Federal Court of Australia

Swiss Re International Se v LCA Marrickville Pty Limited (Second COVID-19 insurance test cases) [2021] FCA 1206

Table of corrections | |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 88, the word “the” has been inserted in the fourth line after “I would also conclude that”, the word “he” has been replaced with the word “the” in the sixth line, and the word “sad” has been replaced with the word “said” in the seventh line. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 238, the subparagraph numbering has been changed from (4), (5), (6) to (1), (2), (3). |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 288, the word “and” has been inserted in the second last line before “(d) accordingly, the risk to public health”. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 347, the word “lige” has been replaced with the word “life” in the third line. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 380, the word “Gravel” has been replaced with the word “Travel” in the last line. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 595, the word “applies” has been replaced with the word “apply” in the last line. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 616, the word “in” has been inserted in the fourth last line after “but the presence”. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 637, subparagraph (6), the word “other” has been inserted after “the 23 March 2020 direction but not the”. |

11 October 2021 | In paragraph 758, arrows have been inserted as follows: “an outbreak of COVID-19 within the radius caused the directions the directions caused other businesses to close the closure of the other businesses caused a precipitous decline in Visintin’s trade as a result of the precipitous decline in Visintin’s trade Ms Visintin closed the Visintin premises.” |

ORDERS

JAGOT J | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions be answered as set out in the reasons for judgment in Swiss Re International Se v LCA Marrickville Pty Limited (Second COVID-19 insurance test cases) [2021] FCA 1206 published today (the judgment).

2. In all proceedings other than NSD133/2021 (Insurance Australia v Meridian Travel), the parties confer and notify the chambers of Justice Jagot by 4.00pm on 12 October 2021 by email: (a) whether any party wishes to be heard further in respect of the making of declarations in each matter as proposed in the judgment, or (b) if not, the terms of any declaration and other orders the party proposes should be made.

3. In proceeding NSD133/2021 (Insurance Australia v Meridian Travel), the parties confer and notify the chambers of Justice Jagot by 4.00pm on 12 October 2021 by email whether any further directions should be made in the proceeding before hearing of any appeal.

4. Leave to appeal be granted to all parties in each proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[9] | |

[21] | |

[21] | |

[40] | |

[52] | |

[83] | |

[83] | |

[84] | |

[89] | |

[97] | |

[98] | |

[101] | |

[101] | |

[107] | |

[114] | |

[121] | |

[121] | |

[125] | |

[152] | |

[172] | |

[174] | |

[176] | |

[180] | |

[181] | |

[181] | |

[196] | |

[199] | |

[199] | |

[204] | |

[215] | |

6.3.4 Effect of exclusion in cl 9.1.2.1 on cll 9.1.2.5 and 9.1.2.6 | [233] |

[255] | |

[255] | |

[256] | |

6.3.5.3 “…as a result of… outbreak or discovery of… likely to result in the occurrence” | [257] |

[315] | |

[326] | |

[331] | |

[341] | |

[355] | |

6.7 Policy provisions – causation, adjustment and basis of settlement | [362] |

[363] | |

[363] | |

[382] | |

[386] | |

[405] | |

[408] | |

[410] | |

[413] | |

[415] | |

[418] | |

[422] | |

[422] | |

[437] | |

[439] | |

[448] | |

[453] | |

[478] | |

[506] | |

[515] | |

[516] | |

[521] | |

8 NSD134/2021: INSURANCE AUSTRALIA V THE TAPHOUSE TOWNSVILLE | [523] |

[523] | |

[542] | |

[544] | |

[558] | |

[560] | |

[560] | |

[564] | |

8.5.2.1 A result of the threat of damage to persons within a 50 kilometre radius | [564] |

[575] | |

[587] | |

[587] | |

[594] | |

[601] | |

[606] | |

[619] | |

[630] | |

[632] | |

[636] | |

[638] | |

[638] | |

[649] | |

[653] | |

[664] | |

[674] | |

[683] | |

[690] | |

[695] | |

[696] | |

[701] | |

[703] | |

[703] | |

[711] | |

[714] | |

[727] | |

[761] | |

[774] | |

[778] | |

[784] | |

[785] | |

[790] | |

[792] | |

[792] | |

[806] | |

[808] | |

[819] | |

[835] | |

[841] | |

[842] | |

[847] | |

[850] | |

[850] | |

[853] | |

[859] | |

[862] | |

[904] | |

[926] | |

[935] | |

[937] | |

[962] | |

[964] | |

[968] | |

[969] | |

[970] | |

[973] | |

[973] | |

[984] | |

[986] | |

[993] | |

[1010] | |

[1013] | |

[1015] | |

[1016] | |

[1019] | |

[1021] | |

[1021] | |

[1031] | |

[1033] | |

[1058] | |

[1060] | |

[1062] | |

[1063] | |

[1065] | |

[1067] | |

[1067] | |

[1076] | |

[1078] | |

[1082] | |

[1085] | |

[1131] | |

[1141] | |

[1142] | |

[1148] | |

[1150] |

JAGOT J:

1 These proceedings are the second test case authorised to be taken by the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA) in accordance with cl A.7.2(b) of AFCA’s Complaint Resolution Scheme Rules. The proceedings concern the proper construction and application of provisions in business interruption insurance policies. The issue is whether the policies apply to losses claimed to have been suffered by various businesses as a result of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

2 In each case: (a) the insurer is the applicant and the insured is the respondent, (b) the insured has made a claim under the policy, (c) the insurer has not paid the claim, (d) by the proceeding it commenced the insurer seeks declarations to the effect that the insured is not entitled to indemnity under the policy or, alternatively, that if the insured is entitled to indemnity under the policy, the insured’s loss is to be determined in a particular manner, and (e) the insured seeks declarations or findings to the effect that the insurer is liable to indemnify the insured.

3 The proceedings have been expedited. The parties have co-operated to ensure that, to the extent possible, the issues of construction can be resolved on the basis of agreed facts. As it has not been possible for all relevant facts to be agreed, the parties proposed an order for separate determination of the issues of construction, mindful of the need for these reasons for judgment to be founded upon a justiciable dispute ripe for determination. To this end, on 24 September 2021, I made the following order:

2. Pursuant to Rule 30.01, the following questions be heard in these proceedings separately from and subsequent to the issues identified in the “List of Issues for Determination” filed on 21 July 2021:

Would the answer to any of such issues which necessarily involve consideration of:

a. the location, prevalence or transmission of COVID-19 cases; and/or

b. the characteristics and transmissibility of COVID-19; and/or

c. in the case of LCA Marrickville only, the alleged “conflagration or other catastrophe”;

be different if evidence were adduced of documents which are sought in the subpoenas issued as at 24 August 2021 (or any further subpoena issued in terms no wider than the subpoenas issued to that date) and expert evidence based on those documents and the expert’s own knowledge and/or expert evidence in relation to (c) above? In the event and to the extent that the answer is “yes”, what is the answer to that issue?

4 While most of the evidence is documentary, affidavits are also in evidence. The parties agreed that the rule in Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 should be taken not to apply. No party is to be precluded from putting a proposition contrary to evidence in an affidavit merely because the proposition was not put to the deponent of the affidavit. By exchange of detailed submissions in advance of the hearing all parties are on notice of the scope of the dispute and, accordingly, no unfairness is involved in adopting this course. Further, I ordered that evidence in one proceeding is evidence in each other proceeding.

5 It is also common ground that while the insurers are the applicants, it is the insureds which are propounding facts said to engage the liability of the insurers to indemnify them. In these circumstances, it is for the insureds to prove “such facts as bring the claim within the terms of the insurer’s promise”: Wallaby Grip Limited v QBE Insurance (Australia) Limited [2010] HCA 9; (2010) 240 CLR 444 at [28] citing Munro Brice & Co v War Risks Association Ltd [1918] 2 KB 78 at 88.

6 For the reasons given below I consider that, other than in proceeding NSD133/2021 (Insurance Australia and Meridian Travel), none of the insuring clauses in any of the policies apply in the circumstances. This conclusion would not be affected by any further evidence.

7 Accordingly, I would propose to make declarations to the effect that in each proceeding other than proceeding NSD133/2021 (Insurance Australia and Meridian Travel) the insurer is not liable to make any payment in response to the claim. In NSD133/2021 (Insurance Australia and Meridian Travel) an insuring clause in the policy (referred to as an infectious disease clause as it requires the outbreak of an infectious disease within a 20 kilometre radius of the insured situation) is satisfied on the agreed facts. However, it has not been proved (and may be impossible to prove) in that case that the insured peril was a proximate cause of any interruption or interference with the business. Meridian Travel will be given an opportunity to consider its position given these reasons for judgment.

8 I have answered the separate questions in each proceeding insofar as possible. The separate questions, as discussed below, tend to obscure rather than expose important aspects of the operation of the policies. Given the nature of the proceedings as a test case, I have also set out views assuming my primary conclusions about the proper construction of the provisions of the policies are wrong.

9 On 31 December 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) was informed of a series of cases of “pneumonia of unknown etiology” detected in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China.

10 On 9 January 2020, the WHO announced that initial information about the cases of pneumonia in Wuhan provided by Chinese authorities pointed to a coronavirus as a possible pathogen causing this cluster. “Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2) is the infective agent that causes COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 is an organism.

11 On 19 January 2020, the first person with COVID-19 entered Australia. This was announced on 25 January 2020.

12 On 21 January 2020, “Human coronavirus with pandemic potential” was determined to be a listed human disease under the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Cth).

13 From 6 February 2020, “Human coronavirus with pandemic potential” has been listed on the “National Notifiable Disease List” under the National Health Security Act 2007 (Cth). COVID-19 is the name given to the disease and SARS-CoV-2 is the name given to the virus that causes the disease.

14 On 11 March 2020, the WHO described COVID-19 as a pandemic.

15 People with COVID-19 may be highly infectious before their symptoms show. Even people with mild or no symptoms can spread COVID-19.

16 There is presently no cure for COVID-19. From 25 January 2020 when the COVID-19 was first detected in Australia there was no vaccine for COVID-19. A vaccination program commenced in Australia on 22 February 2021 and is ongoing.

17 The COVID-19 virus spreads primarily through the small liquid particles expelled by a person infected with COVID-19 when they cough, sneeze, speak, sing, or breathe heavily.

18 The WHO has reported that SARS-CoV-2 spreads mainly between people who are in close contact with each other, typically within 1 metre (short-range). However, the virus can also spread in poorly ventilated and/or crowded indoor settings, where people tend to spend longer periods of time. This is because aerosols remain suspended in the air or travel farther than 1 metre (long-range).

19 A person can become infected with COVID-19 if they inhale or ingest a “sufficient load” of these liquid particles to cause infection, which can occur through: (a) close contact with an infectious person, (b) contact with droplets from an infected person’s cough or sneeze, or (c) touching objects or surfaces that have droplets from an infected person and then touching their mouth or face.

20 Coronaviruses mutate frequently.

21 A number of the parties provided convenient summaries of the principles applicable to the construction of contracts of insurance. Those summaries are adopted and adapted as follows.

22 “Contracts of insurance are to be construed according to the same principles of construction that are applied to commercial instruments in general”: Swashplate Pty Ltd v Liberty Mutual Insurance Company trading as Liberty International Underwriters [2020] FCAFC 137; (2020) 381 ALR 648 at [58].

23 “[T]he policy is to be given a businesslike interpretation, paying attention to the language used by the parties in its ordinary meaning, and to the commercial, and where relevant, the social purpose and object of the contract, in the context of the surrounding circumstances, including the market or commercial context in which the parties are operating, by assessing how a reasonable person in the position of the parties would have understood the language. Preference is to be given to a construction supplying a congruent operation to the various components of the whole”: Todd v Alterra at Lloyds Ltd (on behalf of the underwriting members of Syndicate 1400) [2016] FCAFC 15; (2016) 239 FCR 12 at [42].

24 “[A] policy of insurance is assumed to be an agreement which the parties intend to produce a commercial result … as such, it ought to be given a businesslike interpretation being the construction which a reasonable business person would give to it…a construction that avoids capricious, unreasonable, inconvenient or unjust consequences, is to be preferred where the words of the agreement permit”: Onley v Catlin Syndicate Ltd as the Underwriting Member of Lloyd’s Syndicate 2003 [2018] FCAFC 119 at [33].

25 “[T]he Court gives effect to the common intention of the parties as manifested in the language they have chosen. It requires a consideration of the language used in the instrument, the circumstances addressed by the instrument and the commercial purpose or object that the instrument secures, and it requires a consideration of the instrument as a whole”: Swashplate at [60].

26 In Liberty Mutual Insurance Company Australian Branch trading as Liberty Specialty Markets v Icon Co (NSW) Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 126 the principles were expressed in these terms:

The working out in a coherent and congruent fashion of the operation of a market specific insurance policy requires a businesslike interpretation to bring about a commercial result based on what a reasonable business person would have understood the policy to mean: Electricity Generation Corp v Woodside Energy Ltd [2014] HCA 7; 251 CLR 640 at 656–657 [35]. The principle that a policy is to be construed so as to avoid it “working commercial inconvenience”: Zhu v Treasurer (NSW) [2004] HCA 56; 218 CLR 530 at 559 [82] and so as to bring about commercial efficacy and reflect common sense: Gollin & Co Ltd v Karenlee Nominees Pty Ltd [1983] HCA 38; 153 CLR 455 at 464 is to be given concrete operation, not passing lip-service. To the extent that words used in an insurance policy have the capacity for broader or narrower operation, such constructional choice or ambiguity will be resolved by appreciating the context, including the market, in which the parties are operating, and the extent to which a reading of the words may produce commercial inconvenience or commercial efficacy as part of the ascription of meaning that would be made by a reasonable businessperson considering the language used, the surrounding circumstances known to the parties and the commercial purpose or objects of the policy as a whole to be secured: Electricity Generation Corp 251 CLR at 656–657 [35]; Homburg Houtimport BV v Agrosin Private Ltd (The Starsin) [2004] 1 AC 715 at 737 [10]. It should always be recalled, however, that a broad or a narrow meaning of a policy may only reflect the breadth or the narrowness of cover that has been purchased by the premium: cf Australasian Correctional Services Pty Ltd v AIG Australia Limited [2018] FCA 2043 at [17].

27 In the first COVID-19 insurance test case, HDI Global Specialty SE v Wonkana No. 3 Pty Ltd [2020] NSWCA 296, Meagher JA and Ball J said:

[18] Construing a written contract involves determining the intention of the parties as expressed in the words in which their agreement is recorded. As Lord Wright said in Inland Revenue Commissioners v Raphael [1935] AC 96 at 142: “It must be remembered at the outset that the court, while it seeks to give effect to the intention of the parties, must give effect to that intention as expressed, that is, it must ascertain the meaning of the words actually used”.

[19] That task is to be approached objectively. The meaning of the words used must be ascertained by reference to what a reasonable person would have understood the language of the contract to convey: Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2004) 219 CLR 165; [2004] HCA 52 at [40]; Electricity Generation Corporation v Woodside Energy Ltd (2014) 251 CLR 640; [2014] HCA 7 at [35]. That is because the objective theory of contract requires that the legal rights and obligations of the parties turn “upon what their words and conduct would reasonably be understood to convey”: Equuscorp Pty Ltd v Glengallan Investments Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 471; [2004] HCA 55 at [34], citing Lord Diplock in Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886 at 906 and Ashington Piggeries Ltd v Christopher Hill Ltd [1972] AC 441 at 502.

28 Their Honours continued in these terms:

[21] Where the written contract evidences the terms on which a financial product or service is offered for acquisition, the meaning of its language is to be construed from the perspective of a reasonable person in the position of the offeree, in this case the prospective insured. This analysis was adopted in Australian Casualty Co Ltd v Federico (1986) 160 CLR 513; [1986] HCA 32.

…

[30] There remains the contra proferentem rule which provides that any ambiguity in a policy of insurance should be resolved by adopting the construction favourable to the insured: Halford v Price (1960) 105 CLR 23 at 30; [1960] HCA 38; Darlington Futures [Darlington Futures Ltd v Delco Australia Pty Ltd (1986) 161 CLR 500] at 510; Johnson v American Home Assurance (1998) 192 CLR 266 at 275 (Kirby J, dissenting); [1998] HCA 14; McCann [McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd [2000] HCA 65; (2000) 203 CLR 579] at [74]. The justification for the rule is that the party drafting the words is in the best position to look after its own interests, and has had the opportunity to do so by clear words. It ought only be applied for the purpose of removing a doubt, and not for the purpose of creating a doubt, or magnifying an ambiguity: Cornish v Accident Insurance Co Ltd (1889) 23 QBD 453 at 456 (Lindley LJ).

[31] With acceptance of the principle that ambiguity can be resolved by reference to the surrounding circumstances, the contra proferentem rule is now generally regarded as a doctrine of last resort. However, it continues to have a role to play in insurance and other standard form contracts. That is so for two reasons. First, by their nature, standard form contracts are not negotiated between the parties, and the surrounding circumstances relevant to the entry into one contract or another are less likely to shed much light on the meaning of the written words. Secondly, the contra proferentem rule complements the principle that standard form contracts should be interpreted from the point of view of the offeree. The offeror has the opportunity to, and should, make its intentions plain. The point was made by Dixon CJ (at 30) in Halford v Price, citing with approval the following statement in Halsbury’s Laws of England (Butterworth & Co, 3rd ed, 1958) vol 22, p 214:

The printed parts of a non-marine insurance policy, and usually the written parts also, are framed by the insurers, and it is their language which is going to become binding on both parties. It is therefore their business to see that precision and clarity is attained and, if they fail in this, any ambiguity is resolved by adopting the construction favourable to the assured …

29 In Rockment Pty Ltd t/a Vanilla Lounge v AAI Limited t/a Vero Insurance [2020] FCAFC 228; (2020) 149 ACSR 484 Besanko, Derrington and Colvin JJ said at [54]:

However, disputes as to contractual interpretation necessarily imply that the ordinary meaning of the words used do not satisfactorily expose any clear construction and, in part, those opposing constructions can sometimes be assayed by reference to the commercial result which they produce. In Onley v Catlin Syndicate [Onley v Catlin Syndicate Ltd (as the underwriting member of Lloyd’s Syndicate 2003) [2018] FCAFC 119; (2018) 360 ALR 92] (at 100 – 101 [33]), the Full Court identified the principles on which insurance policies are construed, emphasising an approach that kept in mind that they are commercial agreements which the parties intend will produce a commercial result, consistent with a businesslike interpretation. In this respect, the context in which the policy is entered into, to the extent to which it is known by both parties, will assist in identifying its purpose and commercial objective: McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd (2000) 203 CLR 579 [22] per Gleeson CJ; Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd (2015) 256 CLR 104 (Mount Bruce Mining v Wright Prospecting) [47]; Franklins Pty Ltd v Metcash Trading Ltd (2009) 76 NSWLR 603 [19] per Allsop P; Evolution Precast Systems Pty Ltd v Chubb Insurance Australia Ltd [2020] FCA 1690 [25]. Nevertheless, considerations of the commerciality of any particular construction must be confined to their proper place. In Mount Bruce Mining v Wright Prospecting at 117 [50], French CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ observed:

Other principles are relevant in the construction of commercial contracts. Unless a contrary intention is indicated in the contract, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract an interpretation on the assumption “that the parties … intended to produce a commercial result”. Put another way, a commercial contract should be construed so as to avoid it “making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience”.

This approach was recently applied by the Court of Appeal in New South Wales in Wonkana at [54] per Meagher JA and Ball J; [124] – [125] per Hammerschlag J, to the effect that an interpretation is commercial if it is not commercially absurd. In other words, the topic of commerciality of a particular construction is relevant only when the lack of commerciality is so pronounced that it will indicate that some different construction must have been intended.

30 Consistent with this approach their Honours said this at [56]:

Therefore, references to a commercial result are not intended to invite a consideration of the actual financial consequences for each of the parties of a particular construction in the events which have occurred by the time that a dispute arises. Such inquiries would quickly descend into an assessment with hindsight as to what a fair and reasonable contract might provide given the circumstances that have unfolded. It would be contrary to the very certainties that the law of contract seeks to provide as to the allocation of risks, rights and obligations, if the meaning of agreements were to be adjudicated by reference to such an imprecise foundation.

31 These observations are consistent with the general principle of contractual construction emphasised in WorkPac Pty Ltd v Rossato [2021] HCA 23 at [63] citing Charter Reinsurance Co Ltd v Fagan [1997] AC 313 at 388 that “it is not a legitimate role for a court to force upon the words of the parties’ bargain ‘a meaning which they cannot fairly bear [to] substitute for the bargain actually made one which the court believes could better have been made’”.

32 Similarly in McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Limited [2000] HCA 65; (2000) 203 CLR 579 Kirby J summarised the applicable principles at [74] as including:

2 …Without the authority of statute, no court is authorised to attribute a different meaning to the words of a policy simply because the court regards the meaning as otherwise working a hardship on one of the parties.

…

4 … Courts now generally regard the contra proferentem rule (as it is called) as one of last resort because it is widely accepted that it is preferable that judges should struggle with the words actually used as applied to the unique circumstances of the case and reach their own conclusions by reference to the logic of the matter, rather than by using mechanical formulae. Nevertheless, dictionaries, facts and logic alone will sometimes not provide an answer to the contest before the court. In those cases:

“it is not unreasonable for an insured to contend that, if the insurer proffers a document which is ambiguous, it and not the insured should bear the consequences of the ambiguity because the insurer is usually in the superior position to add a word or a clause clarifying the promise of insurance which it is offering”.

33 In Darlington Futures Ltd v Delco Australia Pty Ltd [1986] HCA 82; (1986) 161 CLR 500 at 510 the High Court said:

… the interpretation of an exclusion clause is to be determined by construing the clause according to its natural and ordinary meaning, read in the light of the contract as a whole, thereby giving due weight to the context in which the clause appears including the nature and object of the contract, and, where appropriate, construing the clause contra proferentem in case of ambiguity.

34 In Dalby Bio-Refinery Ltd v Allianz Australia Insurance Limited [2019] FCAFC 85 the Full Court of the Federal Court said at [32]:

…though one needs to be careful with reliance on the contra proferentem rule, especially when there has been an evident degree of negotiation of the policy, if there are two genuinely available alternatives preference should be given to one that limits rather than expands the exclusion. That is not to approach the matter other than as dictated by the Court in Darlington v Delco 161 CLR at 510.

35 A number of the insurers sought to exclude the potential operation of the contra proferentem rule on the basis that the insureds were represented by brokers. However, I consider that the insurers remained the profferers of the policies. In Commonwealth of Australia v Aurora Energy Pty Ltd [2006] FCAFC 148; (2006) 235 ALR 644 at [41] North and Emmett JJ said:

Some reliance was placed by the parties before the primary judge on the doctrine expressed in the maxim verba chartarum fortius accipiuntur contra proferentem – the words of an instrument should be understood more strongly against the party advancing them. That maxim has nothing to do with the fortuity as to which of the parties actually composed the language in question. The construction of a promise in the common law does not depend upon who drafted the language. The maxim means simply that a promise is to be construed contrary to the interests of the person who makes the promise, irrespective of who the drafter might have been. The ‘proferens’ is, essentially, the promisor under the provision in question, whoever composes the language. The rationale for the maxim is that a party should look after its own interests in agreeing to make a promise. In the event of ambiguity, the promise is to be construed against the promisor.

36 There is also no basis upon which it could be concluded that any policy exhibits an “evident degree of negotiation”: Dalby at [32]. I do not accept that the contra proferentem rule is excluded from operating in respect of any policy. However, it remains a rule of last resort. It cannot be used to introduce ambiguity where there is none. It is only if ambiguity exists that the rule may have some role to play. It is only if there are “two genuinely available alternatives” that preference should be given to one that “limits rather than expands the exclusion”: Dalby at [32]. Otherwise, ambiguities are to be resolved according to the applicable general principles which include the contra proferentem rule.

37 The parties also referred extensively to other decisions, including (in particular) Wonkana, Rockment, Financial Conduct Authority v Arch Insurance (UK) Ltd [2020] EWHC 2448 (Comm) (FCA v Arch EWHC), Financial Conduct Authority v Arch Insurance (UK) Ltd [2021] UKSC 1 (FCA v Arch UKSC), as well as Hyper Trust Limited t/as the Leopards Town Inn & Ors v FBD Insurance plc [2021] IEHC 78 (Hyper Trust No 1), and Hyper Trust Limited t/as the Leopards Town Inn & Ors v FBD Insurance plc (No 2) [2021] IEHC 279 (Hyper Trust No 2). Given the use that was sought to be made of the other decisions, particularly FCA v Arch UKSC, certain observations in other cases identified by the respondent in NSD308/2021 should be noted.

38 In In re Coleman’s Depositories Ltd and Life & Health Assurance Association [1907] 2 KB 798 at 812 Buckley LJ said “[t]he question is one of construction, and upon such a question authorities are of little or no value. Authorities may determine principles of construction, but a decision upon one form of words is no authority upon the construction of another form of words”. In In re an Arbitration between Calf and the Sun Insurance Office [1920] 2 KB 366 at 382 Atkin LJ made the same point, saying “…on a question of construction I protest against one case being treated as an authority in another unless the language and the circumstances are substantially identical”. In Australian Casualty Co Ltd v Federico [1986] HCA 32; (1986) 160 CLR 513 the High Court expressed the same view, saying at 525 that the task of construction required:

…a consideration of what the words of the policy convey, as a matter of contemporary language read in the context of the whole policy, to a reasonable non-expert in this country. If that meaning is plain, it can be of but limited significance if, at other times and in other places, other courts, however eminent, have held that similar words in other policies were to be construed as having had some different meaning.

39 I also consider that the issues in dispute are not to be answered at the level of generality inherent in submissions made by the insurers such as “the policy is not intended to cover/exclude from cover the effects of a pandemic”. Rather, consideration of the meaning of the relevant clauses of the policy is required without pre-conceptions about pandemics one way or another. I do not consider that the Full Court in Rockment intended to suggest otherwise when they said at [59] that:

Cover for loss arising from the consequence of a pandemic disease could for an insurer be, as in the case of pollution, a high risk which would normally be excluded: Derrington D and Ashton R, The Law of Liability Insurance (3rd ed, LexisNexis, 2013) 10-2 p 1828: or specifically included only at an appropriately priced premium. The risk could be heightened by the indeterminacy of the period during which a highly infectious disease might disrupt business and, consequently, the amount of loss which the insured might suffer. In this sense, a construction which makes the presence of Avian Influenza or of the emergency the trigger of the Exclusion reasonably promotes its purpose. Conversely, that reasonably commercial purpose is not advanced by a construction which would confine the Exclusion to a narrow operation in relation to the presence of a highly infectious disease.

40 At [63] in Rockment the Full Court said “Courts could expect that insurers are not likely to offer high-risk cover for matters such as pollution or pandemics, save pursuant to express provisions”. These observations, however, were made in the context of close consideration of the relevant provisions in the policy in issue in Rockment. They were not made as a free-standing statement of principle. The insureds’ arguments in the present case are that the express provisions of the policies provide cover in the circumstances relevant to each insured. Whether that is so or not is not to be answered by applying any pre-conceived statement of general principle and without consideration of each relevant provision of each policy.

41 The insurance policies use various words to describe the causal relationship which must exist between the elements of the insured perils (in consequence of, consequent upon, as a result of, likely to result in, caused by, caused by or results from, resulting from, in direct consequence of, arising from, leading to, arising directly or indirectly from). The elements of the insured perils also require other relationships to exist which are not causal, such as temporal relationships (for example, during), spatial relationships (for example, at a location, within a specified radius), physical relationships (such as preventing, restricting), and substantive relationships (for example, by order).

42 In FCA v Arch UKSC at [320] Lord Briggs JSC said:

The question whether particular consequential harm to a policyholder is subject to indemnity is as much a part of the process of interpreting their bargain as is the identification of the insured peril. It is therefore a quite distinct process from, for example, applying the law about causation and remoteness of loss for the purpose of identifying the harm liable to be made good by tortfeasors to their victims. In terms intelligible to non-lawyers, the question is: for what loss have the parties agreed that the insurers should compensate the policyholders as the result of the occurrence of the insured peril? Both the insured peril and the covered loss lie at the very heart of the contract of insurance, and the process of construction requires that they be addressed together.

43 Where a required relationship is causal, it is generally accepted that the parties to a policy of insurance intend that a proximate causal relationship will suffice even if the cause must be “direct”. A proximate causal relationship involves a search for a “real”, “effective”, “dominant” or “most efficient” cause, even if there are other proximate causes. Depending on the words used, something less than a proximate causal relationship may also suffice (particularly if the contemplated causal requirement may be either direct or indirect). I have kept this in mind below where I refer to “cause” rather than proximate cause.

44 In Lasermax Engineering Pty Limited v QBE Insurance (Australia) Limited & 2 Ors [2005] NSWCA 66; (2005) 13 ANZ Insurance Cases 61-643 McColl JA (with whom Ipp and Tobias JJA agreed) summarised the applicable principles in these terms:

(1) [i]n the law of insurance it early became, and has remained, the rule to look to the proximate and not the remote cause of loss or damage in order to determine the liability of underwriters (causa proxima non remota spectatur) [the immediate cause, and not the remote cause, is to be considered]: [39];

(2) in this context, the words “proximate cause” and “direct cause” came to be used interchangeably: [41];

(3) as Gibbs CJ said in Federico at 521 “… the words ‘caused by an accident’ naturally refer to the proximate or direct cause of the injury, and not to a cause of the cause, or the mere occasion of the injury”: [42];

(4) proximate in this context meant proximate in efficiency rather than in time: [44];

(5) the proximate cause rule was not divorced in the cases from the terms of the particular policy under consideration but was based upon the inferred common intention of the parties and would not apply if it would defeat the manifest intention of the parties: [45]; and

(6) it is consistent with this approach that the proximate cause rule is capable of applying even where the word “directly” expressly qualifies the word “cause” in a policy: [46].

45 In Sheehan v Lloyds Names Munich Re Syndicate Ltd [2017] FCA 1340 at [77] Allsop CJ summarised the relevant principles as follows:

The causal inquiry in insurance law is directed to the proximate cause of the relevant loss or damage. This means proximate in efficiency, not the last in time: Leyland Shipping Co Ltd v Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society Ltd [1918] AC 350 at 369 per Lord Shaw; Global Process Systems Inc v Syarikat Takaful Malaysia Berhad (The “Cendor MOPU”) [2011] UKSC 5; 1 Lloyds Rep 560 at 564 [19] per Lord Saville and 568 [49] per Lord Mance. A proximate cause is determined based upon a judgment as to the “real”, “effective”, “dominant” or “most efficient” cause: see Leyland Shipping [1918] AC at 370 per Lord Shaw; Wayne Tank and Pump Co Ltd v Employers Liability Assurance Corp Ltd [1974] QB 57 at 66 per Lord Denning MR. What is the proximate cause is to be decided as a matter of judgment reached by applying the commonsense knowledge of a business person or seafarer: see The “Cendor MOPU” [2011] l Lloyds Rep at 564 [19] per Lord Saville and 568 [49] and 576 [79] per Lord Mance. There does not need to be a single dominant, proximate or effective cause of loss or damage: McCarthy v St Paul International Insurance Co Ltd [2007] FCAFC 28; 157 FCR 402 at 430 [90]. In City Centre Cold Storage Pty Ltd v Preservatrice Skandia Insurance Ltd (1985) 3 NSWLR 739 (referred to in McCarthy 157 FCR at 430 [90]), Clarke J at 745 approached the question as follows:

… to determine in the first instance whether there is one effective cause. But, recognising that in the present case there are a number of contributing causes, I do not propose straining to isolate one if it seems to me that two or more causes operated with approximately equal effect.

46 In FCA v Arch UKSC Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt JJSC observed at [162] that:

Many different formulations may be found in insurance policy wordings of the required connection between the occurrence of an insured peril and the loss against which the insurer agrees to indemnify the policyholder… We do not think it profitable to search for shades of semantic difference between these phrases. Sometimes the policy language may indicate that a looser form of causal connection will suffice than would normally be required, such as use of the words “directly or indirectly caused by”: see e g Coxe v Employers’ Liability Assurance Corpn Ltd [1916] 2 KB 629…. But it is rare for the test of causation to turn on such nuances. Although the question whether loss has been caused by an insured peril is a question of interpretation of the policy, it is not (unlike the questions of interpretation of the disease, hybrid and prevention of access clauses considered above) a question which depends to any great extent on matters of linguistic meaning and how the words used would be understood by an ordinary member of the public. What is at issue is the legal effect of the insurance contract, as applied to a particular factual situation.

47 In Coxe v Employers’ Liability Assurance Corpn Ltd [1916] 2 KB 629 Scrutton J said at 633-634:

…to all policies of insurance…the maxim causa proxima non remota spectator is to be applied if possible. The immediate cause must be looked at, and not one or more of the variety of the causes which if traced without limit might be said to go back to the birth of the assured. For that reason, when there are words which at first sight go a little further they are still construed in accordance with that universal maxim.

…

The words … “caused by” and “arising from” do not give rise to any difficulty. They are words which always have been construed as relating to the proximate cause… But the words which I find it impossible to escape from are “directly or indirectly”. …I find it impossible to reconcile them with the maxim causa proxima non remota spectator…I am unable to understand what is an indirect proximate cause …the only possible effect which can be given to those words is that the maxim…is excluded and that a more remote link in the chain of causation is contemplated than the proximate and immediate cause.

But a line must be drawn somewhere.

48 Similarly, in Star Entertainment Group Limited v Chubb Insurance Australia Ltd [2021] FCA 907 Allsop CJ noted that “[t]he relational prepositional phrase ‘resulting from’ is wider than a proximate cause, requiring a common sense evaluation of a causal chain: Kooragang Cement Pty Ltd v Bates (1994) 35 NSWLR 452 at 463-464”. See also Davies, M ‘Proximate Cause in Insurance Law’ (1996) 7 Insurance Law Journal 135 in which the author said “[w]here the policy uses the words “results from” or “resulting from”, it is not enough that the insured peril merely creates a predisposition for the loss to occur, but it is sufficient if there is an unbroken causal chain between peril and loss and if the peril provides the relevant causal explanation of the loss”, citing Kooragang Cement.

49 In FCA v Arch UKSC Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt JJSC continued at [168]:

The question whether the occurrence of such a peril was…the proximate (or “efficient”) cause of the loss involves making a judgment as to whether it made the loss inevitable - if not, which could seldom if ever be said, in all conceivable circumstance - then in the ordinary course of events. For this purpose, human actions are not generally regarded as negativing causal connection, provided at least that the actions taken were not wholly unreasonable or erratic.

50 It is now orthodox that there may be more than one proximate cause of loss: McCarthy v St Paul International Insurance Co Ltd [2007] FCAFC 28; (2007) 157 FCR 402 at [88]-[92] per Allsop J (as he then was). As his Honour also explained, where there is more than one proximate cause of an event it is necessary to consider if the policy excludes cover for one of the proximate causes, referring to Wayne Tank and Pump Co Ltd v Employers’ Liability Assurance Corporation [1974] QB 57. His Honour identified that:

(1) when an argument as to causation arises in respect of rival causes under a policy of insurance, the first task of the Court is to look to see whether only one of the causes can be identified as the proximate or efficient cause: [91];

(2) if, applying common-sense principles and recognising the commercial nature of the insurance policy that is the context of the question, two causes can be seen as proximate or efficient, the terms of the policy must then be applied to those circumstances: [91];

(3) if there are two concurrent causes one falling within the policy, the other simply not covered by the terms of the policy, the insured may recover: [91];

(4) if there are two concurrent causes, one falling within the policy, the other excluded from the policy, consideration must be given to the principle in Wayne Tank: [92];

(5) Wayne Tank concerned concurrent and interdependent causes (in that neither cause would have caused the loss but for the other cause), one within the policy and one excluded by the policy. Effect was given to the terms of the contract by applying the exclusion. This can be seen as a result of the fact that the concurrent causes were interdependent: [96];

(6) more difficulty will arise in a case involving independent concurrent causes one of which is within the policy and the other of which is excluded: [104]; and

(7) it is “always essential to pay close attention to the terms of any policy and the commercial context in which it was made, for it is out of these matters that the answer to the application of the policy to the facts will be revealed”: [104]; and

(8) “[o]nce one concludes that, as a matter of construction of the contract, the insurer and insured have agreed that the cover does not extend to any loss caused by a particular cause, and that the loss was caused by that cause, the policy’s lack of response can be seen as evident. It is only if one concludes that the parties have agreed that the policy will not respond if the excluded cause must be the sole cause, for the existence of a concurrent and not excluded cause to be relevant. Again this is a question of construction of the policy”: [114].

51 The same approach is taken in FCA v Arch UKSC at [171]-[176].

52 In the present matter, other than in one case, NSD144/2021 Guild and Gym Franchises, none of the parties drew any distinction between the different causal connectors used in the various insuring provisions. They proceeded on the basis that the principle of proximate cause applied. In those cases, even if a somewhat lesser causal connection than proximate cause would suffice, that lesser causal standard could make no difference to the conclusions reached. The common-sense approach to causation in those cases indicates that there is not the requisite causal connection. In NSD144/2021 Guild and Gym Franchises, however, the causal connection required is much looser, being “arising directly or indirectly from”. In that case, the difference is substantive, as indirect causation would encompass a far more expansive causal chain.

3.3 Causation in FCA v Arch UKSC

53 The parties relied on those parts of the reasoning in FCA v Arch UKSC which suited their purposes.

54 FCA v Arch UKSC contains much which is useful. However, it is necessary to recognise that their Lordships’ reasoning depended on the proper construction of specific insuring clauses in the context of the policies as relevant in that case.

55 The relevant context in FCA v Arch UKSC includes that the United Kingdom has a unitary system of government. Relevant actions were taken by the UK Government and others taken applied, for example, to the whole of the United Kingdom, the whole of England, or the whole of Wales: see FCA v Arch UKSC at [9]-[35]. Further, England and Wales are small in area and densely populated. At [179] Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt JJSC said:

As the FCA has pointed out, the area described by the disease clauses which refer to a radius of 25 miles of the business premises is an area of a little under 2,000 square miles. To put this in perspective, this is bigger than any city in the UK, more than three times the size of Surrey, roughly the combined size of Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire, and around a quarter of the area of Wales. The FCA produced a map to show that the whole of England can be covered, more or less, by just 20 circles each with a 25-mile radius. Nevertheless, if - as the insurers submit - the relevant test in considering the Government measures taken in March 2020 is to ask whether the Government would have acted in the same way on the counterfactual assumption that there were no cases of Covid-19 within 25 miles of the policyholder’s premises but all the other cases elsewhere in the country had occurred as they in fact did, the answer must, in relation to any particular policy, be that it probably would have acted in the same way. As already mentioned, the court below found as a fact (at para 112 of the judgment) that the Government response was a reaction to information about all the cases of Covid-19 in the country and that the response was decided to be national because the outbreak was so widespread. In these circumstances it is unlikely that the existence of an enclave with a radius of 25 miles in any one particular area of the country which was so far free of Covid-19 would have led to that area being excepted from the national measures or otherwise have altered the Government’s response to the epidemic. That in turn means that in the vast majority of cases it would be difficult if not impossible for a policyholder to prove that, but for cases of Covid-19 within a radius of 25 miles of the insured premises, the interruption to its business would have been less.

56 It is an important part of the context of the decision in FCA v Arch UKSC that the outbreak of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom was “so widespread”. It is in that context that their Lordships observed that:

Thus, in the present case it obviously could not be said that any individual case of illness resulting from Covid-19, on its own, caused the UK Government to introduce restrictions which led directly to business interruption. However, as the court below found, the Government measures were taken in response to information about all the cases of Covid-19 in the country as a whole. We agree with the court below that it is realistic to analyse this situation as one in which “all the cases were equal causes of the imposition of national measures” (para 112).

57 They continued in these terms

[181] We agree with counsel for the insurers that in the vast majority of insurance cases, indeed in the vast majority of cases in any field of law or ordinary life, if event Y would still have occurred anyway irrespective of the occurrence of a prior event X, then X cannot be said to have caused Y. The most conspicuous weakness of the “but for” test is not that it wrongly excludes cases in which there is a causal link, but that it fails to exclude a great many cases in which X would not be regarded as an effective or proximate cause of Y….

[182] It has, however, long been recognised that in law as indeed in other areas of life the “but for” test is inadequate, not only because it is over-inclusive, but also because it excludes some cases where one event could or would be regarded as a cause of another event.

58 At [190] their Lordships made this fundamental point:

Whether an event which is one of very many that combine to cause loss should be regarded as a cause of the loss is not a question to which any general answer can be given. It must always depend on the context in which the question is asked. Where the context is a claim under an insurance policy, judgements of fault or responsibility are not relevant. All that matters is what risks the insurers have agreed to cover. We have already indicated that this is a question of contractual interpretation which must accordingly be answered by identifying (objectively) the intended effect of the policy as applied to the relevant factual situation.

59 In other words, the text and the context of the particular policy is determinative.

60 Their Lordships also said this at [195]:

We do not consider it reasonable to attribute to the parties an intention that in such circumstances the question whether business interruption losses were caused by cases of a notifiable disease occurring within the radius is to be answered by asking whether or to what extent, but for those cases of disease, business interruption loss would have been suffered as a result of cases of disease occurring outside the radius. Not only would this potentially give rise to intractable counterfactual questions but, more fundamentally, it seems to us contrary to the commercial intent of the clause to treat uninsured cases of a notifiable disease occurring outside the territorial scope of the cover as depriving the policyholder of an indemnity in respect of interruption also caused by cases of disease which the policy is expressed to cover. We agree with the FCA’s central argument in relation to the radius provisions that the parties could not reasonably be supposed to have intended that cases of disease outside the radius could be set up as a countervailing cause which displaces the causal impact of the disease inside the radius.

61 This passage is critical to understanding the reasoning in FCA v Arch UKSC about causation in respect of the actions of the UK Government. It discloses that the Court assumed or was confronted with a material number of cases of COVID-19 inside and outside of the relevant areas. On this basis, to infer that each and every case (both inside and outside the area) was an equally effective cause of the actions of the UK Government is rational. Given the facts in FCA v Arch UKSC of: (a) a small in area and densely populated country, (b) a national outbreak of COVID-19, (c) material numbers of cases inside and outside of the specified areas, their Lordships reasoned that: (d) even if there were no cases within the specified areas the UK Government would still have taken the actions it did including in respect of those areas, and (e) by inference, the cases inside the specified areas would also have caused the UK Government to take the actions it did, at the least in respect of those areas. The issue was one of two concurrent sufficient causes of the UK Government actions.

62 In the present case, the policies were all made in the context of the Australian constitutional system. The Australian constitutional system is a federal system. The Commonwealth Government and the State and Territory Governments have their own fields of operation. The State and Territory Governments, in accordance with their constitutional mandates, act for the good governance of the State or Territory. The actions the Commonwealth Government is empowered to take are different from the actions the State and Territory Governments are empowered to take. The parties to the policy must be taken to have understood this fact.

63 In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the kinds of actions the Commonwealth Government was empowered to take included banning and restricting international travel and banning and restricting Australian residents from leaving Australia. The kinds of actions the State and Territory Governments were empowered to take included requiring businesses in the State or Territory to cease operating, requiring certain premises in the State or Territory to close, and requiring certain premises in the State of Territory to regulate the number of persons on the premises.

64 The policies were also made in the geographical context of Australia. Australia is large and in many areas is sparsely populated. A 5, 25 or 50 kilometre radius around premises may or may not include a densely populated area. The parties to the policy must also be taken to have understood this fact.

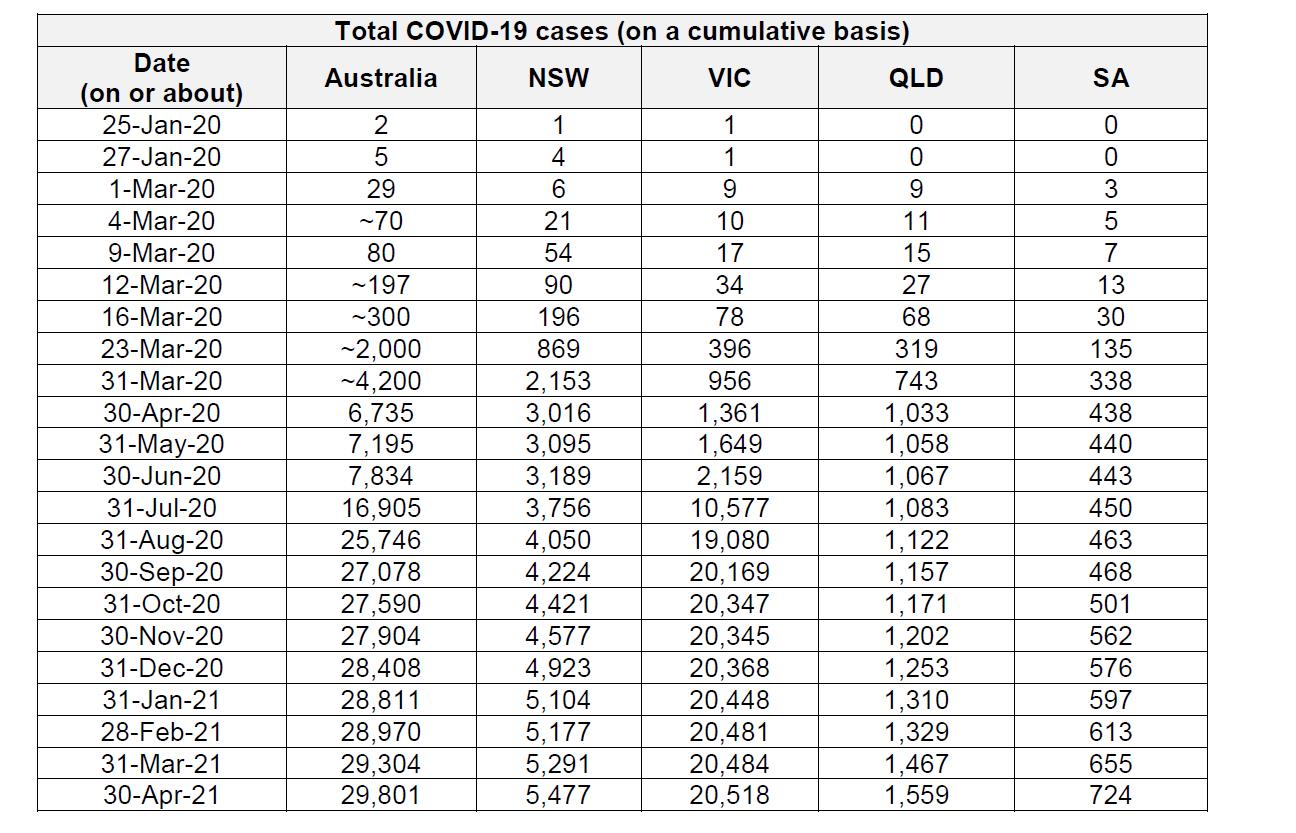

65 Further, and as the evidence discloses, the factual context of the presence of COVID-19 cases in Australia in 2020 was different from the widespread outbreak that occurred in the United Kingdom. The agreed facts include this information about cases of COVID-19 in Australia. The numbers are cumulative. The table does not distinguish between cases associated with community transmission, overseas acquisition, interstate acquisition or cases acquired or located in hospital, hotel quarantine or self-isolation.

66 Given the total population of Australia (say, 26 million people) it is apparent that it could not be said that the occurrence of COVID-19 cases in Australia was widespread. The numbers do indicate, however, the highly contagious nature of COVID-19.

67 As noted, it is also apparent in FCA v Arch UKSC that it was a given that there were cases of COVID-19 within the area identified by the policies (the radius as specified). This is apparent from the reasoning in FCA v Arch UKSC at [179]-[197]. The existence of cases of COVID-19 inside and outside of the specified areas (defined by a radius around the premises) was part of the assumed or undisputed context. On that basis, the actions of the government could be tested by asking would the government have acted as it did if there were no cases within the radius, to which their Lordships’ answer in the circumstances was “yes”. It is this fact which made the “but for” test inapplicable. The underlying fact which is also assumed in this reasoning is that there were enough cases of COVID-19 within the specified radius to have caused the Government to take the same actions with respect, at the least, to that area: see, in particular, the last sentence of [195] set out above.

68 None of these facts or assumptions apply in the present case. The context is materially different from that which underpins this aspect of the reasoning in FCA v Arch UKSC. As will be explained, it cannot be concluded in the context of these matters that each and every known case of COVID-19 in any location in a State was an equally effective cause of the State government actions (in contrast to the threat or risk to each and every person in a State presented by known and unknown cases of COVID-19 given its highly contagious nature).

69 There is another important distinction between the circumstances in FCA v Arch UKSC and the present case. As noted, the context in FCA v Arch UKSC was events which justified the description of “the national outbreak of Covid-19”: [219]. On that basis, Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt JJSC said at [220]:

It seems to us that, having correctly identified the fortuity covered by the insurance as a situation in which all three interconnected elements are present, the court erred by adopting a test which does not reflect that fortuity. The effect of “stripping out” all three elements in considering what the position of the business would have been but for the occurrence of the insured peril is to ask what its position would have been if none of those elements had occurred - including, as the court said, the national outbreak of Covid-19. That, however, is to treat the insured peril as being, not the risk of all three elements occurring (in causal sequence), but the risk of any one or more of the elements occurring. That would include a situation where there was an outbreak of a notifiable disease which caused interruption and loss to the business but which did not lead to any restriction being imposed that resulted in inability to use the premises. That is not the indemnity which the insurer agreed to give.

70 This may readily be accepted; to do otherwise would be to re-write the insuring provisions.

71 Their Lordships continued to examine the causal requirements of the insuring provisions in these terms:

[227] Once it is recognised that the approach for which Hiscox contends logically requires assuming in the counterfactual scenario the imposition of all the restrictions which were in fact imposed by the Government but that those restrictions did not require the insured premises to close, it can readily be seen that this approach is just as open to criticism as that of the court below. That is because it treats the insured peril as the risk that, if there was an outbreak of a notifiable disease sufficiently serious to lead a public authority to impose restrictions, the only effect of those restrictions (and of the outbreak of disease) would be to cause business interruption through inability to use the insured premises. On Hiscox’s interpretation of its policy wording, to the extent that the imposition of the restrictions and/or the outbreak of disease would have caused business interruption anyway even if the policyholder had remained able to use the premises, the interruption is not covered by the policy. In the present case the indemnity is thus confined on this interpretation to loss that would have been avoided if Covid-19 and its consequences, including the imposition of the Government restrictions, had all occurred as they actually did save that the policyholder had (uniquely) been allowed to keep its premises open. No reasonable policyholder would have understood the insurance cover which it was getting to be insurance against such a narrow and fanciful risk. If Hiscox’s interpretation were correct, it would make the public authority clause in the Hiscox policies a wholly uncommercial form of insurance which we cannot imagine that any insurer would see any sense in offering or that anyone running a business would see any sense in buying.

…

[239] We agree and consider the underlying explanation to be that, where insurance is restricted to particular consequences of an adverse event (such as in this example the discovery of vermin in the premises) the parties do not generally intend other consequences of that event, which are inherently likely to arise, to restrict the scope of the indemnity.

…

[243] The conclusion we draw is that, properly interpreted, the public authority clause in the Hiscox policies indemnifies the policyholder against the risk (and only against the risk) of all the elements of the insured peril acting in causal combination to cause business interruption loss; but it does so regardless of whether the loss was concurrently caused by other (uninsured but non-excluded) consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic which was the underlying or originating cause of the insured peril.

[244] This interpretation, in our opinion, gives effect to the public authority clause as it would reasonably be understood and intended to operate. For completeness, we would point out that this interpretation depends on a finding of concurrent causation involving causes of approximately equal efficacy. If it was found that, although all the elements of the insured peril were present, it could not be regarded as a proximate cause of loss and the sole proximate cause of the loss was the Covid-19 pandemic, then there would be no indemnity. An example might be a travel agency which lost almost all its business because of the travel restrictions imposed as a result of the pandemic. Although customer access to its premises might have become impossible, if it was found that the sole proximate cause of the loss of its walk-in customer business was the travel restrictions and not the inability of customers to enter the agency, then the loss would not be covered.

…

72 Their Lordships applied the same analysis to the trends in business clauses which required the loss to be calculated on a basis taking into account the trends and circumstances affecting the business excluding the insured peril. Their Lordships said:

[268] How then are the trends clauses to be construed so as to avoid inconsistency with the insuring clauses? In our view, the simplest and most straightforward way in which the trends clauses can and should be so construed is, absent clear wording to the contrary, by recognising that the aim of such clauses is to arrive at the results that would have been achieved but for the insured peril and circumstances arising out of the same underlying or originating cause. Accordingly, the trends or circumstances referred to in the clause for which adjustments are to be made should generally be construed as meaning trends or circumstances unrelated in that way to the insured peril.

…

287 For the reasons given, we consider that the trends clauses in issue on these appeals should be construed so that the standard turnover or gross profit derived from previous trading is adjusted only to reflect circumstances which are unconnected with the insured peril and not circumstances which are inextricably linked with the insured peril in the sense that they have the same underlying or originating cause. Such an approach ensures that the trends clause is construed consistently with the insuring clause, and not so as to take away cover prima facie provided by that clause.

[288] We therefore reach a similar conclusion to the court below, by a slightly different route. We consider, as they did, that the trends clauses do not require losses to be adjusted on the basis that, if the insured peril had not occurred, the results of the business would still have been affected by other consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

73 In the present case, the insurers maintained that this approach should not be adopted. Rather, the “but for” the insured peril approach in Orient-Express Hotels Ltd v Assicurazioni Generali SA [2010] Lloyd’s Rep IR 531 should be applied. For reasons which will be given, I consider the approach to causation and trends in business clauses in FCA v Arch UKSC to be compelling.

74 However, the persuasiveness of this aspect of their Lordships’ reasoning depends on the fact of the cause or underlying fortuity giving rise to the insured peril being the same as the cause or underlying fortuity giving rise to the uninsured peril. It is the identity of those two matters which enabled it to be concluded that requiring causation of loss and the circumstances affecting the business to exclude the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic would make for “a wholly uncommercial form of insurance”: FCA v Arch UKSC at [227]. Once there is not sameness or identity between the cause or underlying fortuity giving rise to the insured peril and the cause or underlying fortuity giving rise to the uninsured peril, there is nothing uncommercial in a policy operating to require that causation of loss and the circumstances affecting the business be assessed, including the effects of the uninsured peril.

75 On the facts in FCA v Arch UKSC the insured perils, as already noted, were characterised as the “national COVID-19 pandemic”. This made sense in the factual and legal context in the United Kingdom. In the Australian context, however, we have the Commonwealth Government exercising Commonwealth powers and the State and Territory Governments exercising State and Territory powers. The criteria for the exercises of these powers are different and the geographical application of the exercise of these powers is also different. Further, on the facts in Australia, it is not possible to identify the cause of all exercises of governmental power at the same level of generality as in FCA v Arch UKSC as the “national COVID-19 pandemic”.

76 As will be explained, in respect of relevant Commonwealth Government actions the uninsured peril was the existence of COVID-19 cases overseas and the threat this presented to Australia by reason of persons (including travelling Australian residents) from overseas entering Australia. In respect of State actions, the uninsured peril was the existence of COVID-19 cases in the State (known) and the associated threat or risk of COVID-19 to persons (from cases both known and unknown) across the State as a whole.

77 In respect of relevant Commonwealth Government actions it is not possible, in my view, to characterise the cause or underlying fortuity giving rise to the insured peril and the cause or underlying fortuity giving rise to the uninsured peril as the same. Nothing in the text or context of the insuring provisions supports the conclusion that the cause of the insured peril is able to be characterised as the existence of COVID-19 cases overseas and the threat this presented to Australia by reason of persons (including travelling Australian residents) from overseas entering Australia.

78 I have reached a different conclusion in respect of the actions of the State Governments. In each case I have concluded, on the facts, that the cause of the State Government action was the existence of COVID-19 cases in the State (known) and the associated threat or risk of COVID-19 to persons (from cases both known and unknown) across the State as a whole. This characterisation has a number of important consequences.

79 First, it means that, on the basis of the facts, it has not been possible to conclude that any State Government action was caused by, or resulted from, or was in consequence of, the existence of any case of COVID-19 at the location or within area required by the insuring provisions. To the extent any insuring provision required the action of an authority to be caused by, to result from, or be in consequence of an occurrence or outbreak of COVID-19 at a specific location or within a specified area, I have been unable to reach such a conclusion. In particular, on the facts of each case, I am unable to conclude that each and every case of COVID-19, including any case within the area required by the insuring clause, was an equally effective cause of the taking of the State Government action.

80 Second, it means, on the basis of the facts, that I have concluded that the relevant State Government actions were caused by the existence of COVID-19 cases in the State (known) and the associated threat or risk of COVID-19 to persons (from cases both known and unknown) across the State as a whole. That is, I infer that the State Governments acted because they knew cases of COVID-19 existed in certain locations in the State (but not every location in the State) and because they considered that there was a threat or risk of COVID-19 to persons (from cases both known and unknown) across the State as a whole.

81 On this basis, in my view, the State Government actions were caused by or resulted from or were in consequence of the threat or risk of COVID-19 to persons in each and every part of the State including, logically, at or within the location or area required by the insuring provisions. Accordingly, an insuring provision requiring the action of the authority to be caused by or result from or be in consequence of the threat or risk of infectious or contagious disease at a location or within a specified area is satisfied, as the threat or risk to each and every person is an equally effective cause of the action of the State Government.

82 Third, in dealing with the application of the principles of causation and trends in business clauses to the assessment of loss, this distinction between Commonwealth and State means that in the case of action of the Commonwealth Government the cause or fortuity underlying the insured perils is different from the cause or fortuity underlying the uninsured perils. The insured perils concern action of an authority caused by, resulting from or in consequence of infectious or contagious diseases at a location or within a specified area. That is not the same as the cause of the uninsured peril if that uninsured peril involves the actions of the Commonwealth Government, involving actions caused by the existence of COVID-19 cases overseas and the threat this presented to Australia by reason of persons (including travelling Australian residents) from overseas entering Australia.

83 These latter considerations matter (albeit in different ways) in NSD133/2021 Insurance Australia and Meridian Travel, NSD135/2021 Allianz and Mayberg, and NSD308/2021 QBE v Coyne (EWT).

3.4.1 Occurrence/outbreak and risk/threat

84 It will also become apparent that there is an important distinction to be drawn between insuring provisions which depend on an occurrence or outbreak of an infectious or contagious disease within an area and insuring provisions which depend on the threat or risk of an occurrence or outbreak of an infectious or contagious disease within an area. The two concepts are different. Care must be taken not to elide the difference between the two. In particular, as will be explained, where the geographical area is large and the relative number of cases of COVID-19 within the community has been small (at least compared to the widespread outbreak described in the United Kingdom in FCA v Arch UKSC), there is a difference between assessing whether government actions were taken in response to the actual outbreak or occurrence of COVID-19 within a specified area and assessing whether government actions were taken in response to the threat or risk of the spread of COVID-19 across a wide area such as a State.

3.4.2 Role of an authority in hybrid clauses

85 Another important matter is that hybrid clauses depend on the actions of an authority of some kind. Generally, the action must be a result of an occurrence or outbreak of an infectious or contagious disease. In this context, it is important to recognise that the focus of the insuring clause is on the action of the authority. That action must result from the disease. There is a difference between an action resulting from a thing (a disease) and the existence of the thing (the disease). An action of an authority can result from a disease even if the authority is mistaken about the disease.

86 As discussed below, while I would not conclude that the parties to an insurance policy intended that the actions of an authority taken arbitrarily, capriciously or in bad faith would determine liability under the policy, subject to those matters, where parties have made an insuring provision depend on the action of an authority resulting from some or other thing, they have effectively committed themselves to accept the view of the authority about the thing. This is important because, while the thing in question (the disease) must logically exist before the action for the action to result from the thing, explaining a required causal sequence as starting with the objective existence of the thing (the disease), as the insureds do in these matters, is inaccurate because it suggests that it is the objective existence of the thing (the disease) which is determinative. It also suggests that the parties contemplated that they would be able to go behind the action of the authority to determine whether the authority was right or wrong about there being an occurrence or an outbreak of the disease.

87 I do not accept that this is how the insuring clauses were intended by the parties to operate. It does not accord with the language used (usually, action resulting from [disease as specified]) which, in its terms, focuses upon the reason the authority took the action. It does not accord with a common-sense and business-like interpretation of the provisions. The provisions are intended to operate where an authority takes action because of a thing which causes the interruption or interference to the business which causes loss. If an authority acts because of a thing, and the action does interrupt or interfere with the business, and loss is in fact suffered, on what basis could it be inferred that the parties to the policy intended to exclude loss merely because, acting in good faith, the authority is subsequently able to be proved to have made a mistake? In my view, there is no commercially sensible basis upon which it could be concluded that cover was to be excluded, subject only to some clear indication in the policy to the contrary. As noted, I accept that actions of an authority which have been taken arbitrarily, capriciously or in bad faith may not ordinarily have been intended by the parties to be covered, but those concepts are irrelevant in the present case.

88 For this reason, evidence of facts not known to an authority or not relied on by an authority in deciding to take action are likely to be of little use. In such provisions, it is the actions of the authority and what those actions in fact resulted from which are of central importance. Given the nature of the provisions as part of a contract of indemnity I would also conclude that the parties intended that the causal requirement (an action of an authority resulting from some or other thing) would be objectively determined by reference to what the authority in fact did, what it said about what it did at the time it took the action, and the contemporaneous circumstances as may be inferred to have been known to and considered by the authority at the time it acted. The parties could not have intended that they would be able to identify the subjective state of mind of the authority or, as I have said, that they would be able to go behind what the authority did to prove that the authority was wrong.

89 Accordingly, the question of what the actions of an authority resulted from is best answered by reference to what the authority did, why the authority said it did what it did, and other contemporaneous explanations and circumstances casting light upon the actions of the authority. It is not answered by subsequent unearthing of facts or opinions not known to or considered by the authority at the time it took the actions.

90 The context within which these words appear will determine their meaning.

91 Absent a textual or contextual indicator that the words should be taken to be interchangeable, they have a different meaning. The meaning is disease dependent.

92 For COVID-19 key facts are: (a) COVID-19 is highly contagious in a non-controlled environment (that is, not in a hospital, quarantine or isolation), (b) people are likely to be infectious with COVID-19 before they become aware of symptoms, and (c) accordingly, the risk to public health was not from known cases of COVID-19 alone but was also from unknown cases of COVID-19.

93 These facts may be inferred to have been known to relevant authorities within Australia before they took action relating to COVID-19.

94 In a hybrid clause, the focus is not on the objective existence of an outbreak or occurrence of COVID-19 but on the causal relationship between the action of the authority and the circumstances relating to COVID-19 which caused the authority to act.

95 An “occurrence” of COVID-19 would mean an event or case of COVID-19 in any setting. That is, it would not matter if the case of COVID-19 was in a controlled environment (such as a hospital, quarantine or isolation). The fact that the risk of transmission of COVID-19 would be low due to the controlled setting would be immaterial.

96 An “outbreak” of COVID-19 would require more than an “occurrence” of COVID-19. The difference between my conclusions and the submissions of the insurers is that the insurers contended that an “outbreak” of COVID-19 requires a confirmed case of transmission in the community (that is, in a non-controlled setting) of COVID-19. I consider that an “outbreak” of COVID-19 requires only a case of active (that is, infectious) COVID-19 in the community (that is, in a non-controlled setting).