FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 113

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD ACN 000 095 607 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 February 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The notice of appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant is to pay the respondent’s costs, as taxed or agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1858 of 2019 | ||

BETWEEN: | ENERGY BEVERAGES LLC Appellant | |

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD ACN 000 095 607 Respondent | |

order made by: | HALLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 February 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The notice of appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant is to pay the respondent’s costs, as taxed or agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 63 of 2021 | ||

BETWEEN: | ENERGY BEVERAGES LLC Appellant | |

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD ACN 000 095 607 Respondent | |

order made by: | HALLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 February 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended notice of appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant is to pay the respondent’s costs, as taxed or agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[4] | |

[4] | |

[8] | |

[12] | |

[15] | |

[20] | |

[20] | |

[21] | |

[25] | |

[26] | |

[26] | |

[36] | |

[40] | |

[40] | |

[49] | |

[53] | |

[53] | |

[56] | |

[61] | |

[62] | |

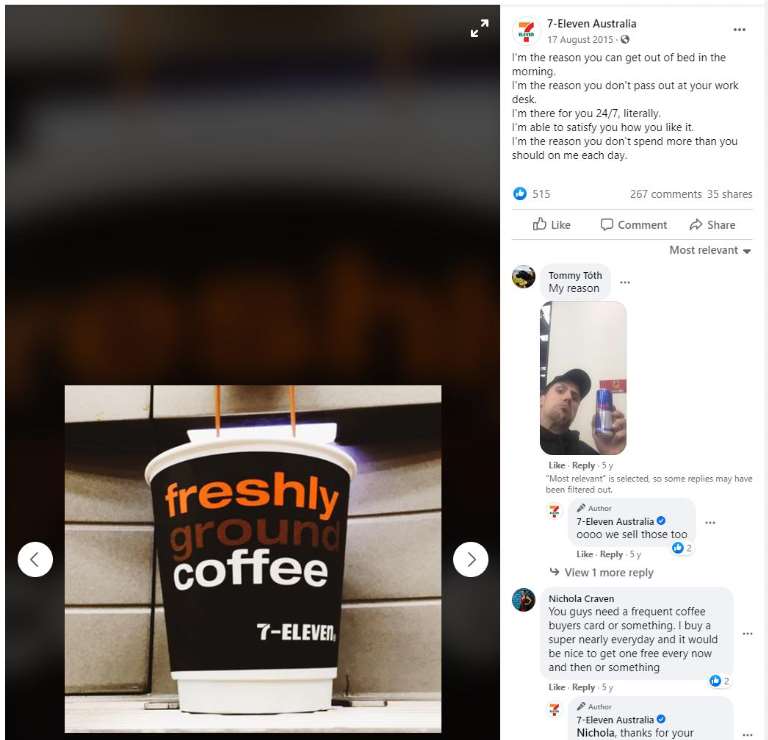

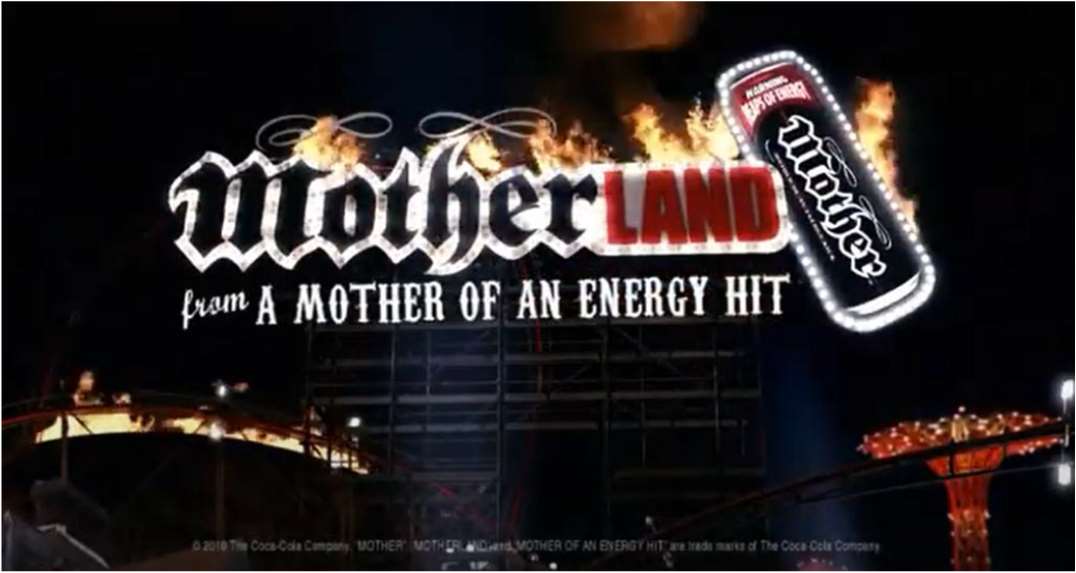

Advertising, marketing and promotion of MOTHER energy drinks | [65] |

[69] | |

[70] | |

[72] | |

[73] | |

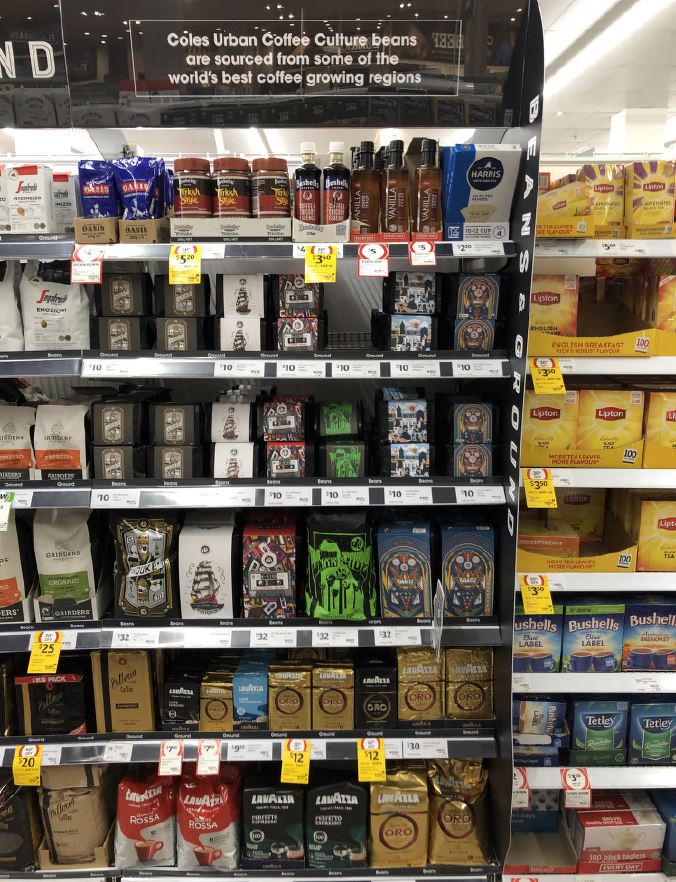

Display and sale of energy drinks and other beverages, particularly coffee | [76] |

[79] | |

[81] | |

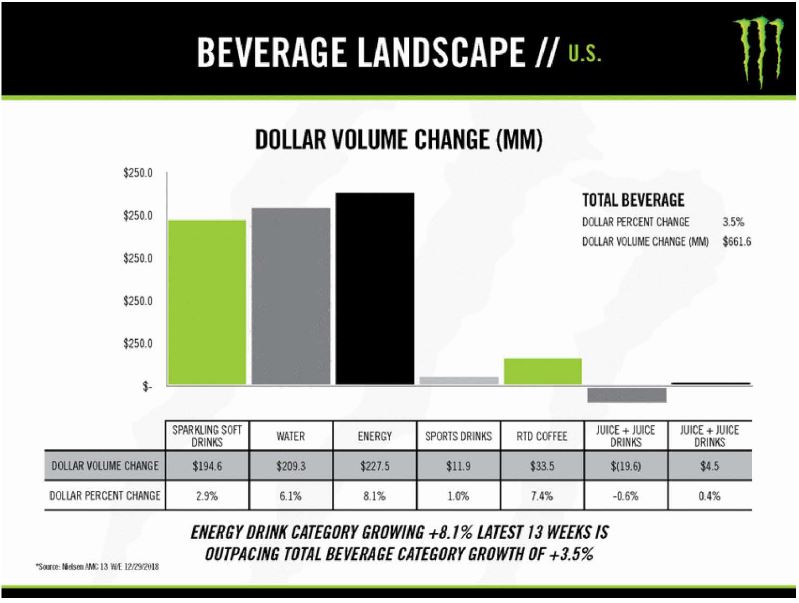

Competitive landscape for energy drinks in the United States | [83] |

[87] | |

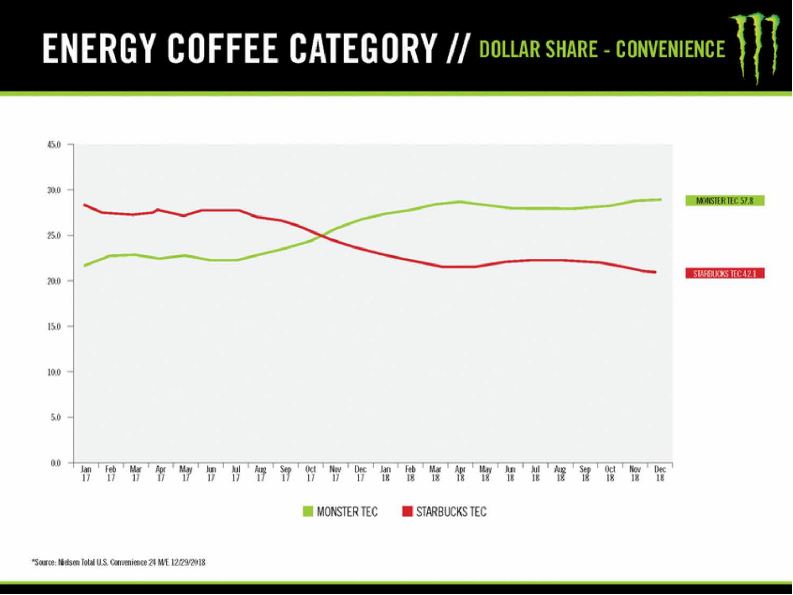

[91] | |

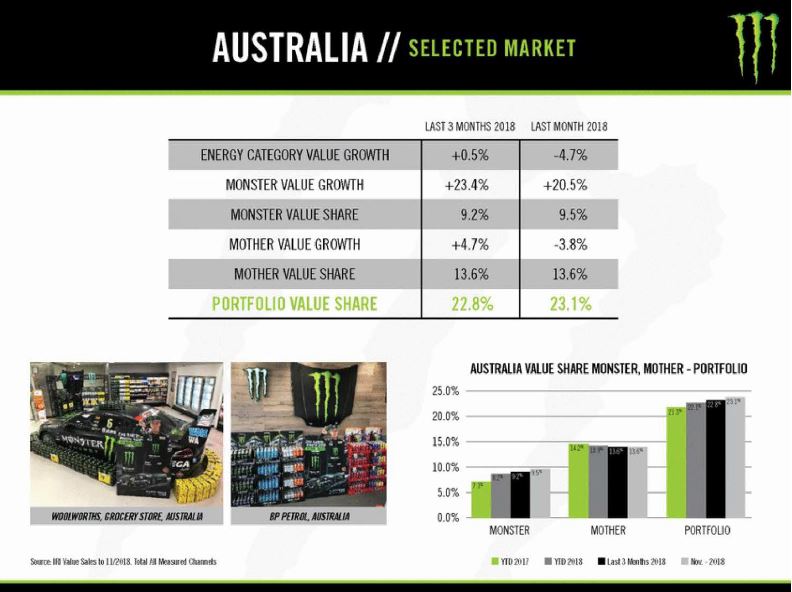

[94] | |

[98] | |

[100] | |

[107] | |

[116] | |

[123] | |

[129] | |

[137] | |

[138] | |

[140] | |

[144] | |

[158] | |

[158] | |

[172] | |

[183] | |

[190] | |

[201] | |

[225] | |

[227] | |

[238] | |

[247] | |

[250] | |

[261] | |

[261] | |

[277] | |

[278] | |

[289] | |

[290] | |

[297] | |

[297] | |

[300] | |

[301] | |

[305] | |

[305] | |

[317] | |

[318] | |

[331] | |

[331] | |

[339] | |

[345] | |

[350] | |

[369] | |

[369] | |

[382] | |

[387] | |

[388] | |

[393] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

HALLEY J:

1 The appellant (EB) appeals from three decisions of delegates of the Registrar of Trade Marks (Delegate or Delegates) comprising two decisions refusing opposition by EB to applications by the respondent (Cantarella) for the removal of trade marks registered in the name of EB and a third decision refusing opposition by EB to an application by Cantarella for the registration of a trade mark.

2 EB, through its wholly owned subsidiary, Energy Beverages Australia Pty Ltd (EB Australia), supplies energy drinks under its MOTHER trademarks and MOTHER-derivative marks and taglines. The MOTHER brand was acquired by EB in June 2015 from The Coca-Cola Company (TCCC).

3 Cantarella is a supplier of pure coffee, either in bean, ground or, more recently capsule form, in Australia under a number of brands. It sells pure coffee to cafés and restaurants, major supermarket chains and wholesale and retail grocery stores, among other establishments.

4 EB was the owner of the registered trade mark “MOTHERLAND” under Australia trade mark registration number 1345404 (MOTHERLAND registration) with respect to the following class 32 goods:

Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices

5 EB now seeks to limit the scope of the goods and services claimed by the MOTHERLAND mark to the following goods and services:

drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks

(together MOTHERLAND Protected Goods)

6 On 12 February 2019, Cantarella applied for the removal of the MOTHERLAND registration pursuant to s 92(4)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Act), alleging non-use in the period 12 January 2016 to 12 January 2019 (MOTHERLAND Relevant Period). EB filed a Notice of Intention to Oppose on 10 April 2019, and a Statement of Grounds and Particulars on 9 May 2019.

7 On 21 December 2020, the Delegate found that Cantarella’s application for removal pursuant to s 92(4)(b) of the Act was successful due to non-use, and directed that the MOTHERLAND mark be removed from the Australian Trade Marks Register (Register): see Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Limited [2020] ATMO 198 (MOTHERLAND decision).

MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark

8 EB was also the owner of the registered trade mark “MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE” under Australia trade mark registration number 1408011 (MLIC registration) with respect to the following goods:

Class 29:

Milk and milk products; flavoured milk beverages; dairy products including milk and yoghurt based products and beverages with or without fruit additives; yoghurt; food supplements and nutritional supplements (other than for medicinal use); natural products in this class incorporating herbal preparations (other than for medicinal use); food supplements with herbs (other than for medicinal use); drinks flavoured with herbs and having a milk base

Class 30:

Coffee; tea; cocoa; chocolate; artificial coffee; ice cream; beverages in this class including coffee based beverages, tea based beverages and chocolate based beverages; herbal extracts (other than for medicinal purposes); herbal infusions (other than for medicinal use) and herbal tea (other than for medicinal use)

9 EB now seeks to limit the scope of the goods and services covered by the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark to the following goods and services:

Class 29:

flavoured milk beverages; milk based beverages with or without fruit additives; liquid food supplements and nutritional supplements (other than for medicinal use); liquid food supplements with herbs (other than for medicinal use); drinks flavoured with herbs and having a milk base

Class 30:

Coffee; cocoa; chocolate; artificial coffee; beverages in this class including coffee based beverages and chocolate based beverages; herbal infusions (other than for medicinal use)

(together MLIC Protected Goods.)

10 On 13 February 2018, Cantarella applied for removal of the MLIC registration pursuant to ss 92(4)(a) and (b) of the Act. On 30 April 2018, EB filed a Notice of Intention to Oppose, and a rectified Statement of Grounds and Particulars on 20 June 2018. Cantarella filed its Notice of Intention to Defend the removal application on 6 August 2018.

11 On 24 September 2019, the Delegate found that Cantarella’s application for removal pursuant to s 92(4)(b) of the Act was successful due to non-use, and directed that the MLIC mark be removed from the Register: see Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2019] ATMO 140 (MLIC decision).

12 On 11 January 2017, Cantarella applied for registration of “MOTHERSKY” in class 30 in respect of coffee, coffee beans and chocolate, and in class 41 in respect of coffee roasting and coffee grinding under Australia trade mark registration number 1819816 (MOTHERSKY application). Originally, Cantarella had also applied for coffee beverages and chocolate beverages in class 30, but deleted those items after EB filed its Notice of Intention to Oppose.

13 On 31 July 2017, EB opposed acceptance of the MOTHERSKY application pursuant to s 52 of the Act. The grounds of the opposition were ss 44, 60 and 42(b) of the Act, which deal with deceptive similarity or marks that are identical, reputation in a trade mark, and whether use of the mark would be contrary to the law, respectively. EB filed a Statement of Grounds and Particulars on 30 August 2017, and Cantarella filed a Notice of Intention to Defend on 16 October 2017.

14 On 18 October 2019, the Delegate found in favour of Cantarella as EB had not established a ground of opposition, and the registration of the MOTHERSKY mark was completed one month later: see Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2019] ATMO 150 (MOTHERSKY decision).

15 Two other trade marks of EB are relevant to a determination of the appeals.

16 First, the MOTHER mark (TM 1230388) (MOTHER 388 mark).

17 The MOTHER 388 mark was a mark with a priority date earlier than MOTHERSKY and was registered in respect of the following goods:

Class 32: Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices.

18 Second, the MOTHER mark (TM 1364858) (MOTHER 858 mark).

19 The MOTHER 858 mark was also a mark with a priority date earlier than MOTHERSKY and was registered in respect of the following goods:

Class 33: Alcoholic beverages (except beers); distilled spirits; liqueurs; wines; wine based alcoholic beverages; spirit based alcoholic beverages

20 The principal agreed issues for determination in NSD1711/2019 (MLIC appeal) and NSD63/2021 (MOTHERLAND appeal) are as follows (noting that the agreed issues for determination document was prepared prior to the order that the MOTHERLAND appeal be heard together with the MLIC appeal and the appeal in NSD1858/2019 (MOTHERSKY appeal)):

(a) as at the filing date of the application for the MLIC registration, did TCCC have an intention in good faith to use, authorise the use of, or assign to a body corporate for use by that body corporate, the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark in Australia in relation to the MLIC Protected Goods pursuant to s 92(4)(a) of the Act?

(b) did EB use the MOTHERLAND mark in relation to goods covered by the registration of the mark during the MOTHERLAND Relevant Period within the meaning of s 100(3)(a) of the Act?

(c) are there facts and circumstances that warrant the exercise of the discretion pursuant to s 101(3) of the Act to allow the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark to remain on the Register in relation to some or all of the MLIC Protected Goods and the MOTHERLAND mark to remain on the Register in relation to some or all of the MOTHERLAND Protected Goods?

21 The principal agreed issues for determination in the MOTHERSKY appeal are as follows.

22 In relation to s 44 of the Act:

(a) is the MOTHERSKY mark substantially identical with or deceptively similar to any of the following marks:

(i) the MOTHER 388 Mark and the MOTHER 858 Mark (together MOTHER marks);

(ii) the MOTHERLAND mark; or

(iii) the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark?;

(b) are “coffee” and “chocolate” specified in the MLIC registration the same goods, or goods of the same description, as “coffee; coffee beans; chocolate”?;

(c) are “coffee” and “chocolate” specified in the MLIC registration closely related to the services of “coffee roasting; coffee grinding”?;

(d) are “cocoa” and “artificial coffee” specified in the MLIC registration goods of the same description as “coffee; coffee beans; chocolate”?;

(e) are “carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks” and “… syrups, concentrates and powders for making … carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks …” specified in the MOTHERLAND registration and the MOTHER 388 mark goods of the same description as “coffee” and “chocolate”?;

(f) are “non-alcoholic beverages” and “syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages” specified in the MOTHERLAND registration and the MOTHER 388 mark goods of the same description as “coffee” and “chocolate”?; and

(g) are “alcoholic beverages (except beers)”, “distilled spirits” and “liqueurs” specified in the MOTHER 858 mark goods of the same description as “coffee” and “chocolate”?

23 In relation to s 60 of the Act:

(a) had the MOTHER marks acquired a reputation in Australia prior to 11 January 2017 (MOTHERSKY Priority Date)?;

(b) if so, what was the nature and extent of that reputation?; and

(c) because of EB’s reputation in the MOTHER mark as at the MOTHERSKY Priority Date, would Cantarella’s use of the MOTHERSKY mark have been likely to deceive or cause confusion as at the MOTHERSKY Priority Date?

24 In relation to s 42(b) of the Act:

(a) because of the reputation of the MOTHER marks in Australia, would the use of the MOTHERSKY mark be contrary to law as at the MOTHERKY Priority Date, on the basis that it:

(i) constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct, contrary to s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL); and/or

(ii) gives rise to a false or misleading representation that Cantarella or its goods and services have a sponsorship, approval or affiliation that they do not have, contrary to ss 29(1)(g) and (h) of the ACL?

25 For the reasons outlined below my principal conclusions are as follows:

(a) TCCC did not have an intention in good faith to use, authorise the use or assign to a body corporate for use by that body corporate of the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark in relation to the MLIC Protected Goods as at its filing date;

(b) EB has not demonstrated that it used the MOTHERLAND mark in relation to goods covered by the registration of the mark during the MOTHERLAND Relevant Period;

(c) there are insufficient facts and circumstances to warrant the exercise of the discretion under s 101(3) of the Act to allow either the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark or the MOTHERLAND mark to remain on the Register;

(d) the MOTHERSKY mark is not substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the MOTHER marks, the MOTHERLAND mark or the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark;

(e) “coffee” and “chocolate” are the same goods as “coffee; coffee beans and chocolate”;

(f) “coffee” but not “chocolate” is closely related to the services of “coffee roasting; coffee grinding”;

(g) “cocoa” and “artificial coffee” are not goods of the same description as “coffee, coffee beans; chocolate”;

(h) “carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks” and syrups, concentrates and powders for making them, are not goods of the same description as “coffee” and “chocolate”;

(i) “non-alcoholic beverages” and syrups, concentrates and powders for making them, are not goods of the same description as “coffee” and “chocolate”

(j) “alcoholic beverages (except beers)”, “distilled spirits” and “liqueurs” are not goods of the same description as “coffee” and “chocolate”;

(k) the MOTHER marks had acquired a significant reputation in Australia for energy drinks prior to the MOTHERSKY Priority Date;

(l) EB’s reputation in the MOTHER marks as at the MOTHERSKY Priority Date did not cause Cantarella’s use of the MOTHERSKY mark to have been likely to deceive or cause confusion as at the MOTHERSKY Priority Date; and

(m) EB’s reputation in the MOTHER marks as at the MOTHERSKY Priority Date did not cause Cantarella’s use of the MOTHERSKY mark to be contrary to law nor did it constitute misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the ACL nor give rise to a false or misleading representation as to sponsorship, approval or affiliation, in contravention of s 29(1)(g) and (h) of the ACL.

Appeals from the Registrar of Trade Marks

26 Appeals to the Federal Court from a decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks are as of right and are heard de novo: see ss 56 and 104 of the Act. They are heard within the Court’s original rather than appellate jurisdiction: Woolworths Ltd v BP plc (2006) 150 FCR 134; [2006] FCAFC 52 at [30] (Black CJ, Sundberg and Bennett JJ); Bauer Consumer Media Ltd v Evergreen Television Pty Ltd (2019) 142 IPR 1; [2019] FCAFC 71 (Bauer) at [2] (Greenwood J) and [256] (Burley J).

27 As a hearing de novo, the Court must approach the matter afresh without undue concern as to the reasons for the decision of the delegate, although weight can be given to the delegate’s opinion as a skilled and experienced person: Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365; [1999] FCA 1020 (Woolworths) at [32] (French J, as his Honour then was); Telstra Corporation Ltd and Another v Phone Directories Company Australia Ltd (ACN 079 290 805) and Others (2015) 237 FCR 388; [2015] FCAFC 156 (Telstra) at [181] (Besanko, Jagot and Edelman JJ).

28 The expression “goods of the same description” is one of impression and different minds may give different answers, and a different conclusion may be reached by the Court after considering the decision of the Registrar: Rowntree plc v Rollbits Pty Ltd and Another (1988) 10 IPR 539 at 546 (Needham J). The degree of weight that can be given will depend on the circumstances of each case, in particular, the extent to which the evidence before the Court might travel beyond or be inconsistent with the evidence before the delegate: Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 227 FCR 511; [2014] FCA 1304 at [23]-[24] (Yates J).

29 EB submits that there is a qualitative difference between its evidence in the hearings before the Delegates and in the appeals.

30 Cantarella submits that although EB has filed fresh affidavits in support of the appeals, the new evidentiary record relied upon by EB “simply gives greater weight to the conclusions which the Delegates formed”. In particular, Cantarella contends that there is no new evidence of “actual intentions” to use the MOTHERLAND nor MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark, nor any intention to produce a “coffee product” under the name “MOTHER” in Australia. It further submits that the late production of documents relied upon by EB to establish a relevant intention (Recent EB Planning Documents) should be accorded little weight because they have “recently been created in the shadow of this litigation, which has been on foot now for a number of years”.

31 Cantarella made two further submissions relevant to the weight to be attributed to the decisions of the Delegates.

32 First, the Delegates, unlike the Court, had the benefit of evidence as to future intentions from the most senior decision maker within EB, Mr Rodney Cyril Sacks, its Chief Executive Officer. I note, however, that Mr Samuel Thiele, the Vice President – Oceania for EB, gives evidence that while EB made recommendations on future product launches in Australia, ultimately all decisions on which products would be launched in this country were made by Monster Energy Company (Monster) in the United States of America.

33 Second, at the contested hearing before the Delegate in relation to the MOTHERSKY application, EB advanced the same contention as it advances before the Court. That submission was that, given the reputation of its MOTHER marks, the use of MOTHERSKY would be likely to deceive or cause confusion. The absence of any attempt to adduce evidence of actual confusion in the two years since the hearing before the Delegate, notwithstanding Cantarella continuing to promote and sell coffee under the MOTHERSKY mark, suggests the Delegate was correct in rejecting EB’s contentions under ss 42(b) and 60 of the Act, and that conclusion ought to be given weight.

(a) the contentions advanced by EB before the Delegates were not materially different to those advanced in these proceedings;

(b) the evidence relied upon by EB in these proceedings was more extensive but not qualitatively different to that relied upon by EB before the Delegates;

(c) from my review of the Recent EB Planning Documents and submissions made in closed court by Mr Murray SC, who appeared for EB:

(i) the documents reflect genuine consideration by Monster and EB of potential future product launches; but

(ii) they do not disclose the existence of any concluded decision to launch any coffee product in Australia with the brand “MOTHER” or any “MOTHER”-derivative; and

(d) the absence of any evidence of confusion given the promotion and sale of coffee under the MOTHERSKY mark in the face of EB’s MOTHER marks is relevant to the weight that should be afforded to the decision of the Delegate in the MOTHERSKY application.

35 I therefore consider that it is appropriate to give weight to the decisions of the Delegates but I recognise that, ultimately, this is a hearing de novo and I must consider the issues raised in the appeals afresh.

36 Generally speaking, EB bears the onus in the MOTHERSKY appeal, as the party seeking to oppose the registration of the MOTHERSKY mark, to establish the grounds of opposition on which it relies. The standard of proof is the ordinary civil standard on the balance of probabilities: Telstra at [132]-[133] (Besanko, Jagot and Edelman JJ).

37 As Cantarella submits, the legislative intent and judicially recognised result of the Act is that there is a presumption of registrability when an application is examined by the Registrar of Trade Marks: Recommended Changes to the Australian Trade Marks Legislation, Working Party to Review the Trade Marks Legislation (1992) p 44; Australia, Senate, Debates (1995) Vol 170, p 2590; Horak I and Davison M, Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off (6th ed, 2016, Lawbook Company) (Shanahan’s) at [25.05]; Woolworths at [24] (French J, as his Honour then was); Sports Warehouse, Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd (2010) 186 FCR 519; [2010] FCA 664 (Sports Warehouse) at [26] (Kenny J).

38 It is against that background and presumption of registrability that the MOTHERSKY appeal is to be determined.

39 As the opponent to the non-use applications, EB also bears the onus in the MOTHERLAND and MLIC appeals to rebut any allegation that the marks have not been used or have not been intended to be used: s 100(1) of the Act; Hungry Spirit Pty Limited ATF The Hungry Spirt Trust v Fit n Fast Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 883 at [9], [11] and [15] (Burley J).

40 Mr Samuel Thiele is the Vice President – Oceania for EB. He has worked continuously for Monster since May 2013 and for EB since its incorporation in 2015. He has 18 years of experience in the beverage industry in Australia in various marketing and business development roles. He was cross-examined.

41 Cantarella submits that except to the extent that Mr Thiele’s evidence was adverse to EB’s own interests it is of limited assistance. It submits that: first, he has no personal knowledge of much of the history and use of the MOTHER, MOTHERLAND and MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE marks and his evidence is largely based upon a consideration of documents; second, he resisted acknowledging that he was aware of matters in the course of his cross examination and only reluctantly, when pressed, conceded that he was in fact aware of those matters; third, he expressed opinions on matters that he was not qualified to express, such as the value of advertisements that were 10 years old; fourth, his evidence concerning the placement of the phrase “HIGH CAFFEINE CONTENT” on cans of MOTHER energy drinks was implausible because he acknowledged in cross examination that he was not part of the relevant decision making process; and fifth, he sought to speak at length about “coffee drinks on the horizon” in the absence of any evidentiary basis at the time his cross examination was concluded and his acknowledgment that EB had produced all evidence that it had of any plans to introduce any product relevant to the issues to be determined in the appeal.

42 I accept that there was at times a reluctance on the part of Mr Thiele to accept what appeared to be relatively uncontentious issues, such as his understanding of how to convert grams of sugar to teaspoons of sugar. On balance, however, I was satisfied that Mr Thiele was answering questions put to him truthfully, bearing in mind the perhaps natural tendency of witnesses to seek to rely upon minor ambiguities or imprecision in questions to avoid answering questions directly and the difficulties many senior executives appear to face in giving evidence limited to recollection rather than reconstruction.

43 Moreover, I am satisfied that the other challenges to Mr Thiele’s evidence go to the weight of the evidence, not whether any reliance can be placed on it. I do not make any adverse credit finding against Mr Thiele and I generally, subject to questions of weight, found his evidence to be of assistance.

44 Mr Thomas Kelly is the Chief Financial Officer of Monster and EB. He was not cross-examined.

45 Ms Elizabeth Godfrey is a principal of Davies Collinson Cave. She was not cross-examined.

46 Ms Emily Maartensz is a solicitor employed by Davies Collinson Cave. She was not cross-examined.

47 Ms Jyoti Goonawardena is a solicitor employed by Davies Collinson Cave. She gives evidence of trade mark searches that she conducted in response to trade mark searches that had been undertaken by Ms Meg Stacey for Canteralla. She was cross-examined.

48 Cantarella submits that her evidence in cross-examination was responsive and she made all appropriate concessions. I agree.

49 Mr Simon Creswick is the General Manager Foodservice at Canteralla. He gives evidence about the manufacturing processes for, and marketing and function of, coffee and energy drinks. He was cross-examined.

50 EB submits that Mr Creswick’s affidavit evidence was of limited value because it focused on the difference between “pure coffee” and “energy drinks” and was therefore of limited value because “coffee” extends well beyond “pure coffee”. The submission reflected the fundamentally different taxonomical approaches taken by EB and Cantarella to “coffee”. I found Mr Creswick’s evidence of assistance in addressing those different approaches and I generally accepted it.

51 Ms Meg Stacey is a solicitor employed by Herbert Smith Freehills. She gave evidence of four trade mark searches that she undertook of the Register on 5 August 2020. She was not cross-examined.

52 Mr Michael Simonetti is an expert witness. He is a computer scientist and software engineer with extensive experience in digital marketing. He gives evidence explaining the technical aspects of posting content to YouTube and Facebook. He was not cross-examined.

53 In early 2007, TCCC launched the MOTHER energy drink in Australia.

54 In June 2015, TCCC transferred the trade marks in Australia associated with the MOTHER range of energy drinks, as well as the business and goodwill pertaining to those trade marks to EB.

55 In December 2015, EB incorporated EB Australia to oversee the distribution of MOTHER energy drinks in Australia and to carry out marketing and promotion activities.

56 Mr Creswick gives evidence that Cantarella’s business was founded in 1947, and since that time Cantarella has continuously traded in Australia, including by importing, distributing, marketing, advertising and promoting, and offering products for sale to both food service and retail customers.

57 Mr Creswick explains that Cantarella first began to import raw coffee beans into Australia in 1958 for the purpose of roasting, grinding and packaging coffee products in for sale to cafés, restaurants and delicatessens under the trade mark VITTORIA.

58 Mr Creswick gives evidence that in the 1980s, after trading in pure coffee under the VITTORIA trade mark for over 20 years, Cantarella commenced selling pure coffee in the Australian grocery market, making it one of the first businesses to offer pure coffee for sale through the grocery channel. Cantarella’s strategy for marketing pure coffee through the grocery channel in Australia involved utilising the reputation it had built up through its sales of pure coffee through the café, restaurant and delicatessen channels, encouraging existing customers of VITTORIA coffee to bring home the pure coffee they had previously experienced in these venues.

59 When VITTORIA was launched in the grocery channel, Cantarella continued to promote the coffee sold under this mark as being a high-quality coffee product with a refined taste, the focus on quality being a point of distinction from the instant coffee that was commonly sold through the grocery channel at the time. Mr Creswick gives evidence that Cantarella now markets and sells coffee under a number of brands, including MOTHERSKY and WILL&CO, which are directed at the growing connoisseur aspect of the Australian coffee market.

60 Mr Creswick explains that with the exception of the AURORA brand, the coffee sold by Cantarella under each of its brands is pure coffee, in bean, ground or more recently capsule form. All of the pure coffee sold by Cantarella in Australia is sourced from high quality local and international sources, and is roasted and blended using sophisticated equipment at Cantarella’s factory in Silverwater, Sydney. He states that this practice of using coffee beans from high-quality sources and sophisticated manufacturing equipment is now expected amongst pure coffee manufacturers if they are to be successful in the pure coffee market Australia.

61 Mr Creswick gave evidence that the name MOTHERSKY was suggested by two contractors who had been engaged by Cantarella to work on developing a boutique coffee brand with an Australian focus. One of the contractors, Mr Greg Mullins, was a member of a band that had a blog called “motherskyrecords” that showed posts as early as 2010. The band subsequently released a single under a “Mother Sky Records” label.

Distribution channels for MOTHER energy drinks

62 Mr Thiele gives evidence that MOTHER energy drinks have been distributed throughout Australia, since before the MOTHERSKY Priority Date, including to supermarkets, retail chains such as Target and Kmart, convenience stores and service stations, restaurants, bars and pubs, liquor outlets, vending machines, universities and TAFEs, cinemas, and food service and independent stores, such as food courts, general stores, bakeries and pharmacies.

63 Mr Thiele also gives evidence that MOTHER energy drinks are available on tap in some pubs in metropolitan cities in Australia.

64 Since at least June 2015, MOTHER energy drinks have also been distributed to a large range of cafés, bars and takeaway food outlets.

Advertising, marketing and promotion of MOTHER energy drinks

65 Mr Thiele gives evidence that since the launch of the original MOTHER energy drink in 2007, the MOTHER brand has been the subject of extensive advertising, marketing and promotion. This has included television commercials, radio advertisements, sponsorship of events, print advertisements, point of sale material, outdoor advertising (such as on bill boards, bus stops and on buses) and promotional campaigns (including partnerships, competitions and giveaways, often in association with radio broadcasters, popular websites or video games).

66 Mr Kelly gives evidence that between 2015 and 2019, EB spent a significant amount on advertising, marketing and promotion of its MOTHER energy drinks in Australia.

67 Mr Thiele gives evidence that EB’s promotional strategy since 2015 has focussed heavily on sponsorship, advertising via its website and other social media pages, in-store promotions and point of sale materials. An example of EB’s promotions on social media provided by Mr Thiele is reproduced below:

68 Mr Thiele states that this strategy was adopted because indirect forms of advertising such as sponsorship and product placement were seen as instrumental in reaching EB’s target audience of 18 to 34 year olds. It was also designed to enable EB to take advantage of unsolicited press coverage at live events, and to engage more directly with its consumers.

Brand pillars for MOTHER energy drinks

69 Mr Thiele gives evidence that EB’s “brand pillars” for the MOTHER brand are music and adventure. He explains that in support of these pillars, EB sponsors music festivals in Australia with consequential promotion of the MOTHER brand in various ways. These include providing entertainment within the event, such as a MOTHER branded “ball pit” and photo booth, selling MOTHER energy drinks (often as the exclusive energy drink supplier for the festival), sampling MOTHER energy drinks at the music festival and nearby towns in the lead up to the event, and sponsorships or collaborations with the festival artists, local artists and bloggers (as demonstrated in the social media image above). He states that in the lead-up to a festival, EB runs competitions in conjunction with supermarkets and selected retailers and prepares point of sale material to be distributed across convenience stores, petrol stations and grocery stores located near the festival precinct.

MOTHER energy drinks brand image

70 Mr Thiele gives evidence that the image EB’s advertising, marketing and promotional activities conveys is that the MOTHER energy drink is “a high energy and rebellious product”. He states that the taglines adopted by the brand reflect this image by emphasising the contents of the products that give energy to the consumer. He refers to a number of examples: HIGH CAFFEINE CONTENT; NATURAL CAFFEINE, ACAI: GUARANA: CAFFEINE: GINSENG; and LEMON LIME FLAVOUR WITH CAFFEINE, TEA & YERBA MATE. Further, he states that this image appeals to consumers who desire an energy “hit” during their day and provides the following examples: 100% NATURAL ENERGY; MOTHER OF AN ENERGY HIT; MOTHER OF AN ENERGY KICK; HEAPS OF ENERGY; BIG SHOT; EXTRA ENERGY; DOUBLE GUARANA & TAURINE; and MOTHER REVIVE.

71 Mr Thiele gives evidence that he had discussions with EB’s marketing directors and regulatory team about the packaging and reference to caffeine content on the can. When asked about the words “HIGH CAFFEINE CONTENT” featured prominently on the MOTHER cans, Mr Thiele said EB “had no obligation to have that on the front of the can” and the intent of the words is, to his understanding, to “market to our consumers because they like high caffeine content”.

Promotion of MOTHER energy drinks on social media accounts

72 Mr Thiele gives evidence that EB has promoted the MOTHER brand heavily in Australia on dedicated MOTHER branded social media accounts. He states that fans and/or followers of those pages are exposed to and engage with the content posted by EB. These include:

(a) the MOTHER Facebook page, which is locally controlled in Australia with a “brief approval process” in the United States. This page has been in operation since 2008 and had over 120,000 followers as at May 2020;

(b) the MOTHER YouTube page, launched in 2008. The videos posted to this account regularly receive over 10,000 (and in some cases, 100,000) views; and

(c) the MOTHER Instagram page. This page has been registered since 2017 and had over 3,500 followers as at May 2020.

MOTHER-derivative marks and taglines

73 The MOTHER brand is promoted by using the word MOTHER in conjunction with other words. For example, each of EB’s MOTHER products (as identified at [95] below) has a different name, which adopts the form of “MOTHER + [additional word or words]”.

74 In addition to product names, EB promotes the MOTHER brand using taglines and slogans, which include the word “MOTHER” in conjunction with other words. For example: MOTHER 100% NATURAL ENERGY (2007); MOTHER: A FORCE OF NATURE (2007); MOTHER OF AN ENERGY KICK (2009 to 2010); MOTHER OF AN ENERGY HIT (2009 to 2013); MOTHERLAND (2010 to 2013); MOTHERLAND IT’S A RUSH (2010); MOTHER MAIDENS (2012); MOTHER MADE ME DO IT (2012); MOTHER SAYS… (2016 to 2017); and MOTHER OF A FESTIVAL (2018).

75 Mr Thiele gives evidence that the strategy of using MOTHER-derivative marks and taglines creates more exposure and increases the reputation and recognition of the MOTHER brand, by creating opportunities to use the MOTHER marks across all of EB’s advertising, marketing and promotional activities.

Display and sale of energy drinks and other beverages, particularly coffee

76 Mr Creswick gives evidence that energy drinks are sold in pre-packaged cans or bottles, and are displayed in refrigerated units or shelves. He further gives evidence that to the extent there is any evidence of energy drinks being sold for consumption at particular venues (such as bars), the evidence is consistent that the marketing similarly emphasises “energy” over all other attributes.

77 Mr Creswick gives evidence that Cantarella’s coffee products are sold in the same aisles and alongside other coffee products sold by competing brands. He states that they are not sold in close proximity to any pre-packaged and ready to drink (RTD) coffee products, such as “iced coffee” flavoured milk, or other RTD beverages such as soft drinks or energy drinks. He annexed to his affidavit copies of photographs taken by Cantarella’s merchandising sales team showing how Cantarella’s VITTORIA pure coffee branded products are displayed on supermarket shelves, an example of which is reproduced below:

78 Mr Thiele annexes to his first affidavit copies of photographs showing how MOTHER energy drinks are typically displayed for sale, an example of which is reproduced below:

Sale of coffee and tea flavoured energy drinks

79 Mr Thiele and Ms Maartensz give evidence that beverage companies, including Monster, have already sold coffee- or tea-flavoured energy drinks in Australia from time to time since 2008, including:

(a) X-PRESSO MONSTER (2010), a dairy based coffee and energy drink;

(b) MONSTER REHAB TEA + ENERGY (2012 to 2014), a non-carbonated energy drink with electrolytes, flavours including “TEA + LEMONADE + ENERGY” and “PEACH TEA + ENERGY”);

(c) V ICED COFFEE (2010 to present), an iced coffee product available in the flavour “DOUBLE ESPRESSO + GUARANA ENERGY”;

(d) MUZZ BUZZ “BIG BUZZ” (2012 to 2015), an energy drink sold by Australian drive-through café chain, Muzz Buzz; and

(e) ICE BREAK LOADED (2008), an iced coffee product containing “a hit of guarana”.

80 Mr Thiele gives evidence that as part of its product innovation strategy, EB (and TCCC) has sold tea based energy drinks in Australia, including MOTHER REVIVE (2014 to 2016), a product which combined energy drink with tea and yerba mate, and MOTHER EXTREME TEA + ENERGY (2013), an “energy tea” sold in partnership with Chatime Australia.

Energy drinks as an alternative to coffee

81 Mr Thiele and Ms Maartensz give evidence of examples of energy drinks in Australia positioning themselves as an alternative to coffee. They point to the following examples:

(a) a post to the MOTHER Facebook page dated 31 March 2014: “When you see those chumps waiting in line for their Monday coffee… and you’ve already had your morning MOTHER”;

(b) a post to the MOTHER Facebook page dated 13 April 2015: “Move over coffee, this is a job for MOTHER. Who has a case of #mondayitis?”; and

(c) a post to the V Energy Drink Australia Facebook page dated 20 August 2012: “Screw coffee, grab a V!”.

82 Mr Thiele conceded in cross-examination that the caffeine in MOTHER energy drinks is synthetic, synthetic caffeine has a higher rate of absorption than naturally occurring caffeine, and none of EB’s current or former products are advertised as having a coffee flavour.

Competitive landscape for energy drinks in the United States

83 Mr Kelly exhibits to his affidavit extracts of Monster’s annual reports and other SEC filings between 2007 and 2020 (Monster US SEC filings) in which references are made to the product offering and competitors of Monster and EB. Those extracts include references to “Caffé Monster® Energy Coffee Drinks” said to be “a line of non-carbonated, 100% Arabica coffee, reduced fat, dairy based energy coffee drinks”, and “Espresso Monster Espresso + Energy Drinks” said to be “a line of non-carbonated dairy based espresso + energy drinks” within what is described as the “Monster Energy Drinks” segment. The Monster Form 10-K SEC filing for the financial year ended 31 December 2019 records:

Our Java Monster®, Espresso Monster® and Caffé Monster® product lines compete directly with Starbucks Frappuccino, Starbucks Doubleshot, Starbucks Doubleshot Energy Plus Coffee, Starbucks Tripleshot and other Starbucks coffee drinks, Costa Coffee, Rockstar Roasted, Dunkin Donuts, Gold Peak, Stok, High Brew, McCafé, hi*ball, Douwe Egberts Coffee, Emmi CAFFÈ, Bang Keto Coffee, Nescafe and International Delight.

84 The Monster Form 8-K SEC filing dated 17 January 2019 (Form 8-K SEC Filing) contained the following “Industry Overview”:

The “alternative” beverage category combines non-carbonated, ready-to-drink iced teas, lemonades, juice cocktails, single-serve juices and fruit beverages, ready-to-drink dairy and coffee drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks and single-serve still waters (flavored, unflavored and enhanced) with “new age” beverages, including sodas that are considered natural, sparkling juices and flavored sparkling beverages. According to Beverage Marketing Corporation, domestic U.S. wholesale sales in 2018 for the “alternative” beverage category of the market are estimated at approximately $55.5 billion, representing an increase of approximately 6.7% over estimated domestic U.S. wholesale sales in 2017 of approximately $52.0 billion.

85 The Form 8-K SEC Filing included a series of charts illustrating market shares of the “Beverage Landscape” and “Brand Performance” within that landscape by reference to “TOTAL U.S. - CONVENIENCE SNAPSHOT”. The “Beverage Landscape” slide included “RTD COFFEE”:

86 The Form 8-K SEC Filing included the following slide showing market shares of the “ENERGY COFFEE CATEGORY”:

Competitive landscape for energy drinks in Australia

87 The Form 8-K SEC Filing also included the following slide entitled “AUSTRALIA//SELECTED MARKET”:

88 Ms Maartensz gives evidence that on 15 April 2020 she conducted trade mark searches of the Register and found a number of examples of energy drink companies in Australia filing for trade mark coverage in respect of “coffee” and “chocolate”. Similarly, she gives evidence that she found a number of examples of coffee beverage manufacturers in Australia filing for trade mark coverage in respect of “energy drinks”.

89 In the February/March 2020 edition of the “Convenience and Impulse Retailing” magazine, published by C&I Media Pty Ltd, exhibited to the affidavit of Mr Thiele, there is an article entitled “Bundle of Energy” that analyses the “evergreen energy drinks segment” including data from the most recent State of the Industry Report from the Australasian Association of Convenience Stores. It states:

Energy is dominated by major players such as Red Bull, Frucor Suntory with its V and Rockstar brands, and by the Monster Energy Company (MEC) which owns both the Monster Energy and Mother Energy brands, which are distributed through a long-term partnership with Coca-Cola Amatil in Australia. From a combined portfolio perspective MEC brands account for approximately one third of energy drink sales in Australia.

90 Mr Thiele gives evidence about the existence of an Australian energy drinks market in which the principal competitors are MOTHER, Monster, Red Bull and V.

Competitive landscape for coffee in Australia

91 As a result of his experience in the coffee industry in both the United States and Australia, Mr Creswick gives evidence that the markets for coffee in Australia and the United States are fundamentally different. He explains that Cantarella sells a higher ratio of pre-ground filter style coffee in the United States than in Australia due to demand from large hospitality venues. In contrast, equivalent venues in Australia commonly sell roasted whole beans.

92 Mr Creswick also gives evidence that the closure by Starbucks of the majority of its retail outlets in Australia also emphasised the extent to which Australia had developed a sophisticated café culture with a focus on quality, and Australian consumers expected a more refined taste than was present in the products offered by Starbucks.

93 Mr Creswick gives evidence that the only Nielsen competitor and market reports that Cantarella subscribes to are those directed solely at the pure coffee market. The reports do not include any data relating to RTD or pre-packaged coffee drinks, energy drinks or instant coffee products.

Product innovation for MOTHER energy drinks

94 Mr Thiele gives evidence that product innovation is a vital element for energy drink suppliers as a means of attracting and retaining customers, and for remaining competitive.

95 Mr Thiele gives evidence that TCCC, and subsequently EB, have launched a variety of sublines or variants of the original MOTHER energy product in Australia since 2010, including: MOTHER BIG SHOT; MOTHER LEMON BITE; MOTHER LOW CARB; MOTHER FROSTY BERRY; MOTHER SUGAR FREE; MOTHER BIG CHILL; MOTHER GREEN STORM; MOTHER SURGE ORANGE; MOTHER REVIVE; MOTHER KICKED APPLE; MOTHER PASSION; MOTHER TROPICAL BLAST; and MOTHER EPIC SWELL.

96 Mr Thiele gives evidence that EB’s product range will likely continue to evolve, and non-carbonated dairy based drinks, such as iced coffee and iced chocolate, are a key opportunity for expansion.

97 The Form 8-K SEC Filing included the following slide entitled “STRATEGIC BRANDS INNOVATION”:

98 Mr Thiele gave the following evidence in the course of his cross examination by senior counsel for Cantarella, Mr Bannon SC, concerning the future intentions of EB in relation to the launch of new products in Australia:

Could you answer my – could you answer my question. You haven’t produced in evidence a single piece of paper to indicate any plan of Monster or Mother to introduce any single new product in this country, have you?---Not that I can recall, no. That’s not saying that they don’t exist, because we do have very thorough plans, and you know, maybe they’re not in evidence here, but we certainly have a lot of new products on the short-term and long-term horizon that are confirmed, so - - -

And if there was a plan in relation to any particular product in existence, it would have been a simple matter for you to include it in your affidavit, wouldn’t it?---I think, you know, since the time of writing - - -

It would have been a simple matter for you to include it in your affidavit, wouldn’t it?

[Objection to question overruled.]

HIS HONOUR: Sorry. I – please continue to answer. Yes?---Yes. This was completed in May 2020, and our innovation plans have moved quite substantially since that time, and so, you know, a year is a long time in the beverage industry and we have, you know, quite a lot of plans confirmed in between. I mean, this is a product we pulled off the production line last week that’s a new Mother product that will be out in August this year, a sugar-free raspberry flavour. We’ve got, you know, coffee drinks on the horizon for both Monster and Mother. We have a multitude of different products coming in. We’ve got a mango-flavoured sugar-free Monster coming in in August as well as the Mother. We’ve got a brand refresh of the Mother sugar-free original flavour to – to give clearer sugar-free cues around the colour of the packaging. So we’re always looking at things, but things evolve pretty quickly and, you know, a year is a long time in the beverage industry since this was written at that time as well.

MR BANNON: If there was a single plan to produce any new product in Australia which is relevant to this case, it will be in a document, firstly; do you agree?---I mean, I can only speak for the plans we’ve got. But yes, I mean, there is documentation of all of those things - - -

And if it - - -?--- - - - in some form.

If it existed, it would have been a simple matter for you to produce it for the purposes of this case, wouldn’t it?---Yes, sure.

What I want to suggest to you is that the company has produced such evidence as it’s able to produce to evidence any plans to introduce any product relevant for the purposes of this case; do you agree?---Yes.

[Emphasis added.]

99 EB sought to rely on the Recent EB Planning Documents to evidence the existence of such plans, including with respect to plans for “coffee drinks on the horizon”. Given their commercial sensitivity, suppression orders were made over the content of the Recent EB Planning Documents. I address the relevance of the Recent EB Planning Documents at [34(c)] above.

Sale of energy drinks and coffee products

100 Mr Thiele gives evidence that MOTHER energy drinks are sold in convenience stores like 7-Eleven, and that freshly ground coffee is also sold in 7-Eleven stores.

101 Mr Creswick accepted in the course of his cross examination that at least one stockist of MOTHERSKY coffee, the Beans & Barrels café in Parramatta, New South Wales, sells a range of beverages including coffee, iced coffee, milkshakes, protein shakes, and energy drinks.

102 Ms Maartensz gives evidence that she visited two service stations and three supermarkets in the period 14 April 2020 to 7 May 2020. She exhibits photographs taken during those visits to her affidavit. One photograph taken at a petrol station energy shows that drinks were located in the same fridge section as what appears to be two canned iced coffee products. Another photograph shows that a large quantity of iced coffee products were displayed in a separate, open fridge section, alongside milk products. In another petrol station, she observed a “Wild Bean” café counter in the petrol station where an attendant was brewing fresh coffee using an espresso machine. The photographs show largely products such as Gatorade and Powerade in one closed fridge, energy drinks in another fridge, and iced coffee products in another fridge.

103 Ms Maartensz also exhibits a photograph taken in a supermarket, in which two iced coffee products are in the same fridge as energy drinks, and another image in which iced coffee products are in a separate refrigerated unit, located next to what appears to be a check-out area, next to a refrigerated unit containing energy drinks. She exhibits another photograph that was taken in the same supermarket of energy drinks of various brands shelved in a non-refrigerated section.

104 She also exhibits photographs taken at a different supermarket in which energy drinks are in a non-refrigerated section, iced coffee products are in a refrigerated section, and in a refrigerated unit next to what appears to be a check-out area, there are energy drinks shelved next to three iced coffee products.

105 At the final supermarket, she exhibits a photograph showing two refrigerated units next to one another: one unit containing energy drinks and water, and the other containing, among other products, iced coffee products and iced tea products.

106 Mr Creswick gives evidence that, in his experience, Cantarella’s pure coffee products sold in major supermarket chains and retail grocery stores are sold in particular aisles and mostly alongside other competitors’ pure coffee products. He gives evidence that in his experience they are not sold in the same aisle as iced coffee milk drinks (such as Dare Iced Coffee) or energy drinks (such as Red Bull or MOTHER drinks); rather, energy drinks are generally sold in refrigerated units near the check-out or in aisles dedicated to pre-packaged beverages such as soft drinks and bottled water.

Marketing of energy drinks and coffee products

107 Ms Maartensz gives evidence that the RTD coffee brands Ice Break, Oak, Dare Iced Coffee and Barista Bros employ advertising and promotional strategies similar to those identified above in relation to MOTHER energy drinks, including sampling, promotions, sponsorships and partnerships with video games.

108 Mr Creswick gives evidence that pure coffee is sold using distinct sales approaches and channels, being sold as an ingredient to be transformed into a beverage, often by a professional barista. He further gives evidence that pure coffee is sold using a particular marketing emphasis; primarily, the quality of the coffee bean and taste. Mr Creswick gives evidence that energy drinks are marketed by reference to their effect, providing energy, with the utility of that quality consistently emphasised.

109 Mr Kelly gives evidence that energy drinks are produced by the preparation of “concentrates” and/or “beverage bases” that are then provided to bottling and canning operations, which combine the concentrates and/or bases with sweeteners, water and other ingredients to produce RTD packaged energy drinks. Mr Thiele gives evidence that energy drinks typically have a sweet and fruity flavour profile.

110 Mr Creswick accepted that pure coffee and RTD coffee can be sweetened by the addition of sugar or sweeteners, and that coffee drinkers add sugar to their coffee in order to meet their taste preferences. He also accepted that some blends of coffee, including MOTHERSKY coffee, may be perceived by coffee drinkers as sweet, and/or as having characteristics of fruit flavours.

111 Mr Thiele acknowledges that sugar is an important aspect of energy drinks, but that the sugar is present “mostly for taste”. Mr Thiele gives evidence that other ingredients in energy drinks, the amount of kilojoules of which are listed on the back of the product, may be described as a type of “energy”. Mr Creswick accepted that coffee marketing refers to coffee as a “pick me up” in the sense that caffeine revives the drinker and makes them feel more “energised”

112 In a 7-Eleven Facebook post dated 17 August 2015, exhibited to Ms Goonawardena’s affidavit, that is reproduced below, 7-Eleven’s freshly ground coffee is advertised as “the reason you can get out of bed in the morning”. In response to this post, a user has commented with a “selfie” with a Red Bull energy drink, captioned “My reason”. 7-Eleven responds, “oooo we sell those too”.

113 Mr Creswick accepted that:

(a) the stimulating benefits of caffeine are regularly invoked in the marketing of coffee in Australia, and that this is a functional benefit for coffee drinkers;

(b) coffee is often advertised as a pick-me-up;

(c) there are references in coffee marketing, including in the advertisements of some of Cantarella’s own coffee brands and competitor brands, to coffee serving the functional purposes of providing sustenance or energy and reviving the drinker, including to “refuel”, “powering your day”, and “get through a big day”;

(d) coffee is often used as a means of delivering caffeine to the drinker;

(e) the stimulant effects of caffeine in coffee acts as a pick-me-up to help you to wake up, to stay focussed, to improve productivity, to “keep you going”, or to feel more energised;

(f) there are references in coffee marketing which invoke a link between coffee and energy drinks;

(g) a consumer would not be taken by surprise to see coffee marketed with a direct or indirect reference to the stimulant effects of caffeine; and

(h) the marketing of coffee in Australia regularly picks up the stimulant qualities of caffeine.

114 Mr Creswick also accepted that the stimulating effects of caffeine in coffee “helps one get going the morning” and “it is a selling benefit that is promoted” but emphasised that:

It’s not the main selling benefit of coffee in the experience of coffee that we promote and that I see generally. A lot of it is about taste and flavour and the experience of having a coffee as opposed to the – the simple delivery of energy or stimulation.

Interface between pure coffee and other products

115 Mr Creswick gives evidence that pure coffee products are produced using particular manufacturing processes (roasting and in some cases grinding of coffee beans, and packaging of beans), and that pure coffee is commonly consumed in a “dining” environment such as a café or restaurant in which the consumption experience is emphasised.

Scope of use of Cantarella’s pure coffee brands

116 Mr Creswick gives evidence that Cantarella’s “pure coffee” brand VITTORIA is also used in relation to biscuits and drinking chocolate.

117 Ms Goonawardena gives evidence that it is also used for mineral water, iced tea, Italian soda, fruit nectars, cheese, confectionary, hazelnut spread, oil, vinegar, wine, tea, pasta and gelato under the VITTORIA or SANTA VITTORIA sub-brands.

118 Mr Creswick gives evidence that Cantarella’s “pure coffee” brand AURORA is also used in relation to instant coffee, tea, olive oil, vinegar and Italian cheese, and Ms Goonawardena gives evidence that it is also used for pasta.

119 Mr Creswick and Ms Goonawardena give evidence that Cantarella’s “pure coffee” brand DELTA is also used in relation to cooking oils.

120 Mr Creswick gives evidence that Cantarella’s “pure coffee” brand WILL&CO is also used in relation to beer (although he notes that this was part of a co-branding partnership with a third party, and the product was marketed and sold by that third-party), and Ms Goonawardena gives evidence that it is also used for drinking chocolate and RTD cold brew and iced coffee products:

121 Ms Goonawardena gives evidence that the CAMPOS COFFEE brand, Cantarella’s competitor, is used in relation to several “extended” products, including:

(a) an RTD “iced latte” product;

(b) an RTD “cold press” product, with or without milk;

(c) a “tiramasu white stout” beer, in collaboration with Young Henry’s Brewery;

(d) a “Campos Cascara Gin” product, in collaboration with Melbourne Moonshine;

(e) a “Campos Espresso Martini” product; and

(f) a coffee liqueur product, in collaboration with Mr Black Spirits.

122 Ms Goonawardena also gives evidence that Pablo & Rusty’s branding is used in relation to “extended” products, including a “Nitro” canned coffee product as shown below:

123 Mr Thiele gives evidence that the MOTHERLAND campaign was run by TCCC in 2010 and 2011. He explains that MOTHERLAND refers to a fictional fantasyland tailored to MOTHER-drinking consumers. He gives evidence that a significant component of that campaign was the “MOTHERLAND” commercial (MOTHERLAND commercial) which was broadcast in various iterations on free-to-air television in 2010, including as a full length version (45-second) version and a shorter (30-second) version. He states that an even shorter (15-second) “Demolition Dodgem” version was posted to the MOTHER YouTube page.

124 Ms Maartensz gives evidence that as at 30 March 2021, the videos of the MOTHERLAND commercial remained on the MOTHER YouTube and Facebook pages. She states that the MOTHERLAND mark is used visually and aurally. Set out below is a screenshot from the MOTHERLAND commercial dated 30 March 2021:

125 Mr Thiele gives evidence that the MOTHERLAND campaign also involved other forms of advertising, including: print advertisements; online advertising on websites such as TV.com, Gamespot.au, NRL.com, bigpond.com, MySpace and Ninemsn; social media advertising, including numerous references to MOTHERLAND in posts and user comments on the MOTHER Facebook page, and in sponsored posts; downloadable “wallpapers”; point of sale materials; and competitions and cross-promotions, including a promotion (in partnership with 2Day FM and Triple M) to win $5,000 and visit “Motherland”.

126 Ms Maartensz gives evidence that many of the above examples, including the MOTHERLAND commercial and various social media posts, remain accessible, at least as at 6 April 2021. She also gives evidence that the phrase “Welcome to MOTHERland!” is in the description that appears in the “About” tab of the MOTHER YouTube Page, at least as at 11 March 2020.

127 Mr Simonetti gives expert evidence that content, including videos, posted to a Facebook page or on YouTube remains there unless and until manually removed or hidden by the user or the person with administration rights for the page. Mr Simonetti also gives evidence that the default settings on Facebook and You Tube are, respectively, “Everyone” and “Public”, meaning that the content is publicly available.

128 Mr Thiele gives evidence that the brand equity built in the MOTHERLAND campaign remains valuable to EB and that consumers still connect the MOTHERLAND mark to the MOTHER brand. Mr Thiele also gives evidence that the MOTHERLAND mark lends itself to EB’s current marketing strategies and is a mark that could be deployed by EB in the future, for example, as part of EB’s online presence or at music festivals.

129 Ms Stacey gives evidence that on 5 August 2020 she conducted searches of registered and pending trade marks on the Register containing the word “MOTHER, either as a standalone word or as a MOTHER-derivative, in the course of which she had located:

(a) 15 results in class 30 in which “coffee” was listed, of which 12 results were not owned by either Cantarella or EB, of which eight were on the Register at the time of the MOTHERSKY Priority Date;

(b) 17 results in all classes in which “coffee” was listed, of which 14 results were not owned by either Cantarella or EB, of which nine were on the Register at the time of the MOTHERSKY Priority Date;

(c) 35 results in class 30, of which 32 results were not owned by either Cantarella or EB, of which 20 were on the Register at the time of the MOTHERSKY Priority Date; and

(d) 104 results in class 30 and its associated classes, of which 99 results were not owned by either Cantarella or EB, of which 64 were on the Register at the time of the MOTHERSKY Priority Date.

130 Ms Stacey annexed copies of the trade marks that she had identified as a result of her searches of the Register to her affidavit affirmed on 12 August 2020 (Stacey affidavit).

131 Ms Goonawardena gives evidence that she had reviewed the results of the trade mark searches undertaken by Ms Stacey and concluded that 21 of the 105 trade marks annexed to the Stacey affidavit were in respect of “beverage and confectionary” products and that these 21 trade marks were registered to only 13 different traders. She also stated that she had found no evidence from searches of the internet that any of the 13 traders had, in fact, used those marks in respect of coffee or chocolate products.

132 Ms Goonawardena also gives evidence that only 30 of the 105 trade marks annexed to the Stacey affidavit were in respect of “any type of beverage”. Ms Goonawardena states that she had found evidence from her internet searches that only one of the trade marks had been used for “beverages” and that was with respect to an apple cider vinegar product.

133 The registered trade mark “Mother Earth” has been in use in Australia since prior to 2017. Prolife Foods Ltd is the owner of the Mother Earth mark. Ms Goonawardena gives evidence that the Prolife Foods website records on its “Our Brands” page:

The brand started on Waiheke Island, close to Auckland, New Zealand … In 1973, the product range comprised just health baked loaves. Mother Earth joined Prolife Foods in 2008 and has grown exponentially since …

134 The registered trade mark “Mother’s Choice” has also been in use in Australia since prior to 2017. Mother’s Choice Flour was advertised in the Australian Women’s Weekly as early as June 1935 and is now listed as a Goodman Fielder brand on its website under “Australia”.

135 In addition, the registered trade mark owned by Scott Anderson “Don’t Mess With Mother Nature” has been in use in Australia since prior to 2017. The website www.organicwine.com.au, exhibited in the affidavit of Ms Goonawardena, states that “Don’t Mess With Mother Nature” is a business name for a winery that was established in 1999, with the first vintage of wines produced in 2005.

136 The evidence is less compelling that other MOTHER-derivative registered trade marks relied upon by Cantarella in their submissions were used prior to 2017 such as Mother Meg’s, Mothers Milkbank and Mother’s Kitchen. I accept that each is currently used but I am not persuaded that I can find on the evidence before me that each was used prior to 2017.

MARKET ISSUES AND EB’S REPUTATION IN MOTHER

137 Prior to considering the particular causes of action relied upon by EB in these appeals it is convenient to address the following overarching propositions advanced by EB and Cantarella in support of their respective positions.

138 The submissions advanced by EB in these appeals are based on two fundamental propositions. First, there is a material interface between energy drinks and other beverages, including coffee, and a material interface between pure coffee and other products. Second, there is a significant overlap in the marketing and sale of energy drinks and other beverages, including pure coffee.

139 EB advances the following principal contentions in support of these two propositions:

(a) product innovation is a vital element for energy drink suppliers to remain competitive;

(b) beverage companies, including Monster, have already sold coffee or tea flavoured energy drinks in Australia;

(c) energy drink companies often position themselves as a direct alternative to coffee;

(d) energy drink companies, such as Monster, consider coffee drink companies to be direct competitors;

(e) energy drink companies routinely file for trade mark coverage for “coffee” and “chocolate” and coffee beverage manufacturers routinely file for trade mark coverage for “energy drinks”;

(f) Cantarella’s coffee products are sold through similar trade channels to energy drinks;

(g) energy drinks, cold brew coffee products, iced coffee products and iced tea products are sold side-by-side in fridges at supermarkets, convenience stores and service stations;

(h) many RTD coffee brands employ advertising and promotional strategies similar to those used for MOTHER energy drinks;

(i) the notion of energy in energy drinks is not limited to their high sugar content;

(j) coffee companies regularly emphasise the functional nature of coffee such as providing a “pick me up”, “wake me up”, “ a recharge” or “energy”; and

(k) brands that sell “pure coffee” do not limit themselves to “pure coffee” products only.

140 Cantarella submits that the evidence incontrovertibly demonstrates two crucial matters that are largely determinative of the appeals. First, the markets for energy drinks and pure coffee are separate and distinct. Second, EB has a reputation in its MOTHER mark (with its distinctive gothic script) that is narrowly confined to the energy drink market.

141 Cantarella refers to the following characterisation of the market in which energy drinks are supplied that was determined by Yates J in Frucor Beverages Limited v The Coca-Cola Company (2018) 358 ALR 336; [2018] FCA 993 (Frucor) at [36]:

Energy drinks are a type of non-alcoholic beverage containing caffeine and other stimulant ingredients, such as guarana, taurine and ginseng. Energy drinks are marketed to consumers on the basis of their mental and physical stimulatory effects, arising from their ingredients. Energy drinks are accepted in the beverage industry as a separate and distinct category of non-alcoholic drink.

142 Cantarella also refers to the following finding by Yates J in Frucor at [48]:

Energy drinks are presented to the public as a stand-alone drinks category. Petrol and convenience stores use “destination doors” to communicate product location.

143 Cantarella submits that the evidence advanced by EB in these proceedings, much of which I have outlined above in the Evidentiary Background, is consistent with the findings made by Yates J in Frucor.

144 The characterisation of the markets in which goods and services are supplied can arise in the context of trade mark disputes, particularly in addressing reputation and the likelihood of deception or confusion. See by way of example: Dunlop Aircraft Tyres Limited v Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company (2018) 262 FCR 76; [2018] FCA 1014 at [15], [53]-[55], [139], [193] and [198] (Nicholas J); Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd (2017) 251 FCR 379; [2017] FCAFC 83 at [65], [74], [82] and [89] (Greenwood, Jagot and Beach JJ); Allergan Australia Pty Ltd v Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd (2021) 393 ALR 595; [2021] FCAFC 163 at [43] (Jagot, Lee and Thawley JJ); Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd (2017) 124 IPR 264; [2017] FCAFC 56 (Accor) (Greenwood, Besanko and Katzmann JJ) at [339].

145 Neither EB nor Cantarella adduced any empirical economic evidence relevant to market definition. Rather, each sought to rely on largely impressionistic or qualitative evidence to support the respective contentions that each advanced on the markets in which energy drinks and coffee were sold. Necessarily, this demanded an evaluative consideration of the significance and weight to be given to the material relied upon by EB and Cantarella to establish those contentions.

146 As explained above, EB approached the market issue by seeking to establish the existence of what it described as a “material interface” between first, energy drinks and other products, including coffee, and second, between “pure coffee” and other products.

147 The effect of this approach was to introduce into the evaluation a very broad range of beverage products that sat between the MOTHER energy drinks sold by EB and the MOTHERSKY pure coffee products sold by Cantarella. These products included RTD beverages such as iced coffee, iced tea and cold brew coffee products sold in cans. The introduction of these “intermediate products” ultimately had a tendency to distract from, rather than assist in, the determination of the likelihood of deception or confusion and the extent of the reputation that EB had established in its MOTHER marks.

148 At times in the course of its submissions Cantarella sought to distinguish between “pure coffee” and “instant coffee”, but the principal distinction drawn by Cantarella and the subject of the most attention by the parties was the distinction between “pure coffee” and what might be described as “coffee flavoured milk” and other coffee flavoured RTD beverages. EB’s expansive taxonomical approach was to include such RTD products within the concept of coffee.

149 Moreover, the evidence adduced in the appeals and summarised in the Evidentiary Background provides only limited support for the material interface market contentions that EB seeks to advance for the following reasons.

150 First, the need for product innovation to remain competitive in the energy drink market cannot in itself give rise to an expectation on the part of consumers that EB could be expected to diversify its product offering to include MOTHER coffee beans and ground coffee. Rather, as illustrated by the Monster “Strategic Brands Innovation” slide in the Form 8-K SEC Filing reproduced at [97] above, consumers could expect diversification in the presentation, packaging and flavour of energy drinks rather than a diversification into products outside the RTD range of product offerings.

151 Second, the evidence relied upon by EB to establish that energy drink companies considered coffee drink companies to be direct competitors inlcluded the Monster US SEC filings. The Monster US SEC filings do not suggest, however, that energy drink companies identified their competitors as extending to pure coffee suppliers. The Monster US SEC filings, as explained in the Evidentiary Background, listed Monster’s competitors as including “dairy based energy coffee drinks” and “non-carbonated dairy based espresso + energy drinks”. The filings included an “Industry Overview” that described the industry as an “alternative” beverage category combining non-carbonated RTD drinks, including RTD dairy and coffee drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks and “single-serve” still waters with “new age” beverages.

152 The Monster US SEC filings included a graph of the “Beverage Landscape” in the United States broken down by segment, including “Sparking Soft Drinks”, “Water”, “Energy” and “RTD Coffee” with the notation that “ENERGY DRINK CATEGORY GROWING +8.1% LATEST 13 WEEKS IS OUTPACING TOTAL BEVERAGE CATEGORY GROWTH OF +3.5%”. The purpose of the graph is evidently to distinguish energy drinks from other segments of the “Beverage Landscape”.

153 The Monster US SEC filings also included a graph entitled “ENERGY COFFEE CATEGORY // DOLLAR SHARE - CONVENIENCE”. It depicted energy coffee sales of Monster and Starbucks.

154 The material in the Monster US SEC filings also extended to a slide entitled “AUSTRALIA // SELECTED MARKET”. The slide depicted photographs of Monster and MOTHER energy drinks for sale and otherwise recorded in a table and a graph growth in the “ENERGY CATEGORY” and fluctuations in sales and value share in that category by Monster and MOTHER.

155 Unlike the analysis of the competitive landscape in the United States, the Australian slide is concerned only with energy drinks. The limitation is significant and emphasises that the competitive landscape in Australia cannot be assumed to be materially the same as in the United States. This conclusion is reinforced by Mr Creswick’s evidence concerning the more refined focus in the Australian coffee market on roasted whole beans in contrast to the pre-ground filter style coffee popular in the United States, the experience of Starbucks in Australia and the description of the “evergreen energy drinks segment” in the February/March 2020 edition of the Convenience and Impulse Retailing magazine referred to above. These provide further reasons why the competitive landscape in the United States is of limited assistance for determining market and reputational issues in Australia.

156 I address below the specific market and reputational issues raised by EB and Cantarella in the course of addressing the matters relied upon by EB in these appeals. In summary, for the reasons that I develop below in the course of addressing the matters relied upon by EB in these appeals, I am not satisfied that energy drink companies “often” position themselves as a direct alternative to coffee. Nor am I satisfied that the fact that some coffee beverage manufacturers, other than Cantarella, may file for trade mark coverage for “energy drinks” is of any particular significance to the question of whether the use of the MOTHERSKY mark by Cantarella is likely to lead to consumers being deceived or confused.

157 It is sufficient to make the following general observations at this point. First, I am satisfied that the markets for coffee and RTD products, such as iced coffee, iced tea and cold brewed coffee sold in cans, are different. Second, I am not persuaded that there is any material interface between energy drinks and coffee or significant overlap between the marketing and sale of energy drinks and coffee. Third, I am not satisfied that the evidence adduced in the appeals establishes that the market in which energy drinks is supplied, at least in Australia, extends to other RTD products such as iced coffee, iced tea and cold brewed coffee sold in cans.

LACK OF USE OR INTENTION TO USE

Section 92(4) of the Act and relevant legal principles

158 Section 92(4) of the Act relevantly provides:

92 Application for removal of trade mark from Register etc.

(1) Subject to subsection (3), a person may apply to the Registrar to have a trade mark that is or may be registered removed from the Register.

…

(4) An application under subsection (1) or (3) (non‑use application) may be made on either or both of the following grounds, and on no other grounds:

(a) that, on the day on which the application for the registration of the trade mark was filed, the applicant for registration had no intention in good faith:

(i) to use the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) to authorise the use of the trade mark in Australia; or

(iii) to assign the trade mark to a body corporate for use by the body corporate in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the non‑use application relates and that the registered owner:

(iv) has not used the trade mark in Australia; or

(v) has not used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to those goods and/or services at any time before the period of one month ending on the day on which the non‑use application is filed;

(b) that the trade mark has remained registered for a continuous period of 3 years ending one month before the day on which the non‑use application is filed, and, at no time during that period, the person who was then the registered owner:

(i) used the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

159 Section 7 of the Act provides that:

(1) If the Registrar or a prescribed court, having regard to the circumstances of a particular case, thinks fit, the Registrar or the court may decide that a person has used a trade mark if it is established that the person has used the trade mark with additions or alterations that do not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark.

Note: For prescribed court see section 190.

(2) To avoid any doubt, it is stated that, if a trade mark consists of the following, or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name or numeral, any aural representation of the trade mark is, for the purposes of this Act, a use of the trade mark.

(3) An authorised use of a trade mark by a person (see section 8) is taken, for the purposes of this Act, to be a use of the trade mark by the owner of the trade mark.

(4) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods).

(5) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to services means use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services.