FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Quirk v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union [2021] FCA 1587

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and, by 21 January 2022, submit agreed short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons for judgment.

2. The parties file and serve written submissions limited to 1,000 words each, on the question of costs, by 21 January 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1027 of 2018 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BRIAN MILLER Applicant | |

AND: | CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MARITIME, MINING AND ENERGY UNION First Respondent CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MINING AND ENERGY UNION (NEW SOUTH WALES BRANCH) Second Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 December 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and, by 21 January 2022, submit agreed short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons for judgment.

2. The parties file and serve written submissions limited to 1,000 words each, on the question of costs, by 21 January 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1028 of 2018 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | ANDREW QUIRK Applicant | |

AND: | CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MARITIME, MINING AND ENERGY UNION First Respondent CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MINING AND ENERGY UNION (NEW SOUTH WALES BRANCH) Second Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 December 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and, by 21 January 2022, submit agreed short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons for judgment.

2. The parties file and serve written submissions limited to 1,000 words each, on the question of costs, by 21 January 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

I INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND MATTERS

1 Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were, until 17 April 2015, elected officials in and employees of the Construction and General Division of the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (‘the CFMMEU’). On 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk and Mr Miller appeared on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (‘ABC’) 7.30 program during which they accused the CFMMEU of corruption. Around the same date, although there is a debate about this in Mr Miller’s case, both men made similar remarks to a journalist from the Sydney Morning Herald which then published the remarks. Neither had sought nor obtained approval from the CFMMEU before speaking to the media. On 17 April 2015 a meeting of the Divisional Executive of the Construction & General Division was held to consider internal charges against Mr Quirk and Mr Miller arising from their actions. They had received notice of the meeting and were invited to appear before the Divisional Executive to answer the charges. Before the meeting, both men forwarded medical certificates indicating that they were not well enough to attend and sought to have the hearing adjourned. At the meeting on 17 April 2015, the Divisional Executive considered the adjournment request but declined it. It then moved to determine the charges and concluded that both were guilty of gross misbehaviour within the meaning of Rule 11 of the rules of the Construction and General Division of the CFMMEU (‘C&G Division’). As such the Divisional Executive removed them from office. As elected organisers Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were required by the rules to be employees of the C&G Division. Upon their removal from office as organisers, the effect appears to have been that their employment with the C&G Division also ended although there is a dispute about this.

The Litigation in the Federal Circuit Court

2 Mr Quirk and Mr Miller then commenced proceedings in the Federal Circuit Court against the CFMMEU seeking compensation and the imposition of pecuniary penalties under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (‘FW Act’). They claimed that they had been denied procedural fairness by the Divisional Executive, that they could not be guilty of gross misbehaviour within the meaning of Rule 11, and that the CFMMEU had terminated their employment for unlawful reasons, principally but not solely, because they expressed political opinions and engaged in protected industrial activity. The CFMMEU took the position that there had been no termination of any relationship of employment but rather that Messrs Quirk and Miller’s positions as elected officers had simply ceased by operation of law upon their removal under Rule 11.

The Litigation in the Federal Court

3 Mr Quirk and Mr Miller then commenced a proceeding in this Court seeking to have Rule 11 declared invalid on a number of bases including that it infringed the constitutionally guaranteed implied freedom of expression on political matters (this bifurcation was necessary because the Federal Circuit Court lacks jurisdiction to hold a rule of a registered organisation invalid). Subsequently, the case in the Federal Circuit Court was transferred to this Court and the two cases were heard together. The trial was heard over 16 days between 9 March 2020 and 31 August 2020. The trial straddled the commencement of the first lockdown imposed in New South Wales in response to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, this case was the first case in Australia to be heard virtually. Consequently, the state of the digital court book and the evidence is somewhat disordered. The parties are not to be blamed for this. The transfer from a paper hearing in a court room on the Friday to a digital hearing the following Monday occurred in circumstances of considerable stress for all parties. To put it in context, the weekend in which the parties did this was the weekend that all of the toilet paper in Sydney disappeared. Whilst, with hindsight, it is plain that the court book would now be prepared in a different way I do not think that criticism can be validly laid at the feet of the parties. To the contrary, they are to be congratulated on rising to the occasion. The state of the evidence has, however, made the preparation of these reasons far more challenging than is usual. I make these remarks chiefly for the benefit of any appellate court that comes afterwards. Ultimately, responsibility for the state of the trial materials lies with the trial judge.

Terminology

4 It is useful now to note something about terminology. There presently exists a federally registered union known as the CFMMEU which I shall refer to as the ‘Federal Union’. Formerly it was known as the CFMEU but a recent merger with the federal Maritime Union has resulted in the addition of an ‘M’. The Federal Union is the net result of the merger of several unions over the years. Although merged, those former unions continue to exist in the form of divisions within the Federal Union (for example, the ‘F’ is the former federal Forestry Union). Largely, those divisions are managed separately from each other.

5 This litigation is concerned with the Construction and General Division which essentially represents the interests of persons working in the construction industry. I will refer to it as the ‘C&G Division’ where necessary. However, because everything in this case involves the C&G Division reference to it is largely unnecessary and I will avoid referring to it save where it is unavoidable. Although the CFMMEU is prominent in national affairs, that prominence is largely driven by the C&G Division (which is the ‘C’) and not the FMMEU (although one or other of the ‘M’s is also frequently mentioned in dispatches). Because the C&G Division is part of a national union, it too is further divided into divisional branches for some of the States. This case is largely concerned with the NSW branch of the C&G Division. Only the CFMMEU has legal personality, however, which is why it is named as the First Respondent to each of the three proceedings presently before the Court. In practical terms, however, the overarching Federal Union has little to do with this case which is really about events within the NSW branch of the C&G Division. For reasons which shortly become apparent I am going to refer to it as the ‘Federal C&G Division (NSW)’. The affairs of the national office of the Federal C&G Division are also involved in this case. I will refer to it as ‘the National Office’. However, as I have said I will largely avoid using this confusing nomenclature and will refer, as often as possible, to the Federal Union.

6 The clumsy nomenclature is necessary because there also exist in most States unions with the same name registered under State industrial laws. In New South Wales this union is known as the CFMEU (one less ‘M’) which is, no doubt, confusing. It too has a Construction and General Division. I will refer to the state registered CFMEU as the ‘State Union’ to distinguish it from the Federal Union. I will refer to its C&G Division as the ‘State C&G Division’. The State Union is the Second Respondent to proceedings NSD 1027 of 2018 and NSD 1028 of 2018.

Who employed Mr Quirk and Mr Miller?

7 Although considerable time at trial was devoted to the issue of whether Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were jointly employed by the Federal Union and State Union, by the end of the trial it became apparent that both sides agreed that they were. In final submissions, Mr Seck said that on this issue both parties were ‘singing from the same hymn sheet’ and Mr Walker SC did not mention the topic in his closing address. In his opening, Mr Walker registered an objection to the use of the technical label ‘joint employment’, an expression apparently laden with baggage from United States labour law, but conceded that the evidence could support a finding that both unions employed Mr Quirk and Mr Miller, as joint or concurrent employers.

8 The convergence on this point was a surprising although relieving turn of events. Previously the State Union had vociferously resisted being joined to the proceeding as the joint employer of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller because as Mr Docking of junior counsel for the State Union told me in no uncertain terms at the time, there was no such thing as joint employment in Australian law: Quirk v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (No 2) [2019] FCA 44 at [23]. By the time of the trial the Respondents’ position, at least as reflected in their opening written submissions, had begun to resemble Dr Strangelove and his disobedient hand. For example, at [10] of those opening submissions, the author opened with this war-like contention: ‘The Applicants have still not adequately particularised any claim for joint employment…’ but then went on to say in as few words as possible ‘The federal registered union and State registered union accept joint employment’. Having said that through gritted teeth the submission then suggested that to accept such a thing ‘would have significant ramifications’ which sounds like a suggestion that I ought not to accept what the Respondents had just told me they were accepting. I was told ‘this Court has previously reasoned that this US labour law concept has not been the subject of decisive consideration by an Australian court and it is far from clear that the concept has anything to do with the common law’. In the Respondents’ closing written submissions (which I declined to entertain since both parties flagrantly ignored the page limit) it is interesting to note that the Respondents’ proposed position was that the employer was the State Union contrary to its opening submission. It included an even longer dissertation on joint employment.

9 It is hard to know what to make of any of this. At the end of the day the Respondents did not seek to persuade me that I should act otherwise than in accordance with the approach adopted by the Applicants. That approach is also consistent with the evidence of Ms Rita Mallia, the State President of both the Federal C&G Division (NSW) and the State C&G Division as well as the Senior Vice President of the State Union, who explained at T918-919 that:

(a) the existence of a state and a federal union in the same industry generated overlapping areas of authority. For persons such as organisers who needed to enter building sites it was necessary for them to hold positions in both unions so that rights of access could be exercised under both the federal and state regimes; and

(b) at the times relevant to this litigation, the way the administrative arrangements worked as between the Federal Union and State Union meant that the State Union processed all the payments to organisers even though ‘apart from the public sector organiser, all the other organisers were really servicing and recruiting members in the Federal system’.

10 It is nevertheless important to identify how a relationship of employment came about. There are several steps to this. First, it is not in dispute that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were both members of the Federal C&G Division (NSW) and the State C&G Division. Secondly, Mr Quirk and Mr Miller had at various times both been employed as organisers by the Federal Union. These positions were obtained not pursuant to any election to office but by entry into ordinary contracts of employment. I accept that these contracts of employment had been joint ones with the State Union. Thirdly, much ink was spilled on who was paying Mr Quirk and Mr Miller. However, since there is no dispute that they were jointly employed by both unions, I do not think it would be useful to spill any more ink on that issue, beyond noting Ms Mallia’s evidence on that topic to which I referred above.

11 Fourthly, in 2012 Mr Quirk was elected in the Federal C&G Division (NSW) to the position of a Divisional Branch Organiser. Mr Quirk thought this happened in 2008 but the Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’) return he said made good this proposition suggests that the election was held on or prior to 11 October 2012. However, whether Mr Quirk was elected in 2012 or 2008 does not matter.

12 Mr Miller came to be an organiser of the Federal C&G Division (NSW) by a slightly different road. He had held positions with predecessor union bodies in the 1980’s and 1990’s and then, in around 2000, was elected a Divisional Branch Organiser of the Federal Union. He was repeatedly re-elected to that position, most recently on 11 October 2012 – i.e., at the same election as Mr Quirk.

13 Fifthly, the Federal C&G Division has a set of rules which are registered under the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 1996 (Cth) (‘the FW(RO) Act’). These governed the conduct of the division and established State divisions. Rule 37(i) provided that the officers of the Federal C&G Division (NSW) would consist of a number of positions including ‘such Organisers as may be deemed necessary and as the Divisional Branch Council or Divisional Branch Management Committee from time to time determine’. Consequently, an organiser was an officer under Rule 37(i). The return of the Australian Electoral Commission suggests that 14 organisers were elected in 2012 from which it may inferred that one of these bodies so determined.

14 Sixthly, however, an organiser was not per se a member of the Divisional Branch Council or the Divisional Branch Management Committee. The Divisional Branch Council was the highest governing body for each divisional branch (here the Federal C&G Division (NSW)): Rule 40(1). It consisted of a number of identified positions which did not include organisers. The same may be said of the Divisional Branch Management Committee: Rule 42. In any event, the point is that neither Mr Quirk nor Mr Miller was a member of either body by virtue of his election as an organiser or by reason of election to any other office.

15 Seventhly, whilst the number of organisers was to be determined by the Divisional Branch Council or the Divisional Branch Management Committee, their election was governed by Rule 38. It provided a qualifying requirement that both Mr Quirk and Mr Miller satisfied: one year’s continuous membership. Rule 38(b) provided that each elected position, including that of an organiser, was for a continuous period of 4 years commencing on 2 January in the year following the election. In this case, because the election was held on or prior to 11 October 2012, it follows that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller commenced the relevant term of office on 2 January 2013 and would, in the ordinary course of events, have remained in office until the end of 1 January 2017.

16 Eighthly, the duties of an organiser were set out in Rule 48(1):

48 – (1) Duties of Organisers

(a) They shall be under the control and supervision of the Divisional Branch Management Committee and shall carry out their duties within the provisions of the Rules.

(b) They shall visit shops and jobs where members of the Divisional Branch and other workers eligible to join are employed and endeavour to enrol new members. They shall co-operate with all Shop and Job Stewards and District Secretaries, and carry out organisational work in any part of the State or Territory as directed by the Divisional Branch Management Committee.

(c) Nothing in this rule affects the right of an organiser elected, in accordance with the rules of the Divisional Branch, as a member of either the Divisional Branch Management Committee or the Divisional Branch Council.

17 Lastly, officers – including organisers – who were elected to a full-time position were said to be employed in the service of the relevant divisional branch (here, the Federal C&G Division (NSW)). Rule 49(a) provided:

A member who has been elected to any positions in a full-time capacity shall be employed full time in the service of the Divisional Branch and be paid such weekly wage as shall be determined at a properly constituted meeting of the Divisional Branch Council; provided however, that the rate fixed shall not be less than the leading hand rate in the highest major Award for carpenters in the building industry.

18 Since the Federal C&G Division (NSW) had no separate legal personality from the Federal Union the words ‘in the service of’ suggest that the employment relationship erected by this rule was between the Federal Union and Mr Quirk and Mr Miller, and that each man was to work in the service of the non-existent legal person which was the Federal C&G Division (NSW). Neither party made any submissions about this quibble and I will say no more of it. The parties also accepted that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s positions were full-time ones.

19 What was the effect of Rule 49(a)? Chapter 5 of the FW(RO) Act provides that industrial associations such as the Federal Union must have rules (s 140). By s 164 a member of an organisation may apply to this Court for an order that a rule be performed. Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s entitlement under Rule 49(a) was to be employed as an organiser for the period 2 January 2013 to 1 January 2017. Correspondingly, Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were bound by Rule 48 and s 164 to perform their duties as an organiser once employed as such under Rule 49(a).

20 One possible view of Rule 49(a) is that it gave rise to an employment relationship by itself. However, neither party suggested that this was the case. There are practical reasons for this. By itself the rule did not specify any of the usual matters which a contract of employment would specify such as, for example, leave entitlements. I therefore read the rule not as creating a relationship of employment but as requiring the Federal Union to enter into a contract of employment with a person who was elected as an organiser. One consequence of that interpretation of events is that while a person remained an elected organiser the Federal Union remained obliged to employ them. This cuts both ways. The effect of Rule 48 was that an elected organiser could not cease performing the duties of an organiser whilst remaining in the elected office. However, in my view, both of these sets of obligations existed outside the contract of employment which they both envisaged.

21 In the case of Mr Miller and Mr Quirk, both had already been employed by the Federal Union as organisers (and as the parties agree, jointly by the State Union). In my view, upon their election as organisers a new contract of employment came into existence under which the Federal Union and State Union employed them as elected organisers in the service of the Divisional Branch. An implied term of that contract was that the employment was coterminous with the holding of the office to which they had been elected: Mylan v Health Services Union NSW [2013] FCA 190 (‘Mylan’) at [26] per Buchanan J (‘I have no doubt that any employment which Mr Mylan may have held with the union was co-extensive with holding office in the union and depended on that circumstance.’). It is apparent from Mylan that Buchanan J accepted that this conclusion rested upon the existence of an implied term. I respectfully agree with his Honour that such a term would be implied into the contract of employment. If such a term were not implied an elected officer would remain employed as such even if he or she failed to be elected at the next election.

22 The effect of Rule 49(a) was that whilst Mr Quirk and Mr Miller remained in office their employment could not be terminated without breaching that rule. In practical terms, Rule 49(a) made the acquisition of a position as an elected organiser more attractive than the position of an ordinarily contracted one. It provided a limited form of tenure subject only to the whimsy of election and Rule 11.

23 On the other hand, the effect of the implied term was that if an elected organiser ceased to hold office the employment contract would be at an end. In practical terms, there would appear to be four ways an elected officer might cease to be such. These are: (a) losing an election; (b) all of the offices of a union being vacated upon the appointment of an administrator to manage its affairs (as occurred in Mylan with the Health Services Union); (c) being removed from office under Rule 11; and, (d) resignation.

The events leading to Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s public statements

24 In 2012, Mr Quirk says he became concerned that the CFMMEU (by which he meant the C&G Division of the CFMMEU) was associating with criminals. These concerns related to Mr George Alex although they were not limited to him. They included concerns too about Mr Mick Gatto. He raised these concerns internally but without any action being taken on them. This was a long and stressful period for Mr Quirk which resulted in him writing a letter on 2 October 2013 to Mr O’Connor, then the National Secretary of the Federal Union, outlining in detail his concerns over the affairs of the previous 12 months. Mr Quirk says that he was experiencing stress and anxiety by reason of the response that the raising of his concerns had engendered in his workplace. Eventually, he took sick leave and in around October 2013 he applied for workers compensation on the basis of anxiety and stress arising from what he felt was a cover up.

25 Subsequently, the Federal Union set up an internal inquiry into the allegations made by Mr Quirk which was to be conducted by a barrister, Mr Slevin. Mr Quirk was concerned about Mr Slevin’s independence because he had formerly worked as the national legal officer for the Federal Union prior to his call to the bar. Mr Seck, for the Applicants, also submitted that at the time Mr Slevin wrote the independent report for the Federal Union he had been retained by it to appear in its interests in the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption (‘Royal Commission’). Mr Quirk met with Mr Slevin and others on 23 November 2013. He met with him again on 12 December 2013 and conveyed further concerns he had about Mr Alex and other matters.

26 Until 1 January 2014 Mr Quirk had been on ‘gardening leave’ but had run out of it on that day. Thereafter he remained away from work taking sick leave. On 9 July 2014 Mr Quirk was given a copy of Mr Slevin’s report (‘the Slevin Report’). Mr Quirk was dissatisfied with the report and did not think that Mr Slevin had adequately investigated the allegations he had made.

27 Mr Miller’s concerns were largely the same as Mr Quirk’s, namely, the infiltration of the CFMMEU by alleged criminal figures such as Mr Alex and Mr Jim Byrnes. As in the case of Mr Quirk his concerns extended beyond this, however. They included, inter alia, the way in which Mr Quirk was being treated. Mr Miller was also concerned that he was being victimised for making these views known. In August 2014, he complained to Mr Parker, then the State Secretary of the Federal C&G Division (NSW) and Mr Hanlon, then the Assistant Secretary, that he was being overworked. On 18 September 2014 Mr Miller went on sick leave and lodged a workers compensation claim. Shortly afterwards, he sent a letter dated 29 September 2014 outlining his views on the problems with the union including its relations with Mr Alex and Mr Byrnes. He also complained that, as he saw it, Mr Quirk was being bullied. He was emailed after this by Ms Mallia who invited him to a meeting of the Divisional Branch Management Committee which he declined.

The public statements of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller

28 On 2 October 2014 Mr Miller was quoted in an article which appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald. The comments attributed to him were these:

In a letter sent on Monday to Mr Parker, Mr Miller raises serious allegations, including claims that:

• A union lawyer was asked to participate in potentially ‘illegal dealings’.

• The union engaged in fundraising activities that may have been ‘fraudulent’.

• CFMEU officials have been attacked for supporting union whistle-blowers Brian Fitzpatrick and Andrew Quirk, who previously raised concerns about alleged corruption and the union’s association with Mr Alex.

…

Mr Miller also reveals another union employee was ‘on workers compensation because of the attacks he was getting at work’.

‘He [the staff member] told me he refused to be involved in any illegal dealings that he was being asked to do … [including] signing documents for other people that he was not authorised to do.’

Mr Miller states union whistleblower Andrew Quirk and one of his supporters were called ‘dogs’ in union meetings, while ‘Terry Kesby is on the outer because of his letter of support for Brian Fitzpatrick.’

‘Organisers have spoken to me as well about their disgust about union tactics, and told me I’m wasting my time complaining to the leadership as they will do nothing,’ Mr Miller writes.

29 Mr Miller says that he did not speak to the journalist before this article was run.

30 On 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk spoke with a journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald, Mr Nick McKenzie, about his concerns. On the same day it published an article entitled ‘CFMEU’s Brian Parker set to be recalled before union royal commission’. The article quoted Mr Quirk in terms which he accepts were correct. These quotations were:

Details of Mr Parker’s recalling come as two more CFMEU officials, Brian “Jock” Miller – a 29-year veteran of the union and senior organiser, Andrew Quirk, have gone public to call for the leaders of Australia’s labour movement to act.

Both want senior ALP and Australian Council of Trade Union leaders to seek an urgent briefing from law enforcement on the alleged “overlap” between certain CFMEU officials and organised crime figures.

…

‘There has been a pretty catastrophic failure of governance in the CFMEU from the level of the management committee [in NSW] to the top of the union’, Mr Quirk told Fairfax Media.

Mr Quirk and Mr Miller, who are also due to appear on the ABC 7.30 program on Thursday night, urged the ALP and the ACTU to speak out against the victimisation of whistleblowers in the union. Mr Quirk said those who speak out were being ‘forced out of their jobs and their careers’.

‘The silence is deafening. If people are really concerned, the way they say that they’re concerned within the union movement and within the labour movement about corruption in the labour movement, then why don’t the relevant people in the senior ranks of the ACTU and the Labor Party go and seek the relevant briefing from the relevant security authorities and from the relevant police authorities on the state of play?’ Mr Quirk said.

‘At what stage is somebody going to get up and act like a mature, responsible grown up, and recognise that dealing with criminals … has nothing to do with the labour movement?’.

…

The pair decided to speak out after the royal commission recently revealed evidence, including phone taps, that appeared to show CFMEU NSW secretary, Mr Parker, supporting a business owned by Mr Alex.

…

Mr Quirk has alleged that Mr O’Connor failed to investigate several allegations he made about the infiltration of criminals into the union in NSW and Victoria. ‘I’m saying to Michael, look … you’ve got a problem in Melbourne and you’ve got a problem in Sydney, mate, right? There’s no good running away from this.’

31 Mr Miller was also quoted in these terms:

Mr Miller said figures in the CFMEU ‘seem to be protecting other people just to save their jobs instead of telling the truth’.

‘We’ve got a problem and we need to fix it. Either that or the union is going to be decimated,’ he said.

32 Mr Miller says that he did not speak to Mr McKenzie before this story was run.

33 On or about the same day Mr Quirk and Mr Miller appeared on the ABC’s 7.30 program. Ms Leigh Sales introduced the story with these remarks:

For the past two months, sensational allegations of corruption, rorting and intimidation have featured at the Royal Commission into unions.

At the centre of much of the scandal has been the construction union, the CFMEU.

Its leaders have consistently denied any wrongdoing.

But tonight, two whistleblowers go public on what they allege was endemic organised criminal infiltration of the union that was ignored by officials.

34 The story was then played. It had been put together by ABC journalist, Mr Dylan Welch. It was unflattering to the CFMMEU. Both Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were interviewed for the story. The relevant parts of the transcript of the program which record Mr Quirk’s remarks are as follows:

Dylan Welch: You’ve been a construction worker since your mid-teens.

Andrew Quirk: Yeah.

Dylan Welch: Your dad was a plumber, a unionist. You’ve been a unionist pretty much your whole life.

Andrew Quirk: Yeah.

Dylan Welch: Your life is the union?

Andrew Quirk. Well, it was. It’s not a union anymore.

….

Andrew Quirk: There have been reports of corruption, association with murderers, association with gangsters, association with terrorists, money being paid to union officials, union officials intimidating other union officials, union officials being forced out of their jobs and their careers and the silence is deafening.

…

Andrew Quirk: In 25 years as a delegate and a union official this company, I have never seen anything like what happened with George Alex. He was eight months behind, nothing happened.

…

Andrew Quirk: We’ve got two murders going on here. We’ve got enormous amounts of money, death threats, coverups, people being sacked for trying to speak out of turn.

Dylan Welch: On October 2, Quirk sent a letter to the union’s national secretary, Michael O’Connor.

Andrew Quirk: It’s on page one: the CMFEU in New South Wales is now at risk of becoming a front for criminal figures for the first time since the early 60s.

Dylan Welch: O’Connor ordered an internal investigation.

Andrew Quirk: I write the letter and then I get back a series of terms of reference. The terms of reference include everything in the letter that I’d wrote, apart from to what extent the national office had contributed to the mess.

…

Andrew Quirk: I gave Michael specific information that George Alex and a organised crime figure from Melbourne had co-invested in a Sydney company. Right? And I’m saying to Michael, ‘Look, you’ve got a problem, here. You’ve got a problem in Melbourne here and you’ve got a problem in Sydney, mate.’ Right? ‘There’s no good running away from this. We’re not talking about, you know, stealing the tuckshop money here.’ Right?

…

Dylan Welch: … After blowing the whistle, Quirk says he was treated like an outcast within the union.

Andrew Quirk: It seeps into your life. Bit by bit, it overwhelms your life. Bit by bit, it consumes you. Um – and, you know, this is all taking place against the backdrop of, you know, going to work every day and dealing with people at your workplace who are pretty experienced thugs, who, you know, are plainly sizing you up to see which leg they want to break first.

….

Dylan Welch: In recent months, the Royal commission has heard compelling evidence of crime and corruption in and around the CMFEU. It’s brought little satisfaction to Quirk.

Andrew Quirk: Look, there has been a pretty catastrophic failure of governance in the CMFEU from the level of the management committee to the top of the union, to the very top.

35 As can be seen, Mr Quirk and Mr Miller both made a number of statements about the CFMMEU which were not flattering.

36 The full transcript is annexed at the end of these reasons as Annexure A. For present purposes, the key points are that Mr Quirk said that the CFMMEU was ‘now at risk of becoming a front for criminal figures for the first time since the early 60s’ and that there had been ‘a pretty catastrophic failure of governance in the CFMEU from the level of the management committee to the top of the union, to the very top.’

37 Mr Miller did not actually say very much during the story. He was quoted only as follows:

Dylan Welch: Another union official, Jock Miller, watched as Quirk was treated like a pariah.

Jock Miller, Union Official: As soon as he went into bat for Brian Fitzpatrick, that was the end of it. They just – they were just trying to get him out the door. He’d get abused when he was at organisers’ meetings and I think that was affecting him and then he’s been there a reasonable amount of time and he’s tried his best and he’s, you know, he’s getting hammered just now, you know. I mean – and, you know, he’s struggling.

Dylan Welch: When Miller stood up for Quirk and Fitzpatrick, he says he too became a target of harassment by union colleagues.

Jock Miller: Yeah, I’ve had sleepless nights because of it. Just can’t believe that, you know, they’re treating me like this. For 29 years as an organiser and, you know, I’ve been pretty loyal and done the best I can for the members and this is the way you get treated.

38 There is in my opinion no doubt that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller had agreed to speak with 7.30 in order to make public their grievances about the way in which the CFMMEU was being conducted. I did not understand the contrary to be suggested by either party. Because it will be presently relevant I will record at this stage my opinion that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s statements were plainly expressions of dissent from the manner in which the Federal Union was being conducted. They were also plainly political in nature. At the time the remarks were made the Royal Commission was ongoing. The Royal Commission was actively and publicly examining the relationship between the Federal Union and criminal elements. The subject matter of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s observations to the media intersected directly with what was taking place before the Royal Commission. Of the Royal Commission there were two views: (a) that it was a long overdue exposure of corruption within the union movement; or (b) that it was a witch hunt launched by the government of the day for political purposes. It is not necessary to express any opinion about which of those views was correct. What does matter, however, is that the debate into which Mr Quirk and Mr Miller fatefully injected themselves was one of the most heated political debates of the day.

The events leading to the removal of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller from office

39 On 5 November 2014 Mr Miller received a summons from Mr David Noonan, the Secretary of the Federal C&G Division. It required him to attend a meeting of the Divisional Executive of the Federal C&G Division to be held at the offices of the Federal C&G Division in Clarence Street in Sydney at 1 pm on 18 November 2014. The Divisional Executive was in effect the national executive body for the Federal C&G Division. As such it included officials from several States. At that meeting Mr Miller was to answer a charge of gross misbehaviour which Mr Noonan had laid against him. The charge was attached to the summons. Two days later he received a bundle of documents which he was told formed the basis of the charge.

40 The summons was in the following terms:

I, David Noonan have charged you under rule 11(a)(ii) of the Rules of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union, Construction and General Division and Construction and General Divisional Branches with gross misbehaviour. The charge is set out in the attachment to this summons.

You are hereby summoned to attend a meeting of the Divisional Executive of the Construction & General Division of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union at 1.00 pm on Tuesday 18 November 2014 at level 11 215-217 Clarence St, Sydney, NSW.

At that meeting the Divisional Executive will consider the charge and afford you the opportunity to reply to it. You will also be afforded an opportunity of being heard in your own defence including an opportunity to cross examine and to give and call evidence.

Rule 11 permits the Divisional Executive to remove you from the office of Branch Organiser if you are found guilty of the charge.

41 The charge was in the following terms:

I, David Noonan, charge Brian Miller with gross misbehaviour. The particulars of the charge are as follows:

On or around 16 October 2014 Brian Miller who is a Divisional Branch Officer in the NSW Branch acted in a manner that amounts to gross misbehaviour.

Particulars:

a) On or around 16 October 2014 Mr Miller spoke to a journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald and program without authorisation of the union and purported to speak as a union officer about matters relating to the union. Mr Miller is quoted in that article as saying:

i. Figures in the union were protecting other people just to save their jobs instead of telling the truth.

ii. That the union has a problem and it needs to fix it or the union is going to be decimated.

The statement that there are figures in the union not telling the truth to protect others is unsubstantiated, it is damaging to the union and it had not been raised within the union by Mr Miller before it was raised publicly.

The statement that the union has a problem, which it needs to fix or be decimated is not substantiated, it is damaging to the union and it had not been raised within the union by Mr Miller before it was raised publicly.

b) On 16 October 2014, Mr Miller appeared on the ABC 7.30 program without authorisation of the union and purported to speak as a union officer about matters relating to the union. During that appearance he made comments which were false and/or adverse to the union. During that appearance Mr Miller:

i. Falsely alleged that the union was trying to get rid of Mr Quirk for supporting Mr Fitzpatrick.

ii. Falsely alleged that Mr Quirk was being mistreated by the union.

iii. Alleged that he had been mistreated by the union.

Mr Miller’s allegations had not been raised by him within the union before he appeared on national television. The allegations were damaging to the union.

42 Mr Quirk received a similar summons on 7 November 2014, this time contemporaneously accompanied by the supporting documentation. He was to attend the same meeting as Mr Miller and to face the same charge. His summons was not materially different to that which had been given to Mr Miller. The annexed charge was different, however. It was in these terms:

I David Noonan, charge Andrew Quirk with gross misbehaviour. The particulars of the charge are as follows:

On 16 October 2014 Andrew Quirk who is a Divisional Branch Officer in the NSW Branch acted in a manner that amounts to gross misbehaviour.

Particulars:

a) On 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk appeared on the ABC 7.30 program without authorisation of the union and purported to speak as a union officer about matters relating to the union. During that appearance he made comments which were false and/or adverse to the union.

b) During his appearance on the ABC 7.30 program on 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk falsely stated that the union had been silent about reports of corruption, association with murderers, association with gangsters, association with terrorists, money being paid to union officials, union officials being forced out of their jobs and their careers. The union has inquired into those reports, deliberated upon them at a number of levels and made public statements about them.

Mr Quirk’s public statement that the union had been silent about those reports was false and it was damaging to the union.

c) During his appearance on the ABC 7.30 program on 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk falsely stated that the union had done nothing about arrears associated with the George Alex companies. The union did not do nothing about those arrears. The NSW Branch recovered over $1.6 million in arrears from companies associated with Mr Alex in the period May 2012 to August 2014.

Mr Quirk’s public statement that the union had done nothing to recover worker’s entitlements was false and it was damaging to the union.

d) During his appearance on the ABC 7.30 program on 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk made adverse comment about the National Secretary by falsely stating that the terms of reference of the National Office Inquiry into allegations made by Mr Quirk about the NSW Branch in October 2013 failed to include an allegation that the National Office had contributed to the matters the subject of investigation. The terms of reference of the investigation did include Mr Quirk’s allegation about the involvement of the National Office.

Mr Quirk’s public statement that the National Secretary failed to investigate his allegation about the National office was false and it was damaging to the National Secretary and the union.

e) During his appearance on the ABC 7.30 program on 16 October 2014 Mr Quirk made false claims about other Officers and employees of the union stating that he went to work every day and dealt with experienced thugs who were sizing him up to assault him.

Mr Quirk’s public statement that the union officers and employees he worked with were experienced thugs who wanted to assault him was false and damaging to those officers and employees and the union.

43 Mr Quirk and Mr Miller attended the meeting on 18 November 2014 and submitted to the Divisional Executive that they were not in a position at that stage to answer the charges. They then left the meeting. The Divisional Executive adjourned consideration of the matter. There was subsequent correspondence between the parties and some further adjournments. The details of those adjournments is relevant to the allegation that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller make that they were denied procedural fairness. I deal with the detail of the adjournments when I arrive at that issue.

44 Finally, the matter was adjourned to 17 April 2015. By their solicitors, Mr Quirk and Mr Miller sought to have this meeting adjourned too and did not attend. On that day, the Divisional Executive decided to proceed in their absence. Both were found guilty of gross misbehaviour. The Divisional Executive decided to remove them from office pursuant to Rule 11 of the Federal C&G Division rules. It provides:

11 – REMOVAL OF OFFICERS

(a)(i) Any Divisional or Divisional Branch Officer may be removed from office by majority decision of the Divisional Executive of the Division in which the Officer holds office, provided that such officer shall not be dismissed from office unless the officer has been found guilty, in accordance with the Rules of the Union, of misappropriation of funds of the Union or a substantial breach of the Rules of the Union or gross misbehaviour or gross neglect of duty or has ceased according to the Rules of the Union to be eligible to hold office.

(a)(ii) An officer may be charged by any member of the Division with the offences referred to l l(a)(i) above, whether the offence occurred before or after this sub-rule came into effect, and where the Divisional Executive is to consider whether or not any Divisional or Divisional Branch Officer is to be removed from office under sub-paragraph (i) herein, the procedure to be adopted shall be as follows:

a) The officer is to be summoned to attend the meeting at least 7 days prior to the meeting,

b) Notice of the charge or allegation is to be given sufficient to enable a reply,

c) The officer is to be afforded an opportunity of being present at the hearing and of being heard in his/her own defence, including an opportunity to cross-examine and to give and call evidence.

(b) Should any officer be removed from office the Divisional Executive may appoint a member to fill the vacancy until the next elections are held and a successor takes office in accordance with the rules, but no person shall be appointed to an office, otherwise than temporarily, where the remainder of the term of office is twelve (12) months or three quarters of the term whichever is the greater.

(c) Any officer so removed from office shall have the right of appeal to the Divisional Conference and therefrom to the National Executive or National Conference.

In the event of the appeal being upheld the Divisional Conference, National Executive or National Conference may order reinstatement to apply on such conditions as it considers the circumstances warrant.

(d) In the event of the re-election of an Officer removed from office under this rule, such officer shall be reimbursed by a payment of monies that represent the difference between such salary that would have received had the officer not been removed from office and the amount of salary the officer received during the period that the officer was removed from office.

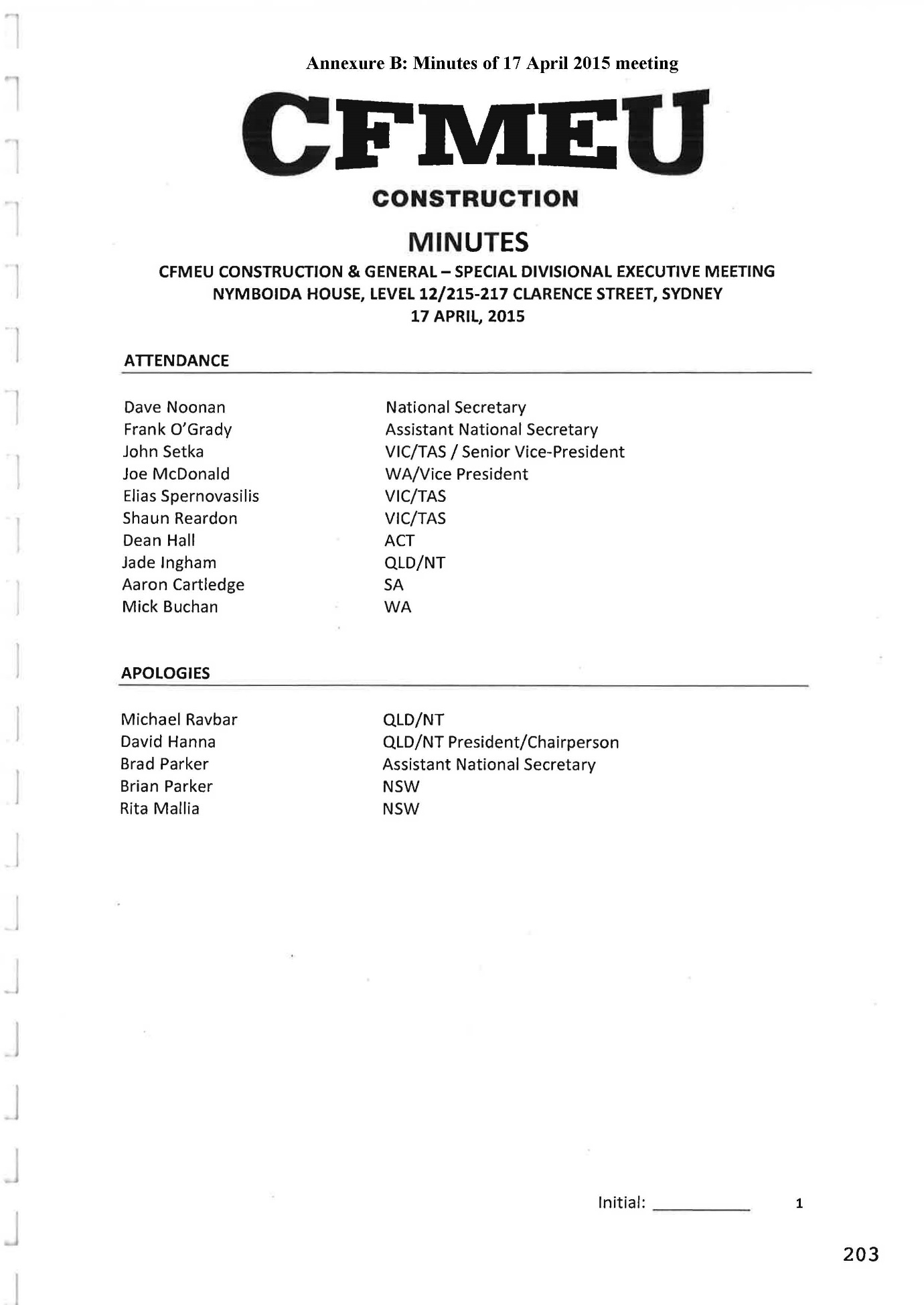

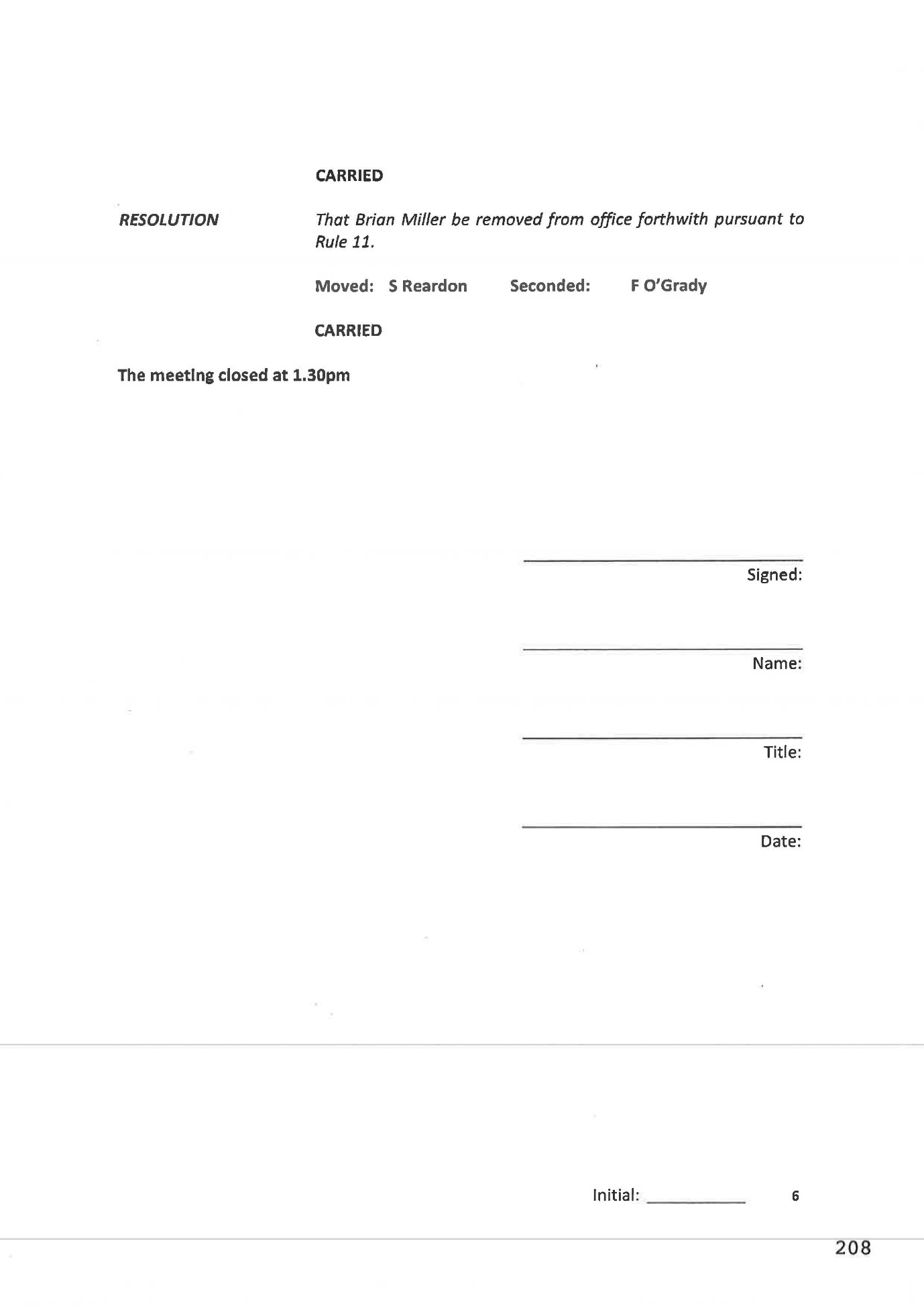

45 The minutes of the Divisional Executive record that present at the meeting were ten of its members. These were David Noonan, Frank O’Grady, John Setka, Joe McDonald, Elias Spernovasilis, Shaun Reardon, Dean Hall, Jade Ingham, Aaron Cartledge and Mick Buchan.

46 The minutes are annexed to these reasons as Annexure B.

47 It will be noted that Mr Noonan, as the person laying the charges, did not participate in the decision.

The termination of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s employment as organisers

48 On 20 April 2015 the Federal Union wrote separate letters to Mr Quirk and Mr Miller informing them that they had been removed from office under Rule 11. The letters did not purport to terminate their contracts of employment. On 27 April 2015 Ms Mallia wrote to both Mr Quirk and Mr Miller referring to the fact that they had been removed from office and observing: ‘A consequence of your removal from office is that your employment with the Branch ceases on the same date.’ Ms Mallia’s evidence about this was at §64-65 of her affidavit:

It was my view that there was no way that the employment of Mr Quirk or Mr Miller with the State Union or the NSW Divisional Branch could continue after they lost office. This was for a number of reasons. First, my view was that the Federal registered union rule meant that being removed from office removed the basis of the underlying employment contract with the federal registered union, and therefore the NSW Divisional Branch of the federal registered union.

The second reason was that, even if there was some employment contract that legally may have subsisted with either the State Union or the NSW Divisional Branch after Mr Quirk and Mr Miller lost office, that contract was frustrated from being performed. The loss of office meant that neither Mr Miller nor Mr Quirk could perform the tasks of an organiser for the members of the State and federal registered unions.

49 I agree with Ms Mallia’s understanding of the position with the Federal Union. As I have explained, the implied term discussed in Mylan had the consequence that upon being removed from office Mr Quirk and Mr Miller ceased to be employed by the Federal Union. I do not agree with Ms Mallia that contracts of employment with either the State Union or the Federal C&G Division (NSW) were frustrated. Rather, as I have explained, the relationship of employment (in this case, joint employment by both the Federal Union and State Union) was coterminous with the holding of office as an organiser of the Federal Union and came to an end with the termination of that office. Consequently, Mr Quirk and Mr Miller ceased to be employed by the Federal and State Union as organisers at the moment that their offices were vacated under Rule 11 (if they were validly removed under that rule – a matter of considerable debate between the parties).

II THE RULES CASE

50 The rules case was based on Rule 11 of the Federal Union’s rules which is set out above.

51 There were two limbs to the case. First, it was said that the Applicants had not been afforded an opportunity of being present at the hearing on 17 April 2015 contrary to the requirement of Rule 11(a)(ii). Broadly speaking, this was because they had not been medically fit to attend on that day and had provided medical evidence to that effect to the Divisional Executive. The Applicants argued that the Divisional Executive had been wrong to reject their medical evidence and should have acceded to the request for an adjournment. I refer to this below as the ‘procedural fairness case’.

52 Secondly, it was said that the conduct with which they were charged could not constitute ‘gross misbehaviour’ within the meaning of Rule 11. As will be seen, this limb took in a wide compass of arguments that relied upon, among other matters, the requirements of the FW(RO) Act and the constitutionally implied freedom of political communication.

The procedural fairness case

Mr Quirk

53 As I have already indicated, the first return of the summonses on 18 November 2014 was adjourned after Mr Quirk and Mr Miller left the meeting having indicated that they were not yet ready to meet the charges. Following that, Mr Quirk received a letter dated 19 November 2014 requiring him to attend before the Divisional Executive on 5 December 2014 for the hearing of the charge against him.

54 On 2 December 2014 Mr Quirk instructed his solicitor to write to the Federal Union to indicate that he was unfit to attend the meeting on 5 December 2014. His solicitor wrote to the union on the same day. The letter claimed that Mr Quirk, by reason of his medical condition, remained unable to participate in a meeting, and sought an adjournment until such time as Mr Quirk was in a fit state. The letter also sought further particulars of the charge. In support of the request for an adjournment the letter relied upon and annexed a medical certificate from Mr Quirk’s treating psychologist, Dr Alison Smith, dated 28 November 2014, and a medical certificate from Dr James Best dated 2 December 2014.

55 Dr Smith’s report was in these terms:

I have seen Mr Quirk intermittently over the last year. Our most recent session occurred on 28/11/2014.

On that occasion, Mr Quirk presented with extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety and stress as assessed by interview and by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale. He met criteria for a Major Depressive Episode (DSM-5, 2013).

As a consequence of his levels of depression, anxiety and stress, he is unable to concentrate or sleep and he is overwhelmed and fatigued. These symptoms make it impossible for him to read and respond to complicated documents and to consider and answer charges at a meeting scheduled for 05/12/2014.

Consequently, I support an extension of time for the hearing of misconduct brought against him.

56 Dr Best’s certificate was in these terms:

Mr Andrew Quirk of [address] is undergoing medical treatment from 24/11/2014 to 25/12/2014 (inclusive) and is unfit to perform any duties related to his workplace or the current disciplinary hearings and Royal Commission.

57 On 4 December 2014 the Federal Union wrote to Mr Quirk’s solicitor and denied any obligation to provide the requested particulars. It doubted that Mr Quirk’s medical condition warranted an adjournment but one was nevertheless granted until 17-19 March 2015. On 5 March 2015 Mr Quirk was notified that the hearing would take place on 17 March 2015 but on 13 March 2015 he was told the meeting would now not take place on that date but would be postponed to a date to be determined. On 30 March 2015, he was served with a fresh summons requiring him to attend a meeting on 17 April 2015. Thereafter he consulted Dr Smith once more as a result of which she produced a certificate dated 14 April 2015. This certificate was annexed to Dr Smith’s affidavit of 22 November 2019 and was in these terms:

I have seen Mr Quirk today.

In my opinion Mr Quirk is extremely depressed and stressed. I believe that he is unable to attend the disciplinary hearing scheduled for 17 April 2015 because of his psychological condition.

58 Mr Quirk also consulted Dr Henry Nowlan who produced a certificate dated 14 April 2015. It was in these terms:

Mr Andrew Quirk of [address] is undergoing medical treatment and is unable to attend any meeting on 17/04/2015.

Clinical psychologist Dr Alison Smith supports this decision.

59 Mr Quirk then wrote to the Federal Union noting that particulars had not been provided and seeking the postponement of the meeting on the basis of the certificate of Dr Nowlan.

60 The Divisional Executive met on 17 April 2015 at which time Mr Quirk did not attend. It declined the adjournment he had sought. Its reasons for doing so are set out in the minutes annexed to these reasons as Annexure B. The reason appears to have been because of a perceived inconsistency between Dr Nowlan’s certificate and a Workcover certificate, the former indicating that he could not attend the meeting, and the latter that he was available for work three days per week.

61 The Workcover certificate in question is dated 9 April 2015 and is signed by Dr Samuel Cheng. From Dr Cheng’s certification it does not appear that he was Mr Quirk’s treating doctor although he did certify that he had examined Mr Quirk. In Part B which was headed ‘Medical Certification’ the diagnosis was recorded as an anxiety disorder which was diagnosed on 17 May 2013 and was caused by ongoing stress-inducing issues in the workplace. In the section headed ‘Management Plan for this Period’ Dr Cheng said:

Requires further psychological therapy from Alison Smith (psychologist) – has seen as of 09/04/2015 and finding beneficial to recovery. Requires this treatment prior to return to work at CFMEU provided suitable duties are provided in safe working environment consistent with the legal obligations of the CFMEU with the relevant state and federal health and safety legislations.

62 In the section headed ‘Capacity for Employment’ Dr Cheng indicated that Mr Quirk had some capacity for work for 8 hours per day for 3 days per week for the period 9 April 2015 to 7 May 2015. This view was subject to a further stipulation:

Following psychological therapy, will be fit for return to work at CFMEU provided suitable duties are provided in safe working environment consistent with the legal obligations of the CFMEU with the relevant state and federal health and safety legislations.

63 I do not agree that Dr Nowlan’s certificate is inconsistent with Dr Cheng’s. The former was discussing Mr Quirk’s attendance at a meeting of the Divisional Executive in which he was to answer in person a charge of gross misbehaviour, the latter was discussing his ability to perform ‘suitable duties in [a] safe working environment’.

64 I should say for completeness, that both sides spent some energy on the topic of whether Mr Quirk was in fact fit to attend the meeting. This is irrelevant. The question of procedural fairness is to be judged by the material before the Divisional Executive.

Mr Miller

65 Following the adjournment of the first return of the summons on 18 November 2014, Mr Miller received a letter from the Federal Union requiring him to attend a further meeting of the Divisional Executive on 5 December 2014. He retained a firm of solicitors to act on his behalf and on 1 December 2014 those solicitors wrote to Mr Noonan. The letter informed Mr Noonan that Mr Miller was ‘unfit and unable to give due and proper consideration to the disciplinary charges’. It enclosed a certificate from Dr John Nguyen dated 27 November 2014 and a report of a psychologist, Emily Peterson, also dated 27 November 2014. Ms Peterson was the psychologist appointed in relation to Mr Miller’s workers compensation claim.

66 The certificate of Dr Nguyen was in these terms:

This is to certify that Brian was examined on 27.11.2014.

In my opinion he is suffering from severe psychological injury.

He was/will be unfit for work or to attend any meetings in relation to work from 27/11/2014 to [undiscernible date] inclusive.

67 The report of Ms Peterson was in these terms:

Brian Miller is a client of Professional Psychological Services under Work Cover. He is currently off work until the 4th January 2015. He is currently receiving psychological treatment for his Work cover claim. Attending work or work related meetings will negatively affect Brian’s psychological state due to increased stress.

68 In addition to enclosing the medical reports and seeking an adjournment of the hearing on 5 December 2014, the letter also sought extensive particulars of the charge. On 4 December 2014 Mr Noonan replied, disputing the unfitness of Mr Miller to attend on 5 December 2014 but nevertheless agreeing to an adjournment to a range of dates between 17-19 March 2015. The request for particulars was denied on the basis that there was no provision in the Rules for such a request.

69 On 3 March 2015 the Federal Union wrote to Mr Miller with a fresh summons requiring him to attend a meeting of the Divisional Executive on 17 March 2015. However, on 13 March 2015 Mr Miller was informed that this meeting had been postponed to a date to be determined. On 30 March 2015 Mr Miller was issued with a fresh summons requiring him to attend a meeting of the Divisional Executive to be held on 17 April 2015.

70 Mr Miller consulted Ms Peterson on 13 April 2015 who produced a report of the same date. It was in these terms:

This is to state that Brian Miller is suffering from Adjustment disorder with anxious and depressed mood due to a work incident in September 2014.

Due to the ongoing psychological distress Brian is suffering from he is, in my opinion, unfit to attend a summons or further work meetings from 13/04/2015 till 13/06/2015.

71 Mr Miller also saw Dr Nguyen on the same day who issued a further certificate. It was as follows:

This is to certify that Brian is suffering from adjustment disorder with anxious and depressed mood since 12/9/2014, after a work incident. He suffers from severe anxiety, depression, insomnia and poor concentration. He is unfit to attend a summons from 13/4-13/6/2015 inclusive.

72 The next day Mr Miller himself wrote to the Federal Union enclosing Dr Nguyen’s certificate. He requested that the meeting be adjourned on the basis of it and also because the Federal Union had not provided the particulars he had sought. It seems that Ms Peterson’s report was also enclosed with the letter, although the body of the letter did not refer to it.

73 The Divisional Executive met on 17 April 2015. Mr Miller did not attend the meeting. It determined not to grant the adjournment he had sought. The reasons it took that course are set out in the minutes at Annexure B to these reasons. In essence it thought that the requested particulars had been provided and that the medical evidence provided by Mr Miller was inconsistent with the ‘Workcover certificate’. It seems clear that the particulars had not been provided because the Federal Union had said on 4 December 2015 that it was under no obligation to provide them. In any event, this does not matter as the procedural fairness case does not turn on any alleged failure to provide particulars.

74 This certificate was entitled ‘WorkCover NSW – Certificate of Capacity’. It had several sections. Part A was to be completed by Mr Miller. He had signed this part on 18 September 2014. Part B was to be completed by a nominated treating doctor. The doctor was Dr Nguyen, i.e. Mr Miller’s doctor. In section B, Dr Nguyen recorded a diagnosis of an adjustment disorder with depressed and anxious mood, which was the same diagnosis he had given in the certificate he provided to Mr Miller dated 13 April 2015 and which Mr Miller had forwarded to the Federal Union.

75 Under a section entitled ‘Capacity for Employment’ Dr Nguyen indicated that Mr Miller had ‘capacity for some type of employment’ from 24 March 2015 to 24 April 2015 and this was for normal hours on normal days. Dr Nguyen’s more recent certificate of 13 April 2015 had been specific in saying that he was unfit to attend the return of the summons between 13 April 2015 and 13 June 2015.

76 Under the heading ‘Capacity’, Dr Nguyen made this stipulation:

mediation to take place before recommencing work, avoid contact with people involved, suitable duties are provided in a safe working environment consistent with the legal obligations of the CFMEU with the relevant state and federal health and safety legislation.

77 Finally Dr Nguyen indicated that there should be another review of Mr Miller’s condition on 24 April 2015. He signed the form on 24 March 2015.

78 I do not think there was any inconsistency between Dr Nguyen’s Workcover certificate of 24 March 2015 and his certificate of 13 April 2015. One was addressed to Mr Miller’s fitness to attend the return of the summons, the other to Mr Miller’s fitness to attend work. These are different topics.

79 One can generate inconsistency only if one characterises the meeting of the Divisional Executive as part of Mr Miller’s work. Making the assumption in favour of the Respondents that Mr Miller’s attendance at the meeting is to be characterised as part of his duties, the effect of Dr Nguyen’s certificate is that work could not occur until a mediation had taken place and that he was, in any event, to avoid contact with the people involved. The meeting of the Divisional Executive on 17 April 2015 satisfied neither requirement. There had been no mediation and I struggle to see how a hearing into gross misbehaviour can be described as ‘suitable duties … provided in a safe working environment’.

80 I do not therefore regard the Divisional Executive’s reasoning for refusing the adjournment as compelling. It is possible to imagine other reasons why the adjournment might have been refused. For example, Mr Setka and Mr Spernovasilis gave affidavit evidence that they thought Mr Miller must have been fit to participate in the meeting if he had been fit to speak to the media. And Mr Noonan in his letters of 4 December 2014 had made the point that Mr Miller and Mr Quirk were well enough to instruct lawyers. But even if such other reasons had been compelling, there is no basis to conclude that they represented the reasons of the Divisional Executive as a whole when it voted to proceed to determine the charges. In this respect, I prefer the minutes of the meeting as a contemporaneous record of the reasoning of the Divisional Executive: ET-China.com International Holdings Ltd v Cheung [2021] NSWCA 24 at [25] per Bell P, Bathurst CJ and Leeming JA agreeing. The minutes disclose only the perceived inconsistency between the Workcover certificates and the medical certificates provided by Mr Miller and Mr Quirk. As I have just explained, I do not accept that such an inconsistency existed.

Was Rule 11(a)(ii) complied with?

81 Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s case was put on the basis that the failure to adjourn the summonses meant that the subsequent decision to find them guilty of gross misbehaviour was afflicted by a want of procedural fairness. Mr Seck submitted that the situation was akin to that in Minister for Immigration and Citzenship v Li [2013] HCA 18; 249 CLR 332 (‘Li’). I do not accept that submission. Li was concerned with the public law question of whether a decision to refuse an adjournment was unreasonable and the content of any requirement for an administrative decision-maker to determine adjournment requests reasonably. It has nothing to do with the operation of Rule 11. He also referred to other public law cases concerned with a failure to grant an adjournment: NAKX v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs [2003] FCA 1559 at [6] per Lindgren J and Luck v Chief Executive Officer of Centrelink [2015] FCAFC 75 at [49] per Collier, Griffiths and Mortimer JJ. As with Li, I do not accept that any of these cases have any bearing on the present situation.

82 The real question is whether Rule 11(a)(ii)(c) was complied with. That requires one to ask whether they were ‘afforded an opportunity of being present at the hearing and of being heard in his/her own defence, including an opportunity to cross-examine and to give and call evidence’. In my view, the opportunity the rule requires is a reasonable opportunity. If a person is not sufficiently well to attend the hearing then to proceed in their absence will mean that they have not been afforded the ‘opportunity of being present’.

83 The question of whether Rule 11(a)(ii)(c) has been complied with is a question for this Court. So much flows from the power of the Court to enforce the rule under s 164 of the FW(RO) Act. To determine whether Rule 11(a)(ii)(c) was complied with by the Divisional Executive this Court must therefore form its own view on the material which was before the Divisional Executive.

84 I accept Mr Seck’s submission that there was no contradiction between the Workcover certificates and the medical opinions obtained by Mr Quirk and Mr Miller. They simply dealt with different topics. Once that is appreciated, the only material before the Divisional Executive touching upon the fitness of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller to attend the hearing was the evidence they had presented that they were not.

85 This is not to say that the Divisional Executive was obliged to adjourn the matter indefinitely. If it were of the opinion that it doubted the correctness of Mr Quirk and Mr Miller’s medical evidence, the proper course was for it to obtain its own medical opinion on the matter by requiring Mr Quirk and Mr Miller to attend upon some independent medical expert. Such a practice is well-known in disciplinary proceedings: Blackadder v Ramsey Butchering Services Pty Ltd [2002] FCA 603; 118 FCR 395 at 411 [67]-[70] per Madgwick J; Fire & Rescue New South Wales v Public Service Association [2018] NSWIRComm 1066. It seems, however, that it was not well-known to the members of the Divisional Executive, for when Mr O’Grady was asked about this during cross-examination, this exchange eventuated (at T624.9-14):

Mr Seck: Did you consider seeking to appoint your own independent medical expert to determine whether or not Mr Miller and Mr Quirk were capable of appearing at the hearing and defending the charges?

Mr O’Grady: You mean like asking them to come before a – someone we appointed?

Mr Seck: Yes?

Mr O’Grady: What, independently? No, we didn’t consider that.

86 It follows that I accept that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were denied a reasonable opportunity to be present at the hearing as required by Rule 11(a)(ii). Consequently, the Divisional Executive breached Rule 11 by proceeding to deal with the substance of the matter.

87 It is not strictly necessary in that circumstance to consider Mr Seck’s further submission that once the medical certificates were tendered Rule 49(e) permitted them to be absent from work which included the hearing. Rule 49(e) provides:

Should any full-time officer through illness or any other physical disability be unable to carry out the duties as prescribed by the Rules, the officer shall furnish a medical certificate to the Divisional Branch Management Committee within seven days of becoming unable to carry out the duties setting out the nature of the disability, and the duration of such incapacity so far as the same can be estimated, and before resuming duties the officer shall furnish to the Divisional Branch Management Committee a medical certificate setting out that he/she has recovered and is capable to carry out the duties in accordance with the Rules.

88 Mr Seck submitted that the word ‘duties’ in Rule 49(e) was to be construed broadly as extending to all matters connected with work citing Kop v The Home for Incurables [1970] SASR 139 (‘Kop’) at 143. Further, he submitted that it was within the lawful authority of an employer to require an employee to participate in a disciplinary process: Patty v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2000] FCA 1072; 101 FCR 389 (‘Patty’) at [94]-[97]; Murray Irrigation Ltd v Balsdon [2006] NSWCA 253; 67 NSWLR 73 at [19]-[20] (‘Murray’).

89 I do not think that Kop assists. It was a workers compensation case where a nurse at a home for incurable patients suffered an injury during a voluntary outing with a patient whilst in the nurse’s time off duty. The majority of the Full Court (Chamberlain and Wells JJ) concluded the injury did not arise from the nurse’s duties. In dissent, Bray CJ at 143 (the passage upon which Mr Seck relies) concluded that the accident occurred in the course of her duties ‘in the more extended sense’ (at 144). Since this was a dissent, I do not think it advances the argument.

90 As to Patty and Murray, the fact that an employer may require an employee to take part in a disciplinary process says nothing about whether a person who in their capacity as an elected official is summoned to appear before a disciplinary tribunal does so as part of their duties as an employee. In other words, not every right or obligation the person has qua elected organiser is a right or duty they have qua employee.

91 The duties referred to in Rule 49(e) are the duties ‘prescribed by the Rules’. This directs attention to the duties imposed on an elected organiser by the Rules. These appear in Rule 48(1). They do not include attending before the Divisional Executive on a charge of gross misbehaviour. Consequently, the presentation of a medical certificate did not have the effect of permitting them not to attend the meeting.

92 Mr Seck pursued a variant of this argument based on the proposition that they both had accrued personal carer’s leave (i.e. sick leave): FW Act s 97(a). As with the Rule 49(e) argument, I do not think this goes anywhere because their appearance before the Divisional Executive was not part of their duties as employees.

93 Nevertheless, as I have said, I accept the submission that the Divisional Executive failed to comply with Rule 11(a)(ii).

Was it open to the Divisional Executive to remove Mr Quirk and Mr Miller for gross misbehaviour under Rule 11(a)?

94 The rule allowing for removal of officers for gross misbehaviour (Rule 11) is authorised in the case of ‘officers’ by s 141(1)(c)(iii) of the FW(RO) Act which provides that the rules of an organisation ‘may provide for the removal from office of a person elected to an office in the organisation only where the person has been found guilty, under the rules of the organisation, of:…(iii) gross misbehaviour or gross neglect of duty’.

95 There is a debate between the parties as to whether Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were ‘officers’ within the meaning of the FW(RO) Act. Mr Quirk and Mr Miller asserted they were whilst the Respondents submitted that they were not. The significance of this debate is minor and obscure. It arises from: (a) the Applicants’ contention (dealt with later in these reasons) that the meaning of ‘gross misbehaviour’ in Rule 11 is constrained by the meaning it bears in s 141(1)(c)(iii) of the FW(RO) Act; (b) the Respondents’ initial contention that s 141(1)(c)(iii) only applies to ‘officers’ under the FW(RO) Act; and, (c) their companion submission that neither Mr Quirk nor Mr Miller was such an officer.

96 In terms, Rule 11 does not apply to officers under the FW(RO) Act but only to ‘Divisional or Divisional Branch Officers’. It is not in dispute that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were Divisional Branch Officers or that Rule 11 applies to them. The Respondents’ point was that Rule 11 is capable of applying to persons who whilst Divisional Branch Officers within the meaning of Rule 11 are not ‘officers’ under the FW(RO) Act. This was then said to provide a reason for not reading ‘misbehaviour’ in Rule 11 as affected by the meaning of the same word in s 141(1)(c)(iii). I reject this argument. The meaning of the word ‘misbehaviour’ in Rule 11 does not vary depending on whether the Divisional Branch Officer charged happens to be an ‘officer’ within the meaning of the FW(RO) Act or not. The one word has the same meaning in both cases. If it is required to have a particular meaning as a result of s 141(1)(c)(iii) in the case of ‘officers’ (a topic to which I will return) then it has the same meaning in relation to all Divisional Branch Officers. In his final address Mr Walker appeared to accept that this was so but the parties persisted in their debate as to whether Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were officers within the meaning of 141(1)(c)(iii). So far as I can see that debate has no continuing relevance.

97 Lest I have failed to understand what was being put, I will nevertheless record my conclusion that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were not officers within the meaning of s 141(1)(c)(iii). The definition of an officer for the purposes of that provision appears in s 9:

(1) In this Act, office, in relation to an organisation or a branch of an organisation means:

(a) an office of president, vice president, secretary or assistant secretary of the organisation or branch; or

(b) the office of a voting member of a collective body of the organisation or branch, being a collective body that has power in relation to any of the following functions:

(i) the management of the affairs of the organisation or branch;

(ii) the determination of policy for the organisation or branch;

(iii) the making, alteration or rescission of rules of the organisation or branch;

(iv) the enforcement of rules of the organisation or branch, or the performance of functions in relation to the enforcement of such rules; or

(c) an office the holder of which is, under the rules of the organisation or branch, entitled to participate directly in any of the functions referred to in subparagraphs (b)(i) and (iv), other than an office the holder of which participates only in accordance with directions given by a collective body or another person for the purpose of implementing:

(i) existing policy of the organisation or branch; or

(ii) decisions concerning the organisation or branch; or

(d) an office the holder of which is, under the rules of the organisation or branch, entitled to participate directly in any of the functions referred to in subparagraphs (b)(ii) and (iii); or

(e) the office of a person holding (whether as trustee or otherwise) property:

(i) of the organisation or branch; or

(ii) in which the organisation or branch has a beneficial interest.

(2) In this Act, a reference to an office in an association or organisation includes a reference to an office in a branch of the association or organisation.

98 It is therefore necessary to identify some collective body upon which Mr Quirk and Mr Miller had an entitlement to vote or the functions of which Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were entitled directly to participate in: s 9(1)(b)-(d). Mr Seck submitted that they were entitled to participate in the divisional branch committee and divisional branch council. These bodies are erected under Rules 40, 41 and 42 which are very long and need not detain these reasons. It suffices to say that I accept that both bodies are collective bodies which fall within s 9(1)(b). However, I do not accept Mr Seck’s submission that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were entitled to participate in the affairs of either body, much less vote. His argument rested on Rule 48(1)(c):

Nothing in this rule affects the right of an organiser elected, in accordance with the rules of the Divisional Branch, as a member of either the Divisional Branch Management Committee or the Divisional Branch Council.

99 But this rule did not make Mr Quirk and Mr Miller members of these committees. What it says is that the ‘right’ of an elected organiser who is elected as a member of either body is not affected by Rule 48. It is not clear to me what the ‘right’ being discussed is but what is clear is that the provision is talking of a situation where an elected organiser is elected to the Divisional Branch Management Committee or the Divisional Branch Council. It provides no support for Mr Seck’s contention that Mr Quirk and Mr Miller were entitled to participate in the affairs of either body simply because they were elected organisers. Consequently, whilst the two bodies fall within the definition in s 9(1)(b), neither Mr Quirk nor Mr Miller were entitled to vote in the deliberations of those bodies. Consequently, they were not officers within the meaning of s 9(1)(b). However, as I have said, this does not matter in light of the conclusion I have recorded above.

Proper construction of gross misbehaviour

100 Mr Seck submitted that the term ‘gross misbehaviour’ in Rule 11 should be interpreted in light of the meaning of gross misbehaviour in s 141(1)(c)(iii) since it was only the latter which authorised the making of the former. For his part, by closing address Mr Walker accepted that the phrase ‘gross misbehaviour’ in Rule 11 must import the same standard as the phrase ‘gross misbehaviour’ in s 141(1)(c)(iii).