FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Biogen International GmbH v Pharmacor Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1591

ORDERS

First Applicant BIOGEN AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | BIOGEN INTERNATIONAL GMBH (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 16 December 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Upon the respondent undertaking to keep accounts:

1. The applicant’s interlocutory application be dismissed.

2. The time for filing an application for leave to appeal from these orders be extended to 31 January 2022.

3. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs of this application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROFE J:

1 This was an application for an interlocutory injunction in proceedings for patent infringement under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act) and misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law (being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL).

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 The parties and the broad issues

2 The applicants, Biogen International GmbH (Biogen Switzerland) and Biogen Australia Pty Ltd (Biogen Australia), commenced proceedings seeking final relief pursuant to the Act and the ACL to restrain the respondent Pharmacor Pty Ltd (Pharmacor) from launching its dimethyl fumerate (DMF) products (Pharmacor Products).

3 Biogen Switzerland is the Patentee of Australian patent number 752733 entitled “Utilisation of dialkyl fumarates” (the Patent). Following an extension of term granted by the patent office on 20 October 2014, the Patent expires on 29 October 2024. The patent claims a priority date of 19 November 1998.

4 Biogen Australia and Biogen Switzerland are members of the same group of companies of which Biogen Inc is the parent company. Biogen Australia is not an exclusive licensee of the Patent. Unless otherwise stated the applicants are collectively referred to below as Biogen.

5 Biogen sells dimethyl fumarate formulations in Australia under the name Tecfidera, for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

6 On 14 July 2021, Pharmacor obtained a listing for the Pharmacor Products on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). Pharmacor is seeking to be listed on the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits (PBS Schedule) pursuant to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) from 1 December 2021. Biogen seeks urgent interlocutory orders to restrain Pharmacor from marketing and offering the Pharmacor Products for sale.

7 When considering an application for an interlocutory injunction, the court must address two main enquiries, namely whether the applicant for relief has established a prima facie case in the sense explained in Beecham Group Limited v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 618 at 622-3 (Beecham), and whether the balance of convenience and justice favours the grant of an injunction or the refusal of that relief.

8 Pharmacor contests the application. For the purposes of the interlocutory hearing, Pharmacor admits that the Pharmacor Products fall within all the asserted claims except claim 17. It asserts that the extension of the Patent term was wrongly granted and that the claims asserted against it are invalid for want of novelty over one prior art document.

9 The hearing of the application for injunctive relief was brought on urgently as Biogen apprehended that the Pharmacor Products might be listed on the PBS on the next listing date, 1 December 2021. Subsequent to the hearing, the Court was advised by the parties that the PBS had advised Pharmacor that the Pharmacor Products would not be listed on the PBS before 1 February 2022.

1.2 Summary of conclusion

10 For the reasons set out below I have concluded that the balance of convenience and justice does not lie in favour of the grant of the interim relief sought.

1.3 The witnesses

11 Biogen relies on evidence from five witnesses:

(a) Kylie Michele Bromley is the managing director of Biogen Australia and has a PhD in pharmacology. She has worked in the pharmaceutical industry in Australia for over 20 years. Dr Bromley gives evidence as to the Patent, the market for MS treatment in Australia, Tecfidera, the Pharmacor Products, the background to the dispute and the effect on Biogen if the Pharmacor Products are launched. Biogen relies on two affidavits from Dr Bromley.

(b) Peter James Davey is a health economist with extensive knowledge of, and experience in, the pharmaceutical sector, including with respect to reimbursement and pharmaceutical pricing issues. Mr Davey has worked in the pharmaceutical sector since 1991 and has extensive experience in preparing economic modelling in that sector. Mr Davey gives opinion evidence as to what he considers would be involved in assessing the loss to Biogen if an interlocutory injunction was not granted and it is ultimately determined that the Patent is valid and infringed. Biogen relies on three affidavits from Mr Davey.

(c) Owain Rhys Stone is a Partner at KordaMentha. He is a forensic accountant with significant experience in the pharmaceutical and life sciences sector including in the quantification of economic loss and damage in the context of pharmaceutical injunction disputes. Mr Stone describes the financial analysis he would employ to assess Biogen’s loss if Pharmacor is not restrained and the court finds the Patent valid and infringed. Biogen relies on two affidavits from Mr Stone.

(d) William Neil Charman is a Sir John Monash distinguished Professor in the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Monash University where he was Dean from 2007 to 2019. Professor Charman has expertise in the field of oral drug delivery and the design and assessment of pharmaceutical formulations for oral administration to humans. He gives evidence as to the prior art relied on by Pharmacor and responds to the evidence of Pharmacor’s expert. Biogen relies on one affidavit from Professor Charman.

(e) Rebekah Frances Gay is a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills, Biogen’s solicitors. Ms Gay’s affidavit annexes search results, a decision of the Australian patent office finding claims 13 to 17 of the Patent novel over a prior art application on re-examination, and correspondence and documents relating to United States proceedings concerning Biogen’s related US patent in a dispute with Pharmacor’s ultimate parent company. Biogen relies on one affidavit from Ms Gay.

12 Pharmacor relies on the evidence of three witnesses:

(a) Ashish Mallela is Pharmacor’s CEO. Mr Mallela gives evidence as to the Pharmacor business, the generic pharmaceutical market in Australia, the planned launch of the Pharmacor products in Australia, the irreparable harm that Pharmacor will suffer if it is restrained, and the difficulties in quantifying Pharmacor’s loss. Pharmacor relies on two affidavits of Mr Mallela.

(b) Anthony Samuel is a forensic accountant and the Managing Director at Sapere Research Group Limited. Mr Samuel gives evidence of the exercise required to estimate the value of a loss suffered by a supplier of a generic pharmaceutical product when that supplier is restrained from offering its product, the exercise required to estimate Biogen’s loss if Pharmacor was not restrained, and responds to Mr Stone’s evidence. Pharmacor relies on three reports of Mr Samuel.

(c) Desmond Berry Williams is a senior researcher in Clinical and Health Sciences with expertise in pharmaceutical formulation. Dr Williams gives evidence as to what is disclosed in the two prior art documents and compares the disclosure in those documents with the claims of the Patent. Pharmacor relies on one affidavit from Mr Williams.

13 Due to the exigencies of the COVID-19 pandemic, the hearing took place via Microsoft Teams. Given the confidential nature of most of the evidence addressing the balance of convenience considerations, the hearing took place in two sessions: an open session relating to all issues other than the balance of convenience, and a confidential session attended by only the parties’ instructors and counsel at which the balance of convenience arguments were made. No witnesses were required for cross examination.

14 Much of the evidence was not the subject of substantial disagreement aside from that relating to the complexity of the task of assessing damage for either party. It is not the role of the court in an application such as this to make findings of fact. I do not purport to do so here.

1.4 Multiple sclerosis

15 Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory autoimmune disorder affecting the central nervous system that causes a loss of function to the nervous system and loss of communications between the brain and the body. It is the most common cause of neurological disability in young adults, and affects approximately 2.8 million people around the world.

16 MS is a chronic and complex disease, which has a very significant impact on the quality of life of patients.

17 MS is a relatively rare disease. Approximately 25,000 Australians suffer from MS, with the number of patients actively seeking treatment for MS in Australia steadily rising at a rate of about 4% per year. This increase in the patient pool accounts for population growth, disease growth, and patients who have previously opted out of treatment, but are choosing to opt back in as new treatment options become available.

18 There is no known cure for MS. The primary purpose of MS treatment is to reduce the frequency of relapses in symptoms and the progression of the disease.

19 There is also no uniform treatment plan for MS patients in Australia. Generally, a treatment regime is developed for individual patients by a medical practitioner, possibly in consultation with a specialist team which might include a patient’s GP, a neurologist, an MS specialist nurse, and a number of allied health practitioners (such as an occupational therapist or physiotherapist). In determining what treatment to prescribe, physicians will consider a number of factors, including how active the MS is based on a clinical or MRI assessment. For example, if the MS is more active, a patient will likely be prescribed an infusion therapy, while for milder forms, patients will typically take oral treatments. The pregnancy prospects of the patient are also a relevant consideration, given that 70% of patients are female and aged between 25 to 30 years when initially diagnosed. While none of the MS treatments have been approved for use during pregnancy, Tecfidera, for example, is suitable for patients who may fall pregnant.

20 Across a lifetime, a patient will typically use two or more MS treatments. This can be due to:

(a) Reduced efficacy with some drugs after a period of time, which causes patients to experience a decrease in the time between relapses;

(b) The patient having difficulty adhering to a particular treatment regime (particularly if the medication is administered by self-injection or infusion); or

(c) Changes in the safety profile for some treatments; for example, some infusion treatments can increase the chance of a patient developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (a disease of the white matter of the brain).

1.5 Overview of the MS market

21 Broadly, the available treatments for MS in Australia fall into three types of products:

(a) Injectables: these have been available in Australia for about 20 years and require patients to regularly self-administer sub-cutaneous or intra-muscular injections. Biogen developed one of the first injectables, being Avonex (interferon beta-1a or IFN β-1a). These were breakthrough treatments in the early 2000s. Given the advances in treatments since their introduction, injectables are now the least commonly prescribed form of treatment for MS accounting for only 15% of the market, as they are considered the least effective form of treatment compared with oral medications or infusions.

(b) Oral medications: these are now the largest group of treatments and include Tecfidera. Oral medications are the primary treatment option for mild forms of MS. The first of this group of treatments was introduced onto the MS market around 2011, some 10 years after the introduction of injectables, and again represented a very significant advancement in the treatment of MS. They are still widely used by the MS population today. Oral treatments account for approximately 47% of the MS treatment market in Australia.

(c) Infusions: These are treatments comprising monoclonal antibodies that are administered by infusion. These types of products are becoming more widely used as a result of their high efficacy. Biogen Australia markets Tysabri, which is administered by an intravenous infusion by a health practitioner every four weeks, which takes approximately one hour. Other infusion therapies require administration once or twice a year. These account for approximately 38% of the MS treatment market in Australia.

22 The following table, taken from Dr Bromley’s evidence, summarises the MS treatments available in Australia as at October 2021:

Product | Active Ingredient | Approved | Supplier | Mode of administration |

Injectables | ||||

REBIF | IFN β-1a | 2000 | Merck | SC injection – 3 per week |

AVONEX | IFN β-1a | 2001 | Biogen | IM injection – once a week |

BETAFERON | IFN β-1b | 2002 | Bayer | SC injection – every other day |

COPAXONE | Glatiramer acetate | 2003 | Teva | SC injection – 3 per week |

PLEGRIDY | Pegylated IFN β-1a | 2014 | Biogen | SC injection – once a fortnight |

Oral Medications | ||||

GILENYA | Fingolimod | 2011 | Novartis | Oral – once daily |

AUBAGIO | Teriflunomide | 2012 | Sanofi | Oral – once daily |

APO Teriflunomide | Teriflunomide | 2019 | Apotex | Oral – once daily |

Teriflagio | Teriflunomide | 2019 | Arrow Pharma | Oral – once daily |

Teriflunomide Dr Reddys | Teriflunomide | 2019 | Dr Reddys Labs | Oral – once daily |

Teriflunomide GH | Teriflunomide | 2019 | Generic Health | Oral – once daily |

Pharmacor Teriflunomide | Teriflunomide | 2019 | Pharmacor Ltd | Oral – once daily |

Teriflunomide Sandoz | Teriflunomide | 2019 | Sandoz | Oral – once daily |

Terimide | Teriflunomide | 2021 | Alphapharm | Oral – once daily |

Tecfidera | Dimethyl fumarate | 2013 | Biogen | Oral – twice daily |

FAMPYRA | Fampridine | 2011 | Biogen | Oral – twice daily |

MAVENCLAD | Cladribine | 2019 | Merck | Oral – yearly regime |

ZEPOSIA | Ozanimod | 2021 | BMS | Oral – once daily |

MAYZENT | Siponimod | 2020 | Novartis | Oral – once daily |

Infusions | ||||

TYSABRI | Natalizumab | 2006 | Biogen | Infusion - monthly |

LEMTRADA | Alemtuzumab | 2013 | Sanofi | Infusion – once a year |

OCREVUS | Ocrelizumab | 2017 | Roche | Infusion – every 6 months |

23 Dr Bromley provided further information about some of the treatments listed in the table which is summarised below.

24 The generic teriflunomide products listed in the table are those that have obtained PBS listing and are on the market. There are additional brands listed on the ARTG, but which are not PBS listed. Dr Bromley’s evidence was that she expected the other generics to also enter the market in the near future. As far as Dr Bromley is aware, Sanofi is no longer providing any significant marketing support for its product, Aubagio, with the result that the overall market share for teriflunomide products has decreased. Sanofi has announced that because of the genericised market it will no longer be marketing Aubagio in Australia beyond October 2021.

25 In March 2021, Novartis obtained approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for its ofatumumab product, Kesimpta, a sub-cutaneous once a month injectable. Kesimpta was approved for PBS listing on 30 September 2021, with effect from 1 October 2021. Dr Bromley expects the launch of Kesimpta to have an impact on oral MS therapies including Tecfidera, as Novartis is an established participant in the MS market with good relationships with neurologists.

26 The Novartis product Gilenya is the only product containing fingolimod currently available. There are 36 generic products on the ARTG which list fingolimod as the active ingredient.

27 All three experts, Mr Davey, Mr Stone and Mr Samuel described the MS market as a “dynamic market”. I discuss the experts’ views on the MS and DMF markets later.

28 Despite the experts’ comments as to the dynamic nature of the MS market, and the frequency of new products entering the market during the period that Tecfidera has been available in Australia, I observe that [redacted].

29 The MS market in Australia was described in the evidence as a small, niche market. It is much smaller than the markets in recent damages cases for pharmaceutical products such as venlafaxine (an anti-depressant) in Sigma Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Ltd v Wyeth (2018) 136 IPR 8, clopidogrel (a platelet aggregation inhibitor) in Commonwealth of Australia v Sanofi (formerly Sanofi-Aventis) (No 5) (2020) 151 IPR 237, or the oral contraceptive pill in Generic Health Pty Ltd & Anor v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft & Anor (2018) 137 IPR 1.

1.6 Biogen and Biogen’s MS products

30 Biogen is a specialist biotechnology business founded in 1978 which conducts research specifically directed to neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. The core areas on which Biogen’s research has focussed are MS, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, neuromuscular disorders (including spinal muscular atrophy) and movement disorders (including Parkinson’s disease).

31 Biogen Switzerland owns all Biogen’s non-US intellectual property rights. It is also responsible for the manufacture and distribution of drug products to a number of countries including Australia, and contributes to the funding and management of Biogen’s research activities.

32 Biogen Australia operates Biogen’s business in Australia. It is responsible for the sales, marketing and regulatory approval of Biogen’s products in Australia, relations with regulators, price negotiations with the Australian Government, providing support for clinicians and patients, supporting ongoing Australian research in relevant areas and sponsoring Australian based clinical trials.

33 Biogen Australia’s product portfolio consists of only six products, all of which bar one are dedicated to relapsing MS treatments (Spinraza is indicated for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy).

Product | Active Ingredient | Date listed on ARTG |

Avonex | Interferon beta 1-A | July 2001 |

Tysabri | Natalizumab | November 2008 |

Fampyra | Fampridine | May 2011 |

Tecfidera | DMF | July 2013 |

Plegridy | Peginterferon beta 1-A | November 2014 |

Spinraza | Nusinersen | November 2017 |

34 Biogen has applied for TGA approval for:

(a) Vumerity (diroximel fumarate), a treatment for relapsing MS; and

(b) Aduhelm (aducanumab), a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

35 The likely launch of Vumerity and its potential disruption of the DMF market is discussed later in the balance of convenience considerations.

36 The active ingredient of Tecfidera is dimethyl fumarate (DMF). It is an oral medication formulated as enteric-coated microtablets contained within a hard gelatin capsule. Tecfidera is approved in Australia for the treatment of patients with relapsing MS to reduce the frequency of relapses and to delay the progression of disability.

37 Tecfidera was first listed on the ARTG in July 2013, 14 years after the complete specification of the Patent was filed. This was the first regulatory approval date for DMF in Australia. The Patent is the only patent that has had a term extension granted based on DMF (Tecfidera).

38 Biogen Australia is the sponsor on the ARTG of the following two dosage forms of Tecfidera:

(a) 120mg modified release capsule blister packs (ARTG ID 197118); and

(b) 240mg modified release capsule blister packs (ARTG ID 197119).

39 Tecfidera was first listed on the PBS on 1 December 2013. Tecfidera is a prescription only medicine, which means that patients can only obtain it from retail pharmacists after obtaining a prescription from their medical practitioner. The starting dose of Tecfidera is 120mg twice a day administered orally. The maintenance dose, which is started after seven days, is 240mg taken twice a day orally.

40 Tecfidera is a significant part of Biogen Australia’s MS portfolio.

1.7 Pharmacor and Pharmacor’s products

41 Pharmacor’s primary business in Australia is the marketing and supply of generic prescription and over the counter medicines to retail pharmacies and public and private hospitals under its own brand. Pharmacor currently markets and sells 202 discrete products under its own brand.

42 Pharmacor supplies its own products to approximately 3,500 of the more than 5,000 pharmacies in Australia. Part of Pharmacor’s marketing and sales strategy involves offering discounts directly to pharmacists where possible.

43 Pharmacor supplies its products to retail pharmacies in the following ways:

(a) Offering its products for sale to all major pharmaceutical wholesalers (including the three largest, Sigma Healthcare Ltd, Australian Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd and Symbion Pty Ltd) who then supply Pharmacor’s products to retail pharmacies; and

(b) Marketing and selling some products directly to pharmacies and large pharmacy groups such as Chemist Warehouse and Priceline Pharmacy.

44 Mr Davey describes Pharmacor as a mid-sized generic supplier with at least 55 unique molecules listed on the PBS.

45 Alkem is the ultimate parent company of Pharmacor. Alkem was established in India in 1973 and listed on the Indian National Stock Exchange in 2015. Alkem currently operates in over 50 countries and has developed over 800 branded generic products.

46 On 14 July 2021, Pharmacor obtained registration on the ARTG for the following six DMF delayed release capsule blister packs:

(a) FURATEC: for 120mg and 240mg;

(b) AKM: for 120mg and 240mg; and

(c) PHARMACOR: for 120mg and 240mg.

47 On 20 August 2021, Pharmacor applied for listing on the PBS for the two PHARMACOR DMF products (being those products referred to as the Pharmacor Products). Pharmacor admits that if the Pharmacor Products are listed on the PBS, they will be a-flagged as substitutable at the pharmacy level for the Tecfidera products.

48 Since August 2021, Pharmacor has been preparing for the launch and commencement of the supply of Pharmacor Products from 1 December 2021. As noted above, the Pharmacor Products will not be listed until at least 1 February 2022.

1.8 Other ARTG registrations of DMF

49 Accelagen Pty Ltd (Accelagen) is another company with ARTG registration for generic versions of DMF products. Accelagen has four DMF ARTG registrations.

50 On 9 June 2021, Biogen commenced proceedings in this court against Accelagen and MSN Laboratories Private Ltd, India (MSN).

51 On 19 July 2021, the Court made orders by consent enjoining Accelagen and MSN from, amongst other things, seeking listing of the Accelagen DMF products on the PBS whilst the Patent remains in force. Accelagen is not restrained from further transferring its ARTG registrations to third parties. Pursuant to the orders made by Beach J, Accelagen must give Biogen notice, within five days of any transfer of the sponsorship of any of its ARTG registrations to a third party.

52 As a result, at the time of the hearing, Pharmacor was the only generic pharmaceutical company likely to be able to enter the DMF market in Australia on 1 December 2021. Subsequent to the hearing the Court was advised that the earliest date that Pharmacor will be able to enter the market if not restrained is 1 February 2022.

1.9 The issues

53 The dispute concerns the question of the strength of the patent infringement case that Biogen advances and whether the balance of convenience and justice warrants the grant of the interlocutory relief sought.

54 In the amended statement of claim Biogen asserts that the Pharmacor products are pharmaceutical preparations within the scope of at least claims 13, 14, 16, 17, 81, 86, 95, 96, 97 101, 102 and 103 of the Patent.

55 Pharmacor admits that the Pharmacor products fall within the scope of claims 13, 14, 16 (as dependent on 13 or 14), 95, 96, 97, 101(as dependent on claims 95, 96 or 97), 102 (as dependent on any of 95, 96, 97 and 101) and 103 (as dependent on any of claims 95, 96, 97, 101 or 102) of the Patent.

56 Pharmacor denies that the Pharmacor products fall within claims 81 or 86 (both of which are omnibus claims) of the Patent.

57 In light of Pharmacor’s admissions, Biogen does not ask the Court to find a prima facie case of infringement on claims 81 and 86.

58 Pharmacor denies that the Pharmacor products fall within claim 17 which claims a product containing an amount of active ingredient corresponding to 10mg to 300mg of fumaric acid.

59 In the context of the strength the prima facie case the remaining issue on the infringement case is whether claim 17 is infringed.

60 Pharmacor submits that the strength of the infringement case is qualified by its foreshadowed cross-claim for revocation of the asserted claims for invalidity, and the assertion that the extension of term of the Patent was invalidly granted. For the purposes of the interlocutory application, Pharmacor confined its invalidity case at the hearing to a novelty attack to the asserted claims, on the basis of one prior art document: Australian patent application no. 21393/99 (the 593 Application).

61 Biogen asserts that it has a strong prima facie case on its ACL claim on the basis of the strength of its infringement case.

1.10 The Patent

62 The Patent is entitled “Utilisation of dialkylfumarates”. The complete specification was filed on 29 October 1999 and the claims have a priority date of 19 November 1998.

63 The relevant form of the Act is the form the Act took prior to the changes introduced by the Patents Amendment Act 2001 (Cth).

64 The Patent commences:

The present invention relates to the use of dialkyl fumarates for preparing pharmaceutical preparations for use in transplantation medicine or the therapy of autoimmune diseases and pharmaceutical preparations in the form of micro-tablets or micro-pellets containing dialkyl fumarates.

On the one hand, therefore, it relates especially to the use of dialkyl fumarates for preparing pharmaceutical preparations for the treatment, reduction or suppression of rejection reactions of the transplant by the recipient, i.e. host-versus-graft reactions, or rejection of the recipient by the transplant, i.e. graft-versus-host reactions. On the other hand, it relates to the use of dialkyl fumarates for preparing pharmaceutical preparations for treating autoimmune diseases such as polyarthritis, multiple sclerosis, juvenile-onset diabetes, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Grave's disease, systemic Lupus erythematodes (SLE), Sjogren's syndrome, pernicious anaemia and chronic active (= lupoid) hepatitis.

Both graft rejection and autoimmune diseases are based on medically undesirable reactions or dysregulation of the immune system. Cytokins such as interleukins or tumour necrose factor α (TNF-α) are substantial mediators influencing the immune system. In general, both are treated by the administration of immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine.

65 At page 4, the Patent sets out two objects of the invention:

The danger in using immunosuppressive agents lies in weakening the body's defence against infectious diseases and the increased risk of malignant diseases. Therefore, it is the object of the invention to provide a pharmaceutical preparation to be employed in transplantation medicine which may be used to treat, especially to suppress, weaken and/or alleviate host-versus-graft reactions and graft-versus-host reactions, but does not have the above disadvantage.

It is another object of the invention to provide a pharmaceutical preparation which may be employed for treating autoimmune diseases, particularly polyarthritis, multiple sclerosis, juvenile-onset diabetes, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Grave's disease, systemic Lupus erythematodes (SLE), Sjogren's syndrome, pernicious anaemia and chronic active (= lupoid) hepatitis, without the disadvantages of immuno suppression.

66 There follows at page 5, line 8 and following, description of 13 aspects of the invention. Each aspect of the invention described includes a therapeutic use directed towards transplantation medicine or therapy for autoimmune diseases. For example:

According to a first aspect, the present invention consists in the use of one or more dialkyl fumarates for preparing a pharmaceutical preparation for treating host-versus-graft reactions or graft-versus-host reactions in organ and/or cell transplantation.

67 A third aspect of the invention corresponds to the invention as claimed in claim 13. See for example:

(a) at page 5b, line 29 to page 5c, line 2:

There is disclosed herein certain dialkyl fumarates for preparing pharmaceutical preparations for use in transplantation medicine and for the therapy of autoimmune diseases and pharmaceutical preparations in the form of micro-tablets and micro-pellets containing these dialkyl fumarates. The individual subject matters of the invention are characterised in detail in the claims. The preparations according to the invention do not contain any free fumaric acids per se.

(b) at page 6:

Surprisingly, it has now been found that dialkyl fumarates are advantageous for preparing pharmaceutical compositions for use in transplantation medicine and for the therapy of autoimmune diseases. This is because compositions containing such dialkyl fumarates surprisingly permit a positive modulation of the immune system in host-versus-graft reactions, graft-versus-host reactions and other autoimmune diseases.

European Patent Application 0 188 749 already describes fumaric acid derivatives and pharmaceutical compositions containing the same for the treatment of psoriasis. Pharmaceutical compositions for the treatment of psoriasis containing a mixture of fumaric acid and other fumaric acid derivatives are known from DE-A- 25 30 372. The content of free fumaric acid is obligatory for these medicaments.

(c) at page 7 to the top of page 8:

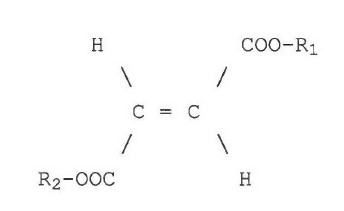

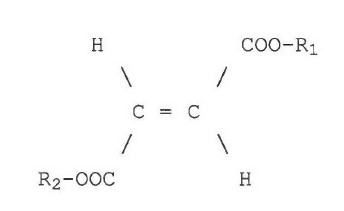

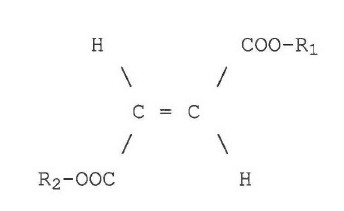

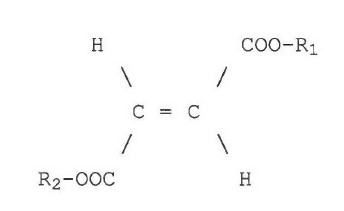

Specifically, the object of the invention is achieved by the use of one or more dialkyl fumarates of the formula

wherein R1 and R2, which may be the same or different, independently represent a linear, branched or cyclic, saturated or unsaturated C1-20 alkyl radical which may be optionally substituted with halogen (Cl, F, I, Br), hydroxy, C1-4 alkoxy, nitro or cyano for preparing a pharmaceutical preparation for use in transplantation medicine or for the therapy of autoimmune diseases.

The C1-20 alkyl radicals, preferably C1-8 alkyl radicals, most preferably C1-5 alkyl radicals are, for example, methyl, ethyl, n-propyl, isopropyl, n-butyl, sec-butyl, t-butyl, pentyl, cyclopentyl, octyl, vinyl, allyl, 2-hydroxy ethyl, 2 or 3-hydroxy propyl, 2-methoxy ethyl, methoxy methyl or 2- or 3-methoxy propyl. Preferably at least one of the radicals R1 or R2 is C1-5 alkyl, especially methyl or ethyl. More preferably, R1 or R2 are the same or different C1-5 alkyl radicals such as methyl, ethyl, n-propyl or t-butyl, methyl and ethyl being especially preferred.

Most preferably, R1 and R2 are identical and are methyl or ethyl. Especially preferred are the dimethyl fumarate, methyl ethyl fumarate and diethyl fumarate.

(d) at page 8, line 5 and following:

The dialkyl fumarates to be used according to the invention are prepared by processes known in the art (see, for example, EP 0 312 697).

Preferably, the active ingredients are used for preparing oral preparations in the form of tablets, pellets or granulates, optionally in capsules or sachets. Preparations in the form of micro-tablets or pellets, optionally filled in capsules or sachets are preferred and are also a subject matter of the invention. The oral preparations may be provided with an enteric coating. Capsules may be soft or hard gelatine capsules.

The dialkyl fumarates used according to the invention may be used alone or as a mixture of several compounds, optionally in combination with the customary carriers and excipients. …

(e) at page 9, last paragraph:

According to the invention, a therapy with dialkyl fumarates may also be carried out in combination with one or more preparations of the triple drug therapy customarily used in organ transplantations or with cyclosporine A alone. For this purpose, the preparations administered may contain a combination of the active ingredients in the known dosages or amounts, respectively. Likewise, the combination therapy may consist of the parallel administration of separate preparations by the same or different routes.

(f) at page 10, in the middle of the page:

By administration of the dialkyl fumarates in the form of micro-tablets, which is preferred, gastrointestinal irritations and side-effects, which are reduced already when conventional tablets are administered but is still observed, may be further reduced vis- à-vis fumaric acid derivatives and salts.

It is presumed that, upon administration of conventional tablets, the ingredients of the tablet are released in the intestine in a concentration which is too high, causing local irritation of the intestinal mucous membrane. This local irritation results in a short-term release of very high TNF-α concentrations which may be responsible for the gastrointestinal side effects. In case of application of enteric-coated micro-tablets in capsules, on the other hand, very low local concentrations of the active ingredients in the intestinal epithelial cells are achieved. The micro-tablets are incrementally released by the stomach and passed into the small intestine by peristaltic movements so that the distribution of the active ingredients is improved.

68 The Patent has four examples, commencing at page 11, which are directed towards the preparation of:

(1) enteric-coated micro-tablets in capsules containing 120mg of DMF which corresponds to 96mg of fumaric acid;

(2) enteric-coated micro-tablets in capsules containing 120mg of DMF which corresponds to 96mg of fumaric acid

(3) micro-pellets in capsules containing 50mg of DMF which corresponds to 40mg of fumaric acid; and

(4) enteric-coated capsules containing 110mg of DMF which corresponds to 88mg of fumaric acid.

1.11 The claims

69 The Patent has 211 claims. Putting the omnibus claims to one side, each claim (or the claim from which it depends) contains a reference in one form or another to use in transplantation medicine and/or for the therapy of autoimmune diseases, or specific examples of such diseases.

70 The first of the asserted claims, claim 13, claims a pharmaceutical preparation in the form of micro-tablets or micro-pellets consisting of one or more dialkyl fumarates of the formula:

wherein R1 and R2 which may be the same or different, independently represent a linear, branched or cyclic, saturated or unsaturated C1-20 alkyl radical which may be optionally substituted with halogen, hydroxy, C1-4 alkoxy, nitro or cyano excipients, and optionally suitable carriers and excipients for use in transplantation medicine or for the therapy of autoimmune diseases or psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, neurodermatitis or enteritis regionalis Crohn.

71 Claim 14 claims a pharmaceutical preparation according to claim 13 wherein the autoimmune disease is polyarthritis, multiple sclerosis, juvenile-onset diabetes, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, systemic Lupus erythematodes (SLE), Sjogren’s syndrome, pernicious anaemia or chronic active (lupoid) hepatitis.

72 Claim 15 claims a preparation according to claim 13 or 14 wherein the halogen is Cl, F, I or Br.

73 Claim 16 claims a preparation according to any one of claims 13 to 15 comprising DMF, diethyl fumarate or methyl ethyl fumarate.

74 Claim 17 claims a preparation according to any one of claims 13 to 16 comprising an amount of the active ingredient corresponding to 10mg to 300 mg of fumaric acid.

75 Claim 95 claims a pharmaceutical preparation in the form of micro-tablets or micro-pellets consisting of dimethyl fumarate which has the formula:

and optionally suitable carriers and excipients; for use in therapy of multiple sclerosis.

1.12 Patent term extension

76 On 15 November 2013, Biogen requested that the Commissioner of Patents extend the term of the Patent pursuant to s 70 of the Act (the Request).

77 In the Request, Biogen asserted that the application for an extension of term of the Patent was based on goods containing or consisting of a pharmaceutical substance, being enteric coated micro-tablets of dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera), currently included on the ARTG.

78 The substance, as it occurs in the goods registered on the ARTG, was said to be in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the Patent as a pharmaceutical preparation in the form of micro-tablets or micro-pellets consisting of a dialkyl fumarate of the formula:

wherein R1 and R2 are CH3 (that is DMF). Biogen refers to this substance as the Propounded Pharmaceutical Substance in its written submissions.

79 In the Request, Biogen also stated that the Propounded Pharmaceutical Substance fell within the scope of at least claims 13 to 17 of the Patent.

80 On 20 October 2014, the Commissioner of Patents granted the extension of term of the Patent. Following the grant of the extension, the Commissioner made an entry in the Register of Patents that the term of the Patent was extended to 29 October 2024.

81 Biogen notes that without the extension, Biogen’s sales of Tecfidera in Australia would only have had patent protection for just over six years. Without the extension, the Patent would have expired on 29 October 2019.

2. RELEVANT LAW

82 The principles concerning the grant of interim injunctive relief are not controversial. When considering an application for an interlocutory injunction the Court must address two main enquiries, namely, whether the applicant for relief has established a prima facie case in the sense explained by the High Court in Beecham, and whether the balance of convenience and justice favours the grant of an injunction or the refusal of that relief.

83 The relevant principles are set out by the Full Court in Samsung Electronics Co. Limited v Apple Inc [2011] FCAFC 156 (Samsung) at [60]-[67]:

At [19] in O’Neill, Gleeson CJ and Crennan J said:

As Doyle CJ said in the last-mentioned case, in all applications for an interlocutory injunction, a court will ask whether the plaintiff has shown that there is a serious question to be tried as to the plaintiff’s entitlement to relief, has shown that the plaintiff is likely to suffer injury for which damages will not be an adequate remedy, and has shown that the balance of convenience favours the granting of an injunction. These are the organising principles, to be applied having regard to the nature and circumstances of the case, under which issues of justice and convenience are addressed. We agree with the explanation of these organising principles in the reasons of Gummow and Hayne JJ.

The requirement that, in order to obtain an interlocutory injunction, the plaintiff must demonstrate that, if no injunction is granted, he or she will suffer irreparable injury for which damages will not be adequate compensation (the second requirement specified by Mason ACJ in Castlemaine Tooheys at CLR 153; ALR 557) was not mentioned in Beecham. Nor was it referred to by Gummow and Hayne JJ in O’Neill. None the less, Gleeson CJ and Crennan J included that requirement in their articulation of the relevant “organising principles” (at [19] in O’Neill). They also agreed with the explanation of those principles given by Gummow and Hayne JJ at [65]–[72] in the same case. One way of reconciling the views of Gleeson CJ and Crennan J with those of Gummow and Hayne JJ on this point is to treat “irreparable harm” as one of the matters which would ordinarily need to be addressed in the court’s consideration of the balance of convenience and justice rather than as a distinct and antecedent consideration. This has been the approach taken by some judges: for example Ashley J in AB Hassle v Pharmacia (Aust) Pty Ltd (1995) 33 IPR 63 at 76–77; Gordon J in Marley New Zealand Ltd v Icon Plastics Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 851 at [3]; Kenny J in Medrad Inc v Alpine Pty Ltd (2009) 82 IPR 101; [2009] FCA 949 at [38]; and Yates J in Instyle Contract Textiles Pty Ltd v Good Environmental Choice Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 38 at [55]–[64].

The assessment of harm to the plaintiff, if there is no injunction, and the assessment of prejudice or harm to the defendant, if an injunction is granted, is at the heart of the basket of discretionary considerations which must be addressed and weighed as part of the court’s consideration of the balance of convenience and justice. The question of whether damages will be an adequate remedy for the alleged infringement of the plaintiff’s rights will always need to be considered when the court has an application for interlocutory injunctive relief before it. It may or may not be determinative in any given case. That question involves an assessment by the court as to whether the plaintiff would, in all material respects, be in as good a position if he were confined to his damages remedy, as he would be in if an injunction were granted: see the discussion of this aspect in I C F Spry, The Principles of Equitable Remedies, 8th ed, Lawbook Co, New South Wales, 2010, pp 383–9; pp 397–9; and pp 457–62.

The interaction between the court’s assessment of the likely harm to the plaintiff, if no injunction is granted, and its assessment of the adequacy of damages as a remedy, will always be an important factor in the court’s determination of where the balance of convenience and justice lies. To elevate these matters into a separate and antecedent inquiry as part of a requirement in every case that the plaintiff establish “irreparable injury” is, in our judgment, to adopt too rigid an approach. These matters are best left to be considered as part of the court’s assessment of the balance of convenience and justice even though they will inevitably fall to be considered in most cases and will almost always be important considerations to be taken into account.

Gleeson CJ also observed in Lenah Game Meats (at [18]), that, where there is little or no room for argument about the legal basis of the applicant’s claimed private right, the court will be more easily persuaded at an interlocutory stage that a prima facie case has been established. The court will then move on to consider discretionary considerations, including the balance of convenience and justice. But, as his Honour also observed at [18]:

The extent to which it is necessary, or appropriate, to examine the legal merits of a plaintiff’s claim for final relief, in determining whether to grant an interlocutory injunction, will depend upon the circumstances of the case. There is no inflexible rule.

The resolution of the question of where the balance of convenience and justice lies requires the court to exercise a discretion.

In exercising that discretion, the court is required to assess and compare the prejudice and hardship likely to be suffered by the defendant, third persons and the public generally if an injunction is granted, with that which is likely to be suffered by the plaintiff if no injunction is granted. In determining this question, the court must make an assessment of the likelihood that the final relief (if granted) will adequately compensate the plaintiff for the continuing breaches which will have occurred between the date of the interlocutory hearing and the date when final relief might be expected to be granted.

As Sundberg J observed in Sigma Pharmaceuticals (Aust) Pty Ltd v Wyeth (2009) 81 IPR 339; [2009] FCA 595 at [15] (Sigma Pharmaceuticals), when considering whether to grant an interlocutory injunction, the issue of whether the plaintiff has made out a prima facie case and whether the balance of convenience and justice favours the grant of an injunction are related inquiries. The question of whether there is a serious question or a prima facie case should not be considered in isolation from the balance of convenience. The apparent strength of the parties’ substantive cases will often be an important consideration to be weighed in the balance: Tidy Tea Ltd v Unilever Australia Ltd (1995) 32 IPR 405 (Tidy Tea) at [416] per Burchett J; Aktiebolaget Hassle v Biochemie Australia Pty Ltd (2003) 57 IPR 1; [2003] FCA 96 at [31] per Sackville J; Hexal Australia Pty Ltd v Roche Therapeutics Inc (2005) 6 IPR 325; [2005] FCA 1218 at [18] per Stone J; and Castlemaine Tooheys at CLR 54; ALR 558 per Mason ACJ.

84 The Full Court at [67] in Samsung recognised that the issue of whether an applicant has made out a prima facie case and whether the balance of convenience favours the grant of an interim injunction are related enquiries. Pharmacor submits that is of particular relevance in this case where Pharmacor, whilst accepting that the Pharmacor products fall prima facie within the scope of the claims, contends that it has a sufficiently strong case as to the expiry of the Patent and the invalidity of the asserted claims so as to weigh materially in Pharmacor’s favour on the question of balance of convenience.

85 Pharmacor asserts that its case on the wrongful extension of the Patent is so strong that it qualifies the conclusion that Biogen has established a prima facie case on infringement. As Jessup J in Interpharma Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2008] FCA 1498 (Interpharma) explained at [17]:

That is to say, as a matter of analysis, unless the case for invalidity is sufficiently strong (at the provisional level) to qualify the conclusion that, overall, the applicant has a serious question, or a probability of success, the court should move to consider the adequacy of damages, the balance of convenience and other discretionary matters. It is the applicant’s title to interlocutory relief which is under consideration, and the bottom-line question, as it were, is whether the applicant has a serious question, or a probability of success, not whether the respondent does in relation to some point of defence raised or foreshadowed.

3. ARGUABLE CASE

3.1 Introduction

86 As discussed above, the only claim which Pharmacor denies that the Pharmacor Products fall within is claim 17. Pharmacor contends that the infringement case is qualified by the wrongful extension of term case and the novelty attack.

3.2 Within the scope of the claims

87 Pharmacor admits that the Pharmacor products fall within the scope of all the asserted claims except for claim 17. Claim 17 claims a preparation according to any one of claims 13 to 16 comprising an amount of the active ingredient corresponding to 10mg to 300mg of fumaric acid.

88 Dr Williams’ evidence is that 12.5mg to 375mg of dimethyl fumarate correspond to 10mg to 300mg of fumaric acid. The Pharmacor products contain either 120mg or 240 mg of DMF. Professor Charman’s evidence is that 120mg or 240mg of DMF is the molar equivalent of 96.7mg or 193.4mg of fumaric acid respectively, which is within the range claimed in claim 17. On the evidence of both Professor Charman and Dr Williams the Pharmacor products appear to fall within the scope of claim 17.

89 Pharmacor did not appear to dispute in oral submissions that the Pharmacor products fall within claim 17 as no submissions were addressed to that point.

90 Biogen has a very strong prima facie case on infringement assuming that the asserted claims are extant and valid.

3.3 Patent term extension

91 Section 70 of the Act provides that a patentee of a standard patent may apply for an extension of the term of their patent if the requirements set out in subsections (2), (3) and (4) are satisfied. The relevant subsection for the purposes of this interlocutory application is (2)(a) which provides:

one more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

92 The phrase “pharmaceutical substance” is defined in Schedule 1 to the Act as follows:

pharmaceutical substance means a substance (including a mixture or compound of substances) for therapeutic use whose application (or one of whose applications) involves:

a) a chemical interaction, or physico-chemical interaction, with a human physiological system; or

b) action on an infectious agent, or on a toxin or other poison, in a human body;

but does not include a substance that is solely for use in in vitro diagnosis or in vitro testing.

93 The phrase “therapeutic use” is also defined in Schedule 1 to the Act:

therapeutic use means use for the purpose of:

(a) preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons; or

(b) influencing, inhibiting or modifying a physiological process in persons; or

(c) testing the susceptibility of persons to a disease or ailment.

94 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Bill 1998 (Cth), which inserted the current s 70 into the Act, contained the following explanation:

The extension of term provisions will be available for patents that include claims to pharmaceutical substances per se (provided that the other criteria are met) [i.e. a product claim]. These claims to pharmaceutical substances per se would usually be restricted to new and inventive substances. Patents that claim pharmaceutical substances when produced by a particular process (product by process claims) will not be eligible unless that process involves the use of recombinant DNA technology. Claims which limit the use of a known substance to a particular environment, for example claims to pharmaceutical substances when used in a new and inventive method of treatment, are not considered to be claims to pharmaceutical substances per se.

(Emphasis added.)

95 In Boehringer Ingelheim International v Commissioner of Patents [2000] FCA 1918 (Boehringer), Heerey J traced the history and antecedents of the extension of term provisions. That case involved claims directed to a container comprising an aerosol or spray composition for nasal administration or the use of such a composition when used in the container. Heerey J concluded that the Act draws a distinction between a pharmaceutical substance that is the subject of a patent claim and a pharmaceutical substance that forms part of a method or process claim.

96 Heerey J was assisted by the Patent Manual. Inter alia, the Patent Manual said at the relevant time:

25.2.2 Pharmaceutical Substance per se

Except for substances produced by a process involving the use of recombinant DNA technology, an extension of term is only available in respect of a pharmaceutical substance per se being within the scope of a claim of the patent.

The explanatory memorandum to the Intellectual Property Laws Bill of 1997 noted that, except for substances produced by a process involving the use of recombinant DNA technology, claims to pharmaceutical substances per se would usually be restricted to new and inventive substances. The memorandum also mentioned a number of specific instances where an extension would not be available:

‘Patents that claim pharmaceutical substances when produced by a particular process (product by process claims) will not be eligible unless that process involves the use of recombinant DNA technology. Claims which limit the use of a known substance to a particular environment, for example claims to pharmaceutical substances when used in a new and inventive method of treatment, are not considered to be claims to pharmaceutical substances per se.’

This distinction is specifically evident as between the reference in the Act to ‘pharmaceutical substances per se’, and to ‘pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology’. The use of the word ‘per se’ requires the claim to the substance to be unqualified by process, temporal, or environmental, components.

Thus, in order that the term of a patent be extended, the patent must contain one or more claims in the form:

a) A substance of formula ****

b) Substance X mixed with substance Y

Examples of claims that are not directed to substances per se are:

a) Substance X when used …

b) Substance X for use …

c) Substance X when produced by method Y

d) An antiseptic comprising substance X [unless the label ‘antiseptic’ was clearly non-limiting on the scope of the claim.]

e) A method of preparing substance X

f) A substance of formula …, where component Y is produced by …

g) [A specified quantum] of substance X

h) ‘Swiss’ – style claims referring to substance X

i) Use of substance X in the treatment of Y

(Emphasis added.)

97 On appeal from Heerey J in Boehringer, the Full Court in Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH v Commissioner of Patents (No. 2) (2001) 52 IPR 529, considered the validity of a patent extension based on an ARTG registration for ATROVENT NASAL (ipratropium bromide) said to fall within a claim to compositions for the treatment of a runny nose.

98 The patentee before the Full Court conceded that a container was fundamental to each of the claims, in the sense that absent the container as described in the claim, there would be no infringement. On the patentee’s argument, it was enough that the complete specification disclose one or more pharmaceutical substances, whether as the sole element in an invention or in combination with other elements.

99 In a passage which was approved and adopted by the Full Court and set out in full at [17], the trial judge, Heerey J, stated at [14]–[15]:

[14] Broadly speaking, a claim in relation to substance can be made in three ways:

(i) a new and inventive product alone;

(ii) an old or known product prepared by new and inventive process;

(iii) an old or known product used in a new and inventive mode of treatment.

[15] What is clear in s 70 is that only the first type of claim to a pharmaceutical product is to be subject to extension rights…[T]he policy to be deduced in the light of the legislative history is that Parliament has decided that what is intended to be fostered is primary research and development in inventive substances, not the way they are made or the way they are used, with the sole (and important) exception of recombinant DNA techniques, this being an area particularly worthy of assistance for research and development.

(Emphasis added.)

100 The Full Court held at [38] that the patentee’s argument “effectively reads out of s 70(2)(a) the words “per se””, noting that if that were the legislative intention, the paragraph could have read: “one or more pharmaceutical substances must in substance be disclosed”. There would have been no need for “per se”.

101 The Full Court in Prejay Holdings Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (2003) 57 IPR 424 (Prejay) considered the validity of an extension of term based on “Premia”, said to be a pharmaceutical substance falling within the scope of a claim (claim 14), being:

a method of hormonally treating menopausal or post-menopausal disorders in a woman, comprising administering to said woman continuously and uninterruptedly both progestogen and oestrogen in daily dosage units of progestogen equivalent to laevo-norgestrel dosages of from about 0.025 mg to 0.05 mg and of estrogen equivalent to estradiol dosages of about 0.5 mg to 1.0 mg.

102 The patentee in Prejay sought to distinguish their invention from that in Boehringer on the basis that claim 14 did not have a physical component.

103 The Full Court upheld the trial judge’s decision. In three passages of his reasons at first instance which were quoted by the Full Court, Heerey J said:

[14] In both Boehringer and the present case the claims included integers other than the pharmaceutical substance itself. The fact that in Boehringer the other integer was a particular physical device and in the present case the other integer is a particular method of use is to my mind a distinction without a difference.

….

[16] The fact remains that claim 14 is a method claim and, mere use of the substance otherwise than in accordance with the specified method would not infringe. The reasoning in Boehringer was applicable and correctly applied by the delegate.

….

[26] Where there is a patent for a method, such as “Substance X when used…”, it would usually follow that there is more than one reasonable use of X. If that were not so, one would expect the patent to be only for Substance X per se.

104 Justice Allsop (as his Honour then was) agreed with the decision of the majority, Wilcox and Cooper JJ, and made some additional comments which are apposite to the present case at [39]–[41]:

The argument of the appellant turns on the meaning of the definition of “pharmaceutical substance”. It requires the definition to be sufficiently wide (because of the presence of the phrase per se in s 70(2)(a) of the Act) to incorporate both the substance and a method integer, as long as the additional method integer is concerned with therapeutic use.

I do not see the definition so widely. The definition refers to a substance, which must have a purpose or use — therapeutic use, and whose application involves the other matters identified in the definition. The definition is of a particular kind of substance, but it is of a substance, and only a substance.

So understood, when one turns to s 70(2)(a) of the Act, the substance (that is the combination of the hormones in the amounts) per se must fall within the scope of the claim. If, as is conceded, use of the substance outside the particular administration regime in the claims is outside the scope of the claim, then it cannot be said that the substance per se falls within the scope of the claim.

105 At [42] Allsop J noted that his construction of s 70(2)(a) at [41] accorded with what appeared to him to be “the burden of the secondary materials, exemplified by the following part of the explanatory memorandum”:

The extension of term provisions will be available for patents that include claims to pharmaceutical substances per se provided the other criteria are met. These claims to pharmaceutical substances per se, would usually be restricted to new and inventive substances. Patents that claim pharmaceutical substances when produced by a product by process claims, will not be eligible unless the process involves the use of recombinant DNA technology. Claims which limit the use of a known substance to a particular environment, for example claims to pharmaceutical substances when used in a new and inventive method of treatment, are not considered to be claims to the pharmaceutical substance per se.

(Emphasis added.)

106 The current version of the Patent Manual still lists claims to “substance X for use…” as not being directed to a substance per se. The current version provides the following examples of claims that are not directed to substances per se:

substance X when used .... ;

substance X when produced by method Y;

a method of preparing substance X;

a substance of formula ...., where component Y is produced by .... ;

'Swiss' style claims referring to substance X;

use of substance X in the treatment of Y;

substance X for use .... ;

(a specified quantum) of substance X;

an antiseptic comprising substance X.

(Emphasis added.)

107 Biogen’s extension of term application was based on the Propounded Pharmaceutical Substance which it said fell within the scope of at least claims 13 to 17.

108 Pharmacor illustrates its case that the term was wrongly extended by reference to claim 13 of the Patent. Pharmacor contends that claim 13 is not a claim to a pharmaceutical substance per se for at least three reasons which can be summarised as follows:

(a) The claim is not for a new and inventive substance;

(b) The claim is a purpose limited product claim in that it claims an actual achievement of a therapeutic act being a functional technical feature of the claim. It is therefore, not a product claim for a pharmaceutical substance per se; and

(c) Claim 13 requires that the pharmaceutical formulation be in the form of micro-pellets or micro-tablets. Pharmacor submits that this brings additional features in the claim rendering the claim not to a pharmaceutical substance per se.

109 The Patent makes clear that dialkyl fumarates per se are not new and inventive. The specification makes reference to patents for processes for preparing dialkyl fumarates. Pharmacor draws attention to EP 0 312 697 which describes and claims the use of certain fumaric acid monoalkyl ester salts together with a dialkyl fumarate (such as dimethyl fumarate) for the production of a pharmaceutical preparation for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis, neurodermatitis and regional enteritis Crohns.

110 At the provisional level, Pharmacor’s arguments at (a) and (c) are weak. As I discuss below, the novelty attack is not made out at a provisional level in relation to the micro-pellet or micro-tablet formulations of DMF for the therapy of auto-immune diseases.

111 Pharmacor submits that claim 13 is a claim of the kind “substance X for use in the treatment of disease Y”. In Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 304 ALR 1, Crennan and Keifel JJ (as the Chief Justice then was) identify such claims as “purpose” claims, as described by Hoffmann LJ in Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals In & Ors v HN Norton & Co Ltd (1995) 33 IPR 1.

112 Pharmacor submits that the fact that “for use” in claim 13 limits the use of the claimed pharmaceutical preparation for actual achievement of claimed therapeutic effect is not only apparent from a plain reading of the claim but also when it is read in the context of the specification as a whole including the other claims.

113 Claim 14, for example, claims a pharmaceutical preparation according to claim 13 wherein the autoimmune disease is polyarthritis, multiple sclerosis, juvenile-onset diabetes, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Grave’s disease, systemic lupus erythematodes (SLE), Sjogren’s syndrome pernicious anaemia or chronic active (lupoid) hepatitis. If “for use” was non-limiting, Pharmacor submits that claims such as claim 14 to specific diseases or conditions would be redundant because they would not be narrower than the claim from which they are dependent.

114 Pharmacor submits that the limiting effect of the “for use” in the claims has been employed in an attempt to confer novelty and inventiveness over dialkyl fumarates per se. Consistent with this the dependent claims also claim different or specific diseases within the broader class claimed in the independent claims.

115 Pharmacor referred to the discussion of purpose-limited claims by the learned editors of Terrell on the Law of Patents (2021) at 14-109 to 14-110:

14-109

Purpose-limited claims arise in several contexts. First, in respect of claims which are for the use of old products for a new use— sometimes referred to as MOBIL-type claims following the decision of the EPO in MOBIL/Friction reducing additive. (G02/88) EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal decision (G02/88) [1990] E.P.O.R. 73. Secondly, in respect of Swiss-type claims where the claim is for the use of a product in the manufacture of a medicament for a particular therapeutic use. Thirdly, in respect of claims in EPC 2000 format (the successor to Swiss-type claims) where the claim is to a product for a particular therapeutic use (such as “substance X for use in the treatment of Y”).

14-110

Each of these claim types is alike in that their novelty resides not in the product per se but in the new use or purpose for that product. The recognition that an old product can have a new and inventive application is the technical contribution of these claims and leads to the conclusion that it would exceed that technical contribution if the word for in such claims was read in the sense of merely suitable for. After all, the old substance was always “suitable” for the new use, it is just that no-one had recognised the benefits of the new use. For this reason, in determining infringement, regard has to be had to the purpose or intent with which the infringer is putting the old product onto the market.

(Emphasis added)

116 Pharmacor submits that the claims should be construed in the same manner as EPC 2000 claims in the UK and EU. Pharmacor referred to the Full Court in Mylan Health Pty Ltd & Anor v Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd & Anor [2020] FCAFC 116 (Mylan) at [111] which noted that the EU Board of Appeal holds that actual achievement of the therapeutic effect is a functional technical feature of the claim, as opposed to a mere statement of purpose or intention.

117 Biogen contends that the words “for use” when followed by “in transplantation medicine or for the therapy of autoimmune diseases or psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, neurodermatitis or enteritis regionalis Crohn” do not change the character of the claim. It remains a claim to a pharmaceutical product per se, which is a product claim; not a method of treatment claim. The concluding words identify that the substance is useful for the indicated purposes, but do not serve to limit the product itself.

118 Biogen submits that claims to products “for use” in particular context are conventionally construed as product per se claims. Biogen places reliance on the construction of “for use” in the context of mechanical product claims to submit that claims to products “for use” in particular contexts are conventionally construed as product per se claims: Garford Pty Ltd v Dywidag Systems International Pty Ltd & Anor (2015) 110 IPR 30 at [122]–[124].

119 Biogen asserts that claim 13 is not limited by purpose and should be construed as a claim to the product, or pharmaceutical substance per se. Biogen points to the first paragraph of the Patent and two paragraphs on bottom half of page 10 as providing a basis for an unlimited claim to DMF formulated as micro-tablets or micro-pellets.

120 According to Biogen, the patent makes it abundantly clear when it is confining the statement monopoly to the treatment of various disorders, and the asserted claims are not in this category. A comparison of claims 13 and 40 is said to demonstrate the point. The uses described in claim 13 are for “transplantation medicine or for the therapy of autoimmune diseases or psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, neurodermatitis or enteritis regionalis Crohn”. Claim 40 is to a preparation according to, amongst others, claim 13 “when used” for the very same uses identified a claim 13.

121 Biogen further submits the claims 14, 16 and 17 merely refine the substance of claim 13 by the identification of suitable uses (claim 14), particular dialkyl fumarates (including DMF) (claim 16), and the quantity of active ingredient (claim 17), respectively. Each too, on Biogen’s analysis, is a claim to a pharmaceutical substance per se, unlimited by therapeutic use.

122 Biogen submitted that Pharmacor’s references to UK and EU construction of Swiss claims and EPC 2000 claims were inappropriate, as the separate jurisprudence that has evolved in the UK and EU in relation to the reason for the existence, and the construction of Swiss claims, and the later EPC 2000 claims, is not part of Australian law.

123 Biogen asserted that the use of DMF micro-tablets for another therapy for which they might also be useful, such as to treat infertility or high blood pressure, would fall within claims 13 and 14, as the micro-tablets would also be suitable for the uses given in claims 13 and 14.

124 I have extracted relevant sections from the Patent above. A review of the specification as a whole does not support Biogen’s contention that claim 13 (and those other claims dependent upon it) is not limited to the therapeutic purposes referred to in the claim.

125 As can be seen from the extracts above, the emphasis of the disclosure in the Patent is on the use of dialkyl fumarates for pharmaceutical preparations for use in transplantation medicine or therapy of auto-immune diseases. Other than the two paragraphs on page 10 referred to by Biogen, each discussion of the invention, the objectives and aspects are tied to use in transplantation medicine or the therapy of autoimmune diseases.

126 Dialkyl fumarates were known at the priority date of the Patent. At page 8, the Patent states that the dialkyl fumarates to be used according to the invention are prepared by processes known in the art. EP 0 312 697 is given as an example.

127 The Patent has 211 claims. Putting aside the two omnibus claims, each of the remaining 209 claims makes express reference to use in transplantation medicine or for therapy of autoimmune diseases. There is not one claim to a pharmaceutical preparation of dialkyl fumarate micro-tablets or micro-pellets alone.

128 The Full Court in Commissioner of Patents v Abbvie Biotechnology Ltd (2017) 125 IPR 398 considered whether claims in the form of Swiss type claims were claims to a pharmaceutical substance for the purposes of s 70(2)(b). Besanko, Yates and Beach JJ held at [60] and [61] that the pharmaceutical substance, adalimumab, even though produced via recombinant DNA technology, did not in substance fall within the scope of the claim in suit. Method of treatment claims or Swiss type claims cannot support an extension of patent term under s 70.

129 Swiss claims in an Australian patent were the subject of consideration by the Full Court in Mylan. The claim in suit was claim 5, which was dependent on claim 1 which claimed:

Use of fenofibrate or a derivative thereof for the manufacture of a medicament for the prevention and/or treatment of retinopathy, in particular diabetic retinopathy.

130 At [194] the Full Court briefly explained the derivation of Swiss claims, being the need to accommodate and satisfy the particular requirements for patentability under the European Patent Convention. Those requirements are not and never have been part of the Australian legal landscape. Nevertheless, as the Court noted, patentees have sought Swiss type claims in their Australian patents.

131 At [195] the Court said it was important to bear in mind that Swiss type claims are method or process claims and to be distinguished from method of treatment claims.

132 The Court at [196] stated that Swiss type claims are purpose limited claims in the sense that the medicament resulting from the method or process is characterised by the therapeutic purpose for which it is manufactured as specified in the claim.

133 The specification of a therapeutic purpose imposes an important limitation on the scope of the Swiss type claim. At [197] the Court noted that in theory it is this limitation which supports the novelty, and hence the patentability of, the invention. The Court continued:

It is appropriate, therefore, to consider this purpose as one that confines the use of the method or process to the achievement of one end and one end only – a medicament for the specified therapeutic purpose; not a medicament for any other therapeutic purpose. Put another way, a Swiss type claim does not claim the invention in terms of a medicament that is useful for, or can be used for, the specified therapeutic purpose and other therapeutic purposes. In order to support its patent ability and preserve its validity, the invention as claimed through a Swiss type claim, is necessarily more limited in scope.

(Emphasis added.)

134 At [198] the Court stated that the characterisation of the medicament by specification of the therapeutic purpose is, therefore, an essential feature of the invention as claimed.

135 The characterisation of the medicament of the Swiss type claim in suit in Mylan by specification of the therapeutic purpose “for the prevention and/or treatment of …” is not dissimilar to the characterisation of the pharmaceutical preparation in claim 13, as “for the therapy of …”.

136 In the context of infringement of Swiss type claims, the Full Court in Mylan at [225] observed that the “mere suitability” of a medicament for a claimed purpose cannot be determinative of the question of infringement. The fact that the patent has been granted on the basis of a second or later therapeutic use necessarily means that there are potentially multiple uses to which the medicament can be put. Use of the medicament for another suitable use (other than the use specified in the claim) would not infringe.

137 Consistent with the disclosure of the invention in the Patent and the reasoning of the Full Court in Mylan, the specified therapeutic purpose in claim 13 is, at least on a provisional view, an essential integer of the claim.

138 On that basis, use of the dialkyl fumarate micro-tablets for a therapy outside the particular therapeutic use in the claims is outside the scope of the claim, and it cannot be said that the substance per se falls within the scope of the claim: see Prejay at [42].

139 My provisional view is that there is a sufficiently strong prospect that the extension of the Patent may have been wrongly granted. That alone is likely to be sufficient to conclude that no injunction should be granted. However, the question of whether or not Biogen has demonstrated a sufficient likelihood of success to justify the preservation of the status quo requires consideration of the basket of discretionary factors which I discuss below: Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57 at [65].

3.4 Novelty

140 Pharmacor contends that the asserted claims lack novelty in light of Australian Patent Application No. 21593/99 (593 Application)

141 The 593 Application was filed before, but published after, the priority date of the Patent. Pharmacor relies on s 7(1)(c) of the Act, which refers to paragraph (b)(ii) of the definition of “prior art base” in Schedule 1 of the Act (often referred to as whole contents publications).

142 Section 18(1)(b)(i) of the Act requires that the invention be novel when compared with the prior art base as it stood before the priority date. This is to be assessed in accordance with s 7(1) of the Act, which requires a comparison with information made publicly available in documents or through the doing of acts.

143 The principles in respect of novelty are well-established. The basic test remains the “the reverse infringement test” as stated by Aickin J in Myers Taylor Pty Ltd v Vicarr Industries Ltd (1977) 137 CLR 228 at 235. That is, the claim may be anticipated by a document that discloses something within a claim: it does not need to disclose claim across its breadth.

144 A claim will lack novelty if a direction, recommendation or suggestion in a prior publication discloses either expressly or implicitly to a skilled addressee what is claimed or the inevitable result of following a direction, recommendation or suggestion in the prior publication is to arrive at the claimed invention: Bristol Myers Squibb v FH Faulding & Co Ltd (2000) 97 FCR 524 at [67].

145 It is a question of the disclosure to the skilled reader. A disclosure may be explicit or in certain circumstances implicit. This may occur where the prior art information is a publication which does not specify integer but the skilled reader would understand that integer to be present. If the prior art does not expressly specify each and every essential integer of the claimed invention, the evidence must clearly establish that to the skilled reader each and every essential integer is included: Meat & Livestock Australia v Cargill, Inc (2018) 129 IPR 278 per Beach J at [518].

146 The 593 Application is entitled “Utilisation of alkyl hydrogen fumarates for treating psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, neurodermatitis and regional enteritis”.

147 Dr Williams understands the 593 Application to describe pharmaceutical compositions containing alkyl hydrogen fumarate alone or in combination with dialkyl fumarate in the form of micro-tablets or micro-pellets for treating psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, neurodermatitis and enteritis regionalis Crohn.

148 The first paragraph on page 3 states:

The compositions in the form of micro-tablets or micro-pellets permit the administration of the free acid instead of its salt without the occurrence of the known side-effects, especially the formation of ulcers. This is probably due to the fact that microtablets or micro pellets permit a uniform distribution in the stomach, thus avoiding irritating local concentrations of the monoalkyl hydrogen fumarate in the form of the free acid.

149 At paragraphs 2 to 4 on page 3, the 593 Application describes a suitable amount of active ingredient for the compositions. In particular, the following amounts and examples:

(a) 20mg to 300mg of the free acid of the article hydrogen fumarate is particularly suitable for oral administration, the total weight of the active ingredients being 100mg to 300mg;

(b) for the start of therapy or the cessation of therapy: 100mg to 120mg of active ingredients, for example, 30mg to 35mg of dimethyl fumarate (a dialkyl fumarate) and 70mg to 90mg of methyl hydrogen fumarate (a monoalkyl fumarate) is advantageous; and

(c) therapeutic dosage after the initial phase: 190mg to 210mg of dimethyl fumarate and 90mg of monoethyl fumarate.

150 Professor Charman notes that this passage is not the only discussion of dosages in the 593 Application. Potential dosage ranges are also discussed in claims 4 and 5, and claim 5 in particular makes it clear that the part portion (by weight) of dialkyl fumarate, which is an optional inclusion, is relative to the part proportion (by weight) of the alkyl hydrogen fumarate. In Professor Charman’s opinion this is significant, as it emphasises that the 593 Application is focused on pharmaceutical compositions that include an alkyl hydrogen fumarate.