Federal Court of Australia

Pharmacia LLC v Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 92

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 37AI of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the text of the reasons for judgment published today may be published and disclosed only to the persons listed in order 1(a) of the orders made on 26 April 2021.

2. The parties confer and, by 1 March 2022, provide to chambers:

(a) an agreed form of the reasons for judgment that is suitable for publication, with redactions noted; and

(b) short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons marked-up to indicate any areas of disagreement.

3. The proceedings be listed for a case management hearing at 9.30am on 17 March 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[1] | |

[8] | |

[14] | |

[15] | |

[16] | |

[24] | |

[31] | |

[32] | |

[53] | |

[76] | |

[76] | |

[106] | |

[107] | |

[107] | |

[111] | |

[117] | |

[117] | |

[122] | |

[136] | |

[136] | |

[148] | |

[154] | |

[170] | |

[174] | |

[175] | |

[175] | |

[182] | |

[186] | |

[190] | |

[197] | |

[199] | |

[215] | |

[219] | |

[219] | |

[223] | |

[227] | |

[232] | |

[232] | |

[235] | |

[257] | |

[277] | |

[277] | |

[283] | |

7.6 Step 3: identification of parecoxib sodium and intravenous administration | [293] |

[297] | |

[298] | |

[306] | |

7.8 Step 5: testing parecoxib sodium and decision to formulate as a lyophilised composition | [322] |

[322] | |

[325] | |

[351] | |

[351] | |

[354] | |

[383] | |

[385] | |

[385] | |

[388] | |

[393] | |

[408] | |

[418] | |

[420] |

BURLEY J:

1 In these proceedings Pharmacia LLC and Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (the applicants) seek relief from Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd and Neo Health (Australia) Pty Ltd (the respondents) for the infringement of patent no. 2002256031, which is entitled “Reconstitutable parenteral composition containing a COX-2 inhibitor”. The respondents deny infringement and advance a cross-claim alleging that the asserted claims in the patent are invalid.

2 Pharmacia and Pfizer, both related entities of Pfizer Inc., are respectively the owner and exclusive licensee in Australia of the patent. The patent relates to the formulation and administration of COX-2 inhibitors. Pharmacia is the developer of products that are marketed in Australia under the Dynastat brand for the management of post-operative pain. Pfizer markets and supplies the Dynastat products in Australia and is the sponsor of the registrations for those products on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG).

3 The active ingredient in Dynastat is parecoxib, which is a “prodrug”, being a molecule that is converted into a pharmacologically active agent after administration to a patient. Parecoxib converts to the selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibiting drug valdecoxib following administration to a patient. The inhibition of COX enzymes, of which one of the isoforms is COX-2, is believed to be a mechanism by which nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, exert anti-inflammatory, antipyretic (anti-fever) and analgesic effects.

4 The patent has a priority date of 3 April 2001 and was filed on 2 April 2002.

5 Juno offers for sale and supplies parecoxib products in Australia and, until August 2020, Neo supplied those products to Juno for sale on the Australian market. The applicants contend that both have infringed each of claims 1, 4, 5, 7, 11, 14, 15, 17-21, 24, 26-28, 30 and 34-42 (the relevant claims) of the patent. Juno has obtained ARTG registration for formulations of parecoxib (as sodium) for the indication “a single peri-operative dose for the management of post-operative pain” (Juno products). The applicants seek a declaration of infringement, injunctive relief, delivery up of infringing product and promotional materials, damages and other ancillary relief.

6 The applicable form of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) is the form that it took following the Patents Amendment Act 2001 (Cth), but before the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

7 On 18 December 2019 orders were made that issues of pecuniary relief (including liability for and quantum of that relief) be heard and determined separately from and after the hearing of all other issues in the proceedings. Accordingly, this judgment concerns liability for non-pecuniary relief.

8 In broad terms the issues for determination by the court are as follows.

9 First, whether the Juno products fall within the relevant claims. The applicants have tendered records concerning the method of production and characteristics of six separate batches of the Juno products. They agree that the resolution of the identified disputes arising from those batches will be able to be applied across other batches produced by or for Juno.

10 Secondly, whether the relevant claims are invalid for lack of inventive step within s 18(1)(b)(ii) of the Patents Act. The respondents rely upon the common general knowledge as at the priority date and two pieces of prior art information that they contend fall within the prior art base. First, a paper by Kewal K Jain in the “Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs” journal entitled “Evaluation of intravenous parecoxib for the relief of acute post-surgical pain” (Jain). Secondly, a paper by John J Talley, et al, in the “Journal of Medicinal Chemistry” entitled “N-[[(5-Methyl-3-phenylisoxazol-4-yl)-phenyl]sulfonyl]propanamide, Sodium Salt, Parecoxib Sodium: A Potent and Selective Inhibitor of COX-2 for Parenteral Administration”, pp 1661-1663 (Talley).

11 Thirdly, whether the relevant claims are invalid for lack of definition and/or clarity within ss 40(2)(b) and 40(3).

12 Fourthly, whether the applicants are entitled to injunctive relief if they are successful in establishing infringement of a valid claim.

13 In their amended particulars of invalidity the respondents additionally pleaded lack of novelty, lack of utility and lack of fair basis. However, in their opening submissions at the hearing they indicated that they did not press the first of these and part of the second and in closing submissions they shed the balance.

14 For the reasons set out in more detail below, I have found that three of the exemplar batches of the Juno products fall within the scope of claims 1, 4, 5, 11, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 and 41 but not claims 7, 26, 27, 28, 30 or 42. I have found that the other three exemplar batches do not fall within the scope of any of the relevant claims. I have rejected the challenges to the validity of the relevant claims. I have also determined that the applicants are entitled to injunctive relief to restrain infringement.

15 Seven witnesses gave evidence for the purposes of the proceedings, six of whom were expert witnesses. Five of the expert witnesses were cross-examined. No challenges were made to the credit of any of the witnesses and I generally found them to be good witnesses who gave evidence in accordance with their obligations as experts to assist the court. In general, the expert witnesses were well qualified to give evidence on the subjects that they addressed. The parties made submissions as to the relative weight to be given to their evidence from time to time. I address specific aspects of those submissions, where relevant, during the course of my reasons.

16 Gerhard Johannes Winter is a professor and chair of Pharmaceutical Technology and Biopharmaceutics in the Department of Pharmacy at Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich. He studied pharmacy at the University of Heidelberg and graduated in 1982. He was awarded a PhD by the University of Heidelberg in 1987. From 1987 to 1988 he worked for Merck KGaA leading a laboratory for solid dosage form development, after which he worked at Boehringer Mannheim (which later became Roche) from 1988 until 1999. There he was responsible for parenteral (including freeze-dried parenteral) and liquid dosage form development across every step in the development process from pre-formulation through to the completion of the product for regulatory submission. During this period he led a large scale aseptic pilot plant to supply worldwide clinical studies with parenteral lyophilisates (freeze-dried products) and sterile injectable solutions. He was also involved in drug delivery research. From 1993, he was promoted to head the department for parenteral and liquid dosage form development and became responsible for overseeing a group of about five PhD level scientists who each oversaw their own teams. In 1997 he was promoted to become the deputy head of pharmaceutics development where he oversaw the formulation department, a group working on solid dosage forms and a group dealing with clinical supplies, manufacturing and managing the packaging of supplies to support clinical studies. While with Boehringer Mannheim/Roche he was involved in the development of a number of major drug products, including erythropoietin (EPO), reteplase (rPA), various antibodies and small molecular weight drugs such as ibandronate (a bisphospohonate), all of which became marketed formulations. In addition, Professor Winter worked on over 50 formulation candidates that did not make it to market, including small and large molecular weight drugs and liquid and lyophilised parenteral dosage forms.

17 In 1999, Professor Winter was appointed as a full professor and the chair of Pharmaceutical Technology and Biopharmaceutics in the Department of Pharmacy at Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich. Between 1999 and 2001, the focus of his academic work and research was on drying technology, including freeze-drying and new methods of freeze-drying. Since his appointment he has worked as a consultant for a number of companies, including Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche and MediGene. Professor Winter is a named author of numerous peer-reviewed publications, about 90% of which he estimates relate to formulation. Of those he estimates that at least 80% relate to parenteral formulations, of which about 30% concern freeze-dried parenteral formulations.

18 In his first affidavit, Professor Winter responds to an overview of the drug development process given by Dr Robertson in his first affidavit. The uncontroversial aspects of these affidavits were distilled into a formulation primer, to which I refer in section 3.1 below. In his second affidavit, Professor Winter was asked to address aspects of the patent and then give his opinion as to whether the Juno products fall within the relevant claims. In his third affidavit, Professor Winter identifies that, before he was given the patent and complied with the instructions to which he refers in his second affidavit, he was provided with the Talley article, and then the Jain article, and commented on their disclosure. He records that he was then asked what steps he would have taken, as at 3 April 2001, to formulate a parecoxib drug product and who he would have expected to have been in the team given that task. He was instructed to have regard to information which he regarded as well-known and generally accepted by pharmaceutical formulators as at 3 April 2001 as well as the information set out in Talley and Jain. After responding to this task he then responds to the second affidavit of Dr Robertson. Professor Winter joined with Dr Robertson in the preparation of a joint expert report and gave concurrent evidence with Dr Robertson during which he was cross-examined.

19 Charles Roger Goucke is a clinical associate professor at the Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine at the University of Western Australia. He also practices as a specialist pain medicine physician. He obtained a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery from the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom in 1972 and worked in various different countries after the completion of his training, working as a general practitioner from 1976 until 1981. He then trained as an anaesthetist and worked in Australia, the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia before commencing work as a staff specialist in the Departments of Anaesthesia and Pain Management at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth, Western Australia. In 1992 he was awarded fellowship of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and in 1994 he became the head of the Department of Pain Management at the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Since the early 1990s his commitments have become increasingly focussed on pain management. In addition, he has held roles at the University of Western Australia as an honorary lecturer from 1989 to March 2005, as a clinical senior lecturer between 2005 and 2008, and since 2008 as a clinical associate professor.

20 Professor Goucke was asked to give evidence about his drug development experience, the hypothetical drug development team, literature searches that he would conduct and various hypothetical search strategies that he was shown. He gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

21 Rodney Ian Lindsay Cruise is an IP researcher and patent attorney and a partner of Phillips Ormonde Fitzpatrick. He has over 31 years of experience in intellectual property research in the area of patents, trade marks and designs. He was awarded a Bachelor of Science (Applied Chemistry) degree by RMIT in 1987 and worked as a trainee patent attorney and then patent attorney from 1989 until he became a partner in 1999. Since 2000, he has managed IP Organisers Pty Ltd, an intellectual property research service company which specialises in conducting research in relation to intellectual property including patents.

22 Mr Cruise gives evidence that as at April 2001 he was experienced in using medical databases, having had experience using these databases since at least the early 1990s. He explains his understanding of using the medical database PubMed and the Medical Subject Headings, or MeSH terms, in that database as at April 2001. He gives evidence of various searches he conducted on PubMed as if he were doing so in April 2001. He also responds to parts of the affidavit evidence of Professor Scott and Dr Mokdsi, and gives evidence regarding the likelihood of Jain being located using MeSH terms. He gave one affidavit and was cross-examined.

23 Nicholas Alexander Tyacke is a partner at DLA Piper Australia and the solicitor with conduct of the proceedings on behalf of the applicants. In his affidavit, he annexes product information about the Juno products and confidential documents produced by the respondents relating to the development and manufacture of the Juno products (Neo confidential documents). Those confidential documents comprise batch records for six batches of Juno products and other documents regarding the manufacture and composition of the Juno products. Mr Tyacke was not cross-examined.

2.2 The respondents’ witnesses

24 Alan Duncan Robertson is a medicinal chemist who completed a Bachelor of Science degree in 1978 and a PhD in synthetic organic chemistry in 1981 at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. He is now the chief executive officer and managing director of Alsonex Pty Ltd, a biopharmaceutical company developing new treatments for neurodegenerative diseases. From 1984 until 1992 Dr Robertson worked at the Wellcome Foundation Ltd in the United Kingdom in the roles of senior chemist, medicinal chemist and senior research scientist. As a senior research scientist he was appointed as leader of a project investigating potential new drugs for the treatment of migraines. That project led to the development of a new drug marketed as Zomig and included the formulation of an oral presentation of the drug. In July 1992, Dr Robertson moved to Australia and worked as product development manager at David Bull Laboratories, a division of F.H. Faulding and Co Ltd in Melbourne, where he was responsible for running the new product development department that included a team of formulation scientists responsible for the development of injectable drugs. There he managed a team of about 12 scientists, including several at PhD level. His work included the development of injectable formulations for generic products, some of which were lyophilised (freeze-dried) products. During this time he directed and supervised formulators in their work and from time to time did benchtop formulation work, although he was mainly in a supervisory position. He was present on a day-to-day basis during the development of lyophilisation processes. From 1994 until 1999, Dr Robertson worked as pharmaceutical development manager at Amrad Operations Pty Ltd. Whilst there he oversaw the building of a drug development laboratory as well as work on new drug formulations, including for a potential HIV treatment known as conocurvone. That compound had significant solubility issues which needed to be addressed by a new formulation. He also worked on formulating Propofol, an anaesthetic product. Another project that he worked on whilst at Amrad was a collaboration with the University of Queensland which targeted pain management and involved synthesising the peptide conotoxin (taken from the cone snail) and formulating a stable solution of the product to be used in clinical trials. In his time at Amrad his role insofar as it concerned the task of formulation was to direct, supervise and formulate work that needed to be done by the formulation scientists. From 1999 until 2002 he worked as an independent contractor for several companies and research organisations in which his roles involved the formulation of new chemical entities for administration to humans and animals.

25 In his first affidavit, Dr Robertson first gives an overview of the drug development process, parts of which form the basis for the formulation primer. In his second affidavit, Dr Robertson was provided with a copy of the Jain article and a copy of the first affidavit of Professor Scott. He was given instructions to consider the task as at 3 April 2001 of formulating a pharmaceutical composition for administration to patients in which parecoxib is the active pharmaceutical ingredient, having regard only to the information contained in the first Scott affidavit, the Jain article, the information in his first affidavit and the common general knowledge of the person skilled in the art as at 3 April 2001. He proceeds to address that task. He then gives evidence about the disclosure of the patent, which was provided to him after he had reached his views regarding the formulation task. In his third affidavit, Dr Robertson responds to the evidence of Professor Winter in relation to his earlier evidence, and takes issue with aspects of Dr Winter’s evidence on the question of infringement.

26 Dr Robertson joined with Professor Winter in the preparation of a joint expert report, gave concurrent evidence with Professor Winter and was cross-examined during the course of the concurrent evidence session.

27 David Anderson Scott has been a specialist anaesthetist since 1985. He was the founder and head of the Acute Pain Service at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne from 1989 until 2009. He has a professional interest in acute pain medicine and acute postoperative pain in particular and, in 1998, undertook a PhD in the neuropharmacology of neuropathic pain, which he completed in 2004. He lectures regularly on the subject of acute pain management and in 2005 was awarded a Fellowship of the Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists.

28 In his first affidavit, Professor Scott provides an overview of the management of acute post-surgical pain as at 3 April 2001 which forms the basis for the pain primer to which I refer in section 3.2 below. In his second affidavit, Professor Scott responds to an instruction to assume that he is part of a notional research group, including one or more additional experts playing different roles such as a pharmaceutical formulation specialist, which has been asked to identify and formulate an analgesic for the Australian market which would be better than, or at least a useful alternative to, the drugs then available for use for the management of acute post-surgical pain. He gives evidence of the strategy that he would adopt to conduct a literature search to address this subject as at the priority date, and exhibits his results. Amongst the materials he locates is the Jain article. After affirming his second affidavit, Professor Scott was then provided with two affidavits given by Dr Mokdsi and one by Mr Cruise. In his third affidavit, Professor Scott confirms his view that Dr Mokdsi correctly implemented his search strategy. Professor Scott was cross-examined.

29 George Mokdsi is a patent searcher and a director of The Patent Searcher Pty Ltd, a company he founded in 2019 that performs patent searches. He was awarded a Bachelor of Science (Hons) and a PhD in chemistry from the University of Sydney in 1996 and 2000 respectively. Since 2000, he has worked as an intellectual property analyst, specialising in patent analysis and research for the duration of his career.

30 In his first affidavit, Dr Mokdsi reports that he conducted a search using the PubMed online database as if it were April 2001 according to a search strategy provided to him by the solicitors for the respondents, and exhibits the results. In his second affidavit, Dr Mokdsi responds to the evidence of Mr Cruise. He refers to receiving supplementary instructions for the conduct of a search and annexes the results of that search, both of which he had omitted to include in his first affidavit. He responds to the criticisms made by Mr Cruise by conducting further searches. Dr Mokdsi was not cross-examined.

3. BACKGROUND COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE

31 The following background information is extracted from the formulation primer and the pain primer. The parties agree that it forms part of the background common general knowledge as at the priority date. In the case of the formulation primer, there were some limited areas of disagreement or differences in emphasis between Professor Winter and Dr Robertson (the formulation experts). To the extent necessary, in what follows I have included my findings as to the (limited) areas of dispute.

32 In the pharmaceutical industry, as the drug molecule moves through its development it is often described as the active ingredient, the drug substance or active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and these terms are often used interchangeably. The API may be defined as the therapeutically active ingredient in a pharmaceutical drug product and is the chemical entity that provides the clinical benefit.

33 One of the important preclinical aspects of testing a new drug molecule is to determine its ADMET properties. ADMET refers to Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity. The ADMET team generally consists of experts in drug metabolism, pharmacokinetics and toxicology and involves the analysis of the drug in various biological matrices. The purpose of ADMET testing is to obtain information that will allow the API to proceed into clinical trials in humans (hence the name "preclinical development stage"). ADMET testing provides an initial view of the API’s toxicity compared with its efficacy. It therefore serves as a means of selecting the starting dosage in healthy volunteers in Phase I clinical trials. The objective of a Phase I clinical trial is to determine if the drug can be delivered safely and engage with its target.

34 The formulation used in the Phase I clinical trials is preferably, but not invariably, the same as that used in the Phase II and Phase III clinical trials and in the commercial product. Because of this, the formulator is typically involved in the preclinical stage. The formulator's role is to formulate the API into a commercially viable formulation that can be used in clinical trials and then to market. The formulation stage is described further below.

35 There is generally a considerable amount of time between the Phase I trials and the commercial product being finalised and changes in the formulation are commonly made during that time due to various reasons. For example, a liquid formulation might be changed to a lyophilisate due to a realisation that the liquid formulation does not remain stable for a sufficient amount of time for a commercial product.

36 A drug development team will consider the optimum route of delivery for the drug, which should be convenient for the person administering the drug and convenient for the person receiving the drug. The selected route of administration of the drug will significantly affect how the drug is formulated.

37 Oral administration is the most desirable and the most common route of drug delivery, however, alternative routes are often used, including, but not limited to, injectable, inhalation, rectal, sublingual and transdermal. Routes of administration other than oral are often used if, for example, the patient is unable to or has difficulties in swallowing oral medication, the patient is unable to or has difficulties in absorbing the oral medication through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or a faster-onset of action is required.

38 Injectable routes of administration typically include, but are not limited to, the subcutaneous (under the skin), intramuscular and intravenous. Reasons for choosing an injectable route over an oral route for example include drugs with low oral bioavailability, patients who are unable to take the drug by mouth (e.g., it irritates the GI tract), the need for immediate effect (e.g., emergency situations), the patient is unconscious or otherwise not able to swallow or there is a desire to control the rate of absorption and duration of effect.

39 When commencing a formulation task, the formulator seeks to understand the properties of the API (having regard to the selected route of administration).

40 Where the drug development involves the formulation of a known drug molecule, the formulator will acquire publicly available information about the relevant properties of the API, for example, from a search of relevant medical or chemical databases. Where the drug is a new drug molecule the formulator will attempt to acquire any information about the relevant properties of similar APIs from a search of relevant medical or chemical databases. In both instances, the formulator will give consideration to the chemical structure of the drug molecule.

41 Properties of the API in which the formulator will be interested include the solubility of the API in aqueous solutions, dissolution rate (which is the speed at which the API can go into dissolution), ionisation potential (which is relevant to the ability of the API to form salts and the pH of the resulting drug substance solution, which may require adjustment of buffering), stability of the API and its salts if any and any excipient interactions with the API.

42 It is generally critical that injectable formulations, particularly formulations prepared for intravenous use, do not contain any particulate matter, and that precipitation of either the API or added excipients does not occur during or following injection. Solid particulate matter can in many cases cause thrombosis and the formation of blood clots that can be dangerous to the subject receiving the injection.

43 For any dosage form and route of administration, a minimum desired stability for a commercial pharmaceutical product is generally about two years. For some vaccines, for example, it can be shorter.

44 Excipients are substances other than the API that may be included in a formulation. Ideally, excipients have no biological activity in their own right and are only included in any given formulation of an API if they are required to solve a particular problem.

45 Consideration which may lead to the use and types of excipients will vary depending upon the form of the drug product (e.g. solid or liquid) and its route of administration. A particular excipient will only be added to a formulation if it achieves a particular purpose. The purposes of adding an excipient to a formulation may include, for example:

(a) to enhance stability, bioavailability or patient acceptability;

(b) to assist in the effectiveness of delivery; and

(c) to assist in maintaining the integrity of a drug product during storage.

46 Compounds used as excipients are intended to be inert, that is, they are intended not to react with the API. In approaching the formulation of an API, formulators will seek to avoid any non-reversible reactions between the API and potential excipients.

47 Excipients are generally selected from a list of Generally Regarded as Safe (GRAS) substances. GRAS substances are those which are already well accepted by government drug regulators, including the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia and the Food and Drug Administration in the United States. There is a very large number of commonly used excipients.

48 Excipients commonly used in pharmaceutical tablets and capsules include diluents or fillers, binders, disintegrants, lubricants, colouring agents and preservatives.

49 Excipients may be required to ensure a satisfactory production process.

50 Fillers, binders and disintegrants may be added to the drug substance to increase its bulk and impart desirable properties lacking in the drug substance alone. Other common excipients for injectable pharmaceutical solutions may include antioxidants and metal ion chelators.

51 pH is a measure of hydrogen ion concentration of a solution. The term translates the values of the concentration of the hydrogen ion – which ordinarily ranges between about 1 and 10-14 gram-equivalents per litre – into numbers between 0 and 14. Aqueous solutions at 25°C with a pH less than 7 are acidic, while those with a pH greater than 7 are basic or alkaline. It is a logarithmic scale based on the number of hydrogen ions (H+) in solution which can be expressed as pH = -log[H+]. The pH changes by 1 for every power of 10 change in hydrogen ion concentration. For example, a solution with a pH of 3 has 10 times the concentration of hydrogen ions than a solution with a pH of 4 and 100 times the concentration of hydrogen ions than a solution with a pH of 5.

52 A physiologically acceptable pH of a pharmaceutical solution for an intravenous injection needs to take into account the pH of blood which is 7.4. Generally, a pH value of no more than plus or minus about 1.0 log unit from 7.4, so a pH of about 6.4 to 8.4, is considered acceptable. Formulations outside this range run the risk of causing irritation and inflammation at the site of injection, although such formulations do exist.

53 Pain is a distressing feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli. Post-surgical pain refers to pain experienced immediately after, and as a consequence of, surgery. Post-surgical pain, or post-operative pain (also referred to as peri-operative pain), is an example of acute pain. Almost all surgical procedures are associated with some form of acute post-surgical pain.

54 Acute postoperative pain can limit recovery from the procedure and may lead to the development of chronic pain. Chronic post-surgical pain is typically defined as pain still present three months after surgery.

55 Acute post-surgical pain is managed, variously, by different classes of analgesics (drugs that relieve pain) in addition to other techniques to manage pain. For example, physical and physiotherapy techniques. The use of a range of drugs and treatment techniques is called multi-modal analgesia.

56 The classes of analgesic drugs used to manage acute post-surgical pain include opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other non-opioid analgesics and adjuvants such as clonidine and ketamine. Other analgesic techniques, often used in combination with these analgesic drugs, include the use of local anaesthetic techniques.

57 A multi-modal approach to managing acute post-surgical pain by treating a patient with a range of analgesic medications is commonly used to reduce the total dose of individual analgesic medications required and to treat pain by targeting different mechanisms and neuronal pathways. This helps to manage acute pain while reducing medication-related side effects.

58 Opioids have long been considered the gold standard for post-surgical analgesia, as they are highly effective for the treatment of acute pain, and able to be administered by a number of routes, including parenterally.

59 Opioids are morphine-like drugs that work by binding to opioid receptors, which are found principally in the central nervous system (spinal cord and brain), and also the gastrointestinal tract. The term opioid encompasses both naturally occurring opiates (e.g. morphine and codeine) derived from the resin of the opium poppy, semi-synthetic (e.g. oxycodone) and synthetic opioids (e.g. fentanyl).

60 Opioids are used primarily for their strong analgesic effect. However, opioid analgesics may have adverse effects such as respiratory depression, sedation, cough suppression, nausea and vomiting and impaired bladder and bowel function. With longer term use, the development of tolerance to their effects, and also opioid-induced hyperalgesia, limit their effectiveness. The onset of opioid dependence and addiction is also a risk factor in a minority of cases.

61 When opioids are used as part of a multi-modal analgesic approach, the dose of opioid required is often able to be decreased resulting in fewer opioid-related side effects (“opioid sparing” benefits).

62 The most common non-opioid analgesics for treating acute post-operative pain are NSAIDs and acetaminophen (paracetamol). Following some types of surgery, these analgesics are used in conjunction with local anesthetic techniques and also adjuvant medications, depending on the circumstances.

63 For milder forms of acute post-operative pain, NSAIDs and paracetamol can each be used alone or in combination for the treatment of acute post-operative pain. Where stronger analgesia is required, other agents (such as opioids) or techniques (such as with local anaesthetics) can be added to these to treat the post-operative pain.

64 Paracetamol is a weak non-opioid analgesic that lacks anti-inflammatory properties, but reduces fever and has good gastrointestinal tolerability. It has minimal side effects. As at April 2001, it could only be administered in Australia by enteral routes (i.e., orally or suppository).

65 NSAIDs are class of drugs that reduce pain and fever and decrease tissue inflammation. They work primarily by inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and/or COX-2). In cells, these enzymes are involved in the synthesis of key biological mediators, including prostaglandins, which are involved in inflammation, and thromboxanes, which are involved in blood clotting. They are also involved in pain processing in the central nervous system. COX-2 enzymes are increased in activity in response to triggers such as tissue injury.

66 There are two types of NSAIDs available: non-selective and COX-2 selective.

67 Most NSAIDs are non-selective and inhibit the activity of both COX-1 and COX-2. These NSAIDs, while reducing inflammation, also inhibit platelet aggregation and may increase bleeding following certain operations. Such NSAIDs also increase the risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeds as a result of decreased gastric cytoprotection. This is because non-selective NSAIDs inhibit COX-1 which ordinarily serves a homeostatic role in the function of kidney, gut mucosa, smooth muscle, platelets and endothelium.

68 The most commonly used non-selective NSAIDs are aspirin, indomethacin, ibuprofen, naproxen and diclofenac all of which are available over the counter (OTC) in tablet form in most countries. In acute post-surgical pain management, the non-selective NSAID ketorolac can be administered orally and parenterally (intravenous or intramuscular).

69 COX-2 selective inhibitors (or Coxibs) preferentially inhibit COX-2 and do not significantly inhibit COX-1 at therapeutic concentrations. They, therefore, have a superior safety and tolerability profile by causing less gastrointestinal and bleeding side effects, whilst providing effective analgesia. As of 3 April 2001 COX-2 selective inhibitors were of considerable interest for use as part of multi-modal analgesia in post-operative acute pain management instead of non-selective NSAIDs.

70 As at 3 April 2001, celecoxib (Celebrex) and rofecoxib (Vioxx), both COX-2 selective inhibitors, were registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods and were available in Australia. Rofecoxib in particular was used for the management of acute post-operative pain. Celecoxib was then being used for a number of indications which also included the treatment of acute post-operative pain. These drugs were only available in oral tablet form.

71 As at 3 April 2001, certain analgesics for the management of acute post-operative pain were available in oral or rectal dosage forms (e.g. tablets/capsules, liquids, suppositories) whereas other analgesics were available to be administered parenterally. A parenteral route of administration is typically one given by injection.

72 The mode of delivery of medication for the treatment of acute post-surgical pain is an important consideration. When managing acute post-operative pain perioperatively, parenteral analgesics are often preferred over oral analgesics, particularly if the analgesic needs to be administered when the patient is under anaesthesia, when rapid onset analgesia is required or when the patient is unable to swallow medications or is unable to absorb medications in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g. following bowel surgery).

73 As at 3 April 2001, the majority of opioid analgesics, when used for the management of acute post-operative pain, were administered parenterally. These included, for example, morphine (available in parenteral and oral forms), pethidine (parenteral) and fentanyl (parenteral). Some opioid analgesics for the treatment of acute post-operative pain were only available in enteral dosage forms such as oxycodone.

74 As at 3 April 2001, most of the non-selective NSAIDs could only be administered enterally. Ketorolac (a non-selective NSAID) was available for intramuscular use (or intravenously, off-label) for acute post-surgical pain management. However, as with other non-selective NSAIDs, it was known to have been associated with complications including operative site bleeding, GI bleeding and ulceration, and renal failure. These complications could sometimes be severe or even fatal.

75 As at 3 April 2001, all of the COX-2 selective inhibitors available in Australia were only available in enteral dosage forms.

76 The patent is entitled “Reconstitutable parenteral composition containing a COX-2 inhibitor”. It commences with a description of the field of the invention which is said to relate to water-soluble selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs and salts and prodrugs thereof, and in particular to parecoxib, such as in the form of its sodium salt (parecoxib sodium). It notes that parecoxib is a water-soluble prodrug of the selective COX-2 inhibitory drug valdecoxib. It goes on to say (page 1 lines 6 – 13):

More particularly, the invention relates to parenterally deliverable, for example injectable, formulations of water-soluble selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs and salts and prodrugs thereof. Even more particularly, the invention relates to such formulations that are prepared as powders for reconstitution in an aqueous carrier prior to parenteral administration. The invention also relates to processes for preparing such reconstitutable formulations, to therapeutic methods of use of such formulations and to use of such formulations in manufacture of medicaments.

77 The background of the invention then provides some information about COX inhibitory drugs. It states that inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes is believed to be at least the primary mechanism by which NSAIDs exert their anti-inflammatory, antipyretic (anti-fever) and analgesic (pain relieving) effects, through inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. It refers to “conventional” NSAIDs such as ketorolac, diclofenac, naproxen and salts thereof as inhibiting both COX-1 and the inflammation-associated or inducible COX-2 isoforms of cyclooxygenase at therapeutic doses. A disadvantage with this is that the inhibition of COX-1, which produces prostaglandins that are necessary for normal cell function, appears to account for adverse side effects associated with the use of conventional NSAIDS (page 1 lines 15 – 23). These side effects are identified later in the background as including (page 2 lines 15 – line 20):

...upper gastrointestinal tract ulceration and bleeding, particularly in elderly subjects; reduced renal function, potentially leading to fluid retention and exacerbation of hypertension; and inhibition of platelet function, potentially predisposing the subject to increased bleeding, for example during surgery. Such side effects have seriously limited the use of parenteral formulations of non-selective NSAIDs.

78 The background states that, by contrast, selective inhibition of COX-2 without substantial inhibition of COX-1 leads to anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, analgesic and other useful therapeutic effects while minimising or eliminating such adverse side effects. Examples are given of COX-2 inhibitory drugs such as celecoxib and rofecoxib, said to have been first commercially available in 1999, that have represented a major advance in the art (page 1 lines 23 – 28).

79 The background then observes that the selective COX-2 inhibitors mentioned are formulated in a variety of orally deliverable dosage forms. It goes on (page 1 line 30 – page 2 line 11):

Parenteral routes of administration, including subcutaneous, intramuscular and intravenous injection, offer numerous benefits over oral delivery in particular situations, for a wide variety of drugs. For example, parenteral administration of a drug typically results in attainment of a therapeutically effective blood serum concentration of the drug in a shorter time than is achievable by oral administration. This is especially true of intravenous injection, whereby the drug is placed directly in the bloodstream. Parenteral administration also results in more predictable blood serum concentrations of the drug, because losses in the gastrointestinal tract due to metabolism, binding to food and other causes are eliminated. For similar reasons, parenteral administration often permits dose reduction. Parenteral administration is generally the preferred method of drug delivery in emergency situations, and is also useful in treating subjects who are uncooperative, unconscious, or otherwise unable or unwilling to accept oral medication.

80 The specification identifies the area of the present invention saying (page 2 lines 21 – 23):

It would therefore represent a further significant advance in the art if a parenterally deliverable formulation of a selective COX-2 inhibitory drug could be provided.

81 The specification continues (page 2 line 24 – page 3 line 3):

It is known to prepare parenteral formulations by a process of lyophilization (freeze-drying) of an aqueous solution of the therapeutic agent. See for example Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy, 19th edition (1995), Mack Publishing, pp.1544-1546. According to Remington, excipients often are added to the therapeutic agent to increase the amount of solids, so that the resulting powder is more readily visible when the amount of the therapeutic agent is very small. “Some consider it ideal for the dried-product plug to occupy essentially the same volume as that of the original solution. To achieve this, the solids content of the original product must be between approximately 5 and 25%. Among the substances found most useful for this purpose, usually as a combination, are sodium or potassium phosphates, citric acid, tartaric acid, gelatin and carbohydrates such as dextrose, mannitol and dextran.” Remington, loc. cit.

82 The specification then states that parecoxib was disclosed in US Patent No. 5,932,598 (598 patent) and is one of a class of water-soluble prodrugs of selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs. It says of the characteristics of the prodrug (page 3 lines 5 – 15):

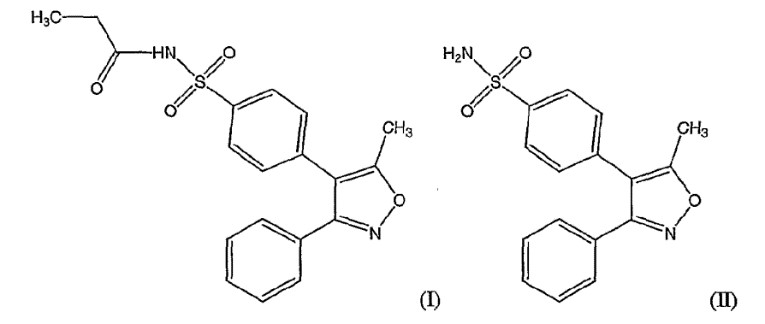

Parecoxib rapidly converts to the substantially water-insoluble selective COX-2 inhibitory drug valdecoxib following administration to a subject. Parecoxib also converts to valdecoxib upon exposure to water, for example upon dissolution in water. The high water solubility of parecoxib, particularly of salts of parecoxib such as the sodium salt, by comparison with most selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs such as celecoxib and valdecoxib, has led to interest in developing parecoxib for parenteral use. Parecoxib, having the structural formula (I) below, itself shows weak in vitro inhibitory activity against both COX-1 and COX-2, while valdecoxib (II) has strong inhibitory activity against COX-2 but is a weak inhibitor of COX-1.

83 The specification then goes on to identify other known water-soluble selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs as including a series of water-soluble benzopyrans, and provides a structural formula for a particular compound within that class.

84 The background concludes with what the applicants characterise as a statement of the problem sought to be solved by the inventors (page 4 lines 2 – 7):

While these and other selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs and prodrugs have been proposed in general terms for parenteral administration, no pharmaceutically acceptable injectable formulation of such drugs or prodrugs has hitherto been described. As will be clear from the disclosure that follows, numerous problems have beset the formulator attempting to prepare such a formulation, illustratively of parecoxib. The present invention provides a solution to these problems.

The invention is thus said to involve a formulation that overcomes particular problems.

85 The specification then has a section entitled “Summary of the Invention”. It commences with what the parties accept is, broadly, a consistory clause for claim 1 (page 4 lines 9 – 17):

There is now provided, in one embodiment, a pharmaceutical composition comprising, in powder form, (a) at least one water-soluble therapeutic agent selected from selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs and prodrugs and salts thereof, in a therapeutically effective total amount constituting about 30% to about 90% by weight, (b) a parenterally acceptable buffering agent in an amount of about 5% to about 60% by weight, and optionally (c) other parenterally acceptable excipient ingredients in a total amount not greater than about 10% by weight, of the composition. The composition is reconsitutable in a parenterally acceptable solvent liquid, preferably an aqueous liquid, to form an injectable solution.

This embodiment is said to include a COX-2 inhibitor in an amount of about 30% to about 90%, a buffer in an amount of about 5% to about 60% and other excipients in up to about 10% by weight of the powder composition.

86 The specification refers to other embodiments of the invention including a process comprising a step of lyophilisation, an injectable solution prepared by the reconstitution of the lyophilised composition, an article of manufacture being a vial containing the lyophilised composition and a method of treatment using the composition.

87 The specification includes a section entitled “Detailed Description of the Invention”. It commences (page 5 lines 25 – page 6 line 8):

A pharmaceutical composition of the present invention comprises as the therapeutic agent:

(a) a water-soluble selective COX-2 inhibitory drug;

(b) a water-soluble salt of a selective COX-2 inhibitory drug, whether or not such drug is itself water-soluble;

(c) a water-soluble prodrug of a selective COX-2 inhibitory drug, whether or not such drug is itself water-soluble; or

(d) a water-soluble salt of a prodrug of a selective COX-2 inhibitory drug, whether or not such drug is itself water-soluble.

More than one such therapeutic agent can be present, but in general it is preferred to include only one such selective COX-2 inhibitory drug or prodrug or salt thereof in the composition.

(emphasis added)

88 The specification gives a definition of “water soluble” and provides, from page 6 to page 11, a lengthy list of selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs that may be used in the formulation of the invention, by reference to registered patents. Parecoxib is identified as a particularly useful prodrug of valdecoxib and more particularly a water-soluble salt of parecoxib, such as parecoxib sodium, is said to be preferred (page 13 lines 8 – 11). Parecoxib is said “illustratively” to be prepared (i.e., synthesised) in the manner set out in the 598 patent (page 13 lines 12 – 13).

89 The specification then addresses the component parts of the invention and their preferable relative amounts. It refers to the therapeutic agents and then the buffering agent, noting that an especially preferred buffering agent is dibasic sodium phosphate (page 14 lines 20 – 22). It states (page 14 lines 23 – 27):

In one embodiment, the pH of the composition upon reconstitution is about 7 to about 9, preferably about 7.5 to about 8.5, for example about 8. If desired, pH can be adjusted by including in the composition, in addition to the buffering agent, a small amount of an acid, for example phosphoric acid, and/or a base, for example sodium hydroxide.

90 The expert evidence and the parties’ submissions use the term pH adjusters to describe the use of a small amount of acids or bases to adjust pH in the formulation.

91 In a passage that is relevant to a number of issues, the specification provides (page 14 line 28 – page 15 line 10):

Excipients other than the buffering agent, if present, constitute not more than about 10%, preferably not more than about 5%, by weight of the composition prior to reconstitution. The term “excipient” herein embraces all non-therapeutically active components of the composition except for water. In one embodiment of the invention, no excipients other than the buffering agent are substantially present.

Surprisingly, it has been found important to include in the composition no more than about 10% by weight, preferably no more than about 5% by weight, and most preferably substantially no amount, of ingredients commonly used as bulking agents in reconstitutable parenteral formulations, other than buffering agents. In particular, the widely used bulking agent mannitol is preferably excluded from the composition, or if included, is present at no more than about 10%, preferably no more than about 5%, by weight of the composition. According to the present invention, it is believed that by minimizing the amount of, or excluding altogether, such bulking agents, especially mannitol, as components of the composition, acceptable chemical stability of the therapeutic agent can be assured.

(emphasis added)

92 The specification then refers to the residual water in the composition of the invention at page 15 lines 14 – 22:

A reconstitutable powder composition of the invention preferably contains less than about 5%, more preferably less than about 2%, and most preferably less than about 1%, by weight of water. Typically the moisture content is about 0.5% to about 1% by weight. It is especially important to keep the amount of water to such a low level where the therapeutic agent has a tendency to degrade or convert to a less soluble form in presence of water. Powder compositions of the invention exhibit acceptable chemical stability of the therapeutic agent for at least about 30 days, preferably at least about 6 months, most preferably at least about 2 years, when stored at room temperature (about 20-25°C) in a sealed vial.

93 The specification then defines what is said to be “acceptable chemical stability”. It then refers further to the circumstance where parecoxib is the therapeutic agent. It notes that partial conversion to valdecoxib can occur in a composition over time, and because valdecoxib is itself therapeutically active, such conversion does not result in a loss of therapeutic effect. However, as valdecoxib has extremely low solubility in water, the specification provides that it is desirable to minimise such conversion prior to reconstitution so that complete dissolution of the therapeutic agent is assured. Furthermore, it notes that particulates in the form of significant quantities of valdecoxib are undesirable. In this context, the specification notes that conversion from parecoxib to valdecoxib in a reconstitutable powder composition can be reduced by the reduction or elimination of bulking agents such as mannitol, as illustrated in examples 1 and 2 (page 16 lines 8 – 11).

94 The specification further addresses the undesirability of the conversion from parecoxib to valdecoxib in the powder composition, and notes that in an aqueous medium such conversion can be greatly reduced by maintaining the medium at a pH of about 7 or higher (page 16 lines 32 – 33). It also notes that aqueous solubility of parecoxib sodium itself is strongly affected by pH.

95 The specification goes on to note that a powder composition of the invention preferably will have sufficient porosity to permit rapid dissolution of the therapeutic agent upon reconstitution in the solvent liquid. It describes a process to prepare the powder by which this can be achieved, by reference to parecoxib sodium (page 17 line 32 – page 18 line 7):

In this process, parecoxib sodium and dibasic sodium phosphate heptahydrate as buffering agent are dissolved in water to form an aqueous solution. Preferably water for injection is used as the solvent. Parecoxib sodium and the buffering agent are present in the solution at concentrations relative to each other consistent with the desired relative concentrations of these ingredients in the final composition. Absolute concentrations of these ingredients are not critical; however, in the interest of process efficiency it is generally preferred that the concentration of parecoxib sodium be as high as can be conveniently prepared without risking exceeding the limit of solubility...

96 The specification then describes how the solution is placed into sterilised vials, each vial receiving “a measured volume of solution having a desired unit dosage amount of parecoxib sodium”. They are stoppered (having an opening for sublimation to occur) and placed in a lyophilisation chamber to be lyophilised, preferably in a three-phase cycle involving:

(1) the solution in each vial being frozen to a temperature below the glass transition temperature of the solution;

(2) freeze-drying by drawing a vacuum in the lyophilisation chamber during which ice sublimates from the frozen solution, forming a partially dried cake. During this phase the temperature is raised from freezing temperature (for example about -40°C to about 0°C over a period of hours) and then held at 0°C for a prolonged period; and

(3) completing the drying under a vacuum during which the temperature is further raised to about 40°C “to drive off remaining moisture and provide a powder having a moisture content of less than about 5%, preferably less than about 2%, more preferably less than about 1%, by weight”.

97 The specification refers in more detail to other embodiments of the invention, including the article of manufacture (a glass vial containing a powder composition), disorders that can be treated and methods of treatment.

98 The specification provides four examples, which are said to illuminate aspects of the invention but “are not to be construed as limitations” (page 29 lines 12 – 13).

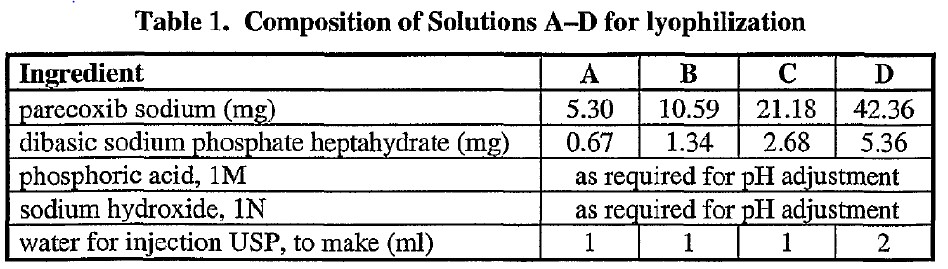

99 Example 1 identifies four reconstitutable powder compositions A, B, C and D containing, respectively, 5, 10, 20 and 40 mg dosage amounts of parecoxib in the form of parecoxib sodium. It describes that solutions for lyophilisation were prepared having compositions set out in Table 1, as follows:

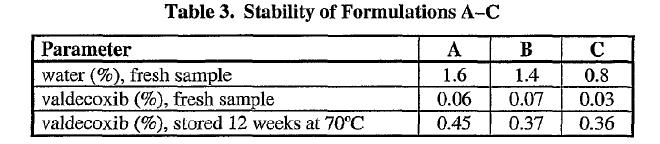

100 The preparation of the solutions is described as follows. Dibasic sodium phosphate heptahydrate was dissolved in a suitable volume of water for injection and pH of the resulting solution adjusted to 8.1 using 1M phosphoric acid. Parecoxib sodium was then dissolved in this solution and the pH checked and readjusted “if necessary” with 1M phosphoric acid or 1N sodium hydroxide and the volume adjusted to a target volume by adding water. The example reports that after being put into stoppered vials and undergoing lyophilisation, the resulting formulations formed cakes in the vials showing good appearance (no cracking or collapsing of the cake). Formulations A, B and C were analysed for residual water content and for valdecoxib. The results are set out in Table 3:

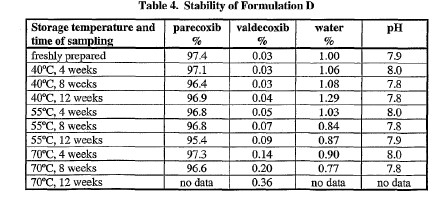

101 Formulation D (40 mg parecoxib) was tested for pH and residual water content and analysed for parecoxib and valdecoxib when freshly prepared and following 4, 8 and 12 weeks storage at various temperatures. The results of tests are shown in Table 4:

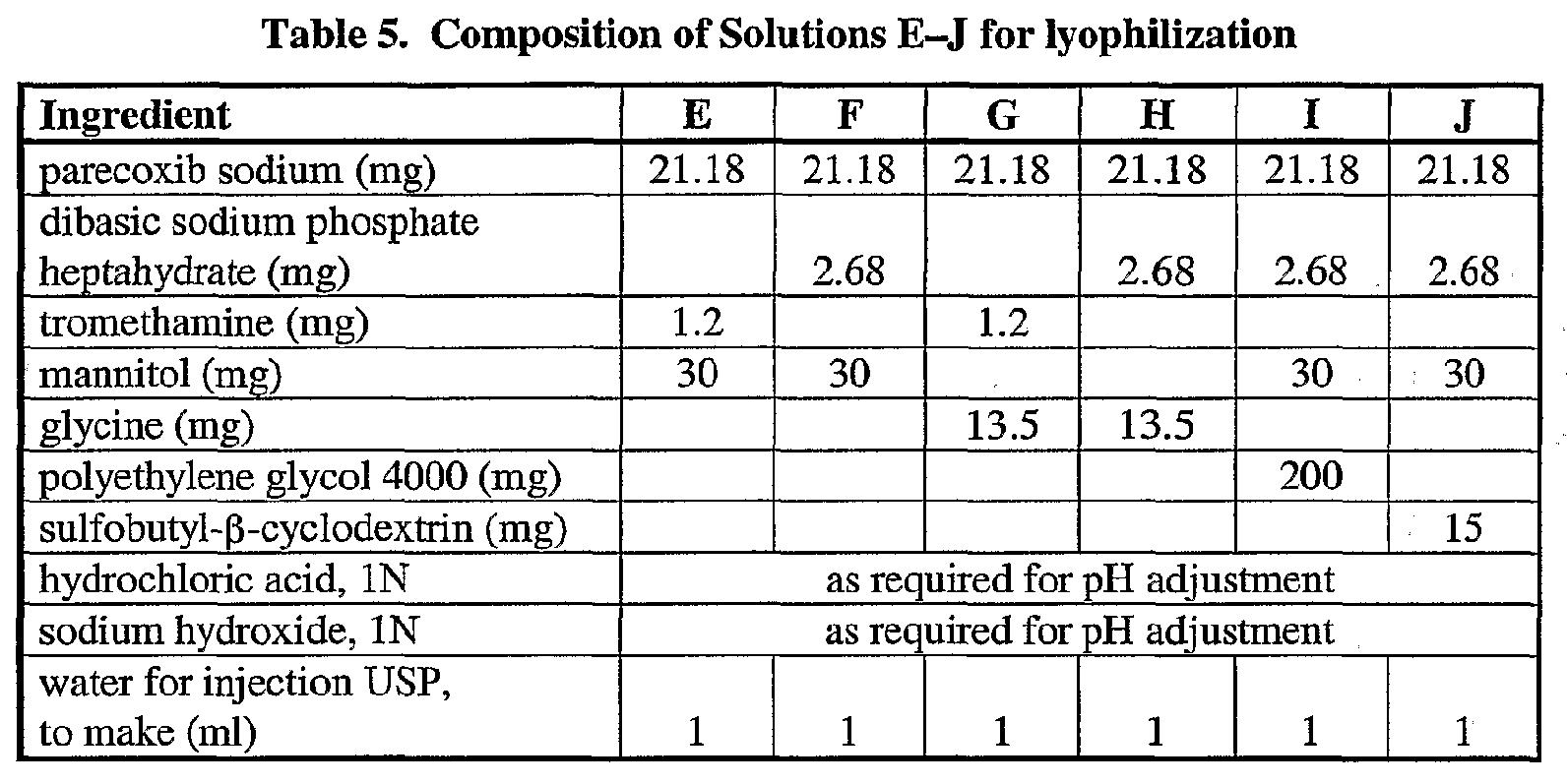

102 Example 2 provides Formulations E – J, each containing 20 mg parecoxib in the form of parecoxib sodium. The specification notes that solutions E – J, corresponding to formulations E – J, were prepared and lyophilised using a similar procedure to formulations A – D. However, it notes that formulations E – J contain more than about 10% of excipient ingredients other than the buffering agent, and that the formulations are presented for comparative purposes. Table 5 sets out the composition of solutions E – J for lyophilisation as follows:

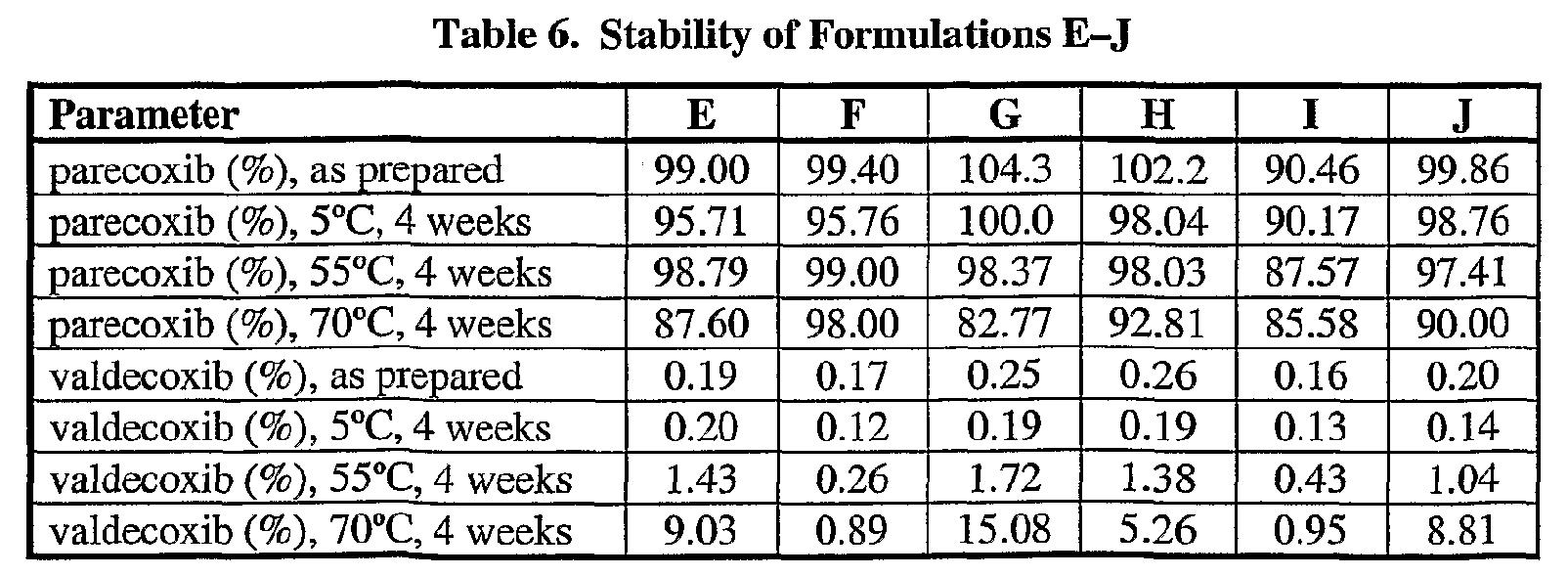

103 The specification then sets out table 6 which contains data regarding the percentages of parecoxb and valdecoxib, expressed on an excipient-free basis, in formulations E – J when freshly prepared and after four weeks storage at various temperatures.

104 The specification then notes (at page 32 line 15 – page 33 line 10):

It will be noted that Formulations E-J exhibited poorer chemical stability than Formulations A-D of the invention. Formulations F and I, each of which contained 30 mg mannitol in addition to dibasic sodium phosphate, exhibited the greatest stability of the formulations tested in this Example, but nonetheless showed a much greater degree of conversion of parecoxib to valdecoxib than did Formulations A-D after storage for 4 weeks at 55°C or 70°C. Chemical stability of Formulations E, G, H and J was unacceptably poor.

Furthermore, none of formulations E-J exhibited instantaneous dissolution upon reconstitution. Formulation I, which contained 200 mg polyethylene glycol 4000 in addition to mannitol and dibasic sodium phosphate, proved especially slow and difficult to dissolve in attempts to reconstitute the formulation.

105 Example 3 describes a pharmacokinetic study of blood plasma concentration of valdecoxib in human subjects given either an intravenous dose of parecoxib sodium or oral dose of valdecoxib. Example 4 describes a clinical study performed on patients undergoing dental surgery regarding the effectiveness of parecoxib as pain relief.

106 The relevant claims are set out below:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising, in powder form:

(a) at least one water-soluble therapeutic agent selected from selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs and prodrugs and salts thereof, in a therapeutically effective total amount constituting about 30% to about 90% by weight,

(b) a parenterally acceptable buffering agent in an amount of about 5% to about 60% by weight, and

(c) other parenterally acceptable excipient ingredients in a total amount of zero to about 10% by weight of the composition;

said composition being reconstitutable in a parenterally acceptable solvent liquid to form an injectable solution.

…

4. The composition of Claim 1, wherein the therapeutic agent comprises parecoxib or a salt thereof.

5. The composition of Claim 1, wherein the therapeutic agent comprises parecoxib sodium.

…

7. The composition of any one of Claims 1 to 6, wherein the therapeutic agent is present in an amount of about 40% of about 85%.

…

11. The composition of any one of Claims 1 to 6, that consists essentially of the therapeutic agent and the buffering agent.

…

14. The composition of any one of Claims 1 to 6, wherein the buffering agent is dibasic sodium phosphate.

15. The composition of any one of Claims 1 to 6, that, upon reconstitution, has a pH of about 7 to about 9.

…

17. An injectable solution prepared by reconstituting a composition of any one of Claims 1 to 16, in a parenterally acceptable solvent.

18. The solution of Claim 17, wherein the solvent is an aqueous solvent.

19. The solution of Claim 17 or 18, having pH of about 7.5 to about 8.5.

20. The solution of any one of Claims 17 to 19, wherein the aqueous solvent contains dextrose and/or sodium chloride.

21. An article of manufacture comprising a sealed vial having contained therewithin a unit dosage amount of a composition of any one of Claims 1 to 16, in a sterile condition.

…

24. The article of manufacture of Claim 21, wherein the composition comprises as the therapeutic agent parecoxib sodium in a dosage amount of about 1 mg to about 200 mg, more preferably about 10 mg to about 100 mg.

…

26. A process for preparing a reconstitutable selective COX-2 inhibitory composition, the process comprising a step of lyophilizing an aqueous solution that comprises:

(a) at least one therapeutic agent selected from selective COX-2 inhibitory drugs and prodrugs and salts thereof, in a therapeutically effective total amount constituting about 30% to about 90% by weight,

(b) a parenterally acceptable buffering agent in an amount of about 5% to about 60% by weight, and

(c) other parenterally acceptable excipient ingredients in a total amount of zero to about 10% by weight of the composition, excluding water;

said lyophilizing step resulting in formation of a readily reconstitutable powder.

27. The process of Claim 26, wherein the therapeutic agent is parecoxib sodium.

28. The process of Claim 26 or 27, wherein the buffering agent is dibasic sodium phosphate.

…

30. The process of Claim 29, wherein, in the step of preparing the solution, the parecoxib sodium is added last.

…

34. A method of treating and/or preventing a COX-2 mediated disorder in a subject, the method comprising reconstituting a unit dosage amount of a composition of any one of Claims 1 to 16, in a physiologically acceptable amount of a parenterally acceptable solvent liquid to form an injectable solution, and administering the solution parenterally to the subject.

35. The method of Claim 34, wherein the parenteral administration is by intradermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, intramedullary, intra-articular, intrasynovial, intraspinal, intrathecal or intracardiac injection or infusion.

36. The method of Claim 34 or 35, wherein the parenteral administration is by intravenous injection or infusion.

37. The method of Claim 34 or 35, wherein the composition is injected intravenously as a bolus.

38. Use of a reconstituted unit dosage amount of a composition of any one of Claims 1 to 16, in a physiologically acceptable amount of a parentally acceptable solvent liquid to form an injectable solution for treating and/or preventing a COX-2 mediator disorder in a subject.

39. The use of Claim 38, wherein the parental administration is by intradermal, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, intramedullary, intra-articular, intrasynovial, intraspinal, intrathecal or intracardiac injection or infusion.

40. The use of Claim 38 or 39, wherein the parental administration is by intravenous injection or infusion.

41. The use of Claim 38 or 39, wherein the composition is injected intravenously as a bolus.

42. A pharmaceutical composition as defined in Claim 1, an injectable solution prepared by reconstituting said composition, an article of manufacture comprising said composition, a process for preparing a reconstitutable selected COX-2 inhibitory composition, or a method of treating and/or preventing a COX-2 mediated disorder in a subject, substantially as herein described with reference to any one of the Examples.

107 The characteristics of the person skilled in the art, whose knowledge may be relevant in the context of the construction of the patent and also for the purposes of the lack of inventive step case, are in dispute, but only to a limited extent. The parties agree that one person skilled in the art to whom the patent is addressed would have experience in pharmaceutical formulation and development, with a PhD or Masters level degree plus relevant experience in the discipline and would be familiar with chemical principles. There is no dispute that the formulation experts, Dr Robertson and Professor Winter, have these skills.

108 The disagreement between the parties as to the identity of the skilled addressee arises primarily in the context of the respondents’ challenge to the patent on the ground of lack of inventive step. However, it is convenient to address the arguments raised at this point.

109 The applicants submit that it is not necessary to resort to the concept of a notional team because in this case Professor Winter and Dr Robertson were able to understand the invention and put it into effect. They submit that the invention of the patent does not lie in the selection of COX-2 inhibitors useful in the treatment of COX-2 mediated disorders, which the patent recites as being well-known, but rather in formulation. They further submit that even if the notional skilled addressee is best conceptualised as a team, it would not include a clinician such as a pain management specialist, thereby excluding the evidence of Professor Scott and Professor Goucke. The applicants adopt the evidence of Professor Winter in contending that the others who would have an interest in formulating parecoxib would likely include an analytical expert, a chemical expert and a pre-clinical development expert who would be someone with expertise in pharmacology and toxicology who would provide information about biological activity of the compound, preliminary doses and toxicological profile.

110 The respondents submit that a conceptual team is appropriate. They generally agree with Professor Winter’s characterisation but submit that the team would include, either in lieu of or in addition to the pre-clinical development expert, a pain expert who is likely to be able to speak to the administration of the formulation under development and the use of the method claimed in the method claims. Such a person would have skills similar to those of Professor Scott. The respondents posit that when seeking to develop an analgesic for the Australian market which would be better than, or at least a useful alternative to, the drugs currently on the market for the management of acute post-surgical pain, the hypothetical team would include not only a formulator but also a pain clinician.

111 The construction of the patent is a function of the court, being a matter of law, but since patents often contain technical subject material, the court must, by evidence, be put in the position of a person of the kind to whom the document is addressed, being a person skilled in the relevant art at the relevant date: General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485 (Sachs LJ); Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; 277 FCR 267 at [73] (Rares, Nicholas and Burley JJ). Skilled addressees are those likely to have a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention: Catnic Components v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 at 242 (Diplock LJ). There may be more than a single person with such an interest, and the notional skilled reader to whom the document is addressed may not be a single person but a team, whose combined skills would normally be employed in that art in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those which are contained in the document to be construed: General Tire at 485. Put another way, the skilled addressee is a notional person who may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Konami Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 735; 114 IPR 28 at [26] (Nicholas J); Hood v Bush Pharmacy Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1686; 158 IPR 229 at [59] (Nicholas J).

112 I disagree with the applicants’ submission that no team is likely to be involved. The task of formulation appears to me to be likely to require a team effort. The formulation experts’ evidence is to the same effect. Furthermore, in my view, the applicants’ characterisation of the invention fails to take into account its breadth which, the patent reveals, concerns not only formulation but also methods of treatment by parenteral administration of COX-2 inhibitors: see claims 34 – 42. Indeed, the background of the patent addresses the clinical advantages of the parenteral administration of drugs for pain relief (page 1 line 30 – page 2 line 11) and the preferred use of selective COX-2 inhibitors in injectable form for that purpose (page 2 lines 22 – 24). The use of COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of pain, including postoperative pain, is identified later in the patent (for example, page 23 lines 19 – 26) and the preferred uses for compositions of the invention specifically include pain management, particularly for post-surgical pain (page 25 lines 4 – 8). Example 4 addresses the clinical use of a COX-2 inhibitor discussing the results of a clinical trial concerning the benefits of the use of an intravenous dose of a parecoxib sodium formulation administered to patients following dental surgery.

113 Moreover, it was common general knowledge by the priority date that selective COX-2 inhibitors were considered to be superior to non-selective NSAIDs and were of considerable interest for use in the treatment of acute pain, particularly post-operative pain, instead of non-selective NSAIDs. Rofecoxib and celecoxib, both selective COX-2 inhibitors, were being used for the management of post-operative pain and were available only in oral tablet form. However, no selective COX-2 inhibitors were available for injection, which was a preferred form of administration when treating acute pain. There was accordingly a known interest in an injectable COX-2 inhibitor for the treatment of acute pain. That interest was particularly known to persons involved in post-surgical pain. The evidence of Professor Scott provides independent support to the content of the patent as to the relevance of COX-2 inhibitors to pain experts.

114 These matters clearly place as persons with a practical interest in the subject matter of the patent those with an interest in the treatment of pain. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine that a formulator could develop an injectable formulation of a selective COX-2 inhibitor without an understanding of its likely clinical effects. Whilst Professor Winter considered that a pre-clinical expert would provide information about the biological activity of the compound, preliminary doses and toxicological profile, it is in my view likely that a formulation team would, either in addition to or in the alternative to a pre-clinical expert, have access to the skills of a person with experience in the administration of the type of drug under development, such as a pain clinician. In this regard, Professor Scott gave evidence that he had undertaken work in the course of undertaking his PhD which involved looking at novel analgesic drugs which might be useful in the treatment of pain. Dr Robertson gave evidence, which I accept, that generally a drug development program commences with the identification of a condition to be treated, generally in consultation with a medical specialist with expertise in the relevant condition to gain an understanding of relevant matters such as existing molecules used to treat the condition and the benefits or side effects of those molecules that might be desirable to target or avoid, as well as any requirements or advantages as to the route of administration to treat the target condition.

115 Of course, the notional person is not an avatar for expert witnesses whose evidence is accepted by the court. It is a tool of analysis which guides the court in determining, as relevant here, whether an invention as claimed does not involve an inventive step: AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 at [23] (French CJ). The evidence from expert witnesses must be understood on that basis.

116 In my view, people with a practical interest in the invention the subject of the patent would include those who are experienced in: (1) pharmaceutical formulation; (2) analytical methods required to characterise the formulation; (3) chemistry and being able to provide information about the synthesis, safety, reactivity and the impurity profile of the drug compound; and (4) the clinical application and use of the drug compound. In my view, the notional team would include a person with clinical knowledge about the treatment of pain, including acute pain, and that person would be someone with clinical experience in that field.

117 Several issues arise concerning the meaning of the claims. For the most part they arise in the context of the infringement case and relate to attempts by the parties to either maximise or minimise (according to their interests) the weight of the components, and the total weight, of the pharmaceutical composition of interest to navigate the boundaries of the monopoly claimed. It is appropriate to consider questions of construction shorn of the distraction of the forensic interests of the parties or, as if the infringer had never been born: CCOM Pty Ltd v Jeijing Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 396; 51 FCR 260 at 267-268 (Spender, Gummow and Heerey J). Accordingly, in these reasons I first consider questions of construction before turning to whether or not the respondents’ products may be said to infringe the claims.

118 The construction disputes concern:

(a) whether residual water is to be considered to form part of the “composition” of claim 1 and claim 26;

(d) the identity of the “at least one water soluble therapeutic agent” in claims 1 and 26 (the water soluble therapeutic agent argument);

(e) the meaning of “about” as it appears in the context of specified percentage weight ranges in claims 1 and 26; and

(f) the meaning of “essentially” in claim 11.

119 Claims 1 and 26 are independent claims upon which a number of the relevant claims depend. Unless otherwise stated, my findings as to construction and infringement in relation to those independent claims will also apply to the relevant claims dependent upon them.

120 It may be noted that the specification provides that except where the context requires otherwise, the word “comprise” or variations of that word is used in an inclusive sense (page 35 lines 8 – 9).

121 The principles of claim construction are not in dispute. They are conveniently set out in Jupiters v Neurizon [2005] FCAFC 90; 65 IPR 86 at [67] (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) as follows:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [81]; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corp Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485-486; the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd, at 485–486.