FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Ross on behalf of the Cape York United #1 Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 3) (Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determination) [2021] FCA 1465

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

BEING SATISFIED that an order in the terms set out below is within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court to do so, pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

1. The Applicant agrees that the areas listed in Schedule 5 are areas where native title has been wholly extinguished.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms proposed in these orders, despite any actual or arguable defect in the authorisation of the applicant to seek and agree to a consent determination pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

BY CONSENT THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms set out below (the determination).

2. Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

BY CONSENT THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION

1. In this determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

|

|

|

|

|

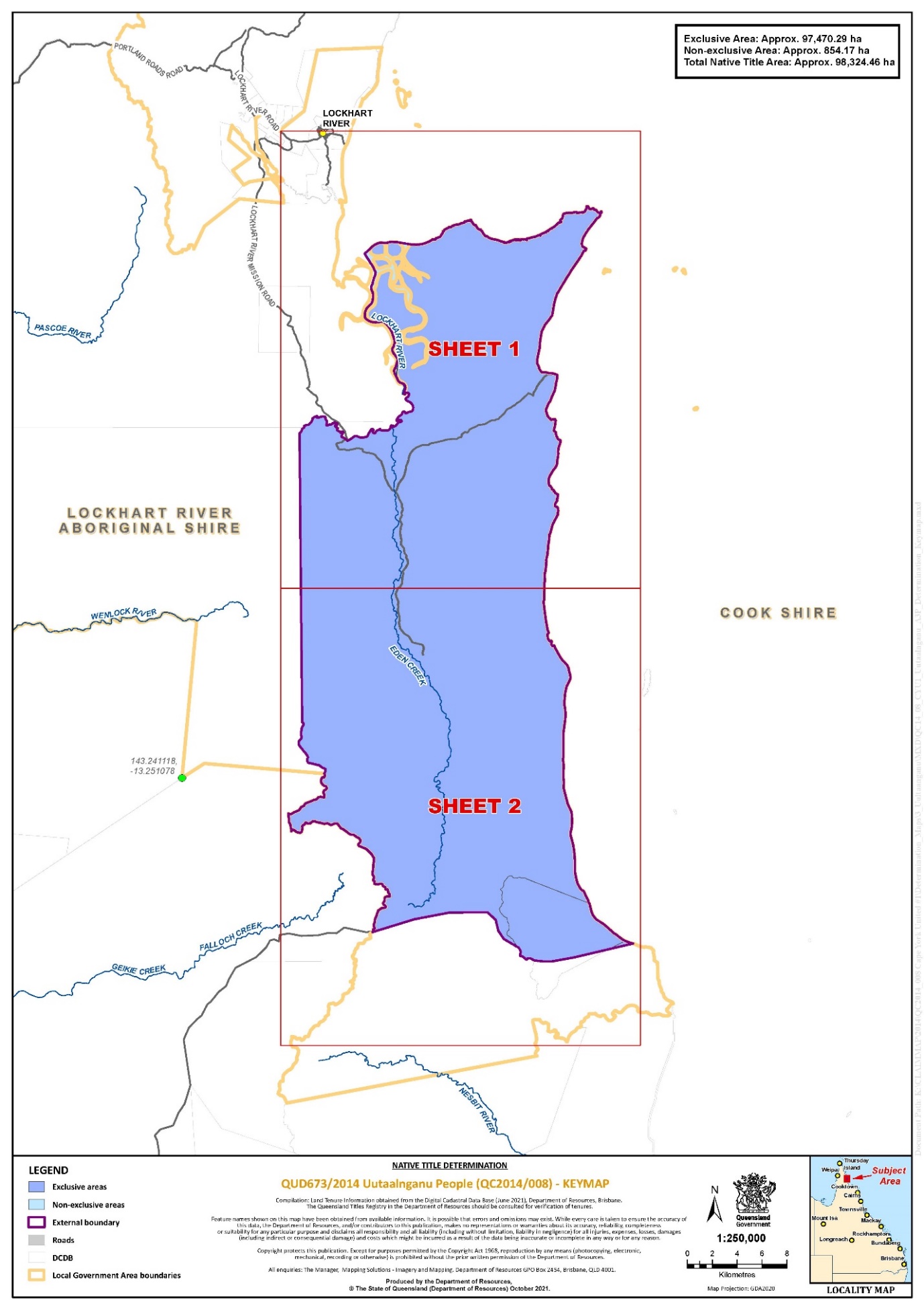

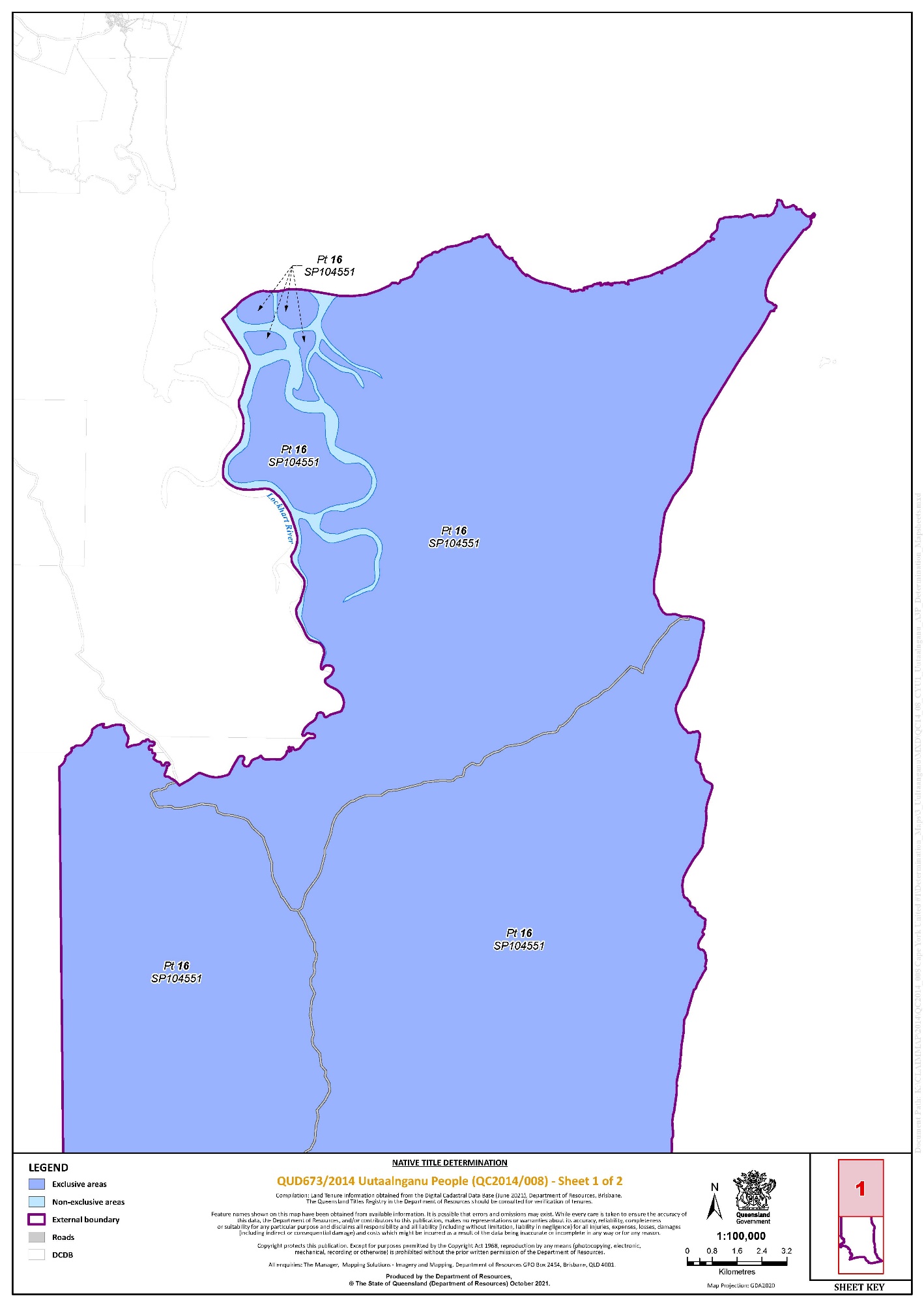

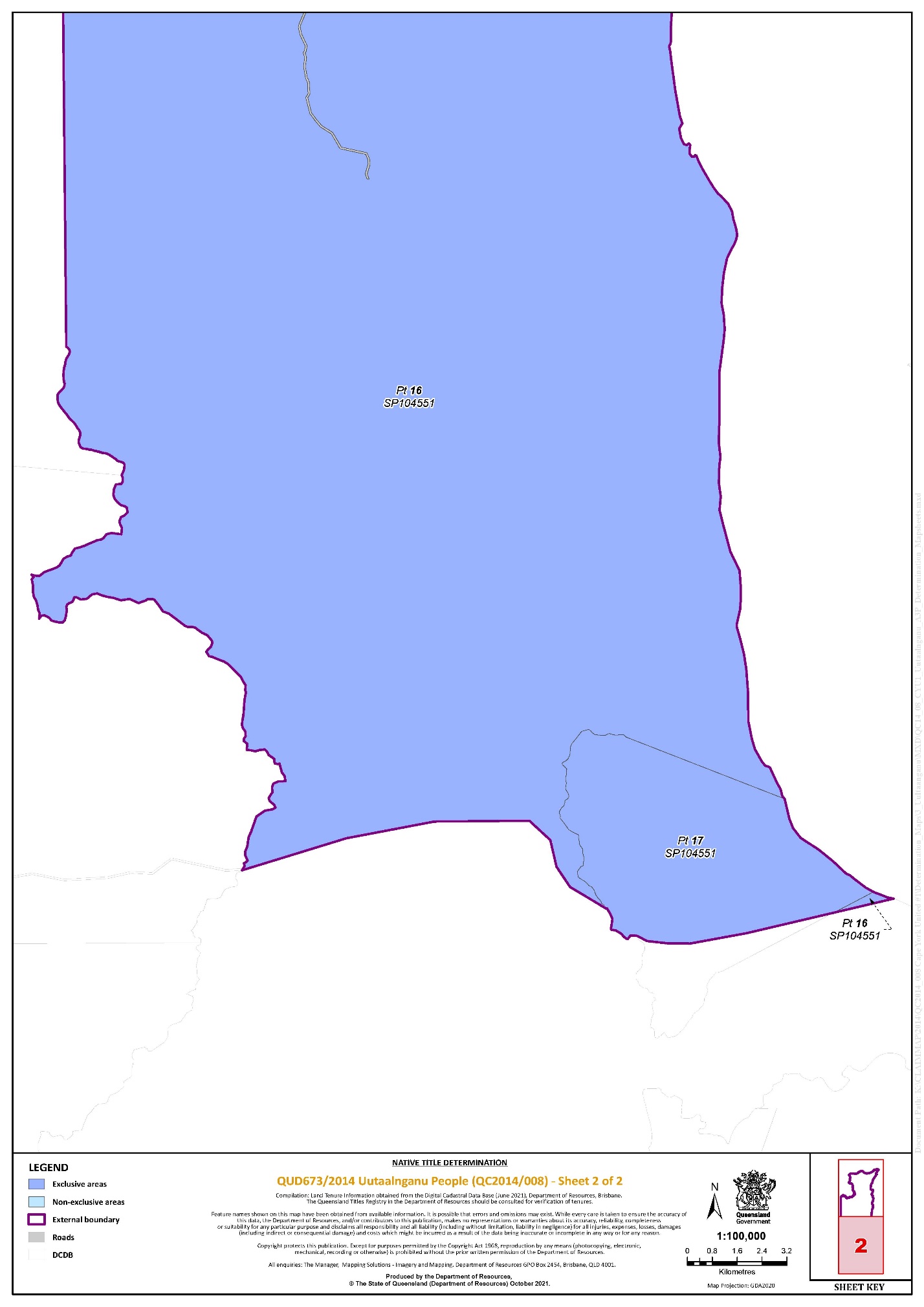

2. The determination area is the land and waters described in Schedule 4 and depicted in the maps attached to Schedule 6 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 5 (the Determination Area). To the extent of any inconsistency between the written description and the map, the written description prevails.

3. Native title exists in the Determination Area.

4. The native title is held by the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People described in Schedule 1 (the Native Title Holders).

5. Subject to orders 7, 8 and 9 below the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 1 of Schedule 4 are:

(a) other than in relation to Water, the right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the area to the exclusion of all others; and

(b) in relation to Water, the non-exclusive right to take the Water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes.

6. Subject to orders 7, 8 and 9 below the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 2 of Schedule 4 are the non-exclusive rights to:

(a) access, be present on, move about on and travel over the area;

(b) live and camp on the area and for those purposes to erect shelters and other structures thereon;

(c) hunt, fish and gather on the land and waters of the area;

(d) take the Natural Resources from the land and waters of the area;

(e) take the Water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(f) be buried and to bury Native Title Holders within the area;

(g) maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the Native Title Holders under their traditional laws and customs on the area and protect those places and areas from harm;

(h) teach on the area the physical and spiritual attributes of the area and the traditional laws and customs of the Native Title Holders to other Native Title Holders or persons otherwise entitled to access the area;

(i) hold meetings on the area;

(j) conduct ceremonies on the area;

(k) light fires on the area for cultural, spiritual or domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation; and

(l) be accompanied on to the area by those persons who, though not Native Title Holders, are:

(i) Spouses of Native Title Holders;

(ii) people who are members of the immediate family of a Spouse of a Native Title Holder; or

(iii) people reasonably required by the Native Title Holders under traditional law and custom for the performance of ceremonies or cultural activities on the area.

7. The native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth; and

(b) the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the Native Title Holders.

8. The native title rights and interests referred to in orders 5(b) and 6 do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.

9. There are no native title rights in or in relation to minerals as defined by the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) and petroleum as defined by the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld).

10. The nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the Determination Area (or respective parts thereof) are set out in Schedule 2.

11. The relationship between the native title rights and interests described in orders 5 and 6 and the other interests described in Schedule 2 (the “Other Interests”) is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by or held under the Other Interests may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title rights and interests;

(b) to the extent the Other Interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters of the Determination Area, the native title rights and interests continue to exist in their entirety but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the Other Interests to the extent of the inconsistency for so long as the Other Interests exist; and

(c) the Other Interests and any activity that is required or permitted by or under, and done in accordance with, the Other Interests, or any activity that is associated with or incidental to such an activity, prevail over the native title rights and interests and any exercise of the native title rights and interests.

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

1. The native title is held in trust.

2. The Uutaalnganu Aboriginal Corporation (ICN: 9606), incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth), is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of s 56(2)(b) and s 56(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE 1 – NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS

1. The Native Title Holders are the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People. The Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People are those Aboriginal persons who are descended by birth, or by adoption in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) group, from one or more of the following apical ancestors:

(a) Sandy Pascoe;

(b) Simon Ropeyarn;

(c) Ku’aka Yalimuku;

(d) King Fred (husband of Taltaninyu);

(e) Taltaninyu (wife of King Fred);

(f) Harry Mathers;

(g) Old Short;

(h) Maria (wife of Johnny Ilnkay Butcher);

(i) Johnny Kulwilma;

(j) Barney Marrott Senior;

(k) Old Yeila Palwu’u;

(l) Peter Underwood;

(m) Nancy (mother of Peter Night Island);

(n) Lizzie (wife of Charlie King, mother’s mother of Douglas Ropeyarn);

(o) Ada (wife of Charlie King);

(p) Rosie (mother of Alick Niger (Naiga));

(q) Mother of Billy Chungo;

(r) Utyaamu (Uchamu aka Osam aka Isagubi)

(s) Mother of Charlie Bezai; or

(t) Charlie Lockhart Senior.

SCHEDULE 2 – OTHER INTERESTS IN THE DETERMINATION AREA

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the Determination Area are the following as they exist as at the date of the determination:

(1) The rights and interests of Telstra Corporation Limited (ACN 051 775 556):

(a) as the owner or operator of telecommunications facilities within the Determination Area;

(b) created pursuant to the Post and Telegraph Act 1901 (Cth), the Telecommunications Act 1975 (Cth), the Australian Telecommunications Corporation Act 1989 (Cth), the Telecommunications Act 1991 (Cth) and the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth), including rights:

(i) to inspect land;

(ii) to install, occupy and operate telecommunication facilities; and

(iii) to alter, remove, replace, maintain, repair and ensure the proper functioning of its telecommunications facilities;

(c) for its employees, agents or contractors to access its telecommunication facilities in and in the vicinity of the Determination Area in the performance of their duties; and

(d) under any lease, licence, access agreement, permit or easement relating to its telecommunications facilities in the Determination Area.

(2) The rights and interests of Cook Shire Council:

(a) under its local government jurisdiction and functions under the Local Government Act 2009 (Qld), under the Stock Route Management Act 2002 (Qld) and under any other legislation, for that part of the Determination Area within the area declared to be its Local Government Area:

(i) lessor under any leases which were validly entered into before the date on which these orders are made and whether separately particularised in these orders or not;

(ii) grantor of any licences or other rights and interests which were validly granted before the date on which these orders were made and whether separately particularised in these orders or not;

(iii) party to an agreement with a third party which relates to land or waters in the Determination Area;

(iv) holder of any estate or any other interest in land, including as trustee of any Reserves, under access agreements and easements that exist in the Determination Area;

(c) as the owner and operator of infrastructure, structures, earthworks, access works and any other facilities and other improvements located in the Determination Area validly constructed or established on or before the date on which these orders are made, including but not limited to any:

(i) undedicated but constructed roads except for those not operated by the council;

(ii) water pipelines and water supply infrastructure;

(iii) drainage facilities;

(iv) watering point facilities;

(v) recreational facilities;

(vi) transport facilities;

(vii) gravel pits operated by the council;

(viii) cemetery and cemetery related facilities; and

(ix) community facilities;

(d) to enter the land for the purposes described in paragraphs 2(a), (b) and (c) above by its employees, agents or contractors to:

(i) exercise any of the rights and interests referred on in this paragraph 2 and paragraph 3 below;

(ii) use, operate, inspect, maintain, replace, restore and repair the infrastructure, facilities and other improvements referred to in paragraph 2(c) above; and

(iii) undertake operational activities in its capacity as a local government such as feral animal control, erosion control, waste management and fire management.

(3) The rights and interests of the State of Queensland, Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council and Cook Shire Council to access, use, operate, maintain and control the dedicated roads in the Determination Area and the rights and interests of the public to use and access the roads.

(4) The rights and interests of the State of Queensland in Reserves, the rights and interests of the trustees of those Reserves and the rights and interests of the persons entitled to access and use those Reserves for the respective purpose for which they are reserved.

(5) The rights and interests of the State of Queensland or any other person existing by reason of the force and operation of the laws of the State of Queensland, including those existing by reason of the following legislation or any regulation, statutory instrument, declaration, plan, authority, permit, lease or licence made, granted, issued or entered into under that legislation:

(a) the Fisheries Act 1994 (Qld);

(b) the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

(c) the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld);

(d) the Forestry Act 1959 (Qld);

(e) the Water Act 2000 (Qld);

(f) the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) or Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

(g) the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld);

(h) the Planning Act 2016 (Qld);

(i) the Transport Infrastructure Act 1994 (Qld); and

(j) the Fire and Emergency Services Act 1990 (Qld) or Ambulance Service Act 1991 (Qld);

(6) The rights and interests of members of the public arising under the common law, including but not limited to the following:

(a) any subsisting public right to fish; and

(b) the public right to navigate.

(7) So far as confirmed pursuant to s 212(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and s 18 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) as at the date of this determination, any existing rights of the public to access and enjoy the following places in the Determination Area:

(a) waterways;

(b) beds and banks or foreshores of waterways;

(c) coastal waters;

(d) stock routes;

(e) beaches; and

(f) areas that were public places at the end of 31 December 1993.

(8) Any other rights and interests:

(a) held by the State of Queensland or Commonwealth of Australia; or

(b) existing by reason of the force and operation of the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth.

SCHEDULE 3 – EXTERNAL BOUNDARY

The area of land and waters:

Commencing at the intersection of the eastern bank of the Lockhart River and Lloyd Bay, a point at Longitude 143.377116° East, Latitude 12.869645° South and extending south-westerly across the mouth of the Lockhart River until its centre point; then generally southerly along the centreline of that river to the intersection with an unnamed creek (Wachi Creek) at Latitude 12.997983° South; then generally westerly along the centreline of that creek to the intersection with an unnamed creek at Longitude 143.360605° East; then generally north-westerly, then south-westerly along the centreline of that unnamed creek to a point at Longitude 143.325933° East, passing through the following coordinate point:

Longitude ° East | Latitude ° South |

143.342895 | 12.990563 |

Then due south to a point on the centreline of the Great Dividing Range at Latitude 13.210972° South; then generally southerly along the centreline of the Great Dividing Range until the intersection with the southern boundary of an unnamed road at Latitude 13.362296° South (Stoney Creek Road), further described as:

Then generally southerly along the centreline of the Great Dividing Range until a point at Latitude 13.246570° South; then south to the northernmost northeast corner of Lot 450 on SP104554; then southerly along the eastern boundary of that lot until the intersection with the northern boundary of an unnamed road at Latitude 13.361150° South; then south-west along the eastern boundary of that road to a point on its southern boundary at Latitude 13.362296° South;

then generally easterly, then south-easterly bisecting the headwaters of the Nesbit River, to a point on the centreline of the Macrossan Range at Latitude 13.373304° South, also being a point on the western boundary of Lot 17 on SP104551, passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude ° East | Latitude ° South |

143.408837 | 13.353059 |

143.434283 | 13.348215 |

143.461714 | 13.347977 |

143.467783 | 13.353562 |

143.469592 | 13.361251 |

143.473512 | 13.367131 |

Then generally south-easterly along the western boundary of Lot 17 on SP104551, also the centreline of the Macrossan Range, intersecting Cone Peak at approximate Longitude 143.491676 East, and onwards until a point at Longitude 143.492882 East, until the intersection with Cone Peak at approx. Longitude 143.491676° East; then easterly to a point on the eastern boundary of Lot 16 on SP104551 at Longitude 143.567011° East, Latitude 13.370487° South (Kaapakachingunuma) passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude ° East | Latitude ° South |

143.495767 | 13.382749 |

143.501651 | 13.383399 |

143.508108 | 13.383481 |

143.524521 | 13.380459 |

then north-westerly along eastern boundary of Lot 16 on SP104551 to the eastern-most point of Lot 17 on SP104551; then northerly along the eastern boundary of that lot to again Lot 16 on SP104551; then generally northerly then westerly along the eastern and northern boundaries of that lot, passing across the mouths of any creeks and rivers, back to the commencement point.

(All Subject to Survey).

Data Reference and source

Cadastral data sourced from Department of Resources, Qld (May 2021).

Watercourse lines sourced from Department of Resources, Qld (May 2021).

Mountain ranges, beaches and sea passages sourced from Department of Resources, Qld (May 2021).

Mountain peaks and capes sourced from Department of Resources, Qld (April 2021).

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994 (GDA94), in decimal degrees.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome to the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Prepared by Department of Resources (25 May 2021).

SCHEDULE 4 – DESCRIPTION OF DETERMINATION AREA

The determination area comprises all of the land and waters described by lots on plan, or relevant parts thereof, and any rivers, streams, creeks or lakes described in the first column of the tables in the Parts immediately below, and depicted in the maps in Schedule 6, to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 5.

All of the land and waters described in the following table and depicted in dark blue on the determination map contained in Schedule 6:

Area description (at the time of the determination) | Determination Map Sheet Reference | Note |

Part of Lot 16 on SP104551 that falls within the External Boundary | 1, 2, 3 | * |

Part of Lot 17 on SP104551 that falls within the External Boundary | 2, 3 | * |

*denotes areas to which s 47A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies.

Part 2 — Non-Exclusive Areas

All of the land and waters described in the following table and depicted in light blue on the determination map contained in Schedule 6:

Area description (at the time of the determination) |

Save for any waters forming part of a lot on plan, all rivers, creeks, streams and lakes within the External Boundary described in Schedule 3, including but not limited to: (i) Lockhart River; and (ii) Eden Creek. |

SCHEDULE 5 – AREAS NOT FORMING PART OF THE DETERMINATION AREA

The following areas of land and waters are excluded from the determination area as described in Part 1 of Schedule 4 and Part 2 of Schedule 4.

(1) Those land and waters within the External Boundary in relation to which one or more Previous Exclusive Possession Acts, within the meaning of s 23B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) was done and was attributable to either the Commonwealth or the State, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied, as they could not be claimed in accordance with s 61A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

(2) Specifically, and to avoid any doubt, the land and waters described in (1) above includes:

(a) the Previous Exclusive Possession Acts described in ss 23B(2) and 23B(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to which s 20 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) applies, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied; and

(b) the land and waters on which any public work, as defined in s 253 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), is or was constructed, established or situated, and to which ss 23B(7) and 23C(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and to which s 21 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld), applies, together with any adjacent land or waters in accordance with s 251D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

(3) Those land and waters within the External Boundary that were excluded from the native title determination application filed on 11 December 2014 on the basis that, at the time of the native title determination application, they were an area where native title rights and interests had been wholly extinguished, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied, including, but not limited to any area over which there was an existing dedicated public road which wholly extinguished native title rights and interests.

(4) Those land and waters within the External Boundary on which, at the time the native title determination application was made, public works were validly constructed, established or situated after 23 December 1996, where s 24JA of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies, and which wholly extinguished native title.

SCHEDULE 6 – MAP OF DETERMINATION AREA

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MORTIMER J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The parties have sought a determination of native title under s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), with associated orders, recognising the native title of the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People. This determination is being made on the same day as a determination recognising the native title of the Kuuku Ya’u People.

2 The description “Night Island” is used in the evidence filed with the Court by some claim group members as well as by anthropologists, hence why I have retained it. It is also the English name for some important ancestors, such as Peter Night Island. Dr David Thompson, the main anthropologist who has worked in these determination areas, explains its origins in his 2017 report at [41]:

The common reference of Uutaalnganu people as “Night Island” by themselves and others has its origins in the contact lugger period when a beche-de-mer base camp was located on the coast opposite Night Island (Chase 1980:218) and both the location and local people were known as “Night Island” in the early pidgin of the time.

3 Much of the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determination areas is freehold Aboriginal land under the Aboriginal Land Act 1991 (Qld) and is therefore held by land trusts under that Act. Most of the balance of the determination areas is subject to a deed of grant in trust for the benefit of Aboriginal peoples granted under the now repealed Land Act 1962 (Qld), held by the Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council. That is why it is agreed that s 47A of the Native Title Act applies to a large proportion of the determination areas.

4 The orders made today recognising the native title held by the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Peoples deserve the description of a landmark. The making of these orders, and the orders made today in the Kuuku Ya’u Determination, are the first successful outcomes of a process which has taken almost 7 years, since the Cape York United #1 claim was filed with the Court. The Cape York United #1 claim was an ambitious attempt to resolve all outstanding native title claims in Cape York. Save for some specified types of tenure which were excluded, the claim covers all land and waters within the external boundaries of the Cape York Representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander Body Area, an area of approximately 79,421 square kilometres. It is the largest filed claimant application area wholly within Queensland. The orders are the culmination of a tremendous amount of work by a large number of people towards the resolution of native title claims and the recognition of native title across all areas of Cape York in which the existence of native title remains to be determined. These orders are the important first achievements in this process, and go some way towards repaying the patience and persistence of the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Peoples.

5 But the importance of today is also deeply personal. I can do no better than refer to the words of Mr G Butcher in his evidence before the Court at [123]-[124].

I believe the spirits of the ancestors still reside in the country. You can feel them sometimes when we go camping. The spirits feel happy when they see us come camping on our country. You can sense they are there with you. Sometimes, you might say something like “we here now, we ngarthi, we home!” to the spirits. Then they know we are home. When we go out on country that’s when we do that. Everybody does that and sometimes the kids take fright. The spirits of the old people can give us good luck when fishing and hunting.

During the night you feel like somebody is there and they are watching. When I get this feeling then I know it’s the ancestors. Then I’ll tell the kids don’t make noise because someone is with us; our ancestors.

6 The Court’s orders, and the long overdue recognition by Australian law, will help protect and preserve the country of the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People so that this deep connection can also be protected and preserved.

7 For the reasons set out below, the Court is satisfied it is appropriate to make the orders sought, and that it is within the power of the Court to do so. These reasons should be read together with the reasons of the Court in this proceeding delivered orally on 23 November 2021, and subsequently published.

THE MATERIAL BEFORE THE COURT

8 The application for consent determination was supported by a principal set of submissions filed on behalf of the applicant on 22 October 2021. Supplementary submissions were filed on 28 October 2021. The State filed comprehensive submissions on 12 November 2021. The Court has been greatly assisted by the parties’ submissions.

9 The applicant relied on the affidavit of Kirstin Donlevy Malyon. Ms Malyon, who is the Principal Legal Officer at the Cape York Land Council (CYLC) and has had the carriage of the Cape York United #1 claim, deposed to how the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) s 87A Agreement was approved, and to how the Uutaalnganu Aboriginal Corporation (ICN 9606) was nominated as the prescribed body corporate (PBC) for the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Determination. Ms Malyon also annexed the notice of nomination for that PBC and its consent to act as the relevant PBC for the determination area.

10 The applicant also filed and relied upon an affidavit of Parkinson Wirrick, a legal officer with the CYLC, affirmed 22 October 2021. Mr Wirrick annexes to his affidavit a bundle of connection material in relation to both the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Determination and the Kuuku Ya’u Determination. In relation to the former, that material comprised:

(a) the witness statement of Father Brian Claudie dated 22 February 2019 and filed on 22 October 2021;

(b) the witness statement of Mr Amos Hobson dated 4 March 2019 and filed on 22 October 2021;

(c) the apical report of Ms Kate Waters dated 15 May 2020 regarding Billy Chungo and filed on 22 October 2021;

(d) the apical report of Ms Waters dated 12 June 2020 regarding Utyaamu and filed on 22 October 2021;

(e) the apical report of Ms Waters dated 9 November 2020 regarding Alick Niger (Naiga) and filed on 22 October 2021;

(f) the apical report of Ms Waters dated 10 November 2020 regarding Charlie Lockhart Snr and filed on 22 October 2021; and

(g) the apical report of Ms Waters dated 14 December 2020 regarding Charlie Bezai and filed on 22 October 2021.

11 The applicant filed, and relied upon, a second affidavit from Mr Wirrick, affirmed 26 October 2021, annexing two further documents in relation to both the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Determination and the Kuuku Ya’u Determination:

(a) a report from Dr David Thompson entitled ‘Response to State Questions’ dated 4 March 2019; and

(b) a witness statement of Mr G Butcher, which was undated.

12 In addition, in relation to both the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Determination and the Kuuku Ya’u Determination, the applicant had previously filed connection material on which it sought to rely for the purposes of the s 87A application:

(a) the expert report of Dr Thompson entitled “Lockhart River Coastal Region” filed on 31 October 2017;

(b) the amended expert report of Ms Waters dated 5 March 2018 and filed on 6 March 2018;

(c) the supplementary expert report of Dr Thompson dated 4 March 2019 and filed on 22 October 2021; and

(d) the affidavit of Mr G Butcher dated 9 December 2019 and filed on 6 March 2020.

THE CHANGE IN APPROACH IN THE CAPE YORK UNITED #1 CLAIM

13 It is appropriate to recount something of the history of the Cape York United #1 claim since it was filed in December 2014. The claim has been subject to intensive case management by the Court since its inception, but especially in the last few years, after a substantial change in approach that occurred around April 2020. It is important to take account of this history, and the change in approach, to understand why the Court considers it appropriate to exercise its discretion under s 84D(4) of the Native Title Act to hear and determine the two s 87A applications, despite any arguable defect in authorisation.

14 From its early days, given its size and complexity, the claim was divided for the purposes of connection assessment and case management into nine “report areas”, the report areas being based on a geographical distribution of connection assessment work between a number of anthropologists. The report areas were initially, and indeed until recently for the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Determination and the Kuuku Ya’u Determination areas, described by reference to the names of the anthropologists who wrote the corresponding connection reports. Thus, the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) Determination and the Kuuku Ya’u Determination areas were within the “Thompson report area”, Dr David Thompson being the anthropologist retained by the CYLC to work on the connection assessments for these areas.

15 In the first half of 2018, the applicant was directed to file a Statement of Issues, Facts and Contentions, and the State was directed to file a response. From these documents emerged a critical issue about whether, as a matter of fact, the whole of the Cape York United #1 claim group was a single society and, if so, whether the members of that society together possessed a single native title for the purposes of s 225(a) of the Native Title Act: see generally Drury on behalf of the Nanda People v Western Australia [2020] FCAFC 69; 276 FCR 203 at [25]-[34]. The applicant and the State adopted different positions on this issue. Close case management continued, and the State filed a very detailed document in July 2019 in respect of all the nine report areas, setting out the facts it considered were open to the Court to find were established if the materials provided to the State to that date were to be tendered. Understandably, for some report areas, the connection materials were not as advanced and far less was able to be confirmed, or agreed, by the State than what could be confirmed or agreed for other areas. It also became apparent that the “society issue” might be a major impediment to any consent determination process moving forward.

16 Therefore, in September 2019, the Court made orders setting down for hearing separate questions to identify the native title holding group or groups with respect to a “test area”, which included the Thompson report area. Programming orders were made, and it was clear the hearing, even if confined to the test area, was going to take many months and be extremely expensive and resource intensive. Sensibly and fortunately, an alternative course was agreed upon as between the State and the applicant.

17 This alternative course was based on the parties’ acknowledgment that across the Cape York United #1 claim area, there were different groups that held different native titles, including in the test area. In April 2020, the Court made orders vacating the separate question hearing and providing workplans to progress, sequentially, the native title claims within each of the nine report areas towards consent determination. As the State has made clear in its submissions, that agreed course does not, yet, mean that there will be consent determinations over all areas within the Cape York United #1 claim. There are still some areas for which the State has not accepted connection. But the change in course, towards sequential determinations by consent covering areas of land and waters to which particular groups are accepted to have a connection and otherwise meet the requirements of s 223 of the Native Title Act, was a welcome, constructive and positive development. The applicant and the State are to be congratulated on being able to change course like this and to embark upon a cooperative resolution of the claim.

18 That said, progress to date on this approach has not been without its challenges, including in the two areas set down for consent determination today. But progress has been made, and today is a landmark event.

19 From April 2020, the parties moved to a time- and resource-intensive process which involved, progressively through the nine report areas, the applicant proposing to the State what it contended were the relevant native title holding groups, the composition of those groups, and their geographic extent. This is what Ms Malyon describes in her affidavit as the Boundary Identification Negotiation and Mediation process. The BINM process had two stages. First, a desktop stage, in which the applicant would put forward proposals based on the ethnographic evidence already produced for the proceeding, and the State would respond. Second, a fieldwork stage involving consultation with the relevant peoples. Ms Malyon’s evidence discloses that considerable efforts by employees of the CYLC were made in this latter stage, to try to ensure the right people were contacted and spoken to.

20 Importantly for today’s orders, this was the process undertaken for the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) and Kuuku Ya’u claim groups. As a result of this process, and after consultation with, and decision making by the respective claim groups, the State and the applicant agreed that these groups held their respective separate and distinct native titles, and also agreed the composition of both groups, and the boundaries of their country.

AUTHORISATION

The Uutaalnganu (Night Island) s 87A agreement

21 Ms Malyon deposes to what I consider to be a methodical process undertaken by the CYLC with the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) native title groups to notify group members of the meetings to authorise the s 87A agreements. These meetings were held on 16 and 17 September 2021 respectively, and resolutions were passed approving the agreements.

22 Like many authorisation processes within native title groups, not everyone may agree with the outcome. Native title outcomes for consent determination do not depend on every single claim group member agreeing. They depend on either the use of a traditional decision making process if one exists, or (as is usually the case) if one does not, on a decision making process being agreed and adopted and a decision being made in accordance with that agreed process. Once decisions are taken, unless there is a legal problem with those decisions, the decisions made at these meetings are the decisions the Court will rely upon in making orders recognising native title. Finality is an important value in the Australian legal system and that is especially so where property rights such as native title are concerned. Disputes must be resolved. In native title, the meeting processes which lead to authorisation of claims, agreements and determinations are designed to do that.

23 I accept that in the unusual circumstances of the Cape York United #1 claim, and its change of course, the BINM process which Ms Malyon describes, and the several stages in the authorisation of the s 87A agreement for each native title holding group, assume more prominence. The BINM process can be described as a “grass roots mediation process” even if members of the claim groups have a variety of opinions about whether it was a good or bad process.

24 The BINM process was localised in nature. A range of steps was taken to ensure wide public notification through a variety of media, including social media. People were invited to attend in person, or using remote technology. Until a week or so before these determinations, the Court was not notified of any formal objections to the authorisation process or to the form and contents of the proposed determinations.

25 However, on 15 November 2021, the Court received an interlocutory application to join the Kuuku Ya’u Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC and an interlocutory application to join two individuals – a descendant of the Kuuku Ya’u People and a descendant of the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People – as respondents to the Cape York United #1 claim. The applications were made on the basis of complaints concerning apical ancestors for the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) groups, disputes about at least one boundary for the Kuuku Ya’u claim, disputes about the correct PBC for the Kuuku Ya’u determination, and allegedly inadequate communication from the CYLC in relation to the determinations. Complaints were also made about the s 87A authorisation process and the adequacy of travel assistance to claim group members.

26 In oral reasons delivered on 23 November 2021, after a hearing on 22 November 2021, the Court dismissed these applications and ordered that the consent determination hearings proceed.

27 These are objections from within the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) groups, not from their neighbours. The absence of any formal objections from neighbouring groups provides a sufficient basis for the Court to infer that the area proposed to be recognised as Uutaalnganu (Night Island) is appropriate and accepted by Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People’s neighbours.

Amendments to the authorisation of the Cape York United #1 applicant

28 The changes in the course of the proceeding which I have described above had another consequence. That was the need to go back to the various native title holding groups to amend the authorisation of the Cape York United #1 claim applicant as it was initially given.

29 The original authorisation of the applicant is in evidence, included in annexure KDM-8 to Ms Malyon’s affidavit. At page 43 of the affidavit, under the heading “Limitations on the authority of the Applicant”, the following statement relevantly appears:

the Applicant has no authority to make any decision:

(i) to approve any consent determination in the proposed Claim[.]

30 Thus, the adopted course of sequential s 87A agreements and consent determinations was not a process the applicant was authorised to undertake. A new authorisation was required. This in itself was a huge task – notifying, co-ordinating and conducting a series of meetings across the Cape York United #1 claim area, and outside it (e.g. in Cairns). There were information meetings held across Cape York, and then the authorisation meetings themselves. All meetings were publicly notified through a variety of media, including social media, emails and telephone calls, and in-person communications. People were invited to attend in person or by remote technology. Organisations such as the registered native title bodies corporate, Aboriginal Corporations and Land Trusts under the Aboriginal Land Act 1991 (Qld), and the 6 Aboriginal Shire Councils within Cape York were also emailed notifications to put up on noticeboards and distribute. Ms Malyon deposes (at [25]):

I attended, either in person or by video-conferencing, 12 out of 16 of the Authorisation Meetings. David Yarrow of counsel attended, either in person or by video-conferencing, 14 out of 16 of these meetings. At each of the meetings that I did not attend, a Legal Officer employed by CYLC attended the meeting. The meetings were also attended by other CYLC staff, including staff from the Community Relations and Dispute Resolution Unit, the Anthropology Unit, consultant anthropologists and administrative staff.

31 As to the outcome of the meetings, Ms Malyon deposes (at [29]-[30]):

A total of 165 people voted for the proposed resolutions, no people voted against them, and 3 people abstained. A copy of these resolutions is annexed hereto and marked “KDM-8”. The resolutions are the same as those contained in the Applicant’s re-authorisation workplan filed on 16 March 2021.

At two meetings (Hopevale and Pormpuraaw) no vote was taken on the resolutions by the persons present, as no motion was moved to adopt the resolutions. A total of 15 people attended these 2 meetings.

32 The applicant submits that, although the two meetings at Hopevale and Pormpuraaw did not make or pass any resolutions, this did not impact upon the effectiveness of the resolutions as a whole. I accept that submission, which is supported by detailed reasoning in the State’s submissions (at [30]-[32]) that need not be repeated here, but which I find is persuasive, and correct.

33 The new authorised limits on the authority of the applicant are set out in the new authorisation Resolutions 4.1 and 4.2:

4.1 The authority of the Applicant is limited as follows:

(a) the Applicant has no authority to make any decisions (including decisions about land use, management or protection) about particular land or waters within the proposed Claim Area – decisions in respect of those matters are to be made by the persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to the particular land or waters;

(b) the Applicant has no authority to make any decision to approve any consent determination in the Claim (whether it deals with the whole of the claim area, is otherwise made in full settlement of the CYU#1 Claim or at all) other than as set out in Resolution 4.2;

(c) the applicant has no authority to change the solicitor for the Applicant in the Claim;

(d) decisions in respect of the matters in paragraph (b) and (c) are to be made by the Native Title Claim Group; and

(e) the Applicant’s authority is otherwise confined to matters arising under the Native Title Act in relation to the Claim.

4.2 It is a condition of the Applicant’s authorisation that the Applicant must not fail to agree to a proposed agreement under s 87 A of the NTA for a determination to be made in relation to part of the Claim Area (s 87 A agreement) if, and only if, the following conditions are satisfied:

(a) a draft of the proposed s 87 A agreement has been prepared by the Applicant and the State of Queensland;

(b) the Applicant, with the assistance of CYLC, has notified each group of persons described in the draft s 87 A agreement as the persons who will be determined to hold native title in the area to which that particulars 87A agreement is intended to apply (the “proposed native title holders”) of the date and location of a meeting (or meetings) for each group of proposed native title holders to consider the draft s 87 A agreement;

(c) at each meeting of a group of proposed native title holders, the Applicant, with the assistance of CYLC, has explained the meaning and effect of the draft s 87A agreement;

(d) at each meeting of a group of proposed native title holders, a resolution is passed that the proposed native title holders as a group agree to the draft s 87 A agreement; and

(e) the resolutions referred to in (d) are passed following a process of decision making chosen by each group of proposed native title holders.

34 For the reasons set out by the applicant and the State in their submissions, the Court finds the applicant’s agreement to the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) consent determinations falls within the scope of the authority given to it by the re-authorisation process.

35 The Court recognises the size of the task that faced the CYLC and its staff, as well as the applicant’s legal representatives in this re-authorisation process. The task was performed as methodically and diligently as could reasonably be expected. It was performed under challenging restrictions and risks due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Court takes account of this. Again, that is not to say it was perfectly done. Perfection is not the standard. I am satisfied reasonable and appropriate efforts were made to notify claim group members, to provide them with information and to give them reasonable opportunities to attend the relevant meetings and information sessions, to voice their opinions and contribute to the decision making process.

Section 84D

36 Notwithstanding the Court’s satisfaction that the amendments to the authorisation of the applicant occurred through an appropriate process, there remain two potential difficulties. The first stems from differences in the claim group descriptions between the original claim and the proposed determinations. The second stems from the fact the State has not yet accepted connection over all areas within the Cape York United #1 claim area.

Claim group descriptions

37 The native title claim group for the Cape York United #1 application is defined in the Form 1 originating application by reference to named apical ancestors, which is one of the most common methods of defining a native title holding group. Both the Kuuku Ya’u and the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) s 87A agreements and proposed determinations contain descriptions of native title holders which include apical ancestors not contained in the Form 1 originating application.

38 As I explained in Smirke on behalf of the Jurruru People v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2021] FCA 1122 at [109], differences of this kind between an initial application under s 61 of the Native Title Act and a proposed determination of native title are “wholly commonplace”. That is because, after a native title application is lodged, as further inquiries are made of claim group members, and as further research is carried out, factual matters about the ancestors of the claim group may become clearer, or change. That is to be expected when what is being examined are the generational histories of families which have often been torn apart and violated by European settlers, where social structures have been misunderstood and countless individuals have been re-named and misnamed by foreigners who did not wish to learn, or deal with, their real names and identities.

39 Yet, as the issues raised in Smirke (No 3) illustrate, and by reason of decisions of this Court, in particular the Full Court decision in Commonwealth v Clifton [2007] FCAFC 190; 164 FCR 355, the wholly commonplace occurrence of changes in apical ancestors is capable of being construed as introducing an impediment to the making of a determination of native title by the Court, even by consent. On one reading, Clifton stands for the proposition that there must be absolute identity between the claim group as defined at the time the s 61 application was authorised, and the claim group as defined at the time of determination of native title. That is, the claim group definition can contain no new or different apical ancestors, because new or different apical ancestors would change the composition of the claim group and result in a differently composed group from the one which authorised the s 61 application.

40 In Smirke (No 3), I found that Clifton should not be read so literally. With respect, in the State’s submissions on the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determinations, the reasoning is well summarised:

The most recent (and, with respect, comprehensive) consideration of this issue is found in the decision of Smirke on behalf of the Jurruru People v State of Western Australia (No 3) (Smirke). In that case, Mortimer J was required to determine whether the Court has jurisdiction to make a determination that native title exists and is held by a particular group that includes persons who did not authorise the application for the determination in question. Although Smirke involved a determination made in a litigated context, much of her Honour’s analysis is applicable to consent determinations. In particular, Mortimer J’s holding that the Court has jurisdiction and power to make a determination of native title that differs substantially from the terms of an application made under s 61(1) of the NTA — with no need for either re-authorisation of the application or express authorisation of the determination ahead of it being made — applies to both a determination made after trial and a consent determination under ss 87 and 87A of the NTA (although in the latter case, specific authorisation of the proposed determination may be necessary to persuade the Court that it is appropriate to make such a determination). Importantly, the path of reasoning followed in Smirke included the following salient points:

(a) When the holding in Clifton is read in context, it is clear that the Full Court’s focus was on a situation where two competing groups claim the same land and waters but only one group had made an application under s 61. The “critical” procedure was the making of a s 61 application, without which a group could not secure a determination in their favour.

(b) The Full Court (at [37]) expressly qualified its holding, by outlining the kinds of disputes that are “an inherent aspect” of the determination of a s 61 application, the resolution of which may lead to a determination of native title by the Court departing from the terms of an authorised s 61 application. These are disputes: (a) as to the true membership of a native title claim group; (b) concerning the boundaries of the area over which the claim group holds native title; or (c) as to the nature and extent of the native title, rights and interests held by the claim group.

(c) There was no suggestion by the Court in Clifton that s 213 is to be read literally. The provision operates on the whole of the procedures in the NTA, which includes s 84D(4). Further, the holding in Clifton cannot be read literally, because (bold added):

If it were to be, it would be incompatible with all the kinds of circumstances to which the Full Court referred at [37], each of which would fall foul of a literal reading of this passage. For example, where an application by a group includes descendants of 5 apical ancestors and those people authorise a claim, but a determination is proposed in respect of 7 apical ancestors, the “particular group” in whose favour the determination is proposed is not the same “particular group” as the one who authorised the claim. Yet this is a wholly commonplace occurrence, in terms of difference between group members as identified in an application, and group membership as identified in a determination.

(d) The fact that neither the Court nor participating parties have ever seen any difficulty in making a determination of native title under s 87 or s 87A where the proposed determination differs substantially from the terms of the s 61 application, confirms that Clifton should be understood in the way explained above. What is critical, and fundamental, is that there must be an initiating process, authorised, by which a claim group seeks a determination of native title. The NTA then gives considerable flexibility to the Court and to the parties to shape the content of the ultimate determination of native title, provided compliance with s 94A and s 225 occurs.

(Citations omitted.)

41 The applicant seeks an order pursuant to s 84D(4) in its submissions. On the analysis extracted above, the State submits (at [25]) that the inclusion of additional apical ancestors in the proposed Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) consent determinations does not give rise to a defect in authorisation.

42 While I tend to agree with the State’s submissions, I consider that the validity of these consent determinations, as the first of what is hoped to be a large number of consent determinations to follow within the Cape York United #1 claim, should not be attended by any doubt. Therefore, out of an abundance of caution, I propose to make an order under s 84D(4) in each of the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) consent determinations.

No acceptance of connection over the whole Cape York United #1 claim area

43 In its submissions, the State points to a further potential difficulty in the Court accepting that both determinations have as their source properly authorised claims for native title. This difficulty is also related to the change of course I have discussed above. A consequence of that change of course was that, while the regional Cape York United #1 claim was authorised by the Cape York United #1 claim group as a whole, the s 87A agreements for the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) consent determination areas were authorised only by the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) groups. And, so far, the State has not accepted connection in relation to all remaining areas of the Cape York United #1 claim, so it cannot be unequivocally stated that all members of the Cape York United #1 claim group, as described in the s 61 application, are “native title holders”. The fulfilment of that statement must await further agreement on connection in other areas within the Cape York United #1 claim area.

44 There is a line of authority in this Court which has been taken to stand for the proposition that all persons who actually hold the native title must authorise the making of the claim: see Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31; 238 ALR 1 at [1188]-[1190] (Lindgren J); Akiba v Queensland (No 3) [2010] FCA 643; 204 FCR 1 at [913] (Finn J); Ashwin (on behalf of the Wutha People) v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2019] FCA 308; 369 ALR 1 at [181] (Bromberg J). In other words, the group as defined after investigations have occurred, and after conclusions are reached, about who are the right people for country. Or to put it another way, it is the group as identified at the end of a process – which may have been a process of many, many years, that must be the group which authorised the claim. If there are changes to the claim group description as a result of evidence from lay witnesses or expert opinion, or both, then an outcome of this nature is unlikely to be achievable. In Smirke (No 3), I explained what an unsatisfactory and potentially unjust approach to the Native Title Act this was, and not one which was required by the legislative scheme in the Native Title Act, read as a whole.

45 The State is, with respect, correct in its submissions at [27] to describe my view as being that that the accepted construction of s 61 must be understood as tolerating a level of difference between the actual holders of native title and the members of the claim group who initially authorised the claim, where the difference is due to the kinds of matters that the Full Court in Clifton accepted are part and parcel of any determination of a s 61 application, such as the “true membership” of the native title claim group.

46 Therefore, where the descriptions of the native title holders in the proposed Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determinations vary from the descriptions in the Cape York United #1 application under s 61, a level of difference can be tolerated, and differences of that kind do not undermine the core processes and requirements of the Native Title Act. That is because what is occurring in these determination areas is that smaller group configurations are being identified generally from within the larger claim group, and most of the native title holders for those smaller group configurations will be members of the group which authorised the Cape York United #1 claim in 2014. As the State submits, there may be minor discrepancies because of the more detailed evidence and research concerning apical ancestors, but these are the kinds of differences the native title application process is designed to sort through – they are the “true membership” kinds of issues.

47 However, as with the first question about whether the determinations are being made in relation to a native title application that has been authorised in accordance with the Native Title Act, out of an abundance of caution I propose to make an order under s 84D(4) in each of the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determinations.

48 It is plainly in the interests of the administration of justice to do so, in circumstances where the overall Cape York United #1 claim is gargantuan, and has already consumed seven years’ worth of resources, mostly sourced from public funds. Substantial, dedicated and methodical efforts have been made to comply with the requirements of the Native Title Act in each step along the way to these first two determinations. Despite significant factual and legal challenges, the two key parties have navigated a consensual path to the recognition of native title for the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) groups. All other respondents have been consulted and given opportunities to participate in the process as it has progressed. They have been included in steps in the complex timetables. All consent to the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determinations. If ever there was a situation in the Court’s native title jurisdiction where a favourable exercise of discretion by the Court is appropriate to ensure resolution of a claim to which all parties agree, this is that situation.

THE CONNECTION OF THE UUTAALNGANU (NIGHT ISLAND) NATIVE TITLE GROUP TO THE DETERMINATION AREA, THROUGH THEIR TRADITIONAL LAW AND CUSTOM

49 Dr David Thompson has worked with the peoples of this region for a very long time. In the introductory sections to his 2017 report, he states that the report draws upon anthropological, linguistic and historical research undertaken by him, and by other researchers, over the past 47 years in the Lockhart River region, including the research undertaken by Professor Athol Chase in the 1970s, which led to Chase’s PhD thesis in 1980. Plainly, all this work pre-dated the Native Title Act.

50 In his 2017 report, Dr Thompson describes the territories and what he calls the “vital society” of four language-named groups of the Lockhart River Coastal region: the Wuthathi, Kuuku Ya’u, Uutaalnganu (“Night Island”) and Umpila peoples. He explains (at [20]) that:

These four language-named groups also form a wider coastal socio-cultural grouping called variously Pama Malngkanichi “sandbeach people”, Pama Pakaychi “down-below people” or Pama Kawaychi “eastern people” to distinguish them from their inland neighbours.

51 And at [40] he explains the origins of the Uutaalnganu group’s language name:

The Uutaalnganu people have been described as pama yi’achi, “people of the middle” (Chase 1984:113). The name Uutaalnganu, which means “people who use the verb uutaalngana for “look”, is used as a distinguishing feature of its speakers.

52 Dr Thompson describes the territory of the Uutaalnganu in this way (at [44]):

Research by Professor Chase and myself with elders and neighbouring groups in the 1970s and since 1995 has established that the Uutaalnganu group of claimants (aka ‘Night Island’) identify themselves, and are identified by other Aboriginal people of the north-eastern and north-central Cape York Peninsula region, as the group of people whose native title rights and interests under Aboriginal law and custom, are to that area of land associated with the Uutaalnganu language dialect. Their coastal land extends from an island called Nguyupalka in the Lockhart River mouth southwards to a coastal point approximately two km north of Friendly Point, and the littoral region extends west to the mountains where it meets the territory of the Kaanju peoples. The sea territory (including islands, reefs, cays and sandbars) extends east to the Great Barrier Reef. This Uutaalnganu territory consists of eleven clan estates extending along the coastal littoral.

53 It is not possible to extract all of the deep and wide research contained in Dr Thompson’s 2017 report, but it is to be hoped that it will prove a valuable resource for the peoples of the Lockhart River Coastal region into the future.

54 Dr Thompson’s more recent work, in response to questions from the State, covers two matters of significance to both the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determination and the Kuuku Ya’u determination: namely, boundary identification and accurate identification of apical ancestors.

55 One of the matters which has proved challenging, and is likely to continue to prove challenging, is the identification of boundaries between the country of one group and another. While this is a requirement for recognition of native title, the need to draw “hard” boundary lines is one of the features of the Australian native title system which has some disconformities with how rights to country are understood and observed in the traditional law and customs of the groups such as those within the Cape York#1 claim. It is a challenge not specific to that region.

56 As Dr Thompson explains at [3]-[6] in his response to State questions:

Inland boundaries of the coastal Kuuku Ya’u, Uutaalnganu and Umpila peoples are those areas of country where these groups adjoin the country of their inland neighbours, namely Southern Kaanju and Northern Kaanju, and to a lesser extent, Wuthathi and Lamalama. Whereas coastal points are more readily identified as rivers, creeks or other geographic features through greater coastal dwelling and gathering of coastal resources, inland areas are less accessible along the rugged hinterland of this region. While mountain ranges, watersheds and creeks may be general boundaries, it is not so simple to draw a line on a map. Many rugged inland areas are not readily accessible as I explain below and it has not been feasible for neighbouring groups to identify continuous boundary lines in every place. Peter Sutton has expressed the situation well for the tropical north.

There are different degrees of boundedness about the edges of even a single Aboriginal estate in the tropical north, where such things have been mapped on the ground in fine detail. It is quite typical for there to be fine and clear demarcation of the edge of an estate at points along a beach or river frontage, where one creek entering the water body is in one estate, and a creek a few score metres away is in the next estate; or where mangrove stands, for example, mark the point where the beachfront sector of an estate comes to an end. Country abundant in vine thickets and permanent lakes may also have rather precise estate boundaries along the edges of rich floodplains and ridges. ....

The very same estates, however, may have their hinterland stretching back into a set of watercourses arising in hills or in relatively monotonous sclerophyll forest uplands, where the watercourses are the bones or structural definers of the insides of estates, but where the edges of estates are heavily blurred. Between these smallish drainage systems (frequently sub-systems) are the intermediate zones usually defined ‘company’ land held by those who hold the adjacent drainage systems (1995:51).

In regard to Sutton’s reference to ‘company land’, Chase refers to them as ‘countryman groups’ that shared [“]a common area as a homeland in the days before European influence.”

These origin localities are said to consist of a number of estates which are “boxed up”. The agglomeration includes a set of estate groups who, in precontact times, formed “one camp” or a community throughout the year at a focal camping site (Chase 1980:219).

In pre-Mission and early Mission periods, Aboriginal people walked long distances through both coastal and inland regions, interacting with neighbouring clan groups, often socially by marriage ties (Chase 1980:176) or having a holiday in another’s country such as between inland bush and the coast. Examples occur in my report at [359], [362], [373], [408], and the accounts in Appendix 5: 5.4.1 and 5.4.2. This travel was customarily by established walking tracks while it is likely that rugged or impenetrable country was much less accessed if at all.

Mapping of much inland country in this east coast region is an arduous task due to difficult terrain while the boundary points that have been identified are in accessible places such as Browns Creek on the main Road from Wenlock to Lockhart River and in relation to pastoral lease country such as in the Bromley claim or in general terms such as a range or watershed. It has not been very practical or even necessary for detailed consultations and inland mapping expeditions to be undertaken in recent times. With those caveats in mind, I can roughly indicate boundary regions as requested but the principle remains that in practice there are no gaps between neighbouring groups, whether clear or not, and any indication of boundaries are subject to further consultation and agreements between the neighbouring groups concerned. Adjoining areas may be implicit, perhaps disputed, but never abandoned as there are always successors to take responsibility for country that becomes vacant of descendants. (See Chase 1980:221-222).

57 Another matter which has been the subject of close scrutiny by the State before agreeing to the proposed native title determination has been the identification of apical ancestors. I have explained above why in a legal sense that is important. Of course, and more centrally to the nature and purpose of native title, it is critical to how the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) People decide membership of their group, and critical to how people conceive of their relationships to country, and to each other. Like many other steps in the complex process of satisfying all the requirements of the Native Title Act, the identification of apical ancestors produces strong emotions and genuinely held different opinions. Since this topic is about people’s families, that is a very human and understandable reaction. It can also be a tremendously difficult subject for Aboriginal peoples, whose families have been torn apart by the policies and practices of European settlement.

58 In his responsive report, Dr Thompson discusses the long and careful process of compiling a picture of the apical ancestors for Uutaalnganu (Night Island) country. These extracts include his account of the same process for Uutaalnganu (Night Island)’s neighbours, the Umpila people. At [50]-[58], he explains:

As noted in my report at [689-690], evidence for apical ancestors and their descendants has been compiled over a long period of time including from old people in the 1970s who lived on country before the Lockhart River Mission began in 1924. Professor Chase has worked extensively with Uutaalnganu and Umpila families since 1970 and he recorded primary evidence from them, which I have expanded on in my research since 1995. Professor Rigsby also assisted from his researches with Lamalama and Umpila groups.

During the mapping trips of 1975-76 to Uutaalnganu and Umpila countries as described above [24-26], the anthropologists Athol Chase, Peter Sutton and John von Sturmer recorded site names and family associations with particular estate regions along the coast. I as linguist also made my own record of site names and associated families. These records from the elders of the time and the knowledge passed on to the descendants provide primary evidence for current cultural knowledge among the families of these two language groups.

During the 1970s, including the Umpila mapping trip, I recorded cultural, historical and life stories from old people and younger adults that included information about their country connections. During linguistic research in 2010-2013, and subsequent research for the CYU#l application, I interviewed and recorded family stories, histories and genealogies from elderly Uutaalnganu and Umpila men and women (most now deceased) that confirmed ancestors and country connections.

The linguist Clair Hill undertook PhD research at Lockhart River commencing in 2002 and recorded significant language material from elderly informants. In a collection of stories in language, she recorded brief biographies of a number of Uutaalnganu and Umpila speakers (Hill 2014:10-13). The following extracts indicate the specific knowledge of their affiliations.

Marla Butcher (deceased) [A descendant of Charlie Captain]. Well, my father come from Blue Mountain and my mother come from Leo River. I was born in Old Site, Lockhart River Mission. My father’s tribe is Apan and my mother from Umpila and grandfather from up Blue Mountain. That’s my father’s country and my mother’s. I was born in Old Site, I grew up in Old Site.

Dorothy Short (deceased) [A descendant of Tommy Clarmont and George Brown]. I born at the Old Mission but my tribe in Umpila. My father comes from Nesbit River and my mother from Pathaku (Sister [Chester] River). My mother’s story is miiku (python) and my father’s story is wunta (wind).

Susie Pascoe [A descendant of Jimmy, father of Douglas Ropeyarn]. I like to say about where my parents come from. My father’s mother come from Night Island. His daddy come from Umpila way, a place called Leo River. My mum’s parents come from Kuuku Ya’u.

Minnie Pascoe (deceased) [A descendant of George Rocky2]. My mother come from Pascoe - Kuuku Ya’u, and my father come from Rocky [Umpila]. I born Old Mission.

Irene Brown [A descendant of Old Short]. My mum come from Pascoe. [Kuuku Ya’u]. Dad from Night Island [Uutaalnganu]. I was born in Old Mission. We old ladies from there. My tribe from Night Island, two ways from Kuuku Ya’u and from Night Island.

Winnie Claudie (deceased) [A descendant of Topsy Clarmont]. My mother from Pathaku [Umpila]. My father from Chinychanaku (Night Island) [Uutaalngaanu]. I was born at Old Lockhart and went to school there. I talk Umpila like Maria Butcher and Dorothy Short.

Elizabeth Giblet [A descendant of Yi’alma, father of Bob Tongali]. Well my father from Umpila, Leo River. In language we call that place Mathamathaku. And my mother come from up Apan way. I speak Umpila language.

When contentions have arisen concerning particular family rights, further research has been undertaken. Regarding the connection of Warradoo and Tucandidgee families to the Massey River region, an archival report records the birth of Mickie Tucandidgee at Massey River in 1894 and also of Billy Warradoo born at the Massey River in about 1918 (prior to the Mission commencement in 1924). Bruce Rigsby also recorded a comparable collection of Umpila family histories and genealogies (of which I have copies) during five weeks research for the Umpila-Lamalama native title sea claim in late April to early June, 1997 (Rigsby 2009).

The family of Peter Night Island who was removed from country has had Uutaalnganu connection of his mother confirmed from Tindale and Palm Island records. The Singleton family’s Umpila connection has been the subject of some contention but their connection was clarified and confirmed in extensive research undertaken by Bruce Rigsby in 2005 including search of Tindale’s and Birdsell’s records.

During my research for my Cape York United #1 report for the Lockhart River region, I met several times with Uutaalnganu and Umpila groups at Lockhart River. I reviewed with them charts of their apical ancestors and descendant families and discussed estate affiliations. Both groups confirmed the list of apical ancestors as provided in [701] and [703] of my report without dissension.

I note here an amendment to [701] in regard to Uutaalnganu estate 4 that includes the old Mission site. In genealogical work I have located one living descendant of King Fred and Taltaninyu for this estate, his great, great granddaughter, Evelyn Sandy. Due to the birth of so many Uutaalnganu people at the Mission site, all Uutaalnganu are given social and historical connection to this estate.

In my opinion, the apical ancestors of Uutaalnganu and Umpila language-named groups are sufficiently verified by the long-standing oral knowledge provided by deceased and living elders and confirmed by current members of these groups.

(Footnotes omitted.)

59 Finally, although the Court is not assessing this evidence in the way it would for a contested trial about connection, it would not be right for these reasons to omit some of the evidence of claim group members. It is their accounts and stories, of their lived experiences and those of their elders and ancestors, which provide the foundation for any determination of native title. They live and understand their law and custom, and how it connects them to their country.

60 The connection material filed in support of the Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determination included evidence from several claim group members. Two are Mr G Butcher, who has passed away, and Father Brian Claudie.

61 Father Claudie has connections to four areas of country: to Payamu, which he describes as the sacred area for the Rainbow Serpent, near Tin Creek and the Pascoe River. He is connected to that country through his father’s uncle, Jimmy Doctor, and his grandmother, Minnie Doctor. Second, Kanthanampu country (as a Kukuu Ya’u person), through his grandfather, Barnie Claudie. Third, the area he calls Night Island, the European name for Uutaalnganu. That connection comes through his grandfather, Jack Giblet. The fourth is Umpila country, where his connection comes through his maternal grandmother, Topsy Clarmont. During the interlocutory hearing, Father Claudie spoke to the Court. My impression of him was that he was serious and thoughtful elder for his communities.

62 Father Claudie describes Uutaalnganu (Night Island) country as going down to Stony Creek. His totem for that country is “the kangaroo, the wallaby”. At [47] of his witness statement, he describes a totem in this way:

The totem is set by the elders, because they knew about where the totems are. For example, the elders knew wallaby was the totem for Night Island because there were lots of wallaby around, especially near Night Island. A totem represents the land in that area; it comes from the land. My grandpa – my Mum’s Dad – and uncle Robert, uncle George and uncle David told me about this.

63 At [57], Father Claudie offers this description of his people:

We are coastal people, my people. We are different from the inside people. In language we call them Kanaji people – ‘on top’ people, people who live inland in places like Wenlock, Coen and those type of places. We speak different languages but we still understand each other. Some of our laws were different. Inside people when they dance corroboree they use bark to hit on the ground, but we would use the drum and clapsticks. Some rules were similar, like the rules about marriage. Now the connections are all over Cape York. Now the bloodline is running all over.

64 At [29]-[30], [67]-[68], [79], and [91]-[94], he describes how he learned about his country and his law and custom, and how it is passed on:

We children would follow the elders – wherever they wanted to go, we would go, and they would teach us what to do. We would meet up with other groups of people – northern people, southern people, all the tribal people. We would talk about cultural things, especially the land and the sea, and where we were going to go camping. We would sit together and listen to the elders. This is all in my memory – what I have been told by my old people, my grandpa and my grandmothers.

When I was a very little fella, I met up with my little grandfather who was Barney Small. I would also go out on country with my big uncle Billy Clarmont, Tiger King, my Dad, my wife’s Dad Jimmy Doctor and his brother William Doctor, Michael Sandy, Alex Sandy and Harry Sieu – I called them all grandfather. They taught me to dance, to hunt, and to speak language. They told me about everything; about bush tucker, seafood, hunting wallaby, everything. My grandfather Charlie Omeenyo was my grandmother Topsy Clarmont’s brother, and we spent a lot of time together. All my life I was among the elders listening to them and the language they were speaking; the words of their customary law. When they spoke language they would speak it very deeply, meaning that they always spoke the language and they pronounced it properly so the younger generation could learn to speak the language the same way. Even when I was in my schooling, when I finished school at 3 pm I was back with my elders taking notice of them and listening to them speak about their laws.

…

We are sandbeach people – we live on the sea, and we live on seafood and bush tucker. Our boys go diving and get crayfish and hunt around in the bush. The elders taught me how to do that.

I went out with my elders; everywhere they went, I went. My knowledge and everything, I learned from them, from sitting beside them. I learned what culture is, everything. My elders included my grandfathers, my Mum’s Mum, and my grandmother’s brother Charlie Omeenyo. I went out on the country with them, with my elders like my grandfathers. I was all over the place, travelling around.

…

I am older now, so don’t really hunt anymore. I have showed my children and grandchildren these things and told them our stories. I have been a role model for a long time. I have passed my knowledge to my son, so when he goes hunting, he will bring some back for me. I was a strong man when I was younger, more strong than I am now! My sons go hunting and fishing with their wives. Out of the respect for the loss of my wife, I don’t go out camping anymore. My sons bring around meat from when they go out hunting, and that’s the right way to respect our old people’s way and share things. Some people only share with their really close family. Sometimes people don’t share and that’s not right.

…