FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AA Machinery Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1293

Table of Corrections: | |

Order 2(a), “1 March 2024” has been replaced with “1 April 2024”. Order 2(b), “1 January 2024, 1 April 2024, 1 July 2024, 1 October 2024, 1 January 2025 and 1 March 2025 has been replaced with “1 January 2025, 1 April 2025, 1 July 2025, 1 October 2025, 1 January 2026 and 1 April 2026”. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Since 1 August 2017:

(a) by representing that its tractors and wheel loaders (Tractors) had a five year nationwide warranty (Warranty) in circumstances where the Warranty was limited to parts only, not all parts were covered for five years or at all and the full cost of all parts was not covered:

(i) AA Machinery Pty Ltd (Agrison) engaged in conduct in trade or commerce which was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA); and

(ii) made false or misleading representations concerning the existence or effect of a condition, warranty, right or remedy in respect of the Warranty, in contravention of s 29(1)(m) of the ACL;

(b) by representing that it had a national service network, and therefore customers requiring after-sales service or repair staff could access them throughout Australia, in circumstances where Agrison did not have a national service network available to customers throughout Australia, Agrison:

(i) engaged in conduct in trade or commerce which was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL; and

(ii) made false or misleading representations concerning the availability of facilities for the repair of goods or of spare parts for goods, in contravention of s 29(1)(j) of the ACL; and

(c) by representing that a customer would be able to obtain all necessary spare parts for Tractors within a reasonable time if and when required, in circumstances where Agrison had no reasonable grounds to make such representation, Agrison:

(i) engaged in conduct in trade or commerce which was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL; and

(ii) made false or misleading representations concerning the availability of facilities for the repair of goods or of spare parts for goods, in contravention of s 29(1)(j) of the ACL.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary Penalty

2. Pursuant to s 224 of the ACL, Agrison pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in sum of $220,000 in respect of the contraventions of ss 29(1)(j) and (m) referred to in the declarations in paragraph 1 of these orders, to be paid in instalments as follows:

(a) $12,500 on each of 1 July 2022, 1 October 2022, 1 January 2023, 1 April 2023, 1 July 2023, 1 October 2023, 1 January 2024 and 1 April 2024; and

(b) $15,000 on each of 1 July 2024, 1 October 2024, 1 January 2025, 1 April 2025, 1 July 2025, 1 October 2025, 1 January 2026 and 1 April 2026.

3. In the event that there is a default in the making of any of the instalment payments referred to in paragraph 2 of these orders and that default continues for fourteen days, the whole of the outstanding amount is immediately due and payable.

Injunctions

4. Pursuant to s 232 of the ACL:

(a) insofar as:

(i) it offers a warranty for defective parts only; and/or

(ii) the term of its warranty in respect of defective parts varies as between the parts in question,

Agrison, by itself, its servants or its agents, be restrained from making any unqualified representation as to either the scope or term of the warranty;

(b) Agrison, by itself, its servants or its agents, be restrained from making any representation that it has a national service network in Australia, while it does not have any formal arrangement with service centres in Australia; and

(c) Agrison, by itself, its servants or its agents, be restrained from making any representation as to the availability of spare parts unless it has reasonable grounds for making the representation.

5. Pursuant to s 239 of the ACL, Agrison pay the total sum of $63,947.50 by way of redress to four particular consumers who have incurred loss and damage as a consequence of the contraventions referred to in the declarations in paragraph 1 of this Order in accordance with the requirements of the Redress Scheme set out in Annexure A to this Order.

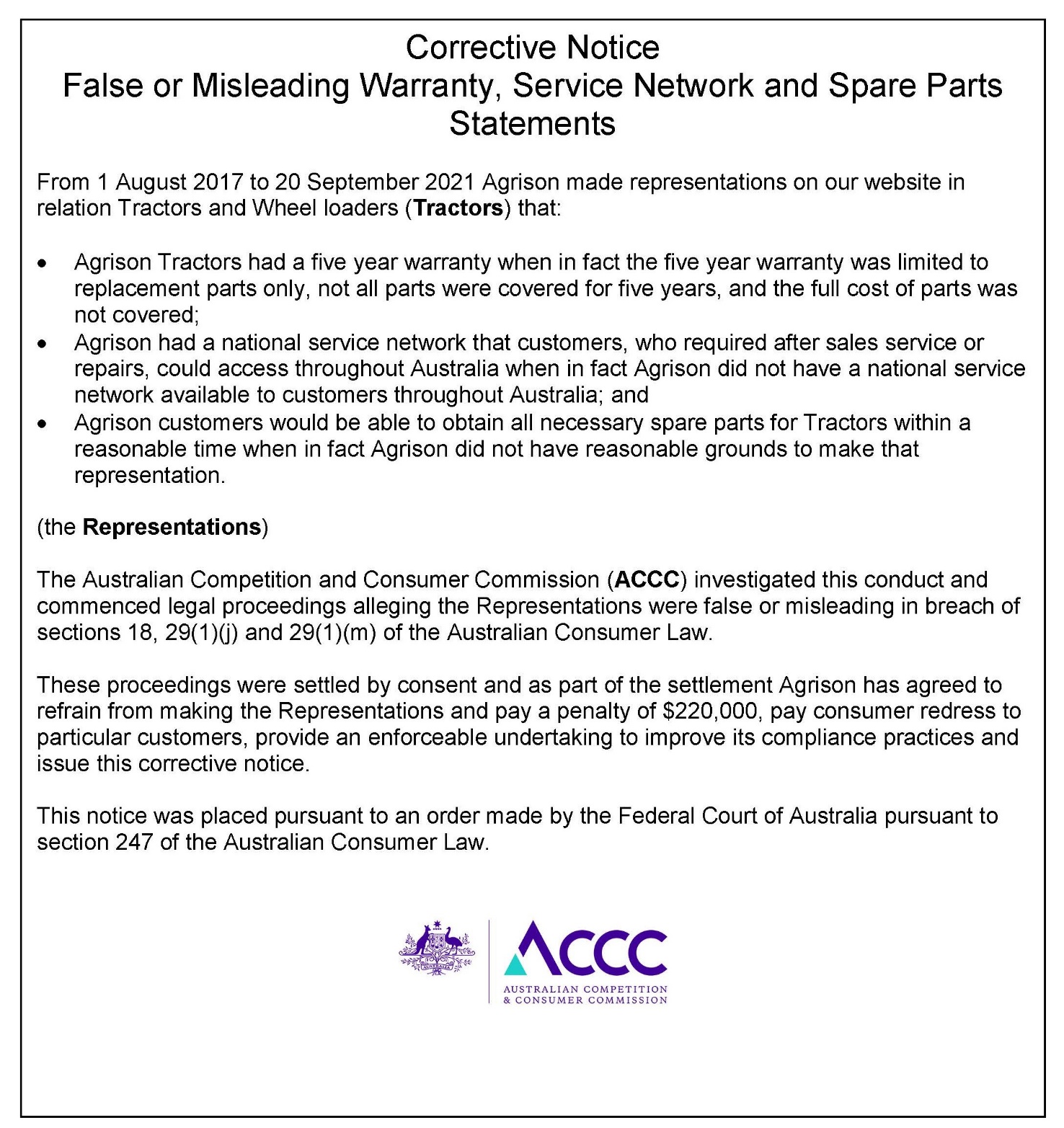

Corrective Notice

6. Pursuant to s 247 of the ACL, within 28 days of the date of this Order, Agrison cause to be published on the homepage of its website at http://www.agrison.com.au for a period of six months, a corrective notice regarding the contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(j) and 29(1)(m) of the ACL declared by the Court:

(a) in the form set out at Annexure B to this Order;

(b) in minimum size 20 font;

(c) using black writing on a white background.

Other

7. The Applicant’s claims against the Respondent are otherwise dismissed.

8. There be no order as to costs.

9. A copy of the Judgment in this proceeding, with the seal of the Court thereon, be retained in the Court for the purposes of s 137H of the CCA.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE A

1. Subject to further order of the Court, the funds described in paragraph 5 of the Order must only be paid in accordance with the terms of the redress scheme (the Redress Scheme) set out in this Annexure.

2. On 15 October 2021 Agrison paid the sum of $60,000 (Initial Funds) into the trust account of Baker McKenzie solicitors.

3. Within 48 hours of the sealing of this Order, the Applicant must email a notice to each of the persons identified as Consumer A, Consumer B, Consumer C and Consumer D in the Applicant’s Concise Statement dated 21 October 2020 stating that:

(a) the Court has ordered Agrison to pay redress of:

(i) in respect of Consumer A, $14,347.50 within 7 days of receipt of the consumer’s acceptance of the redress; and

(ii) in respect of Consumer B, $32,042.50 within 7 days of receipt of the consumer’s acceptance of the redress and $3,947.50 by 8 January 2022;

(iii) in respect of Consumer C, $10,000 within 7 days of receipt of the consumer’s acceptance of the redress;

(iv) in respect of Consumer D, $3,610 within 7 days of receipt of the consumer’s acceptance of the redress;

(b) in respect of Consumers A, C and D, if the consumer wishes to accept the redress, the consumer must email the Applicant and Agrison, within 60 days of the sealing of this Order, accepting the redress;

(c) in respect of Consumer B, if the consumer wishes to accept the redress, the consumer must email the Applicant and Agrison, within 60 days of the sealing of this Order, undertaking to return to Agrison (by way of collection by Agrison at Agrison’s own cost) the Tractor sold to the consumer by Agrison following payment of the initial instalment of $32,042.50; and

(d) if the consumer accepts the redress, they will be bound by the order, and will not be able to bring any claim, action or demand against Agrison in relation to the contravening conduct referred to in the declarations in paragraph 1 of the Order.

4. Within 2 business days of receipt of a consumer’s acceptance of redress, Agrison must direct Baker McKenzie solicitors to pay from the balance of the Initial Funds within 5 days:

(a) in respect of Consumer A, $14,347.50;

(b) in respect of Consumer B, $32,042.50;

(c) in respect of Consumer C, $10,000; and

(d) in respect of Consumer D, $3,610.

5. Within 7 days of receipt of Consumer B’s acceptance of the redress, Agrison must make arrangements for the collection of the Tractor sold to the consumer, such collection to be at Agrison’s expense.

6. By no later than 1 January 2022 Agrison shall pay to the trust account of Baker McKenzie solicitors the further amount of $3,947.50 (Further Funds) and must direct Baker McKenzie solicitors to pay within 7 days the Further Funds to Consumer B, where Consumer B has accepted the redress pursuant to paragraph 3 above.

7. If any consumer does not accept the redress offered to them, Agrison shall be entitled to reduce the amount of the Further Funds to be paid under paragraph 6 by an equivalent amount, and shall not be required to pay the Further Funds to Baker McKenzie solicitors in respect of that consumer.

ANNEXURE B

MURPHY J:

1 The respondent in this proceeding, AA Machinery Pty Ltd (Agrison) is a supplier of a range of agricultural equipment to Australian consumers including several models of Agrison branded tractors and wheel loaders (Tractors). It operates from a single factory, warehouse and retail showroom located in Campbellfield, Victoria, and sources products from a number of manufacturers based predominantly in China. Agrison is owned and operated by Mr Volkan (Nick) Yokus, its sole director.

2 By a Concise Statement dated 21 October 2020 the applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) alleged that Agrison advertised to its customers that Agrison Tractors were a high-quality product, which would be fully supported with nationwide after-sales service, a five year nationwide warranty and access to spare parts. In particular, the ACCC alleged that since 1 August 2017, Agrison has advertised its Tractors through multiple channels and in doing so represented that:

(a) the Tractors had a five year nationwide warranty and therefore, in the event a Tractor was defective, Agrison would cause it to be repaired at no cost to the customer, regardless of its location in Australia, for a period of five years following purchase or, alternatively, Agrison would replace defective parts at no cost to the customer, for a period of five years following purchase (Pleaded Warranty Representation);

(b) Agrison had a national service network, and therefore customers requiring after-sales service or repair staff could access them throughout Australia (Service Network Representation);

(c) Agrison would provide timely after-sales service to customers in the event of a defect or problem with a Tractor (Service Representation); and

(d) a customer would be able to obtain all necessary spare parts for Tractors within a reasonable time, if and when required (Parts Representation).

It alleged the representations made by Agrison in respect of its Tractors were false, misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 and ss 29(1)(b), (j) and (m) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

3 Agrison has now admitted that its advertisements in the relevant period (being 1 August 2017 to 20 September 2021) conveyed the Service Network and Parts Representations and that in making those representations it engaged in conduct that:

(a) was misleading or deceptive in breach of s 18 of the ACL; and

(b) falsely represented that it had a national service network and that spare parts would be available in contravention of s 29(1)(j) of the ACL.

4 Agrison has also admitted that its advertisements in the relevant period conveyed that in the event a Tractor was defective, it would replace all defective parts at no cost to the customer for a period of five years following purchase (Warranty Representation) and that in making the Warranty Representation it engaged in conduct that:

(a) was misleading or deceptive in breach of s 18 of the ACL; and

(b) falsely represented the effect of the Tractor warranty in contravention of s 29(1)(m) of the ACL.

The ACCC does not press the allegations against Agrison in relation to the Service Representation, or the Pleaded Warranty Representation (to the extent that it goes beyond the Warranty Representation).

5 The parties have agreed on proposed terms of settlement in relation to the issues in the proceeding and have submitted a joint Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (SOAFA), and joint submissions on relief. They jointly propose orders which include declarations of contravention, a pecuniary penalty of $220,000, injunctions restraining Agrison from engaging in the contravening conduct in the future, consumer redress orders in the sum of $63,947.50 pursuant to a redress scheme, the publication of a corrective notice, and an order as to findings of fact.

6 As part of the resolution of the proceeding, Agrison and Mr Yokus have also provided an undertaking to the ACCC pursuant to s 87B of the CCA (Undertaking) which provides for:

(a) the removal or amendment of the contravening advertising;

(b) provision of Warranty terms to customers prior to purchase of new Tractors;

(c) ACL compliance training for staff;

(d) the creation and implementation of a consumer complaint handling system and reporting regarding complaint handling to the ACCC; and

(e) an undertaking by Mr Yokus not to be involved (as a director, manager or otherwise) in any other business, importing or selling Tractors, other than Agrison, without the ACCC’s prior consent.

7 For the reasons I explain I am satisfied that it is appropriate to grant the declarations of contravention sought, to impose a pecuniary penalty of $220,000, to grant injunctions to restrain Agrison from similar contravening conduct, to make consumer redress orders in the sum of $63,947.50, to make an adverse publicity order in the form of the corrective notice, and to make findings of fact in terms of the judgment herein for the purpose of s 137H of the CCA.

OVERVIEW OF THE CONTRAVENING CONDUCT

8 The following overview is drawn directly from the SOAFA.

9 Since around 2016 Agrison predominantly supplied Tractors which were imported new from various Chinese manufacturers, with a retail price ranging from $18,000 to $60,000. The Tractors are commonly purchased and used by hobby farmers and owners of large acreage properties, lifestyle properties and small farms.

10 Agrison sells the Tractors from its Campbellfield showroom at major Australian “field days” and agricultural trade shows, and through online sales platforms including Gumtree and Farm Machinery Sales. It promoted its Tractors through brochures distributed at the trade shows; on the Agrison website; and by advertisements on Google, Ebay, Facebook, tradefarmmachinery.com.au, carsales.com.au, gumtree.com.au, constructionsales.com.au, machines4U.com.au and trading post.com.au.

The Tractor Warranty

11 The Tractors were supplied with a five year warranty (the Warranty) which contains terms to the effect that:

(a) some Tractor parts, typically consumable components, are not covered; for example, tyres, filters, hydraulic hoses, cabin glass, clutch, clutch components, engine belts and hoses;

(b) specific Tractor parts are not covered for five years and are only covered for the earlier of:

(i) 12 months of the date of dispatch from Agrison’s premises; or

(ii) up to 500 hours of use of the equipment;

for example, fuse panel gauges, switches, radiators and fitted oil coolers.

(c) certain Tractor parts are covered for the earlier of five years or 2,000 hours of use of the equipment, for example:

(i) engine parts such as pistons, cylinder sleeves, oil pumps, push rods and many more;

(ii) transmission parts such as internally lubricated components of both manual and automatic transmissions;

(iii) differential parts such as internally lubricated components; and

(iv) hydraulic components;

(d) for parts that are covered by the Warranty, coverage is limited to a maximum of $3,000;

(e) to remain covered under the Warranty, customers must comply with various strict requirements to:

(i) install “engineering changes or enhancements recommended by Agrison”;

(ii) have repairs, modifications or other work carried out by Agrison or by Agrison’s authorised service agent or contractor, or with Agrison’s express written authority;

(iii) store the Tractors under cover at all times;

(iv) strictly follow a servicing and maintenance schedule, which required customers to undertake daily checks of various parts of the Tractors, and undertake further checks following specified time periods of use or Tractor ownership; and

(v) submit all Warranty claims in writing by email to Agrison.

12 While the Warranty was hosted on Agrison’s website from at least 26 November 2019, it was not published on Agrison’s website on a page that was accessible to its customers or through a link from a publicly accessible page on the website. Rather, it could only be found by using a keyword search on an internet search engine, which produced a link to the Warranty.

13 While Agrison’s staff were instructed orally to:

(a) inform customers about the Warranty (including how to access it online); and

(b) attach a copy of the Warranty and Tractor manual to the seat of each Tractor prior to delivery,

Agrison accepts that the terms of the Warranty were not provided by Agrison to some customers, either prior to the sale of a Tractor, at the point of sale of a Tractor, or following the sale of a Tractor.

14 The requirements of the Warranty are particularly onerous in circumstances where customers were not provided with, and did not have easy access to, the terms with which they were required to comply.

The availability of parts

15 Agrison maintains stock of certain spare parts for Tractors at its Campbellfield warehouse. Agrison does not keep a written or electronic record of the parts that it has in stock at any one time. Agrison relies on its employees to remember which parts are in stock and where they are located within the warehouse.

16 Agrison does not maintain stock on hand of some parts required by customers to rectify defects in Agrison Tractors, including:

(a) service parts (e.g. filters);

(b) dash clusters;

(c) control valves;

(d) hydraulic pumps;

(e) water pumps; and

(f) transmission parts for engines.

17 Agrison does not maintain stock of all required spare parts for Tractor models including the 926 and 930 Yunnie engine wheel loaders.

18 Spare parts are generally ordered by Agrison from a factory overseas as and when required. The parts generally arrive on the same container as the next shipment of Tractors, every three to four months. Spare parts are also ordered from websites such as Alibaba and Circle D.

19 Throughout the relevant period, many Agrison customers were unable to obtain necessary parts required to repair or maintain their Tractors. In instances where Agrison customers were able to obtain parts, they often waited for long periods, sometimes between three and six months. In some cases, customers were unable to use their Tractor while they waited for parts.

Service of Tractors

20 Agrison does not have a national service network to undertake Warranty or service repairs for its customers.

21 Although the Warranty contains a condition that repairs, modifications or other work on Tractors must be carried out by Agrison or by Agrison’s authorised service agent or contractor, Agrison does not have formal arrangements in place with any mechanics in Australia to undertake servicing or Warranty repairs on Agrison Tractors. When a customer has a defective Tractor, or a service or repair issue, Agrison’s practice is either to refer customers to local mechanics who have no affiliation or formal arrangement with Agrison or to require customers to identify a local mechanic themselves who is able to satisfy Agrison that it can undertake the repair.

22 Until around December 2017, Agrison had a single employee in Victoria who was available on occasion to attend to Warranty repairs within the State. The employee was not a qualified mechanic and was not permitted by Agrison to attend customer sites to undertake repairs if he was required in Agrison’s workshop.

23 Customers located in Queensland and coastal New South Wales are commonly referred by Agrison to a contractor based in Upper Coomera (Contractor). The Contractor is available to travel to repair Tractors, but customers are required to pay for labour and travel as well as any parts that are not covered under the Warranty.

24 During the relevant period, the unavailability of necessary parts meant that Agrison Tractors were unable to be repaired for long periods of time.

Particular consumers

25 The SOAFA set out the facts and circumstances relating to four particular consumers (the Particular Consumers) who purchased Tractors from Agrison in reliance on one or more of the representations set out below, as admitted by Agrison.

The representations

26 During the relevant period, in its promotional material, Agrison made statements to the effect that:

(a) its Tractors come with a “5 year warranty”, “5 Year Nationwide Warranty” or “5 years Nationwide Extended Warranty”. These statements were made without qualification;

(b) it had an “established local and national service network, Agrison customers are backed up after sales”; it services “Agrison customers Australia-wide”, “Servicing Farmers Australia-Wide”, and “Agrison tractors are fully supported in Australia through its after sales service”; and

(c) it had a “spare parts inventory of thousands of items”, “over 20,000 spare parts items in stock at any given time”, and “Spare parts with over 20,000 spare parts inventory”.

27 The statements set out in the preceding paragraph were made in the context of other statements by Agrison in its promotional material, to the effect that:

(a) its Tractors were of the “highest quality”, “best quality”, “Quality, Value, Reliability at its Best!”, “Stamped with Quality”, “market leaders when it comes to quality”; and

(b) “Being an industry leader for over a decade has allowed us to invest a wealth of knowledge into research and development, to deliver exceptional products”.

28 Agrison admits that by making the statements at [26(a)] above it represented to consumers that in the event a Tractor was defective, it would provide a replacement part for all defective parts at no cost to the customer, for a period of five years following purchase (Warranty Representation). It also admits that the Warranty Representation was false and misleading in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(m) of the ACL because not all parts were covered for five years or at all, and the full cost of all parts was not covered.

29 Agrison admits that by making the statements at [26(b)] above it represented to consumers that it had a national service network and therefore customers requiring after-sales service or repair staff could access them throughout Australia (Service Network Representation). It admits that the Service Network Representation was false and misleading in contravention of ss18 and 29(1)(j) of the ACL because Agrison did not have a national service network available to provide after-sales service or repairs throughout Australia.

30 Agrison admits that by making the statements at [26(c)] above it represented that a customer would be able to obtain all necessary parts for Tractors within a reasonable time if and when required (Parts Representation). It admits that the Parts Representation was false and misleading in contravention of s 29(1)(j) of the ACL because during the relevant period Agrison did not have reasonable grounds for making the representation, including because:

(a) Agrison did not keep a record of the number of units of each spare part in stock at any given time;

(b) Agrison did not keep stock on hand of many spare parts that were frequently required by Agrison customers;

(c) many Agrison customers waited for long periods for necessary parts to repair defects in Tractors to be available or delivered; and

(d) the Particular Consumers were unable to obtain required spare parts for Tractors within a reasonable time-frame, or at all.

Consumer harm

31 From 1 January 2015 to 30 July 2021, Agrison supplied approximately 300 Tractors to consumers. During the same period, the ACCC received 58 complaints from customers who purchased Tractors regarding:

(a) defects or problems with the Tractors; and

(b) the inability to obtain necessary parts for Tractors from Agrison; or

(c) the inability to obtain satisfactory service from Agrison to remedy the defects or problems with Tractors.

32 Many consumers reported major defects in Tractors purchased for use on farm properties which had resulted in them being unable to use the Tractors for the purpose for which they were purchased. The complaints to the ACCC included:

(a) farmers unable to conduct work on their property due to defects with the Tractor, resulting in economic loss;

(b) the risk of injury from parts (including slashers) falling off Tractors and from Tractors catching fire;

(c) owners being required to purchase parts understood to have been covered by the Warranty;

(d) the inability to have Tractors serviced or repaired for long periods due to the unavailability of parts or the location of the Tractor in Australia;

(e) owners being required to identify and engage local mechanics who were willing to service or repair the Tractors due to Agrison not having a service network throughout Australia;

(f) Agrison failing to respond to customer complaints or to provide spare parts within a reasonable timeframe or at all; and

(g) Agrison refusing to provide refunds to customers in respect of Tractors with major defects.

Agrison’s financial position

33 Agrison’s financial statements show that its financial position over the relevant period was as follows:

FY | Total Revenue | Cost of Sales | Gross Profit | Expenses | Net Profit (after tax) |

2017/18 | $23,373,144.00 | $19,026,504.00 | $4,346,640.00 | $3,863,936.00 | $337,893.00 |

2018/19 | $16,887,111.00 | $13,352,543.00 | $3,534,568.00 | $2,729,250.00 | $583,856.00 |

2019/20 | $10,058,890.00 | $7,276,543.00 | $2,782,347.00 | $2,392,761.00 | $321,600.00 |

Half Year ended 31 Dec 2020 | $3,299,187.95 | $2,292,198.91 | $1,006,989.04 | $966,791.28 | $40,197.76 |

34 Agrison has not yet completed its accounts for FY21, but it estimates that its results for the second half of the financial year are broadly similar to those recorded in the first half. Thus, the parties estimated Agrison’s net profit after tax for FY21 at $80,395.

35 As Agrison does not keep records of the volume of Tractors sold, it is not possible to calculate the profit that Agrison has made on the sale of the Tractors, although it estimates that 30% of its profits are attributable to Tractors.

Agrison’s business practices

36 During the relevant period Mr Yokus was the sole director of Agrison and all employees reported to him. He was responsible for all aspects of the business of Agrison, including in particular, authorising orders for spare parts for Tractors, authorising Warranty claims and authorising settlement of other claims in respect of defective Tractors.

37 During the relevant period Agrison did not:

(a) keep a full written or electronic record of the volume of Tractors sold or details of customers to whom Tractors were sold;

(b) maintain a system for keeping a record of Warranty claims, defect claims or repair requests in respect of Tractors or the outcome of those claims or requests (with handwritten records kept of current claims until assessed and addressed, following which they were disposed of);

(c) keep records of spare parts sent to customers who made Warranty or other defect claims in respect of Tractors;

(d) provide any training to its employees regarding how Warranty claims, defect claims, repair requests or parts requests from customers should be handled;

(e) have any written procedures in place to provide guidance to employees regarding how Warranty claims, defect claims, repair requests or parts requests from customers should be handled;

(f) provide any training to employees in relation to its obligations under the ACL; and

(g) have an ACL compliance program in place.

Cooperation by Agrison

38 Prior to the commencement of this proceeding, on 30 August 2019 and on 31 July 2020, the ACCC served Agrison with two notices to furnish information and produce documents pursuant to s 155 of the CCA. Due to Agrison’s inadequate record keeping, its responses to the notices were incomplete.

39 Following the commencement of the proceeding, the parties attended a mediation on 6 May and 21 May 2021 and a resolution on the terms set out in the SOAFA and recorded in the proposed orders was agreed.

40 As part of the resolution of the proceeding, Agrison and Mr Yokus provided the ACCC with the Undertaking, pursuant to s 87B of the CCA, under which Agrison will:

(a) cease and remove all advertising (including on its website) that does not comply with the Undertaking within 14 days of the Undertaking being given;

(b) amend its advertising in relation to the Warranty;

(c) provide customers of new Tractors with a full copy of the terms of the applicable Warranty prior to any payment being made;

(d) ensure its directors, employees and representatives that are involved in advertising, sales or after-sale support for Tractors, attend practical training on compliance with the ACL and maintain records relating to the training which can be produced to the ACCC upon request;

(e) create an electronic customer complaint handling system that is compliant with the AS/NZS10002:2014 Guidelines for complaint management;

(f) ensure all Agrison staff and customers are aware of the complaint handling system; and

(g) report to the ACCC in relation to any complaints received.

41 Pursuant to the Undertaking Mr Yokus will:

(a) be prohibited from being involved (whether as director, manager, or otherwise) in any business that imports or sells Tractors other than the business carried on by Agrison without the ACCC’s prior written consent. If the ACCC provides such written consent, Mr Yokus must take all reasonable steps to ensure that the new business complies with each of the undertakings given by Agrison as if each reference to Agrison were a reference to the new business; and

(b) take all reasonable steps to ensure that Agrison complies with the terms of the Undertaking.

DECLARATORY RELIEF

42 The parties’ proposed orders contemplate declarations of contravention. Pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA) the Court has a wide discretionary power to grant declaratory relief. It is undesirable to fetter the exercise of the discretion by laying down rules as to the manner of its exercise, but ordinarily three requirements must be satisfied before a declaration should be made: see Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421 at 437-438 (Gibbs J); Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 at 448 (Lord Dunedin):

(a) the question the subject of the declaration must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor, that is, someone who has a true interest to oppose the declaration sought.

43 Here, each of those requirements is satisfied. There is, or at least was, a real question as to whether Agrison’s conduct contravened the ACL. The contraventions are established by the facts and admissions in the SOAFA, and the terms of the declaration accurately reflect and are confined to Agrison’s admitted contraventions. The ACCC, as the regulator under the ACL, has a real interest in seeking the declarations by reason of that role. The declarations will serve to support the ACCC’s regulatory functions and will enforce and promote compliance with the ACL in relation to false or misleading representations in advertising material. Agrison, as the respondent, is a proper contradictor. Notwithstanding that Agrison “came to see that interest served by not opposing the relief claimed” (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; 201 FCR 378 at [16] (Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ)) it has a genuine interest in opposing the declarations sought. The declarations are appropriate because they will record the Court’s disapproval of the conduct, deter others from engaging in conduct which contravenes the ACL, vindicate the concerns of relevant consumers, assist the ACCC in carrying out the duties as conferred on it by the ACL, serve the public interest in defining and publicising the type of conduct that contravenes the ACL, and make clear to other would-be contraveners that such conduct is unlawful: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v STA Travel Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 723 at [24] (O’Bryan J) and the cases there cited.

INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

44 The parties jointly submit that the Court should grant injunctive relief pursuant to s 232 of the ACL, in the form of paragraph 4 of the proposed orders. I accept the parties’ submission that the proposed injunctions are drafted in terms specifically referable to the admitted contravening conduct, in circumstances where Agrison continues to undertake business of the kind which gave rise to the admitted contraventions. The proposed injunctions will afford appropriate protection to consumers engaging with Agrison to allow them to make informed purchasing decisions by ensuring that Agrison appropriately describes its warranty terms and does not misrepresent the availability of its service network and spare parts.

45 Agrison’s conduct was deliberate and it was not isolated, having occurred over several years. I am satisfied that the proposed injunctions are appropriate to prevent repetition of the offending conduct, to induce compliance with the law and to counterbalance the injury to the public interest: ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 at 268 (French J); Truth About Motorways Pty Ltd v Macquarie Infrastructure Investment Management Ltd [2000] HCA 11; 200 CLR 591 at [79]-[80] (Gummow J). I have granted injunctions in the terms proposed.

PECUNIARY PENALTY

46 Section 29(1) of the ACL provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) in subs (j) - make a false or misleading representation concerning the availability of facilities for the repair of goods or of spare parts for goods; or

(b) in subs (m) - make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy.

47 At all material times s 224(1)(a) of the ACL provided that if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened, inter alia, a provision of Part 3-1 (which includes s 29) the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty as the Court determines to be appropriate.

48 The ACCC seeks the imposition of a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $220,000 payable by Agrison in respect of its admitted contraventions of ss 29(1)(j) and (m). It did not seek the imposition of a penalty in respect of the admitted contraventions of s 18 as that is not a civil penalty provision. Agrison accepts that a $220,000 penalty is appropriate in all the circumstances.

The considerations relevant to penalty

The mandatory considerations

49 At all material times, 224(2) the ACL provided:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Other relevant considerations

50 Other matters relevant to the exercise of the power to impose a penalty are commonly referred to as discretionary factors, and are sometimes called the “French factors”. However, as noted by Edelman J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Ltd [2016] FCA 44 at [123], they are not truly discretionary. Once they become relevant they are considerations that the Court must have regard to. Those factors have been considered in numerous decisions and were conveniently summarised by Perram J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; 282 ALR 246 at [11] to include the following:

(a) the size of the contravening company;

(b) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(c) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravenor or at some lower level;

(d) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the relevant legislation as evidenced by educational programmes and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(e) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act;

(f) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(g) the financial position of the contravener; and

(h) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

51 Further considerations include:

(a) whether a contravener has shown remorse or contrition: Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Gibson (No 3) [2017] FCA 1148 at [50] (Mortimer J); and

(b) whether a contravener has paid or has been ordered to pay compensation so as to ameliorate the loss or damage suffered: Woolworths at [166].

The applicable principles

52 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Colonial First State Investments Limited [2021] FCA 1268 at [39]-[47] I recently set out the applicable principles in relation to determining an appropriate penalty as follows:

Deterrence

[39] The principal object of a pecuniary penalty is deterrence, directed both to discouraging repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (specific deterrence) and discouraging others who might be tempted to engage in similar conduct (general deterrence). The object of a pecuniary penalty is to attempt to put a price on the contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to engage in contraventions: Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762 at 44; [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152 per French J (as his Honour then was), cited with approval in Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [55] (French CJ, Keifel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

[40] The Court must fashion a penalty which makes it clear to the contravener and to the relevant market or industry, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention of consumer protections cannot be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20 at [68]; 287 ALR 249 at 266 (Keane CJ (as his Honour then was), Finn and Gilmour JJ) cited with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54 at [64]; 250 CLR 640 at 659 (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). It must have sufficient sting or burden to achieve the specific and general deterrent effect that are the fundamental reason for imposition of the penalty: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union & Another [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157, 195 at [116] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ)

[41] Having said that, a penalty must not be so high as to be oppressive: Trade Practices Commission v Stihl Chain Saws (Aust) Pty Ltd [1978] FCA 104; ATPR 40-091 at 17,896 (Smithers J) cited with approval in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ (as her Honour then was)).

The maximum penalty

[42] The maximum penalty is not just a limit on power; “it provides a statutory indication of the punishment for the worst type of case, by reference to which the assessment of the proportionate penalty for other offending can be made, according to the will of Parliament”: Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 177; 299 IR 404 at [62] (Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ, with whom Besanko and Bromwich JJ agreed). Careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required because, the legislature has legislated for them; they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, they provide a yardstick: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357 at [31] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

The course of conduct principle

[43] In cases involving multiple contraventions, care must be taken to avoid the contravener being penalised more than once for what is in substance the same underlying misconduct.

[44] The course of conduct principle recognises that where there is a sufficient interrelationship in the legal and factual elements of the acts or omissions that constitute multiple contraventions, the Court may, in its discretion, penalise the acts or omissions as a single course of conduct. It involves treating multiple contraventions arising from the same underlying wrongdoing together, for the purpose of assessing the appropriate penalty for that conduct, so as to ensure that the sentence or penalty fairly reflects the substance of the offending conduct. The principle has been described as just a “tool of analysis” and the question as to whether contraventions should be treated as a single course of conduct requires consideration of all the circumstances of the case: see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 269 ALR 1 at [41]-[47] (Middleton and Gordon JJ).

[45] Whether or not the course of conduct framework of analysis is used, the Court’s task remains the same: that is, to determine an appropriate penalty which is proportionate to the wrongdoing viewed as a whole and having due regard to the need to avoid double punishment: Transport Workers Union of Australia v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203; 267 FCR 40 at [83]-[91] (Allsop CJ, Collier and Rangiah JJ).

The parity principle

[46] Assessments of penalty in analogous cases may provide guidance to the Court in assessing an appropriate penalty, by assisting equal treatment in similar circumstances and thereby meeting the principle of equal justice. The circumstances in different cases are rarely precisely the same as the case then before the Court: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SMS Global Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 855; ATPR 42-364 at [80] and the cases there cited. I was not taken to any case with similar facts to the present case and the application of this principle does not bear on my assessment of the appropriate penalty.

The totality principle

[47] The totality principle is the last step in the sentencing process, to be undertaken after the Court has determined what it considers to be an appropriate penalty for the contravening conduct. Where there are multiple contraventions the Court must apply this principle to ensure that, overall, the total penalty does not exceed what is appropriate for the totality of the contravening conduct involved. It operates as a “final check” to ensure that the aggregate penalty is just and appropriate having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct: Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; 166 CLR 59 at 63 (Wilson, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron JJ); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Wooldridge [2019] FCAFC 172 at [26] (Greenwood, Middleton and Foster JJ).

Consideration regarding penalty

53 For the reasons I now explain, I am satisfied that imposition of a pecuniary penalty of $220,000 is appropriate in the circumstances of the case.

54 First, having regard to the nature and extent of the contravening conduct I consider Agrison’s contravening acts and omissions constitute serious contraventions of ss 29(1)(j) and (m).

55 Agrison made the Warranty Representation, Service Network Representation and the Parts Representation to consumers in the context that it represented itself as an industry leader which offered high quality and reliable Tractors for sale. Its statements conveyed false or misleading representations to consumers that:

(a) in the event a Tractor was defective, it would provide a replacement part for all defective parts at no cost to the customer, for a period of five years following purchase;

(b) it had a national service network and therefore customers requiring after-sales service or repair staff could access them throughout Australia; and

(c) a customer would be able to obtain all necessary parts for Tractors within a reasonable time if and when required.

That was far from the truth.

56 The SOAFA says nothing about the state of mind of Agrison or Mr Yokus, but it is implausible that that the misleading features of Agrison’s promotional material were inadvertent or innocent. For example, it must have been obvious to Mr Yokus that Agrison did not have a national service network such that customers requiring after-sales service or repair staff could access them throughout Australia.

57 While it cannot be known for certain, it is appropriate to infer that at least some proportion of the customers relied upon one or more of those representation in purchasing an expensive Tractor. The high number of complaints to the ACCC speaks to the number of consumers who may have been subject to one or more of those misleading representations, and the fact that some consumers are likely to have relied on them can be seen in the agreed facts pertaining the Particular Consumers. It is relevant that some of Agrison’s customers were unable to use their Tractors for extended periods of time due to defects that Agrison failed to rectify in a timely manner, or because the required spare parts were unavailable.

58 The seriousness of the contravening conduct can also be seen in the fact that it occurred at the senior management level, and that Agrison did not have a corporate culture of compliance with the requirements of the ACL. Mr Yokus was the sole director during the relevant period and all employees reported to him. He was responsible for all aspects of the business, including authorising orders for spare parts and Warranty claims. Notwithstanding the Warranty Representation, Service Network Representation and Parts Representation made by Agrison, it did not keep records of Tractor sales, Warranty claims, defects notified, repair requests, customer complaints or spare parts in stock. It did not provide any training to its staff in relation to its obligations under the ACL or how to deal with Warranty claims. Nor did it have any written procedures or policies in place to provide guidance to employees in respect of those matters.

59 Second, turning to consider the loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravening conduct, it is impossible to know the extent of the losses suffered. But the evidence is that Agrison’s Tractor customers are largely hobby farmers who paid between $18,000 and $60,000 for each Tractor, and the inability of some purchasers to use their Tractors for long periods of time is likely to have caused them loss. The likelihood that Agrison’s customers suffered losses can also be seen in the agreed facts set out in the SOAFA which show that the four Particular Consumers suffered losses totalling $63,947.50. Three of those consumers incurred costs because they were forced to obtain parts and repair defects in their Tractors after Agrison failed do so, and two of them suffered loss by selling their Tractors for less than they paid for them. The Tractor purchased by the fourth of those consumers suffered from major faults, and the consumer sought to return the Tractor and obtain a refund from Agrison, without success.

60 Third, it must be firmly kept in mind that the raison d’être for imposing a pecuniary penalty is deterrence, directed both to discouraging repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (specific deterrence) and discouraging others who might be tempted to engage in similar conduct (general deterrence).

61 In relation to specific deterrence Agrison is essentially a family company with a sole director and 10 employees. It operates from a single location in Victoria. It has suffered a substantial decline in both revenue and profit over the relevant period and estimates its FY21 net profit after tax at $80,395. Given its size and modest profitability I am satisfied that a penalty of $220,000 is likely to deter Agrison from a repetition of similar conduct. Such a penalty is nearly 17% of Agrison’s net profit after tax for the entirety of its business, not just the Tractor Business, for the relevant period, and almost three times its FY21 net profit after tax. The ACCC accepts that Agrison’s financial position and its modest profitability means that it does not have the capacity to pay both the penalty and compensation orders immediately. In my view a penalty of $220,000 carries a sufficient sting or burden that Agrison is unlikely to see as an acceptable cost of doing business.

62 In relation to the requirement for general deterrence, it could be argued that a penalty of $220,000 is unlikely to operate as deterrent to other larger agricultural equipment suppliers in the market. But two things should be noted in this context:

(a) first, it is appropriate to infer that other agricultural equipment suppliers would understand that a penalty of that magnitude takes into account Agrison’s small size and modest profitability. They are likely to understand that larger and financially stronger contraveners are likely to incur a more substantial penalty; and

(b) second, regard must be had to proportionality “because of a balance in the reaching of an ‘appropriate’ penalty between an ‘insistence’ on deterrence and an ‘insistence’ on not imposing more than is reasonably necessary (NW Frozen Foods) as part of the reasonable and lawful exercise of judicial power (cf Banerji) in respect of a contravention before the court and in furtherance of the object of deterrence of contraventions of like kind:” Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 177; 384 ALR 75 at [111] (Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ, with whom Besanko and Bromwich JJ agreed).

63 Fourth, turning to consider the maximum penalty, the relevant period spans a change in the statutory maximum penalty. Pursuant to s 224 of the ACL a different maximum penalty applied in each period, as follows:

(a) before 1 September 2018 the maximum penalty was $1.1 million per contravention (the First Penalty Period): s 224(3) as it applied up to that date; and

(b) from 1 September 2018 the maximum penalty is $10 million per contravention (or three times the value of the benefit obtained from the contravening conduct, or if the benefit cannot be ascertained, 10% of the annual turnover of the corporation) (the Second Penalty Period): s 224(3A) which came into effect from 1 September 2018.

64 It is not possible to identify the precise number of contraventions in the present case. The representations were made in a range of promotional materials through a variety of channels over a period of more than three years. Each occasion on which a representation was made to a consumer may be treated as a separate contravention for the purposes of s 29. Although the precise number of contraventions that occurred cannot be ascertained, this is the type of case where arithmetical calculation of the theoretical maximum (by multiplying the number of contraventions by the prescribed maximum) would be a somewhat arid exercise and would not be meaningful or helpful in providing a yardstick for the Court.

65 As the parties submit, having regard to the course of conduct principle it is appropriate to analyse the contravening conduct as three interrelated courses of conduct, comprising the Warranty Representation, Service Network Representation and Parts Representation. Doing so takes into account the significantly overlapping nature of the contraventions which relate to the same products and the same representations over time, but to different persons. But even when the contravening conduct is analysed as three courses of conduct rather than multiple individual contraventions, the maximum penalty would, in total, be many times more than Agrison’s net profit after tax throughout the relevant period.

66 In my view there is no realistic prospect that Agrison has the financial capacity to pay a penalty in the millions of dollars. Application of the theoretical maximum penalty would vastly exceed what is required to achieve deterrence, and in my view it would result in a penalty so high as to be oppressive: see Trade Practices Commission v Stihl Chain Saws (Aust) Pty Ltd [1978] FCA 104; ATPR 40-091 at 17,896 (Smithers J) cited with approval in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ (as her Honour then was)). While careful attention to the maximum penalty will almost always be required, where, as here, the theoretical maximum rises to such a level, care must be taken to ensure that it is not applied mechanically, instead of it being treated as one of a number of relevant factors, albeit an important one: see Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357 at [31] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [156]-[157] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ); see also Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 (ABCC v CFMEU) at [143]-[146] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ).

67 In the present case a more suitable yardstick against which to determine the appropriate penalty is the $1.32 million derived by Agrison in net profit after tax during the relevant period. Using that as a yardstick, a penalty of $220,000, which comprises nearly 17% of Agrison’s net profit after tax for the entirety of its business, not just the Tractor Business, for the relevant period, and is almost three times its FY21 net profit after tax, is sufficient to provide specific and general deterrence, and deterrence is the fundamental objective of the civil penalty regime.

68 Fifth, the fact that the ACCC, the specialist regulator, has agreed with Agrison to propose a $220,000 penalty to the Court must be given some weight. Where, as here, the Court is persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the agreed penalty jointly proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances, it is highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty: Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [58] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ); Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; 151 ACSR 407 at [124]-[129] (Wigney, Beach and O’Bryan JJ).

69 No single factor is decisive in my determination as to the appropriate penalty. Instead, “[t]he fixing of a penalty involves the identification and balancing of all the factors relevant to the contravention[s] and the circumstances of the defendant, and making a value judgment as to what is the appropriate penalty in light of the protective and deterrent purpose of a pecuniary penalty”: ABCC v CFMEU at [100] as affirmed in Pattinson at [114]. I consider a penalty of $220,000, representing $100,000 in respect of the Warranty Representation and $60,000 in respect of each of the Service Network and Parts Representations is appropriate, as the parties submitted. Standing back and having regard to the totality principle as a final check, I am satisfied that such a penalty is just and appropriate for the totality of the contravening conduct.

CONSUMER REDRESS ORDERS

70 The four Particular Consumers each purchased a Tractor from Agrison in reliance upon the representations. Consumers A, C and D incurred costs in obtaining parts and repairing defects in their Tractors, and Consumers A and C also suffered losses by selling their Tractors for less than they paid for them. The Tractor purchased by Consumer B suffered from major faults, and they sought to return the machine to Agrison and obtain a refund, without success.

71 The consumer redress scheme proposed by the parties provides for substantial redress, in the amount of $63,947.50 to be paid to the Particular Consumers and for Agrison to collect Consumer B’s unwanted Tractor from their property.

The legislative framework

72 Division 4, Subdivision B of the ACL is headed “Orders for non-party consumers”. Section 239 in that subdivision relevantly provided:

Orders to redress etc. loss or damage suffered by non-party consumers

(1) If:

(a) a person:

(i) engaged in conduct (the contravening conduct) in contravention of a provision of Chapter 2, Part 3-1, Division 2, 3 or 4 of Part 3-2 or Chapter 4; or

(ii) is a party to a contract who is advantaged by a term (the declared term) of the contract in relation to which a court has made a declaration under section 250; and

(b) the contravening conduct or declared term caused, or is likely to cause, a class of persons to suffer loss or damage; and

(c) the class includes persons who are non-party consumers in relation to the contravening conduct or declared term;

a court may, on the application of the regulator, make such order or orders (other than an award of damages) as the court thinks appropriate against a person referred to in subsection (2) of this section.

Note 1: For applications for an order or orders under this subsection, see section 242.

Note 2: The orders that the court may make include all or any of the orders set out in section 243.

(2) An order under subsection (1) may be made against:

(a) if subsection (1)(a)(i) applies - the person who engaged in the contravening conduct, or a person involved in that conduct; or

(b) …

(3) The order must be an order that the court considers will:

(a) redress, in whole or in part, the loss or damage suffered by the non-party consumers in relation to the contravening conduct or declared term; or

(b) prevent or reduce the loss or damage suffered, or likely to be suffered, by the non-party consumers in relation to the contravening conduct or declared term.

(4) …

73 Section 240 sets out some matters to which the Court may have regard in determining whether to make an order under s 239(1). It relevantly provided:

Determining whether to make a redress order etc. for non-party consumers

(1) In determining whether to make an order under section 239(1) against a person referred to in s 239(2)(a), the court may have regard to the conduct of the person, and of the non-party consumers in relation to the contravening conduct, since the contravention occurred.

(2) …

(3) In determining whether to make an order under section 239(1), the court need not make a finding about either of the following matters:

(a) which persons are non-party consumers in relation to the contravening conduct…;

(b) the nature of the loss or damage suffered, or likely to be suffered, by such persons.

74 Pursuant to s 241, a non-party redress order under s 239 is binding on a non-party consumer if the loss or damage suffered by the non-party consumer has been redressed in accordance with the order and the non-party consumer has accepted the redress. Section 241 provides:

(1) A non-party consumer is bound by an order made under section 239(1) against a person if:

(a) the loss or damage suffered, or likely to be suffered, by the non-party consumer in relation to the contravening conduct…to which the order relates has been redressed, prevented or reduced in accordance with the order; and

(b) the non-party consumer has accepted the redress, prevention or reduction.

(2) Any other order made under section 239(1) that relates to that loss or damage has no effect in relation to the non-party consumer.

(3) Despite any other provision of:

(a) this Schedule; or

(b) any other law of the Commonwealth, or a State or a Territory;

no claim, action or demand may be made or taken against the person by the non-party consumer in relation to that loss or damage.

75 Section 243 provides a non-exhaustive list of the type of compensation orders that can be made under s 239(1) and other provisions. They include declaring the whole or any part of a contract between the respondent and the injured non-party consumer to be void; to vary the contract; to refuse to enforce any or all provisions of the contract; and to direct the respondent to refund money or return property to the injured non-party consumer.

The applicable principles and their application

76 Pursuant to s 239, to make a non-party consumer redress order in the circumstances of the present case, the Court must be satisfied that:

(a) first, Agrison engaged in conduct in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(j) and (m) of the ACL (s 239(1)(a)(i));

(b) second, the contravening conduct caused, or at least was likely to cause, a class of persons (here, the Particular Consumers) to suffer loss or damage (s 239(1)(b));

(c) third, the class includes persons who are non-party consumers in relation to the contravening conduct (s 239(1)(c)); and

(d) fourth, the order will redress in whole or in part, or prevent or reduce, the loss or damage suffered by the Particular Consumers in relation to the contravening conduct (s 239(3)(a) and (b)).

: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yellow Page Marketing BV (No 2) [2011] FCA 352; 195 FCR 1 at [128]-[129] (Gordon J); Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Domain Register Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 2008 at [14]-[19]. Having regard to the SOAFA I am satisfied as to each of those matters, and I am satisfied on the ACCC’s application that it is appropriate to make the consumer redress orders set out in Annexure A to the orders herein.

ADVERSE PUBLICITY ORDER

77 The Court has power under s 247 of the ACL and s 23 of the FCA to make an adverse publicity order, on the application of the regulator, in relation to a person who has contravened, inter alia, ss 29(1)(j) and (m).

78 The authorities reveal various rationales behind the making of such orders, including to:

(a) alert affected persons to the fact that there has been misleading conduct;

(b) protect the public interest by dispelling the incorrect or false impressions that were created; and

(c) support the primary orders and assist in preventing repetition of the contravening conduct.

: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 629; ATPR 42-402 at [143] and the cases there cited.

79 The parties jointly submit, and I accept, that having regard to the matters set out in the SOAFA it is in the public interest to make an adverse publicity order in the form of the corrective notice in Annexure B to the orders herein.

CONCLUSION

80 I have made orders broadly in the form proposed by the parties.

I certify that the preceding eighty (80) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Murphy. |

Associate: