Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GetSwift Limited (Liability Hearing) [2021] FCA 1384

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 10 NOVEMBER 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties file by 5pm on 17 November 2021 an agreed minute or competing minutes of order to reflect these reasons.

2. The proceeding be adjourned for a case management hearing at 9:30am on 19 November 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CONTENTS:

[1] | |

[3] | |

[20] | |

[29] | |

[35] | |

[38] | |

[44] | |

[49] | |

[49] | |

[53] | |

[57] | |

[59] | |

[61] | |

[70] | |

[71] | |

[72] | |

[79] | |

[83] | |

[86] | |

[94] | |

[102] | |

[103] | |

[107] | |

[108] | |

[113] | |

[116] | |

[123] | |

G FACTUAL BACKGROUND IN RESPECT OF GETSWIFT’S CLIENTS AND SHARE PLACEMENTS | [141] |

[145] | |

[145] | |

[146] | |

[161] | |

[176] | |

[180] | |

[184] | |

Conversation between Ms Gordon and Ms Mikac on 22 March 2017 | [193] |

[195] | |

[198] | |

[200] | |

[203] | |

[204] | |

The First and Second Meeting: 8 December 2016 and 20 January 2017 | [206] |

Non Disclosure Agreement and initial draft terms of the CBA Agreement | [209] |

[215] | |

[222] | |

Provision of draft media announcement to CBA and negotiation of the CBA Agreement | [231] |

[235] | |

[243] | |

[252] | |

CBA proposed amendments to the CBA Agreement and further discussions | [256] |

GetSwift reaction to the CBA revised draft of the media release | [266] |

[268] | |

Mr Hunter reinserts the 55,000 figure into the draft media release and ASX announcement | [273] |

GetSwift provides CBA with the revised media release with the 55,000 figure reinserted | [276] |

Mr Budzevski and Ms Kitchen query whether GetSwift figures in media release are global | [281] |

[289] | |

Further consideration by Mr Budzevski and Ms Kitchen of the 55,000 figure | [296] |

Ms Kitchen again queries the 55,000 figure with Mr Polites and Mr Budzevski | [302] |

Mr Budzevski’s further consideration of the 55,000 retail merchant figure | [317] |

[326] | |

[340] | |

[343] | |

[365] | |

[370] | |

GetSwift responses to the projections queries in the ASX aware letters | [374] |

[381] | |

[383] | |

GPS Delivery Tracking Project and the Pizza Hut Test Store Site | [386] |

[389] | |

[413] | |

[433] | |

[437] | |

[441] | |

[448] | |

[450] | |

[455] | |

[457] | |

Variation of the APT agreement with GetSwift and issues with the csv. file | [462] |

APT’s demonstration of the GetSwift Platform to Mr Nguyen of Fantastic Furniture | [477] |

[482] | |

GetSwift’s Weekly Transaction Reports record zero deliveries for APT | [492] |

[498] | |

[502] | |

[524] | |

[525] | |

[529] | |

[532] | |

CITO participation limited to provision of warehousing services | [536] |

[538] | |

[542] | |

The alleged trial of the PMI online store giving CITO access to the GetSwift Platform | [559] |

[560] | |

[561] | |

[568] | |

[573] | |

[573] | |

[578] | |

[587] | |

[595] | |

Initial dealings and negotiation of the Fantastic Furniture Agreement | [596] |

Clarification of termination prior to the end of the trial period | [608] |

Preparation and release of the Fantastic Furniture and Betta Homes Announcement | [611] |

The initial trial of the GetSwift Platform by Fantastic Furniture | [628] |

[632] | |

[642] | |

Initial dealings and negotiation of the Betta Homes Agreement | [644] |

[669] | |

[672] | |

[685] | |

[686] | |

[696] | |

[709] | |

[714] | |

[719] | |

[722] | |

[724] | |

[739] | |

[741] | |

[749] | |

[763] | |

GetSwift’s knowledge of size of addressable market and competitors’ pricing | [769] |

Further GetSwift internal circulation of a draft of the First NAW Announcement | [772] |

[777] | |

[778] | |

Hunter’s concern that the First NAW Announcement was not marked as price sensitive | [779] |

[783] | |

[796] | |

[801] | |

[802] | |

[803] | |

[814] | |

[816] | |

[826] | |

[829] | |

[831] | |

[833] | |

[834] | |

Negotiations between Pizza Hut International and GetSwift in relation to a Pilot | [840] |

[844] | |

Pizza Hut International unable to secure two test markets for the Pilot | [861] |

[868] | |

[869] | |

[880] | |

[893] | |

[896] | |

[913] | |

[925] | |

[933] | |

[956] | |

[957] | |

[960] | |

[964] | |

[989] | |

[992] | |

[999] | |

[1007] | |

[1008] | |

[1018] | |

Amazon aware, or agreed to, the making of a regulatory announcement | [1023] |

Continued preparation of Service Order and Service Order never entered into | [1029] |

[1034] | |

[1034] | |

[1041] | |

[1050] | |

[1054] | |

[1060] | |

[1065] | |

[1065] | |

[1072] | |

[1075] | |

[1077] | |

[1086] | |

[1091] | |

[1105] | |

[1109] | |

[1116] | |

[1117] | |

[1118] | |

[1121] | |

[1126] | |

[1131] | |

[1142] | |

[1144] | |

[1147] | |

[1148] | |

[1152] | |

[1168] | |

[1196] | |

[1198] | |

[1212] | |

[1230] | |

[1257] | |

Conclusions on the proper approach to materiality in this case | [1259] |

[1265] | |

[1268] | |

[1269] | |

[1270] | |

[1277] | |

[1277] | |

[1278] | |

[1280] | |

[1283] | |

[1292] | |

[1293] | |

[1302] | |

[1302] | |

[1306] | |

[1311] | |

[1312] | |

[1315] | |

[1316] | |

[1317] | |

[1318] | |

[1321] | |

[1321] | |

[1350] | |

[1356] | |

[1357] | |

[1365] | |

[1366] | |

[1367] | |

[1370] | |

[1370] | |

[1379] | |

[1382] | |

[1394] | |

[1403] | |

[1404] | |

[1405] | |

[1406] | |

[1407] | |

[1407] | |

[1408] | |

[1409] | |

[1410] | |

[1418] | |

[1419] | |

[1419] | |

[1434] | |

[1442] | |

[1443] | |

[1450] | |

[1451] | |

[1452] | |

[1453] | |

[1454] | |

[1454] | |

[1458] | |

[1459] | |

[1460] | |

[1470] | |

[1471] | |

[1471] | |

[1480] | |

[1484] | |

[1485] | |

[1488] | |

[1489] | |

[1490] | |

[1491] | |

[1493] | |

[1493] | |

[1495] | |

[1496] | |

[1497] | |

[1499] | |

[1500] | |

[1501] | |

[1502] | |

[1504] | |

[1505] | |

[1506] | |

[1507] | |

[1509] | |

[1509] | |

[1510] | |

[1512] | |

[1513] | |

[1517] | |

[1518] | |

[1518] | |

[1529] | |

[1530] | |

[1531] | |

[1539] | |

[1540] | |

[1541] | |

[1542] | |

[1547] | |

[1547] | |

[1548] | |

[1551] | |

[1552] | |

[1558] | |

[1559] | |

[1559] | |

[1560] | |

[1564] | |

[1565] | |

[1569] | |

[1570] | |

[1571] | |

[1573] | |

[1575] | |

[1575] | |

[1576] | |

[1577] | |

[1578] | |

[1581] | |

[1582] | |

[1583] | |

[1583] | |

[1585] | |

[1589] | |

[1590] | |

[1593] | |

[1594] | |

[1597] | |

[1602] | |

[1602] | |

[1621] | |

[1643] | |

[1652] | |

[1656] | |

[1657] | |

[1661] | |

[1662] | |

[1663] | |

[1665] | |

[1665] | |

[1666] | |

[1667] | |

[1668] | |

[1671] | |

[1672] | |

[1672] | |

[1678] | |

[1681] | |

[1682] | |

[1684] | |

[1685] | |

[1686] | |

[1688] | |

[1690] | |

[1690] | |

[1696] | |

[1701] | |

[1706] | |

[1710] | |

[1711] | |

[1711] | |

[1720] | |

[1731] | |

[1742] | |

[1746] | |

[1747] | |

[1748] | |

[1749] | |

[1751] | |

[1754] | |

[1754] | |

[1755] | |

[1756] | |

[1765] | |

[1775] | |

[1776] | |

[1776] | |

[1778] | |

[1780] | |

[1781] | |

[1782] | |

[1783] | |

[1784] | |

[1786] | |

[1787] | |

[1788] | |

[1790] | |

[1791] | |

[1796] | |

[1808] | |

[1809] | |

Delivery volumes and revenue important to investor expectations | [1831] |

[1835] | |

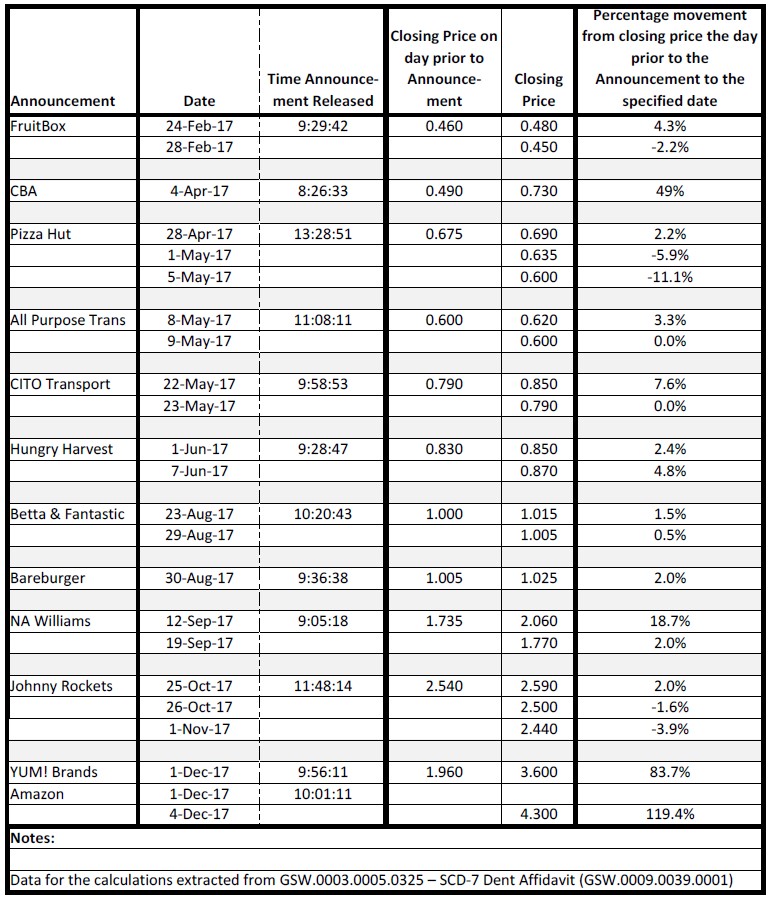

Strategic timing of announcements to maximise impact on share price | [1842] |

[1852] | |

[1869] | |

[1895] | |

[1896] | |

[1901] | |

Giving particularity to the role and knowledge of each director | [1914] |

[1915] | |

[1923] | |

[1940] | |

[1958] | |

[1963] | |

[1970] | |

[1976] | |

[1977] | |

[1979] | |

[1998] | |

Hunter No Financial Benefit Information and Termination Information | [2007] |

[2017] | |

[2021] | |

[2023] | |

[2025] | |

[2049] | |

[2057] | |

[2068] | |

[2071] | |

[2075] | |

[2077] | |

[2093] | |

[2097] | |

[2100] | |

[2102] | |

[2103] | |

[2106] | |

[2106] | |

[2117] | |

[2119] | |

[2130] | |

[2143] | |

[2164] | |

[2175] | |

[2176] | |

[2182] | |

[2190] | |

[2196] | |

[2201] | |

[2206] | |

[2210] | |

[2213] | |

[2214] | |

[2222] | |

[2225] | |

[2226] | |

[2227] | |

[2237] | |

[2240] | |

[2244] | |

[2245] | |

[2246] | |

[2247] | |

[2261] | |

[2266] | |

[2269] | |

[2270] | |

[2271] | |

[2272] | |

[2282] | |

[2285] | |

[2287] | |

[2288] | |

[2289] | |

[2290] | |

[2300] | |

[2303] | |

[2305] | |

[2306] | |

[2313] | |

[2317] | |

[2318] | |

[2319] | |

[2320] | |

[2327] | |

[2330] | |

[2332] | |

[2333] | |

[2343] | |

[2349] | |

[2350] | |

[2351] | |

[2352] | |

[2356] | |

[2358] | |

[2360] | |

[2361] | |

[2362] | |

[2366] | |

[2368] | |

[2369] | |

[2370] | |

[2371] | |

[2374] | |

[2376] | |

[2378] | |

[2383] | |

[2386] | |

[2387] | |

[2388] | |

[2389] | |

[2392] | |

[2394] | |

[2396] | |

[2401] | |

[2404] | |

[2408] | |

[2409] | |

[2410] | |

[2411] | |

[2414] | |

[2416] | |

[2418] | |

[2421] | |

[2422] | |

[2423] | |

[2424] | |

[2438] | |

[2449] | |

[2452] | |

[2453] | |

[2456] | |

[2458] | |

[2459] | |

[2460] | |

[2463] | |

[2469] | |

[2472] | |

[2475] | |

[2478] | |

[2482] | |

[2483] | |

[2484] | |

[2488] | |

[2498] | |

[2502] | |

[2506] | |

[2508] | |

[2509] | |

[2510] | |

[2514] | |

[2516] | |

[2517] | |

[2518] | |

[2522] | |

[2523] | |

[2525] | |

[2525] | |

[2536] | |

The relationship between ss 674(2) and 180(1) contraventions | [2537] |

[2540] | |

[2545] | |

J.2.1 Revisiting some basal facts and the position of each director | [2546] |

[2547] | |

[2548] | |

J.2.2 The degree of care and diligence to be exercised generally | [2553] |

[2562] | |

[2563] | |

[2566] | |

[2573] | |

[2577] | |

[2578] | |

[2581] | |

[2585] | |

[2589] | |

[2590] | |

[2591] | |

[2593] | |

[2614] | |

[2615] |

LEE J:

1 This is a long judgment. I am tempted to say too long, but as will become evident to anyone who has the misfortune of being required to read it, the case advanced by the Australian Securities Investment Commissions (ASIC) was vast in scope, involving the need to wade doggedly through a prodigious documentary case and make innumerable findings along the way. After finally emerging from the Daedalian maze, one suspects that without detracting from the ultimate regulatory outcome, ASIC’s case could have been refined significantly. But alas, this litigious battle was fought on a broad front.

2 In an attempt to make the judgment less unreadable, I have divided it into what can be seen from the index to be manageable chunks, broadly mirroring the hydra-headed case mounted. Additionally, at [1064] and [2105] below, I have included ready-reckoners for the continuous disclosure and misleading and deceptive conduct claims, providing details of my conclusions, and providing a “roadmap” to where important findings are made. Referencing matters in the body of the text would, in a judgment this size, be overwhelming, and so I have adopted the expedient of using footnotes (although, because of a desire to avoid repetition, a footnote or cross reference is often illustrative, rather than the exclusive source of the relevant reference).

3 The case concerns GetSwift Limited (GetSwift), a former market darling listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). As it happens, it is no longer listed on the ASX. In an unusual development during the pendency of regulatory proceedings, at around the same time the evidence concluded in the liability phase of this case before me, GetSwift entered into an implementation deed in relation to a proposed scheme of arrangement, the intended purpose of which was to re-domicile GetSwift to Canada (being a scheme ultimately approved, but over the opposition of ASIC): see GetSwift Limited, in the matter of GetSwift Limited (No 2) [2020] FCA 1733 (at [12], [52], [81], [138], and orders 17 December 2020 per Farrell J).

4 In any event, returning to the period relevant to this liability hearing, this case comes against the background of GetSwift experiencing a dramatic ascension in the value of its shares from an issue price of 20 cents upon listing in December 2016 to over $4, prior to a trading halt announcement in December 2017, in advance of its second placement, by which GetSwift successfully raised $75 million from investors. One year later, on 7 December 2018 the share price dropped to $0.52 – a percentage decrease of almost 90% from its all-time high of $4.30, as recorded on 4 December 2017.1

5 It is notable that GetSwift, which might aptly be described as an early stage “tech” company, was able to generate such significant momentum and interest in its share price at a time when the company had “incurred historic operating losses to date”.2 This is especially so in circumstances where potential investors would have likely faced some difficulties in assessing the true value of GetSwift shares due to the absence of any successful track record and its “limited operating history”.3

6 Put broadly, the case concerns whether GetSwift failed to disclose material information in a series of announcements to the ASX, including by not revealing the status of its actual engagements with regard to its various customers. It also examines whether GetSwift engaged in misleading or deceptive statements regarding the nature and scale of the financial benefit that GetSwift stood to obtain from each agreement.

7 This proceeding also relevantly focusses on the conduct of three directors of GetSwift, namely:

(1) Mr Bane Hunter, the second defendant, who was the executive chairman and chief executive officer of GetSwift;

(2) Mr Joel Macdonald, the third defendant, who was the managing director of GetSwift; and

(3) Mr Brett Eagle, the fourth defendant, a solicitor, who was a non-executive director and GetSwift’s general counsel.

8 Despite the skilful submissions made on behalf of the defendants, a close review of the contemporaneous record reveals with clarity to any sentient person what went on at GetSwift. At the risk of over-generalisation, what follows reveals what might be described as a public-relations-driven approach to corporate disclosure on behalf of those wielding power within the company, motivated by a desire to make regular announcements of successful entry into agreements with a number of national and multinational enterprise clients.

9 There is a plethora of documentary evidence in the form of emails exchanged between some of the directors revealing efforts directed at the strategic timing of ASX announcements, making sure that announcements were marked as “price sensitive”, orchestrating simultaneous media coverage, and evincing an appreciation that the failure to release announcements of new client agreements would or could have a negative impact on investor expectations.

10 As will appear in more detail below, numerous emails from Mr Hunter are most telling as to GetSwift’s approach to communicating with the market, and the level of control he sought to assert. Among many examples is an email to a fellow director, Ms Jamila Gordon (who is not a defendant) sent on 24 February 2017 in the wake of the release of one ASX announcement, in which he stated: “Bit by bit until we get to a $7.50 share price :)”.4 He then followed this email up with the following missive to his fellow directors:

I wanted to take a quick moment and just put some things into context – today’s strategic account contract capture [sic] information and the timing of the release added approx. $3.8m to the companies [sic] market cap. That’s making all our shareholders much happier.

To date since IPO listing price I am pleased to inform you that the company [sic] share price is up 140% - the strongest performer on the ASX. That means that I have driven the market value of the company up by more than $36m in 3 months. We are now worth more than $63M and heading towards $200m in very short order. These results are not accidental.

Therefore please keep that in mind when I insist on certain structural and orderly processes that there are much more complex requirements that are at play.

It is also important to stress that it is imperative that non commercial [sic] structures and resources we have in place are fully supporting the revenue and market cap based portions of the company. These have absolute priority over anything else. Without those as our primary focus not much progress will be made.

We have a tremendous year ahead of us and the timely planning and delivery of key commercial accounts is paramount. … Failure to do so will prompt an [sic] revised management structure.

In May we will be under the spotlight again with another significant investment round planned leading up to a much larger and final round in Oct or thereabouts. So as you can imagine I will not wait until May to course correct this organization staffing [if] we are not tracing as planned or better than planned.

Folks I am serious about this , please do not that there was no fair notice given of the expectations needed. Please do not confuse my friendly attitude for tolerance or forgiveness when it comes to achieving the deliverables set in front of us. There is too much at stake to allow for any lack of control. If you are unable or unwilling to operate as such please let me know.

This company if we achieve or our objectives in 2 years [sic] be valued well above the $800M + market cap, and no excuse will stand in our way to reach that goal. The rewards will be fantastic and amazing especially when you consider the timeline, so let’s stay focussed now more than ever.5

11 Mr Hunter had a habit of writing in evocative terms. This is reflected in many communications including an email sent by Mr Hunter on 6 October 2017 to Mr Macdonald making reference to an apparent long-term aim discussed between them: “no rest till we are north of 1$b and I know you are taken care of for the future - I made you a promise - do or die on my part”.6

12 Not only did Mr Hunter demonstrate a high level of concern over the content of the ASX announcements, it is evident that he sought to exercise close control over the release of such announcements. This is vividly illustrated by Mr Hunter’s emails in late August 2017, including one sent to Ms Susan Cox (of GetSwift) on 25 August 2017 in which he stated: “You know that any market release have [sic] to be vetted by us” (“us” being a reference to both himself and Mr Macdonald).7 In the same email chain, Mr Hunter also said the following to Ms Cox:

You have made an incredible misjudgment [sic] and overstepped your bounds. I am flabbergasted that you thought it was ok to release anything on the ASX without Joel and my approval…Let me make this crystal clear - we have NEVER released anything EVER without Joel or mine [sic] approval or review first.8

13 The intense focus that Mr Hunter and Mr Macdonald placed on the ASX announcements forms an important aspect of this case, to which I will return in detail below (at Part H.4.2). However, at a broad level, these illustrative emails are reflective of another aspect of the evidence; that is, the nature of the relationship between Mr Hunter and his colleagues. As will be seen from the numerous communications (liberally sprinkled with capitalised words) reproduced below, Mr Hunter displayed a management style that owed little to the influence of the late Dale Carnegie. He was demanding, forceful and regularly brusque to the point of rudeness.

14 The evidence does not disclose whether Ms Gordon was conscious of Mr Hunter displaying his self-described “friendly attitude” towards her at any time: c.f. [10] above. What is evident is that their relationship does not appear to have been a congenial one after March 2017, when Ms Gordon started to raise concerns in relation to the processes employed by Messrs Hunter and Macdonald as to announcements GetSwift made to the ASX.9 On one occasion, Mr Hunter told Ms Gordon that he had more experience in corporate governance than her, and suggested that the questions she was asking were naïve.10 But her concerns were not those of an ingénue and it is worth noting that, as at 9 December 2016, Ms Gordon was the only director on the board with any corporate governance training.11

15 On another occasion, at a September 2017 board meeting in which she was participating remotely, Ms Gordon was told by Mr Hunter she was on the “hot spot” in relation to her questions as to the materiality of an ASX announcement.12 Mr Eagle then spoke uninterrupted for about 12 minutes, apparently from a document, upbraiding her for “governance issues”, including causing delays in making announcements. Ms Gordon (who was born in Somalia and escaped that country before civil war broke out in 1991 and studied English at a TAFE college before university)13 was trying to write down what was being said, could not keep up, and asked for a copy of the document that Mr Eagle was reading from so she could counter the criticism properly. Mr Hunter responded by saying words to the effect, “Let me put it to you in English you can understand” and then repeated the details of her perceived deficiencies at similar length. She eventually responded:

[A]s a director I’m accountable having these announcements released without my total understanding and having a board meeting where… my objections, if I have objections, are minuted, therefore I have huge exposure and responsibility and that’s why I’m raising these issues.14

16 To this Mr Hunter responded: “that’s why you have director’s insurance.”15

17 By 24 October 2017, Mr Hunter was writing to his fellow director as follows:

[D]o NOT reach out to our customers where you do not own the relationship without prior approval -you were explicitly told you are not to get involved with commercial discussions . You only own the CBA relationship that’s it. You are NOT authorized to negotiate on behalf of the company with any other entity. This is an instant termination for cause if you do.16

18 Ms Gordon was removed from GetSwift shortly thereafter.

19 I will return below to the importance and clarity of Ms Gordon’s evidence, the way the board of GetSwift operated, the relevance of the relationship between the directors, and their respective roles and power within the entity.

A.2 The GetSwift platform and business model

20 Before progressing further, it is useful to provide a brief summary of the GetSwift platform and its business model.

21 GetSwift’s business and fee structure model was described in a prospectus that GetSwift lodged with ASIC in late 2016 with regard to an initial public offering (Prospectus).17 GetSwift was in the business of providing clients with a “software as a service” (SaaS) platform (GetSwift Platform) for the management of “last-mile delivery” services globally. “Last mile delivery”, as might be expected, describes the carriage of goods from a transportation hub to its final destination. The GetSwift Platform could be used to effect delivery services either through a client’s own driver network or with a contracted service.

22 GetSwift described itself as offering a “white label” solution, enabling technology to companies for a low, “pay as you use” transaction-based fee.18 Its revenue was generated on a “per delivery basis”, which involved charging a $0.29 transaction fee per delivery.19 Discounts were applied to larger clients through a tiered fee structure based on the client’s monthly transactional volume and the length of contract commitment. There were no fixed maintenance or upfront fees. A client could incur additional fixed subscription fees for fleet management and smart routing and SMS charges were “on-charged” as status updates.20

23 The Prospectus highlighted that GetSwift intended to “expand” by capturing market share and scaling its existing footprint.21 Its key strength was its “high growth” and the number of so-called “client industry verticals” it serviced.22 However, there were also risks, including that “[e]ven once clients are successfully attracted to the GetSwift platform and related services, clients may terminate their relationship with the Company at any time”.23 As GetSwift explained, this meant that if clients terminated their relationship, this could adversely impact GetSwift’s business, financial position, results of operations, cash flows and prospects.24 Further, as an “early stage technology company”, the Prospectus stated that GetSwift had accumulated a loss of approximately $946,402 as at 30 June 2016.25

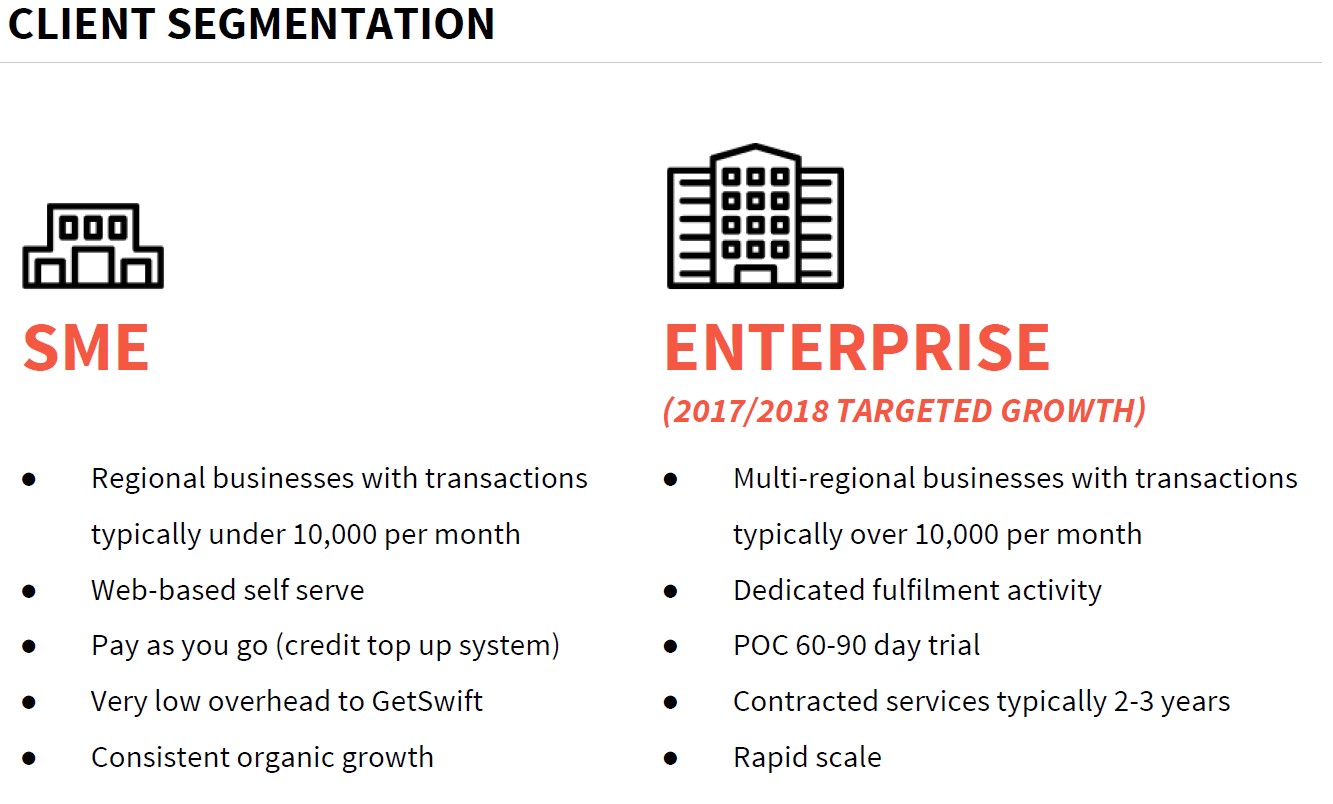

24 GetSwift focussed on two main client segments: larger organisations with multi-site requirements and the capability for 10,000 or more deliveries per month (Enterprise Clients); and small and medium businesses (Self-serve Clients).26

25 In addition to making the general statement that clients may terminate their relationship with GetSwift at any time (see [23]), GetSwift made three important statements in the Prospectus as to its Enterprise Clients: first, GetSwift typically granted a 90-day proof of concept trial (POC) before the client moved to a standard contract; secondly, contracts for Enterprise Clients were initially for two years in length; and thirdly, those Enterprise Clients who had entered into a POC had a 100% sign up rate to contracts as at the date of the Prospectus.27

26 By making each of these statements in its Prospectus, ASIC alleges that GetSwift represented to investors that:

(1) a POC (or trial phase) would be completed before GetSwift entered into an agreement with an Enterprise Client for the supply of GetSwift’s services for a reward;

(2) any agreement entered into by GetSwift with Enterprise Clients for the supply of GetSwift’s services were not conditional upon completion of concept or trial; and

(3) Enterprise Clients would only enter into an agreement after the proof of concept or trial phase had been successfully completed.

(collectively, the First Agreement After Trial Representation)

27 In addition to the statements made in the Prospectus, on 9 May 2017, GetSwift created a PowerPoint presentation for investors, which was submitted to the ASX.28 This presentation stated that Enterprise Clients were multi-regional businesses, typically with over 10,000 transactions per month. Further, it specified that Enterprise Clients have a “POC 60-90 day trial” and that these clients received contracted services for typically two to three years (Second Agreement After Trial Representation).29

28 I will return to whether each of these representations was conveyed below (at Part I.3), where findings are made as to whether the conduct of GetSwift, Mr Hunter and Mr Macdonald was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive.

A.3 Statements regarding continuous disclosure

29 As noted above, the focus of much of this case concerns the alleged continuous disclosure contraventions. GetSwift’s own continuous disclosure policy was referred to in the Prospectus (Continuous Disclosure Policy).30 As is typical, this policy set out certain procedures and measures that were designed to ensure that GetSwift complied with the continuous disclosure requirements of the ASX Listing Rules (Listing Rules) and the applicable sections of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act).31 It also provided protocols related to the review and release of ASX announcements and media releases. Further, the Prospectus relevantly and correctly stated that GetSwift would be required to disclose to the ASX any information concerning the company that was not generally available and that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of its shares.32 I will return to the significance of the Prospectus and Continuous Disclosure Policy below.

30 By publishing the Continuous Disclosure Policy to the ASX, it is said that GetSwift’s executive directors represented that they would conduct themselves consistently with the policy. In addition, during 2017, GetSwift made three important public statements concerning GetSwift’s approach to continuous disclosure.

31 First, in its Appendix 4C and Quarterly Review submitted to and released by the ASX on 28 April 2017 (April Appendix 4C), GetSwift stated (First Quantifiable Announcements Representation):

[T]he company is starting to begin harvesting the markets it has prepared the groundwork over the last 18 months. Transformative and game changing partnerships are expected and will be announced only when they are secure, quantifiable and measurable. The company will not report on MOUs only on executed contracts. Even though this may represent a challenge for some clients that may wish in [some] cases not [sic] publicize the awarded contract, fundamentally the company will stand behind this policy of quantifiable non hype driven announcements even if it results in negative short term perceptions.33

32 Secondly, in its Appendix 4C and Quarterly Review submitted to and released by the ASX on 31 October 2017 (October Appendix 4C), GetSwift stated (Second Quantifiable Announcements Representation):

Please Note: The Company will only report executed commercial agreements. Unlike some other groups it will not publicly report on Memorandum of Understandings (MOU) or Letters of Intent (LOI), which are not commercially binding and do not have a valid assurance of future commercial outcomes.34

33 Thirdly, in its announcement submitted to and released by the ASX on 14 November 2017 and entitled “GetSwift Executes on Key Integration Partnerships”,35 GetSwift stated (Third Quantifiable Announcements Representation):

The Company is taking a measured approach in ensuring that only quantifiable and impactful announcements are delivered to the market. With that in mind it has chosen to announce 9 of these integrations once they all have been completed rather than individually.

The company in addition expects to announce key commercial agreements shortly and is pleased that the overall strategy of becoming a global leader and not just a regional leader is being manifested.36

34 It is alleged that the making of the latter two representations amounted to contravening conduct. Similarly, I will return to whether these representations were conveyed and whether they amounted to contraventions below (at Part I.3).

35 Another component of this case involves analysing the commercial background, content and implications that emanated from the announcements that GetSwift made to the ASX. These announcements, made between 24 February 2018 and 1 December 2017, stem from agreements that GetSwift entered into with respect to 13 individual Enterprise Clients.

36 As noted above, during the period leading up to the second placement, GetSwift announced to the ASX that it had entered into agreements with a number of Enterprise Clients. GetSwift made these announcements, notwithstanding that some of the agreements had allegedly not progressed beyond a “trial period”, and before the potential benefits under the agreements were secure, quantifiable or measurable. In this context, a question arising is whether the release of regular price sensitive announcements to the ASX of GetSwift’s entry into agreements with major Enterprise Clients had the effect of reinforcing and engendering investor expectations that the GetSwift platform was being adopted by a growing number of major Enterprise Clients. These expectations are alleged to have been fashioned by the GetSwift Prospectus, investor presentations and its quarterly Appendix 4C reports (as described above).

37 It is further alleged that, in the same period, GetSwift failed to inform the market of information that materially qualified the ASX announcements. This included, among others, the termination of a number of agreements that had been the subject of an announcement, and decisions by clients that GetSwift’s services would no longer be utilised beyond the expiry of trial periods. In circumstances where GetSwift had a limited operating history and had incurred historic net losses, and where publicly available information about recent operations and performance was lacking, an important issue is whether GetSwift’s failure to disclose such information would have had a significant influence on whether an investor would acquire or dispose of GetSwift Shares. This must be considered in the light of all relevant circumstances, including the share placement which was to take place.

38 As noted above, the claims made by ASIC are complex and multifarious, but can be placed broadly into four categories by reference to each of the defendants.

39 First, ASIC alleges that GetSwift engaged in 22 contraventions of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act. In respect of these contraventions, ASIC seeks an order under s 1317G(1A) of the Corporations Act that GetSwift pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of the alleged continuous disclosure contraventions. Further, ASIC alleges that GetSwift engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and/or s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). It also seeks declaratory relief in respect of each of the alleged contraventions.

40 Secondly, ASIC alleges that Mr Hunter was directly, or indirectly, knowingly concerned, within the meaning of s 79 of the Corporations Act, in the continuous disclosure contraventions by GetSwift of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act, and was knowingly involved in 19 of the 22 contraventions alleged against GetSwift. By reason of this conduct, Mr Hunter contravened s 674(2A) of the Corporations Act. Further, ASIC alleges that Mr Hunter contravened s 1041H of the Corporations Act, and further or alternatively, s 12DA of the ASIC Act. Finally, ASIC alleges that Mr Hunter failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties as a director and executive chairman of GetSwift with the degree of care and diligence; thus contravening s 180(1) of the Corporations Act.

41 Thirdly, ASIC alleges that Mr Macdonald was directly, or indirectly, knowingly concerned, within the meaning of s 79 of the Corporations Act, in the continuous disclosure contraventions by GetSwift of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act, and was knowingly involved in all 22 of the contraventions alleged against GetSwift. By reason of this conduct, Mr Macdonald contravened s 674(2A) of the Corporations Act. Further, ASIC alleges that Mr Macdonald contravened s 1041H of the Corporations Act, and further or alternatively, s 12DA of the ASIC Act. Finally, ASIC alleges that Mr Macdonald failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties as a director and managing director of GetSwift with the degree of care and diligence; thus contravening s 180(1) of the Corporations Act.

42 Fourthly, ASIC alleges that Mr Eagle was directly, or indirectly, knowingly concerned, within the meaning of s 79 of the Corporations Act, in the continuous disclosure contraventions by GetSwift of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act, and was knowingly involved in nine of the 22 contraventions alleged against GetSwift. By reason of this conduct, Mr Eagle contravened s 674(2A) of the Corporations Act. Further, ASIC alleges that Mr Eagle failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties as a director of GetSwift with the degree of care and diligence; thus contravening s 180(1) of the Corporations Act.

43 In respect of each of the contraventions of ss 674(2A) and 180(1) of the Corporations Act by each of the directors, ASIC seeks pecuniary penalties. Further, ASIC seeks disqualification orders pursuant to s 206C(1) and/or s 206E(1) of the Corporations Act. Importantly, with the consent of the parties, the hearing conducted in 2020 was an initial hearing directed to issues of liability and the entitlement of ASIC to declaratory relief. Therefore, any issues of penal orders are to be determined separately and at a later date.

44 Given the length of what follows, it is useful to set out a summary of the principal conclusions that I have reached in relation to each claim.

45 First, GetSwift engaged in:

(1) 22 contraventions of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act; and

(2) 40 contraventions of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act.

46 Secondly, Mr Hunter:

(1) was knowingly involved in 16 of the 22 contraventions of GetSwift and thereby contravened s 674(2A) of the Corporations Act

(2) engaged in 29 contraventions of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act; and

(3) failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties as a director with the degree of care and diligence required and thereby contravened s 180(1) of the Corporations Act.

47 Thirdly, Mr Macdonald:

(1) was knowingly involved in 20 of GetSwift’s 22 contraventions and thereby contravened s 674(2A) of the Corporations Act;

(2) engaged in 33 contraventions of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act; and

(3) failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties as a director with the degree of care and diligence required and thereby contravened s 180(1) of the Corporations Act.

48 Fourthly, Mr Eagle:

(1) was knowingly involved in three of GetSwift’s 22 contraventions and thereby contravened s 674(2A) of the Corporations Act; and

(2) failed to exercise his powers and discharge his duties as a director with the degree of care and diligence required and thereby contravened s 180(1) of the Corporations Act.

C THE DEFENDANTS, THE BOARD AND OTHER KEY PLAYERS

49 GetSwift was incorporated on 6 March 2015 and from 7 December 2016, was a public company registered under the provisions of the Corporations Act. Relevantly, GetSwift was a listed disclosing entity and was subject to the continuous disclosure requirements of s 674 of the Corporations Act; and was subject to and bound by the Listing Rules.37

50 Mr Hunter has been a director of GetSwift since 26 October 2016, is the chief executive officer of GetSwift, and was the executive chairman of GetSwift between 26 October 2016 and 25 April 2018.38 Mr Macdonald has been a director of GetSwift since 26 October 2016, is the so-called “President” of GetSwift, and was the managing director of GetSwift between 26 October 2016 and 25 April 2018.39

51 Mr Eagle was a non-executive director of GetSwift between 26 October 2016 and 29 November 2018, between August 2017 and 21 August 2018, held the position of “General Counsel & Corporate Affairs” at GetSwift pursuant to a retainer between Eagle Corporate Advisers Pty Ltd (Eagle Corporate Advisers) and GetSwift, and between 26 October 2016 and 29 November 2018, was a solicitor admitted in New South Wales and the principal and sole director of Eagle Corporate Advisers.40

52 Beyond the facts as agreed between ASIC and GetSwift, there is additional evidence, as raised by Mr Hunter (and implied by Mr Macdonald) in their submissions, that Mr Eagle carried out the role of general counsel of GetSwift beginning no later than early February 2017 (rather than August 2017).41 Three aspects of the evidence are drawn upon to support this conclusion: first, in an email dated 8 February 2017, it was requested that a GetSwift business card be made for Mr Eagle with the title “General Counsel & Corporate Affairs”;42 secondly, in an email dated 17 March 2017, Mr Eagle stated “I am a director of GetSwift Ltd and also general counsel”;43 and thirdly, in an email dated 24 April 2017, Mr Eagle stated “I am general counsel at GetSwift”.44 In the absence of any explanation by Mr Eagle himself, the evidence supports a conclusion that Mr Eagle was the General Counsel of GetSwift (or at least the de facto General Counsel of the company) from at least 8 February 2017.45 Therefore, between February and August 2017, it would appear that things at GetSwift were simply being done in a relatively informal way concerning Mr Eagle’s position. Although, as will become evident below, this finding is immaterial to the disposition of any aspect of the case.

C.2 Operations of the board of GetSwift

53 During 2017, Messrs Hunter and Macdonald were based in New York,46 Mr Eagle was based in Sydney,47 and Ms Gordon worked in Melbourne from December 2016 to June 2017, and thereafter from Sydney until the conclusion of her engagement in November 2017.48

54 The evidence reveals that board meetings were conducted intermittently when Mr Hunter determined they should be called by the circulation of an invitation from him.49 The formality of the invitation and documentation differed depending on what was required.50 The directors received reports for quarterly, half yearly and annual reporting, but nothing else.51 There were otherwise no “board packs” or equivalent sets of documents circulated before board meetings.52 The board meetings were usually conducted via video conference.53

55 Mr Scott Mison, the company secretary for a large part of 2017, held an essentially administrative role.54 He was not responsible for preparing the agenda for board meetings and he otherwise prepared certain formal documents relating to the issue of shares.55 Shortly after he was appointed as company secretary and sometime in early 2017, Mr Hunter (somewhat unusually for a public company) instructed Mr Mison not to attend board meetings.56 To Mr Mison’s recollection, he only attended a board meeting in December 2016 and in January 2017 by telephone.57

56 Apart from board meetings, most communication between directors was by email, as is revealed by the deluge of emails admitted into evidence.58

C.3 Other personnel at GetSwift

57 GetSwift had few employees or staff. As at September 2016, the non-director employees included Mr Keith Urquhart (software developer and client services) based in Melbourne, Mr Joash Chong (software developer) based in Melbourne, Ms Stephanie Noot (accounts, payroll and finance) based in Sydney, Ms Susan Cox (administration and human resources) based in Perth, and the abovementioned Mr Mison (who was later replaced in August 2017) and was based in Perth.59 Other key employees of GetSwift included Mr Jonathan Ozovek, Mr Daniel Lawrence, Mr Brian Aiken and Mr Kurt Clothier.

58 GetSwift was assisted by Mr Harrison Polites and Ms Elise Hughan (from Media and Capital Partners) (M+C Partners). M+C Partners was responsible for managing GetSwift’s media, including the generation of media, journalist enquiries and the preparation of media releases for the press.60 GetSwift was also assisted by Mr Zane Banson (from The CFO Solution). The CFO Solution was managed by Mr Phillip Hains.61 It provided bookkeeping, accounting, preparation of board papers and company secretarial work.62 In July 2017, The CFO Solution was approached by GetSwift to provide it with accounting services.63 Following the resignation of Mr Mison, Mr Hains and The CFO Solution commenced performing secretarial work for GetSwift in late August 2017.64 While Mr Hains was the company secretary, Mr Banson had primary responsibility for assisting GetSwift (if that is the right word) with the lodgement of ASX announcements.65

59 As indicated above, this case was primarily run on the basis of documentary evidence, supplemented by affidavit and expert evidence.

60 It is useful to make a few observations about the evidence generally.

61 As I noted in Webb v GetSwift Limited (No 6) [2020] FCA 1292 (at [9]):

ASIC relied upon [39] witnesses from customers of GetSwift: four witnesses who were former associates of GetSwift; 10 witnesses from ASIC, the Australian Securities Exchange and Chi-X Australia (a securities and derivatives exchange); and four witnesses from organisations who were large investors in GetSwift. It also relied on opinion evidence from Mr Molony as a “professional investor”. Senior Counsel for GetSwift accepted on this application that none of the witnesses called by ASIC were challenged on their credit.

62 Out of this total of 39 witnesses, ASIC called four witnesses who were GetSwift employees and associate witnesses: Jamila Gordon (GetSwift); Scott Mison (GetSwift); Zane Banson (CFO Solution); and Harrison Polites (MC Partners).

63 The 19 customer witnesses of GetSwift were: Martin Halphen (Fruit Box); Veronika Mikac (Fruit Box); Ciara Dooley (Fruit Box); Allan Madoc (CBA); Bruce Begbie (CBA); Edward Chambers (CBA); David Budzevski (CBA)c; Natalie Kitchen (CBA); Patrick Branley (Pizza Pan); Alex White (APT); Paul Calleja (CITO); Mark Jenkinson (CITO); Devesh Sinha (Yum); Simon Nguyen (Fantastic Furniture); Abdulah Jaafar (Fantastic Furniture); Mariza Hardin (Amazon); Amelia Smith (Betta); Adrian Mitchell (Betta); and Roger McCollum (NAW).

64 The four investor witnesses were: Anthony Vogel; Timothy Hall; Maroun Younes; and Katherine Howitt.

65 The ten witnesses from ASIC, the ASX and Chi-X Australia (a securities and derivatives exchange) were: Kristina Czajkowskyj (ASX); Andrew Black (ASX); Andrew Kabega (ASX); Stuart Dent (ASIC): Benjamin Jackson (ASX); Jamie Halstead (ASX); Stephanie Yu-Ching So (ASX); Michael Somes (Chi-X); Martin Wood (ASIC); and Michael Hassett (ASIC). ASIC also relied on expert opinion evidence from Andrew Molony as a “professional investor”.

66 Out of these witnesses, 25 were cross-examined: Scott Mison; Jamila Gordon; Martin Halphen; Veronika Mikac; Ciara Dooley; Allan Madoc; Edward Chambers; David Budzevski; Natalie Kitchen; Harrison Polites; Patrick Branley; Alex White: Paul Calleja; Mark Jenkinson; Simon Nguyen; Abdulah Jaafar; Amelia Smith; Devesh Sinha; Mariza Hardin; Maroun Younes; Katherine Howitt; Timothy Hall; Anthony Vogul; Roger McCollum; and Andrew Molony.

67 Despite the cross-examination which took place, the evidence of the witnesses was not the subject of any real challenges as to credit: see Webb v GetSwift Limited (No 6) (at [9]). Accordingly, although some findings made below are necessarily based, at least to some extent, on my assessment of the credit of a witness, I have found it unnecessary to make general credit findings for the purposes of determining the relevant facts. Notwithstanding this, I do wish to make one general credit finding in relation to the evidence of one director of GetSwift: Ms Gordon was a highly impressive witness, was both careful and sober in her presentation, made appropriate concessions, and was clearly a witness of truth. I accept her evidence in its entirety.

68 Ms Gordon became a director of GetSwift on 20 March 2016. She was the Global Chief Information Officer (CIO) from 2 February 2017 until 13 June 2017. Ms Gordon undertook a variety of roles at GetSwift. When she was first engaged by GetSwift, Ms Gordon’s role included reviewing the Prospectus, understanding GetSwift’s governance arrangements, “on-boarding” clients once they had been “won”, as well as opening the Melbourne office. As CIO, she expanded GetSwift’s product offering by making it scalable, ensured that the right developers and testers worked on the GetSwift Platform, “on-boarded” clients, and made sure specific customisations were made to the GetSwift Platform. On 13 June 2017, Ms Gordon ceased working as CIO and her responsibilities were significantly reduced. In addition to working as a director, Ms Gordon engaged in a so-called “functional IT” role and managed the relationship with the CBA. As touched on above, her employment was terminated by GetSwift at a board meeting held on 7 November 2017. She ceased to be a director of GetSwift on 15 November 2017.66

69 As a director of GetSwift, Ms Gordon’s evidence sheds an important light on many of the internal happenings at GetSwift. In particular, she explained communications and discussions that she had with her fellow directors, particularly in respect to the timing, nature, and content of the ASX announcements. More specifically, she explained the GetSwift Platform, governance procedures and processes which were adhered to by the directors and employees of GetSwift, details from the 13 June 2017 and 7 September 2017 board meetings, the relationship between GetSwift and Fruit Box, CBA, Genuine Parts Company, and All Purpose Transport and finally, circumstances relating to her termination.67

D.2 The position of the Defendants

70 It is important to make a general observation about the way in which the defendants ran their case. The individual defendants did not go into the witness box, nor did they call any witnesses. Cross-examination of ASIC’s witnesses was primarily conducted on behalf of GetSwift, not by counsel for the directors. Furthermore, although the defendants each had separate counsel teams, they were represented by the same solicitors (except for Mr Eagle, who was represented separately). The individual defendants maintained their privilege against exposure to a penalty.

E A DISPUTE ABOUT ASIC’S PLEADED CONTINUOUS DICLOSURE CASE

71 Before making factual findings, it is necessary at the outset to address one overarching and contested issue which arose at different stages throughout the proceeding, including during the trial. The issue concerned the way in which ASIC’s continuous disclosure case was pleaded and run.

E.1 The iterations of ASIC’s pleaded case

72 Even though ASIC took plenty of time prior to commencing its case, various iterations of the pleaded case have been served throughout this proceeding. This has resulted in unnecessary disputation and controversy as to whether ASIC has gone beyond its pleaded case. More particularly, the dispute concerns the substance of ASIC’s pleaded case in relation to the categories of information relied upon for the purposes of the alleged continuous disclosure contraventions.

73 GetSwift argues that ASIC has pleaded a case that requires it to prove that each individual element of the pleaded categories of information in itself was not generally available and was material. In this way, GetSwift’s contention is that ASIC has pleaded an “all or nothing” case: that is, it must prove that each individual element was both not generally available and material. If but one element or component cannot be proven, the entire relevant continuous disclosure case fails.

74 On the other hand, ASIC maintains that its case does not necessarily fail, even if an element of the pleaded categories of information are not made out. Put somewhat simplistically, ASIC argues that its pleaded case simply requires it to prove that the information as a whole, being the combination of the elements of the pleaded information it proved existed, was not generally available and was material.

75 In determining the substance of ASIC’s pleaded case, it is important to emphasise, as I did during the course of oral submissions on this issue, that ASIC has attempted to run a consistent case from the beginning of the proceeding. This view holds, notwithstanding that the various iterations advanced by ASIC make it appear as though ASIC might have changed its pleaded case, or even resuscitated or revived a previous case. Regrettably, it is necessary to descend into the brume of the various pleadings to explain this further.

76 In its original statement of claim – and all subsequent iterations of it up to and including the further amended statement of claim filed on 24 December 2019 (FASOC) – ASIC adopted the formulation of “individually, collectively or in any combination” in respect of the various defined sets of information alleged for the purposes of the continuous disclosure contraventions. One example suffices. In the FASOC (at [29]), ASIC defined a set of information as: “(individually, collectively, or in any combination, the Fruit Box Agreement Information)” (emphasis altered).

77 In the second further amended statement of claim filed on 14 April 2020 (2FASOC), ASIC deleted the words “individually, collectively or in any combination” and replaced those words with the word “together” in respect of the various defined sets of information. This new formulation prevailed in a third further amended statement of claim filed on 18 June 2020 (3FASOC). In the 3FASOC (at [29]), for example, ASIC states: “(together, the Fruit Box Agreement Information)” (emphasis altered).

78 When it became apparent to ASIC that GetSwift was contending that this change represented a fundamental case shift, ASIC then sought to undo and reverse the amendments made in the 2FASOC in a proposed fourth further amended statement of claim (4FASOC) (which was circulated in June 2020), by reintroducing the deleted words “individually, collectively or in any combination”. The application for leave to amend to make this change was heard during the trial, which I refused.

79 ASIC contended that it had sought to revert to the formulation adopted up to and including the FASOC in the proposed 4FASOC in response to submissions that had been made by GetSwift by way of opening. Relevantly, it was proposed to meet an argument that the word “together” in the 2FASOC had the consequence that ASIC had “to prove each individual element in itself was not generally available and more particularly was material”.68 Since this was not ASIC’s case, and was said to have “never been the case”,69 ASIC explained that it had simply reinserted the previous formulation in the proposed 4FASOC to avoid ambiguity and make it clear that “there is a single contravention, but it may comprise any one or more of those elements”.70

80 Put in another way, ASIC contended that its case, as it had always been, was that it had to prove that “the information as a whole was not generally available and the information as a whole was material”.71

81 As one might expect, GetSwift disagreed with ASIC’s characterisation of the pleading. Its primary contention was that by attempting to reintroduce the deleted words in the proposed 4FASOC, ASIC was essentially resuscitating a case it had “abandoned” when it had filed the 2FASOC.72 GetSwift asserts that leave to amend should be refused and that GetSwift should relevantly be held to the pleaded case as submitted in the 2FASOC and 3FASOC.

82 For example, GetSwift argued it would be unjust for ASIC to “reverse [a] deliberate forensic decision” previously taken absent adequate explanation; that GetSwift would suffer forensic prejudice; and that the amendment, went against the evidence of ASIC’s own expert, Mr Molony.73 GetSwift further contended ASIC had been afforded plenty of opportunities to amend and the delay in seeking the amendment after the commencement of the trial was particularly problematic.74 Finally, GetSwift asserted that granting leave to amend could cause potential loss of public confidence in the legal system; and (less unrealistically) that such a course did not align with the parties’ obligation to act in accordance with the overarching purpose referred to in Pt VB of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

83 Unsurprisingly, there was no dispute between the parties as to the applicable legal principles which do not require excursus, save for two propositions that deserve particular emphasis.

84 First, an abundance of authority confirms the need for precision in pleadings, particularly in cases involving allegations of misleading and deceptive conduct, or which involve the contravention of a civil penalty provision. Indeed, it is of the “utmost importance” that such cases be “finally and precisely pleaded”: Truth About Motorways Pty Ltd v Macquarie Infrastructure Investment Management Ltd (1998) 42 IPR 1 (at 4 per Foster J). Insisting on precise pleading in cases concerning allegations of misleading or deceptive conduct is not mere pedantry. A fair trial of allegations of contravention of law requires “the party making those allegations … to identify the case which it seeks to make and to do that clearly and distinctly”: Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; (2012) 247 CLR 486 (at 502 [25] per French CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Kiefel JJ).

85 Secondly, notwithstanding that the authorities make it clear that pleadings must be drafted with precision, this does not mean that one should lose sight of the fact that the fundamental purpose of pleadings is procedural fairness and ensuring that an opposing party is aware of the case that it is required to meet. Pleadings are a means to an end and not an end in themselves: see Banque Commerciale SA (En Liqn) v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 (at 292–293 per Dawson J); Gould and Birbeck and Bacon v Mount Oxide Mines Ltd (in liq) (1916) 22 CLR 490 (at 517 per Isaacs and Rich JJ); Ethicon Sàrl v Gill [2021] FCAFC 29 (at [687]–[689] per Jagot, Murphy and Lee JJ). The overarching consideration is always whether the opposing party knows the nature of the case they have to meet.

E.4 Pleadings and continuous disclosure cases

86 The real substance of the dispute is adapting and applying these general principles to the particular circumstances of this case.

87 Continuous disclosure cases often present challenges to a pleader. An important challenge, not present here, but present in class actions, is the deficiency in understanding at the outset of litigation the precise nature of the information within the knowledge of a disclosing entity at the time it is alleged that certain information should have been disclosed. This asymmetry of information is cured in ordinary civil cases by discovery or interrogation, which leads to frequent amendment in cases of this type. But that does not apply to the present case. Prior to commencement, the regulator had the means to procure the necessary information to allow it then to make wholly informed decisions as to how the information alleged to be material was to be identified and then pleaded.

88 However, another common challenge was present. It arises because, as explained below, the whole obligation to make continuous disclosure focuses upon the concept of “information”. It is information that is not generally available; and that a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of the relevant securities that must be notified. Several questions arise, the underlying thrust of which is the need to understand the content of the information said to enliven the obligation to disclose. Most obviously, there is a need to examine:

(1) When can it be said that an entity has the information?

(2) When is the information generally available?

(3) When would a reasonable person expect that information to have a material effect on the price or value of the relevant securities?

89 Identifying the relevant information, proving it existed, and also proving it was not generally available and material is fundamental. What is also evident is that in cases of any complexity, there are aspects of the information that are integral and other aspects that might be described as peripheral or supplementary and may not, in and of themselves, be material. An illustration of this can be seen by reference to the James Hardie litigation, in which the question considered here arose in a different context; that is, whether it is each individual element or the information as a whole that must be found to have not been generally available.

90 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Macdonald (No 12) [2009] NSWSC 714; (2009) 259 ALR 116, it was held that a James Hardie entity, JHINV, had failed to notify the ASX of the relevant information (defined as the ABN 60 Information) in an identified period. In doing so, it had contravened s 674 of the Corporations Act. The ABN 60 Information was defined as consisting of a number of distinct elements, including (at [201] per Gzell J):

(1) the execution of a deed of covenant, indemnity and access (DOCIA) by JHINV and another James Hardie entity, JHIL;

(2) the issue of 1000 shares by JHIL to the ABN 60 Foundation; and

(3) the cancellation by JHIL of its one fully paid share owned by JHINV for no consideration.

91 In the Court of Appeal of New South Wales, a dispute arose as to whether some aspects of the ABN 60 Information had, in fact, been generally available: James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010) 274 ALR 85. JHINV contended that it had made available all of the information in a public report, absent the first element (i.e. the indemnity in the DOCIA). It therefore argued that the information required to be disclosed had been “readily available” within the meaning of s 676(2) of the Corporations Act. In this way, JHINV’s case was that, with the exception of one element, the information had been disclosed and was thus “generally available”.

92 This case was rejected by the Court (at 198 [545]) on the basis that the DOCIA was such an integral part of the ABN 60 Information that its absence from the public report meant that there had been no relevant disclosure of the ABN Information. The fact that an integral part of the defined information was not generally available was sufficient to find that there had been no disclosure of the pleaded information as a whole, notwithstanding that other elements of the information were generally available.

93 Here, absent an overly-technical literal reading, any common sense review of the pleading reveals that the material information has been pleaded in such a way as to make it sufficiently evident that some aspects or individual components of the information could not of themselves be material (although they were of significance contextually), whereas some aspects are integral in assessing whether the information not generally available, as a whole, was material.

94 Informed by the above principles and the reality that omitted “information”, if it is of any complexity, will almost always have different components with different degrees of importance, I am unpersuaded by GetSwift’s contention that ASIC has pleaded a case that requires it to prove that each individual element of the pleaded categories of information, however marginal, was not generally available and was material.

95 ASIC’s pleaded case has been substantively consistent throughout the proceeding and was well understood by GetSwift. It is notable that no evidence was adduced indicating directly that those advising GetSwift were labouring under any misapprehension as to the nature of ASIC’s case and made any specific forensic decision based upon such a misapprehension. The reason why there was no such direct evidence is tolerably clear – there was no real misunderstanding and I expect no solicitor could conscientiously swear to the contrary.

96 GetSwift says it made it “expressly clear in its opening submissions that it was holding ASIC strictly to its pleaded case and that it did not acquiesce in the conduct of any trial beyond the pleaded case”,75 and it otherwise made that position clear in the course of the trial. So much may be true, but that is beside the point. GetSwift knew the case it had to meet. To the extent that any of the various iterations of ASIC’s written pleadings were vague or unclear, by way of opening, on 18 June 2020, Mr Halley SC, senior counsel for ASIC, who was not in the case when it was originally pleaded, explained that Mr Darke SC, who appeared for GetSwift:

wishes to advance a case that, if your Honour is not satisfied that every single element is not generally available and every single element, in themselves, is not material, then we fail. And we reject that, understandably, out of hand.

…

[T]hat’s why we moved away from the individually or collectively or in any combination pleading, because that’s not our case. Our case is that the information as a whole was not generally available and the information as a whole was material.76

97 The substance of ASIC’s pleaded case was again articulated and clarified when ASIC applied to the Court for leave to amend its pleadings on 22 June 2020. I asked the following question of Mr Halley:

[D]o you contend … that ASIC’s case is that the contraventions of section 674(2) will be established if the individual elements of the information, as pleaded, taken together, were not generally available and were material in the requisite sense that ASIC intends to convey and continues to maintain that ASIC’s case will not fail if ASIC is not able to establish in that, in isolation, any individual element of the defined information was generally available or any individual element of the defined information was not material in the requisite sense?77

98 He responded with a definitive “yes”.

99 If this still was not clear, or questions remained as to whether ASIC had maintained a consistent pleaded case throughout these proceedings, Mr Halley further explained on 14 August 2020 that:

But what the defendants have done, it seems, is to seek to pick off individual elements or sub-elements or sub-sub-elements and say, “Well, you failed on that. You haven’t proved that … in isolation is material. Therefore, your case must fail with respect to that allegations of contravention of 674(2).” We say that’s not the case that ASIC has advanced, not the case that ASIC has pleaded and not the case that ASIC has otherwise opened, closed and conducted the case on.78

100 Although ASIC took a reactive step to ensure that its case did not ultimately fail on the basis of a technical point, the proposed 4FASOC was consistent with the case it had run from the outset. Of the reasons why I denied leave to amend is that the proposed amendment identified a case that ASIC did not wish to run, and one which would have produced an absurdity if it was read literally (as GetSwift was determined to do). As GetSwift correctly pointed out, the introduction of the words “in any combination” in the proposed amendments had the effect, again if read literally, of vastly multiplying the number of cases on materiality which it would be required to meet. Indeed, GetSwift engaged in a mathematical exercise to work out the number of permutations that a case of this nature would encompass.79 For example, in respect of the NAW Projection Information, there were 18 separate items of information. Thus, the number of possible different combinations which could comprise the defined piece of information would be 262,143. Of course, this was all a bit silly because this was never ASIC’s case. That is why, in the circumstances, I disallowed the amendments and refused leave for ASIC to amend its pleadings during the trial. In my view, there was no need for ASIC to amend its pleadings in the circumstances or to clarify further its case by reformulating its pleadings once again. Despite the various iterations of its pleadings, ASIC maintained at trial the same case that it had maintained from the beginning: if the elements of the information it identified were proved at trial to be not generally available and material, and those elements (taken as a whole) were proved not to have been disclosed, then contravening conduct took place.

101 Contrary to GetSwift’s submissions, ASIC did not make any deliberate forensic decision to abandon an earlier aspect of its case. ASIC’s initial pleading may have been somewhat maladroit and its approach to this issue by serial amendment and proposed amendment may have been less than ideal, but I reject any notion that there has been any want of procedural fairness provided to the defendants in this regard. They all knew the case they needed to meet and proceeded to conduct their defence accordingly. In all the circumstances, it is quite understandable why this pleading point would be taken by the defendants, but in the absence of any proven prejudice, it is devoid of substantive merit.

102 Before making factual findings, it is appropriate to address a number of preliminary issues as to the correct approach that I should adopt.

F.1 The nature of the contest at trial

103 In Webb v GetSwift Limited (No 5) [2019] FCA 1533, I noted the following about the process of fact finding (at [17]–[18]):

17. As those experienced in commercial litigation in general, and in securities class actions in particular, would readily appreciate, what matters most in the determination of the issues in cases such as this is the analysis of such contemporaneous notes and documents as may exist and the probabilities that can be derived from these documents and any other objective facts. Take the example of the dealings between GetSwift and the customers: there is likely to be a documentary record both within the business records of GetSwift and their contractual counterparty which records dealings between them which go beyond the agreement itself. Additionally, experience suggests that it is also likely that there will be informal email exchanges, both between GetSwift and the customers, and within the relevant organisations.

18. As Leggatt J said in Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Limited [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) at [15]–[23], there are a number of difficulties with oral evidence based on recollection of events given the unreliability of human memory. Moreover, considerable interference with memory is also introduced in civil litigation by the procedure of preparing for trial. As his Lordship noted, a witness is asked to make a statement, often when considerable time has already elapsed since the relevant events. The statement is usually drafted by a solicitor who is inevitably conscious of the significance for the case of what the witness does or does not say. The statement is often made after the memory of the witness has been “refreshed” by reading documents. The documents considered can often include argumentative material as well as documents that the witness did not see at the time and which came into existence after the events which the witness is being asked to recall. It may go through several iterations before it is finished. As Lord Buckmaster famously said, the truth “may sometimes leak out from an affidavit, like water from the bottom of a well”. This may be overly cynical, but the surest guide for deciding the case will be as identified by Leggatt J at [22]:

… the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is, in my view, to place little if any reliance at all on the witnesses’ recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known or probable facts.

(Emphasis added).

104 As the Full Court recently observed in Liberty Mutual Insurance Company Australian Branch trading as Liberty Specialty Markets v Icon Co (NSW) Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 126 (at [239] per Allsop CJ, Besanko and Middleton JJ), this approach might be best seen as a helpful working hypothesis rather than something to be enshrined in any rule or general practice of placing little reliance on recollections of conversations.

105 In the present case, the helpful working hypothesis of paying close regard to the contemporaneous documents is of importance. However, the factual issues are not in substantial contest between the parties; what is in contest are the inferences and conclusions (both factual and legal) that are to be drawn from contemporaneous communications.

106 In accordance with this view, the factual findings that I will make are made upon a mixture of the agreed facts between the parties, material drawn from contemporaneous documents, witness and affidavit evidence (which, as I noted earlier, has largely not been challenged in a significant way), as well as inferences drawn from any documents or statements.

F.2 The principled approach to fact finding

107 Leaving aside the significance of the choice of GetSwift and the directors not to call witnesses, which I will deal with separately, both ASIC and GetSwift and the directors made a number of general submissions relating to the approach that the Court should take in respect of fact finding, to which it is appropriate to make a general response.

F.2.1 Affidavits and the documentary case

108 ASIC noted that the evidence contained in the affidavits of its witnesses had remained in large part uncontested. As a consequence, it argued that in making conclusions of fact and drawing relevant inferences, I should rely on the totality of the unchallenged affidavit evidence adduced before this Court.

109 In some cases, including regulatory cases, affidavits need to be approached with some caution as they are often less the authentic account of the lay witness, but rather an elaborate construct, being the result of legal drafting (Lord Woolf MR, Access to Justice Report, Final Report (HMSO), 1996 (at Ch 5, [55])). However, I accept that as a general proposition unchallenged evidence that is not inherently incredible ought to be accepted by the tribunal of fact: Precision Plastics Pty Limited v Demir (1975) 132 CLR 362 (at 370–371 per Gibbs J, Stephen J agreeing, Murphy J generally agreeing); Ashby v Slipper [2014] FCAFC 15; (2014) 219 FCR 322 (at 347 [77] per Mansfield and Gilmour JJ).

110 Although, of course, unchallenged evidence can be rejected if it is contradicted by facts otherwise established by the evidence or particular circumstances point to its rejection, the affidavits, speaking generally, were consistent with the documentary case of ASIC.

111 As to the documentary case, ASIC placed reliance upon the well-known principle that “all evidence is to be weighted according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced, and in the power of the other to have contradicted”: Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 (at 65 per Lord Mansfield), cited with approval in Weissensteiner v The Queen (1993) 178 CLR 217 (at 225 per Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ).

112 Why this is of importance in the present case is a little unclear to me. Although GetSwift had the power to adduce what documents it wished to rely upon to qualify or contradict the conclusions ASIC contends should be drawn from the documentary evidence, ASIC is not an ordinary litigant. It is in the privileged position of having compulsory production powers and can, in this sense, marshall the material it contends is relevant to its case. There was no suggestion that GetSwift had not given full and complete discovery of all documentary evidence following the extensive compulsory document production to ASIC.

F.2.2 The oral evidence generally

113 In addition to stressing, correctly, that the documentary record remains the best foundation for the finding of facts in this case, ASIC asserted that the Court should be cautious about a number of answers in cross-examination where the cross-examiner pressed the witness on accepting the “possibility” that something may have occurred or been said or the “possibility” that some matter could not be ruled out (being an event or comment that was inconsistent with ASIC’s account).

114 A witness’ refusal to rule out a “possibility”, including a hypothetical one, about whether a particular event or conversation occurred was a feature of the evidence. There is a risk of over generalisation in submissions of this type. However, to the extent it is useful in speaking in generalities, confronting a witness with the possibility that an event may have occurred and the witness accepting it as a possibility, is not in itself proof that the fact did exist. It may rationally bear upon whether all the evidence pointing to the existence of the fact should be accepted (or whether ASIC has proved a different state of affairs existed); but these are distinct points.

115 As I will explain, a key difficulty for the defendants in challenging ASIC’s case theory based on the documentary record (and the affidavits in relation to each Enterprise Client), is not only the general lack of challenge to the affidavit material, but the lack of any rational counter-narrative. The evidence as a whole in relation to each Enterprise Client suggests a course of events consistent with ASIC’s allegations and this has been left essentially uncontradicted. This makes the picture emerging from the contemporaneous business records quite compelling. This comment does not amount, of course, to an inversion of onus, for reasons I will now explain.