Federal Court of Australia

Freshfood Holdings Pte Limited v Pablo Enterprise Pte Limited (No 2) [2021] FCA 1404

ORDERS

FRESHFOOD HOLDINGS PTE LIMITED Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent REGISTRAR OF TRADE MARKS Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 12 November 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The decision of the delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks dated 17 December 2020 be set aside.

3. The first respondent pay the costs of the appeal and the opposition proceedings before the Registrar of Trade Marks.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THAWLEY J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding was commenced on 29 January 2021 by the appellant (FreshFood) filing a notice of appeal pursuant to s 104 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA). FreshFood appeals from a decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks: Pablo Enterprise Pte Ltd v Freshfood Holdings Pte Ltd [2020] ATMO 195 (the Decision). The Decision concerned an application filed by Pablo Enterprise Pte Ltd, a Singapore-based company, pursuant to s 96 of the TMA to remove FreshFood’s Australian Registered Trade Mark No 170010 for the word PABLO filed on 25 October 1961 in class 30: coffee (the PABLO Mark). The delegate held pursuant to s 101 of the TMA that the PABLO mark should be removed for non-use pursuant to s 92(4)(b) of the TMA and, therefore, that Pablo Enterprise succeeded in its non-use application (the Non-Use Application).

2 Orders confirming service of FreshFood’s notice of appeal on Pablo Enterprise in Singapore were made on 26 March 2021: Freshfood Holdings Pte Limited v Pablo Enterprise Pte Limited [2021] FCA 323. Orders were also made to join the Registrar as a party if Pablo Enterprise had not taken any steps in the proceeding by 16 April 2021. Pablo Enterprise did and has never taken any steps in this proceeding. The Registrar has been joined as the second respondent. On 10 May 2021, the Registrar filed a notice indicating that she submits to any order the Court may make in the proceeding, save as to costs.

3 Orders have been made for the appeal to be heard on the papers.

4 FreshFood has filed and relies on three affidavits and a considerable number of documents. FreshFood has also filed detailed submissions. The Registrar has filed a “Statement of Position” in accordance with orders made by the Court on 11 May 2021. The Registrar does not oppose the final orders sought by FreshFood. The Registrar indicated she did not wish to take an active role in the matter or make submissions in respect of the evidence filed by FreshFood. She indicated she did not consider it to be appropriate for her to actively prosecute the removal application in the absence of Pablo Enterprise’s participation in the proceeding, appropriately drawing to the Court’s attention the decision of Burley J in Hungry Spirit Pty Limited ATF The Hungry Spirt Trust v Fit n Fast Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 883.

5 In Hungry Spirit, the parties had asked the Court to make an order by consent allowing the appeal. The parties provided to the Court a letter from IP Australia stating that the Registrar did not object in principle to the orders sought by the parties. Fit n Fast had filed a non-use application pursuant to s 92(4)(b). Burley J summarised the operation of the statutory scheme from that point in the following way (emphasis in original):

[8] The Registrar is obliged to give notice of an application under [s] 92, including by advertising the application in the Official Journal: s 95. The application for removal may be referred by the Registrar to a prescribed court for determination: s 94. That step was not taken in this case. Any person may oppose an application for removal by filing a notice of opposition with the Registrar in accordance with the regulations and within the prescribed period: s 96. If the application for removal is unopposed, or the opposition has been dismissed, the Registrar (or the court, if the application is referred to it) must remove the trade mark from the Register in respect of the goods and/or services specified in the application: s 97. If the application is opposed, the registrar must deal with the opposition in accordance with the regulations: s 99. The Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) provide that the applicant must file a notice of intention to defend the application, if a notice of intention to oppose the application is filed: reg 9.15. If a notice of intention to defend is not filed within the period required, the Registrar may decide to take the opposition to have succeeded, and refuse to remove the trade mark from the Register: reg 9.15(3).

[9] Section 100(1) provides that it is for the trade mark owner (as the opponent to the non-use application) to rebut any allegation that the trade mark has not been used or was not intended to be used.

[10] Section 101(1) provides that if the proceedings have not been discontinued or dismissed, and the Registrar is satisfied that the ground on which the application was made have been established the Registrar may decide to remove the trade mark from the Register in respect of any or all of the goods and/or services to which the application relates. Section 101(2) similarly provides that if, at the end of the proceedings relating to the opposed application the court is satisfied that the grounds on which the application was made have been established the court may order the Registrar to remove the trade mark from the register in respect of all or some of the goods or services to which the application relates. However, the Registrar (or the court) may elect not to effect any removal if she (or the court) is satisfied that it is reasonable to decline to do so: s 101(3), (4).

[11] If the application is determined by the Registrar (or her delegate) an appeal lies to this Court or the Federal Circuit Court from the decision: s 104. It is by that route that the present appeal is before the Court. As a hearing de novo, the Court stands in the shoes of the Registrar to consider afresh whether or not the non-use application should be allowed. Accordingly, although in its submissions Hungry Spirit drew specific attention to s 101(2), it is the language of s 101(1) that is directly applicable.

6 Burley J explained the nature of the “appeal” to the Court in the following way at [13]:

As a hearing de novo, the Court considers the application for removal brought pursuant to s 92 afresh. The use of the word “appeal” in s 56 and in s 104 does not confer appellate jurisdiction upon the Court. The Court approaches the matter for the first time exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth, not in order to decide whether the delegate as an executive decision maker was right or wrong, or otherwise to correct error in the executive decision, but to deal with a subject matter, a controversy, for the first time: New England Biolabs Inc v F Hoffmann-La Roche AG [2004] FCAFC 213; 141 FCR 1; 62 IPR 510 at [44] (Kiefel, Allsop (as their Honours then were) and Crennan JJ); Woolworths Ltd v BP PLC (No 2) [2006] FCAFC 132; 154 FLR 97; 235 ALR 698; 70 IPR 25 at [137] (Heerey, Allsop (as his Honour then was) and Young JJ); Bauer Consumer Media Ltd v Evergreen Television Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 71; 367 ALR 393 (Burley J at [228], Greenwood J agreeing generally at [18]).

7 His Honour continued:

[14] The [TM] Act and Regulations make clear that it is the applicant for removal that remains the moving party, despite the fact the appeal was initiated by Hungry Spirit and despite the reversal of onus effected by s 100. In this regard it is significant that the applicant is obliged to file a notice of intention to defend. If it does not do so, then the opposition may be taken to have succeeded and the removal application will fail. Whilst Hungry Spirit was obliged to file a notice of appeal in this Court, because it did not succeed before the delegate, the substantive moving party in the proceeding remained Fit n Fast, as the applicant for removal.

[15] Further, s 101(1) requires the Registrar to be satisfied that the grounds upon which the non-use application was made have been established. Accordingly, despite the reversal of onus, ultimately it is for the applicant for removal to persuade the Registrar of the appropriateness of any order made.

[16] In these circumstances, it is apparent that despite the different scheme set out in the Act and Regulations, the application for non-use must be initiated and prosecuted by the non-use applicant. The position is analogous to that which I considered in Hungry Spirit 1 [Hungry Spirit Pty Ltd ATF The Hungry Spirit Trust v Fit n Fast Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1277].

[17] In the present case, Fit n Fast and Hungry Spirit have reached a compromise, with the consequence that Fit n Fast no longer wishes to prosecute its application for non-use. Hungry Spirit maintains its opposition to the non-use application. Were that to have been the position before the delegate of the Registrar, she could pursuant to reg 9.15 have moved, in effect, to dismiss the application for non-use. Having been notified of the parties’ position, the Registrar does not oppose the orders sought, which will remove the limitation placed on the designation of goods and services. Furthermore, having regard to my consideration of the reasons given by the delegate, I can see no self-evident reason why, in these circumstances, the orders should not be made.

8 The present case differs from Hungry Spirit in that the parties do not seek an order by consent. Nevertheless, the position is analogous in that the non-use applicant, Pablo Enterprise, has not participated in the proceeding, putting forward no evidence or argument as to non-use or as to exercise of the discretion under s 101(3).

9 FreshFood made two broad submissions:

(1) First, it submitted that the ground under s 92(4)(b) is not established because FreshFood used the PABLO Mark as a trade mark in relation to the goods and services to which the non-use application relates during the relevant period, namely 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019.

(2) Secondly, it submitted that the Court should exercise its discretion under s 101(3) of the TMA not to remove the PABLO Mark from the Register.

USE WITHIN THE RELEVANT PERIOD

10 Section 92(4)(b) of the TMA provides:

Application for removal of trade mark from Register etc.

(4) An application under subsection (1) or (3) (non-use application) may be made on either or both of the following grounds, and on no other grounds:

(a) …

(b) that the trade mark has remained registered for a continuous period of 3 years ending one month before the day on which the non-use application is filed, and, at no time during that period, the person who was then the registered owner:

(i) used the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

11 The use of the trade mark contemplated by this provision is use of a sign as a trade mark in relation to the goods and services to which the non-use application relates: s 17, s 100(3)(a) of the TMA: E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144; [2010] HCA 15 (Gallo (HCA)) at [41]-[43] (French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ). Section 7(4) defines the use of a trade mark in relation to goods as “use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods)”. The application of a trade mark in Australia to, or in relation to, goods that are to be exported from Australia, or any other act done in Australia to export goods which, if done in relation to goods provided in the course of trade in Australia, would constitute a use of the trade mark in Australia, also constitutes relevant use: s 228(1) of the TMA.

12 FreshFood made the following submissions in relation to its use of the trade mark (footnotes omitted):

[25] FreshFood has been unable to locate any evidence of any sales of PABLO-branded coffee products during the Relevant Period. Nevertheless, it is clear from FreshFood’s activities that it used the PABLO mark in the course of trade during the Relevant Period.

[26] In particular, having ceased its sales of PABLO-branded coffee to the Australian market from about 2006 onwards, FreshFood continued to export PABLO-branded coffee overseas, on an ad-hoc basis, including to New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. The dates of these export sales span from between 2006 to present; with at least 500kg of PABLO coffee exported mere months after the end of the Relevant Period. The PABLO Mark was used in relation to each of these sales, including on the product jars and/or cans, on the associated packaging material (e.g. on the boxes used for transport) and as the product name on relevant invoices.

[27] Although FreshFood did not make any sales of the PABLO-branded coffee for export during the Relevant Period, it continued to produce, conduct taste tests of and advertise PABLO-branded coffee during the Relevant Period. FreshFood remained “open for business” in relation to PABLO-branded coffee, being ready, willing and able to fill any orders for export that it may have received, throughout the whole of the Relevant Period.

[28] In particular, throughout the Relevant Period, FreshFood:

a. continued to manufacture and test PABLO coffee at its Australian manufacturing premises. For example, within the Relevant Period

i. batches of PABLO coffee were produced on at least 22 November 2018 and 8 March 2019; and

ii. FreshFood performed taste tests in relation to its PABLO coffee product on at least 17 May 2017, 1 August 2018, 17 August 2018, 20 August 2018 and 18 October 2018. These taste tests (often referred to as “triangle” taste tests) generally involved asking between 14 to 17 panellists to taste test different versions of the PABLO coffee formulation, in order to determine any detectible differences to the finished product;

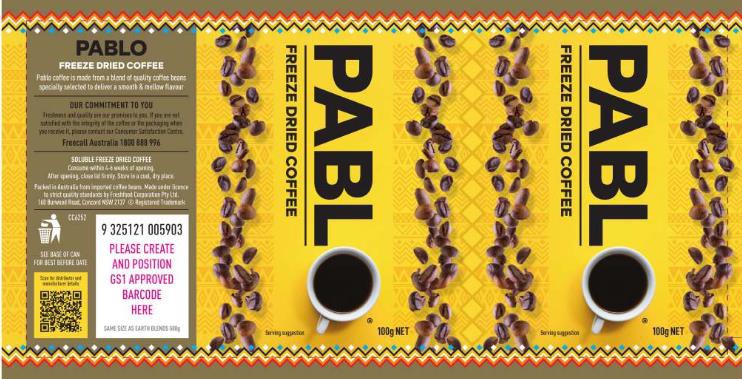

b. advertised the PABLO brand to the public by way of a prominent sign at the front of its manufacturing premises (pictured below). This sign has been on display for many years, and was clearly visible throughout the entire Relevant Period.

[29] The posting of the PABLO Mark in an advertising sign at the FreshFood manufacturing premises had the purpose and effect of promoting FreshFood’s PABLO coffee product, thereby distinguishing FreshFood’s coffee products from the products of others. This was an “ordinary and genuine” use of the PABLO Mark for a commercial purpose, occurring throughout the whole of the Relevant Period.

[30] Further, this advertisement is clearly connected with an offer to trade in, or an intention to offer or supply, the PABLO coffee products in the sense described by Deane J in Moorgate, which is demonstrated by FreshFood’s maintenance of the operational capacity to fill any such orders. The ability and preparedness of FreshFood to fill any order which may have been received is further demonstrated by a sale of the PABLO-branded coffee product occurring only a few months after the Relevant Period, in which a purchase order was received on 23 July 2019, and delivery was able to be effected seven days later, on 30 July 2019.

[31] The facts of this case are distinguishable to cases in which “preliminary activities”, such as the forwarding of samples and brochures in order to ascertain whether a market for particular goods exists, have been held to be insufficient to establish a readiness and willingness to fulfil actual orders. In this case, FreshFood had an “objectively ascertainable commitment” to trade in PABLO-branded coffee throughout the Relevant Period.

[32] In the circumstances, FreshFood submits that the Court ought to find that it had used the PABLO Mark during the Relevant Period and allow the appeal.

13 The submission that “FreshFood continued to export PABLO-branded coffee overseas, on an ad-hoc basis, including to New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands” at dates which “span from between 2006 to present; with at least 500kg of PABLO coffee exported mere months after the end of the Relevant Period” was based on the evidence of Mr John Michael Elliot (the Chief Executive Officer of FreshFood Management Services Pty Ltd) who stated it was his understanding that FreshFood continued to export PABLO coffee from Australia, including during the period 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019, and that the PABLO Mark “would have been used in relation to each of these sales”.

14 Mr Elliot referred to an internal memo dated 19 February 2009 referring to sales in 2008 and 2009. This memo included:

An issue has arisen that requires an urgent response …

SITUATION

- The Pablo brand has lost all distribution is [sic] Australia & New Zealand, and now only the 100g powder coffee packed in plastic jars is produced for export to the Pacific Islands

- Sales of the product are low. Packed in cartons of 12 jars, we sold 1,029 ctns LY (1235kg p.a.), and 633ctns YTD (with a further 600 on order)

- …

PROBLEM

- The order quantity for the proprietary jar is 50, 490 which equates to 3.6 years requirements

- The proprietary jar does not run well on the filling line, with label application being the difficulty. One in three jars have to be reworked due to the size of the base, and resulting distance from applicator.

SOLUTION

- The manufacturing team have suggested a practical solution. They would prefer to use the Black & Gold PETE jar. This will result in common packaging being used, and thus reduce materials SOH, COGS, and cash flow burden.

- Cost of the Pablo jar is $318.80 [footnote omitted] per 1,000, versus $318.08 for the Black & Gold jar

- Both jars have minimum order quantity of 50, 490 units. As mentioned this equates to 3.6 years usage for Pablo, and about ½ a years Black and Gold production.

- …

CONCERNS

- The Operations team cannot justify the inefficient production runs using the existing jar, and the brand could become inactive.

- There is a current order for the Pacific Islands, and a decision is needed by tomorrow (if possible).

I suggest we make the change for production efficiency and the cash flow benefits, and will await you [sic] approval and advice on this matter.

15 There was no documentary evidence of any sale in the period 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019.

16 I would not infer from the evidence before the court that there were sales of coffee overseas, in respect of which the PABLO Mark was used, during the period 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019. It is likely that, if there were any such sales, some documentary evidence would have existed. The basis of Mr Elliot’s understanding that there were such sales, apart from the fact of his employment with FreshFood, was not explained.

17 In any event, FreshFood’s written submissions accepted that there were no sales of PABLO-branded coffee for export during the period 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019.

18 The evidence in support of the submission that FreshFood continued to conduct taste tests of, and advertise, PABLO-branded coffee and that it remained “open for business” was also supplied by Mr Elliot.

19 In relation to the period 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019, Mr Elliot referred to production reports dated 22 November 2018 and 8 March 2019. The first “Daily Production Reports” refers to “PABLO (RS352)” and the second does not evidently concern PABLO coffee at all. The delegate in her reasons had said that “[i]nternal use of the name PABLO prior to a launch could conceal commercially sensitive information such as a new product name from manufacturing workers and ancillary staff”. Despite the delegate’s observation and the substantial evidence adduced on the appeal, there was no direct or persuasive evidence about why apparently substantial quantities of PABLO coffee were being produced in 2018 and 2019 despite the fact that there had been no sales for about 10 years and there were no orders for the product at the time of the asserted production. There was no persuasive evidence of any intention to recommence selling or marketing the product at the time of these production reports. It was not until October 2020 that FreshFood engaged a designer to undertake a “brand refresh” in respect of the PABLO design and packaging.

20 The various taste tests refer to “RS 362 Pablo” and are dated 17 May 2017, 1 August 2018, 17 August 2018, 20 August 2018 and 18 October 2018. The tests indicate that they were directed to determining which sample was the closest match to FreshFood’s “current Pablo standard” or “current standard for Pablo Instant Coffee (RS362)”. The reports reveal that the point of the exercise was to match more closely to the standard the flavour profile of what was being tested. I would not infer from the test result reports that it was coffee anticipated for sale under the PABLO Mark that was being tested, particularly in circumstances where there had been no sales since 2009 and there was no evidence of any campaign or intention to promote or market the product.

21 The “advertising” to which Mr Elliot referred was signs outside FreshFood’s manufacturing premises. The image of one sign was in evidence and is depicted above. These signs had been in place since Mr Elliot commenced employment with FreshFood in 2009. The last sales of PABLO branded coffee before the sale made at the time of FreshFood filing its notice of opposition on 23 July 2019 occurred in 2009. This is not the sort of advertising which, of itself, establishes relevant use of the PABLO Mark during the relevant period.

22 I do not accept, as was submitted, that “FreshFood had an ‘objectively ascertainable commitment’ to trade in PABLO-branded coffee throughout the Relevant Period”. The evidence was, rather, that sales had completely ceased by 2009 and, at least by 28 April 2016, no particular endeavour was being made to trade in PABLO-branded coffee.

23 Notwithstanding the absence of evidence adduced by Pablo Enterprise, I am satisfied that FreshFood did not relevantly use the PABLO mark in the course of trade during the period 28 April 2016 to 28 April 2019.

Discretion to retain the mark on the Register

24 Section 101(3) of the TMA provides:

If satisfied that it is reasonable to do so, the Registrar or the court may decide that the trade mark should not be removed from the Register even if the grounds on which the application was made have been established.

25 In PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd (2021) 391 ALR 608; [2021] FCAFC 128 at [153], the Full Court (Jagot, Nicholas and Burley JJ) made the following observations about the discretion:

(1) It is broad and is unfettered in the sense that there are no express limits on it. It is to be understood as limited only by the subject-matter, scope and purpose of the legislation and, in particular, by the subject-matter scope and purpose of Part 9 of the Trade Marks Act: Austin Nichols & Co Inc v Lodestar Anstalt [2012] FCAFC 8; (2012) 202 FCR 490 at [35] (Jacobson, Yates and Katzmann JJ).

(2) The scope and purpose of the Trade Marks Act strikes a balance between various disparate interests. On the one hand there is the interest of consumers in recognising a trade mark as a badge of origin of goods or services and in avoiding deception or confusion as to that origin. On the other is the interest of traders, both in protecting their goodwill through the creation of a statutory species of property protected by the action against infringement, and in turning the property to valuable account by licensing or assignment. This balance was articulated by the High Court in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [42] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ) and JT International at [30] (French CJ) and [68] (Gummow J); see also Austin Nichols at [36]-[37].

(3) The particular purpose of Part 9, within which s 101 falls, is to provide for the removal of unused trade marks from the Register. It is designed to protect the integrity of the Register and in that way the interests of consumers. At the same time, it seeks to accommodate, where reasonable to do so, the interests of registered trade mark owners: Austin Nichols at [38]. Accordingly, the Court must be positively satisfied that it is reasonable that the trade mark should not be removed. The onus in this respect lies on the trade mark owner to persuade the Court that it is reasonable to exercise the discretion in favour of the owner: Austin Nichols at [44]. This [is] a reflection of the importance of the public interest in maintaining the integrity of the Register (Austin Nicholls at [38]) and so ensuring that trade marks that fail to comply with the conditions that underpin the entitlement to the statutory monopoly are removed from the Register.

(4) The discretion in s 101(3) is expressed in the present tense. It requires consideration of whether, at the time that the Court is called upon to make its decision, it is reasonable not to remove the mark: Austin Nichols at [41].

(5) The range of factors considered in the exercise of the discretion has included whether or not:

(a) there has been abandonment of the mark;

(b) the registered proprietor of the mark still has a residual reputation in the mark;

(c) there have been sales by the registered owner of the mark of the goods for which removal was sought since the relevant period ended;

(d) the applicant for removal had entered the market in knowledge of the registered mark;

(e) the registered proprietors were aware of the applicant’s sales under the mark;

see Hermes Trade Mark [1982] RPC 425 (Falconer J) as followed in E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Limited [2008] FCA 934; (2008) 77 IPR 69 (Flick J[)] at [202]-[203] …

26 The burden is on the removal opponent to show that removal is not reasonable at the time the decision is required to be made: Ritz Hotel Ltd v Charles of the Ritz Ltd (1988) 15 NSWLR 158 at 221 (McLelland J); Austin Nichols & Company Inc v Lodestar Anstalt (No 1) (2012) 202 FCR 490; [2012] FCAFC 8 at [44].

27 FreshFood submitted that the public interest would be advanced, or at least not adversely affected, by the Court exercising its discretion in favour of retaining the PABLO Mark on the register.

28 FreshFood submitted, first, that FreshFood had not abandoned its intention to use the PABLO Mark. I accept this submission. In Rael Marcus v Sabra International Pty Ltd (1995) 30 IPR 261; [1995] FCA 35 Burchett J noted at 266:

… It is not the law that all rights with respect to a trade mark vanish at once upon a mere discontinuance of its use. The connection in the course of trade denoted by it will not immediately be forgotten. That connection may be valuable, and it remains open to the proprietor to resume the use of the mark. Unless he has actually abandoned the mark, its use by another may amount to an appropriation of the benefit of the good name acquired by the mark over an earlier period of years.

29 I would not infer that FreshFood abandoned the PABLO Mark simply on the basis of non-use in the relevant period. I have also taken into account on this issue the subsequent sales referred to next and the retention of the PABLO Mark on advertising signs referred to earlier.

30 Secondly, FreshFood relied on sales of goods since the relevant period ended. It was submitted that the sales were made in good faith – see: Trident Seafoods Corporation v Trident Foods Pty Limited [2018] FCA 1490; (2018) 137 IPR 65 at [110] (Gleeson J) (not relevantly disturbed on appeal: Trident Seafoods Corporation v Trident Foods Pty Ltd (2019) 369 ALR 367; [2019] FCAFC 100); PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd (2021) 391 ALR 608; [2021] FCAFC 128 at [153(5)(d)] (Jagot, Nicholas and Burley JJ); Sensis Pty Ltd v Senses Direct Mail and Fulfillment Pty Ltd (2019) 141 IPR 463; [2019] FCA 719 at [137] (Davies J).

31 In this context, “good faith” use of a trade mark is use for a genuine commercial purpose. In Gallo (HCA) at [62], French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ stated (citations omitted):

In Electrolux Ltd v Electrix Ltd [(1953) 71 RPC 23] a question arose of bona fide use within the meaning of s 26 of the Trade Marks Act 1938 (UK). It was held that bona fide use must be ordinary and genuine use judged by commercial standards. In Imperial Group Ltd v Philip Morris & Co Ltd [[1982] FSR 72], it was held that use of a trade mark for a purpose other than deriving profit and establishing goodwill is not use as required by the legislation. It has also been held that contriving use for the purpose of defeating a trade rival’s plans will lack the necessary quality of genuineness. However, a use does not cease to be genuine even if it only occurs after an appreciation that a registration was vulnerable to an attack on the grounds of non- use. In deciding that a use is not genuine, a court may be influenced by the quantum of sales. In Re Concord Trade Mark [[1987] FSR 209], Falconer J relied on Lawton LJ’s summary of the findings in the Electrolux case in Imperial Group:

“According to the judgments given in this court in that case [Electrolux] a bona fide use should be ‘ordinary and genuine’ (per Lord Evershed MR at 36), ‘perfectly genuine’, ‘substantial in amount’, ‘a real commercial use on a substantial scale’ (per Jenkins LJ at 41) and not ‘some fictitious or colourable use but a real or genuine use’ (per Morris LJ at 42).”

32 Mr Elliot referred to the export on 23 July 2019 by FreshFood of 500kg of PABLO coffee to Central Dairy Limited (via Edart Limited) in Papua New Guinea. This sale was reflected in an invoice dated 23 July 2019. This sale was made on the day FreshFood filed its notice of opposition. Mr Elliot also referred to exports on about 9 February 2021 and 15 June 2021 of 25kg and 100kg respectively of PABLO coffee to Edart Limited in New Zealand.

33 Further, on about 24 March 2021, FreshFood procured an ongoing supply agreement with Foodbank NSW for PABLO-branded coffee to be provided for an initial period of 2 years, with an estimated 6,000 cartons (72,000 products) to be sold in the first year. In early July 2021, FreshFood made a number of additional Australian sales to Triton Food Brokers, Tribe of Judah and Golden Circle Factory Outlet.

34 The evidence also indicates that, in about October 2020, FreshFood engaged a designer to undertake a “refresh” of the logo design and packaging for its PABLO coffee products. Four design options were created by March 2021. The final artwork was approved in April 2021, the final design being:

35 In accordance with a strategy of targeting value stores and “clearance houses”, FreshFood has prepared a trade presenter / flyer to be used in presenting the PABLO brand. Instructions for this to be prepared were given in about May 2021.

36 Production of PABLO-branded coffee products, using the refreshed artwork, continues at FreshFood’s manufacturing facility located in New South Wales. It commenced in June 2021. FreshFood put a video into evidence depicting production of PABLO coffee. The following is a screenshot from that video:

37 I accept that there have been genuine commercial sales made by FreshFood in good faith since the application for non-use was made and that FreshFood has an intention to continue to use the PABLO Mark.

38 Thirdly, FreshFood relies on a residual reputation in respect of coffee. The PABLO Mark was initially registered on 25 October 1961 in the name of Bushell’s Pty Ltd trading as Sierra Coffee Company. It was used extensively throughout the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. It continued to be used thereafter. FreshFood made extensive reference in its submissions to use of the word, including in newspaper articles. These references were not always positive, but I accept that the reputation and brand equity in the PABLO Mark remains an important and valuable asset to FreshFood. I reach this conclusion notwithstanding I am not satisfied that there was relevant use of the PABLO Mark in the period 2016 to 2019.

39 Given that Pablo Enterprise has not appeared or participated in these proceedings, it has not adduced any evidence in relation to its interests or otherwise in relation to exercise of the discretion under s 101(3).

40 In my view, this is an appropriate case in which to exercise the discretion under s 101(3) not to remove the PABLO Mark from the Register.

41 For these reasons, the appeal is allowed, the decision of the delegate given on 17 December 2020 is set aside, the first respondent is ordered to pay the costs of the appeal and the opposition proceedings before the Registrar of Trade Marks.

I certify that the preceding forty-one (41) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Thawley. |