FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

F45 Training Pty Ltd v Body Fit Training Company Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCA 96

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. Australian Innovation Patent No 2015101604 be revoked.

3. Australian Innovation Patent No 2016101429 be revoked.

4. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of this proceeding (including the costs of the cross-claim) as agreed or taxed.

5. Any party contending that any part of the reasons for judgment published today (“the Reasons”) presently designated “Confidential” (“the Relevant Material”) should not be made public must file and serve an interlocutory application seeking a non-publication order in relation to the Relevant Material by 4.00pm, 17 February 2022.

6. In the event that any interlocutory application is filed pursuant to order 5 the interlocutory application shall be fixed for hearing before Nicholas J on a date to be fixed.

7. Subject to any further order or direction:

(a) the Relevant Material not be published or disclosed otherwise than in accordance with the terms of any existing non-publication order up to and including 17 February 2022;

(b) in the event that no interlocutory application is filed pursuant to order 5 hereof, then any existing non-publication order extending to the Relevant Material will be discharged but only in so far as the order would prevent any person from publishing or disclosing any part of the Relevant Material; and

(c) in the event that an interlocutory application is filed pursuant to order 5 hereof, then the Relevant Material not be published or disclosed otherwise than in accordance with the terms of any existing non-publication order until the determination of the interlocutory application.

8. Any party contending for a costs order in Proceeding No NSD 1003 of 2019 different from that foreshadowed in [138] of the Reasons is to file and serve a written submission (limited to 2 pages in length) in support of such contention by 4.00pm, 17 February 2022.

9. Upon the cross-respondent, by its counsel, undertaking to the Court:

A. that it will during the period of the stay prosecute any appeal expeditiously; and

B. forthwith serve on the Commissioner of Patents copies of these orders pursuant to s 140 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) with a request that particulars of orders 2 and 3 (“the Revocation Orders”) be registered in accordance with s 187 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth),

the Revocation Orders be stayed:

(a) initially for a period of 21 days from today; and

(b) if an appeal against either of the Revocation Orders is lodged within that period, until the final determination of that appeal or further order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NICHOLAS J:

INTRODUCTION

1 In this proceeding the applicant (“F45”) seeks relief in respect of alleged infringements of Australian Innovation Patent No 2015101604 (“the 604 patent”) and No 2016101429 (“the 429 patent”). While there are some minor differences between the wording of the independent claims and their related consistory clauses, the 604 patent and the 429 patent (together “the Patents”) are virtually identical.

2 F45, which is the patentee of the Patents, alleges that the first respondent (“BFT”), four of BFT’s franchisees (the second to fifth respondents) and one of BFT’s directors, Mr Cameron Falloon, the sixth respondent, have infringed the Patents.

3 The respondents deny infringement. They also seek, by their cross claim, orders revoking the Patents on the basis that each is for an unpatentable method or scheme for configuring and operating fitness studios which is implemented using general purpose computers to perform their ordinary functions. For reasons which will become apparent I accept that this is an accurate characterisation of the invention described and claimed in the Patents. In my opinion each of the Patents is invalid and should be revoked.

4 I have also concluded, for reasons that will become apparent, that if either of the Patents is valid, then none of its claims is infringed by BFT or any of the other respondents. I will return to the issue of infringement after I have dealt with the issue of validity.

WITNESSES

Expert witnesses

5 The applicant called one independent expert.

6 Professor Aruna Prasad Seneviratne is a Professor of Telecommunications and Deputy Head of School, Industry Research at the School of Electrical Engineering at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, a position he has held since 2017. Professor Seneviratne obtained a PhD in Performance Analysis of Low Bit Rate Speech in Communications Systems from the University of Bath in the United Kingdom and has subsequently held a range of academic positions. Outside of academia, he also worked briefly in industry as an Engineer at Telecom Australia.

7 Professor Seneviratne made three affidavits and was cross-examined. In his first affidavit he gave evidence about his views regarding computing terminology and concepts. He also provided his understanding on claims 1 and 5 of the patents, his views about the components of the Body Fit Training system (“the BFT System”) and their functionality, and his views regarding whether the BFT System incorporates elements of the patents. In his second affidavit he gave evidence responding to Associate Professor Hussain’s evidence. His second affidavit and third affidavit also provided his responses to some of the evidence provided by Mr Plain regarding the BFT System.

8 The respondents called one independent expert.

9 Associate Professor Farookh Khadeer Hussain is an Associate Professor and Head of Discipline for Software Engineering within the School of Computer Science at the University of Technology Sydney (“UTS”). He obtained a PhD from Curtin University of Technology and has a research and teaching background in cloud computing. In addition to his work at UTS, Associate Professor Hussain is involved in a range of projects for private sector clients, including in the areas of manufacturing, logistics and human resources management.

10 Associate Professor Hussain made two affidavits and was cross-examined. In his first affidavit he provided his views on background technical matters, the meaning of technical terms in the patents, a description of how the BFT system operates and a comparison of the BFT system against the patents. In his second affidavit he gave evidence in response to an affidavit made by Mr Luke Armstrong, the Chief Revenue Officer of F45 which was not read.

11 The independent experts also produced a joint expert report which responded to an agreed list of questions. Both the report and the list of questions was admitted into evidence. The independent experts gave their oral evidence concurrently. While I accept that both independent experts were doing their best to assist the Court, I have, as I will explain, preferred the evidence of Professor Hussain on a number of points on the basis that it is more likely to reflect the views of the person skilled in the art reading the patent specification as a whole in light of the common general knowledge.

12 The respondents also called Mr Ben Kingsley Plain. Mr Plain is a Full-Stack Developer at BFT, a position he has held since around mid-2017. Prior to his work for BFT, Mr Plain worked in information technology, web design and software development for over 15 years in both Australia and Samoa, across a range of industries. Mr Plain was responsible for developing, building and programming the BFT system, and is currently responsible for managing and overseeing the IT and technical aspects of the BFT System, including its program code and system architecture.

13 Mr Plain gave evidence in two affidavits about the hardware and software components of the BFT system, including discussing how the system operates and outlining the steps that are performed by administrative and operations staff and the technical processes that are followed. In his second affidavit, Mr Plain clarified the dates covered by his earlier explanation and provided evidence about earlier iterations of the BFT system, including a version between about August 2018 to June 2019 which involved what is referred to in the evidence as a “sync button”. Mr Plain was cross-examined, but his evidence was not challenged in any material respect.

Lay witnesses

14 The sixth respondent, Mr Falloon, who is the founder and joint Chief Executive Officer of BFT, gave evidence for the respondents concerning his work with Gymmy Squatz (which later became BFT) and BFT, and how BFT studios are owned and operated. He also discussed correspondence between F45, Gymmy Squatz and BFT regarding the Patents. Mr Falloon was cross-examined at length mainly in relation to matters which were said by F45 (with some justification) to affect his credit and which were also said to be relevant to F45’s claim for additional damages. Given the conclusions I have reached in relation to both validity and infringement, it is not necessary for me to make any finding in relation to those matters.

15 Evidence was also given by two lawyers, Ms Hewetson (for the applicant) and Mr Bongers (for the respondents). Neither of them was cross-examined, and their evidence has no real bearing on the issues that I am required to decide.

THE PATENTS

The Specification

16 The following discussion is directed to the content and disclosure of the 604 patent. Neither party suggested there was any difference between the Patents relevant to the issue of validity. The parties’ submissions and these reasons focus on the 604 patent, in particular, claim 1. The case was conducted on the basis that if claim 1 was found to be invalid, then all other claims in both the Patents would also be invalid and that if claim 1 is not infringed, then none of the other claims in either of the Patents are infringed.

17 The 604 patent is entitled “Remote configuration and operation of fitness studios from a central server”. The invention is said to relate generally to fitness and exercise equipment and, in particular, to a method and system for remote configuration and operation of fitness studios from a central server.

18 The 604 patent includes a section entitled “Background” which makes brief reference to the ability of fitness studios to provide equipment and training facilities to enable people to achieve their physical fitness goals. This is followed by a summary of the invention which includes two consistory clauses that mirror the independent claims. The summary states at [0003]:

Disclosed are arrangements, referred to as Distributed Periodically Varied, Studio Configuration (DPVSC) arrangements, which download from a central server to a plurality of remote exercise studios, periodic exercise routines which vary different exercise parameters in order to improve the novelty of the exercise environment and thus improve the effectiveness thereof.

19 The acronym DPVSC is used throughout the specification to describe DPVSC arrangements, the DPVSC server, the DPVSC software and DPVSC methods. In the context of the specification as a whole, DPVSC is used to describe the various elements of a system which enables a central server to direct different exercise routines in one or more fitness studios in which there are a number of exercise stations in an open studio environment. Each exercise station has an associated display which provides directions to users in relation to different exercise routines.

20 A preferred embodiment of the invention is described by reference to various figures. The figures are followed by a detailed description.

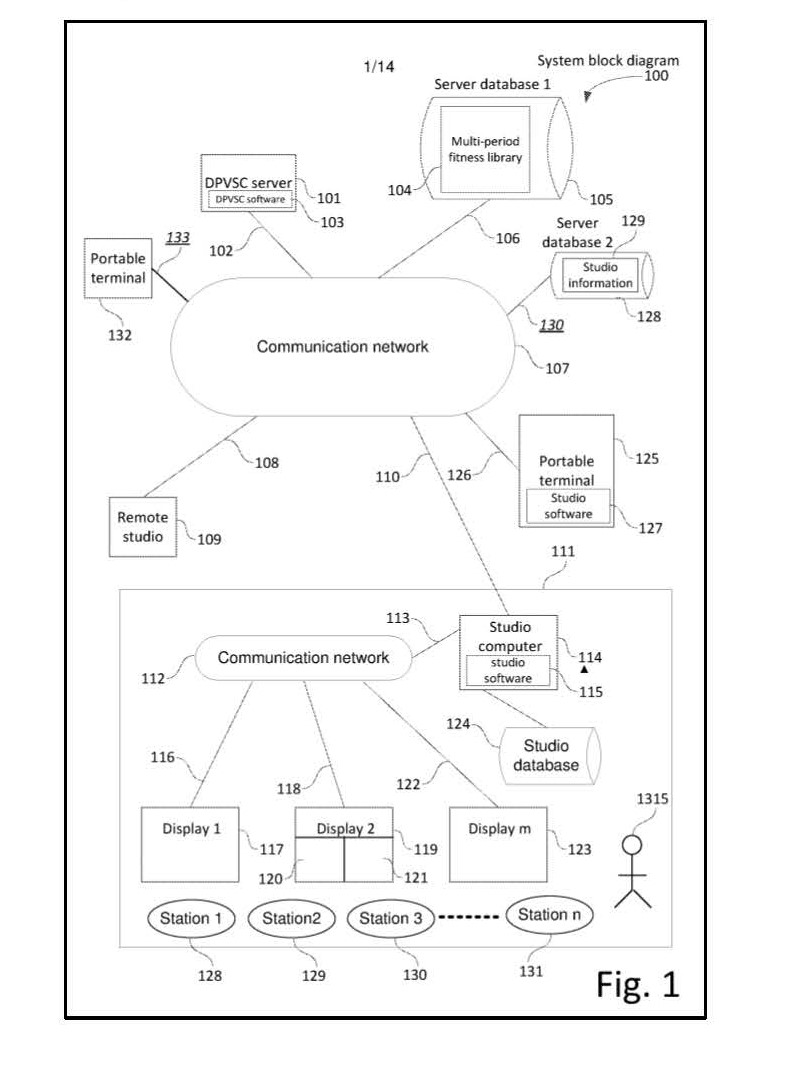

21 The detailed description commences with a description (at [0028] to [0037]) of a system upon which the disclosed DPVSC arrangements can be performed. The specification also describes (at [0059] to [0071]) the operational processes which take place in the back-end DPVSC server (Fig 2) and the front-end fitness studio (Fig 3). The computers upon which these systems and methods may be practised are described as a “general-purpose computer system” (at [0038]) and are illustrated in figures 4A and 4B. The specification does not refer to any particular software or program code for performing the DPVSC arrangements.

22 In general terms, the system disclosed in this section of the specification consists, at its back-end, of a DPVSC server (101) in communication with a database (105) which holds a multi-period fitness library (104) consisting of studio information program files. The DPVSC server is configured to periodically retrieve a studio information program file from the multi-period fitness library and communicate the retrieved file to a number of fitness studios (109, 111) over a communications network (107).

23 The DPVSC server sends the current studio information (213) to the studio computer (114). Once the current studio information has been received at the studio computer (114), the exercise stations (128, 129, 120, 131) and associated fitness equipment (if any) are physically distributed throughout the studio. The studio computers then communicate station directions over a local network based on the received program file to various displays (117, 119, 123) in the studio. Users (1315) are then able to perform exercises at each station based on the directions appearing on the displays. Figure 1 is as follows:

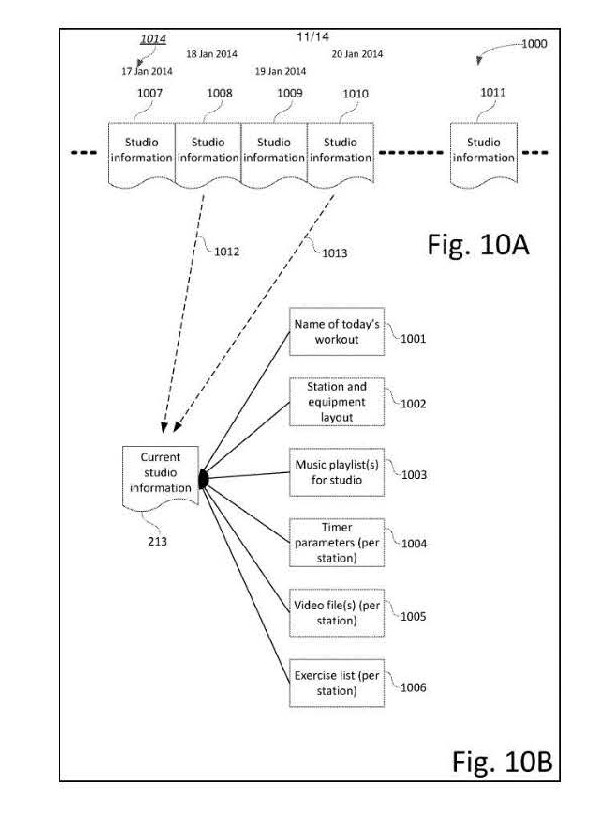

24 The specification describes the periodic retrieval process performed by the DPVSC server (101) and the information contained in the studio information program file in further detail at [0060]-[0064] and figures 10A and 10B. The specification explains at [0062] that the multi-period fitness library is made up of “a succession of studio information program files (1007, 1008, 1009, 1010 … 1011)” which are indexed by date. The content of a current studio information program file (213) is then described at [0064]. As illustrated in figure 10B, the program file consists of various “information segments”, including “Name of Today’s Workout”, “Station and Equipment Layout”, “Music Playlist(s)”, “Timer Parameters (per station)”, “Video file(s) (per station)” and “Exercise list (per station)” as extracted below:

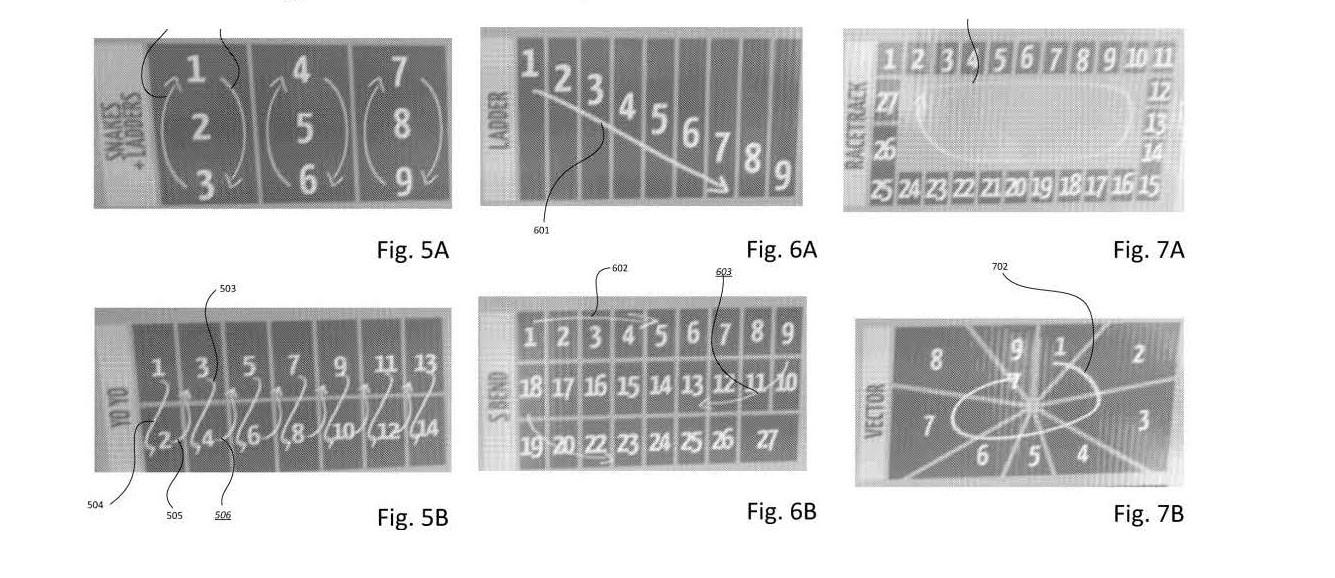

25 The specification also describes at [0066] to [0067] the process by which studio staff configure the studio exercise stations (128, 129 … ) throughout the studio in question in accordance with the current studio information program file. In particular, the specification refers to locating the exercise stations around the studio in question and arranging them in accordance with a station layout and equipment list (1002). Once configured, users perform exercises at each station and then move from station to station based on information on the displays. Preferred station configurations are illustrated in figures 5A to 7B of the specification extracted below:

26 While there are references in the specification to studio equipment, the specification makes it clear that equipment is not required for each station. In particular, the specification states at [0067]:

Figs 5A, 5B, 6A, 6B, 7A and 7B relate to physically locating the exercise stations around the studio in question in a particular physical layout. Another aspect relates to equipment which may be associated with each station …

27 Similar references are found at [0029] which states:

In operation, the exercise stations 128 and their associated fitness equipment (eg a high bar 1207 in Fig. 12) if any, are physically distributed throughout the studio 111 on a periodic basis …

(Emphasis added.)

28 Figure 8 illustrates an example of a daily exercise session referred to as “Athletica”. Athletica is performed across nine different stations that provide for a variety of exercise types including rowing, cycling and skipping. Figure 8 identifies the list of exercises associated with each station and the equipment with which that exercise is performed. As the user progresses through the workout he or she will complete one exercise at the first station before progressing to each of the following eight stations. At each station he or she will be provided with a set of directions via a video display at which the user sees a presentation demonstrating the particular exercise that is to be performed. The display will also direct the user to the next station in accordance with a pre-determined sequence some examples of which appear in figures 5A to 7B.

29 Figure 11 is described as a flow chart showing one example of a process used by a user of the DPVSC arrangement. The information communicated to the user includes details of the station at which the exercise is to be performed, the particular exercise to be performed, the duration of the exercise and the rest time.

30 Following the detailed description, there is a heading entitled “Industrial Applicability” under which it is said at [0087] that “[t]he arrangements described are applicable to the computer and data processing industries and particularly for the fitness industry”.

31 The specification then sets out five claims.

The Claims

32 The claims of the Patents are directed to a computer implemented method for configuring and operating one or more fitness studios (claims 1 to 4), and a computer implemented system for configuring and operating one or more fitness studios (claim 5).

33 Claim 1 of the 604 patent is in the following terms:

A computer implemented method for configuring and operating one or more fitness studios each comprising a plurality of exercise stations in an open studio environment at which users perform associated exercise routines, each exercise station having an associated display, the method comprising the steps of:

periodically retrieving, by a server from a database, a studio information program file for a particular studio for a specified period, from a pre-prepared multi-period fitness library comprising a succession of studio information program files; wherein the studio information program file that is retrieved for a current period is different from a studio information program file that was retrieved for a previous period, thereby providing periodic variation of exercise programs;

communicating, by the server to a studio computer associated with the particular studio, the retrieved studio information program file over a communications network;

receiving, by the studio computer, the communicated studio information program file;

configuring the exercise stations dependent upon the received studio information program file; and

communicating, by the studio computer to the exercise station displays, dependent upon the received studio information program file, station directions to users exercising at the stations for performing an exercise.

34 The method defined by claim 1 works in general terms by having a “server” periodically retrieving a “studio information program file” from a “database” which is then communicated to a “studio computer”. The studio computer then communicates exercise station directions to various displays in the studio.

35 Claims 2 to 4 are dependent on claim 1. These claims further characterise the information contained in the studio information program file, the manner in which it is stored in the database and the repositioning of stations and associated equipment in the studio according to the studio information program file. If claim 1 is invalid on the grounds advanced by the respondents, there is nothing in these claims that would render them valid.

36 Claim 5 is a product claim for:

A computer implemented system for configuring and operating one or more fitness studios each comprising a plurality of exercise stations in an open studio environment at which users perform associated exercise routines, each exercise station having an associated display, the system comprising:

the fitness studios, each comprising a studio computer and a plurality of said exercise stations;

a database storing a multi-period fitness library made up of a succession of studio information program files;

a server for:

periodically retrieving, from the database, a pre-prepared studio information program file for a particular studio for a specified period; wherein the studio information program file that is retrieved for a current period is different from a studio information program file that was retrieved for a previous period, thereby providing periodic variation of exercise programs; and

communicating the retrieved studio information program file over a communications network to a studio computer in the particular studio; and

studio computers for:

receiving communicated studio information program files; and

communicating to exercise station displays, dependent upon the received studio information program files, station directions to users exercising at the stations for performing an exercise; wherein the exercise stations are configured dependent upon the received studio information program file.

VALIDITY

The Parties’ Submissions on Validity

37 The respondents submitted that the invention described in the Patents is in substance a scheme or business method for delivering centrally managed exercise content to remote fitness studios using generic computer technology. The respondents submitted the invention consists of a computer implemented scheme or business method aimed at maintaining the interest and motivation of users in their exercise routines and is not directed to any technical problem in the field of computer technology. Rather, they submitted that the invention is directed to improvements in the management and operation of fitness studios by the use of generic computer technology.

38 The respondents relied on recent decisions of the Full Court including Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd (2015) 238 FCR 27 (“RPL”), Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents (2014) 227 FCR 378 (“Research Affiliates”), Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd (2019) 372 ALR 646 (“Encompass”) and Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd (2020) 277 FCR 267 (“Rokt”) and the High Court’s decision in D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc (2015) 258 CLR 334 (“Myriad”).

39 The respondents submitted:

(a) The relevant inquiry involves asking whether “the invention as claimed is a proper subject of letters patent according to the principles which have been developed for the application of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies” (Rokt at [68]; Encompass at [79]-[80]; Myriad at [12], [18]). This inquiry is separate from the other requirements of s 18(1A)(b) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) which are separate and distinct grounds of invalidity (Rokt at [66]).

(b) The Court must decide whether the claimed invention is, as a matter of substance, a proper subject matter for a patent (Rokt at [69]; Encompass at [81]; Research Affiliates at [106]).

(c) The Court is therefore required to determine the substance or character of the claimed invention disclosed in the specification having regard to established principles (Rokt at [69], [74]; Encompass at [81]). This involves consideration of the claims and body of the specification (Rokt at [86], [91]).

(d) In carrying out this task, evidence is admissible to place the Court in the position of the person skilled in the art at the priority date. However, it is for the Court to determine and characterise the invention (Rokt at [71]-[73]).

(e) A mere business method or scheme is not, per se, a proper subject of letters patent (Rokt at [1], Encompass at [95], RPL at [96]). Abstract ideas, mere intellectual information, or mere directions for use are similarly not a proper subject matter for letters patent.

(f) A computerised business method or scheme can, in some cases, be patentable where the invention lies in that computerisation (RPL at [96]; Rokt at [1]). This requires “some ingenuity in the way in which the computer is utilised” (RPL at [104]). It is not patentable “to simply ‘put’ a business method ‘into’ a computer to implement the business method using the computer for its well-known and understood functions” (RPL at [96]; Rokt at [1]).

(g) Accordingly, where a claimed invention is to a computerised business method, the invention must lie in that computerisation (RPL at [96]; Rokt at [1]). In conducting this analysis, it may be useful to consider:

(i) whether the contribution is “technical” in nature (RPL at [99]; Research Affiliates at [114]);

(ii) whether the invention solves a “technical problem” within or outside the computer (RPL at [99]);

(iii) whether the invention requires “generic computer implementation”, as distinct from steps “foreign to the normal use of computers” (RPL at [99], [102]; Research Affiliates at [111]);

(iv) whether the computers are merely an intermediary, configured to carry out the method using program code, but adding nothing to the substance of the scheme or business method (RPL at [99]).

(h) If the computer-implemented business method “merely require[s] generic implementation” then the invention cannot be a manner of manufacture (Encompass at [108]).

(i) The circumstance that a business method or scheme is not able to be implemented without using computers does not, of itself, provide patentability (RPL at [102]-[104]). Where a business method or scheme is implemented by using computers to perform their ordinary functions, the claimed invention “is still to the business method itself” and therefore unpatentable (RPL at [104]). Similarly, the physical effects that computers ordinarily generate or produce are not, of themselves, sufficient to render a computerised business method or scheme patentable (Research Affiliates at [105]-[106], [114]).

40 F45 submitted that the invention, as claimed in the Patents, “… is patentable subject matter according to traditional principle”. It submitted that this followed from an application of the High Court’s decision in National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252 (“NRDC”) at 277. F45 submitted that, applying the well-known NRDC formulation, the invention gave rise to an artificially created state of affairs of economic significance or utility in a field of economic endeavour, the latter requirement being reflected in what was said by F45 to be the remarkable success of both F45 and BFT in using the invention.

41 F45 submitted that the invention, as claimed, is properly characterised as a technological innovation in that it is a method or system in the nature of a combination of interacting elements involving a computer system to achieve a result or outcome of economic utility: see Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 611.

42 F45 also submitted that the invention as claimed in the Patents is not an abstract idea that relies upon computerisation to satisfy the first limb of the NRDC formulation. It referred to the observations of the Full Court in Research Affiliates at [106] which noted that the use of a computer necessarily involves the writing of information into the computer’s memory and, consequently, some physical effect. F45 submitted that, properly characterised, the invention in the present case is not one that depends on the use of a computer and the writing of information in the computer’s memory as giving rise to the necessary physical effect required under the first limb of the NRDC formulation. Here, according to F45, the claimed method or system is tied to the doing of physical things and the creation of a physical or tangible result (ie. the physical configuration of the exercise stations) that extends beyond the physical effect inherent in any computerised process resulting in the required “artificially created state of affairs”. In developing this submission, F45 placed particular reliance on the need for the exercise stations to be configured based on the information contained in the studio information program files and that this step in the relevant method or system was one that had to be performed by a human being rather than a computer.

43 F45 did not dispute that, for the purpose of determining whether the invention, as claimed, constitutes a manner of manufacture, it was necessary to examine the substance of the invention. However, it submitted that to hold that the invention, as claimed, was not a manner of manufacture, would require one to disregard both the nature of the claimed method or system (a method or system for physically configuring and operating one or more fitness studios comprising a plurality of exercise stations) and an essential integer of the claimed method and system (configuring the exercise stations dependent upon the received studio information program file). It submitted that this outcome is not supported by, and is contrary to, NRDC and the authorities relied upon by the respondents. According to F45, the invention as claimed, is, as a matter of substance, not a mere scheme or abstract idea, but is instead a practical application of a computer implemented method or system that involves physical or tangible steps to produce a physical or tangible result.

44 The parties’ submissions did not address the recent Full Court decisions in Commissioner of Patents v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 202 (“Aristocrat”) and Repipe Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCAFC 223 (“Repipe”) which were decided after the hearing concluded. No party sought leave to make any submissions in relation to those decisions. Aristocrat was a case concerned with what the Full Court characterised as a scheme or set of rules for playing a game (the computer being, or forming part of, an electronic gaming machine) which the Full Court found was not a manner of manufacture. The invention in Repipe was held by the Full Court to be a scheme for sharing and completing workplace health and safety forms implemented using generic computing technology for its well-known and well-understood functions and was similarly found not to be a manner of manufacture.

Consideration

45 It may be noted at the outset that the invention as defined by claim 1 of the 604 patent is “[a] computer implemented method for configuring and operating one or more fitness studios …”. Claim 5 of the 604 patent also defines the invention as a “computer implemented system”. The language of “computer implemented” method or system is also used throughout the body of the specification.

46 There are some differences in language between claim 1 and claim 5 that are relevant to a consideration of F45’s arguments. As pointed out, F45 places considerable reliance on the presence in claim 1 of the step “configuring the exercise stations dependent upon the received studio information file”. It says that this requires that the exercise stations be physically configured and that this is an essential integer of the claim. Whether claim 5 is to the same effect is less clear. Relevantly, claim 5 refers to a system including “studio computers for” performing certain steps. I think the better view of claim 5 is that it is a product claim and that, properly construed, it is concerned with a computer implemented system which permits the exercise stations to be configured using information stored in the studio information program file. On this view claim 5 is describing a system that is merely capable of allowing the exercise stations to be configured in accordance with information stored in the studio information program file. In any event, even if (contrary to my view) claim 5 requires that the exercise stations be physically configured, the substance of the invention described and claimed in the 604 patent is in my opinion not a manner of manufacture.

47 Mr Dimitriadis SC did not make any submission that the invention described and claimed in the 604 patent provided a solution to any technological problem, that it represented an advance in computer technology or that it involved any unusual technical effect due to the way in which the relevant computer technology was utilised. Neither the 604 patent itself nor any expert evidence could support such a submission had it been made. The invention is carried out using generic computing technology facilitating communications between a server with access to a database of files and one or more studio computers which in turn communicate with displays located at the various exercise stations.

48 As Mr Dimitriadis SC acknowledged in his oral submissions, the fact that the invention involves the configuration of exercise studios and exercise stations within them is really the essence of F45’s point on manner of manufacture. By this I understood him to mean that the physical configuration of the studios and stations is a relevant artificial effect that satisfies the requirements of the NRDC formulation and that a finding to that effect would not be inconsistent with the more recent Full Court authorities relied upon by the respondents.

49 The physical effects relied upon by F45 are those achieved using a computer implemented scheme for the configuration of exercise stations. The substance of the invention resides not in the actual physical arrangement of the exercise stations but in the computer implemented scheme which enables those physical arrangements to be made. Although claim 1 of the 604 patent may be understood as requiring that exercise stations be actually configured in accordance with the studio information program file, the substance of the invention disclosed and claimed resides in the computer implemented scheme which enables such configuration to occur on a periodic basis in accordance with the content of the studio information program files.

50 The authorities make clear that the demonstration of a “physical effect” does not necessarily mean that an invention satisfies the NRDC requirement that the invention result in an “artificially created state of affairs”. For example, a scheme for maritime navigation does not satisfy the relevant requirement merely because navigation buoys are required to have particular shapes, colours or other markings or to be located in particular positions relative to channels or hazards. Similarly, a scheme for the management of aircraft during take-off so as to reduce noise would not satisfy the NRDC requirement merely because the aircraft are required to be operated in the particular manner: see TA Blanco White, Patents for Inventions, 5th ed. Stevens & Sons, London, 1983 at 4-903, 4-911 citing Rolls Royce Ltd’s Application [1963] RPC 251 and In the Matter of an Application for a Patent by W (1914) 31 RPC 141.

51 Further, the more recent authorities concerned with computer implemented inventions do not deny the existence of some “physical effect” which can plainly be seen in the workings of computers by the storage of information in RAM and, in many cases, its communication over the internet. But as the Full Court’s decision in RPL Central makes clear, these physical effects are not themselves sufficient to satisfy the NRDC requirement for an “artificially created state of affairs”: see especially [96]-[98]. In the present case the mere fact that the invention contemplates (F45 would say, requires) that exercise stations be physically configured with fitness equipment is not in itself sufficient to result in the required “artificially created state of affairs” any more than would a scheme for the layout or configuration of a sports field or children’s playground which is changed periodically to take account of the seasons. It is the kind of scheme that has historically never been regarded as patentable subject matter. The scheme is not made patentable merely because it is implemented using generic computing technology.

52 In my opinion, the Patents are invalid on the basis that none of the inventions described and claimed is for a manner of manufacture.

INFRINGEMENT

Issues of Construction

53 Given my conclusion in relation to validity, it is not necessary to consider the issue of infringement. However, in deference to the parties’ detailed submissions on the question of infringement, I propose to make some findings on that topic. Before considering the design and operation of the BFT system, and the basis on which it is said to infringe, it is necessary to resolve a number of construction issues relevant to infringement.

54 The parties referred me to the well-known summaries of the relevant principles in Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [81] per Hely J and that of the Full Court in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155 at [67] per Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ.

55 F45 relied in particular upon statements of principle concerned with the “purposive construction” of patents including the well-known statement of Lord Diplock in Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 at 243 and the following statement by Greenwood and Nicholas JJ in Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 21 at [41]:

There are two aspects to the principle which requires that a patent specification be given a purposive rather than a purely literal construction. The first concerns the well recognised need to read words in their proper context. The second is directly related to the nature and function of a patent specification. It is a document that is taken as intended to be read through the eyes of the skilled addressee who is equipped with the common general knowledge in the relevant art. The question is what, in an objective sense, such a person would understand the relevant words of the claim to mean. Ultimately, however, it is the claim that must be construed, and it is not permissible to vary or qualify the plain and unambiguous meaning of the claim by reference to the body of the specification: Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478.

Reference is also made by F45 to the joint judgment of Kenny and Beach JJ in Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC (2015) 240 FCR 85 at [39] where their Honours refer to the purposive approach to construction of patent specifications and the need to avoid “too technical or narrow” an approach.

56 In the present case I approach the claims with the principles discussed in these cases in mind, including the need to avoid a construction of the relevant claims that is excessively technical or narrow. The claims must be read in the context of the patent specification as a whole through the eyes of the skilled addressee who is equipped with the common general knowledge in the relevant art.

57 But it is also important to recognise that a “purposive construction” is not synonymous with the broadest construction that a claim will bear nor one that is necessarily more generous to the interests of the patentee who alleges infringement. This is because the skilled addressee may well understand, from a reading of the specification as a whole, that a word or phrase is to be understood as bearing a more limited meaning than it might bear in a different context. To take an example which I discuss later in these reasons, the skilled addressee would not approach the claims in issue in this case on the basis that the word “file” should necessarily be understood as bearing the broadest of all possible meanings. The meaning to be given to that word depends on the context in which it is used both in the claim and the specification as a whole, construed in light of any relevant common general knowledge.

Communications network

58 Claim 1 requires that the relevant studio information program file be communicated by the server to the relevant studio computer “over a communications network”.

59 In his first affidavit Professor Seneviratne referred to a communications network as “a connection between two devices and the physical infrastructure required to connect them.” The description is useful up to a point but it is clear that a communications network may involve more than two devices. Further, the connection between the devices must be capable of facilitating communications between them.

60 Both experts accepted that there were a number of different technologies that could be used to create a communications network. Some of the technologies referred to in their evidence included electronic, wireless and optical (or some combination thereof) networks which are used to facilitate the communication of information and data, including computer files. However, it is clear from Professor Seneviratne’s oral evidence that he accepts that movement of a computer file from one location to another does not necessarily occur over a communications network. In particular, he accepted that the transfer of a file from one drive on a computer to another drive on the same computer would not constitute communication over a communications network. He said that such a communication occurs over “a computer bus”. It follows that not every means by which a computer file is transferred from one location to another occurs over a communications network.

Computer implemented

61 The evidence does not establish that the expression “computer implemented” is a term of art. I accept F45’s submission that “computer implemented” simply means that the method or system is implemented using computer technology. However, it is important that those words, so understood, be read in the context of the specification as a whole including the claims in which it appears. That context provides an indication as to what steps in the method are computer implemented. Obviously, to the extent that claim 1 may require that exercise equipment be physically configured in accordance with information contained in a studio information program file, the physical configuration (in the sense of physically locating exercise equipment within the room) is not performed by a computer. But it is clear from the context in which the words “computer implemented” are used, that the relevant communications referred to in the claim are computer implemented in the sense that they occur between devices which communicate with each other over a communications network.

62 F45 submitted that the language of the claims did not preclude the possibility that human intervention may occur at various stages of the communication process. I think it is tolerably clear from the language of the claims and the broadest description of the invention as it appears in the body of the specification, that while the relevant communication may be triggered by the entry of commands by a user of the system, the communications themselves must occur across the network connecting the relevant devices. Further, it is not sufficient to point to some part of a communication over the communications network not extending from device to device. The communications network must facilitate end to end communication between devices which, in terms of claim 1, requires that the relevant connection (eg. electronic, wireless or optical) begins at the server and extends to the studio computer so as to facilitate communication between them.

Server

63 Claim 1 requires that a server periodically retrieve from a database a studio information program file. A server is a piece of hardware or software (or a combination of both) that processes, stores and “serves” information (including files), which it makes available to network users. In the language of the claim, the function of the server is to retrieve a studio information program file from the database and communicate it to the studio computer associated with a particular studio.

64 The experts agreed that a server can be central or distributed (either physically or logically). There is an issue between the parties as to whether the reference to “a server” in the claim extends to (as Professor Seneviratne suggests) multiple servers distributed across various physical or logical locations and which together constitute a distributed server and “a server” within the language of the claim. Whether the language of the claim would be understood in this way by the person skilled in the art depends on the context in which the word “server” is used.

65 BFT contends that the claims refer to both a server and a studio information program file in the singular and that this is deliberate and consistent with the description appearing in the body of the specification which refers to “a central server” from which DPVSC arrangements may be downloaded to a plurality of remote exercise stations.

66 There is nothing in the body of the specification to suggest that more than one server can be employed to retrieve the relevant file. The arrangements described in the body of the specification all involve a central server that serves a plurality of remote studio computers. This is also consistent with the opening paragraph of the specification which refers to a method and system for remote configuration and operation of fitness studios from a central server.

67 Of course the claim does not use the word “central” but it does refer to a server in the singular. In my opinion the claim is describing an arrangement in which the single studio information program file is retrieved by a single server.

68 Figure 1 discloses only one DPVSC server (101). What is referred to as “Server database 1” and “Server database 2” are databases and not servers.

69 F45 relied on the statement in [0082] of the 604 patent which refers to Figure 13 and states that “[t]he functional modules may be distributed between the server 101, the studio computer 114 and the users of the studios.” This was said to support Professor Seneviratne’s “distributed system” analysis. However, [0082] refers to distribution of functional modules used in a DPVSC arrangement between the server, the studio computer and the users of the studio. It does not follow that the server referred to in [0082] or elsewhere in the specification may consist of multiple servers.

70 In my view the person skilled in the art would understand claim 1 to be referring to a central server that communicates information to a studio computer associated with a particular studio. The purpose of the invention is to enable communication of DPVSC arrangements from a central server to a plurality of remote exercise studios. A skilled addressee would understand the specification in that light and would therefore understand the role played by the central server is an essential component of the relevant method. There is nothing in the body of the specification that would suggest the role of the central server can be distributed across the communications network so that, for example, a studio computer might itself act as a server to a studio computer associated with a different fitness studio.

Database

71 According to Professor Hussain, a database is a computing system for holding data or files which uses database management software. He says that the term has a technical meaning in the field of computing and does not refer to any storage mechanism without dedicated database management software (“DBMS”). The independent experts agree that there were two forms of databases using DBMS at the priority date namely, “relational” or “SQL databases” and “NoSQL databases”.

72 Professor Seneviratne suggested at one stage during his oral evidence that a database could consist of a single file. He also suggested that a folder (eg. on a drive or on a desktop) that includes a number of files might also be a database. He did not accept that a database necessarily includes, or depends for its management, on a DBMS.

73 I do not accept Professor Seneviratne’s suggestion that a database may consist of nothing more than a single file or a collection of files in a folder. The Macquarie Dictionary defines “database” as meaning “a large volume of information stored in a computer and organised in categories to facilitate retrieval”. That definition broadly reflects the way in which the term is used in the 604 patent, and although there is no reason why the volume of data must be “large”, it must be organised in some fashion to facilitate retrieval. While a database will usually be managed using DBMS, I am not persuaded that this is a defining characteristic of a database as that word is used in the claim.

74 Another issue between the parties, as reflected in the difference of opinion between the experts, is whether the term “a database” as used in the claim refers to a single database which stores the “multi-period fitness library comprising a succession of studio information program files” or whether the database can form part of a distributed system comprising multiple databases (ie. a distributed database).

75 BFT again points to the singular language of “a database” and the task which the database is required to perform. It says that the database described and claimed must perform the function of storing a multi-period fitness library comprising a succession of studio information program files. BFT says that the specification does not disclose any arrangement in which multiple databases are available to perform that function. While what BFT says about the specification is in my opinion true, that does not necessarily mean that the function cannot be performed by more than one database. The question is whether the language of the claim, as construed through the eyes of the skilled addressee, extends to such an arrangement.

76 F45 submitted that the claims do not specify any particular kind of database with any particular format. It also submitted that the patents speak in general and functional terms which are agnostic as to the particular form the database takes. The database could take the form of a distributed database in which certain information was contained in a collection, or library, of computer files. The experts agree that, in practice, a database could be distributed and that Figure 1 in the specification shows a distributed database on the server side (Fig 1, 104 and 129). However, as previously noted, it is clear from Figure 1 that it is only “Server database 1” that holds the multi-period fitness library. I would not accept that Figure 1 shows a distributed database performing that function.

77 I accept that a database can consist of a number of databases which together constitute a distributed database. Such a database is “a database” within the meaning of the claim. Professor Hussain acknowledged that when the term database is used, there could be more than one database “under the hood” to deliver the service (or information) that the distributed database is intended to provide. He focused on the absence of any explicit recognition in the language of the claim which would allow for such an arrangement. But the fact that there is no such explicit acknowledgement does not mean that the term “a database” does not encompass a distributed database. In my view there is nothing in either the claims or the specification that justifies a narrow reading of those words and they would include a distributed database that holds the multi-period fitness library. But the function of the database, whether distributed or not, remains the same. It must hold the studio information program files and the multi-period fitness library comprising a succession of such files so that they may be retrieved by the server and communicated to the studio computer. This excludes any possibility of the studio computer itself hosting the database, or any part of it, including as part of a distributed database.

Studio information program file

78 Claim 1 requires that a studio information program file be retrieved by a server from a database that is then communicated, by the server, to a studio computer. Importantly, the claim requires that the file be retrieved from “a pre-prepared multi-period fitness library comprising a succession of studio information program files.” In my view those words are describing a database that consists of a number of discrete files and is clearly referring to a pre-existing compilation of such files. That is to say, the claimed method requires the server to retrieve a studio information program file from a pre-existing compilation of such files.

79 F45 submitted that the word “file” means no more than a collection of information. F45 submitted that the file need not take any particular form or format and the information in question may consist of links to other files or locations containing the relevant information or some part thereof. On this construction, a “file” consists of a body of relevant information whether it is included in a single file or sourced from other files or locations where it may be located.

80 Professor Hussain’s view was that, in the context of the patent specification and the claim itself, the relevant file is a single or self-contained unit. He explained the concept of a computer file as follows:

… A computer file is used to store data (such as plain text, image data, or any other content) in a discrete and self-contained format. Similar to writing words on paper, information can be written and stored on a computer file. Files can be edited and transferred using the internet between computing systems. The way in which information in a file is encoded in the computer file is referred to as the file format. There are multiple file formats – including “.pdf”, “.doc” and “.json” (being a data file which stores data and objects in JSON format) - which are associated with particular software applications for running or executing the particular file type or format. The file format is generally identified by the file extension (or character string) at the end of the file name. There are many types of computer files, designed for different purposes. A file, for example, may be designed to store a picture, a video, a computer program or wide variety of other data or information contained within the file (such as program data or code).

(original emphasis)

I recognise, of course, that the claim does not use the term “computer file”. The term used is “program file”. I think “program” is not to be understood as referring to an executable computer program but as referring instead to a program in the sense of an exercise timetable, sequence or routine. Nevertheless, the word “file” is used in the context of computer technology and a computer implemented system in which a server is required to retrieve the file and communicate it to another computer over a communications network. I therefore do not regard Professor Hussain’s reference to a “computer file” as inapt. His understanding broadly reflects my own understanding of the concept and that of a “file” when that word is used in the context of generic computing technology and, in particular, a system in which a server is required to retrieve “a file” and communicate it to another computer.

81 Professor Seneviratne contended that a file does not necessarily need to be self-contained and that it may contain, for example, a playlist with links to relevant music files. On this view the music file would form part of the file that contains the playlist even if the music file is located on a different drive of the computer or on a different computer. But Professor Seneviratne’s evidence went somewhat further.

82 It is perhaps worth referring specifically to what I regard as some rather telling evidence given by Professor Seneviratne on this issue. In his third affidavit Professor Seneviratne suggested that the word file relates to information rather than a receptacle for containing information. He was cross-examined on the relevant paragraph of this affidavit as follows (T.254, lines 21-41):

Mr Cobden: Yes. But Professor Seneviratne if you go back to paragraph 8 of your third affidavit.

Prof Seneviratne: Yes, Mr Cobden.

Mr Cobden: … So, you say, there, that based on an understanding you set out in the joint expert report, in which the file relates to information, rather than the receptacle, I consider that the operations etcetera. I thought I heard you just answer the question and say to his Honour, that the receptacle is the file.

Prof Seneviratne: So, at one level – at – it is the file. At another level it could be program memory. At another level it could be bits and – bits of ones and zeros.

Mr Cobden: And it’s only, isn’t it, by interpreting the word “file” at a high level of abstraction, that you’re able to interpret the claims in a manner that causes the BFT system to infringe. That’s correct, isn’t it?

Prof Seneviratne: That is correct, because the patent does not ..... the communication process.

83 The transcript is less than perfect, but there is no doubt that Professor Seneviratne was taking an extremely broad view of the meaning of the word “file” when suggesting that any string of binary information might constitute a file. In my view Professor Seneviratne’s interpretation of the word “file” is much too broad and reflects overreach of the kind that is sometimes seen when a claim is interpreted with an eye fixed on the alleged infringement.

84 It seems to me that when regard is had to the description of the invention in the body of the specification and the language used in the claim, the reference to “a studio information program file” refers to a single file for a particular studio which contains the relevant information used to configure exercise stations within the studio. What is essential is that the relevant information be contained within one identifiable unit which can be retrieved by the server from the pre-prepared multi-period fitness library. Information accessed from external sources (eg. separate computers, databases or files) would not, in my view, form part of the studio information program file referred to in the claim.

85 In circumstances where the experts do not agree that the word “file” is not a term of art, the expert evidence on this issue is of limited assistance. I think the preferable interpretation of “file” is that it is a self-contained storage unit containing information. In this regard I would draw a distinction between a file and its contents and observe that the server referred to in claim 1 retrieves a “studio information program file” rather than “studio information” or “studio program information”. One of the difficulties with Professor Seneviratne’s understanding of the claim is that it does not give the word “file” any real work to do.

86 The parties referred me to some dictionary definitions of the word “file” none of which are particularly helpful. However, the Macquarie Dictionary defines the noun “file” to mean (inter alia) “any device, as a cabinet, in which papers, etc, arranged or classified for convenient reference” or, in the context of computers, “a collection of data with a unique name, held on a storage device such as a magnetic disk”. The reference to “a cabinet” is consistent with a file acting as a receptacle of some kind for the storage of information. And the reference to “a collection of data with a unique name” is also consistent with the relevant information having been collected and included in a uniquely named and self-contained compilation of relevant information. I also refer to the definition of the word “file” in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary which relevantly defines a file as “a collection of data or programs stored under a single identifying name”.

Studio computer

87 BFT submitted that the phrase “a studio computer” as used in the claim refers to a single, general purpose computer in each studio. In support of this submission BFT relies on the evidence of Professor Hussain. Professor Seneviratne, on the other hand, considered that the term “a studio computer” encompasses “multiple computers or a computer with multiple functions in a distributed system”. His evidence was that the claim does not require that there be a single studio computer which receives the studio information program file.

88 In my view the description of the invention and the language used in the claim indicates that the studio information program file is received by a single studio computer associated with the particular studio. That is not to say that the same computer must always be used for that purpose. But the language of the claim does not extend to a situation in which the task of the studio computer is performed by a number of different computers operating as part of what Professor Seneviratne refers to as a distributed system. In my view the language is clear as is the description which contemplates the existence of a single DPVSC server distributing files to a plurality of single computers each operating within its own particular fitness studio.

The BFT system

89 Mr Plain gave a detailed account in his evidence of the configuration of the BFT system which was not challenged in cross-examination. I accept his evidence. The description of the BFT system set out below represents my findings based on Mr Plain’s evidence.

90 The BFT system includes in each BFT gym the following hardware and equipment:

(a) Exercise Equipment: Each gym is of variable size and dimensions and has fixed equipment (such as weightlifting cages) and non-fixed equipment (such as free weights).

(b) Gym PC: Each gym has an office desktop Apple Mac computer with a keyboard, screen, and mouse. Gym operators are required to set up a Gmail email account on the Gym PC. The Gym PC is not connected to the Mac Mini computers (see below) via any LAN or intranet connection.

(c) Mac Mini: Each gym has a “Mac Mini” which is a small Apple computer which is pre-installed with the Gym Application (see below). The Mac Mini is connected, via the Switch and NUCs, to the TVs for displaying exercise content for a workout.

(d) NUCs: Each gym has a NUC for each TV. A “Next Unit of Computing” (“NUC”) is a tiny computing unit designed by Intel. In the BFT gyms the NUC is used as a barebones computing unit without a keyboard, monitor or mouse.

(e) TVs: Each gym has a number of TVs. Some of the TVs display exercise content, while others display biometric information.

(f) Sound Equipment: Each gym has speakers and an amplifier.

(g) Switch: Each gym has a TP Link branded “switch”. A “switch” is a small device for routing communications between connected devices.

91 The BFT system utilises the following back-end hardware and infrastructure, not located in the BFT Gyms:

(a) Admin PCs: These are general-purpose computers used by BFT’s administrative staff.

(b) BFT Server: This is the remote server which hosts the Admin Portal Application, Admin Database and numerous other web applications used by BFT such as its website.

(c) Admin Database: This is a relational database for the Admin Portal Application.

92 The BFT system utilises the following software applications and data file:

(a) BFT File: This is a data file that has been encrypted and has the bespoke extension “.bft”.

(b) Admin Portal Application: This is a web application, called the “BFT Admin Portal”, accessible via a secure portal at https://admin.bodyfittraining.com. The Admin Portal Application is used by BFT’s admin staff to program exercise sessions which are then exported as a BFT file and emailed to gym operators.

(c) Gym Application: This is a software application, called the “Body Fit Training Studio”, installed on each Mac Mini. The Gym Application requires gym operators to enter login details when they open the application for the first time.

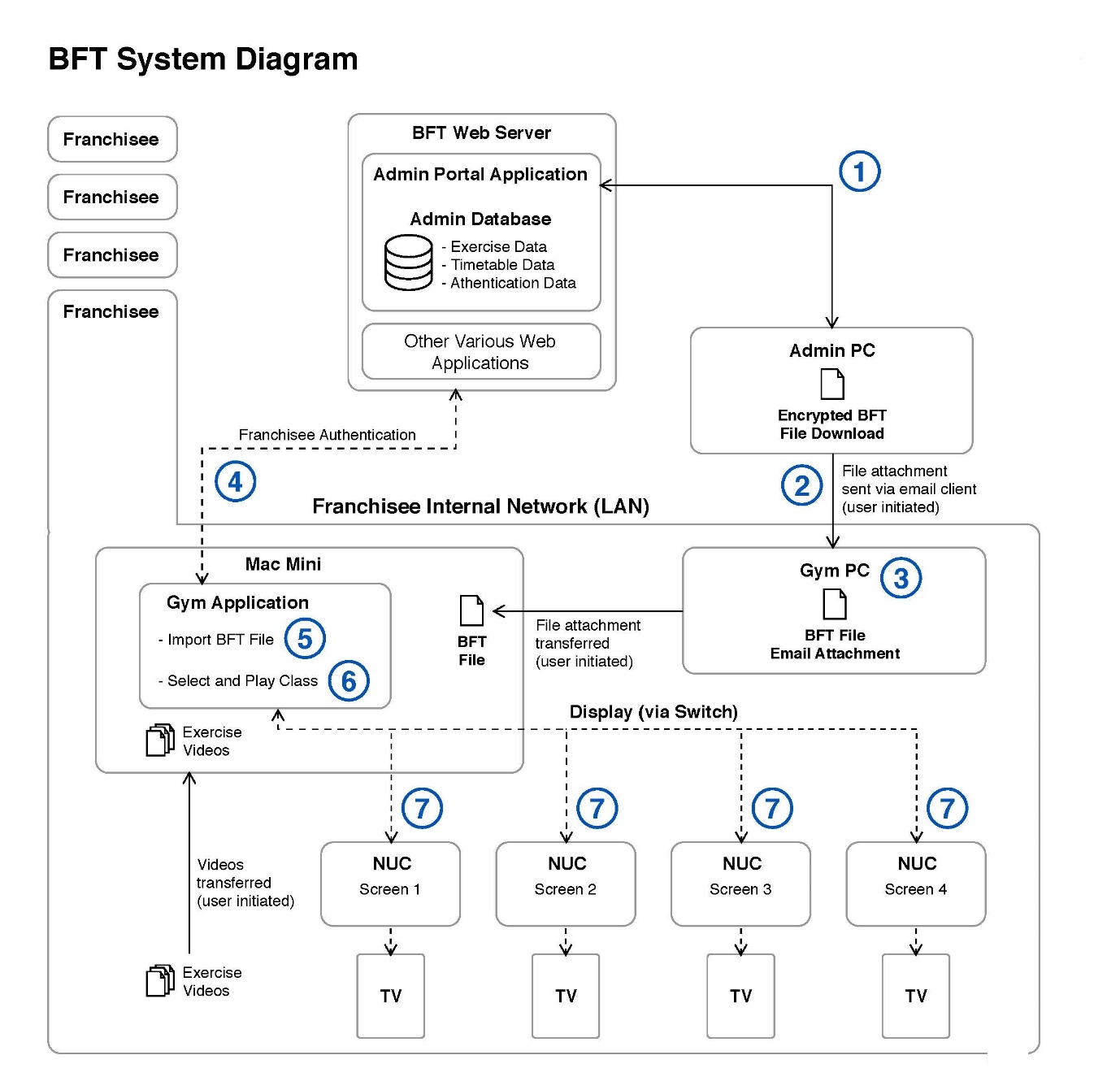

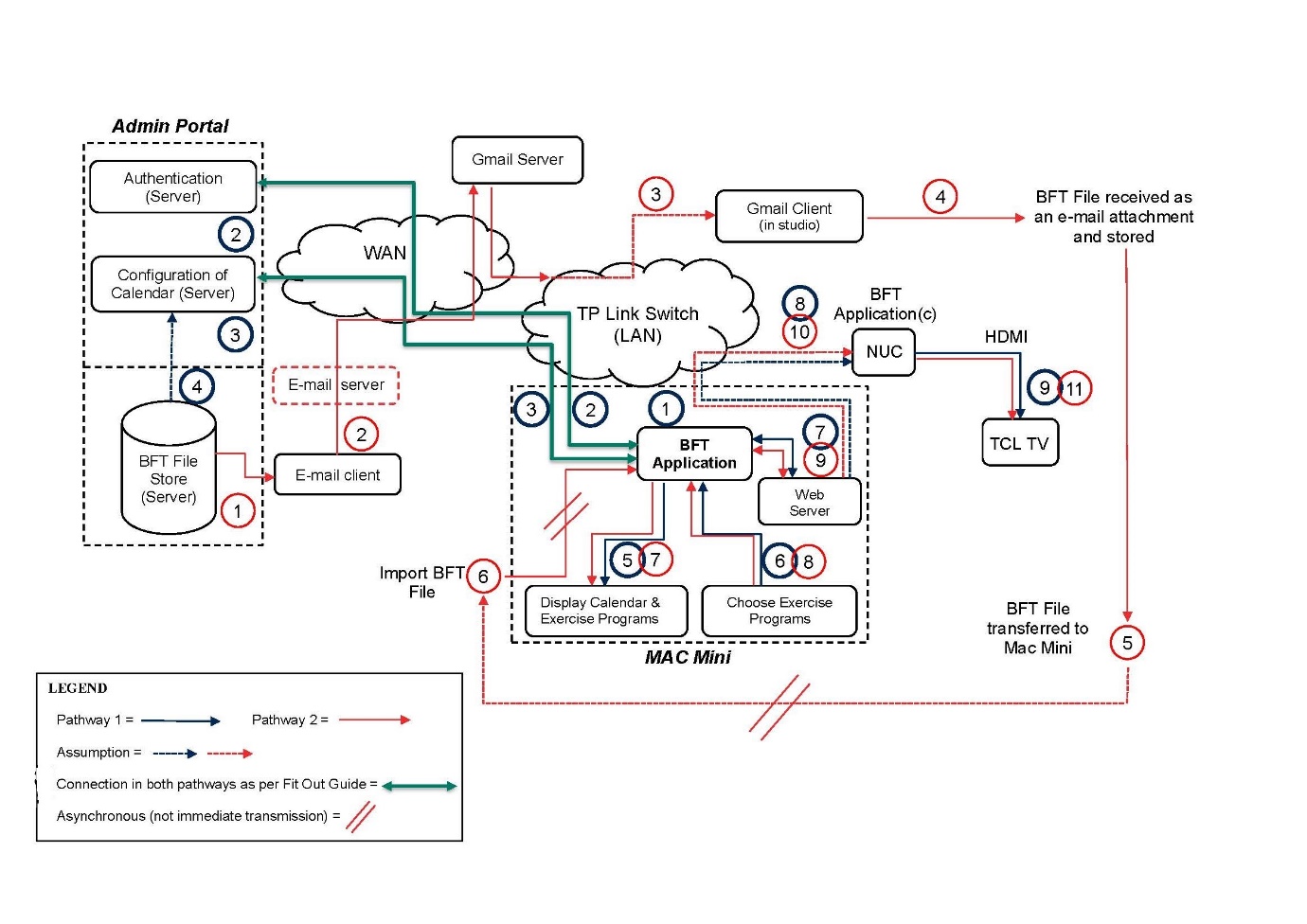

93 Annexure A to these reasons is a reproduction of a diagram entitled “BFT System Diagram” which was created by Mr Plain for the purpose of explaining the various steps involved in the operation of the BFT System. There are seven steps identified in that diagram.

Step 1

94 The process begins by BFT’s admin staff creating a new timetable (eg. a calendar with suggested daily classes). This involves one of the admin staff (admin operator) firstly opening the Admin Portal Application at https://admin.bodyfittraining.com and entering their login details.

95 Once logged in, the admin operator has the option to create or edit a new class (for later inclusion in the new timetable). This involves the admin operator navigating to a “Session Program” webpage and entering data into fields in that page, such as warm-up time, class type, rest time(s) and the like. Once created, the admin operator clicks “save” to save the newly-created class for later recall. It is possible not to create any new classes and proceed straight to the “create new timetable” phase using previously-created classes.

96 To create a new timetable the admin operator enters data into fields in another webform on the Admin Portal Application such as “timetable description”, “start date”, “number of weeks” and the like. The admin operator selects a previously-created class and slots it into an “ordered list” within that webform.

97 The process of creating new classes and timetables is essentially like a person filling out a form on a website. Once all of the fields have been filled out and completed, the admin operator clicks a “Download” button and is presented with a BFT File for downloading on their Admin PC.

98 [Confidential]

99 [Confidential]

Step 2

100 The admin operator opens Gmail on their Admin PC, creates a new email, attaches the BFT File and sends the email and attachment to BFT gym operators.

Step 3

101 The gym operator opens Gmail on their Gym PC, locates the email with the attached BFT File and saves the attachment onto a USB for transfer to the Mac Mini. It is alternatively possible to open and save the attached BFT File using other devices or email software.

Step 4

102 The gym operator opens the Gym Application on the Mac Mini. If the operator is opening or launching the application for the first time, an “Authentication” page will appear requiring the operator to enter their login details.

103 Once the gym operator enters their login details, the Gym Application will send a message to the Admin Portal Application to authenticate the operator’s login details. If the login details are incorrect, then the Gym Application does not progress beyond the login screen. If the operator has already logged-in and entered their sign-in details, an “Authentication” page will appear (albeit briefly) when the operator re-opens the application. In this case, the Gym Application will send a message to the Admin Portal Application to check whether the stored access token is valid. If the token is invalid or the validation message cannot be sent, then the application will default to a blank calendar screen. If the token authentication fails, then the Gym Application will default back to the initial login screen.

104 [Confidential]

Step 5

105 Once the Gym Application is successfully authenticated, the gym operator clicks “Import Timetable” on the home page and navigates to an “Import Timetable” page. When the “Browse” button is pressed, the application displays a file directory browser window which allows the operator to select and import a BFT File.

106 Once the “Open” button is clicked, the Gym Application opens, de-crypts and imports the data from the BFT File. The Gym Application displays a message “Successfully Imported – Click Here to go Back”. Once the “Click Here to go Back” button is pressed, a populated timetable for various classes appears to the gym operator.

107 [Confidential]

108 [Confidential]

Step 6

109 When a gym operator is ready to run a session or class, the operator selects the class they wish to run on the Gym Application, such as “Pump 120”, on the populated timetable. The Gym Application brings up a “class control” page for the selected class. The “class control” page contains, amongst other things, a green “Start” button to begin the class, a work period timeline which plots the duration of the class and a dialogue box for the screens used in the class.

Step 7

110 When the Gym Application is launched, it establishes a connection, via the switch, with the NUCs installed below the TVs. When a “Start” button is pressed on the “class control” page referred to in step 6, the NUCs display the relevant content on the appropriate TVs which are connected via an HDMI cable. Of course, the display will vary from TV to TV depending on the exercise to be performed at that particular exercise station.

111 [Confidential]

Sync button

112 Mr Plain also gave evidence concerning a somewhat different version of the BFT system which appears to have been in use between August 2018 and June 2019 which involved a “Sync button”. His evidence on this topic was not challenged and I accept it.

113 In August 2018, Mr Plain made a software change to add a “Sync” button to the Gym Application. In June 2019, he removed the Sync button and replaced it with the “Import Timetable” button referred to at step 5 above.

114 The effect of the Sync button was to enable the user of the Mac Mini to update timetable information on the Mac Mini. This is done by means of a HTTP request to the Admin Portal Application for newly created data stored in various rows and columns in the Admin Database. In response, the Admin Portal Application would send HTTP response messages to the Gym Application on the Mac Mini, and once that process was complete a newly populated timetable for various classes would appear on the “select class” page in the Gym Application.

115 The Sync button was removed from the Gym Application installed on the Gym operator’s Mac Minis in 2019 when it was replaced with the Import Timetable button currently in use. Mr Plain says that the Sync button could be restored, but that this would require some code changes to the Gym Application.

F45’s Infringement Analysis

116 F45 had two distinct approaches to the issue of infringement.

117 Approach 1: The first approach focuses on the retrieval and communication of timetable information for a particular period (which F45 referred to as “the timetable file”) from the BFT Admin Portal to a Mac Mini in each studio. Under this approach the Mac Mini is the “studio computer” referred to in claim 1 and, in the existing BFT system where the BFT file is sent from the Admin PC to the Gym PC by email, the “server” referred to in the claim is the email server operated by Google (ie. a Gmail server) or some other third party email service provider. However, when the sync button was in use, then, on F45’s analysis, the server referred to in claim 1 was the BFT Web Server.

118 F45 contends that, in the case of the sync system, the “studio information program file” (which F45 referred to as “the timetable file”) comprises “… the collection of information in the BFT Admin database represented by a record in the database for the particular timetable being retrieved” and that the BFT Admin database “is a pre-prepared multi-period library of such files.”

119 F45 contends that it is not to the point that the timetable information that comprises the studio information program file is converted into a different format (eg. a JSON format) before being communicated to the studio computer. It contends that the same logical relationship exists between the components of information that it says make up, in the language of claim 1, the studio information program file, regardless of the particular format it takes.

120 In the case of the existing BFT system (where the sync button is not employed) F45 says that the studio information program file referred to in claim 1 is the BFT file that is retrieved by the email server before it is eventually transferred to the Mac Mini. It says that the email server retrieves a timetable file either from the BFT Admin database or a BFT file store, which (as discussed below) Professor Seneviratne suggested might be located on one of three different servers he identified as associated with the Admin Portal. According to F45, what Professor Seneviratne called the “BFT File Store” in his system diagram reproduced in Annexure B to these reasons might reside on what he identified as the “BFT File Store (server)” forming part of a distributed server made up of the three servers he identified as associated with the Admin Portal. As I understood F45’s case, what it referred to as the timetable file is in fact the information stored in the BFT file which was first retrieved from the BFT Admin Database by the Admin PC or from what Professor Seneviratne called the “BFT File Store”.

121 On F45’s analysis the use of the USB device to transfer the BFT file from the Gym PC to the Mac Mini does not avoid infringement because the method used is still computer-implemented and what it says is the studio information program file (ie. components of information now residing in the BFT file) is communicated over at least some portion of a communications network.

122 Approach 2: F45’s second approach focuses on the retrieval and communication of individual exercise classes within a particular exercise program period from the Mac Mini to the NUCs in each studio. F45 says that this approach is agnostic as to how the timetable information gets to the Mac Mini (whether by email or use of the sync button).

123 On this approach, the server is the BFT Application on the Mac Mini (which F45 says may form part of a distributed system with the BFT Web Server), the database is the local RxDB database on the Mac Mini (which F45 says may form part of a distributed database), and the studio computer is the NUC.

124 On this approach the studio information program file is said by F45 to be the particular timetable information in the local RxDB database on the Mac Mini for a particular exercise program (eg. for one day). F45 referred to this information as an “exercise program file”. F45 contends that the “multi-period fitness library” consisted of the whole of the timetable information stored in the database on the Mac Mini from which the particular timetable information is retrieved. F45 further contends that the “exercise program file” is retrieved by the Mac Mini and is communicated to a NUC.

125 F45 submitted that neither approach to infringement depends upon identifying any distributed server or database, although the servers and databases in Approach 2 are appropriately characterised as being distributed servers and distributed databases for the reasons given by Professor Seneviratne.

Consideration

Approach 1

126 The BFT Server which hosts (inter alia) the Admin Portal Application and the Admin Database does not store any studio information program file within the meaning of claim 1. Nor does the BFT Server store any pre-prepared multi-period fitness library comprising a succession of studio information program files. There are no “studio information program files” stored on the BFT Server nor any pre-prepared library of such files. I do not accept that what F45 refers to as the “timetable file” in its infringement analysis of the sync system is a file within the meaning of the phrase “studio information program file” as used in claim 1. To the extent that F45 contends in its infringement analysis of the email system that the BFT files are “studio information program files” it is clear from the evidence which I have accepted and the findings made based on that evidence that the BFT files are created on the Admin PC and are not stored or referenced on the BFT Server.

127 Further, the BFT file is not communicated by the BFT Server to the Gym PC or the Mac Mini. The BFT file is created on the Admin PC and sent by email to the Gym PC. There is no transfer of files between the BFT Server and either the Gym PC or the Mac Mini and there is no communication of any BFT file over a communications network connecting the BFT Server to the Gym PC or the BFT Server to the Mac Mini.

128 There is a communication over a communications network between the BFT Server and the Mac Mini. However, as Mr Plain’s evidence makes clear, that communication between the Mac Mini and the BFT Server is an authentication step which does not involve the transfer of the BFT file or any exercise or timetable information from the Admin Database to the Mac Mini.

129 In the case of the Admin Database the relevant information is not stored or arranged in files. The information may be arranged in the database in a logical and organised manner, containing, for example, organised entries relating to exercise routines to be performed in particular weeks and on particular days. But it does not follow that any of this information, so arranged, constitutes, or is included within, a file in the sense that the word is used in claim 1. To the extent that Professor Seneviratne suggested otherwise, I do not find his evidence persuasive and I prefer the evidence of Professor Hussain, which is consistent with my own interpretation of the phrase “studio information program file” as used in claim 1.

130 In circumstances where there never is a studio information program file retrieved by a server from a database containing a pre-prepared multi-period fitness library of such files, it is apparent that the whole of F45’s claim analysis based on Approach 1 falls to the ground. This is true in relation to both the existing BFT system and the prior version in which gym operators utilised the sync button on the Mac Minis.

131 If one were to treat the email server as the server referred to in the claim, then it has not been established that the email server retrieves a studio information program file from a database comprising a pre-prepared multi-period fitness library of studio information program files. To the extent that the email server retrieves any file, it could only be the BFT file created on the Admin PC.

132 I understood Professor Seneviratne to suggest that the database referred to in the claim might be a collection of BFT files from which the email server retrieves a BFT file from what he referred to as the “BFT File Store”.