Federal Court of Australia

Frigger v Trenfield (No 10) [2021] FCA 1500

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application is dismissed.

2. On or before 15 December 2021, the first respondent must file and serve written submissions on the question of the costs of the proceeding, including any reserved costs, of no more than three pages in length (excluding header).

3. On or before 12 January 2022, the other parties must file and serve any written submissions in reply, of no more than three pages in length (excluding header).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKSON J:

1 The applicants in this proceeding are Angela and Hartmut Frigger, a wife and husband who at the time of the making of the application were undischarged bankrupts. The first respondent is their trustee in bankruptcy, Kelly Anne Trenfield. The second respondent, H & A Frigger Pty Ltd (HAF), is a former trustee of the applicants' self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF), the Frigger Super Fund (FSF).

2 The issues in this case may be divided into three groups. The first concerns whether certain assets are property divisible amongst the creditors of the bankrupt estates. This turns on whether the applicants hold interests in the assets by way of their interests in the FSF. For some of the assets, the issue arises directly, because the applicants seek declarations that they do hold interests in those assets by way of the FSF. For other assets, while the applicants do not seek declarations to that effect, the issue still arises because they do seek orders that would be consequential on findings that the assets are part of the FSF. There is a related issue about whether the FSF is a regulated superannuation fund within the meaning of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (SIS Act). The assets in question, which I will call the disputed assets, are:

(1) two bank accounts with Bank of Queensland Limited, one of which holds more than $2.8 million (BOQ1), the other of which holds just over $50 (BOQ2);

(2) shares held in a share portfolio (Main Portfolio) administered by the share broker, Commonwealth Securities Limited (CommSec); and

(3) two parcels of residential land in suburbs of Perth, one in Bayswater (Bayswater Property) and the other in Como (Como Property, together the Residential Properties).

3 As will be seen, while not the subject of any of the declarations the applicants seek, it was also in issue whether a Bankwest Retirement Advantage account in Mrs Frigger's name (BW1) was an asset of the FSF.

4 The second group of issues concerns orders relating to costs that were made by the Court of Appeal of Western Australia. There are three relevant orders, each made in a different appeal. The first respondent consented to the orders in her capacity as trustee in bankruptcy of the applicants. The applicants seek declarations that the minutes of consent orders, and the orders that followed them, are 'incompetent', and claim losses they say they have suffered as a result of the orders.

5 The third group of issues concerns the first respondent's conduct of the administration of the bankrupt estate. The main question raised by the applicants is whether the first respondent should be removed as trustee of the applicants' bankrupt estates. There are also issues raised as to whether the court should order that the first respondent may not recover any costs or remuneration associated with the Bank of Queensland accounts, the Residential Properties and the costs orders in the Court of Appeal.

6 There is one other group of issues arising from the relief sought which I mention for completeness. It concerns whether the applicants are entitled to compensation in relation to losses said to have been caused by a hold placed on BOQ1 at the instigation of the first respondent and the applicant's inability to trade the shares in the Main Portfolio. For reasons published as Frigger v Trenfield (No 4) [2020] FCA 797, I ordered, in effect, that any hearing to establish and quantify those alleged losses would take place after delivery of this judgment, if the court determines that any of the relevant assets are indeed FSF assets.

7 The orders the applicants seek in this proceeding are sought under s 30 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) and s 90-15(3) of Schedule 2 to that Act, that is, the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Bankruptcy). Some of the orders are declarations which are sought in the alternative under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). In summary, the applicants seek:

(1) declarations that BOQ1, BOQ2 and the Residential Properties are held in the FSF on trust for the beneficiaries of that fund, and so pursuant to s 116(2)(d)(iii)(A) of the Bankruptcy Act are not assets divisible among creditors;

(2) compensation for losses the applicants say they have incurred as a result of the first respondent having placed holds or freezes on BOQ1;

(3) an order requiring the first respondent to remove caveats she has placed on the Residential Properties and to pay any losses caused by the caveats;

(4) declarations that the various consent orders and costs assessments in the Court of Appeal are 'incompetent' pursuant to s 58(3)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act;

(5) compensation for losses resulting from the Court of Appeal costs orders and orders effectively requiring the first respondent to apply to that court to have the orders set aside;

(6) orders disentitling the first respondent to remuneration and costs in relation to the above matters;

(7) orders requiring the first respondent to write to CommSec and the ASX to remove a trading suspension on the Main Portfolio which appears to have been placed following a previous letter from the first respondent to CommSec, and requiring her to say that the securities in that account have not vested in her pursuant to s 58 of the Bankruptcy Act;

(8) compensation for losses said to have been caused by the suspension of trading in the Main Portfolio;

(9) an order removing the first respondent as the trustee in bankruptcy of the applicants' estates; and

(10) costs.

8 The first respondent opposes all the orders sought.

9 HAF was joined as second respondent for reasons given in Frigger v Trenfield (No 6) [2020] FCA 934 (Frigger (No 6)). It has filed a submitting notice which is qualified, in the sense that it does not submit to any order or finding on three specified issues said to have been raised by the first respondent, namely: (a) HAF's role as trustee or former trustee of the FSF; (b) mortgages registered on the properties in Como, Bayswater and Applecross; and (c) whether or not the second respondent is named as a secured party in the Personal Properties Securities Register (PPSR). It will be necessary to make findings about the identity of the trustees of the FSF over time, including HAF, although it is not clear that those findings are either the result of issues raised by the first respondent or opposed by or adverse to HAF. Save for that, it will not be necessary to deal with the issues specified in HAF's submitting notice or to refer to HAF's position in the litigation separately to the position of the applicants; it is common ground that HAF's interests are identical to those of the applicants.

10 As prolific self-represented litigants, the applicants made a large number of contentions in their many affidavits and submissions. That proliferation of contentions was compounded by the changing nature of the positions they took in the case over time. It is not possible to address every one of those contentions in terms in these reasons. Where I have not addressed a submission that the applicants have made, it is because I do not consider it sufficiently cogent to warrant express mention.

11 For the following reasons the application will be dismissed.

12 Before describing the issues in more detail it is convenient to set out some relatively uncontentious background to the applicants, the respondents and the FSF.

13 The applicants are husband and wife. There was little direct evidence as to their respective backgrounds. But records show that the first applicant, Mrs Frigger, is 68 years old (ACTF 1 p 51 - I will use this format to refer to the 18 affidavits of Mrs Frigger which the applicants put into evidence, which will be numbered in the order in which they were sworn and filed as set out in Schedule 1 to this judgment). Mrs Frigger is now retired, although the volume of litigation in which she and Mr Frigger have been personally involved in the last 13 or so years makes that an incomplete description of her working status. Before her retirement she worked as an accountant. She has a Bachelor of Accounting from the Western Australian Institute of Technology (now Curtin University). She qualified as a Certified Practising Accountant and is a Fellow of the National Tax and Accountants Association.

14 Mr Frigger is 66 years old (ACTF 1 p 53). He too is retired. During his working life he was an engineer. It is clear that through investment, entrepreneurship or other means, he and Mrs Frigger had accumulated substantial assets by the time they were declared bankrupt. Much of this case concerns the capacity in which they held some of those assets.

15 The FSF was formed on about 1 July 1997 by the execution of a deed entitled 'Superannuation Trust Deed for a Self-Managed Fund for Frigger Super Fund' (FSF Deed). Its members, that is the beneficiaries of the trust, may have changed over time, but they have always included the applicants.

16 The first trustee of the FSF was a company called Serenity Holdings Pty Ltd, which subsequently changed its name to Computer and Accounting Tax Pty Ltd (so, while there will occasionally be a need to use the former name, I will define it as CAT). It appears that CAT was trustee of the FSF until about July 2010 (KAT 4 para 66 - I will adopt a similar naming convention for the first respondent's affidavits as I have for those of the applicants - see Schedule 1). An order for its winding up in insolvency was made on 6 May 2010 (KAT 4 para 27). Mervyn Kitay is its liquidator (KAT 4 para 26).

17 When other persons or entities were, and were not, trustees of the FSF proved to be in dispute and has implications for the main issues in the proceeding. I will consider that question later.

18 The applicants' bankruptcies occurred when this court made a sequestration order against their respective estates on 20 July 2018: Kitay, in the matter of Frigger (No 2) [2018] FCA 1032. It is not necessary to describe the events leading up to the bankruptcy in any detail. At one time the applicants claimed that they had an appeal or other proceedings on foot which would have resulted in the setting aside or annulment of their bankruptcies. However by force of an order made by Charlesworth J on 17 April 2020, an application for an extension of time to appeal from the sequestration order was dismissed: Frigger v Kitay (No 2) [2020] FCA 497; (2020) 143 ACSR 655. Therefore the court proceeds on the basis that the applicants' attempts to appeal from or otherwise overturn the sequestration orders have been unsuccessful. There was a fresh application to annul the bankruptcies made after judgment was reserved. I dismissed an attempt by the applicants, based on their application to annul, to have me stay judgment in this proceeding: Frigger v Trenfield (No 9) [2021] FCA 652. As at the date of this judgment, the annulment application had been neither granted nor dismissed.

19 The Official Trustee in Bankruptcy became the applicants' trustee in bankruptcy on the making of the sequestration order. On 31 August 2018 the applicant's creditors passed a special resolution appointing the first respondent and a partner in her firm, Paul Allen, as trustees in bankruptcy, in place of the Official Trustee, pursuant to s 157 of the Bankruptcy Act (KAT 1 paras 3-4, p 30). Mr Allen has since retired from that position (KAT 4 para 21), so the first respondent, Mrs Trenfield, is the applicants' sole trustee in bankruptcy.

20 That is about all that can be said that is uncontentious in this proceeding. I will now describe the issues between the parties in more detail.

Description of the issues - disputed assets and the applicants' interests in the FSF

21 The first group of issues concerns whether, as at the relevant date, the disputed assets were held in the FSF. The significance of that question stems from s 116(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act, which provides that, subject to the Act:

(a) all property that belonged to, or was vested in, a bankrupt at the commencement of the bankruptcy, or has been acquired or is acquired by him or her, or has devolved or devolves on him or her, after the commencement of the bankruptcy and before his or her discharge

… is property divisible amongst the creditors of the bankrupt.

As this indicates, the relevant date is 'the commencement of the bankruptcy', a concept that will be explained below.

22 The applicants rely on s 116(2)(d)(iii)(A) of the Bankruptcy Act as an exception to this. It provides that s 116(1) does not extend to certain specified kinds of property, including 'the interest of the bankrupt in … a regulated superannuation fund (within the meaning of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 [(Cth)])'. The applicants seek declarations that BOQ1, BOQ2 and the Residential Properties fall within this exception, and they also seem to rely on it in relation to the Main Portfolio (although a declaration under it is not sought in the originating application). So the central issue is whether the applicants hold beneficial interests in the disputed assets by way of their interests in the FSF. Since there is no question that between them they held substantial interests in the FSF, the key question is whether the disputed assets were assets of the FSF. Whether the FSF is a regulated superannuation fund within the meaning of the SIS Act is also in issue.

23 For completeness, I note that the applicants do not rely on s 116(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. That section provides that s 116(1) does not extend to 'property held by the bankrupt in trust for another person'. The applicants seek no declaration that s 116(2)(a) applies in relation to any of the disputed assets. If they had, they would have faced the difficulty that the High Court has construed the provision to mean that if a bankrupt holds property on trust for herself along with other persons, that property will still vest in the trustee in bankruptcy under s 116(1), subject to the equities in favour of the other persons: Carter Holt Harvey Wood Products Australia Pty Ltd v Commonwealth [2019] HCA 20; (2019) 268 CLR 524 at [94]; Boensch v Pascoe [2019] HCA 49; (2019) 268 CLR 593 at [4], [88], [91], [93].

24 Before going further it is necessary to make clear how certain terms are used in this judgment.

25 It was effectively common ground that the FSF is an express trust, since the FSF Deed did establish a trust. What is not clear is which assets are held on the terms of that trust. Nevertheless, I will speak of the FSF as an extant trust, on the assumption that it applies to at least some existing assets.

26 In these reasons I will refer to assets as being 'held in the FSF', 'FSF assets', 'an asset of the FSF', 'part of the FSF' or 'FSF funds' as shorthand for saying that the asset is one which is owned at law by persons who hold office as trustees of the FSF pursuant to the FSF Deed, with those trustees accordingly having powers and duties in respect of the asset under the FSF Deed to hold, use, apply and dispose of the asset for the benefit of the beneficiaries, who are identified as such in, or in accordance with, the FSF Deed.

27 The key question in relation to the disputed assets, though, is whether they are part of the fund that is the FSF. That is because s 116(2)(d)(iii)(A) of the Bankruptcy Act speaks in terms of the interest of the bankrupt in a fund. Doubtless if an asset meets the description in the preceding paragraph, it will be part of the FSF. However it will be necessary in these reasons to consider whether circumstances that fall short of that also mean that certain assets are part of the fund.

28 I now describe the particular issues that arise in relation to each of the disputed assets.

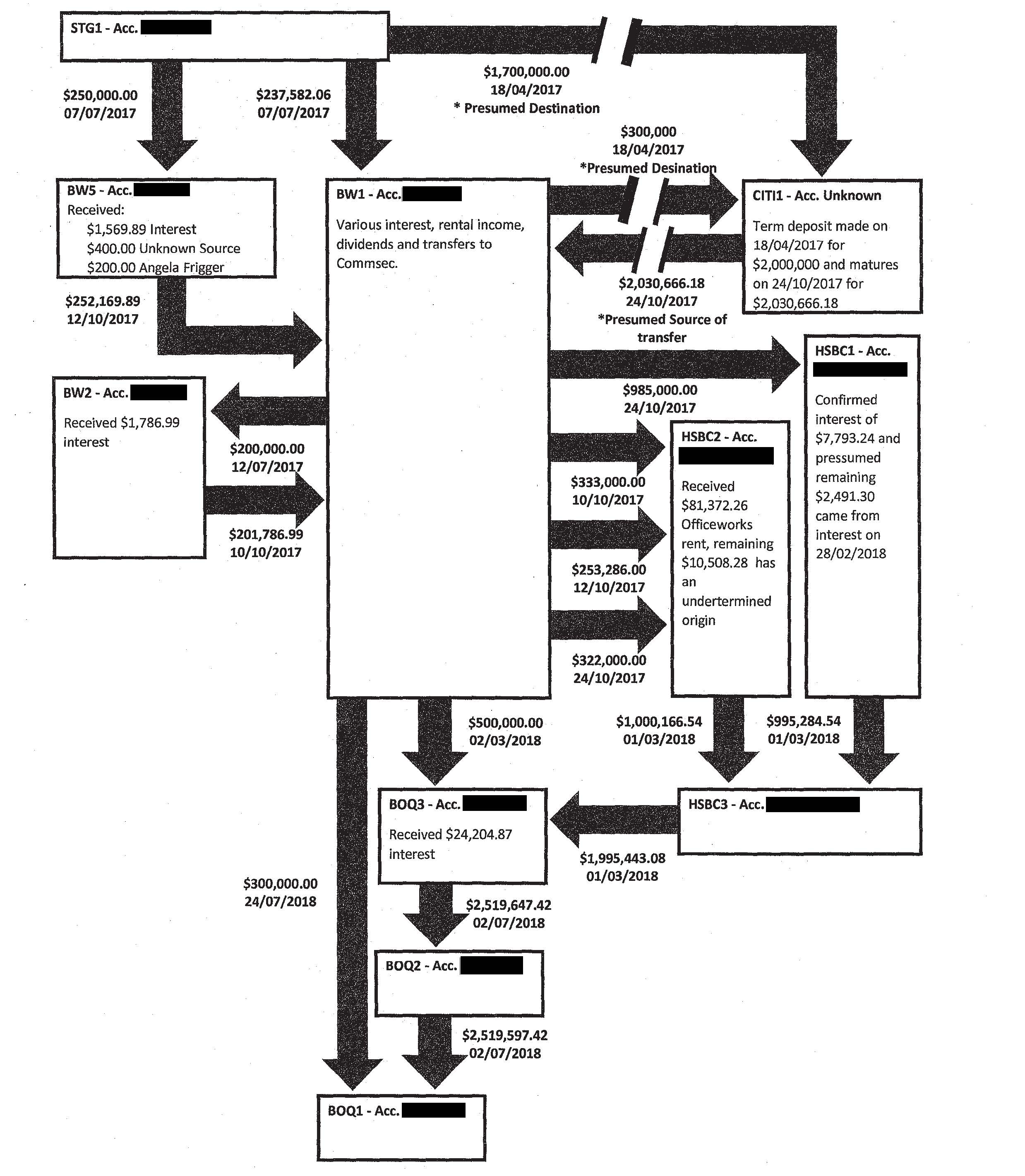

29 The Bank of Queensland accounts are the first of the disputed assets which the applicants claim are FSF assets. In their written opening submissions, the applicants put their case on a narrower basis than appeared from the evidence they filed. They simply allege that the money in those accounts was originally earned by the FSF as rental income from a commercial property in Edward Street, Perth, and a property leased to Officeworks in Hobart. They say that the Hobart property was purchased in their names as trustees, and that there was a declaration of trust over the Edward Street property in 2009 and a registrar's caveat recording the trust lodged on the title. So the rental income from those properties is said to be income of the FSF.

30 The first respondent denies that the money in the Bank of Queensland accounts is held on trust. She points to the fact that BOQ1 is in Mr Frigger's name only, and BOQ2 is in Mrs Frigger's name. She submits that the onus is on the applicants to establish that there was, at any relevant time, an objective manifestation of the intention to hold those accounts on trust on the terms of the FSF, and that they have failed to discharge that onus.

31 While the applicants seek to put their case on a narrower basis than the issue as stated by the first respondent, in my view the applicants' submission is simply the particular manner in which they seek to establish the necessary objective manifestation of intention (as to which see [104] and following below). The ultimate issue is whether there was any such manifestation, having the result that the applicants hold beneficial interests in the accounts as part of their interests in the FSF as a regulated superannuation fund.

32 The Main Portfolio was opened in the name of both of the applicants in 1998. The applicants concede that it was not opened by them in their capacities as trustees, since they were not trustees of the FSF at the time. But they rely on a variety of surrounding circumstances to allege that the shares that are currently held in the Main Portfolio were purchased in their capacity as trustees of the FSF.

33 The first respondent denies this and alleges that the applicants own the shares in the Main Portfolio in their personal capacities, with no division between legal and beneficial ownership. She relies on a number of circumstances to submit that at no time has there been any objective manifestation of an intention that the securities in the Main Portfolio were to be held by the applicants in their capacities as trustees of the FSF.

34 On 28 August 2019 the first respondent wrote to CommSec claiming that the securities in the Main Portfolio vested in her as trustee in bankruptcy of each of the applicants and were considered property divisible among the bankrupt estates' creditors (ACTF 5 p 5). The first respondent asked for a freeze on transactions in the portfolio. This has resulted in the account being locked (ACTF 5 p 7). The applicants thus frame the issue as whether they are prevented as trustees of the FSF from trading shares listed on ASX because of the sequestration order. However that merely describes a practical consequence for them if they fail to establish that the securities were assets of the FSF. The applicants accept that they must establish this in order to obtain the orders they seek in relation to the Main Portfolio.

35 Each of the Residential Properties have houses that are leased to tenants for rental income. For each of them, the name of the owner shown on the certificate of title is Angela Frigger. Mrs Frigger acquired the Bayswater Property before the establishment of the FSF. While she became the registered proprietor of the Como Property after the FSF was established, she did so at a time when CAT, and not either of the applicants, was trustee of the FSF.

36 The applicants say that Mrs Frigger contributed both properties to the FSF by means of written declarations of trust made on 1 July 2014 (2014 Declarations). I will examine the terms of those declarations when I resolve this issue below. The first respondent nevertheless disputes that the Residential Properties are assets of the FSF. She says that on the proper construction of the 2014 Declarations they do not have the result that the properties were held by the applicants in their capacities as trustees of the FSF. She also submits that there would be contraventions of the SIS Act arising from any contribution of the Residential Properties to the FSF which would make them invalid.

37 So the issue to be determined by the court is whether, having regard to those matters, the applicants have established that the Residential Properties are assets of the FSF.

38 The applicants, once again, describe the issue in a narrower way, as whether the first respondent has a caveatable interest in the Residential Properties. That is because the first respondent lodged an absolute caveat on each property on around 11 October 2018, claiming an interest as trustee in bankruptcy (KAT 4 p 295). The interest claimed is the 'vesting in equity' in the first respondent (and Mr Allen) 'as joint and several trustees of the bankrupt estate of the registered proprietor in accordance with section 68 [sic 58] of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth)'.

39 As has been said, the applicants seek orders for the removal of these caveats, so the existence of caveatable interests is in dispute. But it is not a complete description of the issues. In any event, the first respondent submits that even if the properties are assets of the FSF, she still has a caveatable interest in them by reason of the vesting of those properties in her under s 58(1) of the Bankruptcy Act.

Whether the FSF is a regulated superannuation fund

40 The first respondent puts the applicants to proof of the status of the FSF as a regulated superannuation fund within the meaning of the SIS Act. As has been explained, that must be resolved in the applicants' favour for their interests in the FSF to fall outside the pool of property divisible among creditors of their bankrupt estates.

Description of the issues - the orders concerning costs in the Court of Appeal

41 The Court of Appeal orders sought to be impugned were made in three appeals. The first was an appeal which the applicants brought to which Mr Kitay was the respondent. The applicants were ordered to pay $25,000 into court as security for Mr Kitay's costs of the appeal, which they did. The appeal was unsuccessful and before they became bankrupts, the applicants were ordered to pay Mr Kitay's costs of the appeal on an indemnity basis (ACTF 1 p 134). A certificate for the taxation of costs was issued on 18 September 2018 (ACTF1 p 138), after the sequestration order and a little over two weeks after the first respondent's appointment as the applicants' trustee in bankruptcy. The first respondent took no part in that taxation. The Court of Appeal taxed the costs in the sum of $85,363.90 (ACTF 1 p 138). After that, at Mr Kitay's request, Mrs Trenfield signed a minute of consent orders for the payment of the $25,000 out of court to Mr Kitay. The Court of Appeal ordered accordingly.

42 The other two appeals can be dealt with together. The applicants brought them against a law firm, Clavey Legal. The applicants had paid sums into court as security for the costs of those appeals, totalling $62,500. The appeals were unsuccessful and in each, the applicants were ordered to pay Clavey Legal's costs. This occurred before the sequestration order. After the sequestration order, Mrs Trenfield signed minutes of consent orders fixing Clavey Legal's costs in the amount of the security that had been paid in, and authorising payment out. The Court of Appeal made those orders.

43 It was difficult to make out the basis for the applicants' claims about these events from their written submissions. But in oral opening it became clear that they have two complaints. The first is that they say that the costs liabilities were debts provable in the bankruptcy, which should have been dealt with in the course of the process of proving such debts. But instead of calling for proofs and adjudicating on them, the first respondent signed consent orders which led to the payment out of the amounts that had been paid in as security for costs. The applicants' second complaint is that the first respondent should not have consented to that payment out because the applicants had substantial counterclaims against Mr Kitay and Clavey Legal which more than offset the costs liabilities.

44 In oral submissions the applicants also made it clear that, while they seek declarations that the orders are 'incompetent', they do not ask this court to somehow reverse or override the orders made by the Court of Appeal. The reference to lack of competency is a reference to the wording of s 58(3) of the Bankruptcy Act, which provides that after a debtor has become a bankrupt, it is not 'competent' for a creditor to enforce any remedy against the person or the property of the bankrupt in respect of a provable debt. The applicants' principal claim is for a declaration that the first respondent acted contrary to her duties as trustee in bankruptcy and for compensation from the first respondent for losses they say they suffered as a result of the first respondent's signing of the consent orders.

45 The first respondent disputes the applicants' claims about the costs orders on several bases (many of which will not need to be addressed). She says that the claims are untenable.

Description of the issues - removal of the first respondent as the trustee in bankruptcy

46 The conduct of the first respondent on which the applicants rely in order to argue that she should be removed as their trustee in bankruptcy is, to some extent, her conduct in asserting control over the assets which the applicants say are assets of the FSF, or conduct which (broadly speaking) indicates a lack of acceptance of the applicants' claims in that regard.

47 There is also conduct associated with those issues, such as an asserted failure to follow up the Bank of Queensland to obtain a copy of an HSBC bank cheque which would have helped in the process of tracing funds back to BW1, and statements made in affidavits about those things which the applicants say are false. The applicants repeat their complaints about the first respondent signing consent orders in the Court of Appeal. In addition, the applicants rely on what they say were attempts by the first respondent to persuade the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to treat the FSF as an 'unregulated super fund', incorrect statements made to the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA), and emails to share registries which they say disclosed their tax file numbers (TFN) and claimed that they had tried to circumvent the bankruptcy.

48 The applicants also rely on what they say are the first respondent's failures to interview them, to accept proofs of debt and to recognise offsetting claims that they had against certain creditors. There is also an allegation about collusion with Mr Kitay and his lawyers.

49 The first respondent disputes all of these allegations. For the most part she does so by reference to her position in relation to the issues about the ownership of the disputed assets and the Court of Appeal orders: if the applicants cannot establish their case in relation to those issues, then they will not establish that the first respondent's conduct in relation to those assets fell short of the standard to be expected of a trustee in bankruptcy. But the first respondent says that even if the applicants succeed in relation to those claims, her position was still reasonable, especially given what she says were constant difficulties in obtaining information about the matters in question, largely caused by an uncooperative and aggressive stance taken by the applicants themselves, as well as the unreliability of the information they did provide. The first respondent denies that she had any obligation to interview the applicants and says that, given their attitude, an interview would not have been useful. She says that there is no point in calling for proofs of debt unless and until it appears that a dividend will be paid out of the bankrupt estates.

50 Before turning to determine the issues, I will make some observations about the witnesses. There were only two: Mrs Frigger and Mrs Trenfield. Each was cross-examined for some time. My general views about the reliability of their evidence are as follows.

51 I have already described Mrs Frigger's background and qualifications. It is necessary to say at the outset that I have concluded that she knowingly altered documents which she put into evidence, in order to create a false impression that the documents supported the applicants' case. I should explain at once why I have reached that conclusion, conscious of its gravity and the need for clear and cogent proof.

The altered St George Bank statement

52 The question of whether certain assets were held in trust on the terms of the FSF is central to this proceeding. Any matter tending to support a finding that the applicants intended that an asset be held on trust would support their case. Cases on trusts which I discuss below illustrate how simple steps such as referring to a trust in the name of a bank account can help establish that the account is held in trust.

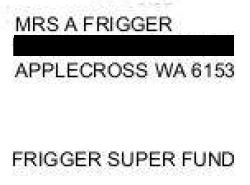

53 Mrs Frigger's affidavit sworn 6 March 2019 (ACTF 1, filed with the originating application in this proceeding) annexed (at p 108) a bank statement from St George Bank. This was for an account with a number ending 718 (STG1). The statement is for the period 26 February 2017 to 7 July 2017 and shows an opening balance of $2,172,753.47, and withdrawals leaving a closing balance of nil. In this version of the bank statement, near the top of the first page, where one normally sees an account name, the following appears (I have redacted the street address):

54 The evidence in the body of affidavit ACTF 1 said nothing specifically about the bank statement. It was annexed as evidence of bank accounts from which money was withdrawn to open accounts with HSBC, which money then was said to have flowed into BOQ2 and then BOQ1.

55 Mrs Frigger annexed the same bank statement to an affidavit she swore on 20 April 2020 (ACTF 14 p 371). I say it is the same because the account number and transactions are all identical. But in this affidavit, the statement has the following as the account name (once again with street address redacted):

56 The person described as 'Miss J Frigger' above is Jessica Frigger, who is the applicants' adult daughter. A third version of the bank statement came into evidence via Mrs Trenfield (Exhibit (Ex) 36). She gave evidence that she obtained that version from St George Bank, along with a statement for the same account for a prior period (transcript (ts) 513). It is effectively identical to the second version I have described. It shows Jessica Frigger as the account name, not Angela Frigger, and it does not mention the Frigger Super Fund.

57 In Mrs Frigger's affidavit ACTF 14 sworn on 20 April 2020, the second version of the St George bank statement is part of annexure AF11. The affidavit contains the following evidence about that annexure (the Michael Frigger mentioned in the quote is the applicants' adult son):

21. Attached and marked AF11 are copies of bank statements of other websaver accounts held by Jessica Frigger and Michael Frigger, the other trustees/directors/members of the FSF. None of the short-term websaver bonus interest accounts allowed the inclusion of the words 'as trustee for the Frigger Super Fund' when it was first opened.

22. Attached and marked AF12 are copies of other investments of the FSF. Each of these investments allowed me to include the words 'as trustee for the Frigger Super Fund' when it was first opened.

23. In order to overcome the above problem, when each websaver account was opened, and I obtained internet access to the account, I logged in and checked if there was an additional 'name' field. I then input the words 'Frigger Super Fund' in the additional name field, sometimes called a 'Nickname' by some banks. This was in compliance with the regulator's direction that the trustees do all that is possible to properly identify an asset as belonging to the SMSF.

58 Then, in an affidavit which Mrs Trenfield swore on 22 May 2020 (KAT 4), she annexes some emails between her staff and Westpac Banking Corporation, of which St George Bank is a division. In the emails, which were sent in late September 2019 (KAT 4 p 868ff), a staff member of FTI asked the bank for bank statements for STG1, giving the account number and saying that it was 'in the name of Angela Frigger'. To this the bank responded that the account was 'not held under Hartmut Hubert Josef Frigger and Angela Cecilia Therese Frigger'. This correspondence was referred to in paras 140-141 of KAT 4.

59 It appears that this prompted Mrs Frigger to change her evidence about the St George statement. In an affidavit sworn on 17 June 2020 (ACTF 18), she sought to explain a transaction listed in a spreadsheet she had sent to her first trustee in bankruptcy, the Official Trustee. This was a withdrawal of $1,800,000 from a Bank of Melbourne account. Mrs Frigger noted that St George Bank and Bank of Melbourne were both divisions of Westpac Banking Corporation. She said she had found a cheque butt showing that the $1,800,000 had been paid into a St George account. The cheque butt shows 'J Frigger ATF FSF' as the recipient. Mrs Frigger then said:

7. I now remember I logged on to Bank of Melbourne website to obtain a copy of bank statements for the auditor. I obtained the bank statement that is in my affidavit of 6 March 2019 page 108 when I had logged on to the Bank of Melbourne. I believed the bank statement was for an account in my name. I filled in my details, without realizing that the statement in fact belonged to the account in Jessica Frigger's name.

8. It was not until I prepared my affidavit of April 2020 that I found the hard copy of the St George Bank statement in Jessica Frigger's name. I still did not connect the two statements until I read the respondent's evidence in [140] - [141].

9. I confirm that the two BankWest cheques totaling $2,150,000 were paid into the St George Bank account in Jessica Frigger's name. I confirm I do not have page 1 of that account and am unable to obtain it from any source.

The 'bank statement that is in my affidavit of 6 March 2019 page 108' is the first version of the St George statement in ACTF 1, which shows Mrs Frigger as the account holder and refers to the FSF.

60 Mrs Frigger expanded on this explanation when she was cross-examined on the different versions of the St George bank statement (ts 431ff). She accepted that STG1, the account for the statement in ACTF 1, was not an account in her name. She said she put the words 'Frigger Super Fund' in the document. She was asked whether she 'logged on to this account'. At that point, she acknowledged that since the account was in Jessica Frigger's name, she would not have been able to log onto it. But she then said she 'accessed' (ts 432) it via the Bank of Melbourne's internet banking site. On questioning from the court, she said she logged on using her (Angela Frigger's) customer number. She claimed that when she logged on to the site, she saw three or four account numbers without any names. She said she 'got it [the statement] without any names on it'. She said 'I put my name on it and I put the Frigger Super Fund [sic] because I knew it was Frigger Super Fund funds … And I had completely forgotten that it was in - actually in Jessica's name'. She admitted to typing those details in herself.

61 On further questioning from the court, Mrs Frigger confirmed that she clicked on links for the account which downloaded the statement as a .pdf file. Her evidence was that there was no account name on that pdf. According to her, the place where the account name appears on all three versions of the statement in evidence was, when she downloaded it on this occasion, blank. She said she assumed that it was a statement in her name, because she had forgotten that it was in Jessica's name and she did not know that by logging in using her (Angela Frigger's) customer number she could get access to an account of Jessica's.

62 Mrs Frigger went on to say that she altered the document on her computer, that is, she did not print it out first and change the printed version, rather she used a pdf editor. She claimed that she did this when she was preparing documents for the audit for the FSF for the year ended 30 June 2017. The 'date audit completed' for that financial year as recorded by the auditor of the FSF was 16 March 2019 (KAT 4 p 381), so if that is when the bank statement was downloaded and altered, that is likely to have occurred in early 2019, at around the same time that this proceeding was commenced and her affidavit ACTF 1 was sworn. The auditors of SMSFs are required to prepare their audit report within 28 days after the trustee of the fund has provided all documents relevant to the preparation of the report: Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994 (Cth) (SIS Regulations) reg 8.03. Mrs Trenfield has put into evidence screen shots of metadata for documents submitted to the auditors which also indicate it is probable that the audit took place in early 2019 (KAT 4 annexures 111, 113).

63 In affidavit KAT 4, Mrs Trenfield says in relation to STG1 that the 'same extract of the SG1 account was in the bundle of documents provided to me by Just SMSF Audits' (KAT 4 para 140). It is not abundantly clear whether she means the extract as doctored by Mrs Frigger, but I will proceed on the basis that she does.

64 Questions from cross-examining counsel confirmed that the second version of the statement, which is annexed to affidavit ACTF 14, was probably in Mrs Frigger's house at the time of the audit (in early 2019), because Jessica had given it to her. But Mrs Frigger said she did not find it until she came to prepare affidavit ACTF 14 in April 2020. Counsel put to Mrs Frigger that in fact, rather than obtain the first version of the bank statement from the Bank of Melbourne website, she photocopied the second version, which was in her possession, and cut and pasted her name and 'Frigger Super Fund' on top of it. She denied this. She sought to explain differences in the print resolution (see images above) by saying that she may have changed printers or perhaps printer cartridges (ts 437). She denied that she changed the statement and put it in affidavit ACTF 1 in order to convince the court that it was an account held in the FSF.

65 I do not accept Mrs Frigger's evidence that the St George bank statement she downloaded had no account name on it, and she mistakenly put her name on it, along with the reference to the FSF. It is an explanation proffered in an attempt to dispel the obvious inference arising from the different versions of the statement in evidence, that Mrs Frigger altered the document so that it no longer showed Jessica Frigger as the account holder, and then put it into evidence in an attempt to persuade the court that it was an asset of the FSF. The case of the applicants, apparent from ACTF 1, was that the flow of funds from STG1 and other accounts to BOQ1 indicated that the funds in BOQ1 were FSF funds (paras 17-19). Establishing that STG1 was an FSF asset was part of that case. That gave Mrs Frigger motive to present the bank statement of STG1 as if the account were an asset of the FSF.

66 It may be, as I have noted, that the same doctored version of the statement was given to the auditor of the FSF at the time of the audit of the 2017 accounts. If Mrs Frigger's initial motivation for altering the bank statement was for the purpose of giving it to the auditor, rather than the court, that would hardly excuse the behaviour. And timing is important here too: Mrs Frigger's evidence was that she altered the bank statement during the audit of the financial year ended 30 June 2017, which audit was completed on 16 March 2019. That means that she probably altered the statement at around the time she swore affidavit ACTF 1 on 6 March 2019. So when swearing that affidavit she cannot have overlooked the fact that she was putting a doctored bank statement into evidence.

67 For Mrs Frigger's explanation to be even remotely plausible, the court would need to accept that the version of the statement which, on her own evidence, she altered, did not have an account name on it. But bank statements issued by Australian banks to ordinary retail or commercial customers always have the name of the account holder on them. The court does not need to draw on common experience to reach that view. It is evident from the very large number of (apparently undoctored) bank statements adduced into evidence in this proceeding. They are issued by a range of different, well-known Australian banks. Having reviewed a large number of them, the court has not identified a single one that does not bear the account name.

68 More specifically, the version of the bank statement which the first respondent obtained directly from St George has the account name on it, as do numerous other bank statements that St George provided (KAT 4 p 793ff). If the account name was missing, one of the basic functions of a bank statement for a bank account would not be fulfilled, namely to identify whose account it is. A reason why, in this one case, a downloaded bank statement might not have any account name on it, does not even occur to one, and no reason was proffered. In closing submissions, Mrs Frigger said that she could prove that downloading a bank statement which does not show an account name is something that can happen when a person is doing online banking (ts 935), and that she would return to that subject. But she never did.

69 It might also be thought to be unlikely that Mrs Frigger could access St George statements through the Bank of Melbourne website, but since the two banks apparently have the same BSB (Bank State Branch) numbers (ACTF 1 p 108; ACTF 18 p 9), I am prepared to accept that is possible. I do not accept, however, that Mrs Frigger could gain access to accounts of Jessica by using her (Angela Frigger's) login.

70 There are other reasons to find that Mrs Frigger's evidence on this point lacked credibility. During cross-examination on this subject she gave the evidence in the manner of someone piecing together past events. But her demeanour at those times was that of a person pretending to only just then remember the events. Throughout almost all of the rest of the proceeding, Mrs Frigger presented as a person of mental acuity who had a detailed recollection of everything to do with her and her husband's financial affairs. Her occasional lapses into vagueness appeared intended to obscure the fact that she had no good explanation for what she was being asked about.

71 Even if I were disposed to accept Mrs Frigger's evidence that she downloaded a bank account statement with no account name, that would not exculpate her. Even if she did not know that it was an account in Jessica Frigger's name, when she swore ACTF 1 she did know that the statement had no name on it (on her version of events), and she did know that it said nothing about the FSF. She knew that she had added a name and FSF notation to it, and she did not tell the court about any of that until she was forced to admit it in response to evidence adduced by the first respondent.

72 But, for the reasons given above, I find that the original bank statement which Mrs Frigger altered did have 'Miss J Frigger' as the account name. It follows, not only that Mrs Frigger deliberately altered the statement before she put it into evidence, but that the evidence she gave about the matter in (at least) her affidavit ACTF 18 and in cross-examination on the point was false.

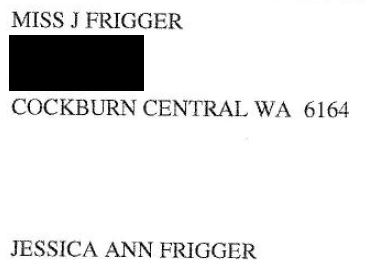

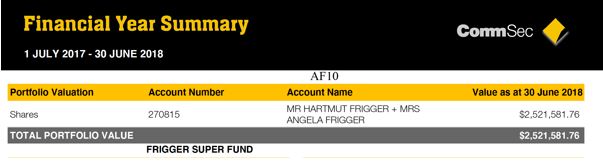

73 The bank statement for STG1 is not the only altered document which Mrs Frigger put into evidence. She also annexed to affidavit ACTF 1 a 'Financial Year Summary' from CommSec showing the value of the Main Portfolio as at 30 June 2018 (annexure AF10). The portfolio is in the names of Mr and Mrs Frigger. The part of the document that is presently relevant appears as follows (ACTF 1 p 80):

74 It can be seen that under the account name is a line labelled 'Total Portfolio Value' and under that appears 'FRIGGER SUPER FUND'. In the body of the affidavit Mrs Frigger said that this annexure was an annual statement for a CommSec share portfolio from which dividends were paid which, the affidavit asserts, ultimately found their way to BOQ1.

75 In affidavits KAT 3 sworn on 11 September 2019 at paras 10-11 and KAT 4 sworn on 22 May 2020 at para 162, Mrs Trenfield deposed to having obtained documents from Just SMSF Audits which included the same CommSec statement for the financial year ending 30 June 2018. She annexed that version of the statement, which is indeed the same as the one annexed to ACTF 1, save that the words 'FRIGGER SUPER FUND' are missing from it. Mrs Trenfield also annexed copies of the equivalent documents for the financial years ending 30 June 2016 and 30 June 2017, neither of which had that notation on them (KAT 4 pp 923-962).

76 Mrs Frigger's initial response to that, in affidavit ACTF 8 sworn on 16 September 2019 (para 2), was to say: 'The reason why I added the words "Frigger Super Fund" (FSF) to the statement from Commonwealth Securities is because the regulator of that Fund, ATO, requires me to identify all documents that relate to the Fund'.

77 In affidavit ACTF 14 sworn on 20 April 2020, Mrs Frigger gave the following evidence (ACTF 14 para 10):

I refer to the notation 'Frigger Super Fund' on statements which I download from the Commsec website each year for the purposes of the external audit. Pursuant to directions of the regulator, the ATO, I inserted those words on the statements in order to identify the list of shares and its market value for the purposes of satisfying the external audit. By making such a notation, I did not intend to mislead anyone in relation to the beneficial ownership of the shares. I have long been aware from studying the Companies Act at university (1980) and being a registered agent with ASIC (1985) that beneficial ownership of shares is noted on the share scrip held by the company in its member share register.

One immediate difficulty with accepting this evidence is that the version of the statement obtained from the auditor does not have the notation 'Frigger Super Fund' on it.

78 Mrs Frigger was cross-examined about the CommSec statement (ts 423-426). She confirmed that she typed the words into the statement. Her evidence about how and when she did this was unsatisfactory. At first she appeared to be saying she edited the pdf in the same way as she edited the St George statement. But then her evidence changed to be that there was a way of inputting the words into CommSec's online platform. Again, she gave this later evidence with an unconvincing air of someone only then just recalling added detail.

79 Also, there are in evidence financial year summaries for a different CommSec account, in the name of Serenity Holdings Pty Ltd (i.e. CAT), which do refer to the FSF (Ex 28, Ex 44). In the financial year summaries for Serenity Holdings, that reference appears as follows:

80 In this financial year summary, the reference to the FSF appears where one would expect it to appear, as part of the account name. In the first extract provided above it appears in an odd unexplained spot under the line for 'Total Portfolio Value'.

81 It was put to Mrs Frigger that she had added the words 'Frigger Super Fund' to the Financial Year Summary for the Main Portfolio just before signing affidavit ACTF 1 of 6 March 2019. She said she could not remember. When questioned about why, if it was a regulatory requirement to add the words, they were not on the versions she gave to the auditors, she had no explanation (ts 423-426).

82 The first respondent submitted that I should infer that Mrs Frigger altered the CommSec statement attached to affidavit ACTF 1 so as to convince this court that it was an asset of the FSF from which dividends were earned that went into BW1. While this allegation was not squarely put to Mrs Frigger in those terms, it was put to her that she altered the statement just before swearing that affidavit and I am satisfied that it must have been obvious to her during cross-examination that it was being suggested that she did not alter it for the purpose of the external audit, but for the purposes of this proceeding. I am therefore satisfied that she was on notice that her evidence on the point was in contest, and that she had a proper opportunity to give any explanation she wished to give (ts 423-426).

83 But she had no plausible explanation. In closing submissions (ts 936) she sought to retract her evidence that she had inserted 'Frigger Super Fund' on the financial year summary for 2018 in order to identify the list of shares and its market value for the purposes of satisfying the external audit. She said 'what I was really meaning was I download documents for the purposes of the external audit'. This was a transparent attempt to revoke a previous explanation which, I infer, Mrs Frigger later realised would not help the applicants because, as I have said, the version of the document given to the auditor did not have 'Frigger Super Fund' written on it. This is an example of how Mrs Frigger changed her story so many times that it was impossible to believe anything she said unless it had sound independent corroboration.

84 I draw the inference the first respondent puts, namely that Mrs Frigger altered the CommSec statement shortly before annexing it to affidavit ACTF 1 with the intention of convincing the court that it was an asset of the Frigger Super Fund. The inference follows from the incentive that Mrs Frigger had to do so - to establish that a valuable portfolio of shares was held in the FSF - and the fact that the explanation she gave, that she added the words for the purpose of the external audit of the FSF, is belied by the fact that the version of the statement provided to the auditor did not have the notation on it. It follows that the evidence in Mrs Frigger's affidavit ACTF 14 which I quote at [77] above was false.

85 But once again, even if I did not draw the inference that Mrs Frigger did doctor the document with the purpose of misleading the court in her mind, that would not exculpate her. The fact would remain that she put a document into evidence which she had altered so as to say something which the original version of it, issued by an independent third party, did not say. She gave no evidence to the effect that she forgot or overlooked the fact that she had altered the document. Even if the stronger finding above is wrong, the alteration of the CommSec statement seriously impacts on Mrs Frigger's credibility.

Other matters concerning Mrs Frigger's credibility

86 Counsel for the first respondent referred in his closing submissions (supported by a written aide memoire) to many other reasons why Mrs Frigger should not be accepted as a credible witness. For example, she was cross-examined on evidence she gave in the hearing of the bankruptcy petition against her and Mr Frigger (ts 379-381). In the judgment of Colvin J after that hearing, Kitay, in the matter of Frigger (No 2) [2018] FCA 1032 at [184]-[185], his Honour referred to a statement Mrs Frigger made in an affidavit that approximately $80,000 in a St George account was an asset of the FSF (Ex 41; ts 379). At the hearing before Colvin J, she sought to resile from that, and said that in fact it was an asset she owned in her personal capacity. If so, that could permit it to be used to 'set-off' the debt that was the subject of the bankruptcy petition.

87 But in cross-examination in this proceeding, Mrs Frigger said that the statement she made to Colvin J was a mistake and the $80,000 was indeed an FSF asset (ts 380-381). She admitted that she had told Colvin J that it was a personal asset 'from the bar table and I was doing it in my desperation not to be put into bankruptcy' (ts 381 ln 25). She then tried to resile from that evidence, or at least qualify it, in re-examination in this proceeding (ts 469). She then attempted to give a further explanation in closing submissions which was, with respect, incomprehensible (ts 960-961). All this displays a readiness on Mrs Frigger's part to change what she tells the court in order to suit what she perceives to be her interests on the particular occasion. Whether prompted by desperation or not, this is by itself damaging to her credibility.

88 It is hardly necessary to multiply further examples here, although further problems with the credibility of Mrs Frigger's evidence will be described when the content of the evidence is assessed below. I need only comment on Mrs Frigger's demeanour in the witness box briefly, as it does not play a large part in my assessment of her credibility. I have already mentioned certain points at which she appeared unconvincing. But for the most part she gave her evidence with a forthright manner and with an appearance of having a sure grasp of specifics. On some occasions where she said she could not remember things, she was being asked about financial details which one would not ordinarily expect a witness to remember. On many occasions where she was challenged in cross-examination she became truculent and obstructive, but allowances need to be made for the fact that she had the mixed roles of witness, litigant and advocate for her own case.

89 Nevertheless, for the above reasons, and for others which will appear in the course of discussion of evidence below, I do not accept Mrs Frigger as a witness of truth. That conclusion has a serious impact on the applicants' case, as it was based entirely on her evidence. I cannot accept her evidence as true unless it is supported by independent evidence or the inherent probabilities of the situation. And the fact that Mrs Frigger is not above altering documents she provides to the court impacts on what can be treated as independent evidence. If a document came from the applicants, it must be treated with caution.

90 The first respondent, Mrs Trenfield, has a Bachelor of Business (Accounting) from the Queensland University of Technology and is a Chartered Accountant. She became a registered trustee in bankruptcy in 2006, a registered liquidator in 2007 and an official liquidator in 2008. She has been the trustee in bankruptcy of more than 200 estates (KAT 4 paras 11-18).

91 Mrs Trenfield appeared as a witness by video link from a courtroom in Brisbane. Mrs Frigger cross-examined Mrs Trenfield for some time.

92 There were occasions on which I considered that Mrs Trenfield could have been more forthcoming in her answers. For example, there was a line of questioning about when Mrs Trenfield could have obtained a copy of a cheque from an HSBC account paid into BOQ2, which helped with tracing the flow of funds to BOQ2. A letter from Bank of Queensland dated 17 October 2018 was put to Mrs Trenfield which said that the bank was unable to give her a copy of the cheque due to privacy reasons (ts 588; ACTF 3 annexure 1). It was put to her that this could have been overcome by asking Mrs Frigger to waive privacy with the bank (ts 590). But rather than accept this fairly straightforward proposition, Mrs Trenfield became argumentative with the cross-examiner (that is, Mrs Frigger) and would only concede that 'you can draw that conclusion from the documents' (ts 591). I will discuss the substance of her evidence on this matter below when I come to deal with the application to remove her as trustee in bankruptcy. The point for present purposes is that it was unhelpful of Mrs Trenfield not to accede to the simple proposition that she could have asked Mrs Frigger to waive the privacy concerns.

93 Mrs Frigger's aim in cross-examination appeared to be to convince the court that Mrs Trenfield is a thoroughgoing liar. But isolated examples of instances where Mrs Trenfield's evidence was unhelpful do not establish such a strong conclusion. They are equally explicable by an unwillingness to concede any point to a cross-examiner with whom she evidently has an antagonistic relationship.

94 The reality is that Mrs Trenfield's credibility was not central to the proceeding. She was not the party with the onus of proof and most of the contentious evidence concerned things the applicants did (or did not do) before her appointment. For the most part Mrs Trenfield relied on documentary evidence and, in contrast to Mrs Frigger, there was no reason to doubt that the documents she presented were what they appeared to be. To the extent that the applicants sought to impugn Mrs Trenfield's conduct as a basis for removing her as their trustee in bankruptcy, the outcome depended more on an objective assessment of that conduct than on any finding about the credibility of her evidence.

95 So while I had concerns that some of Mrs Trenfield's answers in cross-examination were unhelpful, that did not affect my overall view about her evidence. I will need to refer below to further specific allegations of giving false evidence which the applicants made against Mrs Trenfield. They are not made out. Generally she presented in the witness box as an experienced professional who gave straightforward and forthright answers to a large number of questions which were not always very relevant.

FIRST GROUP OF ISSUES - ARE THE DISPUTED ASSETS PART OF THE FSF?

When a court will find that assets are held subject to a trust

96 The first issue in the present case concerns whether the disputed assets are subject to an express trust. That term can be a misnomer, as an express trust can arise by implication from language used or other conduct. In Korda v Australian Executor Trustees (SA) Limited [2015] HCA 6; (2015) 255 CLR 62 at [5], French CJ said (some footnotes omitted):

It has rightly been observed that 'many express trusts are not express at all. They are implied, or inferred, or perhaps imputed to people on the basis of their assumed intent'. The American Law Institute's Restatement Third, Trusts uses the term 'trust' to refer to an express trust as distinct from a resulting or constructive trust and defines it as [§2]:

'a fiduciary relationship with respect to property, arising from a manifestation of intention to create that relationship and subjecting the person who holds title to the property to duties to deal with it for the benefit of charity or for one or more persons, at least one of whom is not the sole trustee.'

The seventh edition of Jacobs' Law of Trusts in Australia [(2006), p 44 [306]] offers the usefully succinct observation that the creator of an express or declared trust will have used language which expresses an intention to create a trust:

'The author of the trust has meant to create a trust, and has used language which explicitly or impliedly expresses that intention, either orally or in writing. The fact that a trust was intended may even be deduced from the conduct of the parties concerned but if there is any uncertainty as to intention, there will be no trust.'

97 On the subject of certainty, it is orthodox to refer to three certainties which are necessary before an express trust will be found to exist: certainty of intention to create a trust, certainty of the property that is its subject matter, and certainty of objects, that is, the beneficiaries: see Kauter v Hilton (1953) 90 CLR 86 at 97; and Associated Alloys Pty Limited v ACN 001 452 106 Pty Limited (in liquidation) [2000] HCA 25; (2005) 202 CLR 588 at [29] and more generally the discussion in Jacobs' Law of Trusts in Australia (8th ed, 2016) Chapter 5.

98 The fiduciary obligations which arise from the trust relationship can be described as being annexed to or impressed upon the property the subject of the trust: Re Lauer; Corby v Lyttleton [2017] VSC 728 at [90] (McMillan J). The question here therefore concerns whether the evidence establishes that the obligations on trustees set out in and arising from the FSF Deed are annexed to any of the disputed assets.

99 To constitute himself or herself a trustee, it is not necessary that a person should use precise words: Re Armstrong (deceased) [1960] VR 202 at 205. In Trident General Insurance Co Ltd v McNiece Bros Ltd (1988) 165 CLR 107 at 121 (Trident v McNiece), Mason CJ and Wilson J held (footnote removed):

… the courts will recognize the existence of a trust when it appears from the language of the parties, construed in its context, including the matrix of circumstances, that the parties so intended. We are speaking of express trusts, the existence of which depends on intention. In divining intention from the language which the parties have employed the courts may look to the nature of the transaction and the circumstances, including commercial necessity, in order to infer or impute intention.

100 It is 'the outward manifestation of the intentions of the parties within the totality of the circumstances' which determines whether a trust has been created: Legal Services Board v Gillespie-Jones [2013] HCA 35; (2013) 249 CLR 493 at [119] (Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ). It may be, though, that this is only when the instrument said to create the trust is not a formal one. In Byrnes v Kendle [2011] HCA 26; (2011) 243 CLR 253 at [54] Gummow and Hayne JJ said (citation removed):

Where an express inter vivos trust respecting land or any interest in land is manifested and proved by some informal writing, or an express inter vivos trust of personalty is said to have been created by informal writing or orally, then a dispute as to the presence of the necessary intention, despite inexplicit language, is resolved by evidence of what the Court in Kauter v Hilton identified as '[a]ll the relevant circumstances'.

101 How clear must the expression of an intention to create a trust be? In Bahr v Nicolay (No 2) (1988) 164 CLR 604 at 618-619 Mason CJ and Dawson J said:

If the inference to be drawn is that the parties intended to create or protect an interest in a third party and the trust relationship is the appropriate means of creating or protecting that interest or of giving effect to the intention, then there is no reason why in a given case an intention to create a trust should not be inferred.

102 It would appear that in this passage their Honours were departing from what they had earlier described as the 'traditional attitude' that 'unless an intention to create a trust is clearly to be collected from the language used and the circumstances of the case … the court ought not to be astute to discover indications of such an intention': see Bahr v Nicolay at 618, quoting from In re Schebsman; Ex parte Official Receiver, the Trustee v Cargo Superintendents (London) Ltd & Schebsman [1944] Ch 83 at 104. But in Byrnes v Kendle at [49], Gummow and Hayne JJ (French CJ agreeing (see [17])) described Mason CJ and Dawson J as having approved of that expression of the traditional attitude. That attitude is also reflected in the passage from Jacobs on Trusts which French CJ quoted in Korda: see also Kauter v Hilton at 97 quoted with approval in Gillespie-Jones at [116] and by Keane J in Korda at [204].

103 I will approach the evidence on the basis that, while the standard of proof remains the civil one of balance of probabilities, and while the manifestation of the necessary intention can be established by inference, that inference must be clear. As Gummow and Hayne JJ pointed out in Byrnes v Kendle at [56], questions of the construction to be placed on the words and actions of alleged settlors are apt to arise long after the event, and trusts may give rise to proprietary interests which affect third parties. Similarly, in Korda at [205] Keane J emphasised that the 'need for clarity as to the intention to create a trust and its subject matter is of particular importance in a commercial context where acceptance of an assertion that assets are held in trust is apt to defeat the interests of creditors of the putative trustee'. While his Honour was speaking in the context of a commercial trading trust, there is no reason to suppose the policy of the law is any different in relation to private superannuation funds, where the effect of relevant dealings may be to defeat both the interests of creditors (where trustees or beneficiaries become bankrupt) and the interests of the revenue of the Commonwealth.

104 It is clear that to speak of the necessary intention is to refer to an intention that has been manifested objectively. In Byrnes v Kendle at [55], after referring to 'all the relevant circumstances', in cases of inexplicit language, Gummow and Hayne JJ said (French CJ agreeing):

But the object of this evidentiary odyssey does not change, and the nature of the intention of the alleged settlor does not differ. The question, as Megarry J put it [In re Kayford Ltd (In liq) [1975] 1 WLR 279 at 282; [1975] 1 All ER 604 at 607], 'is whether in substance a sufficient intention to create a trust has been manifested'. The point was made by Lord Millett in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley [[2002] 2 AC 164 at 185 [71]. See also Mills v Sportsdirect.com Retail Ltd [2010] 2 BCLC 143 at 158 [52]-[54]]:

'A settlor must, of course, possess the necessary intention to create a trust, but his subjective intentions are irrelevant. If he enters into arrangements which have the effect of creating a trust, it is not necessary that he should appreciate that they do so; it is sufficient that he intends to enter into them.'

See also French CJ at [17] and Heydon and Crennan JJ at [105]-[106], [114]. In these reasons I will need to refer to the objective nature of the inquiry often, and will often do so using the shorthand 'manifestation of intention' (an unattractive but necessary phrase: see Byrnes v Kendle at [57]-[58]).

105 The above principles are stated in terms of whether a trust has been created, not whether assets have become subject to an existing trust. But no different approach is required in the latter case. Indeed, the received view under Australian law is that when property is, in common parlance, 'contributed' to a trust, what technically occurs is the creation of a new trust over the property on the same terms as the pre-existing trust: see Atwill v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (1970) 72 SR (NSW) 415 at 426 (Mason JA); Kennon v Spry [2008] HCA 56; (2008) 238 CLR 366 at [229] (Kiefel J); Re Lauer at [99]. This supports the view that the approach to be taken to ascertaining the necessary objective manifestation of intention to make assets subject to an existing trust is the same as the approach taken where a new trust is created.

106 Obviously, the presence of an existing trust on the express terms of a written instrument can be a significant part of the factual matrix, which may make it easier to establish the necessary intention. That is reflected in JW Broomhead (Vic) Pty Ltd (in liq) v JW Broomhead Pty Ltd [1985] VR 891. The facts in Broomhead are instructive for the present case. The defendants were beneficiaries under a trust deed of which the plaintiff company was trustee. The plaintiff had been placed into liquidation, and the liquidator caused the plaintiff to bring proceedings against the defendants claiming that the plaintiff had operated its building business under the terms of the trust deed. If so, the defendants were potentially liable to indemnify the plaintiff for liabilities incurred in the course of the business. The defendants alleged that even if the plaintiff had been bound by the trust deed, 'the business never became part of the trust fund which the plaintiff held on the trusts of the deed' (at 893). That allegation was open because the trust deed did not refer to the business. The trust was established by a contribution of $50 (which was never employed in the business). The trusts were declared in the deed in respect of the $50 and investments into which it may be converted, and also investments derived from 'any moneys which may accrue or be added thereto' (see 926).

107 McGarvie J held that the plaintiff had 'by its conduct declared itself to be holding its building business on the trusts of the deed' (at 921). His Honour then set out the following principles (citations removed):

The plaintiff would hold its business on the trusts of the deed if by its words, or by implication from its conduct, it declared that it intended to do so.

One type of conduct which may amount to an implied declaration of trust by a trustee is adding property of his own to a trust fund of which he is trustee.

A declaration of trust by a person may be implied from entries made by him in his books of account and memoranda, and from his treating property as trust property.

108 Although there was never any express declaration that the plaintiff would hold the business on the trusts of the deed, McGarvie J inferred that from the date of a particular letter sent on behalf of the plaintiff which proposed that it would act as trustee, 'the plaintiff was continually declaring by its conduct that it held its business on the trusts of the proposed deed or the deed' (at 921). The conduct in question included writing to the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation informing him that the plaintiff had been incorporated to act as trustee of the trust. The conduct also included a meeting of members of the plaintiff company which was recorded in minutes noting that the plaintiff would be acting as trustee, opening a bank account for the company as trustee for the trust, including providing a copy of the trust deed to the bank, and the preparation and circulation of accounts which were headed with the name of the trust. In his Honour's view, this 'declaration' by conduct meant that the business had been made part of the trust fund. His Honour observed that it would be natural to treat both the initial $50 and the business 'as part of the one trust fund and artificial to do otherwise'.

109 As Broomhead demonstrates, the conduct relied on to create a trust need not necessarily be communicated to any particular person, such as proposed trustees or beneficiaries. However, although communication is not essential in deciding whether a settlor formed an intention to appropriate property to a trust, the absence of communication raises an inference against an intention to make such an appropriation irrevocable: Re Cozens [1913] 2 Ch 478 at 487. In any event, the intention does need to be manifested in some outwardly observable way. A subjective thought that an asset is held on trust is not enough.

110 La Housse v Counsel [2008] WASCA 207 is also instructive as to what can constitute the necessary manifestation of intention. There, the respondents' father had opened two bank accounts, each in the name of 'James Albert Counsel Trust for' his named respondent daughters. Initially, deposits of $50 were made into each account, and there were other transfers and deposits of small amounts. A few years later, Mr Counsel sold a house, and deposited approximately half of the proceeds into each account, that is $82,167.73 each. A few months later he withdrew nearly all that amount from each account to purchase another property. About a year after that, Mr Counsel died. There was a will leaving the new property to Ms La Housse. A dispute arose between her and Mr Counsel's daughters, who claimed that the property was held on trust for them and so could not be bequeathed to her.

111 The issues in the appeal resolved into the question of whether Mr Counsel intended, when he deposited the proceeds of sale of his previous house into the two accounts, that the resultant choses in action would be held on trust for his daughters: at [37]. The daughters contended that on a consideration of all the circumstances, the court should have inferred that Mr Counsel intended to create a trust in favour of them.

112 Pullin JA (Wheeler and Buss JJA agreeing), held that the daughters had to prove on the balance of probabilities that Mr Counsel intended to place himself under a personal obligation to hold the choses in action for their benefit: at [38]. That intention had to be determined as at the date on which Mr Counsel deposited the sums of $82,167.73: at [39]. Relying on Broomhead, Pullin JA found (at [42]) that it was 'significant that Mr Counsel paid his money into his daughters' accounts because conduct which may amount to an implied declaration of trust by a trustee is where a trustee adds property of his own to a trust fund of which he is trustee'. That, and other evidence of things said by Mr Counsel, led his Honour to the conclusion that Mr Counsel did intend to impose on himself the personal obligation to hold the money deposited for the benefit of his daughters.

113 Pullin JA expressed the burden of proof as lying on the daughters, who were the ones seeking to rely on the existence of the trust. With respect, that is consistent with other authority. Since a trust is a concept which imposes important obligations and confers important rights, the burden of proof lies on the person who contends that such a relationship has been established: Re Snowden (deceased) [1979] Ch 528 at 536 (Megarry VC); Herdegen v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1988) 84 ALR 271 at 277 (Gummow J); Coshott v Prentice [2014] FCAFC 88; (2014) 221 FCR 450 at [80], [82].

114 In Saunders v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2010] WASC 261; (2010) 80 ATR 549 at [22] Kenneth Martin J summarised the position as follows (citations removed):

…

5. Generally speaking, the legal onus of establishing that the intention to create a trust existed at the relevant time remains with the person asserting the existence of the trust.

6. Where there is unambiguous use of language in a written instrument establishing a trust, the evidentiary onus will shift to a contradicting party to show that a trust does not exist through the establishment, if possible, of a contrary intention.

7. The evidentiary onus falls upon the party seeking to show the contrary intention and strong evidence is required to do so.

115 The difficulty here is that while there is a written instrument unambiguously establishing the FSF as a trust, with the possible exception of the Residential Properties, there is no written evidence that, if accepted as true, manifests an express intention that the disputed assets are to be held on the terms of that pre-existing trust. In my view the principles as to the burden of proof apply to the intention to contribute assets to a trust in the same way as they do to an intention to create a trust.

116 The same placement of the burden of proof follows from the fact that the applicants seek declarations as to the existence of the trust over the relevant assets and as to their respective interests in the FSF. A party seeking a declaration has the burden of proof of any matter which is a necessary element of the declaration sought: Gore v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2017] FCAFC 13; (2017) 249 FCR 167 at [28]-[29] (Dowsett and Gleeson JJ).

117 It follows that I do not accept a submission that Mrs Frigger made that, once the applicants had established a prima facie case, the onus shifted to the first respondent to disprove that assets were FSF assets (ts 895-896). In any event, as will be seen, the applicants did not establish any prima facie case that the disputed assets were subject to the trusts of the FSF Deed. It will be necessary to avert to this issue again during the discussion of the Residential Properties. But subject to that, the onus of proof rested on the applicants throughout.

118 For completeness I should mention certain authorities about the evidentiary use that can be made of acts by an alleged trustee subsequent to the date of the alleged declaration of trust. If the existence of an express trust is in issue, it may be against the interests of the alleged trustee to admit the trust. In those situations, evidence of subsequent acts which tend to show the existence of the trust will be admitted as admissions against, but not for, the alleged trustee's interests: see Herdegen at 276-277 (Gummow J) and authorities cited there. But the first respondent did not seek to apply that principle in the present case. The first respondent did submit that, save for statements against interest, subsequent statements of intention must be treated with caution: Wheatley v Kavanagh [2018] NSWSC 1359; (2018) 19 BPR 38,691 at [260] (Ward CJ in Eq). She also submitted, in effect, that Mrs Frigger's evidence was so lacking in credibility that I should only accept it as true if it is against her interest (ts 822). But they are different points.

119 The applicants submitted that somehow the principles I have summarised above do not apply to SMSFs because of requirements in the SIS Act which require trustees of such funds to keep accounting records and financial statements: s 35AE and s 35B. It may be accepted that the inclusion of an asset in such a record could be evidence that it is an asset of the FSF. It may also be accepted, as the applicants go on to submit, that the SIS Act does not require any express declaration of trust for an asset to be part of the FSF. But those propositions are just possible applications of the general principles I have outlined. The stipulations of the SIS Act do not displace the need to establish an objective manifestation of intention to create a trust.

When an asset is part of a fund

120 While the question of whether the applicants hold the disputed assets on trust is an important one, it is not the ultimate question raised by the applicants' claims. As I have said at [23] above, the applicants do not seek any declaration that the assets are 'property held by the bankrupt in trust for another person' within the meaning of s 116(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act, and I have also referred to the difficulties that cases such as Boensch v Pascoe would pose if the applicants did attempt to seek such a declaration. The ultimate question is whether the applicants' interests in the assets are part of their interests in a regulated superannuation fund for the purposes of s 116(2)(d)(iii)(A) of that Act.