Federal Court of Australia

Sanda v PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd (No 8) [2021] FCA 1291

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | PTTEP AUSTRALASIA (ASHMORE CARTIER) PTY LTD (ACN 004 210 164) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in agreed orders giving effect to these reasons and the reasons in Sanda v PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2021] FCA 237 by 4.00 pm on 5 November 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

YATES J:

Introduction

1 On 19 March 2021, I delivered reasons for judgment in which I found that the respondent owed a duty of care to the applicant and the Group Members, and that it had breached that duty. I found that oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout reached certain areas of Indonesia (conveniently described as the Rote/Kupang region), including the area where the applicant grows his seaweed crop. I found that the oil caused or materially contributed to the death and loss of his crop. I assessed his damages as 252,997,200 IDR and said that this sum should be converted to Australian dollars: Sanda v PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2021] FCA 237 (the principal reasons) at J[7] and J[1161]. In the present reasons, paragraph references to the principal reasons are designated by the letter “J”. I will also adopt the same expressions as in the principal reasons.

2 When delivering the principal reasons, I noted that the applicant sought pre-judgment interest and said that, if there was any dispute about that matter, I would hear the parties on that question. As matters turn out, there was a dispute about that matter. However, this has now been resolved, as explained below.

3 When delivering those reasons, I also provided answers to certain common questions. I was not prepared, however, to answer two common questions (Common Question 3 and Common Question 4) without receiving further submissions. The substance of those questions is: (a) which areas in the Rote/Kupang region did oil from the H1 Well blowout reach; (b) when did the oil reach those areas; and (c) did the oil cause or materially contribute to the death or damage of seaweed and/or the production of seaweed in those areas?

4 These reasons address these outstanding issues.

Pre-judgment interest

5 Section 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act) provides:

(1) In any proceedings for the recovery of any money (including any debt or damages or the value of any goods) in respect of a cause of action that arises after the commencement of this section, the Court or a Judge shall, upon application, unless good cause is shown to the contrary, either:

(a) order that there be included in the sum for which judgment is given interest at such rate as the Court or the Judge, as the case may be, thinks fit on the whole or any part of the money for the whole or any part of the period between the date when the cause of action arose and the date as of which judgment is entered; or

(b) without proceeding to calculate interest in accordance with paragraph (a), order that there be included in the sum for which judgment is given a lump sum in lieu of any such interest.

(2) Subsection (1) does not:

(a) authorize the giving of interest upon interest or of a sum in lieu of such interest;

(b) apply in relation to any debt upon which interest is payable as of right whether by virtue of an agreement or otherwise;

(c) affect the damages recoverable for the dishonour of a bill of exchange;

(d) limit the operation of any enactment or rule of law which, apart from this section, provides for the award of interest; or

(e) authorize the giving of interest, or a sum in lieu of interest, otherwise than by consent, upon any sum for which judgment is given by consent.

(3) ...

(4) ...

6 The dispute that was initially raised was not about whether pre-judgment interest should be awarded. Rather, it concerned the question of how that interest should be calculated. The dispute had three aspects.

7 The first aspect of the dispute was whether damages should be awarded in Australian dollars or Indonesian rupiah. As I have noted, in the principal reasons, I assessed the applicant’s damages in Indonesian rupiah but said that the assessed sum should be converted to Australian dollars. This was not an idle comment. The decision was deliberately made. In his closing submissions, the applicant specifically sought damages in Australian dollars to which he said pre-judgment interest should be applied. The respondent did not address that submission in its own closing submissions. In those circumstances, I did not understand there to be any dispute about the fact that damages should be awarded in Australian dollars.

8 However, the respondent has now contended that damages should be awarded in Indonesian rupiah on the basis that this currency best expresses the loss the applicant was found to have suffered. In response, the applicant has subsequently expressed his desire, or at least his preparedness, to have damages awarded in Indonesian rupiah. As there is no impediment to the Court awarding judgment in a foreign currency, and given the common position that has now been adopted, I will award damages accordingly. Nothing further need be said on that score.

9 The second aspect of the dispute has now fallen away. It concerned the time at which conversion should be made, but was premised on damages being awarded in Australian dollars.

10 The third aspect of the dispute has also fallen away. It concerned the question whether interest, at the applicable rate, should be calculated at the beginning of each period of calculation, or at the midpoint of each period (so as to reflect the fact that income would have been earned throughout the period). The applicant now accepts that interest should be calculated at the midpoint of each period of calculation, as the respondent contends.

11 The respondent has undertaken a calculation of the appropriate pre-judgment interest, and the applicant accepts that calculation.

Submissions on common questions 3 and 4

The applicant’s position

12 The applicant submits that the evidence of the observations of oil by the lay witnesses—whose evidence I found to be reliable and to provide a coherent and convincing body of evidence—supports a compelling inference that the oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout reached and caused damage to seaweed not only at the specific locations to which the witnesses’ evidence was directed, but reached and caused damage to seaweed at all the coastal waters surrounding the islands of Rote, Ndana, Ndao, Do’o, Nuse, and Semau, and around the south-western peninsular of Kupang, and Kupang’s western-most coastal waters extending up to Kelapa Lima.

13 In answering Common Questions 3 and 4, the applicant accepts that the impact of dispersants need not be addressed given his acknowledgement that, ultimately, he did not advance a case that dispersants applied to the spilled oil reached the coastal waters of Rote/Kupang.

14 In the course of oral submissions, leading counsel for the applicant, Mr Sexton SC, argued that the Court should adopt a robust approach in answering Common Questions 3 and 4. As he put it, with reference to Robinson Helicopter Company Incorporated v McDermott [2016] HCA 22; 331 ALR 550 at [86]:

… the proof of causation, which is what we are essentially dealing with here, can entail a robust, pragmatic drawing of inferences. And that’s essentially what we contend for here.

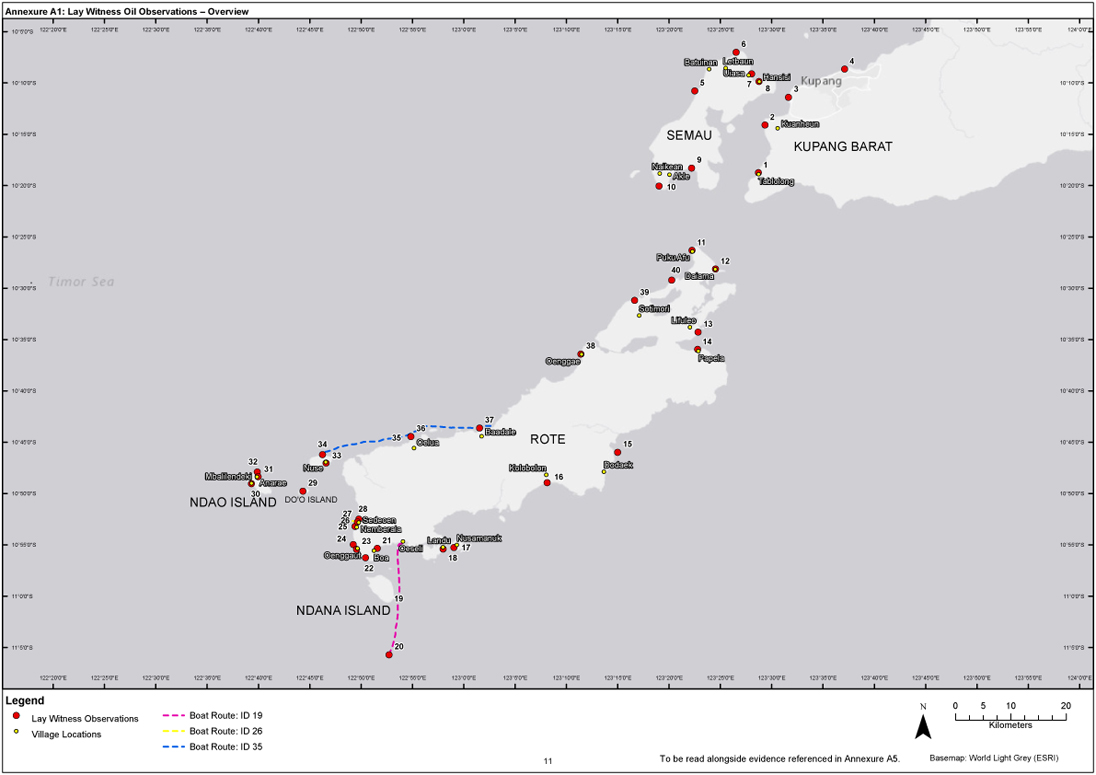

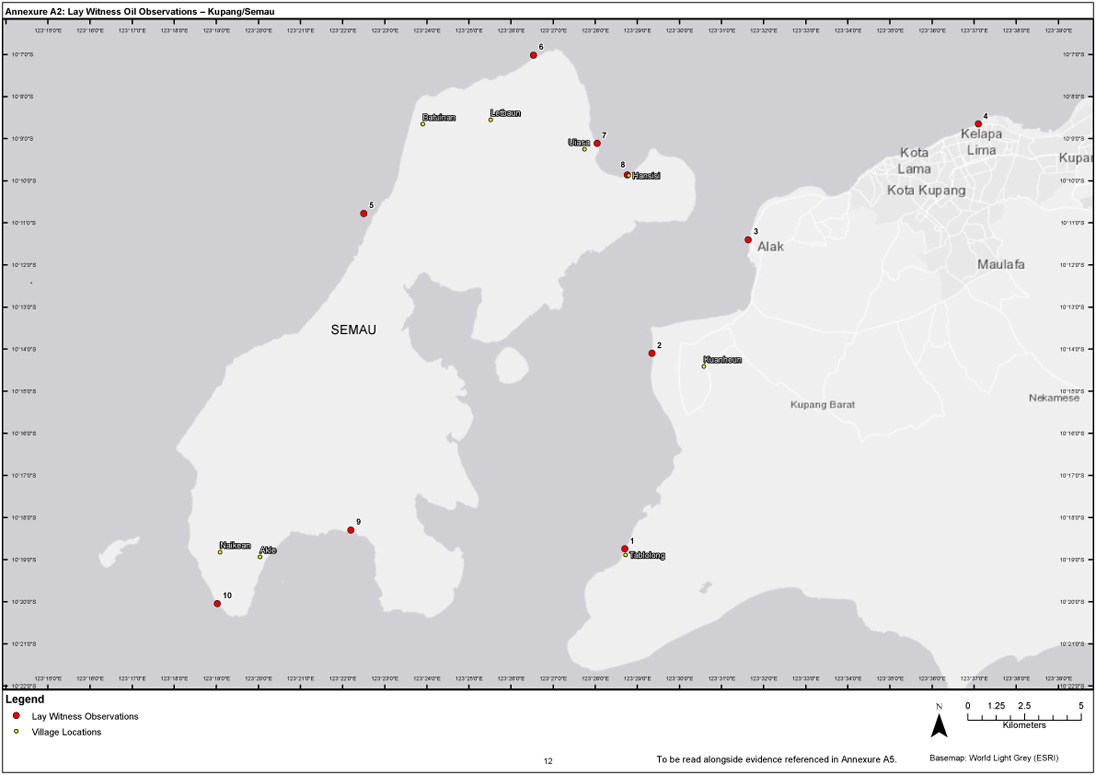

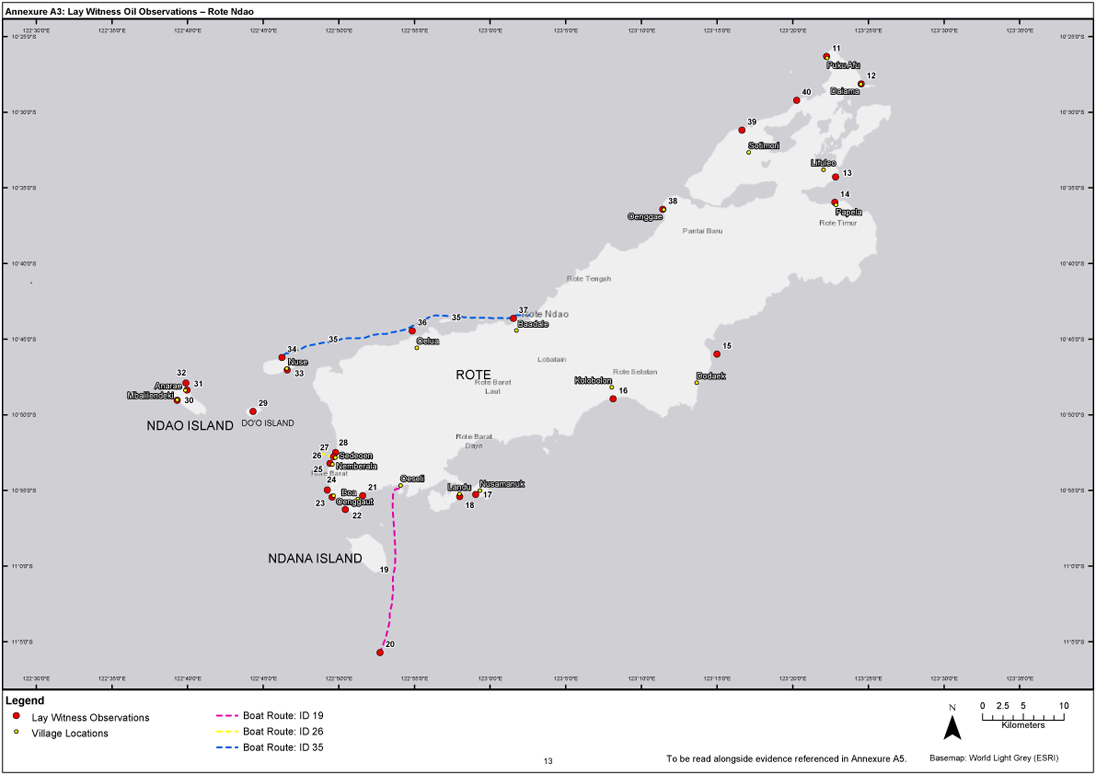

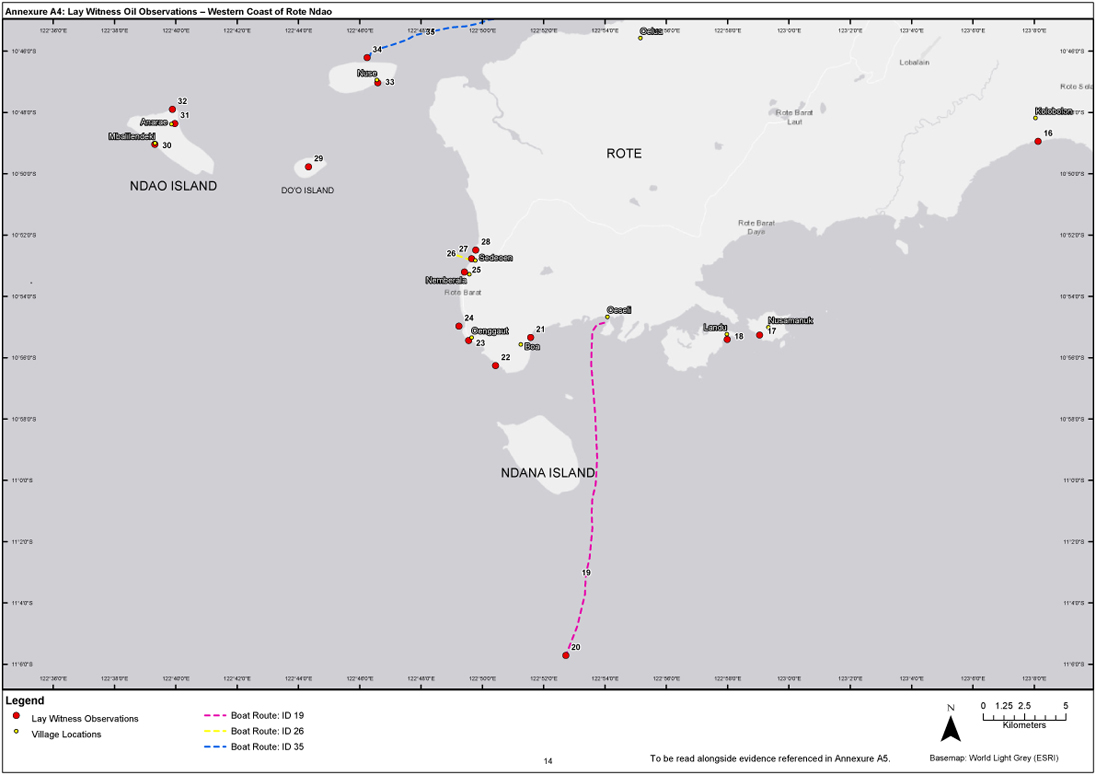

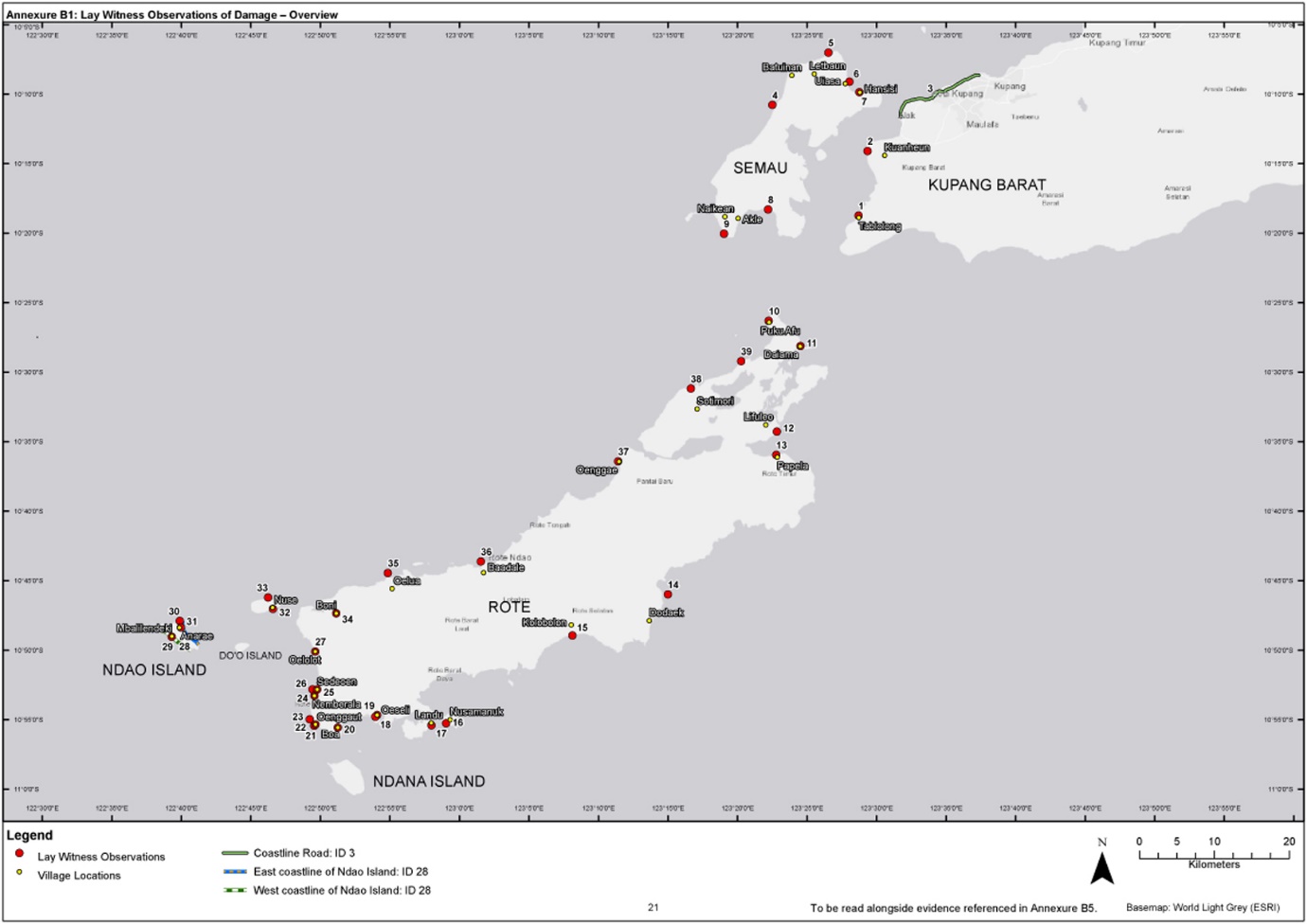

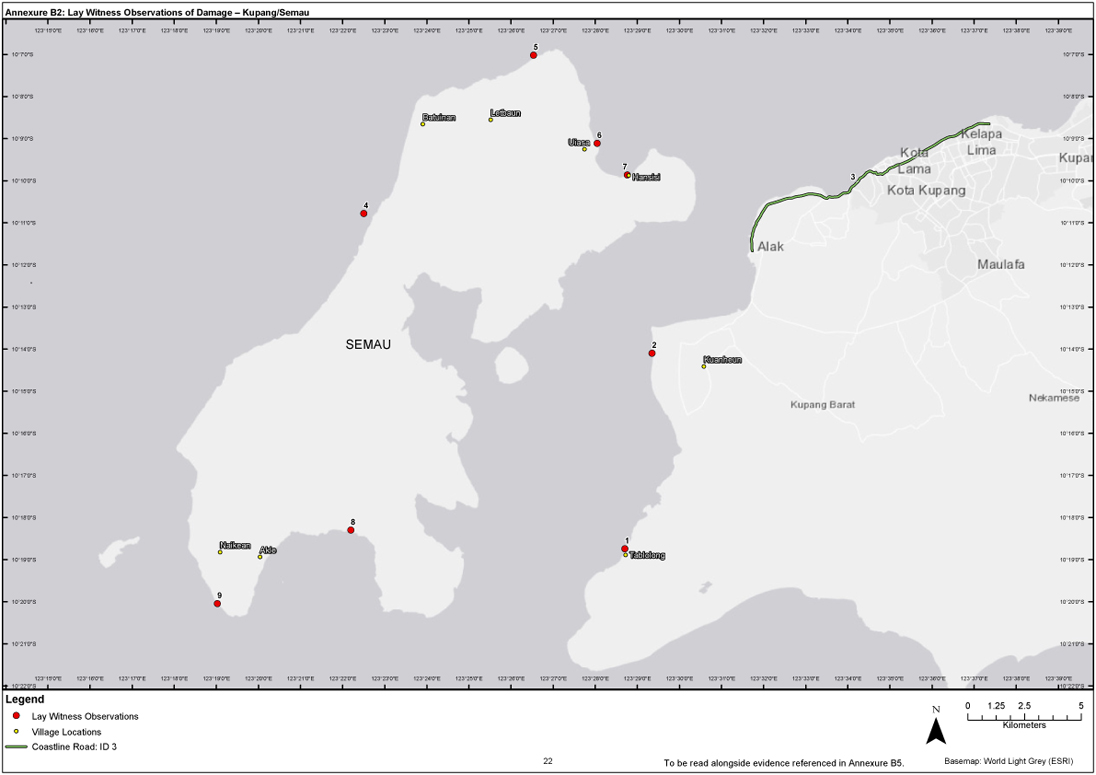

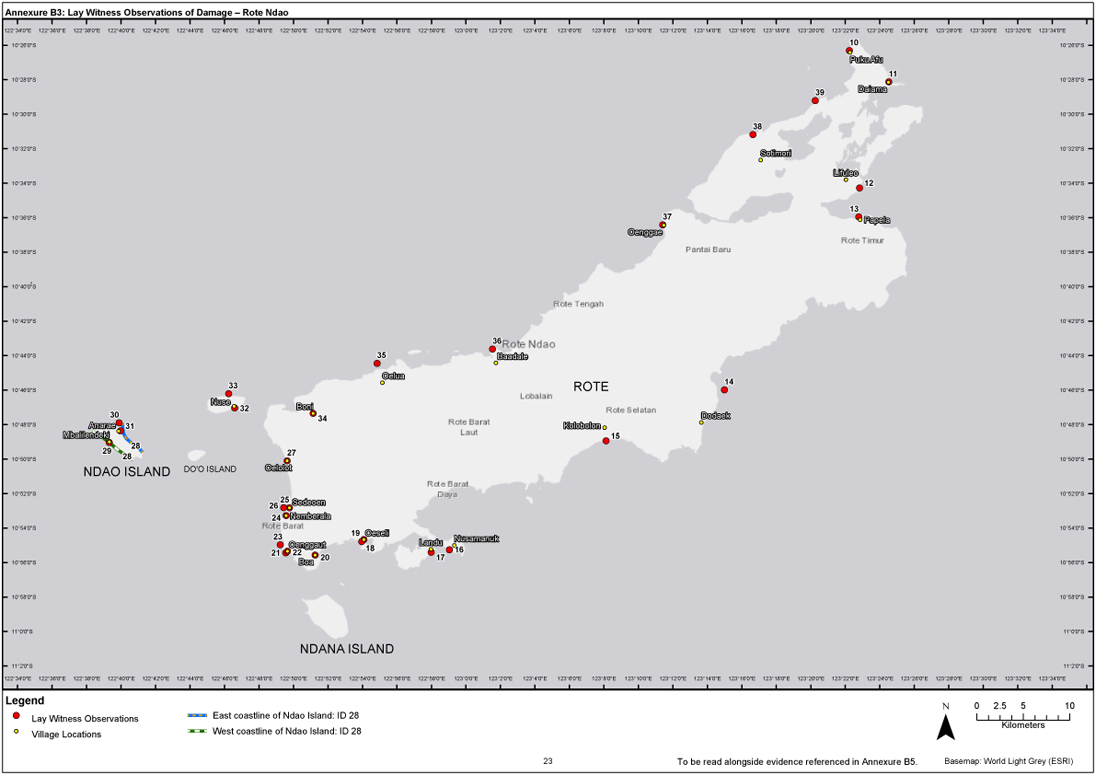

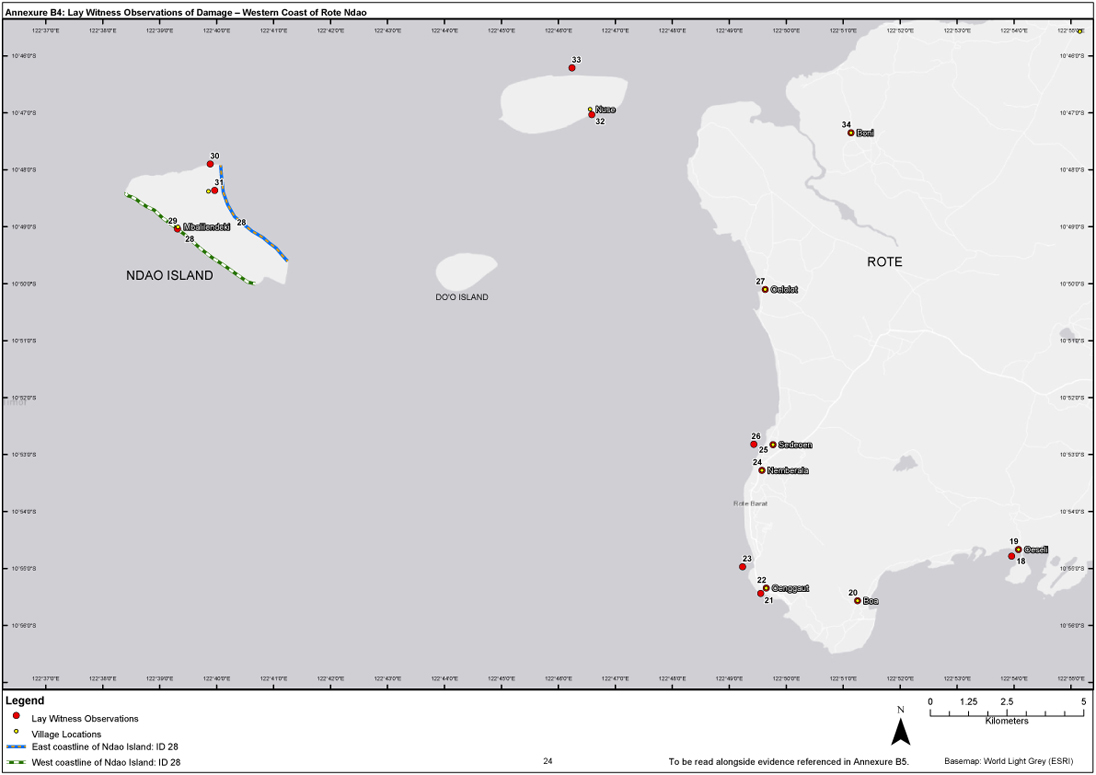

15 The applicant referred me to various maps, which had been prepared for the purposes of his submissions, identifying the locations at which he said observations of oil had been made and locations at which he said damage to seaweed was observed. These maps are reproduced in Schedule A to these reasons, designated as Annexures A1 – A4 (observations of oil) and Annexures B1 – B4 (observations of damage to seaweed).

16 In addition to the evidence of observations of oil by the lay witnesses, the applicant points to a number of findings I made, namely that: oil was being discharged at an uncontrolled rate from the H1 Well in excess of 2,500 bbl/day (J[320]); a very large part of the spilled oil was not treated with dispersants and much of the untreated oil was not dispersed by natural forces, given the prevailing temperature and sea conditions at the time (J[362]); and, as to the oil that was treated, the effectiveness of the dispersants varied (J[363]).

17 The applicant also relies on the findings I made concerning the mechanisms and trajectory by which the spilled oil could have reached the Rote/Kupang region, especially having regard to: Dr Hubbert’s trajectory modelling (J[863] – J[864]); Dr Sprintall’s and Dr Luick’s evidence concerning the complexity of the ITF (J[523] – J[524], J[861], and J[866]); Dr Gundlach’s analysis (J[867]); and the recorded observations that were made at the time (including flight surveillance and other AMSA reports) which showed the extent of the oil which was moving northwardly (including beyond the demarcation of Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone) and eastwardly towards Timor and the Rote/Kupang region (J[660] and J[860]).

18 As to the question of damage to seaweed by oil, the applicant relies on my findings at J[1008] – J[1009] that, given the descriptions of the seaweed farmers, there can be no doubt that seaweed crop death coincided with the arrival of oil and that there is no other plausible explanation for the widespread loss that was observed. Further, at J[1010], I found:

The evidence makes clear that there are multiple mechanisms or pathways by which seaweed can be killed or damaged by both fresh and weathered oil. We will never know the precise mechanism(s) or pathway(s) by which the crops died here. But the fact that: (a) Montara oil from the H1 Well blowout reached the coastal areas of Rote/Kupang; (b) the crops located where the oil was observed died shortly after the oil arrived; (c) this coincident event was widespread in the Rote/Kupang region; and (d) there is no other plausible explanation for this widespread loss, combine to establish the causal connection between the presence of the oil and crop death. The obvious cannot be ignored.

19 The applicant accepts that evidence was not adduced of damage to seaweed along the eastern coastline of Semau or on the islands of Do’o and Ndana. Otherwise, he submits that there was evidence of damage to seaweed and seaweed production in all the areas in which oil was observed.

The respondent’s position

20 The respondent contends that the evidence does not support the answers to Common Questions 3 and 4 that the applicant proposes. It contends that the answer to each question should be more specific, in the sense that each answer should be confined to the specific locations to which the witnesses’ evidence was directed, and in the terms they specifically adopted to describe their observations, including in relation to seaweed damage.

21 The respondent contends that, to confine the answer to Common Questions 3 and 4 in this way, would be consistent with the function that answers to common questions are to serve. In this connection, the respondent relies on the observations of the Full Court in Ethicon Sàrl v Gill [2021] FCAFC 29; 387 ALR 494 (Ethicon) at [815] – [817] and Ethicon Sarl v Gill (No 2) [2021] FCAFC 52 (Ethicon (No 2)) at [7].

22 More fundamentally, the respondent submits that the evidence at trial does not support the more broadly expressed answers proposed by the applicant, for three main reasons.

23 First, the witnesses’ observations were made at specific geographic locations. This evidence was not only specific as to place, but also as to time. According to the respondent, such evidence cannot be generalised to other locations in the way contemplated by the applicant.

24 Secondly, there were significant differences in the witnesses’ descriptions of what was observed at different locations. The respondent submits that this makes it clear that the hydrocarbons (oil) that reached these locations were not homogeneous in appearance or form and that this stands as a reason why each observation, taken at a particular location, must be considered individually. According to the respondent, the observations cannot be reliably extrapolated to cover the locations between them, either as to the presence of hydrocarbons or, relevantly to Common Question 4, damage to seaweed.

25 Thirdly, the expert evidence and the observational evidence (from flight surveillance and other AMSA records) supports the proposition that the spilled oil did not radiate out evenly from its source from the H1 Well as a uniform mass. Instead, it moved in lines and windrows, such as the filaments referred to as “tiger tails”: J[229], J[616], and J[861]. The respondent submits that this “non-uniform movement” would have been further influenced by the highly variable and complex ITF current system.

26 The respondent submits that it follows from these matters that it cannot be assumed or inferred that because oil was observed at two locations on the coastline, it was also present in every other location on the coastline between the two observations. The respondent submits that the way the oil moved, and the variety in the descriptions of what was observed, simply do not permit such an assumption or inference to be made.

27 The respondent submits that the applicant’s answers to Common Questions 3 and 4 overstate the effect of the evidence. It submits that the appropriate approach is to formulate an answer that directly reflects the evidence that was given.

Schedule B

28 To illustrate the competing approaches, and to focus attention on the answers it proposes, the respondent prepared a table, based on tables of evidentiary references that the applicant had prepared to support his more broadly expressed answers to Common Questions 3 and 4.

29 When the matter came before me for oral submissions, the parties had been able to agree on the content of the respondent’s table, except for certain line entries. The table then provided the focus for the oral submissions.

30 Following oral submissions, the parties, at my request, prepared a further, revised table. The contested entries in the revised table concern particular aspects of Entries 3A, 3B, 4, 8, 10, 19, 21A, 21B, 22, 25B, 28, 29, 31, 34, 35, and 37, in relation to column(s) B and/or D thereof.

31 I have considered the contested entries. Schedule B to these reasons reproduces the revised table recording the agreed entries and my findings in relation to the contested entries. The following paragraphs provide the reasons for my findings in relation to the contested entries. In reaching these findings, I have taken into account not only the specific evidence referenced by the parties with respect to each entry (column E), but also the general findings I have made concerning the volume and trajectory of the oil spilled from the H1 Well and the observations of other witnesses as to the appearance of the oil at various times in various locations.

32 There is a further matter to which I should refer. The applicant contends that, in addition to the matters set out in Schedule B, evidence of damage to seaweed farms should be taken into account even if there is no evidence expressly referring to an observation of oil in that same location.

33 I do not accept that contention. First, in terms, Common Question 4 is referable to Common Question 3, and should be answered accordingly. Secondly, and more fundamentally, I am not prepared to infer that evidence of damage to seaweed is, without more, evidence of damage to seaweed by oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout. I acknowledge that causation is a question of fact based on a common sense approach to fact-finding: March v E & MH Strahmare Pty Limited [1991] HCA 12; 171 CLR 506. But it does not follow from that acknowledgement that the applicant’s contention is sound.

34 In support of his contention, the applicant drew attention to the example of Mr Axel Chalvet’s oral evidence. Mr Chalvet and his wife own and manage the Boa Hill Surf House, which is a guest house near the village of Boa. Boa is on the south-western tip of Rote Island. It is contiguous with the coastline on which Kite Beach and Oeseli Harbour are located.

35 Mr Chalvet gave evidence of his observations while travelling from Boa (Oeseli Harbour) to a fishing ground south of Ndana Island:

Did you go fishing during that period?---Yes, sir, I did.

Where to?---To that fishing ground that’s on the map right there. Other places too.

Approximately how far south of Ndana Island is that location?---It’s about 10 kilometres, seven to 10 kilometres I would say approximately.

When you go from Boa down to that location, which side of Ndana Island do you travel?---So we take the east side of Ndana Island.

And why is that?---Because the currents and the waves can be pretty rough on the west side.

All right. And what did you observe on the occasions when you travelled down to that fishing location?---That there was lots of grease floating around too, wax floating around. My boat got really dirty. I had to clean it more than once.

Where do you moor your boat?---In the Oeseli Harbour, it’s on the map right there.

And apart from mooring boats, what else happens in Oeseli Harbour?---It’s a very important seaweed village over there, seaweed farming village.

Had you been travelling through that area for some years before 2009?---Yes.

What had you observed about the seaweed during that period?---To go in and out of the harbour was actual a bit of a mission because there was very restricted area in that the boat could go through because there was seaweed absolutely everywhere, seaweed farming.

And what observations did you make towards the end of 2009 about the seaweed in Oeseli Harbour?---That I could go in and out without any problem and without looking where I had to go because there was no more seaweed.

And when was it approximately that you first made observations of the material you’ve described?---I would say it was just before the rainy season of 2009.

What does that mean in terms of calendar months?---October, November. I can’t remember the dates exactly, it was a while ago.

36 The applicant submitted that Mr Chalvet’s evidence of loss of seaweed from seaweed farms in Oeseli Harbour grounds an inferential finding that oil was present in the waters along the south-western coast of Rote—in particular, in and around Oeseli Harbour—and that the oil caused damage to the seaweed farms which, previously, had prospered in that location.

37 I am satisfied that oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout was present in the vicinity of Oeseli Harbour and was the likely cause of damage to the seaweed farms in the harbour, but not because of the simple contention advanced by the applicant. There is a greater body of evidence, both from Mr Chalvet and others, to support that finding—not just Mr Chalvet’s observation that seaweed was lost from seaweed farms in the harbour itself.

38 For example, Mr Chalvet gave evidence that in September and October 2009 he observed waxy, white substance floating all over the ocean. This observation was made from his home. He said that it looked like a very large river—a couple of hundred metres wide—moving east to west, in the direction of the wind. He observed this substance all over the beach near his home (Boa Beach). He touched it. It felt like greasy wax with salt in it. He had not seen anything like it before. Over the next few days he observed the substance coming and going, “sometimes in very big quantities and sometimes in lesser quantities”. The substance was present for “a couple of weeks”.

39 Kite Beach is to the east of Mr Chalvet’s home, around what appears to be a major headland. At around the same time as he made the observations from his home, he also observed “quite a bit of waxy substance around there [Kite Beach]… accumulate[ing] on the beach”. As I note below, Mr Guiney and Mr Rogers made similar observations at Kite Beach, at around the same time.

40 Oeseli Harbour is further to the east but, as I have said, on the same coastline as Kite Beach. I am satisfied that the grease and wax that Mr Chalvet observed en route from Oeseli Harbour to the fishing ground were from the same source as the substances he observed at Kite Beach and from his home, including at Boa Beach. I am satisfied that this was from oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout and that, more likely than not, it found its way in and around Oeseli Harbour and was the cause of the seaweed loss which Mr Chalvet observed.

Entries 3A and 4

41 These entries should be considered together. They concern the evidence given by Mr Antony La Macchia with respect to observations he made in late August/early September 2009.

42 The issue is whether Mr La Macchia’s evidence supports a finding of hydrocarbons (oil) in the waters of Tenau Harbour and at Kelapa Lima, as well as in adjacent areas in Kupang, and a finding of damage to seaweed at those locations.

43 The respondent submits that Mr La Macchia did not give evidence of damage to seaweed at Tenau Harbour and did not give evidence of the presence of hydrocarbons or of damage to seaweed on the coastline of Kelapa Lima.

44 It is necessary for me to go into more detail in respect of Mr La Macchia’s evidence to refer to matters not summarised in the principal reasons.

45 Between around August 2005 and the end of 2009, Mr La Macchia worked with his father in a family fishing business, which was based in Kupang. Mr La Macchia lived in an area called Kelapa Lima. This is near the coast, just north of the city of Kupang. It lies to the east of Tenau Harbour. His home was only one road back from the coastal road, which hugs the shoreline.

46 Mr La Macchia’s evidence was that he would often drive along the coastal road in order to see friends west of Kupang city. He also often drove further south-west along the road to Tenau Harbour. His home in Kelapa Lima was about 15 km from the harbour. The water can be seen almost all the way between Kelapa Lima and the harbour.

47 When Mr La Macchia drove along the coastal road, he passed, and observed, many seaweed farms. There were also seaweed farms by the beach closest to his house.

48 He said:

… In passing I can see that they were a hive of activity. I could see that the farms were made up of line after line of semi-floating ropes covered in lumps of green seaweed and what looked like hundreds of plastic bottles. … I could see that the farms were in shallow water and that the farmers usually walked between the lines as they tended to their crops. I did see the farmers use boat sometimes, but not often.

I was used to seeing the seaweed farms buzzing with life. As I drove past the farms I would see farmers walking up and down the lines tending to their crops and bringing in harvested seaweed in baskets or by small boat.

49 Mr La Macchia said that, about a week after he got back from his fishing trip to Fantome Shoal and Mangola Shoal (where he made a number of observations of oil, including its smell), he noticed a smell of oil around the coastline near his home. He recognised the smell as the one he experienced in his fishing trip. He said that he did not recall ever smelling oil on the coastline before that time.

50 Mr La Macchia said that, after smelling the oil near his home, he went to Tenau Harbour. At the harbour, he could see an oily sheen shimmering on the water surface, right across the harbour. It appeared to be in streaks. He could smell the oil. He said that it was the same smell as the smell near his home. He could not recall seeing an oily sheen across the harbour on any other occasion. The sheen was visible at Tenau Harbour for at least a few days, and possibly up to a week.

51 Mr La Macchia said that when he first smelled the oil near Kelapa Lima, he could still see lines of seaweed-covered ropes in the water along the coastline. But then, within a week or so, the lines were no longer there. This was about two weeks after his fishing trip. He said:

I noticed that the seaweed farms … had, in what seemed all of a sudden, ceased operating all along the coast between Kelapa Lima and the harbour, that is all along the coastal road … The farmers who farmed near my home at Kelapa Lima had taken all of their ropes and plastic bottles out of the water and had left them on the beaches. I noticed that the ropes and bottles were no longer in the water. It seemed that the seaweed farms were there one minute and then gone the next.

It really struck me as I had not experienced anything in West Timor going through as much of a sudden change as the change in the seaweed farms.

52 Mr La Macchia’s evidence has not been challenged, and I accept it.

53 Having regard to the timing of Mr La Macchia’s observations at Kelapa Lima relative to the observations he made at Fantome Shoal and Mangola Shoal, and the association he drew between the two sets of observations, particularly in relation to smell, it is more likely than not that the smell of oil that Mr La Macchia experienced at his home in Kelapa Lima was from oil that had been spilled from the H1 Well blowout.

54 Further, having regard to my findings concerning the fate of seaweed crops that came into contact with oil from the H1 Well blowout, I am satisfied that Mr La Macchia’s observations concerning the sudden cessation of seaweed farming, and the removal of ropes and bottles, at Kelapa Lima is consistent with the damage to seaweed crops in that area. I am satisfied that oil from the H1 Well blowout caused or contributed to that damage.

55 Further, I am satisfied that Mr La Macchia observed oil in the waters at Tenau Harbour and that it is more likely than not that these observations were of oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout. This finding is supported by the evidence given by Mr Bartolo La Macchia (Entry 3B, referred to below).

56 Based on Mr La Macchia’s observations at Tenau Harbour and at Kelapa Lima, I am also satisfied that oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout was present along the coast between the two locations. Column B in Entry 3A should reflect that finding, and I have amended it accordingly. I am satisfied that Mr La Macchia’s observations concerning the sudden cessation of seaweed farming along the coast between Kelapa Lima and Tenau Harbour is evidence of damage to the seaweed crops in that area and that, more likely than not, oil from the H1 Well blowout caused or contributed to that damage.

57 However, so far as I am aware, there is no evidence of seaweed farming in Tenau Harbour itself.

Entry 3B

58 This entry concerns the evidence given by Mr Bartolo La Macchia (Mr Antony La Macchia’s father) with respect to observations he made in September 2009.

59 The issue is whether Mr Bartolo La Macchia observed damage to seaweed in Tenau Harbour and other adjoining locations. Mr Bartolo La Macchia did not give evidence of damage to seaweed, but his evidence does support the presence of hydrocarbons in Tenau Harbour that stretched south, and north into Kupang Bay.

Entry 8

60 This entry concerns the evidence given by Mr Lorens Hendrik with respect to observations he made in September or October 2009. At the time, Mr Henrik was the village head of Hansisi on the island of Semau, and also a seaweed farmer.

61 The issue is whether Mr Henrik’s evidence supports findings of hydrocarbons at Hansisi and of damage to seaweed at Hansisi. The respondent contends that this finding should not be made. The respondent contends that Mr Hendrik’s observations were made only with respect to his seaweed farm and that Entry 8 should be limited accordingly.

62 Mr Hendrik gave this evidence:

I remember seeing the oil coming into the waters near Hansisi in 2009. In around September / October in 2009 (I cannot exactly remember), when I was in my seaweed plot I saw something strange on the sea surface. I was thinking it might be kind of waste came from berthed ships. There look like lumps in part, a little bit waxy with some black colour, but when current changed, it looked like leaked oil spread across the sea. I smell something unusual and was not really sure whether it smelled like oil or not. Soon after the seaweed went white and soft. It died and washed away and then became difficult to grow like it was sick.

(Errors in original.)

63 I do not read Mr Hendrik’s evidence of the observations of oil as limited to his seaweed farm. His evidence showed the presence of hydrocarbons “on the sea surface” in the waters near Hanisi, “spread across the sea”. I am satisfied, therefore, that the oil was at Hansisi. However, Mr Hendrik did not give evidence of the presence of any seaweed farm at Hansisi, other than his own farm to which his observations of seaweed death and damage were directed.

Entry 10

64 This entry concerns evidence given by Mr Johan Lima with respect to observations he made in 2009. At this time, Mr Lima was the village head of Naikean on the island of Semau, and also a seaweed farmer.

65 The issue is whether Mr Lima’s evidence supports findings of hydrocarbons at Naikean and of damage to seaweed at Naikean. The respondent contends that these findings should not be made. The respondent submits that Mr Lima’s observations were made only with respect to his seaweed farm and that Entry 10 should be limited accordingly.

66 Mr Lima’s evidence was that he observed oily blocks “on the surface of the waters”. I do not accept that these observations were confined to his seaweed farm. I am satisfied, therefore, that the oil was at Naikean. However, Mr Lima did not give evidence of the presence of any seaweed farms at Naikean, other than his own farm to which his observations of seaweed destruction were directed.

Entry 19

67 This entry concerns the evidence given by Mr Axel Chalvet of observations he made in September to October 2009.

68 Part of Mr Chalvet’s evidence was directed to the observations he made en route from Boa (Oeseli Harbour) to a fishing ground, approximately 7 – 10 km south of the island of Ndana: see [35] above.

69 The matter at issue is very minor. The applicant submits that Mr Chalvet’s evidence, in this respect, supports a finding that hydrocarbons were observed along Mr Chalvet’s boat route from Oeseli Harbour to the fishing ground. The respondent submits that Mr Chalvet’s evidence supports a finding that hydrocarbons were observed along “at least part of” the boat route.

70 I do not understand Mr Chalvet’s evidence to be that his observations of hydrocarbons were for the entirety of the route. To this extent, the answer proposed by the respondent is the correct answer. However, for the reasons given above, I am satisfied that there was loss of seaweed, and hence damage to seaweed, from seaweed farms in Oeseli Harbour and that this damage was caused by oil spilled from the H1 Well blowout. In column D, the parties have accepted that the answer should be “No”. I do not accept that answer. The answer should be “Yes, in Oeseli Harbour”. The answer in column D has been amended accordingly.

Entry 21A

71 This entry concerns evidence given by Mr John Guiney with respect to observations he made in late October 2009, and late April or May 2010. The issue is whether this evidence supports a finding of damage to seaweed “in the water and on Kite Beach, near Boa, Rote Ndao”.

72 Mr Guiney gave evidence that while kite-boarding at Kite Beach, near the village of Boa, about 5 or 6 km from Nemberala, he observed a black gummy substance sticking to his kite board equipment. He said that, at around this time, he also saw a white foamy waxy substance collect on the logs and sticks on Kite Beach. Mixed into this substance were black waxy lumps. He said that he saw the same substance build up on the seaweed ropes on the beach in front of his house on Nemberala Beach.

73 Mr Guiney did not give evidence of damage to seaweed at Kite Beach. Indeed, there is no evidence, so far as I can see, that seaweed farms existed on Kite Beach. Mr Guiney’s observations at Kite Beach of black waxy lumps mixed with a white foamy waxy substance was with respect to logs and sticks, not seaweed.

74 The applicant submits that Mr Guiney’s evidence of the presence of oil should be considered with the evidence given by Mr Nikodemus Ndun, who was, at the relevant time, a seaweed trader. The applicant submits that Mr Ndun provided evidence of damage to seaweed in Boa and that there is a compelling inference that seaweed was damaged by oil at Kite Beach because Kite Beach is close to Boa. I do not accept that submission.

75 Mr Ndun’s evidence was that he buys seaweed from Nemberala, Sedeoen, Oelolot and dusun Aduoen, Boni—all villages on Rote Island. He said that, sometimes, he bought seaweed from other villages, including Oeseli and Boa. Although Mr Ndun gave evidence that it was “very difficult” to buy seaweed and that seaweed quality was poor in 2010 (it had many soft and white pieces when it was harvested, and the branches were broken and small), he did not give evidence specifically about seaweed purchased in Boa. He certainly did not give evidence directed to the death or damage of seaweed in Boa.

76 Therefore, even when read with Mr Ndun’s evidence, I do not accept that Mr Guiney’s evidence shows damage to seaweed “in the water and on Kite Beach …”.

Entry 21B

77 The issue with respect to this entry is the same as for Entry 21A, namely whether there is evidence of damage to seaweed “in the water near Kite Beach near Boa, Rote Ndao”. The respondent submits that there is no evidence of such damage.

78 The applicant submits that a finding of damage is supported by the evidence given by Mr John Rogers based on his observations in around October and November 2009, and during the 2010 and 2011 kite-boarding seasons. Relevant to this entry, is Mr Rogers’ observation of a sticky, black gummy substance which he observed to be “almost everywhere” at Kite Beach in October 2009.

79 Like Mr Guiney, Mr Rogers did not give evidence of damage to seaweed at Kite Beach. Once again, the applicant submits that Mr Rogers’ evidence should be considered with Mr Ndun’s evidence and that I should draw the compelling inference for which he contends. I am not prepared to draw that inference, for the reasons given with respect to Entry 21A.

Entry 22

80 The issue with this entry is the same as for Entry 21A and Entry 22A. Based on Mr Chalvet’s evidence read with Mr Ndun’s evidence, the applicant submits that there is a compelling inference of damage to seaweed “on the beach and in the water near Mr Chalvet’s home in Boa, Rote Ndao”. The respondent submits that there is no such evidence.

81 The applicant accepts that Mr Chalvet did not give evidence of damage to seaweed at Boa, despite giving evidence of the presence of a white waxy substance all over the beach near his home. I note that Mr Chalvet does not give evidence of seaweed farming at this beach or at Boa: cf Mr Chalvet’s evidence in relation to seaweed farms in Oeseli Harbour.

82 For the reasons given above in respect of Entry 21A and Entry 21B, Mr Chalvet’s evidence, read with Mr Ndun’s evidence, does not support the inference for which the applicant contends.

Entry 25B

83 The issue in relation to this entry is whether there is evidence of damage to seaweed “along the beach and in the waters of Nemberala…”. The respondent submits that there is insufficient evidence to support this finding. The applicant directs attention to the evidence of Mr Adrian Sibert, read with the evidence of Mr Lot Martinus Heu, and with Mr Ndun’s evidence to which I have already referred.

84 The applicant accepts that Mr Sibert did not give direct evidence of damage to seaweed.

85 Mr Heu was a seaweed trader and, in 2009, a seaweed farmer in the village of Nemberala. He farmed seven plots. In late 2009, oil arrived in Nemberala waters, and the seaweed stopped growing. The respondent accepts that, based on Mr Heu’s evidence, hydrocarbons were observed at Nemberala in September 2009 and that there was damage to seaweed at this location: Entry 25A.

86 Mr Ndun’s evidence was that he bought seaweed from Nemberala, but he did not give direct evidence of damage to seaweed, or of damage to seaweed at any particular location.

87 When all this evidence is taken together, it rises no higher than Mr Heu’s evidence.

88 However, there is also Mr Guiney’s evidence to which I have referred when considering Entry 21A. As I there noted, Mr Guiney observed black waxy lumps mixed with a white foamy substance build up on the seaweed ropes on the beach in front of his home at Nemberala: [72] above.

89 I infer from Mr Guiney’s reference to seaweed ropes that, at the time, seaweed was in fact being grown at this location. I am satisfied that the substances which Mr Guiney observed included hydrocarbons from oil spilled during the H1 Well blowout. As I have previously found, this oil caused or materially contributed to the quick and dramatic loss of local seaweed crops in the coastal areas of Rote/Kupang: J[1008]. This is confirmed by Mr Hue’s evidence of damage to seaweed at Nemberala. I am satisfied, therefore, that seaweed was damaged “along the beach and in the waters at Nemberala…”.

90 In making this finding, I note that Mr Sibert’s recollection was that his observations were made in late September to early October 2009. Mr Guiney’s recollection was that he made his observations in late October 2009. Given the passage of time, I would not expect either Mr Sibert or Mr Guiney to be able to recall, with pinpoint accuracy, when their observations were actually made. I am satisfied that their observations at Nemberala were substantially contemporaneous.

Entry 28

91 This entry also concerns Mr Guiney’s evidence. The issue is whether the evidence supports a finding that seaweed was damaged “in the waters around Mr Guiney’s home at Nemberala…”. The respondent submits that there is insufficient evidence to support this finding. I disagree. For the reasons given with respect to Entry 25B, I am satisfied that a finding of damage should be made.

Entry 29

92 This entry concerns another aspect of Mr Rogers’ evidence. Mr Rogers is the co-owner and the general manager of the Nemberala Beach Resort. He takes guests snorkelling to Do’o Island during the tourist season. He gave evidence that, when undertaking this activity in around October and November 2009, he noticed brown masses floating on the surface of the sea. These masses were about 4 m across, and substantial enough to have collected rubbish from the ocean. He saw these masses on four or five separate occasions over the period of a few weeks.

93 The applicant submits that, although Mr Rogers did not give direct evidence of damage to seaweed in the waters around Do’o Island, there is a compelling inference that damage to seaweed occurred at this location. The respondent submits that Mr Rogers’ evidence is not sufficient to support a finding of damage.

94 My attention has not been directed to evidence of seaweed farming at or around Do’o Island. In the absence of that evidence, I am not prepared to draw the inference that the applicant seeks.

Entry 31

95 This entry concerns the evidence given by Mr Yardin Aplugi. Mr Aplugi was a seaweed farmer at Anarae on Ndao Island. Mr Aplugi gave evidence that, in September or October 2009, his seaweed was damaged by a substance that felt like oil. The substance was in the form of a “clump” that was on the top of the water “in Anarae village”.

96 The issue is the location of this clump and where seaweed was damaged. The applicant submits that Mr Aplugi’s evidence supports a finding that hydrocarbons were observed at Anarae and caused damage to seaweed there. The respondent submits that Mr Aplugi’s evidence only supports a finding that hydrocarbons were observed at his seaweed farming areas in Anarae and that seaweed was damaged at that specific location.

97 I do not understand Mr Aplugi’s observation of the “clump” to be confined only to the area of his seaweed farm. I am satisfied that Mr Aplugi’s observation was of a broader area in the vicinity of his seaweed farm. However, Mr Aplugi’s evidence in respect of damage was directed to his seaweed crop. There is evidence of a number of other seaweed farmers in and around Anarae at the time that Mr Aplugi’s seaweed crop was damaged. It may be that the crops of other seaweed farmers in and around Anarae were also damaged at this time because of the presence of hydrocarbons. Indeed, the respondent accepts that there was damage to seaweed in Mr Silwanus Aplugi’s farming areas at Anarae Beach: Entry 32. The damage to other crops would be consistent with my finding, at J[1008] of the principal reasons, that when oil from the H1 Well blowout reached the coastal area of Rote/Kupang, it caused, or at the very least, materially contributed to, the quick and dramatic loss of local seaweed crops. However, in the absence of more specific evidence concerning other seaweed crops, the evidence of damage, in relation to Entry 31, should be limited to damage in Mr Yardin Aplugi’s seaweed farming area.

Entries 34, 35, and 37

98 These entries should be considered together. They concern evidence given by Mr Petrus Ndolu with respect to observations he made in October and November 2009. The issue concerns the presence of hydrocarbons at Nuse Island and the location of damage to seaweed.

99 Mr Ndolu lives in Baadale on Rote Island. However, in 2009 his seaweed farming was carried out on Nuse Island, off the coast of Rote. This was made clear in Mr Ndolu’s oral evidence. Nuse Island is a significant distance to the west of Baadale—about a five hour boat journey.

100 In his affidavit, Mr Ndolu gave evidence of seeing oil coming into the waters near Baadale in 2009. He also gave evidence of damage to seaweed. This evidence seems to have been directed to Mr Ndolu’s own farming activities. In that regard, he said that he noticed clumps of oil floating on the sea near his plot and that he noticed dead fish on the sea surface, and also on the seashore. However, given his oral evidence that, in 2009, his seaweed farming was carried out on Nuse Island, Mr Ndolu must have been mistaken in suggesting, in his affidavit, that these activities occurred at Baadale.

101 In his oral evidence, Mr Ndolu also spoke of damage to his seaweed in October 2009. With reference to his seaweed farming on Nuse Island, Mr Ndolu said that when he went to his seaweed, he saw that “the sea was the colour of a rainbow” and that there were “dead fish floating on top of the ocean”.

102 In relation to Entry 34, the applicant submits that this evidence supports a finding of hydrocarbons on Nuse Island. The respondent submits that Mr Ndolu’s evidence only shows the presence of hydrocarbons at his seaweed farm on Nuse Island.

103 I do not accept either submission. I do not think that Mr Ndolu was confining his observations of oil to the specific location of his seaweed farm. I take his evidence to refer to oil which he observed not only at his seaweed farm but also in the vicinity of his seaweed farm. On the other hand, I do not understand Mr Ndolu to have intended to make an observation concerning the whole of Nuse Island.

104 Also in relation to Entry 34, the applicant submits that Mr Ndolu’s observation that “the sea was the colour of a rainbow” gives rise to a compelling inference that oil caused damage to seaweed growing in all areas on Nuse Island. I do not accept that submission. In the absence of more specific evidence concerning other seaweed crops, the evidence of damage, in relation to Entry 34, should be limited to damage to seaweed at Mr Ndolu’s seaweed farming area.

105 In relation to Entry 35, which concerns the waters along the coast from Nuse Island to Ba’a on Rote Island, the applicant submits that Mr Ndolu’s evidence gives rise to a compelling inference that oil caused damage to seaweed growing in that area. In his oral evidence, Mr Ndolu said that when travelling by boat from Nuse Island to Ba’a he observed “balls” on the water and that the “ocean was the colour of a rainbow”. However, he did not give evidence of damage to seaweed. The evidence he did give of this boat journey does not support the inference of damage the applicant asks me to draw.

106 In relation to Entry 37, which concerns the waters near Baadale, the applicant submits that Mr Ndolu’s evidence gives rise to a compelling inference that oil caused damage to seaweed growing in those waters. Mr Ndolu’s evidence does not support the drawing of that inference. Whatever observations Mr Ndolu made at Baadale in 2009, his evidence of damage to seaweed was with respect to his seaweed crop. As I have said, his oral evidence makes clear that, in 2009, his seaweed crop was at Nuse Island.

Answers to Common Questions 3 and 4

General comment

107 In the principal reasons, I discussed the chemical composition and physical properties of fresh and weathered Montara oil at J[56] – J[77] and at J[678] – J[762]. At J[678] and J[680], I noted that crude oil is a complex heterogeneous liquid mixture of a very large number of hydrocarbon fractions, organic compounds, and some non-hydrocarbon, inorganic elements. I noted at J[682] that Montara oil is a mixture of thousands of different hydrocarbons. I concluded at J[828] that oil from the H1 Well blowout, in various weathered states, reached the coastal areas of Rote/Kupang. This conclusion informed my answer to Common Question 2. Common Question 2 distinguishes between (a) hydrocarbons and (b) dispersants. In providing my answer, I used the word “oil”—meaning, oil in various weathered states. In so doing, I treated “oil” as synonymous with the “hydrocarbons” that comprised that oil in its various weathered states.

108 When answering Common Questions 3 and 4, I will adopt the same use of the word “oil”. However, in answering those questions, and in answering Common Question 2, I would be equally content to use the word “hydrocarbons” in substitution for “oil”.

Common Question 3

109 The respondent contends that the answer to Common Question 3 should be limited to the locations described in column B of Schedule B. As I have noted, the applicant contends that the answer should not be limited to these locations.

110 I am persuaded that the applicant’s approach to answering Common Question 3 is correct and should be adopted. It would defy common sense to think that oil from the H1 Well blowout reached only the locations in column B and no other locations in the coastal areas of Rote/Kupang. Given the observations of oil at the locations identified in column B, at the times identified in column C, I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that oil from the H1 Well blowout was widespread and present around the coastal areas identified by the applicant in the period September to at least November 2009. This justifies an answer to Common Question 3 at an appropriate level of generality. The answer should be, substantially, as the applicant proposes.

111 My answer is:

The coastal waters surrounding the islands of Rote, Ndana, Ndao, Do’o, Nuse, and Semau, and around the south-western peninsula of Kupang, and Kupang’s westernmost coastal waters extending up to Kelapa Lima, including the specific locations identified in column B of Schedule B to these reasons, in the period September to at least November 2009.

112 In giving this answer, I do not accept the respondent’s implicit contention that an answer, at this level of generality, would not be consonant with the function that answers to common questions are to serve. Common Question 3 is unlike the common question considered in Ethicon and Ethicon (No 2), which was a question directed to identifying why, in light of an earlier answer, particular conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in terms of a particular statutory standard. In the present case, the answer to Common Question 3 addresses a pure question of fact at a level of generality justified by the evidence before the Court.

113 In giving this answer, I also do not ignore the respondent’s submissions recorded at [23] – [25] above. The simple fact is that these submissions do not compel the limited answer that the respondent proposes.

Common Question 4

114 The respondent contends that the answer to Common Question 4 should be limited to the locations described in column D of Schedule B. Once again, the applicant contends that the answer should not be limited to these locations.

115 In my view, the answer to Common Question 4 should not be answered as broadly as the applicant contends. This is because the answer to this question depends not only on the presence of oil from the H1 Well blowout but also, obviously enough, on the presence of seaweed crops at the same location contacted by that oil. The evidence at trial showed that, at the relevant time, there were a great many seaweed farmers in the Rote/Kupang region which, by 2009, was an area of widespread successful farming: see J[91] – J[102], especially at J[94]. However, obviously for practical reasons, evidence could not be led from all the farmers concerned. As matters transpired, evidence was led from only a relatively small number of these farmers.

116 As expressed at J[1008], I am satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that oil from the H1 Well blowout not only reached the coastal areas of Rote/Kupang but also caused, or at the very least, materially contributed to, the quick and dramatic loss of local seaweed crops. This conclusion is borne out by the observations of seaweed crop damage identified in column D of Schedule B. But it is likely that damage to seaweed and/or to the production of seaweed occurred at a great many other locations. I am comfortably satisfied that the locations of damage to seaweed and/or to the production of seaweed were far greater than the locations given in column D. Those other locations cannot be specified on the presently available evidence. The fact that no direct evidence was adduced of seaweed farms at locations at which oil was observed does not mean that there were no seaweed farms at those locations. The answer to Common Question 4 should recognise this reality. The recognition of an absence of direct evidence of damage to seaweed and/or to the production of seaweed at a particular location should not be misunderstood as a positive finding that no damage to seaweed and/or to the production of seaweed occurred, other than at the particular locations identified in column D.

117 By the same token, one should not assume that seaweed farming was being undertaken at all locations where the oil reached the coastal waters. It seems to me that the applicant’s suggested answer to Common Question 4 proceeds on this unwarranted assumption.

118 My answer is:

The oil caused damage to seaweed and/or to the production of seaweed at the locations identified in column D of Schedule B to these reasons. However, it is more likely than not that damage to seaweed and/or to the production of seaweed occurred at other locations, where seaweed farming was being undertaken. The present evidence does not permit a more detailed finding. The absence of evidence to support a more detailed finding should not be taken as a finding that no damage to seaweed and/or the production of seaweed occurred, other than at the particular locations identified in column D.

Disposition

119 I am satisfied that the stage has been reached where the parties are now in a position to bring in an agreed form of orders reflecting the findings I have made in the principal reasons and in these reasons. I will direct the parties to provide draft orders to my Associate by 4.00 pm on 5 November 2021.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and nineteen (119) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Yates. |

Associate:

Schedule A

Schedule B

A | B | C | D | E | ||||

No. | Location where hydrocarbons were observed | Time period in which hydrocarbons were observed | Was there evidence of damage to seaweed at this location? | References to witness, Principal Judgment, and evidence | ||||

1 | Mr Lay’s seaweed farm in Tablolong, Kupang | Late September to October 2009 | Yes | Mr Gustaf A Lay Sanda v PTTEP Australasia Pty limited (No. 7) [2021] FCA 237 (the Principal Judgment) [205], [216], 289 (Schedule B), 295 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.003.0001_OBJ2 at 0004 and 0006, and Annexures GL2 and GL3 TRA.500.007.0001_3 at 0022 to 0024, 0048, and 0052 | ||||

2 | Mr Polin’s seaweed farm in Kuanheun, Kupang | For 5 to 7 days in late September 2009 | Yes | Mr Semin Polin Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 297 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.025.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 TRA.500.008.0001_3 at 0003 to 0006 MFI-9; MSC.SAN.066.0001 | ||||

3A | Waters at Tenau Harbour, Kupang, and on the coast between Tenau Harbour and Kelapa Lima | September 2009 (for up to a week, starting a week following Mr La Macchia’s return from a fishing trip commenced in late August or early September which ran for 2.5 to 3 weeks) | Yes, on the coast between Kelapa Lima and Tenau Harbour | Mr Antony La Macchia Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 326 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.104.0001_OBJ at 0005 to 0010 | ||||

3B | Tenau Harbour, Kupang, and stretching south and north into Kupang Bay | September 2009 (starting 7 to 10 days after his son returned from a fishing trip commenced in late August or early September which ran for 2.5 to 3 weeks) | No, but see 3A above | Mr Bartolo La Macchia Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 325 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.103.0001_OBJ at 0003 to 0005 | ||||

4 | Kelapa Lima, Kupang | September 2009 | Yes | Mr Antony La Macchia LAY.SAN.104.0001_OBJ at 0010, and Annexure ALM-2 | ||||

5 | Mr Pallo’s seaweed farm in Batuinan, Semau | October 2009 | Yes | Mr Abner Yopi Pallo Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 301 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.033.0001_OBJ4 at 0010 TRA.500.009.0001_3 at 0014 to 0016 MFI-14; MSC.SAN.069.0001 | ||||

6 | Mr Patolla-Ballo’s seaweed farm in Letbaun, Semau | End of August 2009 | Yes | Mr Zadrak Patolla-Ballo Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 300 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.037.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 and 0010 TRA.500.009.0001_3 at 0004 to 0007 and 0013 MFI-13; MSC.SAN.070.0001 | ||||

7 | Waters near Uiasa, Semau | October 2009 | Yes | Mr Daud Nenokeba Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 319 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.039.0001_OBJ 4 at 0003 | ||||

8 | Hansisi, Semau | September or October 2009 | Yes, at Mr Hendrik’s seaweed farm | Mr Lorens Hendrik Principal Judment, [811], 289 (Schedule B), 321 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.035.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

9 | Mr Liman’s seaweed farm in Akle, Semau | September or October 2009 | Yes | Mr Dominggus Liman Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 299 (Schedule C) TRA.500.008.0001_3 at 0030 to 0032 MFI-12; MSC.SAN.068.0001 | ||||

10 | Naikean, Semau | 2009 | Yes, at Mr Lima’s seaweed farm | Mr Johan Lima Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 298 (Schedule C) TRA.500.008.0001_3 at 0028 to 0029 MFI-11; MSC.SAN.067.0001 | ||||

11A | Waters in Sonimanu’s seaweed area near Puku Afu, Rote Ndao | 2009 | Yes | Mr Yermias Manafe Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 313 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.059.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

11B | Waters in Oebau’s seaweed farming area near Puku Afu, Rote Ndao | Around October 2009 | Yes | Mr Melkianus Mola Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 317 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.062.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

12 | Mr Aitio’s seaweed farm at Daiama, Rote Ndao | End of September 2009 | Yes | Mr Abdul Rasyid Aitio Principal Judgment, [833] 289 (Schedule B), 304 (Schedule C) TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0019 to 0021 | ||||

13 | Waters near Lifuleo, Rote Ndao | Around the end of 2009 | Yes | Mr Anton Matasina Principal Judgment, [838], 289 (Schedule B), 314 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.093.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

14 | Mr Aitio’s seaweed farm at Papela, Rote Ndao | End of September 2009 | Yes | Mr Abdul Rasyid Aitio Principal Judgment, [833], 289 (Schedule B), 304 (Schedule C) TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0019 to 0022 | ||||

15 | Mr Taek’s seaweed farm in Dodaek, Rote Ndao | Around September 2009, not long after Indonesian Independence Day on 17 August 2009 | Yes | Mr Taftinus Taek Principal Judgment, [813], 289 (Schedule B), 306 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.066.0001_OBJ4 at 0010 TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0045 to 0046 MFI-20; MSC.SAN.073.0001 | ||||

16 | Waters near Kolobolon, Rote Ndao | October 2009 | Yes | Mr Watson Sodi Mbuik Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 315 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.043.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

17 | Waters near Nusamanuk, Rote Ndao | 2009 | Yes | Mr Johan Mooy Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 318 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.069.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

18 | Mr Messakh’s wife’s seaweed farm at Landu Island and the waters near Landu | September 2009 | Yes | Mr Semuel Messakh Principal Judgment, [836] – [841], 289 (Schedule B), 307 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.071.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 and 0010 TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0053 | ||||

MFI-21; MSC.SAN.074.0001 | ||||||||

19 | In the water along at least part of the Boat route from Oeseli Harbour to around 7 to 10 kilometres south of Ndana Island | September to October 2009 | Yes, in Oeseli Harbour | Mr Axel Chalvet Principal Judgment, [191] – [197], 289 (Schedule B), 322 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.005.0001_OBJ2 at Annexure APC5 TRA.500.012.0001_3 at 0002 and 0005 | ||||

20 | Not pressed | |||||||

21A | In the water and on Kite Beach near Boa, Rote Ndao | Late October 2009 and late April or May 2010 | No | Mr John Douglas Guiney Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 324 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.012.0001_OBJ2 at 0004, and Annexure JDJG2 | ||||

21B | In the water near Kite Beach near Boa, Rote Ndao | Around October and November 2009 and during the 2010 and 2011 kite-boarding seasons | No | Mr John Gregory Rogers Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 323 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.013.0001_OBJ3 at 0006 to 0007, and Annexure JGR3 | ||||

21C | On Kite Beach near Boa, Rote Ndao | End of 2009 | No | Mr Axel Chalvet Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 322 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.005.0001_OBJ2 at Annexure APC4 TRA.500.012.0001_2 at 0003 to 0004 | ||||

22 | On the beach and in the water near Mr Chalvet’s home in Boa, Rote Ndao | For a couple of weeks in September and October 2009 | No | Mr Axel Chalvet Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 322 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.005.0001_OBJ2 at Annexure APC4 TRA.500.012.0001_3 at 0003 to 0004 | ||||

23A | On the beach and mostly in the water at Oenggaut Beach, Oenggaut, Rote Ndao | End of 2009 | Yes | Mr Axel Chalvet Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 322 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.005.0001_OBJ2 at Annexure APC4 TRA.500.012.0001_2 at 0006 | ||||

23B | Oenggaut, Rote Ndao | Around September 2009 | Yes | Mr Yermias Lomba LAY.SAN.081.0001_OBJ3 at 0010 | ||||

24 | Mr Sanda’s Seaweed farm, Inggurae Beach | Middle to late (and after) September 2009 | Yes | Mr Daniel Aristabulus Sanda Principal Judgment, 290 (Schedule B) LAY.SAN.001.0001_OBJ2 at 0020, and Annexure DAS4 TRA.500.004.0001_3 at 0018 to 0021 | ||||

25A | Nemberala, Rote Ndao | September 2009 | Yes | Mr Lot Martinus Heu Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 310 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.010.0001_OBJ at 0007, and Annexure LMH1 TRA.500.011.0001_3 at 0019 to 0020 | ||||

25B | Along the beach and in the waters at Nemberala, Rote Ndao | Late September to early October 2009 | Yes | Mr Adrian John Sibert Principal Judgment [752] – [753], 289 (Schedule B), 293 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.006.0001_OBJ3 at 0009 to 0015 TRA.500.006.0001_3 at 0035 to 0037 | ||||

26 | At the bombora reef, about a kilometre and a half out from Sedeoen, Rote Ndao | Late September to early October 2009 | No | Mr Adrian John Sibert Principal Judgment [752] – [754], 289 (Schedule B), 293 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.006.0001_OBJ3 at 0009 to 0015 TRA.500.006.0001_3 at 0035 to 0037 | ||||

27 | In the water and on the beach near Sedeoen, Rote Ndao | Late September to early October 2009 | Yes | Mr Adrian John Sibert Principal Judgment, [752] – [754], 289 (Schedule B), 293 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.006.0001_OBJ3 at 0009 to 0016, and Annexure AS-1 TRA.500.006.0001_3 at 0035 to 0037 | ||||

28 | In the waters around Mr Guiney’s home at Nemberala, Rote Ndao | Late October 2009 | Yes | Mr John Douglas Guiney Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 323 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.012.0001_OBJ2 at 0004 and 0005, and Annexure JDJG1 | ||||

29 | In the water around Do’o Island | On four or five occasions over a few weeks in around October and November 2009 | No | Mr John Gregory Rogers Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 324 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.013.0001_OBJ3 at 0005, and Annexure JGR1 | ||||

30 | Waters near Mbalilendeki, Rote Ndao | Around the end of 2009 | Yes | Mr Resa Rehans Fatu Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 312 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.097.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

31 | In the vicinity of Mr Yardin Aplugi’s seaweed farm at Anarae, Rote Ndao | September or October 2009 | Yes, at Mr Aplugi’s seaweed farming areas | Mr Yardin Aplugi Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 308 (Schedule C) TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0069 and 0071 MFI-22; MSC.SAN.075.0001 | ||||

32 | Mr S Aplugi’s seaweed farming areas at Anarae Beach, Rote Ndao | Mid to late September 2009 | Yes | Mr Silwanus Aplugi Principal Judgment, [184] – [190], 289 (Schedule B), 292 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.002.0001_OBJ3 at 0004 and 0005, and Annexures SA2 and SA3 TRA.500.005.0001 at 0040 | ||||

33 | Waters near Nuse, Rote Ndao | Around October 2009 | Yes | Mr Thomas Detha Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 311 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.100.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

34 | In the vicinity of Mr Ndolu’s seaweed farm at Nuse Island, Rote Ndao | October 2009 | Yes, at Mr Ndolu’s seaweed farming area | Mr Petrus Ndolu Principal Judgment, [854], 289 (Schedule B), 302 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.041.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 to 0006 and 0010 TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0003 to 0005 MFI-16; MSC.SAN.071.0001 | ||||

35 | In the water along the coast from Nuse Island to Ba’a, Rote Ndao | November 2009 | No | Mr Petrus Ndolu Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 302 (Schedule C) TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0006 MFI-16; MSC.SAN.071.0001 | ||||

36 | Mr Mboeik’s seaweed farm near Oelua, Rote Ndao | Around September 2009 | Yes | Mr Gabriel Mboeik II Principal Judgment [199] – [204], 289 (Schedule B), 294 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.004.0001_OBJ at 0004 and 0013, and Annexure GM2 TRA.500.006.0001_3 at 0062 to 0064 | ||||

37 | Waters near Baadale, Rote Ndao | October 2009 | No | Mr Petrus Ndolu Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 302 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.041.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0006 | ||||

38 | Waters near Oenggae, Rote Ndao | Late 2009 | Yes | Mr Marselinus Mesah Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 316 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.063.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

39 | Waters near Sotimori, Rote Ndao | September 2009 | Yes | Mr Ogus Tananggau Principal Judgment, 289 (Schedule B), 320 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.095.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 | ||||

40 | Mr Penna’s seaweed farm near Sotimori, Rote Ndao | September 2009 | Yes | Mr Mica Erwin Johanis Penna Principal Judgment, [813], 289 (Schedule B), 305 (Schedule C) LAY.SAN.049.0001_OBJ4 at 0003 TRA.500.010.0001_3 at 0027 to 0030 and 0032 MFI-18; MSC.SAN.072.0001 | ||||