FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Halal Certification Authority Pty Ltd v Flujo Sanguineo Holdings Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1399

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The second further amended originating application dated 3 July 2020 be dismissed.

2. The amended cross-claim dated 6 August 2020 be partially allowed.

3. The register of trade marks be rectified by cancelling the registration of Trade Mark Number 1005647.

4. Order 3 be stayed for a period of 28 days, or if an appeal proceeding is filed from order 3 within that time, until the hearing and determination of that appeal proceeding.

5. The applicant pay the costs of the respondents of:

(a) the originating application; and

(b) the cross-claim.

6. The parties each be granted leave to make an application for a different costs order in such form as is agreed or directed within 14 days of delivery of this judgment, or such further time as may be allowed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMWICH J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding is concerned with the use of logos on food products to signify that they have been certified to be “halal”. The effect of this is to indicate that food has been prepared, processed and managed in conformity with Islamic rites and requirements. The applicant, Halal Certification Authority Pty Ltd (HCA), is a private company that provides halal certification to businesses and individuals who are engaged in the provision of halal goods, as well as related services.

2 HCA is owned by Mr Mohamed El-Mouelhy. Mr El-Mouelhy was a director of HCA from 23 February 1995 to 1 July 2017. His daughter, Ms Nadia El-Mouelhy, was also a director of the company from 23 February 1995 until 7 February 2003. Both were involved in the running of the business at various times. From 1 July 2017, Ms El-Mouelhy became sole director and company secretary.

3 In February 1995, HCA was registered as a company using the name Halal Certification Services Pty Ltd. In June 2004 HCA was one of approximately a dozen companies that were involved in halal certification in Australia. By the time of the trial in October 2020, that number had risen to some 25.

4 Since 8 June 2004, HCA has had the following logo registered as a device trade mark for services (but not as a certification trade mark in respect of those services):

(Trade Mark)

(Trade Mark)

5 By the time that the trial took place, HCA maintained proceedings against four respondents in relation to printing on packaging for food products. These companies are part of a group known as Flujo Group:

(1) Flujo Sanguineo Holdings Pty Ltd, the parent company, and the following three subsidiaries;

(2) Stevia Sweetener Co Pty Ltd (formerly Natvia Pty Ltd);

(3) Raw Earth Sweetener Co Pty Ltd; and

(4) Natvia IP Pty Ltd.

While these four companies do not comprise all of the members of Flujo Group, it is convenient to refer to them by that collective name in these reasons.

6 In about 2009, Flujo Group was in its infancy, according to the unchallenged evidence of Mr Mark Hanna who was, at that time, the managing director of all the companies in Flujo Group. Flujo Group was developing skills in relation to product development and the delivery of products. The natural sweeteners on the market at that time had a bitter aftertaste. The artificial sweetener product sold under the brand “Equal” had market dominance as a sugar alternative. Flujo Group considered that there was a market for a stevia-based natural sweetener, provided the bitter aftertaste could be minimised, and that it looked like sugar.

7 The development and delivery of packaging for products was handled in-house by companies within Flujo Group. Two of these companies were Natvia and Raw Earth. Raw Earth, the third respondent and second-cross claimant, was responsible for similar packaging-related aspects of sale of other natural sweeteners developed by Flujo Group.

8 The products referred to in the pleadings as the Natvia Products are, in substance:

A. Natvia 40 x 2g sachets 80g pack sweetener;

B. Natvia 80 x 2g sachets 160g pack sweetener

C. Natvia 300g canister sweetener; and

D. Natvia 600g pouch sweetener.

9 The products referred to in the pleadings as the Raw Earth Products are, in substance:

A. Raw Earth 200g canister sweetener; and

B. Raw Earth 40 x 2g sachet 80g pack sweetener.

10 Printed on the packaging for the Natvia Products and for the Raw Earth Products was the following logo:

(Packaging Logo)

(Packaging Logo)

11 There is no dispute that the Trade Mark and the Packaging Logo are substantially the same. The respondents’ defence admits that the Packaging Logo is substantially identical with the Trade Mark within the meaning of s 10 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth).

12 It is also not in dispute that the identical Arabic characters at the centre of both logos can be transliterated as “halal”, which translated into English means “allowed or permitted in accordance with Islamic rites”. That is, the Arabic characters in context are apt to convey that the products are halal. There is a live question as to whether a consumer would be likely to take the two additional steps of understanding that the goods are not just being represented as being halal, but also being represented as certified to be halal, and being represented as being certified by HCA. Nowhere on the packaging logo, nor on the Trade Mark, does it expressly state that goods are certified or otherwise verified as being halal, let alone by HCA. It is left to a reader to infer both:

(a) that someone other than the manufacturer is certifying or otherwise verifying that the products are halal, from the presence of the annulus, or from the impression conveyed by the Trade Mark or Packaging Logo as a whole, without specifically identifying who is providing that verification;

(b) the source of that certification or other verification from the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”, which relies upon those words actually being read, or being likely to be read, and the additional interpretive step then actually being taken or being likely to be taken.

Both steps are affected by the manner of the presentation, including in particular the size and legibility of the Trade Mark or Packaging Logo that is used, including the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”.

13 Numerous examples of different types of packaging for the Natvia Products and Raw Earth Products are in evidence. Corresponding images are reproduced in the pleadings and submissions. The display size of the Packaging Logo on samples of the larger packaging in evidence, giving the biggest, best and clearest presentation of the logo most favourable to the case brought by HCA, is approximately as follows (and correspondingly smaller for smaller packaging in evidence):

(Packaging Logo as able to be seen on the larger packaging in evidence)

(Packaging Logo as able to be seen on the larger packaging in evidence)

14 For all of the packaging in evidence, a logo of the same size tending to suggest kosher certification appeared adjacent to the Packaging Logo. It consisted of a stylised map of Australia containing the letter “K” in the centre, encircled by the words “KOSHER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD WWW.KOSHER.ORG.AU”:

(Kosher Logo as able to be seen on the larger packaging in evidence)

(Kosher Logo as able to be seen on the larger packaging in evidence)

15 Images and hard copies of the Natvia and Raw Earth Products packaging were annexed to the affidavit of Mr O’Connor, the solicitor for HCA, sworn 9 September 2019 (Mr O’Connor’s affidavit). There is no need to reproduce images of all of the products, as it is not in dispute that they bore the Packaging Logo. However, it is useful to provide a representative sample of images of the Natvia Products. Endeavours have been made to ensure that the images reproduced below present the relevant packaging at as near as possible to the size that they appear in real life.

16 The following is the image of one of four samples of packaging reproduced in Annexure B to the second further amended statement of claim, which corresponds in size and appearance to the original Natvia packaging in evidence, being exhibit MOC-3 to Mr O’Connor’s affidavit:

Natvia 40 x 2 g sachets 80 g pack sweetener (approximately actual size)

The Kosher Logo and the Packaging Logo can be seen on the bottom left of the side panel, next to the stylised map of Australia signifying that the goods are made in Australia. A part of the packaging on the other side of the box, and therefore not in view in this image, is the text “Natvia is a registered trademark of Flujo Sanguineo Holdings Pty Ltd”. The same notice appears on the base of the box.

17 As a representative sample of the images of the Raw Earth Products, the following is the image of one of two samples of packaging reproduced in Annexure C to the second further amended statement of claim, which corresponds to the original packaging in evidence, being exhibit MOC-7 to Mr O’Connor’s affidavit:

Raw Earth Stevia and Monk Fruit All Natural Sweetener 40 x 2 g sachets 80g pack (approximately actual size)

The Packaging Logo and the Kosher Logo can be seen in the bottom left hand corner of the image above. On a part of the packaging on the other side of the box, and therefore not in view in this image, is the text “RAW EARTH IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF FLUJO SANGUINEO HOLDINGS PTY LTD”.

18 There is also in evidence packaging for Raw Earth canister versions of the same product, which are smaller than the above. They bear the same Raw Earth trade mark but do not have any trade mark notice for that mark. However, the Packaging Logo is also smaller on the canisters. It is difficult to make out the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia” on the canisters without looking at the packaging closely. It would be difficult for a person to make out the words clearly without holding the canister up to their face for closer inspection. As I will discuss further below, the smaller the size of the Packaging Logo and words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”, the more likely it is that consumers will read this as signifying that a product is halal, but not additionally infer that it is also certified as halal, or by whom.

19 As mentioned above at [11], the Packaging Logo is accepted to be substantially identical with (if not necessarily also deceptively similar to) the Trade Mark as registered. HCA’s case is that by using the logo without first obtaining its permission, each of the four respondents has:

(a) infringed its registered trade mark in breach of ss 120(1) and/or 120(2) of the Trade Marks Act; and/or

(b) contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(a), (b), (g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law in schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL); and/or

(c) engaged in the tort of passing off,

causing HCA to suffer loss and damage.

20 HCA seeks declaratory, injunctive, and pecuniary relief, with the quantum to be assessed separately in the event of success in establishing liability.

21 The respondents:

(a) deny liability principally upon the basis that the use of the Packaging Logo did not constitute “use” of the Trade Mark for the purposes of either ss 120(1) or 120(2)(c) or 120(2)(d) of the Trade Marks Act;

(b) rely in the alternative upon the good faith exception in s 122(1)(b)(i) by reason of use of a sign to indicate the halal quality of the goods, falling short of certification as halal;

(c) deny passing off or any breach of the ACL;

(d) further or alternatively, by way of a cross-claim, seek the rectification of the register by the cancellation of the Trade Mark.

22 Specifically, and independently of the legal arguments advanced in the overall denial of liability, the respondents also rely upon the following in relation to the sale of the Natvia Products and the Raw Earth Products:

(a) Flujo Sanguineo, although the parent company of the other three respondents, was not involved in the business of the sale of those products;

(b) Stevia (formerly Natvia) sold the Natvia Products and Raw Earth Products under the NATVIA trade mark from 2010 until July 2019;

(c) Raw Earth sold the Raw Earth Products under the RAW EARTH trade mark from 1 August 2018 onwards; and

(d) Natvia IP sold the Natvia Products and Raw Earth Products under the NATVIA trade mark from 1 August 2019 onwards.

The key facts as agreed or established by the evidence

23 On 8 June 2004, HCA:

(a) changed its name from Halal Certification Services Pty Ltd to Halal Certification Authority Pty Ltd;

(b) filed an application for registration of the Trade Mark; and

(c) applied for registration of the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”.

24 The application for registration of the Trade Mark was subsequently granted with effect from the filing date, by reference to classes 42 and 45 of the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) sch 1 pt 2 – Classes of services, which refer to:

(a) class 42: “Scientific and technical services; issuing halal certification to businesses and individuals for goods and services if religious and technical requirements are met”; and

(b) class 45: “Personal and social services rendered by others to meet the needs of individuals”.

25 The application for registration of the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia” was refused. The trade mark examiner’s report in relation to that application included the following:

(a) in the section titled “My reasons for not accepting your application”:

Your trade mark consists of the words HALAL CERTIFICATION AUTHORITY AUSTRALIA.

This indicates that you provide HALAL CERTIFICATION services within AUSTRALIA.

Other traders should be able to use HALAL CERTIFICATION AUTHORITY AUSTRALIA in connection with goods or services similar to yours.

(b) in the section titled “The action you can consider” (emphasis in original):

As the trade mark is completely descriptive you will need to provide overwhelming evidence for this trade mark to be considered for acceptance. The evidence will need to show that the ordinary meaning of the word/s has been overshadowed in the marketplace by its significance as your trade mark.

26 The application for registration of the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia” was apparently not taken any further, and automatically lapsed on 12 January 2006, being 15 months from the date of the examiner’s adverse report.

27 HCA’s clients from time to time included companies that manufacture products that are distributed and sold by other companies. That is the situation in this case. In her affidavit of 13 September 2019, Ms El-Mouelhy described such companies as contract manufacturers. She referred to Techniques Incorporated Pty Ltd and Hellay Australia Pty Ltd, who manufactured the products in issue in this proceeding, as examples of contract manufacturers.

28 While Ms El-Mouelhy did not specifically refer to either Techniques or Hellay as being toll manufacturers, the affidavit evidence of Mr Hanna further referred to Techniques and Hellay as being contract manufacturers who produced Natvia products on a toll manufacturing basis. For the purposes of this matter, nothing much turns on the distinction, albeit somewhat fluid, that can be drawn between contract manufacturers and toll manufacturers. Mr Hanna’s evidence sets out that toll manufacturers do not ordinarily supply raw materials or even packaging when manufacturing products for a customer. As a matter of logic, therefore, under such arrangements toll manufacturers have less input into the appearance of the final product because, on the evidence, the packaging is provided by the customer rather than being provided by the manufacturer. That was the situation in this case. Importantly, toll or contract manufacturers are not retailers, and do not produce public-facing products of their own.

29 Techniques produced the Natvia Products on a toll manufacturing basis, with Stevia (formerly Natvia) sourcing all ingredients and packaging. Techniques blended the ingredients in accordance with the formulation and packaged the product into finished goods at their site. The finished product was delivered to Flujo Group’s warehouse ready for distribution. The first retail sales of the Natvia Products were in October 2009.

30 In a closing note in the nature of a submission on the evidence, HCA presented an outline of the history of the application of the Packaging Logo to Natvia Products and Raw Earth Products revealed by the evidence and defence pleadings, as follows:

(a) from 2009 until July 2015 and from October 2018 until the present, Techniques has manufactured Natvia Products;

(b) from around May 2015 until at least November 2020, Hellay manufactured Natvia Products;

(c) from around March 2017 until at least November 2020, Hellay manufactured Raw Earth products;

(d) since at least 2010, Stevia has caused Natvia Products in Australia bearing the Packaging Logo to be advertised, promoted, exhibited, offered for sale, distributed and sold in Australia;

(e) since at least 1 August 2018, Raw Earth has caused Raw Earth Products in Australia bearing the Packaging Logo to be advertised, promoted, exhibited, offered for sale, distributed and sold in Australia;

(f) since at least August 2019, Natvia IP has caused Natvia Products in Australia bearing the Packaging Logo to be advertised, promoted, exhibited, offered for sale, distributed and sold in Australia;

(g) the name of Flujo Sanguineo has been printed on the packaging of the Natvia Products (as the trade mark holder), and at times was the only legal entity named on the packaging;

(h) the respondents undertook the design and prepared the content of product packaging save in relation to the technical information included within the “Nutrition Information” panel;

(i) the respondents undertook the printing and preparation of the product packaging which was then provided to the contract manufacturers.

31 While the above chronology is helpful, there are other relevant historical details as to the manufacturing process and how Flujo Group came to use the Packaging Logo. These are especially relevant to the good faith exception relied upon by the respondents in s 122(1)(b)(i) of the Trade Marks Act, but also to the question of rectification of the register by cancellation of the Trade Mark as raised by the cross-claim. The additional relevant history follows.

32 On 3 September 2003, HCA entered into the first of a number of agreements with Techniques whereby, under its former name Halal Certification Services Pty Ltd, it relevantly agreed to provide halal certification and to allow for the use of its logo to evidence that certification. On that date, being prior to the application for registration of the Trade Mark on 8 June 2004, HCA sent a letter to Techniques enclosing a copy of the completed agreement and a certificate for qualifying products. Thus the agreement for certification did not depend upon the logo having registered trade mark status.

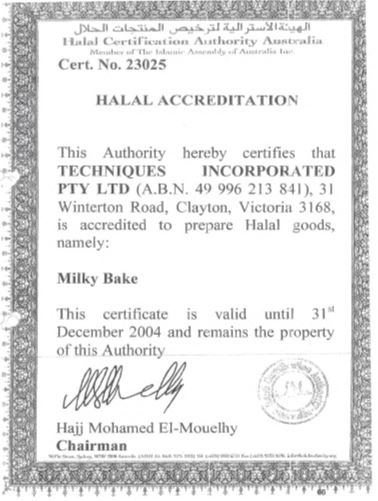

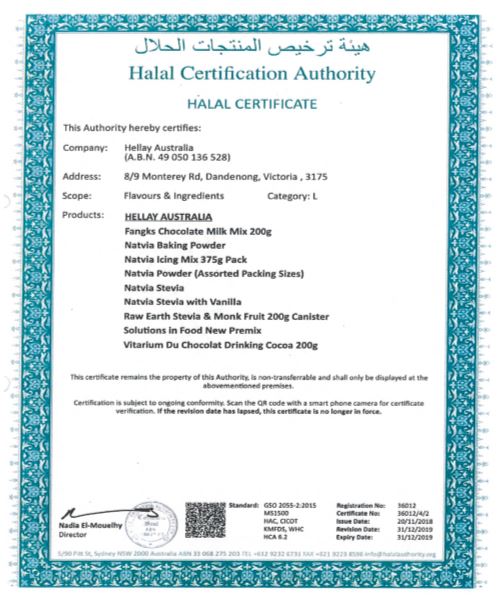

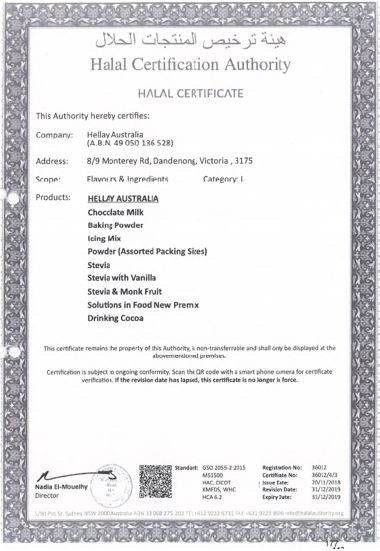

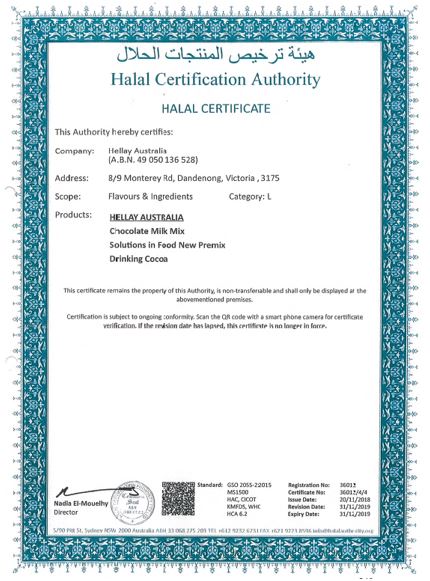

33 The 3 September 2003 letter stated that a logo was available by email for inclusion on Techniques’ “labels, documents, etc. on application”. Although the company name was still Halal Certification Services Pty Ltd, it used a letterhead displaying the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”. The certificate was as follows (size reduced from an about A4 size original, and bearing an unclear but still just readable version of what later became the Trade Mark):

34 On this certificate, and on all subsequent certificates, it is difficult to regard the existence of the Trade Mark (or trade mark status for that logo) as having anything much to do with those agreements regarding certification, let alone any degree of importance to the issues in this proceeding. However, after registration it is at least a presentation of the Trade Mark to the person receiving the certificate.

35 By the terms of the agreement with HCA dated 3 September 2003, Techniques relevantly agreed only to market and sell as halal goods that were in fact halal, and paid fees in accordance with the agreement. Techniques agreed to ensure that it prepared food with equipment that had been cleansed, keeping halal food separate from non-halal food, and obtaining ingredients for the preparation of halal food only from suppliers approved by HCA. The duration of the agreement was 16 months (that is, from 1 September 2003 to 31 December 2004), with Techniques paying a licence fee of $1,760, plus an inspection fee to be paid on invoice.

36 The evidence of Ms El-Mouelhy, after “reviewing the records of HCA and having spoken with [her] father” was that these agreements did not provide “any consent or other approval to use the HCA Logo on packaging for any goods of any kind” and that Techniques had never sought such consent. Further, Ms El-Mouelhy stated that it was “not uncommon” for a contract/toll manufacturer to be approved for halal certification on the basis that they were permitted to display the certification certificate on their premises, and tell their clients that they were certified halal, but not to put the logo on finished goods.

37 Further agreements were entered into between HCA and Techniques over the 17 years between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2016 in similar terms to the 2003 agreement. HCA did not produce a copy of the actual terms of the agreement between HCA and Techniques between 2005-2016. They did produce another agreement with Techniques from 2003-2004, relating to another product, as well as their standard terms. Ms El-Mouelhy stated that each agreement HCA made was in the standard form, with a schedule completed for each client as appropriate to their circumstances.

38 In early to mid-2010, Mr Hanna and a Mr Samuel Tew, who had also been involved in establishing companies in Flujo Group, decided it would be beneficial to have halal and kosher certification for the Natvia Products. This was because it would give some customers comfort that the products were made in a controlled environment, and would provide members of the relevant cultural and religious groups with a means to make food decisions. They considered it was important that customers know who certified the product halal or kosher, and therefore to put the certification symbol with the certifying entity on the packaging. Mr Hanna spoke to Mr Matthew Martin at Techniques about wanting kosher and halal certification for Natvia Products. Mr Hanna understood that the costs of doing this would be built into the unit price charged by Techniques for manufacturing and would have little effect on prices as he also understood that the costs to Techniques of certification were marginal. As there was minimal cost involved, they considered certification was worthwhile, even though they did not see it as increasing marketability domestically.

39 In order to obtain halal certification, Techniques required evidence from Flujo Group that the ingredients had been certified, which I infer must have been passed on to HCA by Techniques. While Mr Hanna was not able to locate the certificates provided at the time of original certification, he was able to produce later certificates. No issue was taken with this having happened. A short time later, also in about mid-2010, Mr Hanna was notified by Techniques that the Natvia Products had been certified halal and kosher. Natvia obtained both the Packaging Logo and the Kosher Logo from Techniques for inclusion on its packaging. Those logos were first included on Natvia Products from about 2011.

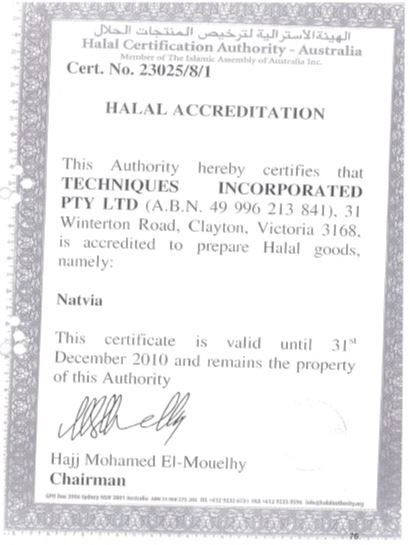

40 On about 10 July 2010, HCA issued a further certificate, in very similar terms to the certificate reproduced above, but referring to “Natvia”:

The above certificate does not at first blush appear to have the Trade Mark affixed, but it seems likely that the faint lines in the bottom right-hand corner of the certificate, adjacent to the conclusion of Mr El-Mouelhy’s typed name, are the Trade Mark.

41 The above certificate was reissued to Techniques in the same terms, but with a clear Trade Mark affixed to each, as follows:

(a) on about 12 January 2010, valid until 31 December 2011

(b) on about 13 December 2011, valid until 31 December 2012;

(c) on 3 April 2014, valid until 31 December 2013, signed by Ms El-Mouelhy as Chief Executive Officer;

(d) on 8 November 2013, valid until 31 December 2014, signed by Ms El-Mouelhy as Chief Executive Officer;

(e) on about 10 December 2014, valid until 31 December 2015, signed by Ms El-Mouelhy as Chief Executive Officer but with the additional words (emphasis in original) “This certificate is for the use and display by Techniques Incorporated Pty Ltd only, is valid until 31st December 2015 and remains the property of this Authority”.

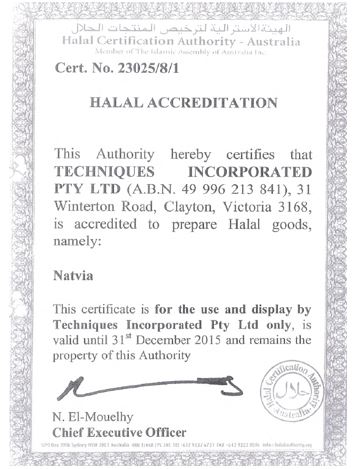

42 The certificate issued to Techniques in 2015 relating to Natvia appeared as follows:

43 As can be observed, over time, the appearance of the certificates issued by HCA changed. The certificates were manually produced until an online system was introduced sometime in about March 2017. From 31 March 2017, HCA required information about products and ingredients to be submitted electronically through an online portal.

44 In about May 2015, there was a dispute between Flujo Group and Techniques which resulted in Techniques ceasing manufacturing of the Natvia Products for over three years until October 2018. As this happened on short notice, Mr Hanna contacted Mr Ashley Hawley, whom he knew at Hellay in Victoria, to produce a run of Natvia Products urgently. That took place upon agreement as to price, in about June 2015. Ms Haley Cornish of Techniques accordingly contacted HCA directly via email to remove Natvia from their list of certified halal products on 22 July 2015, and Ms El-Mouelhy responded on the same day to say the certificate had been terminated.

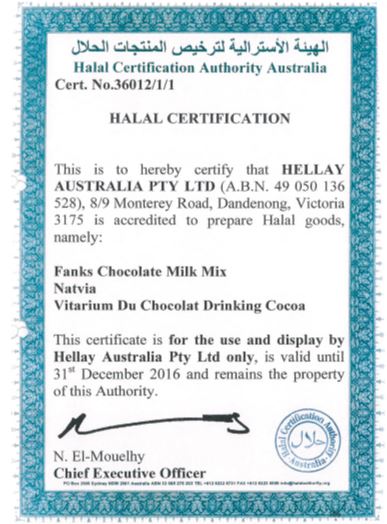

45 In 2016, HCA issued the following certificate to Hellay (although undated, in her affidavit Ms El-Mouelhy states that this certificate was issued on 1 April 2016):

46 By the end of 2017, the form of the certificate had changed, as shown by the following certificate issued to Hellay on 31 December 2017:

47 The above certificate has affixed both a faint copy of HCA’s company seal, and a clear rendering of the Trade Mark. The currency of this certificate using the Trade Mark straddles both the filing of the original notice of cross-claim on 14 December 2018, and the filing of the original statement of cross-claim on 4 April 2019. This is relevant to the ground for rectification by cancellation in s 88(2)(c) sought by the notice of cross-claim in general terms and by the statement of cross-claim in specific terms.

48 The first version of the last-in-time certificate in evidence overtly referring to certain Natvia and Raw Earth products was issued on 20 November 2018. This was shortly before the filing of the original notice of cross-claim on 14 December 2018, and not long before the filing of the original statement of cross-claim on 4 April 2019. It did not appear to have the Trade Mark affixed to it, only an indistinct rendering of the company seal:

49 In her evidence, when asked whether the 20 November 2018 certificate had the Trade Mark on it, Ms El-Mouelhy stated that she hated “to be the bearer of bad news” but the Trade Mark was actually contained within the above certificate, displayed on a water mark in the background of the certificate. She stated that this watermark is only visible on the original certificate, and not any copies, as part of an anti-forgery measure. This watermark is very faintly visible on the certificate displayed at [46] above.

50 According to Ms El-Mouelhy, the references in the above certificate to Natvia and Raw Earth were included in error because she was tired from jetlag, and she reissued the certificate the same day without those brand references. That replacement certificate still provided a revision date of 31 December 2019 and an expiry date of 31 December 2019. Thus those products were in fact certified halal, remembering that HCA certified products, not premises. There is no suggestion that the products or ingredients were not in fact halal, nor that the certificate referred to different ingredients to those used by Hellay. That is, the change was apparently as to branding only and the same products were still manufactured by Hellay. That certificate, being the second version of the last-in-time certificate, is as follows:

51 The final version of the last-in-time certificate was issued in July 2019. An email HCA sent to Hellay on 25 July 2019, annexing that certificate, states “Please find enclosed your updated certificate excluding the Flujo products due to a continuous breach of our agreement”. A new version of the certificate showed that the ingredients previously included on certificates issued to Hellay were removed altogether, clearly supporting the inference that those products had not been excluded before then. The dates of certification remained identical to the first and second versions of the certificate. The final certificate issued is as follows:

52 Mr Hanna stated that it only became clear to Flujo Group what HCA’s position was on the question of permission to use the Packaging Logo in mid-July 2019. This could reasonably be presumed to be either at the time of, or perhaps shortly before, the email dated 25 July 2019 was sent, attaching the above certificate, retrospectively removing the generic products which encompassed the Raw Earth and Natvia Products from the certificate. While it is apparent Hellay communicated the change to Flujo Group, there is no evidence that HCA communicated this change directly to Flujo Group. This is a point of some importance when it comes to the question of continued use of the Packaging Logo, an admitted facsimile of the Trade Mark, in good faith.

53 As set out above, it was Natvia (and then Stevia) that designed and provided the labelling to Techniques, who blended and produced the actual products. In order to facilitate this, Techniques provided Natvia with a certificate of analysis which showed the product ingredients and nutritional information. Natvia retained a graphic design company to develop the packaging. Natvia also obtained regulatory advice from an external food technology consultant, Mr Tony Zipper.

54 There is still further relevant background information to consider. Between 20 and 22 July 2009 – approximately ten years prior to the asserted breach of agreement which led to the removal of certification – there was the following exchange of emails between Mr El-Mouelhy and Ms Cornish of Techniques (salutations and signatures omitted, errors in original):

From: Hayley Cornish [hcornish@techniques.net.au]

Sent: Monday, 20 July 2009 11:55

To: info@halalauthority.org

Subject: Halal Certification

I am enquiring as to the process involved to have formulations certified Halal.

Currently we have 5 formulations which we believe to be Halal suitable.

[What] is the time frame to have formulations certified?

[What] are the costs involved to have formulations certified?

In addition once certified are we able to use the Halal Certification Authority Australia logo on our packaging? Are there any costs involved?

Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions.

From: Halal Authority [mailto:info@halalauthority.org]

Sent: Monday, 20 July 2009 12:09 PM

To: ‘Hayley Cornish’

Subject: RE: Halal Certification

There is no cost involved in adding further products to the certificate. If you send the formulations this afternoon you will get your certificate updated before the close of business.

Attached please find our logo in a variety of files. It should be no less then 10mm in diameter and can be any colour. Approval of the label is required.

From: Hayley Cornish [mailto:hcornish@techniques.net.au]

Sent: Tuesday, 21 July 2009 02:40

To: ‘Halal Authority’

Subject: RE: Halal Certification

I have attached a document with some formulations for you to approve (if applicable).

I am still finalising two more formulations which I will send to you once completed for approval.

I don’t think we will be able to approve the pancake mix.

Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions or require any more information.

From: Halal Authority [info@halalauthority.org]

Sent: Wednesday, 22 July 2009 06:57 AM

To: ‘Hayley Cornish’

Subject: RE: Halal Certification

Please send me more information regarding:

CMC 7HF and Methocel A4M by IMCD

FCMP by Total Foodtec

I+G by Food Traders

WPC 80% by WCB

Also please supply Halal certificate for

Cheese Powder T1 and Cheddar Cheese Plus by Ballantyne

Buttermilk Powder by Murray Goulburn

Saromex Onion by IFF

[Cheese] Buds by IMCD

[unclear] Cheddar Flavour by Michelona

55 The above email exchange makes it clear that the certificate HCA gave to Techniques could have products added to it, and, in context, this applied to products manufactured for other companies.

56 The email exchange also at least implies that the Trade Mark may be added to packaging for such products, subject to the label being approved. Further, Mr El-Mouelhy providing the logo to Techniques in a variety of file formats, as well as instructions for use, effectively handing the tools for using the Packaging Logo over to Techniques (and accordingly, their clients) makes the “required” approval of the label by HCA seem in practice perfunctory at best, so long as the halal approval requirements were met. Further, the evidence indicates that there was nothing much left to be approved in any event. The halal certification was done by reference to the ingredients and a check of the manufacturing premises.

57 Moreover, there is no suggestion in the evidence of any material difference in appearance between the Packaging Logo and the Trade Mark. For a sugar substitute product, not much was involved in certifying the product as halal. There is nothing to suggest that much work on the part of HCA was involved. It seems that what was being provided was knowledge as to the requirements to be halal, and a check on the manufacturing processes. Those requirements would probably be easily met for a product which would be unlikely to involve any meat products (let alone meat that had come from an animal not slaughtered in a halal manner) and most unlikely to involve any alcohol products.

58 More importantly, there was no evidence that Techniques manufactured its own products, or that HCA had any reason to think that it did, having referred to Techniques as a contract manufacturer, if not a toll manufacturer. The unchallenged evidence of Mr El-Mouelhy was that he audited Techniques’ premises each year as part of the halal certification process, at which time he saw packaged goods. The auditors needed to know the manufacturing process in order to certify that the products made there were halal. It seems likely that such an audit would have covered the manufacturing for all the products made there, because the processes for each would either be halal, or not. Therefore, in the case of either a toll or contract manufacturer, any use of a version of the Trade Mark was necessarily used not just by the manufacturer, but by the customer for whom the products were being manufactured. Any other conclusion simply does not make any commercial sense. The alternative is that Techniques and Hellay would have been paying for certification that was of no apparent practical use to them or their customers, which must be rejected.

59 Mr El-Mouelhy initially said in cross-examination that he had been to Techniques’ premises and that they “fill packaging with ingredients”. The next question from counsel after that statement was “They don’t retail the –” at which point Mr El-Mouelhy interrupted counsel and spontaneously answered “No, they don’t retail it”. In the immediately following three questions and answers, he sought to recant, saying that he “recalled that answer” and said he had realised that he did not know whether Techniques was a retailer. I accept and prefer his original answer as being his true position. Further, at another point in his oral evidence, Mr El-Mouelhy even pointed out that he was aware that the Natvia retail packaging was not manufactured by Hellay or Techniques. This may be seen to be somewhat contradictory to his asserted lack of knowledge about whether a toll or contract manufacturer was retailing the products produced. Mr El-Mouelhy went on to say that, regardless, the packaging was not authorised to contain the Packaging Logo, even though the product contained within the packaging was produced by a toll manufacturer which was certified by HCA. While nearly all witnesses from time to time need to correct themselves or realise they have inadvertently said something which is wrong, in this case I do not accept Mr El-Mouelhy’s “recall” of his initial evidence.

60 This conclusion is reinforced by Ms El-Mouelhy’s confusing evidence on a similar line of questioning. This occurred in the context of her correcting counsel for the respondents when he asked her whether one of the products listed on the certificate, Milky Bake, went out into the public for retail sale. In her response she said that she thought he (that is, counsel) would be aware that Techniques was a powder blender. Counsel then asked whether a powder blender was different to a retailer, which she confirmed. In response to the question of whether a powder blender would have any use for the Packaging Logo, she said “not usually”, but not necessarily no, as it was open to the manufacturers to retail the products themselves. She then said that it was a “gross assumption” to expect that because a manufacturer had obtained halal certification, a retailer would want to advertise the logo on its goods, and said it was a “totally untrue statement” that the main reason why a retailer would want halal certification for a product would be to put the Packaging Logo on a product. It was never made clear why that obvious conclusion would not be true. These statements as to the possibility of a toll manufacturer retailing products on their own behalf, when their very existence seems to be predicated on an arrangement where another entity is the retailer of products they make, are divorced from reality and were not supported by any other evidence.

61 I find that on the balance of probabilities, Mr El-Mouelhy and Ms El-Mouelhy, and through them HCA, knew that Techniques was not a retailer, and that HCA correspondingly knew that Hellay and Techniques filled the packaging of customers, and that any application of any version of the Trade Mark would be for the purposes of the packaging of the customers of Techniques. The evidence carries the clear implication that they must have been aware that any approval, express or implied, conveyed by HCA to any such contract manufacturer to use any version of the Trade Mark on packaging as a practical matter was likely to be treated as approval for such use by the contract manufacturer’s customers. This is particularly so in the present circumstances, where Techniques had indicated via email to HCA that they were seeking to incorporate a logo onto packaging, which HCA knew they did not design or produce, logically removing them from the purported category of toll manufacturer customer who only sought the certification to display on their own premises.

62 While there was no express provision permitting any sublicensing by Techniques of the use of the Trade Mark, there is a surreal quality to HCA relying upon the non-existence of such a provision in circumstances where Techniques was a contract manufacturer, so was not obtaining the certification or applying the Trade Mark for its own products. Certification without that taking place was practically useless and would probably have resulted in no revenue for HCA. HCA must have been aware of this, as is clear enough from email traffic in evidence. In context, the certificates and approval to apply the Trade Mark logo was hollow and of no practical use to Techniques unless it applied to use on the packaging of contract manufactured goods. This is reflected in HCA’s conduct in relation to the Natvia products, by which halal certificates in relation to Natvia were issued to Techniques by HCA on numerous occasions over a number of years.

63 Techniques did not seek any further certification or re-certification from HCA in relation to Natvia goods after the termination of the last certificate on 22 July 2015. Nor was any request received to apply the Trade Mark from that time onwards. It follows that if the presence of the Packaging Logo on either the Natvia or Raw Earth Products did constitute use of the Trade Mark, it almost certainly would have been an infringing use for the relatively limited period in which there was no certification in place, which was the only source of any right to use the Packaging Logo as a trade mark. The goods might well have been halal, but they would not have been certified halal. The key live issue is therefore the characterisation of that use.

64 There is still further relevant evidence as to the nature of HCA’s relationship with Flujo Group, Techniques and Hellay. In about 2011, Flujo Group took steps to export some Natvia products. They wanted to use the same packaging. Mr Zipper was asked to check with the halal certifier (that is, HCA) if the same certification could be used, which would also have the benefit of making contact with the certifier whom Flujo Group knew little about.

65 Mr Hanna was subsequently copied into a 5 March 2012 email from Mr Zipper to a Mr Mark Chen at Flujo Group as follows:

I have spoken with Halal Certification Authority Australia in Sydney and they assure me that Natvia can use the current Australian Halal symbol in EU countries, UK and USA without hesitation or extra costs/authority, etc.

However if Natvia was to be sold to a majority Muslim country there may be problems and I suggest that we seek further advice if this scenario eventuates.

This is clear and contemporaneous evidence that HCA knew about its logo being used beyond Techniques since at least 2012. The only evidence from HCA to counter what was conveyed in this email was from Ms El-Mouelhy, who said that this was “inconsistent with HCA’s usual practices”. That evidence was not a denial that someone at HCA had given that assurance, and therefore had that knowledge.

66 Flujo Group eventually found a distributor for the United Arab Emirates in about 2013 and commenced selling Natvia products there with the Australian packaging. The distributor accepted responsibility for labelling requirements, and never raised an issue about the halal certification on the packaging. Mr Hanna therefore did not consider that there were problems nor did he have any cause to contact HCA. After obtaining the certifications, Techniques did not raise any issue regarding certification of the Natvia products and Mr Hanna understood that this meant that the product that they manufactured was certified halal.

67 After the dispute between Techniques and Flujo Group in 2015, Hellay continued to manufacture Natvia products as a toll manufacturer, using the same formula, manufacturing process and packaging as Techniques. It became clear later that halal certification was not obtained by Hellay. The evidence of Mr Hanna, and the case for the respondents, is that this was an oversight, which was sought to be rectified once discovered. The case for HCA was that this was not merely an oversight, but rather a reflection of the respondents’ callous attitude to the use of the Packaging Logo, which reflected no concern that this had taken place. This characterisation is relied upon to demonstrate a lack of good faith for the purposes of the defence in s 122(1)(b)(i) relied upon by the respondents. I ultimately conclude later in these reasons that the evidence establishes that the failure to get Hellay to obtain halal certification was no more than an oversight and falls short of indicating a lack of good faith or worse. In drawing that conclusion, I had regard to the detailed discussion on this topic by Beach J in Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; 118 IPR 239, especially at [108]-[111].

68 In early 2016, Mr Hawley from Hellay told Flujo Group that he had contacted HCA regarding certification. Soon after that, in about March 2016, Mr Hawley was asked by Ms Azrina Iqbal of Flujo Group to obtain halal certification. Mr Hanna was told by Mr Hawley that an application form was completed with HCA and that the Natvia product was certified on 1 April 2016. Mr Hanna was not very familiar with the process because it was the manufacturer who looked after certifications.

69 As noted above and again below, Flujo Group resumed manufacturing arrangements with Techniques in about October 2018, while continuing also to use Hellay. There was no change in the formulation or production and Mr Hanna understood that Techniques maintained the relationship with HCA, including implicitly halal certification for their manufactured products. It is likely that Mr Hanna relied upon knowledge that Techniques was certified by HCA up until 2018, which was the case based on Ms El-Mouelhy’s evidence. It is relevant that no representative of Flujo Group was copied to the email from Techniques to HCA of 22 July 2015 terminating the certificate, apparently solely in respect of the Natvia products. There is otherwise no indication that Techniques, or HCA for that matter, notified Flujo Group that the halal certification had been terminated in respect of either Natvia or equivalent generic ingredients.

70 In about March 2017, Hellay commenced manufacturing a natural sweetener, Raw Earth Sweetener. The sweetener was made from monk fruit, stevia and erythritol, for Raw Earth as a toll manufacturer. When Flujo Group received a letter of demand from HCA on 3 August 2018, and checked with Hellay, the oversight in not obtaining halal certification was discovered. Mr Hanna asked Mr Hawley shortly after that to immediately rectify this and obtain certification for the Raw Earth product. HCA commenced this proceeding on 5 September 2018.

71 Mr Hanna kept in contact with Mr Hawley on the certification issues, and was told in September-October 2018 that certification of Raw Earth was being approved by HCA, but that the new certificate was being withheld due to the court case. I infer from this that there was no issue as to the product in fact being halal, or any factual impediment to certification as such, other than HCA’s interests arising out of this litigation.

72 With this factual history in mind, I now turn to the arguments as to the Trade Mark.

The originating application

Relevant law on infringing use as a trade mark and the good faith exception

73 It is convenient to consider the authorities and competing arguments as to infringing use and the good faith exception together. The following provisions of the Trade Marks Act are relevant to both:

(a) Section 6 relevantly provides:

6 Definitions

(1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears:

…

sign includes the following or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent.

…

7 Use of trade mark

…

(4) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods).

…

(c) Section 17 provides:

17 What is a trade mark?

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

(d) Section 120(1), (2)(c) and (2)(d) provide:

120 When is a registered trade mark infringed?

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

…

(c) services of the same description as that of services (registered services) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(d) goods that are closely related to registered services.

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

(e) Section 122(1)(b)(i) provides:

122 When is a trade mark not infringed?

(1) In spite of section 120, a person does not infringe a registered trade mark when:

…

(b) the person uses a sign in good faith to indicate:

(i) the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or some other characteristic, of goods or services …

74 HCA claims that the following kinds of trade mark infringement, objectively viewed, occurred:

(a) use as a trade mark of a sign that is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the goods or services of registration per s 120(1); and/or

(b) use as a trade mark of a sign that is substantially identical or deceptively similar to the goods or services of registration in relation to services of the same description as, or closely related to, registered services per s 120(2)(c) or (d),

and asserts that the exception in s 122(1)(b)(i) relied upon by the respondents (namely use in good faith to indicate, relevantly, the halal quality or other characteristic of the food) does not apply.

75 The principles and long-standing authority in relation to use “as a trade mark” were conveniently summarised in Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v Nestle Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117; 87 IPR 464, per Stone, Gordon and McKerracher JJ at [19]:

(1) Use as a trade mark is use of the mark as a “badge of origin”, a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else: Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107; 47 IPR 481; [1999] FCA 1721 at [19] (Coca-Cola); E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 265 ALR 645; 86 IPR 224; [2010] HCA 15 [241 CLR 144] at [43] (Lion Nathan).

(2) A mark may contain descriptive elements but still be a “badge of origin”: Johnson & Johnson Aust Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 347–8; 101 ALR 700 at 723; 21 IPR 1 at 24 (Johnson & Johnson); Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd (1996) 135 ALR 192; 33 IPR 161; Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185; 54 IPR 344; [2001] FCA 1874 at [60] (Aldi Stores).

(3) The appropriate question to ask is whether the impugned words would appear to consumers as possessing the character of the brand: Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 422; [1963] ALR 634 at 636; 1B IPR 523 at 532 (Shell Co).

(4) The purpose and nature of the impugned use is the relevant inquiry in answering the question whether the use complained of is use “as a trade mark”: Johnson & Johnson at FCR 347; ALR 723; IPR 24 per Gummow J; Shell Co at CLR 422; ALR 636; IPR 532.

(5) Consideration of the totality of the packaging, including the way in which the words are displayed in relation to the goods and the existence of a label of a clear and dominant brand, are relevant in determining the purpose and nature (or “context”) of the impugned words: Johnson & Johnson at FCR 347; ALR 723; IPR 24; Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182; [2002] FCA 390 (Anheuser-Busch).

(6) In determining the nature and purpose of the impugned words, the court must ask what a person looking at the label would see and take from it: Anheuser-Busch at [186] and the authorities there cited.

76 Certain aspects of the cases cited above in Nature’s Blend, and what was decided in that case, bear closer examination because of their particular relevance to the facts and circumstances of this case.

77 In Nature’s Blend, a registered trade mark for the words “luscious lips” was used in relation to the manufacture and marketing of lip-shaped chocolates wrapped in green. Those words were also used by the respondent, Nestlé, on the packaging for mixed confectionery. The proceeding brought against Nestlé for trade mark infringement failed at trial and on appeal. The primary judge’s reasons, as summarised by the Full Court at [23]-[28], were to the effect that:

(a) the words used by Nestlé were agreed to be substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the registered trade mark;

(b) that use was descriptive or laudatory of the lip-shaped confectionery in the mixed confectionery;

(c) the question of use as a trade mark was approached on the basis of whether that use would have appeared to consumers as possessing the character of a brand – that is to say, whether the words were used so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between Nestlé and the confectionery using the registered trade mark;

(d) upon an examination of the packaging:

(i) the trade mark words appeared on the back of the packet in the blurb to describe the product as part of a list of different confectionary items;

(ii) by contrast, on the front of the packet was Nestlé’s well known registered trade mark in that name, and in the brand name Allen’s, denoted as such for both;

(iii) “luscious” was descriptive and intended to convey a laudatory and perhaps even humorous description of that part of the contents;

(e) some consumers may read the blurb on the back, and others may not, but for those who took the time to look at it, they would have taken it as essentially a humorous way to describe the contents, not as a badge of origin;

(f) the impact of the trade mark words was diluted by the prominence of the well-known mark on the front, and it was the two registered trade marks of Nestlé that performed the role of distinguishing its confectionary product from that of others – as the Full Court noted, “[t]he words ‘Allen’s’ and ‘Nestlé’ were prominent, especially when contrasted with the positioning and use of the words ‘luscious Lips’”; and

(g) Nestlé was not aware of Nature’s Blend’s use of the words “luscious Lips” and therefore had not acted in bad faith.

78 The Full Court in Nature’s Blend (at [38]) quoted the judgment of Allsop J (as the Chief Justice then was) in Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar [2002] FCA 390; 56 IPR 182 at [184]–[186] with approval. The ultimate burden of that quote was the importance of context, and the need for the trade mark use assessment to be “made from the perspective of what a person looking at the label would see and take from it, as to the purpose and nature of its use” (his Honour in turn citing Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 425). The Full Court (at [41]-[49]) understandably rejected an argument advanced by the appellants that the question of trade mark use should be decided upon the basis that a reasonable consumer would actually read the back of the Nestlé/Allens packet as well as the front, and observed:

[42] Even if most consumers may look at the back of Nestlé’s packet before purchase or even read the blurb, such an inspection would simply reveal that one of the mixed lollies in Nestlé’s product is described in a light and amusing context as being “luscious Lips”. However, by the time the consumer has read the blurb, if indeed the consumer does so, he or she has already seen that it is in an Allen’s brand of product with the name of the product variant being retro party mix. If the consumer does go on to read the blurb, the consumer is well aware by that stage that the brand and commercial source is Allen’s. Further, on looking at the back of the packet the consumer would also see another very well known trade mark, namely, nestlé. The consumer then is left in no doubt as to the commercial origin of the product by the time he or she has read the relatively long discursive and humorous description referring to one of the lolly varieties as being “luscious Lips”.

…

[48] The primary judge was correct in taking into account the prominence of the registered allen’s and nestlé marks on the packaging in contrast to the location and style of the expression “luscious Lips”. That approach was entirely in conformity with the authorities on which the primary judge relied.

[49] Nestlé’s use of “luscious Lips” did not infringe the trade mark.

79 In Shell Co, the use in television advertising of a sign was found not to amount to use as a trade mark, because it was not used as a mark for distinguishing Shell’s petrol from other petrol. The sign was in the form of a figurine in the shape of an oil drop which was relevantly identical to a registered trade mark (sans the trading name of the applicant at first instance and respondent on appeal, “Esso”). Kitto J (with whom Dixon CJ, Taylor and Owen JJ, agreed) observed at 422:

[T]he context is all-important, because not every use of a mark which is identical with or deceptively similar to a registered trade mark infringes the right of property which the proprietor of the mark possesses in virtue of the registration. Section 58(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1955-1958 (Cth) defines that right as the right to the exclusive use of the trade mark in relation to the goods in respect of which the trade mark is registered; and s. 62(1) adds that a registered trade mark is infringed by a person who, not being the registered proprietor, or a registered user using by way of permitted use, uses a mark which is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the trade mark, in the course of trade, in relation to goods in respect of which the trade mark is registered. … But in my opinion it is implied both in s. 58(1) and in s. 62(1) that the use which is there referred to is limited to a use of a mark as a trade mark.

At 425 Kitto J went on to say that the question was whether the trade mark would appear to a person seeing it as:

[P]ossessing the character of devices, or brands, which [Shell] was using or proposing to use in relation to petrol for the purpose of indicating, or so as to indicate, a connexion in the course of trade between the petrol and [Shell]. … [T]he connexion … is a connexion limited by the purpose of the occasion.

The use made of the oil drop was only found to convey the qualities of Shell’s petrol, not its brand or origin.

80 In Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326, Sterling Pharmaceuticals held a registered trade mark over the made up word “caplets”. This was a portmanteau of the words “capsule” and “tablet” in the phrase “capsule-shaped tablets”. Johnson & Johnson used the word “caplets” on packaging and in the course of advertising for its own, competing, product. The trial judge found against Johnson & Johnson both as to infringing use and the good faith exception. That was overturned on appeal on the issue of infringing use, obviating the need for a concluded view on the good faith exception.

81 The proposition advanced by Sterling Pharmaceuticals in Johnson & Johnson was that there was trade mark use if the alleged infringer applies the mark so as to refer to the particular goods. This was rejected by the trial judge. On appeal, Lockhart J (at 335) and Gummow J (at 348) also rejected this proposition, holding that this went too far in expanding the exclusive rights given by trade mark legislation to something akin to literary copyright. Rather, following Shell Co, the question was whether the use made of the mark (viewed objectively, rather than subjectively) was to distinguish the commercial origin of goods or services sold under the mark, in the sense of a badge of origin. If the use is not sufficiently connected in some way to origin, including by reference to appearance and other aspects of context, there will be no infringement. Put another way, in the context of that case, the question was whether Johnson & Johnson’s use of the word “caplets”, which was the subject of the Sterling Pharmaceuticals trade mark, indicated that the source of the formation or quality of the product being sold, or its associated goodwill, was Sterling Pharmaceuticals. The answer was that it did not.

82 Johnson & Johnson is also authority for the proposition that there may be trade mark use and thus infringement where the alleged infringer uses the words with the mark to indicate that it, rather than the owner of the trade mark, is the trade origin of the goods or services in question: Gummow J at 349 citing Caterpillar Loader Hire (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Caterpillar Tractor Co (1983) 77 FLR 123 at 141-2. There may still be infringement even if another trade mark belonging to the alleged infringer is also used on the same packaging. Applying these principles, the Full Court concluded that there was no infringing use. That was because, although the word “caplets” was used, it was plainly and markedly subordinate to Johnson & Johnson’s own trade mark brand name “Tylenol”. The two words were not used in any composite way. The reference to “caplets” was confined to indicating the form or method of dosage of the product, and its ease of use, but not to invite consumers to purchase the product as distinguished from the products of other traders. To put it another way, it was to indicate that the products had a particular quality or characteristic, not as a point of distinction from other traders as to origin.

83 In Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd (1996) 135 ALR 192, a finding of infringing use was unanimously overturned on appeal. The alleged infringer respondent, Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd, had used the term “kettle” on packaging to describe the way in which potato chips had been made. That word was the subject of a trade mark registered to the applicant. The problem for the applicant was that while the word had undoubtedly been used, it was used in a descriptive way, which defeated the alleged use as a trade mark. As Lockhart J observed at 193 (substantially in common with Sheppard J at 201 and Sackville J at 208):

It is easier to find infringement of a registered mark where it consists of a coined phrase (see Mark Foy’s Ltd v Davies Coop & Co Ltd (1956) 95 CLR 190 (the Tub Happy case)) than in a case where the registered mark is a generally descriptive word which has acquired a secondary meaning, so becoming distinctive of the plaintiff’s goods as a badge of origin. The reason is that there is always inherent in a word that is originally descriptive the risk that even when it is used by others in trade it will be used in its original descriptive sense. And of course, where a word that is initially descriptive subsequently acquires a secondary meaning, it remains that use of the word in a descriptive sense cannot be restrained by the proprietor of the trade mark.

84 In Mark Foy’s Ltd v Davies Coop & Co Ltd (1956) 95 CLR 190 (the Tub Happy case), the use by the alleged infringer of its own brand name in conjunction with the trade mark of the plaintiff did not save it from being infringing use: see Dixon CJ at 194-5. But, as Kitto J pointed out at 197 (albeit in dissent on the issue of a coined phrase), the words “tub happy” occupied a prominent position, leaving the Court in no doubt that those words were used to indicate the defendant’s goods. The defendants attempted to argue the words were essential to advertising the goods as containing cotton fibres rather than woollen fibres and this was rejected.

85 Similarly, in Shell Co the question posed by Kitto J was whether the distinctive oil drop appeared to be “thrown on to the screen” to distinguish Shell petrol from other petrol. His Honour answered that question evocatively at 425:

At every point of the exhibition, whether the resemblance to the respondent’s trade marks be at the moment close or remote, the purpose and the only purpose that can be seen in the appearance of the little man on the screen is that which unites the quickly moving series of pictures as a whole, namely the purpose of conveying by a combination of pictures and words a particular message about the qualities of Shell petrol. This fact makes it, I think, quite certain that no viewer would ever pick out any of the individual scenes in which the man resembles the respondent’s trade marks, whether those scenes be few or many, and say to himself: “There I see something that the Shell people are showing me as being a mark by which I may know that any petrol in relation to which I see it used is theirs.” And one may fairly affirm with even greater confidence that the viewer would never infer from the films that every one of the forms which the oil drop figure takes appears there as being a mark which has been chosen to serve the specific purpose of branding petrol in reference to its origin.

The analogous dichotomy relied upon by the respondents is halal, as opposed to non-halal, goods, rather than trade origin as to halal certification services.

86 In Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; 96 FCR 107 it was recorded at [19]-[20] that the respondent suggested that Kitto J’s formulation in Shell Co should be adapted so as to pose the question as to whether, just by looking at the respondent’s cola-flavoured confectionary product in the distinctive trade mark registered contour shape of a Coca-Cola bottle, it could be concluded that Coca-Cola Co was the manufacturer of the confectionery. The Full Court rejected that as not being a correct adaptation and as not asking the right question. Rather (emphasis added):

Use “as a trade mark” is use of the mark as a “badge of origin” in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods: see Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 341, 351. That is the concept embodied in the definition of “trade mark” in s 17 – a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else.

The authorities provide no support for the view that in determining whether a sign is used as a trade mark one asks whether the sign indicates a connection between the alleged infringer’s goods and those of the registered owner. [Authority then cited] … the question is whether the sign used indicates origin of goods in the user of the sign; whether there is a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the user of the sign. [Shell Co at 424-5 is then quoted at some length].

The passage in bold above was quoted and expressly approved in E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 15; 241 CLR 144 at [43].

87 It is true that, as Johnson & Johnson at 347-8 makes clear (citing the Tub Happy case), a mark may have a descriptive element but still serve as a badge of trade origin. However, the fundamental question is whether the consumer is being invited to purchase the goods or services of the alleged infringer which are to be distinguished from the goods or services of other traders at least “partly because” (citing the Tub Happy case at 205) they are described by the words in question.

88 In this case, the sole identifying feature of the Trade Mark are the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”. This gives rise to the question of whether, in context, the words on the Packaging Logo were being used beyond an indication as to the quality or characteristic of being halal, largely because of greater specificity than simply stating that the goods were halal, or even halal certified.

89 Finally, in Halal Certification Authority Pty Ltd v Scadilone Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 614; 107 IPR 23, forged versions of HCA’s halal certificates were created by or at the direction of the managing director of a wholesale manufacturer and supplier of kebabs. The fake certificates were provided to two retail customers by a delivery employee of the same supplier, who also put them up for display at the retail premises without the retailers being aware they were forgeries. The wholesale supplier did not deny that the forged certificates had emanated from it, but unsuccessfully sought to blame a rogue employee who had left Australia.

90 Each forged certificate in Scadilone was to the effect that the wholesale supplier’s goods being sold in the shop were certified to be halal by HCA, when in fact such certification had never taken place. It was at least doubtful that the kebabs were halal at all. Thus use as a trade mark by displaying the forged certificates with the trade mark on them was apparently not in issue in that case. The bulk of the judgment in Scadilone concerned the liability of the two retailers and the personal liability of the managing director of the wholesale supplier company, with Perram J noting at [49] that there was no doubt that HCA’s trade mark on the forged certificates had been used by that company in relation to the kebabs it supplied to the retail outlets.

91 The main points of difference between Scadilone and this case are obvious enough. That case concerned the use of HCA’s trade mark in association with forgeries of halal certificates ordinarily issued by it, not the bare application of a very similar mark to packaging as in this case. A further point of difference is that the goods in this case had, at different times, been certified by HCA to be halal and there was no suggestion that the goods were not in fact halal. Those differences alone mean that the application of Scadilone to the present situation has to be approached with some caution. HCA relies upon findings made by Perram J as to use of its registered trade mark on the forged certificates in Scadilone. However, the context is so different so as to make that conclusion of little assistance in this case. In fact, I consider the facts in Scadilone rather highlight why there is not likely to be an issue as to use in the present circumstances, rather than furthering HCA’s case.

92 With primarily the above cases in mind, as well as the other authorities referred to in the submissions of the parties as a background, I now return to the case at hand.

Infringing use as a trade mark (s 120(1), (2)(c) and (d))

93 A practical and realistic approach permeates many of the authorities as to the inquiry required to be undertaken to assess whether infringement has occurred, as considered in some detail by Sackville J in Pepsico. It is an objective inquiry of substance, rather than mere form, although form in the sense of appearance is doubtless also a feature of substance. The assessment is to be made from the perspective of a person looking at the impugned mark and what such a person would take from it as to the purpose and nature of its use: Anheuser-Busch at 186, citing Shell Co at 425; and Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH [2001] FCA 1874; 190 ALR 185 (Full Court) at [22]-[24] and [76].

94 The onus is on HCA to show infringing use. Has it been established, on the balance of probabilities, that, viewed objectively and in context, the use of the Packaging Logo goes any further than indicating that the contents are halal, and perhaps that someone not clearly identified other than the manufacturer was saying that was so? For the following reasons I have concluded that the answer is “no”.

95 The trade mark infringement case brought by HCA can best be summarised by reference to its closing oral submissions in which an analogy is drawn between a computer and the processor within a computer. When a computer has a logo such as “intel inside” or the equivalent, the logo is not signifying that the computer is made by Intel Corporation, but rather only that the processor is made by Intel. HCA’s case is that the Packaging Logo, being substantially the same as the Trade Mark, would have conveyed to a person looking at the Natvia Products and Raw Earth Products packaging that:

(a) the contents were halal, or even that they were certified as halal by someone; and

(b) the trade source of the halal certification service was HCA.

96 By contrast, the respondents’ case is that the size and placement of the Packaging Logo, albeit bearing substantially the same appearance as the Trade Mark, would convey to any consumer who chose to look at it no more than that the product was in fact halal, and perhaps also that it was certified as such, which falls well short of conveying any trade source information.

97 As a first step, I endorse and adopt the conclusion reached by the trade mark examiner, reproduced at [25] above that the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia” are themselves purely descriptive. This is so despite those words constituting the bulk of HCA’s company name. In the absence of the full company name on either the Packaging Logo or the Trade Mark, HCA has an immediate problem in relying upon the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia”, or even the subset words “Halal Certification Authority” as themselves indicating to a consumer the trade origin of the services it supplied. Even this much assumes that it is realistic to conclude that a consumer would even trouble to read those words, which is doubtful given the greater importance of the Arabic lettering signifying halal, and the small size of the logo on the packaging.

98 The live question then is whether a member of the general public, or an ordinary and reasonable reader, would consider that there is any practical difference in using the Packaging Logo as part of a registered trade mark to signify that the products were halal. A recurring example throughout this proceeding was the comparison with the Kosher Logo which also appeared on the relevant Natvia Products and Raw Earth Products. The oral evidence as to the similarities and differences between kosher and halal food indicated that the only substantial difference is that the Islamic faith generally permits rabbits, camels, horses and shellfish to be eaten, while the Jewish faith (and thus kosher) does not. That is certainly not an exhaustive account of the differences, but it does indicate a reasonably high degree of commonality and that much of the food that is kosher is very likely also to be halal. Core limitations of both concern not using porcine products with the addition of limitations on the method of slaughter of other animals.

99 The small display size and relatively obscure placement on the packaging for both the Packaging Logo and the Kosher Logo starkly contrast with the large and dominant size of the “Natvia” and “Raw Earth” trade marks. These trade marks were registered to Flujo Sanguineo, and were the names by which the two types of products in issue were overtly sold. The English words on the Packaging Logo and the Kosher Logo are difficult to read. While it is true the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia” are clearer than the equivalent words on the Kosher Logo, they are both more troublesome to read than just the more immediate “K” symbol and the Arabic lettering indicating halal.

100 Most consumers or other casual readers would probably not even notice that the logo was there, even when they are on the shelf at home, given that the logos are situated on the side of the packaging, usually underneath or near the nutritional information. Annexures MOC-1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 12 and 13 to Mr O’Connor’s affidavit demonstrate this. Annexure MOC-10 to the same affidavit also provides a useful view of what a shopper would see when viewing the Raw Earth and Natvia Products at the supermarket: nearly all of the products are displayed such that the Packaging Logo is not visible. Even when one of the Natvia Products is turned on its side (specifically, either the Natvia 40 x 2g sachets 80g pack sweetener, or the Natvia 80 x 2g sachets 160g pack sweetener) the Packaging Logo is not discernible at any level of clarity, let alone sufficient to see the printing of the words “Halal Certification Authority Australia” while browsing. Finally, in Annexure MOC-8, there is a closer-up picture of some of the Natvia Products, where they appear to have been turned such that the Packaging Logo is clear to the camera. Even in this close-up view, where the products have been positioned for better clarity, it is impossible to make out the words which are on the Packaging Logo or the Kosher Logo from that distance. A shopper would most likely go no further than the immediate “K” symbol and the Arabic lettering indicating halal, which are still somewhat clearer at that distance.

101 In the absence of any direct evidence from any consumer or any independent experts as to how packaging of this kind either was, or was likely to be, read by a consumer, the Court is left to make inferences and draw other conclusions on the face of the packaging. The respondents addressed this briefly; HCA barely at all. The above consideration is more detailed than any submission made.

102 HCA also sought to make use of the evidence of Mr Hanna in cross-examination, and the pleading in relation to the good faith defence in s 122(1)(b)(i) of the Trade Marks Act at [17(d)] of the defence, both of which went to the subjective purpose of using the Packaging Logo. However, it is difficult to see how that subjective purpose will ordinarily serve any useful purpose in relation to the objective assessment of whether there has been use as trade mark, unless, perhaps, it has some direct bearing on the objective assessment required to be carried out. I found that evidence, pleading point, and argument, of no assistance at all in that objective assessment.