Federal Court of Australia

Jahani (liquidator) v Alfabs Mining Equipment Pty Ltd, in the matter of Delta Coal Mining Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2021] FCA 1195

ORDERS

STEWART J | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The report of the referee Robyn McKern dated 9 March 2021 is adopted.

2. The plaintiffs pay the costs of the defendants who applied for the adoption of the referee’s report and opposed the plaintiffs’ application for the variation of the referee’s report.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

STEWART J:

Introduction

1 In this proceeding the joint and several liquidators of four companies bring preference claims against 29 respondents, although at this stage a number of the respondents have dropped out of the picture because of settlements that have been reached with them. A key issue in a preference proceeding is the date on which the company, or in this case the companies in a group of companies, became insolvent. That question was referred to a referee, Ms Robyn McKern, a chartered accountant and partner of McGrathNicol, for determination of a date within the period 1 December 2016 to 31 May 2017, which is referred to as the relevant period. Before me now is consideration of the adoption or variation of the report.

2 The referee concluded that the group of companies was insolvent from 31 January 2017 and thereafter. That is in contradistinction to the opinion of the liquidators who in an earlier report concluded that the group of companies was insolvent from at least 1 December 2016. There is accordingly a period of two months difference between the referee’s conclusion and the liquidators’ conclusion. As will become apparent, the referee had the liquidators’ insolvency report available to her and she considered and responded to the findings and opinions recorded in it.

3 The liquidators have identified four bases on which they contend that the referee erred which, depending on the combination of errors, if any, that are upheld, would justify a remittal of the report to the referee with the possibility that the date of insolvency is determined to be either the end of December 2016 or the end of November 2016.

4 The respondents resist the liquidators’ application for the report not to be adopted and to be remitted to the referee for reconsideration. The respondents support the adoption of the report.

5 For the reasons that follow, the referee’s report should be adopted.

The relevant principles

6 The relevant applicable principles are uncontroversial. Section 54A(3) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) provides that the court may deal with the report of a referee “as it thinks fit” including by adopting the report in whole or in part, varying the report, rejecting the report, or making such orders as the court thinks fit in respect of any proceeding or question referred to the referee. Particularly with reference to Chocolate Factory Apartments Ltd v Westpoint Finance Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 784 at [7] per McDougall J, but also other authority, Allsop CJ in Sheehan v Lloyds Names Munich Re Syndicate Ltd [2017] FCA 1340 at [10] identified the following principles which I gratefully adopt:

(1) The court should be reluctant to allow factual issues determined by a referee to be argued afresh in court.

(2) Some error of principle, absence or excess of jurisdiction or patent misapprehension of the evidence should generally be demonstrated to justify the rejection of the referee’s report.

(3) The court will generally not reconsider disputed questions of fact where there exists factual material that is sufficient to entitle the referee to reach the conclusions that they did, particularly where the disputed conclusions are made in a technical area in which the referee possesses appropriate expertise.

(4) The discretion to reconsider a referee’s factual findings will generally only be exercised if the findings are such that no reasonable finder of fact could have made that finding.

(5) The determination of questions of law and the application of legal principles to the facts found by the referee is a matter for the court.

7 See also Weston in his capacity as liquidator of Starcom Group Pty Ltd (in liq) v Rajan [2019] FCA 1455 at [8]-[10] where I sought to identify the applicable principles.

The referee’s report

8 In order to address the liquidators’ criticisms of the referee’s report, it is necessary to summarise the approach and findings of the referee as reflected in her report.

9 The referee identified that the four companies in question are the following:

(1) Delta Coal Mining Pty Ltd (in liq);

(2) Delta Mining Pty Ltd (in liq);

(3) SBD Services Pty Ltd (in liq); and

(4) Delta SBD Ltd (in liq).

10 Delta SBD was a public, no liability company listed on the ASX, and was the ultimate holding company of the other three companies. The four companies are referred to as the Group. The Group employed approximately 600 staff and provided labour and equipment hire to mine owners in NSW and Queensland.

11 The referee identified that s 95A(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) relevantly provides that a person is solvent if, and only if, the person is able to pay all the person’s debts as and when they become due and payable, which she described as the test of solvency. The approach adopted by the referee in reaching a conclusion as to if, and when, each of the companies in the Group became insolvent was as follows:

(1) The referee considered relevant statute and case law to identify the criteria to be taken into account when considering solvency and insolvency, which she referred to as insolvency indicators.

(2) The referee made inquiries, undertook analysis, and reviewed the information made available to her to identify the factual position with respect to each of the insolvency indicators.

(3) On the basis of her analysis and review, she formed a view as to if, and when, each insolvency indicator pointed towards the companies in the Group being insolvent within the relevant period.

(4) Following the analysis of each of the insolvency indicators, the referee considered the weight of evidence in respect of each insolvency indicator and the relative importance of each insolvency indicator in the context of the Group’s overall position to form her opinion as to the date from which each of the companies was insolvent.

(5) The referee set out in her report her conclusions and her reasoning. In addition, to the extent that her opinion materially differed from the submissions of parties to the proceeding or the conclusions of the liquidators in the liquidators’ solvency report, she identified those differences.

12 The referee said that this is not a case where a specific incident guides the identification of a date when solvency ceased. Rather, the insolvency of the Group arose from a number of trading and financial factors which, whilst some originated in prior periods, converged in early 2017 to render the Group insolvent.

13 The referee is of the opinion that whilst there were indications of potential insolvency at earlier dates, having regard to the primacy of the cash flow test to assess insolvency, the Group was solvent until the end of January 2017 and was insolvent thereafter.

14 Consistently with the approach of the liquidators, the referee took the view that the business and affairs of the four companies were operated as a group.

15 The referee said she assessed the solvency of the Group having regard to the principles she identified as derived from case law and regulatory guidance. She identified a consolidated list of the indicators which, in her opinion, required consideration, in the context of the financial position of the Group as a whole, and having regard to commercial realities, in order to ascertain if and when the Group failed to meet the test of solvency and was therefore insolvent. Each of the indicators, which she drew from ASIC v Plymin [2003] VSC 123; 46 ACSR 126, is addressed in detail in a separate section of her report. They are the following:

(1) Trading and financial performance – continuing losses;

(2) Debts due and payable having regard to an analysis of trade creditors’ terms and ageing profiles leading up to and during the relevant period, arrangements entered into with creditors to amend terms, and debts other than trade creditors, taxes and statutory obligations;

(3) Liabilities and timelines of payment to Commonwealth, State taxes and similar obligations including GST, PAYG and superannuation obligations;

(4) The assets available to meet creditor claims;

(5) Liquidity – capacity to meet creditor claims due and payable from cash on hand or assets able to be readily converted to cash and current and quick ratio analyses;

(6) Relationships with suppliers – changes to terms, cessation of supply, demands or threats issued, payment arrangements implemented;

(7) Relationships with financiers and capacity to raise additional or alternative finance or equity;

(8) Ability to produce timely and accurate information to display the company’s trading performance and financial position and make reliable forecasts; and

(9) Concerns raised about ability to pay debts (by financiers, directors and employees).

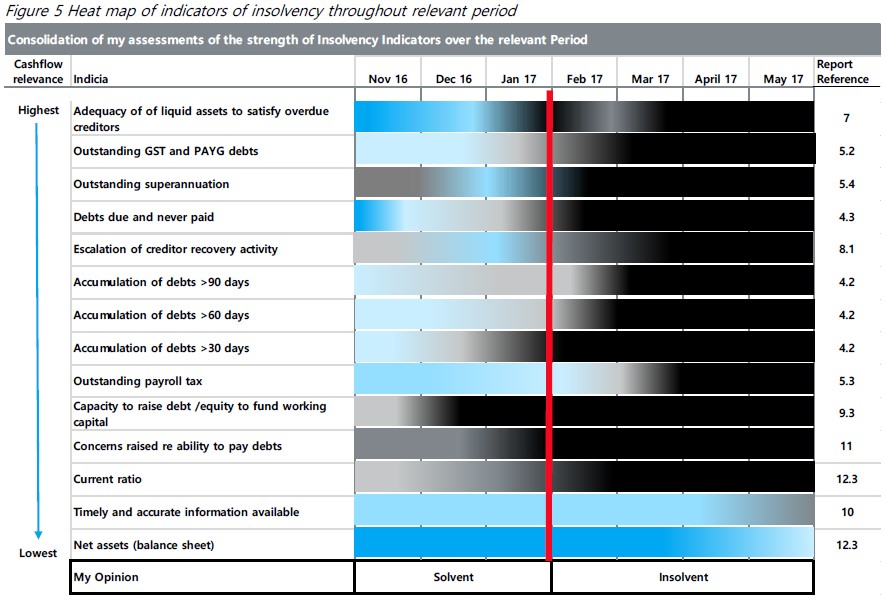

16 After having considered each of those factors in detail, in section 13 of her report the referee considered collectively the findings of her review and analysis undertaken in respect of each of the indicators of insolvency. The referee prepared a pictorial representation, referred to as a “heat map”, of the strength of each of the indicators of insolvency across the relevant period. The pictorial scheme that was applied was the following:

black strongly indicates insolvency;

grey indicates potential insolvency;

pale blue indicates potential solvency; and

blue indicates solvency.

17 The referee ascribed to each indicator of insolvency a different weight because, in her opinion, they do not all carry equal weight in the overall assessment of whether and when a company is insolvent. As the question of insolvency is predominantly a cash flow test, those indicators which inform an understanding at a point in time of a company’s actual available resources to meet the debts then due and payable were given greater weight in the determination of insolvency than indicators which have a lesser focus on the timing of availability of resources. The referee then consolidated a “heat map” of insolvency indicators listing them in descending order of pertinence to a cash flow test. That is represented graphically as follows (noting that it is necessary to observe it in colour in order to appreciate its full impact):

18 Having regard to her analysis and assessment of each of the indicators, the referee was of the opinion that whilst there were indications of potential insolvency at earlier dates, and some indicators remained at a satisfactory level afterwards, having regard to the primacy of the cash flow test, the Group was solvent until the end of January 2017 and was insolvent thereafter. With reference to Figure 5 reproduced above, the referee explained that the vertical redline is positioned at 31 January 2017. To the left of the line, prior to that date, it was her assessment that whilst there were some indicators of insolvency, a number of indicators had not yet emerged or were present at a mild degree, whereas to the right of the line, being after that date, additional factors emerged in the majority of those she considered most pertinent had intensified.

19 The referee drew specific attention to the following:

(1) At 31 December 2016, liquid assets were adequate to satisfy all debts greater than 30 days but by 31 January 2017, the shortfall of liquid assets to debts greater than 30 days was in excess of $1 million and, even if it were reasonable to consider that only debts greater than 60 days were payable on the basis of usual commercial practice, the liquid assets at the end of January 2017 only covered these debts by a small margin.

(2) Prior to 31 December 2016, a relatively small number of invoices in number and quantum fell due which were ultimately never paid, however, through January 2017, such invoices escalated in both number and quantum. Thirty-three invoices totalling approximately $193,000 fell due for payment by 31 January 2017 and remained unpaid at the date the companies went into voluntary administration.

(3) By 31 January 2017, the ageing of creditors had deteriorated and from then the proportion and value of debts greater than 60 and 90 days increased month on month.

(4) At 31 December 2016, liabilities for taxes had been brought back closer to order as a result of payments received from a significant debtor/client, Wollongong Coal Ltd (WCL), in late December, but through January 2017, the Group could only satisfy its obligations through negotiation and renegotiation of payment plans.

(5) A default of a payment plan with the ATO due to failure to lodge and remit November PAYG when due on 28 December 2016 was resolved by the cancellation of the plan and implementation of a new plan. However, from January 2017 onwards payment plans were increasingly being renegotiated and few were fully complied with.

(6) Throughout December and into January there was clear concern within the Group regarding management of cash flow and frequent mention in the management and board minutes of the slowness of WCL in paying invoices and challenges in gaining South 32 Ltd’s (a mining company debtor/client) attention to approve invoices to be raised. The initial pressure was alleviated by payments made by WCL in late December but by the end of January 2017, it was apparent that the relief was short-lived.

(7) In December 2016, the board had identified options to seek additional debt and equity. However, the information available to the referee suggested to her that the board had a range of ideas as to possible options but in her opinion none was likely to be successfully implemented in a short enough timeframe to mitigate the looming cash deficiencies identified in various forecasts and which were inevitable given what was then understood regarding:

(a) industrial problems with the Appin Colliery that would affect profit and invoicing;

(b) significant operational issues on the WCL contract causing it to be unprofitable and exacerbated by WCL being an excluded customer under the Group’s invoice finance facility and WCL having proven itself by that time to be an unreliable payer; and

(c) weak half-year results which would not support the raising of new capital.

(8) Creditor agitation in the form of stop supply, stop credit, and some preliminary steps to more formal recovery action escalated significantly from March 2017 in an attempt to recover debts due in January and December.

20 The referee also took account of the following:

(1) The audit opinion in relation to the accounts at 31 December 2016 included an emphasis on matters with regard to the ability of the Group to continue as a going concern with particular reference to the reliance on timely recovery of WCL debts. Notwithstanding that the auditors, at the time they signed the audit report in late February 2017, did not conclude that it was inappropriate for the Group to prepare its accounts on a going concern basis, in the referee’s assessment by the end of January 2017 it was apparent that timely receipts of WCL debts was a continuing issue and this was exacerbated by the lower revenue and receipts from Appin Colliery as a result of the industrial action in December and January.

(2) In general, but particularly in this case where it is not a single incident which gives rise to the insolvency of the Group, but a range of factors which have developed over time, the referee considered it necessary to consider the financial position of the Group as a whole in order to form a view as to solvency/insolvency. That required reference to complete accounts comprising aged debtors, aged creditors, profit and loss and balance assets which are prepared as at the same date so that they are balanced and internally consistent. The information available to the referee included financial reports of this nature for each month end; they were not available for dates within any month. The referee considered the typical signs or indicators of insolvency across each of the month ends in the relevant period, and formed the opinion that at 31 January 2017, in contrast to the position at 31 December 2016, the key indicators of insolvency were compelling and supported her conclusion that each company in the Group was insolvent on that date.

21 It is apparent from the above synopsis that the referee’s conclusion as to the date of insolvency was reached as an evaluative determination having regard to numerous factors and circumstances where no single factor was decisive. That approach is consistent with the authorities. In those circumstances, if the liquidators identify error in the referee’s consideration of any particular factor it is unlikely to have a material effect of the ultimate determination.

The liquidators’ grounds of challenge

22 As mentioned, the liquidators contend that there are four errors in the approach adopted by the referee, each being relevant to the referee’s liquidity analysis, which they identified and addressed in the following order:

(1) Non-taxation debts: it is said that the referee assumed, in the absence of any evidential basis, that debts of the companies were only payable on 60 days not 30 days;

(2) Taxation debts: it is said that the referee erred as a matter of law in not treating as due and payable taxation debts which were due but were subject to a payment arrangement;

(3) Receivables: it is said that the referee treated as liquid assets all receivables then overdue for payment which was founded on an assumption without foundation that overdue trade debts could be treated as imminently convertible to cash; and

(4) Future debts: it is said that the referee erred as a matter of law in not having regard, at any point in time, to the ability of the Group to meet future debts when they fell due and focused rather on the ability of the Group to meet current debts.

23 On the liquidators’ analysis, the key issue is the treatment of receivables (i.e., issue 3). The liquidators accordingly submit that if I am against them on that issue, then the other three alleged errors must all be established in order to justify the remittal of the report to the referee. They submit that if they are correct on the receivables point then they have a prospect of the referee’s determination being varied back by two months to 30 November 2016. However, if I am against them on that point then, as noted, they would have to be correct on all three of the remaining points to make a difference. That difference would potentially be to vary the determination back by one month to 31 December 2016.

24 The parties were agreed that if I find that there is a material error in the approach by the referee such as to justify the non-adoption of her report, the proper course would be to “remit” the matter to the referee to reconsider her determination in the light of the error or errors identified. That is because of the evaluative nature of her determination in that just what impact the correct approach on the identified issue or issues will have on the ultimate determination would be a matter for the referee to consider along with all the other factors considered by her.

Issue 1: non-taxation debts

25 As mentioned, in respect of this issue the liquidators submit that the referee erred by assuming, without any evidential foundation, that debts of the companies were only payable on 60 days rather than 30 days. They say that the result of that is that the liquidity analysis substantively and materially underestimated the companies’ debts due and payable at any particular point in time. In that regard, the liquidators refer to Southern Cross Interiors Pty Ltd v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2001] NSWSC 621; 53 NSWLR 213 at [54(vi)] where Palmer J identified the following as a proposition that may be drawn from the authorities in assessing a company’s solvency (which proposition was not disturbed on appeal, Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Clark [2003] NSWCA 91; 57 NSWLR 113):

the commercial reality that creditors will normally allow some latitude in time for payment of their debts does not, in itself, warrant a conclusion that the debts are not payable at the times contractually stipulated and have become debts payable only upon demand; …

26 As identified earlier with reference to the referee’s report, one of the indicators considered by the referee was the debts due and payable at the end of each month in the relevant period. In respect of trade creditors the referee explained her approach as follows:

5.2.1 I have reviewed approximately 60 creditor invoices being those provided in Appendix 27 of the Liquidators Solvency Report. I observe that the payment terms stated on the invoices varied from seven days to 45 days, and the majority of invoices reference 30 day terms which from the stated due dates on a number of invoices may mean either 30 days from the date of the invoice or at the end of the month following the invoice date. I have not been provided with evidence that the terms on invoices were consistent with supply contracts entered into by the Companies. For the purpose of my analysis I have assumed that to be the case.

5.2.2 Having regard to case law that allows for regard to be had to the broader commercial conduct between a company and its suppliers, I have also considered the history of the actual terms within which the Group paid its creditors over the period for which I have been provided with information.

5.2.3 In Table 9 below, I summarise the Group’s trade creditor position at each month end from 31 July 2015 to 31 May 2017 by ageing category [excluding liabilities for taxes and superannuation which were considered separately]. I note that to the extent that the Group negotiated alternative (deferred) payment arrangements with creditors (as discussed in section 9), the renegotiated terms were not reflected in the aged creditor reports and accordingly, the aged creditor reports are inaccurate in this regard.

27 Table 9 sets out an analysis of trade creditors of the Group from November 2015 to May 2017, dividing the debt in each month between current, 31-61 days, 61-90 days and 90+ days. The data was then also reflected in graph form in Figure 3. Thereafter, the referee explained that from the available records it is her opinion that notwithstanding the terms stated on invoices, it was the normal commercial practice of the companies to regularly utilise trade credit for up to 60 days and on occasion for up to and beyond 90 days.

28 In effect, what the referee has done is analyse the Group’s trade creditors over a 19-month period and then make a factual and practical assessment as to the Group’s effective commercial trade terms. That had the effect of both excluding from consideration, to the liquidators’ benefit, debts which on their trade terms were due in under 30 days and including, to the respondents’ benefit, debts which on their trade terms would only be due more than 60 days after invoice date. Thus, the approach adopted was in certain respects beneficial to the liquidators and in certain respects not, but it was practical and justifiable. The exercise clearly did not warrant separately analysing every single debt of thousands to identify its exact terms.

29 It is also to be noted that the referee went on to do a comparison between her approach and that of the liquidators in their solvency report and explained and justified the differences.

30 There was accordingly ample basis for the referee to reach the findings that she did, which findings can certainly not be characterised as being of such a nature that no reasonable finder of fact could have made them.

31 I therefore reject the liquidators’ first ground of challenge.

Issue 2: taxation debts

32 As mentioned, the liquidators submit that the referee erred as a matter of law in not treating as due and payable taxation debts which were due but were subject to a payment arrangement. In that regard, the liquidators refer to Clifton (Liquidator) v Kerry J Investment Pty Ltd trading as Clenergy [2020] FCAFC 5; 379 ALR 593 at [477]-[540], in particular [515] and [523]-[532] per Besanko, Markovic and Banks-Smith JJ. It is common ground that these passages are obiter (as explained at [208]-[209]). The liquidators point out that in Re Custom Bus Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) [2021] NSWSC 1036 at [39], Black J accepted that Clenergy at [498]ff supported the approach of treating the liability to the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (DCT) as immediately due and payable, notwithstanding the existence of a payment arrangement, because there was no formal deferral of the tax debt.

33 The first point made by the respondents is that even if the liquidators are correct in their criticism, the error is not material in the liquidity analysis. That is because had the tax debts been included at their full value on their statutory due date rather than on their deferred date there would have been an increased debt of $442,293 as at 30 November 2016 and $444,602 as at 31 December 2016. Given the surpluses of $2,397,932 and $2,327,504 otherwise calculated by the referee in respect of those dates respectively, adjustments by those sums would make no material difference. The liquidators accept that that is correct in respect of the taxation debt (i.e., issue 2) in isolation, but an adjustment in relation to that debt taken together with adjustments in relation to issues 1 and 4 would cumulatively be material.

34 That takes me to the respondents’ second point. It is that what was said in Clenergy does not take account of Keith Smith East Transport Pty Ltd (in liq) v ATO [2002] NSWCA 264; 42 ACSR 501 at [33] per Mason P, Handley and Giles JJA agreeing, where the following was relevantly said in response to the submission that it is necessary to focus exclusively upon the total tax debts due at any point in time and to disregard entirely the ATO’s willingness to defer enforcement action subject to satisfactory arrangements for the gradual reduction in the debt:

The appellants pointed to no authority supporting such an approach to the issue of solvency. Indeed there is much authority to the contrary, because it is clear law that the statutory test of solvency looks at matters on a “cash flow” basis rather than a simple “balance sheet” basis: Brooks v Heritage Hotel Adelaide Pty Ltd (1996) 20 ACSR 61 at 64 see generally A R Keay, “The Insolvency Factor in the Avoidance of Antecedent Transactions in Corporate Liquidations” (1995) 21 Mon L R 305. This does not mean that a company debt is not due and payable at the time stipulated by the creditor (see generally Southern Cross Interiors); but it does mean that, in assessing solvency, the court will pay regard to an express or implied agreement between a company and its creditor for an extension of the time stipulated for payment: Southern Cross Interiors at 225 and authorities cited at [54](v), Sutherland (as liq of Sydney Appliances Pty Ltd (in liq)) v Eurolinx Pty Ltd (2001) 37 ACSR 477.

35 The essence of the relevant decision in Clenergy (at [533]-[534], albeit obiter) is that the agreement by the DCT to a payment of a tax liability in instalments under s 255-15 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (TA Act) does not defer the date of the taxation debt being due and payable, including for the purposes of s 95A of the Corporations Act. Given the express provision of s 255-15(2) that such an arrangement does not vary the time at which the amount is due and payable, that is not a surprising outcome (see Clenergy at [505]). However, a deferment of liability under s 255-10 or the bringing forward of the date that a taxation debt is due and payable under s 255-20 of the TA Act will alter the date that the debt is due and payable. The referee’s report refers to “payment plans” having been agreed with the ATO (really the ATO on behalf of the DCT), which I understand to be agreements to accept payment in instalments under s 255-15 of the TA Act. On the basis of Clenergy (and Custom Bus), the referee therefore erred in treating those debt as being due and payable only on the later dates under the payment plans rather than on the earlier dates that the debts first became due and payable.

36 To the extent that there is a difference between what was said in Clenergy and what was said in Keith Smith, which is with regard to the extent that arrangements to pay tax debts in instalments can be taken into account, I do not have to resolve it in view of the immateriality of the point raised by the liquidators, even if they are correct in their reliance on Clenergy. That is to say, the liquidators have conceded that if this issue is established on its own, and not along with issue 1 and 4 or 3 below (or all issues together), then it will not have an impact on the referee’s determination.

Issue 3: receivables

37 The parties agree that this issue is the most significant with regard to the difference it could make to the referee’s analysis. The liquidators’ contention, it will be recalled, is that the referee treated as liquid assets all receivables then overdue for payment which was founded on an assumption without foundation that overdue trade debts could be treated as imminently convertible to cash. The liquidators say that regardless of whether there was some hope of those debts being realisable into cash at some time in the future, on the date on which solvency was to be assessed, they were not so realisable and thus were not liquid assets available to meet debts due on that date. The inclusion of those figures therefore inflated, impermissibly, the assets actually available to pay debts then due and payable.

38 The source of the liquidators’ criticism is at [2.5.4] of the referee’s report where she said this:

In assessing liquid assets I have included cash and trade receivables which were past due for receipt and could reasonably be considered as being imminently converted to cash. This is a key point of difference between my analysis and that of the Liquidators who, in the Liquidators’ Solvency Report ignore immediately due debtor receipts a source for payment of creditors.

39 The referee explained at [7.1.3] of her report, in the section dealing with the assets available to meet creditor claims:

I have assessed the readily available assets as comprising:

(a) Cash at bank

(b) Trade debtors which are past their due dates for receipt. I include these as near liquid assets because in the absence of information or knowledge that the debts are not recoverable it is reasonable to assume that receipt of cash for overdue debts is imminent.

(c) Deduction of the trade debtors balance which has been factored to recognise that these receipts will flow to the invoice finance provider and not be available to satisfy outstanding creditors.

40 The referee also explained (at [7.1.4]) that she excluded “other current assets such as WIP and Inventory as well as current debtors because these assets will take some time to be realised for cash and accordingly are not readily available to satisfy currently due and payable [debts].”

41 In Sandell v Porter [1966] HCA 28; 115 CLR 666 at 670, Barwick CJ explained that a debtor’s own moneys are not limited to their cash resources immediately available. They extend to monies which they can procure “by realisation by sale or by mortgage or pledge of their assets within a relatively short time – relative to the nature and amount of the debts and to the circumstances, including the nature of the business, of the debtor.” The conclusion of insolvency ought to be clear from a consideration of the debtor’s financial position in its entirety and generally speaking ought not to be drawn simply from evidence of a temporary lack of liquidity.

42 To similar effect, it has been said that commercial reality dictates that the assessment of available funds is not confined to the company’s cash resources. It is legitimate to take into account funds the company can, in a real and reasoned view, realise by sale of assets, borrowing against the security of its assets, or by other reasonable means. It is a question of fact to be determined in accordance with the evidence. See Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 9) [2008] WASC 239; 70 ACSR 1 at [1090] per Owen J.

43 In Hall v Poolman [2007] NSWSC 1330; 65 ACSR 123 at [267], Palmer J explained that he thought that it can be said, as a very broad general rule, that a director would be justified in “expecting solvency” if an asset could be realised to pay accrued and future creditors in full within 90 days. In Xu v Megaward [2018] NSWCA 232; 130 ACSR 412 at [53] per McColl, Meagher and Leeming JJA, it was held on the facts of that case that there was no error in the primary judge regarding a six-week period to realise receivables as being consistent with the nature of business in the relevant industry.

44 What those authorities illustrate is that just what period for the realisation of assets, including getting in payment of due and overdue debts, is reasonable in a particular case is a question of fact. There is no error in principle in the referee’s approach. Rather, the liquidators say that there was no foundation for it in the material available to the referee. However, the referee (in Table 17) undertook a detailed analysis of assets available to meet overdue debts. She also had the liquidators’ insolvency report which in Appendix D1 set out an analysis of debtors. That offered ample basis for her approach. Moreover, the referee treated both sides of the ledger the same – she treated the Group’s debts as not being due and payable in the first month following the date of invoice even if in fact some of those debts were due and payable in that period, and she treated debts to the Group as not being available to meet a given company’s debts in the first month following the invoice date.

45 In effect, the liquidators seek to challenge the referee’s factual finding, or approach, that debtors over 30 days were reasonably regarded as available to meet present and future debts of the Group. There is no error in the referee’s approach, and certainly no error of the type referred to earlier that would justify not accepting her report.

46 I therefore reject the liquidators’ third ground of challenge.

Issue 4: future debts

47 While not strictly necessary to deal with this issue in view of my conclusions on issues 1 and 3, for the sake of completeness I set out my consideration of it below.

48 The liquidators contend that the referee erred as a matter of law in not having regard, at any particular point in time, to the ability of the Group to meet future debts when they fell due and focused rather on the ability of the Group to meet current debts. The liquidators say, as found by the referee (at [4.2.3]), that the Group was loss-making over the relevant period. An analysis of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) shows that the Group’s ability to meet debts was in decline because it was losing money meaning that it was not generating sufficient revenue to pay new debts.

49 The point of law relied on by the liquidators is that the test of insolvency is forward looking – the question is not simply whether the company can pay debts falling due at or around the date the question arises but whether, as at that date, it can pay debts falling due in the future: Anchorage Capital Master Offshore v Sparkes (No 3); Bank of Communications v Sparkes (No 2) [2021] NSWSC 1025 at [259] per Ball J. His Honour explained (at [266]) that that involves a prediction to a high degree of certainty of what was known and knowable at the relevant date. Further and relevantly (at [267]):

The difficulty involved in predicting the future with sufficient certainty so as to be able to say that what is predicted is true at the time of prediction explains the general reluctance of courts, except in special cases, such as long tail insurance claims, to determine the question of solvency by reference to debts that are not payable immediately or in the near future.

50 The referee dealt with trading and financial performance of the Group in section 4 of her report. With reference to financial reports, in Table 5 she summarised the profit and loss accounts and in Table 6 she summarised the balance sheets, in each case with reference to the following time periods: 12 months to June 2015, 12 months to June 2016, 6 months to December 2016, and 6 months to May 2017. The referee recorded her key observations based on the summaries reflected in the tables.

51 The referee then considered the profit and loss and balance sheet positions for each month from November 2016 to May 2017 based on the monthly management accounts. These are reflected in Table 7 and Table 8 respectively. Again, she recorded her key observations based on the tables.

52 The referee then summarised her assessment of the financial position of the Group from her review of the financials as follows:

(a) Over the years the capital of the company has been diminished by accumulated losses totalling approximately $28 million, including $5.8 million in the 11 months to 31 May 2017.

(b) The position around late 2016 was that the bulk of the Group’s equity was fixed assets and there was limited net working capital. Trade debtors has been sold to create liquidity and the Group had little, if any, buffer against adverse business events or shocks.

(c) Notwithstanding revenue growth through the Relevant Period, the revenue was proving unprofitable and the conversion to cash was slowing, causing a drain on cash resources and a build-up of creditors.

(d) Receipts from overdue debtors, notably WCL, in late December 2016 resulted in some respite and an ability to improve the trade creditor profile but lower than usual revenue in December resulted in a lower quantum of invoices to factor and cash pressure resumed through January and did not diminish.

53 From the above it is apparent that the referee paid careful regard to the declining trading position of the Group and factored it into her analysis in her consideration of the Plymin factors.

54 The real question is whether the referee erred in her treatment of future debts in her liquidity analysis. In my view, the referee made a factual evaluative assessment, or determination, which is free of relevant error. She acknowledged that the Group was trading at a loss, but it continued as a going concern and it was not until 28 February 2017 that the auditors raised doubt about the Group’s ability to continue as a going concern (dealt with in the report at [4.1.6]). That arose from delayed customer receipts. Of course, a company that continues over a period of time to trade at a loss will at some stage become insolvent, unless it is recapitalised. But the fact that the Group was trading at a loss does not identify when insolvency set-in. The referee has undertaken an evaluation in order to determine that question. In doing so she has taken into account trading losses and future debts. No error such as to justify the non-adoption of her report in this respect has been made out.

55 I therefore reject the liquidators’ fourth ground of challenge.

Conclusion

56 In the result, there is no justification for doing anything other than adopting the referee’s report and her finding that the companies in the Group were insolvent from 31 January 2017.

57 It was common ground that the costs should follow the event. The plaintiffs should accordingly pay the costs of the defendants who applied for the adoption of the referee’s report and who participated in opposing the plaintiffs’ application to have the referee’s report varied. I will hear from the parties if any party contends that a more specific order on costs is necessary.

I certify that the preceding fifty-seven (57) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Stewart. |

Associate:

SCHEDULE OF PARTIES

NSD 577 of 2020 | |

Second Plaintiff: | SAID JAHANI AND JOHN MCINERNEY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL LIQUIDATORS OF DELTA MINING PTY LIMITED (IN LIQUIDATION) ACN 056 692 883 |

Third Plaintiff: | SAID JAHANI AND JOHN MCINERNEY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL LIQUIDATORS OF SBD SERVICES PTY LIMITED (IN LIQUIDATION) ACN 124 019 816 |

SAID JAHANI AND JOHN MCINERNEY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL LIQUIDATORS OF DELTA SBD LTD (IN LIQUIDATION) ACN 127 894 893 | |

Second Defendant: | AMPCONTROL (QLD) PTY LIMITED ACN 001 335 842 |

Fourth Defendant: | COAL MINES INSURANCE PTY LTD ACN 000 011 727 |

COASTWIDE ENGINEERING PTY LTD ACN 002 244 680 | |

Sixth Defendant: | COUGAR MINING GROUP PTY LTD ACN 142 713 951 |

Eighth Defendant: | ERNST & YOUNG ABN 75 288 172 749 |

Ninth Defendant: | FUCHS LUBRICANTS (AUSTRALASIA) PTY LTD ACN 005 681 916 |

Tenth Defendant: | JENNMAR AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 078 584 531 |

Twelfth Defendant: | MINES RESCUE PTY LIMITED ACN 099 078 261 |

Thirteenth Defendant: | CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF STATE REVENUE |

Fourteenth Defendant: | PARK PTY LTD ACN 093 014 129 TRADING AS PARK FUELS |

Fifteenth Defendant: | SGS HYDRAULICS PTY LTD ACN 104 018 564 |

Seventeenth Defendant: | WARATAH ENGINEERING PTY LTD ACN 614 565 829 |

Twenty First Defendant: | WESTRAC PTY LTD ACN 009 342 572 |

Twenty Ninth Defendant: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION |