Federal Court of Australia

Dutton v Bazzi [2021] FCA 1474

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Applicant, by 4 pm on 29 November 2021, file and serve any affidavits to be relied upon in relation to the issues of costs and interest, together with an outline of submissions concerning these matters, not exceeding five pages.

2. The Respondent, by 4 pm on 3 December 2021, file and serve any affidavits to be relied upon in relation to the issues of costs and interest, together with an outline of submissions, concerning these matters, not exceeding five pages.

3. The Court will hear submissions concerning the orders to be made to give effect to the judgment, including the issues of costs and interest at 3 pm (AEDT) on 8 December 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WHITE J:

Introduction

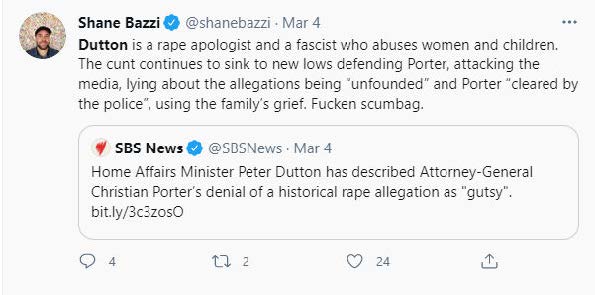

1 On 25 February 2021 at 11.51 pm, the respondent (Mr Bazzi) published on Twitter a tweet (the Tweet) containing the words:

Peter Dutton is a rape apologist.

2 The Tweet contained a link to an article published online in The Guardian Newspaper some 20 months previously, on 20 June 2019. The link in the form of the Tweet which is the subject of this litigation comprised a large photograph of Mr Dutton, the name “The Guardian” and the following words:

Peter Dutton says women using rape and abortion claims as ploy to ge…

Home Affairs minister says ‘some people are trying it on’ in an attempt

to get to Australia from refugee centres on Nauru.

The first of these lines (which is in a black font) comprised part of the headline to The Guardian article. The remainder (in a blue font) constituted the whole of the first sentence in the article.

3 The applicant (Mr Dutton) was the Minister for Home Affairs in the Australian Government as at 25 February 2021 and is now the Minister for Defence. He sues Mr Bazzi in defamation in respect of his posting of the Tweet. It was common ground that Mr Bazzi had composed the Tweet and had published it of and concerning Mr Dutton. It was also common ground that Mr Bazzi had removed the Tweet when he received the demand from Mr Dutton’s solicitors on or shortly after 6 April 2021.

4 Mr Dutton alleges that the Tweet conveyed four defamatory meanings:

(a) The applicant condones rape;

(b) The applicant excuses rape;

(c) The applicant condones the rape of women; and

(d) The applicant excuses the rape of women.

Mr Dutton’s counsel described the first of these imputations as the “most powerfully conveyed”.

5 Mr Dutton seeks by way of relief damages, including aggravated damages, and injunctions restraining Mr Bazzi from publishing further the Tweet or the imputations it is said to convey.

6 Mr Bazzi admits that he maintained and authorised the content of the Twitter page on which the Tweet was published and admits that, if the Tweet did convey the imputations alleged by Mr Dutton, they were defamatory. He denies, however, that the Tweet conveyed any of the pleaded imputations. In addition, he raises two substantive defences:

(a) honest opinion under s 31 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) and its counterparts in the Uniform Defamation Acts of the States and Territories (to which I will refer collectively as the “UDA”); and

(b) the common law defence of fair comment.

7 Counsel for Mr Bazzi said that the common law defence of fair comment was relied upon only in the event that the statutory defence of honest opinion did not succeed.

The parties

8 Mr Dutton is the member for the seat of Dickson in the House of Representatives in the Australian Parliament, having first been elected in November 2001. He said that with the exception of the period between 2007 and 2013 when the Coalition was in opposition, he has been a member of the Ministry in the Australian Government since 2004, as follows:

2004-2007 – Minister for Workplace Participation;

2013-2014 – Minister for Health;

2014-December 2017 – Minister for Immigration and Border Protection;

December 2017-March 2021 – Minister for Home Affairs; and

March 2021-present – Minister for Defence.

9 Between October 1990 and July 1999, Mr Dutton served as a Police Officer in the Queensland Police Service. After about 18 months as a uniformed police officer, he became a plain clothes detective in the State Crime Operations Command. In that capacity, he served for periods in the Sex Offenders Squad, the Drug Squad, the National Crime Authority and in the Corrective Services Investigation Unit. His work in the Sex Offenders Squad involved the investigation of allegations of sexual assaults and, in turn, working with the victims of sexual assaults, including victims of historical sexual assaults. He was also engaged in the prosecution of allegations of sexual assaults. In the Corrective Services Investigation Unit, Mr Dutton was involved in the investigation of criminal offences and possible criminal offences in the Queensland corrective services system. Between leaving the Queensland Police Service in July 1999 and entering the Australian Parliament, Mr Dutton worked in a family business involving the operation of child care centres and property development.

10 Mr Dutton also deposed that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) for which he had had responsibility as Minister for Home Affairs had a definite focus on the protection of women and children against sexual assault. As another indication of the seriousness with which he views sexual assaults, he said that he had directed that police with expertise in forensic investigation go to Nauru to ensure that allegations of sexual assault on those in refugee centres were being investigated properly.

11 Mr Bazzi did not give evidence and there was little evidence of his circumstances. In one document, he is described as an “unemployed Centrelink recipient” and in another as “an unemployed refugee activist”.

The Tweet

12 The Tweet published by Mr Bazzi is set out in full:

Defamatory meaning – principles

13 A defamatory statement for the purposes of the tort of defamation is one published to a third party or to third parties about a person which has a tendency to lower the person’s reputation.

14 The approach of the courts in determining whether an impugned publication did convey the defamatory meaning alleged is settled, and there was little difference between the parties as to the applicable principles. They are established by authorities such as Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton [2009] HCA 16, (2009) 238 CLR 460 at [5]-[6]; John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50, (2003) 77 ALJR 1657 at [26]; Reader’s Digest Services Pty Ltd v Lamb [1982] HCA 4, (1982) 150 CLR 500 at 505-6; Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd v Marsden [1998] NSWSC 4, (1998) 43 NSWLR 158 at 164-5; Farquhar v Bottom [1980] 2 NSWLR 380 at 386-7; and Charleston v News Group Newspapers Ltd [1995] 2 AC 65 at 69-74.

15 The Court is to consider whether ordinary reasonable readers would have understood the impugned words to convey the defamatory meanings pleaded: Radio 2UE v Chesterton at [6]. As ordinary reasonable readers may vary widely in temperament, character, education, life experience and outlook, the Court selects “a mean or midpoint of temperaments and abilities” and assesses the meaning conveyed to such persons: Cummings v Fairfax Digital Australia & New Zealand Pty Ltd [2018] NSWCA 325, (2018) 99 NSWLR 173, at [104].

16 The defamatory meaning may lie in the literal meaning of the words or in that which can be implied or inferred from them. It includes inferences and conclusions which the ordinary reasonable person draws from the words used, taking into account the observation of Lord Reid in Morgan v Odhams Press Ltd [1971] 1 WLR 1239 at 1245, that the reader may engage in a certain amount of “loose thinking”. Lord Reid went on to say:

The ordinary reader does not formulate reasons in his own mind: he gets a general impression and one can expect him to look at it again before coming to a conclusion and acting on it. But formulated reasons are very often an afterthought.

17 When the words in the impugned matter are capable of bearing more than one meaning, the Court must decide on one of those meanings. This is the “single meaning” rule: Slim v Daily Telegraph [1968] 2 QB 157 at 173; Hockey v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 652, (2015) 237 FCR 33 at [73].

18 Ordinary reasonable readers are taken to be persons of ordinary intelligence, experience and education, who are neither perverse nor morbid nor suspicious of mind, nor avid for scandal. They do not live in ivory towers and can and do read between the lines in the light of their general knowledge and experience. They do not engage in over-elaborate analysis and search for hidden meanings, nor do they adopt a strained or forced interpretation. They are not lawyers and their capacity for implication may be greater than that of lawyers.

19 Generally, the courts do not take a narrow view of the meaning conveyed to reasonable readers by words which are imprecise, ambiguous, loose, fanciful or unusual: Marsden at 165. The more sensational the impugned matter, the less likely it is that the ordinary reasonable reader will read it with a degree of analytical care which may otherwise be given to a book and the less the degree of accuracy which may be expected by the reader: Marsden at 165.

20 Context is important in deciding whether a publication conveyed a defamatory meaning: Watney v Kencian [2017] QCA 116; (2018) 1 Qd R 407 at [19]-[21]. That is because the ordinary reasonable reader does not look at the impugned statement in isolation from the whole context in which it is published: John Fairfax & Sons Ltd v Hook [1983] FCA 83; (1983) 72 FLR 190 at 195; Charleston v News Group at 70. Words which are not defamatory in isolation may acquire a different meaning when read in the context of other statements (Watney v Kencian at [20]) and the converse may also be true.

21 The context includes the whole of the publication containing the impugned words, and the ordinary reasonable reader is taken to have read it all: Hockey v Fairfax Media at [65]-[66]; Watney v Kencian at [22]. As was noted by Lord Bridge of Harwich in Charleston v News Group at 72, the law does not contemplate that different groups of readers may read different parts of the entire publication and for that reason understand it to mean different things, some defamatory, and some not.

22 However, consideration of context is not confined to the entirety of the impugned publication. It includes the mode of publication: Duncan and Neill on Defamation, 5th Edition at [5.25]. The medium used can, amongst other things, “affect the way in which the ordinary reader absorbs the information, including the amount of time they devote to reading or viewing it” (Watney v Kencian at [19]) and readers may “react to it in a way that reflect[s] the circumstances in which it was made” (Stocker v Stocker [2019] UKSC 17; [2020] AC 593 at [39]). These authorities reflect the common experience that the way in which words are presented can inform the meaning they convey.

23 The significance in the defamation context of a publication being on social media has now been addressed in a number of authorities in the United Kingdom and one (Monroe v Hopkins [2017] EWHC 433 (QB); [2017] 4 WLR 68) contains in an Appendix a useful explanation of tweets under the heading “How Twitter Works”.

24 In Stocker v Stocker, Lord Kerr, in the judgment of the Supreme Court, said:

[41] The fact that this was a Facebook post is critical. The advent of the 21st century has brought with it a new class of reader: the social media user. The judge tasked with deciding how a Facebook post or a tweet on Twitter would be interpreted by a social media user must keep in mind the way in which such postings and tweets are made and read.

[42] In Monroe v Hopkins [2017] 4 WLR 68, Warby J at para 35 said this about tweets posted on Twitter:

“The most significant lessons to be drawn from the authorities as applied to a case of this kind seem to be the rather obvious ones, that this is a conversational medium; so it would be wrong to engage in elaborate analysis of a 140 character tweet; that an impressionistic approach is much more fitting and appropriate to the medium; but that this impressionistic approach must take account of the whole tweet and the context in which the ordinary reasonable reader would read that tweet. That context includes (a) matters of ordinary general knowledge; and (b) matters that were put before that reader via Twitter.”

[43] I agree with that, particularly the observation that it is wrong to engage in elaborate analysis of a tweet; it is likewise unwise to parse a Facebook posting for its theoretically or logically deducible meaning. The imperative is to ascertain how a typical (ie an ordinary reasonable) reader would interpret the message. That search should reflect the circumstance that this is a casual medium; it is in the nature of conversation rather than carefully chosen expression; and that it is pre-eminently one in which the reader reads and passes on.

[44] That essential message was repeated in Monir v Wood [2018] EWHC (QB) 3525 where at para 90, Nicklin J said, “Twitter is a fast moving medium. People will tend to scroll through messages relatively quickly.” Facebook is similar. People scroll through it quickly. They do not pause and reflect. They do not ponder on what meaning the statement might possibly bear. Their reaction to the post is impressionistic and fleeting. Some observations made by Nicklin J are telling. Again, at para 90 he said:

“It is very important when assessing the meaning of a Tweet not to be over-analytical … Largely, the meaning that an ordinary reasonable reader will receive from a Tweet is likely to be more impressionistic than, say, from a newspaper article which, simply in terms of the amount of time that it takes to read, allows for at least some element of reflection and consideration. The essential message that is being conveyed by a Tweet is likely to be absorbed quickly by the reader.”

25 Three other features of Twitter are pertinent. First, when Twitter commenced, it limited users to 140 characters (not words) but since the end of 2017, the limit has been 280 characters. It is accordingly customary for tweets to be brief, pithy or terse. The ordinary reasonable reader of tweets will know, and expect, that to be so.

26 The second feature is that it is in the nature of the medium for its Twitter users to provide short comments on the issues of the day and to assume some knowledge by readers of those issues.

27 The third is that it is not uncommon for users to provide links to related material.

28 The context may also include matters of public notoriety or public awareness which may have informed the ordinary reasonable reader’s understanding of what was conveyed: Hockey v Fairfax Media at [90]-[92]. That is especially so in the case of Twitter in which, as just indicated, it is commonplace for users to provide, as part of the “conversation”, succinct comments on issues of the day. Again the ordinary reasonable reader will know and expect that to be so.

29 In summary, these authorities suggest that the following approach is appropriate:

(a) the ordinary reasonable readers to be considered are members of the class of users of social media;

(b) Twitter is a conversational medium through which the ordinary reasonable reader tends to scroll quickly and pass on with the consequence that an impressionistic rather than a closely analytical approach is appropriate. The essential message being conveyed by a tweet is likely to be absorbed quickly by the reader; and

(c) in the discernment of the meaning conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader, account should be taken of the whole tweet and the context in which it is read by that reader.

Defamatory meaning – consideration

30 I set out at the commencement of these reasons the imputations alleged by Mr Dutton. The issue to be addressed is whether the Tweet did convey any of those meanings to the ordinary reasonable reader of Twitter.

31 In making the assessment of what the Tweet conveyed, regard must be had not only to the words “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist” but to the whole of the Tweet, including the photograph of Mr Dutton, the words “The Guardian” and the words which followed. Neither counsel contended that regard should be had to the full content of The Guardian article in determining the meaning conveyed by the Tweet.

32 It was common ground that the ordinary reasonable reader of Twitter would have understood the photograph of Mr Dutton, the words “The Guardian”, and the words appearing under the photograph to be a link to The Guardian article. It is less clear that the ordinary reasonable reader would have understood that all the words under the photograph of Mr Dutton were extracts from The Guardian article, but I accept that that was the case, having regard to common usage on Twitter and that the last three lines were in the blue font of a hyperlink.

33 Counsel for Mr Bazzi submitted that an important aspect of the context to be considered is the public reporting of the allegation of rape by Ms Brittany Higgins, with which the publication of the Tweet was closely contemporaneous. Ms Higgins had made public on 15 February 2021 her claim of having been raped in Parliament House on 23 March 2019. The allegation was given widespread coverage in the print, television, radio and online media having regard, amongst other things, to the circumstance that Ms Higgins was, at the time of the alleged rape, employed in the office of the then Minister for Defence (Senator Reynolds); that the rape was said to have taken place in the Ministerial suite; that the perpetrator was said to be another Ministerial staffer; the issues concerning the manner in which Ms Higgins’ allegations had been addressed by the Government at the time she had first made them, including Ms Higgins’ report that she had felt forced to choose between reporting the rape to police and the keeping of her job; and the potential breach of the security of Parliament House by the alleged perpetrator and Ms Higgins entering the building in the circumstances they had.

34 The public attention to Ms Higgins’ allegation is indicated by, amongst other things, the circumstance that the Prime Minister, Mr Morrison, had been questioned in the Parliament on 15 February 2021 about the Government’s response to the alleged rape.

35 Two issues in the publicity which ensued after 15 February 2021 concerned when the Prime Minister had first been informed of Ms Higgins’ allegations and his response to them. On the first of these topics, Mr Dutton gave a “doorstop” interview on 25 February 2021 at about 9 am, which received media coverage. He did so in his then capacity as Minister for Home Affairs. Topics pursued by the journalists in the interview included when Mr Dutton himself had first been informed of Ms Higgins’ allegations, when the Prime Minister’s office had first been informed, and why Mr Dutton had not informed the Prime Minister’s officer earlier. Mr Dutton told the journalists that the AFP had informed him of Ms Higgins’ allegations on the morning of 11 February 2021; that he had decided at that time not to inform the Prime Minister of the allegations because the AFP had given him the information as part of an “in-confidence” briefing; that he had wished to honour the confidence; that he had not thought it necessary or appropriate at that time to pass on the information to the Prime Minister’s office; that he still regarded that as the right judgement; that he had on 12 February 2021 directed staff in his own office to provide the information to the Prime Minister’s office; that they had done so that same day; and that, in the report which he himself had received from the AFP, he had not been provided with “the she said, he said details of the allegations”.

36 Mr Dutton’s office issued a transcript of the doorstop interview which was tendered, in addition to video tapes of portions of the interview. It can be inferred (and I do) that the transcript was issued on 25 February 2021 but the time at which that occurred and the use, if any, made of the transcript before Mr Bazzi published the Tweet was not disclosed in the evidence.

37 The evidence also included an ABC News article entitled “Peter Dutton defends handling of information around Brittany Higgins’ rape allegation” posted online at 9.16 am and updated at 10.55 am on 25 February 2021 which included, in part, an account of the doorstop interview. In addition, the evidence included an article from NEWS.com.au entitled “Peter Dutton describes Brittany Higgins’ alleged rape as ‘he said, she said’” which was posted at 12.25 pm on 25 February 2021. That article contained a report of the doorstop interview.

38 The evidence also indicated that Senator Waters had issued a media release, published tweets and had held a press conference on 25 February 2021 in which she had been critical of Mr Dutton’s statements. This included criticism of Mr Dutton’s use of the expression “the she said, he said details”.

39 It is no part of this judgment to pass comment on whether the criticisms of Mr Dutton were, or were not, justified. The relevant matter is that, earlier on the day on which Mr Bazzi published the Tweet, there had been media coverage, including by mainstream media, of statements by Mr Dutton in relation to aspects of Ms Higgins’ allegations and they had become one of the political issues of the day.

40 I am willing to accept, in a general way, that Mr Dutton’s statements and the media coverage of them formed part of the context in which Mr Bazzi published the Tweet shortly before midnight on the same day. Amongst other things, these matters help explain why Mr Bazzi may have been prompted to make the Tweet on the day he did.

41 However, counsel’s submission did not indicate, in any specific way, how this context had helped inform the Tweet readers’ understanding of what was meant by the statement “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist”. In particular, counsel did not contend that, in the media coverage of the day, the terms “rape apologist” or “apologist” had been used or understood with some particular meaning or connotation which differed from the meaning ordinarily conveyed by the term “apologist”.

42 The third and fourth pleaded imputations differ from the first and second only in their reference to the rape of women. Counsel for Mr Dutton submitted that the reference to women in the link to The Guardian article in the Tweet had the effect of linking the allegation of Mr Dutton being a rape apologist to the rape of women and that this justified these additional imputations.

43 I say immediately that I do not accept this particular submission. In my view, the ordinary reasonable reader of the Tweet would have readily understood the statement that Mr Dutton is a rape apologist to be a statement in respect of the rape of women and not a statement in respect of both sexes. That is confirmed by the words which followed. For that reason, the third and fourth pleaded imputations are not different in substance from the first and second. If those meanings were not conveyed, then neither were the third and fourth. If the first or second were conveyed, then so was the counterpart in (c) and (d) but neither would add to the defamation. Accordingly the third and fourth meanings need not be considered further.

44 The first pleaded imputation is that “the applicant condones rape” and the second “the applicant excuses rape”. The relevant meaning of “condone” in the Macquarie Dictionary is “to pardon or overlook (an offence)” and first meaning of “excuse” in the same Dictionary is “to regard or judge with indulgence; pardon or forgive; overlook (a fault etc)”. This suggests that there is also relatively little difference between imputations (a) and (b). However, in common parlance the word “condone” sometimes also has a connotation of “tacit approval”, which the verb “excuse” does not.

45 Counsel for Mr Bazzi submitted that the Tweet did not convey either of the first two imputations. His submission included the following elements:

(a) the term “rape apologist” has no easily defined meaning for the ordinary reasonable reader. Such a reader would of course understand the meaning of the word “rape’ and would also understand the word “apologist”, considered by itself and without any accompanying words or context, to mean “a person who defends a particular position or action”. He accepted therefore that, in the absence of context to colour its meaning, the term could be understood to have conveyed the meanings of imputations (a) and (b);

(b) however, this meaning, being devoid of context, was no more than a “literal meaning”, and resulted from the use of an inappropriate “technical and linguistically precise” approach;

(c) the assertion that Mr Dutton is a rape apologist would not have been understood in isolation from its context. Instead, in the assessment of the meaning conveyed, the content of the whole Tweet must be considered, including the lines from The Guardian article appearing underneath the photograph of Mr Dutton, as well as the political issue of the day;

(d) the ordinary reasonable reader of Twitter would know that the reference to The Guardian and the words which followed related to the article in The Guardian. Such a reader would treat the words under the photograph as explanatory or introductory to the article, and as allowing them to decide whether or not to read it;

(e) the words beneath the photograph conveyed that Mr Dutton had said that women were using rape and abortion claims as a ploy to get into Australia from refugee centres on Nauru and that, in so doing, they were “trying it on”;

(f) those words coloured the meaning conveyed by the opening statement that Mr Dutton is a rape apologist as the reader would have understood Mr Dutton to be asserting that women were making false claims of rape so as to be able to come from refugee centres in Nauru to Australia to have an abortion; and

(g) additionally, there was nothing to convey to the ordinary reasonable reader that Mr Bazzi was asserting that Mr Dutton condoned or excused rape. Instead, the words in the link to The Guardian article “indubitably contextualise[d]” the meaning of “rape apologist” to the ordinary reader.

46 Counsel’s submission in short was that the two parts of the Tweet have to be read together and, when that is done, the word “apologist” did not convey its ordinary meaning to the Twitter reader.

47 Counsel disparaged the use of dictionary definitions. In doing so, he placed considerable reliance on Stocker v Stocker in which the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom had held that the trial Judge’s use of such definitions had resulted in an error of law. The circumstances were that Mrs Stocker had alleged on Facebook that her former husband had “tried to strangle me”. By reference to the definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary of the verb “strangle” ((a) to kill by external compression of the throat; and (b) to constrict the neck or throat painfully) the trial judge had held that, as Mr Stocker had succeeded in compressing Mrs Stocker’s neck painfully, his action had gone past “trying” to strangle her so that the second of these meanings was not available. Accordingly, the imputation conveyed must have been that Mr Stocker had tried to kill his wife. In effect, the trial judge had used the dictionary definitions as a kind of straightjacket which limited the meanings conveyed by the statement that Mr Stocker had “tried to strangle me” to only one of two alternatives.

48 The Supreme Court found that the trial judge’s error lay in his regarding the two definitions as the only possible meanings which he could consider or, at the very least, the starting point for his analysis, rather than as a cross-check or confirmation of the correct approach, at [24]. Lord Kerr continued with a more general caution about the use of dictionary definitions:

[25] Therein lies the danger of the use of dictionary definitions to provide a guide to the meaning of an alleged defamatory statement. That meaning is to be determined according to how it would be understood by the ordinary reasonable reader. It is not fixed by technical, linguistically precise dictionary definitions, divorced from the context in which the statement was made.

49 Later, at [38], Lord Kerr emphasised that the task of the Court was to “step aside from a lawyerly analysis and to inhabit the world of the typical reader of a Facebook post”.

50 Statements of the caution to be used in applying dictionary definitions in the ascertainment of defamatory meaning can also be found in Australian authorities: Fleming v Advertiser-News Weekend Publishing Co Pty Ltd [2016] SASCFC 109 at [47]; Weeks v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 4) [2019] WASC 350 at [53].

51 In a submission related to that concerning the use of dictionaries, counsel submitted that the Court should not proceed on the basis that words have “immovable literal meanings”. He referred in this respect to Greek Herald Pty Ltd v Nikolopoulos [2002] NSWCA 41; (2002) 54 NSWLR 165 at [21] in which Mason P referred to the statements of Holmes J in Towne v Eisner 245 US 148 (1918) at 425 that “a word is not a crystal, transparent and unchanged, it is the skin of living thought and may vary greatly in colour and content accordingly to the circumstances and the time in which it is used”. See also Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125 at [169].

52 Counsel for Mr Bazzi submitted, correctly, that it was not necessary for Mr Bazzi, in defending Mr Dutton’s claim, to establish that the Tweet conveyed an alternative meaning to those pleaded by Mr Dutton. He said, however, that Mr Bazzi would contend that the Tweet, considered as a whole, conveyed that Mr Dutton “lacks empathy or sympathy towards those women on Nauru who reported that they had been raped”.

53 Finally, counsel posed (adapting that asked by Lord Kerr in Stocker v Stocker at [50]) the question by the hypothetical ordinary reasonable reader that, if Mr Bazzi had intended to convey that Mr Dutton condones or excuses rape, why he would have not said so explicitly?

54 The understanding that the term “apologist” means a person who defends someone or something is supported by the dictionary definitions set out below. I have included a range of definitions so as to allow for the possibility that nuances of meaning have developed over time:

The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edition) 1989 and the Oxford English Dictionary Online 2018 | “One who apologises for, or defends by argument, a professed literary champion.” |

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 1984 and 1993: | “A person who defends another, a belief etc by argument; a literary champion.” |

Macquarie Dictionary, 1997 | “1 One who makes an apology or defence in speech or writing. 2 ecclesiastical A. a defender of Christianity. B. one of the authors of the early Christian apologies.” |

Macquarie Dictionary, 8th Edition, 2020 | “1 Someone who makes an apology or defence in speech or writing. 2 eccles A. a defender of Christianity. B. one of the authors of the early Christian apologies.” |

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, 1993 | “1. one who makes an apology or defense; one who speaks or writes in defense of a faith, a cause, or an institution; esp: one who makes systematic defense of Christianity 2 usu cap: one of a number of 2d century church fathers who wrote treatises in defense of the Christian faith.” |

Websters Comprehensive Dictionary, 1995 | “One who argues in defence of any person or cause.” |

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary | “one who speaks or writes in defense of someone or something.” The Online Dictionary includes the following recent examples: The special rapporteurs to whom Blinken extended an invitation; at least one of those experts, Belarus’s Alena Douham, is an out-and-out apologist for authoritarian governments who regularly speaks to their state media outlets. – Jimmy Quinn, National review, 8 Sep. 2021. You’re seen by your more hawkish peers as an apologist for the Chinese Government. – Annabelle Timsit, Quartz, 17 May 2021. |

55 The common meaning in these definitions is that an apologist is one who speaks or writes in defence of someone or something. This meaning is consistent with the incorporation into the English language of the Latin word “apologia” to denote the formal defence or justification in speech or writing, as of a cause or doctrine. John Henry Newman’s “Apologia Pro Vita Sua” is a well-known example of an apologia.

56 While the Tweet must be read a whole, this does not mean that all the words used in it have the same significance: John Fairfax v Rivkin at [26] (McHugh J); Mirror Newspapers Ltd v World Hosts Pty Ltd [1979] HCA 3, (1979) 141 CLR 632 at 646 (Aickin J); Hockey v Fairfax at [70]-[71]. In this respect, it is pertinent that the statement “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist” is in the opening line of the Tweet. The ordinary reasonable reader of the Tweet would have understood it to be a pithy statement of what Mr Bazzi sought to convey and as being his contribution to the “conversation”. The reader would have understood that contribution to be “new”, i.e, as an addition to the “conversation”. The ordinary reasonable reader would also have readily understood that the words under the photograph of Mr Dutton were not Mr Bazzi’s words. This would have limited the extent to which the reader would have understood the term “rape apologist” to have been coloured by those words.

57 Moreover, the ordinary reasonable reader would have readily understood that Mr Bazzi’s contribution was distinct from the link and the matters which comprised it. In that context, there was no reason for the ordinary reasonable reader to think that the word “apologist” was being used with other than its ordinary meaning.

58 Further, rather than ordinary reasonable readers understanding that the word “apologist” was used with some special meaning to be gleaned from the words in the link, they are more likely to have thought that the link would provide support for Mr Bazzi’s assessment of Mr Dutton stated in the opening line. In this respect, the pithy statement is likely to have had an effect on the ordinary reasonable reader akin to the effect of the headline to a newspaper article, i.e, as giving an indication of what would be found by following the link.

59 This understanding of the meaning conveyed does not require the Court to suppose that the ordinary reasonable readers would, by reason of the content of the link, have understood the term “rape apologist” was used with an idiosyncratic meaning, which counsel’s suggested alternative meaning entails. Nor does this understanding of the meaning suffer from the fault of being “technically or linguistically precise”. It is instead the meaning in which the word “apologist” is normally used and understood.

60 One could turn on its head the rhetorical question posed by Mr Bazzi’s counsel which might be asked by the hypothetical ordinary reasonable reader and ask: if Mr Bazzi had not meant to convey that Mr Dutton was a rape apologist, why did he use that term? Alternatively, if Mr Bazzi had meant to convey that Mr Dutton lacked empathy or sympathy towards the women in the refugee centres in Nauru who claim to have been raped, why did he not say so explicitly? Such an assertion could have been expressed pithily, and well within the 280 character limit for Tweets.

61 It follows that I do not accept the alternative meaning postulated by Mr Bazzi’s counsel to have been conveyed.

62 For these reasons, I do not accept the submission of Mr Bazzi’s counsel as to the way in which the Tweet would have been understood. I consider that the ordinary reasonable reader would have understood Mr Bazzi to be asserting that Mr Dutton was a person who excuses rape, and that the attached link provided support for that characterisation of him. I am not satisfied that the same reader would have understood Mr Bazzi to be saying that Mr Dutton “condoned” rape, given the connotation in that statement that Mr Dutton tacitly approved of rape. The ordinary reasonable reader would not have understood Mr Bazzi as conveying such an extreme statement.

63 Although one cannot be certain, given that Mr Bazzi did not give evidence, I consider it likely that this is a case in which a respondent has used a term without an appreciation of the actual meaning it conveyed. Mr Bazzi may well have intended, subjectively, to have conveyed some other meaning about Mr Dutton, but that is immaterial. The meaning conveyed is not determined by reference to the publisher’s subjective intention.

64 As noted at the commencement of these reasons, Mr Bazzi admitted that his Tweet was defamatory, in the event that it was found to have conveyed one or more of the imputations alleged by Mr Dutton. There is no difficulty in concluding that the imputation that Mr Dutton excuses rape is defamatory.

The defence of honest opinion

65 As previously noted, Mr Bazzi’s principal substantive defence to Mr Dutton’s claim is that of honest opinion.

66 It was common ground that it is s 31 of the UDA as in force on 25 February 2021 which is to be applied in this case, not s 31 as amended with effect from 1 July 2021. As at 25 February 2021, s 31 provided (relevantly):

31 Defences of honest opinion

(1) It is a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that—

(a) the matter was an expression of opinion of the defendant rather than a statement of fact, and

(b) the opinion related to a matter of public interest, and

(c) the opinion is based on proper material.

…

(4) A defence established under this section is defeated if, and only if, the plaintiff proves that—

(a) in the case of a defence under subsection (1)—the opinion was not honestly held by the defendant at the time the defamatory matter was published, or

…

(5) For the purposes of this section, an opinion is based on proper material if it is based on material that—

(a) is substantially true, or

(b) was published on an occasion of absolute or qualified privilege (whether under this Act or at general law), or

(c) was published on an occasion that attracted the protection of a defence under this section or section 28 or 29.

(6) An opinion does not cease to be based on proper material only because some of the material on which it is based is not proper material if the opinion might reasonably be based on such of the material as is proper material.

67 As is apparent, s 31 requires a respondent raising a defence of honest opinion to prove three things concerning the impugned defamatory matter: first, that the defamatory matter was an expression of opinion rather than a statement of fact; secondly, that the opinion related to a matter of public interest; and, thirdly, that the opinion was based on “proper material”. Section 31(5) provides that an opinion will be based on proper material if it is based on material which satisfies at least one of the three internal alternatives within that subsection.

68 An initial question is the identification of the “matter” to which s 31(1)(a) refers. It is natural to understand that to be the “defamatory matter” to which the chapeau to s 31 refers.

69 Section 4 of the UDA gives the following definition of “matter”:

“matter” includes—

(a) an article, report, advertisement or other thing communicated by means of a newspaper, magazine or other periodical, and

(b) a program, report, advertisement or other thing communicated by means of television, radio, the Internet or any other form of electronic communication, and

(c) a letter, note or other writing, and

(d) a picture, gesture or oral utterance, and

(e) any other thing by means of which something may be communicated to a person.

70 This suggests that the term “defamatory matter” could be understood as a reference to the medium by which a defamatory imputation is conveyed, and not as a reference to the defamatory imputation. Such a view may be supported by the contrasting use of the term “imputations” in the defences of justification and contextual truth (ss 25 and 26 respectively in the UDA).

71 However, in the common law defence of fair comment on a matter public interest, it is the defamatory meaning found to have been conveyed which is to be considered. See Channel Seven Adelaide Pty Ltd v Manock [2007] HCA 60; (2007) 232 CLR 245 at [83] and [85] in which Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ said:

[83] [T]he defendant's contention that in this case the meaning pleaded by the plaintiff is irrelevant to the defence of fair comment at common law is wrong. It is wrong because by the time the trial judge comes to consider the fair comment defence the question of meaning will have been decided adversely to the defendant. The meaning found is the comment to be scrutinised for its fairness. An initial question will be whether the ordinary reasonable viewer would have understood that the meaning found to have been conveyed was conveyed as comment. Another question would be whether that meaning was objectively fair. Another would be whether it was based on true facts. Each of the questions must be answered by treating the comment as being the twenty-eight words in the meaning which the court found. If the defendant's contention were not wrong, it would be open to the defendant to contend that the promotion bore some meaning other than the defamatory meaning which the trial judge had already found, which is impossible …

...

[85] Another flaw in the defendant's position is that the defendant accepts, correctly, that the meaning of defamatory words is relevant to the fair comment defence in several ways: in determining whether the comment is fair; in determining the issue of malice, to which an absence of honest belief in the proposition stated is relevant; in determining whether the plaintiff's pleaded meaning was conveyed as a statement of fact or a statement of opinion; in determining whether the plaintiff's pleaded meaning and the defendant's comment relate to the same allegation; in determining whether the comment is based on facts which are true or protected by privilege, a question which cannot be answered without assessing what the comment means; and in determining whether the comment relates to a matter of public interest, which also depends on its meaning. It would be anomalous if the meaning of the comment is relevant in all these respects, but not relevant in an assessment of whether it responds to the meaning of the promotion pleaded by the plaintiff.

[86] Finally, the defendant's submissions would lead to an injustice. In this case the defendant's submissions would lead to the conclusion that if the plaintiff establishes the meaning pleaded, he will have been accused of deliberately concealing evidence, while the defendant will escape liability by saying merely that he was incompetent and mistaken in various respects. There is a great gulf between displaying incompetence and deliberately concealing evidence.

(Emphasis added and citation omitted)

72 In Harbour Radio Pty Ltd v Ahmed [2015] NSWCA 290; (2015) 90 NSWLR 695, the Court of Appeal in New South Wales (McColl, Basten and Meagher JJA) noted the difference in the terminology in ss 25, 26 and 31 but said that it had not been treated as significant in the case law, at [43]. Their Honours continued:

[44] The risk in treating the imputation as the matter which must be identified as an expression of opinion or fact is that the form of the imputation may not accurately reflect the language of the defamatory publication. That is significant, bearing in mind the contextual nature of the inquiry as to whether a statement is opinion.

73 In O’Brien v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2016] NSWSC 1289 at [45]-[46], McCallum J, after referring to Manock and Ahmed, accepted that the meaning pleaded by the plaintiff is relevant to the defence of honest opinion under s 31 and that “a question to be posed for the tribunal of fact is whether the ordinary reasonable viewer would have understood the meaning found to have been conveyed as comment as opposed to fact” (emphasis added). Her Honour noted, however, the caution sounded in Ahmed at [44]. Likewise, in Feldman v Polaris Media Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] NSWSC 1035 (Feldman v Polaris Media) at [43]-[44], McCallum J said that she had understood s 31(1)(a) to require consideration of the question whether the matter was a statement of fact or opinion “through the lens of the defamatory meaning found to have been conveyed”. See also her Honour’s judgment in O’Neill v Fairfax Media Publications (No 2) [2019] NSWSC 655 at [81]-[83]. White JA appears to have taken a different view on appeal in Feldman v Polaris Media Pty Ltd [2020] NSWCA 56; (2020) 102 NSWLR 733 at [66]. Finally, on this topic I refer also to my own reasons in Hockey v Fairfax Media at [308]-[320] in relation to s 30(1)(c) of the UDA and, in particular, to my conclusion that the term “defamatory matter” in that section appears to be used as a term for the defamatory content of a matter, whether it be the single imputation or multiple imputations.

74 In Stead v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 15; (2021) 387 ALR 123, Lee J summarised the position at [131] by stating that the task was “to determine whether the matter would have been understood by the ordinary reasonable reader to be an expression of opinion rather than a statement of fact; and although this contextual inquiry necessarily requires consideration of the meanings found to be conveyed, it is not constrained or dictated by their terms so as to transform the inquiry into a consideration as to how each imputation would be understood”.

The pleading of the defence

75 Mr Bazzi’s pleading of honest opinion in relation to the Tweet is (relevantly) as follows:

[7] …

(a) The Matter Complained Of, so far as it conveyed the imputations pleaded in paragraph 5 of the Statement of Claim, amounted to or contained an expression of opinion of the respondent, rather than a statement of fact;

(b) The opinion related to matters of public interest;

(c) The opinion was:

i. based on proper material, being material that was substantially true and/or published on an occasion of qualified privilege; or

ii. alternatively, based on material which included proper material, and represented an opinion which might reasonably be based on such of that material as was proper material.

…

76 Mr Bazzi particularised the “proper material” on which he relied for the defence of honest opinion in Schedule A to his Defence. The preamble to Schedule A is:

[1] The expression of opinion was based on the following facts which were set out in the matter complained of or implied or sufficiently indicated (by indication of the subject matter which those facts related/and/or by indication of the substratum of fact to which those facts related) in the matter complained of (Schedule A to the Statement of Claim), or alternatively, were ascertainable by readers of the matter complained of as matters of contemporary history and/or general notoriety …

77 In the first three subparagraphs to Schedule A, Mr Bazzi pleaded the Ministries held by Mr Dutton in the Commonwealth Government from 2014, namely, Minister for Immigration and Border Protection between 2014-2017; Minister for Home Affairs between 2017-2021; and Minister for Defence from March 2021.

78 Mr Bazzi then gave the following particulars:

(d) On 20 June 2019 Dutton publicly stated in a television interview on Sky News that “some people are trying it on. Let’s be serious about this, there are people that claimed they’d been raped and came to Australia to seek an abortion because they couldn’t get an abortion on Nauru. They arrived in Australia and then decided that they were not going to have an abortion. They have the baby here, the moment they step off the plane, their lawyers lodge papers in the Federal Court which injuncts us from sending them back.” (This interview was broadcast on Sky News on television and published on the SkyNews.com.au website).

(e) The comments in d) were published online by The Guardian on 20 June 2019 in an article titled, “Peter Dutton says women using rape and abortion claims as ploy to get to Australia”.

(f) On 15 February 2021 a former Liberal Party staff member, Brittany Higgins, publicly alleged that she was raped by a colleague in 2019 inside the ministerial office of her boss, then-Defence Industry Minister Linda Reynolds. (This was reported on multiple media sources).

(g) On or around 11 February 2021, prior to the Higgins allegations being made public, after receiving a briefing from the Australian Police Commissioner about the alleged sexual assault, Dutton elected not to inform the Prime Minster of the briefing or of the allegations of sexual assault (This was reported on ABC Television News on 25 February 2021).

(h) On 18 February 2021, Peter Dutton stated in an interview with Ray Hadley on Radio 2GB:

i. “I’ve been here 20 years, this is the first allegation that I’m aware of, of somebody being raped. No doubt there will be other people who allege that they’ve been sexually assaulted, or they’ve been in a circumstance where somebody believed there was consent and there wasn’t”.

The comments in i. above were published online by The Guardian on 24 February 2021 in an article titled, “Peter Dutton refuses to say if he was notified of Brittany Higgins rape allegations”; and

ii. “I’m not sure how people find the time for extracurricular activities to be honest …”

The comment in ii. above was published on Twitter on 19/02/2021, along with a link to an excerpt of the interview, by the person using the Twitter name @Qldaah.

(i) On 25 February 2021 as reported by ABC News:

i. Dutton confirmed that he did not disclose to the Prime Minister the fact of the briefing by the Australian Federal Police in respect of the alleged sexual assault in Parliament;

ii. Dutton said “I took a decision, I wasn’t going to disclose that to the Prime Minister, I think that was the right decision”; and

iii. Dutton said he wasn’t provided with “the ‘she-said, he-said’ details of the allegations”.

The comments in iii. above were published online on 25 February 2021 on the abc.net.au website in an article titled, “Peter Dutton defends handling of information around Brittany Higgins rape allegation” and also on the same date on the news.com.au website in an article titled, “Peter Dutton describes Brittany Higgins’ alleged rape as ‘he said, she said’”.

(j) On 6 May 2016, the Federal Court found, in relation to a young woman who was raped whilst unconscious and suffering a seizure during the time she was detained in a detention centre in Nauru, that, by procuring (in the sense of obtaining or making available) an abortion for the applicant in Papua New Guinea, Dutton, as the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, failed to exercise reasonable care in the discharge of the responsibility that he assumed to procure for the applicant a safe and lawful abortion (Plaintiff S99/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection and Another (2016) 243 FCR 17 at [405]).

(k) The fact of the finding referred to in j) was published online by The Guardian on 6 May 2016 in an article titled, “Dutton risked safety of asylum seeker sent to PNG for abortion, court finds”.

(l) A link to the article referred to in k) was contained within the article referred to in e), being the article contained in the respondent’s tweet referred to in paragraph 4.

(m) On 11 August 2016 Dutton publicly stated in an interview on Radio 2GB with Ray Hadley “I won’t tolerate any sexual abuse whatsoever. But I have been made aware of some incidents that have been reported, false allegations of sexual assault, because in the end people have paid money to people smugglers and they want to come to our country. Some people have even gone to the extent of self-harming and people have self-immolated in an effort to get to Australia, and certainly some have made false allegations in an attempt to get to Australia.”

(n) The comments in m) were published online by The Guardian on 11 August 2016 in an article titled, “‘People have self-immolated to get to Australia’ – Immigration Minister’s response to Nauru files”.

(Emphasis in the original)

79 Mr Bazzi concluded these particulars with the plea that:

[2] The facts and matters referred to in the preceding sub paragraphs were proper material because each of those facts and matters were (sic) substantially true.

80 In relation to his plea that the pleaded expression of opinion related to matters of public interest, Mr Bazzi provided the following particulars in Schedule B:

[1] The expression of opinion was inherently related to the following subjects, each of which was a matter of proper and legitimate public interest:

(a) The issue of sexual violence against women in Australia and the treatment of those individuals making allegations;

(b) The issue of sexual violence against women working in [the] Australian Parliament and the treatment of those individuals making allegations;

(c) The issue of female refugees in Australia who make rape allegations whilst detained in offshore detention centres and the treatment of those individuals making allegations;

(d) The conduct of a Federal Cabinet Minister in relation to his responses to each of these important public issues; and

(e) The current public discourse concerning the dismissal, denial and distrust of women who make allegations of sexual violence.

81 By his Amended Reply, Mr Dutton denied that the Impugned Words constituted an expression of opinion and that they related to any matter of public interest. He then pleaded, in the alternative, that none of the particulars of proper material, nor any combination of them, constituted proper material because none “justified the conclusion that [he] was a “rape apologist” or that he was fairly to have attributed to him any of the imputations pleaded in the Statement of Claim”.

82 In addition to that plea, Mr Dutton pleaded that if the Tweet did constitute an expression of opinion:

i. …

ii. each of the matters identified in Schedule A to the defence [the Particulars of Proper Material] related to one of the matters public interest particularised in Schedule B to the defence (MPI’s);

iii. whilst the Matter Complained Of related to a matter of public interest – that is, sexual violence against women – it did not relate to any of the MPI’s;

iv. the applicant does not admit that any of the Material was published on any occasion of qualified privilege (whether pursuant to statute or at law);

v. for the reasons pleaded below, it is to be inferred that the respondent did not honestly hold any such opinion.

83 At the hearing, counsel for Mr Dutton did not make any submissions concerning (ii) and (iii) in this pleading and, as Mr Bazzi had not pleaded reliance on s 31(5)(b), the issue of qualified privilege does not arise. The plea that Mr Bazzi had not honestly held the opinion is, however, a live issue.

Are the Impugned Words a statement of fact or of opinion?

84 Counsel for Mr Bazzi emphasised that the courts should not take a narrow view of what constitutes “opinion” for the purposes of the s 31 defence. In this regard, he referred to the approach of the courts in identifying comment for the purposes of the common law defence of fair comment. On this topic, Kirby J in dissent in Manock said:

[115] Bulwark of free speech: The defence of fair comment is extremely important to the exercise of free expression in Australia. It has been rightly described as "the bulwark of free speech in the law of defamation". In effect, it allows everyone to express opinions, so long as the necessary legal preconditions are met. Those preconditions do not distinguish between orthodox and heterodox comments; majority and minority comments; popular and unpopular, "moral" and "immoral", respectful and disrespectful comments.

[116] This Court should not take a narrow view of what constitutes a "comment", for the purpose of attracting the fair comment defence. It has not done so in the past. To the extent that it takes a narrow view, it will place an unwarranted restriction on the availability of the defence of fair comment. It will thereby impose unjustified restrictions upon freedom of discussion and the expression of opinions in our community.

[117] It is by freedom of discussion, including the expression of unorthodox, heretical, unpopular and unsettling opinions, that progress is often made in political, economic, social and scientific thinking. Courts have to give more than lip-service to free expression, including in the making of protected comment, lest legal protection for comment on a matter of public importance becomes illusory or non-existent from a practical point of view. It is by the public expression of diverse opinions, expressed as comment, that our form of society is distinguished from others which enjoy a lesser freedom.

(Citations omitted)

85 Reference may also be made to Pryke v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd (1984) 37 SASR 175 in which King CJ said at 191 that a “great deal of latitude is permitted to those who engage in criticism of the conduct and character of persons in the public arena”.

86 Mr Dutton contends that the Impugned Words comprised a statement of fact, and not a statement of opinion as required by s 31 of the UDA. Both parties made their submissions on the basis that the common law principles concerning the differentiation between fact and opinion were also applicable in the case of s 31. They were correct to do so – see s 6(2) of the UDA and Ahmed at [37].

87 In Manock, Gleeson CJ referred to the following passage in the 8th Edition of Salmond on Law of Torts:

Comment or criticism is essentially a statement of opinion as to the estimate to be formed of a man's writings or actions. Being therefore a mere matter of opinion, and so incapable of definite proof, he who expresses it is not called upon by the law to justify it as being true, but is allowed to express it, even though others disagree with it, provided that it is fair and honest.

(Emphasis added)

88 In the same case, at [35], Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ said:

…

A "discussion or comment" is to be distinguished from "the statement of a fact". "It is not the mere form of words used that determines whether it is comment or not; a most explicit allegation of fact may be treated as comment if it would be understood by the readers or hearers, not as an independent imputation, but as an inference from other facts stated." … [T]he distinction between fact and comment is commonly expressed as equivalent to that between fact and opinion. Cussen J described the primary meaning of "comment" as "something which is or can reasonably be inferred to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, judgment, remark, observation, etc". It follows that a comment can be made by stating a value judgment, and can also be made by stating a fact if it is a deduction from other facts. Thus, in the words of Field J:

"[C]omment may sometimes consist in the statement of a fact, and may be held to be comment if the fact so stated appears to be a deduction or conclusion come to by the speaker from other facts stated or referred to by him, or in the common knowledge of the person speaking and those to whom the words are addressed and from which his conclusion may be reasonably inferred. If a statement in words of a fact stands by itself naked, without reference, either expressed or understood, to other antecedent or surrounding circumstances notorious to the speaker and to those to whom the words are addressed, there would be little, if any, room for the inference that it was understood otherwise than as a bare statement of fact". (emphasis added)

(Citations omitted)

89 In contending that the Tweet constituted a statement of fact, counsel for Mr Dutton referred to the statement of Ferguson J in Myerson v Smith’s Weekly Publishing Co Ltd (1923) 24 SR(NSW) 20 at 26:

To say that a man’s conduct was dishonourable is not comment, it is a statement of fact. To say that he did certain specific things, and that his conduct was dishonourable, is a statement of fact coupled with a comment.

Hence, he contended that the words “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist” is a simple assertion of fact.

90 However, the passage in the judgment of the plurality in Manock quoted above indicates that the true position is more nuanced than that stated in Myerson. Nettle JA in State of New South Wales v IG Index plc [2007] VSCA 212; (2007) 17 VR 87 expressed a similar view, at [48]:

[A] statement may qualify as a comment if it appears to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, judgment, remark or observation come to by the writer or speaker from facts stated or referred to by him, or in the common knowledge of the person writing or speaking and those to whom the words are addressed, and from which his conclusion may reasonably be inferred.

(Citation omitted)

See also Goldsbrough v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd (1934) 34 SR(NSW) 524 at 531 and in O’Brien, McCallum J said at [50], that “[t]he critical question is whether the defamatory sense of the matter complained of was conveyed as an expression of opinion rather than an assertion of fact”.

91 A statement will more easily be understood as one of fact if it asserts some objectively verifiable matter, but this is not essential for such a characterisation.

92 The character of the Tweet is to be assessed objectively, by enquiring whether the ordinary reasonable person would have understood the statement to be an expression of opinion: Bickel v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd [1981] 2 NSWLR 474 at 490. See also Manock at [36] in which Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ said:

The question of construction or characterisation turns on whether the ordinary reasonable "recipient of a communication would understand that a statement of fact was being made, or that an opinion was being offered" – not "an exceptionally subtle" recipient, or one bringing to the task of "interpretation a subtlety and perspicacity well beyond that reasonably to be expected of the ordinary reader whom the defendant was obviously aiming at".

(Citations omitted)

93 Counsel for Mr Dutton submitted that the question of whether the words in the Tweet are a statement of fact or of opinion should be decided by a consideration of the words themselves, citing Gatley on Libel and Slander, 12th Ed, 2013 at [33.20] and Telnikoff v Matusevitch [1992] 2 AC 343 at 352A. However, the true position, as indicated by Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ in Manock at [35], is that a publication may be held to be a statement of opinion if it appears, in the entire relevant context, to be a deduction or conclusion come to by the speaker from other facts stated or referred to by the speaker or in the common knowledge of the person speaking and those to whom the words are addressed and from which the conclusion may be reasonably inferred.

94 Somewhat inconsistently with his primary submission, counsel for Mr Dutton submitted that regard could be had to another tweet of Mr Bazzi published only five minutes earlier than the Tweet. In this tweet, published at 11.46 pm, Mr Bazzi said:

Peter Dutton is a rape apologist. He is also a fascist who kills and tortures refugees. He abuses men, women and children. He is a child abuser. All of these are facts.

95 Counsel submitted that the 11.46 pm tweet formed part of the context in which the fact/opinion assessment is to be made because it was likely, given the short time which elapsed between the two tweets that readers of the Tweet would also have read the earlier tweet. Counsel noted that Mr Bazzi himself, just minutes before publishing the Tweet, had characterised the statement that “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist” as a statement of fact.

96 I am not willing to have regard to the earlier tweet on the basis for which counsel contended, as there is only minimal evidence as to the numbers who had read it. In any event, I would not attach significance to Mr Bazzi’s own characterisation of his statement. As already indicated, the proper characterisation of the statement is to be determined objectively and Mr Bazzi’s subjective intention is not relevant to that determination. The question is whether the ordinary reasonable reader of the Tweet would have understood Mr Bazzi to be expressing a statement of fact or his opinion.

97 One matter bearing on the classification of a statement as opinion or fact is the extent to which the facts on which the opinion is said to have been based are stated or referred to in the publication or are otherwise notorious: Manock at [4], [46]-[47].

98 For the reasons given earlier, I proceed on the basis that the question to be addressed is that of whether the statement with the meaning I have found the Tweet to convey, i.e, that Peter Dutton excuses rape, was one of fact or opinion.

99 In my view, a number of matters would have indicated to the ordinary reasonable reader that Mr Bazzi was stating his own personal assessment of Mr Dutton, rather than stating a fact. In the first place, the very nature of the statement is one of an evaluative judgment: cf Feldman v Polaris Media Pty Ltd as trustee of the Polaris Media Trust t/as The Australian Jewish News [2020] NSWCA 56; (2020) 102 NSWLR 253 at [211]. In the language of Salmond on Law of Torts cited by Gleeson CJ in Manock, it was a statement of “the estimate” formed by Mr Bazzi of Mr Dutton’s conduct and statements. That is to say, the reader would have understood the statement “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist” to have the character of an evaluative conclusion, depending for its merit on inferences to be drawn from other facts.

100 Secondly, the juxtaposition of the statement “Peter Dutton is a rape apologist” with the link to The Guardian article would have added to the readers’ understanding that an opinion was being expressed, i.e, an opinion drawn from the material for which the link was provided. That would be so even if the ordinary reasonable reader chose not to follow the link. The following passage from the judgment of Gleeson CJ in Manock is pertinent in this respect:

[4] … So long as a reader (or viewer, or listener) is able to identify a communication as a comment rather than a statement of fact, and is able sufficiently to identify the facts upon which the comment is based, then such a person is aware that all that he or she has read, viewed or heard is someone else's opinion (or inference, or evaluation, or judgment). The relationship between the two conditions mentioned in the previous sentence is that a statement is more likely to be recognisable as a statement of opinion if the facts on which it is based are identified or identifiable.

(Emphasis added)

101 Thirdly, Mr Dutton’s status as a high profile politician is significant. The ordinary reasonable reader of the Tweet would have understood that it is commonplace for such politicians to attract criticism. This too would have led the reader to understand the statement as Mr Bazzi’s expression of opinion about Mr Dutton.

102 I conclude therefore that Mr Bazzi has established that his statement was an expression of opinion.

Did the opinion relate to a matter of public interest?

103 The term “public interest” is not defined in the UDA so that, again, resort may be had to the common law. In Bellino v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [1996] HCA 47; (1996) 185 CLR 183, Dawson, McHugh and Gummow JJ said that in this context “a subject of public interest mean[s] the actions or omissions of a person or institution engaged in activities that either inherently, expressly or inferentially [invite] public criticism or discussion”.

104 Both Brennan CJ (at 193) and Gaudron J (at 240-2) disagreed with that statement of principle and preferred instead the statement of Lord Denning MR in London Artists Ltd v Littler [1969] 2 QB 375 at 391:

There is no definition in the books as to what is a matter of public interest. All we are given is a list of examples, coupled with the statement that it is for the judge and not for the jury. I would not myself confine it within narrow limits. Whenever a matter is such as to affect people at large, so that they may be legitimately interested in, or concerned at, what is going on; or what may happen to them or to others; then it is a matter of public interest on which everyone is entitled to make fair comment.

105 As counsel for Mr Dutton did not dispute that Mr Bazzi had established this element of the defence of honest opinion, it is not necessary to discuss further this difference in the judgments in Bellino. It is sufficient to say that Mr Bazzi has established this element of the defence.

Was the opinion based on proper material?

106 This element of the defence of honest opinion involves a number of sub-issues:

(a) must the proper material be contained in or referred to in the impugned matter or be otherwise notorious?

(b) were the matters on which Mr Bazzi relies stated in or referred to in the impugned matter or otherwise notorious? and

(c) was Mr Bazzi’s opinion “based on” the proper material on which he relies, as required by s 31(2)(c) of the UDA?

I will address these issues in turn.

Must the matters relied on for “proper material” be stated in or referred to in the impugned matter or be otherwise notorious?

107 The common law defence of fair comment on a matter of public interest requires that the comment be based on material stated or referred to in the impugned matters or be otherwise notorious: Mancock at [5] (Gleeson CJ); at [35], [45], [47] and [72] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ). Section 31 of the UDA, as in force on 25 February 2021, does not contain any express requirement to the same effect. It does now, following the amendments to s 31 which came into effect on 1 July 2021 but, as previously noted, it is s 31 in its pre-amended form which is applicable in the present case.

108 The pleaded reply of Mr Dutton to Mr Bazzi’s defence of honest opinion seemed to accept that the common law position applied to s 31 as, in [(5)(b)], it denied that the opinion was based on facts which were stated, sufficiently indicated or notorious. However, at trial, counsel for Mr Dutton, while noting the common law position, submitted that s 31, properly construed, requires that the proper material be stated or referred to in the impugned matter.

109 Counsel for Mr Bazzi contended for the common law position. This has been the view generally adopted in the authorities. In The Herald & Weekly Times Pty Ltd v Buckley [2009] VSCA 75; (2009) 21 VR 661, the Court of Appeal (Nettle, Ashley and Weinberg JJA) said:

[83] Counsel for the applicants further submitted that the distinction between the common law defence of fair comment and the statutory defence of honest opinion was important because as, under the former, all of the facts on which the comment is based must appear in the publication or otherwise be apparent to the reader but, under the latter, it is necessary only to show that the opinion is honestly based on ‘proper material’ which, according to counsel, need not be known to the reader.

[84] We reject that submission for two reasons. First, we do not consider that there is any difference between the common law and the statute as to the need for facts on which a comment or opinion is based to appear in the publication or otherwise be apparent to the reader. The idea of expanding the defence of comment or opinion to cases where the facts are unspecified and unknown was rejected by the Law Reform Commission (on whose report the legislation is largely based), and there is nothing in the Proposal for uniform defamation laws released by the States and Territories in July 2004 or in the proposed bill which they released in November 2004, or in the Explanatory Memorandum or Second Reading Speech which suggests any difference in that respect. To the contrary, all the indications are that the two were meant to be the same.

(Citations omitted)

See also JWR Productions Australia Pty Ltd v Duncan-Watt (No 2) [2020] FCA 236, (2020) 377 ALR 467 at [471] (Thawley J); and Stead v Fairfax Media at [124].

110 It is also pertinent to note the statement of the Attorney-General for New South Wales in the Explanatory Memorandum provided to the New South Wales Parliament for the Defamation Bill 2005. In respect of what was then cl 31, the Attorney-General said (at 11):

The defences, at least in relation to the opinions personally held by the defendant, largely reflect the defence of fair comment at general law. However, the section clarifies the position at general law in relation to the publication of the opinions of employees, agents and third parties.

111 In the debate following the Second Reading of the Defamation Bill on 12 October 2005, the Attorney-General for NSW said (Hansard at 18528):

I affirm that clause 31 is not intended to alter the position at common law in regard to the pleading of defences or the kinds of facts that can be relied on to support a defamatory opinion. The equivalent defence at common law is the defence of fair comment …

At common law the opinion must be based on proper material, namely, statements of fact that are true or statements that are privileged. Statements of fact may be set out in the matter that expresses the opinion, but facts can be relied on even if they are not set out with the opinion if they are notorious or widely known.

It should be noted that the common law position has been reaffirmed in clause 8 of the Bill. The operation of the common law is also expressly preserved by clause 6.

(Emphasis added)

112 Counsel for Mr Dutton did not advance any submission that, “properly construed”, s 31 requires that the “proper material” be stated or referred to in the impugned matter and that their notoriety is insufficient. I see no reason to construe s 31 as encompassing only part of the common law requirement. In any event, the decision of the Court of Appeal in Buckley, being the decision of an intermediate court of appeal concerning uniform legislation is one to which the Court presently should have particular regard and it is to the contrary. So also are the extrinsic materials to which reference has just been made.

113 Accordingly, I proceed on the basis that s 31 requires that the proper material on which the opinion is based be stated in or, referred to, in the impugned matter or be otherwise notorious.

114 For the sake of completeness, I record that no point was taken at the hearing concerning the form of preamble to Mr Bazzi’s pleaded particulars of the proper material and, in particular, to his reference to matters which were “ascertainable” by readers of the Tweet.

Were the matters on which Mr Bazzi relies stated in or referred to in the impugned matter or otherwise notorious?

115 Earlier in these reasons, I set out the 14 particulars of the proper material pleaded by Mr Bazzi. Mr Bazzi pleaded that each of these matters constituted “proper material” because it was substantially true and, accordingly, within s 31(5)(a).

116 At the trial, counsel for Mr Bazzi confined his reliance to particulars (e), (f), (i) and (j). It has accordingly been unnecessary to consider the remaining particulars.

117 Counsel Mr Bazzi also identified, with reference to particular facts, whether they had been stated in the Tweet itself, were referred to or otherwise sufficiently indicated in the Tweet, and whether they were notorious. It is convenient to set out in these reasons the schedule which counsel provided:

No | Proper material Fact | Substantial truth of proper material | Particular Schedule A |

1 | Mr Dutton stated publicly that women on refugee centres on Nauru use rape and abortion claims as a ploy and are trying it on in an attempt to get to Australia from those refugee centres in Nauru | Television interview with Mr Dutton on 20 June 2019 on Sky News and also published on SkyNews.com.au | 1(e) |

Proper material – Facts referred to/sufficiently indicated | |||

2 | Mr Dutton stated publicly: "Some people are trying it on", he said. "Let's be serious about this. There are people who have claimed that they've been raped and came to Australia to seek an abortion because they couldn't get an abortion on Nauru. They arrived in Australia and then decided they were not going to have an abortion. They have the baby here and the moment they step off the plane their lawyers lodge papers in the federal court which injuncts us from sending them back." Referred to/indicated through a hyperlink in the Tweet, to an article in the Guardian Australia online first published on 20 June 2019 and available online at the date of publication | Television interview with Mr Dutton on 20 June 2019 on Sky News and also published on SkyNews.com.au | 1(e) |

3 | In 2016, the Federal Court found that Mr Dutton had breached his duty of care to a woman who became pregnant as a result of rape by exposing her to serious medical and legal risks in trying to avoid bringing her to Australia for an abortion. Referred to/indicated through a hyperlink in the Tweet, to an article in the Guardian Australia online first published on 20 June 2019 and available online at the date of publication | The findings of Bromberg J in Plaintiff S99/2016 v Minister for Immigration [2016] FCA 483 on 6 May 2016 | 1(j) |

Proper material – notorious facts | |||

4 | On 15 February 2021, Brittany Higgins, a former Liberal party staff member publicly alleged that she was raped by a colleague inside a ministerial office at Parliament House Notorious fact at 25 February 2021 - This was widely reported though the media | TB pages (yet to be finalised) comprising media reports of this fact | 1(f) |