payable to each party proportionately (i.e. 13.64% to the Appellants, 86.36% to the Respondents).

(d) $170,000 of funds held in court as security for our clients’ costs are released to our client within 7 days. Noting that $20,000 held in Court was transferred as the Respondent’s share of security for the costs of the referee pursuant to Order 5 of the orders of 17 December 2020.

(e) The parties jointly approach the Court today requesting a certificate of taxation be issued in the amount of $190,000.

(f) The parties will sign, file and serve all documents necessary to discontinue the taxation within 7 days.

2. Our clients’ offer set out above is open for acceptance until 2:00pm today, Friday 11 March 2022, at which time it will automatically lapse.

3. Should your client accept our clients’ offer, please advise the writer in writing.

4. Our clients’ offer is made under the principles of Calderbank v Calderbank and this letter may be presented on the issue of costs.

This letter, which I will refer to as the 11 March Letter, is central to the respondents’ application.

15 By email sent at 12.35 pm by Mr Leather to Ms Dang, copied to Mr Kerr and Tony Zhen, a paralegal in the employ of the respondents’ solicitors, Mr Leather accepted the offer made in the 11 March Letter on behalf of his client. Specifically, Mr Leather wrote:

We confirm acceptance by our client to the terms set out in the letter attached to your email below.

16 At around 12.37 pm Ms Dang informed Registrar Segal that the parties had reached an agreement to settle and read out the terms. Registrar Segal directed the parties to file consent orders reflecting the agreed terms.

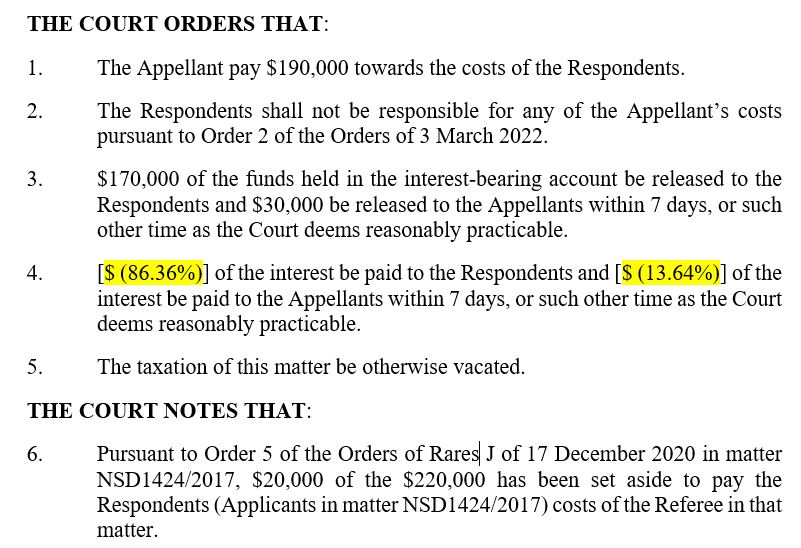

17 Ms Dang directed Mr Kerr by email to draft a form of consent orders to be provided to Neptune. Mr Kerr provided draft orders in the following form to Ms Dang for her review:

(Highlighting in original.)

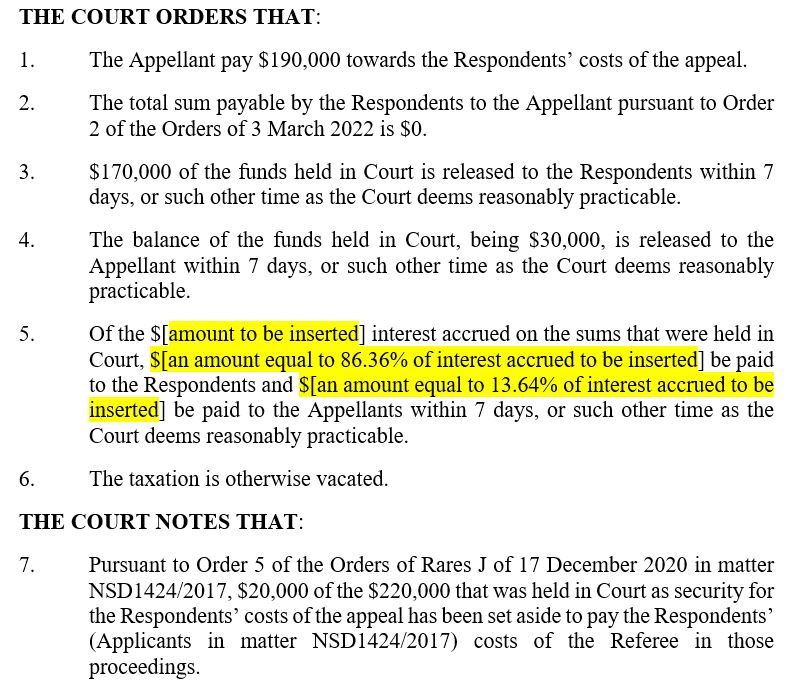

18 Ms Dang made some amendments to the draft document and emailed what she believed to be the updated version of the draft orders to Mr Kerr with instructions to send the draft to Mr Leather. The form of orders which Ms Dang sent to Mr Kerr at that time was as follows:

(Highlighting in original.)

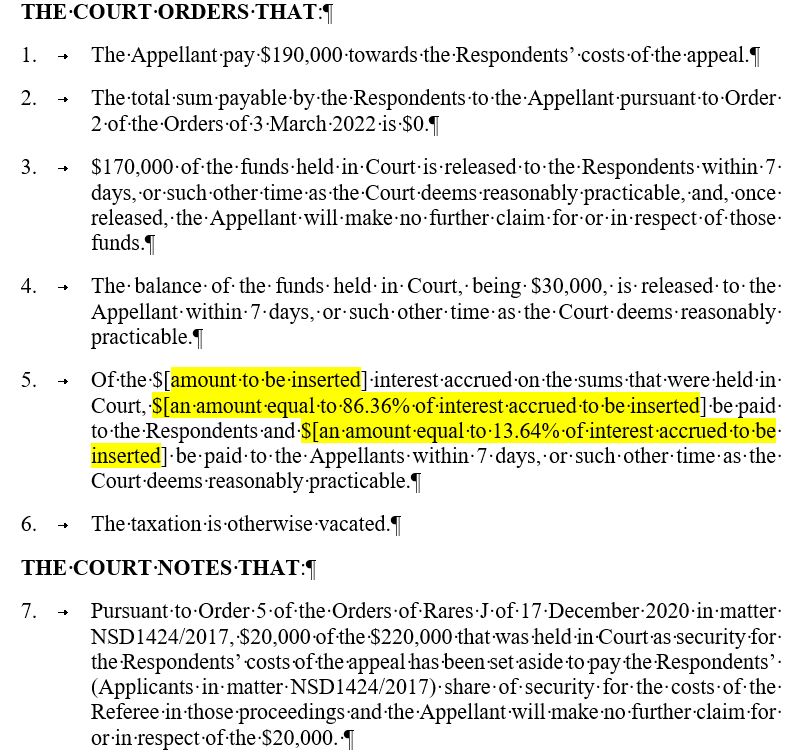

19 However, Ms Dang said that the form of consent orders that in fact contained all of her amendments and which she should have forwarded to Mr Kerr was as follows:

(Highlighting in original.)

20 At about 1.47 pm Ms Dang received an email from Joanna Huynh, Finance Coordinator at the Court’s registry, in which Ms Huynh reported on the amount held by the Court in its Litigants’ Fund account as the security paid for the costs of the taxation. After receiving that email Ms Dang telephoned Mr Kerr and instructed him to:

(1) calculate the interest payable to each party using the percentages in the draft orders; and

(2) amend the draft orders:

(a) to specify the interest component payable to each party;

(b) by adding an order requiring the return of the amount paid for security for the taxation to Neptune; and

(c) by deleting the words “balance of the funds” from proposed order 4.

21 Ms Dang has been informed by Mr Kerr that he amended the form of draft orders that she had sent to him (see [18] above), which according to Ms Dang was the incorrect form of orders, and that he subsequently emailed the updated draft to Mr Leather under cover of an email in which he wrote:

Please find attached consent Orders to give effect to the agreed terms.

Our client agrees to extend to 3pm, its counter-offer made earlier today, in order to give you time to sign and return these orders.

Ms Dang and Mr Zhen were copied into this email.

22 The orders attached to Mr Kerr’s email referred to in the preceding paragraph were signed by the respondents’ solicitor and were in the following form:

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Appellant pay $190,000 towards the Respondents’ costs of the appeal.

2. The total sum payable by the Respondents to the Appellant pursuant to Order 2 of the Orders of 3 March 2022 is $0.

3. $170,000 of the funds held in Court is released to the Respondents within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable.

4. $30,000 of the funds held in Court is released to the Appellant within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable.

5. Of the $381.43 interest accrued on the sums that were held in Court, $329.40 be paid to the Respondents and $52.03 be paid to the Appellants within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable.

6. The $2,000 paid to the court for security for the costs of any taxation of the bill be repaid to the Appellant.

7. The taxation is otherwise vacated.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

8. Pursuant to Order 5 of the Orders of Rares J of 17 December 2020 in matter NSD1424/2017, $20,000 of the $220,000 that was held in Court as security for the Respondents’ costs of the appeal has been set aside to pay the Respondents’ (Applicants in matter NSD1424/2017) costs of the Referee in those proceedings.

23 Ms Dang said that she did not see the updated form of orders before Mr Kerr sent them to Mr Leather and that she did not see them again until after they were made by the Court.

24 By email sent at 2.35 pm by Mr Leather to Mr Kerr and Ms Dang, and copied to Mr Zhen, Mr Leather raised an issue in relation to paragraph 8 of the draft orders. He stated:

The notation at 8 is incorrect. The $20,000 was not set aside to pay the Respondent’s costs of the referee, it was set aside as the Respondents’ share of an order (as varied) for the parties to pay into court a sum of $40,000 as security for the costs of the referee.

25 Mr Kerr called Ms Dang to discuss the amendment sought by Mr Leather to paragraph 8 of the draft orders. Mr Kerr inquired whether it was okay for him to add the words “share of security for the costs” to that paragraph. Ms Dang confirmed that the proposed change was acceptable.

26 By email sent at about 2.47 pm by Mr Kerr to Mr Leather, copied to Ms Dang, Mr Kerr sought Mr Leather’s agreement to a revision to paragraph 8 of the proposed orders. Mr Leather responded noting his agreement to the proposed amendment. Mr Kerr then made the agreed amendment to paragraph 8 in the same document that he had previously circulated to Mr Leather, which Ms Dang said was the incorrect form of orders.

27 At about 3.03 pm Mr Kerr sent an email to the assistant to Registrar Segal, copied to Ms Dang and Mr Leather, attaching “Consent Orders of the parties” and requesting that Registrar Segal make the orders in Chambers. The orders attached to that email were in the form of the 11 March Orders.

The events of 14 March 2022

28 On Monday, 14 March 2022 Ms Dang caused a copy of the sealed orders made on 11 March 2022 to be obtained from the Court portal. They were provided to her by Mr Zhen that morning. Ms Dang said that this was the first time that she had seen the 11 March Orders since her email to Mr Kerr referred to at [18] above. At that time, it came to Ms Dang’s attention that the 11 March Orders were not the same as the version of the document she thought she had sent to Mr Kerr on 11 March 2022. On further investigation Ms Dang discovered that the version of the form of orders that she had attached to her email to Mr Kerr (see [18] above) was the incorrect version of the document and did not have all of the changes that she had in fact made to the draft that had been provided by Mr Kerr.

29 At Ms Dang’s request Mr Kerr sent an email to Mr Leather, copied to Ms Dang and Mr Zhen, in which he wrote:

It has come to our attention that the form of consent orders that we sent to you on Friday was the incorrect version.

Please can you confirm if you agree to Order 3 and Notation 8 which should read:

Order 3

$170,000 of the funds held in Court is released to the Respondents within 7 days, or such other time as the Court deems reasonably practicable, and, once released, the Appellant will make no further claim for or in respect of those funds.

Notation 8

Pursuant to Order 5 of the Orders of Rares J of 17 December 2020 in matter NSD1424/2017, $20,000 of the $220,000 that was held in Court as security for the Respondents’ costs of the appeal has been set aside to pay the Respondents’ (Applicants in matter NSD1424/2017) share of security for the costs of the Referee in those proceedings and the Appellant will make no further claim for or in respect of the $20,000.

Do let us know and we will approach the Court.

(Emphasis in original.)

30 At 9.50 am Mr Kerr sent an email to Registrar Segal’s assistant in which he wrote:

It has come to our attention that we have sent the Court an incorrect version of the consent orders.

We are discussing the correct version with the Appellant's solicitors and will get back to the Court ASAP this morning as soon as we hear back from the Appellant.

(Emphasis in original.)

31 At 9.55 am Mr Leather sent an email to Mr Kerr, copied to Ms Dang and Mr Zhen, in which he wrote:

That is not agreed. The orders as amended to reflect the correction we requested to notation 8 is what was agreed. That correction reflected the wording of paragraph 1(d) of the letter attached to your email received at 11.57am on Friday, 11 March 2022. The offer set out in that letter is what was agreed.

32 Shortly thereafter Ms Dang telephoned Mr Leather. They had a conversation to the following effect:

Ms Dang: There has been a clerical error - caused by me - which resulted in the incorrect version of the form of consent to be sent to you. The language David [Kerr] sent to you is to make it clear that once the $190,000 is released to the Respondents, it can’t be subject to any further claim by Neptune. Because the current language is not entirely clear.

Mr Leather: No. No, that is not agreed. The $20,000 is subject to the proceedings below and is subject to the Appellant’s security.

Ms Dang: Are you referring to the Ships Mortgage?

Mr Leather: Yes.

Ms Dang: Hold on. To be clear, is it just the $20,000 that you’re not agreeing to release fully and finally from all further claims?

Mr Leather: Yes.

Ms Dang: But that doesn’t make sense. We were ahead in the taxation. Why would we agree to settle for $190,000 and only agree to have full release for $170,000? That doesn’t make any sense.

Mr Leather: That’s what we agreed.

Ms Dang: No it wasn’t. The Respondents’ position has always been that the full settlement sum is to be released to the Respondents and cannot be subject to any further claim from Neptune.

33 At around 11.24 am Ms Dang sent an email to the Court requesting that the proceeding be relisted for a continuation of the taxation hearing or for case management hearing.

34 A final relevant factual matter which is evident on the face of the documents recently filed in the proceeding is that both of the respondents are now in liquidation.

legal principles

35 Rule 39.05 of the Rules empowers the Court to vary or set aside an order once entered. The respondents apply for the 11 March Orders to be set aside pursuant to r 39.05(h) of the Rules, sometimes referred to as the slip rule, which provides:

The Court may vary or set aside a judgment or order after it has been entered if:

…

(h) there is an error arising in a judgment or order from an accidental slip or omission.

36 In Australian Securities and Investment Commission v ActiveSuper Pty Ltd (No 4) [2013] FCA 318 at [6] Gordon J said the following in relation to the Court’s power generally under r 39.05 of the Rules:

The power under r 39.05 is discretionary. The power is to be exercised with caution. As Young J observed in Paras v Public Service Body Head of the Department of Infrastructure (No 2) (2006) 152 IR 352 at [4], the power is “ordinarily only exercised in exceptional circumstances”: see Wati v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (1997) 78 FCR 543 at 549-52; Dudzinski v Centrelink [2003] FCA 308 at [11]; McDermott v Richmond Sales Pty Ltd (in liq) [2006] FCA 248 at [25] cited by Young J.

37 In Elyard Corp Pty Ltd v DDB Needham Sydney Pty Ltd (1995) 61 FCR 385 a Full Court of this Court (Black CJ, Lockhart and Lindgren JJ) considered the application of O 35 r 7(3) of the (former) Federal Court Rules which was the predecessor to the power now found in r 39.05(g) and (h). Order 35 r 7(3) relevantly provided:

A clerical mistake in a judgment or order, or an error arising in a judgment from an accidental slip or omission, may at any time be corrected by the Court.

38 Justice Lockhart (with whom Black CJ agreed) noted at 390 that traditionally a court’s power to correct errors in orders arising from accidental slips or omissions is conferred by an express rule of court but exists whether made by express rule or not. His Honour relevantly continued:

The slip rule is a qualification of the rule that a court may not vary a duly passed and entered order which brings a proceeding to an end because it is obviously desirable that the litigation should be brought to an end.

The rule is very wide in its scope, but is not available as a matter of course: Shaddock at CLR 597.

Courts have an inherent or implied jurisdiction to amend judgments which do not correctly state what was actually decided and intended. Indeed, after a decree or order has been passed and entered a court will not, unless by consent, permit it to be altered without a rehearing, except in cases of mistakes or errors arising from accidental slips or omissions.

…

The slip rule applies where the proposed amendment is one upon which no real difference of opinion can exist. It does not apply where the amendment is a matter of controversy, nor does it extend to mistakes that are the consequence of a deliberate decision: see Arnett v Holloway [1960] VR 22; Re Army and Navy Hotel (1886) 31 Ch D 644 and Ivanhoe Gold Corp Ltd v Symonds (1906) 4 CLR 642.

39 His Honour continued at 391:

…

It is well settled that the application of the slip rule is not confined to giving effect to the intention of the judge at the time when the court's order was made, or judgment given. It extends to the intention which the court would have had, but for the failure that caused the accidental slip or omission: Symes v Commonwealth (1987) 89 FLR 356. The rule also extends to permit the correction of an order or decree where the omission results from the inadvertence of a party's legal representative: Fritz v Hobson at 561–562; Chessum & Sons v Gordon [1901] 1 KB 694; Tak Ming Co Ltd at 304; Shaddock at 594–595 per Mason ACJ, Wilson and Deane JJ; and Gould v Vaggelas at 274–275.

40 In Trust Company (Nominees) Limited, in the matter of Angas Securities Limited v Angas Securities Limited (No 4) [2016] FCA 1240 Beach J considered an application by Angas Securities Limited to vary consent orders, referred to by his Honour as run off orders, made pursuant to an interim settlement agreement between Angas and the Trust Company (Nominees) Limited. The context in which Angas’ application arose had some complexity to it, which I do not need to set out. At [11] Beach J noted that a debate had subsequently arisen between the parties which concerned: the construction of a costs order which was included in the run off orders; the terms of the settlement agreement between the parties which resulted in the run off orders including the costs order; and the court’s power to vary the costs order and whether his Honour should exercise his discretion to do so given that it was made pursuant to a settlement agreement between the parties. For the purpose of resolution of those questions it was accepted that the run off orders and the costs order, which was a part of those orders, were interlocutory.

41 At [13]-[15] Beach J observed, based on the what he described as the “plethora of affidavits” relied on, that it was apparent that there was an oral agreement reached between the then senior counsel for each of the parties which culminated in the run off orders and the costs order but that there was nothing in writing that evidenced the oral agreement save for the run off orders themselves. Notwithstanding that, his Honour considered that it was not necessary to set out the detail of the affidavit material which concerned the course of the discussions and the negotiations, what each party thought it was doing, their respective state of knowledge and what ultimately the then senior counsel for each side discussed on the question of costs. Rather, at [17]-[18] his Honour proposed the following course:

17 First, I will take the precise text of the run-off orders including the costs order as reflecting and embodying the anterior oral agreement between the parties.

18 Second, I will construe the costs order in that light and also in an independent objective sense given that it is also an order of the Court. In that latter sense, but for the context of construction only, it is to be construed objectively as distinct from my own subjective views as to what I contemplated by the order or thought was contemplated by the parties in proffering such an order.

42 Commencing at [26] Beach J set out the general principles which guide the Court’s power to vary consent orders. At [27]-[32] his Honour said:

27 First, I have power to vary an interlocutory order (rule 39.05 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth)) even if made by consent and pursuant to an agreement between the parties.

28 Second, the power to vary is more readily exercisable in the context of an interlocutory order as compared with a final order, where in the former case “the finality of litigation does not weigh so heavily in the scales” (Cosdean Investments Pty Ltd v Football Federation Australia Limited (No 5) [2007] FCA 1792 at [17] per Mansfield J).

29 Third, it may be appropriate to vary an interlocutory order where “new facts come into existence or are discovered which render its enforcement unjust” (Adam P. Brown Male Fashions Pty Ltd v Philip Morris Inc (1981) 148 CLR 170 at 178 per Gibbs CJ, Aickin, Wilson and Brennan JJ), although such a statement is not exhaustive of the possibilities.

30 Fourth, in the context of a consent order or judgment that is final and which gives effect to an underlying agreement, the consent order may be set aside or varied on any ground that would impeach the underlying agreement or its enforceability (Harvey v Phillips (1956) 95 CLR 235 at 243 and 244). Correspondingly it has been said that if the underlying agreement or its enforceability is not so impeached, then the consent order or judgment should not be set aside or varied absent an “exceptional” or “rare” case (see Paino v Hofbauer (1988) 13 NSWLR 193 at 198 per McHugh JA and at 201 per Clarke JA and Lachlan v HP Mercantile Pty Ltd (2015) 89 NSWLR 198 at [27] and [28] per Bathurst CJ, Beazley P and McColl JA). Moreover, there may be an implied term of the agreement not to invoke any curial power to set aside or vary such an order.

31 Fifth and relatedly, the Court has power to vary a consent interlocutory order even if made pursuant to an agreement between the parties (R D Werner & Co Inc v Bailey Aluminium Products Pty Ltd (1988) 18 FCR 389 at 392 and 393 per Woodward and Foster JJ). Moreover, the same rigidity applying to varying final orders does not apply where the consent order, based upon an agreement, is interlocutory. Now it is possible that a party may contend for an implied term not to apply to vary, but such an implication is even more problematic when dealing with an interlocutory order. In any event, no such implied term has been contended for in the present case.

32 Before proceeding further, it is appropriate to note one other aspect relating to the fourth and fifth propositions. It has been pointed out in Chavez v Moreton Bay Regional Council [2010] 2 Qd R 299 at [35] per Keane JA that the views expressed in R D Werner & Co Inc v Bailey Aluminium Products Pty Ltd may be considered to be more liberal than those expressed in Paino. Nevertheless, his Honour at [39] applied Paino but used more generous language, viz, “good reason for depriving…” rather than the adjectives “exceptional” or “rare”.

(Emphasis in original).

43 Beach J refused to vary the costs order in the first way sought by Angas. Insofar as that variation was concerned, among other things, his Honour found that there was nothing equivocal in how the costs order had been expressed. In contrast, his Honour accepted that the costs order should be modified in the second way sought by Angus. His Honour formed that view for a number of reasons including having regard to the construction of the costs order.

44 The respondents also referred to the decision in Huddersfield Banking Co Ltd v Henry Lister & Son Ltd [1895] 2 Ch 273 where Lindley LJ said at 280 that he had not “the slightest doubt” that “a consent order can be impeached, not only on the ground of fraud, but upon any grounds which invalidate the agreement it expresses in a more formal way than usual” and “if that agreement cannot be invalidated the consent order is good. If it can be, the consent order is bad”.

the respondents’ submissions

45 The respondents submitted that the 11 March Orders were intended to give effect to an agreement between them and Neptune. That is, on the basis that Neptune agreed to release the settlement sum to the respondents (in full and final settlement of the dispute), the respondents agreed to settle the dispute between the parties in relation to their costs of the appeal in an amount of $190,000.

46 The respondents relied on two alternative grounds to impeach the underlying agreement between them and Neptune: first mistake; and secondly that the orders did not reflect the agreement.

47 In relation to mistake, the respondents submitted that their solicitor had made Neptune’s costs consultant and its solicitor aware that they would only engage in a negotiation of a settlement “if [Neptune] agreed to release the settlement sum (in full) to the respondents” and that this was a fundamental term of any settlement agreement between the parties.

48 They contended that when Notation 8 is read together with Orders 1 and 3 of the 11 March Orders it is not entirely clear that the funds that were to be released to them cannot be subject to any further claim, I infer, by Neptune. They noted that, in fact, Neptune’s solicitor later expressed the view that the $20,000 that had been set aside pursuant to Order 5 of the Orders of 17 December 2020 was open to a further claim by it.

49 The respondents submitted that the effect of the agreement constituted by the 11 March Letter and Neptune’s acceptance of it was that, to the extent that the result of the proceeding was that monies were owed by the respondents to Neptune and Neptune then lodged a proof of debt in one or other of their liquidations and was admitted as a creditor, it would not have access to the amounts that were to be applied in satisfaction of the quantified costs order in the appeal proceeding, namely the sum of $170,000 applied from the funds held in Court as security for the costs of the appeal; and the sum of $20,000 which was released from the funds held in Court as security for the costs of the appeal and applied on behalf of the respondents as their share of the Referee’s Security.

50 The respondents submitted that the clerical error which resulted in the accidental omission of certain language in the consent orders had the effect of making this material term ambiguous in the 11 March Orders. They said that promptly after discovering this slip their solicitor raised the issue with Neptune’s solicitor with a view to correcting the 11 March Orders and that it was only at that point that Neptune’s solicitor expressed, for the first time, that $20,000 of the $190,000 would not be “fully released” by virtue of the effect of Order 5 of the Orders of 17 December 2020 entered in the proceeding below. The respondents submitted that it was at this point that it became apparent that either Neptune had changed its position with respect to the agreement that had been reached between the parties, and had taken advantage of the slip in the form of consent orders, or that there had been no agreement between the parties as to the fundamental term relating to the release of the settlement sum.

51 The respondents contended that if it is the case that Neptune had intended that the $20,000 would be open to further claim by it, despite the terms of Order 1 of the 11 March Orders, by intentionally staying silent about the ambiguity or possible effect of Notation 8, it is unfairly allowed to benefit from a clerical error or accidental slip. The respondents also submitted that, in any event, if it is the case that Neptune had intended that the $20,000 would be open to a further claim by it, then the parties had not reached any agreement to settle as the full and final release of the settlement sum was a fundamental term of the agreement. The respondents submitted that Mr Leather’s conversation with Ms Dang indicates that the former is the better analysis.

52 Finally, the respondents submitted that Notation 8 is ambiguous and that unless it is varied to correct the ambiguity and to make clear that further claims by Neptune are not permitted, it would be unjust for Neptune to benefit from orders which it is aware did not reflect what the respondents had specifically indicated was a fundamental term of any settlement between the parties.

53 In relation to the second basis on which the respondents rely to impeach the underlying agreement, namely their contention that the 11 March Orders do not reflect the agreement, the respondents submitted that Ms Dang’s accidental slip or omission in sending the incorrect form of orders to her associate, Mr Kerr, who, in turn, used that incorrect form of orders to make further amendments requested by Neptune’s solicitor and/or the further accidental slip or omission by Mr Kerr to ensure that the form of orders was unambiguous as to the fundamental term, resulted in orders that did not reflect the underlying agreement between the parties.

54 The respondents submitted that where Order 1 of the 11 March Orders requires Neptune to pay the respondents $190,000 towards their costs of the appeal, if Notation 8 is read to mean that the $20,000 is not fully and finally released to them (and therefore may be subject to a further claim by Neptune) Order 1 does not make sense. Accordingly, an error arising from an accidental slip or omission as contemplated under r 39.05(h) of the Rules has occurred.

Consideration

55 The respondents have not established either basis upon which they contended that the underlying agreement should be impeached and thus the 11 March Orders set aside pursuant to s 39.05(h) of the Rules or otherwise. My reasons for reaching this conclusion follow.

56 The first basis relied upon by the respondents to impeach the underlying agreement was mistake. Insofar as that basis is concerned:

(1) the 11 March Orders came about as a consequence of negotiations between the parties. The respondents’ offer, which was set out in the 11 March Letter, was accepted by Neptune. Contrary to the respondents’ submissions it is not possible to read or imply into those terms a further term that Neptune would not make any further claim in relation to the sums to be released to the respondents pursuant to the terms of that offer;

(2) the terms of the offer made in the 11 March Letter require “a release” of the funds held in Court as security for the respondents’ costs to satisfy the costs payable by Neptune to the respondents pursuant to the costs order made in the appeal proceeding. Those terms do not extend to requiring Neptune to provide any release or undertaking not to make any claim in the future against the respondents or against the funds that are to be released pursuant to the terms of the 11 March Letter;

(3) on no construction of the agreement constituted by the 11 March Letter and Neptune’s acceptance of it, could its terms be construed to mean that there was to be a quarantining of the funds to be released to the respondents in payment of their agreed costs of the appeal such that Neptune, to the extent that it may be a creditor, would not have access to those funds in payment of any debt which might eventually be owed to it. That Ms Dang and/or the respondents, who I note did not give evidence, had that understanding of the purport or intention of the 11 March Letter does not result in a different outcome. In my opinion the 11 March Letter is clear on its face and does not include such a term;

(4) in any event, the fundamental term which the respondents say was not included in the 11 March Orders, namely that Neptune must agree to release the settlement sum in full, fails to recognise that the sum of $20,000 referred to in Notation 8 had already been released to the respondents and used by them as their share of the Referee’s Security;

(5) relatedly, Neptune accepts that the funds have been released to the respondents and that it can make no further claim against those funds in the appeal. However, it notes that as the respondents elected to deploy a part of those funds, namely $20,000, in the first instance proceeding to meet their obligation to pay half of the Referee’s Security, those funds are now subject to any orders that might be made in that proceeding. That must be so. For example, if it ultimately transpires that the respondents are liable for the referee’s costs, in part or in whole, then the funds paid by the respondents as security for those costs would ordinarily be applied to satisfy any such order. There may be other orders made which might affect the amount now held by the Court as the respondents’ share of the Referee’s Security;

(6) the draft consent orders provided by Mr Kerr to Mr Leather (see [21] above), save in one respect which was identified by Mr Leather, reflected the terms of the 11 March Letter. Following the amendment suggested by Mr Leather in relation to what became Notation 8, the draft consent orders in fact reflected the terms of the 11 March Letter. That version of the draft orders was then forwarded to the Court. Critically each of the emails between the solicitors for the parties from the time when the first draft of the orders was provided to Mr Leather until the final draft orders were provided to the Court included as addressees from the respondents’ solicitors Mr Kerr, who it appears had principal carriage of the communications on the part of the respondents, and Ms Dang. Notwithstanding that, at no time did Ms Dang raise any concern that the terms of the draft consent orders did not reflect the respondents’ offer as set out in the 11 March Letter, that they omitted a material term or that that they were ambiguous as to the so called material term; and

(7) there is no ambiguity in the 11 March Orders. They are clear in their terms. Nor could the omission of the language which the respondents contend ought to have been included be classified as a clerical error or an accidental omission. That is particularly so in circumstances where the 11 March Orders reflect the terms of the 11 March Letter.

57 It follows that I do not accept that the respondents entered into the agreement to settle the costs dispute under some serious mistake or misapprehension about a fundamental term. The 11 March Letter, which was signed by Ms Dang, set out the terms of the offer that was accepted by Neptune. The 11 March Orders reflected the terms of that agreement. There is no basis upon which it could be said that Neptune was aware of circumstances which indicated that the respondents were entering into the consent orders under some serious mistake or misapprehension about a term of them or that Neptune deliberately set out to ensure that the respondents did not become aware of the existence of the mistake or misapprehension.

58 The second basis relied upon by the respondents to impeach the underlying agreement was that the 11 March Orders do not reflect the parties’ agreement. Insofar as that basis is concerned:

(1) that Ms Dang may have sent the incorrect form of orders to Mr Kerr which he then sent to Mr Leather cannot be classified as an accidental slip or omission for the purposes of r 39.05(h);

(2) as noted above, Ms Dang was an addressee of all communications undercover of which draft orders were provided to Mr Leather and ultimately the Court. At no stage did she raise an issue about their terms;

(3) in any event the 11 March Orders reflected the agreement recorded in the 11 March Letter which Ms Dang had signed and caused to be sent to Mr Leather; and

(4) similarly, I do not accept that there was an accidental slip or omission on the part of Mr Kerr in providing the draft orders to Mr Leather and ultimately the Court by failing to ensure that the form of the orders was unambiguous as to the fundamental term. As I have already found to be the case, the 11 March Orders did no more than reflect the terms of the 11 March Letter. There is no ambiguity in them.

59 In short, the 11 March Orders reflect the agreement that was reached between the parties as set out in the 11 March Letter.

conclusion

60 For those reasons the interlocutory application filed by the respondents on 21 March 2022 should be dismissed.

61 The parties have requested that I reserve on the question of costs. Accordingly, I will make orders allowing the parties time to consider these reasons and to provide a proposed consent order to be made in Chambers dealing with the question of costs of the interlocutory application. If the parties cannot agree on the question of costs of the interlocutory application, they are to file and serve submissions, not exceeding two pages in length, on that question and thereafter the proceeding will be relisted before me for determination of that question.

62 I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding sixty-two (62) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |