FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Williams v Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (Initial Trial) [2022] FCA 344

ORDERS

First Applicant DIRECT CLAIM SERVICES QLD PTY LTD ACN 167 519 968 Second Applicant | ||

AND: | TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION AUSTRALIA LIMITED (ACN 009 686 097) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 5pm on 19 April 2022 the parties provide to the Associate to Justice Lee an agreed minute or competing minutes of order to reflect these reasons.

2. The proceeding be adjourned part heard for the purpose of the making and entry of final orders at 10.15am on 22 April 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CONTENTS:

LEE J:

1 If there was ever a case demonstrating unnecessary and bewildering complication in the law, it is this one. On one level, it is difficult to imagine a simpler dispute. Picture the familiar scene: a man goes into a car showroom and buys a car. He haggles and settles upon one he likes. He is happy with the look of it, and he is told it is a very good car. He hands over his money and contentedly drives out of the dealership. In his excitement, he is more interested in breathing in the ambrosial new car smell than reflecting on the reality that, as soon as he drove out of the dealership, the market value of the car had diminished.

2 But he was not told something. Unbeknownst to him, and indeed to the dealer, his car had a problem. Although apparently safe to drive, it was not designed to function properly during all driving conditions and, even if driven normally, there was a substantial likelihood that white smoke would come out of the car’s exhaust, along with a malodour. This problem also meant it was likely the car would use more petrol than expected and he would receive excessive notifications requiring him to service the car. Although he bought the car in ignorance of the problem, he did appreciate that if there were any such issues, the cost of fixing them would not be his responsibility.

3 If he had of known the true position, there is no question in my mind that he would likely have paid less for the car. After all, it was not the problem-free car he thought he had purchased.

4 One would intuitively think that such a case should not be in the least complex. This has not proven to be the case. This is partly because a class action has been brought, and partly because of the lamentable drafting of some statutory provisions. Further, the parties (the respondent, Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (TMCA), in particular) have maintained issues, which should have either been conceded or agreed. The result was a hearing taking weeks and hundreds of pages of submissions.

5 Before turning to consider the minutiae of the claims advanced, by way of introduction, it is worth sketching the broad outline of the case.

6 It is not in dispute that between 1 October 2015 and 23 April 2020 (Relevant Period), 264,170 Toyota cars in the Prado, Fortuner and HiLux ranges and fitted with so-called “1GD-FTV” or “2GD-FTV” diesel combustion engines were supplied to consumers in Australia (Relevant Vehicles). Each Relevant Vehicle was supplied with a diesel exhaust after-treatment system (DPF System), which was defective because it was not designed to function effectively during all reasonably expected conditions of normal operation and use of the vehicle.

7 The first applicant in this class action is Mr Kenneth John Williams. The second applicant is a company of which Mr Williams is the sole director, Direct Claim Services Qld Pty Ltd (DCS), and through which he conducts his business as a motor vehicle accidents assessor. It is common ground that DCS acquired a Prado (Relevant Prado) during the Relevant Period and paid the associated tax, financing and fuel costs. The evidence establishes that the Relevant Prado has been plagued with problems associated with the defective DPF System.

8 As it turned out, and despite some initial confusion, any cause of action that exists belongs to DCS. The claim of Mr Williams was dismissed at the conclusion of oral argument (although both Mr Williams and DCS remain representative applicants, pursuant to s 33D(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Act)).

9 TMCA is the “manufacturer” of the Relevant Vehicles for the purpose of s 7 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). TMCA also marketed the Relevant Vehicles in Australia, and in doing so made representations about the quality and characteristics of those vehicles and the DPF System to prospective consumers.

10 The group members whom the applicants represent are persons who acquired a Relevant Vehicle during the Relevant Period (and otherwise meet the description of group members in the second further amended statement of claim (2FASOC)).

11 The claims made by DCS on its own behalf, and by both Mr Williams and DCS on behalf of group members are, in summary, that:

(1) the Relevant Vehicles as supplied were not of “acceptable quality” and therefore failed to comply with the statutory guarantee in s 54 of the ACL; and

(2) TMCA made misleading representations and omissions about the Relevant Vehicles, in contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(a) and (g), and 33 of the ACL.

12 A number of subsidiary issues arise when considering these causes of action and the relief that should be obtained from those actions, but at a general level, this is the case advanced.

13 Finally, by way of introduction, given the size of the record, I have adopted the expedient of incorporating some references to agreed facts and other documents in these reasons (although I should caveat this by noting that a reference is often illustrative, rather than identifying an exclusive source).

B THE RELEVANT FACTS AND EVIDENCE

14 Following the adoption of two reports of a referee (the first dated 15 October 2020 (First Referee’s Report) and the second dated 31 August 2021 (Second Referee’s Report) (together, referee’s reports)), and the preparation of a statement of agreed facts (Agreed Facts or AF) and supplementary statement of agreed facts (SAF) for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act), one would have thought there would only be a simulacrum of a dispute remaining as to the facts. As it transpired, this assumption was somewhat optimistic, and it is necessary to deal with a number of contested factual issues. Before doing so, however, it is convenient to canvass briefly the facts upon which the parties agreed and provide an overview of the evidence adduced at the trial.

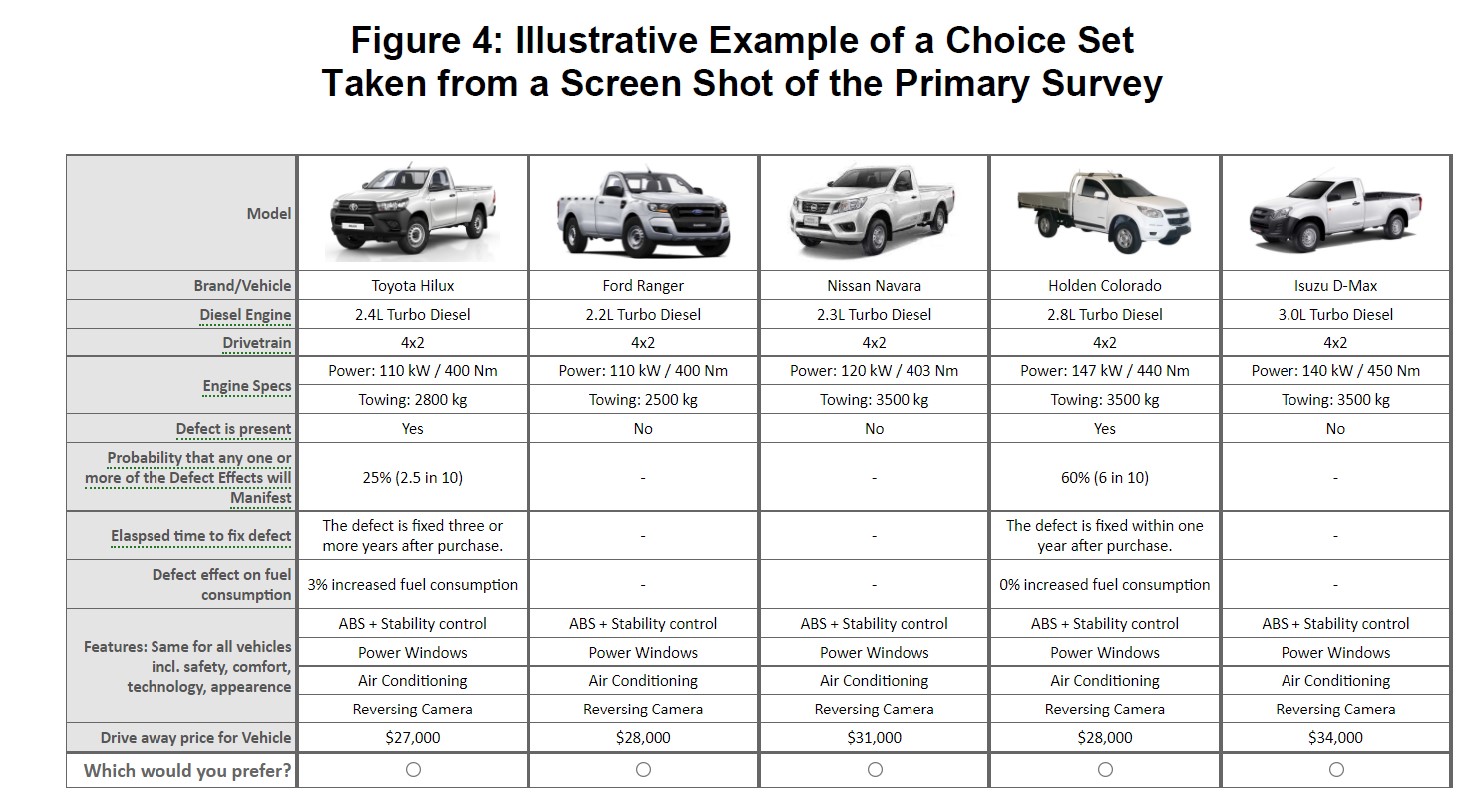

15 Drawing upon the detailed Agreed Facts (which delve into issues with technicality and granularity), it is useful to summarise the DPF System, the Core Defect and the effective remedy:

(1) Each of the Relevant Vehicles contained either a 1GD-FTV or a 2GD-FTV diesel combustion engine. Such diesel combustion engines generate pollutant emissions: AF 34]. The DPF System is designed to capture and convert the pollutant emissions into carbon dioxide and water vapour through a combination of filtration, combustion (that is, ‘oxidation’) and chemical reactions: AF [42].

(2) All Relevant Vehicles were fitted with a DPF System: AF [33], [39]. This was necessary at least because the Relevant Vehicles, throughout the Relevant Period, were required to comply with national emissions standards prescribed by the applicable Australian Design Rules, which standards regulated the emission of Pollutant Emissions: AF [35]–[39].

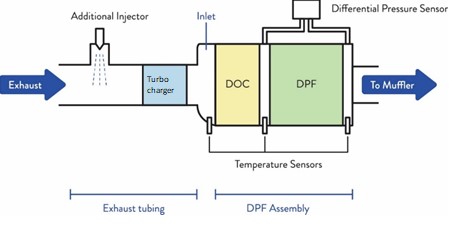

(3) The nature of the DPF System in the Relevant Vehicles is described in detail in the Agreed Facts: AF [33]–[66]. Two core components of the DPF System are the diesel particulate filter (DPF) and the diesel oxidation catalyst (DOC), which sit together in the DPF Assembly: AF [46]–[47]. The basic design of the DPF Assembly in the Relevant Vehicles is illustrated by the following image (showing a cross section):

(4) The DPF is designed to capture what is called diesel particulate matter in the exhaust gas prior to its release, and to store it: AF [42], [47]. The DPFs in the Relevant Vehicles have a finite capacity to capture and store particulate matter: AF [51]. As such, in order for the DPF to function effectively, the particulate matter captured by and stored in the DPF must be burned off periodically in a process called regeneration: AF [53]. Regeneration requires the exhaust temperature to increase to the level required for the particulate matter to oxidise: AF [57], [73(g)].

(5) The DOC comprises a honeycomb ceramic flow-through monolith substrate with a catalyst coating containing precious metals: AF [46(a)]. One of the functions of the DOC is to increase the temperature in the DPF during regeneration: AF [46(b)(ii)]. When the DOC becomes clogged or blocked, the DPF is impeded from regenerating effectively: First Referee’s Report (at [8], [39], [47], [55]).

(6) When regeneration does not occur, or is ineffective, the DPF becomes blocked with particulate matter, and the vehicles experience a range of problems. Indeed, the Core Defect was described by the referee in his initial report in the following terms (at [8]):

The DPF System was defective for the whole of the Relevant Period. The core defect was that the DPF System was not designed to function effectively during all reasonably expected conditions of normal operation and use in the Australian market. In particular, under certain conditions the DPF System was ineffective in preventing the formation of deposits on the DOC surface or coking within the DOC. The deposits and/or coking of the DOC prevented the DPF filter from effective automatic or manual regeneration, and led to excessive white smoke and foul-smelling exhaust during regeneration and/or indications from the engine’s onboard diagnostic (OBD) system that the DPF was “full”.

This defect was inherent in the design of the DPF System. The design defect was comprised of both mechanical defects and defective control logic and associated software calibrations.

(Emphasis in original).

(7) A key occurrence which caused the Core Defect to manifest was the exposure of a Relevant Vehicle to regular continuous driving at approximately 100km per hour (High Speed Driving Pattern): AF [67].

(8) During the Relevant Period, in Relevant Vehicles in which the Core Defect was present, if the Relevant Vehicles were exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern and/or subject to the countermeasures other than those referred to below (at [15(10)]):

(a) the DOC became blocked by deposits forming on the face of the DOC;

(b) regeneration events failed to remove sufficient particulate matter from the DPF to prevent the DPF from becoming or remaining full or blocked;

(c) the DPF System failed to prevent the DPF from becoming full or blocked;

(d) the DOC and DPF did not function effectively;

(e) the catalytic efficiency of the DOC was diminished; and

(f) the exhaust in the DPF did not reach a sufficiently high temperature to effect thermal oxidation (the chemical reaction of particulate matter with oxygen at a sufficiently high temperature, resulting in carbon dioxide and water vapour) (see AF [73]).

(9) In the Relevant Vehicles that experienced the effects of the Core Defect, symptoms included excessive white smoke and foul-smelling exhaust being emitted from the vehicle’s exhaust during regeneration, and DPF notifications displaying on an excessive number of occasions or for an excessive period of time. It will be necessary to address with precision the consequences of the Core Defect in further depth below.

(10) TMCA attempted a series of countermeasures to fix the problem. Two countermeasures are presently relevant: first, the countermeasure introduced and applied to all new Relevant Vehicles at the time of production (2018 Production Change); and secondly, the countermeasure introduced from May 2020 (2020 Field Fix). It is common ground that the 2020 Field Fix was effective and will continue to be effective in remedying the Core Defect and its consequences in all Relevant Vehicles: see AF [180].

(11) Similarly, from June 2020, all Relevant Vehicles were produced with the countermeasure preventing the Core Defect from manifesting (2020 Production Change): AF [175].

16 TMCA’s knowledge concerning these matters, and the development of the issues in relation to the Relevant Vehicles generally, are detailed comprehensively in the Agreed Facts: see AF [125]–[179]. There is no need to set them out here. It sufficies to note that, essentially, from February 2016, TMCA was aware that some Relevant Vehicles were being presented to dealers by customers (called by TMCA, somewhat oddly, as “guests”) who reported concerns with, among other things, the emission of excessive white smoke during regeneration and the illumination of DPF notifications. Over the next four years before the introduction of the 2020 Field Fix; the number of complaints increased dramatically; the issues were escalated to the top levels of TMCA and its parent company in Japan, Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC); and a number of countermeasures were introduced, tested and failed. I will expand upon the relevance of TMCA’s knowledge of the Core Defect and its consequences where necessary below.

17 Despite the parties’ constructive approach to the production of the Agreed Facts, as I foreshadowed, some residual issues relevant to the question of liability remain in dispute.

18 It is also convenient here to survey briefly the evidence that was given at trial. It may be observed from the outset that most of the evidence led concerned issues of loss and damage, and in particular, the quantification of the “reduction in value” resulting from the Core Defect.

19 Mr Williams swore two affidavits and gave evidence for approximately half a day. His first affidavit was sworn on 11 December 2020 (First Williams Affidavit). He was a witness whose credit was not impeached and his affidavit evidence was essentially unchallenged. Mr Williams’ evidence is primarily relevant to three broad issues remaining in dispute, namely:

(1) the Core Defect and its consequences, when those consequences manifested, and the impact of those consequences upon the use and enjoyment of the Relevant Vehicles;

(2) the extent to which he relied upon the representations made by TMCA; and

(3) any consequential loss and damage he suffered by reason of the Core Defect and its consequences, particularly with respect to increased fuel consumption experienced by the Relevant Prado.

B.2.2 Messrs Nelson, Jones, Gray and Berndt

20 Mr Martin John Nelson is the Divisional Manager of TMCA’s Guest First Division, a position he has held since late 2017. He affirmed one affidavit on 5 October 2021 (Nelson Affidavit) concerning communications between TMCA and dealers, and TMCA and customers, and the roll out of the countermeasures, as well as amounts paid and replacement vehicles provided to customers under TMCA’s consumer redress programme. He gave evidence for approximately half a day.

21 Mr Nelson’s evidence indicated that TMCA, at least internally, recognised that the Core Defect and its consequences interfere with the use and enjoyment of the Relevant Vehicles. The findings of fact that emerge from Mr Nelson’s evidence in this respect will be explored in greater detail below, but it is convenient to note here that his evidence establishes that:

(1) TMCA recognised, from an early stage in the Relevant Period, that the issues affecting the DPF System in the Relevant Vehicles posed a serious threat to TMCA’s market reputation: Nelson Affidavit (at [82]);

(2) TMCA has approached the DPF issues as a serious matter deserving of the urgent attention of TMC, and has dedicated substantial resources to attempting to remedy the issues (T84.22–25); and

(3) since the commencement of this proceeding, TMCA has offered refunds and replacement vehicles to “hundreds” of consumers, in recognition of the failure of the vehicles to comply with statutory guarantees under the ACL (T98.25–99.13; 103.39–40).

22 TMCA also relies on the affidavits of three further witnesses:

(1) Mr Brent Andrew Jones, the Manager, Digital Marketplace of TMCA, who gave evidence in relation to webpages published on TMCA’s website about DPF issues and the number of times they were accessed (Jones Affidavit);

(2) Mr Nathanael David Gray, the Manager, National Business Fleet Sales of TMCA, who gave evidence in relation to the categories of purchasers of Relevant Vehicles (Gray Affidavit); and

(3) Mr David Berndt, an employee of TMCA’s solicitors, who gave evidence of what was set out in a spreadsheet which contained details of the Relevant Vehicles (Berndt Affidavit).

23 The evidence of these witnesses was relatively uncontroversial and will be elaborated upon where necessary below.

24 The primary contest relates to the expert evidence adduced in respect of the quantification of a reduction in value of the Relevant Vehicles for the purposes of the applicants’ case concerning acceptable quality under s 54 of the ACL. It is convenient to introduce the general nature of that evidence here and the ambit of the dispute, which I will expand upon in Part E.2.3 below.

25 Both sides adduced valuation evidence. Mr Graeme Cuthbert, engaged by the applicants, is a licensed motor vehicle trader and car valuer with 50 years’ experience. He provided two reports before the trial: one dated 23 July 2021 (First Cuthbert Report) and one dated 22 October 2021 (Second Cuthbert Report). Mr Tim O’Mara, whom TMCA engaged, is a valuer and the Managing Director of O’Maras, a valuation and auction house. Mr O’Mara specialises in valuing company assets for the purposes of merger and acquisition transactions and bank financing. He provided a first report dated 30 September 2021 (First O’Mara Report) and a second dated 26 November 2021 (Second O’Mara Report). Both experts participated in a joint conference and provided a further report dated 10 November 2021 in response to a series of questions put to them by the Court during their concurrent oral evidence. Both valuers gave evidence principally about the true value of the Relevant Prado as at the date of acquisition (8 April 2016), having regard to the presence of the Core Defect and a propensity for the consequences associated with it in the Relevant Prado.

26 Both sides also adduced expert evidence in the field of economics. Mr Edward Stockton, a Vice President and Director of Economic Services at the Fontana Group, is an economist and econometrician with expertise in automobile markets and studies of the impact of defects on motor vehicle prices. Mr Stockton was engaged by the applicants and provided two reports: one dated 23 July 2021 (First Stockton Report) and another dated 22 October 2021 (Second Stockton Report). Dr Christopher Jon Pleatsikas, an economist and a Vice President at Charles River Associates, was called by TMCA, and provided a report dated 30 September 2021 (Pleatsikas Report). Both experts participated in a joint expert conference, out of which they produced a joint report dated 5 November 2021 (Stockton and Pleatsikas Joint Report).

27 Generally speaking, the economic evidence was directed to Mr Stockton’s repair cost model analysis, which essentially used the warranty repair cost that TMCA reimbursed to dealers for performing the 2020 Field Fix as a proxy for the amount of money that would have been required, at the time of purchase, to restore group members to the position they would have been in had there been compliance with the statutory guarantee.

28 The applicants also adduced evidence from Mr Stefan Boedeker, an economist with specialist expertise in conjoint analysis and Managing Director of the Berkeley Research Group. Conjoint analysis, in simple terms, is a survey-based statistical technique deployed in market research to determine how people value different attributes in a product or service. Mr Boedeker prepared three reports: a first dated 23 July 2021 (First Boedeker Report); a second dated 28 October 2021 (Second Boedeker Report); and a third dated 4 December 2021 (Third Boedeker Report). Dr Rossi, an econometrician and Professor of Marketing, Statistics and Economics at the University of California, Los Angeles, was instructed by TMCA and prepared a report dated 4 October 2021 (Rossi Report). Mr Boedeker and Dr Rossi participated in a joint expert conference and produced a joint report dated 19 November 2021, including separate statements summarising the issues between them (Boedeker and Rossi Report).

29 The evidence of Mr Boedeker and Dr Rossi concerned a “choice-based conjoint” survey created by Mr Boedeker for the purposes of assessing any reduction in value resulting from the Core Defect and its consequences. Mr Boedeker engaged a third party vendor (Amplitude) to programme, host and implement the survey and relied on another third party provider (Dynata) to select participants for the survey. Over 4,000 participants were surveyed, and Mr Boedeker’s final analysis considered 3,565 responses (Analysed Responses). Dr Rossi’s evidence was responsive to Mr Boedeker’s evidence.

30 The factual issues in dispute on the question of liability are largely concerned with the scope and frequency of the Core Defect and its consequences. With some degree of simplification, the following four issues remain for determination:

(1) Was the Core Defect present in vehicles which had the 2018 Production Change?

(2) Did all Relevant Vehicles have a propensity to suffer from the consequences of the Core Defect?

(3) What was the significance of the Core Defect and its consequences?

(4) Was the market aware of the Core Defect and its consequences during the Relevant Period?

31 I will deal with each of these contested issues in turn.

B.3.1 Was the Core Defect present in vehicles which had the 2018 Production Change?

32 While it may have been thought that the findings made by the Court upon adoption of the reports of the referee and recorded in the Agreed Facts were clear, TMCA seeks to draw a distinction between the Relevant Vehicles:

(1) produced prior to June 2018 (Pre-MY2018 Production Vehicles); and

(2) produced between 1 June 2018 and 23 April 2020 (MY2018 Relevant Vehicles).

33 The relevance of the date 1 June 2018 is that, as foreshadowed above (at [15(10)–(11)]), the 2018 Production Change countermeasure was introduced by TMCA and applied to all new Relevant Vehicles on this date.

34 Initially, TMCA sought to contend, in its defence, that vehicles that were subject to the 2018 Production Change did not suffer from the Core Defect at the time they were supplied: Defence to Second Further Amended Statement of Claim (D2FASOC) (at [52(a)], [100(c)]; see also [39(c)–(d)], [41(b)]). In TMCA’s opening submissions, however, it was accepted that any submission to the effect that the 2018 Production Change remedied the Core Defect “is unlikely to be accepted”. Accordingly, TMCA initially stated that, “for the purposes of the initial trial, TMCA does not dispute that the Core Defect was present in the DPF Systems of all Relevant Vehicles until such time as they received/receive the 2020 Field Fix”.

35 TMCA now contends that the Core Defect was not present in vehicles which had the 2018 Production Change (that is, the MY2018 Relevant Vehicles), or alternatively that the 2018 Production Change was effective to prevent Relevant Vehicles from suffering from the Core Defect. The issue affects 37 per cent (98,861) of the Relevant Vehicles. In support of this contention, it is said that the referee’s conclusions with respect to the vehicles to which the 2018 Production Change was applied were ambiguous and, in these circumstances, the Court can and should find that the Core Defect was not present in the MY2018 Relevant Vehicles: see T4.12–44.

36 Whether the 2020 Countermeasures included the 2018 Production Change and whether the 2018 Production Change had been effective are matters that were debated by the parties in the submissions provided to the referee as part of the Second Referee’s Report: see Annexure A [50]; Annexure E [13]–[15]; Annexure F [24]–[25]. TMCA submits that notwithstanding those submissions, and while the referee specifically asked for information about the 2018 Production Change, he did not express any indication in his Second Report about the effectiveness of that change, nor did he state whether or not the 2020 Countermeasures (which he defined as the “countermeasures implemented after the Relevant Period”) included the 2018 Production Change. The so-called ambiguity in the First Referee’s Report is said to arise from the following statements (at [12] and [50]):

12. The countermeasures put in place after the Relevant Period appear to remedy the defects in the DPF System, in those Relevant Vehicles which have received the most recent countermeasures.

…

50. Countermeasures released after the Relevant Period appear to have been designed to eliminate the root causes of the core defect in the DPF System identified in the above paragraph.

(Emphasis added).

37 On the assumption this construction will be favoured, TMCA submits the following evidence demonstrates the 2018 Production Change was effective in remedying the Core Defect:

(1) As at 31 July 2021, only 636 MY2018 Relevant Vehicles had DPF-related reimbursement claims made by dealers, comprising 0.64 per cent of MY2018 Relevant Vehicles and 0.24 per cent of the total number of Relevant Vehicles. This is of importance, it is said, given the referee noted in his Second Report (at [33]) that the “primary indicator” that the “2020 Countermeasures” were effective is that only 1.13 per cent of vehicles which had the 2020 Field Fix had any DPF-related claim in the year after it was applied, and the percentage of MY2018 Relevant Vehicles that had DPF-related reimbursement claims made by dealers was lower (0.64 per cent), evidencing the effectiveness of design changes made.

(2) The referee concluded in the First Reference Report (at [18]) that only Pre-MY2018 Production Vehicles required unusual or abnormal maintenance, stating:

All Relevant Vehicles produced from the start of production through the end of MY 2017 [i.e. model year 2017] required unusual or abnormal maintenance according to the criteria set out in paragraph 16.(b) because they were included in at least one CSE to address the DPF System.

(3) Given this conclusion did not apply to MY2018 Production Vehicles, it is said that this indicates the referee accepted that the 2018 Production Change was effective.

(4) Mr Nelson gave unchallenged evidence that “all indications we had was [sic] the 2018 production fix was very effective”: T98.23. Given the effectiveness of the 2018 Production Change, it made sense, it is said, for the action taken after 1 June 2018 to be focussed on Pre-MY2018 Production Vehicles (e.g., the “Special Policy Adjustment + letter” sent only to owners of Pre-MY2018 Production Vehicles extended the warranty for Pre-MY2018 Production Vehicles to 10 years from the first delivery date for DPF issues): AF [178].

38 Finally, it is said that even if the Court finds the Core Defect existed in MY2018 Relevant Vehicles, it is clear that the MY2018 Relevant Vehicles are no more prone to suffer from any of the consequences of the Core Defect than the vehicles that had the 2020 Field Fix.

39 These submissions are devoid of merit and must be rejected. They misconstrue the referee’s reports and the Agreed Facts. Further, any contention that the 2018 Production Change was effective in remedying the Core Defect is unsupported by the evidence. I will deal with each of these topics in turn.

The Referee Reports and the Agreed Facts

40 The contentions advanced by TMCA are inconsistent with the referee’s conclusions and the proper understanding of the Agreed Facts.

41 No complaint was made by TMCA, in the course of adoption of the referee’s reports, that the referee’s findings were ambiguous, materially incomplete, or otherwise failed to have regard to important evidence that TMCA put before the referee. Indeed, TMCA advocated for the adoption of the reports. Having been adopted, the referee’s conclusions constitute findings of the Court, and the parties are bound by them: CPB Contractors Pty Ltd v Celsus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 2112; (2018) 268 FCR 590 (at 604–6 [55]–[62] per Lee J). As such, it is not open to TMCA to seek to contradict those findings at trial, nor advocate a finding which, as a critical step in its reasoning, depends upon a proposition of fact or law which contradicts those findings: Tranquility Pools & Spas Pty Ltd v Huntsman Chemical Co Australia Pty Ltd [2011] NSWSC 75 (at [36], [38(8)] per Einstein J); Wenco Industrial Pty Ltd v W Industries Pty Ltd [2009] VSCA 191; (2009) 25 VR 119 (at 124 [11] per Redlich and Bongiorno JJA and Beach AJA).

42 Additionally, TMCA is not permitted to adduce evidence to contradict or qualify a fact upon which the parties have agreed unless the Court grants it leave to do so: s 191(2)(b) Evidence Act.

43 The inconsistencies between TMCA’s new contentions, on the one hand, and the referee’s findings and the Agreed Facts on the other, are borne out by an analysis of the specifics.

44 The difficulty with TMCA’s contentions is that the referee concluded in his First Report (at [8], [10], [38]–[39], [43]) that the Core Defect was present in all Relevant Vehicles, including those produced from 2018 onwards, and that the DPF System in the Relevant Vehicles was defective for the whole of the Relevant Period. Indeed, it is an agreed fact that the DPF System “was defective for the whole of the Relevant Period” (AF [67] emphasis added), and that this constituted a Core Defect inherent in the design of the DPF System: AF [67]–[69]. The referee also noted in his First Report (at [11]–[12]) that:

11. The countermeasures attempted by the Respondent during the Relevant Period were ineffective to remedy the problem, and in some cases caused the DPF System to malfunction in Relevant Vehicles which had not previously suffered from any defect consequences.

12. The countermeasures put in place after the Relevant Period appear to remedy the defects in the DPF System, in those Relevant Vehicles which have received the most recent countermeasures. The documents provided for my review do not indicate if the [Relevant Prado] has received the most recent countermeasures. If this is not the case, the defects remain present in that vehicle.

(Emphasis added).

45 Similarly, the referee considered that the “[c]ountermeasures released after the Relevant Period appear to have been designed to eliminate the root causes of the core defect in the DPF System”: First Referee’s Report (at [50], emphasis in original).

46 There is nothing ambiguous about the referee’s conclusion. TMCA is wrong to submit that “whether or not the 2018 Production Change was effective was not the subject of any express findings by the Referee”. The conclusion in the First Referee’s Report (at [11]) that the countermeasures attempted by TMCA during the Relevant Period were ineffective and in some cases caused the DPF System to malfunction in Relevant Vehicles which had not previously suffered from any of the consequences of the Core Defect, applies to the 2018 Production Change. Mr Nelson’s evidence confirms what is otherwise obvious; namely, that the 2018 Production Change meets the description of a “countermeasure attempted by [TMCA] during the Relevant Period”: Nelson Affidavit (at [104]–[105], emphasis added).

47 This conclusion is supported by the fact that:

(1) in the First Referee’s Report (at [50]), the countermeasures that the referee concluded to be effective are described as countermeasures “released after” the Relevant Period;

(2) in the Second Referee’s Report (at [32]), the referee enumerates the specific elements of the “2020 Countermeasures” which he considered to be effective, namely “ECM reflash, DPF assembly replacement, Additional Injector Housing Assembly replacement”, which mirror the 2020 Field Fix elements, and do not align with the elements of the 2018 Production Change; and

(3) the referee’s finding the Second Referee’s Report (at [34]) that the 2020 Countermeasures were equally effective for Relevant Vehicles with or without the 2018 Production Change is difficult to reconcile with any submission that 2020 Countermeasures were intended to include the 2018 Production Change itself.

48 Properly read, there is no ambiguity in the referee’s reports or the Agreed Facts.

Effectiveness of 2018 Production Change

49 Even if it were open to TMCA to seek to relitigate the effectiveness of the 2018 Production Change, TMCA has not adduced evidence capable of supporting a finding that the 2018 Production Change was effective in remedying the Core Defect, or rendering the vehicles subject to it less prone to the consequences of the Core Defect.

50 First, the only evidence that TMCA has sought to adduce on this issue is hearsay in the form of a submission made to the referee. Even if this evidence were admissible for a hearsay purpose (and notwithstanding r 28.67(2) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth)), the document simply establishes that vehicles which had the 2018 Production Change have experienced a relatively low incidence of DPF issues in their first three years of service. The fact remains that: (a) the Core Defect is present in these vehicles; and (b) the referee concluded in his First Report (at [43]) that by reason of the presence of the Core Defect, these vehicles will experience one or more consequences of the Core Defect when exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern. In order to prove that the incidence of consequences associated with the Core Defect in the MY2018 Relevant Vehicles will remain low (because the 2018 Production Change was substantially effective in remedying the Core Defect and/or the associated consequences) TMCA would have needed to lead evidence to this effect, which it did not.

51 Secondly, TMCA submits that a significant indicator that the referee accepted that the 2018 Production change was effective is the fact that the referee did not make any finding to the effect that vehicles which had received the 2018 Production Change required unusual or abnormal maintenance. This submission proceeds upon a false premise. The referee noted that the consequences of the Core Defect included that: (a) “Affected Vehicles must be inspected, serviced and/or repaired by a service engineer for the purpose of cleaning, repairing or replacing the DPF, the DPF System, (or components thereof)”; and (b) “Affected Vehicles must be inspected, serviced and/or repaired more regularly than would be required absent the Vehicle Defects”: see First Referee’s Report (at Annexure F [41(o)–(p)]). Those conclusions applied to all Relevant Vehicles and are not limited to those that did not receive the 2018 Production Change.

52 Thirdly, TMCA seeks to draw support from Mr Nelson’s evidence that “all indications we had was [sic] the 2018 production fix was very effective”: T98.23. At best, that is evidence of TMCA’s understanding of the effectiveness of the 2018 Production Change at the particular point in time that Mr Nelson was addressing (that is, August 2019), and falls short of evidence capable of supporting a finding that the 2018 Production Change was in fact effective. In any event, the evidence is inconsistent with the referee’s conclusions for the reasons I have explained.

53 Fourthly, while I do not place a great deal of reliance on this factor, the contention that the 2018 Production Change was itself effective to remedy the Core Defect is inconsistent with TMCA’s own conduct, internal records and analysis. Even after developing the 2018 Production Change, TMCA recognised that the technical changes at the heart of those countermeasures were ineffective to remedy the Core Defect: AF [152]–[155]. As such, TMCA continued to pursue an effective fix and, upon developing the 2020 Field Fix, issued instructions to dealers to apply the 2020 Field Fix to vehicles that had had the 2018 Production Change. Surely this would have been unnecessary if the 2018 Production Change had itself been effective to remedy the Core Defect.

54 Fifthly, TMCA submits that its attempt to extend the warranty of certain Relevant Vehicles in August 2020 (in order to offer the 2020 Field Fix free of charge) was directed only to vehicles produced prior to June 2018 because the 2018 Production Change was effective. In TMCA’s submission, this obviated the need to offer the same extension to vehicles that had had the 2018 Production Change. But Mr Nelson did not proffer this as an explanation for the issuance of the warranty extension letter for vehicles produced prior to June 2018 only. A more plausible explanation is, that having regard to the three year per 100,000km warranty that TMCA provided in respect of new vehicles (until 1 January 2019), the warranty coverage in respect of most vehicles produced prior to June 2018 would have expired (or would soon expire) by August 2020; whereas the warranty coverage in respect of most vehicles produced after June 2018 would not have expired (noting in particular that since 1 January 2019, TMCA has provided a five year warranty for new vehicles): see SAF [10].

55 Hence, even if, contrary to my view, it was open to TMCA to seek to reagitate the effectiveness of the 2018 Production Change, I would not be satisfied that it was effective in remedying the Core Defect.

56 Finally, I should note for completeness that TMCA’s submission that even if the Court finds, consistent with the referee’s reports, that the Core Defect was present in the Relevant Vehicles that had 2018 Production Change, the Court should nevertheless find that those vehicles experience the Core Defect differently from other Relevant Vehicles, should too be rejected. Once it is appreciated that the Core Defect was present in all Relevant Vehicles, including vehicles produced with the 2018 Production Change, it must also be accepted that those vehicles, just like the Pre-MY2018 Production Vehicles, malfunctioned when exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern and had an inherent propensity to experience the associated consequences: AF [73], [75]. The referee’s conclusions concerning the nature of the Core Defect and its consequences, and the Agreed Facts concerning the effect of the Core Defect on Relevant Vehicles in which it is present, apply equally in respect of all Relevant Vehicles.

57 It is highly regrettable that, despite the sensible approach to engaging in the reference process and agreeing to the adoption of the referee’s reports, TMCA persisted with this rather arid dispute. Such a course was devoid of merit and contrary to facilitating the dictates of the overarching purpose in Pt VB of the Act. Nevertheless, this is a convenient segue into the next factual issue in dispute: the nature of the consequences occasioned by the Core Defect.

B.3.2 Did all Relevant Vehicles have a propensity to suffer the consequences of the Core Defect?

58 The parties are in dispute as to whether all the Relevant Vehicles had a propensity to suffer from the Core Defect and the consequences occasioned by the Core Defect. There is also a debate as to the issue of fuel consumption. It is convenient to first deal with the overarching contention as to the consequences occasioned by the Core Defect, before turning to the issue of increased fuel consumption.

59 In the light of the referee’s conclusions and the Agreed Facts, it can be said that if a Relevant Vehicle was exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern, the Relevant Vehicle would experience one or more of the following consequences, by reason of the Core Defect (AF [75]):

(1) damage to the DOC;

(2) the flow of unoxidised fuel through the DPF and the emission of white smoke from the vehicle’s exhaust during and immediately following regeneration;

(3) the emission of excessive white smoke and foul-smelling exhaust from the vehicle’s exhaust during regeneration;

(4) partial or complete blockage of the DPF;

(5) the emission of foul-smelling exhaust from the exhaust pipe when the engine was on during and immediately following automatic regeneration;

(6) the need to have the Relevant Vehicle inspected, serviced and/or repaired by a service engineer for the purpose of cleaning, repairing or replacing the DPF, DPF System (or components thereof);

(7) the need to have the Relevant Vehicle inspected, serviced and/or repaired more regularly than would be required absent the Core Defect;

(8) the need to programme the engine control module (ECM) more often than would be required absent the Core Defect;

(9) the display of DPF notifications on an excessive number of occasions and/or for an excessive period of time;

(10) blockage of the fifth fuel injector in the Relevant Vehicles (Additional Injector) due to carbon deposits on its tip;

(11) the Additional Injector causes deposits forming on the face of the DOC, causing white smoke; and

(12) an increase in fuel consumption and decrease in fuel economy (Second Referee’s Report (at [21], [28]–[29]); see below (at [66]–[74])).

(collectively, the Defect Consequences).

60 It seems that in written closing submissions, the applicants contend for a slight variation of these consequences. No explanation was provided as to why the findings in the Agreed Facts should be departed from, and in any event, there does not appear to be any meaningful difference between the consequences as outlined in the applicants’ closing submissions and those defined above.

61 TMCA submits that the referee did not find that all of the Defect Consequences would occur during the High Speed Driving Pattern, but rather, only one or more of them in many instances. In TMCA’s submission, this is evidenced by the referee’s conclusion in his First Report (at [55]) that “many of the Relevant Vehicles … would have experienced one or more of those consequences” if subjected to the High Speed Driving Pattern (emphasis added). It is said that the referee did not seek to quantify the extent to which each of the Defect Consequences might be or was likely to eventuate whenever the High Speed Driving Pattern was engaged in, given he concluded (at [43]) that “[w]ith the exception of the [Relevant Prado], I am unable to identify which of the Relevant Vehicles experienced symptoms of the core defect during the Relevant Period” (emphasis added). Further, it is said that some group members may not have driven in line with the High Speed Driving Pattern and therefore may have never been affected.

62 It may be accepted that each of the Relevant Vehicles did not actually suffer from the Defect Consequences. However, I reject the contention that only some, not “all”, of the Relevant Vehicles had the propensity to suffer one of the Defect Consequences if exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern. This proposition is clearly established by the referee’s conclusions in his First Report:

(1) as to the class of consequences associated with the Core Defect (see [75]);

(2) that (at [43]):

[the Core Defect] was a feature of all of the Relevant Vehicles during the Relevant Period (at least in latent form) and would result in one or more of the following consequences in vehicles exposed to the high-speed pattern and/or which were the subject of the ineffective countermeasures introduced by the Respondent during the Relevant Period:

(a) excessive white smoke in exhaust during regeneration;

(b) foul odor [sic] during regeneration; and/or

(c) DPF Notifications and MILs being displayed when the DPF became full as a result of ineffective regeneration.

(Emphasis added).

(3) that (at [47]):

[n]umerous Toyota documents recording its investigations into what the [r]espondent has called the ‘DPF issues’ describe the following mechanism(s) and physical manifestations of the core defect which, when a vehicle was exposed to the high-speed pattern and/or ineffective countermeasures, led to defect consequences”;

(4) that (at [28]–[29]) “the Vehicle Defects likely have some negative impact on fuel economy” such that “the fuel consumption of the Relevant Vehicles [is] increased and/or their fuel economy decreased”.

63 By reason of the fact that the Core Defect was present in each Relevant Vehicle at the time it was supplied, each Relevant Vehicle had a propensity to experience one or more of the Defect Consequences. This is because if the Relevant Vehicles were exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern (a normal form of usage of the vehicles) the DPF System would malfunction in the manner described above (at [15(8)]), which in turn caused the vehicles to experience one or more of the Defect Consequences described above (at [59]).

64 Indeed, the likelihood or probability that any given Relevant Vehicle would suffer from one or more Defect Consequences was relatively high. In April 2017, TMCA prepared a “Field Action Proposal” form, in which TMCA sought permission from TMC to implement a “Customer Service Campaign” to address the DPF issues experienced by Relevant Vehicles: Nelson Affidavit (at [91]); T89.38–90.5. The purpose of the Field Action Proposal form was “to demonstrate to TMC the level of importance, severity and potential impact upon guests” of the DPF issues being experienced by the Relevant Vehicles: Nelson Affidavit (at [91]). The Field Action Proposal form included a statistical assessment of the proportion of Relevant Vehicles that would “fail” within five and 10 years of service respectively (that is, would be the subject of a DPF-related complaint concerning excessive white smoke or DPF malfunction, indicated by the illumination of the Malfunction Indicator Lamp (MIL) on the dashboard): Nelson Affidavit (at [92]–[95]); T89.30–91.13. The analysis indicated that 50 per cent of Relevant Vehicles would fail after five years in service, and 94 per cent would fail after 10 years in service: T90.35–91.13.

65 As the evidence before the Court indicates, TMCA’s forecasts in April 2017 were well founded. A large proportion of Relevant Vehicles have in fact already experienced one or more of the Defect Consequences within five years of service. This is borne out by TMCA’s records of warranty claims made in respect of some of the Relevant Vehicles: AF [18]. As at 31 July 2021, at least 154,916 Relevant Vehicles have received servicing related to issues with the DPF System: AF [186].

66 As a subset of this factual dispute, the parties are in contest as to whether the referee’s findings establish that fuel consumption increased and fuel economy decreased in all Relevant Vehicles.

67 TMCA submits that the referee’s conclusions do not establish that fuel consumption increased and fuel economy decreased in all Relevant Vehicles. Relevantly, the referee noted in his Second Report that (at [27]–[28]):

27. While the simple average of the mean fuel consumption increase estimates of the vehicles in the Toyota Fuel Consumption Study is 3%, more than half of the vehicles are estimated to have no more than a marginal impact on fuel consumption, as I expected in my earlier report. I note, however, that the driving patterns associated with the ECM downloads and the corresponding regeneration/non-regeneration distances reported in the TFCS are unknown and may not be directly comparable to the driving pattern of the NEDC used for the Fuel Consumption values from Type Approval, adding uncertainty to the estimates. Further, the ECM downloads reported in the TFCS do not represent a statistically significant sample of any vehicle type or model.

28. Nonetheless, the estimates do suggest that the Vehicle Defects likely have some negative impact of fuel economy in Affected Relevant Vehicles and this conclusion is further supported by the following additional considerations:

(a) the core defect and the impact of the core defect on regeneration frequency and duration (as discussed in my first report);

(b) the Applicant’s affidavit evidence concerning the increased fuel use of his vehicle during periods in which it was emitting excessive white smoke; and

(c) records of customer complaints concerning increased fuel consumption in Relevant Vehicles.

(Citations omitted).

68 Further, TMCA accepts that by reference to the 11 vehicle Toyota Fuel Consumption Study (TFCS), the referee concluded that the vehicles in which the Core Defect was present suffered from increased fuel consumption or decreased fuel economy by reason of the Core Defect and Defect Consequences. However, it is said that it was made plain in the Second Referee’s Report that whether or not each vehicle actually experienced an increase in fuel consumption depended on, inter alia, the driving style and pattern of the individual driver (at [30]):

30. As my observations at 27 above suggest, I am unable to answer the second part of question 3(a) based on the materials available to me. In particular, I cannot provide a reliable single estimate for increased fuel consumption to be applied globally for all Relevant Vehicles for the reasons identified in that paragraph and the following further reasons:

(a) as discussed in my first report, the level of increased regeneration affecting each of the Relevant Vehicles will be dependent on a range of variables, including the driving style and pattern of the individual driver; and

(b) it appears likely that the driving style of the owners of the vehicles in the TFCS may explain much or all of the significant variation of fuel consumption results among the individual vehicles in my analysis of the TFCS as:

(i) the two vehicles with the highest increase in fuel consumption in the sample were the two manual transmission models; and

(ii) of the 10 remaining vehicles in the sample (all of which have automatic transmissions), 7 had only de minimis fuel consumption variations within +/-2% of the Type Approval result for that vehicle (with the remaining 3 showing increased fuel consumption of 5-6% from the Type Approval result).

(Emphasis added).

69 TMCA submits that given the applicants did not pursue a case based on excess fuel consumption at the initial trial, and because the referee could not report on how much fuel consumption increased on an aggregate basis, there is no evidence before the Court about the extent to which fuel consumption was increased in the Relevant Vehicles, or indeed the extent to which all of the Relevant Vehicles experienced such an increase.

70 I reject this submission for the following two reasons.

71 First, TMCA’s submission that the referee did not conclude that all of the Relevant Vehicles experienced an increase in fuel consumption is incorrect. In the Second Referee’s Report, the referee was presented the following question:

3. Is the fuel consumption of the Relevant Vehicles increased and/or their fuel economy decreased, by reason of:

a. the Vehicle Defects and/or Vehicle Defect Consequences to which a “D” or “C” was allocated in Annexure F of the Referee’s Report and, if so, by how much; and/or

b. if Supplementary Question 1 is answered “yes”, the Relevant Vehicles’ reliance on Automatic Regeneration and Manual Regeneration, rather than Passive Regeneration, to regenerate the DPF and, if so, by how much?

72 The referee’s answer to question 3(a) was ‘yes’”: see [29]. While it is true that the referee was unable to determine the answer to the second part of the question (“by how much”) on the materials at his disposal, that does not alter his conclusion in relation to the first part of the question, or his finding in the First Referee’s Report that the Core Defect did “have some negative impact on fuel economy” in the Relevant Vehicles: see [28].

73 Secondly, to the extent it is said the “[a]pplicants [did] not pursue a case based on excess fuel consumption at the initial trial”, that submission should too should be rejected. The applicants do contend that a consequence of the Core Defect was that fuel consumption increased, and that this is relevant in a number of respects, including to assessing: (a) whether the Relevant Vehicles were of acceptable quality at the time of supply, having regard to the class of consequences associated with the Core Defect (which was present in all Relevant Vehicles); and (b) the amount of the reduction in value of the Relevant Vehicles resulting from the Core Defect.

74 Thirdly, insofar as TMCA is to be understood as accepting that the class of consequences associated with the Core Defect included that “the fuel consumption of the Relevant Vehicles increased and/or their fuel economy decreased”, but not accepting that every single vehicle in fact experienced increased fuel consumption, then TMCA’s submission, for present purposes, is not really to the point. At the initial trial, the applicants seek damages on behalf of group members for the reduction in value resulting from the defect under s 272(1)(a) of the ACL (in which case it is not necessary to prove which individual vehicles experienced which specific consequences and to what extent), not under s 272(1)(b) for the cost of the additional fuel actually consumed by each Relevant Vehicle as a result of the Core Defect. This is because the applicants accept that damages for the costs of the additional fuel actually consumed would need to be determined on an individualised basis. The only caveat to this comment is that Mr Williams and DCS do seek damages of this type. I address this aspect of the claim separately below: see [522]–[530].

B.3.3 What was the significance of the Core Defect and the Defect Consequences?

75 The parties dispute the significance of the Core Defect and the Defect Consequences.

76 A subset of this contention is that the Core Defect was a defect of the DPF System, not a defect of the entire vehicle. In making this submission, TMCA places reliance on two passages of the First Referee’s Report which state (at [8] and [38], emphasis added):

(1) “[t]he DPF System was defective for the whole of the Relevant Period. The core defect was that the DPF System was not designed to function effectively during all reasonably expected conditions of normal operation and use in the Australian market”; and

(2) “[a]s explained below, the DPF System was defective for the whole of the Relevant Period”.

77 The distinction is important, it is said, because the Court is required to assess whether the good that was purchased was defective, and the group members did not purchase a DPF System – rather, they purchased a HiLux, Prado or Fortuner vehicle.

78 Further, TMCA advances the following submissions which it says militate against the significance of the Core Defect and the Defect Consequences:

(1) none of the Defect Consequences affect the operation of the Relevant Vehicles (the ability to get from A to B safely) and they remained able to be driven in all environments;

(2) the DPF System is not essential to the operation of the Relevant Vehicles;

(3) it is not suggested that the problems with the DPF System caused any safety issue; and

(4) notwithstanding the Core Defect, the Relevant Vehicles operated in a non-defective manner and the condition of each vehicle as a whole was “indisputably sound”.

79 TMCA’s attempt to downplay the significance of the Core Defect and the Defect Consequences does not withstand scrutiny.

80 First, the DPF System performs a vital function in the Relevant Vehicles and any attempt to divorce issues with the DPF system from the Relevant Vehicles is entirely superficial. As TMCA itself submitted, the DPF System is in place to ensure compliance with emissions rules: AF [39]. If a vehicle does not comply with the applicable rules, it is in breach of a range of statutory requirements, including that it cannot be registered by a state or territory registering authority for use, or driven, on Australian roads. It does not matter that the applicants have not sought to prove that by reason of the Core Defect, the Relevant Vehicles in fact failed to comply with emissions standards. The point is that, contrary to the thrust of TMCA’s submissions, the DPF System is a critically important component of the Relevant vehicles, the proper functioning of which is likely to be of concern to a reasonable consumer.

81 Secondly, even adopting the starting point that the acceptable quality of a brand new motor vehicle costing around $50,000 is to be measured only by reference to whether it is still capable of being used to drive from A to B, the consequences of the Core Defect are such as to substantially interfere with the normal use and operation of the Relevant Vehicles. Take, for example, the following implication of the Core Defect:

(1) by reason of the Core Defect, if the Relevant Vehicles were exposed to the High Speed Driving Pattern, regeneration events failed to remove sufficient particulate matter from the DPF to prevent the DPF from becoming or remaining full or blocked (AF [73(b)]);

(2) when the DPF becomes full or blocked, the vehicle “warns” the driver of this fact by displaying DPF notifications and/or illuminating the MIL on the vehicle’s dash and consistently with instructions in the Owner’s Manual, owners are directed to take the Relevant Vehicle to an authorised dealership for unscheduled maintenance to have the DPF System inspected, repaired, or replaced (First Referee’s Report (at [43(c)], [47(b)(iv)(A)], [55(b)], [56], [63]–[64]));

(3) if the driver continues to operate the Relevant Vehicle despite those warnings, the ECM causes the vehicle to go into Limp Mode, whereby the ECM will prevent the vehicle from going into fifth gear and will limit acceleration (Nelson Affidavit (at [76]); D2FASOC (at [17(b)(xvi)])); and

(4) if Limp Mode occurs, the vehicle must be taken to a dealer and various TMCA instruction materials state that damage may be caused to a Relevant Vehicle, or an accident may occur, if a Relevant Vehicle continues to be driven when the DPF warning light is flashing or the DPF system warning message appears.

82 TMCA submits that Limp Mode is not a consequence of the Core Defect, but rather a consequence of improper usage. This is superficial. One of the Defect Consequences is triggering DPF notifications to the driver: AF [75(i)]. Once those notifications appear, the driver must take their vehicle in for servicing to address the problem, or the vehicle will go into Limp Mode. What TMCA’s submission appears to imply is that if a driver gets to the point of experiencing Limp Mode triggered by the Core Defect, it is the fault of the driver. That submission should be rejected.

83 This also casts further light on TMCA’s submission that the Relevant Vehicles are not defective because they are still capable of getting people from A to B. Is one to limp from A to B unless they respond promptly to the warnings that are triggered by the Core Defect? I reject any contention that the Core Defect does not impact upon or interfere with the operation of the Relevant Vehicles, or that the Relevant Vehicles continued to be suitable for use in all driving conditions, including the High Speed Driving Pattern, even with the Core Defect present.

84 Thirdly, while I accept that no case was advanced on the basis that the Core Defect gave rise to any issue of safety, plumes of dense white smoke are hardly conducive to a safe driving environment. TMCA’s contemporaneous records of complaints made by Mr Williams about the Relevant Prado record Mr Williams’ view that the white smoke entering the cabin of the car was “dangerous”: First Williams Affidavit (at [173]). Mr Williams was not challenged on this evidence. Needless to say, I place minimal weight on this factor in reaching my conclusion.

85 Fourthly, tens of thousands of customer complaints illustrate the obvious point that the Defect Consequences are not trivial. They have a significant impact upon consumers’ use and enjoyment of the Relevant Vehicles: see, for example, those referred to at [183] below. Indeed, TMCA ignores Mr Williams’ unchallenged evidence of the lived experience of the excessive white smoke issue: First Williams Affidavit (at [117]–[119]).

86 Fifthly, TMCA’s attempt to downplay the significance of the Core Defect is inconsistent with its contemporaneous conduct and internal communications. TMCA had significant concerns about how the problems experienced by the Relevant Vehicles would impact upon TMCA’s brand and reputation; it apprehended that the issues experienced by the Relevant Vehicles were of a serious nature and materially affected consumers’ use and enjoyment of the Relevant Vehicles. For example, the Global Registration Notice issued on 31 August 2016, in explaining that a countermeasure was “urgently necessary”, referred to “several customers getting stopped by the police, and also other road users”.

B.3.4 Market Awareness of the Core Defect and Defect Consequences

87 A key issue in dispute between the parties is whether (and to what extent) consumers were aware of the Core Defect and Defect Consequences during the Relevant Period.

88 The relevance of this fact to TMCA’s case arises as follows. Mr Stockton gave evidence that he analysed the secondary market data from the vehicle valuation and information website RedBook, and vehicle auctions both for Relevant Vehicles and the vehicles he identified as comparator vehicles: First Stockton Report (at [254]–[260]). He compared resale prices as a percentage of manufacturers’ suggested retail price (MSRP) for Relevant Vehicles and comparator vehicles over time, including through regression analysis: First Stockton Report (at tab DVI 2). Mr Stockton found that the retained value of Relevant Vehicles in the resale market exceeded that of comparator vehicles: First Stockton Report (at [262(a)]). He also found that the relative value retention of Relevant Vehicles was higher in 2020 and 2021 than in earlier periods: First Stockton Report (at [262(b)]). Mr Stockton determined these results to be inconsistent with a mature market response to information about the Core Defect and in part counterintuitive, and so did not finalise his analysis and instead investigated whether the market was maturely informed of the Core Defect: First Stockton Report (at [250], [265]).

89 TMCA seizes upon the preliminary conclusions reached by Mr Stockton as proof that:

(1) a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the Core Defect and Defect Consequences would nevertheless regard the Relevant Vehicles as being of acceptable quality; and

(2) the presence of the Core Defect in the Relevant Vehicles did not result in a reduction in the value of the Relevant Vehicles at the time they were supplied.

90 A critical premise in TMCA’s reasoning is that at some point during the Relevant Period, the market became fully informed of the Core Defect and Defect Consequences, such that the secondary market data analysed by Mr Stockton should be taken as reflecting an informed market response to the Core Defect and Defect Consequences.

91 TMCA submits that there are numerous means by which information was available to market participants in respect of the Core Defect in the Relevant Vehicles, namely:

(1) From February 2016, owners of the Relevant Vehicles took their vehicles to dealers in respect of the problems and dealers sought to have the problems fixed. Between February 2016 and September 2018, TMCA received at least 4,000 Dealer Product Reports and more than 100,000 warranty claims: AF [149], [155]. It is said the total number of those owners amounts to a substantial volume of people in the market.

(2) The various dealers received formal communications from TMCA in relation to the DPF issues and the fixes that were attempted at different points in time: SAF [8]. TMCA also delivered presentations to regional offices and dealers: AF [124]. TMCA submits that there is no evidence to the effect that dealers kept this information from anyone.

(3) In March 2018, TMCA received enquiries from dealers about a social media post which suggested that TMCA had announced a recall campaign “to fix failing DPFs”. That post was not correct, but the fact that it referred to a recall, it is said, suggested a more serious problem than was actually present.

(4) Problems with Toyota DPFs were the subject of discussion in “multiple” web forums by around late 2016 or early 2017 and from July 2018 (prior to any mention of a class action), there were various media reports about issues with Relevant Vehicles: AF [123].

(5) From around December 2018, there were media reports of the possibility of a class action in respect of DPF issues and since these proceedings were commenced on 26 July 2019 a number of articles have reported on the proceedings: AF [123].

(6) On 5 September 2019, TMCA launched a webpage dedicated to the DPF System and this litigation which, between September 2019 and April 2020, was viewed between 2,713 to 4,544 times per month: AF [114]; Jones Affidavit (at [11]).

(7) There is evidence that some purchasers purchased a vast number of vehicles over the period (it is common ground that 16,961 unique purchasers purchased more than one Relevant Vehicle). For example, Mr Berndt refers to companies with the acronym “BHP” contained in their name being responsible for the purchase of around 1,700 vehicles: Berndt Affidavit (at [9]). The first of those purchases was in November 2015 and the last was in April 2020. Although the Court is not in a position to understand the way that the BHP companies share information among themselves, it is said one can readily infer that if the DPF defect consequences manifested in respect of vehicles purchased by BHP early in the period, that would affect the purchase decisions of BHP later in the period.

92 While I accept that there were articles concerning potential issues with Toyota vehicles over the Relevant Period, it cannot seriously be said that I can be satisfied that the secondary market was aware of the Core Defect and Defect Consequences. As Mr Stockton put it, and as I accept, there would need to be an awareness generally on the part of consumers in the resale market of a systematic forward-looking propensity in Relevant Vehicles before it could be said the market was informed: T285.1–9, T293.23–294.16, T296.22–36. TMCA contends that this does not accord with common sense, because unknown future problems would have a greater adverse impact on consumers. I disagree. The fact that a consumer is aware of a past problem in one vehicle does not mean they would associate this with a systemic problem in all vehicles going forward.

93 Further, I reject TMCA’s contention that the Court “would accept the market data as reflecting an informed market, unless shown otherwise”. The very existence of the Core Defect as an objective fact is something that TMCA was still disputing up to and during the reference process in 2021. Even after the reference process, TMCA continues to dispute whether the Core Defect was present in the 2018 Production Change Vehicles as a matter of objective fact. It would be artificial, and a subversion of the evidentiary onus, to start with an a priori assumption that the market must nevertheless have known the truth about the Core Defect from 2015, and then ask whether the applicants have disproved that assumption.

94 Beyond these general comments, it is necessary to say something about each of the categories of information relied upon to evidence market awareness.

95 There are several issues with the print and online media relied upon by TMCA.

96 First, none of the articles published prior to October 2020 disclose that the Relevant Vehicles are defective in the way concluded by referee and found by the court. As regards to an article dated 23 October 2020, by the time that article was published, an effective fix had become available (as is explained in the article). Even if one assumes that the information in this article was absorbed by the resale market and reflected in market prices for used Relevant Vehicles from October 2020, it says nothing about the reduction in value of those vehicles resulting from the defect at the time they were initially supplied, when no effective fix was available.

97 Secondly, there is no evidence or reason to infer that the resale market for Relevant Vehicles is an “efficient market” in the sense that information published on a trade website or in a newspaper should be taken to be absorbed by the resale market and reflected in the market price of the Relevant Vehicles.

98 Thirdly, although certain of the articles refer to problems experienced by certain of the Relevant Vehicles, they also contain statements from TMCA to the effect that the problems referred to have been remedied, or that an effective remedy is at least available. For example, two of the articles contain statements such as:

(1) “[TMCA] apologised for the inconvenience to affected customers and confirmed the above technical issues are being addressed”; and

(2) “[i]n a statement, [TMCA] said it ‘launched the latest in a series of initiatives, a customer service campaign, to resolve the potential DPF issue’ in October. ‘All customers with potentially affected vehicles have been, or are in the process of being, contacted by letter and are requested to make contact with their closest/preferred Toyota dealer,’ the company said”.

99 It is arguable that a reasonable consumer reading these articles would understand that the problems or issues with the vehicles referred to in the articles have been or are able to be fixed. But this was not the case.

100 Fourthly, insofar as certain of the articles refer to details of allegations made in this legal proceeding, it should be recalled that TMCA has, since the commencement of the proceedings, denied the core allegation that the Relevant Vehicles are defective in design and have an inherent propensity to experience adverse consequences. It is curious to submit that a reasonable consumer reading articles describing allegations made in this proceeding would understand from such articles that the Relevant Vehicles are defective in the manner alleged, in circumstances where the allegation has been consistently denied by TMCA.

101 Sixthly, and while I place minimal, if any, weight on this factor, it is true to say that in carrying out TMCA’s “DPF Consumer Redress Program”, TMCA has not denied a consumer redress on the basis that the consumer ought to have known about the Core Defect and Defect Consequences when they purchased the vehicle, having regard to statements made in print and online media about problems with the vehicles: see the evidence of Mr Nelson at T103.42–46.

Knowledge derived from prior ownership

102 TMCA also appears to contend that consumers may have become fully informed about the Core Defect and Defect Consequences by reason of their prior ownership or experience of a Relevant Vehicle. This contention is also problematic.

103 First, knowledge that one’s vehicle has experienced problematic behaviours (for example, the emission of excessive white smoke or foul-smelling exhaust) does not equate to knowledge that the root cause of those problems or issues is that the DPF System in the vehicle is defective in design. Nor does knowledge that one particular vehicle acquired in the past experienced certain problems associated with the DPF System translate into an awareness that a new vehicle acquired at a later date will have the same underlying defect.

104 Thirdly, even assuming that some consumers acquired knowledge of the Core Defect through their own experience of owning a Relevant Vehicle, there is nothing to attribute this knowledge to the market generally. During Mr Williams’ cross-examination, there was some faint suggestion that such knowledge might be disseminated throughout the market by way of “pub chats” or ad hoc carpark conversations: T65.20–21; T61.1–13. While TMCA accepts that, in isolation, Mr Williams’ evidence in this respect would not take matters very far, Mr Williams’ evidence that he discussed these matters with other Prado drivers is said to be a useful real world example of the dissemination of the issues. While I accept schooners were no doubt downed over frustrated conversations about car issues, it cannot seriously be said that the exchange of information in this context resulted in a fully informed resale market.

105 Finally, the number of group members who acquired two or more Relevant Vehicles during the Relevant Period is relatively miniscule. On the basis of TMCA’s evidence on this issue, there were 185,816 unique purchasers of the 264,170 “new” Relevant Vehicles, of which 16,961 unique purchasers purchased two or more vehicles: Berndt Affidavit (at [6], [9]). Of those unique purchasers, 582 purchased more than 20 vehicles, and five purchased more than 500 vehicles: Berndt Affidavit (at [9], [12]–[13]).

106 TMCA also postulates that the market may have become informed about the Core Defect and Defect Consequences through information disseminated by dealers. The hypothesis advanced by TMCA is that dealers may have been informing individual consumers about the Core Defect and Defect Consequences at the point of sale. There are a number of issues with this submission.

107 First, as TMCA accepts, there is no evidence to support this assertion. TMCA itself sold 7,316 Relevant Vehicles directly to consumers but did not lead evidence of instances in which it disclosed the Core Defect to consumers at the point of purchase.

108 Secondly, this assertion is inconsistent with TMCA’s admission that it failed to disclose the Core Defect or Defect Consequences during the Relevant Period: see [244]–[250]. It is also inconsistent with the admitted fact that, throughout the Relevant Period, TMCA represented that the Relevant Vehicles were, in their design and manufacturing, not defective, of good quality, reliable, durable and suitable for use in any driving environment: see [215]–[217].

109 Thirdly, TMCA’s hypothesis is contrary to the evidence given by Mr Nelson, who described the way in which TMCA controlled the information conveyed by dealers to consumers about the Relevant Vehicles, namely that:

(1) dealers in the TMCA network are encouraged to raise with TMCA any technical issues they encounter at an early stage. Those dealers then rely on TMCA to give them guidance about how to manage those issues (T74.44–75.6; T76.17–27);

(2) this arrangement is adopted to try and manage technical issues in a uniform way across the network of dealerships (T75.8–9) and ensure that dealers respond to technical issues in a way that is consistent with TMCA’s advice (T75.43–45); and

(3) TMCA has a contractual relationship with its dealers which requires them to comply with TMCA’s communications concerning technical issues, including “bulletins”, “all dealer service letters” (ADSL) and “technical newsflashes”. On occasion, the ADSLs would be structured in a “Q&A” format, intended to anticipate the kind of questions that guests might ask dealers about the technical issue the subject of the ADSL in order to “encourage [dealers] to manage the guests in a consistent way by answering these kinds of questions in a consistent way” (T77.10–78.7; T79.25–46; T80.9–81.8).

110 Mr Nelson’s evidence is supported by contemporaneous documentary evidence, which shows that dealers sought and relied on the “Q&As” provided by TMCA to determine what information they could provide to guests in respect of the DPF issues. Generally speaking, throughout the Relevant Period, dealers were informed by TMCA that, insofar as TMCA had identified issues with certain of the Relevant Vehicles: (a) TMCA had developed a fix for those issues; (b) dealers were to apply the fix to any affected vehicles in stock (that is, unsold vehicles); and (c) the application of the fix to such vehicles would solve the issues otherwise affecting the vehicles: see e.g. T92.24–93.21; T94.25–95.5; T95.27–46; T96.2–41; T.97.4–98.23. Hence, on the basis of the information provided to the dealers by TMCA, they were never selling defective vehicles to consumers.

111 Indeed, if a consumer purchasing a new vehicle asked whether the vehicle to be purchased was affected by the DPF issues the subject of this legal proceeding, dealers were instructed to tell them that they were not. That was contrary to the true position (even if TMCA and its dealers may have been labouring under a mistaken belief that the problem had been solved). As the referee concluded, the Core Defect was present in all Relevant Vehicles supplied during the Relevant Period (that is, up to 23 April 2020). Further, nothing in the materials provided to dealers by TMCA disclosed to dealers the nature of the Core Defect as concluded by the referee.

112 In the light of the above evidence, the suggestion that dealers were nevertheless disclosing the Core Defect to consumers at the point of purchase is fanciful. Such dealers would have been acting in breach of their contractual obligations to TMCA and against their own commercial interests in selling Relevant Vehicles. Further, such dealers would have had to have acquired an understanding of the Core Defect that was not explained in any of the bulletins provided by TMCA to dealers for the purpose of educating dealers about the DPF issues experienced by Relevant Vehicles.

113 Finally, TMCA contends that one of “the means by which information [about the Core Defect] was available to market participants” was a webpage launched by TMCA in September 2019 concerning this litigation. But there was no disclosure on the webpage of any defect in the Relevant Vehicles, let alone disclosure of the consequences of any defect. While there is a reference to a “DPF issue”, the nature of the “DPF issue” is neither described nor explained. Further, the webpage explained that only vehicles produced prior to June 2018 were affected by the DPF issue, which was false. I am not satisfied that the webpage was a means by which the market came to be aware of the Core Defect or Defect Consequences.

Conclusions on market awareness of Defect Consequences

114 Overall, I am satisfied that the market was not apprised of the Core Defect and the Defect Consequences. It will be necessary to say something further about the secondary market data below.