FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Henley Arch Pty Ltd v Henley Constructions Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1369

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent PATRICK SARKIS Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 November 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of this order, the parties are to have conferred and provided to the Associate to Justice Anderson proposed minutes of orders to give effect to the Reasons for Judgment of Justice Anderson in this proceeding, and to timetable the steps required for a hearing on the relief sought by the applicant of an account of profits.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANDERSON J:

1 The applicant (Henley Arch) claims that the first respondent (Henley Constructions) has infringed, and continues to infringe, Henley Arch’s various registered and unregistered trade marks, and has also contravened ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) by using various marks branded with the name “Henley”, or variations of that name in Henley Constructions’ building, construction and design business. This includes Henley Constructions’ use of the marks “HENLEY CONSTRUCTIONS”, “HENLEY”, “THE HENLEY DISPLAY GALLERY”, and “1300HENLEY” as its contact telephone number, various logos containing the name “Henley Constructions” as well as a number of instances where this name was used such as websites, number plates and on social media platforms. Henley Arch also contends that the second respondent (Mr Sarkis) is jointly liable for Henley Constructions’ conduct.

2 Henley Constructions denies that it has infringed Henley Arch’s trade marks or engaged in conduct which contravenes ss 18 and 29 of the ACL.

Henley Constructions’ cross-claim

3 Henley Constructions, by its cross-claim, makes the following four claims. First, Henley Constructions submits that the trade marks registered by Henley Arch as at the priority date were non-distinctive and ought be cancelled under ss 41 and 88 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA).

4 Second, Henley Constructions submits that Henley Arch’s trade marks were accepted on the basis of representations that were false in material particulars and ought be cancelled under ss 62(b) and 88 and of the TMA.

5 Third, and in the alternative to the first two grounds above, Henley Constructions submits that Henley Arch’s trade marks had not been used in the State of New South Wales between 7 October 2015 and 7 October 2018 (non-use period). Henley Constructions submits that there is considerable evidence that the building and construction industry is a State-based market rather than a national market and because, in its contention Henley Arch’s trade mark registration does not cover the State of New South Wales, these trade marks ought be subject to limitations under ss 92(4)(b)(i) and/or (ii), and ss 102(1)(b) and (2) of the TMA. Henley Constructions submits that the following limitations should be placed on the trade marks:

(1) at the end of the class 37 services specification, the words “none of the above being in relation to multi-dwelling residential apartment buildings”, should be added. Because of this and other contentions raised in this proceeding, there was a good deal of evidence concerning whether the construction market can be segmented into different types of services, being the construction of detached or semi-detached houses, and the construction of “multi-dwelling residential apartment buildings”.

6 Fourth, Henley Constructions contends that, during the non-use period of between 7 October 2015 and 7 October 2018, the trade mark No. 1152818  (“HENLEY PROPERTIES” Device Mark) had not been used for the services for which it was registered in Australia or, in the alternative, in the State of New South Wales, and:

(“HENLEY PROPERTIES” Device Mark) had not been used for the services for which it was registered in Australia or, in the alternative, in the State of New South Wales, and:

(1) ought be wholly removed from the register under s 92(4)(b) and s 101 of the TMA; or

(2) in the alternative, ought be subject to limitations under s 92(4)(b) and s 102 of the TMA which read:

(a) registration does not cover the State of New South Wales; and

(b) at the end of the class 37 services specification, the words “none of the above being in relation to multi-dwelling residential apartment buildings”, should be added.

7 This judgment proceeds as follows. First, I set out Henley Arch’s trade marks. Second, I set out the evidence of Henley Arch and the evidence of Henley Constructions. Third, I set out my findings on the evidence. Fourth, I consider the issue of trade mark infringement. Fifth, I consider the alleged contravention of the ACL. Sixth, I consider Henley Constructions’ defences. Seventh, I consider Henley Constructions’ cross-claims. Eighth, I consider any ancillary liability of the second respondent, Mr Patrick Sarkis. Ninth, I consider the issue of relief.

8 For the reasons that follow, there will be judgment for Henley Arch in this proceeding.

9 Since 1989, Henley Arch has traded under and by reference to the following trade marks which it has used to promote its business.

10 From 1989 until in or about 2005 (Initial Henley Devices):

11 From in or about 2005 (2005 Henley Devices):

12 From in or about 2017 (2017 Devices):

13 Henley Arch is also the owner of various trade marks registered under the TMA which each include the word “Henley”.

14 The following table provides the particulars of Henley Arch’s registered trade marks:

Mark | Reg. No | Priority Date | Registered Services |

HENLEY | 1152820 | 18 December 2006 | Building and construction services (class 37); architectural, engineering, design, drafting and interior design services (class 42) |

| 1152818 | 18 December 2006 | |

HENLEY WORLD OF HOMES | 1152819 | 18 December 2006 | |

HENLEY ESSENCE | 1806558 | 2 November 2016 | Building and construction services (class 37); architectural, engineers, design, drafting and interior design services including construction design and construction drafting (class 42) |

HENLEY RESERVE | 1806561 | 2 November 2016 | |

HENLEY COLLECTION | 1806570 | 2 November 2016 |

15 The parties in this proceeding have tendered voluminous evidence from a number of witnesses. Much of that evidence was of limited assistance. The key witnesses were Mr Harvey for Henley Arch, and Mr and Mrs Sarkis for Henley Constructions. The other witnesses were of marginal relevance to the critical issues in this proceeding. However, I have set out in some detail the evidence that was put before the Court, so that there can be an appropriate appreciation of the evidentiary matters which the parties considered were relevant to the issues in this proceeding.

16 I turn to set out the evidence of Henley Arch.

17 The parties agreed upon a consolidated list of documentary evidence that was tendered in evidence at the trial of the proceeding (Tender Bundle). That list of documents is Annexure A to orders made in this proceeding on 11 May 2021.

18 Henley Arch tendered in evidence the affidavits of:

(1) Damien Boyer affirmed 8 May 2019 and 6 May 2020;

(2) John Edward Harvey sworn 10 May 2019, 20 December 2019 and18 June 2020;

(3) Joanna Margaret Lawrence affirmed 10 May 2019, 31 October 2019 and 6 May 2020;

(4) Patrick Prentice affirmed 5 June 2020;

(5) Iain Brian Whyley affirmed 5 June 2020; and

(6) Christopher Butler dated 23 March 2021.

19 Henley Arch’s witnesses relevantly gave the following evidence.

20 Mr John Harvey has sworn three affidavits in this proceeding, being an affidavit sworn 10 May 2019 (First Harvey Affidavit), an affidavit sworn 20 December 2019 (Second Harvey Affidavit), and an affidavit sworn 18 June 2020 (Third Harvey Affidavit). Mr Harvey gave honest and considered evidence which I accept as a truthful account of events.

21 In the First Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey deposed to the following matters.

22 In 1989, Mr Harvey co-founded Henley Arch and was a director up until his retirement on 21 March 2020.

23 Mr Harvey began his career in the building industry in May 1973 as a survey assistant with the Land Division of Hooker Corporation, undertaking both field and office training in all aspects of residential land development while also undertaking studies at night between 1974 and 1977 to obtain a Certificate of Survey Drafting and subsequently between 1978 and 1984 a Bachelor of Applied Science in Planning. In 1984, Mr Harvey transferred to the Housing Division of Hooker Corporation and was appointed Assistant Sales Manager until he resigned in June 1987 to undertake the role of General Manager with Merchant Builders. In 1989, Mr Harvey left Merchant Builders to establish Henley Arch with two co-founders, Peter Anthony Hayes and Robert Evan Bowen.

24 Mr Harvey, whilst a director of Henley Arch, was involved in the day to day management of the Henley Properties Group. The Henley Properties Group, at all material times, comprised Henley Arch and its subsidiaries. Mr Harvey was involved in the major business strategy decisions across the Henley Properties Group including in relation to the geographic markets and customer demographics targeted by the group. Mr Harvey’s evidence was that the customer base for the Henley Properties Group has always included owner-occupiers (that is, people who purchase and/or build a residence on land with the intention of living in it) but also a significant number of investors, who may reside in a particular State in Australia and choose to purchase land in another State and engage Henley Arch to construct a dwelling on that land. Mr Harvey said that many of the Henley Properties Group’s owner-occupier customers come from States other than Victoria, or from another country and choose to relocate in a new State and purchase land upon which to construct a new dwelling.

25 Mr Harvey deposed that, from around October 1989, Henley Arch began by selling “spec” homes to consumers in the south-east suburbs of Melbourne, Victoria. “Spec” homes are homes that Henley Arch constructed on land it owned, which it then sold to customers after construction of the house had been completed.

26 Since late 1993 or early 1994, Henley Arch began selling “contract homes”, being homes that Henley Arch would build on land owned by the customer, and broadened its operations throughout the Melbourne suburbs and surrounding the Geelong area. Mr Harvey’s evidence was that, by 1997, Henley Arch operated not only in Victoria, but in New South Wales, particularly in the greater metropolitan Sydney area and on the New South Wales central coast. Henley Arch was also operating in Queensland, in Brisbane, Gold Coast and the Sunshine Coast as well as having operations in South Australia.

27 By 2019, the Henley Properties Group had expanded to employ approximately 557 people including part-time and casual employees, and to have engaged approximately 1,320 contractors and subcontractors, throughout the residential building industry throughout Australia.

28 Mr Harvey deposed that Henley Arch employs marketing executives who develop and execute marketing strategies for the Henley Properties Group. Marketing teams exist both at a national level and also in each State market.

29 Mr Harvey deposed that, since around 2003, Henley Arch has promoted its business and the business of the Henley Properties Group at its website, www.henley.com.au (Henley Website).

30 Mr Harvey gave evidence that Henley Arch has, over time, used Google Analytics to track visits to the Henley Website. Henley Arch does not have access to Google Analytics data for the Henley Website prior to 2013, as visits to the Henley Website were not tracked prior to 2013. From 1 January 2013 to 17 January 2017, traffic data for the mobile version of the Henley Website was recorded separately from the desktop version, following which the mobile and desktop versions were combined into the current version of the Henley Website.

31 On or around 27 March 2019, Mr Harvey caused to be produced Google Analytics data for the Henley Website dating back to 2013. The information in the following table represents the traffic to both versions of the Henley Website from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2018.

Year | Desktop website visits | Mobile website visits | Total |

2013 | 152,116 | 4,149 | 156,265 |

2014 | 259,457 | 60,524 | 319,981 |

2015 | 235,741 | 82,565 | 318,306 |

2016 | 212,713 | 94,879 | 307,592 |

2017 | 321,459 | 6,848 | 328,307 |

2018 | 299,510 | N/A | 299,510 |

32 Mr Harvey exhibited to the First Harvey Affidavit evidence of the traffic to both the Henley desktop website and the mobile website from IP addresses in Victoria between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2018. That data is collated in the following table:

Year | Desktop website visits from Victoria | Mobile website visits from Victoria | Total |

2013 | 110,439 | 3,610 | 114,049 |

2014 | 179,823 | 52,259 | 232,082 |

2015 | 180,969 | 71,417 | 252,386 |

2016 | 159,928 | 82,947 | 242,875 |

2017 | 275,336 | 6,149 | 281,485 |

2018 | 261,860 | N/A | 261,860 |

33 Mr Harvey gave evidence that Henley Arch has used various social media platforms to promote the Henley Properties Group and its business throughout Australia. By way of example:

(1) LinkedIn: The Group uses a LinkedIn account (https://www.linkedin.com/company/henley-properties), which as of 1 April 2019 was followed by 6,202 LinkedIn users. The earliest post on this page is from around April 2018.

(2) Instagram: the Group uses a dedicated Instagram account (https://www.instagram.com/henley homes/), which as at 1 April 2019 had 7,524 followers and featured 250 posts. The earliest post on this page is dated 10 February 2017 and the profile was opened on or around 21 January 2017.

(3) Pinterest: the Group uses a Pinterest page (https://www.pinterest.corn.au/HenleyAU/), which as at 28 March 2019 had 374 followers. The Group uses its Pinterest page to promote its services, including in relation to interior design, and to direct viewers of its Pinterest page to the Henley Website.

(4) Facebook: the Group uses a Facebook account (https://www.facebook.com/Henley-Homes-928470900610618/). This account was created on 18 December 2018.

(5) YouTube: since January 2017, the Group has used a dedicated “Henley Properties” YouTube channel, which as of 1 April 2019 was followed by 232 YouTube subscribers with its videos receiving a total of 13,284 views.

(6) Vimeo: the Group publishes videos on Vimeo, a video streaming platform.

34 Mr Harvey’s evidence was that, since January 1990, Henley Arch has contracted with persons located throughout Australia to build and/or sell homes in Victoria. Henley Arch uses various premises and showrooms throughout Victoria to promote the business of the Henley Properties Group including a “Henley Design” showroom in Victoria, which has been operational since 21 August 2017, and five “World of Homes Experience Centres” located in Victoria, which have been variously operational since October 2014, April 2016, October 2016, January 2017 and January 2018.

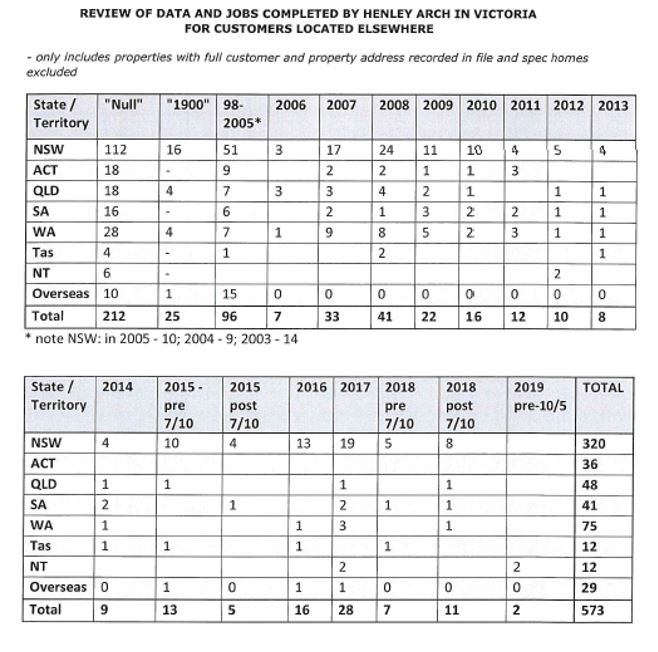

35 Confidential annexure “JH-24” to the First Harvey Affidavit provides copies of Henley Arch’s trading results for its operations in Victoria from 2000 to 2017. These figures reflect the number of homes built and completed by Henley Properties Group on customer land, and “spec” homes settled during this period. The confidential annexures to the First Harvey Affidavit disclose that Henley Arch, since 2000, has built hundreds of homes expanding recently to in excess of 1,000 homes per annum in Victoria.

36 In cross-examination, Mr Harvey was taken to confidential annexure “JH-26” to the First Harvey Affidavit. Mr Harvey said that the purpose of this annexure was to demonstrate, over an extended period, how many houses located in Victoria had been sold by Henley Arch to people residing outside of Victoria, including in New South Wales. Mr Harvey accepted that there were aspects of this annexure, which is a spreadsheet, that were anomalous. First, there were entries in the spreadsheet which recorded that the “Settled Date” for a home was “Null”. Mr Harvey explained that these “Null” entries, in his experience with the records of Henley Arch, indicate that there was no settlement date entered into the relevant Henley Arch database, but that did not mean that no settlement occurred. Mr Harvey accepted that these “Null” entries were data entry errors. These errors occurred when a person did not enter the settlement date for the relevant home construction into the database. Mr Harvey accepted that he had not reviewed each of these “Null” entries to identify whether a data entry omission could explain each of them, but Mr Harvey’s experience was that “Null” entries generally indicated that a staff member had omitted to enter the relevant settlement date data into the relevant database.

37 Second, there were entries in this spreadsheet that had a settlement date of “1 January 1900”. Mr Harvey accepted that this was obviously an error. Mr Harvey said that he had not been able to identify the cause of that error.

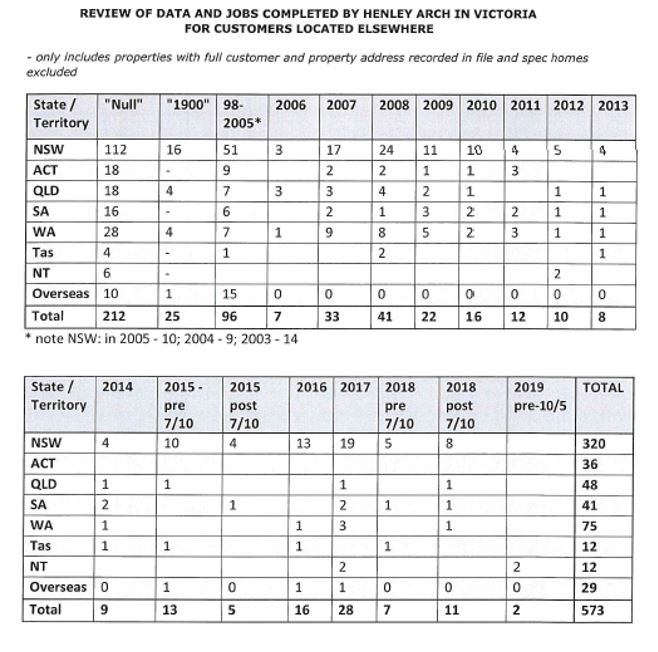

38 As matters transpired during the trial, Henley Arch ultimately produced a summary document, which provided a summary of confidential annexure “JH-26”, including by identifying the number of “Null” entries and the entries which had a settlement date of “1 January 1900”. That summary document was Exhibit A23. It provides as follows:

39 Confidential annexure “JH-27” to the First Harvey Affidavit sets out extracts of building contracts and tender acceptance forms for the period 2001 to 2017 from customers having an address in New South Wales or the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) who purchased homes from, or had homes constructed by, Henley Arch on land located in Victoria. Confidential annexure “JH-27” included extracts of the following:

(1) 18 “authorised tender acceptance” documents dated between 10 May 2001 and 5 June 2008, for customers located in the ACT or New South Wales, in relation to construction projects located in Victoria. On its face, the “authorised tender acceptance” document appears to record the relevant customer’s acceptance of Henley Arch’s tender to construct the relevant project at the relevant property;

(2) eight building contracts dated between 10 June 2005 and 14 December 2017, between Henley Arch and customers located in New South Wales, in relation to construction sites located in Victoria;

(3) two “post contract variation” documents dated 8 November 2007 and 27 November 2007, concerning customers located in New South Wales, and in relation to houses located in Victoria; and

(4) two contracts for the sale of real estate dated 24 September 2013 and 8 September 2016, between Henley Arch and a customer located in New South Wales, in relation to a property located in Victoria.

40 I should state that there were other documents which were included within confidential annexure “JH-27” to the First Harvey Affidavit that are not referred to in the summary above. These documents were not referred to because it was not clear whether the customer was based in New South Wales, or whether the relevant site was located in Victoria. In some cases, the date of the document was also not immediately apparent.

41 Mr Harvey deposed that the documents extracted as confidential annexure “JH-27” to the First Harvey Affidavit provide examples of relevant transactions between 2001 and 2017 and do not represent an exhaustive record of all transactions during this period. However, they do represent the way the contracts and tender acceptance forms appeared for all such customers at their respective dates.

42 Mr Harvey said that all customers of Henley Arch that purchased homes in Victoria entered into contracts with “Henley Arch” rather than a subsidiary of the Henley Properties Group, or an entity bearing the name of the site in which the homes were marketed for purchase. This was so regardless of the trading name Henley Arch used (such as “Clendon Vale Homes”, “Northridge Homes” or “MainVue”).

43 Mr Harvey said that, from 1995 to 2001, the Henley Properties Group has contracted with persons to build and/or sell homes in Queensland through its licensee, and now wholly owned subsidiary, Henley Properties (Qld) Pty Ltd (Henley Queensland). Since 2001, the Henley Properties Group has contracted with persons to build and/or sell homes in Queensland under the trading name “Plantation Homes” which is a business name owned by Henley Queensland.

44 Mr Harvey’s evidence was that, for homes being built in Queensland, all customers of the Henley Properties Group have always entered into contracts with Henley Queensland. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) Current and Historical Organisation Extract for Henley Queensland obtained on 15 April 2019 records that Henley Queensland is a company registered on 4 April 1995 and, as at 15 April 2019, all of Henley Queensland’s shares were held by Henley Arch and Henley Queensland had six directors, including Mr Harvey.

45 Mr Harvey tendered in evidence the business records of Henley Queensland’s trading results from its operations in Queensland from 2000 to 2017. These figures reflect the number of homes built and completed by Henley Queensland on customer land, and “spec” homes settled during this period. The records were annexed as confidential annexure “JH-34” to the First Harvey Affidavit, and were summarised at confidential annexure “JH-35” of the First Harvey Affidavit. Those records show that, with the exception of 2002/2003, Henley Queensland in the period 2000/01 to 2017 completed more than 300 homes per year. In the period 2004 to 2007, Henley Queensland completed more than 400 homes in each year.

46 Mr Harvey tendered in evidence Google Analytics records which show the website visits from IP addresses in Queensland, to both the Henley Arch desktop website and the mobile website, for Queensland between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2018. Set out below is a table which records that data.

Year | Desktop website visits from Queensland | Mobile website visits from Queensland | Total |

2013 | 17,233 | 122 | 17,355 |

2014 | 40,526 | 2,137 | 42,663 |

2015 | 19,980 | 2,768 | 22,766 |

2016 | 18,633 | 3,358 | 21,991 |

2017 | 12,152 | 189 | 12,152 |

2018 | 8,548 | N/A | 8,548 |

47 Since 1997, Henley Arch has contracted with persons located throughout Australia to build and/or to sell homes constructed by Henley Arch in South Australia. In South Australia, Henley Arch has traded under the business names “Clendon Vale Homes” and “MainVue”. All customers of Henley Arch located in South Australia have always entered into contracts with “Henley Arch”.

48 Mr Harvey tendered in evidence, from the business records of Henley Arch, its trading results for its operations in South Australia from 2000 to 2017. This data records the number of homes built and completed by Henley Arch on customers’ land, and “spec” homes settled during this period. These records were provided in confidential annexures “JH-38” and “JH-39” to the First Harvey Affidavit. Those records show that, in the period 2000/2001 to 2008/2009, Henley Arch consistently completed more than 100 homes per annum in South Australia. In the period July 2009 to 2012, Henley Arch completed more than 40 homes per annum in South Australia. In the years 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017, Henley Arch respectively completed in South Australia 7 homes, 2 homes, 1 home and 17 homes.

49 Mr Harvey tendered in evidence Google Analytics records, which show traffic or visits to both the Henley desktop website and the mobile website, from IP addresses in South Australia between 9 January 2013 and 31 December 2018. That data is recorded in the following table.

Year | Desktop website visits from South Australia | Mobile website visits from South Australia | Total |

2013 | 6,287 | 76 | 6,363 |

2014 | 6,281 | 1,229 | 7,510 |

2015 | 5,256 | 1,472 | 6,728 |

2016 | 3,842 | 1,833 | 5,675 |

2017 | 4,964 | 108 | 5,072 |

2018 | 5,313 | N/A | 5,313 |

50 Mr Harvey gave evidence that, between February 1995 and 2008, Henley Arch, through its wholly owned subsidiary, Henley Properties (NSW) Pty Ltd (Henley NSW), contracted with persons located throughout Australia to build and/or to sell homes constructed by the Henley Properties Group in New South Wales.

51 From 2008 until 2010, the Henley Properties Group contracted with persons located throughout Australia to build and/or to sell homes constructed by Henley Arch and located in New South Wales. Since 2010, Henley Arch, through its wholly owned subsidiary, Edgewater Homes Pty Ltd (Edgewater), has contracted with persons located throughout Australia to build and/or to sell homes constructed by Edgewater in New South Wales.

52 Henley NSW was registered as a company on 15 December 1993 and was deregistered on 15 December 2017. Edgewater was registered as a company on 12 January 2010 and is the subsidiary of Henley Arch which conducts the business of the Henley Properties Group through New South Wales.

53 Mr Harvey gave evidence that Henley Arch and Henley NSW have, from time to time, registered Australian business names in New South Wales as follows:

(1) the business name “Henley Property Group” was first registered in New South Wales jointly by Henley Arch and Henley NSW on 6 March 1997, and was cancelled on 15 May 2016;

(2) the business name “Henley Homes” was first registered in New South Wales jointly by Henley Arch and Henley NSW on 13 April 1995, and was cancelled on 23 June 2018; and

(3) the business name “Henley Properties – A World of Homes” was first registered in New South Wales jointly by Henley Arch and Henley NSW on 26 October 1998.

54 Mr Harvey gave evidence that, in or about late 2000, Henley Arch experienced some quality control issues in New South Wales. These issues were the subject of extensive media coverage in New South Wales, including Henley Arch featuring on the television show “A Current Affair”. Henley Arch had encountered problems with the Henley Properties Group expanding too quickly in New South Wales at a time when there was a shortage of quality tradesmen due to the property boom prior to the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax in Australia on 1 July 2000. Mr Harvey said that, due to reputational damage and changes to the industry at that time, the Henley Properties Group had decided to significantly reduce its operations in New South Wales. The New South Wales office remained open primarily for the purposes of undertaking maintenance work as part of Henley Arch’s warranty obligations. As a consequence, during the period 2001 until 2017, the Henley Properties Group constructed a relatively small number of houses in New South Wales.

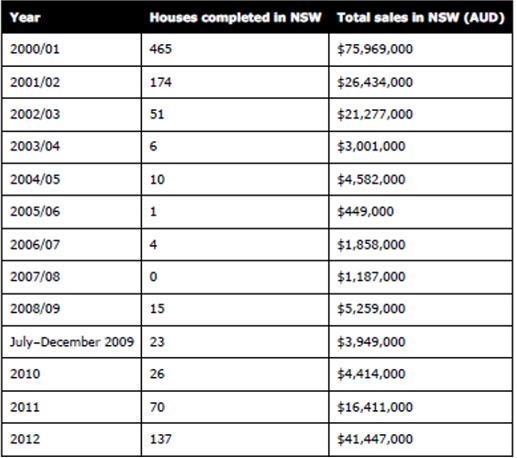

55 This is evident from confidential annexures “JH-50” and “JH-51” to the First Harvey affidavit. The following table shows the number of houses completed in New South Wales by Henley Arch between 2000/2001 and 2017.

Year | Houses completed in NSW |

2000/01 | 465 |

2001/02 | 174 |

2002/03 | 51 |

2003/04 | 6 |

2004/05 | 10 |

2005/06 | 1 |

2006/07 | 4 |

2007/08 | 0 |

2008/09 | 15 |

July–December 2009 | 23 |

2010 | 26 |

2011 | 70 |

2012 | 137 |

2013 | 178 |

2014 | 208 |

2015 | 165 |

2016 | 174 |

2017 | 175 |

56 Mr Harvey tendered in evidence Google Analytics records which showed traffic or visits to the Henley desktop website and the mobile website, from IP addresses in New South Wales between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2018. That data is collated in the following table:

Year | Desktop website visits from New South Wales | Mobile website visits from New South Wales | Total |

2013 | 15,295 | 351 | 15,646 |

2014 | 24,805 | 5,029 | 29,834 |

2015 | 25,329 | 6,774 | 32,103 |

2016 | 25,635 | 7,554 | 33,189 |

2017 | 25,682 | 406 | 26,088 |

2018 | 21,098 | N/A | 21,098 |

The 13 April 2017 letter to Henley Constructions from Henley Arch

57 Mr Harvey deposed that on 22 February 2017, Mr Harvey first became aware of the existence of Henley Constructions and its website at www.henleyconstructions.com.au. On 22 February 2017, a then employee of James Hardie, Mr Damien Boyer, sent an email to a representative of Henley Arch, Mr Simon Gough. Mr Boyer provided a hyperlink to a news story which referred to Henley Constructions. Mr Boyer stated in his email that Henley Constructions “[m]ight be just another business in Sydney that goes by the name of Henley?”. Mr Gough forwarded this email to Mr Harvey on 22 February 2017. Mr Gough stated “[t]hought you [ie Mr Harvey] may like to know about this – Henley Constructions?”.

58 Mr Harvey deposed that he is not aware of any person employed by the Henley Properties Group, or any contractor engaged by the Henley Properties Group, prior to 22 February 2017, having knowledge of Henley Constructions and its activities, or the Henley Constructions website.

59 On 13 April 2017, Mr Harvey on behalf of Henley Arch sent the first letter to Henley Constructions in relation to this matter. That letter stated:

Dear Mr Sarkis

UNAUTHORISED USE OF HENLEY TRADE MARK

We have recently become aware that your company, Henley Constructions Pty Ltd, is advertising and providing property development and building services in relation to residential properties in New South Wales through its website at www.henleyconstructions.com.au. We became aware of this conduct through one of our suppliers who mistakenly thought that your company was our company, or related to our company.

As you would be aware, Henley Arch Pty Ltd (trading as Henley and Henley Properties) is one of Australia's largest and most well-known homebuilders, and has been operating for more than 27 years under the “Henley” name. The company name Henley Arch Pty Ltd was first registered in October 1989. The business names HENLEY HOMES and HENLEY PROPERTIES were registered by Henley and its wholly owned subsidiaries in 1995. Henley is also the owner of Australian Trade Mark Registration No. 1152820 for HENLEY in classes 37 and 42 covering “building and construction services” and “architectural, engineering, design, drafting and interior design services”. Henley has continuously used this trade mark since 1989. We are also the owner of the domain name www.henley.com.au, from which we have operated our website and promoted our services since at least 2003.

The name “Henley Constructions” is very similar to, and likely to be mistaken for, “Henley”. On your company’s website and at your new business premises, the business is also referred to simply as “Henley”. Your use of “Henley Constructions” and “Henley” is likely to give the impression that your company is our company (for example, a division or subsidiary of Henley) and/or Henley’s services are your company’s services and/or that your company is licensed by Henley to use the “Henley” name, when that is not the case. As evidenced by the enquiry from one of our suppliers mentioned above, actual confusion has and is occurring in the construction market.

It is our view that your use of “Henley Constructions” and “Henley” infringes our trade mark and is also misleading. These are matters that can be the subject of legal action against your company.

We consider that this matter can be resolved by you agreeing to change your company’s name and cease using “Henley” in the promotion of your services. We would be open to allowing a grace period for you to inform your customers of the name change ahead of it taking effect.

In the meantime, we reserve our right to take whatever further action is necessary to protect our rights, including seeking injunctions and damages.

I look forward to your response by no later than 27 April 2017. Please direct your response to this letter to me … Should a positive response not be received by that date, I will put this matter into the hands of our lawyers.

…

60 In the Second Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey deposed that he is not aware of any intention on the part of the Henley Properties Group at any time to “geographically limit” its use of “Henley” in Australia. Mr Harvey stated that, while in the First Harvey Affidavit he discussed the reduction of the Henley Properties Group’s on-the-ground operations in New South Wales that occurred in or around 2001, the Henley Properties Group never ceased, nor intended to cease (and nor did he, as a Director of the Henley Properties Group, intend the Henley Properties Group to cease), providing services under the “Henley” brand in relation to customers in New South Wales.

61 Mr Harvey deposed that the building, sale and/or maintenance of homes located in New South Wales by the Henley Properties Group in or around 2006 was completed under the “Henley” brand (or a brand containing “Henley”). That is, the promotional and customer-facing materials displayed “Henley” alone or in conjunction with other words. In respect of the “Edgewater” brand, it was only used as a key brand in New South Wales (as distinct from the name of a particular product range sold under the core “Henley” brand) from approximately 2010 onwards (which is around the time Edgewater Homes Pty Ltd was registered as a company and obtained a building licence in New South Wales).

62 In relation to operations in Queensland, Mr Harvey deposed that while “Plantation Homes” was a key brand for the Henley Properties Group in Queensland from around this time, Henley Queensland’s customer-facing materials usually stated that Plantation Homes was a division of Henley Queensland, and customer-facing materials often contained references to the “Henley” brand.

63 In relation to operations in South Australia, Mr Harvey deposed that, at least since 1997, the key name used on promotional and other customer-facing material by the Henley Properties Group in South Australia has been “Henley” (or “Henley Properties South Australia”), with “Clendon Vale Homes” and “MainVue” being used as sub-brands for particular ranges in the Henley Properties Group’s “order homes business” (that is, homes built to order). The sub-brands “Summerhill Homes” and “Ready Built” have been used for the Henley Properties Group’s “spec” homes business in South Australia, often accompanied by the words “By Henley”. Mr Harvey deposed that the Henley Properties Group has used the following sub-brands in South Australia at the dates indicated:

(1) “Clendon Vale Homes” from in or around 2009 to 2013 for a range of homes on offer in the Henley Properties Group’s order homes business;

(2) “Summerhill Homes By Henley” from around 2008 to 2012 for the Henley Properties Group’s spec homes business;

(3) “Ready Built By Henley” from around 2012 to 2019 for the Henley Properties Group’s spec homes business; and

(4) “MainVue” from around 2012 to 2015 for a range of homes on offer in the Henley Properties Group’s order homes business.

64 However, Mr Harvey notes that the builder of the Henley Properties Group’s houses sold in South Australia has always been Henley Arch, and the name “Henley Properties South Australia” has always been displayed on promotional and other customer-facing material for the Henley Properties Group’s order homes business.

65 As to Western Australia and Tasmania, confidential annexure “JH-69” to the Second Harvey Affidavit included extracts from building contracts and tender acceptance forms signed by customers having an address in either Western Australia or Tasmania, in relation to the sale and/or construction of homes at sites located in Victoria. These extracts are examples of such transactions between 2001 and 2009 and do not represent an exhaustive record of such transactions during this period. However, they do represent the way the contracts and tender acceptance forms appeared for all such customers at their respective dates.

66 Mr Harvey also gave evidence concerning the inputs in the construction process for Henley Arch homes, the various trades and sub-contractors used, and the different types of construction undertaken in the range of building types which Henley Arch offers to its customers or constructs to sell to its customers. Mr Harvey gave evidence about the cost estimation process used by Henley Arch in relation to the construction of homes built by Henley Arch. Mr Harvey set out the various categories of activities which are required to complete the construction of a Henley Arch home, such as site excavation, engineering, plumbing and electronic connection. Mr Harvey said that, in his experience, the essential inputs and processes are common to the construction of most buildings that are designed to be occupied, whether they are detached single dwelling houses, rows of terrace houses/townhouses, low-rise apartment buildings, and high-rise apartment buildings. Mr Harvey said that building a multi-storey apartment building is essentially the same process as building a detached single dwelling house or a row of terrace houses, save that apartments are built on top of each other, rather than side by side.

67 Mr Harvey deposed that Henley Arch’s primary role as the builder of its homes, including single dwelling and multi-dwelling constructions, is to manage and supervise the project. In Mr Harvey’s experience, this is the same role that a builder has in construction projects for a detached single dwelling house, row of terrace houses/townhouses, low-rise apartment buildings or high-rise apartment buildings. This involves coordinating the suppliers and subcontractors, including determining when they are required (and the stage of the construction process they need to be on site), calling them to let them know when they are required, and giving them high level instructions of what is required and the outcome that is expected (including providing them with the design documentation relevant to their supply). Mr Harvey stated that the builder relies on the technical expertise of its suppliers and subcontractors in the actual performance of their roles in the project.

68 The Third Harvey Affidavit also set out a selection of Henley Arch’s multi-dwelling residential developments.

Cross-examination of Mr Harvey

69 Mr Harvey, in cross-examination, said that he was one of the founders of the company in 1989, and participated in the selection of the name Henley Arch. Mr Harvey said, at the time of selecting the name Henley Arch (presumably in or around 1989 when Henley Arch was founded), he could not recall as to whether he was aware of any geographic locations in Australia with the word “Henley” in their name. He accepted that Henley was a surname, but this was not something that he had considered at the time.

70 In December 2006, when Henley Arch filed its first set of trade mark applications, Mr Harvey was aware that there were other geographic locations within Australia with the word “Henley” in their name. He was not aware of other developers such as W P Property Group in Adelaide constructing the Henley Apartments at Henley Beach nor was Mr Harvey aware that Mirvac had developed a development known as the Henley Brook development in Henley Brook, a suburb of Perth.

71 Mr Harvey accepted that, since March 2020, he has not had involvement in a management capacity at Henley Arch. Mr Harvey was cross-examined about the scope of his authority on behalf of Henley Arch and its subsidiaries to give evidence about their future intentions. Mr Harvey said that a representative of the majority shareholder of Henley Arch had asked Mr Harvey to stay involved in the Henley Arch business after Mr Harvey had resigned. I should state here that I do not accept that Mr Harvey did not have authority, or was otherwise not authorised, to give evidence about Henley Arch’s business or its future intentions. The fact is that Mr Harvey has sworn three affidavits in this proceeding, all of which were filed by Henley Arch. Mr Harvey gave evidence and was cross-examined about the contents of those affidavits. In these circumstances, I do not accept that Mr Harvey is not authorised to give evidence on behalf of Henley Arch, or as to Henley Arch’s future intentions.

72 Mr Harvey accepted that Henley Arch started construction of homes in about October 1989. The homes were detached homes. Subsequently, Mr Harvey said that Henley Arch had built both detached and semi-detached homes as time progressed. Mr Harvey accepted that the dwellings constructed by the Henley Properties Group are overwhelmingly detached and semi-detached houses. Mr Harvey also accepted that, as a general proposition, Henley Arch’s promotional material has, overwhelmingly been directed to the sale of detached and semi-detached houses.

73 Mr Harvey, however, did not accept that Henley Arch’s promotional materials were directed to owner-occupiers. Mr Harvey said that Henley Arch’s customers were both owner-occupiers and investors. Mr Harvey did not accept that the majority of the people purchasing Henley Arch houses are owner-occupiers. Mr Harvey said that Henley Arch’s customers are a combination of owner-occupiers and investors.

74 Mr Harvey said in cross-examination that Henley Arch promoted its business as the business of the Henley Properties Group, and the purpose of the Henley Website since 2003 had been to promote the business of the Henley Properties Group and its subsidiaries.

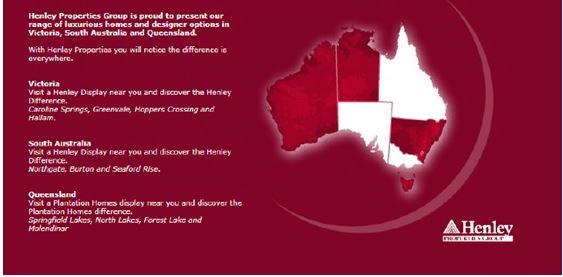

75 In cross-examination, Mr Harvey was taken to an extract of the Henley Properties Group website as at 28 March 2005. Mr Harvey accepted that website drew attention to the Henley Properties Group’s business in Victoria, South Australia and Queensland. In respect of Queensland, visitors to the website were invited to visit a “Plantation Homes” display home in Queensland. Mr Harvey accepted that “Plantation Homes” was the Henley Properties Group’s brand in Queensland.

76 Mr Harvey was then taken to a version of the Henley Properties Group website as it appeared on 30 November 2006. The date of 30 November 2006 was approximately 13 days before Henley Constructions was incorporated and approximately 18 days before Henley Arch applied to register as trade marks “HENLEY”, “HENLEY PROPERTIES” and “HENLEY WORLD OF HOMES”. Mr Harvey accepted that, as at 30 November 2006, the Henley Properties Group website welcomed visitors from Victoria, South Australia and Queensland. Mr Harvey accepted that in Victoria and South Australia, visitors to the website were directed to a “Henley Display”, whereas for Queensland, website visitors were directed to a “Plantation Homes Display”.

77 Mr Harvey was then taken to a snapshot of the Henley Properties Group website as at 22 June 2013. Mr Harvey accepted that this website also segmented Henley Properties Group’s business by reference to three States, being Victoria, Queensland and South Australia.

78 Mr Harvey was then taken to a snapshot of the Henley Properties Group website as at 21 December 2014. Mr Harvey accepted that the website at this date made reference to two locations, being Victoria and Queensland. Mr Harvey said that, if a customer visiting this website wanted to visit a display home in a particular State, this website enabled the customer to identify where that display home was located in Victoria and Queensland. Mr Harvey accepted that this website showed different brands being used in different States. In Victoria, the brands “Henley”, “MainVue Homes”, “Ready Built by Henley” and “Henley House and Land” were used. In Queensland, “Plantation Homes”, “Ready Built by Plantation Homes” and “Plantation House and Land” were used. Mr Harvey accepted that, at this time, the Henley Properties Group stated that Henley Arch was “[o]perating in Victoria as Henley Properties and Main Vue Homes, and in Queensland as Plantation Homes”. Mr Harvey accepted that was a correct statement.

79 Mr Harvey said that, whilst Henley Arch operated under different brand names in different States (i.e. in Victoria, “Henley”, “MainVue Homes”, “Ready Built by Henley” and “Henley House and Land”; and, in Queensland, “Plantation Homes”, “Ready Built by Plantation Homes” and “Plantation House and Land”), Henley Arch’s market was not tied to a particular State. Mr Harvey said that the references to different States indicates where Henley Arch’s display homes are located.

80 Mr Harvey said that it was Henley Arch who determined the marketing strategy nationally which was then implemented by each State office. The marketing strategy was both national and international and not restricted to State-based marketing. Henley Arch had customers who resided overseas who were sent Henley Properties Group marketing material and were subsequently sent tenders and quotations that led to a contract being signed for the construction of a dwelling on land which they owned in Victoria (if the Henley brand was being used) or in Queensland (if the Plantation Homes brand was being used). Mr Harvey said that Henley Arch’s market was anywhere across Australia and overseas.

81 When taken to snapshots of the Henley Properties Group website taken on 11 February 2019 (at annexure “JH-17” to the First Harvey Affidavit) Mr Harvey accepted that the Henley Properties Group website promoted the business of the Henley Properties Group and that there were references to Victoria, South Australia and Queensland but not a reference to New South Wales. Mr Harvey accepted that, in Queensland, increasingly over time, Plantation Homes had been promoted as a standalone business, including using its own website. Mr Harvey said that Plantation Homes was associated with Henley Arch, and was presented as part of the Henley Properties Group both in documentation and marketing material that was offered to customers. Mr Harvey said that in Queensland, Plantation Homes would undertake construction of a dwelling with direction from head office, which is Henley Arch in Melbourne.

82 In cross-examination, Mr Harvey was taken to screenshots of the Henley Website as it appeared on 3 March 2019 (Exhibit R18). Mr Harvey accepted that, under the “Where We Build” section, the website stated “Henley builds across the greater Melbourne metropolitan area as well as Geelong”. Mr Harvey was also taken to a separate section of this website which was titled “Featured estates we build in”. Mr Harvey accepted that all of these estates were located in Victoria. Mr Harvey was then taken to another part of this website titled “Our Displays”. Mr Harvey accepted that this page related to homes in Melbourne.

83 Mr Harvey was then taken to a snapshot of the Henley Website as at 2 April 2021 (Exhibit R19). Mr Harvey accepted that this snapshot of the website was promoting “Single Storey Home Designs”. Mr Harvey accepted that this website contained a map of where such homes are located, and that they were all located in Victoria. Mr Harvey accepted that the “Where We Build” section of this website contained a map of locations in Victoria. Mr Harvey accepted that the “Featured estates we build in” section of this website showed estates located in Victoria.

84 In cross-examination, Mr Harvey accepted that the Henley Properties Group promotes itself by reference to various social media platforms. Those social media platforms include LinkedIn, Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook, YouTube and the Vimeo streaming platform. Mr Harvey accepted the screenshot pages that he had been taken to from these social media platforms (at annexure “JH-20” to the First Harvey Affidavit) featured Victoria and Queensland initiatives or employees located in Victoria, but did not feature matters associated with the Henley Properties Group’s business in New South Wales. Mr Harvey accepted that this material (at annexure “JH-20” to the First Harvey Affidavit), being the social media platforms used to promote the Henley Properties Group business, in fact promotes the business insofar as it operates in Victoria. Mr Harvey accepted that he did not annex to his affidavits material relating to social media platforms operated by other brands within the Henley Properties Group, including Edgewater and Plantation Homes (which relate to operations in New South Wales and Queensland respectively). When asked why he had not provided such material, Mr Harvey said he could not recall. Mr Harvey denied that he had not annexed such material to his affidavits because it was inconvenient to Henley Arch’s case. Mr Harvey said that other brands in the Henley Properties Group, such as Edgewater and Plantation Homes, promoted those businesses in New South Wales and Queensland respectively, using different websites and different social media platforms. Mr Harvey said he did not deliberately omit from his affidavits material relating to those sites and social media platforms.

85 Mr Harvey said that the Henley Properties Group used a combination of platforms to promote its business, and this advertising included references to Edgewater Homes in New South Wales, Plantation Homes in Queensland and Henley Arch in Victoria respectively. Mr Harvey said he did not deliberately omit material from his affidavits relating to those websites and social media platforms.

86 Mr Harvey was taken to an extract of the Edgewater Homes Facebook page. That page stated that Edgewater Homes offers “fixed price house and land contracts” in New South Wales. Mr Harvey accepted that statement was a correct description of Edgewater Homes’ product offering.

87 Mr Harvey was then taken to the “Henley Homes” Facebook page. Mr Harvey accepted that this page made various references to the Victorian market, including making reference to the “Grand Final long weekend” in Victoria.

88 Mr Harvey accepted that, in the First Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey set out the Henley Properties Group’s operations in Victoria, Queensland and South Australia and, in doing so, annexed actual contracts entered into by the entities operating in those States in relation to the construction of homes. Mr Harvey accepted that, when discussing the Henley Properties Group’s operations in New South Wales in the First Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey did not annex a copy of any contracts entered into by the relevant entity operating in New South Wales.

89 Mr Harvey accepted in cross-examination that, as a consequence of the adverse publicity in 2000 stemming from problematic workmanship undertaken by Henley Arch in New South Wales, the business in that State was substantially wound down. However, maintenance operations were still undertaken in that State for existing dwellings to meet warranty obligations.

90 Mr Harvey in cross-examination was also taken to confidential annexure “JH-49” to the First Harvey Affidavit. That annexure is a memorandum from the Directors of the Henley Properties Group to all staff of the Henley Properties Group dated 31 May 2001. It states:

Henley continues to maintain it’s [sic] status as the largest home builder in Australia, continuing to strengthen our position in our largest market Victoria. Our strength is reflected in our inclusion in Australia’s Top 500 privately owned companies, we are ranked No 44.

We constantly review the potential of each of our operations and we have decided to restructure the operations in NSW. This decision is based on a number of variables including the price and availability of land in Sydney, consistency of building trades and supply and the appropriateness of Henley’s products in Sydney.

This decision will necessitate a temporary suspension of sales of its project homes in the NSW market. As a result, it has been necessary for Henley to reduce the number of employees in departments servicing the sales front of the business.

The NSW branch including maintenance and warranties will continue to operate servicing and building homes for our current clients. Any client inquiring regarding this strategic decision can be assured these decisions are not related to our other state operations and were in no way a result of the companies [sic] financial position.

Should the client have further questions please refer the call to your business or state manager.

91 It was put to Mr Harvey in cross-examination that this memorandum reflected a reality that, in May 2001, for all intents and purposes, the Henley Properties Group business, insofar as it operated in New South Wales, was being put into a “deep freeze”. Mr Harvey accepted that its “contract housing business” was in May 2001 put into a “deep freeze”. Mr Harvey accepted that this was reflected in confidential annexure “JH-50” to the First Harvey Affidavit, being the trading results for the Henley Properties Group’s New South Wales operations in the period 2000 to 2017. Those results showed that, in 2006, Henley Properties Group constructed one house in New South Wales. Mr Harvey also accepted in cross-examination that this one house construction in 2006 was not a significant reduction from the 10 houses constructed in New South Wales in 2005.

92 It was in these circumstances that Mr Harvey was taken to confidential annexure “JH-48” to the First Harvey Affidavit, being copies of communications between the Henley Properties Group and its customers in relation to homes built by Henley Arch in New South Wales dated between 1999 and 2013. That annexure contains communications dated in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2012 and 2013. Mr Harvey was asked whether the gap in these documents between 2002 and 2012 indicated that there was nothing in between those years that Mr Harvey could identify to evidence commercial activity in New South Wales in that period. Mr Harvey said he had no doubt there would have been documents which could evidence such commercial activity, but they had not been annexed to his affidavit.

93 Mr Harvey was also cross-examined about the Second Harvey Affidavit. In the Second Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey deposed that he was not aware of any intention on the part of the Henley Properties Group in 2008, or at any time, to “geographically limit” its use of “Henley” in Australia. Mr Harvey stated that his recollection of the Henley Properties Group’s intentions, as at 2008, was that Henley Arch intended to extend its use of the trade mark “Henley” in the future to additional television advertising and promotional campaigns, on-going publication and distribution of brochures and fliers, billboard content design and construction, display signage and also print advertising and promotional posters. It was put to Mr Harvey that he had not annexed to his affidavit any document to support this statement in his affidavit. Mr Harvey stated that there were many meetings regarding the marketing strategy, and, at that time in 2008, most of those discussions would have been, in the main, verbal. Mr Harvey said he had attempted to identify documents to support these statements, but Henley Arch had moved offices on several occasions and, essentially, any such records could not be located. However, Mr Harvey said that, despite not locating any such documents, Mr Harvey could say with absolute confidence that there was, in 2008, a marketing strategy for the Henley Properties Group. It was put to Mr Harvey that, in truth, he had identified a hole in Henley Arch’s case, and he had sought to fill that hole by assertions in the Second Harvey Affidavit that are unsupported by documents. Mr Harvey said he did not agree with that proposition.

94 Mr Harvey was then cross-examined about the Third Harvey Affidavit. In the Third Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey stated that building a multi-storey apartment building is essentially the same process as building a detached single dwelling house or a row of terrace houses, save that apartments are built on top of each other, rather than side by side. In cross-examination, Mr Harvey accepted that, while he was aware of the National Construction Code, he could not say “off the top of his head” what the different classes are in the National Construction Code, save that Mr Harvey was aware that there are different classes in that Code.

95 In the Third Harvey Affidavit, Mr Harvey also stated that, at least as early as 2000, Mr Harvey planned for Henley Arch to enter the construction and marketing of multi-dwelling developments (that is, any of townhouses/terrace houses side by side, low rise and high rise apartments) under the “Henley” brand (or using a sub-brand under, and in conjunction with, the “Henley” brand). In cross-examination, Mr Harvey accepted that, as early as 2000, Henley Arch did not necessarily intend to construct high-rise apartments. Mr Harvey said that, in December of 2006, Henley Arch did not intend to construct high-rise apartments. Mr Harvey also stated that, at no time after 2006, has Henley Arch intended to construct high-rise apartments. Earlier in his evidence, Mr Harvey had stated that “high-rise”, to Mr Harvey, means “very tall” buildings such as “20 storeys or 30 storey apartment buildings” (Transcript, p 221).

96 As mentioned above, I accept the entirety of Mr Harvey’s evidence as a truthful account of events and matters on which he gave evidence.

Ms Lawrence’s evidence in chief

97 Ms Lawrence has affirmed four affidavits in this proceeding, being an affidavit affirmed 10 May 2019 (First Lawrence Affidavit), an affidavit affirmed 31 October 2019 (Second Lawrence Affidavit), an affidavit affirmed 20 December 2019 (Third Lawrence Affidavit), and an affidavit affirmed 5 June 2020 (Fourth Lawrence Affidavit).

98 Ms Lawrence is a legal practitioner employed by Henley Arch’s solicitors, Ashurst. Ms Lawrence was admitted as a legal practitioner in New Zealand on 10 June 1994 and in the State of Victoria on 7 July 1999. Ms Lawrence has practised as a trade mark lawyer in New Zealand for approximately three years and in Australia for approximately seventeen years (that is, approximately twenty years less two years and seven months of parental leave).

99 Ms Lawrence gave honest and considered evidence. I accept Ms Lawrence’s evidence in respect to the steps that she took to investigate the use by Henley Constructions of the mark Henley Constructions with and without the relevant device during the period in or around 2007/2008 up until in or around 2019. Ms Lawrence’s evidence was that, after the cease and desist letter was sent to Henley Constructions by Henley Arch on 13 April 2017, Henley Constructions “ramped up” the activity and content on its website. This was evident, Ms Lawrence said, by the screenshots of the Henley Constructions website which were exhibited to her affidavits.

100 On 24 July 2017, Ms Lawrence requested a private investigator, Trade Mark Investigation Services (TMIS), a division of Risk & Security Management Ltd, to investigate the use of the trade mark “Henley” by Henley Constructions. On 11 August 2017, Ms Lawrence received TMIS’s report. The TMIS report attached the following items concerning Henley Constructions’ use of “Henley Constructions” or “Henley” in or around August 2017.

101 First, the report attached copies of photographs of Henley Constructions’ place of business at unit 23, 72 Parramatta Road, Camperdown, New South Wales. Those photographs included the following photographs:

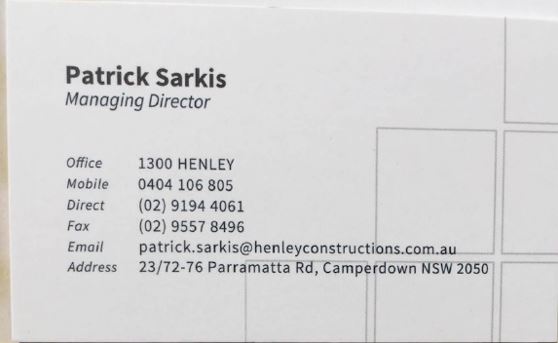

102 Second, the TMIS report attached business cards for Mr Patrick Sarkis and Mr John Nasr of Henley Constructions. One side of the business card appeared as follows:

103 The other side of the business card appeared as follows:

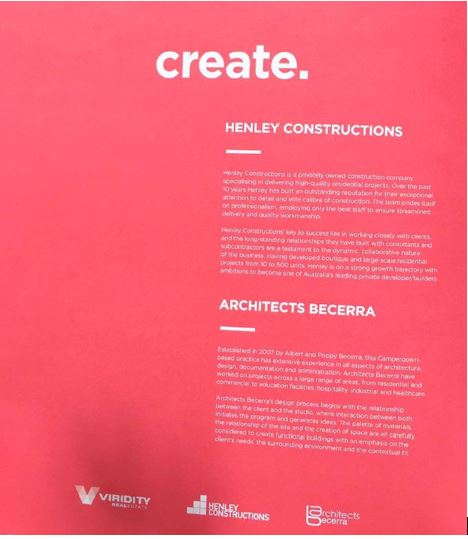

104 The report also attached advertising material for the Aperture Apartments, Marrickville which referred to Henley Constructions and stated “Henley is on a strong growth trajectory with ambitions to become one of Australia’s leading private developers/builders”. That advertising material was reproduced in the report as follows:

105 Ms Lawrence also conducted searches of the “Wayback Machine” internet website (at https://web.archive) in relation to the website www.henleyconstructions.com.au. These searches produced records or “snapshots” or “screenshots” of the Henley Constructions website at 19 October 2008, 20 November 2009, 9 April 2013, 4 February 2017, 18 February 2017, 26 February 2018, 15 March 2018 and 19 April 2018. Annexure “JML-14” to the First Lawrence Affidavit also showed screenshots of the Henley Constructions website as at 27 February 2017.

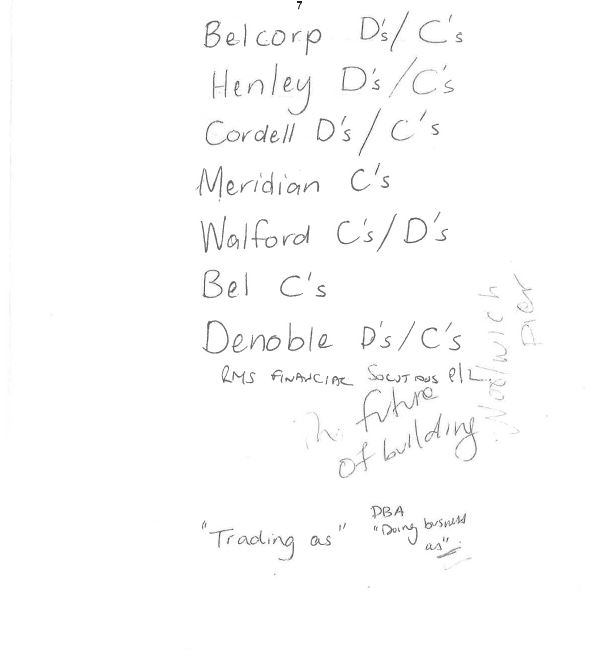

106 In the Second Lawrence Affidavit, Ms Lawrence referred to receiving the first affidavit of Patrick Sarkis sworn 25 July 2019 and the affidavit of Vanessa Sarkis, being Mr Sarkis’s wife, sworn 25 July 2019. Those affidavits referred to a list of names said to have been handwritten by Mrs Sarkis in late September or early October 2006 (see annexure “VS-1” to the affidavit of Vanessa Sarkis sworn 25 July 2019). Annexure “VS-1” to the affidavit of Vanessa Sarkis sworn 25 July 2019 is a handwritten note which relevantly listed the following: “Belcorp D’s/C’s”, “Henley D’s/C’s”, “Cordell D’s/C’s”, “Meridian C’s”, “Walford C’s/D’s”, “Bel C’s”, “Denoble D’s/C’s”, and “RMS Financial Solutions P/L”.

107 After receiving the first affidavit of Patrick Sarkis sworn 25 July 2019 and the affidavit of Vanessa Sarkis sworn 25 July 2019, on or around 27 August 2019, Ms Lawrence caused searches of ASIC’s online companies and business names register to be undertaken for the names appearing on the list in annexure VS-1, other than “Henley”. The searches returned the following results for companies and business names on the list in annexure “VS-1”:

(1) Belcorp Holdings Pty Ltd (ACN 115 727 243) registered on 11 August 2005;

(2) Belco RP Developments Pty Ltd (ACN 131 161 807) (formerly named Sarkis Property Group Pty Ltd between 19 May 2008 and 5 September 2008) registered on 19 May 2008;

(3) Belcorp Construction Pty Ltd (ACN 620 794 210) registered on 31 July 2017;

(4) Australian Business Name Registration for Meridian Construction Co cancelled on 13 August 1993;

(5) Meridian Construction (Australia) Pty Limited (ACN 103 706 618) registered on 12 February 2003;

(6) Meridian Construction Services Pty Limited (ACN 079 377 316) registered on 17 July 1997;

(7) Reed Elsevier Construction Information Services Pty Limited (ACN 076 286 836) (formerly named Cordell Construction Information Services Pty Limited between 6 January 1997 and 2 November 2015), registered on 27 November 1996;

(8) Nobel Developments Pty Ltd (ACN 072 241 948) registered on 20 December1995; and

(9) Walford Constructions Pty Ltd (ACN 000 459 183) de-registered on 6 June 1978.

108 Ms Lawrence tendered evidence of internet searches conducted on 26 July 2019 and 9 September 2019 for the names appearing on the list in annexure “VS-1”. These searches resulted in the following websites:

(1) www.belcorp.com.au, which appears to be for a construction company called “Belcorp Services” in Sydney, which is stated on the website to have “started in 2005”;

(2) a LinkedIn profile for “Cordell Information”, which appears to be a construction project information provider stated to have been founded in Australia in 1969. This profile links to the website at www.cordell.com.au;

(3) www.cordell.com.au, which redirects to www.corelogic.com.au. This website refers to “Cordell Connect”, which is stated on the website to be a construction project database in Australia and New Zealand;

(4) www.meridianconstruction.com.au, which appears to be for a construction company called “Meridian Construction Services” in Banksia, Sydney, stated to have been “established in 1997”;

(5) a LinkedIn profile for “BEL Contracting”, which appears to be a civil contractor in the utility and road construction industry in Western Canada, stated in the LinkedIn profile to have been operating for “over 40 years”. This profile links to the website at www.belcontracting.com;

(6) www.belcontracting.com, which appears to be the website for the abovementioned “BEL Contracting”;

(7) www.walfordhomes.ca, which appears to be for a construction company called “Walford Homes” in Vancouver, Canada;

(8) www.denoblehomes.com, which appears to be for a home building company called “Denoble Homes” in Canada, stated on the website to have been “founded in 1988”; and

(9) www.rmsbuilders.ca, which appears to be for a group of construction companies in Canada called “RMS Group”, stated on the website to have been “created in 1994”.

109 Screenshots of the above websites were provided in annexure “JML-33” to the Second Lawrence Affidavit.

110 Ms Lawrence’s evidence was that, after receiving the respondents’ affidavits, she undertook further investigations into the development projects which the respondents said they had undertaken during the period early 2007 to 2021. Those projects included 20 projects concerning the construction of residential units in suburbs of Sydney. Those investigations included conducting searches of ASIC’s online company register; searches of New South Wales government websites which contained information in relation to licensed builders in that State; Google Maps searches of the addresses of the project that had been undertaken by the respondents to identify any evidence of use of the mark Henley Constructions, either with or without the device mark; and searches of real estate agents’ websites to obtain screenshots of the projects undertaken by the respondents to ascertain whether the mark Henley Constructions, either with or without the device mark, was on display at these various project sites.

111 As a consequence of undertaking these many searches, Ms Lawrence exhibited to her affidavits a vast number of screenshots of the development projects that had been undertaken by the respondents. The screenshots exhibited to Ms Lawrence’s affidavits show the use of the mark Henley Constructions, either with or without the relevant device mark, on awnings and signs on some, but not all, of Henley Constructions’ developments. By way of example, the following photographs were annexed to the Second Lawrence Affidavit in relation to these projects:

112 Ms Lawrence’s evidence was that, based on her investigations of the 21 development projects referred to in the first affidavit of Patrick Sarkis sworn 25 July 2019, in 18 of those projects, the developer was a company controlled, at least in part, by Mr Patrick Sarkis.

113 The Second Lawrence Affidavit also referred to the website www.henleygallery.com.au. Annexure “JML-59” to the Second Lawrence Affidavit contained screenshots of this website taken on 12 February 2019 and 2 September 2019. The website at 12 February 2019 stated (among other things):

Visit Henley Constructions at the new Henley Display Gallery showcasing our latest projects all under the one roof. Discuss your requirements with our talented sales team and let us find your perfect home, whether you are an owner occupier, investor or undecided, we’re here to help.

114 In the Second Lawrence Affidavit, Ms Lawrence, as a practitioner experienced in trade marks law, set out the steps Ms Lawrence takes when she is asked to provide trade mark availability advice to clients before they commence use of a new trade mark. Ms Lawrence stated that, in addition to conducting searches of the Australian Trade Marks Register, Ms Lawrence typically recommends conducting common law searches to identify any use of similar unregistered trade marks in Australia that may pose a risk to the client’s use of the proposed mark. Ms Lawrence stated that, to identify any such common law trade marks, Ms Lawrence would typically conduct as a bare minimum the following searches in addition to ASIC business and company name searches:

(1) internet searches (that is, Google searches) for both the whole of the proposed mark and each distinctive element (eg, in this case, each of “Henley Constructions” and “Henley”);

(2) searches of any websites arising from internet URLs compromising the proposed mark, or distinctive elements of the mark, and “.com” or “.com.au” (eg, by typing “www.henleyconstructions.com.au” and “www.henley.com.au” directly into the address bar of an internet browser);

(3) domain name searches of the “Whois database” for “.com.au” domain names, for the whole of the proposed mark, and each of the distinctive elements of the mark (eg “Henley.com.au” and “henleyconstructions.com.au”); and

(4) searches of the Yellow Pages and White Pages directories for any listings of businesses with names which contain the proposed mark or the essential elements of the proposed mark.

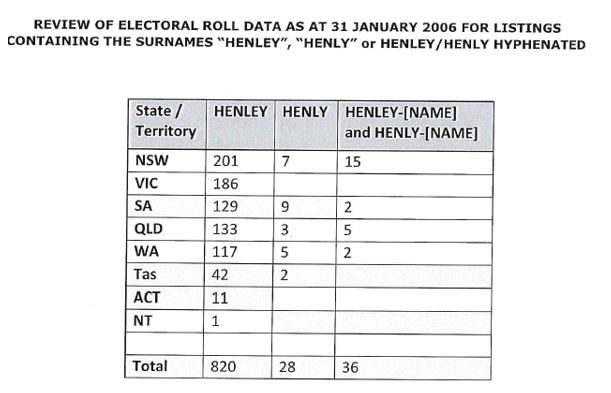

115 I accept Ms Lawrence’s evidence that, even as far back as December 2006, the prudent course to adopt in ascertaining the availability of a trade mark included these searches.

116 I accept Ms Lawrence’s evidence that the above searches are the typical searches which she would have conducted in December 2006 to ascertain whether the trade mark Henley Constructions or Henley was available. In this regard, I expressly reject the proposition put to Ms Lawrence in cross-examination that a less sophisticated business or a small business seeking to ascertain the availability of a trade mark would not at least undertake a Google search or another relevant search of websites. I accept Ms Lawrence’s evidence that, in December 2006, clients, both large and sophisticated or small, typically undertook at least internet searches, including that often clients had already undertaken their own such searches before engaging Ms Lawrence. In this respect, counsel for the respondents had the following exchange with Ms Lawrence:

Well, do you accept that, at least 10 or so years ago, in your experience, there could be a deal of confusion on the part of small businesses between the role of company names, business names and trademarks?---10 years ago?

Yes?---Look, I – I think, … with the internet becoming a lot more user friendly and people using it more, I think, over the last 10, 15 years, I think, … I’ve noticed that my clients have become more sophisticated in using it.

…

And would you accept that whilst that might be what you, as a member of a top-tier law firm, would search for on behalf of clients, something less than those inquiries may well be undertaken by, for example, small business operators who don’t enjoy the services of trademark lawyers like you?---I think – I think it varies considerably, and sometimes that has not got to do with the size of the business. I think that many people and many businesses are a lot savvier these days. You know, but … even back in the early 2000s, I had clients who performed at least Google searches before coming to me. And certainly now, I have many clients who do their own searching and – and just come to me when they – when they think they’ve identified a problem.

(Emphasis added.)

117 In the Third Lawrence Affidavit, Ms Lawrence set out matters relevant to the prosecution of the “HENLEY” trade mark application. Ms Lawrence said that, at the time that Henley Arch filed and prosecuted Australian trade mark application number 1152820 for the trade mark “HENLEY” (HENLEY trade mark application), Henley Arch was represented by the law firm Blake Dawson Waldron and, in particular, by the intellectual property team of Blake Dawson Waldron. Ms Lawrence deposed that, on 1 May 2007, a lawyer then employed in the intellectual property team at Blake Dawson Waldron, Ms Vicki Huang, had two telephone conversations with a trade mark examiner at the Australian Trade Marks Office, Mr Peter Jarvis. Mr Jarvis was the trade mark examiner who examined the “HENLEY” trade mark application and issued an examination report on 28 March 2007 in relation to that application. The examination report is produced as annexure “LNS-7” to the affidavit of Mr Lance Newman Scott affirmed 9 May 2019 in this proceeding.

Cross-examination of Ms Lawrence

118 In cross-examination, Ms Lawrence was referred to the following photograph (which was annexed to the TMIS report dated 11 August 2017 (referred to above)):

119 Ms Lawrence was asked what the purpose was of putting this photograph into evidence. Ms Lawrence said that Henley Arch put into evidence everything that showed a reference to the place of business for Henley Constructions and also how that name was being used. Ms Lawrence said she did not give specific thought as to whether the purpose of putting this photograph into evidence was to show trade mark use. However, Ms Lawrence said that this page of the TMIS report was put into evidence “to address trade mark use”.

120 Ms Lawrence was then taken to the following photograph which was attached to the TMIS report:

121 This is a photo of the door of Henley Constructions’ business premises. Ms Lawrence noted that this door used the Henley Constructions logo and used the telephone number “1300 Henley”. Ms Lawrence was asked what she noticed about that telephone number and Ms Lawrence said that it “had the word “Henley” in it”, and that looked to Ms Lawrence like trade mark use. As to the website on this door, www.henleyconstructions.com.au, Ms Lawrence said that a website address can function as a trade mark. Ms Lawrence said that she considered these features on this door were evidence of trade mark use.

122 Ms Lawrence was also taken to a brochure where Henley Constructions referred to itself as “Henley”. Ms Lawrence said that there were a number of examples of the use of this name which appeared to her to constitute trade mark usage. Ms Lawrence was also referred to Mr Sarkis’s business card, which contained contact details such as “1300 Henley” and the email address “@henleyconstructions.com.au”. Ms Lawrence said that these matters were also potentially trade mark use. Ms Lawrence said that, in the context of these details being on a business card, those contact details appeared to be “projecting the brand” of Henley Constructions. However, Ms Lawrence conceded that she was “less certain” as to whether the email address constituted trade mark usage. In contrast, Ms Lawrence considered the use of the word “Henley” in the “1300 Henley” telephone number to be “quite prominent”.

123 Ms Lawrence was taken to a number of snapshots, of the Henley Constructions website at various dates, which were annexed to the First Lawrence Affidavit. Ms Lawrence, in particular, was taken to a snapshot of the Henley Constructions website as at 4 February 2017. Ms Lawrence said that the purpose of putting this snapshot of the website into evidence was to demonstrate that there had been a “change or a ramping up of the website” in about 2017. By “ramping up”, Ms Lawrence said that she meant the use of the Henley Constructions website was becoming more extensive. That is, there was more content shown on the website. As to the trade mark usage on these websites, Ms Lawrence said that the use of the Henley Constructions mark on the website and the website address (www.henleyconstructions.com.au) were examples of trade mark usage. Ms Lawrence also said that the use of the word “Henley” in narrative or descriptive parts of the website (such as “Henley prides itself on delivering projects both on schedule and within budget”) were also examples of trade mark usage.

124 Ms Lawrence was also taken to the following photograph, which appeared on the Henley Constructions website as at 18 February 2017:

125 Ms Lawrence noted that this use of the word “Henley” on the frontage the building pictured above appeared to be trade mark use. It was put to Ms Lawrence that the name of the building is in fact “Henley”. Ms Lawrence said that, at the time this photograph was included in her affidavit evidence, she was not aware that the relevant building was in fact called “Henley”. Ms Lawrence accepted that, in those circumstances, the use of the word “Henley” on this building was not trade mark usage.

126 Ms Lawrence was then referred to the various Google Maps photographs annexed to the Second Lawrence Affidavit. Those photographs showed Henley Constructions’ various projects approximately before and after the commencement and completion of the relevant project. Ms Lawrence confirmed that a purpose of conducting these Google Maps searches was to identify whether or not Henley Constructions had used any relevant branding on the relevant construction sites during the development of those projects.

127 Ms Lawrence was, in particular, taken to annexure “JML-38” to the Second Lawrence Affidavit, being a Google Maps screenshot of the “Church Street project” by Henley Constructions in November 2007. That screenshot did not appear to contain any obvious Henley Constructions signage. However, a Google Maps photograph identified by Henley Constructions’ solicitors, being Exhibit R1, was put to Ms Lawrence and, in Exhibit R1, it can be seen that, as at November 2007, the Church Street project had a small sign erected which stated “Henley Constructions”. Ms Lawrence said she did not know why the image depicted in Exhibit R1 was not annexed to her affidavit.

128 Ms Lawrence was also taken to various photographs that were taken by Mr Sarkis or other employees of Henley Constructions, and which were tendered as Exhibit R22. Those photographs depicted the various projects that were also depicted in the Google Maps photographs annexed to Ms Lawrence’s affidavit. It can be seen from the photographs in Exhibit R22 that Henley Constructions signage was affixed to the fencing or hoarding which was erected around those developments.