Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v NQCranes Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1270

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent’s amended interlocutory application, dated 8 March 2021, is dismissed.

2. The respondent is to pay the applicant’s costs, to be agreed or assessed.

3. The applicant has leave to amend its amended statement of claim, dated 22 February 2021, in respect to the matters identified in the reasons for judgment of Abraham J at [49] and [78].

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ABRAHAM J:

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), by its amended originating application (AOA) and amended statement of claim (ASOC), filed on 22 February 2021, alleges that the respondent, NQCranes Pty Ltd (NQCranes), contravened the cartel provisions in the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA):

(1) by making and giving effect to an agreement or understanding with MHE-Demag Australia Pty Ltd (MHE-Demag), described as a “Non-Targeting Arrangement”; and

(2) by making an agreement, namely the Distributorship Agreement executed on 26 August 2016 with MHE-Demag, which contained the “Co-Ordinated Approach Provision”, a cartel provision, and giving effect to that provision.

2 NQCranes seeks an order under r 16.21 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules), or alternatively under s 37P of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), that the relevant paragraphs in the pleadings relating to the making and giving effect to the Non-Targeting Arrangement, and giving effect to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision, be struck out.

3 For the reasons below, the application to strike out [9]-[9G] (set out at [63] and [88]) and [18]-[19] of the ASOC and [1], [1A], [2] and [4] of the AOA is refused.

Legal principles

4 A strike out application is directed to the sufficiency of the pleadings or equivalent documentation, as opposed to the underlying prospects of success of the proceedings: Spencer v Commonwealth [2010] HCA 28; (2010) 241 CLR 118 (Spencer) at [23], citing Lindgren J in White Industries Australia Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2007] FCA 511; (2007) 160 FCR 298 at 309.

5 Where the evidence shows that a person may have a reasonable cause of action or reasonable prospects of success, but the person’s pleading does not disclose that to be the case, the Court may be empowered to strike out the pleading under r 16.21(1)(e) of the Rules. An application for the striking out of pleadings may be made on one or more of the grounds in r 16.21, which relevantly include that the pleading: contains frivolous or vexatious material: r 16.21(1)(b); is evasive or ambiguous: r 16.21(1)(c); is likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding: r 16.21(1)(d); fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action or defence or other case appropriate to the nature of the pleading: r 16.21(1)(e); or is otherwise an abuse of the process of the Court: r 16.21(1)(f).

6 Rule 16.21 is critically concerned with the sufficiency of the pleadings. Rule 16.02 sets out the general rules concerning the content of pleadings. The failure to comply with any of the rules in r 16.02(2) may found an application to strike out a pleading under r 16.21. The requirements for a pleading were described in Wride v Schulze [2004] FCAFC 216 at [25] as follows:

[T]he pleadings must disclose a reasonable cause of action against the party against whom the cause of action is brought and must state all material facts necessary to establish that cause of action and the relief sought. A “reasonable cause of action” for this purpose means one which has some chance of success if regard is had only to the allegations and the pleadings relied on by the applicant.

7 The general principles concerning the Court’s power to strike out a pleading were summarised in Polar Aviation Pty Ltd v Civil Aviation Safety Authority [2012] FCAFC 97; (2012) 203 FCR 325 (Polar Aviation) at [43], citing Beaumont J in Allstate Life Insurance Co v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [1994] FCA 636; (1994) 217 ALR 226 (Allstate) at 236.

8 A pleading will be insufficiently specific where it is cast at such a high level of generality that it fails to inform the respondents of the case they have to meet: Charlie Carter Pty Ltd v The Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association of Western Australia (1987) 13 FCR 413, at 417-418; Pharm-a-Care Laboratories Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (No 3) [2010] FCA 361; (2010) 267 ALR 494 at [98]-[99]. Pleadings must fulfil the basic function of identifying the issues between the parties, disclosing an arguable cause of action or defence, and ensuring that parties are apprised of the case to be met: Plaintiff M83A-2019 v Morrison (No 2) [2020] FCA 1198 at [50] (Plaintiff M83A-2019 v Morrison).

9 A pleading is embarrassing where it is unintelligible, ambiguous, vague or too general, such that the opposite party does not know what is alleged against him or her: Fair Work Ombudsman v Eastern Colour Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 803; (2019) 209 IR 263 (Eastern Colour) at [18], citing Meckiff v Simpson [1968] VR 62 at 70. A pleading may be considered to be embarrassing if it suffers from narrative, prolixity or irrelevancies to the extent it is not a pleading to which the other party can reasonably be expected to plead to: Fuller v Toms [2012] FCA 27; (2012) 247 FCR 440 at [80], [83]. It has been said that a pleading is embarrassing if it “is susceptible to various meanings, or contains inconsistent allegations or in which alternatives are confusingly intermixed or in which irrelevant allegations are made tending to increase expense”: Bartlett v Swan Television and Radio Broadcasters Pty Ltd [1995] ATPR 41-434 at [25]; Faruqi v Latham [2018] FCA 1328 at [94]. Although facts or characterisations of facts can be pleaded in the alternative, a pleading should not “[plant] a forest of forensic contingencies” which are only pulled together in final submissions: Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; (2012) 247 CLR 486 at 503.

10 Although the categories are not closed to circumstances which will amount to an abuse of process, in the context of determining an application to stay proceedings on abuse of process grounds, the High Court recognised that such circumstances extend “to all those categories of cases in which the processes and procedures of the court, which exist to administer justice with fairness and impartiality, may be converted into instruments of injustice or unfairness”: Walton v Gardiner [1993] HCA 77; (1993) 177 CLR 378 (Walton) at 392-393. This includes bringing proceedings which are clearly foredoomed to fail or which are manifestly unfair to a party to the litigation: Walton at 392-393.

11 For the purposes of r 16.21(1)(e), a “reasonable cause of action” is one that has some chance of success having regard to the allegations pleaded: Polar Aviation at [42]-[43]; Chandrasekaran v Commonwealth of Australia (No 3) [2020] FCA 1629 (Chandrasekaran) at [108]-[111]. A cause of action cannot be struck out merely on the basis that it appears to be weak: Chandrasekaran at [108]; Allstate at 236.

12 The power to strike out will not be exercised unless no reasonable amendment could cure the alleged defect such that there is no reasonable question to be tried: Polar Aviation at [43]; Chandrasekaran at [102].

13 Although r 16.21 is directed to “pleadings”, which are defined in the Dictionary to the Rules so as not to include an originating application, r 6.01 provides a similar power applicable to any “document filed in a proceeding”. That includes an originating application. Where a document filed in a proceeding contains a matter that is scandalous, vexatious or oppressive, the Court is empowered to order that the document be removed from the file or that the matter be struck from the document. To the extent that an originating application is drafted in such a way that it does not disclose a reasonable cause of action, or is insufficiently specific and thereby oppressive, it would attract the operation of this rule: see Abela v Minister for Home Affairs [2021] FCA 96 at [20].

14 Rules 16.02 and 16.21 must be interpreted and applied in light of s 37M of the FCA Act, which provides that the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions is to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to law as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible: Chandrasekaran at [101].

15 In that context I note also that at least in contemporary times with the development of case management procedures, it has been recognised that courts do not take an “unduly technical or restrictive approach to pleadings”, provided they fulfil their function: Thomson v STX Pan Ocean Co Ltd [2012] FCAFC 15 at [13], citing Barclay Mowlem Construction Ltd v Dampier Port Authority [2006] WASC 281; (2006) 33 WAR 82 at [4]-[8] and see Allianz Australia Insurance Limited v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 [2021] FCAFC 121 at [152].

16 For completeness, the respondent also relies in the alternative, on s 37P of the FCA Act, which confers power on the Court to give directions about practice and procedure to be followed in relation to a civil proceeding before the Court, in accordance with the overarching purpose of civil practice and procedure provisions under s 37M of the FCA Act.

Submissions

NQCranes

17 NQCranes’ submission is directed to two aspects of the ACCC’s case; (i) giving effect to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision; and (ii) making and giving effect to the Non-Targeting Arrangement. The effect of the first aspect is to strike out the whole of the Non-Targeting Arrangement case.

Co-Ordinated Approach Provision

18 NQCranes’ submission was directed to the give effect allegation in respect to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. The submission commenced with the legal principles. NQCranes submitted that the words “give effect to” in s 4 were recently considered in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 (Yazaki). In Yazaki, the Court said at [70] that “[i]t is apparent from s 4 that ‘give effect to’ focuses on the implementation of the contract, arrangement or understanding at issue” (emphasis in submissions). It was submitted that to be properly characterised as “giving effect to” a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding, “it must be demonstrated sufficiently to have been actually undertaken pursuant to, in accordance with, or otherwise enacting, implementing or administering that agreement”: Yazaki at [71] (emphasis in submissions). This is ultimately a question of fact decided in light of the circumstances of the particular case: Yazaki at [71] and [76].

19 It was submitted that the giving effect to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision as pleaded alleges various categories of communications, which are also said to constitute giving effect to the Non-Targeting Arrangement (with the addition of two further communications pleaded in paragraphs [9F(a)] and [9F(b)]).

20 In summary, it was submitted that the ACCC relies on various categories of communications between senior managers at NQCranes, including: proposing but not effecting the exchange of customer lists with MHE-Demag; exchanging emails and attending meetings with senior managers of MHE-Demag; meetings with operational managers at NQCranes; and raising and responding to complaints arising out of the mutual targeting of customers by both NQCranes and MHE-Demag. Many of these communications themselves indicate that the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision and the alleged Non-Targeting Agreement were not in fact implemented. The receipt of communications which in substance indicate that NQCranes was not acting in accordance with the alleged cartel provisions cannot be conduct which gives effect to those provisions. It was submitted that the ASOC alleged the respondent “retract[ed] an offer to provide services to a potential client, Mesh and Bar, in Brisbane, which was identified as being a MHE-Demag client at the relevant time”, but the particular does not support the allegation.

21 It was submitted that the ACCC has conducted an investigation utilising its compulsory powers but it is apparent on the face of its pleading that it has not identified any conduct of NQCranes of avoiding targeting MHE-Demag’s existing customers. It was submitted that the give effect case ought to be struck out without leave to replead.

22 It was also submitted that as a result of the significant overlap between the give effect conduct pleaded in respect of the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision and the Non-Targeting Arrangement, in effect, it is said that NQCranes and MHE-Demag gave effect to two overlapping cartel provisions concurrently and by the same conduct. This contention, NQCranes submits, is embarrassing: r 16.21(1)(d).

Non-Targeting Arrangement

23 As to the Non-Targeting Arrangement, this is pleaded as an arrangement separate to the Distributorship Agreement and is said to arise out of “negotiations in relation to the Distributorship Agreement”. It was submitted that it aligns with the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision for the purposes of NQCranes and MHE-Demag refraining from targeting each other’s customers in the Brisbane and Newcastle area but differs in respect of it not forming part of an overall Distributorship Agreement for supply.

24 NQCranes submitted there are two critical problems.

25 First, the ACCC’s new case concerning the Non-Targeting Arrangement cannot satisfy the meeting of minds or commitment elements for an arrangement under the CCA. The facts particularised in [9] of the ASOC are part of the negotiations for the Distributorship Agreement. The effect of the allegation is that those negotiations gave rise to a separate arrangement immediately prior to the execution of the Distributorship Agreement and is constituted by just one of the provisions of the soon-to-be executed Distributorship Agreement. There are no material facts pleaded which would support the conclusion that the Non-Targeting Arrangement was made.

26 It was submitted that the ACCC’s attempt to sever the negotiations from the written Distributorship Agreement and a single part of that agreement from the rest of the agreement, is a contrivance. This problem means that no reasonable cause of action is disclosed and, by itself or together with other matters, leads to the conclusion that the new allegations are an abuse of process.

27 Second, the ACCC’s case is now incoherent. The Non-Targeting Arrangement is not alleged to be an alternative to the case based on the Distributorship Agreement or the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. The ASOC does not grapple with how the Non-Targeting Arrangement could operate concurrently with the Distributorship Agreement and the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. The consequence is that the same conduct of NQCranes is alleged to be both giving effect to the Non-Targeting Arrangement and giving effect to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. It was submitted that the present case is analogous to that considered by Sheppard J in Trade Practices Commission v Allied Mills Industries Pty Ltd (1980) 32 ALR 570 (Allied Mills). Therefore, the new allegations are likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding and are an abuse of process.

28 NQCranes accepted during the hearing that if the pleading is not deficient in the manner it contends, that is the end of the matter. The issue of abuse of process does not arise, as it is only relevant to the question of whether the ACCC should be given leave to replead.

29 It submitted in reply, that the ACCC’s case on this pleading is not one of the parties having reached a consensus about some of the terms which gave rise to an arrangement preceding the formal entry into a written contract. Rather, the ACCC alleges that there was an arrangement that was entered into by 17 August 2016 that continued for the entire period that the agreement was in operation, up until at least 18 October 2018.

ACCC

Co-Ordinated Approach Provision

30 The ACCC also made submissions as to what amounts to “give effect to”, including by reference to Yazaki at [64] and [71]; Tradestock Pty Ltd v TNT (Management) Pty Ltd (No 2) [1978] FCA 1; (1978) 17 ALR 257 (Tradestock) at [26]–[27], Trade Practices Commission v TNT Management Pty Ltd (1985) 6 FCR 1; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (No 2) [2015] FCA 1304; (2015) 332 ALR 396 at [221]–[223], Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cascade Coal Pty Ltd (No 3) [2018] FCA 1019 at [528], and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd [2014] FCA 1157; (2014) 319 ALR 388 (ACCC v Air New Zealand) at [464].

31 It submitted that it is at least a debatable question of fact and/or law as to whether one or more of the pleaded acts or things were given effect to, in the sense of enacting, implementing or administering, the relevant arrangement/provision. It submitted that the issue of whether NQCranes has, as a matter of law and in the terms of s 4 of the CCA, “given effect” to the arrangement/provision, is appropriately considered in the context of the facts as they emerge from the evidence in the proceeding. It may be difficult for this Court to reach a decision on the legal question of “give effect” with only the pleadings to guide the Court on the facts, and before all the facts have been fully explored. It submitted that it will be for the Court to weigh all the evidence, and rather than in a piecemeal fashion in isolation from all the other evidence, identify whether particular conduct rises to the level of giving effect to the arrangement, understanding or contract. The ACCC submitted that the respondent’s approach is inimical to the caution that courts have said should be displayed when approaching a case on a strikeout application. It submitted that it is also possible that further evidence will be adduced in the proceeding that proves acts or things that constitute giving effect to the arrangement/provision, although the ACCC accepted if the pleading is now defective it cannot rely on what may be obtained in the future as a basis on which the pleading should not be struck out.

Non-Targeting Arrangement

32 The ACCC submitted that there is no difficulty in the ACCC alleging both the Non-Targeting Arrangement and the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. There is no barrier to the ACCC pleading the existence of both of these arrangements, as to which the Court may be persuaded as to one, both, or none. It submitted that although NQCranes characterises the separate allegations as a “contrivance,” it does not submit that it does not understand the case as put by the ACCC.

33 The ACCC emphasised that there are two important distinctions between the Non-Targeting Arrangement and the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision: (i) the geographic dimensions of those two agreements; and (ii) that the Non-Targeting Arrangement was given effect to prior to entering into the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision.

34 In that regard, it was submitted that the ASOC makes clear the differences between the Non-Targeting Arrangement and the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision, which includes as to the date they were made (being for the Non-Targeting Arrangement no later than 17 August 2016 and the Co- Ordinated Approach Provision from 26 August 2016) and their scope (being for the Non-Targeting Arrangement that NQCranes and MHE-Demag would not target each other’s servicing clients in the Brisbane and Newcastle area, and for the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision that NQCranes and MHE-Demag would operate in the service markets in a co-ordinated approach so that current customers are not targeted and for potential future customers they focus their energies on the other service competitors and not each other).

35 As to the submission that the ACCC’s case is now incoherent, it was submitted that issue can be resolved by an amendment to the commencement of [10] of the ASOC which addressed the Distributorship Agreement, inserting the words, “further, or in the alternative”, to make it clear that it is a separate agreement that has been entered into.

36 As to the submission that there is no particular or basis to establish the necessary meeting of the minds in respect to the Non-Targeting Arrangement, the ACCC submitted that one is not looking at it from the approach of a contract but from that of an understanding which is something less than a contract. The existence of the arrangement can be inferred from the particulars in [9] of the ASOC, and in the context of what is alleged in [7]-[8] of the ASOC. The ACCC submitted that during the course of negotiating the Distributorship Agreement, NQCranes and MHE-Demag reached an understanding in relation to at least one matter, which is the non-targeting of customers in the Brisbane and Newcastle area, and as a matter of law there is no reason why this cannot be a separate agreement. In effect, it is alleged that the parties may have adopted the approach that the entirety of the deal is still to be negotiated, but in the meantime they decided to give effect to this aspect. Emphasis was placed on the reference in the particulars to the Brisbane and Newcastle area as opposed to the broader area that the Distributorship Agreement is directed to. The ACCC submitted the approach adopted in its pleadings which alleges the existence of both agreements is permissible. It is for NQCranes to either admit or deny those facts, and ultimately a matter for this Court to determine, at a final hearing, whether or not they are made out.

37 The ACCC submitted that this case is different to the situation in Allied Mills.

38 It submitted that NQCranes’ submission as to the anti-overlap provisions is not relevant to the consideration of this application, and as such the ACCC has not made any submissions as to its operation. The ACCC noted that no defence has yet been filed by NQCranes.

39 The ACCC submitted that the respondent’s reliance on s 37P is unclear, however, it is unnecessary to resolve for the purposes of this application.

Consideration

40 There is no issue between the parties as to the relevant principles applicable to NQCranes’ application seeking to strike out aspects of the ACCC’s pleadings. The power to strike out should be exercised with caution, and only in a plain and obvious case. That the case appears to be a weak one is not of itself sufficient to justify striking out the action.

Co-Ordinated Approach Provision

41 This relates to [18]-[19] of the ASOC and [2] of the AOA. There is some degree of overlap in respect to the conduct which is alleged to constitute giving effect to both the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision and the Non-Targeting Arrangement. To the extent that there is overlap, aspects of my consideration regarding the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision, are also relevant to my consideration of NQCranes’ application to strike out the Non-Targeting Arrangement give effect pleadings, discussed below at [88]-[90].

42 The crux of NQCranes’ submission is that the matters pleaded, even if they could be accepted, could not establish that NQCranes gave effect to any provision of an arrangement within s 4 of the CCA. For example, it was submitted that internal communications, as pleaded in this case, are not sufficient to establish that the arrangement was given effect to by NQCranes, as the ACCC is required to establish that NQCranes refrained from doing some external act (namely, targeting customers). In particular, the ACCC’s pleading, that senior managers within the company informed their junior employees about the provisions of the contract or arrangement, could not ever constitute implementing a cartel provision that required NQCranes to do or refrain from doing external acts. It was accepted by NQCranes if it had been alleged it had given these instructions, and in accordance with those instructions junior employees had refrained from targeting MHE-Demag’s customers, that would be an allegation of giving effect to the provision. However, it was contended, that was not the allegation made by the ACCC in its pleadings.

43 In Yazaki, which was referred to by both parties, the Court observed at [71]:

We agree that the ordinary meaning of “give effect to” – at least taken in isolation – does not necessarily compel a knowledge requirement. In our view, its ordinary meaning is not ambiguous in that regard. Conceptually, it is a term whose principal concern is the existence of certain conduct and whether such conduct implements, enacts, or otherwise administers an agreement. As a concept, its ordinary meaning does not immediately or necessarily evoke the subjective intentions that may underlie such conduct. Of course, in order for conduct to be said to “give effect to” an agreement, it must be demonstrated sufficiently to have been actually undertaken pursuant to, in accordance with, or otherwise enacting, implementing or administering that agreement. However, that is a question of fact rather than a matter of legal interpretation. The fact that the actor undertaking the impugned conduct had knowledge, in a subjective sense, of the scheme in question would likely be probative evidence towards satisfying the legal standard of “give effect to”. However, adducing such evidence is not necessarily the only means of satisfying the legal standard of “give effect to”, at least based on its ordinary meaning.

44 Relevantly, given the submission advanced in this case, in Tradestock, Smithers J addressed an argument that acting “in accordance with” a contract, arrangement or understanding required proof of the reason the actor acted as he or she did. His Honour rejected this submission. He said at 269-270:

Since the Trade Practices Act 1974 has been operative it has been the will of Parliament that contracts arrangements or understandings such as that now alleged should not be made and if made should not be given effect to. And Parliament has said that in relation to a provision of a contract arrangement or understanding the words “give effect to” are to include “do an act or thing in pursuance of or in accordance with or enforce or purport to enforce” (s 4(1)). It is to be observed that an act done by way of implementation of a contract arrangement or understanding would necessarily be done “in pursuance thereof”. If the only acts struck at by the Act are those done by way of implementation of the contract arrangement or understanding then there is no work left to be done by the words “or in accordance with”. And there is good reason for thinking that those words are intended to cover the situation where what is done is or may be done for reasons other than to implement the understanding. In such circumstances proof of the real or dominant motive or reason actuating the actor is likely to be a matter of great difficulty and may in many cases be impossible. To adopt the view submitted by Mr Rogers would be to conclude that Parliament which has stated its disapproval of the relevant contract arrangement or understanding and the kind of action for which it provides was content to allow such action to proceed as though it were lawful in circumstances where the evidence was insufficient to prove the precise motive for or actuating reason of the conduct in question.

45 At the very least, it is clear from the passages recited above, that there is a reasonable argument that the concept of “give effect to” in s 4 is not as narrow as contended for by NQCranes.

46 It is plain that there is an issue in this case as to the breadth of the phrase “give effect to” and whether evidence of certain acts is capable of satisfying the relevant criteria. It has been said that where a point of law has to be decided, and the judge is satisfied that this can be done appropriately at this stage, thereby avoiding the necessity of, and expense in going to trial, the court is entitled to determine the point: cf Williams & Humbert v W & H Trade Marks (Jersey) Ltd [1986] AC 368 cited in Polar Aviation at [43]. However, given the submissions on this application, the dispute in this case necessarily also involves a consideration of the evidence, and in particular, a consideration of that evidence in combination as opposed to a piecemeal approach (which occurred on this application). This ought only to occur at the end of the hearing.

47 Moreover, NQCranes approached each of the impugned particulars in a vacuum, and restricted the consideration of material facts to direct implementation. That is unduly narrow. There is no logical reason why a case of giving effect to a cartel understanding or arrangement cannot be proved by circumstantial evidence, with inferences being drawn that acts have been done in pursuance of or in accordance with the implementation of the arrangement: see for example Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 794; (2007) 160 FCR 321. First, as explained above, NQCranes complains that the pleadings of internal communications are incapable of supporting the give effect case unless those communications concerned, in effect, giving an instruction to be followed not to target MHE-Demag customers (and that instruction was followed). However, for the reasons given above, that approach is arguably too narrow. It is at least arguable that such communications, considered in context, are capable of giving effect to the arrangement. Second, NQCranes submitted that the receipt of communications which in substance indicate that it was not acting in accordance with the alleged cartel provisions cannot be conduct which gives effect to those provisions. This is a reference to the ASOC at [18(d)] and [18(e)] which refers to NQCranes raising complaints with MHE-Demag, and responding to complaints raised by MHE-Demag in relation to targeting of clients in the Brisbane and Newcastle area. NQCranes’ submission was that the existence of complaints regarding a failure to comply with the alleged cartel provisions indicates that it was not acting in pursuit of or otherwise in accordance with those provisions, as a matter of fact. However, in certain circumstances, evidence of complaints can give rise to giving effect to a cartel provision: see for example Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Renegade Gas Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1135. Again, that is at least arguable.

48 It is appropriate to refer to one final matter, which is the complaint by NQCranes that at [18(f)] of the ASOC the ACCC alleges that NQCranes retracted an offer for services to a potential client, Mesh and Bar, in Brisbane. NQCranes submitted that was not a retraction by NQCranes. That may well be correct. The particular to the pleading in the ASOC is as follows:

NQC retracting an offer to provide services to a potential client, Mesh and Bar, in Brisbane, which was identified as being a Demag client at the relevant time.

49 The ACCC accepted during submissions that, although not pleaded in this manner, the better view might be either that the purchase order was pulled by Mesh and Bar because of the approach that had been made to it by MHE-Demag, or that MHE-Demag caused the offer to be pulled. The ACCC accepted they would need leave to amend the pleading to this effect. Nonetheless, as the ACCC submitted, it is still the same point being made, that the parties were giving effect to this arrangement. Leave is given to amend this particular.

50 In my view, NQCranes has not established that the give effect case in respect to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision ought to be struck out.

Non-Targeting Arrangement

51 The submissions on this topic must be considered in the following context. As pleaded in the ASOC, on 26 August 2016, NQCranes and MHE-Demag signed a written agreement, which as noted above, was described as a Distributorship Agreement. The Co-Ordinated Approach Provision in that agreement pleaded by the ACCC is that in relation to Territory 2 (the area in Queensland south of Gladstone and in Newcastle), NQCranes and MHE-Demag will operate in the service markets in a coordinated approach so that their current customers are not targeted by the other. For potential future customers, the two organisations will ensure that their energies are focused on the other service competitors and not each other. This was the alleged cartel provision the subject of the originating application, before the ASOC was filed which included the Non-Targeting Arrangement.

52 On its face, the Non-Targeting Arrangement, as alleged in the ASOC, is that NQCranes and MHE-Demag were not to target each other’s customers in respect of the servicing of overhead cranes, in the Brisbane and Newcastle area. It is separate from the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision.

53 The ACCC identify what it alleges are two differences in the arrangements, as pleaded: first, the timing, with the Non-Targeting Arrangement existing no later than 17 August 2016, whereas the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision was from 26 August 2016, some 10 days later; and second, the geographic reach of the provisions, with the Non-Targeting Arrangement relating to the Brisbane and Newcastle areas, and the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision relating to the area of Queensland south of Gladstone and Newcastle, a much broader area. Pausing there, I note that Brisbane is south of Gladstone. The ACCC also submitted that this arrangement was given effect to before the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision.

54 In that context, I turn to the issues raised.

55 NQCranes seeks to strike out both the make and give effect pleadings in relation to the Non-Targeting Arrangement, and I will address each separately.

56 Before doing so, it is appropriate to refer to NQCranes’ submission that the Non-Targeting Arrangement pleading is as a result of the ACCC being aware of its reliance on the anti-overlap provisions, that this is an attempt to circumvent that, and the pleading is therefore an abuse of process. The submission by NQCranes appeared to proceed on the basis that it is correct when it contends the defence applies. Although the anti-overlap provisions in s 45AR(1) have been raised by NQCranes (including at the first case management hearing of this matter), no defence has yet been filed, and as such it has not yet been pleaded as relied upon. The pleadings are not yet closed. Therefore, there is no evidence in relation to matters relevant to that defence. This application is not the occasion to consider its application to these proceedings. The legal principles relevant to this application, and what NQCranes is required to establish to have the impugned pleadings struck out, are summarised above. They are not in dispute. It was not suggested by NQCranes that a party is not entitled to revisit its pleading in light of information it receives from the opposing party. The issue is whether the ASOC is deficient in the manner contended. If it is not (or not to the extent that would result in a strike out), the purported motivation for the pleading in this case does not convert this pleading into an abuse of process. NQCranes ultimately did not submit otherwise. That is, even if the amendments may have arisen as a result of the ACCC having reconsidered its pleading (and evidence) after NQCranes flagged the anti-overlap defence that does not, by itself, give rise to the pleading being an abuse of process. NQCranes accepted during the hearing that if the pleadings were not deficient in the manner contended, then the issue it raises as an abuse of process was only relevant to any issue of leave to replead.

Non-Targeting Arrangement – Make

57 This relates to [9]-[9E] of the ASOC and [1]-[1A] of the AOA.

58 Although a number of complaints were made by NQCranes in this regard, as noted above, two were highlighted as critical. First, NQCranes submitted that there was no meeting of the minds in respect to this “single” provision. Second, the ACCC’s case is now incoherent. Each will be addressed separately.

59 Paragraph [9] of the ASOC, which the respondent impugns in its submissions, must be considered in the context of the pleading as a whole.

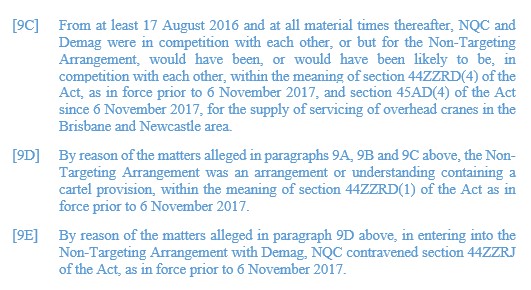

60 The paragraphs in the ASOC preceding [9] address the following. The ASOC describes the parties at [3]. The relevant markets are identified in [4], with particulars. It is pleaded at [5] that at all material times, NQCranes and MHE-Demag were participants in the Overhead Crane Servicing Markets. At [6] it is pleaded that at all material times, NQCranes and MHE-Demag were in competition with each other, or but for the arrangements would have been, or would have been likely to be, in competition with each other, within the meaning of s 44ZZRD(4) of the CCA, as in force prior to 6 November 2017, and s 45AD(4) of the CCA since 6 November 2017, in the Overhead Crane Servicing Markets.

61 Although NQCranes criticised [7] and [8] of the ASOC, NQCranes does not seek to strike out those paragraphs. It is appropriate to recite [7] and [8] because that is the immediate context in which [9] is pleaded. Paragraphs [7] and [8] are as follows:

62 It is accepted that the Non-Targeting Arrangement is said to have occurred during the negotiation process which resulted in the Distributorship Agreement.

63 In that context [9] is in the following terms:

64 Before directly addressing the submission as to the first basis, the meeting of the minds, it is appropriate to make two preliminary observations.

65 First, the ACCC’s submission that during a negotiation, parties might reach an understanding about an aspect(s) and put that into effect as a separate arrangement to that ultimately negotiated, can be accepted for present purposes. To put it another way, there is no reason as a matter of law why that could not occur.

66 Second, it can also be accepted, as contended by the ACCC, that whether an understanding or arrangement is reached can be established by circumstantial evidence, the strength coming from the inference drawn from the combination of considerations: see for example ACCC v Air New Zealand at [464] and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate Palm-Olive Pty Ltd (No 4) [2017] FCA 1590; (2017) 353 ALR 460 at [428]-[429].

67 Turning to NQCranes’ submission as to the first basis. NQCranes contended that the pleading in [9] is conclusory, citing Trade Practices Commission v David Jones (Australia) Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 109 (TPC v David Jones) per Fisher J. Contrary to NQCranes’ submission, TPC v David Jones does not stand for the proposition that a mere conclusory statement in a pleading, without more, will necessarily be liable to be struck out: see for example Kernel Holdings Pty Ltd v Rothmans of Pall Mall (Australia) Pty Ltd [1991] FCA 557; (1991) 217 ALR 171 at [7] and Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union v Stanwell Corporation Ltd (No 3) [2014] FCA 1324 at [12]. For example, a pleading of a conclusion may, in some circumstances, constitute a material fact: Eastern Colour at [40]. Even if that be so, it is not sufficient simply to plead a conclusion drawn from unstated facts, or otherwise stated at too high a level of generality, such that the other party does not know the case it has to meet: Wright Rubber Products Pty Ltd v Bayer AG [2008] FCA 1510 at [5]; Eastern Colour at [40]. Whether that is so is case specific.

68 I note at the outset that although the respondent complained in oral submissions that [9A] and [9B] (and as a result the paragraphs which follow) are deficient because, inter alia, they adopt the language of the statute without pleading material facts, such paragraphs are also pleaded in respect to the Distributorship Agreement at ASOC [13]-[16] without complaint by the respondent. It is not suggested that [13]-[16] insufficiently pleads matters relevant to the Distributorship Agreement such as they ought to be struck out, or that as a result of those paragraphs of the pleading the respondent does not know the case it has to meet. I note also that the pleading in respect to the make allegation in relation to the Distributorship Agreement, in effect does no more at [10]-[12] than plead the terms of the agreement. No challenge is made to the adequacy of that pleading. As a consequence, I focus the consideration on [9], which was in practical terms, the pleading to which most attention was directed in the respondent’s submission.

69 In [9], it is alleged that the existence of the Non-Targeting Arrangement can be inferred from what is then identified or referred to as three particulars.

70 The respondent’s submission on [9] was directed, at least in part, to the evidence and documents underpinning these particulars, to address what the respondent said could, or on its submission, could not, be inferred from them. It involved an assessment of the evidence underpinning these particulars, leading to a submission that the Non-Targeting Arrangement could not be established. For example, in respect to the particular (iii) it was contended that what is pleaded is “plucked” from a longer document, and the document read as a whole does not support the particular. However, on a strike out application, one is only addressing the face of the ASOC. As observed in Imobilari Pty Ltd v Opes Prime Stockbroking Ltd [2008] FCA 1920; (2008) 252 ALR 41 at 43 (emphasis in original):

The fundamental thing to understand about the strike-out rule, which the language of O 11 r 16 itself makes clear, is that the rule is concerned only with the adequacy of the pleading (or to be more precise, the allegations and the causes of action asserted therein) as a matter of law. The rule does not permit or allow consideration of facts or evidence outside the pleadings: Dey v Victorian Railway Cmrs [1949] HCA 1; (1949) 78 CLR 62 at 91 and 109; see also General Steel Industries Inc v Cmr for Railways (NSW) (1964) 112 CLR 125 at 129; [1965] 165 ALR 636 at 638 (General Steel). Indeed…the court must, for purposes of deciding the strike-out motion and deciding whether a pleading discloses a reasonable cause of action, assume the truth of the allegations in the statement of claim and draw all inferences in favour of the non-moving party because the question is whether those allegations, even if proved, cannot succeed as a matter of law: General Steel at CLR at 129; ALR 638.

71 It must be apparent on the face of the ASOC that the facts pleaded, if proved, could establish the cause of action relied upon by the relevant plaintiff or plaintiffs. Moreover, a “reasonable cause of action” in this context means “one with some chance of success, having regard to the allegations pleaded, even if weak”: Polar Aviation at [42]; and see Allstate at 236; Sabapathy v Jetstar Airways [2021] FCAFC 25 at [50]. It is a high hurdle that the respondent must cross to establish that a pleading be struck out: Uber Australia Pty Ltd v Andrianakis [2020] VSCA 186; (2020) 61 VR 580 at [35] (considering an application under r 23.02 of the Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 2015 (Vic) to strike out a statement of claim as either not disclosing a cause of action or being embarrassing), cited in Gall v Domino’s Pizza Enterprises Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 345; (2021) 304 IR 300 at [60]; Impiombato v BHP Group Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 1720 at [142] (I note that leave was given by the Full Court on a limited basis, and the primary judge’s conclusions in respect to the strike out application were not disturbed: BHP Group Ltd v Impiombato [2021] FCAFC 93).

72 On its face, particular (iii) appears to be minutes of a meeting of NQCranes’ management on 17 August 2016, and not a communication between the parties, and particulars (i) and (ii) are communications between Mr Pidgeon of NQCranes and Mr Costanzo of MHE-Demag on 15 and 16 August 2016 respectively. In respect to the inter-parties communications, as pleaded, particular (ii) is not without its difficulties in the absence of the full documents. If it refers to the list of topics discussed, referred to in particular (i), it appears that MHE-Demag is responding to that list, which includes a statement to the effect that the non-targeting “all looks good”, except for one unrelated aspect. However, this is in the context of the pleading in [7] and [8]. Particular (iii) and the meeting of NQCranes’ management is in the context of those communications in (i) and (ii).

73 I note ultimately the issue as pleaded is not whether only this provision was agreed in the negotiations, but whether it has been established that by no later than 17 August 2016, there was an arrangement to do as alleged. For present purposes, the issue is whether, given the basis of this application as articulated, it is established that there is no reasonable cause of action disclosed.

74 I appreciate that the respondent contended that the documents do not support the particulars and therefore the pleading is an abuse of process. NQCranes in its written submissions contended that in considering whether to strike out part of a pleading on the basis of an abuse of process, the Court is entitled to examine the cause of action which may involve a consideration of the evidence in the substantive case. For that proposition, the respondent refers to Parbery & Ors v QNI Metals Pty Ltd & Ors [2018] QSC 240 (Parbery) per Jackson J at [146]-[147], noting that the rule under consideration in Parbery was r 171 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999 (Qld), which by r 171(3) expressly refers to the receipt of evidence by the Court in a strike out application. No such provision exists in the Rules. The respondent also referred to Batistatos v Roads & Traffic Authority of New South Wales [2006] HCA 27; (2006) 226 CLR 256 where the High Court referred to the power of the Court to “inform… its conscience upon affidavits” in protecting its own processes, per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Crennan JJ at [11]. I note that there the High Court was considering whether a stay of proceedings ought to be granted on the basis that the proceedings are an abuse of process. There will be circumstances where, given the basis of an application for a stay, it will be necessary for evidence to be considered (for example a stay based on prejudicial publicity, or the ill health of an accused). This is a strike out application, and considered at an early stage of the proceedings. The basis for the abuse of process argument in this case appears to be because it is alleged that the pleading has been introduced to get around the anti-overlap defence, which I have addressed above at [56]. I note that the respondent did not contend that the ACCC’s conduct in amending the pleading per se was improper. In effect, the respondent alleges that the pleading is an abuse of process because there is no reasonable cause of action as the evidence does not support the pleading. The failure to disclose a reasonable cause of action is a separate identified basis on which a pleading can be struck out. The argument was rather circular. In the circumstances of this case, the submission ought not circumvent the orthodox approach to an application to strike out the pleading on the basis that there is, inter alia, no reasonable cause of action. The submission is dependent on an assessment of the documents to which attention was drawn. That is a submission on the merits as to what inferences can be drawn. In any event, in this case, it is plainly not appropriate to determine what inferences, or which competing inferences, ought to be drawn or accepted from the documents which were addressed separately at this stage of the proceedings, and in isolation from other evidence. Lastly, in any case, I note that the respondent accepted at the hearing that if the arrangement is properly pleaded, the pleading is not an abuse of process (as noted above at [28]).

75 Although there may be some strength to aspects of NQCranes’ submission, considering the pleading in [9] in its context, the respondent has not established that there is no reasonable cause of action. NQCranes has not overcome the substantial hurdle necessary to succeed on this basis of the application.

76 Turning to the matter identified by NQCranes as the second basis of the complaint, that the pleading in relation to the Non-Targeting Arrangement is incoherent, likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay. This submission also encompassed an allegation that the pleading is an abuse of process.

77 It was apparent from NQCranes’ submissions that it did not appear really to be contended that it did not know the case it had to meet. Leaving aside the issue of proof, the allegation as pleaded is straight forward. Rather, NQCranes’ complaint was really focussed on the Non-Targeting Arrangement being a contrivance.

78 There was some issue raised as to whether this arrangement was pleaded as an alternative. The ACCC submitted it is apparent from the ASOC that what is alleged is a separate arrangement. In its written submission NQCranes approached its argument on the basis that it is a separate arrangement. Indeed, that is the basis of the argument as to incoherence, that the same conduct is said to relate to separate arrangements. As the ACCC submitted, if that needed clarification they could do so by insertion of the words “further, or in the alternative” at the commencement of [10] of the ASOC, to make it clear that this is alleged to be a separate arrangement entered into by the parties. I would grant leave for that amendment to be made.

79 This second submission, although advanced in addressing the pleadings concerning the making of the Non-Targeting Arrangement, relied also on the pleadings in respect to the give effect case for the Non-Targeting Arrangement.

80 In this context, NQCranes submitted that there were “two separate and complete meeting of minds” relevantly to the same effect, and which were concurrent and operated for two years so that the same conduct was giving effect to both the Non-Targeting Arrangement and the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. The submission is concerned with the artificiality of the allegation, which is said to be a contrivance to overcome the anti-overlap provisions

81 As previously observed, there is no logical basis to suggest that an understanding or arrangement cannot be reached and put into effect before a formal agreement. It is appropriate to return to that discussion. The submission advanced by the ACCC to illustrate the proposition was by reference to the fact that an interim agreement may be put in place. To be more specific, in that context, the ACCC submitted that:

It may turn out that the evidence will be that…the parties decided that they wanted to in the interim put in place – or maybe not even in the interim. Maybe an ongoing arrangement whereby, before finalising the detail of the distribution agreement, they would give effect to Brisbane and Newcastle.

82 The give effect case concerning the Non-Targeting Arrangement is pleaded as continuing at least until 18 October 2018, not as an interim arrangement. Two of the matters pleaded as giving effect to the Non-Targeting Arrangement are alleged to have occurred before entering into the Distributorship Agreement. The remainder are those also pleaded in relation to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision.

83 Speaking at a level of generality, there appears to be no reason why, as a matter of logic, actions could not be undertaken pursuant to more than one agreement. That, of course, says nothing about whether that is so in the circumstances of this case. That was not the subject of any direct submission in this case. In any event, whether that occurred in this case would be a matter of evidence, and not a matter to be decided on a strike out application.

84 This aspect of the second submission by NQCranes was the basis of its contention that the Non-Targeting Arrangement should be treated analogously to Allied Mills, and therefore struck out as an abuse of process. It was submitted Allied Mills stood for the proposition that where a conspiracy to make an unlawful arrangement or understanding is pleaded in the alternative to making an identical unlawful arrangement or understanding in order to gain a forensic advantage, the conspiracy will be struck out on the basis that it is an abuse of process.

85 It may be accepted, as contended for by the ACCC, that the facts in this case are not analogous with those considered in Allied Mills, where Sheppard J concluded that the allegations were, in reality, identical. Sheppard J concluded that it was not appropriate to allege on the same facts as an alternative to an arrangement or understanding made unlawful by the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (then in operation), conspiracies which are themselves such arrangements or understandings. Nonetheless, only the part of the pleading which related to the conspiracy was struck out. Sheppard J found that in relation to the remainder of the pleadings, which he described as somewhat vague and unspecific, it was impossible to conclude that there was not a real question to be tried. Allied Mills obviously turned on an analysis of the pleadings in that case.

86 In this case, the Non-Targeting Arrangement is pleaded in the ASOC to have commenced at an earlier point of time to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision, relates to a narrower geographical area and on the pleading was given effect to before the entry into the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision by the parties.

87 I am troubled at the commonality between aspects of the give effect pleading. However, as previously observed, as a general proposition whether an act could be in pursuance of one or both arrangements, if they are established, is a factual matter, dependent on the evidence. NQCranes have not established that overall the pleading is incoherent, causes prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding or is otherwise an abuse of process. NQCranes has not overcome the substantial hurdle necessary to succeed on this basis of the application.

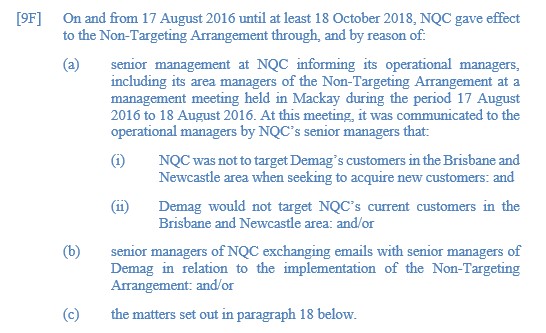

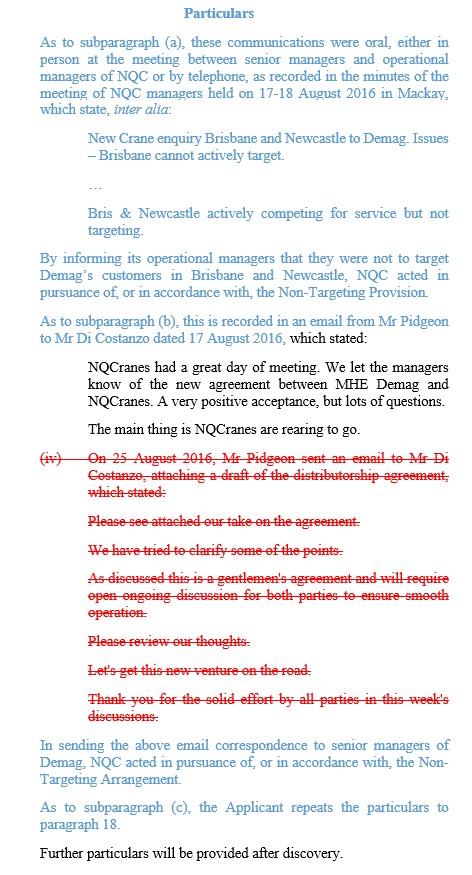

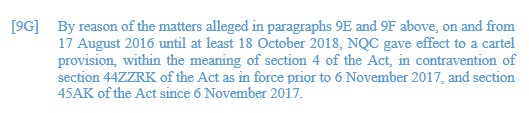

Non-Targeting Arrangement – give effect

88 This relates to [9F]-[9G] of the ASOC which is as follows:

89 This matter has been addressed in part in the preceding discussion at [41]-[50].

90 As to NQCranes’ submission in relation to the give effect pleading for the Non-Targeting Arrangement, this relates to the criticisms also relied on in relation to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision. For the reasons given in relation to the Co-Ordinated Approach Provision, NQCranes has not established that this aspect ought to be struck out. The two additional matters pleaded in relation to the Non-Targeting Arrangement, fall into the same category, and give rise to an argument of the meaning of “give effect to”, the practical breadth of which is in dispute in this hearing and its application to the matters pleaded in this case. Therefore, for the same reasons as previously articulated, NQCranes has not established that those particulars ought to be struck from the pleading.

Section 37P

91 Although the respondent also relied on s 37P of the FCA Act in support of its claim, no separate submission was advanced as to the relevance of that provision to its submission. In particular, no submission was advanced that s 37P had work to do over and above the principles in relation to a strike out application under r 16.21. That is, it was not suggested that if the application under r 16.21 did not succeed, s 37P provided a separate basis for the proceedings to be struck out in this case. The ACCC questioned the application of the provision to this application. In my view, on the application as argued by NQCranes, in the circumstances of this case, nothing turns on s 37P.

Conclusion

92 For the reasons above, the respondent’s application is dismissed.

93 As noted above, I give leave for the applicant to amend the particular matters identified at [49] and at [78].

I certify that the preceding ninety-three (93) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Abraham. |

Associate: