Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Trivago N.V. (No 2) [2022] FCA 417

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent (Trivago) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties as follows:

(a) in respect of the contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law, which is Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Australian Consumer Law), referred to in paragraph 1 of the declarations made on 28 February 2020 – a pecuniary penalty of $30,600,000;

(b) in respect of the contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law referred to in paragraph 2 of the declarations made on 28 February 2020 – a pecuniary penalty of $7,100,000;

(c) in respect of the contraventions of s 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law referred to in paragraph 3 of the declarations made on 28 February 2020 – a pecuniary penalty of $2,100,000; and

(d) in respect of the contraventions of s 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law referred to in paragraph 4 of the declarations made on 28 February 2020 – a pecuniary penalty of $4,900,000.

2. The pecuniary penalties referred to in paragraph 1 are to be paid within 60 days of the date of this order.

3. Trivago be restrained, whether by itself, its servants, agents or howsoever otherwise for a period of five years from, in trade or commerce, representing that Top Position Offers are the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel, or have some other characteristic which make them more attractive than any other offer for that hotel, if the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest available offer for the hotel or did not have some other characteristic that made it more attractive than any other available offer for the hotel.

4. Trivago pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding, as agreed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 These reasons for judgment deal with issues of relief. In particular, they address: (a) the amount of any pecuniary penalty to be imposed on the respondent (Trivago); (b) whether an injunction should be ordered restraining Trivago from engaging in certain conduct in the future; and (c) the issue of costs. These reasons should be read together with the judgment on liability: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Trivago N.V. (2020) 142 ACSR 338; [2020] FCA 16 (the Liability Judgment). I will adopt the abbreviations used in the Liability Judgment.

2 In this proceeding, the applicant (the ACCC) alleged that Trivago engaged in contraventions of ss 18, 29 and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Australian Consumer Law), during the period from 1 December 2016 to 13 September 2019 (the Relevant Period). The alleged contraventions related to Trivago’s Australian website, being the website located at “www.trivago.com.au” (the Trivago website), and Trivago’s marketing of that website. (These reasons are concerned with Trivago’s Australian website and not its overseas websites.)

3 Sections 29(1)(i) and 34, which are pecuniary penalty provisions, relevantly provide:

(a) section 29(1)(i) prohibits the making of false or misleading representations, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services (or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services), with respect to the price of goods or services; and

(b) section 34 provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any services.

4 In order to understand the ACCC’s allegations, and the findings of contravention, it is necessary to outline certain key elements of the Trivago website. The following description relates to the Trivago website as it operated during the Relevant Period.

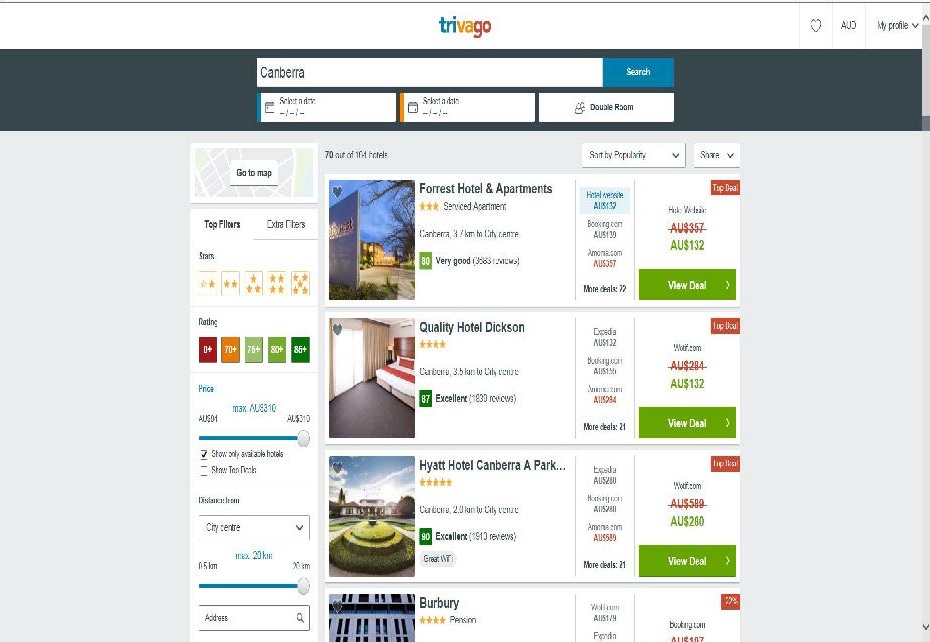

5 Consumers visiting the Trivago website are prompted to enter a city or region in a search bar and select their desired dates and room type (eg, single, double, family or multiple rooms). Consumers are also able to search by hotel. When a consumer initiates a search in a given city or region, the Trivago website displays an initial set of search results for the city or region, stay dates and room type the consumer has selected (the Initial Search Results Page). For example, during the first part of the Relevant Period, the Initial Search Results Page appeared in the following format:

6 Each hotel listing on the Initial Search Results Page is displayed in substantially the same way, with the following features:

(a) To the left, there is a square image relating to the particular hotel (typically, this is a photograph of one of the hotel’s rooms or of the hotel’s façade).

(b) To the right of that image is the hotel’s name and beneath the name is information about the hotel, including its star rating, location and a user survey rating.

(c) Further to the right, there are prices for the hotel as offered by online booking sites, online travel agencies and (sometimes) the hotel itself (referred to collectively as Online Booking Sites). It will be convenient to refer to these prices as “offers”. Further relevant aspects are as follows:

(i) In the far right column, one offer is displayed in green text, in a relatively large font and with space around it (the Top Position Offer). The Top Position Offer is displayed together with the name of the Online Booking Site making that offer and a green “View Deal” click-out button.

(ii) Juxtaposed above the Top Position Offer is another offer displayed in red. During part of the Relevant Period, this offer was displayed in red strike-through text (the Strike-Through Price) (as depicted above). Subsequently, this offer was displayed in red text without the strike-through (the Red Price).

(iii) Three offers are displayed in the column that is second from the right. These appear in a smaller font compared with the Top Position Offer. These offers are referred to as the Second Position Offer, the Third Position Offer and the Fourth Position Offer.

(iv) Underneath the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers, a “More Deals” button is displayed in bolded black text (the More Deals button). If clicked, the More Deals button shows, by way of a ‘slide-out’ function (the More Deals slide-out), other offers from Online Booking Sites for the selected hotel. In the first part of the Relevant Period, the More Deals button indicated the number of additional offers presented in the slide-out (as depicted above). Subsequently, the More Deals button was changed to indicate the lowest offer presented in the More Deals slide-out (eg, “More Deals from AU$226”).

7 If a consumer clicks on an Online Booking Site’s offer on the Trivago website, the consumer is taken to the Online Booking Site’s website and may complete the booking by using the Online Booking Site’s website’s booking service.

8 A number of changes were made to the Trivago website during the Relevant Period. In addition to the changes already referred to, the changes included the introduction of a number of ‘hover-overs’. If a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over a particular part of the Initial Search Results Page, text would be displayed that provided additional information. Other changes are described in the Liability Judgment.

9 In the early part of the Relevant Period, Trivago conducted a television advertising campaign. Many of these advertisements contained a statement to the effect that Trivago makes it easy “to find the ideal hotel for the best price”. See, for example, the television advertisement set out in the Liability Judgment at [3]. See also the Liability Judgement at [47]-[51]. Further, during the early part of the Relevant Period, the landing page for the Trivago website included the statement: “Find your ideal hotel for the best price.”

10 In fact, however, the price that appeared as the Top Position Offer was in many cases not the cheapest offer for the particular hotel room. First, the Trivago website only displayed offers made by Online Booking Sites that had agreed to pay an amount of money – referred to as the Cost Per Click or “CPC” – to Trivago. Secondly, unless the CPC offered to be paid by the Online Booking Site exceeded a minimum threshold set by Trivago, the offer did not appear on the Trivago website. Thirdly, Trivago used an algorithm (the Top Position algorithm) to select the offer to appear as the Top Position Offer. A very significant factor in determining which offer would be the Top Position Offer was the amount of the CPC to be paid by the Online Booking Site to Trivago.

11 The experts at the trial on liability agreed that higher offers were selected as the Top Position Offer over alternative lower priced offers in 66.8% of listings.

12 In the Liability Judgment dated 20 January 2020, I concluded that Trivago had contravened ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law. The findings of contravention were subsequently reflected in declarations made on 28 February 2020. The declarations are set out in the next section of these reasons.

13 The main issue to be determined in these reasons is the amount of any pecuniary penalty to be imposed on Trivago for its contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34. There is a considerable gulf between the parties’ positions on this issue. Trivago contends that a penalty of up to $15 million should be imposed. The ACCC contends that a penalty of at least $90 million is appropriate.

14 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that pecuniary penalties totalling $44.7 million should be imposed on Trivago in respect of its contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law during the Relevant Period. In my view, pecuniary penalties totalling this amount are appropriate in the circumstances of this case, and are necessary to achieve the purposes of specific and general deterrence. By way of summary, I note the following facts and matters:

(a) Trivago’s contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law are extremely serious. The television advertising conducted by Trivago during the early part of the Relevant Period was highly misleading. The advertising conveyed that the Trivago website would quickly and easily identify the cheapest rates available for a hotel room responding to a consumer’s search (see the Liability Judgment at [196]-[202]), but in fact the website did not do this. As noted above, higher offers were selected as the Top Position Offer over alternative lower priced offers in 66.8% of listings.

(b) Further, Trivago represented that the Top Position Offers were the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel, or had some other characteristic which made them more attractive than any other offer for that hotel (see the Liability Judgment at, eg, [212]-[218]). This too was highly misleading.

(c) The conduct extended over a lengthy period of time. Although the television advertisements related to only the early part of the Relevant Period, other conduct engaged in by Trivago in contravention of the relevant provisions extended for nearly three years.

(d) A large number of consumers were affected by the conduct. The evidence presented for the relief hearing shows that, during the Relevant Period, there were approximately 111 million click-outs on the Trivago website. The overwhelming majority (approximately 104 million or 93%) of the click-outs were on the Top Position Offer. There were approximately 57 million click-outs on a Top Position Offer for an identified hotel where the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer for that hotel (non-cheapest Top Position Offers).

(e) The loss or damage caused by Trivago’s contraventions was substantial, as discussed below.

(f) Trivago derived substantial revenue from its contravening conduct, as detailed later in these reasons.

15 The issue of an injunction occupied little time at the hearing on relief. I consider it appropriate to order an injunction restraining Trivago from engaging in certain conduct. There is no issue between the parties as to the wording of the injunction.

16 It is also appropriate to order Trivago to pay the ACCC’s costs of the proceeding.

The ACCC’s allegations and the declarations of contravention

17 The ACCC’s allegations in the proceeding related to four sub-periods within the Relevant Period. The four sub-periods were as follows:

(a) the period from 1 December 2016 to 29 April 2018 (the first relevant sub-period), a period of approximately 17 months;

(b) the period from 29 April 2018 to 20 November 2018 (the second relevant sub-period), a period of approximately seven months;

(c) the period from 20 November 2018 to 13 February 2019 (the third relevant sub-period), a period of approximately three months; and

(d) the period from 13 February 2019 to 13 September 2019 (the fourth relevant sub-period), a period of approximately seven months.

18 The ACCC alleged that Trivago made four representations at various times during the Relevant Period, namely:

(a) that the Trivago website would quickly and easily identify the cheapest rates available for a hotel room responding to a consumer’s search (the Cheapest Price Representation);

(b) that the Top Position Offers were the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel, or had some other characteristic which made them more attractive than any other offer for that hotel (the Top Position Representation);

(c) that the Strike-Through Price was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel (the Strike-Through Representation); and

(d) that the Red Price was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel (the Red Price Representation).

19 The ACCC also alleged that Trivago engaged in conduct that led consumers to believe that the Trivago website provided an impartial, objective and transparent price comparison which would enable them to quickly and easily identify the cheapest available offer for a particular (or the exact same) room at a particular hotel (the additional conduct allegations).

20 Trivago admitted the part of the ACCC’s case based on the Cheapest Price Representation. With respect to a portion of the Relevant Period, Trivago also admitted the part of the ACCC’s case based on the Strike-Through Representation. However, the balance of the ACCC’s case was contested.

21 In the Liability Judgment, I considered each relevant sub-period separately: see [190]-[277]. In respect of each relevant sub-period, I held that the ACCC’s allegations were substantially made out. These conclusions were reflected in the declarations made on 28 February 2020. It is convenient to set out the declarations, as they provide a summary of the conclusions reached for each of the four relevant sub-periods:

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Between 1 December 2016 and 29 April 2018, the respondent (Trivago) in trade or commerce:

a. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), and engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of services in contravention of s 34 of the ACL, by representing in online and television advertising that its website, “www.trivago.com.au” (the Trivago website), would quickly and easily identify the cheapest rates available for a hotel room responding to a consumer’s search (the Cheapest Price Representation), when in fact the Trivago website did not enable consumers to quickly or easily identify the cheapest rates available for particular hotel rooms;

b. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by representing that the Strike-Through Price (being an offer in respect of a particular hotel that was displayed in red strike-[through] text) was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel (the Strike-Through Representation), when in fact the Strike-Through Price did not always relate to the same room category as the Top Position Offer (being an offer for a particular hotel displayed in green text, in a relatively large font);

c. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by representing that the Top Position Offers were the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel, or had some other characteristic which made them more attractive than any other offer for that hotel (the Top Position Representation), when in fact in many cases the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer for the hotel, nor did it have some other characteristic that made it more attractive than any other offer for the hotel; and

d. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of services in contravention of s 34 of the ACL, by making the Cheapest Price Representation, and by making Top Position Offers together with the Top Position Representation and the Strike-Through Representation, which led consumers to believe that the Trivago website provided an impartial, objective and transparent price comparison which would enable them to quickly and easily identify the cheapest available offer for a particular (or the exact same) room at a particular hotel, when this was not the case.

2. Between 29 April 2018 and 20 November 2018, Trivago in trade or commerce:

a. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by making the Strike-Through Representation, when in fact the Strike-Through Price did not always relate to the same room category as the Top Position Offer;

b. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by making the Top Position Representation, when in fact in many cases the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer for the hotel, nor did it have some other characteristic that made it more attractive than any other offer for the hotel; and

c. (in the period up to 2 July 2018) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of services in contravention of s 34 of the ACL, by making Top Position Offers on the Trivago website, making the Top Position Representation, making the Strike-Through Representation, and advertising the Trivago website, which led consumers to believe that the Trivago website provided an impartial, objective and transparent price comparison which would enable them to quickly and easily identify the cheapest available offer for a particular (or the exact same) room at a particular hotel, when this was not the case.

3. Between 20 November 2018 and 13 February 2019, Trivago in trade or commerce:

a. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by making the Strike-Through Representation in the map portion of the Trivago website, when in fact the Strike-Through Price did not always relate to the same room category as the Top Position Offer;

b. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by representing that the Red Price (being an offer in respect of a particular hotel displayed in red) was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel (the Red Price Representation), when in fact the Red Price did not always relate to the same room category as the Top Position Offer; and

c. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by making the Top Position Representation, when in fact in many cases the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer for the hotel, nor did it have some other characteristic that made it more attractive than any other offer for the hotel.

4. Between 13 February 2019 and 13 September 2019, Trivago, in trade or commerce:

a. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by making the Red Price Representation, when in fact the Red Price did not always relate to the same room category as the Top Position Offer; and

b. engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and (in connection with the supply of services) made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of those services in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by making the Top Position Representation, when in fact in many cases the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer for the hotel, nor did it have some other characteristic that made it more attractive than any other offer for the hotel.

The hearing and the evidence

22 The relief hearing was conducted by video-conference (using Microsoft Teams) due to restrictions in place because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

23 The parties prepared a statement of agreed facts (SOAF) dated 15 September 2021 for the purposes of the relief hearing. This deals with the CPC revenue obtained by Trivago during the Relevant Period, and also contains estimates of additional amounts paid by consumers. I will discuss this material later in these reasons.

24 The ACCC relies on an affidavit of Daniel Marquet, a partner of Corrs Chambers Westgarth, the solicitors for the ACCC, dated 20 September 2021. Mr Marquet was not cross-examined. The ACCC also relies on a number of documents.

25 Trivago relies on the following affidavits:

(a) an affidavit of Alexander Forstbach, the Chief Data Officer at Trivago – this deals with Trivago’s business and the market in which it operates; Trivago’s marketplace; the Top Position algorithm; the consumer journey before booking; Trivago’s search engine and the process of ‘caching’ offers; the search results in Mr Marquet’s affidavit; and Trivago’s conduct in misleading Australian consumers;

(b) an affidavit of Steffen Pyka, the Head of Accounting and Financial Planning & Analysis at Trivago – this deals with Trivago’s profit/loss between 2017 and 2020 (inclusive), and Trivago’s profit/loss from the Australian platform;

(c) an affidavit of Bryan Farrington, the Director of Metasearch Data & Bidding Operations for the Expedia group of companies (Expedia) – this provides booking cancellation information relating to bookings on online booking site brands affiliated with Expedia, which were sourced from Trivago’s Australian platform, during the Relevant Period; and

(d) an affidavit of Benjamin Kiely, a partner of King & Wood Mallesons, the solicitors acting for Trivago, dated 11 October 2021.

26 There was no cross-examination of these deponents. Several passages in the affidavits were held to be inadmissible.

Factual findings

27 As noted above, these reasons should be read together with the Liability Judgment. I will not repeat the factual findings made in that judgment, which are also relevant for present purposes. I now make some additional factual findings.

28 The currency used in the SOAF is Euros. The parties have agreed upon a figure as the average AUD/EUR exchange rate for the Relevant Period (0.64724) and have prepared a one-page document that converts each of the currency figures in the SOAF from Euros to Australian dollars at the agreed average exchange rate. I will set out the relevant currency figures in Australian dollars, rather than Euros, in the reasons that follow. All references to dollars ($) are to Australian dollars.

29 The expression “map view” appears in several places in the SOAF. This was referred to as the “map portion” of the Trivago website in the Liability Judgment. For consistency with the SOAF, I will refer to it as “map view” in these reasons. Some of the figures in the SOAF are expressed to include the map view, and some are expressed as not including the map view, depending on the data available to Trivago.

Trivago’s revenue relating to the Trivago website

30 The total CPC revenue that Trivago earned from all click-outs on the Trivago website (including click-outs on the map view) was:

(a) approximately $178 million during the Relevant Period;

(b) approximately $104 million during the first relevant sub-period;

(c) approximately $33 million during the second relevant sub-period;

(d) approximately $12 million during the third relevant sub-period; and

(e) approximately $29 million during the fourth relevant sub-period.

31 The total CPC revenue that Trivago earned from all click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers on the Trivago website (excluding click-outs on the map view) was:

(a) approximately $92 million during the Relevant Period;

(b) approximately $55 million during the first relevant sub-period;

(c) approximately $17 million during the second relevant sub-period;

(d) approximately $5 million during the third relevant sub-period; and

(e) approximately $15 million during the fourth relevant sub-period.

32 The SOAF uses the expressions “Higher CPC Cheapest Offer” and “Lower CPC Cheapest Offer”. These expressions relate to situations where equal cheapest offers were received by Trivago. In such cases, the “Higher CPC Cheapest Offer” refers to the equal cheapest offer with the highest CPC, and the “Lower CPC Cheapest Offer” refers to the equal cheapest offer with the lowest CPC.

(a) the CPC revenue Trivago earned from all click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers on the Trivago website (excluding click-outs on the map view); and

(b) the CPC revenue Trivago would have obtained if, in respect of each such click-out, the consumers had instead clicked out on the cheapest offer for the relevant listing,

was:

(c) during the Relevant Period:

(i) approximately $53 million (if the consumer had clicked out on the Higher CPC Cheapest Offer); or

(ii) approximately $58 million (if the consumer had clicked-out on the Lower CPC Cheapest Offer);

(d) during the first relevant sub-period:

(i) approximately $32 million (if the consumer had clicked out on the Higher CPC Cheapest Offer); or

(ii) approximately $36 million (if the consumer had clicked-out on the Lower CPC Cheapest Offer);

(e) during the second relevant sub-period:

(i) approximately $10 million (if the consumer had clicked out on the Higher CPC Cheapest Offer); or

(ii) approximately $11 million (if the consumer had clicked-out on the Lower CPC Cheapest Offer);

(f) during the third relevant sub-period:

(i) approximately $3.1 million (if the consumer had clicked out on the Higher CPC Cheapest Offer); or

(ii) approximately $3.4 million (if the consumer had clicked-out on the Lower CPC Cheapest Offer);

(g) during the fourth relevant sub-period:

(i) approximately $8 million (if the consumer had clicked out on the Higher CPC Cheapest Offer); or

(ii) approximately $9 million (if the consumer had clicked-out on the Lower CPC Cheapest Offer).

Click-outs from the Trivago website

34 During the Relevant Period, excluding click-outs on the map view, there were 53,906,872 click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers, representing approximately 52% of all click-outs on Top Position Offers (including on the map view). If that figure is ‘scaled up’ to take into account click-outs on the map view, then during the Relevant Period there were approximately 57 million click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers, representing approximately 54% of all click-outs on Top Position Offers.

Bookings where consumer clicked on non-cheapest Top Position Offer

35 Trivago does not have data which enables it to determine, in respect of each and every click-out on a non-cheapest Top Position Offer during the Relevant Period, whether that click-out resulted in a booking. However, it does have data on this issue in relation to click-outs to Tracking Partners (defined in the SOAF as Online Booking Sites who provide Trivago with booking data via “the pixel” or via the “conversion API”). In relation to all click-outs to Tracking Partners, a mean (average) of 2.96% led to a booking during the Relevant Period.

36 Trivago does not have data which enables it to determine precisely any of the following matters:

(a) the amenities included in, or room type of, each particular Top Position Offer or cheapest offer;

(b) all of the click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers throughout the Relevant Period that in fact resulted in a consumer booking a hotel room on an Online Booking Site at the same price as the non-cheapest Top Position Offer (completed hotel bookings);

(c) the total amount that consumers paid in respect of all completed hotel bookings; or

(d) in respect of each completed hotel booking, the total price consumers would have paid assuming they had instead clicked out on the cheapest offer and assuming that click-out in fact resulted in a consumer booking a hotel room on an Online Booking Site at the same price as the cheapest offer.

37 Based on the data that Trivago does have, the parties estimate that the difference between:

(a) the price for hotel rooms booked by consumers on Online Booking Sites through click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers on the Trivago website; and

(b) what the price for those hotel rooms would have been had they instead been booked by consumers on Online Booking Sites through click-outs on the cheapest offer for the relevant listings,

is as follows:

(c) for the Relevant Period – $36,985,090;

(d) for the first relevant sub-period – $21,873,761;

(e) for the second relevant sub-period – $7,941,356;

(f) for the third relevant sub-period – $1,841,720; and

(g) for the fourth relevant sub-period – $5,306,050.

38 The above figures do not take into account cancellations, which are relevant if one is considering loss or damage to consumers. Mr Farrington’s evidence provides an indication of the rate of cancellation, based on bookings on online booking site brands affiliated with Expedia that were sourced from Trivago’s Australian platform. Mr Farrington gives evidence (and I accept) that, based on Expedia records and the data in the spreadsheets described in his affidavit, 18.94% of the total dollar value of bookings sourced from Trivago’s Australian platform during the Relevant Period were refunded (including full and partial refunds) from cancellations. I accept that this percentage is indicative of refunds of bookings made on other Online Booking Sites that were sourced from the Trivago website during the Relevant Period. Accordingly, taking cancellations into account, the figures would be reduced by 18.94%. This produces the following approximate figures in place of those set out in the preceding paragraph:

(a) for the Relevant Period – approximately $30 million;

(b) for the first relevant sub-period – approximately $18 million;

(c) for the second relevant sub-period – approximately $6 million;

(d) for the third relevant sub-period – approximately $1 million; and

(e) for the fourth relevant sub-period – approximately $4 million.

Trivago’s business and business model

39 In December 2016, Trivago completed an initial public offering on the Nasdaq Stock Exchange. From that time, the ultimate holding company of the Trivago group has been Trivago N.V., a limited liability company incorporated in the Netherlands.

40 Trivago’s corporate headquarters are located in Düsseldorf, Germany. Mr Forstbach gives evidence, and I accept, that: substantially all of Trivago’s operations (including the vast majority of its staff and fixed assets) are based in Germany; Trivago does not employ any staff in Australia; all work in connection with its Australian website (including, for example, all sales and marketing work and all technical management of Trivago’s Australian website and back-end infrastructure) are undertaken at a group level by Trivago head office staff.

41 Trivago’s business involves aggregating online hotel offers made by participating hotels or online travel agents (referred to in the Liability Judgment and these reasons as “Online Booking Sites”) and displaying hotel offers in response to consumers’ searches. Trivago’s revenue is generated primarily on a CPC basis whereby Online Booking Sites pay Trivago a CPC fee each time a user clicks on an offer for accommodation. The click takes the user to the Online Booking Site, where the user can complete the booking.

42 Trivago has always operated in a highly competitive online travel industry. Trivago’s main competitors include: online metasearch and review websites (such as Google Hotel Ads, TripAdvisor and Kayak); search engines (such as Microsoft Bing, Google and Yahoo!); independent hotel chains (such as Accor, Hilton and Marriott); online travel agencies (such as Booking.com, Hotels.com, Wotif and Brand Expedia); and alternative accommodation providers (such as Airbnb and Vrbo).

43 Trivago competes with other advertising channels for hotel advertisers’ marketing spend. These include traditional offline media and online marketing channels.

44 Trivago receives an extremely large number of price points a day. Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that, the sheer volume of this data means that it is technically and commercially impracticable for Trivago to display rates to consumers on a “live” or “real time” basis, as this would cause a significant slowdown of the Trivago website, and many of the Online Booking Sites which have commercial arrangements with Trivago, especially independent hotels and smaller operators, would not have the capacity to respond to such a large volume of data requests.

45 Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that to deal with this issue, Trivago uses a multi-layered caching system whereby it requests data from Online Booking Sites which make offers on the Trivago website as frequently and as technically and commercially practicable for both Trivago and the Online Booking Site. Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that the following typically occurs:

(a) When a consumer generates a search in a given region, Trivago sends a request to all Online Booking Sites which make offers on the Trivago website asking for their lowest available rate for each hotel in the relevant search region for the relevant stay dates. There is no way for Trivago to verify that an Online Booking Site has in fact submitted its lowest available rate for each hotel. These rates remain cached for up to four hours, meaning that a user who makes an identical search (in terms of the relevant search region for the relevant stay dates) to one made by another user an hour earlier may see the same cached rates which had been provided by Online Booking Sites in response to Trivago’s request an hour earlier.

(b) When a consumer clicks on the More Deals button located on the initial results page, Trivago sends another request to Online Booking Sites, this time for all rates from each Online Booking Site for that specific hotel (i.e. it can cover more than one room category and rate plan, not just the lowest submitted rate from that Online Booking Site). The reason for this separate and subsequent request for all rates is that there is significantly more data (i.e. more load on both Online Booking Sites and Trivago), which is why this is limited to a user’s specific request for more information in relation to a given hotel (whereas the initial request by region will span multiple hotels). These rates will also be cached and remain in that pool for up to 30 minutes.

46 Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that: the reason for caching is to allow Trivago to identify, with the first request to Online Booking Sites, the lowest rates available for hotels in a particular region; that minimises the load for the initial search; with the second request, after a user has clicked on the More Deals button, Online Booking Sites are asked to supply all available rates and it is possible for those to be cheaper than the first rate Trivago received.

47 Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that: the process of caching is unrelated to the operation of the Top Position algorithm; the effect of caching is that the Top Position Offer may be drawn from a cache of offers that was created up to four hours earlier, while clicking on the More Deals button generates a new request for offer rates, which may load entirely new prices from Online Booking Sites, which were not known to Trivago previously (in the sense that the information is new or has changed since Trivago last requested rates); this caching process can result in rate discrepancies, for example, where the Online Booking Site has increased or decreased their rate for a hotel on their own platform and this has not yet been updated on Trivago’s website or, more generally, where the Online Booking Site responds to the Automatic Programming Interface (or API) request with another price.

Trivago’s apology, policies and training

48 Mr Forstbach states in his affidavit that Trivago “apologises unequivocally to Australian consumers for its contravening conduct, as found by the Court”.

49 Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that, to ensure that the contravening conduct is not repeated, Trivago has taken steps to mandate compliance with Australian consumer laws. He states that Trivago has in place: (a) a “Code of Business Conduct and Ethics” (Code), which was first issued on 9 December 2016 (and subsequently updated on 25 April 2019); and (b) a “Consumer Protection Compliance – General Principles and Process Memorandum” (Principles), which was first issued on 12 August 2019. Copies of these documents are annexed to Mr Forstbach’s affidavit.

50 Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that: the Code applies to all of Trivago’s employees, including the members of Trivago’s management and supervisory boards; the Code sets out fundamental principles that apply to employees’ conduct to ensure there is compliance with the law and that high ethical and professional standards are upheld; section 3 of the Code deals with compliance with laws, regulations and rules; the Code is explained to every new hire at Trivago at the time of onboarding and is available on the company’s intranet; all Trivago employees are required to certify, on a yearly basis, that they comply with the policy.

51 Mr Forstbach gives evidence (and I accept) that: as part of his role, he attends regular compliance meetings (or has a senior member of his team attend on his behalf); these monthly meetings involve members of Trivago’s legal team and the operational leads for various teams; they cover topics such as planned changes to the algorithm and proposed A/B tests to be run on Trivago’s platforms; Trivago’s current compliance program aims to ensure that the changing nature of Trivago’s business conforms and complies with relevant legal and regulatory developments.

Trivago’s net income from its Australian platform

52 Mr Pyka gives the following evidence, which I accept:

(a) Trivago’s financial reporting is done on a calendar year basis.

(b) Trivago’s main source of revenue is the CPC payments that it receives from Online Booking Sites when users of Trivago’s platform click on hotel offers in Trivago’s search results (Referral Revenue).

(c) Trivago’s largest expense is advertising expenses (Advertising Spend).

(d) Between 2017 and 2020, the vast majority of Trivago’s revenue was consumed by its Advertising Spend.

(e) Trivago’s total revenues for the 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020 calendar years were approximately €1.035 billion, approximately €915 million, approximately €839 million and approximately €249 million, respectively.

(f) Trivago’s business has operated with negative or very slim profit margins in the period 2017 to 2020.

(g) In 2020, Trivago sustained a net loss of approximately €245 million globally. The most significant factor causing this was the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Trivago’s business.

53 Mr Pyka gives evidence (and I accept) that: Trivago does not in the ordinary course of its business prepare or report separate profit and loss statements on a country-by-country basis; thus, it does not prepare separate profit and loss statements in relation to the Australian platform; however, Trivago can determine from the data in its accounts, for any given year, both the total Referral Revenue and Advertising Spend relating to its Australian platform.

54 As explained in paragraphs 29-35 of his affidavit, Mr Pyka caused to be prepared an analysis of the net profit/loss that Trivago earned in relation to its Australian platform, which involved adopting a basis for allocating a portion of the unallocated group expenses. Mr Pyka caused to be prepared “Australian P&Ls” on two alternative bases, namely the “revenue allocation basis”, and the “contribution allocation basis”. Of these, the former is the approach that management would be most likely to apply for financial reporting purposes.

55 In paragraphs 43 and 44 of his affidavit, Mr Pyka sets out a summary of Trivago’s profit/loss from Australia for 2017-2020, on each of the alternative bases referred to above. In paragraph 45 of his affidavit, Mr Pyka notes the following key aspects of the Australian P&Ls (which I accept):

(a) The total Referral Revenue from the Australian platform (that is, the Australian website and app) from 2017-2019 was approximately $206.8 million (applying the agreed exchange rate of Australian dollars to Euros of 0.64724).

(b) The total Advertising Spend in relation to the Australian platform during the same period was approximately $157.1 million (using the same exchange rate). In each of 2017, 2018 and 2019, the Advertising Spend accounted for 73.63%, 75.1 % and 80.39% of Referral Revenue.

(c) Based on the revenue allocation basis, the total net income/loss from the Australian platform during that period was approximately $6.72 million (applying the same exchange rate). This equates to a profit margin (i.e. net income as a percentage of Referral Revenue) of 3.25%.

Applicable principles – pecuniary penalties

56 Section 224(1) of the Australian Consumer Law relevantly provides that, if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of Pt 3-1 (which includes ss 29 and 34), the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which the section applies, as the court determines to be appropriate.

57 Section 224(2) provides that, in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission;

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Ch 4 or Pt 5-2 of the Australian Consumer Law to have engaged in any similar conduct.

58 The maximum pecuniary penalty changed during the Relevant Period. In the period up to 1 September 2018, the maximum pecuniary penalty for each act or omission to which s 224 applies (that relates to s 29 or 34) was, if the person was a body corporate, $1.1 million. In the period from 1 September 2018, the maximum pecuniary penalty for each such act or omission was, if the person was a body corporate, the greater of the three amounts mentioned in s 224(3A), namely:

(a) $10 million;

(b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission – 3 times the value of that benefit; and

(c) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit – 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred or started to occur.

59 Section 224(4) provides as follows:

If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more provisions referred to in subsection (1)(a):

(a) a proceeding may be instituted under this Schedule [ie, the Australian Consumer Law] against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of the provisions; but

(b) a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

60 The principles applicable to the discretion to impose pecuniary penalties have been discussed in many cases.

61 In Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (the Agreed Penalties Case), the High Court emphasised that the primary purpose of civil penalties is to secure deterrence. In contrast to criminal sentences, they are not concerned with retribution and rehabilitation but are “primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”: Agreed Penalties Case at [55] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ; see also at [110] per Keane J. This point was also emphasised by the High Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13 (Pattinson) at [15]-[16], [43], [45], [55] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ.

62 The primacy of deterrence has been emphasised in various cases in relation to contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law. For example:

(a) The Full Court of this Court has explained the need to ensure that the penalty in such cases “is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business” and will deter them “from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention”: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249 (Singtel Optus) at [62]-[63]; see also Pattinson at [17].

(b) The High Court, applying the observations in Singtel Optus, has referred to the “primary role” of deterrence in assessing the appropriate penalty for contraventions where commercial profit is the driver of the contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [64]-[66].

(c) The Full Court of this Court has emphasised that the “critical importance of effective deterrence must inform the assessment of the appropriate penalty”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [153]. The Court explained that “the greater the risk of consumers being misled and the greater the prospect of gain to the contravener, the greater the sanction required, so as to make the risk/benefit equation less palatable to a potential wrongdoer and the deterrence sufficiently effective in achieving voluntary compliance”: Reckitt Benckiser at [151]; see also at [57], [148]-[153], [164] and [176].

63 The plurality in Pattinson affirmed (at [18]) the well-known statements of French J, as his Honour then was, in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR ¶41-076; [1990] FCA 762 (CSR). In that case, his Honour listed several factors that informed the assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). His Honour stated:

The assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to a number of factors which have been canvassed in the cases. These include the following:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

64 After setting out the above passage, the plurality in Pattinson stated at [19]:

It may readily be seen that this list of factors includes matters pertaining both to the character of the contravening conduct (such as factors 1 to 3) and to the character of the contravenor (such as factors 4, 5, 8 and 9). It is important, however, not to regard the list of possible relevant considerations as a “rigid catalogue of matters for attention” as if it were a legal checklist. The court’s task remains to determine what is an “appropriate” penalty in the circumstances of the particular case.

(Footnotes omitted.)

65 The plurality in Pattinson considered the role of the prescribed maximum penalty as a yardstick in a civil penalty context, affirming (at [53]) the explanation provided by the Full Court of this Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [155]-[156]. See also Pattinson at [54]-[55].

66 In cases involving a very large number of contraventions, it may be unhelpful to seek to make a finding as to the precise number of contraventions, or to calculate a maximum aggregate penalty by reference to such a number: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [18] and [82] per Allsop CJ; Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68 at [143] per Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ.

67 It is relevant to refer to the course of conduct principle, which was considered by the Full Court of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [421]-[428]. The Full Court (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ) stated at [424] that the course of conduct principle is a useful “tool” in the determination of appropriate civil penalties. The Full Court continued:

As we have already indicated, the principal object of the penalties imposed by s 76 of the [Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)] is that of specific and general deterrence. With this in mind, in a civil penalty context, the course of conduct principle can be conceived of as a recognition by the courts that the deterrent effect in respect of a civil penalty (at both a specific and general level) is measured by reference to the nature of the conduct for which it is imposed. It is therefore of paramount importance to identify whether multiple contraventions constitute a single course of conduct or separate instances of conduct, so as to ensure that an appropriate deterrent effect is achieved by the imposition of the penalty or penalties in respect of that particular conduct.

68 In relation to the course of conduct principle, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698, Beach J stated at [25]:

… the “course of conduct” principle does not have paramountcy in the process of assessing an appropriate penalty. It cannot of itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions of the ACL. Further, its application and utility must be tailored to the circumstances. In some cases, the contravening conduct may involve many acts of contravention that affect a very large number of consumers and a large monetary value of commerce, but the conduct might be characterised as involving a single course of conduct. Contrastingly, in other cases, there may be a small number of contraventions, affecting few consumers and having small commercial significance, but the conduct might be characterised as involving several separate courses of conduct. It might be anomalous to apply the concept to the former scenario, yet be precluded from applying it to the latter scenario. The “course of conduct” principle cannot unduly fetter the proper application of s 224.

69 The above passage was cited with approval by the Full Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [141].

70 Where multiple separate penalties are to be imposed upon a particular wrongdoer, the ‘totality principle’ requires the Court to make a ‘final check’ of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole. It will not necessarily result in a reduction. However, in cases where the Court believes that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too high, the Court should alter the final penalties to ensure that they are ‘just and appropriate’: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53 per Goldberg J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Energy Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 234 FCR 343 at [101]-[102] per Middleton J.

71 In determining the appropriate penalty, it is relevant to consider steps taken to ameliorate loss or damage (such as payment of compensation) as potentially mitigatory considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] ATPR ¶42-251; [2016] FCA 44 at [166]-[167] per Edelman J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 146 ALD 385; [2015] FCA 399 at [38] per White J.

72 Co-operation with authorities in the course of investigations and subsequent proceedings can properly reduce the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. The reduction reflects the fact that such co-operation: increases the likelihood of co-operation in future cases in a way that furthers the object of the legislation; frees up the regulator’s resources, thereby increasing the likelihood that other contravenors will be detected and brought to justice; and facilitates the course of justice: see, eg, Agreed Penalties Case at [46]; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293-294.

Application of principles to the present case

General matters

73 The task before the Court is to determine pecuniary penalties of appropriate deterrent value in relation to the contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law that were the subject of the declarations of contravention set out above.

74 This case falls into that category of case where the number of contraventions is so large that it is not practicable to determine a precise number of contraventions or the total maximum penalty. The number of contraventions is in the millions. In relation to the maximum penalty, for the part of the Relevant Period up to 1 September 2018, the maximum penalty was $1.1 million per contravention. In relation to the period from 1 September 2018, the maximum penalty per contravention was the greater of the three amounts referred to at [58] above. The ACCC submits that, for practical purposes, I can proceed on the basis that the greater of the three amounts was $10 million. I accept that submission. It follows that, for the period from 1 September 2018, the maximum penalty was effectively $10 million per contravention. Accordingly, both for the part of the Relevant Period up to 1 September 2018, and for the part of the Relevant Period from 1 September 2018, the total maximum penalty is in the hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more.

75 Notwithstanding the above observations, it remains relevant to have regard to the maximum penalty per contravention at different times during the Relevant Period. As discussed later in these reasons, I consider it appropriate to determine a separate pecuniary penalty for each of the relevant sub-periods. In considering the appropriate pecuniary penalty for each relevant sub-period, it is important to take into account the maximum penalty per contravention during that sub-period. During the first relevant sub-period and part of the second relevant sub-period (i.e. up to 1 September 2018), the maximum penalty per contravention was $1.1 million. During the balance of the second relevant sub-period and during the third and fourth relevant sub-periods, the maximum penalty per contravention was effectively $10 million.

76 I will first consider the relevant considerations in relation to the Relevant Period generally. I will then consider the appropriate penalty for each relevant sub-period.

Relevant considerations

The nature and extent of the contravening conduct

77 The nature of the contravening conduct is described in the Liability Judgment. I refer, in particular, to the section of the Liability Judgment where I consider the representations made by, and the other conduct of, Trivago, and whether Trivago contravened the Australian Consumer Law: see the Liability Reasons at [190]-[277].

78 In my view, as noted above, Trivago’s contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law are extremely serious. The television advertising conducted by Trivago during the early part of the Relevant Period was highly misleading. The advertising conveyed that the Trivago website would quickly and easily identify the cheapest rates available for a hotel room responding to a consumer’s search (see the Liability Judgment at [196]-[202]), but in fact the website did not do this. As noted above, higher priced offers were selected as the Top Position Offer over alternative lower priced offers in 66.8% of listings.

79 Further, as noted above, Trivago represented that the Top Position Offers were the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel, or had some other characteristic which made them more attractive than any other offer for that hotel (see the Liability Judgment at, eg, [212]-[218]). This too was highly misleading, for the reasons given above and in the Liability Judgment.

80 The ACCC submits, and I accept, that the false and misleading nature of the representations made in Trivago’s advertising and on its website was obscured by the business model and algorithm that lay behind it, and that the true position was not in any meaningful way exposed to consumers.

81 Trivago’s contravening conduct extended over a lengthy period of time. Although the television advertisements related to only the early part of the Relevant Period, other contraventions took place over a period of nearly three years.

82 I note that Trivago made changes to its website over the course of the Relevant Period. These are described in the Liability Judgment, particularly at [62]-[81]. While these changes rendered the website less misleading, the Top Position Representation continued to be made throughout the Relevant Period.

83 A large number of consumers were affected by the conduct. As set out above, the evidence presented for the relief hearing shows that, during the Relevant Period, there were approximately 111 million click-outs on the Trivago website. The overwhelming majority (approximately 104 million or 93%) of the click-outs were on the Top Position Offer. There were approximately 57 million click-outs on a Top Position Offer for an identified hotel where the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer for that hotel.

The circumstances of the contravening conduct

84 Trivago derived substantial revenue from its contravening conduct. As set out above, the difference between:

(a) the CPC revenue Trivago earned from all click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers on the Trivago website (excluding click-outs on the map view); and

(b) the CPC revenue Trivago would have obtained if, in respect of each such click-out, the consumers had instead clicked out on the cheapest offer for the relevant listing,

during the Relevant Period was at least $53 million.

85 It may be inferred that in nearly all such cases, the consumer would not have clicked-out on the Top Position Offer if they had appreciated that the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer. They would, instead, have clicked-out on the cheapest offer for a room at the same hotel. Thus, it may be inferred that nearly all of the figure of approximately $53 million represents revenue derived by Trivago as a result of the contraventions.

86 The ACCC submits, and I accept, that Trivago’s contraventions of ss 29(1)(i) and 34 of the Australian Consumer Law were systemic and were the product of its business model.

87 I find that Trivago’s conduct in designing the Trivago website in the way that it did, and in preparing its television advertising in the way that it did, was intentional (in the sense of not accidental). Further, I find that Trivago’s conduct in designing the Top Position algorithm to operate in the way that it did was intentional. These matters did not appear to be disputed by Trivago at the relief hearing.

88 Insofar as the ACCC makes submissions, at paragraphs 43-48 of its outline of submissions, as to Trivago’s state of mind, I do not consider it necessary for present purposes to determine whether these submissions are established. In circumstances where the onus is on the ACCC to establish these propositions, it is doubtful whether there is sufficient evidence to establish these propositions. It is not possible to reach a concluded view as to the involvement of Trivago’s senior management in the contravening conduct.

Loss or damage

89 The loss or damage caused by Trivago’s contraventions was substantial.

90 Most obviously, this arose from consumers making a booking in relation to a non-cheapest Top Position Offer when they could have booked a room at the same hotel at a cheaper price.

91 As set out above, based on the data available to Trivago, the parties estimate, based on a number of assumptions, that the difference between:

(a) the price for hotel rooms booked by consumers on Online Booking Sites through click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers on the Trivago website; and

(b) what the price for those hotel rooms would have been had they instead been booked by consumers on Online Booking Sites through click-outs on the cheapest offer for the relevant listings,

for the Relevant Period was $36,985,090.

92 If cancellations are taken into account, the estimated figure reduces to approximately $30 million – still a substantial sum.

93 It may be inferred that in nearly all such cases, the consumer would not have clicked-out on the Top Position Offer and made the booking if they had appreciated that the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer. They would, instead, have clicked-out on the cheapest offer for a room at the same hotel. Thus, it may be inferred that nearly all of the estimated figure of approximately $30 million represents consumer detriment caused by Trivago’s contraventions.

94 There is no evidence of Trivago paying compensation, or making any other form of reparation, to affected consumers.

95 Thus, the position is that Trivago’s contraventions have caused loss or damage to Australian consumers in the order of $30 million, and no remediation has occurred. In my view, this calls for a substantial penalty.

96 The consumer detriment caused by Trivago’s contraventions may extend beyond the aspect discussed above. Likewise, Trivago’s contraventions may have caused detriment to competitors. However, it is sufficient for present purposes to focus on the loss or damage outlined above.

Trivago’s size and financial position

97 Trivago is, and was during the Relevant Period, a large global internet business. An indication of its size during the Relevant Period is provided by its revenues for the 2017, 2018 and 2019 calendar years, which were approximately €1.035 billion, approximately €915 million and approximately €839 million respectively.

98 The size of Trivago’s Australian operations was also substantial. As set out above, the total CPC revenue that Trivago earned from all click-outs on the Trivago website, including click-outs on the map view, during the Relevant Period was approximately $178 million.

99 Other details of Trivago’s size and financial position have been referred to earlier in these reasons.

Benefits to Trivago from the contraventions

100 There is an issue between the parties as to the proper approach to ascertaining the benefits that Trivago obtained from the contravening conduct. The ACCC focuses on the CPC revenue that Trivago obtained from click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers (approximately $92 million), and the difference between the CPC revenue that it obtained from such click-outs and the CPC revenue that it would have obtained if consumers had instead clicked-out on the cheapest offer (at least approximately $53 million).

101 On the other hand, Trivago focuses on the profit it derived from the contravening conduct. Trivago notes that its profit margin (net income as a percentage of Referral Revenue) was 3.25%. Applying that percentage to the revenue figure of $53 million referred to above, the profit was approximately $1.7 million. Trivago submits that, even if one were to assess Trivago’s benefit from the contravening conduct by reference to the net profit it earned from all CPC revenue generated through click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers during the Relevant Period (i.e. the figure of $92 million referred to above), the net profit is $2,996,678.

102 Further, Trivago notes that the net income it derived from its Australian operation over the 2017, 2018 and 2019 calendar years was approximately $6.72 million. Trivago notes that this figure includes revenue from its Australian app, which is not part of the present proceeding, and therefore overstates the position for present purposes.

103 In my view, each of the above matters is relevant for present purposes. Insofar as Trivago submits that the revenue figures are not relevant for the purposes of assessing benefits, I do not accept that proposition. In particular, the difference between the CPC revenue that Trivago obtained from click-outs on Top Position Offers that were not the cheapest offer, and the CPC revenue that it would have obtained if consumers had instead clicked-out on the cheapest offer was at least approximately $53 million. As discussed at [85] above, it may be inferred that in nearly all such cases, the consumer would not have clicked-out on the Top Position Offer if they had appreciated that the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer. In circumstances where a large proportion (in the order of 75%) of Trivago’s revenue was spent on advertising, which attracted more consumers to the website, I consider this additional revenue (or at least a large part of it) to have been a benefit to Trivago.

Culture of compliance

104 Mr Forstbach’s evidence regarding policies and training has been summarised above. The Code, which was first issued on 9 December 2016 (and subsequently updated on 25 April 2016), is not specifically directed to Australian consumer laws. The Principles, which relate to consumer protection compliance, were issued on 12 August 2019, about one month before the end of the Relevant Period. There is no evidence of Trivago having in place, before 12 August 2019, any policies or procedures to ensure compliance with Australian consumer laws. This is despite the fact that Trivago had an Australian website that was directed at Australian consumers.

105 I accept that Trivago has now, belatedly, taken some steps to ensure that it complies with Australian consumer laws. However, the evidence about this is not very detailed. It is unclear whether or not these policies are sufficient to ensure compliance with Australian consumer laws.

106 Trivago has, through the affidavit of Mr Forstbach, apologised for its contravening conduct. This is a factor in Trivago’s favour for the purposes of determining the appropriate penalties. However, Trivago has not provided any detailed explanation as to how the contravening conduct came to occur. Such evidence would have assisted in demonstrating that it has insight into its contravening conduct.

Co-operation with the ACCC

107 Trivago made some limited admissions before trial. However, these did not shorten the trial by any appreciable amount. I consider that these admissions were merely an acceptance of the almost inevitable conclusion regarding the relevant representations. Accordingly, I give these admissions little weight.

108 Trivago co-operated with the ACCC in the preparation of a statement of agreed facts for the purposes of the hearing on liability. This dealt with some basic matters regarding the Trivago website and Trivago’s advertising and marketing. My impression is that these matters were not particularly controversial. While Trivago’s co-operation in the preparation of this document should be taken into account, I do not give this factor significant weight.

109 Trivago has also co-operated with the ACCC in the preparation of the SOAF for the purposes of the relief hearing. This contains agreed facts regarding substantive matters relevant to penalty. As the ACCC accepts, Trivago’s co-operation in the preparation of the SOAF is a significant matter and is to be taken into account in Trivago’s favour in considering the appropriate penalties. The ACCC submits, and I accept, that this should lower the penalties that would otherwise be ordered by 10%.

Prior similar conduct

110 Trivago has not previously been found by a court in Australia to have engaged in similar conduct.

The appropriate penalty for each relevant sub-period

111 In the circumstances of this case, I consider it appropriate to determine a separate penalty for each relevant sub-period (rather than determining a single penalty for all of the contraventions during the Relevant Period). This is consistent with the structure of the Liability Judgment, which described the form of the website during each relevant sub-period (see [62]-[81]) and considered whether the ACCC’s case was made out separately in respect of each relevant sub-period (see [190]-[277]). It is also consistent with the form of the declarations made on 28 February 2020, which comprised a separate declaration for each of the four relevant sub-periods.

112 I consider that the contravening conduct in each relevant sub-period should be treated as a single course of conduct, given the overlap and inter-relationship between the contraventions; they all had the effect of misleading consumers in a broadly similar way. However, this does not mean that the maximum penalty for each relevant sub-period is the maximum penalty for a single contravention. As the authorities discussed above make clear, to take such an approach (i.e. identifying a course of conduct) does not convert the many separate contraventions during a relevant sub-period into a single contravention; nor does it constrain the available maximum penalty.

113 In considering the appropriate penalty for each relevant sub-period, it is important to have regard to the overlap and inter-relationship between the contravening conduct during the sub-period, so that Trivago is not penalised more than is appropriate given that overlap and inter-relationship.

114 Further, it is necessary to have regard to the ‘same conduct’ constraint in s 224(4) of the Australian Consumer Law, set out above. In determining a single pecuniary penalty in respect of each relevant sub-period, I will take into account the overlap between the “additional conduct” contraventions (see paragraphs 1(d) and 2(c) of the declarations made on 28 February 2020) and the other contraventions, and ensure that Trivago is not liable to more than one penalty in respect of the same conduct.

115 As discussed above in the section headed “Applicable principles – pecuniary penalties”, it is necessary to consider what penalties are appropriate for the purposes of specific and general deterrence. In doing so, it is necessary to have regard to the particular contraventions that occurred in each relevant sub-period and the maximum penalty per contravention during the relevant sub-period. In the circumstances of this case, two numerical yardsticks or benchmarks that are of assistance in determining the appropriate penalty in respect of each relevant sub-period are the estimated loss or damage suffered by consumers (with the estimates adjusted for cancellations) (see [38] above) and the difference between the CPC revenue that Trivago obtained from click-outs on non-cheapest Top Position Offers and the CPC revenue that it would have obtained if consumers had instead clicked-out on the cheapest offer (see [33] above).

First relevant sub-period

116 The first relevant sub-period runs from 1 December 2016 to 29 April 2018, a period of approximately 17 months.

117 The contraventions during this period were considered in the Liability Judgment at [193]-[225].

118 I consider the conduct during this relevant sub-period to be the most serious, because Trivago’s conduct included the Cheapest Price Representations and because of the form of the Trivago website during this period. While the conduct during this period was the most serious, the maximum penalty during the period was $1.1 million per contravention, rather than $10 million per contravention, which applied later in the Relevant Period.

119 Having regard to these matters, and the relevant considerations discussed above as applicable to the first relevant sub-period, I consider an appropriate penalty for the contraventions during this sub-period to be $30.6 million.

Second relevant sub-period

120 The second relevant sub-period runs from 29 April 2018 to 20 November 2018, a period of approximately seven months.

121 The contraventions during this period were considered in the Liability Judgment at [226]-[248].

122 This relevant sub-period is more complicated than the others, because the contravening conduct was not uniform during the sub-period and the maximum penalty per contravention changed during this sub-period. In the period up to 2 July 2018, the contravening conduct included the “additional conduct” contraventions identified in paragraph 2(c) of the declarations. The maximum penalty for period up to 1 September 2018 was $1.1 million per contravention. From 1 September 2018, the maximum penalty was effectively $10 million per contravention.

123 Having regard to these matters, and the relevant considerations discussed above as applicable to the second relevant sub-period, I consider an appropriate penalty for the contraventions during this sub-period to be $7.1 million.

Third relevant sub-period

124 The third relevant sub-period runs from 20 November 2018 to 13 February 2019, a period of approximately three months.

125 The contraventions during this period were considered in the Liability Judgment at [249]-[264].

126 The maximum penalty during this sub-period was effectively $10 million per contravention.

127 Having regard to these matters, and the relevant considerations discussed above as applicable to the third relevant sub-period, I consider an appropriate penalty for the contraventions during this sub-period to be $2.1 million.

Fourth relevant sub-period

128 The fourth relevant sub-period runs from 13 February 2019 to 13 September 2019, a period of approximately seven months.

129 The contraventions during this period were considered in the Liability Judgment at [265]-[277].

130 The maximum penalty during this sub-period was effectively $10 million per contravention.

131 Having regard to these matters, and the relevant considerations discussed above as applicable to the fourth relevant sub-period, I consider an appropriate penalty for the contraventions during this sub-period to be $4.9 million.

Conclusion as to pecuniary penalties

132 For the reasons set out above, and subject to the following comment regarding the totality principle, I have concluded that the following penalties are appropriate:

(a) in respect of the contraventions during the first relevant sub-period – a pecuniary penalty of $30.6 million;

(b) in respect of the contraventions during the second relevant sub-period – a pecuniary penalty of $7.1 million;

(c) in respect of the contraventions during the third relevant sub-period – a pecuniary penalty of $2.1 million; and