FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Singapore Telecom Australia Investments Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2021] FCA 1597

ORDERS

SINGAPORE TELECOM AUSTRALIA INVESTMENTS PTY LTD Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 4.00 pm on 22 December 2021, the parties provide a proposed minute of orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment of the date of this order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[20] | |

[29] | |

[30] | |

[33] | |

[52] | |

[56] | |

[70] | |

[72] | |

[80] | |

[83] | |

[97] | |

[101] | |

[107] | |

[110] | |

[110] | |

[121] | |

[126] | |

[127] | |

[136] | |

[156] | |

[157] | |

[157] | |

[162] | |

[167] | |

[168] | |

[169] | |

[176] | |

[181] | |

[182] | |

[190] | |

[191] | |

[196] | |

General matters relating to stand-alone creditworthiness and implicit support | [205] |

[215] | |

[219] | |

[223] | |

[229] | |

[230] | |

[233] | |

[235] | |

Outline of Mr Chigas’s views as to the profits that might have been expected | [247] |

[268] | |

[271] | |

Outline of Mr Johnson’s views as to the profits that might have been expected | [281] |

[290] | |

[292] | |

[294] | |

[298] | |

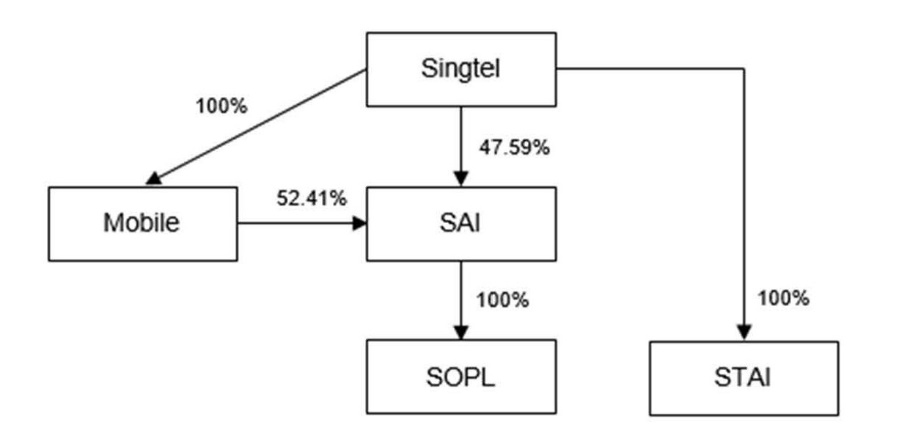

[298] | |

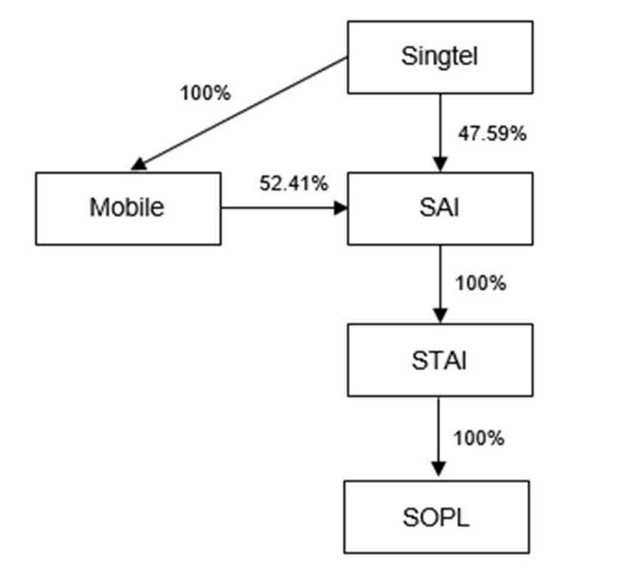

[301] | |

[317] | |

[349] | |

[353] | |

[355] |

MOSHINSKY J:

1 The issues to be determined in this proceeding concern the transfer pricing provisions of taxation legislation. Specifically, the issues concern the application of those provisions to a Loan Note Issuance Agreement (the LNIA) between:

(a) the applicant, Singapore Telecom Australia Investments Pty Ltd (STAI), a company incorporated and resident in Australia, as issuer of loan notes; and

(b) Singtel Australia Investment Ltd (SAI), a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands and resident in Singapore, as subscriber.

2 Both STAI and SAI are, and were at all material times, ultimately 100% owned by Singapore Telecommunications Ltd (SingTel), a Singapore-resident publicly listed company.

3 The immediate commercial context of the LNIA included the following. In June 2002, SAI sold 100% of the issued capital of Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (SOPL) to STAI, in consideration for approximately $14.2 billion. (References in these reasons to “$” are to Australian dollars unless otherwise indicated.) The consideration was satisfied (as to $9 billion) by STAI issuing ordinary shares to SAI and (as to approximately $5.2 billion) by STAI issuing loan notes under the LNIA to SAI. As a result of the transaction, and another transaction on 28 June 2002, STAI became a wholly-owned subsidiary of SAI.

4 The LNIA was entered into on 28 June 2002. It was subsequently amended by the following agreements:

(a) an agreement dated 31 December 2002 (the First Amendment);

(b) an agreement dated 31 March 2003 (the Second Amendment); and

(c) an agreement dated 30 March 2009 (the Third Amendment).

5 Pursuant to the LNIA as originally entered into, on 28 June 2002 STAI issued ten loan notes (the Loan Notes) totalling approximately $5.2 billion to SAI. Each Loan Note was redeemable at any time, and the maximum period for an advance was the period commencing on the first day on which interest accrued on the advance and ending on the last day of the tenth year following the year in which the advance was made. The interest rate under the LNIA as originally entered into was the 1 year Bank Bill Swap Rate (BBSW) plus 1% per annum. The applicable rate was the interest rate multiplied by 10/9.

6 The First Amendment amended the LNIA by providing that the maturity date in respect of a Loan Note could not be later than the tenth anniversary of the issue date less one day. The amendment was expressed to have effect from the date when the LNIA was originally entered into (28 June 2002). The First Amendment attracted little attention in the course of submissions in the present case, and does not appear to be particularly significant for present purposes.

7 The Second Amendment amended the LNIA by making the accrual and payment of interest contingent on certain benchmarks being met. The amendment agreement also increased the applicable rate by adding a premium of 4.552%. Again, the amendment was expressed to have effect from the date when the LNIA was originally entered into.

8 The Third Amendment changed the interest rate by replacing the 1 year BBSW with a fixed rate of 6.835%. The applicable rate therefore became: (a) the interest rate (6.835% plus 1%) multiplied by 10/9; plus (b) the premium (4.552%). This produced an applicable rate of 13.2575%.

9 In October 2016, the respondent (the Commissioner) made determinations under Div 13 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (the ITAA 1936) and under Subdiv 815-A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (the ITAA 1997) relating to STAI and in respect of the years ending 31 March 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013 (in lieu of the years of income ending 30 June 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013). The determinations under Div 13 and under Subdiv 815-A were in the alternative to the other.

10 The Commissioner issued notices of amended assessment to STAI in respect of the years ended 31 March 2011, 2012 and 2013. Although determinations were made for four years, the effect of each determination for the year ending 31 March 2010 was a reduction in carry forward losses. Consequently, that adjustment was reflected in the amended assessment for the year ending 31 March 2011, which gave effect to the determinations for the years ending 31 March 2010 and 2011.

11 The following table, which is based on a table set out in STAI’s written submissions, sets out key details regarding the actual interest paid by STAI to SAI in the years ending 31 March 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013 and the deductions denied by the Commissioner’s determinations:

Year ending | Actual interest paid | Interest determined to be deductible | Denied Deductions | Increased taxable income/ decreased loss |

31 March 2010 | $1,022,939,526 | $1,020,198,432 | $2,741,094 | $2,741,094 |

31 March 2011 | $898,998,264 | $423,994,155 | $475,004,109 | $475,004,109 |

31 March 2012 | $669,769,864 | $333,813,495 | $335,956,369 | $335,956,369 |

31 March 2013 | $162,141,041 | $81,068,245 | $81,072,796 | $81,072,796 |

Total | $894,774,368 | $894,774,368 |

12 In December 2016, STAI lodged objections against the amended assessments. In September 2019, the Commissioner disallowed STAI’s objections.

13 STAI appeals to this Court pursuant to Pt IVC of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) against the Commissioner’s objection decisions.

14 Although the case involves both Div 13 of the ITAA 1936 and Subdiv 815-A of the ITAA 1997, the focus of argument on both sides was on Subdiv 815-A of the ITAA 1997.

15 The main issues to be determined under Subdiv 815-A can be summarised as follows. Under s 815-15(1) (set out later in these reasons), an entity (here, STAI) obtains a “transfer pricing benefit” if the matters set out in paragraphs (a) to (d) of s 815-15(1) are satisfied. Those paragraphs refer to the following facts and matters:

(a) the entity is an Australian resident – here, there is no issue that STAI is and was at all relevant times an Australian resident;

(b) the requirements in the “associated enterprises article” for the application of that article to the entity are met – here, the relevant article is Art 6 of the Agreement between Australia and Singapore for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income, and the protocols to that agreement (the Singapore DTA) (set out below) and the relevant requirements are:

(i) an enterprise of one of the Contracting States participates directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of an enterprise of the other Contracting State – here, there is no issue that SAI (which is resident in Singapore) participated directly in the management, control and capital of STAI (which is resident in Australia) in each of the relevant years;

(ii) conditions operate between the two enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which might be expected to operate between independent enterprises dealing wholly independently with one another – this is one of the issues to be addressed; it will be referred to as the Conditions Issue;

(c) but for the conditions mentioned in the associated enterprises article, an amount of profits might have been expected to accrue to the entity; and, by reason of those conditions, the amount of profits has not so accrued – this is another issue to be addressed; it will be referred to as the Profits Issue; and

(d) had that amount of profits so accrued to the entity, the amount of the taxable income of the entity for the income year would be greater than its actual amount, or the amount of a tax loss of the entity for an income year would be less than its actual amount – this matter is consequential on the issues identified above.

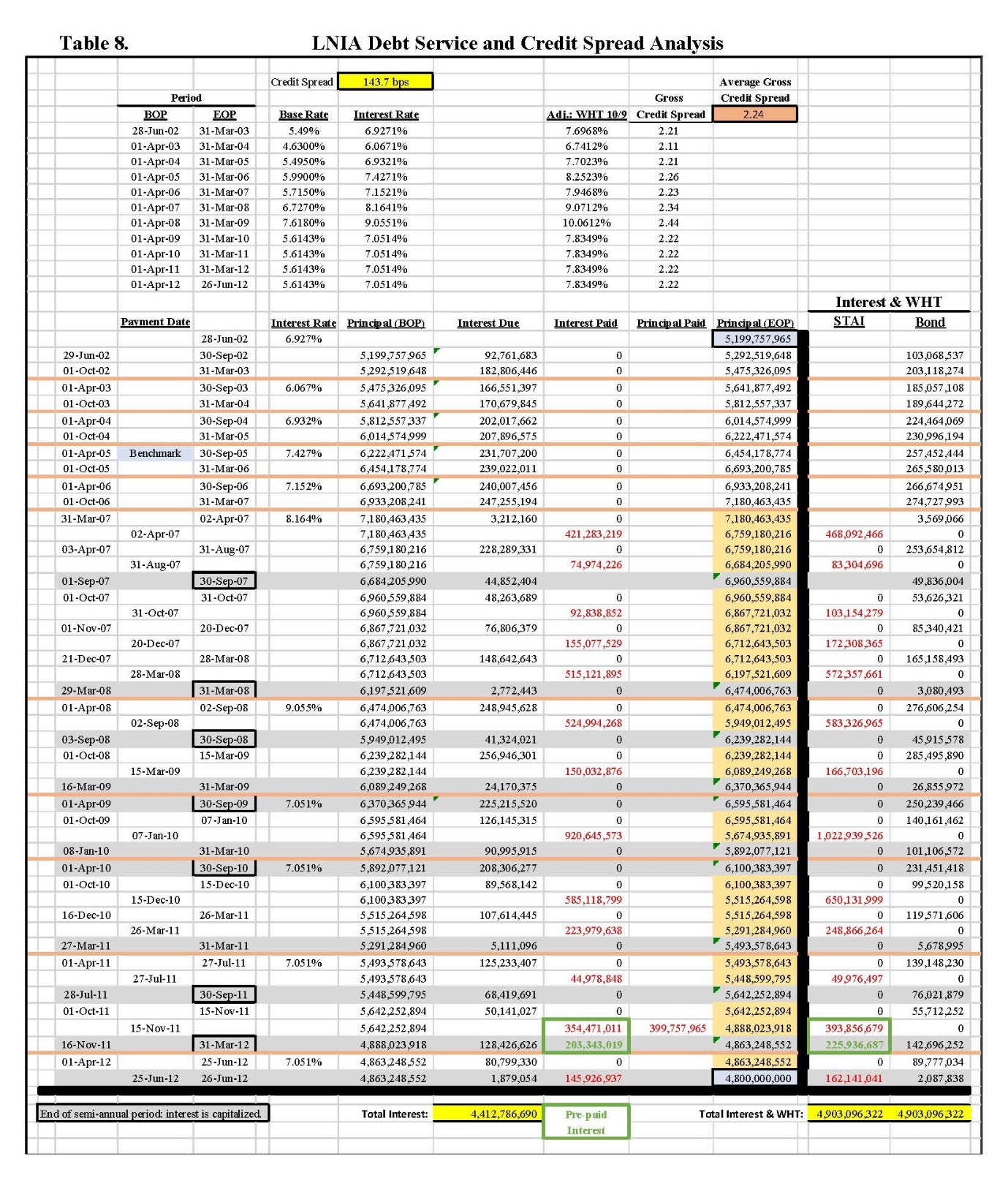

16 STAI contends, in summary, that its actual cost of borrowing under the LNIA was not greater (and in fact was significantly less) than the costs that a party in STAI’s position might be expected to have paid to an independent party acting wholly independently so as to achieve the same cash flow advantages as STAI actually achieved. Specifically, STAI contends that the effective credit spread of the LNIA over the life of the LNIA (which its expert witness, Mr Charles W Chigas, calculates to have been 144 basis points (bps) plus a withholding tax gross-up) is lower than the credit spread that might reasonably be expected to have been agreed in an arm’s length debt capital markets (DCM) transaction between independent parties.

17 The principal difficulty with STAI’s approach, in my respectful opinion, is that it departs too far from the actual transaction and the characteristics of the parties to that transaction, and thus departs from the approach required under Subdiv 815-A. The actual transaction involved a vendor and a purchaser of shares, and an issue of loan notes totalling approximately $5.2 billion by way of partial consideration for the acquisition of the shares. It did not involve a DCM bond issue. Further, I consider there to be significant differences between the terms of the LNIA and the terms of a typical DCM bond issue. A second difficulty with STAI’s approach is that it involves the calculation (in hindsight) of the effective credit spread of the LNIA, and a comparison of this credit spread with that of an STAI-issued DCM bond issue, rather than an approach which focuses on what independent parties in the positions of SAI and STAI, dealing independently with each other, might be expected to have agreed in June 2002, and at the time of each relevant amendment to the LNIA.

18 For the reasons set out below, I have concluded as follows:

(a) In relation to the Conditions Issue, I have concluded that conditions were operating between STAI and SAI in their commercial and financial relations which differed from those which might be expected to operate between independent enterprises dealing wholly independently with one another. The conditions are described later in these reasons.

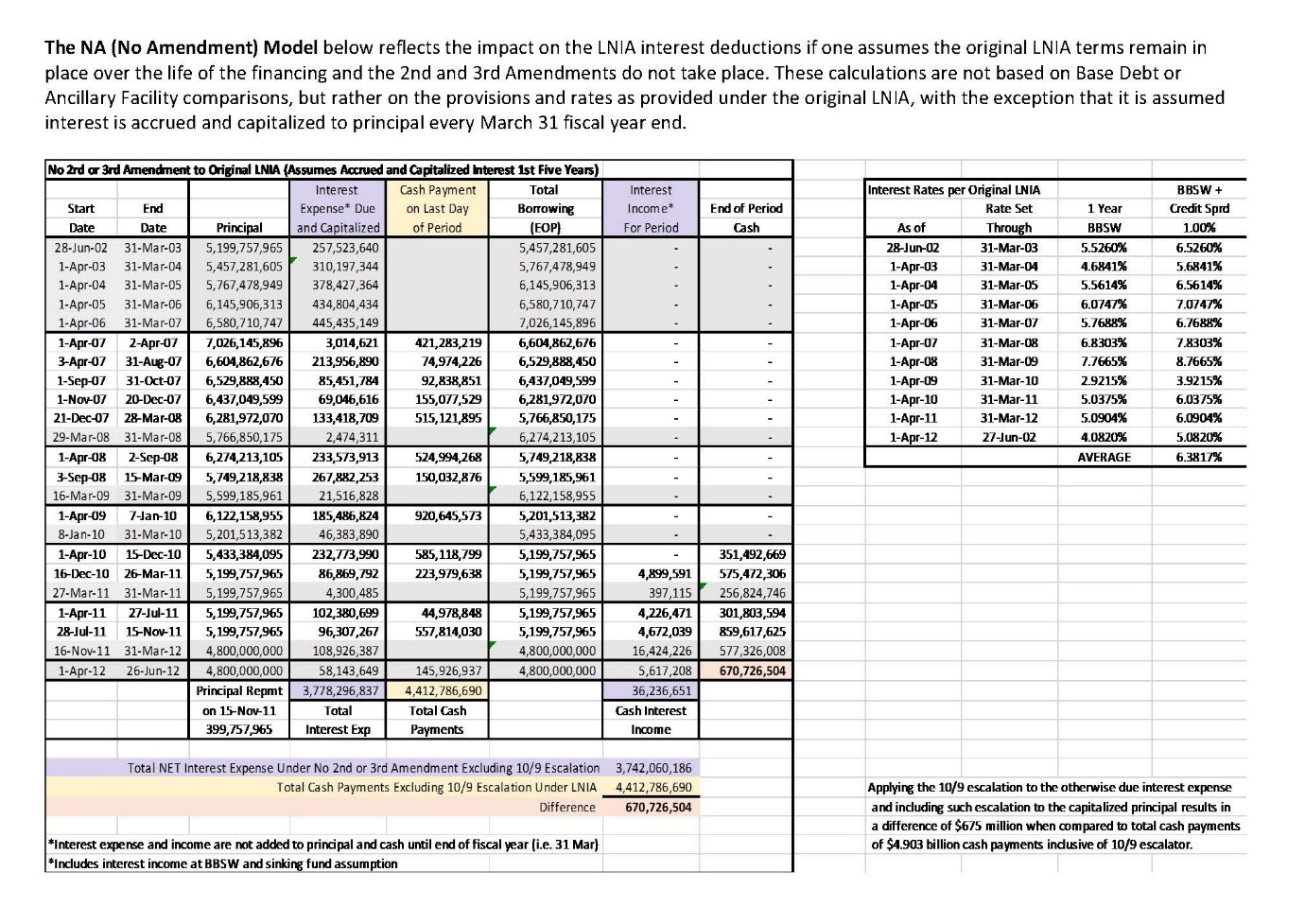

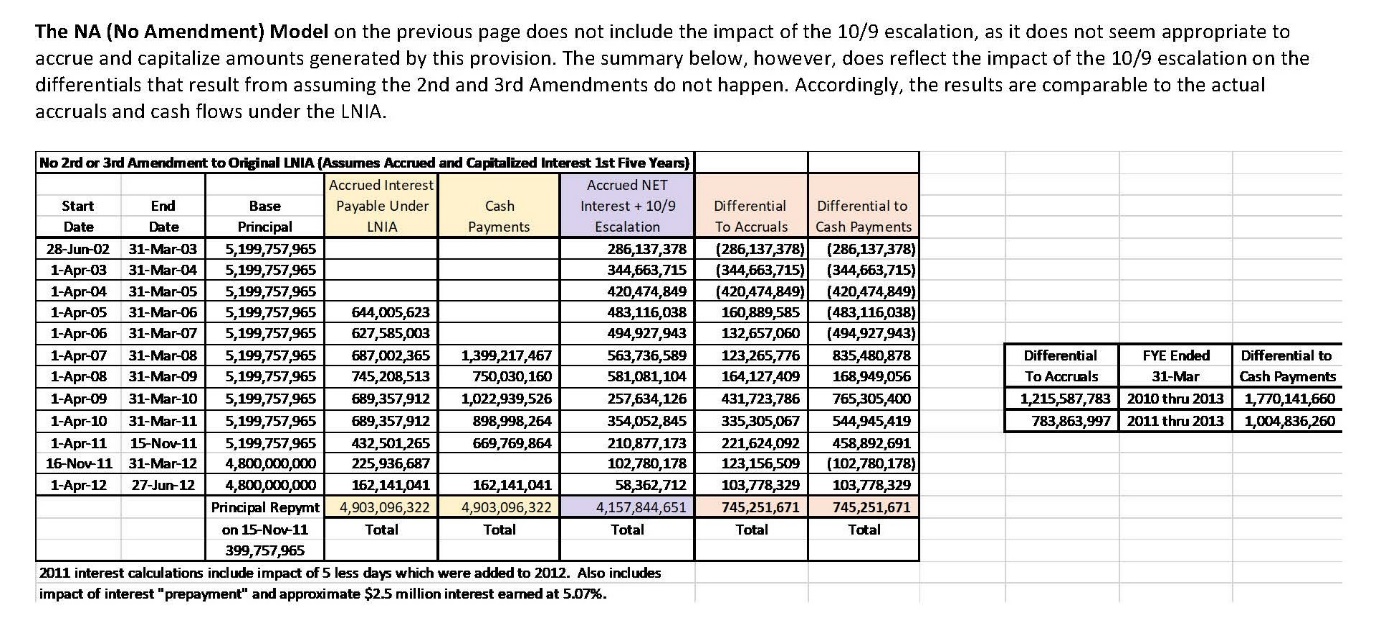

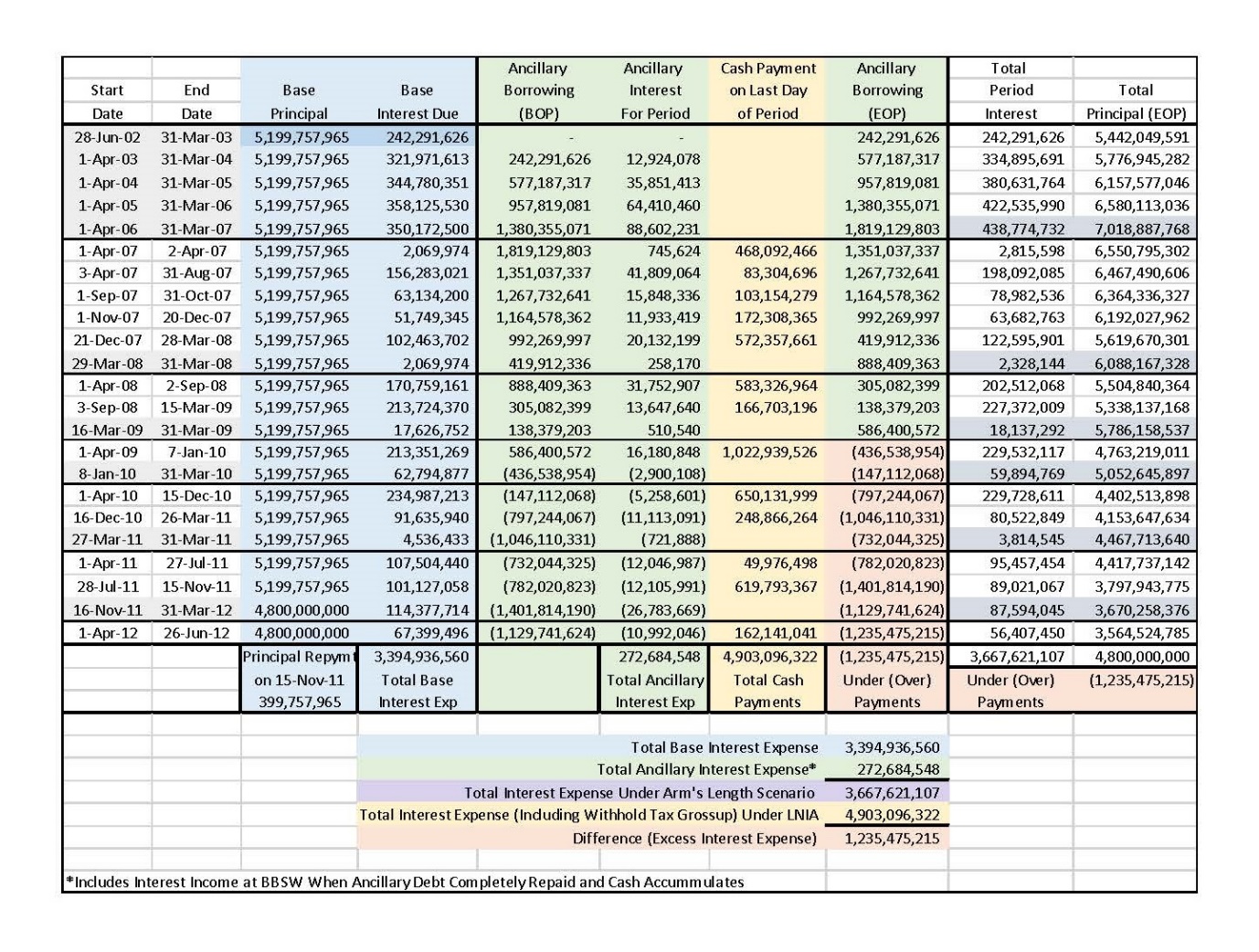

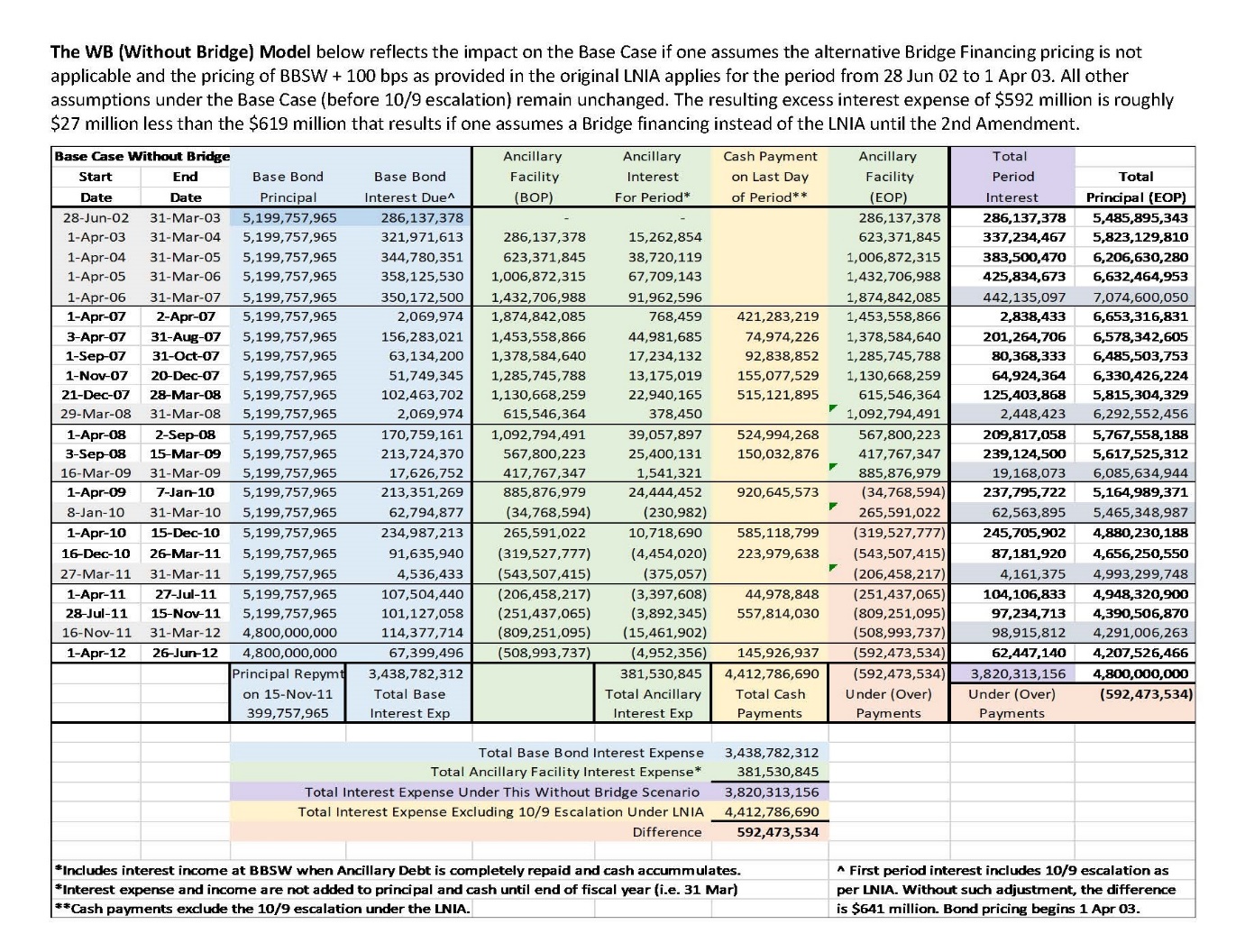

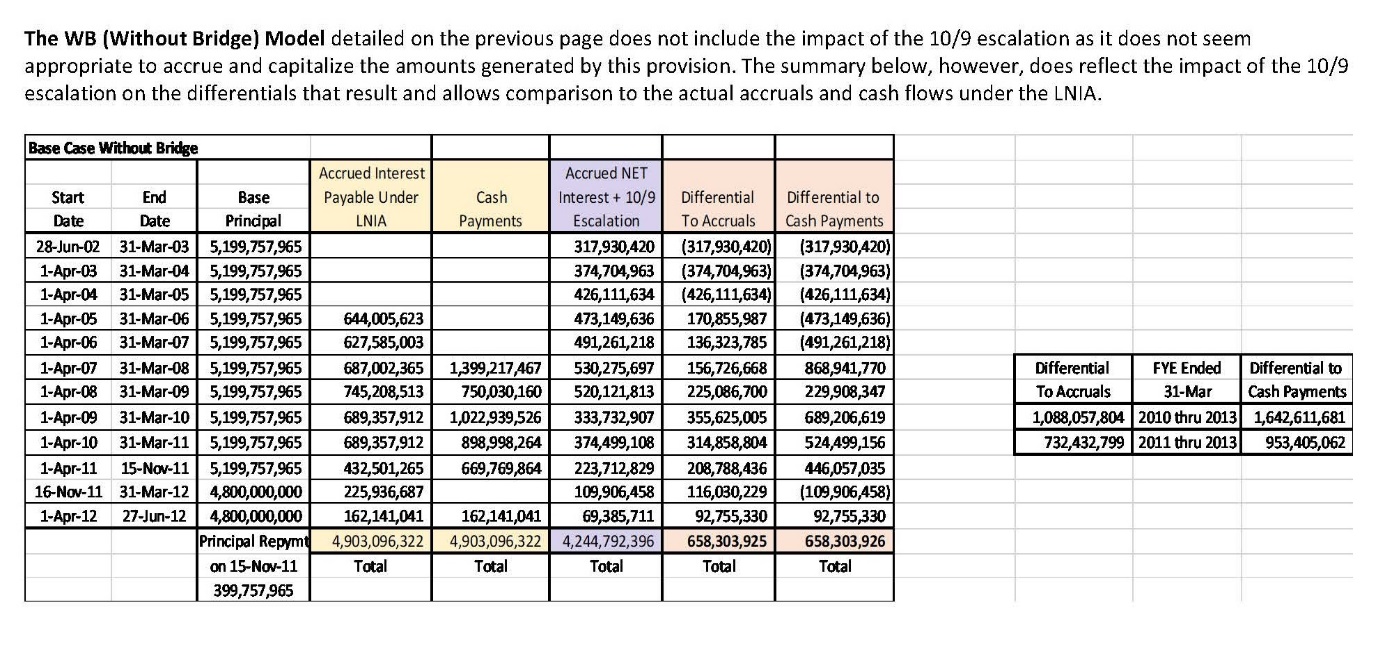

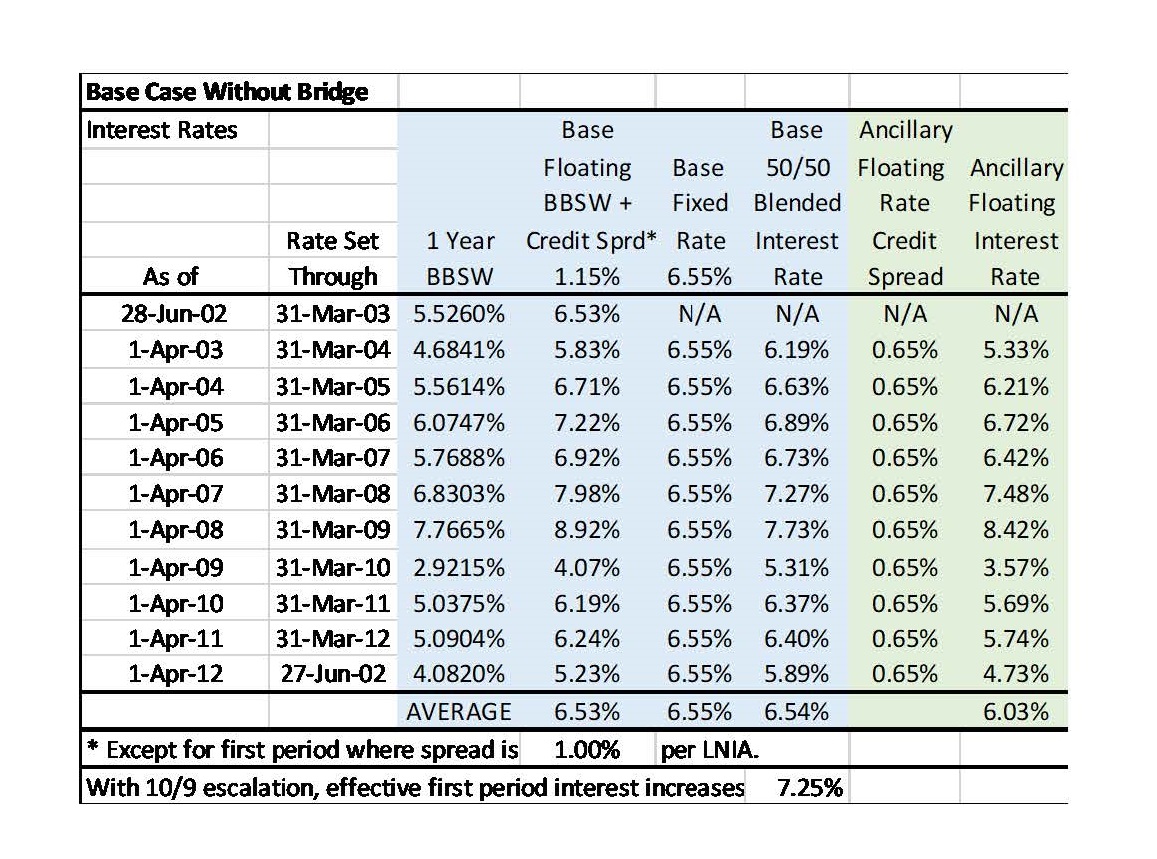

(b) In relation to the Profits Issue, I have concluded that a reliable hypothesis is that independent parties in the positions of SAI and STAI (and SingTel) might have been expected to have agreed in June 2002 that: the interest rate applicable to the loan notes would be the 1 year BBSW plus 1%, with the resulting amount grossed-up by 10/9 (that is, the same rate as was actually agreed in the original LNIA); interest under the loan notes could be deferred and capitalised; and, there would be a parent guarantee from a company like SingTel of the obligations of the company in the position of STAI. Further, having agreed to a transaction with these components in June 2002, a reliable hypothesis is that independent parties in the positions of SAI and STAI would not have agreed to make the changes contained in the Second or Third Amendments. The Commissioner has provided calculations of the interest that would have been payable for each year of the life of the LNIA on the assumption that the interest rate was the rate originally agreed by the parties and on the further assumption that the Second and Third Amendments did not take place. These calculations are set out in the “No Amendment Model” in calculations prepared by Mr Gregory Johnson, an expert witness called by the Commissioner, dated 8 August 2021 titled “STAI Alternative No Bridge and No Amendment Assumptions” (exhibit R4) (Mr Johnson’s Further Calculations). A copy of the No Amendment Model is annexed as Annexure D to these reasons. On the basis of these calculations, I have concluded that, for each of the years ended 31 March 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013, but for the conditions referred to in (a) above, an amount of profits might have been expected to accrue to STAI; and that, by reason of those conditions, the amount of profits has not so accrued.

19 It follows from those conclusions that STAI has not demonstrated that the amended assessments are excessive.

20 Due to restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the hearing of this proceeding took place by video-conference, using Microsoft Teams.

21 The hearing was conducted with an electronic Court Book. This was supplemented with additional documents (also in electronic form).

22 STAI called one lay witness, Mr Paul O’Sullivan (Mr O’Sullivan), the Chairman and a director of SOPL. Mr O’Sullivan was the Chief Operating Officer of SOPL from September 2001 to August 2004. He was the Chief Executive Officer of SOPL from September 2004 to March 2012. He was a director of STAI from 27 September 2004 to 8 October 2014. Mr O’Sullivan’s evidence-in-chief was largely contained in an affidavit dated 28 May 2020. Mr O’Sullivan also gave some additional oral evidence-in-chief. Mr O’Sullivan was cross-examined. Mr O’Sullivan gave evidence in a clear and straightforward manner. He demonstrated a good command of the material.

23 STAI called the following expert witnesses:

(a) Dr William J Chambers, in relation to credit rating; and

(b) Mr Charles W Chigas, primarily in relation to DCM matters, but also in relation to credit rating.

24 The evidence relating to credit rating was, in effect, one of the ‘inputs’ for the purposes of the DCM evidence. That is because the DCM evidence discussed a hypothetical DCM transaction by STAI (or a company in STAI’s position). In order to consider the interest rate for that transaction, it was necessary to consider the credit rating of STAI (or the company in STAI’s position).

25 The Commissioner called the following expert witnesses:

(a) Mr Robert A Weiss, in relation to credit rating; and

(b) Mr Gregory Johnson, in relation to DCM matters.

26 In relation to credit rating, Mr Weiss and Dr Chambers each prepared a report. Mr Chigas also referred to credit rating in his reports. In addition, a joint report was prepared by Dr Chambers, Mr Weiss and Mr Chigas dated 27 January 2021 (the Joint Credit Rating Report). These three witnesses gave evidence concurrently in relation to credit rating.

27 In relation to DCM matters, Mr Chigas prepared an initial report and a reply report, and Mr Johnson prepared a report. A joint report on DCM matters dated 26 January 2021 was prepared by Mr Chigas and Mr Johnson (the Joint DCM Report), and they gave evidence concurrently in relation to DCM matters.

28 I will outline the qualifications of the experts, and discuss their evidence, later in these reasons.

29 There is no real dispute about the background facts, which are set out in this section.

30 SingTel is, and was at all material times, a publicly listed company resident in Singapore, principally engaged in the operation and provision of telecommunications systems and services.

31 On 1 May 2001, SAI was incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. It was resident in Singapore. At all material times, it was owned 47.59% by SingTel and 52.41% by Singapore Telecom Mobile Pte Ltd (Mobile), a company resident in Singapore and wholly owned by SingTel.

32 On 3 May 2001, STAI was incorporated in Australia. It is, and was at all material times, an Australian resident.

SAI’s acquisition of CWO (2001)

33 Prior to October 2001, Cable & Wireless Optus Ltd (CWO) operated a telecommunications business known as “Optus” in Australia. Approximately 52% of the shares in CWO were held by a subsidiary of Cable & Wireless plc (C&W Plc). The balance was held by numerous public shareholders.

34 In March 2001, SingTel submitted a non-binding offer to C&W Plc to acquire 52% to 100% of CWO and was selected as the preferred bidder for CWO.

35 On 25 March 2001, SingTel entered into an Implementation Agreement with CWO with respect to implementing a transaction under which all CWO shareholders would be invited by the bidder (a non-Australian subsidiary of SingTel or SingTel itself) to dispose of their CWO shares, and SingTel then announced to the market that it had reached agreement with CWO on the terms of an offer to acquire CWO. This agreement was subsequently amended on 18 May 2001 (as so amended, referred to in these reasons as the Implementation Agreement).

36 Under the terms of the Implementation Agreement, SingTel was required (among other things):

(a) to nominate a bid vehicle that was not an Australian resident, which was to make an offer to all CWO shareholders to acquire their shares on the terms set out in the Implementation Agreement;

(b) to include alternative mechanisms for the disposal by a CWO shareholder of its CWO shares, including an option to have all or any of its shares bought back by CWO under a share buy-back; and

(c) in the case of CWO shareholders who elected to take the buy-back alternative, to lend on a subordinated and interest-free basis to CWO the funds necessary for CWO to pay the price payable by CWO to its shareholders under the share buy-back.

37 On 18 May 2001, SingTel, through SAI, made a takeover offer for CWO.

38 On 20 August 2001, SAI and STAI entered into an option agreement (the Option Agreement) under which:

(a) STAI was granted a call option to purchase CWO shares from SAI; and

(b) SAI was granted a put option to sell the CWO shares to STAI.

39 The price of the CWO shares under the call option and the put option was the sum of the amount shown in SAI’s accounts as the average price paid by SAI for the CWO shares, plus the incidental costs (such as transaction costs and interest) to SAI of acquiring and holding the CWO shares.

40 On 23 October 2001, SAI acquired 100% of the issued shares in CWO (comprising 2,143,668,118 ordinary shares, after deducting the shares bought back).

41 On 30 October 2001, the subordinated loan advanced by SingTel to CWO to fund the share buy-back was converted to 1,643,098,304 ordinary shares in CWO issued to SAI, which was equal to the number of CWO shares bought back by CWO.

42 The total consideration paid by SAI to acquire the 3,786,766,521 ordinary shares in CWO was S$13,002.4 million (approximately $14 billion), comprising:

(a) S$7,225.9 million (approximately $7.8 billion) in cash;

(b) S$4,559.9 million (approximately $4.9 billion) in SingTel ordinary shares; and

(c) S$1,236.6 million (approximately $1.3 billion) in fixed rate securities.

43 To fund its acquisition of CWO, SAI obtained $3.5 billion in debt from SingTel and $10.484 billion in equity contributions from SingTel, either directly or via Mobile.

44 SingTel in turn obtained the funds required to fund SAI’s acquisition of CWO (including the subordinated loan that SingTel made to CWO under the Implementation Agreement), as follows:

(a) a S$1 billion (approximately $1.14 billion) issue of 5 year bonds with a coupon rate of 3.21%, issued on 15 March 2001;

(b) a $3 billion short-term bridge facility obtained on 11 May 2001 for a term of 6 months (with options to renew for a further 6 months);

(c) approximately US$700 million in 5 year and 7 year US bonds, issued on 6 September 2001, offered as part of the consideration for the takeover of CWO.

45 In late September and early October 2001, before completion of the acquisition of CWO SingTel identified that it needed to raise additional funding totalling approximately S$4.85 billion or US$2.8 billion (approximately $5.6 billion) in order to refinance the $3 billion short-term bridge facility (referred to above) and meet certain other commitments, and decided to raise that amount by putting in place new borrowings with an average debt maturity of 8 years.

46 In October 2001, shortly after the acquisition of CWO was completed, SingTel had a Standard & Poor’s (S&P) credit rating of AA-.

47 It is convenient at this point to set out the rating scales of both S&P and Moody’s, which are well-known rating agencies. Details of their rating scales are set out in the following table, which is based on Table 3 of the Joint Credit Rating Report:

S&P and Moody’s Rating Scales | ||||||

S&P | Moody’s | Rating Category | S&P | Moody’s | Rating Category | |

AAA AA+ AA+ AA- A+ A A- BBB+ BBB BBB- | Aaa Aa1 Aa2 Aa3 A1 A2 A3 Baa1 Baa2 Baa3 | Investment Grade | BB+ BB BB- B+ B B- CCC+ CCC CCC- CC | Ba1 Ba2 Ba3 B1 B2 B3 Caa1 Caa2 Caa3 Ca | Non- Investment Grade | |

C D | C | |||||

48 The levels in the rating scales are referred to as “notches”.

49 In November 2001, SingTel made a US$2.3 billion global bond issue, which was used to refinance short-term borrowings, including the $3 billion short-term bridge facility.

50 Following SAI’s acquisition of CWO (on 23 October 2001), CWO changed its name to Singtel Optus Ltd (on 30 October 2001) and then to Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (referred to as “SOPL” in these reasons) (on 13 December 2001).

51 Following the acquisition, SOPL’s credit rating was upgraded by S&P and Moody’s to A+ and A2 respectively. I note that these ratings do not correspond with each other in the table set out in [47] above. The expert evidence was that, as at 2002, there was a split of one notch as between S&P and Moody’s, with the Moody’s rating being one notch lower than the S&P rating.

The period December 2001 to June 2002

52 In or around December 2001, a decision was made within SingTel that SAI would exercise the put option in the option agreement.

53 By 11 March 2002, Optus Finance Pty Ltd (a wholly-owned subsidiary of SOPL) had applied to refinance its syndicated bank facility of $2 billion (which was due to mature in December 2002) on the basis that SingTel would provide a guarantee.

54 In May 2002, Optus Finance Pty Ltd entered into a $2 billion bank facility (with a guarantee from SingTel). There is no evidence that SingTel charged Optus Finance Pty Ltd a fee for the provision of the guarantee.

55 In April 2002, the SingTel Board formally approved the decision that SAI would exercise the put option in the Option Agreement.

STAI restructure and entry into the LNIA (28 June 2002)

56 On 28 June 2002, SAI exercised the put option under the Option Agreement and STAI acquired all the issued shares in SOPL for a price of approximately $14.2 billion. This was satisfied by:

(a) $9 billion of equity issued by STAI to SAI; and

(b) approximately $5.2 billion of debt, by way of issue of the Loan Notes under the LNIA.

57 Also on 28 June 2002, SingTel transferred its shareholding in STAI to SAI for $2.

58 As a result of the transactions that took place on 28 June 2002, STAI became a wholly-owned subsidiary of SAI. STAI also became the holding company of a group of companies, including SOPL, that operated the Optus telecommunications business in Australia.

59 The following diagram shows the relevant entities in the group before STAI’s acquisition of SOPL from SAI on 28 June 2002:

60 The following diagram shows the relevant entities in the group after STAI’s acquisition of SOPL from SAI on 28 June 2002:

61 On 28 June 2002, SAI and STAI entered into the LNIA. Recital A stated that STAI proposed to raise financial accommodation by the issue of unsecured, registered and transferable loan notes, to be subscribed for by SAI, to partially fund the acquisition of shares in SOPL.

62 The provisions of the LNIA are described in more detail below. In outline, the key provisions of the LNIA were, in summary, as follows:

(a) the “Interest Rate” was the 1 year BBSW, plus 1% per annum;

(b) the “Applicable Rate” was the Interest Rate multiplied by 10/9;

(c) interest accrued from the commencement of the LNIA, but was only payable if SAI issued a “Variation Notice” to STAI;

(d) interest that accrued but was not paid was capitalised;

(e) SAI could at any time require STAI to redeem the Loan Notes (cl 7.1); and

(f) STAI could repay the Loan Notes at any time on one business day’s notice (cl 7.3).

63 The provisions of the LNIA are now set out in more detail. The “Subscriber” was SAI and the “Issuer” was STAI. The following definitions were set out in cl 1.1 of the LNIA:

Advance means the face value of a Note issue or proposed to be issued by the Issuer in accordance with an Issue Request together with any interest capitalised under clause 8.3.

Applicable Rate means 10/9 of the Interest Rate.

…

Interest Period means, for an Advance, one month (or such other period or periods as the Holder may select in a Variation Notice), commencing on the first day on which interest accrues on an Advance, as specified in a Variation Notice, and ending on the date specified in that Notice.

Interest Rate means the sum of the 1 Year Swap Rate (mid) as determined by the Australian Financial Markets Association (AFMA) and displayed on the “Interest Rates Swaps 10AM Page” (as displayed on Reuters page “IRSW10AM”, Bloomberg page “AFRP 11 <GO>” or MoneyLine Telerate Pages 50352 - 50353) expressed as a percentage per annum and 1% per annum. The Interest Rate will be set on the Issue Date and on the first Business Day of the year and will not change during the year.

…

Issue Request means a notice from the Issuer to the Subscriber requesting the Subscriber to subscribe for Notes in accordance with this agreement.

Issuer’s Debt means, in respect of a Note, at any time the aggregate of:

(a) the amount of each Advance which has not been repaid to a Holder; and

(b) interest (including capitalised interest), fees and any other amounts owing at any time by the Issuer to a Holder whether under this agreement or a Note.

Maturity Date in respect of a Note means the date specified in a notice from the Holder of the Note to the Issuer demanding redemption of that Note or Notes in accordance with clause 7.1 of this agreement.

Maximum Period means, for an Advance, the period commencing on the first day on which interest accrues on an Advance, and ending on the last day of the tenth year following the year in which the Advance is made, or repayment of a Note, whichever occurs first.

Note means a note issued in accordance with an Issue Request pursuant to Clause 5.1 in the form set out in Schedule 1.

…

Variation Date means the date of issue of a Variation Notice as specified in the Variation Notice.

Variation Notice means a notice served by the Holder under clause 8.1. It may be in the form or having the effect of Schedule 2.

64 Clause 2.1 provided that SAI may, from time to time, subscribe for the Notes to be issued by STAI upon and subject to the terms of the LNIA. Clause 3 dealt with a Register of Holders. Clause 4 dealt with conditions precedent to Advances. Clause 5 dealt with Issue Requests. Clause 5.2 provided that each Note could have a face value, as agreed between the parties, of an amount up to $1 billion, which was repayable in accordance with cl 7. Clause 6 dealt with transfer of Notes.

65 Clauses 7 and 8 were as follows:

7. REPAYMENT OF ADVANCES

7.1 Maturity Date

A Holder may at any time require the Issuer to redeem all or any Notes registered in the name of the Holder by notice in writing. The date on which the Holder specifies the relevant Note is to be redeemed is the Maturity Date.

7.2 Redemption and Payment

On any Maturity Date, the relevant Note must be redeemed by the Issuer paying the Issuer’s Debt in respect of that Note to the Holder. Upon redemption of any Note, the Note must be cancelled and removed from the Register in accordance with clause 3.3.

7.3 Prepayment

On giving not less than one Business Day prior written notice to a Holder, the Issuer may prepay the Issuers Debt applicable to all or any of the Notes held by a Holder or Holders.

8. INTEREST

8.1 Holders may charge interest

(a) Each Holder may at any time determine to charge interest on all or any of the Notes registered in the name of the Holder by serving a Variation Notice on the Issuer which specifies:

(i) the Variation Date,

(ii) the details of the Note to be varied, and

(iii) the Interest Period. The Interest Period may be for a period of time before, including and after, the date of a Variation Notice.

(b) If a Holder serves a Variation Notice, clause 8.2 to 8.4 (inclusive) will apply.

(c) If a Holder does not serve a Variation Notice within the Maximum Period, clause 8.5 will apply.

8.2 Calculation of interest on issue of Variation Notice

8.2.1 Interest will accrue during an Interest Period on the relevant Advance at the Applicable Rate.

8.2.2 Interest:

(a) will accrue from day to day in an Interest Period,

(b) be computed on a daily basis on a year of 365 days, and

(c) is payable on the last day of an Interest Period or such other time as agreed between the parties.

8.3 Payment of interest on overdue interest

8.3.1 Interest not paid when due may as at the due date for its payment be capitalised and form part of the Advance.

8.3.2 Payment of any amount of interest capitalised under clause 8.3.1 is not waived or postponed because of such capitalisation and the Issuer will continue to be in default in respect of such payment.

8.4 Place for payment of interest

The Issuer must pay all interest instalments directly into such account as the Holder may nominate to the Issuer from time to time.

8.5 Calculation of interest for Maximum Period

8.5.1 Interest will accrue during the Maximum Period on the relevant Advance at the Applicable Rate.

8.5.2 Interest, to the extent not already due and payable as a result of the issue of a Variation Notice:

(a) will accrue from day to day in the Maximum Period,

(b) be computed on a daily basis on a year of 365 days, and

(c) is only payable on the last day of the Maximum Period or such other time as agreed between the parties.

8.6 Accrual of Interest in Issuer’s Accounts

The Issuer may make provisions for accrued, but unpaid, interest in its accounts provided that a Holder will not be entitled to payment of any interest unless and until:

(a) it serves a Variation Notice on the Issuer, or

(b) the expiry of the Maximum Period.

8.7 Payment by 12.00pm without deduction or set off

8.7.1 All payments required to be made by the Issuer under this agreement or a Note must be made to a Holder in full in immediately available funds prior to 12.00pm on the relevant due date (or any earlier time specified) without any deduction.

8.7.2 The Issuer irrevocably and unconditionally waives any right of set off, combination or counterclaim in relation to any such payments.

8.8 Credit for payment

8.8.1 The Issuer will be given credit for a payment only upon its actual receipt by a Holder in immediately available funds in the currency in which it is due.

8.9 Application of payments

8.9.1 The Issuer irrevocably waives its right to determine the appropriation of any money paid to a Holder. All payments will be applied at the sole election of the Holder and any rule determining application of payments does not apply. If the Holder has not made an election it will be deemed to have applied payments in the manner and against such money which is payable, as is in its best interests.

8.10 Taxation

If the Issuer is required to make any deduction or withholding in respect of Taxes (other than Excluded Taxes) from any payment due to a Holder under any Transaction Document, the Issuer:

(a) must pay the deduction or withholding to the relevant Government Agency by the due date; and

(b) promptly give the Holder any evidence it requires to prove that the payment has been made;

66 Clause 9 dealt with an indemnity if payment was received in a currency other than that of a Note. Clause 10 dealt with warranties and indemnities. Clause 11 dealt with events of default. Clause 12 dealt with the appointment of SAI as attorney for STAI. Clause 13 dealt with financial institutions duty and other duties, taxes and imposts in connection with the LNIA. Clause 14 dealt with notices. Clause 15 dealt with general matters. Under cl 15.5, the applicable law of the LNIA was New South Wales law. Clause 15.7 provided that the parties could only vary the agreement if the variation was in writing, signed by both the Issuer and the Holders.

67 Schedule 1 to the LNIA set out the form of a Note. The form stated that the amount was payable “on demand”. Schedule 2 to the LNIA set out two forms of Variation Notice.

68 On 28 June 2002, STAI issued the Loan Notes to SAI, totalling $5,199,757,965, in the following tranches:

(a) four Loan Notes of $1 billion each;

(b) five Loan Notes of $200 million each; and

(c) one Loan Note of $199,757,965.

69 On 1 July 2002, the group of companies headed by STAI elected to consolidate for tax purposes, with STAI as the head company of the consolidated group. This fact is noted for completeness. It is not significant for present purposes.

The First Amendment (31 December 2002)

70 On 31 December 2002, SAI and STAI entered into the First Amendment. By this agreement, the LNIA was amended by providing that the maturity date in respect of a Loan Note could not be later than the tenth anniversary of the issue date less one day. Given that the issue date was 28 June 2002, I would calculate the tenth anniversary less one day as being 27 June 2012. I note that in STAI’s submissions the date is said to be 26 June 2012. Nothing turns on this difference for present purposes. The amendments in the First Amendment were set out in clause 2 of the First Amendment:

2. VARIATION OF LOAN NOTE ISSUANCE AGREEMENT

2.1 Maturity Date

(a) The Subscriber and the Issuer agree that, effective from the date of the Loan Note Issuance Agreement, the Notes issued under the Loan Note Issuance Agreement will mature on demand, but in any event no later than the tenth anniversary of the Issue Date less one day.

(b) Consequently, the Loan Note Issuance Agreement is deemed to always have been entered into with the following definition of Maturity Date:

“Maturity Date” in respect of a Note means the date specified in a notice from the Holder to the Issuer demanding redemption of that Note or Notes in accordance with clause 7.1 of this agreement, but in any event no later than the tenth anniversary of the Issue Date less one day.

2.2 Maximum Period

(a) The Subscriber and the Issuer agree that, effective from the date of the Loan Note Issuance Agreement, the definition of Maximum Period is amended by deleting the words “last day of the tenth year following the year in which the Advance is made” and substituting those words with “Maturity Date”.

(b) Consequently, the Loan Note Issuance Agreement is deemed to always have been entered into with the following definition of Maximum Period:

“Maximum Period” means, for an Advance, the period commencing on the first day on which interest accrues on an Advance, and ending on the Maturity Date, or repayment of a Note, which ever occur first.

71 Clause 3.1 provided that, as soon as possible after the agreement, STAI would provide amended Notes to SAI. By cl 3.2, it was agreed that the amended Notes did not constitute new obligations of STAI, but merely amounted to an amendment to the Notes on issue at the date of the agreement. By cl 4, the parties otherwise confirmed the terms of the LNIA.

The Second Amendment (31 March 2003)

72 On 31 March 2003, SAI and STAI entered into the Second Amendment. The Recitals to the agreement stated that SAI and STAI had agreed to make a number of amendments to the LNIA, in particular in relation to the circumstances in which interest may become payable by STAI in respect of a Note and consequently when a Variation Notice could be served on STAI. The Recitals stated that SAI and STAI agreed to make amendments in accordance with the agreement and that all amendments were to take effect as at the date of the LNIA. Further, it was stated that all Notes issued under the LNIA were deemed always to have been issued subject to the terms of the LNIA as amended by the agreement.

73 In outline, the amendments effected by the Second Amendment were as follows:

(a) definitions of “Default Benchmark” and “Primary Benchmark” were introduced;

(b) the expression “Benchmark”, which was defined as meaning the Primary Benchmark and the Default Benchmark, was introduced;

(c) the provisions relating to the accrual and payment of interest were amended with the effect that the accrual and payment of interest were contingent on the occurrence of a Benchmark; and

(d) the Applicable Rate was amended by the addition of the “Premium”, which was 4.552%. The Applicable Rate therefore became the sum of: (a) the Interest Rate (which was the 1 year BBSW plus 1%) multiplied by 10/9; and (b) the Premium of 4.552%.

74 The terms of the Second Amendment are now set out in more detail. Clauses 2.1 and 2.2 of the Second Amendment inserted new definitions into the LNIA and amended existing definitions:

2.1 Insertion of Definitions in the Loan Note Issuance Agreement

The following definitions are deemed to have been inserted into the Loan Note Issuance Agreement effective from 28 June 2002.

Accumulated Free Cashflow as at the commencement of any quarter, means the sum of all cashflow of the Optus Group for all quarters, commencing on the Issue Date and ending on the last day of the previous quarter that are designated as “free cash-flow” in the Management Accounts.

Benchmark means the Primary Benchmark and Default Benchmark. A Benchmark occurs (if at all) when either Benchmark occurs.

Break Costs means $1,538,000,000 or such other amount the Issuer and a Holder agree to be the Holder’s genuine pre-estimate of the value of Premium it has forgone as a result of the Issuer’s Debt being prepaid in accordance with clause 7.3. It must be calculated by the Issuer and Holder in good faith having regard to:

(a) the time between prepayment of the Issuer’s Debt and the Maturity Date,

(b) if a Benchmark has not occurred the likelihood a Primary Benchmark will occur based on forecasts of results of the Consolidated Issuer Group,

(c) the opinion of any expert retained by the Issuer or Holder, and

(d) any other matters then relevant.

Consolidated Issuer Group means the Issuer and its wholly owned subsidiaries.

Default Benchmark occurs when any of the following occurs:

(a) An announcement of, or board resolution to effect, a change in at least 50% of the ownership of the Issuer;

(b) An Insolvency Event taking place in respect of the Issuer;

(c) A dividend declared by the directors of the Issuer in excess of $50,000,000;

(d) A return of capital of the Issuer in excess of $50,000,000 is approved by the holding company of the Issuer; or

(e) Projected tax payable in any year in the Consolidated Issuer Group, based on the Management Accounts, before any interest expense arising from this Agreement, is determined to be in excess of $100,000,000.

Default Interest Day is deemed to occur on the first day of the year in which a Default Benchmark occurs.

Government Agency means any Australian:

(a) state, federal or legal government department or authority;

(b) statutory corporation;

(c) government minister;

(d) governmental, semi-governmental, administrative or judicial person; and

(e) person (whether autonomous or not) charged with the administration of any applicable law.

Management Accounts means accounts prepared by the Optus Group in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles and practices in Singapore so as to show a true and fair view of the results of the Optus Group for the relevant period and of their assets and liabilities at that date.

Optus Group means SingTel Optus Pty Ltd ACN 052 833 208 and its subsidiaries.

PBT is calculated as at the last day of a quarter based on profits and losses of the Optus Group for each quarter since the Issue Date as disclosed in the Management Accounts. It is the sum of all profits and losses before taxation of the Optus Group calculated for all quarters commencing on the first day of the next quarter after the Issue Date, as disclosed in the Management Accounts.

Premium means 4.552%.

Primary Benchmark occurs in a quarter, when, as at the last day of that quarter:

(a) PBT was or exceeds $1,800,000,000; and

(b) Accumulated Free Cashflow was or exceeds $2,050,000,000.

Primary Interest Day means the first day of the quarter in which a Primary Benchmark occurred.

quarter date means 31 March, 30 June, 30 September and 31 December in any year.

quarter means each period of 3 months ending on a quarter date other than,

(a) the first quarter which commences on the Issue Date and ends on the next quarter date, and

(b) if the Maturity Date occurs on a date other than quarter date, the last quarter will commence on the day immediately after the previous quarter date and end on the Maturity Date.

Regulatory Change means:

(a) the introduction of, or change in, an applicable law or regulatory requirement or in its interpretation or administration by a Government Agency; or

(b) compliance by the Holder or by related body corporate of the Holder with an applicable direction, request or requirement (whether or not having the force of law and whether existing or future) of a Government Agency.

2.2 Amendments to Existing Definitions

The following definitions in the Loan Note Issuance Agreement are deemed to have been amended with effect from 28 June 2002.

(a) The definition of “Applicable Rate” is deleted and the following definition substituted as follows:

Applicable Rate means the sum of:

(a) 10/9 of the Interest Rate, and

(b) the Premium.

(b) The definition of “Business Day” is amended by inserting the following words after the word “Sydney”:

“(other than a Saturday, Sunday or public holiday)”.

(c) In the definition of “Excluded Tax” delete the words:

“Subscriber or”.

(d) In the definition of “Interest Period” delete:

(i) the words “one month (or” and “other” in the first line;

(ii) the bracket in the second line.

(e) [The] definition of “Interest Rate” is deleted and the following definition substituted as follows:

“Interest Rate during any year means the sum of:

(a) the 1 Year Swap Rate (mid) as determined by the Australian Financial Markets Association (AFMA) and displayed on the “Interest Rates Swaps 10AM Page” (as displayed on Reuters page “IRSW10AM”, Bloomberg page “AFRP 11 <GO>” or MoneyLine Telerate Pages 50352 - 50353) expressed as a percentage per annum, and

(b) 1%

as at the Issue Date and subsequently on the first Business Day of each year.”

(f) The definition of “Maturity Date” is deleted and the following definition substituted as follows:

“Maturity Date in respect of a Note means the first to occur of:

(a) the date specified in a notice from the Holder to the Issuer demanding redemption of that Note in accordance with clause 7.1,

(b) the date on which the Issuer’s Debt is prepaid in accordance with clause 7.3, or

(c) the tenth anniversary of the Issue Date less one day.”

(g) The definition of “Maximum Period” is deleted and the following definition substituted as follow[s]:

“Maximum Period means, for an Advance, the period commencing on a Default Interest Day or the Primary Interest Day (as the case may be) and ending on the Maturity Date.”

(h) In the definition of “Variation Notice” the cross reference to clause 8.1 is deleted and substituted with a cross reference to clause 8.2

(i) In clause 1.4.1 (d) add the following words at the end of the sentence:

“except the first year which will commence on the Issue Date and the last year which will end on the last day of the Maximum Period”.

75 Clauses 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5 amended clauses 7.1, 7.4 and 8 of the LNIA as follows:

2.3 Amendment to clause 7.1

2.3.1 The Subscriber and the Issuer agree that, effective from the date of the Loan Note Issuance Agreement clause 7.1 is amended by:

(a) inserting the following words after the word “time” in the first line:

“after a Benchmark occurs”.

2.4 Insert new clause 7.4

2.4.1 The Subscriber and the Issuer agree that, effective from the date of the Loan Note Issuance Agreement, the following words are inserted as clause 7.4

7.4 Break Costs on Prepayment

(a) Where a Benchmark has not occurred and the Issuer prepays the Issuer’s Debt in accordance with clause 7.3 before the tenth anniversary of the Issue Date less one day, the Issuer must pay the Break Costs to the relevant Holder.

(b) Where the Issuer prepays the Issuer’s Debt under clause 7.3 on or after the day when a Benchmark has occurred but before the tenth anniversary of the Issue Date less one day, the Issuer must pay the Holder an amount equal to the Premium multiplied by the Advance for the remaining period from the date of prepayment up to the tenth anniversary of the Issue Date less one day.

2.5 Amendment to clause 8

The Subscriber and the Issuer agree that effective from the date of the Loan Note Issuance Agreement, clause 8 is deleted and the following substituted:

“8. INTEREST

8.1 Payment of Interest

Interest is not payable on a Note unless:

(a) a Benchmark occurs; and

(b) (i) a Holder serves a Variation Notice, or

(ii) the Maximum Period expires.

8.2 Holders may charge interest

(a) If a Benchmark occurs each Holder may at any time, and on more than one occasion, determine to charge interest on all or any of the Notes registered in the name of the Holder by serving a Variation Notice on the Issuer which specifies:

(i) the Variation Date,

(ii) the details of the Note to be varied, and

(iii) the Interest Period.

(b) The Interest Period may be for a period of time before, including and after, the date of a Variation Notice provided it commences,

(i) if a Primary Benchmark occurs, on or after the Primary Interest Day; or

(ii) if a Default Benchmark occurs, on or after the Default Interest Day

For the avoidance of doubt, an Interest Period cannot exceed the Maximum Period.

(c) If a Holder serves a Variation Notice, clause 8.3 to 8.4 (inclusive) will apply.

(d) If a Holder does not serve a Variation Notice prior to the expiration of the Maximum Period, or if the Holder has served a Variation Notice or Notices are served and the Interest Period specified in the Variation Notice or Notices is less than the Maximum Period clause 8.6 will apply.

8.3 Calculation of interest on issue of Variation Notice

8.3.1 Interest:

(a) will accrue from day to day during an Interest Period at the Applicable Rate,

(b) will be computed on a daily basis on a year of 365 days, and

(c) is payable on the last day of an Interest Period or such other time as agreed between the parties.

8.4 Payment of interest on overdue interest

8.4.1 Interest not paid when due may as at the due date for its payment be capitalised and form part of the Advance.

8.4.2 Payment of any amount of interest capitalised under clause 8.4.1 is not waived or postponed because of such capitalisation and the Issuer will continue to be in default in respect of such payment.

8.5 Place for payment of interest

The Issuer must pay all interest instalments directly into such account as the Holder may nominate to the Issuer from time to time.

8.6 Calculation of interest for Maximum Period

8.6.1 Subject to clause 8.6.2 if a Benchmark occurs, interest will accrue during the Maximum Period on a relevant Advance, at the Applicable Rate.

8.6.2 Interest, to the extent not payable as a result of the issue of a Variation Notice or Notices:

(a) will accrue from day to day in the Maximum Period at the Applicable Rate,

(b) be computed on a daily basis on a year of 365 days, and

(c) is payable on the last day of the Maximum Period or such other time as agreed between the parties.

8.7 Accrual of Interest in Issuer’s Accounts

The Issuer may make provisions for accrued, but unpaid, interest in its accounts provided that a Holder will not be entitled to payment of any interest unless and until a Benchmark occurs, and:

(a) it serves a Variation Notice on the Issuer, or

(b) the expiry of the Maximum Period.

8.8 Payment by 5.00pm without deduction or set off

8.8.1 Subject to clause 8.11 all payments required to be made by the Issuer under this agreement or a Note must be made to a Holder in full in immediately available funds prior to 5.00 pm on the relevant due date (or any earlier time specified) without any deduction.

8.8.2 The Issuer irrevocably and unconditionally waives any right of set off, combination or counterclaim in relation to any such payments.

8.9 Credit for payment

8.9.1 The Issuer will be given credit for a payment only upon its actual receipt by a Holder in immediately available funds in the currency in which it is due.

8.10 Application of payments

8.10.1 The Issuer irrevocably waives its right to determine the appropriation of any money paid to a Holder. All payments will be applied at the sole election of the Holder and any rule determining application of payments does not apply. If the Holder has not made an election it will be deemed to have applied payments in the manner and against such money which is payable, as is in its best interests.

8.11 Taxation

If the Issuer is required to make any deduction or withholding in respect of Taxes (other than Excluded Taxes) from any payment due to a Holder under any Transaction Document, the Issuer:

(a) must pay the deduction or withholding to the relevant Government Agency by the due date; and

(b) promptly give the Holder any evidence it requires to prove that the payment has been made.”

76 Clause 2.6 contained amendments to cl 11 of the LNIA. Clause 2.7 dealt with increased costs and regulatory changes. Clause 2.8 dealt with notices. Clause 2.9 contained amendments to the terms and conditions of each Note. Clause 2.10 contained amendments to the Variation Notice in Schedule 2.

77 By cl 3.1 of the Second Amendment, STAI and SAI otherwise confirmed the terms of the LNIA, subject to any consequential renumbering to give effect to the amendments. By cl 3.2, STAI agreed to issue Amended Notes in the form of Schedule 1.

78 The Primary Benchmark linked the accrual of interest under the LNIA to SOPL’s financial performance. A Primary Benchmark was stated to occur when, as at the last day of a quarter, PBT was or exceeded $1.8 billion and Accumulated Free Cashflow was or exceeded $2.05 billion. The alternative to the Primary Benchmark was any of the five “Default Benchmarks”, which included projected tax payable by the consolidated STAI group based on the Management Accounts, before interest payable under the LNIA, exceeding $100 million.

79 The Premium was calculated to compensate SAI for allowing what was estimated by SAI and STAI to be an interest-free period of approximately 3.5 years (i.e. the period from 28 June 2002 to 31 December 2005). The Premium was calculated by reference to a notional amount of compound interest for that period of approximately $1.54 billion. This included the 10/9 gross-up. It was estimated by SAI and STAI the interest-free period would continue to the quarter ended 31 December 2005, and that interest would become payable from the quarter ending on 31 March 2006.

The accrual and payment of interest

80 In the event, the Primary Benchmark was met in the 30 June 2005 quarter, and interest began to accrue on the Loan Notes from the first day of that quarter (i.e. 1 April 2005). No adjustment was made to the Premium to recognise the fact that STAI had met the Primary Benchmark earlier than was estimated in setting the Premium.

81 On 28 March 2007, SAI issued the first Variation Notice. The interest was payable on 2 April 2007. STAI borrowed funds from SOPL to fund the interest payment.

82 Thereafter, SAI issued 137 further Variation Notices. Each notice set out:

(a) the details of the Loan Note to be varied;

(b) the period or periods in respect of which interest was to be paid; and

(c) the applicable rate or rates of interest in respect of the period or periods.

83 Although the Third Amendment was entered into on 30 March 2009, the amendments to the LNIA contained in that document were substantively agreed between SAI and STAI in October 2008.

84 On 31 July 2008, the CFO of SOPL asked two Optus employees “Can we make sure we close the loop on STAI additional facility and also the necessary renegotiation/refinancing of [the] current $5.2 bn facility”, and asked “will it make sense for steve chubb (sic) to [meet] with us and give us views/advice from [EY]?”, to which a positive response was received.

85 At this time, the LNIA was not due to mature for almost four years, on 27 June 2012.

86 In August 2008, a SOPL funding strategy paper considered whether SOPL should make a new bond issue. The paper commented (on page 4):

Capital markets continue to remain difficult for issuers and reflect significantly higher pricing for longer term issues. Given Optus’ modest funding requirements, desired flexibility, and existing funding mix at a group level, we do not believe that a debt capital market issue is appropriate in the current environment (see 5.1 below). It is however recommended that Optus update [its] capital markets documentation to maintain flexibility in accessing funding opportunities as and when they arise in the future should our funding needs change and market conditions improve (this may be more relevant at a SingTel level.)

The funding strategy paper recommended that SOPL increase the existing syndicated loan (maturing in March 2009) from $700 million to $950 million and for 2010-maturing bonds to be considered later in 2009.

87 On 18 September 2008, STAI requested that SAI refinance the LNIA (after it reached maturity), sending a draft term sheet.

88 On 13 October 2008, Ms Tan Yong Choo of SingTel sent an email to Ms Samantha Chng and others of SingTel, relating to a variation of the interest rate of the LNIA. The email stated: “we will fix the rate at 6.373% on 30 Sep 2008 for future periods from FY 2010 onwards. No more caps and floor, too complex. We will let you know of progress.”

89 On 20 October 2008, Ms Tan Yong Choo sent a further email stating: “[w]e shall use 6.835%, being the rate as at 26 Sep 2008 (used as a proxy for 30 September 2008), as the interest rate for the A$5.2 bil loan for future periods.” The email also stated that two changes would be made: first, changing the variable rate to a fixed rate of 6.835% from 1 April 2009 onwards; secondly, “SAI to [provide] committed loan facility of A$X billion for X period after 2012”. Fang Fang replied: “This is and should remain a SingTel email. We need not communicate with Optus on this. The 6.835% is a good proxy, subject to TP review”.

90 On 23 October 2008, Mr Stephen Chubb of Ernst & Young provided observations from an Australian taxation perspective on the proposed change to the interest rate under the LNIA.

91 On 24 October 2008, Mr Paul Balkus of Ernst & Young sent an email to Mr Brett Nichols, Director - Treasury at SOPL. Mr Balkus made the following observations:

1. Just to be clear, when you state that your “rationale for the interest rate to be set a 6.853%” I assume you mean the base rate on which the margin and uplift is to be applied. That is, the actual interest on the loan (excluding the 4.552% premium) would be equal to (6.853+1)*10/9 or 8.72% - This is the interest rate that we need to ensure is “consistent with the arm’s length principle”.

2. Interest rate measurement date - Why are you using 10/10 rather than 30 September 2008? We understood that the effective date for the change in terms on the note was 30 September 2008? This is potentially significant given that the RBA dropped interest rates by 100bps on 7 October 2008.

3. Given that we are changing to a fixed rate instrument for three and half years we have used quoted rates for Australian Corporate Bond Index for A rated four year securities at 30 September 2008 (i.e. 7.9%). This rate would compare with your 3 year swap rate plus the 100bp margin (i.e. 6.435). In this regard what is your rationale for maintaining the same credit spread margin that was used on a 1 year swap rate? If I add the 100bps to the 6.435% to adjust for the RBA reduction in interest rates, it would appear that the margin for a four instrument would be 50bps higher.

4. As discussed, we need to make sure that the total interest charge including the uplift (i.e. 10/9) is within the arm’s length range. Therefore, we would compare 8.72% (i.e. the actual interest that we propose charging on the loan) with the arm’s length amount of interest which based on your calculation would be 7.853%. (i.e. the rate at which STAI could expect to borrow in the Australian market).

Therefore, having regard to the above, our calculation would be as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This would then be compared to the 8.72%. given that 8.72% is lower we would then conclude that the 8.72% is arm’s length.

The key differences between our calculations are as follows:

Measurement date - which can add as much as 100bps to the interest rate.

New issue premium - we have assumed a lower amount (i.e. 50bps) recognising that it could potentially be higher.

Margin - we have used A rated securities and you appear to have used the old 1% margin on a 3 year swap rate (our margin is 1.5% rather than 1%).

92 On 27 October 2008, Mr Chubb forwarded to SingTel and SOPL a further email from Mr Balkus and added, in relation to Mr Balkus’s transfer pricing analysis, “this analysis does not consider the premium issue etc. which is out of scope at this stage”.

93 On 28 October 2008, SAI sent a letter to STAI proposing a refinancing of the LNIA, which was due to mature in June 2012, and fixing a component of the interest rate under the LNIA. The letter stated:

We refer to our earlier discussions in September and your letter of request dated 24 October 2008. We are pleased to offer the attached proposal for refinancing of the A$5.2bn Loan Note Facility which matures in June 2012.

In consideration of SAI agreeing to provide a commitment in advance of the existing facility and to allow certainty on the quantum of interest for both parties for the remaining term of the existing Loan Notes, SAI proposes that the interest rate on the existing $5.2b facility be fixed. It is proposed that the floating AFMA swap rate currently used in paragraph (a) of the definition of “interest rate” in the existing loan facility agreement be substituted with a fixed rate of 6.835%.

The remaining terms and conditions of the proposal are summarised in the attached proposed Term Sheet for the new committed facility. Long form documents will be prepared to reflect the terms of the Term Sheet and to deal with any related or consequential issues which the parties deem necessary.

Please confirm your acceptance by 28 October 2008 of:

(i) the proposed terms of the facility (as summarised in the proposed Term Sheet); and

(ii) the proposed fixing of a component of the interest rate at 6.835% with effect from 1 April 2009.

The attached term sheet set out the terms for a facility that would commence upon the maturity of the LNIA in June 2012. The margin for that facility was stated to be subject to prevailing market conditions. The interest rate was stated to be the aggregate of the margin and the bank bill rate multiplied by 10/9.

94 On 30 October 2008, STAI sent a letter to SAI confirming its acceptance of the proposal as set out in the letter of 28 October 2008 and the enclosed term sheet.

95 On 30 March 2009, SAI and STAI entered into the Third Amendment. In summary, this amended the definition of “Interest Rate” by replacing the 1 year BBSW with a fixed rate of 6.835%, with effect from 1 April 2009. As a result, the Applicable Rate under the LNIA became: (a) the Interest Rate (6.835% plus 1%) multiplied by 10/9; and (b) the Premium of 4.552%. This produced an Applicable Rate of 13.2575%.

96 In addition to the amendment to the definition of “Interest Rate”, the Third Amendment (by cl 3) introduced a termination fee. Little attention was given to this amendment in the course of the present proceeding. Clause 4 of the Third Amendment was headed “Confirmation” and provided that, other than the amendments to the terms of the LNIA and any previous amendments thereto, STAI and SAI confirmed the terms of the LNIA and any previous amendments.

Total interest paid by STAI to SAI

97 The total interest paid by STAI to SAI pursuant to the Variation Notices referred to above was $4,903,096,322.

98 On 2 November 2011, SAI requested that STAI repay Loan Notes 9 and 10 (which totalled around $400 million) and pay interest on the face value of the Loan Notes in accordance with Variation Notices 113 to 130.

99 On 27 June 2012, the outstanding Loan Notes (totalling $4.8 billion) matured and SAI approved the advance of an Intercompany Cash Advance Facility Agreement to STAI in an amount of up to $5.2 billion.

100 During the term of the LNIA, STAI paid on behalf of SAI withholding tax in the amount of $490,309,632 (calculated as 10% of the total interest paid under the LNIA).

THE DETERMINATIONS AND AMENDED ASSESSMENTS

101 On 25 October 2016, the Commissioner made determinations under Div 13 of the ITAA 1936 and Subdiv 815-A of the ITAA 1997 relating to STAI and in respect of the years ending 31 March 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. A covering letter from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) of the same date stated that the Subdiv 815A determinations were alternative to the Div 13 determinations. The amounts in the determinations are summarised in the table in [11] above.

102 By way of example, the determination under Div 13 of the ITAA 1936 for the year ending 31 March 2011 was as follows:

DETERMINATION MADE PURSUANT TO SUBSECTION 136AD(3) AND SUBSECTION 136AD(4) OF THE INCOME TAX ASSESSMENT ACT 1936 (“THE ACT”)

TAXPAYER: SINGAPORE TELECOMMUNICATIONS AUSTRALIA INVESTMENTS PTY LTD (“STAI”)

Year ended 31 March 2011 (in lieu of year of income ended 30 June 2011)

I, Jeremy Hirschhorn, Deputy Commissioner of Taxation, Public Groups and International, in the exercise of the powers and functions delegated to me by the Commissioner of Taxation:

1. find that, for the purpose of paragraph 136AD(3)(a) of the Act, STAI has acquired property under an international agreement; and

2. am satisfied, for the purpose of paragraph 136AD(3)(b) of the Act, that having regard to:

a. the connection between any 2 or more parties to the international agreement; and

b. to other relevant circumstances,

that the parties to the international agreement or any 2 or more of those parties were not dealing at arm’s length with each other in relation to the acquisition;

3. find that, for the purpose of subsection 136AD(4) of the Act, it is not possible or not practicable for the Commissioner to ascertain the arm’s length consideration in respect of the acquisition of the property;

4. determine, for the purpose of subsection 136AD(4) of the Act, that the arm’s length consideration in respect of the acquisition of property shall be the amount of $423,994,154;

5. find that, for the purposes of paragraph 136AD(3)(c) of the Act, STAI gave or agreed to give consideration in respect to the acquisition of the property and the amount of that consideration (that is, $898,998,263) exceeded the arm’s length consideration determined by the Commissioner under subsection 136AD(4) of the Act in respect of the acquisition of the property (that is, $423,994,154); and

6. determine, for the purpose of paragraph 136AD(3)(d) of the Act, that subsection 136AD(3) should apply in relation to STAI in relation to the acquisition.

It follows from the above that, for the purposes of the application of the Act in relation to STAI, consideration equal to the arm’s length consideration in respect of the acquisition shall be deemed to be the consideration given or agreed to be given by STAI in respect of the acquisition.

103 By way of further example, the determination under Subdiv 815-A of the ITAA 1997 for the year ending 31 March 2011 was as follows:

DETERMINATION MADE PURSUANT TO SECTION 815-30 OF DIVISION 815 OF THE INCOME TAX ASSESSMENT ACT 1997 (“THE ACT”)

TAXPAYER: SINGAPORE TELECOMMUNICATIONS AUSTRALIA INVESTMENTS PTY LTD

I, Jeremy Hirschhorn, Deputy Commissioner of Taxation, Public Groups and International, in the exercise of the powers and functions delegated to me by the Commissioner of Taxation;

1. determine under paragraphs 815-10(1) and 815-30(1)(a) of the Act that the taxable income of SINGAPORE TELECOMMUNICATIONS AUSTRALIA INVESTMENTS PTY LTD be increased by the amount of $475,004,109 for the year ended 31 March 2011 (in lieu of income tax year 30 June 2011).

2. I further determine under paragraph 815-30(2)(b) of the Act, that the determination referred to in paragraph 1 is attributable to a decrease of $475,004,109 in allowable deductions of SINGAPORE TELECOMMUNICATIONS AUSTRALIA INVESTMENTS PTY LTD associated with the interest payments particularised in the Economist Practice Report Second Addendum issued on 25 October 2016, in the year ended 31 March 2011 (in lieu of income tax year 30 June 2011).

104 The letter from the ATO dated 25 October 2016 enclosing the determinations stated that the arm’s length consideration had been calculated using a modified or updated version of a model referred to as the “Economist Practice model”. Details of the updated model were provided in Attachment B to the ATO’s letter. This included a table headed “EP Transfer Pricing Adjustment Calculations – Updated model” (EP Report). One of the points made in STAI’s submissions is that the case now put by the Commissioner through his expert witnesses differs in material ways from the case based on the EP Report. This will be discussed later in these reasons.

105 As noted above, the Commissioner issued notices of amended assessment to STAI in respect of the years ending 31 March 2011, 2012 and 2013. STAI objected to the amended assessments.

106 On 27 September 2019, the Commissioner disallowed STAI’s objections and provided reasons for decision. In the reasons for decision, the Commissioner primarily relied on Subdiv 815-A of the ITAA 1997; Div 13 of the ITAA 1936 was relied on in the alternative. In the covering letter from the ATO (dated 27 September 2019), reference was made to STAI’s request for remission of the shortfall interest charge. The letter stated that: the request made for the year ending 31 March 2011 had been treated as an objection to the amended assessment; and the requests made for the years ending 31 March 2012 and 2013 had not been treated as valid objections. It was explained that there was no right to object to a shortfall interest charge imposed for those years unless the amount exceeded 20% of the tax shortfall amount; and that, in this case, it was 19.9% of the 31 March 2012 tax shortfall and 15% of the 31 March 2013 tax shortfall.

107 By notice of appeal dated 11 November 2019, STAI appeals to this Court pursuant to Pt IVC of the Taxation Administration Act against the Commissioner’s objection decisions. STAI seeks the following substantive relief:

(a) to have set aside the Commissioner’s objection decisions;

(b) to allow the objections in full, or alternatively, to allow the objections in part as the Court may determine; and

(c) to set aside the shortfall interest charge to nil, alternatively, to remit the matter to the Commissioner for reassessment in accordance with law.

108 The notice of appeal sets out 14 grounds relied on by STAI.

109 STAI bears the burden of proving that the amended assessments are excessive: Taxation Administration Act, s 14ZZO(b).

THE KEY LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS

Subdivision 815A of the ITAA 1997

110 I will refer to the version of Subdiv 815-A of the ITAA 1997 compiled on 20 October 2016, which is the version provided in the parties’ joint bundle of authorities.

111 Subdivision 815-A of the ITAA 1997 was enacted in 2012 by the Tax Laws Amendment (Cross-Border Transfer Pricing) Act (No 1) 2012 (Cth) and, pursuant to s 815-1 of the Income Tax (Transitional Provisions) Act 1997 (Cth) (Transitional Act), was made to apply retrospectively to income years starting on or after 1 July 2004. After the Tax Laws Amendment (Countering Tax Avoidance and Multinational Profit Shifting) Act 2013 (Cth) received Royal Assent on 29 June 2013, Subdiv 815-A was replaced by Subdivisions 815-B to 815-D for income years commencing on or after 29 June 2013: Transitional Act, ss 815-1(2) and 815-15.

112 The object of the Subdivision is set out in s 815-5 of the ITAA 1997, which relevantly provides:

815-5 Object

The object of this Subdivision is to ensure the following amounts are appropriately brought to tax in Australia, consistent with the arm’s length principle:

(a) profits which would have accrued to an Australian entity if it had been dealing at *arm’s length, but, by reason of non-arm’s length conditions operating between the entity and its foreign associated entities, have not so accrued …

113 Section 815-10(1) provides that the Commissioner may make a determination mentioned in s 815-30(1), in writing, for the purpose of negating a “transfer pricing benefit” (a defined expression, discussed below) an entity gets. However, s 815-10 only applies to an entity if (relevantly for present purposes) the entity gets the transfer pricing benefit under s 815-15(1) at a time when an “international tax agreement” containing an “associated enterprises article” applies to the entity. Here, there is no issue that the Singapore DTA is an international tax agreement. The expression “associated enterprises article” is discussed below.

114 Section 815-15(1) is the key provision for present purposes. It provides:

815-15 When an entity gets a transfer pricing benefit

Transfer pricing benefit—associated enterprises

(1) An entity gets a transfer pricing benefit if:

(a) the entity is an Australian resident; and

(b) the requirements in the *associated enterprises article for the application of that article to the entity are met; and

(c) an amount of profits which, but for the conditions mentioned in the article, might have been expected to accrue to the entity, has, by reason of those conditions, not so accrued; and

(d) had that amount of profits so accrued to the entity:

(i) the amount of the taxable income of the entity for an income year would be greater than its actual amount; or

(ii) the amount of a tax loss of the entity for an income year would be less than its actual amount; or

(iii) the amount of a *net capital loss of the entity for an income year would be less than its actual amount.

The amount of the transfer pricing benefit is the difference between the amounts mentioned in subparagraph (d)(i), (ii) or (iii) (as the case requires).

The relevant entity for present purposes is STAI. There is no issue that the requirement in paragraph s 815-15(1)(a) is satisfied as STAI is an Australian resident.

115 The expression “associated enterprises article” is defined in s 815-15(5) as meaning: (a) Art 9 of the United Kingdom convention; or (b) a corresponding provision of another international tax agreement. There is no issue in the present case that Art 6 of the Singapore DTA is an associated enterprises article.

116 The relevant version of Art 6 of the Singapore DTA is that set out in the protocol amending the double taxation agreement that entered into force on 5 January 1990 (a copy of which was provided by the Commissioner to the Court on day 2 of the hearing). Article 6 of the Singapore DTA relevantly provides:

Article 6

(1) Where-

(a) an enterprise of one of the Contracting States participates directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of an enterprise of the other Contracting State; or

(b) the same person participates directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of an enterprise of one of the Contracting States and an enterprise of the other Contracting State,

and in either case conditions operate between the two enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which might be expected to operate between independent enterprises dealing wholly independently with one another, then any profits which, but for those conditions, might have been expected to accrue to one of the enterprises, but, by reason of those conditions, have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly.

Here, STAI accepts that the condition in paragraph (a) above is satisfied. That is, it is accepted that SAI (an enterprise of one of the Contracting States, Singapore) participates directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of STAI (an enterprise of the other Contracting State, Australia). It is therefore unnecessary to consider the condition in paragraph (b).

117 Section 815-20, which relates to matters of interpretation, provides in part:

815-20 Cross-border transfer pricing guidance

(1) For the purpose of determining the effect this Subdivision has in relation to an entity:

(a) work out whether an entity gets a *transfer pricing benefit consistently with the documents covered by this section, to the extent the documents are relevant; and

(b) interpret a provision of an *international tax agreement consistently with those documents, to the extent they are relevant.

(2) The documents covered by this section are as follows:

(a) the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital, and its Commentaries, as adopted by the Council of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and last amended on 22 July 2010;

(b) the Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, as approved by that Council and last amended on 22 July 2010;

(c) a document, or part of a document, prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this paragraph.

118 The effect of s 815-20 is modified by s 815-5 of the Transitional Act for the income years before 1 July 2012. Accordingly, the relevant OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for the 2010 and 2011 income years are the 1995 Guidelines and the relevant guidelines for the 2012 and 2013 income years are the 2010 Guidelines. I will refer to these respectively as the 1995 Guidelines and the 2010 Guidelines.

119 Section 815-30(1) relevantly provides that the Commissioner may make a determination of an amount by which the taxable income of the entity for an income year is increased. Section 815-30(2) provides:

(2) If the Commissioner makes a determination under subsection (1), the determination is taken to be attributable, to the relevant extent, to such of the following as the Commissioner may determine:

(a) an increase of a particular amount in assessable income of the entity for an income year under a particular provision of this Act;

(b) a decrease of a particular amount in particular deductions of the entity for an income year;

(c) an increase of a particular amount in particular capital gains of the entity for an income year;

(d) a decrease of a particular amount in particular capital losses of the entity for an income year.

120 Section 815-35 deals with consequential adjustments, and s 815-40 deals with there being no double taxation.

121 I will refer to the version of Div 13 of the ITAA 1936 compiled on 28 June 2013, being the version provided by the parties in the joint bundle of authorities.

122 Section 136AA deals with interpretation. Given the limited focus in this case on Div 13, I will not set out all of the relevant definitions. The definitions in s 136AA(1) include:

property includes:

(a) a chose in action;

(b) any estate, interest, right or power, whether at law or in equity, in or over property;

(c) any right to receive income; and

(d) services.

…

services includes any rights, benefits, privileges or facilities and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing, includes the rights, benefits, privileges or facilities that are, or are to be, provided, granted or conferred under:

…

(d) an agreement for or in relation to the lending of moneys.

123 Section 136AA(3) relevantly provides:

(3) In this Division, unless the contrary intention appears:

…