Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australasian Food Group Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 308

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALASIAN FOOD GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 154 314 913) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. From 21 November 2014 to around December 2019, the respondent, trading as Peters Ice Cream, in trade or commerce, engaged in the practice of exclusive dealing in contravention of s 47(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) as defined in paragraphs (a) and (d) of s 47(4) of the CCA, by acquiring distribution services from PFD Food Services Pty Ltd (PFD) pursuant to an agreement between PFD and the respondent (Distribution Agreement) on the condition that PFD would not, without the prior written consent of the respondent, sell or distribute single serve ice cream products that competed with the respondent’s single serve ice cream products in the various geographic areas throughout Australia specified in the Distribution Agreement as amended from time to time, where engaging in that conduct had the likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the market for the supply by manufacturers of single serve ice cream and frozen confectionery products in Australia.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Pursuant to s 76(1) of the CCA, the respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the total amount of $12,000,000 in respect of the contravention referred to in the declaration in paragraph 1 of these orders, to be paid within 30 days of the date of this order.

3. Pursuant to s 86C(1) of the CCA, within three months of the date of this order, the respondent, at its own expense, establish a program which has the purpose of ensuring compliance by the respondent, its employees and agents with Part IV of the CCA, particularly s 47, which meets the requirements set out in Annexure A and maintain the compliance program for three years from the date on which it is established.

4. Subject to further order, pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), and on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information marked as confidential in the Statement of Agreed Facts and the Joint Submissions not be published or otherwise disclosed to any person other than the parties or their external legal representatives.

5. The respondent pay the applicant, within 30 days of the date of this order, a contribution to the applicant’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding fixed in the sum of $250,000.

6. The proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 The respondent, Australasian Food Group Pty Ltd, which trades as “Peters” (Peters), is an Australian manufacturer and wholesale supplier of ice cream products. It is one of the two largest suppliers of single-wrapped ice cream and frozen confectionery products (referred to in the materials filed in this proceeding as Single Serve Ice Cream Products or SSICP) in Australia.

2 In this proceeding, the applicant (the ACCC) alleges that Peters engaged in the practice of exclusive dealing in contravention of s 47(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) during the period from 21 November 2014 to in or around December 2019 (the Relevant Period) by acquiring distribution services from PFD Food Services Pty Ltd (PFD), pursuant to an agreement between PFD and Peters (the Distribution Agreement), on the condition that PFD would not, without the prior written consent of Peters, sell or distribute Single Serve Ice Cream Products that competed with Peters’ Single Serve Ice Cream Products in the various geographic areas throughout Australia specified in the Distribution Agreement (as amended from time to time), where engaging in that conduct had the likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the market for the supply by manufacturers of Single Serve Ice Cream Products in Australia (the Market).

3 Peters has now admitted the alleged contravention of s 47(1) of the CCA described above, and the parties have reached agreement as to the terms on which they seek the resolution of this proceeding.

4 The parties have prepared a statement of agreed facts dated 23 March 2022 (SOAF), a copy of which is annexed to these reasons.

5 The parties have also prepared joint written submissions dated 23 March 2022 (the Joint Submissions). Set out in a schedule to the Joint Submissions are the declaration and orders proposed by the parties (the Minute of Proposed Orders).

6 Both the SOAF and the Joint Submissions contain some details that are commercially confidential. The respondent has applied for a confidentiality order in respect of that material, and has provided an affidavit and written submissions in support of such an order. I consider it appropriate in the circumstances to make the confidentiality order sought in respect of that material.

7 The parties propose that the Court make a declaration of contravention as follows:

From 21 November 2014 to around December 2019, the respondent, trading as Peters Ice Cream, in trade or commerce, engaged in the practice of exclusive dealing in contravention of s 47(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) as defined in paragraphs (a) and (d) of s 47(4) of the CCA, by acquiring distribution services from PFD Food Services Pty Ltd (PFD) pursuant to an agreement between PFD and the respondent (Distribution Agreement) on the condition that PFD would not, without the prior written consent of the respondent, sell or distribute single serve ice cream products that competed with the respondent’s single serve ice cream products in the various geographic areas throughout Australia specified in the Distribution Agreement as amended from time to time, where engaging in that conduct had the likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the market for the supply by manufacturers of single serve ice cream and frozen confectionery products in Australia.

8 The parties also propose that the respondent be ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty of $12 million in respect of the contravention referred to in the declaration.

9 Further, the parties propose that, pursuant to s 86C(1) of the CCA, within three months of the date of the order, the respondent, at its own expense, establish a program which has the purpose of ensuring compliance by the respondent, its employers and agents with Pt IV of the CCA, particularly s 47, which meets the requirements set out in Annexure A to the Minute of Proposed Orders, and maintain the compliance program for three years from the date on which it is established.

10 The parties also agree that there be an order that the respondent pay the applicant a contribution to its costs of the proceeding, fixed in the sum of $250,000.

11 Further, it is agreed that there be an order that the proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

12 For the reasons that follow, I consider there to be a proper basis for the making of the proposed declaration. I also consider the proposed penalty of $12 million to be appropriate, and will make an order for the payment of a pecuniary penalty of this amount. In particular, the proposed penalty is appropriate having regard to the nature of the contravention and the circumstances of the case. The proposed penalty should operate as a deterrent against such conduct being engaged in by the respondent or other companies in the future. I will also make the other orders proposed by the parties.

Applicable principles

Making of orders by agreement and declaration

13 The applicable principles as regards the making of orders by agreement and as regards declarations were summarised by Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [70]-[79] as follows:

2.3.1 Orders sought by agreement

…

70 The applicable principles are well established. First, there is a well-recognised public interest in the settlement of cases under the [CCA]: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 291. Second, the orders proposed by agreement of the parties must be not contrary to the public interest and at least consistent with it: Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc (1999) 161 ALR 79 at [18].

71 Third, when deciding whether to make orders that are consented to by the parties, the Court must be satisfied that it has the power to make the orders proposed and that the orders are appropriate: Real Estate Institute at [17] and [20] and Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Virgin Mobile Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2002] FCA 1548 at [1]. Parties cannot by consent confer power to make orders that the Court otherwise lacks the power to make: Thomson Australian Holdings Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1981) 148 CLR 150 at 163.

72 Fourth, once the Court is satisfied that orders are within power and appropriate, it should exercise a degree of restraint when scrutinising the proposed settlement terms, particularly where both parties are legally represented and able to understand and evaluate the desirability of the settlement: Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Woolworths (South Australia) Pty Ltd (Trading as Mac’s Liquor) [2003] FCA 530 at [21]; Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Target Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1326 at [24]; Real Estate Institute at [20]-[21]; Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Econovite Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 964 at [11] and [22] and Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v The Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2007] FCA 1370 at [4].

73 Finally, in deciding whether agreed orders conform with legal principle, the Court is entitled to treat the consent of Coles as an admission of all facts necessary or appropriate to the granting of the relief sought against it: Thomson Australian Holdings at 164.

2.3.2 Declarations

74 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court Act: Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437-8; Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564 at 581-2 and Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (No 2) (1993) 41 FCR 89 at 99.

75 Where a declaration is sought with the consent of the parties, the Court’s discretion is not supplanted, but nor will the Court refuse to give effect to terms of settlement by refusing to make orders where they are within the Court’s jurisdiction and are otherwise unobjectionable: see, for example, Econovite at [11].

76 However, before making declarations, three requirements should be satisfied:

(1) The question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(2) The applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(3) There must be a proper contradictor:

Forster v Jododex at 437-8.

77 In this proceeding, these requirements are satisfied. The proposed declarations relate to conduct that contravenes the ACL and the matters in issue have been identified and particularised by the parties with precision: Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [35]. The proposed declarations contain sufficient indication of how and why the relevant conduct is a contravention of the ACL: BMW Australia Ltd v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission [2004] FCAFC 167 at [35].

78 It is in the public interest for the ACCC to seek to have the declarations made and for the declarations to be made (see the factors outlined in ACCC v CFMEU at [6]). There is a significant legal controversy in this case which is being resolved. The ACCC, as a public regulator under the ACL, has a genuine interest in seeking the declaratory relief and Coles is a proper contradictor because it has contravened the ACL and is the subject of the declarations. Coles has an interest in opposing the making of them: MSY Technology at [30]. No less importantly, the declarations sought are appropriate because they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the ACCC’s claim that Coles contravened the ACL, assist the ACCC to carry out the duties conferred upon it by the Act (including the ACL) in relation to other similar conduct, inform the public of the harm arising from Coles’ contravening conduct and deter other corporations from contravening the ACL.

79 Finally, the facts and admissions in Annexure 1 provide a sufficient factual foundation for the making of the declarations: s 191 of the Evidence Act; Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (2006) 236 ALR 665 at [57]-[59] endorsed by the Full Court in Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (2007) 161 FCR 513 at [92]; Hadgkiss v Aldin (No 2) [2007] FCA 2069 at [21]–[22]; Secretary, Department of Health & Ageing v Pagasa Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1545 at [77]-[79] and Ponzio v B & P Caelli Constructions Pty Ltd (2007) 158 FCR 543.

Pecuniary penalties

14 The contravention alleged in the present case is of s 47(1) of the CCA (set out later in these reasons).

15 Under s 76(1)(a) of the CCA, the Court may, in respect of certain provisions of Pt IV of the CCA (which includes s 47) order the contravener to pay such pecuniary penalties as the Court determines to be appropriate. Section 76(1) provides that the Court is to order the person to pay such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which the section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters, including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place, and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under Pt VI or Pt XIB to have engaged in any similar conduct.

16 Under s 76(1A)(b), the maximum civil pecuniary penalty for a body corporate in respect of each act or omission constituting a contravention is the greatest of:

(a) $10 million;

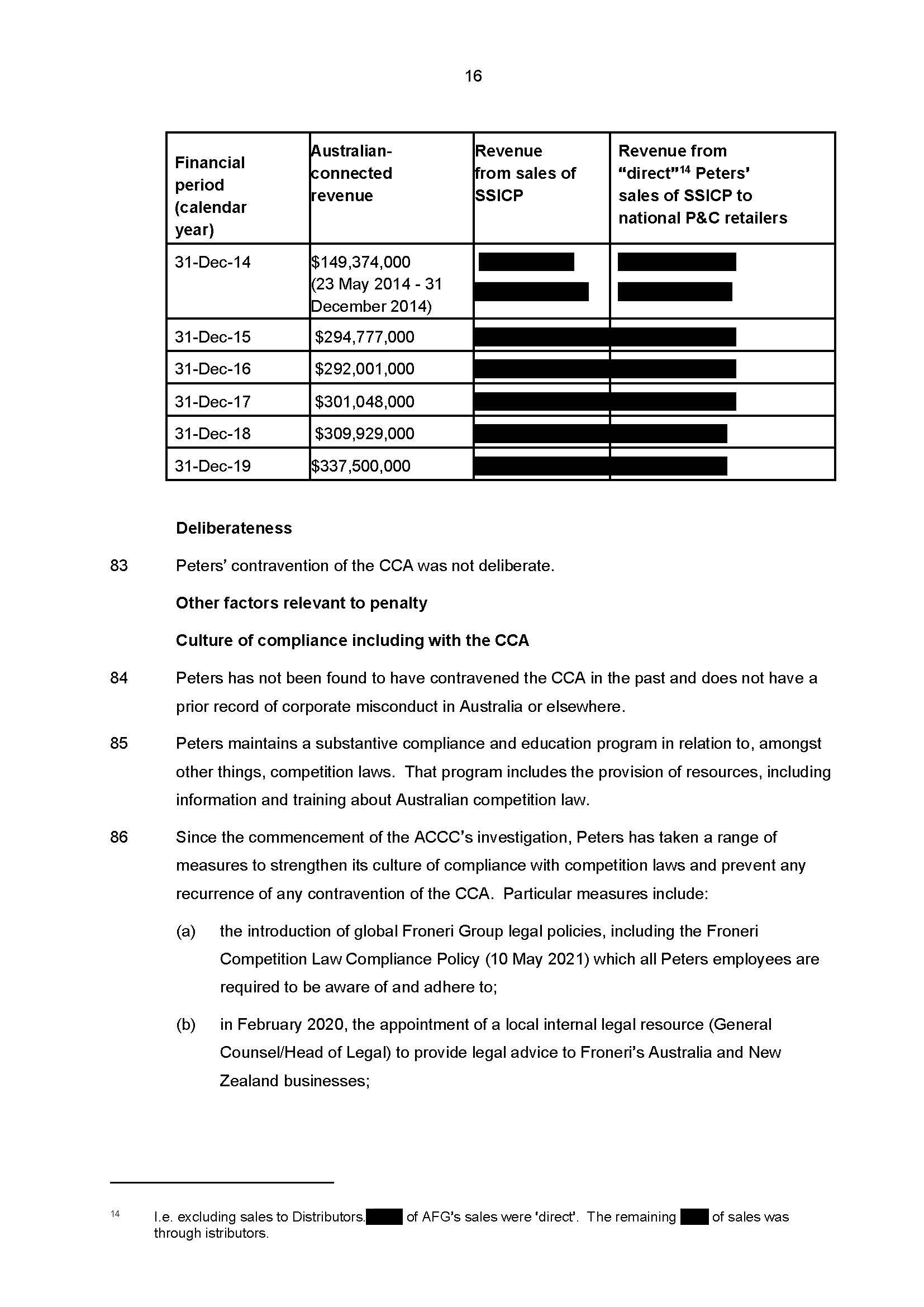

(b) if the Court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate (and any related body corporate) has obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission, three times the value of the benefit; or

(c) if the Court cannot determine the value of that benefit, 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the period of 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred.

17 The principles applicable to the discretion to impose pecuniary penalties have been discussed in many cases. I discussed the applicable principles in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Aware Financial Services Australia Ltd [2022] FCA 146 (ASIC v Aware) at [26]-[29].

18 The principles relating to the situation where pecuniary penalties are proposed by the parties have been settled by the High Court in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (FWBII). I summarised that authority in ASIC v Aware at [31]-[34]. I draw on that summary in the following paragraphs.

19 In FWBII, the High Court held that, in the context of civil penalty provisions, it was open to the Court to receive submissions, including joint submissions, as to an appropriate penalty. Chief Justice French and Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ (with whom Keane J agreed) stated at [46] that there is “an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings” and that “the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers”. Their Honours stated that, as was recognised in Trade Practices Commission v Allied Mills Industries Pty Ltd (No 4) (1981) 60 FLR 38; 37 ALR 256 and determined in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285, “such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention”.

20 Their Honours stated, at [57], that in civil proceedings there is generally very considerable scope for the parties to agree on the facts and their consequences, and that there “is also very considerable scope for them to agree upon the appropriate remedy and for the court to be persuaded that it is an appropriate remedy”. In relation to civil penalty proceedings, their Honours stated at [58]:

Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and, for the reasons identified in Allied Mills, highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

(Footnote omitted.)

21 Their Honours in FWBII also made observations, at [60]-[61], regarding submissions by a regulator in such a context.

22 It follows from the above that the questions to be determined in the present case include: first, whether the Court is sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences; and secondly, whether the penalty that the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed.

Section 47 of the CCA

23 The following statement of the applicable principles relating to s 47 of the CCA is drawn from the Joint Submissions, which I accept.

24 Subject to one qualification, s 47 of the CCA relevantly provided as follows during the Relevant Period:

(1) Subject to this section, a corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in the practice of exclusive dealing.

…

(4) A corporation … engages in the practice of exclusive dealing if the corporation:

(a) acquires, or offers to acquire, goods or services; …

on the condition that the person from whom the corporation acquires or offers to acquire the goods or services or, if that person is a body corporate, a body corporate related to that body corporate will not supply goods or services, or goods or services of a particular kind or description, to any person, or will not, or will not except to a limited extent, supply goods or services, or goods or services of a particular kind or description:

…

(d) in particular places or classes of places or in places other than particular places or classes of places.

…

(10) Subsection (1) does not apply to the practice of exclusive dealing by a corporation unless:

(a) the engaging by the corporation in the conduct that constitutes the practice of exclusive dealing has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition; or

(b) the engaging by the corporation in the conduct that constitutes the practice of exclusive dealing, and the engaging by the corporation, or by a body corporate related to the corporation, in other conduct of the same or a similar kind, together have or are likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition.

25 The one qualification is that, prior to 6 November 2017, the chapeau to subsection (10) was differently worded so as to refer to most, but not all, forms of exclusive dealing described in s 47. The result was that some forms of exclusive dealing amounted to contraventions of s 47 irrespective of the purpose, effect or likely effect of the exclusive dealing. However, the exclusive dealing described in subsection (4), being the admitted exclusive dealing in this proceeding, did not fall into that category.

26 Whether conduct is “likely” to have the relevant effect is assessed by asking whether, as at the date of the impugned conduct, by reference to the circumstances existing at the time (including the degree of available knowledge), it was likely, that is, there was a “real chance” (see Monroe Topple & Associates Pty Ltd v Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (2002) 122 FCR 110 at [111] per Heerey J; Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (2009) 182 FCR 160 (Seven) at [750] per Dowsett and Lander JJ) that the conduct would effect a substantial lessening of competition in the market: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 310 ALR 165 (Cement Australia) at [3015]-[3016] per Greenwood J; Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 131 FCR 529 (Universal Music) at [247]. It does not matter whether the likely effect as at the date of the exclusive dealing conduct in fact eventuates: Seven at [791]. Subsequent events may, however, illustrate one possible effect of the exclusive dealing conduct at the time of that conduct: Universal Music at [247].

27 Whether conduct is likely to have the effect of “substantially lessening competition” is assessed by determining the likely state of future competition with and without the conduct and comparing the two: Stirling Harbour Services Pty Ltd v Bunbury Port Authority [2000] ATPR 41-783; [2000] FCA 1381 at [12] per Burchett and Hely JJ; Dandy Power Equipment Pty Ltd v Mercury Marine Pty Ltd (1982) 44 ALR 173 (Dandy Power) at 191-192 per Smithers J.

28 During the Relevant Period, s 4G of the CCA defined “lessening of competition” to include “preventing or hindering competition”. That phrase is given a broad construction: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 323 ALR 429 (Pfizer) at [73]-[75] per Flick J. “Prevent” suggests a total cessation, whereas “hinder” includes any conduct “in any way affecting to an appreciable extent the ease of the usual way of supplying or acquiring goods or services”: Australian Wool Innovation Ltd v Newkirk [2005] ATPR 42-053; [2005] FCA 290 at [34] per Hely J, citing Devenish v Jewel Food Stores Pty Ltd (1991) 172 CLR 32 at 45-46 per Mason CJ.

29 A “substantial” lessening of competition is one that is “meaningful or relevant” to the competitive process: Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53 (Rural Press) at [41] per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ. Depending on the circumstances, it may be established where the conduct has the effect of raising barriers to entry, thereby lessening the competitive constraint afforded by the potential for new entry: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd (2020) 277 FCR 49 at [265] per Middleton and O’Bryan JJ.

30 A “substantial” lessening of competition is a relative concept and does not necessarily require an impact on the whole of the market. A lessening of competition in a significant section of a market can be a substantial lessening of competition in that market: Dandy Power at 192; Parmalat Australia Pty Ltd v VIP Plastic Packaging Pty Ltd (2013) 210 FCR 1 at [28]. Where there is a dominant player in a market, ‘nipping competition in the bud’ may be substantial, even if the actual or potential competition only operates in one component of the relevant market. The Full Court of this Court said this in Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) 118 FCR 236 at [129]:

What Rural Press and Bridge Printing did was to nip the actual and potential competition in the Murray Bridge newspaper market “in the bud”. … Not only did their actions effectively snuff out the services actually provided by the River News to readers and advertisers in the Mannum, but also the potential for the River News to expand those services and compete more effectively with the Standard on price and quality. The section of the public that might have benefited from the competition in a market previously (and subsequently) dominated by a single player was denied that opportunity.

(Citation omitted.)

31 On appeal from the Full Federal Court, the High Court held that, even though the excluded competitor was small and the impact was upon only part of the market, they were a “potentially significant competitor” and that “[t]he presence of even one competitor of that kind tended to dilute the impact of the existing monopoly”: Rural Press at [46] per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ.

32 In Cement Australia, Greenwood J was satisfied that a contract conferring exclusive supply of flyash had the effect and the continuing likely effect of substantially lessening competition because it prevented new entry by rivals in a market where the existing two participants had a “substantial position” and where “any nascent competition” from new entry would have been very significant to the competitive process: at [3227]. His Honour concluded that the effect of the exclusive terms was relevant to the competitive process even though only small volumes of competing product may have been brought into the relevant market: at [3014].

33 “Competition in a market” is “a situation in which there is sufficient rivalry to compel firms to produce with internal efficiency, to price in accordance with costs, to meet consumers’ demands for variety, and to strive for product and process improvement”: Brunt M, “Legislation in Search of an Objective” in Nieuwenhuysen JP (ed), Australian Trade Practices: Readings (Cheshire, 1970) at 238, cited in Walker J, “An Economic Perspective on Part IV”, in Gvozdenovic M and Puttick S (eds), Current Issues in Competition Law – Vol I: Context and Interpretation (Federation Press, 2021) at 63. Structural features of the market are relevant to assessing potential impacts on competition, for example whether relevant conduct will lessen rivalrous behaviour. The most important aspect of market structure “is the height of barriers to entry, that is the ease with which new firms may enter and secure a viable market”, “[f]or it is the ease with which firms may enter which establishes the possibilities of market concentration over time; and it is the threat of entry of a new firm … into a market which operates as the ultimate regulator of competitive conduct”: Re Queensland Co-Operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 8 ALR 481 at 512.

34 During the Relevant Period, “market” was defined in s 4E of the CCA as “a market in Australia, and, when used in relation to any goods or services, includes a market for those goods or services and other goods or services that are substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with, the first mentioned goods or services”. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre Travel Group Ltd (2017) 261 CLR 203 at [66], Kiefel and Gageler JJ described “market” in s 4E in the following terms:

A market is a metaphorical description of an area or a space (which is not necessarily a place) for the occurrence of transactions. Competition in a market is rivalrous behaviour in respect of those transactions. A market for the supply of services is a market in which those services are supplied and in which other services that are substitutable for, or otherwise competitive with, those services also are actually or potentially supplied.

Application of principles in the present case

The contravention of s 47(1)

35 Peters has admitted that it engaged in the conduct described in [2] above (the Exclusive Dealing Conduct) and that this contravened s 47(1) of the CCA. This is set out in paragraph 79 of the SOAF, which is in the following terms:

Pursuant to the Distribution Agreement, and during the Relevant Period, by acquiring distribution services from PFD on the condition that PFD would not, without the prior written consent of Peters, sell or distribute SSICP that competed with Peters SSICP in the various geographic areas throughout Australia specified in the Distribution Agreement as amended from time to time (Exclusive Dealing Conduct), Peters, in trade or commerce, engaged in the practice of exclusive dealing in contravention of section 47(1) of the CCA as defined in paragraphs (a) and (d) of s 47(4) of the CCA.

36 The parties submit, and I accept, that the Exclusive Dealing Conduct had the likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the Market, in circumstances where, as at the date of that conduct (i.e. during the Relevant Period):

(a) Peters and Streets were the two largest suppliers of SSICP in Australia. They were each other’s largest competitor. Together, they had over 95% of sales of SSICP in the Route Channel (as defined in the SOAF) and 62% of the Grocery Channel (as defined in the SOAF);

(b) there were significant economies of scale and scope in manufacturing and supplying SSICP;

(c) there were significant barriers to mobility for potential competitors in the supply of SSICP;

(d) national P&C Retailers (as defined in the SOAF) comprised a material part of the Market;

(e) Bulla, The Nieve Company and Pure Pops (as defined in the SOAF) were looking for opportunities to supply SSICP to national P&C Retailers during the Relevant Period,

(f) the Exclusive Dealing Conduct had the likely effect of raising the existing barriers to entry to the Market because:

(i) PFD was a national Distributor and was able to distribute products to most national P&C Retailers’ outlets;

(ii) if manufacturers used a single national Distributor (rather different distributors in different areas or a network of distributors such as Countrywide or NAFDA) the administrative and financial burden of dealing with Distributors would be lower;

(iii) some P&C Retailers (including some national P&C Retailers) had a preference for PFD;

(iv) Distributors generally imposed a minimum order quantity (MOQ) per delivery, either expressed as a dollar value per delivery (eg, $200) or a number of units per delivery (eg, four cartons per delivery) that manufacturers were required to satisfy in order for a Distributor to deliver an order to a P&C Retailer. Generally a Distributor imposed an MOQ when it was not already visiting a store for any manufacturer. Since PFD was already distributing products to many national P&C Retailer outlets, it was less likely than other Distributors to require manufacturers that sought to enter or expand in the Market to meet MOQs for the distribution of SSICP to national P&C Retailer outlets;

(v) Bidfood distributed to 777 of 6,995 P&C Retailers;

(vi) Countrywide members and NAFDA members did not supply SSICP to all national P&C Retailer outlets, though some Countrywide members and some NAFDA members had existing P&C Retailer distribution arrangements;

(vii) Streets’ agreements with its Distributors prevented those Distributors from distributing the SSICP of Streets’ competitors.

(g) the Exclusive Dealing Conduct operated throughout the Relevant Period for five years, in each of Western Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and PFD’s Darwin distribution centre distribution zone, and in regional areas in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia and, from 3 August 2015, Adelaide;

(h) PFD was approached by Bulla, the Nieve Company and Pure Pops to distribute new SSICP to some national P&C Retailers. However, PFD advised that it could not distribute Bulla and Pure Pops SSICP due to its exclusivity arrangement with Peters; and

(i) absent the Exclusive Dealing Conduct, one or more potential competitors were likely to have entered or expanded in the Market by distributing some SSICP through PFD to one or more national P&C Retailers.

37 On the basis of the facts set out in the SOAF, and the admissions by Peters, I am satisfied that Peters contravened s 47(1) of the CCA in the manner alleged, as described in [2] above.

38 Each of the requirements for the making of a declaration is satisfied in the present case. I therefore consider it appropriate to make a declaration of contravention in the terms proposed by the parties.

Pecuniary penalty

39 As noted above, the parties propose a pecuniary penalty of $12 million for the contravention of s 47(1).

40 I consider this penalty to be appropriate. My reasons are as follows. In the discussion that follows, I will refer to the mandatory considerations referred to in the legislation and the factors identified by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076; [1990] FCA 762.

Maximum penalty

41 The maximum penalty under s 76(1A)(b) has been set out at [16] above.

42 The parties submit that the Exclusive Dealing Conduct constitutes a single contravention.

43 In the alternative, the parties submit that, while the Exclusive Dealing Conduct could be characterised as multiple instances of the practice of exclusive dealing, and aggregated under s 47(10)(b) of the CCA, it is not reasonably possible to ascertain the number of such instances and that in this case such instances are properly characterised as forming a single course of conduct.

44 The parties submit that Peters benefited from the Exclusive Dealing Conduct, but the value of that benefit cannot be determined. This is explained in the Joint Submissions at paragraphs 54 and 55. In summary, absent the Exclusive Dealing Conduct, one or more competitors were likely to have entered or expanded in the Market by distributing some SSICP through PFD to one or more national P&C Retailers.

45 The parties submit that, in circumstances where there is a benefit from the Exclusive Dealing Conduct but the actual value of that benefit cannot be determined, the maximum penalty will be the greater of $10 million or 10% of the annual turnover of Peters during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred.

46 The parties submit that: the Exclusive Dealing Conduct concluded in December 2019; Peters’ revenue for the 12 months ending 31 December 2019 was approximately $337,500,000; 10% of this is $33,750,000; thus, the maximum penalty for a contravention is $33,750,000.

47 I accept the parties’ submission that, in the circumstances of this case, and for the reasons provided by the parties, the maximum penalty for a contravention is $33,750,000. I do not consider it necessary for present purposes to reach a final view on whether there was a single contravention or multiple contraventions. If there was a single contravention, then the maximum penalty is $33,750,000. If there were multiple contraventions, then it is not reasonably possible to ascertain the number of contraventions (and therefore the maximum penalty) and the contraventions are properly characterised as forming a single course of conduct, which is a relevant matter for the purposes of determining the appropriate penalty.

Nature, extent and duration of the conduct

48 The Exclusive Dealing Conduct contravened s 47(1) of the CCA. It had the likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the Market. The parties submit, and I accept, that it was serious.

49 On four occasions, Peters was made aware by PFD that it had been approached by another SSICP manufacturer to distribute SSICP to P&C Retailers, including national P&C Retailers.

50 On one of the four occasions, Peters advised PFD that PFD could not distribute the product under the terms of the Distribution Agreement. On the other three occasions, Peters did not respond to PFD’s request and PFD refused to distribute. The Exclusive Dealing Conduct occurred in circumstances where PFD was some national P&C Retailers’ preferred Distributor.

51 The geographic scope of the Exclusive Dealing Conduct was also broad: it prevented PFD from distributing competing products in various areas of Australia, namely to Western Australia, Tasmania, ACT and PFD’s Darwin distribution centre distribution zone, and regional areas in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia (and, from 3 August 2015, Adelaide).

52 The Exclusive Dealing Conduct concerned a product that had peculiar and demanding distribution requirements.

53 The Exclusive Dealing Conduct occurred over a period of five years.

Size and financial position

54 Details of Peters’ share of sales are set out in paragraph 72 of the joint submissions. Combined with Streets, Peters and Streets made approximately 95% of sales of SSICP in the Route Channel and 62% of the Grocery Channel.

55 Peters is a large company. Details of Peters’ overall revenue, as well as revenue obtained from sales of SSICP are set out in paragraph 82 of the SOAF.

Benefits / loss or damage from the contraventions, including effects on competition

56 The parties submit, and I accept, that Peters benefited from the Exclusive Dealing Conduct. The parties submit, and I accept, that the value of the benefit flowing from the Exclusive Dealing Conduct cannot be determined with certainty. Absent the Exclusive Dealing Conduct, one or more potential competitors were likely to have entered or expanded in the Market by distributing some SSICP through PFD to one or more national P&C Retailers.

Deliberateness of the contraventions, and knowledge of senior management

57 The parties submit, and I accept, that Peters did not deliberately contravene the CCA.

58 Peters provided to PFD information and know-how to assist PFD to perform its obligations under the Distribution Agreement, which Peters considered to be confidential and commercially sensitive. Peters considered that the Exclusivity Clause (as defined in the SOAF) helped protect that information, by ensuring that PFD would not disclose that information to, or use it for the benefit of, one of Peters’ competitors (even inadvertently).

59 On four occasions, Peters was made aware by PFD that it had been approached by another SSICP manufacturer to distribute SSICP to P&C Retailers, including national P&C Retailers and on one occasion Peters advised PFD that PFD could not distribute the product under the terms of the Distribution Agreement.

60 Those at Peters who enforced the Exclusivity Clause were at management level: they were not ‘low level’ employees.

Prior / similar or relevant conduct

61 The ACCC has not previously brought litigation against Peters for any alleged contraventions of the CCA and Peters does not have a prior record of corporate misconduct in Australia or elsewhere.

Culture of compliance, corrective action and co-operation

62 Peters has a culture of compliance with the CCA and maintains a substantive compliance and education program in relation to, among other things, competition laws. That program includes the provision of resources, including information and training about Australian competition law. Since the commencement of the ACCC’s investigation, Peters has taken a range of measures to strengthen its culture of compliance with competition laws and prevent any recurrence of any contravention of the CCA. Peters has agreed to implement the compliance program referred to in the orders, which specifically addresses s 47 of the CCA.

63 Peters has undertaken corrective action. When Peters entered a new distribution agreement in September 2020 with PFD (prior to the ACCC commencing these proceedings), Peters did not include the Exclusivity Clause in the new agreement, but added further confidentiality protections to help address some (although not all) of Peters’ concerns about use of its confidential and commercially sensitive information.

64 Peters regrets the substantial lessening of completion that it accepts was likely to have occurred by reason of the Exclusive Dealing Conduct. Significantly, Peters has admitted the contravention. It has also agreed to the facts set out in the SOAF. These matters are practical manifestations of its contrition.

Summary

65 In summary, in my view, the proposed penalty reflects the nature and circumstances of Peters’ contravention of s 47(1) of the CCA, and should operate as a deterrent against such conduct being engaged in by Peters or other companies in the future.

Compliance program

66 The parties seek an order requiring Peters to undertake a compliance and education program in the form of Annexure A to the Minute of Proposed Orders.

67 Section 86C of the CCA empowers the Court to make such an order. In this case, the order is sought in relation to a corporation which has admitted to contravening a provision of Pt IV of the CCA, for the purpose of ensuring that it does not engage in the same, similar, or related conduct.

68 Having regard to the nature of the Exclusive Dealing Conduct and the declaration sought, it is appropriate to require Peters to, among other things, provide staff training and conduct compliance reviews, to ensure ongoing compliance with the CCA. To improve compliance in such ways secures an important purpose of the statutory regime.

Conclusion

69 For the above reasons, I will make the declaration and will make orders substantially in the form proposed by the parties.

I certify that the preceding sixty-nine (69) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Moshinsky. |

Associate: