Federal Court of Australia

Carna Group Pty Ltd v The Griffin Coal Mining Company (No 6) [2021] FCA 1214

ORDERS

CARNA GROUP PTY LTD ACN 063 629 630 (IN LIQUIDATION) Applicant | ||

AND: | THE GRIFFIN COAL MINING COMPANY PTY LTD ACN 008 667 285 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Judgment be entered for the applicant.

2. The respondent pay damages in the principal sum of $5,116,400.27 (incl. GST) to the applicant.

3. Within 14 days, the applicant is to file and serve written submissions (not exceeding 5 pages) on the question of interest, if any, payable on the principal sum referred to in order 2 above and costs.

4. Within 14 days from the applicant’s compliance with order 3 above, the respondent is to file and serve written submissions (not exceeding 5 pages) in response.

5. Unless the Court orders otherwise, the issues of interest and costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[8] | |

[9] | |

[24] | |

[42] | |

[44] | |

Admissions by Griffin’s officers in liquidators’ examinations | [47] |

[52] | |

[53] | |

[102] | |

[150] | |

[181] | |

[182] | |

[187] | |

[189] | |

[192] | |

[194] | |

[195] | |

[203] | |

[206] | |

[210] | |

[211] | |

[212] | |

[213] | |

[214] | |

[216] | |

[217] | |

[219] | |

[221] | |

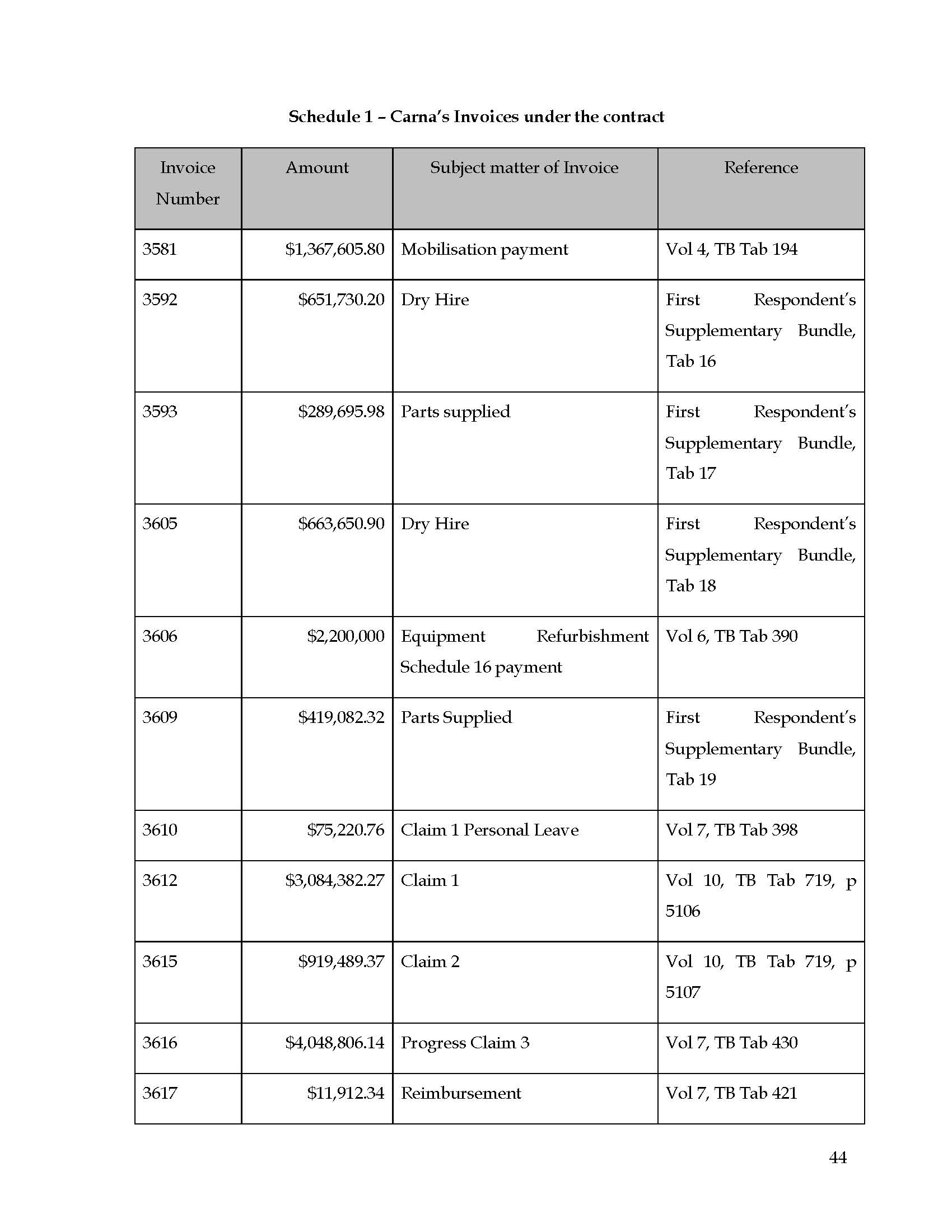

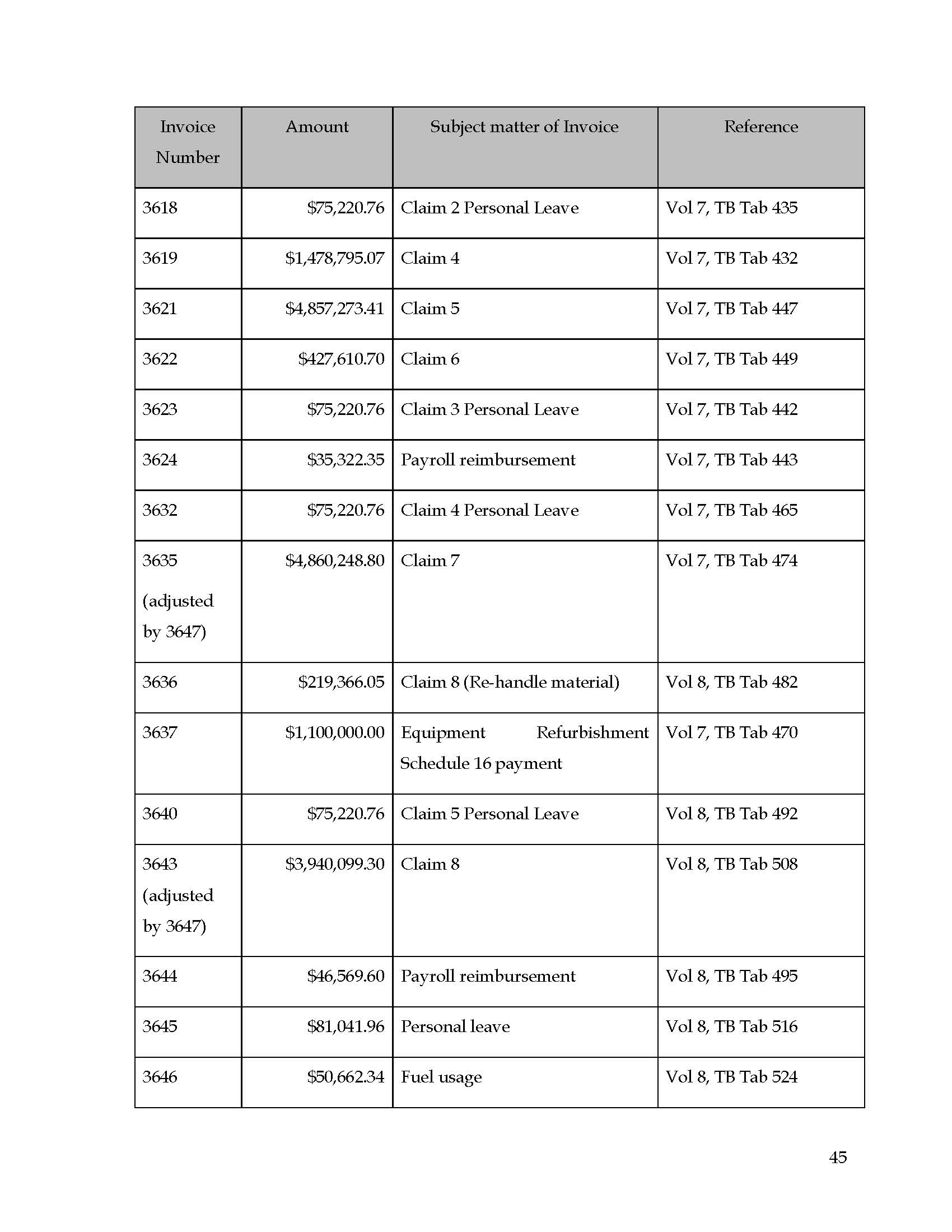

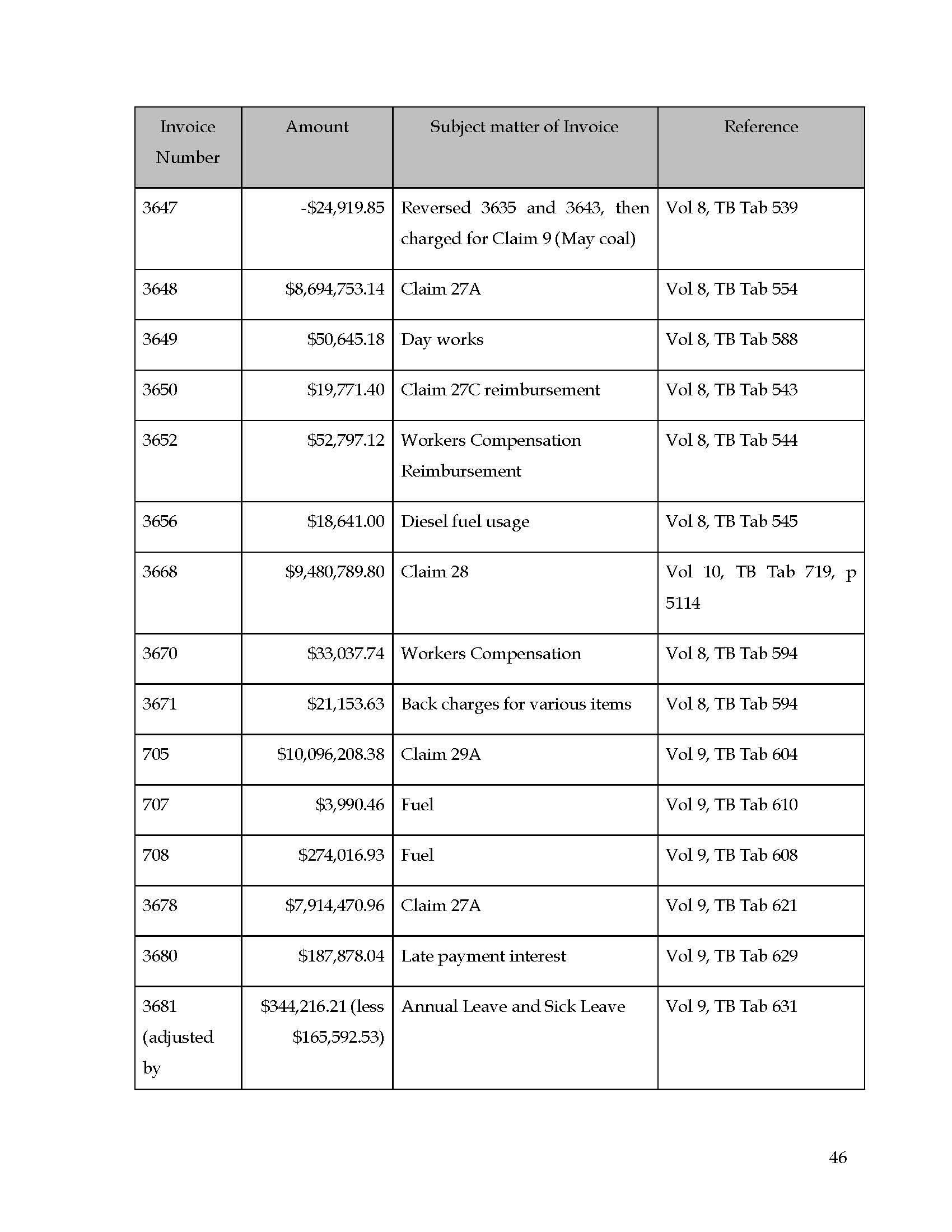

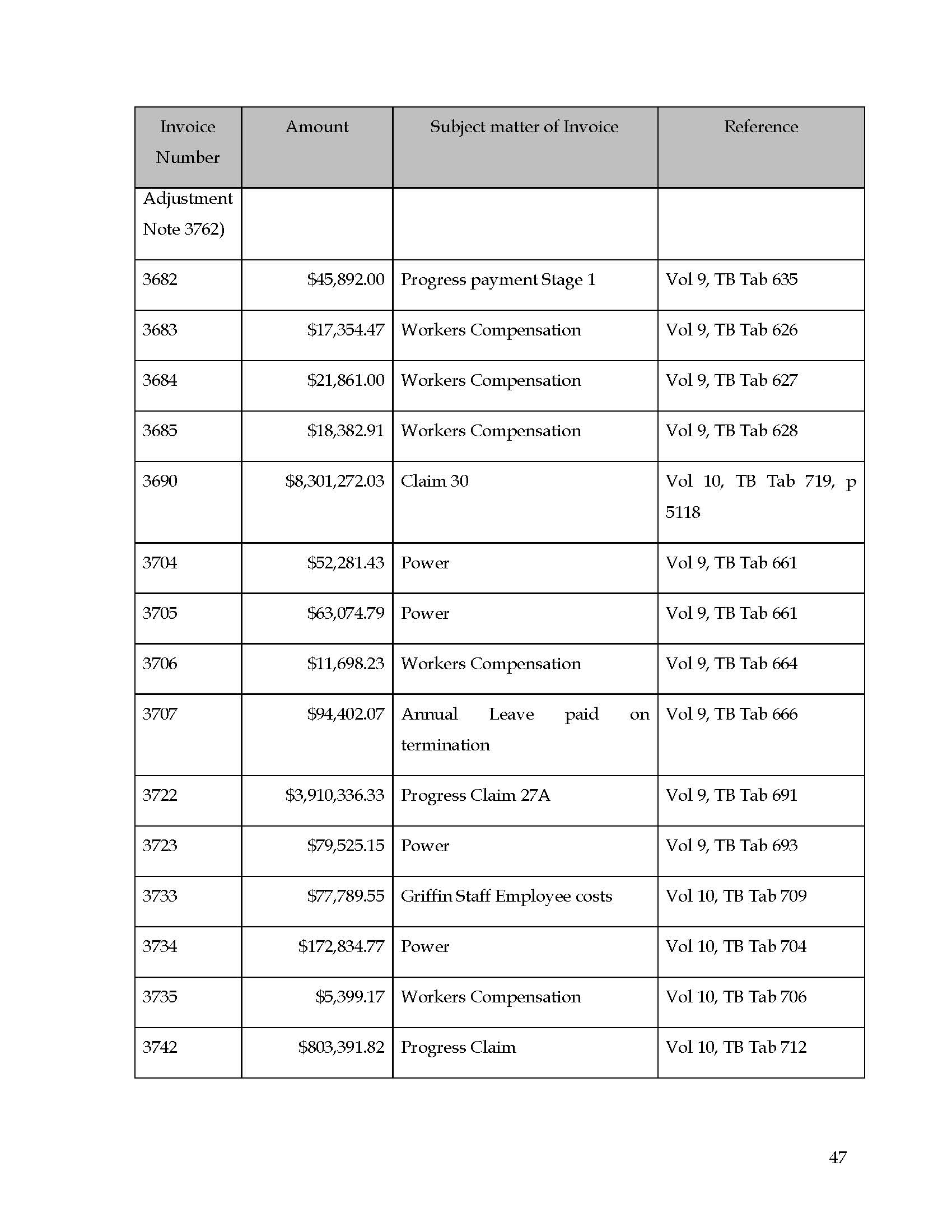

[240] | |

[243] | |

[249] | |

[253] | |

[256] | |

[257] | |

[257] | |

[261] | |

Admissibility of certain ‘business records’ going to quantum | [269] |

[285] | |

[288] | |

[289] | |

[290] | |

[291] | |

[292] | |

[296] | |

Monthly Progress Claims up to the date of termination – Sch 15(1)(b) | [297] |

Schedule 15 and the Schedule 13 Annual Reconciliation Invoice | [304] |

[320] | |

[324] | |

[328] | |

[330] | |

[335] | |

[341] | |

[363] | |

[368] | |

[369] | |

[374] | |

[376] | |

[378] | |

[380] | |

[382] | |

[389] | |

[401] |

MCKERRACHER J:

1 The applicant (Carna Group Pty Ltd) has been in liquidation since June 2015. In January 2014, Carna entered into a Contract with the first respondent (The Griffin Coal Mining Company Pty Ltd) to provide mining services at Griffin’s Mine. On 4 December 2014, Carna purported to terminate that Contract based on breaches allegedly committed by Griffin. The former second respondent (Mr Raj Kumar Roy) and the former third respondent (Mr James Riordan), against whom Carna has settled its claims in this proceeding, were very much involved in the dealings between Carna and Griffin on behalf of Griffin. Mr Riordan was the financial controller of Griffin and Mr Roy was director and president of Griffin (effectively its chief executive officer). Primarily, their dealings were with Mr Michael Grey, business development manager of Carna and formerly a respondent in these proceedings. Mr Harry Carna was a director of Carna and Mr Andrew Henshaw was the financial controller of Carna. Two other individuals who feature in the evidence are Mr Vinod Kumar, vice-president of operations at Griffin and Mr Srinivasa Rao Peddu, director of operations for Griffin.

2 Griffin has long been a coal mining company in Western Australia, with its operations in the southern town of Collie. Carna was a family company providing for some years earth-moving services, before expanding into mining services. Carna was also based near Collie and had some experience providing mining services for many of the large companies operating in Western Australia’s mining sector. The Contract the subject of dispute in these proceedings presented a substantial opportunity for Carna to continue and consolidate its expansion into the area of mining services.

3 This litigation has had a number of manifestations. The most significant aspects of Carna’s claim against Griffin, Mr Roy and Mr Riordan concerned allegations of misleading and deceptive conduct and related allegations under the Australian Consumer law in relation to representations purportedly made in the ‘negotiation of, and entry into the Contract’ (the statutory claims). That aspect was settled, and formalised by consent orders dismissing the statutory claims on 9 March 2021. The trial of this matter, originally set down for 17 days, was delayed to facilitate this settlement. With the settlement of the statutory claims, a cross-claim raised by Griffin against Carna also fell away.

4 What has remained is Carna’s claim against Griffin alone, for two alleged breaches of the Contract.

5 The case, as ultimately presented at trial over two days, was shorn of any of the oral evidence which had been foreshadowed on the statutory case. The contractual case that was presented depended upon the proper construction to be given to the Contract and on the construction to be given to a large number of documents.

6 The two contractual issues are, first, whether or not Griffin committed an ‘Insolvency Default’ as defined under the Contract (Insolvency Default Breach), and second, whether Griffin failed to establish a ‘Payment Account’ as required under the Contract, for payment of invoices to Carna (Payment Account Breach). For the reasons that follow, the Insolvency Default Breach has been established. The Payment Account Breach was also established, but was not a substantial breach and therefore not an ‘Event of Default’ under the Contract.

7 The sums involved in the Contract are substantial. So also were Griffin’s financial problems, which ultimately at trial, senior counsel for Griffin accepted. A point he persistently emphasised though was that Griffin recovered. Griffin continues to trade today. Its problems, on which Carna’s case depends were, according to Griffin, simply temporary.

8 The issues at trial were ultimately these:

(1) Did Griffin materially breach the Contract by reason of an ‘Insolvency Default’, as defined in the Contract (the Insolvency Default Breach)?

(2) Did Griffin fail to establish a ‘Payment Account’ in accordance with cl 10.9 of the Contract (the Payment Account Breach)?

(3) If the answer to 2 above is ‘yes’, was that failure a substantial breach within the meaning of ‘Event of Default’ under the Contract?

(4) If the answers to 2 and 3 above are ‘yes’, did Carna seek to rely on this ‘Event of Default’ in its letter to Griffin on 3 December 2014?

(5) If an ‘Insolvency Default’ or any breach entitling Carna to terminate is found, what is the quantum of Carna’s entitlement to compensation for breach of contract under Sch 15 of the Contract?

(6) Pursuant to what provision, and at what rate, should interest be awarded on any sum awarded to Carna? (it is agreed that this issue be deferred pending the resolution of issues (1)-(5)).

9 Although there were references in the arguments to both a Contract and a ‘Substituted Contract’, the distinction between the two fell away on the case as finally advanced. The only relevance, in the failed negotiation of the Contract, followed by the immediate re-negotiation of the ‘Substituted Contract’, is that these events give context to the issues now in dispute. For convenience however, the agreement ultimately reached between the parties is simply referred to as the ‘Contract’.

10 On 28 January 2014, Griffin as principal and Carna as contractor entered into the Contract. It was a mining services contract. The commencement date was defined as being 1 March 2014 or four weeks from satisfaction of conditions precedent, whichever was later. The conditions precedent required the parties to agree on a series of schedules to deal with the particulars of the operation. Those schedules were not agreed until mid-March 2014, such that the Contract was terminated and replaced by a Substituted Contract.

11 In consideration for the provision of the Mining Services, Griffin agreed to pay Carna a Mining Fee. With the removal of the statutory claims upon which Griffin’s cross-claim was predicated, there is no challenge to the adequacy of Carna’s provision of the Mining Services, though Griffin does raise one argument in resisting the alleged Insolvency Default Breach which touches upon Carna’s own financial position during the Contract.

12 Griffin’s obligation to pay the Mining Fee to Carna is contained in cl 10.1 of the Contract which provides:

10 Payment

10.1 [Griffin’s] payment obligation

(a) Subject to the proper performance of the Mining Services, [Griffin] must pay [Carna] the:

(i) Mining Fee calculated in accordance with Schedule 13; and

(ii) any other amounts which may become due to [Carna] under this agreement.

(b) Subject to the other provisions of the agreement which provide for payment to [Carna], [Carna] accepts the payment of the Mining Fee in accordance with this agreement as full payment for the provision of the Mining Services and the performance of its other obligations under this agreement.

13 The terms Mining Services and Mining Fee were defined by reference to both cl 1.1 (Definitions) and the schedules to the Contract. Pursuant to Sch 13, the Mining Fee comprised a Monthly Progress Claim component and an Annual Reconciliation Invoice component. Amongst other things, the costs of consumables (including fuel, power and explosives) were to be factored into Carna’s Monthly Progress Claim invoices to Griffin. Schedule 13 relevantly provided that:

(a) the actual cost of power consumed by Carna each month was an item for which Carna would charge Griffin in Monthly Progress Claim invoices; and

(b) the actual cost of consumable items provided by Griffin to Carna each month (net of payments made by Carna to Griffin for those items) could be deducted from Carna’s Monthly Progress Claim invoices to Griffin.

14 Monthly Progress Claim was also defined in cl 1.1(Definitions) of the Contract as being a claim for payment in the form approved by Griffin’s Representative showing the value of the Mining Services and other amounts claimed by Carna for a given month as calculated by Carna from information available to Carna and in compliance with the Contract. Clause 10.2 then provided for a process by which Monthly Progress Claim invoices were to be received, verified and paid by Griffin:

10.2 Payment

(a) [Carna] must submit to [Griffin’s] Representative within 5 days after the end of each month a Monthly Progress Claim for the previous month including:

(i) the quantities of Coal Dispatched and received by the Buyers during the month for which there are specific rates in the Schedule 14;

(ii) the Mining Fee payable calculated in accordance with Schedule 13;

(iii) all evidence reasonably acceptable to [Griffin’s] Representative verifying or substantiating amounts used for the purposes of calculating the Monthly Progress Claim;

(iv) details of [Carna’s] calculations of the Monthly Progress Claim; and

(v) any other monies due to [Carna] under any other provision of this agreement.

(b) Following receipt of a Monthly Progress Claim, [Griffin’s] Representative must, within 7 days, determine the amount payable in respect of the Monthly Progress Claim and issue a payment certificate to [Griffin] and [Carna] setting out that determination showing:

(i) the amount payable to [Carna] for the month; less

(ii) the total of any monies which are due from [Carna] to [Griffin] under a provision this agreement [sic] (Payment Certificate).

The Payment Certificate must include or enclose details of [Griffin’s] Representative’s calculations of the stated amounts and, if [Griffin’s] Representative does not accept [Carna’s] calculations, a statement of reasons for the differences in calculation. If [Griffin] does not issue a Payment Certificate, then it is deemed to have accepted [Carna’s] claim in full.

(c) [Carna] must give [Griffin] a Valid Tax Invoice in respect of the items and amount shown in the Payment Certificate within 2 business days of receipt of that certificate.

(d) If requested by [Griffin’s] Representative before the date for the issue of a Payment Certificate, [Carna] must give [Griffin] a statutory declaration in the form set out in Schedule 3 before it receives a payment under a Payment Certificate.

(e) Provided that [Carna] has provided [Griffin] with a Valid Tax Invoice, and clause 10.2(d) where applicable has been complied with, [Griffin] must pay the amount in the Payment Certificate to [Carna] (less any amounts which [Griffin] is entitled to set off under this agreement) or, if [Griffin] has not issued a Payment Certificate, the whole of the amount claimed, within 20 days of receipt of a Valid Tax Invoice.

(f) If [Griffin] does not pay the amount assessed in the Payment Certificate or [Carna’s] claim (whichever applies), by the due date for payment in subparagraph (e) above, [Carna] may suspend the work upon 7 days’ written notice to [Griffin] provided that non-payment is subsisting at the end of the 7 days notice period.

(g) Any disputed amounts or amended amounts set out in a Payment Certificate will be paid to [Carna] or [Griffin] (as the case may be) within 14 days of it being resolved that [Carna] or [Griffin] (as the case may be) is entitled to such disputed or amended amount (including any amounts subject to dispute over whether or not they were erroneously included in the Payment Certificate).

(h) If the payment is due on a day that is not a business day then that payment is due and payable on the next business day.

(Emphasis added.)

15 The balance of cl 10 then provided for the payment of various amounts in certain circumstances as follows:

10.3 Interest

If any monies due to either party remain unpaid after the due date, then interest is payable on the amount due from, but excluding, the due date to and including the date upon which the monies are paid. The rate of interest is the average bid rate for bills (as defined in the Bills of Exchange Act 1909 (Cth)) having a tenor of 90 days which is displayed on the page of the Reuters Monitor System designated “BBSY” plus one percent. Interest must be compounded at 3 monthly intervals.

10.4 Set-off

Notwithstanding any other provision of this agreement or any Payment Certificate issued by [Griffin’s] Representative, [Griffin] may set-off or deduct from any amounts due to [Carna] under this agreement any monies due from [Carna] to [Griffin] on any account under this agreement.

10.5 Annual Reconciliation Payment

(a) At the end of every 12 (twelve) calendar months from the Commencement Date, [Carna] shall raise an annual reconciliation invoice for the immediate preceding 12 (twelve) months to [Griffin] (“Annual Reconciliation Invoice”) for reconciliation and payment of any outstanding dues under this agreement except that the Year 1 annual reconciliation would be carried out at the end of 13 months from the Commencement Date. The Annual Reconciliation Invoice should clearly specify the requisite details as mentioned in Schedule 14. For the avoidance of doubt, it is clarified the remaining provisions of Clause 10 shall apply mutatis mutandis to the monies payable by [Griffin] on the basis of Annual Reconciliation Invoice

(b) [Griffin] and [Carna] agree on the following process for the annual [sic] Annual Reconciliation Invoice process

(i) [Griffin] and [Carna] are to agree on an external third party to be engaged to perform any services (including joint survey (at first instance) or to check if there is any difference in joint survey findings) (with the cost jointly borne by [Griffin] and [Carna]) to assist or confirm the annual reconciliation amount. This is to be agreed at least 1 calendar month prior to each 12 month annual reconciliation period.

(ii) [Griffin] and [Carna] envisage that the external third party would take 4 weeks to produce its report, and upon the release of the report to both [Griffin] and [Carna], [Carna] is to provide its annual reconciliation invoice

10.6 Payment adjustments

The parties agree that confirmation or payment by [Griffin] of any amount relating to the Mining Fee does not prevent either party from requiring a further adjustment to the amount confirmed or paid to ensure that actual amounts finally paid to [Carna] are the amounts required to be paid under this agreement taking into account any relevant actual information not available at the time that the calculation or payment of amounts was made.

10.7 Taxes

(a) Unless otherwise expressly provided in this agreement, [Carna] must pay all taxes including sales tax, payroll tax, fringe benefits tax, levies, duties and assessments due in connection with the provision of Mining Services and [Carna’s] performance of its other obligations under this agreement.

(b) If any supply made under this agreement is subject to GST the party to whom the supply is made (Recipient) must pay to the party making the supply (Supplier), subject to the Supplier first issuing a Valid Tax Invoice to the Recipient, an additional amount equal to the GST payable on that supply. The additional amount is payable at the same time and in the same manner as the consideration for the supply, unless a Valid Tax Invoice has not been issued in which case the additional amount is payable on receipt of a Valid Tax Invoice. This sub-clause does not apply to the extent that the consideration for a supply is expressed to be GST inclusive.

(c) If any party is required to reimburse or indemnify the other party for a cost, expense or liability (Cost) incurred by the other party, the amount of that Cost for the purpose of this agreement is the amount of the Cost incurred less the amount of any credit or refund of GST to which the party incurring the Cost is entitled to claim in respect of the Cost.

10.8 Standby

(a) In its pricing for the Mining Fee, [Carna] has made allowance for:

(i) 3 public holidays; and

(ii) 39 days (or part thereof) for inclement weather and noise (inclusive),

where [Carna] is unable to utilise its labour and/or equipment or is required to ‘stand down’ labour and equipment (Standby). [Carna] will bear its own costs for Standby for that duration.

For the purpose of this clause [Carna] will keep [Griffin] regularly informed about these occurrences and the number of hours on cummulative [sic] basis.

(b) After the allowance for Standby as set out in paragraph (a) above is exhausted, Standby related to noise and/ or inclement weather for up to an additional 8 days to that set out in paragraph (a), [Carna] shall be paid 50% of the Standby Rates for the period of Standby;

(c) In all other respect[s], [Carna] shall be paid for Standby as follows:

(i) for Standby caused or contributed to by [Griffin] i.e. failure to obtain mine approvals, licences, mine planning, directions to [Carna] as required under this agreement, [Carna] will be paid 100% of the Standby Rates for each day (or part thereof) of Standby; and

(ii) for Standby caused or influenced by external authorities (other than on a default by [Carna]), [Carna] will be paid 100% of the Standby Rates for each day (or part thereof) of Standby,

provided that where it is reasonable and practicable to do so, [Carna] will divert labour and equipment to non-affected areas of the Site.

For the avoidance of doubt, Standby Rates are paid on a pro-rata basis such that those rates are paid to the extent that [Carna] is required to “stand down” labour and equipment.

Notwithstanding anything in this agreement Standby Rates are payable provided that there is no subsisting default by [Carna] and provided that [Carna] informs [Griffin] of any delays, disruption or the applicability of the Standby Rates or payments in a timely manner and in any event within 4 hours of the commencement of the delay, disruption or applicability of the Standby Rates or payments.

10.9 Payment Account

[Griffin] and [Carna] agrees [sic] to utilise a Payment Account for the purposes of ensuring payments are made to [Carna] by the due date under this agreement. [Griffin] must ensure as on the due date for payment, that there are sufficient [sic] funds in Payment Account to meet the amount payable for the relevant Monthly Progress Claim.

(Emphasis added.)

16 It can be seen that cl 10.2 provided a mechanism for the resolution of late payments required to be made by Griffin and included cl 10.2(f) which enabled Carna to suspend its provision of services to Griffin. Clause 10.8(c)(ii) also enabled Carna to recover standby rates during any such suspension. In fact, on the occasions when Carna suspended works for non-payment, it charged and was paid such standby rates. This is relevant to an argument for Griffin that the availability of these mechanisms tells against a construction of the definition of ‘Insolvent’ which would permit Carna to rely on delays in payments by Griffin to generate a right to terminate the Contract for an Insolvency Default Breach. Griffin argues that Carna’s construction would effectively elevate any minor payment-related breach to enlivening a contractual power to terminate. Griffin says that contention would render these contractual provisions of limited utility. This argument is addressed below.

17 As cl 10.9 sets out, Carna and Griffin agreed to utilise a ‘Payment Account’ to ensure Carna was paid on time for its Monthly Progress Claim invoices, as settled under cl 10.2. The term ‘Payment Account’ was also defined in cl 1.1 to be:

an arrangement between [Griffin] and [Carna] where moneys would be received by Griffin under the Coal Supply Agreements or other coal sale agreements and would be paid to [Carna] in accordance with [the Contract].

‘Coal Supply Agreements’ was further defined to mean the agreements entered into by Griffin with third party buyers who would purchase the coal produced at the Mine.

18 Clause 17 of the Contract made provision for the suspension and termination of the Contract in certain circumstances. It is central to many of the contractual arguments raised. The relevant parts provide as follows:

17.3 Termination by Principal for convenience

(a) Notwithstanding any other provision of this agreement, [Griffin] may, at its sole discretion, terminate this agreement for its convenience at any time, where in the sole opinion of [Griffin], to continue with the mining operation would cause it significant ongoing financial losses, by giving [Carna] 60 days’ written notice in which case [Griffin] (without prejudice to any other rights or remedies it has) must pay to [Carna] the Early Termination Amount.

…

17.4 Default and termination for default

If a party commits an Event of Default, then the non-defaulting party may serve on the defaulting party, a notice of default which shall:

(a) state that it is a notice under this clause;

(b) specify the breach upon which it is based; and

(c) specify the time within which the default must be rectified (which must be a reasonable time, but in any event, not less than 7 days).

If the Event of Default:

(a) is not remedied within the time allowed by the notice of default; or

(b) is a default not capable of remedy and the party in default has not provided a reasonable:

(i) explanation for the default; and

(ii) basis for concluding that the default will not reoccur (together with any information necessary to support the basis for this conclusion),

The non-defaulting party may terminate this agreement by 14 days written notice to the other party.

17.5 Termination on a Termination Event occurring

If a Termination Event continues for a period of 28 days, then either party may may [sic] terminate this agreement by giving the other party 14 days written notice specifying the Termination Event relied upon. For the purposes of clause 3.2(c) only, once the Termination Event occurs, then [Griffin] may terminate this agreement immediately by giving [Carna] 14 days written notice specifying the Termination Event relied upon.

In the event of a termination under this clause or under clauses 17.2(f), 17.4, 17.5, 17.11 or 21.3(e):

(a) where it is not the default of [Carna], [Carna’s] entitlements will be calculated in accordance with Schedule 15 as if the termination was for [Griffin’s] convenience; and

(b) where it is default of [Carna], [Carna] will be paid the refurbishment costs set out in Schedule 16 and any other claim accured [sic] under this agreement. [Carna] remains liable for anything it is liable for under this agreement including under clause 3.

This provision survives termination of this agreement.

…

17.7 Preservation of rights on termination

Termination of this agreement for any reason does not affect the rights of a party that arise before the termination, or as a consequence of the event or occurrence giving rise to the termination, or as a consequence of the breach of any obligation under this agreement which continues to take effect after termination.

…

17.11 Termination for insolvency

Either party may terminate this agreement immediately upon written notice if the other party (or its ultimate parent entity or any institution who provides security on behalf of a party for the purposes of this agreement) commits an Insolvency Default.

(Emphasis added.)

19 As to the Payment Account Breach, Carna relies principally on cl 17.4 which sets out the process by which the Contract is to be terminated if an ‘ ’ occurs. The Contract defines an Event of Default as meaning, in respect of a party, any of the following:

(a) if a party commits a substantial breach of its obligations under this agreement which is capable of being remedied; or

(b) the party commits a substantial breach of its obligations under this agreement which is not capable of being remedied.

(Emphasis added.)

20 As noted in the list of agreed issues above, a question of construction arises in relation to the work of the adjective ‘substantial’ in relation to whether the Payment Account Breach was an Event of Default.

21 As to the Insolvency Default Breach, the ability of a party to terminate the Contract with immediate effect under cl 17.11 was predicated on the other party committing an ‘Insolvency Default’. Clause 1.1 of the Contract defined ‘Insolvency Default’ by direct reference to the separate definition in the same clause of the term ‘Insolvent’. Critically, for the purposes of the Contract, ‘Insolvent’ means, in respect of a party, that it:

(a) is (or states that it is) insolvent (as defined in the Corporations Act [2001 (Cth)]);

(b) has a controller (as defined in the Corporations Act) appointed to any part of its property;

(c) is in receivership, in receivership and management, in liquidation, in provisional liquidation, under administration or wound up or has had a receiver or a receiver and manager appointed to any part of its property;

(d) is subject to any arrangement, assignment, moratorium or composition, protected from creditors under any statute or dissolved (other than to carry out a reconstruction or amalgamation while solvent on terms approved by the other party to this agreement);

(e) is taken (under section 459(F)(1) of the Corporations Act to have failed to comply with a statutory demand;

(f) is the subject of an event described in s 459(C)(2)(b) or s 585 of the Corporations Act (or it makes a statement from which the other party to this agreement reasonably deduces it is so subject); or

(g) is otherwise unable to pay its debts when they fall due.

(Emphasis added.)

22 Carna particularly relies upon subpara (g) of the definition of ‘Insolvent’. It contends that Griffin was otherwise unable to pay its debts when they fell due.

23 Helpfully, the parties are (correctly) agreed that if the Contract was validly terminated under cl 17.4 or cl 17.11, Carna’s entitlement, if any, is to be calculated in accordance with Sch 15 of the Contract ‘as if the termination was for [Griffin’s] convenience …’: cl 17.5. Schedule 15 provides for the calculation of the Early Termination Amount. It provides as follows:

Schedule 15 – Early Termination Amount

1. Calculation of Early Termination Amount

The Early Termination Amount payable by [Griffin] for termination for convenience is the sum of:

(a) the amount outstanding under any unpaid Monthly Progress Claim less any amount due by [Carna] to [Griffin] up to the date of termination;

(b) the amount of any Monthly Progress Claim made by [Carna] for work performed up to the date of termination less any amount previously paid by [Griffin] in respect of such Monthly Progress Claim;

(c) the balance of the refurbishment costs due in respect of the residual period as per Schedule 16;

(d) [Carna’s] demobilisation costs (by excluding employee costs unless agreed between the parties);

(e) any other amount due for payment to [Carna] net of any sum to be recovered from [Carna], as per the provisions of this agreement;

(f) an amount of $4,500,000.00 to compensate [Carna] for premature termination

provided that [Carna] must use all reasonable endeavours to minimize the costs, expenses and liabilities which may be incurred by [Griffin] under this Schedule as a result of early termination for convenience by [Griffin].

In the case of a termination for [Carna’s] default, notwithstanding any rights [Griffin] may otherwise have to claim damages from [Carna], [Griffin] must still pay to (subject to any set off rights of [Griffin]) [Carna] all unrecovered refurbishment costs as set out in Schedule 16. The refurbishment cost is to be paid in equal installments and over a period that is 50% of the residual Initial Term of this agreement.

24 As will be seen, Carna contends that Griffin was ‘Insolvent’ within the meaning of subpara (g) of the contractual definition by 3 December 2014, being the date on which Carna purported to terminate the Contract with immediate effect under cl 17.11. The proper construction and meaning of subpara (g) is strongly contested.

25 The principles applicable to the construction of a commercial contract have been summarised by the High Court in Electricity Generation Corporation t/as Verve Energy v Woodside Energy Ltd [2014] HCA 7; (2014) 251 CLR 640 per French CJ, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ (at [35]), where their Honours said:

Both Verve and the Sellers recognised that this Court has reaffirmed the objective approach to be adopted in determining the rights and liabilities of parties to a contract. The meaning of the terms of a commercial contract is to be determined by what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean. That approach is not unfamiliar. As reaffirmed, it will require consideration of the language used by the parties, the surrounding circumstances known to them and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract. Appreciation of the commercial purpose or objects is facilitated by an understanding “of the genesis of the transaction, the background, the context [and] the market in which the parties are operating”. As Arden LJ observed in Re Golden Key Ltd, unless a contrary intention is indicated, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract a businesslike interpretation on the assumption “that the parties … intended to produce a commercial result”. A commercial contract is to be construed so as to avoid it “making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience”.

(Emphasis added, citations omitted.)

26 Similar statements of principle appear in Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; (2015) 256 CLR 104 per French CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ (at [46]-[51]) where their Honours said:

46 The rights and liabilities of parties under a provision of a contract are determined objectively, by reference to its text, context (the entire text of the contract as well as any contract, document or statutory provision referred to in the text of the contract) and purpose.

47 In determining the meaning of the terms of a commercial contract, it is necessary to ask what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean. That inquiry will require consideration of the language used by the parties in the contract, the circumstances addressed by the contract and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract.

48 Ordinarily, this process of construction is possible by reference to the contract alone. Indeed, if an expression in a contract is unambiguous or susceptible of only one meaning, evidence of surrounding circumstances (events, circumstances and things external to the contract) cannot be adduced to contradict its plain meaning.

49 However, sometimes, recourse to events, circumstances and things external to the contract is necessary. It may be necessary in identifying the commercial purpose or objects of the contract where that task is facilitated by an understanding “of the genesis of the transaction, the background, the context [and] the market in which the parties are operating”. It may be necessary in determining the proper construction where there is a constructional choice. The question whether events, circumstances and things external to the contract may be resorted to, in order to identify the existence of a constructional choice, does not arise in these appeals.

50 Each of the events, circumstances and things external to the contract to which recourse may be had is objective. What may be referred to are events, circumstances and things external to the contract which are known to the parties or which assist in identifying the purpose or object of the transaction, which may include its history, background and context and the market in which the parties were operating. What is inadmissible is evidence of the parties’ statements and actions reflecting their actual intentions and expectations.

51 Other principles are relevant in the construction of commercial contracts. Unless a contrary intention is indicated in the contract, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract an interpretation on the assumption “that the parties … intended to produce a commercial result”. Put another way, a commercial contract should be construed so as to avoid it “making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience”.

(Emphasis added, citations omitted.)

27 More recently, in Ecosse Property Holdings Pty Ltd v Gee Dee Nominees Pty Ltd [2017] HCA 12; (2017) 261 CLR 544, Kiefel, Bell and Gordon JJ reiterated this objective approach (at [16]-[17]):

16 It is well established that the terms of a commercial contract are to be understood objectively, by what a reasonable businessperson would have understood them to mean, rather than by reference to the subjectively stated intentions of the parties to the contract. In a practical sense, this requires that the reasonable businessperson be placed in the position of the parties. It is from that perspective that the court considers the circumstances surrounding the contract and the commercial purpose and objects to be achieved by it.

17 Clause 4 is to be construed by reference to the commercial purpose sought to be achieved by the terms of the lease. It follows, as was pointed out in the joint judgment in Electricity Generation Corporation v Woodside Energy Ltd, that the court is entitled to approach the task of construction of the clause on the basis that the parties intended to produce a commercial result, one which makes commercial sense. It goes without saying that this requires that the construction placed upon cl 4 be consistent with the commercial object of the agreement.

(Citations omitted.)

28 Finally, the Full Court in Findex Group Limited v McKay [2020] FCAFC 182 per Markovic, Banks-Smith and Anderson JJ last year applied these principles as follows (at [78]-[87]):

78 A commercial contract is to be construed so as to avoid it making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience: Woodside Energy, [35]; Zhu v Treasurer (NSW) [2004] HCA 56; 218 CLR 530, [83]; Hide & Skin Trading Pty Ltd v Oceanic Meat Traders Ltd (1990) 20 NSWLR 310, 313-314.

79 Commercial contracts must be interpreted fairly and broadly, without being too astute or subtle in finding defects: Pan Foods Company Importers and Distributors Pty Ltd v Australia and New Zealand Banking [2000] HCA 20; 170 ALR 579, [14]; Australasian Performing Right Association, 109-110.

80 A construction that avoids unreasonable results is to be preferred to one that does not, even though it may not be the most obvious, or the most grammatically accurate: Australasian Performing Right Association, 109-110.

81 Determining the meaning of a contractual term normally requires consideration not only of the text, but also of the surrounding circumstances known to the parties, and the purpose and object of the transaction: Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165, [40] (Toll); Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority (NSW) (1982) 149 CLR 337, 350; Pacific Carriers Ltd v BNP Paribas [2004] HCA 35; 218 CLR 451 (Pacific Carriers), [22]; Woodside Energy, [35]; Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; 256 CLR 104 (Mount Bruce Mining), [47] and [49]-[50]; Ecosse Property, [17].

82 Words may generally be supplied, omitted or corrected, in an instrument, where it is clearly necessary in order to avoid absurdity or inconsistency: Fitzgerald v Masters (1956) 95 CLR 420, 426-427.

…

85 If a clause is valid in all ordinary circumstances which have been contemplated by the parties, it is equally valid notwithstanding that it might cover circumstances which are so ‘extravagant’, ‘fantastic’, ‘unlikely or improbable’ that they must have been entirely outside the contemplation of the parties: Home Counties Dairies Ltd v Skilton [1970] 1 WLR 526, 536 endorsed in Rentokil, 304 (Doyle CJ), 320-321 (Matheson J) and 339 (Debelle J). See also Marion White Ltd v Frances [1972] 1 WLR 1423; Littlewoods Organisation Ltd v Harris [1978] 1 All ER 1026; Clarke v Newland [1991] 1 All ER 397.

...

87 A construction which will preserve the validity of the contract is to be preferred to one which will make it void: Pearson v HRX Holdings Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 111; 205 FCR 187, [45].

29 A provision in a contract is to be construed objectively by reference to its text, context (the entire text of the contract as well as any contract, document or statutory provision referred to in the text of the contract) and purpose. Ordinarily, the process of construction is possible by reference to the contract alone. If an expression in a contract is unambiguous or susceptible of only one meaning, extrinsic evidence of surrounding circumstances external to the contract is not admissible to contradict its plain meaning.

30 Against the backdrop of these accepted principles lies the primary ground of dispute in this case concerning the alleged Insolvency Default Breach. The parties disagree first, as to the correct construction of the definition of ‘Insolvent’ set out in cl 1.1 of the Contract and second, whether the evidence establishes that Griffin was in fact ‘Insolvent’ at the relevant times, indeed Griffin contends that it could not be considered ‘Insolvent’ on any proper construction because its cash flow problems were temporary rather than endemic.

31 The Contract comprehensively defines the term ‘Insolvent’ by setting out seven specific circumstances which, if one or more applies to either party, will mean that party is ‘Insolvent’. The only relevant circumstances for the purposes of this dispute are those set out at (a) and (g) of the definition:

Insolvent means, in respect of a party, that it:

(a) is (or states that it is) insolvent (as defined in the Corporations Act [2001 (Cth)]);

…

(g) is otherwise unable to pay its debts when they fall due.

32 Insolvent is defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) by s 95A which provides:

95A Solvency and insolvency

(1) A person is solvent if, and only if, the person is able to pay all the person’s debts, as and when they become due and payable.

(2) A person who is not solvent is insolvent.

Note: A company is taken to be insolvent if the company proposes a restructuring plan to creditors (see subsection 455A(2)).

33 As noted, Carna relies solely on subpara (g) and, as will be developed below, contends that Griffin was ‘Insolvent’ within the meaning of subpara (g) by 3 December 2014. Carna argues that each subparagraph is a separate head of liability that will attract the definition and thus constitute the state of being ‘Insolvent’ under the Contract. Each part of the definition must be given work to do and accordingly, there is no reason to read subpara (g) down by reason of its similarity to subpara (a) by reference to s 95A(1) of the Corporations Act. To the contrary, Carna contends that the presence of the word ‘otherwise’ indicates a means of demonstrating a state of ‘Insolvency’ in a different way to that contemplated by the other subparagraphs. The upshot of this argument for Carna is that, while similar legal tests may be utilised in assessing whether a party is ‘Insolvent’ under both subpara (a) and subpara (g), it is not necessary under subpara (g) to establish insolvency under s 95A of the Corporations Act. All that is required, Carna says, is a factual finding that Griffin was ‘unable to pay its debts when they fell due’ at the relevant point in time.

34 Griffin proffers an alternative construction to explain the inclusion of both subpara (a) and (g) in the contractual definition of ‘Insolvent’. It notes that governments repeal legislation from time to time and if the Corporations Act were to be relevantly repealed or amended, cl 1.2(e) of the Contract could well operate to alter the content of subpara (a) of the definition. Clause 1.2(e) is in the following terms:

1.2 Interpretation

In this agreement (unless the context otherwise requires):

…

(e) a reference to any legislation or legislative provision includes any statutory modification or re-enactment of, or legislative provision substituted for, and any subordinated legislation issued or made under, that legislation or legislative provision; …

35 There is therefore no warrant, Griffin says, to read subpara (g) more broadly than subpara (a) of the definition. Griffin argues that subpara (a) is intended to pick up the definition of insolvent under the Corporations Act, whatever that may be throughout the life of the Contract, while subpara (g) seeks to immortalise that definition by effectively setting it (or the converse) out. Properly construed, Griffin argues, the clause is intended to pick up the well-understood concept of insolvency considered by cases under the Corporations Act adopting the natural and ordinary meaning of the words used.

36 Griffin says it follows that as a matter of construction, Carna did not have a right to invoke cl 17.11 in circumstances where Griffin has never been found to be insolvent under the Corporations Act and indeed continues to trade today. This fact is strenuously emphasised by Griffin throughout each of its arguments.

37 Carna’s construction is to be preferred. The text of the definition discloses no basis upon which subpara (g) is to be confined and read down by reference to subpara (a). Rather, each subparagraph should be construed as providing independent and different ways of demonstrating that a party to the Contract could be said to be ‘Insolvent’ within the meaning of the Contract. Such a construction is far more plausible than Griffin’s contention that subpara (g) was only included as a contingency in the event that the Corporations Act was repealed or amended to alter the s 95A insolvency definition. Carna’s construction is strengthened by the word ‘otherwise’ in subpara (g). It suggests that subpara (g) was intended to be different from subpara (a). Accordingly, subpara (g) operates to enable a party to terminate under cl 17.11 if the other party is ‘otherwise unable to pay its debts when they fall due’. That expression in itself which will require explanation.

38 A debate then arises between the parties as to the correct test to be applied to determine whether a party is ‘Insolvent’ under the Contract by operation of subpara (g). Griffin notes Carna’s arguments all proceed by reference to authorities which have applied the test for insolvency under s 95A of the Corporations Act and that this is so because of the clear similarity between subpara (g) and the statutory concept. For instance, Carna relies on Crema (Vic) Pty Ltd v Land Mark Property Developments (Vic) Ltd [2006] VSC 338; (2006) 58 ACSR 631 in which Dodds-Streeton J (at 652) enshrined the cash flow test of insolvency under s 95A.

39 There is no doubt that the analysis required under subpara (g) is similar to that which would be required under subpara (a) such that the same authorities may be relevant to both considerations. Subpara (g) is triggered on proof of debts that are not able to be paid when they fall due. That is a question of fact. It is accepted by Carna, however, that subpara (g), as is the case under s 95A, is not satisfied by viewing a single day in isolation. Carna points to the orthodox summary in The Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 9) [2008] WASC 239; (2008) 39 WAR 1; (2008) 225 FLR 1 per Owen J (at [1065]-[1067], [1070] and [1072]-[1074]), which dealt with events over a 12-16 month period, revealing the importance of having regard to the months before and after the relevant moment in time. Debts that would arise in the immediate future, payment out of terms (whether the subject of demand or not) and similar factors which, as a matter of commercial reality and common sense should be considered at the date of insolvency, are relevant.

40 In Bell, Owen J said (and I respectfully agree) (at [1066] and [1070]-[1074]):

1066 The “cash flow” or “commercial insolvency” test is an assessment of solvency based on a company’s ability to meet its debts (current liabilities), as and when they fall due. This test assesses the financial health of a company by reference to its capacity to finance its current operations. In other words, it looks at whether the company’s business is viable and can continue to operate by meeting the present demands upon it. As the authors of Ford, Austin and Ramsay, Ford’s Principles of Corporations Law (12th ed, 2005) point out, the essential features of the cash flow test include an assessment of the company’s existing debts and debts that will arise in the near future, the date each debt is due for payment, the company’s present and expected cash resources and the date each inflow item will be received (at [25.050]).

…

1070 To add to the confusion, it is possible that a company might be cash flow insolvent but show a positive balance sheet where assets exceed liabilities. A company may be, at the same time, insolvent and wealthy. It may have wealth locked up in investments that are not easy to realise. Regardless of its wealth in this sense), unless it has assets available to meet its current liabilities, it is commercially insolvent and therefore liable to be wound up: Re Tweeds Garages Ltd [1962] Ch 406 at 460 (Plowman J, referring to an extract from the Buckley’s Companies Acts, 13th ed, 1957).

…

1072 There is no unanimity of approach across common law jurisdictions. In Australia, however, the cash flow test is generally viewed as the more appropriate mechanism for assessing solvency, both for individuals and companies. For example, in Bank of Australasia v Hall (1907) 4 CLR 1514 at 1521, Isaacs J said: “The debtor’s position depends on whether he can pay his debts, not on whether a balance sheet will show a surplus of assets over liabilities”. The cash flow test is more in keeping with the definitions of solvency in the Bankruptcy Act and the Corporations Law.

1073 That having been said, it would be wrong to dismiss the balance sheet test as irrelevant. It can be useful, for example, in providing contextual evidence for the proper application of the cash flow test. In Coburn N, Coburn’s Insolvent Trading (2nd ed, 2003), p 66, the author says that:

The courts have moved to a far wider consideration of solvency, rather than just applying a cash flow test, which is viewed as a basic starting point in the consideration of solvency. This is because the statutory emphasis is on “solvency” rather than “liquidity”. The consideration will be as a question of fact: in the light of commercial reality, all things considered, could the company pay its debts as and when they became due? Such an approach includes the balance sheet test, and other commercial realities such as access to money from third parties, raising capital or credit and financial support are all relevant considerations in determining a company’s ability to pay debts.

1074 The proposition that a balance sheet assessment continues to have some relevance is supported by other authorities: see, eg Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Edwards (2005) 220 ALR 148 at [96] (Barrett J); ACE Contractors & Staff Pty Ltd v Westgarth Development Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 728 at [44] (Weinberg J).

(Emphasis added.)

41 Thus, in order to consider whether Griffin’s financial position fell within the contractual definition of ‘Insolvent’ under subpara (g), it is necessary to consider in detail, the events in the months leading up to Carna’s purported termination of the Contract on 3 December 2014.

ADMISSIBILITY OF RECORDS GOING TO LIABILITY

42 Carna bases its contractual claims entirely on the documentary evidence. It has not served any expert evidence from an insolvency practitioner expressing the opinion that Griffin was ‘Insolvent’ by at least 3 December 2014. There is no doubt that it was open to Carna to put on such evidence. It had intended to rely on an expert in relation to its statutory claims. Instead, it relies for the Insolvency Default Breach on documentary evidence and answers given by Mr Roy and Mr Riordan in examinations by Carna’s liquidators. By and large, the parties have agreed that thousands of pages of documentary evidence could be admitted without objection. Griffin raises objections to a relatively small number of documents, and the parties agreed that these could be resolved in these reasons for judgment.

43 For the purpose of establishing the Insolvency Default Breach, the only disputed document upon which Carna relies is the Dunn & Bradstreet Report. There is also a question of the weight to be given to admissions purportedly made by Mr Riordan and Mr Roy during liquidators’ examinations conducted between 2016 and 2019. These issues are dealt with below. The other disputed documents comprise business records of Carna which are said to demonstrate various amounts that were owing by Griffin to Carna following termination of the Contract. The admissibility or proper weight to be given to those business records is considered later in these reasons together with the substantive question as to the calculation of Carna’s entitlement under Sch 15 of the Contract.

44 In its letter to Griffin of 3 December 2014 purporting to terminate the Contract on, amongst other things, insolvency grounds, Carna relied on a report produced by Dun & Bradstreet examining Griffin’s credit worthiness. Dun & Bradstreet provide for a fee, views on, inter alia, states of solvency of companies. The report was compiled on 2 December 2014 and provides conclusions and scores calculated by Dun & Bradstreet pertaining to various measures of financial standing.

45 Griffin initially objected to this report on the grounds of relevance and alternatively by way of seeking a limitation as to the use of its contents under s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). This limitation would admit the matters recorded in the document but not the truth of these matters. In oral submissions, senior counsel for Griffin accepted that the objection was not so much as to admissibility but rather as to weight. Nothing more was said about the underlying facts on which the report was based. The report lists the commencement of 17 court actions which are sourced from publicly accessible documents. It also lists 15 collection notices issued on Griffin. The latter information appears to be derived from entities who participate in a Dunn and Bradstreet program by providing their invoice registers.

46 I give very little weight to the recommendations and conclusions in the report. I give no weight to the ‘collections’ referred to in the report. Nonetheless, the existence of court actions (to the extent they fall within the relevant time period) and the existence of substantial financial pressure ultimately was not seriously disputed in the proceeding. To this extent, the list is consistent with the history otherwise recorded in these reasons. However as senior counsel for Griffin said, ‘there is a far better forensic landscape to trawl through to determine’ the issue before the Court. I agree with that submission. No express objection was taken to the court actions listed in the report which are said to be sourced from public documents. That is true of some courts. But as the better records are expressly canvassed in these reasons, I also give them little to no weight or treat them as material pursuant to s 136 of the Evidence Act.

Admissions by Griffin’s officers in liquidators’ examinations

47 As has been noted, following the settlement of Carna’s statutory claims and the removal of Mr Riordan and Mr Roy as respondents, Carna’s contractual case proceeded entirely on documentary evidence. Neither Mr Riordan nor Mr Roy were called to give evidence. Carna relies however, on a number of admissions made by these two Griffin officers in the course of various liquidators’ examinations conducted between 2016 and 2019. Carna sought to adduce evidence of those examinations by tendering the transcripts. In particular, Carna relies on what it says are clear admissions from both Mr Roy and Mr Riordan that Griffin was unable to pay its debts when they fell due in 2014.

48 Griffin does not object to the tender of the transcripts, but says that a careful reading of the exchanges recorded therein is required for the Court to form a view that the admissions as Carna frames them were actually made. Griffin points out that in some cases, Carna’s construction as to the purported admission is put too high, or ignores qualifications that both individuals made in response to what appears to be fairly rigorous questioning. For instance, it is clear from the transcripts that both Mr Riordan and Mr Roy sought to qualify their answers to the proposition that Griffin was unable to pay its debts when they fell due by repeatedly saying that this was only true ‘in some cases’ or in ‘certain instances’ or absent parent company support. Griffin says the Court should give appropriate weight to these exchanges, rather than accept, as Carna appears to assert, that they demonstrate that Griffin was ‘Insolvent’ essentially by its own admission at the relevant times.

49 Griffin is undoubtedly correct on this point. I do not consider very much is gained from the examination transcripts on the specific question of whether Griffin was able to pay its debts when they fell due at the relevant times. Again, that is the ultimate question for the Court and, in a case which was run by both parties exclusively on a vast corpus of documents, it could hardly be thought that certain admissions, made some years ago under examinations in a different context, could add anything of substance as to the ultimate factual conclusion the Court is required to reach that is not already apparent from the documents. Mr Riordan and Mr Roy are not expert witnesses, or witnesses at all. (No doubt the examinations were useful for other purposes.)

50 A number of the admissions that Carna puts forward were clearly made by Mr Riordan or Mr Roy but are also readily apparent from the documents and not seriously contested by Griffin; for instance, that it was reliant on parent company support or that it paid some creditors late. Griffin does not shy away from the financial problems it was facing.

51 Perhaps the only admission on which any weight has been placed in these reasons is that of Mr Riordan in relation to Griffin’s difficulties in borrowing from banks. This state of affairs is not expressly revealed on the documentary record, however it is a reasonable inference to be drawn by virtue of Griffin’s reliance on other, more expensive forms of finance discussed below.

THE FINANCIAL ATMOSPHERE DURING THE CONTRACT

52 Against the backdrop of the claim and certain evidentiary rulings, it is necessary now to examine the financial circumstances during and around the performance of the Contract with an eye particularly to the alleged Insolvency Default Breach.

Griffin’s position in 2013 and early 2014

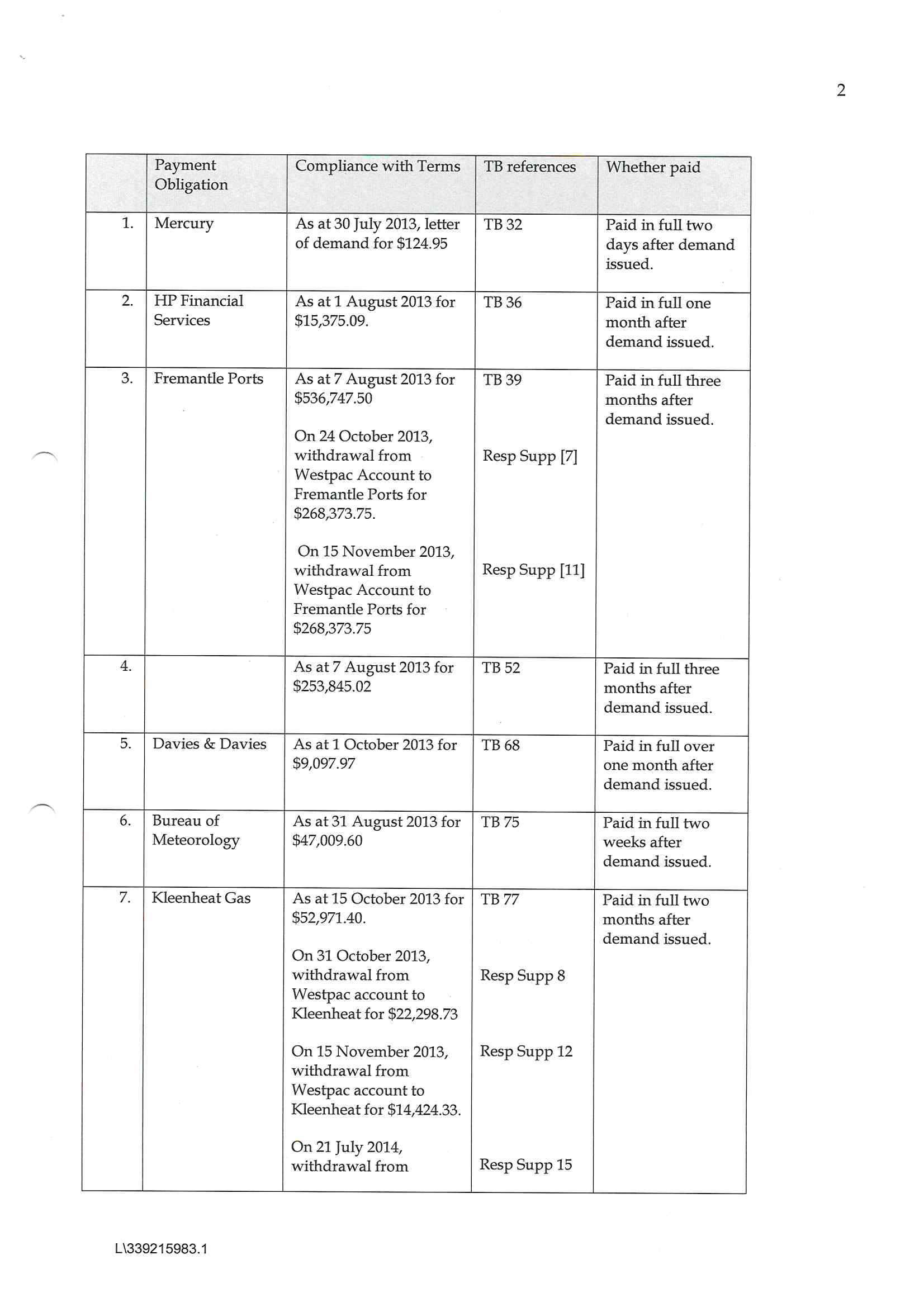

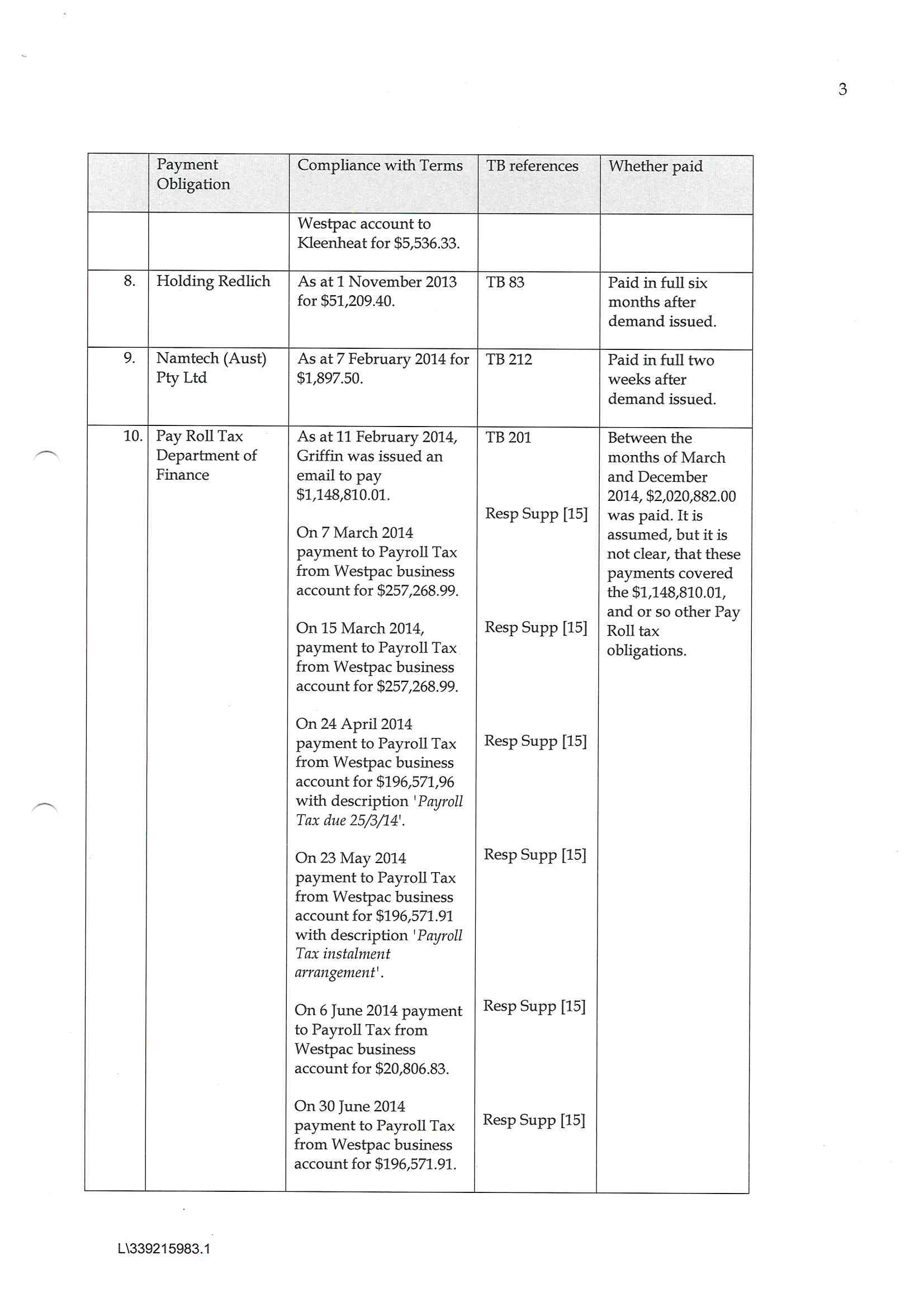

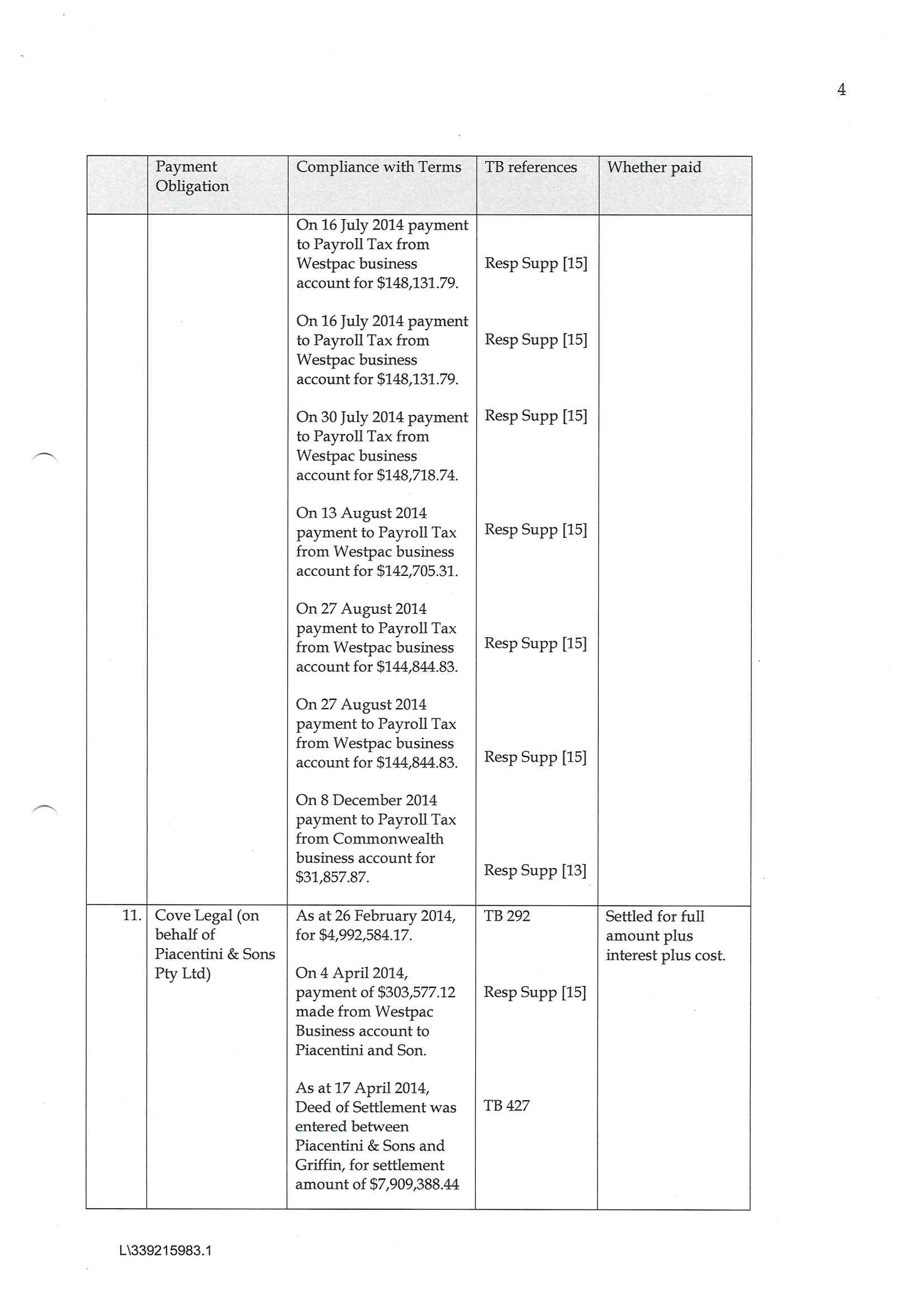

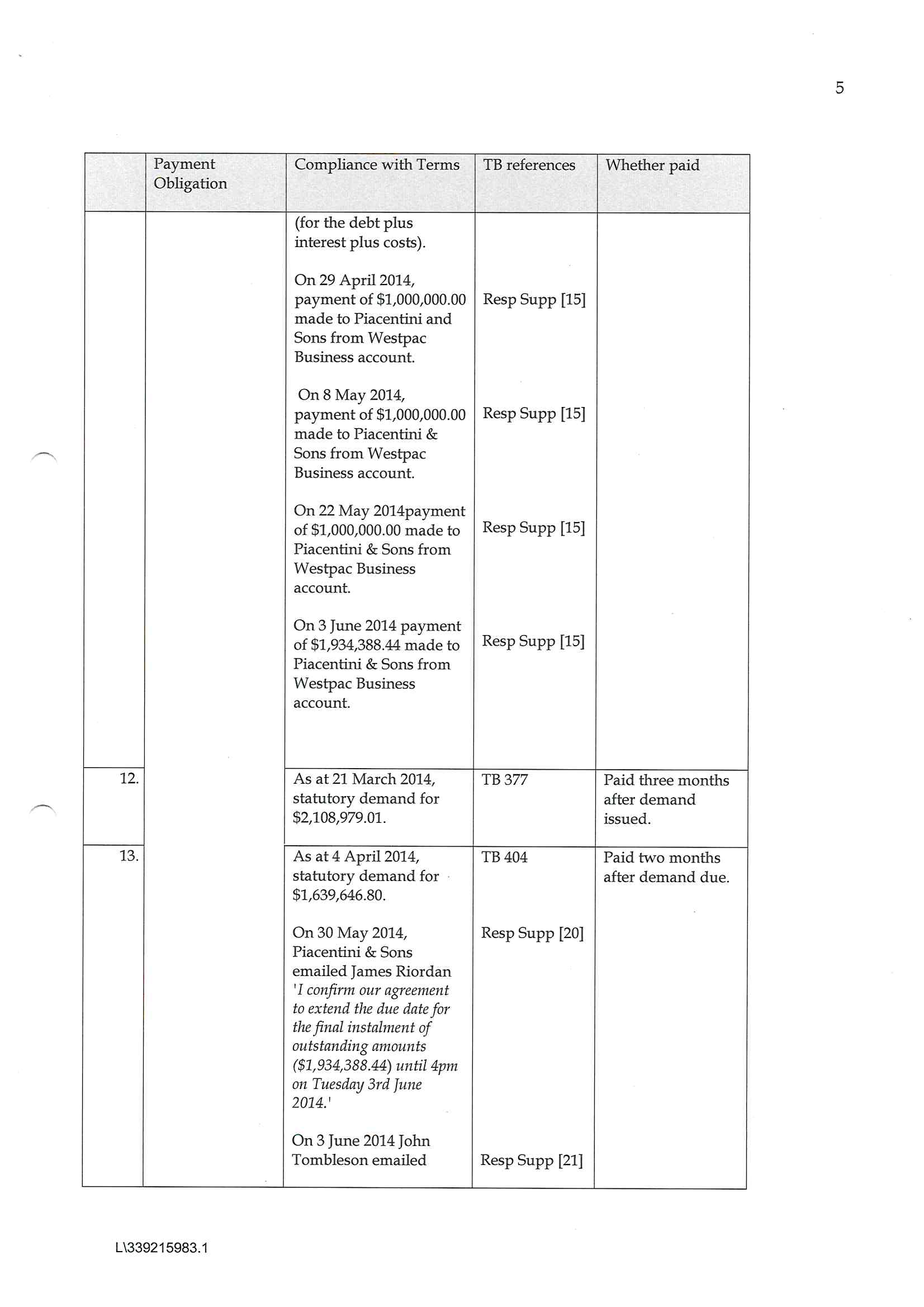

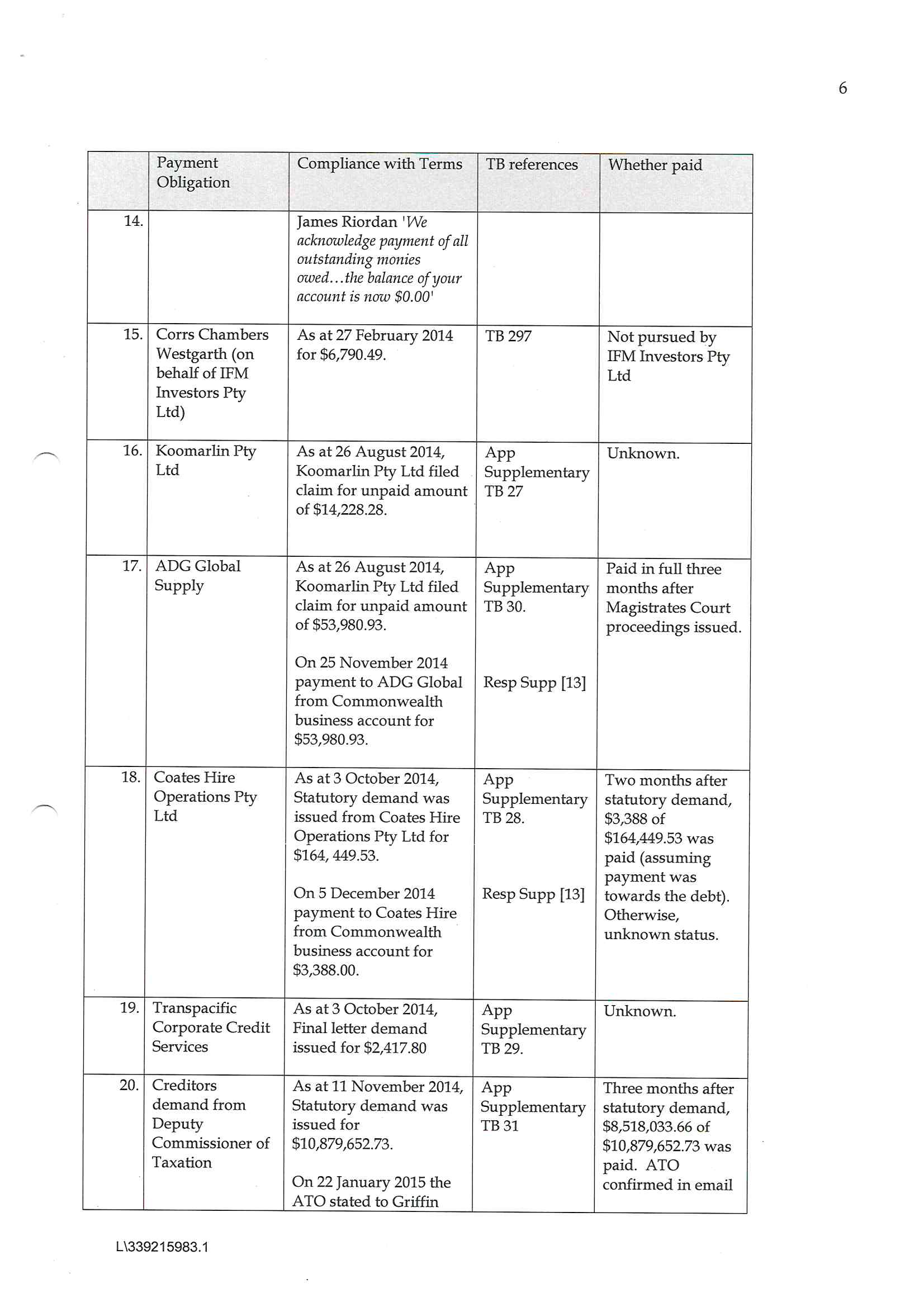

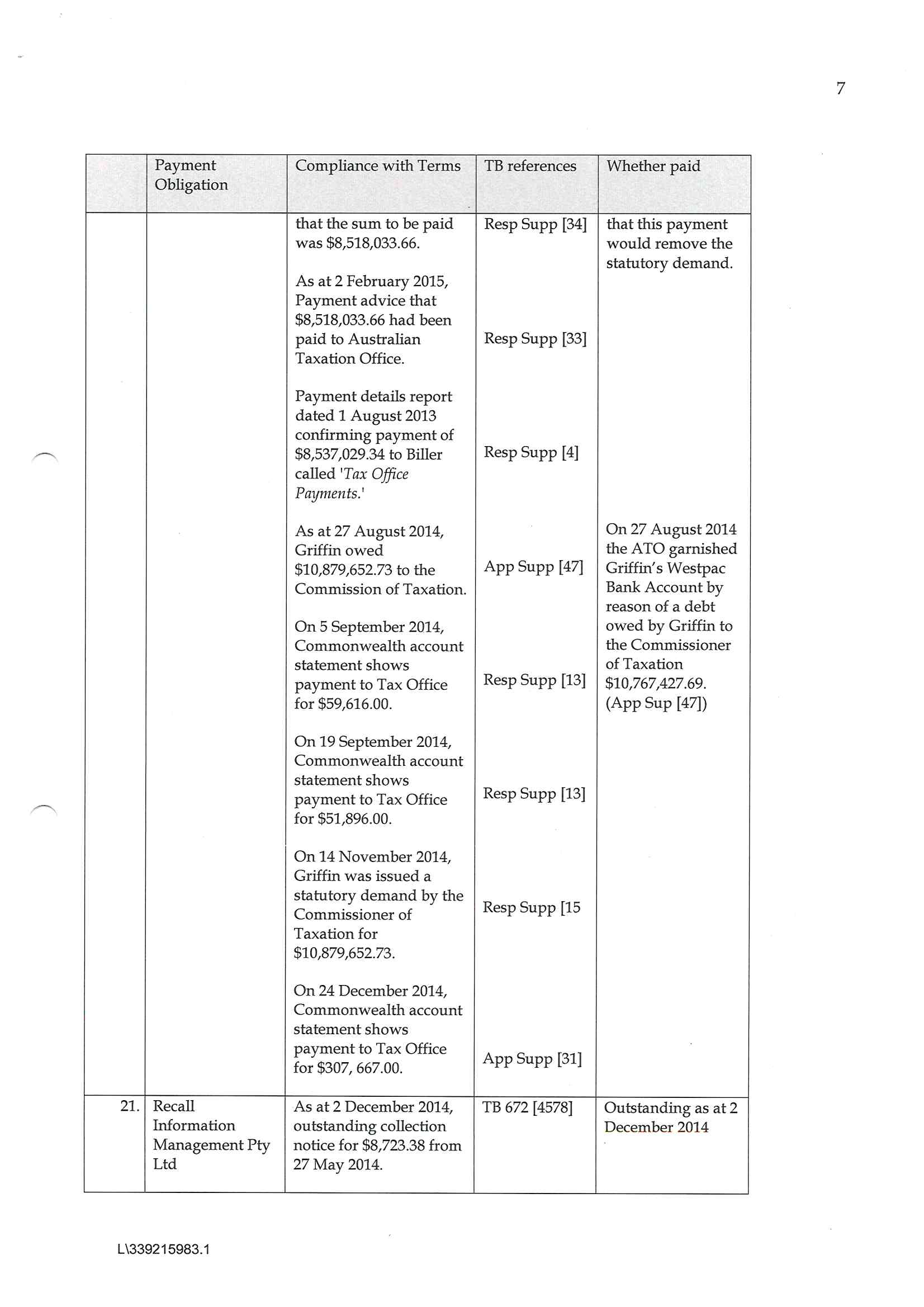

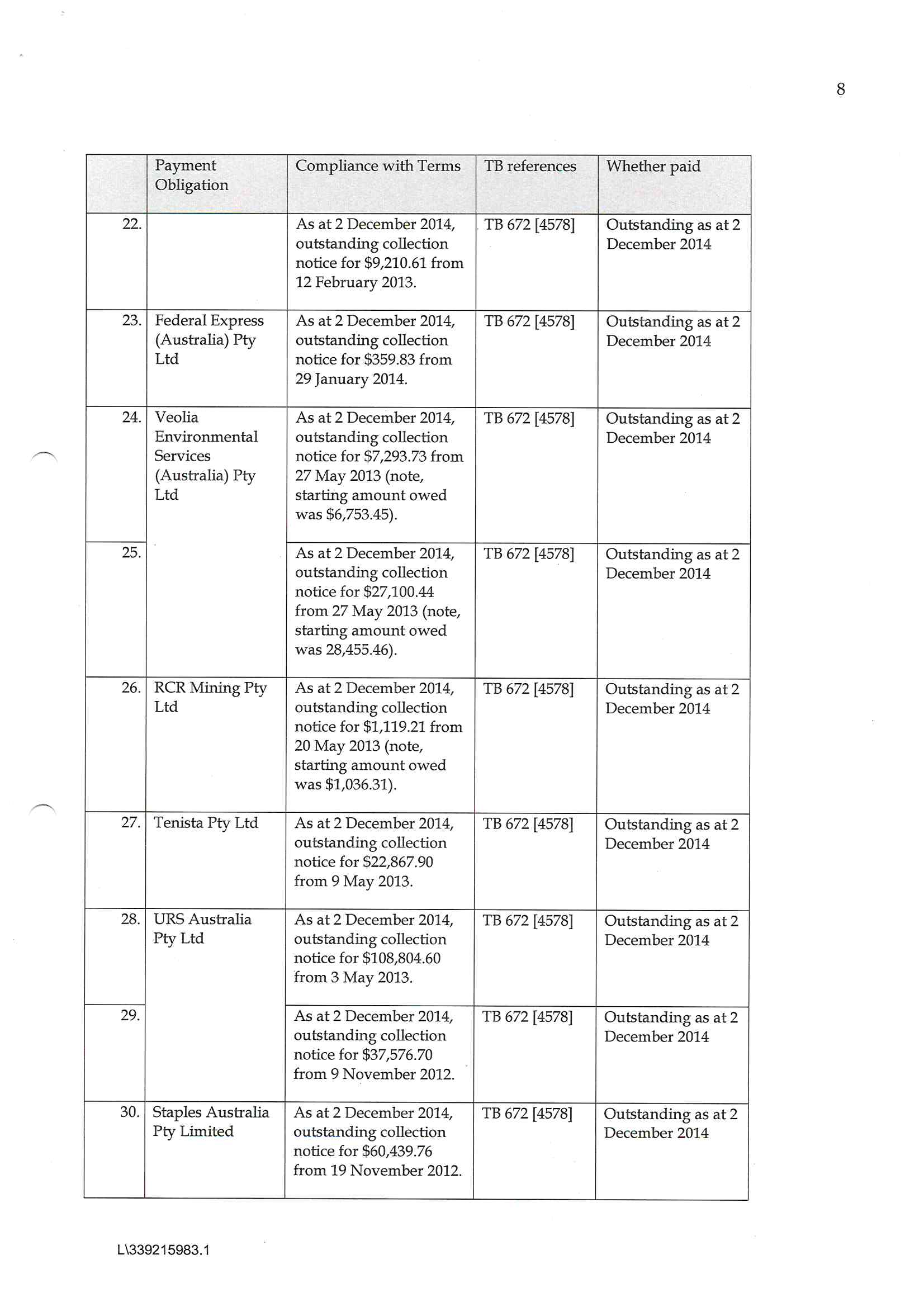

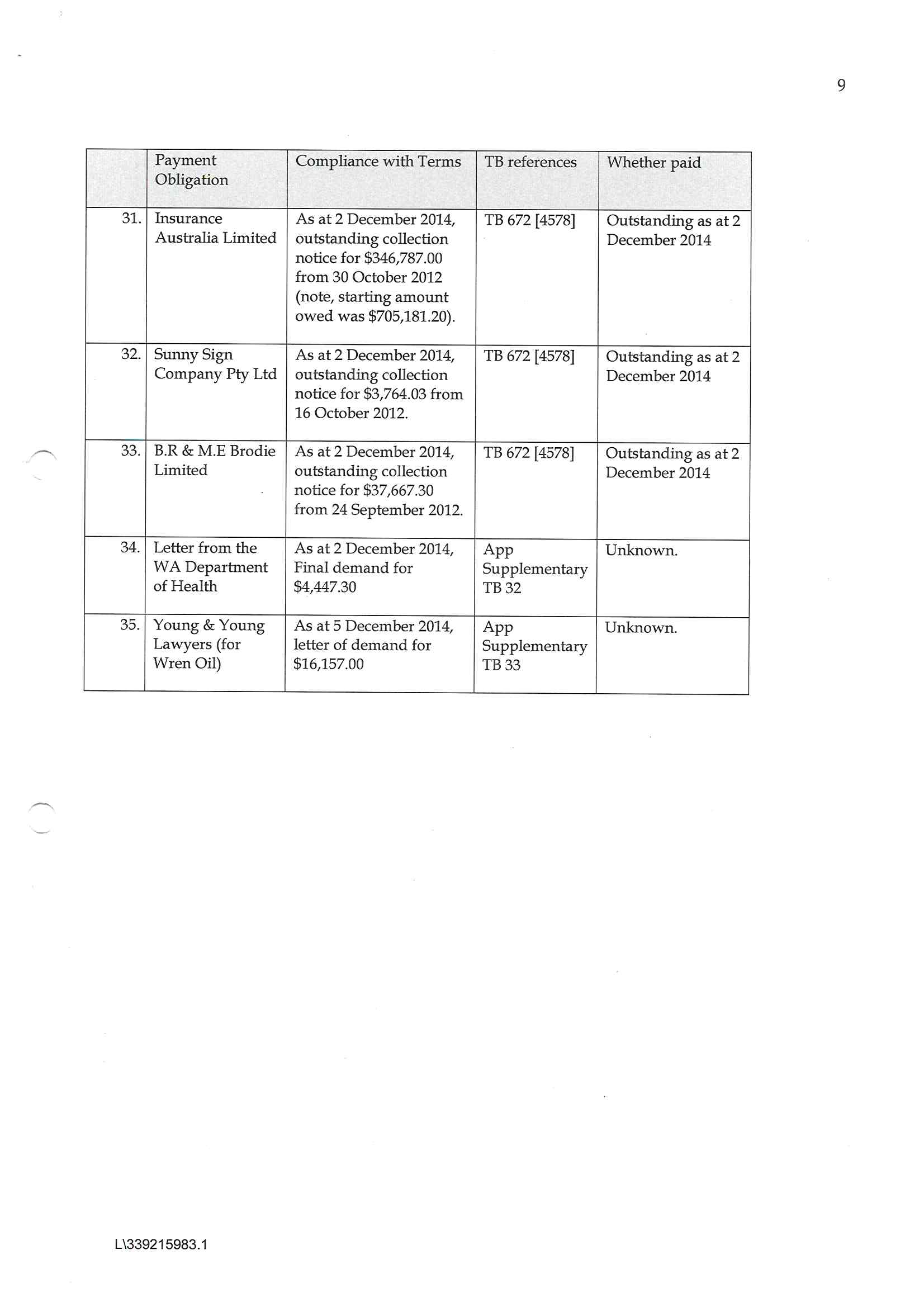

53 A convenient summary of Griffin’s creditors in 2014 was prepared in a schedule produced by Carna derived from the documentary records. That schedule is annexed to these reasons as Annexure A. It includes 12 creditors for which the only evidence is the collection notices listed in the Dunn & Bradstreet report, described in Annexure A as ‘TB 672’. I have limited the uses that the report can be put to and have disregarded these references.

54 As the following reasons reveal, Griffin was in a precarious financial situation for much of 2013 and 2014, frequently paying creditors months after letters of demand were issued, and in a few instances, after proceedings were commenced. Counsel for Griffin could not shy away from those matters at trial, but maintained that Griffin eventually managed to pay off its debts and that now, more than six years later, it continues to trade. Thus, by reference to the authorities discussed in the next section, Griffin attempted to characterise this period as a time of temporary, yet surmountable liquidity problems. While there is some disagreement as to the exact timings, circumstances and amount of some payments, the main dispute concerns the correct characterisation to be given to Griffin’s financial position at the relevant times and whether, as Carna claims, such characterisation reaches the threshold of an Insolvency Default Breach under the Contract.

55 Some contextual background is of assistance before looking at the evidence in detail.

56 Although the parties commenced communicating about the Contract in November 2013, and Carna did not commence on the Mine site until March 2014, a good deal of Carna’s evidence was directed to Griffin’s financial situation leading up to the Contract in 2013. Carna contends, relying on Bell, that the period of months before and after the alleged ‘Insolvency’ are relevant to the Court’s assessment.

57 Since February 2011, Griffin was part of the Lanco Group of companies. The Lanco Group’s acquisition of Griffin was funded by an $800 million facility provided by the Singapore branches of the Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI Bank). The Lanco Group, at material times, comprised:

(a) Griffin’s parent, Lanco Resources Australia Pty Ltd;

(b) Lanco Australia’s parent, Lanco Resources International Pte Ltd, which was incorporated in Singapore (Lanco Singapore); and

(c) Lanco Singapore’s parent, Lanco Infratech Ltd, which was incorporated in India (Lanco India).

58 It was ultimately accepted at trial that Griffin was dependent on funding from Lanco Australia (and the Lanco Group more broadly) to meets its debts. The nature and relative timeliness of this ‘parent support’ is critical to both parties’ arguments on the Insolvency Default Breach.

59 In addition to their positions in Griffin, Mr Roy was a director of Lanco Australia from 18 January 2014 and Mr Riordan was the company secretary from 26 August 2011. In April 2017, receivers and managers were appointed to Lanco Singapore.

60 Mr L Madhusudhan Rao, was the executive chairman of Lanco India, which underwent a restructure in December 2013 as the Lanco Group did not earn its estimated profits for the preceding three years. On 11 December 2013, the Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) approved that restructure, which proposed to utilise cash flow for business operations by obtaining a moratorium on debt servicing as well as additional funding. Support to Lanco Australia, Griffin and Carpenter Mine Management Pty Ltd (CMM) was factored into the restructure proposal. On 12 December 2013, Lanco India accepted the letter of approval from IDBI and passed necessary resolutions to implement the restructure. Mr Riordan reported at that stage that Griffin received about $25 million in funding from banks through the restructure. As pointed out by Carna at trial however, this funding was not received as a lump sum, and certain instalments were received later than Griffin had anticipated.

61 On July 2016 a further restructure was attempted, but it failed and on 27 August 2018, Lanco India went into liquidation. Nonetheless, Griffin itself has continued to trade.

62 Mr Riordan also holds the position of company secretary of CMM and financial controller of CMM. Mr Roy, at the relevant times was a director of CMM. At all times relevant to this proceeding, the ultimate holding company of Griffin and CMM was Lanco India. In about 2004, Griffin and CMM entered into a mining services contract under which CMM was responsible for certain costs incurred by Griffin. Griffin recharged these costs on a monthly basis to CMM.

63 Throughout the history of dealings between the parties, the documents reveal that the Lanco Group was struggling financially. It acquired Griffin in 2011 and Griffin had been a loss-making company at least for the period leading up to and including the Contract. Griffin frequently requested funding from Lanco India. If approved, that money was provided by Lanco India via Lanco Singapore, which transferred it to Lanco Australia and to CMM, which then ultimately transferred it to Griffin. Nothing particularly significant turns on this rather complex trail of funding.

64 There were times when Lanco India provided letters of support to its subsidiaries. For example, on 13 May 2013, Lanco India wrote to Lanco Australia that it undertook to arrange sufficient financial assistance for Lanco Australia as and when it was needed to enable Lanco Australia to continue its current operations and pay post-acquisition debts for at least one year from the time that the directors signed the 31 March 2013 financial statements. Griffin was not specifically mentioned. However, by letters of 16 August 2013, 19 May 2014 and 5 August 2014, Lanco India undertook to arrange sufficient financial assistance for Lanco Australia, Griffin and CMM as and when it was needed to enable them to continue current operations for at least one year from the time the directors signed the relevant financial statements, being for the years ending 31 March 2013 and 31 March 2014.

65 The correspondence in evidence suggests that Mr Riordan did not question Lanco India’s assurances that it would provide funding to Griffin, nor did he conduct investigations into Lanco India’s affairs, other than by speaking to Mr Roy. He relied upon Lanco India’s prior instances of funding support and Lanco India’s accounts. Mr Riordan was informed by Mr Roy that the ICICI Bank would continue to support Griffin through Lanco India. Mr Riordan was aware of media reports in late 2013 about the significant debt of Lanco India and that it was highly leveraged and was working with a group of banks to restructure its debt. In the liquidators’ examinations, Mr Roy accepted that Lanco India was in a very difficult financial position in 2013 and 2014 and that is why it had to be restructured.

66 As will be seen below, Griffin clearly had no control over the degree, nature or timing of the support that Lanco India would provide.

67 The evidence shows that the support from Lanco India was not easily obtained and if it was received, it was often too late for Griffin to meet payments on time or as and when they fell due. The documents indicate that there was quite a deal of frustration between Mr Roy and Mr Riordan on behalf of Griffin about the inadequacy of funding from Lanco India.

68 The relevant background also includes dealings with a financier, Greensill Capital Australia Pty Ltd and Greensill Capital (UK) Limited (together, Greensill). Those companies were controlled by Mr Alexander (Lex) Greensill. The companies provided invoice factoring facilities, which enabled the principal, in this case Griffin, to sell invoices that were issued by its suppliers to the factor, in this case Greensill, at a discount. This required the suppliers of the principal to agree to have their invoices paid through the facility. Greensill would pay a supplier on the invoice, subject to a charge for its fees. The principal would then be liable to repay the full sum of the invoice over an extended period of time, up to between six months and a year, and subject to interest accruals. One of the advantages of a factoring facility is to assist businesses to pay their suppliers on time during times of low cash flow.

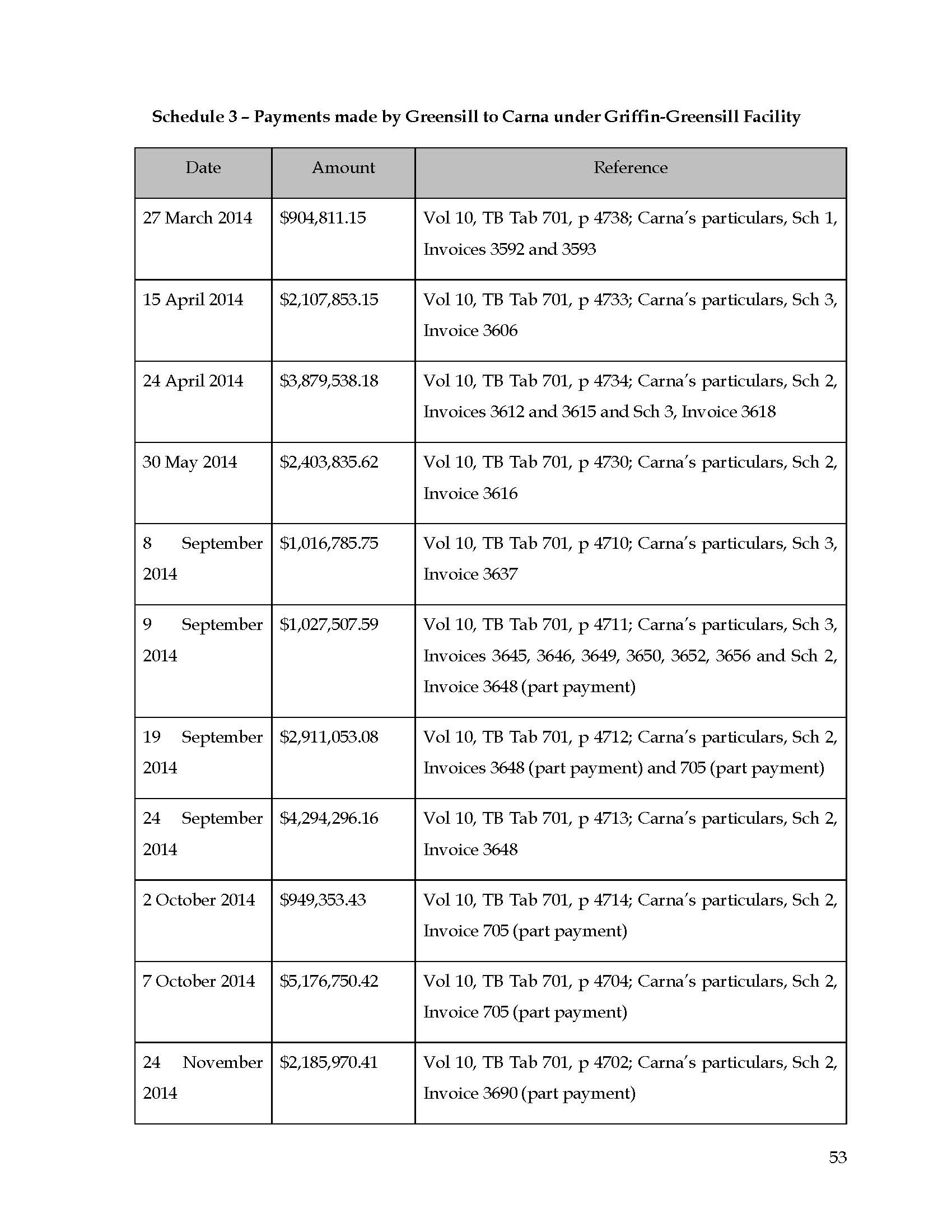

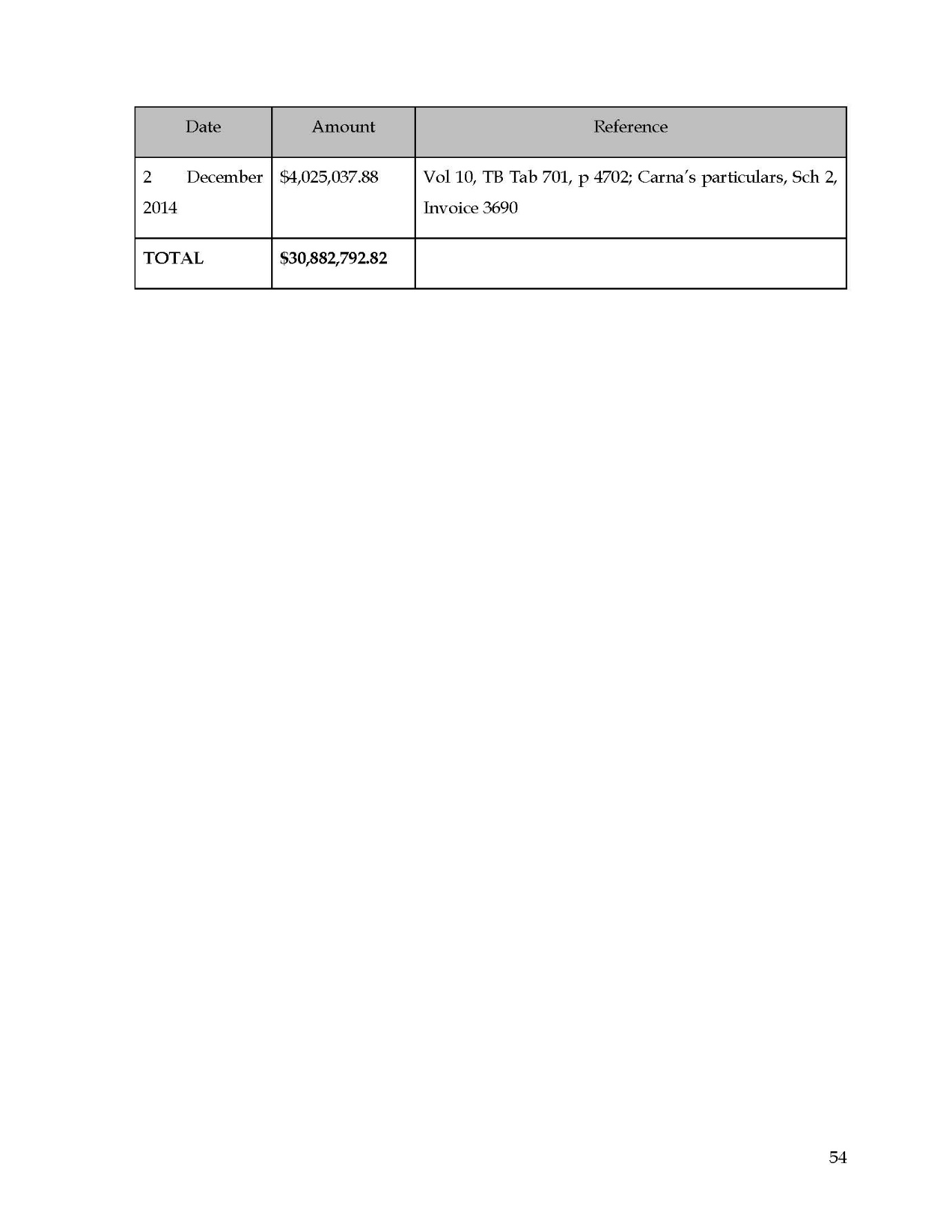

69 Such a facility was provided by Greensill Australia on 16 April 2012 to Griffin and to Lanco Singapore, Lanco Australia and CMM. Griffin was the primary debtor under this facility and would submit invoices from its suppliers for payment by Greensill. As noted, Griffin was obliged to eventually repay Greensill with interest. On 26 October 2012, that facility was transferred to, and replaced by, a new facility between Greensill UK and Lanco Australia, Griffin and CMM under which Griffin became the new ‘parent’ responsible for paying Greensill UK (the Griffin-Greensill Facility). That facility was used by CMM and Griffin to assist them in paying suppliers. When it did not have sufficient cash, Griffin was able to pay suppliers by using that Facility. In May 2014, Carna became a supplier under the Griffin-Greensill Facility to enable its invoices under the Contract to be paid.

70 There was a deal of evidence that the anticipated support from Lanco India was late and, on occasions, very late in arriving (if at all) to the point where the correspondence reveals that those operating Griffin locally may fairly be described as having been in a state of alarm. Griffin’s own financial reports clearly showed in 2013 that its ability to continue as a going concern and to pay its debts as and when they fell due was ‘primarily dependent’ upon the continued support of Lanco India and the Griffin-Greensill Facility which was said to be ‘to the value of $75 million’ and necessary in order to ‘further free cash flow for normal business activities’. In fact, the Griffin-Greensill Facility was never available to that amount, let alone by 31 March 2013.

71 The position as now known and as established on the evidence, is that numerous demands were made of Griffin by its creditors during 2013 ranging from small debts to significant amounts resulting in winding up proceedings being filed. Those demands included the following:

Date | Creditor | Amount |

22 March 2013 | Australian Taxation Office (ATO) | $13.9 million |

4 July 2013 | ATO – winding up application | $8.613 million (reduced from $13.9 million) |

30 July 2013 | Mercury Messengers Pty Ltd | $124.95 |

1 August 2013 | Hewlett-Packard Financial Services Australia Pty Ltd | $15,375.09 |

7 August 2013 | Fremantle Ports | $536,747.50 |

15 August 2013 | Piacentini & Son (Piacentini) | Amount unknown |

27 August 2013 | Fremantle Ports | $253,845.02 |

1 October 2013 | Davies & Davies | $9,097.97 |

9 October 2013 | Bureau of Metrology | $47,009.60 |

15 October 2013 | Wesfarmers Kleenheat Gas Pty Ltd | $52,971.40 |

1 November 2013 | Kreab Gavin Anderson (Australia) Ltd | $51,209.40 |

72 As can be seen from the above table, the ATO filed a winding up application in July 2013, causing Griffin to pay its outstanding debt due to the ATO. Shortly after that, the winding up application was dismissed and Griffin was ordered to pay the costs of the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation.

73 Another supplier listed in the above table that will feature further in the narrative was Piacentini. It was a supplier to Griffin of dry hire and equipment repair/services for the Mine. It was another significant and frequent creditor that had agreed to receive payment of invoices through the Griffin-Greensill Facility. It raised concerns in August 2013 directly with Mr Greensill that its officers had ‘not been able to speak to [Mr] Riordan for some time and we have not been receiving regular updates and/or payment from Griffin…’. They further expressed a ‘growing concern as promises are not being kept.’ The evidence shows that Mr Greensill brought this communication to the attention of Mr Riordan who advised that Griffin expected to be able to ‘address these matters shortly.’

74 It is common ground that Griffin was reliant upon its parent for funding in 2013, and equally common ground that this factor alone would not be determinative of whether or not Griffin was able to pay its debts when they fell due within the meaning of those words in the Contract.

75 Griffin’s income statement to the end of December 2013 showed its losses before interest and tax were approximately $38.6 million.

76 Griffin was able to control its financial affairs in a sporadic way through 2013 into early 2014. But by early 2014, Griffin had no contractor operating at the Mine and was concerned that it would not be able to continue to make payments to suppliers. That, in turn, would affect Griffin’s ability to mine and to earn revenue. The internal documents demonstrate, and I find, that in late 2013 Griffin needed to execute a mining contract, in this case the Contract, as soon as possible.

77 It was in this context that Carna and Griffin commenced communicating about the prospect of a contract in November 2013. A series of proposals and meetings ensued. On 19 December 2013, Griffin expressed interest in engaging Carna to provide mining services and, following Carna’s presentation of a five-year mine plan on 22 December, Griffin expressed its intention to award a mining services contract to Carna on 24 December 2013. Numerous drafts were exchanged from 3 January 2014.

78 Griffin’s need to secure a contract with Carna for the provision of mining services is most starkly illustrated by an internal email of 14 January 2014 sent by Mr Kumar to Messrs Riordan, Roy and Peddu stating relevantly that:

Production numbers are going down rapidly …

You are aware the main reason being the lack of working capital and failure to maintain the gear …

As mentioned earlier several times, if this situation continues, we are at grave risk of failing to meet the supplies to domestic customers.

If we can’t utilise January, February and March months effectively, even if [Carna] takes over operations, we can’t expect better volumes from them during winter.

We need:

A. Immediate operational funding to maintain operations at a level which will give us minimum comfort to meet the domestic supplies.

B. Whatif [sic] contract agreement doesn’t happen?

What is our Plan “B”???

PLEASE ACT IMMEDIATELY ON “A” &

GIVE A SERIOUS THOUGHT ON “B”

(Emphasis added.)

79 A month later, on 14 February 2014, Mr Kumar sent a follow up email noting that:

[a]s found, the production volumes continued to slide and we failed to supply to blue waters the required quantities due to the same continuing issue of lack of operational funding

Still my request regarding item “A” remains unaddressed …

(Emphasis added.)

Mr Roy responded to Mr Kumar’s email later on 14 February 2014 stating that ‘[in] the given situation, Plan B is a definite closure, very frankly’.

80 Griffin’s financial difficulties became public around this time. In January 2014, the media reported that the Office of State Revenue had lodged a charge under s 77A and s 78 of the Taxation Administration Act 2003 (WA) to secure Lanco Australia’s stamp duty liability to the Commissioner of State Revenue. The next day, Mr Greensill emailed Mr Riordan raising concerns that he had only learned about this development from media reports. He sought an explanation from Mr Riordan which was provided later that day. Mr Grey also raised concerns the day after the media reports regarding Griffin’s financial position and ways in which it could be ensured that payments to Carna would not be compromised. Noting Carna’s potential exposure under the Contract (in draft form at this stage) would be $35 million in outlays, Mr Grey sought some form of security of payment from Griffin given that certain other options such as an escrow arrangement had fallen out of the Contract negotiations.

81 In any event, and despite what appears to have been some concerns on the part of Carna, the Contract was executed on 28 January 2014. Initially, in these proceedings there was much disputation as to whether this was the final form of the Contract or merely an initial contract, but as discussed, that issue has fallen away.

82 Under the Contract, Carna was to provide Griffin with Mining Services at its coal mines called Ewington 1 and Ewington 2 (together, the Mine), in exchange for payment. Those coal mines are multi-seam, multi-pit open cut coal mines located close to Collie. Griffin’s processing plant comprised buildings and infrastructure for processing the coal from those mines, including conveyors which went to the Bluewaters Power Station, which was a Griffin customer as well as a supplier of power to the Mine. The total delivery capacity of the processing plant was 5 million tonnes per annum of coal.

83 The initial term of the Contract was for four years and one month from 1 March 2014 or four weeks from satisfaction of certain conditions precedent, whichever was the later date. The conditions precedent required agreement of various schedules to the Contract. These schedules were to deal with the particulars of the operation, such as the site, the detail of the mining operations, and the equipment. Griffin was to pay Carna to assist it to mobilise onto the Mine, and thereafter for the amount of coal mined by Carna, with various adjustments for consumables.

84 On 24 February 2014, Carna purported to terminate the Contract due to the non-satisfaction of conditions precedent, but at the same time, indicated it was willing to enter into a new contract on similar terms if issues as to equipment, the outstanding schedules to the Contract, and financing issues could be agreed. This ultimately occurred, and again nothing turns on this, except to observe that Carna did not commence on the Mine until mid-March 2014.

85 There were to be ongoing payments pursuant to cl 10 of the Contract known as Monthly Progress Claims. As noted, cl 10 established a process by which Carna was to submit invoices for Griffin’s approval and payment.

86 At least on the face of the Contract, there was an expectation by cl 2.1(b) that each party warranted that it had the financial standing and capacity to fulfil its obligations under the Contract. This was despite the fact that at the time of execution of the Contract, Carna says Griffin’s financial position was not sound, in that:

(a) only two days before execution, on 26 January 2014, Mr Riordan had informed Mr Roy about a delayed transfer of USD$7 million from the Lanco Group which resulted, on 29 January 2014, in Griffin missing its deadlines for payment of superannuation, payroll, stamp duty, fuel and Greensill obligations;

(b) on 23 January 2014, Piacentini’s lawyers had made a demand for payment of over $8 million, arising from Piacentini’s loan of equipment to Griffin on the Mine;

(c) Griffin’s income statement showed that to the end of January 2014, its loss so far for the year ended 31 March 2014, before interest and tax, was approximately $39.724 million;

(d) the Griffin-Greensill Facility was still capped at $25 million. Griffin had reported to the ICICI Bank earlier in the month that Greensill wanted the export of coal from Bunbury Port to commence before increasing the Griffin-Greensill Facility to $75 million; and

(e) approximately $23.7 million of the then $25 million Griffin-Greensill Facility had already been utilised by Griffin. Most of that was to pay invoices from CMM and Piacentini.

It seems unlikely that the entirety of this state of affairs was known to Carna when it entered the Contract, but there is clear evidence of Carna expressing concern to Griffin about its financial condition. That concern increased throughout 2014. The warranty at cl 2.1(b) demonstrates the parties’ basic concern that each should be able to perform its contractual role in relation to matters such as payment due to the other under the Contract.

87 Griffin’s position did not improve in February and March 2014 in the lead up to Carna’s commencement on the Mine. At least three letters of demand were issued to Griffin in February 2014. The first for a small sum on 7 February 2014 from Namtech (Aust) Pty Ltd was followed on 11 February by a demand from the Office of State Revenue for $1,148,810.01 in payroll tax liabilities which sought payment within seven days, failing which a garnishee notice would be issued. This was around the time that Mr Kumar was advising Messrs Roy and Riordan that production volumes ‘continued to slide’ and Mr Roy frankly replying that ‘Plan B is a definite closure’. On 26 February, Piacentini issued the first of three further statutory demands, which were to issue over of the ensuing months. This first demand was for $4,992,584.17 and followed an email to Mr Riordan advising him that ‘Griffin has not been able to respond with any feedback or commitment regarding the proposed deed and/or timing of payments’.

88 In relation to Griffin’s ongoing liabilities to the ATO for which a payment plan had previously been agreed, the ATO advised Mr Riordan on 5 March 2014 that:

(a) on 10 March 2014, it would garnish one of Griffin’s bank accounts to the value of $2 million; and

(b) on 31 March 2014, it would garnish that same account for the balance of the debt (then estimated at approximately $9.235 million).