Federal Court of Australia

Stack v AMP Financial Planning Pty Limited (No 2) [2021] FCA 1479

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondents’ application under s 33N(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) be dismissed.

2. The parties’ costs of and incidental to such application be their costs in the cause.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 In this representative proceeding the applicants and group members seek compensation for commissions and premiums paid in relation to financial products acquired on the advice of their financial advisers, who were at the relevant time authorised representatives of the first to third respondents.

2 The respondents have applied for an order under s 33N(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that the proceeding no longer continue as a representative proceeding. They have invoked s 33N(1)(c) as the condition upon which they rely to trigger the power to de-class.

3 In support of their s 33N(1)(c) argument the respondents say that the applicants’ central case predominantly necessitates individual inquiries concerning the particular advice given to each group member, and does not give rise to a set of common questions that could meaningfully be asked and answered on behalf of all group members. Now I should note at this point that there has been no challenge to the validity of the proceeding in terms of s 33C, including as to the satisfaction of the s 33C(1)(c) requirement, although one could be forgiven for construing the respondents’ submissions as not even formally conceding that there are substantial common issues of law or fact. Of course I have proceeded on the basis that, first, the claims of all group members are in respect of, or arise out of, the same, similar or related circumstances (s 33C(1)(b)) and, second, that the claims of all group members give rise to a substantial common issue of law or fact.

4 Further, the respondents say that the lack of commonality in the claims entails that the proceeding will likely become procedurally unwieldy, and particularly will require the respondents to interrogate numerous systems and to give broad ranging discovery. I must say that I do not share such pessimism given the extensive powers in my armoury that can be wielded to ensure efficiency and fairness within the structure of the Part IVA setting.

5 Further, it is said that the continuation of the proceeding as a representative proceeding will not facilitate the settlement of group members’ claims. Indeed, the respondents go so far as to say that the structure of the proceeding is likely to impede settlement and delay group members’ redress by other avenues, including through the respondents’ remediation programs. I will dispose of this argument later.

6 Now the applicants oppose the s 33N(1) application.

7 First, they say that there are many substantial common issues.

8 Now as to the claims concerning the ss 961B(1) and 961J(1) breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and breaches of fiduciary duties, the applicants accept that these claims give rise to individual issues, but they say that there are still substantial issues of commonality that could effectively be resolved as part of the initial trial.

9 Further, they say that on any view the applicants’ claims under s 961L are core claims and are common. Moreover, they say that such claims require an investigation of the knowledge of the respondents and their systems and processes, not just the individual circumstances of group members.

10 Further, they say that the anti-avoidance claims under s 965(1) are common although questions of loss and damage are not common.

11 Second, they say that given that the s 33N power must be exercised having regard to the “interests of justice”, if the proceeding were to be declassed it is said that the likely counterfactual will not be 1.5 million individual group members pursuing the allegations made in this case, but rather group members being shut out from litigating their claims because of the cost and expense. That counterfactual is said to be unpalatable. And equally, the other possible counterfactual of numerous individual proceedings self-evidently justifies why a s 33N order ought not be made.

12 Third, the applicants say that the size of the group member cohort here makes it difficult to conceive of a scenario where there is a more efficient vehicle than Part IVA to resolve the claims.

13 In summary I reject the respondents’ application.

14 First, the respondents have not established the trigger condition of s 33N(1)(c). Moreover, on the respondents’ case the alternative trigger condition of s 33N(1)(d) is not in play.

15 Second, even if they had established such a trigger, it would not have been in the interests of justice to de-class the proceeding. At the least I am not so presently satisfied.

16 Now in terms of the interests of justice, one principal purpose of the Pt IVA regime is to promote efficiency in dealing with multiple claims so as to avoid multiple proceedings, inconsistent findings and respondents being unnecessarily vexed. Another principal purpose is to provide access to justice and a potential remedy for multiple claimants where it may be uneconomic to bring individual proceedings.

17 If I was to accede to the respondents’ application, the likely counterfactual would be that either no proceeding would be brought at all or there would be a huge number of individual suits. After all, there are approximately 1.5 million group members. Either outcome would be the antithesis of the principal purposes of Pt IVA.

18 Now I have considered as a possible counterfactual whether there could be several new representative proceedings launched. But one difficulty with that is that they may be treated as a managed investment scheme commencing after 22 August 2020 given that one would necessarily have a new class, even if a sub-set of the present class, a new funding model and strictly a new dominant purpose for the association. In any event that is not the relevant counterfactual for s 33N(1)(c) as I will shortly explain, although such a counterfactual may be relevant to the interests of justice question.

19 Let me turn first to the relevant principles.

Relevant principles

20 Section 33N(1) of the FCA Act provides:

(1) The Court may, on application by the respondent or of its own motion, order that a proceeding no longer continue under this Part where it is satisfied that it is in the interests of justice to do so because:

(a) the costs that would be incurred if the proceeding were to continue as a representative proceeding are likely to exceed the costs that would be incurred if each group member conducted a separate proceeding; or

(b) all the relief sought can be obtained by means of a proceeding other than a representative proceeding under this Part; or

(c) the representative proceeding will not provide an efficient and effective means of dealing with the claims of group members; or

(d) it is otherwise inappropriate that the claims be pursued by means of a representative proceeding.

…

21 Now as to the identification of the triggering condition in s 33N(1), one does not simply tick off seriatim any of ss 33N(1)(a) to (d). By that I mean that s 33N(1)(d) is an alternative, where none of ss 33N(1)(a) to (c) have been established; hence the phrase “it is otherwise inappropriate” (my emphasis). But in the present case, the respondents have not sought to invoke s 33N(1)(d), so I need say little more about it.

22 But there is another point to make. Assume, as in the present case, that the respondents have only sought to invoke s 33N(1)(c) and have not sought to invoke ss 33N(1)(a) or (b). That does not make their subject matter irrelevant to the broader “interests of justice” inquiry. The party seeking a s 33N(1) order may not have established either such trigger. That is one thing. But assume that the party opposing such an order establishes the negative propositions to either s 33N(1)(a) or s 33N(1)(b), that is, establishes that the costs that would be incurred if the proceeding were to continue as a representative proceeding are not likely to exceed or could be less than the costs that would be incurred if each group member conducted a separate proceeding or establishes that the relief sought could not be obtained by means of a proceeding other than a representative proceeding (e.g. an aggregate damages award (s 33Z(1)(f)). Establishing such matters would assist the opponent to a s 33N(1) order to argue against it being in the interests of justice to make a s 33N(1) order or even perhaps as a discretionary factor going against making the order.

23 In that context, I should say now that although the respondents in the present case have not sought to establish the s 33N(1)(a) trigger, the applicants do assert the converse of that trigger as being a relevant consideration.

24 I should make one other point. Interestingly the respondents have not sought to use the s 33N(1)(b) trigger, although that is usually satisfied in most cases.

25 Let me turn to another topic concerning the relevant comparators.

26 Generally speaking, s 33N(1) requires consideration of the comparator of whether it is in the interests of justice that the proceeding be determined in numerous non-representative proceedings. One compares how the factors specified in ss 33N(1)(a) to 33N(1)(d) would apply to hypothetical non-representative proceedings. Such a comparison is expressed in ss 33N(1)(a) and 33N(1)(b) and implied by ss 33N(1)(c) and 33N(1)(d). The implicit focus in s 33N(1)(c) is on the commonality of issues and whether the representative proceeding is efficient and effective to resolve the common issues, rather than resolution by way of individual proceedings. Section 33N(1)(d) is concerned with whether the representative proceeding is an appropriate vehicle to pursue the claims. Generally, the focus of ss 33N(1)(c) and 33N(1)(d) is on the efficiency or appropriateness of the group members’ claims being pursued in a representative proceeding.

27 Relevantly to the present context, s 33N(1)(c) does not involve a comparison between the representative proceeding and another identical or hypothetical set of representative proceedings. The efficiencies referred to in s 33N(1)(c) are focused upon whether the representative proceeding is an efficient mechanism to resolve the claims and common issues, which requires considering the representative applicant’s case and a comparison between the representative proceeding and the hypothetical non-representative proceedings. The inquiry is not whether the common issues might be more efficiently resolved by way of some other representative proceeding. Now s 33N(1)(c) uses the definite article “the representive proceeding[s]” rather than the indefinite article (cf ss 33N(1)(a), 33N(1)(b) and 33N(1)(d)), so that it is open to argue that it could be satisfied if another set of representative proceedings were available and could efficiently deal with group members’ claims made in the hypothesised to be declassed proceeding. In other words, another available representative proceeding may make it less efficient and less effective to pursue the proposed to be declassed proceeding. But generally, the better construction of s 33N(1)(c) is as I have indicated. Conceptual coherence dictates that I read s 33N(1)(c) through the general lens of s 33N(1) by comparing a representative proceeding with non-representative proceedings. I will discuss later whether another possible comparison is available between a representative proceeding and no proceedings at all but rather a separate remediation or settlement scheme.

28 Further, it is trite to observe that s 33N(1) is not about the efficiency of a representative proceeding in an absolute sense. Indeed, it is not about whether the continuance of such a proceeding is efficient in an absolute sense. Rather, the ideas embodied in ss 33N(1)(a) to (c) whether explicitly or implicitly are about relative efficiency concerning the particular context and case at hand in terms of a comparison between the representative proceeding on the one hand, and the comparator non-representative proceedings on the other hand.

29 Now let me address the asserted triggering condition under s 33N(1)(c) before dealing with the availability and exercise of power under s 33N(1). The availability requires satisfaction of the stipulation “in the interests of justice to do so” linked to the triggering condition. The exercise, assuming that a triggering condition is established and such satisfaction is reached, is an exercise of discretionary power rather than just a permissive power, although it would only be a highly unusual case where the “interests of justice” satisfaction was reached, but in the exercise of discretion no s 33N (1) order was considered appropriate.

30 In relation to s 33N(1)(c), which the respondents have focused on, the following factors are relevant and must be directed to the particular circumstances of the case.

31 First, to what extent do the individual issues outweigh common issues? In other words, is the area of issues common to all claims so limited, in comparison with the totality of the issues that have to be resolved both as to liability and relief as between each of the group members and the respondents, that the proceeding so much involves an investigation of individual circumstances as to justify a s 33N order?

32 Second, would the determination of non-common issues add to the complexity of the preparation for and the duration of the trial as compared with a case in which those issues were common to all group members?

33 Third, is there any single event or system of conduct that makes the claims suitable for representative proceedings? In this case, the respondents say that given the differences in products, AMP authorised representatives, AMP licensees, agreements and disclosures relevant to the applicants and group members, there is no common element.

34 Fourth, is it the case that the resolution of the applicants’ claims offers no real guidance for group member claims, for example, where there is such a lack of commonality between an applicant’s claim and those of group members such that the determination of the applicant’s claim will not offer any real guidance as to how group members’ claims would be determined? The respondents say that this applies to the present case given the nature of the claims made by each applicant.

35 Fifth, are the documents and evidence common to the applicants and group members? The respondents say here that the documents, systems and agreements relied upon to establish the claims in the present case have insufficient commonality.

36 Sixth, as I have indicated, it is generally necessary to compare the cost and expense of the existing representative proceeding against the hypothetical cost and expense of the alternative non-representative proceedings.

37 Further, whether it will be in the interests of justice to de-class a proceeding, in the present context using the s 33N(1)(c) trigger, requires a consideration of the public interest in the administration of justice and requires a consideration of the principal objects of Part IVA, including promoting the efficient use of court time. In other words, to show the existence of a trigger does not inevitably lead to it being in the interests of justice to de-class. There may be other good reasons why the proceeding ought not be de-classed.

The pleaded case

38 The various parties, other entities and the case as pleaded in the consolidated statement of claim taking into account proposed amendments may be summarised as follows.

39 The applicants and the group members are those who acquired, renewed or continued to hold commissioned products in respect of which commissions were paid from 23 July 2014 and who received personal advice from an AMP authorised representative.

40 There are four applicants, each of whom received advice from a different AMP authorised representative and invested in different financial products issued by different product issuers.

41 The first applicant, Mr Stack, received personal advice from an individual at U-First Financial Solutions Pty Ltd, an authorised representative of the first respondent (AMPFP). He invested in a product known as “Flexible Super – Flexible Protection” which was issued by AMP Life Limited, the fifth respondent. This product was an insurance product held within a superannuation product.

42 The second applicant, Ms Winterton, received personal advice from an individual at Bayside Financial Planners Pty Ltd, an authorised representative of AMPFP. She invested in a product known as “Flexible Lifetime – Protection Plan” which was an insurance product issued by AMP Life. Ms Winterton also invested in the “Flexible Super – Flexible Protection” product issued by AMP Life.

43 The third applicant, Mr Brotton, received advice from an individual at Precept Financial Services Pty Ltd, an authorised representative of the second respondent (Charter). He invested in a pension product known as “North Personal Pension” issued by N.M. Superannuation Pty Ltd.

44 The fourth applicant, Mr Brittain, received personal advice from an individual at the third respondent (Hillross). He invested in a product known as “PortfolioCare Investment Service”, an investment product issued by Hillross.

45 There are also two sub-sets of group members known as the Stack sub-group members and the OSF sub-group members; OSF is a short-hand reference to ongoing service fees paid under an AMP ongoing service package.

46 The Stack sub-group members are defined in the consolidated pleading as those group members who on or after 23 July 2014 acquired, renewed or continued to hold an AMP Life product and received personal advice from an AMP authorised representative.

47 The OSF sub-group members are defined as those group members who on or after 23 July 2014 paid OSFs to one or more AMP authorised representatives and did not receive (in whole or in part) the AMP ongoing service package from the AMP authorised representative.

48 The first three respondents, AMPFP, Charter and Hillross were part of the AMP group of companies. They held AFSLs and were in the business of providing financial services to clients. The fourth respondent, AMP Ltd was the ultimate holding company of these AMP licensees. AMP Life was also part of the AMP group of companies up to 30 June 2020 and carried on a life insurance business. The applicants’ case against these respondents involves conduct over the period 23 July 2014 to 15 February 2021 inclusive (the relevant period).

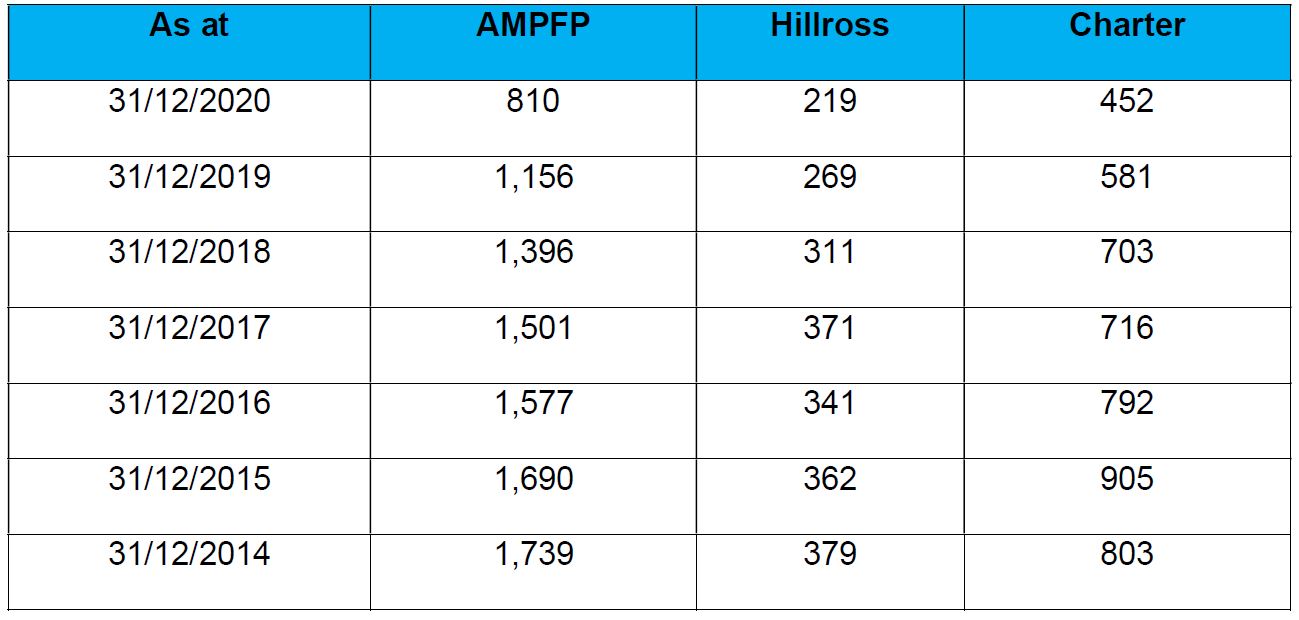

49 During most of the relevant period, the AMP group including the AMP licensees operated a network of financial advisers (AMP authorised representatives). Approximately 90% of those advisers were appointed as self-employed authorised representatives, and so were not partners or employees of the AMP licensees. They operated throughout Australia from premises and through businesses (practices) not owned by the AMP licensees or any of their related entities. I should note that the evidence before me reveals that in any given year in the relevant period, there were hundreds of AMP authorised representatives of the AMP licensees. In an affidavit sworn by the solicitor for the respondents, it was said:

…[T]he number of AMP authorised representatives authorised by each of Charter, Hillross and AMPFP from 2014 to 2020 were as follows:

…

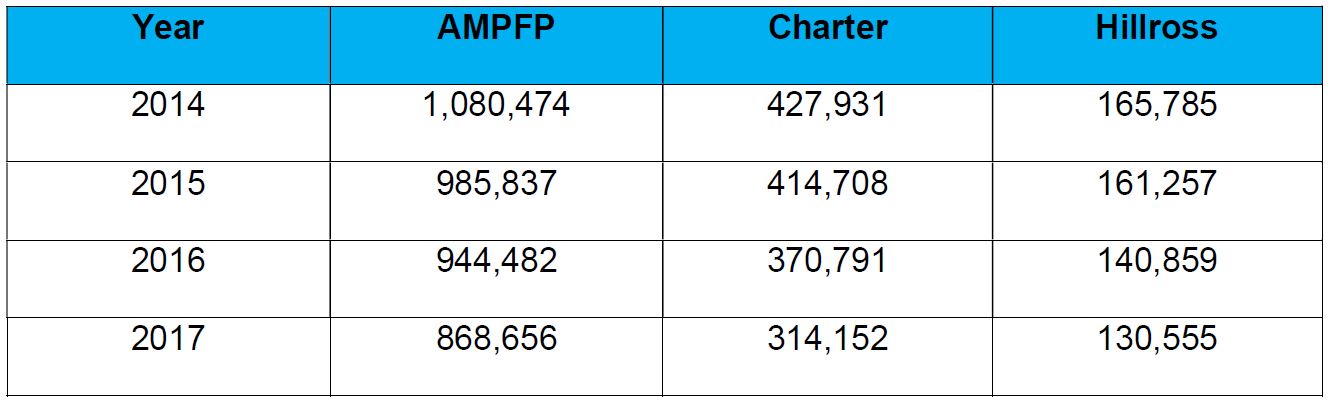

Whilst not a calculation of the potential number of group members, … the total number of clients of AMP authorised representatives of the AMP licensees from 2014 to 2017 were as follows:

…[T]he number of clients of AMP authorised representatives of the AMP licensees for the period 2018 to the end of the relevant period (being 15 February 2021) were not able to be verified at the time of swearing this affidavit. I note that the potential group member cohort may be larger than this because individuals may have purchased a commissioned product earlier than the relevant period and still be within the group member definition.

50 Further, during the relevant period the AMP licensees had in place agreements or arrangements with the AMP authorised representatives. These agreements typically comprised an authorised representative agreement and master terms for AMPFP and Hillross, and a representative services agreement and/or deed of appointment for Charter. There are different versions of those agreements that were in place during the relevant period.

51 During the relevant period, the AMP licensees also had in place arrangements with AMP Life and other providers of financial products including insurance products. These outlined the circumstances under which commissions in relation to those products would be paid to the AMP licensees.

52 Now the commissions payable via the AMP licensees to AMP authorised representatives are central to the issues in this proceeding.

53 The term “commissioned products” is defined as “financial products within the meaning of s 763A(1) … in respect of which commissions were payable… including insurance and financial products other than insurance products”. The term “commissions” is defined as those commissions paid to the AMP licensees by financial product issuers pursuant to agreements or arrangements in place between them, which includes insurance products, superannuation products and investment products. It also includes the products on the AMP licensees’ approved product lists (APLs) that were continually updated.

54 Now according to the respondents, working out the number of commissioned products as defined requires a detailed reconciliation of data from different systems given the likely number and types of products involved.

55 As to how commissions were paid, the material before me reveals that they were not paid directly from a product issuer to an AMP authorised representative. Rather, AMP licensees would receive all fees and commissions referable to a client of an AMP authorised representative. From those fees and commissions, the AMP licensee would deduct relevant license fees or other charges, as agreed with the AMP authorised representative, and then pay the remaining amount to the AMP authorised representative. Remuneration of an individual adviser within the business or practice of an authorised representative, including remuneration by way of commission, was then determined between the adviser and their business or practice, rather than by the relevant AMP licensee.

56 So, to work out what commission, if any, an individual AMP authorised representative was paid in relation to any particular group member in respect of any personal advice entails a consideration of whether the AMP authorised representative was entitled to receive commissions as a result of providing any personal advice, whether the practice received a “net” payment of fees less the licence fees and any miscellaneous payables, and whether it is possible to calculate any commission referable to the actual advice provided by the AMP authorised representative to that group member.

57 Let me now address the principal claims. For present purposes I will refer to the consolidated pleading as sought to be further amended.

58 It is alleged that the AMP licensees contravened ss 961B, 961J and 961L of the Corporations Act.

59 The allegations commence with the personal advice given to each of the applicants and group members, and decisions which they individually took upon receipt of that advice. The respondents say that the advice each applicant or group member received will necessarily have had regard to the individual circumstances and needs of the relevant client.

60 Then it is said that the premiums paid for the financial products acquired or held by them were higher than premiums on substantially equivalent or better products which could have been obtained by them. But the respondents say that whether such excess premiums were paid is an individual inquiry.

61 It is then alleged that the prospect of the receipt of commissions or incentives could reasonably be expected to influence the personal advice given to each of the applicants and group members by the AMP authorised representatives. But the respondents say that this is not a proposition which is capable of a blanket answer and will depend on matters including whether the particular AMP authorised representative who gave the advice stood to receive a commission as a result of recommending the acquisition or holding of a given product and whether there were in fact other equally suitable products available for the client in question.

62 These allegations then underpin the allegation that there was a conflict between the interests of each of the applicants and group members and the interests of those advising them. This is the foundation for the alleged breaches of the best interests duty (s 961B).

63 Now the respondents say that the allegations as to the reasons why the AMP authorised representatives are said to have failed to act in the best interests of the applicants or group members necessitate an inquiry into the circumstances of each applicant and group member, and the specific personal advice provided to them.

64 Further, in terms of the separate breach of s 961B alleged in respect of the OSF sub-group members to the effect that the AMP authorised representatives failed to provide ongoing advice in circumstances where they were contractually obliged to provide that advice, with the AMP licensees continuing to charge fees for that advice, the respondents say that these allegations raise individual questions.

65 Further, it is said that the same factual allegations underpin the asserted contraventions of s 961J concerning conflict of interests. Section 961J is alleged to have been breached by the AMP authorised representatives of the AMP licensees failing to give priority to the interests of the applicants and group members, where the AMP authorised representatives gave personal advice and failed to disclose that the personal advice could reasonably be expected to have been influenced by the commissions.

66 According to the respondents, the pleaded reasons why the individual AMP authorised representatives allegedly failed to give priority to the interests of their respective clients illustrate the difficulty of making findings which could determine liability without examination of the individual claims.

67 Further, there is a further separate breach of s 961J alleged in respect of the OSF sub-group members to the effect that there was a failure to give priority to the interests of those group members in circumstances where there was a conflict between the interests of those group members and the interests of the AMP authorised representatives who advised them.

68 As for the contraventions of s 961L, the provision is alleged to have been breached by the AMP licensees failing to take reasonable steps to ensure that the AMP authorised representatives complied with ss 961B and 961L.

69 I will return to the significance of these claims later in the context of the s 33N(1)(c) question.

70 The applicants seek compensation under s 1317HA(1) from the AMP licensees in relation to these claims.

71 Let me say something about the breach of fiduciary duty claims.

72 It is alleged that a fiduciary duty was owed by each of the AMP licensees and/or each of the AMP authorised representatives to each of the applicants and group members.

73 But the respondents say that the question of whether a fiduciary duty exists in any given adviser–client relationship will depend upon the individual circumstances of that relationship. I agree. So much is clear, and indeed not disputed by the applicants. Questions going to the existence of a fiduciary duty are individual ones.

74 Now the fiduciary duties allegedly owed by the AMP licensees to the applicants and group members are said to have been breached by the AMP licensees failing to avoid a conflict of interests between the AMP licensees and AMP authorised representatives, on the one hand, and group members, on the other hand, due to the payment of commissions, and improperly using their position to gain a benefit for themselves and the AMP authorised representatives.

75 There is a parallel allegation in respect of the Stack sub-group members to the effect that the fiduciary duty allegedly owed was breached by the AMP licensees failing to avoid a conflict of interests between the AMP licensees, AMP authorised representatives or AMP Life, on the one hand, and Mr Stack and the Stack sub-group members, on the other hand, having regard to the commissions payable in respect of particular products issued by AMP Life. Further, the fiduciary duties allegedly owed by the AMP authorised representatives are said to have been breached in the same way.

76 The applicants seek compensation from the AMP licensees pursuant to s 917E in relation to these claims.

77 Further, there is a knowing receipt allegation made against AMP Life.

78 It is said that at the time AMP Life received the excess premiums, AMP Life knew the material facts giving rise to the existence of the alleged fiduciary duties owed by the AMP licensees and AMP authorised representatives to the applicants, group members and the Stack sub-group members. Equitable compensation is sought in respect of this claim.

79 Let me now say something concerning the OSF questions. In this respect the relevant allegations are restricted to Ms Winterton, Mr Brittain and the OSF sub-group members.

80 It is said that the contracts entered into between these group members and their AMP authorised representatives were breached by those representatives failing to provide ongoing personal advice to them.

81 In the alternative it is said that to the extent such advice was given, it did not comply with ss 961B and 961J, essentially on a similar basis to what I have summarised earlier. It is also alleged that the AMP licensees were responsible for the impugned conduct of the AMP authorised representatives, and accordingly damages under s 917E are sought from them.

82 Now the respondents say that these allegations assume that there was a single set of contractual terms that applied across the group, but that assumption is not correct. Whether there was a breach of a given authorised representative of his obligations to his client, in terms of any obligation to provide ongoing advice which complied with the requirements of ss 961B and 961J, is an individual one.

83 Further, it is alleged that the AMP licensees engaged in unconscionable conduct in respect of the OSF sub-group members. First, it is said that the OSF sub-group members were in a position of special disadvantage with respect to the AMP licensees. Second, it is said that the commissions could reasonably be expected to have influenced the personal advice given to the OSF sub-group members and whether to give personal advice because that advice would have led to the termination of the commissions. Third, it is said that the commissions could reasonably be expected to have influenced the AMP licensees not to properly oversee whether the AMP authorised representatives were providing ongoing advice because that advice would have led to the termination of commissions.

84 Accordingly, it is said that the AMP licensees acted unconscionably in continuing to receive commissions in circumstances where the AMP authorised representatives did not discharge their obligations to provide ongoing personal advice to the OSF sub-group members. Damages are sought under s 12GF(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

85 Now generally speaking I agree with the respondents that unconscionability is a matter which depends upon the individual facts and circumstances pertaining to the relationship between adviser and client, although aspects of the claims made here may to some extent involve an analysis of systems, procedures and processes that were in place.

86 Further, it is alleged that the AMP licensees themselves or through the AMP authorised representatives engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct concerning the making of what are described as the commissions representations and the premiums representations.

87 The commissions representations are to the effect that the AMP licensees:

(a) had systems and processes to address and manage risks in the advice business generated by the commissions and incentives and any associated conflicts;

(b) had adequate systems and processes to address and manage various risks and conflicts in their advice business;

(c) had taken reasonable steps to ensure that the AMP authorised representatives complied with their obligations to act in the best interests of their clients in relation to personal advice;

(d) had taken reasonable steps to ensure that the AMP authorised representatives had complied with their obligations to prioritise their clients’ interests over their own interests when giving advice;

(e) had done all things necessary to ensure that the financial services provided to the applicants and group members were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly;

(f) had adequate systems and processes to ensure that ongoing services were provided; and

(g) by themselves or through the AMP authorised representatives would inform the applicants and relevant group members of circumstances that would make it inappropriate for the AMP authorised representatives to continue to charge and receive OSFs and commissions.

88 The premiums representations, which are alleged to have been made to the Stack sub-group members, are to the effect that there were no substantially equivalent or better policies of insurance available from third-party insurers for a lower premium than the recommended AMP life products.

89 Now the respondents say that either class of representations raises individual factual issues in terms of the representations made to and relied on by each applicant and group member.

90 Of course I would interpolate here that the fact that a claim may be based on representations which are said to have been made to various group members at different times and in different forms may not be as powerful a point as the respondents would have it if the relevant representation said to have been made on each occasion is to the same substance or effect.

91 It is also said that the premium representations are problematic. No particulars of the representations are actually given. Further, it is said that the question whether there was in fact some substantially equivalent or better product available would depend on the individual circumstances of the applicant or group member in question.

92 Finally, at this point, I should say something briefly about the anti-avoidance claims.

93 It is alleged that in or around May or June 2013, the AMP licensees and AMP Limited entered into and carried out a restructuring, one of the purposes for which was so that grandfathered commissions would continue to be paid after 1 July 2013.

94 It is alleged that this restructuring was effected by the AMP licensees and AMP Limited “establishing Register Co which held the AMP licensees and AMP authorised representatives register (or book) or clients in a central pool so that they could be transitioned between AMP AFSL holders in order to maintain Financial Product Commissions”.

95 It is alleged that the restructuring with the relevant purpose involved a scheme for avoiding the application of the ban on conflicted remuneration in Part 7.7A, and therefore was in breach of s 965.

Has s 33N(1)(c) been made out?

96 The respondents say that the causes of action that I have briefly outlined require an investigation into the individual circumstances of each group member. Further, they say that an initial trial of the applicants’ claims will not be determinative of the substance of group members’ claims. Accordingly, they say that the representative proceeding will not provide an efficient and effective means of dealing with the claims of group members, and therefore it is in the interests of justice to declass the proceedings utilising the criterion in s 33N(1)(c).

97 Now I would accept the two premises but reject the conclusion. But for the moment, let me address, relevantly to s 33N(1)(c), the causes of action involved and the extent to which they raise individual issues.

Sections 961B and 961J claims

98 The respondents say that the factual foundations for the alleged breaches of ss 961B and 961J are individual to each of the applicants and group members concerned. They say that whether those provisions were contravened requires a consideration of whether each of the AMP authorised representatives who provided personal advice to the applicants and group members was to receive the commission as a result of providing the personal advice, and whether there was an alternative but comparable product reasonably available with a different level of commission payable.

99 Now as I have noted, commissions were not paid directly from a product issuer to an AMP authorised representative. Moreover, whether an AMP authorised representative received a commission was a matter to be determined between the AMP authorised representative and his practice. Further, one cannot assume that the entitlement was the same with respect to every AMP authorised representative. Further, there were up to 2,921 AMP authorised representatives in any one year during the relevant period. So, the magnitude and individualised nature of the inquiry is readily apparent.

100 Further, the applicants have asserted that there was a conflict of interest as between the AMP authorised representatives’ interests and the group members’ interests. But the AMP authorised representatives’ business practices in respect of how they received commissions were not the same.

101 Further, it has been alleged that substantially equivalent or better financial products including insurance products were available to group members, which did not yield the payment of commissions or yielded a different level of commission payable. But such an allegation requires the following matters to be considered. The substantially equivalent or better financial products have to be identified. But the applicants have only done this at a general level, save that they have identified one product said to have been substantially equivalent or better than the AMP life product. Further, there has to be a consideration of the individual circumstances of each of the group members, given that the applicants accept that the words ‘substantially equivalent’ and ‘better’ means substantially equivalent and better by reference to the interests of Mr Stack and the Stack sub-group members, and otherwise have their natural and ordinary meaning.

102 Now it may be accepted that each group member’s loss assessment is different. But the respondents say that the division between the group members’ cases occurs not just at the time of assessment of their loss, but also at the time of the assessment of any liability of the respondents to them, including whether they were the victim of a breach of s 961B or s 961J. So, whilst in some cases it has been held that a class action ought to continue despite the divergence in the way group members’ losses ought to be assessed, that is not the only point of difference as between the group members’ claims in the present case. Here there is a divergence at the liability stage.

103 In my view there is considerable force in the respondents’ arguments on this aspect. Clearly, the question of whether a Stack sub-group member paid excess premiums in relation to an AMP life product will require an investigation of the individual circumstances of that group member, including the availability of a substantially equivalent or better life product at a lower premium.

104 Further, the extent to which the commission was kept by an AMP licensee or the AMP authorised representative and the amount of commission paid will involve a consideration of individual circumstances.

105 But it must be noted that the alleged breaches of ss 961B and 961J do not just turn on the sum of the commissions received. The allegations include that breach occurred by reason of the failure of the AMP authorised representatives to rebate, switch-off or dial-down the commissions, irrespective of the sum or recipient of the commission.

106 Further, notwithstanding the individual features of excess premiums and the recipient of the commission, there still remains utility for group members’ claims generally for me to determine the applicants’ claims and some sample group members’ claims for breaches of ss 961B and 961J at the initial trial.

107 Findings can be made on issues that could assist but not necessarily be determinative of group member claims, including findings on some of the common systems that are foundational for the ss 961B and 961J claims, including the following matters.

108 First, the defence pleads the existence of several standard form agreements which govern how commissions were received by the AMP licensees from providers of insurance and financial products including the template agreements particularised.

109 Second, there appears to have been some system in place which determined how the AMP licensee would remit commissions. The defence refers to the AMP authorised representative agreements which apparently were updated from time to time. Those agreements governed how the relevant practices would be paid the commissions. Further, AMP licensees had template agreements which typically consisted of an authorised representative agreement, master terms and representative services agreement. The applicants’ case as now sought to be clarified by the amendments proposed does identify these systems aspects.

110 Third, the applicants allege that the incentives were similarly paid pursuant to agreements between the AMP licensees and their respective AMP authorised representatives. Again, the applicants’ proposed amendments seek to clarify the existence of this common system.

111 Fourth, the applicants have also put forward proposed amendments regarding the application of a common set of policies and processes for determining the composition of the APLs.

112 Fifth, it is alleged that there were common systems and policies for one off approvals for AMP authorised representatives to recommend products not on an APL. Further, it is said that there was a common system which impeded group members from paying third party insurance premiums from an AMP super fund.

113 Further, I may make findings on the scope of the relevant legal duties in the context of determining the applicants’ claims. Now if I made such findings in relation to the scope of the duties under ss 961B and 961J, then it would still be necessary for each group member to prove the relevant facts establishing breach. But that does not deprive the findings of the character of being such as could assist group member claims.

114 These matters entail that the ss 961B and 961J case can be more efficiently determined as part of a representative proceeding.

115 Now the respondents say that the matters which relate to how commissions and incentives were paid to AMP licensees and the processes involved in determining the composition of APLs tell one nothing about whether a particular AMP authorised representative acted in the best interests of his or her client, or failed to give priority to the client’s interests in providing them with personal advice.

116 Further, it is said that any difficulty is not remedied by determining the applicants’ claims and sample group members’ claims only. And indeed, any such exemplar findings merely illustrate the individual nature of the claims.

117 So the respondents say that a finding that there was a breach of s 961J for Mr Stack’s adviser to recommend to him that he acquire the Flexible Super – Flexible Protection Product when there was a substantially equivalent or better third-party insurance product available at a lower price will not assist in determining other Stack sub-group members’ claims. The identification, and determination of an alternative product which may or may not be substantially equivalent or better necessitates an inquiry into each Stack sub-group member’s idiosyncrasies.

118 Further, the respondents say that the applicants have no explanation as to how their allegations that the AMP authorised representatives contravened ss 961B and 961J could be efficiently and effectively determined in a representative proceeding.

119 Further, the respondents say that there is little purpose in the Court only determining a handful of claims at an initial trial. Such a determination will offer no meaningful guidance as to how the balance of the group members’ claims ought to be determined. All it will do is add a layer of cost, and delay the inevitable time when any claims that are to be pursued are advanced individually.

120 But in my view this is all too pessimistic. I have no doubt that this is an appropriate case where it is likely that at the first stage trial up to, say, 20 sample group members’ individual claims may need to be dealt with to cover many of the broader issues.

121 As I discussed in Earglow Pty Ltd v Newcrest Mining Ltd (2015) 230 FCR 469 at [53] and [55] to [60] and [62] to [64]:

53 The identification of sample group claimants who have their cases adjudicated on at the first stage trial is not unprecedented. And there is no doubt that this can be useful (not the test required by s 33ZF) in an appropriate case.

…

55 In Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2001] VSC 372, the trial judge permitted group members to give evidence at trial in relation to specific categories of claim. Sample group members gave evidence in relation to issues relevant to their claims, even though that evidence was not relevant to the claim of the representative plaintiffs.

56 The utility of permitting sample group members to give evidence in the Johnson Tiles litigation was highlighted in the judgment on the determination of the common questions, where it was found that, while the representative plaintiffs failed in their claims, two members of the “business users” group of claimants (being Barrett Burston Malting Co Pty Ltd and Nando’s Australia Pty Ltd), whose claims were tried as sample group members, succeeded: Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia Pty Ltd [2003] Aust Torts Reports 81-692.

57 The successful sample group members gave evidence as to their own loss, which was found to be compensable loss, and were subsequently awarded damages: Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd (Barrett Burston Malting Company Pty Ltd) v Esso Australia Pty Ltd [2003] VSC 211; Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia Pty Ltd [2003] VSC 244 and Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia (No 4) [2004] VSC 466.

58 Woodcroft-Brown v Timbercorp Securities Ltd (2011) 253 FLR 240 was a representative proceeding commenced by Mr Woodcroft-Brown as lead plaintiff on his own behalf and on behalf of persons who had acquired or held an interest in certain managed investment schemes of which Timbercorp Securities Ltd (in liq) was the responsible entity.

59 The plaintiff’s case was that the defendants had failed to disclose information about risks relating to certain managed investments schemes, and that the failure to make such disclosures to the group member investors amounted to misleading or deceptive conduct. In that case, the parties agreed that a sample group member ought be identified as a representative of “early investors”, that is, persons who invested in managed investment schemes which pre-dated the relevant period. The sample group member selected, Mr Van Hoff, had invested both in the “early schemes”, which the lead plaintiff had not, and the “recent schemes”, in which the lead plaintiff had invested. Prior to the trial of the Timbercorp proceeding, Mr Van Hoff delivered particulars of his claim, and gave evidence at trial in respect of it.

60 In Matthews v SPI Electricity Pty Ltd (No 5) (2012) 35 VR 615, J Forrest J observed that determination of the claim of the representative plaintiff, Mrs Matthews, would not cover the field in relation to the potential claims of all members of the class, and held that four “sample group members” would be permitted to give evidence at the trial of the proceeding in relation to the question of the liability of the defendants. In Matthews, which concerned a bushfire that had ignited on Black Saturday and burned through the Kilmore East and Kinglake areas, the characteristic which went to selecting the sample group members related to both:

(a) the type of loss and damage suffered by each relevant sample group member, in circumstances where the lead plaintiff’s claim did not include a claim for pure economic loss, nor loss of dependency; and

(b) the geographical location of each relevant sample group member relative to the fire ignition point, in circumstances where J Forrest J considered that different considerations of duty, breach, damage and causation might apply in respect of areas geographically distant from the lead plaintiff’s property.

…

62 But one has to be careful with the use of these examples.

63 First, the individual selection and procedure used in a particular case may have proceeded on the basis of consent or non-opposition…

64 Second, the individual selection and procedure used in a particular case may have been justified because of significant differences in the liability cases of individual claimants apart from just individual causation and damages issues. Three of the four cases discussed above related to common law representative proceedings where there were different duty cases… Further, in the Timbercorp representative proceeding, multiple managed investments schemes were involved and it was necessary to ensure that the first stage trial had an investor claim covering each scheme…

122 Findings concerning sample group members’ individual claims may be able to be more broadly extrapolated and could facilitate settlement or at least may narrow the scope for dispute at later stages of the proceeding.

123 Further, in addition to sample group members and depending upon how the proceeding develops, I may give consideration to the formalisation of sub-groups before the first stage trial.

Section 961L claims

124 It is alleged that contrary to s 961L, the AMP licensees failed to take reasonable steps to ensure that their authorised representatives complied with their obligations under ss 961B and 961J.

125 It is said that during the relevant period the AMP licensees had in place training, supervision and monitoring systems and processes for the detection and management of conflicts of interest, but it is alleged that there were a series of deficiencies in those systems and processes and that the AMP licensees had knowledge of those matters.

126 Now it would seem to me that the common issues that arise on the pleadings include the following.

127 First, it is alleged that each of the AMP licensees had policies which concerned their AMP authorised representatives’ obligations pursuant to ss 961B and 961J. It is alleged that none of these policies adequately identified, gave guidance on or instructed the AMP authorised representatives in relation to various matters, including that the commissions and incentives paid to the AMP authorised representatives might give rise to conflicts of interest.

128 Now the respondents admit the existence of the general conflict of interest policies, but deny the alleged deficiencies and provide examples of the policies the AMP licensees had in place.

129 Second, there is said to be alleged deficiencies in the policies, training, supervision and monitoring systems and processes that the AMP licensees had in place. It is said that these systems were premised on it being appropriate for the AMP licensees and AMP authorised representatives to continue pursuing and receiving commissions and did not ensure that advisers complied with any contractual obligation to provide ongoing personal advice.

130 Third, it is alleged that there was actual or constructive knowledge of these matters by AMP licensees.

131 In my view the issues concerning training, supervision and monitoring processes and systems that the AMP licensees had in place during the relevant period for the detection and management of conflicts of interest, and whether they contained the deficiencies alleged, are common issues.

132 Further, it would seem that in some respects the relevant policies and systems were applied uniformly by the AMP licensees across their networks of AMP authorised representatives and associated practices.

133 Further, it would seem that the alleged deficiencies in the AMP licensees’ systems and processes will turn on the same common factual inquiry into those systems and processes. I note in that context that the applicants have proposed amendments to the consolidated pleading to remove any doubt on that aspect. Such amendments make it plain that the allegations about the payments of commissions, incentives and buy-back benefits are allegations based on policies, systems and processes.

134 Now the applicants say that the determination of their s 961L case does not depend on any findings of underlying breaches of ss 961B and 961J by the AMP authorised representatives. They say that the focus of s 961L is on taking reasonable steps. And in this context they have prayed in aid what was said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) (2020) 377 ALR 55 by Lee J at [106] to [107].

135 The applicants say that s 961L reflects an independent obligation on the AMP licensees to take reasonable steps to ensure that the AMP authorised representatives were complying with their own statutory duties. It follows, so it is said, that the common factual inquiry to be undertaken in relation to this claim at the initial trial of the proceeding will be determinative of the s 961L claims of the group members, at least on the question of breach.

136 Further, the applicants say that to the extent the applicants seek compensation on behalf of group members in relation to the contravention of s 961L on the basis of profit, rather than loss, as permitted by s 961M(4), it will not be necessary to prove individual group member causation or loss. The profits made as a result of a systems failure can be assessed on an aggregate basis.

137 Further, it is said that even if compensation is sought on the basis of actual loss, individual issues of causation and loss do not deny a common question utility.

138 Now as to the further s 961L claim brought by the first applicant on behalf of the Stack sub-group members, it is said that similar considerations arise. It is alleged that the AMP licensees maintained policies that incentivised AMP authorised representatives to recommend AMP life products, rather than life and risk products issued by third-party issuers. It is alleged that during the relevant period the AMP licensees maintained insurance APLs which contained AMP life products, but not relevant life products issued by third-party issuers, and that restrictions were imposed by the AMP licensees on AMP authorised representatives recommending products that were not on the insurance APLs. Further, the proposed amendments introduce further allegations regarding the policies that restricted AMP authorised representatives from recommending non-APL insurance products. Further, it is alleged that AMP licensees had in place platform APLs, which were primarily limited to AMP’s own platforms, and that the only life products which could be placed on AMP’s platforms were insurance products issued by AMP life. It is said that these APLs and platform APLs were developed according to a common system, involving common policies and a common decision-making organ. It is said that the effect of these systems was that 90% of new clients who received advice from an AMP authorised representative invested funds or paid premiums in an in-house AMP product and 60 to 70% of new client funds or premiums were directed to in-house products.

139 In summary, a case is put for the Stack sub-group members that by maintaining these systems and policies, AMP failed to take reasonable steps contrary to s 961L to ensure that its authorised representatives complied with their duties under ss 961B and 961J.

140 So, the applicants say that various common issues arise in respect of these allegations. What products were contained on the APLs during the relevant period? What approvals were required by the authorised representatives to recommend an insurance product not listed on the insurance APLs?

141 It is said that these issues are common to the Stack sub-group, and that their investigation will not require consideration of the group members’ individual circumstances or necessitate establishing breaches of ss 961B and 961J by any individual AMP authorised representatives.

142 But in my view the respondents are correct in saying that the applicants’ pleading links their allegations of contravention of s 961L with other alleged breaches which themselves necessarily require an analysis of individual group members’ claims.

143 The applicants allege as the only foundation for their allegation of breach of s 961L, that the AMP licensees failed to ensure that the AMP authorised representatives complied with ss 961B and 961J with respect to all group members and/or Stack sub-group members by reason of various factors.

144 Those factors travel beyond assertions that the AMP licensees failed to take reasonable steps to implement appropriate policies, systems and processes and do raise individual matters, even allowing for the applicants’ proposed amendments.

145 Further, although the amendments proffered breathe life into the argument that the s 961L allegations may be determined as common issues, they arguably sever the factual link between the alleged breaches of ss 961B and 961J, and the failure of the AMP licensees to comply with s 961L.

146 Further, the respondents dispute that the applicants can step around these realities by asserting that the determination of the s 961L claims does not depend on the findings of underlying breaches of ss 961B and 961J by the AMP authorised representatives, and say that their position is unassisted by the observations in AMP (No 2) which in any event appear to reflect common ground (see [106] and [116]). I agree. Such observations were made in the context of a civil penalty proceeding and where the regulator did not have to establish that the clients of AMPFP suffered any loss or damage.

147 But in the present case a finding of a contravention of s 961L by any of the AMP licensees would not advance the applicants’ and group members’ claim for loss or damage without a related finding that they suffered economic loss by reason of their AMP authorised representatives failing in their best interests duty or failing to give priority to their clients’ interests. Accordingly, those related findings necessitate individual inquiries.

148 Further, it may be said that even if some deficiency in training or policy were to be established, it would only beg the question of whether that deficiency led to a breach of ss 961B or 961J which caused the relevant applicant or group member loss or damage. And that question is an individual one.

149 Now the applicants have sought to circumvent these individual issues of causation and loss by contending that the applicants and group members are entitled to seek compensation on behalf of group members in relation to the contravention of s 961L on the basis of profit rather than loss. But this may not work. And in any event any such recovery still depends on making out the underlying breaches of ss 961B and 961J pleaded. Further, arguably invoking s 961M(4) does not assist the applicants to remove the necessity to establish the requisite causal link.

150 In my view the respondents have made many points of substance concerning s 961L including the limited utility of the observations in AMP (No 2) concerning civil claims for damages or profits. Nevertheless, despite their best efforts, clearly there are broader systems issues and common issues involved, although they would not be dispositive of these claims.

Anti-avoidance claims

151 It is alleged that contrary to s 965(1) AMP Limited and the AMP licensees carried out a restructuring for the purpose of avoiding the ban on conflicted remuneration contained in Div 4 of Part 7.7A.

152 Now the anti-avoidance allegations are of a different nature to the other claims. They do not for the most part require an investigation into the individual circumstances of each of the group members.

153 But to determine the compensation claimed by reason of the alleged breach of s 965, the respondents say that one needs to consider whether each group member in fact paid commissions, alternatively what commissions the respondents received and the profit earned on those commissions.

154 Further, it is said that none of the applicants invested in products which yielded the payment of non-insurance product commissions as defined. Accordingly, a determination of the applicants’ claims will not resolve the anti-avoidance allegations.

155 Further, it is said that the cohort of group members who now claim loss by reason of the respondents’ breach of s 965(1) is confined to those group members whose investments caused the payment of non-insurance product commissions and whose AMP authorised representative transitioned from one AMP authorised representative to another AMP authorised representative with a different AFSL, or from one AMP authorised representative’s AFSL to another.

156 But the respondents say that the group members who fall within this cohort may well be limited and do not justify the separate trial of questions relating to this claim, even if they could be characterised as common to that cohort.

157 Further, the respondents say that it is difficult to see how it is alleged that this sub-set of group members could have suffered any loss by reason of the implementation of the alleged scheme. The impugned non-incidental purpose of the scheme was to permit non-insurance product commissions to continue after 1 July 2013. But such commissions are those payable by financial product issuers of such non-insurance products to the AMP licensees. They are not payable by the sub-set of group members who make the anti-avoidance claim.

158 So, by the time the alleged scheme is implemented, the relevant group members have by definition already bought the non-insurance products in respect of which the product issuer paid and continued to pay commissions after 1 July 2013. Accordingly, those group members suffered no loss through the continuation of that commission stream.

159 In those circumstances, it is said that the only conceivable remaining claim would be for the profits made by the AMP licensees in respect of the scheme. But even then, those group members still have to establish that they suffered damage before s 1317HA(2) can be invoked. It is said that as those clients are not paying the commissions, it is difficult to see how the applicants could satisfy this threshold by reference to implementation of the scheme.

160 Further, it is said that any loss or damage as a result of such contraventions will vary on an individual group member basis and will not be answered by determining a sample group member’s claim.

161 But in my view the anti-avoidance claims do raise common issues.

162 The claims concern a common decision to implement a scheme to avoid the operation of the ban on conflicted remuneration. The investigation of the purpose behind the scheme will yield a common answer that will either support or negate a finding of breach.

163 Further, although the respondents complain that none of the applicants invested in products which yielded the payment of non-insurance product commissions, the applicants have indicated that they will identify a sample group member who paid non-insurance product commissions.

Fiduciary duty and derivative claims

164 Now there are fiduciary duties allegedly owed by the AMP licensees and separately owed by the AMP authorised representatives, for whom the AMP licensees are responsible.

165 It may be accepted that the existence of a fiduciary relationship between an AMP licensee or AMP authorised representative and an applicant and/or group member must be informed by the nature of the relationship with the applicant or group member. Moreover, in any one year there were numerous AMP authorised representatives across the AMP licensees as I have already indicated.

166 Further, to a large extent the determination of the existence of a fiduciary duty, the scope of that duty, as well as whether there was a breach of that duty necessitates an investigation into the circumstances of each of the group members.

167 Further, even if a fiduciary duty is found to exist, the determination of that duty’s scope will also depend on an examination of all of the facts and circumstances on a case by case basis. This would require an examination of the relationship between each of the group members and their particular AMP authorised representatives.

168 These claims, of course, raise many individual questions. But selecting a sufficient number of sample group member claims for adjudication may be an efficient way to proceed in the first instance.

169 As for the knowing receipt claim against AMP Life, the allegations are a derivative of the breach of fiduciary duties claims. Being such derivative claims, they also require a consideration of the circumstances of each group member with respect to the fiduciary duty allegations.

170 Now that may be true. But that does not entail that there are not broader questions and systems that will need to be addressed.

OSF contractual breaches

171 As to the contractual breaches alleged in relation to the OSF sub-group members, the ongoing services contractually offered to any OSF sub-group member depended on the specific AMP authorised representative as well as the needs of, and the terms of the ongoing fee arrangement with, the individual client.

172 So, for example, with respect to the second applicant, during the time she held the Flexible Lifetime Protection Plan product, she did not pay any ongoing service fees for the product. But with respect to her holding of the Flexible Super – Flexible Protection product, she agreed to pay an ongoing advice fee to include particular services.

173 With respect to the fourth applicant, whilst the limited advice financial plan for the PortfolioCare Investment Service product he invested in disclosed that he was required to pay particular fees, during the time that he held that product he did not pay any ongoing service fees in respect of that product.

174 Now I accept to some extent that the present case is distinguishable from say a case where a determinative factor is that the documents relied upon for the breach of contract claim are identical in each case. The circumstances are also distinguishable from a case where, if the common questions were determined affirmatively, all individual group members then needed to do was to show that they entered into the same standardised system as the applicant.

175 The respondents say that the circumstances of the present case more closely align with those in Meaden v Bell Potter Securities Limited (No 2) (2012) 291 ALR 482 and the observations made by Edmonds J at [65]. It is said that there is such a lack of commonality that any determination of the second and fourth applicants’ OSF contractual breaches claims would offer no real guidance as to how the balance of the contractual claims by the OSF sub-group members would be determined were they to proceed to be determined individually.

176 Now the applicants submit that the respondents have failed to appreciate that the range of services offered to each individual OSF sub-group member still placed them into a common cohort of people who obtained the AMP ongoing service package and who paid OSFs, but did not receive the service.

177 But that ignores, so the respondents say, the respondents’ defence where the notion of the “AMP Ongoing Service Package” is not admitted. Rather, it is pleaded that ongoing fee arrangements were negotiated directly as between AMP authorised representatives and their client and that any ongoing services offered depended on the specific AMP authorised representative as well as the needs of, and the terms of the ongoing fee arrangement with, the individual client.

178 The respondents say that there was no one template package offered to OSF sub-group members. The services that any given OSF sub-group member was entitled to, and did or did not receive from his AMP authorised representative will be an individual question.

179 Moreover, the anterior step of actually working out which group members formed part of the alleged common cohort of people who entered into ongoing service fee arrangements, but who did not receive the service in whole or in part, is one which must be addressed by reference to each individual OSF sub-group member.

180 Further, whether there was a breach by an authorised representative of his obligations to his client, in terms of any obligation to provide ongoing advice which complied with the requirements of ss 961B and 961J, is necessarily an individual one.

181 Now the applicants counter that the respondents’ attempt to characterise the ongoing service issue as individualised fails to appreciate that the range of services offered to each individual OSF sub-group member still place them into a common cohort of people who obtained the AMP ongoing service package and who paid OSFs, but did not receive the service. That is true in its generality, but I am here considering common issues not common cohorts.

182 It is said that the commonality is in the payment of OSFs for services that were never received. And it is said that the fact that some group members were offered additional services that were not provided does not detract from the contention that the OSF sub-group members were promised, and paid for, services that were not provided. All true, but this is pitched at too high a level of abstraction.

183 Further, it is said that the ongoing services offered to any OSF sub-group members had no differences of substance, they were all differences of form. I am not necessarily convinced of this.

184 In my view, most of the issues here are non-common, but I can efficiently deal with some representative sample group member claims.

Unconscionable conduct claim

185 The applicants’ unconscionable conduct case is limited to statutory unconscionable conduct under s 12CB(1) of the ASIC Act.

186 Now the applicants’ pleaded case is not one that focuses on a system of conduct or a pattern of behaviour of the respondents but rather one that directs attention to the individual circumstances of each of the applicants and group members.

187 The respondents say that only by examining the circumstances of each of the group members and the advice they were given can one determine whether each of those group members was subject to the alleged disadvantage which affected their ability to make a judgment as to their own best interests. Further, they say that the examination of individual circumstances are necessary to determine whether the AMP authorised representatives and the AMP licensees took advantage of any such disadvantage. It is said that all of these inquiries are necessary in respect of the unconscionable conduct claim as pleaded.

188 I am inclined to agree, but it is difficult for the respondents to contend that no investigation of their systems and procedures will be necessary as part of dealing with these claims.

Misleading or deceptive conduct claims

189 The applicants say that the primary basis on which it is alleged that the commissions representations arose was by silence, in the circumstances of the receipt of personal advice from an AMP authorised representative and the payment of commissions, or in the case of the OSF subgroup, the payment of OSFs. It is said that this is the “common nucleus of facts” which give rise to the allegations.

190 Further, it is said that to the extent that there are circumstances of a particular group member’s case such that the relevant silence is said not to arise, there may still be utility in answering the question of whether the representations were made, leaving aside any fact relevant to the issues which are peculiar to a particular group member.

191 The applicants say that the alternative case advanced is that the relevant representations were implied from the terms of the pro-forma AMP ongoing service packages, product disclosure statements and financial services guides.

192 Again, it is accepted that there may not be complete uniformity in the terms of documents provided to all group members. But the applicants say that they will only seek findings in relation to the applicants’ documents and any standard terms. It is said that there will be utility in determining whether the representations were implied from those standard terms.

193 But I agree with the respondents that there is significant diversity in the circumstances which might support individual claims as to what representations were made to them with respect to commissions and premiums, and whether those representations were misleading or deceptive.

194 Now the respondents correctly point out that the circumstances particularised as to when and how the impugned representations were allegedly made are wide reaching. They range from allegedly being conveyed by the following matters.

195 First, they are said to be conveyed in the “AMP Ongoing Service Package”, which is not a uniform document or package received by group members.

196 Second, they are said to be conveyed by silence, allegedly creating a reasonable expectation that the AMP authorised representatives or AMP licensees would have disclosed the matters the subject of the representation. But the determination of whether a failure to disclose a matter is misleading or deceptive requires examination of all the circumstances, including the circumstances and knowledge of the representee.

197 Third, they are said to arise by implication from the product disclosure statements and financial services guides for the commissioned products. But the product disclosure statements and financial services guides are not a neat set of documents which are identical or nearly identical in terms of what was conveyed by them.

198 Further, as the respondents point out, before one even gets to the product disclosure statements for each of the commissioned products, there is a difficulty in working out the number of commissioned products that were issued throughout the relevant period. Apparently, determining the number of commissioned products in relation to which a commission was paid and which were available to AMP licensees requires a detailed and lengthy reconciliation of data from a number of different systems given the likely number and types of products involved.

199 Further, the respondents say that the submission that the circumstances of a client’s receipt of personal advice from his or her AMP authorised representative and the payment of commissions somehow make up the “common nucleus of facts” in respect of the commission representations said to arise by silence is misconceived.

200 To determine whether there was misleading or deceptive conduct by silence requires an analysis of all of the circumstances, including the awareness of the persons to whom the commission representations were allegedly conveyed. To determine whether there was a reasonable expectation that the matters comprising the commissions representations ought to have been but were not disclosed to any group member requires analysis of the peculiar circumstances of each of those group members. It is insufficient to establish that those group members received personal advice from an AMP authorised representative and that commissions might have been paid in respect of any investment they made. Put another way, the quality of these commonalities identified by the applicants is de minimis to the extent they assist in determining the misleading or deceptive conduct allegations.

201 The respondents say that it is difficult to understand how there is utility in attempting to answer the question of whether the representations were made when the commission representations are said to have been made by the silence of the AMP authorised representatives. How can I answer this question without considering what each of the AMP authorised representatives in fact said, or did not say, to their clients? The fact of whether the commission representations were made is peculiar to each group member.

202 As to the alternative misleading or deceptive conduct case advanced, being that the representations are implied from the circumstances and the product disclosure statements and financial services guides for the commissioned products, that too lacks commonality. The circumstances are the individual circumstances referable to the relationship between the individual group members and their authorised representatives identified in the particulars. The only alleged representation said to arise from the PDS and the Guide is to the effect that OSFs were paid in exchange for ongoing personal advice. The establishment of a representation of this character does not advance matters, since the question of whether it was misleading is necessarily an individual one.

203 Further, there is no admission in the defence that the documents received by the applicants or group members were pro forma documents. Rather, the defence makes it apparent that the arrangements between, and documents provided by, the AMP authorised representatives to their clients were bespoke to each individual client and their adviser; see for example the statements of advice and associated documents given to Mr Stack and Mr & Mrs Winterton.