FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Dhu v Karlka Nyiyaparli Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (No 2) [2021] FCA 1496

ORDERS

First Applicant BRENDAN DHU Second Applicant | ||

AND: | KARLKA NYIYAPARLI ABORIGINAL CORPORATION RNTBC ICN 3649 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Resolutions 5 and 6 passed by the Nyiyaparli common law holders at the meeting held on 2 December 2020 were not decisions made under Nyiyaparli traditional law and custom and are not effective to refuse recognition of the applicants as Nyiyaparli people.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application otherwise be dismissed.

2. The respondent pay 75% of the applicants’ costs of the proceeding, to be fixed by way of an agreed lump sum.

3. If the parties cannot agree on an appropriate lump sum for the purposes of Order 2, the matter be referred to a Registrar for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 The applicants, Steven and Brendan Dhu, seek orders and declarations in relation to their membership of the Nyiyaparli People, as that group is defined in the determination of native title made by this Court in Stock on behalf of the Nyiyaparli People v State of Western Australia (No 5) [2018] FCA 1453 (Nyiyaparli determination). Their membership of the Nyiyaparli People is also said to have consequences for their eligibility to be entered on to the Register kept by the respondent Karlka Nyiyaparli Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC ICN 3649, and to become members of Karlka.

2 Karlka is the prescribed body corporate determined under s 56(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to hold the native title of the Nyiyaparli People on trust for the common law holders of that title. After a resolution of the common law holders in December 2020, the applicants were refused recognition as Nyiyaparli People, and refused membership of Karlka.

3 The applicants sought two alternative kinds of orders. First, declaratory relief about their status as members of the Nyiyaparli People. Second, orders requiring Karlka to add the details of the applicants to the Register of Nyiyaparli People under rule 5 of Karlka’s Rule Book, and a declaration that the applicants are eligible for membership of Karlka under rule 6 of the Rule Book.

4 The applicants’ counsel made this point in final oral submissions:

I think one of the difficulties this case throws up is that if – say, if the court were – if there were to be a finding that they were not Nyiyaparli people, or that the decision of the common law holders was to be accepted and that it – that those decisions established that they are not identified as Nyiyaparli people, then, really, Steven and Brendan Dhu and others, sort of, find themselves stranded, in a sense. They can’t be identified as Native Title holders through Banjima, and they wouldn’t be able to be identified as Native Title holders through Nyiyaparli ..... is no answer, in my submission, to say, “Well, go to Nganluma”, for the reasons I have just given. I mean, that’s no answer, to say that they’d be stranded, because – well, really, what you have is a situation where these – Steven and Brendan and their father, they have really, in a sense, made consistent claim for many, many, many years.

5 The substance of this submission has force, and it will be apparent from the reasons below that while the applicants are not entitled to the specific relief they seek, the Court considers it need not remain the case that they are “stranded”, and unable to take their place as native title holders through a line of descent from Ijiyangu, a named apical ancestor for the Nyiyaparli determination. The applicants are entitled to declaratory relief to remove any actual or perceived impediment to their future recognition as Nyiyaparli People, by making it clear the 2020 resolutions were ineffective.

AGREED FACTUAL BACKGROUND

6 In this section, I set out my findings on the factual background, which is not in dispute between the parties. Contested factual issues are dealt with separately later in my reasons.

7 The parties filed an agreed statement of facts, which was admissible pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). In addition, the parties relied on a number of affidavits, and documents.

8 The applicants relied on the affidavits of:

(a) Steven Dhu, affirmed on 16 April 2020;

(b) Christina Stone, affirmed on 16 February 2021;

(c) Alec McKay, affirmed 22 February 2021;

(d) Kathleen Hicks, affirmed on 22 February 2021;

(e) Kevin Banks-Smith, affirmed on 24 February 2021;

(f) Colin Peterson, affirmed 5 May 2021;

(g) Steven Dhu, affirmed 12 May 2021; and

(h) Brendan Dhu, affirmed 14 June 2021.

9 Paragraph [33] of Ms Stone’s affidavit was not read, by agreement between the parties.

10 The respondent relied on the affidavits of:

(a) Nicholas Preece, affirmed 18 May 2020;

(b) Nicholas Preece, affirmed 29 January 2021;

(c) David Stock, affirmed 14 May 2021;

(d) Lindsay Yuline, affirmed 14 May 2021;

(e) Leonard Stream, affirmed 21 May 2021; and

(f) Keith Hall, affirmed 11 June 2021.

11 The respondent did not read paragraphs [17] and [20] of Mr Hall’s affidavit. Paragraphs [15], [26] and [27] were read but the respondent conceded they should be admissible only as statements of Mr Hall’s opinion and belief. In addition, the Court upheld an objection to the final two sentences of [44] of Mr Hall’s affidavit.

12 A document produced in discovery, being a table said to summarise certain distributions made to the applicants from a trust was the subjection of objection by the applicants. It was marked for identification but ultimately not tendered, and instead treated as part of Karlka’s submissions.

A brief chronology

13 It is agreed that the applicants are descended from an Aboriginal woman called Ijiyangu through their father as follows:

(a) Their father’s father (maarli) was a man called Ned Dhu;

(b) Ned’s mother (the applicants’ great-grandmother) was Susan Swan;

(c) Susan Swan was Ijiyangu’s daughter.

Thus, Ijiyangu is the applicants’ great-great grandmother.

14 On 30 September 1998, two claims were filed on behalf of the Banjima People: the Innawonga Bunjima claim (IB claim) (WAD 6096 of 1998) and the Martidja Banjima/Martu Idja Banjima claim (MIB claim) (WAD 6278 of 1998). Around the same time, on 29 September 1998, the first application for a determination of native title in favour of the Nyiyaparli People (WAD 6280 of 1998) was also filed. The claims all concerned land in the central Pilbara region.

15 Around 1999 or 2000, the applicants joined the MIB claim group, relying on their connection to an apical ancestor named Ijiyangu. The English name she has been given was Daisy. In October 2010, a claim purporting to be on behalf of all Banjima people was filed. There was also a second MIB claim filed. The hearing conducted by Barker J, which ultimately resulted in the decision in Banjima People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2013] FCA 868; 305 ALR 1, concerned all three claims. Before Barker J, the IB claimants and the MIB claimants initially filed different contentions, but ultimately the IB and MIB applications were combined: see Banjima (No 2) at [18].

16 On 28 August 2013, the Court gave judgment in Banjima (No 2). The Court found the claimants were entitled to a determination of native title under the Native Title Act and invited the claimants to file a minute of proposed determination. On 12 March 2014, the Court made the Banjima determination: Banjima People v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2014] FCA 201.

17 The decision in Banjima (No 2) is discussed further below, but for the purposes of this chronology what must be highlighted is the finding of Barker J that there was insufficient evidence for the Court to conclude the nominated apical ancestor Ijiyangu was a Banjima woman. His Honour found there was evidence which “pointed in the direction” of her being Nyiyaparli. Accordingly, Ijiyangu was not included as an apical ancestor on the Banjima determination. Both before and after the Banjima (No 2) decision, there was a series of disputes about the status of descendants of Ijiyangu as Banjima People and the entitlements of those descendants to monies flowing from the holding of Banjima native title. I describe these below.

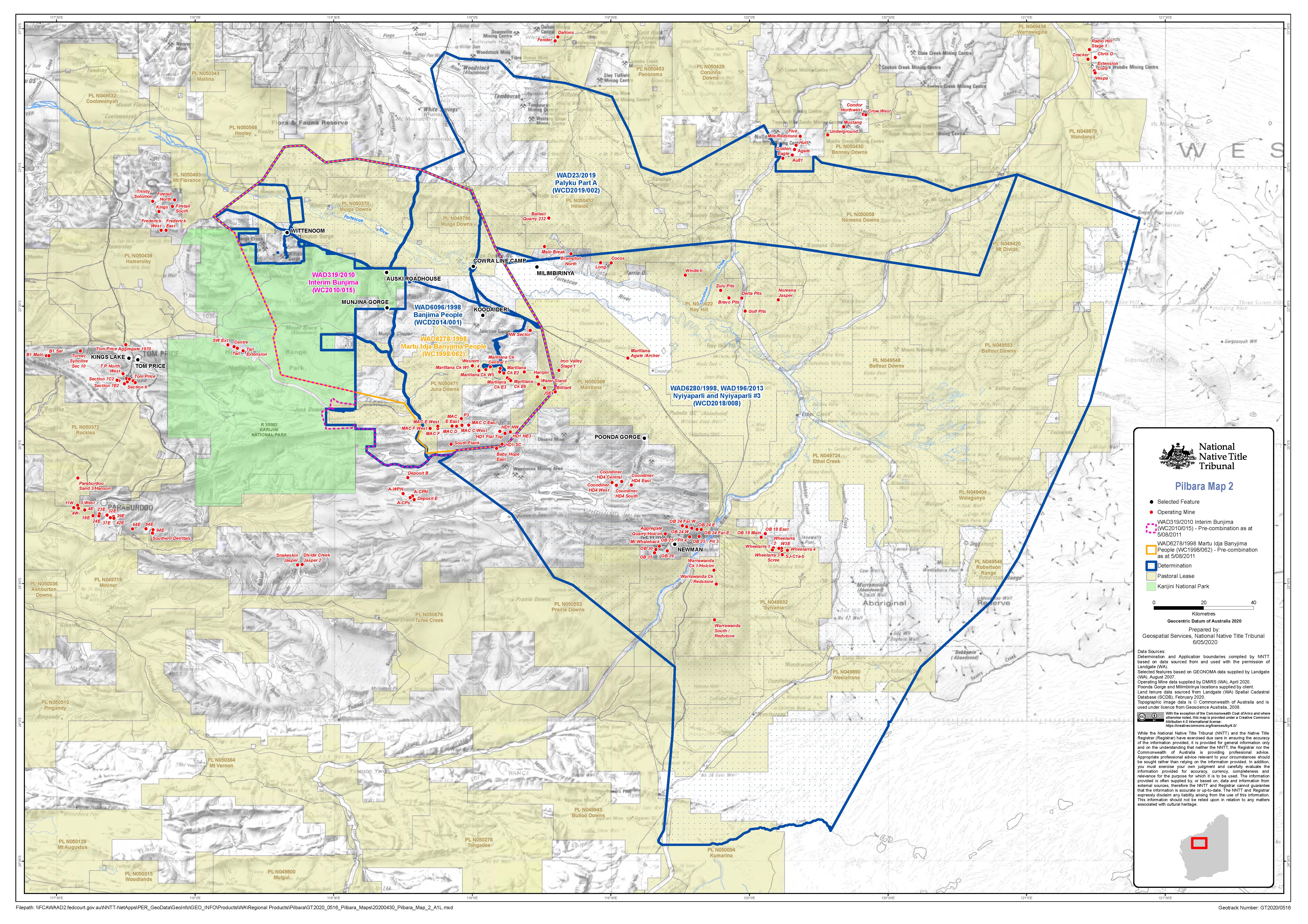

18 On 26 September 2018, the Court made the Nyiyaparli determination by consent, on the basis of the 1998 application. Ijiyangu was listed as an apical ancestor on this determination. Nyiyaparli country is to the east of Banjima country. Palyku country is to the north. A map tendered in evidence showing these three determinations, and some of the key locations to which the evidence referred, is Annexure A to these reasons.

19 On 7 and 14 August 2019, the applicants and their father applied for membership of Karlka.

20 At a meeting held on 29 October 2019, the Karlka directors decided not to accept the applicants as members of Karlka. The directors did not accept that each of the applicants “identify as a Nyiyaparli person and are recognised by others as a Nyiyaparli person”, being one of the requirements in the Karlka Rule Book. This decision was reaffirmed at a further directors’ meeting in December 2019. In February 2020, the directors decided to refer the question of the applicants’ recognition as Nyiyaparli People to a meeting of the Nyiyaparli common law holders.

21 On 17 April 2020, the applicants and their father commenced this proceeding. The applicants’ father, Mr H Dhu, passed away in June 2020 and was removed as an applicant by order of the Court dated 15 June 2020.

22 On 2 December 2020, a Nyiyaparli native title holders’ meeting was held in Karratha (December 2020 meeting). A series of resolutions were passed, the effect of which was to refuse to recognise the applicants as Nyiyaparli People. That position was maintained at trial by Karlka, on its own behalf and on behalf of the Nyiyaparli People.

The applicants’ ancestor and her country

23 The applicants say Ijiyangu and her children were from Mulga Downs station. Their traditional country ran from Munjina to Martuyitha (Fortescue Marsh). Steven Dhu deposed that his maarli, Ned, told him that this was a shared area of country for Banjima and Nyiyaparli people. That evidence was not accepted by Karlka, and there was cross-examination of Steven and Brendan Dhu about where they placed Ijiyangu’s country, and where they placed their own country. However, and curiously given it is the RNTBC for the Nyiyaparli People, Karlka made no positive submissions about where Ijiyangu’s country was, if it was not where the applicants placed it.

24 It is an agreed fact that there are 7 descendants of Ijiyangu who are members of Karlka. They are all descended from one Peter Derschaw, who in turn was the grandson of Ivy Swan, the sister of Susan Swan. The parties each relied on this fact in different ways.

The Banjima determination and the exclusion of Ijiyangu

25 In evidence that was not challenged, Steven Dhu explained that, prior to the Banjima (No 2) decision, there was a proposal that in order to reflect the two underlying claims in Banjima (MIB and IB), two different trust structures should be created. Steven Dhu deposed:

Graham O’Dell, a lawyer at YMAC, told me it was proposed that all the descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy) would be members of the Number 2 Trust. I disagreed with this proposal. At that stage I thought that all members of my family would get native title and that once this happened the MIB and IBN claim groups would be reflected in the trust structure. I maintained that my father, Brendan and I were connected to the MIB claim area through Ijiyangu (Daisy). This all went out the window when the Banjima decision came down.

26 As I understood Steven Dhu’s written and oral evidence, the underlying basis for his disagreement, and for the applicants initially joining the MIB claim, and then objecting to their proposed membership of the B2 trust, all stemmed from their understanding of where their country was located within the claim areas (that is, the country to which Ijiyangu was connected). In his first affidavit (at [34]) Steven Dhu identified this country as being the “Fortescue valley area and includes Karijini national park and those parts of Mulga Downs and Hooley stations in the Banjima determination area”. This area was covered by the MIB claim, which is why (he deposed) he and his brother and father joined that claim. He deposed:

When we joined the MIB claim I did not know whether Ijiyangu (Daisy) was included as an apical ancestor for the MIB claim group description. I later learned that she was not and that she was included as an apical ancestor for the IBN claim group description. Ijiyangu’s exclusion from the Banjima Determination created an obstacle for her descendants who identified as Banjima.

27 In Banjima (No 2) Ijiyangu is referred to as “Daisy Yijiyangu”. She was put forward by the claimants as an apical ancestor. Ijiyangu was not the only apical ancestor about whom there was debate in Banjima (No 2). However, Barker J acknowledged the challenges for his Honour’s fact finding at [572]:

Daisy Yijiyangu: Daisy produces a much more difficult case than either Sam Coffin or Whitehead, as there is not unanimity among the Aboriginal witnesses that she was Banjima, the archival external and independent data suggests she was not Banjima, and the anthropologists express doubt as to her Banjima identity.

28 At [573], Barker J found:

Not all of the Aboriginal evidence is supportive of the claim that Daisy was Banjima, although there is some powerful support within sections of the claim group for accepting that Daisy was a Banjima woman. Charles Smith, for example, gave evidence that his mother had told him about old Banjima people that she knew when she was young. He said, “[m]y mum told me that Yijiyangu (Daisy) was a Banjima woman from Mulga Downs”. It is important to note in this regard that Mr Smith’s mother, Mrs A Smith, is the oldest claimant in the Banjima native title claim group and has a deep genealogical knowledge. Similarly, Joyce Injie, an 84 year old Innawonga woman gave evidence that she knew Billy Swan (Daisy’s son) and that he was a Banjima man.

29 Consistently with what his Honour says in this paragraph, elsewhere in his Honour’s reasons he places considerable weight on the evidence of Mrs A Smith and Joyce Injie. At [574]-[575], Barker J describes the evidence of John Todd, whom he describes as a direct descendant of Ijiyangu and whose grandmother he identifies as Susie, the daughter of Ijiyangu. This would appear to be the same “Susie” from whom the applicants are descended and who in the evidence in this proceeding was identified as Susan Swan. However there was no evidence before the Court in this proceeding about the applicants’ connection to John Todd.

30 In this context, Barker J referred to the applicants’ grandfather, at [576]:

Another old person that John Todd spent time with as a child and as a young adult was Ned Dhu. Ned Dhu was the oldest child of Susie Dhu (nee Swan) and he was born and worked on Mulga Downs Station. Mr Todd gave evidence that Uncle Ned had a lot of knowledge of Banjima country. Uncle Ned learnt a lot from Ivy, another of Daisy’s children, when he was living at Derschaw’s Outcamp on Mulga Downs Station. Ned passed on knowledge about Banjima country to Mr Todd. He camped in the riverbeds on Mulga Downs and Cowra with Ned.

31 The “Ivy” in this passage would appear to be Ivy Swan, the grandmother of Peter Derschaw and the sister of Susan Swan: see [24] above.

32 There was also expert evidence about Ijiyangu before Barker J, to which his Honour refers. This is part of the anthropological report of Dr Palmer, recorded at [578]:

Dr Palmer noted that Daisy has many descendants that include members of descendants of the Swan, Dhu and Derschaw families. He received, he stated at [791], some “limited information” about Daisy from the Dhu and Derschaw families. He noted that some thought she was generally associated with Mulga Downs and that her son, Billy, was an important ritual leader there. Bill Dhu told him that he could remember his mother’s mother, Daisy, from when he was a young boy and that she spoke the Banjima language and used to travel from Mulga Downs to Roy Hill Station. She died at Roy Hill during one of those visits. He was also told that Daisy’s mother may have identified as Nyiyabarli, but details were not known by those with whom he spoke.

33 At [579], Barker J recorded this statement from Dr Palmer, which is of some significance in the present context:

Dr Palmer noted that members of the Dhu and Derschaw families were “adamant” as to the Banjima identity of Daisy, although others amongst the claim group had questioned this, stating that she may have been Nyiyabarli.

(Emphasis added.)

34 From [580] onwards, Barker J traces what appears to have been something of a development in the opinions of Dr Palmer, in part influenced by the views of other anthropologists, and then by the views of one particular informant, a woman identified as Bonny Tucker. The three anthropologists appeared to move from a position where they considered Ijiyangu’s mother was likely Nyiyaparli, and her father Banjima, to a position where they agreed there was “no certainty” about this matter. At [588], Barker J notes the opinions expressed by the three experts (Dr Palmer, Mr Robinson and Dr Vachon) in a joint experts’ report, where they speak of Ijiyangu’s “Banjima identity” which, as the following passages in Barker J’s reasons demonstrate, encompassed more than descent. The experts referred to the concept of the “jural public”, being, in Barker J’s words, Aboriginal people “who were generally in the area, not necessarily Banjima but able to speak with some authority”. Barker J noted the experts placed differing weight on the opinions of such people about Ijiyangu’s identity.

35 At [593]-[594], Barker J set out the competing views:

Dr Palmer said that the genealogical connection of a person to an area on its own is not sufficient in a customary system, in his view, for people to be recognised and actually having rights in country. There might be potential rights that could be realised. But in a cognatic system there is an exercise of choice which has to be made. Otherwise the system would not function as a normative system.

Mr Robinson agreed that genealogy is important and indeed fundamental. He added that it is fundamental in the sense that Aboriginal societies are based on kinship and “people’s interconnectedness through kinship”. These are societies where status is ascribed: “You become a member of the society as a result of who you’re descended from, not how you achieve it. Your achievements during life might add or take away some of those rights or restrict them in some ways, but the very fact of descent … fundamentally gives an individual certain rights which cannot be taken away.” So he placed more emphasis on genealogy than Dr Palmer would.

36 At [595]-[601], Barker J expressed his conclusions on the question:

For the Court it is a very difficult thing to have to decide at this distance of time from when Daisy was born and lived whether Daisy was a member of the Banjima language group, that is to say had Banjima ancestry. It is understandable that, as a woman who apparently lived on Mulga Downs station for many years, which I accept (as noted above) is part of traditional Banjima country, and may have spoken the Banjima language, she may have been considered by some, if not many, as a Banjima woman for general cultural purposes. Her children and their children may well have grown up mixing with Banjima people and considering Daisy’s identity was Banjima.

If one looks for independent ethnographic data to show that Daisy had any Banjima ancestry, however, the evidence is lacking. The data provided by Dr Vachon to Dr Palmer strongly suggests Daisy’s father was not Puurna, a Banjima man, as some in the group had previously thought. Rather, he was married to a “sister” of Daisy and was not the father to any of Daisy’s siblings. Neither of the anthropologists have doubted the veracity of this data and the Court also accepts it is proper to regard it as reliable.

There are some circumstances in which the lack of an independent ethnographic record supporting the inclusion of a claimed apical ancestor amongst the ancestors who may be taken to have possessed native title rights in the claim area at sovereignty may be of relatively little moment, and the evidence of claimants themselves concerning the reputation of a claimed apical ancestor will be determinative and lead to a finding that the claimed apical ancestor was indeed an ancestor for native title purposes – as indeed I have found above in the cases of Sam Coffin and Whitehead. In this particular instance, however, there is no clear agreement amongst members of the claim group themselves as to Daisy’s identity. There are those who emphasise Daisy’s Nyiyabarli ancestry and those who say she was Banjima.

The Court accepts that, for native title purposes, it is not enough that a community or segments of a community of Aboriginal people acknowledge a person as part of their group if that person does not also have a relevant ancestry within that group by their law and custom, as Mr Robinson and Dr Palmer explained in their evidence. It is not enough, if a person’s ancestry is in question, for example, merely to show that a person has lived for many years in the relevant claim area and been involved in the relevant community’s cultural activities, if there is some real doubt about their ancestral connection or traditional incorporation within that community. This is one of the difficult issues governing native title claim group membership.

Based on the evidence as a whole, the Court is unable to conclude, on the balance of probabilities, that Daisy had any relevant ancestral connection to the Banjima people. The tipping point in the weighing process is the serious doubt conveyed by the data provided by Dr Vachon to Dr Palmer, which has also plainly influenced the serious uncertainties about her ancestry expressed by the anthropologists.

What can be said, as indeed the anthropologists have concluded, is that there is a “possibility” that Daisy had Banjima connections. However, in the light of all the evidence, that possibility does not enable the Court to conclude, on the balance of probabilities, that she had a Banjima ancestry.

The Court must, therefore, conclude, for the purposes of the NTA and this proceeding, that Daisy Yijiyangu is not an apical ancestor as claimed in the application.

37 What should be emphasised from these passages is that the matter which troubled Barker J the most, and led to the finding his Honour made, was the “ancestry” of Ijiyangu. That is, there was insufficient evidence about the fact of her descent from (relevantly) a Banjima man. It would appear that both the anthropologists and the Court placed significant weight on what had been said by Bonny Tucker. I return to Mrs Tucker’s accounts below, because they were raised by the applicants.

38 The applicants have each deposed to the effect the Court’s decision had on them. Mr Steven Dhu stated:

I became aware in August 2013 of Barker J’s finding that Ijiyangu (Daisy) was not a Banjima person with the result that her descendants were not Banjima native title holders. I was very surprised by this finding. Based on what I had been told during my involvement in native title I believed she was a Banjima person.

The descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy) disputed Barker J’s finding that she was not a Banjima person. My father, Brendan and I (and other descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy) that I am aware of) thought that YMAC had not done its job properly. We were also concerned about our status under native title agreements and in relation to existing trusts through which benefits were distributed.

39 And Mr Brendan Dhu stated:

In 2013 I learned that the Federal Court did not accept that Ijiyangu (Daisy) was a Banjima Apical. This left me without the identity as a Pilbara common law holder that I had hoped for from that case.

40 Steven Dhu deposed there was no consultation with him, or his brother, about Ijiyangu, and they were not asked for any information they might have supplied about her ancestry. In a passage which was not challenged in cross-examination, Steven Dhu deposed:

Sometime around 2009 I had a conversation in Roebourne with Mr Ibrahim Kakay who I knew then to be a lawyer working for YMAC. I was working for the Ngarluma Aboriginal Corporation at the time. I was walking out of the Ngarluma office when I bumped into him. Mr Kakay told me that Ijiyangu (Daisy) had been put forward as a Banjima apical ancestor in support of the combined Banjima claim that YMAC were running in the Federal Court. He told me that he was involved in preparing evidence in support of that case and would make contact with me again to discuss my knowledge of Ijiyangu (Daisy). He asked me for the address of my father so he could take a statement from him. That was the last that I heard form Mr Kakay or YMAC about the trial. Neither I, nor my father, nor my brother Brendan nor any other immediate members of my family were called as witnesses to give evidence about Ijiyangu (Daisy) at the trial. I am not aware that any anthropologist came and spoke with us either. It was a passing conversation the significance of which I did not appreciate until Barker J handed his decision down in the Banjima native title claims.

(Typographical errors in original.)

41 The Banjima Native Title Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (Banjima PBC) became the determined prescribed body corporate for the Banjima determination.

42 The Banjima determination defined the Banjima People in the following way:

The Banjima People are those Aboriginal persons who:

(a) are descendants of one or more of the following apical ancestors:

(i) Bob Tucker (Wirilimura);

(ii) Gawi;

(iii) Yinini (Arju);

(iv) Sam Coffin;

(v) George Marndu;

(vi) Whitehead;

(vii) Yidingganin;

(viii) Maggie (Nyukayi);

(ix) Yandikuji; and

(b) recognise themselves as a Banjima person, and are recognised by others as a Banjima person.

The aftermath of Banjima (No 2)

43 After the decision in Banjima (No 2) in 2013, there were disputes about the position of Ijiyangu’s descendants in terms of their eligibility for benefits. There were eventually resolved through the Banjima Internal Settlement Deed in 2014.

44 The Banjima PBC and Yaramarri Banjima Corporation Limited are both parties to the Banjima Deed. Banjima PBC is a party on its own behalf and on behalf of the Banjima People. Yaramarri is a party to the Banjima Deed on its own behalf and on behalf of descendants of Ijiyangu, including the applicants in this proceeding.

45 The agreed facts are:

The Banjima Internal Settlement Deed provides, amongst other things:

a. the Daisy Descendants will not appeal or seek to appeal the Banjima Decision, and will not seek to vary or revoke the Banjima Determination;

b. the Banjima prescribed body corporate will provide a class of membership for all current and future descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy) who will be entitled to attend meetings and receive benefits (amongst other rights);

c. the parties will establish a benefits management structure (BMS) comprising the Banjima Charitable Trust, the Banjima Direct Benefits Trust (B1 Trust) and the Yaramarri Banjima Direct Benefits Trust (B2 Trust);

d. descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy) and Banjima people not entitled to be beneficiaries of the B1 Trust [but] are entitled to be members of the B2 Trust;

e. the Applicants and their late father were named as Additional Beneficiaries for the B1 Trust and listed in Schedule 3 – List of Initial Beneficiaries of the B1 Trust who are Banjima People;

f. the other descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy) were to be beneficiaries of the B2 Trust; and

g. the objects of the Charitable Trust were to be any charitable purpose which benefits a class of Aboriginal people that includes the Banjima people and the descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy).

46 It is further agreed that in or about March 2015 the applicants applied for membership of the B1 Trust, and signed an agreement that enabled them to receive a distribution from a Sub Fund of the B1 Trust. Each of the applicants and their late father received payments from the B1 Trust in 2015, and in 2017 Mr Steven Dhu received a further payment.

47 There was some debate during the hearing about the amounts of the payments received, and how many were received. I do not consider the precise amounts are material to the issues in the proceeding, but there can be no debate on the evidence that Steven and Brendan Dhu received substantial payments from the B1 Trust during this period. The evidence does not disclose how, proportionally, the payments they received measured against the payments received by other group members.

48 As I explain below, in my opinion it is the case that some of the negativity towards the applicants from some Nyiyaparli common law holders appeared to stem from the substantial amounts of money the applicants had received from what might be called Banjima-related sources, on the basis they identified as Banjima people. Criticism and resentment of the applicants voluntarily taking large sums of money on the basis of being Banjima people, and yet now seeking to be included as Nyiyaparli People and asserting rights to receive benefits pursuant to that identification, was apparent. In my opinion, the evidence disclosed a sense from some Nyiyaparli people that the applicants are, to use a colloquial term, ‘double dipping’.

49 In late 2017 a dispute arose between the applicants and the trustee of the B1 Trust (Australian Executor Trustees Ltd) in relation to a distribution policy which had been introduced in August 2017. That distribution policy related to “individual non-IBN beneficiaries” of the trust, and included a change to the policy regarding “additional beneficiaries”, being the class that included the applicants and their father.

50 The policy stated that the additional beneficiaries would be eligible for a one-off payment of $10,000, and not be entitled to any further payments. The policy then stated:

The rationale behind these payments is that these beneficiaries have no connection to MIB Apical Ancestors and had little or no involvement within the MIB Community…

51 The applicants commenced a proceeding against the trustee in the Supreme Court of Western Australia, which was settled in 2019.

52 As part of the settlement, the agreed facts are that in June 2019, by a letter to the trustee, the applicants:

a. requested [the trustee] to remove their names from the Register of B1 Banjima Beneficiaries;

b. relinquished and disclaimed their position and any rights as Additional Beneficiaries of the B1 Trust; and

c. advised that they had no objection to the removal of the Additional Beneficiary class from the B1 Trust.

53 It is agreed that the applicants remain eligible to receive payments under the Banjima Charitable Trust. It is also agreed that Brendan Dhu has in fact relied on this eligibility, and has made various applications for assistance to the Banjima Charitable Trust between August 2018 and October 2020, at least some of which I infer have been granted.

The Nyiyaparli determination

54 The Nyiyaparli determination was made on 26 September 2018. In a chronological sense, this consent determination was agreed to prior to the applicants relinquishing their interests in the B1 trust, but after the dispute about their entitlements as Banjima people under that trust had commenced. This Court ordered that Karlka shall hold the determined native title in trust for the Nyiyaparli common law holders pursuant to s 56(2)(b) of the Native Title Act. The determination defines the Nyiyaparli People, and therefore the common law holders of native title, in the following way (with my emphasis):

The Nyiyaparli People are those persons who:

(a) are descended from, in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Nyiyaparli People, one or more of the following persons:

(i) Mintaramunya;

(ii) Pitjirrpangu;

(iii) Yirkanpangu (Jesse);

(iv) Kitjiempa (Molly);

(v) Mapa (Rosie);

(vi) Iringkulayi (Billy Martin Moses);

(vii) Parnkahanha (Toby Cadigan);

(viii) Wirlpangunha (Rabbity-Bung);

(ix) Wuruwurunha (Tommy Malana);

(x) Ijiyangu (Daisy);

(xi) Sibling set of Ivy, Solomon and Mildred; and

(xii) Sibling set of Maynha and Itika,

or, though not descended from those persons, have been incorporated into the Nyiyaparli group in accordance with Nyiyaparli traditional laws and customs,

and

(b) identify themselves as Nyiyaparli under traditional law and custom and are so identified by other Nyiyaparli People as Nyiyaparli;

and

(c) have a connection with the land and waters of the Determination Area, in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Nyiyaparli People.

55 The definition thus incorporates the primary pathway of descent, coupled with mutual recognition (see Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1 at 70); and the existence of a traditional “connection” to the land and waters in the Nyiyaparli determination area.

56 Karlka’s Rule Book was registered by a delegate of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations on 4 September 2018. The Rule Book uses the same definition for the Nyiyaparli People as that used in the Nyiyaparli determination.

How Ijiyangu came to be an apical on the Nyiyaparli determination

57 The description of the Nyiyaparli People extracted above from the determination differs from that included in the original Nyiyaparli native title applications in several respects. One difference is the inclusion of an additional three sets of apical ancestors, not listed in the Nyiyaparli applications. One of the additional apical ancestors was Ijiyangu.

58 This discrepancy appears to be a result of the long and complex procedural history of the determination, which included significant disagreement between groups within the Nyiyaparli People and adjacent and overlapping claims. That history is set out in the Court’s reasons in the Nyiyaparli determination itself from [44] to [49], and in Stock on behalf of the Nyiyaparli People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2018] FCA 1091. The latter was an interlocutory decision by Barker J relating to the proposed joinder by a person within the Nyiyaparli claim group who objected to the inclusion of the additional ancestors. Although Barker J does not name the apical ancestors, or the families descended from them, I infer this included Ijiyangu.

59 It is appropriate to set out the history relating to Ijiyangu’s inclusion as an apical on the Nyiyaparli determination.

60 The claim group description was amended several times between the filing of the applications and the Nyiyaparli determination. As part of negotiations occurring between the Nyiyaparli applicant and the respondent parties in the early-mid 2010s, the Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation (YMAC) on behalf of the applicant commissioned further anthropological research to that which had already been undertaken. That research was done in the period of 2015 to 2017 by Mr Kim McCaul, and identified potential additional apical ancestors to be included in the description of native title holders. One of these apical ancestors was Ijiyangu. I note that this was a period of time after the Banjima decision, and Barker J’s conclusion about Ijiyangu.

61 In Stock on behalf of the Nyiyaparli People v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2018] FCA 1306, the Court dismissed an application of a Mr Phillip William Dhu to be joined as a party to the proceeding. This decision came a few months after the joinder decision in Stock (No 2). I infer that Mr Phillip Dhu is related to the applicants in this proceeding, and Karlka made a submission to that effect.

62 Mr Phillip Dhu contended that his interests would be affected if the Nyiyaparli determination were made with Ijiyangu as an apical ancestor. He referred to, but did not produce, an agreement which he had described as a “private commercial document”. He contended he, and people associated with him, would be deprived of payments that, in Barker J’s words “are otherwise due to the party called the ‘Banjima common law holders’”. One of the reasons Barker J dismissed his joinder application was because, without that document, it was difficult for the Court to see how Mr Phillip Dhu’s interests could be adversely affected if Ijiyangu was listed as an apical ancestor.

63 Barker J noted at [10] that:

It is not an application made by Mr Dhu in a representative capacity for other people, although it is reasonable to say that, in his affidavit and the affidavit of Ms Helen Cynthia Smith made 16 August 2018 and the affidavit of Peter Dodd made 16 August 2018, that Mr Dhu relies upon, he is endeavouring, in a broad sense, to indicate that there are other people, in a similar position to him, who would like, in effect, to be heard in relation to the adding of Daisy to the list of apical ancestors on the Nyiyaparli application. But be that as it may, the evidence before me also suggests, whilst Mr Dhu and those others would appear to be descendants of Daisy, that there are other descendants of Daisy in a similar position to them who do not actually take the same stance as Mr Dhu.

64 At [15], Barker J referred to Mr Phillip Dhu’s “key argument” that he and some of the others identify as Banjima People. Barker J recorded that Mr Phillip Dhu was proposing that there be an inquiry conducted by the National Native Title Tribunal to ascertain if, indeed, they were, or were not, Banjima People. Barker J then noted that the Court had decided this matter in the Banjima decision, by its finding that Ijiyangu was not a Banjima ancestor. Barker J then explained that “relatively recently” the Nyiyaparli group had decided to change the description of the claim group to add Ijiyangu, and then observed (at [17]) “but it is not as simple as that”, referring to the other two criteria for membership of the Nyiyaparli people, which I have set out at [54] above; namely mutual recognition and traditional connection to land and waters.

65 The qualifiers at (b) and (c) of the definition of Nyiyaparli People were also introduced into the description following Mr McCaul’s research. Barker J found at [48] of the Nyiyaparli determination that these qualifiers

provide a more accurate way of describing the proposed native title holders and are consistent with the traditional laws and customs of the Nyiyaparli People as disclosed in the connection materials.

66 One of the consequences of the introduction of the qualifiers is that, as Barker J noted at [20]-[21] of Stock (No 3):

If, as appears to be the case, Mr Dhu and others do not identify as Nyiyaparli People or do not want to identify as Nyiyaparli People, then they will not be within the claim group on the Nyiyaparli application, because they will not satisfy the description of native title holders that I have just referred to, especially in (b) and (c).

The simple fact that an apical ancestor of theirs is Daisy does not automatically mean that they are members of the Nyiyaparli claim group. They also have to identify as Nyiyaparli and have a connection under Nyiyaparli traditional law and custom to the area. They are steadfastly asserting in the submissions and the affidavits that they are Banjima People – and do not have Nyiyaparli connections, if I can put it that way.

67 Barker J refused Mr Phillip Dhu’s application to be joined as a party to the proceeding on the basis that his Honour was not satisfied that to do so was in the interests of justice. His Honour indicated that on the evidence before him there was nothing to suggest that the “automatic” result of Ijiyangu’s inclusion as a Nyiyaparli apical would “see the cessation of payments” under the Banjima agreement with Ijiyangu’s descendants. This finding was in part because of the additional qualifiers introduced to the definition of Nyiyaparli People, requiring self-identification as a Nyiyaparli person. At [32], Barker J described the concern of Mr Phillip Dhu in the following terms:

It is a concern that, as Ms Smith put it, the Banjima common law holders will point to the Nyiyaparli native title determination to exclude her and other Daisy descendants from benefitting under the charitable trust programs, and escalate what is now an (asserted) emerging trend of depriving of them of their fair, just and equitable rights and interests through the distributions of the Banjima charitable trust programs.

68 The denial of benefits, of course, is precisely what the evidence demonstrates came to pass in respect of the present applicants. However in Stock (No 3) Barker J framed this as more relevantly an issue for the Banjima trustees, and not a basis on which to join Mr Phillip Dhu to the Nyiyaparli determination.

69 The joinder application by Mr Phillip Dhu was made only a couple of months before the proposed date for the Nyiyaparli consent determination. Barker J’s decision in Stock (No 3) meant the Nyiyaparli determination could be made as proposed. The disputes about entitlements of the descendants of Ijiyangu to benefits under the Banjima trusts continued alongside these developments.

Karlka and its decision making

70 The chronology relating to the applicants’ interactions with Karlka is generally agreed. The applicants made written applications for membership of Karlka in August 2019, which were refused in accordance with r 6.13 of the Rule Book. The refusal was on the basis that Karlka was not satisfied that the applicants identify themselves as Nyiyaparli persons, or are so identified by other Nyiyaparli people. The applicants were notified of the refusal on 5 November 2019, and of their right to appeal under r 6.1.4 of the Rule Book. It is agreed that the applicants did not pursue an appeal.

Relevant Rule Book provisions

71 Rule 5 of the Rule Book requires that Karlka maintain a Register of Nyiyaparli People, which under r 5.2(e), is separate from the Register of Members of the Corporation. Rule 5.3 provides for the process by which the Register is to be updated:

5.3 Process for updating the Register

(a) Subject to that person not already being included on the Register of Nyiyaparli People, should the Corporation become aware that a person claims to be a member of the Nyiyaparli People then the Corporation must as soon as reasonably practicable consider the claim and decide whether to include the person on the Register of Nyiyaparli People (whether or not the person applies directly to the Corporation to be recognised as a member of the Nyiyaparli People).

(b) If a person ceases to be a Nyiyaparli Person (including because they are deceased) then the Corporation must as soon as reasonably practicable remove the person from the Register of Nyiyaparli People.

(c) For the purposes of rules 5.2(a), 5.3(a) and 5.3(b), whether a person is or continues to be included on the Register of Nyiyaparli People will be determined by the Directors applying the following criteria. If there is any inconsistency, a criterion higher in the list prevails over one that is lower in the list. The Corporation:

(i) must include a person on or remove a person from the current Register of Nyiyaparli People if a court of competent jurisdiction determines that the person is or is not (as the case may be) a Nyiyaparli Person;

(ii) must include a person on or remove a person from the current Register of Nyiyaparli People if the Common Law Holders of Native Title in respect of a Nyiyaparli Determination or the members of the Native Title Claim Group in respect of the Native Title Claim make a decision in accordance with an Approved Process that the person is or is not (as the case may be) a Nyiyaparli Person; and

(iii) may request and act upon the advice of:

(A) the Representative Body for the Nyiyaparli Claim; or

(B) the solicitor on the record for the Nyiyaparli Claim.

72 The “Approved Process” is defined in Schedule 1 of the Rule Book:

(a) in the case of a decision by the Native Title Claim Group of a Nyiyaparli Claim, a traditional decision making process, or if there is no such process, then an agreed and adopted decision making process, by which the members of the Native Title Claim Group make decisions in relation to the Nyiyaparli Claim; and in the absence of any traditional or agreed and adopted decision making process of that kind, means the decision making process by which the members of the Native Title Claim Group authorised the making of the Nyiyaparli Claim; and

(b) in the case of a decision by the Common Law Holders of the native title in respect of a Nyiyaparli Determination, a traditional decision making process, or if there is no such process, then an agreed and adopted decision making process, by which the Common Law Holders make a Native Title Decision.

73 Membership of Karlka is governed by r 6 of the Rule Book. Membership applications are decided under r 6.1.3, which provides a process and criteria by which the Directors of Karlka are to consider and decide to accept or reject the application. Rule 6.1.3 provides:

6.1.3 Deciding Membership applications

(a) The Directors will consider and decide membership applications in accordance with this rule 6.1.3.

(b) The Directors must take into account and are bound by:

(i) the description of the Native Title Claim Group in the Nyiyaparli Claim from time from time;

(ii) the description of the Native Title Holders in any relevant Nyiyaparli Determination; and

(iii) any declaration or determination by a court of competent jurisdiction as to whether a person or class of persons is or is not a member of the Native Title Claim Group in respect of the Nyiyaparli Claim, or a Common Law Holder of Native Title in respect of a Nyiyaparli Determination.

(c) The Directors may take into account any other information they consider to be relevant including:

(i) the advice or opinion of an anthropologist; or

(ii) whether or not the person’s name appears on the Register of Nyiyaparli People at the relevant time; or

(iii) the advice of the Representative Body for the Nyiyaparli Claim; or

(iv) the advice of the solicitor on the record for the Nyiyaparli Claim.

(d) At the next meeting of the Directors following receipt of an application for membership that complies with the Rule Book, the Directors must consider the application and determine whether to accept or reject the application.

(e) The Directors must not consider or accept a membership application that is not compliant with the Rule Book.

(f) Membership applications will be considered and decided in the order in which they are received by the Corporation.

(g) The Directors may refuse to accept a membership application even if the Applicant has applied in writing and complies with all the eligibility requirements.

(h) If an application for membership is accepted, the Corporation must notify the Applicant in writing and add the Applicant’s name to the Register of Members within 14 days of the decision.

(i) If an application for membership is rejected, the Corporation must notify the Applicant within 14 days of the decision and provide in writing:

(i) reasons for the rejection; and

(ii) a copy of rule 6.1.4 detailing the appeal process.

74 The evidence shows the directors’ decision in relation to the applicants was expressed in the following terms:

Pursuant to Rule 6.1.3 (i) of the KNAC Rulebook, the KNAC Board has refused your membership application because it is not satisfied that:

(a) you identify as a Nyiyaparli person or are recognised by others a Nyiyaparli person.

The December 2020 meeting

75 There was then some correspondence between the applicants’ lawyer and Karlka’s lawyer about whether the applicants would take up the process set out in Karlka’s Rule Book for an appeal. For reasons that are not relevant to the resolution of the appeal, the applicants decided not to do so. Karlka’s eventual response was expressed in correspondence in the following terms:

In these circumstances the KNAC Board has considered its legal and cultural obligations and has decided to convene a meeting of the Nyiyaparli common law holders for the purpose of making a decision on whether your clients are Nyiyaparli People. Consideration of this issue is not a legal matter alone and must properly be put to the native title holding group of which your clients assert they are members. This is reflected in Rule 5.3(c)(ii) of the KNAC Rule Book which criteria the KNAC Board intends to apply to the question of whether or not your clients are Nyiyapar1i persons.

Your clients will each be invited to attend the meeting and may bring to the attention of the common law holders any matters they believe relevant to their status as Nyiyaparli persons.

Any proceedings commenced before this required process occurs would be premature and should your clients instruct you to take such steps, my client will seek to rely upon this correspondence in relation to the issue of costs.

76 This correspondence reflected a decision made by the Karlka Board on 25 February 2020. However, for a number of reasons, that meeting did not occur until 2 December 2020.

77 On 17 April 2020 the applicants commenced this proceeding. Some discussion occurred between the parties during this period, including a mediation on 14 October 2020, which was facilitated by the Court. After the mediation, on 26 October 2020, the applicants provided Karlka with a final version of a statement in support of their assertions for membership of Karlka, to be used at the planned common law holders meeting. Their lawyer indicated the applicants did not propose to attend the December meeting in person.

78 The statement was:

Steven and Brendan Dhu are Nyiyaparli People and would like to become members of KNAC. They are descendants of Ijiyangu (Daisy), a Nyiyaparli apical. The connection to Ijiyangu is through their father and their maarli Ned Dhu. Ned Dhu was the eldest of Susan Swan’s children. Susan Swan was the daughter of Ijiyanugu. Her brothers and sister were Billy Swan, Ivy Swan and Jackie Parker.

Ned Dhu grew up on country near or around the Martuyitha. He lived at Cowra outcamp and Weediana station. Waniba sister to Ijiyangu helped grow him up. When he was older Ned worked at Comet mine. He married Margaret Lockyer. Ned, Margaret and their children spent many years living at Marble Bar. Steven and Brendan’s grandmother, uncles and aunty, Margaret Dhu, Wally Dhu, Arnold Dhu, Victoria Dhu (Spuddy), Mark Dhu still lives there and Arnold works at the school.

79 The December 2020 common law holders’ meeting was held at the Red Earth Arts Precinct, Karratha, Western Australia. At the meeting, the statement prepared by the applicants was read out and displayed on a screen. The Nyiyaparli common law holders who voted (about half of the attendees) refused to recognise the applicants as Nyiyaparli people.

80 It is an agreed fact that that decision of the Nyiyaparli common law holders was made in accordance with r 5.3(c)(ii) of the Rule Book, including in accordance with the Approved Process set out in Schedule 1 of that Rule Book.

81 A significant part of the affidavit evidence describes what occurred at the meeting from the deponents’ varying perspectives. In general, the respondent emphasised evidence that the meeting proceeded as normal for meetings of the Nyiyaparli common law holders. The applicants emphasised the evidence of Ms Christina Stone that there was a significant disruption to the meeting in which a person was removed, and Ms Stone’s evidence that she felt intimidated and chose not to vote on the resolutions.

THE PARTIES’ ARGUMENTS IN SUMMARY

The applicants

82 Counsel emphasised that the challenge brought in these proceedings is not to the decision of the respondent’s board of directors about the applicants’ membership applications. The applicants accept there was an available appeal process, which they did not use (in contrast to the Derschaw family, whom I discuss later in these reasons). They are not therefore pursuing any challenge to their inability to become members of Karlka as a registered native title body corporate. As they submit, and Karlka did not dispute, Nyiyaparli common law holders do not have to be members of Karlka.

83 The challenge is to the function of the respondent, as a fiduciary to the common law holders, to maintain an accurate Register of Nyiyaparli People under r 5 of the its Rule Book. That Register, the applicants submit, must accurately reflect those people who are, by reason of the definition of Nyiyaparli People in the Nyiyaparli determination, entitled to be common law holders and therefore entitled to be on that Register.

84 What matters therefore, is the effect of the resolutions passed at the December 2020 meeting and the fact those resolutions precluded the applicants’ names being entered on the Register. The applicants submit the resolutions as proposed and passed are not compatible with the requirements in the Nyiyaparli determination. The resolutions were not carried out in accordance with traditional law and custom, either as to process or as to content of the resolutions. In part, the applicants’ submissions on this point appear to involve impugning r 5 itself, which they submit “cuts across” the definition of the common law holders in the Nyiyaparli determination. They do not however seek any relief in relation to r 5 itself.

85 As I understand them, the applicants’ contentions follow two alternative paths.

86 First, and as their principal contention, the applicants contend the Nyiyaparli common law holders were not, in law, able to use an “agreed and adopted decision-making process” (namely; a vote by majority show of hands) at their December 2020 meeting to decide to reject the applicants as Nyiyaparli people. The applicants contend the process of recognition had to be done in accordance with traditional Nyiyaparli law and custom.

87 In the alternative, if the applicants are wrong in their principal contention, they contend the common law holders’ decision is reviewable by this Court, and the decision is affected by error and has no legal effect. That is because the resolutions were passed on what the applicants describe in their submissions as “an incorrect factual footing”. Namely, that the Dhus were “of Banjima descent”, in some sense that is exclusive of them having and maintaining a Nyiyaparli identity. This is factually incorrect, the applicants submit. Since their descent from Ijiyangu is agreed, and the genealogical connections are explained in detail in the evidence, and since there are other members of Karlka who have the same descent line, and who are members of both Karlka and the Banjima PBC, the applicants’ exclusion cannot objectively be because of this fact. Their connection to country has always been a connection to Ijiyangu’s country.

88 Ijiyangu’s connection to country is said by the applicants to be central to this dispute. They relied on a number of different pieces of evidence to prove that her connection to country was to Nyiyaparli country. They rely on Bonny Tucker’s preservation evidence affidavit in the Nyiyaparli applications.

89 If the applicants succeed in impugning the decision of the common law holders to reject the applicants as Nyiyaparli People, the applicants then contend there are two options for the Court. The first is to order Karlka to convene a further meeting to consider whether the applicants are Nyiyaparli People. The applicants submit this has occurred, or a similar approach has been taken in Sandy v Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (No 4) [2018] WASC 124; 126 ACSR 370. The second is for the Court to determine whether the applicants are Nyiyaparli People on the evidence before it. The applicants submit this has been done before, relying on Warrie (on behalf of the Yindjibarndi People) v State of Western Australia [2017] FCA 803; 365 ALR 624, where Rares J made a decision whether or not three individuals were or were not Yindjibarndi People. The applicants submit a similar task was performed by McKerracher J in Murray on behalf of the Yilka Native Title Claimants v State of Western Australia (No 5) [2016] FCA 752, and that indeed Banjima (No 2) itself had this effect, because of findings such as those about Ijiyangu.

90 The applicants submit the second option is preferable, because

in the circumstances Karlka or a meeting of common law holders “is unlikely to give the necessary measured consideration to the question in order to arrive at an informed and fair decision”: Aplin on behalf of the Waanyi Peoples v State of Queensland per Dowsett J at [269].

The traditional law and custom of identification of Nyiyaparli People

91 Counsel for the applicants drew attention to Bonny Tucker’s evidence given in the Nyiyaparli proceeding that:

They can follow a different group too and stay as Nyiyaparli. There is no rule that says you cannot be Nyiyaparli and Banjima.

92 Counsel also suggested that Mr David Stock is an example of a person who is associated with both Banjima and Nyiyaparli, in that Mr Stock is a member of the Banjima Elders group, and is also a member of Karlka. Mr Stock identified himself, in his affidavit filed in the Nyiyaparli proceeding, as “a Nyiyaparli elder. I am also a Banjima man, I can go both ways”. Counsel submitted that this is not an uncommon position, relying on the affidavit evidence of Kevin Banks-Smith affirmed 24 February 2021. Mr Banks-Smith annexes the member lists of Karlka, Banjima PBC and the Palyku Aboriginal Corporation, which the applicants contend demonstrate “substantial overlap”.

93 The applicants submitted that the evidence of Nyiyaparli elders is that while knowledge of Nyiyaparli country was an integral part of being a Nyiyaparli person, where “people don’t necessarily know where they’re from or their family or their country … elders can help out and teach them”. In this sense, lack of knowledge does not “exclude” a person from belonging to or having a connection with country or from identifying as Nyiyaparli. Further, in the applicants’ submission, this could not be so, because connection to country through descent is “inalienable”. In oral submissions, counsel for the applicants relied on Bonny Tucker’s and Mr Stock’s witness statements filed in the Nyiyaparli proceeding. He emphasised Mr Stock’s statements that:

It is the same culture way. You can’t throw away your country. It belongs to you.

94 And that:

You can’t take away that connection. People choose which way to follow –

95 The applicants submitted that this evidence constrained the second aspect of the mutual recognition limb; in other words constrained the circumstances in which recognition could be withheld by the Nyiyaparli People. In this sense, counsel for the applicants submitted that the decisions of the Nyiyaparli common law holders not to “recognise” the applicants as Nyiyaparli people were not made according to traditional law and custom. The inference was that there were non-traditional reasons at work, such as resentment about monies received and the like.

96 When asked how this submission could be reconciled with the definition of Nyiyaparli People in the Nyiyaparli determination, counsel submitted the mutual recognition aspect is conditioned on recognition being in accordance with the traditional law and custom of the Nyiyaparli People. Counsel submitted that evidence of the content of that traditional law and custom comes from the evidence of Mr Stock and Bonny Tucker. On the applicants’ account of that evidence, the traditional law and custom of how a person is to be identified as Nyiyaparli requires knowledge of and connection to country, but when people who may have been removed from country or otherwise denied that knowledge seek to reconnect, the door cannot “be permanently closed; … there’s a process to regain that connection”, including a willingness to learn from elders and elders’ obligations to pass on knowledge to such people. In contrast to a person who had been forcibly removed, or disconnected, from their country and who needed to “reconnect”, the applicants “lived for substantial periods on their country” and “always maintained a connection to that country”.

97 Counsel submitted that the appropriate process under traditional law and custom for deciding whether persons such as the applicants should be recognised as Nyiyaparli people was not a large meeting of common law holders, but consideration by a group of senior Nyiyaparli people. Counsel went on in oral submissions to emphasise that, while the minutes of the meeting record the presence of 215 people, the votes for each resolution are recorded as being around 100 people for and 0 against. The inference is that a large number of attendees abstained from voting, and their views on recognition of the applicants as Nyiyaparli remain unknown. Counsel submitted that the Court should “disregard” these resolutions and substitute its own determination on the question whether the applicants should properly be recognised as Nyiyaparli people.

Incorrect factual premise

98 Secondly and alternatively, the applicants contended that if the common law holders were able by majority show of hands not to recognise the applicants as Nyiyaparli people, resolutions 5 and 6 of the December 2020 meeting have no effect, because they were passed on an incorrect factual footing. The applicants submit that at the December 2020 meeting, “there was a general view that [the applicants] were of Banjima descent”, which counsel submitted “is just clearly wrong”. Counsel pointed to the minutes of the December 2020 meeting, which record the following:

There were some questions regarding the process and discussion throughout the group which concluded with the general view that both men were of Banjima descent.

99 Counsel emphasised that the issue in dispute in this proceeding had arisen because of Barker J’s finding that Ijiyangu was not a Banjima person. The applicants were following what they understood to be Ijiyangu’s country by participating in the MIB claim. As well being found by Barker J not to be a Banjima person, Ijiyangu has been found by this Court (in the Nyiyaparli determination) to be a Nyiyaparli person. Therefore, through Ijiyangu, the applicants do not have Banjima descent.

100 If the view attributed to people at the December 2020 meeting is understood as a reference to the applicants being descended from other Banjima ancestors (and not Ijiyangu), the applicants submit it is clear on the evidence that being “of Banjima descent”, or otherwise associated with Banjima, does not necessarily exclude a person from also being a Nyiyaparli person.

The respondent

101 Karlka framed this case as one about “the capacity and authority of a prescribed body corporate to determine its membership in accordance with the processes in its Rule Book”.

Nyiyaparli traditional law and custom

The applicants are not, or have not proven, they are Nyiyaparli people

102 The respondent contended that in effect the applicants seek to be identified as Nyiyaparli people on the basis of descent alone, without accepting or acknowledging that the mutual recognition requirement goes beyond recognition of descent. Karlka submitted that the applicants have not provided any evidence that they identify as Nyiyaparli in accordance with Nyiyaparli traditional law and custom. Relevantly, under traditional law and custom recognition as a Nyiyaparli person by other Nyiyaparli people

depends not only on descent but also on choices as to which group a person identifies with and the extent of their involvement with the group.

103 The respondent accepts that individuals may identify with and be recognised as belonging to more than one group. The respondent also accepts that decisions about whether a person is Nyiyaparli must be made in accordance with Nyiyaparli traditional law and custom, but contends that:

However, for the purposes of the membership of KNAC and entry on the Register of Nyiyaparli People, those decisions must also be made in accordance with the processes set out in the KNAC Rule Book.

104 Karlka submits the applicants are required to prove that they meet all the aspects of the definition of Nyiyaparli people set out in the Nyiyaparli determination (and extracted at [54] above). That definition requires, in addition to descent from a Nyiyaparli ancestor, mutual recognition and connection to the land and waters covered by the determination.

105 In oral submissions, senior counsel for the respondent submitted that the evidence provided by the applicants about connection to country was in large part about Ijiyangu’s connection to country rather than their own connection, and in fact mainly related to areas within the Banjima determination. Further, the applicants did not adduce evidence about “how they personally have a connection to the [Nyiyaparli] determination area in accordance with the traditional laws and customs of the Nyiyaparli people”. Senior counsel submitted that the evidence the applicants did put before the Court, that for example the applicants camped on Nyiyaparli country, is evidence of “an association” with the area only.

106 Any connection the applicants may have had with the Nyiyaparli People through Ijiyangu, the respondent contends, was broken by their, and their family’s, choice to identify as Banjima. The respondent submits that on the evidence this “break” may have occurred as early as with Ijiyangu’s daughter (the applicants’ great grandmother), Susan Swan. In its written submissions, Karlka contends that Susan Swan

did not continue to acknowledge and observe Nyiyaparli traditional law and custom and [was] not a part of the Nyiyaparli community. Suzie Swan, born in or about 1905, is described as having “married out” and not maintaining any known connections to local Aboriginal families (Banjima, Nyiyaparli or otherwise).

107 The phrase “married out” is attributed to an extract from the website “www.drbilldayanthropologist.com”, which appeared as annexure SD13 to Mr Steven Dhu’s first affidavit.

108 Referring to the evidence of Mr McCaul contained in a document entitled “Excerpts from Draft of Nyiyaparli Connection Report by Vachon and Pannell”, which was produced for the purposes of the Nyiyaparli determination, senior counsel for the respondents submitted:

[W]here there’s a need to activate some rights or some historical connection that might be there, what is required under traditional law and custom to be accepted is a re-establishing of links with the Nyiyaparli People, participating in Nyiyaparli social affairs, visiting and learning about Nyiyaparli country and sites, and by the applicants’ own evidence, none of these steps have been taken by the applicants. They have not taken any active steps to re-join any break in connection that may have occurred.

109 Karlka highlighted Brendan Dhu’s oral evidence that he could not name any significant Nyiyaparli sites in the Determination Area and submitted that the applicants have not attempted to learn about Nyiyaparli sites, by for example attending the meetings of the common law holders. The transcript reflects some confusion by the respondent’s counsel between the brother’s names in submissions, but it is clear that only Brendan Dhu was cross-examined on this matter. The respondents submitted that the applicants have not “activated” or “exercised” their connection to Nyiyaparli. While it may be open to people with descent connections to other groups to identify as “both ways”, the respondents submit that “what is important, indeed essential, is knowing both ways and following them”. That is not the case for the applicants, who have until recently only identified as Banjima. The respondents highlight that it is an agreed fact that the applicants have not attended any Nyiyaparli meetings, prior to or since making their membership applications.

The resolutions were made in accordance with traditional law and custom

110 Relying on the affidavit evidence of Mr Leonard Stream, Karlka submitted that the Nyiyaparli People do not have a traditional decision-making process, and instead used an agreed and adopted process to pass the resolutions as set out in the Rule Book. That the process is “agreed and adopted” does not mean, however, that the resolutions were made without regard to traditional law and custom. Counsel referred to Mr Stream’s evidence that:

We do not have a traditional decision making process we have to follow. We vote by show of hands on these types of decisions. We do discuss things the cultural way. The community listen to the senior people talk if they want to talk, and then we have our vote.

The resolutions were not made on the basis of an incorrect premise

111 Karlka submitted that it was clear from the materials sent out to common law holders ahead of the December 2020 meeting how the applicants claimed to be eligible for membership of the Nyiyaparli people. In particular, the statement by the applicants circulated with the meeting papers identified them as descendants of Ijiyangu.

112 The respondent submitted that accordingly the resolutions of the common law holders did not proceed upon any mistake of fact, but rather on the basis asserted by the applicants. As to the statement in the minutes of the meeting that there was a view among the attendees that the applicants “were of Banjima descent”, Karlka submitted:

(a) It is an agreed fact that the applicants have until recently identified as Banjima;

(b) It is true that the applicants are of Banjima descent through their father and grandfather, Ned, who the applicants themselves describe as Banjima men. The respondents emphasise Steven Dhu’s affidavit evidence that Ned Dhu spoke Banjima fluently, and submit that there is no evidence that the applicants’ father or grandfather asserted any connection to the Nyiyaparli determination area or spoke Nyiyaparli;

(c) No inferences should be drawn from the use of the word “descent” in the minutes. The minutes are not a statement of reasons, but simply a record of the decisions made at the meeting.

113 The respondents also submit that on the affidavit evidence before the Court, the circumstances of and atmosphere at the meeting were “typical”, noting that while the affidavit evidence of Ms Christina Stone contradicts this, she is alone in her view. Counsel for the respondent submitted that regardless of whether the discussion at the meeting became heated, Mr Stream’s evidence was that:

The meeting went how all our meetings usually go.

RESOLUTION

114 In my opinion, the personal view expressed by Keith Hall in his affidavit at [25]-[26] informs consideration of the resolutions at the meeting and Karlka’s emphasis on mutual recognition and connection criteria:

You cannot just switch over who you identify as, that is not the proper way. Under law it does not work that way, that does not make you one of our people. I thought the court protected that in our determination.

115 He continued:

Now, because Nyiyaparli have native title and our trust has money they want to come over here and say they are Nyiyaparli.

116 The mixing of more traditional understandings with antagonism arising from contemporary issues like eligibility for financial benefits was a constant theme of the respondents’ evidence and its case.

117 On the applicants’ case, what they have sought to do is to follow their ancestor, and maintain a connection to the country of that ancestor. The workings of the native title system have shifted them from one native title group to another. The applicants’ counsel put it this way:

Since the late 1990s, they have consistently claimed connections to that area. They have consistently claimed to hold Native Title based on that connection to that area. In addition, a finding that the resolution of this meeting established they are no[t] Nyiyaparli, really, does in a profound way mean that they have no place. They have no place in this part of the Pilbara as Native Title holders, and that is part of what makes this case so important, your Honour.

118 These reasons disclose that in substance I accept the applicant’s case to this point.

119 While the perceived motivations of the applicants loomed large in the evidence on behalf of Karlka, it is not their motivations which are determinative of the question whether they are members of the Nyiyaparli people. On the other side of the debate, nor is it enough to point to a descent connection to an apical ancestor on the Nyiyaparli determination.

120 The question whether the applicants are, or should be accepted as, Nyiyaparli People depends on the satisfaction of the three criteria for group membership in Sch 7 of the Nyiyaparli determination.

121 The second of those criteria depends upon mutual recognition. As I explained in Helmbright v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs (No 2) [2021] FCA 647, the adjective “mutual” is critical. The recognition is by an individual of their membership of a particular group; and by that same group of the individual. The recognition must be granted or withheld “under” traditional law and custom – that is, consistently with how group membership has been determined traditionally, by law and custom passed down from one generation to another. There is no room for contemporary motivations to either prompt or withhold recognition of certain individuals. That would be a licence for the operation of an unprincipled system for the holding of native title, without any normative content.

122 One of the unique features of the present proceeding is that the applicants’ former identification as Banjima came through Ijiyangu, and their present identification as Nyiyaparli comes through Ijiyangu. Thus, this is not really a situation of an individual deciding to go “both ways” through different parents or grandparents, and therefore seeking to be a member of two different native title-holding groups. As I explain below, the applicants have been consistent in their singular identification of the ancestor they follow, and what they understand to be her country, and therefore their country. The claimed descent connection has always been to Ijiyangu. The applicants provided persuasive evidence about how that choice was made, which I accept. Rather than any attempt to “go both ways”, there has been a quest by the applicants (and other members of their family) to go one way; a quest for the acceptance of Ijiyangu and acceptance of their connection to her country. Their predicament arises from judicial findings, in both the Banjima and Nyiyaparli determinations. Nevertheless, both the Banjima and Nyiyaparli determinations represent part of the law that is to be applied in considering the applicants’ contentions about the resolutions at the December 2020 meeting, and the failure to enter the applicants on the Register of Nyiyaparli common law holders.

The Karlka Register

123 Rule 5 of the Karlka Rule Book concerns the Register of Nyiyaparli People and r 5.2 requires Karlka to maintain the Register. By r 5.2(a), the Register must contain the names of all Aboriginal persons who are over 18 years of age and “members of the Nyiyaparli People”. Rule 5.2(a) also requires Karlka to “regularly update” the Register. Rule 5.2(e) makes it clear, if it were not otherwise, that the Register is separate from the register of Karlka corporation members.

124 Under r 5.3(c), there are two methods by which the directors of Karlka will be required to either enter a person in the Register, or remove a person. I infer this rule is applicable after the Register has been created, with the original list of common law holders following a determination of native title. In other words, the rule is intended to operate on an existing register of common law holders. One method for entry on the Register is by reason of a determination of a court of competent jurisdiction (this Court being such a Court): r 5.3(c)(i). The second method is because of a decision by the common law holders “in accordance with an Approved Process” as set out at [72] above.

125 The applicants contend the December 2020 resolutions were not made under an “Approved Process” as defined, because there was a traditional decision-making process that the common law holders should have followed, rather than agreeing and adopting a majority vote by show of hands.

126 As I explain below, I reject the applicants’ contention that the voting by majority show of hands at the December 2020 meeting, as an agreed and adopted process for the purposes of the definition of “Approved Process” was erroneous or invalid. However, I agree with what I understood to be the applicants’ underlying contention: namely that the common law holders’ decision was not made “under traditional Nyiyaparli law and custom”, and that is what Sch 7 of the Nyiyaparli determination requires. The failure was not because of the voting process; it was because of what I find, on the evidence, were the likely factors which governed the approach taken by the common law holders, being contemporary factors.

The applicants’ identity and connection to country

My conclusions about the applicants’ evidence of their identity and connection