Federal Court of Australia

Rainbow on behalf of the Kurtjar People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2021] FCA 1251

ORDERS

JOSEPH RAINBOW ON BEHALF OF THE KURTJAR PEOPLE Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent STANBROKE PTY LTD (and others named in the schedule) Seventh Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 October 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to order 2, the parties confer and prepare a determination of native title consistent with their prior agreements and the Court’s reasons for judgment delivered today.

2. If any party wishes to contend that the determination of native title to be made by the Court not include a non-exclusive native title right expressed as “to access and take for any purpose resources in the claim area”;

(a) each party so contending file and serve written submissions limited to 5 pages on or before 5 November 2021;

(b) any other party file and serve written submissions limited to 5 pages as to its position on or before 26 November 2021.

3. The proceeding be listed for the making of final orders on a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[6] | |

[6] | |

[15] | |

[17] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

[36] | |

[60] | |

[66] | |

[81] | |

[118] | |

[126] | |

[134] | |

[143] | |

[143] | |

[145] | |

[146] | |

[162] | |

[164] | |

[203] | |

[212] | |

[231] | |

[232] | |

[236] | |

[244] | |

[252] | |

[259] | |

[264] | |

4.1.5 (5) Iffley Tommy senior, Paddy Macaroni and Macaroni Tommy | [267] |

[280] | |

[282] | |

[285] | |

[290] | |

[300] | |

[306] | |

[328] |

RARES J:

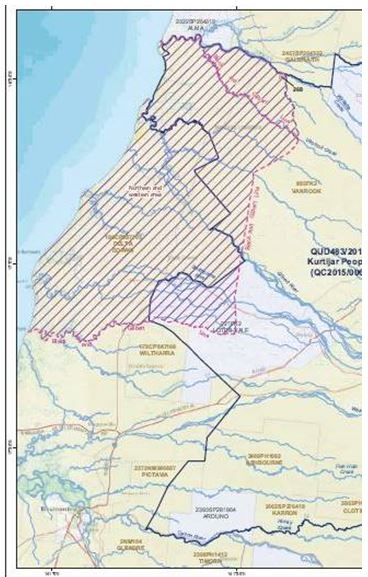

1 The Kurtjar people seek a determination under s 225 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) of non-exclusive native title over a large area of land and waters. The Kurtjar people’s traditional land and waters are located in the south-west of Cape York, extending inland from the Gulf of Carpentaria in the State of Queensland.

2 One of the three issues in this proceeding is whether the Kurtjar people have been the traditional owners of, either since before 26 January 1788, when Capt Arthur Phillip claimed British sovereignty or, and by what process, have succeeded to, the land and waters, included in a large pastoral lease holding, Miranda Downs, to the east of what is undisputed Kurtjar country (the succession issue). The Kurtjar people and the State accept that Kurtjar country now includes Miranda Downs, but the holder of the pastoral lease over it, Stanbroke Pty Ltd, disputed this at all times until 9 July 2021 when it sold its interest to Hughes Holdings and Investments No 700 Pty Ltd, which became a respondent under s 85(4) of the Act. By consent on 28 September 2021, Hughes agreed that it would be bound by previously agreed statements of fact on extinguishment and would only make submissions as to the form of any orders to give effect to these reasons.

3 The essential dispute involved in the succession issue centres around whether the connection that the Kurtjar people now have in managing and exercising control over the spiritual potency of Miranda Downs has been continuous since before sovereignty, as they contend, or has evolved, as the State and, alternatively, the Kurtjar people contend. In contrast, Stanbroke contends that the Kurtjar people’s connection with Miranda Downs, needed to, but did not, evolve, by a process of licit or normative succession to the rights and interests of one or more now extinct indigenous peoples (the Walangama people, and or the people variously called the Ariba, Aripa or Rib people) who, pre-sovereignty, held native title rights and interests in the land and waters of Miranda Downs.

4 The other issues are:

(1) whether, as the applicant (comprising Joseph (Joey) Rainbow, Irene Pascoe and Shirley McPherson) contends, eight persons should be included as apical ancestors of the Kurtjar people in the description of the present common law holders of the native title rights and interests of Kurtjar country (the apical ancestor issue); and

(2) the correct description of one non-exclusive right and interest that will be recognised in a determination of native title, namely “the right to access natural resources and to take, use, share and exchange those resources for any purpose” with, or without, a limitation for which the State contends constraining commercial exploitation (the right to take resources issue).

5 There have been several spellings of the English language rendering of “Kurtjar”, including “Kurtijar”, used earlier in this proceeding, but I will use in these reasons the version that the applicant has now adopted.

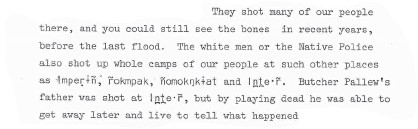

6 The Kurtjar people’s first contact with Europeans was when Ludwig Leichhardt’s expedition arrived in 1845. One of his party, John Gilbert, a naturalist, was killed in an attack by Aboriginal people and the Gilbert River was named in his memory. In 1868, the township of Norman River was established, which later was called Normanton. The impact of European settlement, which began in the mid to late 1860s, in the Gulf country was profound, as it has been in most of Australia.

7 In the late 1960s, the Queensland Government moved many first nations persons then living in camps on pastoral stations into a reserve at Normanton (the Normanton reserve).

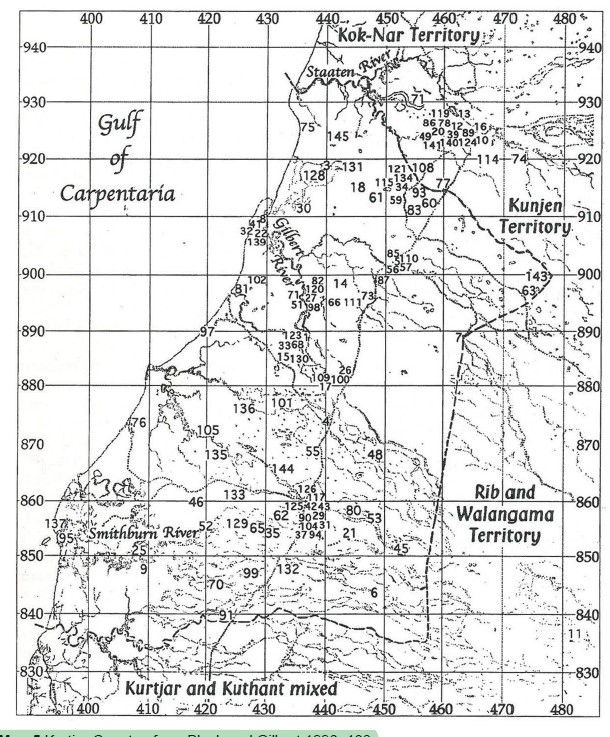

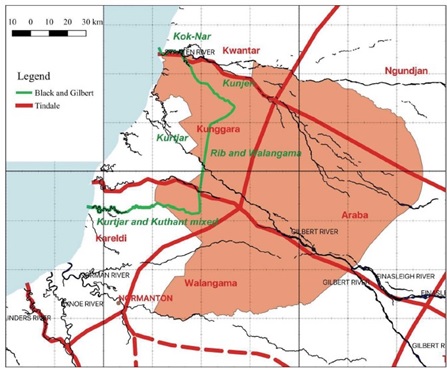

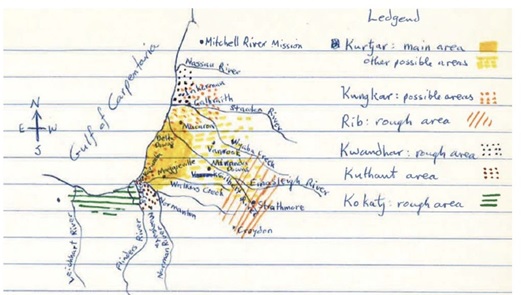

8 In the 1970s, a linguist, Dr Paul Black, conducted linguistic research with Kurtjar speakers, including an elder, Rolly Gilbert, who appears to have been one of Dr Black’s principal informants. Dr Black supported the attempts of Kurtjar people to obtain ownership of a pastoral lease of Delta Downs station. In the course of those efforts he made a map with Rolly Gilbert (the Black and Gilbert map) that purported to identify Kurtjar country as centred on Delta Downs. Stanbroke emphasised that this map did not include, as Kurtjar country, Miranda Downs and other large parts of what is now the claim area to its east.

9 In 1982, the Aboriginal Development Commission of the Commonwealth acquired the lease of Delta Downs on behalf of the Kurtjar people. In 2002, that lease was transferred to Morr Morr Pastoral Company Pty Ltd which continues to hold it for the benefit of the Kurtjar people.

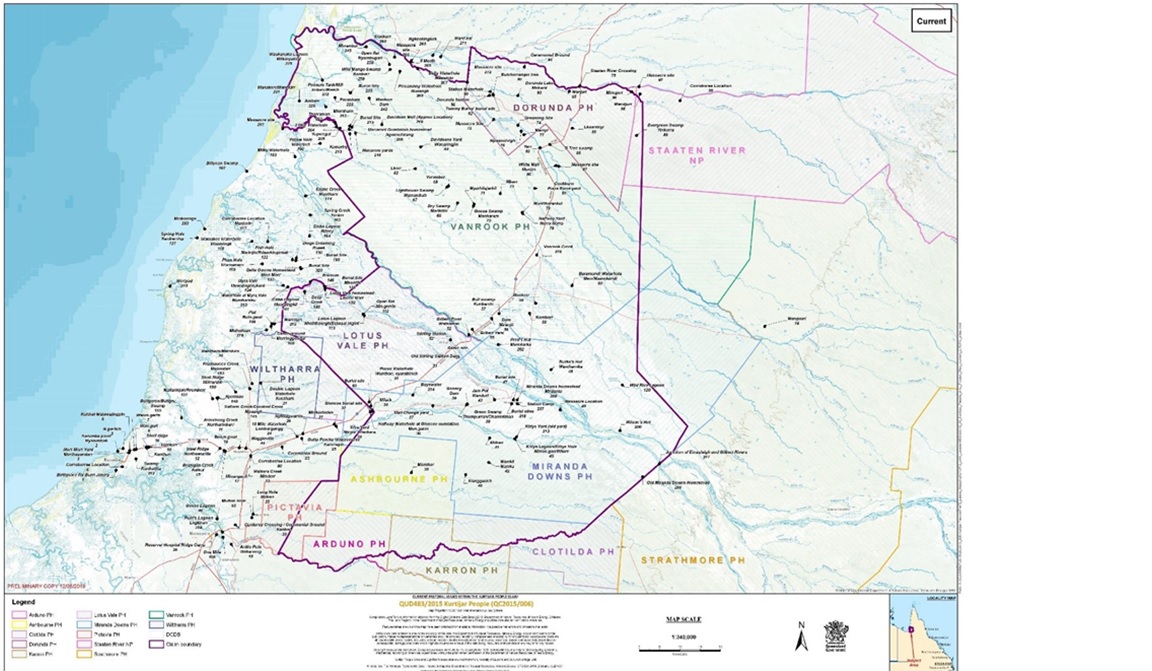

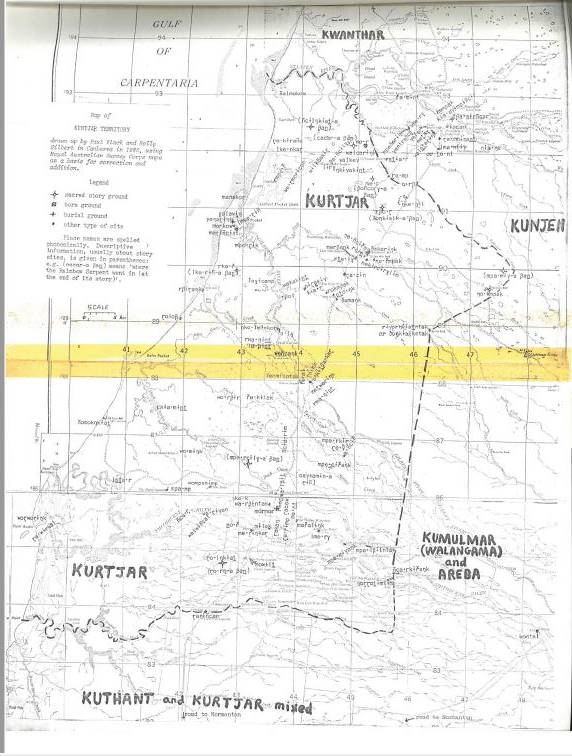

10 Below is a map of the claim area with pastoral lease boundaries and annotations of significant sites recorded by Dr Richard Martin, who was the applicant’s expert anthropologist.

11 The Miranda Downs pastoral lease is in the south-east of the claim area, below the Vanrook pastoral lease to its north. Vanrook station also extends along the western boundary of Miranda Downs. The southern boundary of Miranda Downs is also within the claim area. Stirling/Lotus Vale station (the two stations are now merged) is a smaller holding between Delta Downs on its west, Vanrook on its north-east and Miranda Downs on its east and south-east. The Dorunda pastoral lease is located in the north-east of the claim area, south of the Staaten River. Delta Downs station is located to the west of the claim area.

12 The parties’ expert anthropologists, Dr Martin, Dr Kingsley Palmer, retained by the State and Dr Ron Brunton, retained by Stanbroke (with Dr Kevin Murphy, who had been retained by the owners of the Vanrook, Stirling/Lotus Vale and Dorunda pastoral leases, namely, Vanrook Station Pty Ltd, Stirling/Lotus Vale Station Pty Ltd and Dorunda Station Pty Ltd (the Gulf Coast parties)) met together on 28 and 29 March 2019 and again on 16 April 2019, and, with the assistance of the Registrar, prepared two joint reports.

13 On 16 August 2019, the solicitors for the Gulf Coast parties emailed the other parties and the Court to advise that the Gulf Coast parties would no longer contest the claim of the Kurtjar people to non-exclusive native title rights and interests in the area of each of Vanrook, Stirling/Lotus Vale and Dorunda stations. That occurred shortly before the on country hearing began on 27 August 2019. The Gulf Coast parties changed their position after I refused them leave to adduce further evidence from Dr Murphy, in which he sought to withdraw from the position he had agreed with the other experts in the second joint report, namely, that the Kurtjar people held rights and interests in the land and waters of Vanrook, Stirling/Lotus Vale and Dorunda stations: Rainbow on behalf of the Kurtijar People v State of Queensland [2019] FCA 1638.

14 The Court sat on country at the Delta Downs homestead when not visiting sites in the claim area.

15 The parties filed a statement of agreed facts and substantive issues in dispute as to connection on 23 July 2019. Much of the basis for the agreement on those facts came about from the two joint expert reports.

16 The parties agreed as facts that:

prior to sovereignty, and at effective sovereignty (i.e. when European settlement occurred in the claim area), there were Aboriginal peoples in occupation of the claim area;

those peoples acknowledged and observed a common body of normative laws and customs by which they held rights and interests in, and had connection with, the claim area (pre-sovereignty laws and customs) that are likely to have included those claimed in the application, including (relevantly, to the right to take resources issue) “the right to access natural resources in those areas and to take, use, share and exchange those natural resources for any purpose”;

the Kurtjar people and their ancestors have continued to acknowledge and observe at least some of the pre-sovereignty laws and customs;

the Kurtjar people’s contemporary system of laws and customs under which rights in land are held remains rooted in the pre-sovereignty system of laws and customs, notwithstanding that parts of the system have undergone varying degrees of adaption, loss and change;

the rights and interests so held in land and waters are inalienable and held communally;

since effective sovereignty, it is likely that estate groups (i.e. a group with native title rights and interests in the particular land and waters) in relation to parts of the claim area have become extinct and those areas are now included in the claims of the Kurtjar people;

the pre-sovereignty laws and customs provided for succession to country in situations in which a group holding rights became, or was becoming, extinct;

succession did not necessarily occur on the basis that the neighbouring clan estate would succeed to the country of the extinct or nearly extinct clan estate; and

a critical component of succession in the region in which the present claim is made was that the succeeded and the succeeding clans had to share spiritual correspondence, such as totemic commonality, shared dreaming tracks, spirits and associated rituals.

1.3 Proof of historical matters

17 Both the common law and the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) address the question of how to prove what laws and customs once existed and their content, even though no-one is now alive who can testify about what occurred in the past and there is no written documentation of that subject matter, as is often the case with cultures that, like Australia’s First Nations peoples, had no written tradition.

18 First, s 74(1) of the Evidence Act provides that the hearsay rule does not apply to evidence of reputation concerning the existence, nature or extent of a public or general right. Secondly, s 140(2) requires a court, in deciding whether it is satisfied that a party has proved its case on the balance of probabilities, at a minimum, to take into account the nature of the cause of action or defence, the nature of the subject matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged. At common law, evidence of rights and events alleged to have existed or occurred beyond living memory can be proved by both expert evidence and lay evidence of living persons, including members of groups claiming to hold native title or similar rights (which Lord Cohen, giving the opinion of the Judicial Committee comprising Lord Normand, Lord Reid and himself, termed “traditional evidence”: Stool of Abinabina v Chief Kojo Enyimadu [1953] AC 207 at 216).

19 In Gumana v Northern Territory (2005) 141 FCR 457 at 510–511 [194]–[201], Selway J discussed the method of proving custom and genealogies by oral evidence where there is no, or limited, documentary evidence or where the fact to be proved occurred at a “time immemorial”. He said that the difficulties in obtaining evidence from times well past “were ameliorated by the readiness of the common law courts to infer from proof of the existence of a current custom that that custom had continued from time immemorial” (at 511 [198]).

20 In Sampi (on behalf of the Bardi and Jawi People) v Western Australia (2010) 266 ALR 537 at 558 [63], North and Mansfield JJ said:

On the basis of this and like evidence the primary judge should have found that the Bardi and Jawi people acknowledged the same laws and observed the same customs concerning rights and interests held in land and waters at least from the present back until the time of these witnesses’ “old people” or grandparents, namely, the latter part of the 19th century.

The question then arises whether the court can infer the existence of that acknowledgement and observance from about the latter part of the 19th century back to sovereignty. Selway J addressed this issue in Gumana v Northern Territory (2005) 141 FCR 457; 218 ALR 292; [2005] FCA 50 and said at [201] by reference to the history of the approach of the common law to the proof of custom:

[201] … where there is a clear claim of the continuous existence of a custom or tradition that has existed at least since settlement supported by creditable evidence from persons who have observed that custom or tradition and evidence of a general reputation that the custom or tradition had “always” been observed then, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, there is an inference that the tradition or custom has existed at least since the date of settlement.

In the present circumstances the constitutional status and elaborate nature of the rules in question make it improbable that the system arose in the relatively short period between sovereignty and the time of the witnesses’ “old people”…

(emphasis added)

21 And, in Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1 at 99–100 [341]–[343], Lindgren J applied Gumana 141 FCR at 510–511 [194]–[201], noting that an inference should be drawn by applying logic and human experience to the facts proved by admissible evidence: see too Isaac (on behalf of the Rrumburriya Borroloola Claim Group) v Northern Territory (2016) 339 ALR 98 at 133 [222] per Mansfield J; Mason v Tritton (1994) 34 NSWLR 572 at 586E–588E per Kirby P, 604D–F per Priestley JA with whom Gleeson CJ agreed at 574C; The Cloverdell Lumber Co Pty Ltd v Abbott (1924) 34 CLR 122 at 137–138 per Isaacs J.

22 In reaching his conclusion in Gumana 141 FCR at 510–511 [194]–[201], Selway J drew on the lucid exposition by Sir George Jessel MR in Hammerton v Honey (1876) 24 WR 603 at 604 of the principles that applied at common law to determine whether a right could be claimed by custom, as opposed to by prescription. Jessel MR explained (at 603) that at common law:

… A custom… is local common law. It is common law because it is not statute law; it is local common law because it is the law of a particular place as distinguished from the general common law. Now, what is the meaning of local common law? Local common law, like general common law, is the law of the country as it existed before the time of legal memory, which is generally considered the time of Richard I.

(emphasis added)

23 Jessel MR said that the common law of a place, as a general rule, was proved by usage. He held that any usage to prove a custom as an exception to the general common law had to be both reasonable and continuous, that is “there must be long, continuous, habitual usage without interruption”. He explained that this conclusion followed from the fact that people do not usually acquiesce in the disturbance of their rights (at 603–604). As Jessel MR recognised (at 604):

It is impossible to prove actual usage in all time by living testimony. The usual course taken is this: persons of middle or old age are called, who state that in their time, usually at least half a century, the usage has always prevailed. That is considered, in the absence of countervailing evidence, to show that the usage has prevailed from all time.

(emphasis added)

24 The Master of the Rolls said that there were two kinds of countervailing evidence, namely, first, that of other old persons who testify to the contrary of what their counterparts had said and show that there was interruption to the usage, or, secondly, evidence that, based on the nature of the case, there was a legal difficulty or obstacle that made the alleged assertion of the right impossible. And, as Jessel MR recognised, both prescription and custom “are legal fictions invented by judges for the purpose of giving a legal foundation or origin to long usage” (at 604).

25 The Kurtjar people have a traditional custom or ritual of “warming up” persons who are strangers to their country. This consists of the Kurtjar person rubbing sweat from his or her underarm on the stranger’s face and body. The purpose is to inform the Kurtjar spirits, that might otherwise harm the stranger, that he or she has come onto Kurtjar country properly (i.e. with permission from a Kurtjar person able to grant such authority). In addition, as Fred Pascoe, who was born in 1967, said:

When I go to places that I haven’t been before on Kurtijar country, if I’m there with old people they sing out. Otherwise I sing out and introduce myself, say who I am and where I come – well, what I’m there for.

26 Fred Pascoe said that, as a Kurtjar, he could go anywhere on Kurtjar country “as long as I sing out to… the spirits of my ancestors”. He tells them who he is in Kurtjar language, to whom he is connected and what he is there for, such as “to get wanthork (fish), or yaangirr (turtle)”.

27 His mother, Irene Pascoe (a member of the applicant), was Kurtjar, but his father was not. He said that when his grandfather, Jubilee Slattery, an elder and leader of the Kurtjar people, or another took him to a place on Kurtjar country for the first time or to one that the person did not visit regularly, his grandfather (or other old people) would call out in Kurtjar language to let the spirits know who they were, what they were doing there and why they had come.

28 Fred Pascoe’s grandfather, Nardoo Burns, gave his totem, the black cockatoo, to Mr Pascoe and later told him: “That’s all our old people, that’s our totem, that’s where we go when we finish… we come from the Smithburne [River]”. He said that his grandparents had explained to him that the significance of having a totem was that “[i]t ties me to that country… to the animals of that country” and that “the red black cockatoo is our ancestor, so he ties me to this country” as an aspect of the Dreamtime, when “the animals walked this earth in that time as our… ancestors”. Fred Pascoe told Dr Martin that Nardoo Burns had said that the black cockatoo was the totem of his brothers, most of whom were born on the Smithburne River, and that their family came from the Smithburne River. Fred Pascoe also said that Nardoo Burns had told him that Judy and Biddy Captain were both born and reared on the Smithburne River and that they married two Staaten River men; namely Tommy Burns (Nardoo Burns’ father) and Rainbow Christie. He said that Nardoo Burns did not tell him how the family got the black cockatoo as its totem. Fred Pascoe also told his children that it was their totem and whenever he sees one flying he tells his children: “That’s our old people flying… don’t be afraid because that’s our old people who have gone before”.

29 Fred Pascoe grew up at the bottom camp on the Normanton reserve at which only Kurtjar people lived. The reserve was established in 1948 for Aboriginal people. Its population increased in the 1960s when indigenous stockmen and their families were forcibly removed from the pastoral holdings on which they worked. The reserve was discontinued in about the late 1970s or early 1980s. It was not on Kurtjar country. Fred Pascoe said that he and others living at the reserve would swim and, depending on the season, fish various species in the Norman River. He said that a mixture of Aboriginal persons, including Kurtjar, Gkuthaarn and Kukatj, lived at the top camp at the reserve because of inter-marriages. He remembered corroborees occurring regularly outside Jubilee Slattery’s house. He said that these kept Kurtjar culture active with, mainly men, singing old songs in Kurtjar and dancing traditional dances. He said that the children participated and learnt the songs and dances.

30 Jubilee Slattery and his wife, Lily, took their grandchildren, including Fred Pascoe, and others hunting on Kurtjar country, including, relevantly, on Miranda Downs, at Glencoe and Picnic Waterhole (both located at or around the western edge of Miranda Downs). They visited the Mail Chain Yard (which was used to hold or receive mail), near Walker’s Creek and Kitty’s Hole, both of which are located well inside Miranda Downs. Fred Pascoe said that his grandfather “would always sing out to our old people at those places”.

31 Fred Pascoe recognised that, as with him and his family in respect of Myra Vale station on the Smithburne River (which is now an outstation on Delta Downs), some families have a particular connection with an area on Kurtjar country. Where that is the case, if he intends to visit there, he will inform that family, or one of its members, both as a courtesy and because “it’s more so to protect me as well in case being younger… I might not have the intimate knowledge of that country that someone who’s senior… would have”. This is necessary to ensure that where he wants to visit is not, for instance, a bora ground, a burial ground or an area where Kurtjar law prohibits some activity or there is spiritual danger.

32 Fred Pascoe explained that in the early 20th century, Kurtjar and other Aboriginal peoples were rounded up and put into camps to live on cattle stations or, if they did not go into the camps, the pastoralists shot them. Thus, each of the pastoral leaseholdings, like Delta Downs and others that are within the claim area, namely, Miranda Downs, Vanrook, Stirling/Lotus Vale, and Macaroni (which was in the north-west) had camps filled predominantly with the Aboriginal clan or tribe on whose country the station was located. Because those people knew their country well, the pastoralists could use them as ringers and stockmen.

33 As a child, Fred Pascoe was a frequent visitor to a camp of Kurtjar people at Glencoe after it had become part of Miranda Downs station in the 1970s. He remembered that Fred and Jane Midlan, Barney Rapson (senior) (being the husband of Doris Rapson, née Buckley: various witnesses spell his name as either “Barnie” or “Barney” and I have used “Barney” in these reasons to signify this person), his brother, Royal Tommy, and Katie Tommy (née Burns, who was Mr Pascoe’s grandmother) were working there. Mr Pascoe said that the then manager of Miranda Downs, Phil Schaffert, was supportive of using Aboriginal ringers who lived in the camp at Glencoe. Mr Pascoe worked with lots of older Kurtjar men, including his grandfather, Nardoo Burns, Fred Midlan and Sandy Rainbow, as well as his uncles, Roy Beasley, Rolly Beasley, Warren Beasley, Paul Casey, Hector Casey and Frank Casey, who told him about Kurtjar sites not only on Delta Downs, but also on other stations including Miranda Downs. They told Fred Pascoe, from the time he was a child, that Miranda Downs was Kurtjar country and took him there to fish and hunt. When they went onto Miranda Downs:

… whether it was with Jubilee Slattery or with some of the other elders, they’d – you know, they’d sing out in our language and told the spirits that we were there, our old people….And they used to tell us kids, “This is your country, you’re right to come here and you can fish at this waterhole and you can shoot that wallaby off that land, and you can hunt and fish.”

34 Mr Pascoe recounted that the “old fellas” with whom he worked on cattle stations always talked about a senior lawman, Saltwater Jack, who was an acknowledged Kurtjar tribal leader. The old fellas described Saltwater Jack’s status and travels around Kurtjar country. They told him that Saltwater Jack swam in the Gilbert River in flood (in the south of the claim area), went to visit Kurtjar people on Macaroni station (in the north-west) for ceremonies, the Staaten River area (in the north) in the wet season to participate in Kurtjar corroboree and would walk through to Vanrook and Miranda Downs stations to see family. Mr Pascoe had always been told that the Kurtjar people’s southern boundary was the Norman River.

35 Importantly, Fred Pascoe said that he believed that, under Kurtjar law, he had a right to the resources of his country without limitation and “I can take what I want as long as I don’t break the laws of my country – my people” and “I have the right to take those resources… as long as I don’t break my laws in doing that… That’s my resource. That’s my country”.

36 Warren Beasley was born under a tree in 1947 on Myra Vale station. He calls the tree, which is still standing, “mil ntoong, my home. It means that’s mine”. He was a knowledgeable Kurtjar elder and a laakinchargh or witchdoctor. He gave detailed evidence at the hearing. His father was Beasley Bumble, who was the son of Bumble B. Bumble B was the equivalent of a king of the Kurtjar.

37 Bumble B was a ringer who spoke Kurtjar and taught his grandson, Warren Beasley, about his family. Warren Beasley had retired by the time of the hearing and lived at Delta Downs. Over the years, he worked with many senior Kurtjar men on various stations in Kurtjar country who showed and told him of how far Kurtjar country extended, important Kurtjar places, secret places, poison grounds and Kurtjar laws. Warren Beasley said that, when he was young, Bumble B told him that he had worked at, and knew a lot about, Miranda Downs and that he (Warren Beasley) should see Miranda Downs for himself. In his youth, Warren Beasley worked a lot with Bumble B on stations.

38 When Warren Beasley worked as a ringer and stockman on Miranda Downs, Bumble B visited him from his home on Myra Vale. They rode to places over a week or so at a time, where Bumble B showed Warren Beasley burial, bora, poison, dangerous and secret grounds. Bumble B showed his grandson areas to which he warned him not go on his own because “you won’t come back”. They went riding with Royal Tommy to the junction of the Einasleigh and Gilbert Rivers, which was near the old Miranda Downs homestead, and both older men told Warren Beasley that the extent (in effect, the eastern boundary) of Kurtjar country was up to the Einasleigh River and that on the other (eastern) side of the junction was Tagalaka country. The older men told Warren Beasley that he could not go across that boundary. They also showed him burial sites nearby. In video evidence, Warren Beasley pointed out where Bumble B and Royal Tommy had told him that two Kurtjar men were buried at a site near the current Miranda Downs’ homestead.

39 Bumble B and Royal Tommy told Warren Beasley that as the Gilbert River flowed west towards the sea, it ran through Kurtjar country, traversing, among other land, Miranda Downs. Warren Beasley said that the Smithburne River (which runs north-west towards the Gulf a relatively small distance south of the Gilbert River) was also on Kurtjar country. They showed him the out camp at (Wild) Rice Lagoon (which is north-west of the junction of the Einasleigh and Gilbert Rivers), where Warren Beasley’s younger brother, Rolly, worked as caretaker when Warren Beasley also worked on Miranda Downs. The older men told Warren Beasley that this was also Kurtjar country.

40 Bumble B and Royal Tommy also took Warren Beasley to numerous places along Walker’s Creek (which runs south-west towards the Gulf, further south again from the Smithburne River), including Rocky Waterhole, Kitty’s Yard (an old bronco yard) and Kitty’s Hole. Warren Beasley said that there was a permanent waterhole at Kitty’s Yard with the Kurtjar name Injerrilk. There were spirits of old fellas all around there. Royal Tommy, Bumble B and his parents also told Warren Beasley that the country between Rocky Creek (that flows into the Carron River, well south of Bayswater waterhole) and Walker’s Creek to its north was Kurtjar country. That area lies to the south and west of the old Miranda Downs homestead, and Rocky Creek and the Carron River both flow west, south of Kitty’s Hole.

41 The southern boundary of the claim area for this application follows the Carron River from the extreme south-west point of the western boundary and then follows Rocky Creek to the east for some distance until the boundary heads north-east below Kitty’s Yard.

42 Warren Beasley said that old Tagalaka men were also working on Miranda Downs when he was there with Royal Tommy, Bumble B and Beasley Bumble. The elders told him that he had to protect and visit Miranda Downs “and I also even talk Kurtjar – because they’re all Kurtjar and the spirits understand what I mean”.

43 Warren Beasley visited Kitty’s Yard, on Walker’s Creek, with Joey Rainbow, Lance Rapson, Irene Pascoe, two of his grandchildren and the applicants’ lawyers where they made a video that was in evidence. During this video, Warren Beasley explained that when they arrived, because they had not there before, he had warmed up both his grandchildren and the lawyers by putting his underarm scent over them and blowing in their ears “so they don’t get sick… and they won’t be annoyed by the old fellas”. As Joey Rainbow explained, it was necessary for Warren Beasley to warm the grandchildren up, even though they were Kurtjar. That was because Kurtjar law and custom required a Kurtjar person who had not been to a site before to be introduced, to let “the old people know that we [were] bringing them young ones through… [w]hen they first visit”. He said that Kitty’s Yard was Kurtjar country and there was a chacharr in the waterhole there as well as spirits of old Kurtjar ancestors.

44 A chacharr is a rainbow serpent or spiritual being that Kurtjar people believe lives in waterholes. They believe that if they go to a waterhole where a chacharr is, they must be quiet and show respect else the chacharr will make them sick, cause them to become lost or, as Warren Beasley described it, “you will walk away and not know how to come back”. He said that one could not dig, make a disturbance or throw matter into the waterhole because that would upset the chacharr, which would then leave and cause the waterhole to go dry. As Warren Beasley explained, if a stranger wants to visit a waterhole where a chacharr is, he or she needs to get permission and must be warmed up by a Kurtjar person, who then also rubs wet mud on him or her and blows in the person’s ears to protect them. If that occurs, the stranger can then safely go into the water.

45 The Kurtjar also believe that one cannot take greasy food or have greasy hands near the water because if the chacharr smells the grease, it will make the person sick. However, a Kurtjar person can wash or clean his or her hands with mud from the bank before going near the water without needing to be warmed up properly, as a stranger would need to be (using the ceremony described above). In addition, Kurtjar people believe that pregnant women must not go into waterholes where a chacharr is because it will smell her and both she and the baby will become sick, unless she is protected by having mud rubbed all over her. Warren Beasley said that all Kurtjar women are told this story.

46 Moreover, Warren Beasley, as a witchdoctor, can use a chacharr to help a Kurtjar woman fall pregnant when a couple is having trouble conceiving. The male tells the laakinchargh and he gets the couple to go into the water at a waterhole where a chacharr is present. The woman will be unaware of the chacharr, which will then bite her on the stomach. She will say that something in the water bit her there, and the laakinchargh will tell her that it was something such as a little fish, but, in fact, will know that the chacharr put a baby there. Importantly, once the woman is pregnant she cannot go back into the water.

47 Warren Beasley became a laakinchargh like his father and grandfather (Bumble B). This occurred when Warren Beasley was being chased by another dangerous spiritual creature, a red legged (or leg) devil (dhaarrichergh). The chacharr protected him by swallowing him until the red legged devil went away, when it regurgitated him. After this, he had healing and other powers. Warren Beasley said that a red legged devil would not come to a waterhole which had a chacharr if it wanted to harm him because the chacharr would protect him. He said that he is the only laakinchargh. Warren Beasley believed that, as a laakinchargh, he could make it rain during the dry season by going to a waterhole where a chacharr is and either breaking its tail (dhoon) in half or, if he had a spear, spearing it anywhere along its body. If he breaks the dhoon, the crack of the bone on its break creates a big wind and then rain. If he spears the chacharr, the spear will shake and then he has to retrieve the spear and get away. The aftermath of the spearing is that the chacharr becomes very upset, raises its head and a wild thunderstorm, with wind and dust, ensues.

48 On the first occasion that Warren Beasley worked at Miranda Downs, Bumble B visited him and took him on horseback to Rocky Waterhole on Walker’s Creek. They went there with Royal Tommy and Gordon and Sandy Rolly. The old fellas told him it was Kurtjar country and that a waterhole with plenty of water and a chacharr was there. Bumble B told him its Kurtjar name was Milkarr and that it was a secret place that was not safe to visit without permission, because of the chacharr there. Bumble B said that one had to have a lawman perform a special ceremony and have mud from the waterhole rubbed on him or her.

49 Warren Beasley gave further video evidence on a visit to Milkarr. He said that the Kurtjar call the chacharr that lives at Kitty’s Hole Mirran.gan. He said that he needed no permission to go there because it was Kurtjar country but if others, such as a Tagalaka person, went there without permission they would get sick because the chacharr would smell them. He said that the spirits, including Royal Tommy’s, were there too.

50 Bumble B also took Warren Beasley to other waterholes including one south of Milkarr called Warrkil Warrka and another to the south-west of Milkarr called Wanggarich (on Jerry Creek near the boundary between Miranda Downs and Ashbourne Station) at both of which the chacharr lived.

51 He said that his father and Bumble B told him that they had been to corroborees at a large corroboree or bora ground at a place near Kitty’s Hole that was about a kilometre south of Walker’s Creek. Warren Beasley said that there was also a Kurtjar burial ground near this bora ground.

52 The Kurtjar call the spirits of their ancestors mighath, also called rrorkird, and must pay them respect else the mighath “will go against you”, as Warren Beasley said. Under Kurtjar traditional customs, when a person successfully hunts or fishes, he must leave a portion of the spoils for the spirits of the ancestors at the place where he found the food. The mighath, if upset, can cause a person to lose their way, prevent him or her catching any fish or animals or follow the person home and choke him or her. The Kurtjar believe that they need to be quiet in the bush to pay respect to the mighath. They have to sing out to the mighath when they want to fish at a waterhole telling them that they have come for fish and turtle and have nothing. Warren Beasley explained an important Kurtjar custom, namely that “you can’t take too much and you have to cook and leave some for the mighath. If you don’t, next time you come you will get nothing”.

53 When giving evidence on country at Halfway Waterhole at Glencoe, just to the west of the western boundary of Miranda Downs, Warren Beasley said that that was Kurtjar country. He said that a chacharr was in the waterhole there and, because of its presence, it would never go dry. He said that the waterhole contained plenty of fish and turtle to eat. He pointed to a bank on the other side of the waterhole from where he was giving evidence and said that was where Kurtjar ancestors were buried. He said that Bumble B and Royal Tommy had told him that Halfway Waterhole was a meeting place where Tagalaka people would come for meetings at the invitation of the leader or “king” of the Kurtjar people, such as Bumble B. He said that Bumble B sent a messenger with a stick east to find the leader of the Tagalaka people to invite them to a corroboree at Halfway Waterhole. The Tagalaka made their way there by following Walker’s Creek west from their country to Halfway Waterhole, where the two peoples had a big meeting at which several activities occurred. Warren Beasley was present, in his youth (when he was about 14, 15 or 16 years of age and before he began working there) when one such meeting occurred. The Kurtjar elders would warm the visitors up and welcome them. The elders of both peoples would talk to each other. They would then spear fish and turtle in the waterhole for all those present to eat after cooking them over a big fire. Warren Beasley said that after the “big feed” or feast the two tribes would “shake a leg” together, play music, sing, dance and have a corroboree together, where each tribe would swap (or, I infer, trade) weapons, such as spears and boomerangs, for grinding stones or shields. Warren Beasley said that the laakinchargh would break the chacharr’s tail at Halfway Waterhole during the corroboree with the Tagalaka people “to show them what a Kurtjar can do, and they show us something now what they can do”.

54 Because of the significant influence of the tropical wet and dry seasons on the land and waters in the Gulf of Carpentaria, the ability of indigenous peoples to manage the spiritual dangers of places involving water can be seen as fundamental. Much of the on country evidence reinforced the importance to Kurtjar witnesses of the ability to know of and manage the presence of a chacharr, if present, at any waterhole and other spiritual beings or influences at particular places.

55 Wilson’s Hut was a main stock camp located in Miranda Downs on the Gilbert River, to the south of Rice Lagoon. Warren Beasley said that it was also in Kurtjar country. To the north-west of Wilson’s Hut is Fred’s Hut, which is on the Gilbert River, and also on Miranda Downs, close to its north most boundary with Vanrook station. Warren Beasley said that Fred’s Hut was also in Kurtjar country. South-west of that, near the western boundary of Miranda Downs with Lotus Vale station, is Bayswater waterhole, another permanent waterhole, which Mr Beasley said in video evidence Royal Tommy, Bumble B and other old fellas, who worked on Glencoe and Miranda Downs, had told him was also Kurtjar country.

56 He said that there was a water fairy or water gin at Bayswater waterhole, as well as a chacharr. He said that the water gin lived in rocky waterholes and was like a mermaid, namely, she had long hair, a woman’s head and torso and a lower body in the form of a fish’s tail. The old fellas told him that a water fairy had powers like a laakinchargh. He said his old people had told him that people had to be careful of the water gin. If a man jumped in the water to catch her, she would create a whirlpool, pull him under, he would never resurface and his body would never be found. However, if the man caught her on the bank of the waterhole, he had to cut and burn her hair, warm her up and smoke her. If the man did that, her tail would fall off and she would become an ordinary woman who would be his wife for life, have children with him and give him the special healing powers of a laakinchargh. Moreover, if the man did not destroy her hair and she ever retrieved it, she would return to the waterhole and become a water gin again.

57 The old fellas told Warren Beasley that Bayswater waterhole would never dry out because of the presence of the water fairy. He said that if a stranger went there without a Kurtjar person to warm him or her up and speak to the water fairy, the stranger would get very sick. If the stranger went near the water, either the chacharr or water fairy would use its tail to swipe him or her into the water as powerfully as a crocodile. The spiritual being would then create a whirlpool, take the stranger underwater and his or her body would never be found.

58 Warren Beasley gave evidence at a site called warrgi’s (or black dingo) dreaming adjacent to a road on Delta Downs station, north-east of the homestead. He said that Bumble B and Beasley Bumble (his grandfather and father) and another elder, “old Midlan”, had told him of this place and its significance. He said that dingos had two names in Kurtjar, warrgi and ruaak, the former being black and the latter white or red. He said that he was told that, at this dreaming site, a warrgi mated with a ruaak after they had travelled there from Shell Ridge (which was well to the south on Delta Downs). After the mating, the ruaak turned black, returned to Shell Ridge and had a litter of red and white pups. The warrgi went north to Kowanyama country. Since then, the location of the warrgi dreaming was the place where dingos mated in the season. Because he was responsible for the site, Warren Beasley created a song and dance to memorialise the events that occurred there and caused a fence to be erected around the site to protect it as the home for the dingos. He said that it was like a bora or poisoned ground, in the sense that if one hurt a dingo there “you’re crippled for life”. But this is not a bora ground, that’s a difference place. But this is the place belong to that warrgi, the dog”. He said that dingos could not be killed there.

59 Warren Beasley said that Kurtjar have magic men, being a laakinchargh, as I have noted, and also a wherrte (fireman). He was also a wherrte, which means “I am the boss of fire”. Four Kurtjar men can be in a fire ceremony. The knowledge of what a fireman does is secret and can only be passed on to an appropriate elder. Firemen can also use a smoking ceremony to cleanse the spirit of a dead person from a house so that someone can live there.

Stanbroke’s challenges to Warren Beasley’s evidence

60 At one stage on the morning of the fourth day of his oral evidence, Warren Beasley said that his grandfather, Rolly Gilbert, had not talked to him about the boundaries of Kurtjar country. He said that the only people who had were Royal Tommy, Bumble B and his father and that they had told him that the boundary went to “Walker’s Creek that runs, leave the Gilbert, that’s our boundary”.

61 Stanbroke submitted that this evidence supported its contention that the boundary of Kurtjar country was considerably north of the claim area boundary of Rocky Creek. However, I understood Mr Beasley’s answer to refer to the eastern extent of Kurtjar country because, first, the question was about where the boundary went to, and, secondly, the answer referred to the junction of the Gilbert River and Walker’s Creek, which is near Wilson’s Hut and the junction of Gilbert and Einasleigh Rivers. I also observed that Mr Beasley, who was elderly, appeared to be tired when he gave that answer.

62 Stanbroke also placed considerable reliance on what Dr Martin had recorded in his first report, namely, that very early during his fieldwork on 20 July 2015, Warren Beasley had told him “how Kurtjar people had come to ‘keep an eye on’ Miranda Downs station. Dr Martin recorded Mr Beasley saying:

Tribe here [at Miranda], they’re all gone…. I just forget them…. Lance [Rapson] mob know ‘em … from Croydon. Tagalaka people, like Lance [Rapson] now, his father [Lance Owens] from up around there…. They all gone from over here. They call ‘em Tagalaka… But they don’t worry about this country see…. Some went away and I don’t know the rest they might have buried them here. There’s a lot of place here that I don’t know around here. There was half of them mob sort of married into the family. Casey mob, and the Beasley and the Bynoe, see they all mated up with their mob in the family. They married their way into Kurtjar then they sort of come to their country, to Normanton, we all sort of went together…. Where they went out … we keep an eye on it, Kurtjar keep it, in my line with the Kurtjar, even though they gone out, we keep it going, don’t want to let it go to nothing. Like Kurtjar, me, if I let it go to the pack [i.e. fail to look after it], then no-one’s gotta think about it. They’ll say, ‘oh well, there’s a place there where them old people was’, but they won’t worry about it, that’s why I like to keep go on with it, keep an eye on it and carry that name for it…. I reckon, see like a place where they all gone I reckon like you say to me, if I keep it going save letting it go to nothing, you understand? When they talk, they Tagalaka mob, I can understand a fair bit of it, I understand what they mean and what they’re talking about. If I talk language, they understand what I’m talking about.

(emphasis added)

63 Dr Martin characterised what Warren Beasley told him on that occasion as “an ambiguous example of a historical succession event”. In his report, he opined that Mr Beasley was referring to Lance Rapson’s father, Lance Owens, who was a member of the Tagalaka Aboriginal Corporation Registered Native Title Body Corporate (RNTBC). Dr Martin said that it was not his view that Mr Beasley referred to the area on Miranda Downs as having been originally Tagalaka and wrote:

Rather, in my view, Warren Beasley is here illustrating what is described in the anthropological literature as ‘strategic amnesia’ based on ‘the brief reach of history and limit of recall’ (Sansom 2001, 2006). As I discuss in my August 2017 Report at [233] and [234], such examples of ‘strategic amnesia’ are to be expected in the context of succession, as contemporary research participants come to see areas into which their forebears succeeded as simply always belonging to their group, as previous groups’ histories are forgotten.

(emphasis added)

64 Dr Brunton said that the term “strategic amnesia” was not generally accepted in anthropology, but said that it was considered that there is, in Aboriginal peoples, “amnesia about earlier generations in genealogies” and that the correct term was “cultural amnesia”. However, importantly, he did not disagree with Dr Martin’s reasoning, saying that “it certainly occurs”. Dr Palmer also expressed doubts about the expressions “strategic amnesia”, “cultural amnesia” and “amnesia” in this context, but said that it was generally accepted by a number of anthropologists that:

… when the process of succession is complete, then there is no knowledge within the group who have taken over that it was anything other than their own country. How long that takes is another matter and is probably context driven.

65 The experts agreed that Aboriginal peoples’ oral histories, or oral traditions, have a shallowness over three or more generations. I will return to this topic in discussing the succession issue below. However, I consider that Warren Beasley’s evidence that the boundary of Kurtjar country went to where Walker’s Creek left the Gilbert River is an illustration of the shallowness or frailty of orality in recording histories and traditions. I formed the view that his other evidence, to which I have referred, more accurately reflected his belief about the historical information that his old fellas or elders had passed onto him as to the extent of Kurtjar country going further east to the junction of the Einasleigh and Gilbert Rivers. I accept the evidence of Dr Martin and Dr Palmer that what and how Warren Beasley told Dr Martin on the 2015 field trip about country “we keep an eye on” is some evidence of the loss of traditional memory about earlier land ownership in the Miranda Downs area.

66 Joey Rainbow, who is a member of the applicant, was born in 1960 on Myra Vale station. His father, Sandy Rainbow, was Kurtjar, his mother, Sheila, was Kukatj and his grandfather, Rainbow Christie, had been born on Dorunda station. Joey Rainbow’s grandmother was Biddy Captain, who was the daughter of two Kurtjar, Captain and Rosie. In about the mid-1960s, the family and all the other Kurtjar living on Myra Vale and other stations were moved to the Normanton reserve.

67 Rainbow Christie and other old fellas told Joey Rainbow that the Norman River is the southern boundary of Kurtjar country and to its south was Kukatj country (being outside the claim area). Joey Rainbow also said that, when he went there in his youth with Rainbow Christie and his father, they told him as they headed eastwards along, and north of, the Carron River, Fish Hole, and Rocky and Willis Creeks, that Kurtjar country was on the north side of those water courses. His grandfather and father told him of places to which he could not go or which were sacred sites as they went there to hunt and fish with a spear (because, in those days “none of our people were allowed with a gun”).

68 After he left school in about 1974 or 1975, Joey Rainbow worked as a stockman. In about the early 1980s, Joey Rainbow was droving cattle from Stirling Station (which is on the western side of Miranda Downs and south of the Gilbert River) to Strathmore Station (which is on the eastern boundary of Miranda Downs) towards old Miranda Downs homestead, which is on Miranda Creek near the junction of the Einasleigh and Gilbert Rivers on the eastern boundary of the claim area. On that occasion, Joey Rainbow worked with Sandy Rolly, Gordon Rolly, Alec McDermott, Lester George, Percy Midlan and Lionel Bee, who were all Kurtjar men. Alec McDermott was an old fella who would ride next to Joey Rainbow from time to time as they worked the cattle east. Alec McDermott told Mr Rainbow to avoid some areas because they were burial sites for old Kurtjar, being stockmen and persons before there were stockmen (which I infer was before European settlement). On the cattle drive, old fellas told Mr Rainbow, when around the old Miranda Downs homestead, that it was Kurtjar country up to there but on the eastern side it was Tagalaka country. Alec McDermott, Sandy Rainbow and Gordon Rolly pointed out massacre sites that were important for Kurtjar in the vicinity of Kitty’s Yard or Hole and going north-westwards up from there towards the Staaten River. Just west of the most eastern point on the claim area boundary, north-east of the junction of the Einasleigh and Gilbert Rivers, there used to be a trading post for Cobb & Co.

69 Joey Rainbow said each of Alec McDermott, Sandy Rainbow and Gordon Rolly told him that, as one went eastwards, the country to the north of the Carron River and Rocky Creek (which run along parts of the southern boundary of the claim area) is Kurtjar, to the south is Tagalaka and north of Tagalaka country on Strathmore station (which is the east of the claim area) is Ewamian country.

70 In a video taken at Station Waterhole, Joey Rainbow said that a water gin lived in that site. He said that a water gin was a “very sacred thing”. He explained that she would flap her tail on the water at night to coax a single man, because a water gin was “always looking for a husband”. However, if she could lure him into the water, she would kill him instead. He said the man had to convince a water gin that he wanted her to be his wife and persuade her to get out of the water and, if he did so, he had to warm her with leaves, her tail would fall off and she would assume the body of a woman who would never leave the man. He also said that the successful male would “become a very clever man” like a laakinchargh. Mr Rainbow also said that some people cut the water gin’s hair, others did not, and that if the man did so he could not give her hair back to her. He also said that he knew of numerous waterholes where there was a water gin, including Evergreen (in the Staaten River National Park, Bayswater, Kitty’s Hole and Rocky’s Hole. He too emphasised that it was essential to get and keep the water gin away from the waterhole whence she came. Mr Rainbow said that Kurtjar people had a duty to look after and protect the sacred place so that they and others would not get really sick.

71 Prior to the experts agreeing during their concurrent evidence that Tommy Burns was a “top end” apical ancestor of the Kurtjar people (i.e. from the north of Kurtjar country), his status was in dispute. There was video evidence that recorded Warren Beasley, his nephew, Lance Rapson and Joey Rainbow, visiting the burial site of Tommy Burns on Dorunda Downs station, in the north of the claim area. Warren Beasley pointed out a mark placed by Tommy Burns’ family (including Warren Beasley’s uncle, Royal Tommy, who was the deceased’s son in law) on an old tree adjacent to a stockyard that indicated where the site was. He said that Tommy Burns’ spirit was at the site and moved around its immediate environs, including to some nearby dongas. As they left the site, Warren Beasley spoke a loworr, a ritual in Kurtjar language. He spoke to the spirit as if it were a son of his to comfort and inform it that it could now go to sleep.

72 The group involved in that video evidence walked to Station Waterhole close to Tommy Burns’ burial site. As they did so, a large goanna followed them. Mr Beasley, Mr Rapson, and Mr Rainbow said that this was unusual behaviour because normally a goanna would stay away from people. The three men explained that this creature was a rrorkird, or as Mr Beasley explained “he belongs to that old fella up there”, namely at the burial site. Mr Rainbow said that the goanna’s behaviour was attributable to the spirit of Tommy Burns coming to “welcome us back on country”. The three men said that it was not possible to hurt an animal that behaved like that goanna because such an animal was the totem of a deceased’s spirit. Warren Beasley said in the video made the next day at Kitty’s Hole (see [43] above) that he had dreamt overnight about the goanna that had followed them at Station Waterhole the day before and realised that it “was the spirit of my old boy”, Tommy Burns.

73 During his oral evidence, Joey Rainbow expanded on the significance for the Kurtjar of animal totems, also called dreamings. He said that under their laws and customs every person has such a totem and that “when they come up, they are all a part of us”. A baby is given a totem at birth, “when they take your navel cord”. As a consequence, a Kurtjar person cannot eat the creature that is his or her totem. For example, Mr Rainbow said that the barramundi was the totem of his grandfather, Rainbow Christie, and the albino saltwater crocodile was his totem. He said that, under Kurtjar law and custom, his totem connects him to not only Kurtjar country but also other people with the same crocodile totem.

74 Joey Rainbow said that his crocodile totem connected him to Kurtjar country and to the “whole crocodile family”. Rainbow Christie had given him that totem by taking his navel cord and smoking it with ironwood “so I would stay true to the law and so that smoke would form the shape of my totem”. Rainbow Christie told Joey Rainbow that he, his grandmother Biddy and other “old grannies” gave him his albino crocodile totem at Dorunda Lakes. He said that he cannot eat any species of crocodile because of the nature of it being his totem. When Joey Rainbow goes to the river he talks to the crocodiles and believes that they are not a threat to him nor he to them. He said that Dorunda Lakes was a special space for him because of his totem but he could not disclose the story of the saltwater albino crocodile because it was “secret stuff”:

I can just tell you that when I go there… I can talk to it, and know that he can understand me and I can understand him. It’s that connection for me to that – and of that animal to me. We have that special connection and that. And it’s hard to explain. And plus there are things I cannot and will not say about it.

75 He explained that his grandfather’s barramundi dreaming related to both the saltwater and freshwater fish wherever it was on Kurtjar country. Thus, if a person who had the barramundi as his totem, like his grandfather, caught a barramundi, he or she could not eat it because “that fish is very sacred to him”, but any other Kurtjar person could cook and eat it. Joey Rainbow said, in response to a question about whether there was a comparable place on Kurtjar country where Rainbow Christie’s totem or barramundi dreaming was, like Dorunda Lake for his albino crocodile, that “there’s a lot of stuff I can’t say. All I can say is that is his dreaming”. Joey Rainbow added that for his grandfather “it’s not only his dreaming, that’s his totem… it’s only just related to that fish. He can’t eat him… But it’s just to the fish; can’t eat it and, no, there’s no particular dreaming area. It’s about that fish”.

76 Joey Rainbow was a director of Morr Morr Pastoral, the owner of Delta Downs station. He was a chairman of both the Kurtjar Land Trust Aboriginal Corporation and of the shareholder of Morr Morr Pastoral’s issued shares, Morr Morr Kurtjar Aboriginal Corporation (KAC). He said that KAC was established “to look after the Kurtjar community”. He explained that, while the use of Kurtjar country to run the business of Morr Morr Pastoral was not traditional, Kurtjar people had the right to do so on their country and that the conduct of such an enterprise was not contrary to their traditional laws and customs. He said:

It's an opportunity there for Kurtijar mob as an employment – like, with the sandalwood, the fishing, even, you know, pig shooting or something, you know? That sort of thing will create employment because not everyone can be employed at one place. You know, you can't have hundred people running round on the station, you know?

If there's a enterprise set up there, we'd have a lot more on country employed doing these things, you know, instead of being in town as a lot in the news say, “You fellas are looking for handouts”, you know, welfare-dependent. We can be getting back and creating our own employment for our own mob. And this is all starting to fall into place now, as we going along.

…

These resources, yes, of course we could use it.

(emphasis added)

77 He explained that the sandalwood tree is a source of bush medicine, but that Kurtjar traditional laws and customs allow Kurtjar people to “harvest the older trees, not the younger ones… So you’re not getting rid of all your resources”. He said that Morr Morr Pastoral distributed some of its profits to the Kurtjar community and to the Kurtjar Land Trust and that these funds could be used to buy businesses, create employment or take other steps to help the Kurtjar people become self-sufficient using the natural resources of their country. Similarly, he said that it would not contravene their traditional laws and customs if the Kurtjar people set up commercial fisheries to use the abundant fish in the rivers on their country in the same way as Morr Morr Pastoral ran Delta Downs station.

78 Joey Rainbow said that Kurtjar people can camp, hunt, fish and take things for food or medicine all over Kurtjar country, but cannot be too greedy and must ensure that they both have left some for the next person and “leave the big breeders so that there is always some for next time”. He said that he was taught by the old people that one never took more than enough for oneself and one’s family and one had to share it with the spirits. He said “you never rape your country for everything” and that this rule applied to all resources.

79 He said that his father (Sandy Rainbow) and grandfather (Rainbow Christie) told him that Kurtjar, including themselves, would trade with the Gkuthaarn and Kukatj at points along the Norman River. He said that they traded sugarbag (which was, as I understood the evidence, honey harvested in a wallaby’s bladder) from the wild native bee. Kurtjar traded the sugarbag for rocks, boomerangs and spears, or gidgi (wattle) gum. He said his father, grandfather, Uncle Kenny Jimmy and Fred Midlan told him that, in the past, there were trading points all along the Gulf coastline where they met people using small canoes from the Northern Territory, Cape York and Mornington Island. He said that Fred Midlan told him the old people had taken him to see such trading. Joey Rainbow said that when he was working in that area, Kowanyama persons told him that the Kurtjar had trading points with the Kowanyama north of the Staaten River at a big waterhole called Gum Hole where they also had corroborees and marriages.

80 He also said that his father and Sandy Rolly told him that Kurtjar traded with the Tagalaka and Ewamian at places around Red River, the old Miranda Homestead, Bobby Town and Maytown. He said that the Tagalaka had good stone for axes and spears that was lacking on Kurtjar country. He said that his father and grandfather also told him that on Pandanus Creek in the Staaten River National Park, Kurtjar traded with the mob from Chillagoe side (a town to the east).

81 Merna Beasley was born in 1951 to a Kurtjar mother, Ethel Hayes (née Gee), the daughter of Alice Gee, and a Tagalaka father. She married Rolly Beasley, Warren Beasley’s brother, in 1972. Her husband worked for the then owner of Magowra (which is not on Kurtjar country) and Miranda Downs stations. Her husband worked as a grader driver and they lived on Miranda Downs, usually near the main homestead but sometimes they stayed at an outstation at Rice Lagoon, which her husband said was on Kurtjar country. She said that her husband used to tell her “about where our old Kurtjar people were on Miranda Downs”. He did not talk about Magowra station because it “wasn’t our country” and he was always much happier to be on Miranda Downs because “[h]e called it his country”. Her mother (a Kurtjar) and mother in law, Daisy Tommy, told her when she was about 18 that the boundaries of Kurtjar country went from Miranda Downs up to Delta Downs.

82 Their children lived at Normanton but, when they came to visit, Merna and Rolly Beasley took them fishing and hunting to Cobb & Co (near the junction of the Einasleigh and Gilbert Rivers) where there was a little waterhole, Boat Crossing (near Wilson’s Hut), Policeman Waterhole (to the north-west of Wild Rice Lagoon, which is slightly to the west of the eastern boundary of the claim area, north of Wilson’s Hut), Kitty’s Hole (on Walker’s Creek) and old Miranda Downs homestead. When they arrived at those places, Rolly Beasley always got out of the car first and went a little way talking language and calling out to the old people to let them know of the family’s presence. Her husband told her that the country to the west of the junction of the two rivers on Miranda Downs was Kurtjar and that to the east, on Strathmore station, was Tagalaka country. She said that this junction was near to where Tagalaka and Kurtjar met.

83 Merna Beasley said that when they caught fish and cooked them at the waterholes, before they left, they had to “leave some there for the old people”. She also said that if they had greasy hands they had to rub them with dirt or sand before putting them in the water “for the rainbow serpent” and that “[y]ou always know it’s there if you come from that country”.

84 Merna Beasley said that when she followed her husband’s grader in their car with fuel for the grader in forested areas on Miranda Downs, he would tell her to keep up with him and not stop or stay too long in those places because of the danger from red leg devils. He told her they could hurt or kill her.

85 The late Bernie Rapson swore an affidavit on 11 July 2017 that was read at the trial. He was born at the homestead on Miranda Downs station in 1948 and lived in a camp near there until he was about ten. He returned to Miranda Downs in 1962 to work as a stockman on horseback for about eight years. Royal Tommy, Caesar Rolly, Roy, Warren, Phillip and Rolly Beasley, and Nardoo, Don, Noble, Bob and Neville Burns were there and Bernie Rapson spent a lot of time in the bush with them. They told him that Miranda Downs was Kurtjar country. His father, Barney Rapson, whose brother was Royal Tommy, was also working on Miranda Downs but Bernie Rapson did not see much of his father when he worked there.

86 Bernie Rapson worked a lot at Glencoe but he also had to look after the stock camps at Burke’s Hut (which is to the north of Miranda Downs homestead) and Wilson’s Hut. He said that Royal Tommy and the Beasley and Burns brothers knew a lot about the country around Burke’s Hut and showed him where to catch bream, catfish and turtle in the nearby Maxwell Creek. He said that he spent a fair bit of time with Royal Tommy on Miranda Downs, who showed him “story places”, including bora grounds near Yellow Dinner Camp Lagoon in sand ridge country (about seven to eight kilometres east of Kitty’s Yard), which Royal Tommy warned him not to go to, and another at Wire Yard (which is west of Glencoe) which he was also told was “poison ground”. Royal Tommy told Bernie Rapson that another story place was at Goosey Dam (which is east of Glencoe on Bayswater Creek) where there used to be big corroborees with Kowanyama, Coen, Tagalaka and Kurtjar lawmen.

87 Royal Tommy also told Bernie Rapson that he had to be careful around waterholes and that he could not go to some places without a lawman to warm him up. The old men also told him that when he went on country he had to sing out to the old people’s spirits to let them know he was coming.

88 Lance Rapson was born in 1980. His father was Lance Owens, a Tagalaka, and his mother, Tessie Rapson, is Kurtjar and the daughter of Barney and Doris Rapson. Warren Beasley, Barry Casey and Bernie Rapson are uncles of his. He has spent a lot of time with Warren Beasley, who is passing knowledge of Kurtjar laws, customs and places to him so that he will be able to look after Kurtjar country in the future.

89 He said that Kurtjar neighbours are the Kowanyama to the north of the Staaten River, the “Red River mob” to the east on Strathmore Station, the Ewamian (also to the east), the Tagalaka in the south-east and the Gkuthaarn and Kukatj to the south-west. Lance Rapson said that his mother, her family and his grandmother, Doris Rapson’s first cousins, Barbara and Janet Casey, told him that Kurtjar country went from the Norman to the Staaten Rivers and that Bernie Rapson had told him Miranda Downs was on Kurtjar country. His late uncles, Mervyn and Freddie Edwards, and Warren Beasley had told Lance Rapson that the boundary between Kurtjar and Tagalaka country was “[f]rom the Walker’s past Rocky”.

90 Lance Rapson said that, if he wanted to hunt or fish on Kurtjar country at a place for the first time, he had to see a senior elder to ascertain whether there were sites or concerns at his proposed destination, such as a bora ground or burial places.

91 Barbara Casey told Lance Rapson, when he was in his late 20s, that in the old days, her mother’s generation of Kurtjar, Kowanyama, Tagalaka and the Red River mob traded items like boomerangs and spears. He said that there were grinding stones on Delta Downs station that were from a type of rock that did not belong to Kurtjar country. He said that it was important for Kurtjar people to look after and control how much is taken from their country. He explained that, when one went fishing or hunting, one only took what was needed and that it was important to leave some for the spirits. Similarly, he said that if one wanted to take sandalwood, one could take a proportion, but “not too much”, because it is a medicine.

92 Harold Banjo was born in 1959. He followed his father (also named Harold) who was a Kurtjar by adoption and grew up on Macaroni station. Harold Banjo’s father told him that Kurtjar country goes from the Staaten River down to the Norman River and includes Miranda Downs, Vanrook, Lotus Vale/Stirling, Delta Downs, Dorunda and a small portion of Strathmore stations.

93 Harold Banjo worked on Miranda Downs for about four years from when he was about 19 years old. He mustered cattle with Charlie and Noel Bumble, Stanley Bynoe, Hector and Frank Casey, Norman, Warren and Neal Beasley, Alec George, as well as Alec and Dudley Sailor.

94 Kitty’s Hole was a special place for him. That was because, before he was born, his father, mother and Ernest Teddy, his maternal Kurtjar grandfather, who also was working on Miranda Downs, were fishing there, whistling for turtle and then spearing them when their heads appeared above the surface. His father saw a barramundi swim past and speared it behind the gill. When Harold Banjo’s father pulled the fish onto the bank, his grandfather told his parents that the barramundi “is a baby”. He said that this was because no-one ever caught fish at Kitty’s Hold and they only caught turtles. Soon after, his mother fell pregnant and the barramundi became Harold Banjo’s totem.

95 Jenice Bee was born in 1968. Her parents were Rolly and Merna Beasley, both of whom were Kurtjar. She grew up in Normanton. In her teenage years, when Merna Beasley joined her husband to work on Miranda Downs, Ms Bee and her siblings went to that station every Friday to be with their parents. They went fishing and hunting as a family in the late 1980s and early 1990s at various places on Miranda Downs, but principally in the east of the claim area at Kitty’s Hole, Cobb & Co, H Lagoon, Wilson’s Hut and Boat Crossing. Her parents told her that Miranda Downs was Kurtjar country. They hunted goanna and foraged for bush tucker such as water lily and bush fruit. Ms Bee said that, although her father was born at Myra Vale, “Miranda was his country. He had been taught by the old people for that country. It was where his heart was”. She said that her father was a quiet person when he was not on Miranda Downs, but when there “he would be talking all the time. He said it was because he was home”. She said that he told them where three young Kurtjar people were buried on the way to Kitty’s Hole.

96 Ms Bee said that whenever he arrived at places with his wife, children and grandchildren to fish and hunt, Rolly Beasley always got out of the car before anyone else and walked off “talking language”. He then returned to the car and reminded the family that they had to “look after, tidy your land up, leave some fish there beside the fire there for them old people”. He told her that he was speaking language to the old people. Ms Bee still speaks to the old people when she visits places on country, but in English as she does not speak Kurtjar. She does this to show respect for the spirits and because, if she did not, the next time she visited she would not be able to get anything. She also always leaves some food behind for the old people when she leaves. She teaches her children those customs.

97 Rolly Beasley told Ms Bee that Fred’s Waterhole was a special place for him. She said that after visiting her parents at Miranda Downs for years, one day her father told her and her husband “I found it” and took them to Fred’s Waterhole. She said that when they arrived, he walked off and that she had never seen him as emotional as then. He told Ms Bee and her husband that when he was young he met up all the time there with Halo and Comet Ward and Stewart Nimble. Rolly Beasley said to his daughter that those three men and Royal Tommy had told him that Miranda Downs was Kurtjar country and that, when he was young, “all of these old people taught me [Rolly Beasley] what I know today” when they met up at Fred’s Waterhole.

98 Jenice Bee had been told that red legged devils were on Miranda Downs and Delta Downs. She said that they were in forested areas on Miranda Downs and that “[s]oon as you go in that country, you can just feel it… It’s no good place”. She had been told not to go in there and believed that she had to respect that prohibition. She learnt of the chacharr when she was about five, when she went fishing with her father’s parents. They told her that, before she put her hands into the waterhole or Willis Creek, she had to wash them with mud or sand.

99 Mildred Burns was born in 1956. Her mother, Betty Harold (née Bynoe), was the daughter of Bynoe B and Sarah Bynoe, all of whom were Kurtjar. Ms Burns married Claude Burns who is also Kurtjar. His parents were Sandy Rainbow and Vera Midlan, the daughter of Jimmy and Judy Midlan. Ms Burns grew up at the top camp in the Normanton reserve because, like her father, her paternal grandparents, with whom she lived, were Gkuthaarn.

100 In her childhood, she spent a lot of time at the bottom camp around Jubilee and Lily Slattery’s home. She said that corroborees were held around that home frequently and there was always singing and playing the drum. She said that Warren Beasley and Fred Midlan both sang in Kurtjar at the corroborees. She said that the songs always had a meaning and a dance often accompanied the songs which could be about animals, like wallabies, or different birds. The old people explained what the songs and dances were about and Jubilee Slattery also joined in the corroborees.

101 In 1978, Ms Burns and her husband went to Miranda Downs where he worked as a ringer and she as a housemaid. They lived at an outstation at Glencoe at the same time as Royal Tommy, Fred Midlan and Roy Beasley (Warren Beasley’s brother) and their wives were there. She said that the men were very knowledgeable about the country on Miranda Downs and spoke about it among themselves. She said that the men spoke to the spirits of the old people and knew all the places to go. She, with the other women, accompanied the men to get bush tucker at water bodies down the Gilbert River such as Two Mile and Four Mile Waterhole, Bayswater Creek, Picnic Waterhole (near Glencoe), Goosey Dam, Toby’s Waterhole (which is near Mail Change Waterhole), Jam Pot Waterhole (which is about half way between the western and eastern boundaries of Miranda Downs) and, further to the east of Glencoe, Kitty’s Hole. When they went there they always sang out to the spirits and talked in language saying who they were, who they were with, that they were family and what they wanted to eat. She said that if they caught something, their custom was to cook it and leave some for the old people to show respect. If they did not leave something, “you won’t have luck the next time”.

102 Ms Burns said that Warren Beasley told her about when old people were fishing on the Gilbert River and were chased by a red legged devil. Ms Burns also recounted the Kurtjar customs concerning the need to seek permission to go on Kurtjar country, to ask about the locale (so as to find out about any dangerous places), to show respect and to have a totem.

103 Harry Daphne, who was born in 1965, lived with Jubilee and Lily Slattery at the bottom camp on the Normanton Reserve. He recalled lots of corroborees there, sometimes with “waltzing”. He said that Jubilee and Lily Slattery took him out to get food at various places including Walker’s Creek and Glencoe. They taught him to be careful and to have respect when on Kurtjar country and that there were places that were poison ground.

104 The late Fred Edwards affirmed an affidavit on 4 September 2017. He was born in 1939 and both his parents were Kurtjar. His late elder brother, Mervyn Edwards, born in 1937, affirmed an affidavit on 3 March 2017. Their father, Albert Edwards, was a stockman who worked all over Kurtjar country, including on Miranda Downs. Mervyn Edwards was familiar with the danger from the chacharr and going into waterholes with grease on his skin.

105 Fred Edwards said that his father was “under the Act”; i.e. under the Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act 1939 (Qld) and under the control of a “protector” appointed under that Act. No-one was entitled to employ an Aboriginal person without permission of a protector by force of s 14. That Act subjugated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders under Queensland law to the effective and pervasive control of the protector and other State officials. The Act denied them the respect, dignity and autonomy that any human being ought to have been able to enjoy as of right. The legacy of that and similar legislation in other States and Territories has continued to have profound, shameful and adverse social consequences for the First Nations people of this country. That Act remained in force until its repeal in 1966, despite Australia having been one of the nations that voted to approve the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the United Nations on 10 December 1948. As Fred Edwards recounted: “The Protector would tell [Dad] where he was going to work. The Protector would tell us all we had to go with Dad. We were not allowed to go into Normanton. Same with many of the other Kurtjar people living out on the stations”. He said: “I was taken away by the Protector once”.

106 He said that the stations “gave us rations, but they didn’t pay us anything. Kurtjar people also lived on bush food from their country. We lived off the land”. The people living on stations who were too old to work would show others where the waterholes and best fishing places were. Fred Edwards said that, if the “old-timers” sang out in language to the spirits of the old people asking for fish, “we would catch a lot of them”. The “old-timers” said that spirits were responsible. They left some fish behind for the spirits. He remembered corroborees on Lotus Vale, Myra Vale and Delta Downs stations.

107 Fred Edwards worked on Miranda Downs as an adult. Because he was “under the Act”, he had to sign up for a year. Royal Tommy and Barney Rapson senior were then working with him there. Royal Tommy told Fred Edwards that he was born on Myra Vale but grew up on Miranda Downs and said that he belonged to it (Miranda Downs) as his country.