Federal Court of Australia

Ripani v Century Legend Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 242

VID 266 of 2020 | ||

BETWEEN: | WALTER RIPANI First Applicant NINA RIPANI Second Applicant | |

AND: | CENTURY LEGEND PTY LTD Respondent | |

order made by: | ANASTASSIOU J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 March 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The contract of sale for the purchase by the Applicants of apartment 14.01 at 20-21 Queens Road, Melbourne, made on or about 29 August 2017, be rescinded.

2. By no later than 4:00pm on 25 March 2022, the Respondent return to the Applicants the bank guarantee provided on behalf of the Applicants by the Bank of Melbourne on 29 August 2017 in lieu of a deposit.

3. The Respondent pay damages and pre‑judgment interest to the Applicants in an amount to be determined in accordance with paragraph 4 of these orders.

4. By no later than 4:00pm on 25 March 2022, the parties file:

(a) an agreed minute of the sums payable for damages and pre-judgment interest in accordance with these reasons for judgment; or

(b) failing agreement, the parties are to file separate minutes and submissions, limited to four pages, concerning their respective calculations of damages and pre-judgment interest payable in accordance with these reasons.

5. The Respondent pay the Applicants’ costs of and incidental to the proceeding, to be agreed and in default of agreement assessed on a standard basis.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

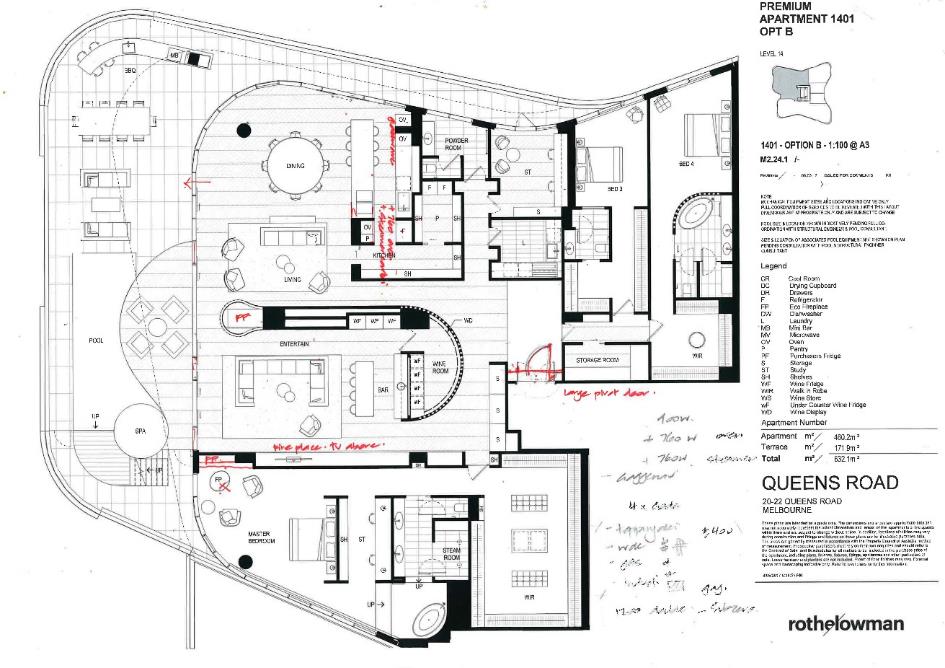

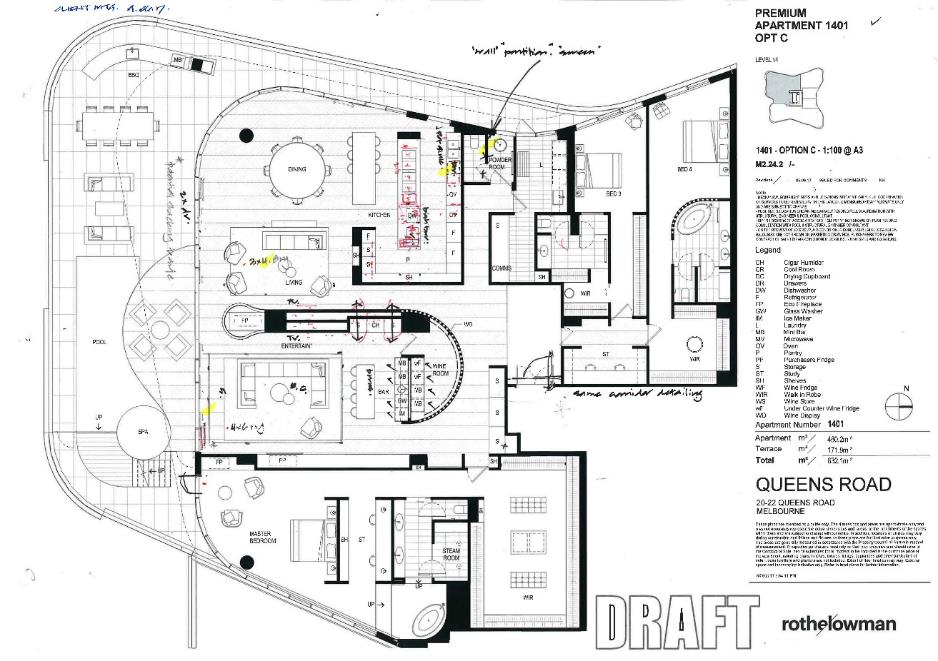

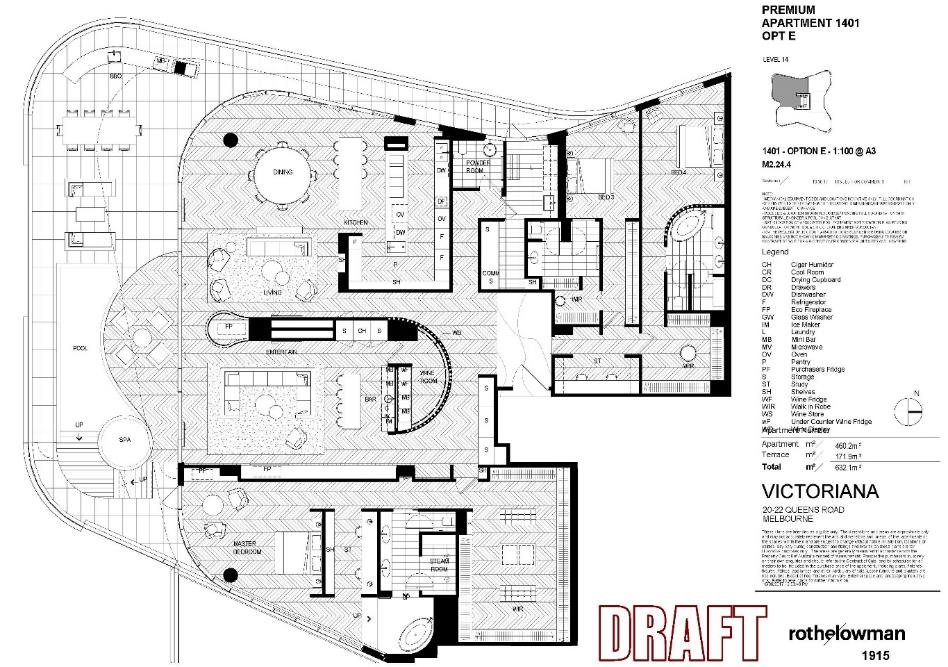

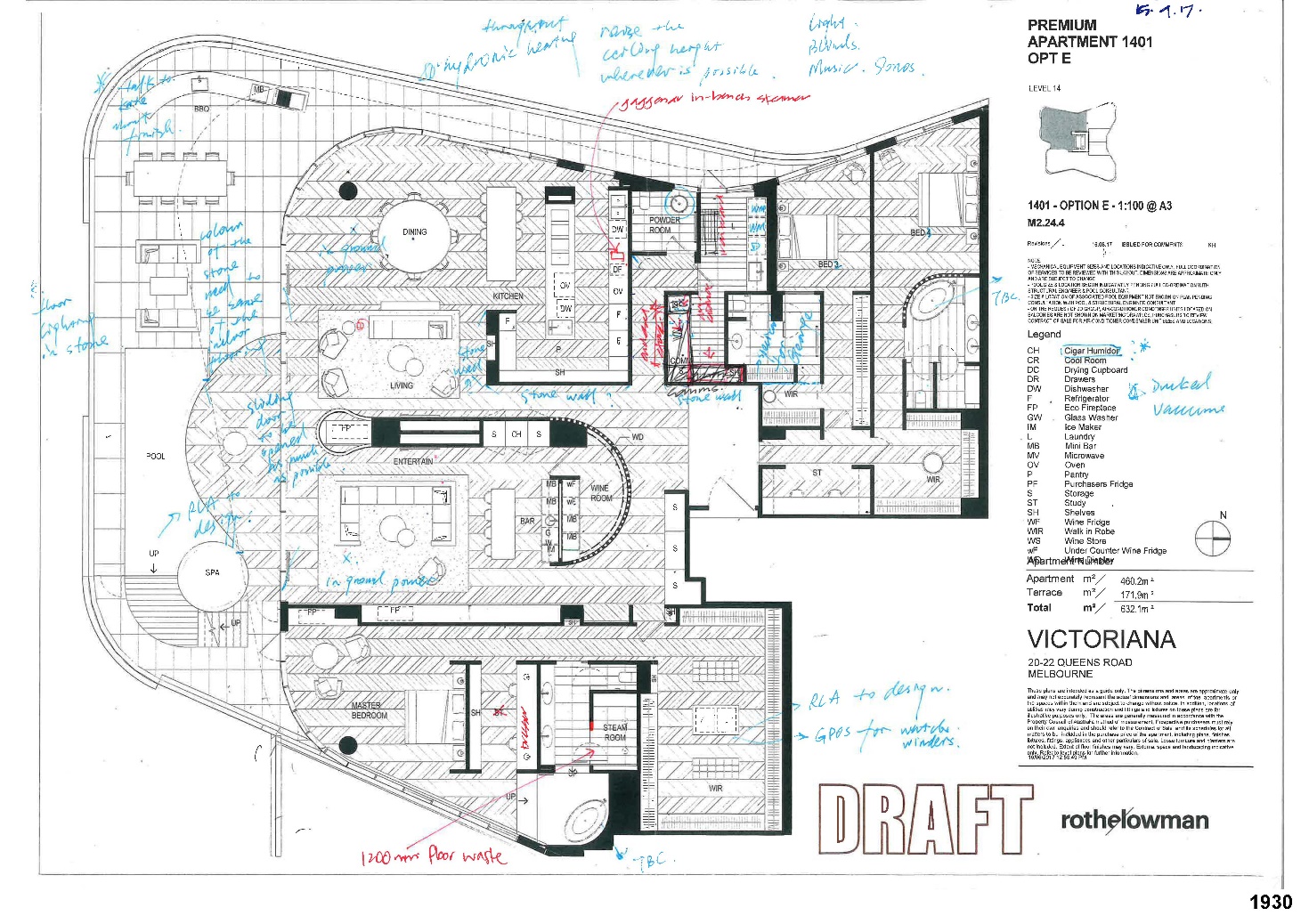

ANASTASSIOU J:

Introduction

1 This case concerns the sale of an apartment ‘off-the-plan’, specifically whether the purchasers were misled or deceived by statements made by or on behalf of the vendor concerning certain features of the apartment prior to the parties entering into a contract of sale. The vendor is the Respondent to this proceeding, Century Legend Pty Ltd, which traded under the business name JD Group during the relevant period. The purchasers are the Applicants, Mr Walter Ripani and Mrs Nina Ripani (collectively, the Ripanis).

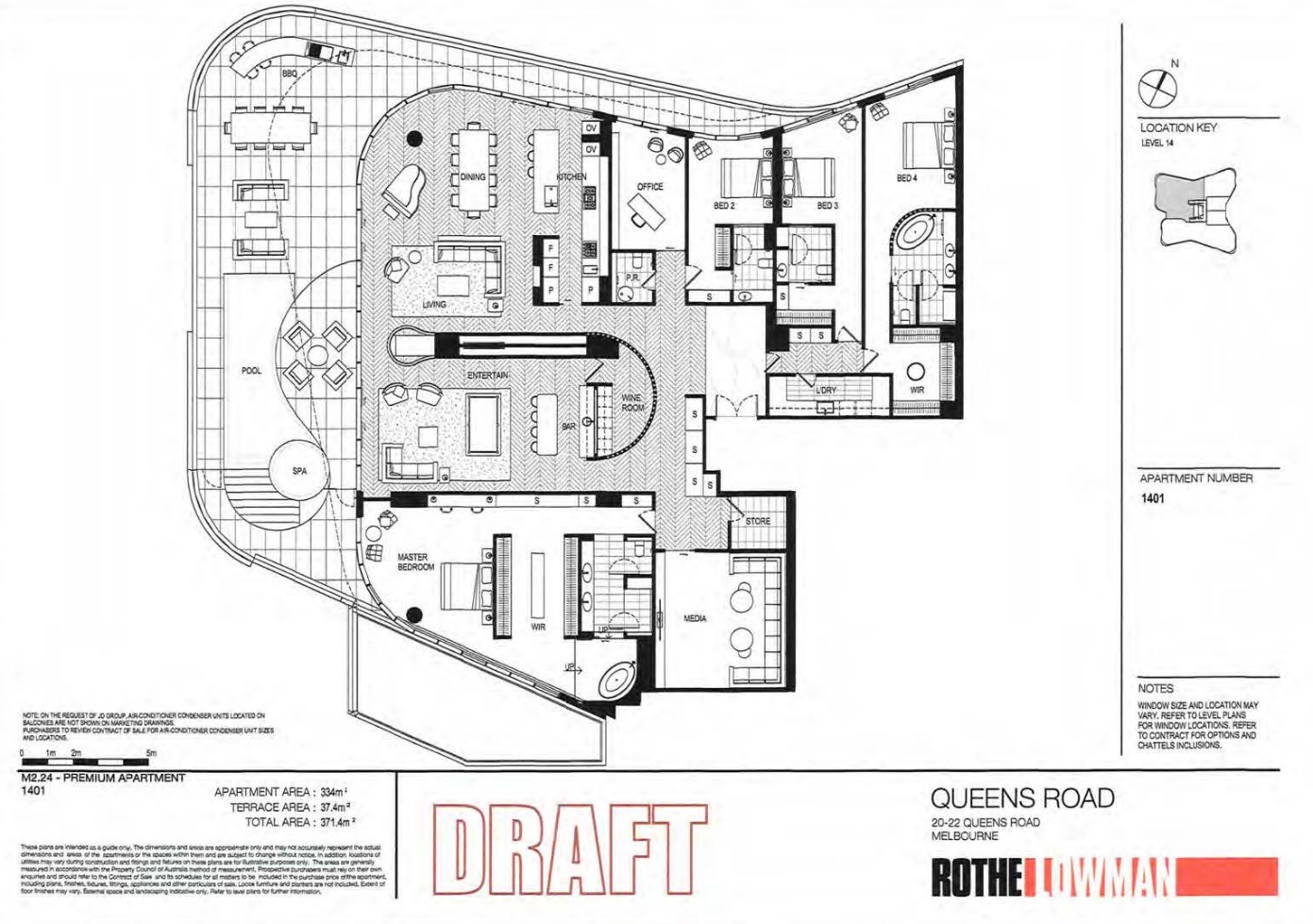

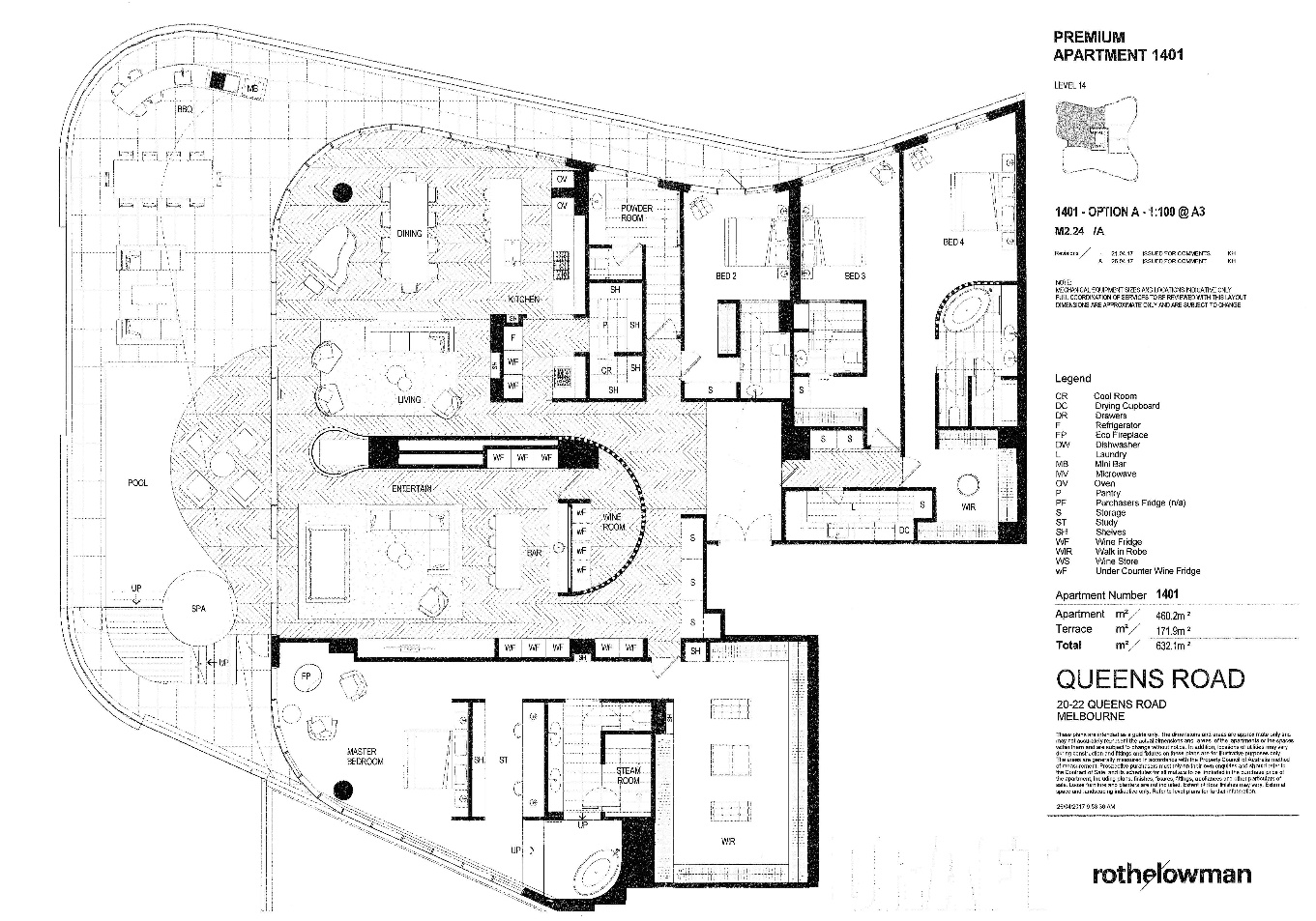

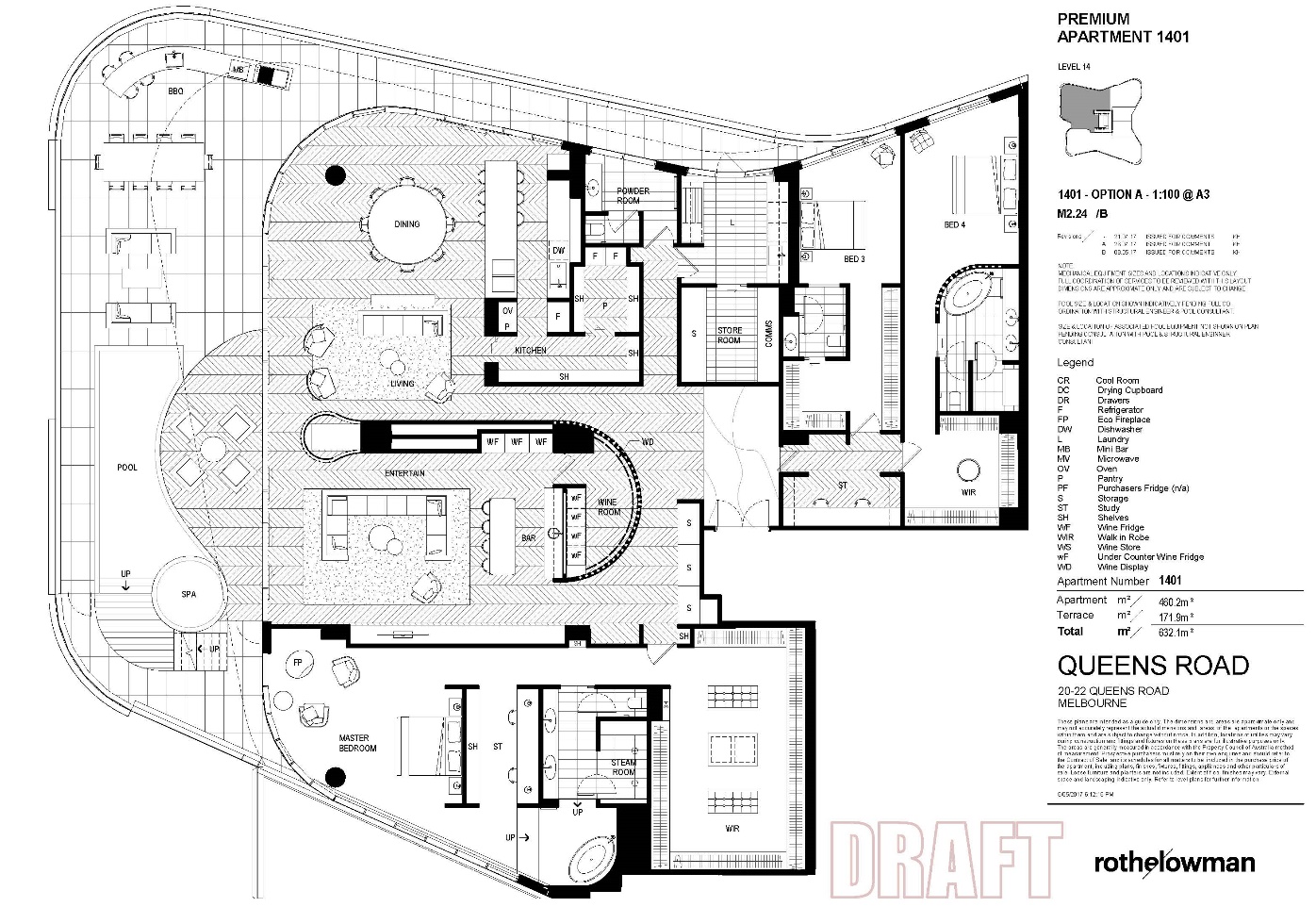

2 The Ripanis purchased an apartment ‘off-the-plan’ to be constructed at 20-21 Queens Road, Melbourne. Century Legend was the developer of the site upon which it proposed to construct a multi-storey apartment building to be known as ‘the Victoriana’. Mrs and Mr Ripani chose to purchase what was to become apartment 14.01, one of the premium apartments to be located on the 14th floor on the western side of the building. On 1 April 2017, the Ripanis signed a contract under which they agreed to pay $9.58 million for the apartment, subject to a floor plan satisfactory to them being agreed.

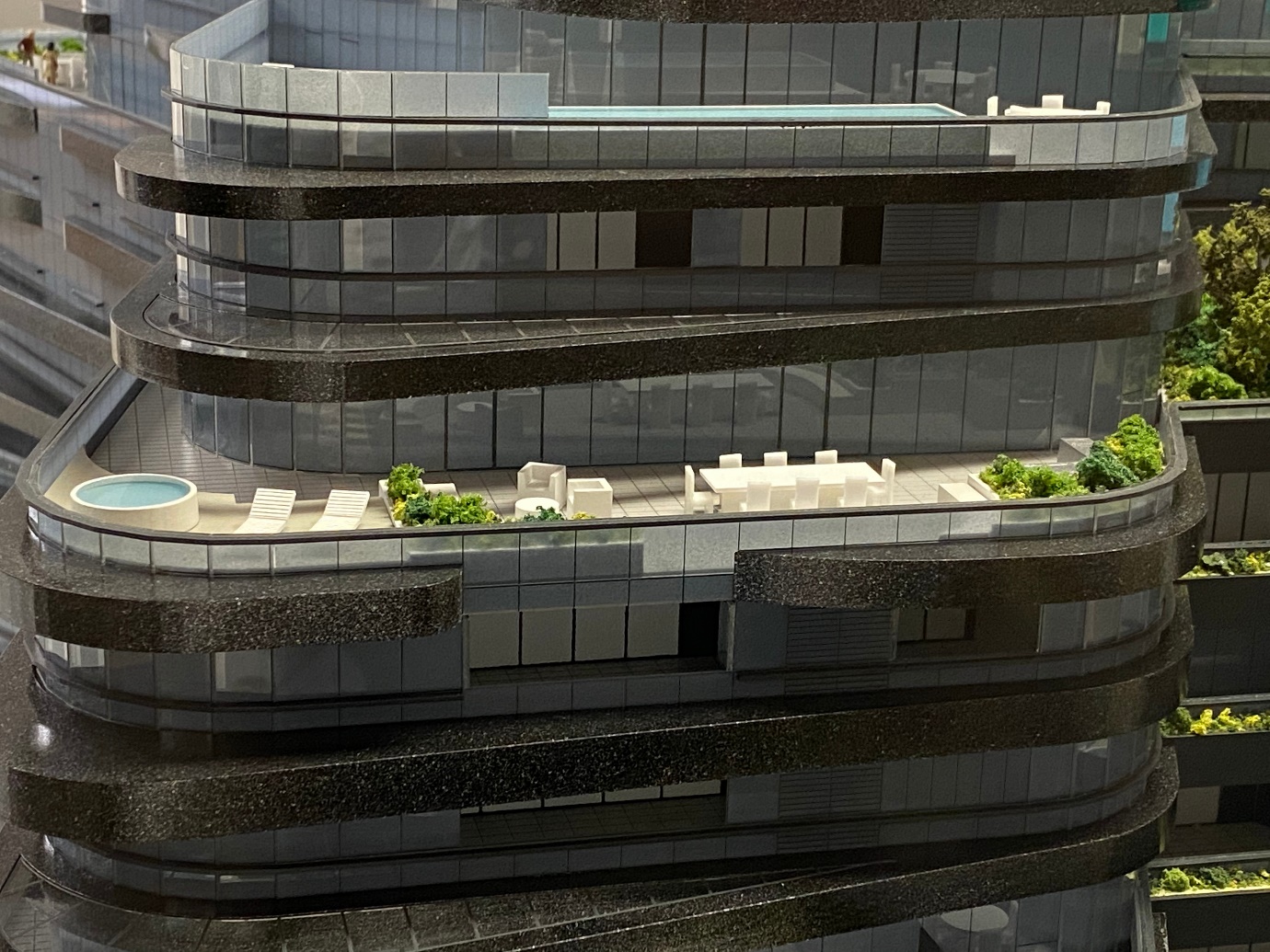

3 In 2016, Century Legend prepared promotional materials to be used in marketing the Victoriana and to assist with making ‘off-the-plan’ sales. It engaged real estate agents CBRE to assist it in marketing the apartments and established a display suite located at the site, at which promotional materials, as well as a scale model of the Victoriana, were available for inspection by prospective buyers. These materials included a hard-bound brochure containing various images, known as ‘renders’, of what the development, or aspects of it, would look like once constructed. Those renders were produced by a company called Squint Opera, which was engaged in the business of generating computer graphics for such purposes.

4 Promotional materials of this kind were essential if Century Legend was to be able, practically, to sell the apartments ‘off-the-plan’. At the centre of this proceeding is the question of what, if any, reliance the Ripanis could reasonably place on one of the renders in particular. When considering this question, it must be borne in mind that there was of course no building to inspect, only indicative floor plans, a scale model of the Victoriana and renders of various aspects of the building and of apartments within the development. The renders included images of external and internal areas. Necessarily, the renders were artistic impressions of what the Victoriana would look like on completion. The promotional material also contained indicative floor plans for several of the apartments within the 16 levels of the Victoriana. I shall discuss the floor plans and their significance below.

5 One of the images, in particular, caught the attention of the Ripanis. It was an image of apartment 14.01, a copy of which is reproduced below and also at Annexure I. The render depicts the western aspect of apartment 14.01, specifically a large free span opening between the inside of the living areas and the outside terrace. In the image, there is no differentiation between the interior floor level and the external terrace. The Ripanis contend that the render therefore depicts a space where the indoor and outdoor areas flow seamlessly into each other when the doors are drawn back.

6 Though this render was specific to apartment 14.01, it was also selected by Century Legend as an image to be used more widely in promoting and marketing the Victoriana. The use of this particular render as a visual medium by which to depict certain features and characteristics of the Victoriana is evident from the prominence given to it in the marketing brochure for the high rise premium apartments, of which apartment 14.01 was one. This render was also displayed as a large exhibit on the wall of the display suite established at the development site.

7 The use of certain images for broader marketing or branding purposes is common in relation to ‘off-the-plan’ sales. I shall refer below to the evidence of Mr Kevin Tran of CBRE concerning the use of this image, which Mr Tran referred to as one of the ‘hero shots’ because of its prominence in the marketing of the Victoriana to prospective purchasers. Senior Counsel for the Ripanis subsequently described the image as the ‘hero render’, which is the phrase I adopt in my reasons.

8 The ‘hero render’ is of central relevance to the bases upon which the Ripanis seek to be relieved of their contractual obligations to complete the purchase of apartment 14.01. Save for some oral representations made by Mr Tran of CBRE to the effect that the ‘hero render’ was an image of apartment 14.01, and that the Ripanis could expect the apartment to conform to the render, the image itself was the principal medium by which the representations about which the Ripanis complain were made. The Ripanis’ case is essentially that the representations conveyed by the ‘hero render’ were misleading or deceptive within the meaning of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

9 The Ripanis’ claim for relief consequent upon a contravention of s 18 of the ACL turns upon essentially three questions. First, did the render convey the representations as alleged by them, essentially that there would be a free span opening and seamless transition between the internal living areas of the apartment and the terrace? Second, did the Ripanis rely upon any representations conveyed by the render at the time they entered into the contract to purchase the apartment? Third, would the Ripanis have entered into the contract to purchase apartment 14.01 had they not believed at the time that the apartment would be constructed in conformity with the image depicted in the render?

10 Leaving aside the effect of disclaimers and certain contractual exclusion clauses, to which I shall refer below, if the answers to each of the first and second questions is yes, and the answer to the third question is no, in my view the Ripanis are entitled to an order in the nature of rescission of the contract of sale pursuant to ss 237 and 243(a) of the ACL, or, alternatively, to an order in equity that the contract of sale be rescinded.

11 The statutory power to make an order in the nature of rescission is relevantly pre-conditioned by two matters: first, it only arises on the application of the Ripanis if they suffered, or are likely to suffer, loss or damage because of the contravening conduct; and second, the order must be one that the court considers will compensate the Ripanis, in whole or in part for the loss or damage, or prevent or reduce the loss or damage suffered, or likely to be suffered: see s 237(2) of the ACL; Harvard Nominees Pty Ltd v Tiller [2020] FCAFC 229; 282 FCR 530 at [18]-[21] (Lee, Anastassiou and Stewart JJ). For reasons I shall discuss below, I am satisfied of those pre-conditions in this instance. In any event, the Ripanis are concurrently entitled to an order in equity for rescission of the contract of sale.

12 Century Legend’s first level of defence to the Ripanis’ claim is that the render did not convey any meaningful representation. I reject that defence. Further, I accept that the render conveyed in substance the principal representations alleged by the Ripanis. I shall discuss below the representations as pleaded. I also find that there was no reasonable basis for making the representations. This is because Century Legend knew, prior to using the ‘hero render’ in connection with marketing the apartments at the Victoriana, including apartment 14.01, that it was impossible to construct apartment 14.01 in a way that would bear a reasonable resemblance to the render. I reject the evidence of Mr Peter Hu (Sales Manager at Century Legend) to the contrary.

13 I will also refer below to the evidence of Mr Cameron De Mooy, a project manager employed by the builder of the Victoriana, Hickory Group, with responsibility for the day to day building works at the development site. Mr De Mooy was called as a witness by Century Legend and explained the reasons why it was impossible to construct the free span opening depicted in the render. I shall also refer below to the warnings Century Legend was given by its architects, RotheLowman, concerning the use of the render in marketing the Victoriana. As a result of those warnings, I find that Century Legend knew of the impossibility of constructing apartment 14.01 in the manner depicted in the hero render before it was deployed for marketing purposes.

14 I find that the representations made by or on behalf of Century Legend were misleading and deceptive and further that they did not have reasonable grounds for making those representations. In particular, I find that Century Legend engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the ACL by publishing (that is to say, using) the ‘hero render’ for the purpose of marketing the Victoriana generally, and for the purpose of marketing apartment 14.01 in particular; and, relevantly to the present claim, by providing the ‘hero render’ to the Ripanis in the circumstances to which I shall refer.

15 The second question referred to above at [9] concerns the factual issue of whether the Ripanis relied upon the representations conveyed by the render when they decided to purchase the apartment. Century Legend revealed at trial, for the first time, that it would contend that any misapprehension on the part of the Ripanis based upon the render was corrected prior to them entering into the contract to purchase apartment 14.01. Ms Kate Hart, an architect employed by RotheLowman, gave evidence to the effect that she informed the Ripanis in May or June 2017, prior to the contract being entered into, that the free span opening for apartment 14.01 could not be constructed in accordance with what was depicted in the render. Indeed, Ms Hart gave evidence that she told the Ripanis there would be multiple openings between the interior and exterior of the apartment and the main opening to be centred on the fireplace could not be more than about 3 to 4 metres width.

16 I shall refer below to the evidence given by the Ripanis and Ms Hart concerning discussions between them prior to, and following, the purchase of the apartment. In summary, for introductory purposes, Century Legend led evidence from Ms Hart that she had extensive dealings with the Ripanis both before and after the contract of sale was signed, principally to assist the Ripanis in specifying, or ‘customising’, the internal floor plan of apartment 14.01 to meet their particular requirements. The discussions between the Ripanis and Ms Hart concerned a variety of features of the internal design of the apartment, the selection of particular appliances, as well as certain features of the layout of the western terrace. These discussions occurred by reference to a number of proposed floor plans prepared by Ms Hart, usually following discussions with the Ripanis.

17 As I shall explain, these discussions focused on details of importance to the Ripanis in relation to the floor plan and bespoke fit out of the apartment. In retrospect, the discussions proved to be a ‘red-herring’ so far as the Ripanis’ real interest in the apartment was concerned. The feature which was of most significance to the Ripanis; namely, the free span opening between the internal living areas and the western terrace, was not a subject of discussion between the Ripanis and Ms Hart. Mrs Ripani unequivocally denied having any conversation with Ms Hart in relation to the width, or location, of the door opening on the western façade of apartment 14.01 prior to purchasing the apartment. Mr Ripani encapsulated the Ripanis’ understanding when he said in his evidence he thought it “was a given” that the apartment would have a large opening onto the terrace and therefore did not raise the question of the opening prior to entering into the contract of sale.

18 I reject Ms Hart’s evidence concerning statements allegedly made by her to the Ripanis, which, if accepted, would have cured the misleading representations conveyed by the render so far as the Ripanis are concerned. Conversely, I accept the evidence given by each of Mrs Ripani and Mr Ripani to the effect that they believed that the opening on the western side of the apartment would conform in substance to the image depicted in the ‘hero render’.

19 I also accept the evidence of Mr Tran, who was called as a witness by the Ripanis. Mr Tran gave evidence that his usual practice was to sell ‘off-the-plan’ apartments by reference to marketing materials, including any visual renders, building models, floor plans and other materials and that such materials were available in the Victoriana display suite. Indeed, Mr Tran said that he specifically told the Ripanis that the ‘hero render’ depicted apartment 14.01. Mr Tran also gave evidence that although the opening was not specifically discussed, the Ripanis were attracted to the large entertaining area and transition from the living areas to the terrace.

20 Having regard to these matters, I find that the Ripanis’ understanding at all relevant times prior to entering into the contract of sale was that apartment 14.01 would be constructed in conformity with the render, and, in particular, that the scale of the free span opening to the terrace would be as depicted in the render, allowing for the fact that it is impressionistic.

21 In relation to the third question posed above at [9], I accept the Ripanis’ evidence that the opening between the living areas and the western terrace was a feature of the apartment that was of significant attraction to them. Their evidence is consistent with Mr Tran’s evidence that the Ripanis were specifically looking for an apartment with a suitable outdoor area for entertaining guests and were attracted to the “type” and “feel” of the apartment. It is also consistent with Mr Tran’s evidence that Mr Ripani pointed to the ‘hero render’ and said words to the effect: “Look, you know, I’m after something like that.” I find that had the Ripanis been told that the apartment would, or could, not be constructed to the design depicted in the render, they would not have contracted to purchase it.

22 I note at this point, it was not until a considerable time after the Ripanis had agreed to purchase the apartment that they were told the truth concerning the opening to be constructed between the internal living areas and the terrace. After the Ripanis had entered into the contract, they were told different things at different times about what they could expect in relation to the width of the opening. In my view, the Ripanis were surprisingly tolerant of having their expectations disappointed after being told for the first time on 9 October 2018, more than a year after they entered into the contract, that the free span opening depicted in the render was not achievable. However, at that time the Ripanis were told that a free span opening of 6.4 metres might be achievable. When it was finally revealed to them on 3 June 2019 that the opening would be only 3.4 metres, they resolved not to complete the purchase and to seek relief from the Court. I shall refer in further detail below to what the Ripanis were told after entering into the contract to purchase the apartment about the opening between the living areas and the terrace.

23 I have concluded that the conduct of Century Legend was not only misleading and deceptive within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL, but deliberately so, having regard to its knowledge that the free span opening depicted in the so called ‘hero render’ could not be constructed for design and engineering reasons. Despite this knowledge, Century Legend continued to use the ‘hero render’. They did so notwithstanding that Mr Stephen Perkins of RotheLowman described the renders as “misleading” in October 2016 and told Century Legend that the free span opening could not be constructed due to development and structural requirements. Ms Hart also acknowledged that she knew the ‘hero render’ was “completely inaccurate” in the period during which she was meeting with the Ripanis to finalise the floor plan. Further, she told Century Legend in June 2017 that it was “extremely important” that JD Group make potential purchasers aware of the actual door opening and transition from the internal living area to the outdoor terrace.

24 I pause to note at this juncture that Mr Perkins was a senior architect within RotheLowman responsible for the design of the Victoriana. Ms Hart gave evidence that she reported to Mr Perkins and they consulted regularly in relation to the Victoriana project. In particular, Ms Hart explained that she was responsible for the interior design of the building, and Mr Perkins was responsible for the external design of the building.

25 As I have said, I reject the evidence of Ms Hart to the effect that she told the Ripanis about the impossibility of constructing the free span opening as depicted in the ‘hero render’. For completeness, there is no suggestion that any person from RotheLowman other than Ms Hart had relevant communications with the Ripanis prior to their entry into the contract.

26 Following the conclusion of the hearing, on 27 August 2021, Century Legend’s conveyancers, Hailes Lawyers, notified the Ripanis’ legal representatives, Zervos Lawyers, that the plan of subdivision was registered on 3 June 2021, and that they had received a “Stage 5 of the Occupancy Permit” for apartment 14.01. Century Legend’s conveyancer therefore gave notice that settlement of the contract of sale for apartment 14.01 was to take place on 10 September 2021. On 30 August 2021, the Court was notified by email that Century Legend’s conveyancers had called for settlement to occur on 10 September 2021. On 3 September 2021, my Associate wrote to the parties saying: “His [H]onour has also asked me to inform the parties that he expects the present status quo to be maintained, that is, settlement of the contract of purchase should be deferred pending his judgment. If there is opposition to this course, the parties have leave to raise the matter and a hearing will be arranged before 10 September.” On 7 September 2021, the parties notified the Court that they had agreed to defer settlement until 14 days after final judgment.

27 Having set out those introductory matters, and expressed the principal conclusions which I have reached, I proceed first to consider in more detail the representations conveyed by the render, having regard also to the context in which the render was given to the Ripanis and what they were told about it.

The representations

28 Leaving aside for the moment oral representations made on behalf of Century Legend by its real estate agent Mr Tran of CBRE, the representations about which the Ripanis complain were conveyed by the ‘hero render’.

29 It is trite to say that meaning may be conveyed by a picture, whether it be an oil painting or a computer generated image, without requiring explanation in language. It is equally well understood that in many contexts a picture may be more effective than a description of the subject, hence the well-known saying about ‘a thousand words’. In other contexts, for example the graphic depiction of a building represented by a plan, specific detail such as measurements and dimensions may be required, depending on whether the plan is merely conceptual or, on the other hand, is to be used for construction purposes. Indeed, the use of imagery to convey meaning is a form of human expression which is likely as old as mankind. The rock art of the Kimberley is evidence that the pictorial medium of communication existed from a very early time in human history: see, eg, Walsh, G L, Bradshaw Art of the Kimberley (Takarakkar Nowan Kas Publications, 2000).

30 The ‘hero render’ is properly characterised as a conceptual image. It does not contain any notation specifying the width or height of the free span opening between the living areas and the terrace. But that does not mean the render was inapt at, and much less incapable of, conveying the representations about which the Ripanis complain. Contrary to one of the principal contentions advanced by Century Legend, the render was by no means meaningless or incapable of being reasonably relied upon by prospective purchasers because it did not specify any dimensions of the free span opening.

31 Though conceptual, an impression was clearly communicated by the render; namely, that there would be a large free span opening between the terrace and the internal living areas when apartment 14.01 was built, which opening is depicted to extend almost entirely the length of the living areas adjacent to the terrace. In my view, that representation was demonstrably conveyed by the ‘hero render’. Further, having regard to the purpose for which the render was used and provided to the Ripanis, it was not necessary that it contain specifications as to the dimensions of the free span opening. In context, it was sufficient for the Ripanis’ purposes that the render showed there would be a free span opening, the scale of which is depicted by reference to the adjacent internal living areas.

32 The Ripanis each gave evidence that Mr Tran specifically told them that the render depicted apartment 14.01. Mr Tran also gave evidence that he told the Ripanis, in effect, that apartment 14.01 would be constructed as depicted in the render, with an expansive opening onto the terrace from the internal living areas. Although Mr Tran referred to the render as an “artist’s impression”, he did not otherwise qualify the impression conveyed by the render. That evidence was not challenged by Century Legend.

33 Mr Tran’s representations, in his capacity as a sales agent for Century Legend, are relied upon by the Ripanis as the basis for further causes of action for misleading and deceptive conduct and/or misrepresentation on the part of Century Legend. In this regard, I note Mr Tran was plainly the agent of Century Legend and acting within the scope of his actual or apparent authority in making those representations: see, eg, Walplan Pty Ltd v Wallace [1985] FCA 619; 8 FCR 27 at 36-37 (Lockhart J, Sweeney and Neaves JJ agreeing), cited in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Productivity Partners Pty Ltd (trading as Captain Cook College) (No 3) [2021] FCA 737 at [112] (Stewart J). For reasons I explain below, I find that the representations made by Mr Tran on behalf of Century Legend were misleading and deceptive. I note, however, that Mr Tran was merely a conduit for the representations as he was unaware at the time he made those representations that the free span opening could not be constructed and believed what he said to the Ripanis to be true.

34 I return to the representations conveyed by the render considered in context. The statements made to the Ripanis by Mr Tran provide important context relevant to whether the render conveyed any representations upon which the Ripanis could reasonably rely. Mr Tran’s statements were, of course, consistent with the purpose for which the render was created. Plainly, the render was a selling document. It was an image that had been created to assist in selling apartment 14.01 ‘off-the-plan’ and to promote the sale of apartments at the Victoriana more generally.

35 During the design process, Century Legend requested that Squint Opera designate the ‘hero render’ as one of four “priority images” to be released for marketing the Victoriana development. Moreover, once produced, the ‘hero render’ featured prominently in the marketing materials for the Victoriana. It was included in a hard-bound brochure comprising images and text for use in marketing the premium level apartments. That brochure was given to the Ripanis when they visited the display suite on 31 March 2017. The render also appeared on the home page of the website for the Victoriana development and as a large exhibit on one of the walls of the display suite.

36 Thus, the render was self-evidently intended to be used for the purpose of encouraging interest from potential purchasers of apartments in the Victoriana. Further, the render had specific relevance to the Ripanis because it was an image referable to apartment 14.01. Indeed, it was the render which captured their interest in the development, and in due course, apartment 14.01.

37 The context in which the render was provided to the Ripanis also included them telling Mr Tran that they were particularly attracted to the opening between the internal living areas and the outside terrace. Far from disabusing the Ripanis of a mistaken impression that the render depicted what they may expect apartment 14.01 to look like upon completion, Mr Tran’s statements effectively reiterated, or corroborated, the representations conveyed by the render. Again, it is hardly surprising Mr Tran said what he did considering the render formed part of the package of materials available to CBRE to assist it to market and sell apartments at the Victoriana.

38 If the connection was less direct and proximate between the circumstances under which the render came to the attention of the Ripanis and their decision to purchase the apartment, the answer to the question about what representations were reasonably conveyed by the render may have been quite different. For example, if the ‘hero render’ were to have been featured on a billboard promoting the Victoriana generally, and the purchaser was not interested in purchasing apartment 14.01 specifically, but rather one of the low rise apartments; the answer to the question of what, if any, representation the render reasonably conveyed to such hypothetical purchaser would likely be very different. Taking the billboard example, in that context it may be said that all a reasonable purchaser could infer from the render would be characteristics of the Victoriana at a general level, such as that the apartments will be luxurious, or some other such generalised impression, I believe commonly described as ‘branding’.

39 But the Ripanis did not see the render on a billboard and it was apartment 14.01 in particular which caught their attention, precisely because they were attracted to the seamless transition between the internal living areas and the outside terrace. The Ripanis saw the ‘hero render’ featured prominently on the wall of the display suite at the Victoriana and were told, in effect, that it depicted what they could expect apartment 14.01 to be like in relation to the free span opening between the living areas and the terrace, though it was an ‘artist’s impression’. It is in this context that the render was shown to the Ripanis and a copy of the marketing materials given to them.

40 Having regard to those matters, I reject Century Legend’s contention that the render is inapt to convey the representations about which the Ripanis’ now complain, much less that it is to be characterised as, in effect, meaningless puffery.

41 As I have sought to explain above, in my view, there is an important connection between the meaning visually conveyed by the render and the circumstances in which the render was shown to the Ripanis, as well as between those circumstances and what was said to the Ripanis concerning the render and what it should be understood to convey. When considered in the full context I have described, the proposition that the render could, or should, not have been relied upon by the Ripanis is untenable.

42 Further, such a defence is also untenable, to put it neutrally, because knowing what it did, Century Legend’s conduct was deliberately misleading. I shall say more about Century Legend’s knowledge of the impossibility of constructing apartment 14.01 in conformity with the render below. However, it is relevant at this point to refer to Century Legend’s knowledge of another matter. The Ripanis disclosed the reason for their particular interest in apartment 14.01 to Mr Tran from the time of their first visit to the display suite of the Victoriana. For instance, the Ripanis said that they were interested in moving to an apartment with an outdoor pool and area for entertaining, in which the internal and external areas could be seamlessly converted into one space. Mr Tran understood that to be the Ripanis’ preference and therefore suggested apartment 14.01, at least in part, because of the free span opening depicted in the render.

43 I find that Century Legend must therefore be taken to have known that the feature it knew could not be constructed was the very feature of the apartment of particular appeal to the Ripanis. Further, I find that, at the least, Century Legend had no reason to believe that the Ripanis knew, prior to entering into the contract to purchase the apartment, the truth; namely, that it was impossible to construct the free span opening depicted in the render. I shall refer below to the reasons for this finding in the context of the competing evidence given by the Ripanis, Ms Hart and Mr Hu.

44 If I were wrong to find that the render, read in context, conveys the representations complained of by the Ripanis, I would find independently that the representations made by Mr Tran on behalf of Century Legend were misleading and deceptive within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL. As I have said, Mr Tran provided the Ripanis with a hard-bound brochure promoting the Victoriana when they visited the display suite on 31 March 2017, having earlier sent them a photo of the ‘hero render’ by email on 22 March 2017. During that visit, Mr Tran spoke about the development by reference to the renders, including, in particular, the ‘hero render’ which was said to depict apartment 14.01. As a result of what they were told at the display suite on 31 March 2017, the Ripanis believed that the apartment they were invited to buy would be constructed in accordance with the render. To put it briefly, even if the render did not convey the principal representations about which the Ripanis’ complain, Mr Tran represented that it did. That representation, made innocently by Mr Tran, was misleading and deceptive.

Century Legend’s contentions in relation to the representations conveyed by the render

45 Century Legend contests any finding that the render conveyed a material representation relating to the width or scale of the free span opening onto the terrace. It does so on a number of bases, some of which are also relevant to the question of whether the Ripanis relied upon any representation conveyed by the render prior to entering into the contract to purchase the apartment. I have discussed Century Legend’s principal contention above; namely, that the render did not convey a representation concerning the width or scale of the free span opening capable of being relied upon by prospective purchasers such as the Ripanis. I shall discuss that question further in the context of Century Legend’s submissions concerning this issue.

46 Century Legend contends that the render should not be looked at in isolation and, in any event, did not convey a misleading representation when regard is had to: (i) the fact it is an artist’s impression only; (ii) the relevant contractual and non-contractual disclaimers; and (iii) the fact that various iterations of the floor plans for apartment 14.01 showed the opening would not be built as depicted in the render. It is necessary to consider each reason separately, as well as in combination with the contextual factors which Century Legend says informs what may be reasonably understood to be conveyed by the render. However, this analysis must also include the objective matters and surrounding circumstances which Century Legend does not address.

47 Before considering the contextual factors relied upon by Century Legend as informing any representation contained in the render, I refer to Century Legend’s contention as to what the image conveys:

Furthermore, the marketing render Mr Tran sent to Mr Ripani on 22 March 2017 was not a precise depiction of Apartment 1401. It was an artist’s impression with respect to an “off the plan” apartment that had not yet been built. Indeed, the large void without any mullions in the picture was patently unrealistic. Other parts of the brochure that Mr Tran provided to the Ripanis showed vertical mullions along the façade near the pool. Mr Tran of CBRE gave evidence that the marketing render “is actually an artist’s impression”. He also gave evidence that “… with the artist’s impression, we always refer to this as a artist’s impression…”. Indeed, Mr Tran said he pointed out to the Ripanis that the marketing materials were an artistic impression.

[Emphasis added]

48 That the render is an ‘artist’s impression’ is not in issue. What is in issue is what does that image, albeit an ‘artist’s impression’, communicate? Century Legend does not offer any interpretation of what information or meaning is conveyed by the image, save to assert that the “large void without any mullions was patently unrealistic”. That begs the question: to whom was it patently unrealistic?

49 The Ripanis did not appreciate that it was unrealistic. Mr Ripani is an experienced businessman. Mrs Ripani presented as an articulate and astute person. Both have some experience looking at ‘off-the plan’ properties, yet neither of them discerned from the render that the free span opening as depicted was patently unrealistic. Moreover, Mr Tran did not tell them it was patently unrealistic and it was not suggested to Mr Tran in cross examination that he was aware that the large void without any mullions was patently unrealistic.

50 I regard Century Legend’s contentions in this respect as disingenuous. Century Legend purports to approbate and reprobate; that is, having deployed the render as the ‘hero image’ for marketing purposes, it now purports in this proceeding to characterise the impression created by it as “patently unrealistic”. Further, in my view, this is a bold submission considering that Century Legend knew that the Ripanis were attracted by the feature of the apartment it now seeks to characterise as “patently unrealistic”, while also knowing that such free span opening could not be constructed. Century Legend’s submission conflates its apparent knowledge that the large void without mullions was unrealistic, with the Ripanis’ ignorance of that reality, notwithstanding that it was responsible for the use of the render in the circumstances I have described above.

51 The remaining submissions by Century Legend on this point are directed to what the render did not say. For instance, Century Legend says that the render was not a “precise depiction” of apartment 14.01, but rather an artist’s impression with respect to an ‘off-the-plan’ apartment that had not yet been built. That may be accepted and so much is accepted by the Ripanis. However, describing the render as an ‘artist’s impression’ does not mean that it is incapable of conveying representations to the effect complained of by the Ripanis. The representations conveyed by the render are sufficiently clear and precise to constitute misleading and deceptive conduct within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL. I reject Century Legend’s contention to the contrary for the reasons I have already explained.

52 Century Legend further submitted that the render did not convey any representation as to the dimension of the ‘large void’, to use Century Legend’s description. As I have already said, while the render does not specify any dimension, it conveys the scale of the free span opening by depicting the opening along with the internal living areas and external terrace of apartment 14.01. It is the scale of the free span opening, depicted as extending most of the length of the internal living areas, which conveys the representation as to the dimensions of the opening onto the outside terrace (see Annexure A). The render is not deprived of meaning merely because there are no dimensions annotated on the image.

53 For completeness, I note that I shall address further below Century Legend’s contention that the floor plans, in themselves, dispel the misleading nature of the render. I do so in the context of considering Ms Hart’s evidence, in relation to which the floor plans are highly relevant.

Effect of notation ‘artist impression’

54 As I have said, the view apparently taken by Century Legend was that it was sufficient to annotate the render with the words ‘artist impression’ to avoid responsibility for misrepresenting a salient design feature of apartment 14.01. Before considering that issue, I explain the circumstances in which the words ‘artist impression’ were added as an annotation to the render, including the warnings given by RotheLowman to Century Legend concerning the render.

55 On 12 October 2016, Mr Perkins of RotheLowman raised concerns about the render in an email to Mr Shawn Lu (Marketing Manager at Century Legend) and Ms Kylie Xu (General Manager at Century Legend). The email was also copied to Ms Hart and relevantly said:

Further to my email last night I would like to advise JD Group that several of the design changes (architecture and interiors) made by JD Group during the render stage are not in accordance with the Town Planning Permit or the current Design Development drawings. Also should a purchaser want exactly what is shown in the renders, for example, a flush inside to outside threshold, or uninterrupted floor to ceiling glazing it will not be possible due to the overall height restriction of the development and structural requirements. The changes made to the interior design of the standard apartment may be possible but will require further review, design development/documentation. There are also some safety issues with the design of the landscaping and pool areas that will need to be resolved after marketing.

Due to the extent of the changes, the misleading nature of the renders, and our inability to follow through on the render design I would advise JD Group to have the renders amended before marketing launch. Should this not be possible I would advise JD Group to be transparent with all potential purchasers in relation to the render content and to ensure that all “Artists Impressions” are accompanied with a suitably comprehensive disclaimer to cover the discrepancies/inaccuracies. This disclaimer should also be included in all marketing material and contract of sale documents.

Please don’t hesitate o [sic] call should you wish to discuss the above.

…

[Emphasis added]

56 Mr Lu responded on the same day saying: “Hi Stephen I tried ringing you just now. Did not get through. Please call me back when you are free.” Neither Mr Lu nor Mr Perkins were called as witnesses and it is not clear whether they did in fact have a telephone conversation. However, on 11 November 2016, Mr Perkins wrote a further email addressed to Mr Hu, which recorded “a couple of suggestions” following a meeting with an agent from Melbourne Real Estate in relation to the Victoriana development. Amongst the matters to be addressed was: “[t]he inconsistencies between the renders and the marketing plans/elevation.” Mr Perkins added: “Please let me know how JD Group wish to proceed with the items above.” Minutes later, Mr Lu replied on behalf of Century Legend, copying in Mr Lu, Ms Xu and Ms Hart, saying simply: “Leave them with us for now. Thanks.”

57 Mr Hu’s evidence was that upon receiving the 11 November 2016 email, he discussed the matter with Century Legend’s Board and marketing team. Present during those discussions was Mr Lu, Ms Xu and Mr John Yun (the CEO of Century Legend). Mr Hu gave evidence that, in response to Mr Perkins’ “suggestions”, Century Legend determined it was appropriate to put the words ‘artist impression’ on each render.

58 A third cautionary email was sent by Ms Hart on 23 June 2017. By this time, Ms Hart had concluded her meetings with the Ripanis concerning the floor plan and fit out of apartment 14.01. The email included the following statements:

Following up on our last conversation with regards to the perimeter banding for each level of Victoriana.

As mentioned, as part of the building architecture and structure there is perimeter edge banding that follows the building’s form, running along the building boundary and in some instances, glazing line.

…

Please see some quick internal images taken from the current Revit model to help illustrate the above. You will also notice in the attached images, the number of glazing mullions and transoms required for the glazing. This structure is required for wind loading and to achieve the building forms.

Also for your reference, please see the schematic structural drawings attached. These drawings highlight the location and extent of the structural banding at the building perimeter.

While structure does need to be reviewed, the edge banding will still be required, especially with the additional loading of spas and potential pools to terraces. The banding is also part of the architecture.

We feel that it is extremely important that JD Group make Purchasers aware of the actual internal / external transition and break-up in glazing that will be achieved, as this is not accurately shown in the JD Group commissioned marketing renders. It needs to be reiterated that marketing renders are ‘artist’s impression’ only and not actual building images.

Please do not hesitate to give me a call if you wish to discuss further.

[Emphasis added]

59 Ms Hart’s email of 23 June 2017 was addressed to Mr Hu, and copied to Mr Lu, Ms Xu and other architects from RotheLowman. It is significant that the email was sent as a reply to the 12 October 2016 email sent by Mr Perkins, demonstrating, if nothing else, that Ms Hart appreciated that a “hot potato” had been dropped in her hands and there was potential for the rather to mislead a potential purchaser. As I shall explain, the 23 June 2017 email is incongruous with Ms Hart’s evidence that, by this time, she had already explained to the Ripanis that the free span opening could not be constructed as depicted in the render.

60 Mr Hu responded to Ms Hart on 23 June 2017, copying in all of the recipients from the aforementioned email. Mr Hu’s email read as follows:

Hi Kate,

Thanks again for your email. We have put artist impression in all our renders and we have disclaimer as well. See below.

[Examples of the “artist impression” inscription and disclaimer exhibited in text of the email]

61 Ms Hart gave evidence that it was her understanding that another architectural firm, Carr Design, which had original been engaged by Century Legend to design the interior of the high-rise ‘premium’ apartments, had “walked away” from the Victoriana project because they did not believe the renders were an accurate depiction of what was intended to be built. Having regard to Ms Hart’s understanding of the position apparently taken by Carr Design, the warnings given by RotheLowman concerning the use of the render, and its disconformity with what was in fact to be built, there is no doubt that Ms Hart was aware of the importance of potential purchasers of the apartments at the Victoriana not being misled by the inaccuracy of the render. Indeed, Ms Hart gave evidence to the effect that she knew she was in a fraught position and appreciated, by mid-2017, that there was every prospect she would find herself in a witness box giving evidence about communications she had with the purchasers of apartments.

62 Ms Hart’s knowledge of the inaccuracy of the render, and of the correspondence about that with Century Legend, is also significant in relation to my reasons for rejecting Ms Hart’s evidence, as I explain below. She accepted that the issue concerning the render was a “potential timebomb”. I note further at this point, there was no suggestion in the correspondence from RotheLowman that it considered the render to be too vague or imprecise to convey any impression in the absence of precise dimensions of the width of the opening. Of course, whether the render conveys representations that were misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, is a question for the Court. I mention this because RotheLowman’s assessment, including as reflected in Ms Hart’s email dated 23 June 2017, that the render was inaccurate and, at a minimum, apt to mislead, is also relevant when it comes to considering the veracity of Ms Hart’s evidence concerning what she claims to have said to the Ripanis in relation to the opening between the internal living areas and the terrace, prior to the contract of sale being entered into.

63 A further significant feature of Ms Hart’s email of 23 June 2017 is that while she expresses the importance of Century Legend making purchasers aware of the inaccuracy of the render, she does not say in that email that she had made the Ripanis aware of the inaccuracy during meetings in May and June 2017. Instead, Ms Hart places that responsibility squarely on Century Legend. This too is relevant to evaluating Ms Hart’s evidence about what she claims to have told the Ripanis. Further, I note that in Mr Perkins’ email of 12 October 2016, he too places responsibility for informing purchasers of the inaccuracy of the render on Century Legend.

64 I return to the question of what significance, if any, the notation ‘artist impression’ has in connection with the representations conveyed by the render. In my view, that inscription does not have the effect of curing the misleading representation conveyed by the render. I do not accept the words ‘artist impression’ are akin to a disclaimer or exclusion clause in a contract, and even if those words may be analogous in other circumstances, that characterisation is not applicable in the present case. The Ripanis expressed their interest in the particular feature of the design depicted by the render, and were told by Mr Tran that the render depicted the apartment they ultimately decided to purchase.

65 More generally, in my view the inscription ‘artist impression’ is not sufficient to qualify representations of the kind conveyed by the render in this case. The inscription conveys merely that the apartment as constructed will not appear precisely as depicted in the render. To my observation, the render is self-evidently an artist’s impression and that needs hardly be said. However, I accept there may be utility to including such an inscription as a matter of abundant caution, having regard to the very high resolution and realism of computer generated graphics. I agree with the Ripanis’ submission that the addition of the words ‘artist impression’ “tells a viewer that the render is not a photographic image (and they are so realistic that an uninformed person might mistake them for one).” In context, those words reasonably communicate that the finished apartment may not accord with the image in all its detailed particulars. However, the words do not suggest that the key elements of the render will not be constructed, or at the very least, are not then intended to be constructed.

66 Importantly, the fact that the render is an ‘artist’s impression’ does not detract from the materiality of the image and the representations it conveys, for the very reason that in the context of an ‘off-the-plan’ sale, such renders are a proxy for an inspection. Objectively, it is surely understood by vendors and purchasers that the render, albeit an ‘artist’s impression’, is a medium by which the purchaser may gain an understanding of the salient design features of the yet-to-be constructed apartment. The advantage of imagery over language is that an image, whether or not an ‘artist’s impression’, is capable of conveying meaning holistically. Accordingly, in my view, the words ‘artist impression’ are incapable, either alone or in combination with the other disclaimers and exclusions clauses to which I will now refer, of curing the misleading character of the representations made by Century Legend.

67 Further, Century Legend says the decision in HW Thompson Building Pty Ltd v Allen Property Services Pty Ltd (1983) 48 ALR 667 is analogous. In that case, St John J held at 673 that a comparison of the artist's impression on the brochure, showing the position of the swimming pools, and the plan annexed to the contract, would easily dispel the applicant’s understanding that all the recreational facilities specified in the brochure would be available to the occupants of an apartment tower. However, his Honour’s findings in relation to whether the developer’s conduct was misleading or deceptive in that case were based on the purchaser’s previous experience buying units ‘off-the-plan’; the common understanding that a solicitor would be advising the purchaser; the subject-matter of the contract; and the price paid for each unit. For the reasons I explain below, I regard the present circumstances as distinguishable from those in HW Thompson when regard is had to the whole of the context and surrounding circumstances, including the allied representations by Mr Tran to the effect I have discussed above.

Effect of disclaimer

68 In addition to the inscription ‘artist impression’, Century Legend relied upon a disclaimer contained inside the hard-bound marketing brochure given to the Ripanis. The disclaimer was in the following terms:

While all reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this brochure and the particulars contained herein, it is intended to be a visual aid and does not necessarily depict the finished state of the property or object shown. No liability whatsoever is accepted for any direct or indirect loss, or consequential loss or damage arising in any way out of any reliance upon this brochure. Purchasers must rely upon their own enquiries and inspections. Furniture is not included with the property. Dimension and specifics are subject to change without notice. Illustrations and photographs are for presentation purposes and are to be regarded as indicative only. This brochure does not form part of, and is not, an offer or a contract of sale.

69 For context, the disclaimer appeared on page 96 of the brochure and was given no prominence at all in the marketing materials. In fact, it appeared at the end of a lengthy volume, in much smaller font than most of the writing within the brochure and the font was barely legible against a dark background. Senior Counsel for the Ripanis accurately described the disclaimer as being “hidden” at the very back of the brochure.

70 Supposing hypothetically that the Ripanis had read the disclaimer, what does it communicate to them which might be found to have cured the impression created by the render? More precisely, leaving aside for present purposes the context in which the Ripanis were provided with the brochure containing the ‘hero render’, as well as Mr Tran’s representations, what do the words of the disclaimer communicate to the Ripanis as reasonably informed and astute purchasers of an apartment ‘off-the-plan’? The short answer is equivocal and misleading propositions.

71 The first sentence of the disclaimer says that the brochure is a visual aid “and does not necessarily depict the finished state of the property or object sown.” The implication that is embedded in the qualification “not necessarily” is that generally the visual aid will depict the finished state, and that is consistent with the purpose for which such renders are created, as a selling aid, if not a proxy for inspection. The penultimate sentences says: “Illustrations and photographs are for presentation purposes and are to be regarded as indicative only.” This sentence is consistent with the renders being used as indicative of the ‘as-built’ apartments, though not precisely the same or identical to the renders. Indeed, in the present context, the use of the word “indicative” fortifies the impression created by the render that the image depicts what the apartment may be expected to be like upon completion. In my view, in the present context, the render has no work to do, save to mislead, if it is not indicative of the apartment.

72 It is unnecessary to construe or grapple with what is communicated by the remaining sentences of the disclaimer, save at a general level. The second sentence is a vague, ambiguous and meaningless assertion. Expressed in the passive voice, it implies that it is somehow a matter for the publisher of the brochure to accept liability. Such disclaimer, or exclusion, may be apposite and effective in other contexts, for example a bailment for reward, where the terms of the bailment contract may discernibly allocate risk in a particular way. Plainly, the present case is not analogous to a bailment. Further, presumably the second sentence should be read together with the third, and indeed the clause in its entirety. The difficulty is that the third sentence, “Purchasers must rely upon their own enquiries and inspections”, brings one full circle, so to speak, back to the fact that the only inspection capable of being made was an ‘inspection’ of the renders. I do not know whether this incongruity is the result of the disclaimer having been transposed from another context, but ultimately it does not matter. As expressed, the disclaimer is in my view inutile in the circumstances of the present case, particularly when compared to the ‘indicative’ depiction of what the Ripanis were led to believe they may expect, as conveyed by the render.

73 I turn now to some authorities which have considered the effect, or efficacy, of disclaimers and exclusion clauses in the context of claims founded upon misleading or deceptive conduct.

74 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 676; 371 ALR 396, Bromwich J summarised the authorities in relation to the relevance of disclaimers in the following terms at [33]:

(1) There may be occasions upon which the effect of otherwise misleading or deceptive conduct may be neutralised by an appropriate disclaimer: Abundant Earth Pty Ltd v R & C Products Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 233 at 239.

(2) A person engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct cannot readily or easily use the device of a disclaimer to evade responsibility, unless that disclaimer erases the proscribed effect: Benlist Pty Ltd v Olivetti Australia Pty Ltd (1990) ATPR 41-043; (1990) ASC 55-997.

(3) A disclaimer having the effect of dispelling otherwise misleading or deceptive effects of conduct may be a rare occurrence given the onus that is ordinarily on the person making the otherwise contravening representation to establish that the disclaimer it relies upon creates an overall effect that is benign: Hutchence v South Seas Bubble Co Pty Ltd (1986) 64 ALR 330 at 338.

(4) Disclaimers or qualifications must be taken into account in evaluating the conduct as a whole: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304 at [25].

(5) Carelessness on the part of consumers in how they treat or view a representation, including any disclaimers or additional information, may be relevant: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at [49].

(6) It may be relevant to consider whether or not an advertisement or other representation or conduct has the capacity to lead a consumer into error because it selects some words for emphasis and relegates the balance, including any disclaimer or other information, to relative obscurity: TPG Internet at [51].

(7) A disclaimer must be very clear when there is a substantial disparity between the primary representation and the true position: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; 49 ACSR 369 at [55]. In National Exchange, shareholders had been offered $2 per share when the current share price was $1.93. But they were only told in a different and less prominent location that payment would be made by 15 annual instalments making the offer worth less in current value than $2 and also less in current value than $1.93. Without the qualifying context the primary representation was false because the shareholder was not being offered $2 in value per share at the time the offer was made, and was in fact being offered less than the current share price.

(8) A disclaimer that is static may bear more weight than one that is evanescent. In a printed format, even an asterisk that indicates the presence of additional information, if it is sufficiently prominent and the qualifying text is sufficiently proximate, may be effective to draw attention to an explanation of, or qualification upon, a statement made in advertising: George Weston Foods Ltd v Goodman Fielder Ltd [2000] FCA 1632; 49 IPR 553 at [46].

That summary of the principles has been cited with approval by this Court on several occasions: see, eg, Bonham as Trustee for the Aucham Super Fund v Iluka Resources Ltd [2022] FCA 71 at [627] (Jagot J); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v La Trobe Financial Asset Management Ltd [2021] FCA 1417 at [12] (O’Bryan J).

75 In the present proceeding, the render was a visually impressive depiction of apartment 14.01. It was variously described as the ‘hero shot’, ‘hero image’ or ‘hero render’ and Ms Hart gave evidence that, in her view, the render was one of the most important images in respect of the marketing of the Victoriana. Indeed, it featured prominently in the marketing of the Victoriana to prospective purchasers generally and also in marketing apartment 14.01 to the Ripanis specifically. In circumstances where the disparity between the representation and the true state of affairs was so stark, a necessary but not sufficient condition was that the disclaimer be drawn to the Ripanis attention in the clearest possible way if it was to be effective: National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; 49 ACSR 369 at [55] (Jacobson J).

76 There is no evidence to suggest that Century legend, or CBRE through Mr Tran, took steps to ensure the disclaimer was drawn to the Ripanis’ attention. Irrespective of that, for the reasons I have explained above, the disclaimer was expressed in terms which were themselves ambiguous, and, if anything, more likely to reiterate the representations implicitly conveyed by the render than to correct any misapprehension created by it.

77 Given those considerations, I find that this disclaimer was inutile in correcting the overwhelmingly misleading impression conveyed by the render. The disclaimer was written in general, boilerplate language and located in the back of a lengthy, glossy hard-bound brochure. Further, the disclaimer was not specifically drawn to the Ripanis’ attention and in any event, objectively it should not be expected that potential purchasers, like the Ripanis, would study a glossy marketing brochure with an eye to the fine print of a disclaimer at the back of the booklet. Thus, for all of the reasons above, the disclaimer did not have the effect of curing the misleading and deceptive representations made by, or on behalf of, Century Legend.

Effect of exclusion clauses

78 Century Legend also contends that certain disclaimers, or exclusion clauses, in the contract of sale exculpate it from any misleading impression which may have been conveyed by the render or by pre-contractual representations made by Mr Tran. Century Legend relies upon two clauses in the contract of sale, which it submits made it plain to the Ripanis that they were not entitled to rely on any pre-contractual representations made by, or on behalf of, Century Legend.

79 The first is cl 2.4 of the Special Conditions:

The Purchaser acknowledges that:

(a) no information, representation or warranty by the Vendor, the Vendor’s Agent or the Vendor’s Legal Practitioners was supplied or made with the intention or knowledge that it would be relied upon by the Purchaser; and

(b) no information, representation or warranty has been relied upon; and

(c) this Contract contains the entire agreement between the parties for the sale and purchase of the Property and supersedes all previous negotiations and agreements in relation to the transaction.

80 The second is cl 3.1 of the Special Conditions:

The Purchaser acknowledges that:

(a) It has purchased the Property as a result of the Purchaser’s own inspection and enquiry and that the Purchaser does not rely on any representation or warranty of any kind made by or on behalf of the Vendor or its agents or consultants;

(b) The description of areas and measurements appearing in any marketing material for the Development are approximate descriptions only and may differ from actual areas and measurements of the Development (including the Property) on completion of the Development;

(c) The Vendor has not made any representations or warranties of the views available from the Development or Property;

(d) Any photographs and other images created for the marketing of the Development are for illustrative purposes only and subject to change and cannot be relied upon by the Purchaser;

(e) Any potential views depicted in the photographs and other images may not be available from the completed Development or Property;

(f) The Vendor has no control over any development by parties unrelated to the Vendor of property surrounding or nearby the Development; and

(g) Information contained in any promotional and marketing material is a guide only and does not constitute an offer, inducement, representation, warranty or contract.

The Purchaser will not be entitled to exercise any Excluded Rights in relation to the matters in this special condition.

81 It is well settled, and accepted by all parties, that disclaimers and exclusion clauses cannot be relied upon to exclude the operation of the ACL: Clark Equipment Australia Ltd v Covcat Pty Ltd (1987) 71 ALR 367 at 371 (Shepherd J, with whom Fox and Jackson JJ agreed); Henjo Investments Pty Ltd v Collins Marrickville Pty Ltd (No 1) (1988) 39 FCR 546; 79 ALR 83 at 561 (Lockhart J, with whom Burchett J and Foster J agreed); and, more recently, Cargill Australia Ltd v Viterra Malt Pty Ltd (No 28) [2022] VSC 13 at [4357] (Elliot J).

82 However, as Connock J recently observed in Oliana Foods Pty Ltd v Culinary Co Pty Ltd (In Liq) [2020] VSC 693 at [535]:

… the existence and context of such clauses are often part of the context and circumstances to consider in deciding whether there has been misleading or deceptive conduct, and whether or not, for example, pre-contractual representations were relied upon, or the claimed misleading conduct has been causative of loss.

It is evident from what I have said above concerning the importance of context that I respectfully agree with his Honour’s observations in Oliana Foods.

83 In Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; 238 CLR 304, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ said at 348:

It is as well to add, however, that, of itself, neither the inclusion of an entire agreement clause in an agreement nor the inclusion of a provision expressly denying reliance upon pre-contractual representations will necessarily prevent the provision of misleading information before a contract was made constituting a contravention of the prohibition against misleading or deceptive conduct by which loss or damage was sustained. As pointed out earlier, by reference to the reasons of McHugh J in [Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; 218 CLR 592], whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is a question of fact to be decided by reference to all of the relevant circumstances, of which the terms of the contract are but one.

84 A similar observation was made by French CJ in Backoffice Investments at 320:

A person accused of engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct may claim that its effects were negated by a contemporaneous disclaimer by that person, or a subsequent disclaimer of reliance by the person allegedly affected by the conduct. The contemporaneous disclaimer by the person engaging in the impugned conduct is likely to go to the characterisation of the conduct. A subsequent declaration of non-reliance by a person said to have been affected by the conduct is more likely to be relevant to the question of causation.

85 Century Legend submits that the above clauses are contextually relevant. In particular, it submits that these clauses made it clear that the marketing materials provided by Mr Tran in relation to the Victoriana were not intended to be, and were not, representations of what the Ripanis might expect apartment 14.01 to look like when constructed. Century Legend says the Ripanis’ failure to read the contract before signing it does not negate this effect. It adds that the Ripanis should have taken time to read and review the contract given they had ample time to do so, or alternatively should have sought legal advice in relation to the same.

86 Century Legend further submits that it is important to take into account that the Ripanis were sophisticated purchasers, with some previous experience purchasing ‘off-the-plan’, not naïve, inexperienced first home-buyers: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 60; 218 CLR 592 at 605-606 (Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ). Moreover, Century Legend submits that given the Ripanis were entering into a contract to purchase a luxury apartment for a price of nearly $10 million, it was reasonable to expect that they would have carefully reviewed the contract and appreciated the significance of the above exclusion clauses.

87 Accordingly, Century Legend contends that the exclusions clauses weigh against a finding that the Ripanis reasonably relied on any of the representations. That is a central tenet of Century Legend’s broader submission that it did not engage in misleading or deceptive conduct by making any representation that apartment 14.01 would accord with the marketing render when constructed.

88 Considering firstly the last proposition, I disagree that the ex post facto effect of the exclusion clauses, assuming they were capable as expressed of having that effect, goes to the characterisation of the representation conveyed by the render. That is particularly so when the effect of the exclusion clauses is considered by comparison to the objective impact of the marketing materials, including the render. Instead, I agree with the observations of French CJ in Backoffice Investments, referred to above, that because the exclusion clauses are a subsequent disclaimer of reliance, they are more likely to be relevant to the question of causation.

89 For Century Legend’s analysis to be accepted, it would require at the least that the exclusion clauses were objectively capable of correcting the impression created by the render. An assessment of the efficacy of the exclusion clauses in this respect must include the context in which the Ripanis were given the render and what Mr Tran said to them about it. In the present case, the context in which the Ripanis were given the render meant they were entitled to expect that what was depicted would in substance be constructed. In my view, to do the work necessary to correct the impression created by the render, the exclusion clauses would therefore need to be expressed in terms such that purchasers would be aware that the render is not a depiction of what apartment 14.01 would look like when constructed.

90 If I am wrong to conclude that the exclusion clauses would need to be so specific and explicit to have a corrective effect in the present circumstances, the exclusion clauses as drafted would nevertheless fail a much lower threshold in relation to their curative effect. The exclusion clauses would appear to be boilerplate provisions. As such, they contain elements which are inapposite, the obvious example being an acknowledgment on the part of the purchasers, here the Ripanis, that they entered into the contract as a result of their own inspection and enquiry. I refer to what I have said above in relation to similar terms contained in the disclaimer. Had the exclusion clauses been negotiated between the parties, their effect would very likely have been different, going not to an ex post facto acknowledgement of non-reliance but rather to the characterisation of the conduct. Equally, if the exclusion clauses were negotiated they would not, rationally, contain an acknowledgement by the Ripanis of any inspection of the yet-to-be constructed apartment.

Conclusions in relation to representations

91 Though the ‘hero render’ speaks for itself for the purposes of the present claim for contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and/or misrepresentation actionable in equity, it is necessary to describe in language the meaning conveyed by the render.

92 At [9] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim, the Ripanis plead that the render conveyed the following representations:

(a) Apartment 1401 when constructed would accord with the Visual Representation and in particular would include the flow-through design;

(b) as at March 2017 the Respondent intended to construct the development and Apartment 1401 so that it would accord with the Visual Representation and in particular intended to include the flow-through design;

(c) the flow through design shown in the Visual Representation was in accordance with architectural designs prepared by Rothelowman;

(d) the building design shown in the Visual Representation accorded with the design for the construction of the building prepared by a reasonably skilled and competent architect;

(e) the building design shown in the Visual Representation was achievable given existing building methods.

93 In order to understand the pleaded representations, it is also necessary to have regard to [6] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim:

6. In order to show the Applicants what Apartment 1401 would look like when completed and thereby what they were invited to purchase, the Respondent by its agent provided to the Applicants:

(a) a promotional volume produced by it or at its direction describing the development and containing computer generated pictures showing the completed development (“the Volume”); and

(b) a computer generated image of a penthouse apartment (“the Visual Representation”) showing a large open plan space and a large rooftop terrace both at the same level with a raised concrete and glass swimming pool and a retracted glass three stack window panel system with the resultant effect that the outside and the inside formed a seamless single space (“flow-through design”).

94 The Ripanis’ verbal formulation of the representation conveyed by the render in [9](a) of the Further Amended Statement of Claim is but one of a number of ways the representation may be expressed in language. It is a reasonable formulation of the meaning conveyed by the render in the context in which it was used and conveyed to the Ripanis. The formulation of the representations in [9](b)–(e) of the Further Amended Statement of Claim are reasonable inferences that may be drawn from the render, again having regard to the relevant context.

95 It is sufficient for the purpose of determining the Ripanis’ claim in this proceeding to find that the render conveyed the representation in [9](a). I find that the render contained that representation. That representation is at the core of the Ripanis’ claim. The representation in [9](b) is also implicitly conveyed by the render, as well as by the use of it as the ‘hero render’ for marketing the Victoriana. I also conclude that the representation in [9](e) is implicitly conveyed by the render, having regard to the same contextual facts I have mentioned. The representations pleaded in (c) and (d) above are arguably also implicit in the render having regard to the context. However, those representations are more granular than what might objectively be discerned from the render, or implicitly conveyed by it. Accordingly, I do not accept that the render conveyed those representations.

96 In reaching this view, I have had regard to the well understood principle that conduct is misleading or deceptive if it induces or is capable of inducing error: see, eg, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at 655 (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). The question is one of fact, which requires the Court to examine the relevant conduct or representation as a whole in light of the surrounding facts and circumstances: Butcher at 625 (McHugh J). Viewed in its proper context, Century Legend submits that the render did not convey the representations the Ripanis allege and, moreover, that it did not engage in misleading and deceptive conduct. I do not agree.

97 The representation that apartment 14.01 would, when constructed, have a large free span opening and seamless transition from the interior to the terrace area was a representation as to a future matter. The Ripanis therefore also rely upon the deeming operation of s 4(1) of the ACL. Century Legend did not adduce any evidence that it had reasonable grounds for making the representation. That is unsurprising given that Century Legend never intended to build apartment 14.01 in accordance with the ‘hero render’, nor was it able to do so.

98 Accordingly, for the above reasons, I find that the representations referred to above in [92](a), (b) and (e) were made by Century Legend by providing the render to the Ripanis in the context I have described. Those representations were confirmed by the oral representations made by Mr Tran concerning the render and its correlation to apartment 14.01. Mr Tran’s representations also constitute separate actionable representations made on behalf of Century Legend. I also find that the representations made by, or on behalf of Century Legend were misleading and deceptive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL and that they were false representations actionable in equity for misrepresentation.

Relevant contextual facts

99 The narrative of events to follow is divided into two periods – the pre-contractual period and the post-contractual period.

100 The first period (pre-contractual period) is between mid-late January 2017 and 29 August 2017. That period commences when the Ripanis first visited the display suite at 20 Queens Road, met Mr Tran and were told about apartment 14.01, and concludes after a series of meetings held for the purpose of settling the Ripanis’ desired floor plan, when the Bank of Melbourne issued a bank guarantee in the amount of $944,000 in lieu of the deposit of 10% payable under the contract.

101 The second period (the post-contractual period) is between 29 August 2017 and June to July 2019. The 3rd of June 2019 is a significant date because it is when I find the Ripanis were informed for the first time that the opening on the western façade would be no more than 3.4 metres in width. The 3rd of July 2019 is similarly important because it is when Mr De Mooy told the Ripanis that it was “impossible” to build the free span opening depicted in the ‘hero render’. Although the Ripanis did not file this proceeding until April 2020, they sent a letter to Century Legend’s legal representatives on 8 July 2019 communicating their displeasure with the situation and foreshadowed their intention to commence proceedings to avoid the contract of sale, insist on specific performance and/or obtain an order for damages.

102 I shall describe the relevant post-contractual events, before returning to the pre-contractual period in the context of the principal evidentiary contest in this proceeding; namely, whether Ms Hart disabused the Ripanis of any misleading impression created by the render. However, before turning to these events, it is necessary to say something about the date on which the contract of sale was entered into.

Date of entry into contract of sale

103 A preliminary matter to determine is the dispute between the parties as to the date upon which the contract of sale for apartment 14.01 was formed and became binding on the parties. The dispute occupied significant time during the hearing, both in evidence and submissions, and resulted in amendments to the pleadings. Having regard to the findings I have made concerning reliance by the Ripanis on the representations, the dispute is arid. However, in case it should be relevant hereafter, I find that the contract of sale was formed and became binding on or about 29 August 2017, when the Ripanis provided a bank guarantee from the Bank of Melbourne in the sum of $944,000 in lieu of the payment of the deposit. The reasons for this finding are as follows.

104 On 1 April 2017, the day after the Ripanis visited the display suite for the second time, Mr Tran attended the Ripanis’ personal residence. He brought with him three copies of the contract of sale to be signed: one for the Ripanis, one to be countersigned by the developer and one to be exchanged with the conveyancer. The Ripanis originally pleaded that the contract was formed on 1 April 2017 when they signed a contract in writing. However, at that time, the contract contained a handwritten clause 43 which stated: “subject to satisfactory [sic] of floor plan within 21 days.” The contract was, at that time, subject to a condition subsequent which remained unsatisfied for some months.