Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited (No 3) [2021] FCA 1147

EVIDENTIARY RULINGS

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | BLUESCOPE STEEL LIMITED (ACN 000 011 058) First Respondent JASON THOMAS ELLIS Second Respondent | |

O’BRYAN J:

Introduction

1 The trial of this proceeding commenced on 30 August 2021 and is continuing.

2 During the course of the trial, I made rulings with respect to the admissibility of the following categories of evidence:

(a) transcripts of an examination conducted by the applicant (ACCC) under s 155 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Act) (ruling 1);

(b) documents provided to the ACCC by the first respondent, BlueScope Steel Limited (BlueScope), in about August 2013 in support of an application for informal clearance of a proposed acquisition of OneSteel Limited (ruling 2);

(c) statements within witness statements expressing a conclusion about competitors or competition in markets relevant to allegations in the proceeding (ruling 3);

(d) statements within witness statements expressing the witness’ understanding about the meaning or effect of a communication to which the witness was privy (ruling 4);

(e) evidence concerning the formulation and circulation by BlueScope of a recommended resale price list in respect of sheet and coil processing services (ruling 5);

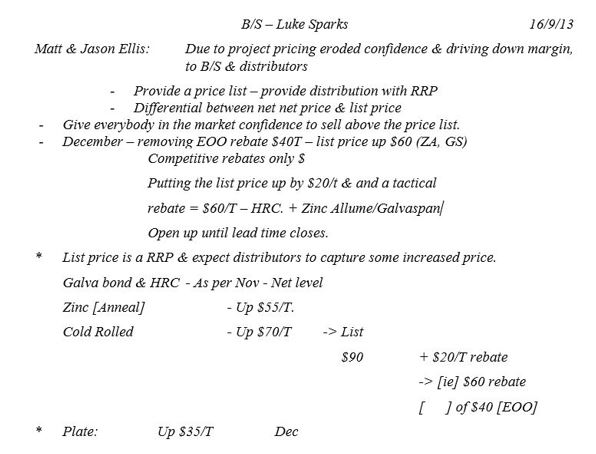

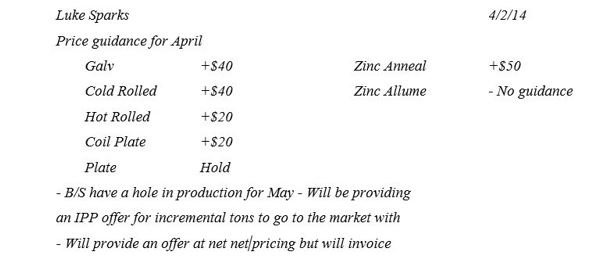

(f) handwritten notes written by an employee of another distributor of flat steel products (ruling 6);

(g) written statements signed by Luke Sparks, a current employee of BlueScope (ruling 7); and

(h) a written statement signed by Anthony Calleja and certain questions asked of Mr Calleja in examination-in-chief with respect to that statement (ruling 8).

3 These are my reasons for those rulings.

Overview of allegations

4 At all relevant times, BlueScope manufactured and supplied various flat steel products in Australia through its division titled BlueScope Coated Industrial Products Australia (BlueScope CIPA). The second respondent, Mr Jason Ellis, was BlueScope CIPA’s General Manager of Sales and Marketing. BlueScope’s subsidiary, BlueScope Distribution Pty Ltd (BlueScope Distribution), distributed in Australia flat steel products manufactured by BlueScope CIPA. BlueScope’s New Zealand subsidiary, New Zealand Steel Limited (NZ Steel), manufactured and supplied various flat steel products in New Zealand. Another New Zealand subsidiary, New Zealand Steel (Australia) Limited (NZSA), imported into Australia flat steel products manufactured in New Zealand by NZ Steel.

5 The ACCC alleges that each of BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain suppliers of flat steel products in Australia to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding that contained a cartel provision in contravention of s 44ZZRJ of the Act. At the time of the alleged conduct, s 44ZZRJ prohibited a corporation from making a contract or arrangement or arriving at an understanding that contains a cartel provision. Relevantly, a provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding is a cartel provision if the provision has the purpose or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price of goods supplied by any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding, and two or more of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding are in competition with each other in relation to the supply of those goods.

6 The ACCC alleges that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce each of the following nine suppliers of flat steel products in Australia (which I will refer to as counter-parties) to make a separate arrangement or arrive at a separate understanding containing a provision that had the purpose or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining the price for flat steel products supplied, or likely to be supplied, by BlueScope or the counter-party concerned:

(a) Southern Steel Group Pty Limited (Southern Steel), OneSteel Pty Ltd (OneSteel), CMC Steel Distribution Pty Ltd (CMC), Apex Steel Pty Ltd (Apex Steel), Selection Steel Trading Pty Ltd (Selection Steel), Celhurst Pty Ltd trading as Selwood Steel (Selwood Steel) and Vulcan Steel Pty Ltd (Vulcan Steel), which were distributors of flat steel products in Australia;

(b) Wright Steel (Sales) Pty Ltd (Wright Steel), which was an import trader of flat steel products, acquiring flat steel products from overseas steel manufacturers; and

(c) Yieh Phui Enterprise Co Ltd (Yieh Phui), which was a Taiwanese steel manufacturer that exported flat steel products to Australia.

7 The ACCC alleges that the conduct constituting the unlawful attempts began in around September 2013. The conduct continued for different periods for each of the counter-parties referred to above but in general terms continued until June 2014.

8 It is common ground that, to establish that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce the above counter-parties to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding that contained a cartel provision, the ACCC must show that BlueScope and Mr Ellis (respectively):

(a) engaged in conduct necessary to constitute an attempt to induce, meaning each took a sufficient step towards inducing the proposed counter-party to make the arrangement or arrive at the understanding; and

(b) intended to bring about the arrangement or understanding.

9 In respect of its allegations against BlueScope, the ACCC alleges that both the conduct and the intention of certain employees of BlueScope are to be attributed to BlueScope pursuant to s 84 of the Act. In respect of intention, the ACCC alleges that the intention of Mr Ellis, Matthew Hennessy, Mr Sparks, Brian Kelso, Denzil Whitfield and Troy Gent are to be attributed to BlueScope in respect of different alleged attempts. Accordingly, an issue in the proceeding concerns the intention of each of those persons when engaging in conduct alleged by the ACCC to constitute an attempt to induce the proposed counter-parties to make the arrangements or arrive at the understandings.

Ruling 1: Section 155 transcripts

10 The ACCC tendered transcripts of an examination of Mr Gent conducted under s 155 of the Act on 26 February 2018 and 27 February 2018. The transcripts would ordinarily be inadmissible by reason of the hearsay rule in s 59 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act). However, the ACCC submitted that the transcripts were an admission of BlueScope within the meaning of s 81 of the Evidence Act such that the hearsay rule would not apply. In that respect, the ACCC relied on s 87(1)(a) and (b) to contend that:

(a) when the representations were made, Mr Gent had authority to make statements on behalf of BlueScope in relation to the matters with respect to which the representations were made; and

(b) when the representations were made, Mr Gent was an employee of BlueScope and the representations related to a matter within the scope of his employment.

11 In the period of the allegedly infringing conduct (September 2013 to June 2014), Mr Gent was Sales Manager NSW and Acting Sales Manager Vic/Tas for BlueScope CIPA, a role in which his primary responsibility was sales to distribution customers. In the course of the examinations, the ACCC asked Mr Gent questions relevant to his activities within BlueScope CIPA during that period. However, at the time of the examination, Mr Gent had a new role within BlueScope CIPA, being National Manager Manufacturing, a role in which his primary responsibility was sales to manufacturing customers.

12 BlueScope submitted that when Mr Gent was examined, he was asked about a role he no longer held. As Mr Gent deposes, BlueScope CIPA supplied flat steel products to three categories of customers through its sales channels being distribution, manufacturing and building markets. Within BlueScope CIPA’s sales and marketing team, there were three sub-teams each dedicated to one of those three sales channels (although between July 2014 and June 2015 the manufacturing and distribution channels were managed by the same sub-team). By the time of Mr Gent’s interview in February 2018, he had fully transitioned from a role in the distribution division to a role in the manufacturing division.

13 The ACCC submitted that it is reasonably open to find that at the time Mr Gent was examined, he had some ongoing responsibility, focus or concern with BlueScope CIPA’s distribution channel, even though his primary responsibility had shifted to manufacturing. At the time of his interview, Mr Gent had continuously held manager roles within the distribution or manufacturing divisions of BlueScope CIPA’s sales and marketing team for 13 years (and from June 2014 to an unspecified month in 2017, held responsibilities for both).

14 There was no disagreement between the parties as to meaning and effect of s 87(1)(a) and (b). As Beach J observed in Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Westpac Banking Corp (No 2) [2018] FCA 751; 127 ACSR 110 at [479] (emphasis added):

Section 87(1) is engaged when a finding about one of the matters in paras (a)–(c) is “reasonably open”. The paragraphs “do not require a concluded finding of the relevant authority or common purpose. They merely require a conclusion that such a finding be one that ‘is reasonably open’” (Ingot Capital Investments Pty Ltd v Macquarie Equity Capital Markets Ltd (No 4) [2006] NSWSC 90 (Ingot (No 4)) at [11] per McDougall J). The relevant time upon which attention must focus is the time when the previous representation was made.

15 In my view, BlueScope’s submission must be accepted. It is not reasonably open to find that, at the time of the s 155 interview, Mr Gent had authority to make statements in relation to the sale of products through the distribution channel of BlueScope CIPA. In respect of s 87(1)(b), while the evidence shows that Mr Gent was previously employed in the distribution channel of BlueScope CIPA, and had a joint distribution/manufacturing role up until shortly before he was examined, the evidence indicates that he had ceased in that capacity by the time of the interview.

16 For those reasons, the transcripts of Mr Gent’s examinations are not admissions of BlueScope and are therefore inadmissible under the hearsay rule.

Ruling 2: Merger documents

17 In August 2013, BlueScope wrote to the ACCC seeking informal clearance of the proposed acquisition of certain OneSteel Sheet & Coil distribution business assets from Arrium Limited. In the course of that application, BlueScope provided a number of documents to the ACCC. In this proceeding, the ACCC tendered the following of those documents (merger documents):

(a) a document titled “Background briefing on the Australian steel industry” prepared by BlueScope dated 25 August 2013;

(b) a document titled “Request for confidential informal merger pre-assessment by ACCC - BlueScope Supporting Submission dated 29 August 2013” authored by BlueScope’s external lawyers, Ashurst Australia;

(c) a report by NERA Economic Consulting titled “The Competitive Effects of the Proposed Acquisition of OneSteel Sheet and Coil Distribution” dated 29 August 2013;

(d) a document titled “Response to ACCC request to BlueScope Steel for documents and information dated 18 September 2013” authored by BlueScope’s external lawyers, Ashurst Australia and dated 2 October 2013;

(e) an email from BlueScope’s external lawyers, Ashurst Australia, to the ACCC dated 8 November 2013 and its attachment being a presentation titled “Proposed Acquisitions of Orrcon, Fielders and OneSteel Sheet and Coil assets”;

(f) a document titled “Response to ACCC request to BlueScope Steel for documents and information dated 14 November 2013” authored by BlueScope’s external lawyers, Ashurst Australia and dated 29 November 2013; and

(g) a letter dated 3 December 2013 from BlueScope’s external lawyers, Ashurst Australia, to the ACCC in relation to the proposed acquisition of Arrium Ltd’s OneSteel Sheet & Coil business.

18 The merger documents contained information that BlueScope considered to be relevant to the ACCC’s assessment of whether BlueScope’s proposed acquisition would contravene s 50 of the Act. In that context, the merger documents contained many statements describing BlueScope’s steel business, including in relation to the manufacture, importation and distribution of flat steel products in Australia and competitors in relation to those commercial activities. The documents also contained economic analysis and submissions relating to the question, raised by s 50, whether the proposed acquisition would be likely to substantially lessen competition in any market.

19 BlueScope made a general complaint that the ACCC had not identified the parts of the merger documents that it sought to rely upon in the proceeding. The complaint is fair and, as discussed below, I consider that the ACCC should provide such notification to BlueScope. Nevertheless, it is apparent from even a cursory review of the merger documents that they contain representations relating to the nature and extent of competition in respect of the manufacture, importation and distribution of flat steel products in Australia, being matters that are relevant to the issues in dispute in this proceeding. Further, the representations are contemporaneous with the beginning of the period of the alleged infringing conduct.

20 The merger documents would ordinarily be inadmissible by reason of the hearsay rule in s 59 of the Evidence Act. However, the ACCC submitted that the documents were admissible as either business records of BlueScope under s 69(2) or admissions of BlueScope under s 81 of the Evidence Act. In so far as the merger documents were authored by representatives of BlueScope (its legal advisers, Ashurst Australia, and its retained economic expert, NERA), the ACCC relied on s 87(1).

21 BlueScope submitted that the documents were not admissible for the following reasons:

(a) first, the business record exception in s 69 was inapplicable because the merger documents were prepared for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, an Australian proceeding within the meaning of s 69(3)(a);

(b) second, the representations in the merger documents were not admissions within s 81 because they were statements of law or mixed fact and law;

(c) third, the representations were not admissions of BlueScope because they were neither made by a person who had the authority to make statements on behalf of BlueScope in relation to the matter with respect to which the representation was made (within the meaning of s 87(1)(a)), nor made by a person who was an employee of BlueScope or had authority otherwise to act for BlueScope and relating to a matter within the scope of that person’s employment or authority (within the meaning of s 87(1)(b)); and

(d) fourth, the representations constituted inadmissible opinion evidence.

22 Alternatively, BlueScope submitted that the merger documents should be excluded because their low probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of causing an undue waste of time debating the relevance or significance of multiple parts of lengthy documents from the merger process.

23 It is convenient to begin with the question whether the merger documents are business records within s 69 of the Evidence Act.

24 BlueScope did not contend that subss (1) and (2) of s 69 were not satisfied and therefore it is unnecessary to consider those subsections. Rather, BlueScope argued that the merger documents were prepared or obtained for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, a proceeding under s 50 of the Act in respect of the proposed merger, within the meaning of s 69(3)(a). In that regard, BlueScope argued that the informal merger clearance process conducted by the ACCC is a process by which a company may obtain comfort that the ACCC will not commence a proceeding against them in relation to the merger. By engaging in the informal merger clearance process, BlueScope submitted, a company is trying to persuade the ACCC not to bring a proceeding under s 50 of the Act to enjoin the merger and therefore the company prepares the merger documents “in contemplation” of such a proceeding within the meaning of s 69(3)(a). BlueScope argued that submissions to a regulator to persuade it not to commence a proceeding fall squarely within the purpose of s 69(3)(a), because such documents are unlikely to assist in the proof of a fact relevant to the contemplated proceeding. BlueScope accepted that it bears the burden of establishing that the exception under s 69(3)(a) applies.

25 The purpose of s 69(3)(a) is to exclude from the business record exception to the hearsay rule documents that may be self-serving, and therefore unreliable, because they have been prepared for the purpose of, for or in contemplation of litigation: Vitali v Stachnik [2001] NSWSC 303 at [12] per Barrett J; Averkin v Insurance Australia Ltd (2016) 92 NSWLR 68 (Averkin) at [114] per Leeming JA (with whom McColl JA agreed). It is unusual, to say the least, for the Court to receive a submission from BlueScope that formal submissions made on its behalf to the ACCC, a statutory authority having responsibility for enforcement of Australia’s mergers laws, should be excluded from evidence on the basis of s 69(3)(a), implicitly suggesting that its own submissions to the ACCC in that context were self-serving and unreliable.

26 Section 69(3)(a) concerns the purpose for the preparation or obtaining of the representation contained in the document: the representation must be prepared or obtained for the purpose of conducting a proceeding, for a proceeding, in contemplation of a proceeding, or in connection with a proceeding: Averkin at [112] per Leeming JA (with whom McColl JA agreed). The test is subjective and it is necessary to consider the purpose or the contemplation of the person who prepared or obtained the representation: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Advanced Medical Institute Pty Ltd (No 2) (2005) 147 FCR 235 (ACCC v AMI) at [23] per Lindgren J. The relevant proceeding may have commenced or may be “in contemplation”. For the purposes of the exception, a proceeding is in contemplation if it is likely or reasonably probable and not merely a possibility: ACCC v AMI at [43] per Lindgren J; Nikolaidis v Legal Services Commissioner [2007] NSWCA 130 at [61] per Beazley JA; Lewincamp v ACP Magazines Ltd [2008] ACTSC 69, Annexure 2 ‘Reasons for Ruling’ at [23]-[24].

27 BlueScope did not adduce evidence with respect to the purpose of the preparation of the merger documents. Nevertheless, in considering the application of s 69(3)(a) to the merger documents, the Court may examine the documents and draw any reasonable inferences from them as well as from other matters from which inferences may properly be drawn (see s 183 of the Evidence Act). Neither party adduced evidence about the ACCC’s informal merger clearance processes and both parties assumed that the Court is familiar with those processes. The Court is able to take a degree of judicial notice of the ACCC’s processes, at least at a general level. However, the absence of evidence in that respect must count against the party that bears the burden of establishing that the exception in s 69(3) applies, BlueScope. In general terms, it is common for businesses that intend to undertake an acquisition of shares or assets that may give rise to a risk of contravention of s 50 of the Act to inform the ACCC of the proposed acquisition and seek an indication from the ACCC whether it will oppose the merger through the institution of legal proceedings under s 50. The indication that may be given by the ACCC is commonly referred to as informal merger clearance because it does not involve the exercise of a formal statutory power. It is a statement by the ACCC whether or not it intends to exercise statutory powers to institute proceedings to enjoin the proposed acquisition.

28 BlueScope has failed to persuade me that the merger documents were prepared or obtained for the purpose of conducting, or for or in contemplation of or in connection with, an Australian proceeding within the meaning of s 69(3)(a). At the time the documents were prepared, there is no evidence to suggest that legal proceedings were likely or reasonably probable and such a conclusion cannot be inferred from the documents. There is no evidence to suggest that, at the time the documents were prepared, the ACCC had threatened legal proceedings to prevent the merger (or BlueScope had threatened proceedings to seek declaratory relief from the Court in respect of the proposed merger). I infer from the fact that BlueScope was seeking informal clearance that BlueScope’s purpose, at the time of preparing the documents, was to avoid legal proceedings in respect of the proposed merger. In the circumstances, I consider that, at the time the documents were prepared, the prospect of litigation in respect of the merger was a mere possibility.

29 I am therefore satisfied that the merger documents are admissible as business records of BlueScope under s 69(2). It is therefore unnecessary to consider whether they are admissible in the case against BlueScope as admissions. For completeness, though, I record that I would have had no hesitation in concluding that the documents contain passages that are admissions (being representations adverse to BlueScope’s interests in the proceeding) and, in circumstances where the documents were prepared by BlueScope’s legal advisor and appointed economic advisor, I would have readily inferred that the legal and economic advisors had authority to make the representations on behalf of BlueScope for the purposes of s 87(1)(a).

30 I reject BlueScope’s generalised submissions that the merger documents are inadmissible because the representations contained in the documents are opinions or matters of mixed law and fact. An examination of the documents demonstrates that the submission is incorrect. The merger documents contain a detailed description of BlueScope’s business including its manufacturing processes, the products it produces, the quantities it produces, the distribution channels through which it supplies those products, the prices at which it supplies those products, the companies which supply similar or equivalent products, the uses to which the products are put and the acquirers of such products. I consider that all such matters are primary facts, not matters of opinion, which bear upon the issue of competition that is raised in the proceeding as well as providing the factual background or context for the alleged infringing conduct.

31 In so far as the merger documents contain statements concerning competition and competitors in respect of the supply of flat steel products in Australia, BlueScope submitted that such statements are irrelevant to the present proceeding. BlueScope argued that the relevant issue and legal standard that must be considered under s 50 of the Act, whether the proposed merger would substantially lessen competition, differs from the issue and legal standard that must be considered in the present case, whether the parties to the alleged attempted arrangement or understanding were in competition with each other in relation to the supply of the flat steel products (being the products the subject of the alleged cartel provisions). BlueScope argued that market definition (which, I interpolate, is a conceptual tool in the identification and analysis of competition), is purposive and depends on the issue at hand. It followed, according to BlueScope, that statements concerning competition in a merger context have no relevance to the present case.

32 I reject those submissions. The prohibitions in Part IV of the Act are all concerned with conduct that may lessen competition in Australian markets. The word “competition” has the same meaning in each of the prohibitions in Part IV. The word is used in a commercial or economic sense: Adamson v West Perth Football Club Inc [1979] FCA 81; 27 ALR 475 at 502 per Northrop J; Outboard Marine Australia Pty Ltd v Hecar Investments (No 6) Pty Ltd (1982) 44 ALR 667 at 669 per Bowen CJ and Fisher J. It means rivalrous market behaviour in the supply of goods and services in respect of the price, quality and quantity of supply: see Re Queensland Co-operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 25 FLR 169 at 187-189. It can be accepted that the focus of the factual enquiry required to consider “competition” in the context of a merger under s 50 of the Act differs from the focus of the factual enquiry required to consider “competition” in the context of cartel conduct (specifically, in the definition of cartel provisions in what was s 44ZZRD and is now s 45AD). Section 50 requires an enquiry into the nature and extent of competition in relevant markets and the likely effect of the merger on that competition. Thus, it requires a “market level” focus. In contrast, the definition of cartel provisions requires an enquiry into whether at least two of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding are or are likely to be in competition with each other in relation to the goods or services the subject of the cartel provision. Thus, the definition of cartel provisions focuses upon competition between individual suppliers. That means that the factual enquiry required in the context of cartel conduct is a subset of the factual enquiry required in the context of a merger. Ultimately, though, the enquiry concerns the same question: the existence of competition in respect of the supply of particular goods or services. It follows that representations made by BlueScope, in the context of an application for informal clearance of a merger, identifying its competitors in respect of the supply of flat steel products in 2013, are relevant (indeed likely to be highly relevant) to the issue of competition that arises in this proceeding. To the extent that such representations involve opinions, I consider that the opinions are admissible under s 78 of the Evidence Act for the reasons explained below in connection with ruling 3.

33 As indicated above, I indicated to the ACCC that it should identify, for the benefit of the respondents and the Court, which parts of the merger documents it seeks to rely upon in this proceeding. The documents contain a substantial volume of material that deals only with the specifics of the particular merger that BlueScope was addressing at the time and which has no apparent relevance to this proceeding. I would expect such material to be excluded on the ground of relevance.

Ruling 3: Representations about competition

34 BlueScope objected to certain passages in lay witnesses statements, and the transcript of the examination of Mr Mark Vassella (the Chief Executive Officer of BlueScope Australia and New Zealand, a division of BlueScope) conducted under s 155 of the Act, proposed to be tendered by the ACCC that contain statements to the effect that BlueScope (and its related entities) was “in competition with” one or more of the proposed counter-parties to the alleged attempts (the competition statements). For example, BlueScope objected to the bolded portions of the following extract from the first witness statement of Mr Hennessy, Executive National Sales Manager for BlueScope CIPA for the relevant period:

The companies I listed in this email were competitors to BSL CIPA in Australia and not companies that I had identified as being of particular 'dumping' concern. I provided the information to Jason ELLIS, at his request, to assist Dieter SCHULZ, BSL CIPA's Manager of International Trade, in an upcoming trip involving visits to overseas competitor mills.

35 I note for completeness that BlueScope requested, and the ACCC agreed, that the above part of Mr Hennessy’s witness statement would not be tendered but the ACCC would adduce vive voce evidence on that topic from Mr Hennessy. Therefore, a formal ruling in respect of the above extract is not required. It is nonetheless illustrative of the broader category of proposed evidence that BlueScope objected to.

36 BlueScope submitted that its objection related to statements containing “bare assertions” that particular suppliers were competitors of BlueScope, as compared to other statements that provide more concrete or specific evidence in respect of competition. BlueScope argued that, where the witness does not explain the basis or foundation for the assertion, the Court cannot be satisfied that the witness’ understanding of competition is consistent with the statutory conception or that there is proper basis for the opinion. In those circumstances, BlueScope argued that this kind of evidence was both irrelevant for the purposes of s 55 of the Evidence Act and inadmissible opinion evidence under s 76 of the Evidence Act. Alternatively, BlueScope argued that the Court should exclude the evidence pursuant to s 135 of the Evidence Act on the basis that the probative value of such evidence is very low and substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might be unfairly prejudicial.

37 The ACCC submitted that to the extent that evidence in the ACCC’s lay witness statements relating to competition is opinion evidence, it is admissible pursuant to the exceptions to the opinion rule in ss 78 or 79 of the Evidence Act.

38 I accept the ACCC’s submission that the competition statements are admissible statements of opinion pursuant to s 78 and, as such, constitute relevant evidence. In the context of competition cases, the views and perceptions of market participants are often the best evidence as to matters relevant to the competitive dynamics and relevant field of rivalry in the marketplace. For that reason, I would not exclude the evidence under s 135.

39 A statement by a trader in the market that another trader is a competitor can properly be characterised as an opinion within the meaning of the opinion rule in s 76. It is “an inference from observed and communicable data”: Allstate Life Insurance Co v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (No 5) (1996) 64 FCR 73 at 75 per Lindgren J. Nevertheless, pursuant to s 78, the opinion rule does not apply to exclude evidence of an opinion expressed by a person if:

(a) the opinion is based on what the person saw, heard or otherwise perceived about a matter or event; and

(b) evidence of the opinion is necessary to obtain an adequate account or understanding of the person’s perception of the matter or event.

40 As observed by French CJ, Heydon and Bell JJ (with whom Gummow J agreed) in Lithgow City Council v Jackson (2011) 244 CLR 352 (at [45]), the common law permitted the reception of non-expert opinion evidence where it was very difficult for witnesses to convey what they had perceived about an event or condition without using rolled-up summaries of lay opinion – impressions or inferences – either in lieu of or in addition to whatever evidence of specific matters of primary fact they could give about that event or condition. Their Honours said that “the usual examples are age, sobriety, speed, time, distance, weather, handwriting, identity, bodily health and emotional state, but a thorough search would uncover very many more”. Their Honours further observed that, whether or not s 78 is precisely identical with the common law, s 78 permits reception of an opinion where the primary facts on which it is based are too evanescent to remember or too complicated to be separately narrated (at [48]).

41 In my view, a statement by a trader in the market that another trader is a competitor falls into the same category of evidence – an impression or inference where the primary facts on which it is based are too evanescent to remember or too complicated to be separately narrated. As referred to above, competition as used in the Act refers to rivalrous market behaviour. Whether one trader is acting in a rivalrous manner toward another trader, by taking away or threatening to take away custom from the other, is an impression or inference usually drawn from myriad events and circumstances in the relevant market including knowledge of the products being offered and supplied by another trader and the ebb and flow of custom between traders.

42 In the context of competition law, it has long been recognised that the opinions of traders in the marketplace as to their competitors is both admissible evidence and highly probative of that issue. In Arnotts Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1990) 24 FCR 313 (Arnotts), the Full Court held that there was no reason in principle not to allow “perception” evidence of industry participants as relevant to matters of market definition in merger cases (at 354-355). That approach has been affirmed by the High Court. In Boral Besser Masonry Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 215 CLR 374 (Boral), McHugh J said (at [257], citing Arnotts):

The views and practices of those within the industry are often most instructive on the question of achieving a realistic definition of the market. The internal documents and papers of firms within the industry and who they perceive to be their competitors and whose conduct they seek to counter is always relevant to the question of market definition.

43 Similarly, in Rural Press Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ stated at [45] (citing McHugh J in Boral at [257]):

The views and practices of those within an industry can often be most instructive not only on the question of achieving a realistic definition of the market, but also on the question of assessing the quality of particular competitive conduct in relation to the level of competition and the impact of its cessation.

44 It can be accepted that the weight that will be given to such opinion evidence will be affected by the extent to which the witness gives evidence of supporting primary facts, such as evidence of the products being offered or supplied by the competing trader and whether the witness has lost custom to, or gained custom from, the competing trader. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc [1999] FCA 675, the Court was asked to consider the admissibility of statements in the form of “I believe I compete with A, B and C in this market”, from lay witnesses. French J (as his Honour then was) admitted the evidence, stating (at [8], [10]):

[8] The real gravamen of the complaint is that statements of this kind are at too high a level of generalisation. I do not consider that this is a basis for striking them out. To the extent that they reflect a perception on the part of the franchisee which may affect the franchisee’s behaviour in the market, they are admissible. …

[10] To the extent that the evidence is relied upon as evidence of perception or as explanatory of the behaviour of industry participants, it would appear to attract the operation of [sections 77 or 78 of the Evidence Act] … It may be that an opinion is based upon observations which are not specifically analysed but expressed compendiously. The weight of such compendious expression, eg about the extent and nature of competition in a market, will depend upon a variety of factors. The more general such statements the less weight they are likely to be given. However this is not a matter that goes to admissibility. The difficulty of distinguishing between inferences and underlying facts in expressions of compendious impression is principally, in my opinion, a matter of weight.

45 Finally, I do not consider that the admission of this category of evidence is unfairly prejudicial to BlueScope. BlueScope submitted that “bare assertions” of competition, that do not disclose any basis for the witness’ perception of competition, make it difficult for it to cross-examine the witness effectively on that particular proposition because of a risk of the witness “ambushing” the cross-examiner with unanticipated evidence of the basis for their perception. I do not accept that submission in the context of this case, where the contested evidence concerns, in the case of BlueScope, its own business, and in the case of Mr Ellis, a business division which he managed at the relevant time.

Ruling 4: Evidence of the meaning or effect of a communication

46 In proof of its allegation that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain companies (the counter-parties) to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding containing a cartel provision, the ACCC relies on evidence of written and oral communications made by certain employees of BlueScope (particularly Messrs Ellis, Hennessy, Sparks, Kelso, Whitfield and Gent) to representatives of the counter-parties. The evidence sought to be adduced by the ACCC includes evidence given by Mr Hennessy in respect of communications of Mr Ellis to which he was privy and by other witnesses who were recipients of the communications (in their capacity as officers or employees of the counter-parties). The evidence includes the witness’ recollection of oral communications passing from representatives of BlueScope (including particularly Mr Ellis) to the witness and evidence given by the witness of their understanding of the meaning and effect of the communication. The respondents objected to evidence of the latter type (the witness’ understanding of the meaning of the communication) on the basis that it is not relevant (because it is not probative of what the communicator meant) and is inadmissible opinion evidence under s 76 of the Evidence Act.

47 A relevant illustration can be taken from the witness statements of Neil Lobb who, in the relevant period, was the Managing Director of CMC. Mr Lobb signed two witness statements, the second correcting aspects of the first and providing additional evidence. Mr Lobb’s first witness statement contains the following passage (as corrected by the second):

Communications with Jason Ellis at BlueScope

42. In his role as General Manager of BlueScope Sales & Marketing, Jason Ellis would call me to discuss various matters, including changes to BlueScope's market offer or a general catch up in relation to industry information.

43. I would also call Jason Ellis, on occasion, to have discussions with him about BlueScope's price to CMC SD on a national basis, and also service and product issues. I understood that the reason why Jason Ellis was speaking to me about prices for CMC SD on a national basis was because: Jason Ellis had a broad network of people he talked to on a regular basis; Jason Ellis and I had a pre-existing relationship from working together at CMC SD; and I had more experience in relation to sheet & coil distribution business than my managers at CMC SD.

44. I recall that, shortly after he had commenced his role at BlueScope, Jason Ellis telephoned me and we had a conversation. Whilst I cannot now recall the exact words that Jason Ellis said to me in that conversation, I recall the gist of that conversation and Jason Ellis telling me, in words to the following effect:

Ellis: We've made a change to our price list. You will notice now there's a recommended resale price that will give our distributors the opportunity to price at that level to your customers.

We are increasing our list price and offering higher distributor discounts to CMC so that your net price doesn't change.

This will give you an opportunity to Increase your profit margins. [This will restore profitability in the steel market.]

45. I cannot now recall whether Jason Ellis told me about this proposal over one or two phone calls.

46. I recall that during telephone conversations, Jason Ellis also told me that he was telling other distributors the same message, in words to the following effect:

Ellis: I have spoken to Jim Larkin [General Manager of Southern SC] about using the recommended resale price to price to their customers as well.

Jim has agreed to set their prices [Southern SC's prices] to their customers at BlueScope's recommended resale price.

I have also spoken to SMS and they have agreed to do this also [to set their prices to their customers at BlueScope's recommended resale price].

47. I understood Jason Ellis was seeking to reassure me that CMC SD would not lose business to Southern SC and SMS by increasing CMC SD's prices to CMC SD's customers so that they were at the level of BlueScope's recommended resale price (RRP), because both Southern SC and SMS had agreed to do the same.

48 I note for completeness that BlueScope requested, and the ACCC agreed, not to tender paragraphs 44 to 47 above but to adduce vive voce evidence from Mr Lobb on that topic. The parties nevertheless sought a ruling on the admissibility of evidence of this kind. In his second witness statement, Mr Lobb gives evidence to the effect that the passages extracted above which are contained within square brackets were not words that Mr Lobb recalls being used by Mr Ellis but express what Mr Lobb understood from the communication or, in the case of the reference to Mr Larkin, Mr Lobb’s understanding of Mr Larkin’s title or role.

49 The respondents objected to the evidence of Mr Lobb in so far as it expressed Mr Lobb’s understanding of the meaning and effect of the communication; i.e. the passages which are contained within square brackets and paragraph 47 in the extract above. The respondents submitted that the only evidence that is relevant and admissible is evidence of the words used by Mr Ellis and Mr Lobb’s understanding of the communication is irrelevant and therefore inadmissible.

50 A second illustration can be taken from the witness statements of Mr Hennessy. In his first witness statement (at paragraph 283), Mr Hennessy recalls the following discussion with Mr Ellis:

Soon after I returned from leave in October 2013, Jason ELLIS and I had a discussion in words to the following effect:

Jason: We need to align the New Zealand Steel's list price with the BSL CIPA list price so that there is an alignment with our price benchmarking strategy. We need to talk to Sean O'Brien.

Me: Okay. I'll have a chat to Anthony [PALERMO] about that.

51 In his second witness statement, Mr Hennessy states with regard to this conversation (at paragraph 125):

I understood based on my conversation with Jason ELLIS… that Jason ELLIS also wanted NZSA to price at the BSL CIPA List Price as part of his Price Benchmarking Strategy. The effect of this would be that all of BlueScope's subsidiaries, whether SMS/BSD or NZSA, would distribute the same BSL List Prices or RRP as Bluescope CIPA distributed. This was for the purpose of reassuring distributors, that Jason ELLIS and I had had discussions with, that Bluescope and its subsidiaries were using the BSL CIPA List Price.

52 The respondents objected to paragraph 125 on the basis of relevance, in that it is not probative of Mr Ellis’ intention, and on the basis that it is inadmissible opinion evidence in that it is Mr Hennessy’s interpretation of the meaning and effect of the conversation that he recounts at paragraph 283 of his first statement. Again, I note for completeness that BlueScope requested, and the ACCC agreed, not to tender paragraph 125 above but to adduce vive voce evidence from Mr Hennessy on that topic. The parties nevertheless sought a ruling on the admissibility of evidence of this kind.

53 Each of the parties agreed, and I accept, that the opinion of a person as to the state of mind (intention) of another person (relevantly in this case, Messrs Ellis, Hennessy, Sparks, Kelso, Whitfield and Gent) is inadmissible as it inevitably involves speculation. By way of illustration, in Petch v The Queen (2020) 103 NSWLR 1, the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal concluded that, in so far as evidence of a witness’s opinion concerns another person’s intention or state of mind, it is not an opinion based on what the witness “saw, heard or otherwise perceived” about a matter or event (that is, by reference to the five senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste or touch) as required to fall within the exception to the opinion rule (at [87] per Hamill J, Hoeben CJ at CL agreeing and Cavanagh J in dissent but agreeing on that issue); see also Medich v The Queen [2021] NSWCCA 36; 390 ALR 398 at [106] per Bathurst CJ and at [831] per Hamill J (in dissent). It follows that the proposed evidence of Mr Lobb and Mr Hennessy set out above is not admissible as direct evidence of Mr Ellis’ intention in making the communications. The existence of the requisite intention on the part of Mr Ellis and the other BlueScope employees referred to above is a question of fact capable of proof by inference drawn from the primary facts as found: see Kural v The Queen (1987) 162 CLR 502 at 505 per Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ; Saad v The Queen [1987] HCA 14; 70 ALR 667 at 669 per Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ; Pereira v Director of Public Prosecutions [1988] HCA 57; 82 ALR 217 at 219.

54 The ACCC submitted that the above proposed evidence is relevant to two issues in the proceeding. The first issue is Mr Hennessy’s intention (where Mr Hennessy’s intention is relied on by the ACCC as attributable to BlueScope). The ACCC submitted that Mr Hennessy’s evidence of his understanding of the meaning and effect of Mr Ellis’ communications is relevant to an assessment of Mr Hennessy’s intention when carrying out Mr Ellis’ instructions or otherwise engaging in conduct which the ACCC alleges constitutes the attempts. The second issue concerns the content or substance of communications made to counter-parties by relevant representatives of BlueScope, which is relied on by the ACCC as conduct constituting the attempt. On that issue, the ACCC submitted that the evidence is relevant in two ways. First, in circumstances where the witness may not be able to recall the whole of a relevant communication that the witness was privy to, it is permissible for the witness to give evidence of their understanding of the overall meaning or effect of the communication. Second, in a proceeding involving an alleged attempt to induce a counter-party to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding containing a cartel provision, the counter-party’s understanding of the communications made to it is relevant to establish that sufficient steps were taken toward the arrangement or understanding.

55 I dismissed the respondents’ objections with respect to this category of evidence and allowed the evidence largely on the bases propounded by the ACCC. I made the following general rulings with respect to the admissibility of such evidence:

(a) first, in so far as the witness’ state of mind is relevant (as it is in the case of Mr Hennessy), evidence of what the witness understood a communication to mean is admissible in so far as it is relevant to the witness’ state of mind (witness state of mind);

(b) second, evidence from a representative of a counter-party as to what they understood from a communication in the context in which it was made is admissible in so far as the evidence bears upon an objective assessment of the substance and content of the communication and the meaning that would reasonably be expected to be understood by a person in the position of the recipient of the communication (objective meaning or effect of the communication).

56 I reiterate that, in so far as the evidence concerns communications of Mr Ellis, the evidence is not admissible as direct evidence of Mr Ellis’ intention in making the communications. However, in so far as the evidence enables the Court to make findings on the balance of probabilities about the substance and meaning of the communications, such findings may then provide a foundation for drawing inferences as to Mr Ellis’ intention in making the communications.

57 My reasons for these rulings are as follows.

Witness state of mind

58 The ACCC’s allegations that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain counter-parties to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding that contained a cartel provision require it to prove that BlueScope and Mr Ellis intended, by their conduct, to bring about the arrangement or understanding.

59 In respect of BlueScope’s intention, the ACCC alleges that the relevant intention was held by particular BlueScope employees in respect of the attempts with different counter-parties. For all of the alleged attempts, the ACCC relies on the alleged intention of Mr Ellis and says that his intention is to be attributed to BlueScope under s 84 of the Act. For most of the alleged attempts, the ACCC also relies on the intention of Mr Hennessy.

60 The intention of relevant individuals (particularly Messrs Ellis and Hennessy) can be proved in two ways. First, by direct evidence of their intention: evidence given by Mr Ellis or Mr Hennessy in the proceeding respectively as to their own intention or evidence given by another witness of contemporaneous representations made by Mr Ellis or Mr Hennessy as to their intention (which is admissible under s 66A of the Evidence Act). Second, by inference from conduct engaged in by Mr Ellis or Mr Hennessy whether in the form of oral or written communications or other actions taken.

61 Subject to the form of the evidence, Mr Hennessy can give evidence about his understanding of matters that were communicated to him in so far as they bear upon or are relevant to his own state of mind. Such evidence is admissible as evidence going to Mr Hennessy’s own intention (where his intention is a relevant issue in the proceeding).

Objective meaning or effect of the communication

62 The ACCC’s allegations that BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce certain counter-parties to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding that contained a cartel provision also require it to prove that BlueScope and Mr Ellis engaged in conduct necessary to constitute an attempt: i.e., that each took a sufficient step towards inducing the proposed counter-party to make the arrangement or arrive at the understanding. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Egg Corporation Ltd (2017) 254 FCR 311, the Full Court summarised the applicable principles as follows (at [93]):

The conduct which is necessary to constitute an attempt is a step towards the commission of a contravention, which is immediately and not merely remotely connected with it (Tubemakers at 472; 736 per Toohey J referring to Archbold’s Pleading Evidence & Practice 36th, para 4101). The Full Court of this Court in Trade Practices Commission v Parkfield Operations Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 534 (Parkfield Operations) at 538-539 made a similar point when it said that an attempt must involve taking a step towards the commission of contravening conduct and that it is not sufficient that it be merely remotely connected or preparatory to the commission of it. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SIP Australia Pty Ltd [2002] ATPR 41-877 (ACCC v SIP Australia) at 45-015, Goldberg J made the point that what is required for an inducement is that “there be an affirmative or positive act or course of conduct directed to the person who is said to be the object of the inducement”. In addition to that point, his Honour also referred to the decision of the Full Court of this Court in Heating Centre Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1986) 9 FCR 153 at 164 where it was said that mere persuasion, with no promise or threat, may well be an attempt to induce.

63 In assessing whether conduct constitutes a sufficient step towards inducing the proposed counter-party to make the arrangement or arrive at the understanding, it is necessary to have in mind the principles as to what constitutes an arrangement or understanding. As explained by Beach J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Olex Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 222; ATPR 42-540 (at [477]):

…an arrangement or understanding is something less than a binding contract or agreement (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (2007) 160 FCR 321 at [26] to [30] per Gray J and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (2004) 141 FCR 183 at [54] per Merkel J). The concept of an understanding is a “broad and flexible” concept (Norcast S.ár.L v Bradken Ltd (No 2) (2013) 219 FCR 14 at [263] per Gordon J; ACCC v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (2004) 141 FCR 183 at [54] per Merkel J). An “understanding” may be a looser concept than an “arrangement” (ACCC v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (2007) 160 FCR 321 at [27]). An arrangement or understanding requires a consensus or a “meeting of the minds of the parties” under which parties assume obligations or give assurances or undertakings that they will act in a particular way. The “meeting of the minds” will usually embody a mutual obligation between the parties, but it is not required (Norcast v Bradken at [263]). Reciprocity of obligations is common but unnecessary. To establish such an arrangement or understanding it is sufficient that “the minds of the parties are at one that a proposed transaction between them proceeds on the basis of the maintenance of a particular state of affairs or the adoption of a particular course of conduct” (Top Performance Motors Pty Ltd v Ira Berk (Qld) Pty Ltd (1975) 24 FLR 286 at 291 per Smithers J). It is sufficient that an arrangement or understanding creates moral obligations or obligations binding in honour only (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CC (NSW) Pty Ltd (No 8) (1999) 92 FCR 375 at [136]–[137]). An arrangement may be informal as well as unenforceable, with the parties free to withdraw from it or to act inconsistently with it notwithstanding their adoption of it (Norcast v Bradken at [263]). A mere expectation in a non-normative sense or a hope that something might be done or happen or that a party will act in a particular way is not of itself sufficient to found an arrangement or understanding (Trade Practices Commission v Email Ltd (1980) 43 FLR 383 at 385; ACCC v CC (NSW) Pty Ltd (No 8) at [141]). There will be no understanding where one party decides unilaterally to act in a particular way in response to a pricing manoeuvre by a competitor.

64 It is well established that the making of an arrangement or the arriving at an understanding may be proved by direct or circumstantial evidence. Direct evidence includes the content of communications passing between the parties to the alleged arrangement or understanding. Circumstantial evidence includes conduct consistent with the making or acting upon (giving effect to) the alleged arrangement or understanding. A wide range of evidence of communications and conduct may be admissible in proof of an arrangement or understanding. Not all communications need be between the alleged parties to the arrangement or understanding. As Perram J explained in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd (No 1) (2012) 207 FCR 448 (at [25]-[26]):

I do accept the principle invoked by the ACCC, namely: that one may prove an agreement or understanding between a group of people by proving behaviour of individual group members consistent with the existence of the agreement; that such behaviour may include evidence of what members of the group said to each other or even to third parties; and, that this use of conduct as circumstantial evidence of an agreement does not involve a hearsay use of the words used when some or all of the conduct relied upon consists of speech acts. This is straightforward: Ahern at 93-94. If three airlines go to dinner and discuss reaching an agreement not to compete on a fuel surcharge on cargo, this is evidence which is capable of bearing on the existence of such an agreement. Whether that evidence is ultimately accepted is a different question, as is the question of whether AirNZ and Garuda are shown to be parties to such an arrangement. But as an element in a circumstantial case, I do not doubt its relevance.

I do not accept that I am required to ask whether this individual communication shows that AirNZ or Garuda were parties to the agreement or understanding. Talking, it is true, of the application of the standard of proof to a civil case of fraud by circumstantial evidence, Ipp JA (with whom Tobias and Basten JJA agreed) referred with approval to what had been said by Winneke P in Transport Industries Insurance Company Ltd v Longmuir [1997] 1 VR 125 at 129: “It is erroneous to divide the process into stages and, at each state, apply some particular standard of proof. To do so destroys the integrity of [a] circumstantial case”: Palmer v Dolman [2005] NSWCA 361 at [41], [125], [126]. Of course here the question is not, as it was in Palmer, whether the particular integer alleged proved the fraud. Here the question is whether the integer is admissible to prove the existence of the agreement.

65 In the present case, the ACCC proposes to call a number of witnesses, including Mr Lobb, who will give evidence of written and oral communications made to them by BlueScope representatives and Mr Ellis. In determining whether BlueScope and Mr Ellis attempted to induce the proposed counter-party to make an arrangement or arrive at the understanding containing a cartel provision, the Court will be required to make findings as to the content and substance of the communication, and whether it had the potential to induce a consensus or “meeting of minds”.

66 The respondents argue that while evidence is admissible in so far as it recounts communications made to them by a BlueScope representative, it is inadmissible in so far as it recounts their understanding of the communications. The respondents argue that the Court must determine the objective meaning of the words used by the relevant BlueScope representative in a communication for itself and the Court cannot be assisted in that task by evidence of the understanding of the recipient of the communication.

67 I do not accept that submission and consider that the evidence is admissible on two bases.

68 First, in context, it is apparent that the evidence is the witness’ overall impression of the meaning and effect of the relevant communication (usually a conversation) in circumstances where the witness cannot recall the precise words used or the entirety of the conversation. There are many examples in the witness statements where the witness records “words to the effect” spoken by a BlueScope representative, which is set out in the form of direct speech, and then the witness states what the witness understood from the conversation. The respondents argued that only the “direct speech” aspect of the evidence is admissible, with the witness’ understanding being impermissible opinion. I disagree. The “direct speech” component of the evidence is not purporting to be the actual words used in the conversation, but only the effect of the conversation. I consider that the further evidence as to the witness’ understanding of the conversation is supplementary to the “direct speech” aspect and is intended to provide a more complete impression of the conversation. As recently observed by Bromwich J in Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v The Country Care Group Pty Ltd (Ruling No 1) [2020] FCA 1670 at [11], while it is preferable for evidence to be given of an actual recollection of words used in a communication (and to be given in the form of direct speech), where that is not possible it is permissible to give evidence of the substance or effect of the communication. To the extent it is necessary to rely upon it, I consider that the evidence is admissible under s 78 of the Evidence Act as being necessary to obtain an adequate account or understanding of the witness’ perception of the conversation. In Connex Group Australia Pty Ltd v Butt [2004] NSWSC 379, White J admitted under s 78 a file note which recorded “the gist of [a] conversation” including that the note taker was left with a particular “impression” as to what people would do (at [21], [27]). Similarly, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (No 2) [2015] FCA 1304; 332 ALR 396, Besanko J admitted a witness’ evidence of discussions of which the witness did not have a clear recollection, though he recalled the substance and “aim” of those discussions. His Honour accepted that this evidence was admissible, and, if it was opinion evidence, that it fell within the terms of s 78 of the Evidence Act (see [61]-[63]).

69 Second, in so far as the witness is a representative of a counter-party to an alleged attempted arrangement or understanding, the witness’ understanding of the communication is relevant to the question whether the conduct involved a sufficient step towards inducing the counter-party to make the arrangement or arrive at the understanding. As noted above, the Court will be required to make findings as to the content and substance of the communication, and whether it had the potential to induce a consensus or “meeting of minds”. In assessing that potential, the Court must determine the meaning of the communication as would reasonably be expected to be understood by a person in the position of the recipient of the communication. In a case such as the present, numerous aspects of context may be relevant to a consideration of the meaning of the communications by such a person including the relevant area of trade or commerce of the parties to the conversation, the trading conditions at the time, the trading relationship between the parties to the conversation, the personal relationship between the parties to the conversation and the history of dealings between the parties to the conversation. An additional matter of context may also be important. As the making of an arrangement or understanding containing a cartel provision is a criminal offence and a civil wrong, communications between parties directed to that end may be guarded, if not coded. The relevant communication may hint at a proposed arrangement or understanding rather than express the proposal clearly and overtly. The fact that a written or oral statement contains hints or suggestions of a cartel arrangement or understanding may only be revealed by a party to the communication that is able to provide an “insider’s” view or explanation of the communication, being a person who is informed by the context of the communication. Such evidence cannot be determinative of the meaning of the communication (far less the meaning intended by the communicator), but in my view it is probative of an objective assessment of the meaning that would reasonably be expected to be understood by a person in the position of the recipient of the communication.

70 The receipt of such evidence in these circumstances is analogous to receipt of evidence of a consumer, in the context of a proceeding under s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Act (Australian Consumer Law), that the consumer formed a particular mistaken belief by reason of a communication. It has long been held that such evidence is relevant and admissible, although neither necessary nor determinative of the ultimate issue: see for example Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 198-199 per Gibbs CJ; Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 at [45] per Allsop CJ; Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Careline Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 422 at [55]-[57] per Murphy, Gleeson and Markovic JJ. Counsel for Mr Ellis submitted that the present circumstance differs from the context of misleading and deceptive conduct in that the present case involves no question about the effect of the conduct on the minds of the persons who were the subject of the conduct. For the reasons set out above, I do not accept that submission. An issue in the proceeding is whether BlueScope and Mr Ellis engaged in conduct that constituted a sufficient step towards inducing a “meeting of minds” on the subject of the alleged cartel provision. It is therefore necessary for the Court to consider what would reasonably be expected to be understood from the communication by a person in the position of the counter-party.

71 Finally, BlueScope sought to draw support from Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2018) 266 FCR 631 (Unique) and Capic v Ford Motor Company of Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 715 (Capic). Neither case affords support for BlueScope’s objection. In Unique, the Full Court observed (at [162]) that in a case of alleged unconscionable conduct against a group of consumers that involves a system or pattern of behaviour and where the nature of the system and the nature of unconscionability depends on the attributes of individual consumers, or the specifics of transactions with individual consumers, there will need to be evidence about either a material proportion of individual consumers, or evidence about how and why the individual consumers were chosen, or evidence about the representativeness of the individual consumers, or a combination of all three. In Capic, Perram J concluded (at [103]-[107]) that in determining whether goods are of acceptable quality within the meaning of s 54 of the Australian Consumer Law, which requires an assessment of whether a reasonable consumer would regard them as acceptable, evidence from a sample of 52 consumers who purchased the goods (out of a known class of consumers of 64,963) could not assist the Court. The present case raises a different issue: whether BlueScope attempted to induce certain companies to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding through specific communications made to representatives of each of those companies. The evidence to which objection is taken is proposed to be given by witnesses who were the recipients (and intended recipients) of the communications alleged to constitute the acts of contempt. The reasoning in Unique and Capic has no application in those circumstances.

Ruling 5: Evidence about a recommended resale price list for processing services

72 In its pleading, the ACCC alleges that Mr Ellis developed a strategy to increase the value to BlueScope and distributors of sales of flat steel products in Australia (referred to as the benchmarking strategy) which comprised BlueScope:

(a) providing to distributors a recommended resale price for flat steel products;

(b) persuading distributors to use the recommended resale price to set the price at which those distributors would sell flat steel products (on the basis that BlueScope would cause BlueScope Distribution and NZSA to price in accordance with the recommended resale price); and

(c) causing BlueScope Distribution and NZSA to price in accordance with the recommended resale price.

73 The ACCC alleges that the benchmarking strategy formed part of the conduct by which BlueScope attempted to induce distributors of flat steel products in Australia (Southern Steel, OneSteel, CMC, Apex Steel, Selection Steel, Selwood Steel and Vulcan Steel), and the import trader Wright Steel, to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding to fix, maintain or control the price of flat steel products supplied by one or more of BlueScope, BlueScope Distribution, NZSA and the respective distributor or Wright Steel.

74 The ACCC sought to adduce evidence about the above benchmarking strategy, and there is no objection to that evidence. The evidence includes price lists produced by BlueScope which contained a recommended resale price for the different types and categories of flat steel products manufactured and supplied by BlueScope in Australia.

75 However, the ACCC also sought to adduce evidence about a separate “recommended resale price” list produced by BlueScope in respect of “processing charges” for flat steel products. The evidence indicates that distributors of flat steel products provided a number of processing services to their customers in respect of flat steel products including shearing (cutting a flat steel coil to a specified length), splitting (cutting a flat steel coil length-wise to a specified width) and recoiling the flat steel coil after it has been sheared or split. The ACCC sought to adduce evidence that BlueScope prepared a draft document titled “BlueScope Recommended Processing Charges” which contained recommended charges for, amongst other things, shearing, splitting and recoiling services, and provided the document to certain distributors for feedback. Ultimately, BlueScope did not implement the “recommended resale price” for processing services.

76 BlueScope objected to the evidence concerning the “recommended resale price” for processing services on the grounds of relevance as the ACCC does not allege that BlueScope attempted to induce an arrangement or understanding containing a cartel provision relating to the price of processing services, and the ACCC did not rely on that conduct in its pleaded case against BlueScope and Mr Ellis in respect of flat steel products.

77 The ACCC submitted that the evidence is relevant as bearing upon Mr Ellis’ intention in implementing the benchmarking strategy for flat steel products. In that respect, the ACCC referred to other evidence (particularly an internal BlueScope presentation dated 9 April 2014 said to be authored by Mr Ellis) which suggested that the “recommended resale price” for processing services was intended to be an extension of the benchmarking strategy for flat steel products, thereby linking the two strategies. The ACCC said that it will contend that the “recommended resale price” for processing services was not a usual recommended resale price because BlueScope did not provide processing services to distributors for resale or resupply. The ACCC will submit that the document reveals that BlueScope’s intention was to encourage or induce distributors to increase their charges for processing services, and that that was the same intention that lay behind the benchmarking strategy.

78 I ruled that this category of evidence would be received on a provisional basis under s 57 of the Evidence Act. The relevance of the evidence will depend upon an assessment of the entirety of the evidence bearing upon the question whether, and to what extent, the “recommended resale price” for processing services was an extension of the benchmarking strategy such that it might be inferred that the benchmarking strategy was motivated by the same intention as the “recommended resale price” for processing services.

79 I also consider that the evidence may prove to be relevant to another factual issue arising in the proceeding, as identified by the ACCC. The opening submissions of the parties indicate that a factual matter in dispute between them is whether it was commercially feasible or realistic for BlueScope to implement the benchmarking strategy in the form alleged by the ACCC as a means by which to induce distributors to make an arrangement or arrive at an understanding with respect to distributors’ prices. I apprehend that BlueScope will contend that it was not commercially feasible or realistic because distributors did not merely resupply or resell flat steel products but also processed the flat steel products including by shearing, splitting and recoiling the products. The processing activities involved costs which needed to be recovered by the distributors, and therefore a recommended resale price in respect of flat steel products could not be a means to induce a price fixing arrangement or understanding in respect of distributors’ prices. It appears to me, at this stage of the proceeding, that the force of that contention may depend upon the relative cost and prices for flat steel products and processing services. Different conclusions with respect to commercial feasibility may be reached depending on whether the cost for processing services is a relatively small component of distributors’ prices for “processed” flat steel products, or is a relatively large component. The evidence relating to the “recommended resale price” for processing services is likely to bear on the question of relative costs and prices and is likely to be relevant to that issue.

Ruling 6: Handwritten notes produced by Southern Steel

80 The ACCC sought to tender two handwritten notes. The notes are contained in annexure GME-2 to the affidavit of Grant Michael Elliott affirmed 9 September 2021. The ACCC contends that the notes were created by David Lander, an employee of Brice Metals Australia Pty Ltd which is a subsidiary of Southern Steel, and record conversations he had with Mr Sparks, an employee of BlueScope, on 16 September 2013 and 4 February 2014 concerning matters relevant to the proceeding. The ACCC does not propose to call Mr Lander as a witness in the proceeding, but argues that other admissible evidence establishes that Mr Lander authored the notes and that they are a business record of Southern Steel. The ACCC argues that the notes are sufficiently intelligible in their own terms to constitute relevant admissible evidence.

81 BlueScope objects to the tender on the grounds of relevance and hearsay. Mr Ellis objects to the tender on those grounds and also submits that the Court should exercise its discretion to exclude the notes under s 135 of the Evidence Act on the basis that the probative value of the notes is substantially outweighed by the danger that they might be unfairly prejudicial to Mr Ellis.

Hearsay objection

82 It is convenient to address the hearsay objection first. The ACCC contends that the notes are admissible as business records under s 69 of the Evidence Act, which provides, relevantly, as follows:

69 Exception: business records

(1) This section applies to a document that:

(a) either:

(i) is or forms part of the records belonging to or kept by a person, body or organisation in the course of, or for the purposes of, a business; or

(ii) at any time was or formed part of such a record; and

(b) contains a previous representation made or recorded in the document in the course of, or for the purposes of, the business.

(2) The hearsay rule does not apply to the document (so far as it contains the representation) if the representation was made:

(a) by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact; or

(b) on the basis of information directly or indirectly supplied by a person who had or might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the asserted fact.

…

(5) For the purposes of this section, a person is taken to have had personal knowledge of a fact if the person’s knowledge of the fact was or might reasonably be supposed to have been based on what the person saw, heard or otherwise perceived (other than a previous representation made by a person about the fact).

83 In considering the application of s 69 to a document, the Court may examine the document and draw any reasonable inferences from it as well as from other matters from which inferences may properly be drawn (see s 183 of the Evidence Act).

84 The evidence shows that the handwritten notes were produced to the ACCC by Southern Steel in response to a notice issued to Southern Steel under s 155 of the Act. I infer from the production of the notes by Southern Steel pursuant to the s 155 notice issued to it that the notes had been retained or held by Southern Steel as part of its records. That fact was not disputed by the respondents.

85 The notes are written on two separate pages in a lined note pad, which is consistent with the notes being created on separate dates. Each page contains other notes that are not relied on by the ACCC, but serve to confirm that the author kept notes in the note pad over time. The handwriting in each of the notes is not identical. In particular, the handwriting on the page bearing the date 16 September 2013 is not slanted, whereas the handwriting on the page bearing the date 4 February 2014 is slanted to the right. Apart from that, though, the handwriting has a similar overall appearance and both pages use some distinctive notations, such as the use of a crossed epsilon to indicate an ampersand. I am satisfied based on the appearance of the notes that they have the same author. The handwriting in the notes is, for the most part, legible, although certain words can only be deciphered by reference to context and some words are unclear.

86 The first note contains the following statements with the following (approximate) format (with words or figures that are unclear placed in square brackets):

87 The second note contains the following statements with the following (approximate) format:

88 In support of authorship of the notes, the ACCC relies on a business record of BlueScope from its “Salesforce” system. In that system there is a record of a telephone call between Mr Sparks of BlueScope and Mr Lander of Brice Metals on 16 September 2013. It is not disputed by the respondents that Brice Metals Australia Pty Limited is a subsidiary of Southern Steel, which is a distributor of flat steel products. The business record identifies that the record was created on 17 September 2013 and the author of the record was Mr Sparks. It includes the following note of the telephone call:

Discussed our December pricing position. Dave supportive of an increase in List price and the inclusion of a Distributor Support rebate, meaning removal of the EOO. - Concerned that CMC pass on all of the rebates into the market. - Our tactical pricing in SA has been significantly less than in other markets and hasn't driven the same lack of clarity on our market offer. - Believes a $35/t increase on plate is justified based on the offer he has seen. $925/t East Coast ($15/t Adelaide and $35/t Perth)

89 The respondents did not contend that the above Salesforce record was inadmissible.

90 In addition, Mr Hennessy, a former employee of BlueScope, has given evidence in the proceeding that:

(a) Southern Steel is one of BlueScope’s aligned distributors (being a long term customer of BlueScope which purchased a large percentage of its steel from BlueScope);

(b) at the relevant time, Mr Sparks reported to Mr Hennessy;

(c) before BlueScope provided its December price offer to distributors (including Southern Steel) in mid-September 2013, Mr Ellis instructed Mr Hennessy to have conversations with distributors about the BlueScope price list and “benchmarking strategy” and send them the December price offer;