Federal Court of Australia

Mulley v Hayes [2021] FCA 1111

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate question identified by Order 1 of the orders made on 16 March 2021 be answered as follows:

Yes, the jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia has been properly invoked.

2. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the hearing of the separate question.

3. The proceeding be listed for a case management hearing at 2.15pm on 23 September 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

1 This matter raises novel issues as to the metes and bounds of this Court’s jurisdiction. I have previously had occasion to consider the jurisdiction of the Court in what is sometimes described as a “pure” defamation matter; but, for reasons that will become evident, the present proceeding cannot be accurately characterised as a “pure” defamation proceeding.

2 A preliminary point should be made. The vast bulk of disputes as to this Court’s subject-matter jurisdiction are determined by simply ascertaining whether the proceeding is in federal jurisdiction. This is because, as explained below, for almost a quarter of a century, this Court has been one of general federal jurisdiction in civil matters. But this is a different case. The applicant is resident in New South Wales and the respondent is resident in Queensland. Both are natural persons. It follows that there is a matter between residents of different States within the meaning of s 75(iv) of the Constitution and, as a consequence, this matter is indubitably in federal jurisdiction. But this is not an answer to whether this Court has authority to decide the matter because there is no general conferral of this diversity jurisdiction on the Federal Court. There are, of course, other examples where this Court lacks jurisdiction in a federal matter because a law enacted pursuant to s 77(ii) of the Constitution makes the jurisdiction of another federal court exclusive, but these aspects of federal jurisdiction need not detain us. I simply make the point to emphasise that the question that arises in this case is not simply whether there is a matter in federal jurisdiction, but rather a more precise one: whether this is a proceeding relating to a matter, which attracts the subject-matter jurisdiction of the Federal Court?

3 The basal facts are ones that in the age of social media have become common: they involve the sending of messages on “Facebook Messenger”. The following is not in dispute:

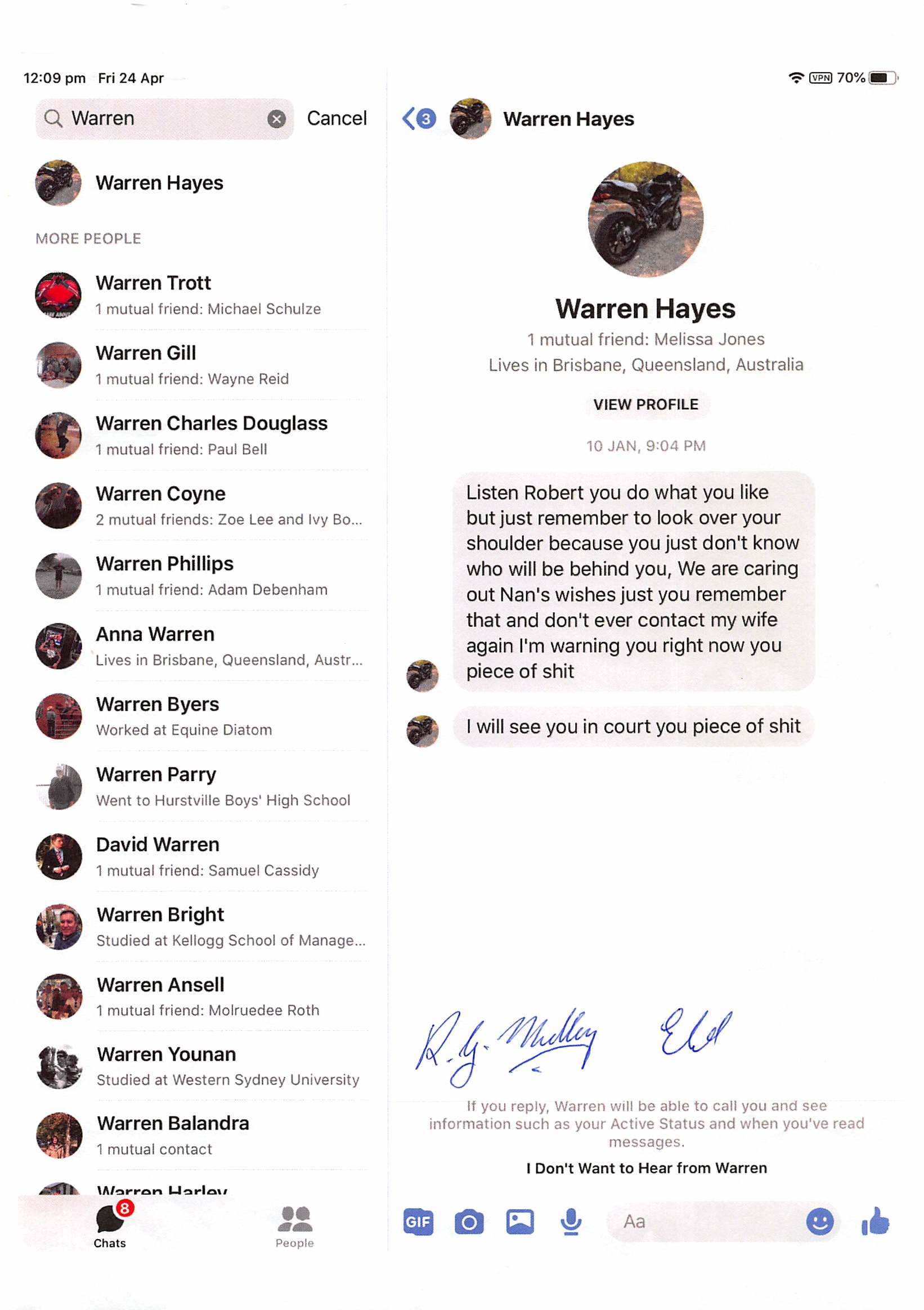

(1) the first relevant message was sent on 10 January 2020 by the respondent, Mr Hayes, to the applicant, Mr Mulley (January Message); the January Message was received only by Mr Mulley; and

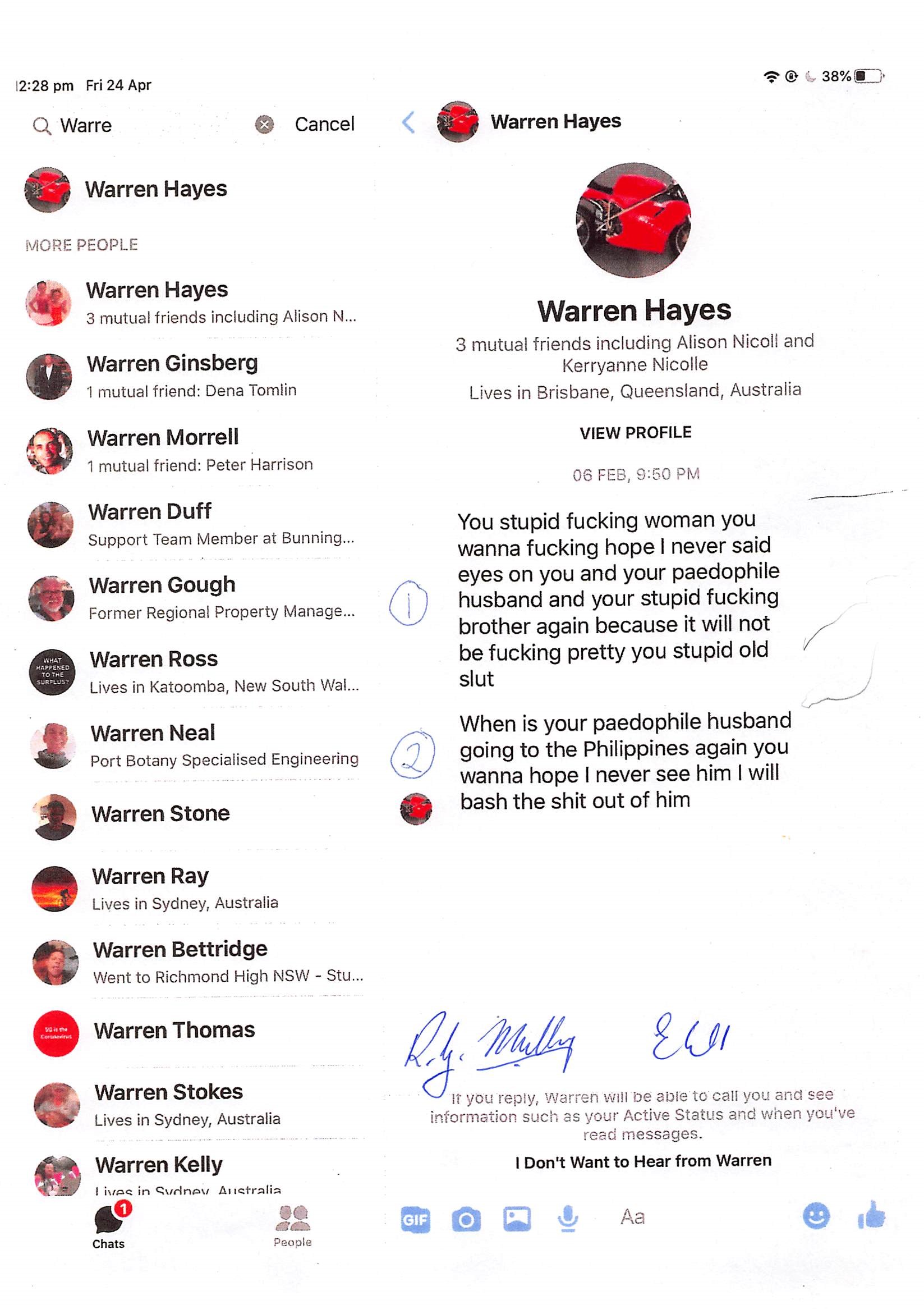

(2) the second (and only other relevant) message was sent on 6 February 2020, by Mr Hayes to Mrs Mulley, the wife of Mr Mulley (February Message); the February Message – although subsequently seen by Mr Mulley – was initially published only to his wife.

4 A copy of the January Message and a copy of the February Message are reproduced as Annexures A and B to these reasons.

5 By way of background, it is worth recording that when the proceeding came before me for a first case management hearing (FCMH) on 5 March 2021, the originating application had one prayer for relief (“[d]amages for defamation”) and the statement of claim (SOC) relied upon one allegedly defamatory publication, being the February Message that had been sent to Mrs Mulley.

6 Mr Mulley is a retired solicitor. At the FCMH, he told me that during his professional life he worked “almost entirely in indictable crime”: T2.17. I indicated to Mr Mulley (at T2.26–7) that it was not “immediately obvious to me” that the Federal Court was seized with jurisdiction, and I entreated him to take legal advice as to this issue. Further, I noted that I may be amenable to granting him leave to discontinue the current proceeding with no order as to costs if, upon obtaining advice, he considered it appropriate to commence a substitute proceeding in the District Court of New South Wales. I also noted that if the Court was not seized with jurisdiction, it was not apparent that this Court had power to cross-vest the current proceeding to the Supreme Court (with the possibility that it would thereafter be transferred by that Court to the District Court).

7 In the light of the information I conveyed to Mr Mulley at the FCMH, I stood the matter over for almost a fortnight. When the matter returned for a further case management hearing, Mr Mulley expressly informed me that he wished to maintain his proceeding in the Federal Court. Accordingly, this brought into focus the issue as to whether this Court has jurisdiction to deal with this matter, beyond its so-called “preliminary jurisdiction” to deal with the question as to whether the Court has jurisdiction: see Mercator Property Consultants Pty Ltd v Christmas Island Resort Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1572; (1999) 94 FCR 384 (at 389 [20] per French J).

8 I then indicated to the parties that it was necessary for the issue of jurisdiction to be determined with alacrity. Hence, on 16 March 2021, I made an order that the question of whether the jurisdiction of the Court has been properly invoked be determined separately and before any other issue in the proceeding (Separate Question) pursuant to s 37P of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCAA) and r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR).

9 Upon reflection, it seemed to me that the Separate Question raised issues of potential complexity and novelty. Consequently, I arranged for the Court to be assisted by an amicus curiae and, in due course, granted Mr Mulley a certificate to receive pro bono legal assistance pursuant to FCR 4.12. The Referral Certificate expressly provided that the extent of legal assistance was to prepare any necessary court documents and appear at the hearing of the Separate Question. For the avoidance of doubt, I noted that “the referral does not extend beyond matters raised by the Separate Question, nor does it extend to providing general advice to the applicant”. I am grateful for the generous assistance of the amicus and pro bono counsel for Mr Mulley.

10 It is appropriate to commence by identifying some uncontroversial matters relating to jurisdiction before then coming to the relevant facts and matters which give rise to the controversy that Mr Mulley asks the Federal Court to quell. Absent limited exceptions not here relevant, whether this Court should exercise its jurisdiction if it is properly invoked is not to be seen as a matter of discretion; it is a matter of duty: see the discussion in Leeming M, Authority to Decide: The Law of Jurisdiction in Australia (2nd ed, Federation Press, 2020) (at pp 111–5).

11 Notwithstanding its length, as to both general principles regarding jurisdiction and the necessity for such questions to be determined with celerity, it is convenient here to set out what I wrote in Oliver v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 583 (at [7]–[18]):

7. … as the Full Court (Bennett, Perram and Robertson JJ) explained in Crosby v Kelly [2012] FCAFC 96; (2012) 203 FCR 451, s 9(3) of the Jurisdiction of Courts (Cross-Vesting) Act 1987 (Cth) has the effect of conferring upon this Court original jurisdiction over a proceeding that would be within the jurisdiction of the Australian Capital Territory or Northern Territory Supreme Courts.

8. As another Full Court (Allsop CJ, Besanko and White JJ) put it in Rana v Google Inc [2017] FCAFC 156; (2017) 254 FCR 1 at 8 [24]:

… s 9(3) confers on the [Federal] Court the jurisdiction of those Territory Supreme Courts to hear and determine defamation matters that would be within their jurisdiction: Crosby v Kelly [2012] FCAFC 96; 203 FCR 451 at 458 [35] per Robertson J. As Perram J also explained at 203 FCR 452 [2], the provision creates a surrogate Commonwealth law by reference to the jurisdiction of those Territory Supreme Courts which then acts as a law of the Commonwealth under which matters may then arise.

9. … it is trite that jurisdiction cannot be conferred by agreement and the views of the parties are not determinative of a jurisdictional question. As Griffith CJ explained in Federated Engine-Drivers and Firemen’s Association of Australasia v The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (1911) 12 CLR 398 at 415, the “first duty of every judicial officer is to satisfy himself that he has jurisdiction”. This duty was referred to by Gageler J in Re Culleton [2017] HCA 3; (2017) 91 ALJR 302 at 306-307 [23]-[24], where his Honour regarded it of the “utmost importance” that a jurisdictional issue be raised at the earliest opportunity and for it to be considered and determined. For my part, in the light of the issue being raised, I consider it necessary that jurisdiction be established, regardless of the pragmatic approach adopted by the parties.

10. … it is worth observing that it is now somewhat unusual for there to be any issue as to the jurisdiction of this Court where the complaint arises in relation to a mass media or social media publication. Apart from the obvious point that most such publications would, one expects, be published to persons within the Territories, there are other bases upon which jurisdiction may be attracted. Without seeking to delimit these circumstances, for the purposes of illustration, I will mention a few.

11. The first merits mentioning notwithstanding it requires a short explanation of how federal jurisdiction works. For those interested (and everyone practising in courts exercising federal jurisdiction should be), the principles are explained in detail by Allsop J (as the Chief Justice then was) writing extracurially in the article Federal Jurisdiction and the Jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia in 2002 (2002) 23 Aust Bar Rev 29). The starting point is s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (JA) which provides:

The original jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia also includes jurisdiction in any matter: ... (c) arising under any laws made by the Parliament, other than a matter in respect of which a criminal prosecution is instituted or any other criminal matter.

(emphasis added)

12. The “matter” is the justiciable controversy between the actors involved, comprised of the substratum of facts representing or amounting to the dispute or controversy between them. It is not the cause of action and is identifiable independently of a proceeding or proceedings brought for its determination: Fencott v Muller (1983) 152 CLR 570 at 603-608; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Edensor Nominees Pty Limited [2001] HCA 1; (2001) 204 CLR 559 at 584-585 [50].

13. When s 39B(1A)(c) of the JA was introduced in 1997, Parliament changed this Court from being a court of specific federal jurisdiction into a court of more general federal jurisdiction, extending its reach to all controversies or “matters” across all areas with respect to which the Parliament of the Commonwealth has made laws. So long as a “matter” can be said to “arise under” a law of the Parliament, then the Federal Court is vested with jurisdiction to hear the whole of the dispute. It follows that once the jurisdiction of the Court has been invoked by reference to a justiciable issue within federal jurisdiction (say, a related claim under a federal statute), the Court has “accrued” jurisdiction to determine the whole “matter” or controversy between the parties: Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally [1999] HCA 27; (1999) 198 CLR 511 at 584-588 [136]-[147]. Accordingly, as a matter of impression and practical judgment, if a claim for defamation not otherwise within federal jurisdiction arises out of the same “matter” which is within federal jurisdiction, then it will form part of the one justiciable controversy and, if the jurisdiction of this Court is invoked, it will be the duty of this Court, exercising Chapter III judicial power, to quell the whole controversy. It is, of course, heterodox to speak of any notion of concurrent state and federal jurisdiction.

14. Secondly, the Federal Court has original jurisdiction to hear a “pure” defamation action (that is, without the addition of any other cause of action or defence arising under a federal statute) where the publication somehow involves the consideration of the implied constitutional freedom of communication on governmental and political matters even if, as will commonly be the case, it is contended that the implied constitutional freedom will be raised by a respondent by way of defence. I have already made reference above to s 39B(1A) of the JA. Subsection (b) of that section provides that the original jurisdiction of the Court also includes jurisdiction in any matter “arising under the Constitution, or involving its interpretation”.

15. Thirdly, again focussing on s 39B(1A)(b) of the JA, where there is a publication in more than one “Australian jurisdictional area” being a State (see ss 11(1) and (5) of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Act) and its cognates), the full faith and credit provision of the Constitution (s 118) is engaged so as to enable courts to recognise and apply the provisions of the various uniform Defamation Acts as modifications of the laws of each Australian jurisdictional area and the common law of Australia. This is because where publications in more than one Australian jurisdictional area are sued upon, the law of each place of publication will create a substantive right to sue on that publication in that jurisdiction: see Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick [2002] HCA 56; (2002) 210 CLR 575.

16. Fourthly, and more broadly, as Gibbs CJ, Mason, Wilson, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ explained in LNC Industries Limited v BMW (Australia) Limited (1983) 151 CLR 575 at 581, a federal matter arises if a right, duty or obligation in issue in the matter “owes its existence to federal law or depends upon federal law for its enforcement” including where the right claimed is in respect of a right or property that is the creation of federal law. Whether or not a matter arises does not depend upon the form of the relief sought: LNC Industries at 581. This would involve when a right or duty based on a Commonwealth statute in issue arises (even where it has not been pleaded by the parties, or a federal issue is unnecessary to decide). A common example illustrates the potential breadth of this concept. It seems to me arguable that if a respondent is a corporation, the relevant matter arises under a law made by the Parliament within the meaning of s 39B(1A)(c) of the JA. Chapter 2B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) provides for the basic features of a company. As is explained in Ford, Austin & Ramsay’s Principles of Corporations Law (Lexis) at [4,050], the capacity of a company created under the Corporations Act, including its ability to be sued, is to be found in s 119 when it provides that a company on registration comes into existence as a body corporate. It is s 124(1) which gives the entity powers of a body corporate (as to a company registered before the commencement of the relevant Commonwealth law, being the Corporations Act, s 1378 provides that registration under earlier state law has effect as if it were registration under Pt 2A.2 of the Corporations Act). The ability to sue the respondent as an entity now arises under and depends upon a law of the Commonwealth.

17. This and other recondite ways that jurisdiction is attracted can be put to one side for present purposes, however, because the invocation of federal jurisdiction in the present case is quite straightforward. Even if I were to find, contrary to Mr Oliver’s assertion in the initial statement of claim, that upon consideration of the evidence there was no proof of publication outside New South Wales, that does not mean the matter has not always been within federal jurisdiction since the assertion was made: Burgundy Royale Investments Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation (1987) 18 FCR 212 at 219. As the now Chief Justice noted in (2002) 23 Aust Bar Rev 29 at 45:

Once a non-colourable assertion is made, that clothes the court with federal jurisdiction, which, once gained, is never lost. Owen Dixon KC’s testimony to the Royal Commission on the Constitution in 1927 put the matter in pungent practical terms:

So, if a tramp about to cross the bridge at Swan Hill is arrested for vagrancy and is intelligent enough to object that he is engaged in interstate commerce and cannot be obstructed, a matter arises under the Constitution. His objection may be constitutional nonsense, but his case is at once one of Federal jurisdiction.

‘Colourable’ imports improper purpose, or a lack of bona fides. It is not judged by reference to the strength and weakness of the case alone. Improper purpose or lack of bona fides carries with it the notion of an abuse of process.

18. There is no suggestion here that that the relevant assertion as to publication in the Territories made in the initial statement of claim was colourable. Federal jurisdiction was thereby attracted and once federal, the matter is always federal: Hooper v Kirella Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1584; (1999) 96 FCR 1 at 13-16 [45]-[55]. If an allegation of publication in the Territories is made bona fide, the Court is properly seized with jurisdiction to deal with the controversy and always will be even if the non-colourable allegation was unnecessary to decide, abandoned, struck out, or otherwise rejected on the evidence adduced at trial. As it turns out in this case, no evidence was adduced by Mr Oliver to prove publication in the Territories being a material fact pleaded and upon which issue was joined. As a consequence, the allegation fails for want of proof, but this does not mean that federal jurisdiction, properly invoked upon the bona fide making of the allegation, somehow disappeared like a will-o’-the-wisp.

(Emphasis in original).

12 This summary remains accurate, although any reference to “accrued jurisdiction” is now best avoided: see Rizeq v Western Australia [2017] HCA 23; (2017) 262 CLR 1 (at 24 [55] per Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ). Apart from the fact that “accrued jurisdiction” has sometimes been confused with the wholly distinct concept of “associated jurisdiction” in s 32 of the FCAA, the use of the term “accrued jurisdiction” tends to obscure the reality that where federal and “non-federal” claims comprise the same justiciable controversy, a court will have jurisdiction to resolve the entire matter, which is wholly federal, in the exercise of its federal jurisdiction.

13 For reasons I will explain, using the numbering adopted in Oliver, it is the fourth and potentially the most complicated way that jurisdiction may be attracted that is presently relevant (although this point is necessarily related to the first point made in Oliver at [11]–[13]). Therefore, after outlining the nature of Mr Mulley’s claim in section C, I will return to the issue in section D to expand on what I said by way of obiter in Oliver (at [16]).

C THE NATURE OF MR MULLEY’S CLAIM

14 The amended statement of claim (ASOC), prepared by Mr Mulley without the assistance of lawyers, is not a model of drafting.

15 As pleaded, it might be thought that there are four aspects of Mr Mulley’s claim. I will proceed on this basis notwithstanding it became apparent during argument that the first two aspects are now not pressed as distinct claims (although historically they were different causes of action). For present purposes, two related aspects of the pleaded claim are untenable and can be put to one side (and are also irrelevant to the issue I am required to determine on the Separate Question). The first is a claim for the loss of “conjical [sic] rights and friendship”, which does not sound in damages and is not pressed by Mr Mulley in a way that is distinct from his second pleaded claim, being for damages in tort for loss of consortium. As to the loss of conjugal rights, before 2018, s 114(2) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) provided that in exercising its power under s 114(1), the Court “may make an order relieving a party to a marriage from any obligation to perform marital services or render conjugal rights”. However, this section was repealed by the Family Law Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2018 (Cth). The Explanatory Memorandum to this Act provided (at [13]) that “the [Act] would remove misleading and unnecessary wording that suggests that conjugal rights and an obligation to perform marital services still exist in Australian law”. As to the claim for damages for loss of consortium, it is sufficient for present purposes to note that the Family Law Act, as a law of the Commonwealth, did not provide the basis upon which a defence to the action for damages was created. Rather, the cause of action itself was abolished by reason of a state law, being s 3 of the Law Reform (Marital Consortium) Act 1984 (NSW). It is not necessary to consider the related first and second aspects of Mr Mulley’s claim further.

16 The third aspect is a claim in defamation in relation to the February Message sent to Mr Mulley’s wife which is said to carry an imputation that Mr Mulley is a paedophile. This requires no further elaboration for present purposes.

17 The fourth aspect of the claim requires a detailed explanation. Mr Mulley claims damages for alleged psychological injury caused by the January Message and the February Message, the first of which, it will be recalled, was sent only to him (and not otherwise conveyed to another person). In bringing this claim, Mr Mulley has characterised the sending of both the January Message and the February Message as unlawful, amounting to conduct by Mr Hayes contrary to s 474.17 of the Criminal Code (being in the Schedule to the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) (Code)).

18 Section 474.17 of the Code relevantly provides:

474.17 Using a carriage service to menace, harass or cause offence

(1) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person uses a carriage service; and

(b) the person does so in a way (whether by the method of use or the content of a communication, or both) that reasonable persons would regard as being, in all the circumstances, menacing, harassing or offensive.

Penalty: Imprisonment for 3 years.

19 The Dictionary provides that a “carriage service” has the same meaning as in the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth), which in turn, by s 7 of that Act, provides that it “means a service for carrying communications by means of guided and/or unguided electromagnetic energy”. It is not in dispute that it is arguable that the sending of the January Message and the February Message involved the use of a carriage service by Mr Hayes.

20 It seems to me that what Mr Mulley is now doing is seeking relief by way of common law damages arising from a tort of the kind arguably left open in Northern Territory v Mengel (1995) 185 CLR 307, which overruled Beaudesert Shire Council v Smith (1966) 120 CLR 145 (Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ): see also Kitano v Commonwealth (1974) 129 CLR 151 (at 173–5 per Mason J).

21 In Beaudesert Shire Council v Smith, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ observed (at 156):

… it appears that the authorities cited do justify a proposition that, independently of trespass, negligence or nuisance but by an action for damages upon the case, a person who suffers harm or loss as the inevitable consequence of the unlawful, intentional and positive acts of another is entitled to recover damages from that other.

(Emphasis added).

22 In Northern Territory v Mengel, the High Court rejected the principle articulated in Beaudesert because it went further than the authorities cited in support of it, most of which were taken from Kiralfy A K, The Action on the Case (Sweet & Maxwell, 1951). Despite this, and importantly for present purposes, Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ (at 344–5) “left open the question whether the law of Australia recognises tortious liability for harm caused by unlawful acts directed against an applicant”: News Limited v Australian Rugby Football League Limited (1996) 64 FCR 410 (at 517 per Lockhart, von Doussa and Sackville JJ); see also Scott v Secretary, Department of Social Security [2000] FCA 1241; (2000) 65 ALD 79 (at 87 [16] per Beaumont and French JJ); Scott v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission [2010] FCA 1323 (at [82] per North J).

23 Unlike the cause of action in defamation based on the publication of the February Message which, it is alleged, conveyed the imputation of paedophilia, this fourth aspect of Mr Mulley’s case is a distinct action on the case based upon the allegation of unlawful acts directed against Mr Mulley by Mr Hayes using a carriage service to send both the January Message and the February Message in a way that reasonable persons would regard as being, in all the circumstances, menacing, harassing or offensive, and causing damage to Mr Mulley.

24 No doubt it is obvious, but it merits recording that this distinct fourth claim, based upon the alleged unlawful conveyance of the January Message and the February Message, is not a tort concerned with damage to reputation in which publication to a third party is thus essential: Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick [2002] HCA 56; (2002) 210 CLR 575 (at 600 [26], 606 [42] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ).

25 As can be seen, the fourth claim has, as its foundation, an allegation of a breach of a criminal norm contained in a law of the Parliament (being the Code). Although the justiciable controversy is in federal jurisdiction (for the reason explained at [2] above), the question that arises is: whether the assertion of this novel common law action on the case by Mr Mulley means the Federal Court has subject-matter jurisdiction to quell the dispute?

26 It is appropriate to commence answering this question by outlining the relevant principles and, in doing so, saying something more about what I described in Oliver as the more recondite way that jurisdiction may be attracted.

D.1 LNC Industries and its application

27 Of course, as has been explained many times, a “matter” will “arise under” a law of the Parliament in a number of ways. As Allsop CJ, Besanko and White JJ noted in Rana v Google Inc [2017] FCAFC 156; (2017) 254 FCR 1 (at 5–6 [18]), examples include:

[W]here a cause of action is created by a Commonwealth statute; where a Commonwealth statute is relied upon as establishing a right to be vindicated; where a Commonwealth statute is the source of a defence that is asserted; where the subject matter of the controversy owes its existence to Commonwealth legislation – that is where the claim is in respect of or over a right which owes its existence to federal law; where it is necessary to decide whether a right or duty based on a Commonwealth statute exists even where that has not been pleaded by the parties, or where a federal issue is raised on the pleadings but it is unnecessary to decide.

…

There is a difference, however, between a matter “arising under” a law of the Parliament and a matter that merely involves the interpretation of a federal law (and which will not on its own attract federal jurisdiction): see [Felton v Mulligan (1971) 124 CLR 367] at 374, 408-409, 416.

(Emphasis added).

28 But this difference explained by the Full Court as to the limits of a matter “arising under” a law of the Parliament, although important, can at the margins be somewhat difficult to draw.

29 By way of background, it is useful to step back and contextualise LNC Industries v BMW (Australia) Ltd (1983) 151 CLR 575, as the restatement in that case of the conclusion of Latham CJ in R v Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration; Ex parte Barrett (1945) 70 CLR 141 (at 154), is often cited as marking the outer limits of matters “arising under” a law of the Parliament. In LNC Industries, Gibbs CJ, Mason, Wilson, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ explained (at 581):

[A] matter may arise under a law of the Parliament although the interpretation or validity of the law is not involved: R v Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration; Ex parte Barrett [(1945) 70 CLR 141 at 154]. The conclusion reached by Latham CJ in that case, and stated in a passage that has often been cited with approval, is “that a matter may properly be said to arise under a federal law if the right or duty in question in the matter owes its existence to federal law or depends upon federal law for its enforcement, whether or not the determination of the controversy involves the interpretation (or validity) of the law”

…

A claim for damages for breach or for specific performance of a contract, or a claim for relief for breach of trust, is a claim for relief of a kind which is available under State law, but if the contract or trust is in respect of a right or property which is the creation of federal law, the claim arises under federal law. The subject matter of the contract or trust in such a case exists as a result of the federal law.

(Footnotes omitted, emphasis added).

30 The emphasised part of the quotation taken from Latham CJ is of some importance, and I will return to it below.

31 LNC Industries was a case relating to the contractual sale of quota entitlements for the importation of vehicles into Australia pursuant to the Customs (Import Licensing) Regulations made under the Customs Act 1901 (Cth). The High Court held (at 582) that the claim was within federal jurisdiction on the basis that the contracts being considered were “concerned solely with entitlements under the Regulations” and that “the very subject of the issue between the parties [was] an entitlement under the Regulations”.

32 It is clear why the principled outer limits of federal jurisdiction were brought into sharp relief around the time LNC Industries was decided: it had relevance in the last stages of the complicated process of the abolition of Privy Council appeals. From 1903, the condition imposed by s 39(2)(a) of Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) on the exercise of federal jurisdiction by state courts had the effect of making the exercise of federal jurisdiction by a state Supreme Court final except for an appeal to the High Court (although the Privy Council decided in Webb v Outtrim (1906) 4 CLR 356 that this did not prevent an appeal from a state court to the Privy Council in the exercise of invested federal jurisdiction, the High Court refused to follow this approach in Baxter v Commissioners of Taxation (NSW) (1907) 4 CLR 1087 (at 1137–40)). It was not until the passage of the Australia Act 1986 (Cth) and the Australia Act 1986 (UK) that the remaining channel of appeal to the Privy Council from state Supreme Courts in matters of state law was eliminated. This removed the perceived difficulty existing since 1975 that in matters of state law there were two final courts of appeal: the High Court and the Privy Council: see Australian Law Reform Commission, The Judicial Power of the Commonwealth: A Review of the Judiciary Act and related legislation (DP 64, December 2000) (at pp 106–7).

33 In any event, as noted above, the limits of the application of what was said in LNC Industries can sometimes be difficult to identify. Nine examples, including two very recent ones, are worth mentioning.

34 First, is Edwards v Santos Ltd [2011] HCA 8; (2011) 242 CLR 421. The plaintiffs were registered native title claimants and had commenced negotiations for an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). Two of the defendants held an authority to prospect in respect of land in Queensland falling within the boundaries of the claimed land (petroleum defendants). The authority to prospect was granted by the State of Queensland, under the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld). The plaintiffs and the petroleum defendants negotiated entry into an ILUA in relation to future grants which might be “future acts” within the meaning of the NTA. The petroleum defendants asserted that the authority to prospect was not subject to the “right to negotiate” under the NTA. The plaintiffs took issue with this contention and instituted proceedings in the Federal Court seeking declaratory and injunctive relief. The proceeding was dismissed summarily by the primary judge for want of jurisdiction and leave to appeal was refused. Because no appeal lay against such a decision by virtue of s 33(4B)(a) of the FCAA, relief was sought under s 75(v) of the Constitution, which was granted. In doing so, Heydon J (with whom French CJ, Gummow, Kiefel and Bell JJ agreed) explained (at 438–9 [45]):

While a claim to damages for breach of contract is a claim for relief under State law, if the contract is in respect of a right which is a creature of federal law, the claim arises under the federal law [LNC Industries at 581]. That is true whether the State law is common law, like the law of contract, or statute law, like the position of the ATP in relation to the “production licences”, that is leases, under s 40 of the Petroleum Act. And there is also a matter arising under a federal law if the source of a defence which asserts that the defendant is immune from a liability or obligation of that defendant is a law of the Commonwealth [Felton v Mulligan (1971) 124 CLR 367 at 408; Agtrack (NT) Pty Ltd v Hatfield (2005) 223 CLR 251]. Here the petroleum defendants are alleging that they are immune from the “right to negotiate provisions of the NTA” because of the pre-existing rights based acts provisions of the NTA. Hence there is a matter arising under a federal law.

35 Secondly, in TCL Air Conditioner (Zhongshan) Co Ltd v Judges of the Federal Court of Australia [2013] HCA 5; (2013) 251 CLR 533, the High Court considered whether the International Arbitration Act 1974 (Cth) gave force of law in Australia to the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration. French CJ and Gagelar J determined (at 555 [32]) that the enforcement of an arbitral award by a competent court under Art 35 of the Model Law is an exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth. Their Honours, applying LNC Industries, noted (at 543–4 [2]) that an application to enforce an arbitral award is:

… a “matter … arising under [a law] made by the [Commonwealth] Parliament” within s 76(ii) of the Constitution. That is because rights in issue in the application depend on Art 35 of the Model Law for their recognition and enforcement and because the Model Law is a law made by the Commonwealth Parliament.

(Footnotes omitted, emphasis added).

36 Thirdly, in PT Bayan Resources TBK v BCBC Singapore PTE Ltd [2015] HCA 36; (2015) 258 CLR 1, the High Court held that it was within the inherent power of the Supreme Court of Western Australia to make a freezing order in relation to an anticipated judgment of a foreign court which, when delivered, would be registrable by order of the Supreme Court under the Foreign Judgments Act 1991 (Cth). French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Gageler and Gordon JJ (with whom Keane and Nettle JJ agreed) held (at 22 [55]):

An application for a freezing order in relation to a prospective judgment of a foreign court, which when made would be registrable by order of the Supreme Court under the Foreign Judgments Act, is sufficiently characterised as a matter arising under a law of the Commonwealth on the basis that the prospective enforcement process to be protected by the making of the freezing order depends on the present existence of the Foreign Judgments Act.

(Emphasis added).

37 Fourthly, in CGU Insurance Ltd v Blakeley [2016] HCA 2; (2016) 259 CLR 339, claims brought by liquidators against CGU Insurance were identified as arising under a law of the Commonwealth. In doing so, French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ, referred specifically to the observation of Latham CJ in R v Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration; Ex parte Barrett, stating (at 351–2 [29]):

It is a particular application of that general statement to say that a matter will arise under a federal law if it involves a claim at common law or equity or under a law of a State where the claim is “in respect of a right or property which is the creation of federal law”. If the source of a defence to a claim at common law or equity or under a law of a State is a law of the Commonwealth, then on that account also the matter may be said to arise under federal law.

(Footnotes omitted, emphasis added).

38 Fifthly, in Sagacious Legal Pty Ltd v Wesfarmers General Insurance Ltd (No 4) [2010] FCA 482; (2010) 268 ALR 108, Rares J dealt with a claim for indemnity under a motor car insurance policy. His Honour referred (at 111–2 [6]) to the fact that the insured applicant pleaded a claim for interest under s 57 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) asserting this enlivened the jurisdiction of this Court. However, Rares J noted (at 111–2 [5]–[6]) that jurisdiction was attracted well before the pleading, and the matter had been in federal jurisdiction since at least the time of the insurer’s refusal of indemnity because (referring to LNC Industries (at 581)) the claim involved rights and liabilities under a contract of insurance that owed their existence to a federal law, namely the Insurance Contracts Act: cf Agtrack (NT) Pty Ltd v Hatfield [2005] HCA 38; (2005) 223 CLR 251 (at 262–3 [29], [32] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ).

39 Sixthly, in Buckee v Commonwealth of Australia [2014] FCA 242; (2014) 220 FCR 541, a different conclusion was reached by Barker J, notwithstanding that one of the arguments advanced to his Honour as to why federal jurisdiction was attracted involved, like in Sagacious Legal, a denial of indemnity under an insurance policy. Additionally, Barker J said (at 544 [24]) that a further “intriguing argument” was advanced as to why federal jurisdiction is attracted, which his Honour outlined (at 544–5 [26]):

The argument is developed in the following way:

• Section 64 of the Judiciary Act provides that in any suit in which the Commonwealth or a State is a party “the rights of parties shall as nearly as possible be the same, and judgment may be given and costs awarded on either side, as in a suit between subject and subject”.

• This proceeding is a “suit” for the purposes of the Judiciary Act, as it is an “action or original proceeding between parties” as defined in s 2 of the Judiciary Act.

• As explained in Bass v Permanent Trustee Company Limited [1999] HCA 9; (1999) 198 CLR 334, s 64 is of fundamental importance to understanding the juridical basis of an action maintained against the Crown. There it was said by the plurality that s 64 has an ambulatory operation so that it may extend rights in proceedings in which the Commonwealth or a State is a party by reference to subsequent legislation. It was also held that s 64 operates to apply substantive as well as procedural laws. It was accepted that it follows that s 64 may operate to confer a cause of action against the Commonwealth which would not have existed if s 64 had not equated the substantive rights of the parties to those in a suit between subject and subject.

• Without s 64, Mr and Mrs Buckee and group members would have no right to agitate a cause against the Commonwealth. However, Commonwealth v Evans Deakin Industries Limited [1986] HCA 51; (1986) 161 CLR 254 rejected an argument that s 64 did not create a right and it is clear from that case that in every suit to which the Commonwealth is a party, s 64 requires the rights of the parties to be ascertained as nearly as possible by the same rules of the law, substantive and procedural, statutory and otherwise as would apply if the Commonwealth were a subject instead of being the Crown.

• The position prior to the enactment of s 64 was explained in Baume v The Commonwealth (1906) 4 CLR 97 by O’Connor J by reference to the “temporary” statute that was replaced by s 64.

• In British American Tobacco Australia Limited v Western Australia [2003] HCA 47; (2003) 217 CLR 30 at [72], McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ (with whom Callinan J concurred) observed that the remark of O’Connor J in Baume emphasised the importance of s 64 in the structure of federal jurisdiction “which provided for species of litigation unknown at common law and in the Colonies before federation”.

• Without s 64, any subject would need to call in aid the ancient procedure of the petition of right.

• It follows that this action against the Commonwealth, being a species of litigation unknown at common law, arises under a law made by the Parliament, namely, s 64.

40 This further argument was rejected (at 545 [28]–[29]) on the basis that s 64 of the Judiciary Act is intended to have application “in a matter in which the Court has jurisdiction independently of s 64” and, in such circumstances, s 64 by its terms then makes the rights of the parties as nearly as possible the same. In this way, his Honour considered that s 64 is to be seen as a procedural provision which facilitates the making of a claim against the Commonwealth, thus supplanting the petition of right, but without giving any substantive rights. Justice Leeming, writing extracurially, described this case as being brought “ambitiously” in the Federal Court (Leeming at p 203 fn 13) and went on to identify, correctly, that the availability of the class action regime in this Court was the reason why the case was brought in the Federal Court. But it might not have been thought to have been too ambitious, given the first basis upon which it was suggested jurisdiction was attracted was relevantly indistinguishable from that which Rares J held applied in Sagacious Legal. In any event, the case settled before the determination of an appeal from the dismissal of the proceeding on the basis of a lack of jurisdiction. I will come back to Buckee below, when returning to Oliver.

41 Seventhly, in RNB Equities Pty Ltd v Credit Suisse Investment Services (Australia) Limited [2019] FCA 760; (2019) 370 ALR 88, Anderson J was required to consider whether the applicants’ claims attracted the jurisdiction of the Court, where the claims were purely contractual in nature and the applicants did not expressly allege reliance on any provision of a law of the Parliament for the purposes of their claims. The applicants argued the connexion between their claim and federal law on the basis of the nature of, and the statutory framework surrounding, certain warrants, being financial products offered pursuant to the relevant contractual arrangements. The subject matter of the dispute concerned the rights and obligations pertaining to the warrants, but there was no power or mechanism under any relevant federal law for the creation of the warrants. Anderson J found (at 102–4 [59]–[64]) that the warrants were not created by federal law; their existence instead arose by reason of contractual arrangements. His Honour distinguished that case from LNC Industries in the following terms (at 103–4 [64]):

The factual circumstances of this case are a degree removed from that of LNC Industries. What was at stake in LNC Industries may be broadly summarised as a contractual right to a statutory entitlement. Thus, as the plurality of the High Court observed, the ultimate subject of the dispute was a statutory entitlement. But, in this case, the ultimate subject of the dispute between the applicants and Credit Suisse, as pleaded, is not an entitlement under federal law. In fact, even assuming that the [warrants] may be characterised as a creature of statute (which, for the reasons above, they may not), an entitlement to the [warrants] is not in issue at all. Instead, the essence of the applicants’ dispute with Credit Suisse is the alleged misapplication of a contractual discretion which resulted in the reduction of the valuation of the [warrants]. The ultimate complaint the applicants advance in their pleadings is in respect of the valuation of, not their entitlement to, the [warrants].

42 Eighthly, in the recent decision of Seven Network v Cricket Australia [2021] FCA 1031, Anastassiou J dealt with an application for an order for preliminary discovery pursuant to FCR 7.23 where, among other things, it was asserted by Cricket Australia that the Federal Court did not have jurisdiction to entertain a claim of the type foreshadowed by Seven. Seven contended that the Court’s jurisdiction was invoked as an agreement conferring “Media Rights” concerned matters governed by federal law, or the rights otherwise depended for their provision and enjoyment on the acquirer having a broadcasting services licence under federal law (as to which Seven pointed to the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 (Cth) and/or intellectual property rights which owe their existence to federal law). His Honour, applying LNC Industries (and distinguishing RNB Equities), noted (at [50]) that a claim for damages for breach of contract in respect of a right or property which is the creation of federal law or where the subject matter of the contract exists as a result of federal law “is patently broad” and, at a minimum, encompassed a claim for breach of contract “where the rights in controversy, and the entitlement to enforce them in court, are inextricably linked to Commonwealth legislation”.

43 His Honour made reference (at [55]–[63]) to what I said by way of obiter in Oliver about it being “arguable” that if a respondent is a corporation, the relevant matter arises under a law made by the Parliament. This observation had previously been referred to in Hafertepen v Network Ten Pty Limited [2020] FCA 1456 (at [38]–[44] per Katzmann J) and in Clarence City Council v Commonwealth of Australia [2020] FCAFC 134; (2020) 280 FCR 265 (at 320–1 [171]–[172] per Jagot, Kerr and Anderson JJ), in which the Full Court declined to express a view on its correctness. It was argued before Anastassiou J in Seven Network (see [60]–[61]) that the proposition advanced in Oliver was wrong as it does not address the correct issue, being whether the subject matter of the dispute involves a right, duty or obligation that owes its existence to federal law or depends upon federal law for enforcement and that “to so construe federal jurisdiction would be to take it far beyond that which has been previously recognised”.

44 Without deciding the point, his Honour expressed his view as follows (at [62]):

In my view, there is persuasive force in Cricket Australia’s submission on this point. There are several ways this point may be put to convey that there is a substantive distinction between, on the one hand, a controversy between the parties involving a right, duty or obligation that owes its existence to federal law, or depends on federal law for its enforcement, and, on the other hand, the character of a party as a corporation, that is incorporated under and capable of being sued by reason of federal law. There is arguably a conflation between federal law as a wellspring from which a corporate entity comes and a matter which owes its existence to federal law. As the Chief Justice observed extracurially…, federal jurisdiction is founded upon a matter and a matter is the justiciable controversy between “the actors involved”. The fact that a corporate entity is a party to the controversy does not mean that … there is any controversy about the legal identity of any corporate entity that is a party to the proceeding. To adopt the linguistic metaphor, corporate entities may be seen as no more than “actors involved” in the broader justiciable controversy: see also Fencott v Muller [1983] HCA 12; 152 CLR 570 at 603-608 (Mason, Murphy, Brennan and Deane JJ).

45 Ninthly, again very recently, in DJ Builders & Son Pty Ltd (in liq), in the matter of DJ Builders & Son Pty Ltd (in liq) v Queensland Building and Construction Commission (No 3) [2021] FCA 1041, Derrington J, in the course of, with respect, a learned summary of the principles, turned to LNC Industries and noted as follows (at [16]–[17]):

16. … the essence of the above passage in LNC Industries Ltd v BMW from which Lee J drew his observations actually requires attention be focused on the “right or duty in question in the matter” and whether it “owes its existence to federal law or depends on federal law for its enforcement”. In Oliver v Nine Network, the existence of the company and its powers were irrelevant to the right or duty in question. The proceedings involved an action for defamation in which the question of the Court’s jurisdiction arose consequent upon the fact that the broadcast in question had only occurred in New South Wales. Despite that, an allegation which had been made in the statement of claim was that the broadcast had been Australia-wide and his Honour held this sufficiently attracted jurisdiction even though not ultimately made out: Burgundy Royale Investments Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation (1987) 18 FCR 212 at 219; Allsop J, “Federal jurisdiction and the jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia in 2002” (2002) 23 Aust Bar Rev 29 at 45. Although Lee J’s catechism on the scope of the Court’s jurisdiction is both erudite and illuminating, the issues before his Honour did not necessitate the making of any determination as to whether jurisdiction was attracted merely by reason of the respondent being a corporation. In any event, I accept Mr Forrest’s submission that the right or duty in question in that case, being the defaming of the applicant by the respondent and the subsequent suffering of damage, did not relevantly owe its existence to the status of the defendant company as a corporation. Whilst it is true that the status of the corporate entity was necessary in order for it to be sued, that was merely part of the context in which the right, duty or liability arose. However, neither the right, duty nor liability “in question in the matter” owed their existence to the company’s status. The importance of this discussion is that it emphasises that attention must be focused on the relevant “controversy” in question rather than on the characteristics of the parties to it or the matrix of surrounding facts in which it arose. This was made explicit in CGU Insurance Limited v Blakeley, where the majority opined (at 349 [24]) that, “Jurisdiction with respect to a particular subject matter is authority to adjudicate upon a class of questions concerning that subject matter”. Where no question arises as to the corporate existence of a defendant, there is no relevant federal subject matter requiring an adjudication. If, however, an issue in the controversy was a purported company’s entitlement to sue by reason of a question concerning its corporate status, different issues would arise.

17. In this context, it is apt to recall the observations of the High Court in Crouch v Commissioner for Railways (1985) 159 CLR 22 at 37 that the concept of the expression “matter” as used in the Judiciary Act and the Constitution focuses attention on the substance of the dispute between the parties and denotes in wide terms the types of controversies which might come before a Court of Justice. Further, it is used in s 75(iv) of the Constitution to refer to matters between designated parties and that tends to suggest that it is the dispute rather than the parties’ characteristics which is critical.

46 His Honour went on to note (at [19]) that “the common thread” that emerges from the authorities is “that the rights, duties, or subject matter with which the controversy is concerned have their origin in or owe their existence to a law of the Commonwealth”.

47 In observing that it was “arguable” if a respondent is a corporation, the relevant matter arises under a law made by the Parliament within the meaning of s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act, I chose that word advisedly for three reasons.

48 First, as Griffiths J memorably noted in his opening paragraph in Page v Sydney Seaplanes Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 537; (2020) 277 FCR 658 (at 660 [1]):

In his foreword to Professor Geoffrey Lindell’s book, Cowen and Zines’s Federal Jurisdiction in Australia (4th Edition, The Federation Press, 2016)…, Sir Anthony Mason described how “[t]he very mention of “federal jurisdiction” is enough to strike terror in the hearts and minds of Australian lawyers who do not fully understand arcane mysteries”.

49 It is arcane and complicated, but history suggests that “the increase in the area of federal jurisdiction by judicial decision” is part of a “long tradition” and that the tendency to favour expansion has continued: see Zines L, Cowen and Zines’s Federal Jurisdiction in Australia (4th ed, Federation Press, 2016) (at p 109). But whatever uncertainties exist, it is sufficiently clear that LNC Industries took the meaning of “matter arising under” a “stage further” and that it is too restrictive (as seems to be suggested in some discussion in this area) to consider that the interpretation or application of an aspect of a Commonwealth law needs to be in dispute for federal jurisdiction to exist: see Cowen and Zines’s Federal Jurisdiction in Australia (at p 108).

50 Secondly, I was conscious of the use of the disjunctive in the critical and “general” statement made by Latham CJ quoted in LNC industries (see the extract at [29] above) by which, it seems to me, the High Court was saying a matter arises under a federal law if the right or duty in question in the matter: (a) owes its existence to federal law; or (b) depends upon federal law for its enforcement. I was also aware that in Buckee a distinction had been drawn between the relevant federal statutory provision creating the right by which an entity could be sued (in that case, to create a species of litigation not otherwise available), and the invocation of federal jurisdiction to quell the underlying controversy which is the subject matter of the dispute. As noted above, a somewhat similar distinction was made by Anastassiou J in Seven Network and Derrington J in DJ Builders.

51 For my part, if an asserted right or claim “depends upon federal law for its enforcement” – that is, the law of the Parliament itself creates the very right of the applicant to sue to vindicate or enforce the asserted right – the distinction relied upon in Buckee is one that might be thought to be at least open to some question. Without the relevant law of the Parliament (s 64 of the Judiciary Act), the contested contractual and common law rights in controversy between the claimants and the Commonwealth could not be enforced by way of right in litigation. Even though there was no controversy over the status of the Commonwealth or its ability to be sued because of the existence of the statute, as in TCL Air Conditioner, it was uncontroversial that it was a law of the Parliament that allowed the rights in issue to be enforced. Similarly, in PT Bayan Resources, the “present existence” of a law of the Parliament (allowing a prospective enforcement process) and its potential applicability was uncontroversial.

52 Of course, whenever one talks about the jurisdiction of this Court, the significance of the enactment in 1997 of s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act cannot be overstated. Although extracted above, it is worth setting out again:

39B Original jurisdiction of Federal Court of Australia

…

(1A) The original jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia also includes jurisdiction in any matter:

…

(c) arising under any laws made by the Parliament.

(Emphasis added).

53 Evidently, it quickly became apparent that the scope of the section as initially enacted was too broad and, two years later, s 39B(1A)(c) was qualified, by adding “other than a matter in respect of which a criminal prosecution is instituted or any other criminal matter”.

54 But this provision as amended still had a profound effect. This is because it is allied with the expansive concept of what constitutes a “matter”, and the broad meaning of “arising under”, as explained in LNC Industries. It amounted to a general and plenary conferral of jurisdiction on the Federal Court in all (non-criminal) matters arising under any law of the Commonwealth Parliament. Perhaps the outer limits of the extent of this conferral might not have been fully appreciated at the end of the last century; but that is not to the point.

55 Returning to what was said in Oliver, a company is an artificial legal person and, leaving aside the irrelevant exceptions of any corporation created under their own statute or Royal Charter, its very existence – its ability to contract, to sue and be sued, to own property against which judgment may be levied – is now a product of its status as a corporation registered under a law of the Commonwealth: see Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Ch 2B and, in particular, s 124. As a direct consequence of the States having referred their powers concerning the formation of trading corporations to the Commonwealth and the enactment of the Corporations Act, the ability of an applicant to have any asserted right in dispute enforceable by way of litigation against a respondent corporation can only arise because of a statutory provision (a law of the Parliament).

56 Thirdly, I was conscious to go no further than merely to describe the point as arguable, because it is a large and controversial proposition, it was not determinative, and I was not assisted by any argument. The point was not raised in Page v Sydney Seaplanes Pty Ltd; but, with respect, Griffiths J’s pellucid explanation as to why federal jurisdiction did not exist in that case, notwithstanding that the respondent was a corporation (because the rights and liabilities created by the relevant legislation did not apply to an intrastate flight) has, as recently as last week, been accepted by the Court of Appeal of New South Wales as being correct: see Sydney Seaplanes Pty Ltd v Page [2021] NSWCA 204 (at [12] per Bell P, at [146] per Leeming JA, and at [168] per Emmett AJA). In this regard, Leeming JA’s judgment contains, with respect, a lucid and persuasive survey as to the law relating to the jurisdiction of this Court.

57 Further, I accept the force of Judge Cardozo’s warning of “pushing a principle to ‘the limit of its logic’”: see Assistant Commissioner Condon v Pompano Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 7; (2013) 252 CLR 38 (at 94 [137] per Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ), quoting Cardozo B N, The Nature of the Judicial Process (Yale University Press, 1921) (at p 51). Any acceptance of the correctness of the point could have, for example, very significant consequences for state administrative bodies in dealing with disputes involving corporations. This is because, as was explained in Burns v Corbett [2018] HCA 15; (2018) 265 CLR 304, Ch III of the Constitution exhaustively provides for the exercise of adjudicative power in relation to the matters listed under ss 75 and 76 by the High Court, other federal courts created by the Commonwealth Parliament, and by state courts invested with federal jurisdiction by the Commonwealth Parliament: see 325–6 [2]–[3], 335 [43], 336–7 [45]–[46], 339 [50], 341 [55] per Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ, and at 346 [68], 355–6 [95]–[97], 237 [99] per Gageler J.

58 Of course, there is no artificial legal person involved in this case. I am, with respect, conscious of the well-expressed criticisms of the merits of the argument described as arguable in Oliver, but the width of what was said by Latham CJ and later applied in LNC Industries might be thought to create some uncertainty at the boundaries (and in a case where, unlike here, it is determinative, no doubt the issue will be resolved following full argument). I have only dealt with the point, perhaps at excessive length, because understanding LNC Industries and its principled application (and its potentialities) is important in understanding why the subject-matter jurisdiction of the Court may be attracted in this case.

E JURISDICTION AND THIS PROCEEDING

E.1 “Arising under” and the scope of the matter

59 It is now necessary to return to the specifics of this case.

60 Although featuring an unusual set of facts, by reference to the principles explained above, this is not a case at the margins. As noted above, the justiciable controversy between Mr Mulley and Mr Hayes includes an action on the case for conduct directed at Mr Mulley that is claimed to be unlawful. It is unlawful because it is alleged to constitute conduct contrary to a norm created by, and owing its existence to, a law of the Parliament. Hence, the entire controversy out of which this fourth pleaded claim arises is one “arising under” a law of the Parliament.

61 It is then necessary to identify the scope of the matter. Mr Hayes made three points regarding the scope of the matter, specifically, the separate and distinct nature of the third pleaded claim (the claim made in defamation) and the fourth pleaded claim (the action on the case). These submissions must be rejected, for reasons that follow.

62 The first submission was directed towards the commonality of the facts. Mr Hayes contended that, because Mr Mulley’s claims involve different publications, different recipients, and different dates, they are completely separate and distinct so as not to be properly regarded as part of a common substratum of facts.

63 As was identified by the Full Court in Rana v Google Inc (at 9 [29]), “there is no requirement for a complete overlapping of the underlying substratum of facts”; rather, there will be sufficient commonality where there is “common substance, a substantial overlapping of the underlying facts and allegations in the federal claim and the non-federal claim out of which the different claims arise”.

64 As an illustration of what will amount to a common substratum of facts in a case such as the present, in Hunt Australia Pty Ltd v Davidson’s Arnhemland Safaris Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1690; (2000) 179 ALR 738, the Full Court (Spender, Drummond and Kiefel J) held a claim in defamation arising out of the first of a series of contentious letters formed part of the same justiciable controversy as a claim that one of the subsequent letters contravened the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). Their Honours said (at 746 [30]):

In this case the defamation claim is not “a completely disparate claim constituting in substance a separate proceeding”, nor is it “a non-federal matter which is completely separate and distinct from the matter which attracted federal jurisdiction”. The claim for defamation arises out of the first letter in a series of correspondence fuelled by the mutually acrimonious relationship between the parties. The claim in defamation is based on assertions in the Davidsons’ first letter to the Minister, which requests his “assistance” concerning the competence of Hunt Australia to engage in its business. It is the dissemination of the requested response from the Minister which founds the federal claim. It was well open to the primary judge to conclude, “as a matter of impression and practical judgment”, that there was a common substratum of facts, and that the non-federal defamation matter was not “completely separate and distinct” from the Trade Practices Act matter.

65 The underlying dispute includes the January Message being sent to Mr Mulley and the February Message being sent to his wife less than a month later. Although only the February Message is said to give rise to a claim in defamation, both publications are said to give rise to a tortious claim on the basis of unlawful conduct (the fourth claim). Accordingly, it is plain both the claims evidently arise out of a common substratum. They cannot be described as distinct and unrelated, and are, therefore, non-severable: see Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Philip Morris Ltd (1980) 145 CLR 457 (at 481 per Stephen, Mason, Aickin and Wilson JJ).

66 The second point appeared to be directed towards a matter of process. Mr Hayes submitted that the Court cannot determine Mr Mulley’s fourth claim of tortious liability without a determination of unlawfulness at first instance. Instead, it was suggested that Mr Mulley would be required to first make a complaint to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions or, otherwise file “the proceeding in the State jurisdiction”: see T22.35–47. I interpreted this to be a submission to the effect that Mr Hayes would have to be found guilty of an offence pursuant to s 474.17 of the Code before this Court could determine whether Mr Mulley’s claim in tort was partly based upon an allegation of unlawfulness. The proposition needs only to be stated to be rejected. The unlawfulness alleged is an element in the proof of a civil cause of action: it would entail a determination being made on the balance of probabilities in a civil case as mandated by s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) as to whether this element of the cause of action is made out.

67 The third point was directed towards whether there was a factual overlap in the claims, specifically whether the February Message raised a claim in defamation and a claim in tortious liability for unlawful conduct. Mr Hayes relied on the authority of Northern Territory v Mengel to the effect that a tortious claim on the basis of unlawful conduct does not arise in relation to the February Message as it was not directed to Mr Mulley, but rather, to his wife. In Northern Territory v Mengel, Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ said (at 345):

Subject to the qualification that there may be cases in which there is liability for harm caused by unlawful acts directed against a plaintiff or the lawful activities in which he or she is engaged, the Beaudesert principle should be overruled.

(Emphasis added).

68 Mr Hayes submitted that the words “directed against a plaintiff” were to be applied to the present case to mean that it is insufficient that Mr Mulley became aware of the February Message through his wife. Instead, it was said the February Message would satisfy the language in Northern Territory v Mengel only if it had been sent to Mr Mulley directly.

69 Although it will no doubt be argued that the notion of “directed against a plaintiff” might be thought to be focussed upon an intention to harm, this submission directed to the merits of the cause of action is misconceived for present purposes. It is fundamental that once a federal claim is made, even a bad one, and even one that is abandoned, or liable to be struck out, the whole matter in which that claim is made is within, and remains within, federal jurisdiction: see Macteldir Pty Ltd v Dimovski [2005] FCA 1528 (at [36] per Allsop J). Hence, even if the conclusion that is reached is that the common law of Australia does not recognise the tort alleged or the facts proved prevent it from being maintained, this Court’s jurisdiction has been properly invoked, provided Mr Mulley’s claim of civil liability relying on conduct in alleged contravention of the Code was made “genuinely” and “in good faith”: see Kowalski v MMAL Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1069; (2007) 242 ALR 370 (at 378 [32]–[33] per Finn J).

E.2 Is the Court’s jurisdiction invoked?

70 In the light of the above, the answer to whether this Court has jurisdiction might be thought to be straightforward given that a matter, including the claim for damages for defamation and for damages based on an action on the case (whatever their merits), is wholly within federal jurisdiction. However, in assessing whether the Court’s subject-matter jurisdiction has been properly invoked, it is necessary to deal with Mr Hayes’ submission that the Court should characterise Mr Mulley’s fourth claim as colourable; that is, the claim was made for “the improper purpose of ‘fabricating’ jurisdiction”: Burgundy Royale Investments Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation (1987) 18 FCR 212 (at 219 per Bowen CJ, Morling and Beaumont JJ).

71 In support of his allegation, Mr Hayes sought to draw a parallel between this case and Tucker v McKee [2021] FCA 828, in which Anastassiou J found (at [37]–[38]) that, while the matter as pleaded in the amended statement of claim asserted a right or duty that owed its existence to a federal statute, the Court did not have jurisdiction due to the claim being colourable.

72 It is important to stress that, consistent with Macteldir Pty Ltd v Dimovski, an assertion that a claim is colourable does not mean that it is weak or infirm or is otherwise misconceived. It is an allegation of improper purpose. As the oft-quoted testimony of Owen Dixon KC to the Royal Commission on the Constitution of the Commonwealth (Minutes of Evidence, 13 December 1927) graphically explained (at p 788):

So, if a tramp about to cross the bridge at Swan Hill is arrested for vagrancy and is intelligent enough to object that he is engaged in interstate commerce and cannot be obstructed, a matter arises under the Constitution. His objection may be constitutional nonsense, but his case is at once one of Federal jurisdiction.

(Emphasis added).

73 The weakness of a case may be relevant, but only to the extent that it can rationally inform an assessment as to whether the claim was advanced for an improper purpose to fabricate jurisdiction. As Perry J explained in Qantas Airways Limited v Lustig [2015] FCA 253; (2015) 228 FCR 148 (at 169 [88]):

The question, therefore, of whether a claim is tenable will be relevant to that question but not determinative save (rarely) where a claim is so obviously untenable, and would have been so to those who propounded it, that the claim is found to be colourable: Cook v Pasminco [2000] FCA 677; (2000) 99 FCR 548 at 550 [14] and [16] (Lindgren J); Ahmed v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 1113; (2009) 180 FCR 313 at 327-329 [58]-[64] (Foster J). For example, in Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia [2000] FCA 1572; (2000) 104 FCR 564…, French J (with whose reasons Beaumont and Finkelstein JJ agreed) explained at 598-599 [88] that:

In the ordinary course the contention that a claim is not tenable will not go to jurisdiction unless dependent upon a submission that the claim is outside jurisdiction. And indeed, within that class a claim may be untenable because its very nature denies its character as an element of any matter or controversy in respect of which the Court can exercise jurisdiction. So a proceeding based upon the proposition that the Commonwealth Constitution is invalid does not disclose a matter arising under the Constitution or involving its interpretation – Nikolic v MGICA Ltd [1999] FCA 849. A claim may also be a sham reflecting no genuine controversy and therefore establishing no matter in respect of which the Court may exercise its jurisdiction. There has been discussion of so called “colourable” claims made under the Trade Practices Act for the improper purpose of fabricating jurisdiction. The mere fact that a claim is struck out as untenable does not mean it is colourable in that sense.

74 In the present case, there is no basis to find that Mr Mulley is motivated in bringing the fourth claim by anything other than the proper purpose of attempting to recover common law damages for harm caused by the alleged unlawful conduct. Although it was suggested in argument that Mr Mulley added the fourth claim in an attempt to rectify his mistaken belief that this Court has jurisdiction to hear his defamation claim, this cannot be accepted. Mr Mulley gave evidence at the hearing of the Separate Question. His affidavit of 3 February 2021 was read, and although it did not address the question of his motivation for bringing any aspect of his claims, this is hardly surprising. No suggestion was made prior to submissions at the hearing that Mr Mulley’s state of mind in making the fourth claim was anything other than genuine. No cross-examination occurred and no allegation of improper purpose or any other contention otherwise related to colourability was put to him. It was not suggested any inference should be drawn of the type explained by Handley JA in Commercial Union Assurance Company of Australia Limited v Ferrcom Pty Limited (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 (at 418), which concerned a failure to lead evidence in chief from a witness on a central issue. In any event, such a submission would have been hopeless, given the manner and timing by which the argument as to colourability was advanced.

75 In this respect, the present case bears some resemblance to McCully v Sydney Trains [2021] FCA 562, in which a submission of a similar nature was raised. Relevantly, White J said (at [53]):

The respondents’ claim that the applicants’ claim was colourable was raised for the first time in counsel’s submissions at the hearing. The absence of prior notice to the applicants means that it would not be appropriate to draw any inference adverse to them by reason of an absence of evidence on their part.

76 As to the criticism that the case advanced as to jurisdiction has developed with subsequent amendments, this too is hardly unexpected. The SOC and FASOC were prepared by Mr Mulley without the benefit of specialist legal assistance. The case on jurisdiction was, if I may say so, ably advanced orally by junior counsel for Mr Mulley at the hearing and no doubt was more fully developed than would otherwise have been the case had Mr Mulley not been represented. But although the fourth claim was not initially formulated distinctly, Mr Mulley fastened upon it himself in the ASOC, and the threats made in the January Message had always been relied upon by Mr Mulley from the outset: T18.1–5. Again, White J’s remarks in McCully (at [54]) have some relevance:

It is plain that the applicants’ position with respect to the jurisdiction of this Court has developed as time has gone by in response to the critique made by the respondents. That may suggest that insufficient attention was given to the basis of this Court’s jurisdiction at the time it was invoked. However, there is no reason to suppose that the applicants’ mistake was other than genuine. That is to say, that they commenced the proceedings in this Court in the belief that it had jurisdiction to hear and determine their claims but came to realise in the light of the respondents’ critique that the issue of jurisdiction was more “live” than they had appreciated. In that circumstance, the applicants’ ultimate reliance on a different basis for the Court’s jurisdiction than that initially asserted does not support an inference that the claim is colourable.

77 Mr Mulley’s claim attracting the jurisdiction of the Court is not colourable nor artificial.

78 The answer to the Separate Question is “yes”: the jurisdiction of this Court has been properly invoked. At the hearing, I raised the question as to whether this Court would have the power to rely on the cross-vesting provisions to transfer the matter to another court, in the event that the Separate Question was answered in the negative. As I have found that the jurisdiction of this Court was indeed properly invoked, the issue as to the scope of the Court’s power to rely on the cross-vesting provisions does not arise. This does not mean, however, that it is not open to Mr Hayes to bring an application to cross-vest the proceeding to the Supreme Court to allow the case, if thought appropriate by a judge of that Court, by a further transfer, to be sent to the District Court of New South Wales (or for it to be transferred directly to the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia).

79 During the course of oral submissions, I invited the parties to make any submissions concerning the issue of costs. The parties did not dispute that the appropriate order would be that costs follow the event of the separate determination.

I certify that the preceding seventy-nine (79) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

Dated: 13 September 2021

ANNEXURE A

ANNEXURE B