Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 1488

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | EMPLOYSURE PTY LTD ACN 145 676 026 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Employsure Pty Ltd is to pay to the Commonwealth within 28 days of the date of this order a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $1 million, in respect of the contraventions the subject of the declaration made by the Full Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCAFC 157.

2. The Court declines to grant any injunctive relief.

3. The parties should consider these orders and the reasons for judgment and, within 14 days hereof, each should file and serve written submissions (not exceeding five pages in length) and adduce any additional evidence on the question of costs, not only costs of the original trial, but also in relation to the question of relief. Each party should within a further seven days file any written submissions in response, not to exceed two pages, and any objections to evidence.

4. The issue of costs of both the trial and hearing on relief will then be determined on the papers and without a further oral hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GRIFFITHS J:

Introduction

1 By orders dated 27 August 2021, the Full Court declared that the respondent (Employsure) contravened ss 18, 29(1)(b) and 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (see Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), through six Google advertisements (the six Google Ads) the subject of the appeal. Those advertisements were displayed in response to Google searches for “fair work ombudsman” and other related search terms over the period from 10 August 2016 to 31 August 2018 (Relevant Period). The contraventions related to representations made in the six Google Ads which the Full Court found represented that Employsure was affiliated with three government agencies (Affiliated Government Representation).

2 The primary reasons of judgment are reported as Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1409 (Employsure PJ). At trial, the ACCC failed in all its claims, which involved claims of contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(b), 29(1)(h) and 34 of the ACL, unconscionable conduct and unfair contract terms. The ACCC appealed only a part of the primary judgment, namely that relating to six Google Ads which appeared in response to Google searches for particular keywords. The appeal was upheld (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 142; 392 ALR 205 (ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1)) and see also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCAFC 157; 392 ALR 452. In the latter judgment, the Full Court granted declaratory relief and remitted other matters to the primary judge.

3 The remitted matters which require determination concern pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 224 of the ACL in relation to the s 29 contraventions, whether injunctive relief should be granted pursuant to s 232 of the ACL, and costs of the trial having regard to the ACCC’s success on the appeal. As will shortly emerge, in the present proceeding, the parties asked the Court to defer determining the issue of costs.

The ACCC’s case summarised

4 The ACCC sought the following orders in the remitted proceeding:

(a) a pecuniary penalty of $5 million in relation to the s 29 contraventions;

(b) in summary terms, an injunction pursuant to s 232 of the ACL restraining the respondent for a period of 5 years from making any representation that it is affiliated with, or endorsed by, in any way, a government agency, when that is not the case; and

(c) regarding costs, Employsure should repay 25% of the costs paid by the ACCC to Employsure in respect of the trial (i.e. an amount of $220,115.44). It should be noted, however, that the parties informed the Court at the commencement of the remitted hearing that they both agreed that costs issues should be deferred until after the other issues were determined. They said that this was primarily because they may need to adduce further evidence at that time. Moreover, they agreed that if the evidence was put before the Court now, it might lead the Court into error. The Court agreed to defer the issue of costs so nothing more needs to be said about that matter at this time.

5 In brief, the ACCC’s submissions in support of the proposed orders (other than costs) may be summarised as follows.

(a) Pecuniary penalty

6 Under s 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL, if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of Pt 3-1 of the ACL (which includes s 29), the Court may order the person to pay such pecuniary penalty, “in respect of each act or omission” by the person to which it applies, as the Court “determines to be appropriate”.

7 The multiple and repeated contraventions relevantly caused consumers erroneously to consider that they were dealing with a government entity. The ACCC acknowledged that, while it is not possible to quantify precisely how many individual contraventions occurred during the Relevant Period, it submitted that a reasonable inference was that there were, at the very least, hundreds of contraventions, if not thousands. This is based on the available “click” and “impression” data, which provides a basis for the Court to infer the number of times that the six Google Ads were viewed by consumers (that is, the number of “impressions”, as opposed to “clicks” which involve persons who view a Google search page then clicking on to a particular Google Ad). For example, the available data indicates that 174,487 views occurred over only part of the Relevant Period (noting, however, that this figure relates to more than just the six Google Ads). If the six Google Ads accounted for only 5% of these total views over a portion of the Relevant Period, the ACCC submitted that the contravening representations would have been conveyed on approximately 8,700 occasions on the known data set. If the 6 Google Ads accounted for 20% of the 174,487 views then there were more than 34,000 individual contraventions on the known data set over a part of the Relevant Period. It may be interpolated at this point that Employsure urged the Court to draw difference inferences from the available data, while also acknowledging the limitations of that data.

8 Each of the (at least) hundreds of individual contraventions in the Relevant Period is capable of attracting a maximum penalty of $1.1 million.

9 The ACCC submitted that, because of the large number of individual contraventions (whether in the order of hundreds, or thousands), there is no meaningful overall maximum penalty. The ACCC contended that these contraventions in the Relevant Period are best conceived of as six “courses of conduct” (being one for each of the six Google Ads). Alternatively, the ACCC submitted that the contraventions should be assessed as involving three courses of conduct, reflecting the three government agencies who figured in the six Google Ads.

10 The ACCC contended that Employsure’s size and profitability, both during the Relevant Period and now, necessitate a penalty of $5 million as a sufficient deterrent.

11 In short, and noting (a) that the setting of an appropriate penalty is multifactorial in nature and involves a process of instinctive synthesis and (b) that in the present matter there are difficulties in identifying the gains to Employsure or the harm to consumers, the ACCC submitted that a global penalty of $5 million for six (or, alternatively, three) courses of conduct for an entity of Employsure’s size and position in the relevant market meets the central objective of deterrence (both general and specific) and is appropriate in all the circumstances.

12 It is desirable to elaborate upon some of the ACCC’s primary contentions.

13 General deterrence: As to general deterrence, the ACCC relied on the following matters. First, it said that there was a need for a penalty which will strongly deter other businesses that may be minded to contravene the ACL in a similar way. Search engine advertising accounts for about 45% of digital advertising spend in Australia. The use of Google Ads is a prevalent form of digital marketing.

14 Secondly, the ACCC warned that if the pecuniary penalty was not set at an appropriate level a perception that civil penalties for gains won by publishing misleading Google Ads to drive up traffic and lure consumers into a particular marketing web could be absorbed as a mere “cost of doing business”. The absence of strong deterrence would give rise to the potential for widespread and significant harm to consumers. It is also important that the penalty be set at an amount that will sufficiently deter businesses from suggesting an affiliation with government in order to increase their customer base, market share and/or website traffic. In its oral address, the ACCC emphasised the significance, in setting an appropriate penalty, of the nature of the Government Affiliation Representation, namely Employsure representing that its advertised free advice was to be provided by a government agency named in the headline.

15 Thirdly, if misrepresentations in the employment relations and work health and safety (WHS) advice industry are not seen to attract sufficient penalties, confidence of business consumers in the industry will be undermined (as may occur in any industry). This will undermine market efficiency, which depends upon business confidence in being given reliable, truthful and accurate information: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 at [95] per Allsop CJ. It will also harm compliant businesses, which may be wrongly assumed to operate in a like manner, so submitted the ACCC.

16 Fourthly, operators in the employment relations and WHS advice industry in Australia — and in comparable business contexts — should be left in no doubt that a strong ACL compliance program, sufficient to pick up and address conduct of the present kind, is not optional. If the burden of a penalty is seen to be less than the cost or effort of such a program, businesses may be tempted to prefer to absorb the risk of being caught over careful compliance with the ACL. Such an approach would, in turn, give contraveners an advantage over those that appropriately incur the costs of compliance, citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [152] per Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ.

17 Fifthly, the ACCC submitted that the penalties imposed on Employsure will be of interest to affected consumers and the public more broadly. The Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) issued a public statement on 4 July 2017 about Employsure following complaints received by the FWO that consumers had been misled into believing businesses such as Employsure were connected or affiliated with the FWO or other government agencies.

18 Specific deterrence: As to specific deterrence, the ACCC pointed to the following matters. First, there are “commercial drivers” for Employsure to encourage potential customers to click on its Google Ads, or call its hotline when searching online for terms like “fair work ombudsman”, “fair work commission”, “fair work australia” and other related search terms. In cross-examination during the liability hearing, Mr Mallet accepted that Google Ads are an “important aspect” of Employsure’s marketing.

19 Secondly, Employsure’s then-existing compliance system was not robust enough to prevent the wrongdoing on this occasion. The six Google Ads were published, and remained published, notwithstanding the approval system that Employsure introduced later in the period.

20 Thirdly, the ACCC claimed that a Google search conducted by it as recently as 28 September 2021 produced Google Ads published on Employsure’s behalf that still have some of the key features identified by the Full Court in finding that the six Google Ads conveyed the Government Affiliation Representation.

21 Nature, extent and duration of conduct: Each of the six Google Ads, being published for between 12 to 21 months in the overall Relevant Period, was found to have conveyed the Government Affiliation Representation, and thereby resulted in contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(b) and 29(1)(h) of the ACL.

22 A $5 million penalty reflects the seriousness of the prolonged contravening courses of conduct. All of the misleading representations had the following in common:

(a) they deprived consumers of the opportunity to make choices free from the misleading representations as to the nature of the service they were being offered; and

(b) they were a result of a specific and successful strategy to increase revenue, undertaken by one of Australia’s largest and growing providers in the employment and WHS advice sector.

23 As already noted, the ACCC acknowledged that it is not possible to quantify precisely how many individual contraventions occurred during the Relevant Period because it is not known precisely how many times each of the six Google Ads were viewed. The wrongdoing, however, is not trivial or fleeting in nature; rather it is prolonged and repetitive.

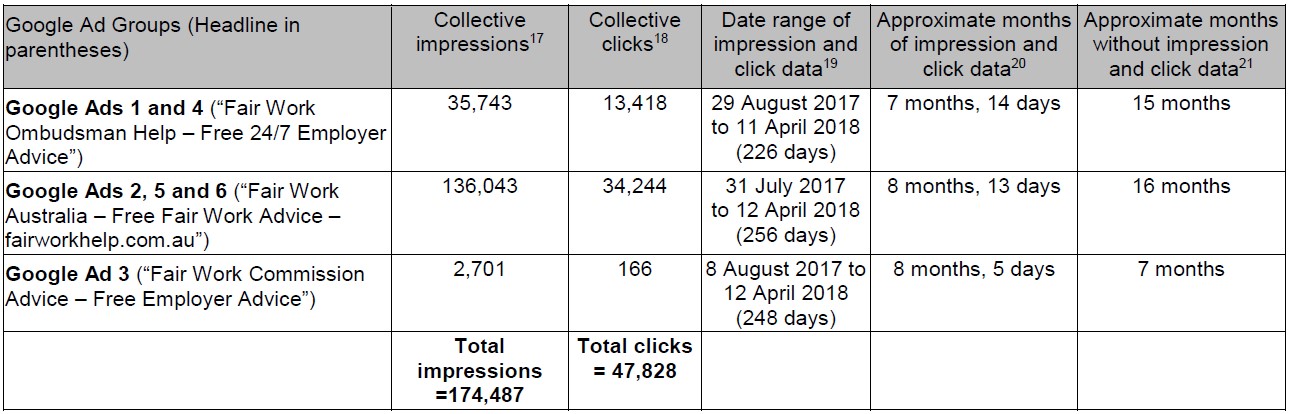

24 Collectively, the six Google Ads were part of Ad Groups that received 174,487 views or “impressions”, and 47,828 “clicks” during a period of seven or eight months, which is a subset of the Relevant Period. The available data (which the ACCC acknowledged was imperfect) is broken down by Ad Groups in the table below (because only aggregated data is available for (a) Ads 1 and 4, and (b) Ads 2, 5 and 6):

25 The ACCC acknowledged that the collective impressions and clicks for each Ad Group are an upper bound for views of the Google Ads for the seven or eight month period because some of the impressions and clicks may have resulted from variations of the Ads which were largely identical to the six Google Ads in the proceeding — in terms of their headline, URL, and first line description — but where the description in subsequent lines of the adcopy, for example, may have varied.

26 According to the ACCC, the conduct involved six different and serious categories of misrepresentations. In particular, as found by the Full Court, the headline of each Google Ad advertised free “help” or “advice” that it associated with a named major government agency in blue font, in the largest typeface and in the most prominent place in the advertisement. The impression created by the headline was furthered because none of the Google Ads made any mention of “Employsure”. The Full Court in ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1) noted at [157] that Google Ads 1, 2, 3 and 4 sometimes appeared in response to search terms being either “Fair Work Ombudsman”, “Fair Work Australia” or “Fair Work Commission” and inferred that by using those search terms, an ordinary or reasonable business owner may be seeking to get information from that government agency.

27 The fact that the “help” or “advice” advertised in each Google Ad was “free” and the text of the URLs immediately below the headlines in the next most prominent part of the Ad also featured text like “fairworkhelp”, were also likely to support the impression that the advice was to be provided by the named government agency, so submitted the ACCC.

28 The seriousness of the conduct is accentuated by the fact that the representations go to the core of Employsure’s business strategy for acquiring new customers. As the Full Court observed at [146]:

The purpose of each Google Ad, placed as it was at the top of the list of search results, was to arrest the attention of a business owner conducting an employment-related internet search and have them contact Employsure by clicking on the hypertext or calling the telephone number (in relation to those advertisements in which a telephone number was provided). …

The ACCC claimed that the contravening conduct was a fundamental part of Employsure’s business operations.

29 Role of Employsure’s management and deliberateness of the marketing strategy: Mr Mallett, Employsure’s former Managing Director, gave evidence during the liability hearing that he personally oversaw Employsure’s marketing activities from 2010 and over the Relevant Period, and engaged with experts to assist with Employsure’s marketing and advertising. In cross-examination, Mr Mallett admitted that although he did not design the Ads, he was involved at the level of “setting the strategy”. The strategy included not referring to Employsure in the Google Ads. Mr Mallett noted in cross-examination there was a risk that Employsure would lose prospective leads if they included “Employsure” in the Google Ads.

30 The ACCC submitted that the marketing strategy was significant, citing Employsure (FFC No 1) at [151].

31 The ACCC acknowledged that the evidence does not identify precisely who drafted and authorised the six Google Ads. However, in addition to Mr Mallett’s role in setting the strategy, it is also clear that Employsure’s Senior Digital Marketing Manager, Mr Rocky Vu, was heavily involved in the day-to-day design and monitoring of Employsure’s Google Ads. The staff involved in the drafting and publication of Google Ads during the Relevant Period were all in senior positions (holding managerial positions such as ‘Digital Performance Manager’, ‘Senior Digital Manager’, ‘Marketing and Events Manager’, ‘Head of Digital’, and ‘Digital Performance Specialist’). Further, Employsure did not have a formal Google Ads drafting and approval process in place at the time the relevant Google Ads were drafted and activated. It is enough to observe that the serious and basic falsity of the representations was readily avoidable and that a corporation of Employsure’s size, status and resources should have had compliance arrangements in place to prevent the wrongdoing at the outset. That it occurred at all, and continued for the period it did, points to a most serious compliance failure, so submitted the ACCC.

32 Moreover, following the commencement of the ACCC’s investigation in December 2017, it was not until December 2018 that Employsure admitted that there were “areas of improvement needed” in its compliance framework.

33 Benefits to Employsure: While precisely unquantifiable, the ACCC contended that Employsure obtained commercial benefits from making the representations. Indeed, the “Premier 1 channel” of Employsure’s marketing plan is recorded in Employsure’s internal documents as being the biggest source of leads — and ultimately contracts — for Employsure in the Relevant Period. Further, the contravening representations may have resulted in Employsure gaining a competitive advantage and establishing its prominence. This form of commercial benefit is not readily quantifiable, but it is not likely to have been insubstantial, including given the significance of its Google Ads campaign to its sales figures.

34 Amount of loss or damage caused: The Government Affiliation Representation likely caused harm to consumers who were exposed to it and who otherwise could have, for example, sought assistance directly from a government agency — at no cost — like the Fair Work Ombudsman. Indeed, such consumers may have:

(a) been denied the opportunity to obtain advice from a government agency, including to receive indemnified advice;

(b) disclosed confidential commercial information and committed to a meeting with Employsure that they may not have otherwise done so had they been aware that Employsure was a private entity unaffiliated with the government; and

(c) entered into a contract with Employsure under the mistaken belief that Employsure was, or was affiliated with or endorsed by, a government agency, including in circumstances where they could have obtained the advice they were seeking free from the government.

35 While the amount of this loss is not readily or precisely quantifiable, the ACCC urged the Court to infer that it is unlikely to be insubstantial given the extent of the contraventions. Employsure’s business model is to require employers to pay a fixed fee subscription, as opposed to paying a fee for service, and then be entitled to access Employsure’s products and services as required. During the Relevant Period, Employsure entered into 14,458 contracts for its services, an average of 88% of which were with small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs). The average contract value was $21,224. During the Relevant Period, the majority of contracts were also automatically renewed, for the same amount or higher.

36 Size of contravener and financial position: Employsure is a specialist workplace relations consultancy, which advises employers and business owners regarding the requirements of workplace relations and WHS legislation and provides products and services and operates nationally, having offices in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth. It is a large and well-resourced entity.

37 Customer base: As at August 2018, Employsure had approximately 18,700 clients, including SMEs and large employers (with more than 20 employees). As at June 2021, Employsure had approximately 23,500 clients.

38 Earnings during the Relevant Period: In the Relevant Period (August 2016 to August 2018), Employsure’s:

(a) total revenue was $217,612,258;

(b) gross profit was $172,065,852; and

(c) profit after tax was $35,116,457.

39 In the last financial year, Employsure’s:

(a) total revenue was $148,043,488;

(b) gross profit was $119,701,391; and

(c) profit after tax was $24,025,036.

40 The ACCC submitted that Employsure’s apparent financial strength and prominent position require that a substantial penalty be imposed. The proposed penalty represents approximately 3.5% to 4.5% of Employsure’s annual turnover and gross profit, respectively, in the last financial year, and approximately 2.5% to 3% of Employsure’s revenue and gross profit, respectively, in the Relevant Period.

41 Growth post contravening conduct: Furthermore, as evidenced in part by its increased customer base (being an increase of about 26%), Employsure has grown substantially since the Relevant Period. Indeed, Employsure’s own website states that it “is one of the fastest-growing professional service companies in Australia”. Employsure itself represents that it is one of Australia’s largest providers of workplace relations advice. In the financial year 2017-18, Employsure’s revenue was approximately $116 million, however, in the financial year 2020-21, its revenue increased to approximately $148 million (being a 28% increase).

42 Cooperation: Cooperation with a regulatory body in the course of investigations and subsequent proceedings can properly reduce the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. The reduction reflects the fact that such cooperation, for example, frees up the regulator’s resources and thereby increasing the likelihood that other contraveners will be detected and thus facilitates the course of justice: see, for example, Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 252 CLR 482 (FWBII) at [46] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293-294 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; ATPR 41-993 at [55] per Branson, Sackville and Gyles JJ.

43 The ACCC submitted that, while Employsure provided limited cooperation in the form of a Statement of Agreed Facts and produced some information voluntarily to the ACCC during its investigation, this cooperation was minimal, the proposed penalties accommodate it, and no further deduction is required. The ACCC added that Employsure had contested the proceeding. While Employsure was on notice from the ACCC in late 2017 about concerns regarding its Google Ads, it did not change the format of its Google Ads more generally until after proceedings had been instituted in December 2018 by inserting the word “Employsure” into the text of its Google Ads in 2019. It was also aware of concerns raised by the FWO in relation to its Google Ads from mid-2016. The FWO engaged with Employsure about its concerns of possible intellectual property infringements and misleading conduct from early 2016, including in relation to Employsure’s Google Ads. Employsure made some changes to its broader marketing strategy in response to FWO concerns, but continued to publish the six Google Ads which have now been found to have contravened the ACL. Moreover, as recently as October 2021, Employsure published a Google Ad in which the first three words in the headline were “Fair Work Commission”.

(b) Injunctive relief

44 In addition to the penalty sought, the ACCC sought an injunction under s 232 of the ACL in the following terms:

An order restraining Employsure, whether by itself, its directors, officers, employees, consultants, agents or otherwise howsoever, for a period of five years from the date of this order, in connection with the supply, or possible supply, and marketing of its advisory services to business owners, from making, or aiding, abetting, counselling, or procuring, or being directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in or party to the making of a representation, in trade or commerce, that Employsure is, is affiliated with, or endorsed by, in any way, a government agency, when that is not the case.

45 Injunctive relief is sought on the basis that it will serve the public interest and protect consumers viewing Employsure’s ongoing Google Ad campaigns and other forms of marketing, by restraining Employsure from a repetition of similar conduct. This is in circumstances where Employsure continues to refrain from using the word “Employsure” upfront in the headline of all of its Google Ads and use of language associated with government agencies (e.g. “Fair Work” or “Fair Work Commission”) in the headline of its Google Ads, and thus continues to publish Google Ads of a similar nature.

Employsure’s case summarised

46 In circumstances where Employsure’s submissions on relief and costs have been substantially adopted in rejecting the ACCC’s case, I will not separately summarise those submissions here at any length. They are reflected in the reasons I will give below for declining to make the orders sought by the ACCC. It may assist, however, if I set out a very broad outline of Employsure’s position on pecuniary penalty.

47 Employsure accepted that a penalty should be imposed reflecting the findings of the Full Court and, in particular, to achieve the objectives of general and specific deterrence. Employsure submitted that an appropriate penalty would be one within the range of $500,000 to $750,000. In brief, Employsure’s contentions on pecuniary penalties may be summarised as follows.

48 First, the maximum statutory penalty is $1.1 million per contravention throughout the relevant period.

49 Secondly, Employsure submitted that the findings of the Full Court (and of this Court), the technical context, and the manner in which the ACCC pleaded and ran its case, all support a characterisation of the contraventions as comprising a single course of conduct. Acceptance of this characterisation does not set a penalty cap of $1.1 million, but it can inform an appropriate analysis.

50 Thirdly, Employsure submitted that the best available evidence is that the benefit realised by Employsure — which can be used as a proxy for loss or damage — may have been $53,820 per annum, or perhaps $107,640 in total over the Relevant Period. Accordingly, the amount of loss or damage caused by the six Google Ads is likely to be small: s 224(2)(a) of the ACL. That is especially so where the evidence suggested that consumers would have understood that Employsure was not affiliated with the government by the time they entered into any contract with Employsure, so it submitted.

51 Fourthly, Employsure has not previously been found by a court to have engaged in any similar conduct: s 224(2)(c) of the ACL. That factor operates in mitigation in ascertaining an appropriate penalty.

52 Fifthly, the conduct did not involve a deliberate marketing ploy: Employsure PJ at [253]. Employsure was not deliberately trying to lure people away from the services offered by agencies such as the FWO or the Fair Work Commission (FWC): ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1) at [63] and Employsure PJ at [295]. The breach was an inadvertent one. That, again, Employsure submitted, is a mitigating circumstance, when assessing all of the circumstances in which the conduct took place: s 224(2)(b) of the ACL.

53 Sixthly, the factors identified by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 521; (1991) ATPR 41-076 also point to a penalty at the mid-lower end of the available spectrum. For example, the involvement of senior management was limited, and while the six Google Ads were misleading, there was nonetheless a culture of compliance, which culture has improved since the Relevant Period.

54 Seventhly, Employsure submitted that the significance to be ascribed to specific deterrence is reduced by the fact that the six Google Ads have not been run since 2018, the non-deliberate nature of the conduct, and Employsure’s improved compliance systems. The risk of Employsure contravening again is low. And, having regard to the best estimate of the profits derived from the contravening conduct, the idea that the proposed penalty could be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business is a remote one. General deterrence requires careful attention to the character of the contravening conduct, including recognition of its narrow character.

Consideration and determination

(a) Relevant statutory provisions

55 It is desirable to set out the relevant parts of ss 224 and 232 of the ACL as in force at the relevant time:

224 Pecuniary penalties

(1) If a court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened any of the following provisions:

…

(ii) a provision of Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices);

…

the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth, State or Territory, as the case may be, such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the court determines to be appropriate.

(2) In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

(3) The pecuniary penalty payable under subsection (1) is not to exceed the amount worked out using the following table:

Amount of pecuniary penalty | ||

Item | For each act or omission to which this section applies that relates to ... | the pecuniary penalty is not to exceed ... |

… | . | |

2 | a provision of Part 3-1 (other than section 47(1)) | (a) if the person is a body corporate—$1.1 million; or (b) if the person is not a body corporate—$220,000. |

… | ||

…

232 Injunctions

(1) A court may grant an injunction, in such terms as the court considers appropriate, if the court is satisfied that a person has engaged, or is proposing to engage, in conduct that constitutes or would constitute:

(a) a contravention of a provision of Chapter 2, 3 or 4; or

…

(2) The court may grant the injunction on application by the regulator or any other person.

…

(4) The power of the court to grant an injunction under subsection (1) restraining a person from engaging in conduct may be exercised:

(a) whether or not it appears to the court that the person intends to engage again, or to continue to engage, in conduct of a kind referred to in that subsection; and

(b) whether or not the person has previously engaged in conduct of that kind; and

(c) whether or not there is an imminent danger of substantial damage to any other person if the person engages in conduct of that kind.

…

(b) Some legal principles summarised`

56 The parties were in substantial agreement regarding the relevant legal principles. Their dispute related to the application of those principles to the particular circumstances of this case. The principles may be summarised as follows.

(i) Deterrence as the central purpose

57 In FWBII, the High Court confirmed that the primary purpose of civil pecuniary penalties is to secure deterrence. In contrast to criminal sentences, civil penalties are not concerned with retribution and rehabilitation but are “primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”: at [55], and see also [59] and [110].

58 The High Court affirmed and applied a long line of authority, including the well-known statements of French J (as his Honour then was), in CSR. His Honour there referred to at [52,152] the “primacy of the deterrent purpose in the imposition of penalty” and described deterrence, both specific and general, as the “principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties”. Accordingly, the various penalty factors (the French factors) were to be considered in setting a penalty of “appropriate deterrent value”.

59 The importance of deterrence in granting relief for breaches of the ACL has been emphasised in other cases:

(a) The Full Court has explained the need to ensure that the penalty in such cases “is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business” and will deter them “from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention”: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 24 at [62] and [63] per Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ.

(b) The High Court, applying the observations in Singtel Optus, has referred to the “primary role” of deterrence in assessing the appropriate penalty for contraventions where commercial profit is the driver of the contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at [64]-[66] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ.

(c) The Full Court has emphasised that the “critical importance of effective deterrence must inform the assessment of the appropriate penalty”: Reckitt at [153]. The Full Court explained that “the greater the risk of consumers being misled and the greater the prospect of gain to the contravener, the greater the sanction required, so as to make the risk/benefit equation less palatable to a potential wrongdoer and the deterrence sufficiently effective in achieving voluntary compliance”: at [151] and see also [57], [148]-[153], [164] and [176].

(d) As Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ said recently in Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 177; 282 FCR 580 at [100] (after referring to the French factors):

The setting out of such factors is of assistance, however, not only in capturing relevant matters, but also in providing the necessary focus: that it is to the contravention in question to which the penalty is directed. This is not because there is a retributive principle that there must be equality between act and punishment for the crime, but because the contravention (and its nature, quality and seriousness) must be considered and understood such that the appropriate penalty be imposed to deter such a contravention in the future. The features of the contravention that can be seen to be relevant to its seriousness will find their place, not in the operation of some freestanding retributively-derived principle of proportionality, but in understanding the degree of deterrence necessary to be reflected in the size of the penalty: Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53; 260 FCR 68 at 86 [71]. Importantly, however, the imposition of an appropriate penalty, given the object of deterrence, does not authorise and empower the imposition of an oppressive penalty that is one that is more than is appropriate to deter a contravention of the kind before the court. The primacy of the object of deterrence does not unmoor or untether the consideration of appropriateness from the circumstances and the contravention before the court and what is reasonably necessary to deter contraventions of the kind before the court. Notions of reasonableness inhering in statutes as part of the principle of legality would deny a construction that sought to do so, at least without the clearest language. Any such construction would entail the risk of personal predilection, not principle, guiding the imposition of penal sanction with necessary attendant problems of inconsistency, a consequence not to be attributed to Parliament. As Burchett and Kiefel JJ said in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293:

As Smithers J emphasised in Stihl Chain Saws (at 17,896), insistence upon the deterrent quality of a penalty should be balanced by insistence that it “not be so high as to be oppressive”. Plainly, if deterrence is the object, the penalty should not be greater than is necessary to achieve this object; severity beyond that would be oppression.

(ii) Imposing penalties for multiple contraventions

60 Each time a consumer viewed any one of the six Google Ads, there was a separate contravention of the ACL under ss 29(1)(b) and 29(1)(h): ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1) at [177] and [178]. Three key principles are relevant when imposing penalties for multiple contraventions.

61 Separate penalties should not be imposed for the same wrongful act: Section 224(4) of the ACL provides that where conduct constitutes a contravention of “2 or more provisions” the person is not liable to more than one penalty “in respect of the same conduct”. Such provisions apply to conduct which is truly “the same”, not merely similar, closely related or repeated, and can therefore be differentiated from the “course of conduct” principle (see, for example, Australian Energy Regulator v Snowy Hydro Limited (No 2) [2015] FCA 58 at [107] per Beach J; Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Hallmark Computer Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 678; 334 ALR 677 at [28] per Buchanan J).

62 While each contravention may breach both ss 29(1)(b) and (h) of the ACL, Employsure would only be exposed to one pecuniary penalty for conduct founding both contraventions.

63 Contraventions grouped as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: Separate contraventions arising from separate acts should ordinarily attract separate penalties. However, a different principle may apply where separate acts, giving rise to separate contraventions, are nonetheless so inextricably interrelated that they should be viewed as one multi-faceted “course of conduct”. It is well-established that this provides one way of avoiding double-punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing.

64 The question whether certain contraventions should be treated as a single course of conduct is a factual enquiry in all the relevant circumstances of the case. It is a “tool of analysis” which can, but need not, be used in any given case: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 269 ALR 1 at [39]-[42] per Middleton and Gordon JJ; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; 258 FCR 312 at [421]-[424] per Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ and Singtel Optus at [53]. The principle has been applied consistently in imposing penalties for breaches of the consumer law, particularly when the number of legally distinct breaches is large: Coles Supermarkets at [82]-[85] and [103]; Reckitt at [139]-[145] and [157]; TPG Internet at [60]-[61] and Singtel Optus at [51]-[55].

65 The “totality” principle: Where multiple separate penalties are to be imposed upon a particular wrongdoer, the totality principle requires the Court to make a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole. It will not necessarily result in a reduction. However, in cases where the Court believes that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too low or too high, the Court should alter the final penalties to ensure that they are “just and appropriate” (see, for example, Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan [2008] FCAFC 70; 168 FCR 383 at [42] per Stone and Buchanan JJ and Clean Energy Regulator v MT Solar Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 205 at [80]-[83] per Foster J).

66 I have applied the totality principle here, with a view to ensuring that Employsure is not punished twice for common contraventions. Application of the totality principle should ensure that, overall, a sentence or penalty is appropriate and that the sum of the penalties imposed for several contraventions does not result in the total of the penalties exceeding what is proper having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53 per Goldberg J).

67 As Middleton and Gordon JJ stated in Cahill at [39] (emphasis in original):

… The principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality” and that is necessarily a factually specific enquiry. …

(c) Determining an appropriate penalty amount

68 The following principles guide the determination of an appropriate penalty amount.

69 Statutory maximum: In Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357 at [31], a plurality of the High Court (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) held that:

… careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

The same considerations apply in relation to civil penalties: Reckitt at [154]-[155] and Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53; 260 FCR 68 at [55] per Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ.

70 During the Relevant Period the maximum penalty for contraventions by a company of a provision in Pt 3-1 of the ACL was $1.1 million: item 2 of s 224(3). This $1.1 million maximum applies to each of Employsure’s individual contraventions. However, given that Employsure engaged in numerous individual contraventions during the Relevant Period, the ACCC acknowledged that there “is no sensible aggregate maximum penalty” in this case (see Reckitt at [156]-[157]). I accept the ACCC’s submission that the course of conduct principle therefore provides a more useful analytical tool through which to assess the proportionality of a pecuniary penalty (see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees [2020] FCA 1306 at [130] per Yates J and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Viagogo AG (No 3) [2020] FCA 1423 at [120]-[122] per Burley J).

71 Identifying the various factors: Section 224(2) of the ACL requires the Court to have regard to “all relevant matters” in determining the appropriate penalty. It specifies a number of (non-exhaustive) statutory factors: the nature and extent of the wrongdoing, any loss or damage suffered, the circumstances of the wrongdoing and any Court findings as to prior similar conduct. Numerous other relevant factors have been identified and applied, most of which have their genesis in the French factors set out in CSR. In the consumer law context, a modified form of that list has been developed: see Singtel Optus at [37] and Coles Supermarkets at [8]. While not a “rigid catalogue”, the factors include:

(a) the size of the contravener;

(b) whether the wrongdoing was deliberate or covert;

(c) the role of senior management;

(d) whether the contravener has a culture of compliance; and

(e) any relevant prior conduct.

72 It may not be necessary, or even helpful, to address each factor seriatim. This is particularly so given the significant overlap between the statutory factors and various of the other factors identified in Singtel Optus. The critical requirement is that all relevant matters are in fact addressed in substance, transparently and having regard to the individual circumstances of the particular case. The list of relevant factors should not be approached in a mechanical or formulaic way. As Wigney J observed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visa Inc [2015] FCA 1020 at [83], this “would impermissibly constrain or formalise what is, at the end of the day, a broad evaluative judgment”.

73 Synthesising the factors: The reasoning process in deriving a penalty figure having regard to the various relevant factors is conventionally described as one of “instinctive synthesis”, as explained by the High Court in Markarian. The process requires a weighing together of all relevant factors, rather than a sequential, mathematical process (such as starting from some pre-determined figure and making incremental additions or subtractions for each separate factor). The High Court emphasised the importance of ensuring the reasoning process is transparent.

74 I respectfully agree with Perry J’s observations in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2015] FCA 1090 at [23] (emphasis in original and denotes a defined expression):

The process of arriving at the appropriate sentence for a criminal offence involves an intuitive or instinctive synthesis of all of the relevant factors: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 (Markarian) at 373-374 [35]-[37] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ). The same approach has been held to apply to civil penalties under the ACL and its predecessor provision in the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth): TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 190; (2012) 210 FCR 227 at 294 [145] (the Court); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 274 at [103] (Gordon J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330 (ACCC v Coles) at [6] (Allsop CJ). Instinctive synthesis was helpfully described by McHugh J in Markarian as meaning “the method of sentencing by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case” (at 378 [51]). In short, as Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ explained in Wong v The Queen [2001] HCA 64; (2001) 207 CLR 584 at 611 [75] (in a passage approved in Markarian at 374 [37]), “the task of the sentencer is to take account of all of the relevant factors and to arrive at a single result which takes due account of them all”.

A. Pecuniary penalty

75 For the following reasons, I consider that an appropriate pecuniary penalty in this case is $1 million.

(a) A single course of conduct

76 In my view, characterising Employsure’s contravening conduct as a single course of conduct conforms with the findings of the Full Court (and this Court), the technical context, and the manner in which the ACCC pleaded and ran its case below.

77 I do not accept the ACCC’s position that either six or three courses of conduct are involved. It should be noted, however, that, in oral address, Mr Owens SC (who appeared for the ACCC together with Ms Forrester) said that the significance of the dispute between the parties on this subject matter “shouldn’t be overstated”, because even if there was a single course of conduct, the penalty which could be imposed could exceed the $1.1 million penalty for an individual contravention. Mr Owens SC added that the fewer courses of conduct, “the greater the diversity and the richness of the individual contraventions contained within it”.

78 It is desirable to elaborate on some primary matters of principle on the issue of course of conduct (see generally Coles Supermarkets at [20] per Allsop CJ).

79 As noted above, rather than imposing separate penalties for each technically available contravention, the Court may, in its discretion, apply the “course of conduct” or “one transaction” principle. That principle recognises that, where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. Its application requires careful identification of “the same criminality”, which is necessarily a factually specific enquiry: see Cahill at [39]-[43] per Middleton and Gordon JJ). A court is not compelled to utilise the principle because “[d]iscretionary judgments require the weighing of elements, not the formulation of adjustable rules or benchmarks”: see Royer v Western Australia [2009] WASCA 139 at [28] per Owen JA. Where utilised, the principle is almost always applied to separate events constituting contraventions, which have occurred over a period of time, as is the case here. Importantly, however, use of the principle does not convert the maximum penalty for one contravention into the maximum penalty for the course of conduct as a whole.

80 The Courts’ findings: The Full Court found, and declared, that each of the six Google Ads conveyed the same misleading representation of affiliation with, or endorsement by, a government agency: ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1) at [175]-[179] and order 1 of 27 August 2021. That will not always be the case in proceedings brought under ss 18 and 29 of the ACL — different representations may exhibit different misleading characteristics. For example, in Coles Supermarkets, a representation “Baked Today” was found to convey a temporal representation that was false; while the representation “Baked Fresh” (and cognates) conveyed a representation about ingredients that was false. Here, however, the six Google Ads were all published on the same medium and were found to convey the same representation, on the basis of the same statements and omissions, albeit with reference to three government agencies: ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1) at [150].

81 A group of representations can constitute a single course of conduct, even where they are factually separate and independent representations. For example, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 797; 136 ACSR 603 at [64], Perry J agreed with the parties that the preferable course was to treat two separate sets of representations – the No Refund Representations and the Exclusion of ACL and Limitation of Liability Representations – as a single course of conduct.

82 In contrast, in Oticon, a case which the ACCC relied upon in the present proceeding, Perry J concluded at [55] that there were two courses of conduct. The first course of conduct related to Oticon’s decision to publish the first contravening advertisement. The second course of conduct stemmed from the fresh and separate decision by Oticon to publish the second Oticon advertisement. Similar reasoning was applied to the second respondent. It is evident from [55] of Oticon that in assessing penalty by reference to these two courses of conduct, her Honour also acted in accordance with the parties’ agreed position.

83 In Viagogo AG at [120]-[122], Burley J found that four misleading or deceptive representations published on online advertisements and various parts of a website constituted four distinct courses of conduct.

84 What each of these cases demonstrate is that analysis of the course of conduct principle is a very fact-specific exercise.

85 In the present case, there is no significant legal or factual separation in the six Google Ads. Each conveys the Government Affiliation Representation, albeit by reference to three government agencies (and noting that two of those agencies were effectively the same, because Fair Work Australia was replaced by the FWC). Furthermore, all six Google Ads were published on the same medium (unlike the position in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pental Limited [2018] FCA 491 at [60]-[67] per Lee J or Viagogo AG at [120]-[122] per Burley J).

86 The technical context: The technical context sits uncomfortably with the ACCC’s submission that the six Google Ads constitute either six or three courses of conduct. I accept Employsure’s submission that at all times, it was ultimately a matter for Google, through operation of its proprietary algorithms, to determine whether a particular Google Ad was displayed, as well as the precise manner in which it was displayed, taking into account a range of different matters. Employsure played a limited role in these outcomes. The ACCC did not contest these matters.

87 The manner in which the ACCC ran its case: The suggestion of six (or three) courses of conduct is inconsistent with how the ACCC ran its case below. In its Concise Statement, the ACCC identified the six Google Ads as “examples” of advertisements that gave rise to the single pleaded Government Affiliation Representation. The making of the Government Affiliation Representation was said to arise “by its use of Google Ads”, which involve use of different words and affiliations with three different government agencies.

88 In its submissions below at the liability hearing, the ACCC contended that the same representation was conveyed by each Google Ad. So too, it submitted that “the Government Affiliation Representation was conveyed by 7 Google Ads”.

89 I accept Employsure’s submission that the impugned Google Ads are appropriately viewed as a series of advertisements that had the common feature of conveying an affiliation with a government agency, and therefore should be treated as a single course of conduct.

(b) Instinctive synthesis

90 It is well established that the process of imposing a penalty requires an “instinctive synthesis”: Markarian at [37]. It is also uncontroversial that this does not excuse the Court from the obligation to engage in a transparent reasoning process. The two are not antonyms: Markarian at [36]. The decision to penalise must be reasoned and not merely a concatenation of factors.

(c) General and specific deterrence

91 There is no contest as to the role of deterrence in imposing a penalty. The principal, and perhaps the only, object of the penalty is to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the ACL: CSR at [40] per French J. However, any penalty ought not be so disproportionate as to be oppressive and the character of the contravention must be the central determinant of the penalty taking into account any ameliorating circumstances: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 146; 161 FCR 513 at [60] per Moore, Dowsett and Greenwood JJ and Pattinson at [100] per Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ.

92 Specific deterrence directs attention to whether the person is likely to contravene again, and to whether the penalty is such as not merely to be a cost of doing business. General deterrence looks to the capacity of the penalty to act as a reminder to the community of the consequences of the contraventions.

93 Although the parties generally agreed on these principles, they disagreed on their application to the particular circumstances here.

94 I find that the need for specific deterrence in the present case is very low. The contravening conduct was not deliberate. Indeed, Mr Owens SC candidly (and properly) acknowledged that Employsure “was a company that wanted to comply with its legal obligations”. Compliance systems within Employsure have been improved: see [118] below. Mr Owens SC properly acknowledged that he did not claim that there was any deficiency in Employsure’s current compliance system. The contravening conduct should not happen again. Much of the work of specific deterrence has already been achieved, including by the resources which Employsure has had to expend in defending the proceedings. I also accept Employsure’s submission that the mere fact that the use of Google Ads remains prevalent, and the nature of “the work health and safety advice industry”, do not significantly advance questions of deterrence.

95 The ACCC submitted that “commercial drivers” remain in place which may cause Employsure not to maintain proper compliance and vigilance. I reject that submission. It is inconsistent with the undisputed fact that the contraventions were inadvertent and the evidence concerning the improved compliance measures which Employsure has put in place. There is no evidentiary basis to justify any concern that Employsure needs to be reminded by a higher pecuniary penalty in the amount sought by the ACCC so that it and others do not view the contravening conduct as an acceptable cost of doing business.

96 As to general deterrence, the Court is required to set a penalty which deters other corporations from engaging in similar contravening conduct. This necessarily requires close attention to be given to the character of that conduct. I accept the ACCC’s submission that it is relevant to take into account the need to set a pecuniary penalty, with a view to general deterrence, so as to emphasise to start-up or growth companies (as Employsure was during the Relevant Period) to ensure that their compliance systems are adequate to meet their legal obligations. In my view, however, a penalty of $5 million far exceeds that which is appropriate in order to achieve this and other relevant objectives.

97 For completeness, I should also state that I consider that the fact that, on 4 July 2017, the FWO published a press release in which it stated that it had received complaints relating to a website at the address www.fairworkhelp.com.au and telephone advisory services operated by Employsure, does not help answer the question as to whether any particular penalty will remind the community of the consequences of contravening the ACL. The press release made clear that the services provided by the FWO were provided free of charge and included assistance via its info line and the resources available through its website. Significantly, as found in Employsure PJ at [176] and [177](c), in response to the FWO’s concerns, Employsure added a further statement to its “fairworkhelp” landing page that it had no affiliation with any Government agency, including the FWO. This was done in direct response to the FWO’s concerns.

(d) Nature and extent of the conduct, and the circumstances in which it took place

98 The nature and extent of the contravening conduct, and the circumstances in which the conduct took place, are set out in Employsure PJ and ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1). The following key points should be noted.

99 First, the ACCC submitted that consumers considered that they were dealing with the government and were thereby deprived of the ability to make choices. The ACCC also emphasised the need to bring to account in assessing penalty the fact that the six Google Ads played an important role in enticing potential clients into Employsure’s “marketing web”. The evidence demonstrates, however, that by the time customers entered into any contractual arrangement with Employsure, they ought to have been well aware of the fact that Employsure was not associated with the government. This evidence is reflected in the findings made in Employsure PJ relating to Employsure’s practices (see Employsure PJ [86], [175], [176], [177] (c)-(d) and [319](h)).

100 That is not to contest the finding of the Full Court to the effect that the six Google Ads misled, or were likely to mislead, consumers. However, by the time a consumer visited a landing page, had a telephone call with a business sales consultant, and had a meeting with a business development manager, Employsure’s internal practices required that the consumer be told that the services were provided by Employsure, and that it was not affiliated with or endorsed by the government (accepting, as I do, Mr Edmund Mallett’s evidence in his affidavit dated 28 October 2021 at [30], [35], [39](d) and [46]). I accept, however, the ACCC’s submission that even if customers were disabused by the time they signed a contract with Employsure, Employsure’s misleading conduct gave it a marketing opportunity which it otherwise may not have had. The evidence does not indicate, however, that that opportunity was particularly profound.

101 Secondly, in support of its proposed pecuniary penalty amount, the ACCC focussed on the number of “impressions” or “views”. The significance of those matters should not be overstated. An “impression” or “view” tells one only that a Google Ad was displayed in response to a search, in some manner, on the screen of a device. It says nothing about whether any consumer read or even noticed that Google Ad. Also, as Mr Owen SC acknowledged, some impressions and clicks on the six Google Ads may have involved people who did not fall within the relevant class of consumers. I accept Employsure’s submission that the more important guide is the number of “clicks”, which signals that a person has embarked on a further stage of enquiry based on the Google Ad. However, even then it is necessary to consider the number of people who took some positive step beyond a mere click, about which the evidence is inexact.

102 Thirdly, contrary to the ACCC’s submission, I consider that the fact that substantial sums of money are spent by businesses on Google Ads, and the nature of the industry in which Employsure operates, do not, without more, justify an increase in the penalty that might otherwise be ordered.

103 Fourthly, contrary to the ACCC’s submission, the features of Employsure’s current Google Ads are quite different to those that were the subject of the Full Court’s findings. In particular, the word Employsure appears at a prominent place in those advertisements (cf ACCC v Employsure (FFC No 1) at [150](b) and [156]). Significantly, at the hearing on relief, the ACCC disavowed any contention that Employsure’s current Google Ads are misleading. There is no evidentiary basis for any concern that Employsure’s contravening conduct is continuing.

104 Fifthly, I consider that there is no evidentiary foundation for the ACCC’s claim that the six Google Ads amounted to a specific and successful strategy to increase revenue. As discussed below, the evidence (with all its deficiencies) suggests the profit generated may have been modest. The number of clicks on the relevant Google Ads (or slight variations thereof) represent approximately 1.01% of clicks on all Employsure Google Ads. While Google Ads are a central component of Employsure’s advertising, Employsure also secures new customers through a range of channels apart from Google Ads.

105 Sixthly, it is relevant to take into account the period of time over which the contravening conduct occurred. According to the declaration made by the Full Court that conduct occurred over slightly more than a two year period. In determining penalty, however, I think it also relevant to take into account that the evidence before the Court in respect of the hearing on relief indicated that the “impressions” or “clicks” on Employsure’s Google Ads (including but not limited to the six Google Ads) related to a period of approximately ten months during the Relevant Period. The parties were agreed that this data was somewhat imprecise but the ACCC did not claim that there was any evidence which indicated that the six Google Ads were accessed by anyone outside that ten month period.

106 Seventhly, I accept the ACCC’s submission that, in setting an appropriate pecuniary penalty, it is relevant to take into account the subject matter of the contravening conduct which, in effect, involved Employsure passing itself off as having an affiliation with one or more of the three government agencies. This involved persons in the relevant class who search the internet looking for a free government advice service could be misled by the six Google Ads and result in them contacting Employsure, which presents Employsure with a potentially effective marketing opportunity which it otherwise may not have had. I respectfully consider, however, that the ACCC has overstated the availability of an indemnity where wrong advice is provided by a government agency. On the evidence presented, the only one of the three government agencies who provided such an indemnity was the FWO. The FWO’s indemnity was limited to an assurance that it would not pursue a penalty where a person acted upon the FWO’s incorrect advice about minimum wages or conditions of employment. There is no reason to doubt that Employsure would also be liable if persons acted to their detriment in reliance upon its advice and in circumstances giving rise to a legal cause of action.

(e) Amount of loss or damage

107 The ACCC challenged Employsure’s claim that the benefit it determined from the contravening conduct was a proxy for the loss or damage produced by that conduct. As noted above, both parties were agreed that the amount of loss or damage suffered cannot be quantified with any precision. Each party was also critical of the other party’s methodology, while acknowledging the unavoidable imprecision of the task. Those criticisms may have had some force and I find that no decisive estimate can be made of the amount of loss or damage or the benefit to Employsure. I consider, however, given that consumers would likely have been disabused of any misapprehension by the time they contracted with Employsure, any loss is likely to have been relatively modest.

108 Employsure contended that the benefit to it from the contravening conduct could be calculated by what it called a “click to contract” calculation. The total client list of Employsure as at 30 May 2019 was 20,500: Employsure PJ at [157]. At the time, Employsure generated an annual profit of approximately $24 million. Assuming that this profit is spread evenly across Employsure’s clients, that results in a profit of approximately $1,170 per client. On that basis, the benefit achieved by the contravening conduct is in the order of $53,820 per annum (being the 46 new clients resulting from the six Google Ads multiplied by the average profit). Employsure contended that the total benefit secured by the contravening conduct over the period of the contravening conduct (of approximately two years) may therefore be in the order of $107,640.

109 The ACCC rejected a number of the assumptions underlying Employsure’s calculation. In particular, Mr Owens SC emphasised that the ACCC denied the assumption that the six Google Ads were no more or less successful than other Google Ads used by Employsure. Mr Owens SC pointed to “click to call” data provided by Employsure to the ACCC which suggested that there were approximately 9000 “click to calls” during the Relevant Period for the six Google Ads, as opposed to a figure of 743 reached on Employsure’s calculation.

110 Using the “click to call” data for the six Google Ads, and calculations deriving from Mr Mallett’s evidence that suggested that approximately 5% of all phone calls to Employsure resulted in contracts being signed, the ACCC suggested another estimate of the revenue from those Ads was over $10 million. Employsure in turn criticised this calculation of potential benefit, highlighting a number of salient limitations of the “click to call” data, including that:

(a) The “click to call” data is not the number of calls resulting from the six Google Ads, rather it is the number of clicks on a phone number. It does not reliably indicate how many phone calls directly resulted from the six Google Ads, as after clicking on the phone number in the Ads, the consumer would have to click again on their device to dial Employsure’s phone number. Dr Higgins SC (who appeared with Mr Bannan for Employsure) frankly acknowledged that the click to call data could also understate the number of phone calls that were made to Employsure, as consumers could also type the number directly into their phone without clicking on the six Google Ads.

(b) The click to call data does not provide a reliable indicator of how many contracts were in fact signed as a result of “click to calls” on the six Google Ads.

111 Ultimately, there is no reliable indication of the benefit obtained by Employsure by the six Google Ads, a fact that the ACCC candidly acknowledged and embraced. In addition to the limitations raised above, the evidence does not permit the available data to be isolated to the six Google Ads alone. As the ACCC correctly acknowledged, the available data captured the number of clicks and impressions from the six Google Ads as well as any other Google Ads that contain the same headlines and description.

112 Finally, contrary to the ACCC’s suggestion, it is not the case that the FWO provided the same services as Employsure, but at no cost. Employsure provided free advice (Employsure PJ at [5]), and its paid services were materially different from those offered by the FWO. Employsure’s services included not only advice, but template contracts, insurance and legal representation: Employsure PJ at [72], [155] and [165].

(f) Size of the contravening company

113 I accept the ACCC’s summary of the relevant matters concerning Employsure’s size, which were not contested by Employsure. Employsure is a medium-size private business with an annual revenue of around $150 million and an annual profit of approximately $25 million. I accept Employsure’s submission that its size “is not something that can be propounded as a metric for penalty divorced from an examination of the contravening conduct”.

(g) Deliberateness

114 At trial the Court found that the conduct was not deliberate and this finding was not challenged on appeal. As noted above, Mr Owens SC did not assert in the hearing on relief that the conduct was anything but inadvertent. This operates to mitigate the pecuniary penalty that might otherwise be ordered.

(h) Involvement of senior management

115 As the ACCC correctly noted, Mr Mallett was not involved in the drafting of the six Google Ads, but he was involved in setting the advertising strategy of which the Google Ads formed a part. Although Mr Mallett had overall responsibility for digital marketing, he had limited personal involvement in the contravening conduct. Moreover, it should be noted that the ACCC confirmed that no significance should attach to the fact that Mr Mallett, whom the Court previously found to be an impressive witness, had ceased to be managing director of Employsure in April 2021.

116 The ACCC submitted that the identified members of the digital marketing team were members of senior management. That submission appears to rely on the titles of the relevant individuals, and the fact that the word “senior” is used in one of those titles. As Employsure pointed out, however, regard must be had to the substance of the position and not merely nomenclature. The relevant staff were some distance from being senior management: Mr Vu (who had the word “senior” in his title) was three levels below Mr Mallett in the reporting hierarchy across the relevant period. Mr Owens SC confirmed that the ACCC did not contend that there was “a bad apple here that was setting out to try and achieve an illegitimate gain”.

(i) Culture of compliance

117 There is no basis in the evidence to find that there was a culture of non-compliance within Employsure during the Relevant Period. I accept Employsure’s submission that, during the Relevant Period, it was a rapidly growing organisation and doing its best to implement a culture of compliance. I also find that, in the Relevant Period and/or after that period ended, additional steps have been taken by Employsure to improve compliance. Those steps were comprehensively described in Mr Mallett’s affidavit dated 28 October 2021 (noting that he was not required for cross-examination). During either the Relevant Period or subsequently, Employsure has:

(a) engaged a provider of CCA compliance training;

(b) introduced CCA compliance guidelines;

(c) implemented recommendations from the CCA compliance training provider;

(d) appointed risk officers and a Head of Risk;

(e) created a Compliance Handbook;

(f) organised compliance refresher training;

(g) used automated technology to identify compliance risks in telephone calls with potential clients; and

(h) implemented a program to improve Employsure’s search engine marketing practices.

(j) Co-operation

118 I do not accept the ACCC’s contention that Employsure provided only “limited cooperation”. As noted above, it acted responsibly after the FWO published its press release dated 4 July 2017. As to the ACCC’s claim that it took almost a year after it commenced its investigation in December 2017 for Employsure to acknowledge that it needed to improve its compliance program, I do not find that delay unreasonable, particularly in circumstances where following the ACCC’s investigation and claims related to conduct, Employsure subsequently was found by the Court not to be in contravention of four of the five causes of action ultimately run by the ACCC.

119 No or little weight should attach to the fact that Employsure contested liability below. It was entitled to do so. It succeeded in defending most of the ACCC’s serious allegations. Its conduct in so doing does not act as an aggravating factor or otherwise require the penalty to be increased: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v IPM Operation & Maintenance Loy Yang Pty Ltd [2006] FCA 1777; 157 FCR 162 at [61]-[65] per Young J. Further, as the ACCC acknowledged, Employsure voluntarily provided documents prior to the commencement of proceedings, and agreed to a Statement of Agreed Facts which avoided the need to prove a range of matters in relation to the operation of Google Ads. In addition, there is evidence which indicates that Employsure was pro-active in seeking to resolve the matter before proceedings were commenced: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dodo Services Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 589 at [96]-[97] per Murphy J and Jetstar at [93] per Perry J.

(k) Parity

120 All things being equal, similar contraventions should incur similar penalties. Parity of penalties against contraveners in other comparable proceedings is a relevant factor in assessing penalty: see, for example, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cabcharge [2010] FCA 1261 at [54] per Finkelstein J and Lowe v R [1984] HCA 46; 154 CLR 606 at 610-611 per Mason J. In the real world, however, it will be rare for the facts and circumstances of any cases to be the same. While acknowledging these realities, however, I accept that there is some utility in comparing the penalties imposed in other cases concerning cognate contravening conduct in the Relevant Period. I have taken into account the cases referred to by the parties but I see little point in analysing those cases in minute detail given that each has its own peculiar features which reflect different facts and circumstances. I accept Employsure’s submission that the penalty proposed by the ACCC is out of step with penalties imposed in other cases for similar conduct in the period 2016-2018 (see, for example, Dodo Services; Viagogo AG; Oticon; Jetstar; and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Private Networks Pty Ltd (t/as Activ8me) [2019] FCA 284). Nevertheless, I consider that the range proposed by Employsure is too low and needs to be increased, albeit by a relatively small amount.

(l) Previous contraventions

121 Employsure has not previously contravened the ACL. The absence of prior contraventions operates to mitigate the penalty the Court would otherwise order. It is also a matter that bears upon the assessment of specific deterrence.

122 For all these reasons, I consider that the appropriate pecuniary penalty is more than that advanced by Employsure, but significantly less than that sought by the ACCC. I will order Employsure to pay a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $1 million.

B. Injunction

123 I accept Employsure’s contention that no injunction should be ordered in the circumstances of this case.

124 As the Full Court (Moore, Dowsett and Greenwood JJ) observed in Dataline at [111] (emphasis added):

Many contraventions simply will not justify injunctive relief. We doubt whether unintentional misconduct in contravention of s 52 would lead to such relief. An isolated intentional breach may also not warrant it. Conduct which occurred many years before the enforcement proceedings may not do so, especially if the offender has not recently infringed the law, or is no longer in a position where contravention is likely. These are obvious cases, but they raise questions as to the relevant factors in considering whether to grant such relief. The discretion is at large. It is for the relevant applicant to demonstrate that the injunction will serve a purpose. That purpose may involve the protection of the public interest or private rights.

125 I consider that injunctive relief is not justified in the present case. The ACCC has failed to demonstrate that any useful purpose will be served by an injunction. The conduct was not deliberate. It ceased more than three years ago and is highly unlikely to recur.

126 The sole matter advanced by the ACCC is that Employsure continues to use Google Ads, including that aspects of the current Google Ads are similar to the six Google Ads. As noted above, I have rejected that submission. No issue has been taken with Employsure’s current overall digital marketing strategy.

Conclusion