Federal Court of Australia

Malone v State of Queensland (The Clermont-Belyando Area Native Title Claim) (No 5) [2021] FCA 1639

Table of Corrections | |

In [18], in line 10 of quote, delete “[a kind of gourd which, when dried, coud be used for carrying water]” | |

In [63], in line 1 of quote, insert “[sic]” after “under” | |

In [100(b)], in line 2 of quote, insert “[sic – claimants’]” | |

In [114], in line 1, insert “the” before “15 December 2017” | |

In [115(a)], in line 1, insert “the” before “15 December 2017” | |

In [118], delete the first ellipsis | |

In [154], in line 7, delete “identified?”” and replace with “identified”.” | |

In [157], in line 8, insert “(italics in original)” | |

In [171], in line 4, delete “sine” and replace with “since” | |

In [183], in line 5, delete “because” and replace with “became” | |

In [195], in line 6, insert “(at [40] and [42])” after “following term” | |

In [204(5)], in line 5 of the quote, insert “[sic – basis]” after “base” | |

In [206], in line 4, delete “insight to” and replace with “insight into” | |

In [221], in line 6, insert “(at [483] and [485])” after “as follows” | |

In [263], in line 6, insert “(at [20]-[22])” after “as follows” | |

In [266], in line 4, change “Wieri” to “Wierdi” | |

In [271], in line 12, delete “Sandy Camp” and replace with “Sandy Creek camp” | |

In [273], in line 4, delete “(see [4] and [131])” and replace with “(see at [4] and [131] above)” | |

In [275], in line 3, insert “second” between “its FASOC” | |

In [277], in line 5, delete “in [9]” | |

In [290], delete the ellipsis in the quote | |

In [292], in line 3, delete “Ms Kemppi” and replace with “Ms Delia Kemppi” | |

In [292], in line 7, delete “Ms Barnard” and replace with “Ms Lester Barnard” | |

In [292], in line 10, delete “Mr Tilley and Ms Gyemore” and replace with “Mr Leslie Tilley and Ms Priscilla Gyemore” | |

In [305], delete the last sentence and replace with “She also said that “we have a spirit within us that connects to the land … I know in my – within my spirit that I’m connected to the land”.” | |

In [306], in line 5, delete “have” and replace with “had” | |

In [324], delete the last two sentences | |

In [325], in line 1, delete “scared” and replace with “sacred” | |

In [332], in line 2, delete “Uncle Beau” and replace with “Uncle Bow” | |

In [359], in line 2, insert “that” after “She said” | |

In [359], in line 7, delete “granddaughter” and replace with “daughter” | |

In [372], insert quotation marks around both quotes, remove the indentation and run them on to form two sentences | |

Delete [387]-[401] | |

In old [411], in line 2, insert “(italics in original)” after the quote | |

In olf [413], in line 5, insert “Johnson” after “Uncle Hedley” | |

In old [414], in the last line, delete “ Auntie Liz and brother Hedley” and replace with “ Aunty Lizzie and by his brother Hedley” | |

In old [423], in line 1, insert “Coedie” between “Mr McAvoy” | |

In old [423], in line 1, delete “2 December” and replace with “3 December” | |

In old [434], in line 4, delete “lead” and replace with “led” | |

In old [442], in line 2, insert “that” after “Alpha and” | |

In old [443], in line 3, delete the second “from the” | |

In old [445], in line 1, delete the first “She” and replace with “Ms Irene Simpson” | |

In old [446(4)], in line 2, delete “Simson” and replace with “Simpson” | |

In old [460], in line 1, delete “that that” and replace with “that” | |

In old [461], in line 1, insert “She said that” before “Dolly’s body” | |

In old [462], in line 1, delete “near” | |

In old [463], insert “She said that” at the beginning of the last sentence | |

In old [481], in line 4, insert “that” after “She said” | |

In old [484], in line 1, delete “scared” and replace with “sacred” | |

In old [485], in line 5, delete “her father that” and replace with “her father” | |

In old [494], in line 3, delete “the” | |

In old [498], in line 2, add “[sic]” after “before” | |

In old [507], in line 1, delete “[her]” and replace with “[m]y” | |

In old [507], in line 9, delete the second “she” and replace with “Granny Daisy” | |

In old [520], in line 2, delete “law and custom” and replace with ““lore and custom”” | |

In old [522], in line 2, delete “saplings for burial pots” and replace with “saplings to mark burial plots” | |

In old [523], in line 4, delete “because she was the eldest and because her older sister” and replace with “because she was the next oldest as her older sister” | |

In old [538], delete the third last sentence | |

In old [551], in line 3, delete “by elders in Cherbourg” and replace with “by the elders in his family in Cherbourg” | |

In old [554], in line 5, insert a full stop after “close”” | |

In old [554], in line 5, delete “he” and replace with “He” | |

In old [555], in line 2, delete the quote and replace with “let me go to [a] funeral because they reckon[ed] I was too young to go to a funeral … so I climbed up on the roof and watched the procession” | |

In old [556], in line 1, delete “when” and replace with “where” | |

In old [557], in line 4, delete “onto neighbour’s” and replace with “onto [his] neighbour’s” | |

In old [560], in line 3, delete “hands out” and replace with “hangs out” | |

In old [564], in line 4, delete “an” | |

In old [571], in the last line, delete “to step in front of elders out of respect” and replace with ““[to step] over/across Elders”” | |

In old [579], delete the last sentence | |

In old [585], in line 1, insert “Delia” between “Ms Kemppi” | |

In old [592], in line 2, delete “Mrs Kemppi” and replace with “Ms Kemppi” | |

In old [600], in line 1, insert “Adrian” between “Mr Burragubba” | |

In old [601], in line 4, insert “mother” after “remembered her” | |

In old [602], in line 1, insert “Wakka” after “Wakka” | |

In old [616], in line 2, insert “that” after “He said” | |

In old [616], in line 2, delete “[his]” and replace with “my” | |

In old [617], in line 1, delete “Jangga Overlap Area” and replace with “[CB/J#3 claim area]” | |

In old [617], in line 4, delete “overlap area” and replace with “[CB/J#3 claim area] | |

In old [617], in line 5, delete “overlap” and replace with “[CB/J#3 claim area] | |

In old [621], at the beginning of line 1 of the second paragraph of the quote, insert “[MR LLOYD:]” | |

In old [623], at the beginning of line 1 of the second paragraph of the quote, insert “[MR LLOYD:]” | |

In old [625], at the beginning of line 1 of the second paragraph of the quote, insert “[MR LLOYD:]” | |

In old [627], at the beginning of line 1 of the second paragraph of the quote, insert “[MR LLOYD:]” | |

In old [629], in line 1, delete “overlap area” and replace with “[CB/J#3 claim area] | |

In old [630], in line 6, insert “[sic]” after “Down [R]anges” | |

In old [633], in line 2, delete “Mithera” and replace with “Mit’thera” | |

In old [633], in line 5, delete “stumpy tail” and replace with “stumpy tailed” | |

In old [633], in line 8, delete “Mundagutt” and replace with “Mundagutta” | |

In old [633], in line 10, insert “Springs” after “Doongmabulla” | |

In old [633], in line 11, insert “[sic]” after “Mithera” | |

In old [635], in the last line, insert “ceremonies” after “initiation” | |

In old [637], in line 1, insert “had” after “He said that he” | |

In old [637], in line 2, delete “and that he” and replace with “and he” | |

In old [640], in the last line, insert “had” after “because they” | |

In old [647], in line 3, delete “doolabineta” and replace with “doolabienta” | |

In old [649], in line 4, delete “CD/J#3” and replace with “CB/J#3” | |

In old [650], in line 1, delete “[his]” and replace with “my” | |

In old [652], in the last line, delete “CB people” and replace with “Clermont-Belyando people” | |

In old [653], in line 4, delete “[himself]” and replace with “myself” | |

In old [655], in line 4, delete “Eastmeere” and replace with “Eastmere” | |

In old [665], in line 1, delete “overlap” and replace with “[CB/J#3 claim]” | |

In old [665], in line 2, delete “sacred area” and replace with “sacred sites” | |

In old [666], in line 6, delete “the” before “stumpy tailed” | |

In old [670], in line 4, delete “where” and replace with “when” | |

In old [683], in line 1, insert “to” after “and her mother” | |

In old [687], in line 5, delete “[her]” and replace with “me” | |

In old [690], in line 1, insert “that” after “She claimed” | |

In old [694], in line 2, delete “our” and replace with “[her]” | |

In old [697], in line 1, insert “that” after “She said” | |

In old [697], in line 2, insert “that” before “he told her” | |

In old [701], in line 3, insert “said that her mother had” after “As well she” | |

In old [711], in line 9, delete “some sort of” and replace with “a” | |

In old [721], in line 5, insert quotation marks around “by his grandparents, his ancestors” | |

In old [721], in line 3, delete “[and] that my father is classed as a brother” and replace with “[and] my father is classed … as a brother” | |

In old [721], in line 3, insert quotation marks around “didn’t like talking about the past much” | |

In old [722], in line 5, delete “the travelling” and replace with “these travelling” | |

In old [729], in the quote, delete “[claim area](??)” and replace with “[c]laim [a]rea” | |

In old [732], in line 3, delete “cognatic decent” and replace with “cognatic descent” | |

In old [732], in line 5, delete “of on the” and replace with “of the” | |

In old [769], in the quote, delete “anthologists” and replace with “anthropologists” | |

In old [773], in line 14, delete “was” and replace with “were” | |

In old [806], in line 5, “delete “us experts” and replace with “[the] experts” | |

In old [814], in line 10, delete “he acknowledged that” | |

In old [824], in line 3, insert “Mr Gordon” before “Pullar” | |

In old [851], in line 5, delete “Mr Gordon” | |

In old [860], delete “[116]” after the quote | |

In old [868], in line 4, delete “[were linked” and replace with “[being linked” | |

In old [871], in line 2, delete “sister” and replace with “brother” | |

In old [889], in line 5 of the paragraph after the table, delete “Johnston” and replace with “Johnson” | |

In old [914], in the last line, delete “Section B” | |

In old [991], in line 2, delete “Section B” | |

In old [1049], remove the bold | |

In old [1067], in line 4, delete “Section B” | |

In old [1067], in line 6, delete “Section B” | |

In old [1144], in line 3, delete “Section A” | |

In old [1138(e)], in line 3, delete [6.1] and replace with [6] | |

In old [1159], in line 2, delete “21 April” and replace with “29 April” | |

In old [1193], in line 4, delete “[…]” and replace with “[1194”] | |

In old [1235(c)], in line 1, delete “(d) above” and replace with “(b) above” | |

As a result of the deletion of [387]-[401] mentioned above, the cross-referencing has therefore changed |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions stated be answered as follows:

But for any question of extinguishment of native title:

a) Does native title exist in relation to any and what land and waters of the claim area?

b) In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

i. Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising native title?

ii. What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

Answer

a) no;

b) not applicable.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

QUD 296 of 2020 | ||

BETWEEN: | COLIN MCLENNAN, MARIE WALLACE, LESLIE MCLENNAN, REBECCA BUDBY AND JUSTIN POWER ON BEHALF OF THE JANGGA PEOPLE #3 Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND First Respondent SUZANNE ENID THOMPSON Second Respondent JOABEN CHARLES JEFFREY THOMPSON (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | REEVES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 December 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions stated be answered as follows:

But for any question of extinguishment of native title:

a) Does native title exist in relation to any and what land and waters of the claim area?

b) In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

i. Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising native title?

ii. What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

Answer

a) no;

b) not applicable.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REEVES J:

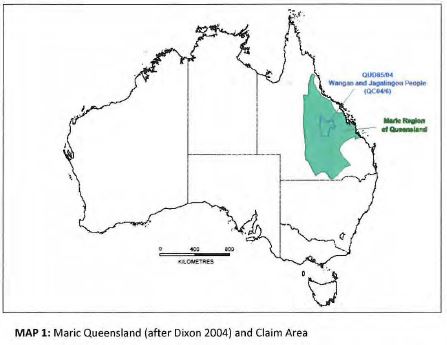

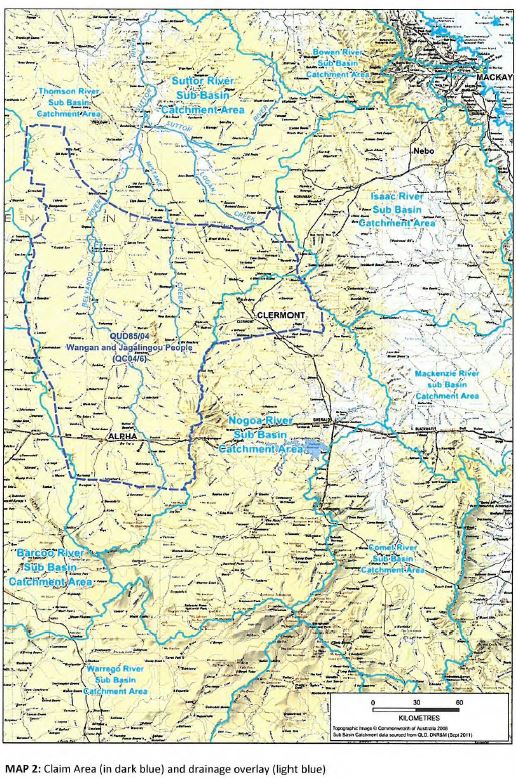

1 In September 2019 the authorised applicant of the Clermont-Belyando claim group (the CB claim group) filed an amended native title determination application under s 13 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA) over a large area of land and waters (approximately 30,200 square kilometres) in Central Queensland. That claim was the final iteration of a claim that was originally filed with the Court in 2004 on behalf of a claim group calling itself the Wangan and Jagalingou people.

2 As the name of the present claim group implies, the claim area surrounds the town of Clermont in Central Queensland, particularly to its south, west and north. The other component of the claim group’s name refers to the Belyando River. It rises in the Drummond Range just north of the southern boundary of the claim area and flows through its western side more than 200 kilometres in a broadly northerly direction. It eventually joins with the Suttor River about 70 kilometres north of the northern boundary of the claim area. These distances may serve to indicate why the Belyando River is said to be one of the longest watercourses in Queensland.

3 On 21 July 2017, the following separate questions were stated in respect of the then extant Wangan/Jagalingou claim:

Pursuant to rule 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the following questions be decided separately from and before any other questions in the proceedings:

“But for any question of extinguishment of native title:

a) Does native title exist in relation to any and what land and waters of the claim area?

b) In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

i. Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising native title?

ii. What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?”

(Italics in original)

4 After a number of adjournments, the trial of these separate questions began at Clermont in early December 2019. Shortly thereafter a separate group of people claiming to be from the Clermont-Belyando area filed a native title determination application which entirely overlapped the CB claim area (the CB#2 claim). As required by s 67 of the NTA, orders were made for that claim to be heard concurrently with the CB claim. That trial continued in December 2019 and recommenced in early February 2020. It was then to be continued in April 2020, but that was prevented by the onset of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In late September 2020, before the trial had resumed, the authorised applicant of the Jangga people filed a native title determination application which overlapped the northern half, approximately, of the CB claim area (the J#3 claim). At about the same time, the CB#2 claim was discontinued.

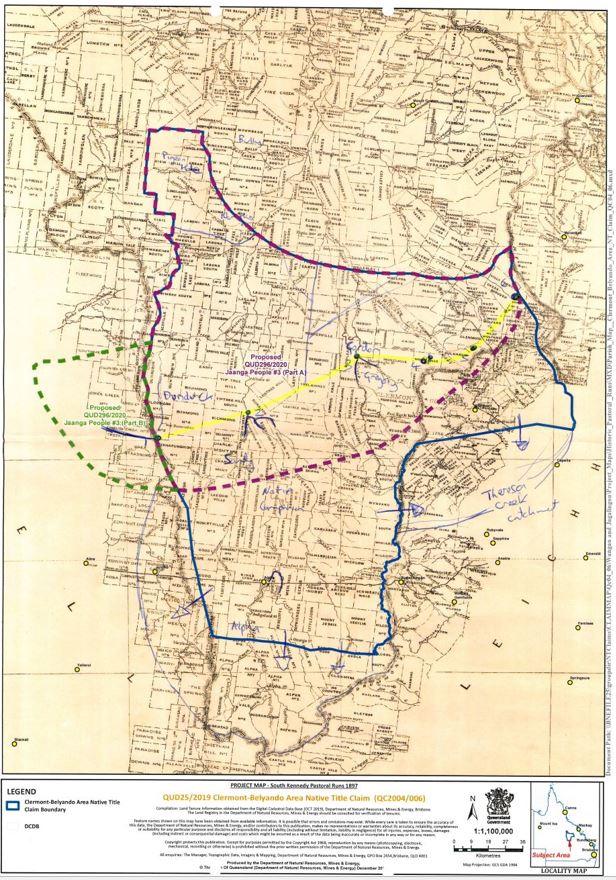

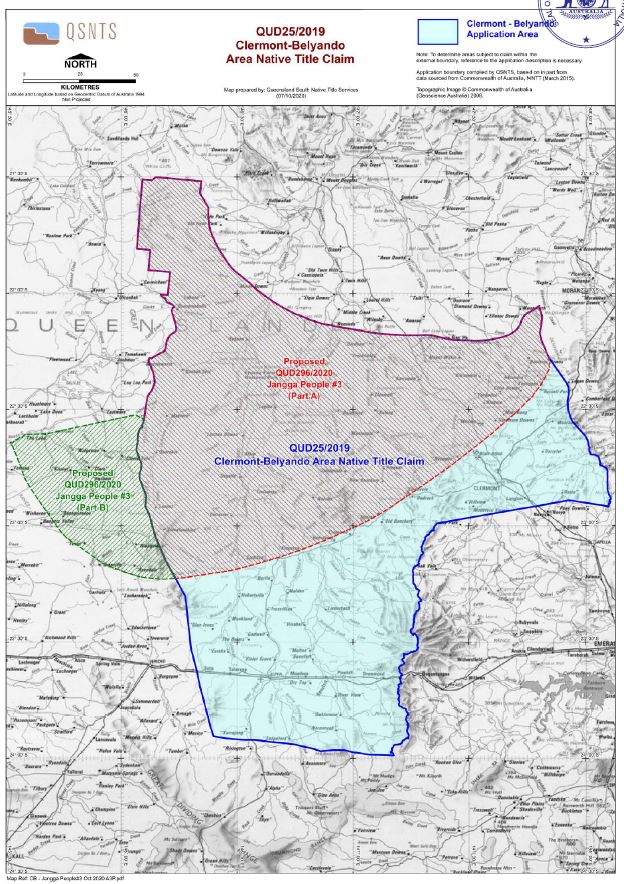

5 On 9 October 2020, again as required by s 67 of the NTA, orders were made for the two remaining claims to be heard together: the original CB claim and the J#3 claim. As a part of those orders, the J#3 claim area was divided into two Parts: A and B. Part A comprised that part of the claim which overlapped a portion of the CB claim area, as shown on the map annexed to these reasons (Schedule A). As well, those orders stated substantially identical separate questions to those above with respect to that area (the CB/J#3 claim area). Part B of the J#3 claim lies to the west of the CB/J#3 claim area and is not affected by this judgment. The separate questions in the CB claim are still to be answered with respect to the whole of that claim area (the CB claim area). However, henceforth in these reasons, unless greater specificity is required, I will generally refer to the area of land and waters affected by this judgment as simply “the claim area”.

6 The trial of the two sets of separate questions mentioned above proceeded in December 2020 and was concluded in late April 2021. This judgment provides answers to those two sets of separate questions. For the reasons that follow, the answers are:

In the CB claim:

(a) No;

(b) Not applicable.

In the J#3 claim:

(a) No;

(b) Not applicable.

THE STRUCTURE OF THESE REASONS

7 Including the introductory section above, these reasons are structured as follows:

8 The British Crown claimed sovereignty over the then Colony of New South Wales on 7 February 1788. Its claim included that part of the Australian continent extending from Cape York in the north to the southern tip of Van Diemen’s Land in the south. In the west, it extended to the 135th degree of longitude, which runs from a point west of the Gulf of Carpentaria in the north to a point west of Spencer’s Gulf in the south (Alex C. Castles, An Australian Legal History, The Law Book Company Limited, pp 24-25). While that acquisition of sovereignty affected land title in the claim area, British settlement of Australia did not directly affect the Aboriginal inhabitants of that area until more than half a century later.

9 This hiatus raises the concept of effective sovereignty. It is an admitted fact on the pleadings in these matters that “effective sovereignty” occurred “circa the mid-1850s”. It should, however, be noted that this concept does not involve a recasting of what true sovereignty entails. Rather, it fixes a later point in time up to which it may be inferred that the acknowledgement of laws and observance of customs by the original peoples of the country continued essentially unchanged. In Gudjala People No 2 v Native Title Registrar (2008) 171 FCR 317; [2008] FCAFC 157 (Gudjala), the Full Court referred to the primary judge’s interpretation of the use that a delegate of the National Native Title Registrar had made of that concept and observed, with apparent approval (at [72]):

His Honour referred to the delegate’s conclusion that effective sovereignty occurred at about 1850-1860. He took that conclusion to mean that European occupation had occurred at about that time. He defined the task before him as identification of the existence in 1850-1860 of a society of people living according to identifiable laws and customs having a normative content. Such laws and customs must establish normal standards of conduct or perhaps be prescriptive of such standards.

10 Since Gudjala, numerous first instance judgments and some Full Courts have adopted the same approach (see, for example, Banjima People v Western Australia (No 2) (2013) 305 ALR 1; [2013] FCA 868 (Banjima) at [82] per Barker J; Dempsey (on behalf of the Bularnu, Waluwarra and Wangkayujuru People) v Queensland (No 2) (2014) 317 ALR 432; [2014] FCA 528 (Dempsey) at [532] per Mortimer J; Coconut on behalf of the Northern Cape York #2 Native Title Claim Group v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 629 at [34] per Greenwood J; Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia (2015) 325 ALR 213; [2015] FCA 9 (Croft) at [209] per Mansfield J; Anderson on behalf of the Wulli Wulli People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2015] FCA 821 at [56] per Collier J; Ashwin on behalf of the Wutha People v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2019] FCA 308 (Ashwin) at [276] per Bromberg J and Fortescue Metals Group v Warrie (2019) 273 FCR 350; [2019] FCAFC 177 at [197]-[202] per Jagot and Mortimer JJ, with Robertson, Griffiths and White JJ agreeing). The same approach will be adopted in these reasons.

(3) The early European explorers – several encounters with Aboriginal people

11 The reports of Dr Fiona Skyring (tendered by the Clermont-Belyando applicant (the CB applicant)) and Dr Phillip Clarke and Mr Daniel Leo (tendered by the J#3 applicant) all contain histories of the CB/J#3 claim area, although it is important to note that, since it was prepared in 2011 for the purposes of the J#1 claim, Mr Leo’s report is largely confined to the claim area, subsequently determination area, of that claim (the J#1 determination area): see McLennan on behalf of the Jangga People v State of Queensland [2012] FCA 1082 (McLennan). That area lies immediately to the north of the present CB/J#3 claim area. What follows has been extracted from those reports. However, it is worth noting at the outset the following cautions that Dr Clarke included in the introductory paragraphs to his history:

13 In keeping with the nature of historical records over much of Australia, the sources utilised here are predominately by non-Aboriginal men who were involved as colonists, pastoralists or officials in areas remote from major town centres. In my experience with working on land claims and on other native title claims, such records have a tendency to focus on the transformation of the country through the establishment of pastoral runs and mines, and to either overstate the extent to which Aboriginal people were removed from the region or to at least understate their role in opening up the country. In analysing this historical material, it must be considered that the lack of records is not evidence for the absence of Aboriginal people within the [c]laim [a]rea. The official historical accounts have tended to down play the agency that Aboriginal people had in conducting their own affairs and maintaining their cultural identity.

14 The historical accounts of the earliest period of European settlement do not generally identify the Aboriginal individuals and groups encountered, and in the available records they are often referred to simply as ‘blacks’, ‘natives’ and ‘savages’, and also as ‘wild blacks’ and ‘Myalls’, the latter being a commonly used colonial term used to mean Aboriginal people who were living traditionally beyond the control of the European authorities. The names of the Aboriginal people involved in significant events are only rarely given, and their cultural identities are generally unrecognised. Most of the men who left eye witness accounts of these events showed little or no interest in Aboriginal resource use and ceremony, and the Aboriginal occupation of country was to many of them an impediment to the establishment of profitable ‘runs’ or stations.

(Footnote omitted)

12 From the mid-1840s, there were three recorded European exploratory expeditions through the claim area or in its vicinity. In chronological order, they were Dr Ludwig Leichhardt (1845), Surveyor-General Sir Thomas Mitchell (1846) and Mr Augustus Gregory (1855). Each of them recorded the presence of Aboriginal people.

13 The Prussian naturalist and botanist, Leichhardt, set out from Jimbour Station on the Darling Downs on 1 October 1844. He passed through the claim area in early 1845. According to Dr Skyring’s report:

Much of the description in Leichhardt’s journal concerned the type of vegetation and the botanical curiosities in the landscape they traversed, and he and his party were constantly preoccupied with obtaining water and food. Leichhardt travelled through what is now called central Queensland during the hottest months of the year. From the junction of the Comet and Nogoa Rivers, they headed north, and reached the Isaac River in February 1845. Leichhardt named several landmarks near the eastern most point of the … claim area; Scott’s Peak, Calvert Peak, Lord’s Table Mountain, Campbell Peak and Mt Phillips. All of these places were named after Leichhardt’s travelling companions, or the sponsors who had financially supported the expedition.

14 On 14 January 1845, at the Mackenzie River, about 60 kilometres south east of the claim area, near the present town of Emerald, Leichhardt recorded the following journal entry concerning the presence of Aboriginal people:

Farther on, we came again to scrub, which uniformly covered the edge of the high land towards the river. Here, within the scrub, on the side towards the open country we found many deserted camps of the natives, which, from their position, seemed to have been used for shelter from the weather, or as hiding-places from enemies: several places had evidently been used for corroborris, (sic) and also for fighting.

(Footnote omitted)

15 On the same day, farther along the Mackenzie River, Leichhardt recorded observing that the area appeared to be “very populous” as follows:

Large heaps of mussel-shells, which have given food to successive generations of the natives, cover the steep sloping banks of the river, and indicate that this part of the country is very populous. The tracks of the natives were well beaten, and the fire-places in their camps numerous. The whole country had been on fire; smoldering [sic] logs, scattered in every direction, were often rekindled by the usual night breeze, and made us think that the Blackfellows were collecting in numbers around us — and more particularly on the opposite side of the river…

(Footnote omitted)

16 Two days later, still on the Mackenzie River, Leichhardt recorded the following encounter with two Aboriginal men who informed him, through an interpreter, the direction of flow of the Mackenzie River:

[W]e heard the cooee of a native, and in a short time two men were seen approaching and apparently desirous of having a parley. Accordingly, I went up to them; the elder, a well made man, had his left front tooth out, whilst the younger had all his teeth perfect; he was of a muscular and powerful figure, but, like the generality of Australian aborigines, had rather slender bones; he had a splendid pair of moustachios, [sic] but his beard was thin. They spoke a language entirely different from that of the natives of Darling Downs, but “yarrai” still meant water. Charley [an Aboriginal man who assisted Leichhardt as an interpreter], who conversed with them for some time, told me that they had informed him, as well as he could understand, that the Mackenzie flowed to the north-east.

(Footnote omitted)

17 About a month later (15 February 1845), having travelled to the north-west, and therefore likely to have been east or north of the claim area, Leichhardt made the following observations about the way in which the local Aboriginal inhabitants protected and used the available water resources, including digging wells and filtering water through sand:

[W]e came to a water-hole in the bed of the river, at its junction with a large oak tree creek coming from the northward…the natives had fenced it round with branches to prevent the sand from filling it up, and had dug small wells near it, evidently to obtain a purer and cooler water, by filtration through the sand…We continued our ride six miles higher up the river, without finding any water, with the exception of some wells made by the natives, and which were generally observed where watercourses or creeks joined the river…

Charley had, during my absence from the camp, had an interview with the natives, who made him several presents, among which were two fine calabashes which they had cleaned and used for carrying water; the larger one was pear-shaped, about a foot in length, and nine inches in diameter in the broadest part, and held about three pints. The natives patted his head, and hair, and clothing; but they retired immediately, when he afterwards returned to them, accompanied by Mr. Calvert [a member of Leichhardt’s party] on horseback.

(Footnote omitted)

18 On 24 February 1845, on the Isaac River, about 60 to 70 kilometres east of the claim area, Leichhardt recorded the following about obtaining water (without permission) from some wells near to a “camp of the natives” and the observations he made concerning the items that had been left in the camp, including an iron tomahawk made “apparently of the head of a hammer: a proof that they had had some communication with the sea-coast”:

I dismounted and cooeed; they answered; but when they saw me, they took such of their things as they could and crossed to the opposite side of the river in great hurry and confusion. When Brown [a member of Leichhardt’s party], who had stopped behind, came up to me, I took the calabash and put it to my mouth, and asked for ‘yarrai, yarrai’. They answered, but their intended information was lost to me; and they were unwilling to approach us. Their camp was in the bed of the river amongst some small Casuarinas. Their numerous tracks, however, soon led me to two wells, surrounded by high reeds, where we quenched our thirst. My horse was very much frightened by the great number of hornets buzzing about the water. After filling our calabash [a kind of gourd which, when dried, could be used for carrying water], we returned to the camp of the natives, and examined the things which they had left behind; we found a shield, four calabashes, of which I took two, leaving in their place a bright penny, for payment; there were also, a small water-tight basket containing acacia-gum; some unravelled fibrous bark, used for straining honey; a fire-stick, neatly tied up in tea-tree bark; a kangaroo net; and two tomahawks, one of stone, and a smaller one of iron, made apparently of the head of a hammer: a proof that they had had some communication with the sea-coast. The natives had disappeared.

(Footnote omitted)

19 Despite having amicable relations with the Aboriginal people he met, Leichhardt recorded in his journal (on 27 February 1845) that “they seemed very anxious to induce us to go down the river”, as the following entry demonstrates:

The natives had, in my absence, visited my companions, and behaved very quietly, making them presents of emu feathers, boomerangs, and waddies. Mr. Phillips [a member of Leichhardt’s party] gave them a medal of the coronation of her Majesty Queen Victoria, which they seemed to prize very highly. They were fine, stout, well made people, and most of them young; but a few old women, with white circles painted on their faces, kept in the back ground. They were much struck with the white skins of my companions, and repeatedly patted them in admiration. Their replies to inquiries respecting water were not understood; but they seemed very anxious to induce us to go down the river.

(Footnote omitted)

20 Sir Thomas Mitchell travelled in the vicinity of the claim area between July and September 1846. Dr Skyring noted in her report that Mitchell recorded his progress on a map which showed that “he reached a point on the Belyando River about 40 kilometres north of the northern boundary of the … claim area, then decided to return south along the river and back to his depot camp on the Maranoa”. She went on to observe that Mitchell’s map contained several notations of “Natives” including: near Mt Chantry, close to present day Alpha; near the junction with a tributary of the Belyando River, which he described as “‘w.s.w’ (west south west)”; and at a place on the northernmost part of his journey along the Belyando River about 40 kilometres north of the claim area.

21 Like Leichhardt, Mitchell was concerned to identify the local water resources. An example was his journal entry on 21 July 1846 as follows:

On turning my horse, he trod on an old heap of fresh water mussels, at an old fireplace of the natives. This was a cheering proof that water was not distant.

(Footnote omitted)

22 On 28 July 1846, further north along the Belyando River, Mitchell recorded having come across “still smoking fires, water-vessels, etc., of a tribe of natives”. However, the people concerned had left.

23 Farther north-west along the Belyando River, on 9 August 1846, Mitchell recorded the following interaction with a group of Aboriginal people who made it clear that they wanted him to leave the area:

We watered our horses and took some breakfast…one of the men observed some natives looking at us from a point of the opposite bank. I held up a green bough to one who stood forward in a rather menacing attitude, and who instantly replied to my signal of peace by holding up his boomerang. It was a brief but intelligible interview; no words could have been better understood on both sides; and I had fortunately determined, before we saw these natives, to return by tracing the river upwards … Graham got [our horses] together while I was telegraphing with the natives, some of whom I perceived filling some vessel with water, with which they retired into the woods. We saddled, and advanced to examine their track and the spot they had quitted, also that they might afterwards see our horses’ tracks there, lest our green bough and subsequent return might have encouraged them to follow us. Yuranigh [an Aboriginal man who acted as interpreter to Mitchell] was burning the mutton bones we had picked; but I directed him to throw them about, that the natives might see that we neither eat their kangaroos nor emus.

(Footnote omitted)

24 On the next day (10 August 1846), Mitchell recorded the following “hostile” encounter with a group of “seventeen natives” which occurred while he was away from the camp and during which it was made clear to the members of his party present in the camp that “the whole country belonged to the old man [the head of the group]” and that they should “leave that place”:

The camp had just been visited by seventeen natives, apparently bent on hostile purposes, all very strong, several of them upwards of six feet high. Each of them carried three or four missile clubs. They were headed by an old man, and a gigantic sort of bully, who would not keep his hands off our carts. They said, by signs, that the whole country belonged to the old man. They pointed in the direction in which I had gone, and to where Mr. Stephenson happened to be at the time, down in the river bed; and then beckoned to the party that they also should follow or go where I had gone, or leave that place. They were received very firmly, but civilly and patiently, by the men, and were requested to sit down at a distance, my man Brown, being very desirous that I should return before they departed; thinking the old man might have given me some information about the river, which he called ‘Belyando’. But a noisy altercation seemed to arise between the old chief and the tallest man, about the clubs, during which the latter again came forward, and beckoned to others behind, who came close up also. Each carried a club under each arm, and another in each hand, and from the gestures made to this advanced party, by the rest of the tribe of young men at a distance, it appeared that this was intended to be a hostile movement. Brown accordingly drew out the men in line before the tents, with their arms in their hands, and forbade the natives to approach the tents…these strong men stood still and looked foolish, when they saw the five men in line, with incomprehensible weapons in their hands. Just then, our three dogs ran at them, and no charge of cavalry ever succeeded better. They all took to their heels, greatly laughed at, even by the rest of their tribe; and the only casualty befell the shepherd’s dog, which biting at the legs of a native running away, he turned round, and hit the dog so cleverly with his missile on the rump, that it was dangerously ill for months after; the native having again, with great dexterity, picked up his club …

(Footnote omitted)

25 Mitchell added the following observations in his journal about his decision to change his plans to explore the upper reaches of the “Belyando”, as a result of this encounter:

That these natives were fully determined to attack the white strangers, seems to admit of no doubt, and the result is but another of the many instances that might be adduced, that an open fight, without treachery, would be contrary to their habits and disposition. That they did not, on any occasion, way-lay me or the doctor, when detached from the body of the party, may perhaps, with equal truth, be set down as a favourable trait in the character of the aborigines; for whenever they visited my camp, it was during my absence, when they knew I was absent, and of course must have known where I was to be found. The old man had very intelligibly pointed out to Brown the direction in which this river came, i. e., from the S. W. (southwest), and I therefore abandoned the intention of exploring it upwards, and determined to examine how it joined, and what the character of the river might be, about and below that junction, in hopes I might still obtain an interview with the natives, and learn something of the country to the north-west.

(Footnote omitted)

26 Three days later (13 August 1846), Mitchell recorded observing areas of grass fire and noted that, while they heard Aboriginal voices, they did not see anyone. He apparently thought his group was being followed to ensure that they left this area because he recorded in his diary:

Even to the lagoon, their track along our route was also plainly visible. I was now, apparently to them, at their request, leaving the country; and we should soon see if their purpose in visiting our camp was an honest one, and whether their reasonable and fair demand, was really all they contemplated on that occasion.

(Footnote omitted)

27 About three weeks later (on 4 September 1846), Mitchell recorded a further encounter with another group of Aboriginal men and women and the measures they took to avoid his party and to protect themselves from any harm:

[W]e perceived a line of about twelve or fourteen natives before they had observed us. Through my glass, I saw they were painted red about the face, and that there were females amongst them. They halted on seeing us, but some soon began to run, while two very courageously and judiciously took up a position on each side of a reedy swamp, evidently with the intention of covering the retreat of the rest. The men who ran had taken on their backs the heavy loads of the gins, and it was rather curious to see long-bearded figures stooping under such loads. Such an instance of civility, I had never before witnessed in the Australian natives towards their females; for these men appeared to carry also some of the uncouth-shaped loads like mummies. The two acting as a rear guard behaved as if they thought we had not the faculty of sight as well as themselves, and evidently believed that by standing perfectly still, and stooping slowly to a level with the dry grass, when we passed nearest to them, they could deceive us into the idea that they were stumps of burnt trees. After we had passed, they were seen to enter the brigalow, and make ahead of us; by which movement I learnt that part of the tribe was still before us. Sometime afterwards, we overtook that portion when crossing an open interval of the woods; they made for the scrub on seeing us. Meanwhile columns of smoke ascended in various directions before us, and two natives beyond the river were seen to set up a great blaze there.

(Footnote omitted)

28 As already mentioned, Mr Augustus Gregory travelled in the vicinity of the claim area in 1855 having originally set out from Victoria River in the present day Northern Territory and travelled through the desert regions of Western Australia before travelling east. Noting that Peak Downs is to the east of the claim area, Dr Skyring recorded in her report that:

On 5 November 1856 they travelled past Mitchell’s most northerly camp on the Belyando River, and decided to travel south east towards Peak Downs. The next day they struggled through brigalow scrubs and near a small gully with rainwater ‘a camp of blacks was observed; but they ran into the scrub on our approach’. They were out of water, expedition member Melville was injured and the horses were all nearly lame from falling so often in the dense scrub, so they stopped to camp at a place where there was ‘a fine creek with grassy flats’.

(Footnotes omitted; bold added)

29 About a week later (on 13 November 1855), Gregory recorded in his journal: “saw some blacks, who, when asked by signs where water could be found, pointed down the creek and into the scrub” (footnote omitted). On the next day (14 November 1855), he recorded the following observations in his journal about the potential of the area:

If this part of the country were well supplied with water it would form splendid stations for the squatter; but from its level character and geological structure, permanent surface-water is very scarce, and where it does exist it is surrounded by scrubby country, which renders it almost unavailable.

(Footnote omitted)

30 As Dr Skyring remarked in her report, these records do “not provide comprehensive evidence of patterns of residence of Aboriginal people across the claim area because neither Mitchell nor Gregory covered enough territory”. However, as she went on to observe, they do show that “[t]hey encountered evidence of Aboriginal occupation wherever they went, and Mitchell was told angrily that they were not welcome in country that was not theirs”. Furthermore, while Gregory’s records are essentially limited as to the presence of Aboriginal people in the claim area, or the area surrounding it, both Leichhardt and/or Mitchell’s records attest to the use of vessels to carry water, the use of woven nets and baskets, the use of weapons including boomerangs, the use of fire as a land management practice and the harvesting of river food such as mussels. Leichhardt also described having observed a cleared area which he assumed was used for ceremonies.

(4) The pastoral and mining influx – 1850s to 1860s

31 The settler influx to the claim area began from the early 1850s, some years before Queensland was declared a separate Colony from New South Wales in 1859. That influx occurred soon after the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement (established in 1824) was declared open for free settlement by the then Governor of the Colony of New South Wales, Governor Gipps, in February 1842. But, as Dr Skyring noted in her report, “the colonial government, though, was one step behind the settlers in the rush to occupy land, and it was estimated that in the early 1840s about half of the sheep in the new [Moreton Bay] district were illegally grazing on land that had not been officially leased”.

32 This land rush soon affected the claim area. By the early to mid-1850s, Dr Skyring observed that the influx of European settlers to that area was “eventually massive”, “not uniform” and “for the most part unregulated”. In respect of Dr Skyring’s “not uniform” comment, it should be noted that there is evidence that the southern part of the claim area was settled by about 1854 whereas that did not occur in the northern part until almost a decade later. Further, in respect of her “eventually massive” comment, Mr Leo included in his report a table, albeit concerning the Kennedy Pastoral District to the north of the claim area, which showed the number of settlers in that District between 1862 and 1876 as follows:

Year | Settlers |

1862 | 86 |

… | |

1865 | 1,086 |

1868 | 4,955 |

… | |

1876 | 27,489 |

33 The Unoccupied Crown Lands Occupation Act 1860 (Qld) came into effect on 1 January 1861. It divided Queensland into 12 pastoral districts and established a process for claiming and leasing pastoral land. The present claim area was covered or surrounded by the Leichhardt Pastoral District to the east, the Kennedy Pastoral District to the north and the Mitchell Pastoral District to the west. The first lease was granted in the claim area under that statutory regime in 1852 when Mr Jeremiah Rolfe took up a lease at a place he called Pioneer Station on Mistake Creek. It was located in the northern part of the claim area. Dr Skyring recorded in her report that:

For two years it remained unoccupied by Rolfe, and it was not until 1854 that he stocked the run. Later he brought his family, and in December 1856 his first granddaughter was born there. His granddaughter later recalled that the homestead was,

built like a fort, with loopholes [for guns] in the walls of heavy split logs. The Aborigines had been truculent, and had shown their feelings by spearing cattle ever since Jeremiah Rolfe first settled there.

(Footnotes omitted)

34 At about the same time that Mistake Creek was being stocked, the Archer brothers purchased leases at Peak Downs, Retro, Capella and Gordon Downs, all east of present day Clermont and the claim area. By 1859, when Mr Gordon Sandemand and Mr James Milson bought those leases, they included Wolfang, Huntley and Crinium, and which were together described as Peak Downs. They appointed Mr Oscar de Satge as their manager in 1861. However, it took some time for de Satge to develop and stock the leases. Other leases were taken up in the general vicinity, as Dr Skyring noted in her report:

De Satge himself purchased Cheeseborough (also known in the records as Chessborough) a block northeast of Peak Range, about 20 kilometres from Peak Downs station. When de Satge went to manage the Peak Downs leases, including Capella and Retro, in 1863 he was based at Wolfang, described as the ‘head station’. De Satge’s nearest neighbour was Cheeseborough Macdonald (after whom he had named his own lease) at Logan Downs. De Satge’s brother Henri managed Gordon Downs near Crinium station, just to the east of the … claim area. For a period in 1864-65, Oscar de Satge was also associated with Huntley station, a short distance east of Clermont.

(Footnotes omitted)

35 To the west of the Peak Downs region on Gordon Creek near Clermont was Banchory Station. It was originally leased by Mr John Muirhead in 1860. As well, during the same period in the 1860s, a number of runs were leased in, or in the vicinity of, the claim area as follows:

In 1863 Bathahmpton Run was leased, at an area where the Blair Athol coal seam was later discovered. Further inland was Surbiton station, and in 1865 these runs were leased to William Kilgour. In 1861 the Dunrobin run was listed for sale, although it was not shown as a station on the early historical maps.

(Footnotes omitted)

36 In her report, Dr Skyring recorded that these early settlers were confronted with disease and experienced shortages of food and water. For instance, she cited the writings of Mr Cuthbert Fetherstonaugh who, in 1864, brought cattle overland from Rockhampton to his property at Burton Downs and recorded that the men in his droving team “were often short of food and water”. Furthermore, during his journey, Fetherstonaugh wrote that he met with Muirhead of Banchory Station, who informed him that his (Muirhead’s) wife had already died of scurvy. As well, Fetherstonaugh noted that Muirhead himself later died of disease. At Logan Downs, Fetherstonaugh wrote that “[a]ll of the supplies … were exhausted and they did not know when they would be getting more”.

37 When he arrived at Burton Downs, Fetherstonaugh wrote that a German family who had been working for him at the Station had all perished from fever and “ague”, a malarial fever. Fetherstonaugh also recorded that he was too nervous to sleep or light a fire during his journey because “these scrubs were full of wild blacks”. At a place about seven miles from Burton Downs, he camped in a clearing which he recorded was a “big pad…made by the blacks on the soft ground”. Dr Skyring speculated that this may have been the same clearing that Leichhardt recorded in his journal in 1845 as a place for “corroborris, (sic) and also for fighting” (see at [14] above).

38 Dr Skyring noted that, by 1864, the following stations had been established in the vicinity of the claim area, albeit that it remained “isolated”:

Mr. Black occupied Eaglefield station just west of Burton Downs, and William Gaden had a station on Mistake Creek. Tinwald Downs station on Kilcummin Creek was established in 1864 by James Wilkin and Co., and in the late 1860s was, for a while, managed by Fetherstonaugh. About ten miles west of Tinwald was the old Kilcummin head station. Craven’s station was southwest of where the town of Clermont would later be established. But ‘neighbours’ were still isolated. For instance it took two days along Clermont Road to ride from Tinwald Downs to Avon Downs. Craven’s station was effectively under siege in the early 1860s, and Aboriginal people regularly robbed the huts.

39 In addition to this influx of European settlers seeking to occupy land for pastoral purposes, others came in search of minerals. Copper was discovered at Peak Downs in 1860 and at a place later named Copperfield about seven kilometres south of Clermont. As well, gold was found at Sandy Creek near Clermont in 1861.

40 In his report, Dr Clarke recorded the following observations of historians Stringer and Stringer concerning the early development of the town of Clermont:

With water near at hand and the promise of alluvial gold, tents and shanties quickly appeared. There was no thought given to the suitability of the site as a permanent town: the prospectors were after gold. However, as the field continued to yield gold in payable quantities, the town of Clermont was surveyed by C. F. Gregory in December 1863 and the first sale of land took place four months later.

(Footnote omitted)

He added that:

Gold mining continued through the 1880s, and with the rail link reaching Clermont from Rockhampton via Emerald in 1884, Clermont became a regional centre.

(Footnote omitted)

41 As for the Aboriginal residents of Clermont, Dr Clarke noted in his report that:

The main Clermont Aboriginal camp was about two kilometres out of town, located near the junction of the Sandy and Wolfang Creeks. From newspaper accounts, the camp appears to have been quite large at the turn of the century, and it remained there until the early 1950s … The camp was populated with Aboriginal people originating from a wide area, who resided there while seasonally out of work.

(Footnotes omitted)

As an indication of the size of the camp by the late 1800s, Dr Skyring recorded that:

There were 161 blankets provided to the Clermont camp in 1897, and 150 proposed for 1898.

(Footnote omitted)

(5) The reverberating violence which ensued – from the 1860s

42 This wave of European settlement was resisted by the local Aboriginal people. Some of the newspaper accounts of that resistance, published during the 1860s and early 1870s, were reproduced in Dr Clarke’s report as follows:

29 … It was said that at Bowen Downs in 1862, to the near west of the [c]laim [a]rea, that:

When they [pastoralists Landsborough, Cornish and Buchanan] first formed a settlement, … the aborigines showed decidedly hostile tendencies. So warlike were these dusky neighbours that the station employees had to carry arms continually. The natives had their haunts in the Great Dividing Range, and in the desert country embracing the Belyando. The tribes from there appeared to cherish greater hostility against the whites than those who found their homes in the vicinity of the Thomson and Landsborough rivers.

…

32 … in 1864 the Elgin Downs Station was established in the area just north of the [c]laim [a]rea, and it was reported that …:

The sheep appeared to thrive well at the outset, but it was soon manifest that the ravages of the aborigines and native dogs would cause it to be inexpedient to continue with sheep. The blacks at that period were very hostile to the whites, and also so destructive to the stock that the flocks had to be continually watched. This entailed the employing of a number of shepherds. Several of these were murdered by the blacks, and a reign of terror supervened. In fact, so afraid were some of the shepherds that they could not be prevailed upon to go out alone. One shepherd in charge of a flock at an outstation had been murdered some days before the people at the head station were aware of the occurrence. The flocks in the meantime became scattered and much loss ensued.

…

36 … in the Rockhampton Bulletin on the 23rd of November 1869, [it was] announced that ‘That all hands have been murdered by the blacks at Elgin Downs Station, and that the Police Magistrate had started to inquire into the report’. Elgin Downs is to the north of the [c]laim [a]rea, but the killings had a wider impact across the region which includes the [c]laim [a]rea. It was explained that:

It is not likely there were more than a married couple and one or two hands on the station. The isolated position of the station, and the presence of only a few hands on it, would make the reported massacre more probable. We hear of another massacre on Avon Downs, situated ninety miles [145 kms] from Clermont, in the Port Mackay direction. It is reported that two troopers have been murdered by the blacks. This, though not confirmed, has come from a quarter we think reliable, and there is too much reason to fear that it is true.

…

39 In 1871 a newspaper item, titled ‘Black Outrages in Northern Queensland’, summarised the recent disappearance of three Europeans, who it was thought had all been killed by Aboriginal people in the Bowen Downs district, which is to the near west of the [c]laim [a]rea. The same account added that:

We also hear that the Belyando blacks have become very saucy, and announce their intention of driving the white men out of the country. However ridiculous this threat may be, it is still indicative of the frame of mind of our black neighbors [sic], and shows that in mercy to both races a lesson should be taught them to convince them of the absurdity of their ideas, and to inculcate the wisdom of submission.

(Footnotes omitted)

43 Dr Skyring’s report is replete with similar accounts. In particular, she described two massacres by Aboriginal men that had occurred on pastoral properties – one at Hornet Bank Station on the Dawson River (south of the claim area) in 1857 and the other at Cullin-la-Ringo Station (about 50 kilometres south of the claim area) in October 1861. Eleven settlers were killed in the first incident and 19 were killed in the second. By way of retribution, she noted that:

In his 1861 despatch to his colonial superiors in London, Queensland Governor Sir George Bowen wrote that approximately 70 Aboriginal people were killed in the aftermath of Cullin-la-Ringo …

However, she added that, based on unofficial accounts at the time, this was likely to have been an underestimate.

44 One of the main impacts of the Cullin-la-Ringo’s killings was an increased presence of the Native Police in and around the claim area. Dr Skyring opined that this increased presence “in turn prompted a continuing cycle of retaliatory violence by local Aboriginal people”. She added that “[t]he stationing of police barracks in the area seemed to exacerbate rather than diminish the violence”.

45 The origins and tactics of the Queensland Native Police Force were described by Dr Skyring in her report in the following terms:

The Native Police were established as a distinct branch of the colonial police force in northern NSW in 1848, and they soon gained a reputation for brutality towards Aboriginal people …

The Queensland Native Mounted Police Force (NMP) was established in 1859, and was organized along the same lines as the Native Police in New South Wales, in that it was force of displaced Aboriginal men commanded by European officers … The central policy in the recruitment of Aboriginal troopers was that they were foreigners to the area being policed. For instance, Aboriginal men from New South Wales were recruited to conduct ‘dispersals’ of Aboriginal groups in the south east of the Moreton Bay district and in the Darling Downs. In turn, Aboriginal men from the Condamine River and from the Albert and Logan River valleys west of Moreton Bay were recruited for action in northern and far western Queensland …

Some squatters and their employees joined with the Native Police in what were called ‘dispersals’, which despite the innocuous sounding name were organised murderous raids on groups of Aboriginal men, women and children. When asked at a Parliamentary inquiry in 1861 what he meant by ‘dispersing’ an Aboriginal camp, Native Police Lieutenant Frederick Wheeler simply responded, ‘firing at them’. Wheeler claimed he gave strict orders that his troopers do not shoot at women. But ‘indiscriminate slaughter’ of Aboriginal people was one of the many allegations of brutality investigate [sic] by the Queensland Legislative Assembly Select Committee in 1861.

(Footnotes omitted)

She added that:

Lieutenant Murray [the Northern District Commander of the Native Police] was clear that the role of the police under his command was to drive Aboriginal people away from the stations with murderous force.

With respect to the “dispersal” activities of the Native Police mentioned above, Dr Skyring noted in her report that “local squatters and their employees were every bit as homicidal as the Native Police”.

46 This violent period was described by several contemporary commentators as a “war”. For instance, Dr Skyring referred in her report to:

… an account published in [Ethnographer] Edward Curr’s second volume of The Australian race [1886-1887], [where] one of Curr’s ethnographic informants, William Chatfield of Natal Downs station on Cape River [about 35 kilometres north of the claim area], described the operation of the Native Police [in the following terms]:

the Blacks are attacked and some of them shot down. In revenge, a shepherd or stockman is speared. Recourse is then had to the Government; half-a-dozen or more young Blacks in some part of the colony remote from the scene of the outrage are enlisted, mounted, armed, liberally supplied with ball cartridges, and despatched to the spot under the charge of a Sub-inspector of Police. Hot for blood, the Black troopers are laid on the trail of the tribe; then follow the careful tracking, the surprise, the shooting at a distance safe from spears, the deaths of many of the males, the capture of the women, who know that if they abstain from flight they will be spared; the gratified lust of the savage, and the Sub-inspector’s report that the tribe has been ‘dispersed’, for such is the official term used to convey the occurrence of these proceedings. When the tribe has gone through several repetitions of this experience, and the chief part of its young men been butchered, the women, the remnant of the men, and such children as the Black troopers have not troubled themselves to shoot, are let in, or allowed to come to the settler’s homestead, and the war is at an end.

(Footnote omitted; bold added)

47 Mr Leo’s report included some similar commentary. He summarised the 1970 publication by historian Noel Loos in the following terms:

To begin with, Aboriginal people killed settlers, pillaged their huts, killed livestock, and disturbed sheep and cattle herds. This resulted in shepherds being ‘scare and expensive’, and frightened and isolated station workers resorted to guns and poisoned food to defend themselves. Also in response to such concerns a Native Police force, with the purpose of ‘subduing’ and ‘dispersing’ Aboriginal populations, was established. Successful Aboriginal resistance, plus a few well-publicised massacres of settlers by Aboriginal people, only served to intensify the punitive nature of the conflict. All this was in the context of a system of rule of law that did not effectively protect Aboriginal people from violence to their life and property. With unsettled areas legally conceived of as ‘waste and unoccupied’, settlers were therefore officially regarded as acting in self-defence, whereas Aboriginal people were seen as committing crimes against the settler’s life and property.

(Page numbers omitted)

(6) The “letting in” period which followed

48 One reaction to this widespread violence among some of the pastoral settlers was a practice called “letting in”. In Curr’s publication mentioned above, William Chatfield described that practice in the following terms:

Generally, after the first occupation of a tract of country by a settler, from three to ten years elapse before the tribe or tribes to which the land has belonged from time immemorial is let in, that is, is allowed to come to the homestead, or seek for food within a radius of five or ten miles of it. During this period the squatter’s party and the tribe live in a state of warfare; the former shooting down a savage now and then when opportunity offers, and calling in the aid of the Black Police from time to time to avenge in a wholesale way the killing or frightening of stock off the run by the tribe.

(Footnote omitted; bold added)

49 This “letting in” practice caused tension within the local settler community. Lieutenant Murray of the Native Police complained about it in a report to his superiors in 1867 and, as Dr Skyring noted:

Lieutenant Murray’s complaint about some squatters ‘letting in’ Aboriginal people to their head stations was an argument that was waged at the time by colonists, with the Peak Downs Telegram editors firmly on the side of the squatters who demanded the police ‘disperse’ Aboriginal people whose country they occupied.

50 In his report, Mr Leo quoted Loos’ more colourful description of the “keeping the blacks out” and “letting the blacks” in as:

… firstly, the act of open warfare and secondly, the acceptance of unconditional surrender by the Aborigines …

51 From the 1870s, this “letting in” approach became more common. Dr Skyring recorded in her report:

Despite the hounding of Aboriginal people by Native Police patrols in the previous decade [the 1860s], records indicated that people continued to camp on or close to the stations … At Avon Downs, one of Edward Curr’s informants, whose name he did not record, wrote that when the station was originally occupied in 1863 there were about 500 of the local tribe, which he called Nurboo Murre. By the early 1880s, this number had declined to about 100 people.

In the southern part of the … claim area, around the present day towns of Jericho and Alpha, the stations were stocked and employed large numbers of people. Isabel Hoch wrote that the station workforce in this area usually included Chinese people as cooks and gardeners, and Aboriginal people were employed as stockmen and general ‘hands’.

(Footnotes omitted)

52 Because the station managers did not routinely record the presence of Aboriginal workers on pastoral stations, Dr Skyring found it difficult to determine from the records she was able to examine at the John Oxley Library how many Aboriginal people living in and around the claim area took advantage of this “letting in” practice. Nonetheless, a separate set of records she was able to access for Alpha Station for the period 1884 to 1919 “showed a regular Aboriginal station workforce over decades”. Furthermore, she noted that some pastoralists treated the Aboriginal people living on their stations more kindly. In this respect, she noted that:

Other records depicted a peaceful routine of work on the stations, and in places like Ducabrook station Aboriginal people were able to continue the conduct of ceremony, inviting their neighbours for formal gatherings such as funerals and for less formal visits.

(7) The resultant declines in and migration within the Aboriginal population

53 Unsurprisingly, this violence, together with introduced diseases, caused a significant decline in the Aboriginal population in and around the claim area from the 1860s. Dr Clarke recorded various features of that phenomenon by reference to several newspaper articles and other reports, including the following:

54 [F]requent and relentless killings of Aboriginal people had taken place in the region of the [c]laim [a]rea from the 1860s until at least the 1880s. Newspaper accounts document the rapid Indigenous depopulation of the region. A pastoralist at Cape River to the near north of the [c]laim [a]rea remarked in the Queenslander newspaper that ‘measles in ‘65 [1865] and the vices of civilisation since have caused this rapid decrease,’ and he claimed that until 1868 the undisciplined Mounted Native Police were frequent visitors to the station and killed many of his Aboriginal shepherds and terrorised their families. In 1868, Rev. J.K. Black wrote to the Brisbane Courier about the Aboriginal ‘war of extermination’ taking place in north central Queensland, and he announced that he was making arrangements for sending orphaned children from the Cape River district across to Bowen for adoption by Europeans.

…

57 A newspaper journalist said in 1875 that ‘The aborigines in the Natal Downs country are reported to be dying in large numbers of measles’. In 1887, the early ethnographer MacGlashan remarked that ‘since the coming of the Whites a great many young children die of cold and low fever’ in the area between Belyando and Cape Rivers, which is to the north of the [c]laim [a]rea. Other deaths were due to the brutal actions, referred to euphemistically as ‘dispersals’ by the Mounted Native Police.

(Footnotes omitted; bold added)

54 Dr Skyring observed that it was difficult to estimate how many Aboriginal people had been killed or died in this period. However, she did note that one feature of the violence was that the:

[D]eliberate targeting of young Aboriginal men … seemed to be a pattern repeated across the region. The accounts from the squatters themselves usually referred to shooting Aboriginal men; in one of Fetherstonaugh’s accounts a woman was shot by mistake. The decimation of the male population would have had a devastating effect on Aboriginal groups in the … claim area. Yet, the records showed that Aboriginal people survived the slaughter and were eventually ‘let in’ to the stations to work.

55 On the extent of depopulation, again referring to Loos’ 1970 publication, Mr Leo noted in his report that, in the Bowen region to the north and east of the claim area:

As conflict generally abated and ‘letting in’ progressed, … by 1870 the Aboriginal population of the Bowen region, then numbering approximately 1,500 people, were able to resume “as much of their traditional life as possible” … New hazards, however, presented themselves to the Aboriginal population as it dwindled to an estimated 200 people by 1900, affected by such ills as poor diet, disease, alcohol and opium.

56 A measure of the “rapid decline” and partial extinction of some of the various “bura group populations relevant to Jangga [c]ountry and the surrounding region” from the 1860s was provided by Dr Clarke in his 2020 report where he included the following table of population estimates:

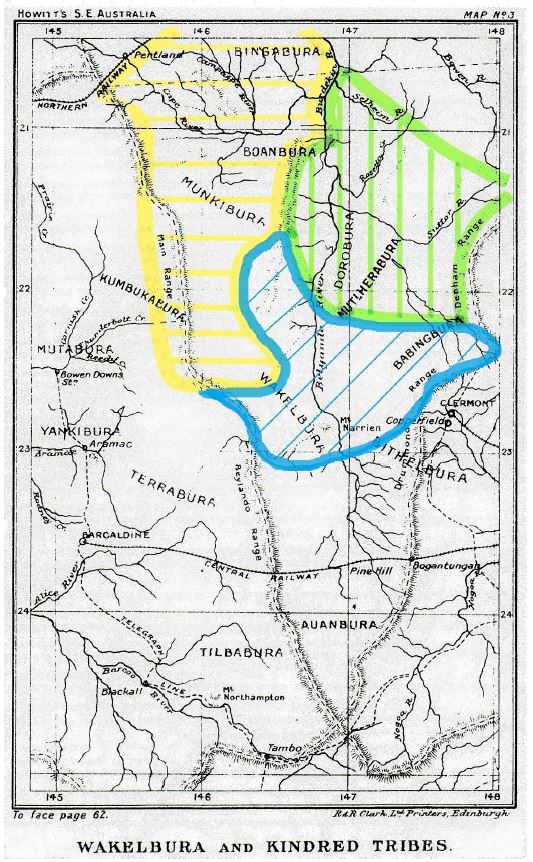

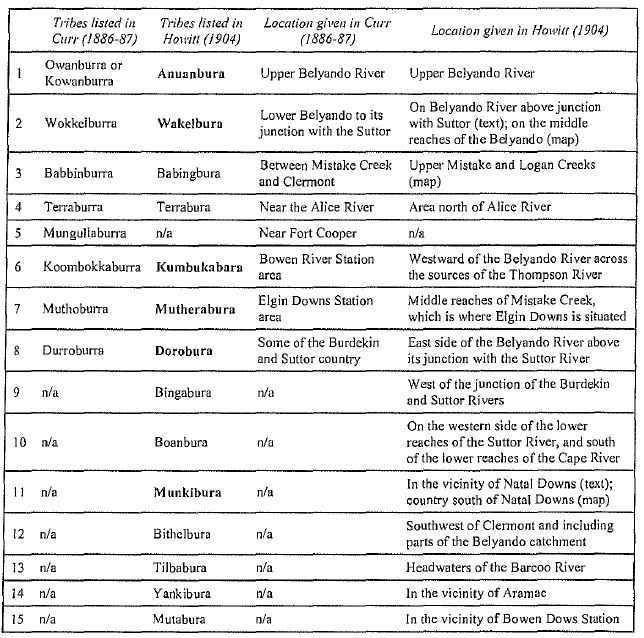

Table 1. Decline in bura group populations relevant to Jangga Country and the surrounding region.

Grouping [bura groups] | Location | First population estimate | Second population estimate | Source |

Auanbura (Owanburra, Kowanburra) | Upper Belyando River | 100 to 120 people in 1874 | 20 in 1908 | Muirhead (AIATSIS, cited Leo, 2011, Fig.17, p.71) |

Babingbura | North side of Drummond Range | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.826 |

Bingabura | Charters Towers area | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.826 |

Bithelbura | Southwest of Clermont | N/A | Extinct by 1865 | Howitt, 1904, p.63 |

Boanbura | Cape River | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.63 |

Dorobura | East of the Belyando River, along the Suttor River | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.62 |

Koombokkaburra (Howitt’s Kumbukabura) | Main Range between Cape & Belyando Rivers | 400 people in 1862 | 200 people in 1880 | Curr, 1878, p.18 |

Minkibura | Between Main Range & Belyando River | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.63 |

Mutabura | Tompson River, Bowen Downs to the Main Range | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.63 |

Mutherabura | Lower Mistake Creek | 80 people ‘once’ | Extinct by 1908 | Muirhead (AIATSIS, cited Leo, 2011, Fig.17, p.71) |

Pegulloburra [possibly Howitt’s Bingabura] | Natal Downs Station | 125 men plus many women & children in 1868 | 30 men, 50 women & some children in 1880 | Tompson & Chatfield, 1886, pp.470-471 |

Terrabura | Barcaldine area | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, p.826 |

Tilbabura | Upper Barcoo River | N/A | Extinct by 1865 | Howitt, 1904, p.63 |

Wakelbura [Chatfield’s Wokkulburra & Muirhead’s Wokkelburra] | Lower to mid Belyando River | 250-300 people in 1874 | 50 in 1908 | Muirhead (AIATSIS, cited Leo, 2011, Fig.17, p.71) |

Wudillaburra | N/A | 80 people ‘once’ | Extinct by 1908 | Muirhead (AIATSIS, cited Leo, 2011, Fig.17, p.71) |

Yambeena | Clermont district | 100 people in 1880 | N/A | Wilson & Murray, 1887, p.64 |

Yankibura | Aramac to Belyando Range | N/A | N/A | Howitt, 1904, pp.63-64 |

Yukkaburra [equivalent to Chatfield’s 1875 Yuckaburra] | Natal Downs Station | N/A | Extinct before 1862 | Tompson & Chatfield, 1886, p.468 |

Six Chatfield/Curr groupings (Yukkaburra, Pegulloburra, Wokkulburra, Mungooburra, Mungullaburra & Goondoolooburra) | Cape River catchment | N/A | 200 men & more women in 1880 | Tompson & Chatfield, 1886, p.471 |

57 In addition to this rapid decline in the Aboriginal population of the region, a significant migration occurred in and around the claim area. As already mentioned, some Aboriginal people moved closer to pastoral properties. As well, some moved to the relative safety of towns like Clermont. Dr Clarke observed, with respect to this migration, that:

With so much of the region surrounding the [c]laim [a]rea taken up by pastoralists and miners, Aboriginal people were forced to live in fringecamps on the edge of large towns, where they could stay when out of work or not required due to the season. People living here required rations in order to exist, and in towns like Clermont to the near southeast of the [c]laim [a]rea the levels of substance abuse within the Aboriginal community was severe. For instance, in 1896 it was reported in a Brisbane newspaper that:

The aboriginals in the Clermont district were presented with the usual blanket this afternoon. About thirty blacks attended, and among the number were to be seen a few splendid specimens of the native man, but the majority bore evidence of the white man’s civilisation in the shape of rum and opium.

(Footnote omitted)

(8) Controls and removals – the late 19th and early 20th centuries

58 The next stage of the European presence, while not associated with the same violence, had a very significant impact on almost every aspect of the lives of those Aboriginal people who remained living in, or around, the claim area. That occurred from the late 19th century with the passing of the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Qld) (the Protection Act). Dr Skyring summarised the controls that were introduced by that legislation in the following terms:

[T]he effects of the introduction of the [Protection] Act was that most Aboriginal people in Queensland ‘now became wards of the state’. The theme of policing which was central to the legislation was illustrated by the fact that police officers in each district were made the local ‘protectors’, and the newly appointed Northern Protector Dr. Roth and Southern Protector Archibald Meston reported to the Police Commissioner. Those appointed as ‘protectors’ had wide powers over the employment and removal of Aboriginal people, and all Aboriginal women in employment were under the supervision of a protector. Through the protectors, employers were required to secure permits from the Chief Protector’s Officer in order to employ Aboriginal workers, and this was supposed to be a way of vetting exploitative and abusive employers. Under the [Protection] Act, a written agreement had to be entered into between the employer and the Aboriginal worker.

(Footnotes omitted)

59 It was, however, possible to obtain an exemption from these provisions, as Dr Skyring noted:

While the assessment of applicants was an arbitrary and capricious process for Aboriginal people, for successful applicants it provided tangible benefits. They and their families were no longer ‘under the Act’, and could not be forcibly removed to a mission or settlement. For those who were granted exemption the documentation of their movement and employment ceased, and they mostly disappeared from the records of the Office of the Chief Protector. A number of families and individuals from the [claim area] applied for and were granted exemption, so their lives were not monitored and therefore not recorded under the wide ambit of departmental control.

60 One unusual side effect of this regime was the need for those Aboriginal people in employment to adopt surnames. That was so because, as Mr Leo noted in his report:

[E]specially in terms of setting up bank savings accounts: “many Aboriginal people at the time were known to whites only by a single Christen [sic] name”, hence, “Some took on the name of a European employer, others the name of the station; a few used their traditional names”.

61 Under this regime, from the late 1800s through to about the 1960s, “hundreds of Aboriginal people” were removed to reserves such as Durundur near present day Woodford (established prior to the passing of the Protection Act in 1877), Fraser Island (established in October 1897), Barambah near Murgon (officially gazetted as a reserve in 1904 and renamed Cherbourg in 1932), Yarrabah near Cairns, Palm Island and Woorabinda. When the Durundur and Fraser Island reserves were closed in the early 1900s, many of the occupants were moved to Barambah reserve. As a result, Barambah (later Cherbourg) became the largest Aboriginal reserve in Queensland. A total of 1,587 Aboriginal people were removed there after 1905 so that, by 1939, it had a total population of more than 1,000 people. In 1900, approximately two years after this regime was established, Mr Archibald Meston, the Southern Protector of Aborigines, reported that:

Since the passing of the Act I have removed to Frasers [sic] Island, Durundur and Deebing Creek over 300 men, women and children brought from all parts of Queensland … I have supplied the police of Queensland with 22 trackers and Victoria with two. Nearly 100 Aboriginals and half-castes have been removed from one locality to another for some special reason.

(Footnote omitted)

62 Most of the people who were removed from Clermont were taken to Durundur and, when it was closed, to Cherbourg. However, some were taken to Woorabinda (approximately 200 kilometres south east of Emerald) after it was established in 1927. As well, several Jangga people were removed to Woorabinda and to Palm Island.

63 One cause of those removals was the “Federation drought” (1895-1903) which had a dire effect on the residents of Clermont, including those living in the Sandy Creek camp. The collapse of the regional economy and the widespread unemployment that followed led to starvation among the camp residents, as reflected in a letter the Clermont Town Clerk wrote to the Home Secretary in early October 1902, as follows:

I am advised by this Council to bring under [sic] your notice the fact that the aboriginals in this district are in a condition of starvation and to ask if your Department can see its way to alleviate their condition, or render them assistance.

(Footnote omitted)

64 The solution devised by Meston, the Southern Protector of Aborigines, in May 1903 was to remove the Aboriginal people concerned to various reserves. As already mentioned, those people removed from Clermont at this time were taken to Durundur. Dr Skyring’s report included a list of people who were present at Durundur in late 1903, which included “fifteen people from Clermont, as well as several people from Jericho, Emerald, Logan Downs, Huntley, Peak Downs and Alpha”. The full list was as follows:

- Jack and Jim Malone from Jericho, also Possum, Maggie (27 yrs old) and Annie Grey (40 years old)

- Lizzie Thomas (34) from Gordon Downs

- Jim and George McEvoy from Logan Downs

- Jim Flourbag (47 years old) from Clermont, also Billie Barlow, Charlie 47 yrs old, Charlie 63 yrs old and Charlie 47, Maggie, 26 yrs old, Rosie, 19, Polly (49), and Polly (42), Kittie (40), and Kitty (27), Johannah (35), Tommy, George and Tom (72). Also from Clermont there was Tommy Thomas, Johnnie Robinson and Toby Widum

- From Alpha was Bob (36 yrs old), Harry (43), Peter and Bobby.

- From Emerald there was Pat Barney, Jennie, Sam, Tommy, Georgina, Agnes, Walter and Maggie

- From Peak Downs 5year old Nellie and from Huntley station 12 year old Herbert

65 Despite these removals, some Aboriginal people managed to remain in the Clermont area. For example, Dr Skyring recorded that:

Archival records from 1908 showed that there was a camp of Aboriginal people at Black Ridge, about twenty-four kilometres from Clermont.

It would appear that there were approximately 28 people living in that camp because, as Dr Skyring recorded in her report, the postmistress at Black Ridge, Mrs Matheson, wrote to her local Member of Parliament in April 1908 asking to be supplied with 28 blankets for the people living there.

66 The residents of Clermont were also drastically affected by floods in 1916, as Dr Skyring recorded:

The lower part of the town of Clermont was completely submerged, and Sapphire and Peak Downs were also flooded. In Clermont families sheltered on rooftops and 61 people lost their lives.

However, there is no evidence that similar removals occurred after this event possibly because, as Dr Skyring went on to note:

Aboriginal people at the Clermont camp had moved to higher ground because they knew that the floods were coming, sung by Hoppy Johnny as revenge for the mistreatment of him and his people by Europeans.

(Footnote omitted)

(9) Aboriginal employees in the cattle industry 1900 to 1970