FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Caddick [2021] FCA 1443

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | First Defendant MALIVER PTY LTD Second Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

In these orders:

Investor Funds means the monies received by either the first or second defendant from investors as itemised in Updated Annexure I, including amounts paid as “management fees”.

Out of Pocket Investors includes the investors whose “total estimated amount” owing is greater than zero as identified by the Receivers in the last column of Updated Annexure I.

Receivership Property means all property (as defined in section 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) of the first defendant.

Receivers’ Report means the report prepared by Bruce Gleeson and Daniel Robert Soire as receivers of the property of the first defendant dated 15 February 2021.

Updated Annexure I means the updated version of annexure I to the Receivers’ Report, a confidential copy of which is attached to the affidavit of Bruce Gleeson sworn 12 May 2021 in this proceeding and identified with the heading “Updated Annexure I” (as updated from time to time).

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Each of the defendants, by providing financial product advice and dealing in a financial product, contravened s 911A of the Corporations Act in that they carried on a financial services business without holding an Australian Financial Services Licence:

(a) in the case of the first defendant, from about October 2012 and continuing until about November 2020; and

(b) in the case of the second defendant, from about June 2013 and continuing until about November 2020.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Leave be granted to the plaintiff to file and serve a third further amended originating process in the form provided to the Court on 30 June 2021, to be filed electronically by 5.00 pm on 23 November 2021.

3. Leave be granted nunc pro tunc to the plaintiff, pursuant to s 471B of the Corporations Act, to continue this proceeding against the second defendant.

4. Pursuant to s 1101B(1) of the Corporations Act, Bruce Gleeson and Daniel Robert Soire of Jones Partners of Level 13, 189 Kent St, Sydney NSW 2000 be appointed as joint and several receivers (Receivers) of the Receivership Property for the purpose of:

(a) identifying, collecting and securing the Receivership Property;

(b) to the extent necessary, ascertaining the total quantum of Investor Funds and any funds advanced by any interested party to the first defendant and the identity of all investors who, in the Receivers’ view, ought to be included as an Out of Pocket Investor as well as any interested party who may be a creditor of the first defendant;

(c) subject to Order 6 below, taking possession of and realising the Receivership Property;

(d) to the extent necessary, establishing an interest-bearing account with an authorised deposit taking institution nominated by the Receivers for the purposes of holding any net proceeds of realisation of the Receivership Property (Receivers’ Trust Account); and

(e) subject to Order 7 below, seeking directions in relation to the distribution of funds in the Receivers’ Trust Account.

5. The Receivers have the following powers:

(a) the power to do all things reasonably necessary or convenient to be done, in Australia and elsewhere, for or in connection with, or as incidental to the attainment of, the objectives for which the Receivers are appointed;

(b) the powers under s 1101B(8) of the Corporations Act;

(c) the powers set out in s 420 of the Corporations Act save for the powers set out in subs 420(2)(d), (h), (j), (m), (n), (o), (s), (t) and (u) and provided that, wherever in that section the word ‘corporation’ appears, it shall be taken to include reference to the first defendant;

(d) the power to seek directions from the Court regarding any matter relating to the exercise of the Receivers’ powers; and

(e) the power to require, by request in writing, any employee, agent, banker, solicitor, stockbroker, accountant, consultant or other professionally qualified person who has provided services or advice to the first defendant, to provide such reasonable assistance (including access to any documents, books or records to which the first defendant has a right of access or control) to the Receivers as may be required from time to time.

6. Before taking possession of or realising any of the Receivership Property, the Receivers shall:

(a) give notice to any interested party of their intention to do so and inform those parties in writing that they should:

(i) advise the Receivers within 15 business days if they object to the taking possession of or sale of any of the Receivership Property and specify the basis of their objection; and

(ii) provide documentary evidence in support of their objection; and

(b) seek directions from the Court in relation to their intention to do so.

7. Before making any distribution of funds in the Receivers’ Trust Account, the Receivers shall:

(a) give notice to any interested party of their intention to do so and inform the said parties in writing that they should:

(i) advise the Receivers within 15 business days if they object to the distribution of funds in the Receivers’ Trust Account and specify the basis of their objection; and

(ii) provide documentary evidence in support of their objection; and

(b) seek directions from the Court in relation to their intention to do so.

8. The above Orders do not affect the rights of any secured creditor holding a mortgage or other security interest over any of the Receivership Property.

9. For the avoidance of doubt, nothing in these Orders is intended to limit the right of the Receivers to seek directions from the Court.

10. Immediately upon Order 4 above taking effect, the appointment of Bruce Gleeson and Daniel Robert Soire of Jones Partners of Level 13, 189 Kent St, Sydney NSW 2000 as receivers pursuant Order 5 of the Orders made on 15 December 2020 (Interim Receivers) be terminated.

11. Pursuant to s 461(1)(k) of the Corporations Act, the second defendant, Maliver Pty Ltd (ACN 164 334 918), be wound up.

12. Bruce Gleeson and Daniel Robert Soire of Jones Partners of Level 13, 189 Kent St, Sydney NSW 2000 be appointed as joint and several liquidators of the second defendant (Liquidators).

13. Order 7 of the Orders made on 10 November 2020 be varied and leave be granted to the plaintiff to provide the Liquidators with unredacted copies of the affidavits filed by the plaintiff in this proceeding.

14. The remuneration, costs and expenses of the Interim Receivers for the period from 15 December 2020 to 22 February 2021 be fixed in the sum of $188,017.84 inclusive of GST.

15. Paragraphs 9E, 9H, 19D and 26 of the plaintiff’s third further amended originating process and paragraphs 2-4 of the Interim Receivers’ interlocutory application filed on 2 March 2021 be stood over to a date to be notified.

16. Any party who wishes to make submissions in relation to the outstanding questions of costs referred to in Order 15 above is to file and serve written submissions, not exceeding four pages in length, by 13 December 2021.

THE COURT NOTES:

17. The redactions made in the copy of the reasons for judgment to be published on 24 November 2021 at 2.15 pm AEDT are made in accordance with the non-publication orders of this Court made in this proceeding.

18. The undertaking proffered by Bruce Gleeson and Daniel Robert Soire of Jones Partners that, if a possibility of conflict in or as between their roles as Receivers and Liquidators arises, they will approach the Court and give notice to the plaintiff and investors of that circumstance.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[4] | |

[11] | |

[15] | |

[16] | |

[19] | |

[22] | |

[24] | |

[25] | |

[26] | |

[30] | |

[32] | |

[46] | |

[49] | |

[55] | |

[59] | |

[64] | |

[65] | |

[66] | |

[74] | |

3.4.2.2 Appointment of Maliver as advisor for the Wilson Super Fund | [77] |

3.4.2.3 Appointment of Maliver as advisor for Mr Wilson’s personal investments | [79] |

[84] | |

[86] | |

[90] | |

[93] | |

[105] | |

3.4.3.3 Establishment of the self-managed superannuation fund and associated bank account | [107] |

[111] | |

[117] | |

[125] | |

[130] | |

[135] | |

[141] | |

[148] | |

[150] | |

[159] | |

[169] | |

[185] | |

[197] | |

[201] | |

[203] | |

[204] | |

4.2 A financial services business without an AFSL – s 911A of the Corporations Act | [211] |

[213] | |

4.2.2 Have Ms Caddick or Maliver contravened s 911A of the Corporations Act? | [227] |

[236] | |

[256] | |

[285] | |

[285] | |

4.3.2 Appointment of receivers pursuant to s 1101B of the Corporations Act | [288] |

[296] | |

[309] | |

[315] | |

[317] | |

4.3.2.5 Should an order be made under s 1101B(1) of the Corporations Act? | [330] |

[360] | |

[369] | |

[381] | |

[384] | |

[396] | |

[398] | |

5.4 Conclusion on the Interim Receivers’ interlocutory application | [408] |

[409] | |

[411] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 For many years Melissa Louise Caddick and Maliver Pty Ltd, the first and second defendants respectively (together the defendants), operated what might be described as a financial services business. However, as the events described below show, that business was not what it seemed.

2 On 10 November 2020 the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) commenced this proceeding and obtained ex parte orders including orders restraining the defendants from dealing with their assets and requiring Ms Caddick to deliver up her passports. On 11 November 2020 ASIC served those orders on Ms Caddick at her residential address (Caddick Residence) and executed search warrants issued pursuant to s 39D of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) including at that address.

3 On or about 13 November 2020 Ms Caddick’s partner, Anthony Koletti, informed the Australian Federal Police that he believed his wife to be missing. It was common ground between the parties that, since about 12 November 2020, Ms Caddick has been missing. That fact is not only a matter of understandable concern to a number of interested parties, including Ms Caddick’s family and clients of the financial advice business described below, but has also affected the conduct of this proceeding, the issues that arise for the Court’s consideration and their resolution.

4 As set out above this proceeding was commenced by ASIC on 10 November 2020 at which time it sought and obtained orders on an ex parte basis against Ms Caddick and Maliver. Thereafter, the proceeding was listed before the Court on a number of occasions in November and December 2020. Given her disappearance Ms Caddick did not appear but was, for a time, represented by her brother, Adam Grimley, pursuant to an enduring power of attorney in his favour. There was no appearance on any occasion for or on behalf of Maliver.

5 On 15 December 2020, on ASIC’s application, orders were made (December Orders) including:

(1) an order pursuant to s 1323(1)(h)(i) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) appointing Bruce Gleeson and Daniel Robert Soire of Jones Partners as joint and several receivers (Interim Receivers) of the Property (as defined) of Ms Caddick for the purpose of:

(a) identifying, collecting and securing the Property of [Ms Caddick];

(b) approving or making the payments from the Property of [Ms Caddick] permitted by Order 11 of the Orders made on 10 November 2020 as varied;

(c) ascertaining the amount of money received by [Ms Caddick] from funds paid to [Maliver] by investors for investment (Investor Funds);

(d) identifying any Investor Funds held by [Ms Caddick], any Property acquired by [Ms Caddick] with Investor Funds and any payments made by [Ms Caddick] to third parties with Investor Funds and any other dealings by [Ms Caddick] with Investor Funds; and

(e) ascertaining whether any money was paid directly to [Ms Caddick] by investors for investment and identifying the matters set out in paragraph (d) above in relation to any such money.

(2) an order requiring the [Interim Receivers] to provide to the Court and to ASIC a report regarding:

(a) the assets and liabilities of [Ms Caddick];

(b) an opinion as to the solvency of [Ms Caddick];

(c) the amount of Investor Funds received by [Ms Caddick];

(d) any Investor Funds held by [Ms Caddick], any property acquired by [Ms Caddick] with Investor Funds and any payments made by [Ms Caddick] to third parties with Investor Funds and any other dealings by [Ms Caddick] with Investor Funds;

(e) any money paid directly to [Ms Caddick] by investors for investment and any property acquired, any payments made and any other dealings, by [Ms Caddick] with such money; and

(f) the [Interim Receivers’] remuneration, costs and expenses.

(3) an order pursuant to s 472(2) of the Corporations Act appointing Messrs Gleeson and Soire as joint and several provisional liquidators (Provisional Liquidators) of Maliver and requiring them to provide a report to the Court and to ASIC in relation to the provisional liquidation of Maliver including:

(a) the persons who have paid money to [Maliver] for investment, the amounts they invested, and whether, and to what extent, these amounts have been repaid;

(b) identifying any bank accounts in which Investor Funds are held, any Property acquired with Investor Funds or any other dealings with Investor Funds;

(c) the assets and liabilities of [Maliver], including any assets in which [Maliver] has any legal or beneficial interest and an estimate of the value of each asset;

(d) an opinion as to the solvency of [Maliver];

(e) an opinion as to whether [Maliver] has proper financial records;

(f) an opinion as to the claims that may be available to the Liquidators for the recovery of funds for the benefit of creditors, including claims pursuant to Pt 5.7B of the Act;

(g) the likely return to creditors;

(h) any other information necessary to enable the financial position of [Maliver] to be assessed;

(i) an opinion as to whether [Maliver] has contravened any provisions of the [Corporations Act] and/or any other legislation; and

(j) any suspected contraventions of the [Corporations Act] by any directors or officers of [Maliver].

6 On 24 February 2021 the Interim Receivers and the Provisional Liquidators each filed their reports dated 15 February 2021 with the Court (respectively Interim Receivers’ Report and Provisional Liquidators’ Report and collectively Appointees’ Reports).

7 On 1 March 2021 the Interim Receivers filed an interlocutory application seeking a number of orders including an order that their remuneration, costs and expenses incurred in that capacity for the period 15 December 2020 to 2 February 2021 be fixed in the sum of $189,148.09 inclusive of GST or such other amount as the Court considers fit and proper and that the sum be paid out of Ms Caddick’s property in priority.

8 On 24 May 2021, among others, an order was made pursuant to s 23 or alternatively s 37P of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) for the appointment of counsel nominated by the President of the Bar Association of New South Wales to act as contradictor for the purposes of making submissions as contradictor to ASIC’s application for relief against Ms Caddick. I will refer to counsel so appointed as the Contradictor.

9 On 15 June 2021 leave was granted to ASIC to file a second further amended originating process.

10 On 29 June 2021, the first day of the hearing, I granted leave pursuant to r 2.13 of the Federal Court (Corporations) Rules 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Rules) to Barbara and Edward Grimley, Ms Caddick’s parents, to be heard in the proceeding without becoming a party to it.

11 By its second further amended originating process ASIC sought:

(1) declarations of contravention of s 911A of the Corporations Act against each of Ms Caddick and Maliver;

(2) an order pursuant to s 1101B(1) of the Corporations Act appointing Messrs Gleeson and Soire as joint and several receivers (Receivers) of the Receivership Property (as defined) for the purpose of, among other things, identifying, collecting, taking possession of and realising that property and distributing the proceeds of its realisation to Investors (as defined) and any Interested Party (as defined), in accordance with this Court’s directions;

(3) an order that before realising any of the Receivership Property the Receivers shall:

(a) give notice to any Interested Party of their intention to realise the property and inform the said parties in writing that:

(i) Interested Parties should advise the [Receivers] within 10 business days if they object to the sale of any of the property, specify the precise nature of the property and the basis of their objection and provide documentary evidence in support of their objection;

(ii) in the case of the Real Property, that they seek the written consent of the occupiers of any such property, which is to be provided by the occupiers within 28 days of the date of the [Receivers] giving such notice, that they will vacate the said property by a date acceptable to the [Receivers];

(iii) in the event Interested Parties advise the [Receivers] of any objection to sale, the [Receivers] are required by the Court to re-list the matter and seek further directions from the Court in which case the Interested Party may be susceptible to an adverse order for costs.

(b) in the event the [Receivers]:

(i) receive no objections to the sale of the property within the notice period referred to in sub-paragraph 9C(a)(i) above; and

(ii) in respect of the Real Property, obtain the written consent of the occupiers of the Real Property to vacate the said property in accordance with sub-paragraph 9C(a)(ii);

the [Receivers] shall as soon as practicable following the expiry of the notice period referred to in sub-paragraph 9C(a)(i), and the agreed date for vacation of the Real Property, take steps to realise that property;

(c) in the event objections are received within the notice period referred to in sub-paragraph 9C(a)(i) above, or in the event the [Receivers] do not procure the written consent of the occupiers of the Real Property to vacate the property within the time period, and as provided for, in subparagraph 9C(a)(ii), the [Receivers] shall seek directions from the Court as to whether they are justified in taking all necessary steps to realise the property (in respect of which objections have been received or which the occupants have not agreed to vacate) having regard to the said objections and in doing so join all parties they consider necessary to be joined to any such application.

(4) an order pursuant to s 461(1)(k) of the Corporations Act that Maliver be wound up and that Messrs Gleeson and Soire be appointed as liquidators; and

(5) an order pursuant to s 90-15(1) of the Insolvency Practice Schedule, being Sch 2 to the Corporations Act, that the liquidators not take any steps to pursue any claims through any court proceedings that may be available to Maliver against any person or issue any examination summonses under Part 5.9 Division 1 of the Corporations Act without first seeking the Court’s approval and that they provide no less than 14 days’ written notice to ASIC of any such proposed application.

12 The second further amended originating process includes the following definitions:

“Interested Party” includes Anthony Koletti, [REDACTED], Adam Grimley and Edward and Barbara Grimley, National Australia Bank Limited as the mortgagee of the Real Property and the Investors identified by the [Receivers] from time to time.

“Investors” means the parties set out in Updated Annexure I.

“Real Property” means the real property located at [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] and contained in folio identifier [REDACTED] and [REDACTED] [REDACTED] and contained in folio identifier [REDACTED].

“Receivership Property” means:

(a) the Real Property;

(b) the Motor Vehicles;

(c) the Shares;

(d) the Caddick Services Trust Property;

(e) such of the Jewellery identified in Annexure B to Annexure H “Pickles Valuations Appraisal Report” of the [Interim Receivers’ Report] as is identified in the affidavit of Bruce Gleeson to be sworn in these proceedings as having been purchased using Investor Funds;

(f) any further real or personal property of the First or Second Defendant that the [Receivers] may determine was purchased using Investor Funds or funds provided by Edward Grimley, Barbara Grimley or Adam Grimley;

(g) any other personal property of the First Defendant that the [Receivers] may identify.

(Underlining omitted.)

13 In the course of the hearing ASIC sought leave to file a third further amended originating process. The key amendments are:

(1) the definition of “Receivership Property” has been amended to mean “all property (as defined in section 9 of the [Corporations Act]) of [Ms Caddick]”;

(2) an amendment to the date from which the declaration of breach of s 911A of the Corporations Act is sought against Ms Caddick;

(3) an amendment to para 9A(h) so that it is in the following terms:

(4) to the extent necessary seeking directions in relation to the distribution of funds in the Receivers’ Trust Account.

(5) amendments to para 9B which concerns the powers to be given to the Receivers, if appointed;

(6) the addition of para 9DD which provides:

(7) For the avoidance of doubt, nothing in these orders is intended to limit the right of the [Receivers] to seek directions from the Court.

(8) the deletion of para 9M which sought to curtail the steps that the Liquidators could take if appointed such that they could not issue examination summons or pursue any claims available to Maliver through court proceedings without first seeking the Court’s approval and giving notice to ASIC.

14 The filing of the third further amended originating process should be allowed. Only Ms Caddick’s parents made submissions in relation to its filing. However, those submissions address the relief sought by the third further amended originating process, rather than the question of leave to file it, and are set out at [309]-[314] below.

15 ASIC relied on a significant volume of evidence which, in broad terms, included evidence given by: ASIC as to documents obtained and findings from its investigations into Maliver and Ms Caddick; the director of the entity that held the Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) which Ms Caddick claimed to hold; four investors regarding their dealings with Ms Caddick; officers of CommSec regarding the existence of CommSec Accounts referred to in documents provided by Ms Caddick to investors; and the Interim Receivers and Provisional Liquidators in relation to the work they have undertaken. It is neither possible nor, indeed, desirable to set out that evidence in full. It is summarised below to the extent it is relevant to the issues that arise for resolution.

16 Maliver was incorporated on 18 June 2013. Ms Caddick is the sole director, secretary and shareholder of Maliver.

17 ASIC is the authority that regulates the Australian financial services industry and is responsible for the supervision and granting of AFSLs pursuant to Pt 7.6 of the Corporations Act. Details of all AFSL holders and their authorised representatives are maintained by ASIC in registers within databases maintained by it pursuant to s 1274 of the Corporations Act which include the Australian Securities Commission on Time (ASCOT) database and the Seibel database.

18 Based on searches undertaken by ASIC on the ASCOT and Seibel databases, neither Ms Caddick nor Maliver currently hold or have previously held an AFSL, Maliver is not and has never been an authorised representative of an AFSL holder and since 9 October 2009 Ms Caddick has not been and is not presently an authorised representative of an AFSL holder.

3.2 Documents provided to investors by Maliver

19 Isabella Lucy Allen is an investigator in ASIC’s financial services enforcement team as part of the Office of Enforcement. Ms Allen has been the case officer in charge of the investigation into Maliver and Ms Caddick since its commencement on 8 September 2020. Ms Allen explains that as part of its investigation ASIC has obtained more than 50,000 documents which relate to Identified Investors, who are the 72 investors listed in the document described as “Updated Annexure I” to Mr Gleeson’s affidavit sworn on 12 May 2021 and which is described at [180] below. Those documents were obtained from the following sources:

(1) voluntary production by Identified Investors;

(2) 14 devices seized under a search warrant issued under s 39D of the ASIC Act at the Caddick Residence;

(3) Ms Caddick’s email account; and

(4) notices issued under s 30 of the ASIC Act.

20 Based on her review of documents obtained from the sources referred to in the preceding paragraph, Ms Allen has identified that:

(1) on and from Maliver’s incorporation, Ms Caddick generally provided the following documents to investors prior to the commencement of their investment:

(a) a financial services guide from Maliver (Maliver FSG);

(b) an appointment letter;

(c) a letter of authority;

(d) a document titled “Fact Finder”; and

(e) a document titled “Investor Risk Profile”;

(2) usually at the end of each month Identified Investors were provided with the following documents that appeared to be a summary of their investment:

(a) a document titled “Portfolio Statement” which purported to be a print out from an Identified Investor’s CommSec account listing that investor’s current shareholding; and

(b) a document titled “Transaction Summary Statement” which purported to be a print out from an Identified Investor’s CommSec account listing the shares that had been purchased or sold during a specified period through that investor’s CommSec account;

(together, Portfolio Valuations); and

(3) certain investors were also provided with the following documents:

(a) a document titled “Appointment & Implementation of Maliver Pty Ltd as your Adviser”;

(b) a document titled “Statement of Advice”; and

(c) a document titled “Request for personal information form”.

The documents listed at (1) and (2) above are more fully described below.

21 Based on her review of the documents obtained by ASIC, Ms Allen has ascertained in relation to the Identified Investors that 24 of them received a Maliver FSG, 27 of them received an appointment letter, 31 of them received an authority letter, 10 of them received a “Fact Finder”, nine of them received an “Investor Risk Profile” and 30 Identified Investors did not receive any of these pre-investment documents. Ms Allen provides the following explanation for the latter:

(1) seven of those Identified Investors became clients and made their investments prior to Maliver’s incorporation; and

(2) the balance were, for the most part, related to other Identified Investors (e.g. they were family members or a related entity, such as a self-managed super fund, of an existing investor). It appears that where that occurred, Ms Caddick did not reissue pre-investment documents setting up the client relationship, providing information about Maliver and seeking information about the client.

22 During the period 28 July 2018 to 11 November 2020 Ms Caddick provided a number of investors with the Maliver FSG. Based on Ms Allen’s review of the documentation obtained by ASIC there were five versions of the Maliver FSG, identified as follows:

(1) Maliver Financial Services Guide v 1.0.pdf;

(2) Maliver Financial Services Guide v 1.1.pdf;

(3) Maliver Financial Services Guide v 1.3 0814;

(4) Maliver Financial Services Guide v 1.8 0717; and

(5) Maliver Financial Services Guide v 1.8 012020.

23 Each version of the Maliver FSG included the following:

(1) under the heading “What is a financial services guide?”

The Financial Services Guide (FSG) is an important document. It is designed to provide information about the financial services provided by Maliver and its representatives. It aims to assist you in deciding whether to use the services we offer. It also provides you with an understanding of what to expect from your dealings with Maliver.

(2) under the heading “Who is responsible for the services you receive?”:

Maliver is an independent financial planning company and the holder of an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL); Licence Number [REDACTED]. As an AFSL holder it is Maliver who is responsible for the services that are provided to you. Your Adviser will be acting on behalf of Maliver when recommending both strategic solutions and products. Your Adviser does not act as a representative of any other licensee in providing financial services to you.

(3) under the heading “Who is my Adviser?”

Your Adviser is Melissa Caddick, who operates under the business name Maliver Pty Limited (A.C.N 164334918). Maliver is the holder of an Australian Financial Services Licence as issued by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC); Licence Number [REDACTED].

(4) under the heading “Remuneration received by Maliver”:

Maliver charges a yearly Portfolio Management Fee based on:

Total Funds Under Management at 0.75% inclusive of GST

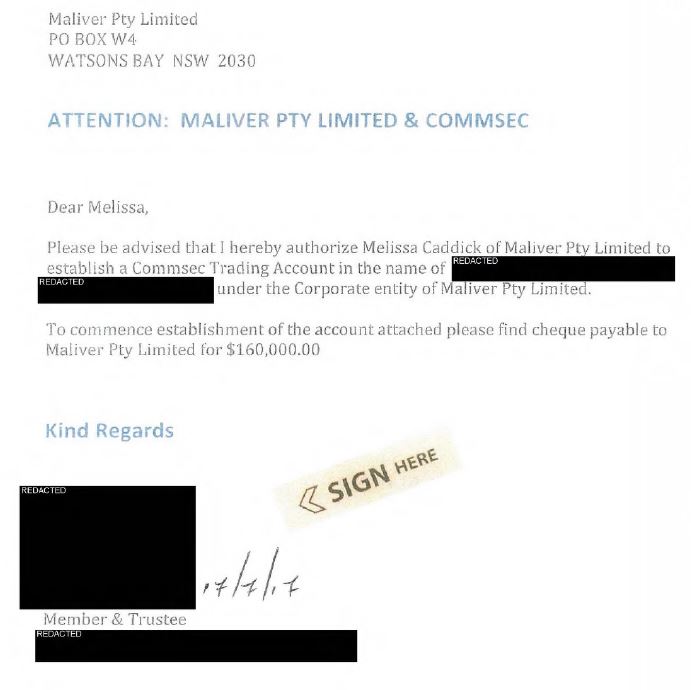

24 The purpose of the appointment letter was to authorise the establishment of a CommSec account in the name of a particular investor. Such a letter, examples of which were in evidence before me, provided (with personal identifiers omitted):

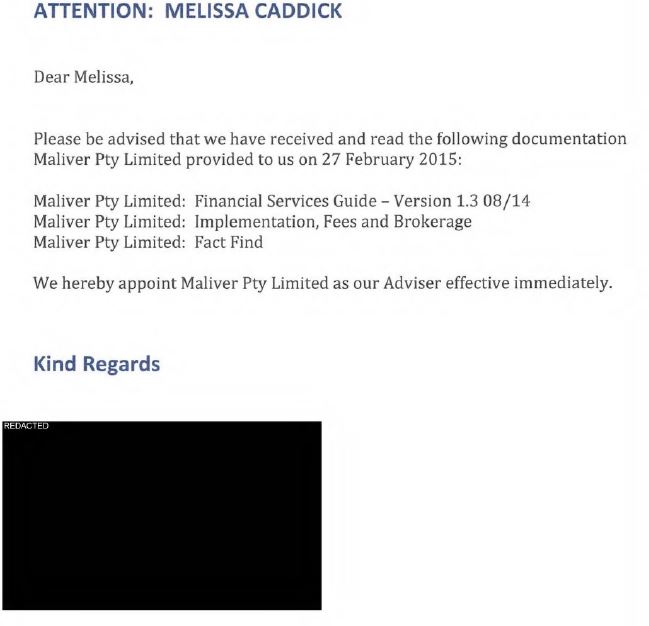

25 The letter of authority sought confirmation from a new client that he or she had read the documentation provided. Such a letter, examples of which were also in evidence before me, were addressed to Maliver and relevantly provided (with personal identifiers omitted):

3.2.4 Fact finder and investor risk profile

26 The fact finder sought information from investors about their personal circumstances and financial situation. The investor was asked to complete the document by providing information including their full name, date and place of birth, nationality, marital status, contact details, employment status and details, and whether they have a will or insurance. It also contained a section for “adviser notes” and a table for the investor to list his or her assets and liabilities.

27 An investor risk profile sought to understand the risk appetite of the particular investor. It included at its commencement:

Your attitude to risk is probably the most important factor to consider before investing. To achieve higher returns, you will have to be prepared to accept a higher risk of capital loss. This is because the funds and assets that offer high returns are generally more volatile than those producing lower returns. It is what we call ‘risk/return trade off”.

We will recommend investment strategies to match your investments to your risk profile. Investing across the various investment sectors according to your risk profile is called diversification. For example, instead of investing only in property, or only in shares, you might invest proportion in both, or even include cash or fixed interest to create a balanced portfolio.

The workbook will help us to understand what type of Investor you can afford to be and will enable us to recommend a personal asset allocation tailored to your needs. Please complete questions below by circling the answer that most closely describes you for each question.

There followed a series of questions to which the client was asked to respond by picking the answer he or she considered to be most appropriate in each case.

28 The last page of the investor risk profile included the “investor profile” to be assessed against four categories: conservative, moderate, balanced, growth and high growth. Based on the answers given to each of the questions an investor was allocated points, the total of which determined which of these categories applied to the investor.

29 Finally, by signing the investor risk profile, the client was asked to acknowledge the following (as written):

I/We confirm that I/We have read though the Personal Risk Profile Questionnaire and I/We are comfortable with the above Personal Risk Profile selection.

I/We have discussed the potential risks fully with our Advisor and I/We fully accept the consequences of my/our

30 Ms Allen has located multiple Portfolio Valuations for each Identified Investor which, based on her review, she says were emailed by Ms Caddick to each Identified Investor. Ms Allen has extracted from the documents obtained by ASIC a copy of a covering email and attached Portfolio Valuation for each Identified Investor. An example of an email and the accompanying Portfolio Valuation for one of the Identified Investors, Katherine Horn, who has also given evidence (see below), is as follows:

(1) the covering email dated 31 March 2016 from Ms Caddick to Ms Horn provides:

Dear Kate,

attached please find portfolio valuations for the period ending 31 March 2016.

In the first 10 weeks of 2016, share markets were regularly described as turbulent. Globally, shares shed 11$ of their value between the start of the year and mid February. Predictions of a global recession were frequent and shrill. Oil and iron prices tanked. Adding further to the gloom, reports did their rounds of predicting a collapse in Australian house prices and bank shares.

Then, the widespread gloom dissipated. By mid March, key share indexes in the US and Australia, and surprisingly, those in emerging economies – had recovered most of their earlier losses. Bulk commodity prices shot upwards, with iron ore up by an impressive 66% from its low point. Bank shares were keenly sought.

Periodically, claims are made that Australian housing is in a bubble, house prices are about to crash and the prices of bank shares will crumble because of bad debts.

When sentiment on the global economy is fragile, the accumulation of even mildly negative news can drive share markets a lot lower and we have experienced this albeit with recovery since January 1, 2016.

There is now a more balanced outlook, with shares of companies with strong growth earnings. It is important to remember that it (sic) times of market stress, sensible diversification makes sense, which is how your portfolio is positioned.

Lets arrange a lunch or a Friday night dinner - let me know your schedule, missing you!!!!!

Kind Regards

Melissa Caddick

(2) the email attached:

(a) a single cover page on Maliver letterhead stating: “[a]ttached please find portfolio valuation for the period ending 31 March 2016”;

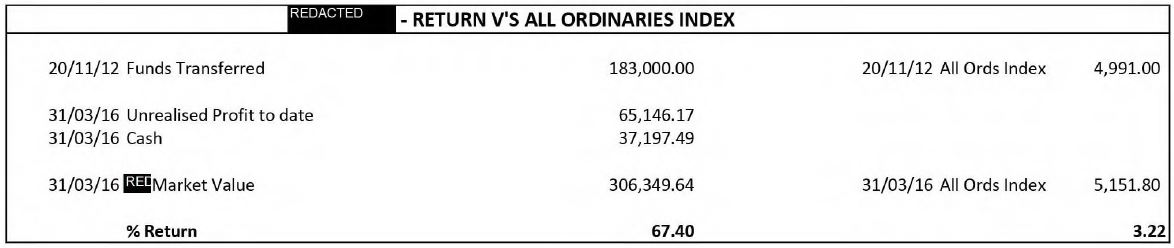

(b) a summary document titled “Kate Horn – RETURN V’S ALL ORDINARIES INDEX”;

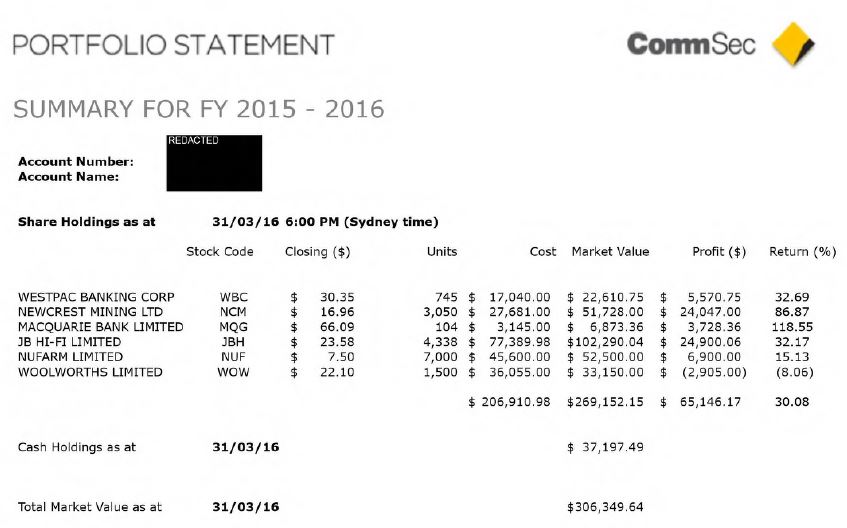

(c) a CommSec portfolio statement showing shareholdings as at 31 March 2016;

(d) a CommSec transaction summary statement for the period 1 July 2015 to 31 March 2016;

(e) a CommSec portfolio statement summary for the period 1 July 2015 to 31 March 2016 showing dividend payments and cash deposits and withdrawals; and

(f) a CommSec portfolio statement dividend summary for the period 1 July 2015 to 31 March 2016.

31 By way of illustration, reproduced below are the documents referred to at [30(2)(b) and (c)] above:

And:

32 [REDACTED] is a certified financial advisor and the sole director and owner of [REDACTED] which provides financial planning, investment, superannuation and insurance advice services.

33 [REDACTED] first met Ms Caddick in about 2003 when she was the New South Wales Development Manager of Tandem Advice Pty Ltd which held an AFSL and was a dealer group owned by ING. [REDACTED] explains that a dealer group is a group of authorised representatives licensed to provide financial advice under a single AFSL. [REDACTED]’s role was to support and develop the businesses that were being brought under Tandem’s AFSL. This role required her to coach businesses to improve their processes and procedures and to assist with their growth, compliance and business development.

34 In that capacity [REDACTED] had frequent dealings with Wise Financial Services, which was part of the Tandem dealer group, and, in particular, with two of Wise Financial’s advisors, one of whom was Ms Caddick. [REDACTED] understood that Ms Caddick was a shareholder in Wise Financial which predominantly arranged superannuation for employees of its corporate clients but, over time, became more tailored in its offering and provided advice to individuals as well as corporate members.

35 [REDACTED] recalls that in 2005 Ms Caddick informed her that she was leaving Wise Financial. Thereafter, she had infrequent contact with Ms Caddick until about 2007 or 2008 when she bumped into her and they again established more regular contact.

36 In 2008 [REDACTED] established [REDACTED]. Her husband is its general manager and it does not currently have any employees. [REDACTED] and her husband work as consultants to [REDACTED].

37 From about 2009 [REDACTED] arranged personal insurance for Ms Caddick and members of Ms Caddick’s family.

38 In about 2009 [REDACTED] recalls having discussions with Ms Caddick during which Ms Caddick mentioned that she wanted to start her own advice business focusing on investment advice and assisting high net-worth clients. Beyond that [REDACTED] had no insight into Ms Caddick’s proposed business.

39 Initially [REDACTED] operated under the AFSL of [REDACTED] as a corporate authorised representative. However, in 2013 [REDACTED] applied for and obtained its own AFSL which permits it to provide investment, insurance, superannuation and direct equities advice. [REDACTED] has never appointed anyone as an authorised representative to provide service on its behalf under its AFSL and neither [REDACTED] nor her husband have allowed anyone to provide any service on behalf of [REDACTED] other than in the case of para-planning, compliance reviews and audits, for which external providers are usually hired.

40 By letter dated 20 June 2013 from [REDACTED], [REDACTED] informed Ms Caddick that [REDACTED] had recently been issued with its own AFSL by ASIC. The letter included:

As of 1st July 2013 I will no longer be licenced by our current Financial Services Licence provider, [REDACTED], rather I will operate under [REDACTED]’s new AFSL. [REDACTED]’s AFSL number as issued by ASIC is [REDACTED].

This in no way changes our relationship as your Financial Adviser, nor the plans we have put in place. Everything will stay the same unless you opt to retain PATRON Financial Advice as your Financial Services Licensee.

In this event please notify me within 30 days and I will advise PATRON who will allocate another adviser to look after you.

41 On 2 July 2013 [REDACTED] sent Ms Caddick a copy of the financial services guide developed for [REDACTED] titled “FINANCIAL SERVICES GUIDE Version 1.0 – 1 July 2013 [REDACTED]” and displaying AFSL number [REDACTED] ([REDACTED] FSG). As Ms Caddick was a client of [REDACTED], [REDACTED] understood that she was obliged to share the document with her. [REDACTED] explained that when a financial advice business comes under a new AFSL it has to advise all of its clients of the change to ensure that they are aware of a number of things including how to find the business, make a complaint and any material changes such as a change in licence number, services or fees.

42 The [REDACTED] FSG included the following:

(1) under the heading “What is a financial services guide?”:

The Financial Services Guide (FSG) is an important document. It is designed to provide information about the financial services provided by [REDACTED] and its representatives. It aims to assist you in deciding whether to use the services we offer. It also provides you with an understanding of what to expect from your dealings with [REDACTED].

(2) under the heading “Who is responsible for the services you receive?”:

[REDACTED] is an independent financial planning company and the holder of an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL); Licence Number [REDACTED]. As an AFSL holder it is [REDACTED] who is responsible for the services that are provided to you. Your Adviser will be acting on behalf of [REDACTED] when recommending both strategic solutions and specific products. Your Adviser does not act as a representative of any other licensee in providing financial services to you.

(3) under the heading “Who is my Adviser?”

Your Adviser is [REDACTED], who operates under the business name [REDACTED]. [REDACTED] is the holder of an Australian Financial Services Licence as issued by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC); Licence Number [REDACTED].

43 In or around July 2013 [REDACTED] had a telephone conversation with Ms Caddick during the course of which they had an exchange to the following effect:

Ms Caddick: Would you consider having me under your licence?

[REDACTED]: Let me talk to [my husband], I will think about it.

44 A day or so later, after speaking with her husband, [REDACTED] telephoned Ms Caddick and explained that she would not authorise or permit her to provide financial services on behalf of [REDACTED]. [REDACTED] recalls that at the time she said words to the following effect to Ms Caddick:

We don’t want any risk. Having advisors doing whatever they want under our licence is a risk and I never wanted that.

And:

I never wanted to start a dealer group and I didn’t want the responsibility of supervision of other advisers.

[REDACTED] recalls that Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

That okay, no hard feelings. I understand and I will get my own AFSL.

45 [REDACTED] did not have any further discussions with Ms Caddick in relation to her request to operate under [REDACTED]’s AFSL and at no time has [REDACTED] given Ms Caddick or Maliver permission to operate under [REDACTED]’s AFSL.

3.4 Maliver’s client relationships

46 Annexure A to each of the Interim Receivers’ Report and the Provisional Liquidators’ Report is identical. According to the Interim Receivers and Provisional Liquidators, it sets out the typical steps undertaken by Maliver to procure an investment from its clients or investors. It is based on the Interim Receivers’ and Provisional Liquidators’ investigations as at the date of their respective reports, 15 February 2021, including interviews, analysis of bank and shareholding statements, meetings and correspondence with investors. The file note reflects the Interim Receivers’ and Provisional Liquidators’ understanding and, as ASIC accepted, is their opinion of the way in which Maliver and Ms Caddick operated, particularly in their characterisation of some of Ms Caddick’s conduct. While it must be viewed in that light, it provides a useful starting point to consider Maliver’s client interactions.

47 Annexure A includes:

1. Investors would generally be introduced to Ms Caddick via word of mouth / contacts.

2. Some investors were known to Ms Caddick in her day-to-day life and she built strong personal relationships with them.

3. Some investors were part of Ms Caddick’s immediate and extended family.

4. Ms Caddick would often provide a background story as part of her sales pitch to the investors which involved her:

a. receiving a big payout from her previous employment;

b. having a restraint of trade after leaving her previous employment;

c. managing a limited number of investors and only having space when investors closed their portfolios; and

d. boasting about her existing clients and their satisfaction with the returns achieved.

5. Ms Caddick would then discuss with the investors their personal financial position (if she did not know already), their goals and develop with them an investment strategy and risk profile.

6. Investor would be asked to sign a letter to CommSec authorising Melissa Caddick of [Maliver] to establish a CommSec Trading Account in the name of investors. The letter also authorised [Maliver] to act as the investor’s advisor. …

7. Depending on the type of investment (e.g., individual or SMSF), and existing bank accounts, investors would take steps to transfer funds to [Maliver’s] bank account or their SMSF bank accounts to commence investment. For certain investors, Ms Caddick and the investors would both attend the branch to open bank accounts which Ms Caddick was a signatory.

8. The Financial Services Guide provided by Ms Caddick to Investors … noted an AFSL of [REDACTED]. It also advised that the adviser (being Ms Caddick) will be acting on behalf of [Maliver]. [Maliver] charged an Annual Portfolio Management Fee on total funds under management at 0.75% inclusive of GST.

9. Certain sole beneficiary investors established their SMSF through Ms Caddick and had Ms Caddick as one of the Trustees as there is a requirement to have two (2) Trustees for a sole member SMSF.

10. Ms Caddick would organise the process of setting up the SMSF including any rollover from existing accounts. Documents would be signed by the investors to facilitate the rollover.

11. Investors would also sign a letter saying they have read the Financial Services Guide, Implementation, Fees & Brokerage and Fact Find. …

12. Once the funds were received by [Maliver] or into bank accounts controlled by Ms Caddick, there would be a portfolio statement in the name of the superannuation fund provided to the investor showing the initial investment and portfolio composition. …

13. The investor would then receive a … monthly portfolio statements from [Maliver]. This would be enclosed in a letter from [Maliver] with a summary of their investment including the details of funds transferred, any withdrawals of their investment and portfolio composition (e.g., cash and shares) and a comparison between the investor’s ‘return’ and the All Ords Index return. …

14. For the SMSFs, every year a checklist would be sent to the Trustees in order for the superannuation accounting firms to complete the required financials and tax lodgements.

15. Investors would be sent a yearly invoice (on the anniversary of the initial investment) for the portfolio management fees that would be paid separately by the investors.

16. If the investors wanted to invest more, they did so and their monthly portfolio statements would be updated to reflect same.

48 ASIC relied on the evidence of four of the Identified Investors: Katherine Anne Horn, Cheryl Olga Kraft-Reid, Susan Margaret Coetzee and David John Wilson. I will refer to this subset of Identified Investors collectively as the Investor Witnesses. In summary, each of the Investor Witnesses describes how they met Ms Caddick, their decision to either, in the case of Ms Horn, engage Ms Caddick as her advisor or, in the case of the other Investor Witnesses, become a client of Maliver including the material they received, the establishment of self-managed superannuation funds, bank accounts and share trading accounts, and how reports were provided on investments and the client relationship was thereafter managed. In a number of respects their experiences were similar and bear out the general description included in Annexure A to the Appointees’ Reports. I set out below a summary of their evidence.

49 Ms Horn is a [REDACTED] and currently works as a [REDACTED]. She does have not a detailed understanding of investment products or the financial services industry. Prior to investing with Ms Caddick she held her superannuation in an industry super fund and also held some shares.

50 Ms Horn has known Ms Caddick for many years. She lived three doors down from Ms Caddick while growing up and she and Ms Caddick attended the same preschool and high school. Ms Caddick moved overseas when Ms Horn was in her 20s but upon Ms Caddick’s return to Australia they became “quite good friends”.

51 Ms Horn believes that she started investing with Ms Caddick prior to the incorporation of Maliver. She recalls hearing about Maliver in late 2014, sometime after she had made her first investment and soon after Ms Caddick married. In any event, Ms Horn considered that as far as her investments were concerned Maliver and Ms Caddick were one and the same.

52 Ms Horn recalls that in about 2012, just after Ms Caddick returned from overseas, she visited her at her home and they had a conversation during which Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

I am starting up a business for people in similar positions to you and me.

And:

Are you interested in investing your superannuation though me?

And:

I will invest your superannuation in shares.

And:

I will charge you a fee of 0.5 percent of funds under management. This is less than I charge other people, because you are my friend.

53 About a month later Ms Caddick again raised with Ms Horn the issue of investing her superannuation with her and they had another conversation about the topic during which Ms Caddick said words to the effect that “it is all very low risk and simple”. Ms Caddick did not provide Ms Horn with any documents, advertising or other informational material during their discussions. All of the information Ms Horn had about what Ms Caddick was intending to do came from their conversations.

54 Shortly thereafter Ms Horn agreed to take Ms Caddick up on her offer. She thought, given Ms Caddick’s experience in the finance industry, that she could achieve better returns than she would by investing with an industry fund. Ms Horn recalls that Ms Caddick’s explanation of how she would invest her superannuation in shares sounded very simple.

3.4.1.1 Establishment of and investment by the [REDACTED]

55 In about October 2012 Ms Caddick assisted Ms Horn to set up a self-managed superannuation fund styled “[REDACTED]” (KH Super Fund) and an account with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) styled “[REDACTED]” (KH Super Fund Account) and with the rollover of her superannuation from First State Super to the KH Super Fund Account. Ms Horn recalls that the latter was done in two tranches: an initial amount was rolled over in October 2012; and the balance was rolled over in 2013.

56 Ms Caddick provided advice on the contributions Ms Horn should make to the KH Super Fund and assisted her with its administration and management including organising for its audit by a superannuation accounting company.

57 Monthly statements for the KH Super Fund Account were provided to Ms Caddick. Initially Ms Horn sent a copy of each statement to Ms Caddick and, from a time in 2019 or 2020, they were sent directly to Ms Caddick at her post office box address which was the address listed on the account. Ms Horn did not allow Ms Caddick to access the KH Super Fund Account. She transferred funds as required by cheque or electronic funds transfer to accounts nominated by Ms Caddick.

58 In the period from October 2012 to June 2018 Ms Horn transferred $135,300 from the KH Super Fund Account to Ms Caddick and Maliver for investment and, in the period October 2013 to October 2019, Ms Horn transferred $14,461.26 from the KH Super Fund Account to Ms Caddick and Maliver for annual management fees.

3.4.1.2 Ms Horn’s personal investments

59 About one month after Ms Horn started investing her superannuation with Ms Caddick, Ms Caddick inquired whether she would like to create an investment portfolio to be managed by her, outside of her superannuation investments. Ms Horn recalls that Ms Caddick informed her that the dividends from any shares purchased would go into the cash section of her investment portfolio and that she would then reinvest those amounts. As a result Ms Horn did not expect to have funds transferred back into her account.

60 Ms Horn informed Ms Caddick that she was happy for her to create and manage an investment portfolio for her. She trusted that Ms Caddick had her best interests at heart and understood that she had experience in investing. Ms Horn’s goal was to build up sufficient funds to enable her to assist her children to pay for a deposit on a house when they were older and she believed that Ms Caddick may be able to help her to do that.

61 Ms Horn had a CBA Smart Access account in her name (CBA Personal Account). In the period from November 2012 to March 2019 Ms Horn transferred $488,050 from that account to Ms Caddick and Maliver, either via cheque or electronic funds transfer, for investment in her name. In the period October 2013 to October 2019 Ms Horn also paid approximately $16,600 in annual account management fees.

62 Ms Horn recalls that Ms Caddick only asked her to invest more money with her on one occasion when, in about March 2019, she told Ms Caddick about a term deposit she had. At the time Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

The interest rate isn’t very good. I can invest this for you.

After this conversation Ms Horn withdrew $170,000 from the term deposit and provided that amount by bank cheque, which appears to have been facilitated via the CBA Personal Account, Ms Caddick. This amount, which is included in the total referred to in the preceding paragraph, was the last amount Ms Horn invested with Ms Caddick. This was because she was happy with the value of her investment based on the quarterly updates (i.e. the Portfolio Valuations) she had been receiving.

63 In 2019 and 2020 Ms Horn was aware of payments being made by her family into her personal investment portfolio. According to Ms Horn, these payments were not paid by her via the CBA Personal Account but were paid by Ms Horn’s family members directly to Ms Caddick for the purpose of investment into Ms Horn’s investment portfolio. Although the evidence is unclear, they appear to comprise:

(1) two payments of $100,000 each made by Ms Horn’s mother on 23 September 2019 and 6 December 2019 respectively. Ms Horn identified these payments into her investment portfolio, which she believes were from the proceeds of sale of her father’s bank note collection after his death, in quarterly reports she received from Ms Caddick; and

(2) a payment of $500,000 made by Ms Horn’s mother on 6 May 2020 recorded in a Portfolio Valuation for the period ending 29 May 2020. Ms Horn recalls speaking with her brother, David Wilson, about an amount of $500,000 that her mother intended to transfer to her investment portfolio.

3.4.1.3 Interactions between Ms Horn and Ms Caddick

64 During the period in which she made her investments, Ms Horn had the following interactions with Ms Caddick:

(1) she spoke with Ms Caddick about once a fortnight. Ms Horn described these conversations as mostly personal in nature. It was uncommon for them to discuss business;

(2) she received emails, usually on a quarterly basis, with updates on her investments. There were two documents or sets of Portfolio Valuations provided, one for the CommSec account set up for the KH Super Fund and the other for her personal investments; and

(3) she met with Ms Caddick every year around October for an annual review of her investments, usually over lunch in the Sydney suburb of Brighton Le Sands which was halfway between Ms Horn’s and Ms Caddick’s homes. During these meetings Ms Caddick would inform Ms Horn which shares she had invested in, sometimes telling her why she had done so.

3.4.1.4 Summary of funds invested

65 By way of summary Ms Horn gives the following evidence:

(1) since 2012 she has paid $149,761.26 from the KH Super Fund Account and $504,637.97 from the CBA Personal Account to Ms Caddick and Maliver, inclusive of $31,099.23 in annual management fees. I pause to observe that there are a number of discrepancies in Ms Horn’s evidence regarding the total sums paid from those accounts;

(2) of that amount the KH Super Fund received a payment of $15,000 from Ms Caddick or Maliver to assist in paying a tax liability. No other amounts have been received. However, Ms Horn did not expect that investment returns would be paid because of her earlier conversation with Ms Caddick (see [59] above);

(3) the monies referred to at (1) above represent Ms Horn’s life savings and the majority of her superannuation; and

(4) as at 30 September 2020, based on the Portfolio Valuations she received, Ms Horn was under the impression that the KH Super Fund’s investment portfolio was valued at $831,688.06 and her personal investment portfolio was valued at $1,960,976.72.

66 Mr Wilson is a [REDACTED] who operates as a sole trader and is Ms Horn’s brother. Mr Wilson has a general understanding of financial products and investing. Prior to making investments with Ms Caddick he invested in shares both personally and via his self-managed superannuation fund.

67 Mr Wilson has known Ms Caddick since he was about eight or nine years old when his family lived a few doors down from Ms Caddick’s family. He recalls that Ms Caddick and her brother, Adam Grimley, attended the same primary and high schools as he did, that he and Mr Grimley were in the same school year and that Ms Caddick was in the same school year as Ms Horn. In about the late 1970s Ms Caddick’s family moved house and after that Mr Wilson did not see Ms Caddick regularly. He described his relationship with Ms Caddick as mostly professional.

68 On 7 November 2007 Mr Wilson established his self-managed superannuation fund styled the “[REDACTED]” (Wilson Super Fund), at the suggestion of his father and with the assistance of his accountant.

69 Mr Wilson’s father passed away in 2008 and Mr Wilson thereafter took responsibility for looking after his mother’s retirement savings. From 2008 to 2015 he managed those investments, which were primarily investments in shares.

70 Mr Wilson recalls that in about 2012 he learnt from Ms Horn that she had invested through Ms Caddick’s business. In about 2013 Ms Horn asked Mr Wilson to look at a set of documents provided by Ms Caddick in relation to her investment with Maliver. Mr Wilson recalls that he reviewed the documents, which appeared to be print outs from a CommSec account and a bank statement, and that he had a conversation with Ms Horn which included informing her that “it all adds up and everything seems fine”. Based on his conversation with Ms Horn, Mr Wilson understood that Ms Caddick had established a company, Maliver, through which she was offering financial advice and investment services.

71 In about late 2014 Mr Wilson had a conversation with his brother about, among other things, his role in managing their mother’s retirement savings. He recalls that his brother made a suggestion in words to the following effect:

Why don’t you think about giving the money to Melissa and then you don’t have the headache of looking after it?

Mr Wilson understood the reference to Melissa to be a reference to Ms Caddick.

72 At about the same time Mr Wilson recalls having a conversation with Ms Horn about the performance of her investments being managed by Ms Caddick and that Ms Horn informed him that they were “performing well”.

73 Mr Wilson believes that his brother made a phone call to Ms Caddick to arrange an in person meeting.

3.4.2.1 Mr Wilson’s first meeting with Ms Caddick

74 On 6 May 2015 Mr Wilson and his brother attended a meeting with Ms Caddick at the Caddick Residence. Mr Wilson recalls that the following exchanges took place at that meeting:

(1) he asked Ms Caddick how she would invest their money and recalls that Ms Caddick said words to the effect of her being “only interested in Australian equities, and only about ten”. By this Mr Wilson understood Ms Caddick to mean that she was only following and investing in about 10 Australian stocks at that time;

(2) he also asked Ms Caddick how she charged for her services to which Ms Caddick replied that she “charged an annual management fee of 0.75% of the total funds managed”; and

(3) he asked Ms Caddick whether she was a member of a professional body for financial advisors in response to which Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

Well are you a member of your professional organisation?

Mr Wilson replied that he was not. By this exchange Mr Wilson understood that Ms Caddick had decided not to join a professional body and that membership was a matter of choice.

75 During the meeting Ms Caddick showed Mr Wilson and his brother documents relating to a sample portfolio of shares to explain what she planned to do with their investments and the sort of documentation they could expect to receive. Mr Wilson recalls that he told her about his financial circumstances and that Ms Caddick drew up a draft investment strategy incorporating the relevant figures. Mr Wilson understood that the strategy was for Ms Caddick to make a selection from 10 Australian shares and invest on Mr Wilson’s behalf using a CommSec account and an associated CBA Commonwealth Direct Investment Account (CDI Account) which she would establish in his name.

76 During the meeting Ms Caddick also provided Mr Wilson with a copy of a Maliver FSG. Mr Wilson recalls seeing an AFSL on the first page of that document.

3.4.2.2 Appointment of Maliver as advisor for the Wilson Super Fund

77 On 11 May 2015 Mr Wilson received an email from Ms Caddick attaching a document titled “David Wilson SF DRAFT Recommendation” which, in turn, attached a number of documents including:

(1) a file note of Mr Wilson’s discussion with Ms Caddick outlining his financial situation and objectives;

(2) a pro-forma will;

(3) a document appointing Maliver as his advisor;

(4) an authorisation for Ms Caddick or Maliver to establish a CommSec account in the name of the Wilson Super Fund; and

(5) a “personal portfolio summary”.

Mr Wilson recalls that he read the documents provided and that he understood that to buy Australian equities Ms Caddick would establish a CommSec account in his name and an associated CDI Account.

78 On 22 May 2015 Mr Wilson signed a document authorising Ms Caddick or Maliver to establish a CommSec account in the name of the Wilson Super Fund. He understood that by doing so he was permitting Ms Caddick to establish that account in his name.

3.4.2.3 Appointment of Maliver as advisor for Mr Wilson’s personal investments

79 In about August 2016 Mr Wilson decided to ask Ms Caddick to invest his personal savings in the same way as she was already doing for the Wilson Super Fund. Mr Wilson recalls he made his decision to do this after reviewing the CommSec printouts he had regularly received from Ms Caddick in relation to the performance of the Wilson Super Fund, noting that the returns were significantly better than those for his personal share portfolio which he was managing himself.

80 On 22 August 2016 Ms Caddick sent an email to Mr Wilson which included:

lovely chatting with you earlier today.

I have put together a short form recommendation for you. What I mean by short, is that I haven’t included the FSG, renumeration (sic) structure as you are an existing client and the service you will receive on this additional portfolio will be same as current. However, if you are not satisfied with the service received or wish to change the regularity of reporting please don’t hesitate to discuss with me.

I have had a look at my diary, presently I am available to meet with you as follows:

...

Attached to the email was a document on Maliver letterhead bearing an AFSL number [REDACTED] which set out a proposed asset allocation for an initial contribution by Mr Wilson of $200,000 for four Australian listed securities and recommended fund allocation ranges for each security.

81 At the time Mr Wilson was using CMC Markets as his stockbroker which required him to have a Bankwest trading account connected to its platform. When Ms Caddick agreed to manage his personal investments, Mr Wilson set about liquidating his shares held on the CMC Markets platform so that he could transfer a sum of money to Ms Caddick for the purposes of her trading on his behalf.

82 Although Mr Wilson can no longer recall the exact date, he met with Ms Caddick on a date after 23 August 2016 at which time, he recalls, he signed documents.

83 On 30 August 2016 Mr Wilson signed documents provided to him by Ms Caddick in relation to the establishment of what he understood was to be his personal investment portfolio. Included with those documents was a letter authorising Ms Caddick “to establish a CommSec Trading Account in the name of [Mr Wilson] under the Corporate Entity of [Maliver]”. On the same day Mr Wilson paid $260,000, by way of cheque, to Maliver to be invested on his behalf.

84 According to Mr Wilson, in the period from 10 June 2015 to 18 March 2020 he transferred a total of $1.32 million to Maliver comprising:

(1) $630,000 by way of contribution to the Wilson Super Fund; and

(2) $690,000 for his personal share portfolio.

85 Mr Wilson made each of the payments referred to in the preceding paragraph based on what Ms Caddick had told him at the meeting on 6 May 2015 and the documents subsequently provided to him. He understood that Ms Caddick or Maliver would invest the funds on his behalf and on behalf of the Wilson Super Fund. Mr Wilson would not have transferred any money to Ms Caddick or Maliver had he known that those monies were not to be invested in that way. Mr Wilson also understood that Ms Caddick would transfer the money from the Maliver account to a CDI Account which she had established in his name and which was linked to a CommSec trading account also established in his name. He understood that upon transferring the money from the CDI Account to the CommSec trading account Ms Caddick would buy and sell shares on his behalf for the purposes of receiving a return on the invested funds.

3.4.2.5 Maliver’s management of the investments

86 Mr Wilson had the following interactions for the purpose of Maliver’s management of both his personal investments and those made by the Wilson Super Fund:

(1) on 11 May 2016, he met with Ms Caddick for his first annual meeting to discuss the Wilson Super Fund. At the meeting he authorised Ms Caddick to pay the yearly management fee by electronic funds transfer;

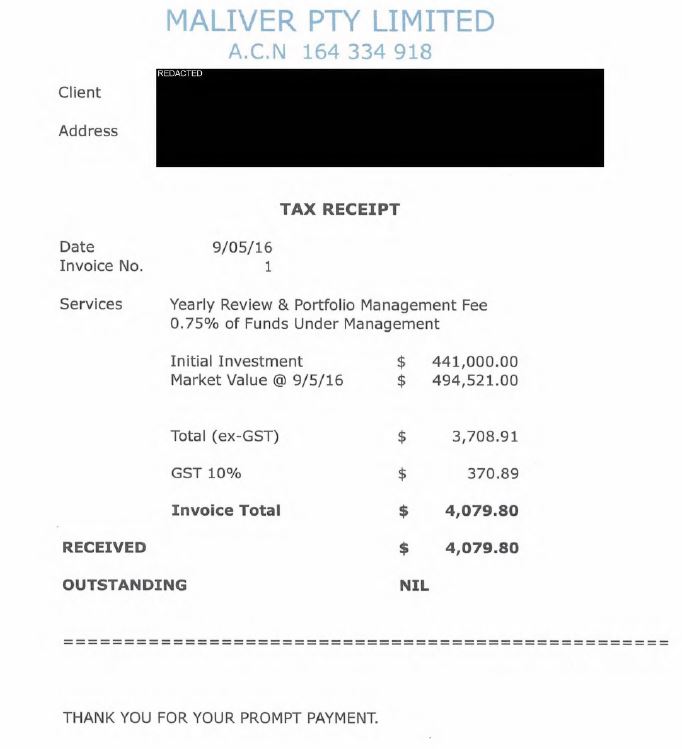

(2) in about May 2016, a “Tax Receipt” dated 9 May 2016 was issued for yearly management fees charged by Maliver to the Wilson Super Fund which was as follows:

(3) on 20 July 2016, Mr Wilson received an email from Ms Caddick attaching end of year financial year documentation for his records and for provision to his accountant;

(4) in about February 2017, Mr Wilson signed documents authorising Edmond Ong of Superannuation Accounting Services Pty Ltd to complete the annual accounting and auditing for the Wilson Super Fund and authorising Mr Ong to direct all correspondence to Ms Caddick;

(5) on 5 June 2017 Mr Wilson attended an annual meeting with Ms Caddick;

(6) in about June 2017 Mr Wilson was issued with two tax invoices dated 5 June 2017 from Maliver for yearly management fees for:

(a) the Wilson Super Fund. The tax invoice was in substantially the same form as the document set out at [86(2)] above but stated that the funds invested by the Wilson Super Fund had a market value of $721,436.20 as at 5 June 2017 and provided for a management fee, based on that sum, of $5,951.58 (incl GST);

(b) his personal investment. Once again the tax invoice was in substantially the same form as that set out at [86(2)] above but stated that the funds Mr Wilson had invested had a market value of $307,809.30 as at 28 April 2017 and provided for a management fee, based on that amount, of $2,539.51 (incl GST);

(7) on 5 June 2017 Mr Wilson received tax receipts dated 5 June 2017 for payment of the management fees referred to at [86(6)] above;

(8) between July and September 2017 Mr Wilson received copies of documents in relation to the end of year reporting being undertaken by Superannuation Accounting Services for the Wilson Super Fund;

(9) in about April 2018 Mr Wilson received tax invoices dated 30 April 2018 from Maliver for yearly management fees for the Wilson Super Fund and for his personal investments. Once again those tax invoices were in substantially the same form as set out at [86(2)] above. The invoice for the Wilson Super Fund stated that the funds invested had a market value of $785,349.35 as at 30 April 2018 and, based on that amount, a management fee of $6,479.13 was payable and the invoice for Mr Wilson’s personal investments stated that the funds invested had a market value of $402,803.54 as at 30 April 2018 and, based on that amount, a management fee of $3,213.13 was payable;

(10) on 7 May 2018 Mr Wilson attended the Caddick Residence for an annual meeting;

(11) between July and September 2018 Mr Wilson received correspondence in relation to the end of year reporting for the Wilson Super Fund;

(12) in about May 2019 Mr Wilson received tax invoices dated 7 May 2019 from Maliver for yearly management fees for the Wilson Super Fund and his personal investments, substantially in the form of the invoice at [86(2)] above. The tax invoice for the Wilson Super Fund stated that the funds invested had a market value of $992,950.22 as at 7 May 2019 based on which a management fee of $8,191.84 was payable and the tax invoice for Mr Wilson’s personal investment stated that the funds invested had a market value of $454,633.01 as at 7 May 2019 based on which a management fee of $3,750.72 was payable;

(13) on 15 May 2019 Mr Wilson attended the Caddick Residence for an annual meeting;

(14) between July 2019 and August 2019 Mr Wilson received correspondence in relation to the end of year reporting for the Wilson Super Fund;

(15) on 30 April 2020 Mr Wilson received an email from Ms Caddick attaching tax invoices dated 30 April 2019 for Maliver’s annual portfolio management fees and Portfolio Valuations. The tax invoice for the Wilson Super Fund stated that the funds invested had a market value of $1,003,002.78 as at 30 April 2020 based on which a management fee of $8,274.77 was payable and the tax invoice for Mr Wilson’s personal investments stated the funds invested had a market value of $947,232.29 based on which a management fee of $7,814.67 was payable;

(16) on 4 May 2020 Mr Wilson had an annual meeting with Ms Caddick which was held by telephone due to the COVID-19 pandemic; and

(17) between July 2020 and September 2020 Mr Wilson received correspondence in relation to the end of financial year reporting for the Wilson Super Fund.

87 In the period from 2015 to 2020 Mr Wilson also received regular updates about the investments made by the Wilson Super Fund and on his own account. Those updates generally included:

(1) printouts from the CommSec accounts set up in the name of the Wilson Super Fund and in his name, titled “Portfolio Statement” and “Transaction Summary Statement”;

(2) a document titled “EOFY Economic Commentary” which was a four or five page document from Maliver setting out insights into the economy; and

(3) documents sent at the end of the financial year comprising a CDI Account statement, holding statement, CommSec tax invoices and an investment strategy agreement.

88 Mr Wilson did not ask for or receive any payments from returns on his investments throughout the investment period.

89 On 30 April 2021 Mr Wilson contacted the Cronulla branch of the CBA to confirm the status of his accounts. Upon enquiring whether the two CommSec accounts and the two CDI Accounts in his name and the name of the Wilson Super Fund existed, he was informed that they did not.

90 Cheryl Olga Kraft-Reid is a [REDACTED].

91 Ms Kraft-Reid first became aware of Ms Caddick and her services through her sister in about December 2013. At the time her sister mentioned that Ms Caddick was running a business called Maliver, that she had invested money with Ms Caddick but that Ms Caddick was not taking on any new clients. Ms Kraft-Reid requested that her sister speak with Ms Caddick about taking her and her wife, [REDACTED] (who without meaning any disrespect and for convenience I will refer to as [REDACTED]), on as clients. Sometime after this conversation Ms Kraft-Reid’s sister informed her that Ms Caddick had agreed to do so. However, Ms Kraft-Reid did not contact Ms Caddick at that time.

92 It was not until 9 November 2015 that Ms Kraft-Reid contacted Ms Caddick by telephone to gain an understanding of the investment services she provided. Following their call Ms Kraft-Reid received an email from Ms Caddick setting out the documents which she required her and [REDACTED] to bring to a meeting which had been scheduled, namely tax returns, superannuation statements, loan statements and cash balance. Ms Kraft-Reid recalls going through her files to locate these documents.

3.4.3.1 Initial meeting with Ms Caddick

93 On 10 November 2015, Ms Kraft-Reid and her wife met with Ms Caddick at the Caddick Residence. Ms Kraft-Reid recalls that during the meeting:

(1) she asked Ms Caddick how many clients she had and what she was doing for those clients. In response Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

I am wealthy in my own right. I don’t need to do this – I’m doing it to help people, and it’s very much restricted to family and friends. I only have about 50 clients.

(2) she asked Ms Caddick how investing with her worked. Ms Kraft-Reid recalls that, in response, Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

You would be investing with Maliver directly.

And:

You need to set up a self-managed super fund and be the trustees. You then need to transfer the money from your existing superannuation accounts to Maliver. I will then use the money to trade shares on your behalf on the stock market and the income from that will grow your super fund.

There was then discussion about the possible names for the proposed self-managed super fund, the amount that they had already accumulated in superannuation at the time and the performance of Ms Kraft-Reid’s superannuation account which at the time was held with AMP. Ms Kraft-Reid recalls that Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

I can do better than your current super with AMP.

And:

There isn’t someone like me at AMP watching the market and investing in shares to grow your super the way I can.

94 Ms Kraft-Reid recalls that she had a conversation with Ms Caddick to the following effect:

Ms Kraft-Reid: I am sitting on about $330,000 in super and I want to retire when I’m 60. What I want is for, by that time, the amount in my super account to be comfortable.

Ms Caddick: That is do-able.

Ms Kraft-Reid: I have 15 years to work and as close to one million would be great for me. I would be willing to go a bit higher in risk to get that.

Ms Caddick: That is achievable.

Ms Kraft-Reid: [My wife] and I would like to live off the growth of our super, not the principal.

Ms Caddick: That is absolutely possible.

95 The conversation then turned to compliance issues. Ms Kraft-Reid said words to the following effect:

Because we would be the trustees on the super fund but you would be operating on our behalf, how would be sure you would be meeting all the compliance requirements for a self-managed super fund?

In response Ms Caddick opened the cupboards in her office to show Ms Kraft-Reid folders relating to investments made by her family members, including their contents. Ms Kraft-Reid was left with the impression that Ms Caddick’s filing system was meticulous and efficient.

96 Ms Caddick also informed Ms Kraft-Reid that there would be an auditor, its role and the annual fee that the auditor would charge. Ms Kraft-Reid recalls asking in relation to the auditor “what do they check”. In response Ms Caddick said words to the following effect:

They check I’m managing your fund because you’re the trustees and I would be operating on your behalf.

And:

They will check the transfers from your existing super funds to Maliver, that all required taxes are being paid, and the money from my trading is going back into the self-managed super fund account.

And:

They will check Maliver’s trading and management of your account is meeting all the requirements.

97 Ms Kraft-Reid understood that their Maliver managed superannuation fund account would be separate to the bank account which she and her wife would have to set up as trustees of their self-managed super fund and into which funds from their existing superannuation accounts would be transferred.

98 Ms Kraft-Reid recalls that she and her wife asked further questions about the work of the auditor. In response, Ms Caddick took another client file and showed them some of the auditor’s reports that had been prepared for that client, including a compliance check list.

99 Ms Kraft-Reid recalls that there were three chairs and a long table in Ms Caddick’s office and that Ms Caddick showed her and [REDACTED] her set up. Ms Kraft-Reid observed that there were two very large screens on Ms Caddick’s desk: one showing the CommSec platform and the other showing what Ms Kraft-Reid understood to be the ASX. Ms Kraft-Reid told Ms Caddick that she had a personal CommSec account because she traded shares herself and inquired whether Ms Caddick could invest on her behalf through that account. Ms Caddick said that she could not and that she would set up an account for Ms Kraft-Reid.