FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Enagic Co Ltd v Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 1512

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | HORIZONS (ASIA) PTY LTD ACN 124 967 835 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is allowed.

2. The decision of the delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks given on 27 November 2018 in relation to trade mark application No. 1798917 be set aside and in lieu thereof there be a decision that trade mark application No. 1798917 be refused registration.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHARLESWORTH J

1 On 24 September 2016 the respondent, Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd, filed an application under s 27(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA) for registration of the trade mark “KANGEN” in respect of specified services in Class 35. In these reasons, the mark forming the subject of that application (Trade Mark 1798917) will be referred to as the Opposed Mark.

2 The appellant, Enagic Co Ltd, opposed the registration on five grounds.

3 A delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks determined that Enagic had failed to establish each of its grounds of opposition and allowed the registration of the Opposed Mark in respect of the specified services: Enagic Co Ltd v Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd [2018] ATMO 192. This is an appeal from the delegate’s decision.

4 Enagic maintains all of the grounds of opposition advanced before the delegate, founded on ss 42(b), 44, 58, 62 and 62A of the TMA. For the reasons given below, the grounds founded on ss 44, 58 and 62A are upheld and, accordingly, the appeal will be allowed. The delegate’s decision will be set aside and substituted with a decision that Horizons’ application for registration of the Opposed Mark be refused.

THE TMA

5 A trade mark is a sign that is used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person: TMA, s 17. A trade mark may be registered under the TMA in respect of goods, services, or both goods and services: TMA, s 19(1). The Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) provide for 45 classes into which goods and services are divided. Classes 1 to 34 relate to goods. Classes 35 to 45 relate to services. Trade mark protection only applies to the specific goods and services listed in the trade mark application.

6 For the purposes of the TMA, use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to the goods: TMA, s 7(4). Use of a trade mark in relation to services means the use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services: TMA, s 7(5). Section 9 of the TMA provides:

Definition of applied to and applied in relation to

(1) For the purposes of this Act:

(a) a trade mark is taken to be applied to any goods, material or thing if it is woven in, impressed on, worked into, or affixed or annexed to, the goods, material or thing; and

(b) a trade mark is taken to be applied in relation to goods or services:

(i) if it is applied to any covering, document, label, reel or thing in or with which the goods are, or are intended to be, dealt with or provided in the course of trade; or

(ii) if it is used in a manner likely to lead persons to believe that it refers to, describes or designates the goods or services; and

(c) a trade mark is taken also to be applied in relation to goods or services if it is used:

(i) on a signboard or in an advertisement (including a televised advertisement); or

(ii) in an invoice, wine list, catalogue, business letter, business paper, price list or other commercial document;

and goods are delivered, or services provided (as the case may be) to a person following a request or order made by referring to the trade mark as so used.

(2) In subparagraph (1)(b)(i):

covering includes packaging, frame, wrapper, container, stopper, lid or cap.

label includes a band or ticket.

7 There will be trade mark use where goods are offered or advertised for sale in Australia: Shell Co of Australia Limited v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 (at 422). By extension, there will be use of a trade mark in respect of services where the services are offered to or advertised to persons situated here. In Ward Group Pty Ltd v Brodie & Stone Plc (2005) 143 FCR 479, Merkel J explained the circumstances in which use of a trade mark on a website operated from a place outside of Australia may constitute use of the mark within Australia (at [43]):

… use of a trade mark on the internet, uploaded on a website outside of Australia, without more, is not a use by the website proprietor of the mark in each jurisdiction where the mark is downloaded. However, as explained above, if there is evidence that the use was specifically intended to be made in, or directed or targeted at, a particular jurisdiction then there is likely to be a use in that jurisdiction when the mark is downloaded. …

8 As Gummow J observed in Carnival Cruise Lines Inc v Sitmar Cruises Ltd [1994] FCA 68; 120 ALR 495, a service “will not exist before its supply”. Accordingly, his Honour said, the use of a trade mark in relation to services “may readily be understood as a use in and about the soliciting and conclusion of contracts for the supply thereafter of services” (at 509).

9 An “authorised use” of a trade mark by a person is taken, for the purposes of the TMA, to be a use of the trade mark by the owner of the trade mark: TMA, s 7(3). A person is an “authorised user” of the trade mark if the person uses the trade mark in relation to goods or services under the control of the owner of the trade mark: TMA, s 8(1). If the owner of a trade mark exercises quality control over goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by another person in relation to which the trade mark is used, the other person is taken to use the trade mark in relation to the goods or services under the control of the owner: TMA, s 8(3).

10 Regulation 4.4 prescribes the manner in which a trade mark application should specify the goods and/or services in respect of which registration is sought. It relevantly states:

…

(2) The expression ‘all goods’, ‘all services’, ‘all other goods’, or ‘all other services’ must not be used in an application for registration of a trade mark to specify the goods and/or services in respect of which registration is sought.

(3) The goods and/or services must be grouped according to the appropriate classes described in Schedule 1.

(4) The applicant must nominate the class number that is appropriate to the goods or services in each group.

…

(6) The goods and/or services must, as far as practicable, be specified in terms appearing in any listing of goods and services that is:

(a) published by the Registrar; and

(b) made available for inspection by the public at the Trade Marks Office and its sub-offices (if any).

…

11 The Registrar must examine and report on whether a trade mark application has been made in accordance with the TMA and whether there are grounds for rejecting it: TMA, s 31. The Grounds for rejecting an application are prescribed in Div 2 of Pt 4 of the TMA (which includes s 42 and s 44).

12 After examination, the Registrar must accept the application unless he or she is satisfied that the application has not been made in accordance with the TMA, or there are grounds for rejecting it: TMA, s 33(1). Conversely, if the Registrar is satisfied that the application has not been made in accordance with the TMA, or there are grounds for rejecting it, the Registrar must reject the application: TMA, s 33(3).

13 Part 5 of the TMA is headed “Opposition to registration”. Section 52(1) provides that if the Registrar has accepted an application for a trade mark, a person may oppose the registration by filing a notice of opposition. The registration of a trade mark may be opposed on any of the grounds specified in the TMA and on no other grounds: TMA, s 52(4). After hearing from the applicant and the opponent, the Registrar must decide either to refuse to register the trade mark or to register the trade mark (with or without conditions) having regard to the extent (if any) to which any grounds of opposition have been established: TMA, s 55. The grounds upon which an application may be opposed are prescribed in Div 1 of Pt 5. Subject to an exception that does not apply, s 57 of the TMA provides that the registration may be opposed on any of the grounds on which an application for the registration of the mark may be rejected under the TMA.

APPLICATION AND OPPOSITION

14 Horizons’ application for registration of the Opposed Mark was lodged on 24 September 2016. Horizons sought registration of the mark in respect of a broad array of services falling within class 35, extracted at [24] of these reasons.

15 In most cases (including the present case) the registration of a trade mark is taken to have had effect from (and including) the filing date of the application for registration: TMA, s 72(1). As Horizons’ application was filed on 24 September 2016 that is the “priority date” for the purposes of determining the grounds of opposition: TMA, s 12 and see: Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 595.

16 Enagic’s grounds for opposition invoked two grounds for rejection (contained in Div 2 of Pt 4), being those provided for in s 42(b) and s 44. The additional grounds of opposition (contained in Div 2 of Pt 5) were founded on ss 58, 60 and 62A extracted elsewhere in these reasons. The notice of opposition also invoked s 43 and s 59 of the TMA, however those grounds were not pressed before the delegate and do not feature in the grounds of appeal.

THE APPEAL

17 An appeal under s 56 of the TMA is a hearing de novo and is determined in the exercise of the Court’s original jurisdiction: Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd (2010) 186 FCR 519 (at [24]). The Court is to determine the opposition issues for itself and is not limited to the material before the delegate: Blount Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (1998) 83 FCR 50, Branson J (at 58 – 59); Sports Warehouse (at [24]). The parties may adduce further evidence and examine and cross-examine witnesses. There is no general presumption that the Registrar’s decision is correct, although appropriate weight will be given to the Registrar’s opinion as a “skilled and experienced person”: Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365, French J (at [33]). In Woolworths, French J went on to say that:

… there is room for a degree of deference to the evaluative judgment actually made by the Registrar. That does not mean the Court is bound to accept the Registrar’s factual judgment. Rather it can be treated as a factor relevant to the Court’s own evaluation.

18 The onus of making out the grounds of opposition rests with the party opposing the registration: Food Channel Network Pty Ltd v Television Food Network GP (2010) 185 FCR 9 (at [32]); Pfizer Products Inc v Karam (2006) 219 FCR 585 (at [8]). The Court must be satisfied that Enagic’s case has been proved on the balance of probabilities: Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), s 140(1). In deciding whether it is so satisfied, the Court is to take into account the nature of the case, the nature of the subject matter of the appeal and the gravity of the matters alleged: Evidence Act, s 140(2).

19 The appeal has a complicated procedural history, some of which is set out at the conclusion of these reasons to the extent necessary to explain why the Court refused Horizons’ application for an adjournment of the hearing.

SECTION 44

20 Section 44 of the TMA provides:

Identical etc. trade marks

(1) Subject to subsections (3) and (4), an application for the registration of a trade mark (applicant’s trade mark) in respect of goods (applicant’s goods) must be rejected if:

(a) the applicant’s trade mark is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to:

(i) a trade mark registered by another person in respect of similar goods or closely related services; or

(ii) a trade mark whose registration in respect of similar goods or closely related services is being sought by another person; and

(b) the priority date for the registration of the applicant’s trade mark in respect of the applicant’s goods is not earlier than the priority date for the registration of the other trade mark in respect of the similar goods or closely related services.

(2) Subject to subsections (3) and (4), an application for the registration of a trade mark (applicant’s trade mark) in respect of services (applicant’s services) must be rejected if:

(a) it is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to:

(i) a trade mark registered by another person in respect of similar services or closely related goods; or

(ii) a trade mark whose registration in respect of similar services or closely related goods is being sought by another person; and

(b) the priority date for the registration of the applicant’s trade mark in respect of the applicant’s services is not earlier than the priority date for the registration of the other trade mark in respect of the similar services or closely related goods.

(3) If the Registrar in either case is satisfied:

(a) that there has been honest concurrent use of the 2 trade marks; or

(b) that, because of other circumstances, it is proper to do so;

the Registrar may accept the application for the registration of the applicant’s trade mark subject to any conditions or limitations that the Registrar thinks fit to impose. If the applicant’s trade mark has been used only in a particular area, the limitations may include that the use of the trade mark is to be restricted to that particular area.

(4) If the Registrar in either case is satisfied that the applicant, or the applicant and the predecessor in title of the applicant, have continuously used the applicant’s trade mark for a period:

(a) beginning before the priority date for the registration of the other trade mark in respect of:

(i) the similar goods or closely related services; or

(ii) the similar services or closely related goods; and

(b) ending on the priority date for the registration of the applicant’s trade mark;

the Registrar may not reject the application because of the existence of the other trade mark.

21 Enagic is the registered proprietor of the mark “KANGEN WATER” (Trade Mark 1756433) in respect of goods in class 11, which has the heading “Apparatus for lighting, heating, steam generating, cooking, refrigerating, drying, ventilating, water supply and sanitary purposes”: Regulations, Sch 1, Pt 1, item 11. The specified goods are:

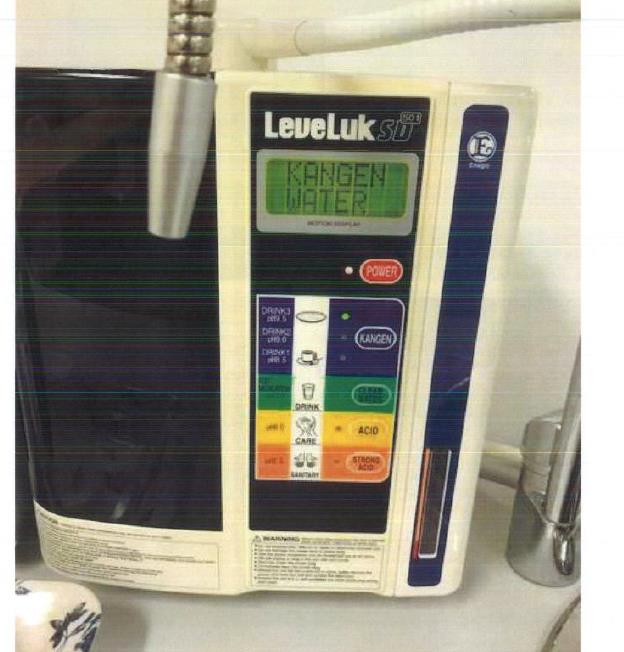

Class 11: Electrolytic water generators for electrically decomposing tap water to generate electrolytic water and for removing chlorine odor [sic] from tap water

22 I will refer to that mark as Enagic’s Goods Mark, and to the specified goods as the Class 11 Goods.

23 The Enagic Goods Mark has an earlier priority date of 11 February 2016, thus fulfilling s 44(2)(b) of the TMA.

24 Horizons sought registration of the Opposed Mark in respect of services in class 35, which has the heading “Advertising; business management; business administration; office functions”: Regulations, Sch 1, Pt 2, item 35. The specified services are.

Class 35: Distribution of goods (not being transport services) (agent, wholesale, representative services, by any means); wholesale; retail; sales by any means; advertising, marketing, promotion and public relations; operation, supervision and management of loyalty programs, sales and promotional incentive schemes; discount services (retail, wholesale, or sales promotion services); customer support services; compilation and maintenance of directories, mailing lists including such lists compiled and maintained via the global computer network; conferences and exhibitions for commercial purposes; business administration; business development; dissemination of commercial information; distribution of prospectus; importing services; exporting services; providing information, advisory and consultancy services, including by electronic means, for all of the aforesaid services

25 I will refer to those services as the Class 35 Services.

26 For the purposes of the TMA, “a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion”: TMA, s 10. As Nicholas J said in Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc [2012] FCAFC 159; 294 ALR 661 (at [114], Dowsett J agreeing):

… it is the statutory rights of use that are to be compared rather than any actual use, and in considering whether an application for a mark should be rejected under s 44(1) because it is deceptively similar to an existing registered trade mark, it is necessary to have regard to all legitimate uses to which each mark might be put by its owner: see Re Application by Smith Hayden & Coy Ld (1946) 63 RPC 97 at 101; Berlei Hestia at CLR 362; ALR 449 and Polo Textile Industries Pty Ltd v Domestic Textile Corporation Pty Ltd (1993) 42 FCR 227 at 230-1; 114 ALR 157 at 161–2; 26 IPR 246 at 249–50.

27 The delegate concluded that Enagic’s Goods Mark (KANGEN WATER) and the Opposed Mark (KANGEN) are deceptively similar. I agree with that conclusion. Whilst Enagic’s Goods Mark includes the word “WATER”, the word “KANGEN” is a memorable feature of the mark that is likely to have the greater impression on consumers. The two marks are such that it is likely that consumers will be caused to wonder whether the goods or services in respect of which the marks are used come from the same source: Coca-Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 (at [39]); Southern Cross Refrigerating Co (at 595). I have arrived at that conclusion by a textual comparison of the marks, having regard to the trade context in which each mark might legitimately be used.

28 It is necessary to determine whether the Class 35 Services specified for the Opposed Mark are “closely related to” the Class 11 Goods specified for the Enagic Goods Mark within the meaning of s 44(2)(ii).

29 As French J said in Woolworths, the term “closely related” recognises the obvious circumstance that goods and services are not the same thing: at [37]. His Honour said that the expression “closely related” is of wider import than the word “similar”, and observed:

… There will be classes of goods which are similar to each other. There will also be classes of services which are similar to each other. But the word ‘similar’ does not apply as between goods and services. So there must be some other form of relationship between the services covered by one mark and the goods covered by another to enable the goods or services in question to be described as ‘closely related’. …

30 The meaning of the word “services” in the TMA was considered by Lockhart J in Caterpillar Loader Hire (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Caterpillar Tractor Co (1983) 48 ALR 511 (at 522) at a time when service marks were in their infancy in Australia. His Honour predicted that they may give rise to confusion between goods and service marks “of greater difficulty and subtlety than has previously been experienced in the case of goods marks alone”. His Honour gave the following examples of cases where there the potential for confusion in the minds of consumers might arise:

… the sale of goods such as data processing equipment and the sale of programs for their operation; the sale of curtains and furnishing materials on the one hand, and the sewing of curtains on the other, as interior decorators often sell curtains and perform the service of sewing; the sale of clothes on the one hand and tailoring on the other because the service of custom tailoring is frequently provided in addition to the sale of ready-made clothes; and the sale of educational material on the one hand and educational services (language courses, home study programmes) on the other.

31 A further example was identified by French J in Woolworths (at [38]):

… Services which provide for the installation, operation, maintenance or repair of goods are likely to be treated as closely related to them. Television repair services in this sense are clearly related to television sets as a class of goods. A trade mark used by a television repair services which resembles (to use the language of s 10) the trade mark used on a prominent brand of television sets would be deceptively similar for suggesting an association between the provider of the services and the manufacturer of the sets. …

32 As these examples illustrate, it is relevant to consider the nature of the goods or services, the use or purpose of the goods or services, and the channels of trade: Southern Cross Refrigerating Co at 606 – 607.

33 The phrase “closely related” is to be interpreted having regard to the objects of the TMA, which can be discerned in part in the definition of a trade mark as an indicia of the origin of goods or services. Section 44(2) is plainly intended to address the mischief that may be created where two marks are the same or deceptively similar. It recognises the potential for confusion in the minds of consumers as to the origin of goods in respect of which a mark is registered or sought to be registered and the origin of services in which an identical or a deceptively similar mark is registered, or sought to be registered as the case may be. The more closely related the goods on the one hand and the services on the other, the greater the potential for confusion as to whether they originate from the same person. Whether the relevant services and the relevant goods are “closely related” is to be assessed in that context and in a commercially sensible way, having regard to all legitimate uses of the Opposed Mark.

34 In its closing submissions in support of this ground of opposition, Enagic submitted:

Enagic’s water filtration products are a bespoke, high end product, retailing for several thousands of dollars, sold through a direct selling model where its customers in turn become prospective distributors. There is synergy in the Appellant’s business model between the product and the Relevant Services, whereby its distributors have a certain level of expertise common to the provision of goods and services.

35 In my view, that submission introduces an irrelevant consideration for the purposes of s 44(2), namely the services said to be provided in fact by Enagic. Whether Enagic has used any relevant mark in respect of any services is relevant to other grounds of opposition. However, the Court is not presently concerned with a comparison between the services allegedly provided by Enagic on the one hand and the services in respect of which the Opposed Mark is sought to be registered on the other. For the purposes of s 44(2)(a)(ii) of the TMA, the relevant inquiry is whether the narrowly described Class 11 Goods referred to in Enagic’s Goods Mark registration are closely related to the broadly described Class 35 Services referred to in the Opposed Mark registration.

36 On their face, the headings used in the Regulations for the goods classification 11 and the services classification 35 appear to be disparate. By reference to the headings alone, it is not immediately apparent how goods in the nature of “Class 11 Apparatus for lighting, heating, steam generating, cooking, refrigerating, drying, ventilating, water supply and sanitary purposes” could be closely related to services in the nature of “Class 35 Advertising; business management; business administration; office functions”.

37 Horizons referred the Court to the Trade Marks Office Manual of Practice and Procedure and a “Cross Class Search List” contained within it. The list identifies goods or services which the Trade Marks Office considers “are most likely to be goods or services that are similar or closely related”. I consider the list to be of limited assistance to the Court in performing its task under s 44(2), and indeed liable to detract from it. The Court must interpret the particular words chosen by the trade mark applicant to describe the services so as to identify the nature and scope of the trading activities in respect of which trade mark protection is sought. In the present case, the descriptions in the specification are of very broad import. As discussed below, it is significant that most of the specified services are either inherently concerned with or expressly connected to the marketing, sale and distribution of goods. As explained in Southern Cross Refrigerating Co, it is relevant to consider their purpose. For the most part, the purpose of the broadly described services is to facilitate the promotion of goods for sale, as well as their actual sale.

38 It is open to a trade mark applicant to describe services in the widest of terms so as to achieve the greatest possible protection provided that the services are specified in accordance with the Regulations: TMA, ss 27(3)(b), (4) and (5); 33(1)(a); 57. Enagic has not advanced any argument to the effect that the Class 35 Services did not in fact fall within the parameters of the relevant class, nor any argument that the services described are impermissibly broad or vague so as to require the application to be rejected in accordance with the provisions just cited. That is not surprising, given that most of the specification was copied by Horizons from an earlier trade mark registration obtained by Enagic in 2014 (as discussed later in these reasons).

39 By their nature, any or all of the listed “services” are services in relation to which the Opposed Mark may legitimately be used in the course of Horizons’ trade. The focus is on the use of the Opposed Mark as an indicia of the origin of the services by Horizons in the course of trade with other persons. It is in the nature of services that they are provided by one entity to another. They are not to be understood as incorporating inherent business activities internal to Horizons.

40 The services expressly include “distribution of goods”, which must be understood as a service for the distribution of goods. There is no limitation on the goods that are to be the subject of the distribution services. Notionally, registration of the Opposed Mark would permit its use in connection with the provision of distribution services where the subject of the distribution includes goods of an infinite variety. More importantly for present purposes, the legitimate use of the mark also includes its use as an indicia of the origin of distribution services in connection with goods of a singular description or specialised nature. The services described as “sales by any means” must also be taken to include services for the sale of goods of all descriptions or a singular description, and so on. The services also include advertising, marketing, promotion and public relations, which must be understood to include services for the advertising and marketing of goods of a specific kind or all kinds. Moreover, the phrase “providing information, advisory and consultancy services, including by electronic means, for all of the aforesaid services” is not limiting. It is expressed as a discrete service in addition to all other services preceding it and so significantly expands the field of services in respect of which the Opposed Mark may be used exclusively by Horizons as a trade mark.

41 On the topic of whether the relevant services and goods were closely related, the delegate said:

The Opponent’s Goods relate to a very specific type of water generator and purifier. The Applicant’s Services are distribution and business administration services that have no specific connection to the Opponent’s Goods. The mere fact that an entity could engage in distribution and business administration services incidental to the course of selling the Opponent’s Goods is not a basis to find that they are closely related. There is no particular relationship between the Applicant’s Services and the Opponent’s Goods and hence no basis to conclude that these services are closely related to the Opponent’s Goods. I find that the Opponent has failed to establish the ground of opposition under s 44 of the Act.

42 I respectfully disagree with the delegate’s reasoning. I do not consider the sale of particular goods (for example) as being merely incidental to the provision of the services described. The phrase “sales by any means” as listed in the specification must be understood as “service” in its own right. That aspect of the specification necessarily encompasses services for the sale of goods.

43 Moreover, Horizons has chosen to draft the list of services commencing with the phrase “distribution of goods”. Read in its proper context, the phrase “distribution of goods” must be understood to refer to a service offered or provided in the course of trade between Horizons and other persons. The activity of “distributing” the goods is not merely incidental to such a service, it is the very essence of it.

44 As I have said above, that drafting encompasses services for the distribution of goods either of a confined kind or of infinite variety. Absent words of limitation, the specification must be understood to encompass both, as if both were separately described in the text. In respect of the former, the specification encompasses any or all goods falling within classes 1 to 34, which necessarily encapsulates all goods in class 11, including “Electrolytic water generators for electrically decomposing tap water to generate electrolytic water and for removing chlorine odor [sic] from tap water”. The distribution services referred to in the registration may be provided (and promoted) in respect of only those goods.

45 I have no difficulty concluding that services for the distribution of goods “X” are closely related to goods “X” within the meaning of s 44(2)(ii) of the TMA. To illustrate the point, the words “electrolytic water generators” may be inserted in Horizon’s Class 35 Services specification so as to illuminate the protection afforded by the registration of the word KANGEN. The word may be used as an indicia of the trade origin of the following services: distribution services in connection with electrolytic water generators (not being transport services); services for the sale of electrolytic water generators by any means; services for the advertising, marketing, promotion and public relations in connection with electrolytic water generators; services involving operation, supervision and management of loyalty programs in respect of electrolytic water generators; services involving the sales and promotional incentive schemes in respect of electrolytic water generators; customer support services in respect of electrolytic water generators; services for compilation and maintenance of directories in respect of electrolytic water generators; services for the provision of conferences and exhibitions for commercial purposes in connection with electrolytic water generators; import and export services in connection with electrolytic water generators; services for the provision of information and advisory and consultancy services for all of the aforesaid.

46 Once the permitted use of the Opposed Mark is understood in that way, it is readily apparent how the Class 11 Goods are closely related to the Class 35 Services. That consequence follows from Horizons’ choice to capture within the services description all goods without exception or qualification, so capturing the goods the subject of Enagic’s Goods Mark. It follows that the requirements for the successful opposition of the mark under s 44(2) are fulfilled.

47 It is of course open to the Registrar to consider whether to accept the registration subject to a condition or limitation, so as to confine the use of the mark to exclude services that are closely related to goods in the same class in respect of which the Enagic Goods Mark is registered: TMA, s 33(2). A discretion of the same kind applies in opposition proceedings and may also be exercised by this Court on appeal: TMA, s 55(1)(b).

48 However, I have determined not to embark upon that exercise or to hear further from Horizons in respect of it. That is because I am satisfied that the appeal should be allowed on multiple grounds such that registration should not proceed on a more limited specification, as it might otherwise have done had the ground of opposition under s 44 of the TMA been the only successful ground.

Sub-section 44(3)

49 In its closing submissions, Horizons sought to invoke s 44(3)(a) and (b) of the TMA so as to allege honest concurrent use of the two marks and to suggest “other circumstances” that might make it proper to accept the Opposed Mark for registration. These issues were not dealt with by the delegate because he was not satisfied that the conditions in s 44(2) were fulfilled.

50 Enagic submits that Horizons has abandoned any prior reliance on both limbs of s 44(3). That submission should be accepted.

51 Enagic first filed Points of Claim on 28 March 2019. By its Points of Defence filed on 12 April 2019, Horizons expressly invoked s 44(3)(a) and (b) and provided brief particulars (at [2(f)] and [2(g)]).

52 Enagic filed Amended Points of Claim on 12 December 2019. Horizon did not file an amended pleading in response until 14 August 2020. The Amended Points of Defence filed on that day invoked neither s 44(3)(a) nor s 44(3)(b). An unnumbered introductory paragraph states that Horizons relied on any Points of Defence filed by its former legal representatives “in respect of the Amended Points of Claim dated 13 December 2019”. However, Horizons’ former representatives had filed no prior pleading in response to the Amended Points of Claim. Horizons filed Further Amended Points of Defence on 14 December 2020. It contains no reference to s 44(3) of the TMA. Whilst it also contains a statement to the effect that Horizons relied on any points of defence filed by its former legal representatives in respect of the Amended Points of Claim filed on 12 December 2019, that statement could not operate to pick up and re-enliven the previously abandoned plea. My interpretation of the documents is reinforced by the circumstance that the various iterations of the amended defences for the most part simply repeat other aspects of the previous versions. To the extent that there is ambiguity, I do not consider it to be in the interests of justice to interpret the documents beneficially toward Horizons. In my view, an appellant in Enagic’s position ought to be entitled to refer to the latest iteration of the defence to identify the issues that are in dispute.

53 If I am wrong in interpreting Horizons’ pleadings in that way, I would conclude in any event that the evidence adduced on Horizons’ case was insufficient to enable a finding to be made as to honest concurrent use. The reasons for that conclusion will become apparent in my discussion of the grounds of opposition founded on s 58 and s 62A of the TMA. My conclusions in respect of those grounds also weigh against the exercise of the discretion under s 44(3)(a) and (b) or otherwise render s 44 of the TMA inapplicable.

SECTIONS 58 AND 60

54 Section 58 of the TMA provides:

Applicant not owner of trade mark

The registration of a trade mark may be opposed on the ground that the applicant is not the owner of the trade mark.

55 For Enagic to succeed on this ground it must establish that:

(1) the mark KANGEN (being a mark used by Enagic before the priority date for the Opposed Mark) is identical or substantially identical to the Opposed Mark;

(2) it has used the mark in respect of goods or services that are the same, or the “same kind of thing” as the Class 35 Services: Aston v Harlee Manufacturing Co (1960) 103 CLR 391, Fullagar J (at 399 – 400); Hicks’ Trade Mark (1897) 22 VLR 626; Carnival at 514; Colorado Group Ltd v Strandbags Group Pty Ltd (2007) 164 FCR 506 (at [89]), and

(3) as at the priority date for the Opposed Mark, it had the earlier claim to ownership based on its use of the mark before Horizons’ first use: Settef SpA v Riv-Oland Marble Co (Vic) Pty Ltd (1987) 10 IPR 402.

56 The first requirement is uncontentious. Horizons accepts that the marks are identical or substantially identical.

57 In Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Philip Morris Ltd (No 2) (1984) 156 CLR 414, Deane J said (at 432 – 434), (Gibbs CJ, Mason, Wilson and Dawson JJ agreeing):

The prior use of a trade mark which may suffice, at least if combined with local authorship, to establish that a person has acquired in Australia the statutory status of ‘proprietor’ of the mark, is public use in Australia of the mark as a trade mark, that is to say, a use of the mark in relation to goods for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connexion in the course of trade between the goods with respect to which the mark is used and that person: see, generally, Shell Co (Aust) Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd; Re Registered Trade Mark ‘Yanx’; Ex parte Amalgamated Tobacco Corporation Ltd; and the definition of ‘trade mark’ in s 6(1) of the Trade Marks Act. The requisite use of the mark need not be sufficient to establish a local reputation and there is authority to support the proposition that evidence of but slight use in Australia will suffice to protect a person who is the owner and user overseas of a mark which another is seeking to appropriate by registration under the Trade Marks Act. In such a case, the court ‘seizes upon a very small amount of use of the foreign mark in Australia to hold that it has become identified with and distinctive of the goods of the foreign trader in Australia’: see Seven Up Co v O.T. Ltd; Aston v Harlee Manufacturing Co.

…

… The cases establish that it is not necessary that there be an actual dealing in goods bearing the trade mark before there can be a local use of the mark as a trade mark. It may suffice that imported goods which have not actually reached Australia have been offered for sale in Australia under the mark (Re Registered Trade Mark ‘Yanx’;Ex parte Amalgamated Tobacco Corporation Ltd) or that the mark has been used in an advertisement of the goods in the course of trade: Shell Co of Australia v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd. In such cases, however, it is possible to identify an actual trade or offer to trade in the goods bearing the mark or an existing intention to offer or supply goods bearing the mark in trade. …

(footnotes omitted)

58 See also Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd (2018) 259 FCR 514 (at [49]).

59 The requirement that use of the mark be in respect of the “same kind of thing” was discussed by Allsop J (as his Honour then was) in Colorado Group. In respect of a comparison between goods (including backpacks, handbags, purses and wallets) his Honour said:

88 In Carnival Cruise Lines v Sitmar Cruises 120 ALR at 514, Gummow J referred to there being no differences of ‘character or quality’ of the services in that case to gainsay that they were the ‘same kind of thing’.

89 There is a certain difficulty in fixing upon the proper frame of reference for the enquiry identified by the words used by Holroyd J, ‘same kind of thing’. Assistance is gained from the statutory context in which the question arises (see above), the common law notion of the right to registration from use, when that was the defining requirement: see Edwards v Dennis (1885) 30 Ch D 454 and Jackson & Company v Napper (1886) 35 Ch D 162 and the notion of the ownership of a common law trade mark: see the cases referred to by the primary judge at [25] of his first judgment (set out at [66] above). The aim of the enquiry is not to find some broad genus in which some common functional or aesthetic purpose can be identified. Nor is it an enquiry about the type of trade in which concurrent use might cause confusion. Rather, it is identifying, in a practical, common sense way, the true equivalent kind of thing or article. For example, use of a mark on hatchets or small axes, created proprietorship in relation to axes: Jackson v Napper 35 Ch D 160. This approach recognises ownership or proprietorship in a mark beyond the very goods on which the mark is used, to goods ‘though not identical … yet substantially the same’ (Hemming HB, Sebastian’s Law of Trade Marks (4th ed, Stevens and Sons, 1899) p 91) or ‘goods essentially the same … though they pass under a different name owing to slight variations in shape and size’ (Kerly DM and Underhay FG, Kerly on Trade Marks (3rd ed, Sweet & Maxwell) p 206). This approach is conformable with the terms of the 1995 Act.

90 That backpacks are a type or style of bag does not answer the question as to whether they should be viewed as essentially the same goods as any bag or receptacle. The backpack is a bag with straps to be worn on the back. It is not essentially the same or the same kind of thing as other bags, handbags, purses or wallets. The task is not to identify the genus into which the goods upon which the mark was used fall, but to identify the goods.

60 Section 60 of the TMA provides:

Trade mark similar to trade mark that has acquired a reputation in Australia

The registration of a trade mark in respect of particular goods or services may be opposed on the ground that:

(a) another trade mark had, before the priority date for the registration of the first-mentioned trade mark in respect of those goods or services, acquired a reputation in Australia; and

(b) because of the reputation of that other trade mark, the use of the first-mentioned trade mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

61 As O’Bryan J said in Rodney Jane Racing Pty Ltd v Monster Energy Company [2019] FCA 923; 370 ALR 140 (at [83]), the reputation of a trade mark has both quantitative and qualitative dimensions:

The quantitative dimension concerns the breadth of the public that are likely to be aware of the mark, which can be evidenced by the quantum of sales, advertising and promotion of goods or services to which the mark is applied. The qualitative dimension concerns the image and values projected by the trade mark, which affects the esteem or favour in which the mark is held by the public generally …

62 In McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick (2000) 51 IPR 102, Kenny J confirmed that “reputation” in s 60 of the TMA refers to recognition of the mark by the public generally. In Le Cordon Bleu BV v Cordon Bleu International Ltee [2000] FCA 1587; 50 IPR1, Heerey J (at [91]) said that the reputation to be demonstrated was to be:

… one of which a significant number of persons were aware … What is ‘significant’ or ‘substantial’ will depend on the nature of the goods or services in question. For some highly specialised products, awareness among a few thousand persons, or even less, might be sufficient. …

63 As Kenny J said in McCormick (at [86]):

In practice, it is commonplace to infer reputation from a high volume of sales, together with substantial advertising expenditures and other promotions, without any direct evidence of consumer appreciation of the mark, as opposed to the product: see, eg, Isuzu-General Motors Australia Ltd v Jackeroo World Pty Ltd (1999) 47 IPR 198; Marks & Spencer Plc v Effem Foods Pty Ltd (2000) AIPC 91-560; Photo Disc Inc v Gibson (1998) 42 IPR 473; and RS Components Ltd v Holophane Corp (1999) 46 IPR 451. This court has followed this approach as well, acknowledging that public awareness of and regard for a mark tends to correlate with appreciation of the products with which that mark is associated, as evidenced by sales volume, among other things. Thus, in Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd v Gymboree Pty Ltd (2001) 51 IPR 1, Moore J accepted at [94] that the applicant had established a reputation for the purposes of s 60 solely on the basis of use and promotion of the relevant mark. Another example of this approach is Nettlefold Advertising Pty Ltd v Nettlefold Signs Pty Ltd (1997) 38 IPR 495 (Nettlefold), in which Heerey J relied upon the public visibility of the applicant’s marks over approximately two decades as well as a $100,000 promotional campaign in finding that a reputation for the purposes of S 28 of the 1955 Act existed.

The parties’ cases

64 For the purposes of s 58 of the TMA, both Enagic and Horizons allege that they are the owner of the Opposed Mark, based on the first use of the word as a trade mark in respect of the Class 35 Services or in respect of goods or services that are the “same kind of thing”.

65 Horizons alleges that it first used the word KANGEN as a trade mark as early as 10 January 2009, being the date of its registration of the mark in respect of certain goods in Class 11, including bottled water (Trade Mark 1280502). It alleges that it has, since that time, used the mark in connection with a distribution and export business, specifically in relation to air purifiers and bottled water products.

66 Enagic alleges that it is the owner of the Opposed Mark by virtue of having been the first user of the word KANGEN or the words KANGEN WATER as a trade mark in Australia in the provision of “distribution, sales and marketing” services. It contends that it first used the Opposed Mark in connection with goods and services in Australia as early as 2007.

67 For the purposes of s 60 of the TMA, Enagic alleges that the mark KANGEN WATER had, before the priority date for the Opposed Mark, acquired a reputation in Australia such that use by Horizons of the mark KANGEN would be likely to deceive or cause confusion. The reputation is alleged to have been acquired both in respect of the Class 35 Services and in respect of water purifying, electrolytic and alkaline-ioniser apparatus, and “related goods and services”. It relies on its activities conducted overseas (including those of its predecessor), particularly the manufacture and sale of water-ionisation systems to produce alkaline water as early as 1990.

68 It is convenient to first make factual findings as to the parties’ activities in connection with the word KANGEN before the priority date. Each ground will then be resolved separately having regard to the facts as found.

Horizons’ activities

69 Horizons was registered in Australia on 18 April 2007. Between that date and 4 April 2016 it had as its director, secretary and shareholder Ms Cheung Hoi Lan Penson. The current director, secretary and shareholder is Mr Pyng Lee Shih. Neither Ms Penson nor Mr Shih gave evidence on the appeal.

70 Records from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission show that Ms Penson is:

(1) the former director and company secretary of Aquaqueen Australian Spring Water Pty Ltd (12 November 1993 to 28 December 2012), its former Principal Executive Officer (12 November 1993 to 8 December 1995); and the former owner of all of its 100 ordinary shares; and

(2) the former director and company secretary of Aquaqueen International Pty Ltd (ACN 094 129 389) (14 August 2008 to its deregistration on 6 February 2017).

Ng Lee

71 Ms Ng was the only officer or employee of Horizons called to give evidence on the appeal. In her affidavit evidence-in-chief, Ms Ng said that she was “instructed” to make the application for the Opposed Mark. That instruction could only have come from Mr Shih.

72 Ms Ng first commenced employment with Horizons in 2014. She was originally engaged to work as the personal assistant to the original sole director and shareholder, Ms Penson. Until 2016, Ms Ng was assigned clerical and administrative and research tasks. From 2016, Ms Ng’s duties “evolved into that of a Manager”. I take that to mean that there was no formal process by which Ms Ng was assigned greater responsibility within the business.

73 Ms Ng deposes to there being six to eight people working for Horizons, but does not specify which of them were engaged in particular roles at particular times.

74 To a large extent, Ms Ng’s evidence-in-chief was said to be based upon her knowledge of Horizons’ business records, said to have been gained from her responsibility for gathering evidence to assist Horizons in intellectual property disputes (including disputes with Enagic) as a part of her current role. She states, “Conservatively, I would have spent countless hours reviewing and analysing the business records of Horizons dating back to 2009”. Notwithstanding that statement, the business records annexed to Ms Ng’s affidavits are lacking in probative force (both qualitatively and quantitatively) in the several respects discussed below. And, as explained below, Ms Ng’s personal knowledge about the events allegedly recorded in the business records predating her employment (and to some extent afterward) was also lacking. In cross-examination, she could not explain some matters concerning the transactions recorded within the documents because the events occurred before her employment commenced. To the extent that Ms Ng has expressly or implicitly asserted that she is familiar with actual events occurring prior to her employment, the assertion is rejected. In my view, she is in no better position to draw inferences from the content of the documents than the Court itself. Her inability to explain the transactions and to give contextual evidence concerning the transactions affects the weight to be given to the documents as well as to the broad assertions in the body of her affidavit about Horizons’ trading activities and its use of trade marks in respect of them.

75 In addition, as with the evidence of Enagic’s witnesses, the evidence of Ms Ng is in part expressed in conclusionary terms in the description of trading activities. For example, Ms Ng deposes that since its establishment in Australia in 2007, Horizons has:

… engaged in trading and distribution of consumer goods and services relating to packaged drinks, including bottled water and related products (for example, water coolers), beverage dispensing units and also a selected range of apparatus goods, including air purifiers, to customers around Australia and certain other countries overseas.

76 The words “trading and distribution” is there used without any explanation of the difference between them or the particular activities said to meet each description. Whilst the words “goods and services” are used, Ms Ng does not personally identify any person to whom services have been provided. Instead, Horizons invites the Court to draw inferences from the annexed business records on that critical topic. In addition, to the extent that it is alleged that all of the activities described in the above passages have been undertaken since 2007, the affidavit annexes no business records providing objective support for such a claim. That is significant, given that Ms Ng cannot describe the trading activities of Horizons on the basis of her personal knowledge at any time prior to 2014, and for some time afterward. The circumstance that Ms Ng has made a sweeping assertion of fact in respect of matters not within her own knowledge affects the reliability of her evidence more generally.

77 Ms Ng goes on to refer to two types of “distribution”, one relating to the products sourced directly from a manufacturer in respect of “selected brands”, the other is described as follows:

… Horizons also owns and sells products under its own brands, including “KANGEN®”. KANGEN is one of Horizons’ household brands for bottled water and air purifiers as well as Horizons’ signature distribution services. …

78 It is of course necessary to read the affidavit as a whole to understand what is intended by the phrase “signature distribution services” but it yields little on the topic. The other thing to note in respect of the above passage is the acknowledgement that Horizons’ trading activities include the distribution of its own goods, being goods in the nature of bottled water and air purifiers. The affidavit does not identify any other person to whom distribution “services” have been provided. As explained below, the objective evidence does not demonstrate that Horizons distributed goods on behalf of any entity other than itself.

79 In light of the above observations, I have afforded little weight to the broadly stated facts deposed to by Ms Ng, except where they find support in reliable objective material. As explained below, the business records are insufficient to support a claim that Horizons used the Opposed Mark in the provision of the Class 35 Services (or the same kind of thing) to any person in the course of trade before the priority date for the Opposed Mark.

Prior trade mark registrations

80 Horizons is the registered owner of the trade mark KANGEN in respect of goods in classes 11 and 32 (Trade Mark 1280502). Enagic was unsuccessful in opposing the registration of that mark: Enagic Australia Pty Ltd and Enagic Co Ltd v Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd [2014] ATMO 72.

81 Trade Mark 1280502 is relevant to the extent that its priority date is said to be the date from which Horizons also used the Opposed Mark (being the same word, KANGEN) in relation to Class 35 Services such that it is to be regarded as the owner of the mark in respect of such services for the purposes of s 58 of the TMA.

82 I have concluded that the earlier registration is of limited evidentiary value for the purposes of the grounds of opposition presently under consideration. For the purposes of s 58 of the TMA, the focus is on Horizons’ earliest use of the Opposed Mark in relation to the Class 35 Services, not upon rights it might have previously secured to exclusive use of the word KANGEN in relation to goods. As explained by the Full Court in Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd (2017) 251 FCR 379 (at [19]):

In either case, be it ownership by authorship and prior use or ownership by the combination of authorship, the filing of the application and an intention to use, the scheme of the legislation under both the 1995 Act and its predecessors, the Trade Marks Act 1905 (Cth) (the 1905 Act) and the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth) (the 1955 Act) provide for ‘registration of ownership not ownership by Registration’ (PB Foods Ltd v Malanda Dairy Foods Ltd (1999) 47 IPR 47 at [78]-[80] per Carr J cited in Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd (2017) 345 ALR 205 (Accor) at [170]).

83 Similarly, the circumstance that Enagic was previously unsuccessful in opposing a prior registration is of little relevance, this Court having the task of determining grounds of opposition to a different registration having a different priority date on the basis of different evidence. The present focus is on the actual uses Horizons in fact made of the Opposed Mark, not on the existence of registered rights of use.

Logo design

84 On 5 January 2009, Horizons was invoiced for the preparation of a logo utilising the word KANGEN. A copy of the logo accompanies the invoice for the artwork. That occurred shortly prior to Horizons securing registration of the mark KANGEN on 10 January 2009 in connection with (among other things) bottled water. The invoice goes some way to demonstrate Horizons’ intention to use the mark KANGEN in relation to the particular goods specified in that earlier trade mark registration at that time.

Bottled water products

85 On the basis of the evidence concerning Horizons’ only operational website (discussed below), I am satisfied that Horizons has, since July 2012, offered for sale in Australia a 600ml water product and a 10 litre water product each having the product name KANGEN. A photograph on the website shows a plastic bottle bearing a label on which the word is prominently displayed. There is no image for the 10 litre water product and there is otherwise no evidence as to how that product was packaged or labelled.

86 Ms Ng asserts that these products have been offered for sale (and sold in fact) to consumers situated in Australia since 2009. She states that the word KANGEN has been “extensively used on promotion materials, products packaging, customer orders, and invoices in the course of marketing and trading these products” which I take to refer to times as early as 2009. That assertion has been read as a submission. As explained below, I do not accept that submission is made good on the evidence, both because it concerns a period of time in respect of which Ms Ng has no personal knowledge and because it finds no support in the records upon which Horizons relies.

Domain names

87 Ms Ng annexes two invoices dated 4 September 2012 and 14 December 2012 said to have been issued to Horizons by a website developer in connection with the website address www.wateronline.net.au. The invoices make no reference to the url for that website. Ms Ng’s evidence that Horizons has conducted a business primarily through that website is nonetheless supported by objective evidence as to the content of the website at various times. On the basis of that evidence, I am satisfied that Horizons has operated a website using the address www.wateronline.net.au since around July 2012. I will refer to it as the WaterOnline website.

88 Ms Ng deposes to there being 59 additional domain names registered to Horizons, each of which contains the word KANGEN, with dates of registration ranging from 10 January 2009 to 30 January 2018. I proceed on the assumption that the domain names are registered to Horizons or its related entities.

89 Ms Ng acknowledged that the domains had been deployed to direct web enquiries using the word KANGEN to the WaterOnline website. The evidence does not support a conclusion that Horizons operated any website with readable content from any one of the KANGEN domains, nor that it conducted any business under or from websites having the domain names, other than for the purpose of redirecting internet users searching the word KANGEN to the WaterOnline website.

90 There is a single leaflet in evidence displaying an email address support@mykangenwater.com.au, however, the evidence does not establish whether, when and how that leaflet was used in any particular course of trade and the leaflet does not refer to any website utilising the domain. The email address does not appear on any other document before me. The evidence does not establish that it has ever been used.

91 Affidavit evidence of Enagic’s solicitor confirms that at the present day, the landing pages for the domain names are pages from the WaterOnline website from which users can purchase the two KANGEN bottled water products. The earliest date from which the domains were utilised in that way is not established on the evidence, except to say that such uses could not pre-date the earliest date of operation of the WaterOnline website in July 2012. To the extent that any of the domain names were registered prior to that time, I am not satisfied that the act of registration constitutes “use” of the Opposed Mark in the sense defined in the TMA at any time before July 2012 (if at all).

Kangen as a business name

92 On 26 April 2016, Horizons registered the business name KANGEN AIR & WATER TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA. Also in evidence is an extract from the Australian Investments and Securities Commission recording the registration of the business name KANGEN AIR & WATER TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA on 6 January 2011 (now cancelled). However, the holder of the business name is not identified in that earlier extract.

93 Ms Ng deposes that Horizons used the business name KANGEN AIR & WATER TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA “to distinguish its distribution services” from 2011. Ms Ng asserts that she was responsible for applying for the business name and that she “routinely observed its application to those invoices since 2011”. It is to be recalled that Ms Ng did not commence employment with Horizons until 2014. Accordingly, I do not consider she could have had made any personal observations in respect of the application of the business name to invoices or any other document before that time. In addition, Ms Ng acknowledged in cross-examination that she had no involvement in the issuing of invoices. I am not satisfied that she has any personal knowledge about the transactions referred to in them or the commercial context in which they occurred, and I give no weight to her assertion as to the purpose for which the name was employed in 2011.

94 The use of the business name in the provision of “distribution services” is said to be evidenced by three leaflets, together with seven invoices annexed to Ms Ng’s affidavit. The invoices are given separate consideration at [99] to [113] below.

95 The first leaflet is a single page document depicting the use of the stylised word KANGEN in its application to an air purifier product. The leaflet is undated. Ms Ng asserts that the leaflet was “distributed to prospective customers of Horizons no later than early 2009”, however that assertion is not based on her personal knowledge but rather upon her “significant involvement in reviewing the business records of Horizons during the preparation of evidence in this and related trade mark disputes”. No business records objectively evidencing the distribution or other use of the leaflet from early 2009 in Australia were adduced by Horizons.

96 The next leaflet is also headed with the stylised word KANGEN at the top. It shows the word KANGEN in connection with a bottled “alkaline water” product. The leaflet is undated. That leaflet is also said to have been distributed to prospective customers of Horizons from 2009 however the assertion is also based on Ms Ng’s review of Horizons’ business records and not upon her personal knowledge. Horizons has adduced no business records to support Ms Ng’s assertion as to when and how the leaflet was deployed in its business.

97 The third leaflet does include the words KANGEN AIR & WATER TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA at the top. The undated leaflet contains information about an air purifier product described as having the “Brand Name” KANGEN. It goes some way to evidence the use of the Opposed Mark in connection with goods of that nature. It also goes some way to evidence the use of the business name KANGEN AIR & WATER TECHNOLOGIES as a business name in connection with the sale of that product. However, as with the other leaflets, the actual use of that document in the course of trade is not explained by any person having personal knowledge of the facts. Ms Ng deposes that the leaflet was “distributed no later than around 2015”, but that assertion is also said to be based on her review of Horizons’ business records. Again, no further business records are adduced to support the assertion as to the use of the leaflet whether in 2015 or otherwise.

98 In the absence of evidence from a person with knowledge as to whether and how the leaflets were distributed, I attribute them little weight, especially having regard to the lack of cogency attending other documentary evidence upon which Horizons relied in support of its claimed activities between early 2009 and at least July 2012. Even if the leaflets were capable of supporting a conclusion that they were used in the course of any trade, it would not follow that the Opposed Mark had been used in Australia as opposed to in a foreign place in which goods may have been promoted to prospective importers.

Invoices

99 The invoices relied upon by Horizons may be considered in three categories: those bearing the issuer name Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd, those bearing the issuer name “Kangen Air & Water Technologies Australia – Division of Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd” and those bearing the issuer name WATER ONLINE.

100 As has been mentioned, Ms Ng confirmed that she has had no involvement in the issuing of invoices by Horizons. She told the Court that the fulfilment of orders is the responsibility of a warehouse operated by an “external third party”. It is not her usual duty to visit the warehouse. Ms Ng also confirmed that she has no general involvement in Horizons’ finances. She confirmed that her role is concerned with the maintenance of Horizons’ trademarks, domain names, business registrations and the like.

101 When Ms Ng’s affidavit was first filed, the invoices annexed to it were redacted, purportedly for the purpose of protecting the confidentiality of information concerning their recipients. In the course of cross-examination, Ms Ng was taken to the invoices in their unredacted form, as provided to Enagic on discovery.

102 The three invoices in the first category are dated 2 February 2009, 18 February 2009 and 8 May 2010. Each of them contain the heading “Payment” after which the words “as arranged” appear. No other information about method of payment is included. The first of them is issued to an entity named Hung Fung Trading Co, situated in Hong Kong. It relates to a shipment of a quantity of goods referred to as “KANGEN Air Ioniser” (100 units) and “KANGEN RO Water Purifiers” (10 units) direct from a factory, with shipment to Hong Kong. As discussed below, I am not satisfied that transactions with an entity trading under the name Hung Fung Trading Co are arm’s length transactions so as to evidence the use of the mark KANGEN in the course of trade in Australia. The remaining two invoices in this category are issued to “Aquaqueen Int’l Pty Ltd”. They relate to the purchase of product referred to as “KANGEN Natural Mineral Water”, with shipment in each case to Hong Kong. As explained below, I am not satisfied these transaction are arm’s length transactions. When viewed together with the invoices in the next category, this evidence causes me to place little weight on Ms Ng’s assertions about Horizons’ trading activities at any time prior to the commencement of her employment in 2014, and for some time afterward. The three invoices referred to by Ms Ng in respect of this period are insufficient to support her claim that Horizons provided or promoted distribution services to consumers in Australia. To the extent that they evidence the existence of goods bearing the name KANGEN, I am not satisfied that such goods were promoted for sale in Australia in the period to which these early invoices relate. Whilst to an extent they evidence the movement of stock between entities having common directors, they are insufficient to show the use of the mark KANGEN in its application to goods sold or promoted for sale in Australia.

103 The second category of invoices are those issued under the name “Kangen Air & Water Technologies Australia – Division of Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd”. There are seven of them. They each require payment within 14 days, but no details are provided as to how payment might be made.

104 Five of them (dated between 28 October 2011 and 10 August 2016) are addressed to purchasers situated in Hong Kong. No GST is charged in respect of any of the transactions recorded in them. The recipient of two of them is “Horizons Asia P/L (HK)”. When asked in cross-examination whether that company was a separate entity from Horizons, Ms Ng responded “If you say so. I understand it was.” Ms Ng did not disclose the information upon which her asserted understanding was based, nor was she re-examined on the topic. Ms Ng later denied that the company to whom the product was sold was an entity related to Horizons. The cross-examination continued:

Q: So you can’t say one way or the other whether the company is related or not?

A: To my knowledge, no.

105 Given the name of the entity and in light of the vague responses given by Ms Ng I am not satisfied that the transactions recorded in those invoices are arm’s length transactions evidencing the use of a trade mark in the course of trade with consumers in Australia.

106 A further invoice in this category names AquaQueen International Pty Ltd as the recipient. Ms Ng was taken to a company extract showing that the owner and director of AquaQueen was Ms Penson (the original owner and director of Horizons for whom Ms Ng acted as a personal assistant). When it was put to Ms Ng that the company AquaQueen is related to Horizons, Ms Ng responded “It was before my era. If you say so”. She said that she did not know that Ms Penson was a director of AquaQueen. She said it was “before my time” at Horizons. Ms Ng said that at the time of preparing her affidavit she was unaware of Ms Penson’s relationship with AquaQueen. When it was put to Ms Ng that Ms Penson remained a director of AquaQueen until 2016, Ms Ng responded that whilst acting as Ms Penson’s personal assistant she was confined to tasks of a clerical and administrative nature. She said “I was personally assisting. I did not know anything else other than assisting Ms Penson”. In light of that response, I conclude that Ms Ng is unable to give evidence about Horizons’ activities from her own knowledge from the commencement of her employment until she assumed different duties some time in 2016.

107 Other invoices in this category are addressed to an entity referred to as “Hung Fung Trading Co Limited”. Considering the evidence as a whole, I do not accept Ms Ng’s general assertion that these invoices were issued in the course of the conduct of a distribution business trading under the name KANGEN. The entity Hung Fung Trading Co utilises the same address as the entity Horizons Asia P/L (HK) so raising a question as to the relationship between them (a topic about which Ms Ng had no personal knowledge). Second, Ms Ng’s ignorance of the relations between Horizons and AquaQueen, together with her vague response to the questions to whether Horizons Asia P/L (HK) was a separate entity to Horizons, affects the reliability of all of her assertions concerning Horizons’ trading activities by reference to the invoices. I do not accept that she has any personal knowledge about the conduct of any distribution business in the period to which these invoices relate, nor about the entities to which Horizons might have issued invoices, nor about the commercial context in which the invoices to Hung Fung Trading Co were issued.

108 I have taken into account Ms Ng’s assertion that she has spent hundreds of hours scrutinising Horizons’ business records, including those relating to periods of time to which these invoices relate. However, if the evidence of the extent of her scrutiny of Horizons’ records is to be accepted, it is reasonable to expect that she would locate and produce invoices (as they exist) evidencing transactions in the course of trade with entities that she knows are truly external to Horizons and to which its goods and services have been promoted in the critical early times at which Enagic asserts it was using the same mark.

109 In addition, I consider the redaction of the invoices annexed to Ms Ng’s affidavit to have gone well beyond what was necessary to protect confidential information. The redaction of the “ship to” address is demonstrative, as is the redaction of the invoice number. Those redactions initially concealed probative material that undermined Horizons’ case and cannot, on any reasonable view, be characterised as commercially confidential. An additional effect of redacting invoices in that way was to conceal the fact that Ms Ng had annexed the same invoices to her affidavit three times (Annexures NG-9, NG-11 and NG-14) and to conceal the fact that the goods referred to in the invoices were not delivered to places situated in Australia. Ms Ng denied that the invoice numbers had been redacted for the purpose of concealing the duplication of invoices so as to convey the impression that there were more transactions evidenced by them than in fact was the case. She could not provide adequate explanation as to why the “ship to” location had been redacted. When afforded the opportunity to explain why the annexures to her affidavit were redacted in that way no explanation was forthcoming, other than a denial of any involvement in the redaction process. Ms Ng was not re-examined on that topic. The circumstances just described further reinforce my concerns as to the reliability of Ms Ng’s evidence as a whole.

110 In addition, it may reasonably be expected that Ms Ng would have selected invoices that she considered to be truly representative of Horizons’ trading activities to provide objective support for her testimony. To the extent that the invoices are a representative of any activity, they indicate that in the period to which the invoices relate, Horizons was involved in transactions directing the shipment of goods from a factory (the whereabouts of which is unknown) to entities situated in Hong Kong that were either related to it, or otherwise for purposes that are not explained by any person with knowledge of the commercial context of the transactions. Additionally, at least until the establishment of the WaterOnline website in 2012, there is insufficient evidence to show that the products described in the invoices were in fact promoted for sale to consumers in Australia, whether by reference to the Opposed Mark or otherwise.

111 It is curious that there are no invoices in respect of sales generated from the WaterOnline website in the period between mid-2012, when the website was established until May 2017 (after the priority date), but that anomaly was not the subject of cross-examination and I draw no adverse inference from it for the purposes of s 58 and s 60 of the TMA.

112 Of the remaining two invoices in this category, only one predates the priority date for the Opposed Mark. It is dated 13 June 2016, and appears to relate to 30 personal air purifier products shipped to an address in Botany in New South Wales. Ordinarily, I would regard that invoice as capable of evidencing the conduct of a business at that time for the sale of goods in the nature of personal air purifiers. However, I am not satisfied that it is sufficient, in and of itself, to evidence the conduct of a business for the provision of distribution services offered or provided to any person in Australia whether under the name KANGEN (or similar) or otherwise. To the extent that air purifiers were distributed by Horizons, I am not satisfied that the distribution occurred other than as an internal delivery activity to complete the transfer of possession of the goods to the end consumer. Given my concerns about the reliability of Ms Ng’s evidence generally I do not accept her assertion (expressed or implied) as to the existence of a distribution business and I am not prepared to draw an inference favourable to Horizons by reference to that document.

113 The third category of invoices are those issued under the name WATER ONLINE. There are 21 of them. They all bear dates after the priority date for the Opposed Mark, ranging from 30 May 2017 to 19 April 2019. Each of them records the sale of water products in 10 litre or 600ml units, with delivery addresses in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia. The amounts vary from $173.80 at the lowest to $422.40 at the highest.

Horizons’ use of the Opposed Mark before the priority date

114 On 29 February 2012 Horizons became the registered owner of the business name AQUARIAN WATER ONLINE AUSTRALIA. The business name WATER ONLINE was first registered to Horizons on 10 October 2017. On 17 April 2012, Horizons secured registration of a logo incorporating the stylised words WATER ONLINE. The logo is registered in respect of goods in class 32 (waters including spring waters, mineral waters and aerated waters and other non-alcoholic beverages; fruit beverages and juices; beer; syrups and other preparations for making beverages) and services in class 35 (advertising; business management; direct marketing and selling).

115 Both parties have adduced evidence obtained by use of an internet archive known as the Wayback Machine to demonstrate the content of various websites at various times. The Court has before it evidence as to how the internet archive operates: Affidavit of Elizabeth Rosenberg affirmed on 2 November 2020. The Court may rely on the extracts from the websites as reliable representations of the textual content of web pages at the times of their capture, although in some respects the captured pages do not depict all visual features one might expect to see on a web page. As to the use and reliability of such evidence, see: Pinnacle Runway Pty Ltd v Triangl Limited [2019] FCA 1662; 375 ALR 251.

116 The earliest content captured from the WaterOnline website is dated 26 July 2012.

117 A capture dated 27 July 2012 shows products promoted for sale via the WaterOnline website under the brand KANGEN. Two products are referred to: a 10 litre quantity (the receptacle and packaging for which is not proven) and a 600ml plastic bottle (sold in quantities of 20 bottles per case). Both products are described as “NEW”. On the basis of that evidence, I am satisfied that the word KANGEN was used in relation to goods in the nature of drinking water. It was used in physical relation to the 600ml product by the affixation of a label prominently displaying the word and otherwise as a name for both products, under which they were promoted for sale. I am satisfied those two products were offered for sale to consumers situated in Australia via the WaterOnline website in July 2012.

118 It is otherwise apparent that the business operated by Horizons via the WaterOnline website does not involve the provision of any service to consumers in Australia. Rather, the website is the trade channel by which Horizons offers its own goods for sale. To the extent that goods might be delivered for the purpose of transferring them into the possession of the purchaser following their sale, that is an activity internal to Horizons. Delivery of the goods to the end consumer in the context of a sale does not constitute the provision of a service to the end consumer.

119 If I am wrong about that, I would conclude in any event that any service offered to be provided in Australia via the WaterOnline website was not a service in respect of which the Opposed Mark was used.