FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Commissioner of Taxation v PricewaterhouseCoopers [2022] FCA 278

CORRIGENDUM

1. The paragraph before paragraph 95 (without a paragraph number) is renumbered paragraph 95.

2. Paragraph 95 is renumbered paragraph 96.

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 21 days, the parties provide any agreed proposed minute of orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 28 days, each party file and serve:

(a) a proposed minute of orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment; and

(b) a brief written submission in support of the proposed orders.

3. Subject to further order, on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the Court’s reasons for judgment of the date of this order be published only to the respondents and the amici curiae, and be kept confidential (save that the orders, the sections headed “Introduction”, “The Sample Documents”, “The Hearing and Evidence” and “Conclusion”, and the Annexure will be provided to the applicant and made available to the public).

4. Within seven days, the respondents prepare, and provide to the Court, proposed redactions to the Court’s reasons for judgment. The Court will then prepare a redacted version of the reasons for judgment, which will be provided to the applicant and made available to the public.

5. The proceeding be listed for a case management hearing on a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[26] | |

[29] | |

[37] | |

[38] | |

[44] | |

[46] | |

[48] | |

[49] | |

[54] | |

[61] | |

[65] | |

[88] | |

[118] | |

[123] | |

[125] | |

[135] | |

[135] | |

[143] | |

[148] | |

[154] | |

[156] | |

[171] | |

[174] | |

[175] | |

[176] | |

[183] | |

[195] | |

[209] | |

[209] | |

[222] | |

[930] | |

[933] |

MOSHINSKY J:

1 The issue to be dealt with in these reasons is whether certain documents are subject to legal professional privilege.

2 The issue arises in the following way.

3 Flora Green Pty Ltd (Flora Green), JBS Holdco Australia Pty Ltd (JBS Holdco Australia) and JBS Australia Pty Ltd (JBS Australia) are Australian companies that are wholly owned (directly or indirectly) by JBS SA, a Brazilian multinational company listed on the Brazil Stock Exchange. JBS SA’s Australian subsidiaries, including Flora Green, JBS Holdco Australia and JBS Australia, are referred to as the JBS Australia Group in these reasons. JBS SA and its subsidiaries, including the JBS Australia Group, are referred to as the JBS Global Group. Flora Green is the head company of a multiple entry consolidated (MEC) group, and JBS Holdco Australia and JBS Australia are subsidiary members of the group.

4 In February 2019, the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) commenced an audit of Flora Green, as head company of the MEC group. In the course of the audit, the Commissioner issued notices to produce documents under s 353-10 of Sch 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth). The notices were issued to: (a) Glenn Russell, a partner of PricewaterhouseCoopers Australia (PwC Australia), which is a multi-disciplinary partnership that provided services to the JBS Australia Group; and (b) Flora Green.

5 In response to the notices, legal professional privilege was claimed by PwC Australia (on behalf of Flora Green or another member of the JBS Global Group) and by Flora Green or another member of the JBS Global Group over approximately 44,000 documents.

6 The Commissioner disputes the claims of privilege over approximately 15,500 documents (the Documents in Dispute). They comprise emails and attachments to emails brought into existence between 3 September 2013 and 6 May 2016 (the Relevant Period).

7 By the present proceeding, the Commissioner seeks declaratory relief to the effect that the Documents in Dispute are not subject to legal professional privilege. The respondents to the proceeding are PwC Australia, Flora Green, JBS Holdco Australia and JBS Australia. I will refer to Flora Green, JBS Holdco Australia and JBS Australia as the JBS Parties.

8 In his amended originating application, the Commissioner relies on three grounds, which can be summarised as follows:

(a) The form of the engagements, reflected in the relevant ‘Statements of Work’ by which PwC Australia purported to provide legal services to the JBS Parties, did not establish a relationship of lawyer and client sufficient to ground a claim for legal professional privilege.

(b) Further or alternatively, as a matter of substance, the services provided by PwC Australia to the JBS Parties pursuant to the engagements, were not provided pursuant to a relationship of lawyer and client sufficient to ground a claim for legal professional privilege.

(c) Alternatively, the Documents in Dispute are not, or do not record, communications made for the dominant purpose of giving or obtaining of legal advice from one or more lawyers (of PwC Australia).

9 The first two grounds are general grounds which, if made out, would apply to all of the Documents in Dispute. In contrast, the third ground requires a document-by-document analysis to determine whether the document is subject to legal professional privilege.

10 In his amended originating application, the Commissioner seeks declarations as follows:

(a) A declaration that the Documents in Dispute are not, and do not record, communications fairly referable to a relationship of lawyer and client.

(b) Further and alternatively, a declaration that the Documents in Dispute are not, and do not record, communications which are protected by legal professional privilege.

11 A number of case management hearings took place at which there was discussion as to how best to manage the proceeding given the large number of Documents in Dispute. That discussion took place in the context of the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions, namely to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to law, and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible: see s 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

12 Ultimately, the Court decided to set down for hearing a separate question relating to 100 sample documents: 50 to be selected by the Commissioner, and 50 to be selected by the respondents. By an order made on 18 December 2020 (as varied by an order made on 7 May 2021), the following question (the Separate Question) was ordered to be determined separately and in advance of the other questions in the proceeding:

In respect of the 50 sample documents identified by the applicant and the 50 sample documents identified by the respondents, is the applicant entitled to the relief sought in the amended application?

13 The Separate Question was set down for hearing in circumstances where the Commissioner (and his lawyers) did not have access (and were not expected to have access) to the Documents in Dispute, the documents being the subject of extant legal professional privilege claims. Thus, while the respondents had access to the Documents in Dispute in selecting their 50 sample documents, the Commissioner did not. The Commissioner had access to a schedule that listed the documents and provided some details about them. But he did not have access to the documents themselves. The Commissioner was therefore required to select his 50 sample documents without seeing the documents.

14 In circumstances where the Commissioner and his lawyers did not have access to the sample documents, the Court appointed three barristers as amici curiae to assist the Court in relation to the Separate Question (the Amici Curiae). The respondents did not object to the Amici Curiae having access to the sample documents and to the confidential material relied on by the respondents in relation to the privilege issue.

15 I will refer to the 50 sample documents selected by the Commissioner in his revised list of sample documents and the 50 sample documents selected by the respondents in their revised list of sample documents as the Sample Documents.

16 The respondents have provided a copy of the Sample Documents to the Court, with the documents arranged in chronological order, and with an index of the documents. Where a Sample Document comprises an email and an attachment or attachments, the respondents have treated this as two or more documents. Accordingly, the respondents’ index comprises 116, rather than 100, documents.

17 As already noted, PwC Australia is a multi-disciplinary partnership, as distinct from a traditional law firm. It provides both non-legal and legal services. Some of its partners are Australian legal practitioners and some are not.

18 For present purposes, the relevant services were generally provided by PwC Australia to the JBS Parties pursuant to an umbrella engagement agreement dated 26 February 2014 and signed on 16 July 2014 (the Umbrella Engagement Agreement) and nine statements of work (with dates ranging from 31 October 2014 to 22 April 2016) (the Statements of Work). Each Statement of Work identified the particular work to be carried out and described the services to be provided as “legal services”. Each Statement of Work:

(a) identified the “PwC team” that would carry out the work under two headings: “Australian Legal practitioners” (ALPs) and “Non legal practitioners” (NLPs);

(b) contained a statement to the effect that “Non legal practitioners may assist in the provision of the legal services under the direction of the Australian legal practitioners”; and

(c) contained a statement to the effect that, “[t]o facilitate delivery of the services you [that is, the JBS Parties] appoint the non legal practitioners who assist in the provision of the legal services as your agents for the purpose of communications to and from the legal services team. This includes giving instructions to and receiving legal advice and services from the Australian legal practitioners”.

19 Further, some of the Statements of Work set out the charge-out rates for each Australian legal practitioner and each non-legal practitioner. It is notable that, in such cases, the charge-out rate for at least one of the non-legal practitioners was higher than the charge-out rate (or rates) for the Australian legal practitioner (or practitioners).

20 For the reasons that follow, I do not accept the general propositions encapsulated in grounds (a) and (b) of the Commissioner’s amended originating application. In summary, I am not satisfied that, as a general proposition, no relationship of lawyer and client (sufficient to ground a claim for legal professional privilege) came into existence. I am satisfied that, at least in some relevant circumstances, a lawyer-client relationship existed between Mr Russell (an Australian legal practitioner) (and other Australian legal practitioners at PwC Australia) and one or more of the JBS Parties.

21 It is therefore necessary to consider, on a document-by-document basis, whether each Sample Document is subject to legal professional privilege. This requires consideration of whether the Sample Documents are, or record, communications made for the dominant purpose of giving or receiving legal advice. This question is to be determined by reference to the content of the document, its context, and the relevant evidence relating to the document. A critical part of the context in the present case is that the services were provided by a multi-disciplinary partnership and that the team carrying out the work comprised both lawyers and non-lawyers. Another contextual matter is the involvement of overseas PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) firms in many of the same projects (under separate engagements). At least in the case of PwC Brazil and PwC USA, the overseas firms were not able to provide legal advice and made clear that they were not doing so.

22 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that many of the Sample Documents are privileged, but that many are not. The Annexure to these reasons sets out, for each of the documents listed in the respondents’ index of 116 documents, my conclusion as to whether the document is privileged (“P”), partly privileged (“PP”) or not privileged (“NP”). Of the 116 documents listed in the Annexure, I have concluded that:

(a) 49 are privileged;

(b) 6 are partly privileged; and

(c) 61 are not privileged.

23 These conclusions have been reached through a process of consideration of each of the Sample Documents. In many cases, I have concluded that the communication does not satisfy the dominant purpose test, that is, I have concluded that the document is not (and does not record) a communication made for the dominant purpose of giving or receiving legal advice.

24 For ease of reference in these reasons, I will refer to the Sample Documents by reference to the number appearing in the first column of the Annexure. Thus, Document 1 is the first document in the Annexure, which is the applicant’s Sample Document 18.

25 Parts of my reasons are confidential because they disclose the contents of documents over which privilege is claimed. In the circumstances, I will make an order that, subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment of the date of this order be published only to the respondents and the Amici Curiae, and be kept confidential (save that the orders, the sections headed “Introduction”, “The Sample Documents”, “The Hearing and Evidence” and “Conclusion”, and the Annexure will be provided to the applicant and made available to the public). This is to enable the respondents to prepare, within a period of seven days, proposed redactions to the Court’s reasons for judgment. The Court will then prepare and publish redacted reasons for judgment, which will be provided to the applicant and made available to the public.

26 The process of identifying the 50 sample documents was somewhat iterative because, after the Commissioner had served a draft list of 50 sample documents (dated 23 April 2021), the JBS Parties withdrew their claims of privilege over some of those documents (and released them to the Commissioner). It was therefore necessary for the Commissioner to identify additional documents to complete his list of 50 sample documents.

27 Subsequently, after the Commissioner had filed and served his list of 50 sample documents (dated 14 May 2021), the JBS Parties withdrew their claims of privilege over some of those documents (and released those documents to the Commissioner). The Commissioner then identified potential replacement sample documents, but the JBS Parties withdrew their claims of privilege over many of those documents (and released them to the Commissioner). The Commissioner then selected replacement sample documents, and filed and served a revised list of 50 sample documents (dated 11 June 2021). The respondents also revised their list of 50 sample documents, and filed and served a revised list of sample documents (dated 6 May 2021).

28 Since the filing and service of the parties’ revised lists of sample documents, the JBS Parties have withdrawn their claims of privilege over some of the documents in the revised lists (and released the documents to the Commissioner) and have withdrawn their claims of privilege over parts of other documents in the revised lists (and partially released those documents to the Commissioner). However, the revised lists of sample documents have not been further revised. Accordingly, the revised lists of sample documents (which form the basis of the index of Sample Documents in the Annexure to these reasons) contain some documents over which privilege is no longer claimed or over which privilege is no longer claimed over the whole of the document. I will identify the relevant documents in due course in these reasons.

29 The hearing of the Separate Question took place over five hearing days. Given restrictions in place due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the hearing was conducted by video-conference using Microsoft Teams.

30 The Commissioner relied on six affidavits of Suzanne Emery, an Acting Client Engagement Director in the Australian Taxation Office, dated 1 June 2020, 3 December 2020, 2 June 2021, 16 June 2021, 9 August 2021 and 2 September 2021. Ms Emery was not cross-examined. The Commissioner also tendered a number of documents.

31 PwC Australia called Mr Russell to give evidence. Mr Russell was PwC Australia’s overall engagement partner for the JBS Australia Group during the Relevant Period. Mr Russell’s evidence in chief was contained in an affidavit dated 19 July 2021, supplemented by some oral evidence. Mr Russell was cross-examined. To some extent, Mr Russell’s evidence involved matters of legal characterisation (eg whether certain advice was legal advice). While I accept that Mr Russell holds the views that he expressed, ultimately, the correct legal characterisation is a matter for the Court to determine. I will discuss Mr Russell’s evidence in more detail later in these reasons.

32 PwC Australia also relied on two affidavits of Andrew Korlos, an employee solicitor at PwC Australia. Mr Korlos was not cross-examined.

33 The JBS Parties called the following witnesses, who were cross-examined:

(a) Maria Cristina de Almeida Manzano, the Legal Manager (Taxation) of JBS SA; and

(b) Edison Alvares, the Chief Financial Officer of the JBS Australia Group.

Ms Manzano answered questions in a straightforward manner. I accept her evidence. Mr Alvares answered questions clearly, concisely and candidly. I accept his evidence.

34 As noted above, the respondents provided a copy of the Sample Documents to the Court. I indicated during the hearing that I would read the Sample Documents, and I confirm that I have done so.

35 Parts of the hearing were conducted on a confidential basis, without the Commissioner or his lawyers or the public being ‘present’ (i.e. without the Commissioner or his lawyers or the public having access to the online hearing), because it was necessary to refer to the contents of the Sample Documents (in respect of which privilege was claimed). Senior counsel for the Commissioner accepted that this procedure was appropriate in the circumstances.

36 The Amici Curiae made submissions at the hearing, but did not cross-examine any witnesses. They were ‘present’ throughout the hearing, including the confidential parts. Parts of the Amici Curiae’s (written and oral) submissions were provided on a confidential basis.

37 In this section of the reasons, I set out my findings as to general factual matters, by way of background and context for the consideration of the Separate Question. These background facts are based on the affidavit and oral evidence, and the documents tendered in evidence.

38 JBS SA is a Brazilian multinational company listed on the Brazil Stock Exchange. It is a global leader in the processing of animal protein and operates through five business units in more than 15 countries, including the United States of America and Australia.

39 The JBS Global Group conducts its operations in Australia through the JBS Australia Group, which includes Flora Green, JBS Holdco Australia and JBS Australia. Each of those three companies is wholly owned (directly or indirectly) by JBS SA. Until late 2015, the JBS Australia Group was held by an intermediate holding company in the United States, JBS US Holding, LLC (US Holding). In around September 2015, US Holding was migrated to Australia and renamed Flora Green.

40 The JBS Global Group also conducts operations through subsidiaries in the United States (JBS USA).

41 The key relevant personnel at the JBS Australia Group during the Relevant Period were:

(a) Mr Alvares, who has been the Chief Financial Officer of the JBS Australia Group since October 2007. He is also the public officer and a director of Flora Green, a director of JBS Holdco Australia and a director of JBS Australia.

(b) Jason Sinokula, who was the Tax Manager of JBS Australia from March 2008 until February 2016. Mr Sinokula reported to Mr Alvares until around January 2016. His responsibilities included managing the taxation affairs of JBS Australia.

(c) Jose Marinho, who has been the Treasurer of JBS Australia since January 2014.

(d) Jacinta Dale, the General Counsel and Company Secretary of JBS Australia, and an in-house lawyer at JBS Australia during the Relevant Period. Ms Dale was admitted as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of Queensland on 16 December 2005.

42 The key relevant personnel at JBS SA during the Relevant Period were:

(a) Khalil Kaddissi, who was the Legal Director (Corporate and Tax) of JBS SA from September 2014 until late 2017. Mr Kaddissi is registered to practise law in Brazil. During the Relevant Period, Mr Kaddissi reported to the Chief General Counsel of JBS SA. His responsibilities included advising the JBS SA Board on corporate and taxation issues arising from transactions and proposals to be undertaken by the JBS Global Group.

(b) Ms Manzano, who has been the Legal Manager (Taxation) of JBS SA since July 2014. Ms Manzano is registered to practise law in Brazil. During the Relevant Period, Ms Manzano reported to Mr Kaddissi. Her responsibilities included corporate restructuring and international corporate and tax matters.

43 The key relevant personnel at JBS USA during the Relevant Period were:

(a) Denilson Molina, who has been the Chief Financial Officer of JBS USA since 2011.

(b) Cindy Garland, who was the Taxation Manager of JBS USA from September 2002 until February 2017. During the Relevant Period, Ms Garland reported to Mr Molina. Her responsibilities included all tax matters concerning JBS USA.

(c) Nicholas White, who was the General Counsel of JBS USA. He is admitted to practise law in the Supreme Court of Colorado.

44 PwC Australia was registered as a multi-disciplinary partnership on 1 February 2008. PwC Australia describes a multi-disciplinary partnership as a partnership between legal and non-legal practitioners where the business of the partnership includes the provision of legal and non-legal services. PwC Australia is part of a global network of firms operating in 158 countries under the PricewaterhouseCoopers, or PwC, brand. Three offices of the global network are particularly relevant in this proceeding: PwC Brazil, PwC USA and PwC Australia.

45 Practitioners from PwC Australia who are referred to in documents that are relevant to this proceeding were either ALPs, NLPs or admitted as a lawyer but not holding a practising certificate during the Relevant Period. The key relevant personnel at PwC Australia during the Relevant Period were:

(a) Mr Russell, who has worked at PwC Australia since February 2005 and has been a partner since July 2012. He has been the overall engagement partner for the JBS Australia Group since late 2013. Mr Russell was admitted as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of Queensland on 14 July 2014. On 15 September 2014, Mr Russell received an unrestricted principal practising certificate authorising him to engage in legal practice, subject to certain conditions, and subject to an undertaking to complete a practice management course. One of the conditions was that Mr Russell practise only in the area of taxation law. Following completion of the Queensland Law Society Practice Management Course – Partial Course in about December 2014, he received a new practising certificate that omitted the undertaking referred to in the earlier practising certificate. On 15 May 2020, Mr Russell received an email from the Queensland Law Society informing him that the conditions annexed to his unrestricted principal practising certificate had been removed. Mr Russell’s professional background is set out in his affidavit. He became a partner of PwC Australia in July 2012, as an equity partner. During his time at PwC Australia (both before and after he became a partner) he has worked almost entirely in tax advisory work, which has included advising on corporate and international tax matters and the provision of consulting services in relation to the operation of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (ITAA 1997), the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA 1936) and the Taxation Administration Act, and the provision of advice on Australia’s various tax treaties for the avoidance of double taxation as incorporated into Australian legislation by the International Tax Agreements Act 1953 (Cth). Mr Russell sat within the tax practice at PwC Australia, which is known as the Tax and Legal Group, and within that group in an area known as Corporate Tax Queensland.

(b) Neil Fuller, who was an international tax partner at PwC Australia from 1988 to July 2019. During the Relevant Period he was what was known in PwC as a “rover”, being an experienced tax partner who was available to tax engagement partners as a resource on client matters, and was based in Sydney. Mr Fuller was an NLP during the Relevant Period.

(c) Chris Stewart, who has worked at PwC Australia since at least 2005 and was a Director in Mr Russell’s team during the Relevant Period. Mr Stewart was an NLP during the Relevant Period.

(d) Theo Denovan, who has worked at PwC Australia since 2012 and has been a partner since around July 2016. He worked in International Tax Services, which was a group within the Tax and Legal Services line of business at PwC Australia, and was an NLP during the Relevant Period.

(e) Tom Seymour, who is the Chief Executive Officer of PwC Australia. He was the Managing Partner of the Tax and Legal Business from July 2012 until June 2016. Mr Seymour was an NLP during the Relevant Period.

(f) Ben Lannan, who has been a partner at PwC Australia since January 2010. He was a transfer pricing partner until June 2017 and is currently an International Trade partner. Mr Lannan was an NLP during the Relevant Period.

(g) Stefan DeBellis, who has worked at PwC Australia since around July 1992. He was a Principal during the Relevant Period and is a stamp duty specialist. Mr DeBellis was an NLP during the Relevant Period. He was assisted by Rachael Cullen and Jess Fantin, who were ALPs during the Relevant Period.

(h) Peter Dunn, who was a partner at PwC Australia from around 1999 until mid-2019. Mr Dunn was an NLP during the Relevant Period.

(i) Benn Wogan, who was a Director – Legal at PwC Australia from July 2012 until February 2018. Mr Wogan was an ALP during the Relevant Period. He was located on the same floor as Mr Russell in PwC Australia’s Brisbane office.

(j) Zameer Ali, who was a Manager at PwC Australia from around 2012 and a Senior Manager from July 2015 until February 2018. Mr Ali was an ALP from 19 September 2014 to 18 April 2016.

46 The key relevant personnel at PwC Brazil during the Relevant Period were:

(a) Mark Conomy, an International Tax Director at PwC Brazil. He was a Manager at PwC Brazil from February 2014 until June 2016.

(b) Priscila Vergueiro, a tax partner at PwC Brazil. She was a Senior Tax Manager at PwC Brazil between July 2011 and July 2016.

47 The key relevant personnel at PwC USA during the Relevant Period were:

(a) John Kulich, who has been a Principal at PwC USA since August 2002. Mr Kulich was the relationship partner for JBS USA in relation to tax work during the Relevant Period.

(b) Robert Stout, who worked at PwC USA during the Relevant Period (although it is unclear on the evidence what position he held during that time). He has been an International Tax Services Principal at PwC USA since July 2017.

(c) Jon Cox, who has been an International Tax Associate at PwC USA since August 2015.

48 Apart from PwC Australia, other external lawyers were engaged in Australia, the United States and Brazil to assist JBS on various legal aspects of the relevant projects (described below), in particular GRAP and Project Chelsea. For example, Allens in Australia, White & Case in the United States and Mattos Filho in Brazil.

PwC Australia’s MDP Protocols for legal services

49 The evidence includes a PwC Australia document headed “MDP Protocols for legal services” dated 27 September 2013 (the MDP Protocols). The document is 38 pages in length, including Appendices A, B and C. The letters “MDP” refer to multi-disciplinary partnership. Mr Russell gave evidence during cross-examination that the protocols were part of a suite of policies that partners and staff are aware of, and that it is generally known that they need to be followed.

50 Section 2 of the MDP Protocols is headed “Legal Services” and states in part:

Tax advisory services such as tax structuring advice and other advice about compliance with taxation legislation can be provided as either legal or non-legal services depending on the capacity in which the service is provided and the disclosure to the client about the nature of that service.

(Emphasis added.)

As the words highlighted in bold indicate, the MDP Protocols proceed on the basis that certain services can be provided as legal services or as non-legal services. I note that this is a recurrent theme in PwC Australia’s documentation and in its affidavit evidence in this proceeding.

51 Section 2 of the MDP Protocols also includes the following:

2.5 Can non-legal Partners and staff be involved in the provision of legal services?

Not all aspects of legal services must be provided by persons holding the requisite legal qualifications. For example, law graduates who have not yet been admitted to practice (known within the firm as ‘Graduates’) and paralegals, working under the supervision of AALP Partners or Principals, can perform tasks to assist an AALP to provide legal services.

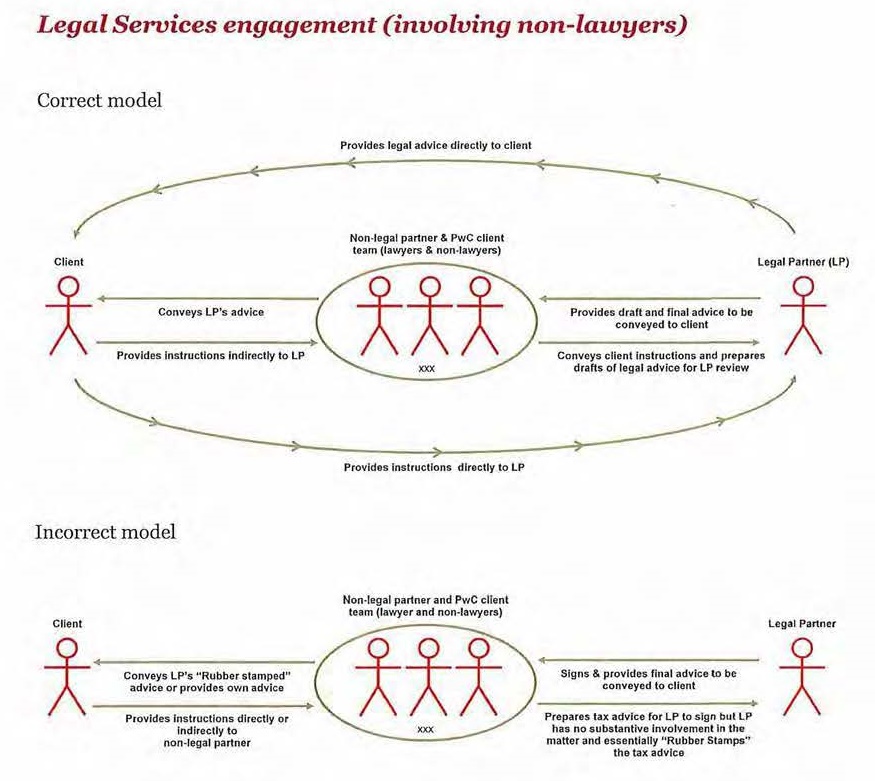

Provided the client has received the appropriate statutory disclosures regarding the involvement of non-lawyers in the delivery of particular legal services, where a Partner or staff member not listed on the AALP list provides assistance to a Partner or staff member on the AALP list to enable the latter to provide legal services to a client, that assistance can form part of the legal services. Any communications that the non-legal Partner or staff members have with the client in respect of matters which relate to the legal advice must be communicated to, or at the direction of, the AALP Partner or Principal. This is depicted in Appendix A (Correct Model).

Importantly, advice given to a client by a non-lawyer (who is not acting at the direction of a lawyer) will not attract LPP.

An AALP Partner or Principal must not perform an engagement to provide legal services if he or she does not possess sufficient relevant professional expertise to form his or her own view about the subject matter (with support from a relevant technical expert). For example, an AALP Partner or Principal who is not a transfer pricing specialist must not issue legal advice about transfer pricing prepared by a transfer pricing technical expert, unless he or she possesses sufficient relevant professional expertise to understand the advice and conclude that there is no reason to doubt the technical accuracy of its content.

This can be likened to a litigation solicitor who briefs Counsel for an advice on evidence prior to a court hearing. Although the solicitor has extensive experience in the conduct of litigation, he or she is not a specialist in the rules of evidence. Nevertheless, the solicitor does possess sufficient relevant professional expertise to review Counsel’s advice and consider whether there is any reason to doubt its accuracy (eg. failure to consider an essential part of the client’s case or overlooking an obvious evidentiary requirement) before advising the client on evidence.

Another example is where a partner in a traditional (non-MDP) law firm has been engaged by a corporate client to advise on the state of compliance by the client with all of the external legal and regulatory compliance obligations which the client is required to meet. The partner leading the engagement may enlist the support of a colleague who has specialist expertise in the area of environmental law. Although not possessing the same degree of specialist expertise, the lead partner’s general experience with compliance work will allow him or her to review the specialist advice prepared by the colleague and form a view as to whether it is well-reasoned, complete and accurate.

In contrast to the above examples, an AALP Partner or Principal who has little or no professional experience in providing tax advice (eg. a lawyer whose sole professional expertise is in the field of real property transactions) will not be able to provide a client with tax advice as a legal service (even with the support of a tax technical expert) because he or she will not possess sufficient relevant professional experience to understand and form a view about the technical accuracy of the tax advice.

52 Section 8 of the MDP Protocols is headed “Legal Professional Privilege” and states in part:

Privilege will generally be available where a lawyer requests a third party expert to assist with a matter that is beyond the lawyer’s own expertise but upon which the lawyer needs expert advice in order to provide legal advice to his or her client. The client is able to claim LPP over the expert’s report/advice because it came into existence so that the lawyer could advise his or her client.

This is what happens in the conduct of our MDP when an ALP who has been engaged by a client to provide legal advice, informs the client and obtains instructions that in order to provide that legal advice he or she will be calling on the assistance of expert tax practitioners who are not themselves lawyers but who will assist the ALP in providing legal advice or whose tax advice will be incorporated into and become an integral part of the legal advice.

In so far as the non−legal team relay information to and from the client to the ALP providing legal services, they must do so as an agent of the client under the terms of the legal engagement letter or SoW in order for the client to be able to claim LPP in respect of those communications.

I note that the particular engagements in issue in the present case appear to have been established with the above principles in mind.

53 Appendix A to the MDP Protocols sets out the following diagrams regarding the “correct model” and the “incorrect model” of engagement where a legal services engagement involves non-lawyers:

Again, I note that the particular engagements in issue in this case appear to have been established with the above principles in mind.

Background to the relevant engagements

54 In early 2014, PwC Australia delivered a presentation to JBS SA regarding the services it proposed to provide in relation to the “global reorganisation” of the JBS Global Group. These services are described in the initial “global reorganizational proposal” as relating to a “tax structuring initiative” and the “selection of a more efficient global structure”. The “global reorganizational proposal” contained no reference to services being provided as legal services, and expressly excluded drafting legal documentation from the scope of the services.

55 In late May 2014, Mr Russell and Mr Fuller went to Sao Paulo to meet with JBS SA, together with Mr Kulich from PwC USA and representatives from PwC Brazil. During these meetings, they discussed potential streams of work that PwC Australia could undertake for JBS SA.

56 Subsequently, Mr Russell received an email from Philippe Jeffrey, who was a partner in the Sao Paulo office of PwC Brazil, informing him that JBS SA had accepted parts of the proposal discussed during the meetings.

57 Mr Russell gave the following evidence in his affidavit regarding the proposed engagements of PwC Australia:

127. Before I learned that JBS wished to engage PwC Australia for this further work, I gave some consideration to the form of any engagement by JBS from an Australian perspective in respect of the work for which we had pitched in Sao Paulo. This included the possibility that JBS may prefer to have its tax advice provided as a legal service. In this regard, I refer to my discussion in paragraphs 32 to 34 above concerning the provision of tax advice. I considered that I should raise with JBS whether they wanted their tax advice provided as a legal service and obtain clarity from them as to this matter before any engagement on the contemplated work was entered into.

128. At this time, I was completing my practical legal training and anticipated that I would be very shortly admitted as a legal practitioner. I also considered that the work under the proposed engagement would go on for some extended period of time. As such, I anticipated that I would, within a fairly short period of time, be in a position to assume a lead partner role on a legal engagement, and provide legal advice under that engagement, if that was what JBS wanted. But until that time I could not enter into a Legal SoW. I therefore spoke to one of my partners who was a tax specialist and admitted as a lawyer, Chris McLean. The SoW to JBS to which I refer in paragraph 47(a) and 134 was then issued. While this engagement did not ultimately proceed, to the extent some preliminary work was done in relation to it, I became the relevant lawyer partner for that engagement after I was admitted.

129. In about late May 2014 or early June 2014, I attended a meeting at JBS’ premises in Dinmore, Queensland, with Mr Alvares and Mr Lannan. During the meeting, I said to Mr Alvares words to the effect that: “I will soon be admitted as a solicitor. It is possible for tax advice provided by PwC Australia to be provided as a legal service, which would include the benefit of communications attracting legal professional privilege”. He said to me words to the effect that he would think about it.

130. I subsequently had a telephone conversation with Mr Alvares, which to the best of my recollection occurred in early June 2014, in which I said words to the effect:

Me: “Do you remember how we recently had a conversation about potentially providing tax advice as legal advice and the benefits of that? Whilst I have not yet been admitted, if you are interested in our Australian work being provided as legal advice, would you like me to bring in a colleague who is a lawyer ?”

Mr Alvares: “Yes, let’s do that.”

131. I cannot now recall if I mentioned Mr McLean by name, but it is likely that I did so.

132. Following my discussion with Mr Alvares, it was my understanding that the JBS Australia Group wished to obtain tax advice as a legal service. Going forward, when I prepared SoWs for tax advice for the JBS Australia Group (or for JBS entities outside Australia), I prepared them as Legal SoWs. To the best of my recollection, no one at JBS ever suggested that these services should not be provided as legal services. I did not consider this to apply to the due diligence work undertaken by PwC Securities or to compliance work (of the kind done under the non-legal SoW dated 18 December 2015 to which I refer at paragraph 45).

(Emphasis added.)

58 Mr Alvares gave evidence in his affidavit (which I accept) that, after June or July 2014, he expected that Mr Russell would be giving him legal advice under future engagements and that it would be subject to legal professional privilege.

59 On 10 June 2014, Mr Russell sent an email to Gustavo Carmona (PwC Brazil), copied to Neil Fuller (PwC Australia), John Kulich (PwC USA), Robert Stout (PwC USA), Theo Denovan (PwC Australia), Philippe Jeffrey (PwC Brazil) and Mark Conomy (PwC Brazil) with the subject line, “JBS work – adm aspects”. The email stated:

Hi Gustavo,

We would like to set up the Australian component of the work as a legal engagement, which will need a separate Australian engagement letter. Undertaking an engagement of this nature as a legal services is highly preferred and common in Australia. We would recommend that this separate engagement letter is addressed to and signed by both JBS Brazil and JBS Australia. Contracting in this way will also simplify matters from an Australian GST perspective − i.e. will ensure that JBS (who will be paying for the Australian component of the work) will be able to claim input tax credits for the GST that will apply to the work.

Let me know if you would like to discuss in more detail.

Regards

Glenn

60 Subsequently, on the same day, Mr Russell sent the following further email:

Gustavo,

The other advantage of setting the engagement up as a legal engagement is that provided certain protocols are followed, legal advice is privileged and therefore the Australian Taxation Office should not be able to obtain copies of it in the event of any ATO review activity. Mark will be able to explain in more detail, otherwise let me know if you would like to discuss further.

Regards

Glenn

(Emphasis added.)

The Umbrella Engagement Agreement

61 Under cover of a letter dated 26 February 2014, PwC Australia provided a proposed umbrella engagement agreement to JBS Holdco Australia. The covering letter was from Mr Russell to Mr Alvares. Mr Alvares signified his acceptance of the terms by signing the letter on behalf of JBS Holdco Australia on 16 July 2014. Thus, the Umbrella Engagement Agreement was entered into on that date.

62 The Umbrella Engagement Agreement provided in part:

1. Our work

This agreement sets out the terms on which we will provide you with tax and legal services. When you request us to provide services under this agreement, we will agree with you:

• the scope of the services we will provide

• the members of the Group who are our clients for those services

• your responsibilities relating to the services

• the basis on which we will calculate our fee for the services

• details of the proposed timeframe for providing the services

• details of the PwC team providing the services

• any special terms agreed between us in relation to the services.

We will normally agree these with you in a Statement of Work or other correspondence we agree in relation to our services (SoW).

If we perform tax services at your request without a SoW or separate engagement letter the terms of this agreement apply to those services. Legal services will only be provided under the terms of an SoW or separate engagement agreement.

The services will be provided solely for the members of the Group described as clients in the relevant SoW or other agreement. A client named in a SoW may disclose a deliverable provided under the SoW to members of the Group who are not clients under the SoW. The disclosees who are not clients under the SoW each agree that they will not:

(a) rely on the deliverable;

(b) bring any claim against us in relation to the deliverable; or

(c) disclose the deliverable except as required by law.

The services we are able to provide under this agreement include:

• income tax consulting

• assisting you with your income tax compliance obligations

• assisting you and your expatriates in relation to their taxation affairs

• Goods and Services Tax (GST) services

• assisting you with R&D matters

• transfer pricing services

• assisting you with customs matters

• stamp duty services

• assisting you with employment tax matters

• legal services.

In identifying the types of services in this way, the agreement (at least arguably) distinguished between legal services (being the last item in the above list) and the other types of services in the list.

63 The Umbrella Agreement contained a paragraph with the subject, “Legal services or non-legal services”. This stated that services would not be provided as legal services “unless specifically disclosed as such under an SoW [statement of work] or engagement letter”. It was also stated that services which are not provided as legal services may still be provided by partners or professional staff of PwC Australia who are ALPs, who are acting in a capacity other than as an ALP (for example, as a registered tax agent). It was stated that, in those circumstances, the rights and obligations of the parties would be different from those arising had the services been provided as legal services.

64 During cross-examination of Mr Russell, the following exchange took place about the tax advice services provided by Mr Russell to JBS Australia before and after he was admitted as a lawyer (in July 2014):

[SENIOR COUNSEL FOR THE COMMISSIONER]: And until you became a lawyer in mid-2014, you were providing that advice in your role at PwC as a tax adviser, weren’t you?---Yes, I was.

And would you say you were providing it in your role as an accountant tax adviser?---To the extent that I have an accounting designation, that – that would be correct, but – yes.

Right. And once you became a lawyer, you continued to give the same type of advice, didn’t you?---To some extent, yes.

So the only difference was that now you were a lawyer, you say you were able to provide the same advice as legal advice and not as non-legal advice; is that right?---It is, yes.

65 In this section, the relevant projects undertaken by PwC Australia for the JBS Australia Group or the JBS Global Group are summarised. (The Statements of Work will be discussed in the next section.) I note that some projects were the subject of multiple Statements of Work. Further, it is not necessarily the case that a Statement of Work covered a single project.

66 Project Twiggy was undertaken by the JBS Global Group between October 2014 and April 2015. It related to the acquisition by JBS Australia of the Primo group of companies (Primo). Primo was a leading producer of smallgoods in Australia.

67 Because JBS Australia was (at that time) held indirectly by JBS SA through entities in the United States, the proposal to acquire Primo raised taxation and corporate issues in Australia, the United States and Brazil. PwC Australia and PwC USA were therefore engaged to advise on the acquisition and were assisted by PwC Brazil. Project Twiggy involved consideration of the structure and finance of the acquisition of Primo and the tax effects of different options.

68 PwC Australia performed work in relation to Project Twiggy pursuant to the Statement of Work dated 13 November 2014 and the Statement of Work dated 9 December 2014.

69 Mr Alvares gave evidence in his affidavit (which I accept) that Mr Russell was the principal point of contact for JBS Australia in relation to Project Twiggy, and he expected that any final advice would be either from him or reviewed and approved by him. Mr Alvares gave evidence (which I accept) that, while he understood that others would be working and providing their expertise on the matter, he always expected that Mr Russell would give the final assurance and approval for the content of the advice JBS Australia would receive from PwC Australia, and when he saw views expressed by other PwC Australia personnel in emails and memos or during meetings, it was his practice to always speak to Mr Russell and ask for his views on the subject.

70 Mr Alvares gave evidence in his affidavit (which I accept) that he expected Mr Russell to liaise with PwC USA, and that he (Mr Alvares) had many conversations during 2014 and 2015 with various members of the JBS and PwC teams about the need to communicate with each other to ensure that all were well informed of what each other was doing.

71 Project Twiggy Phase 2 was undertaken by the JBS Global Group between around January 2015 and November 2015.

72 The JBS Global Group had taken certain restructuring steps to address a change in Brazilian tax law. One of those steps was to insert an Australian company, Burcher Pty Ltd (Burcher), into the JBS Global Group, above US Holding (the intermediate holding company of the JBS Australia Group). Project Twiggy Phase 2 commenced when JBS SA became aware that taking this step [redacted].

73 PwC Australia was engaged to advise the JBS Australia Group and the broader JBS Global Group on how to fix this problem, including considering issues relating to the creation of a new tax consolidated group for the JBS Australia Group.

74 Project Twiggy Phase 2 was related to the advice being given by PwC Australia on the structure and finance of the Primo acquisition, [redacted].

75 The scope of Project Twiggy Phase 2 was subsequently expanded to include consideration of migrating US Holding to Australia. This involved US Holding becoming an Australian resident company, being incorporated and registered in Australia, being renamed Flora Green and being appointed as the head company of a new income tax consolidated group.

76 PwC Australia performed work in relation to Project Twiggy Phase 2 pursuant to the Statements of Work dated 9 December 2014, 15 January 2015, 25 June 2015 (as expanded by a letter dated 25 July 2015) and 31 August 2015.

Global Regional Alignment Project

77 The Global Regional Alignment Project (GRAP) was undertaken by the JBS Global Group between July 2015 and December 2015. The key objective of the GRAP was to create a group structure that allowed for the efficient movement of funds around the group, the repatriation of funds to Brazil, and the possibility of an initial public offering. Other aspects of the GRAP included:

(a) [redacted];

(b) the transfer of the JBS Australia Group out of the ownership structure of JBS USA ([redacted]).

78 The GRAP was required to be approved by the JBS SA Board and was managed by Mr Kaddissi.

79 The JBS Global Group engaged a team of advisors including PwC in Brazil, the United States, Australia, Ireland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. Work on the GRAP principally involved the development of several step plans, on which PwC personnel provided input on the tax issues and implications arising in each jurisdiction.

80 PwC Australia performed work in relation to the GRAP pursuant to the Statements of Work dated 9 December 2014, 15 January 2015, 25 June 2015 (as expanded by the letter dated 25 July 2015) and 11 September 2015.

81 Mr Alvares gave evidence in his affidavit (which I accept) that, while he understood and expected that all the PwC Australia team members listed on the statements of work would be working on the GRAP, he was looking to Mr Russell to give the final advice to him, and he was expecting that all the advices received by JBS Australia from PwC Australia would be reviewed and approved by him. Mr Alvares also gave evidence (which I accept) that it was critical to him that Mr Russell and the PwC Australia team kept in regular contact with the PwC team in the USA, to ensure they were each fully aware of what was happening in each other’s jurisdiction to avoid the possibility that a step or event in one place had an adverse impact in another.

82 The return of capital project was undertaken by the JBS Global Group between April 2016 and June 2016. It related to the repatriation of funds from JBS Australia to JBS USA by way of a return of capital so that JBS USA could avoid using debt facilities.

83 PwC Australia performed work on this project pursuant to the Statement of Work dated 18 April 2016.

84 Project Chelsea was undertaken by the JBS Global Group between November 2015 and 2017. It related to a proposal to list part of the JBS Global Group on the New York Stock Exchange. This was referred to as an “inversion”. The JBS Global Group required consent from one of its largest shareholders, the Brazilian Development Bank, before Project Chelsea could proceed.

85 Several law firms were engaged to advise on the potential initial public offering including White & Case in the United States and Mattos Filho in Brazil.

86 Project Chelsea did not ultimately complete.

87 PwC Australia performed work in relation to Project Chelsea pursuant to the Statement of Work dated 22 April 2016.

88 The nine statements of work (or SoWs) that are directly relevant for present purposes are referred to in these reasons as the “Statements of Work”. I note that in some of the affidavits these statements of work are referred to as the “Contested SoWs”. The key details are:

(a) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 31 October 2014 with the description “Project Twiggy Legal Services” (Statement of Work No 1).

(b) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 13 November 2014 with the description “Project Twiggy Legal Services – Income tax and stamp duty advice” (Statement of Work No 2).

(c) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 9 December 2014 with the description “Project Twiggy Legal Services – Income tax and stamp duty advice (Phase 2)” (Statement of Work No 3).

(d) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 15 January 2015 with the description “Global Restructure Project – Australian Income Tax and Stamp Duty Legal Advice” (Statement of Work No 4). This Statement of Work was signed by Mr Sinokula on behalf of JBS Holdco Australia on 16 January 2015.

(e) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS SA dated 25 June 2015 with the description “Legal services in relation to a global reorganisation of the JBS group”. The scope of the Statement of Work dated 25 June 2015 was expanded to include specified accounting services by an email from Mr Russell and Mr Fuller to Mr Alvares dated 25 July 2015. This Statement of Work, as extended, is referred to as Statement of Work No 5.

(f) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 31 August 2015 with the description “Legal Services – Project Twiggy Phase 2” (Statement of Work No 6). This Statement of Work was signed by Mr Alvares on behalf of JBS Australia.

(g) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 11 September 2015 with the description “Legal Services – Global Regional Alignment Project” (Statement of Work No 7). This Statement of Work was signed by Mr Alvares on behalf of JBS Australia.

(h) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS Australia dated 18 April 2016 with the description “Legal Services – Assistance with Return of Capital” (Statement of Work No 8).

(i) Statement of Work between PwC Australia and JBS SA dated 22 April 2016 with the description “Legal Services – Project Chelsea”. This Statement of Work was signed by Mr Kaddissi on behalf of JBS SA on 27 April 2016 (Statement of Work No 9).

89 Each of the Statements of Work:

(a) identified the client as JBS Australia (save for Statements of Work Nos 5 and 9);

(b) was expressly stated to be for the provision of legal services;

(c) provided that the services the subject of the Statement of Work would be provided by identified ALPs including, but not limited to, Mr Russell (other than in the case of the Statements of Work Nos 1 and 5, where Mr Russell was the only ALP referred to);

(d) distinguished between the PwC personnel who would provide the services as either ALPs or NLPs;

(e) stated that “[n]on legal practitioners may assist in the provision of legal services under the direction of the Australian legal practitioners”;

(f) included a “Communications Protocol” in the following terms:

Communications Protocol

To facilitate delivery of the services you appoint the non legal practitioners who assist in the provision of the legal services as your agents for the purpose of communications to and from the legal services team. This includes giving instructions to and receiving legal advice and services from the Australian legal practitioners.

We will communicate with you regarding our legal services and provide our legal advice separately from communications and advice regarding any non-legal matters.

(g) incorporated the additional terms of business for legal services set out in the Umbrella Engagement Agreement; and

(h) was sent under cover of a letter stating that the Statement of Work took precedence over the Umbrella Engagement Agreement to the extent of any inconsistency.

90 Each Statement of Work set out in broad terms the nature and ambit of the services that PwC Australia was to provide under the Statement of Work. These sections of the Statements of Work are important for present purposes and are set out below, in addition to certain other parts of the Statements of Work.

91 During cross-examination, Mr Alvares was asked questions about the distinction between legal statements of work and non-legal statements of work:

[SENIOR COUNSEL FOR THE COMMISSIONER]: Yes. Now, when you are entering into a statement of work, you have to make a decision whether it’s going to be called a legal statement of work or a non-legal statement of work; are you aware of that?---No, I am not, to be honest.

Right. So you don’t – you’re not aware that there is two types of statements of work, what they call an SOW. There’s a legal SOW and a non-legal SOW?---No, for me, they’re all the same.

92 Statement of Work No 1 (Project Twiggy Legal Services) included the following covering letter dated 31 October 2014:

Dear Edison [Mr Alvares]

This Statement of Work (SoW) sets out the legal services we will provide under our Umbrella Engagement Agreement with JBS Holdco Australia Pty Ltd dated 16 July 2014.

Terms defined in the Umbrella Engagement Agreement have the same meaning when used in this SoW, except where otherwise indicated. If anything in this SoW is inconsistent with the Umbrella Engagement Agreement, this SoW takes precedence.

JBS Australia Pty Ltd (Client or you) is our client under this SoW.

If you have any questions in relation to this document, please call me on [number omitted] or Neil Fuller on [number omitted].

Yours sincerely

Glenn Russell

Partner

Each of the Statements of Work included a similar covering letter.

93 The Statement of Work identified the scope of the services to be provided as follows:

1 Scope of our services

PwC is a regulated Multi-Disciplinary Partnership in certain States of Australia. The services described in this letter are legal services regulated by the Legal Profession Act 2004 (NSW) or a corresponding law (as defined in the Act) and the ‘additional terms of business for legal services’ in the Umbrella Engagement Agreement apply. The scope of the legal services we will provide under this SoW is set out below.

This document is also an offer to enter into a costs agreement with you for the legal services. The additional terms of business for legal services include important disclosures about legal costs. lf we become aware of a substantial change to any disclosure regarding costs that we have made to comply with the Act or a corresponding law, we will disclose the change in writing as soon as reasonably practicable after we become aware of it.

The scope of the services we will provide is set out below (the Services) in two phases. Any amendment to this scope must be agreed in writing between us.

1.1 Phase 1 – [Redacted]

[Redacted].

[Redacted].

1.2 Phase 2 – [Redacted]

[Redacted].

[Redacted].

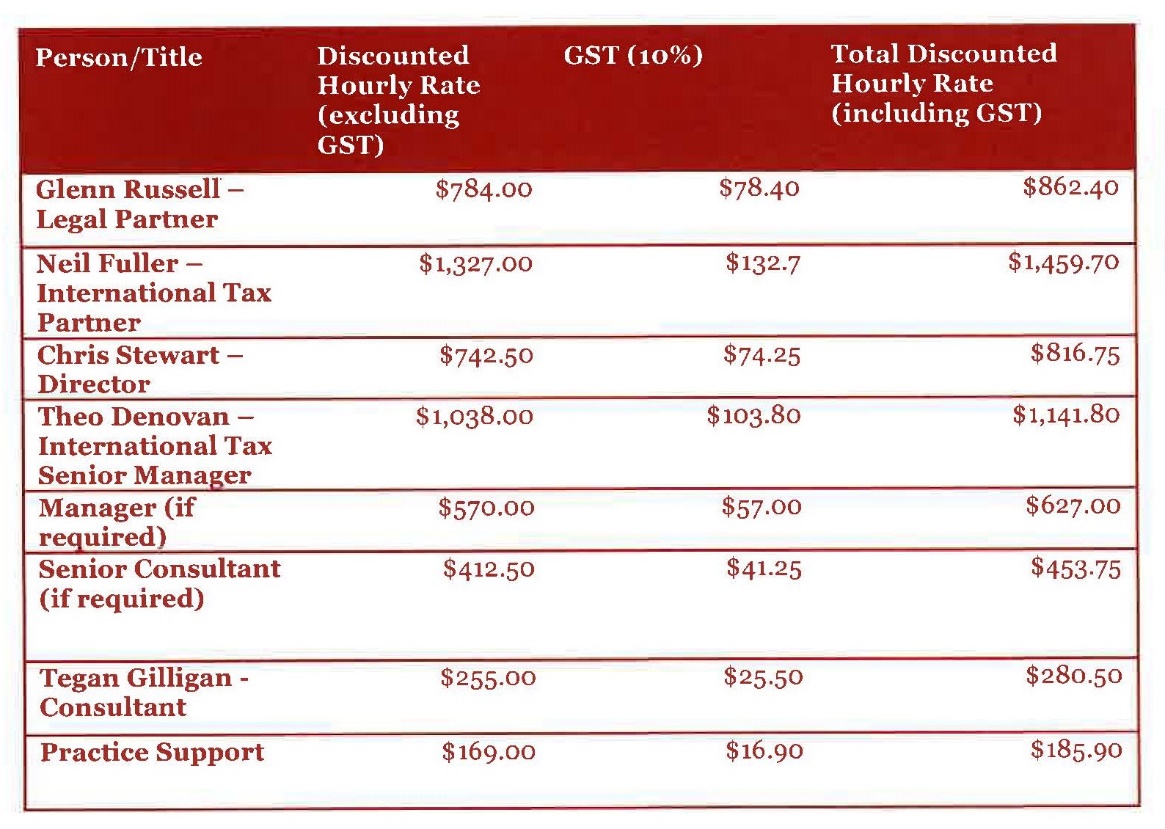

94 Section 2 was headed “Fees and expenses” and set out estimated costs for different phases of the work. This was followed by a table, setting out the hourly rate for various personnel (and categories of personnel):

95 A similar form of table appeared in several of the other Statements of Work.

96 Section 3 was headed “PwC team” and was in the following terms:

The services will be provided by the following Australian legal practitioners.

Australian legal practitioners | |||

Name | Role | Telephone | |

Glenn Russell | Legal Partner | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Non legal practitioners may assist in the provision of the legal services under the direction of the Australian legal practitioners. It is anticipated that the following non legal practitioners will assist in the provisions of the legal services.

Non legal practitioners | |||

Name | Role | Telephone | |

Neil Fuller | International Tax Partner | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Chris Stewart | Director | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Theo Denovan | International Tax Senior Manager | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Tegan Gilligan | Consultant | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

97 Section 4 was headed “Communications Protocol” and comprised the text set out [89] above.

98 Statement of Work No 2 (Project Twiggy Legal Services – Income tax and stamp duty advice) stated (in Section 1) that, broadly, the scope of work covered advice in relation to: income tax implications of Project Twiggy; and stamp duty advice in relation to Project Twiggy. Sections 2 and 3 then stated:

2 Income Tax

Our income tax advice will be provided in two phases. The services to be provided under each phase are set out below.

1.1 Phase 1 – [Redacted]

This Phase of work will include all work undertaken to the point of signing the SPA. Phase 1 will include work and advice necessary to determine, in principle, [redacted].

[Redacted].

[Redacted].

- [redacted]

- [redacted]

- [redacted]

- [redacted]

- [redacted]

- [redacted]

We will work closely in conjunction with PwC in the US in undertaking this Phase of work. At the conclusion of our work, [redacted]. Our work will also involve us participating in [sic]

Scope exclusions

Excluded from the scope of our work is the following:

- Accounting advice

- Advice in respect of the Corporations Law, or any other legal advice that does not relate to income tax.

- Reviewing or commenting upon any financial model developed

- Valuation advice

1.2 Phase 2 – [Redacted]

[Redacted].

[Redacted].

3 Stamp Duty

Background and assumptions

The scope of our stamp duty advice will be based on the understand that:

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

Work to be performed

Our stamp duty services will be provided in three phases. The services to be provided under each phase are set out below.

3.1 Phase 1 – [Redacted]

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

3.2 Phase Two – [Redacted]

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

3.3 Phase Three - [Redacted]

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted]:

o [redacted];

o [redacted];

o [redacted];

o [redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

Deliverable

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

99 Section 4 was headed “Fees and expenses” and included a table listing various PwC personnel (and categories of personnel) and their hourly charge-out rates. Section 5 was headed “PwC team” and comprised two tables: a table listing four ALPs, and a table listing five NLPs. Section 6 was headed “Communications Protocol” and had the same text as referred to above.

100 Statement of Work No 3 (Project Twiggy Legal Services – Income tax and stamp duty advice (Phase 2)) stated (in Section 1) that, broadly, the scope of the work covered advice in relation to: income tax implications of implementing the Project Twiggy acquisition structure; and stamp duty advice in relation to Project Twiggy implementation. Sections 2 and 3 stated in part:

2. Income Tax

Our income tax advice will be provided in two phases. The services to be provided under each phase are set out below.

1.1 Phase 2 – [Redacted]

[Redacted]. Our work will include advice on the following components:

1) [Redacted]

2) [Redacted]

3) [Redacted]

4) [Redacted]

5) [Redacted]

6) [Redacted]

7) [Redacted]

8) [Redacted]

We will work closely in conjunction with PwC in the US in undertaking this Phase of work. At the conclusion of our work, we issue a detailed letter of advice summarising our work.

…

3 Stamp Duty

Background and assumptions

The scope of our stamp duty advice will be based on the understanding that:

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

Work to be performed

Our stamp duty services will be provided in three phases. The services to be provided under each phases Two and Three are set out below.

3.1 Phase Two – [Redacted]

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

3.3 Phase Three - [Redacted]

• Preparation of a detailed estimate of the landholder duty payable in each relevant jurisdiction, ensuring duty is quarantined from non-dutiable items, duty is confined to the transaction value and any exclusions for interests previously held are properly claimed;

• Preparation and lodgement of:

o [redacted];

o [redacted];

o [redacted];

o [redacted];

• [Redacted];

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

Deliverable

• [Redacted]; and

• [Redacted].

101 Section 4 was headed “Fees and expenses” and adopted a similar form to that section in the Statements of Work described above. Section 5 was headed “PwC team” and identified four ALPs and five NLPs. The Communications Protocol was set out in section 6.

102 Statement of Work No 4 (Global Restructure Project – Australian Income Tax and Stamp Duty Legal Advice) stated (in Section 1) that, broadly, the scope of work covered advice in relation to Australian income tax and stamp duty issues associated with the global restructure executed by the JBS Global Group in December 2014. Sections 2 and 3 stated:

2. Income Tax

We have been asked to undertake the following specific items of work under this engagement:

1) Preparation of calculations required to be undertaken as a result of the JBS Australia multiple entry consolidated (MEC) tax group deconsolidating. These calculations will result in the quantification of any tax payable as a result of the deconsolidation.

2) Preparation of Allocable Cost Amount (ACA) calculations for a potential tax consolidation of the JBS Australia Group. We will also prepare a summary of the calculations that outlines the potential benefits and costs of consolidating for tax purposes.

3) Planning/Structuring advice associated with the issues associated with the broader Global Restructure.

3 Stamp Duty

The scope of this engagement will also cover any advice required in relation to potential Australian Stamp Duty issues associated with the work that we will assist JBS with in relation to its global restructure.

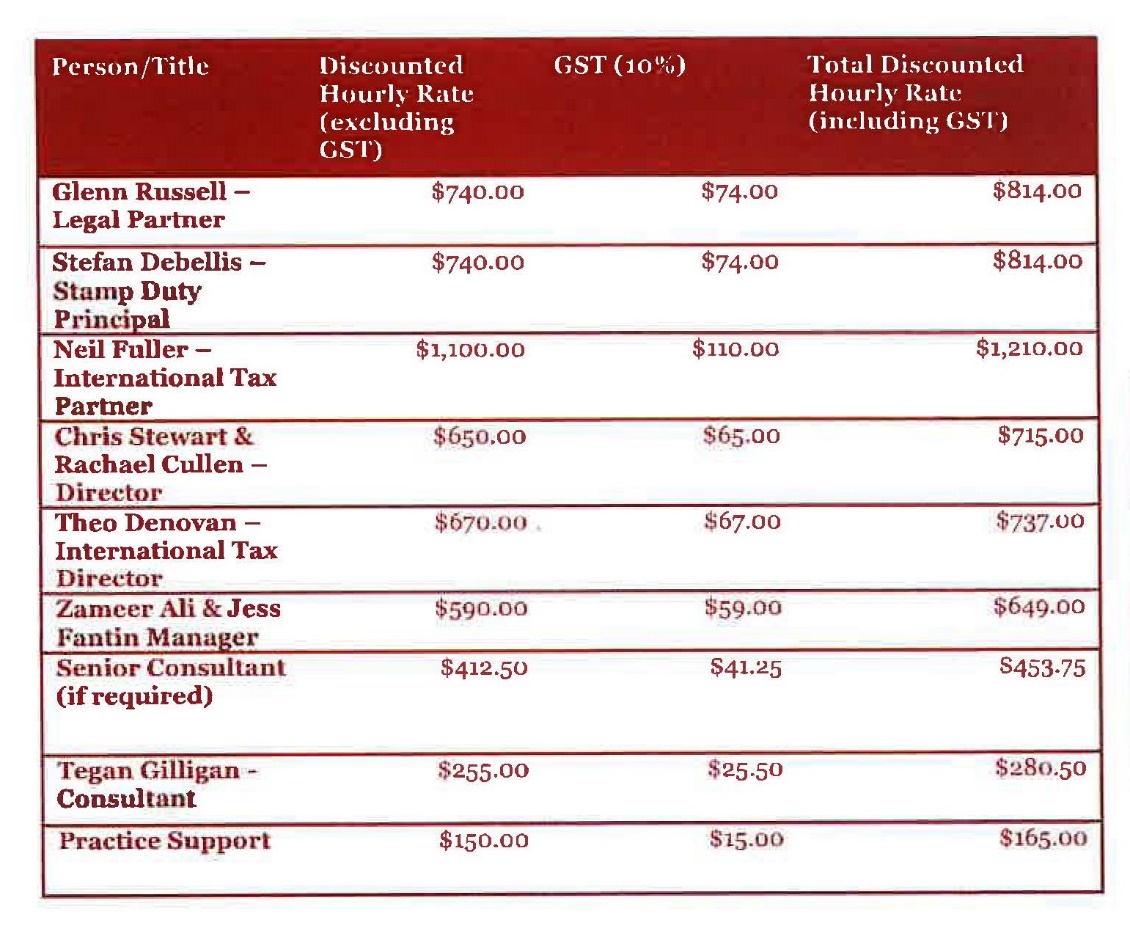

103 Section 6 was headed “Fees and expenses” and set out a table of PwC personnel (and categories of personnel) and their charge-out rates:

104 The “PwC team” was set out in section 7. This section was as follows:

Australian legal practitioners | |||

Name | Role | Telephone | |

Glenn Russell | Legal Partner | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Zameer Ali | Manager (Income Tax) | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Rachael Cullen | Director (Stamp Duty) | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Jess Fantin | Manager (Stamp Duty) | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Non legal practitioners | |||

Name | Role | Telephone | |

Income Tax | |||

Neil Fuller | International Tax Partner | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Chris Stewart | Director | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Theo Denovan | International Tax Senior Manager | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Tegan Gilligan | Consultant | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

Stamp Duty | |||

Stefan Debellis | Principal | [number omitted] | [address omitted] |

105 Section 8 was headed “Communications Protocol” and was in the same terms as referred to above.

106 Mr Russell gave the following evidence with reference to Statement of Work No 4, dated 15 January 2015, and in particular the description of the scope of work in that document:

[SENIOR COUNSEL FOR THE COMMISSIONER]: … Do you regard the presentation of calculations as legal work?---In – in respect of item - - -

Number 1. Preparation of calculations?---In respect of 2.1 there I – absolutely I do.

So the preparation of the calculations is legal work and the actual quantifications of the tax payable, is that legal work?---Yes, it is.

Did you regard the preparation of the allocable cost amount as legal work?---I did.

And the summary of the ACA calculations, is that legal work?---It is.

Do you regard the planning, the structure advice associated with the broader global structure as legal advice?---Yes, I do.

…

Do you regard the preparation of advice about Australian stamp duty as legal work?---Yes, I do.

While I accept that Mr Russell holds the views he expressed in the above passage, I consider the issue raised to be one of legal characterisation, which is ultimately for the Court to determine.

107 Statement of Work No 5 (Legal services in relation to a global reorganisation of the JBS group) stated (in Section 1) that, broadly, the scope of work covered advice in relation to Australian income tax and stamp duty issues associated with the global reorganisation of the JBS Global Group, [redacted]. The work to be performed was then identified:

We will provide legal services as requested by you. In particular, we will provide legal services relating to the proposed global reorganisation of the JBS Group and any other transactions associated with the reorganisation. We expect that this will include [redacted]:

• [Redacted]

• [Redacted]

• [Redacted]

• [Redacted]

• [Redacted]

• [Redacted]

108 Section 2 was headed “Fees and expenses” and identified PwC personnel (and categories of personnel) and charge-out rates. Section 3 described the “PwC team” – the only ALP was Mr Russell; two NLPs were identified. Section 4 was the “Communications Protocol”, in the same form as set out above.

109 The email dated 25 July 2015 from Mr Russell and Mr Fuller to Mr Alvares extended the scope of the engagement as follows:

Following the recent meeting in the US between JBS and PwC, PwC was requested to expand the scope of the originally agreed tax advice to include certain accounting assistance. The scope of this work is as follows:

Scope of the accounting services

The accounting services [we] will provide under this scope extension include:

• reviewing multiple iterations of the draft steps plans, discussions with PwC US and PwC global tax teams

• consideration of applicability of fair value accounting on incorporation of Australian newco’s when assets and investments are contributed by the parent for equity;

• consideration of the requirements in the literature for parent entity accounting when a subsidiary recognises gains/losses

• consideration of distribution accounting and gain recognition where subsidiaries make distributions to a parent

• preparation of summary of accounting concepts and issues regarding the Australian entities within the proposed re-organisation plan

We will not be commenting on the commercial or other desirability of transactions or accounting treatment. Our work will not constitute an audit conducted in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards, or other attestation or review services. Accordingly, we will not express an audit opinion or provide any other form of assurance under the terms of this engagement.

The initial scope of work that we will perform is the provision of a summary outline setting out accounting issues, concepts and considerations under Australian Accounting Standards for the proposed re-organisation of the JBS group as set out in the draft steps plan circulated by JBS in the individual Australian JBS group companies.

110 Statement of Work No 6 (Legal Services – Project Twiggy Phase 2) included the following statement of the work to be performed:

We will provide legal services as requested by you. In particular, we will provide legal services relating to Phase 2 of Project Twiggy. In the course of providing these legal services we may seek advice on accounting and tax issues from non-legal members of PwC.

To the extent that our services include tax compliance services such as the documentation and preparation of taxation returns and related filings, these will not attract legal professional privilege. Only communications and documents created for the dominant purpose of providing legal advice can attract legal professional privilege.

Legal Services

1. Income Tax

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

2. Corporate Legal Services

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [redacted;.

• [Redacted];

• [redacted]; and

• [redacted].

• [Redacted].

3. Accounting

• Accounting advisory assistance on the proposed transaction steps to undertake Project Twiggy Phase 2.

Our work will not constitute an audit conducted in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards, or other attestation or review services. Accordingly, we will not express an audit opinion or provide any other form of assurance under the terms of this engagement.

The accounting services outlined in this letter will be prepared for JBS Australia Pty Ltd for its sole purpose in the context of assisting the management in formulating the accounting treatment for the relevant subject confirmed in this SoW. However, we acknowledge that you will provide a copy of the related accounting deliverables to your auditor.

Deliverable

Our deliverables in respect of this engagement may include the following:

• Preparation of the detailed step plan.

• Formal tax opinions - for example, in relation to tax consolidation outcomes and the application of Australia’s General Anti-Avoidance Provisions.

• Drafting all Australian legal documents to complete the step plan and completion assistance.

• Accounting advice in the form of a technical memorandum.

• Meetings and discussions with relevant stakeholders.

111 Section 3 was headed “Fees and expenses” and set out an overall fee for the work. Section 4 was headed “Our team” and set out two tables – the first with the names of three ALPs; the second with the names of six NLPs. Immediately after those tables, there was a heading “Communications Protocol”, with the text set out above.

112 Statement of Work No 7 (Legal Services – Global Regional Alignment Project) outlined the following work to be performed:

We will provide legal services as requested by you. In particular, we will provide legal services relating to the proposed global regional alignment of the JBS Group and any other transactions associated with the group reorganisation. In the course of providing these legal services we may seek advice on accounting and tax issues from non-legal members of PwC.

Legal Services

1. Income Tax

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

2. Stamp Duty

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

3. Accounting

• Accounting advisory assistance on the proposed transaction steps to undertake the global restructure.

• Accounting balance sheet modelling of the proposed steps.

• Attendance at discussions with your auditor in relation to the outcomes from our accounting advice.

Our work will not constitute an audit conducted in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards, or other attestation or review services. Accordingly, we will not express an audit opinion or provide any other form of assurance under the terms of this engagement.

The accounting services outlined in this letter will be prepared for JBS Australia Pty Ltd for its sole purpose in the context of assisting the management in formulating the accounting treatment for the relevant subject confirmed in this SoW. However, we acknowledge that you will provide a copy of the related accounting deliverables to your auditor.

4. Corporate Legal Services

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [Redacted].

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted];

• [redacted]; and

• [redacted].

• [Redacted].

To the extent that our services include tax compliance services such as the documentation and preparation of taxation returns and related filings, these will not attract legal professional privilege. Only communications and documents created for the dominant purpose of providing legal advice can attract legal professional privilege.

Deliverable

Our deliverables in respect of this engagement may include the following:

• Preparation of the detailed … global regional alignment step plans,

• Formal tax opinions - for example, in relation to financing and the application of Australia’s General Anti-Avoidance Provisions.

• Transfer Pricing documentation in the form of an Arm’s Length Debt Test Report and/or interest rate benchmarking report.

• Stamp duty advice on the transaction steps and lodgements for the relevant Offices of State Revenue.

• Drafting all Australian legal documents to complete the step plan and completion assistance.

• Accounting advice in the form of a technical memorandum.

• Meetings and discussions with relevant stakeholders.

113 During cross-examination, Mr Russell said that this Statement of Work described a very large amount of work. He said it was the largest Statement of Work in terms of work required and fees charged over the Relevant Period.