FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Limited [2021] FCA 1013

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | NATIONAL AUSTRALIA BANK LIMITED ACN 004 044 937 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 26 august 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and s 1317E of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) the Court makes the declarations in the terms set out in Annexure E to these Orders (Declarations).

2. Pursuant to:

(a) s 1317G(1E) of the Corporations Act in respect of the contraventions the subject of paragraphs 1 and 2 of the Declarations; and

(b) s 12GBA(1)(a) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) in respect of the contraventions of ss 12DB(1)(a) and (g) of the ASIC Act the subject of paragraphs 3 and 4 of the Declarations,

the defendant pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth of Australia in the sum of $18,500,000.

3. Pursuant to s 1101B(1) of the Corporations Act and s 12GLA(1) of the ASIC Act, that before the defendant enters into any ongoing fee arrangement(s) within the meaning of s 962A of the Corporations Act within 3 years of this order being made it must first:

(a) engage an independent expert, the identity of whom is to be agreed between the parties, and in the absence of agreement, to be appointed by the Court, who will be required to:

(i) review the defendant’s systems and controls for the purpose of reporting on the adequacy of those systems and controls for ensuring compliance by the defendant with Division 3 of Part 7.7A of the Corporations Act;

(ii) where any aspect of the systems and controls is considered to be inadequate, make recommendations as to the steps which should be taken to make the relevant systems and controls adequate;

(iii) prepare a written report setting out the results of the review and recommendations referred to above, and deliver a copy of the report to the plaintiff and the defendant; and

(b) following receipt of the report referred to in paragraph 3(a)(iii) above, establish a compliance program designed to ensure the defendant’s systems and controls are reasonably adequate to secure compliance with Division 3 of Part 7.7A of the Corporations Act which incorporates to the extent reasonably practicable the recommendations made by the independent expert.

4. The defendant pay the plaintiff’s costs of and incidental to these proceedings.

5. The proceedings otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

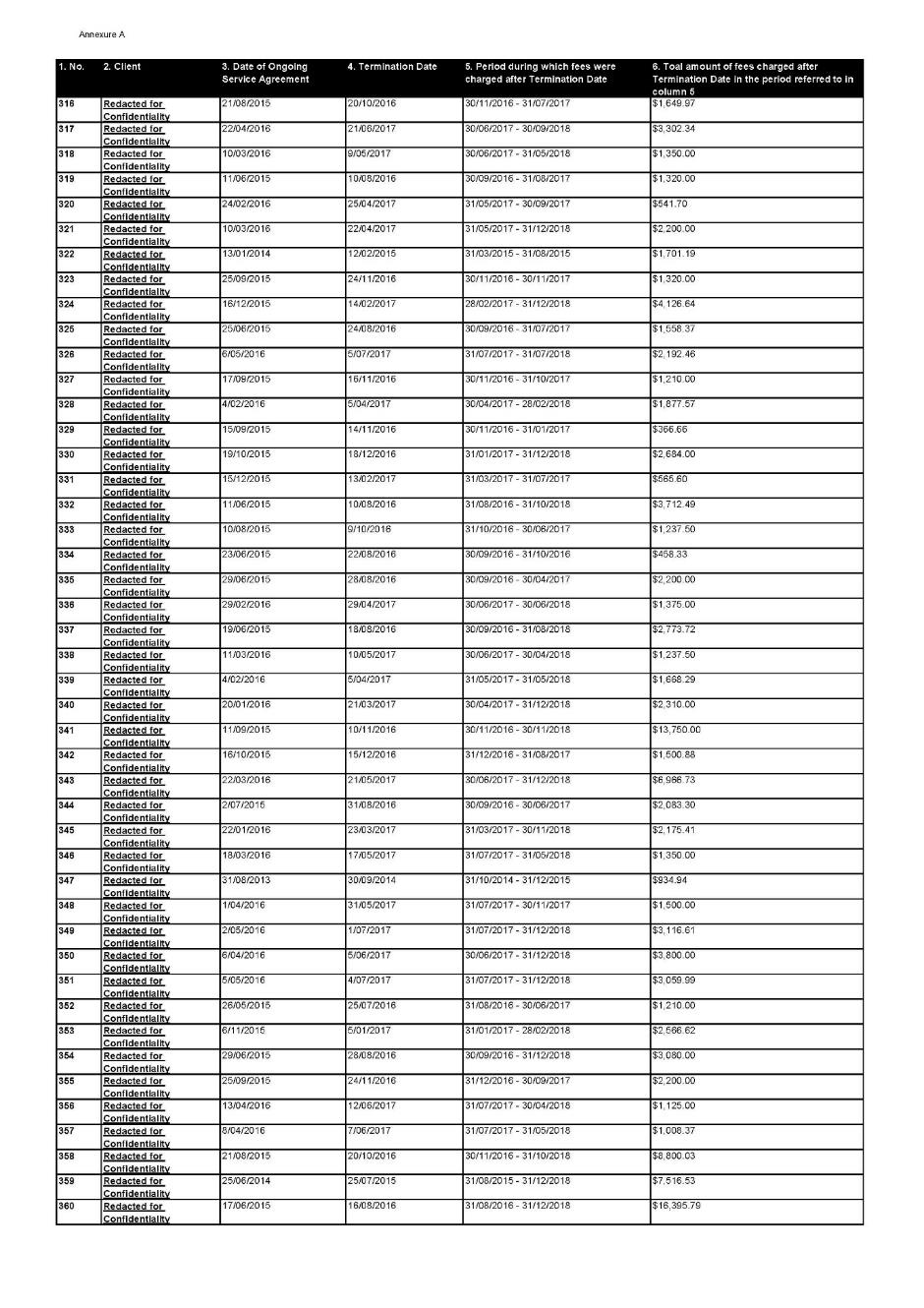

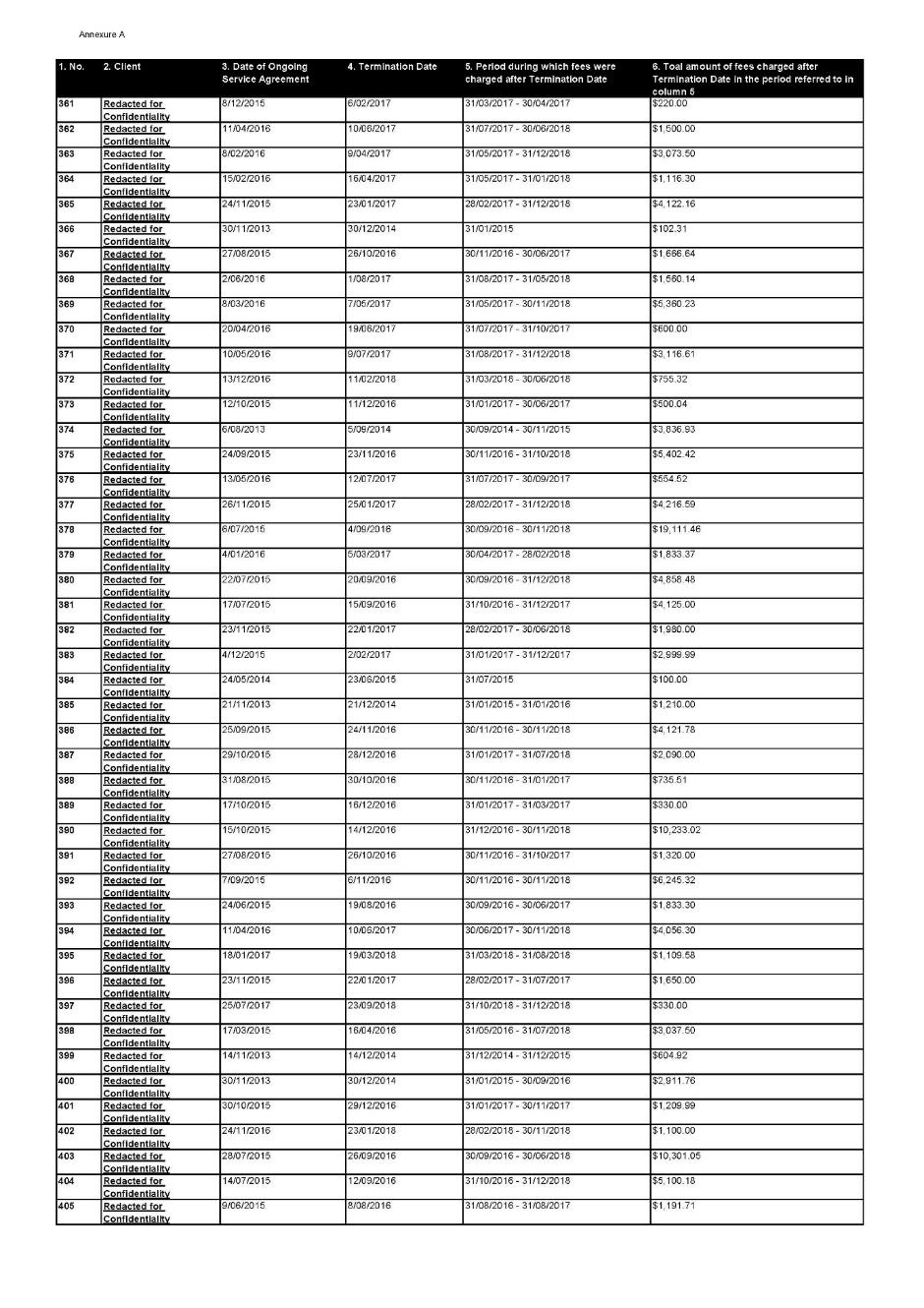

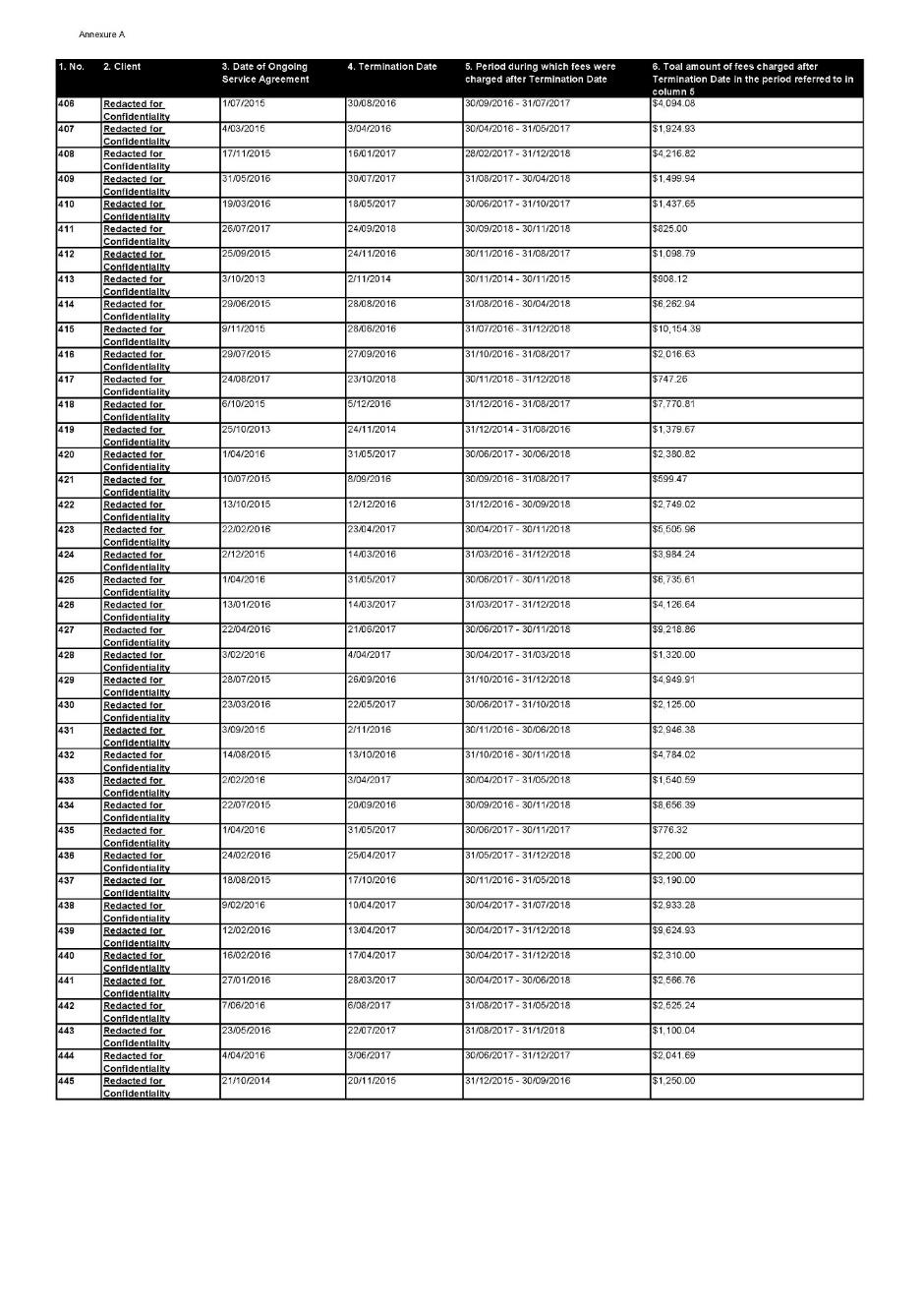

ANNEXURE A

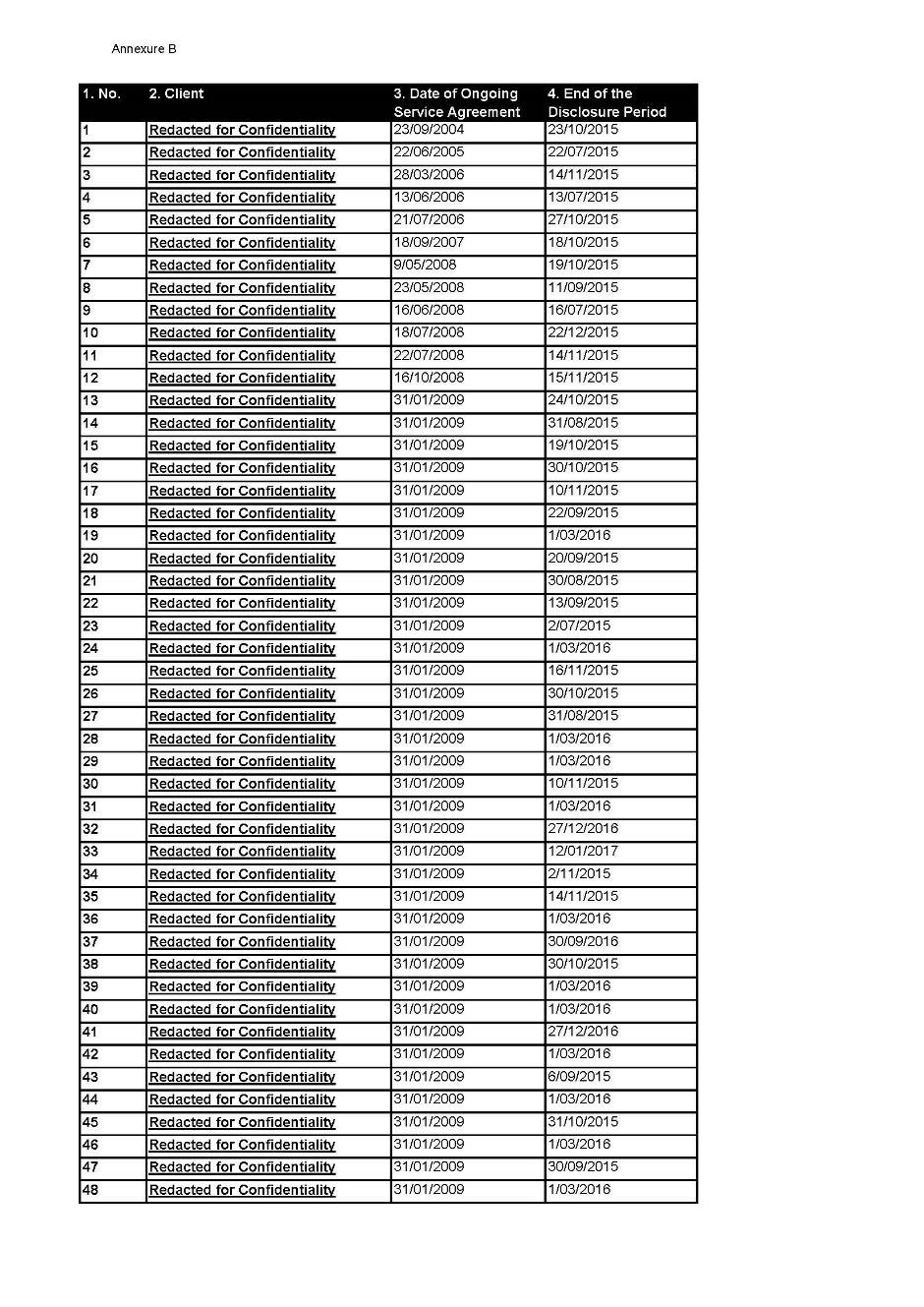

ANNEXURE B

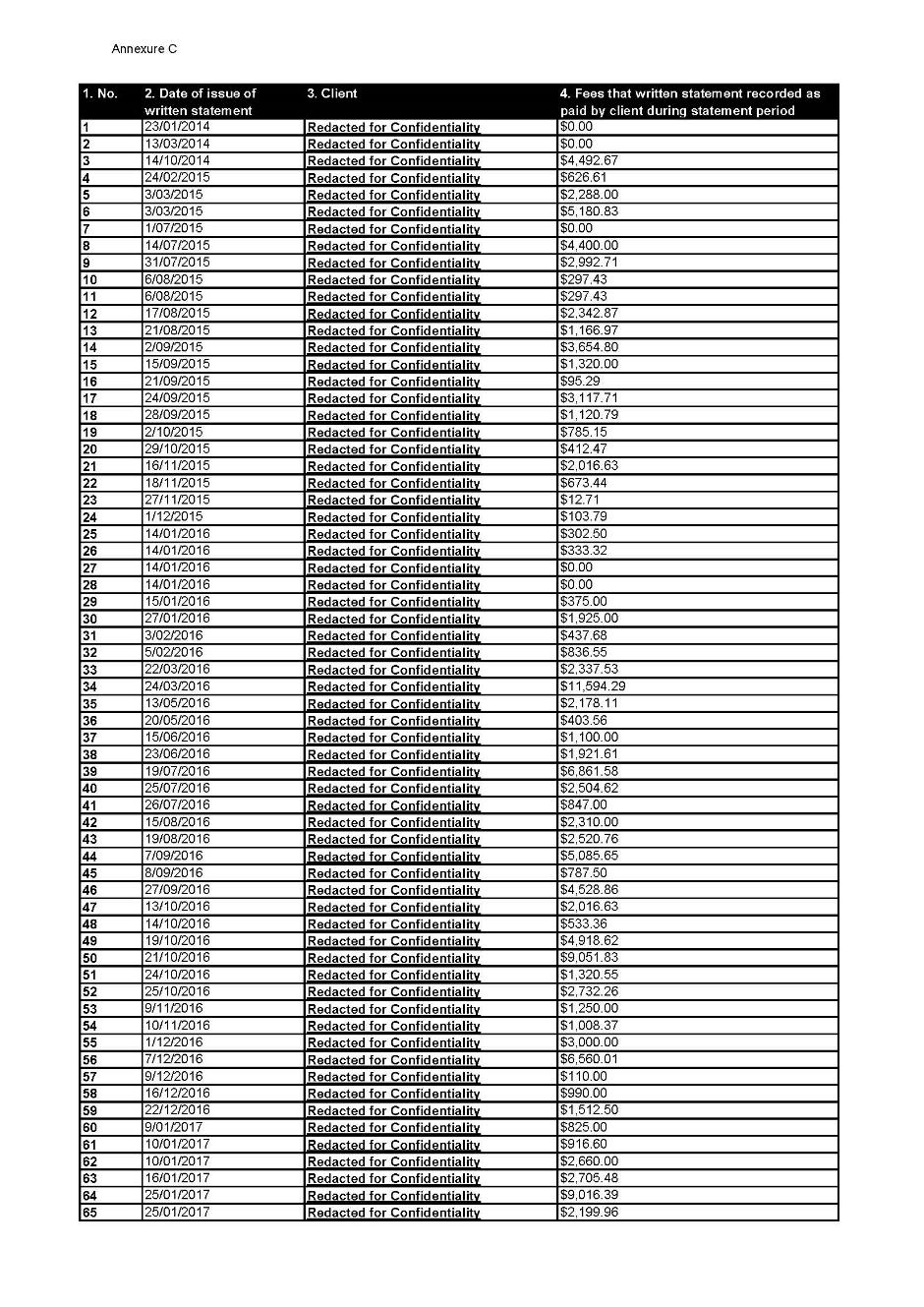

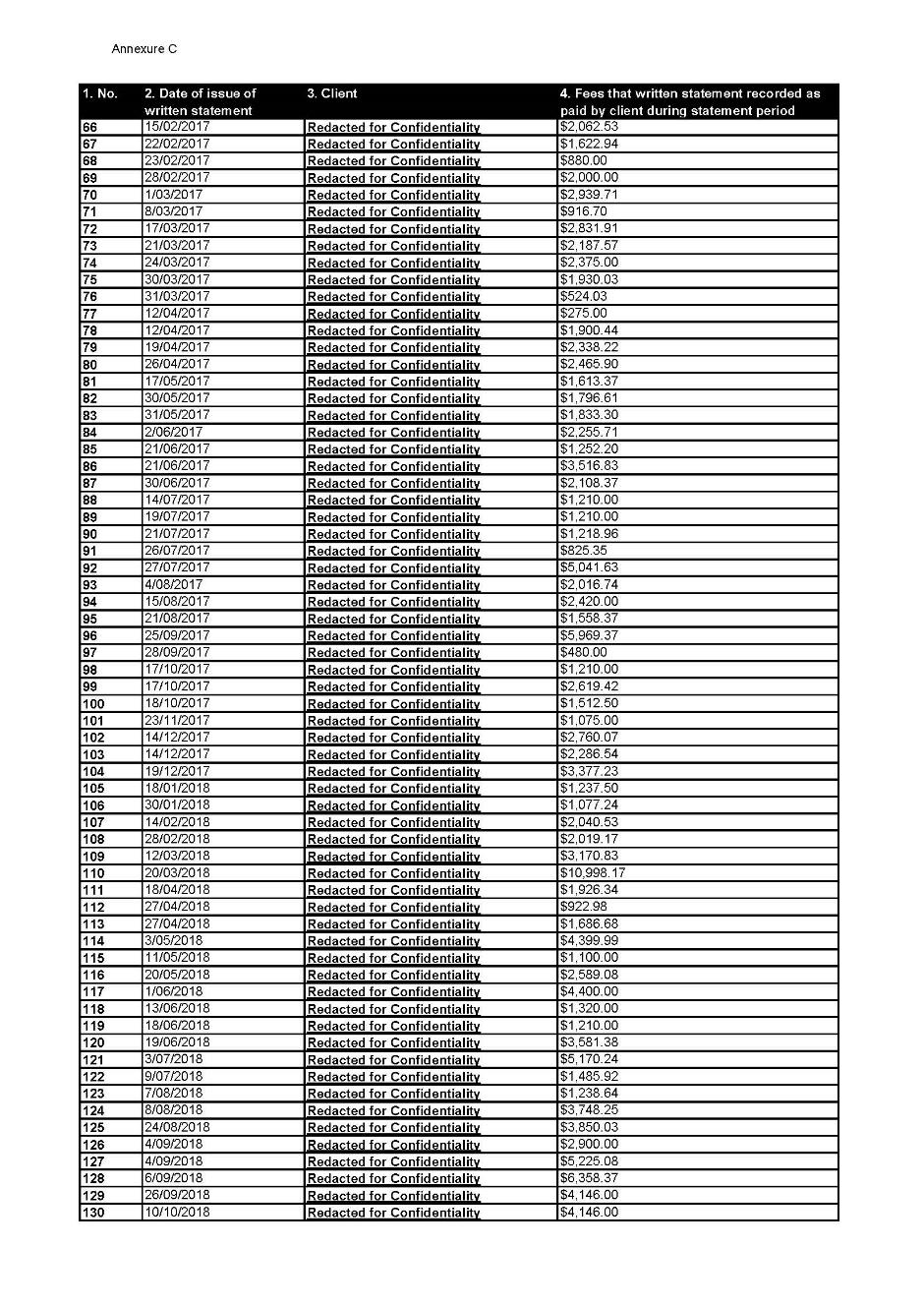

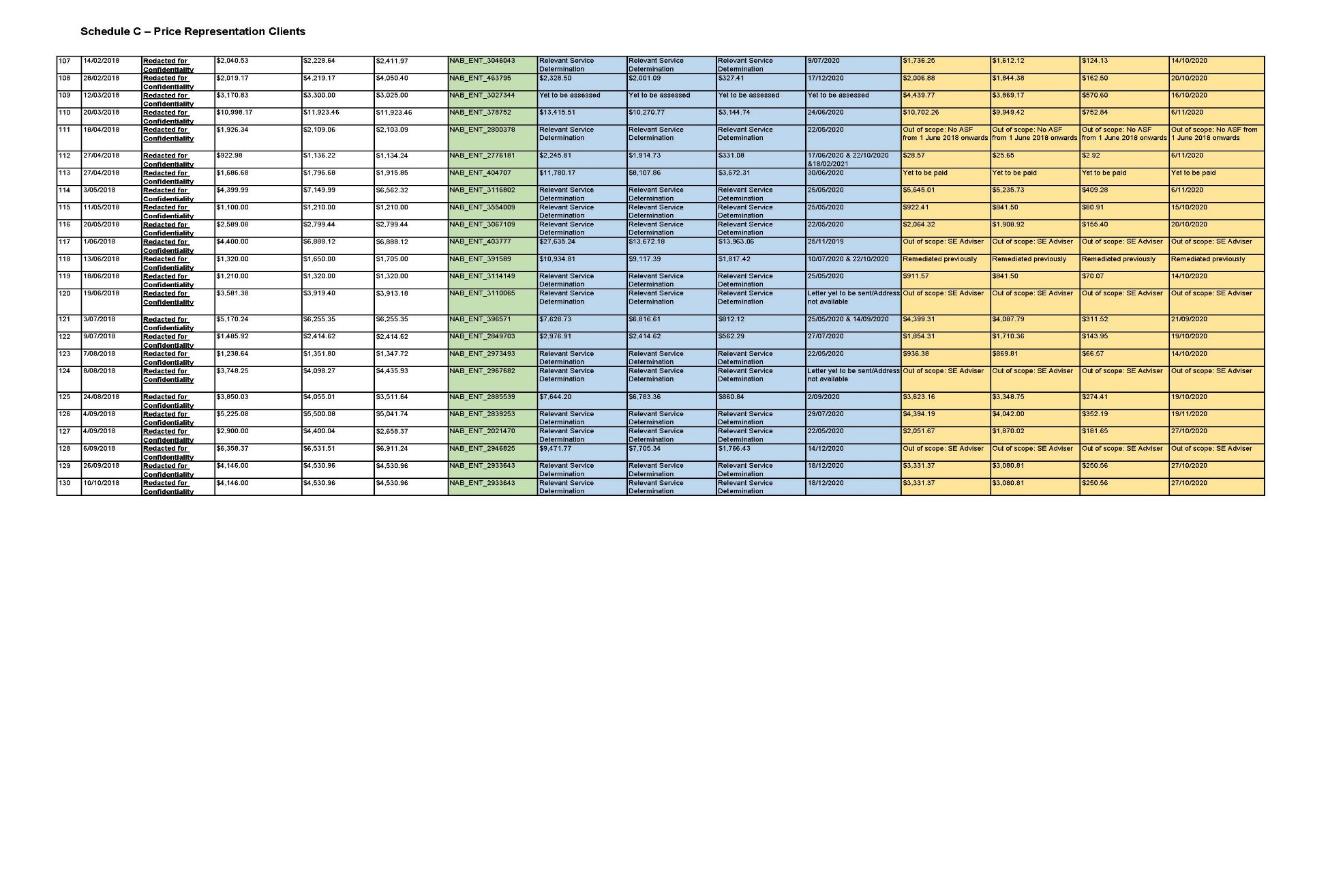

ANNEXURE C

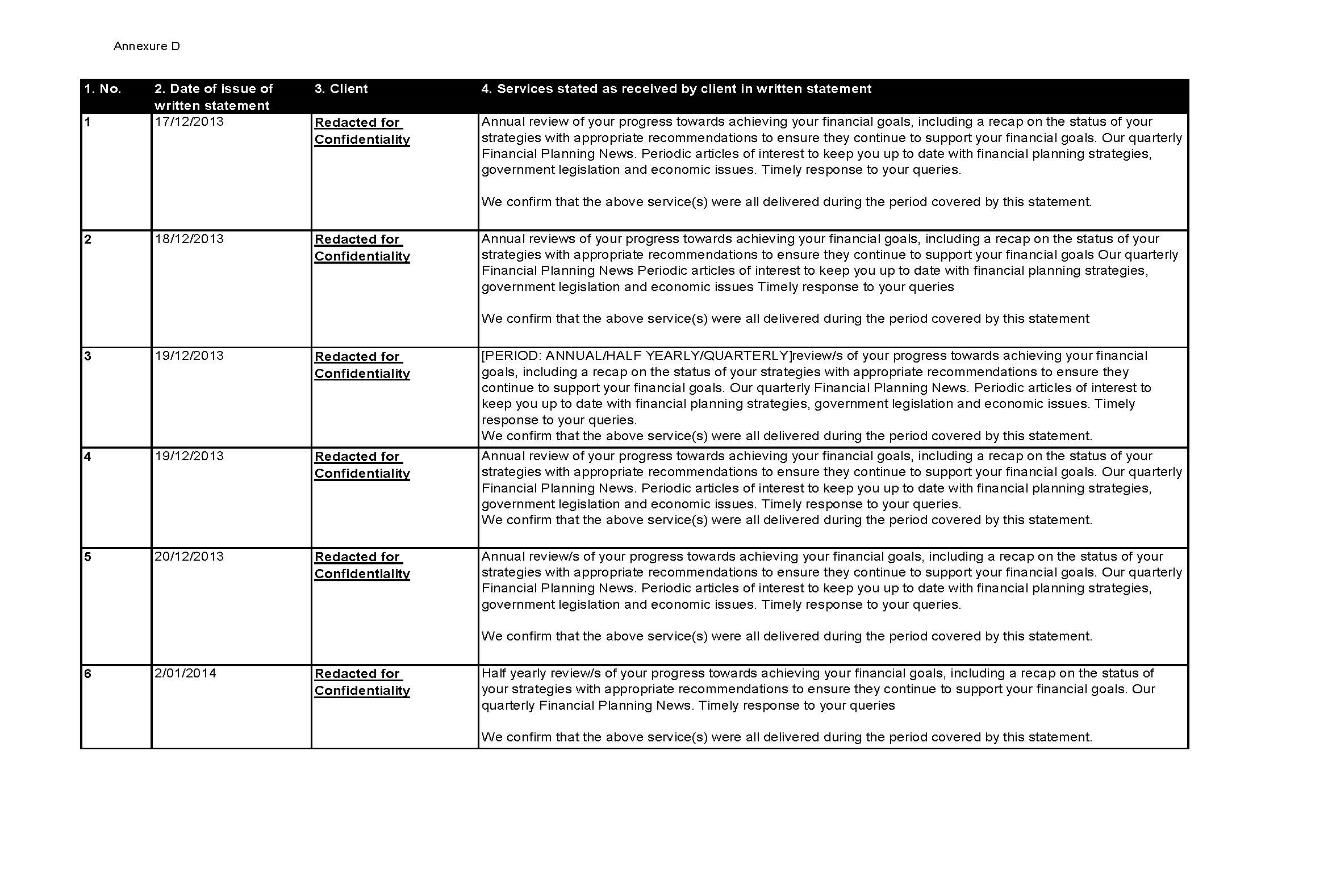

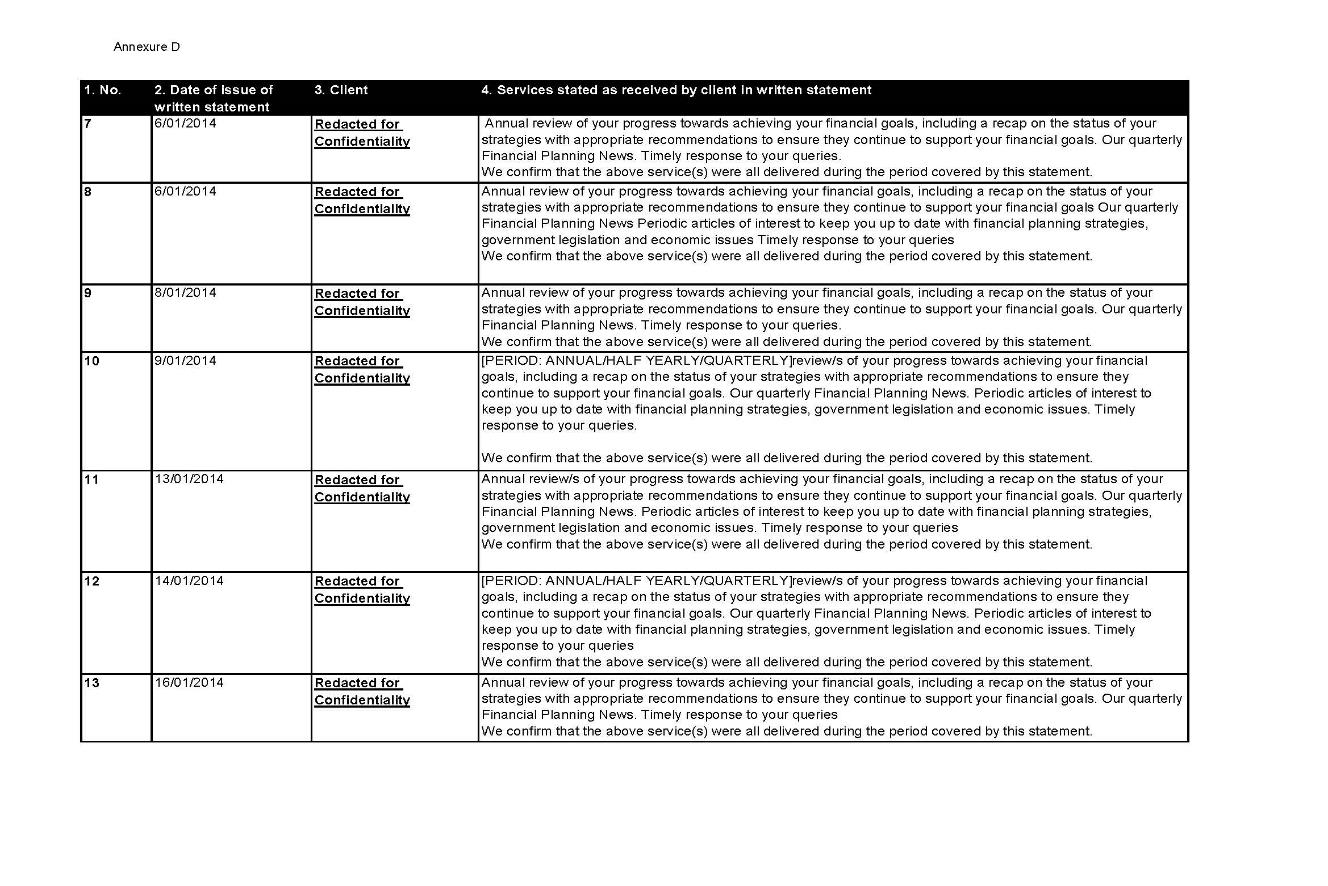

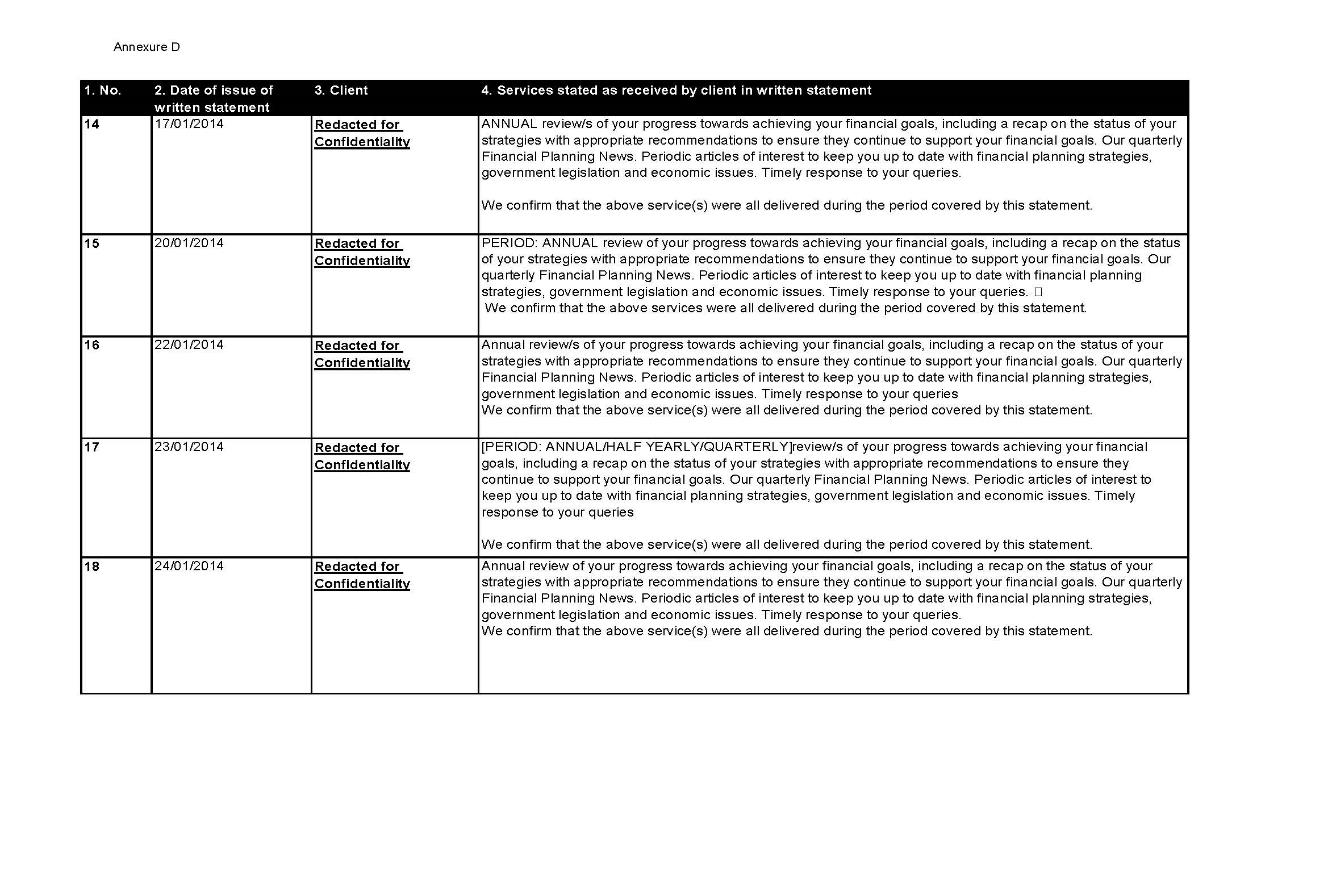

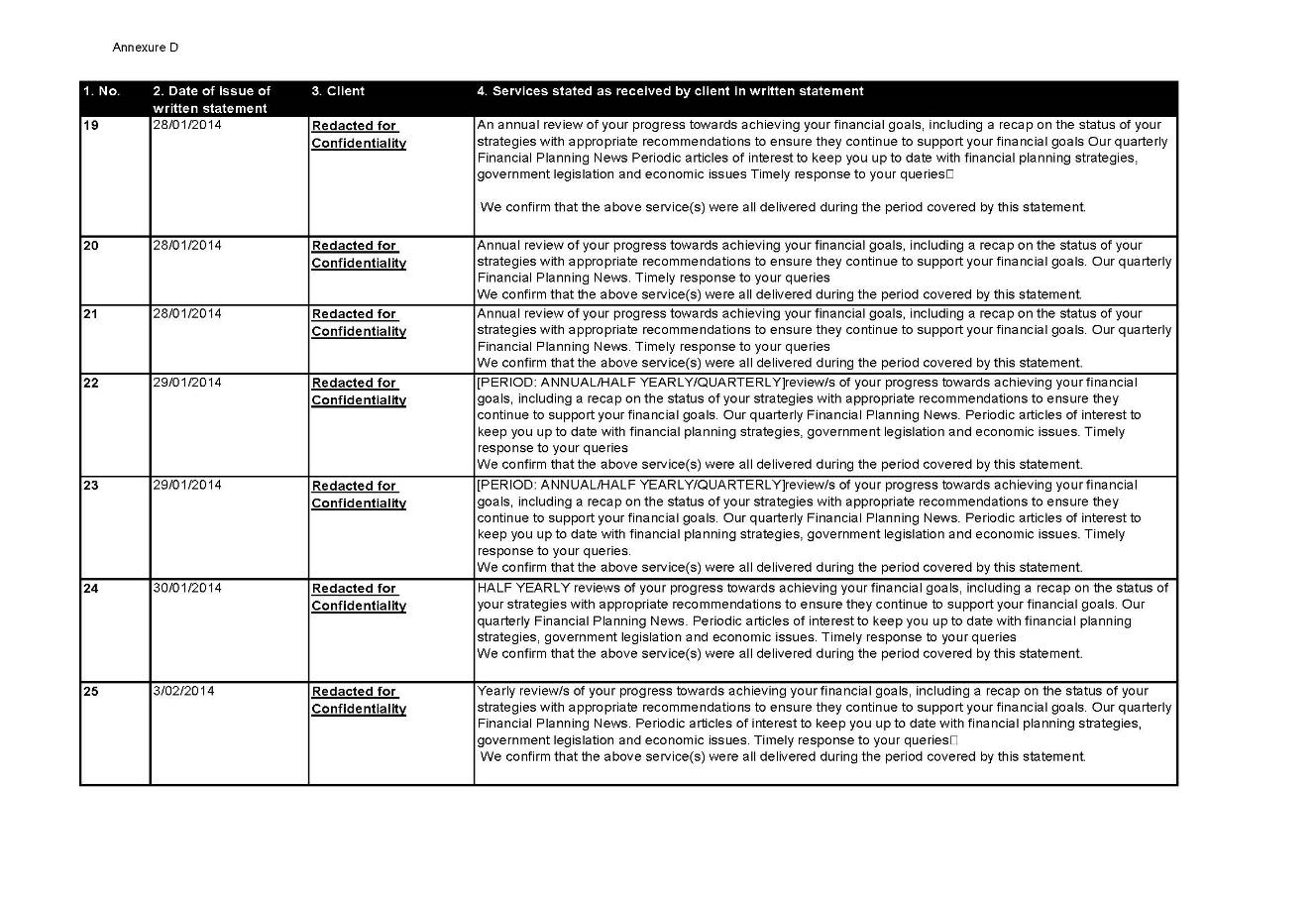

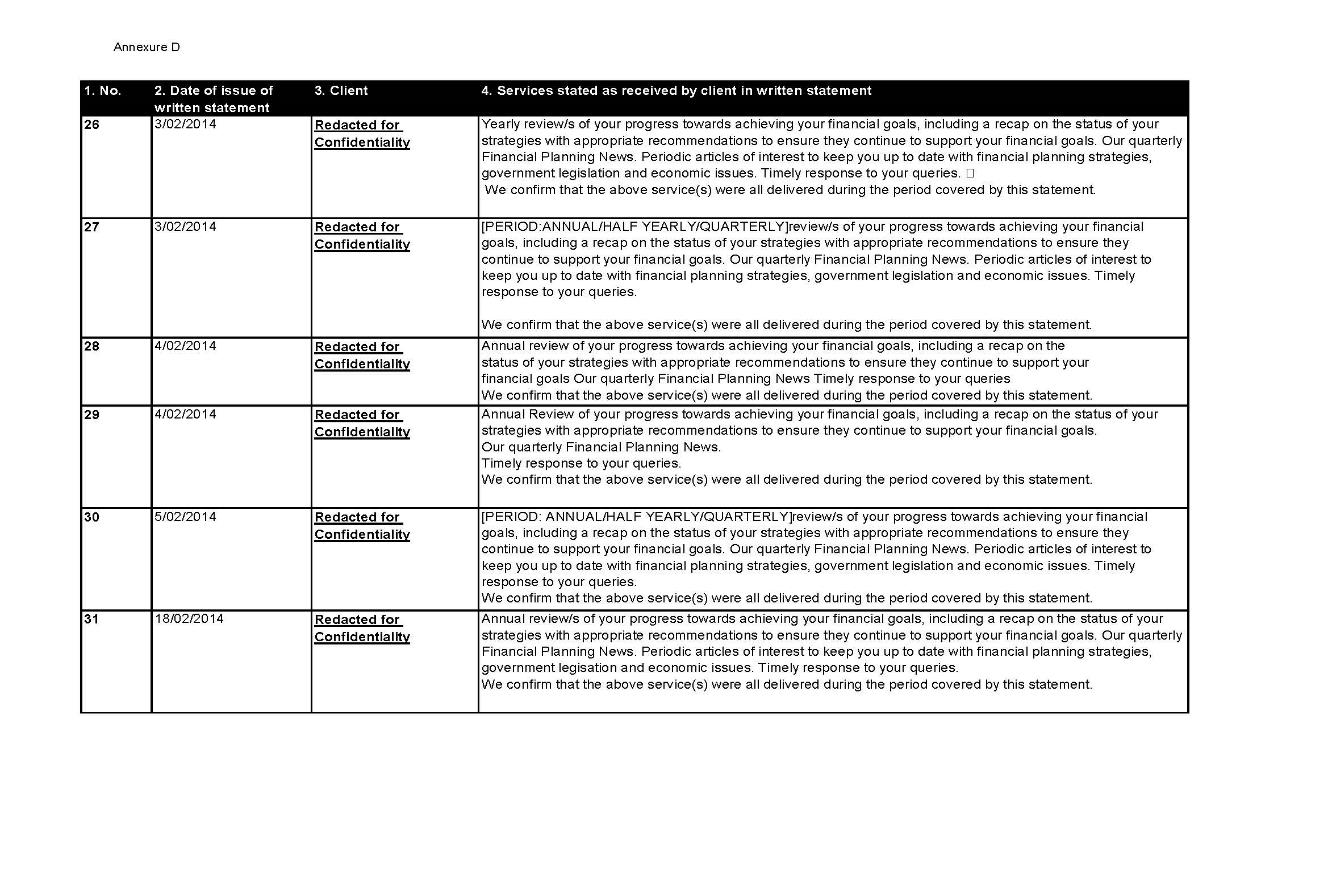

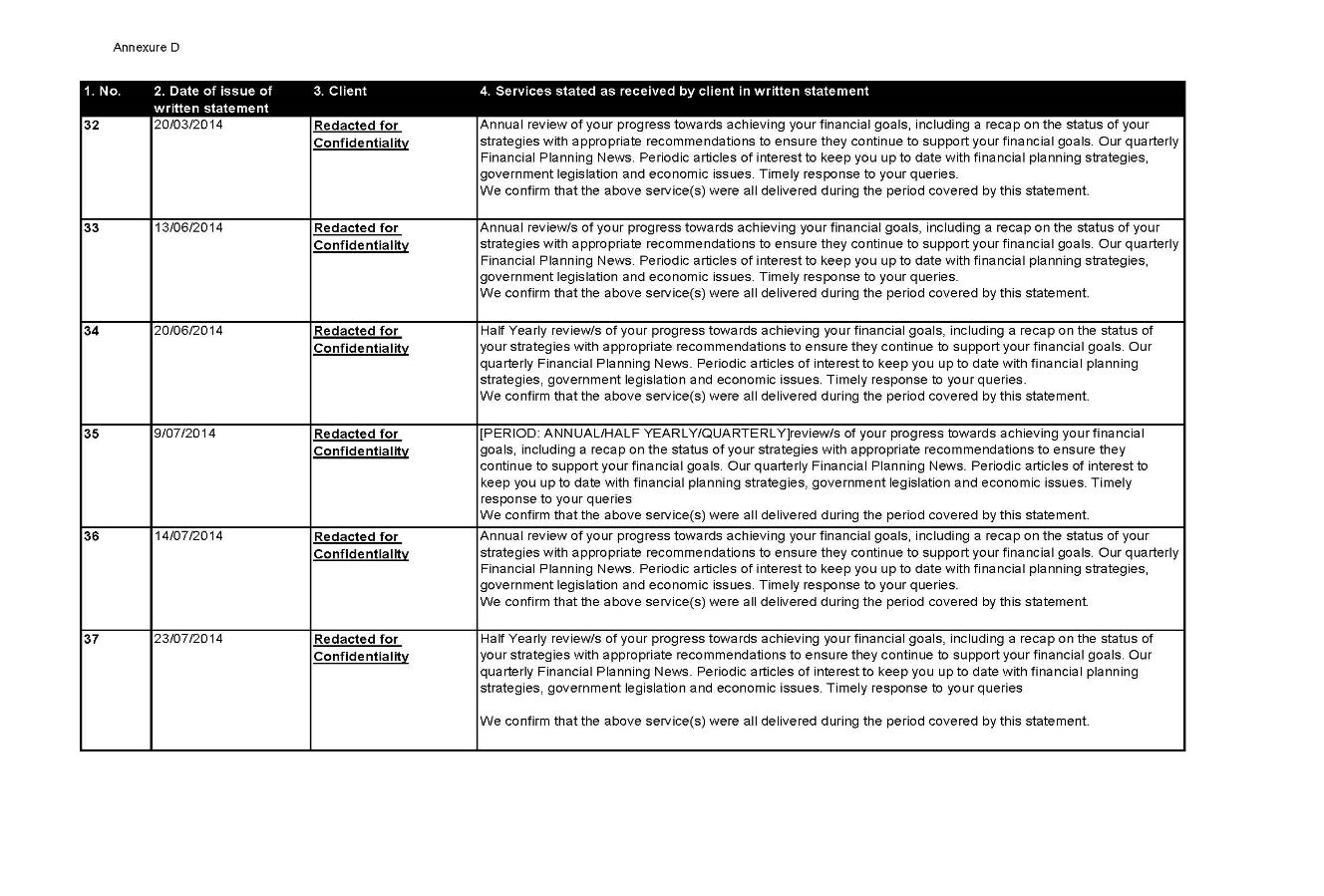

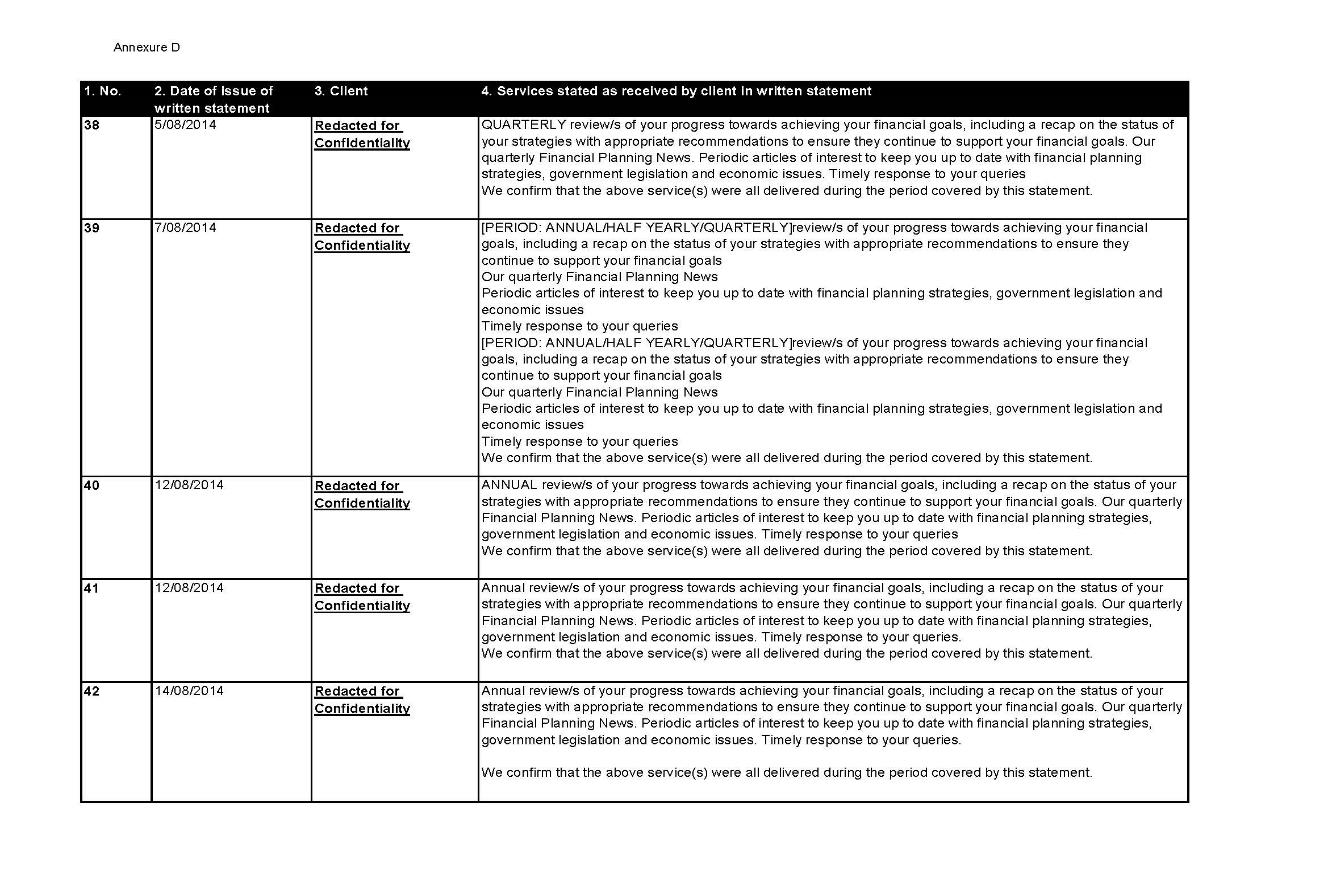

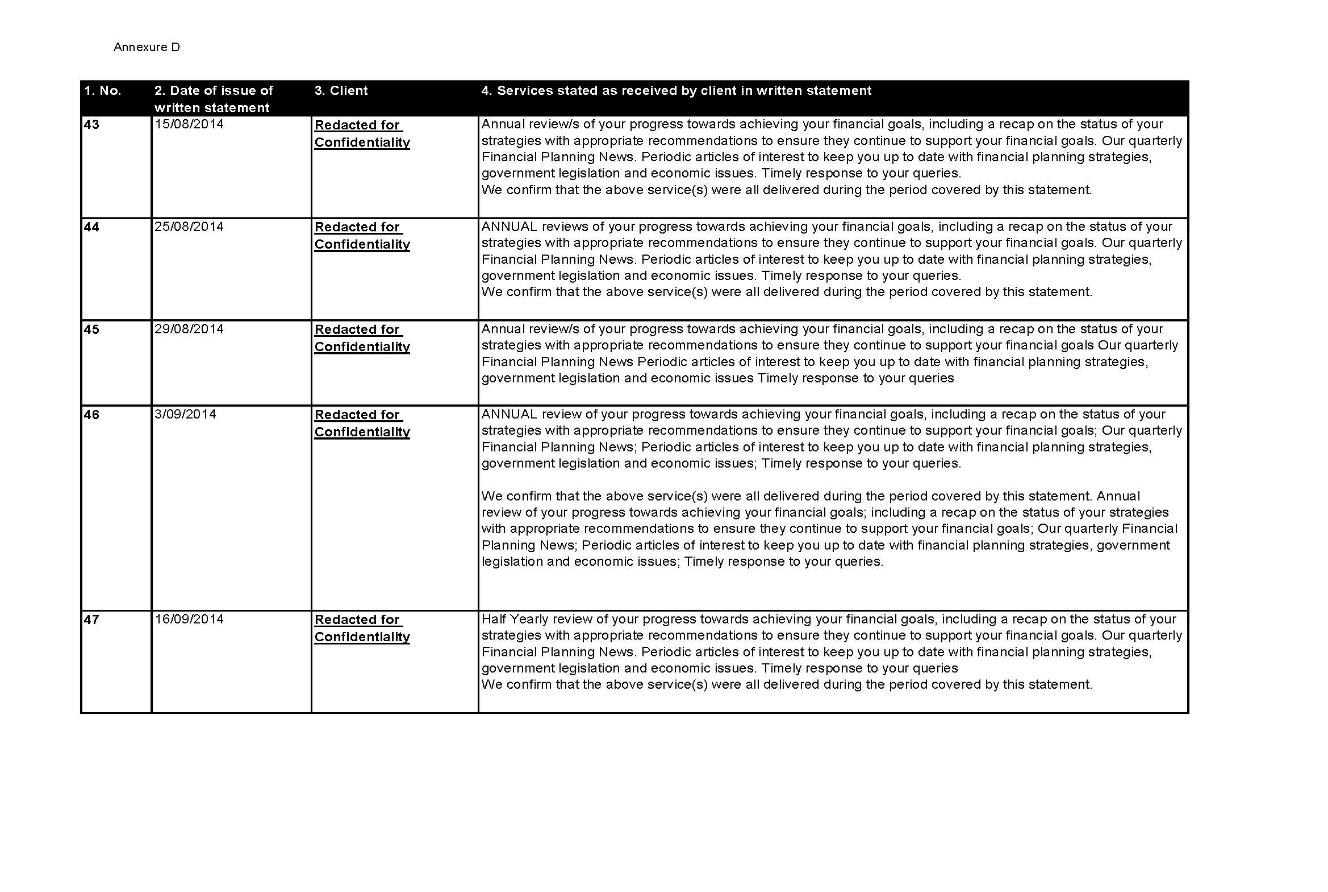

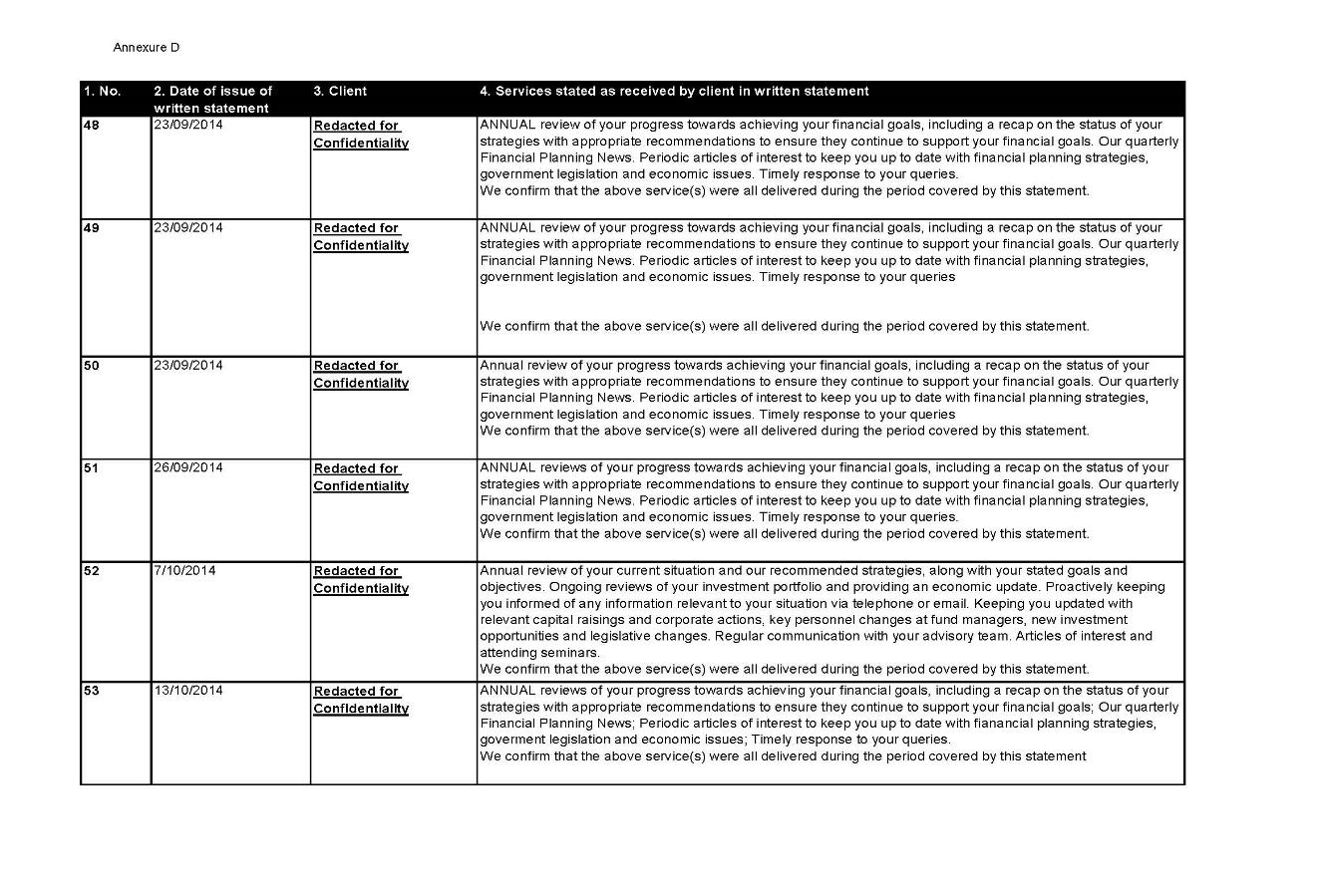

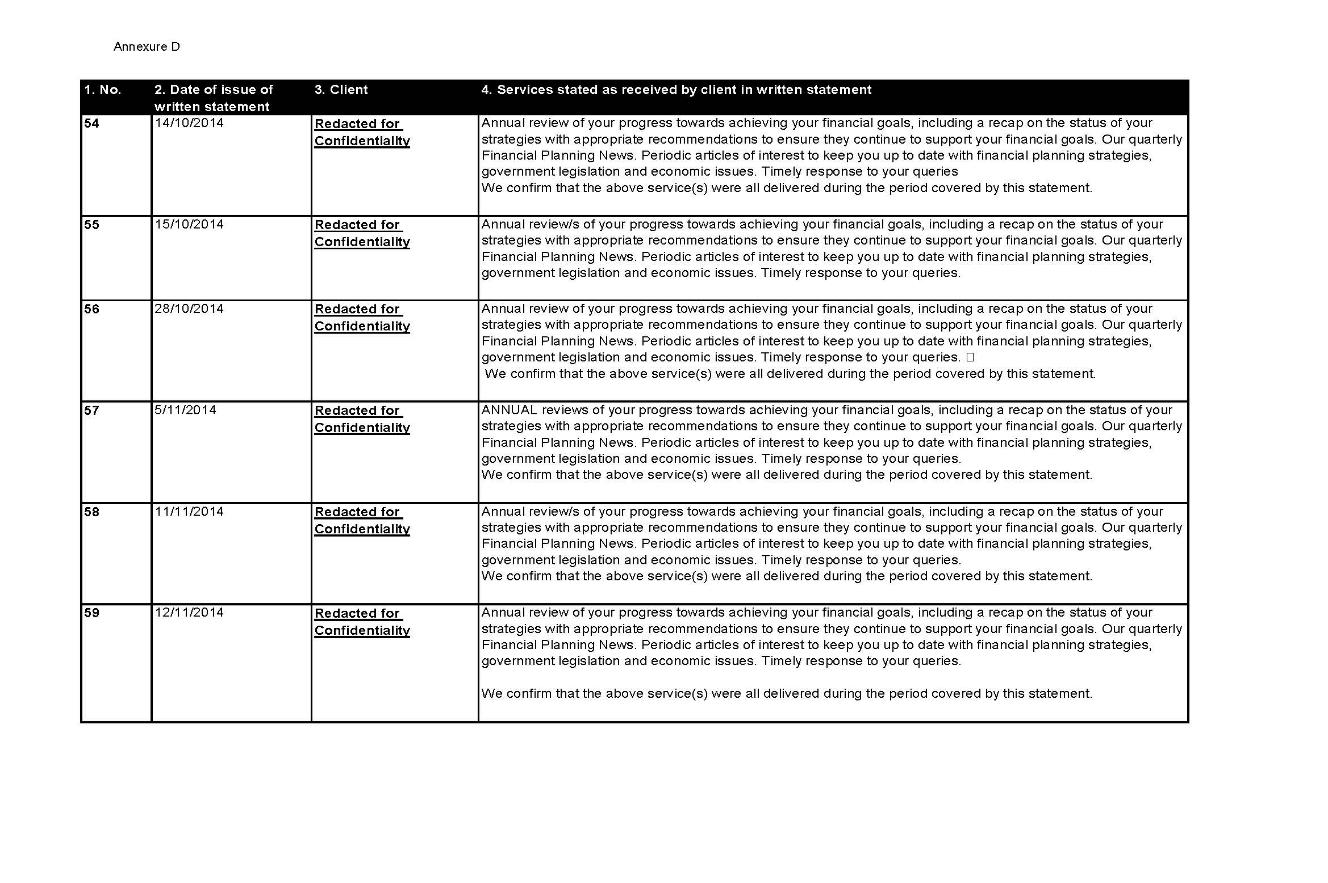

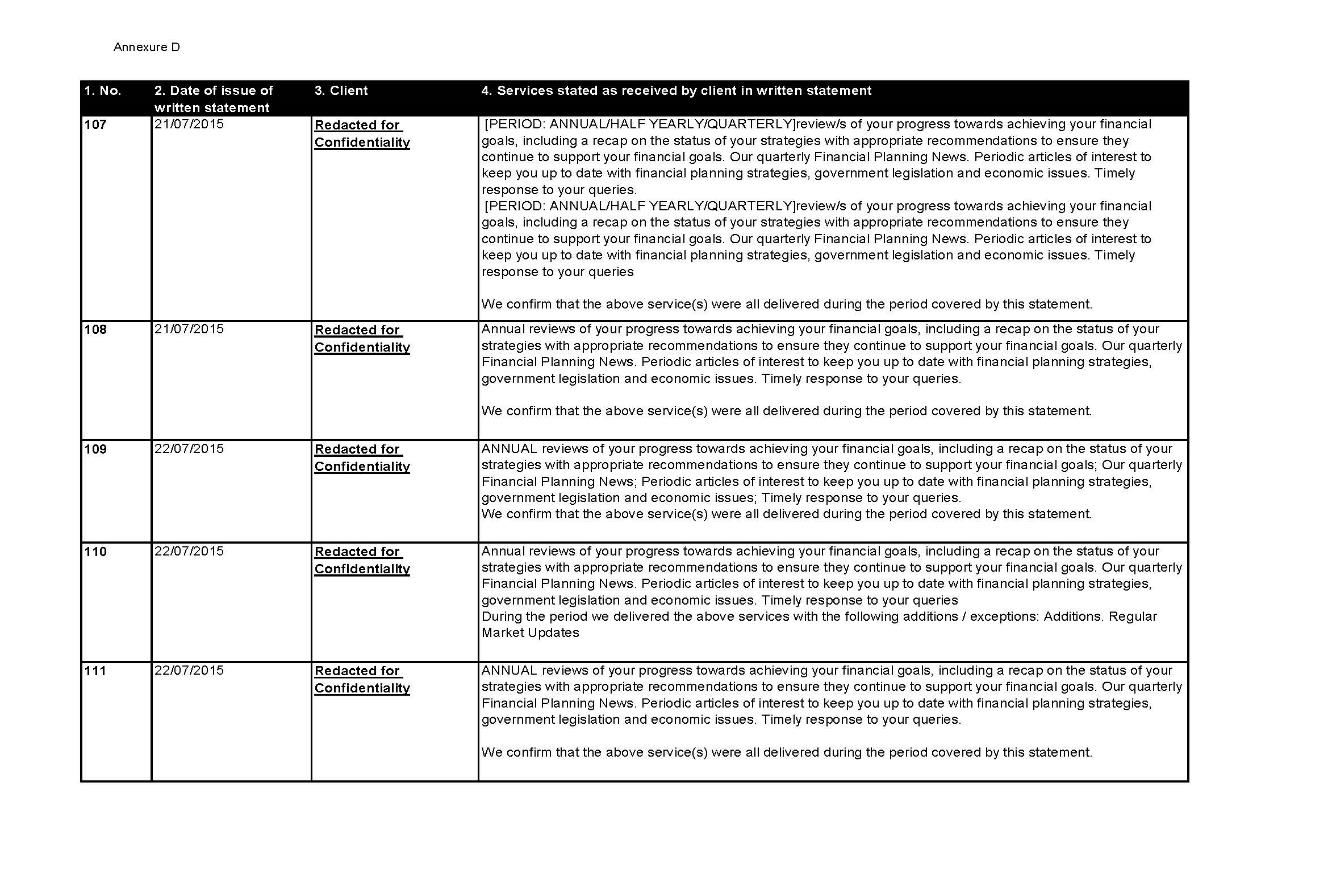

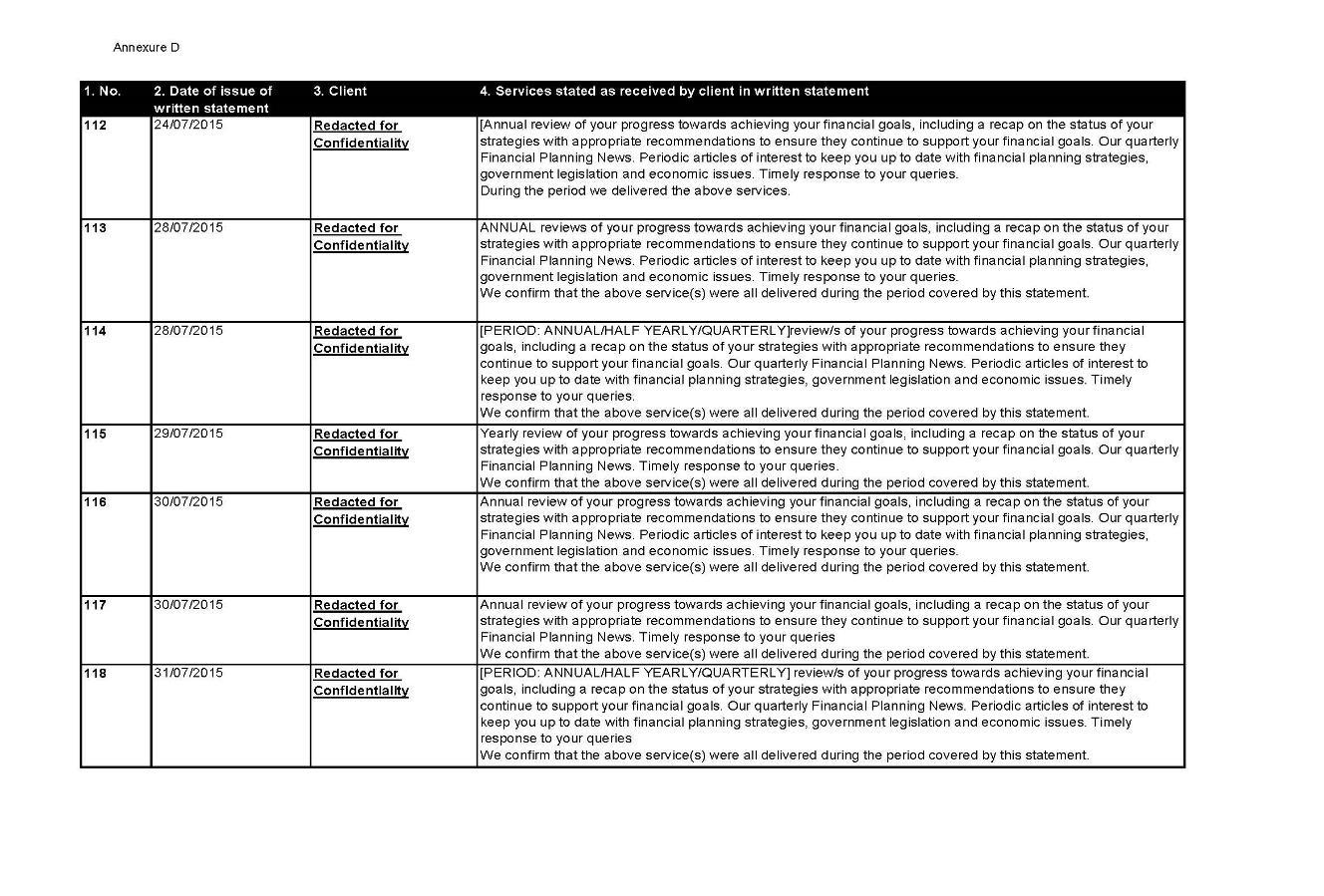

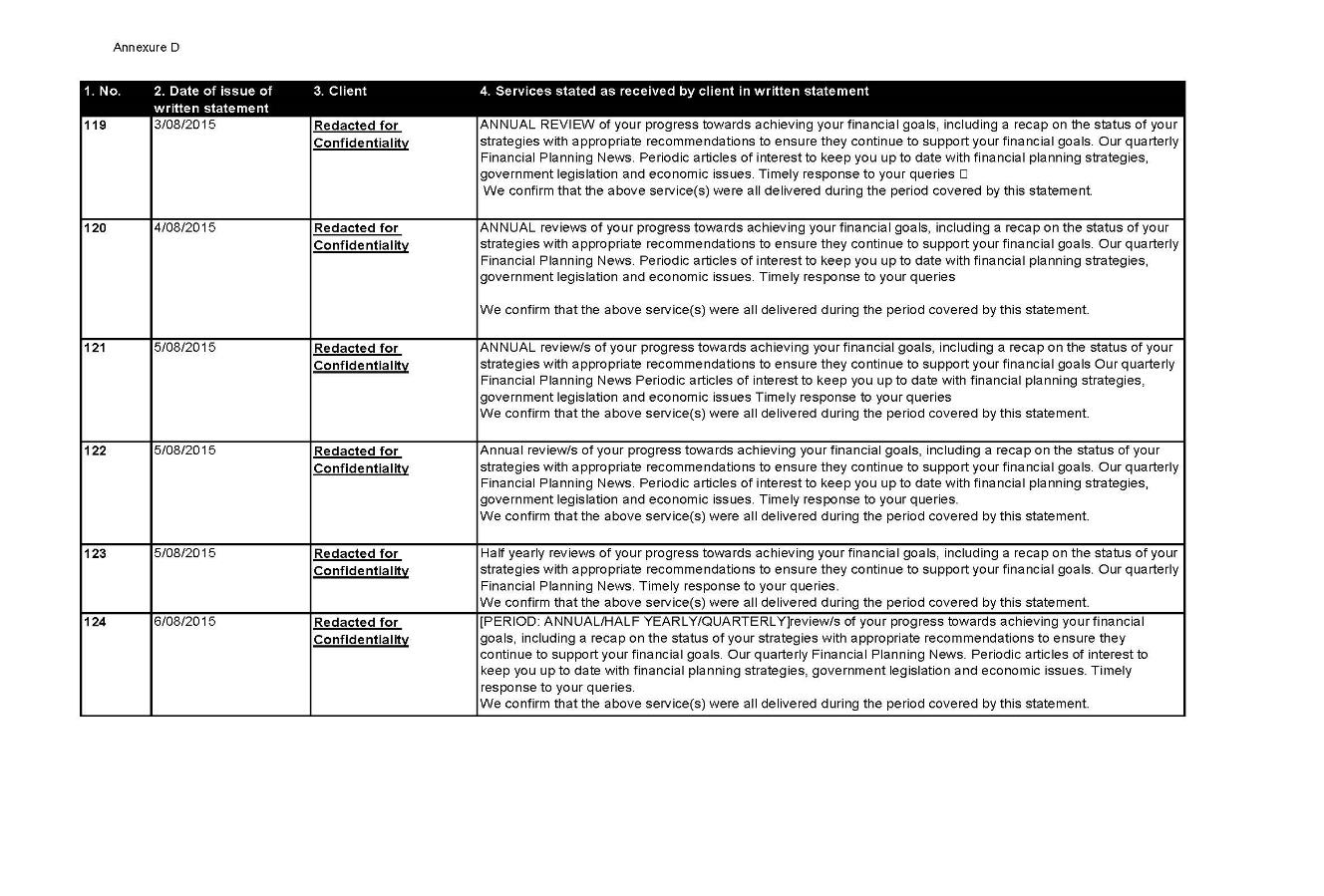

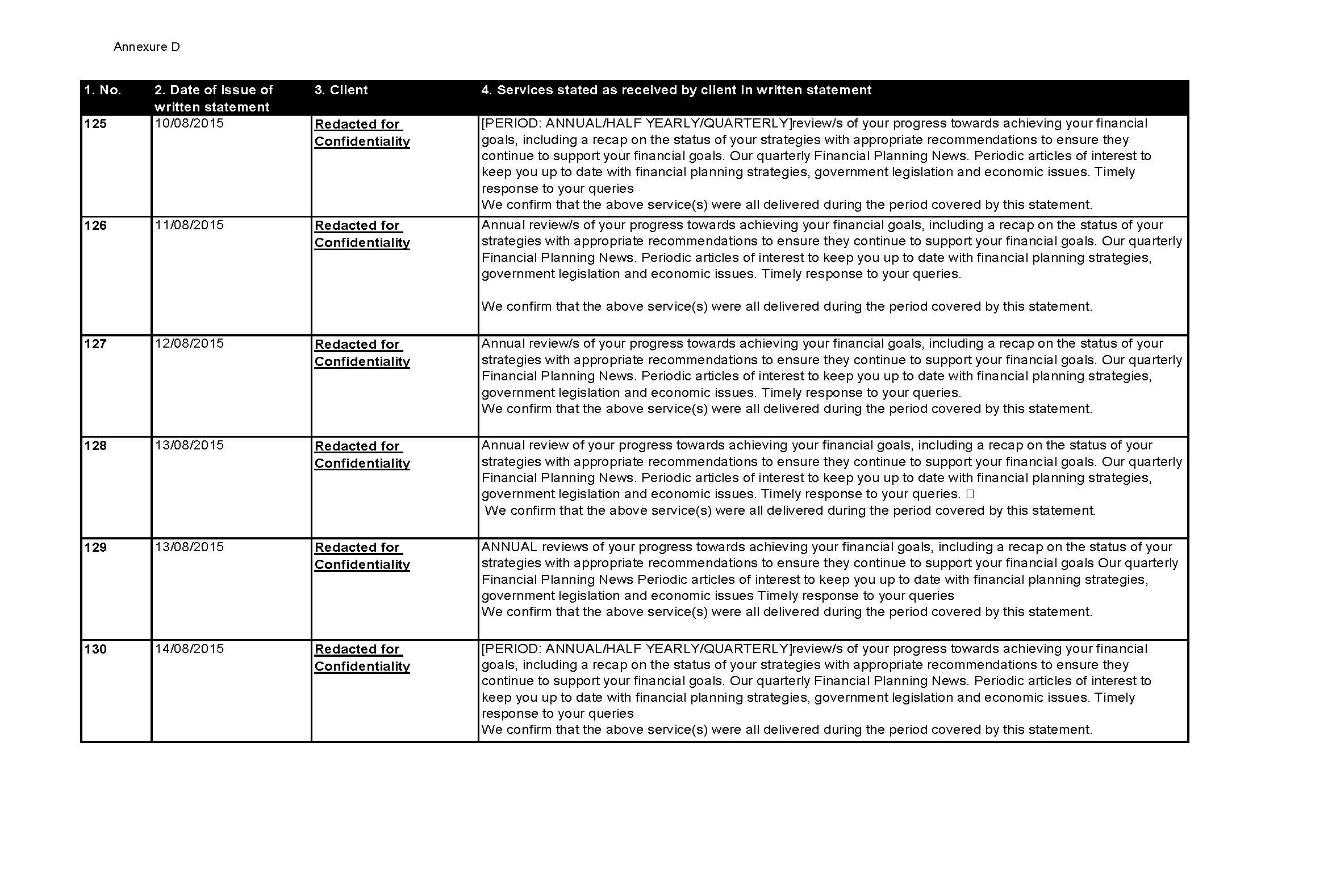

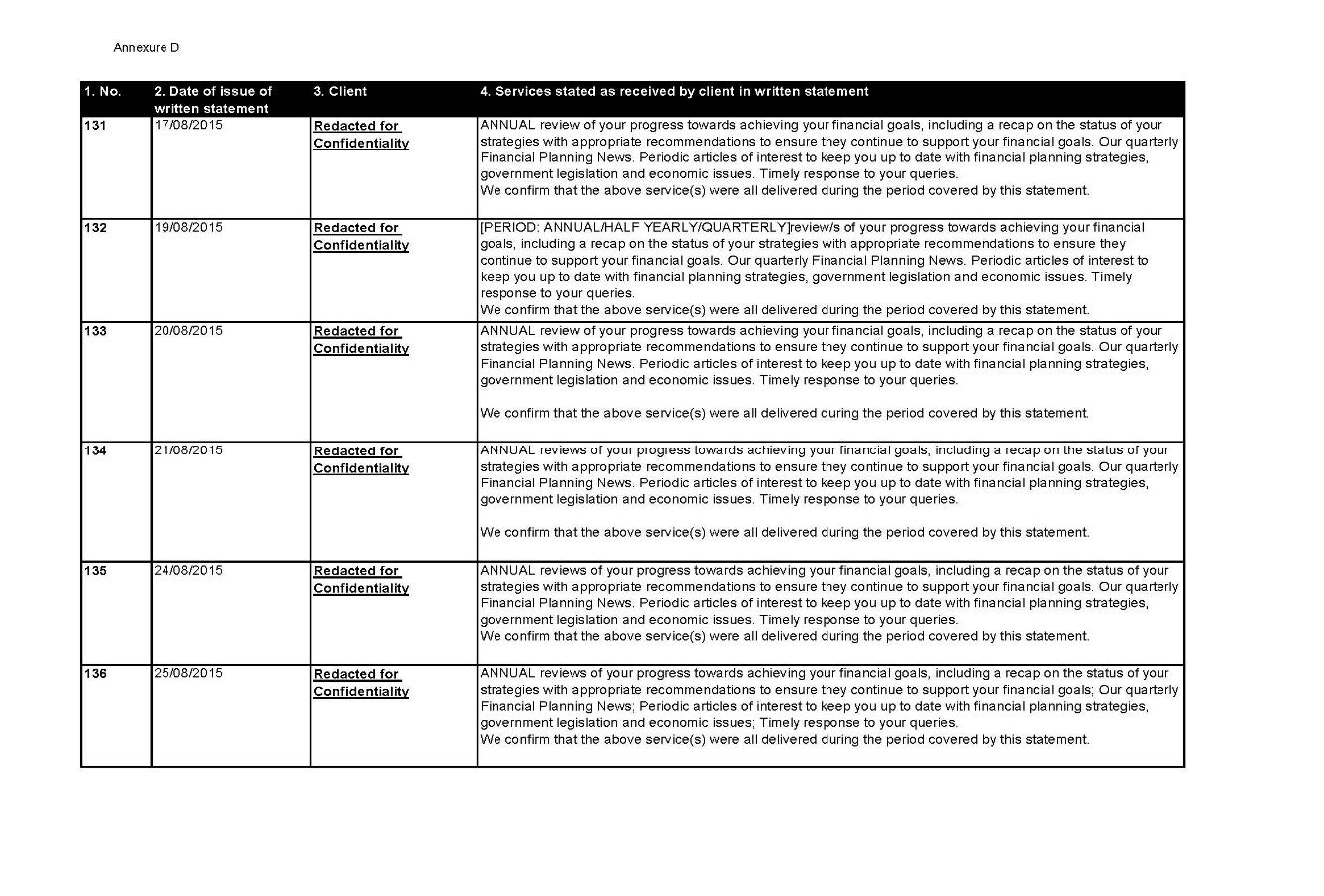

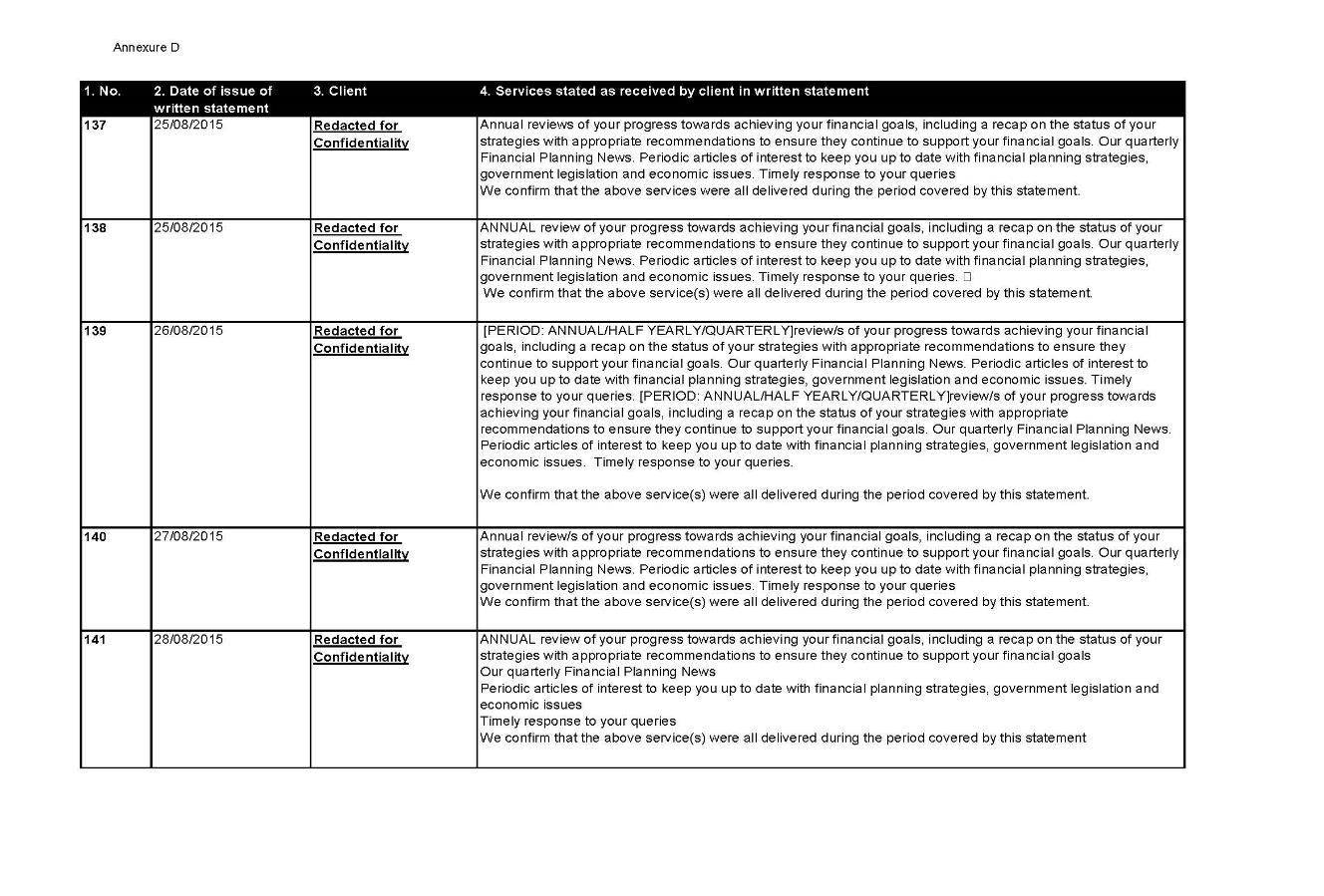

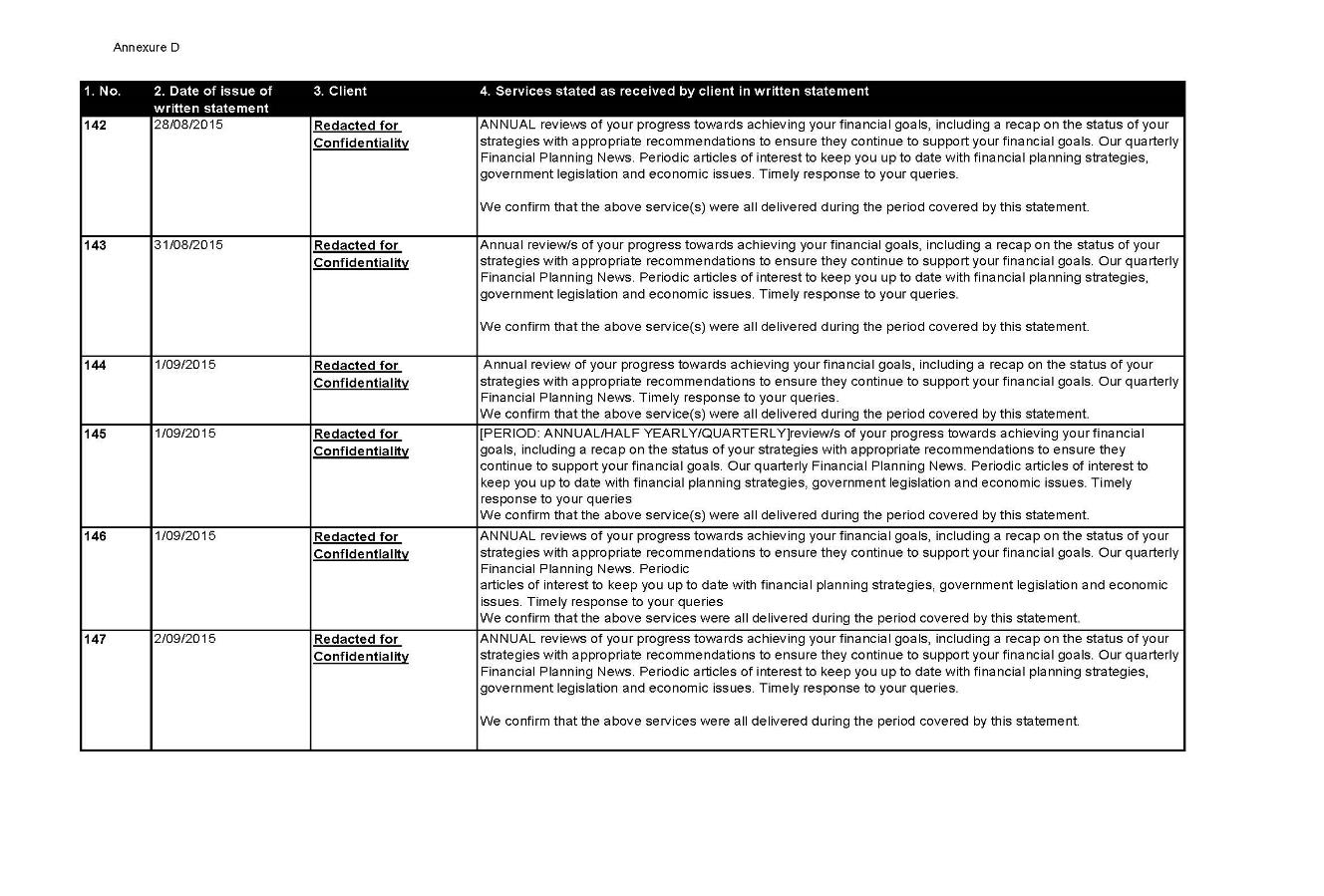

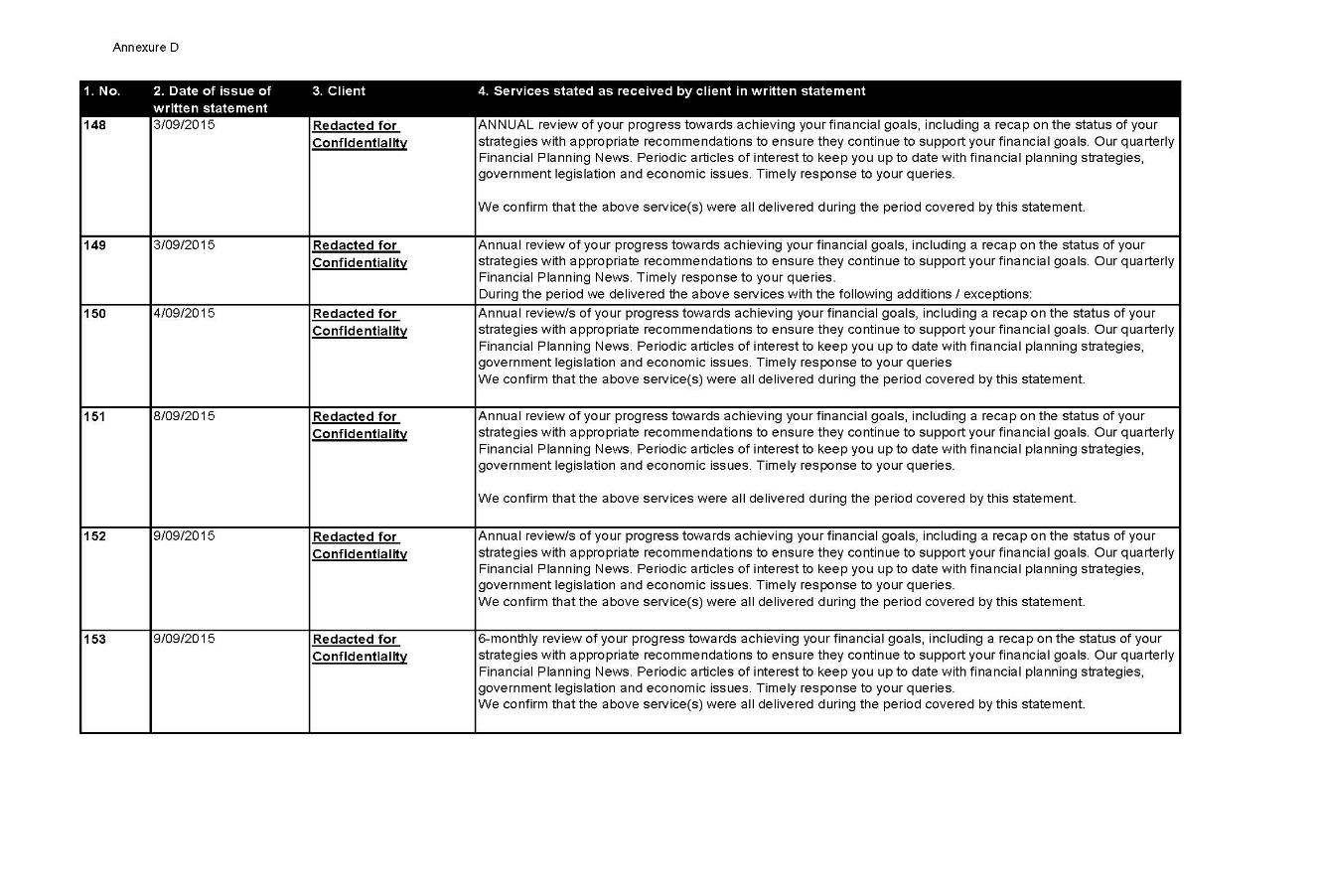

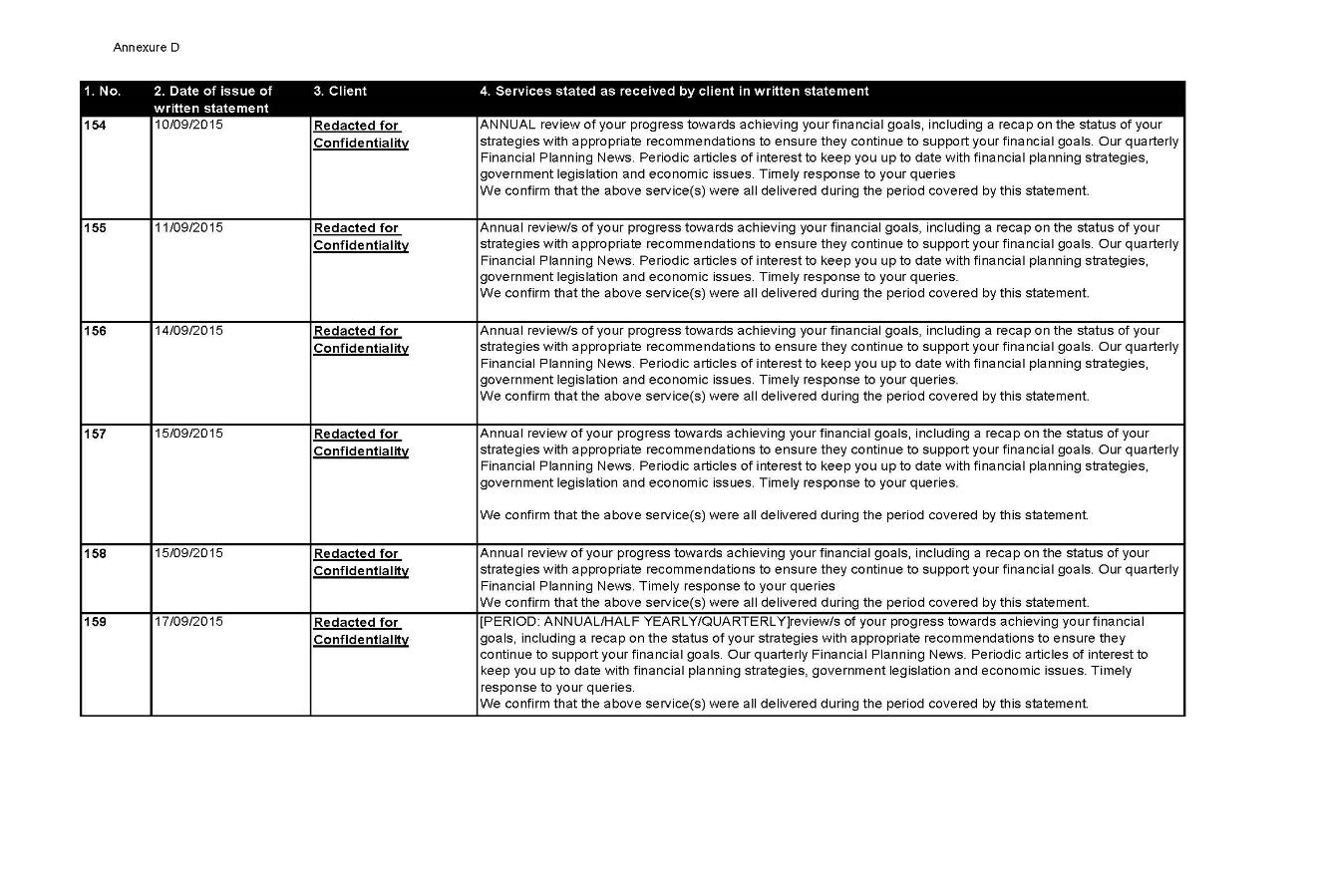

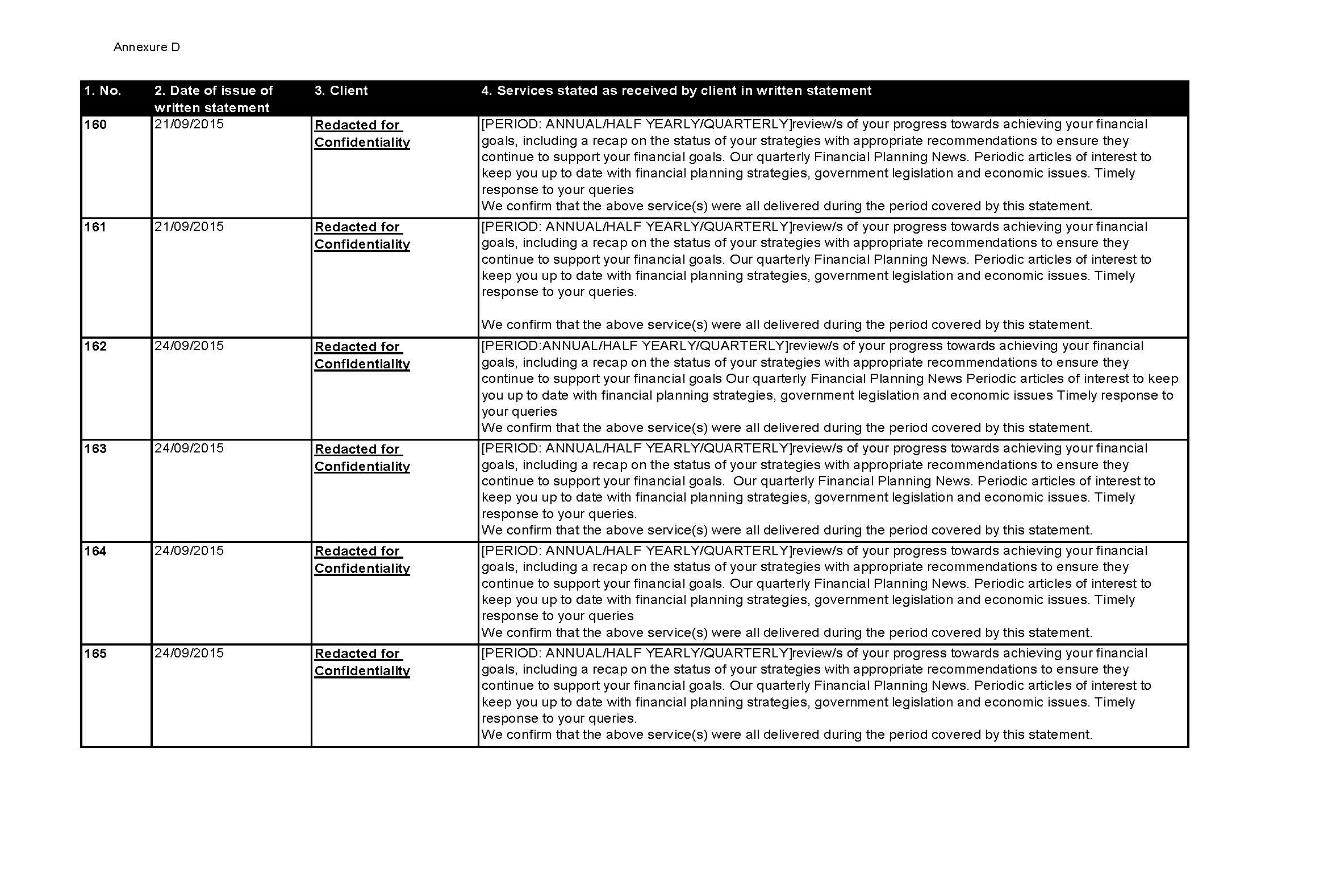

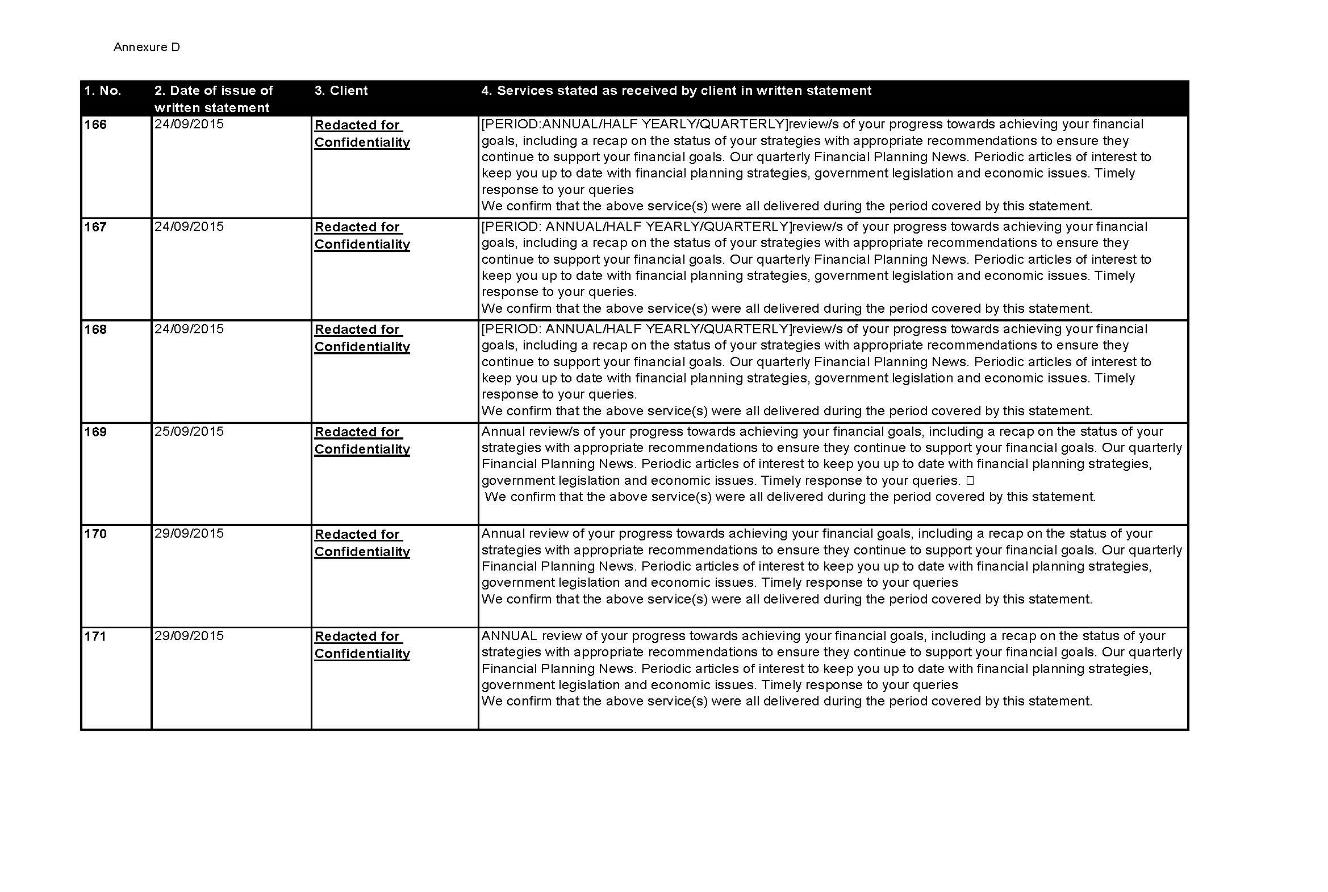

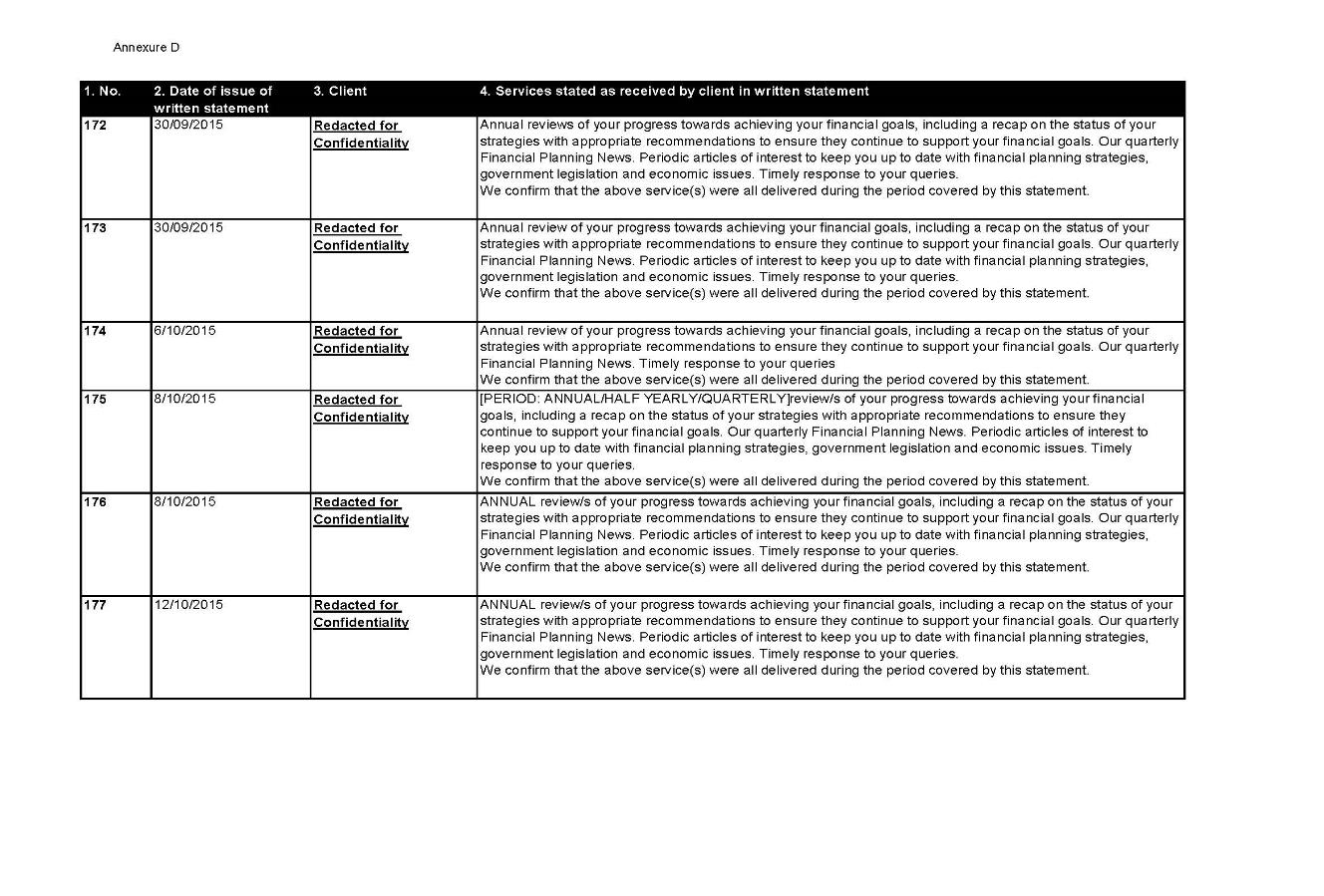

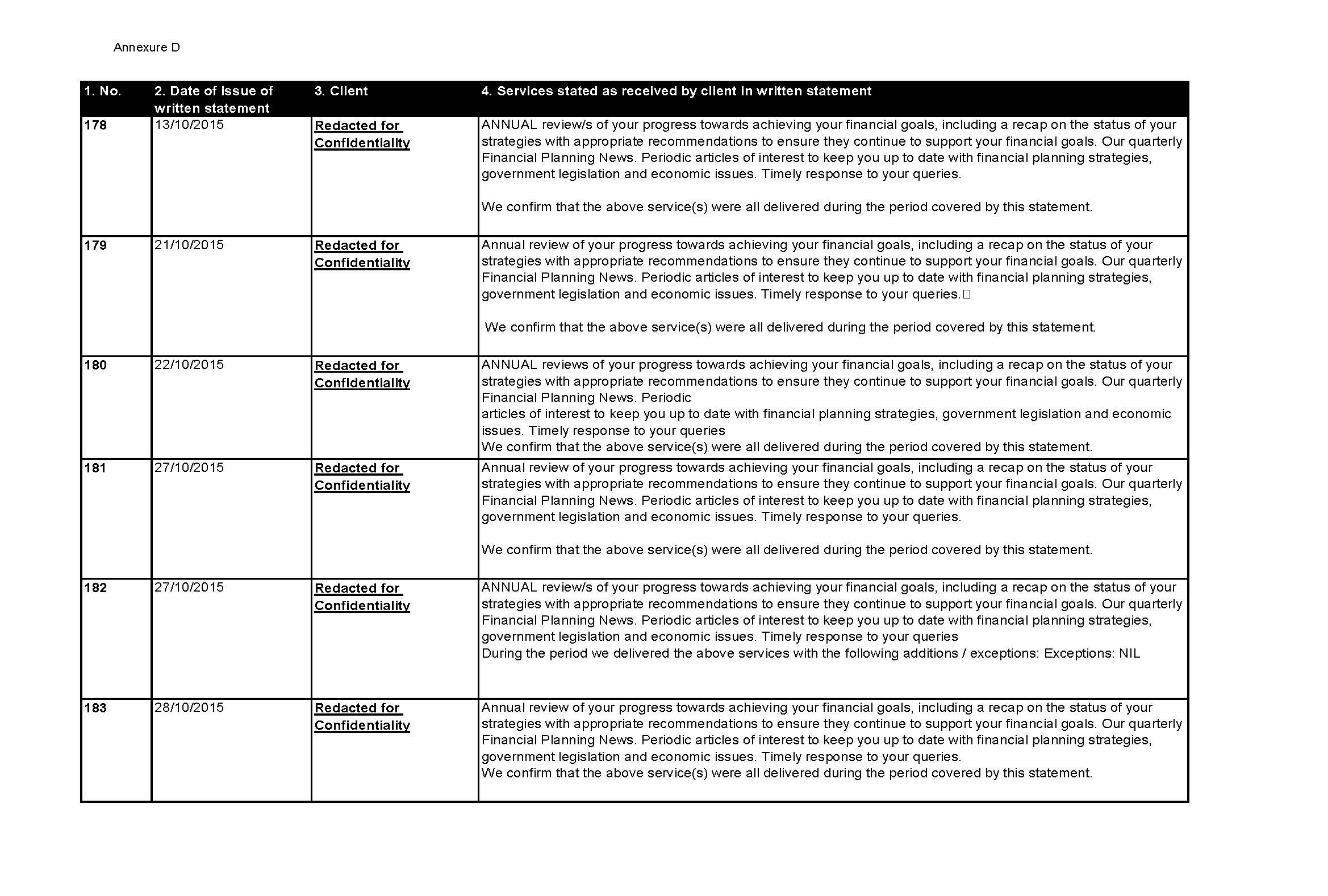

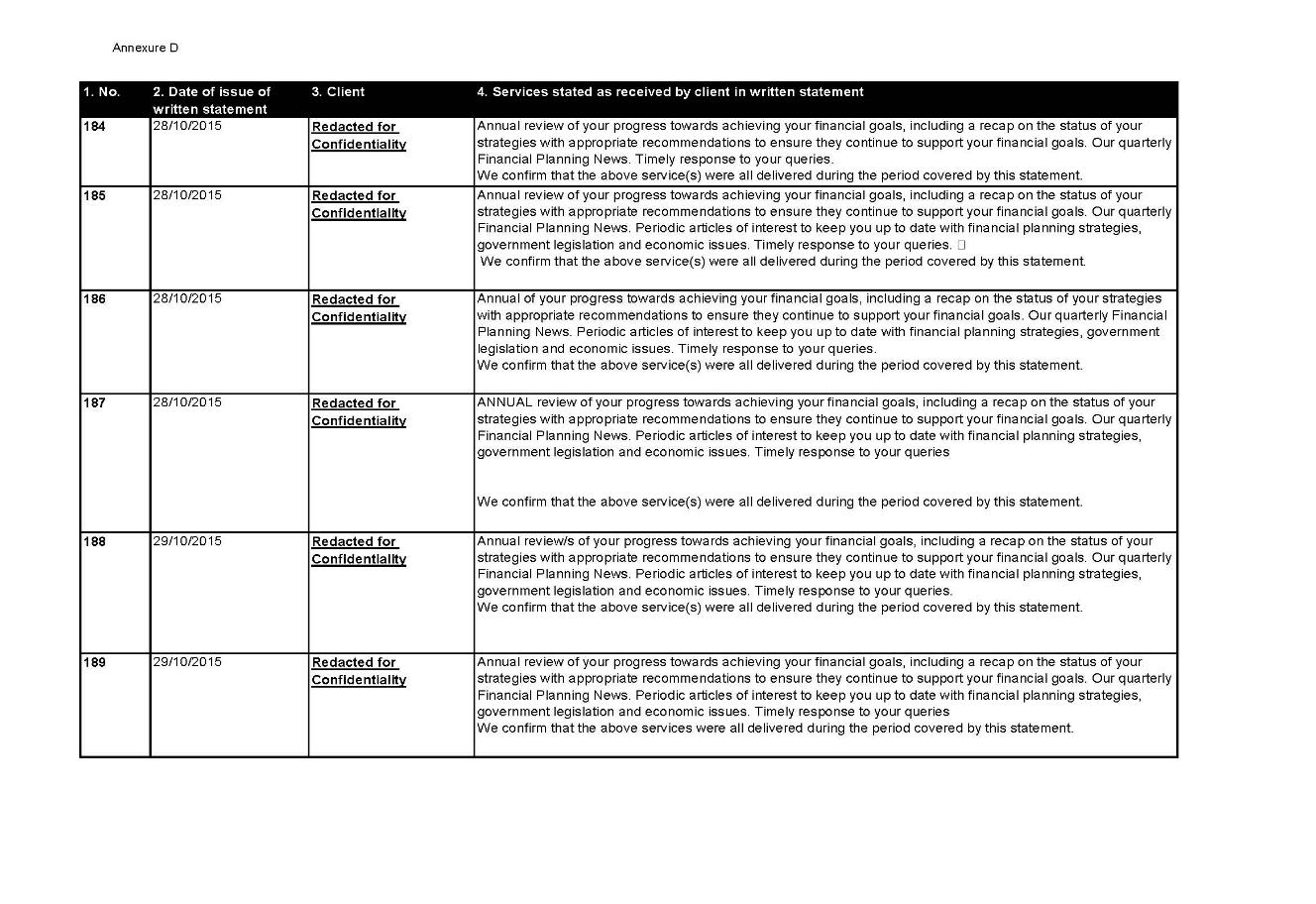

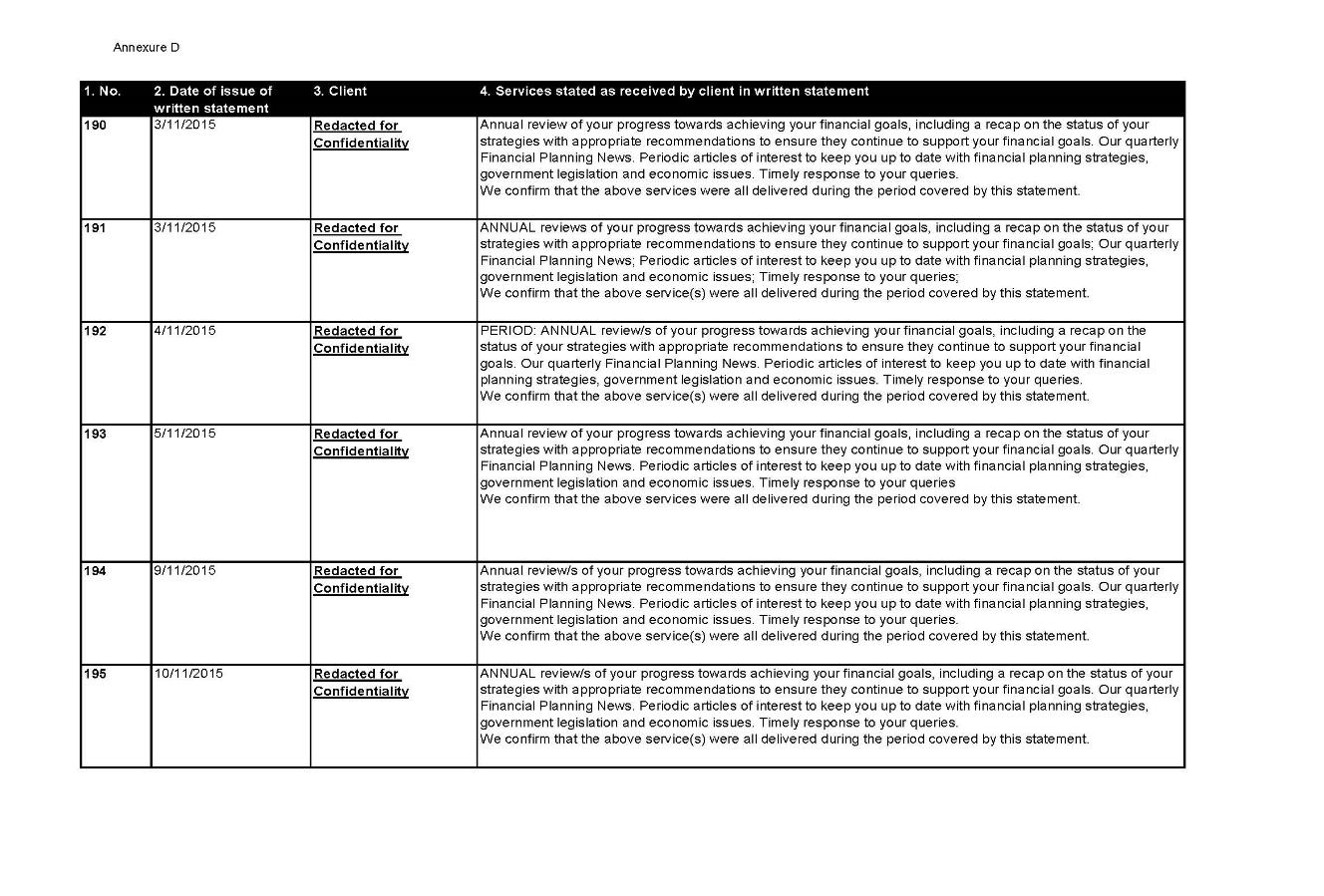

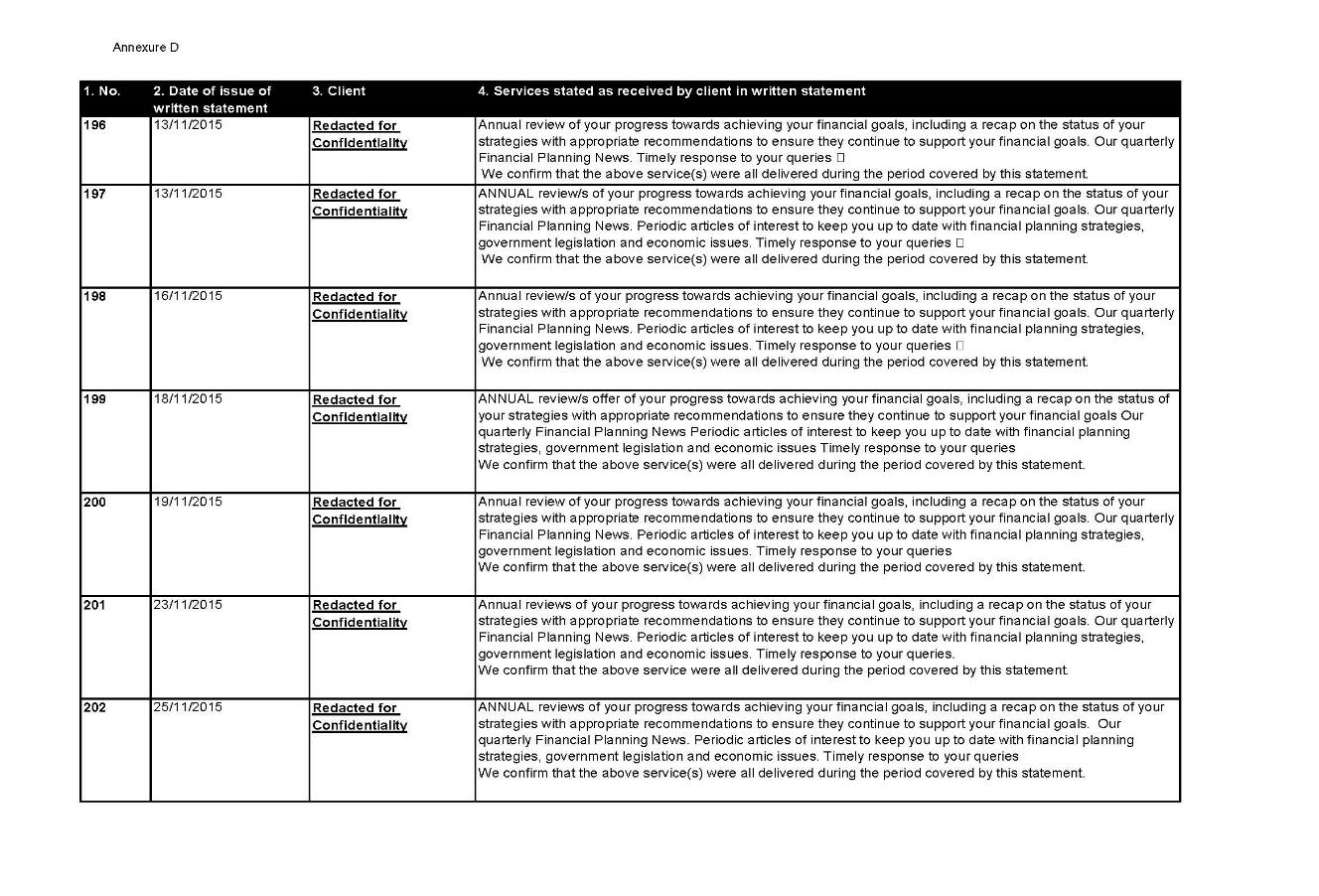

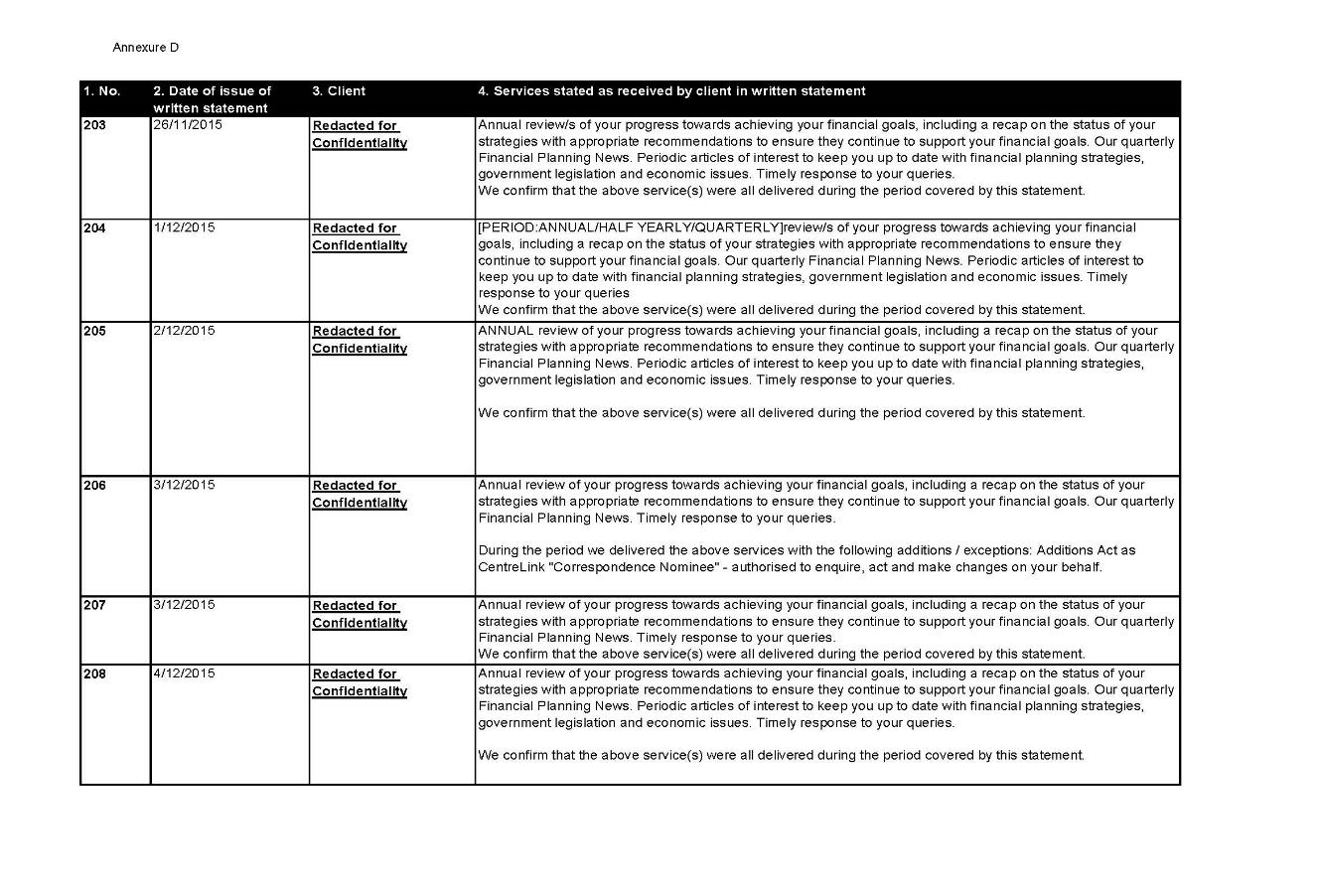

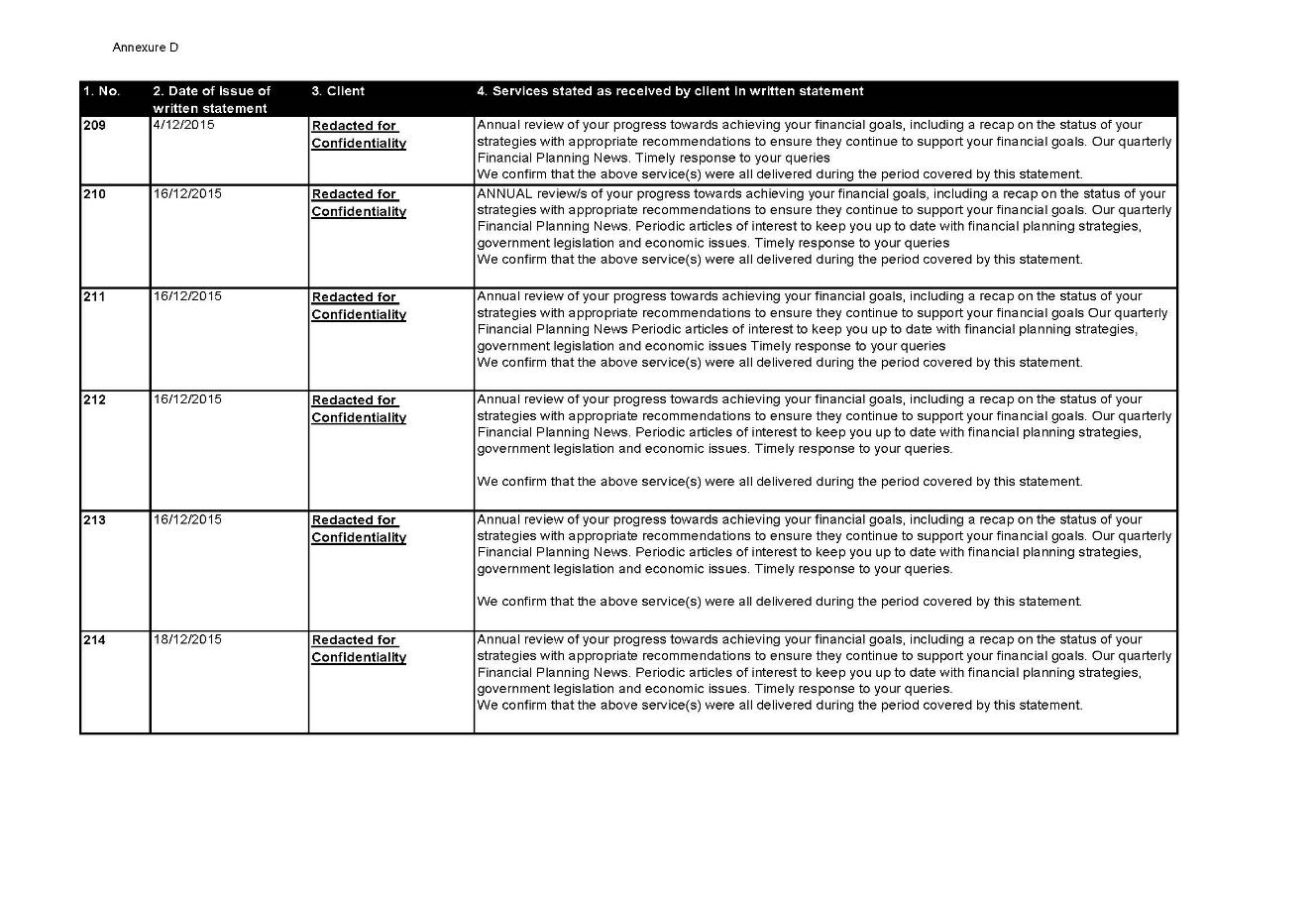

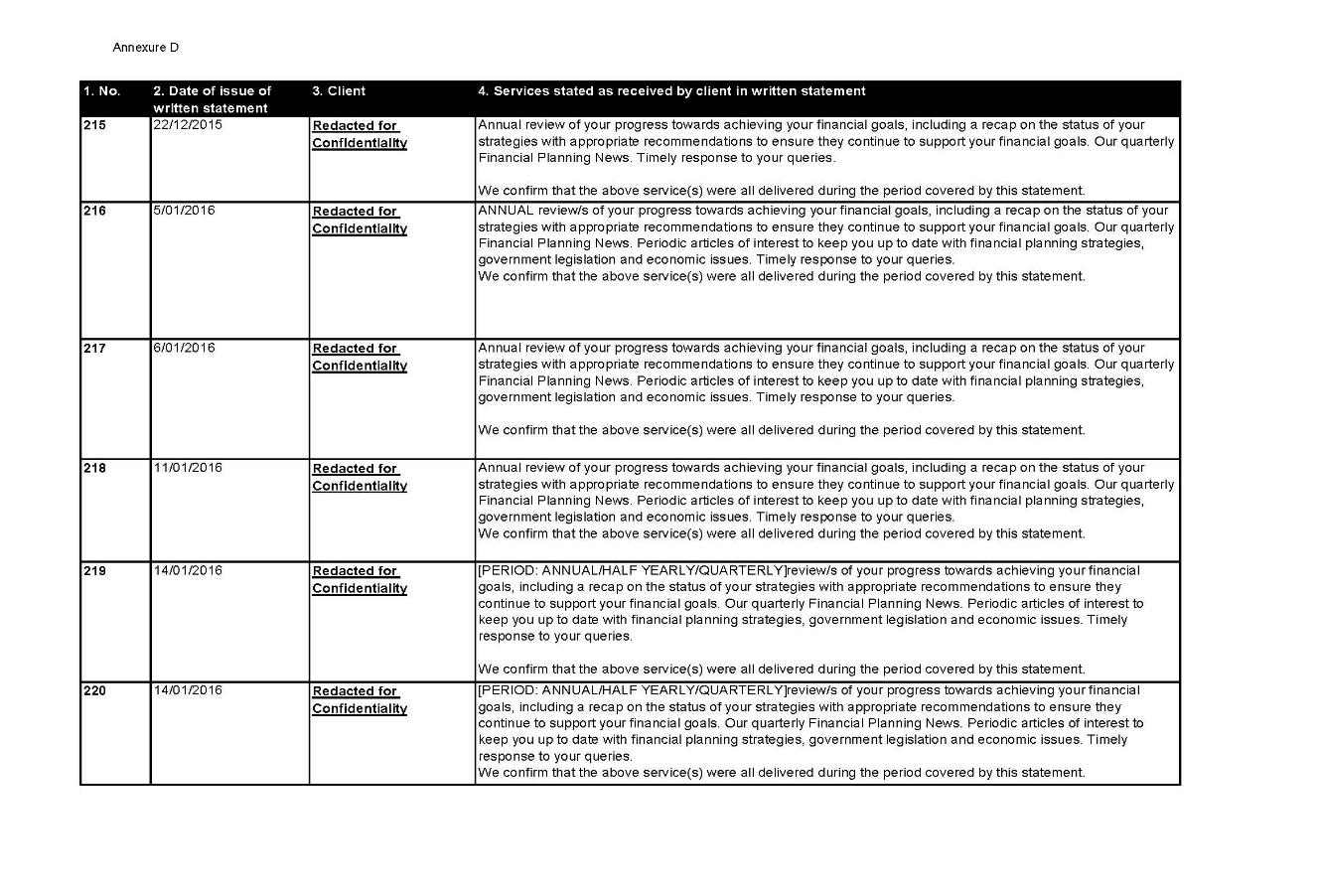

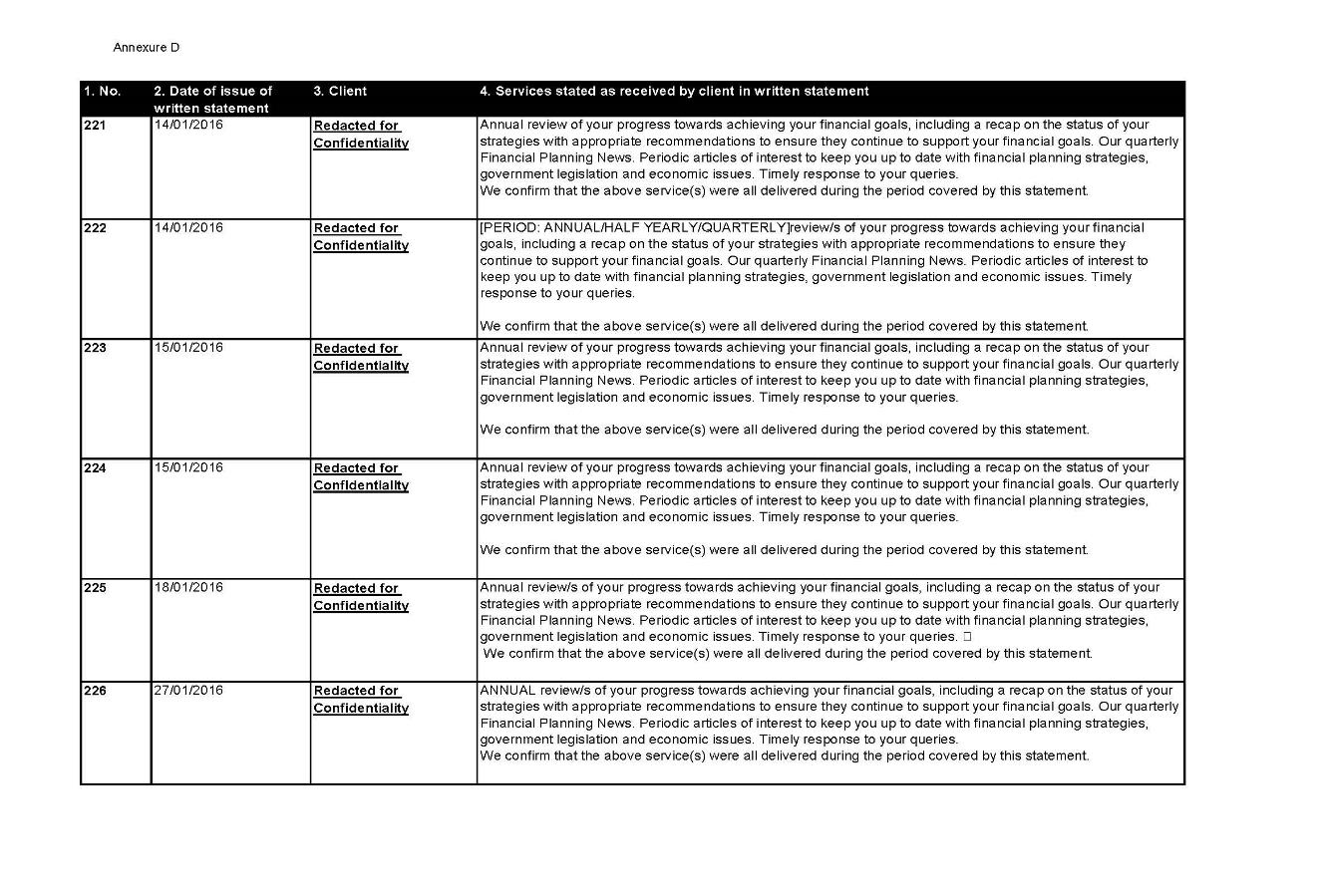

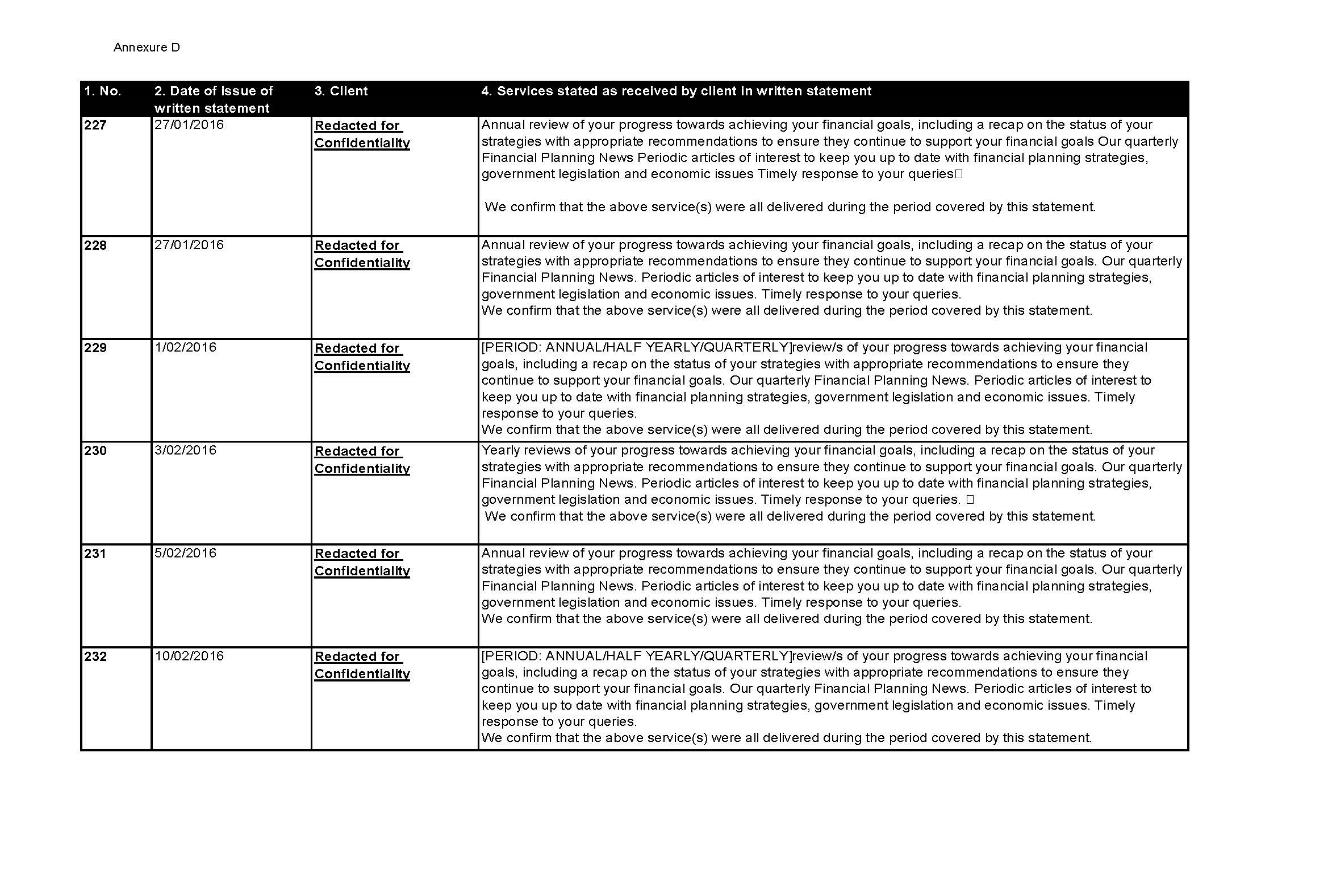

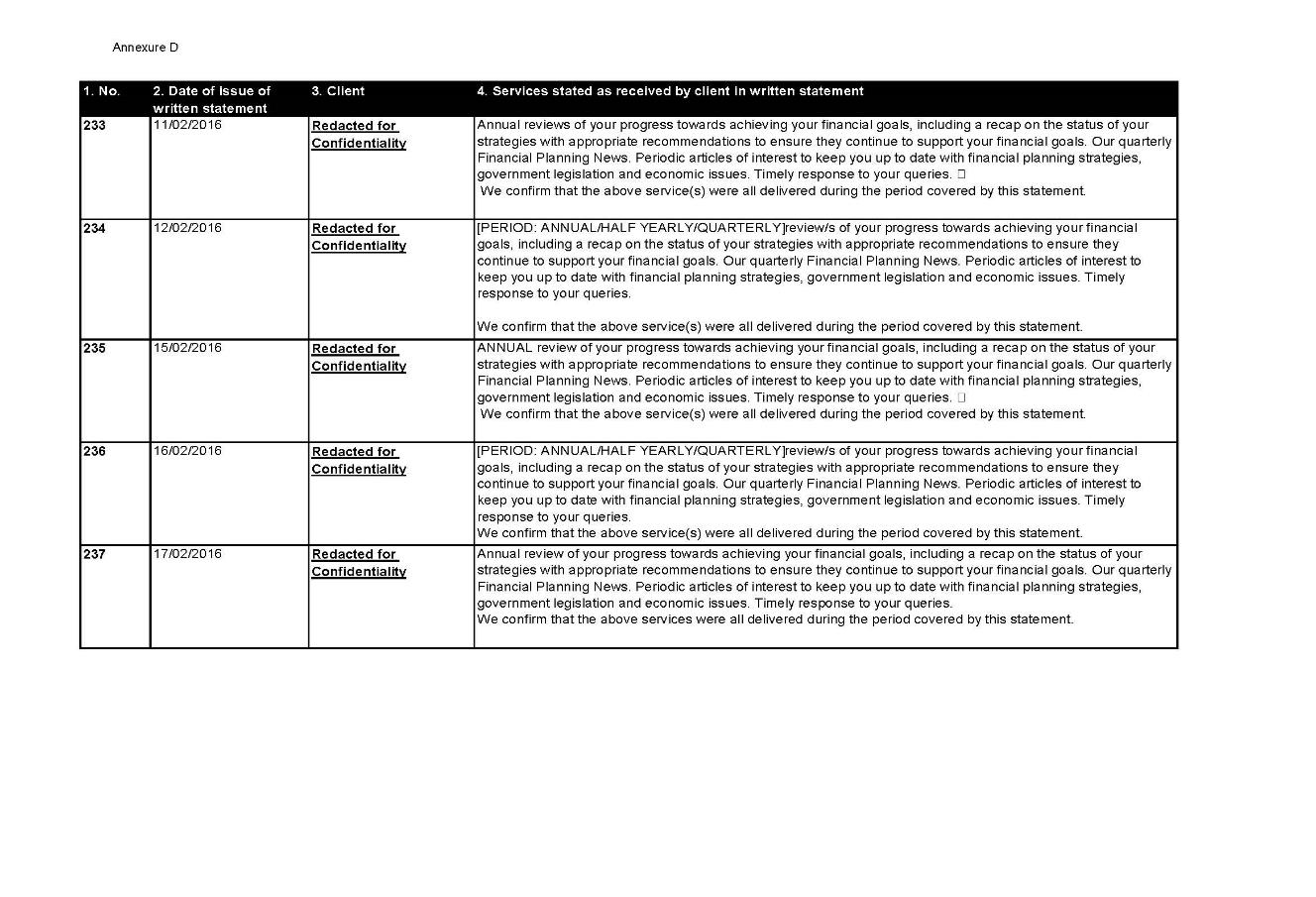

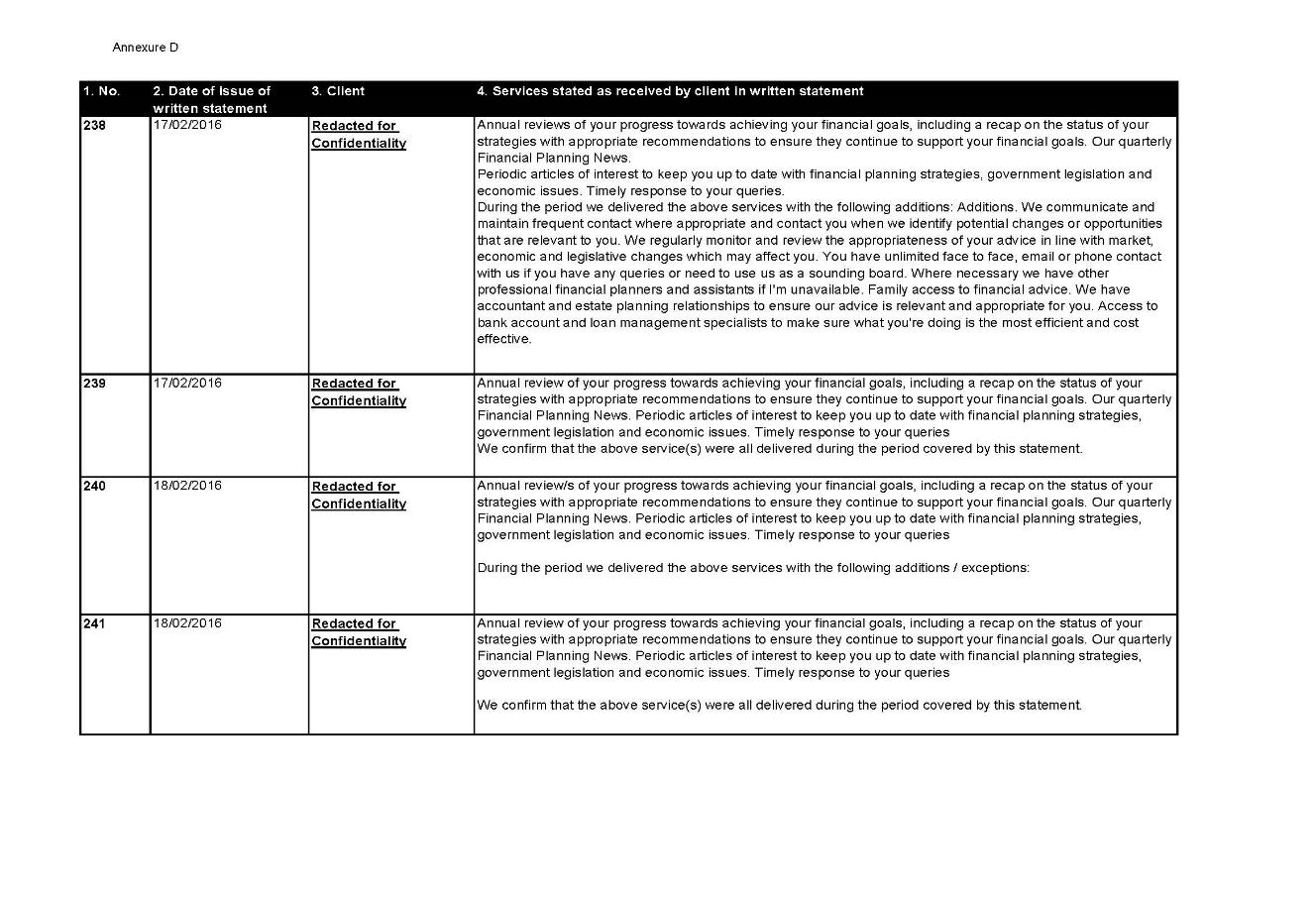

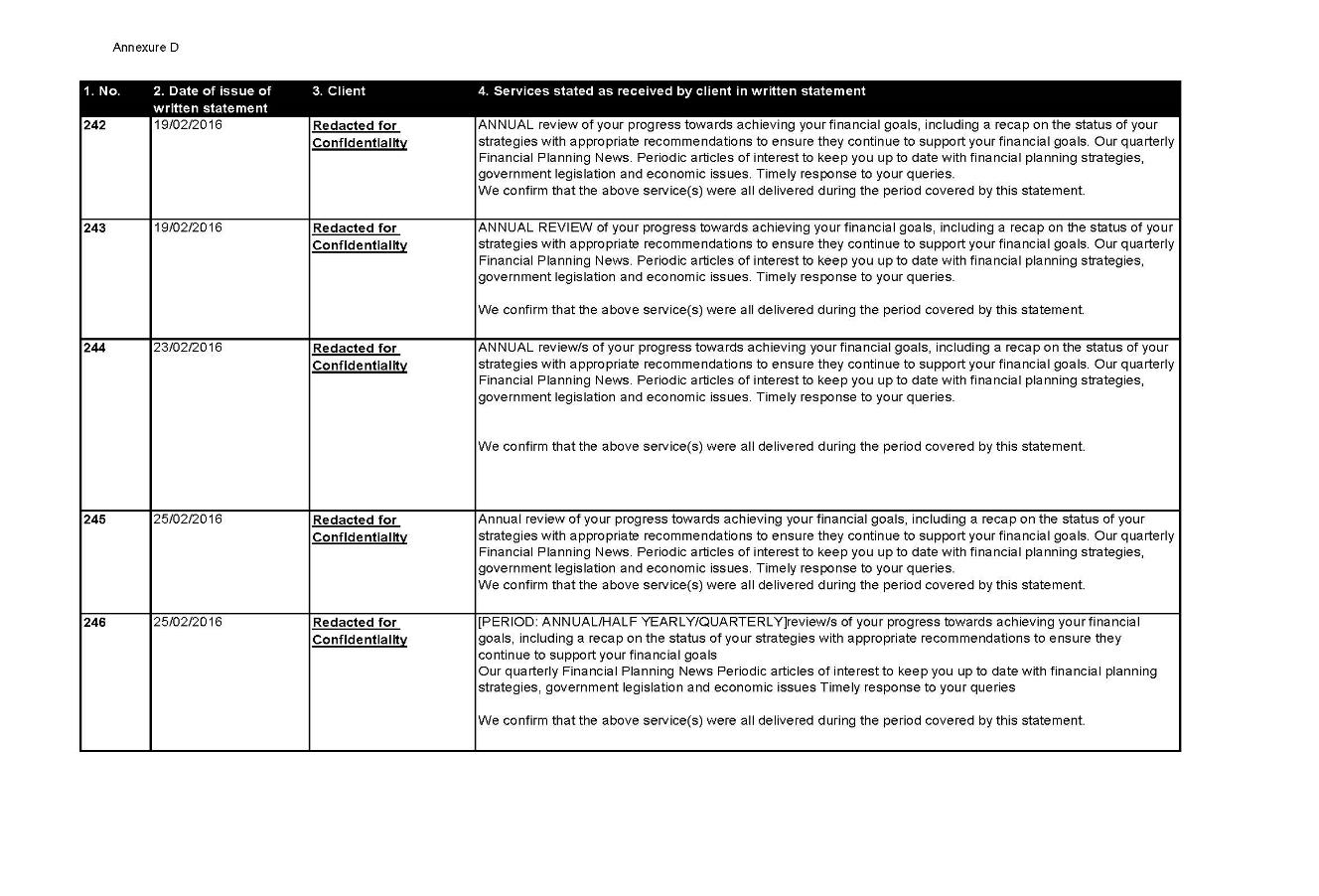

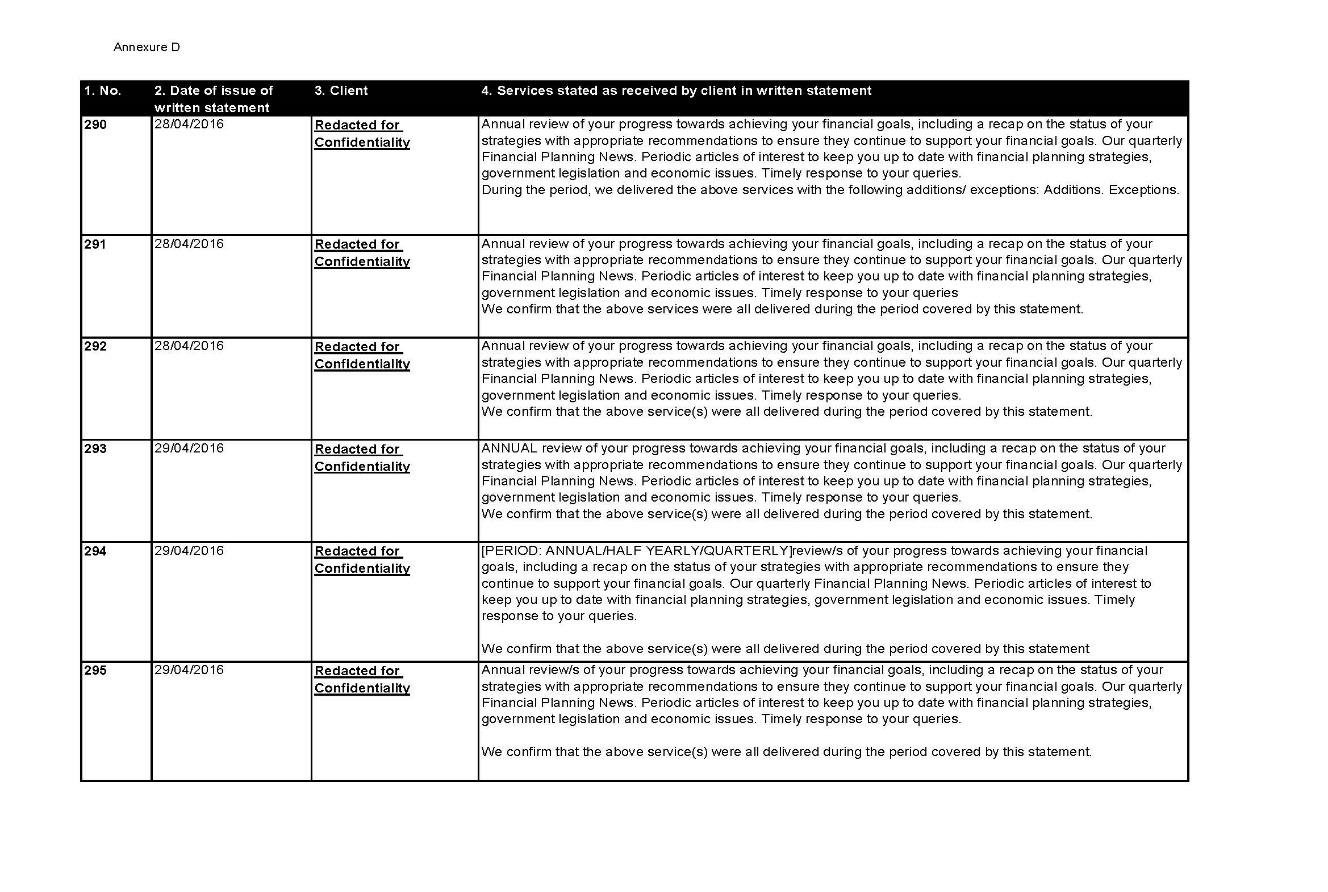

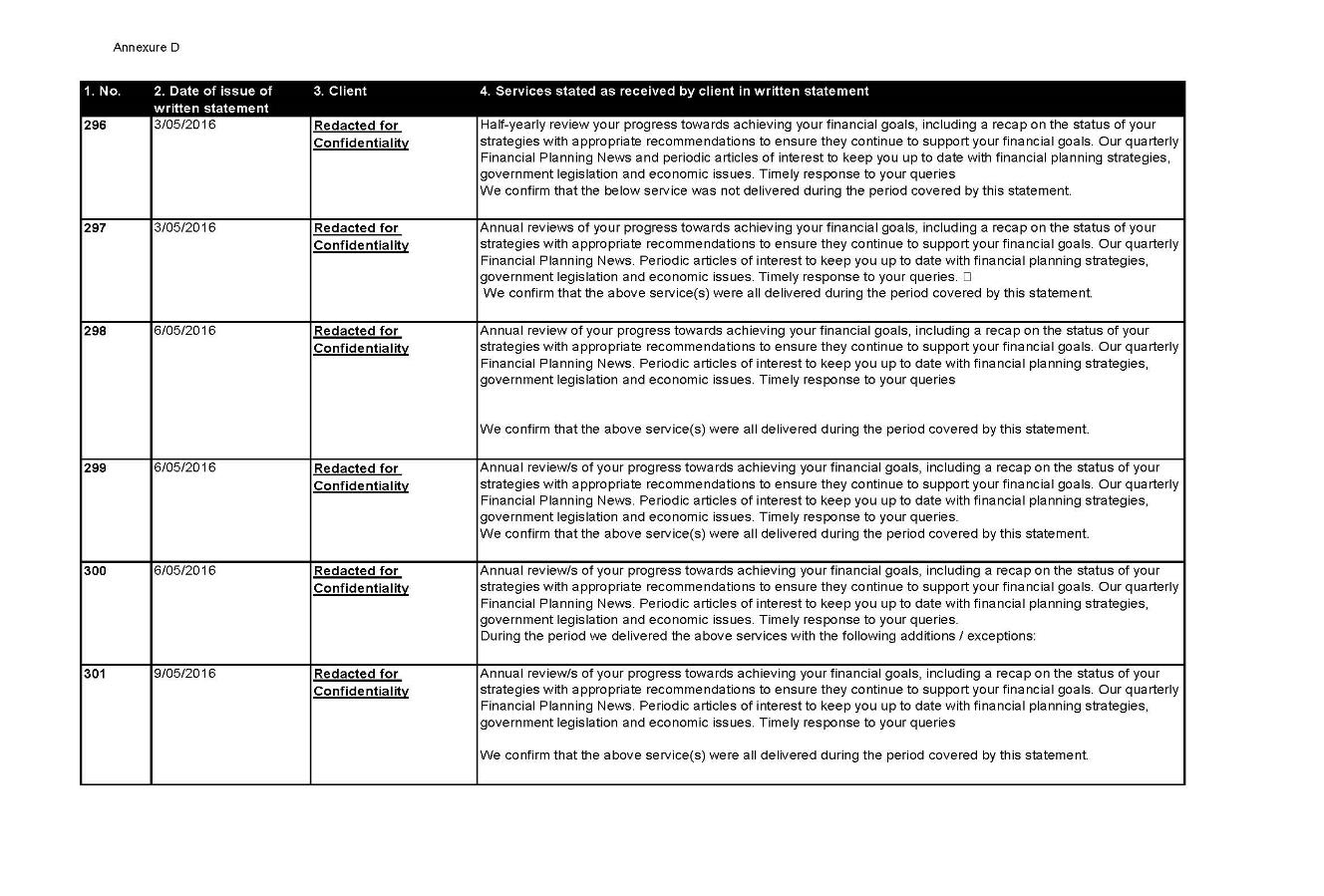

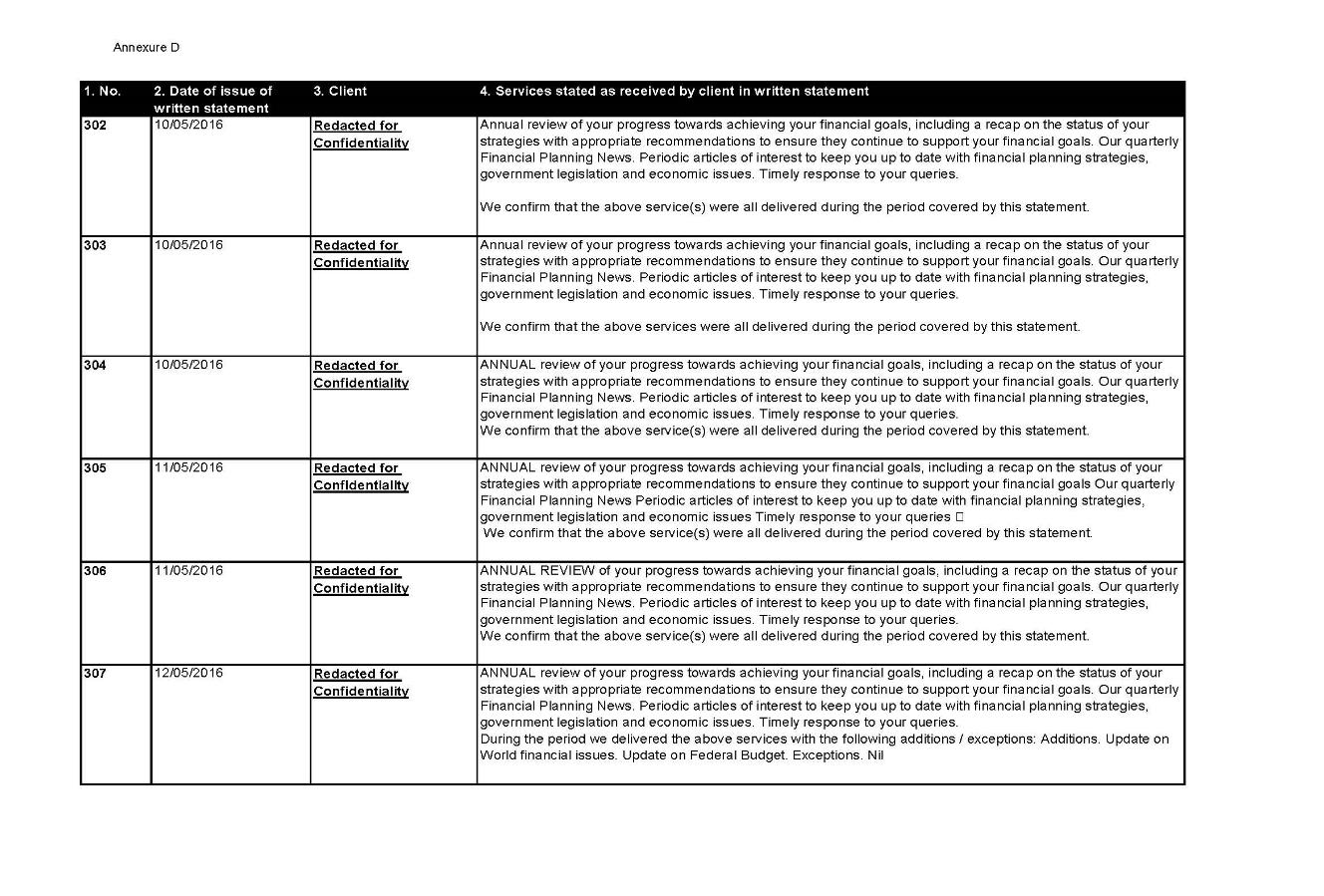

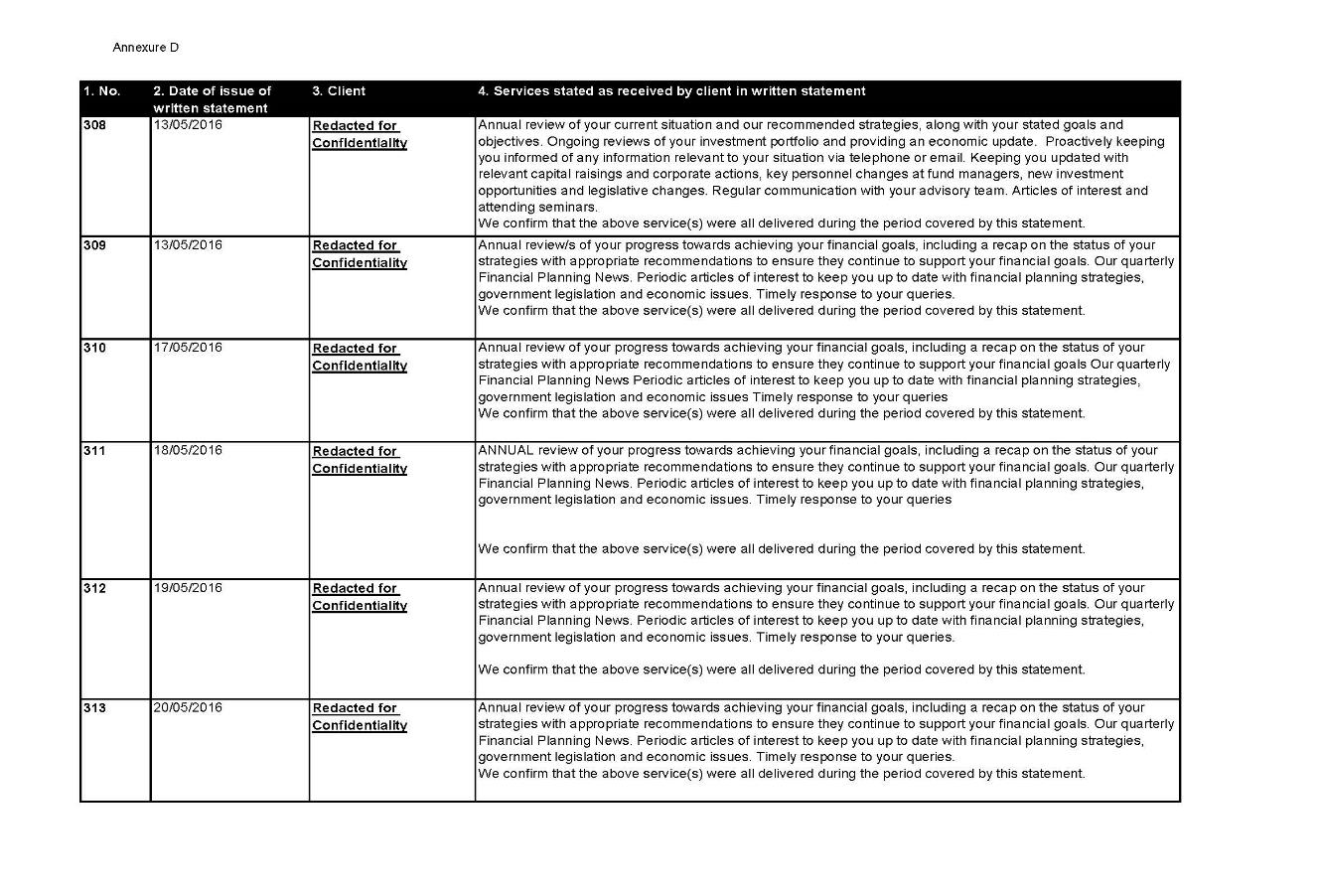

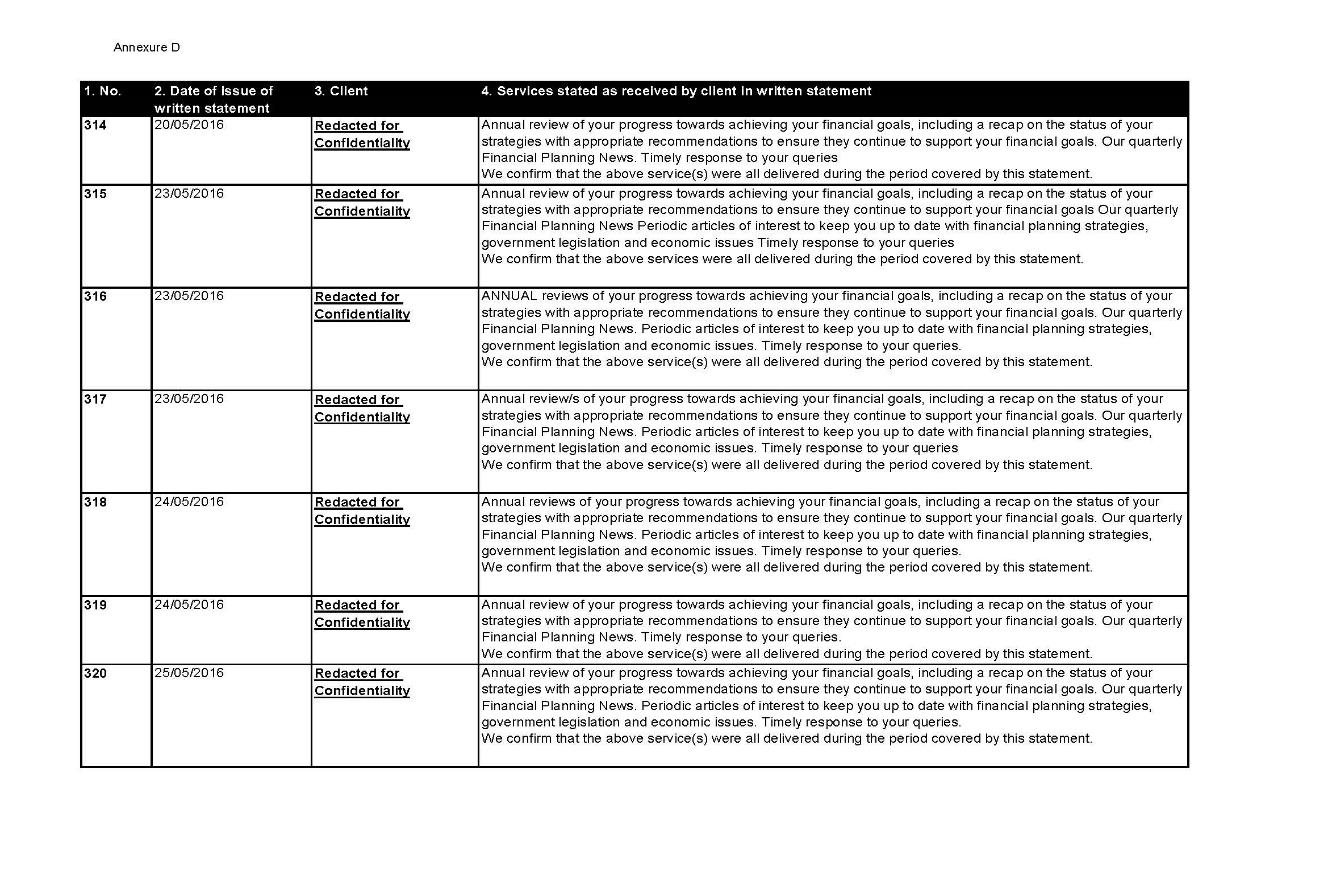

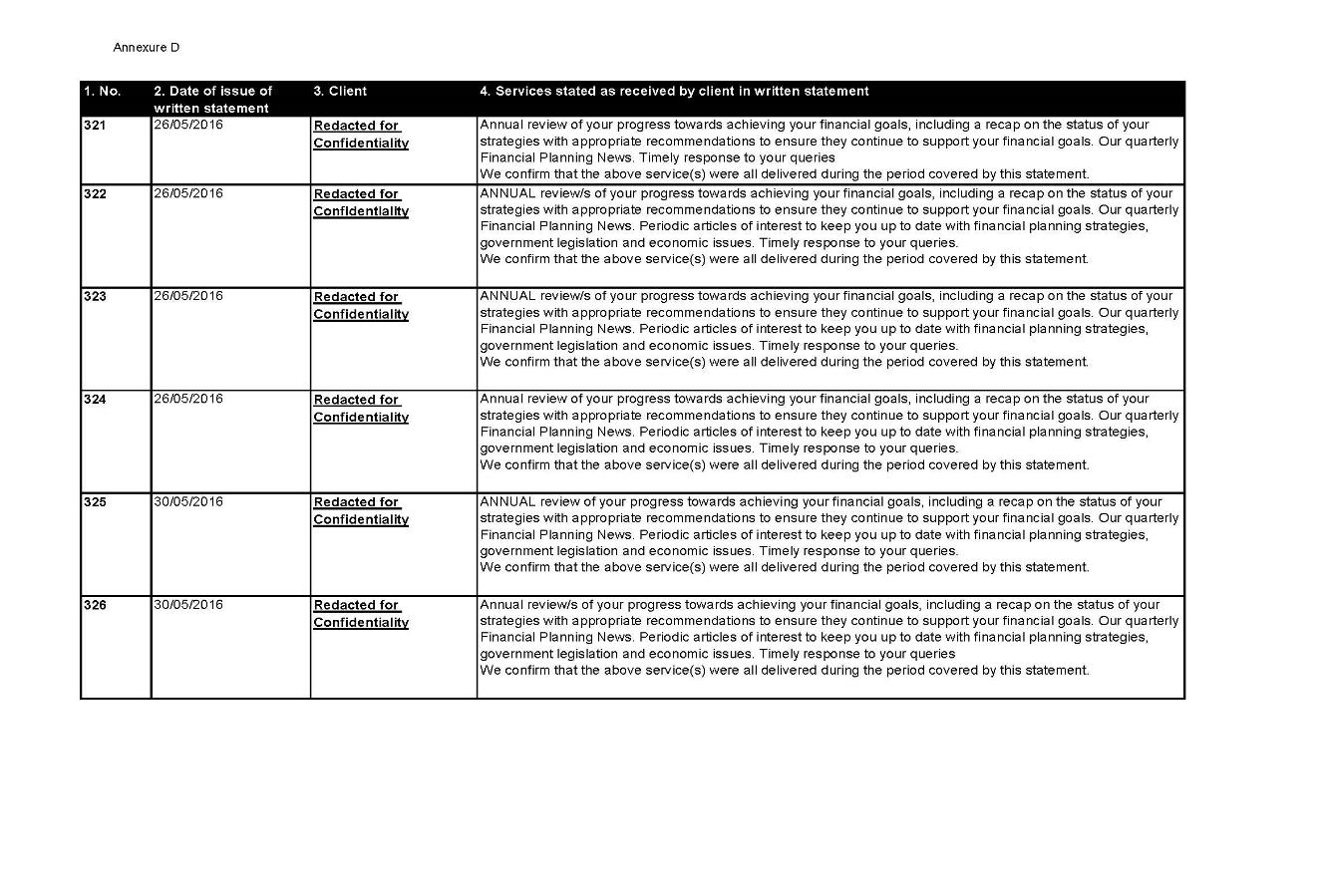

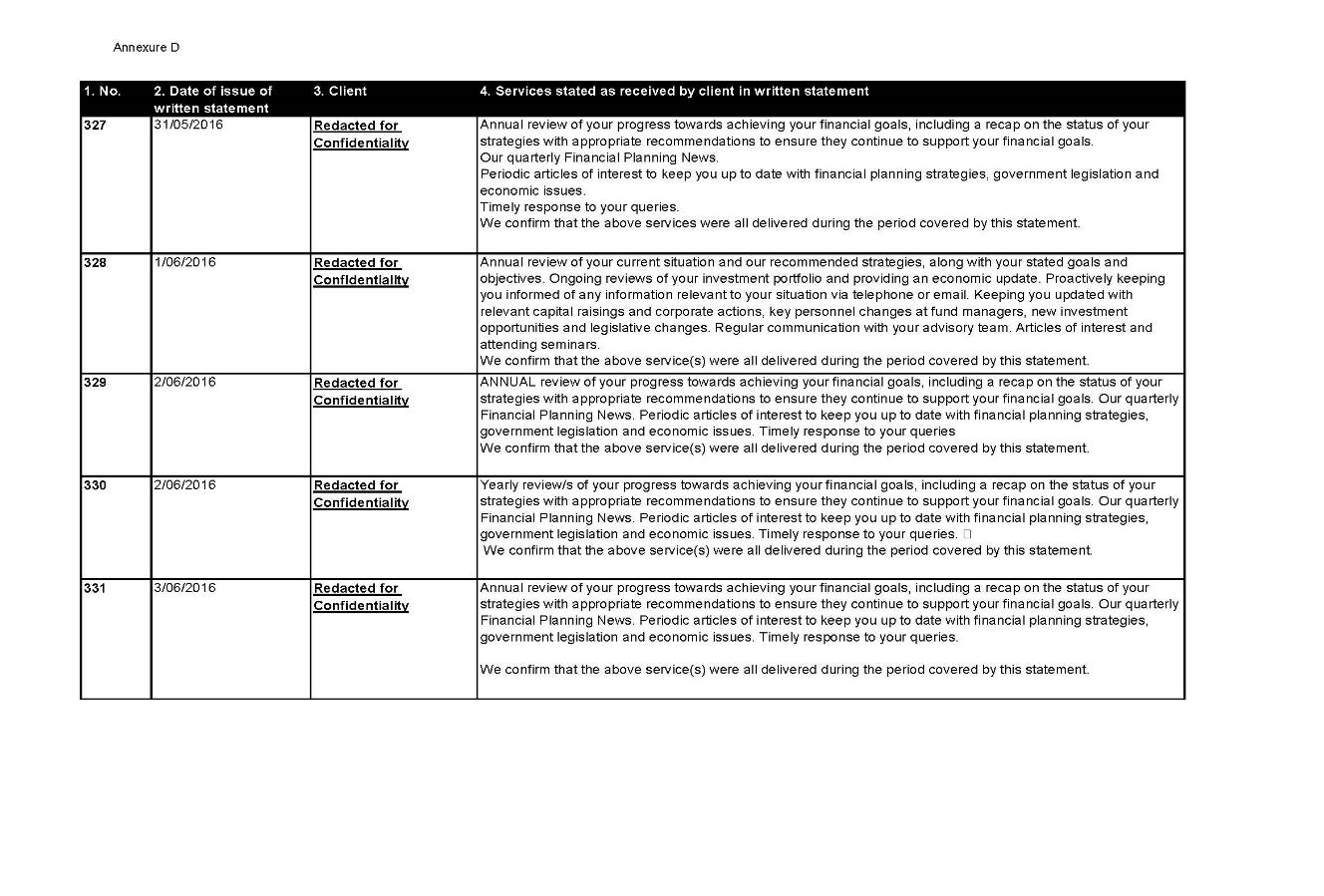

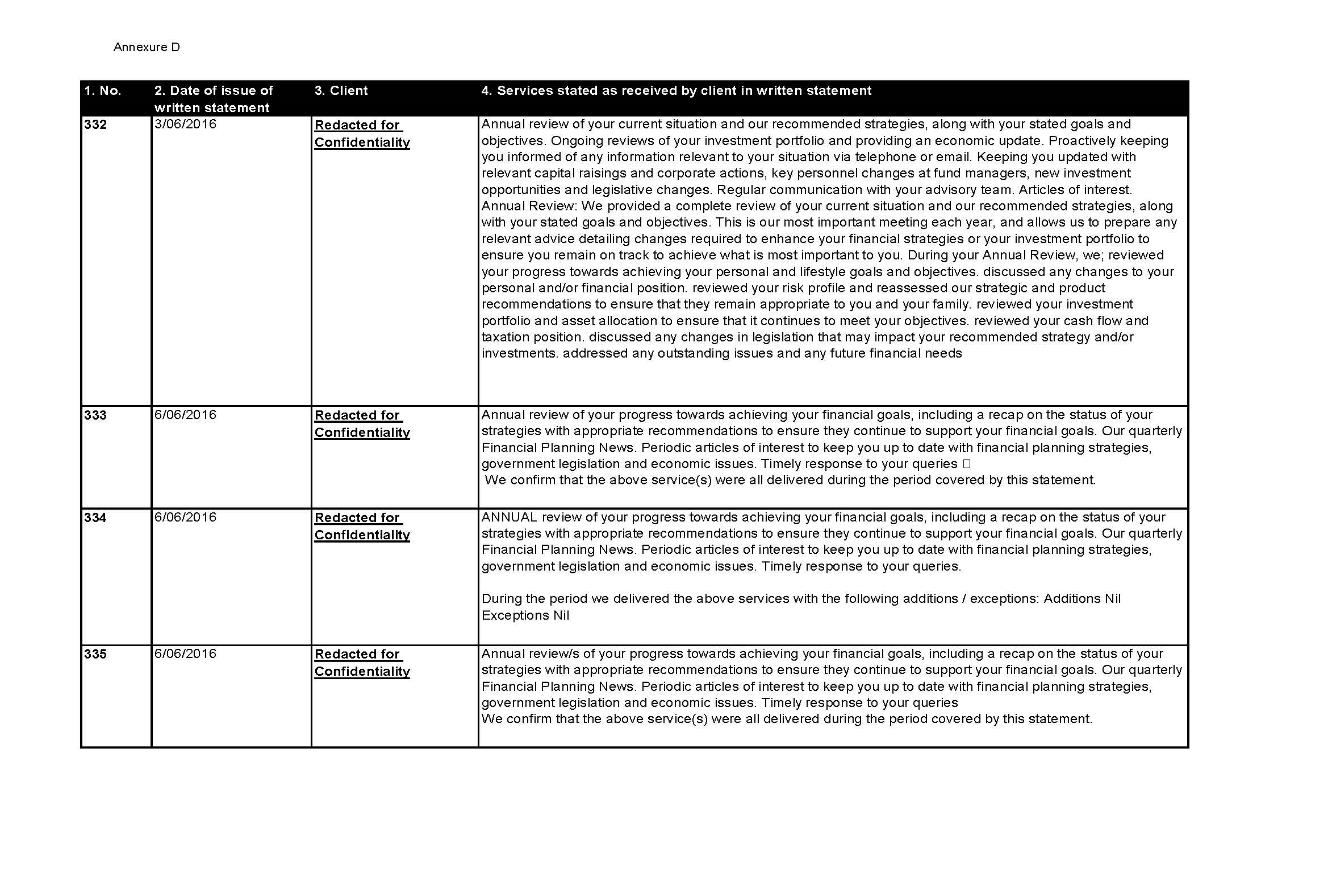

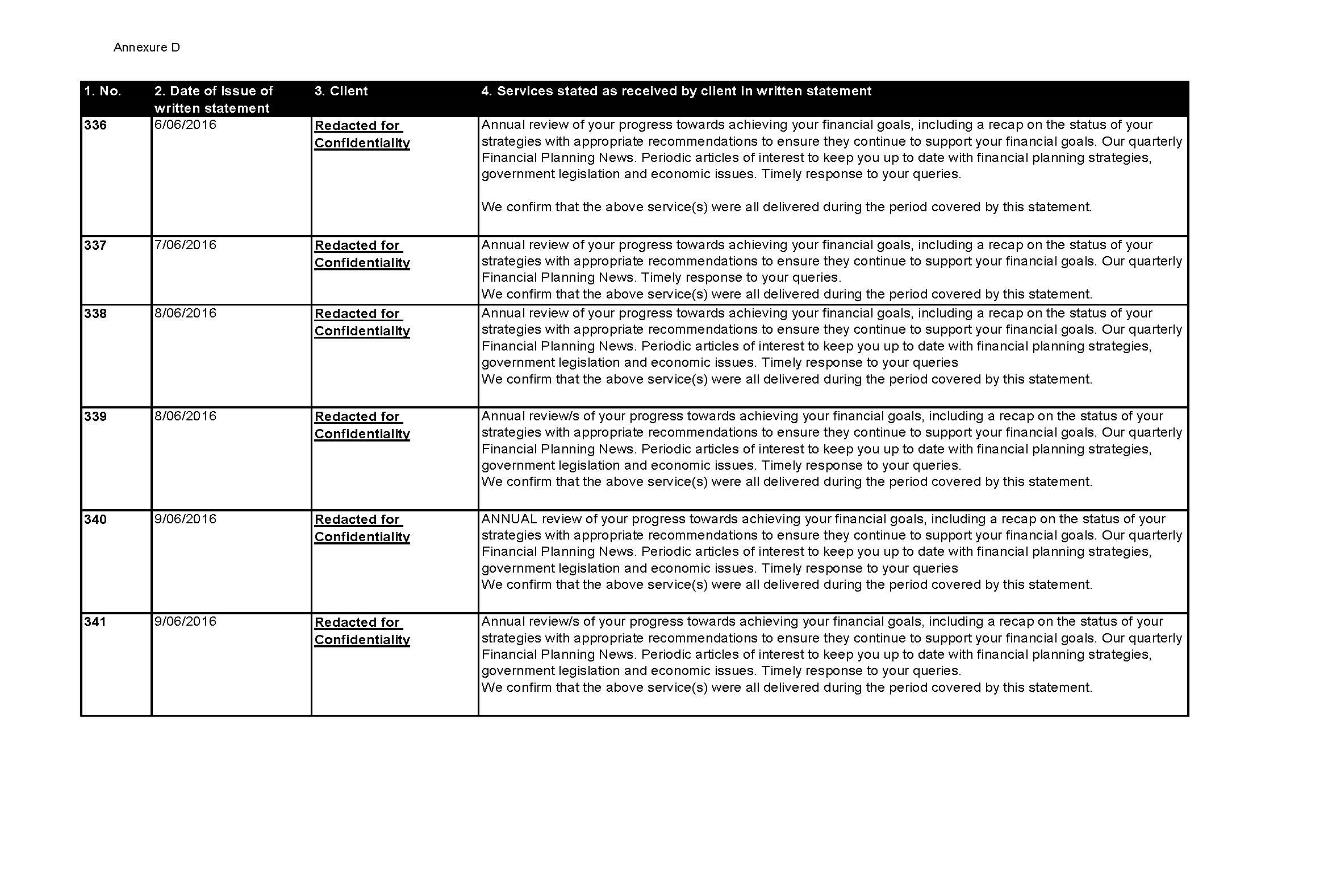

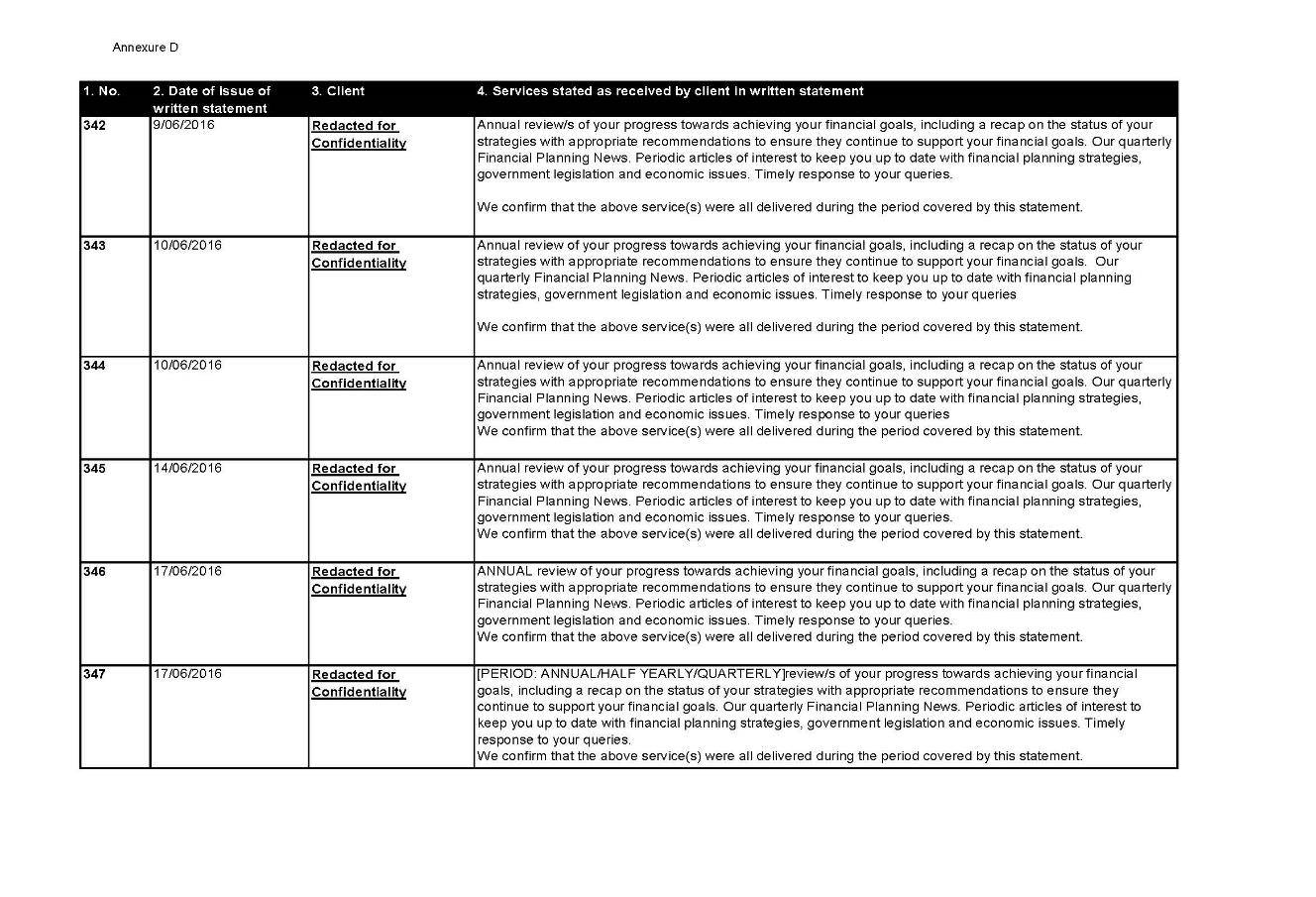

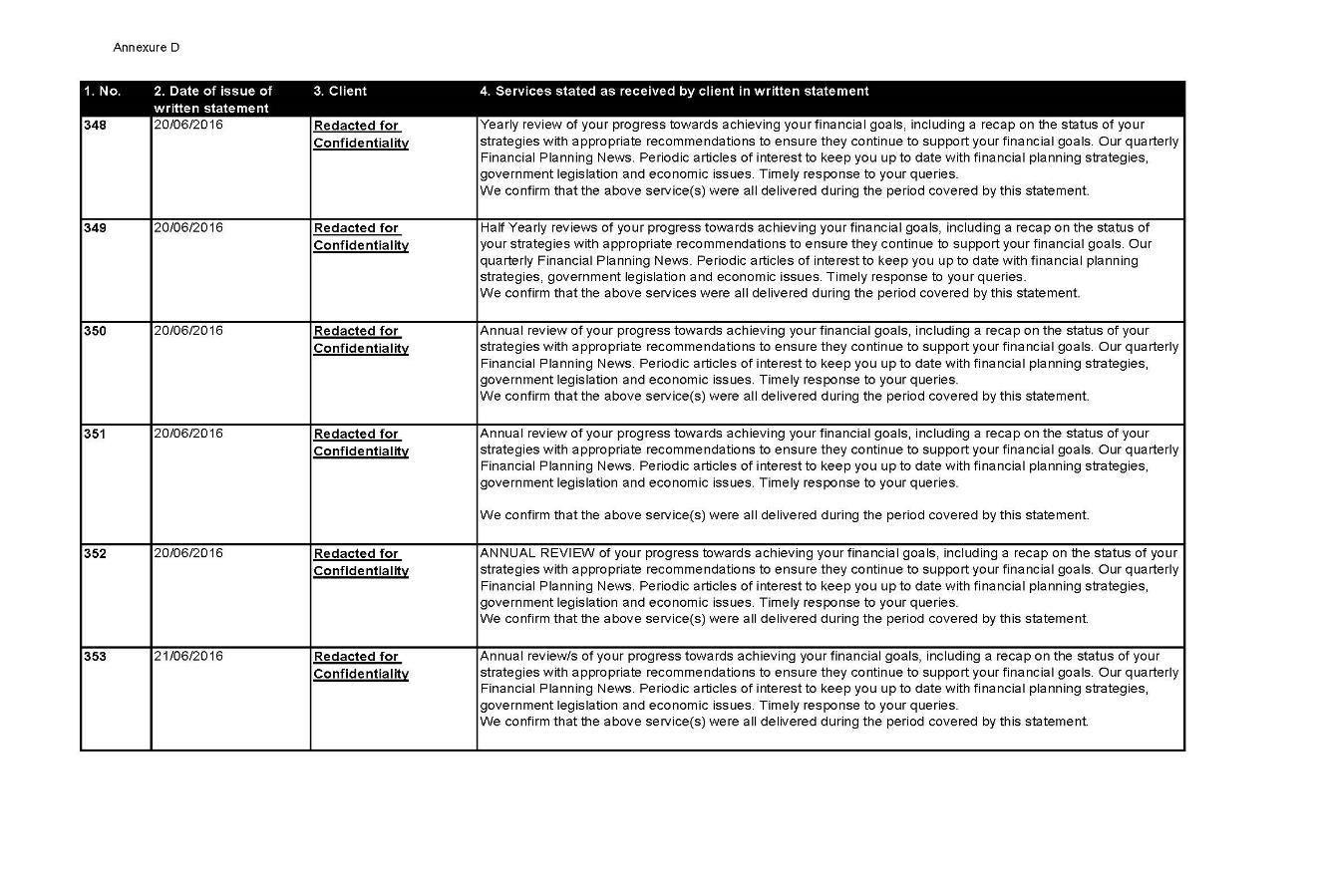

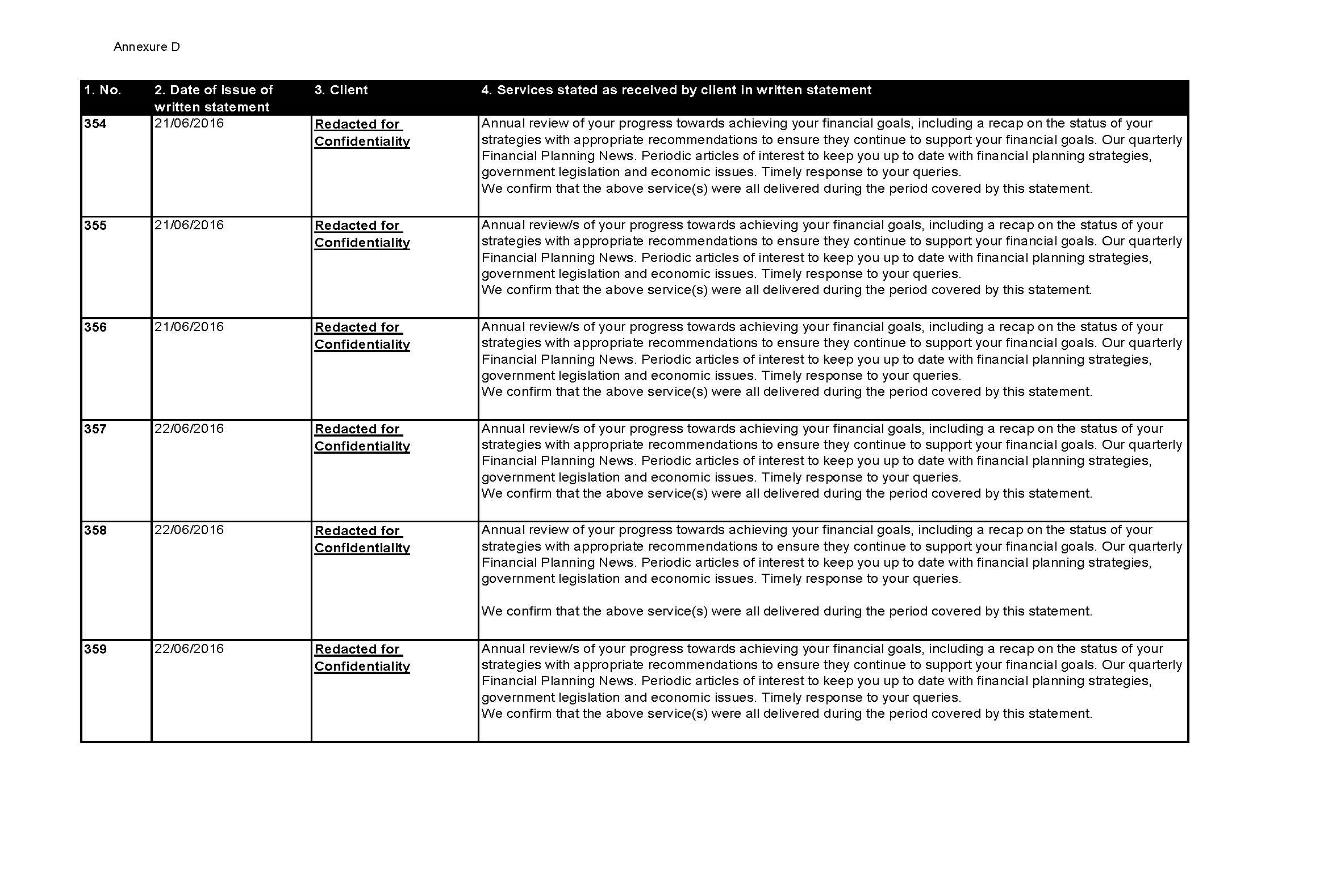

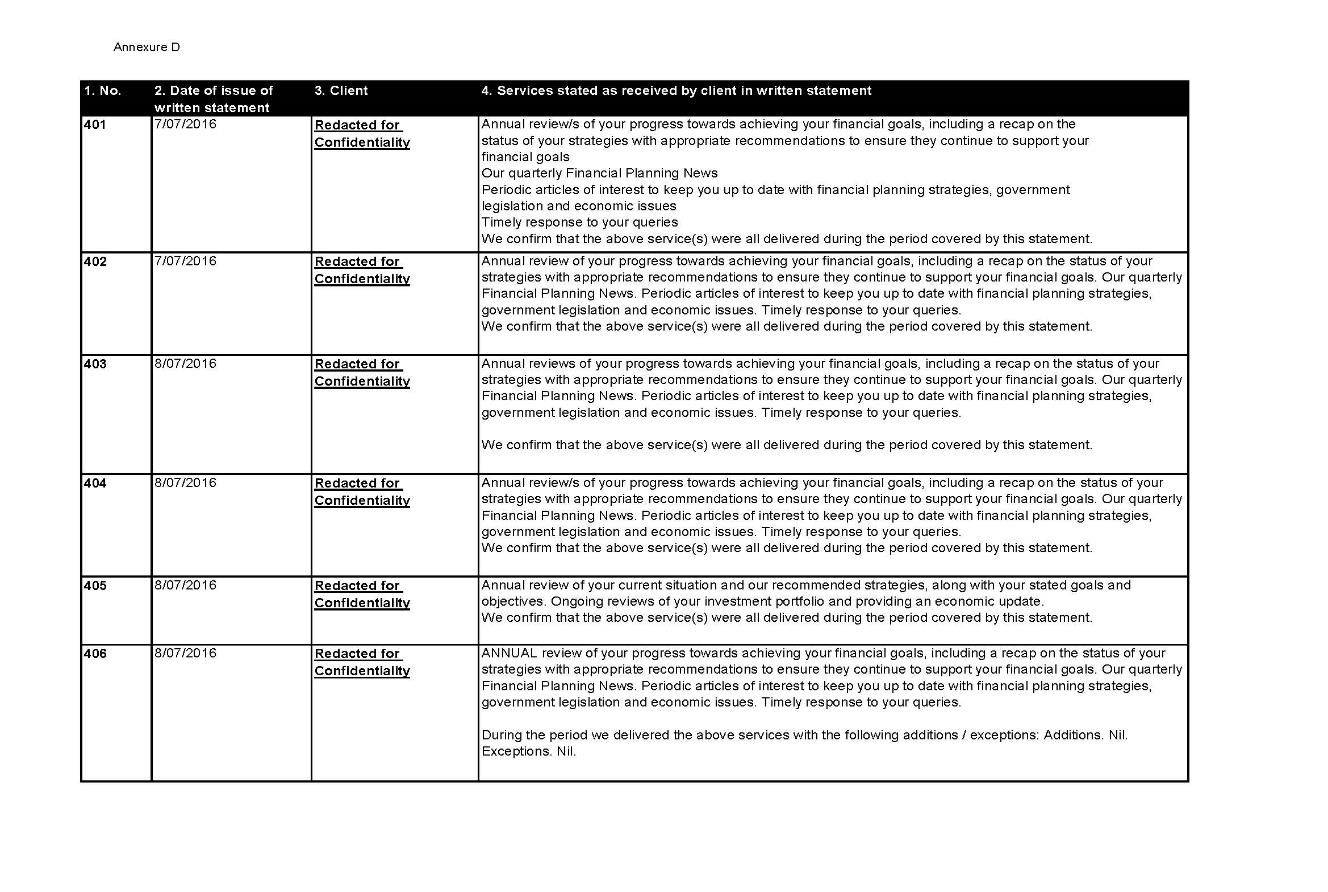

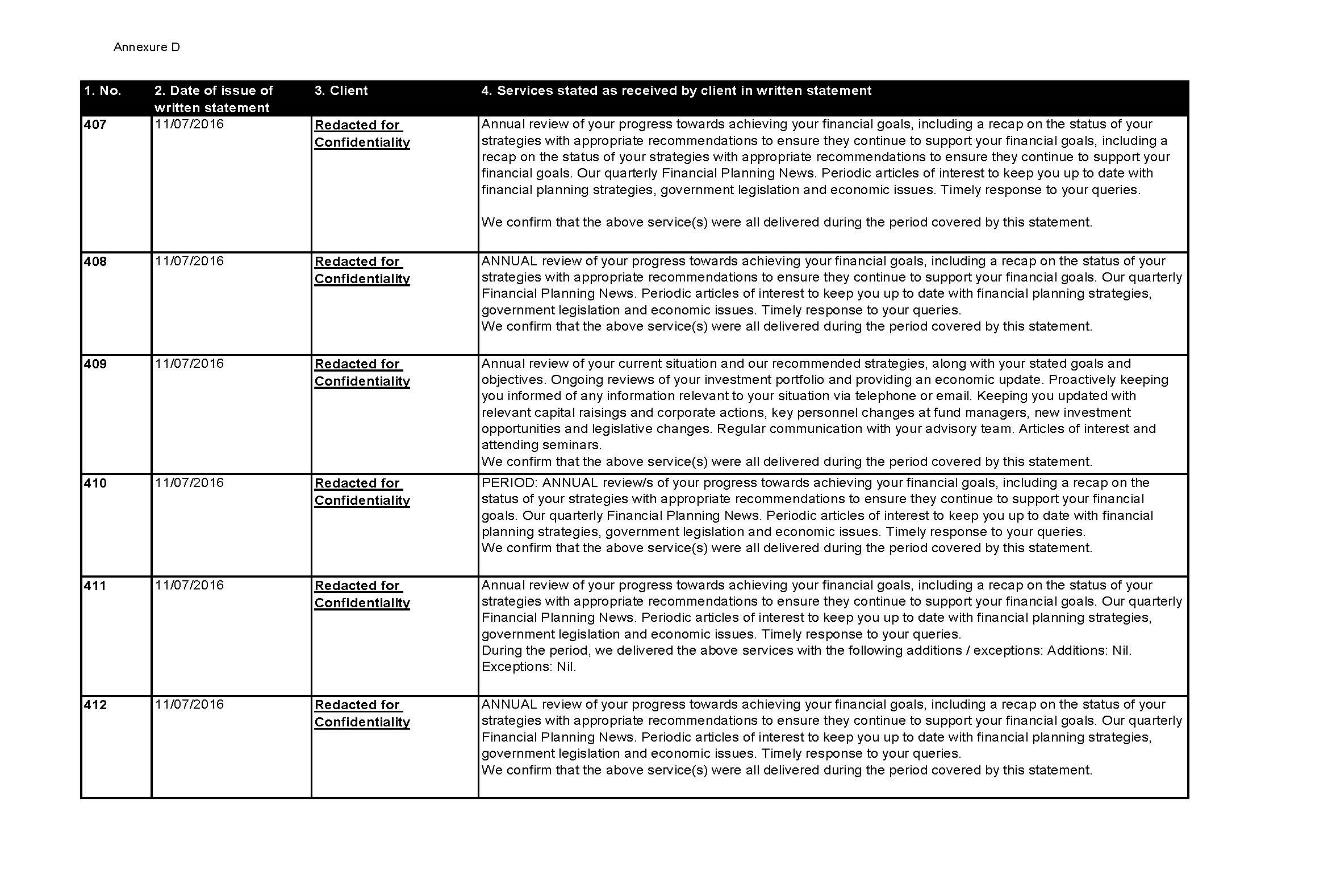

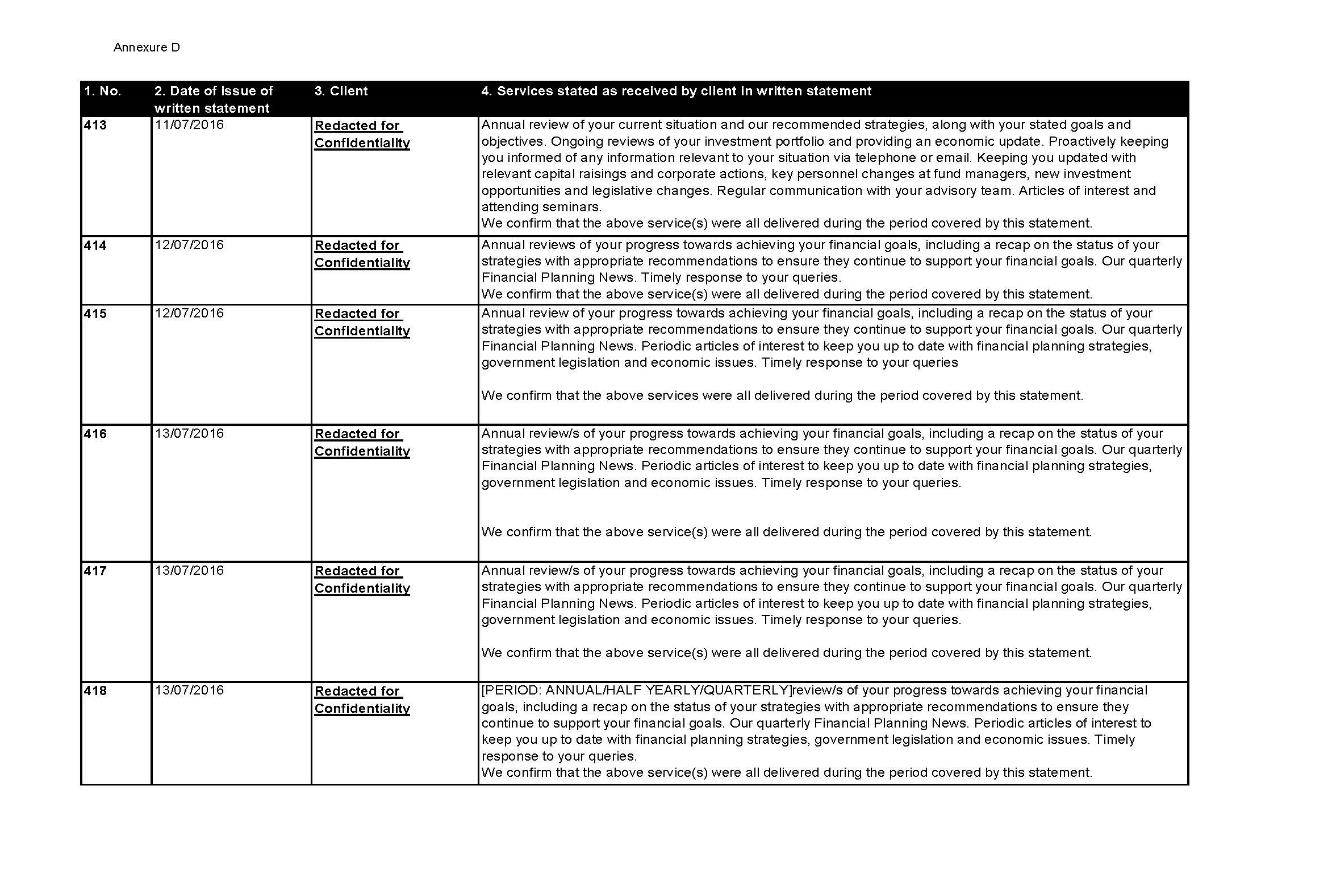

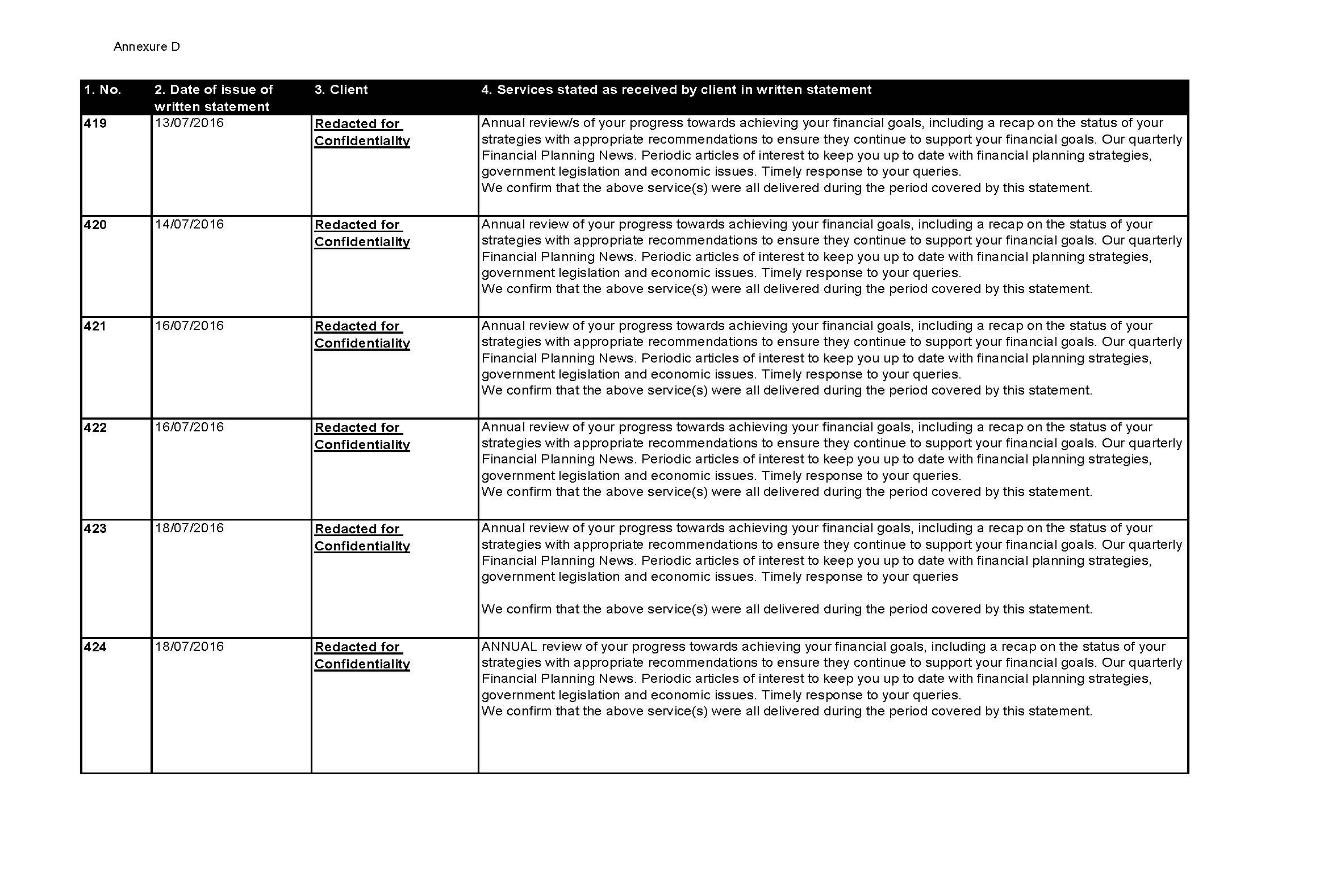

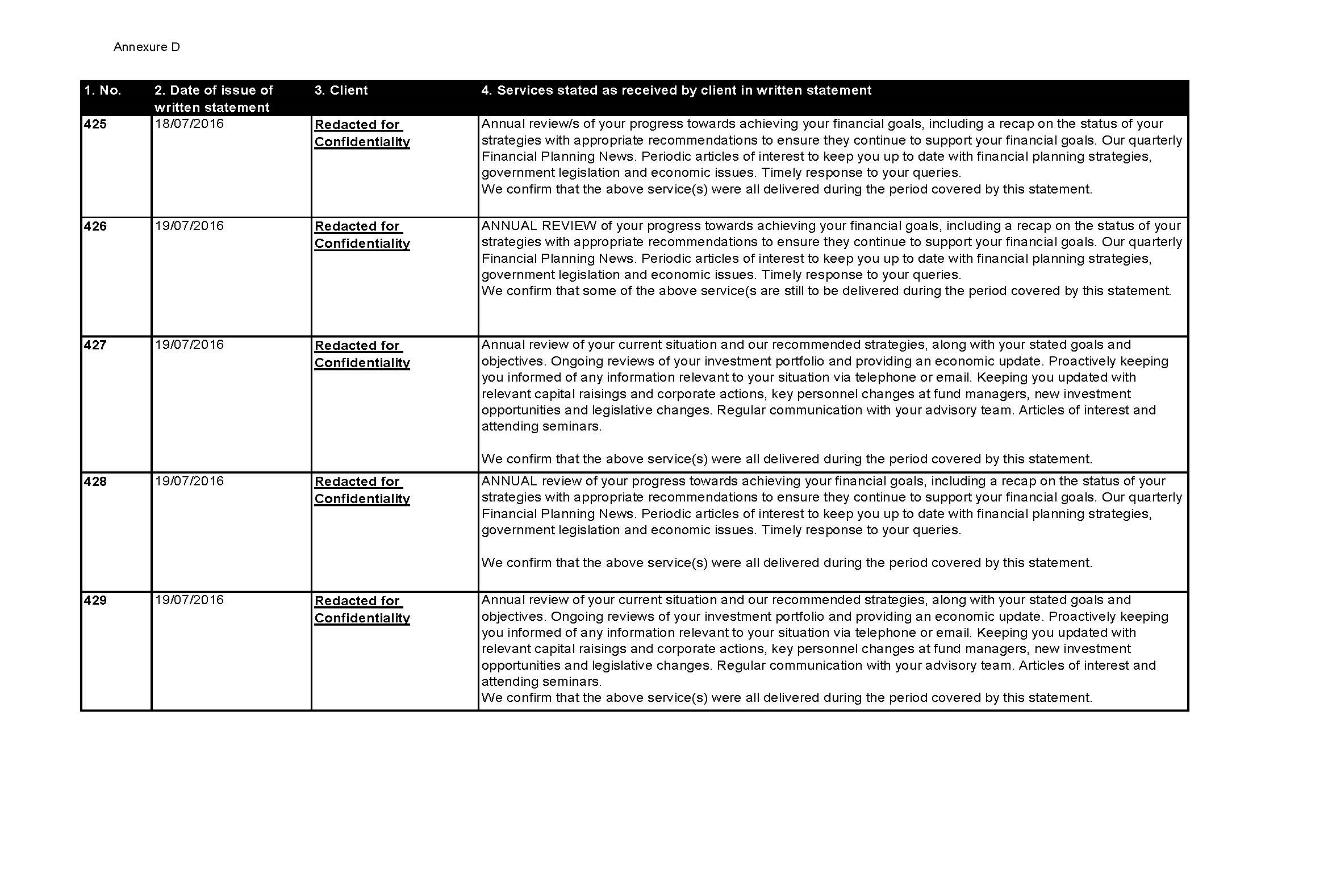

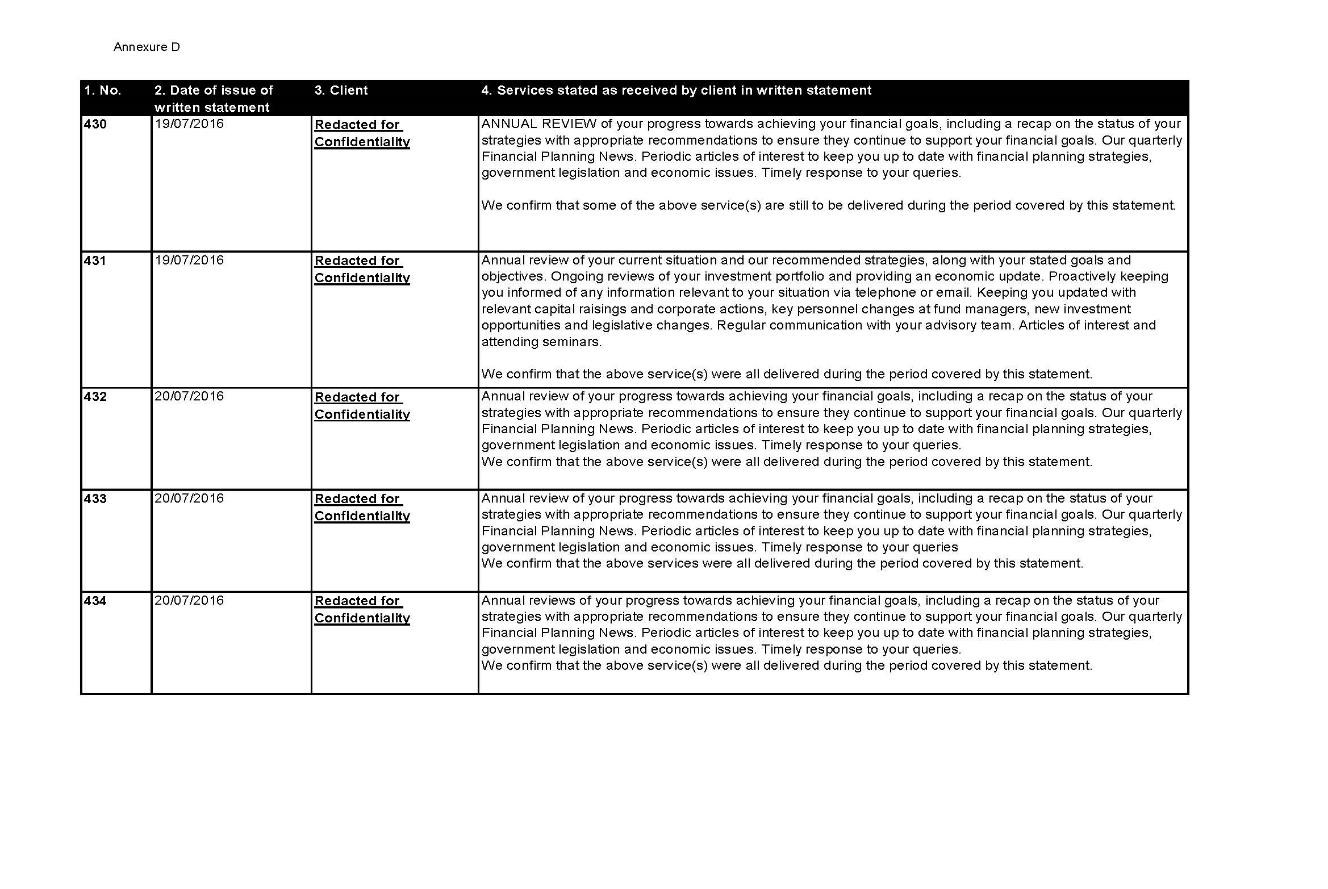

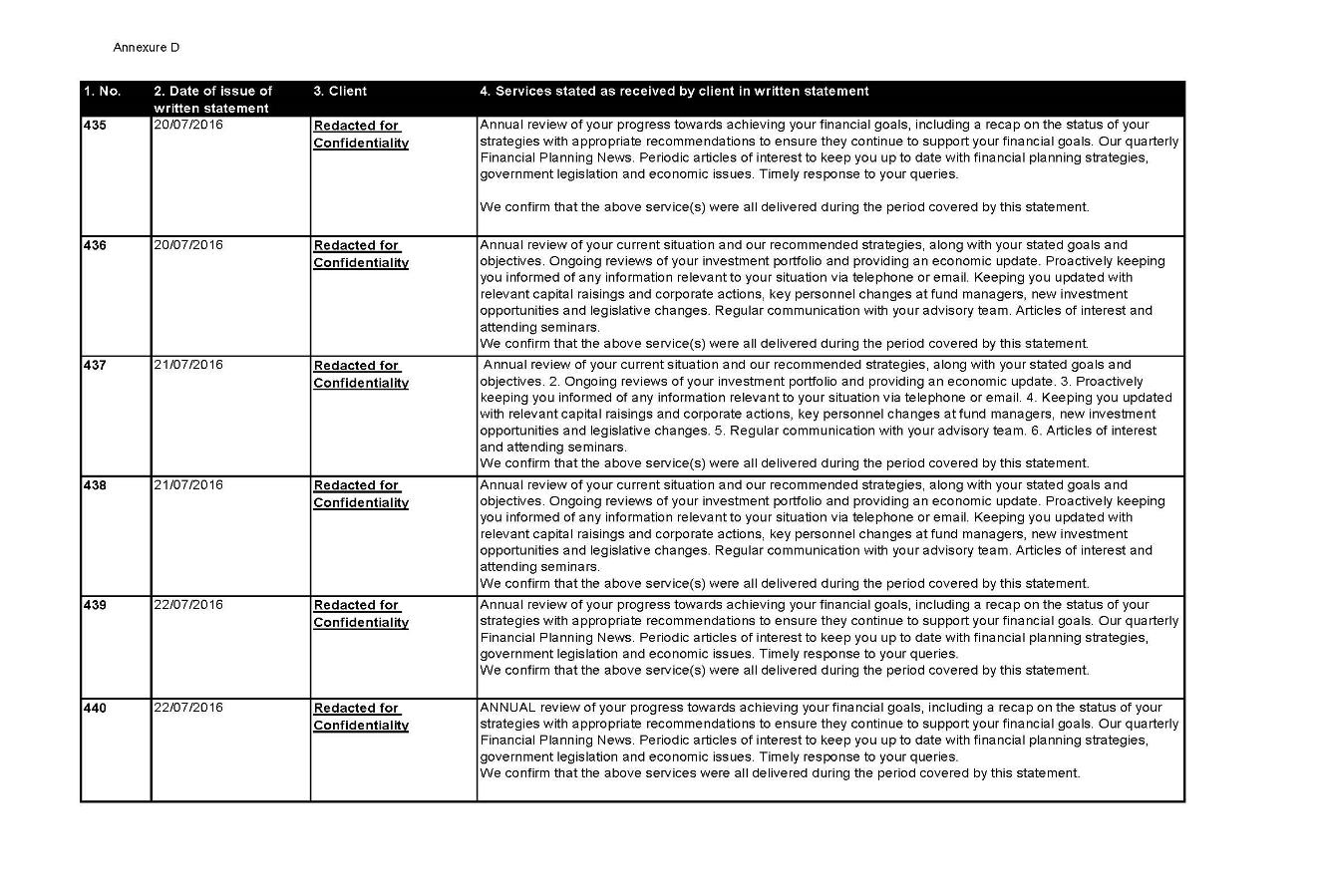

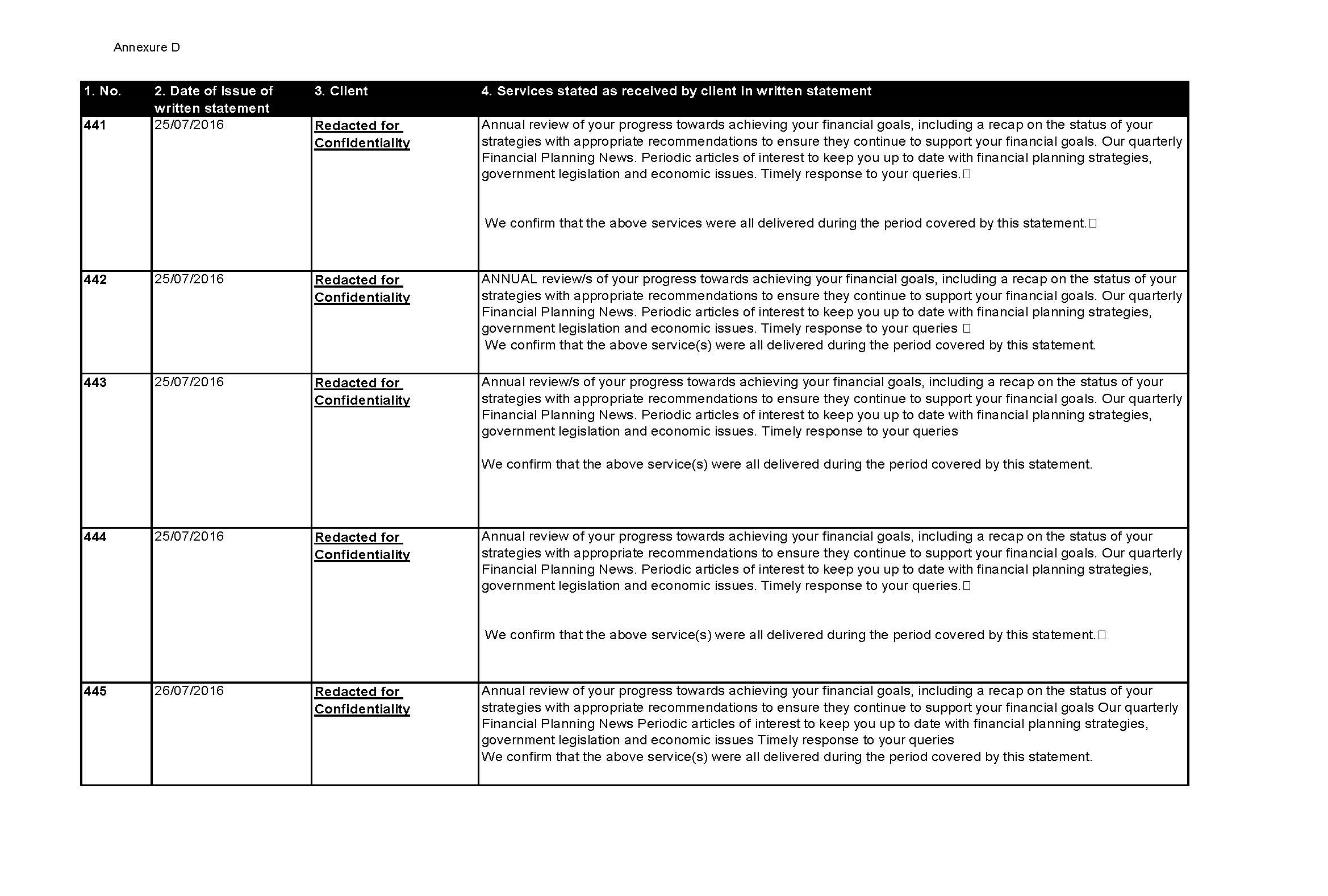

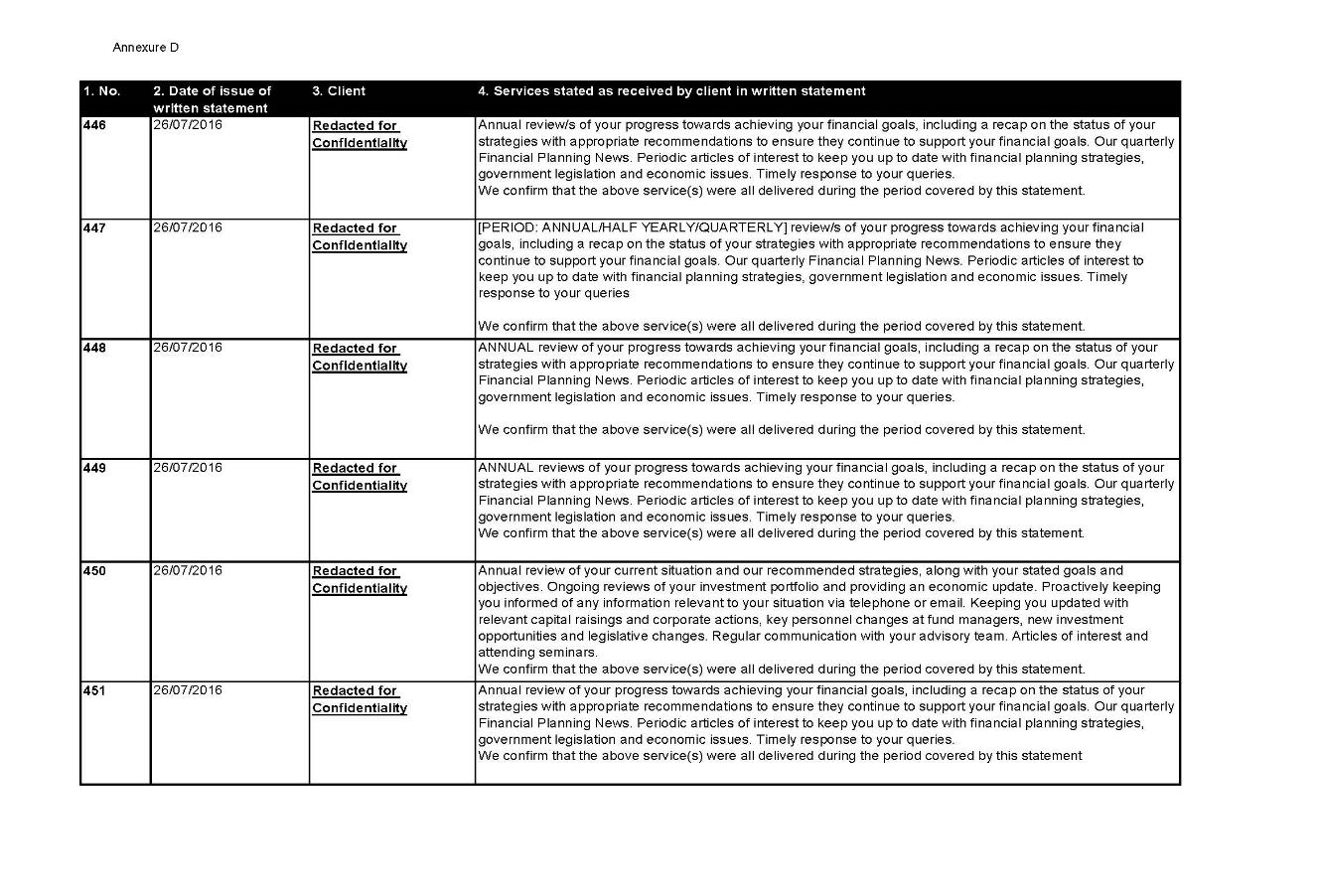

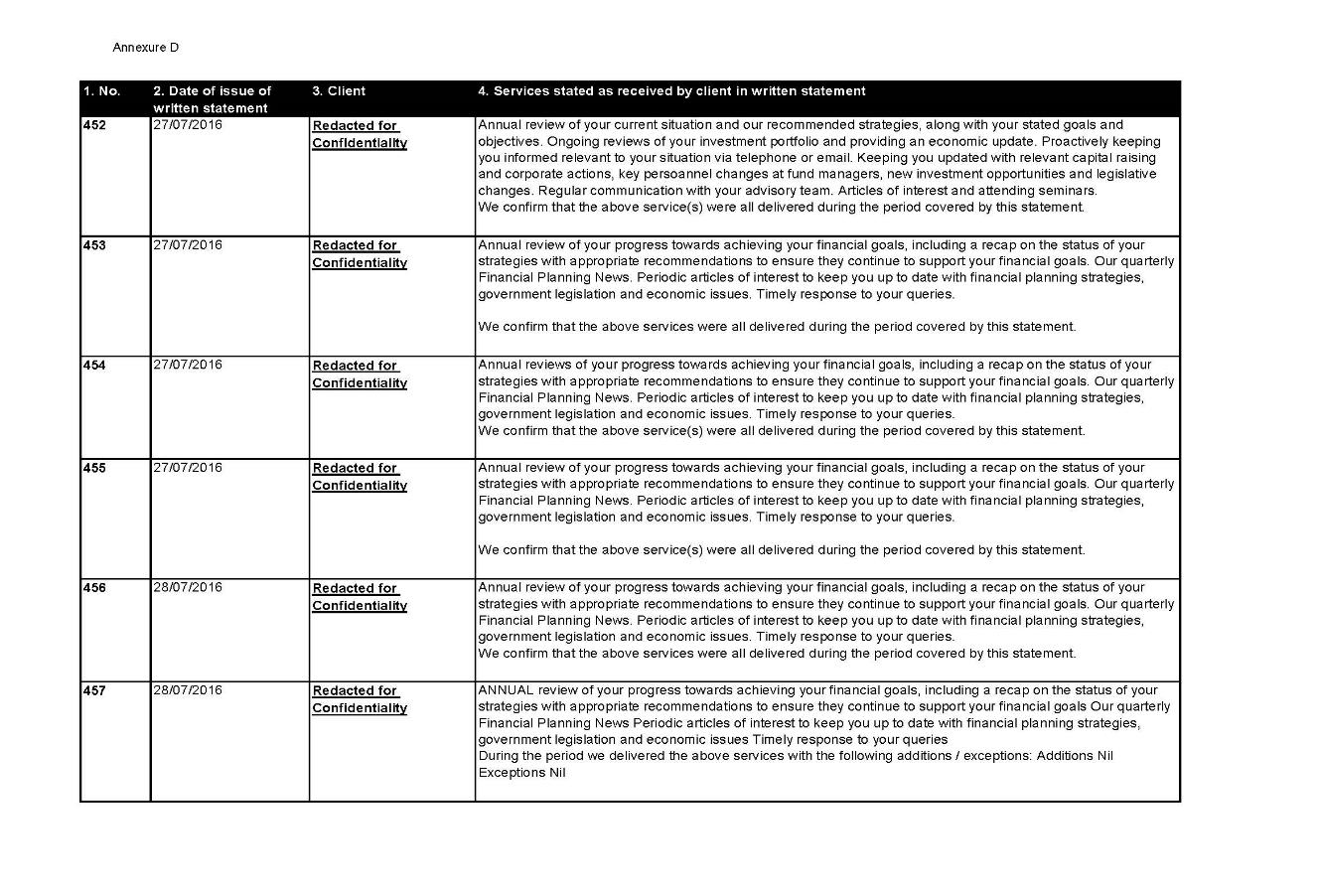

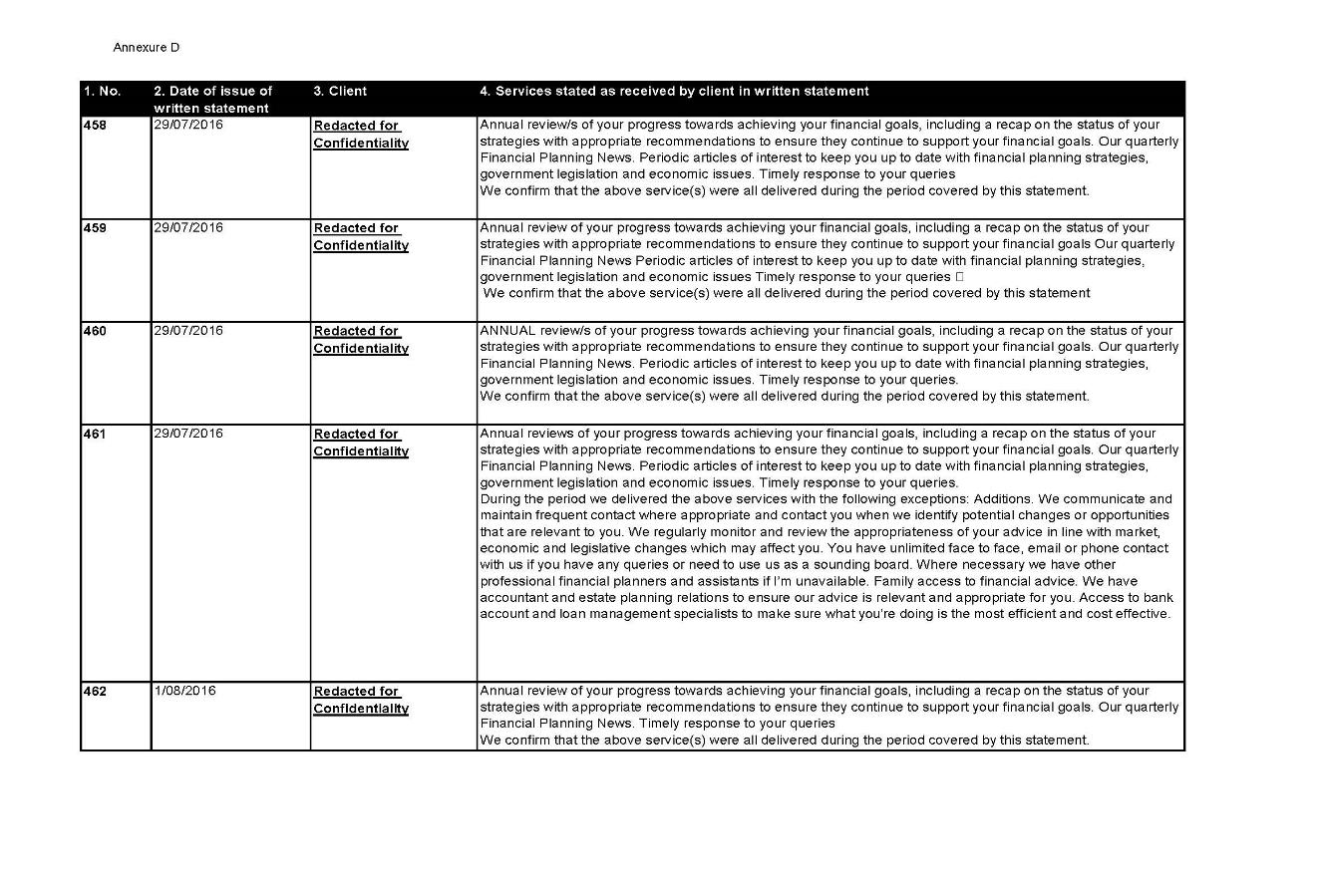

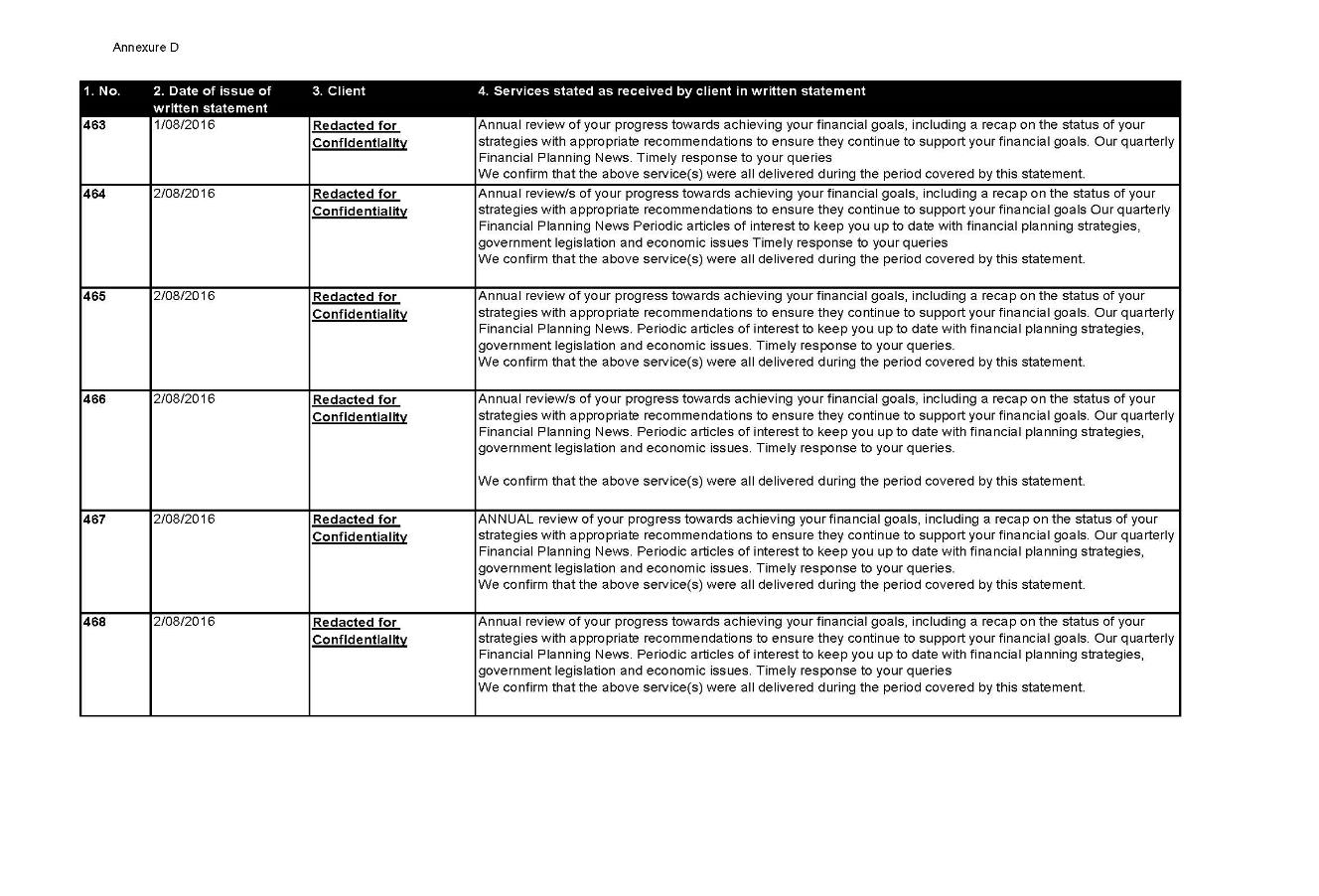

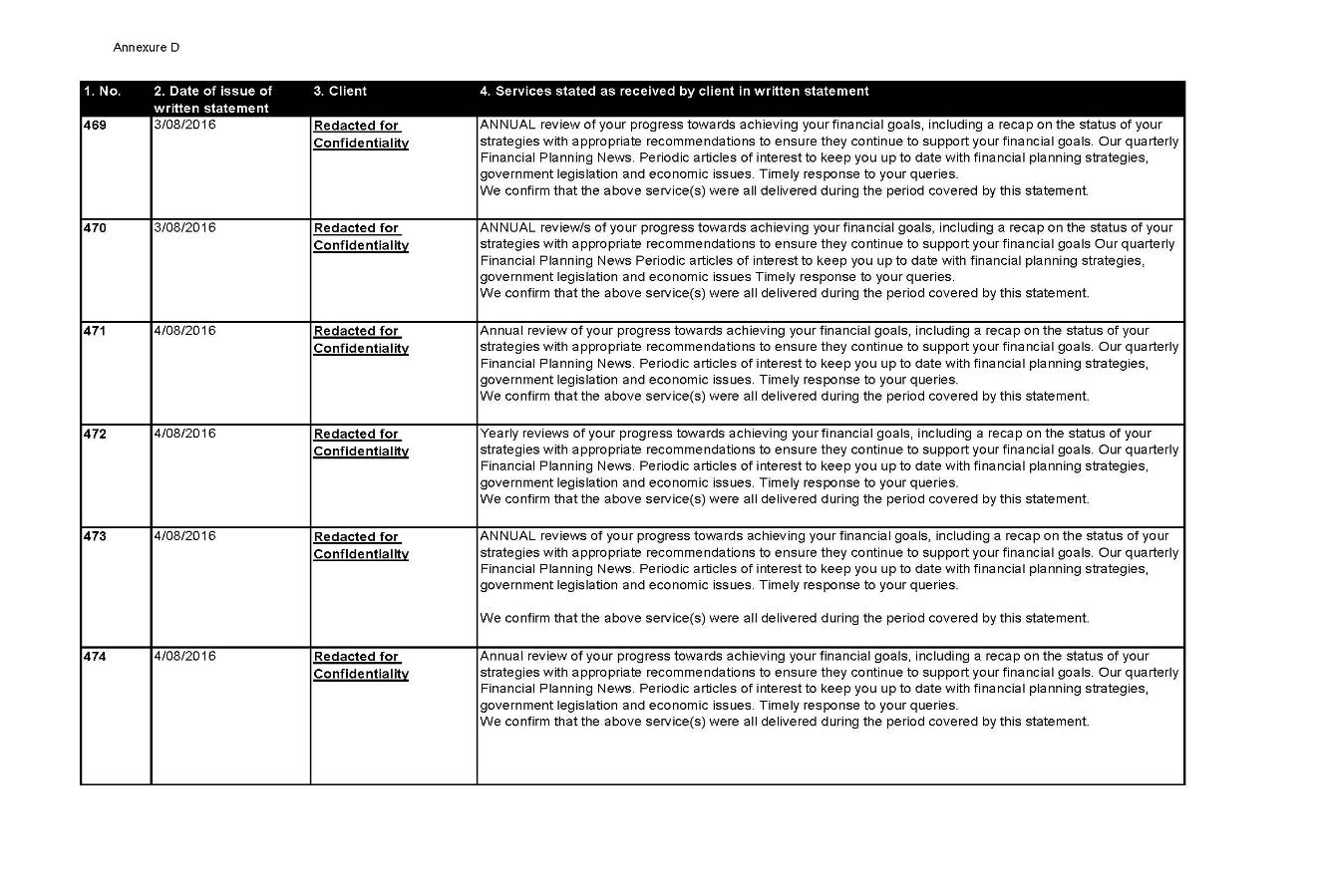

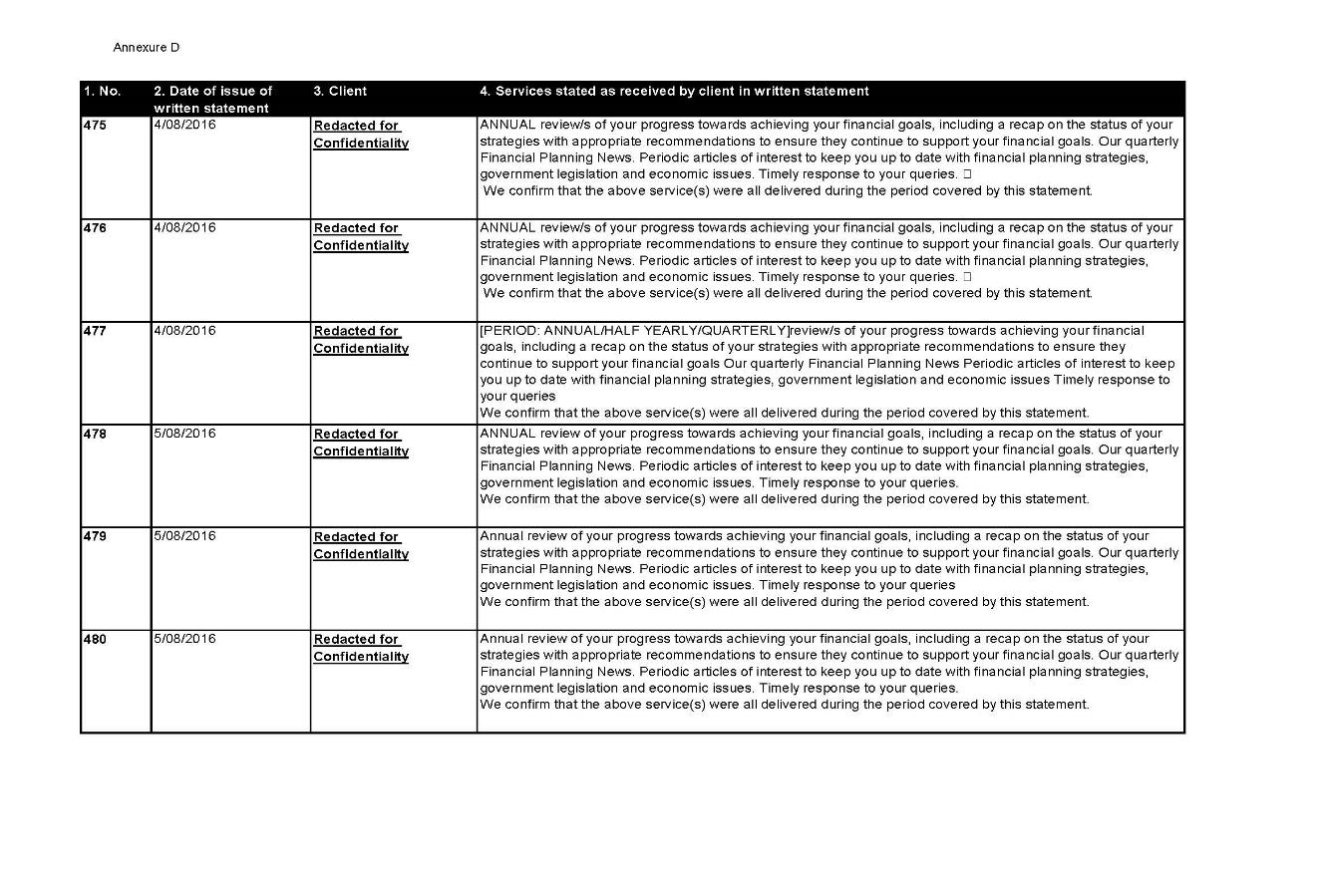

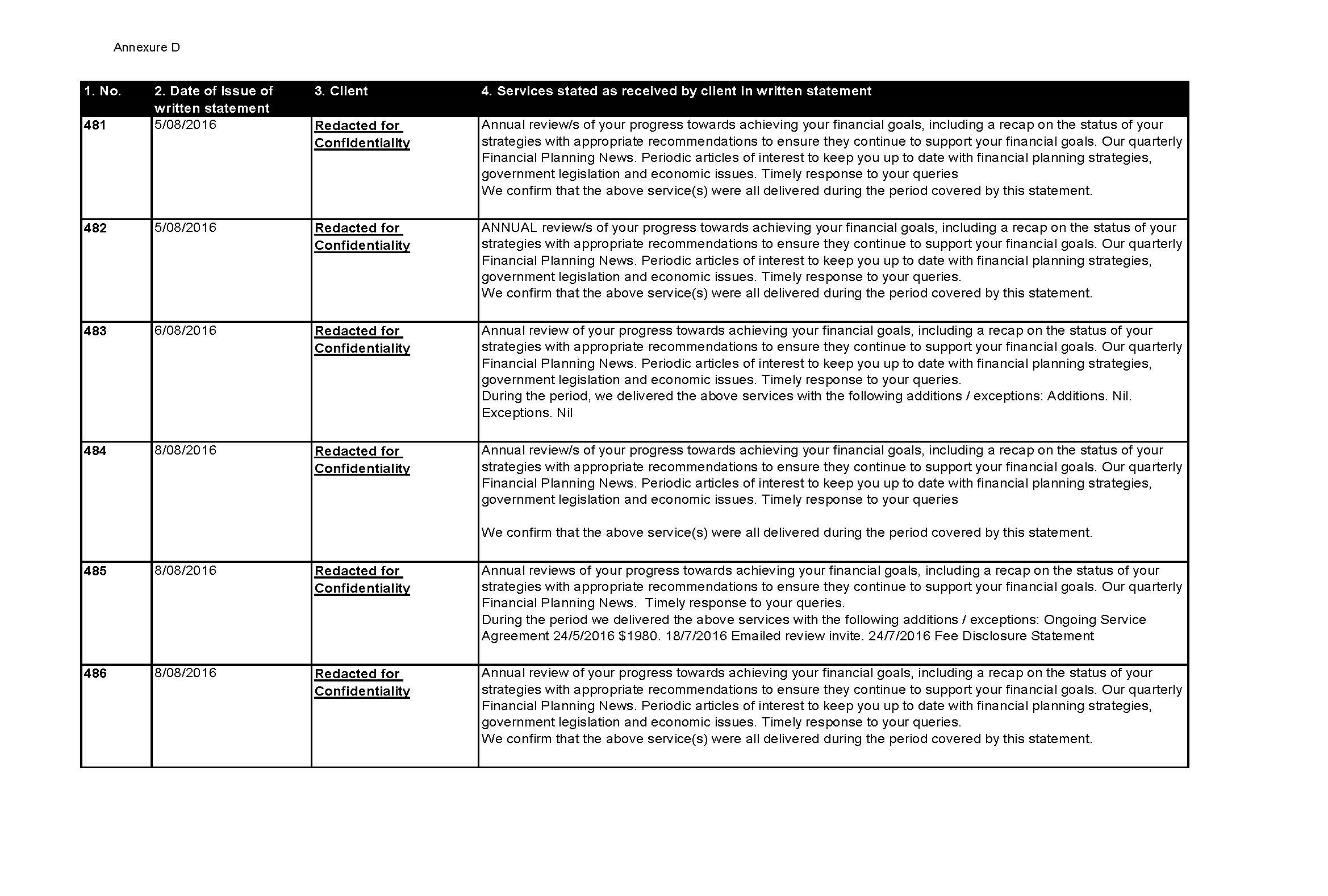

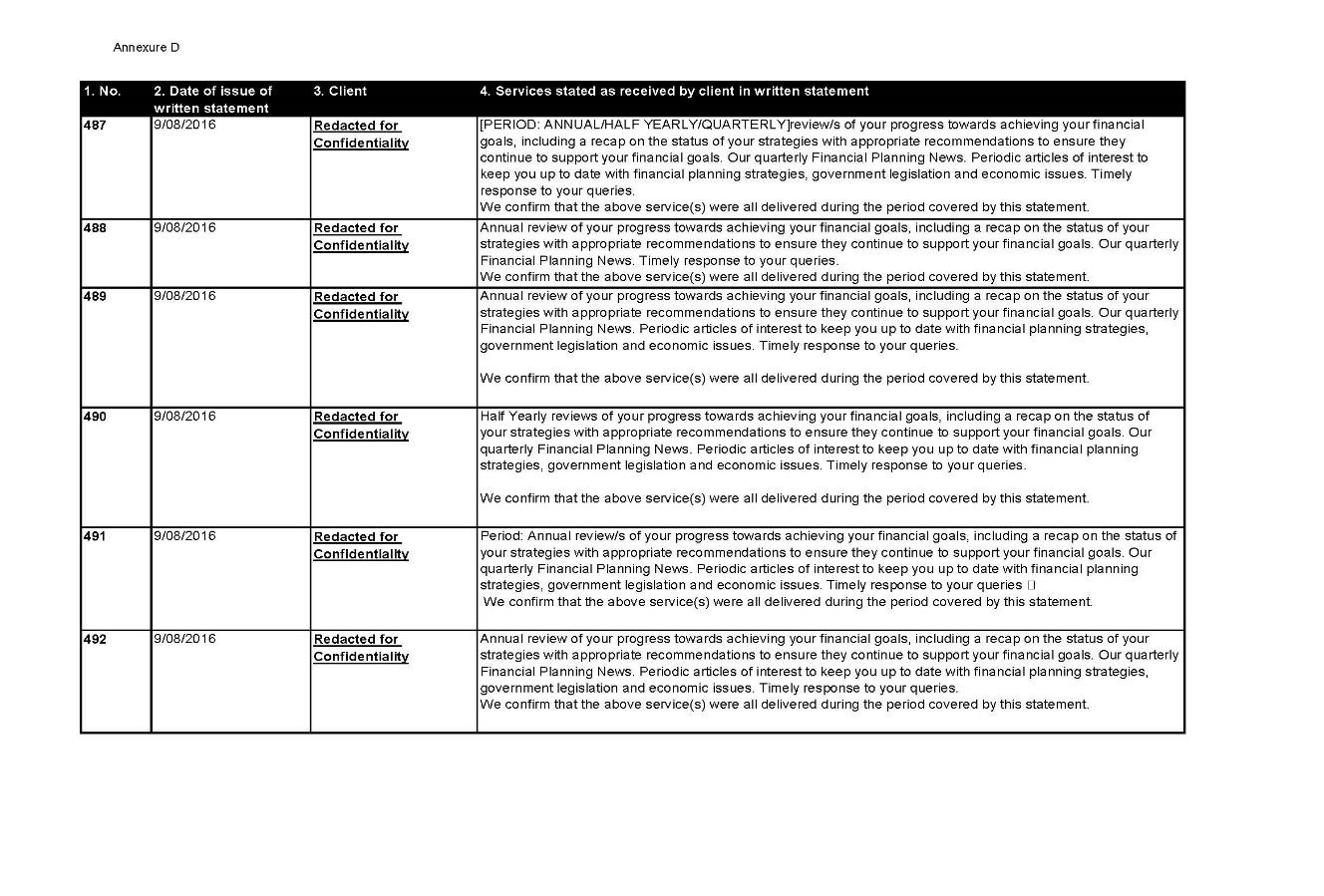

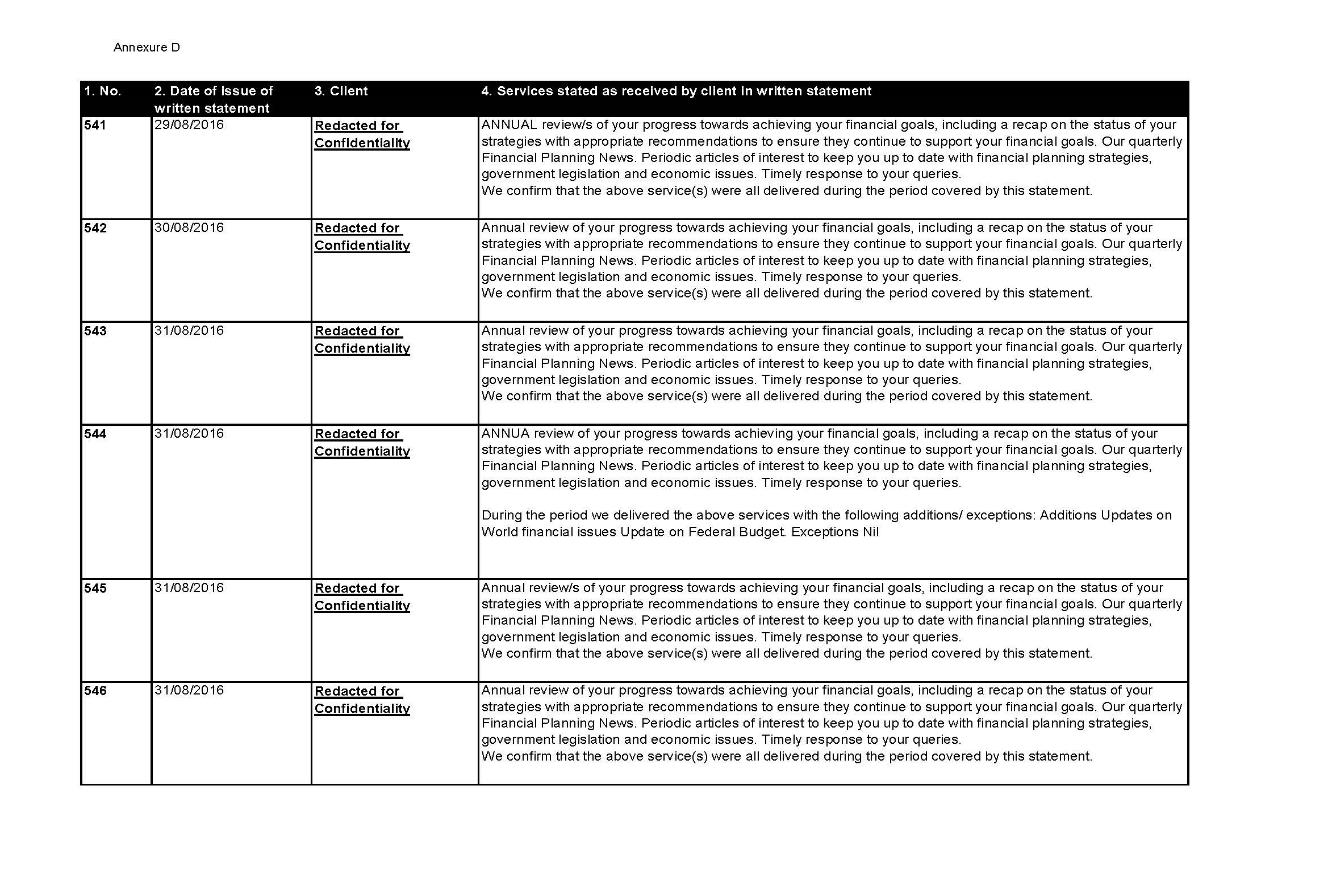

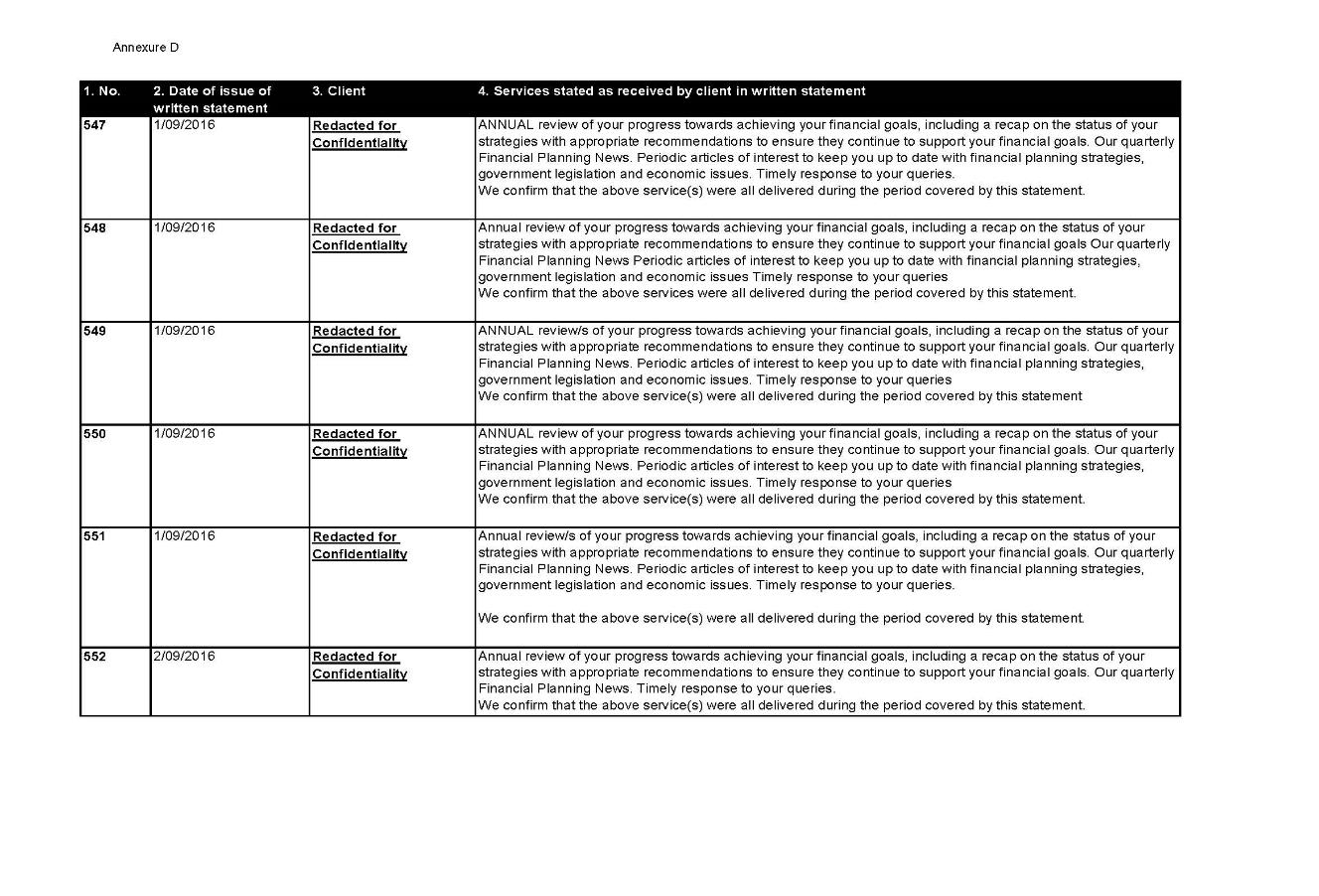

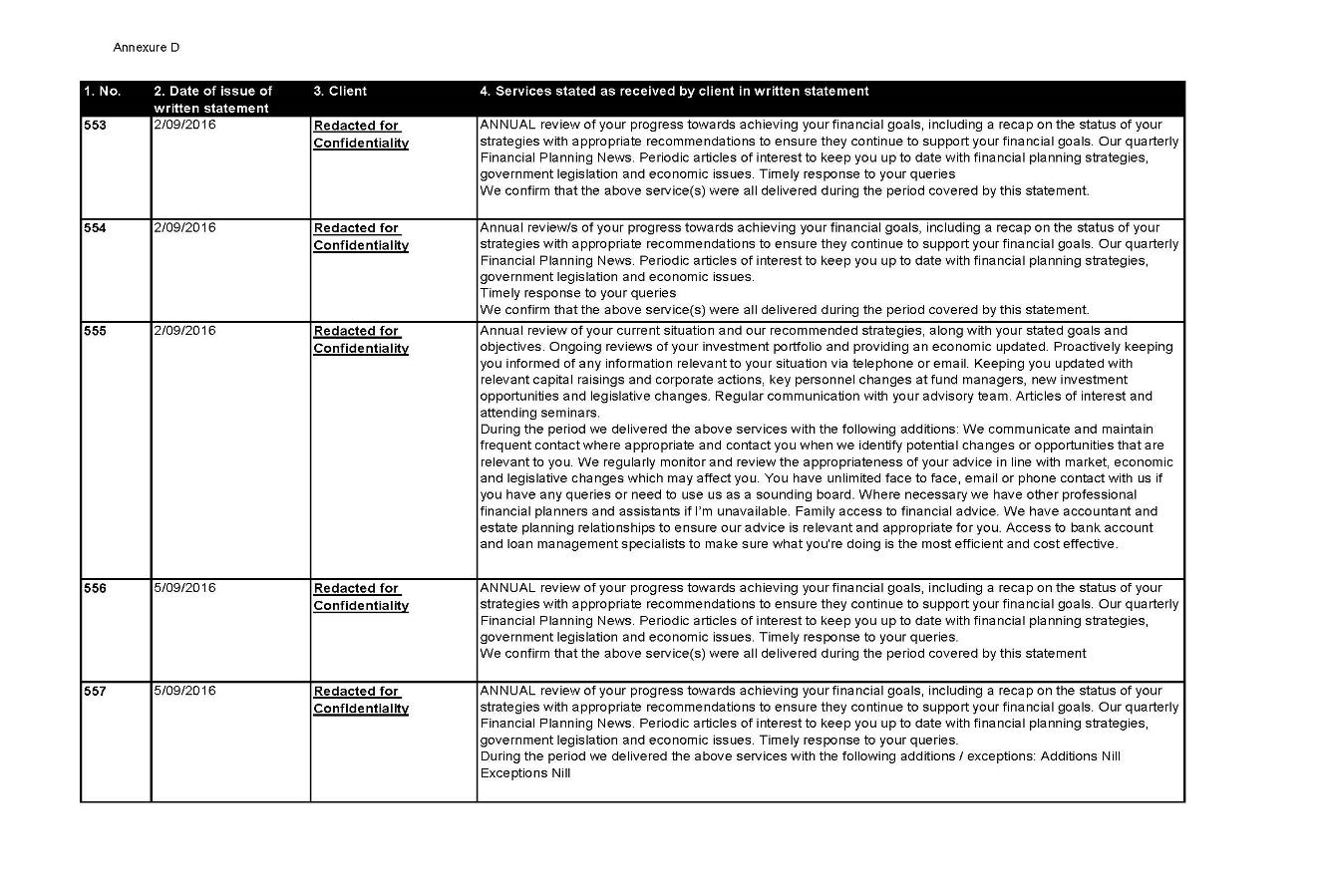

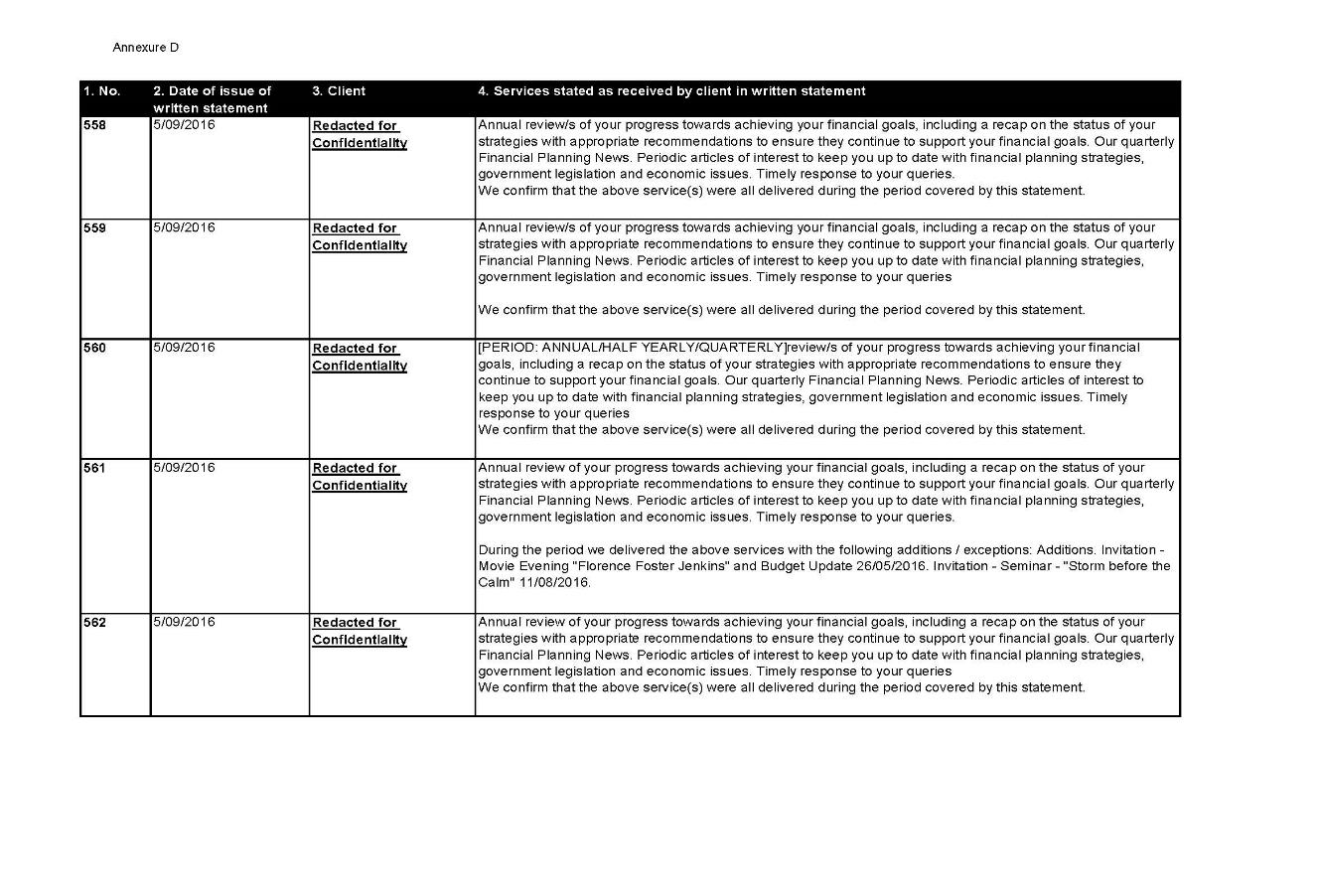

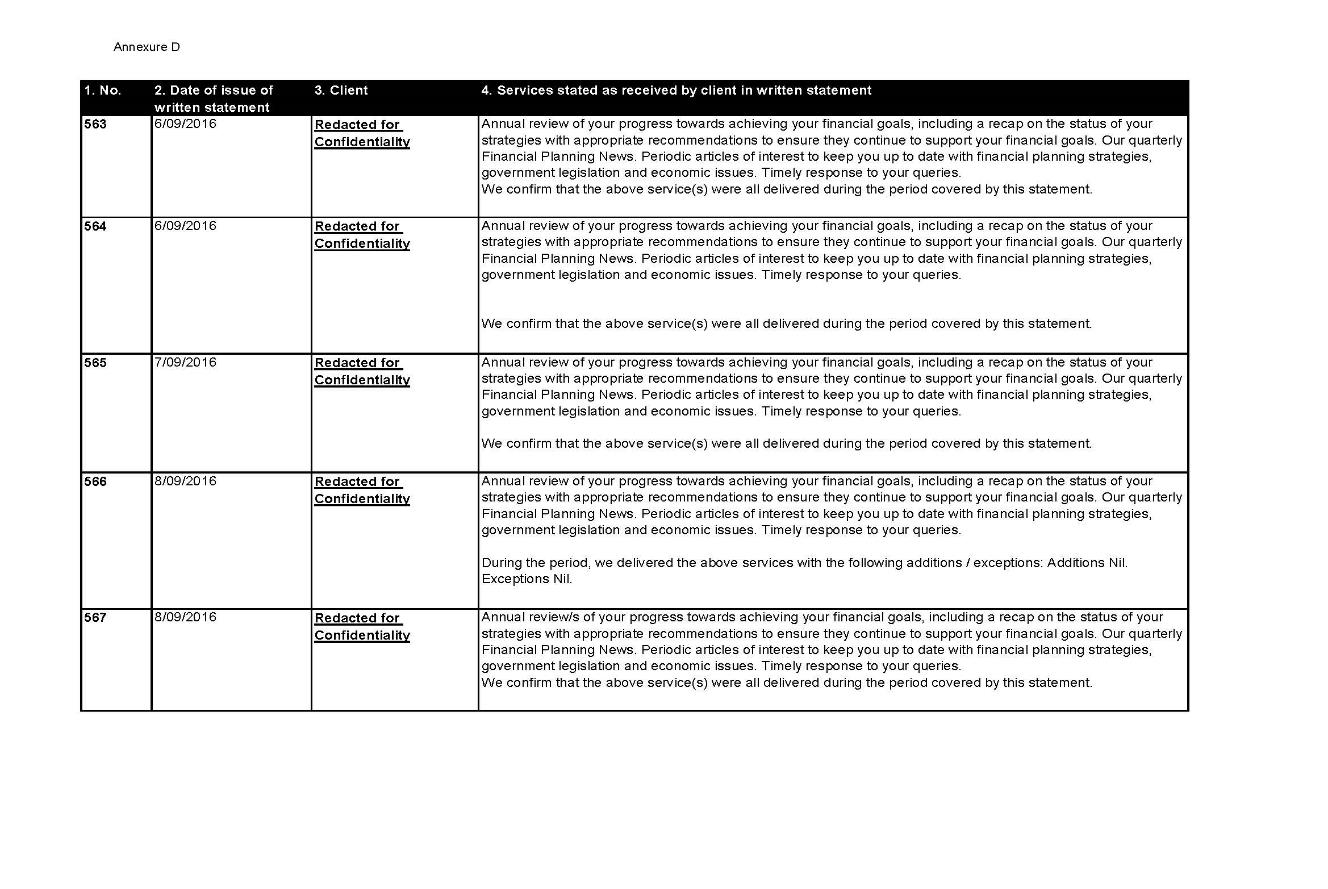

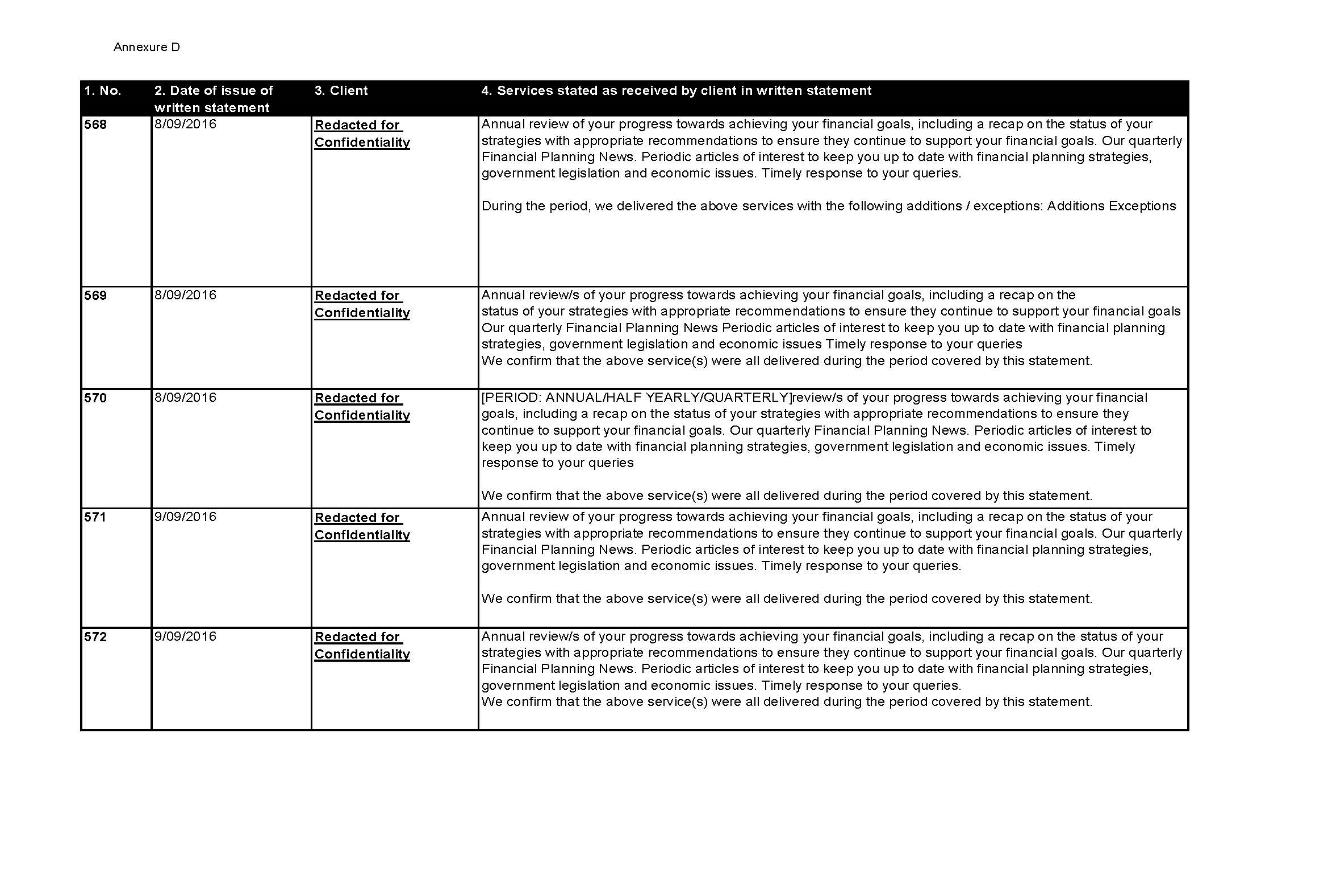

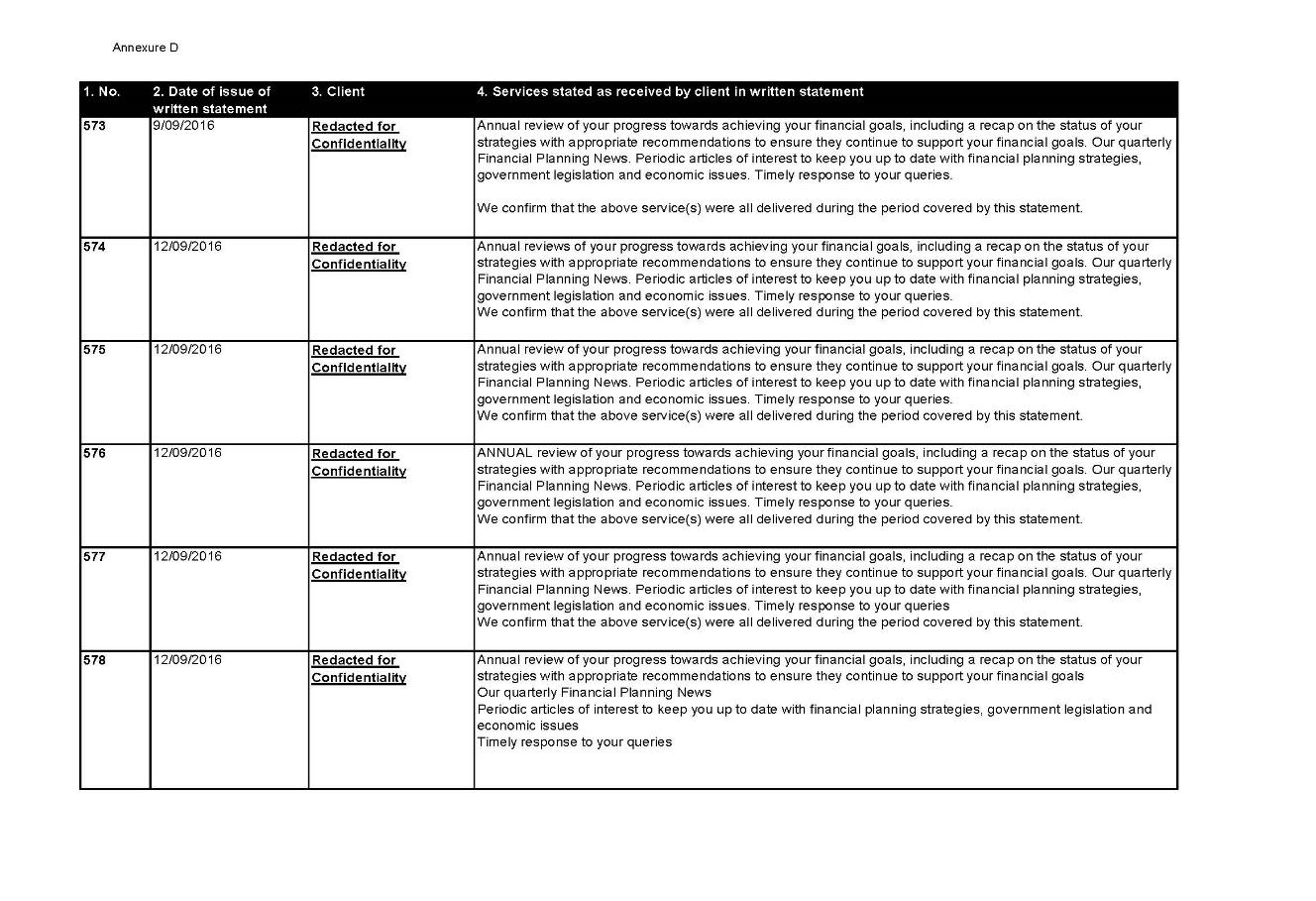

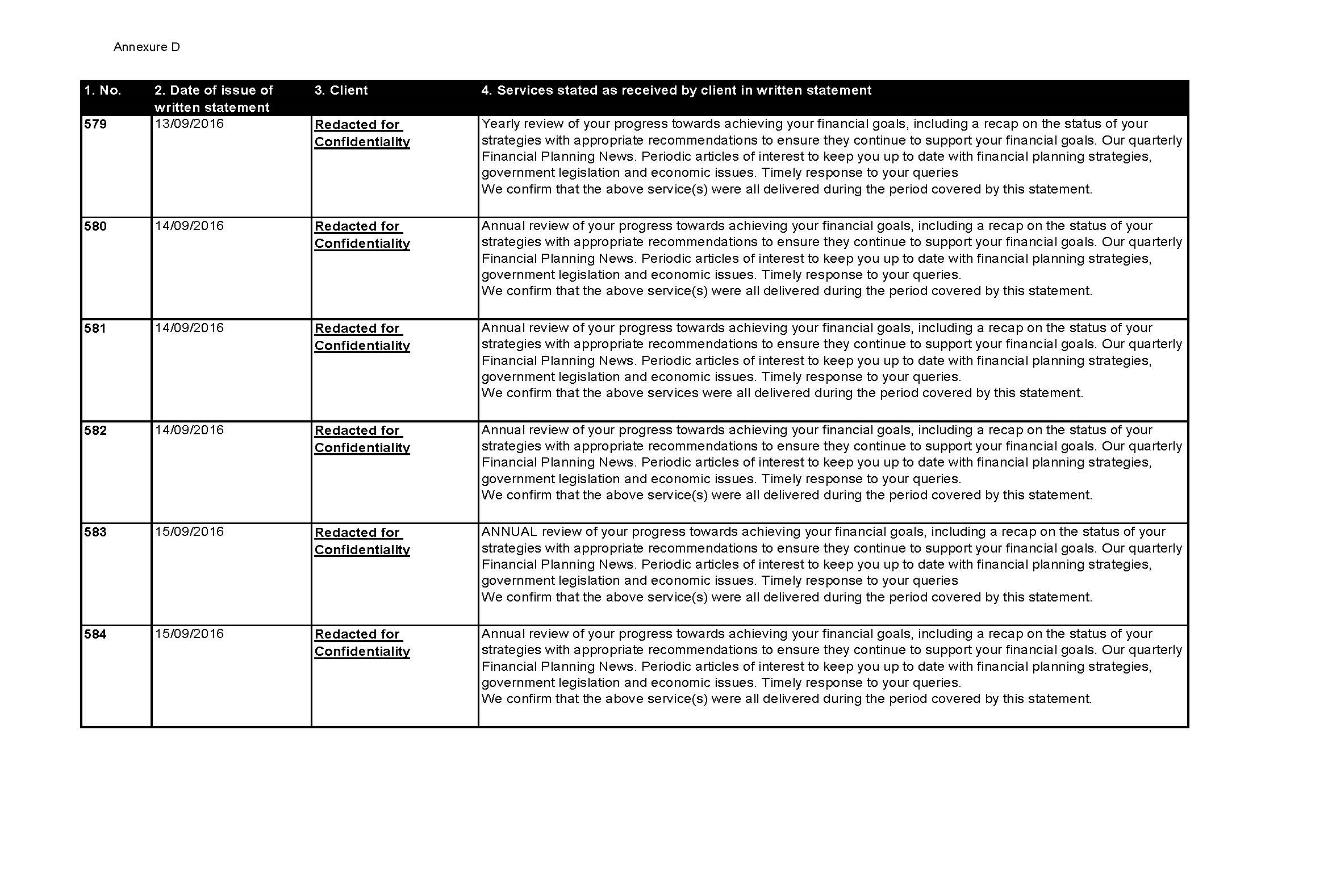

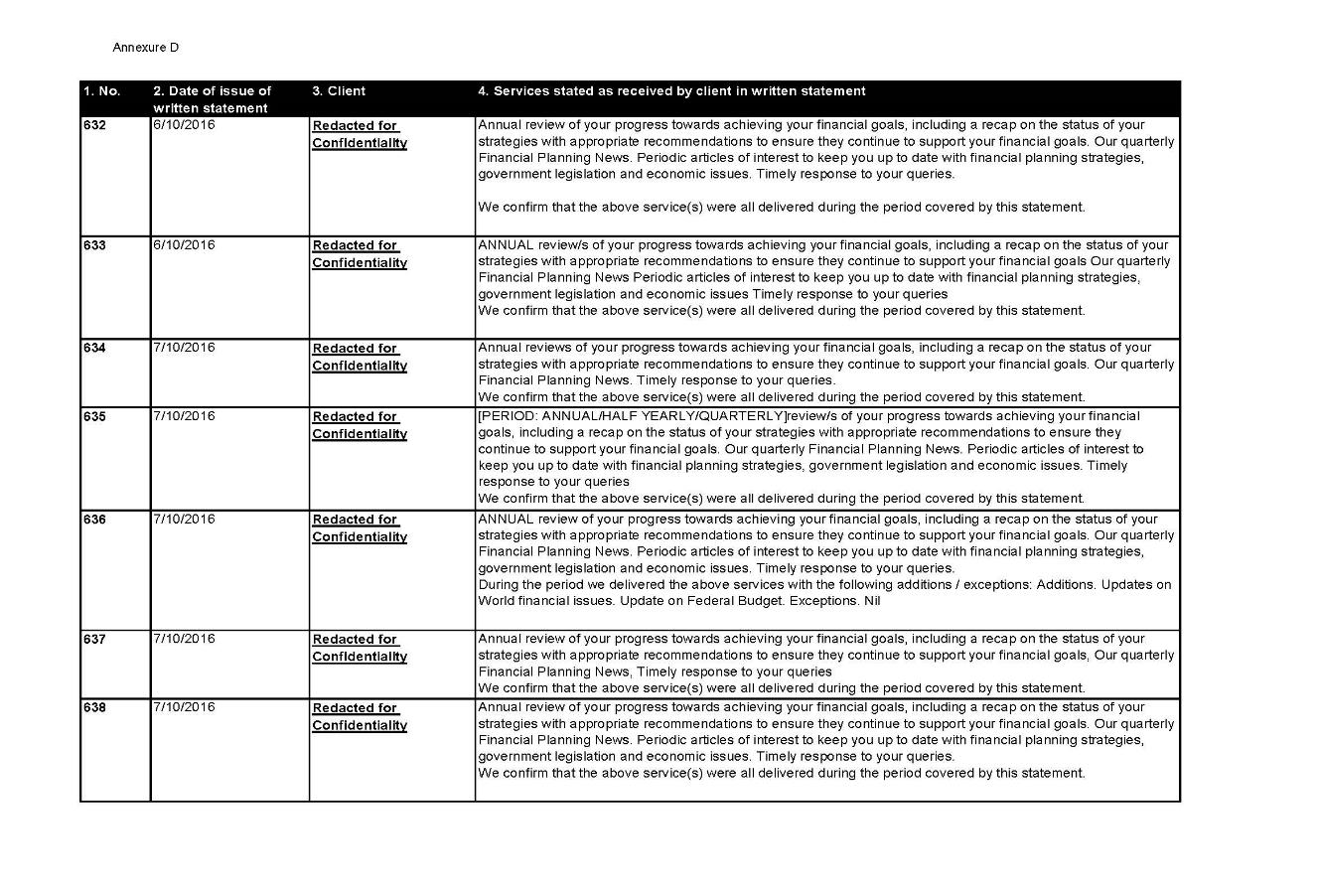

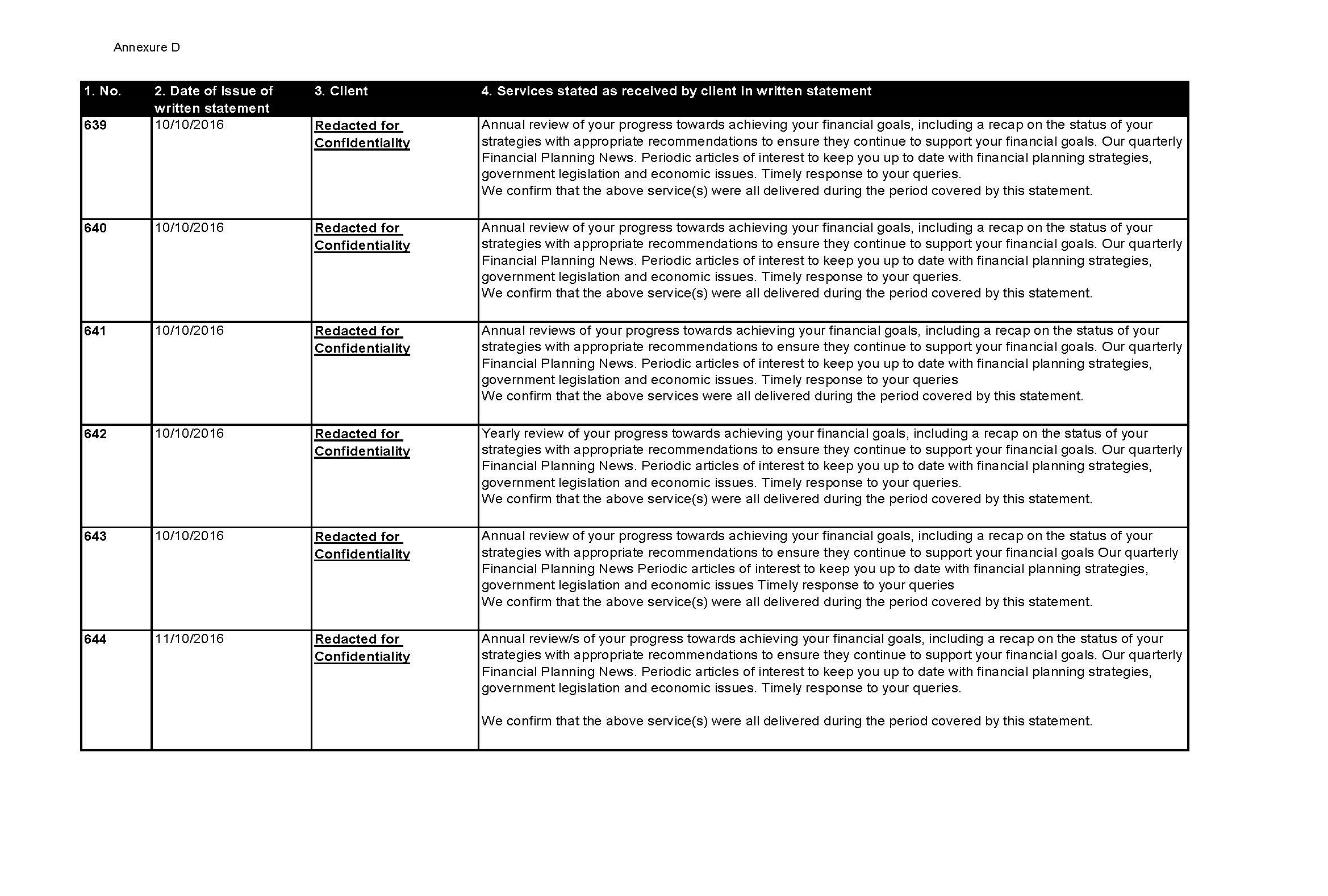

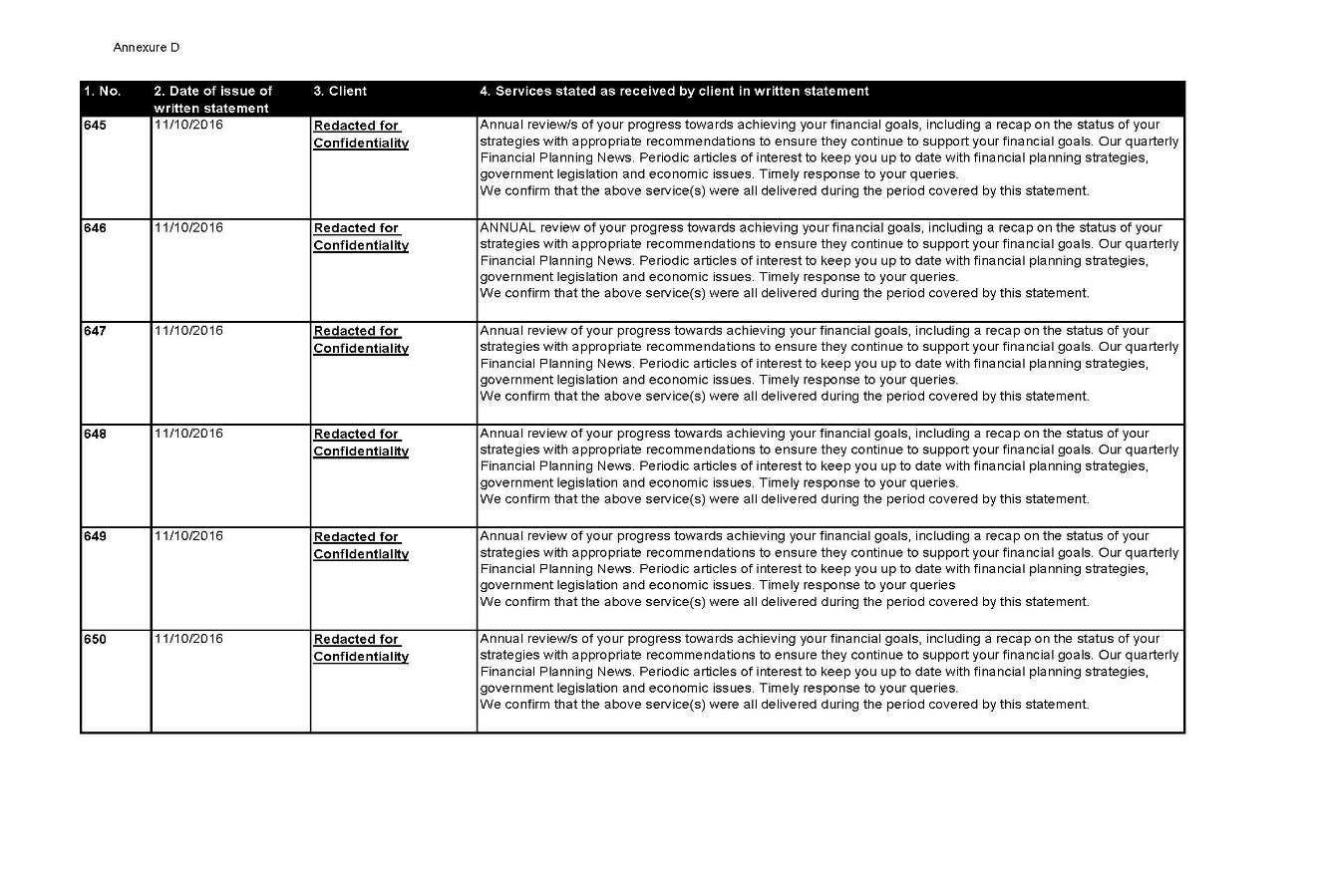

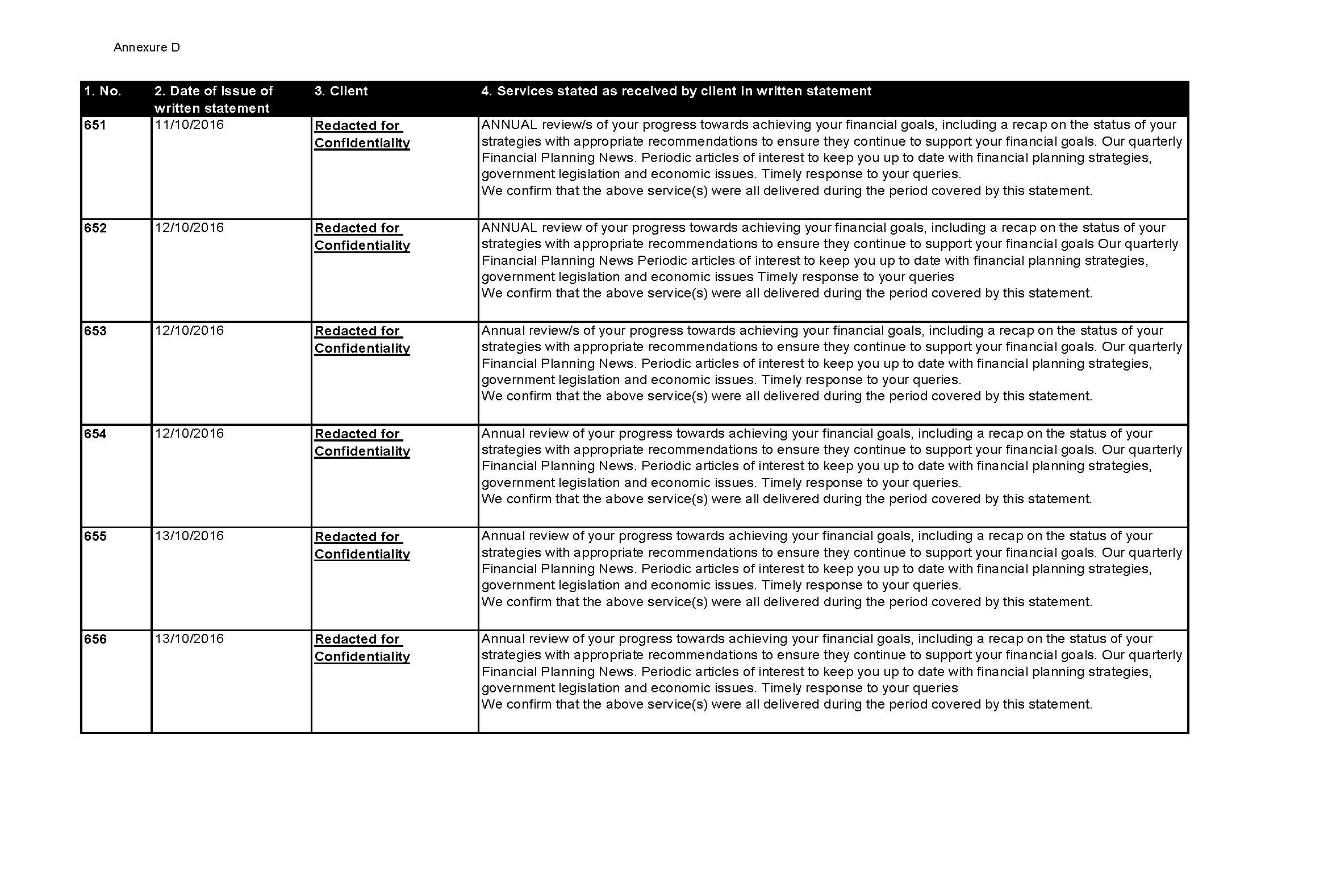

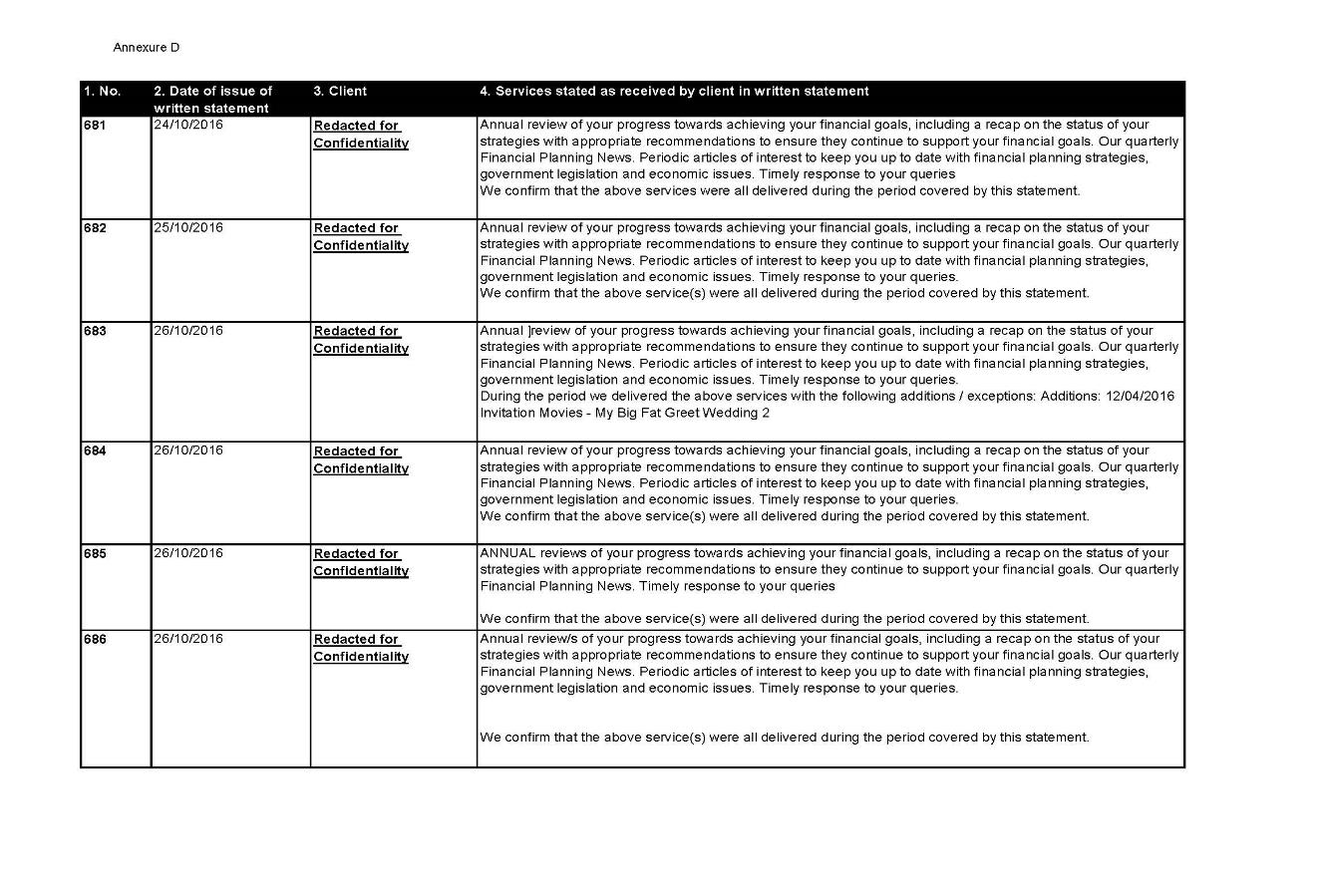

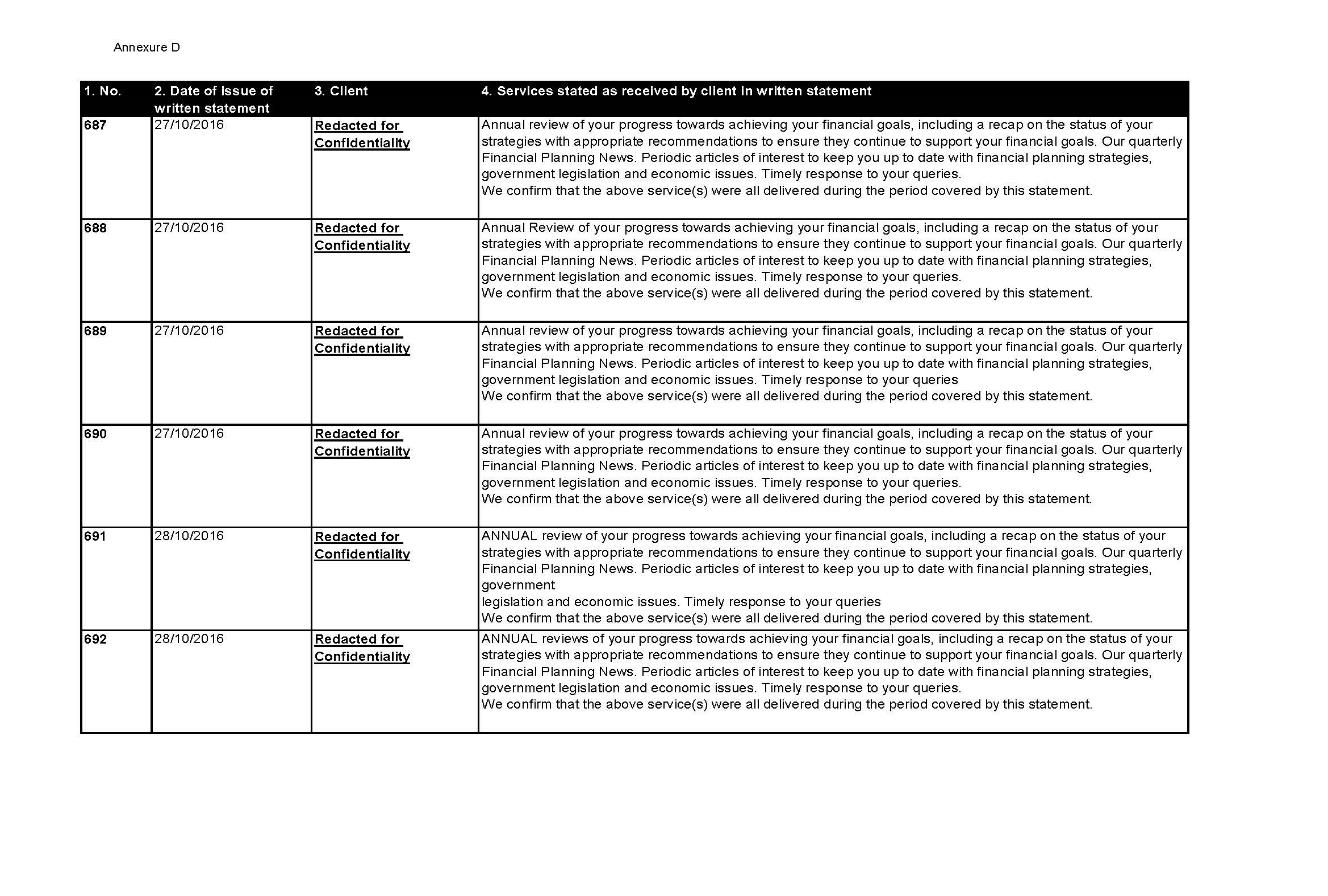

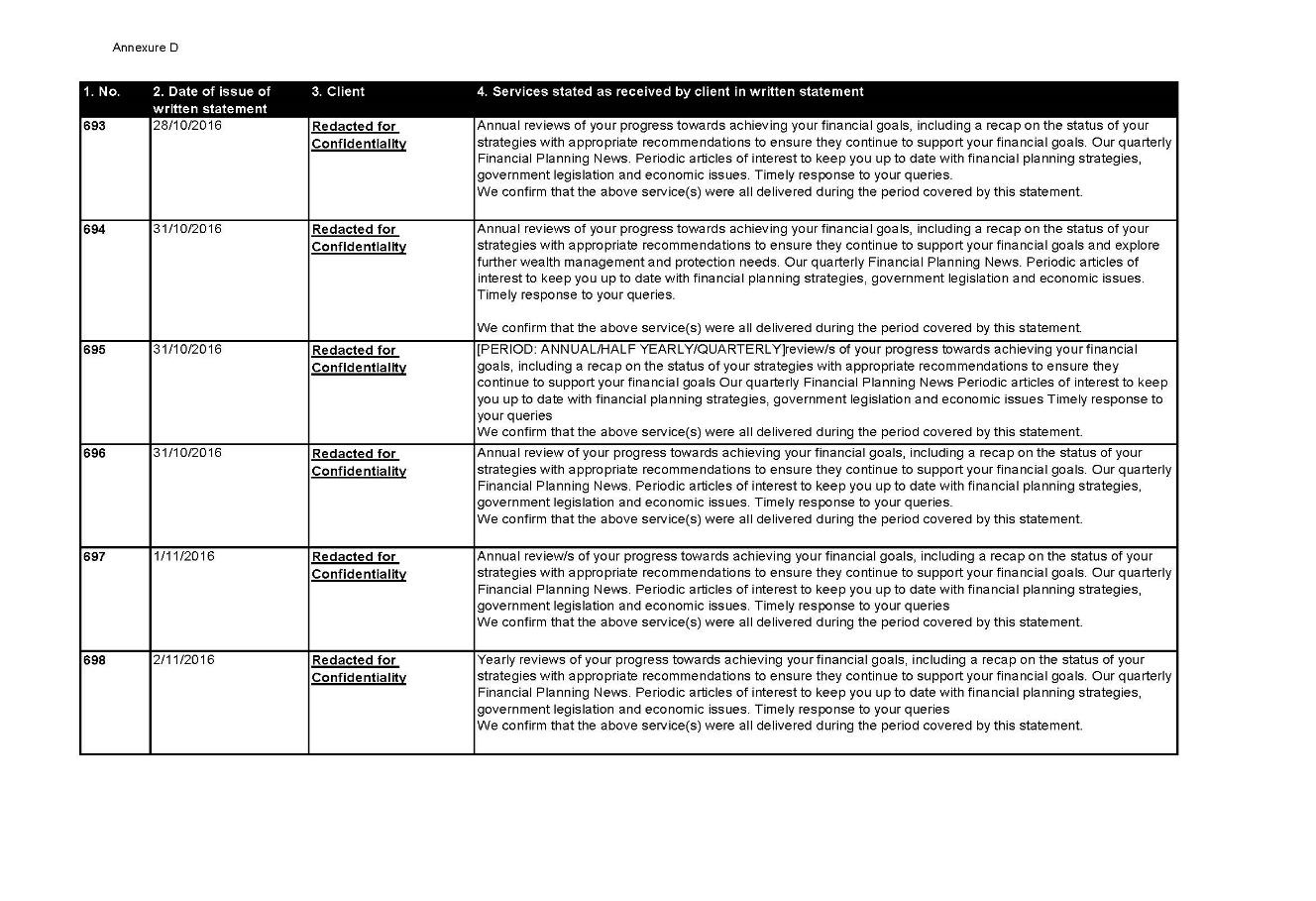

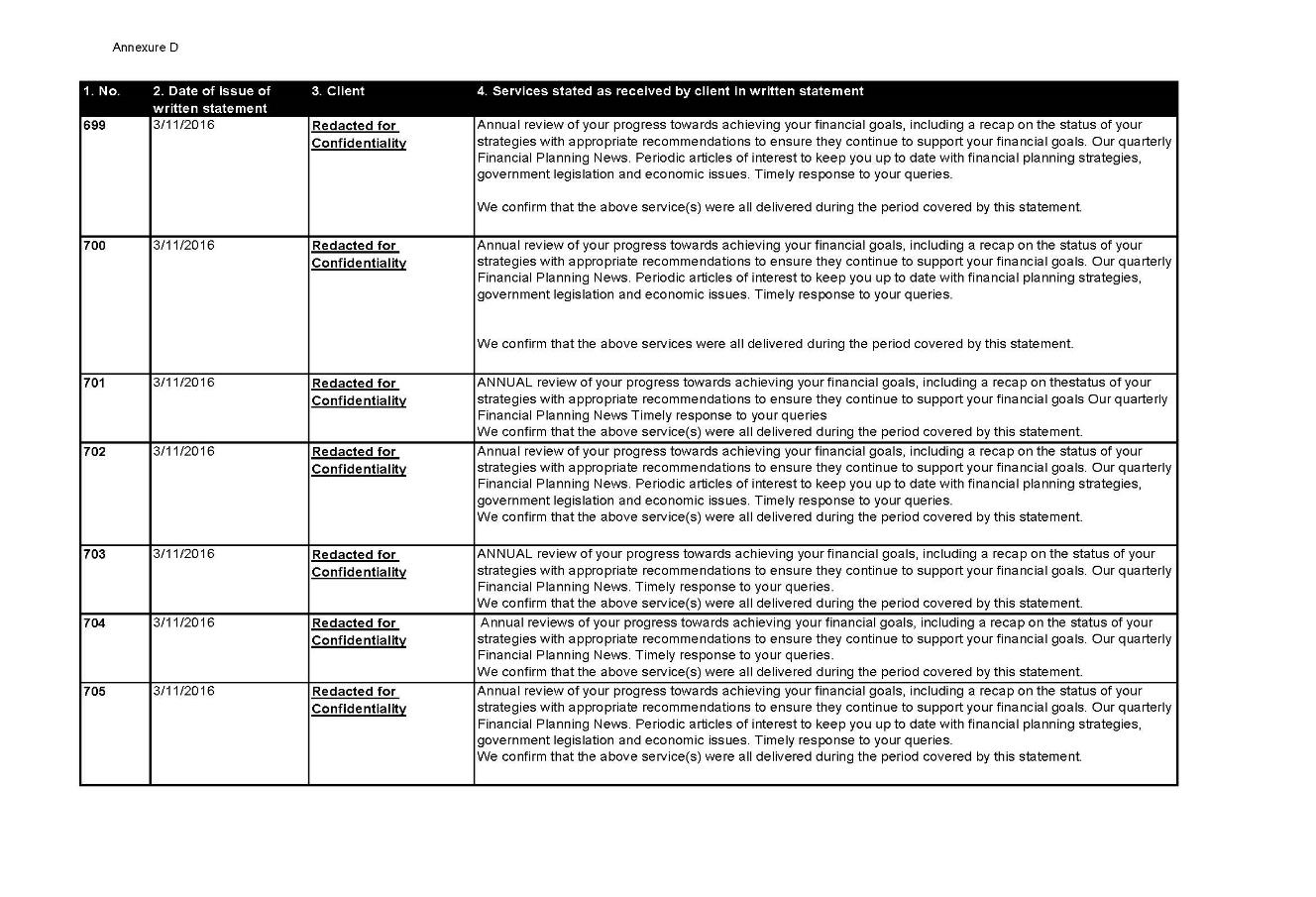

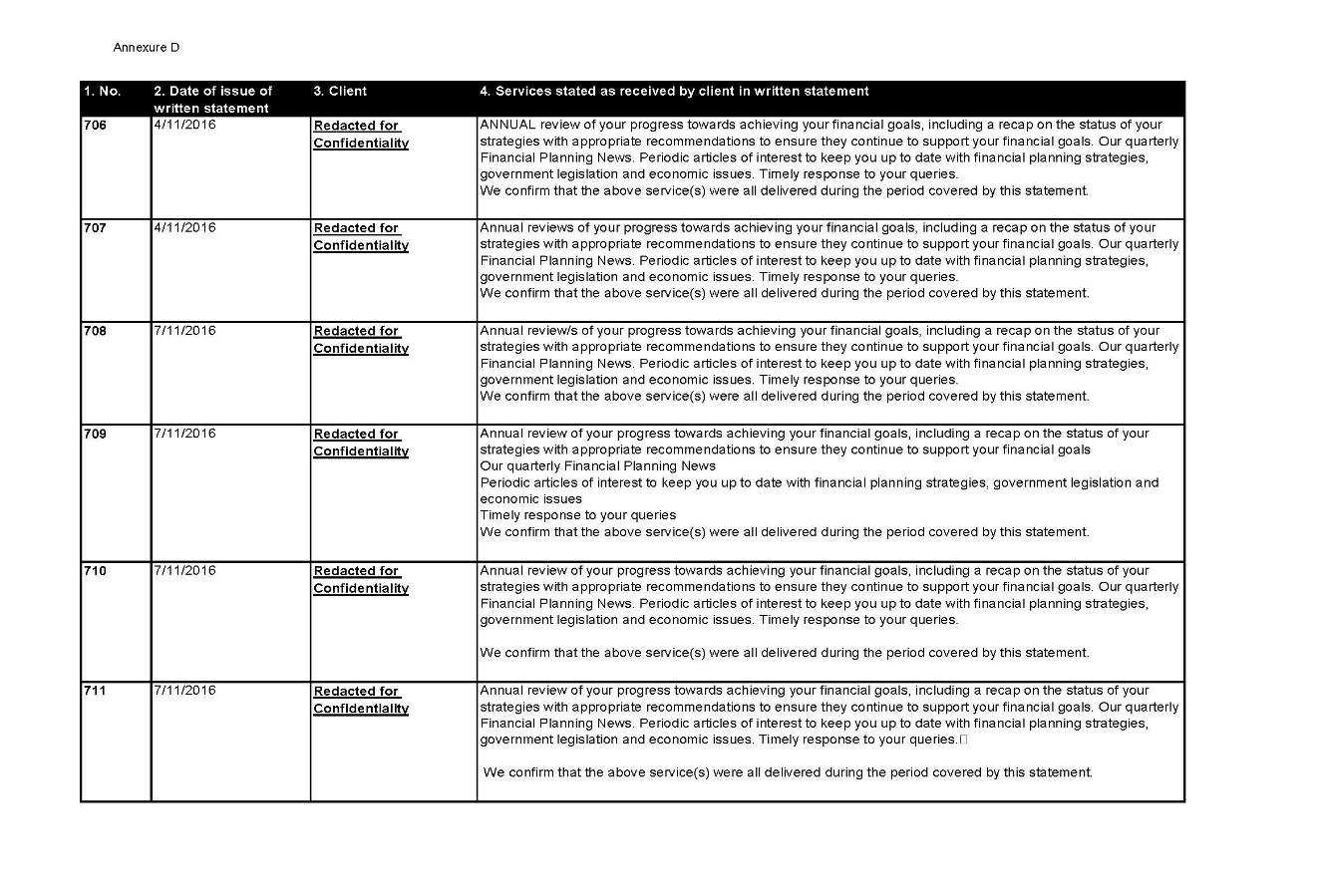

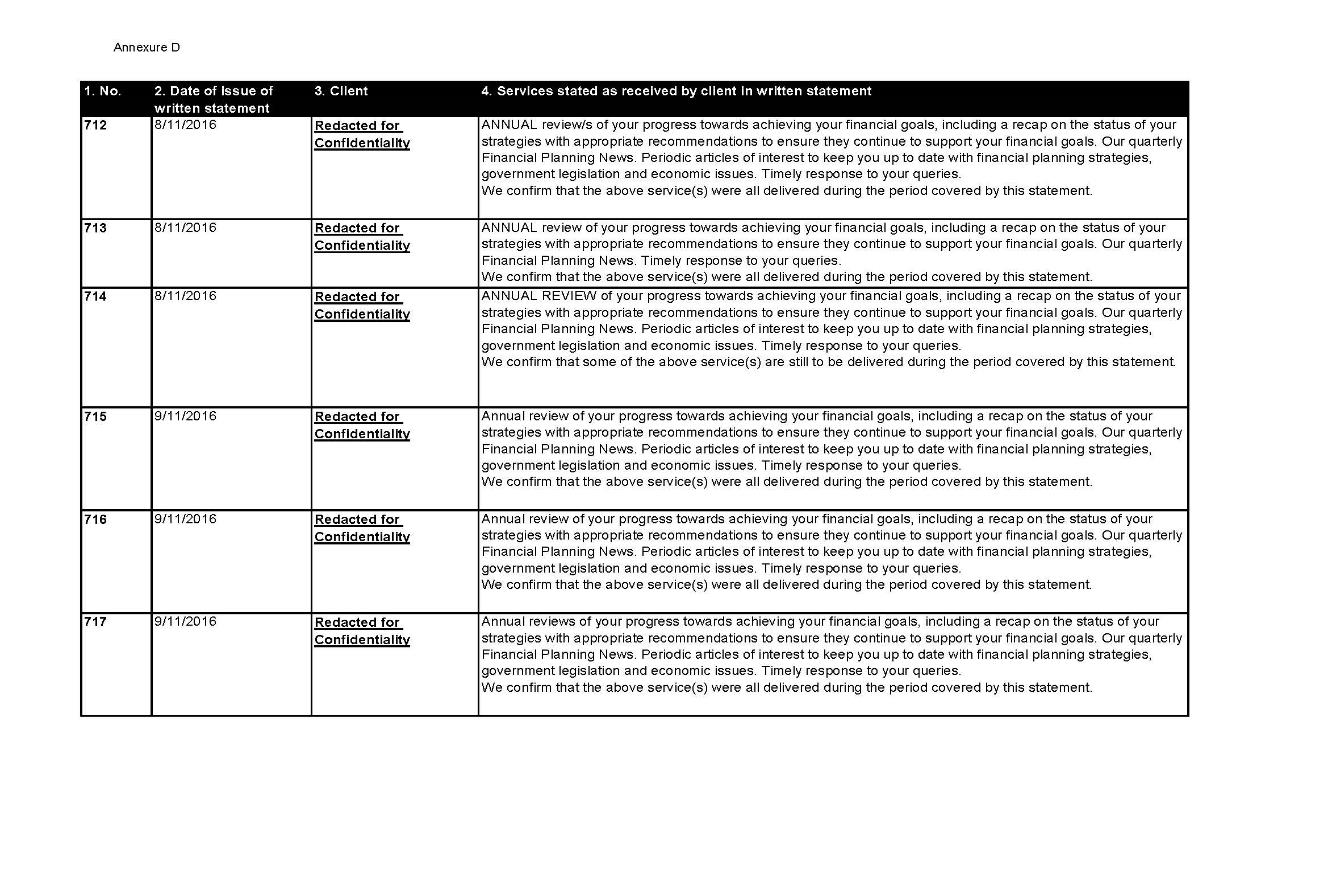

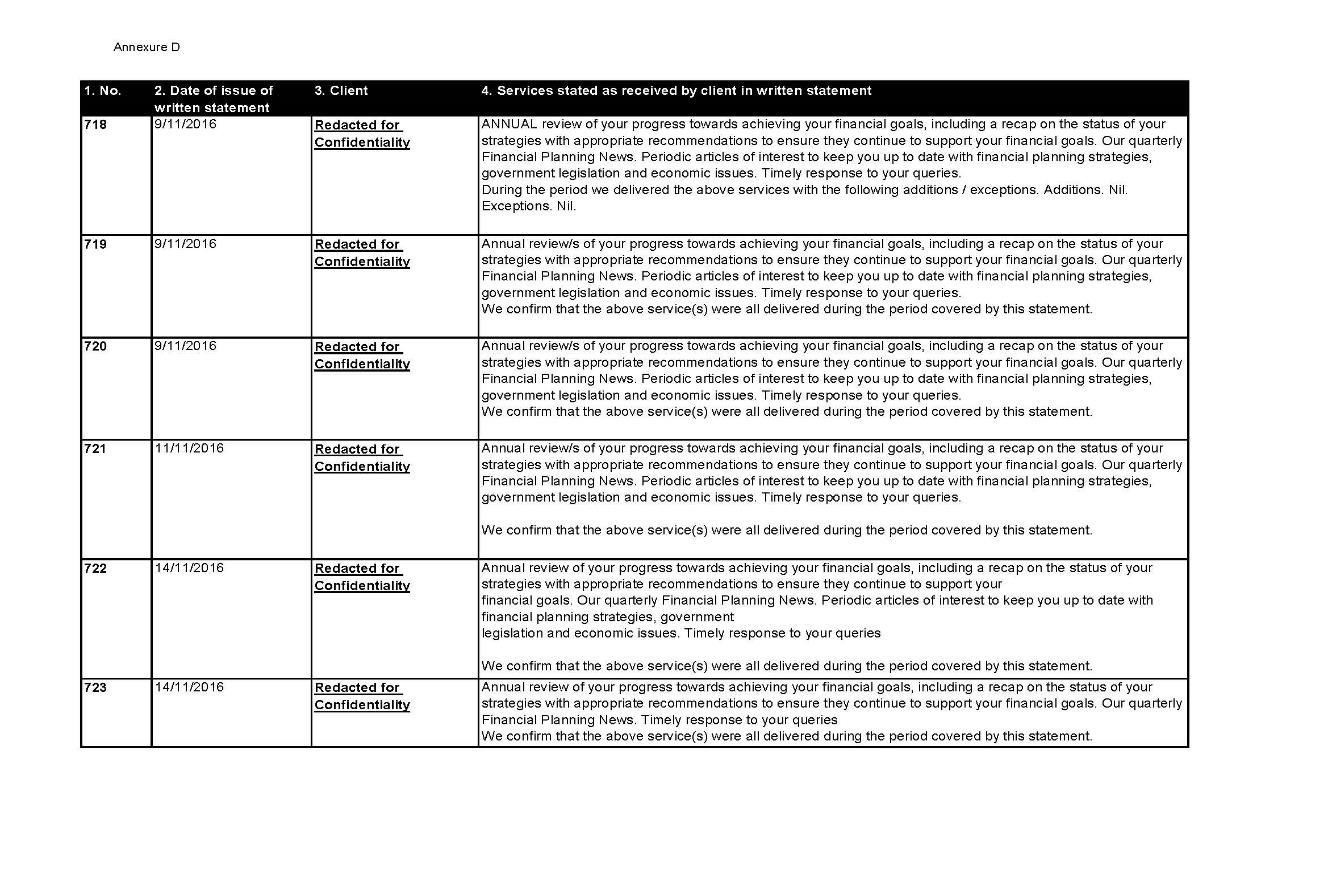

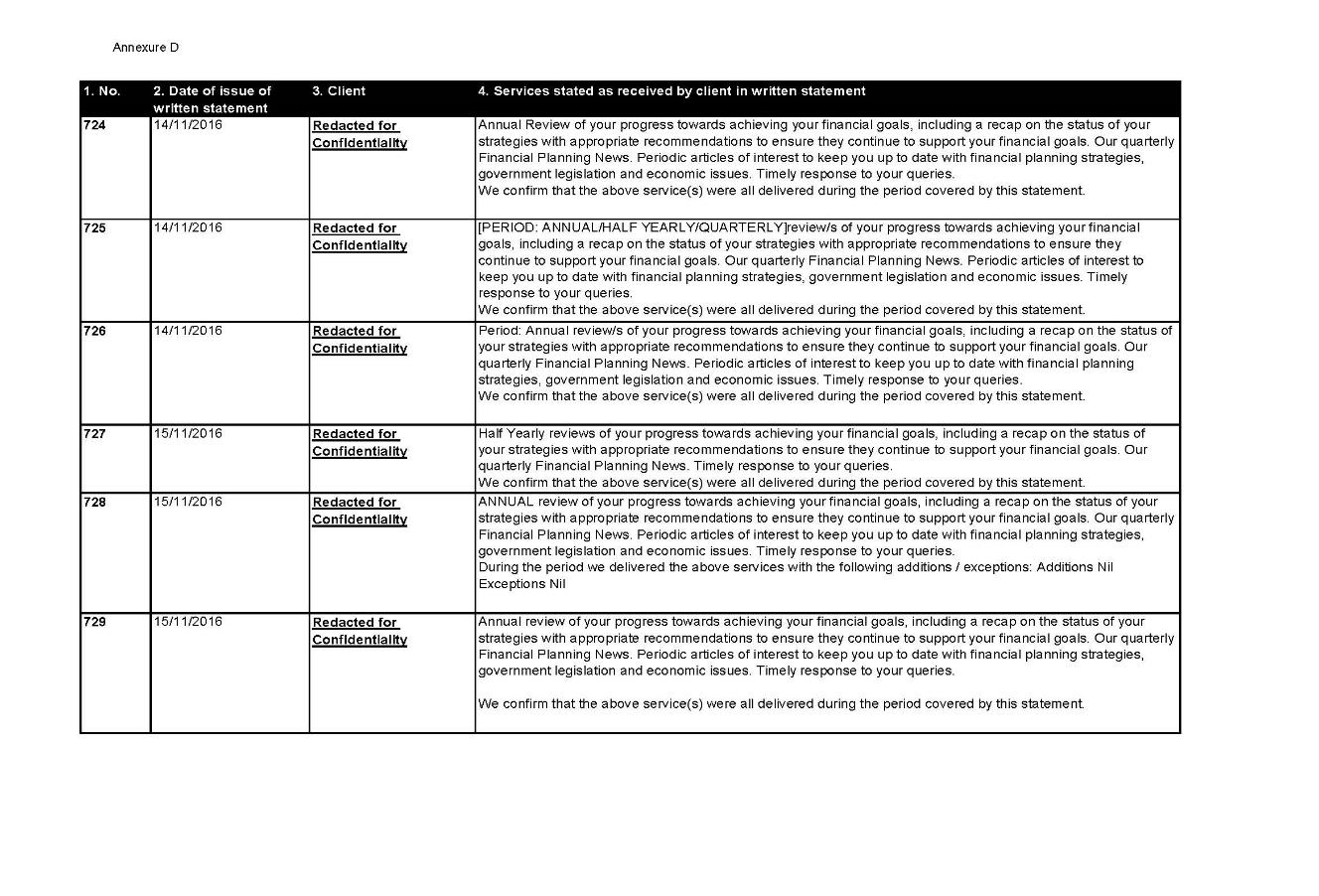

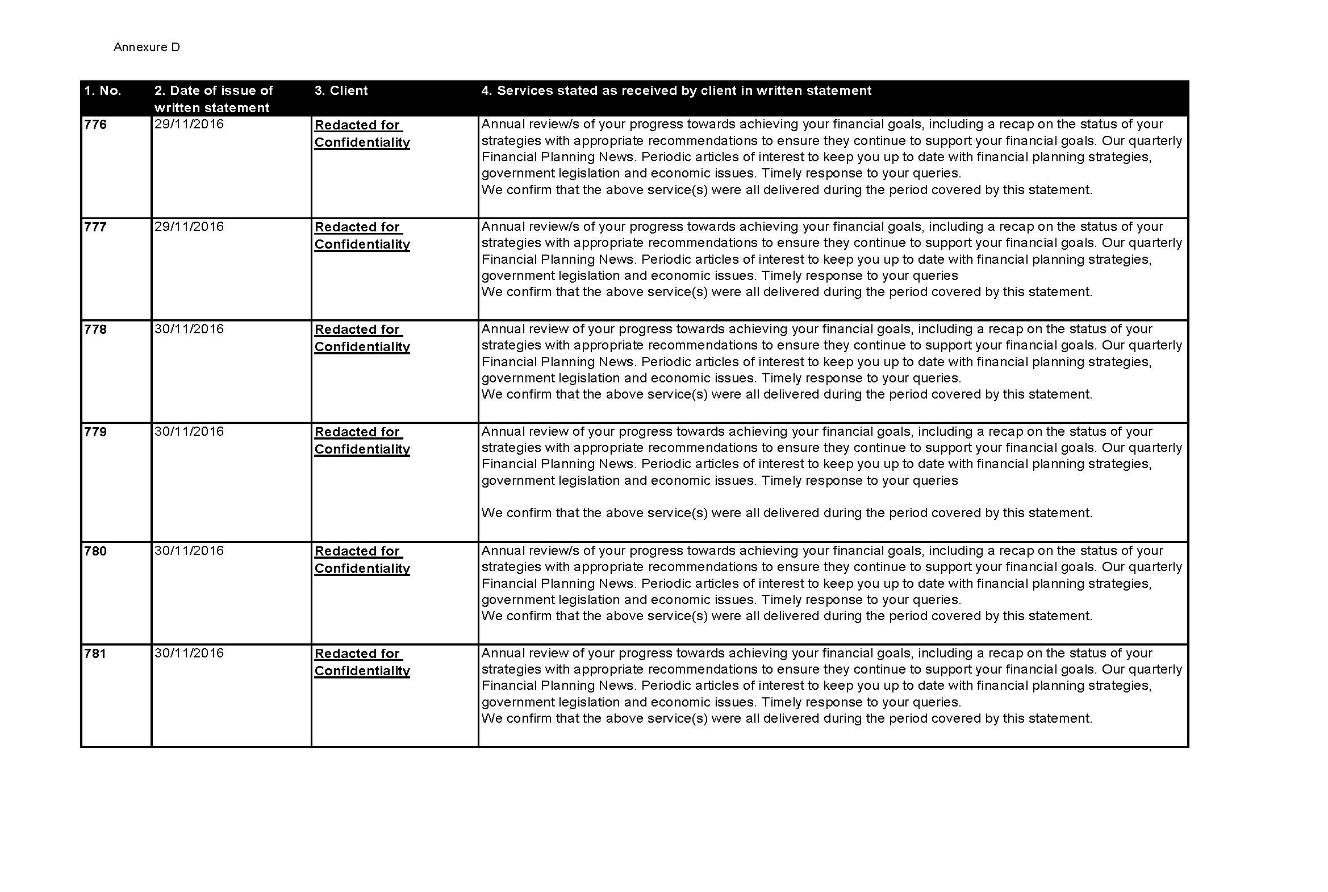

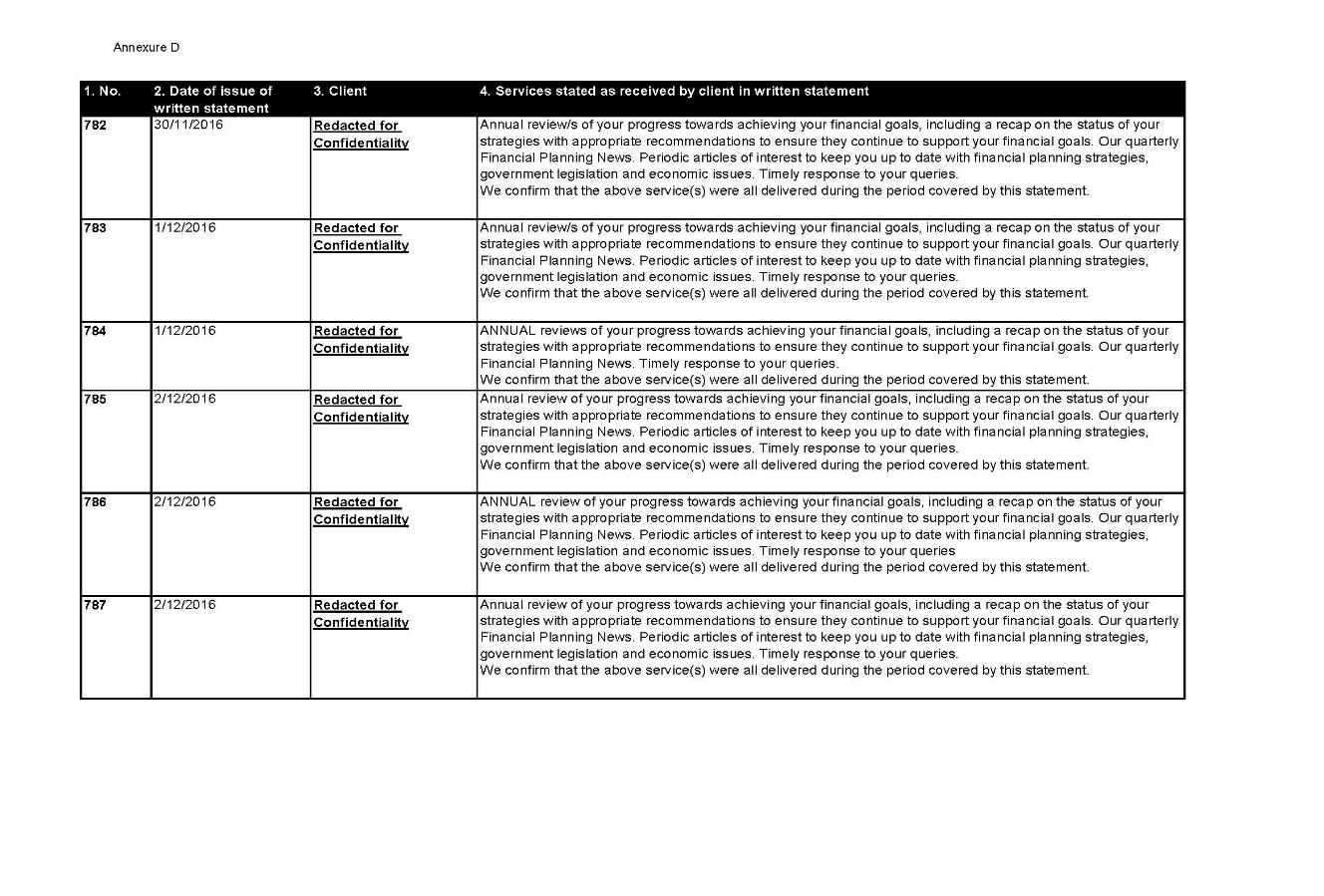

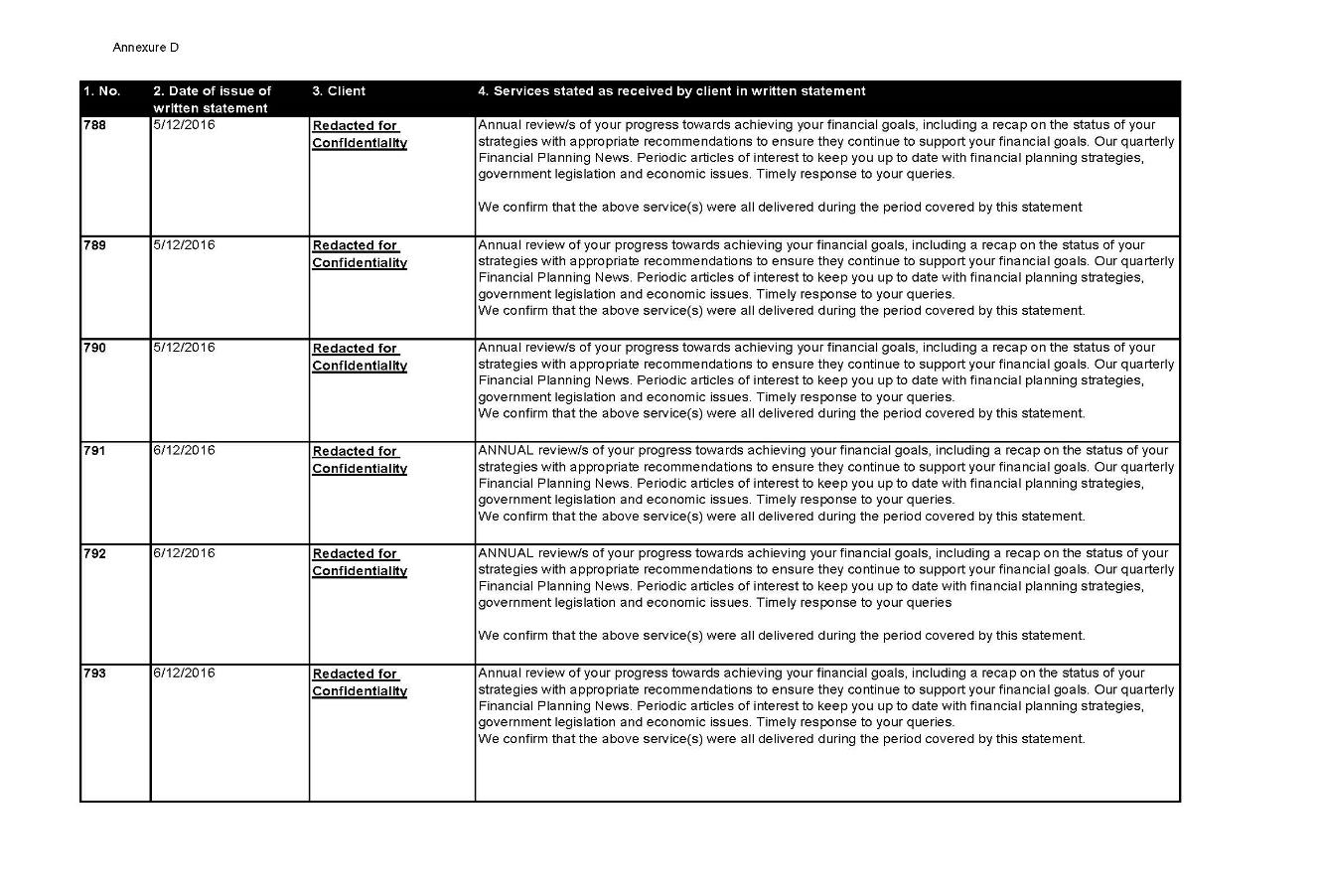

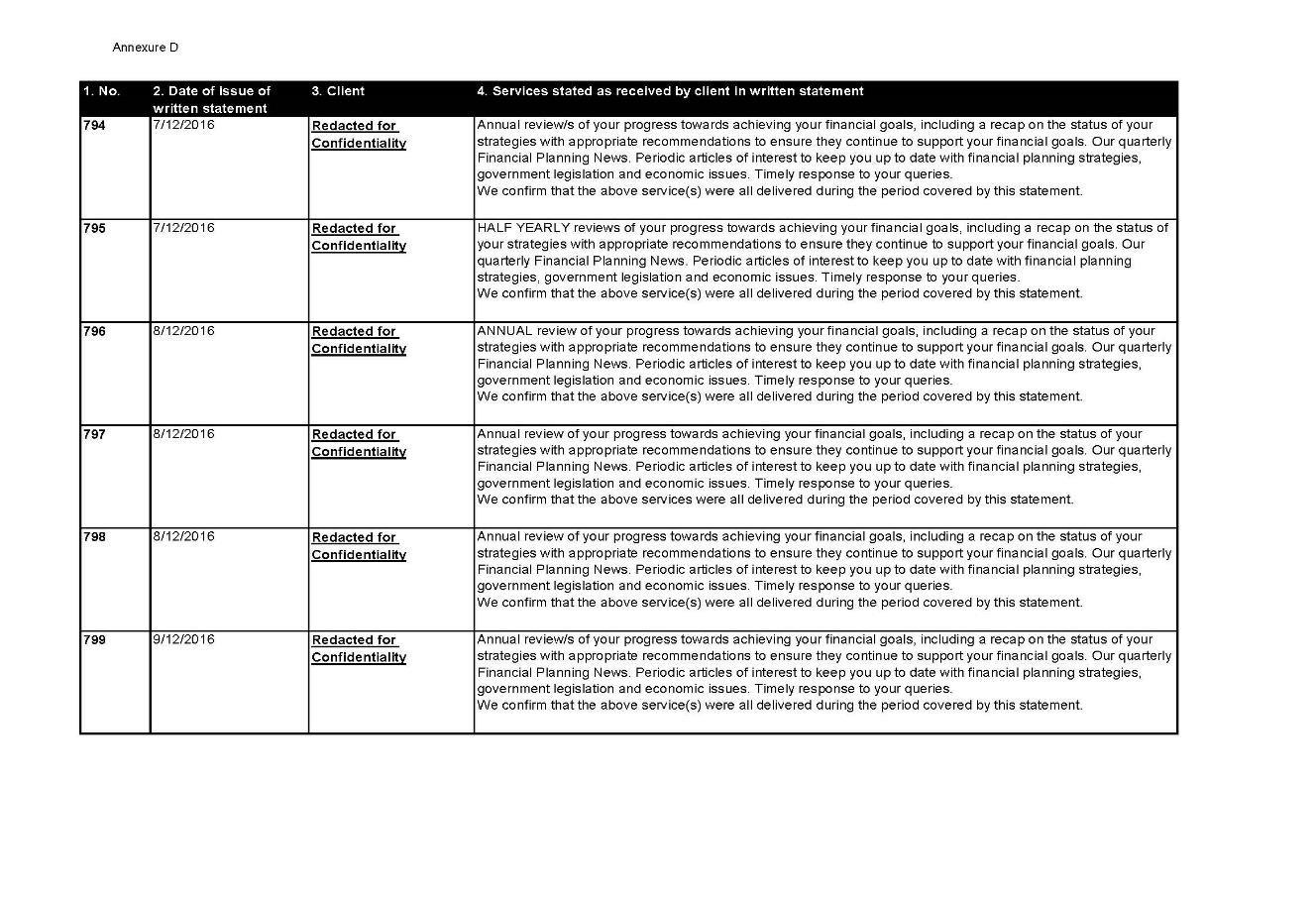

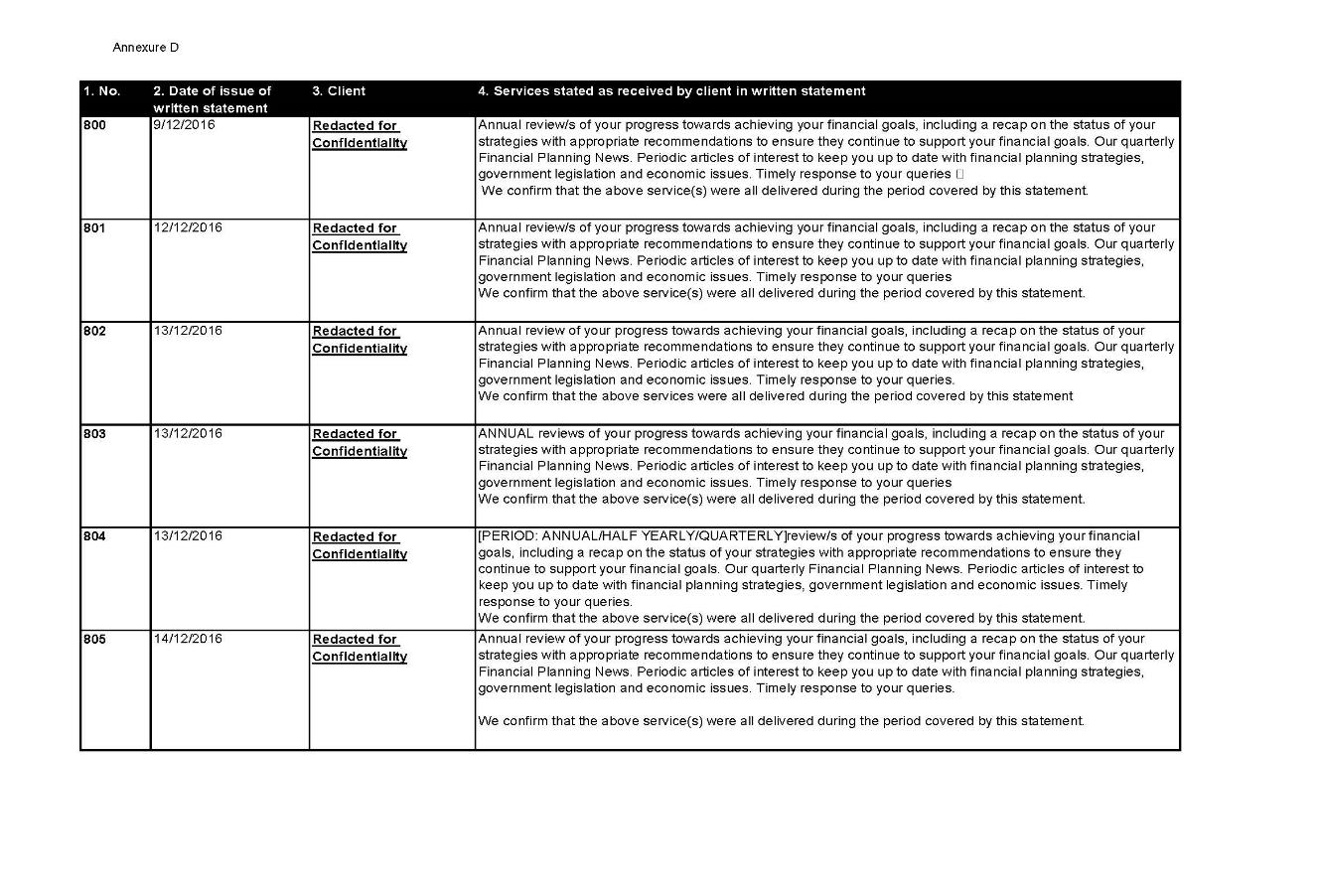

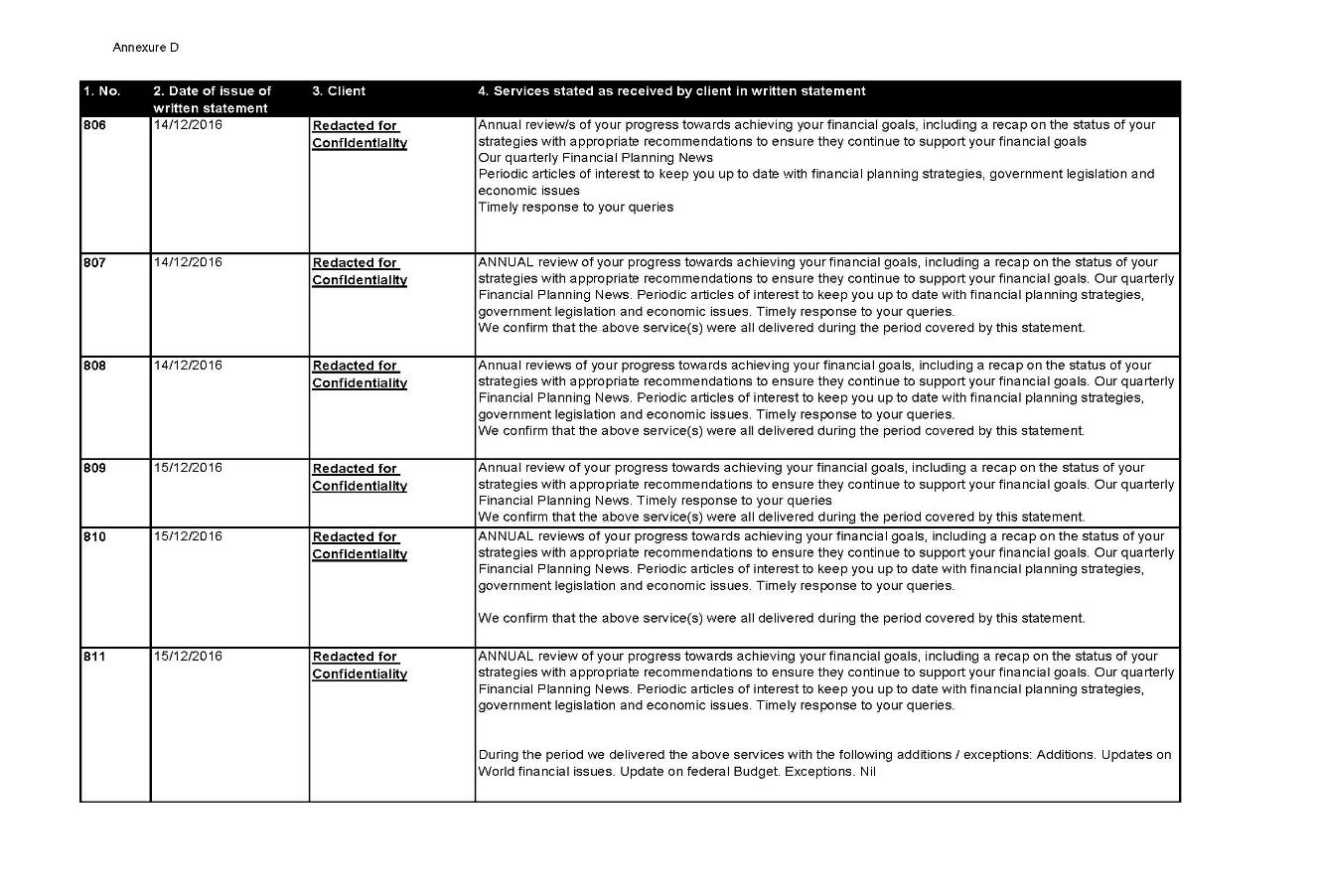

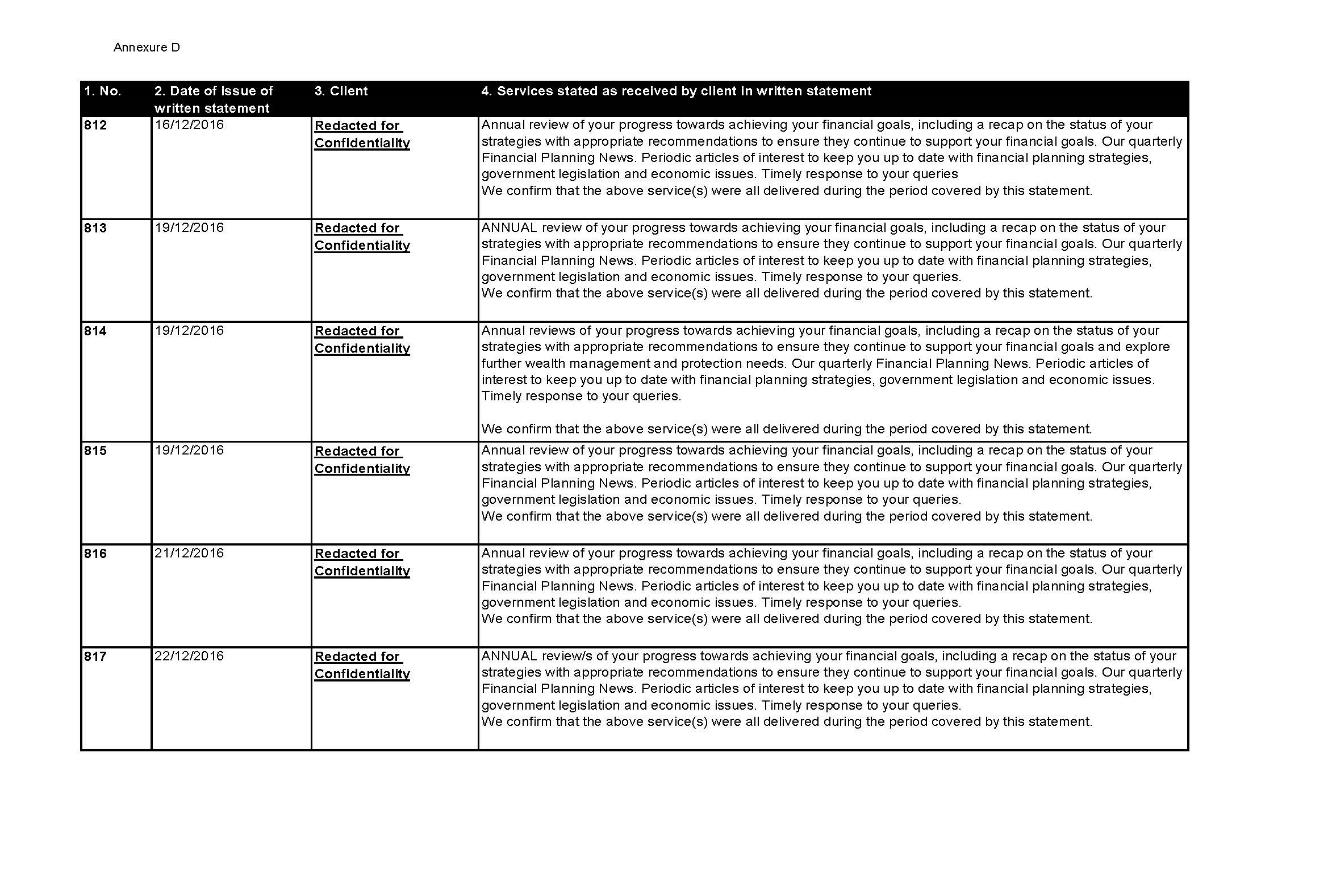

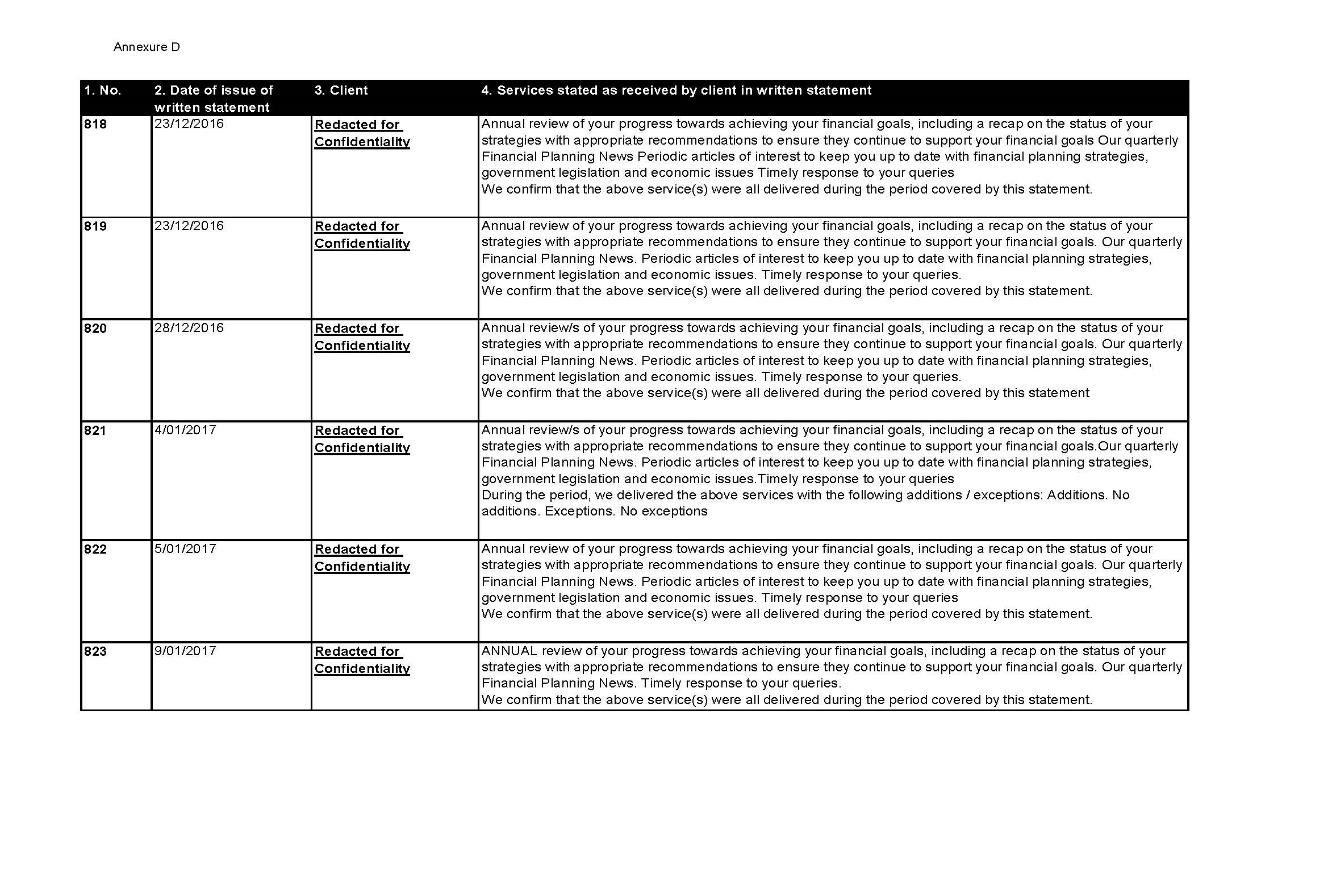

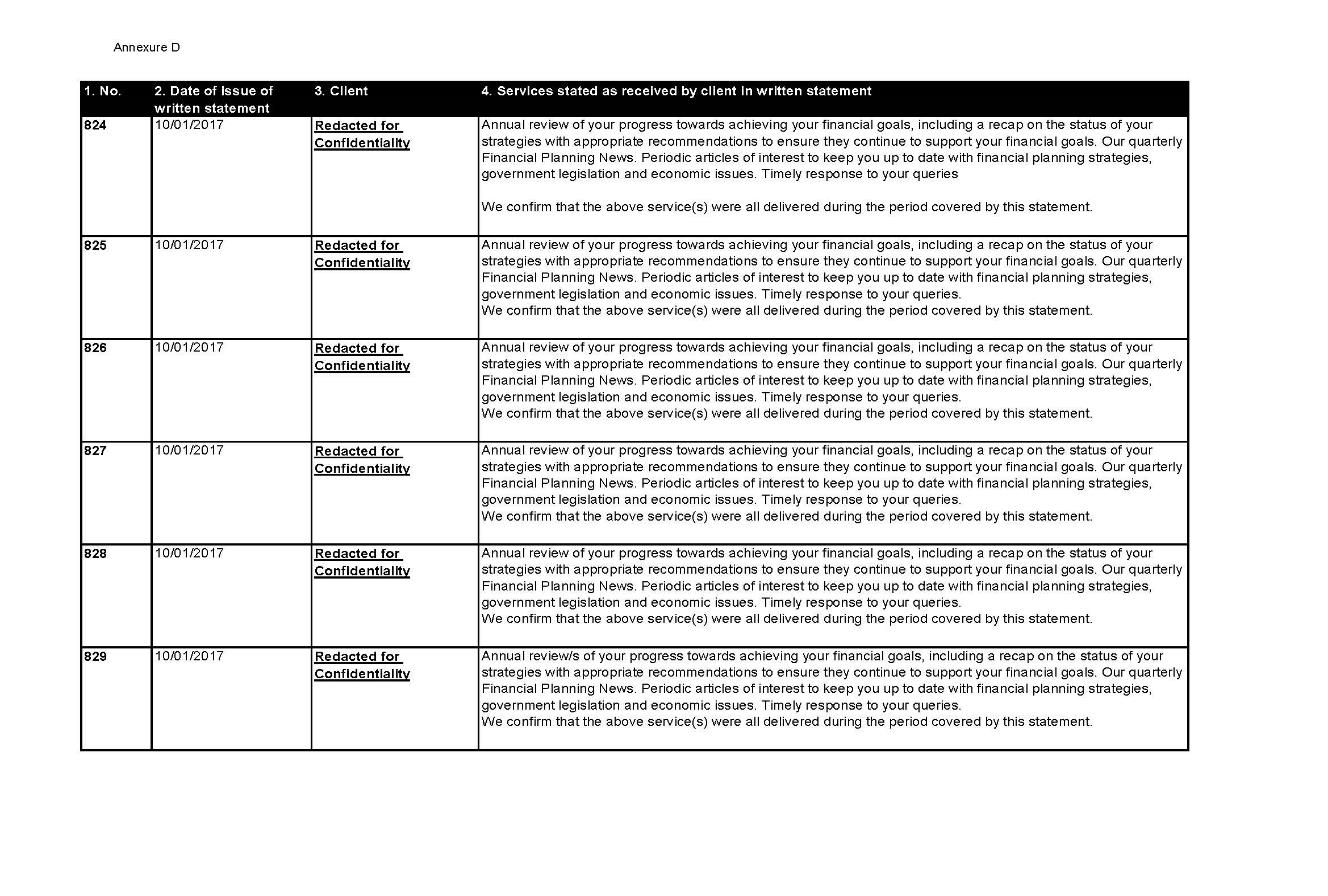

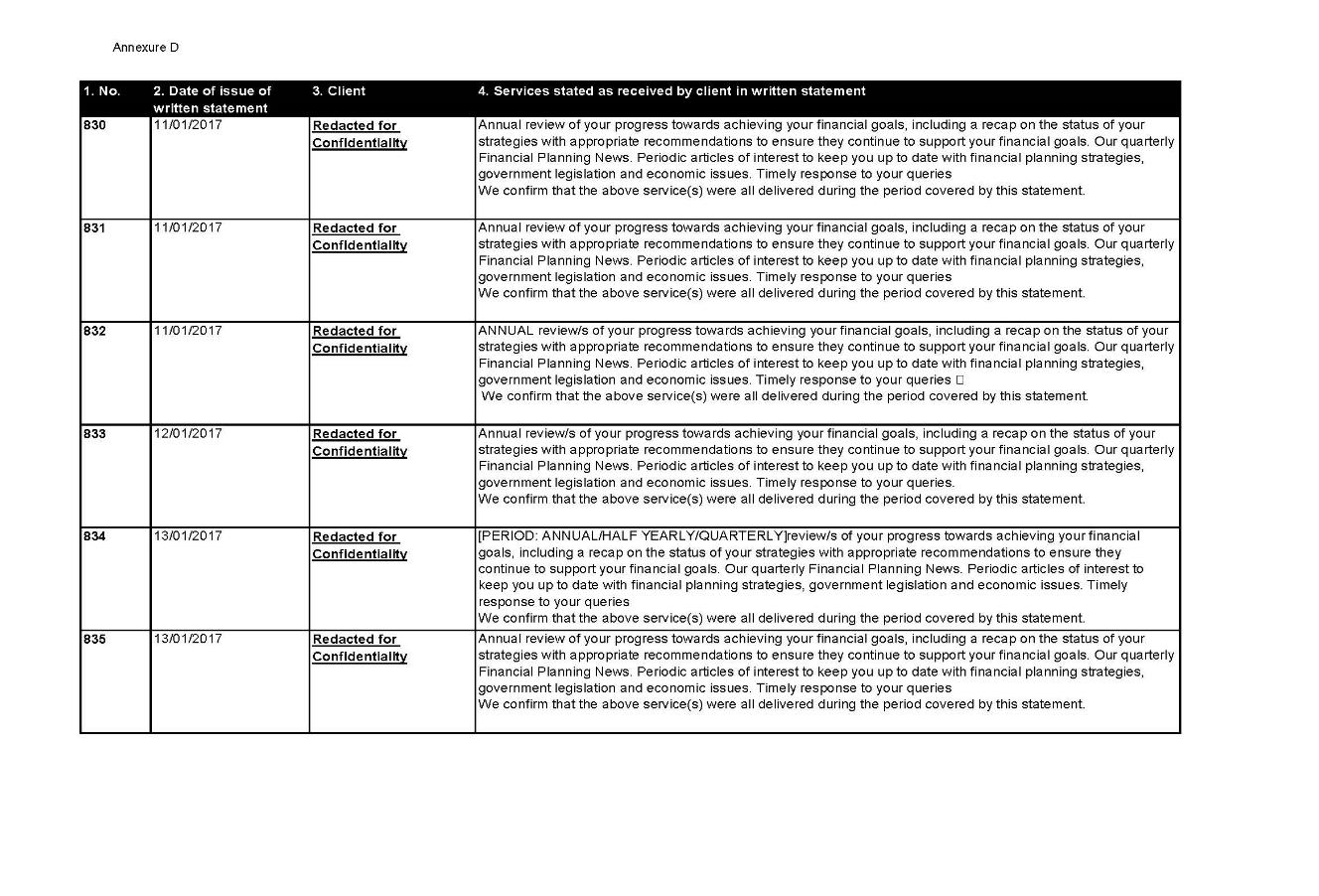

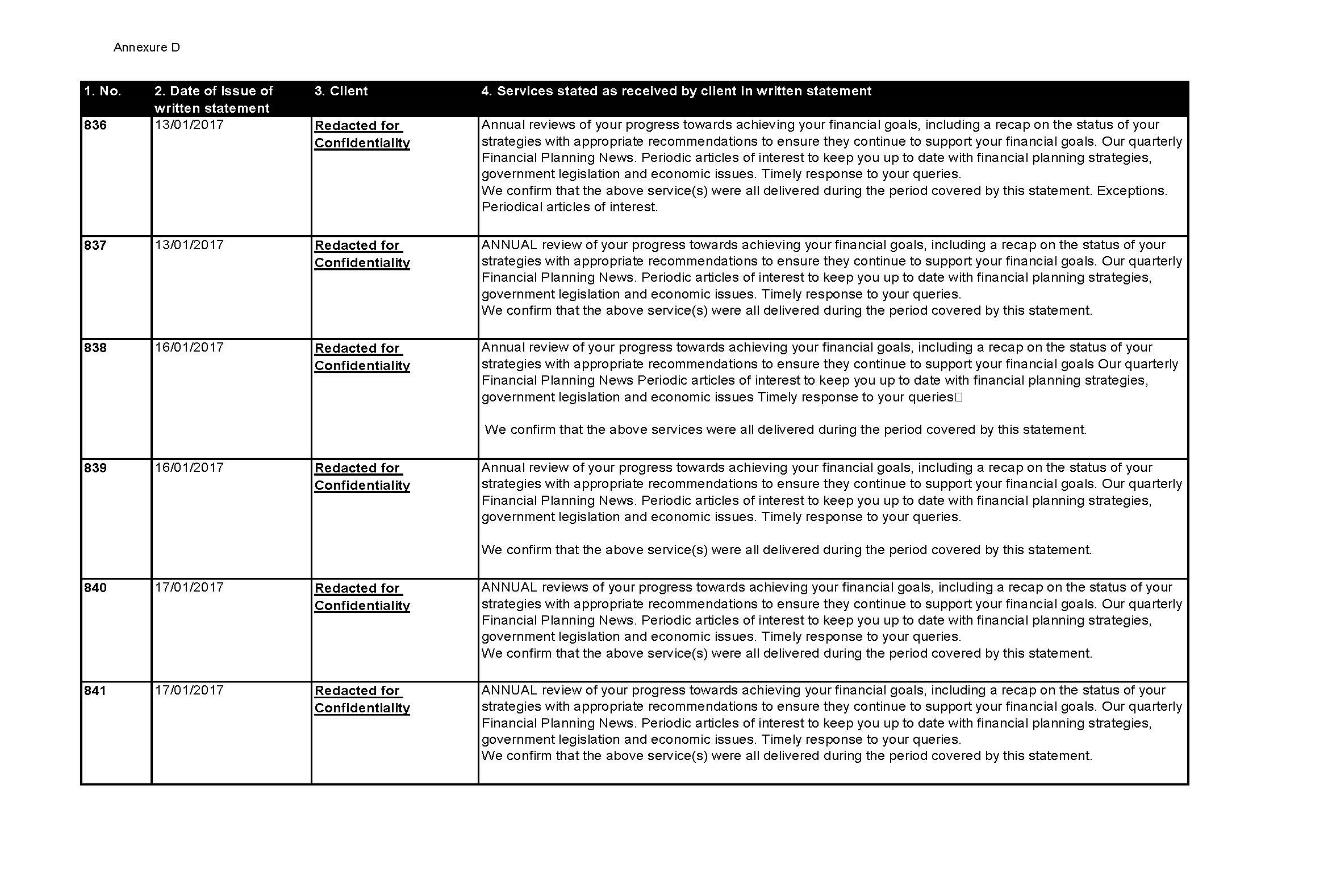

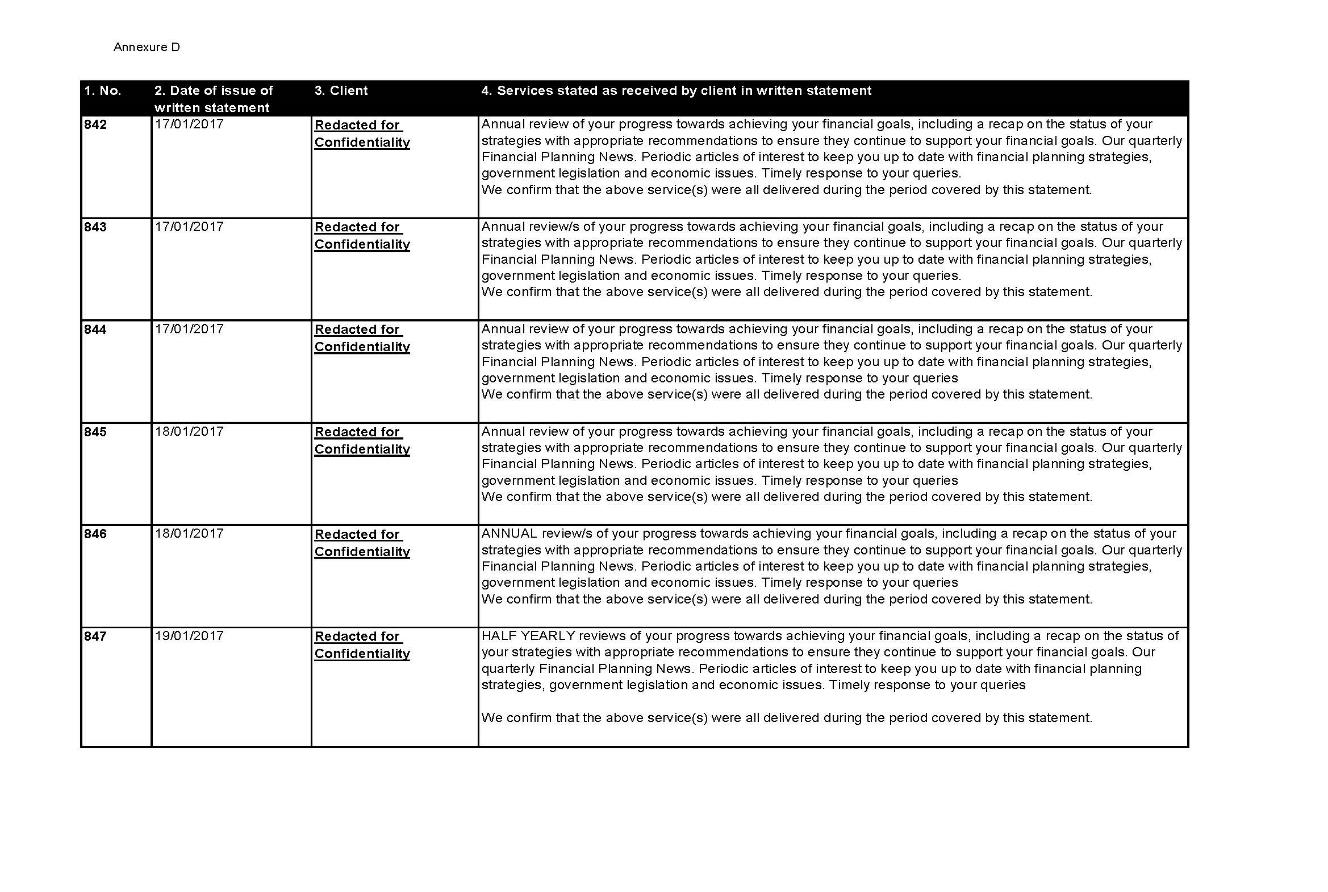

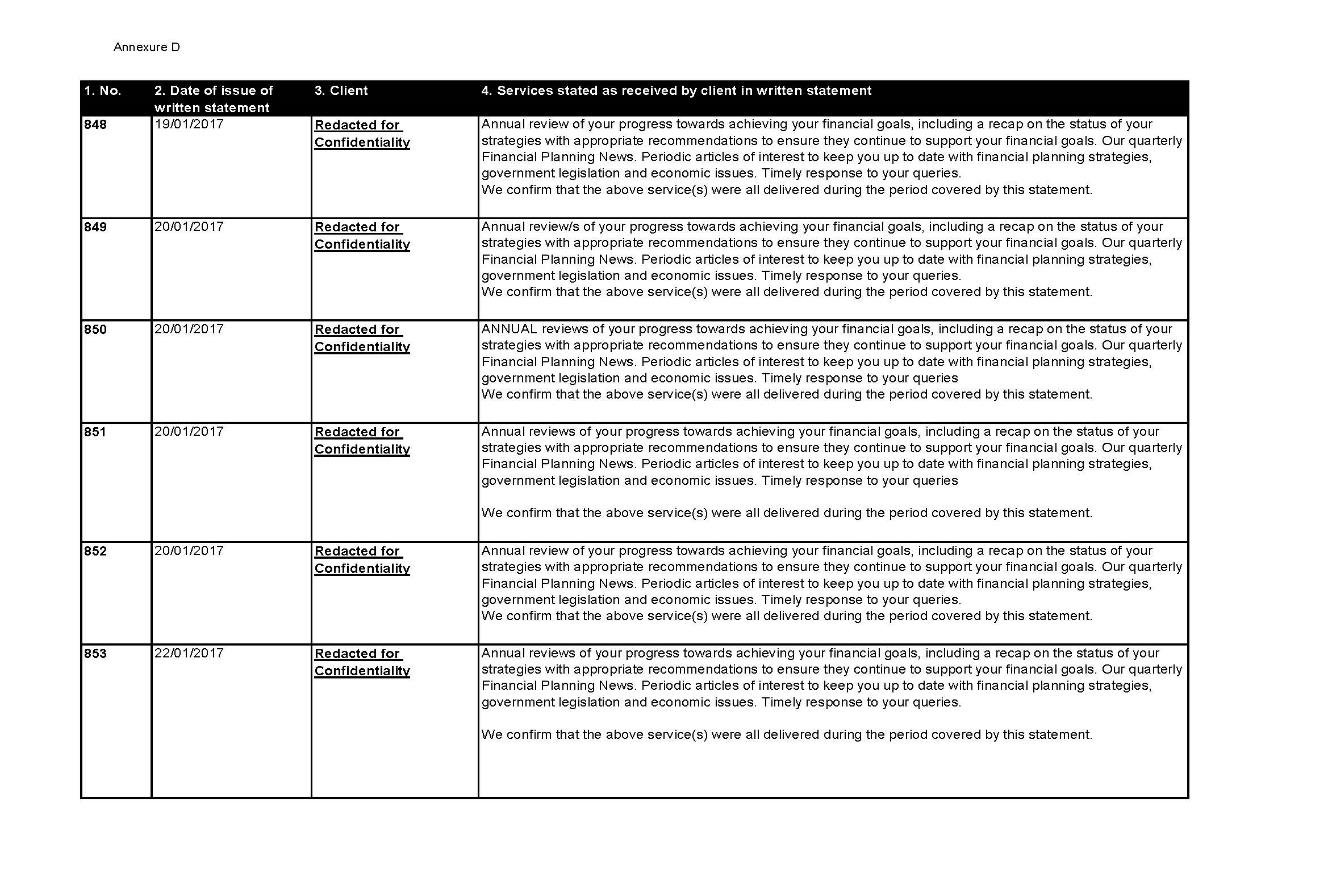

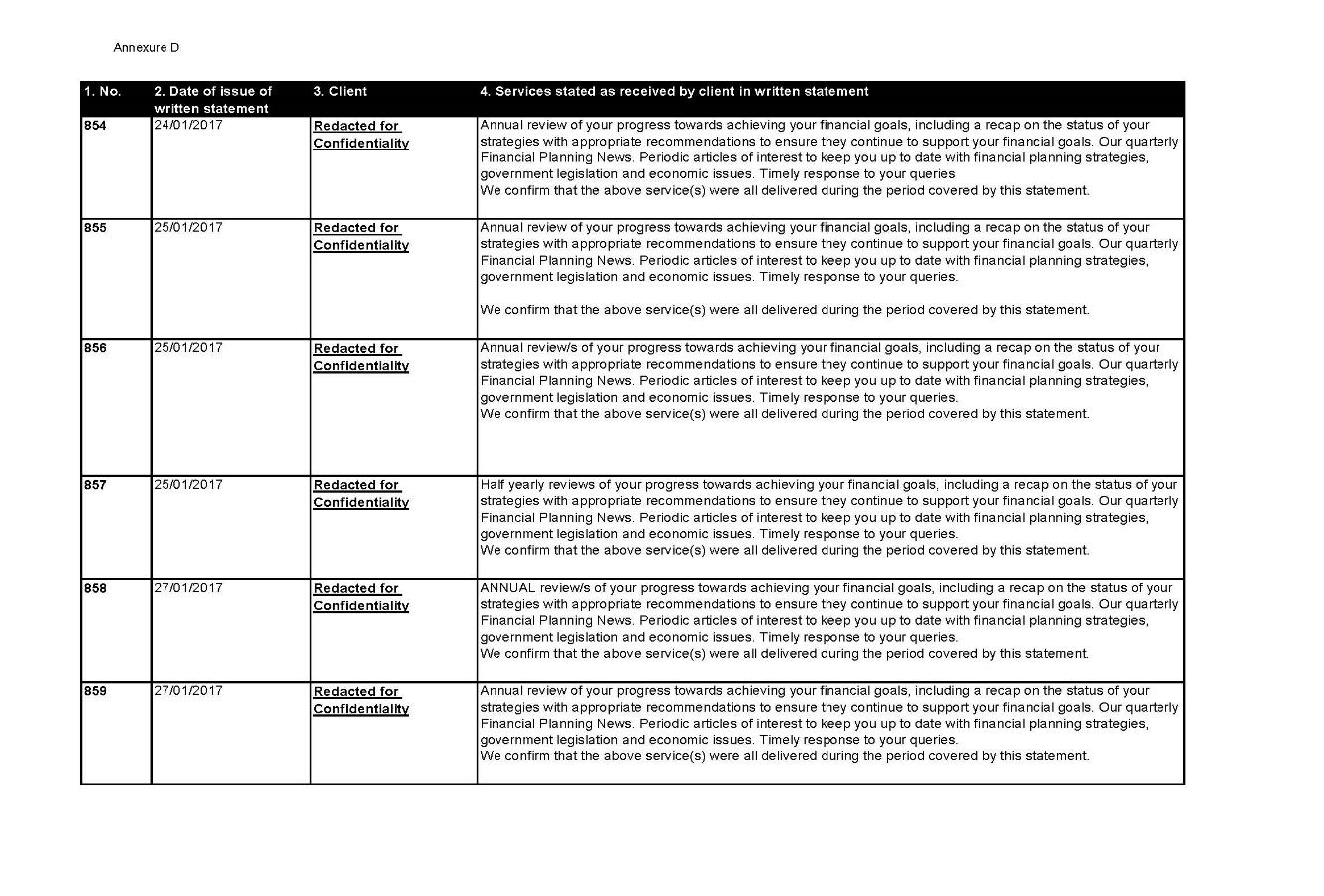

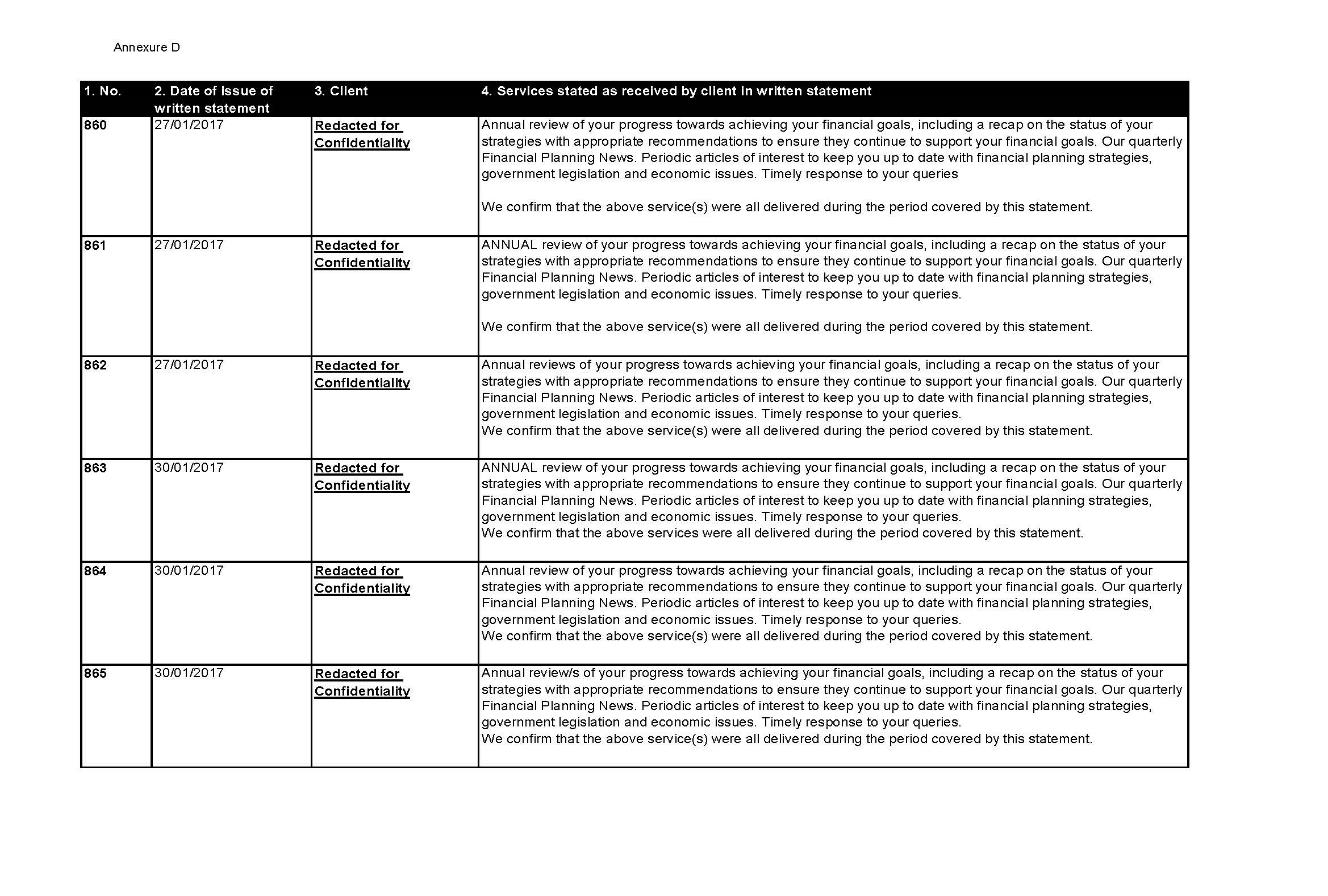

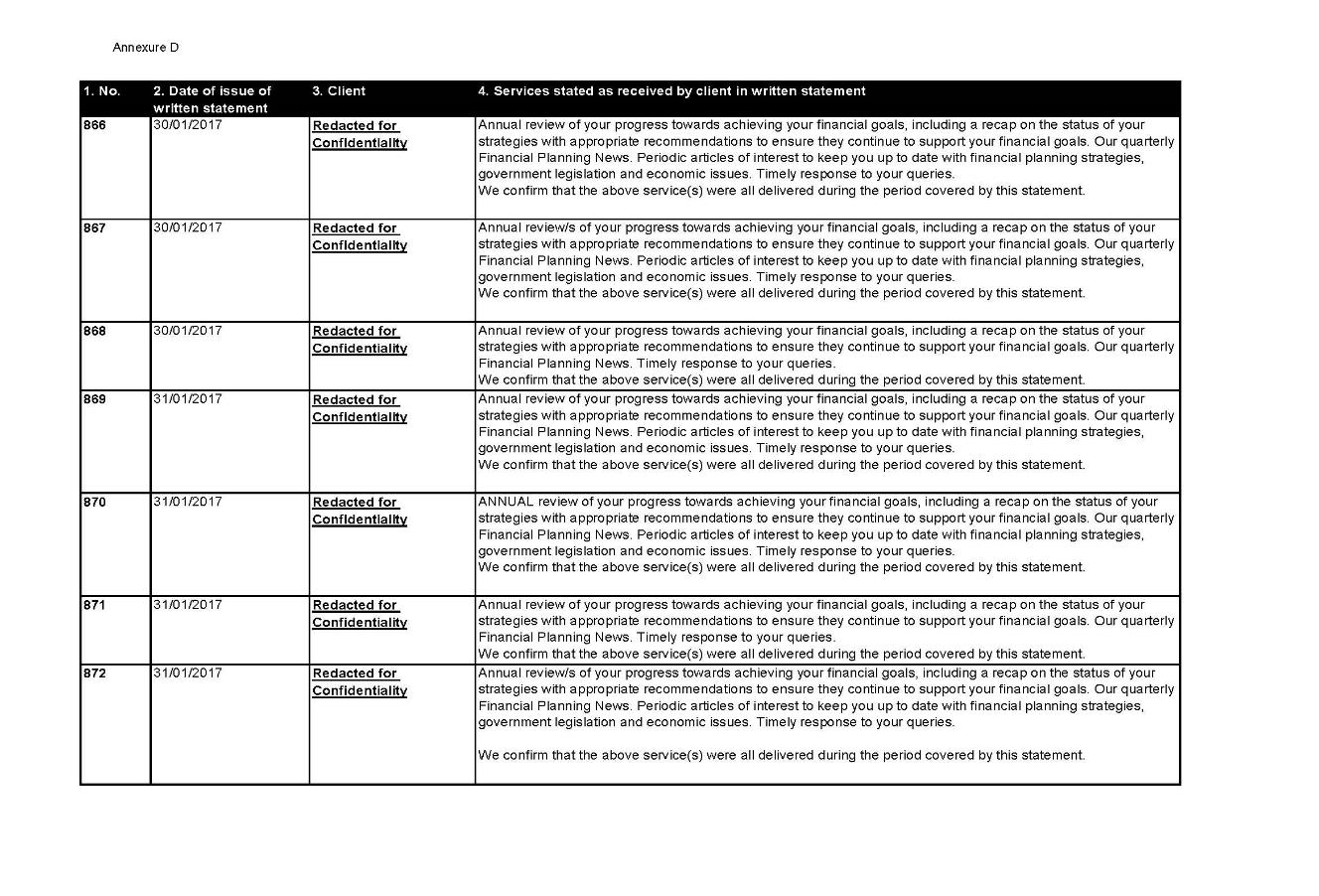

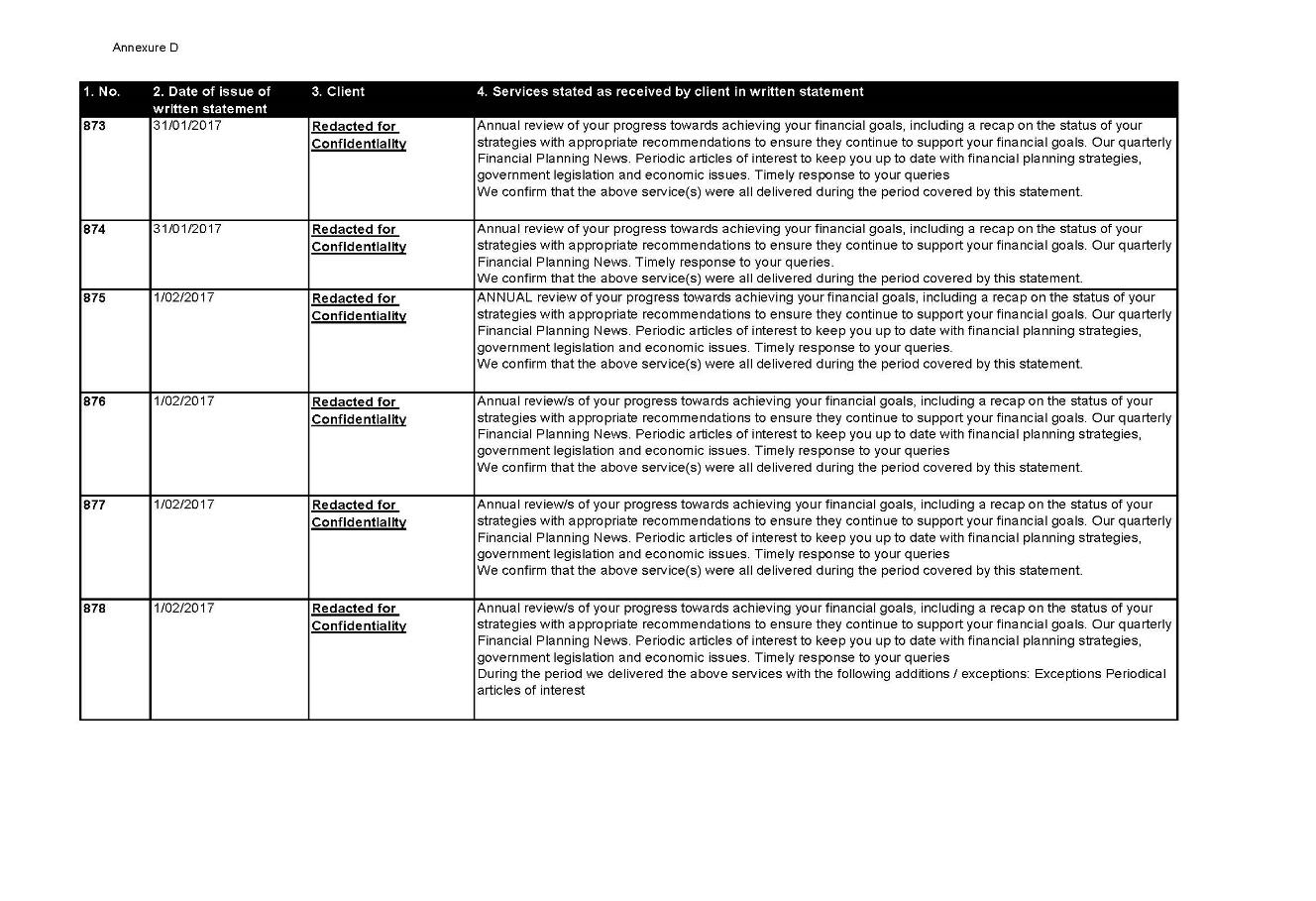

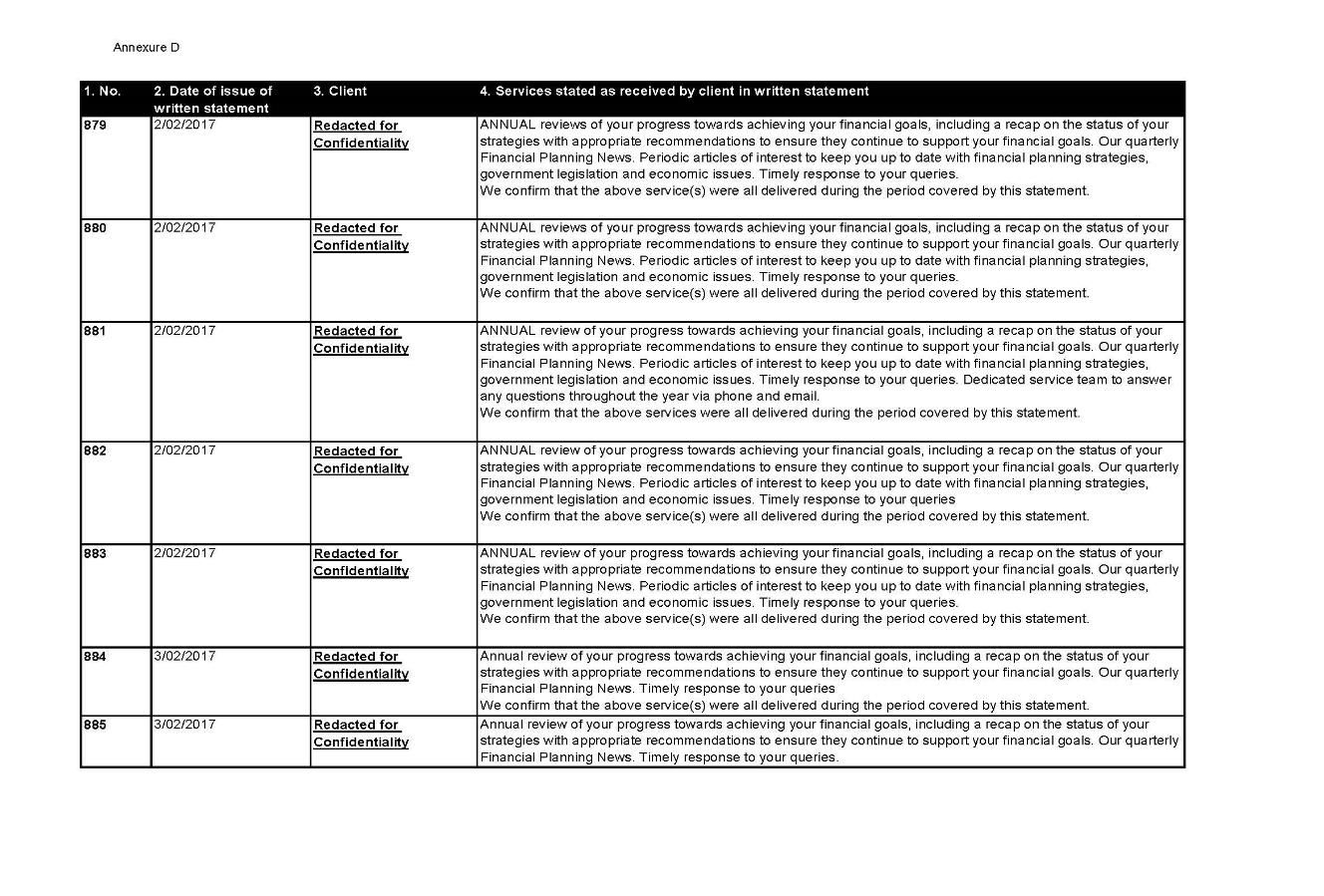

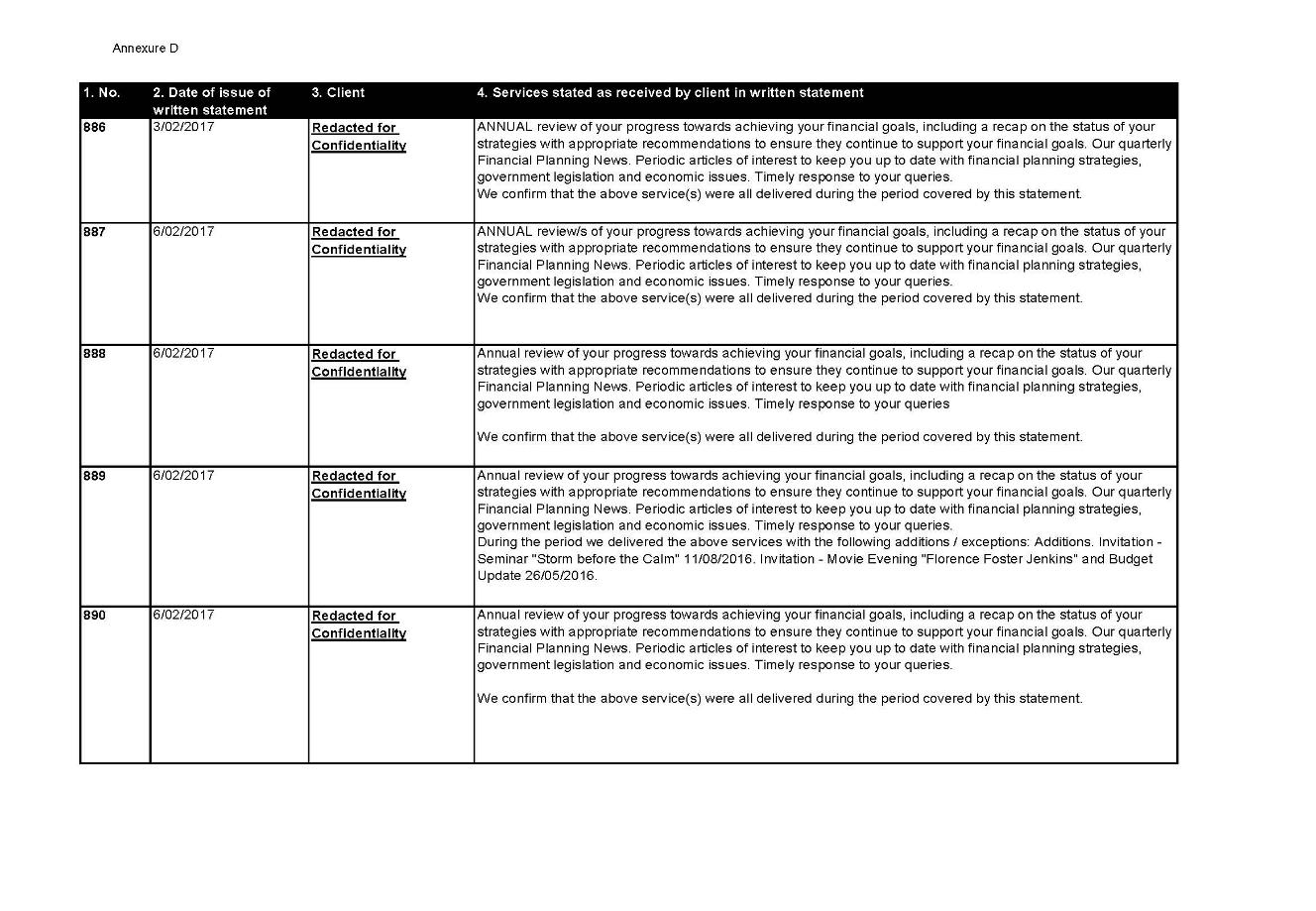

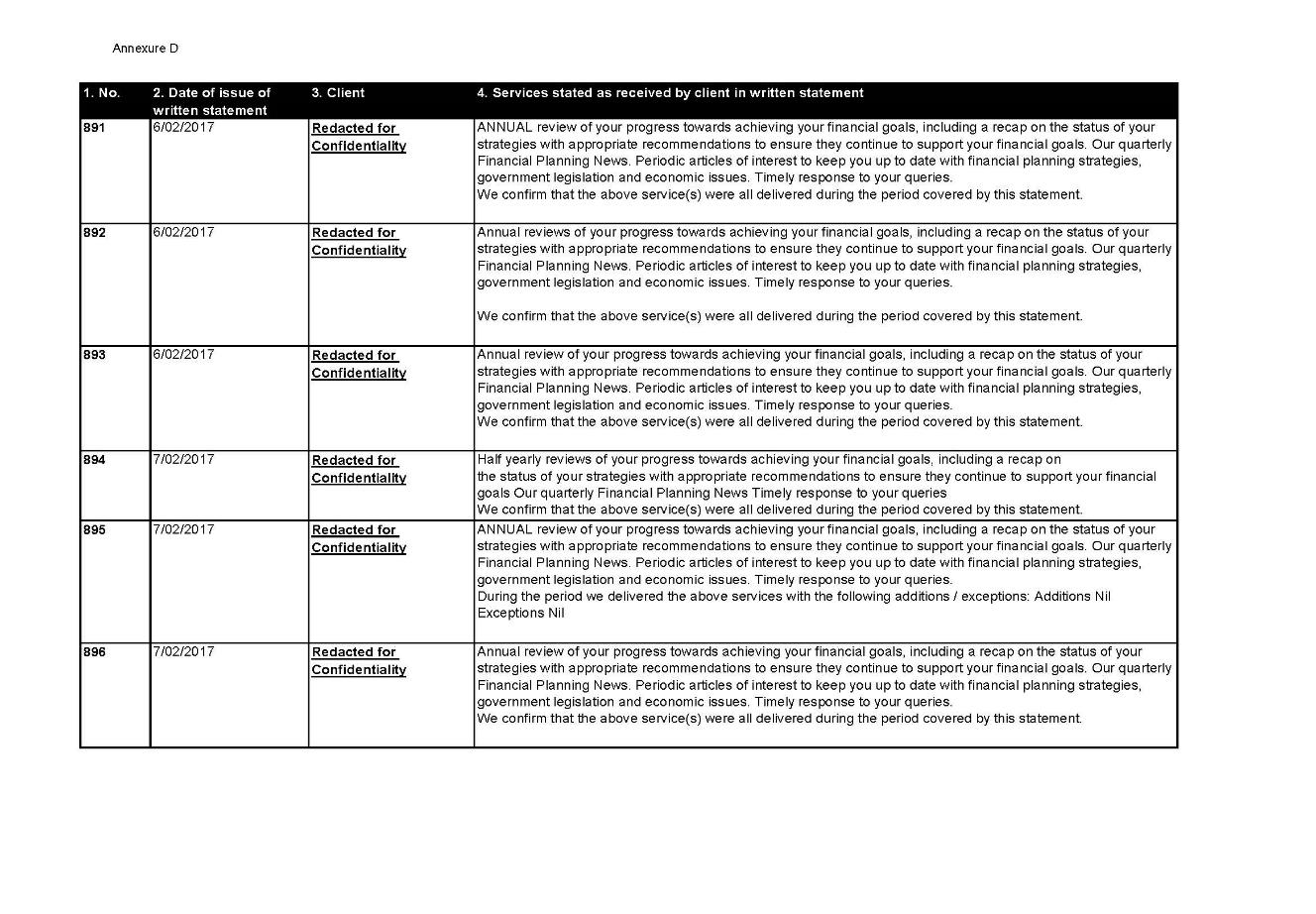

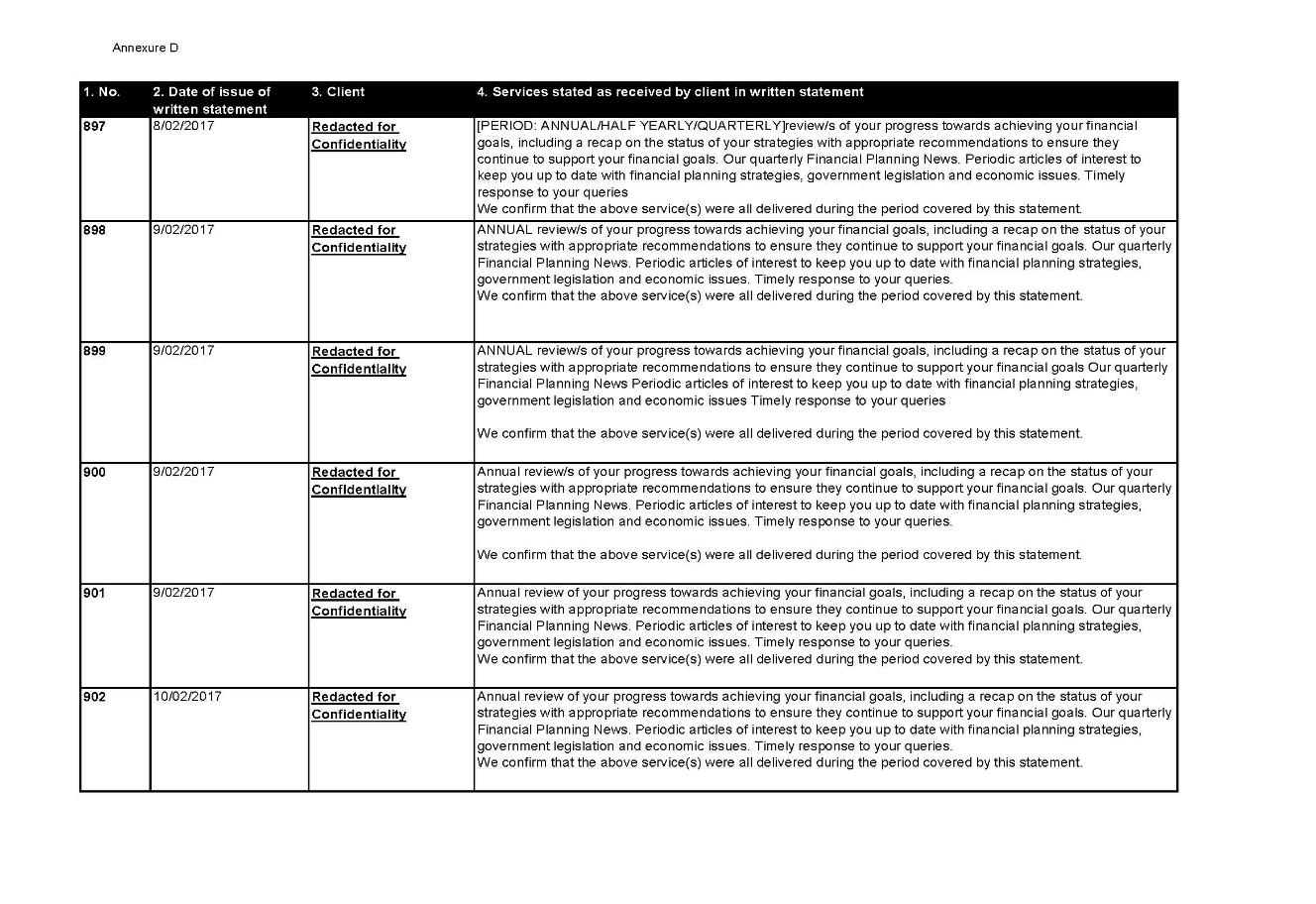

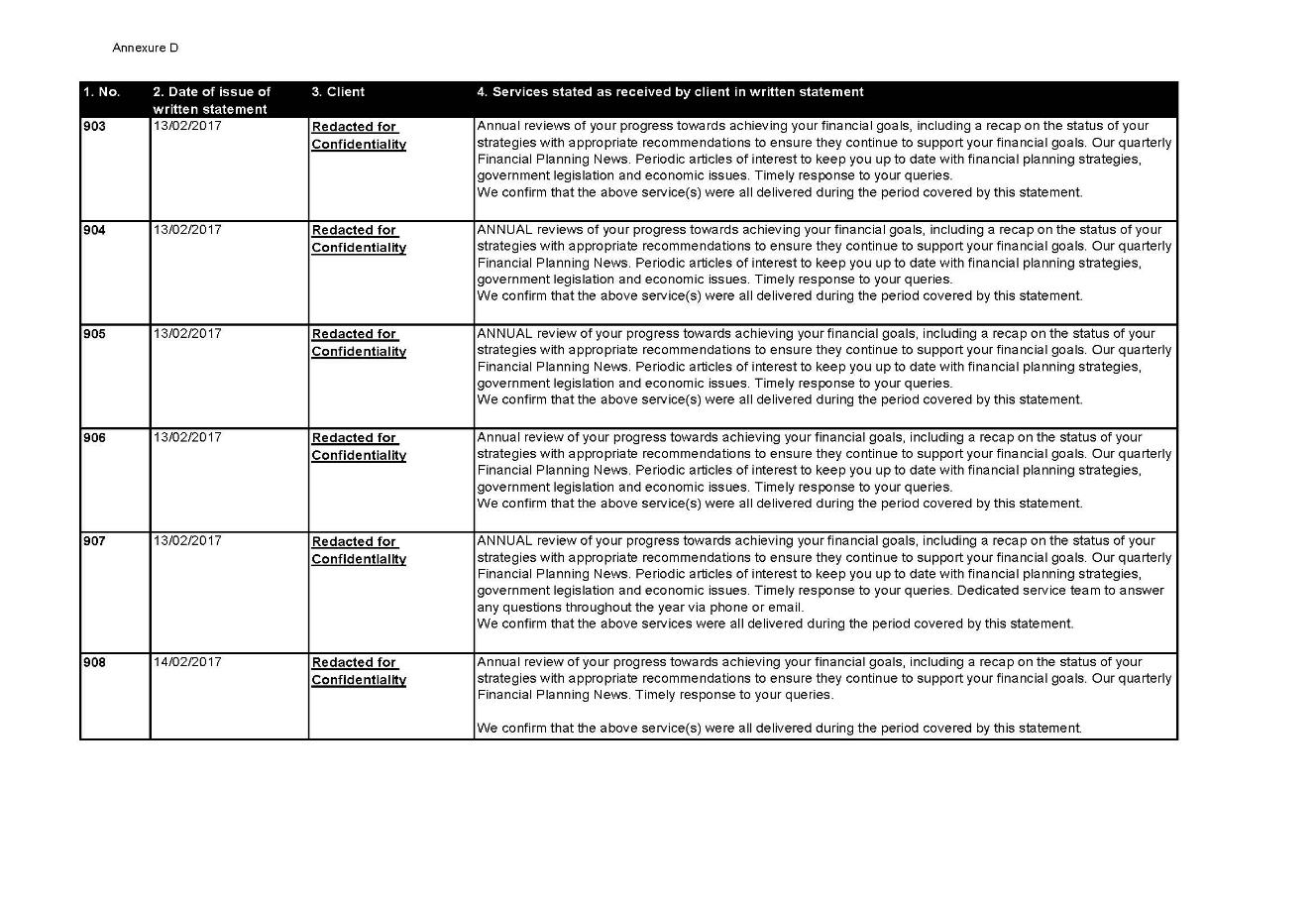

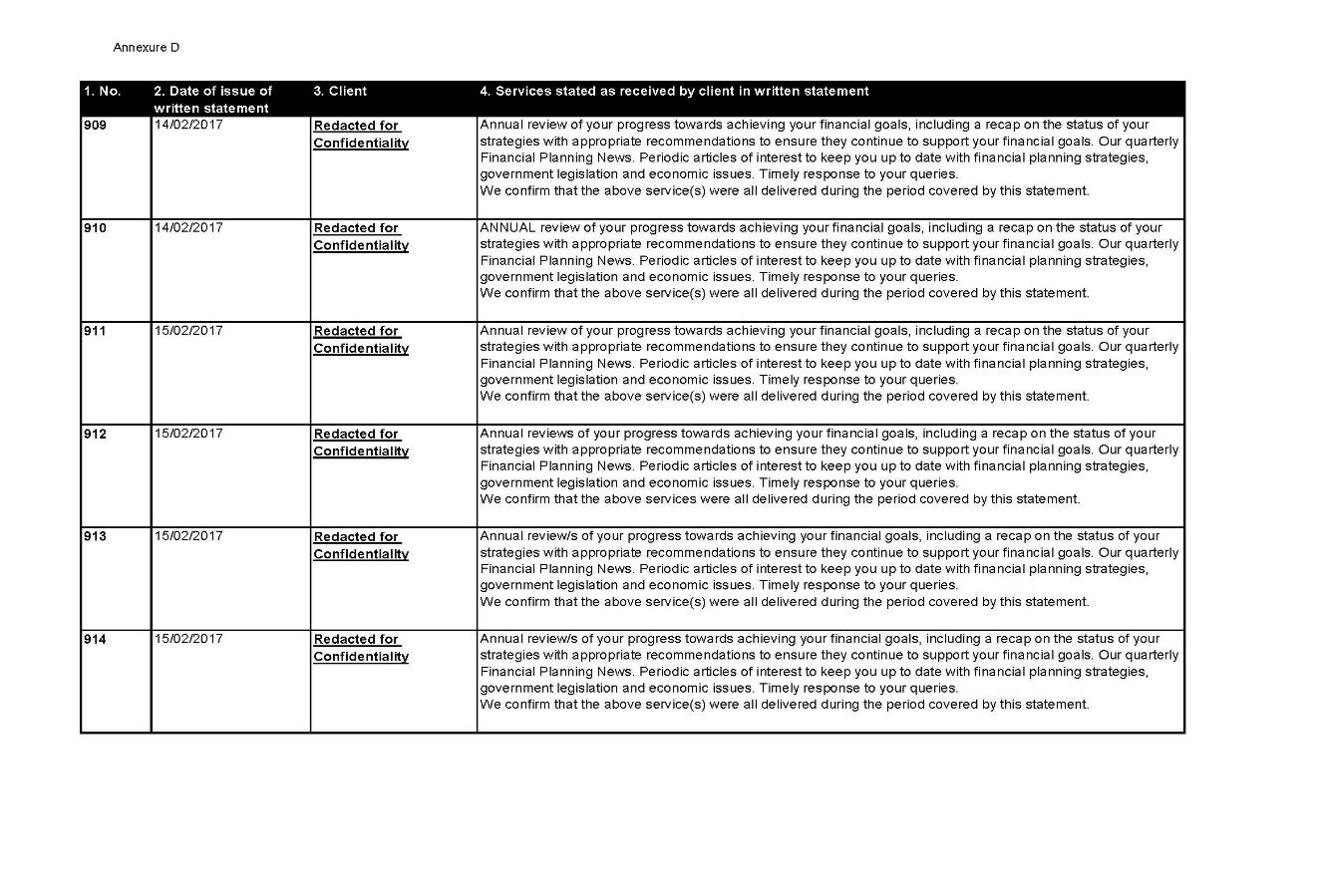

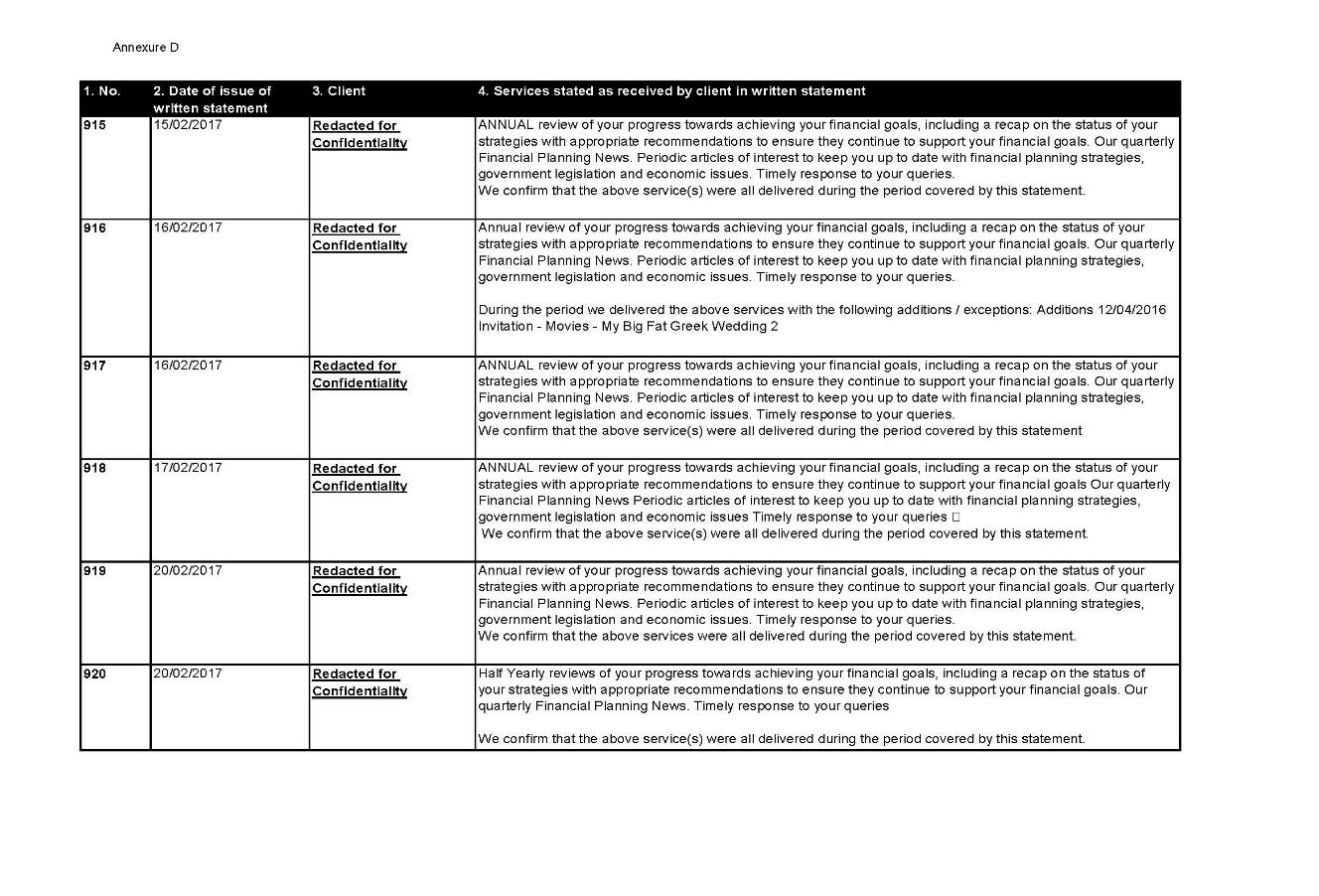

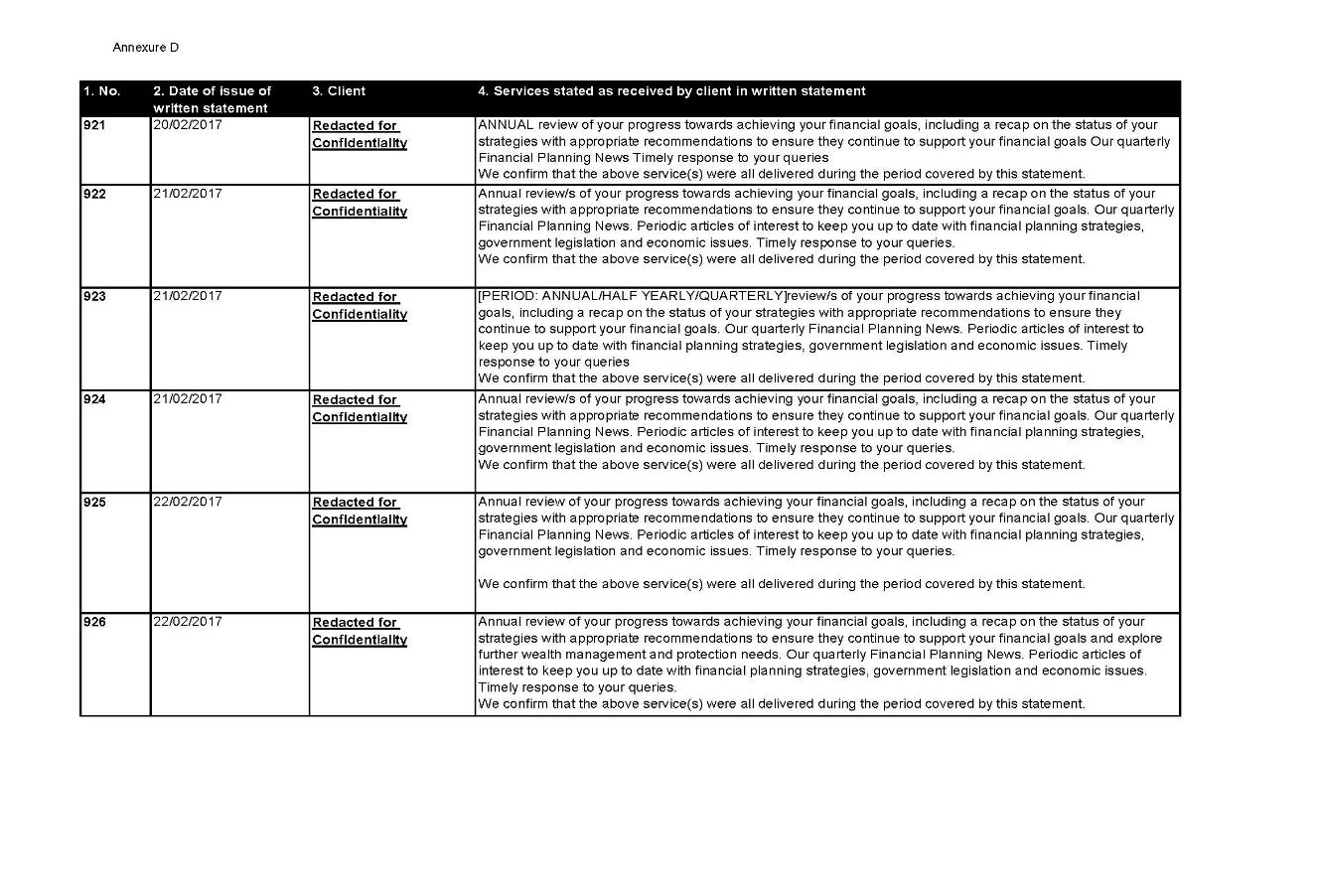

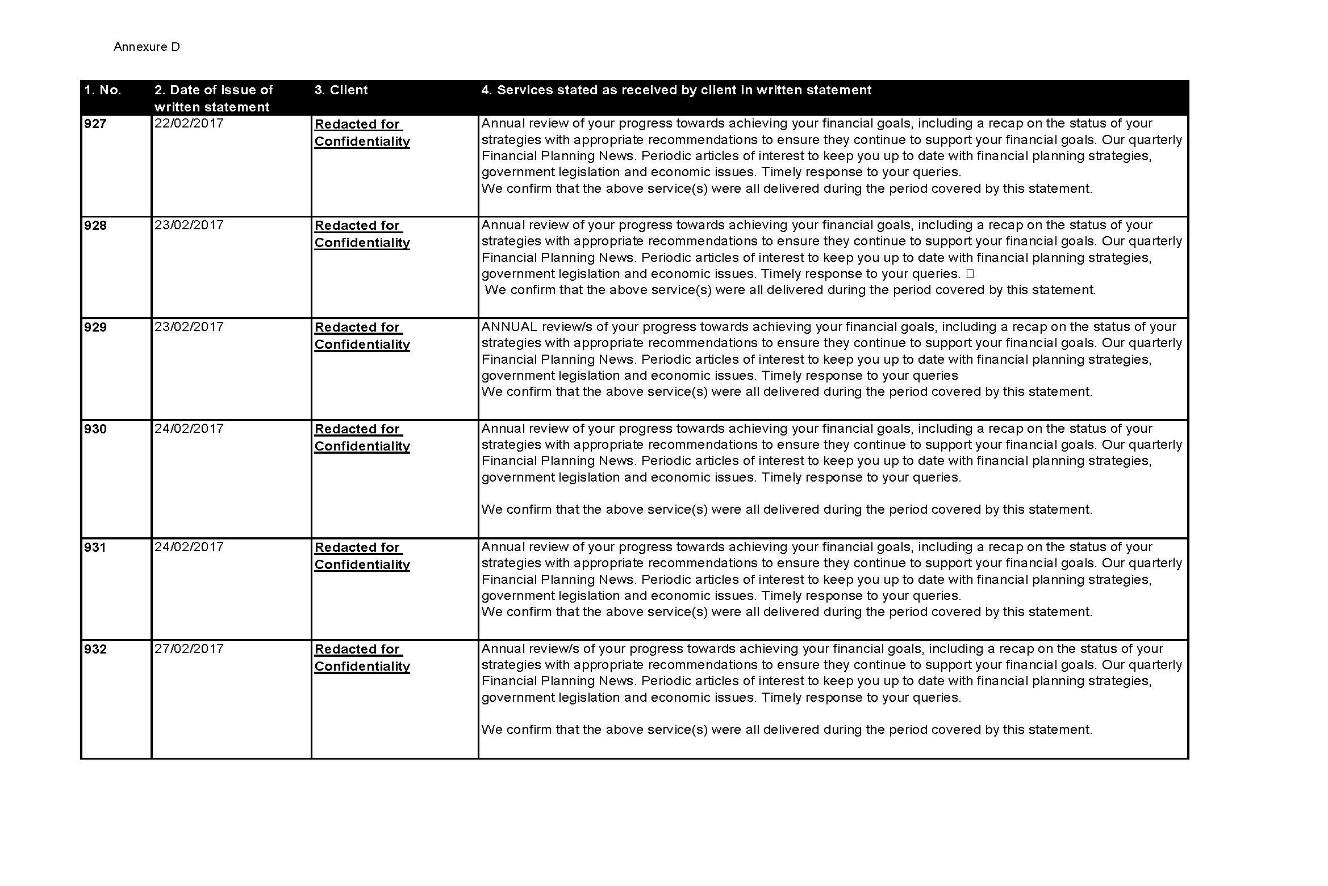

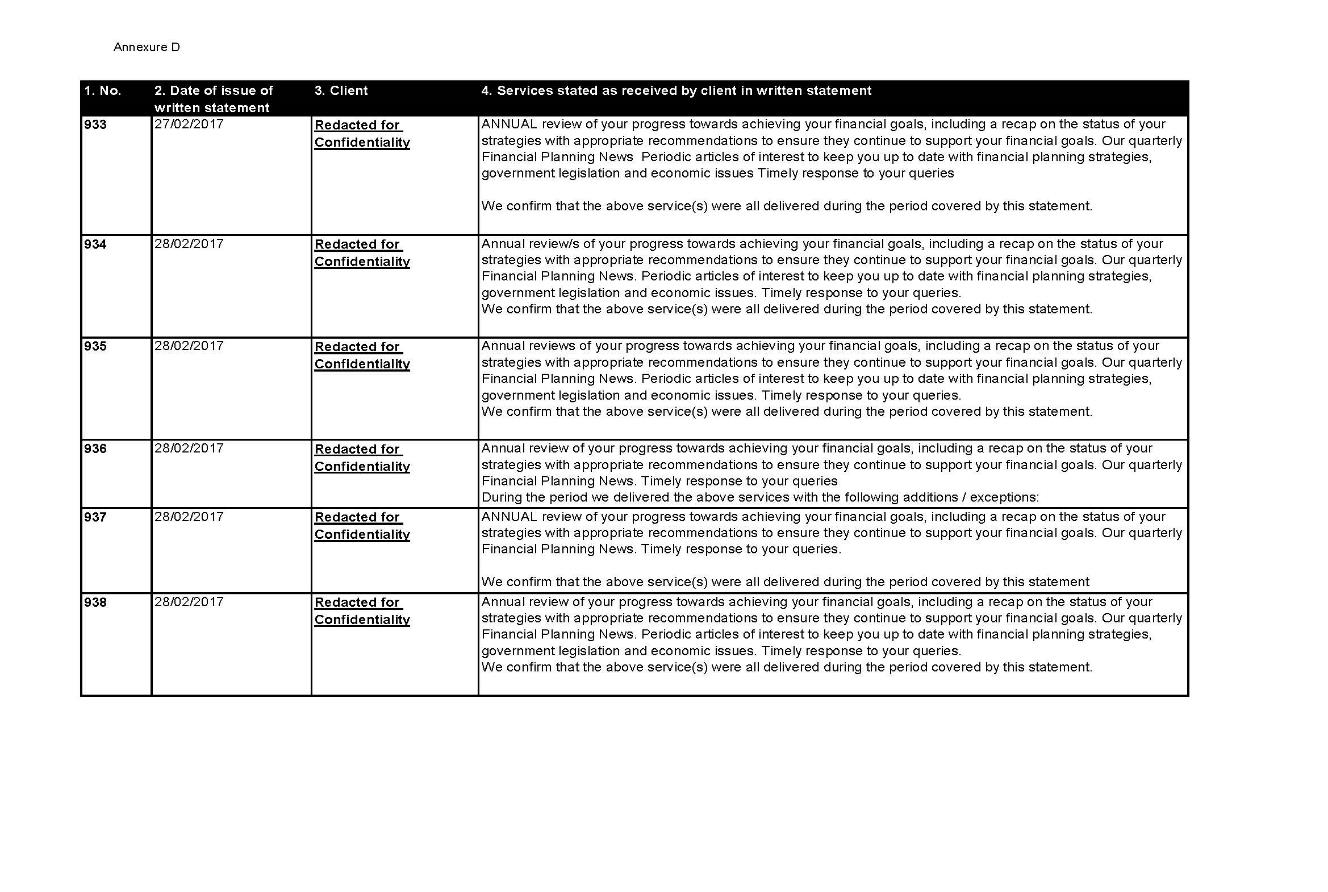

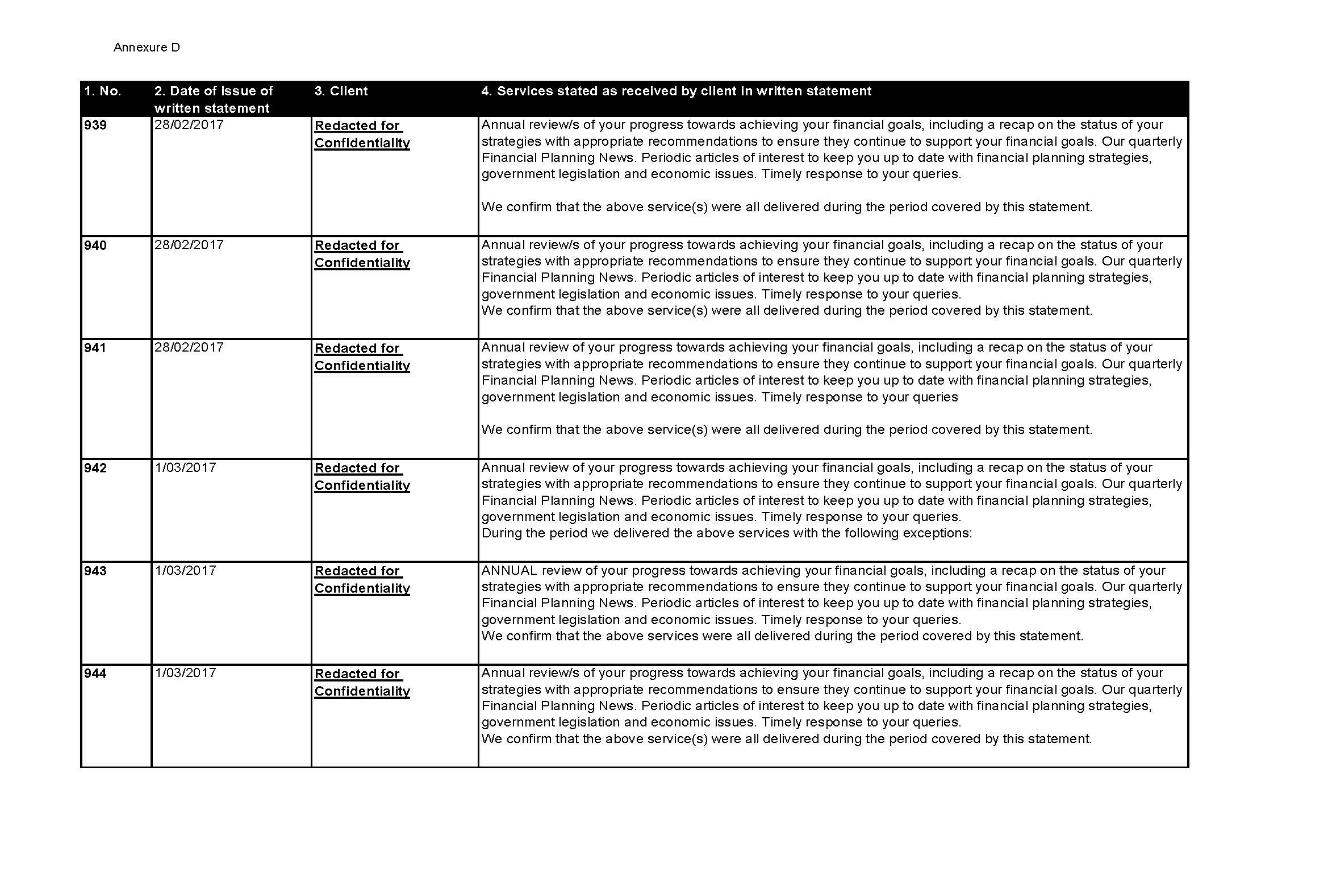

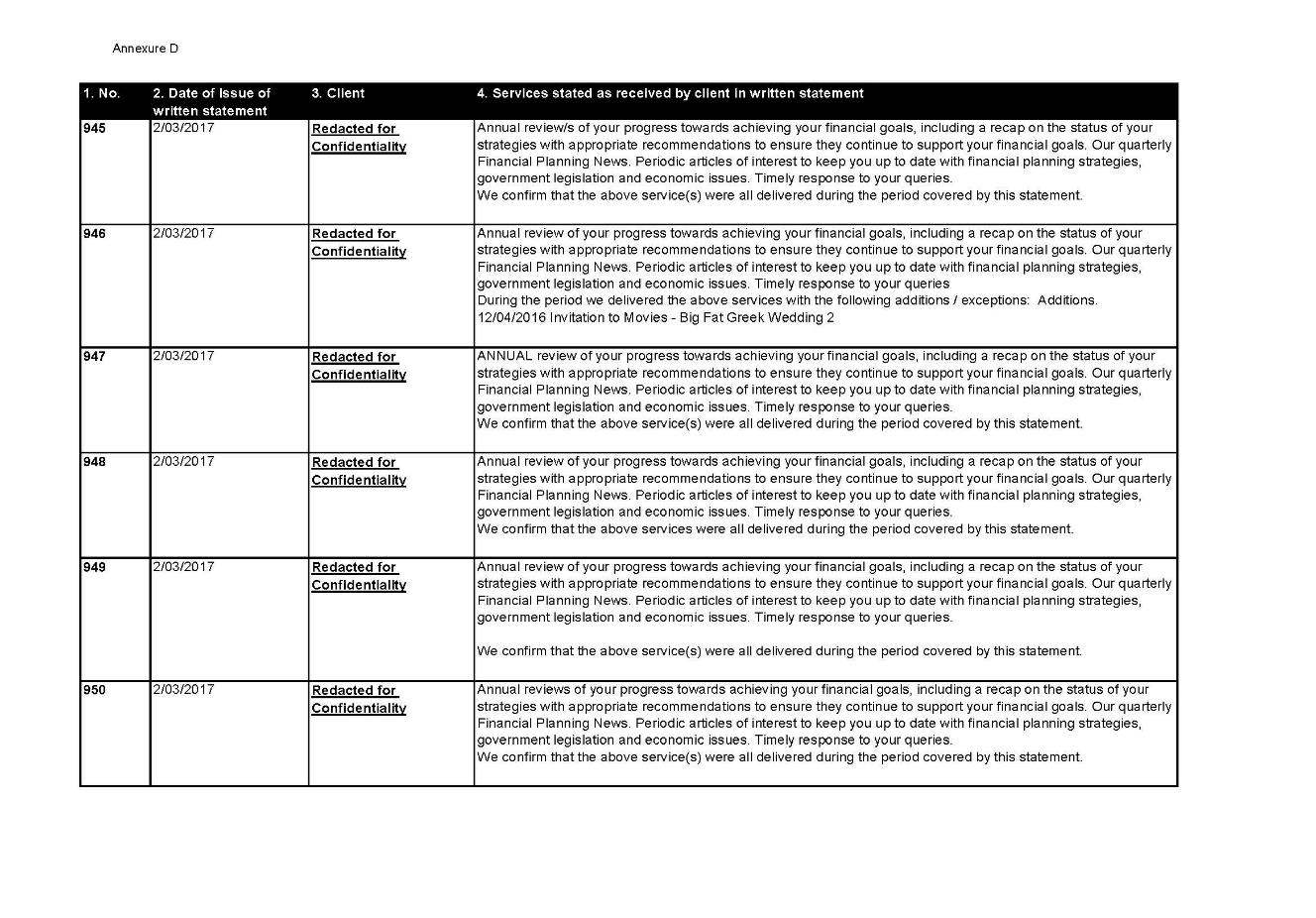

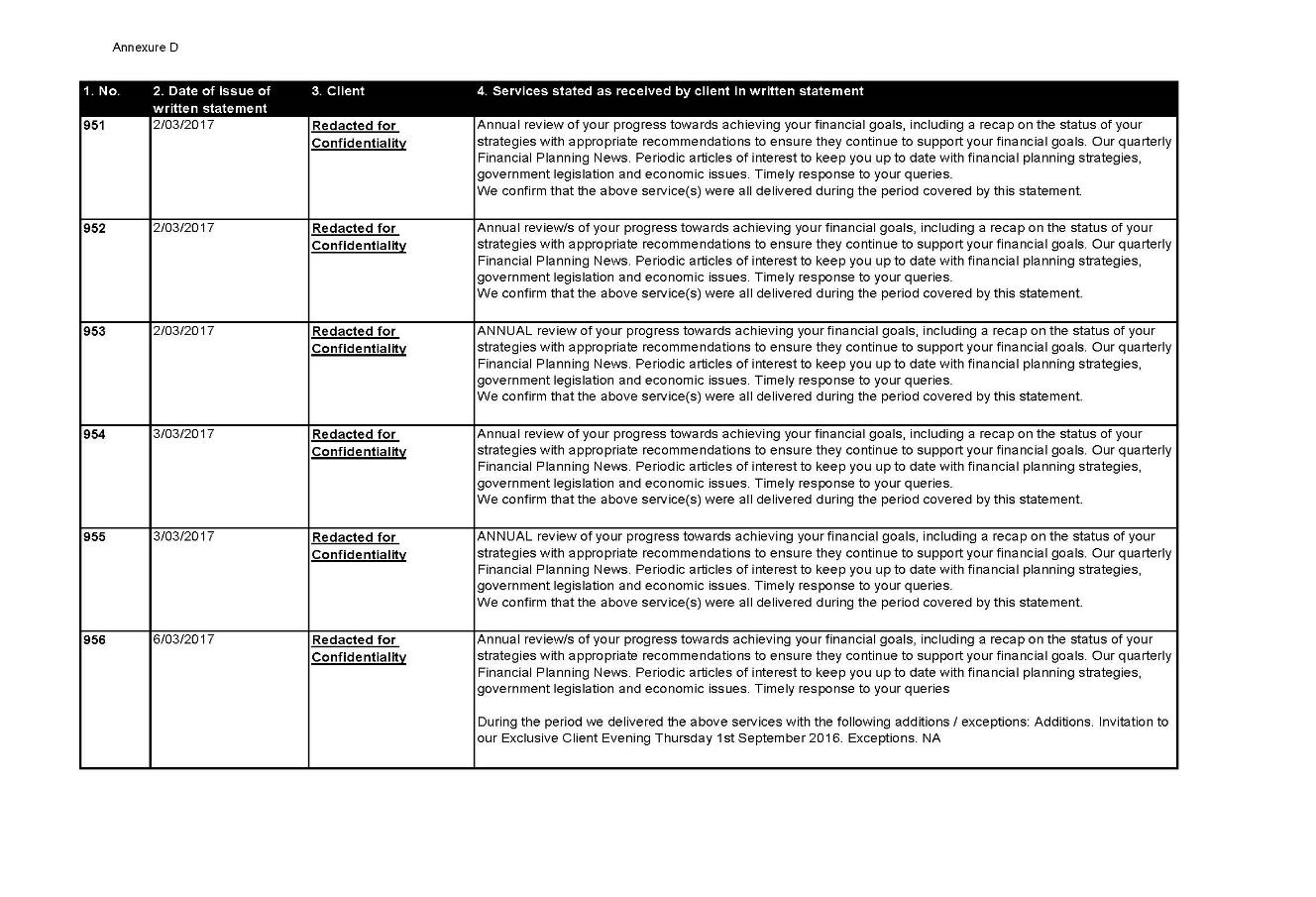

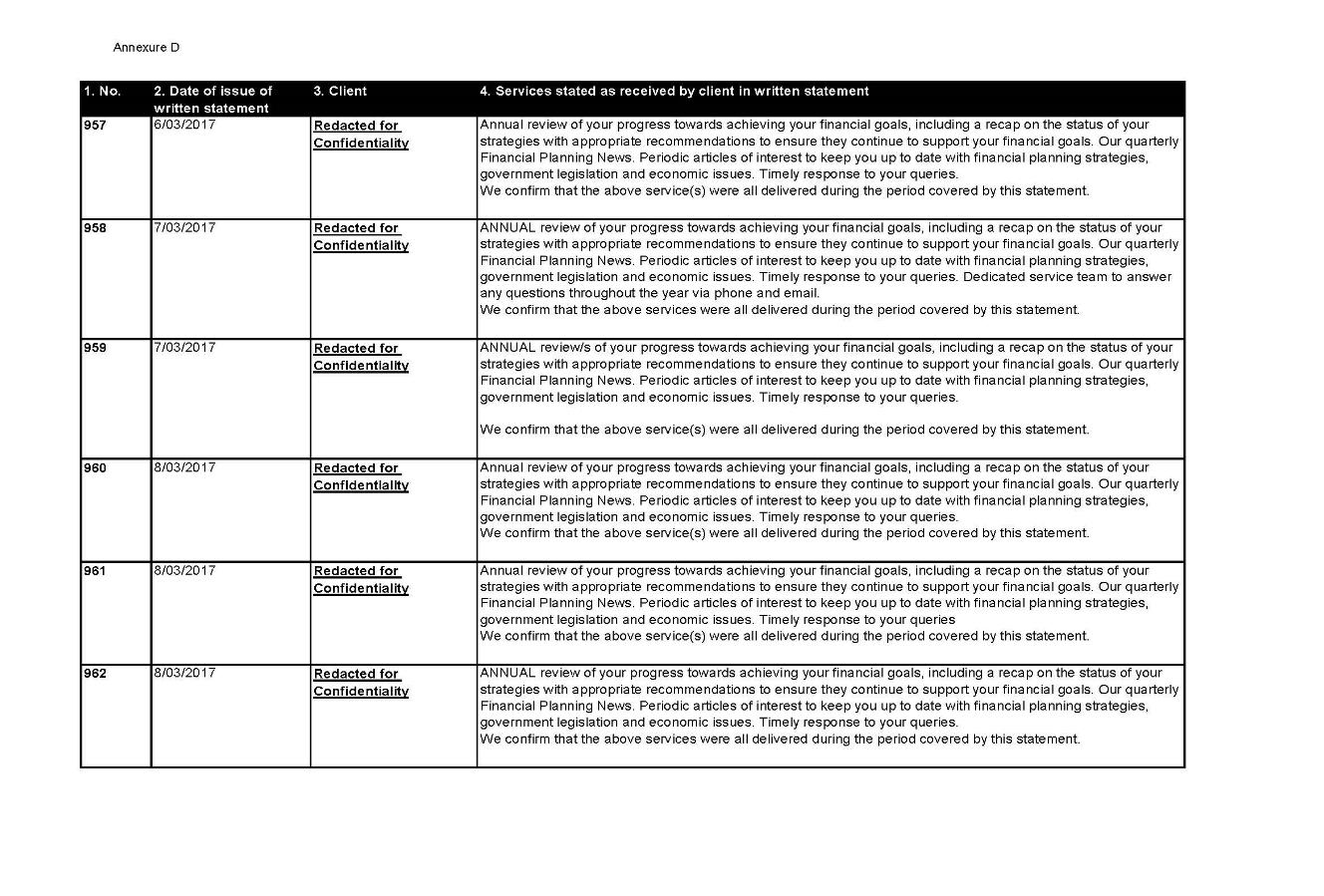

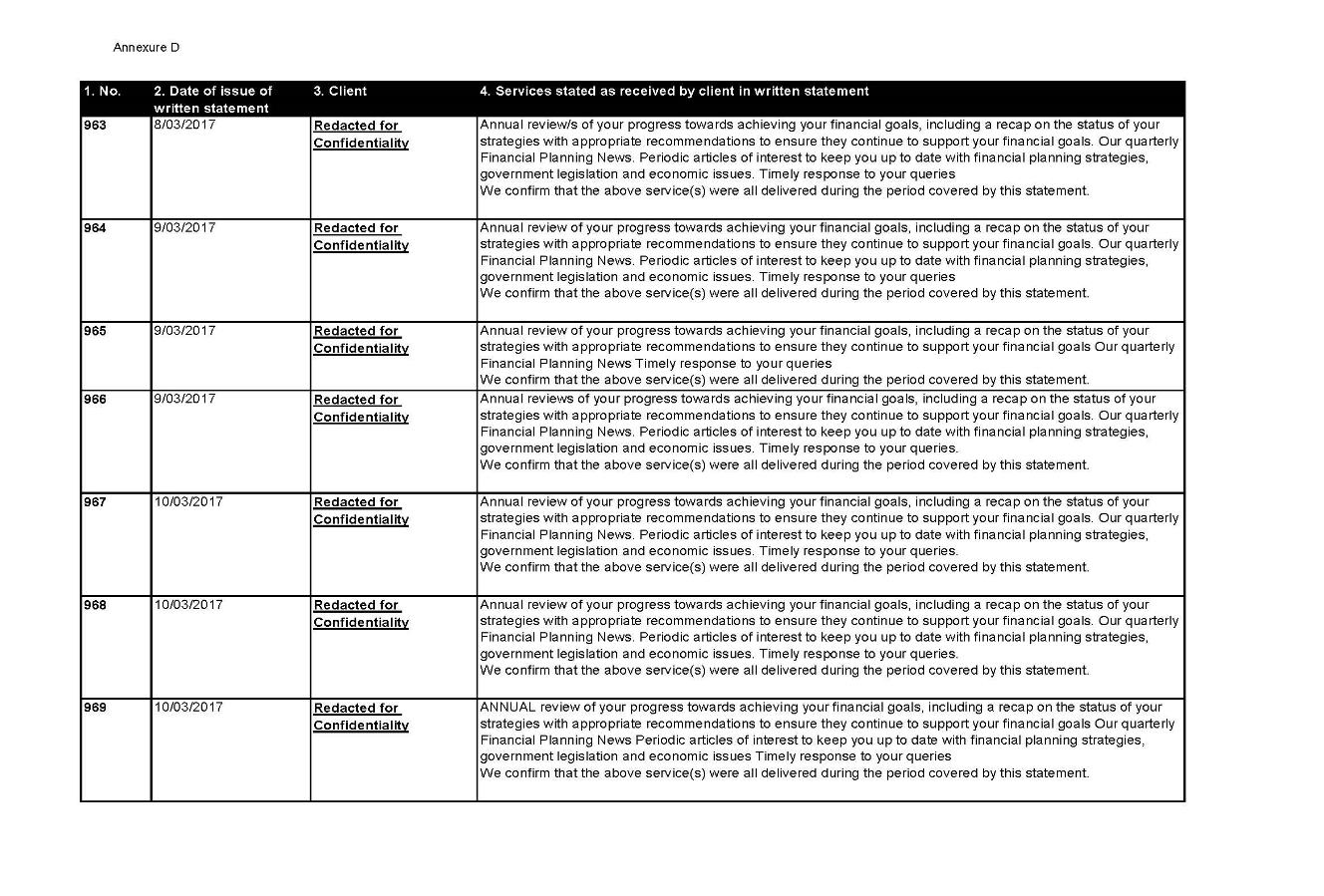

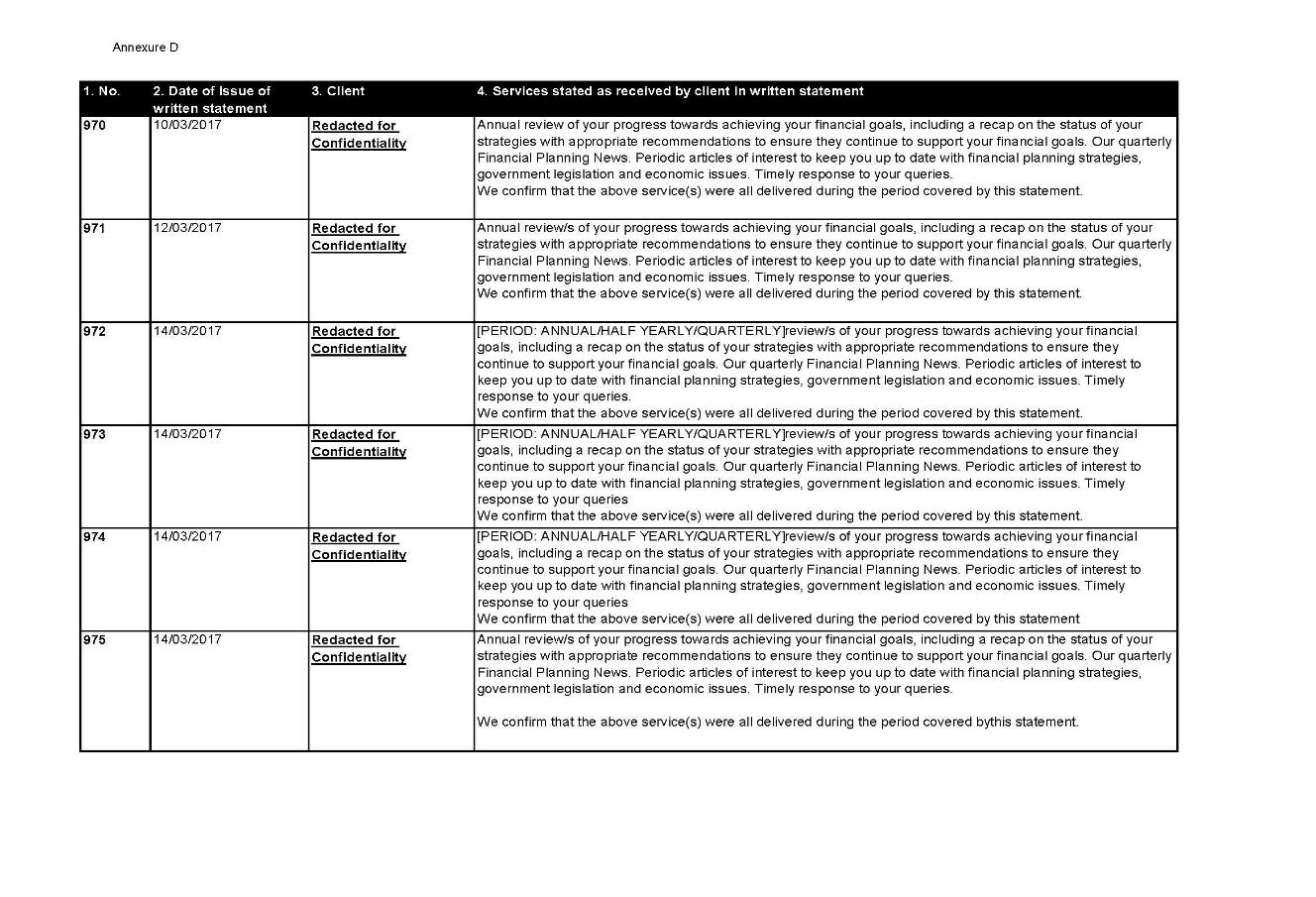

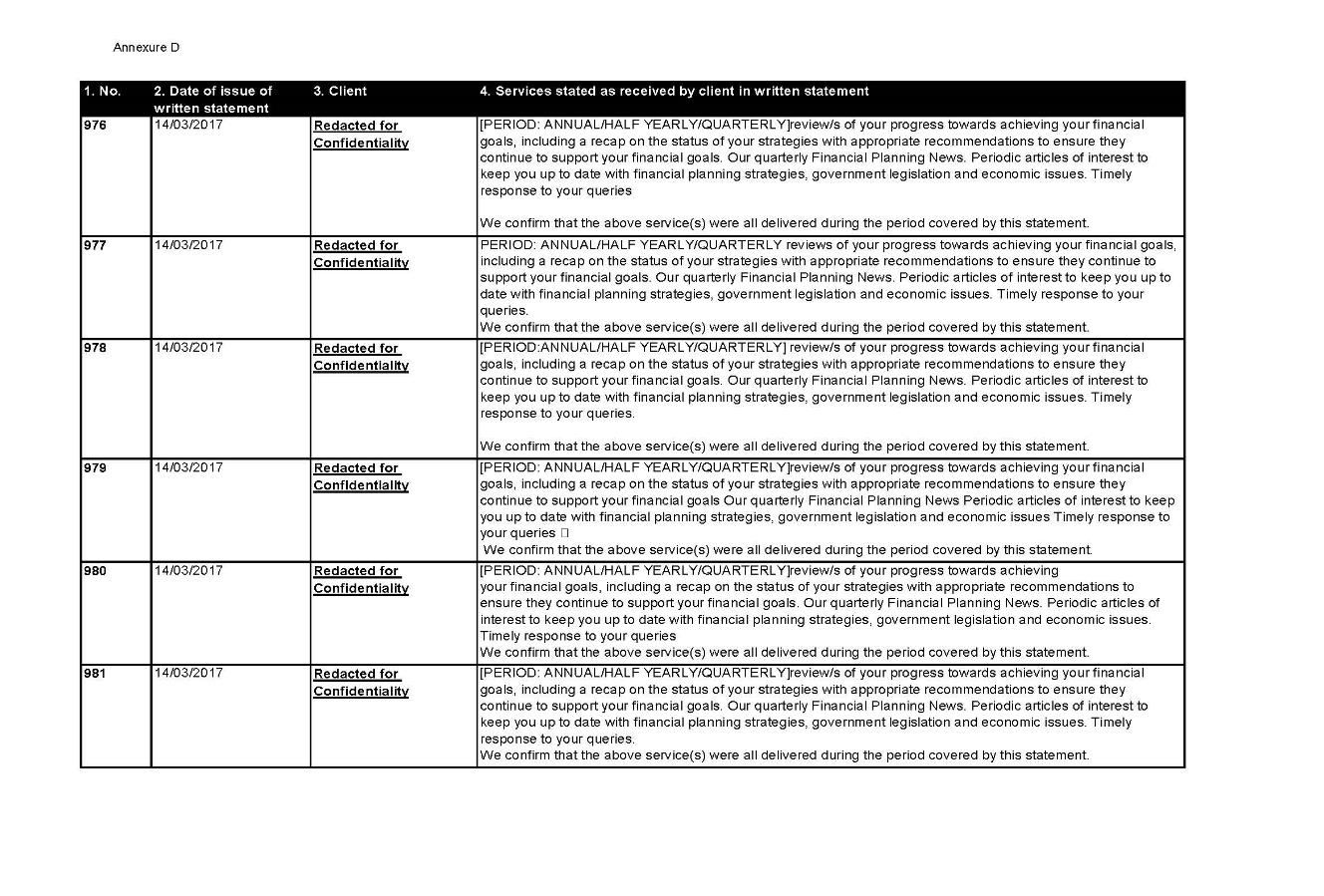

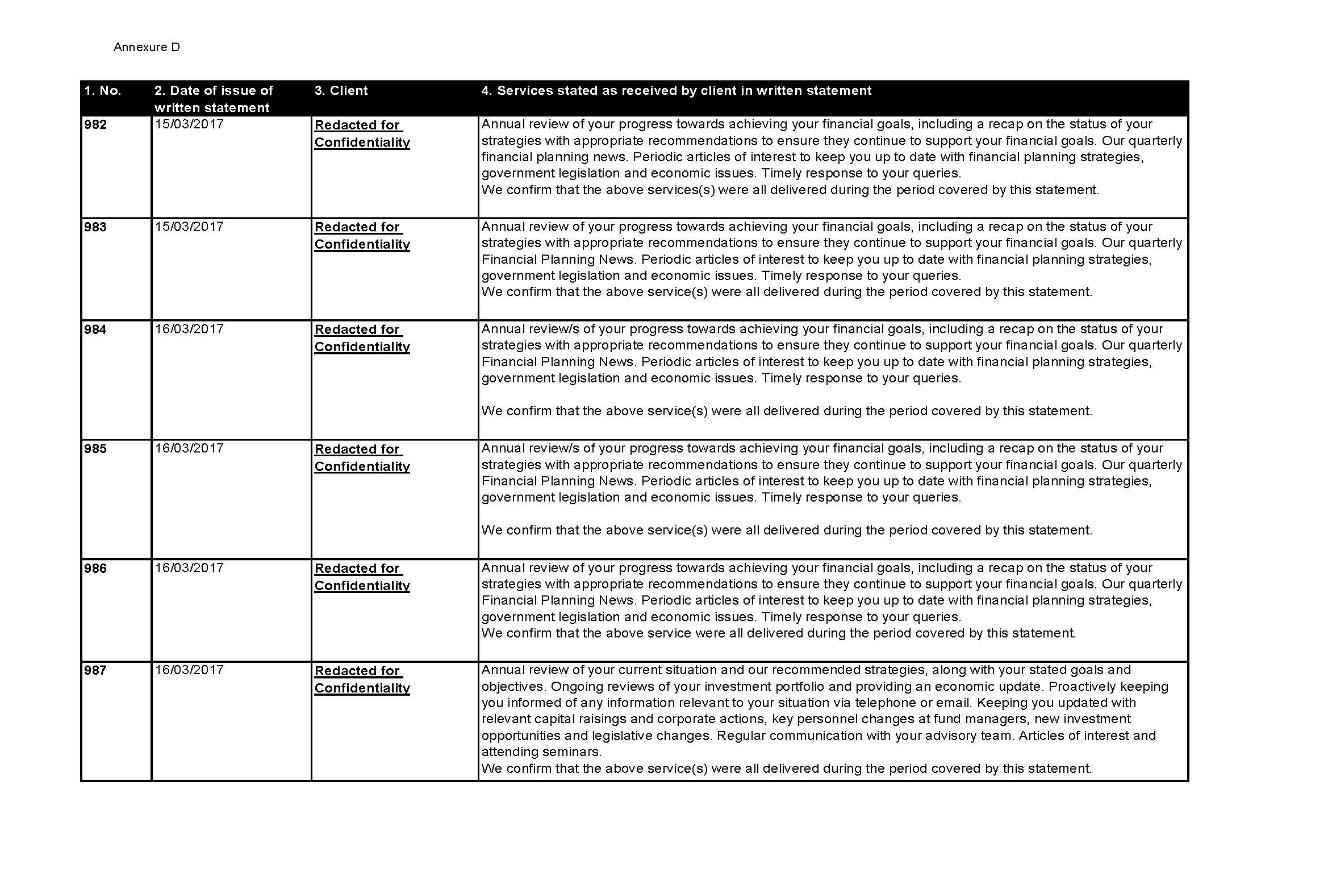

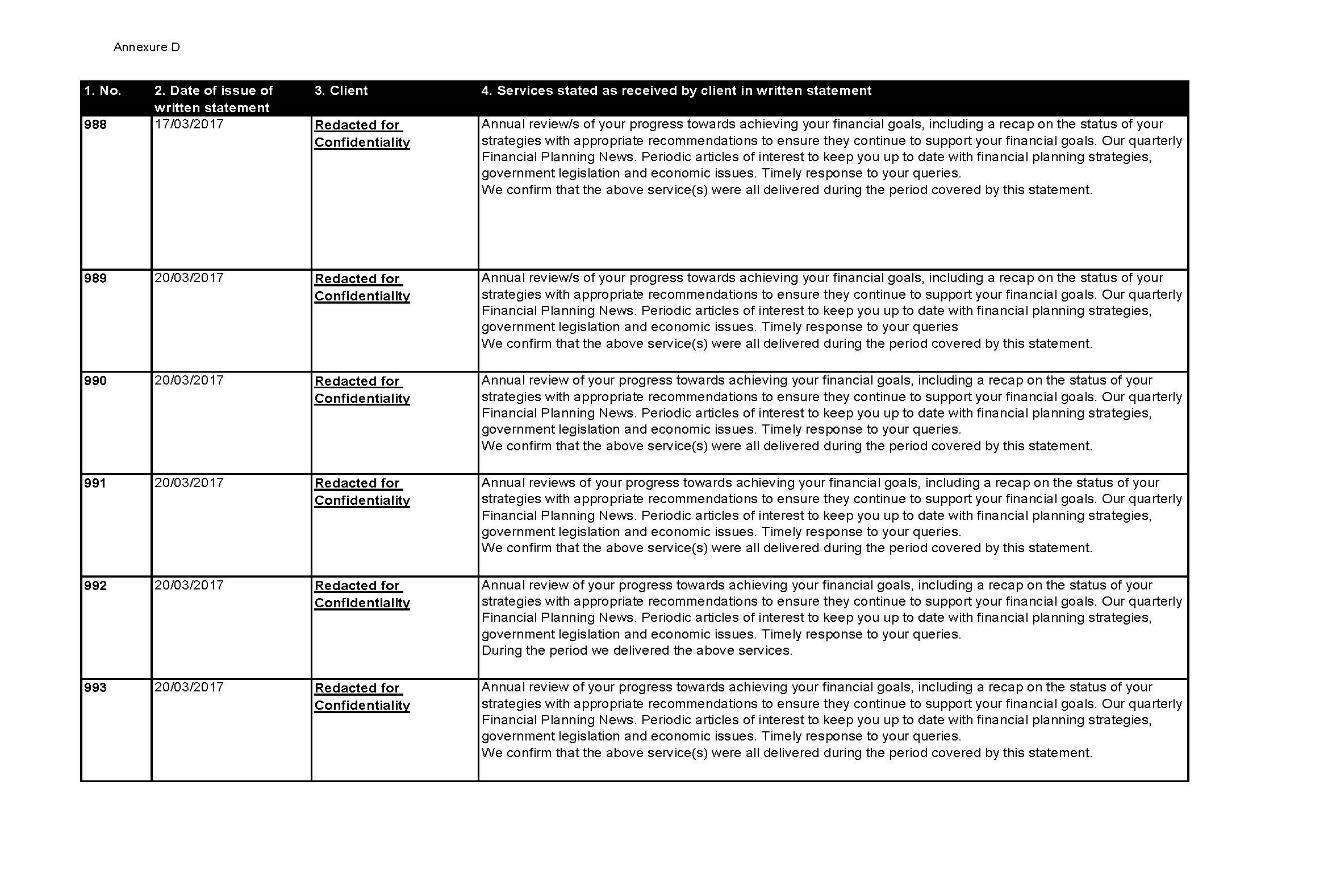

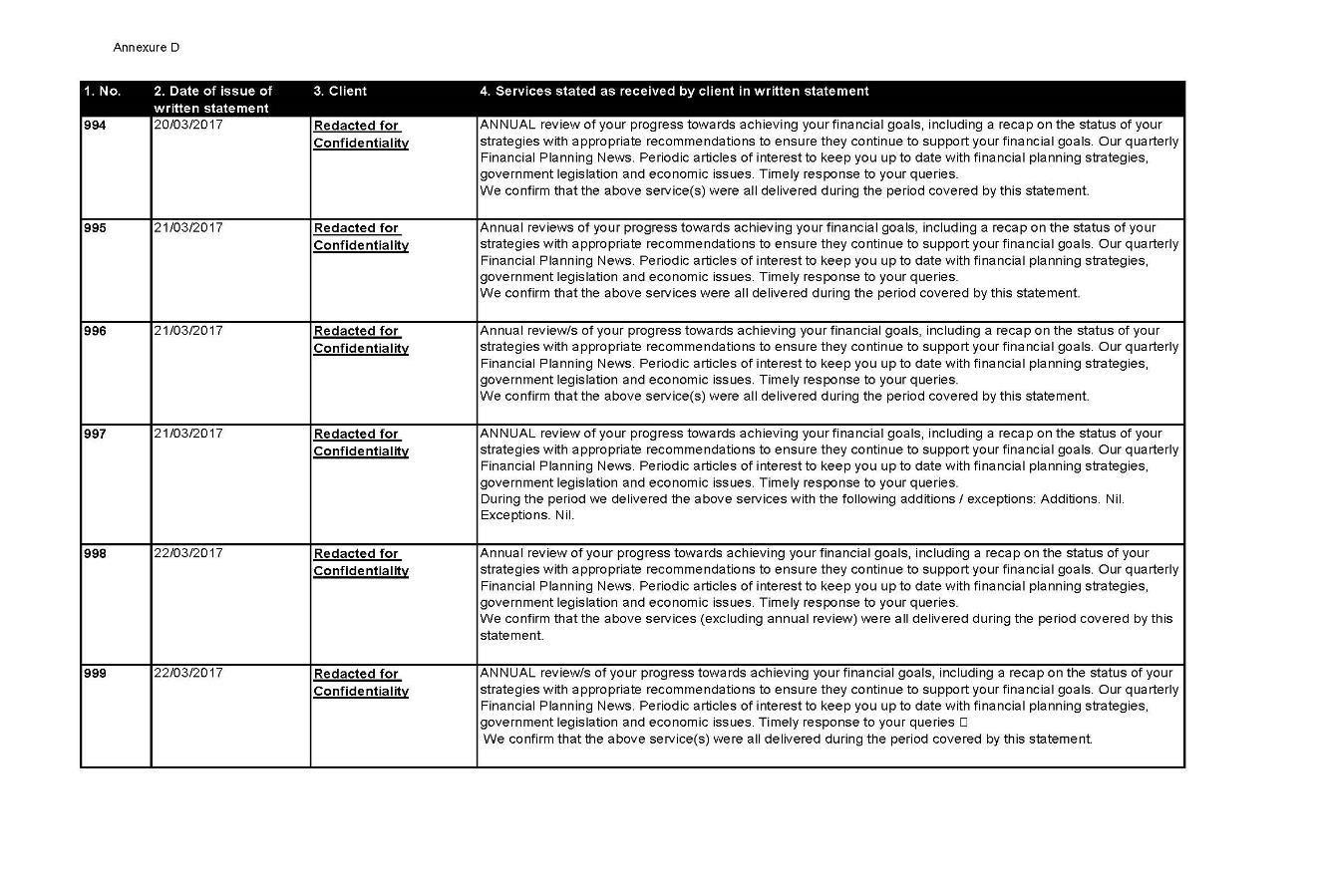

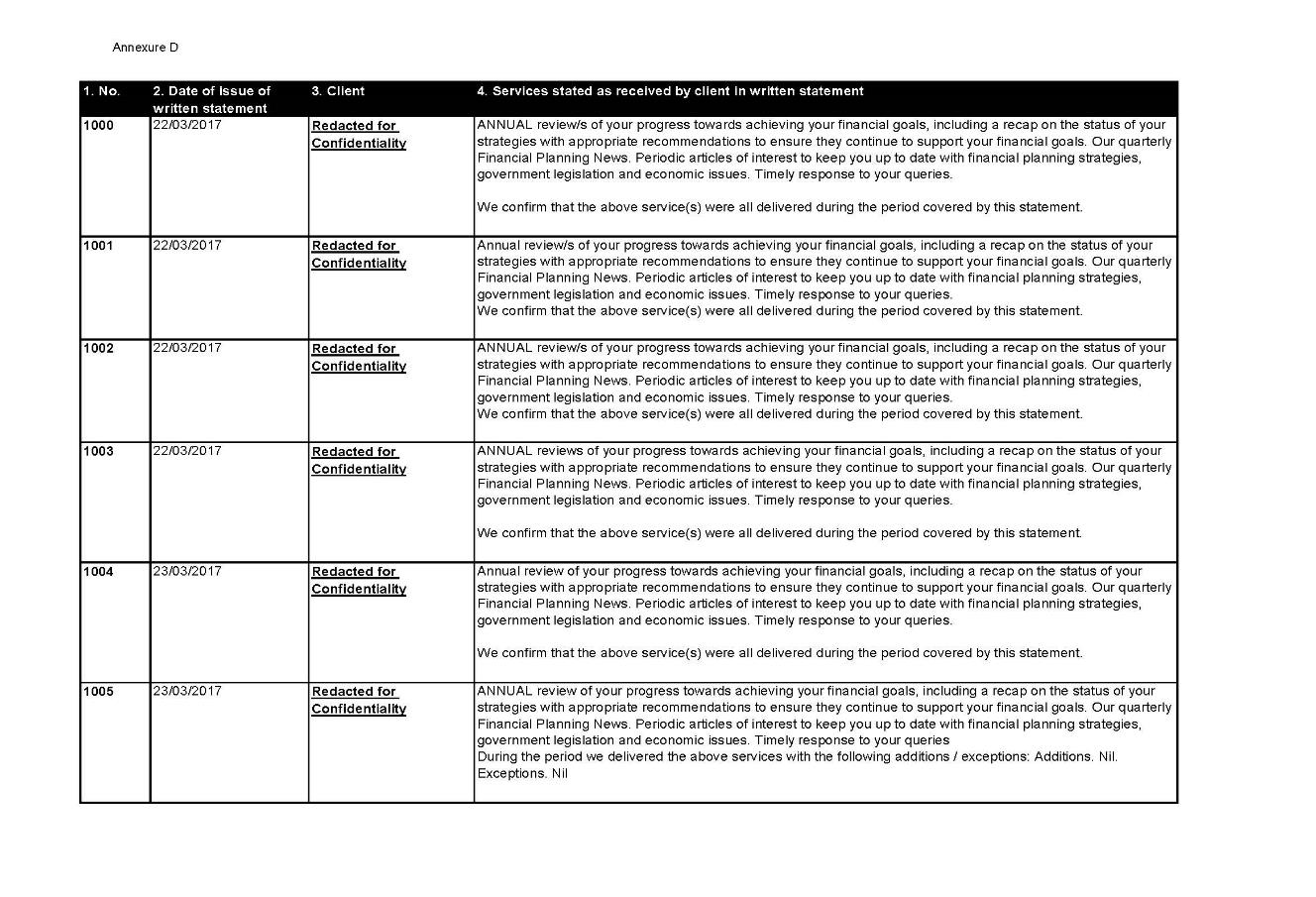

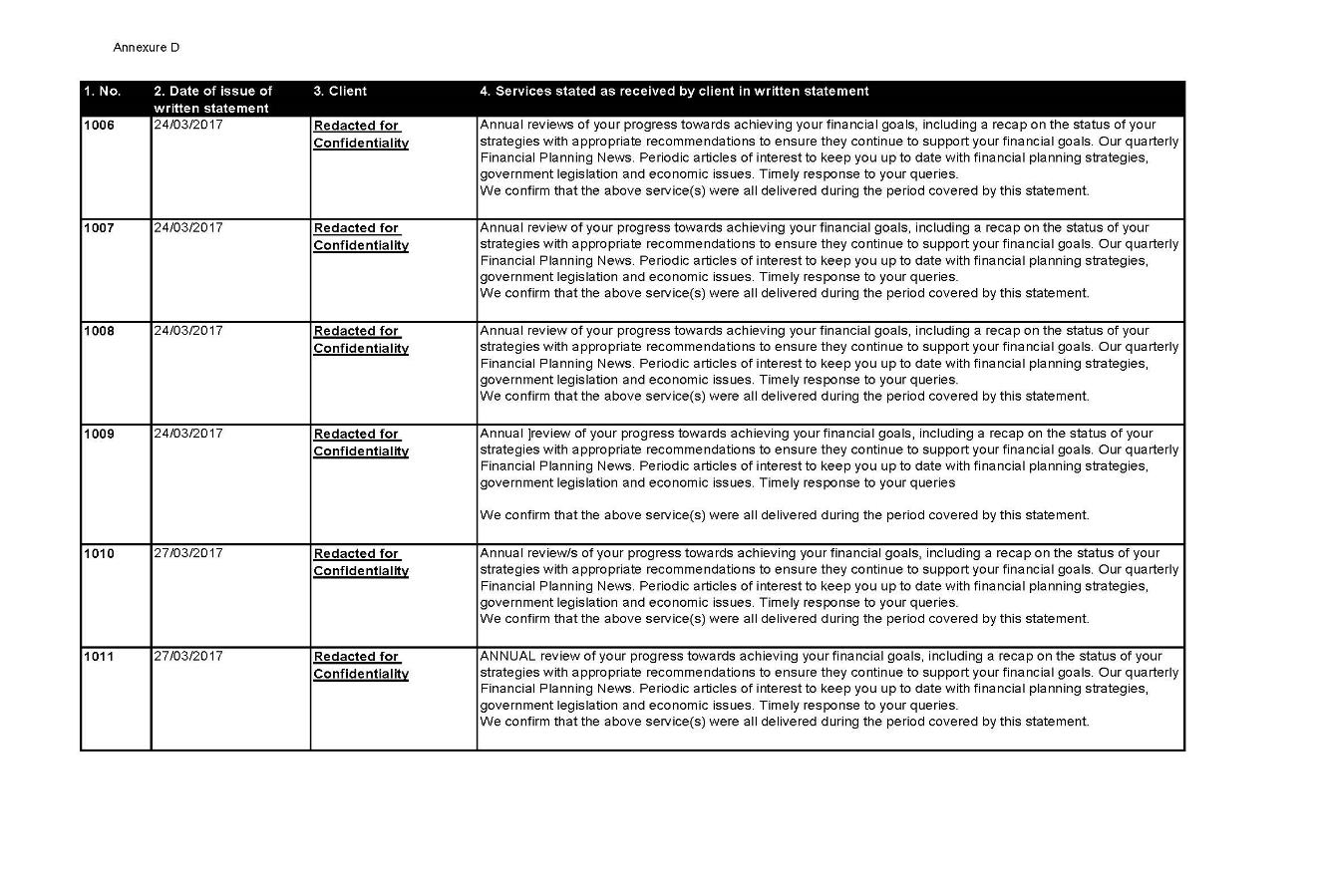

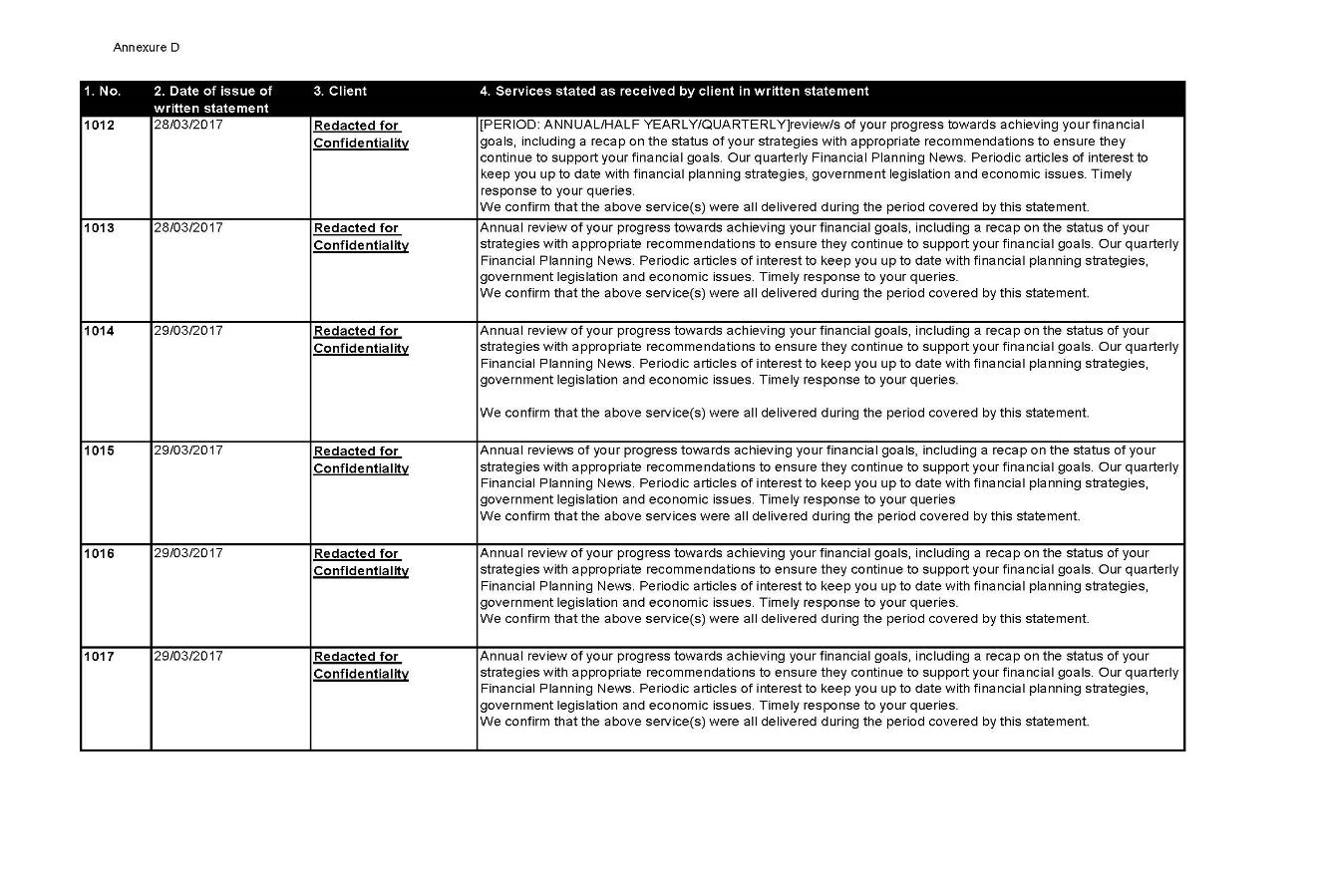

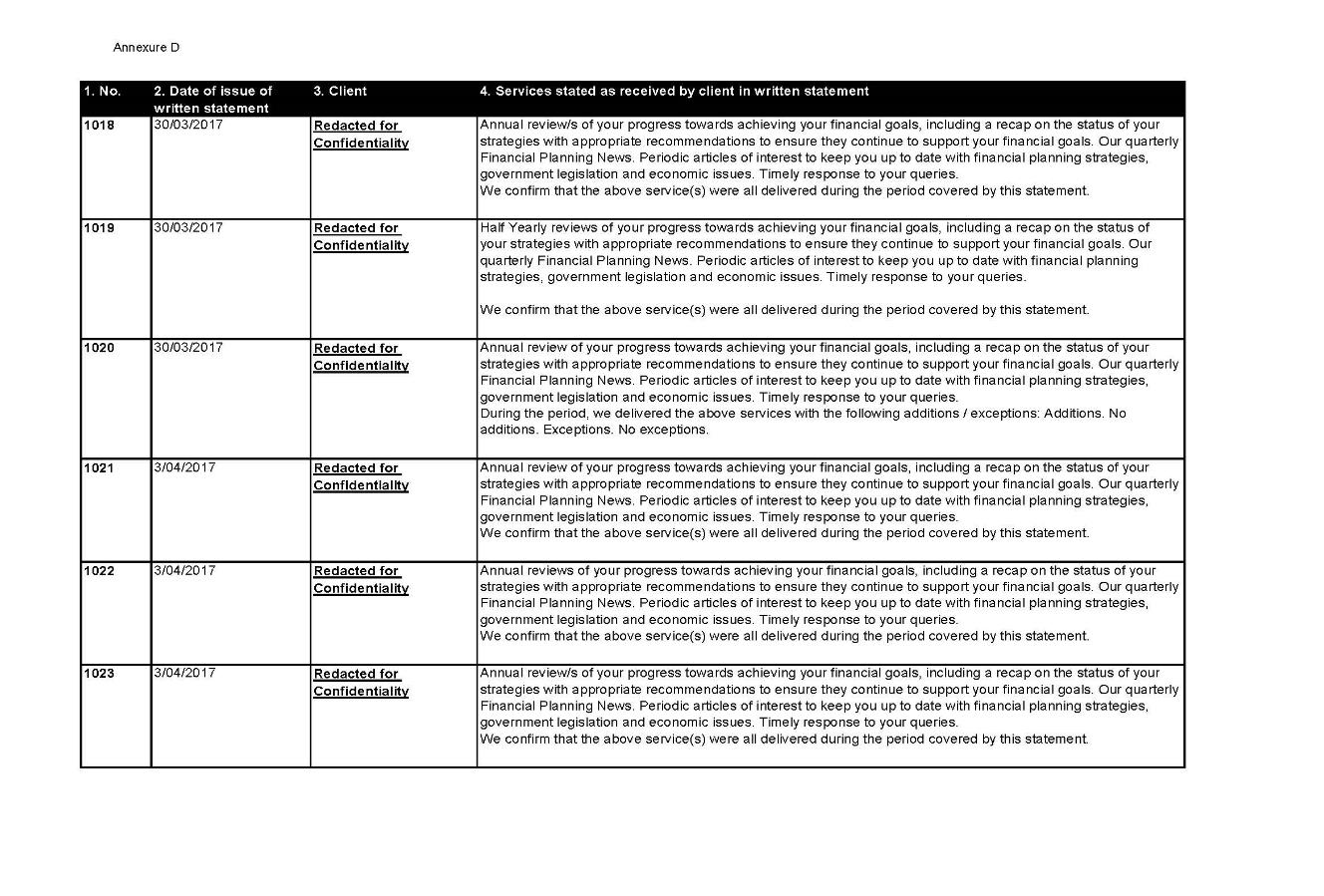

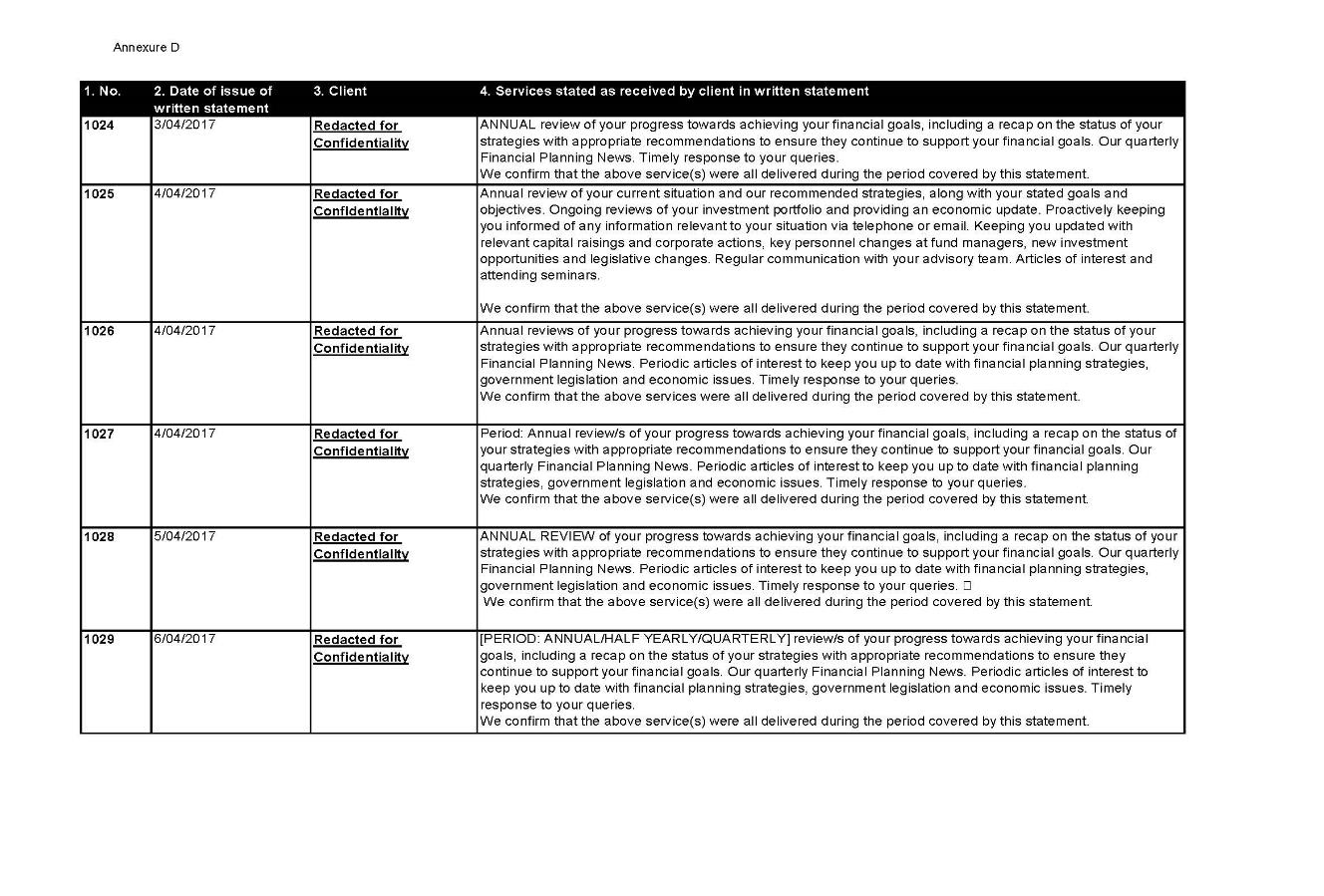

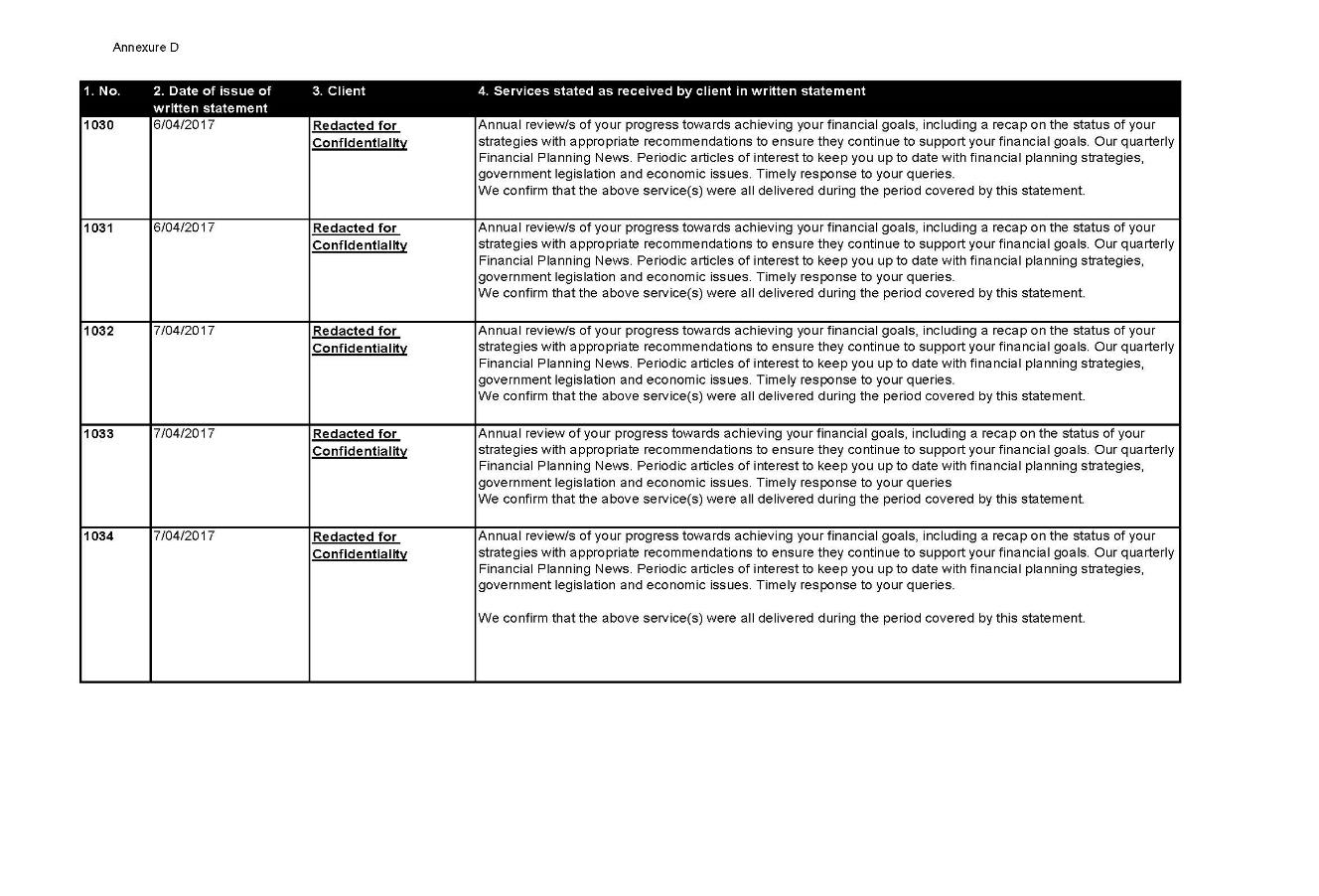

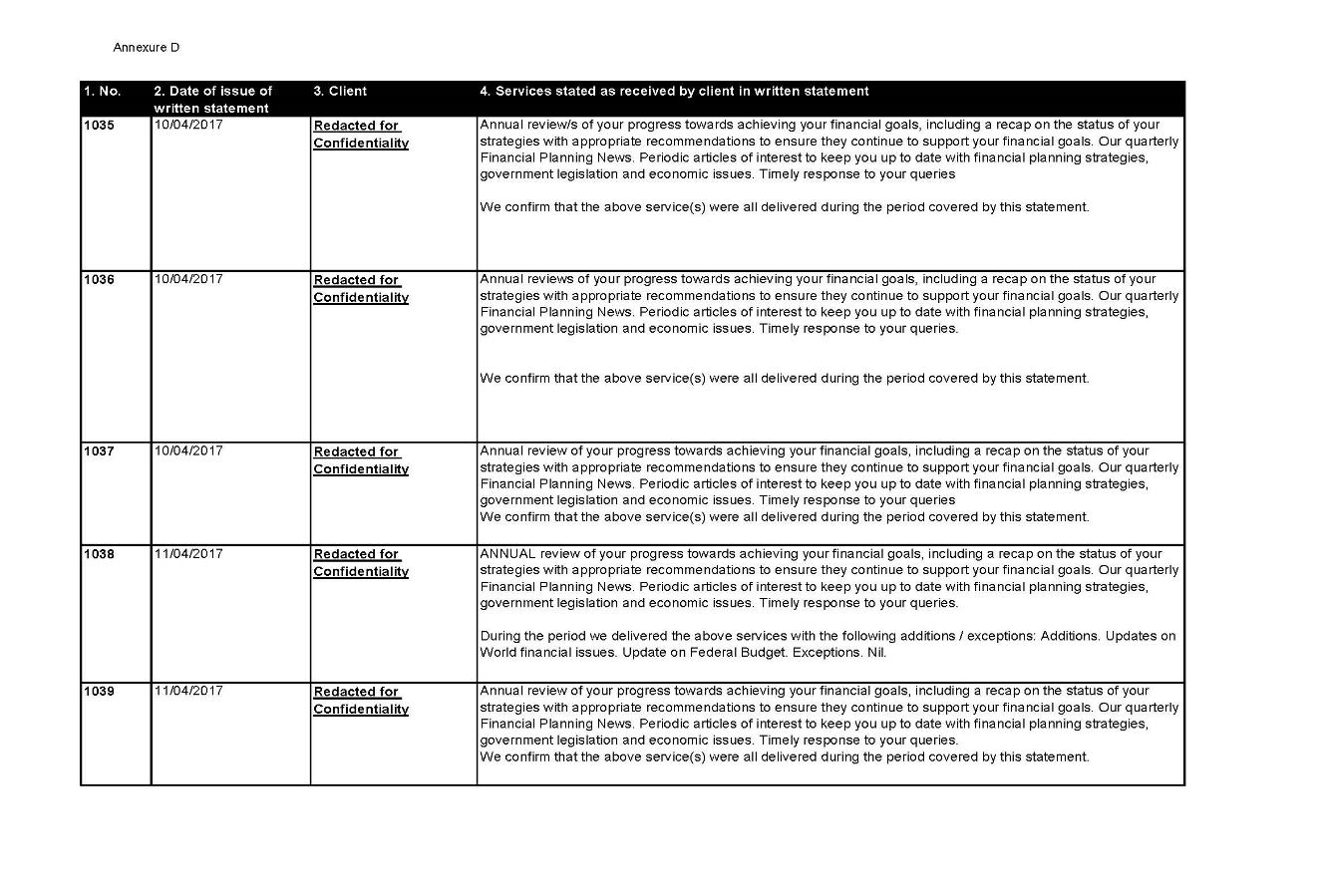

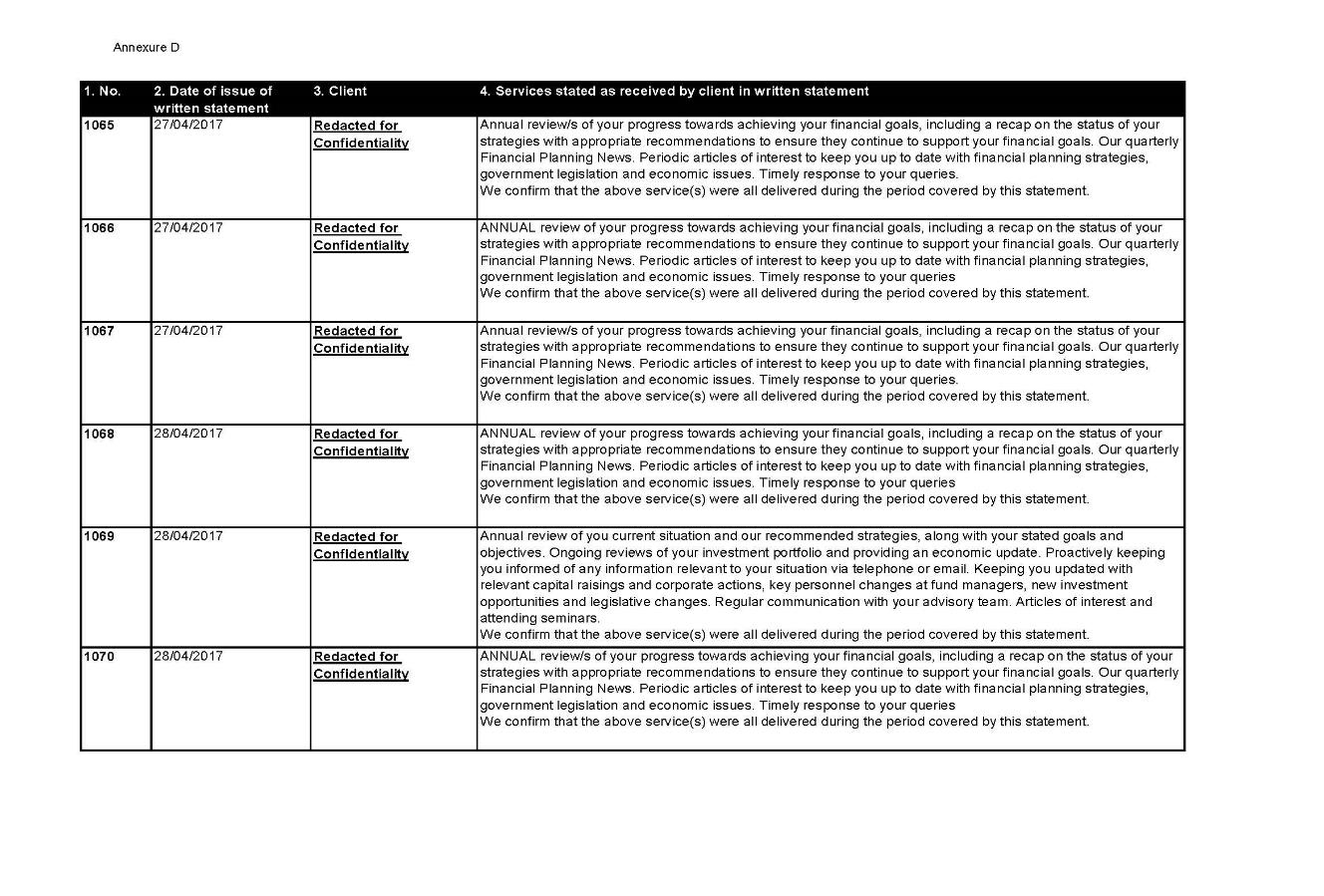

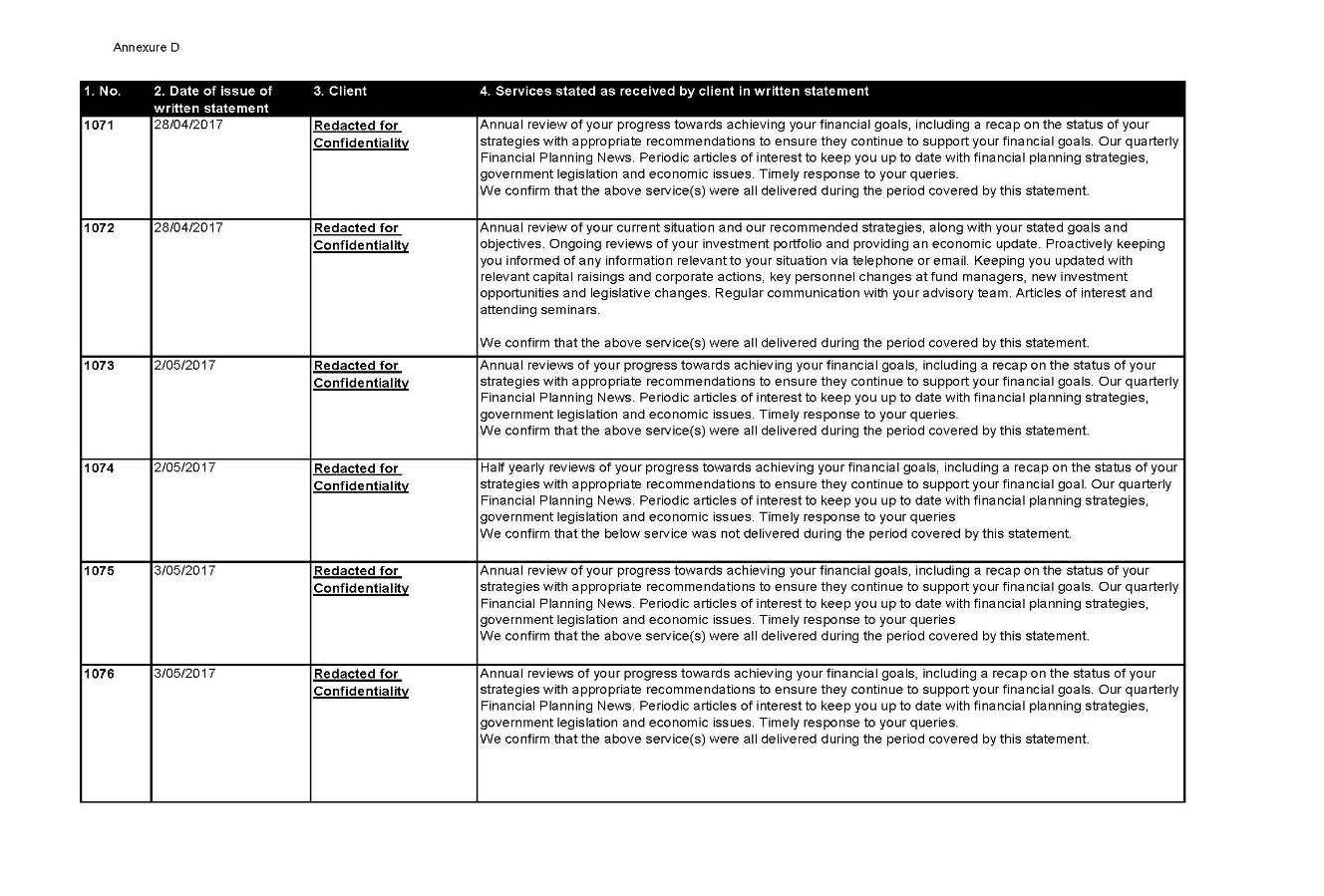

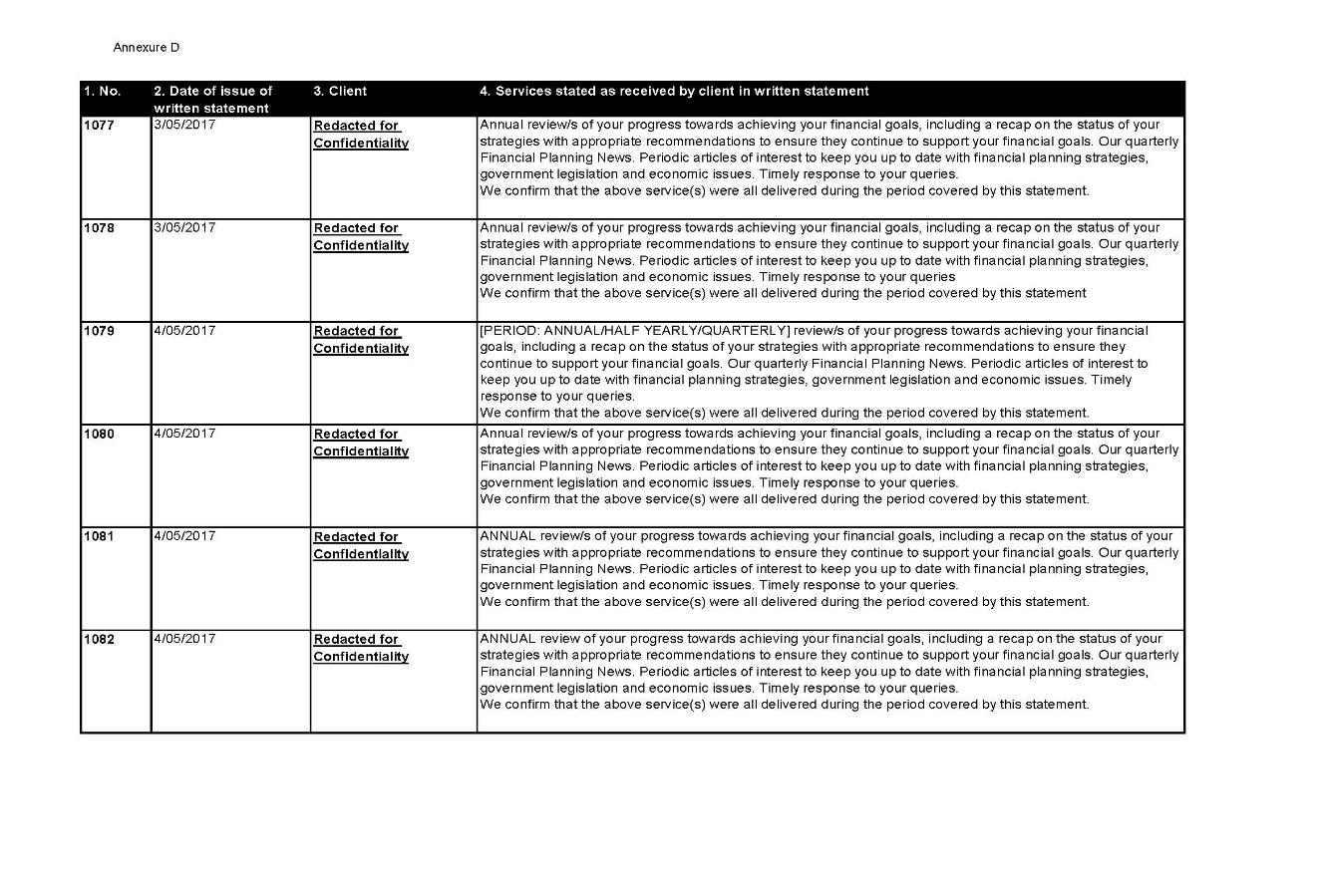

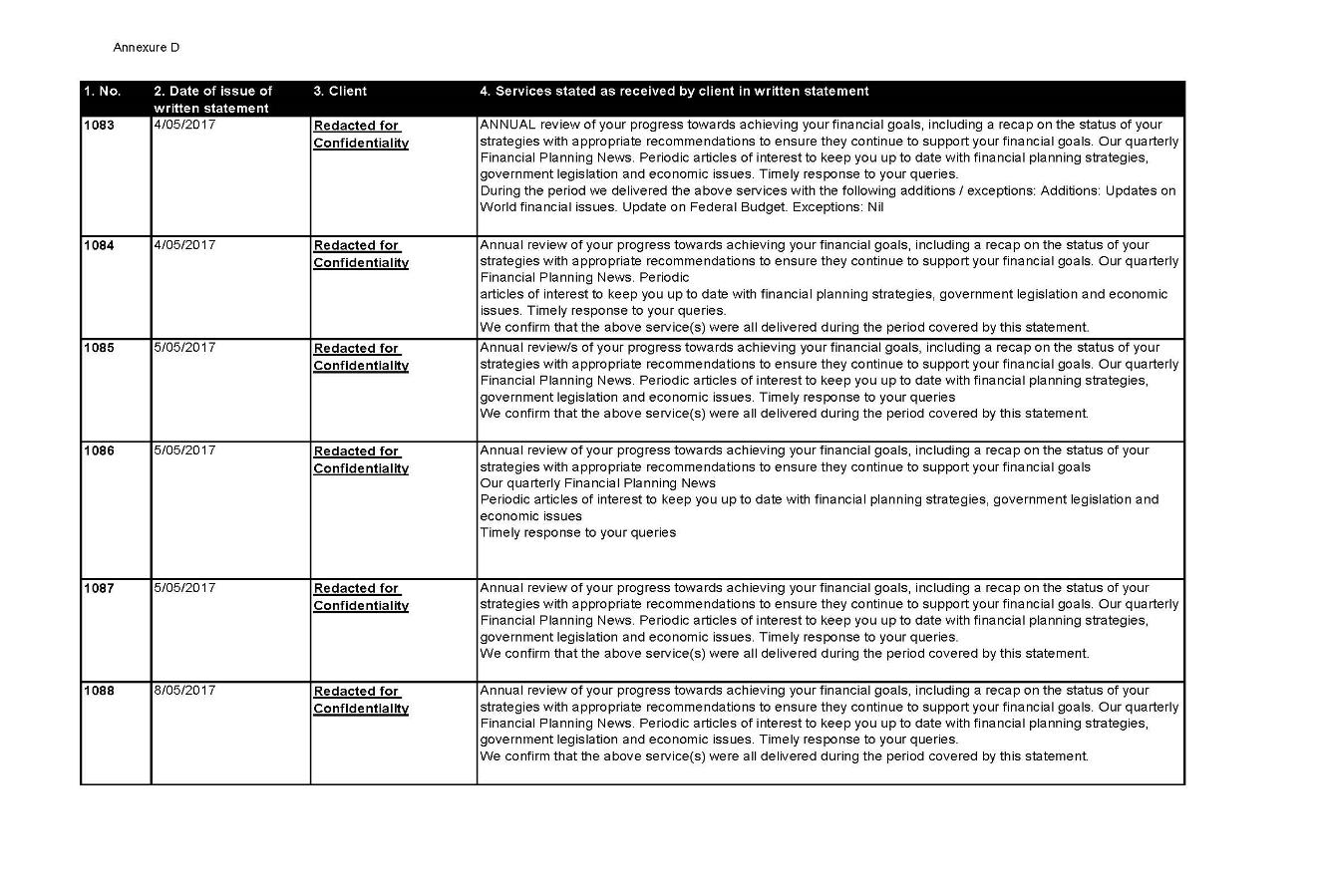

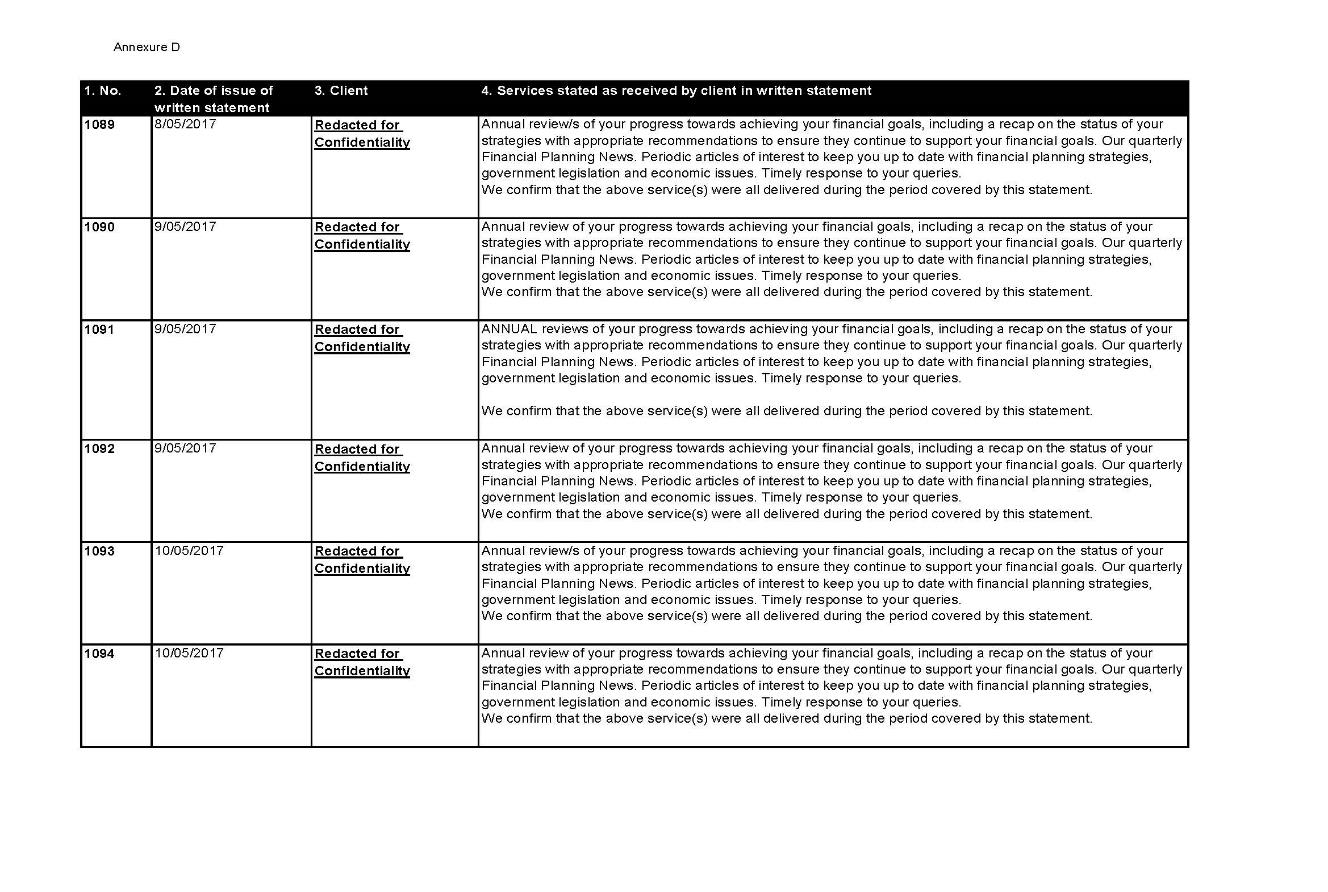

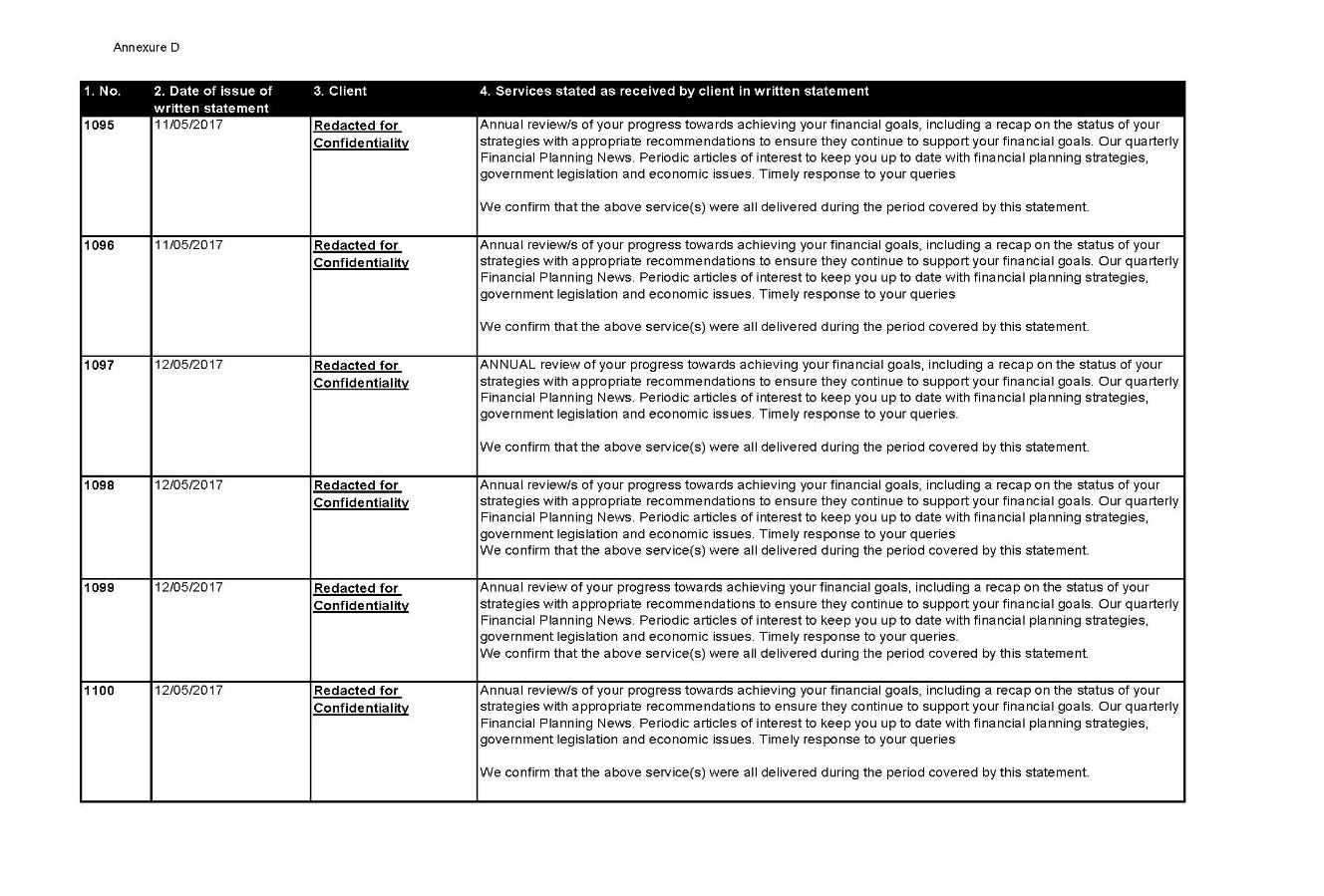

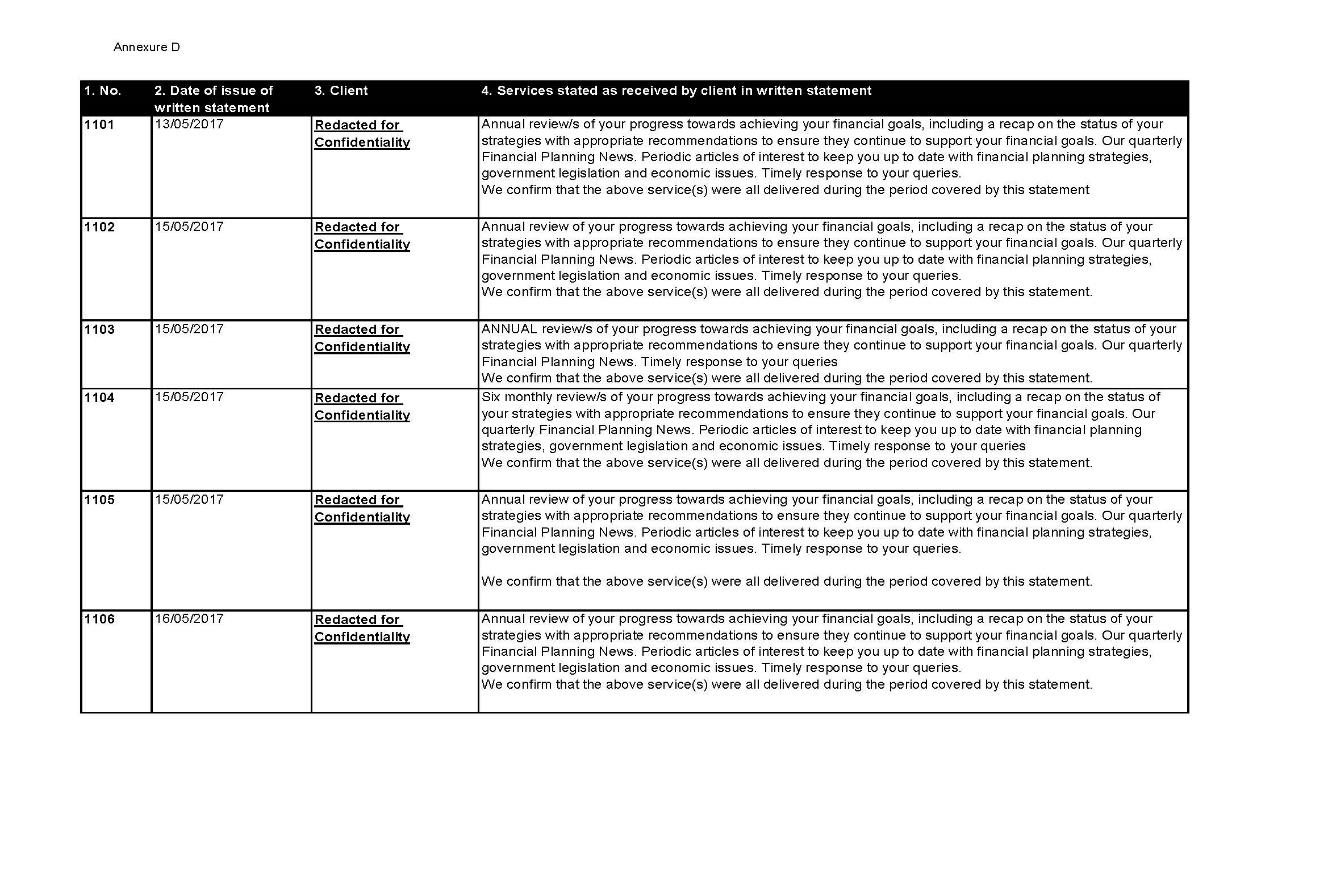

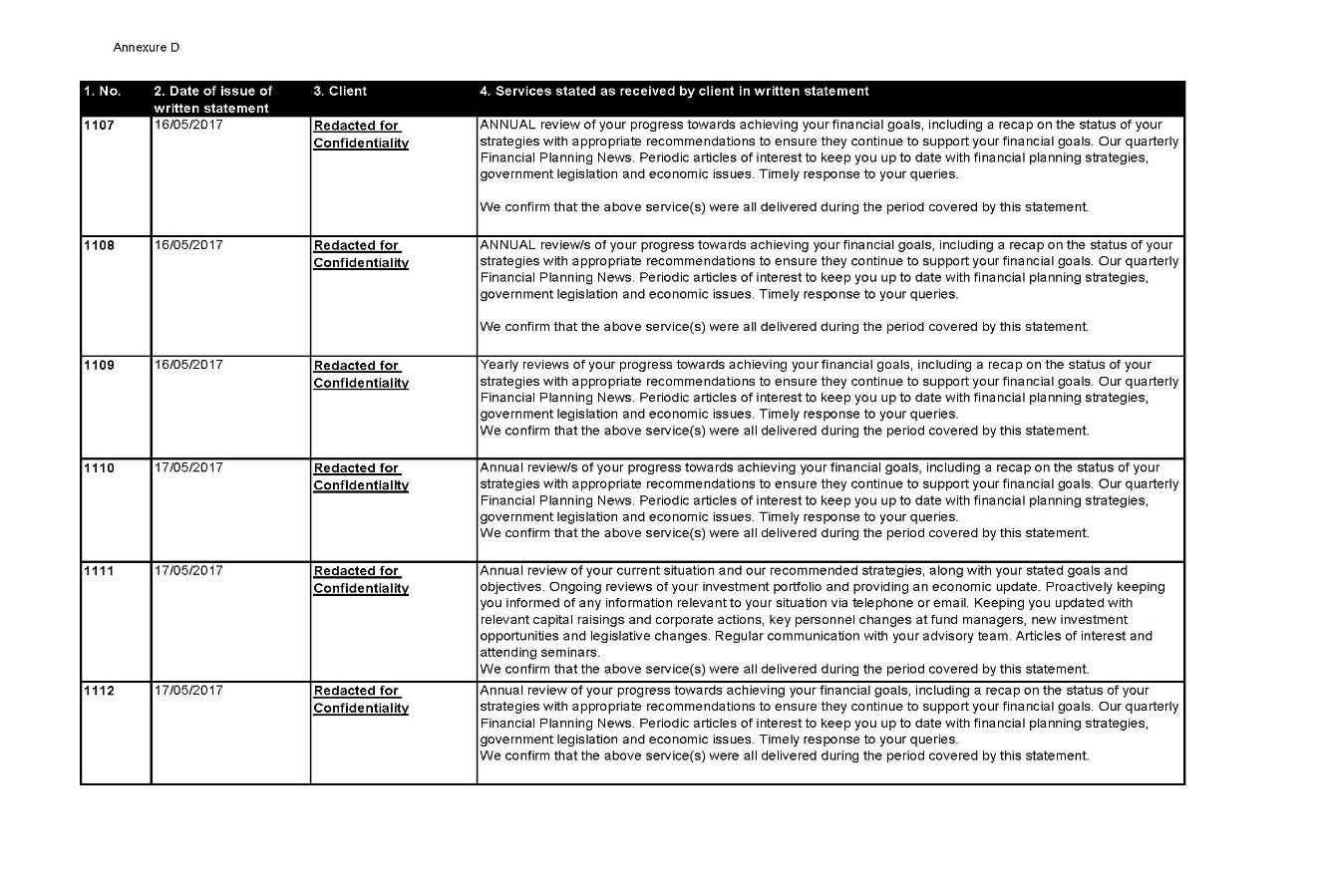

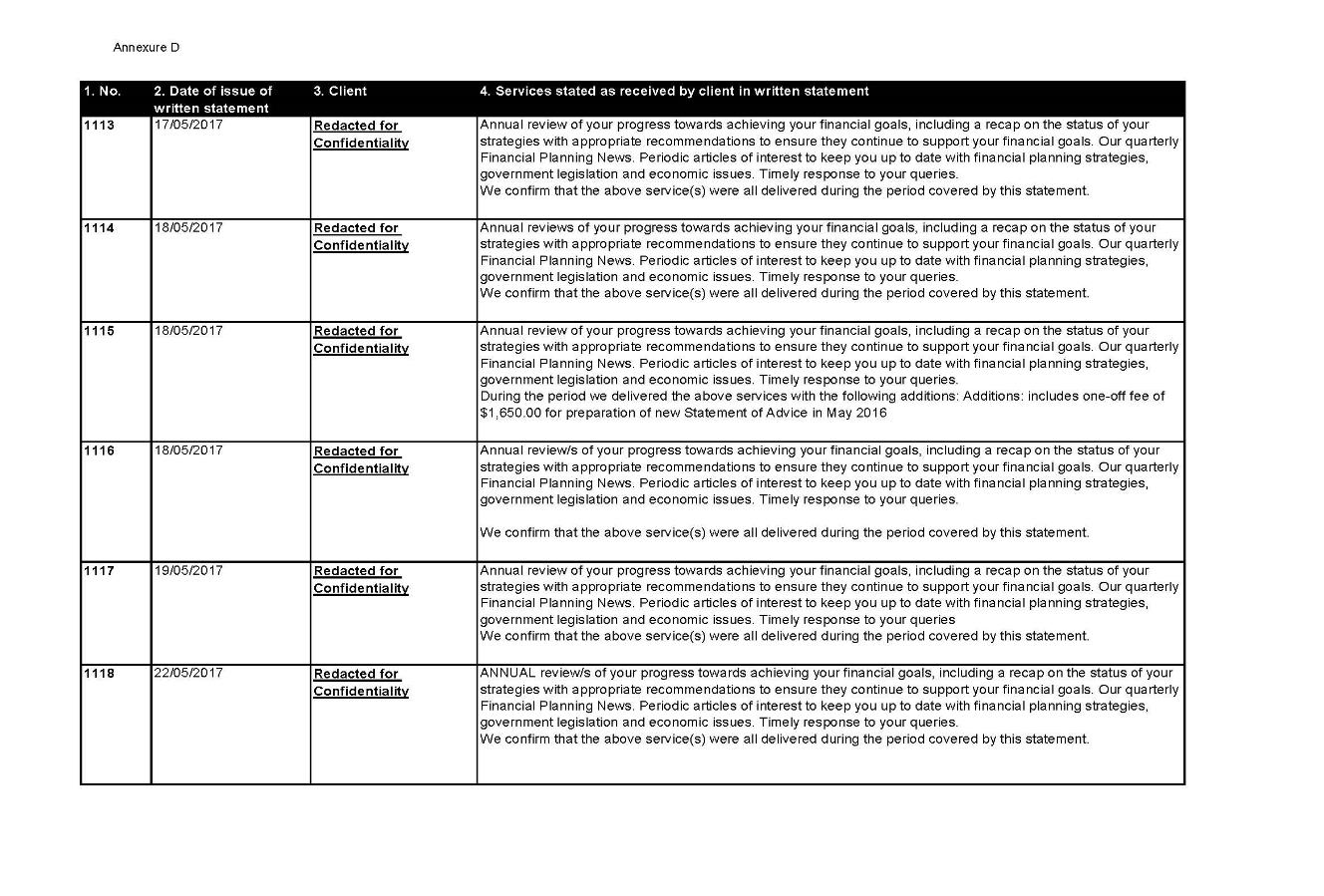

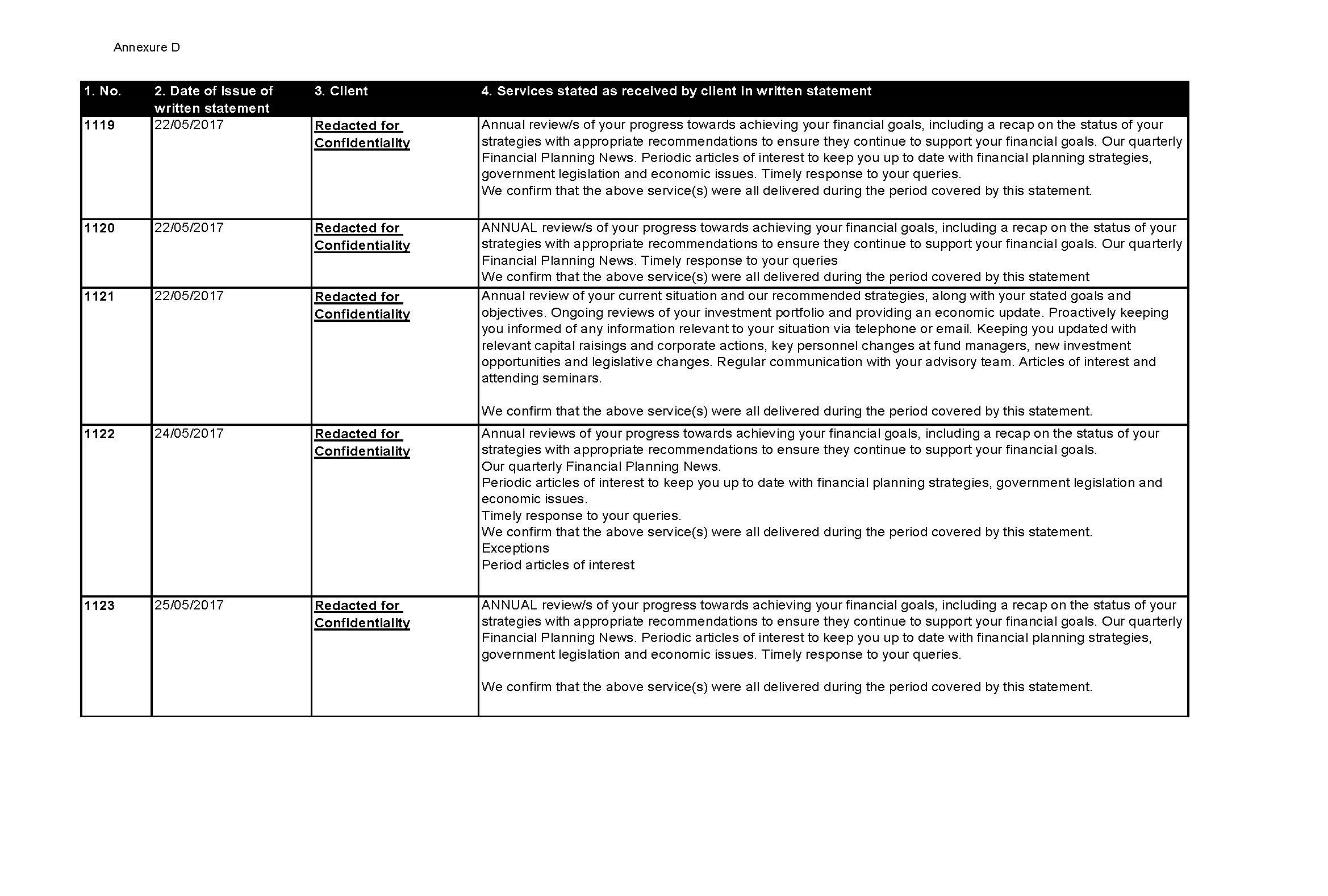

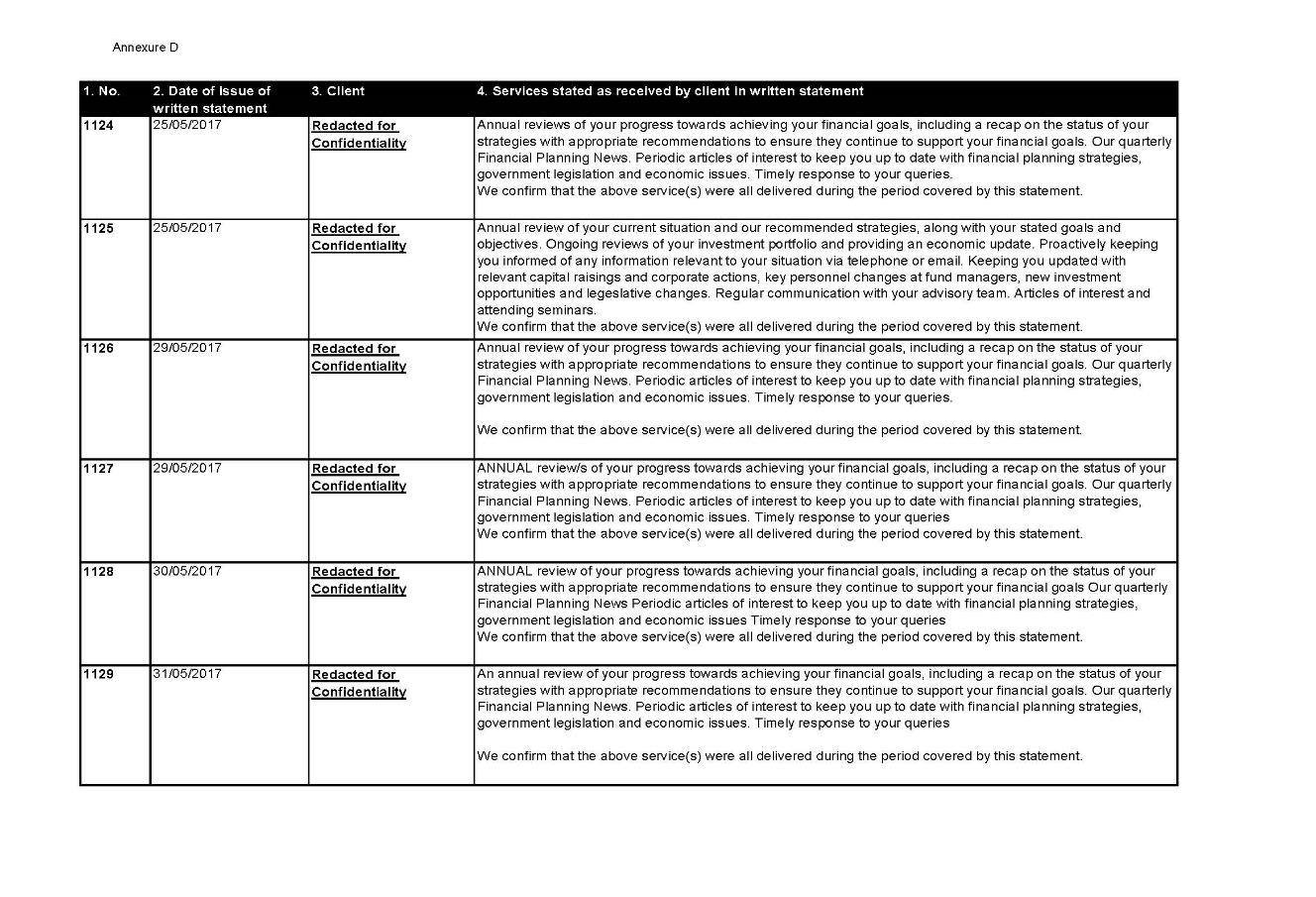

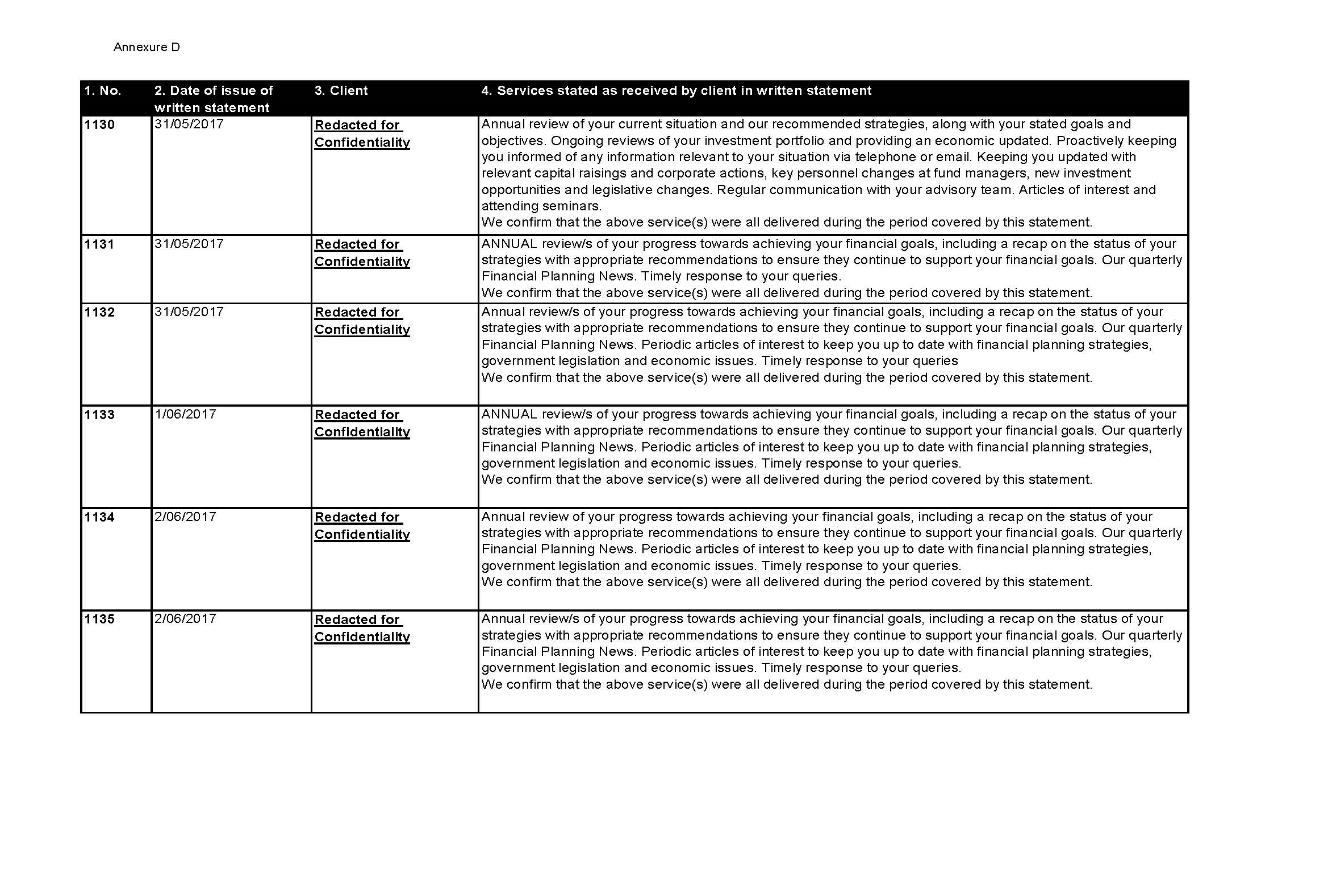

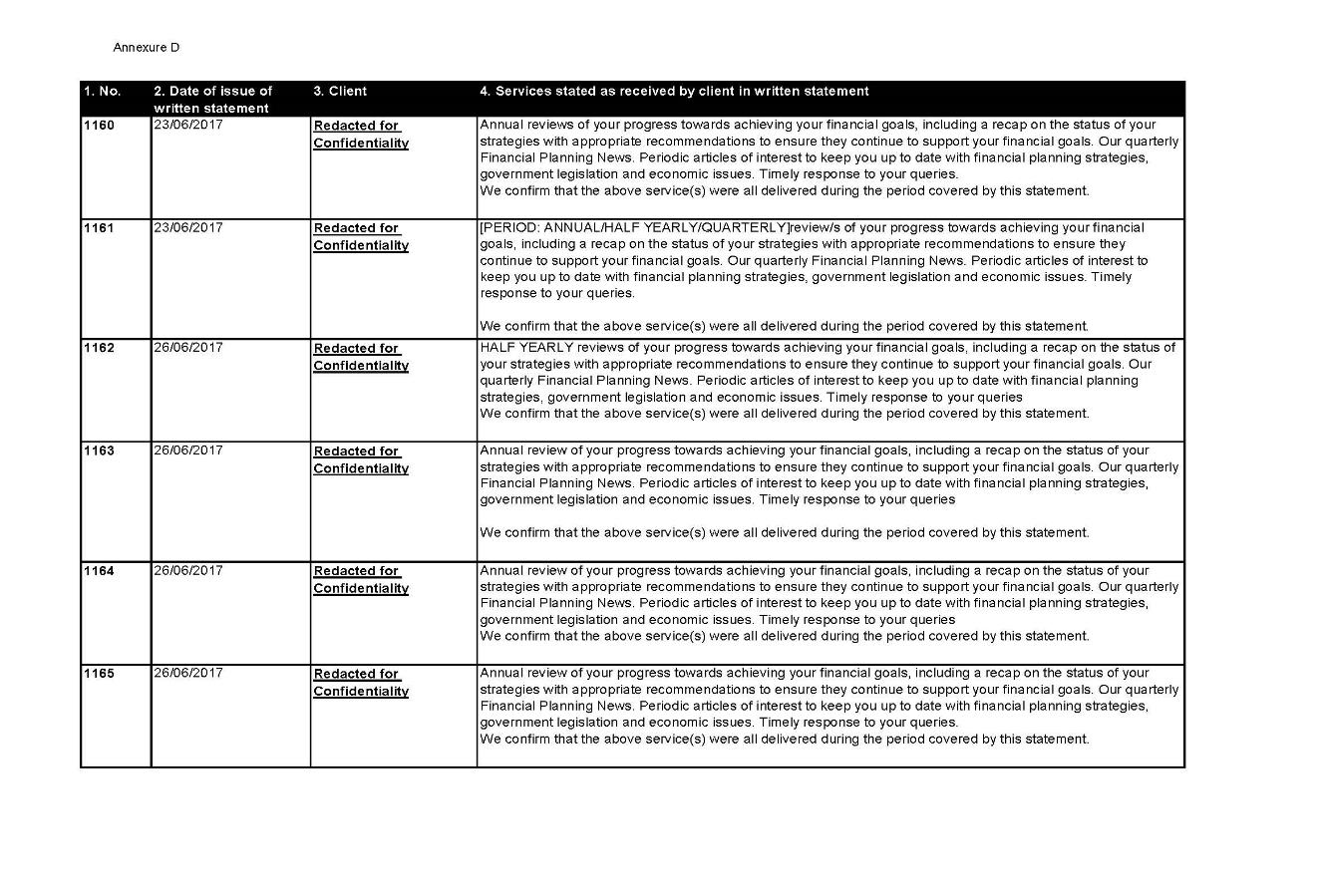

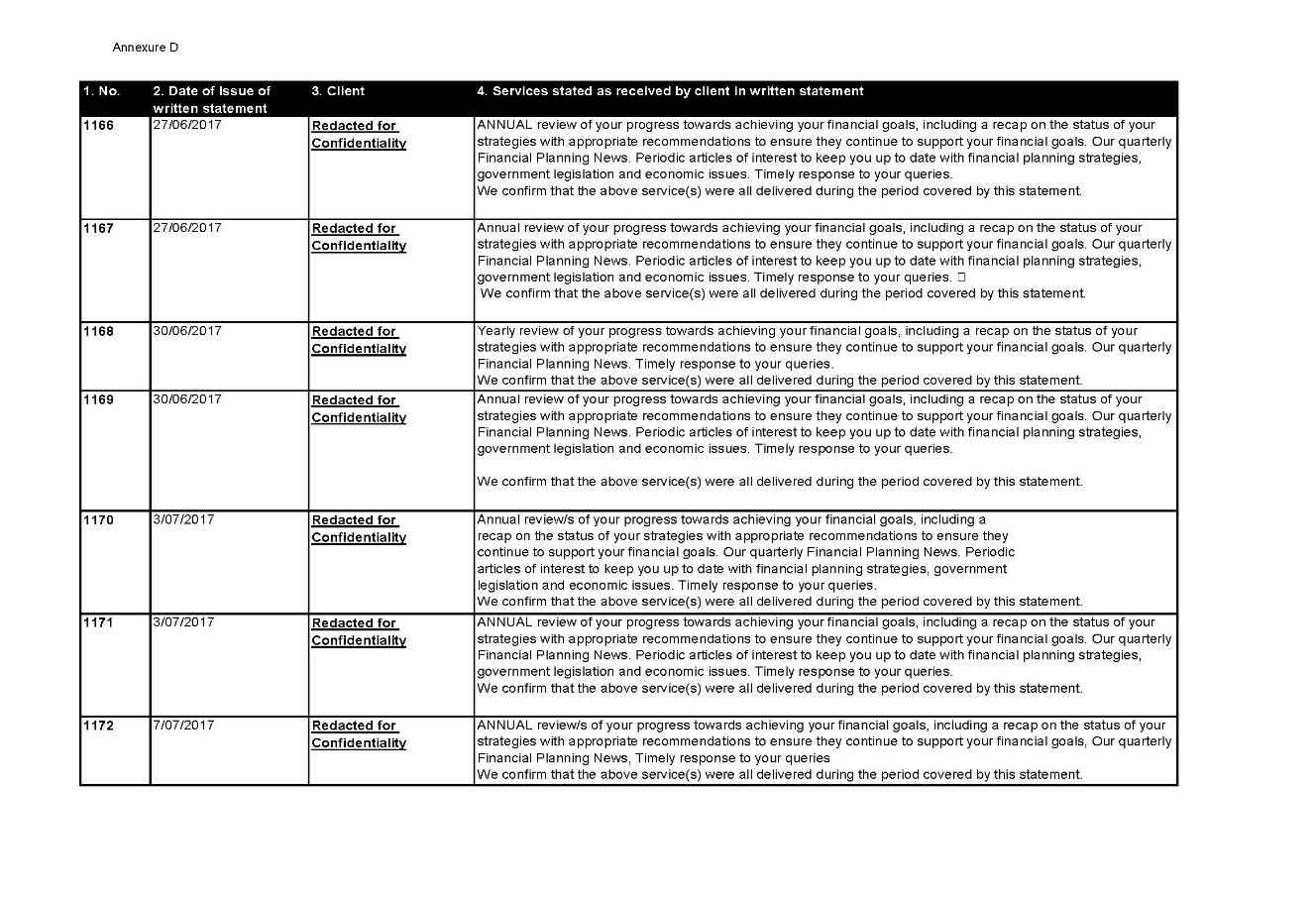

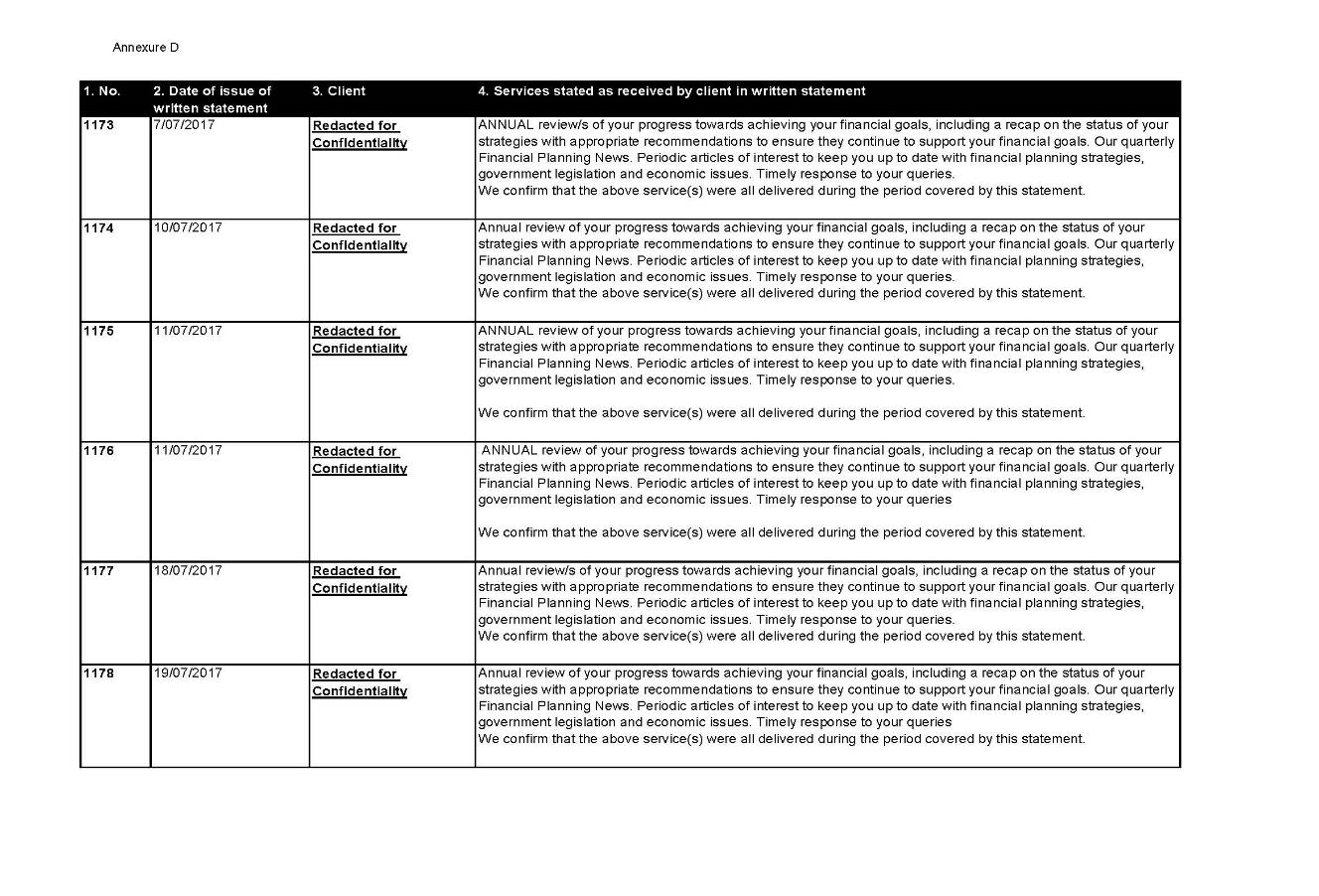

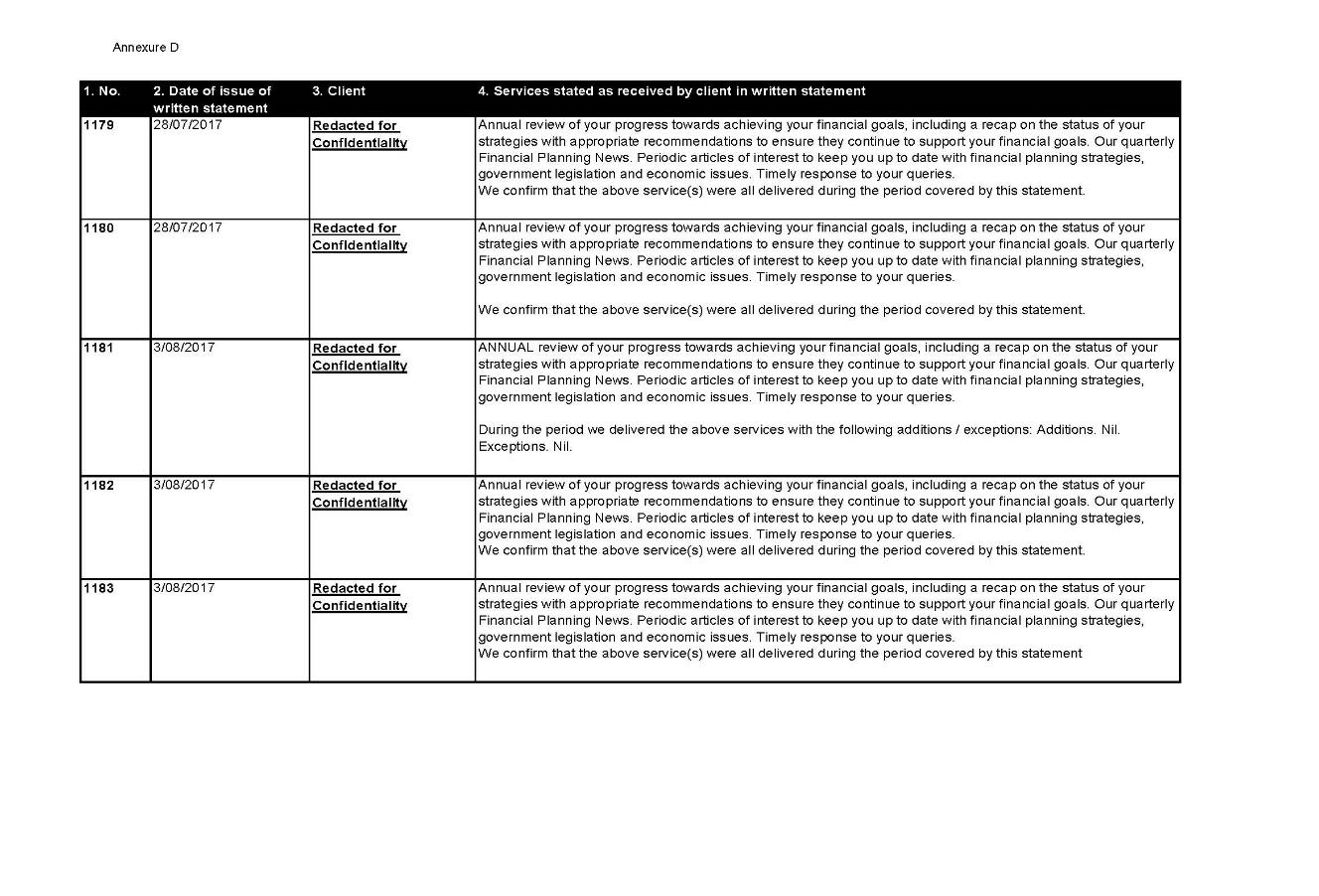

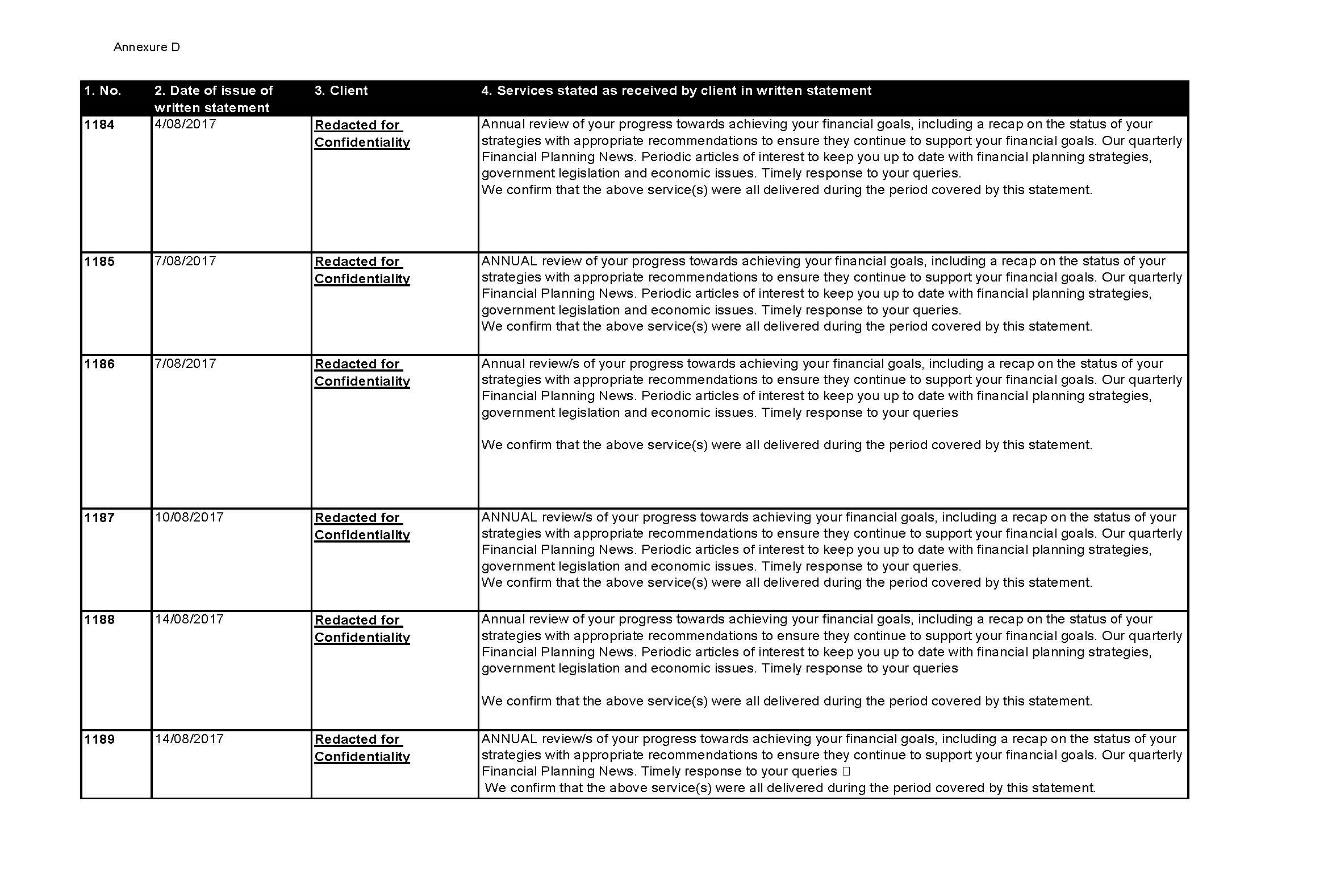

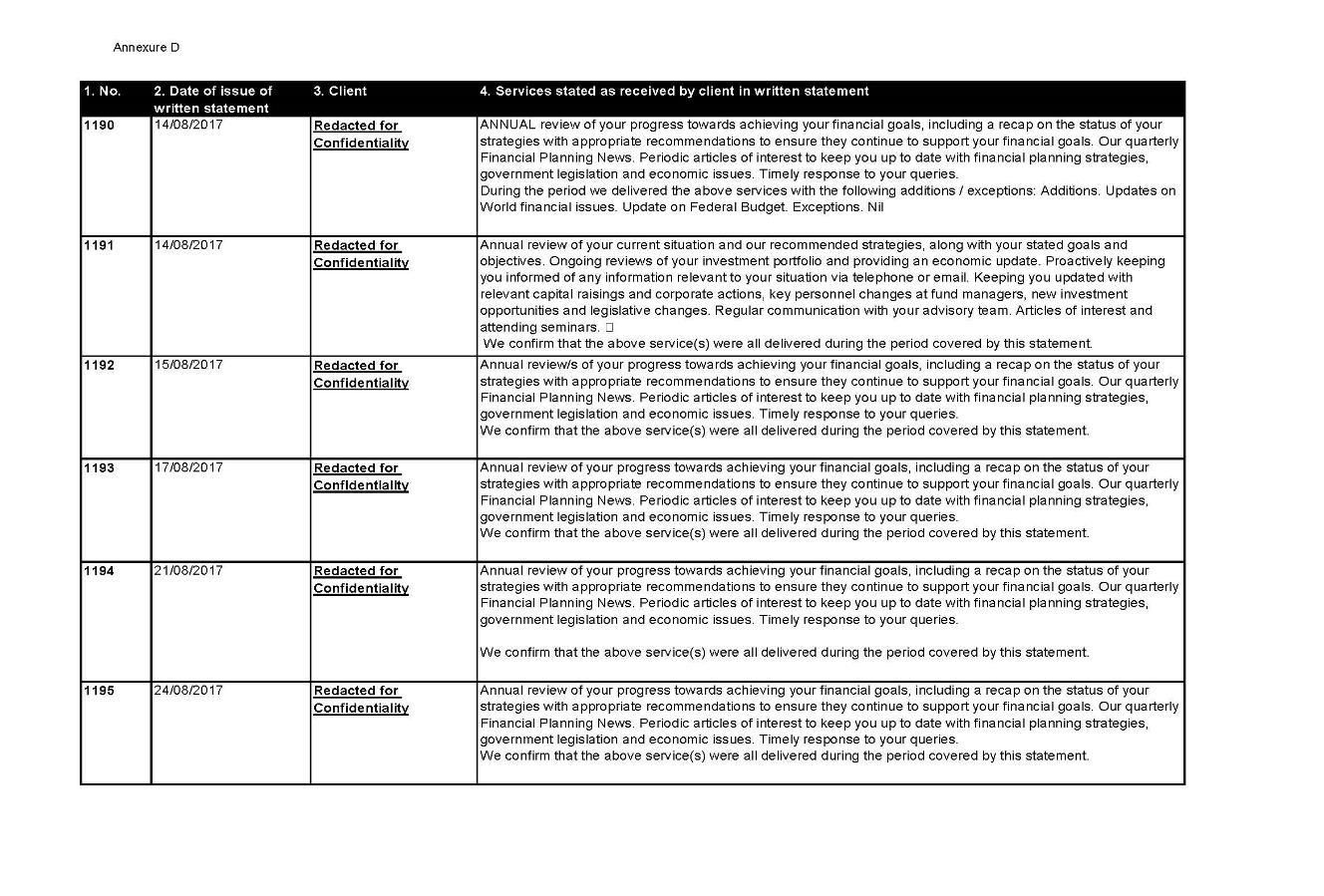

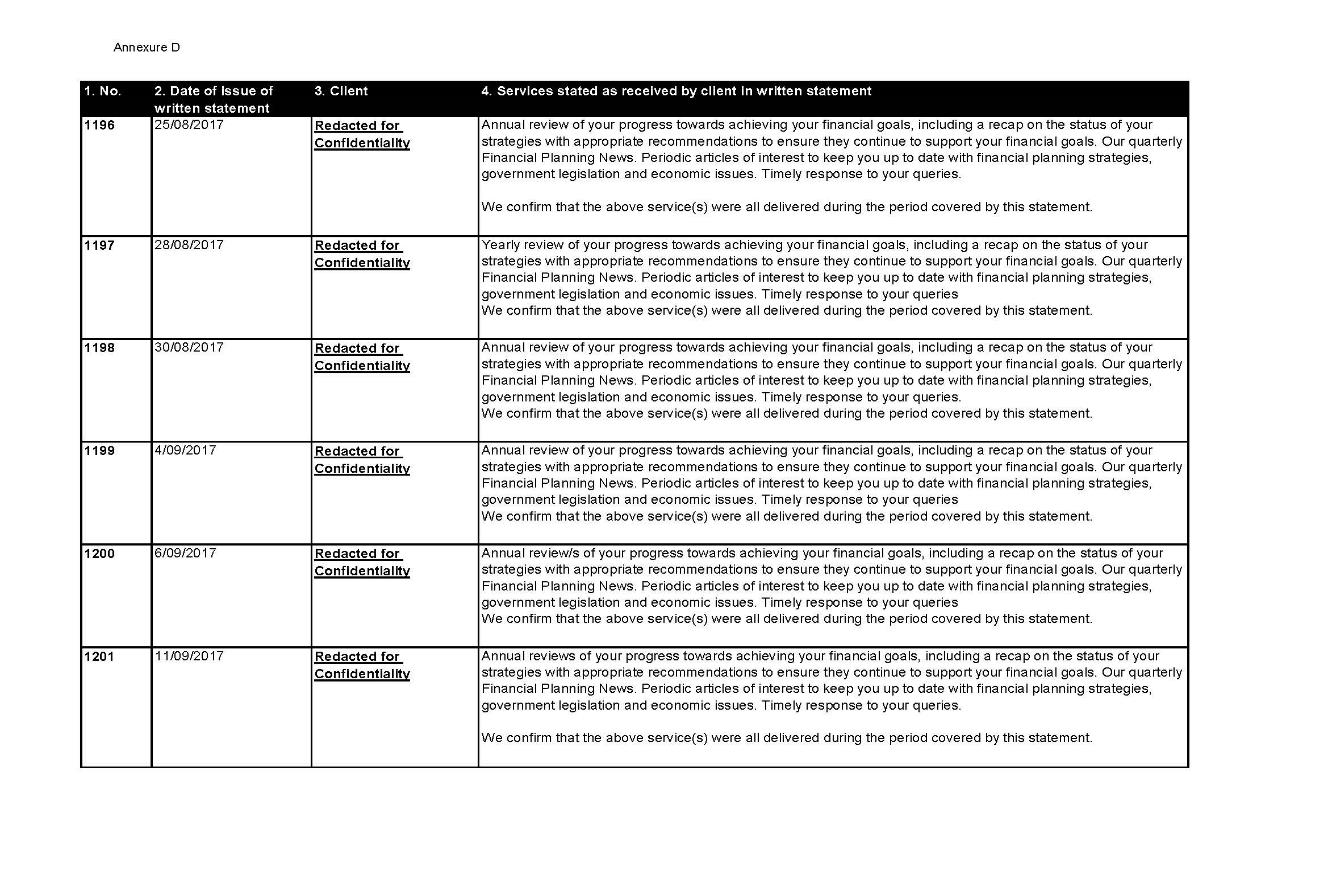

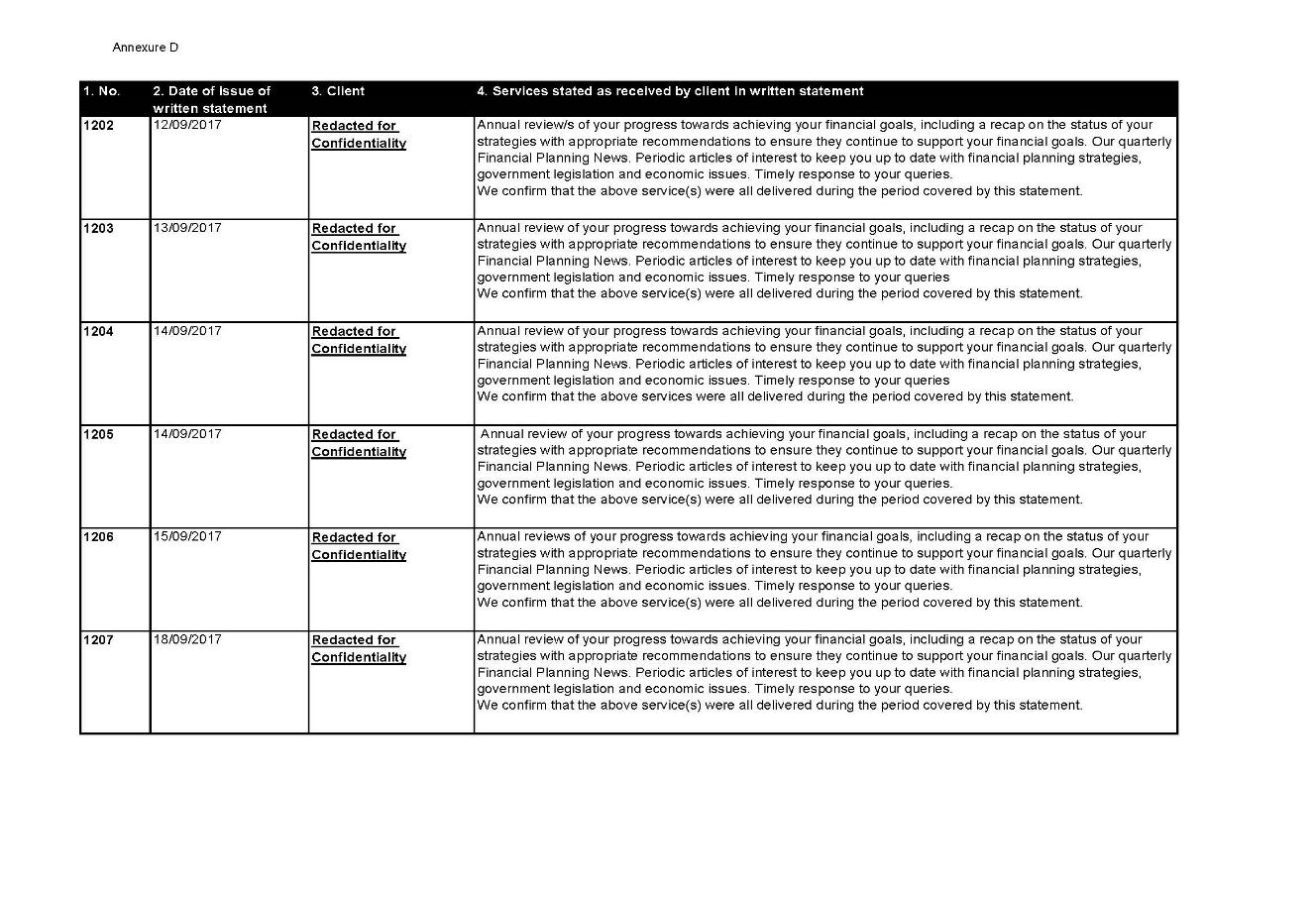

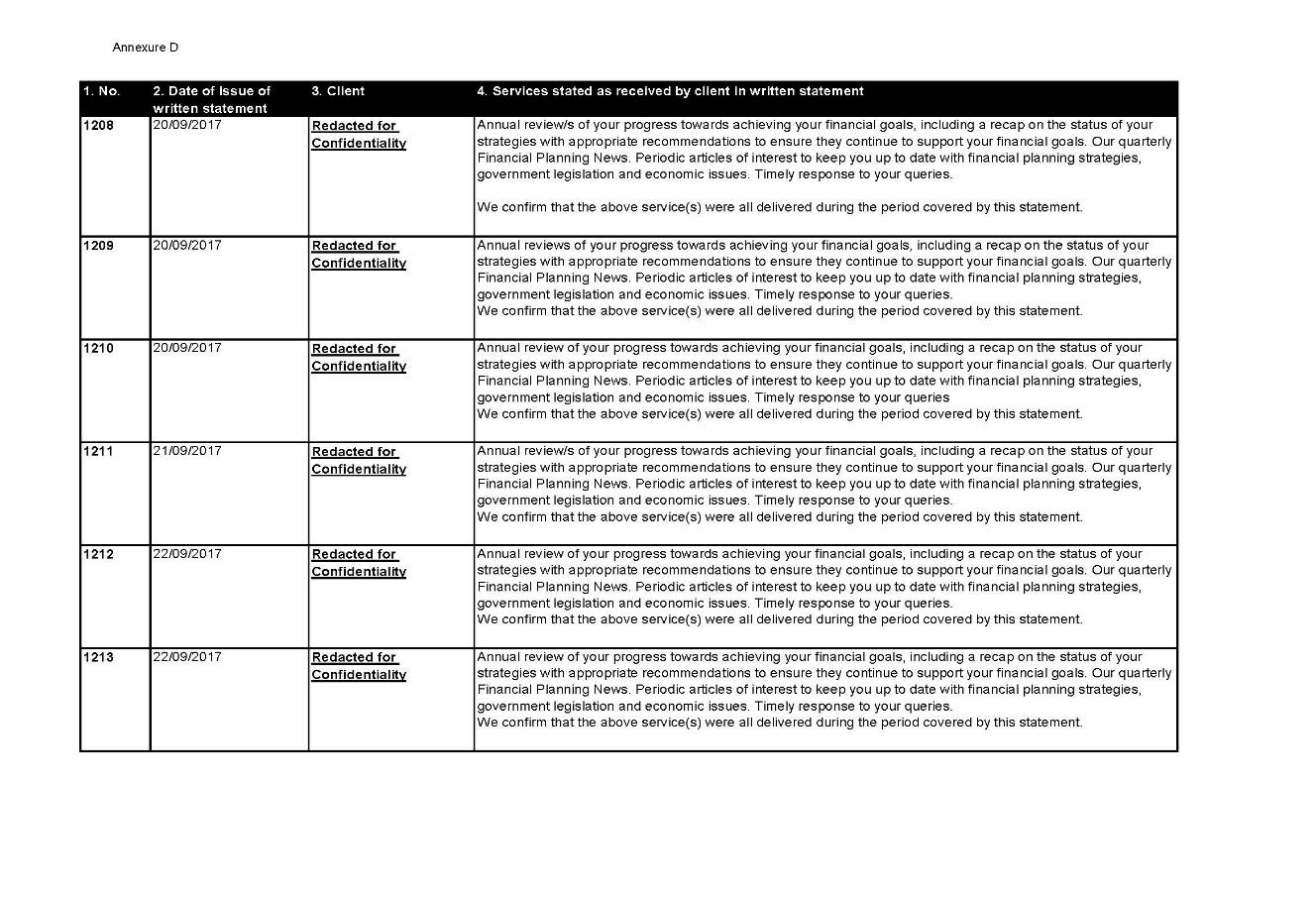

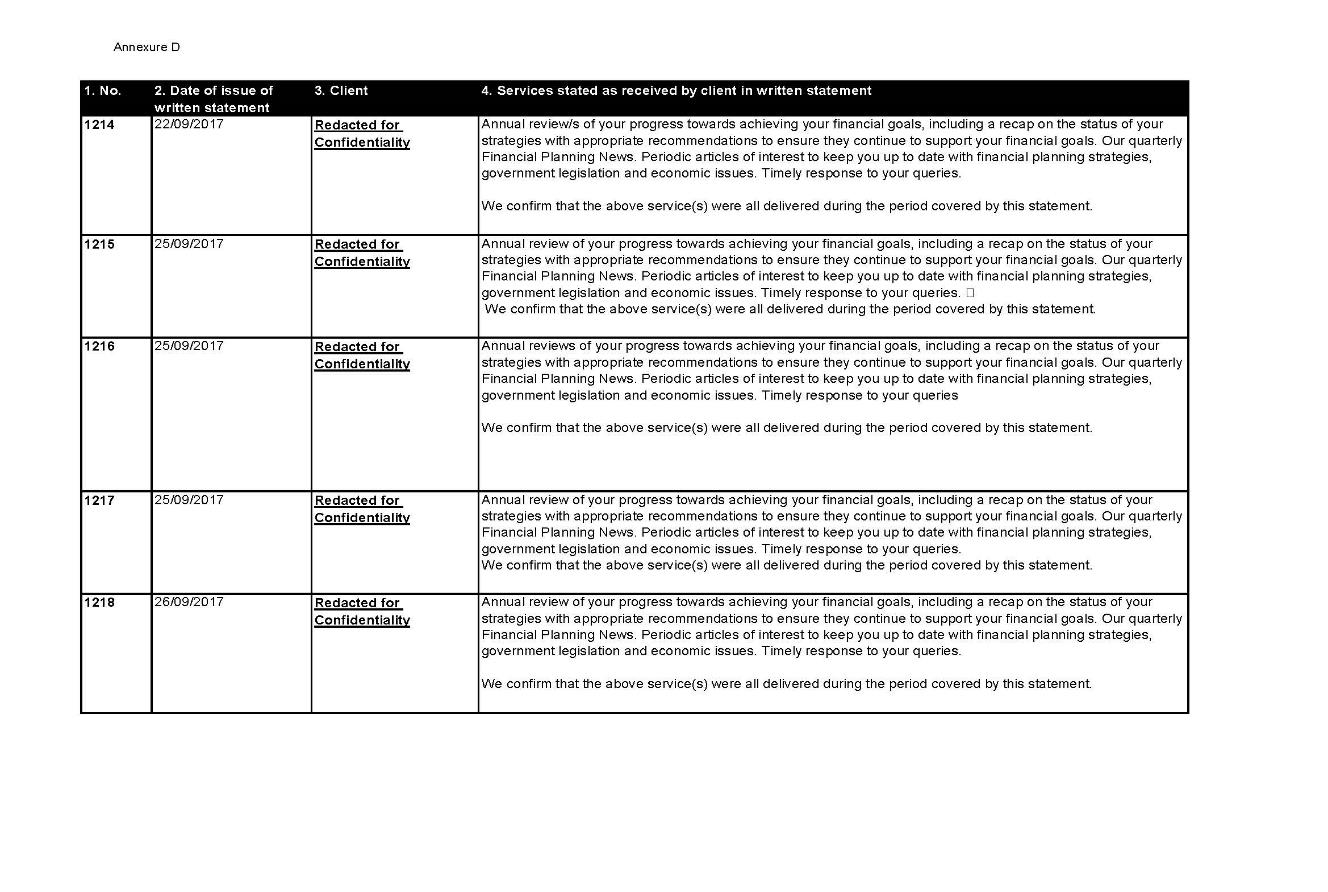

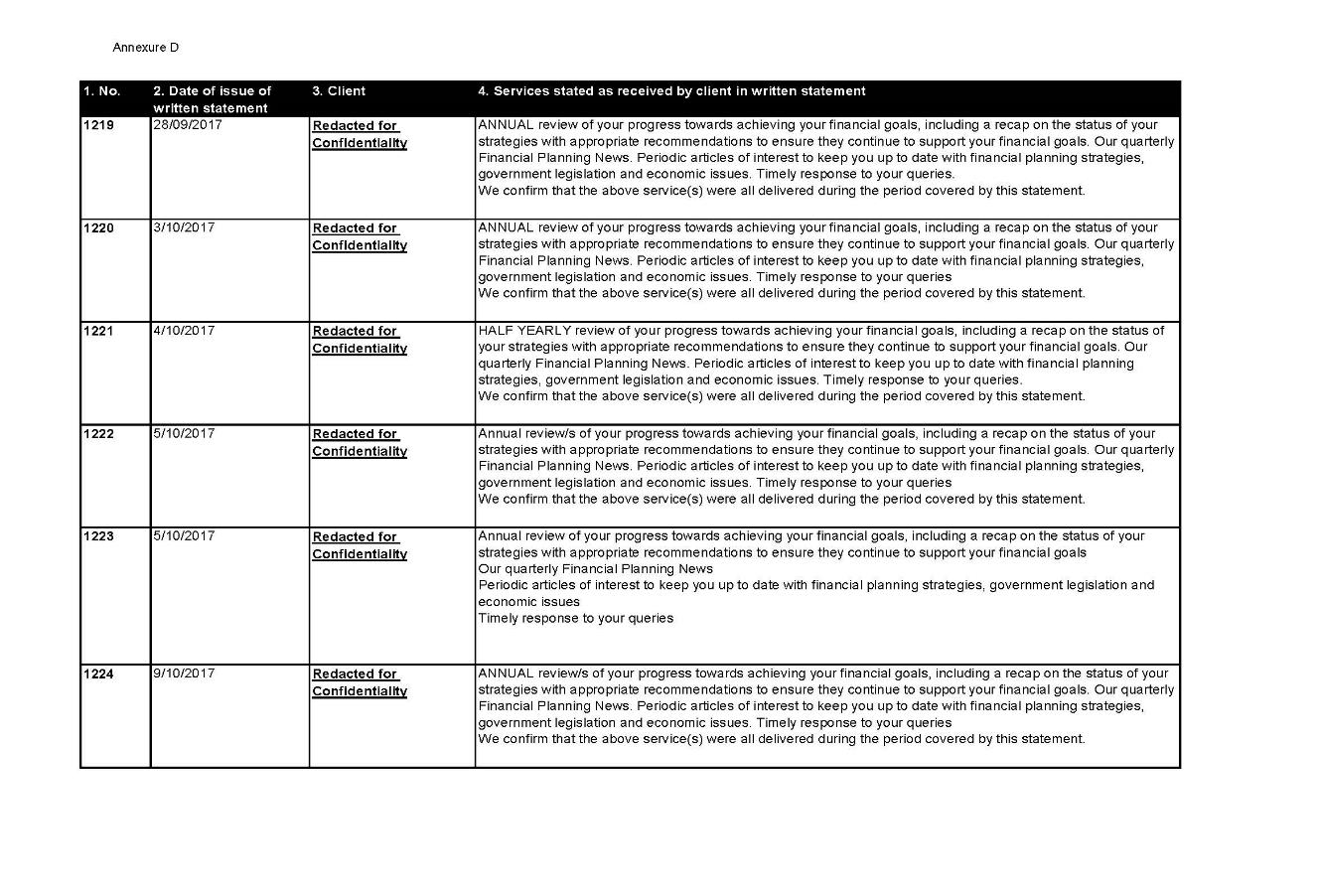

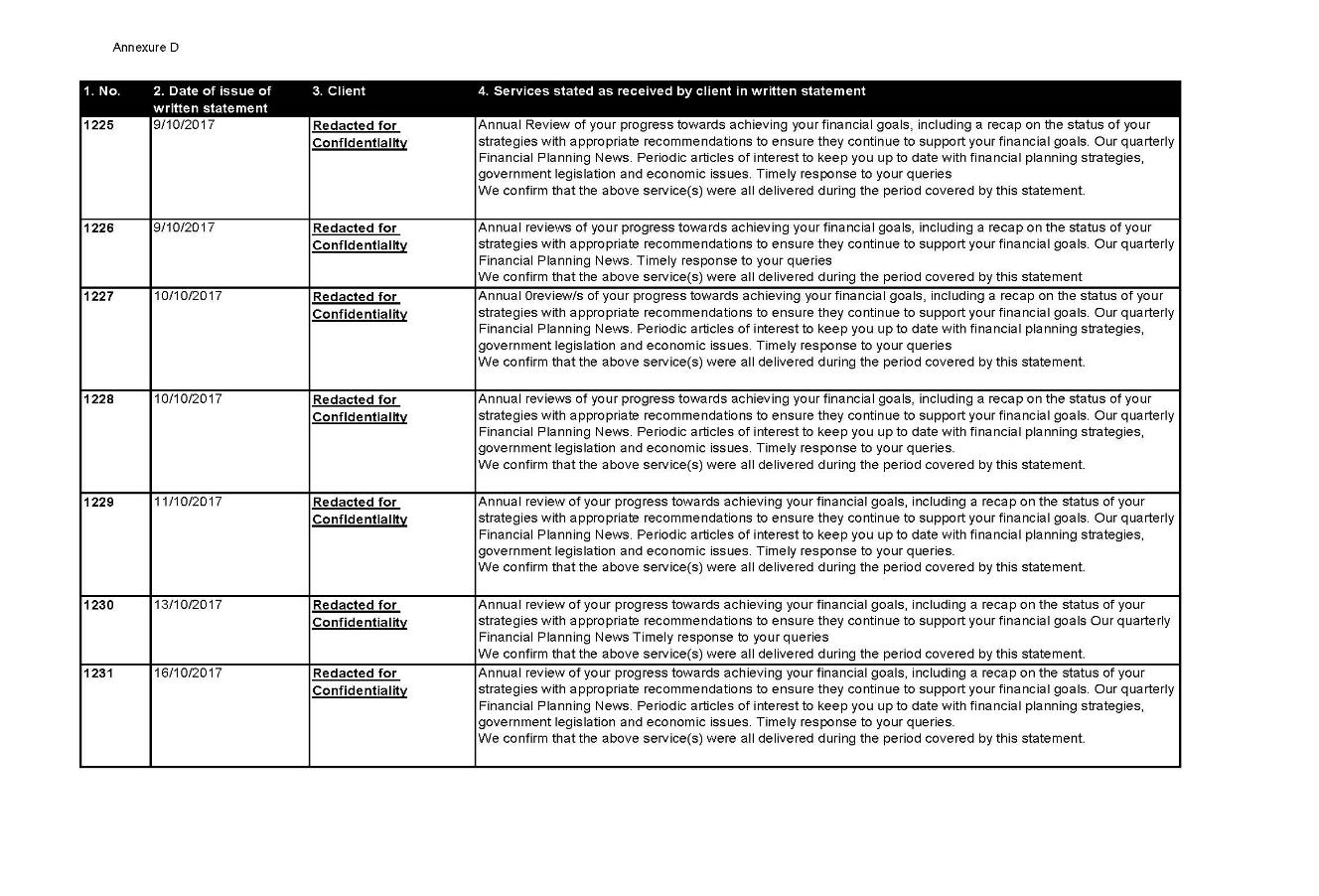

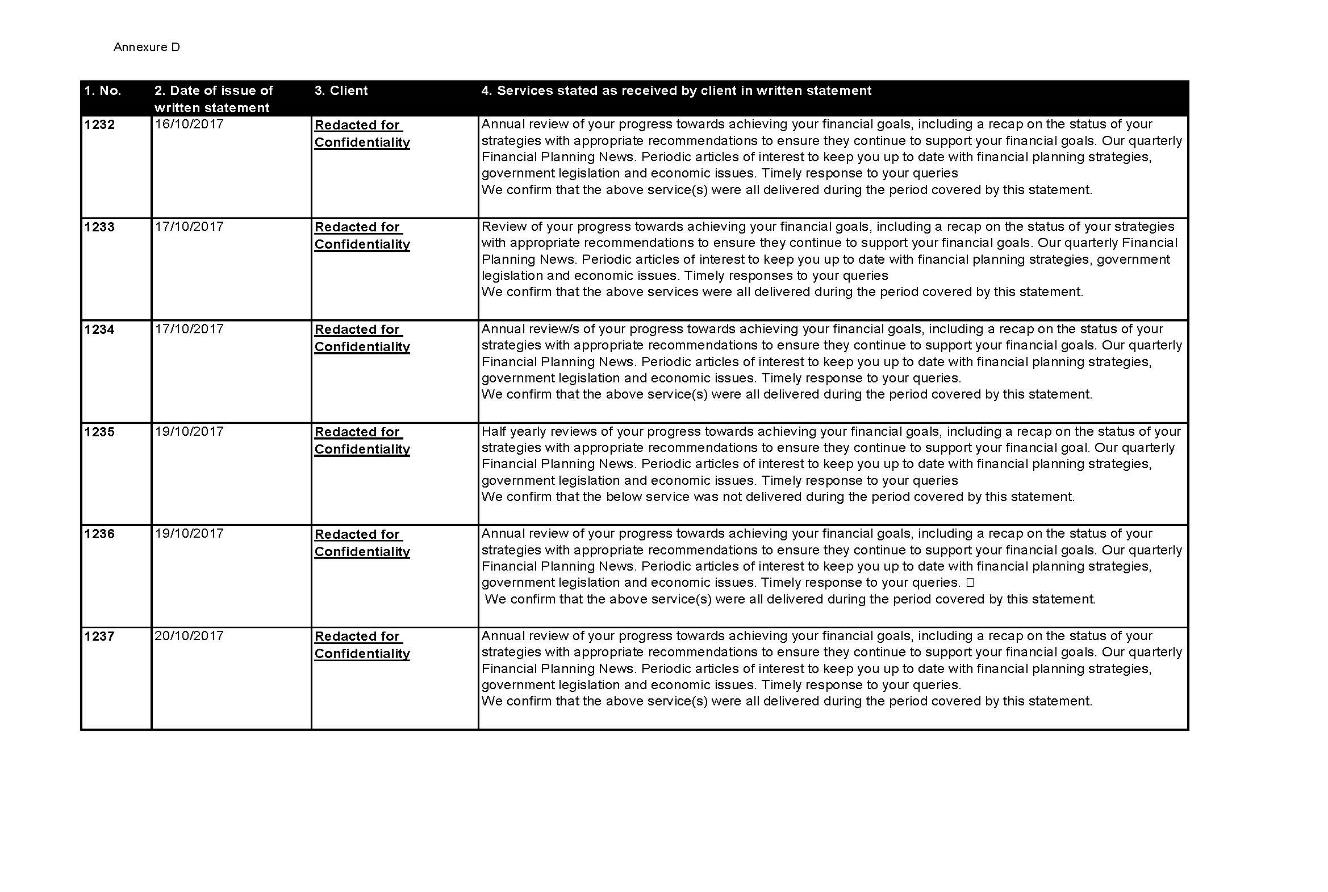

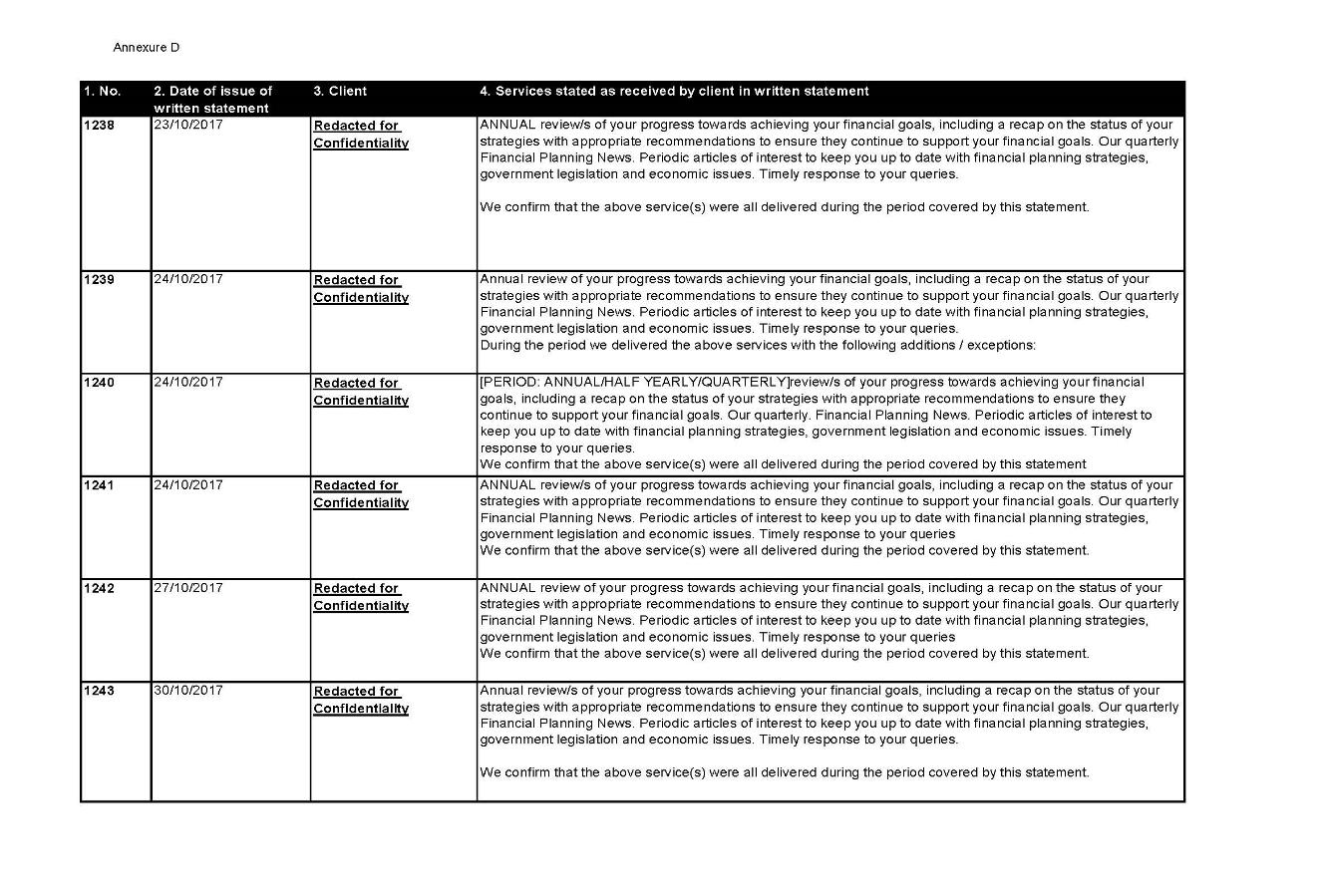

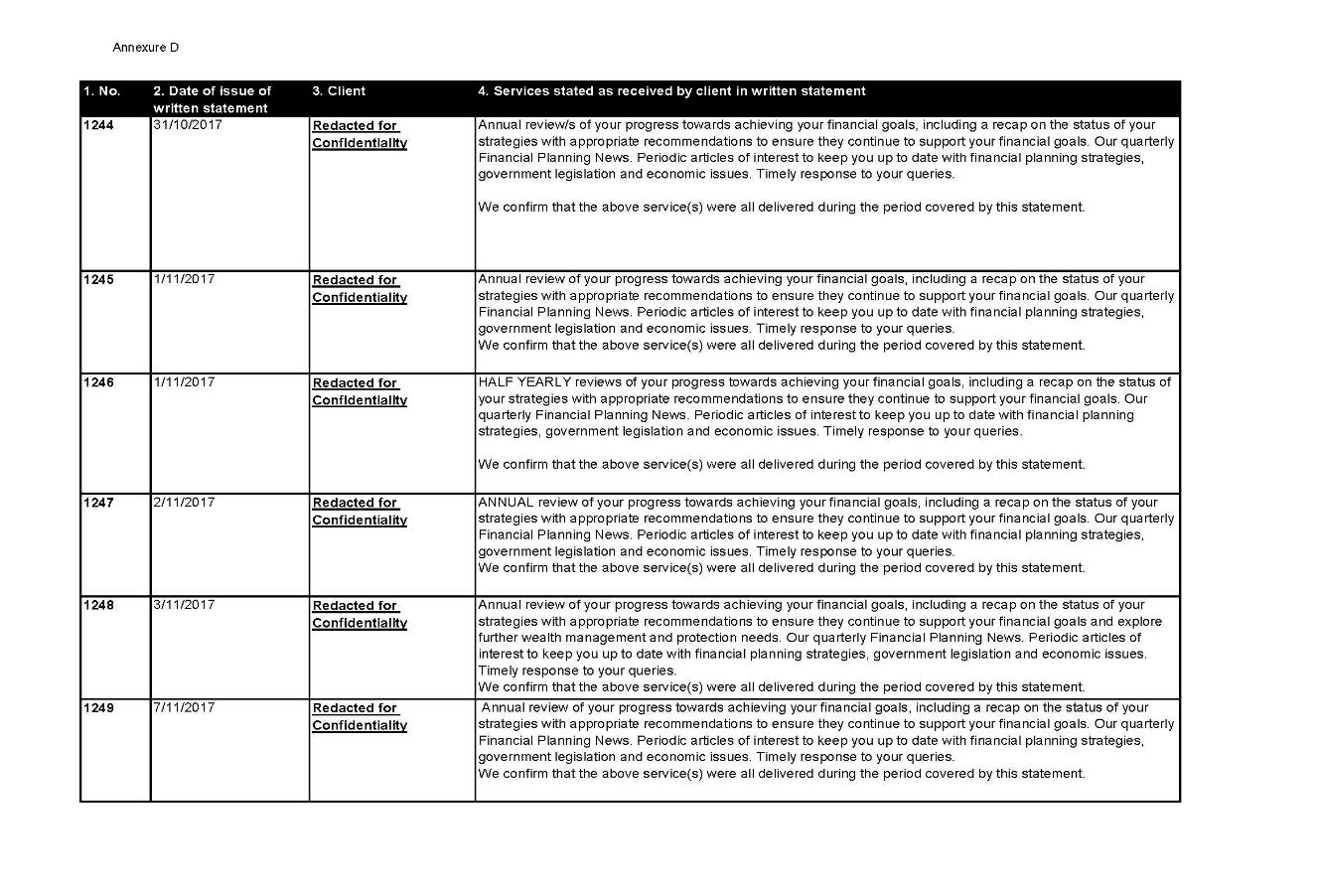

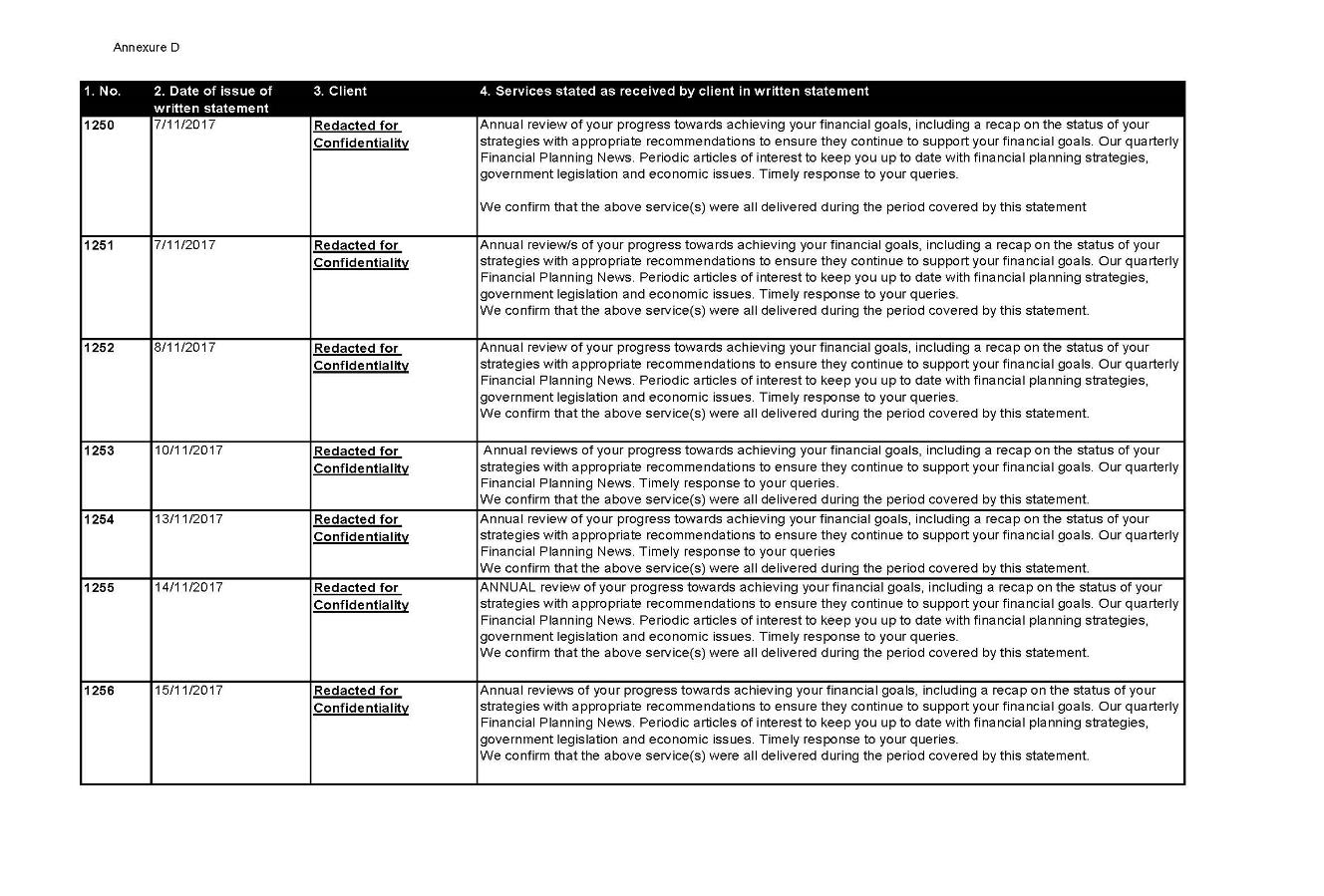

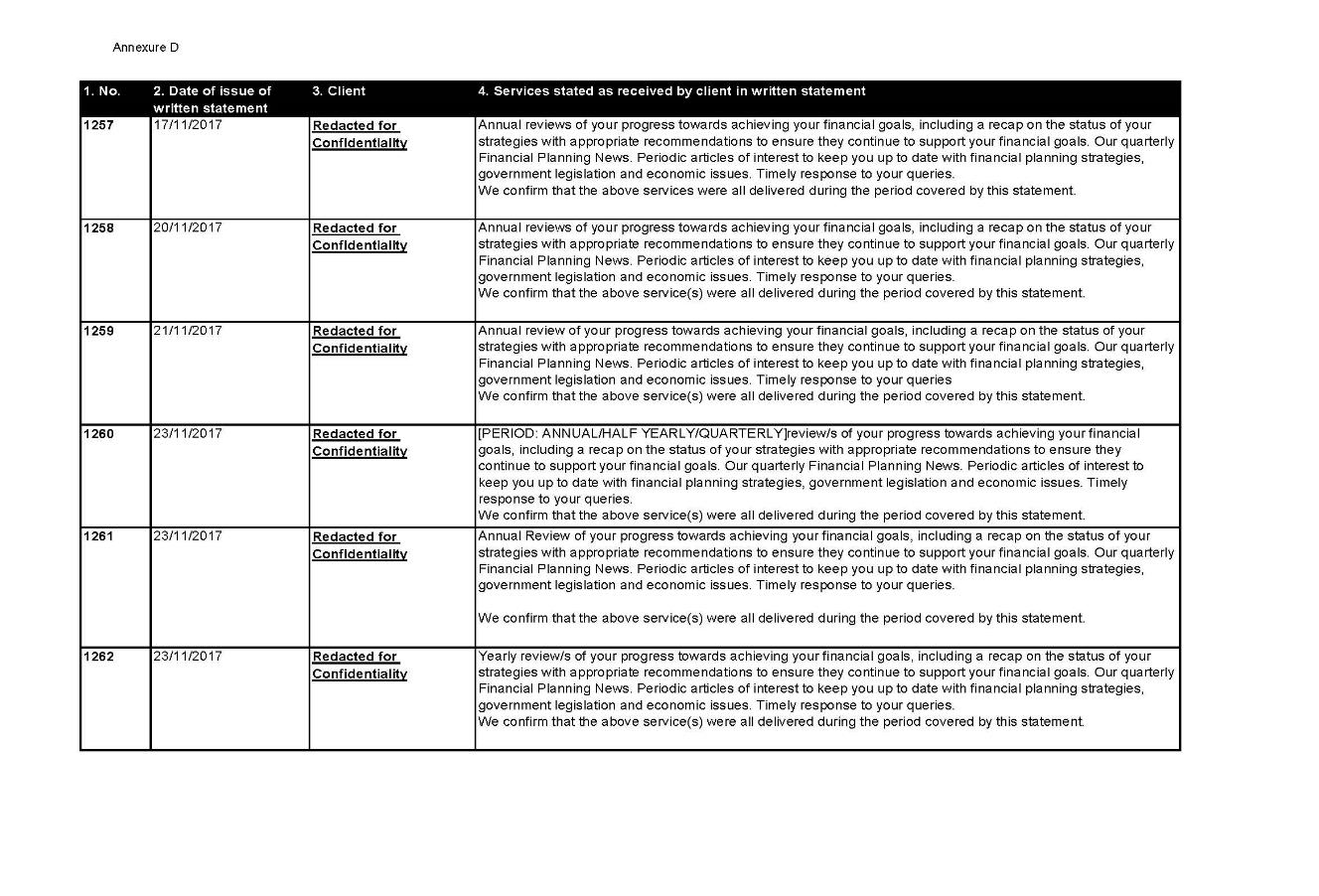

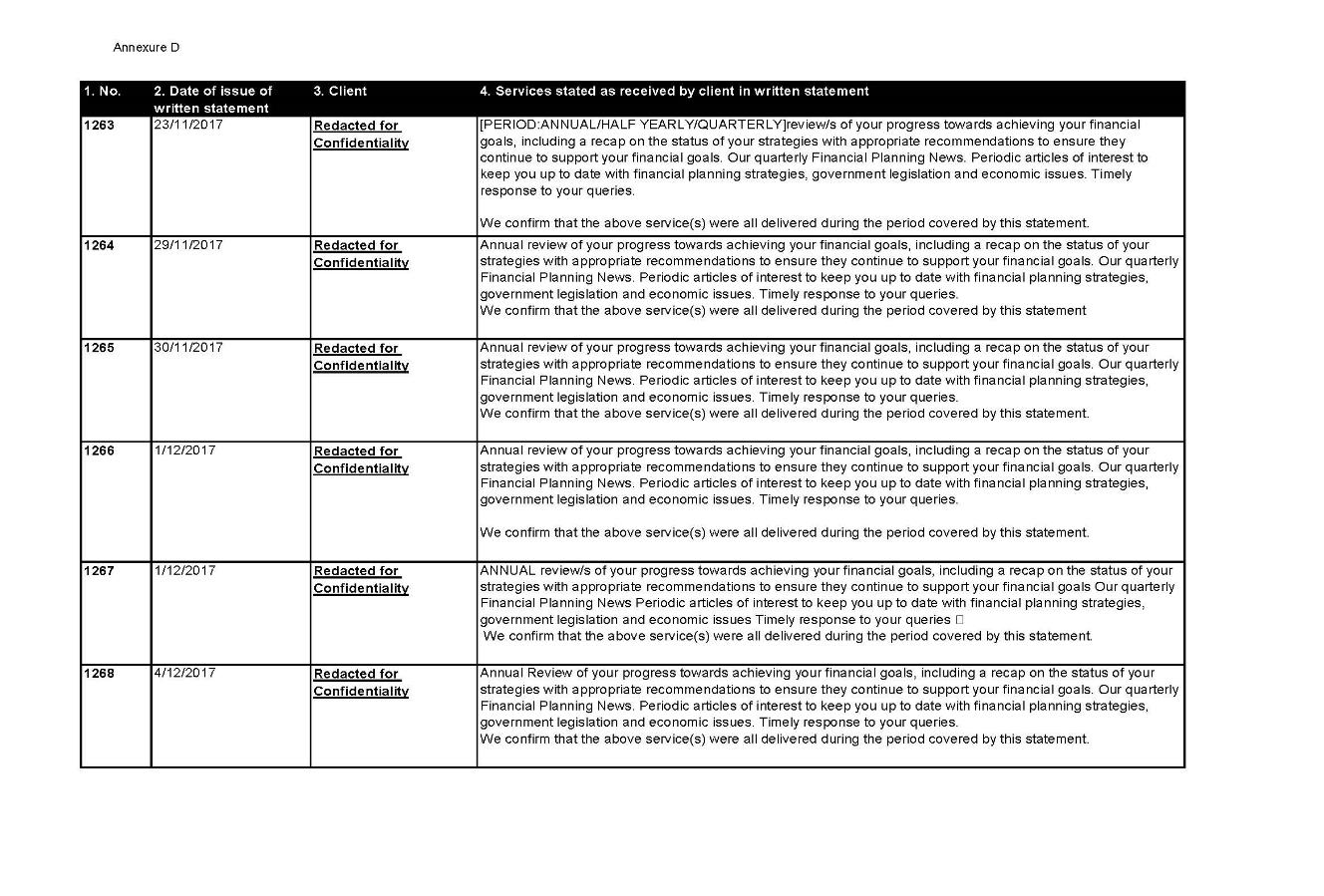

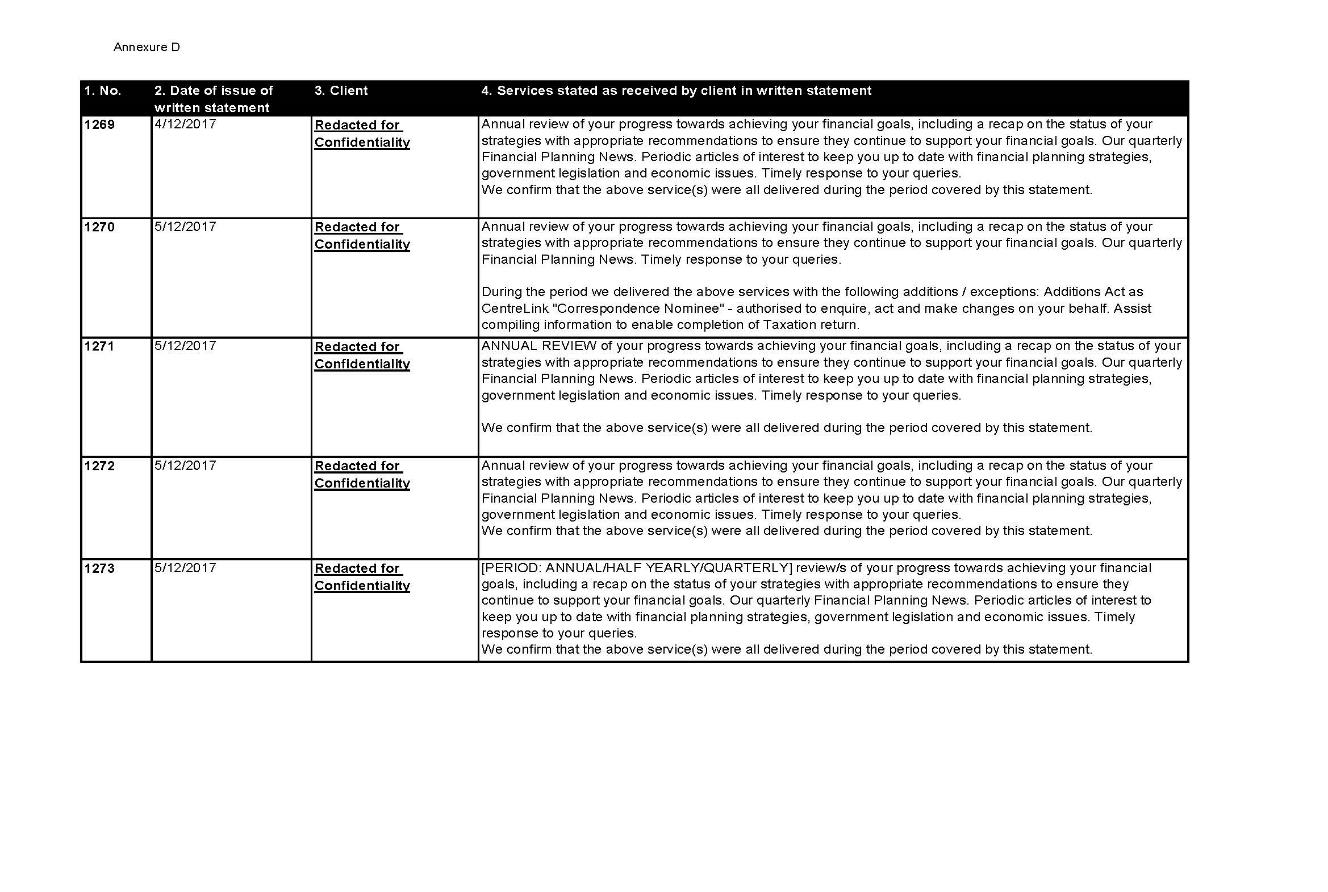

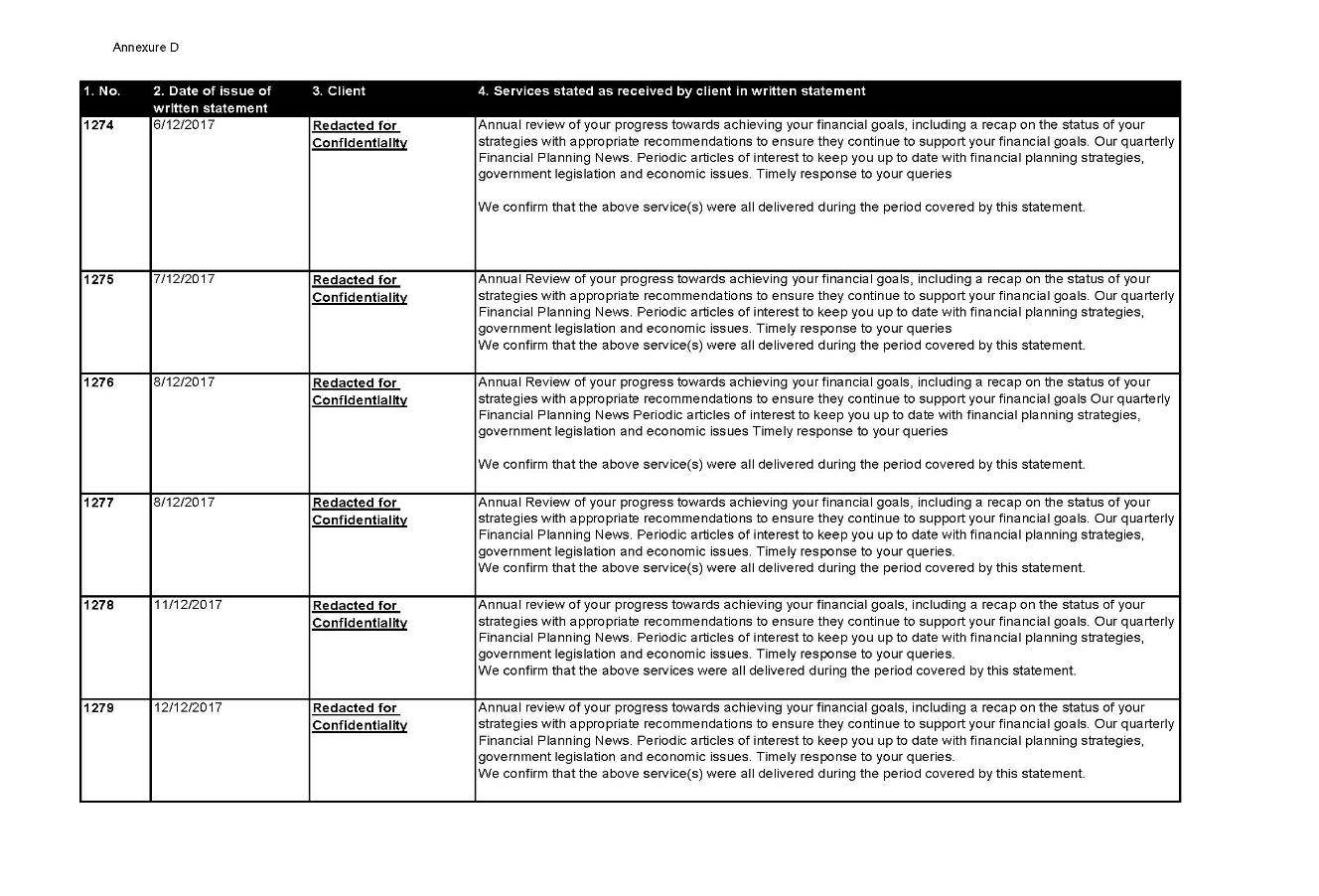

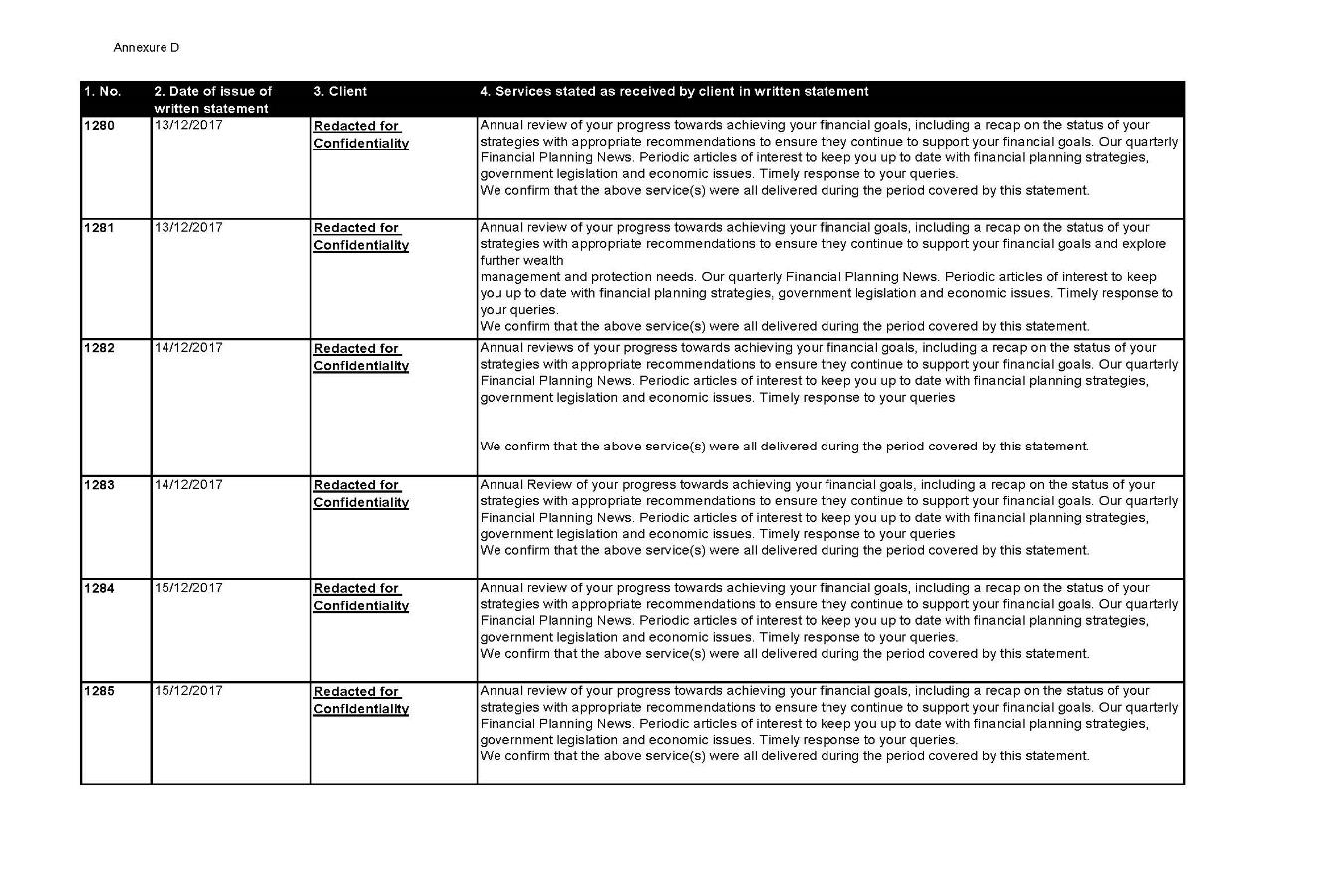

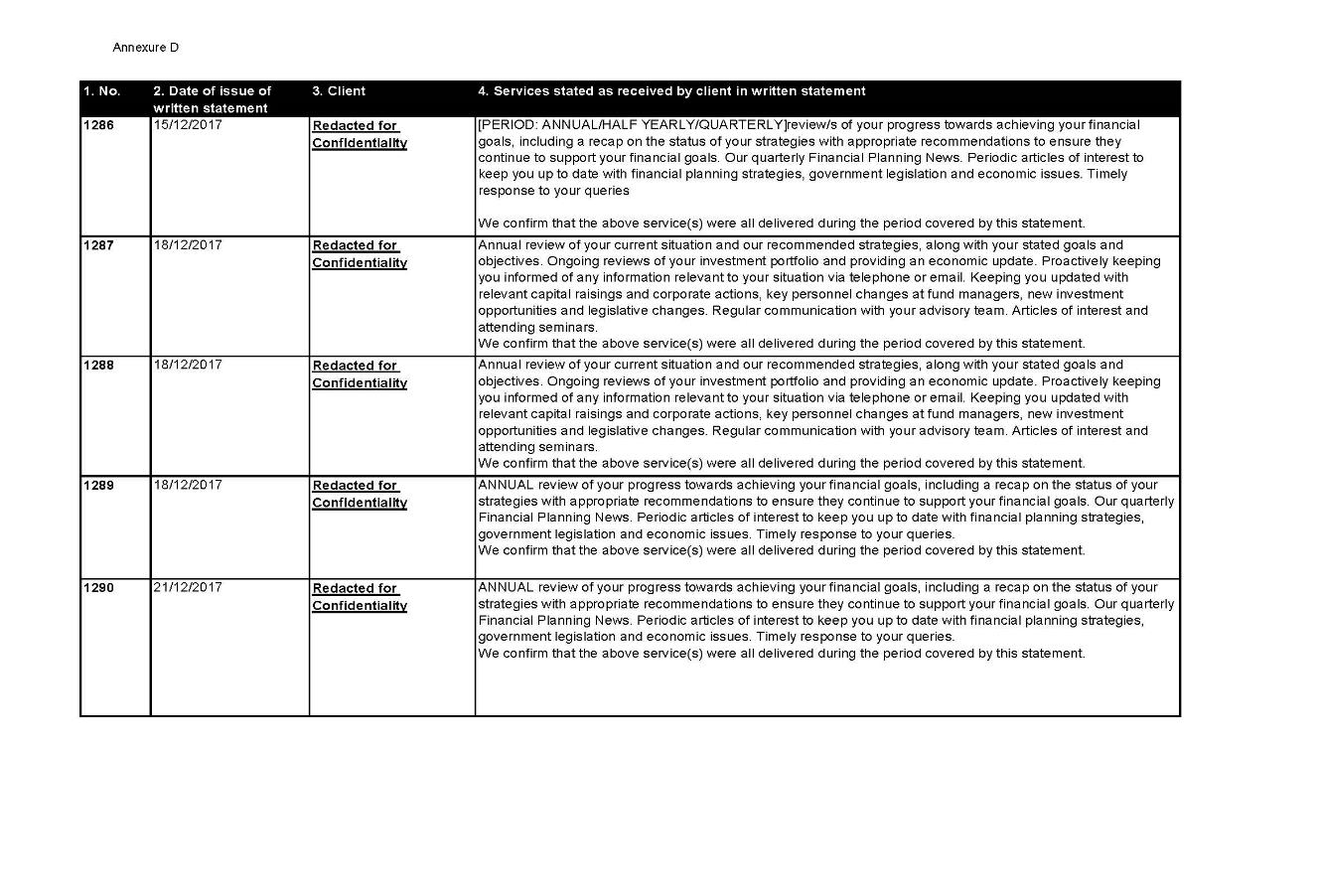

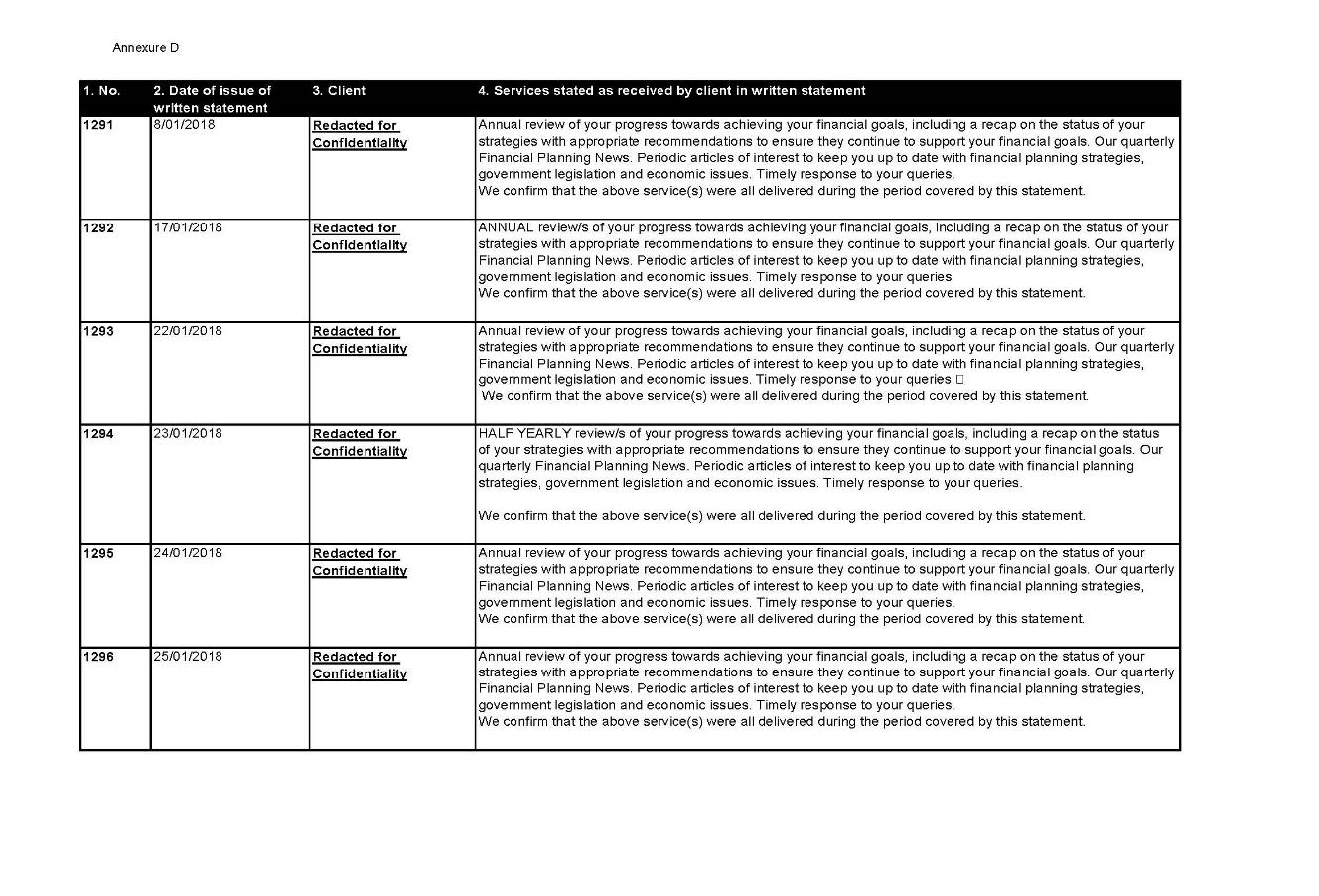

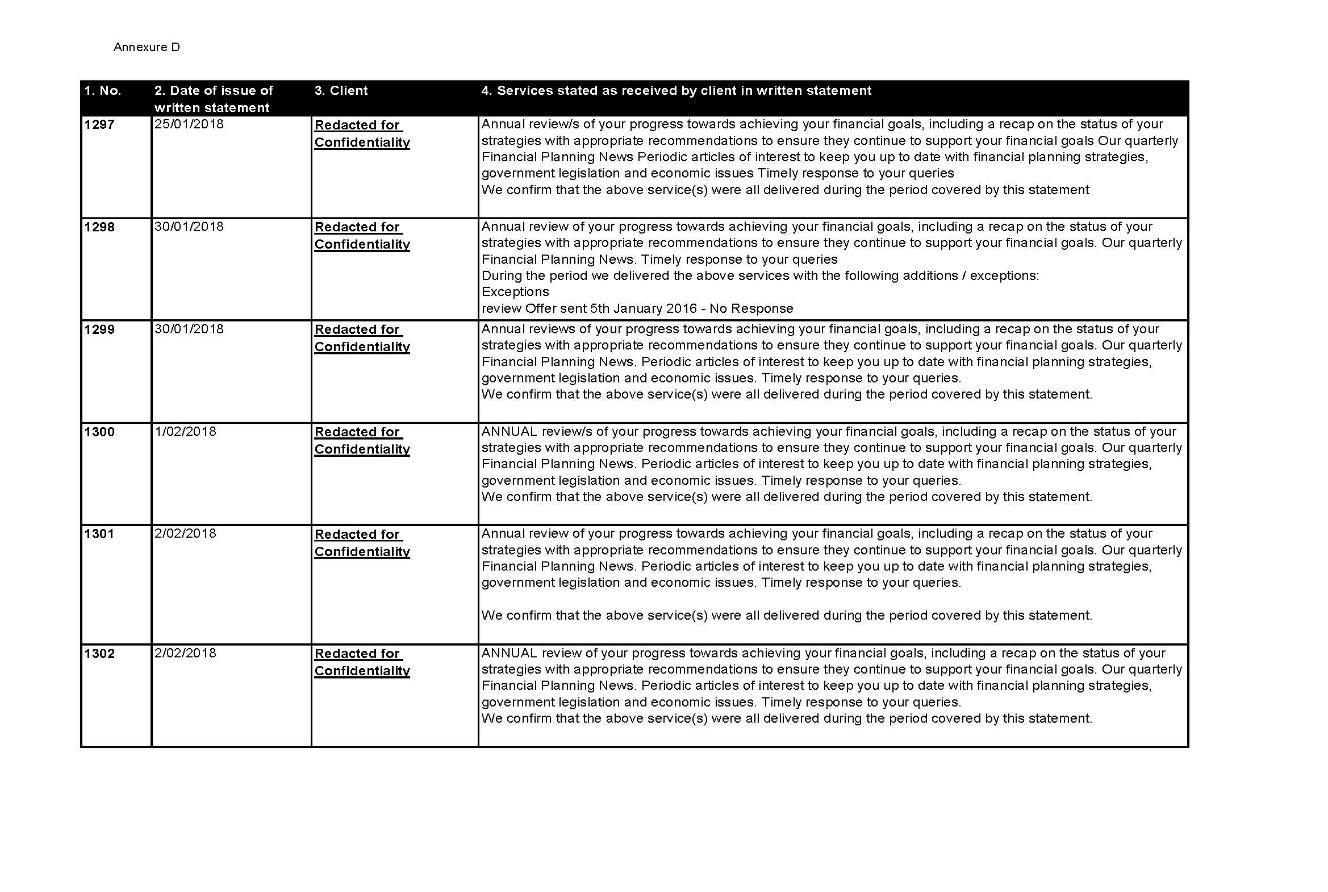

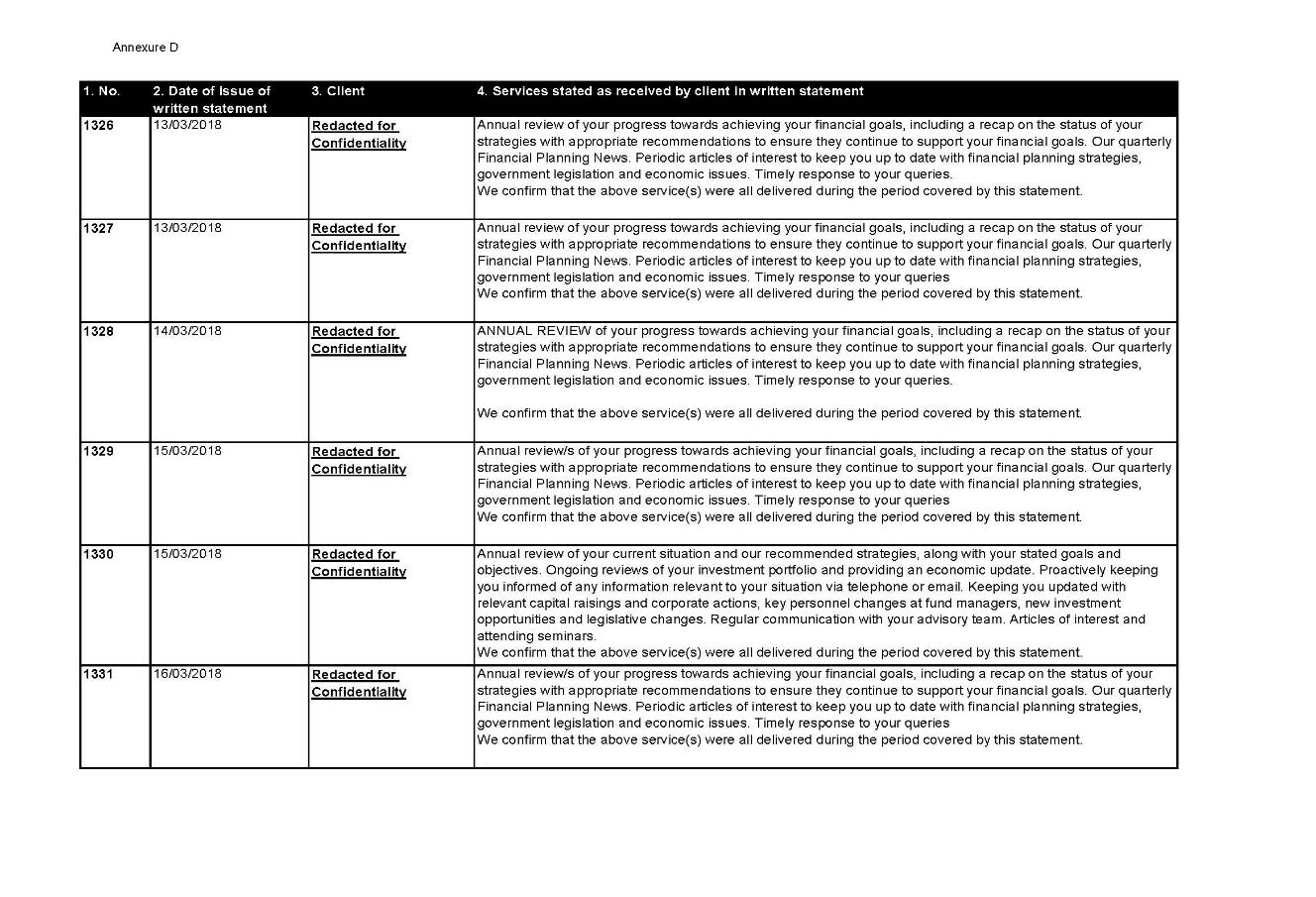

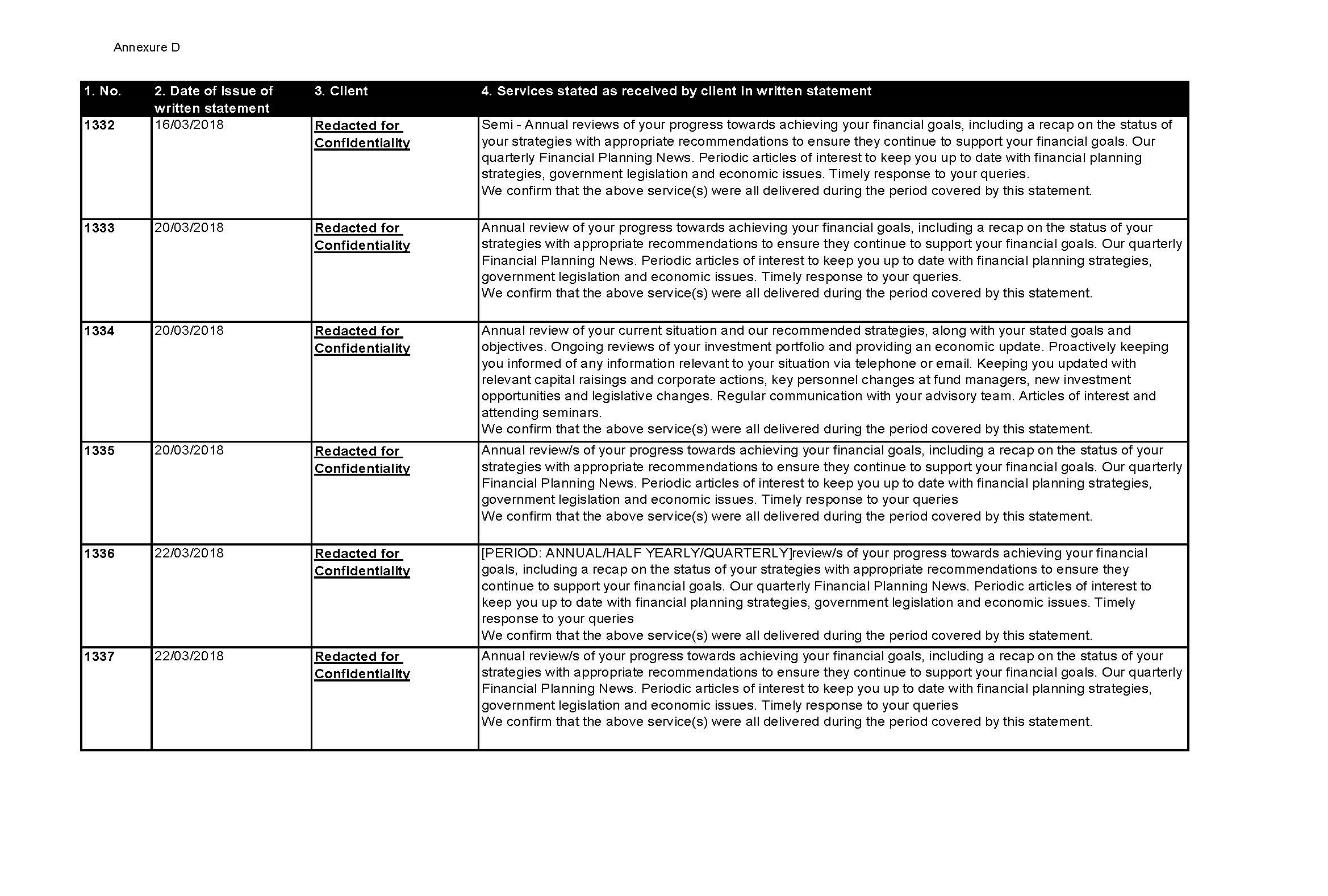

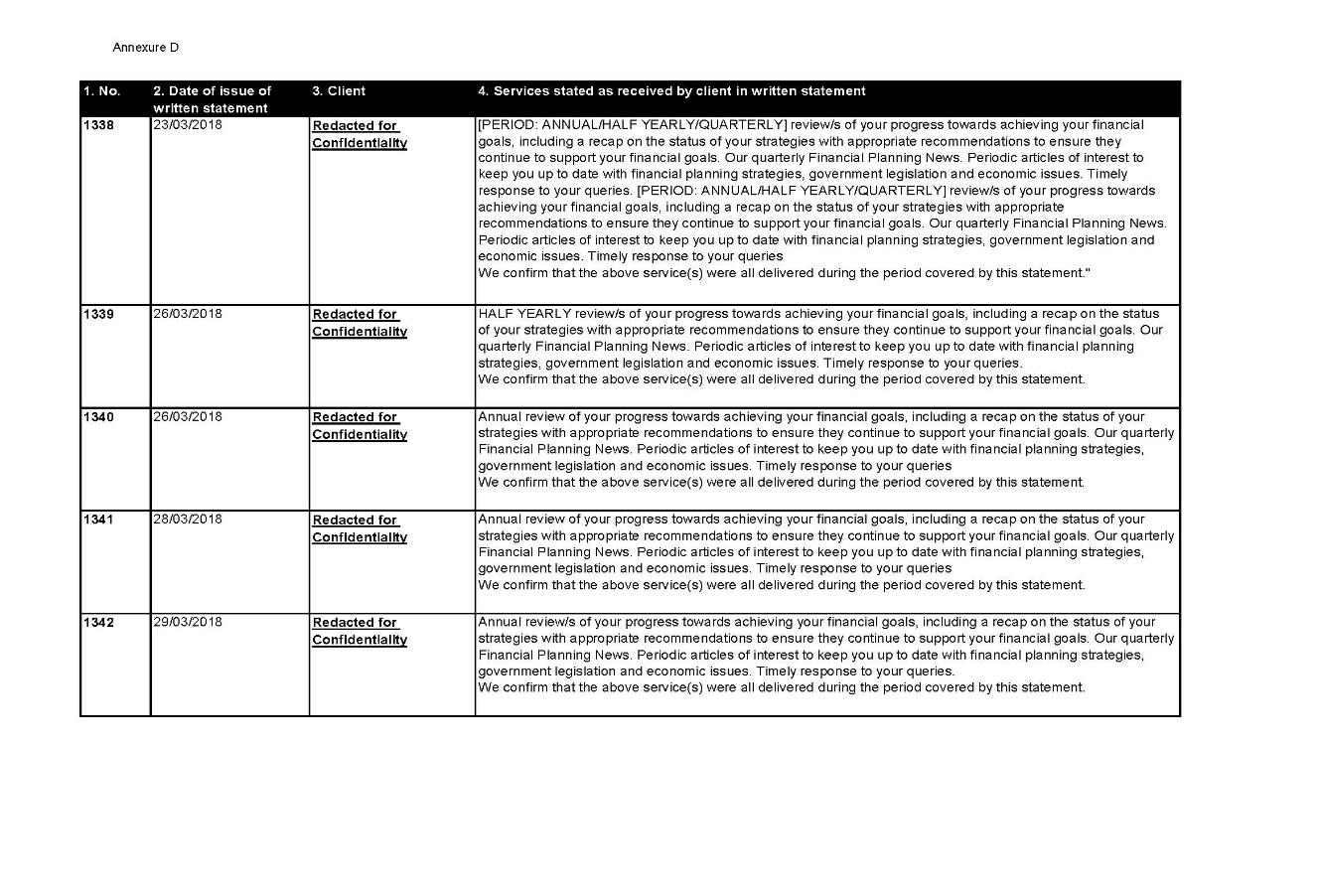

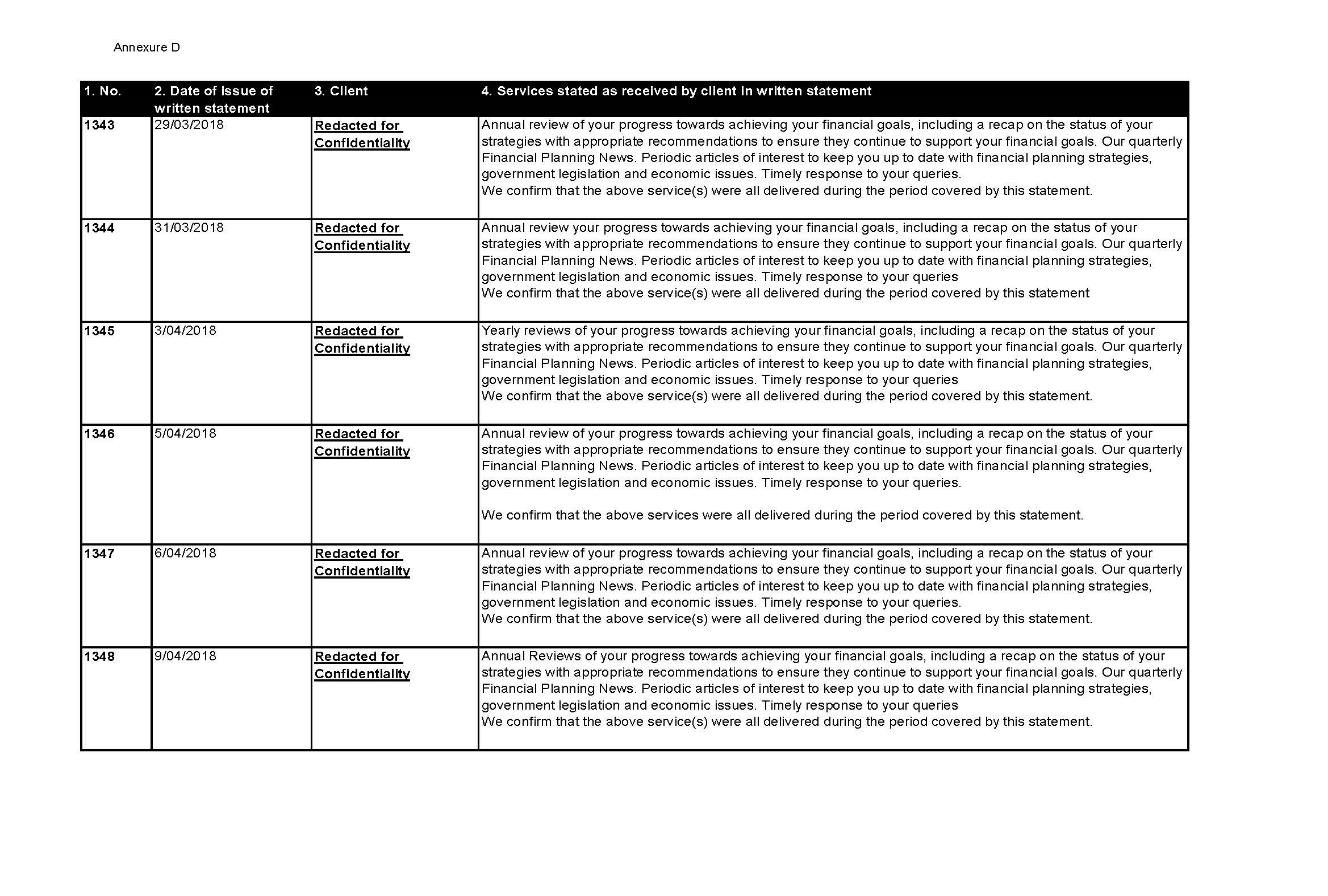

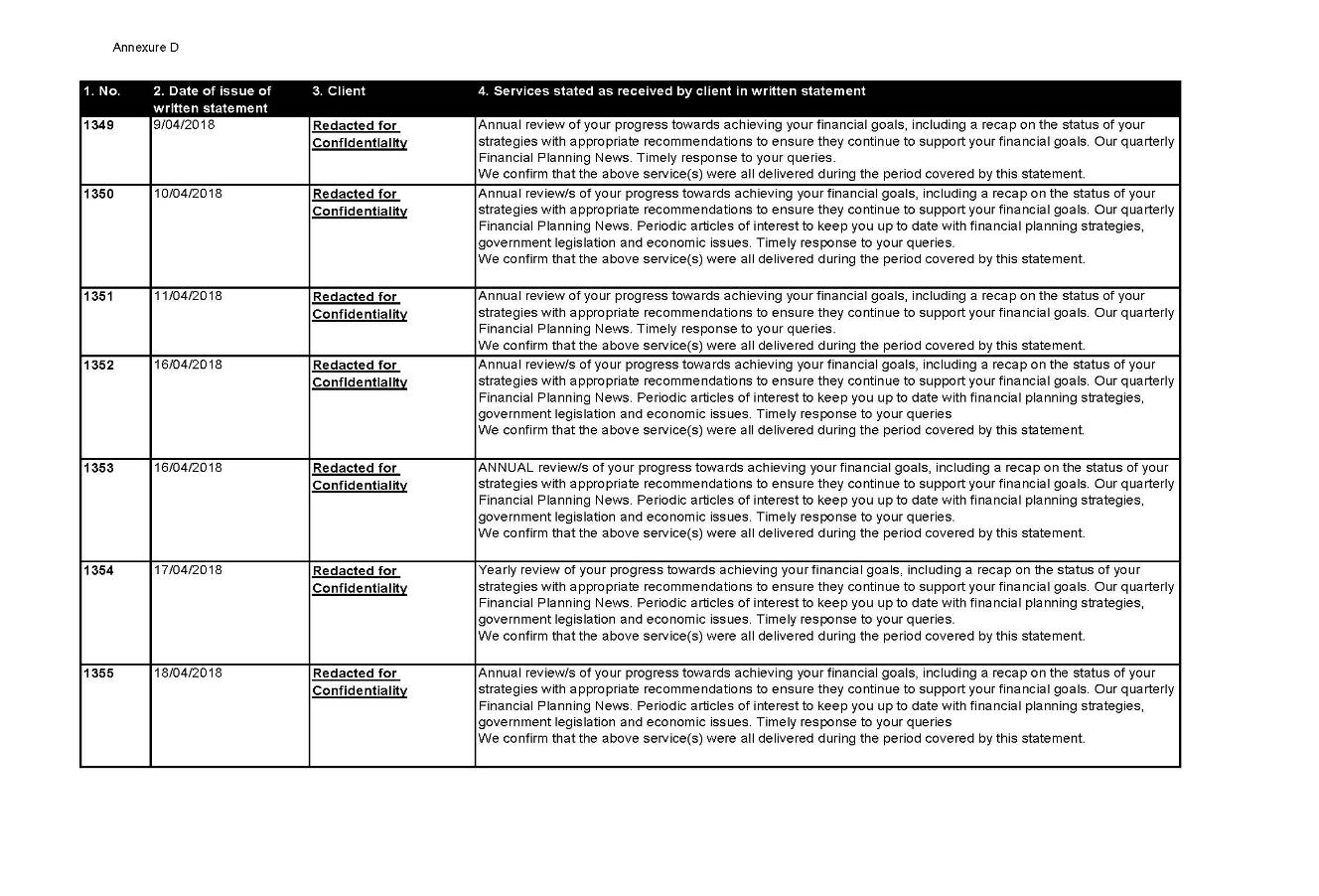

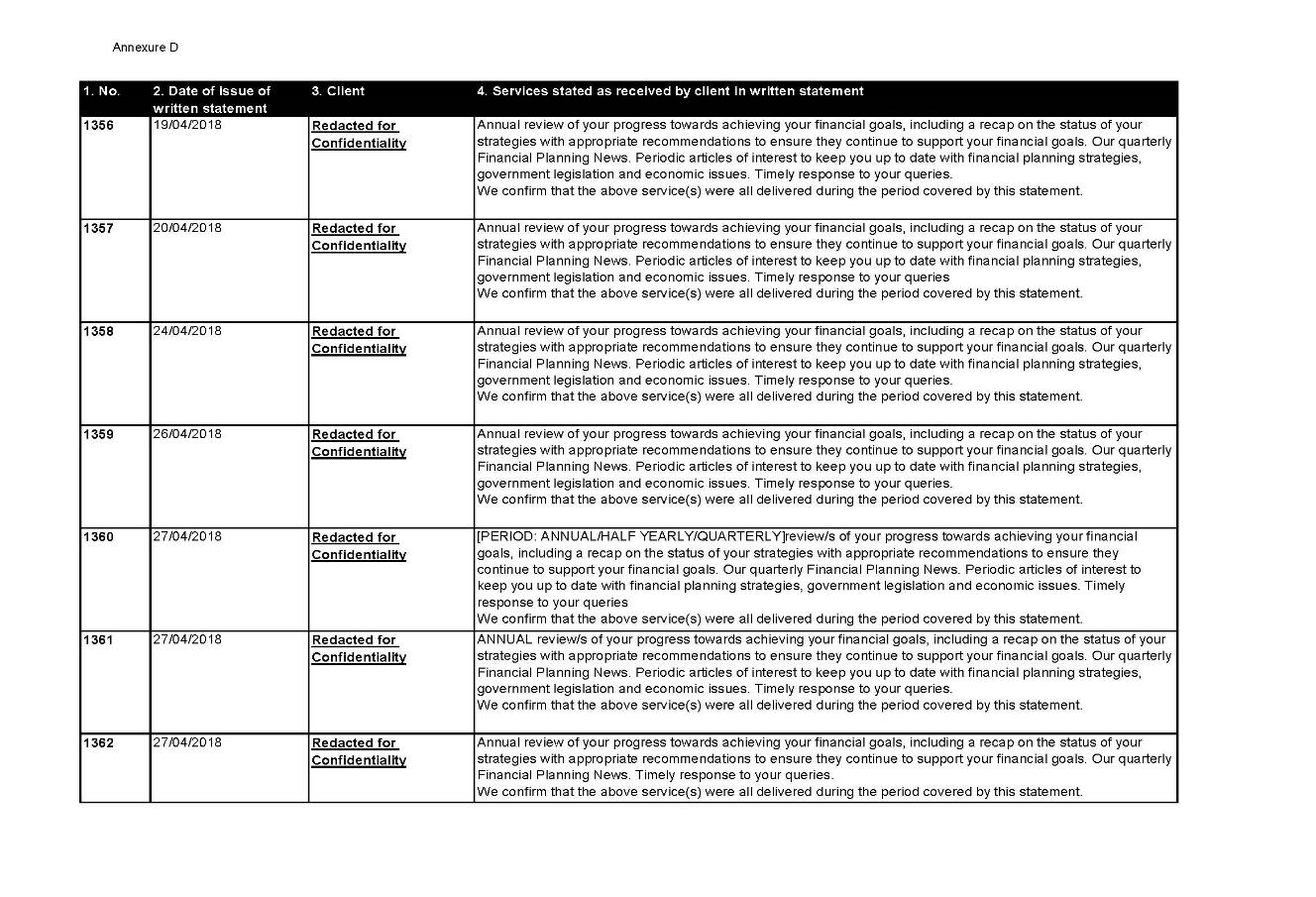

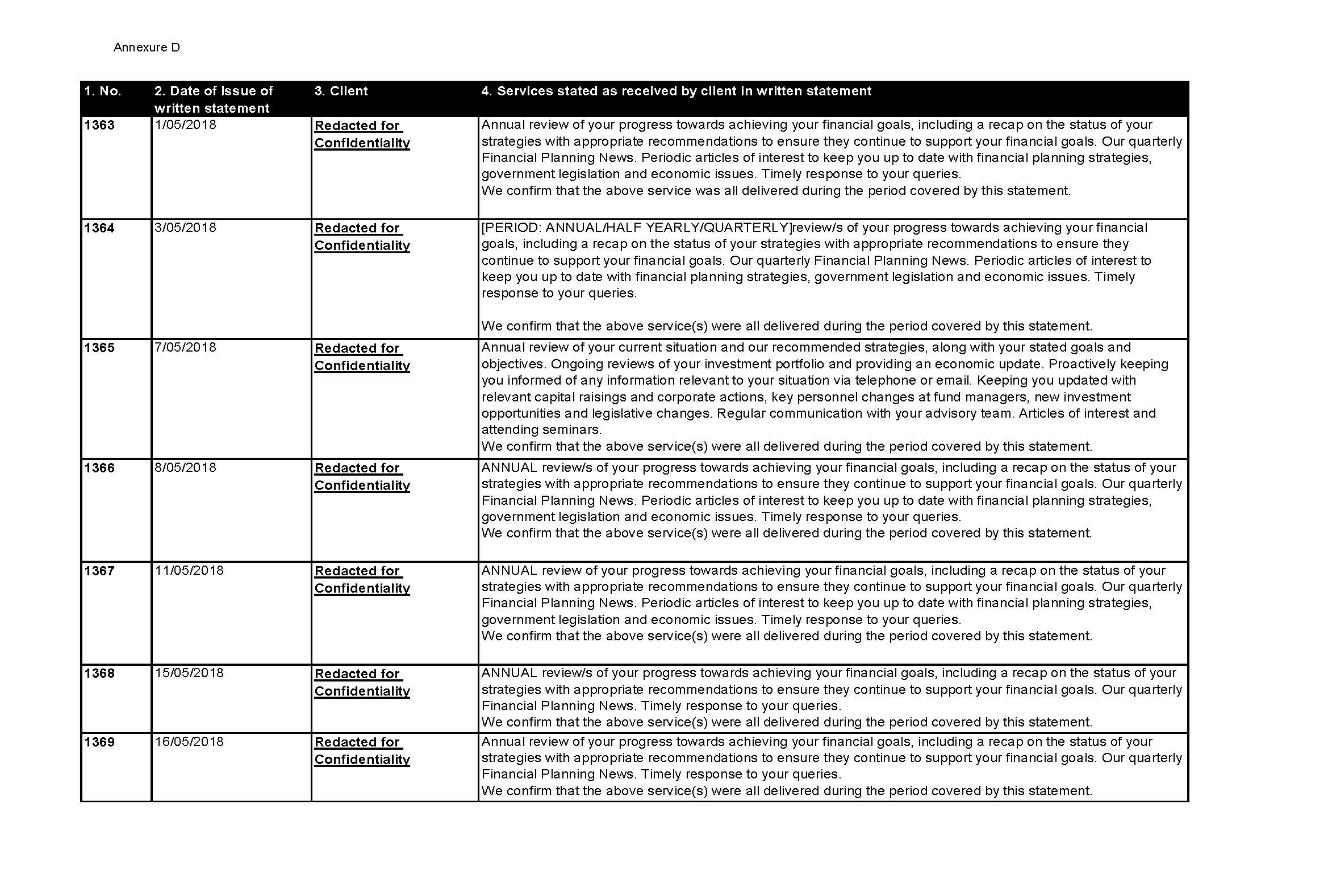

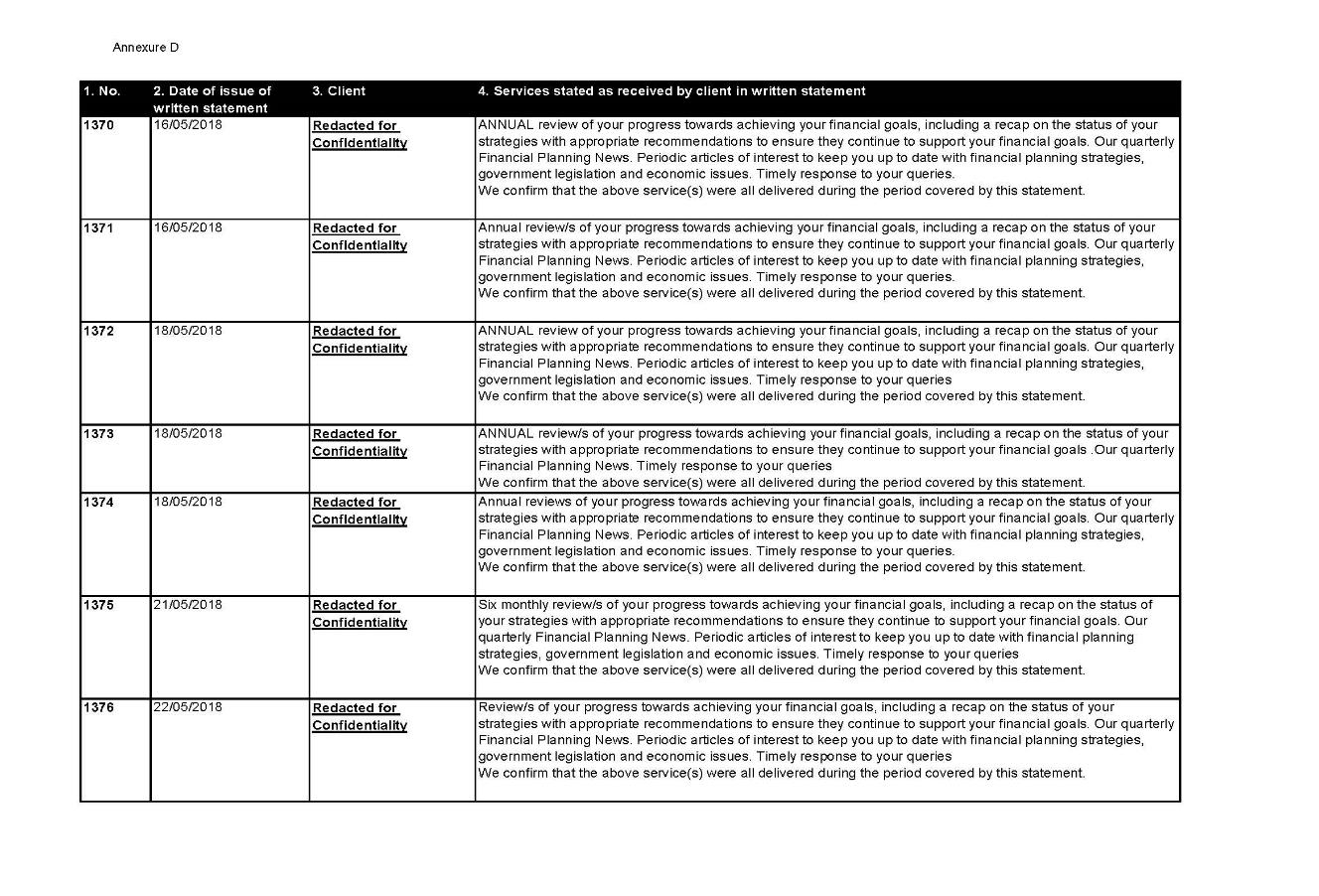

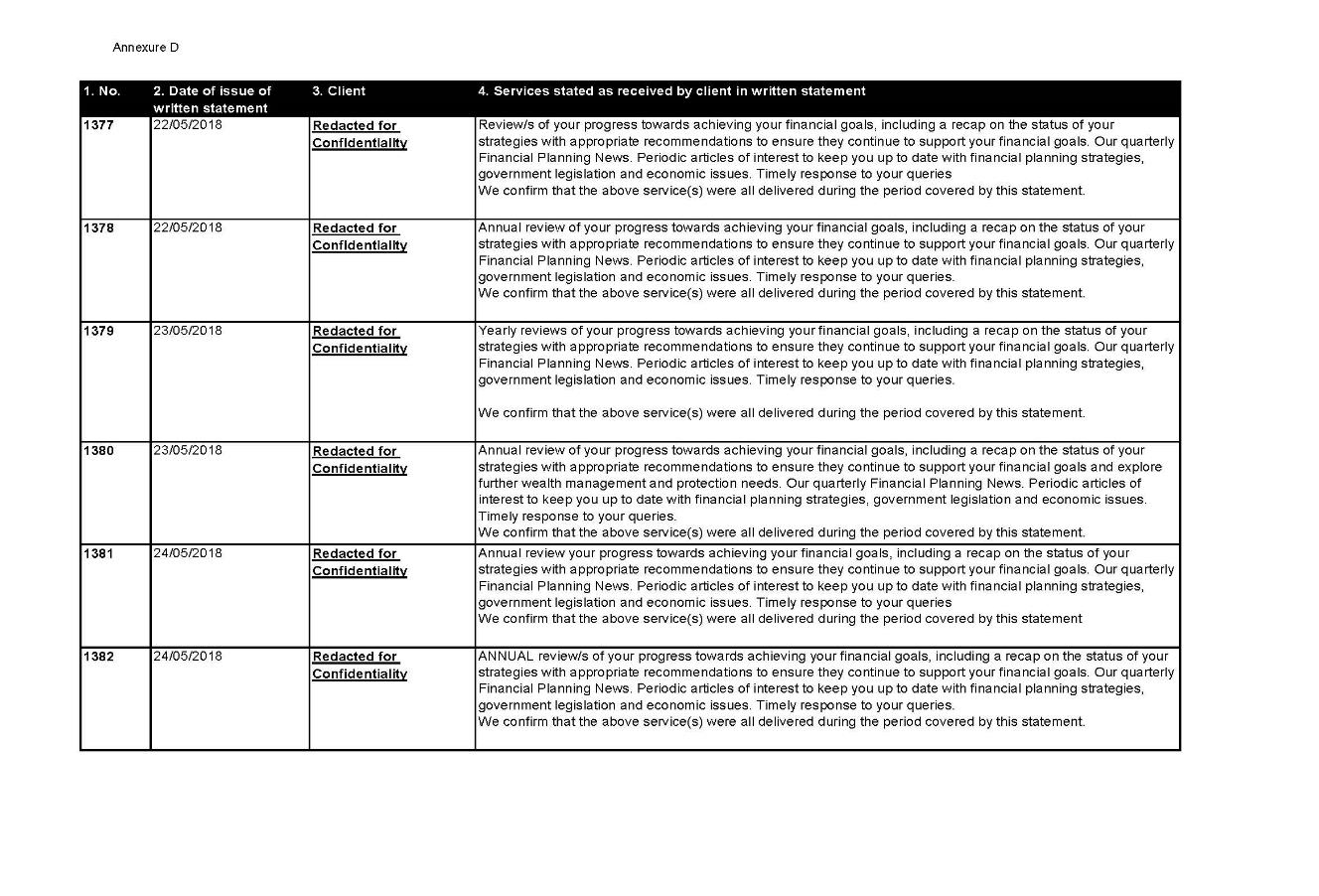

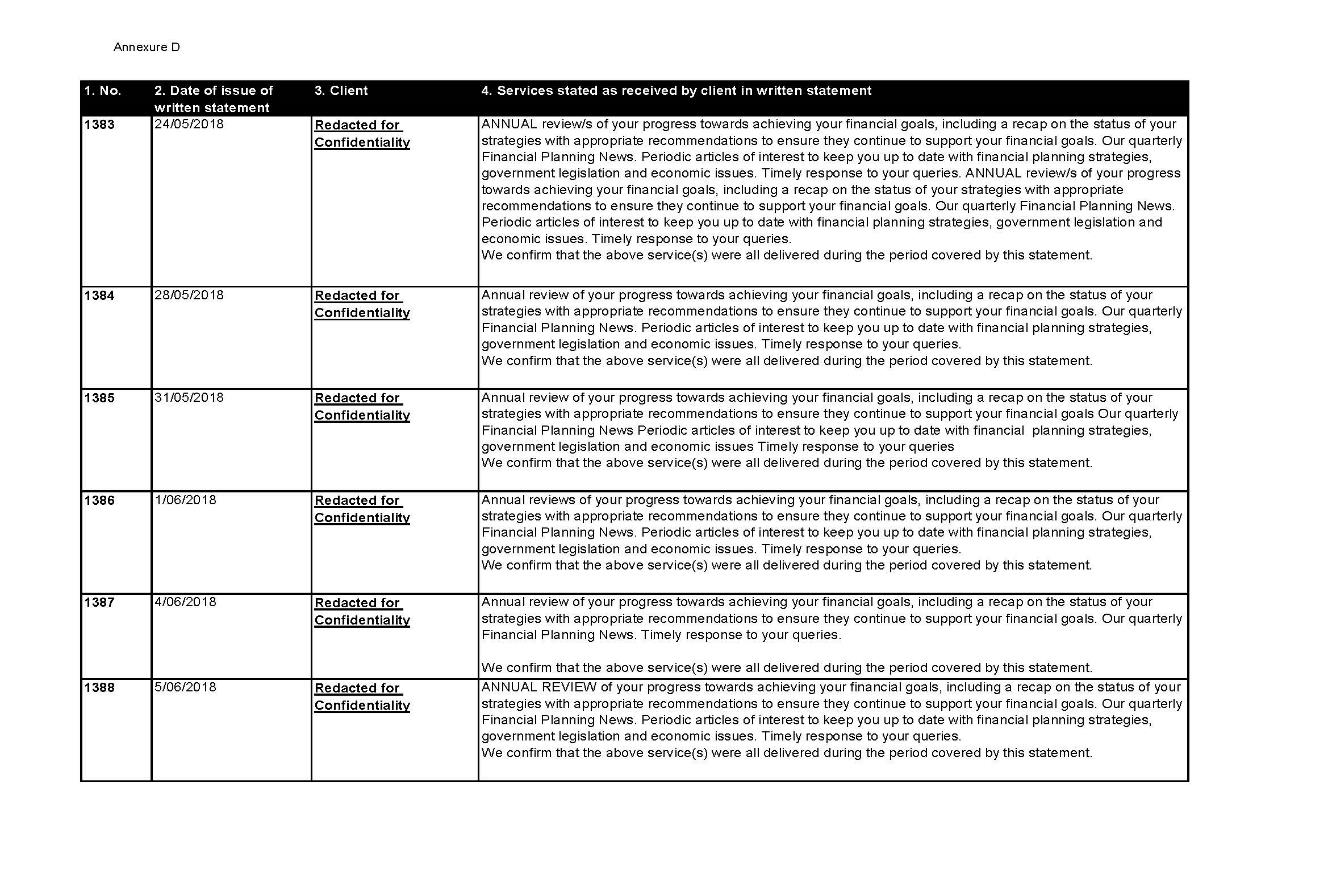

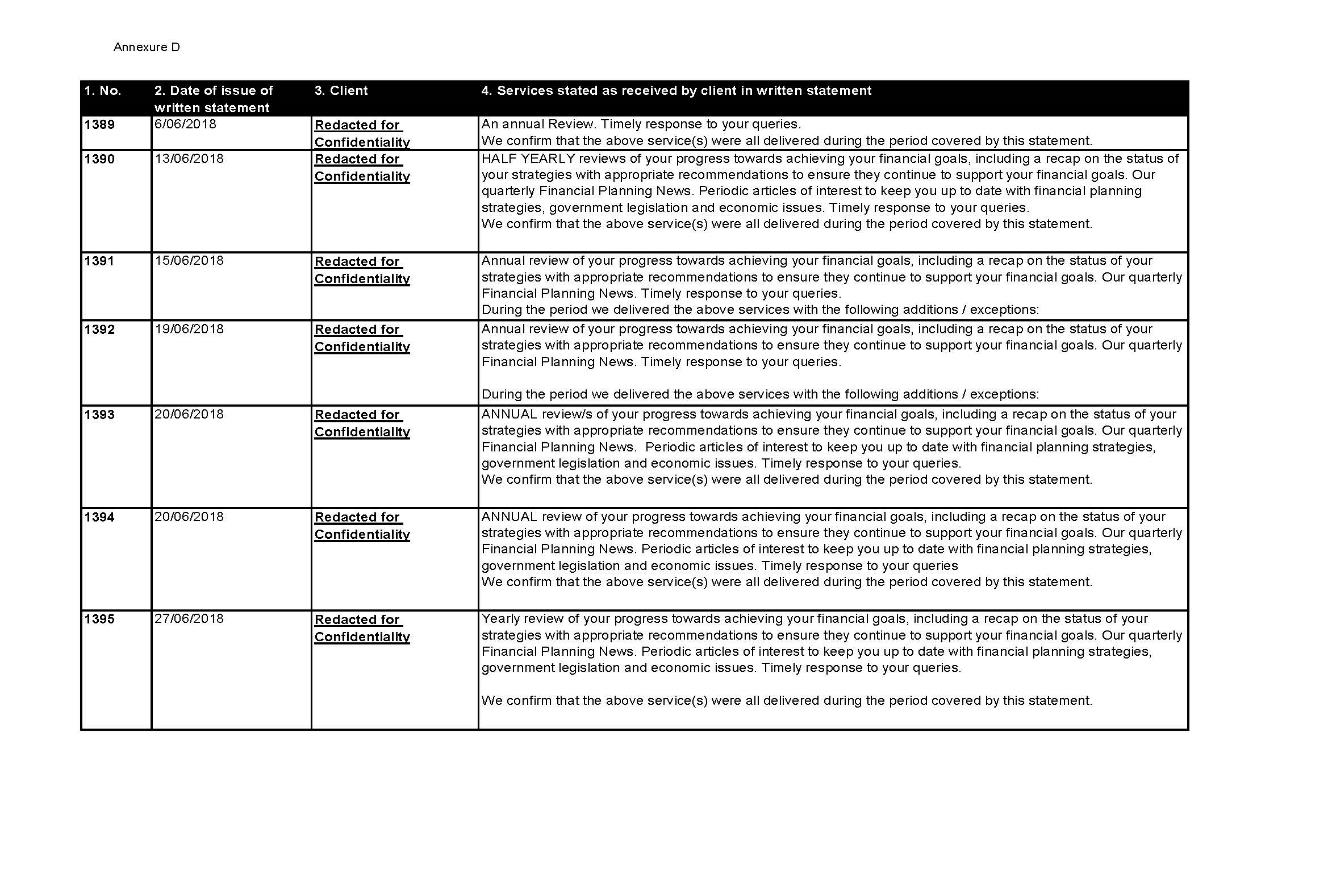

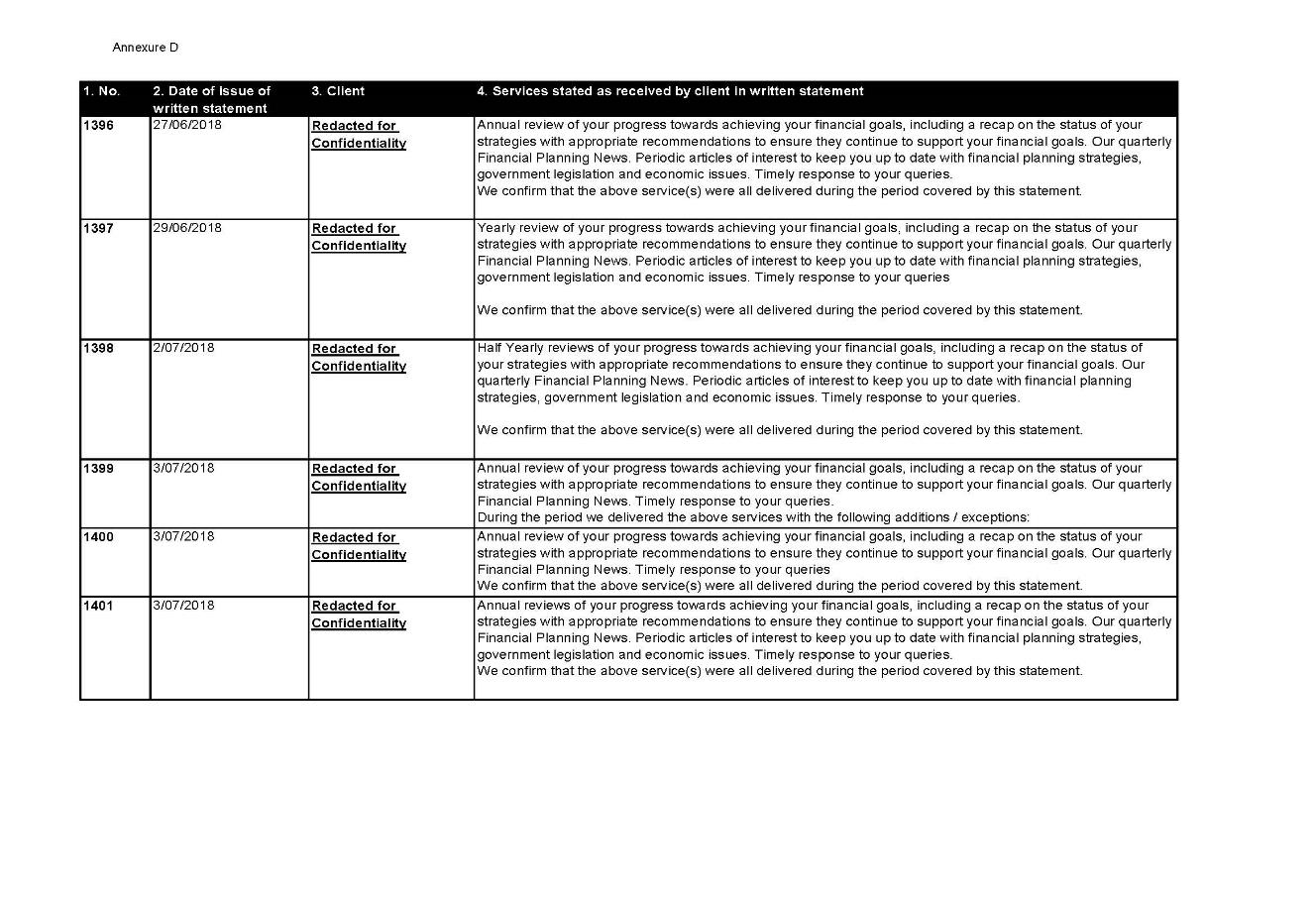

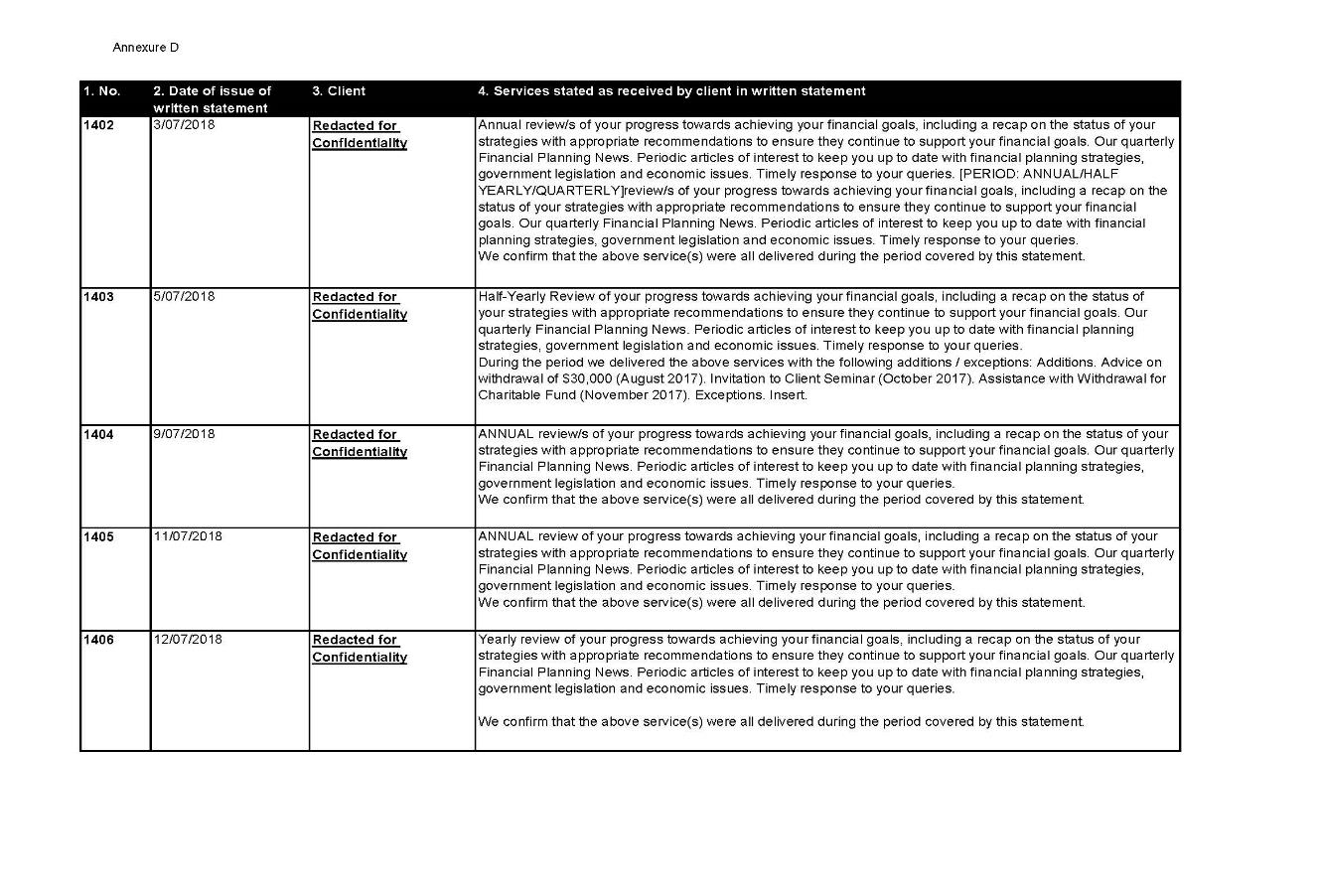

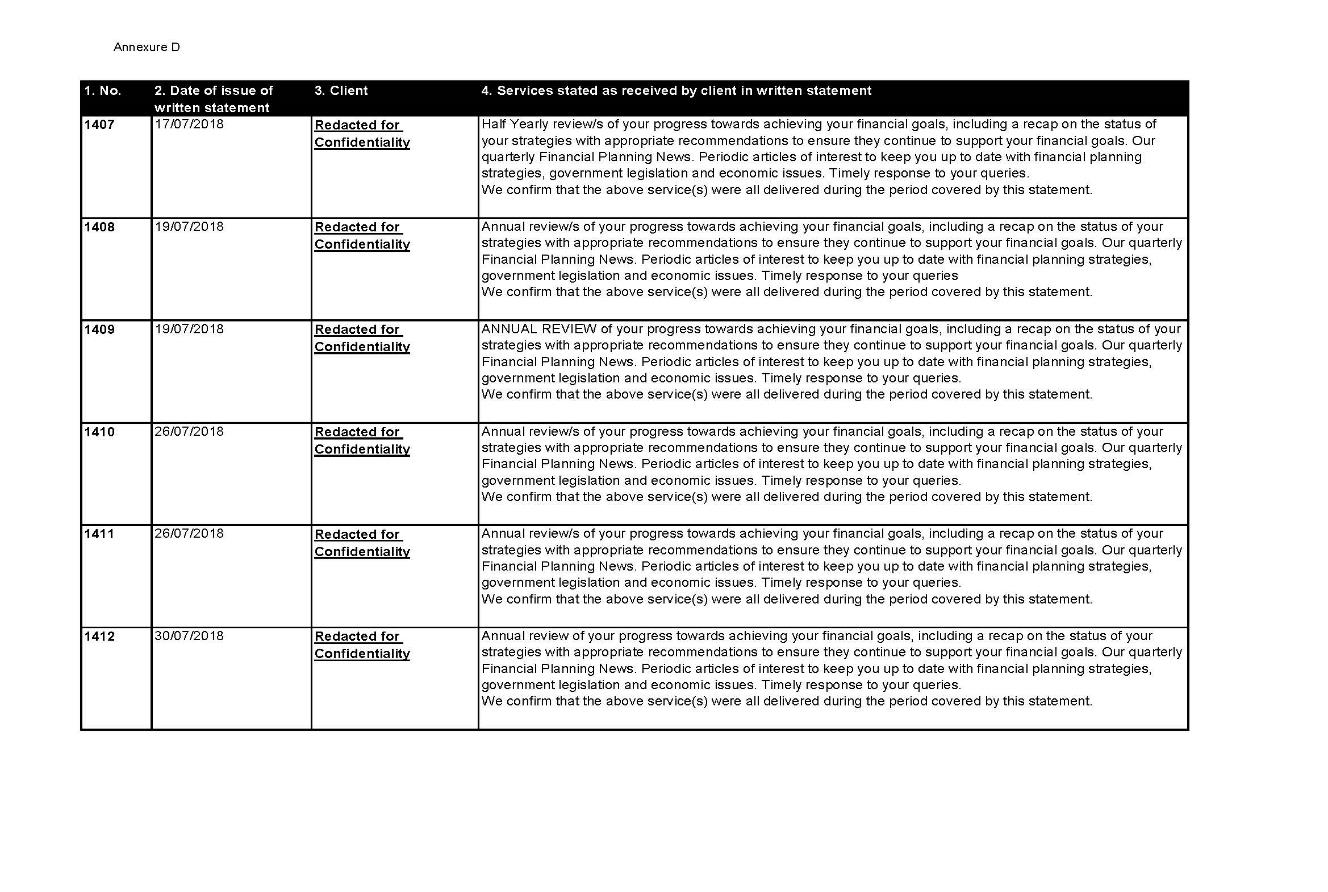

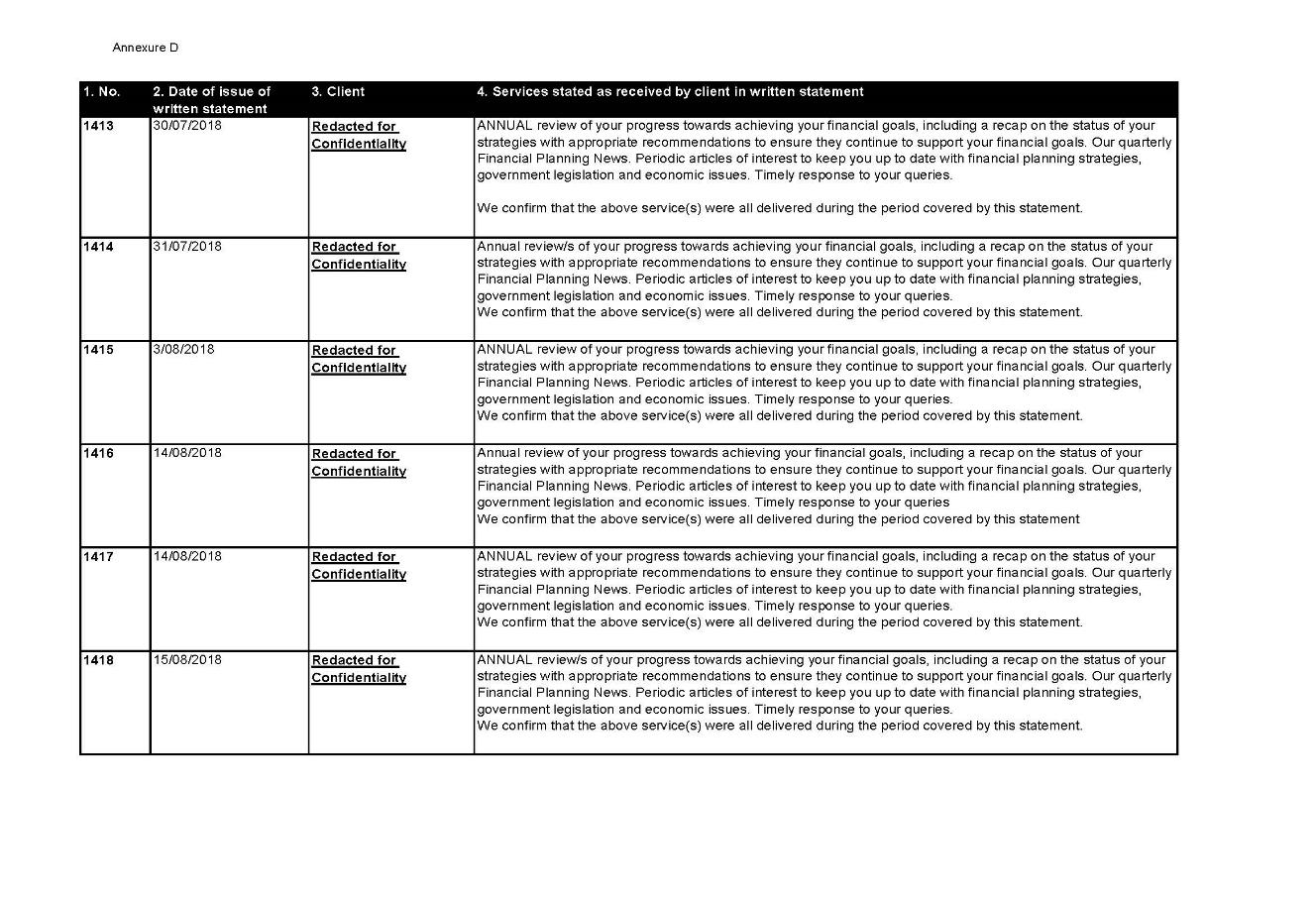

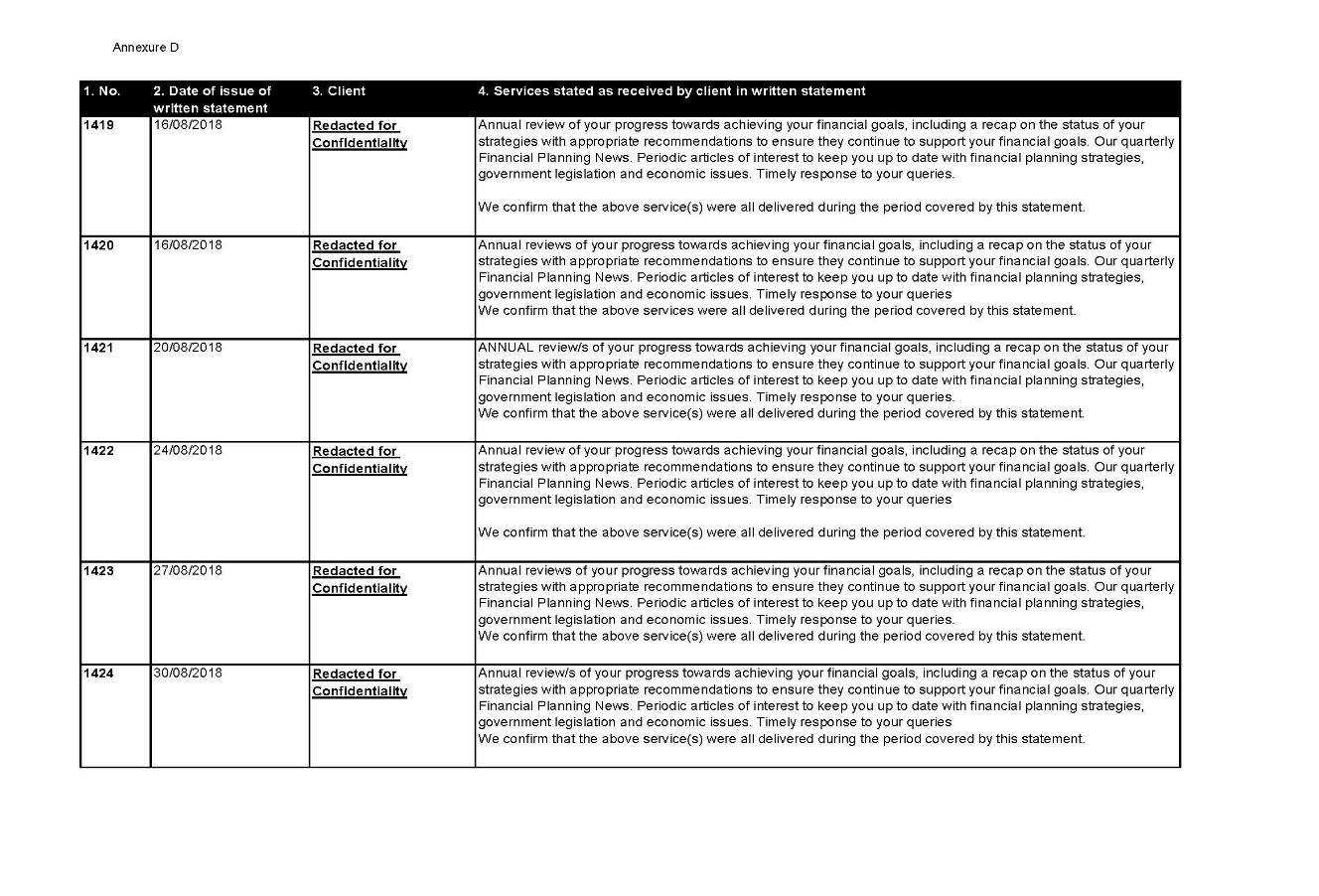

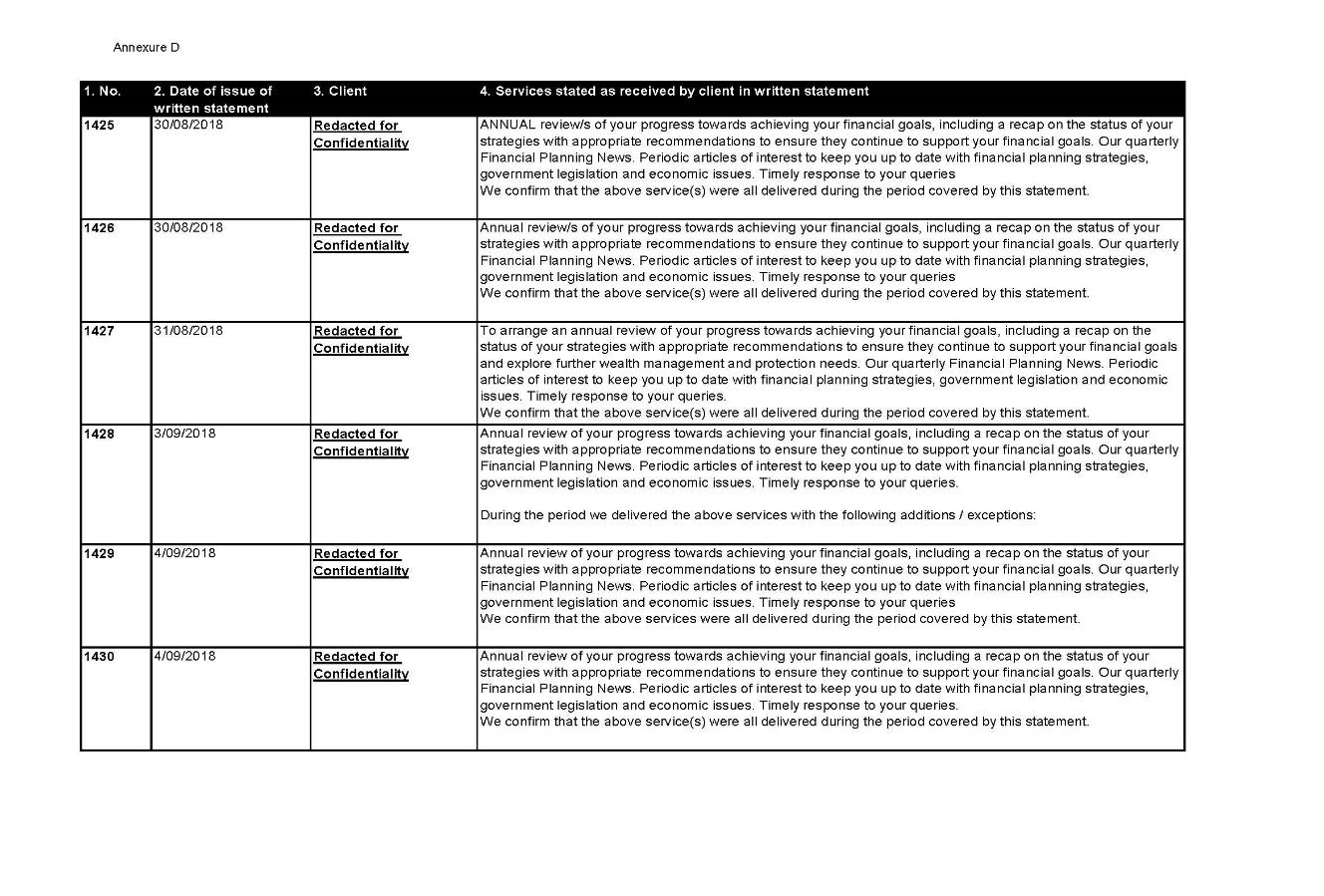

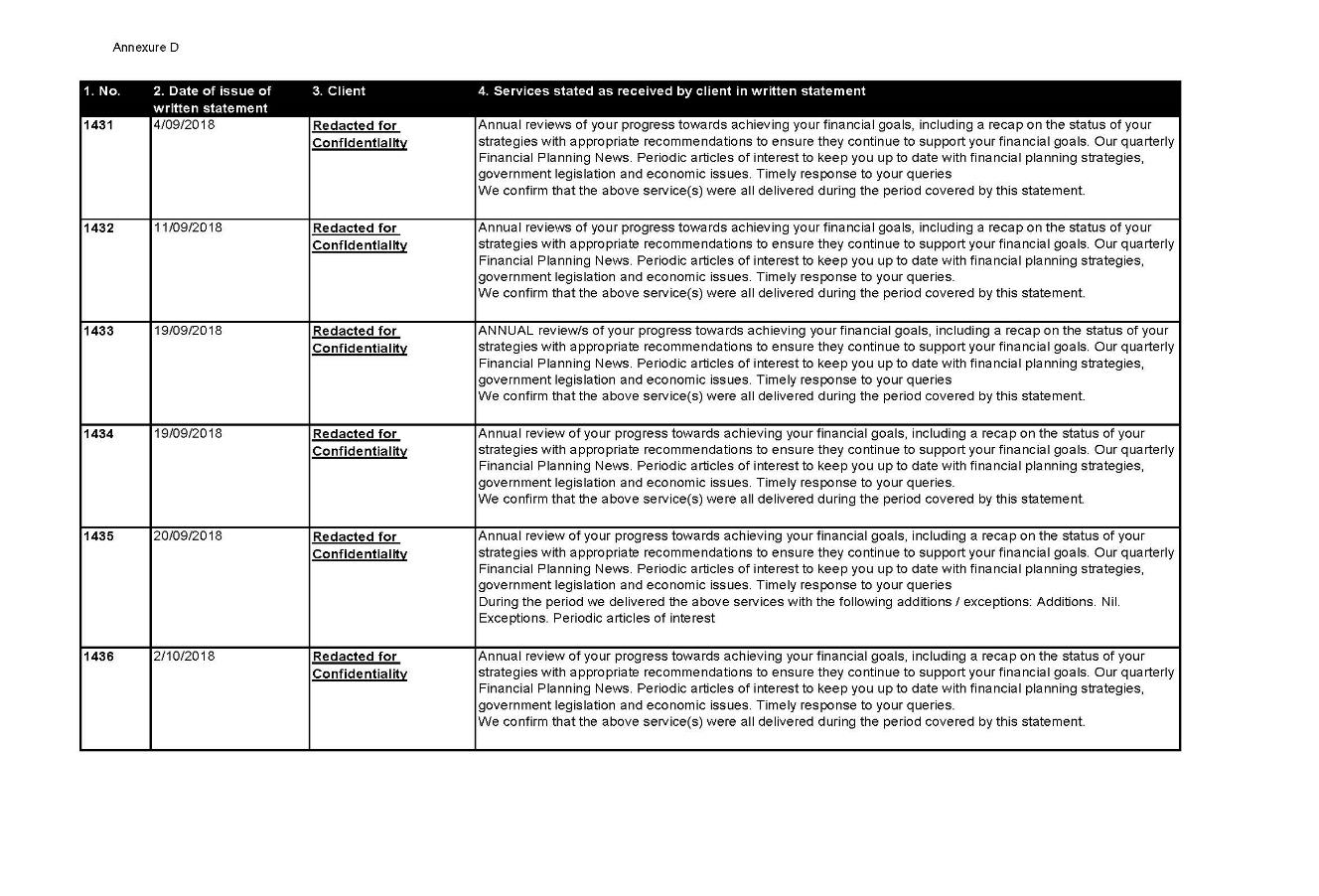

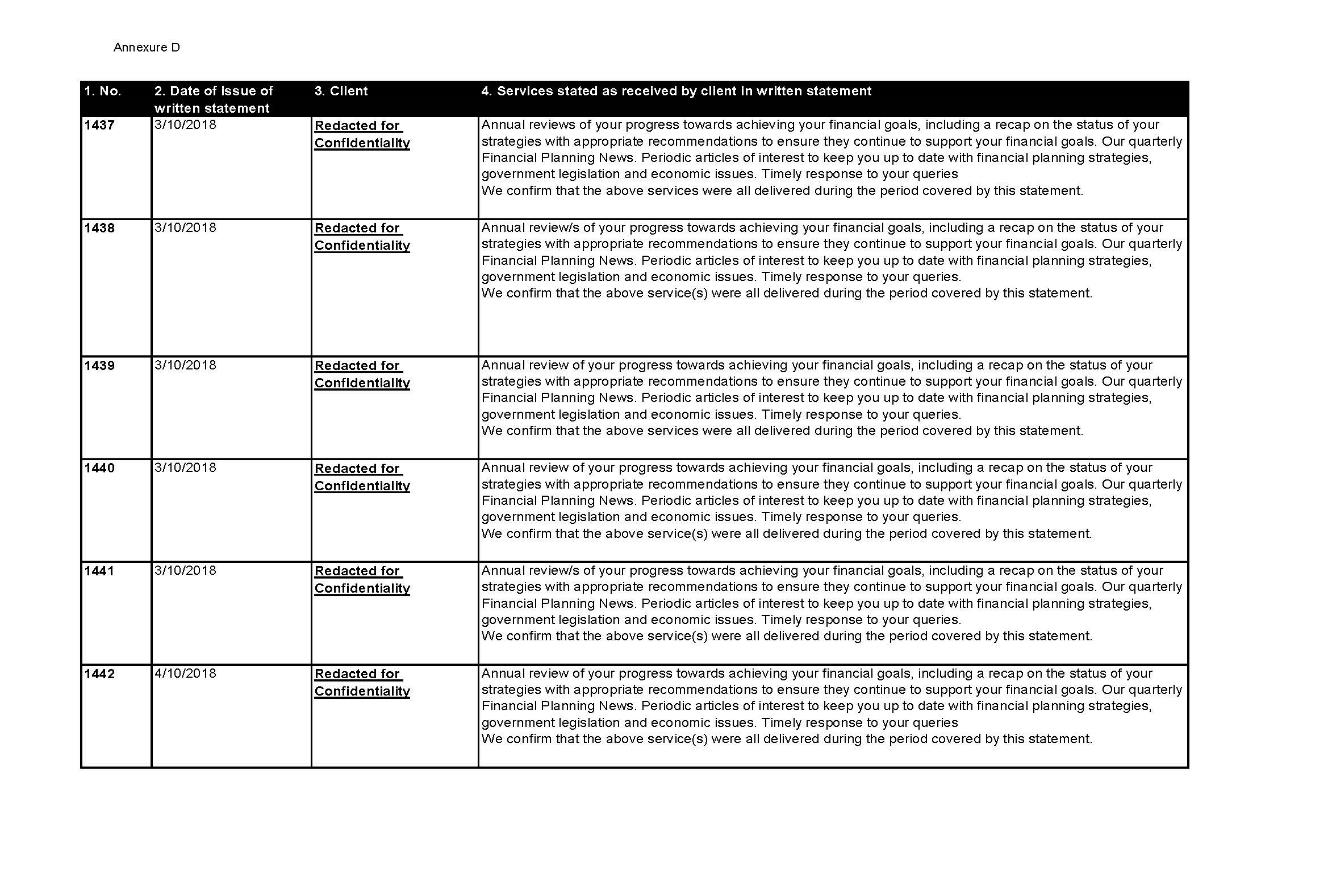

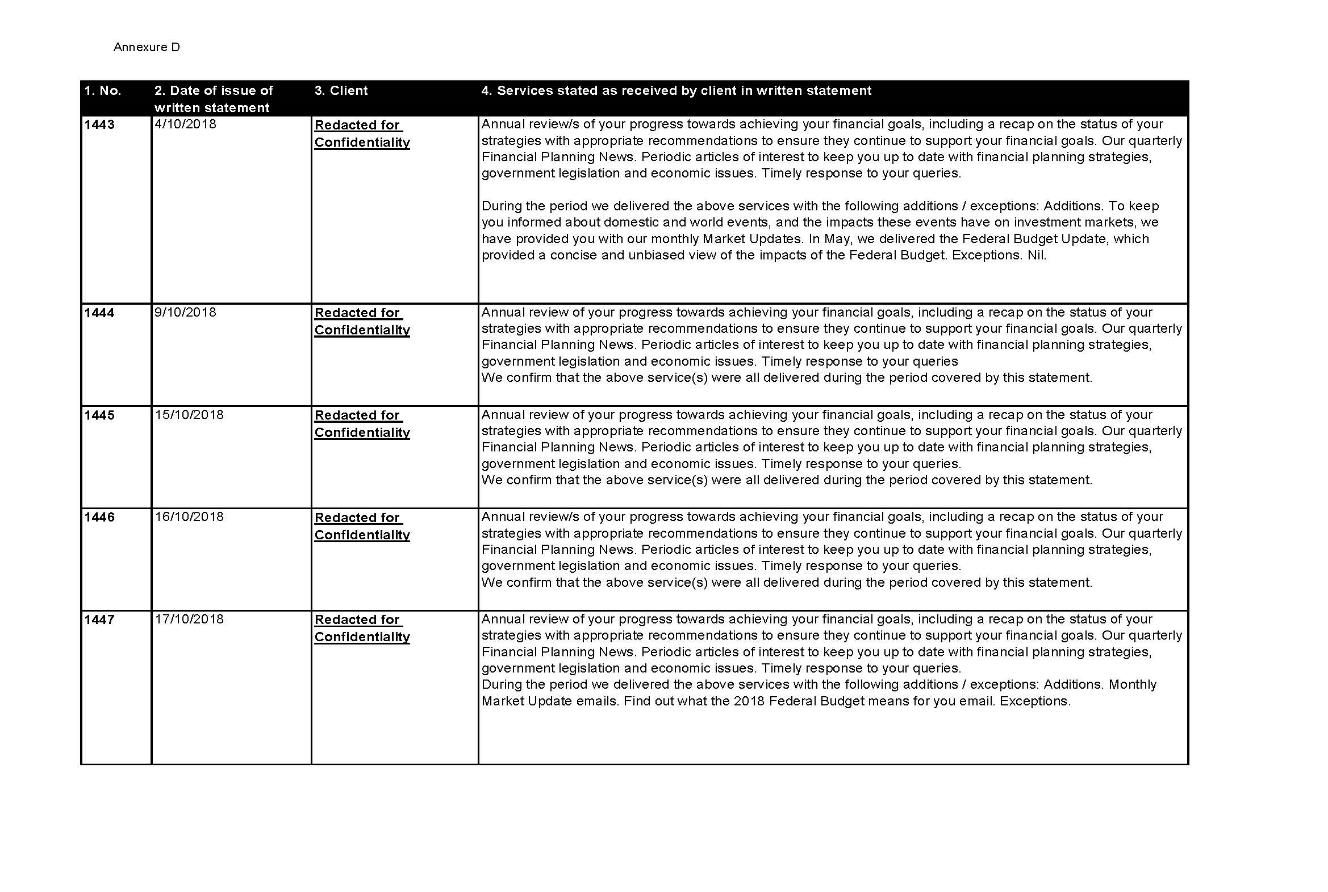

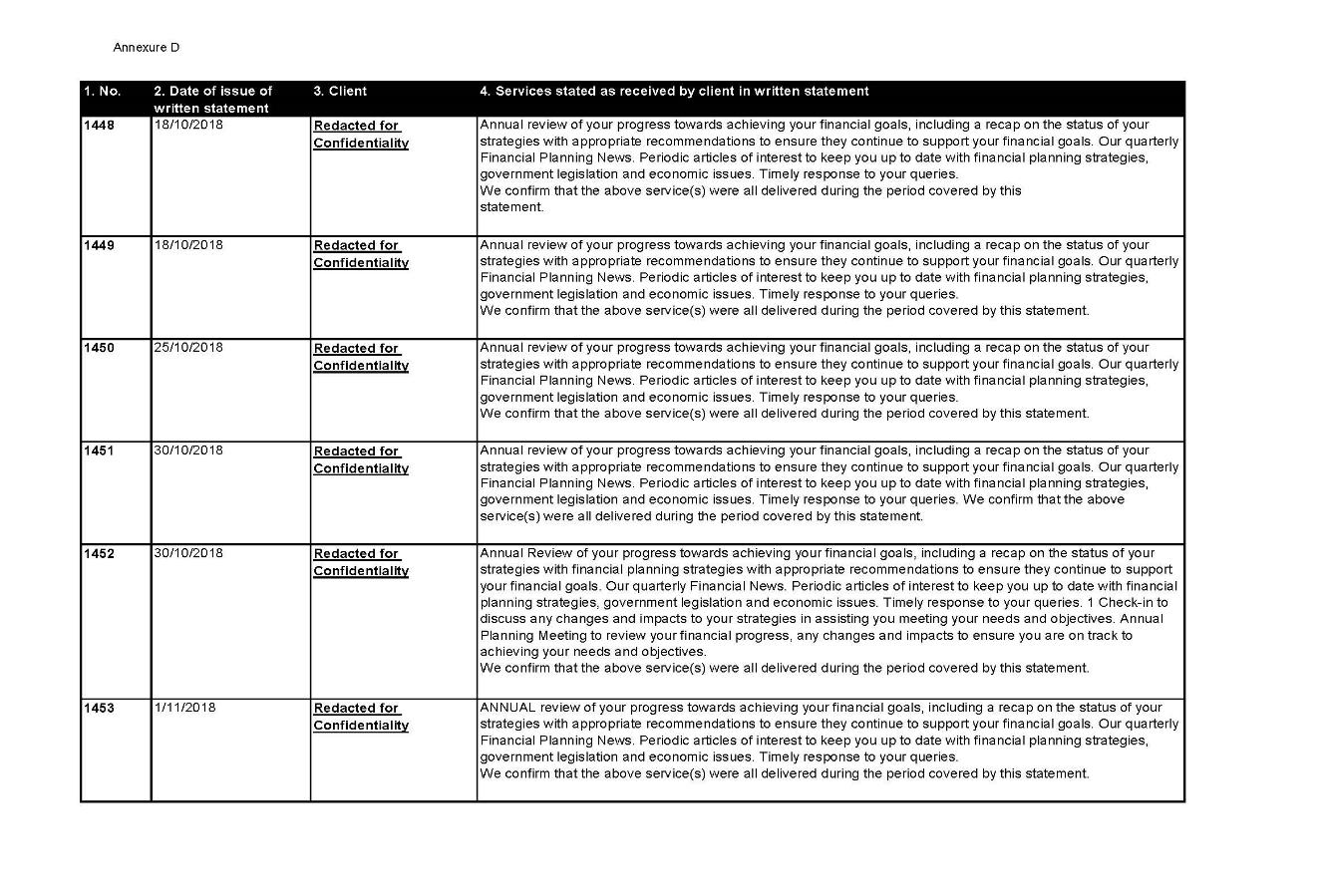

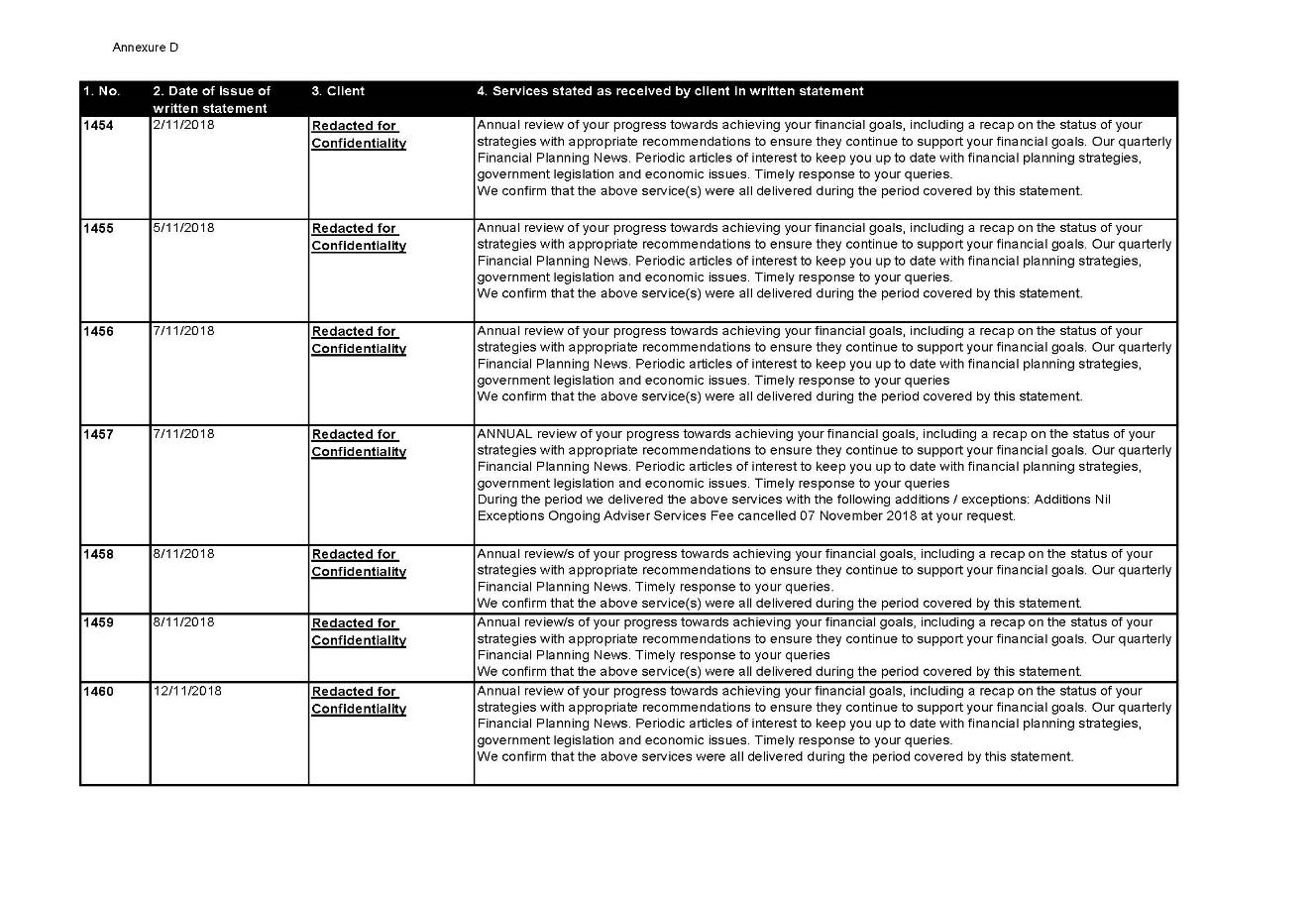

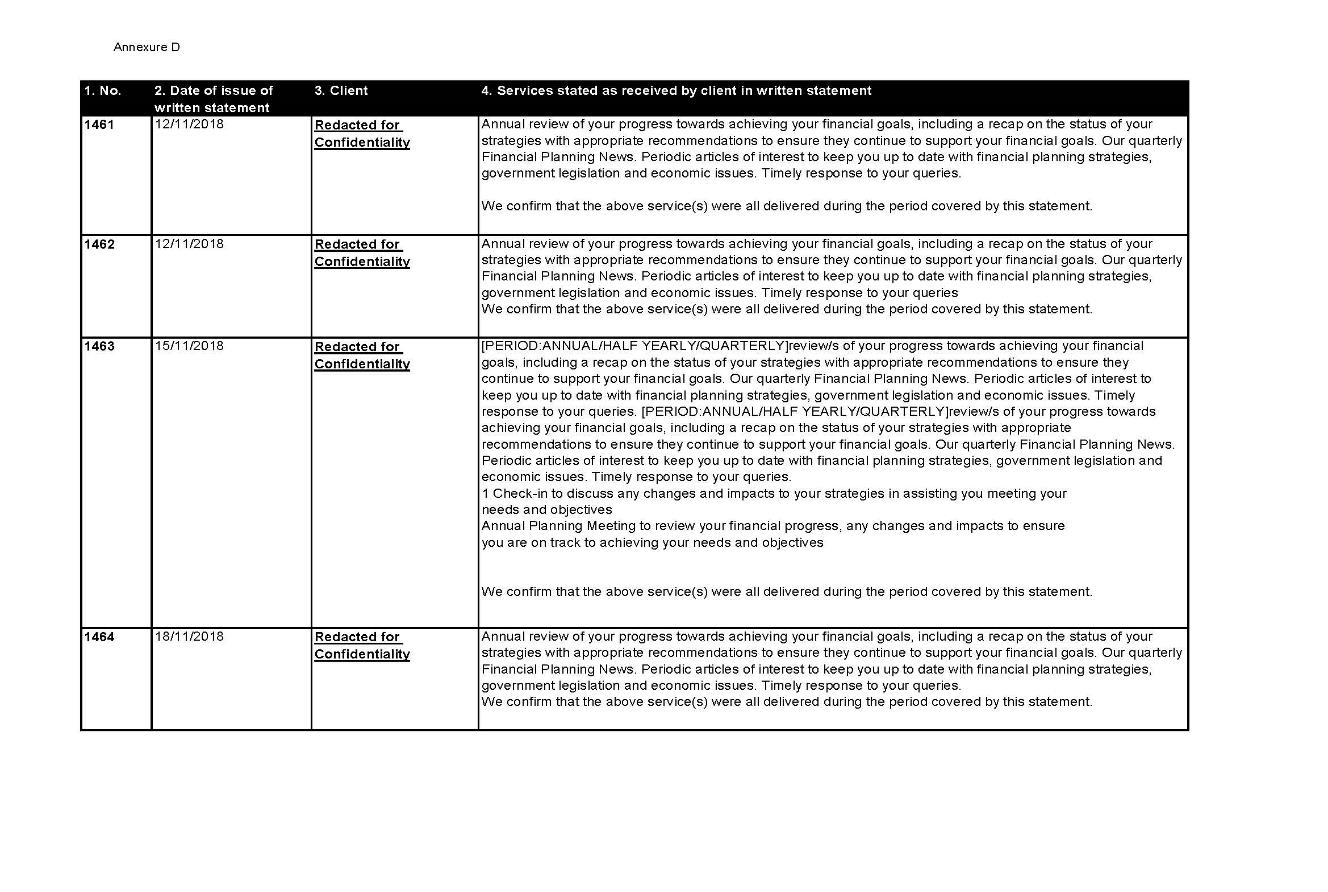

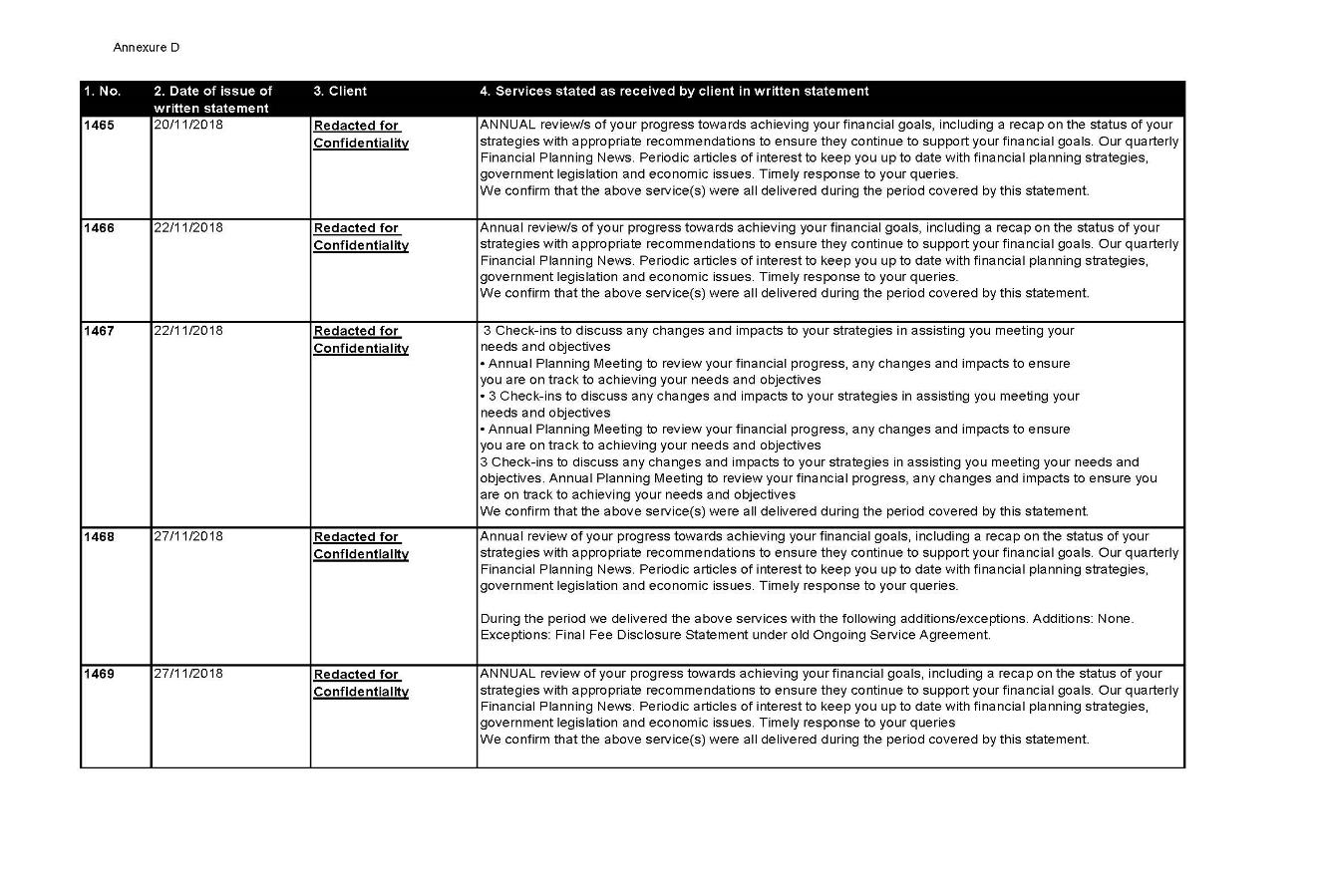

ANNEXURE D

ANNEXURE E

DAVIES J:

INTRODUCTION

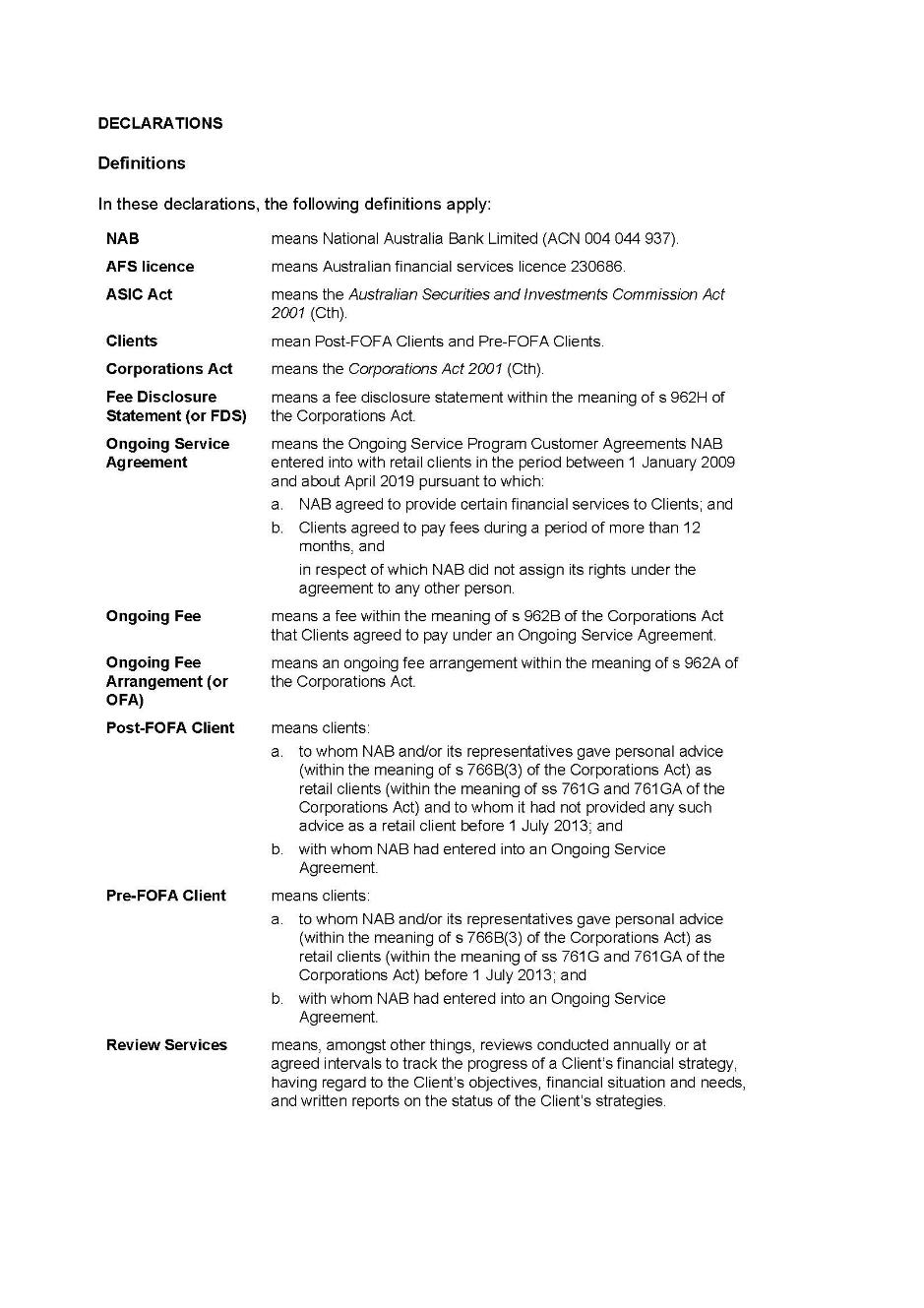

1 The defendant (NAB) has admitted contraventions of various provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) between 17 December 2013 and 4 February 2019 (the relevant period) in connection with NAB’s financial planning business. The contraventions arise from:

(a) NAB’s failure to give fee disclosure statements to a number of financial planning clients with ongoing service program customer agreements (ongoing service agreements), as required by pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act; and by charging ongoing fees to those clients when it was not entitled to do so because of the breach of the disclosure obligations;

(b) false or misleading representations made to clients in fee disclosure statements which contained incorrect information about ongoing fees paid by clients and/or services provided to them; and

(c) NAB’s failure to establish and maintain documented policies, procedures and systems that were adequate to identify whether it had provided review services to clients in accordance with ongoing service agreements, and financial disclosure statements in accordance with ss 962G and 962S of the Corporations Act, and whether it was prohibited from charging any particular client ongoing fees.

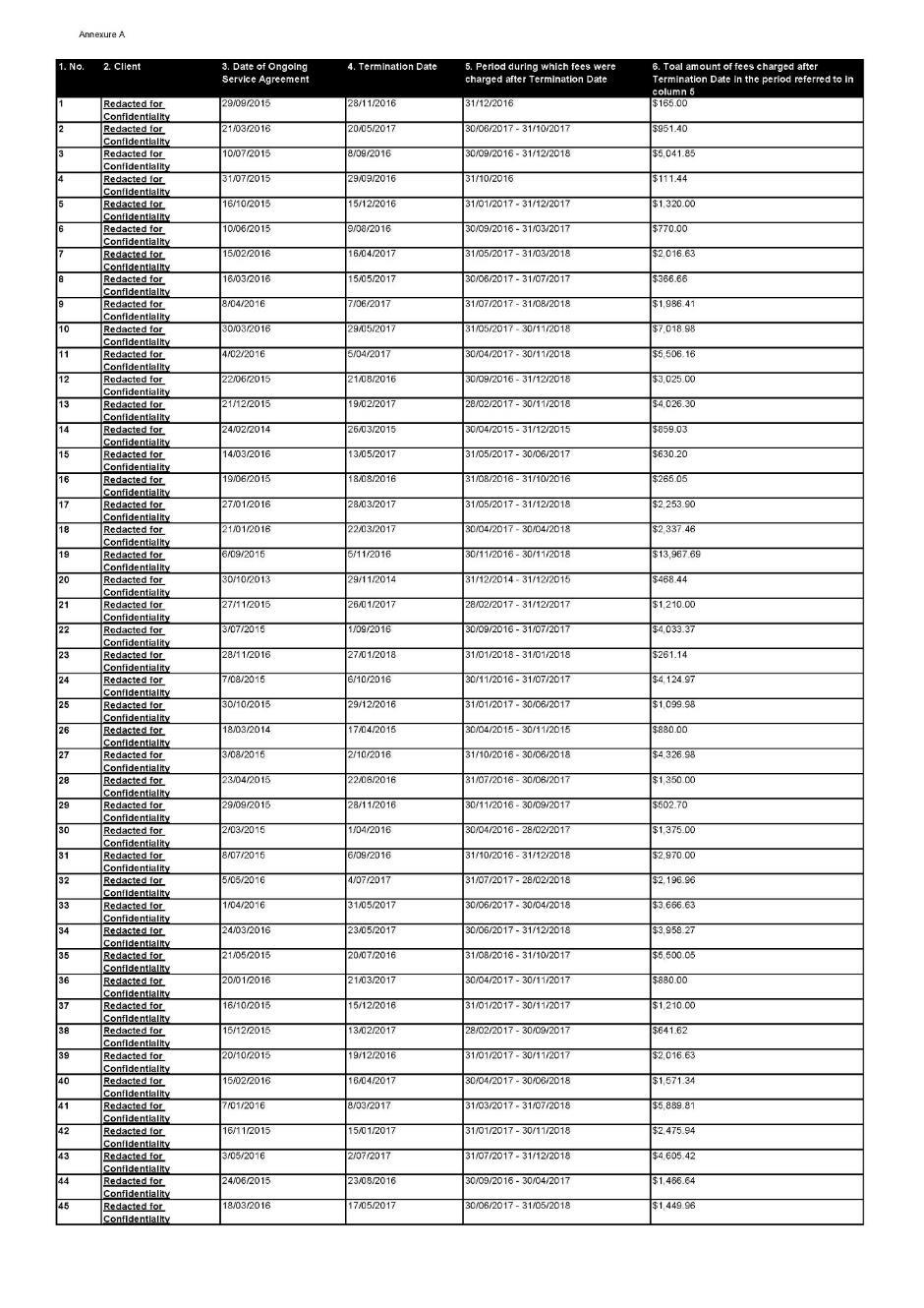

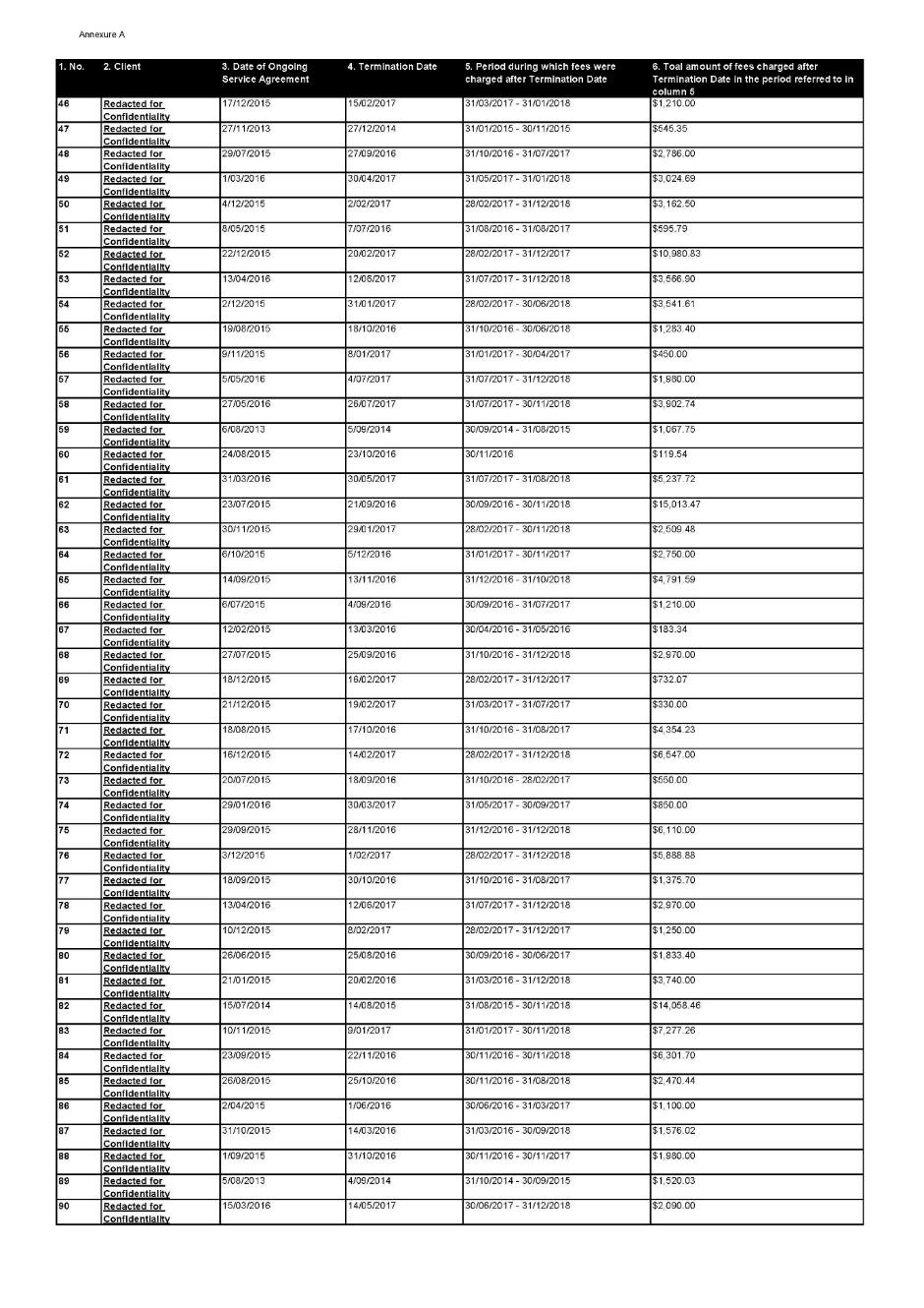

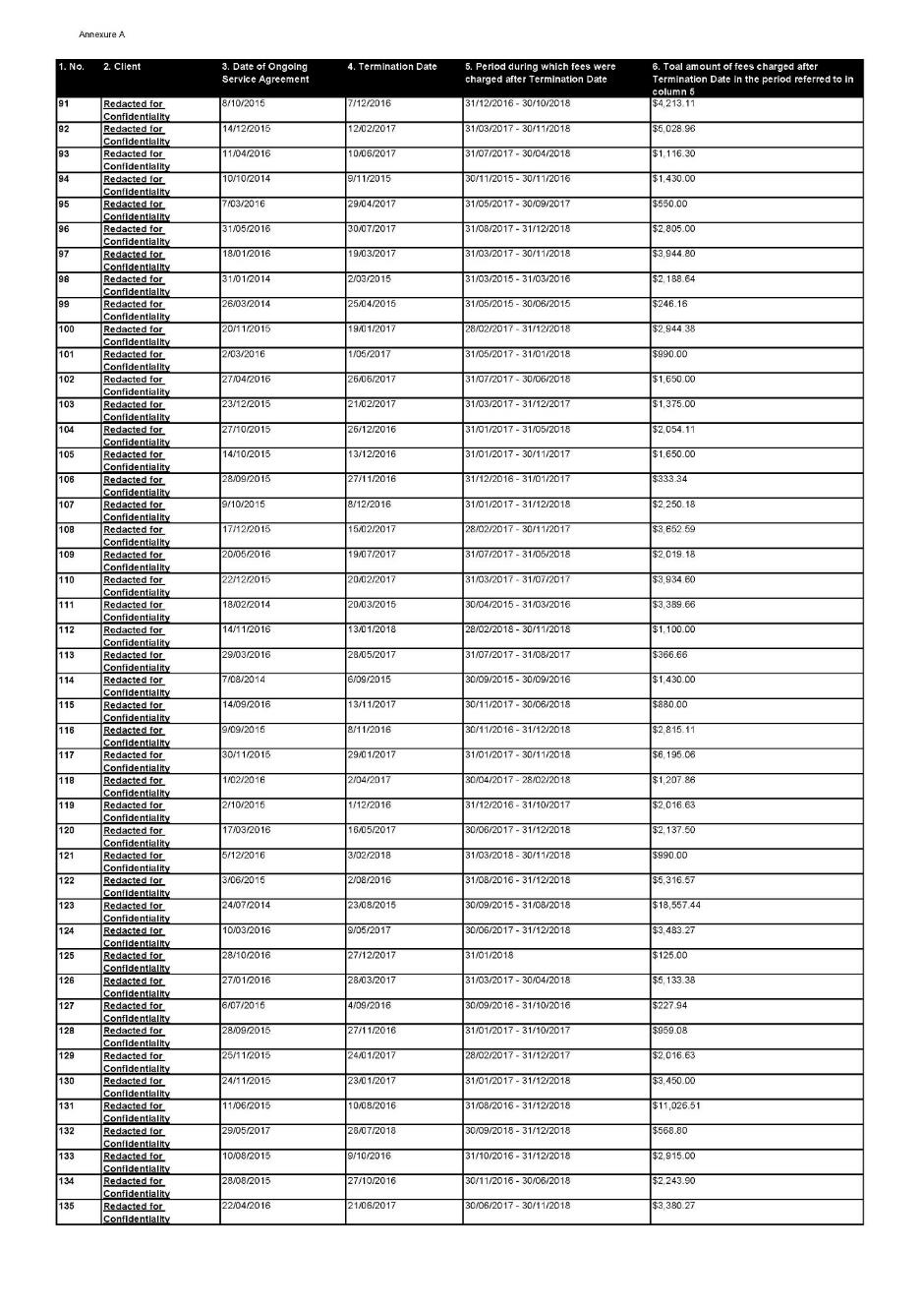

2 The plaintiff (ASIC) and NAB have agreed on orders resolving issues of liability and put before the Court an agreed form of proposed orders, an amended agreed statement of facts and admissions (Annexure 1 to these reasons) (agreed facts) and an outline of joint submissions on liability. The joint position of the parties is that:

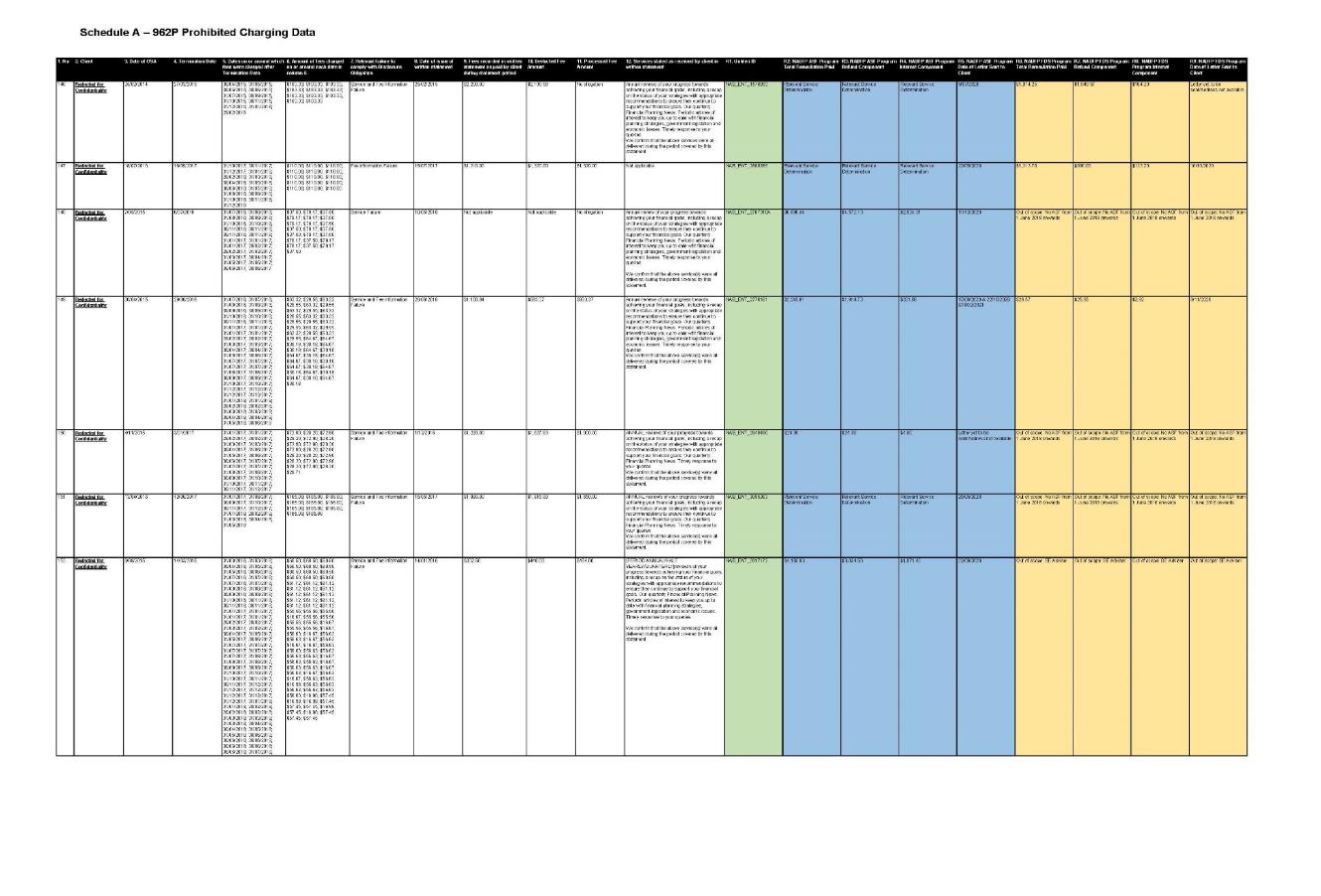

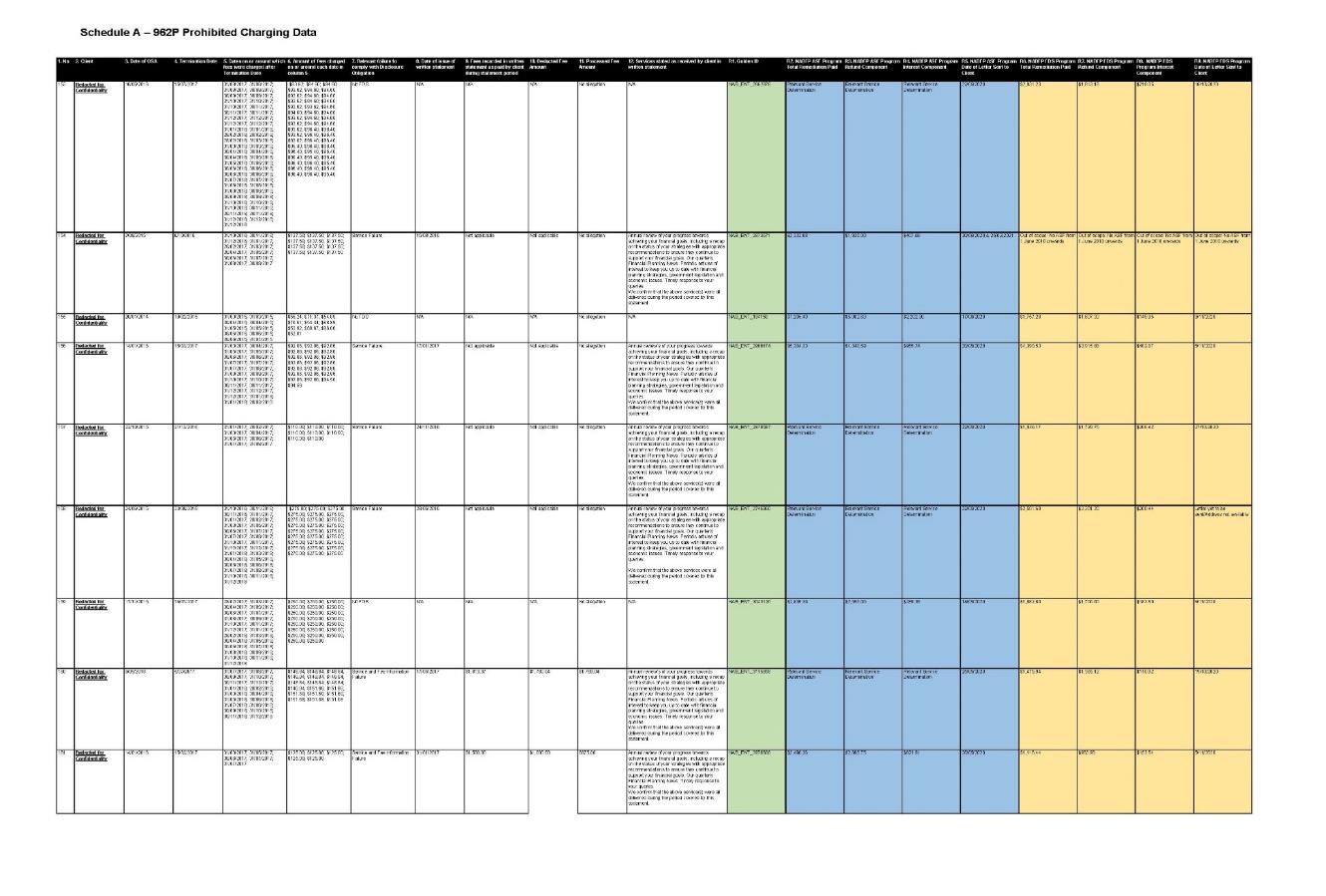

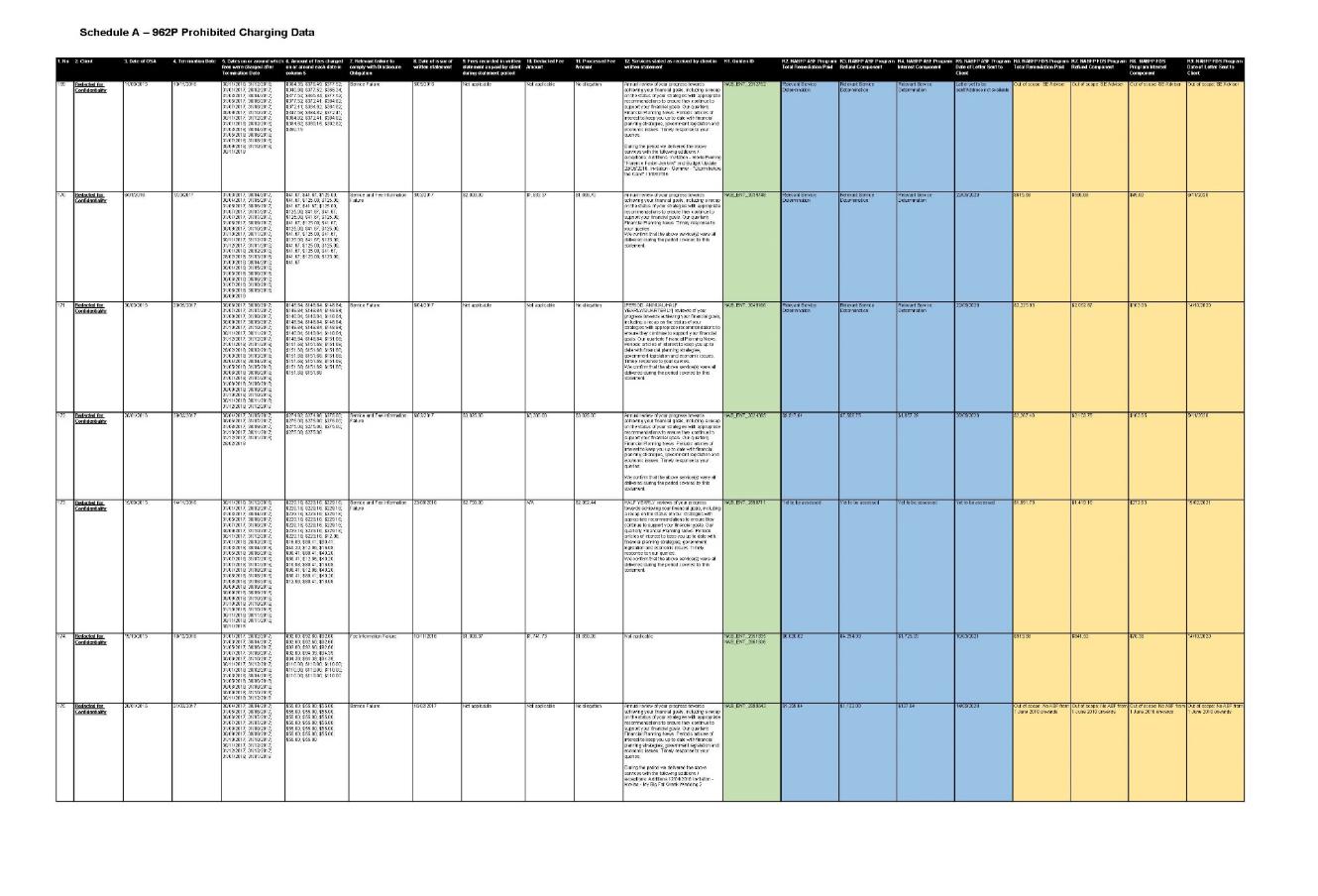

(a) NAB contravened s 962P of the Corporations Act on 445 occasions (between 30 September 2014 and 31 December 2018) in respect of 439 retail clients to whom NAB first provided personal advice after 1 July 2013 (post-FOFA clients), by charging them ongoing fees when it was prohibited from doing so. NAB was not authorised to charge such clients because NAB had failed to give them a fee disclosure statement in compliance with s 962G, as a result of which their ongoing fee arrangement terminated pursuant to s 962F of the Corporations Act;

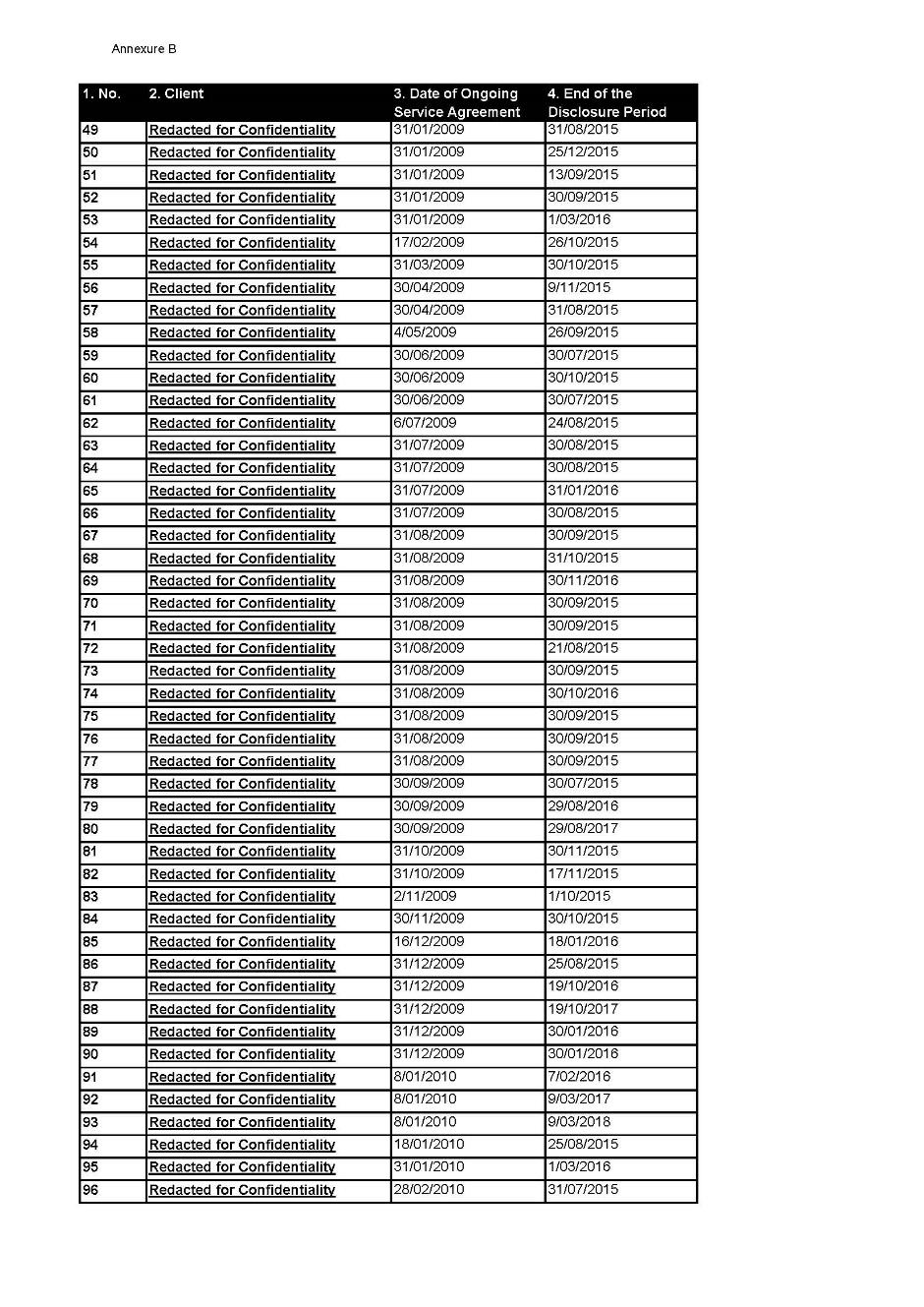

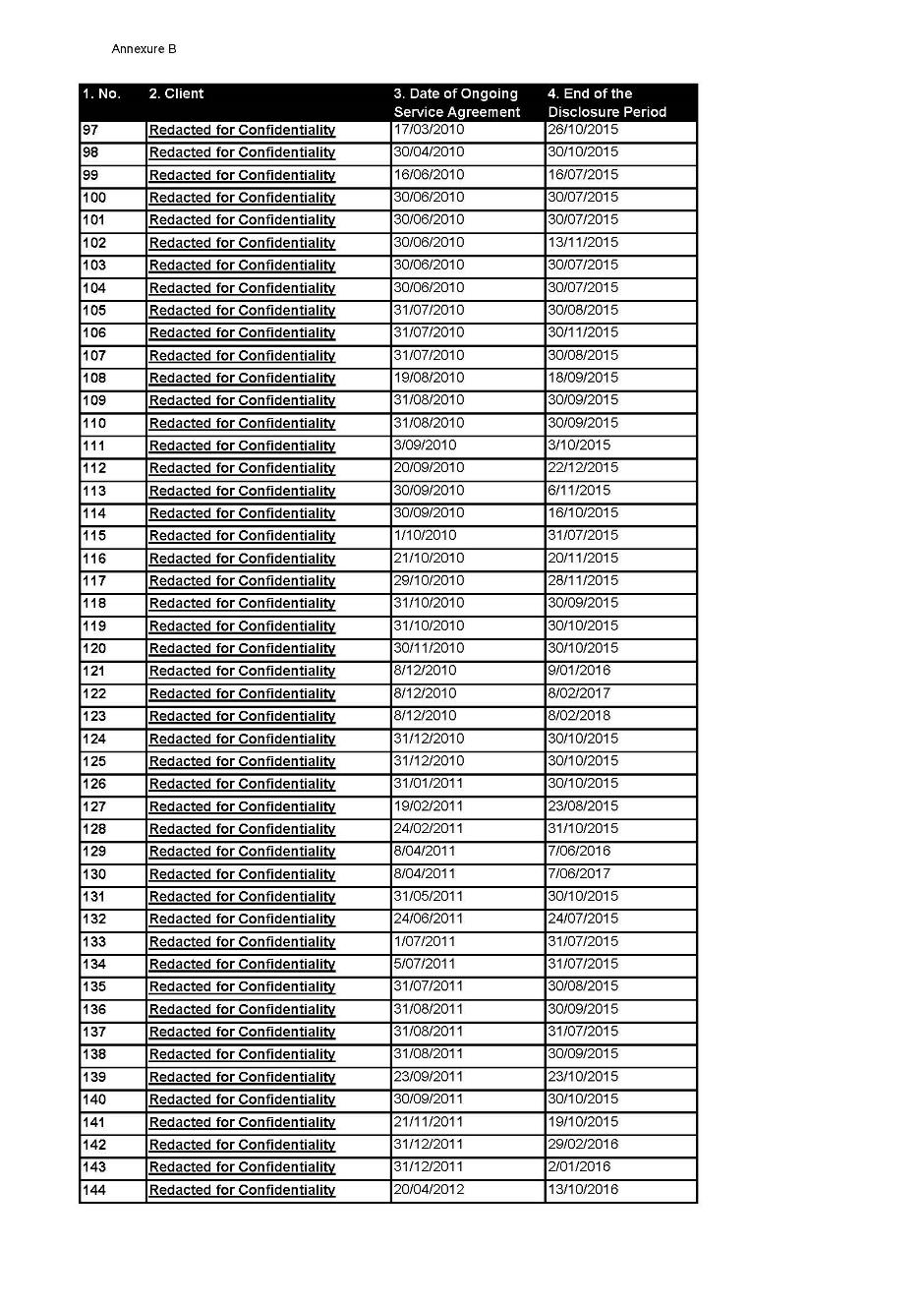

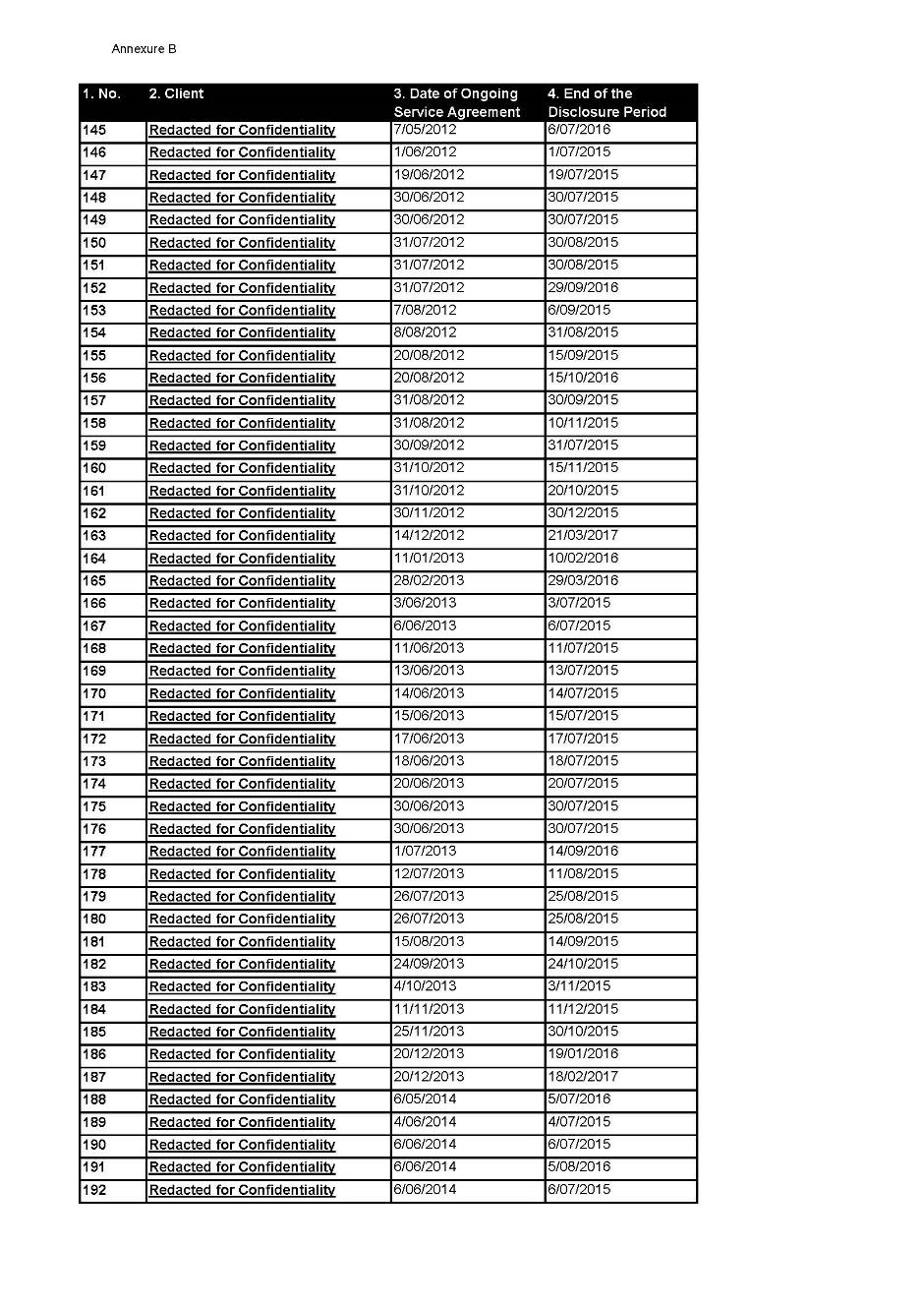

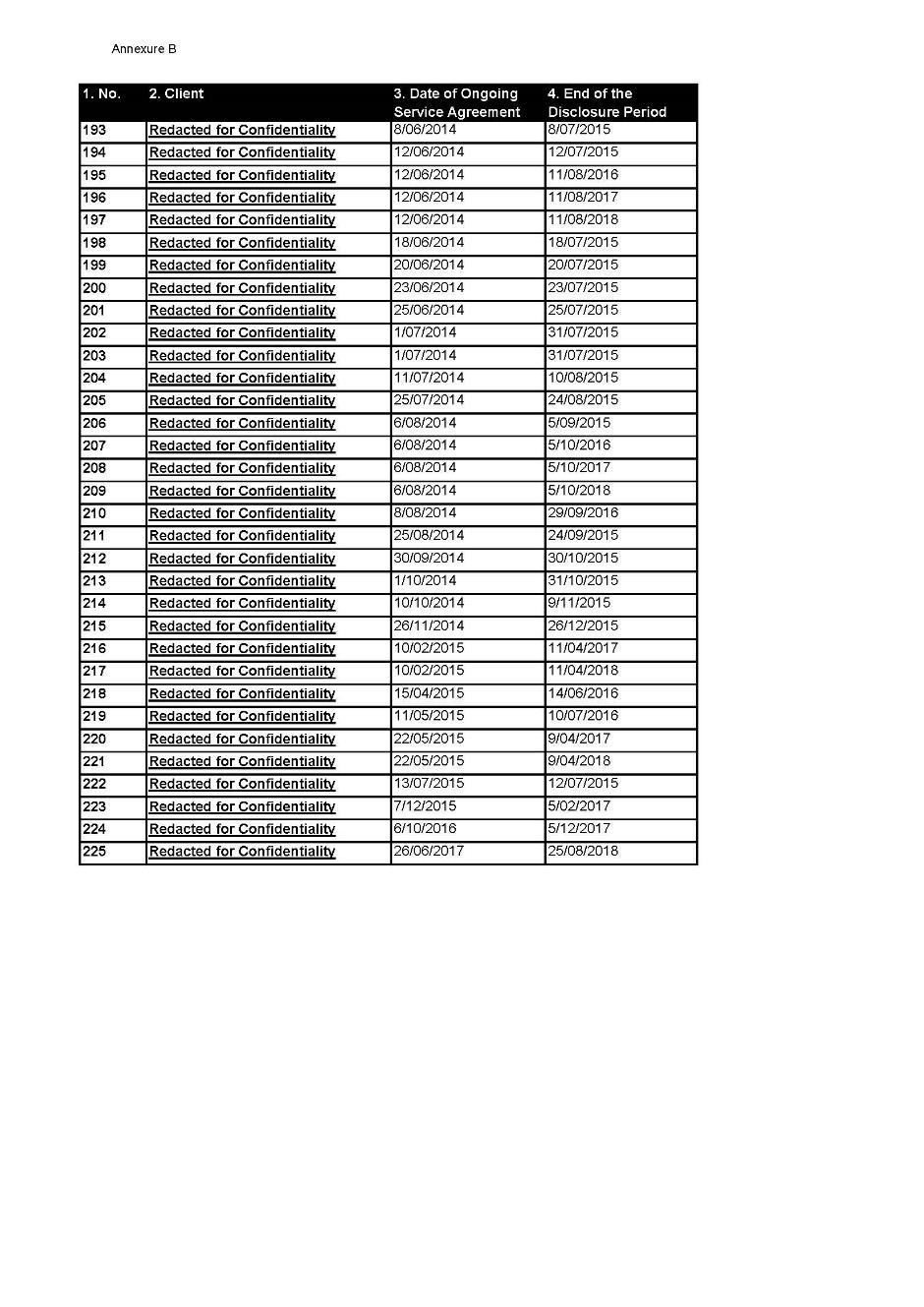

(b) NAB contravened s 962S of the Corporations Act on 225 occasions (between 1 July 2015 and 5 October 2015) by failing to provide a compliant fee disclosure statement to 202 retail clients to whom NAB had provided personal advice prior to 1 July 2013 (pre-FOFA clients) within the time period required by s 962S;

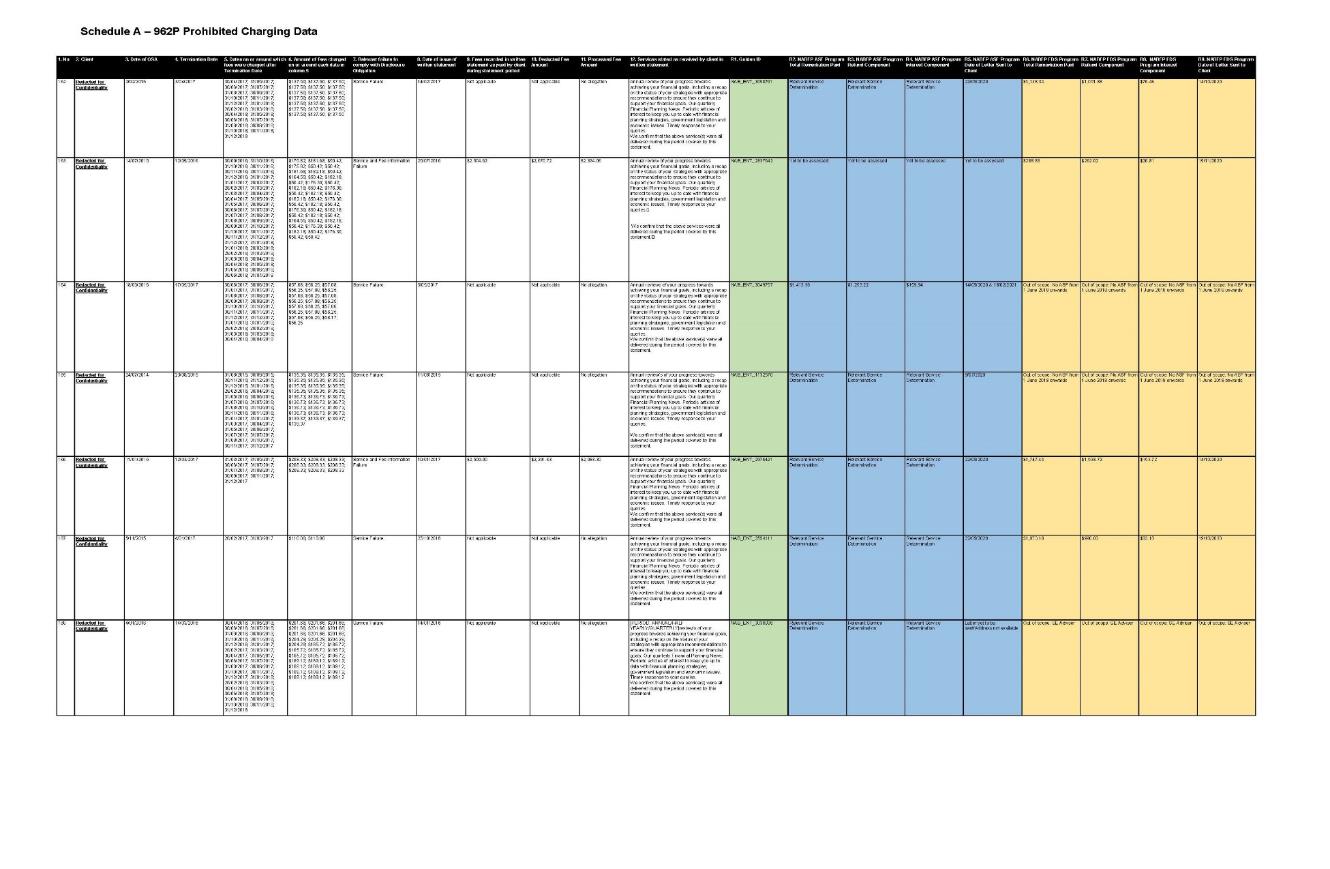

(c) NAB contravened ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(g) of the ASIC Act and s 1041H of the Corporations Act on 130 occasions (between 23 January 2014 and 10 October 2018) by making false or misleading representations to clients in fee disclosure statements that they had paid ongoing fees in a particular amount during the statement period when the clients had not paid that amount (price representations);

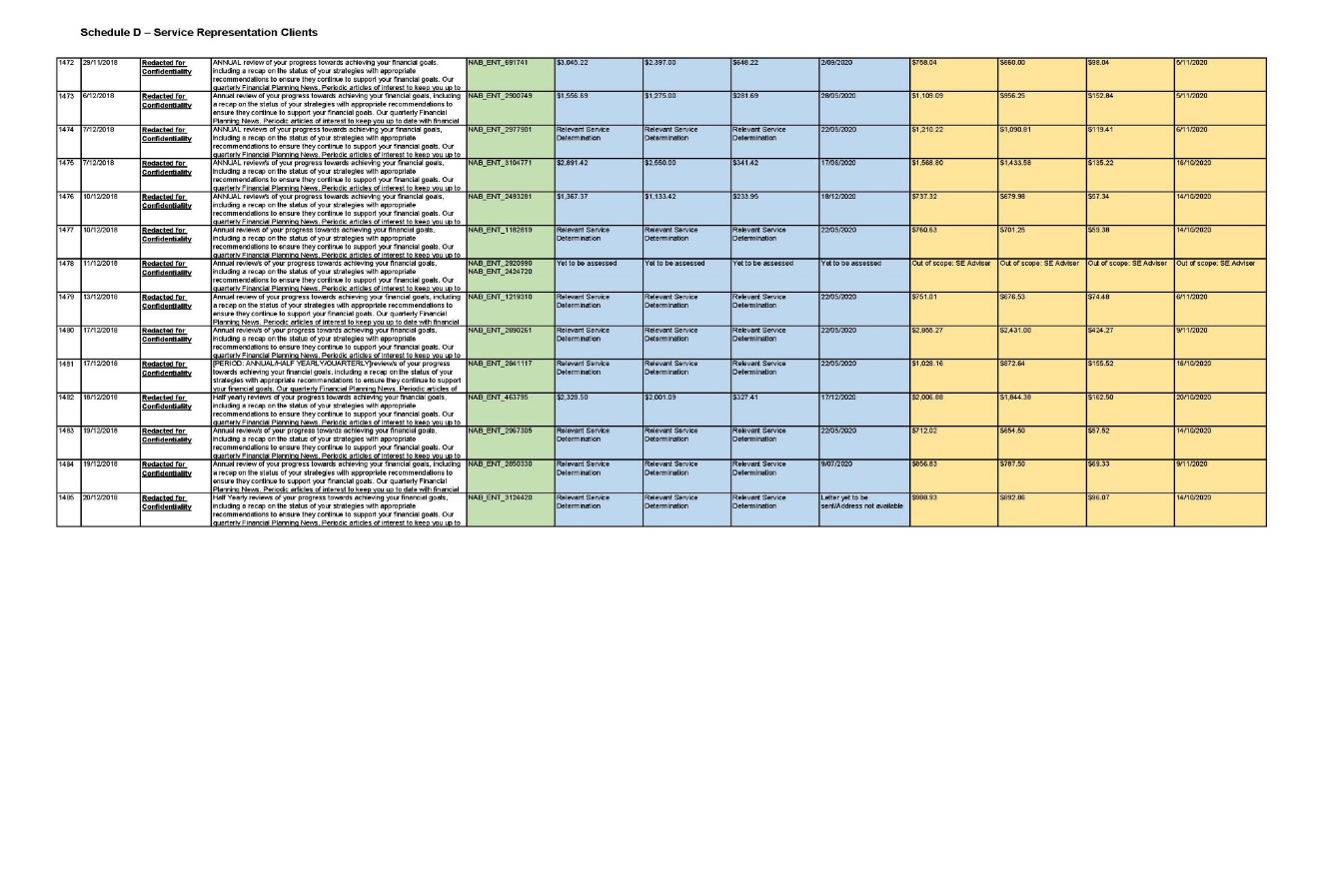

(d) NAB contravened ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act and s 1041H of the Corporations Act on 1,485 occasions (between 17 December 2013 and 20 December 2018) by making false or misleading representations to clients in fee disclosure statements that they had received particular services during the statement period, when the clients had not received those services in that period (service representations);

(e) by reason of the contraventions in (a)-(d), NAB failed to comply with the financial services laws and therefore contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act;

(f) during the relevant period, NAB did not establish and maintain adequate documented policies, procedures and systems to identify whether:

(i) review services were provided to clients in accordance with clients’ ongoing service agreements;

(ii) it had provided fee disclosure statements to clients for the purposes of satisfying ss 962G or 962S of the Corporations Act that accurately recorded the statement period, the services to which the client was entitled in the statement period, the services the client received during a statement period and the amount of ongoing fees paid by the client during the statement period;

(iii) it had provided to clients subject to ongoing fee arrangements a fee disclosure statement in accordance with its obligations under ss 962G and 962S of the Corporations Act; and

(iv) NAB was prohibited from charging any particular client ongoing fees;

(g) NAB knew or ought to have known of the matters referred to at (f) above;

(h) by reason of the matters in (a)-(g), NAB contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act during the relevant period by failing to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its Australian Financial Services Licence (AFS licence) were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly;

(i) by reason of the matters in (a)-(f), NAB, during the relevant period contravened:

(i) s 912A(1)(b) of the Corporations Act by failing to comply with the condition on its AFS licence, requiring it to establish and maintain compliance measures that ensured as far as is reasonably practicable that it complied with the financial services laws;

(ii) s 912A(1)(ca) of the Corporations Act by failing to take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives complied with the financial services laws;

(iii) s 912A(1)(e) of the Corporations Act by failing to maintain the competence to provide the review services pursuant to its ongoing service agreements; and

(iv) s 912A(1)(f) of the Corporations Act by failing to do all things necessary to ensure that its representatives were adequately trained, and were competent, to provide financial services.

3 The orders agreed on by the parties seek declarations as to each of the admitted contraventions, the imposition of pecuniary penalties on NAB and orders that NAB, before it enters into any ongoing fee arrangements within the next three years, engage an independent expert to review, recommend and report on NAB’s systems and controls for ensuring compliance with div 7.7A of the Corporations Act and establish a compliance system that incorporates the recommendations of the expert to the extent reasonably practicable. The parties have not agreed on the quantum of the pecuniary penalties and it has been left to the Court to determine the appropriate quantum.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK FOR CONTRAVENTIONS OF SECTION 962P AND SECTION 962S OF THE CORPORATIONS ACT

Division 3 of Part 7.7A of the Corporations Act: Charging Ongoing Fees to Clients

4 Division 3 of pt 7.7A was incorporated into the Corporations Act with effect from 1 July 2012 by the Corporations Amendment (Future of Financial Advice) Act 2012 (Cth) (FOFA) and applies to a financial services licensee or their representative entering into an “ongoing fee arrangement” with another person: s 962(1) of the Corporations Act.

5 Section 962A prescribes that an arrangement is an “ongoing fee arrangement” if:

(a) a financial services licensee (or its representative) gives personal advice to a person as a retail client;

(b) that person enters into an arrangement with the financial services licensee (or its representative); and

(c) under the terms of the arrangement, a fee (however described or structured) is to be paid during a period of more than 12 months.

6 A fee that is payable under an ongoing fee arrangement is referred to in div 3 as an “ongoing fee”: s 962B.

7 A financial services licensee (or its representative) that is party to an ongoing fee arrangement that has not assigned to another person their rights under the arrangement is referred to in div 3 as a “fee recipient”: s 962C.

8 Subdivisions B and C of div 3 impose substantive obligations on fee recipients including in relation to issuing fee disclosure statements to ongoing fee arrangement clients. The context of the amendments inserting the fee disclosure statement requirements was described in the Revised Explanatory Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2012 (Cth) (2012 Explanatory Memorandum) as follows:

1.6 Although ongoing fees are disclosed to clients upon engagement of the adviser’s services (via the Statement of Advice requirement prescribed under the Corporations Act), there is no ongoing advice fee disclosure requirement. This initial disclosure requirement alone is not a guaranteed safeguard for clients that become disengaged after a number of years of ‘passively’ paying ongoing advice fees.

9 The particular disclosure obligations arising in respect of a given client depend on whether advice was first provided to the client under an ongoing fee arrangement:

(a) on or after 1 July 2013 – in which case sub-div B applies (post-FOFA ongoing fee arrangements) ; or

(b) before 1 July 2013 – in which case sub-div C applies (pre-FOFA ongoing fee arrangements).

Subdivision B: Post-FOFA Ongoing Fee Arrangements

10 By s 962G of the Corporations Act, a fee recipient in relation to a post-FOFA ongoing fee arrangement must give the client a fee disclosure statement in respect of the arrangement before the end of a period of 60 days beginning on the disclosure day for the arrangement (disclosure obligation).

11 Pursuant to s 962J, the “disclosure day” is:

(a) if no fee disclosure statement has been given since the arrangement was entered into – the anniversary of the day on which the arrangement was entered into; or

(b) if a fee disclosure statement has been given since the arrangement was entered into – the anniversary of the day immediately after the end of the earliest period of 12 months to which the last fee disclosure statement given to the client related.

12 A “fee disclosure statement” is a statement in writing that includes the information required under s 962H and relates to a period of 12 months (the previous year) that ends on a day that is no more than 60 days before that on which the statement is given: s 962H(1). The information required under s 962H is prescribed is sub-s (2), which provides that the following information is required for a fee disclosure statement:

(a) the amount of each ongoing fee paid under the arrangement by the client in the previous year, expressed in Australian dollars unless an alternative is provided in the regulations;

(c) information about the services that the client was entitled to receive from the current and any previous fee recipient under the arrangement during the previous year;

(d) information about the services that the client received from the current and any previous fee recipient under the arrangement during the previous year;

(f) information about any other prescribed matters, including information that relates to a period that begins after the previous year.

13 It is a condition of post-FOFA ongoing fee arrangements that non-compliance with the disclosure obligation terminates the ongoing fee arrangement: s 962F(1). By s 962Q, the obligation to continue to provide services under the ongoing fee arrangement also terminates on termination of the ongoing fee arrangement.

14 By 962F(2), the client is not taken to have waived the client’s rights under the s 962F(1) condition or to have entered into a new ongoing fee arrangement if the client makes a payment of an ongoing fee after a failure to comply with s 962G. However, by s 962F(3), if the client makes a payment of an ongoing fee after a failure to comply with s 962G in relation to the ongoing fee arrangement, the fee recipient is not obliged to refund the payment (subject to s 1317GA considered below). The 2012 Explanatory Memorandum explained at 1.29-1.30 that as the mechanism by which clients pay for ongoing advice services is often through an automated process (for example, by a monthly direct debit from the client’s investment), a statutory right to a full refund after a failure to discharge the disclosure obligation would potentially result in a disproportionate and unjust result at the expense of the fee recipient, as it would mean that one single accidental breach by a fee recipient could result in the forced refund of advice fees over a number of years, regardless of whether the client continued to engage and access the services of the fee recipient.

15 There is a right to redress though, as explained at 1.31 of the 2012 Explanatory Memorandum. Section 962P provides that the fee recipient must not continue to charge an ongoing fee, if an ongoing fee arrangement terminates for any reason and, by s 1317GA, the Court may order the fee recipient to refund the fee paid by the client, if the Court is satisfied that the fee recipient knowingly or recklessly contravened s 962P in charging the ongoing fee after termination of the ongoing fee arrangement and it is reasonable in all the circumstances to make the order.

16 It is noted that non-compliance with the disclosure obligation under s 962G of itself does not give rise to a liability for a civil penalty. Section 962P is the civil penalty provision (s 1317E) and the liability arises when an ongoing fee arrangement terminates pursuant to s 962F in consequence of the non-compliance with the disclosure obligation under s 962G and the fee recipient continues charging fees following termination.

Subdivision C: Pre-FOFA Ongoing Fee Arrangements

17 Prior to 19 March 2016, the disclosure obligation on the fee recipient was to provide a fee disclosure statement in relation to the ongoing fee arrangements within a period of 30 days beginning on the disclosure day for the arrangement: s 962S(1) (as it then was). Since 19 March 2016, the period under s 962S(1) is before the end of a period of 60 days beginning on the disclosure day for the arrangement. In s 962S, “fee disclosure statement” has the meaning given by s 962H(1): s 960.

18 Section 962S, unlike s 962G, is a civil penalty provision. However, sub-div C does not contain any provision that corresponds to s 962P or which otherwise prohibits the charging of fees to pre-FOFA clients after there has been non-compliance with the requirement to provide a fee disclosure statement in s 962S.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK FOR CONTRAVENTIONS OF SECTION 1041H OF THE CORPORATIONS ACT AND SECTIONS 12DA AND 12DB OF THE ASIC ACT

19 Section 1041H(1) of the Corporations Act provides that:

A person must not, in this jurisdiction, engage in conduct, in relation to a financial product or a financial service, that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

20 Section 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct in relation to financial services that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

21 Section 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

[…]

(g) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of services…

22 Section 1041H of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act are in analogous terms and the same principles are applicable to both provisions. Further, although the statutory language in s 12DB of the ASIC Act (“false or misleading”) is not identical (“misleading or deceptive”), the authorities establish that there is no material difference between these expressions in terms of their legal application: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682, [14]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73; [2014] FCA 634, [40].

23 The central question arising under each provision is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error – that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter. It is well settled that is not necessary to show an intention to mislead or deceive or to show that anyone was actually deceived or misled: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216; [1978] HCA 11, 228 (Stephen J, Barwick CJ agreeing at 221, Jacobs J agreeing at 232), 234 (Murphy J); Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191; [1984] HCA 44, 197 (Gibbs CJ).

24 Section 12DB(1)(a) prohibits false or misleading representations that services are of a particular “standard, quality, value or grade”. Relevantly, representations that a person offers a particular service (when in fact they do not offer that service) or has performed particular services (when in fact they have not performed such services) may constitute representations as to the quality or standard of the services: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Wizard Mortgage Corporation Limited [2002] FCA 1317; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cash King Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 1429.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK FOR CONTRAVENTIONS OF SECTION 912A OF THE CORPORATIONS ACT

25 NAB, as holder of an AFS licence, is subject to the general obligations imposed on financial services licensees by s 912A of the Corporations Act. Subsection 912A(1) relevantly provides:

A financial services licensee must:

(a) do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by the licence are provided efficiently, honestly and fairly; and

…

(b) comply with the conditions on the licence; and

(c) comply with the financial services laws; and

(ca) take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives comply with the financial services laws; and

…

(e) maintain the competence to provide those financial; and

(f) ensure that its representatives are adequately trained (including by complying with section 921D), and are competent, to provide those financial services; and …

26 There is some conflict in the case law as to whether the words “efficiently, honestly and fairly” in s 912A(1)(a) should be read compendiously (Story v National Companies and Securities Commission (1988) 13 NSWLR 661, 672; cf Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Securities Administration Ltd (2019) 272 FCR 170; [2019] FCAFC 187), however it is unnecessary to consider that question in the present case. The salient point is that contravention of the “efficiently, honestly and fairly” standard does not require a contravention or breach of a separately existing legal duty or obligation, whether statutory, fiduciary, common law or otherwise. The statutory standard itself is the source of the obligation: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AGM Markets Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) (2020) 275 FCR 57; [2020] FCA 208, [512].

FACTUAL OVERVIEW

27 NAB is the holder of an AFS licence and carries on a financial services business in Australia within the meaning of s 911D of the Corporations Act. During the relevant period, NAB entered into ongoing service arrangements, under which NAB provided financial services to clients through its business unit, NAB Financial Planning, and clients agreed to pay fees on an ongoing basis. The services included financial reviews conducted annually or at agreed intervals, personal consultations, offers of personal consultations, recaps and written reports on the status of the client’s strategies (review services). Fees were generally paid monthly by direct debit from a nominated account, including product deductions or deductions from bank account or credit card. Approximately 26,000 pre-FOFA clients and approximately 11,000 post-FOFA clients are estimated to have had an ongoing service arrangement with NAB at some time in the relevant period.

28 During the relevant period, NAB had policies, procedures and systems in place for the monitoring and oversight of the delivery of services under ongoing service arrangements and the provision of fee disclosure statements. These policies, procedures and systems are detailed at [145]–[147] of the agreed facts. NAB accepts that these policies, procedures and systems were inadequate to identify:

(a) whether review services were provided to clients in accordance with clients’ ongoing service arrangements;

(b) whether NAB had provided fee disclosures statements to clients in accordance with its obligations under ss 962G and 962S of the Corporations Act;

(c) whether fee disclosures statements that were provided accurately recorded the statement period, the services to which the client was entitled in the statement period, the services the client received during a statement period and the amount of ongoing fees paid by the client during the statement period; and

(d) whether NAB Financial Planning was prohibited from charging any particular client ongoing fees.

(NAB’s compliance deficiencies)

29 NAB’s compliance deficiencies arose in the circumstances identified at [148]–[156] of the agreed facts.

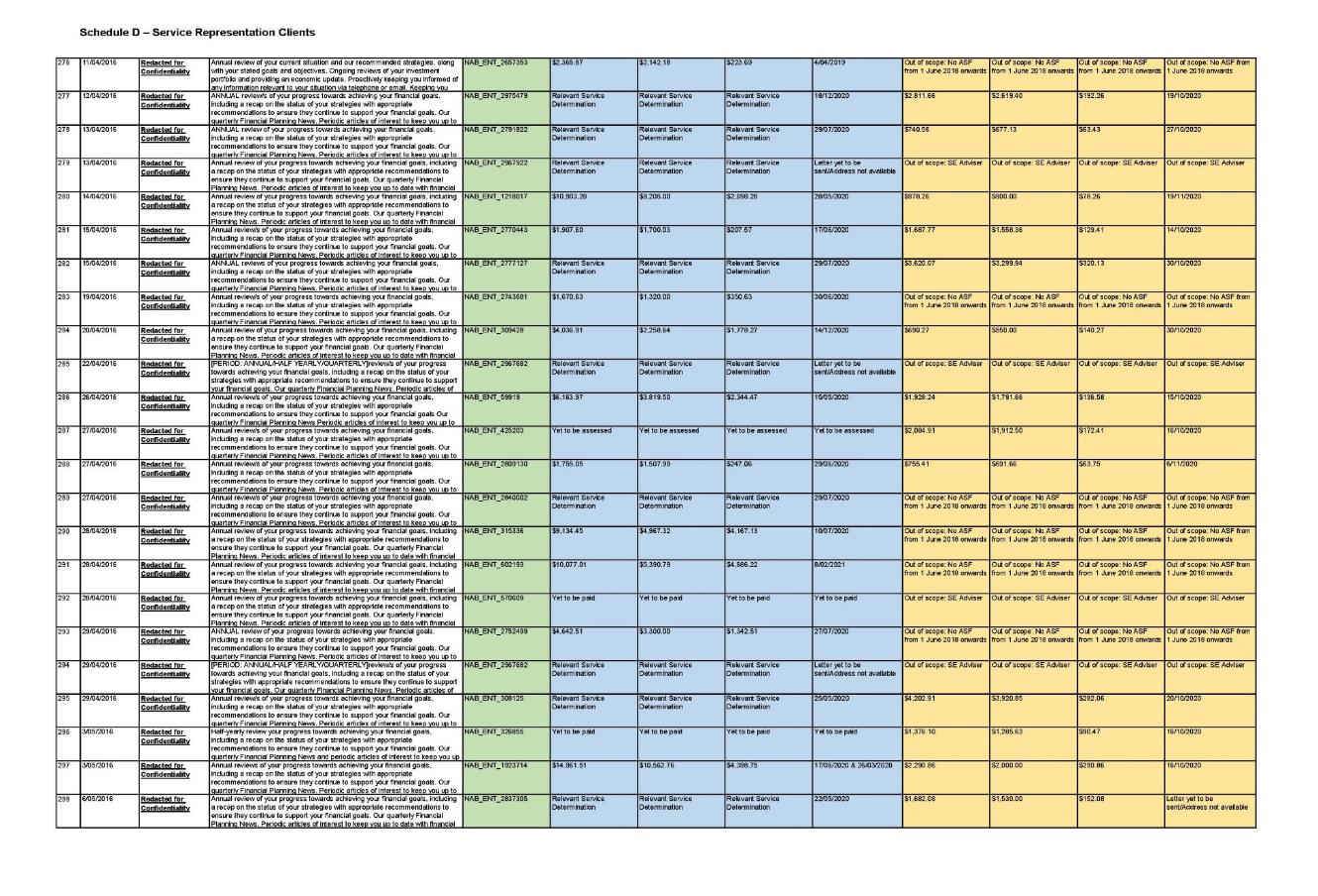

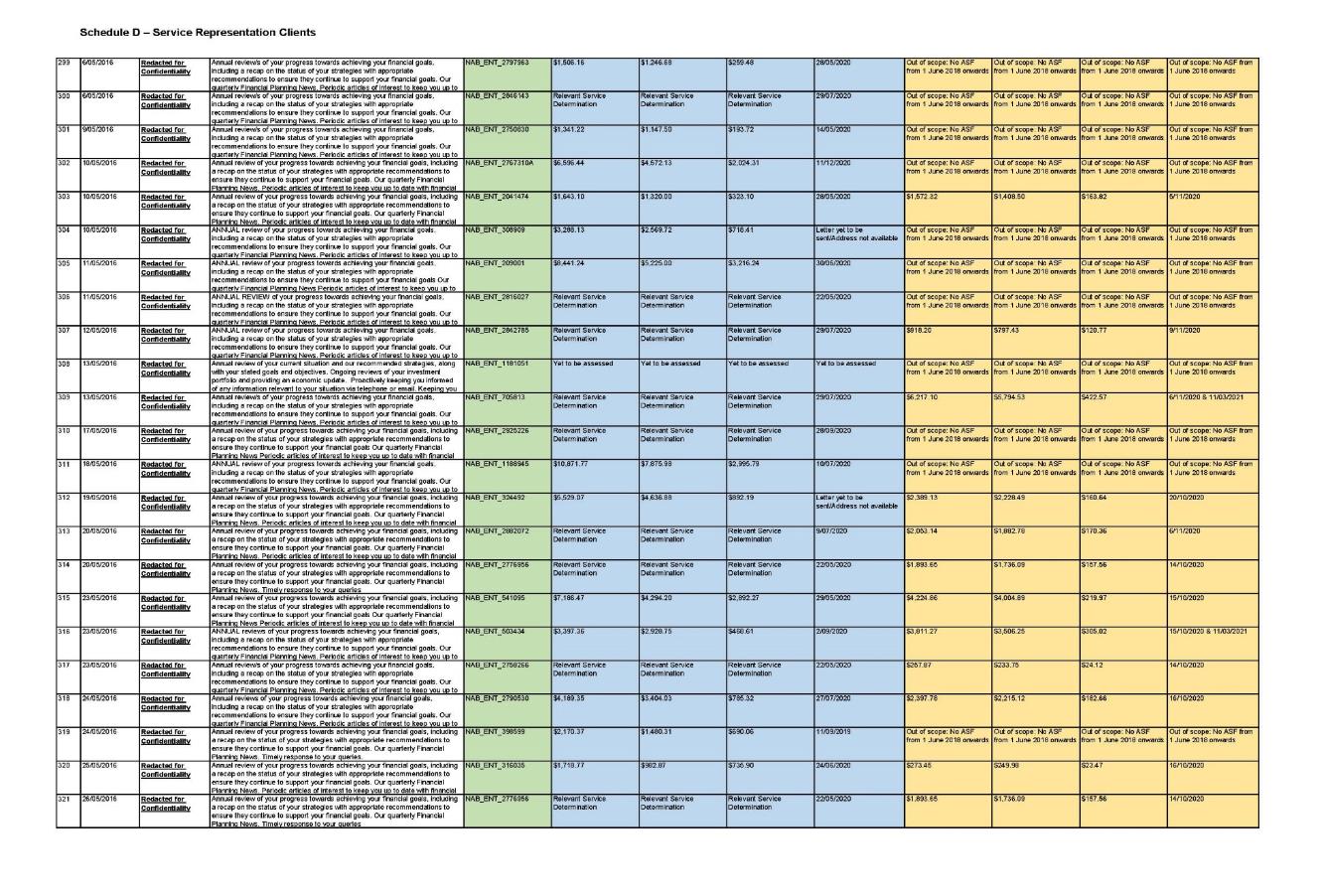

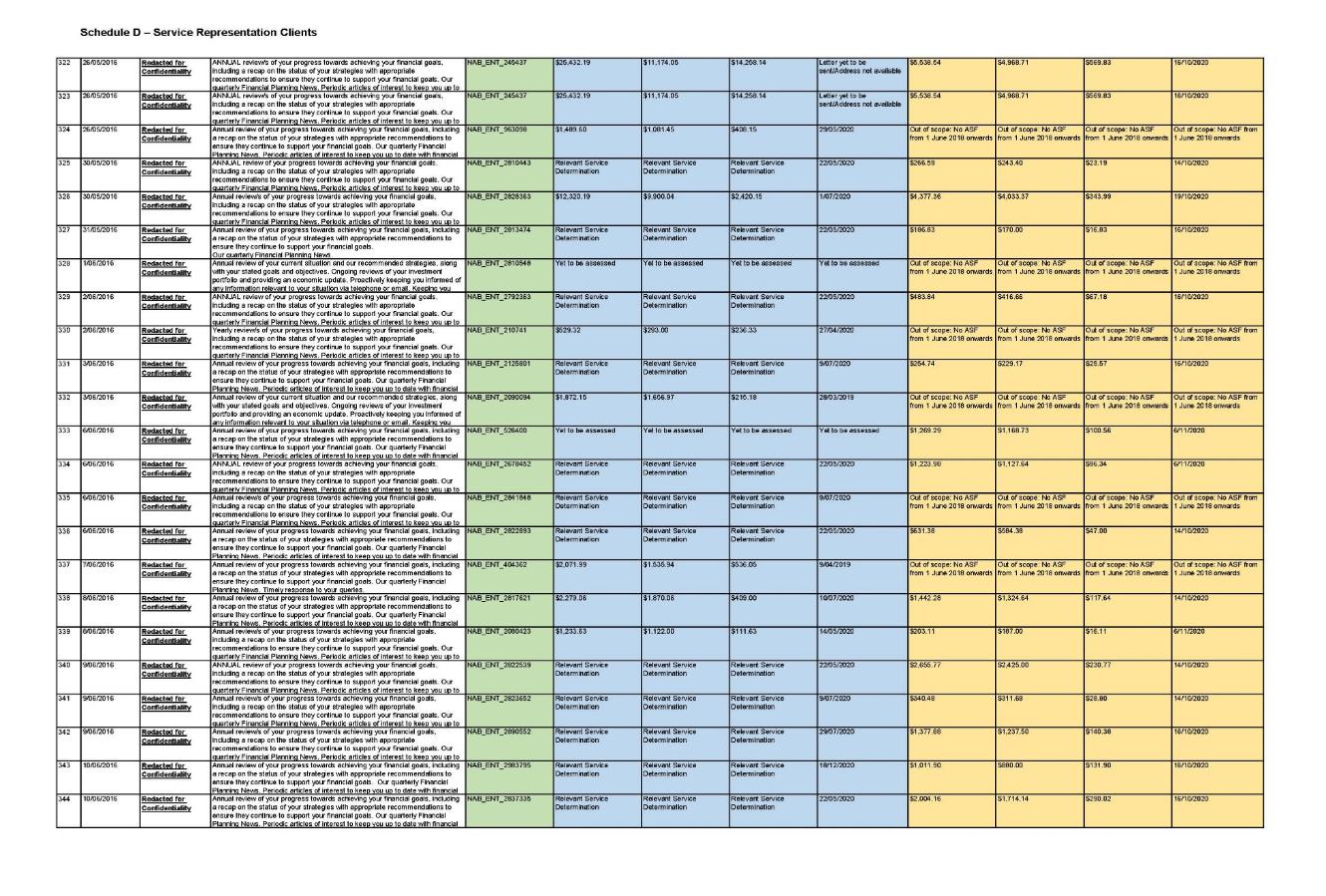

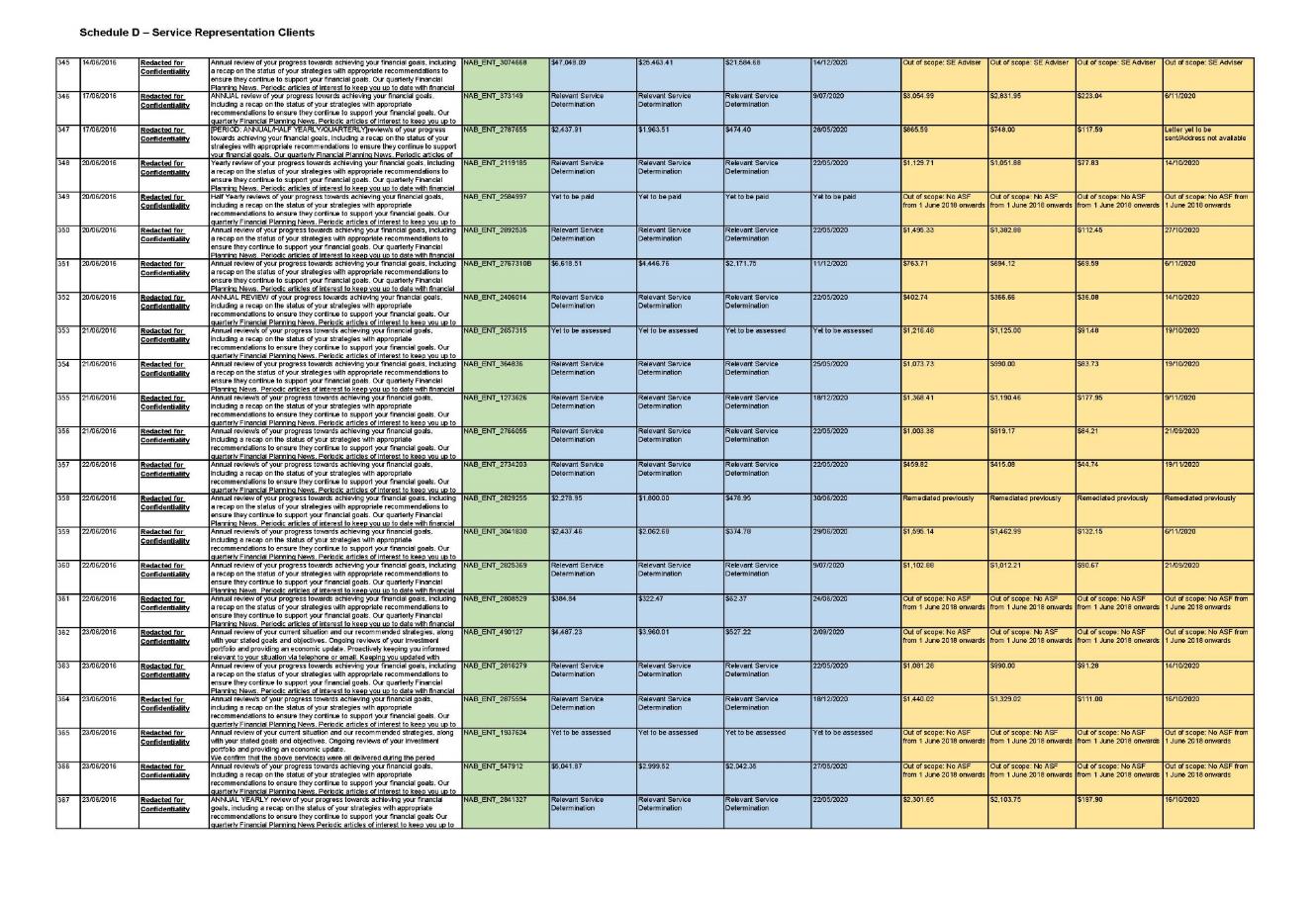

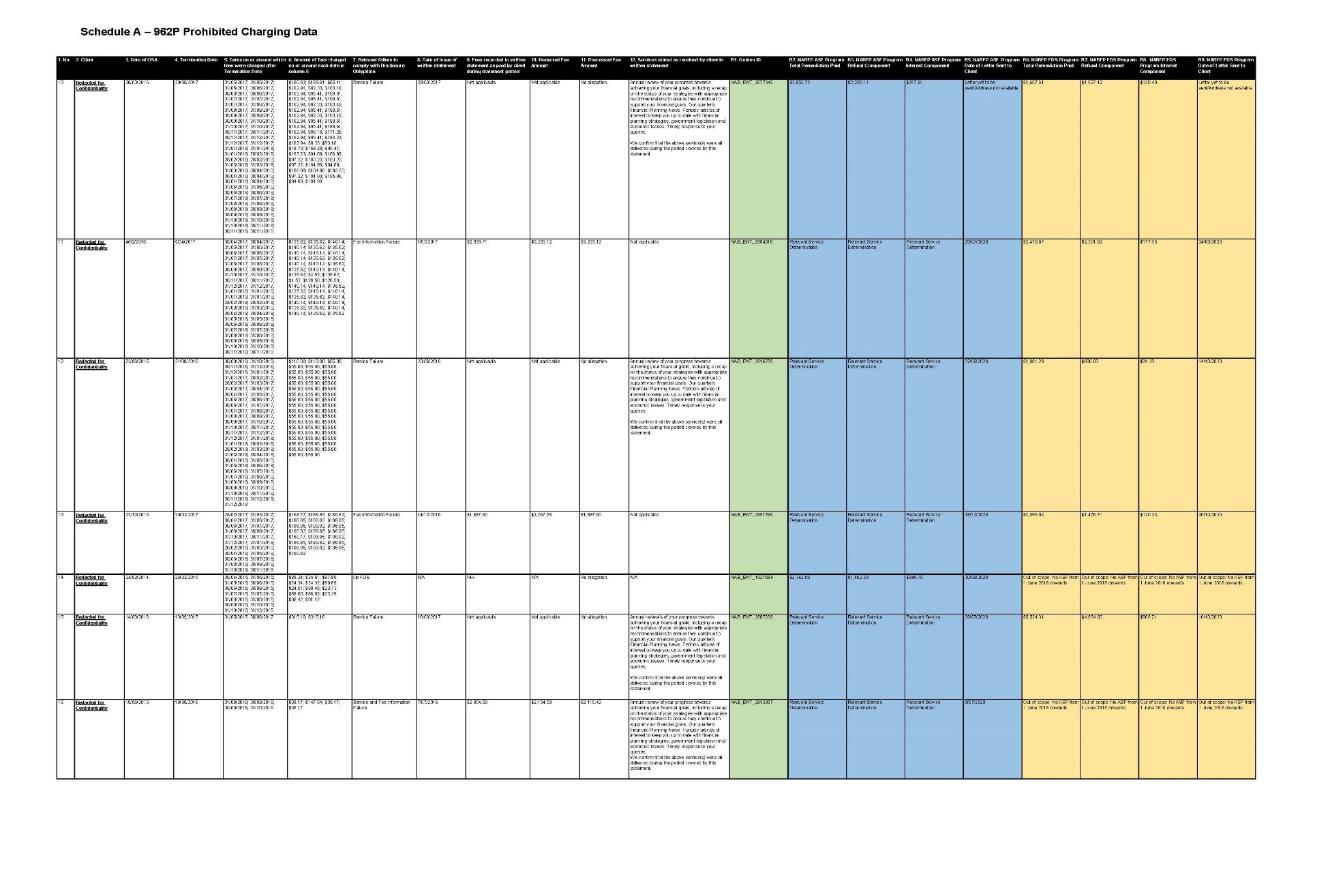

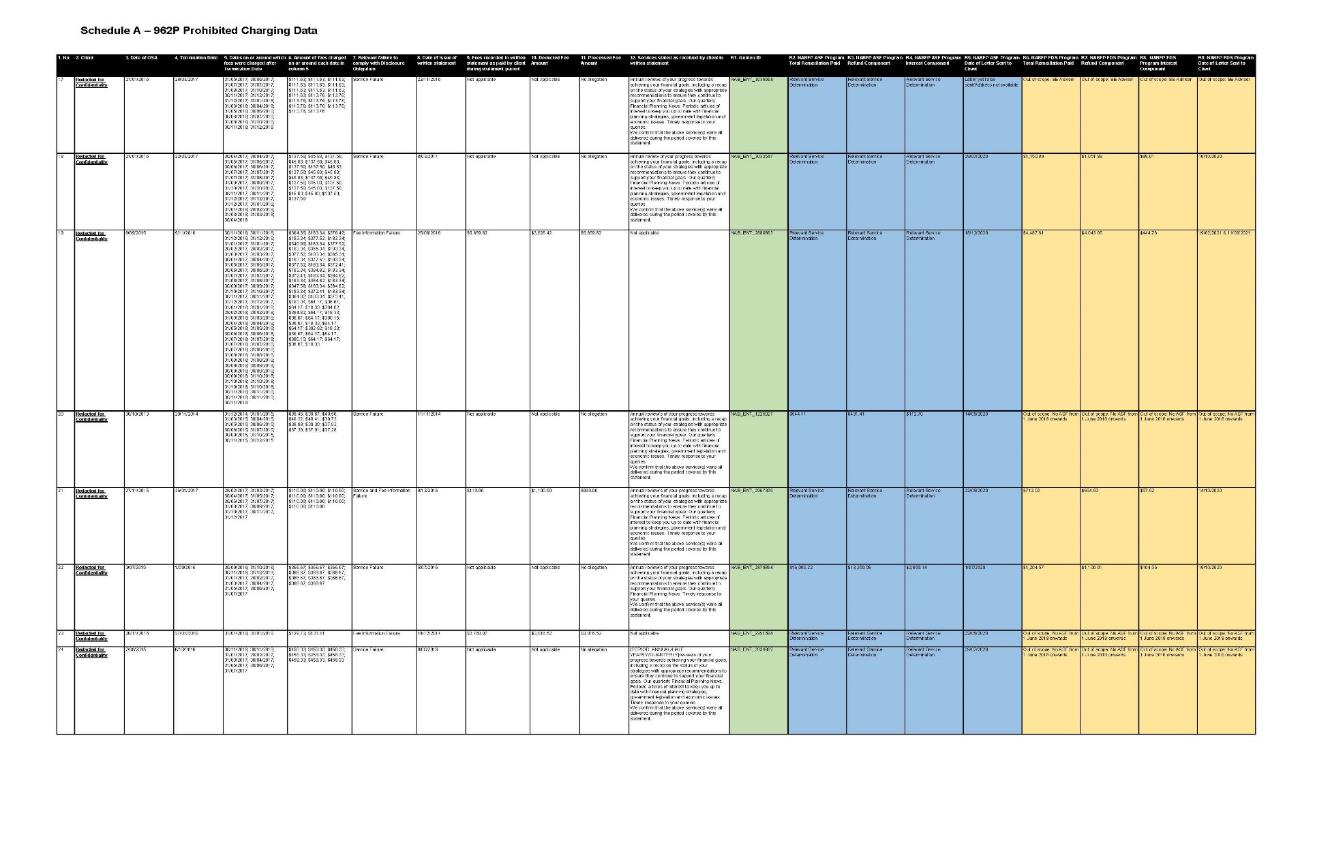

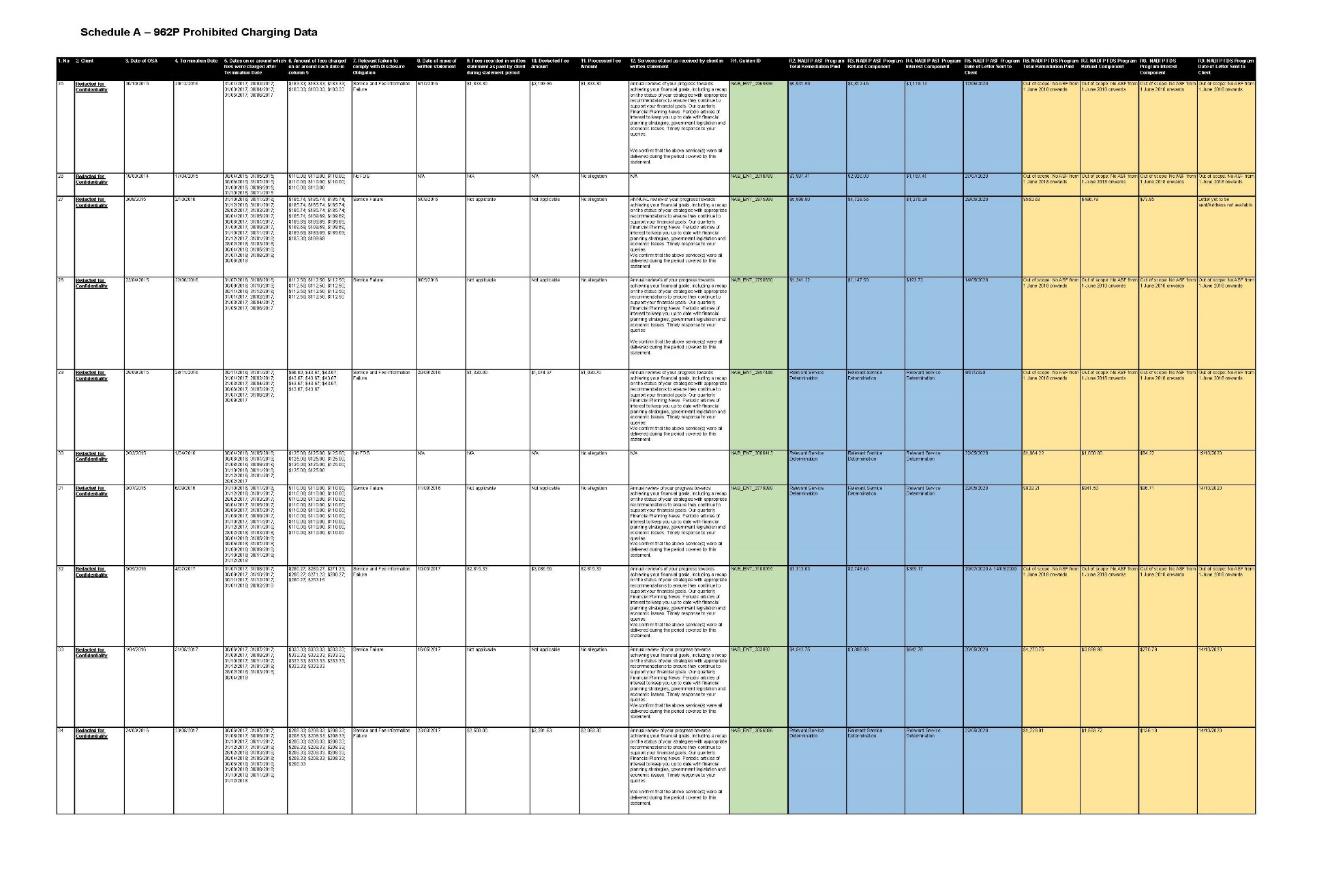

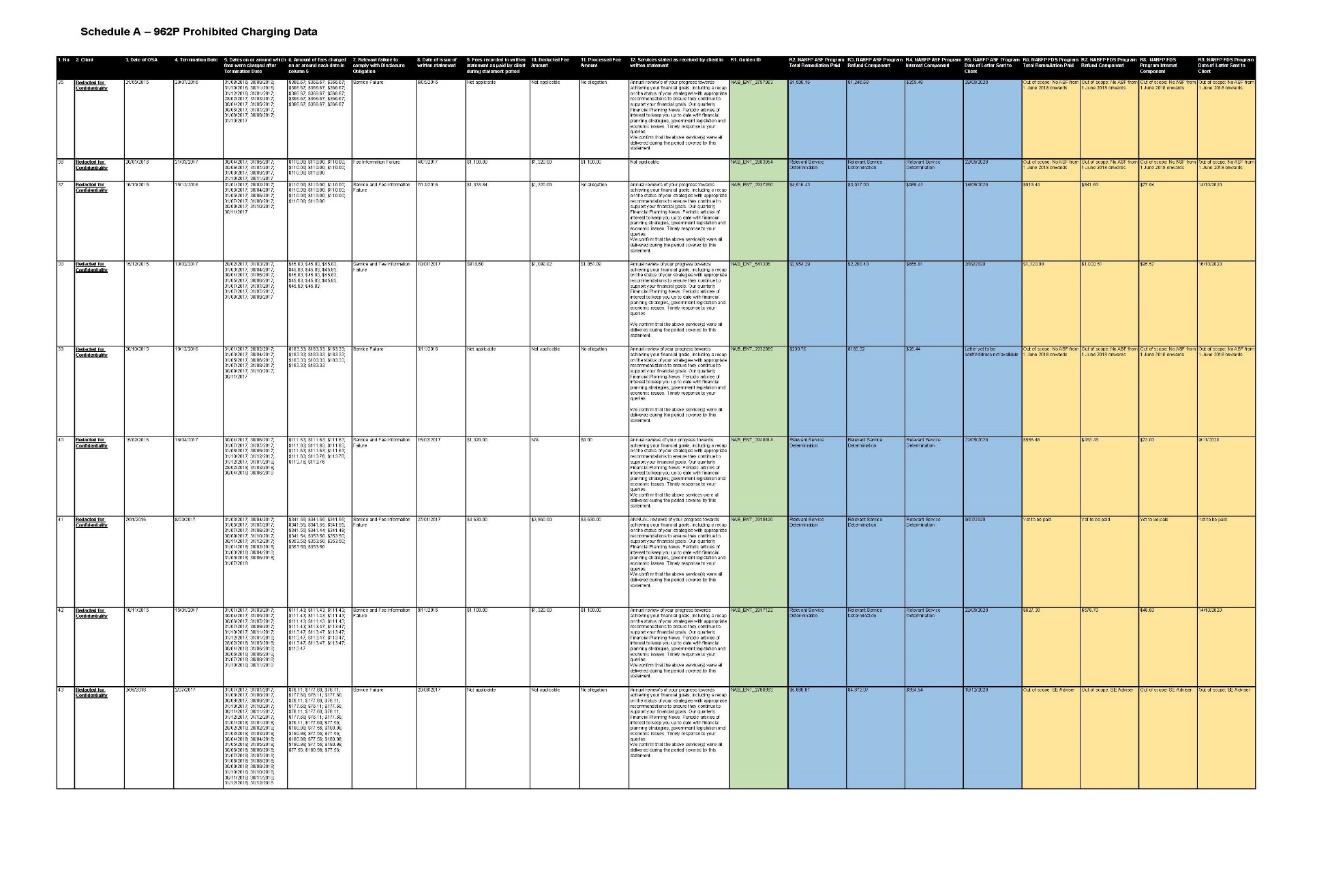

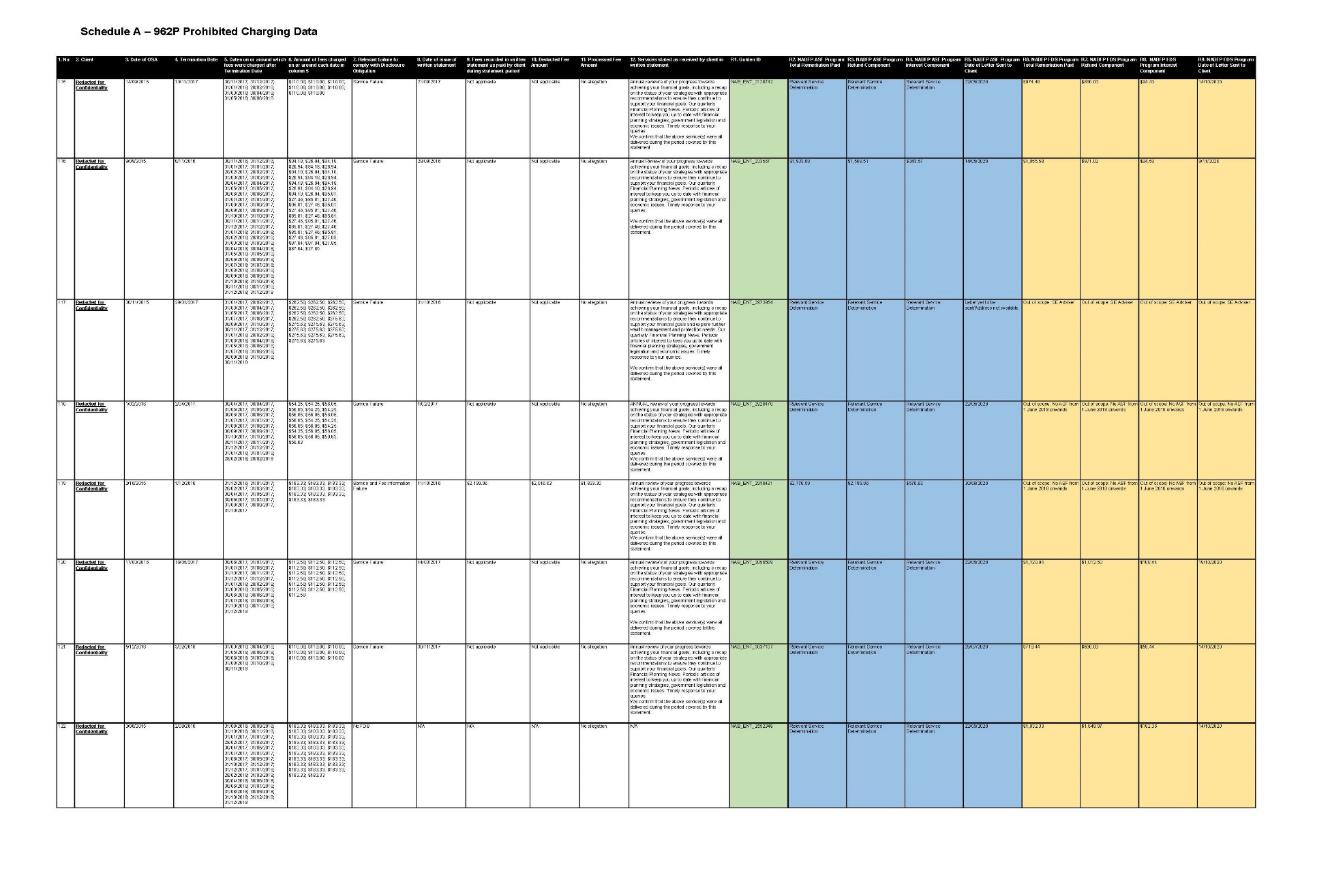

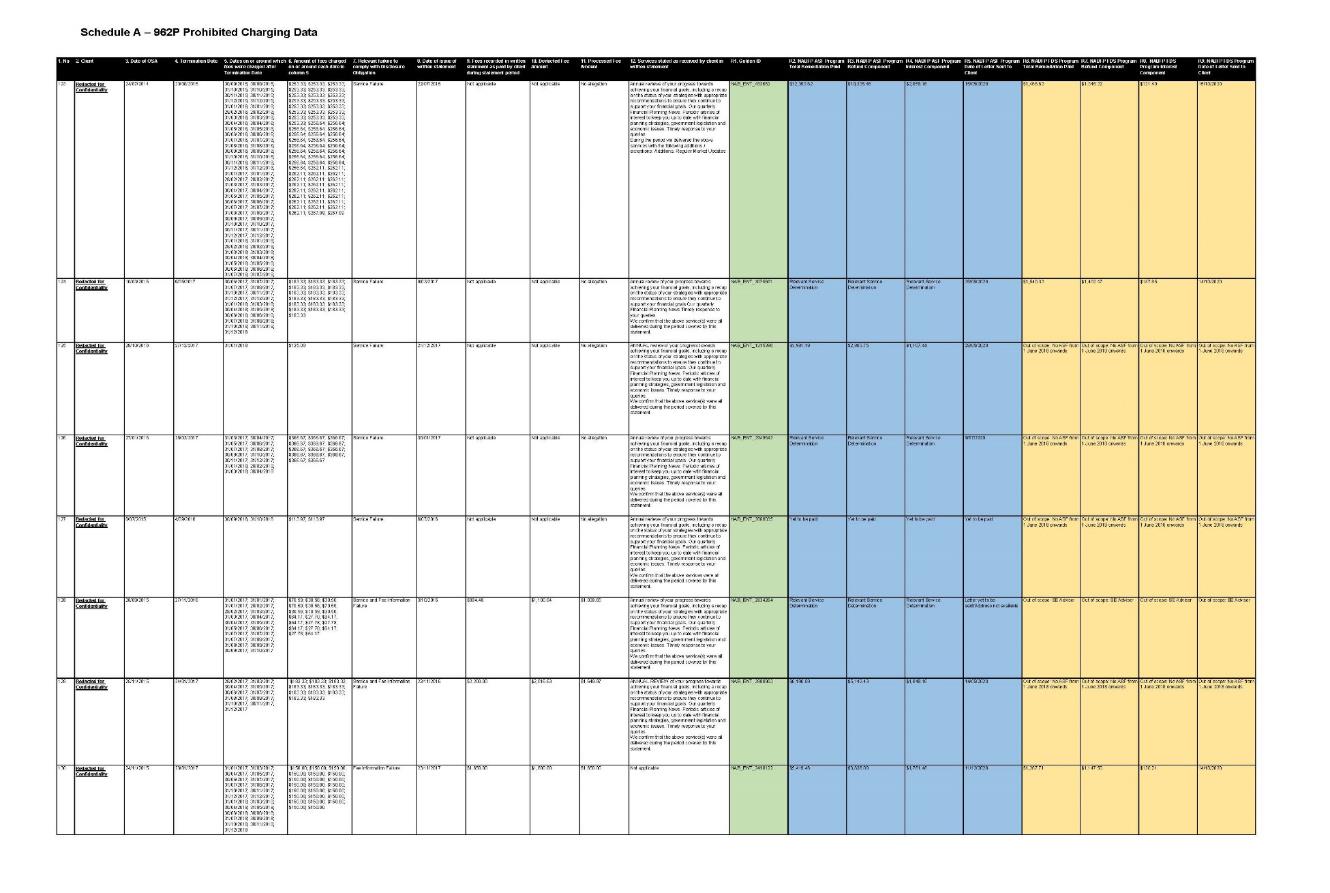

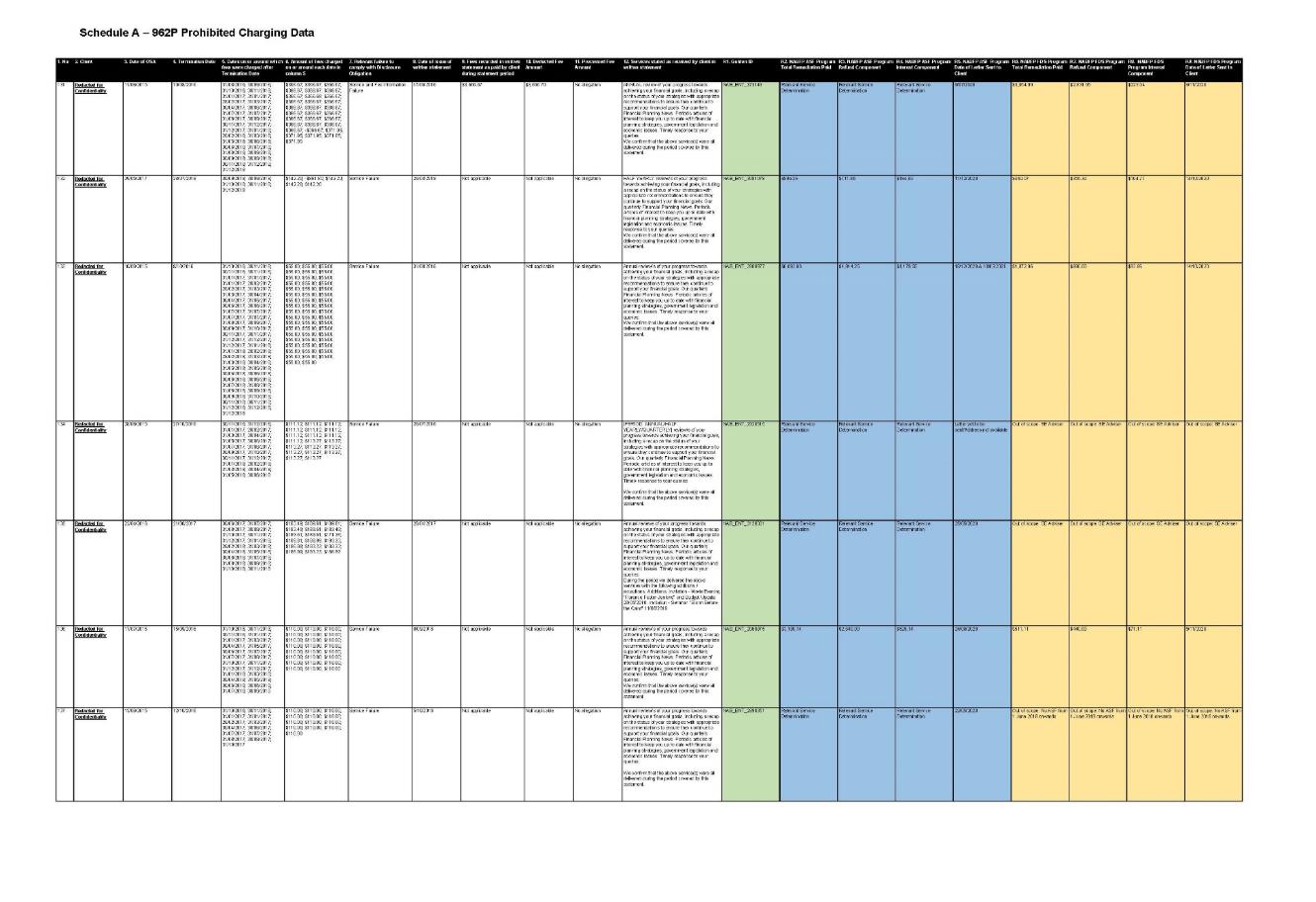

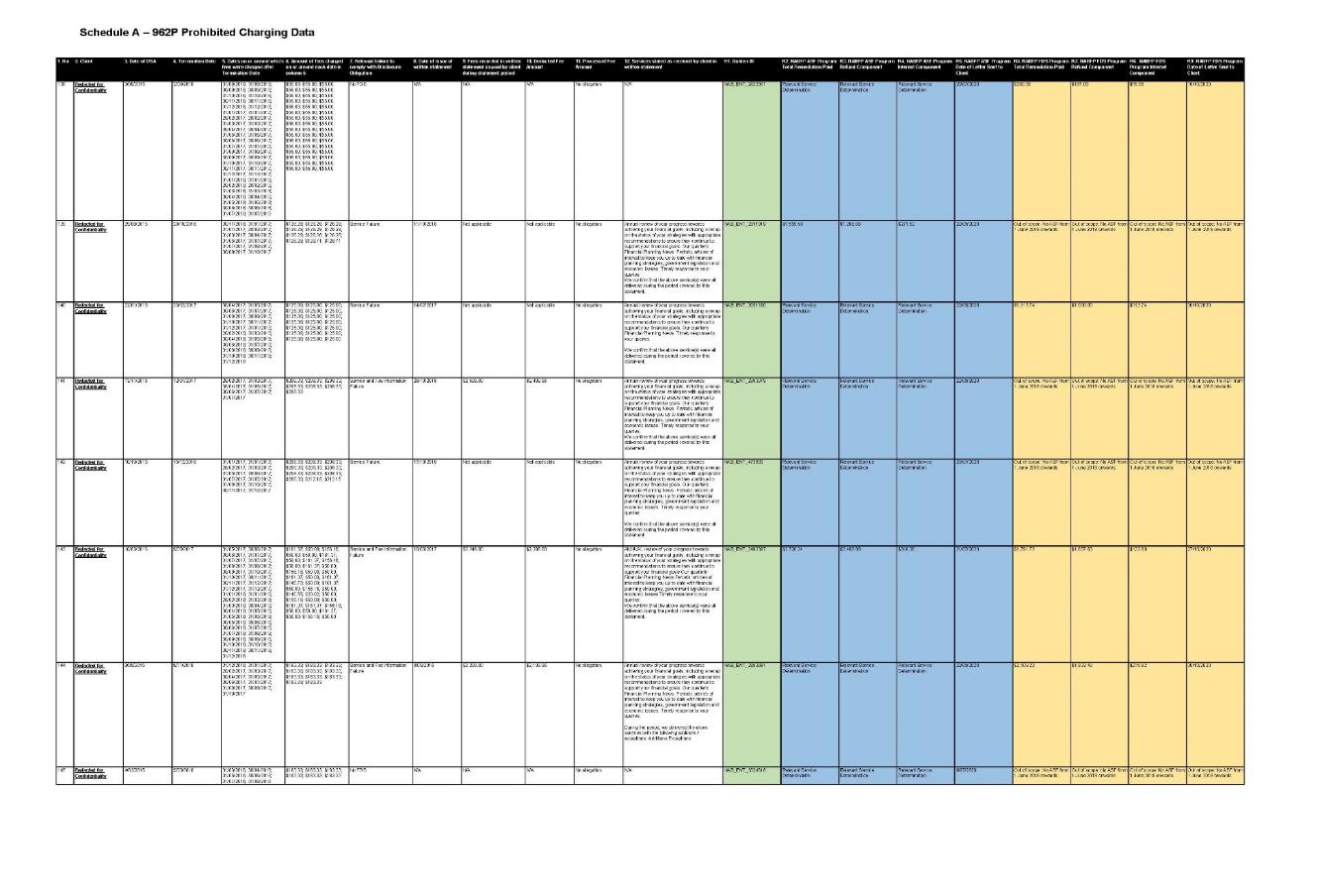

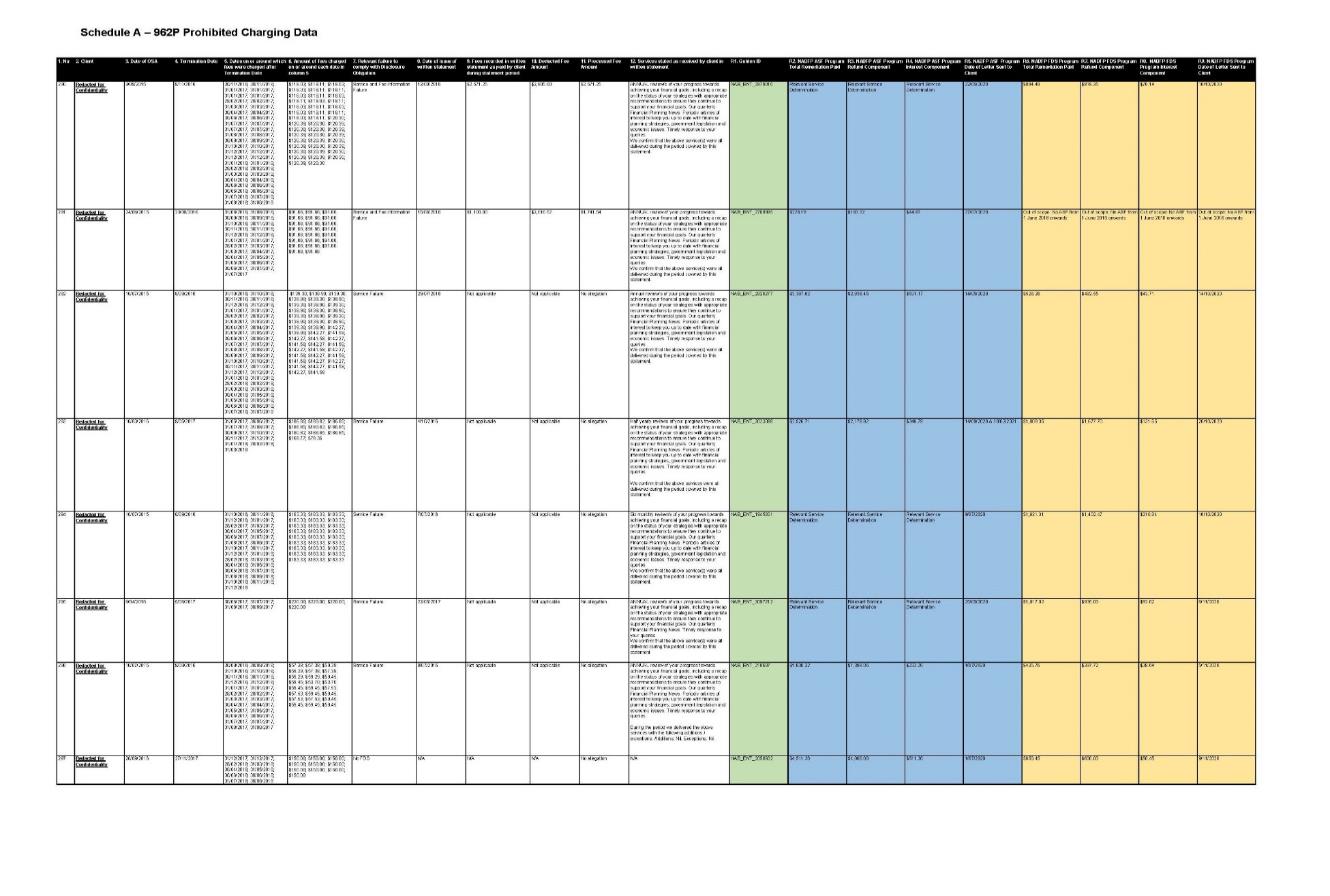

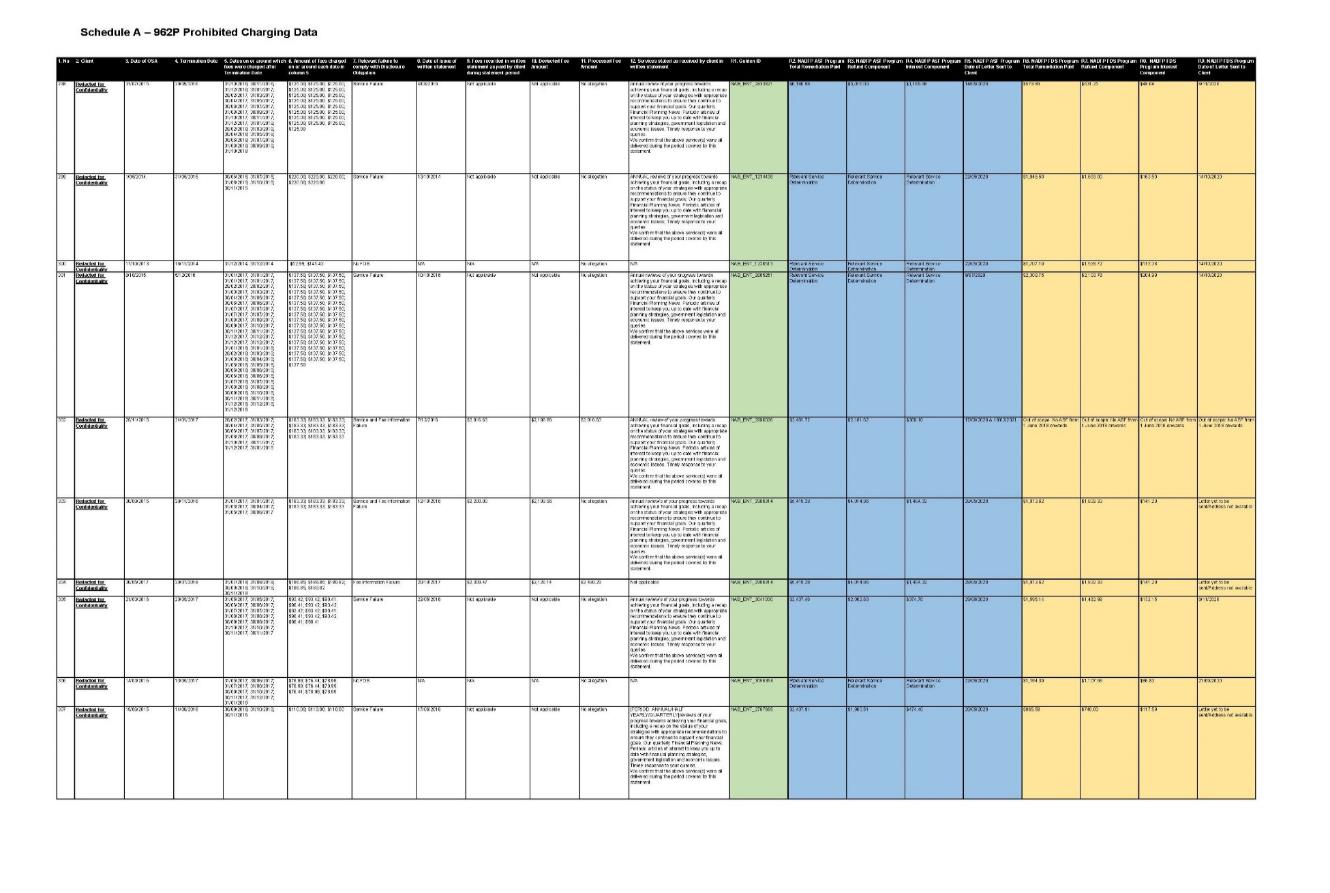

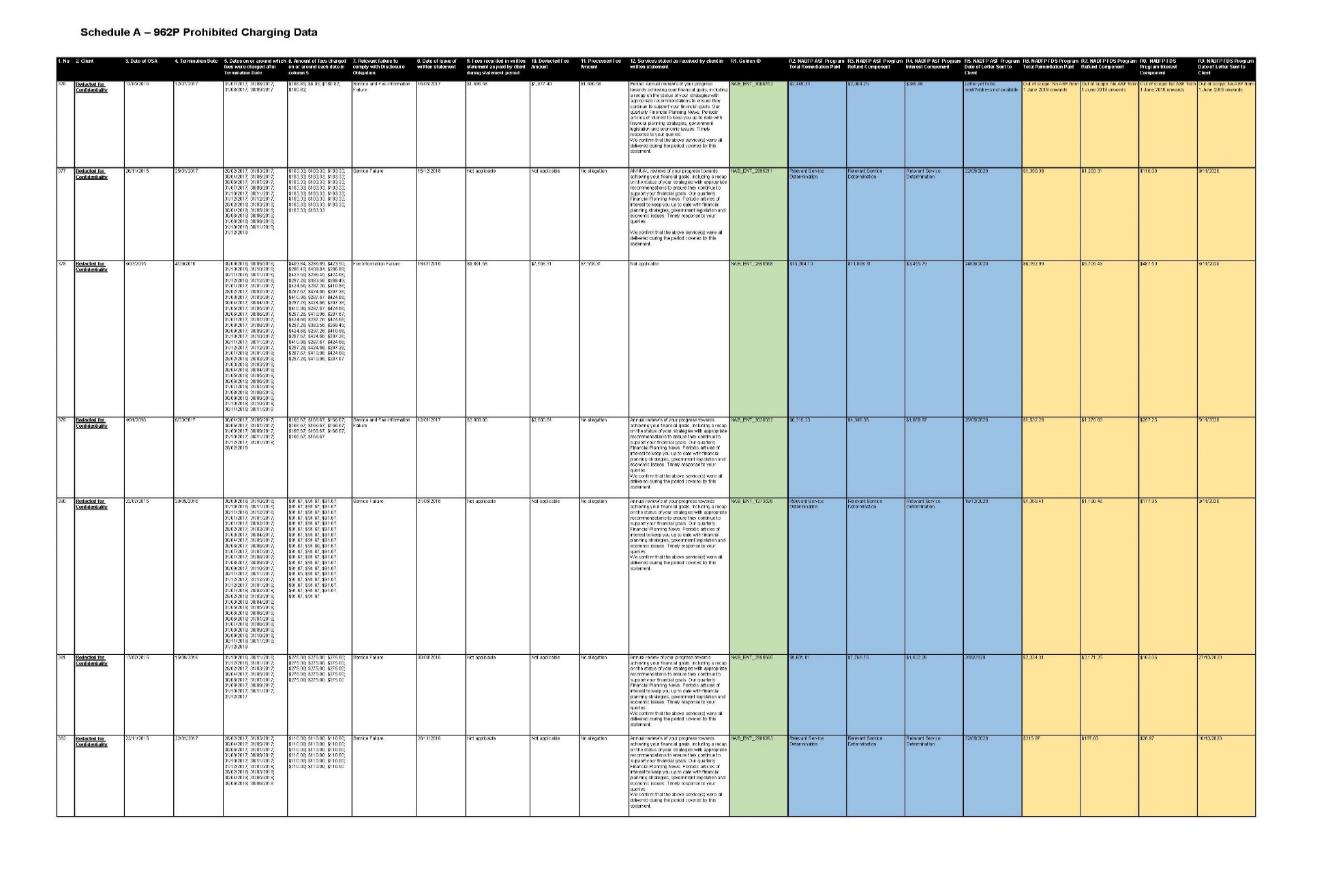

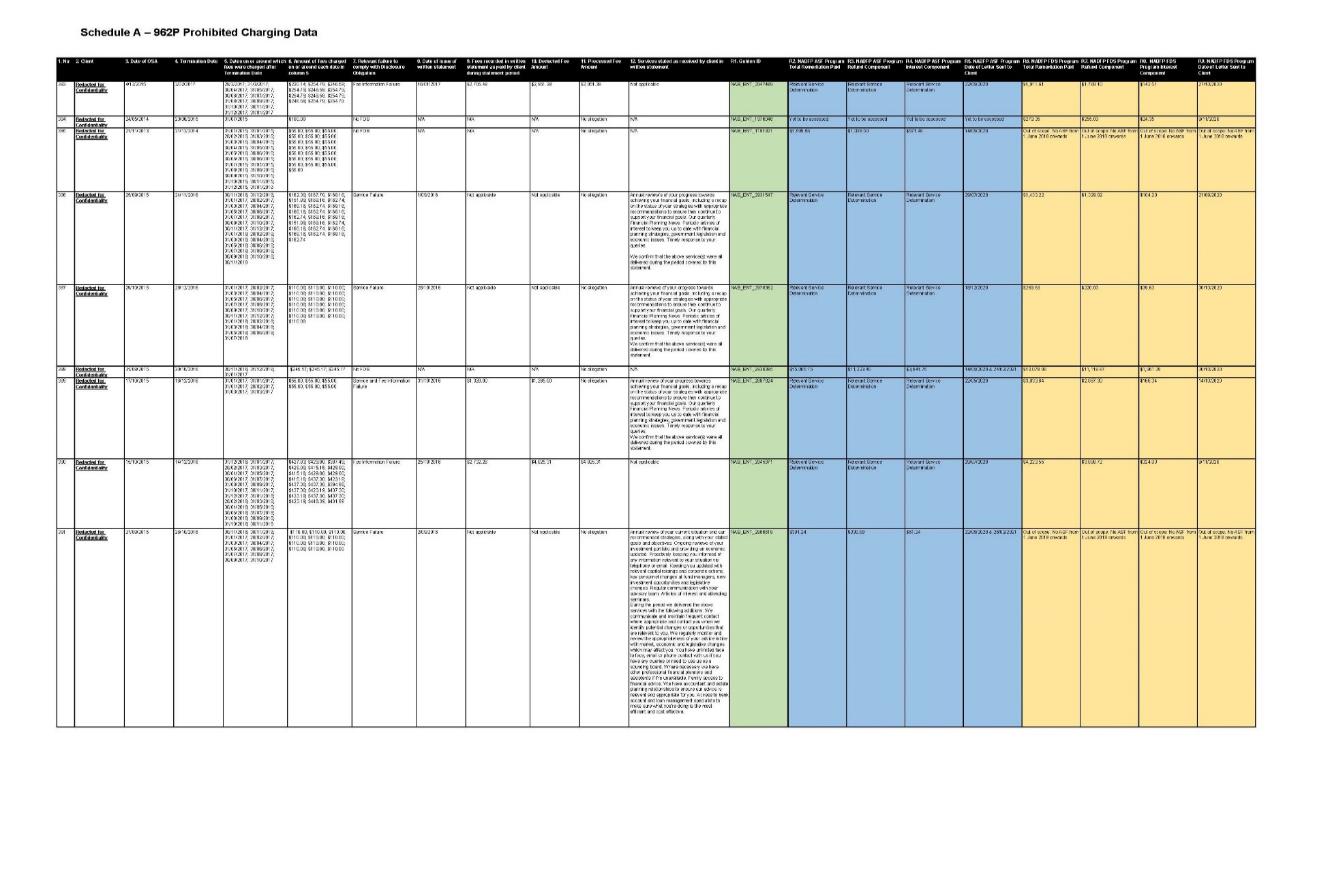

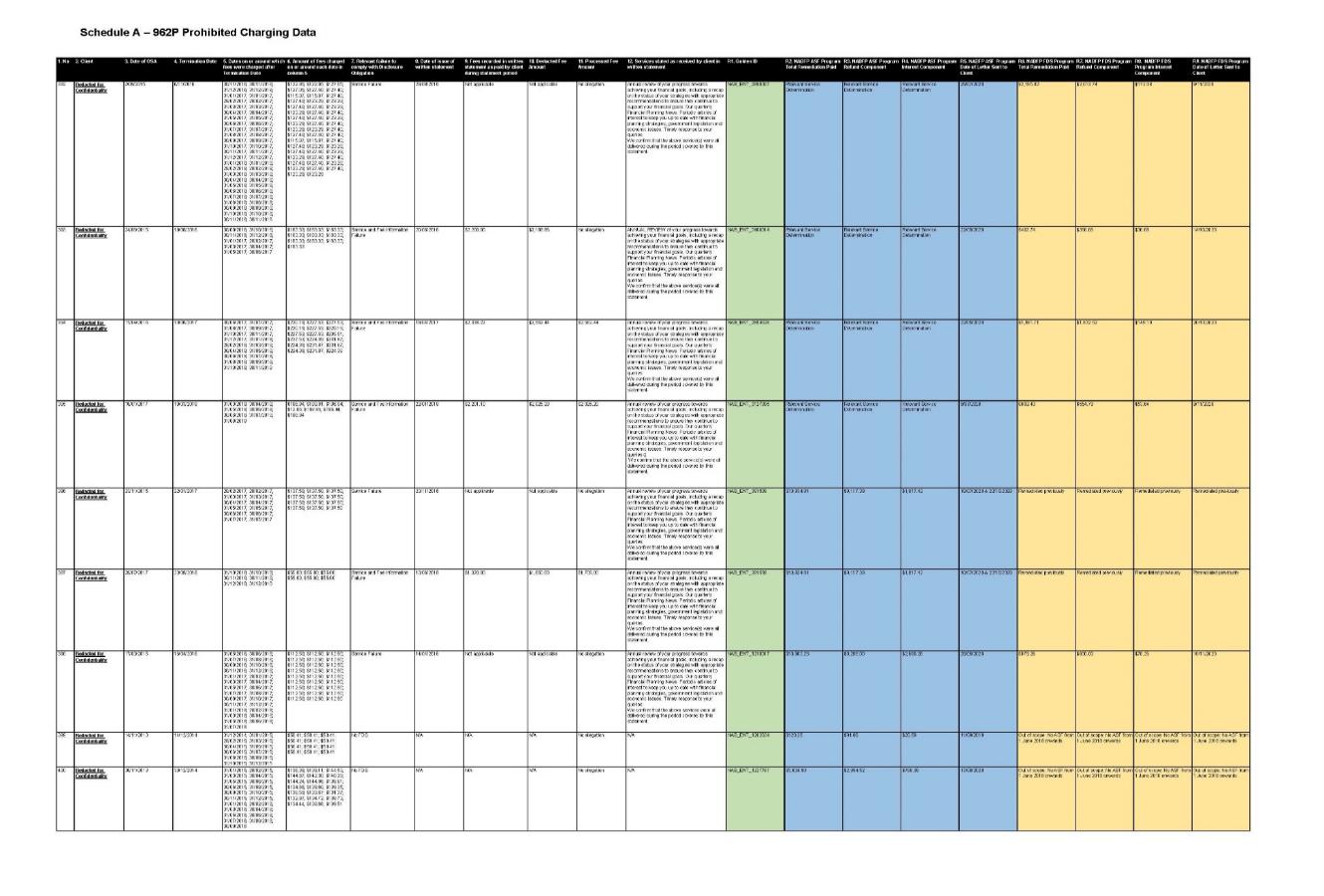

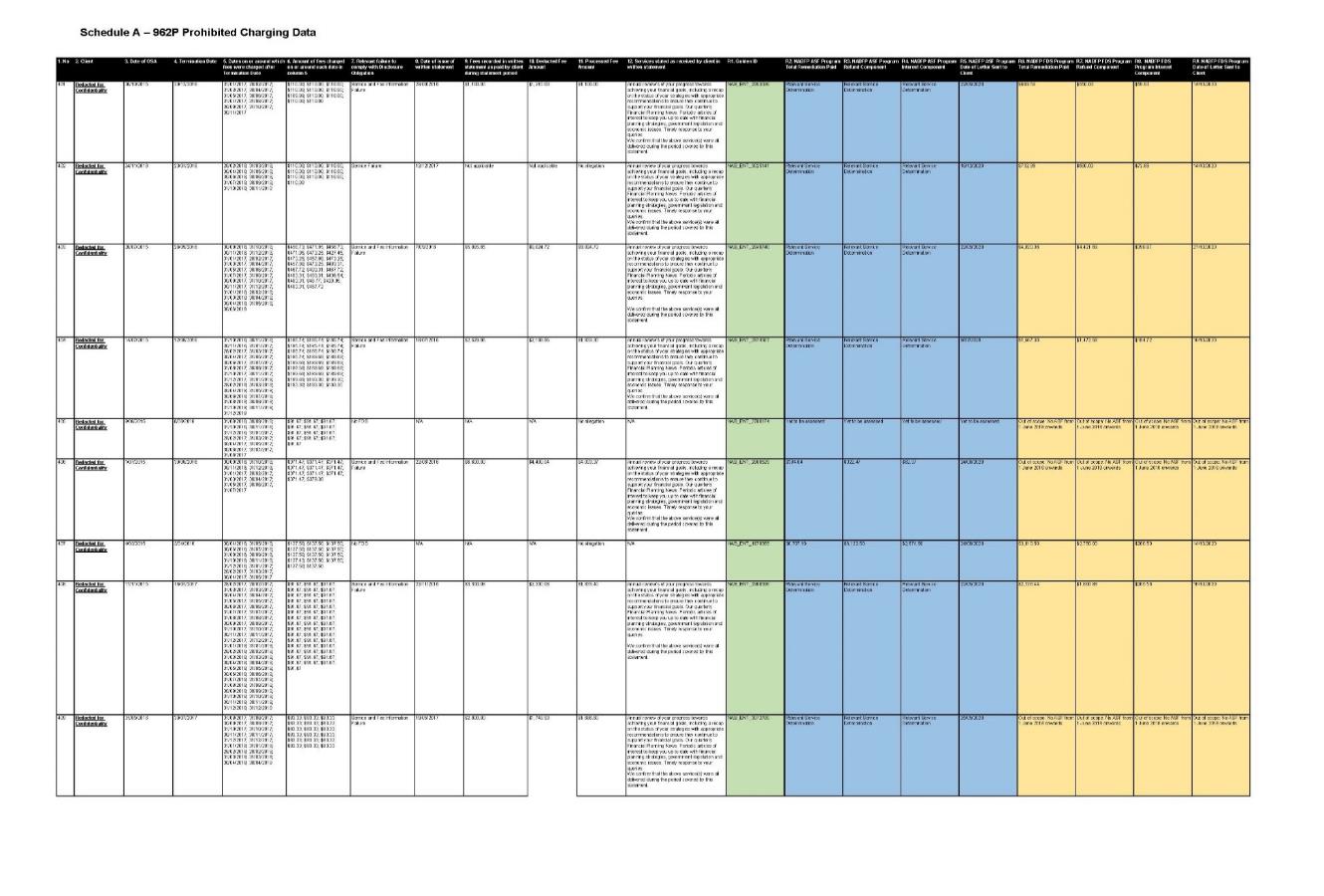

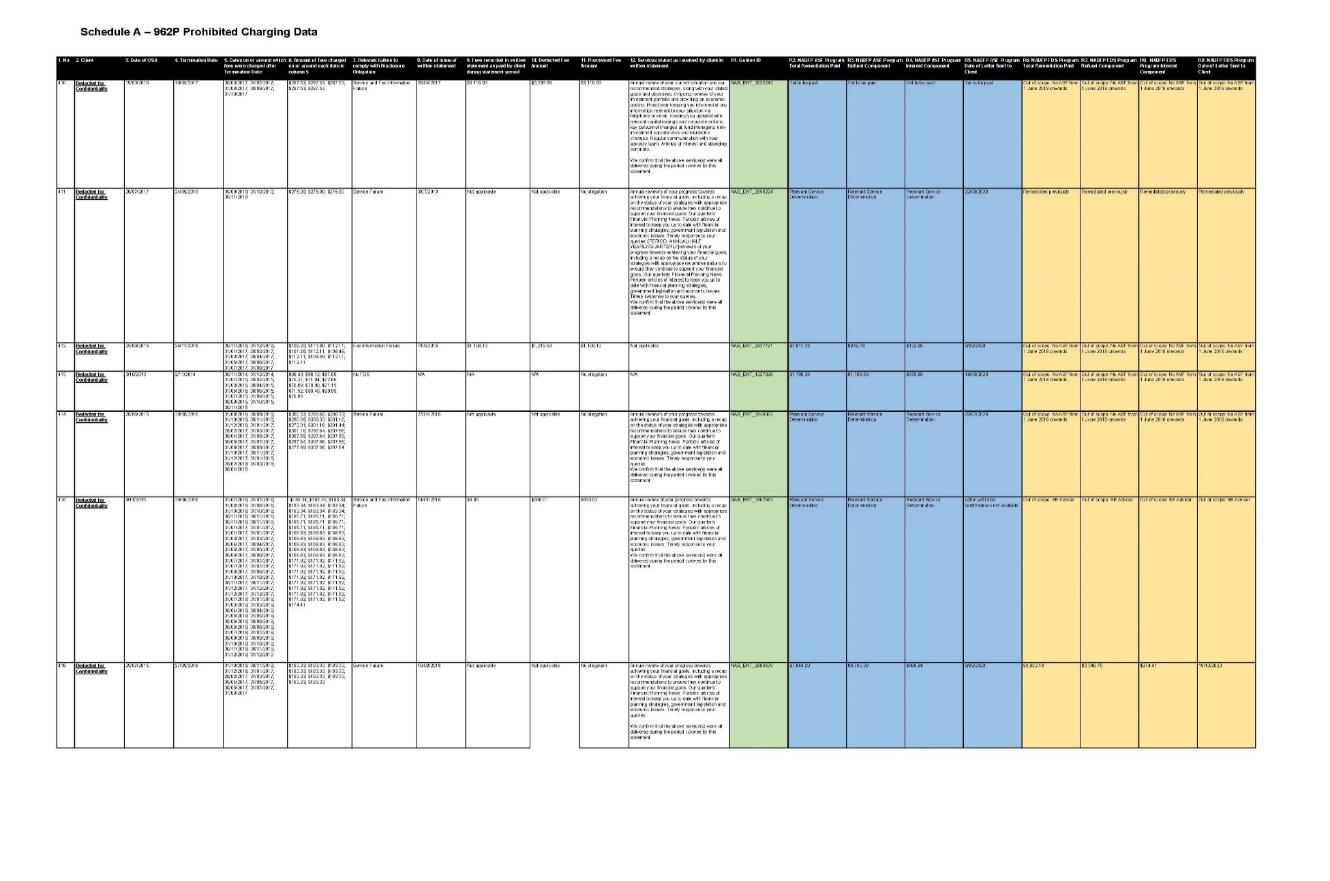

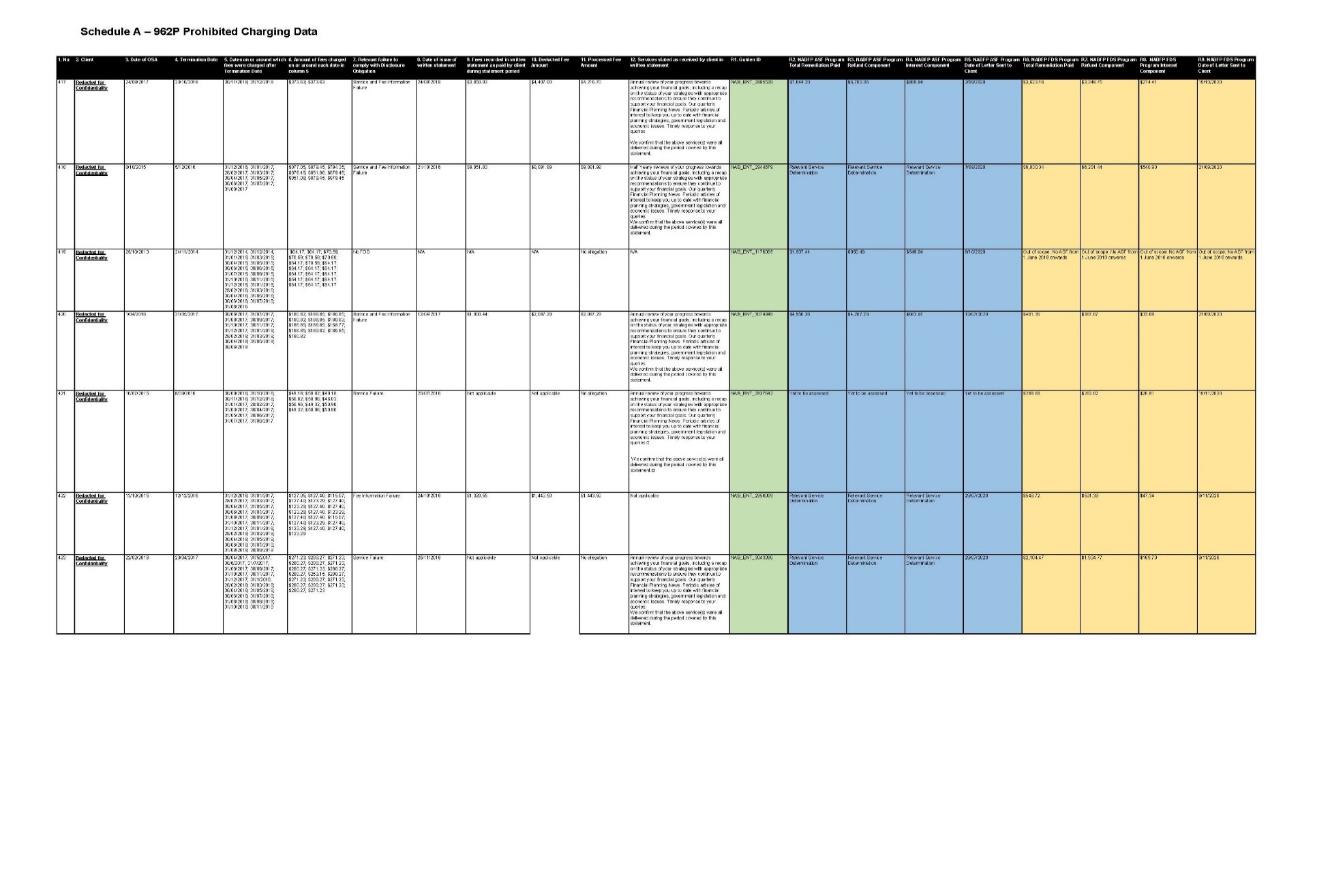

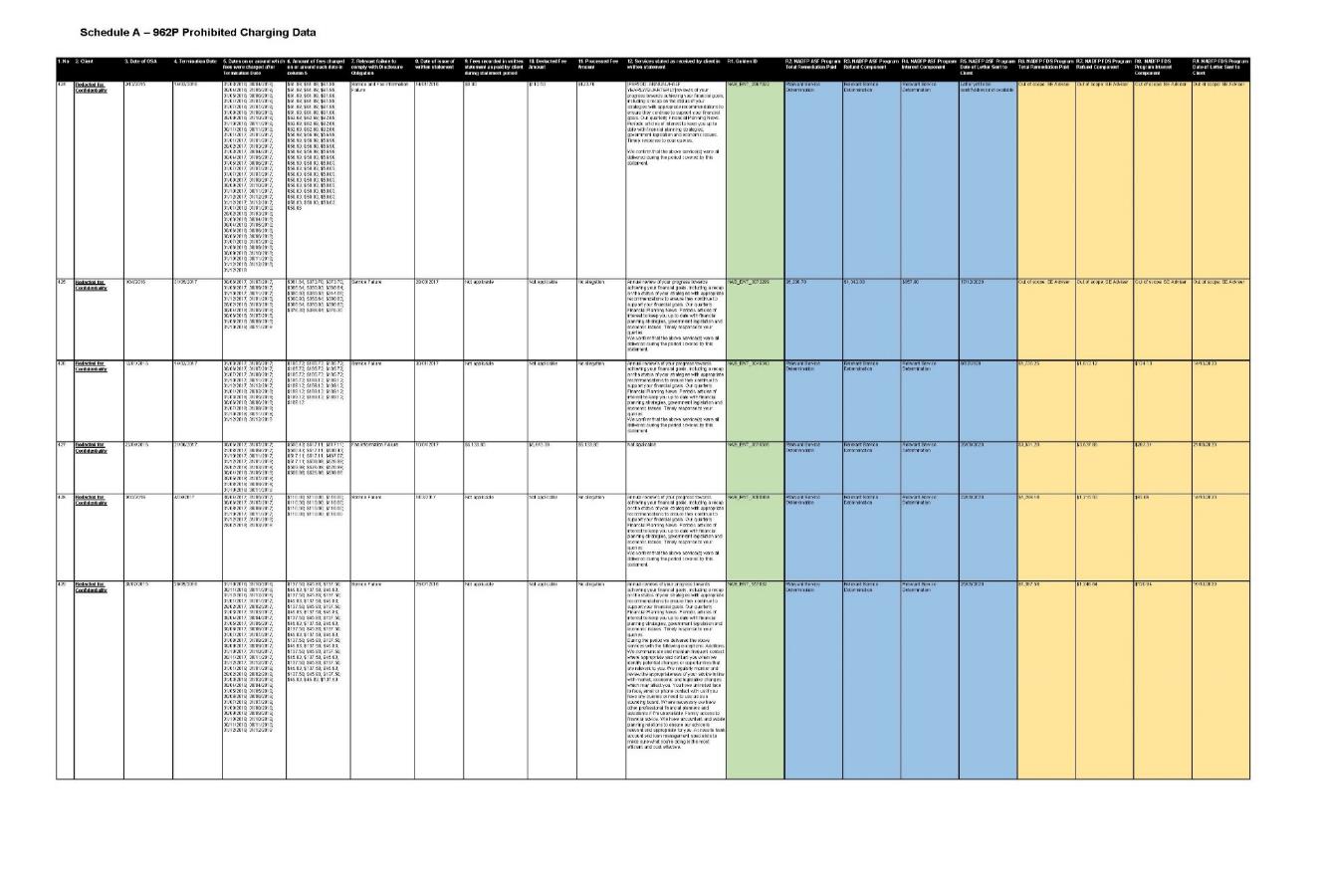

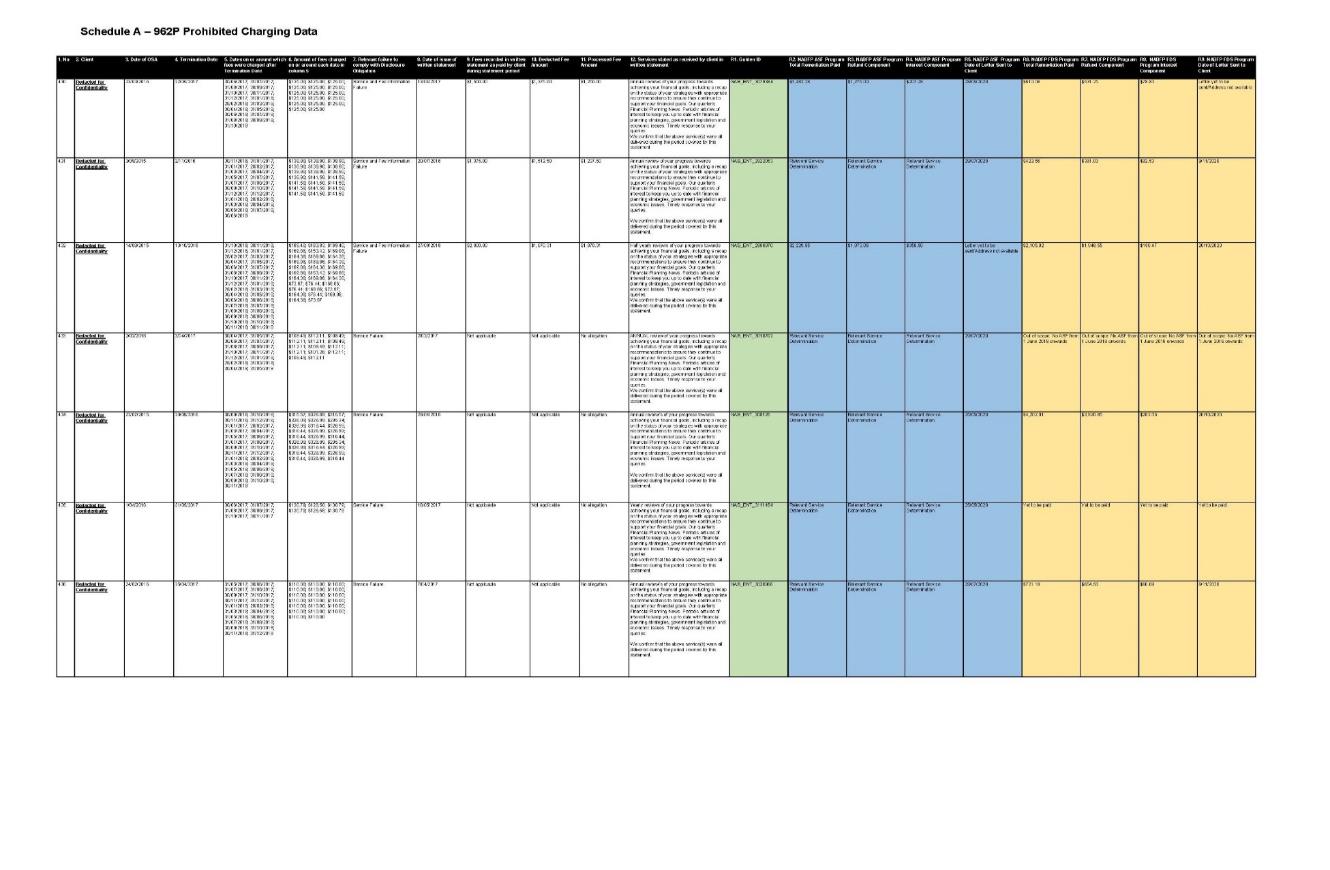

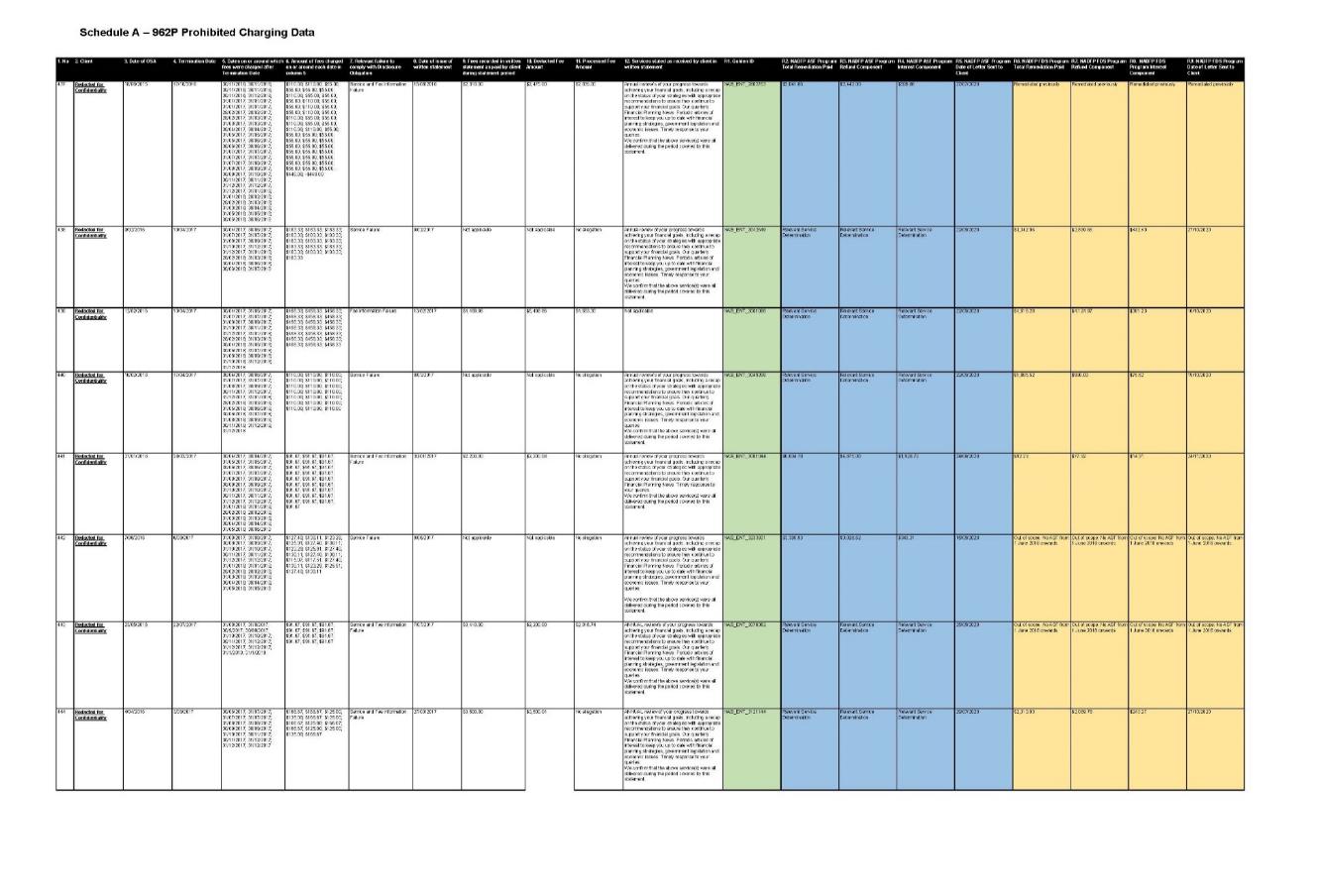

BASIS OF THE SECTION 962P CONTRAVENTIONS

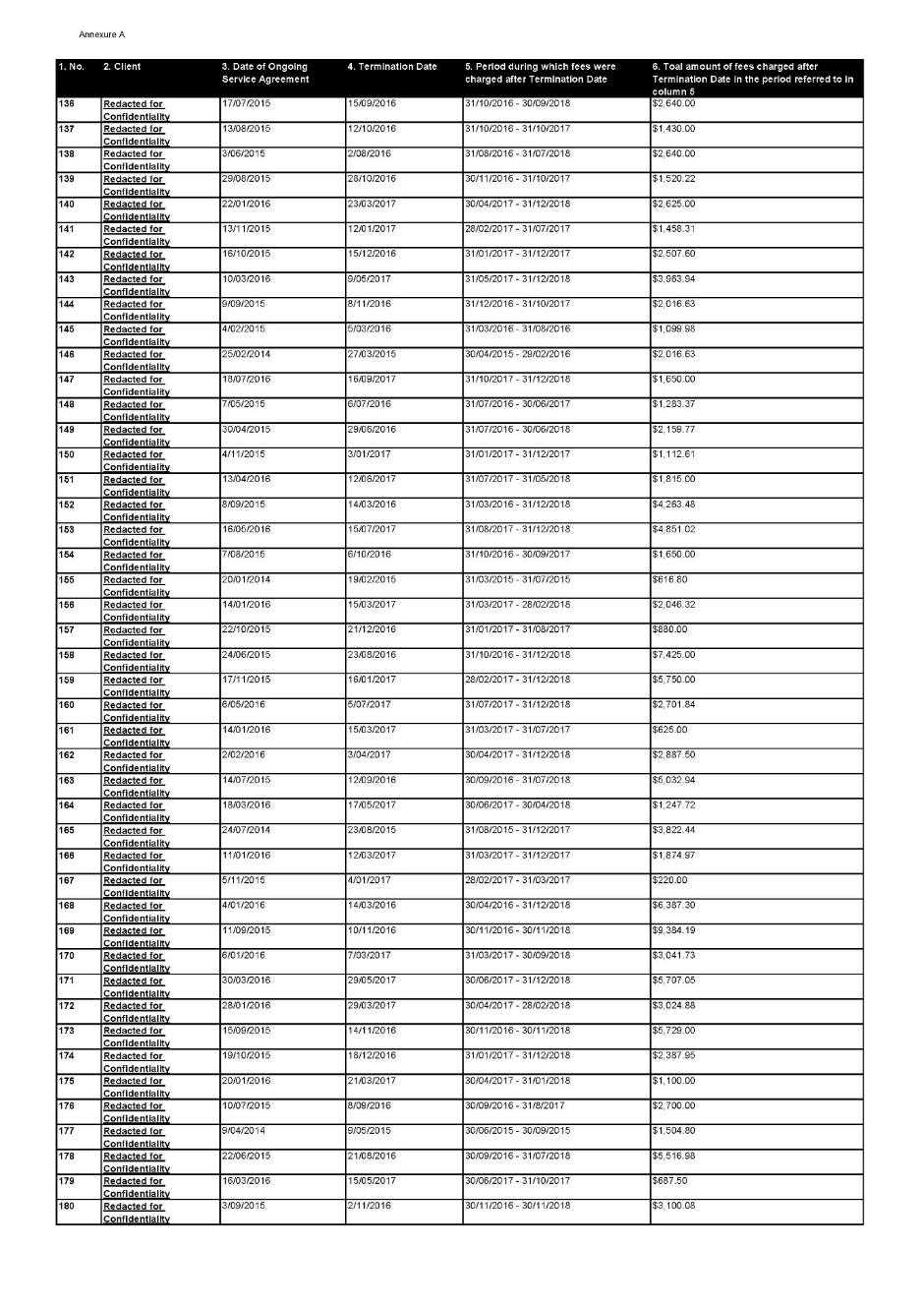

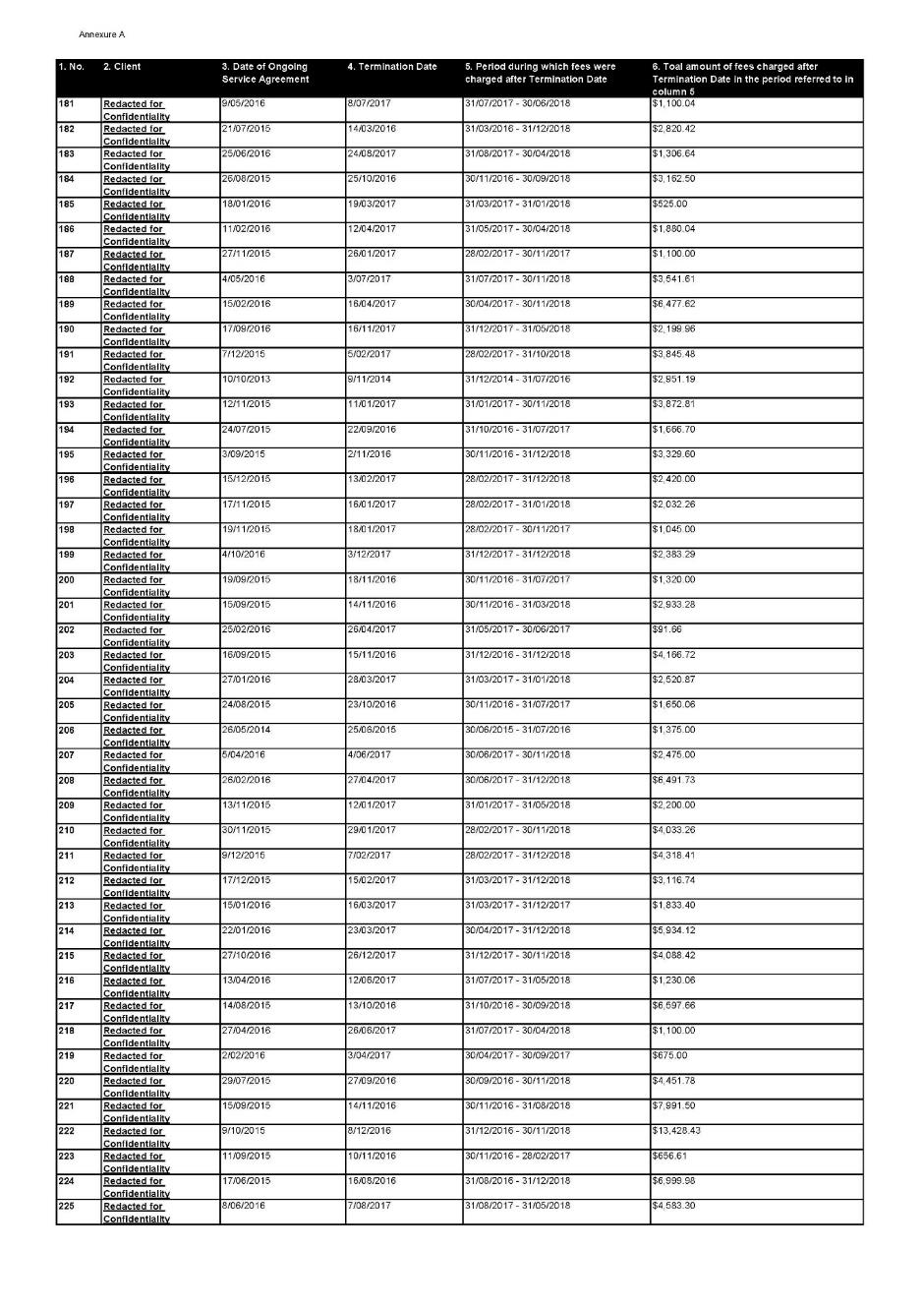

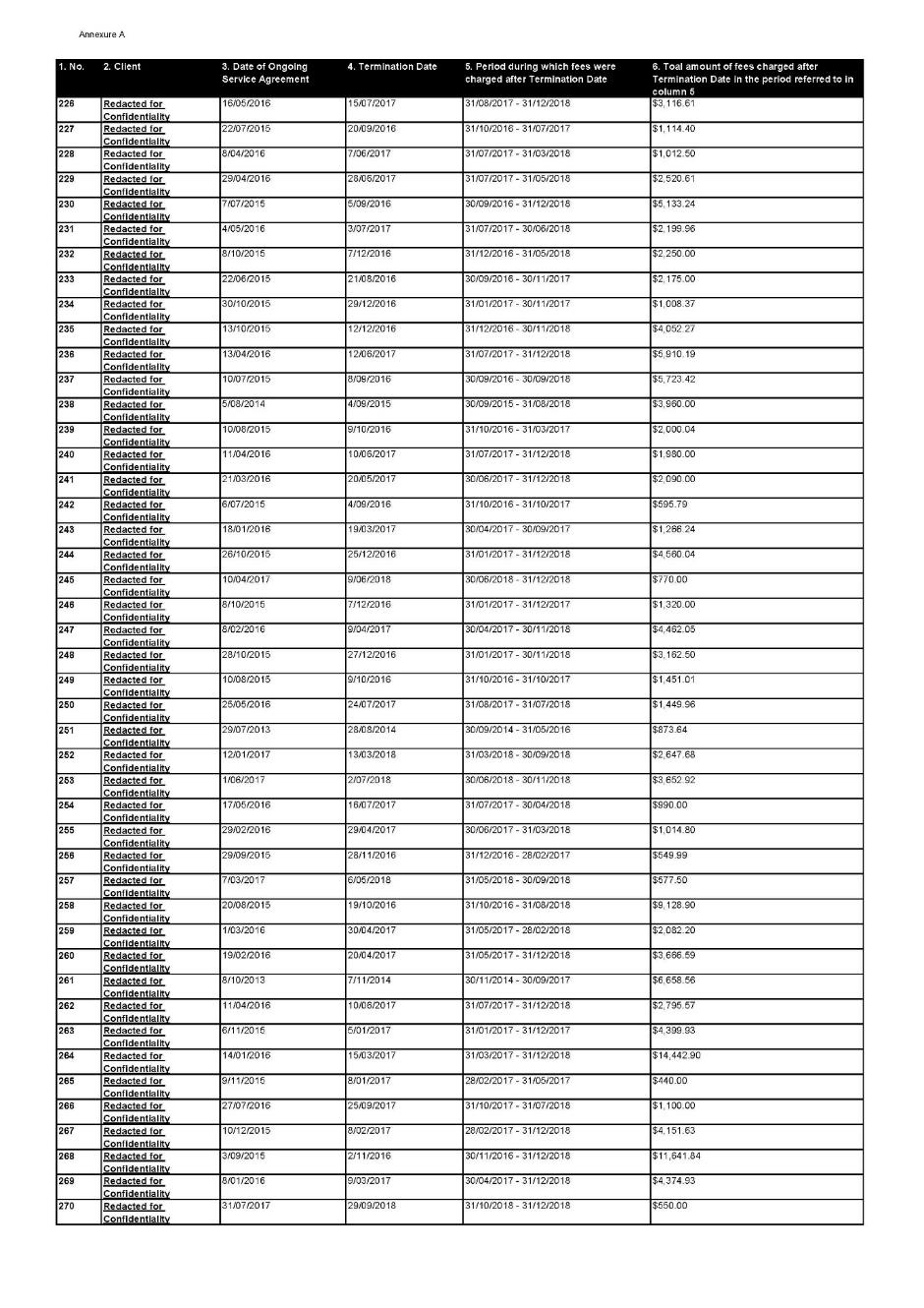

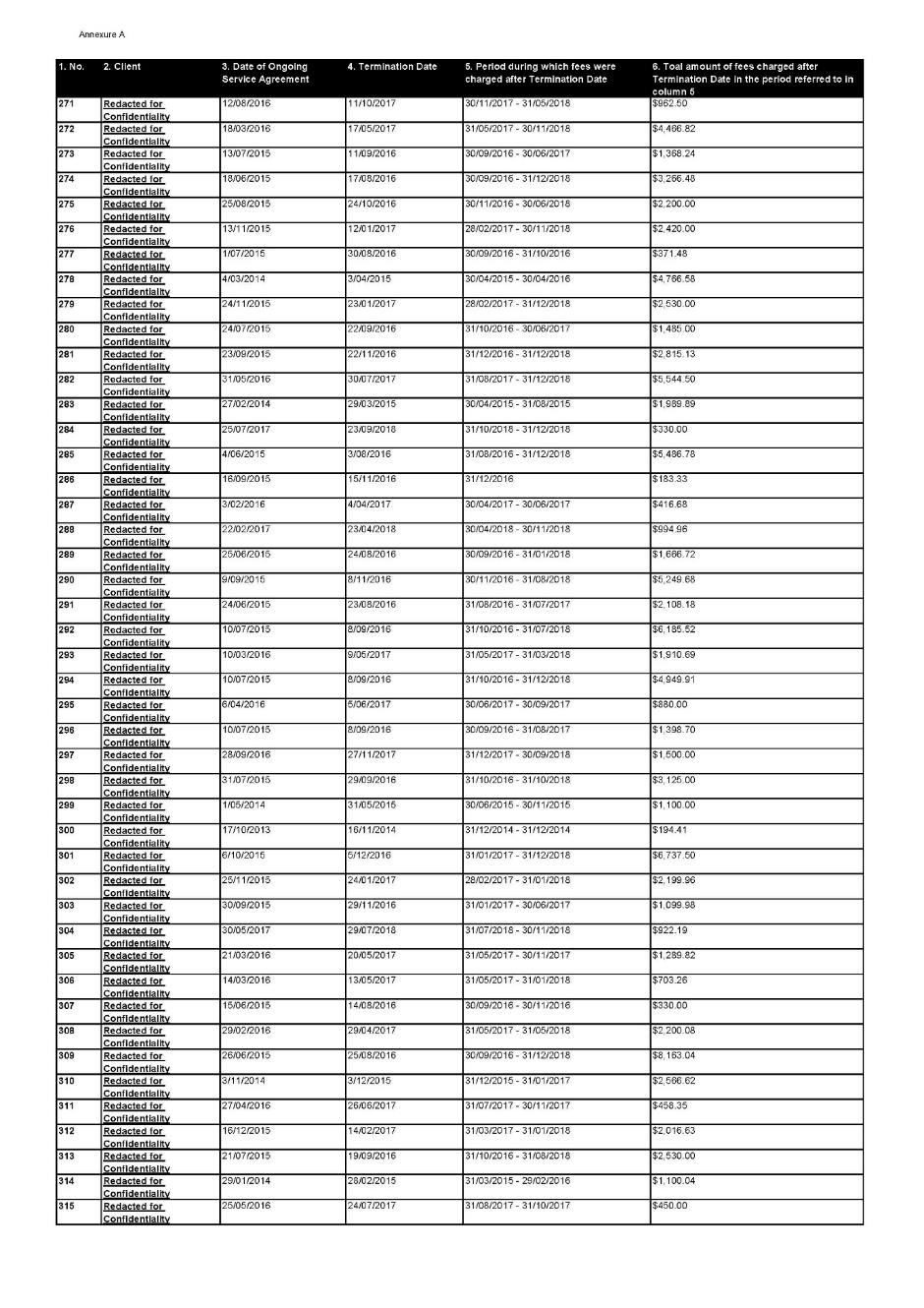

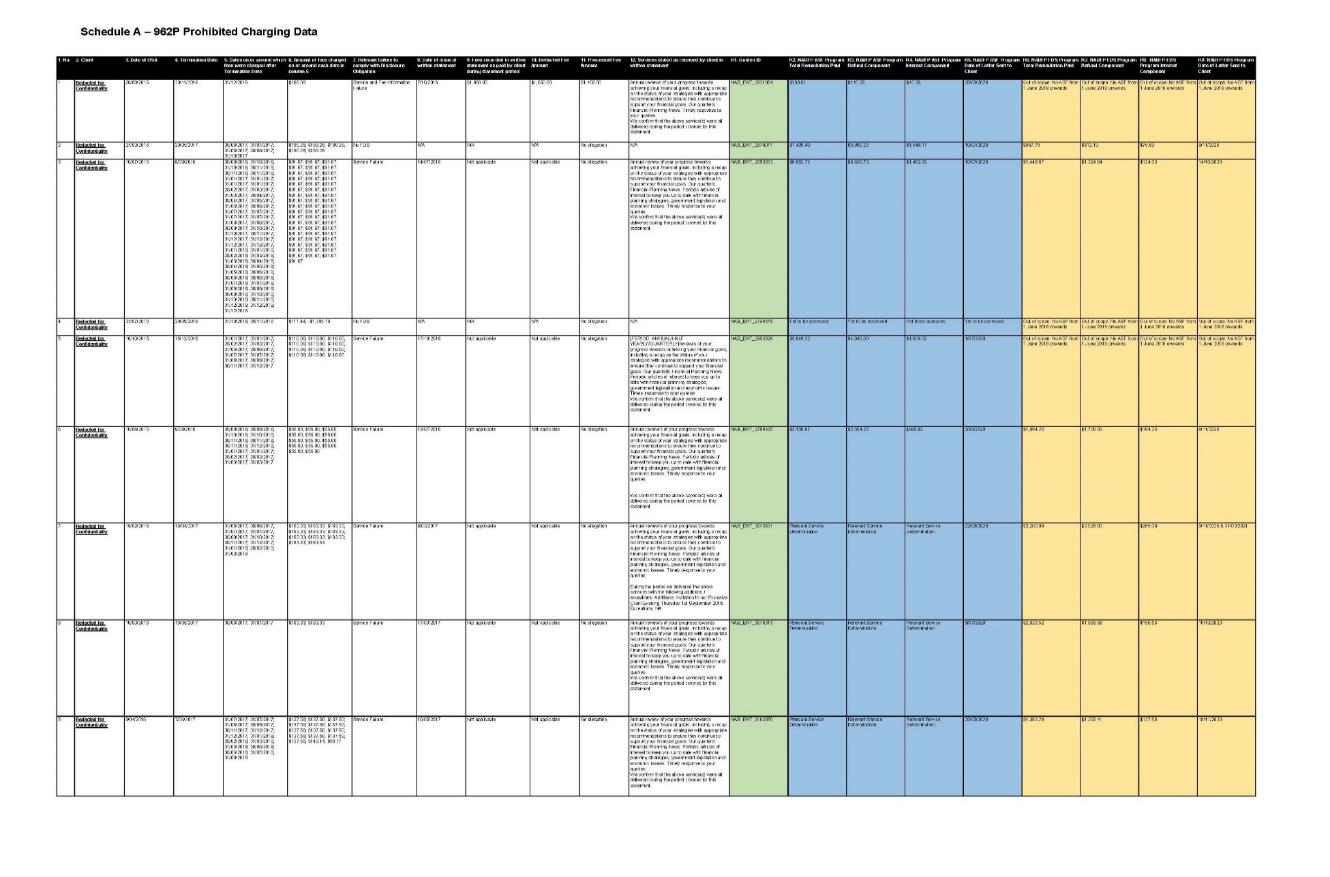

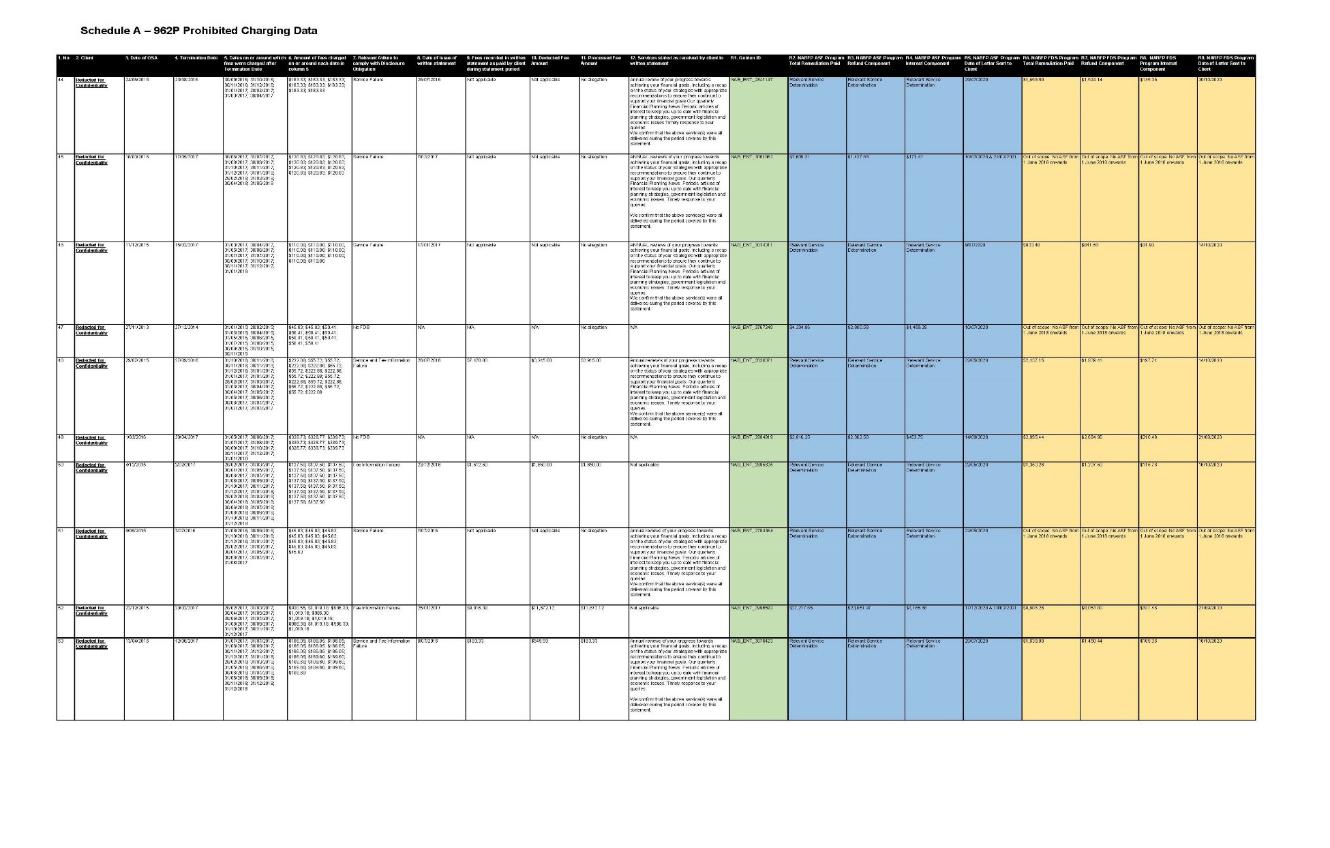

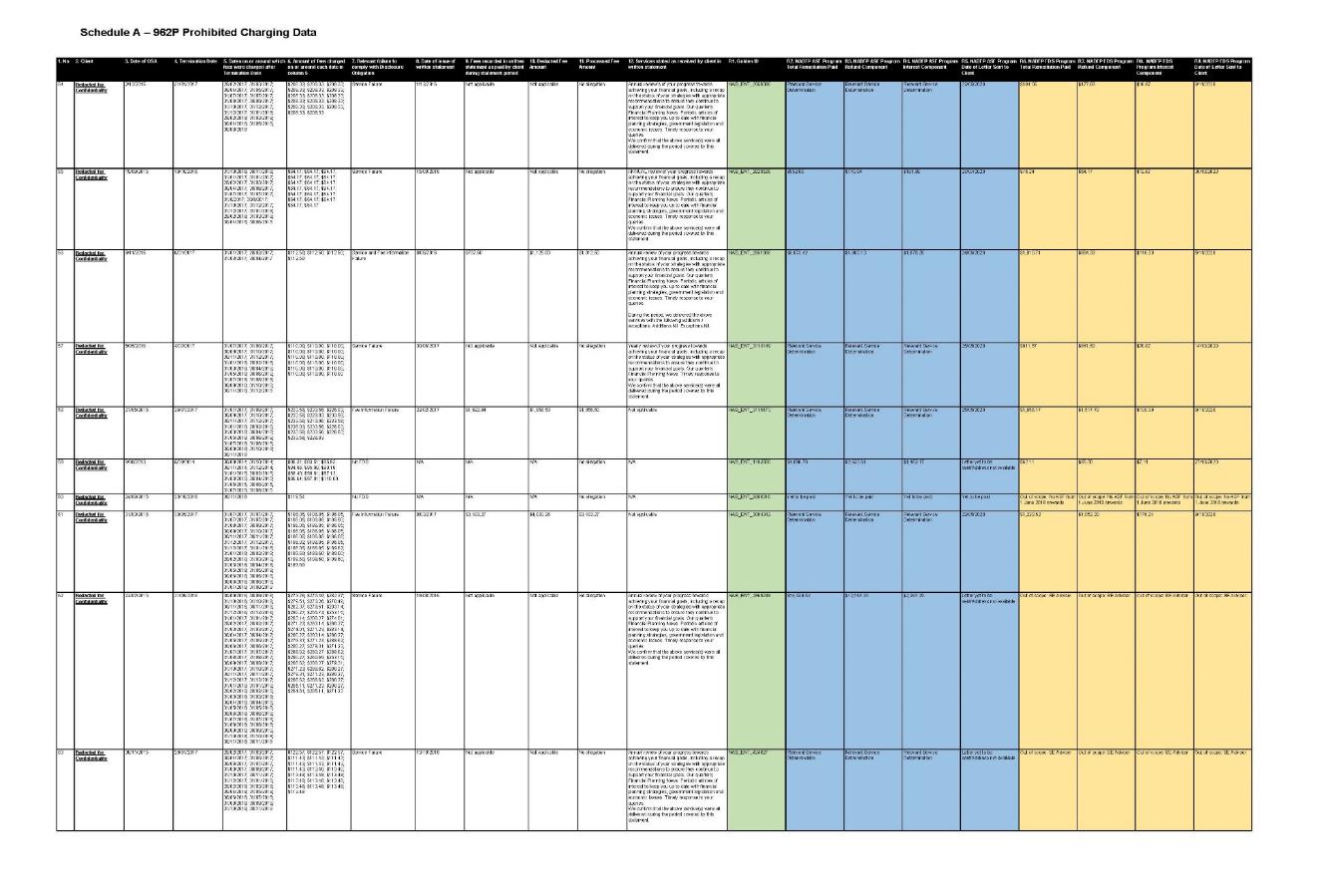

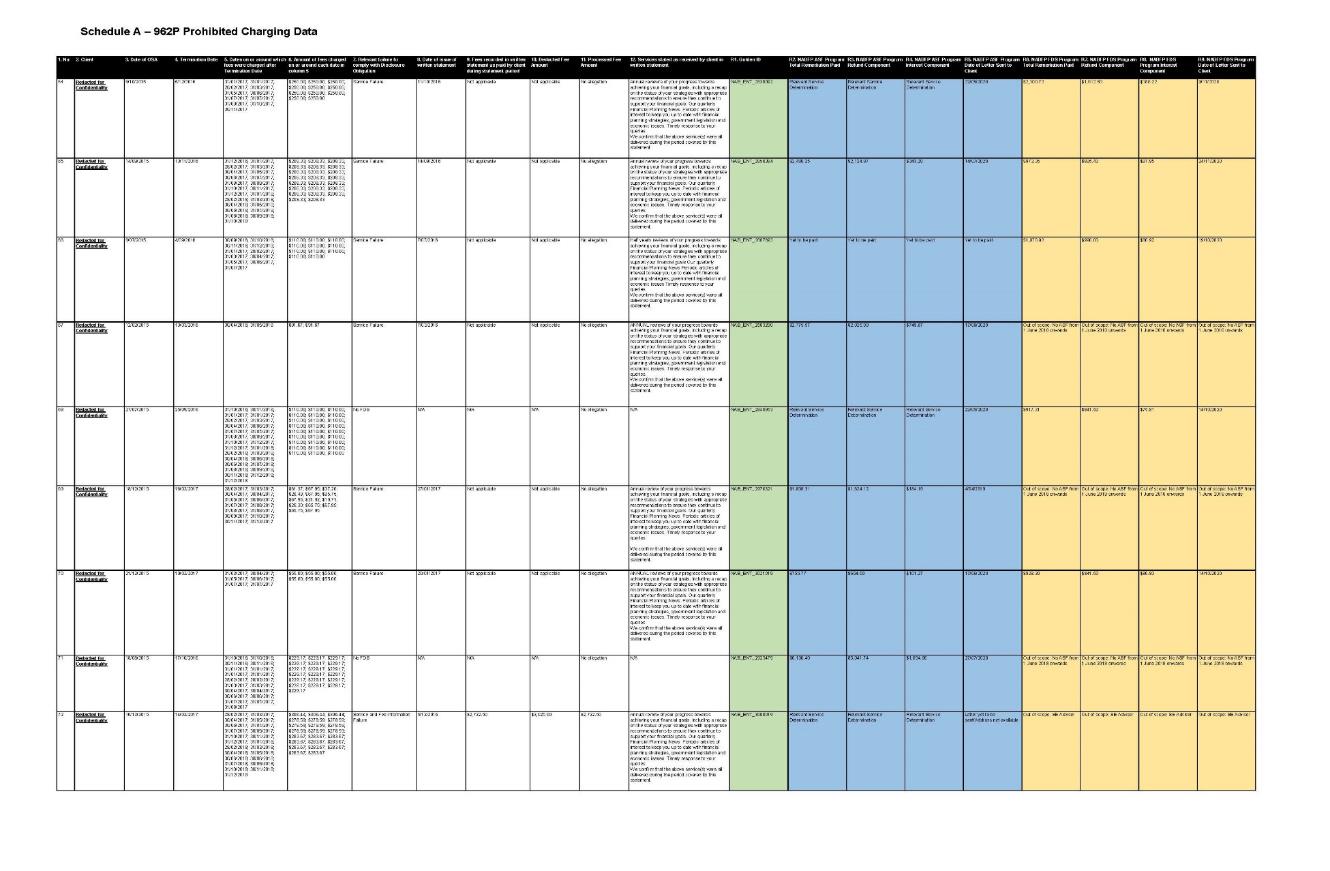

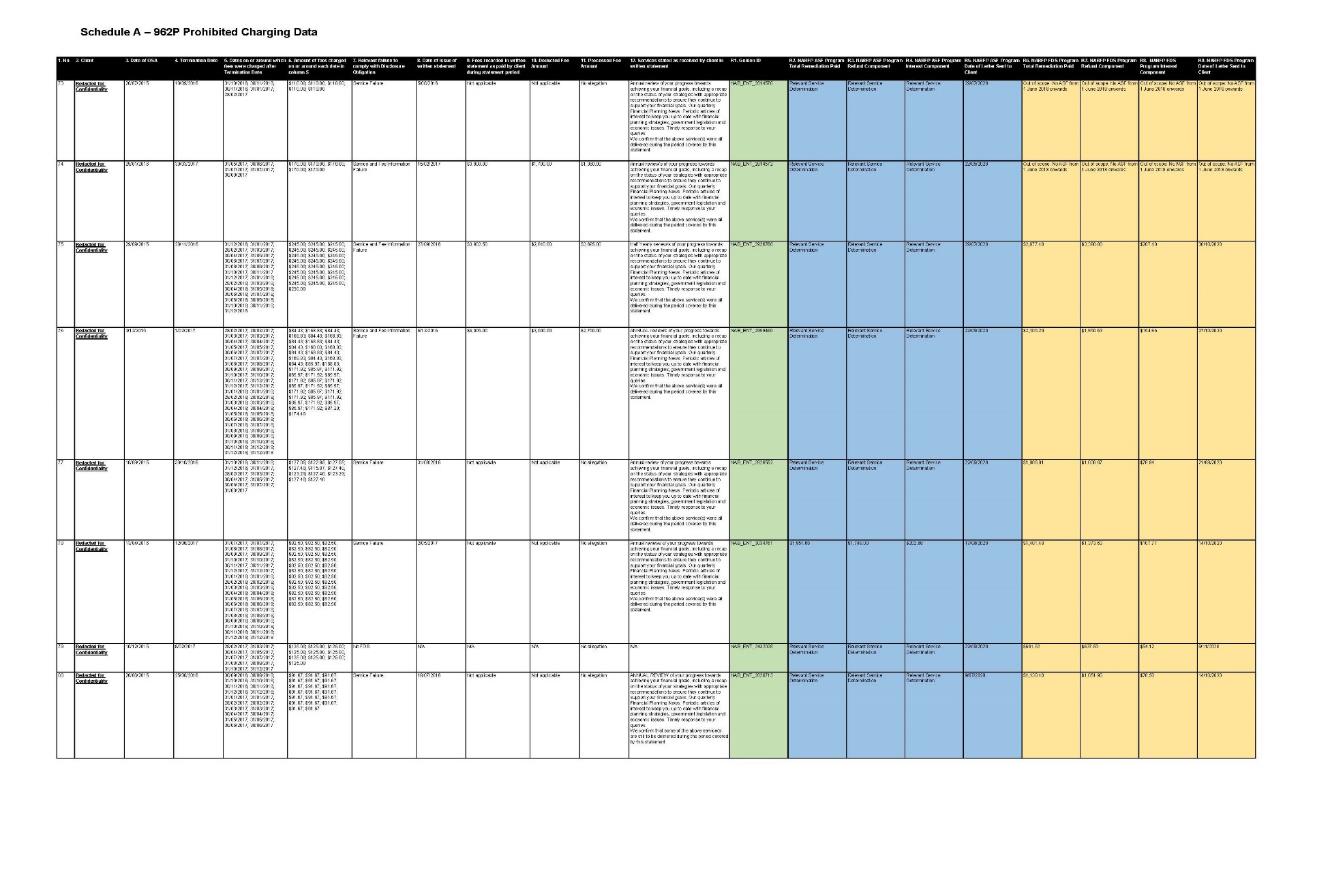

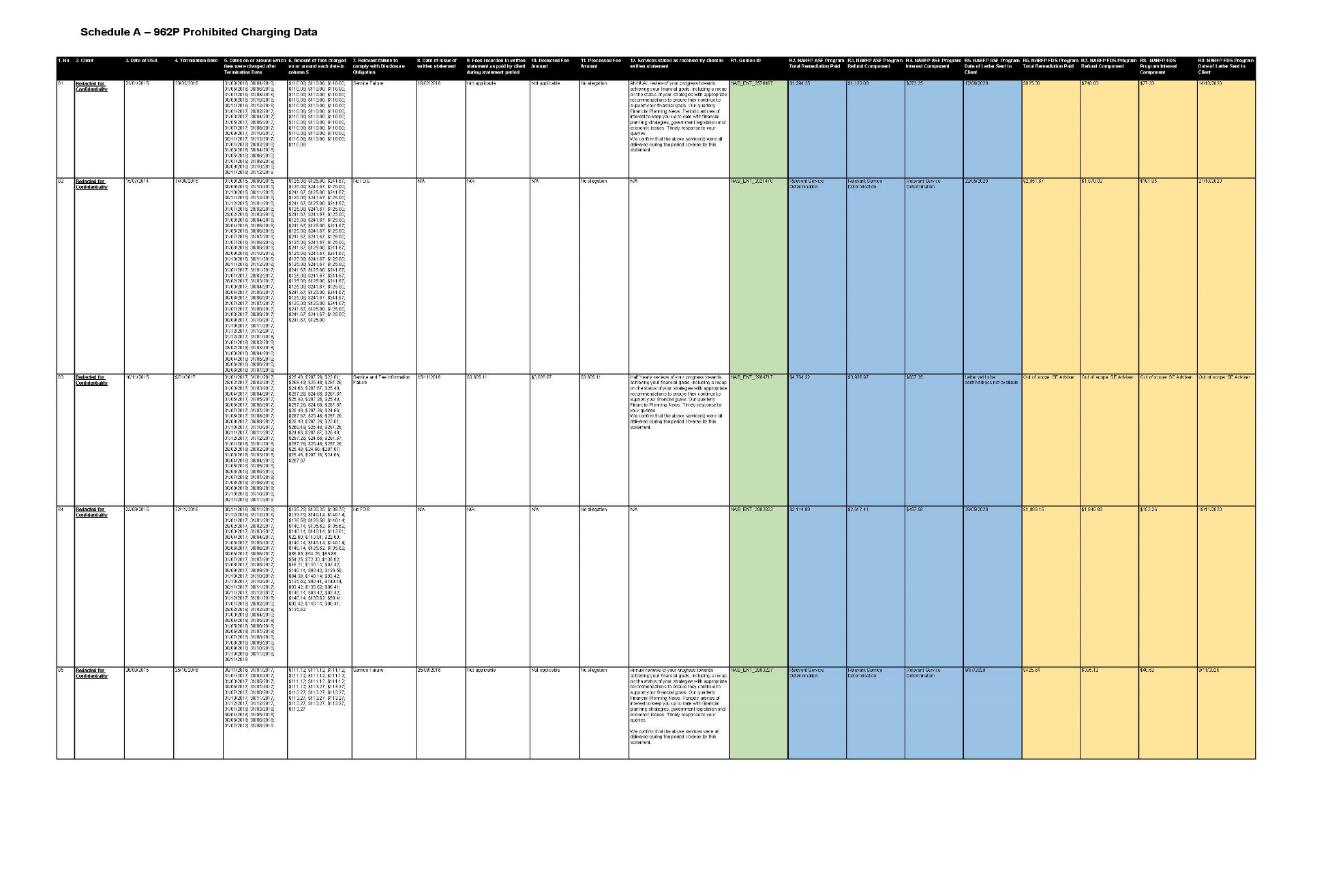

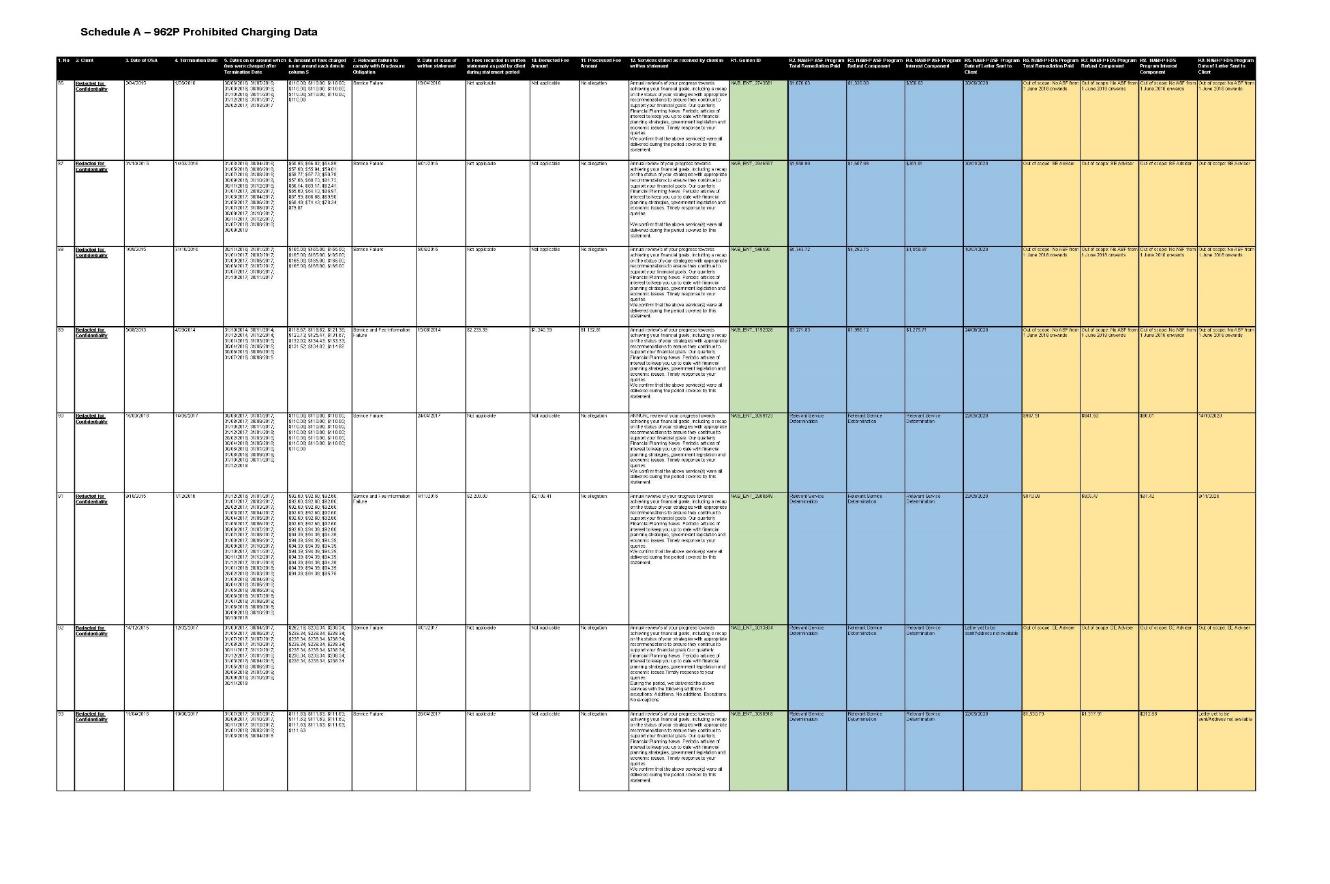

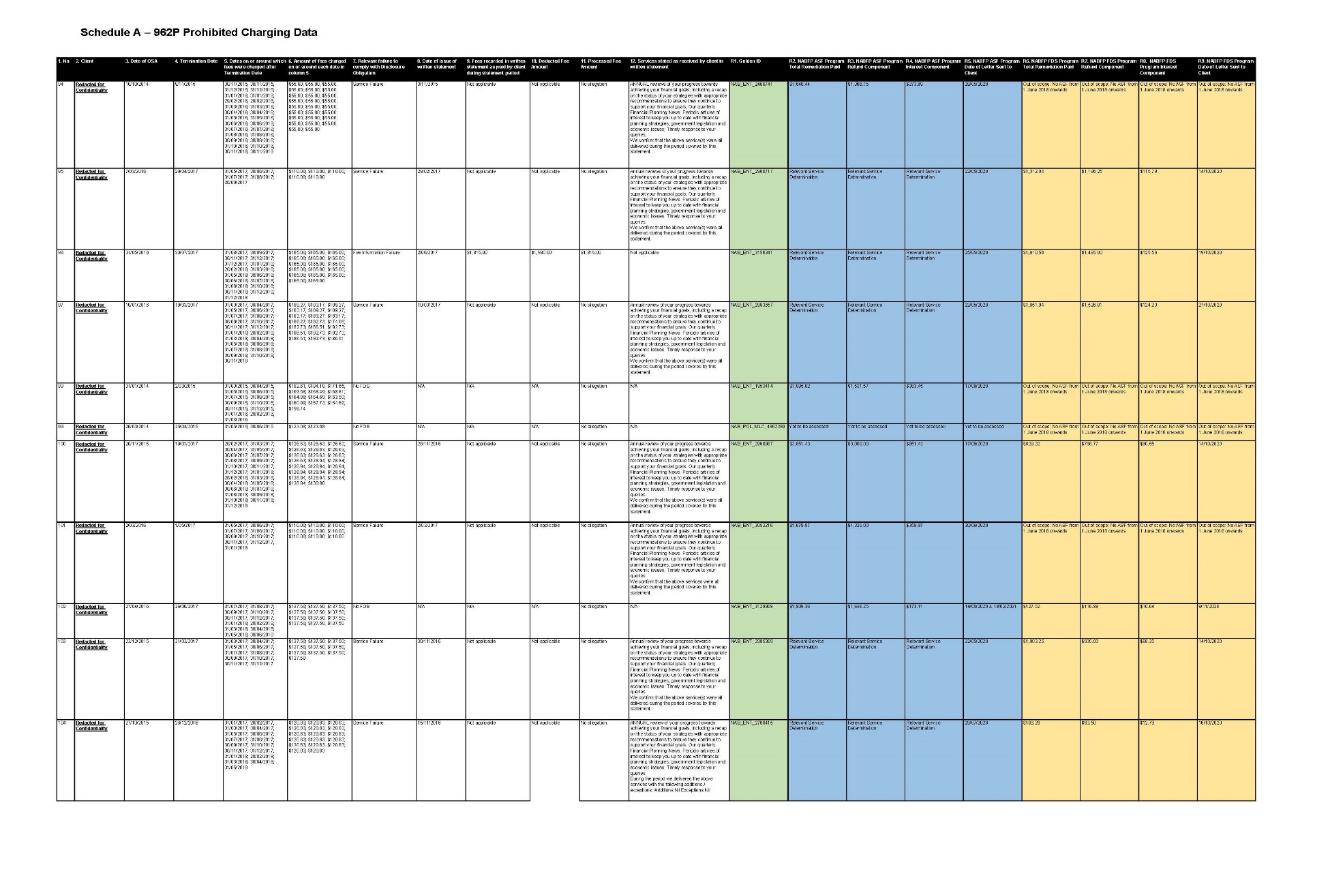

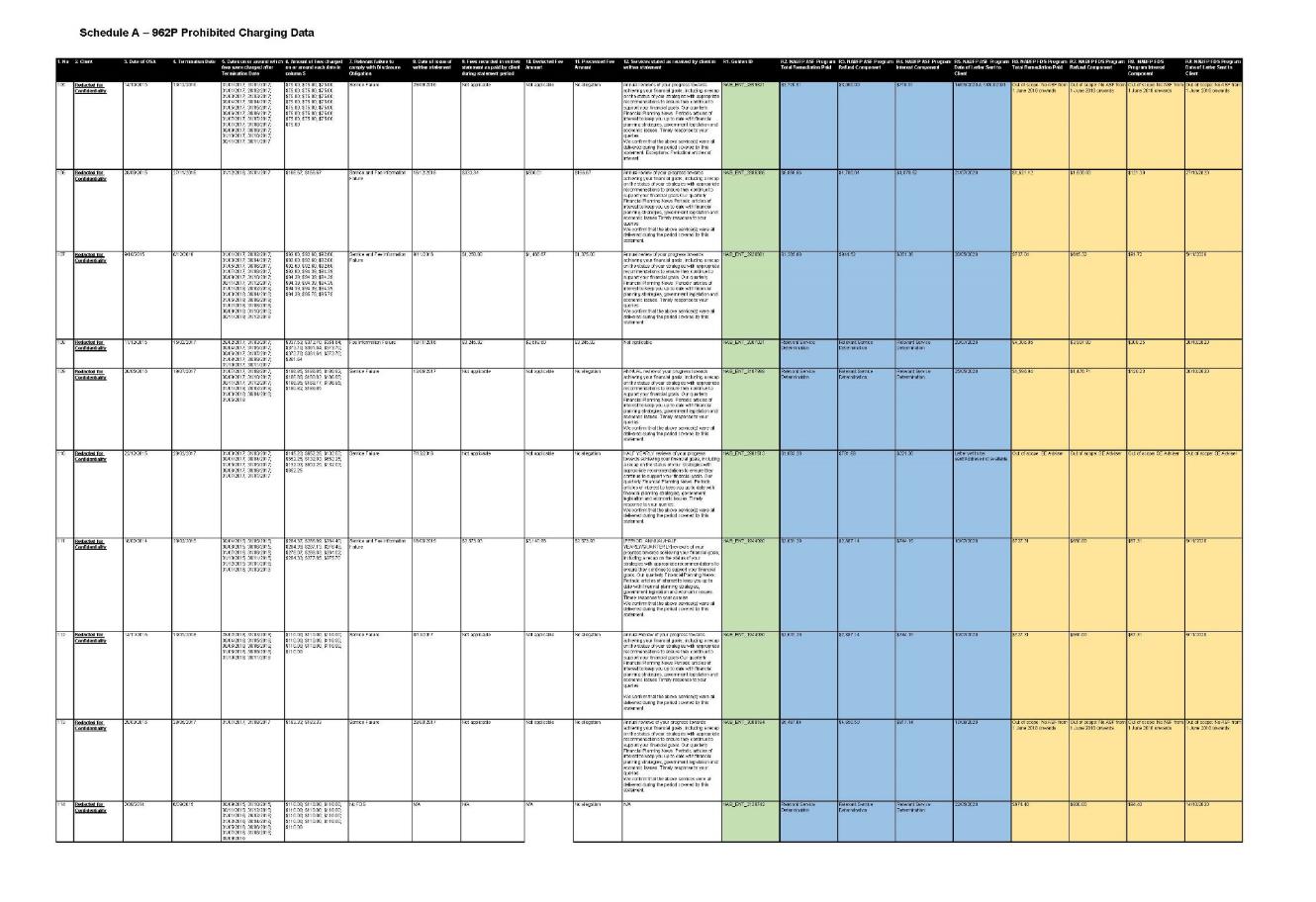

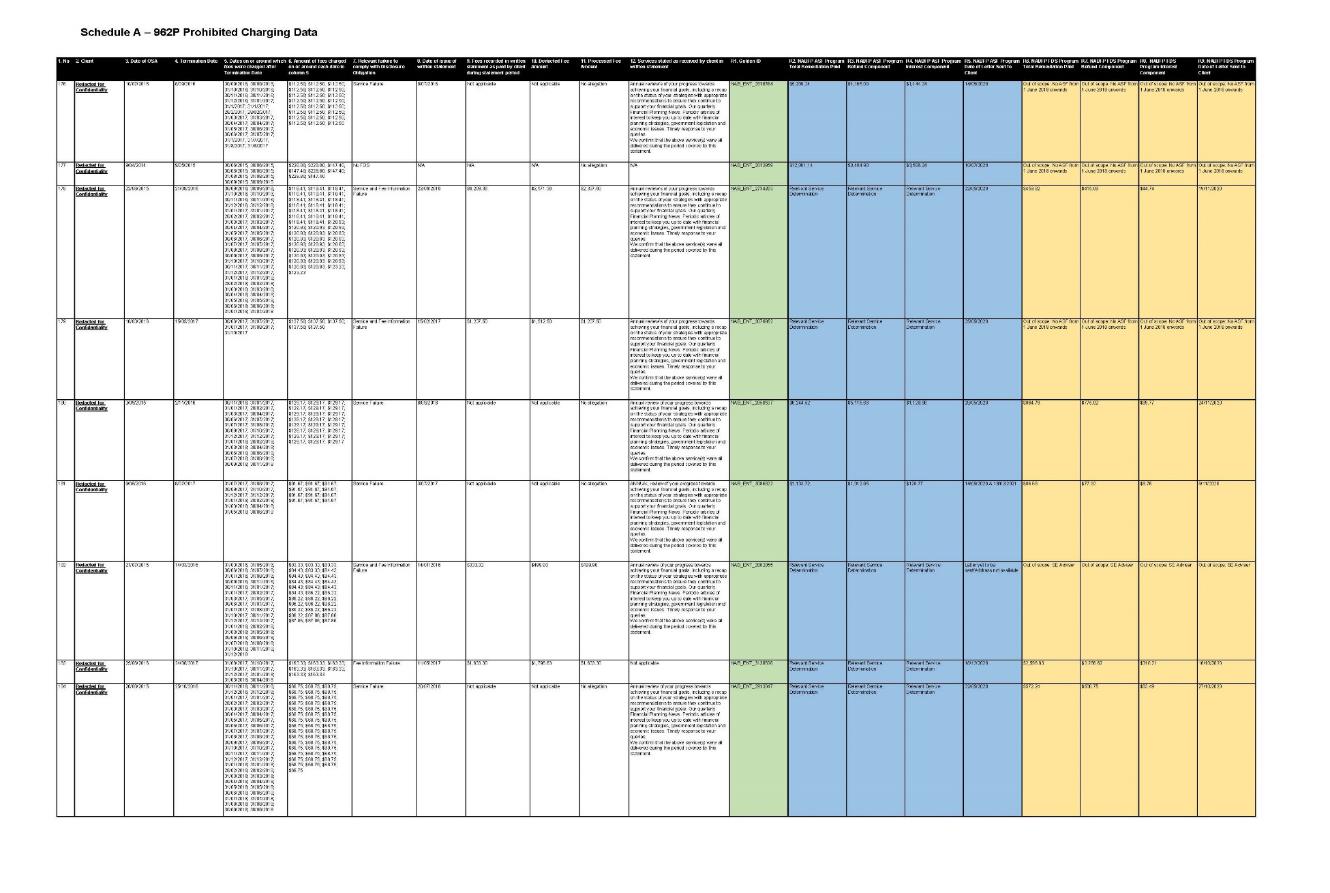

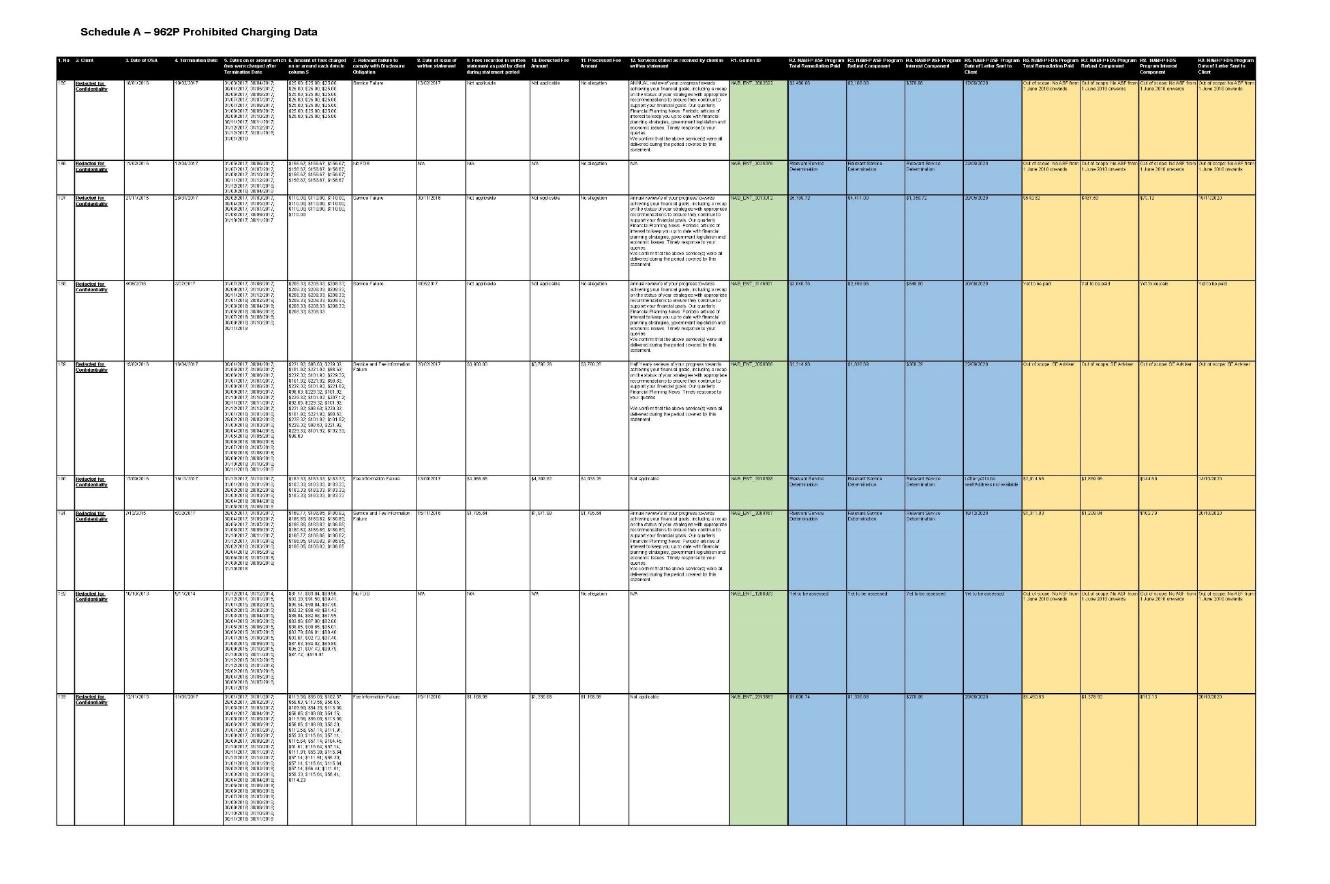

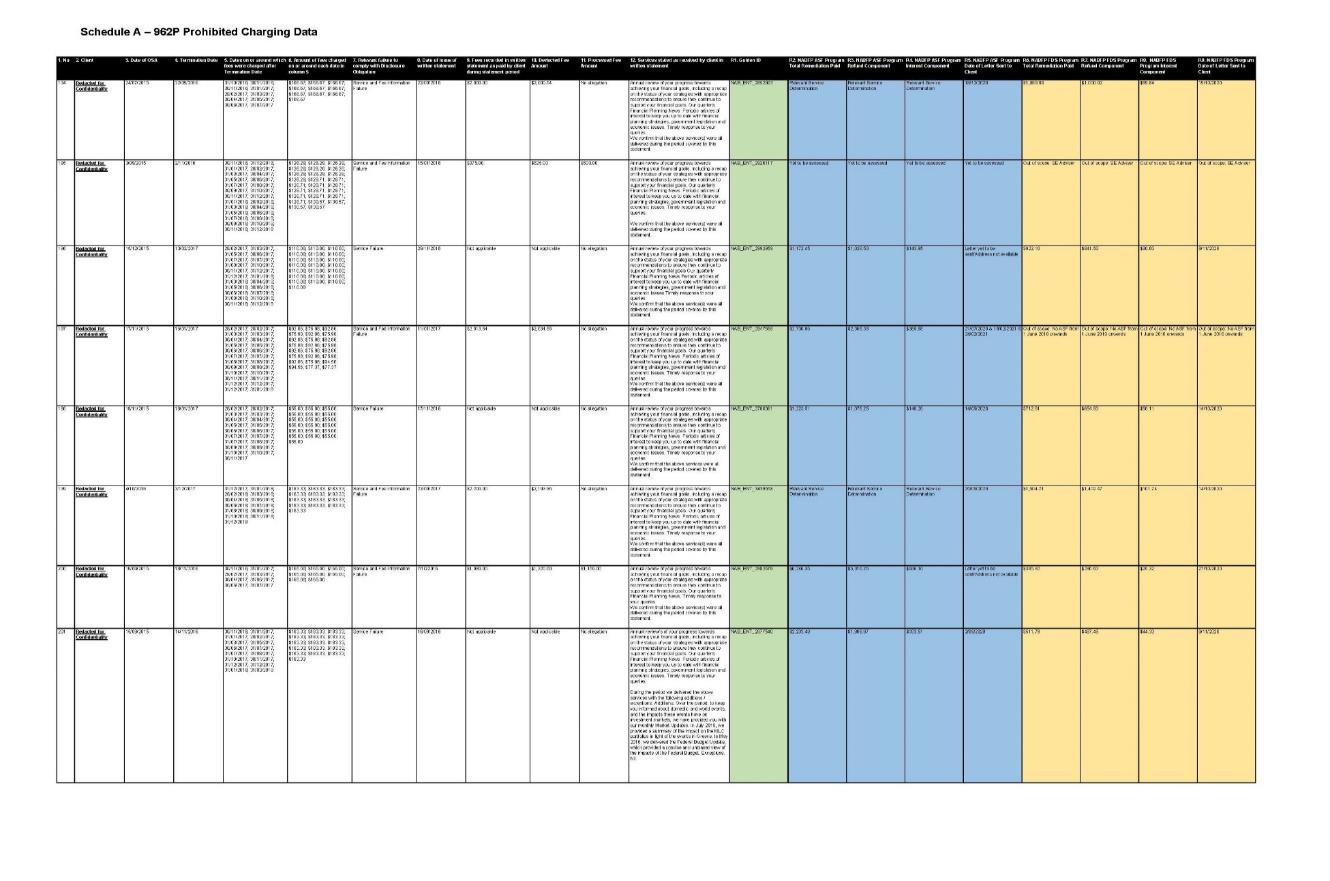

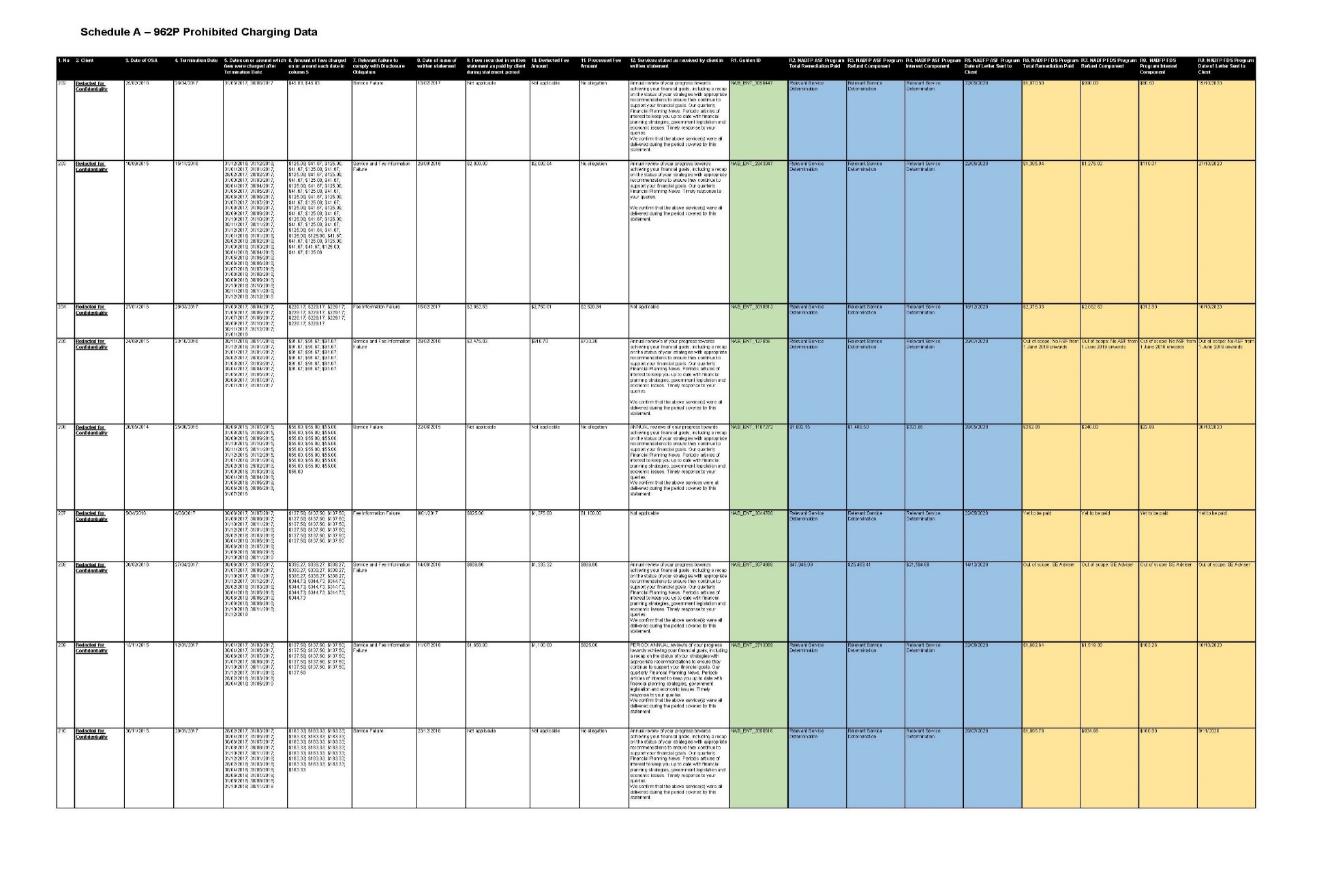

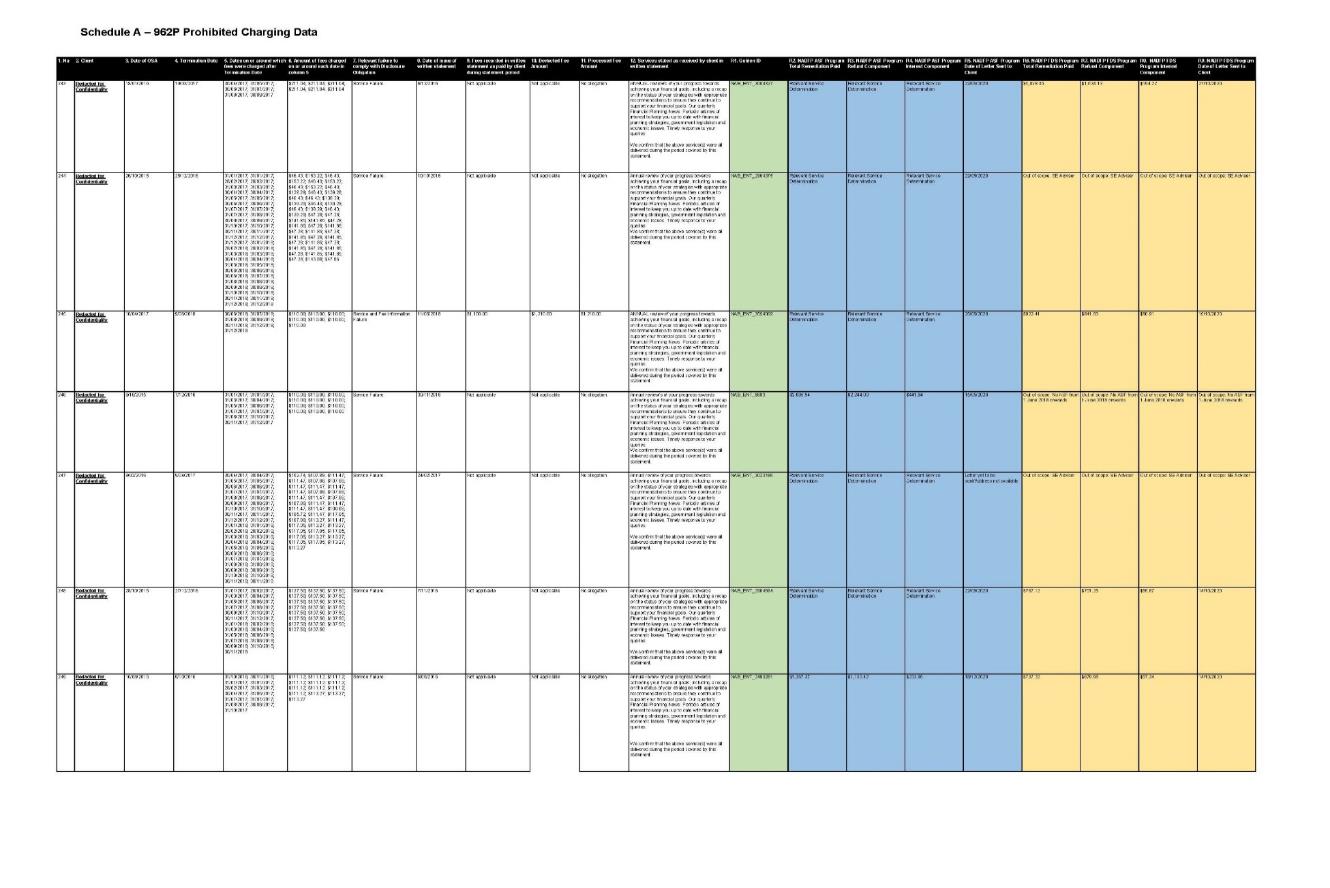

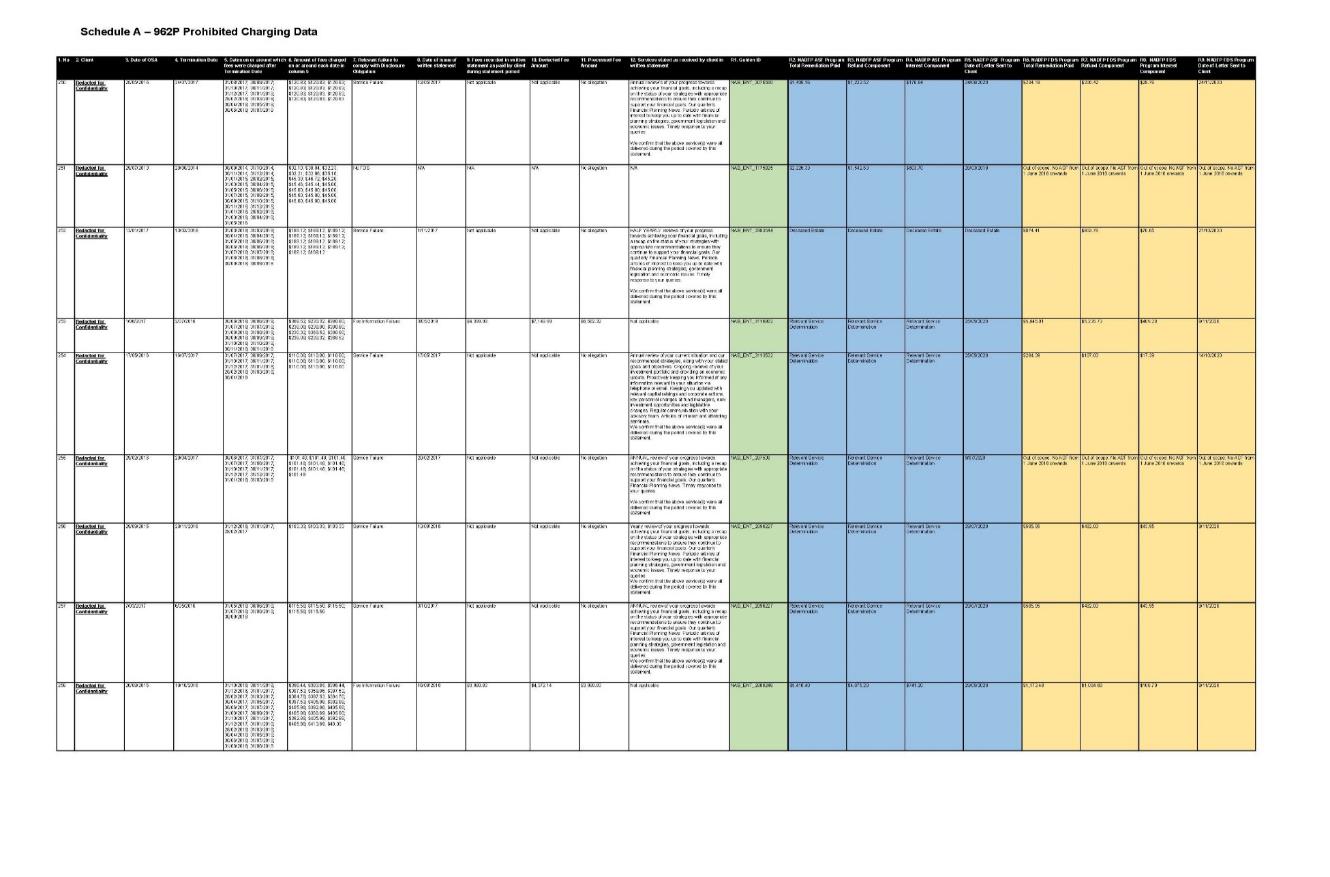

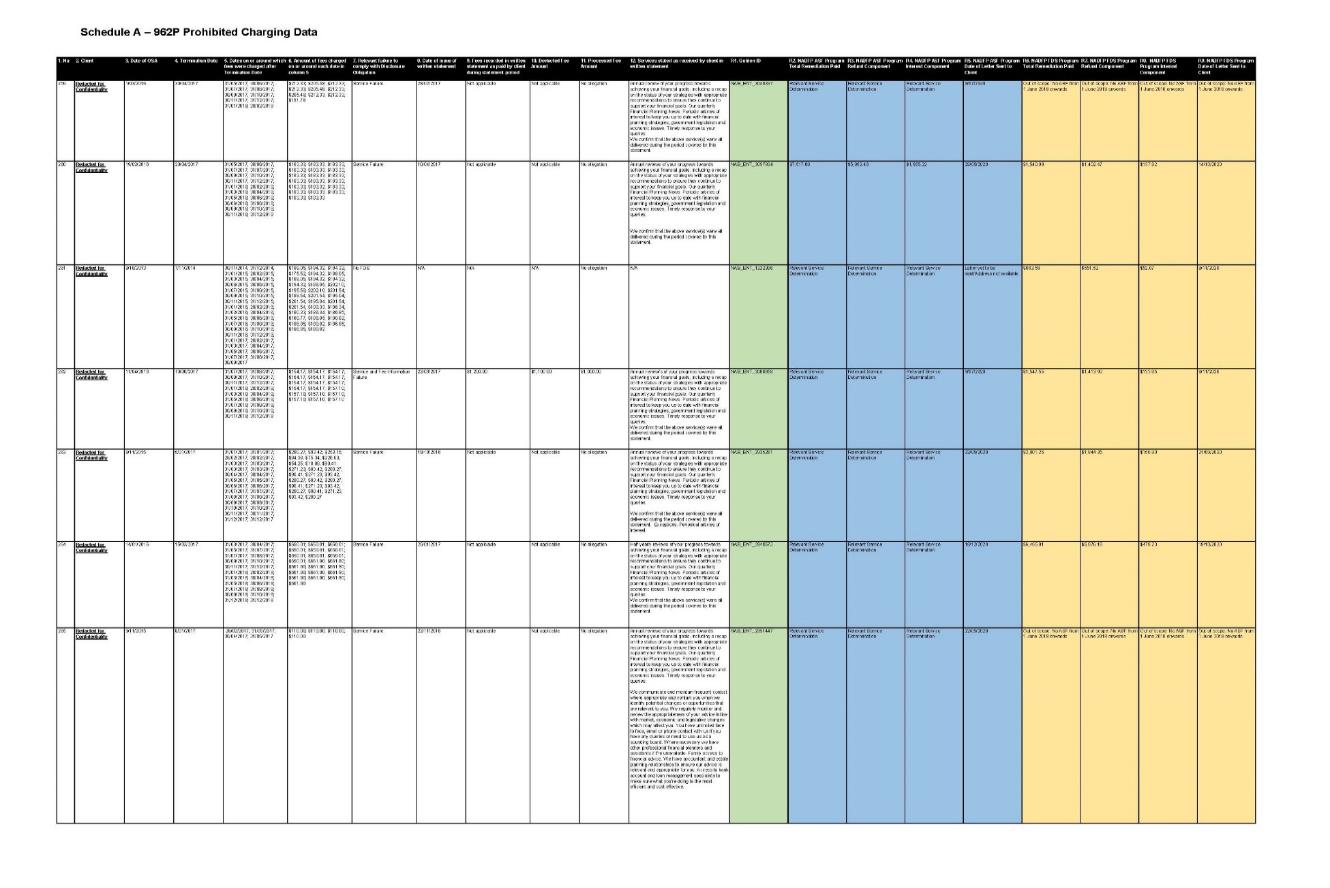

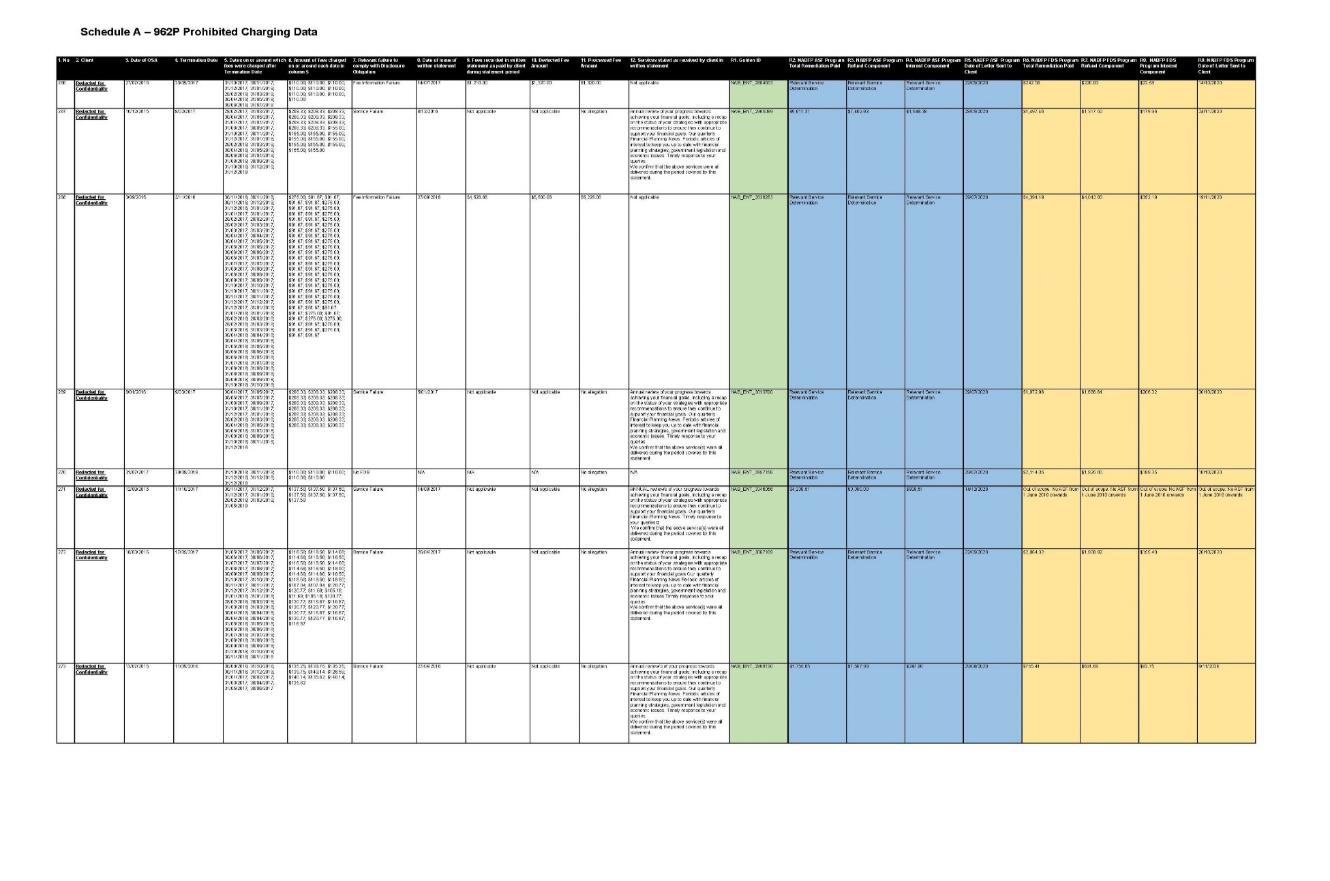

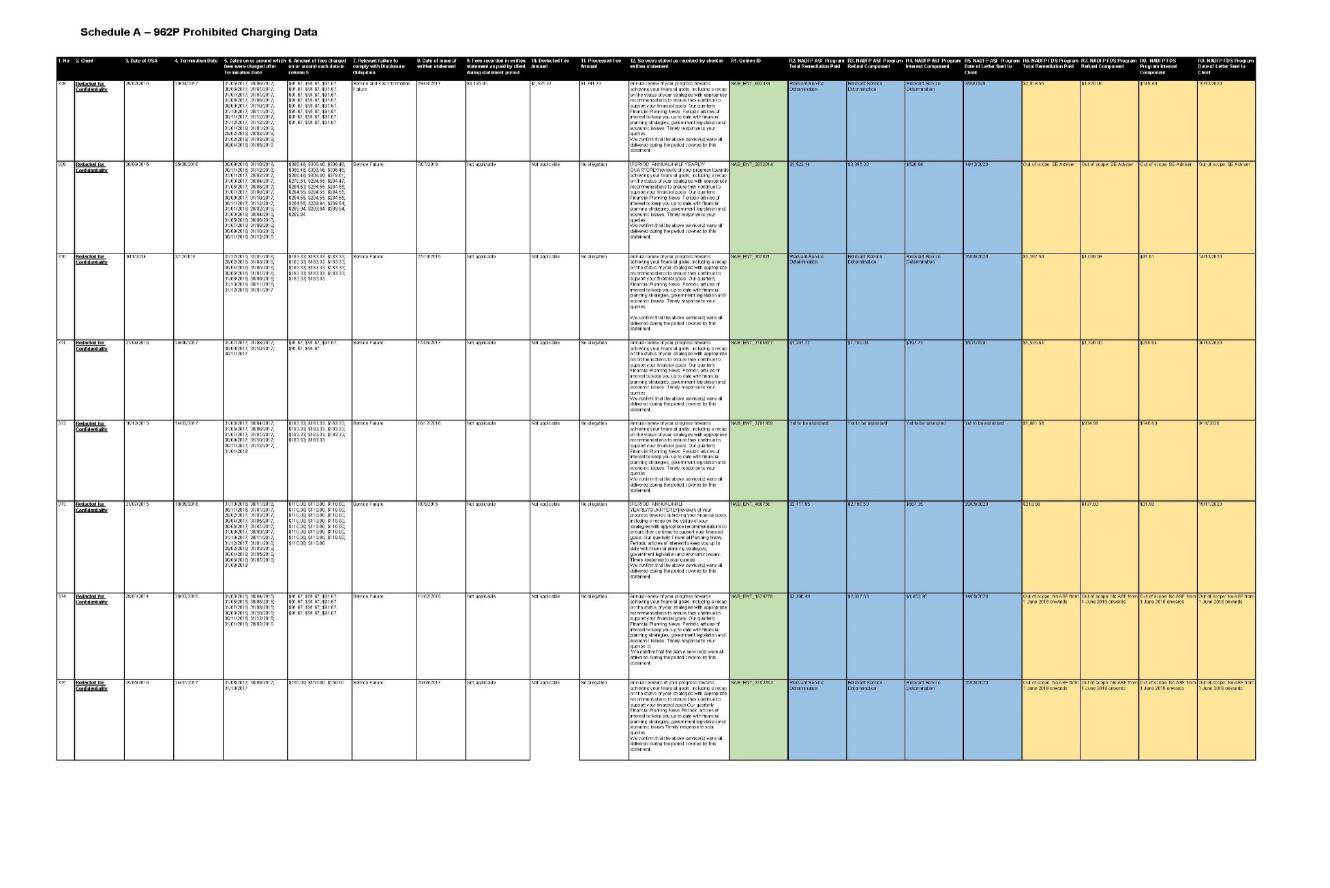

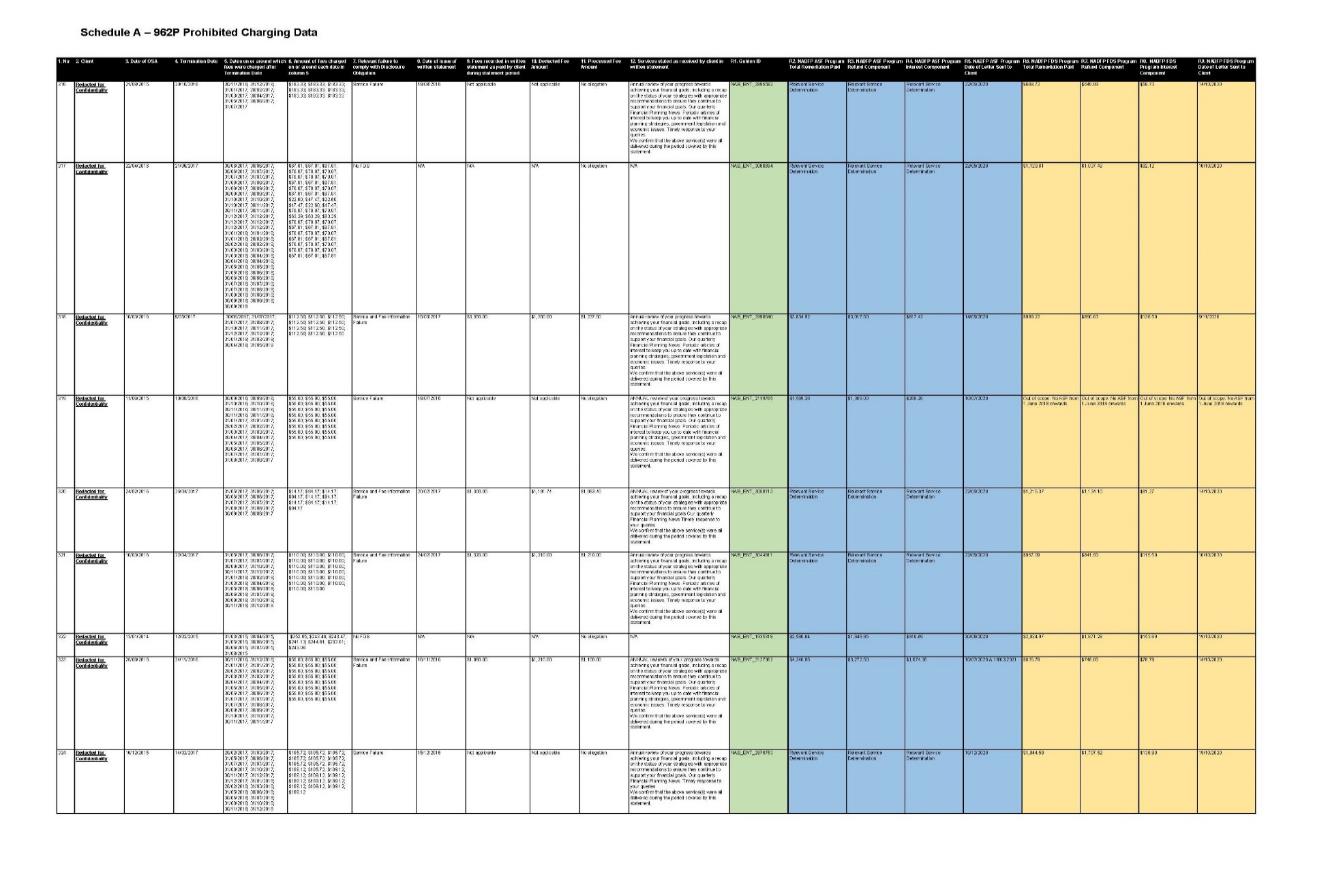

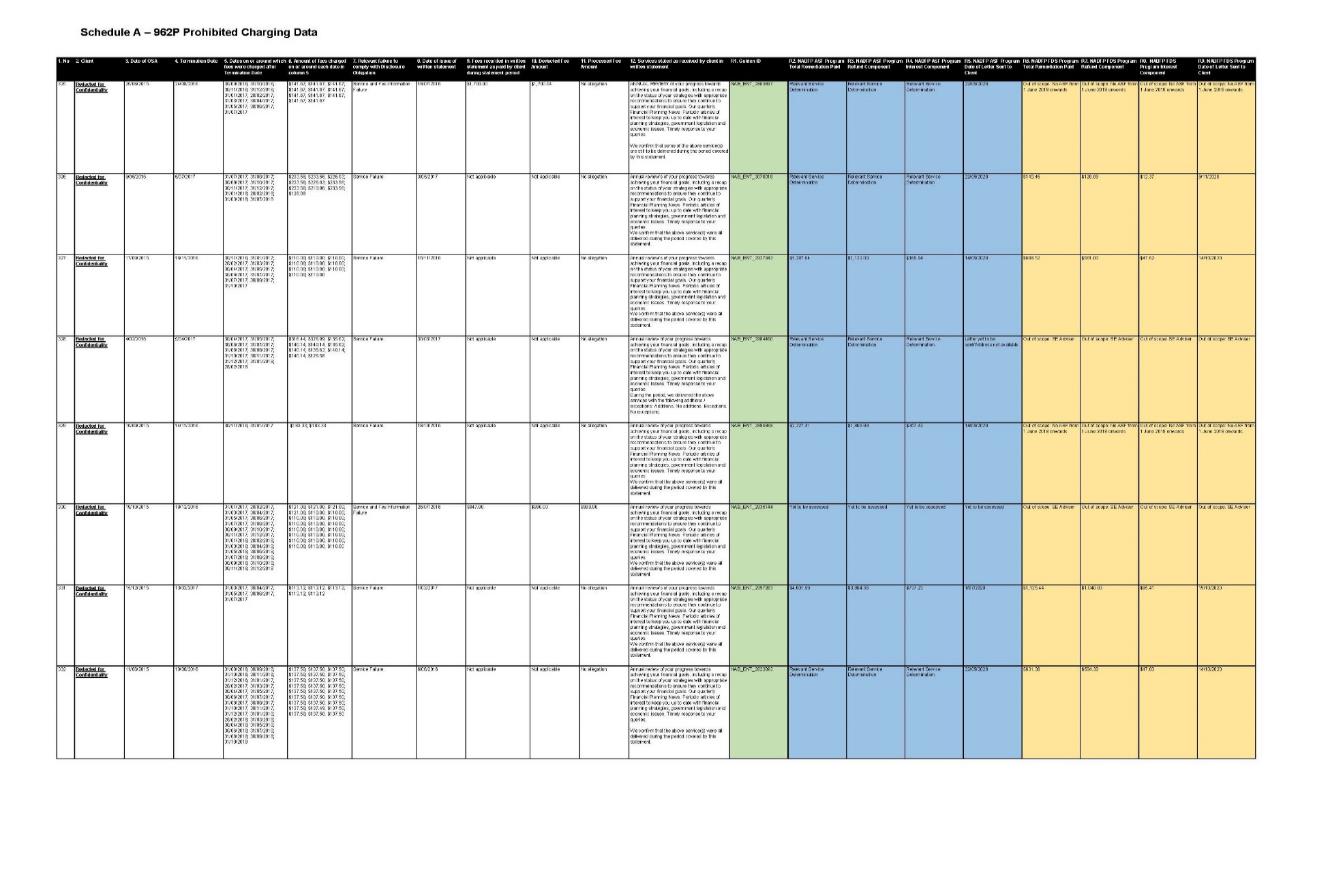

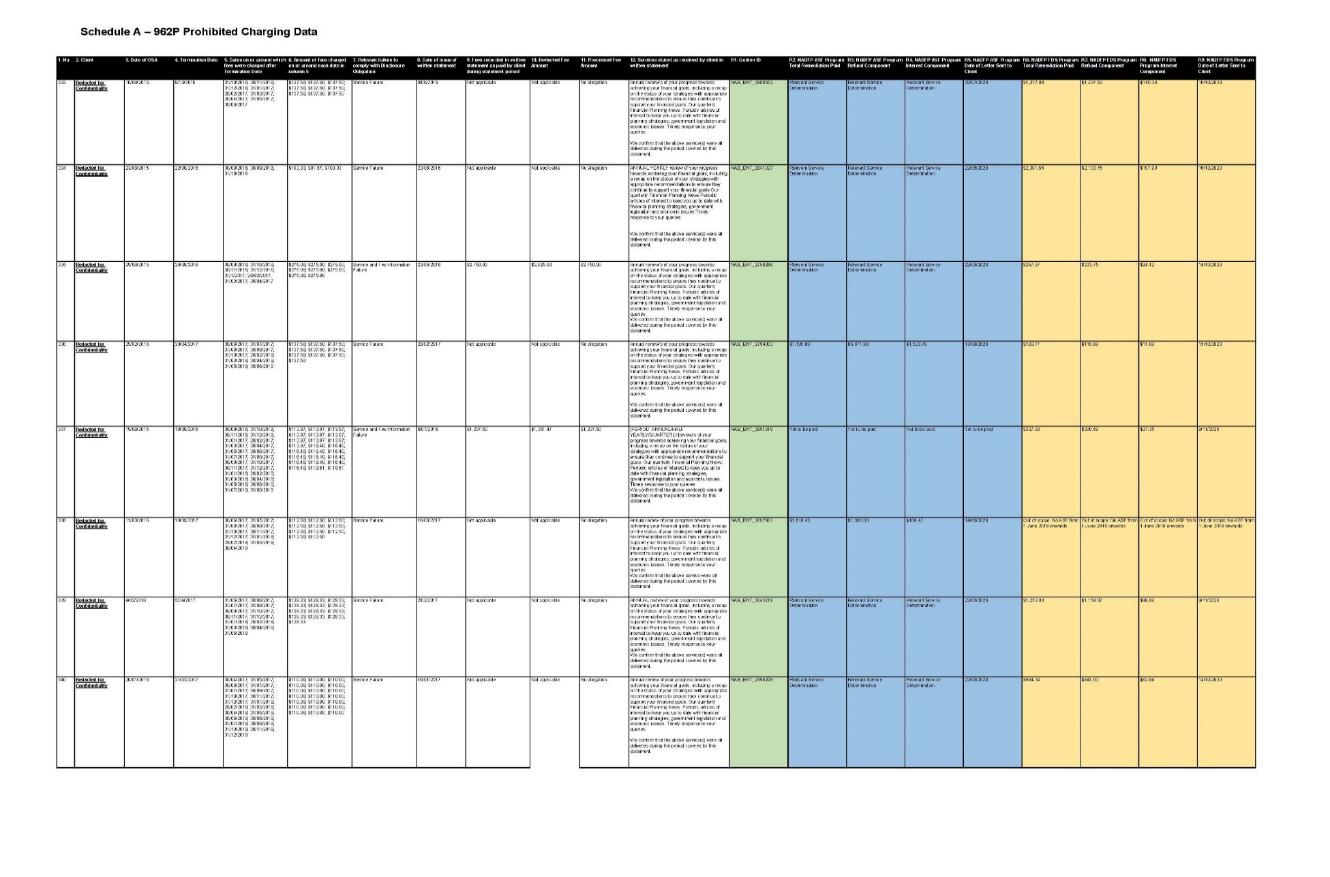

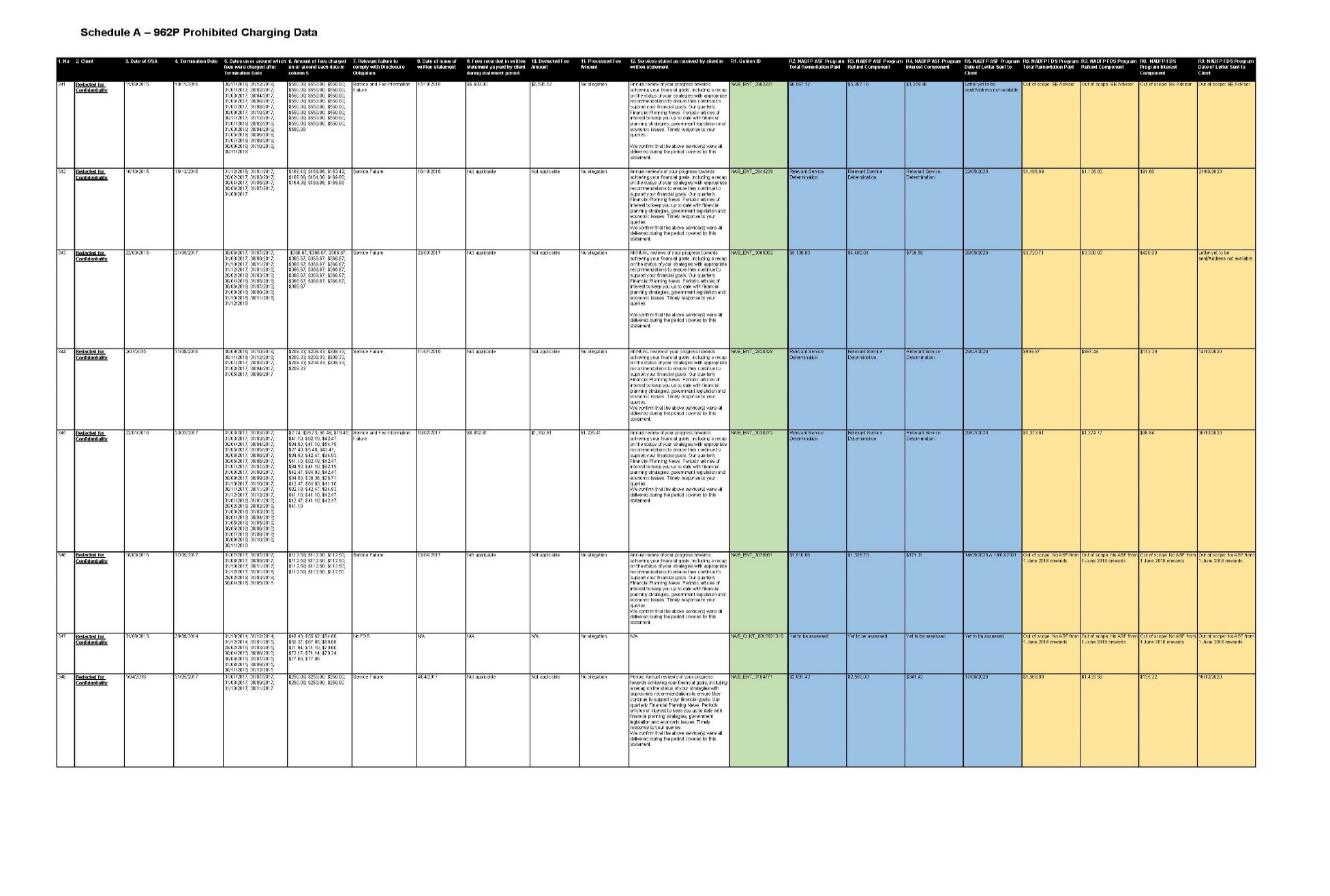

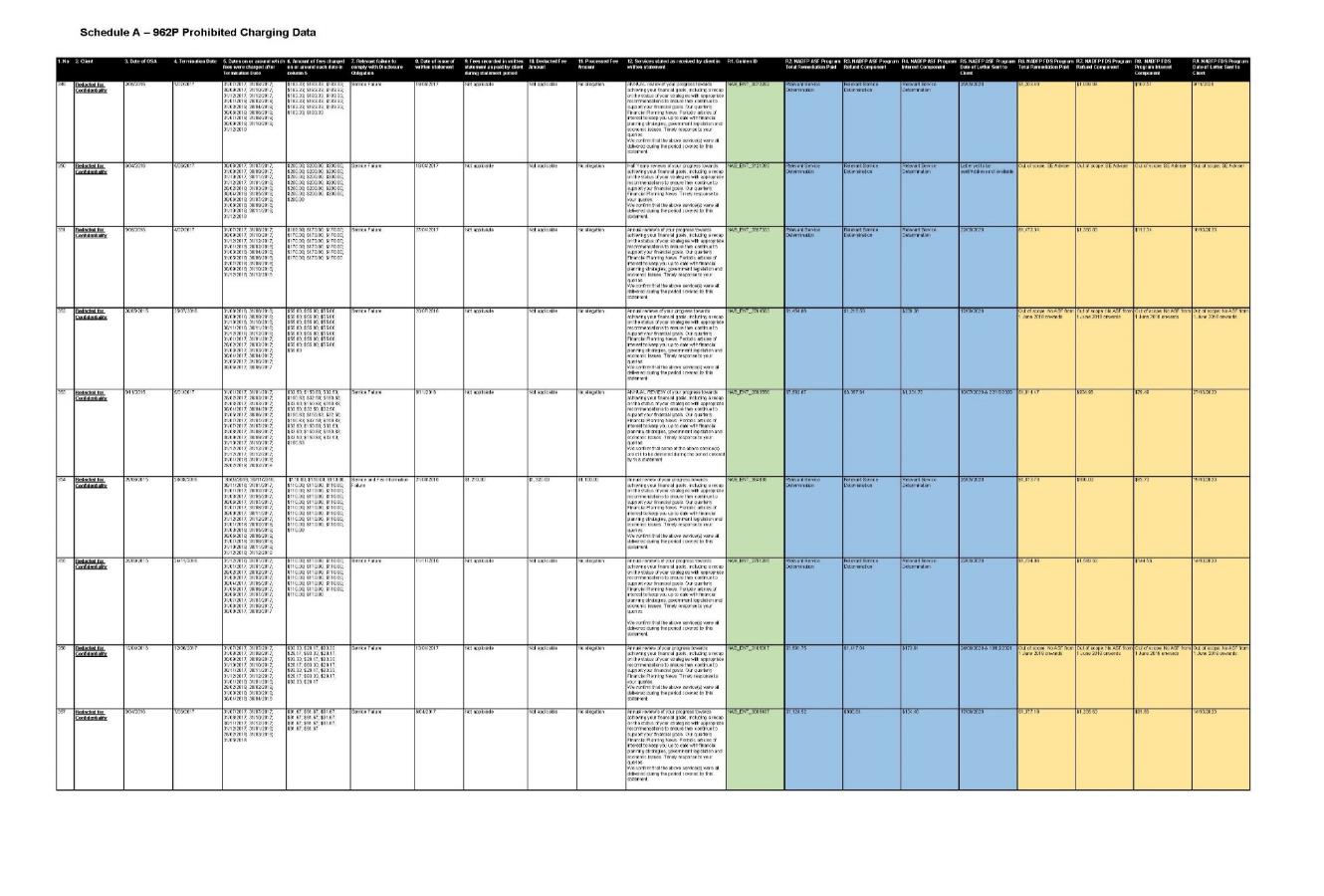

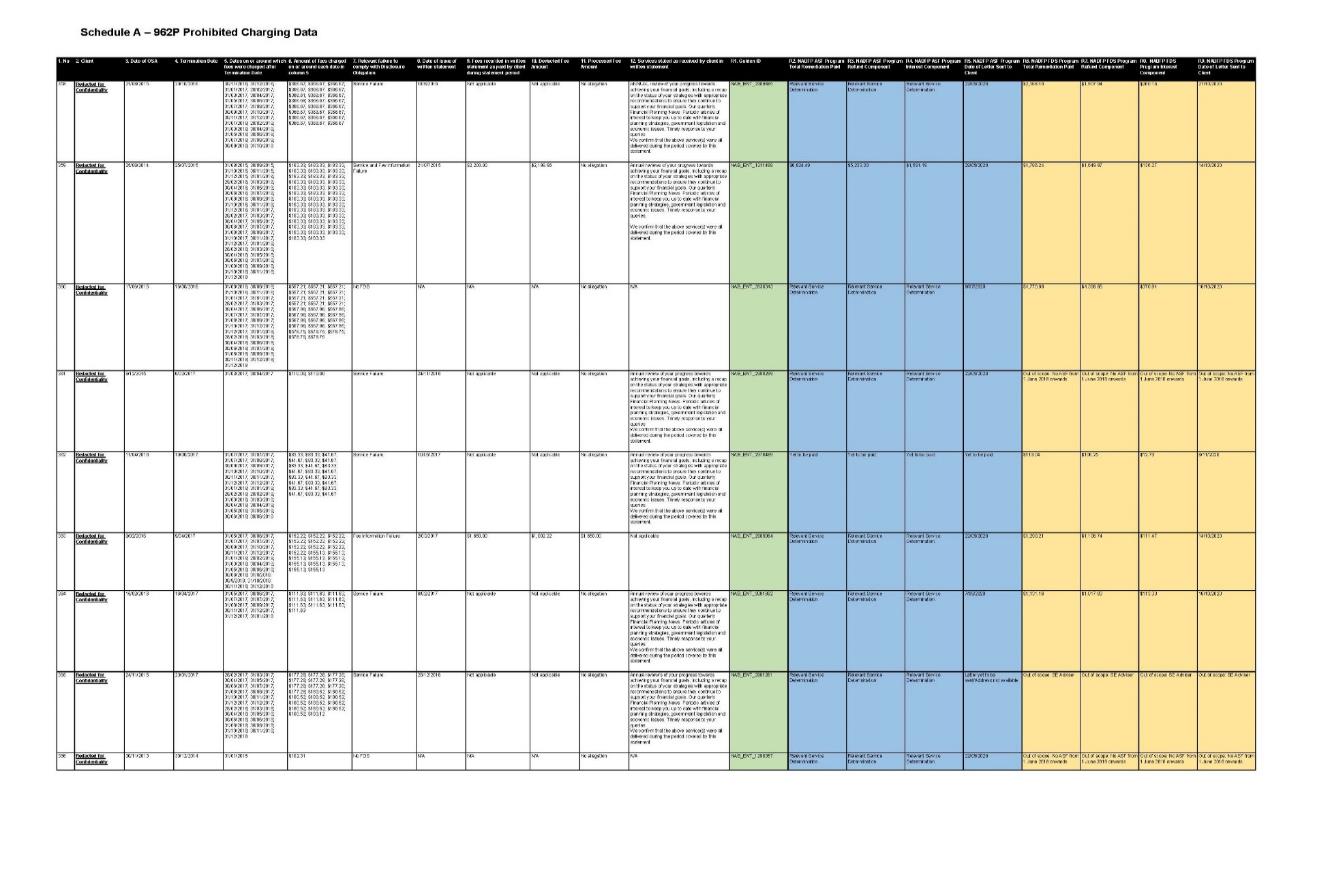

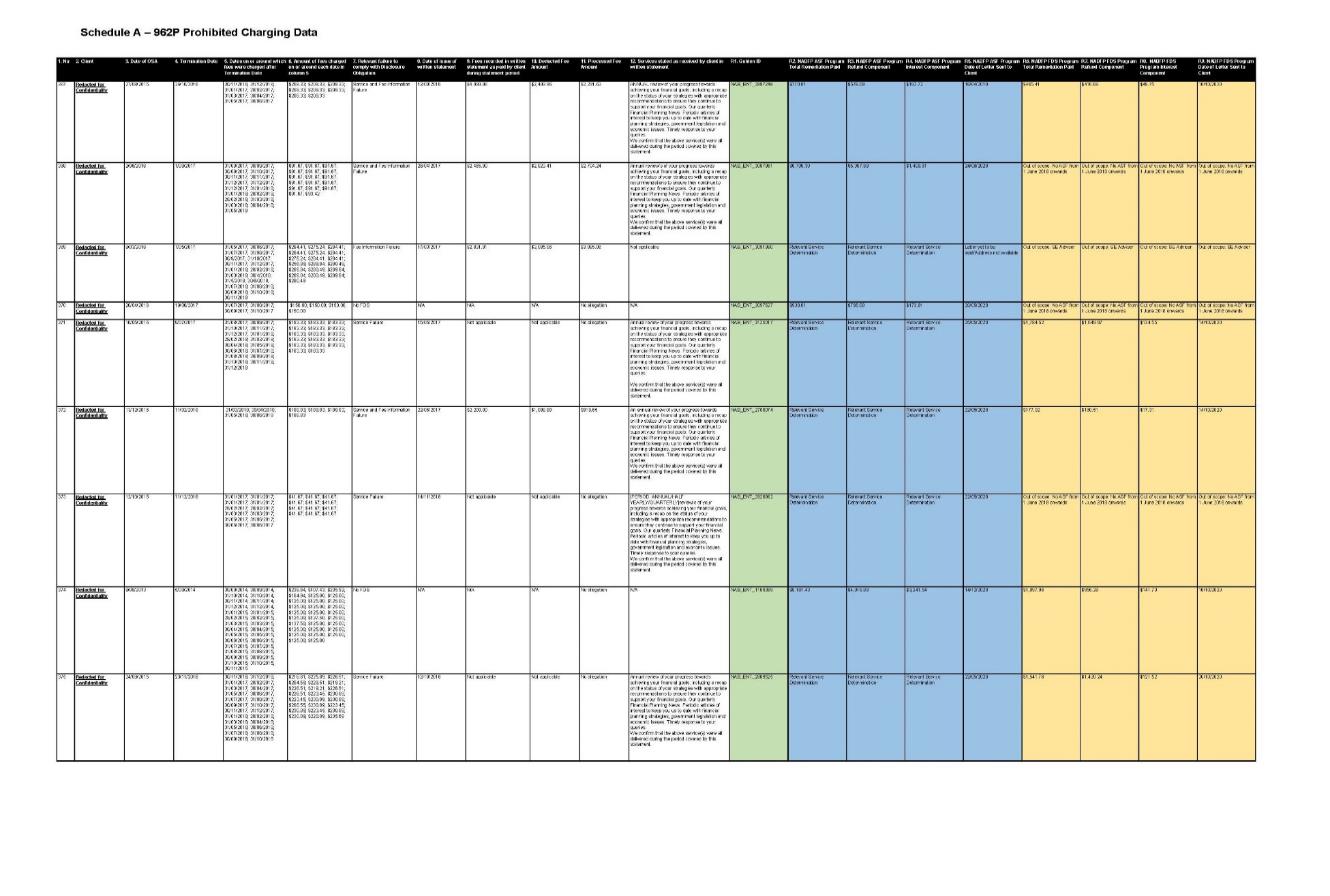

30 ASIC alleged and NAB has admitted that, between 30 September 2014 and 31 December 2018, NAB contravened s 962P of the Corporations Act on 445 occasions by continuing to charge ongoing fees to the 439 post-FOFA clients listed in Schedule A to the agreed facts, when it was prohibited from doing so. That prohibition arose because NAB failed to give those clients a fee disclosure statement in compliance with s 962G of the Corporations Act by the applicable date, as a result of which their ongoing fee arrangements terminated pursuant to s 962F:

(a) in 55 cases, NAB did not give the client any statement in writing that purported to be a fee disclosure statement by the time prescribed by s 962G of the Corporations Act;

(b) in 240 cases, NAB gave the client a statement that did not correctly state the services received by the client during the relevant statement period, as required by s 962H(2)(d) of the Corporations Act;

(c) in 36 cases, NAB gave the client a statement that did not correctly state the amount of ongoing fees the client had paid during the relevant statement period, as required by s 962H(2)(a) of the Corporations Act; and

(d) in 114 cases, NAB gave the client a statement that did not correctly state either the services received by the client or the ongoing fees paid by the client during the relevant statement period, as required by ss 962H(2)(a) and (d) of the Corporations Act.

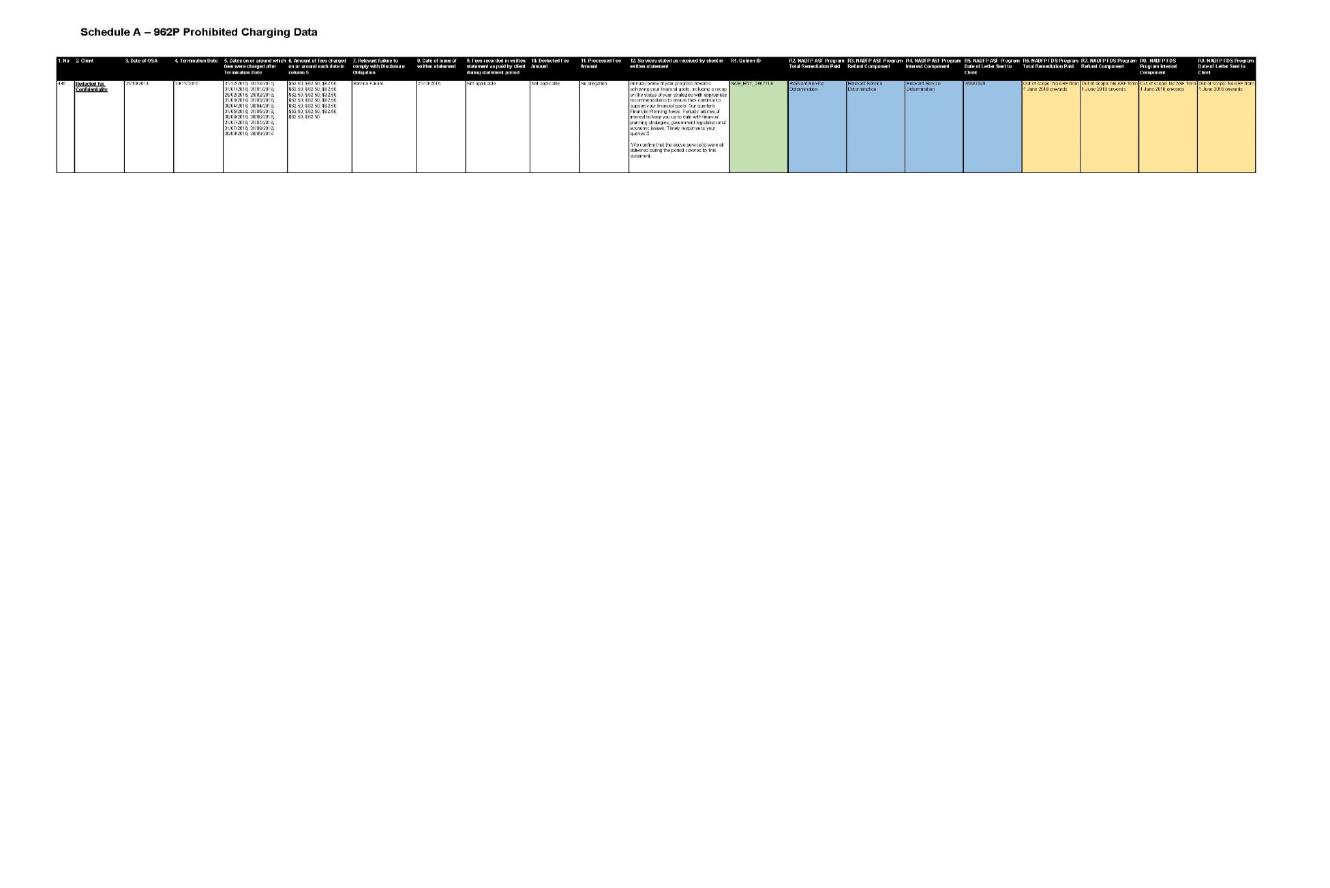

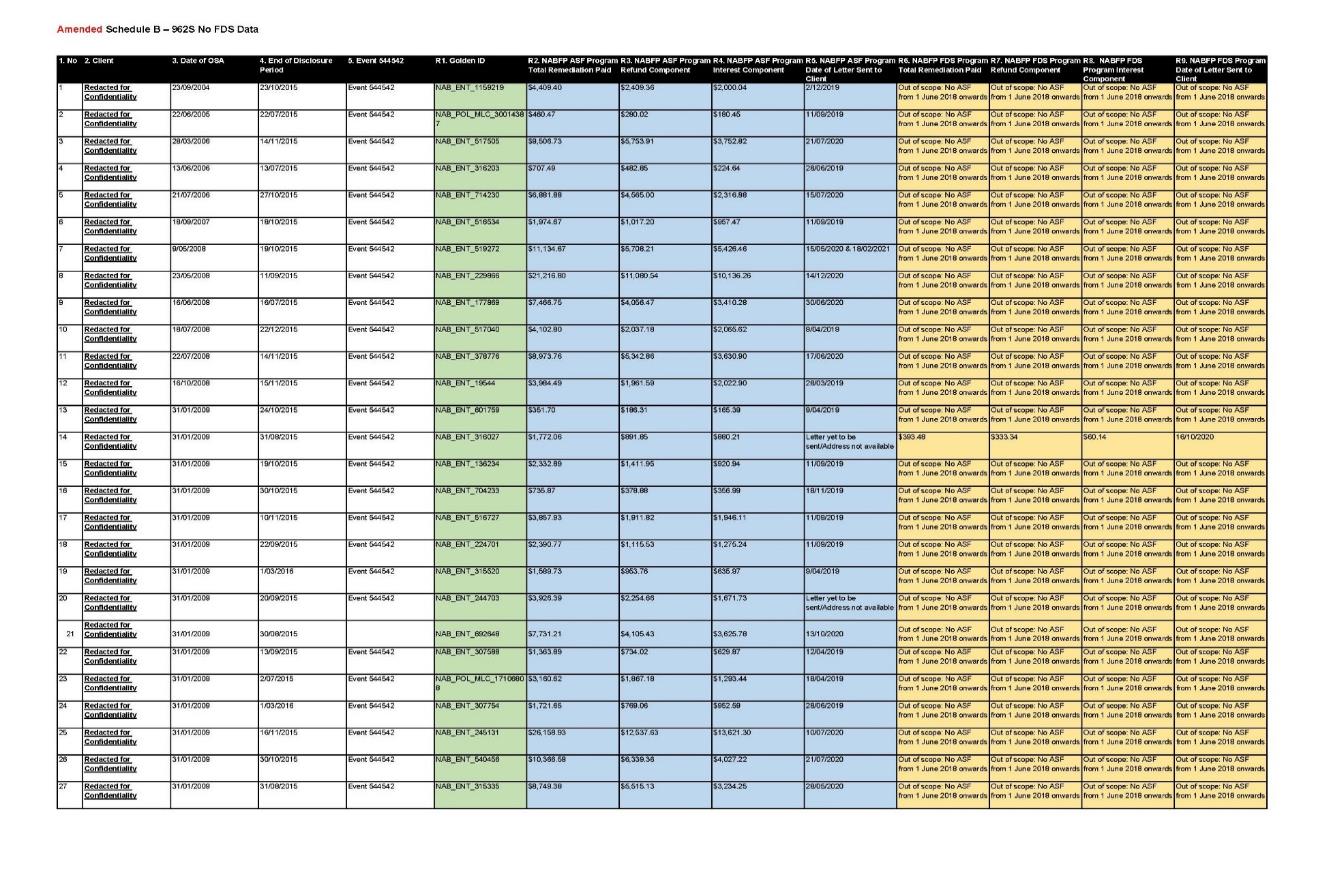

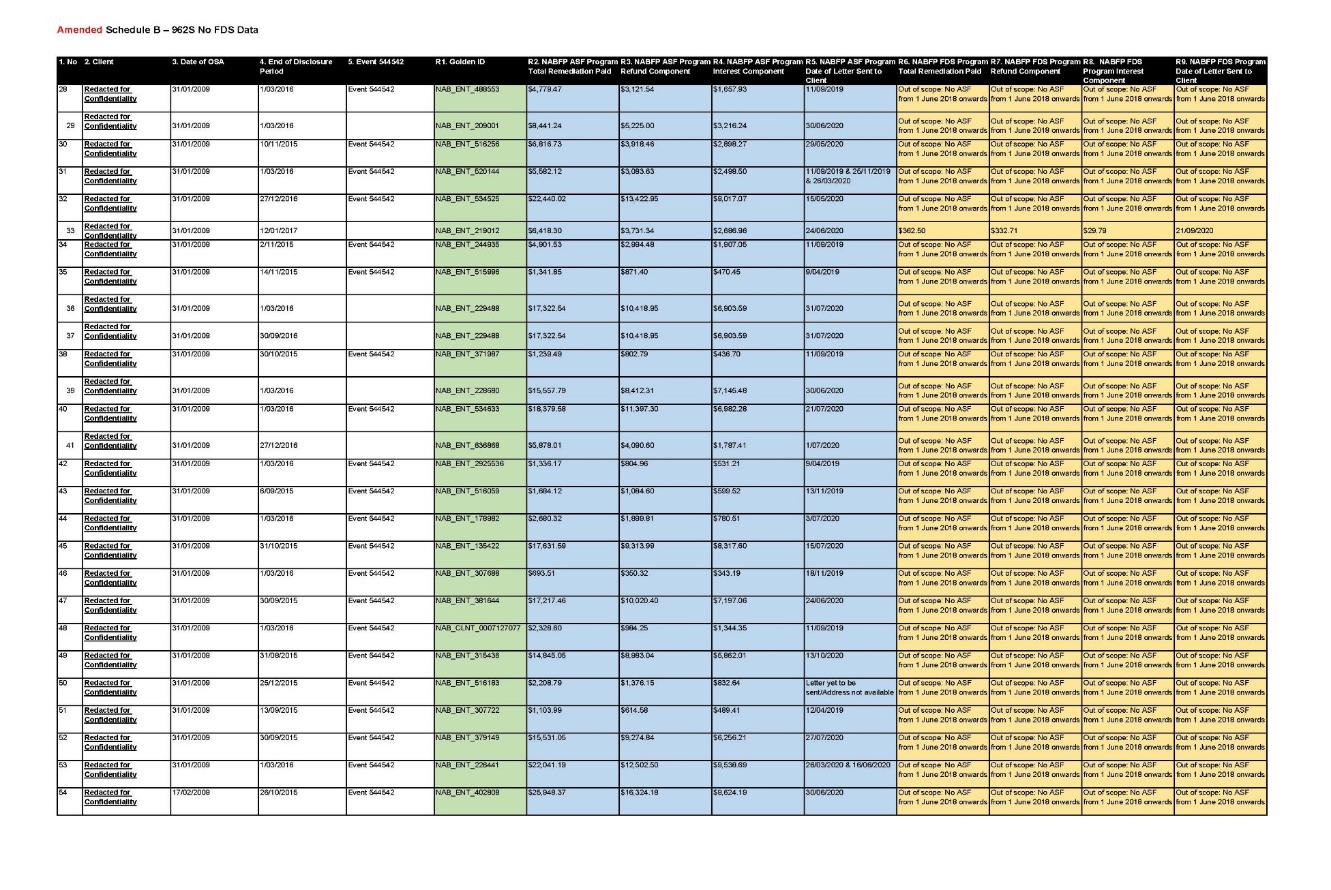

BASIS OF SECTION 962S CONTRAVENTIONS

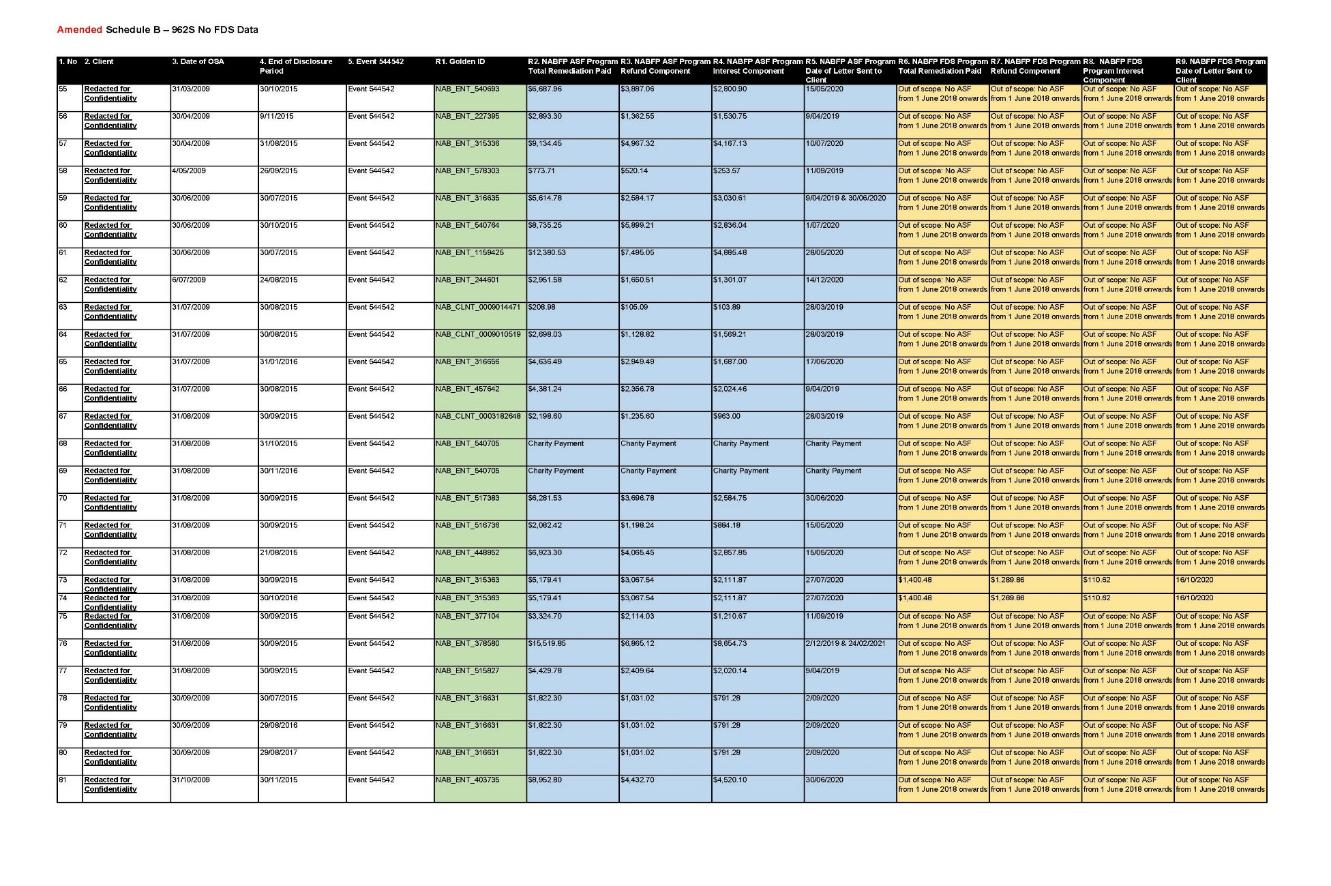

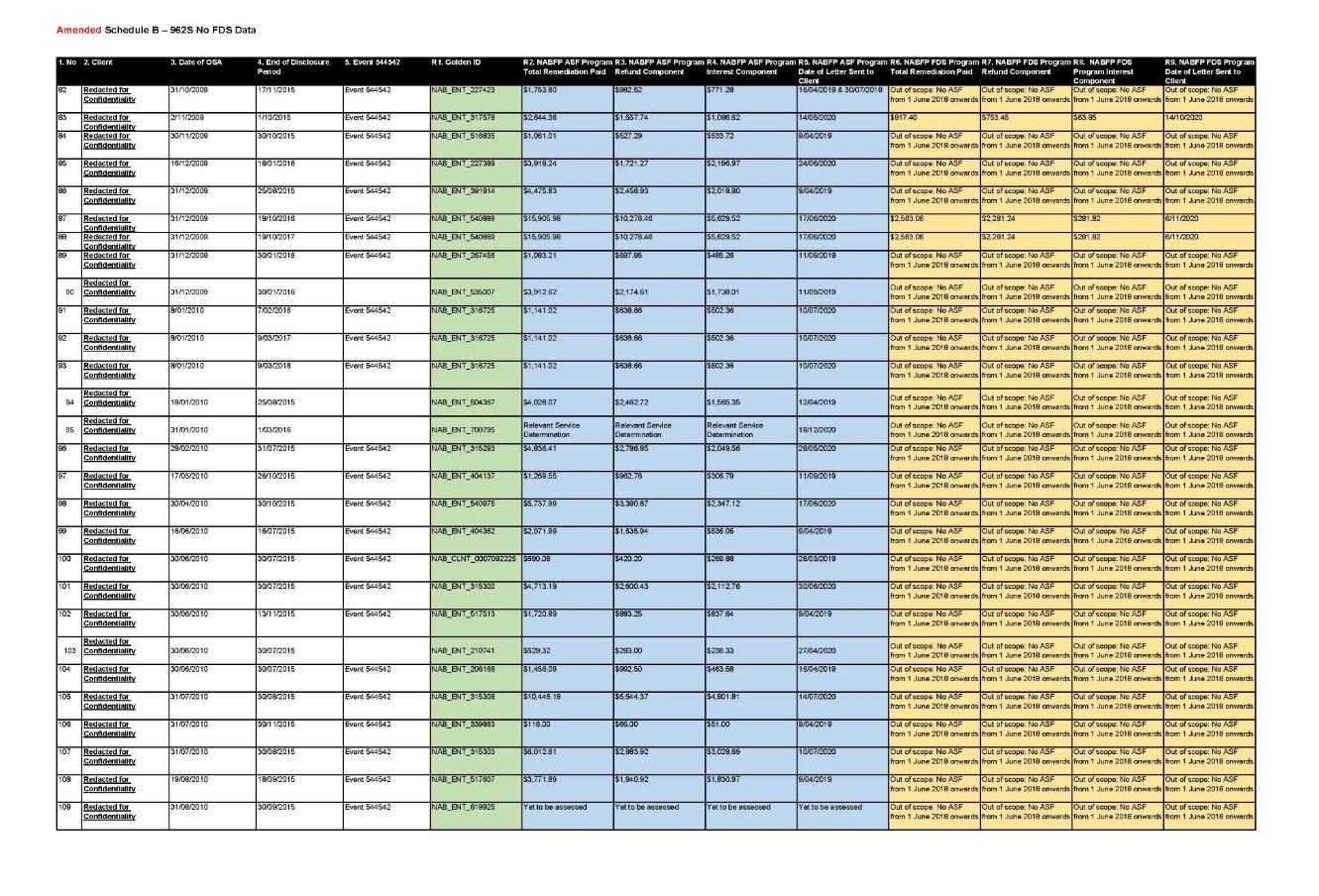

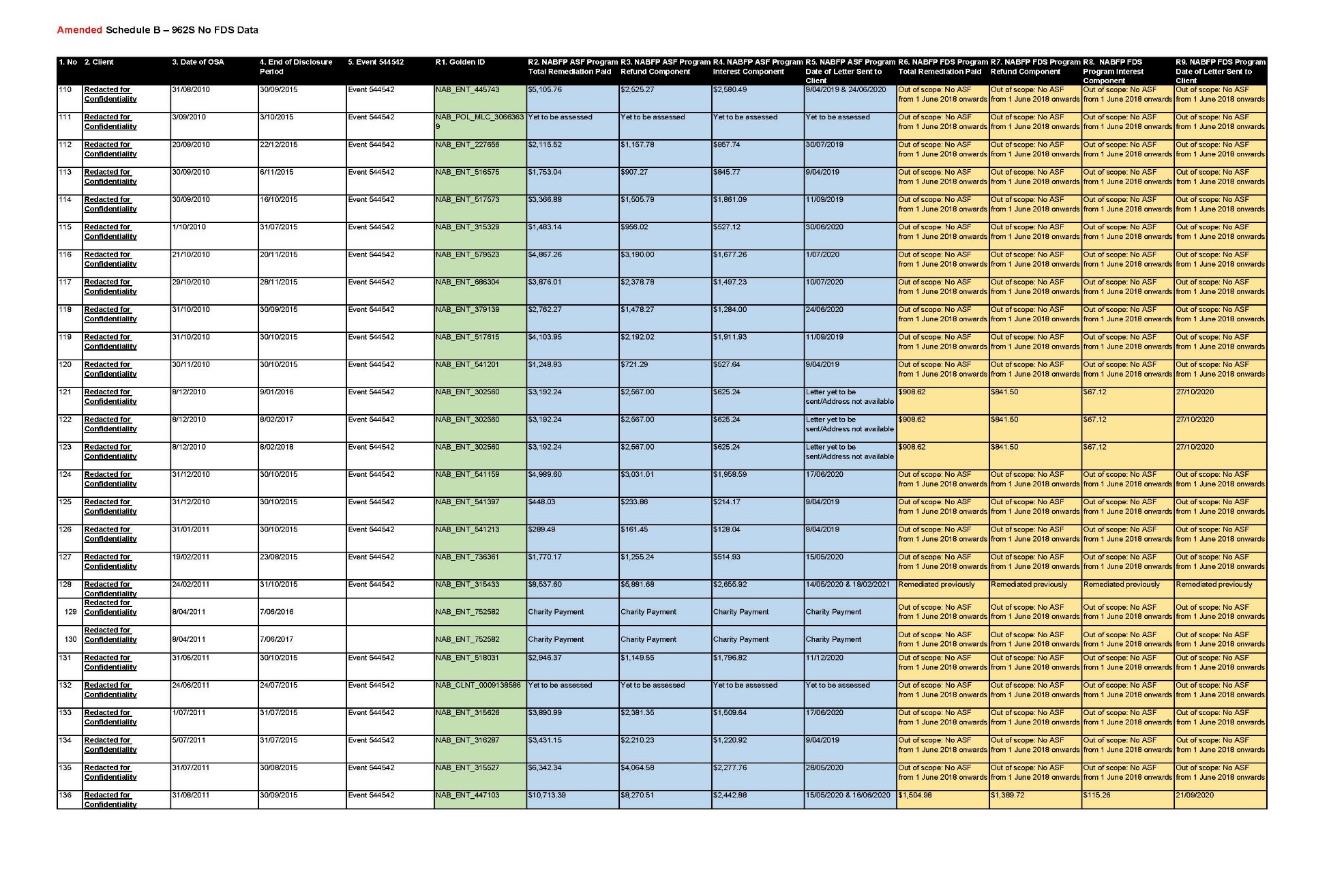

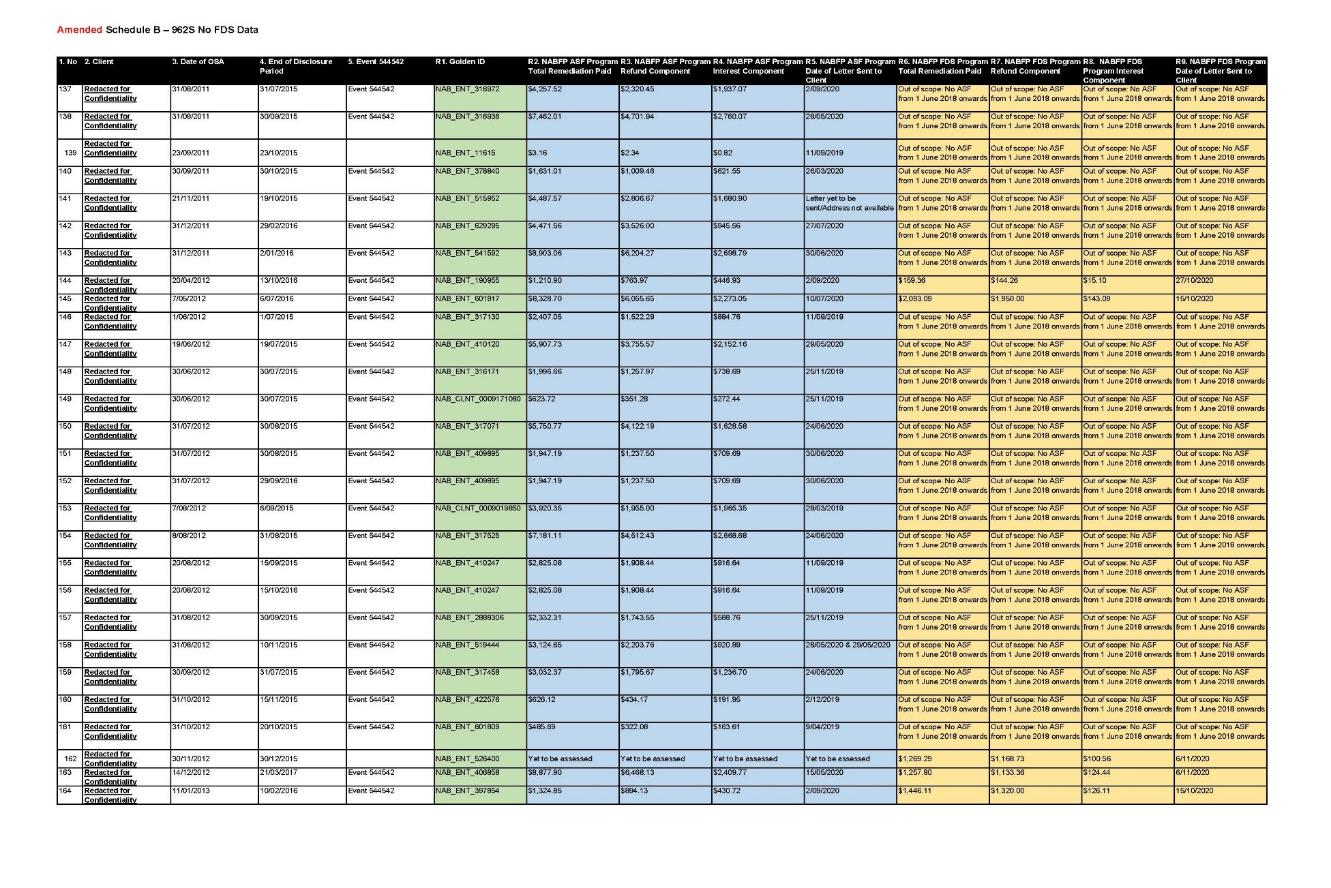

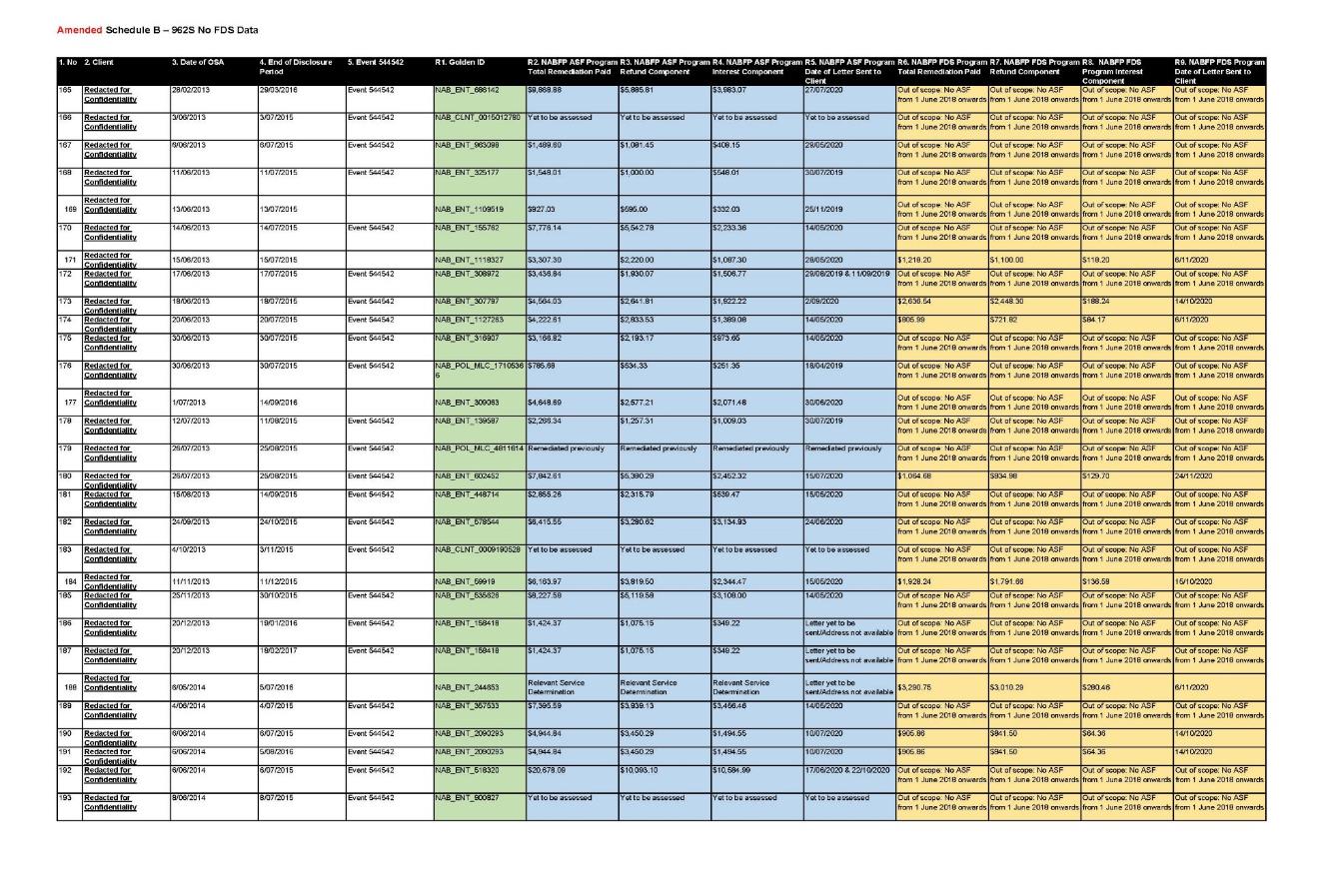

31 ASIC alleges and NAB admits that between 1 July 2015 and 5 October 2018, NAB contravened s 962S of the Corporations Act on 225 occasions by failing to provide the 202 pre-FOFA clients listed in Schedule B to the agreed facts with any statement in writing that purported to be a fee disclosure statement by the end of the 30 day or 60 day period applicable to that client following the disclosure day.

BASIS OF CONTRAVENTIONS OF SECTION 1041H OF THE CORPORATIONS ACT, AND SECTIONS 12DA AND 12DB OF THE ASIC ACT

32 NAB has admitted that between 17 December 2013 and 20 December 2018:

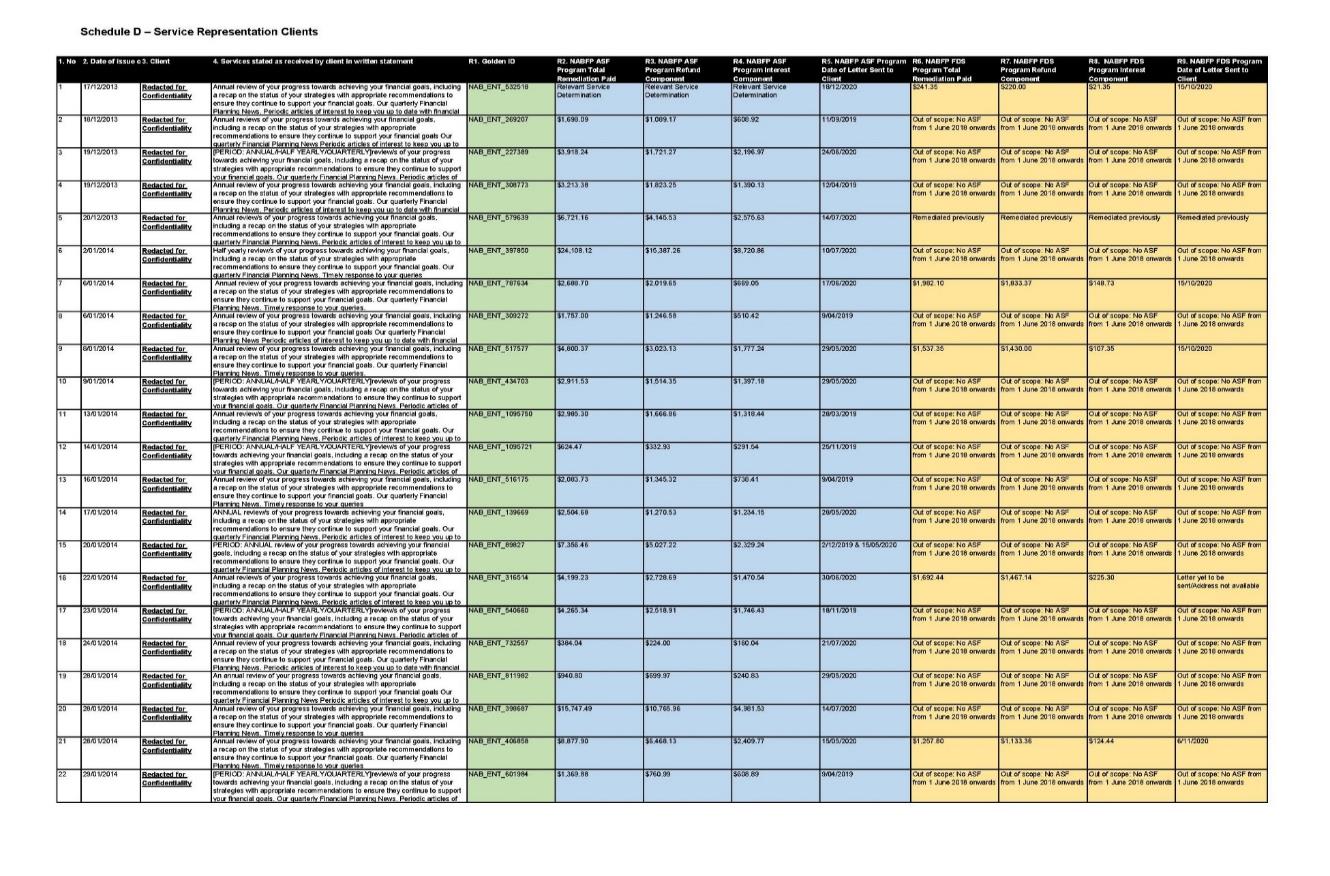

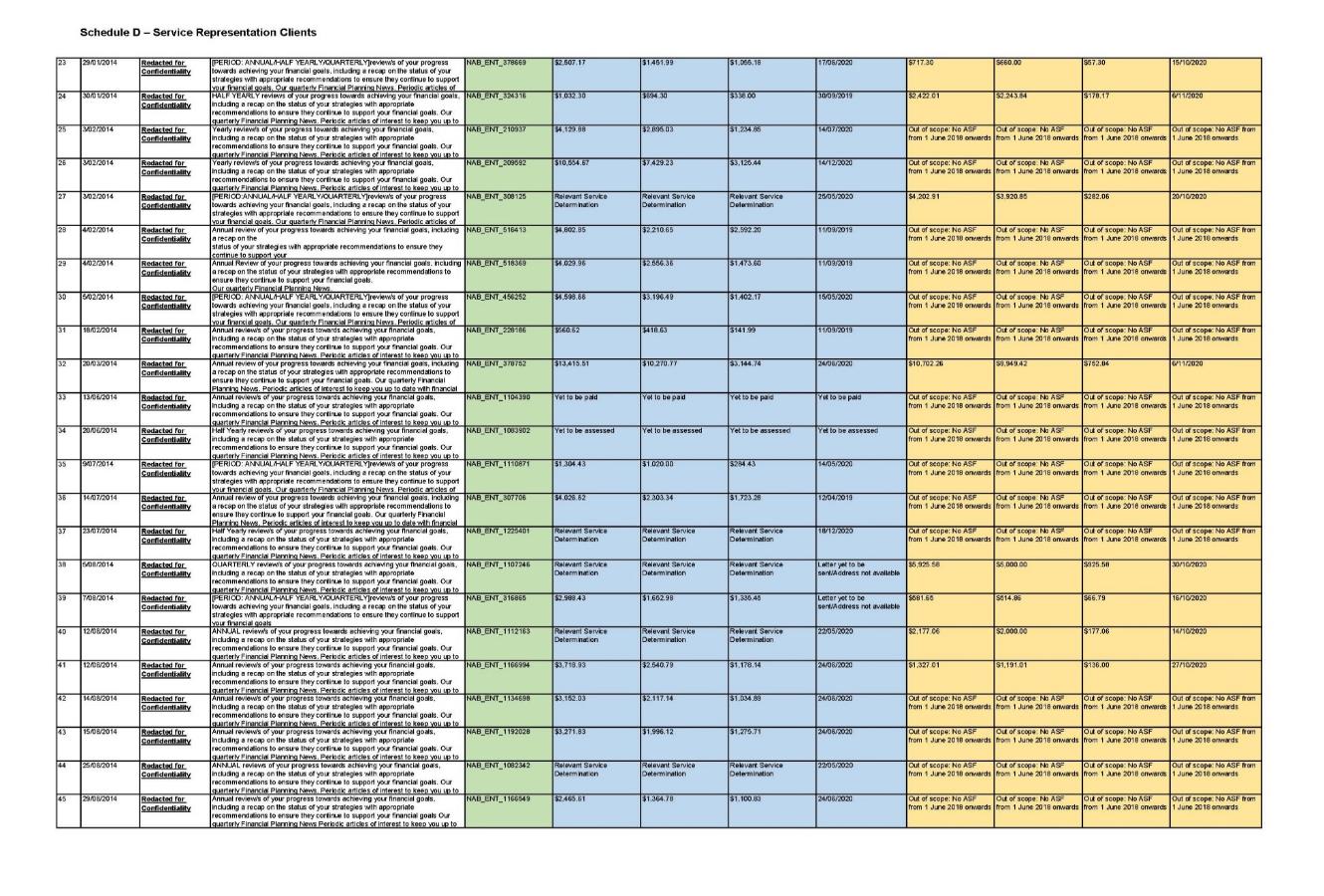

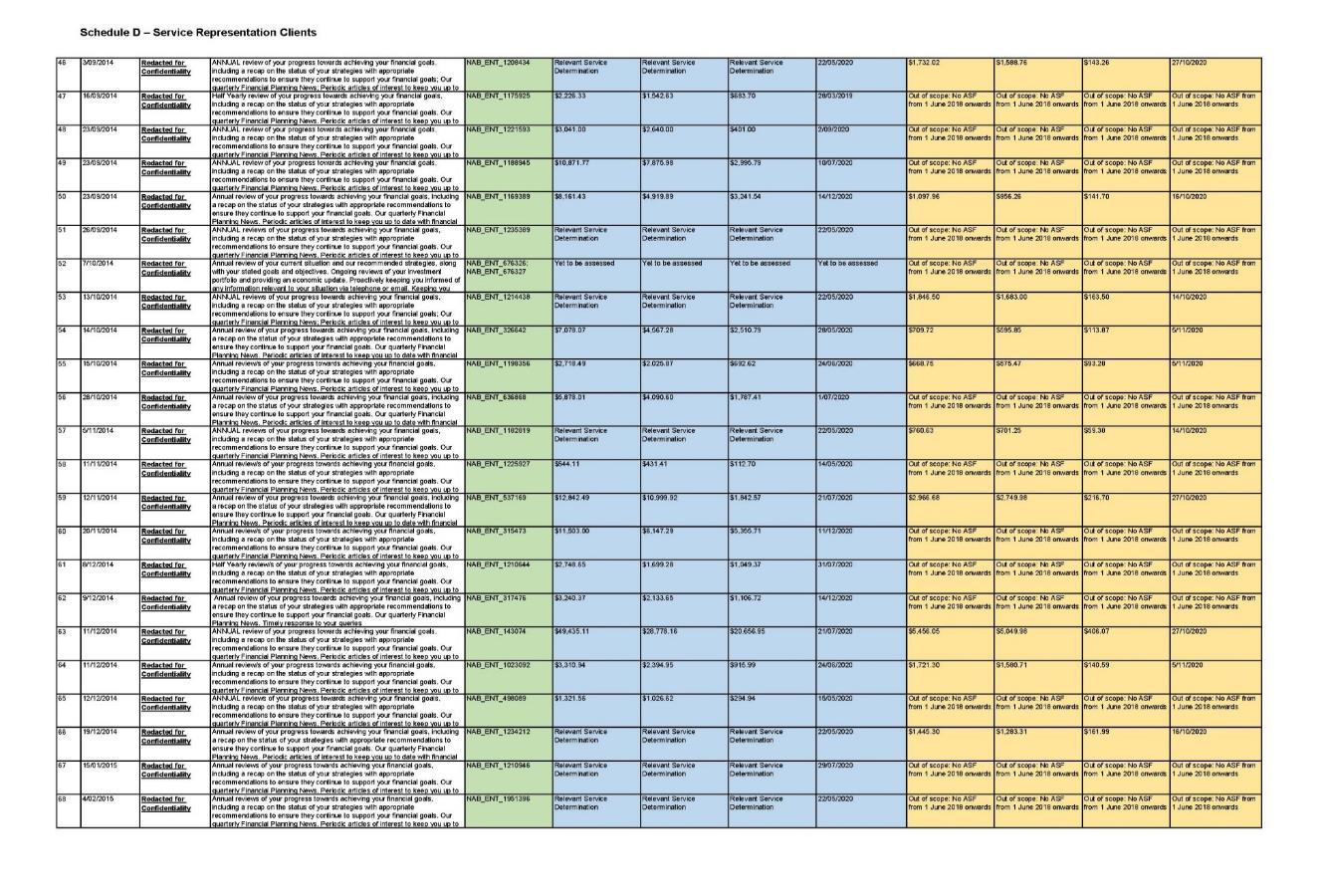

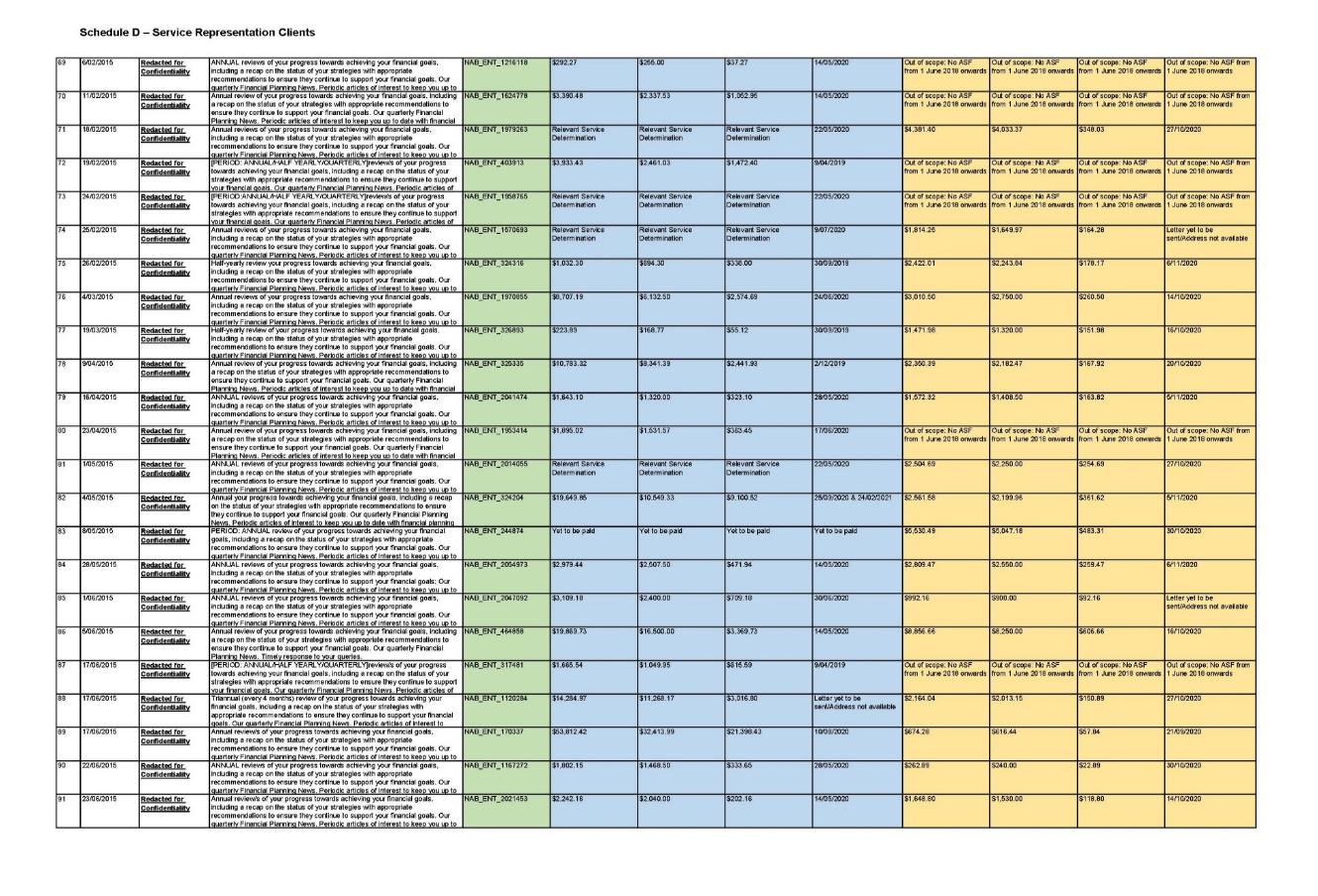

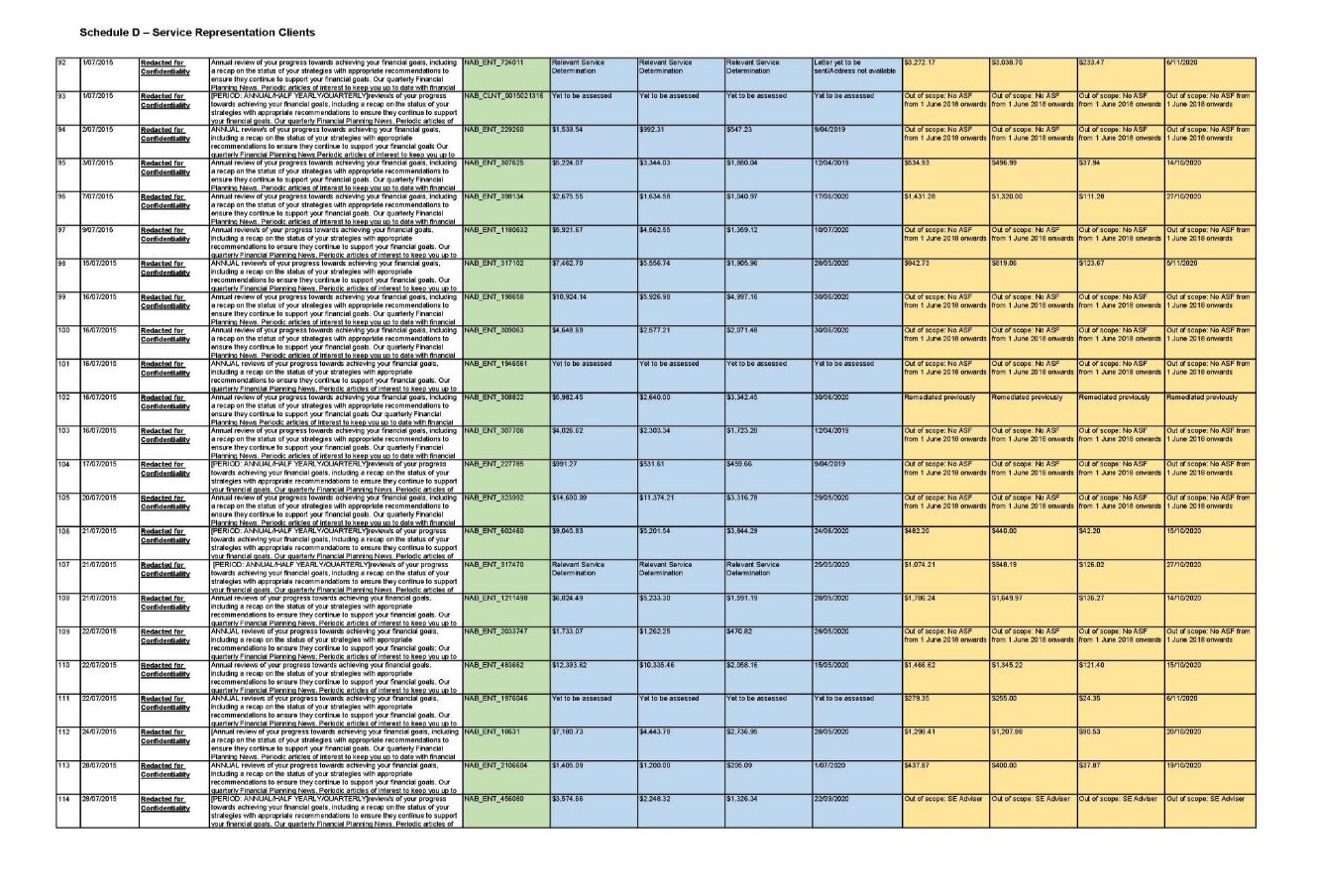

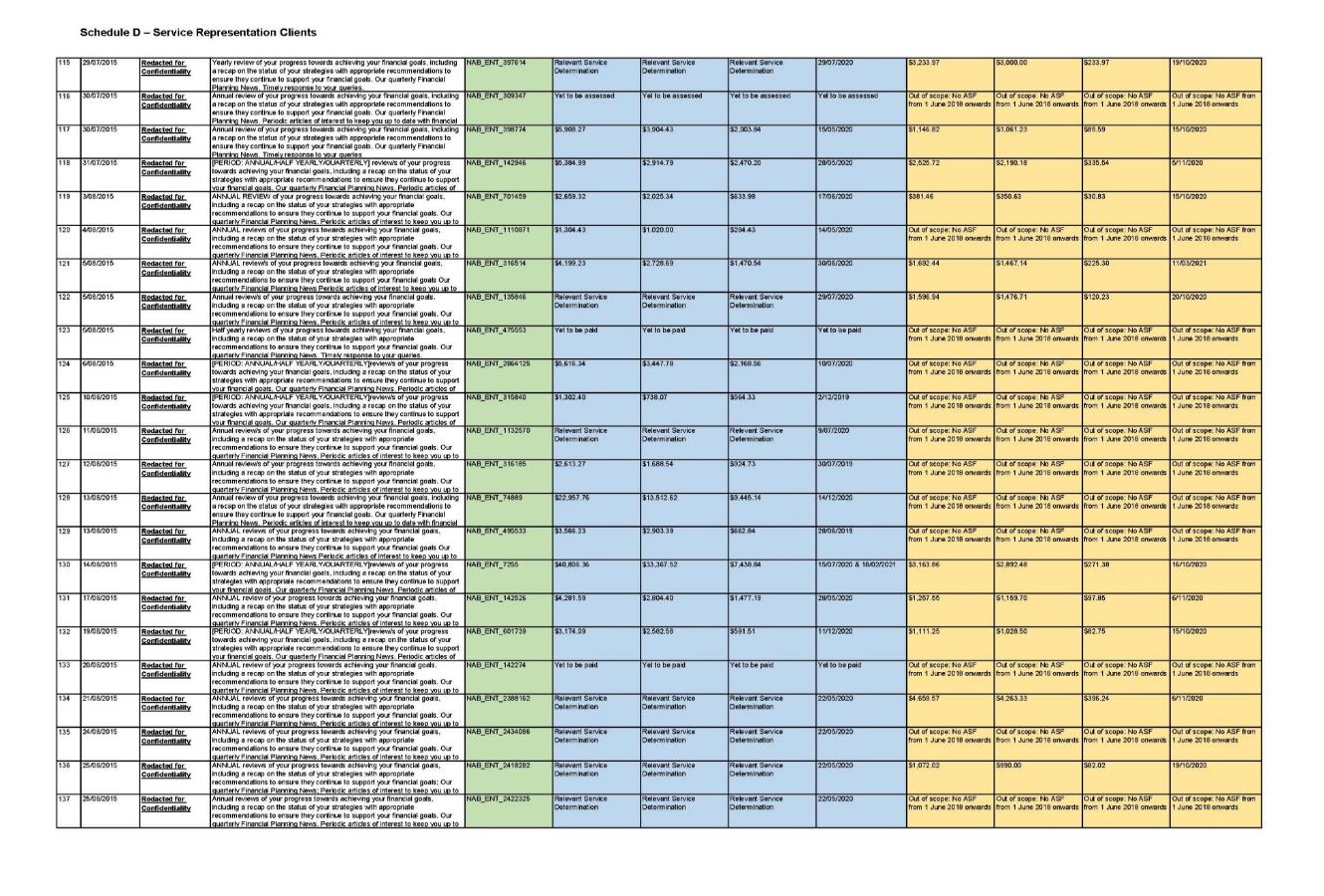

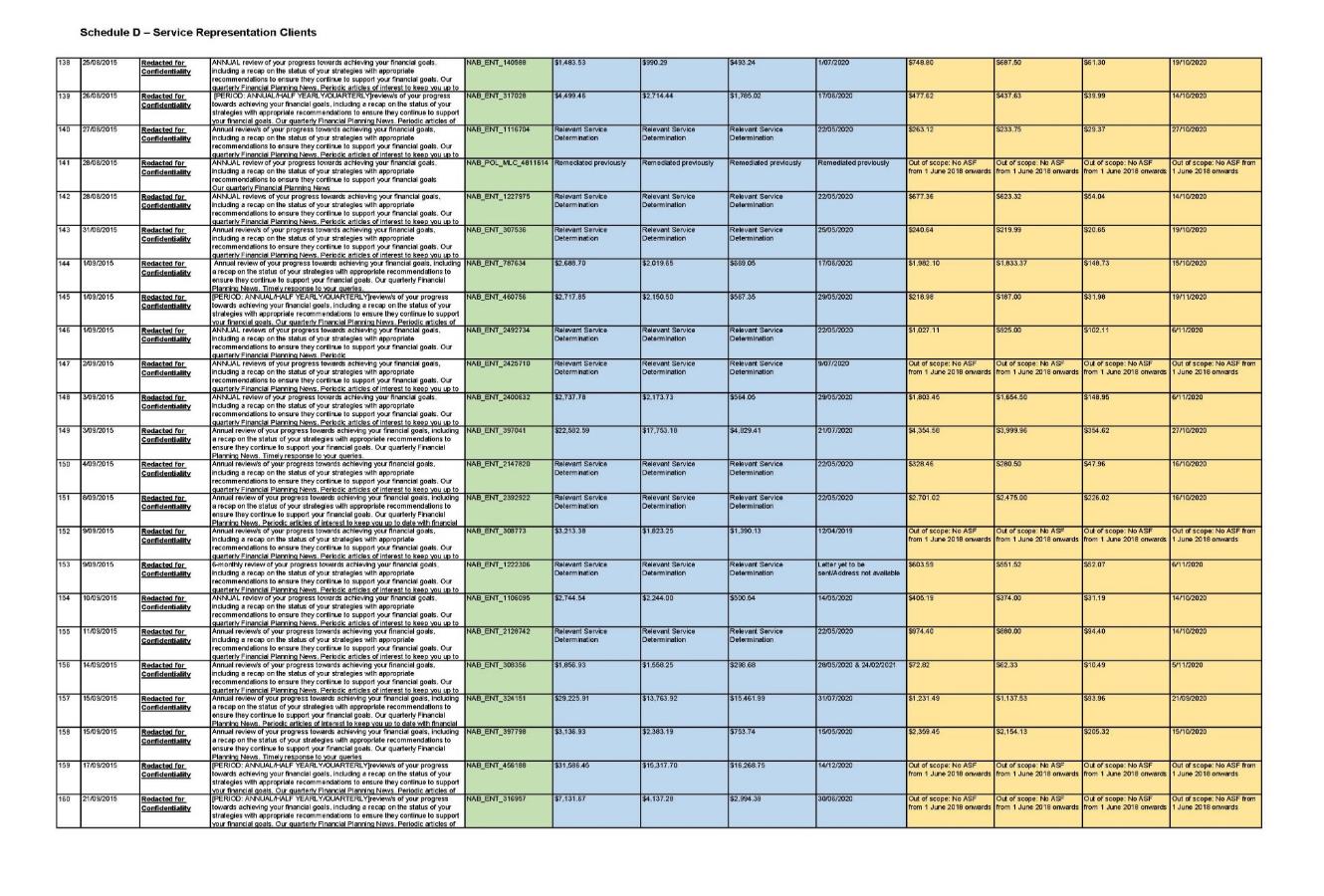

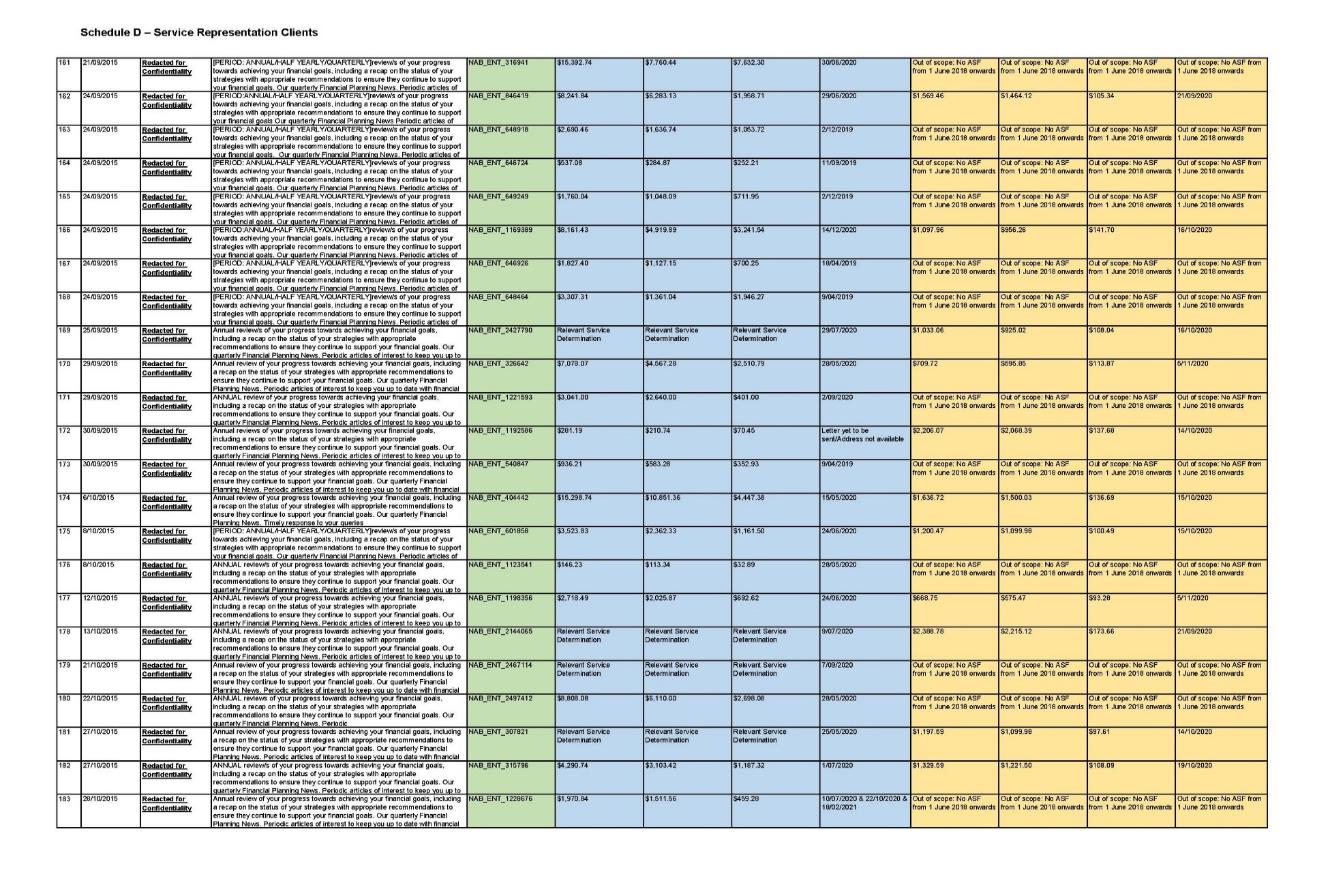

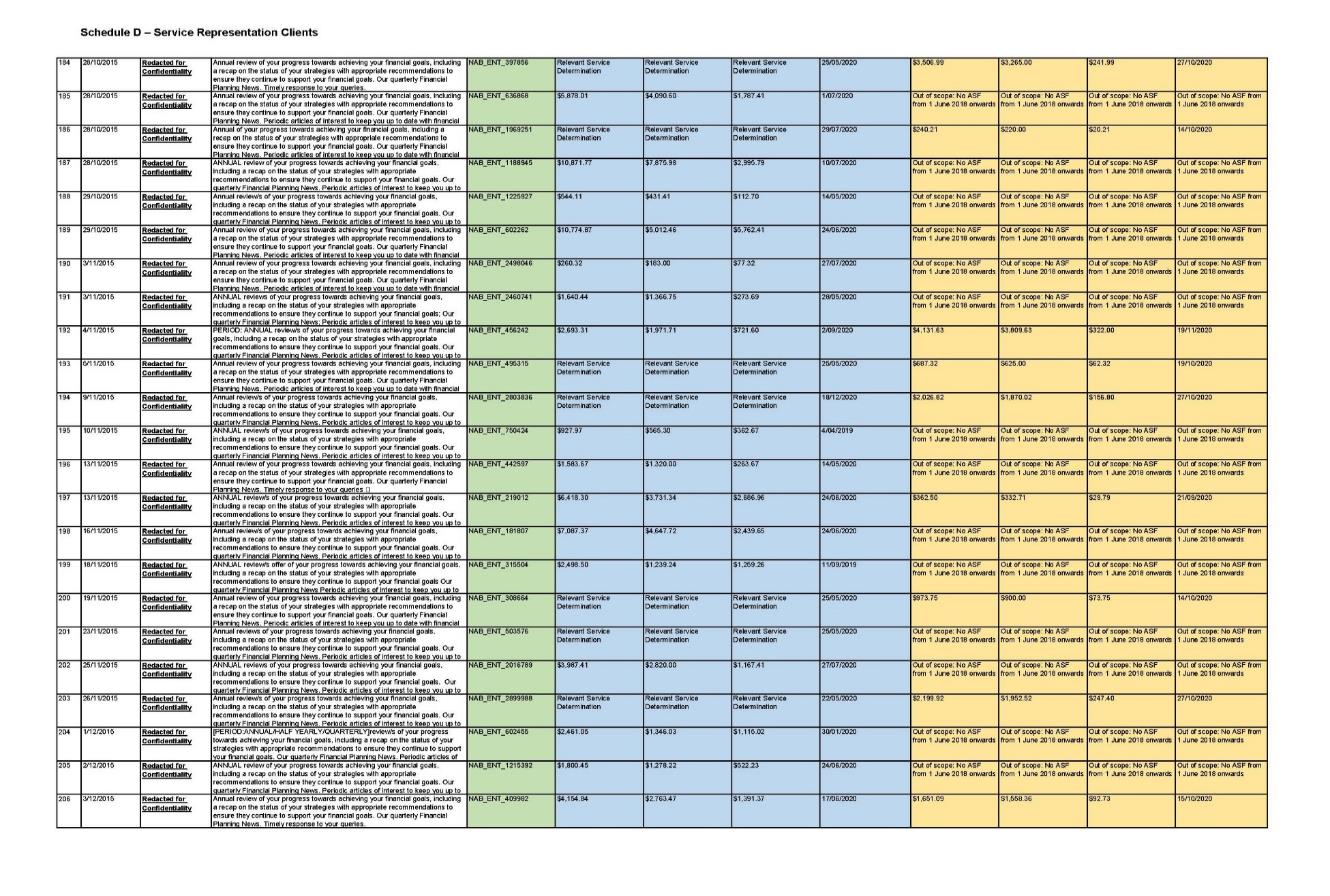

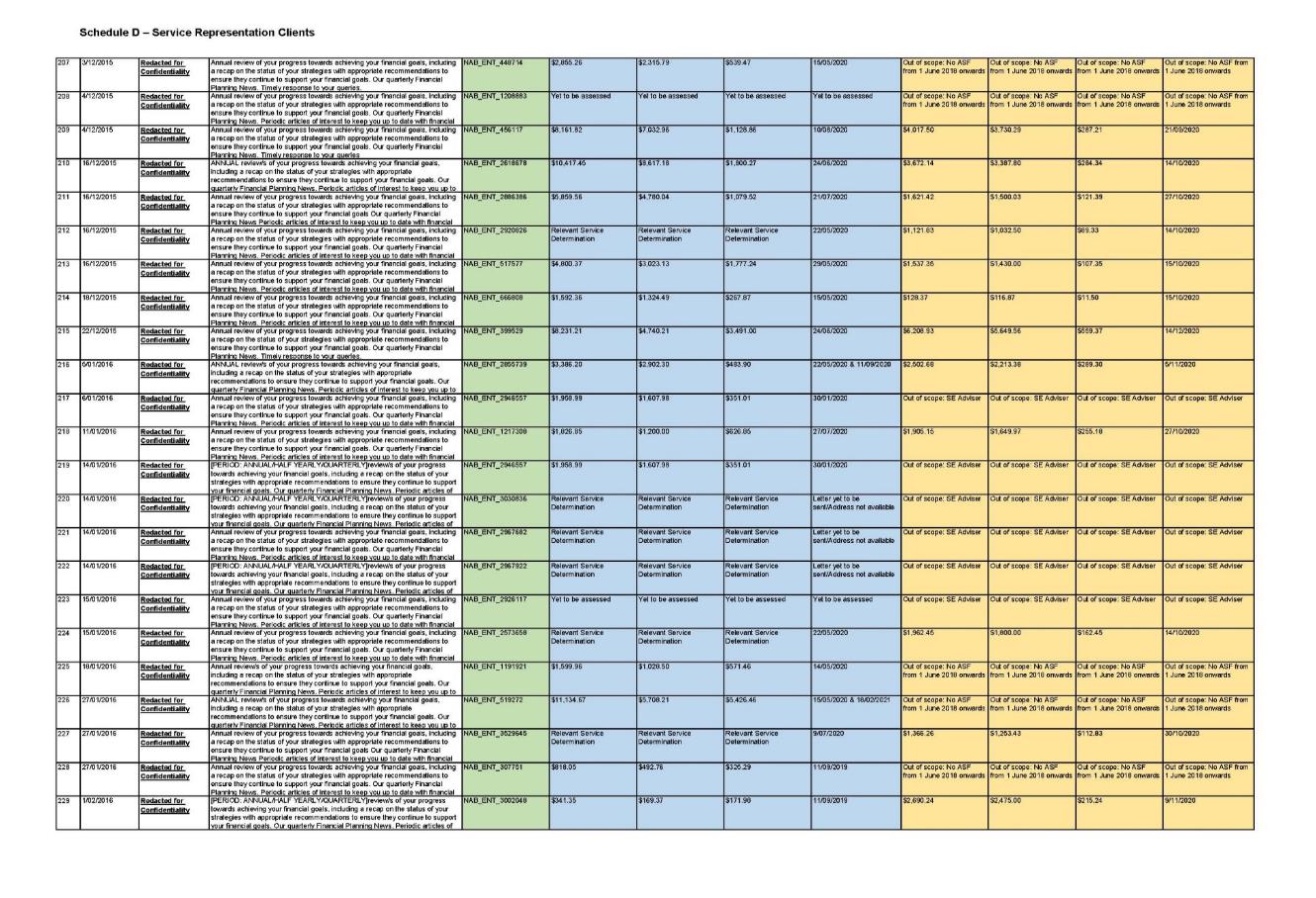

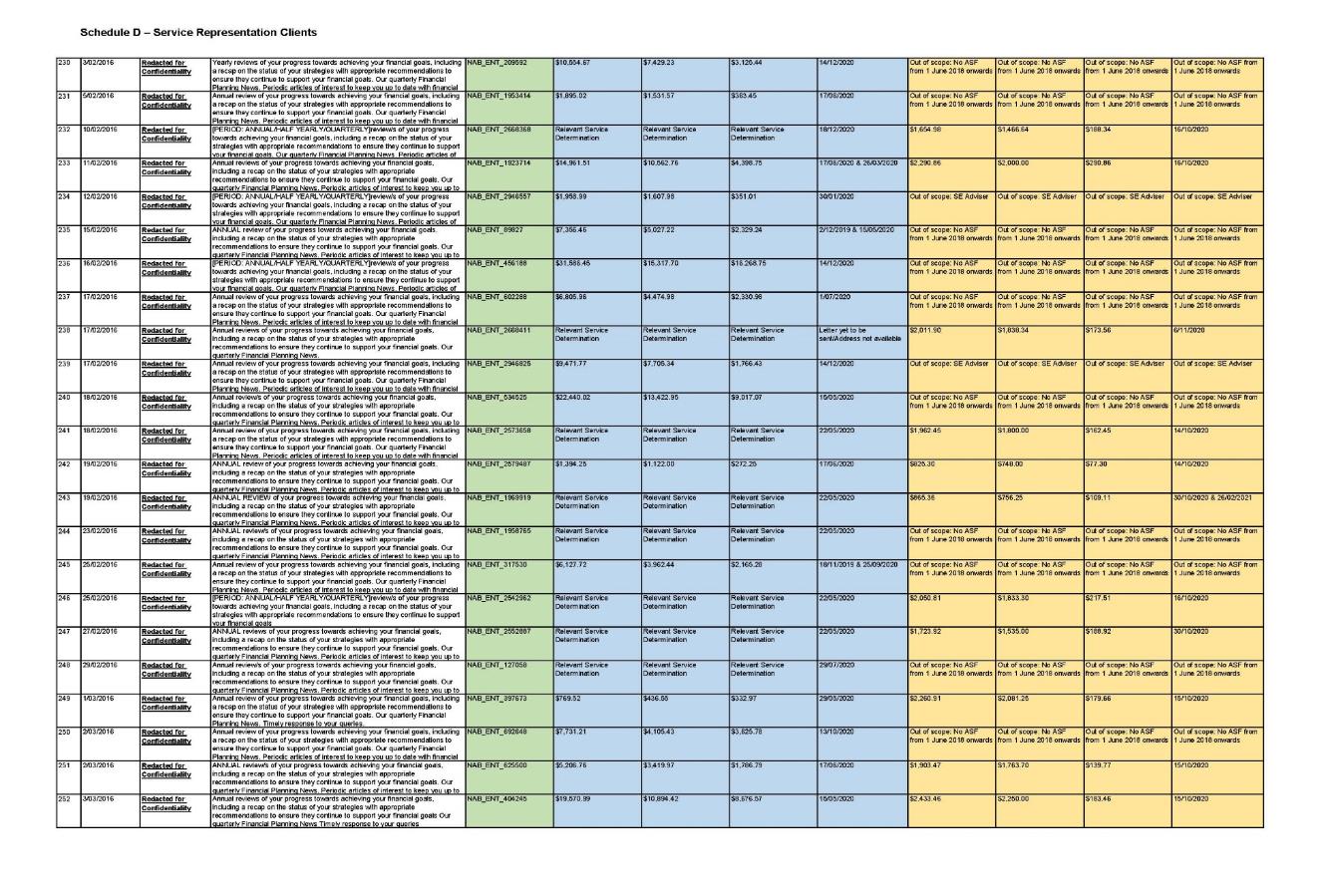

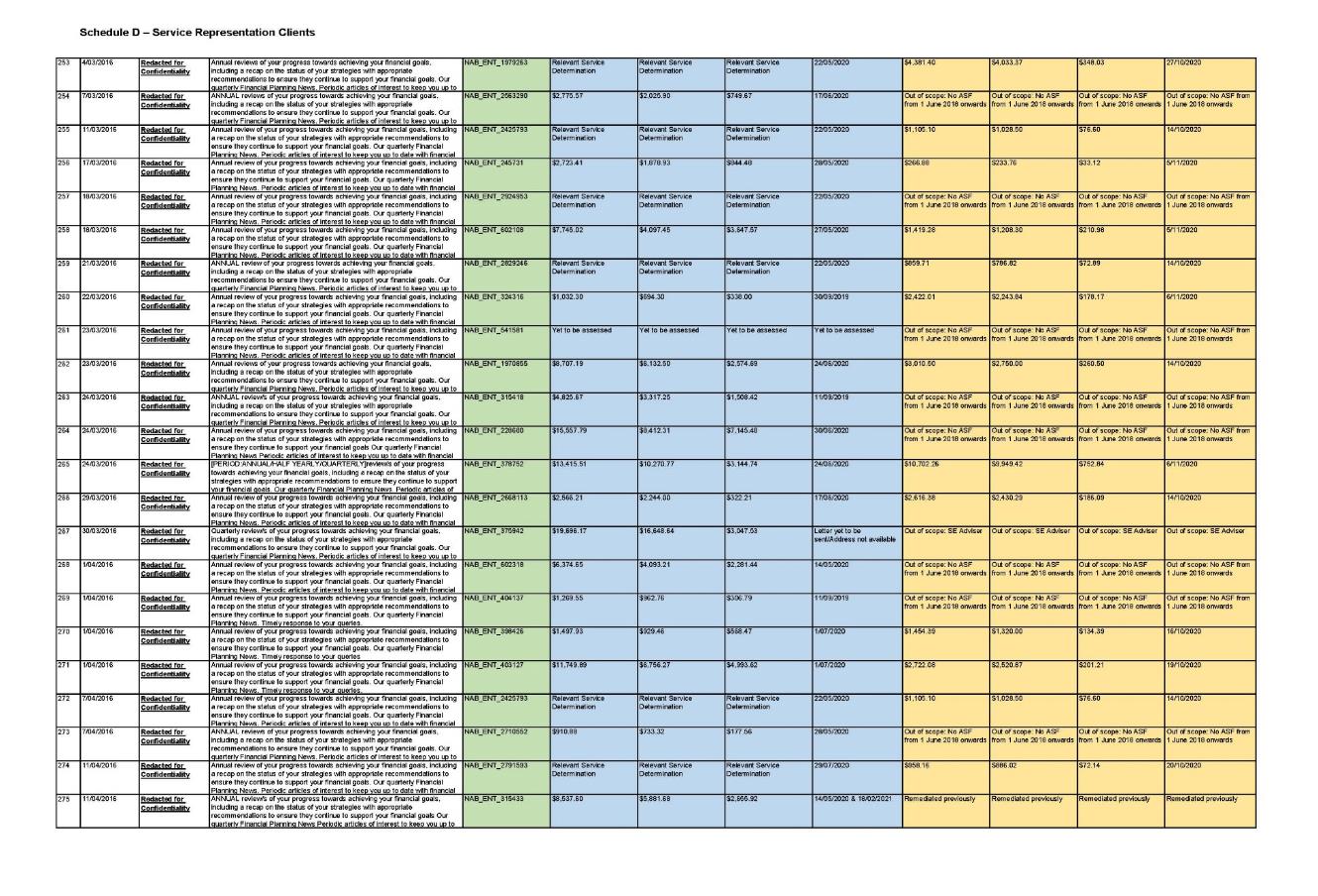

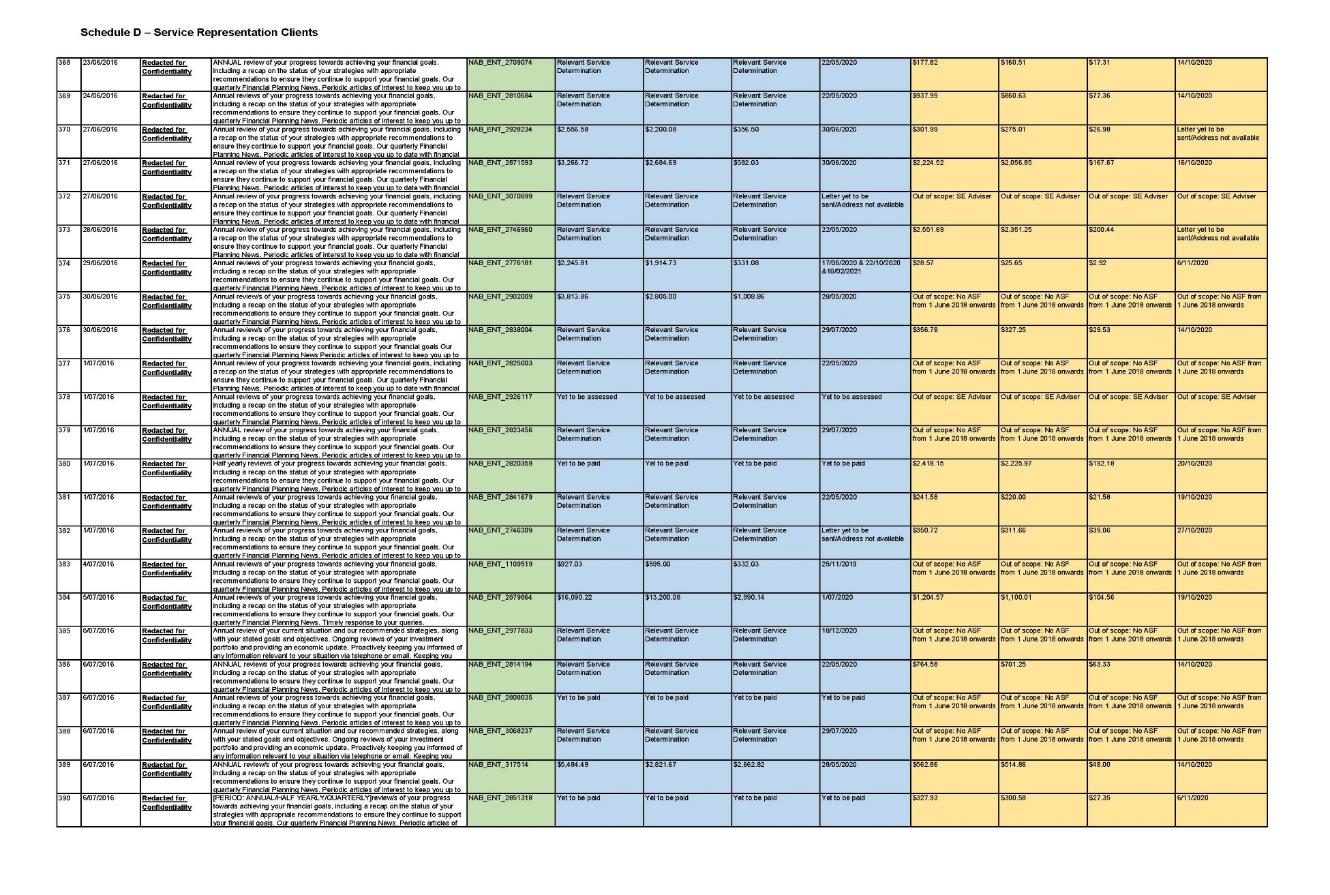

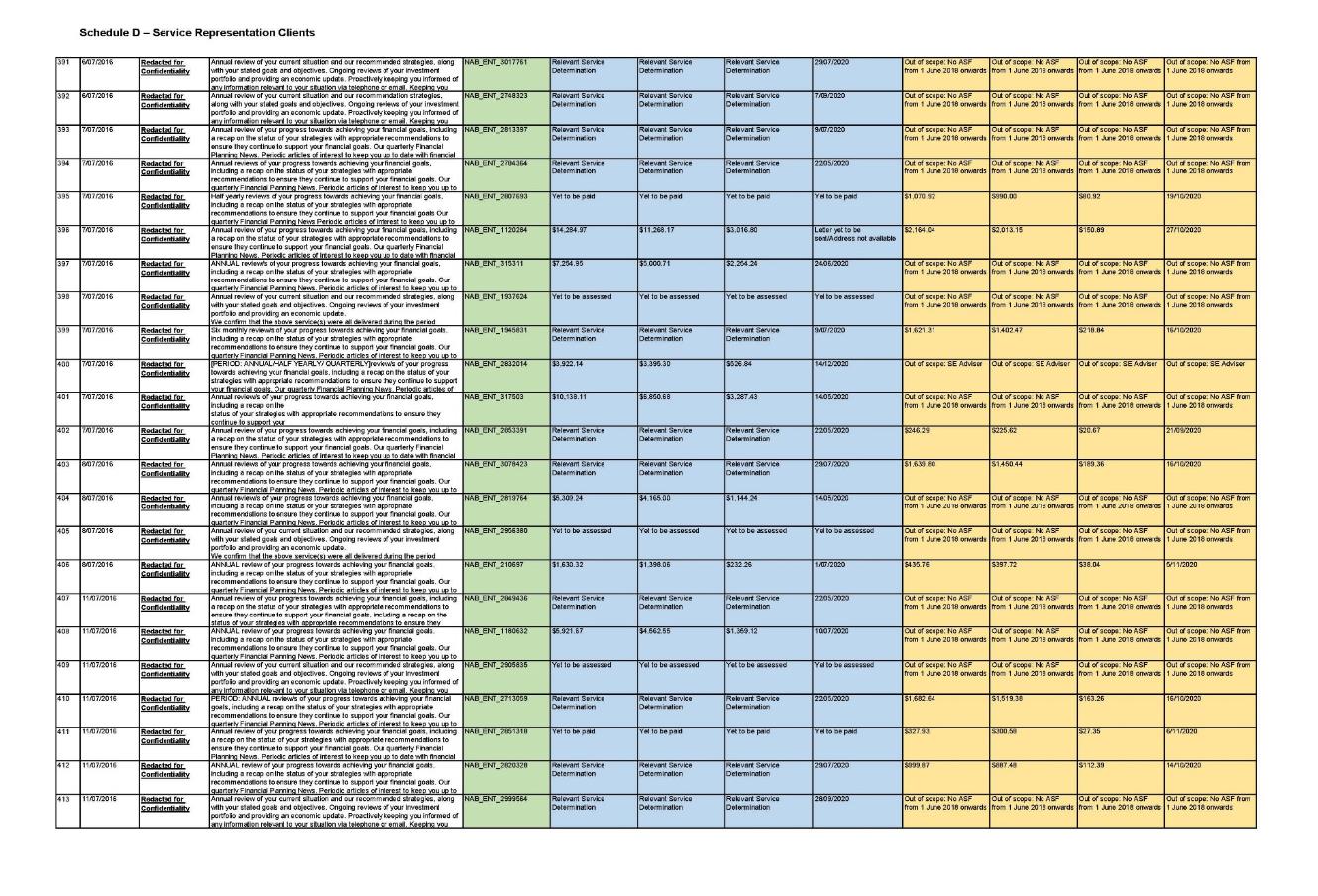

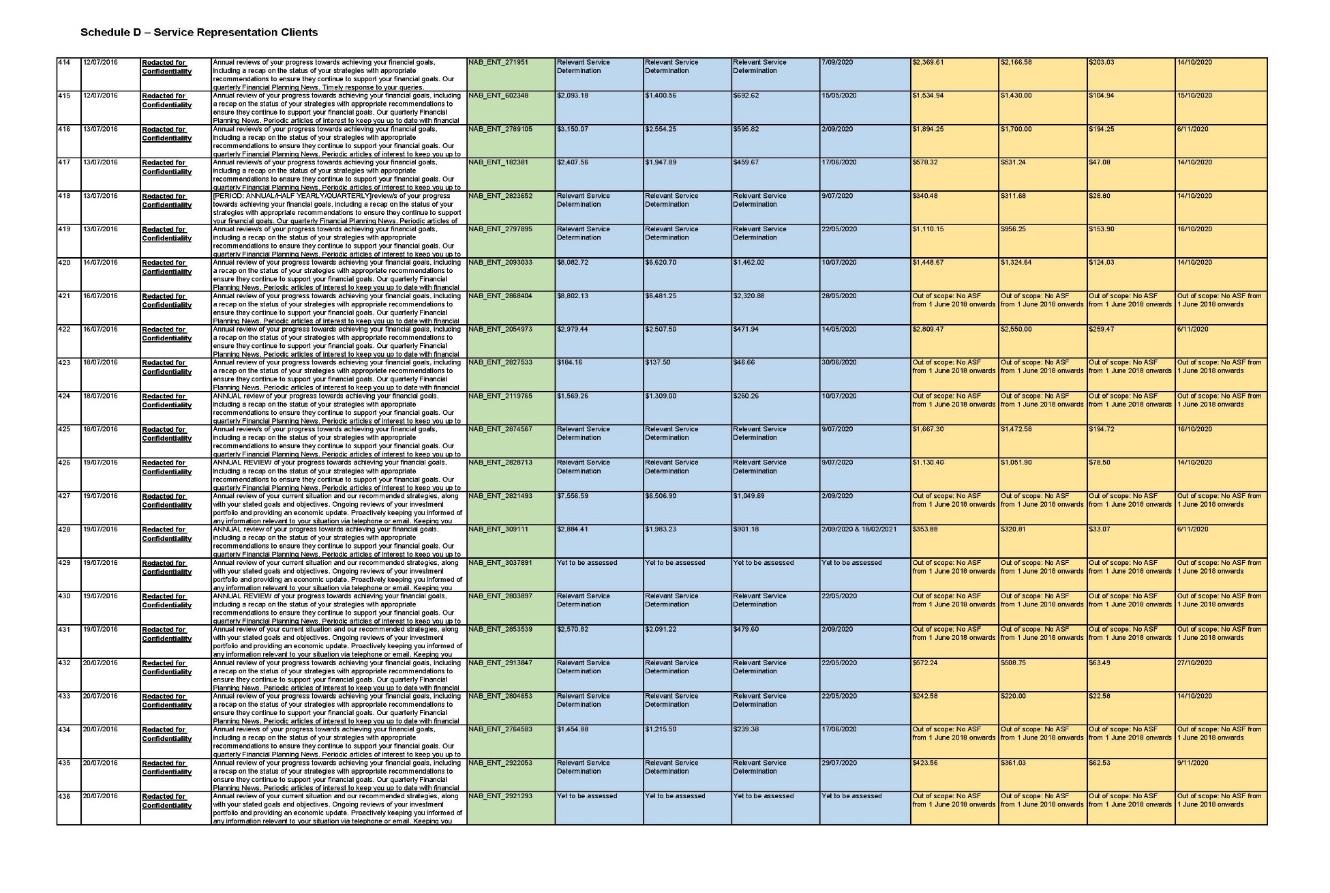

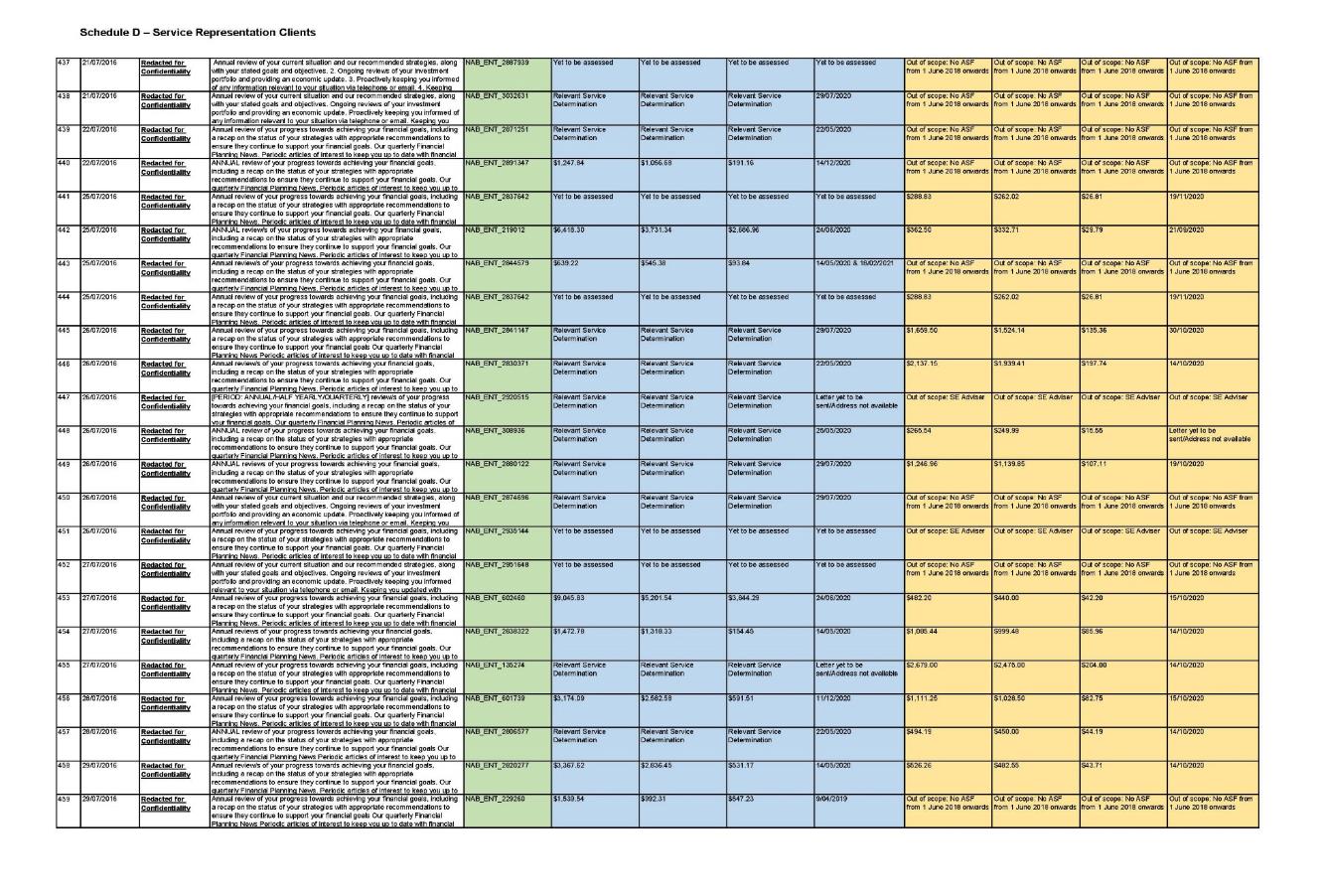

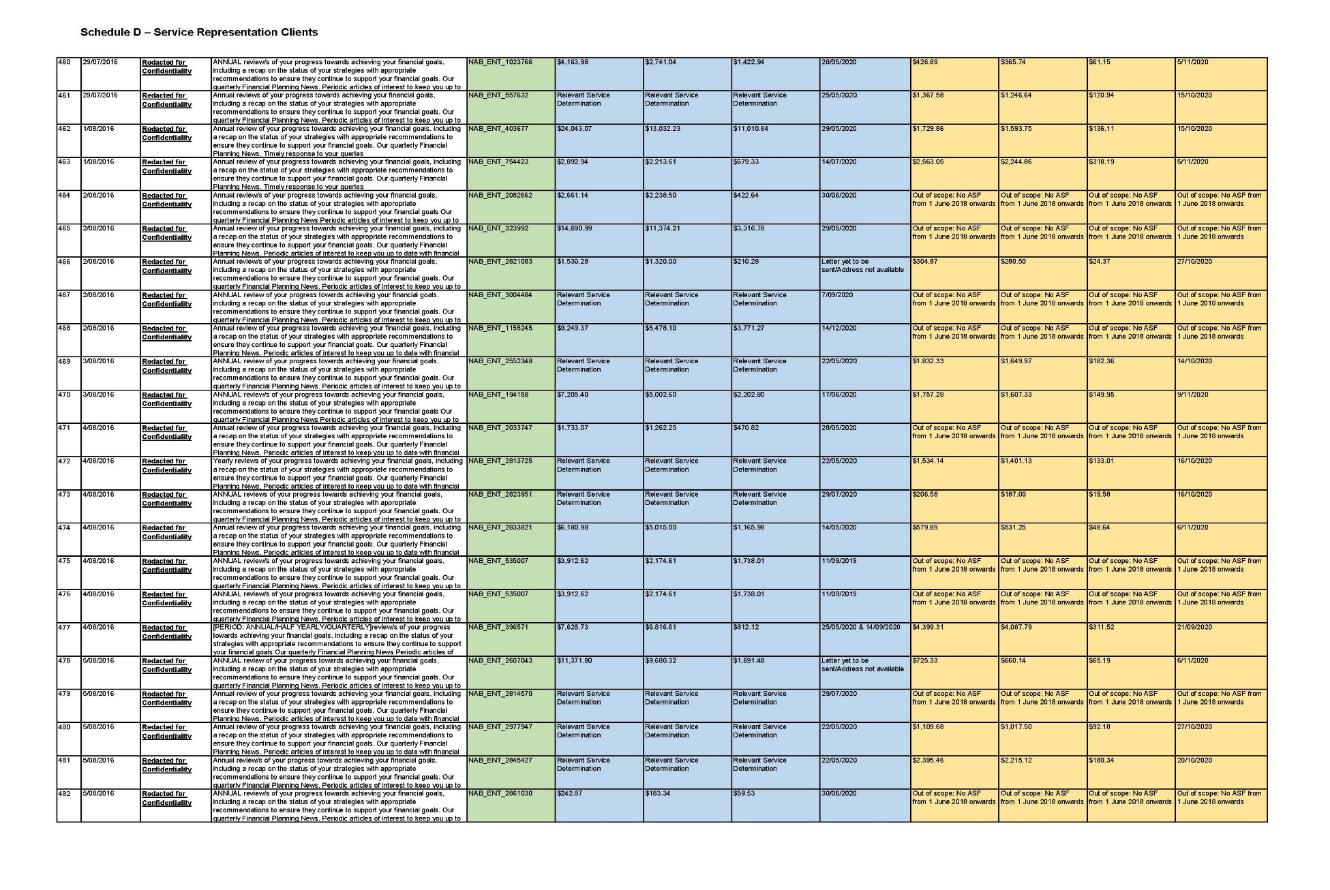

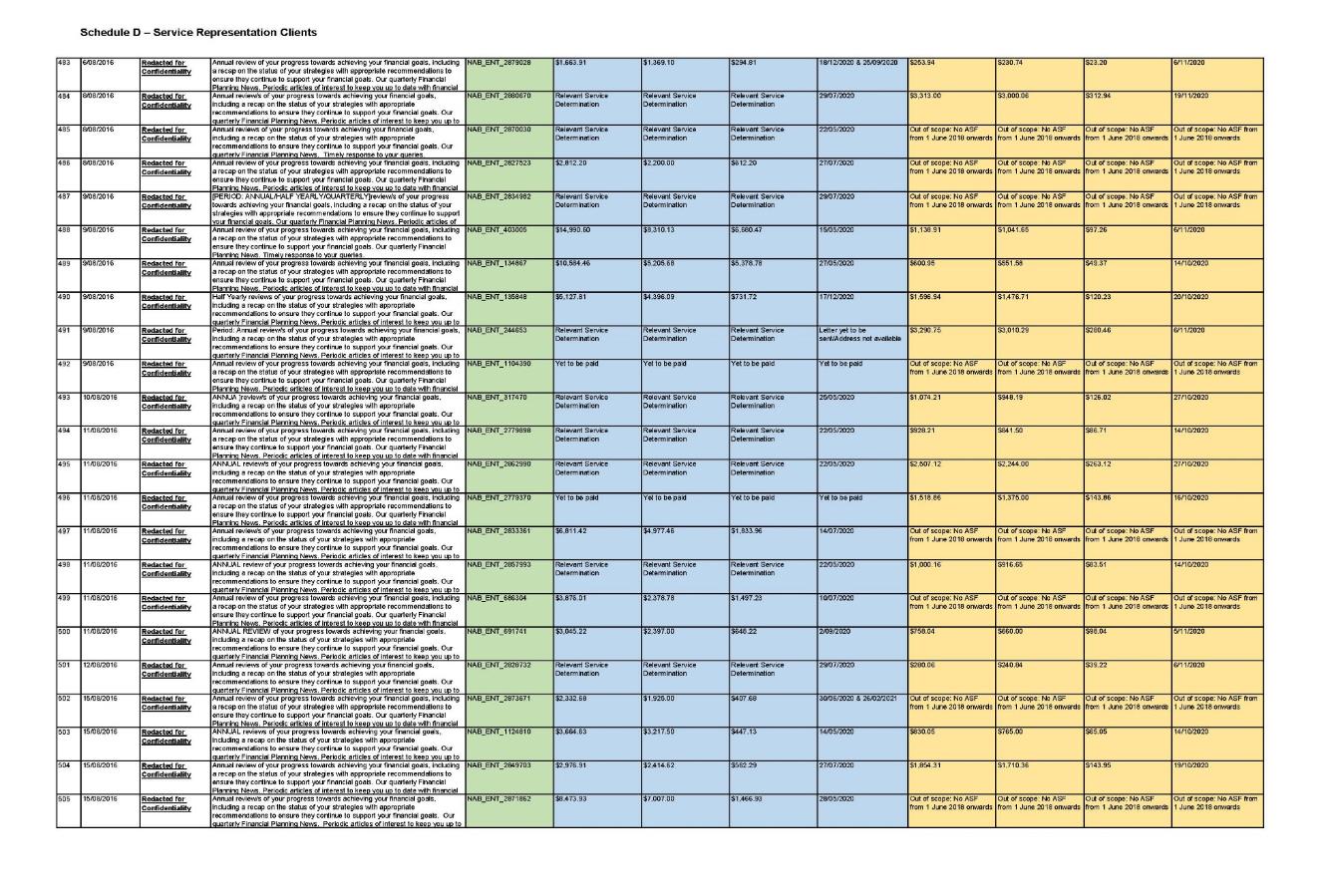

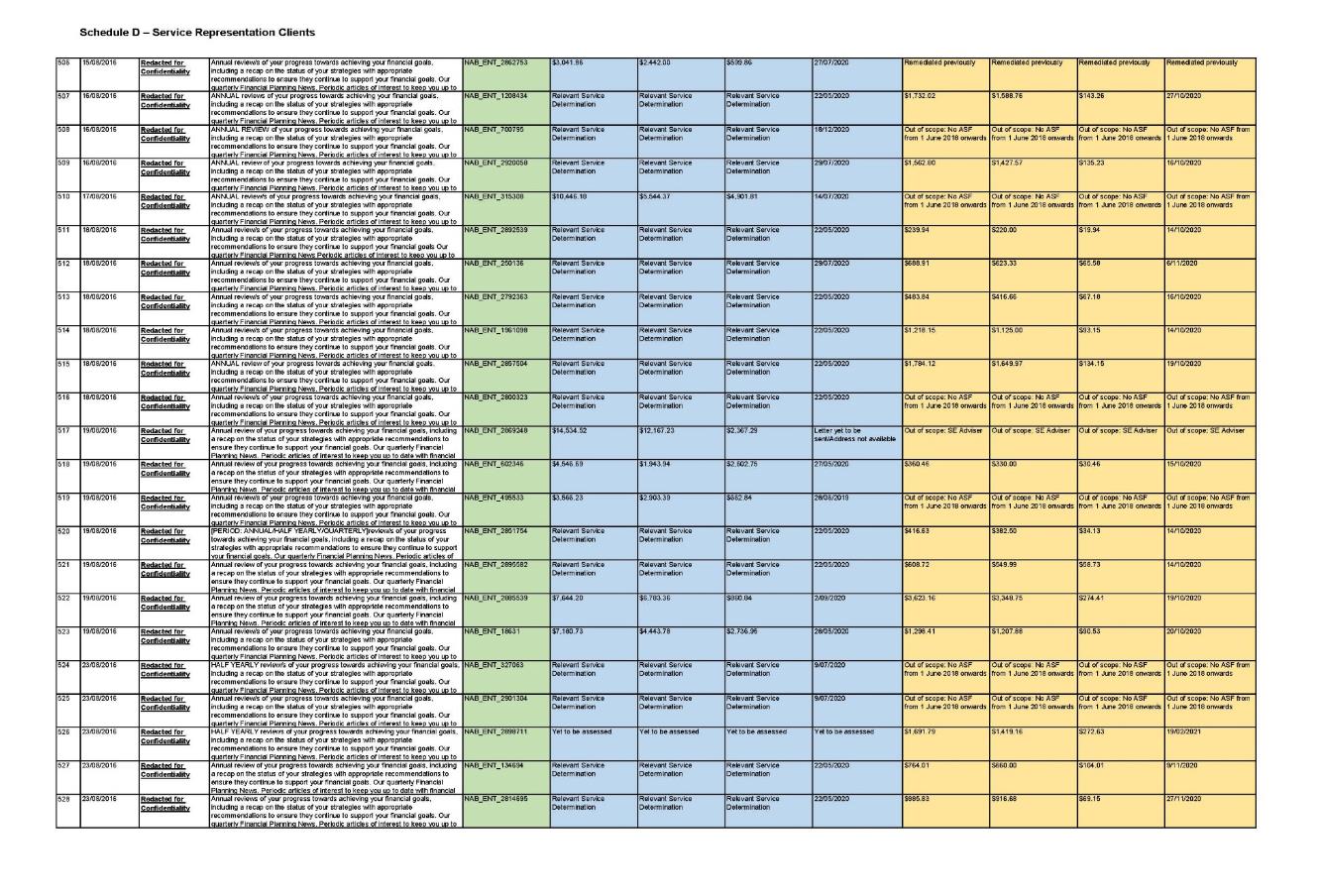

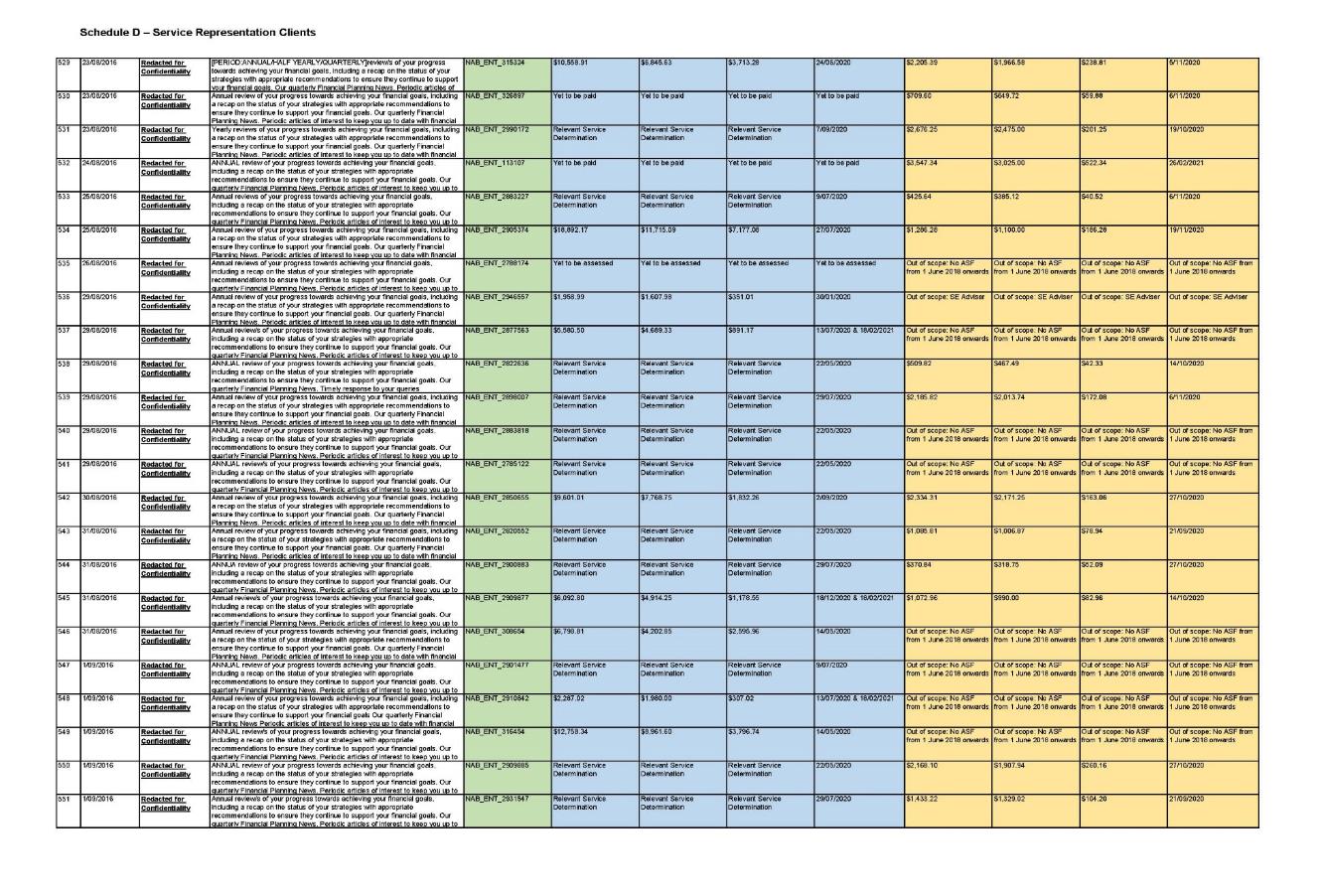

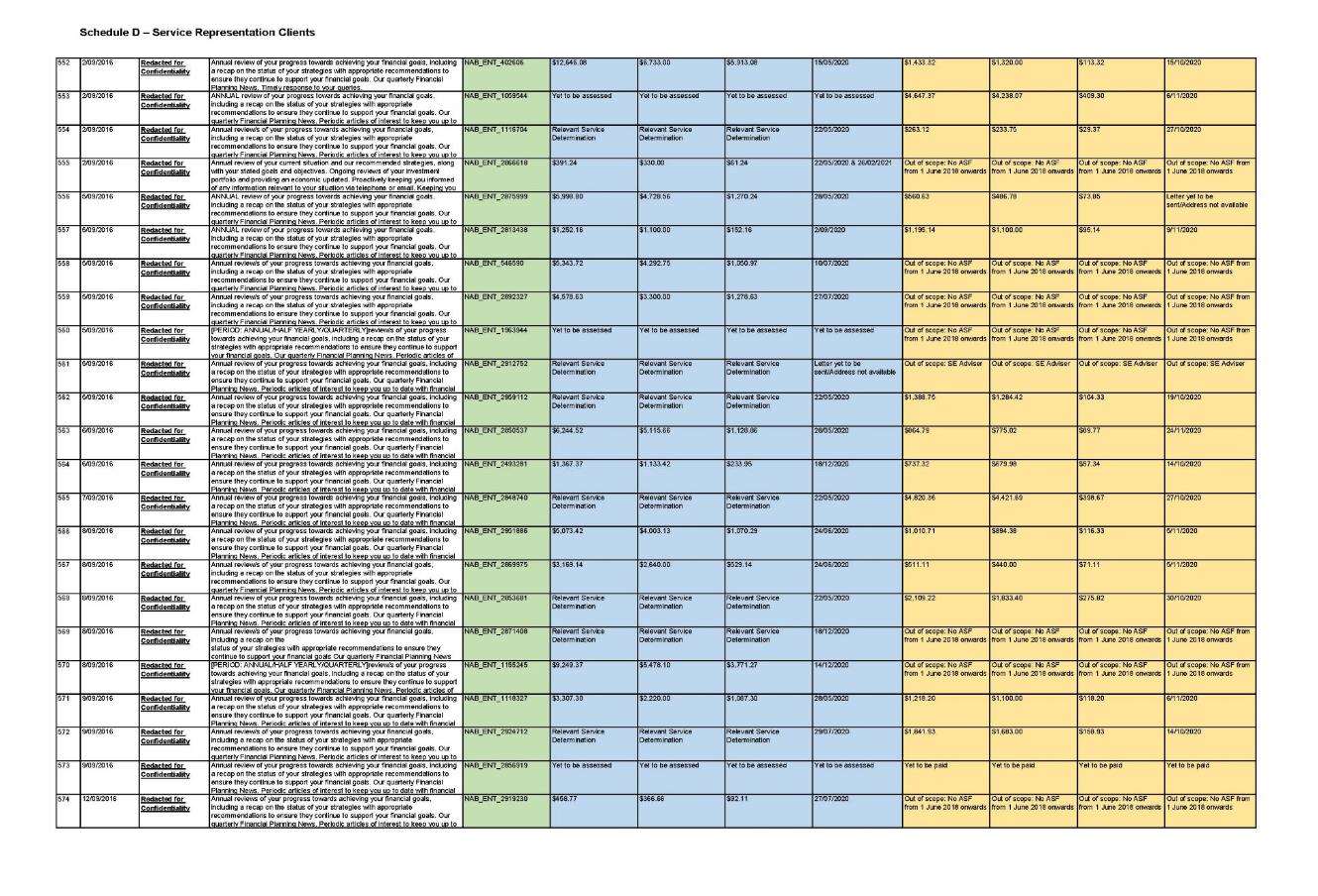

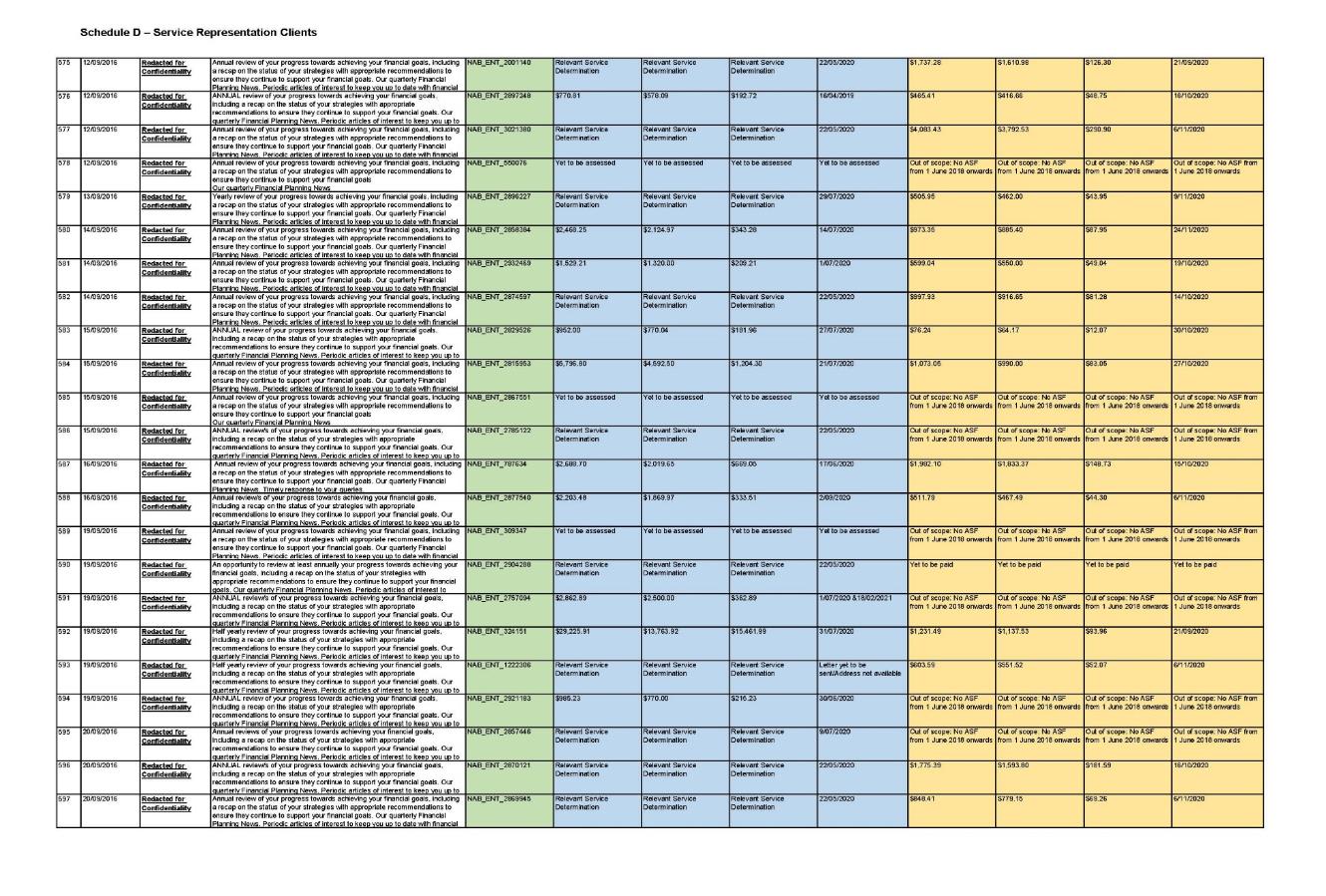

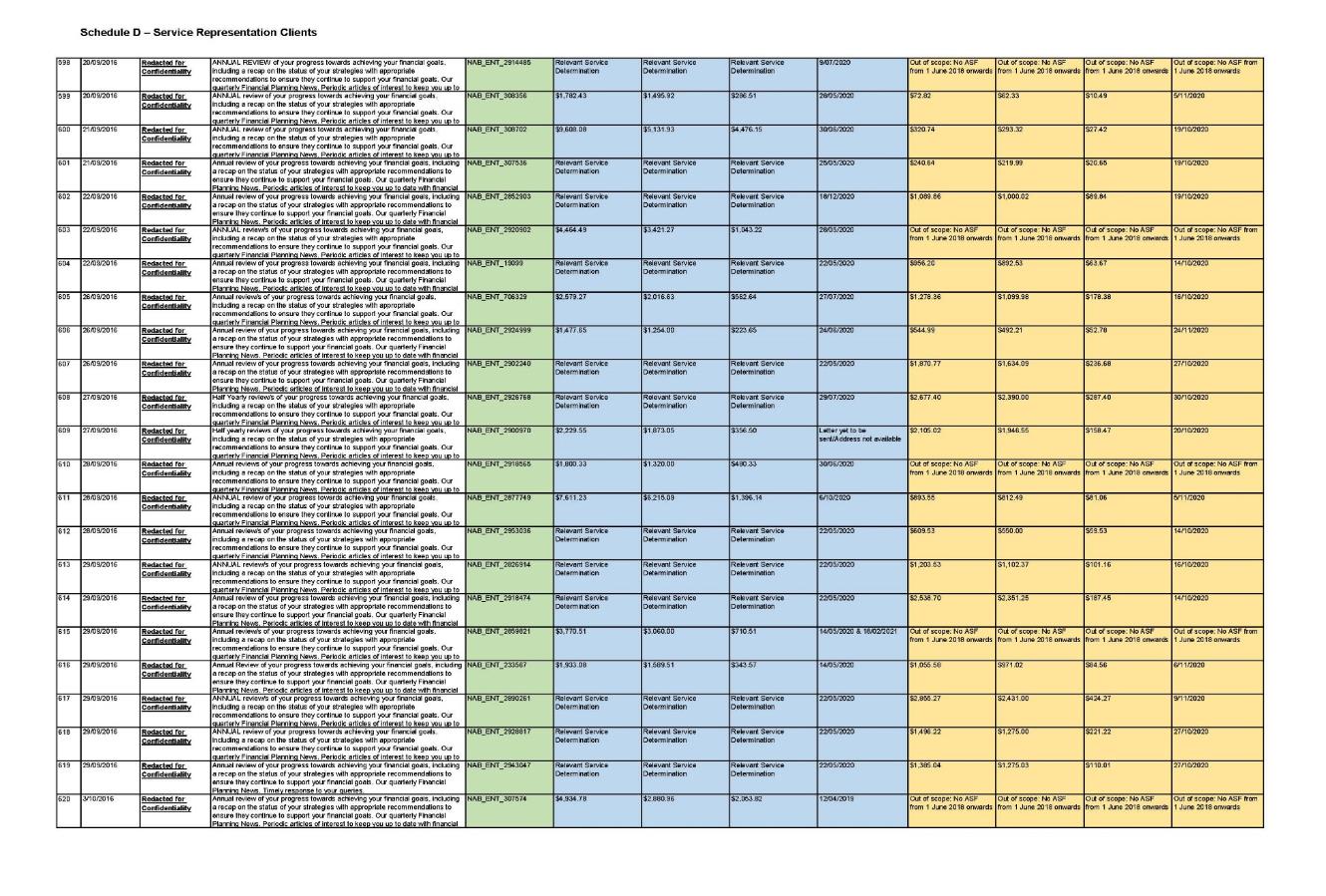

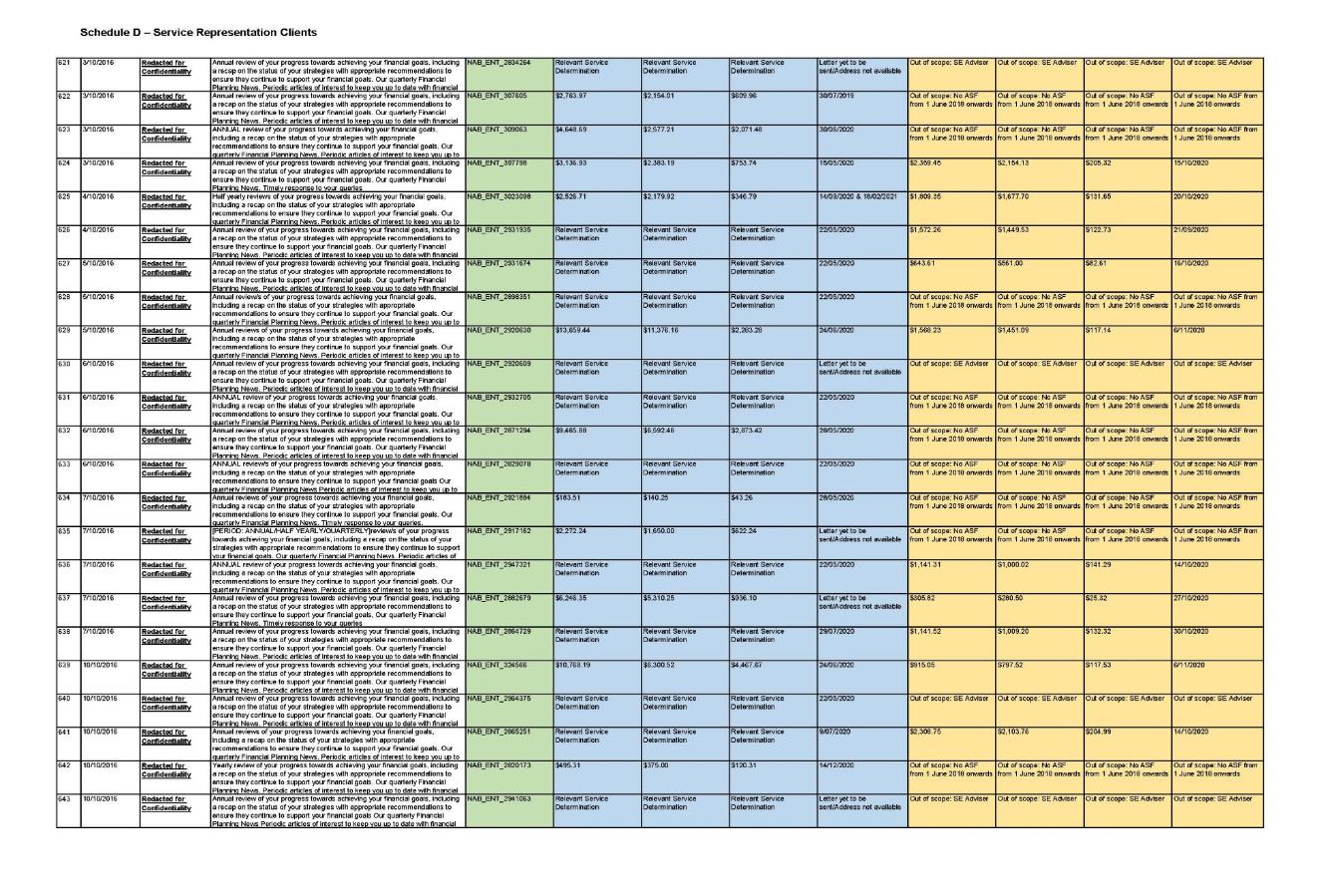

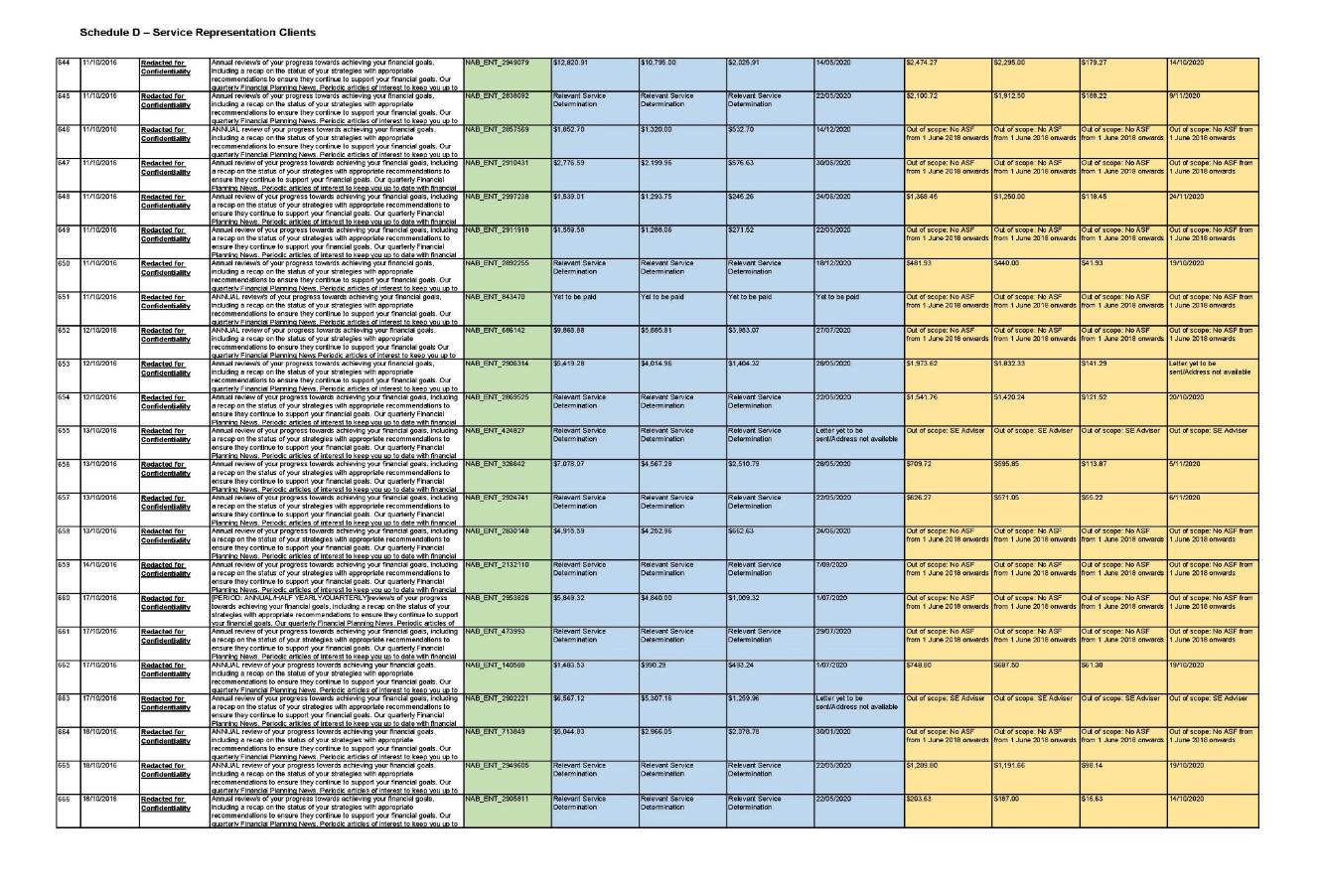

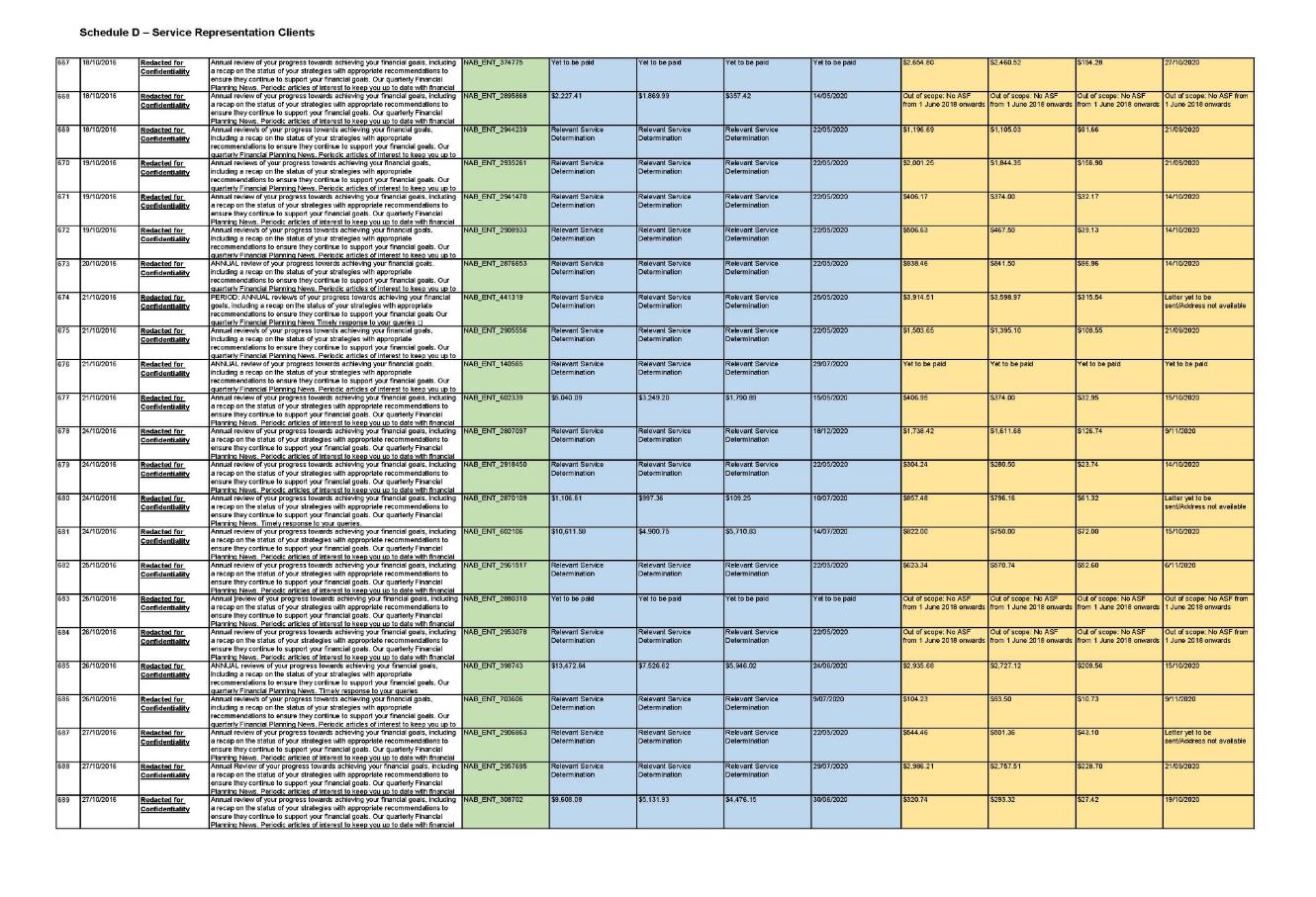

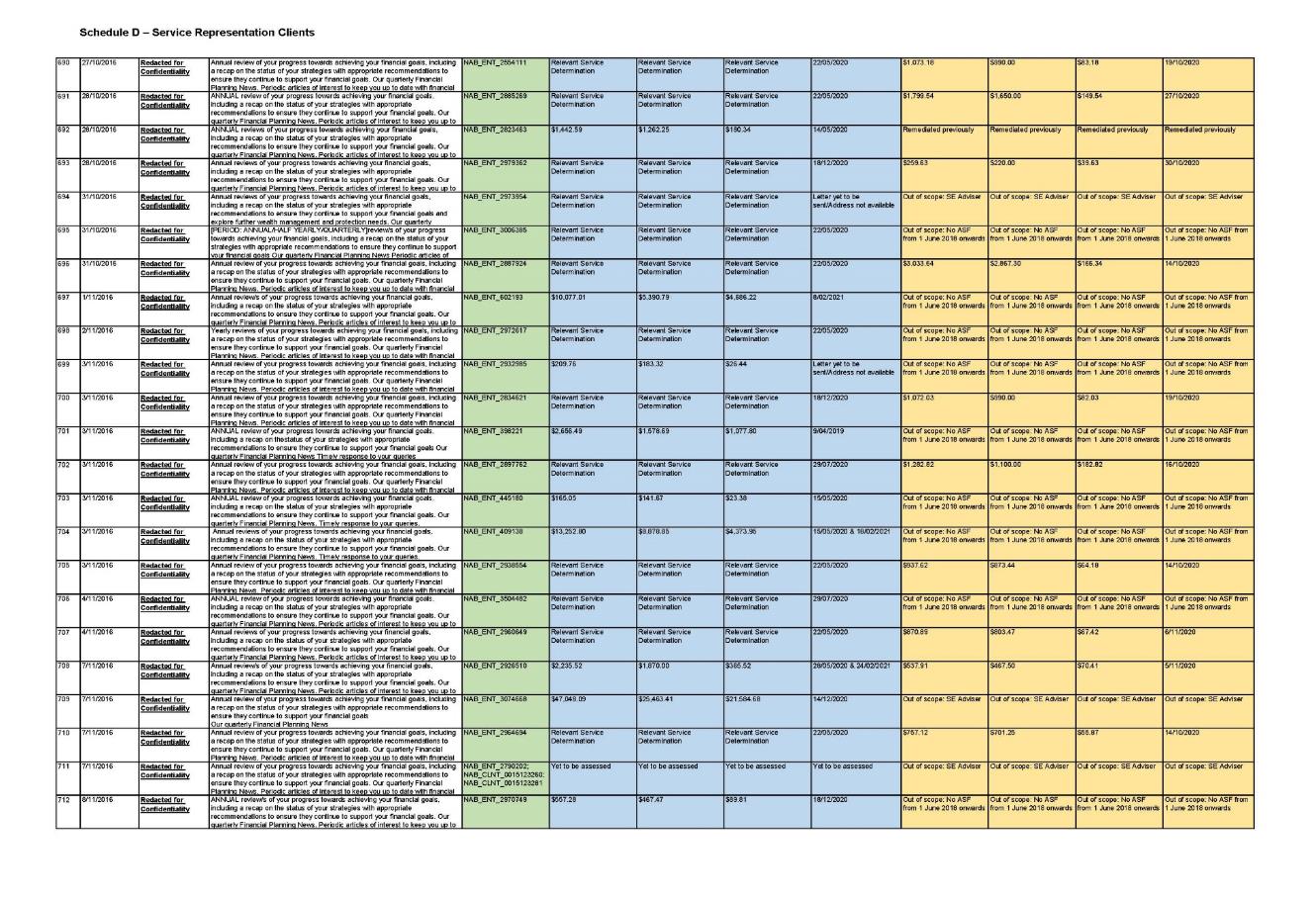

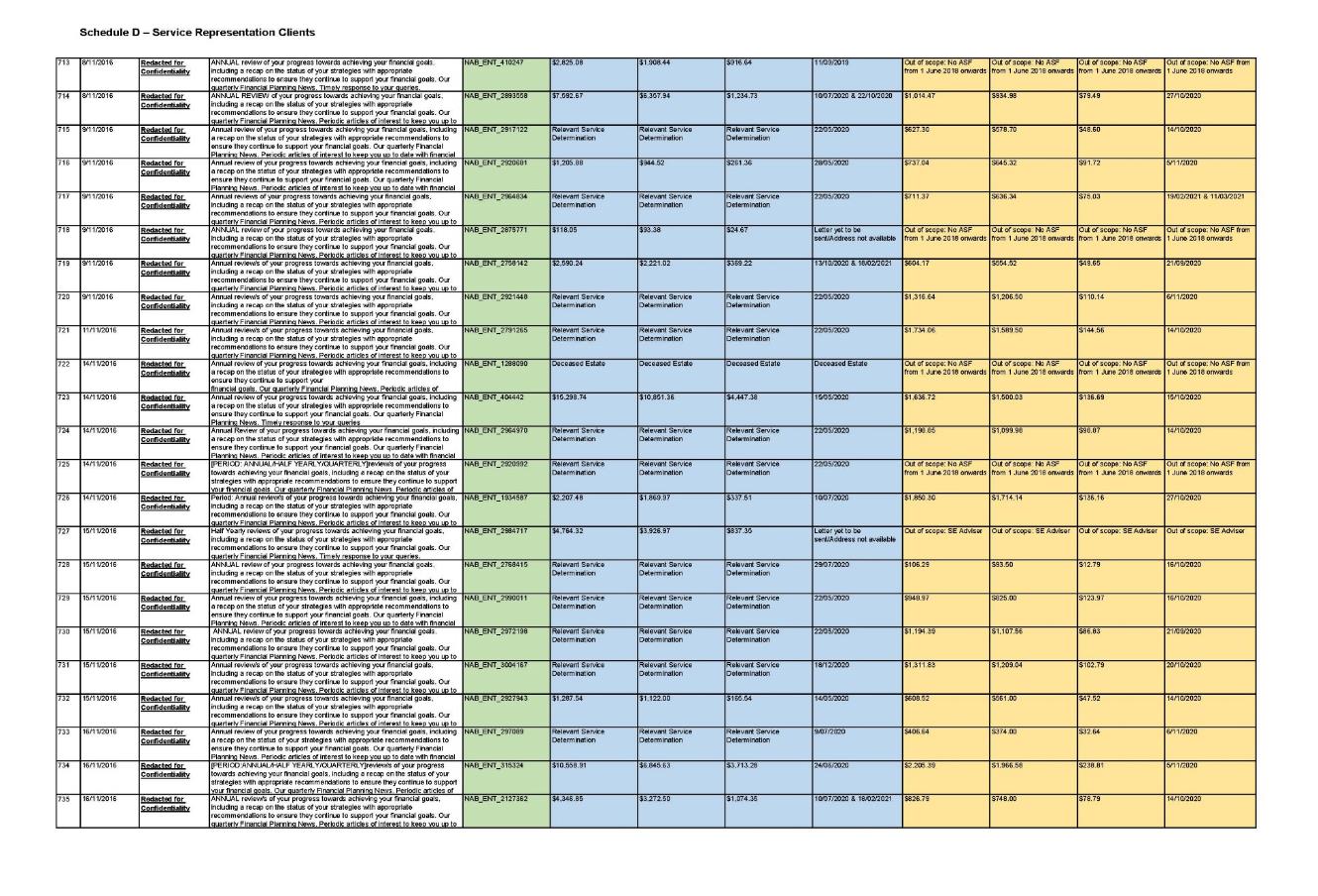

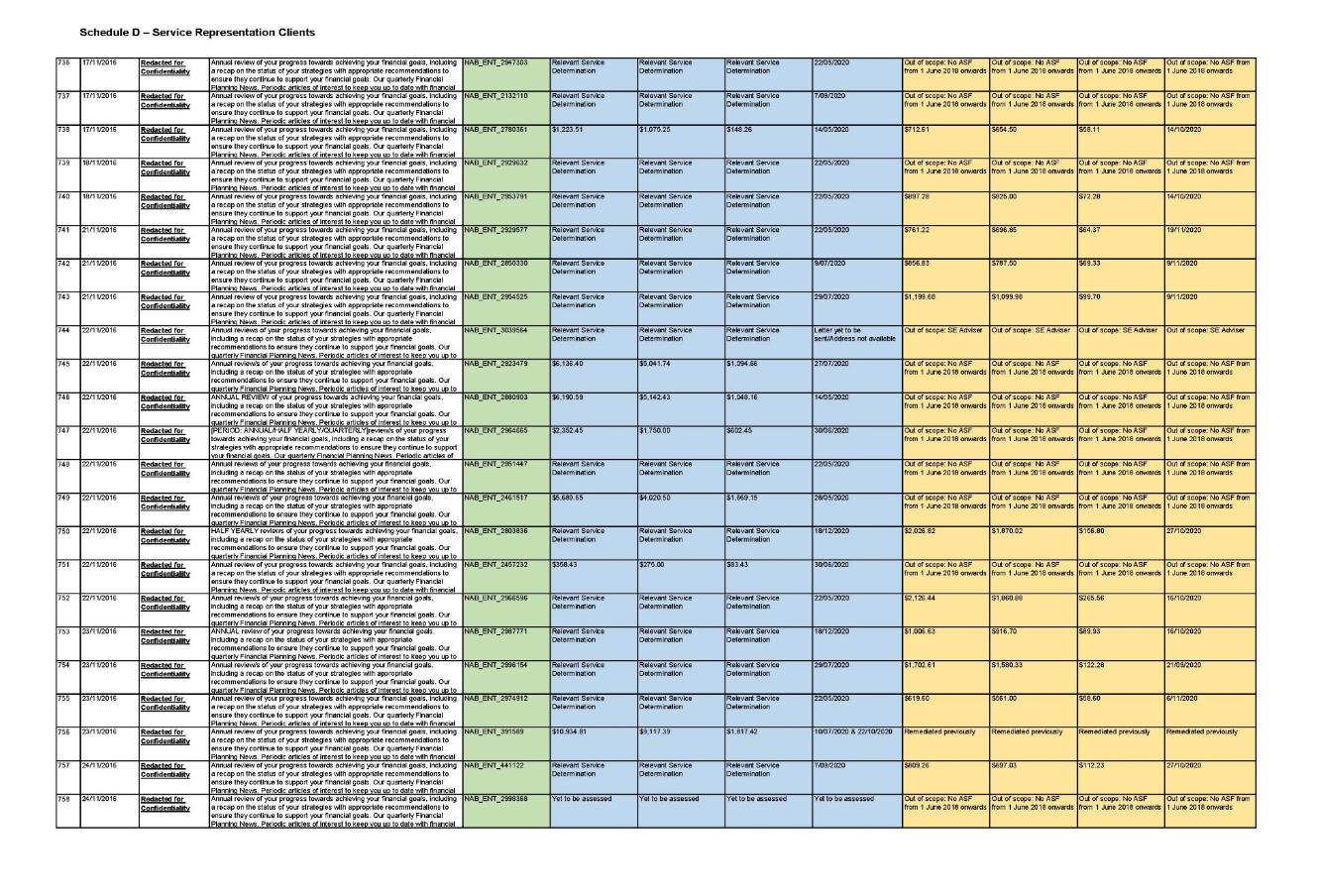

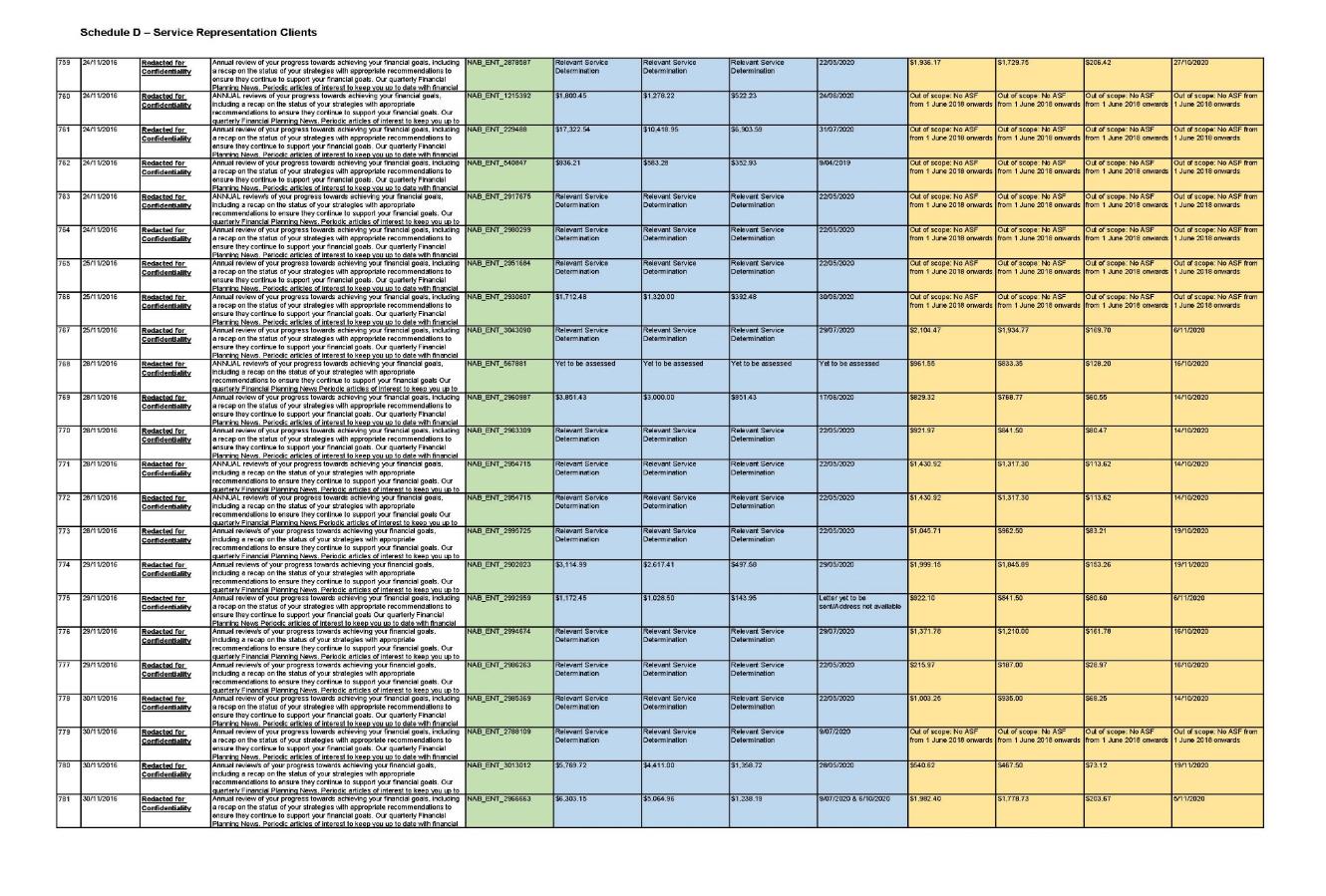

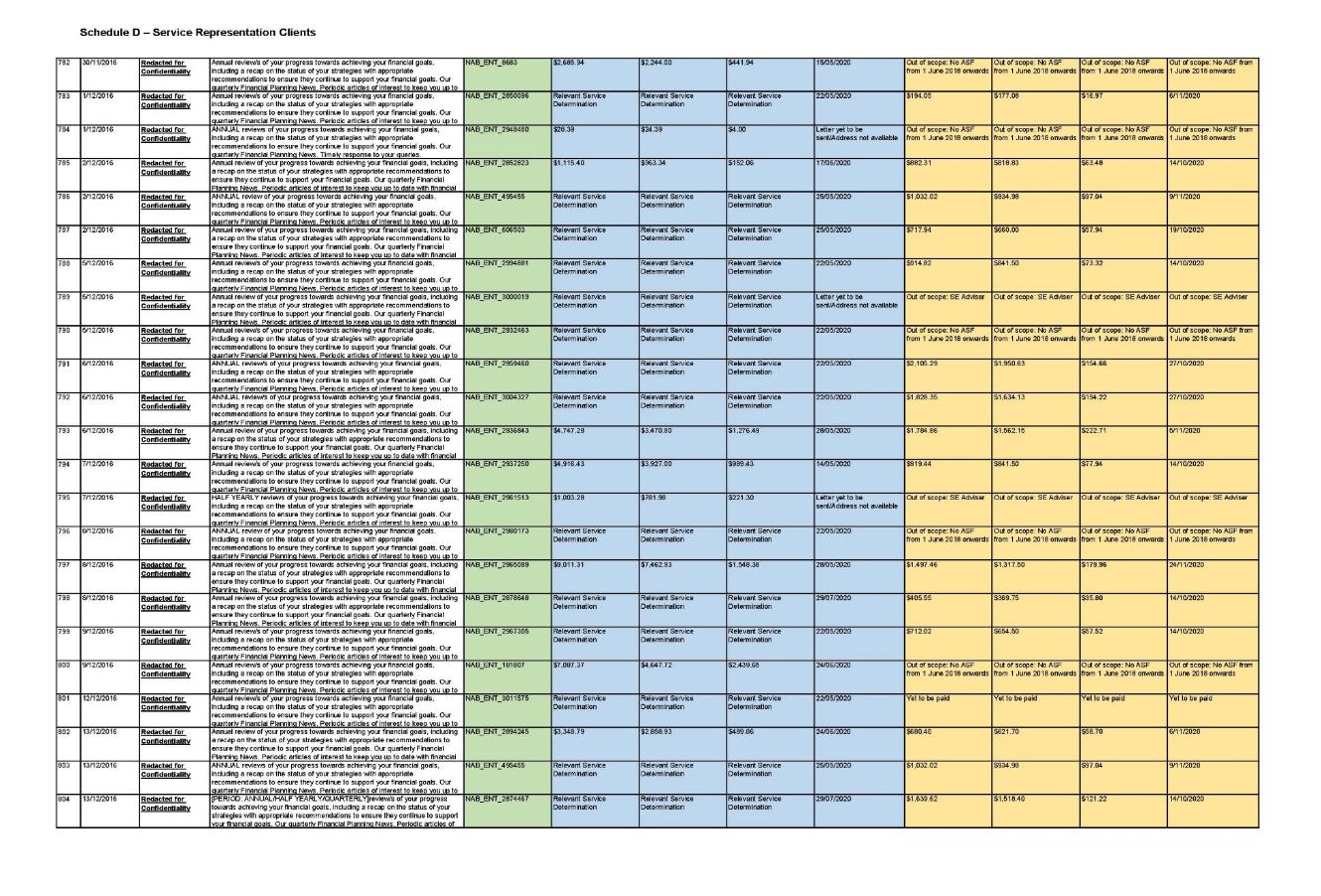

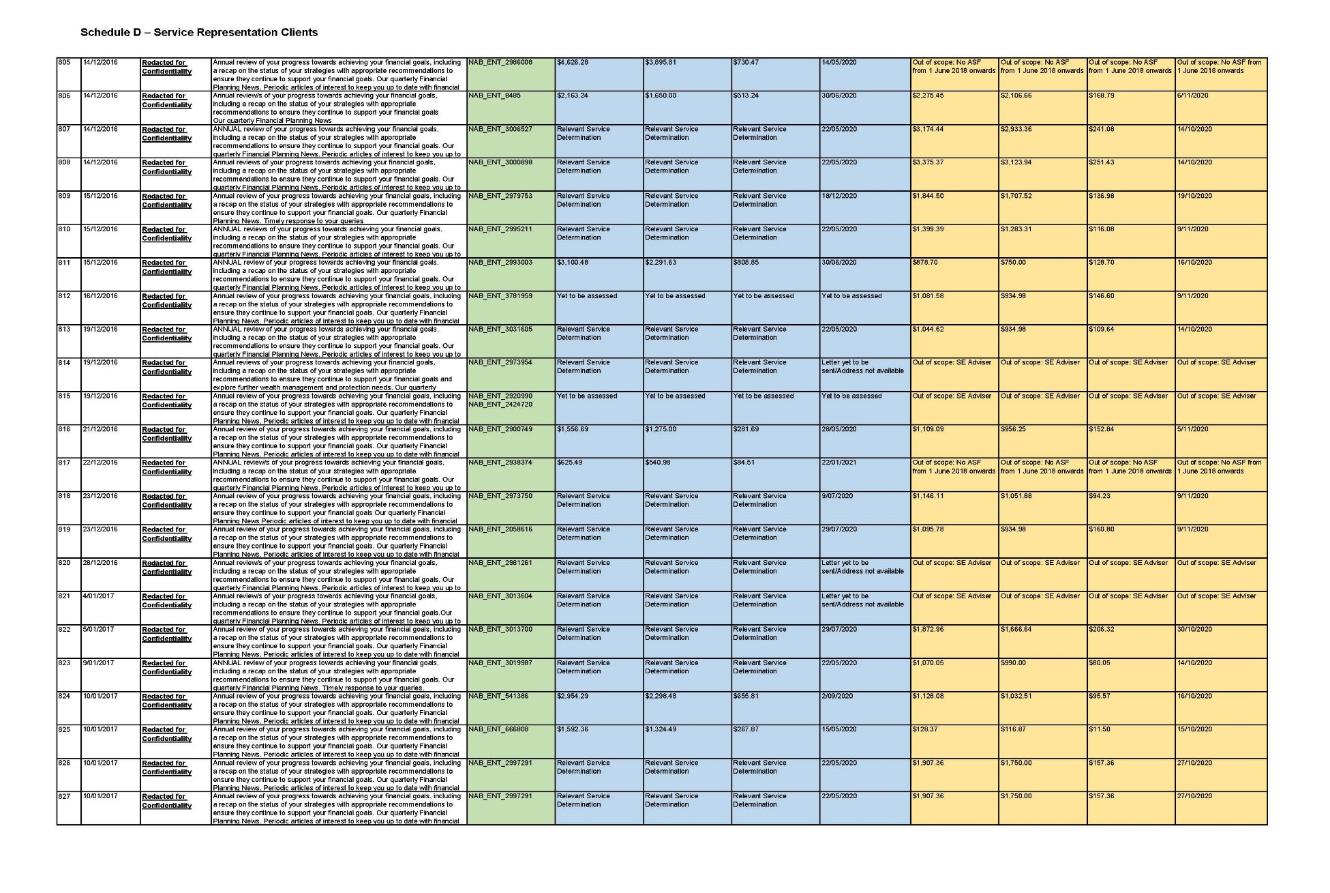

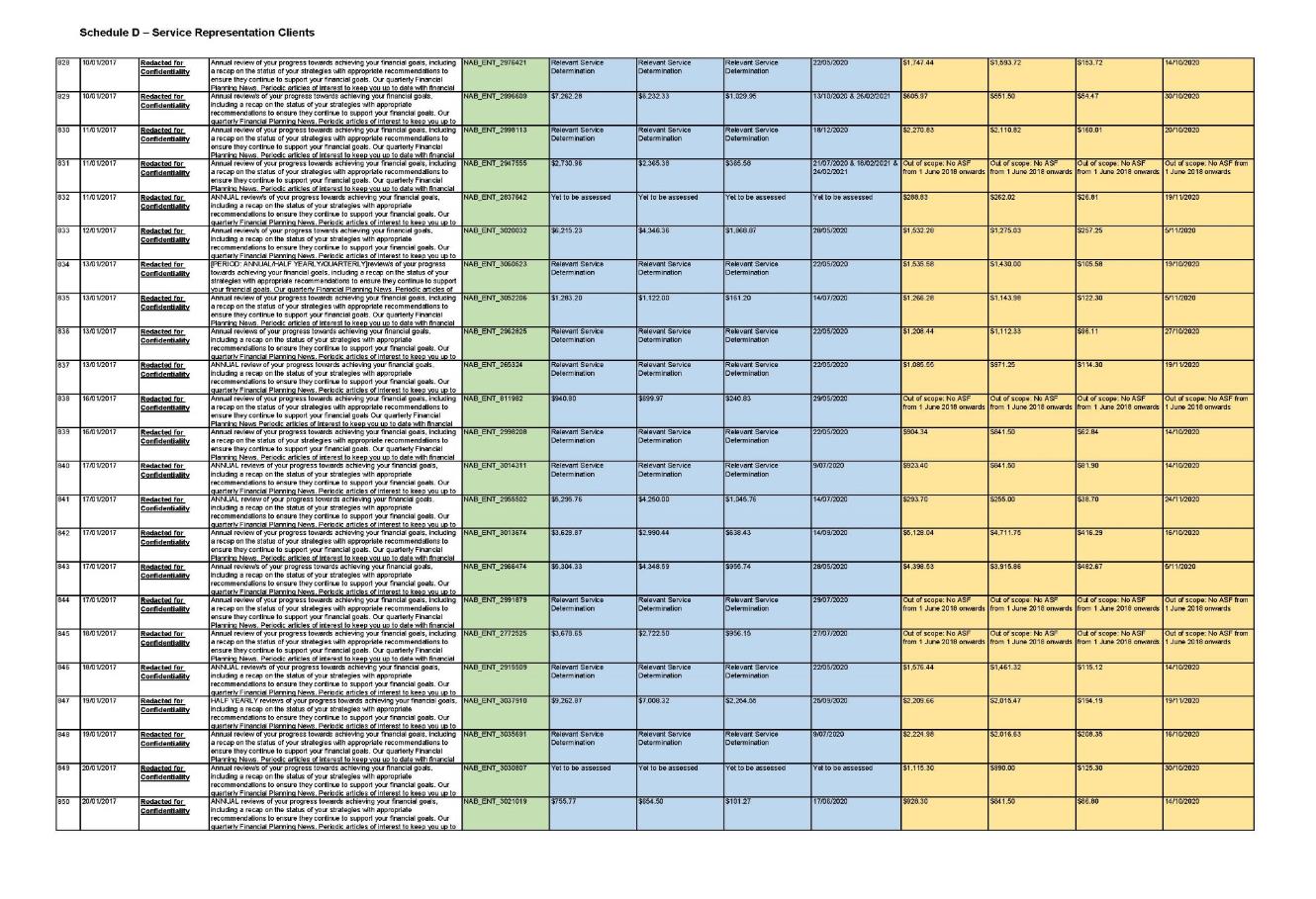

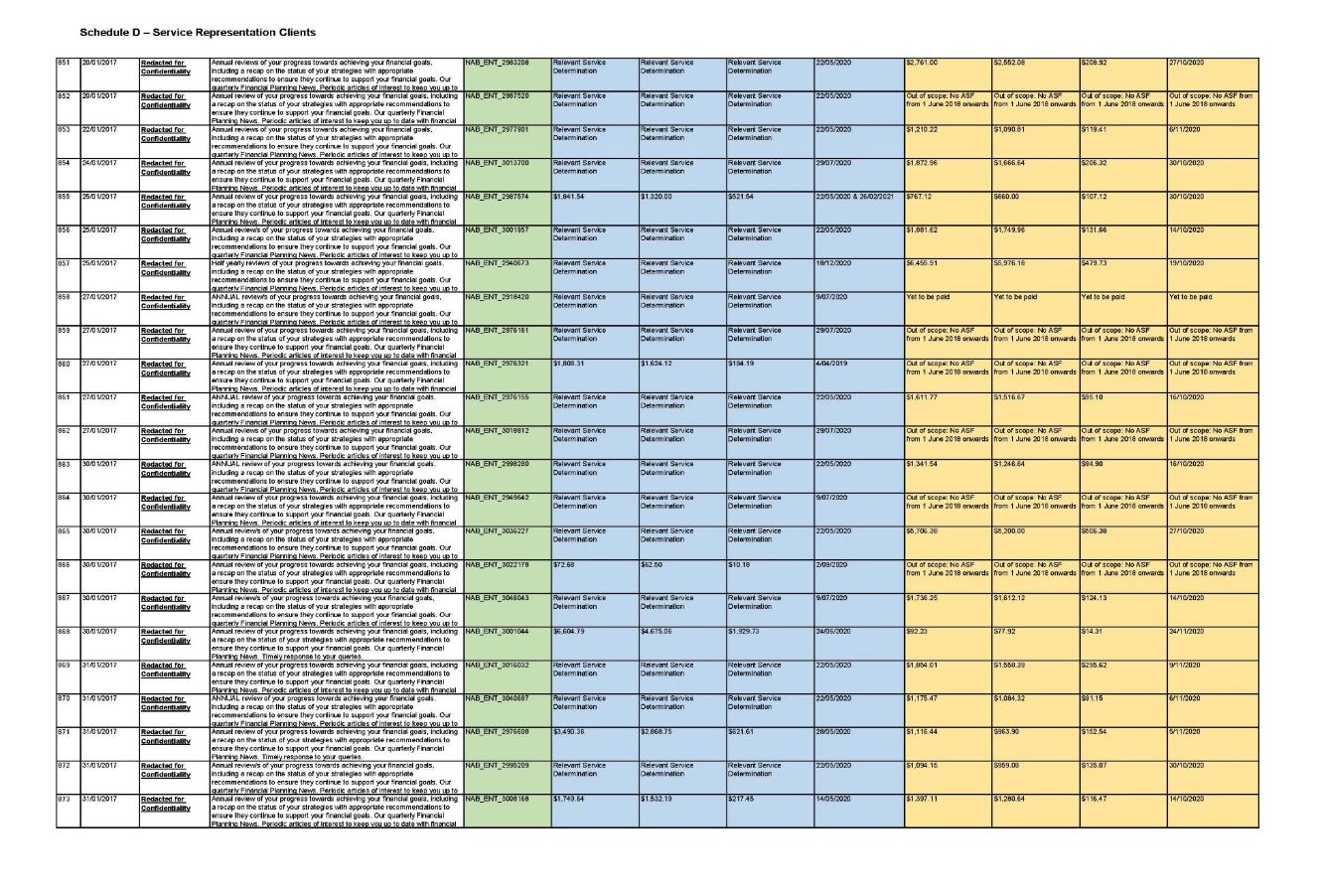

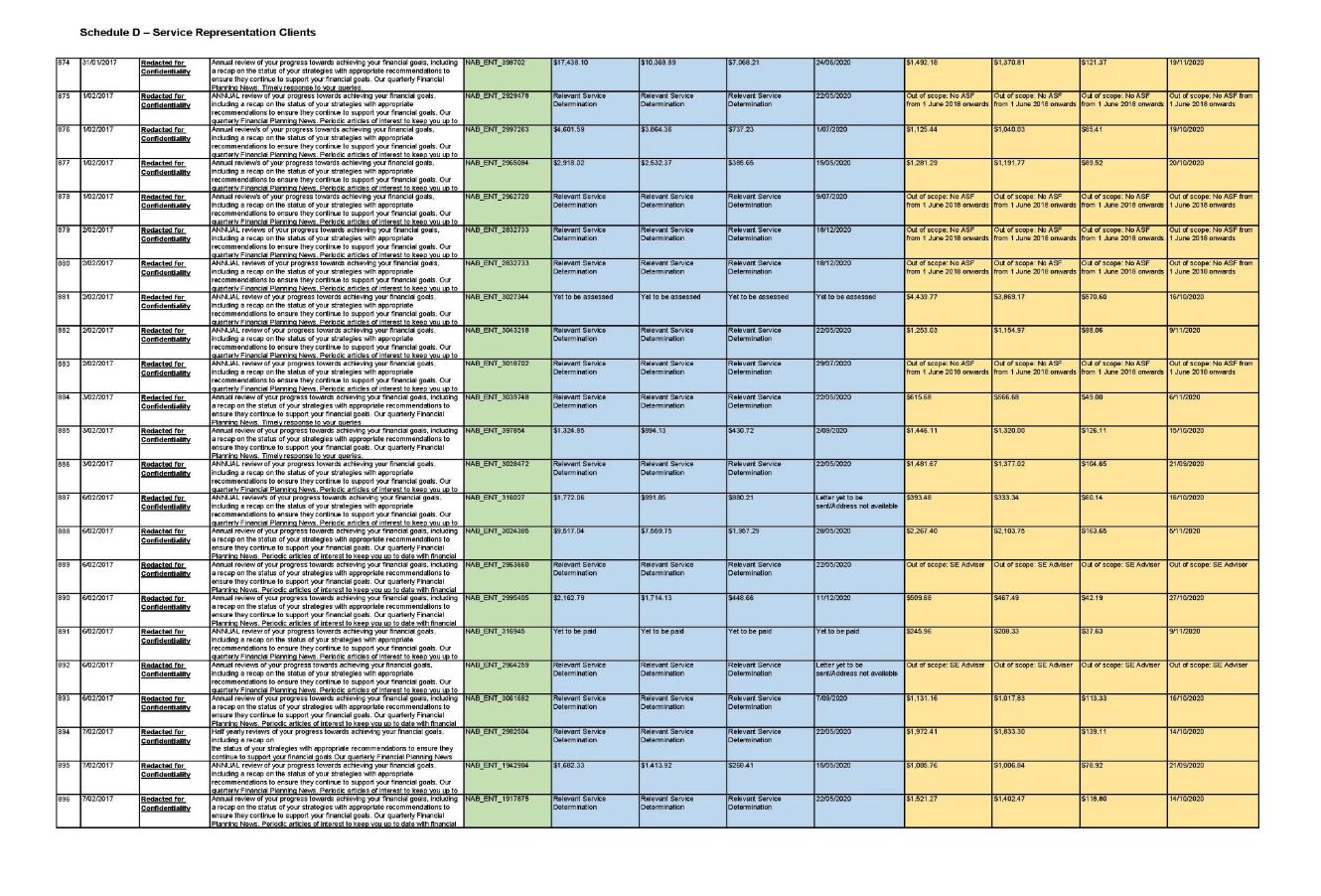

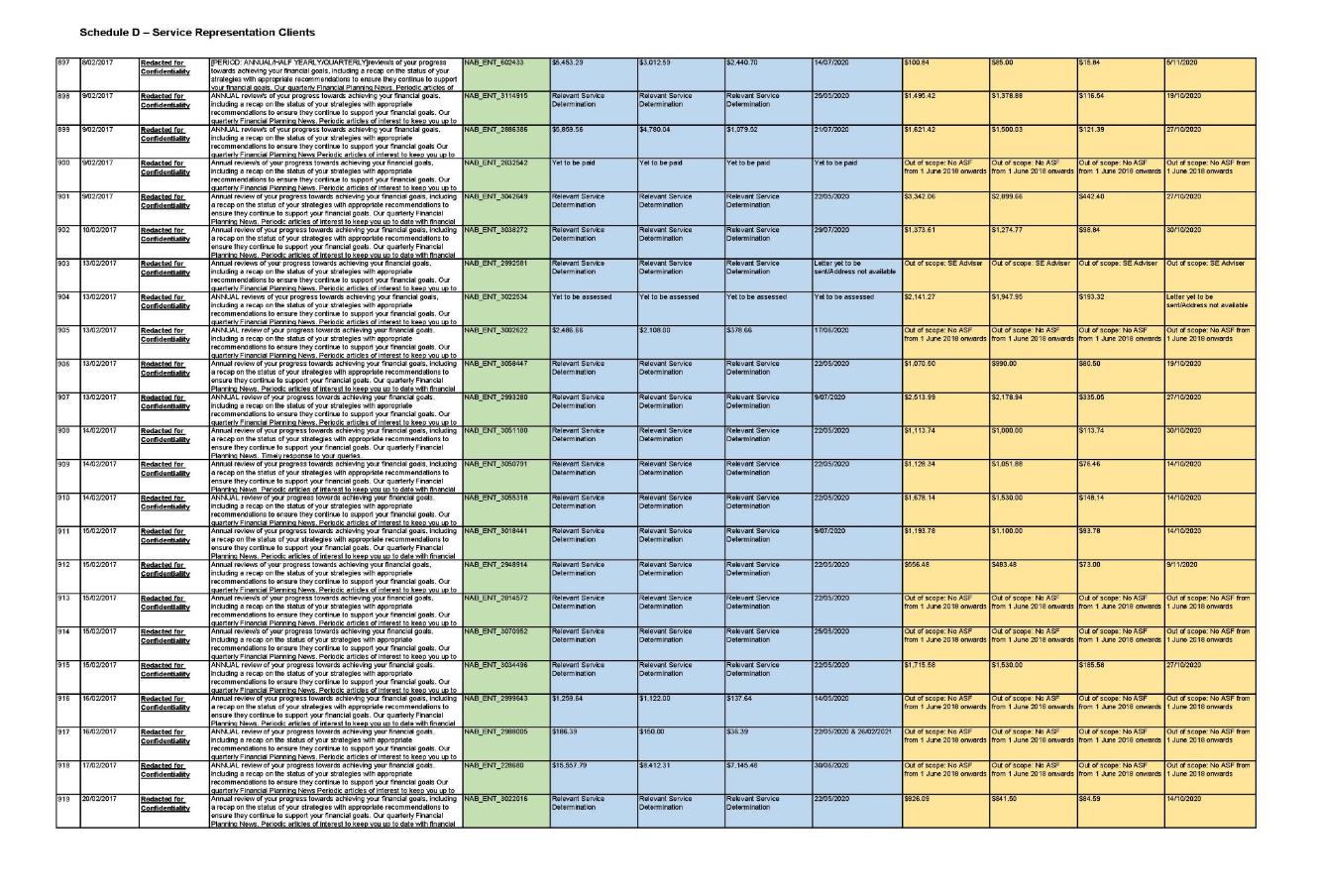

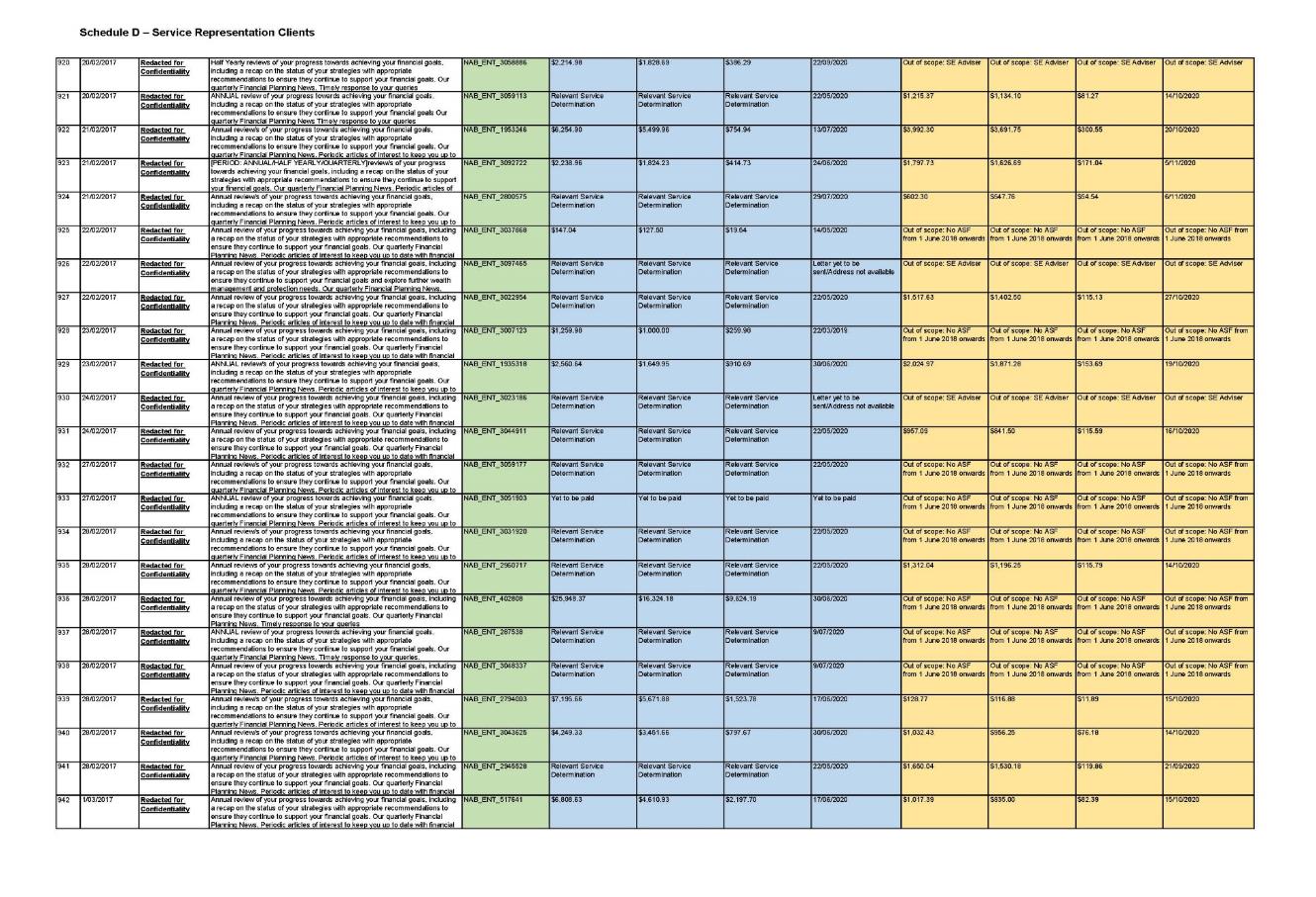

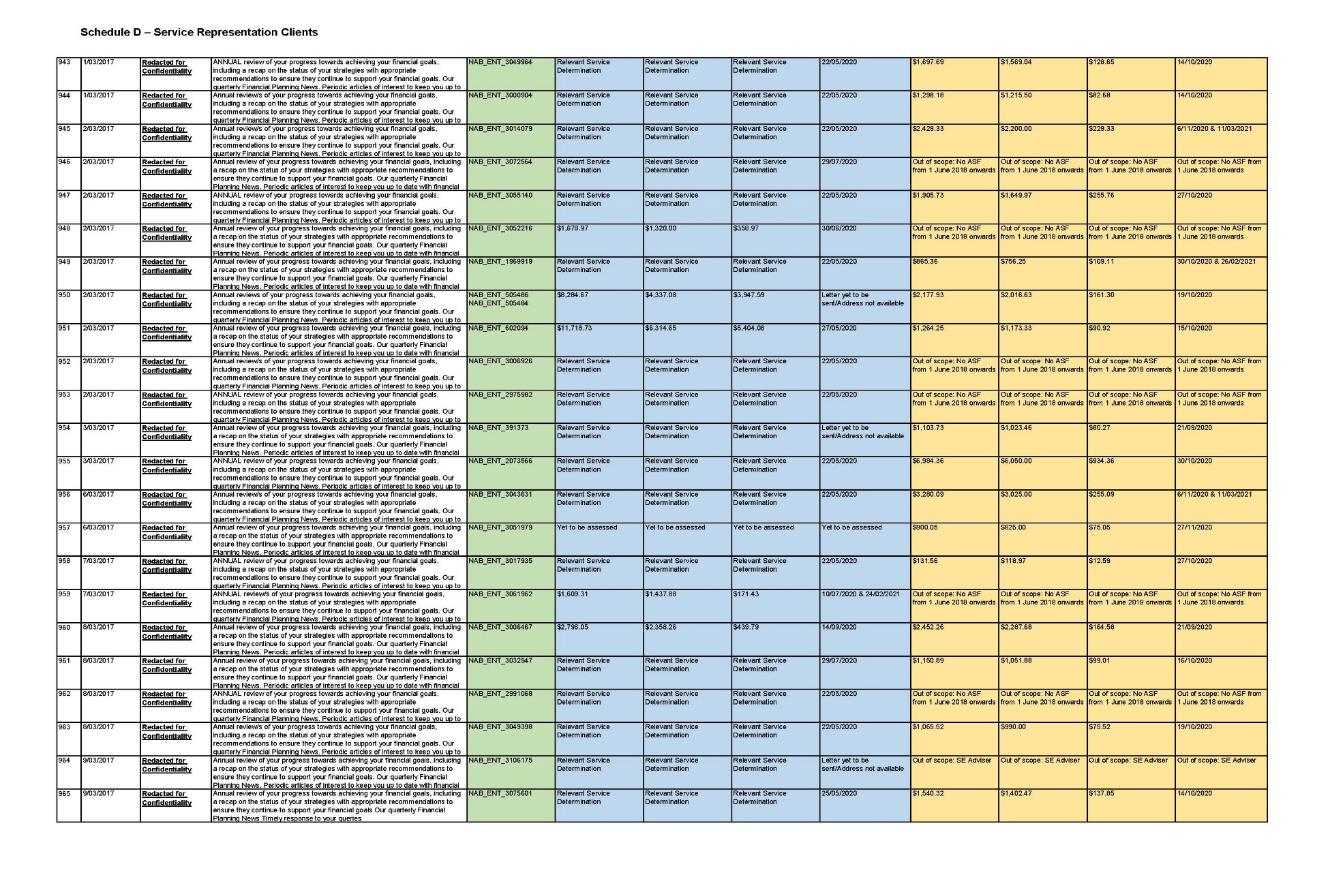

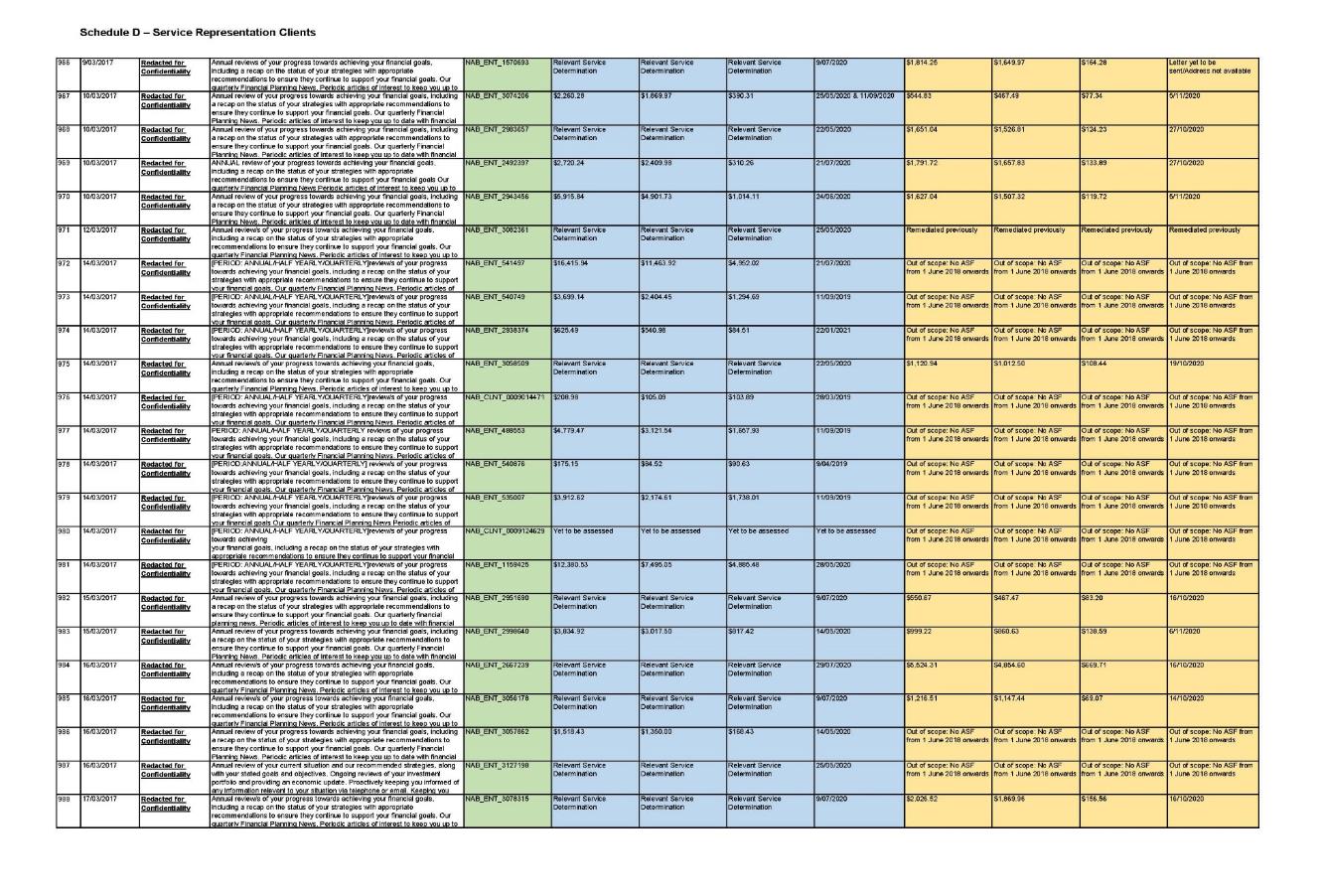

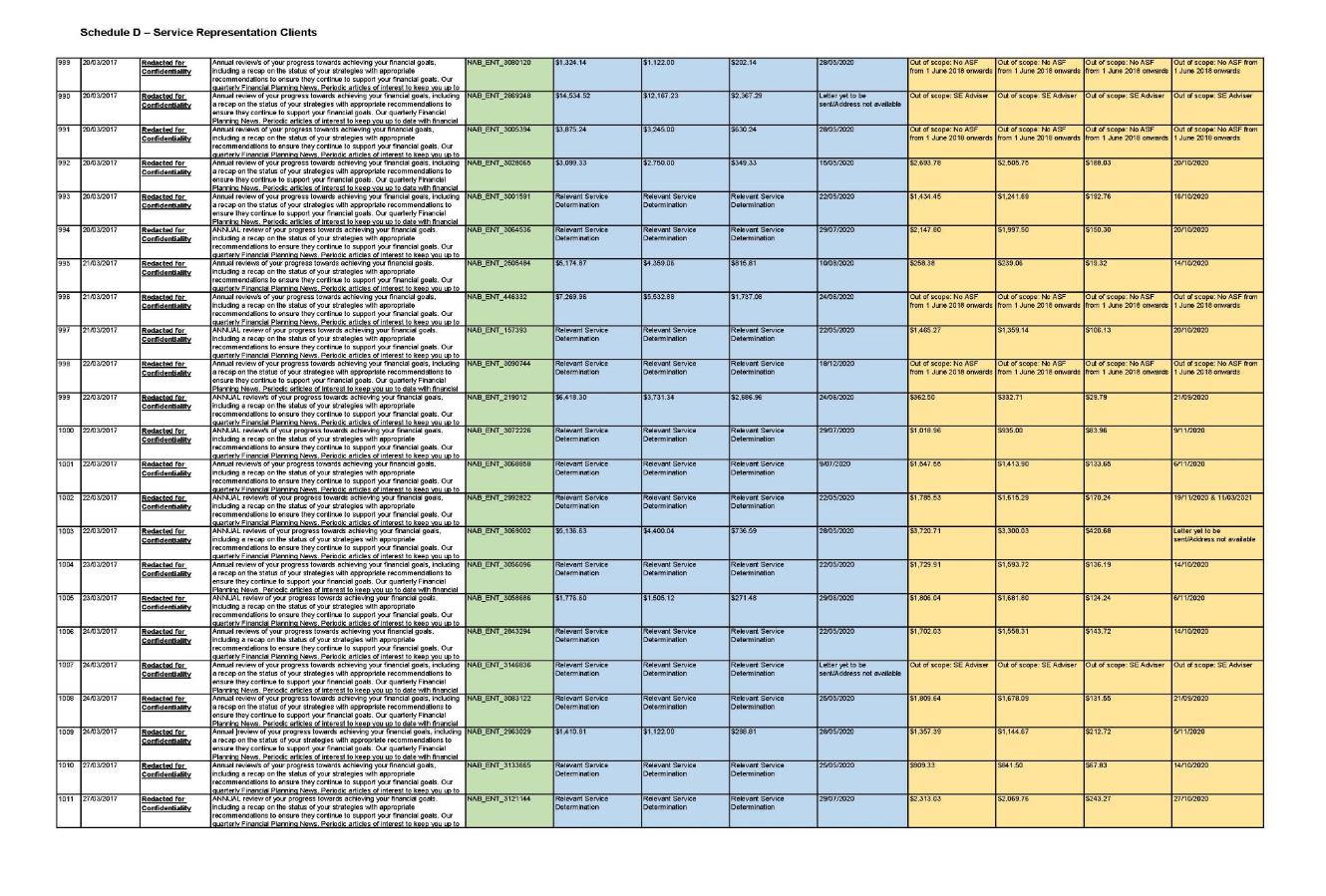

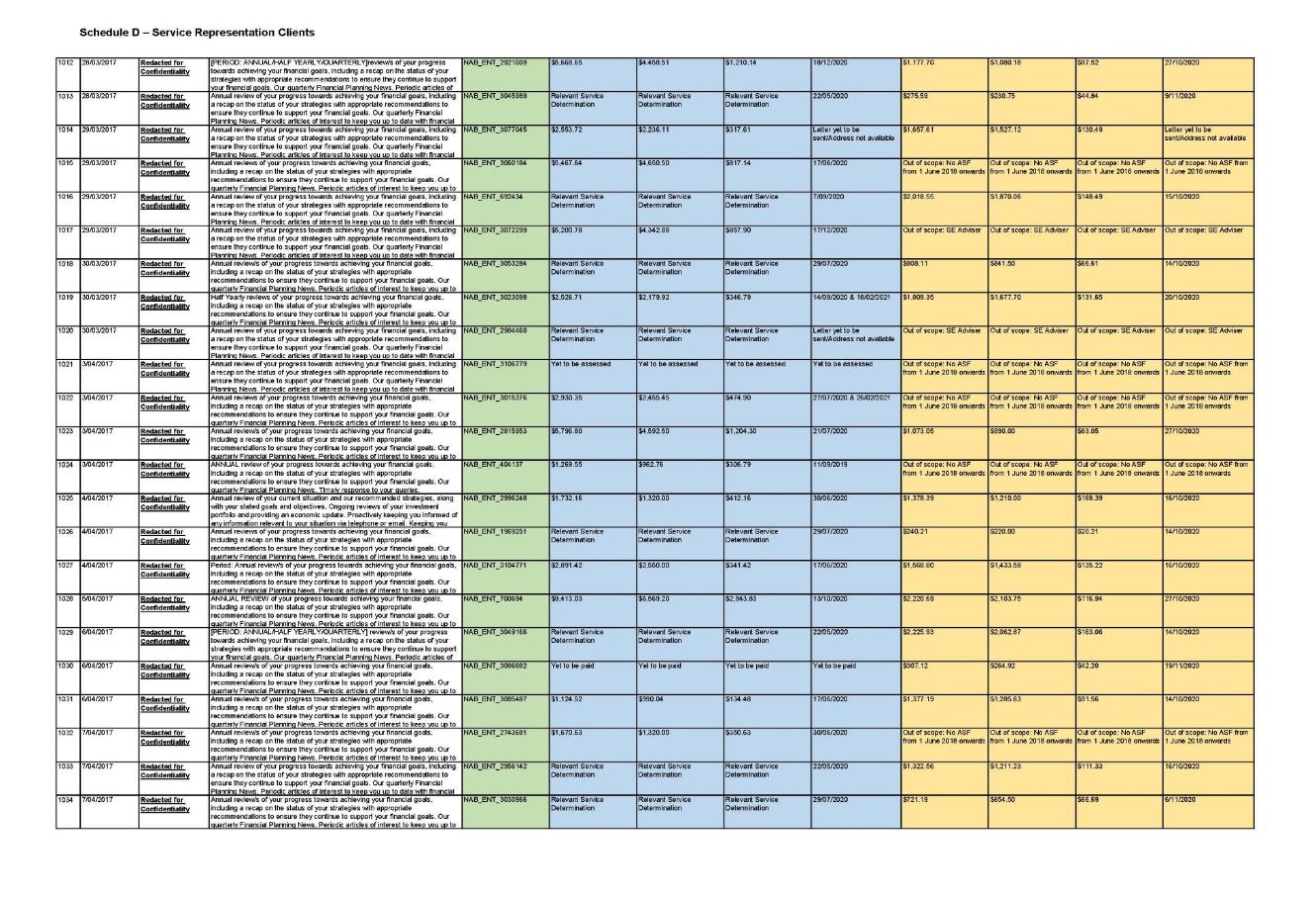

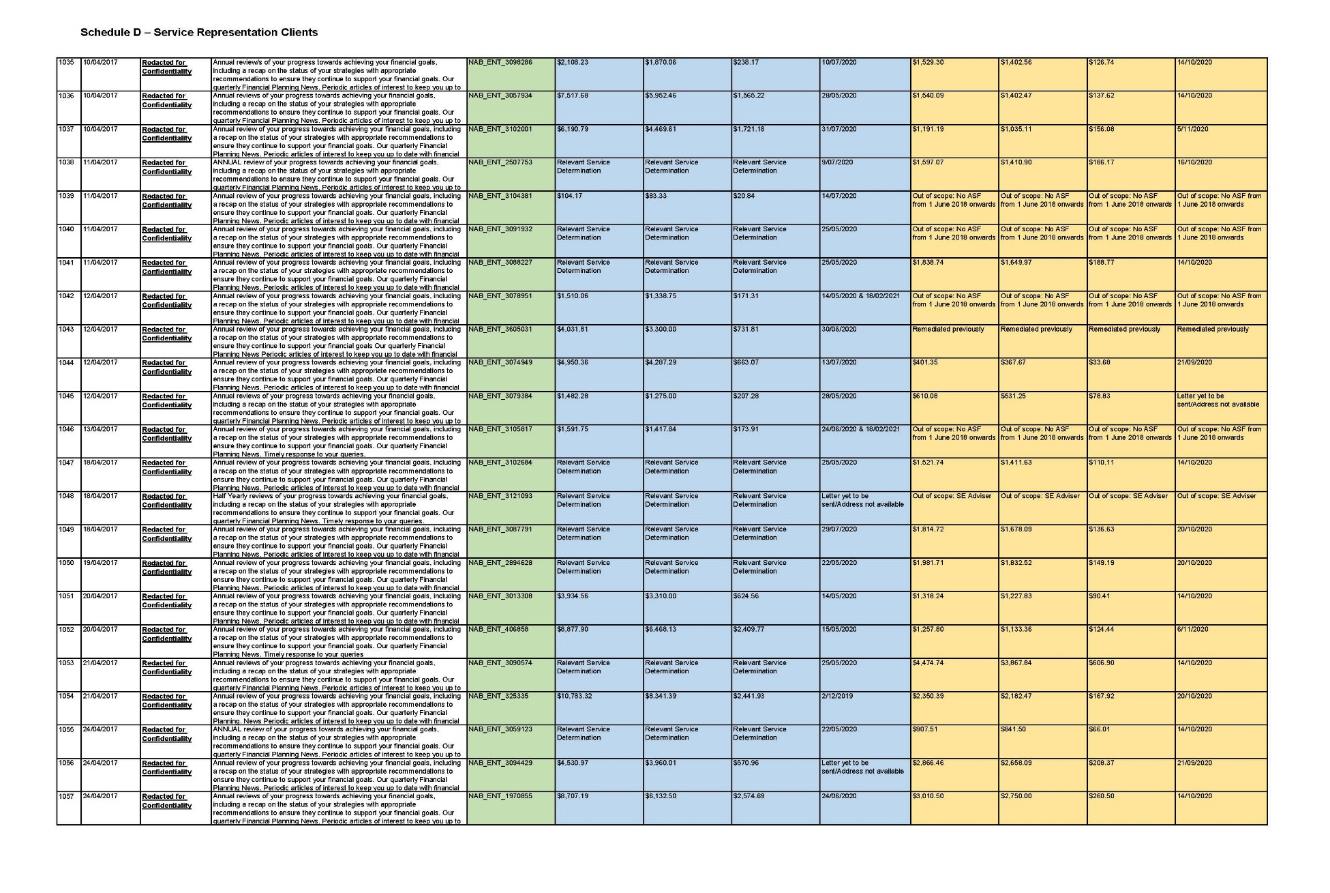

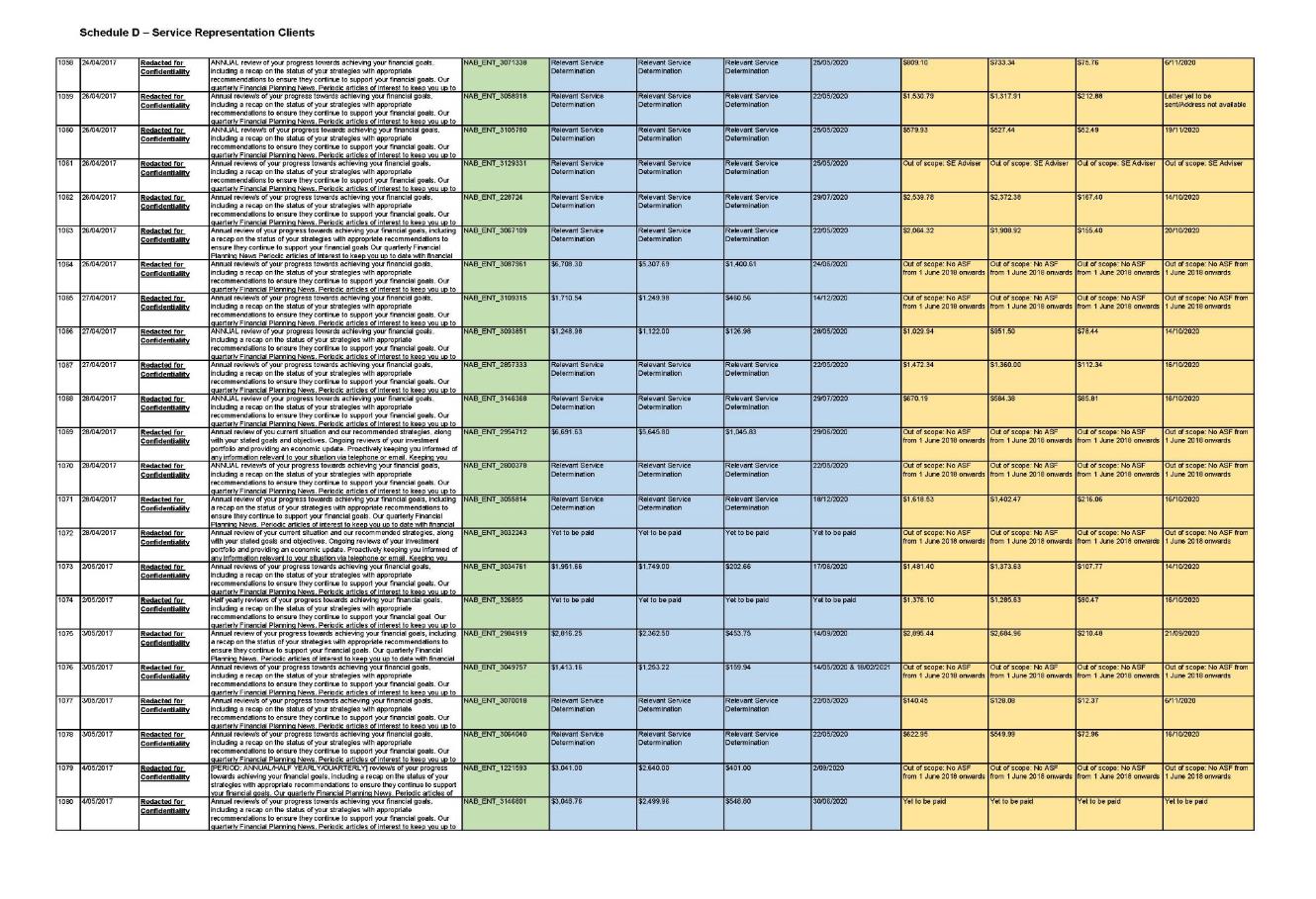

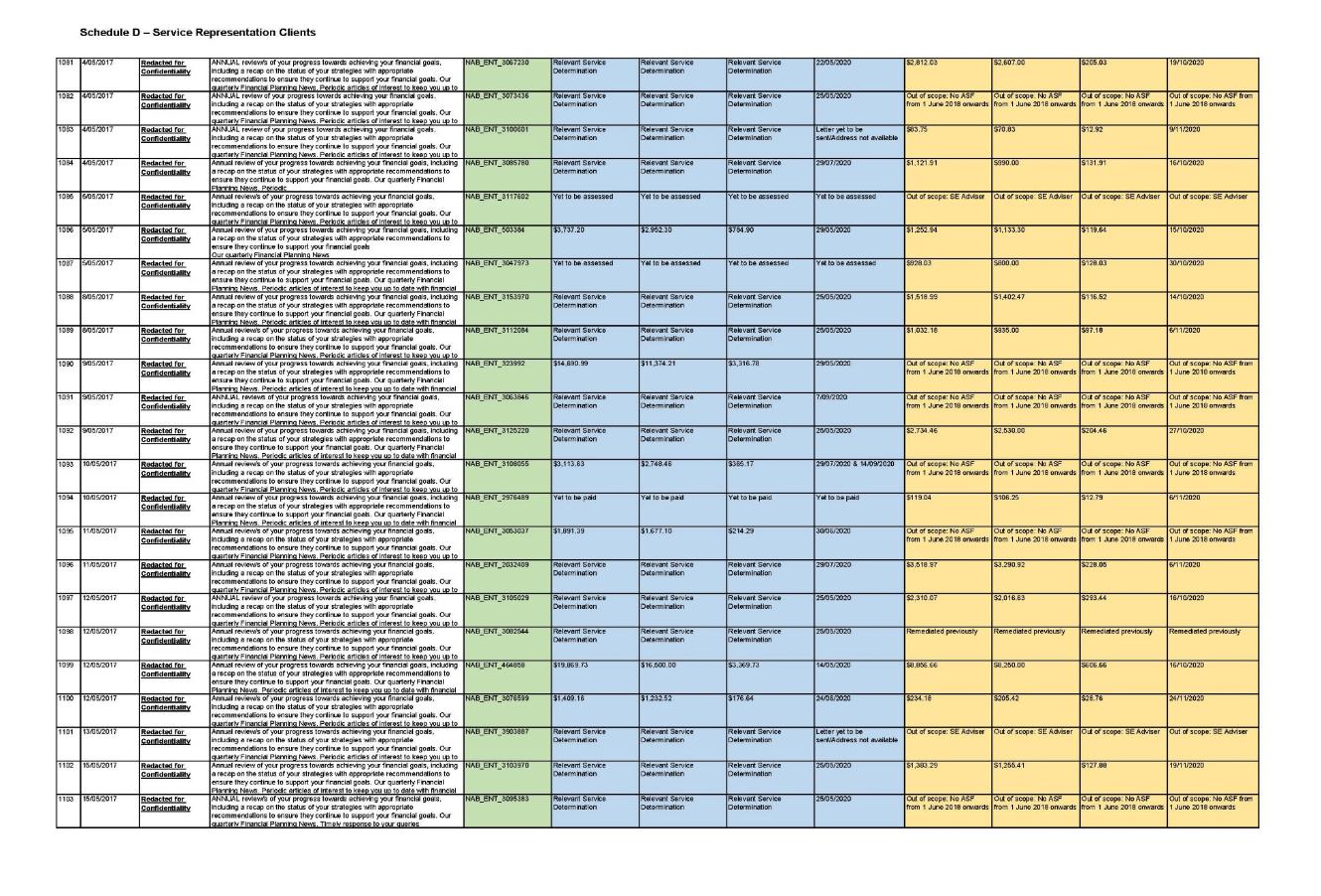

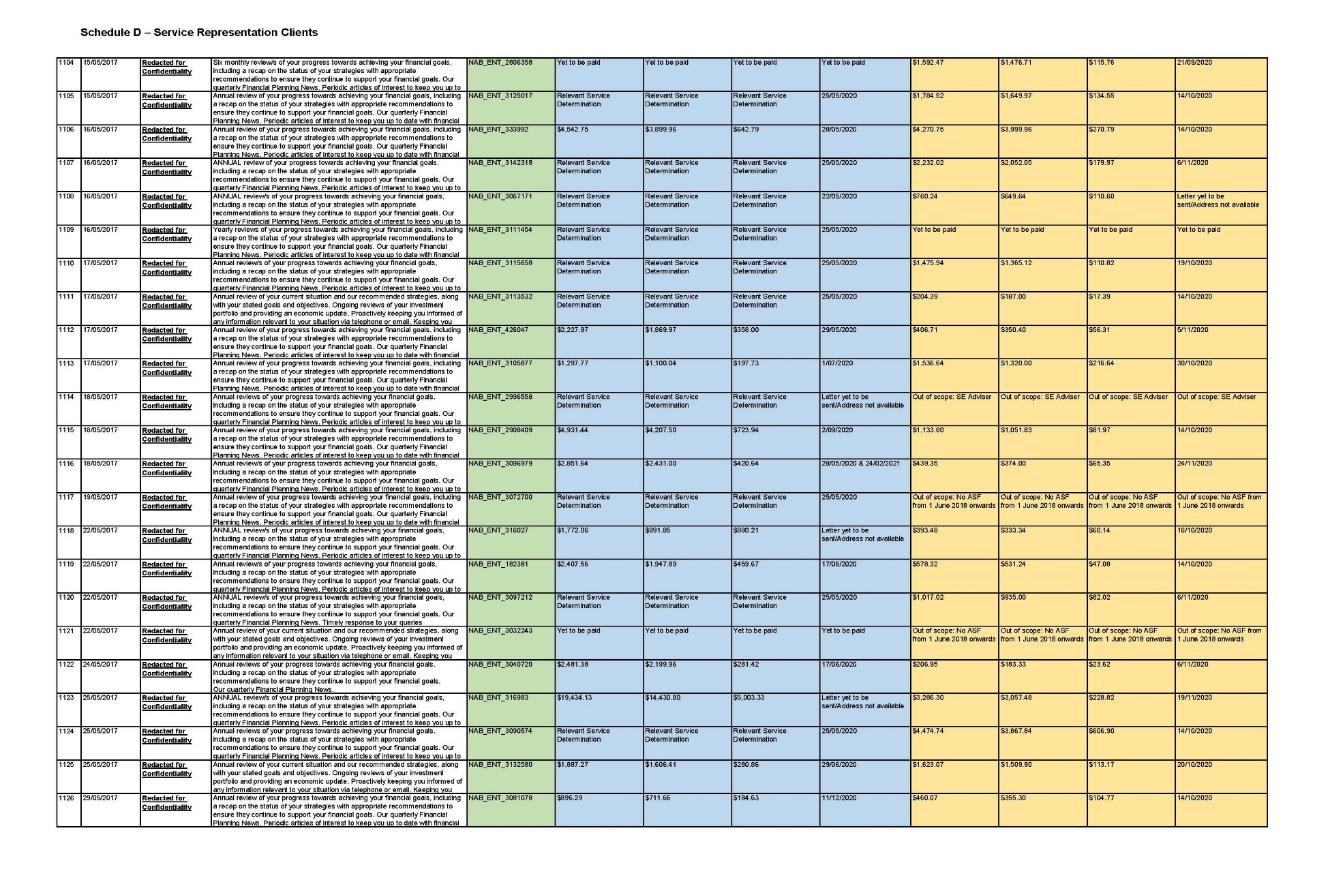

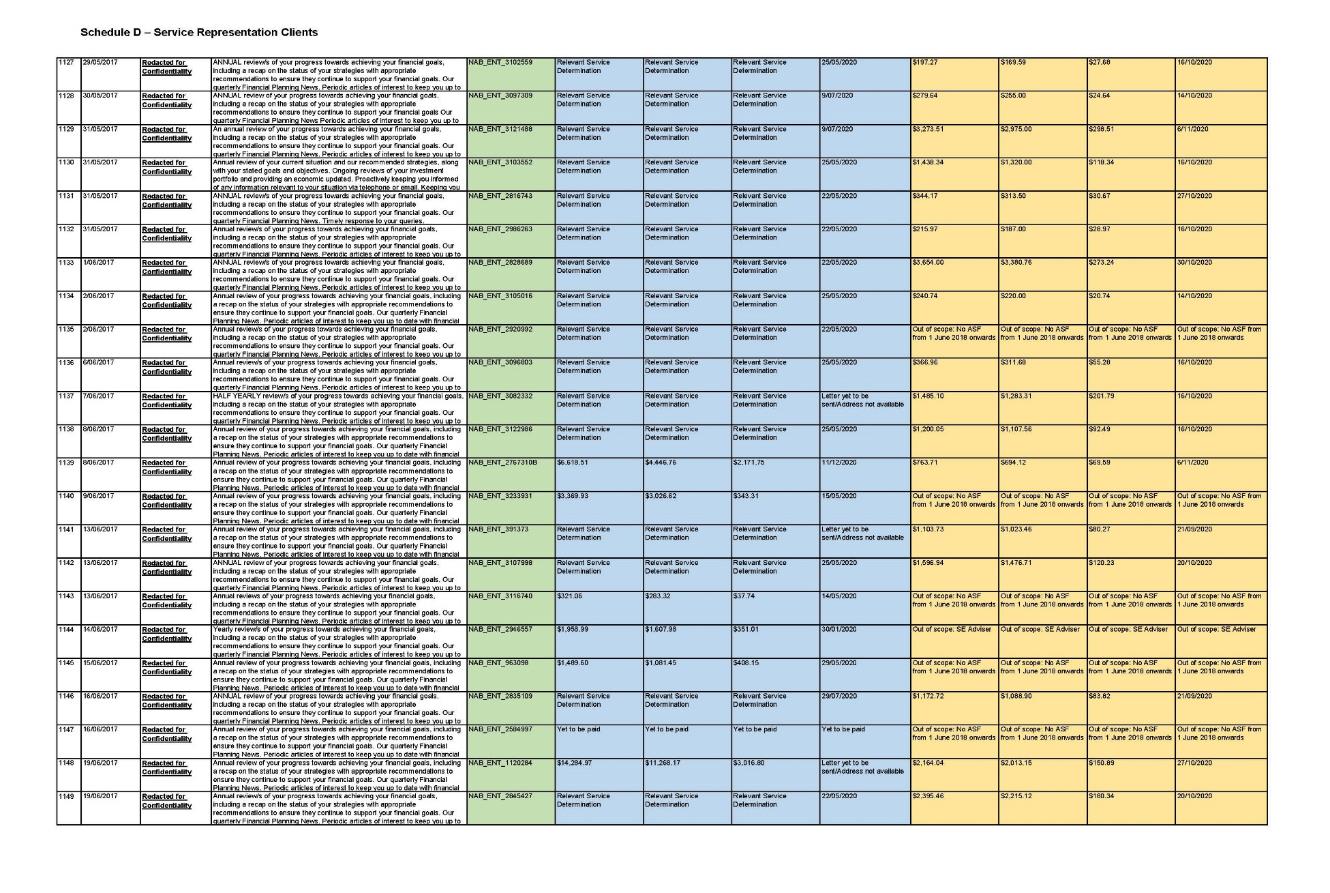

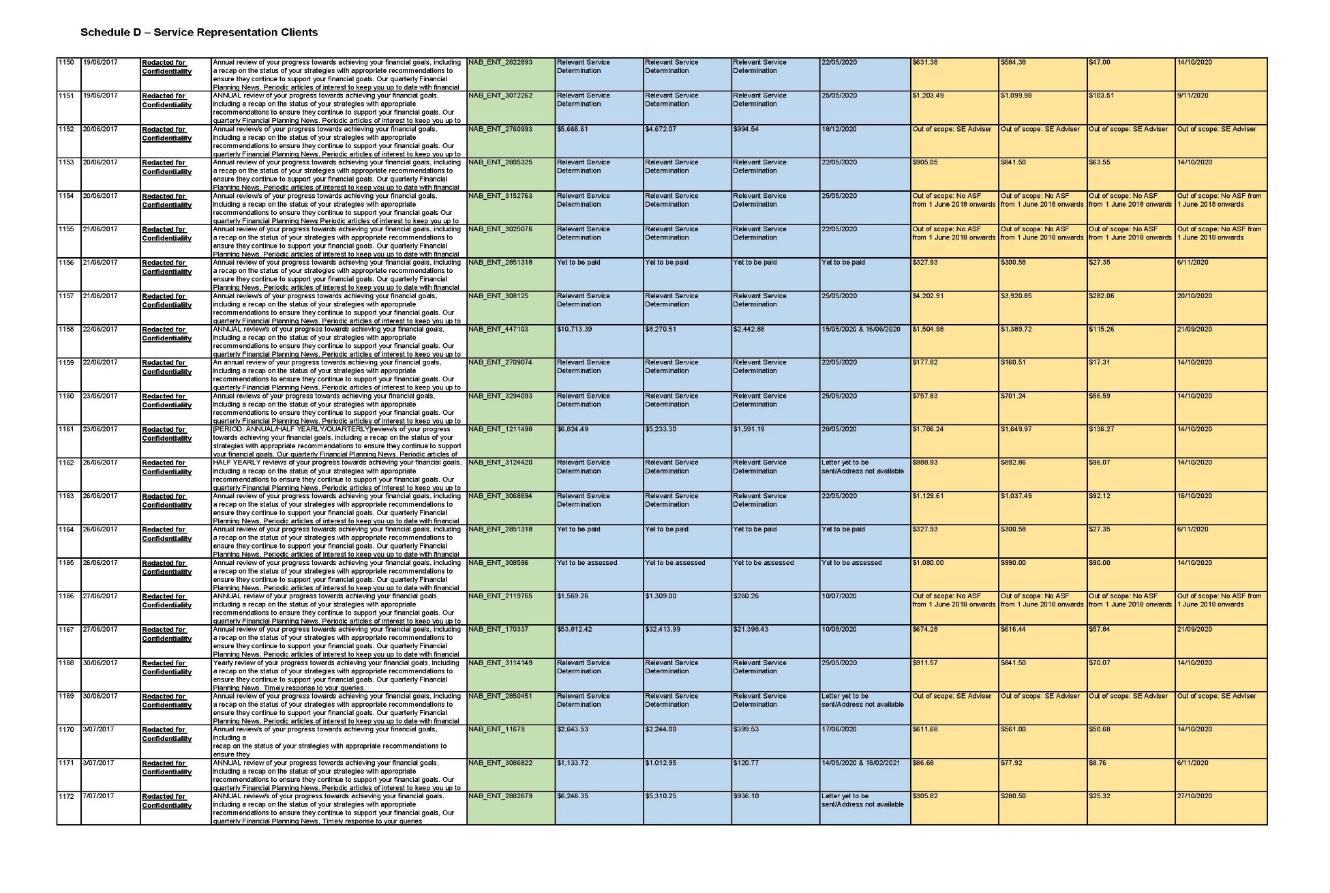

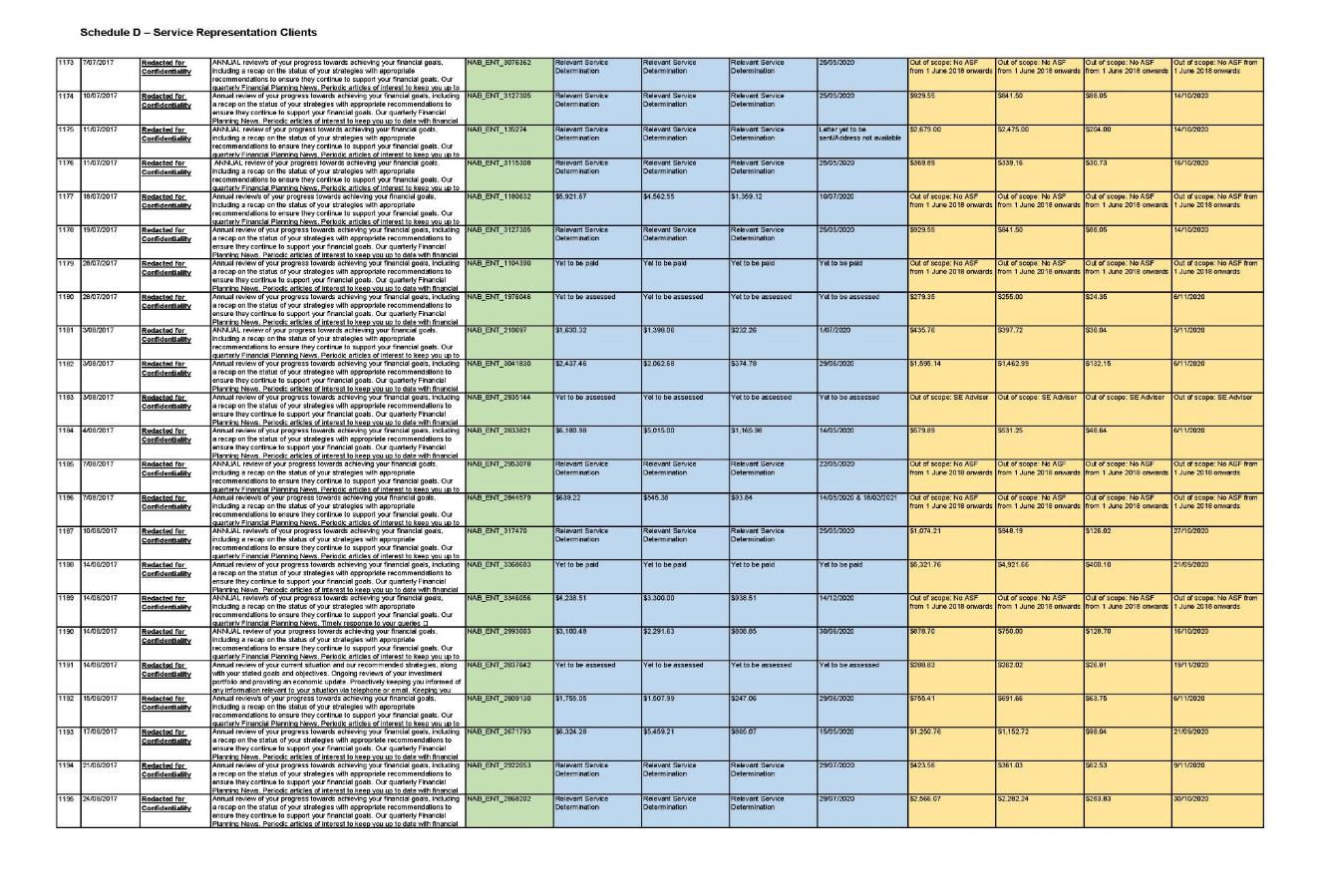

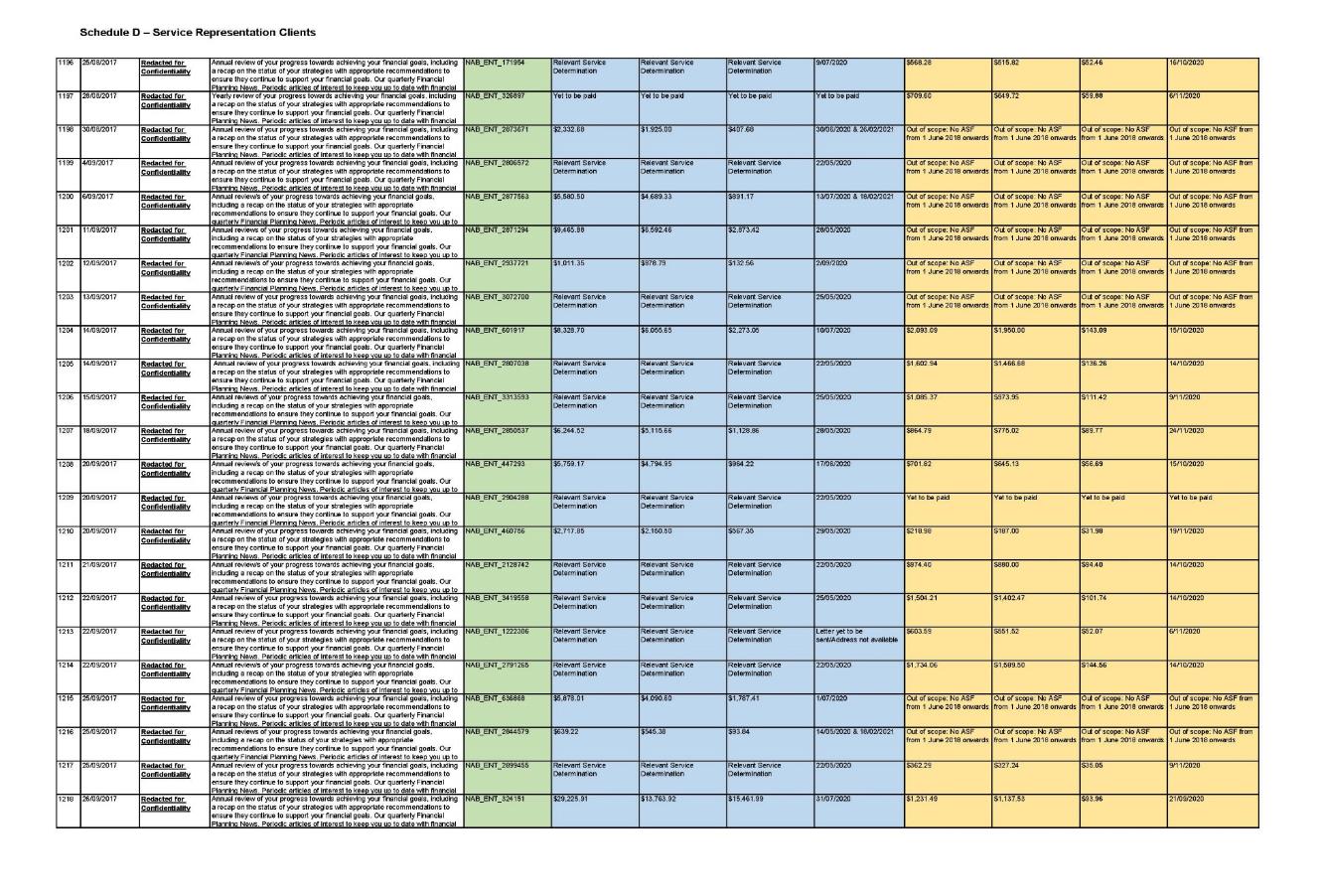

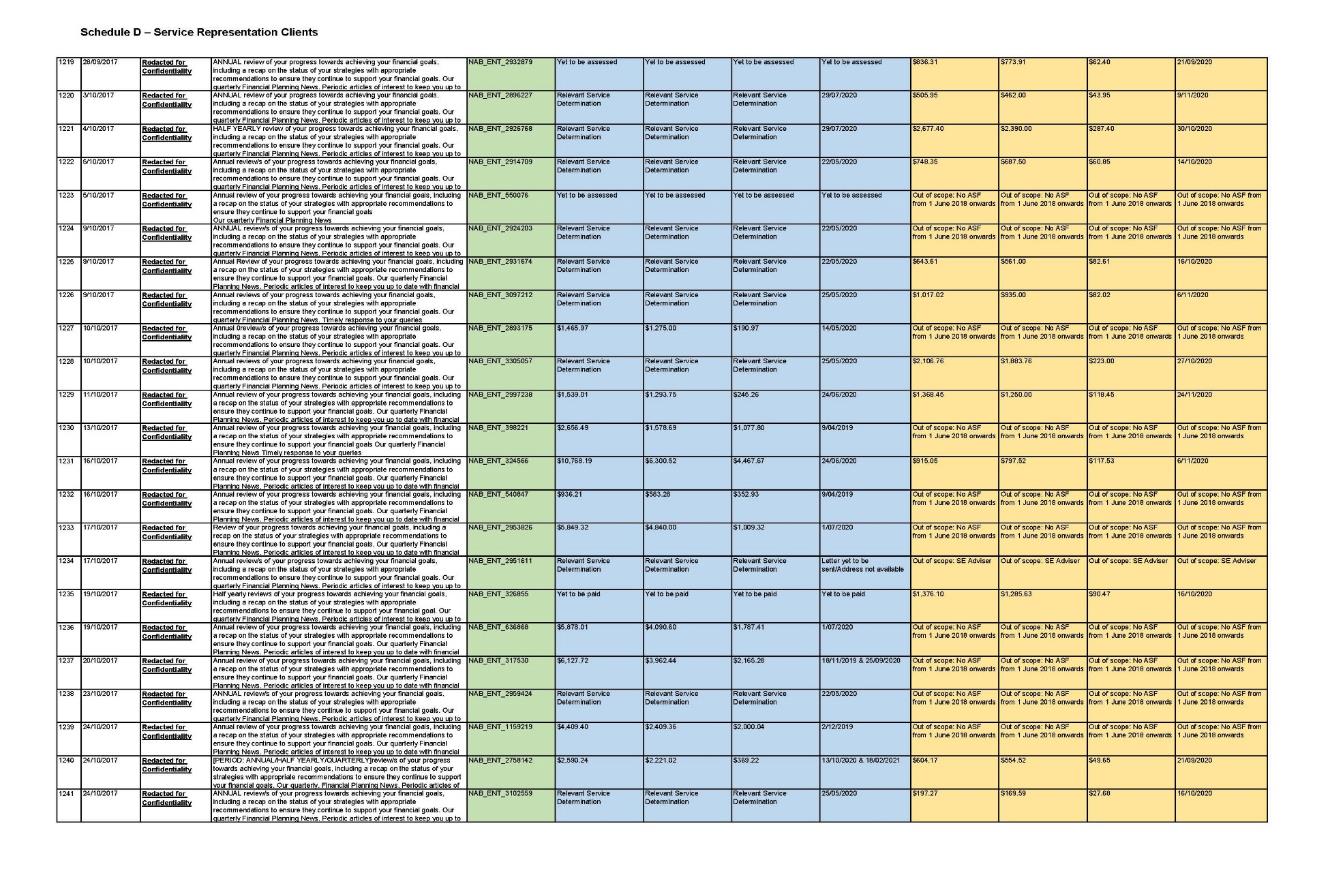

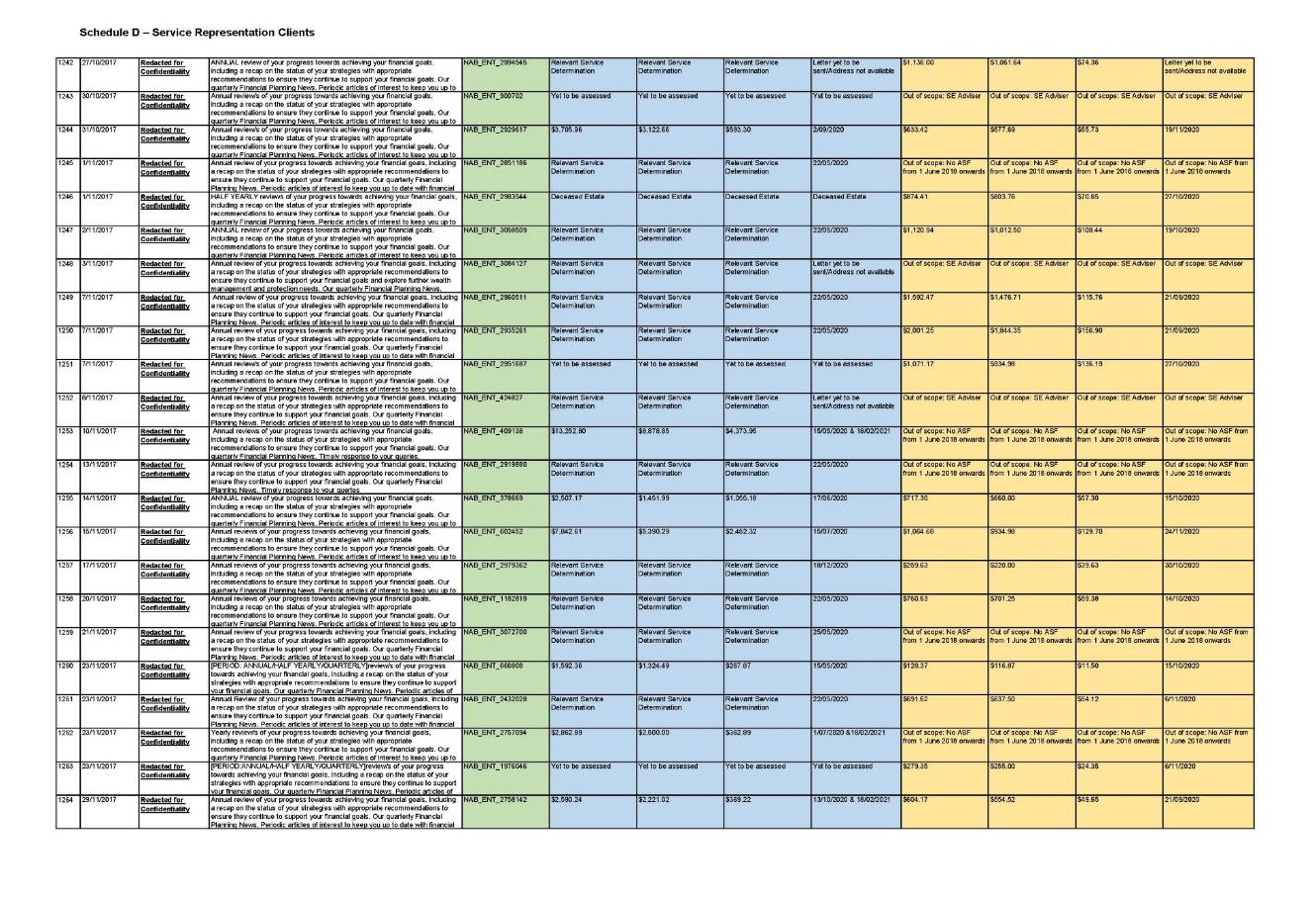

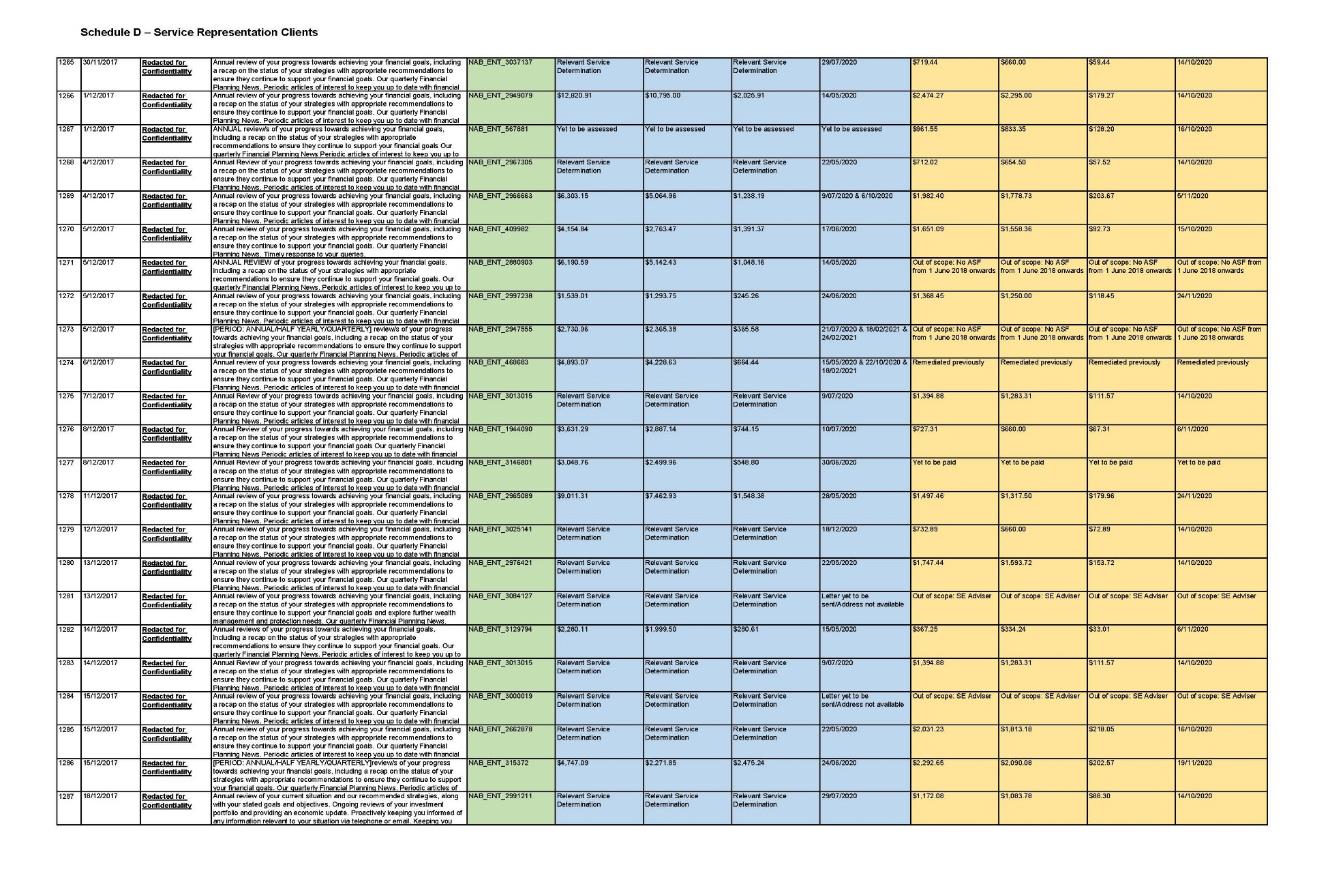

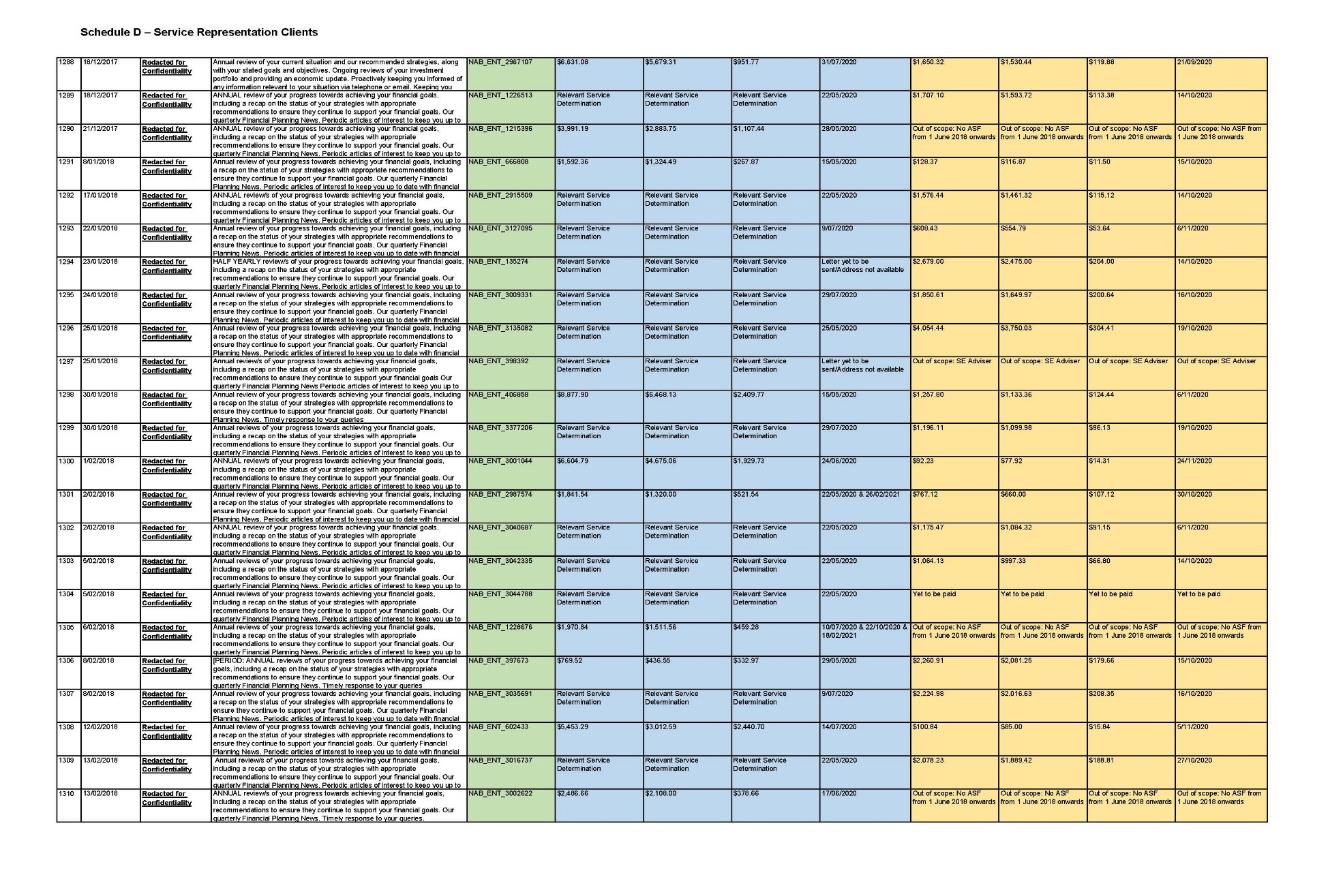

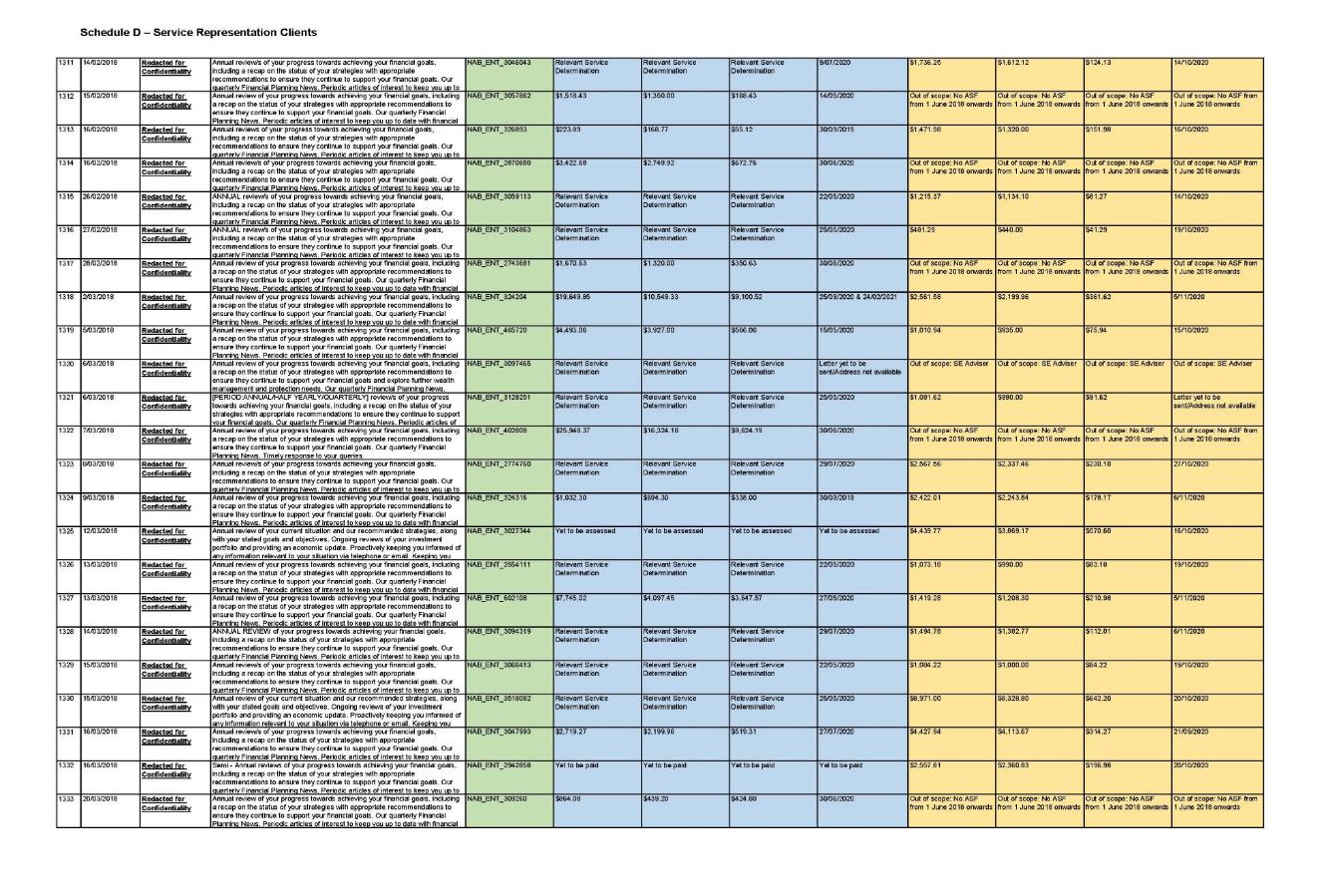

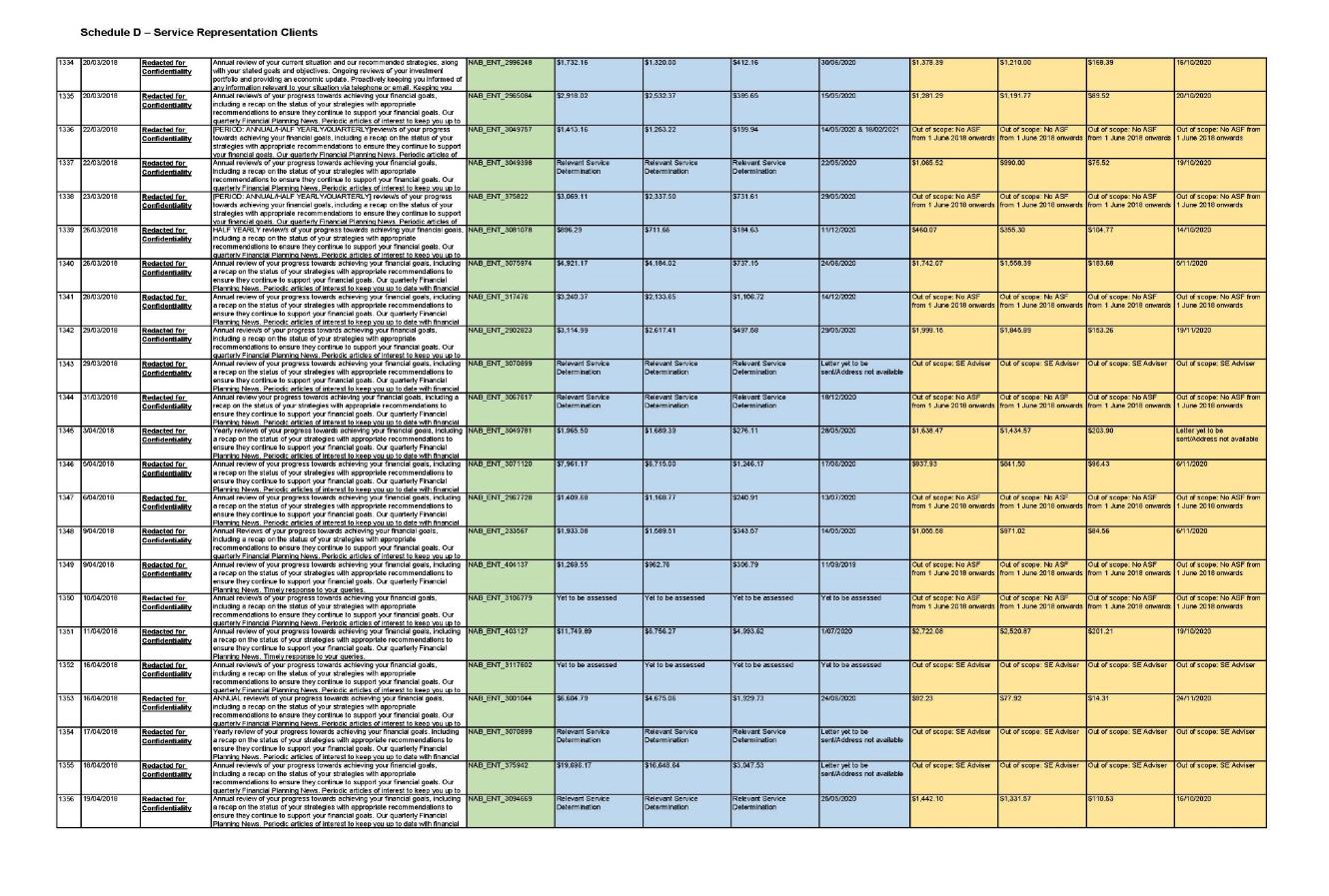

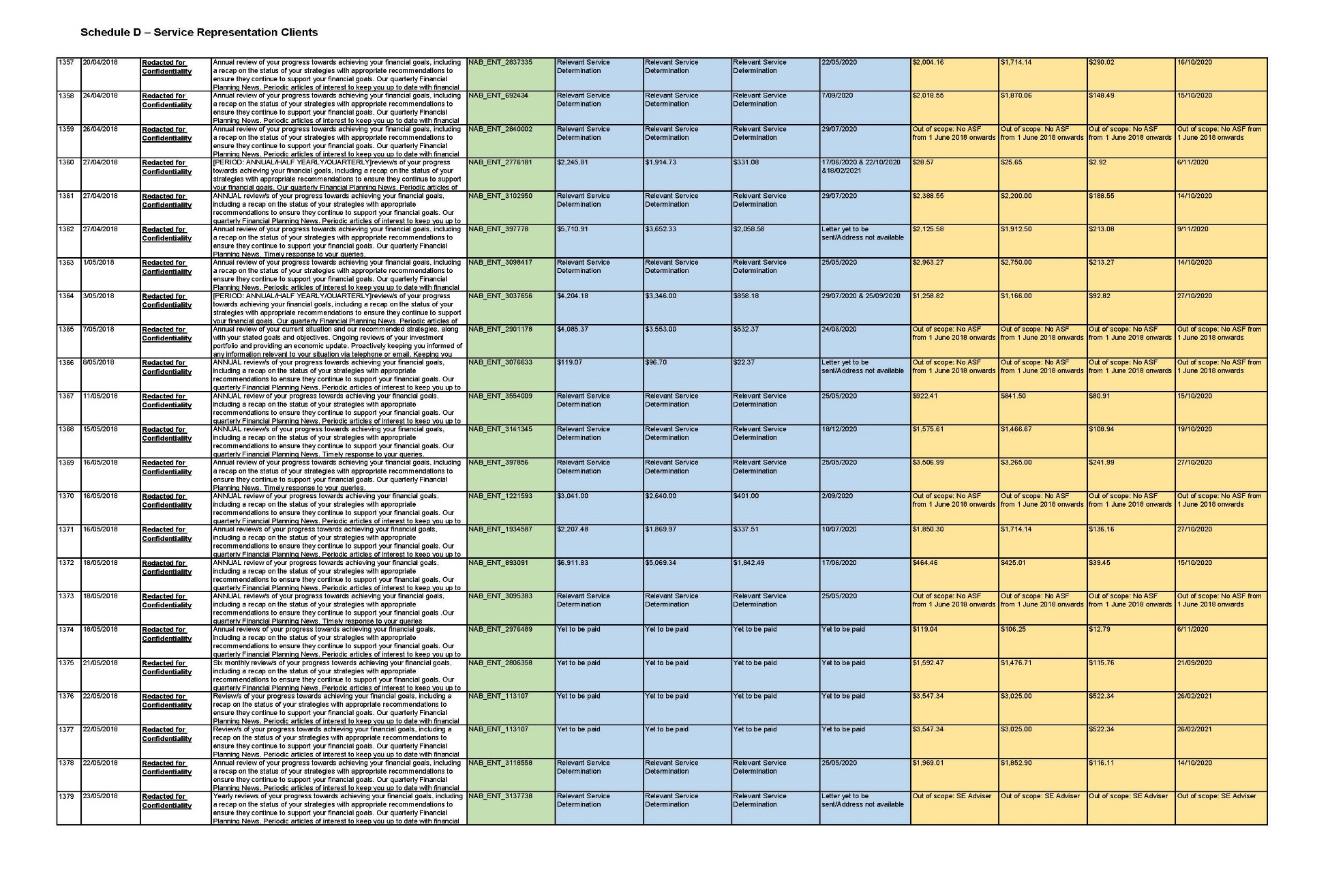

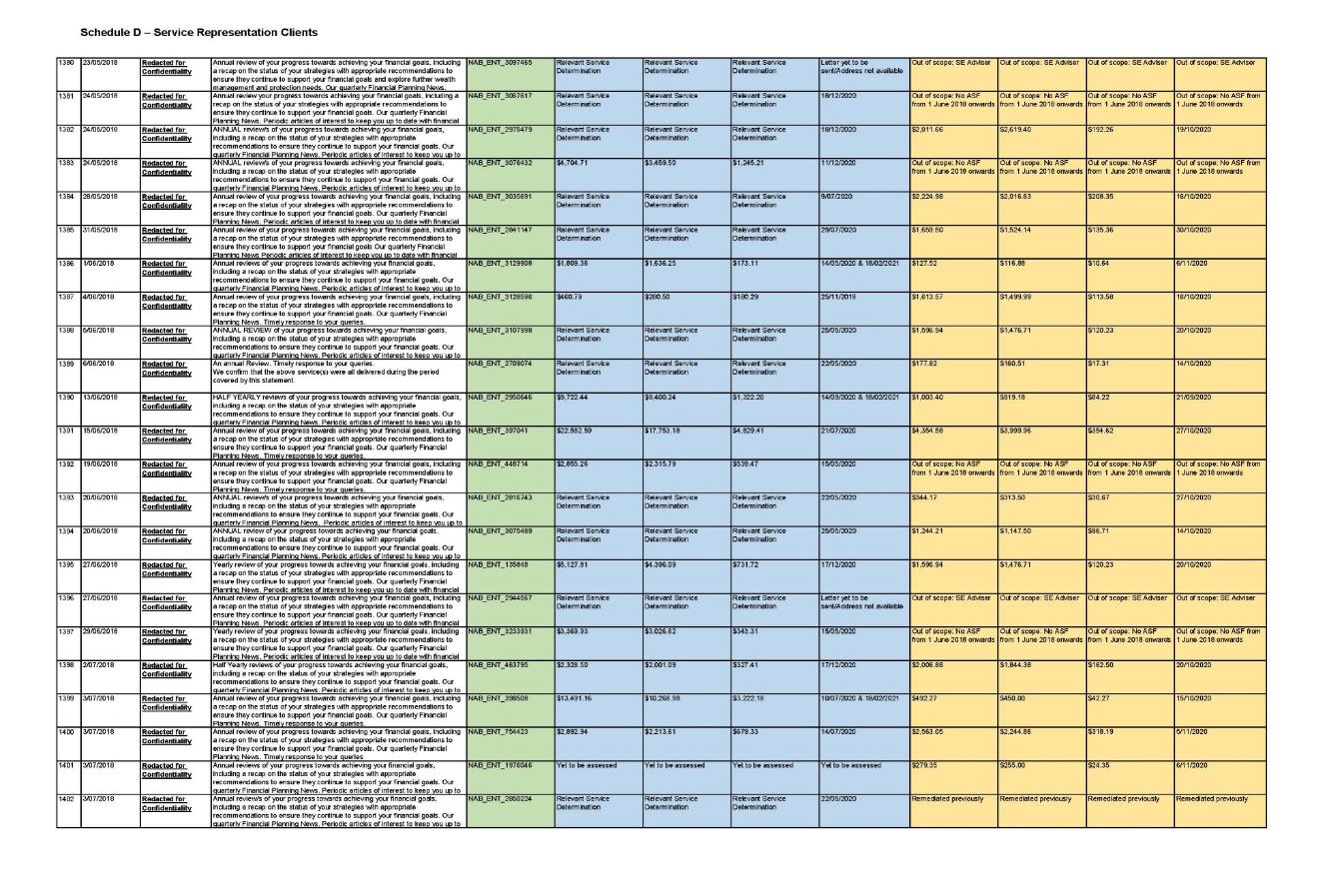

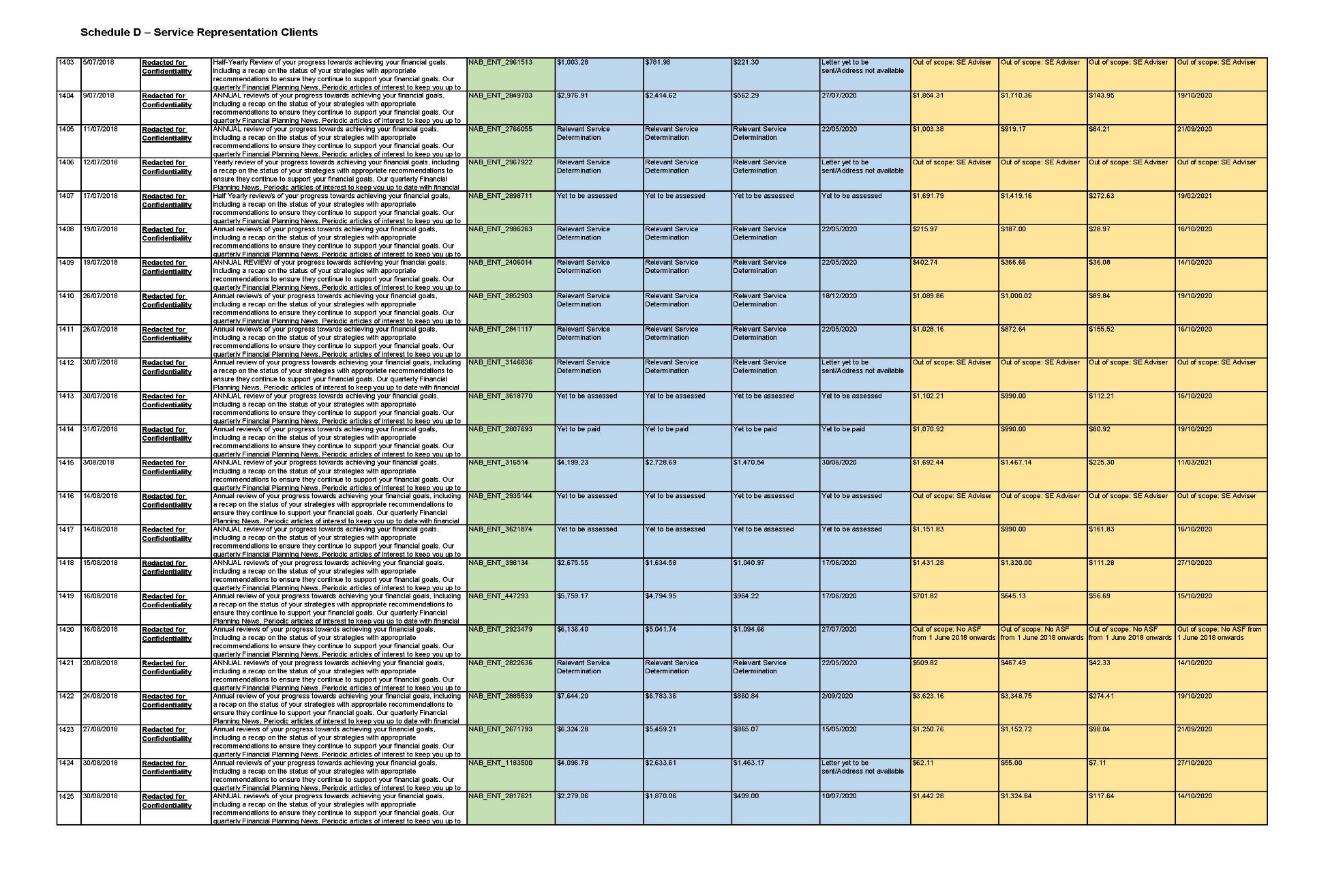

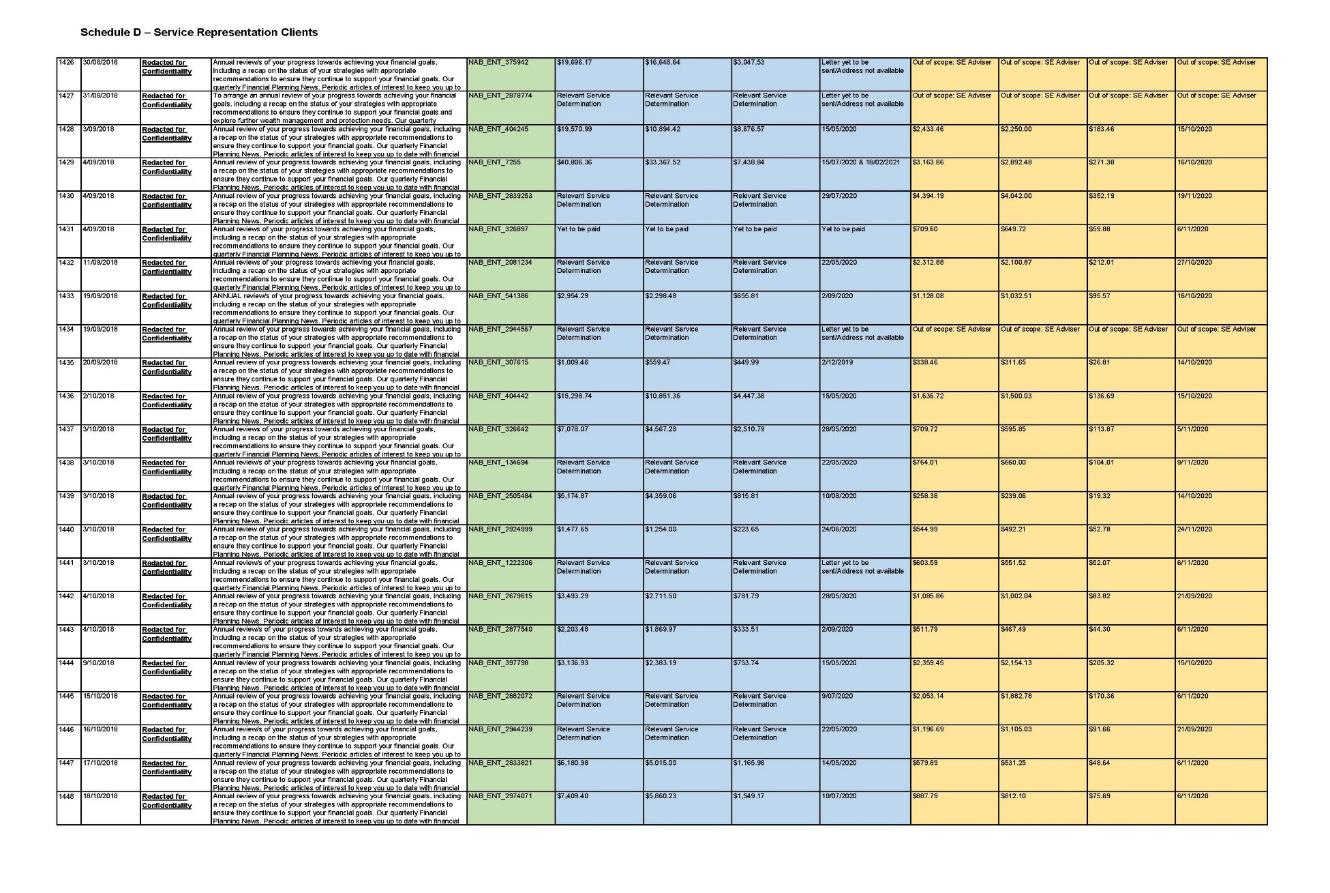

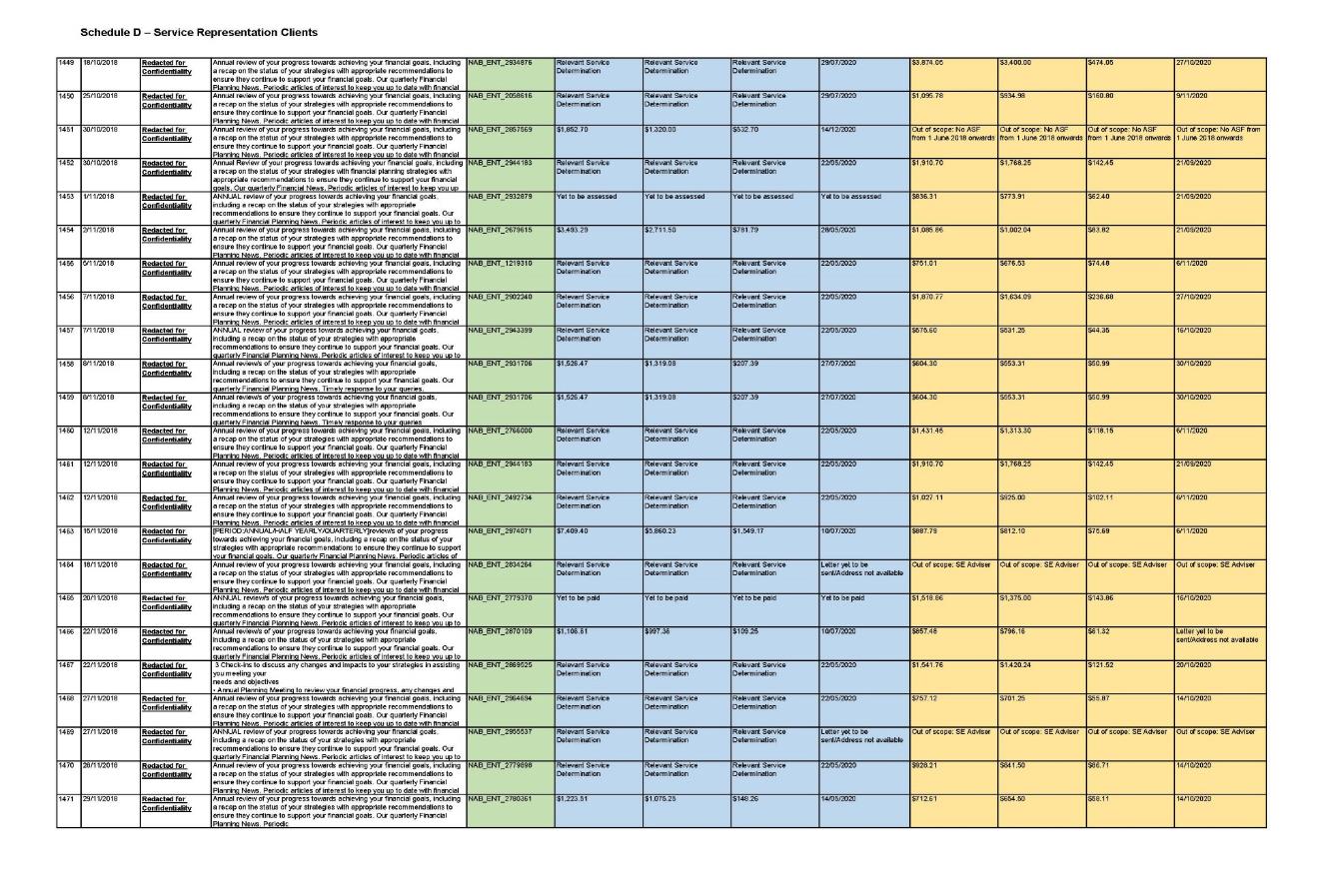

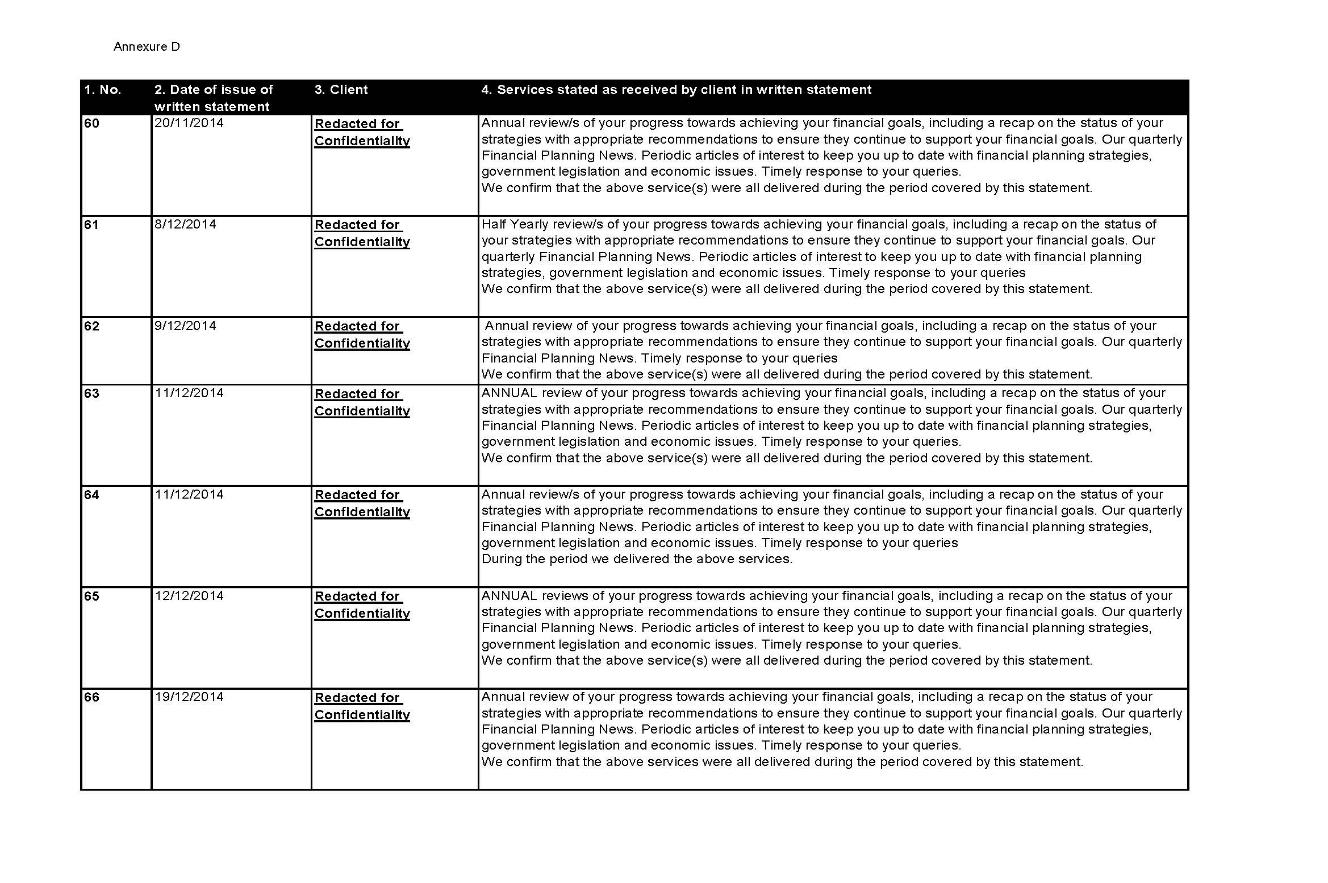

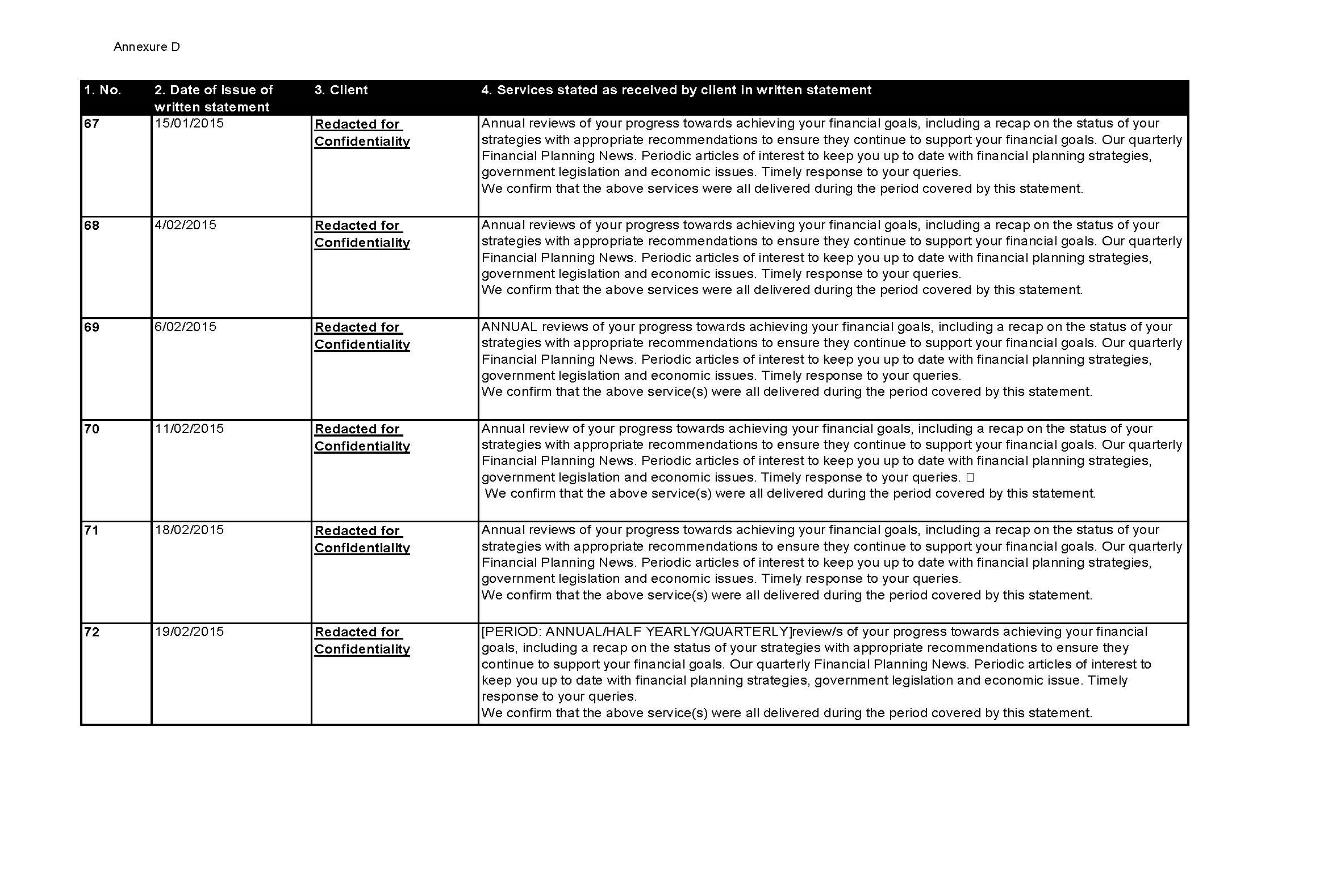

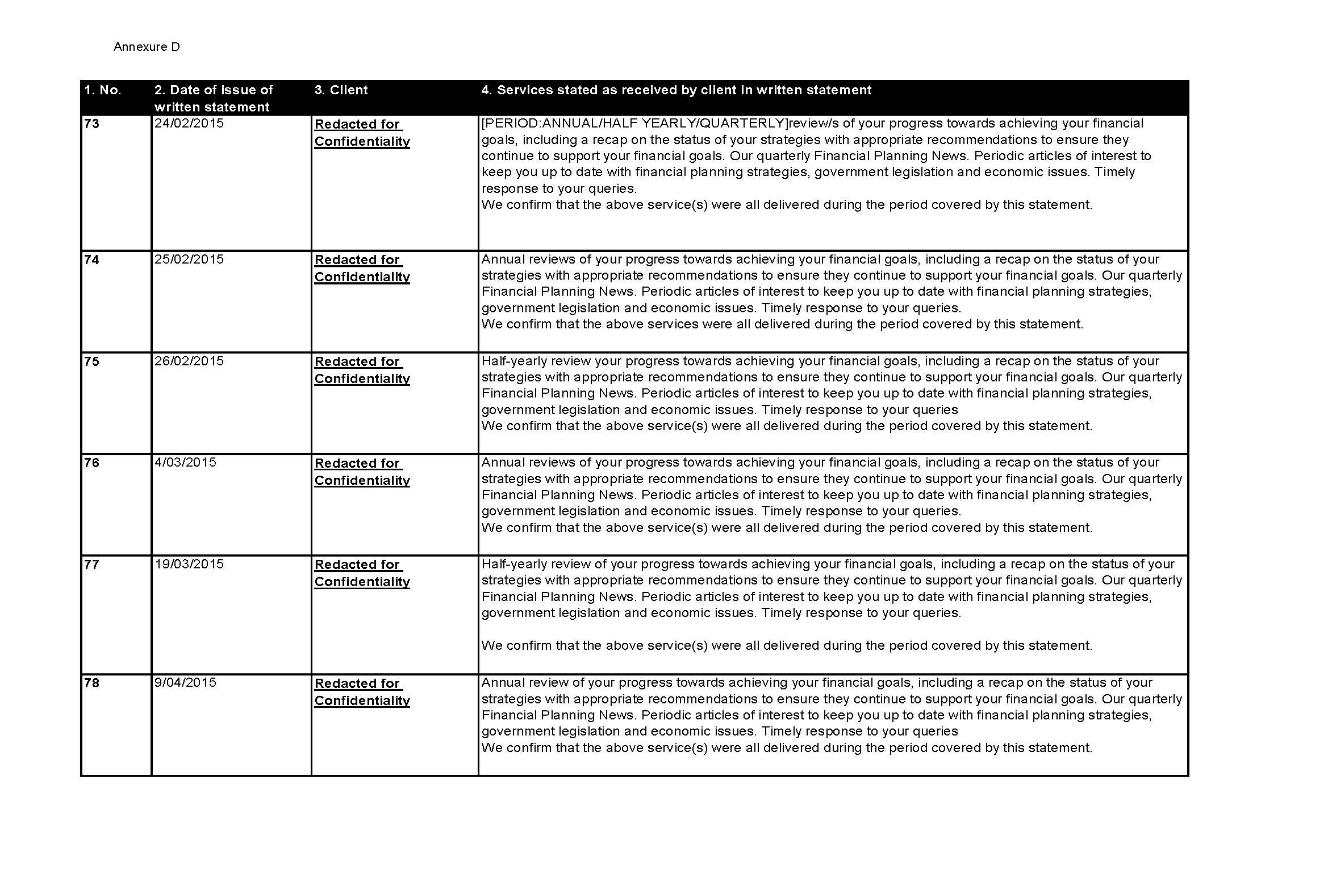

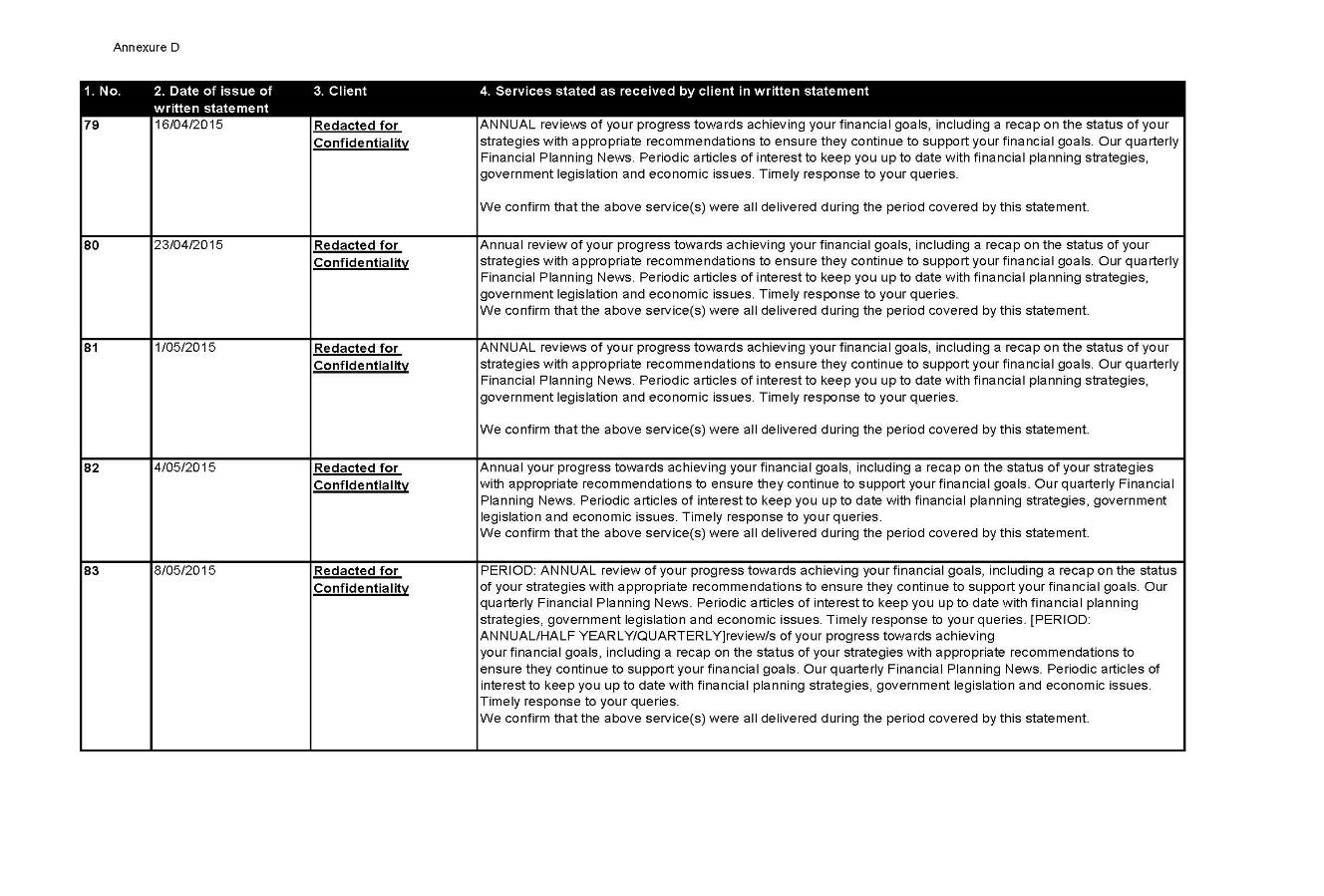

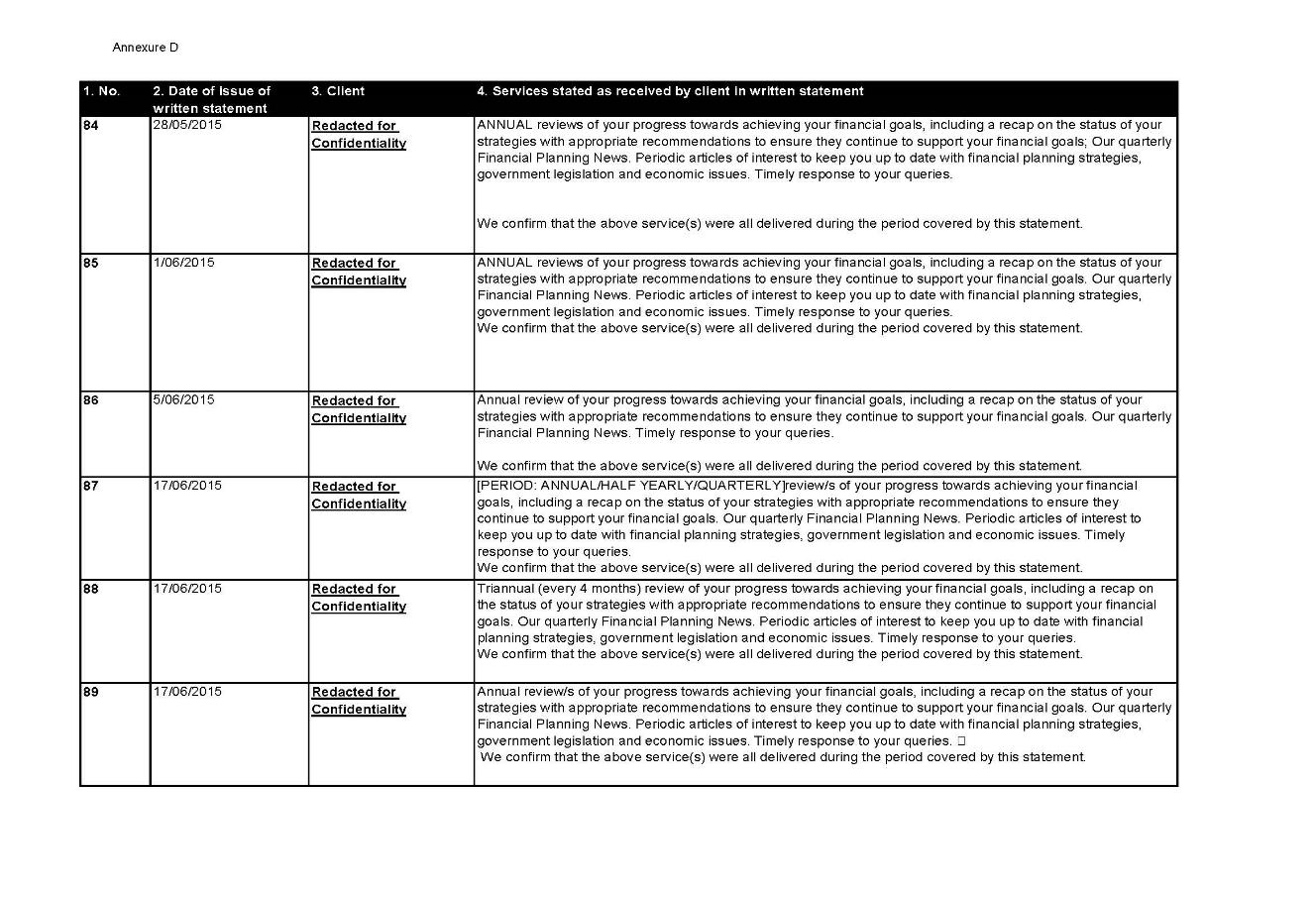

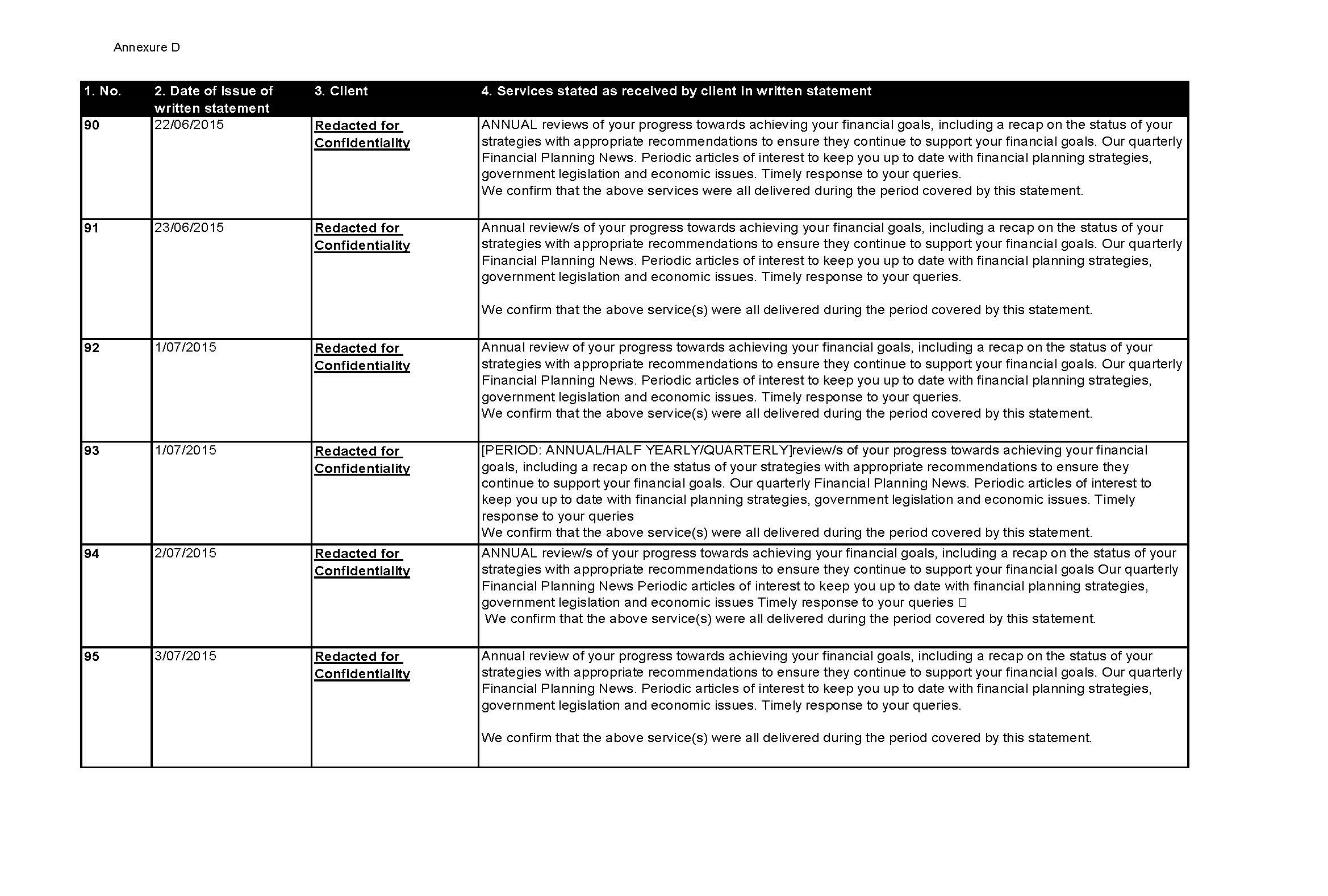

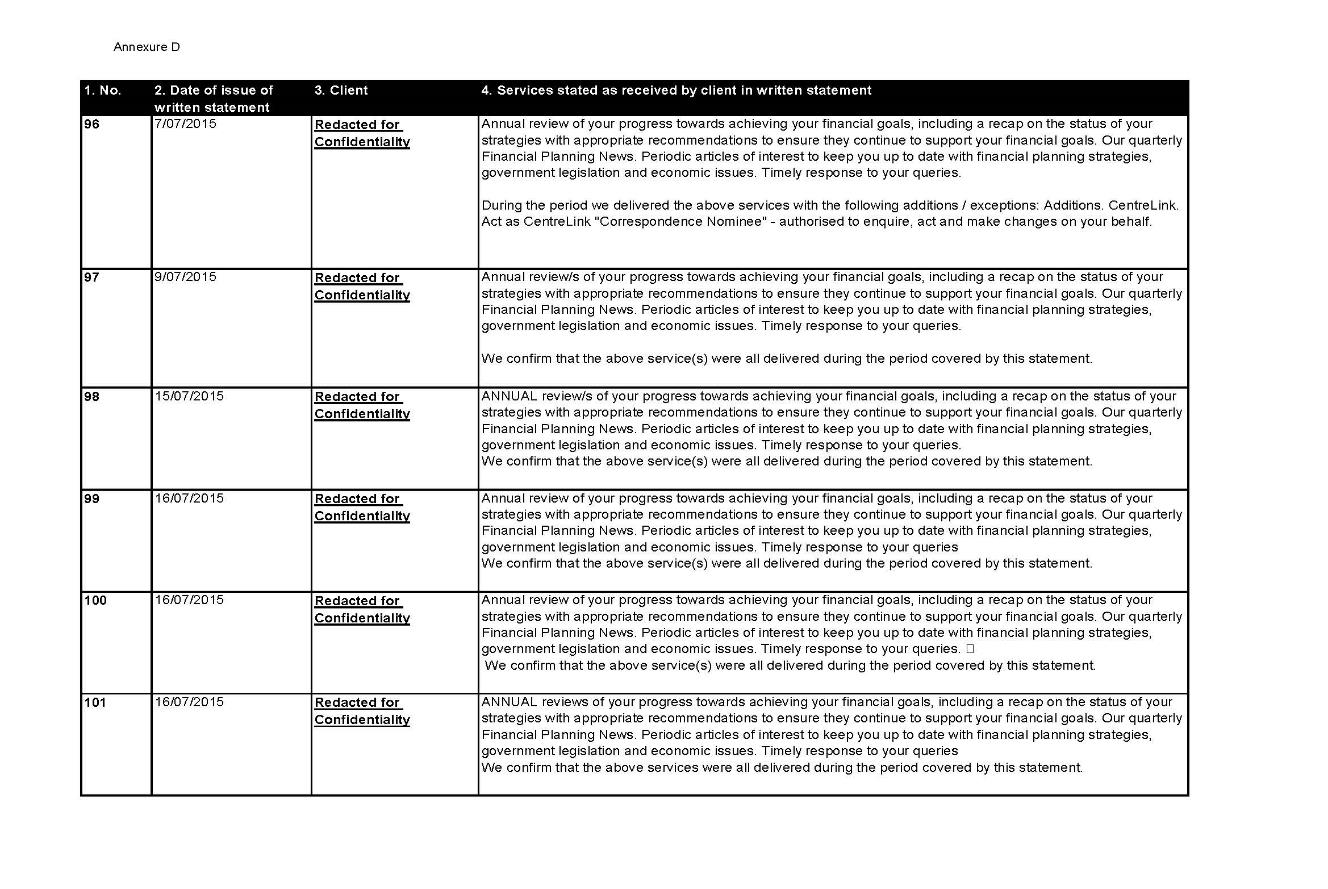

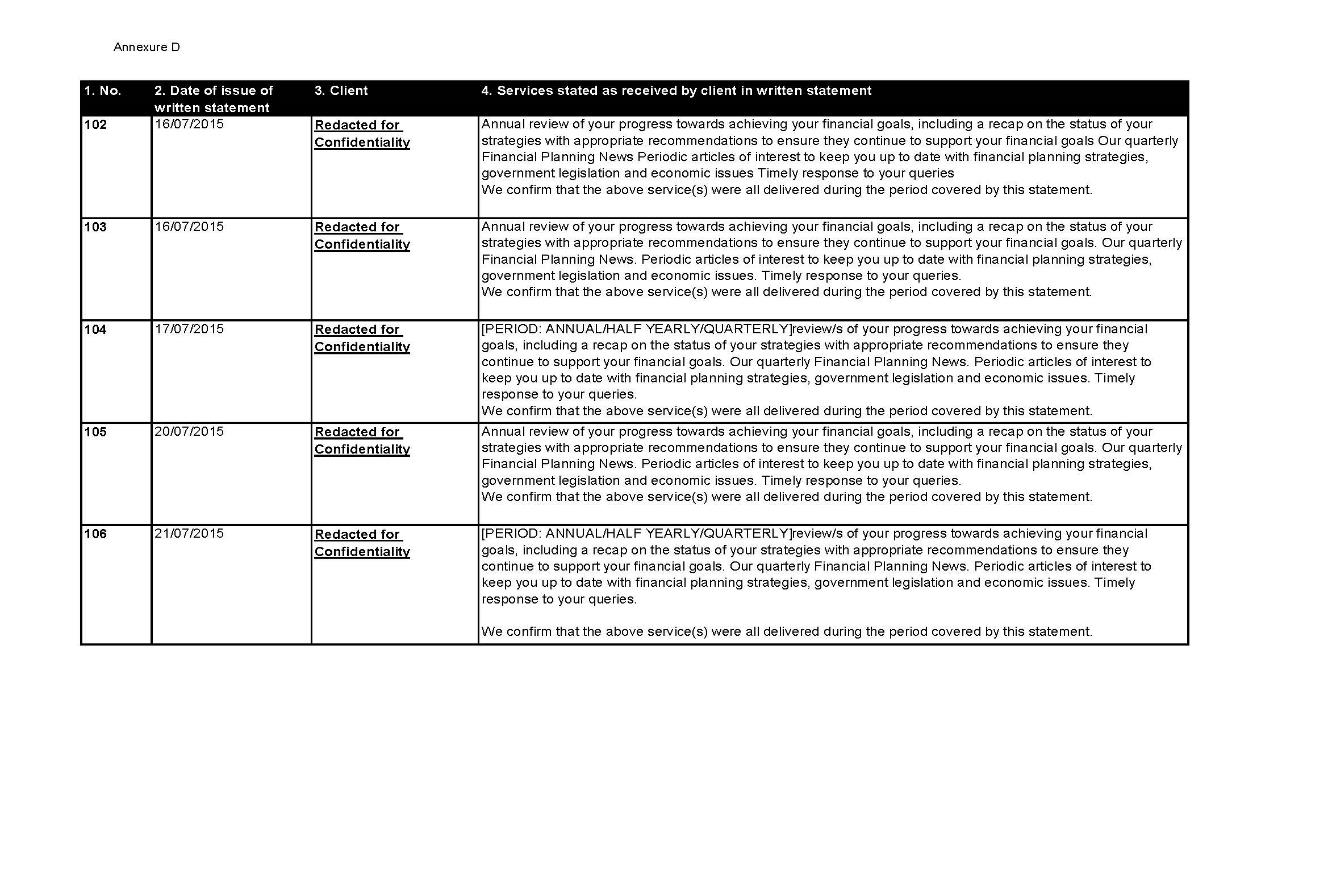

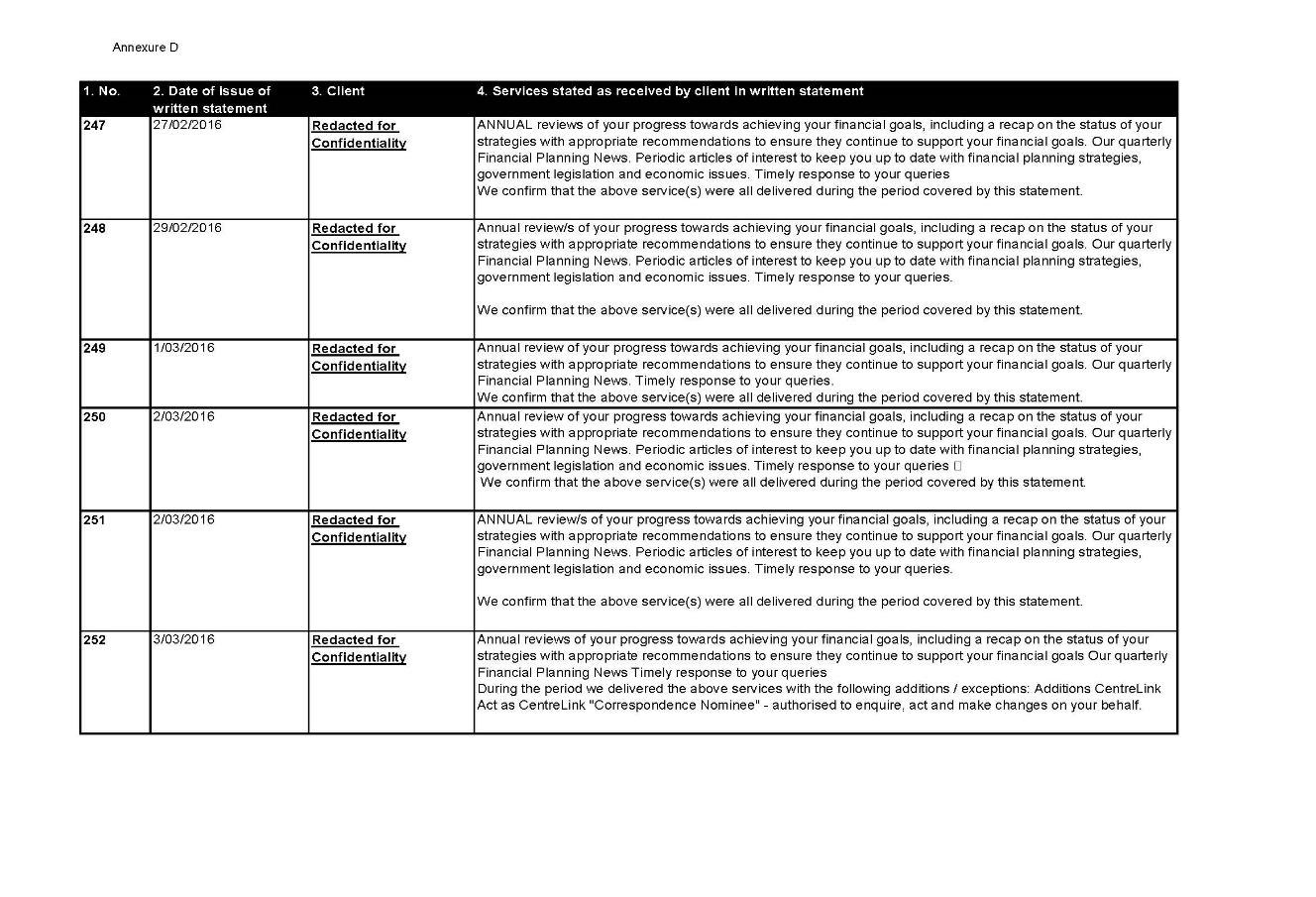

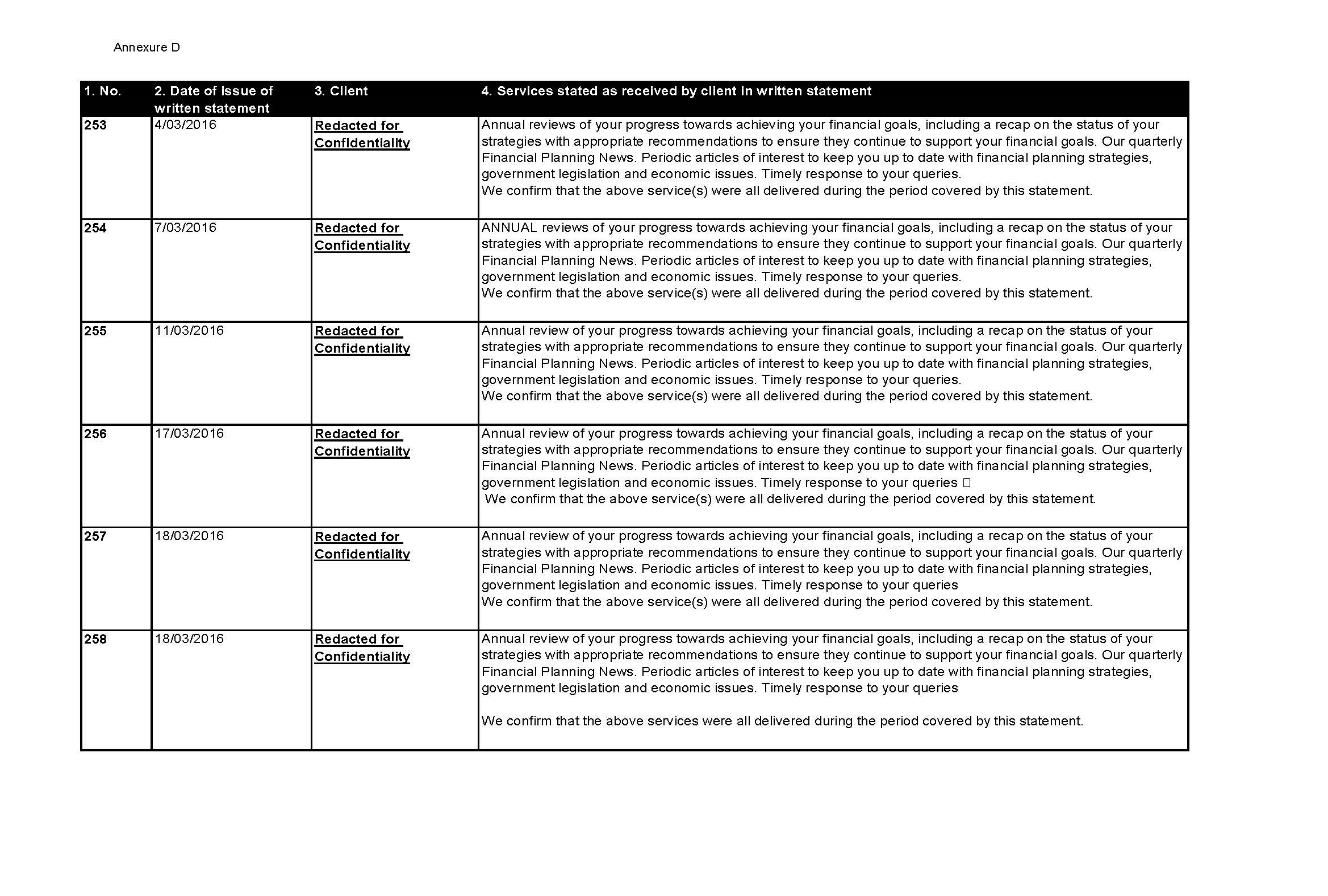

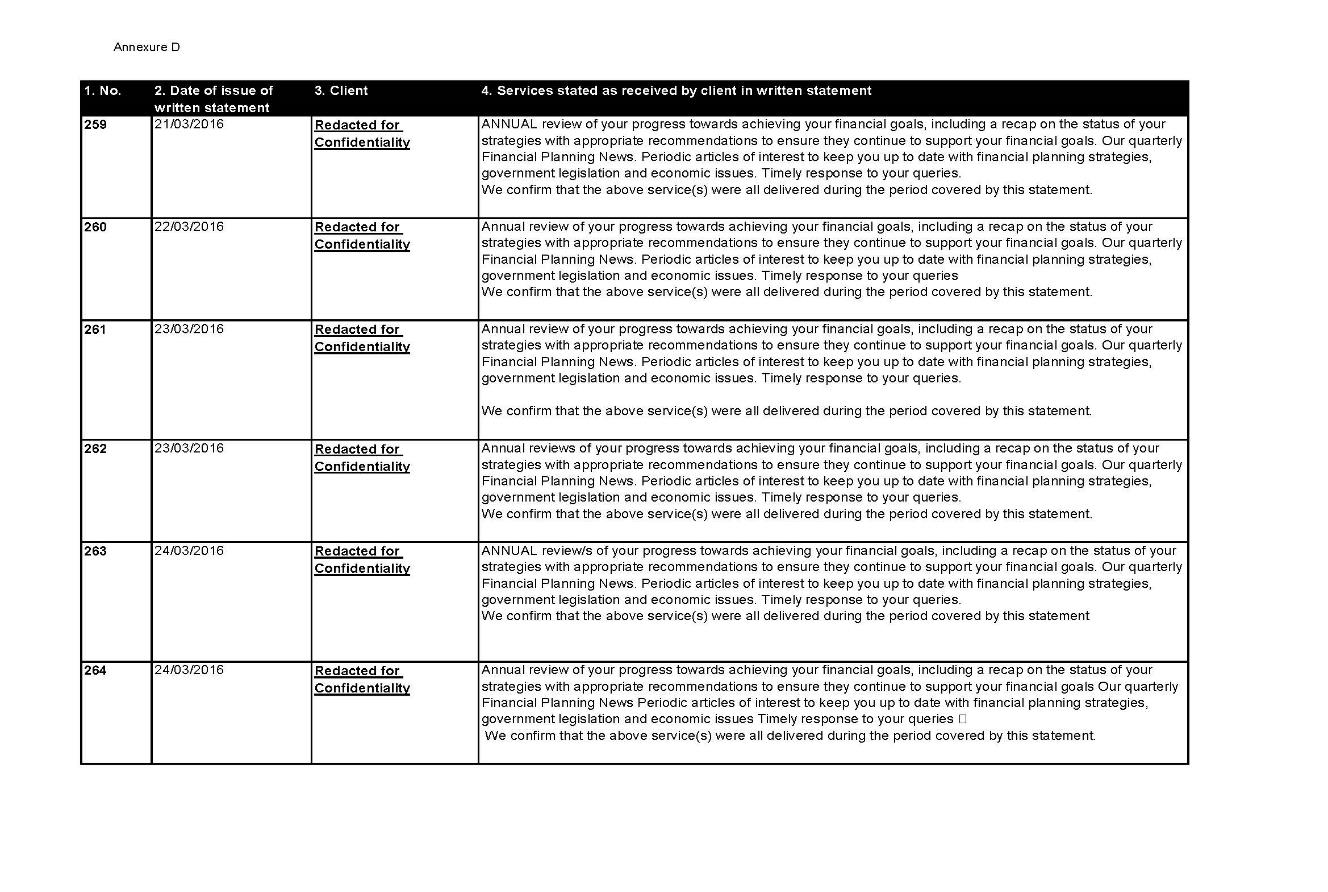

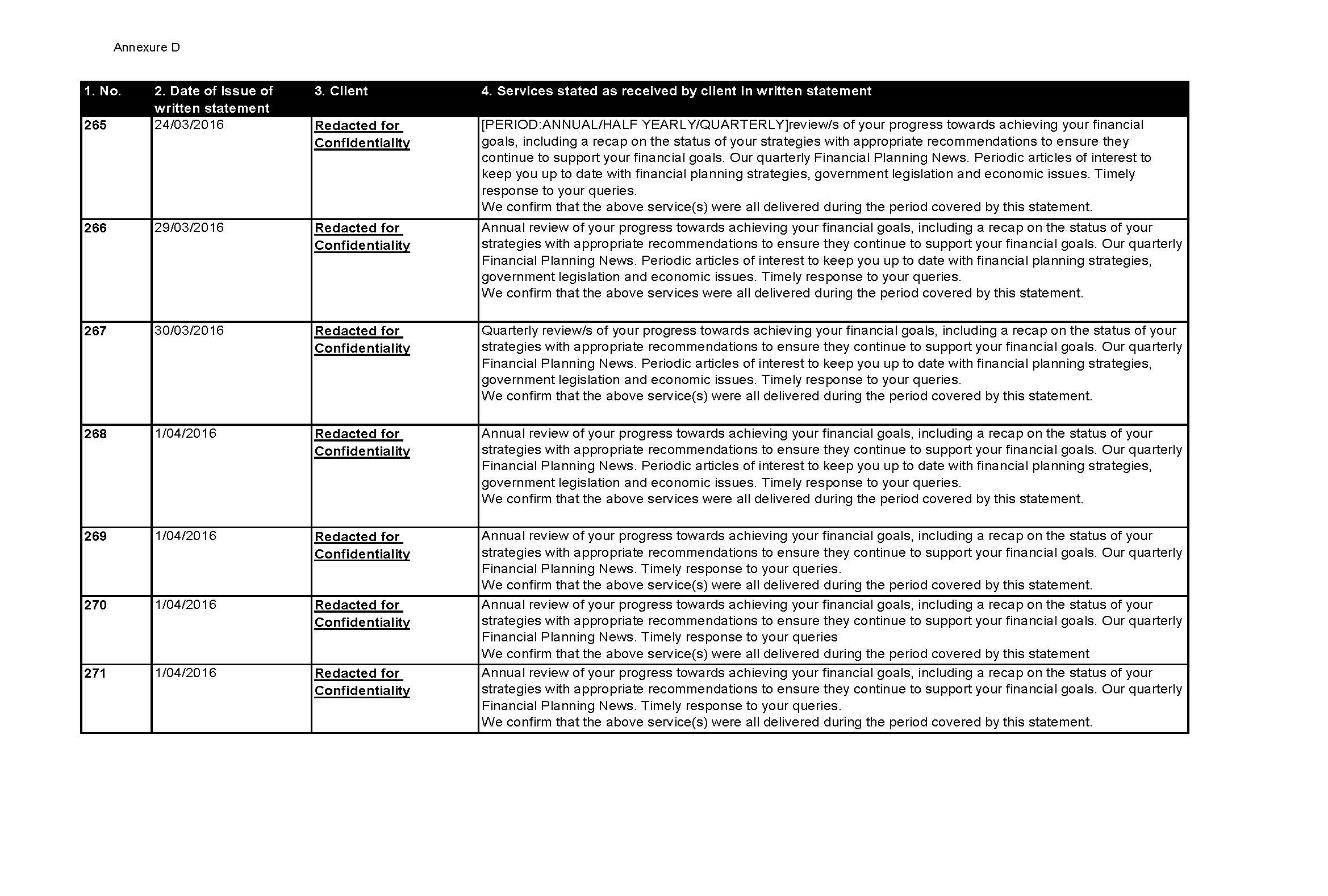

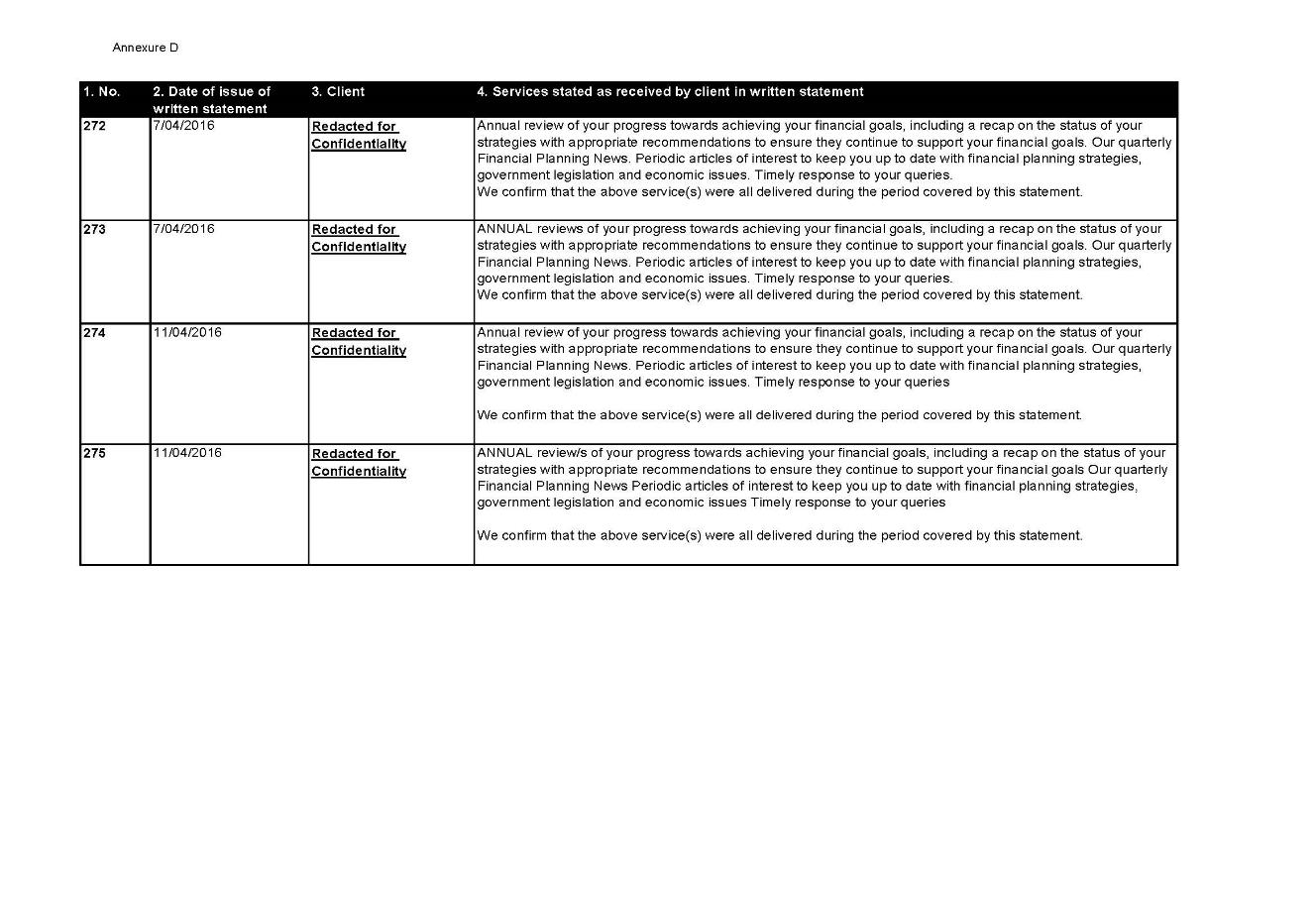

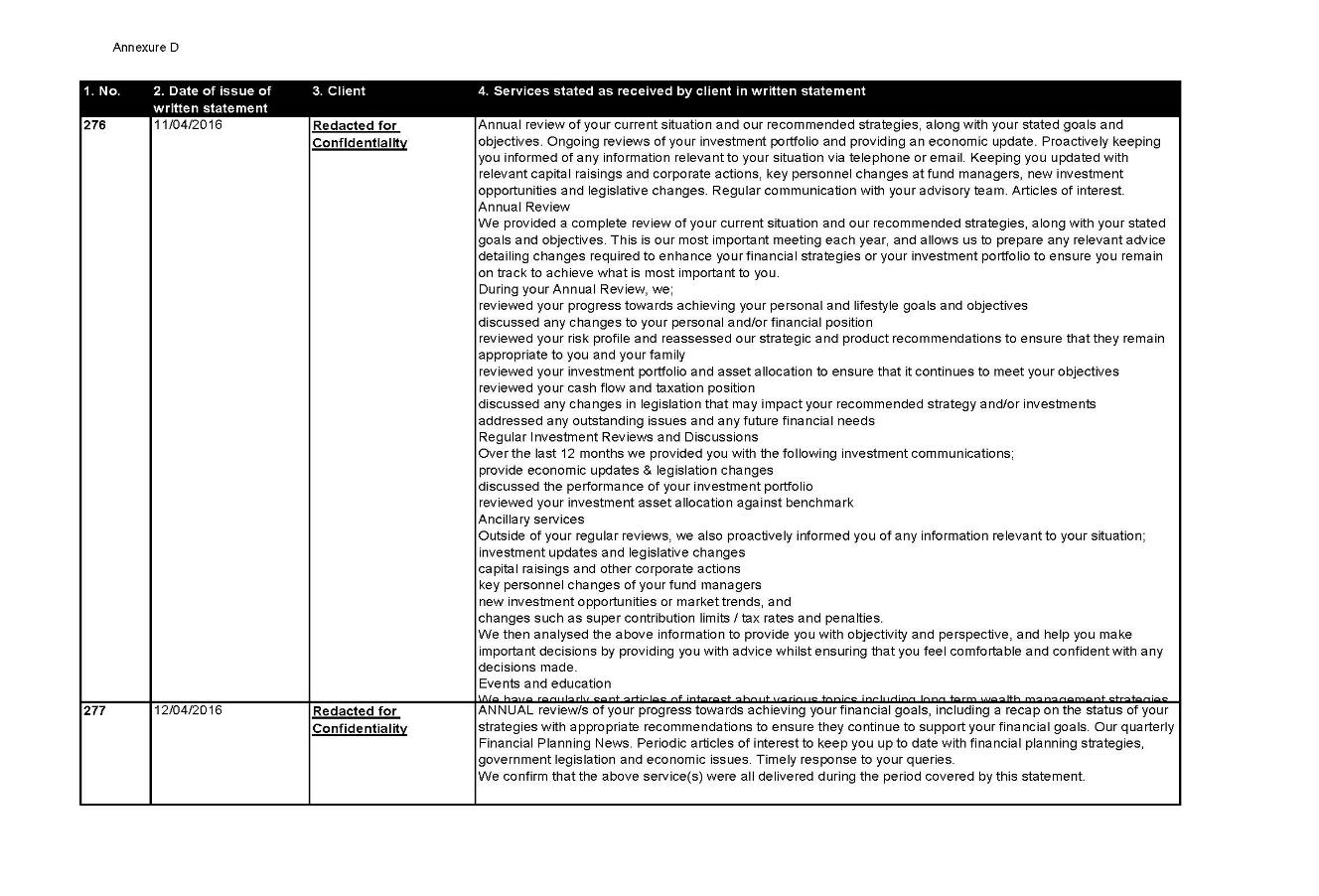

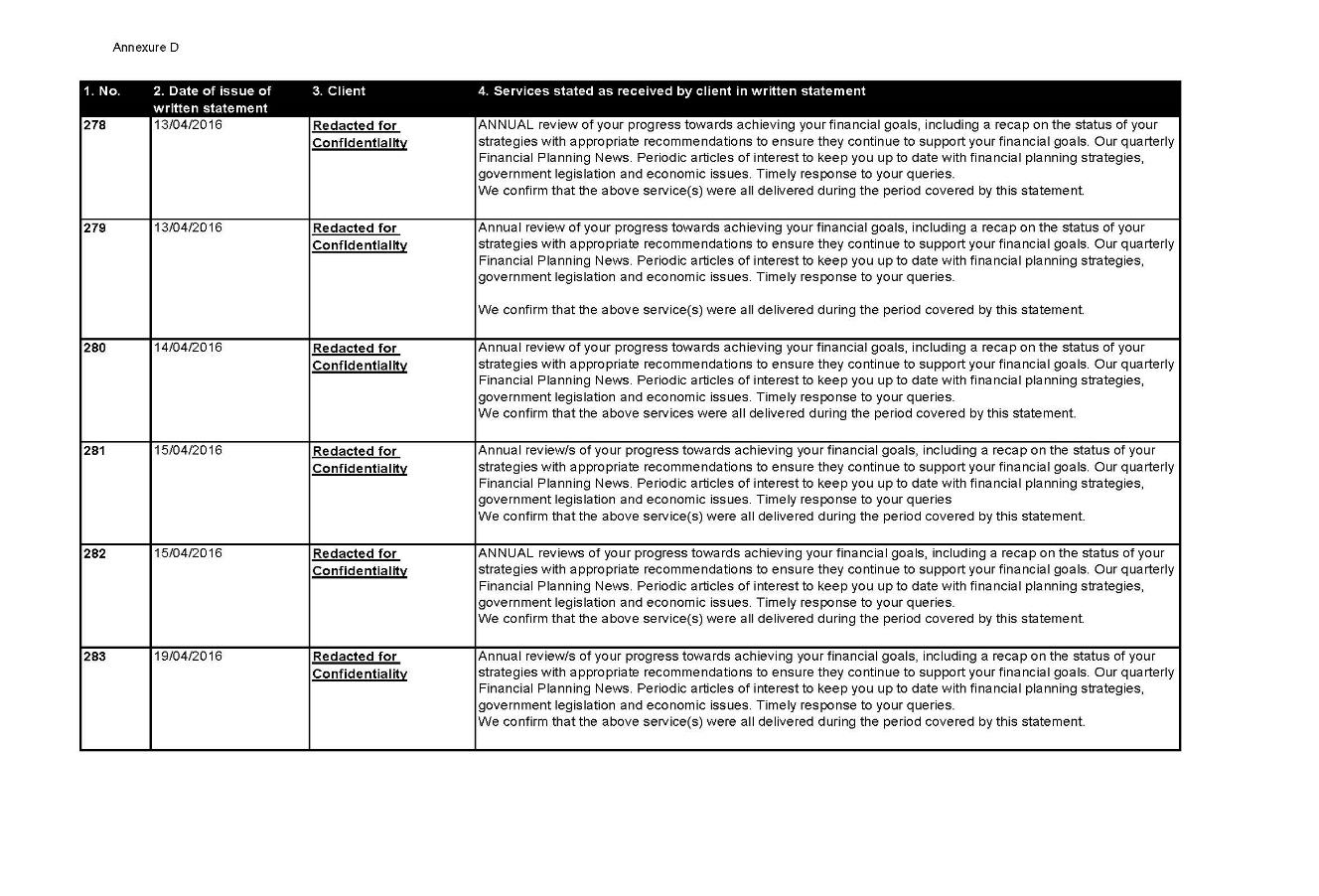

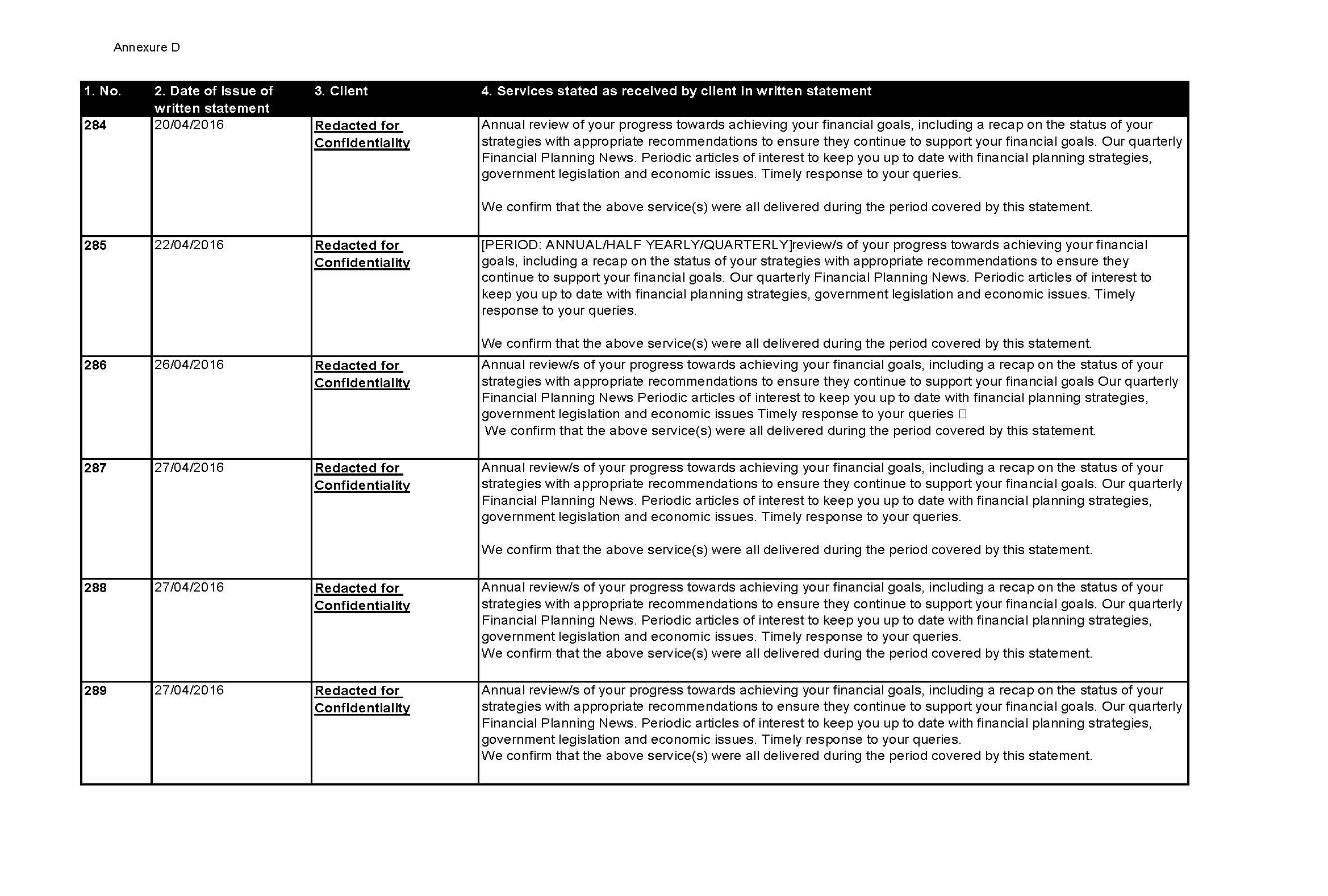

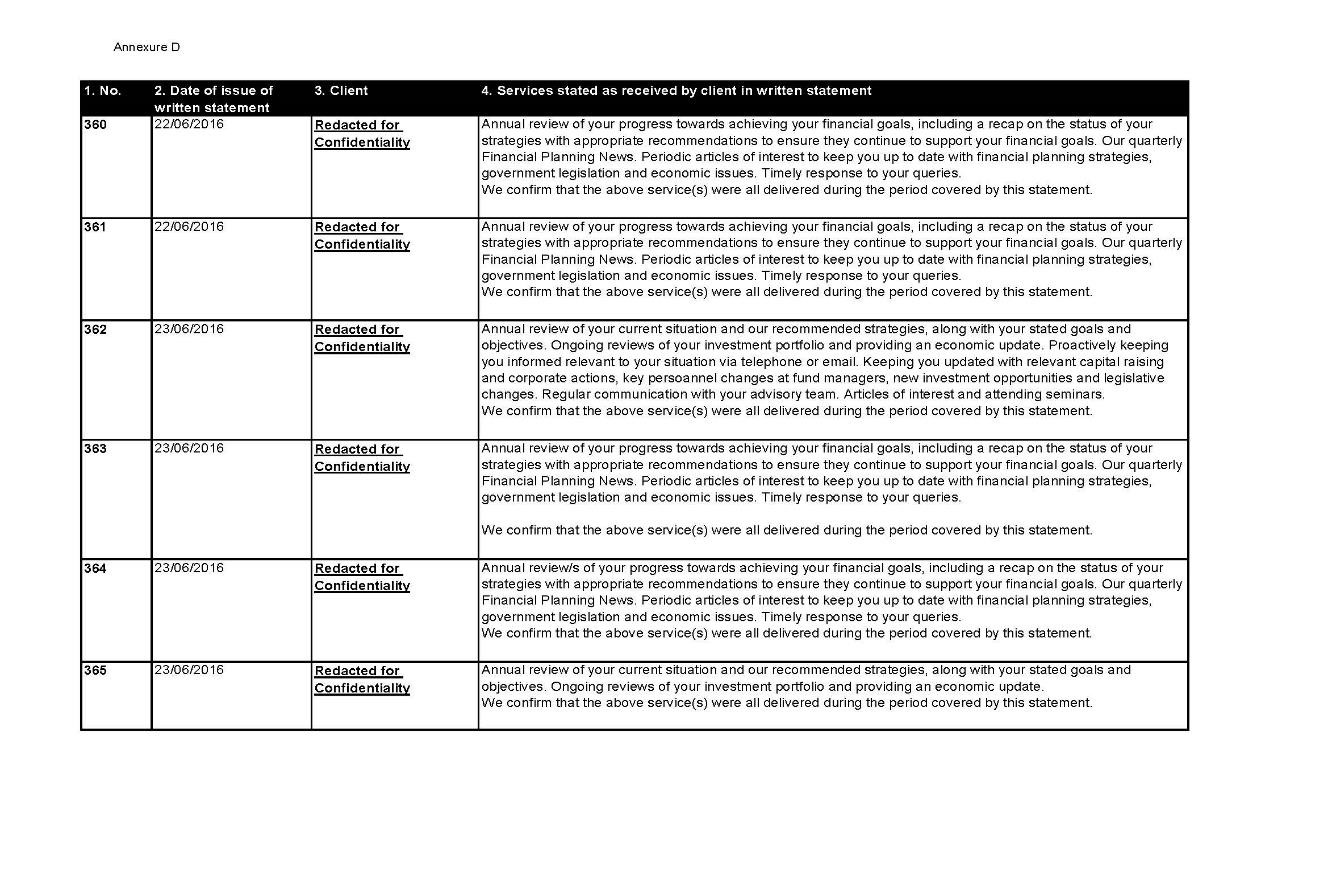

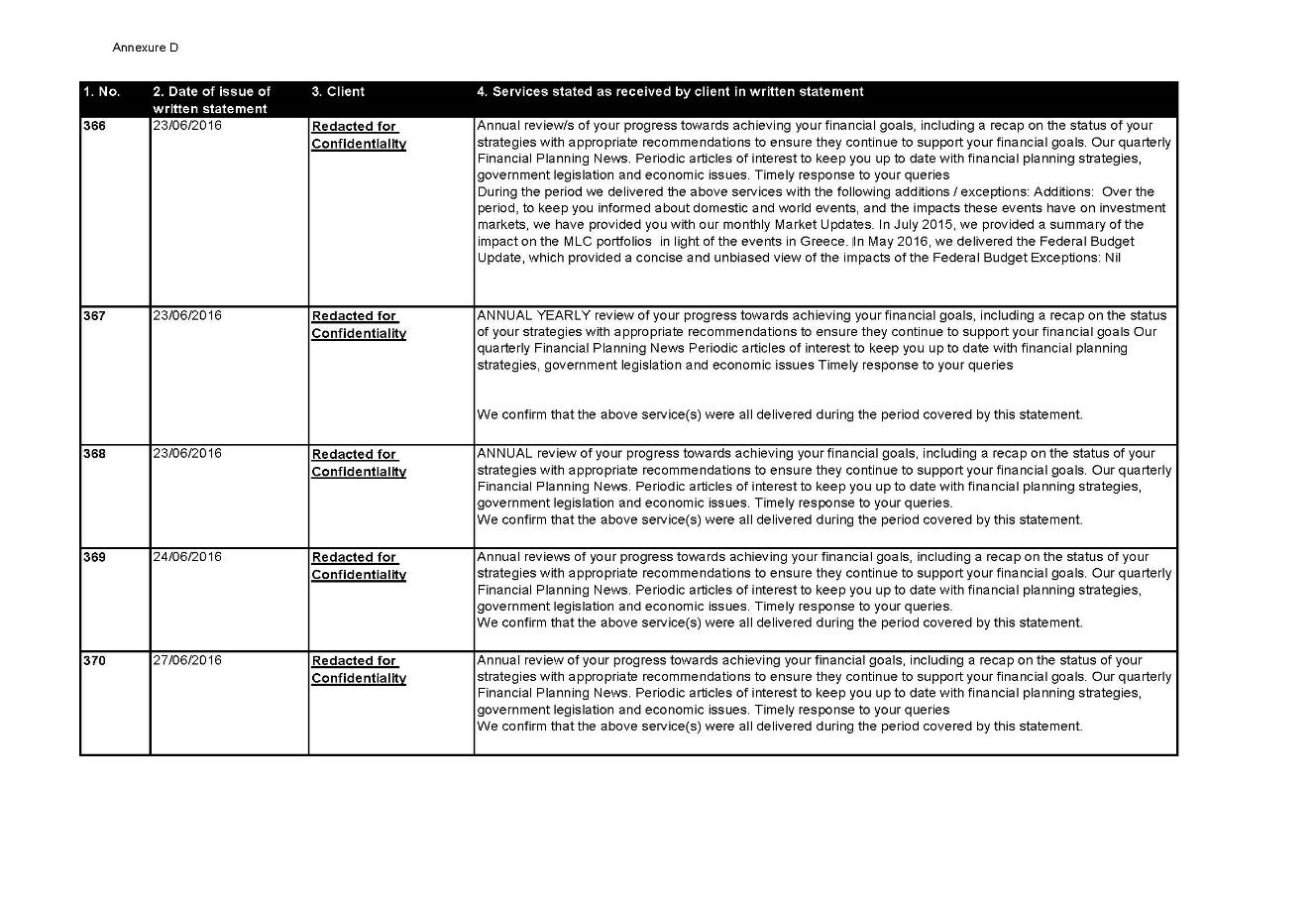

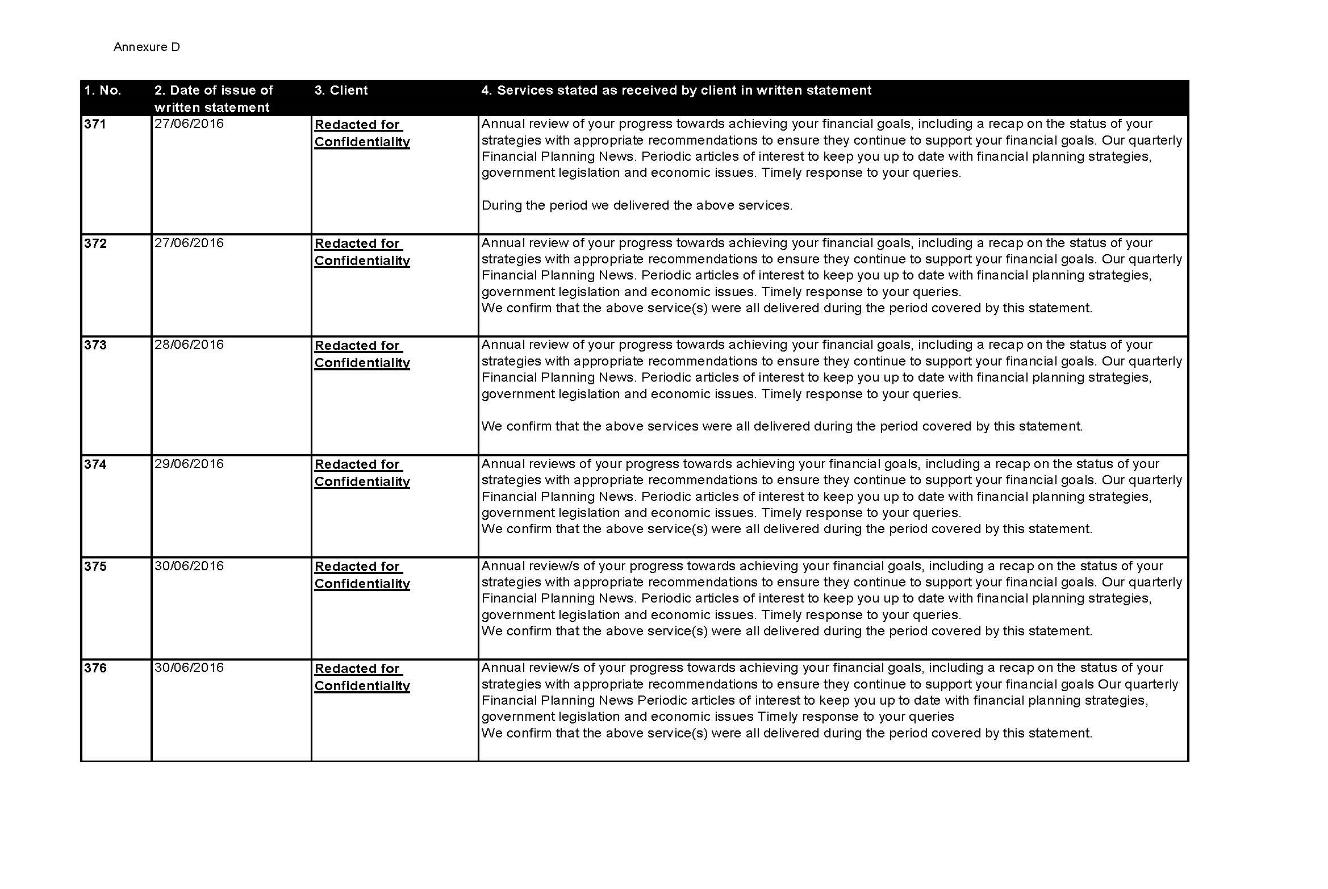

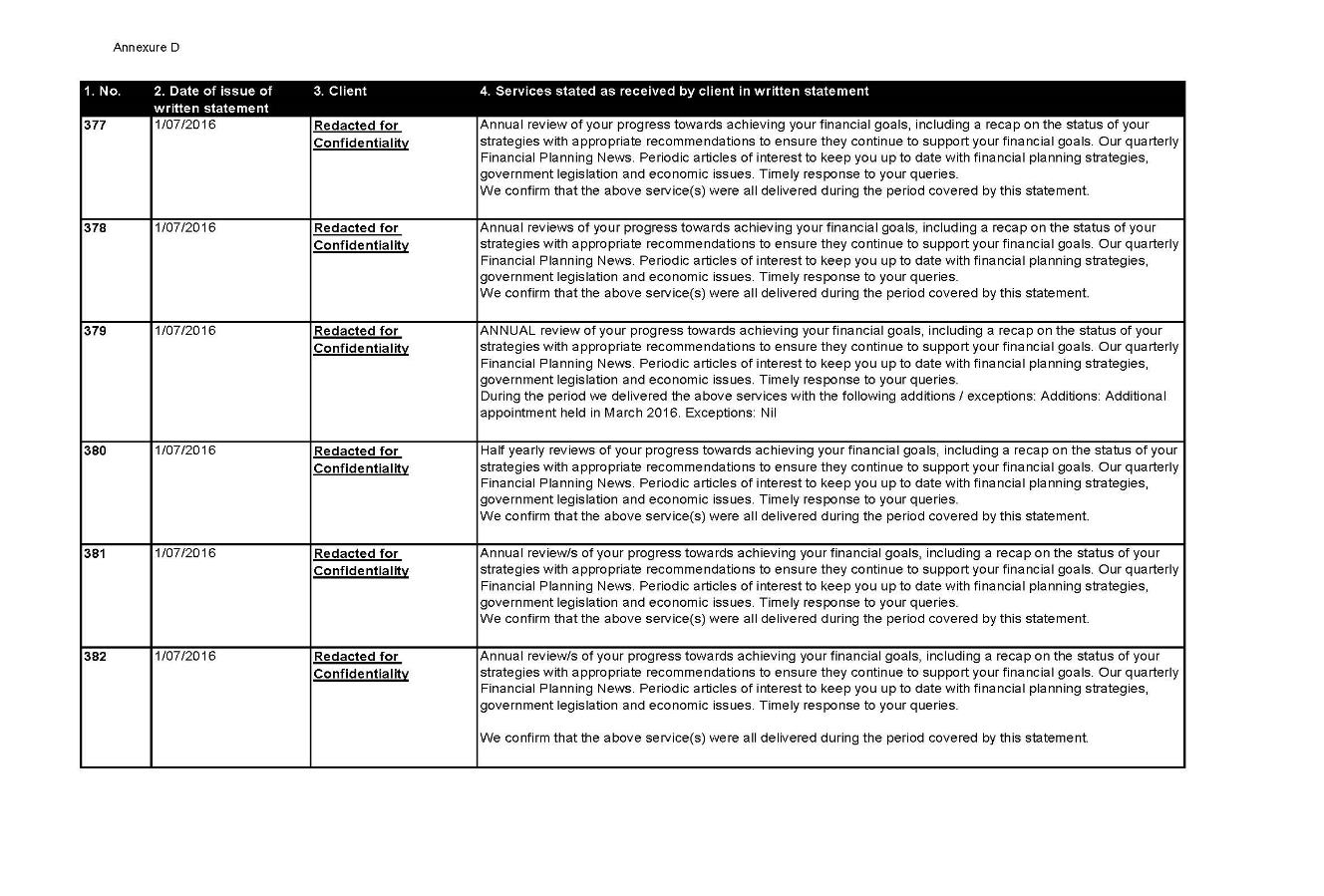

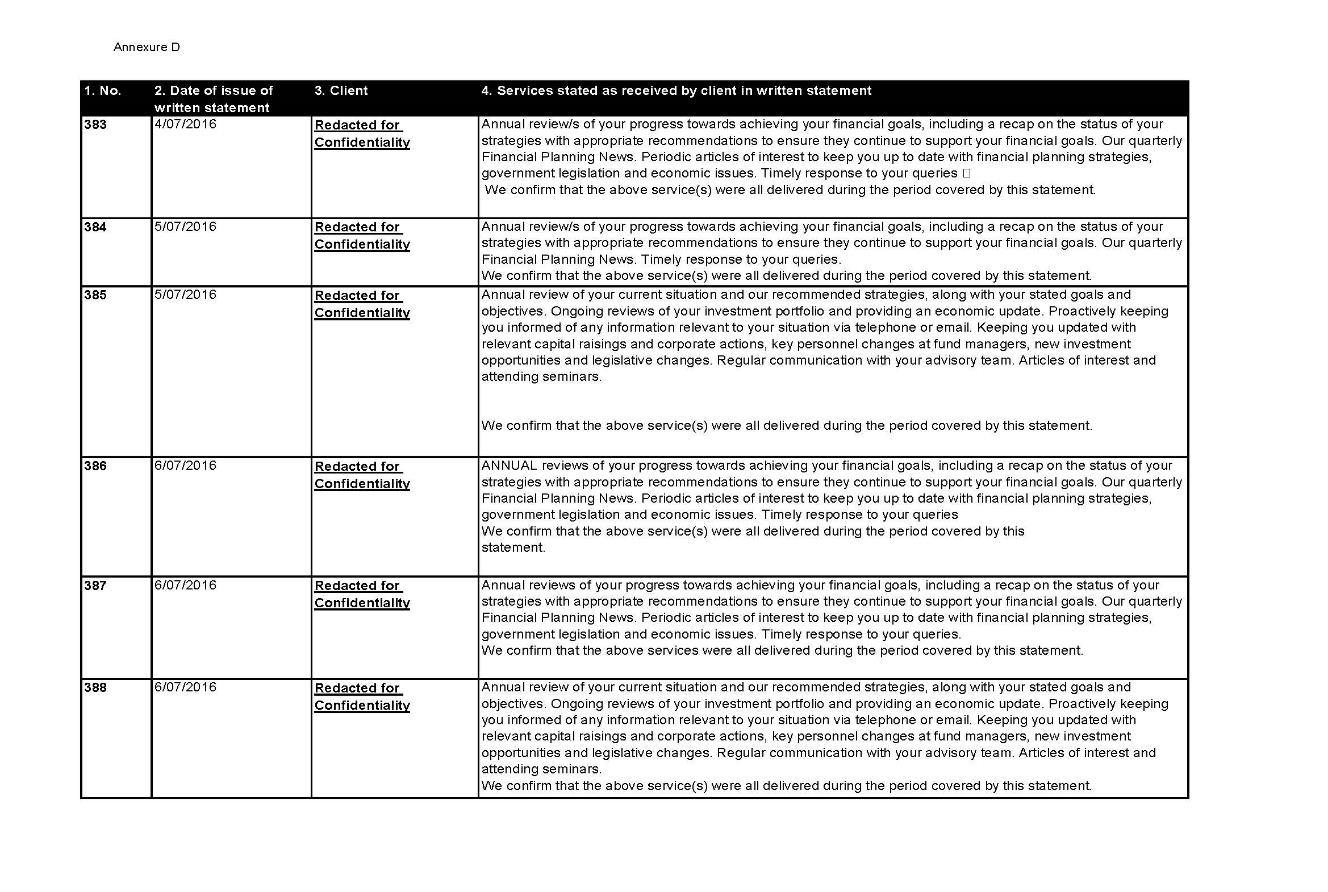

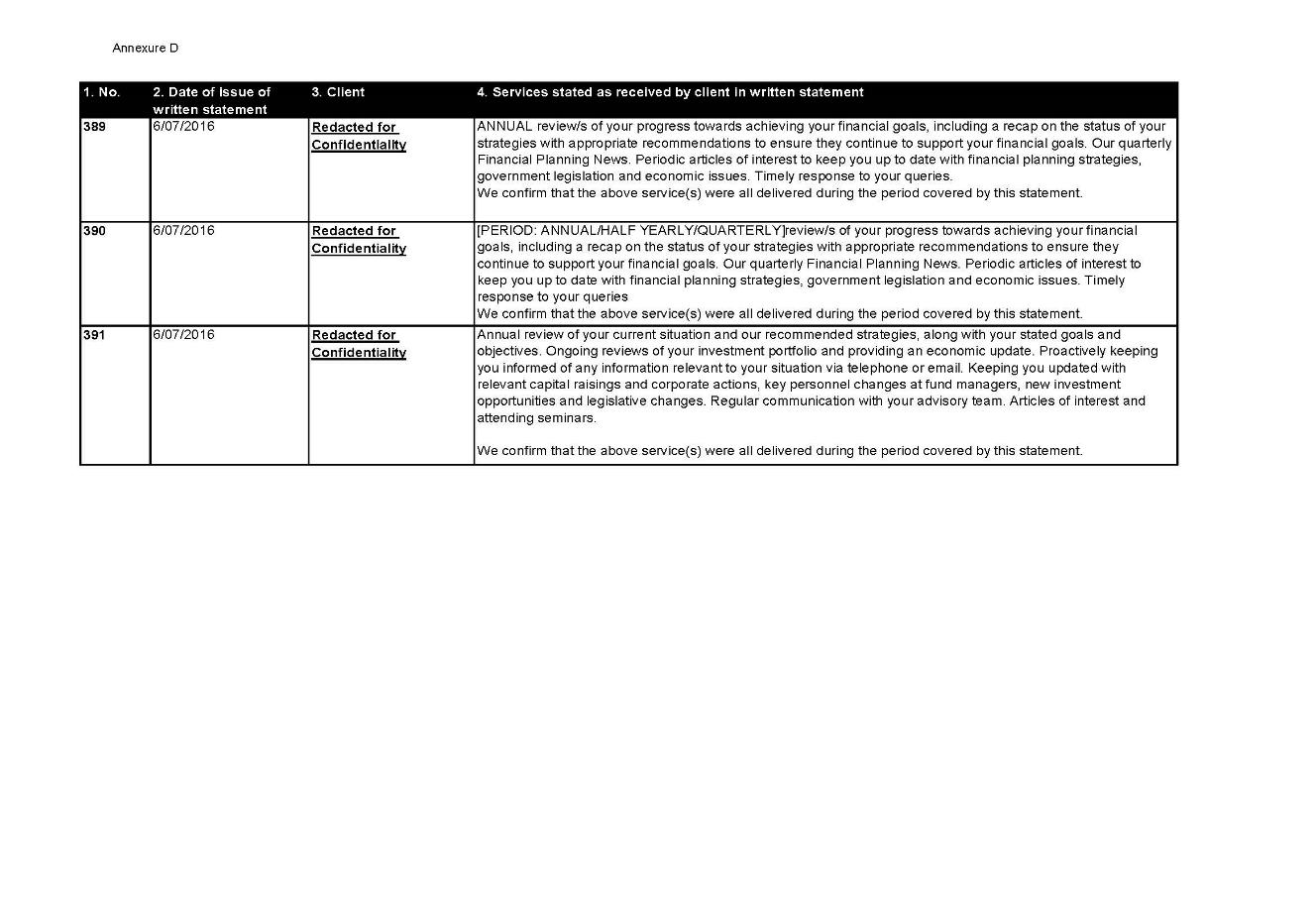

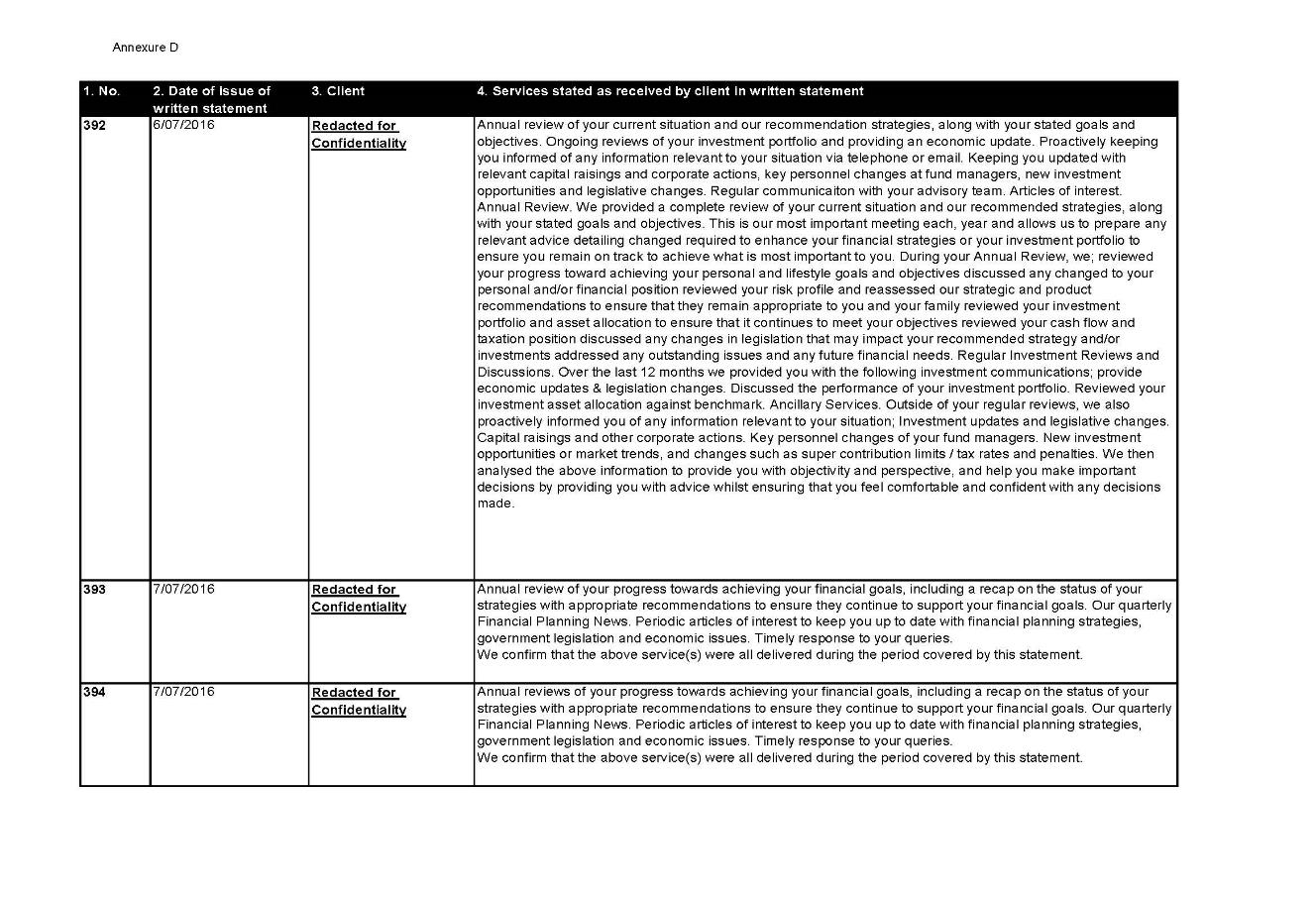

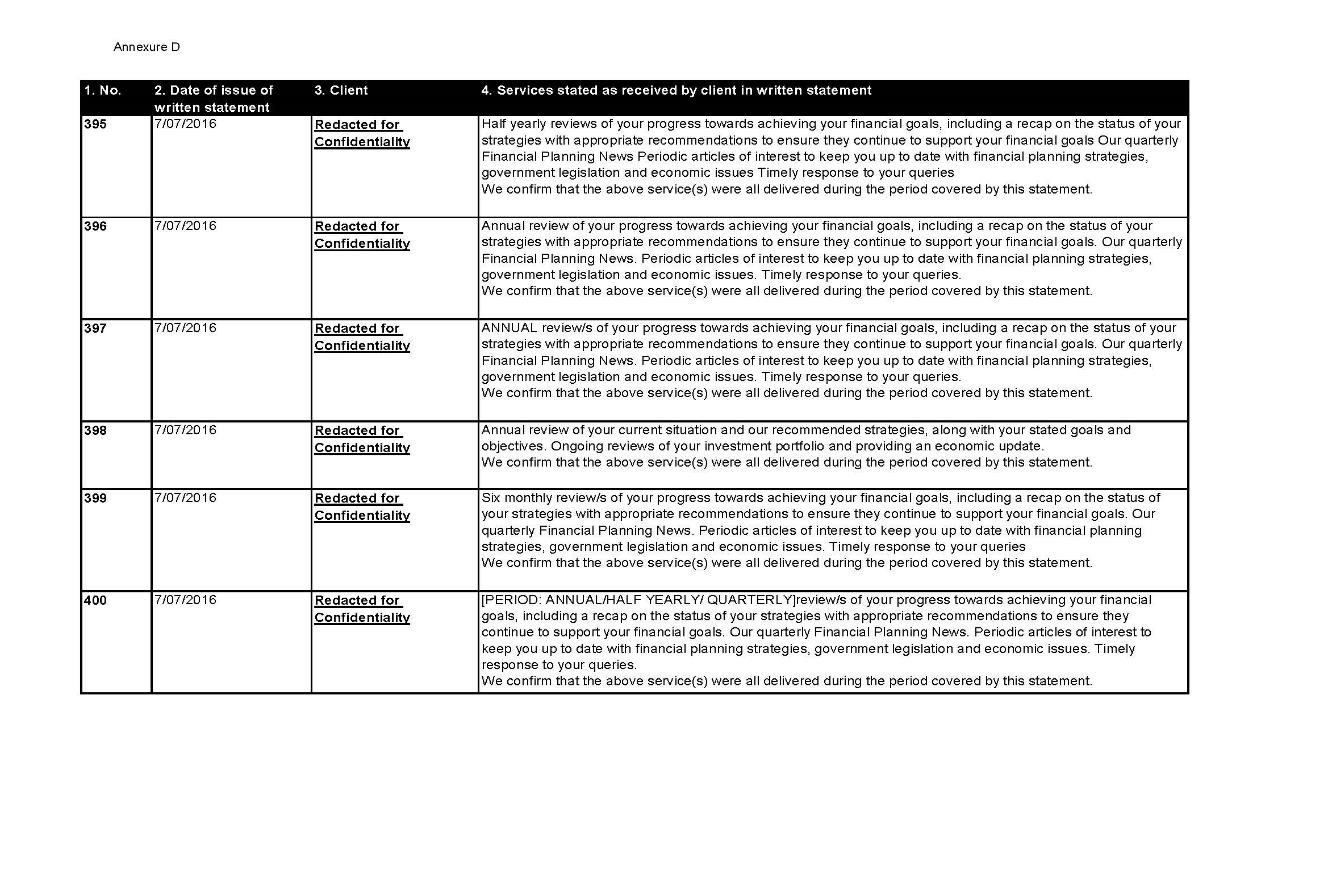

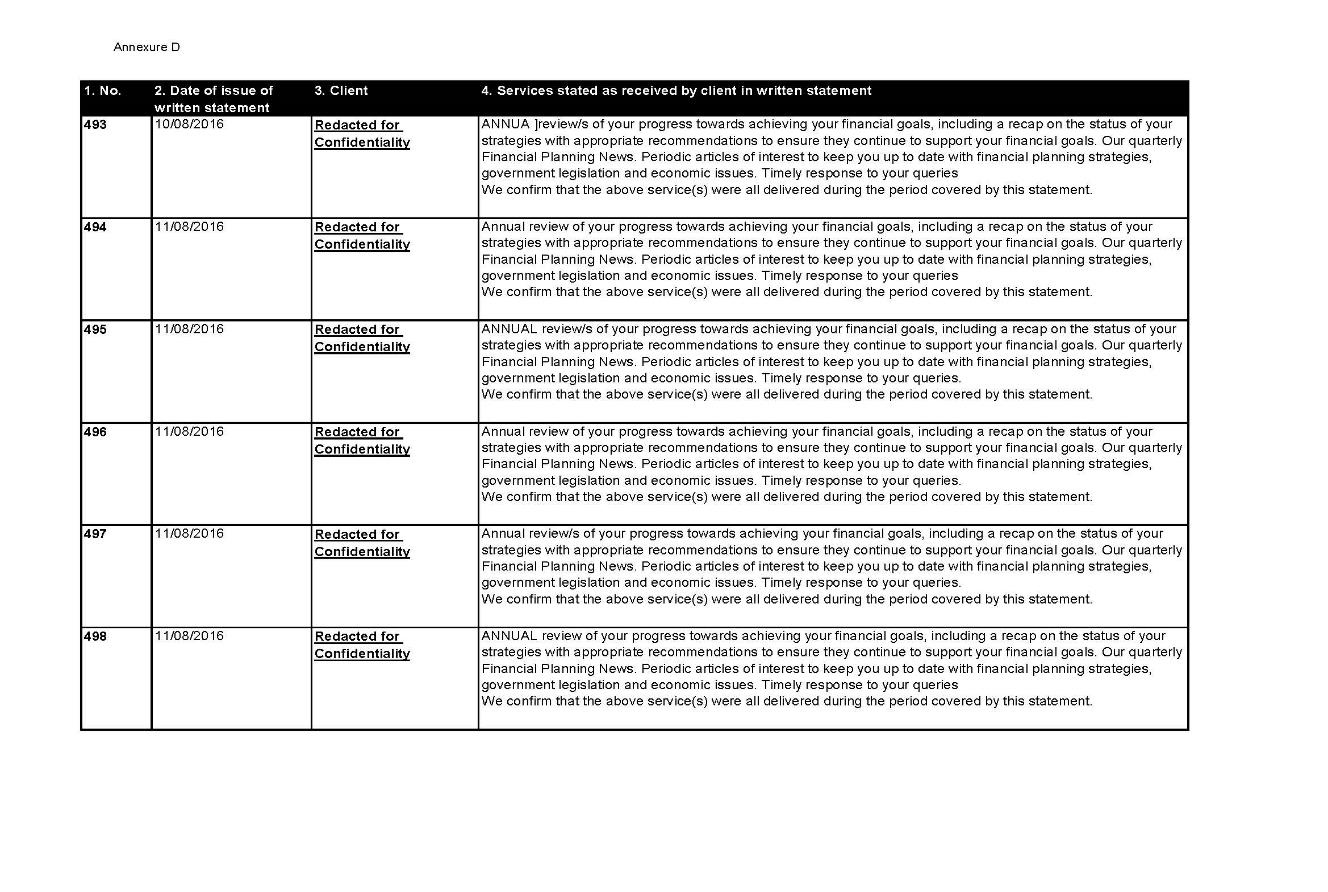

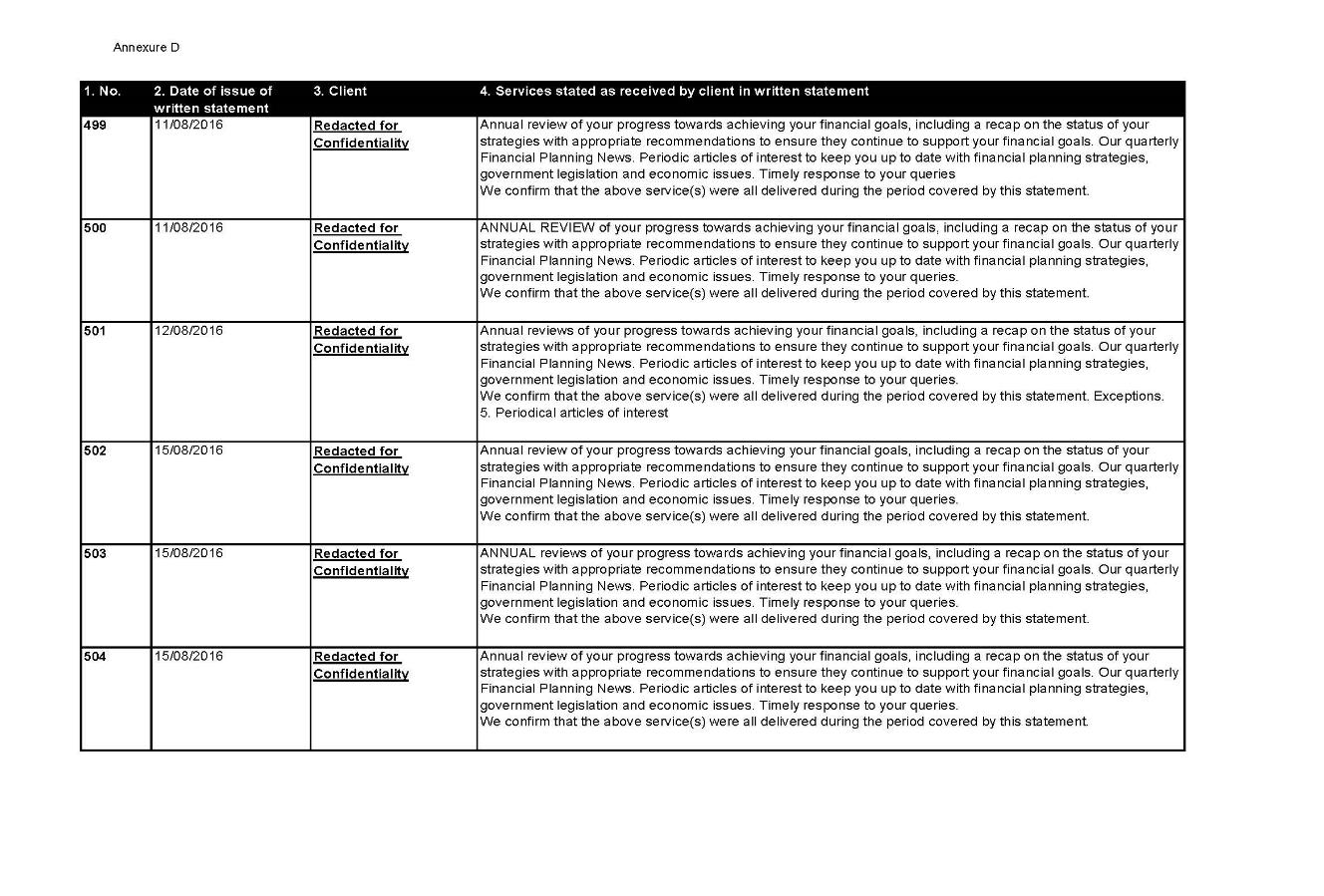

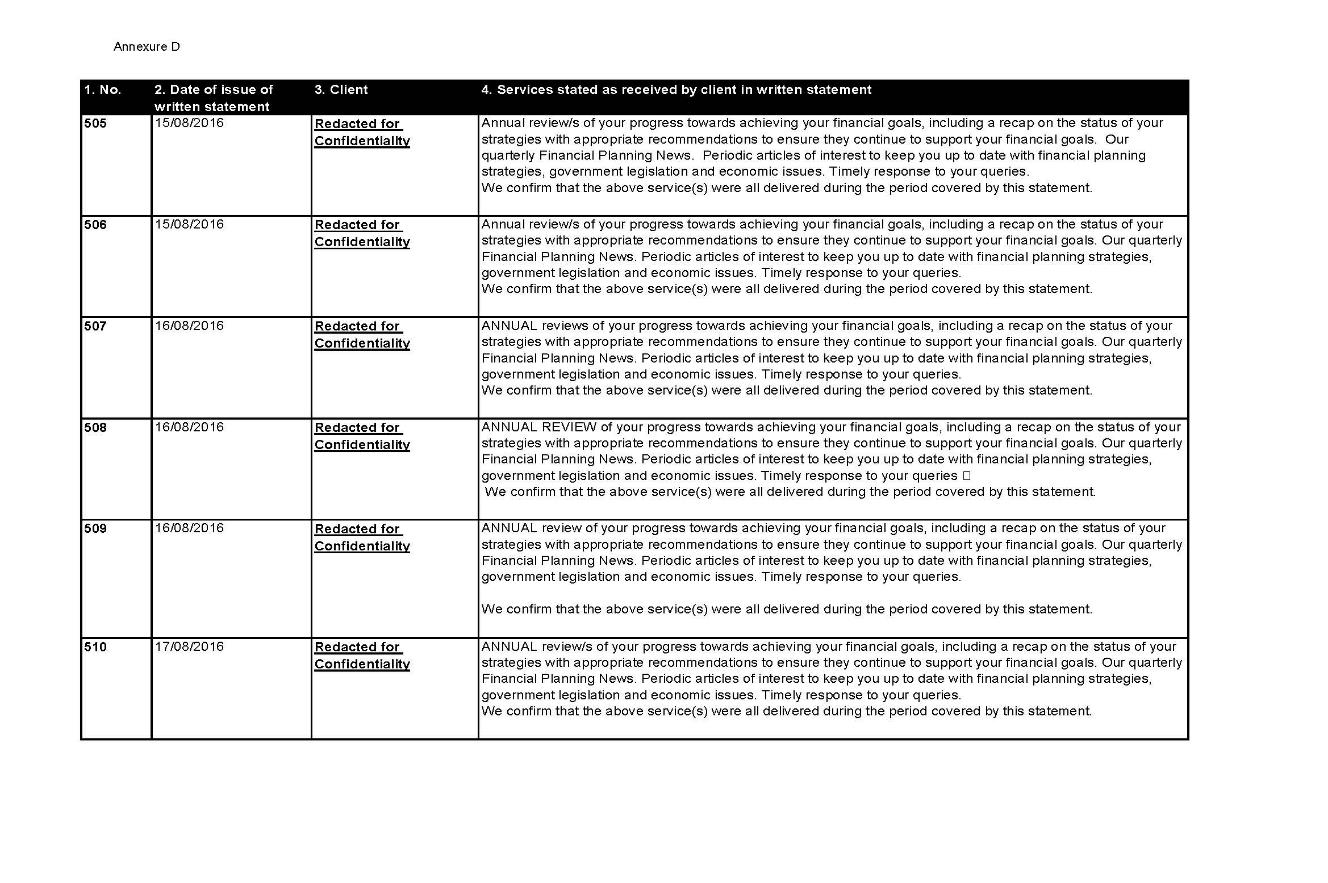

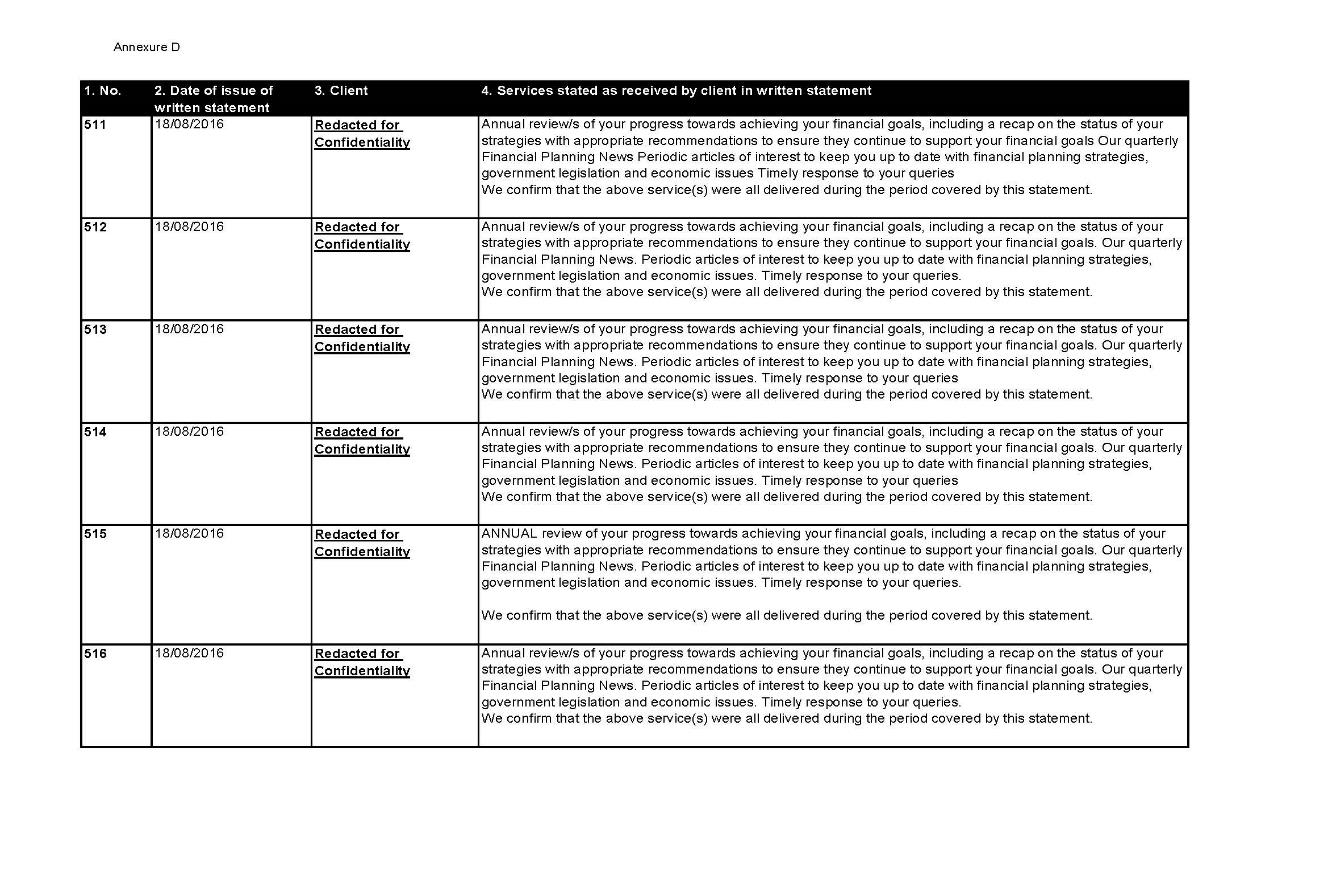

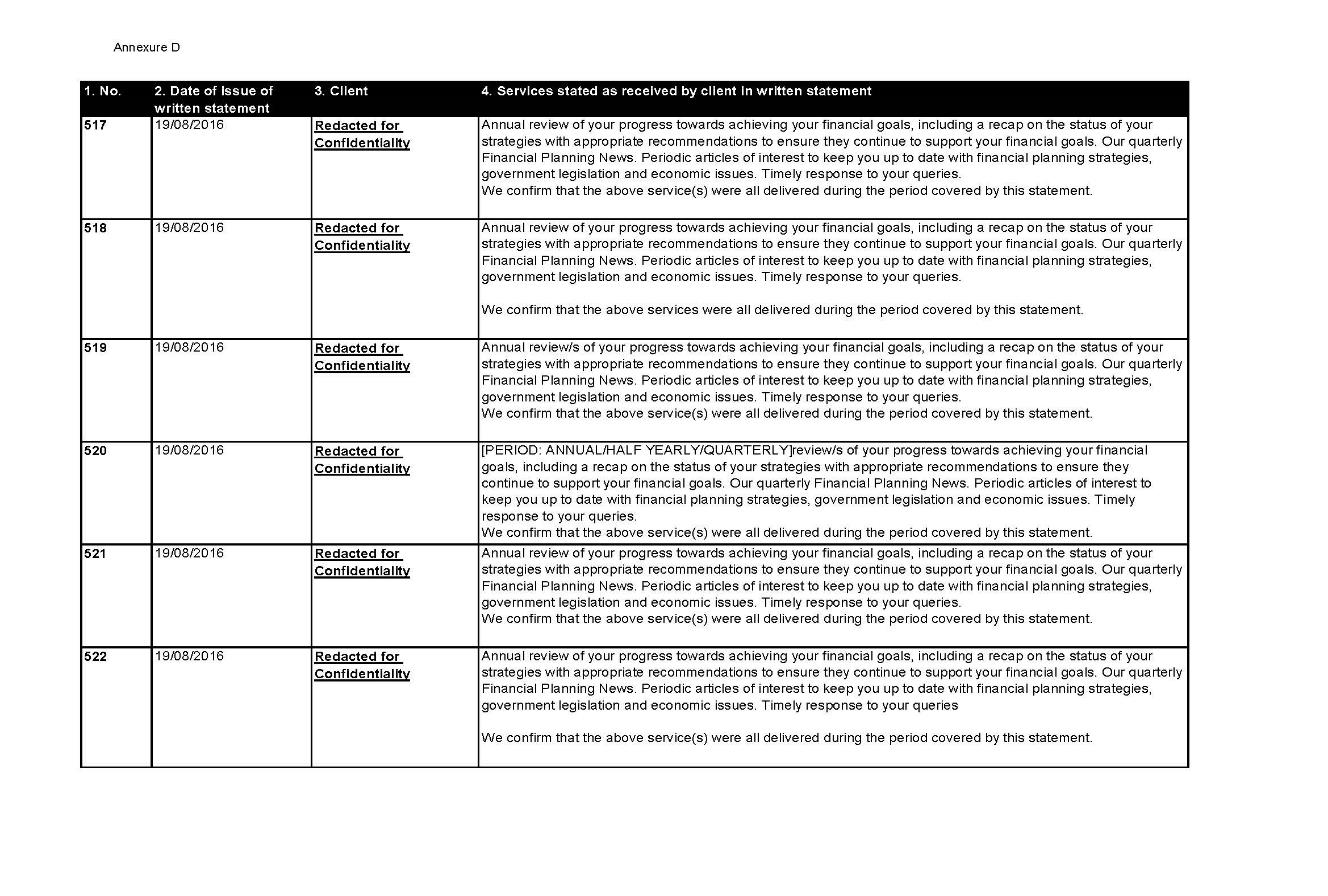

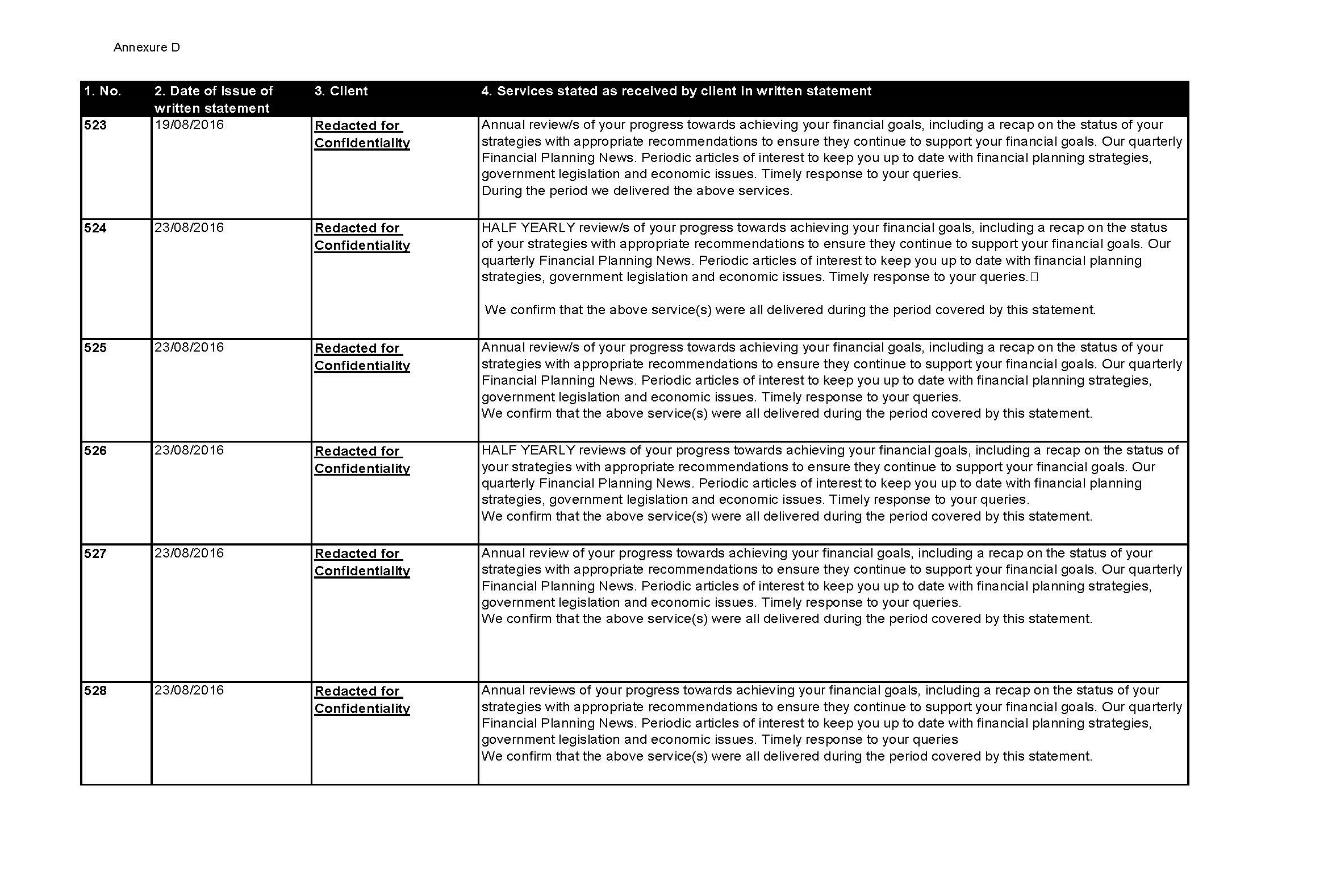

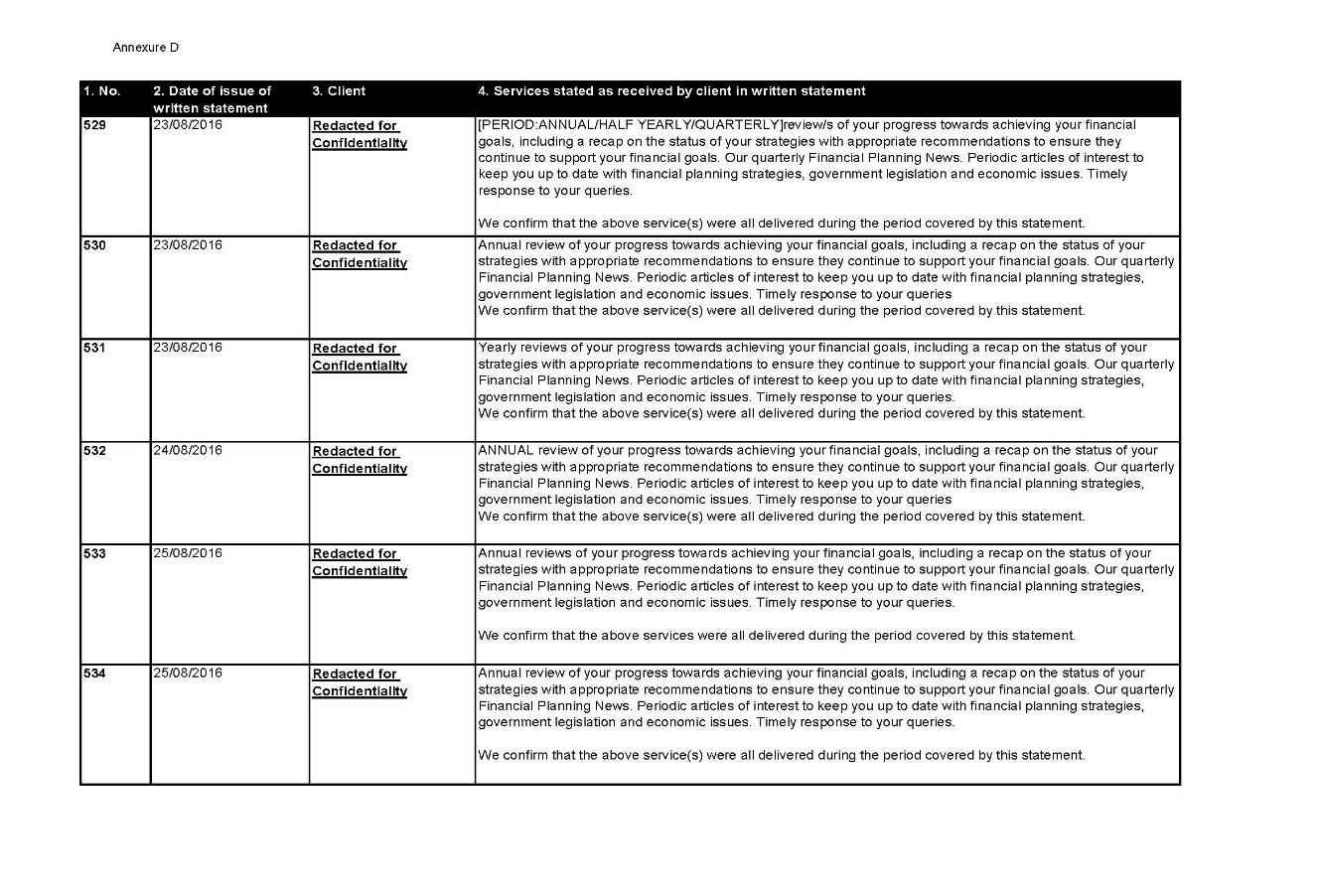

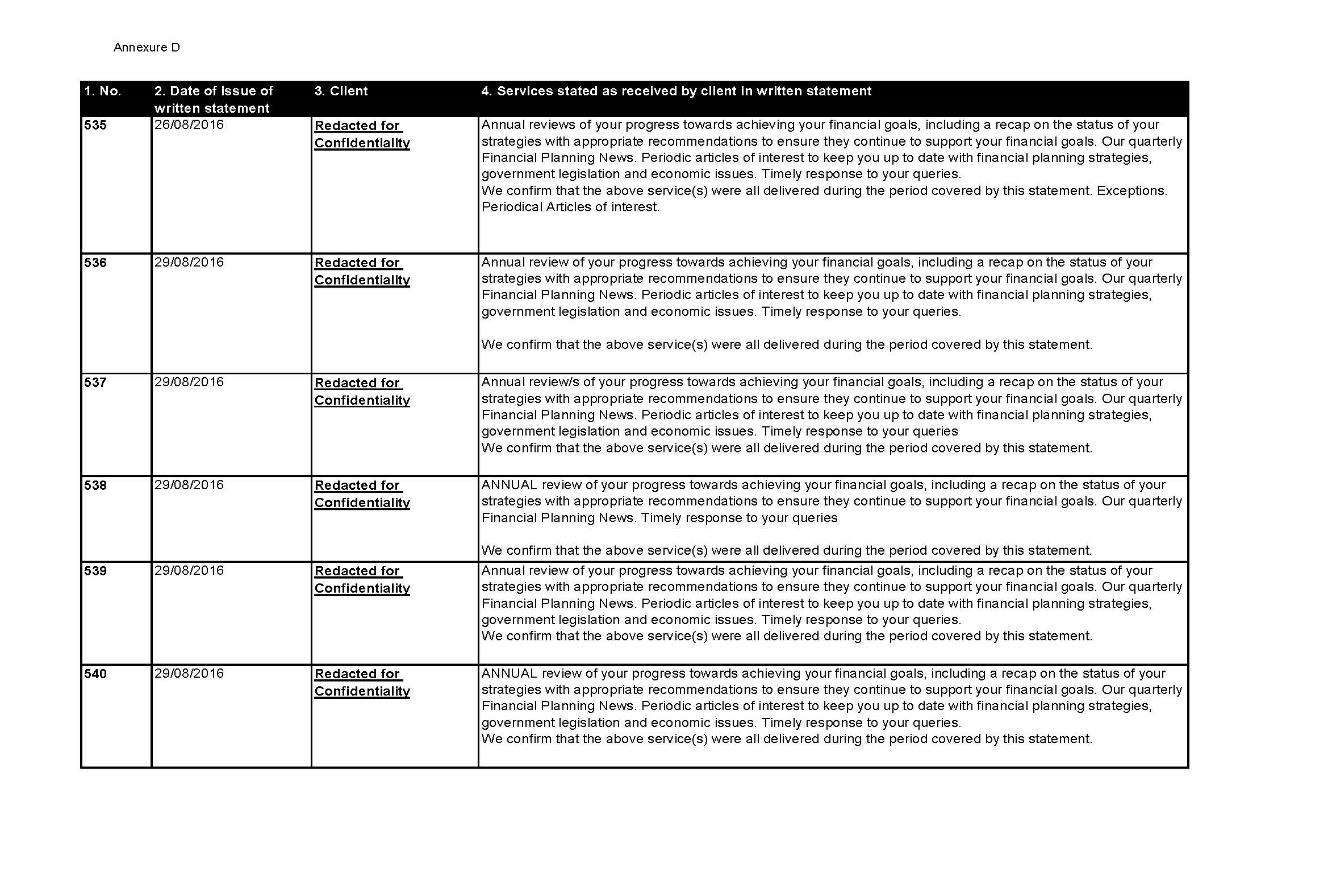

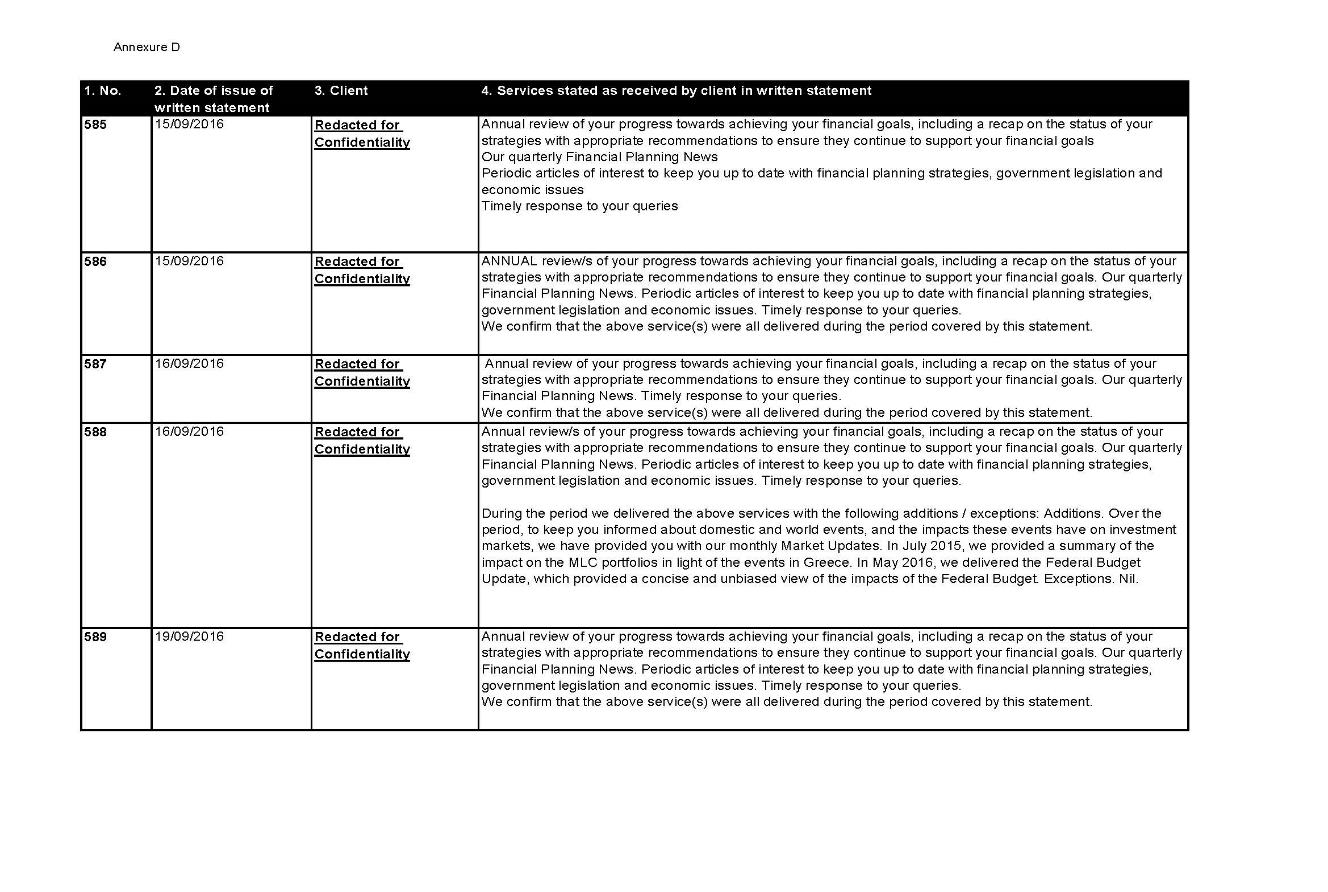

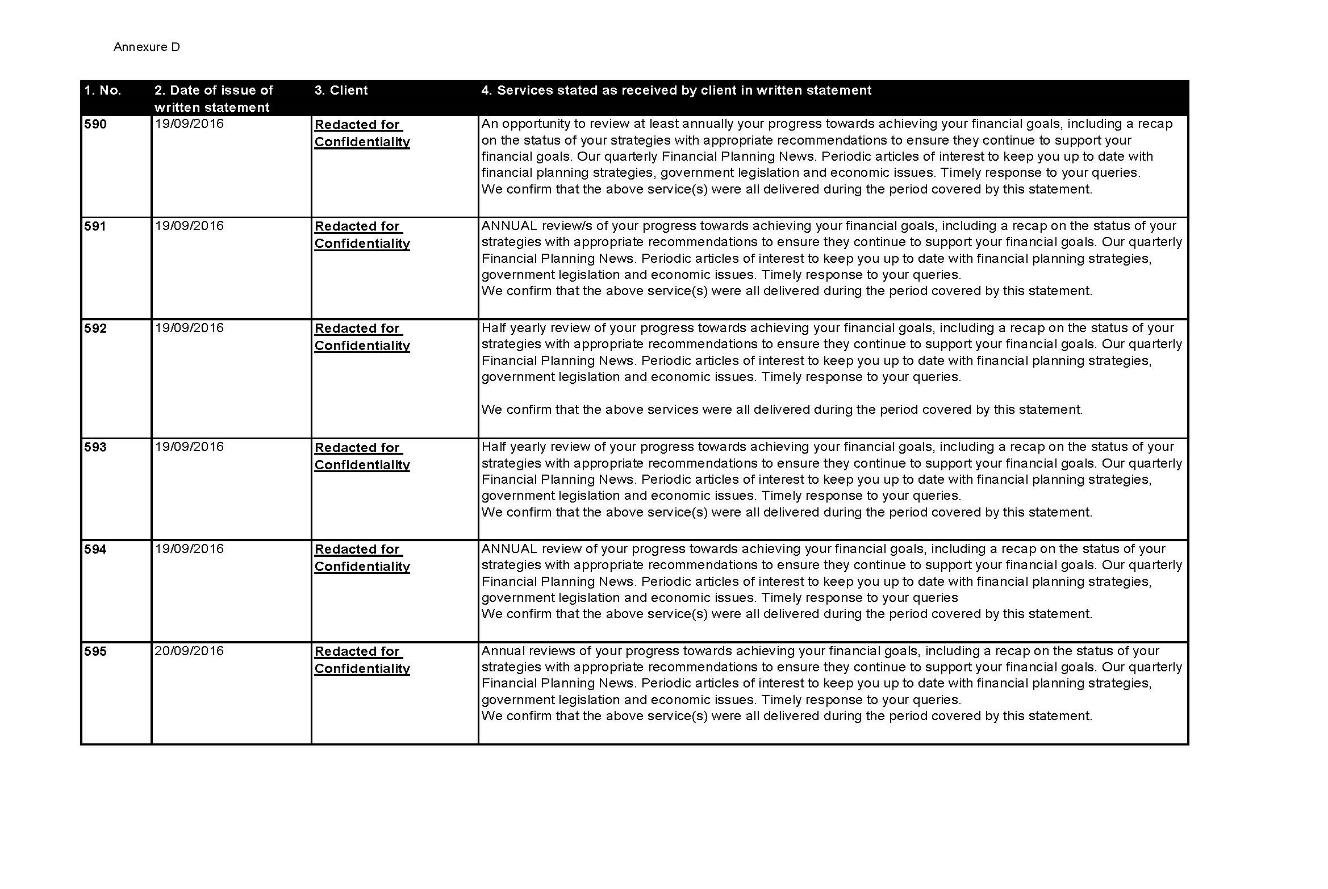

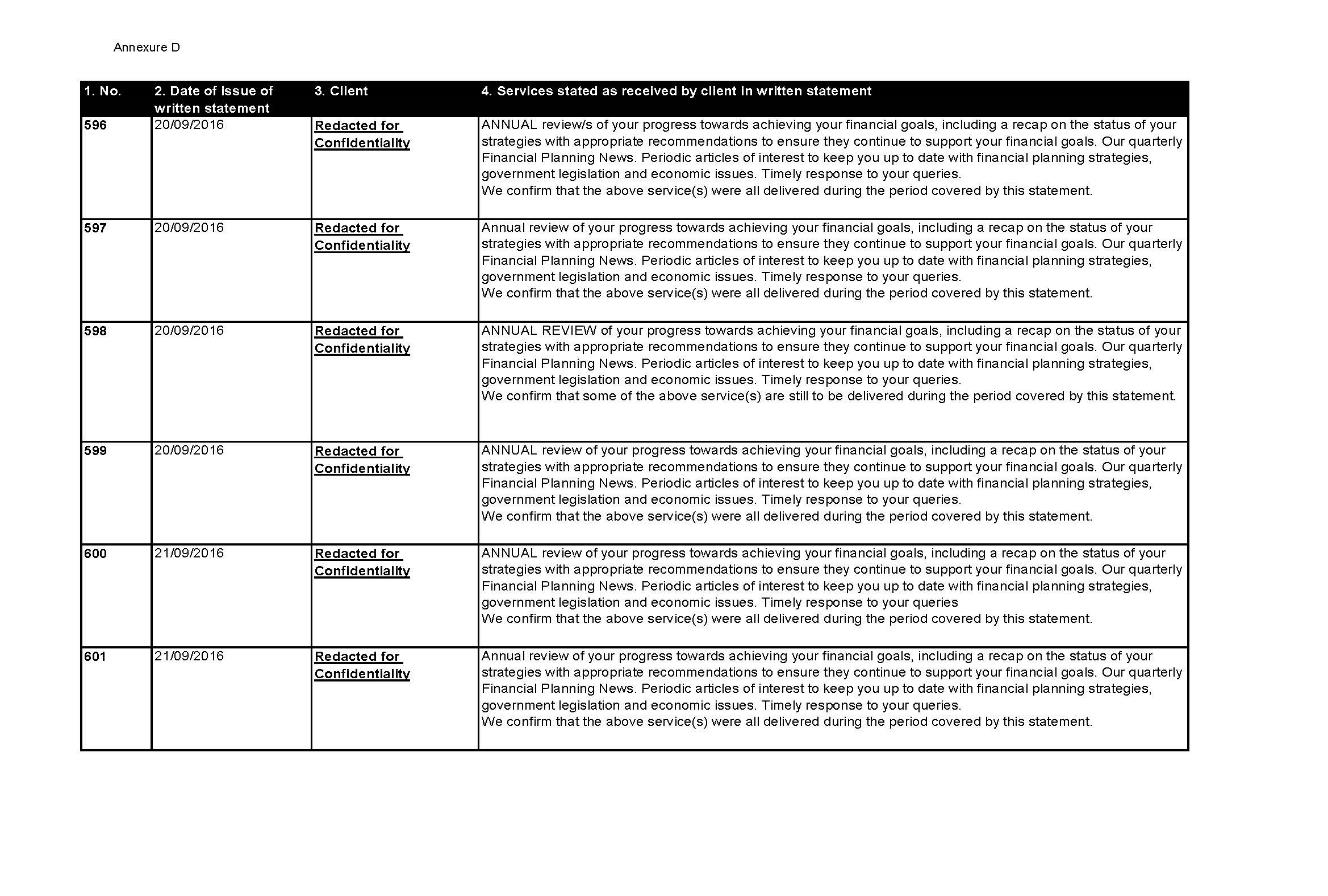

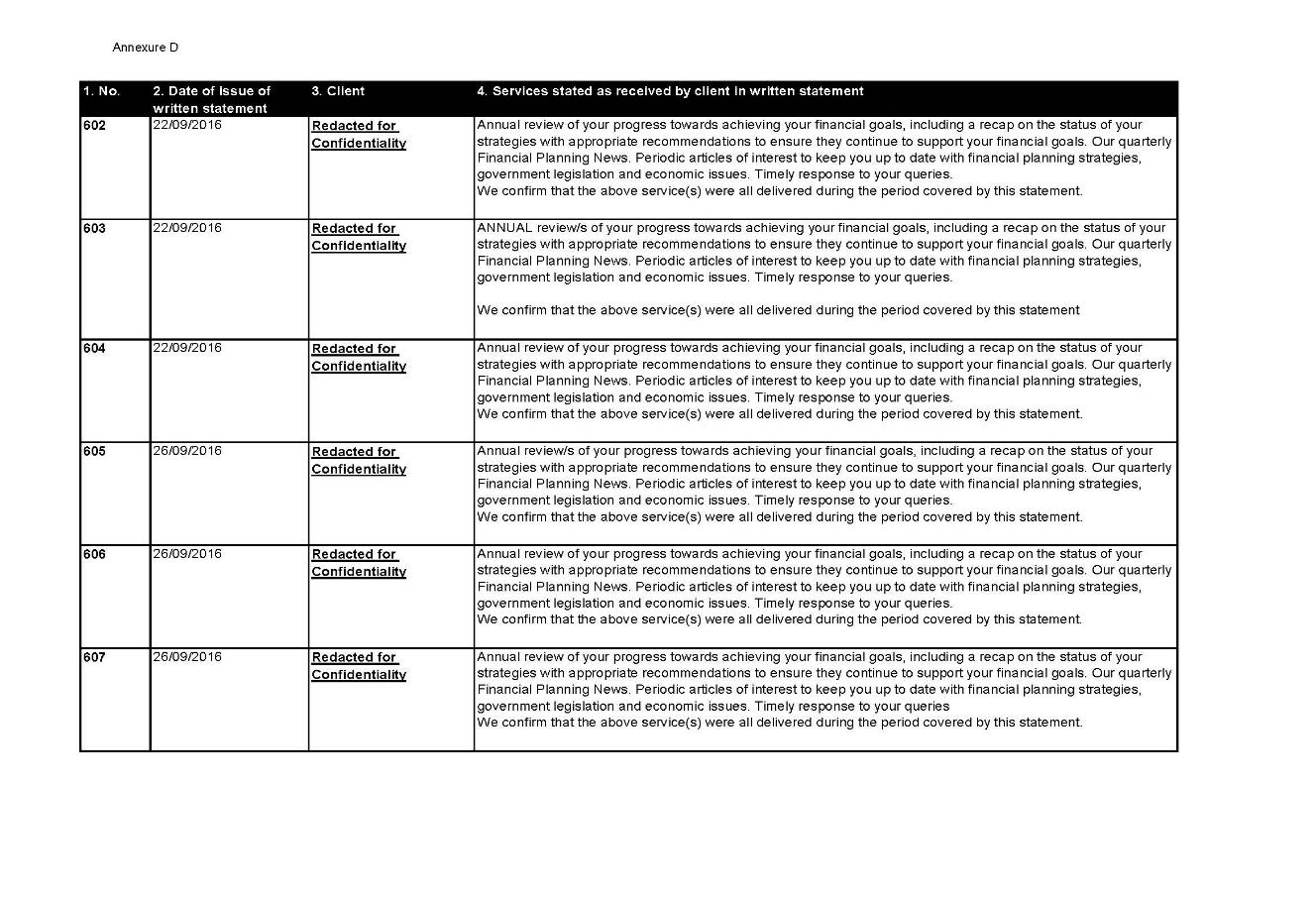

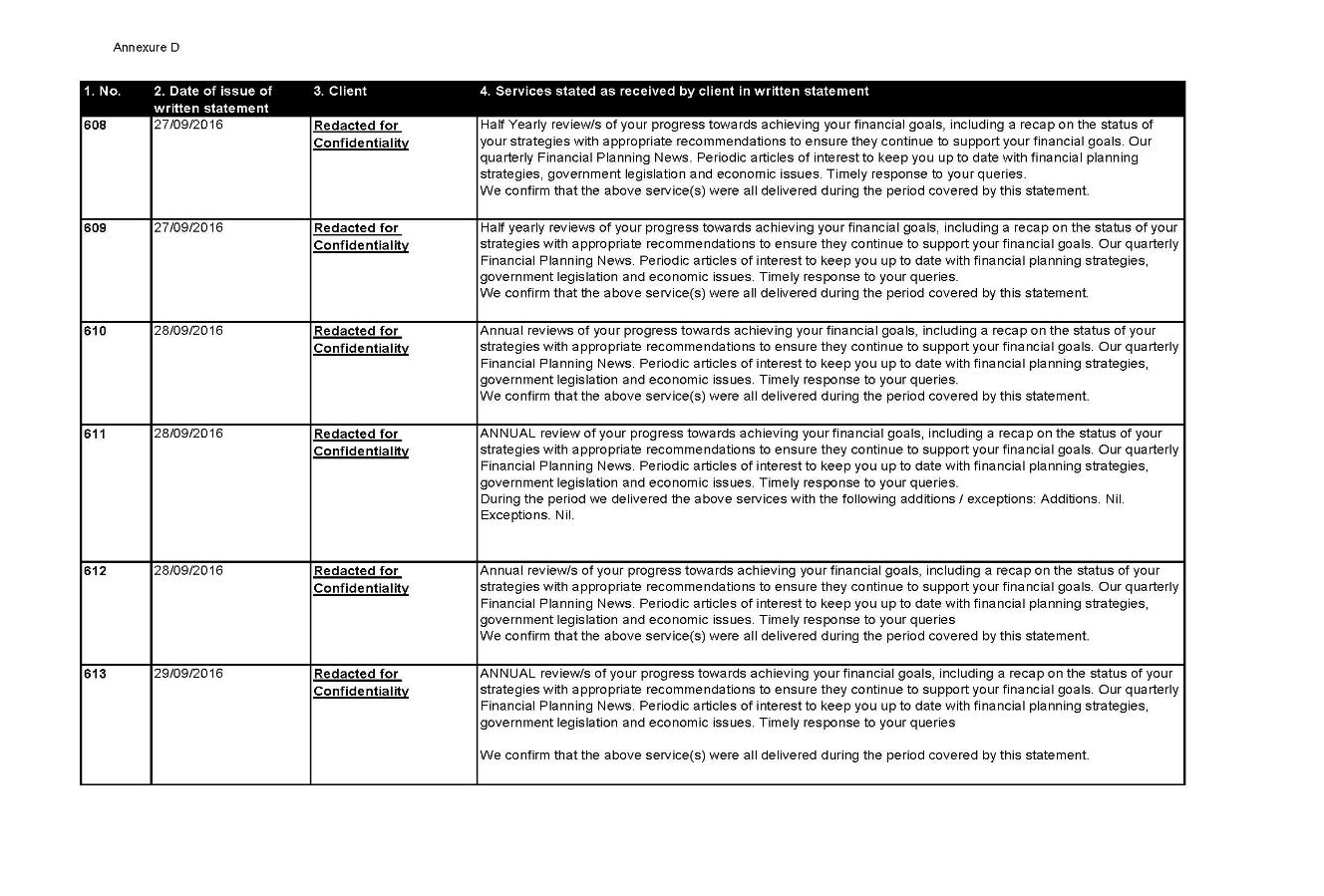

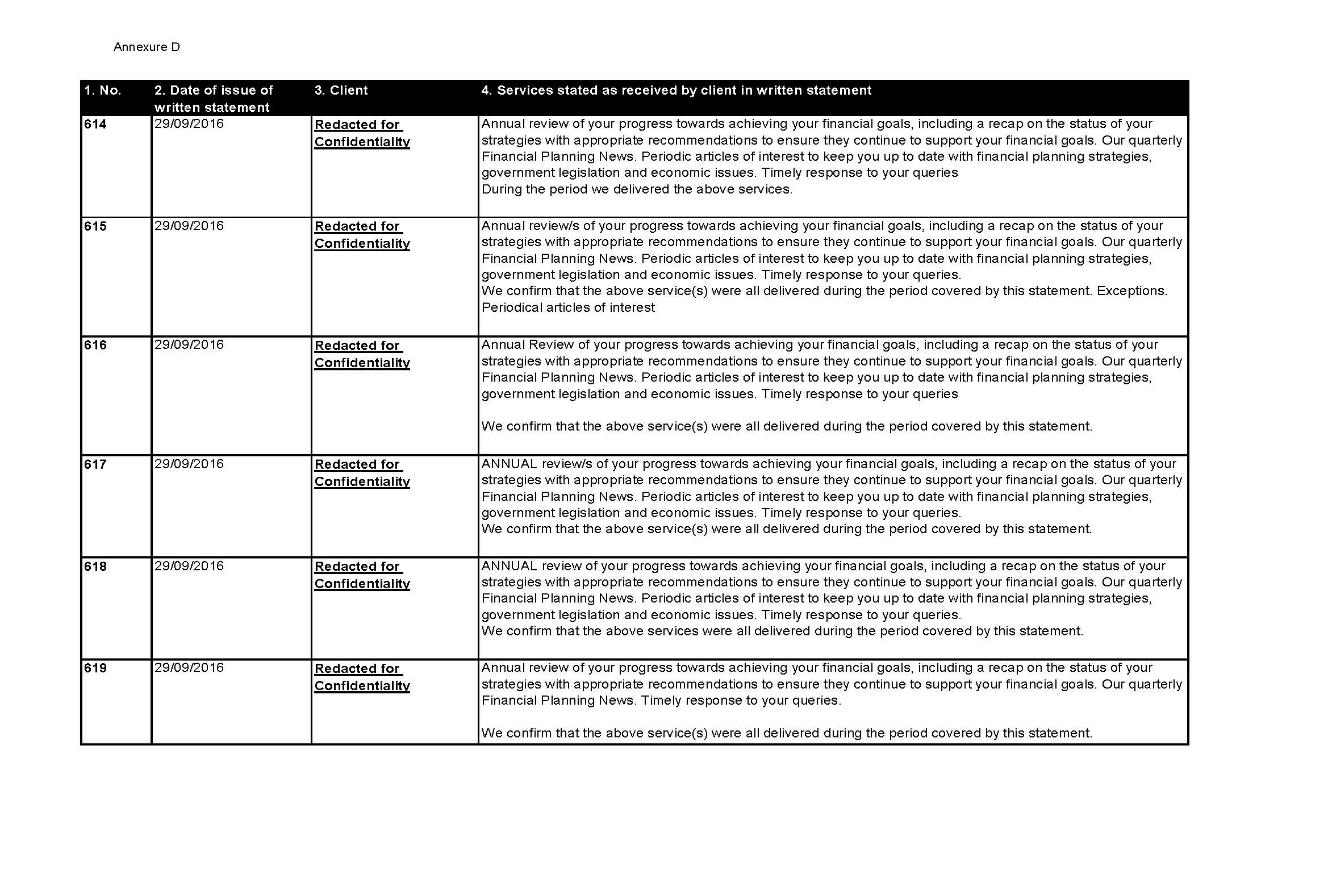

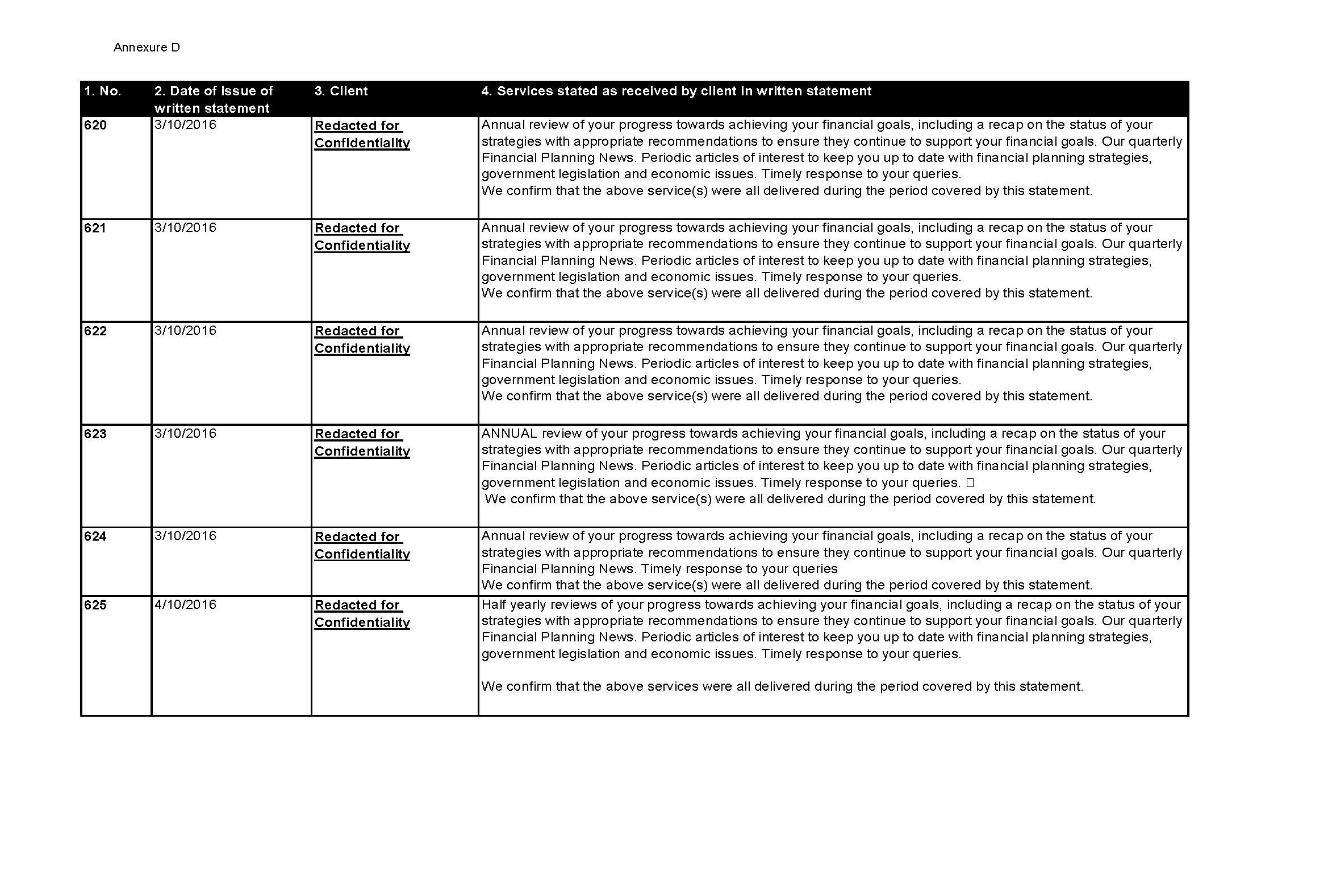

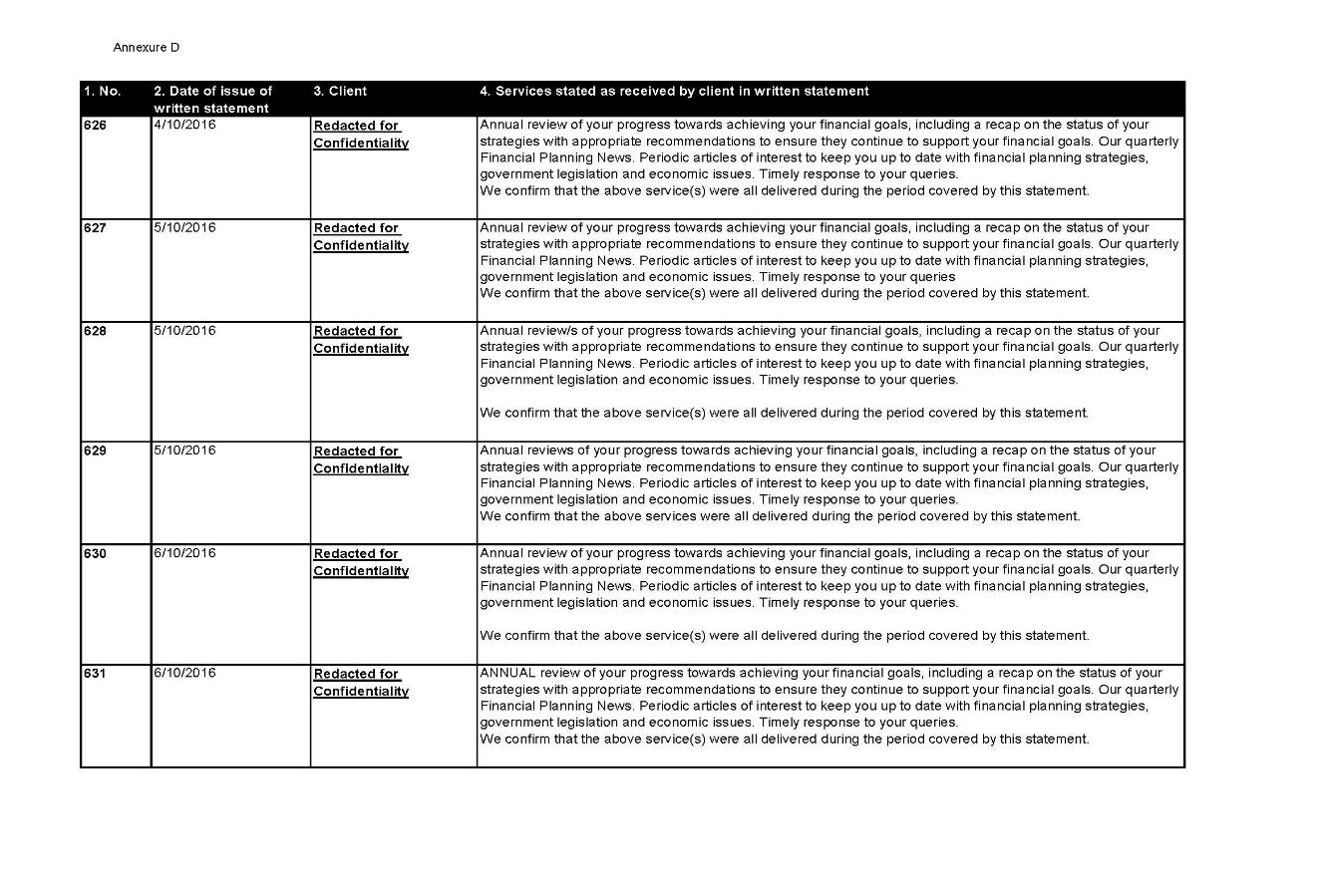

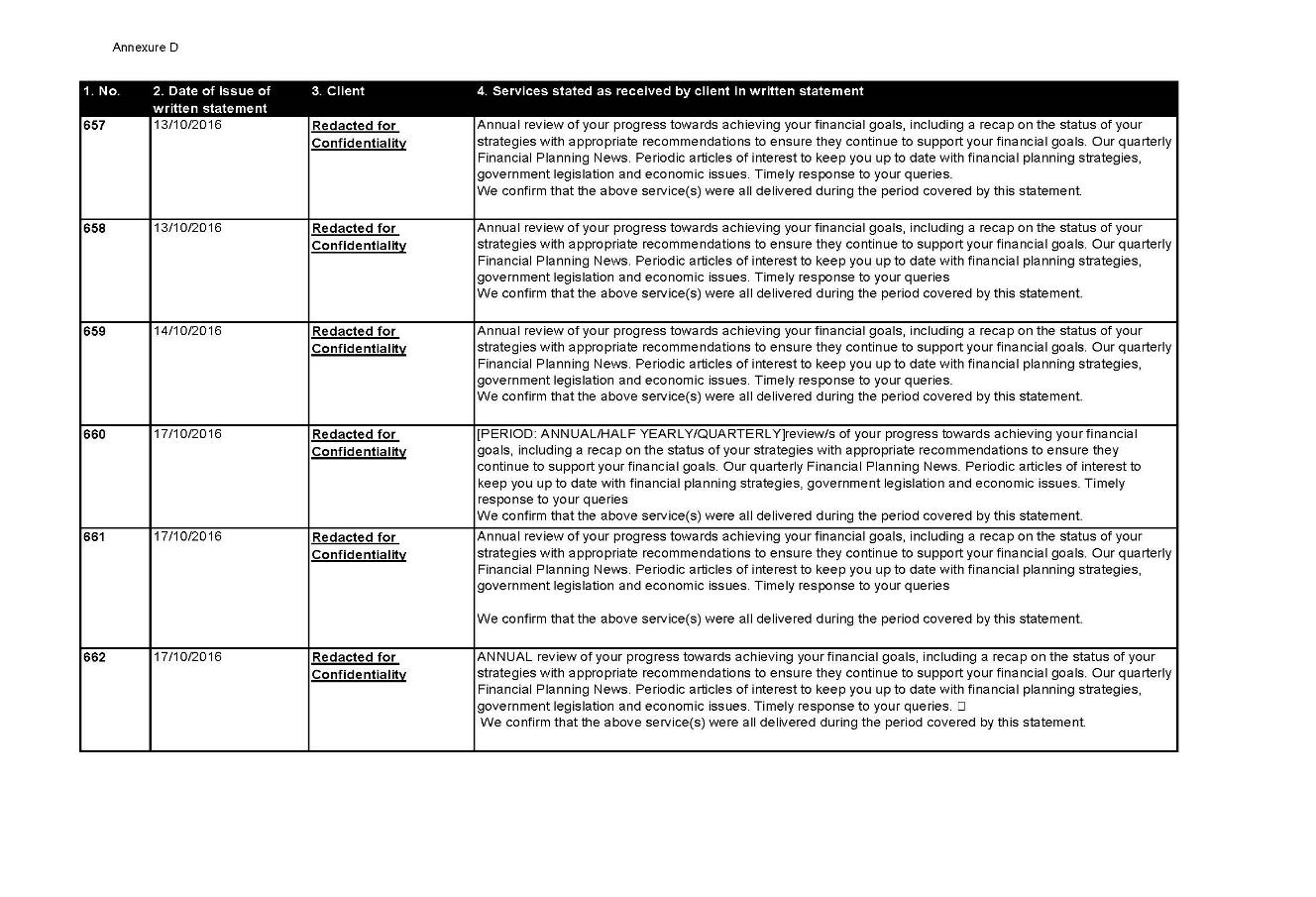

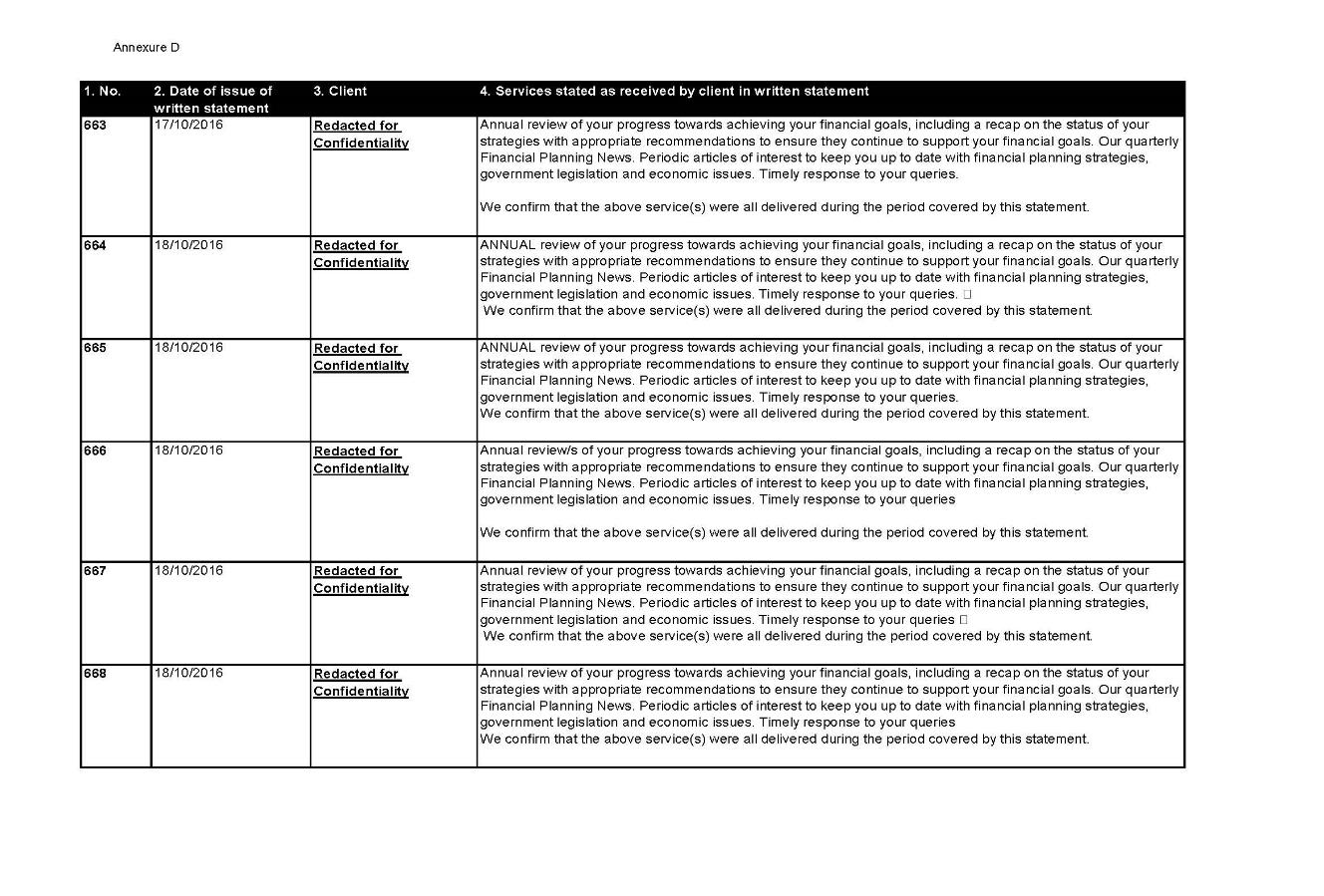

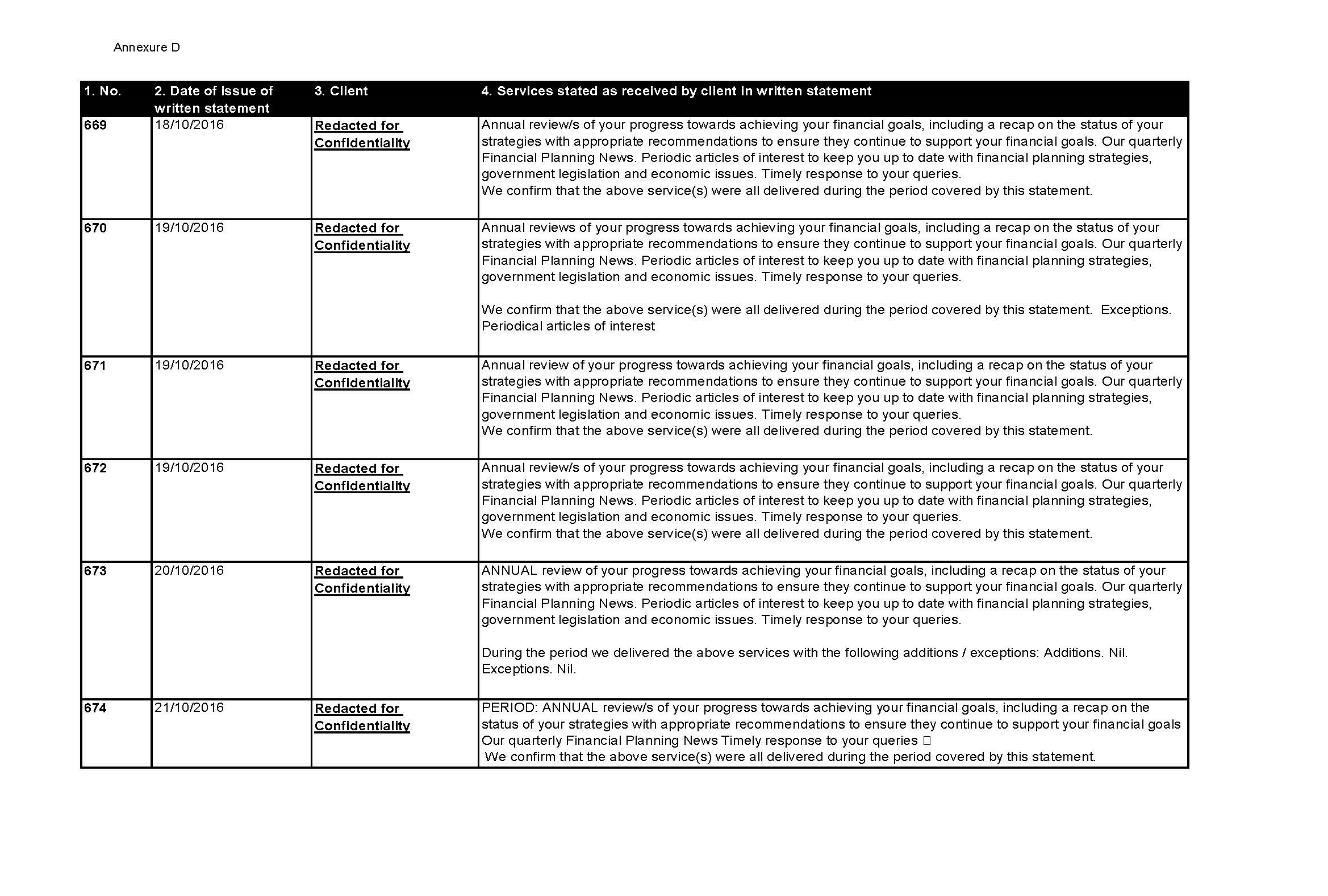

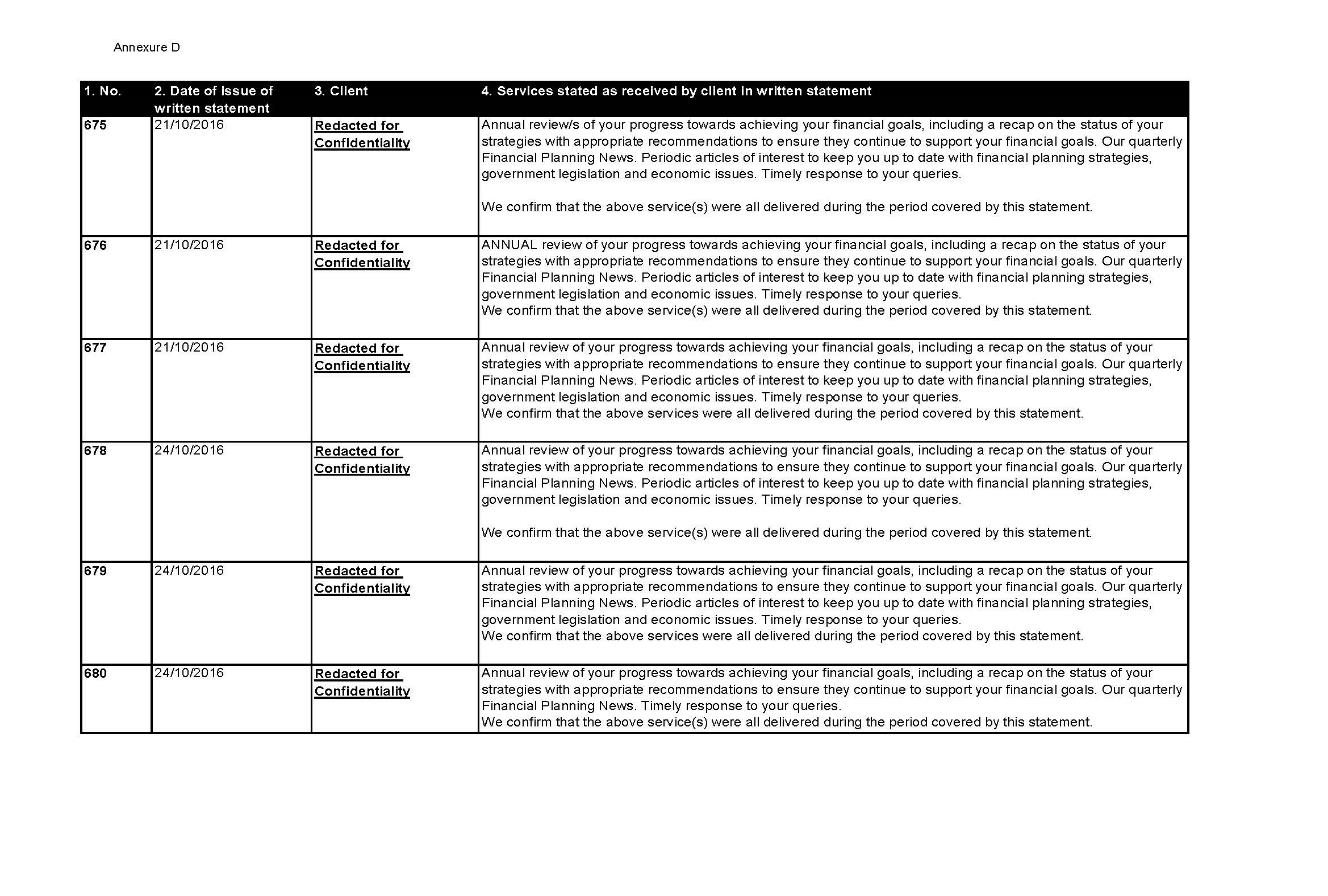

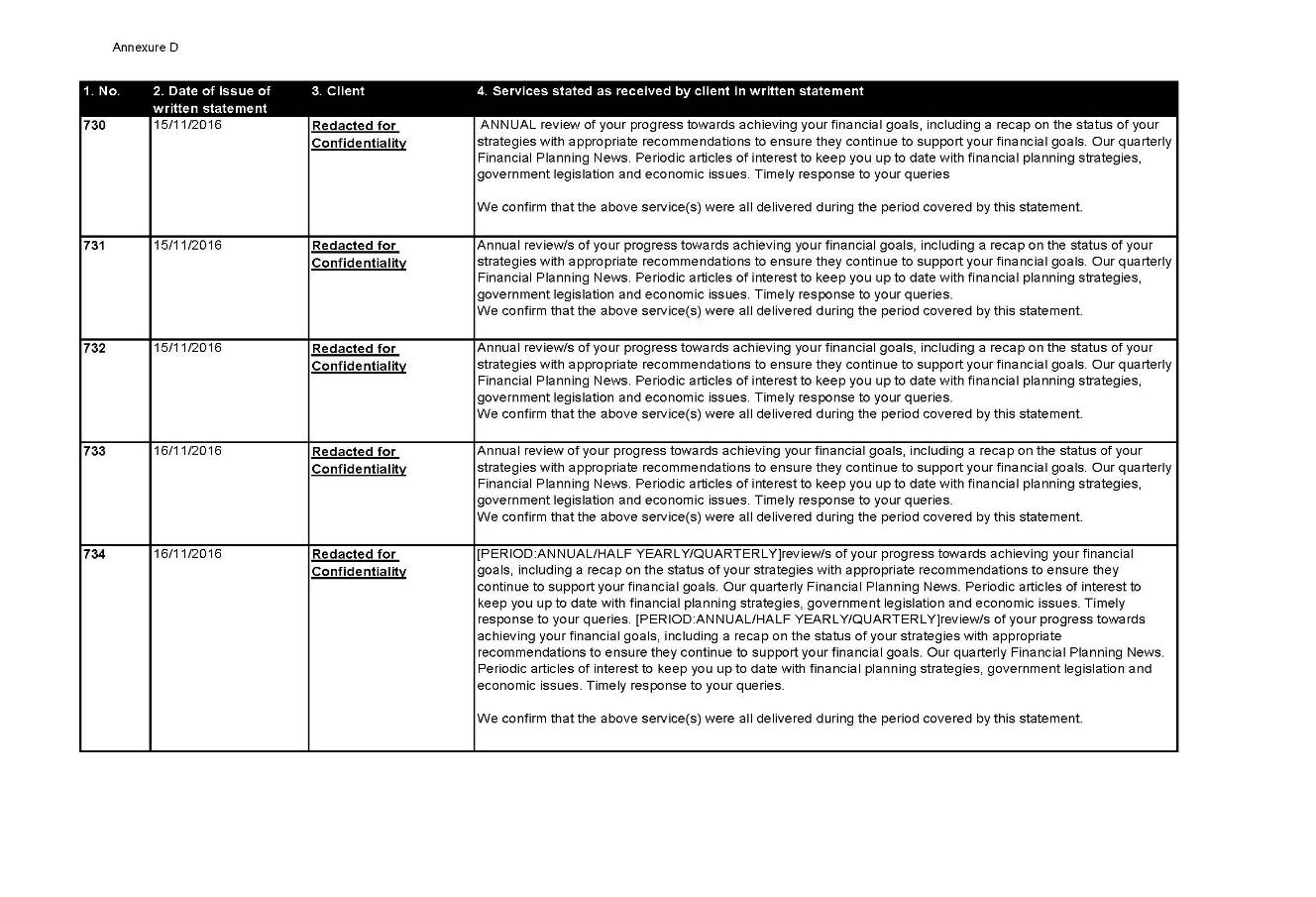

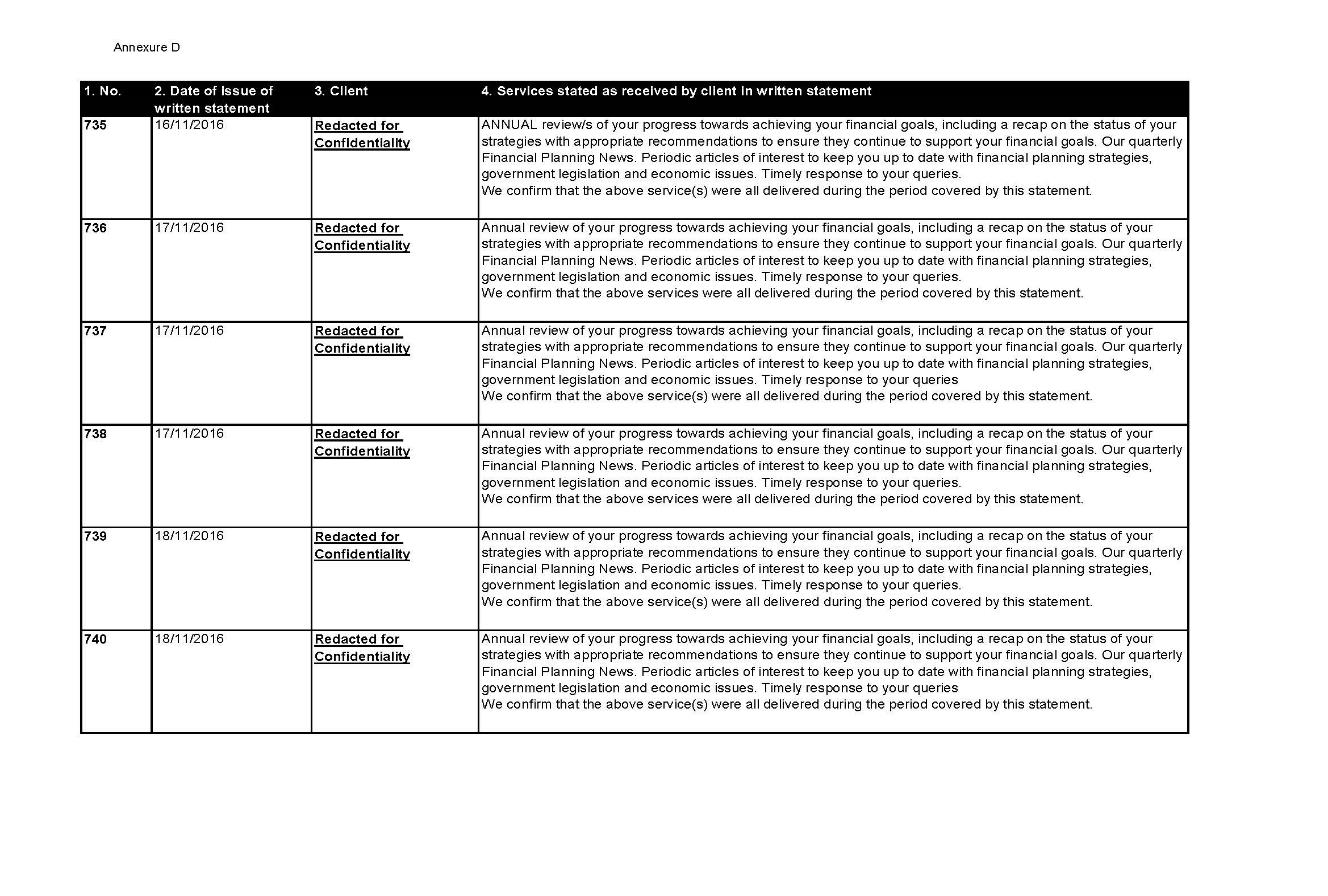

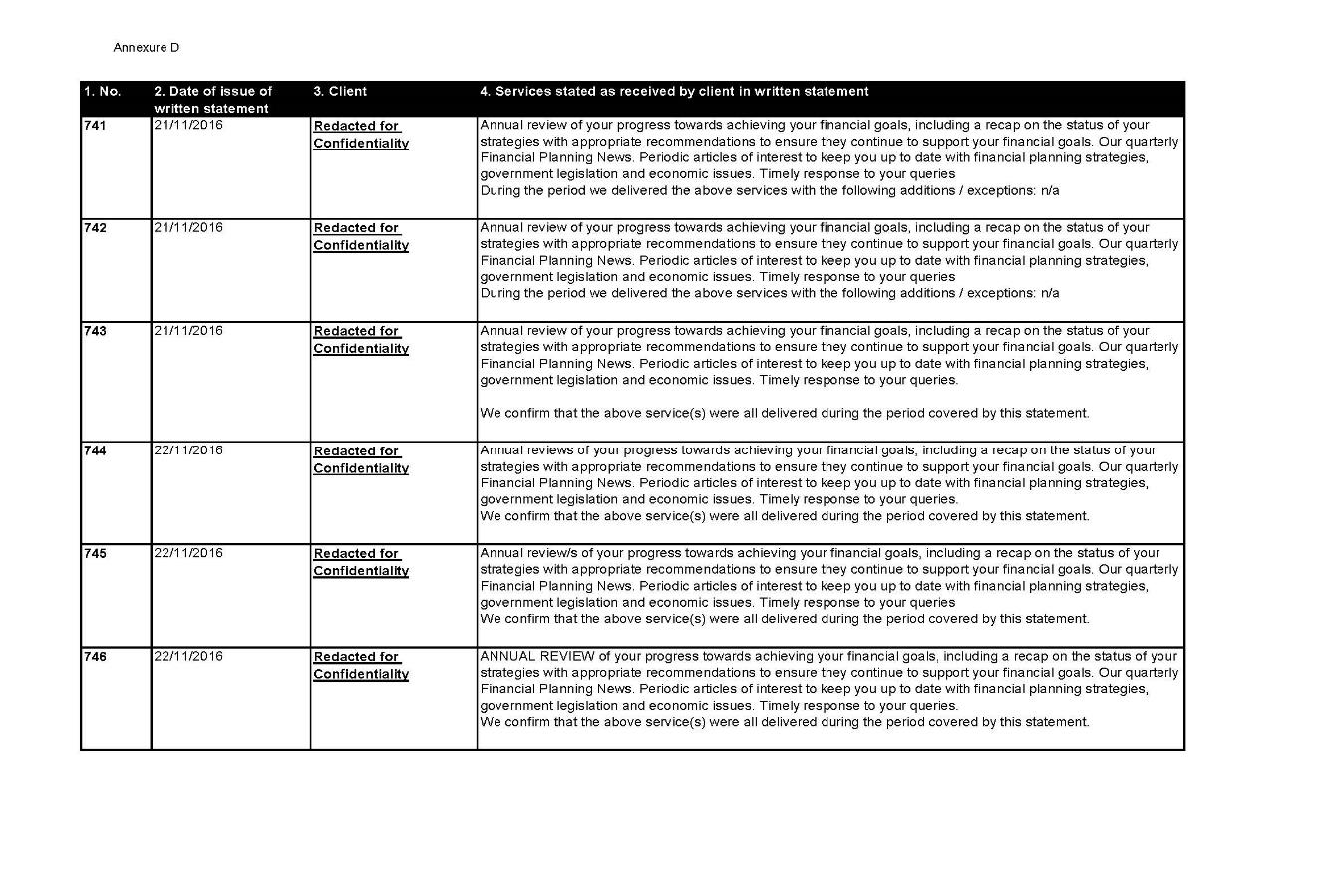

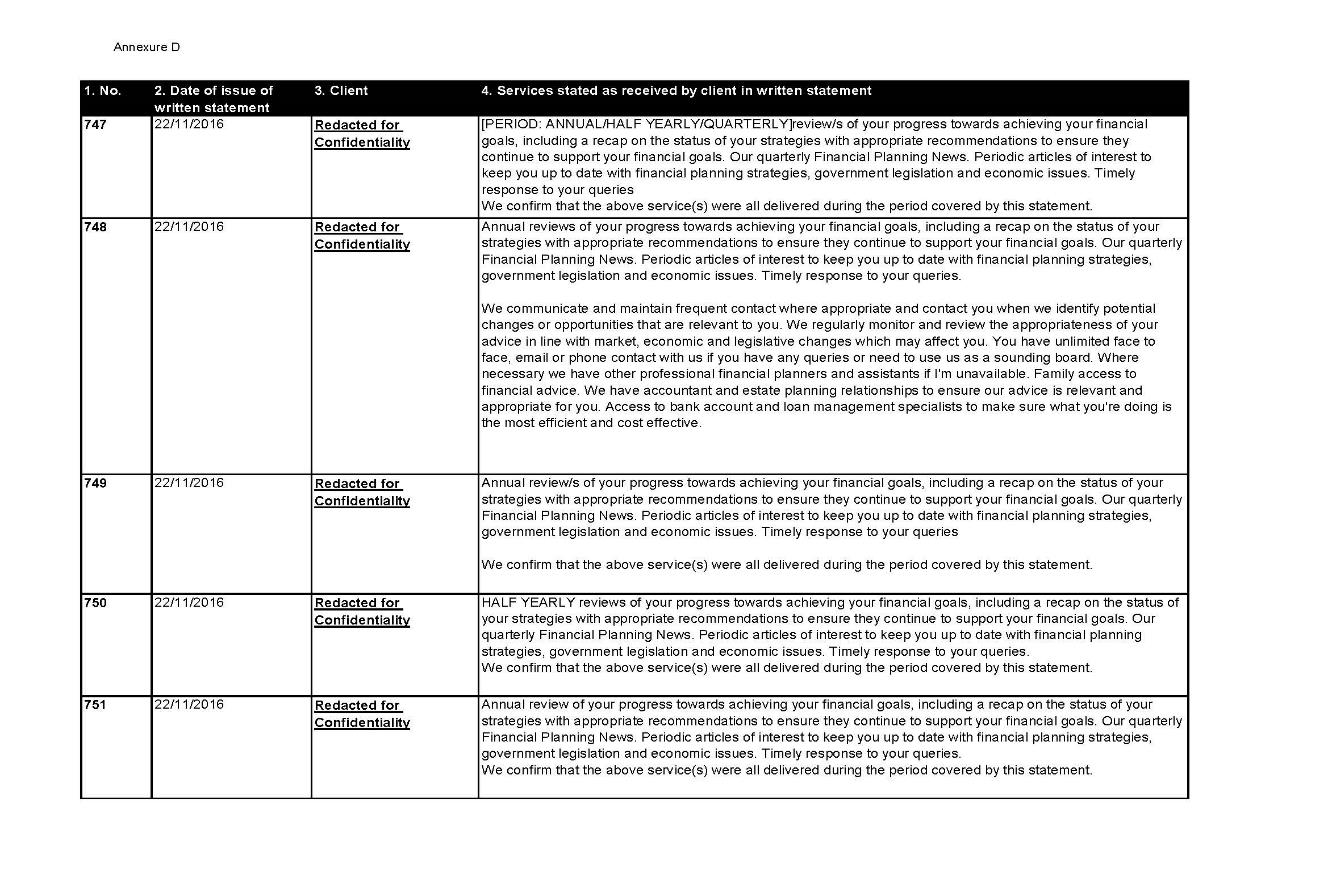

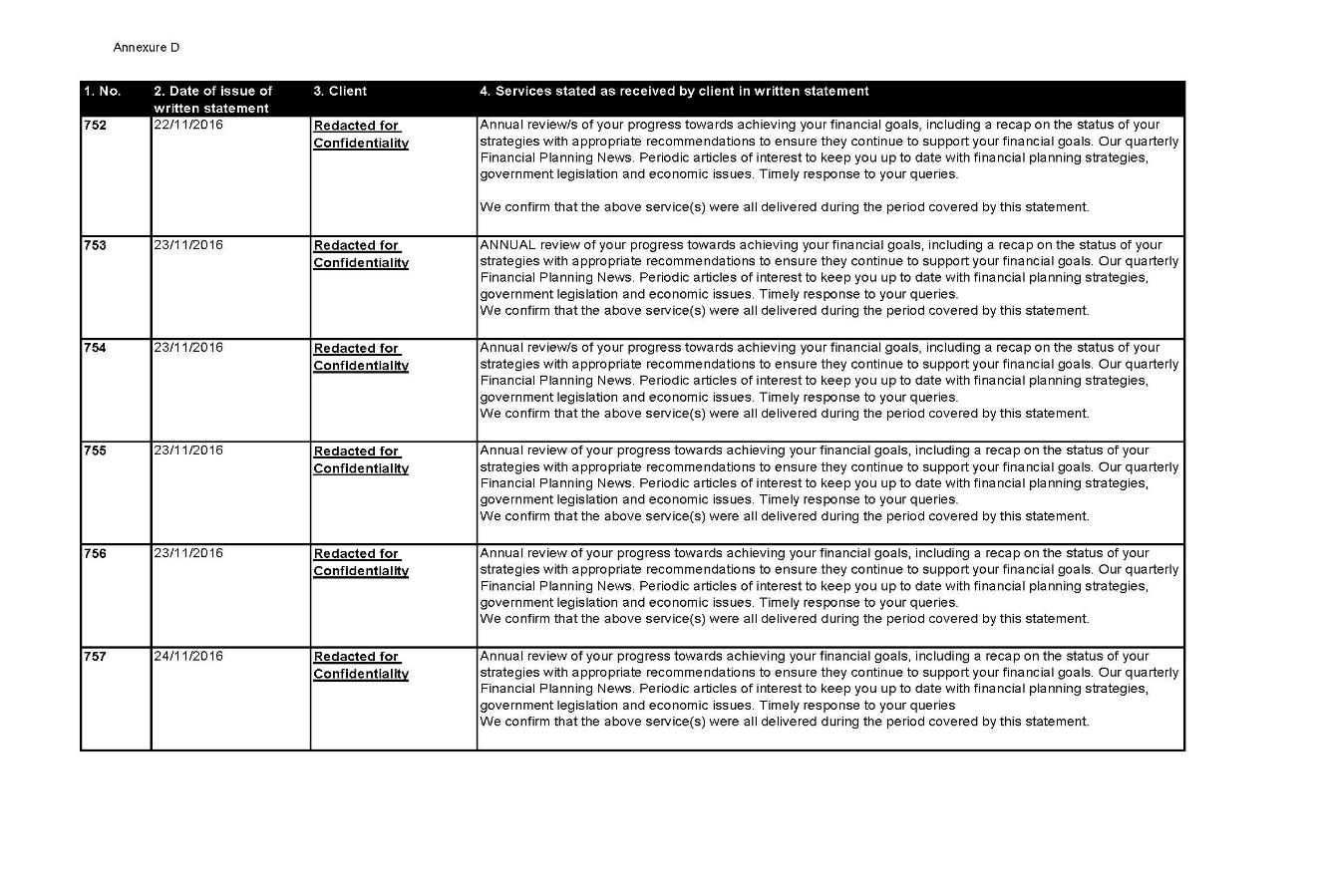

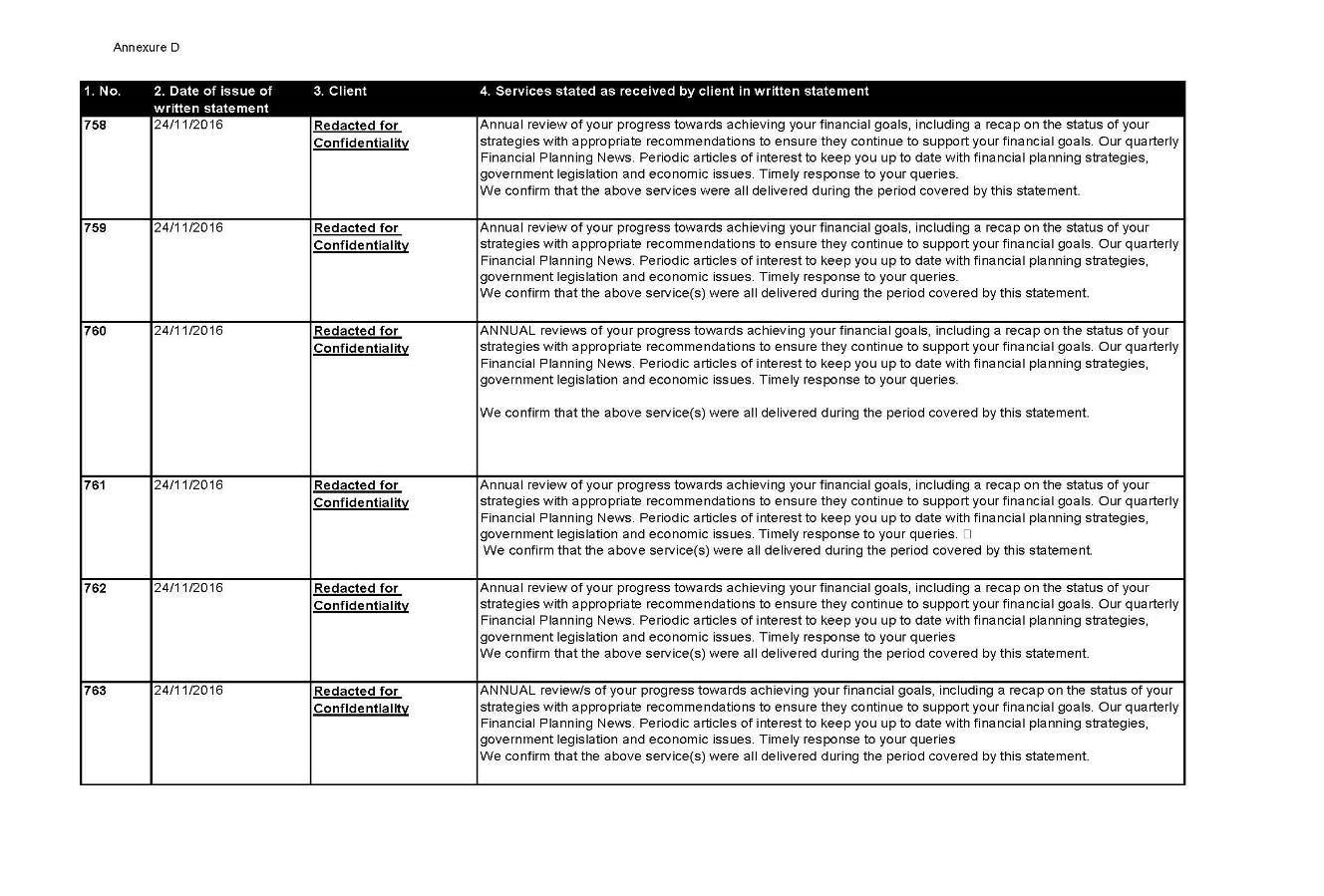

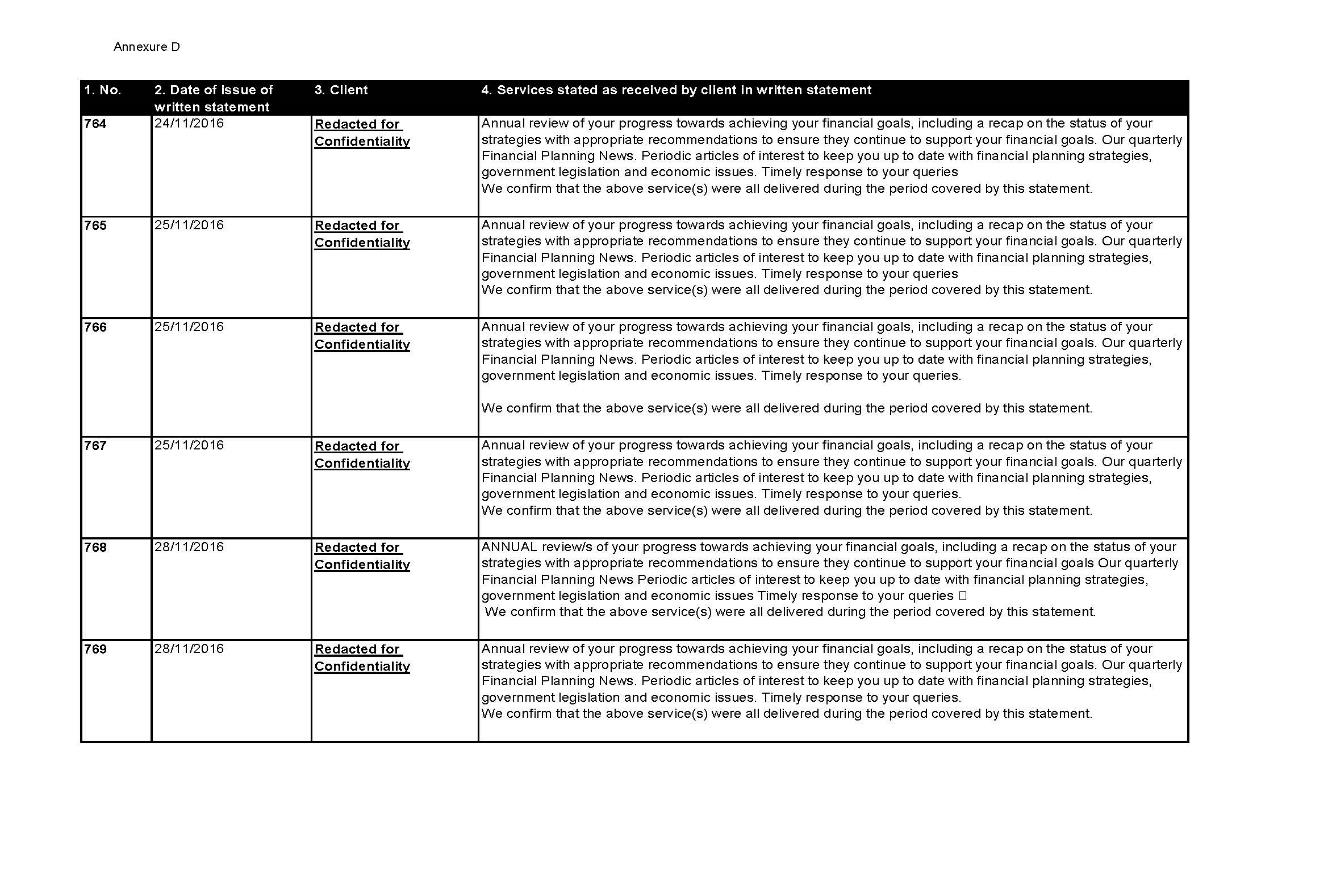

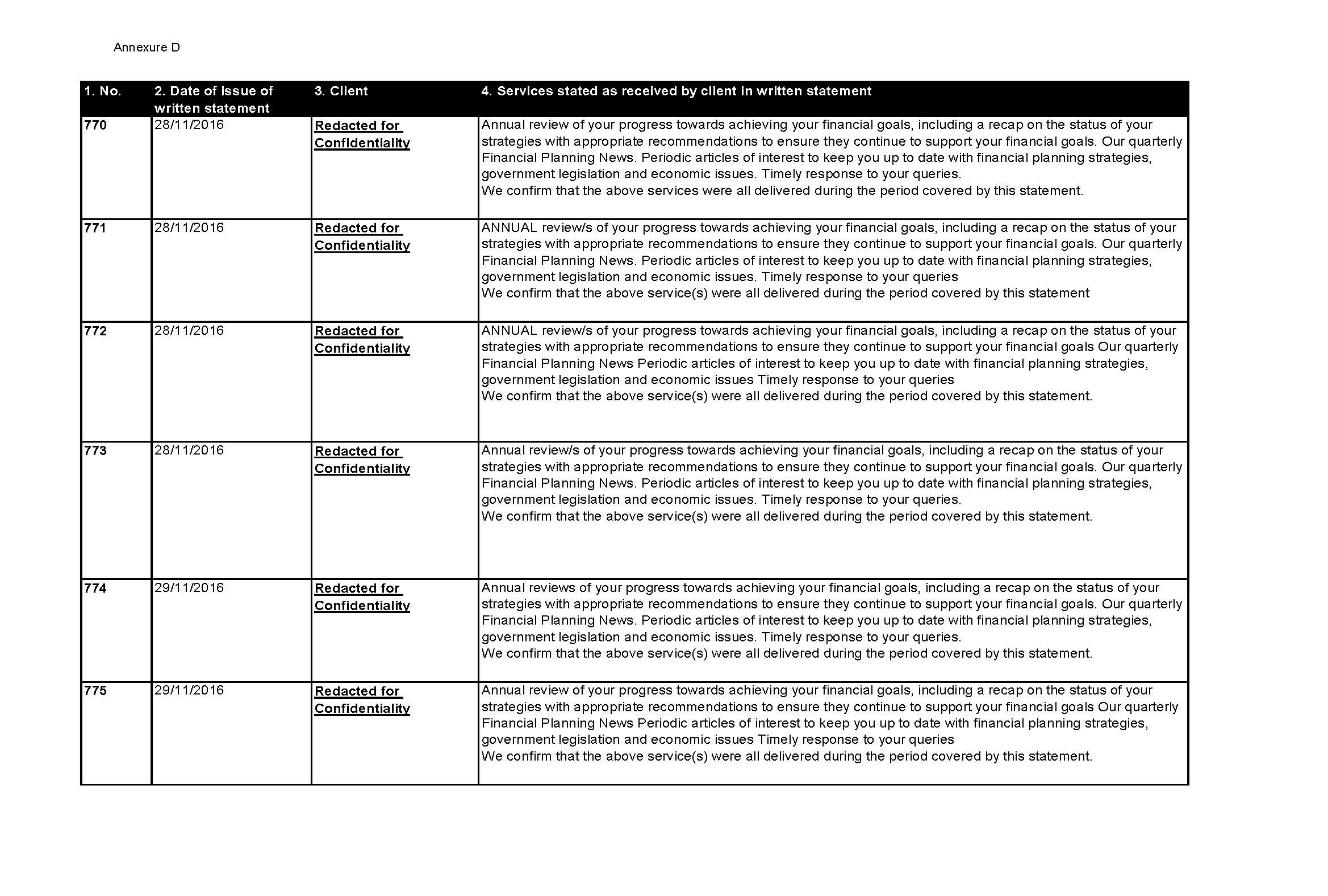

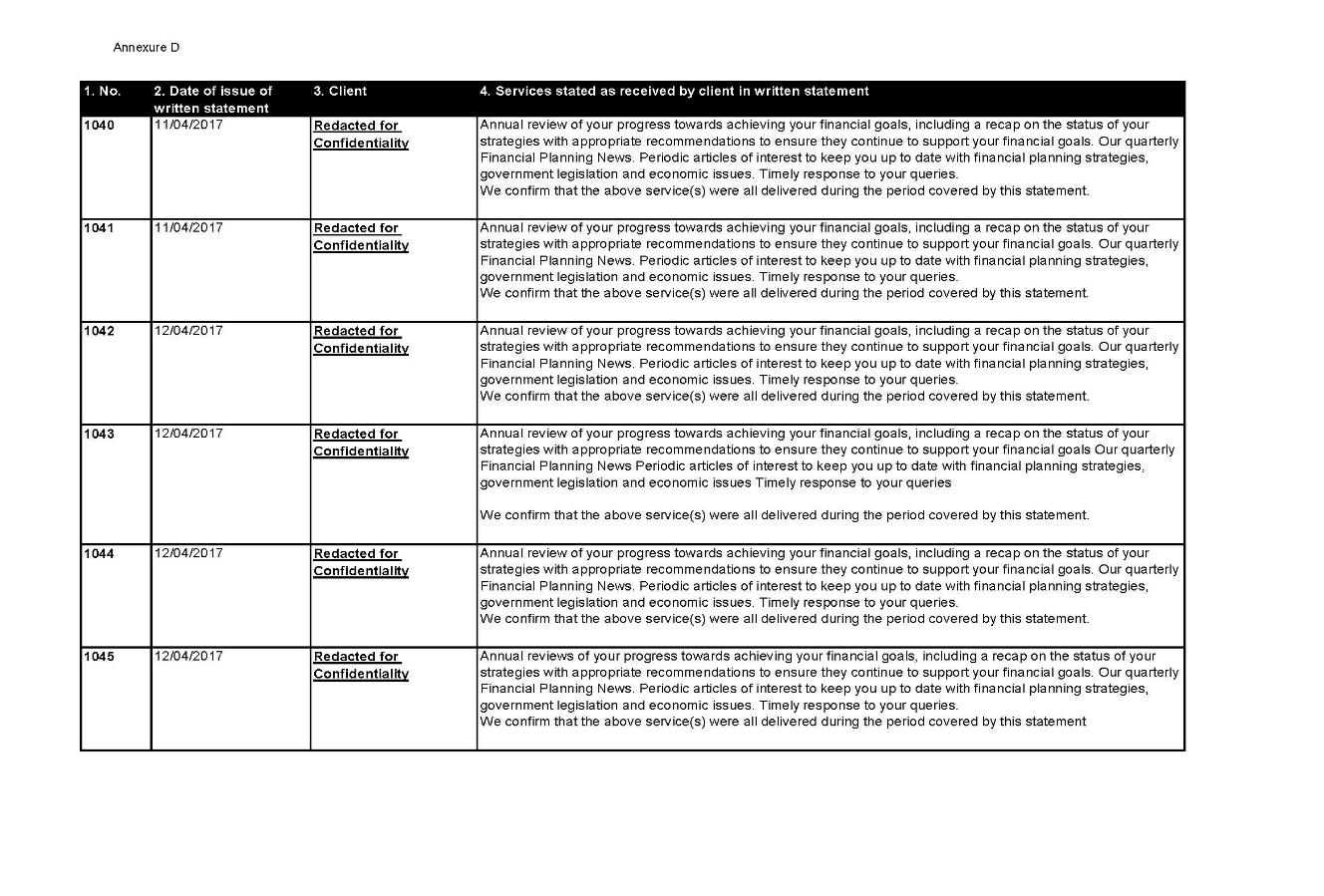

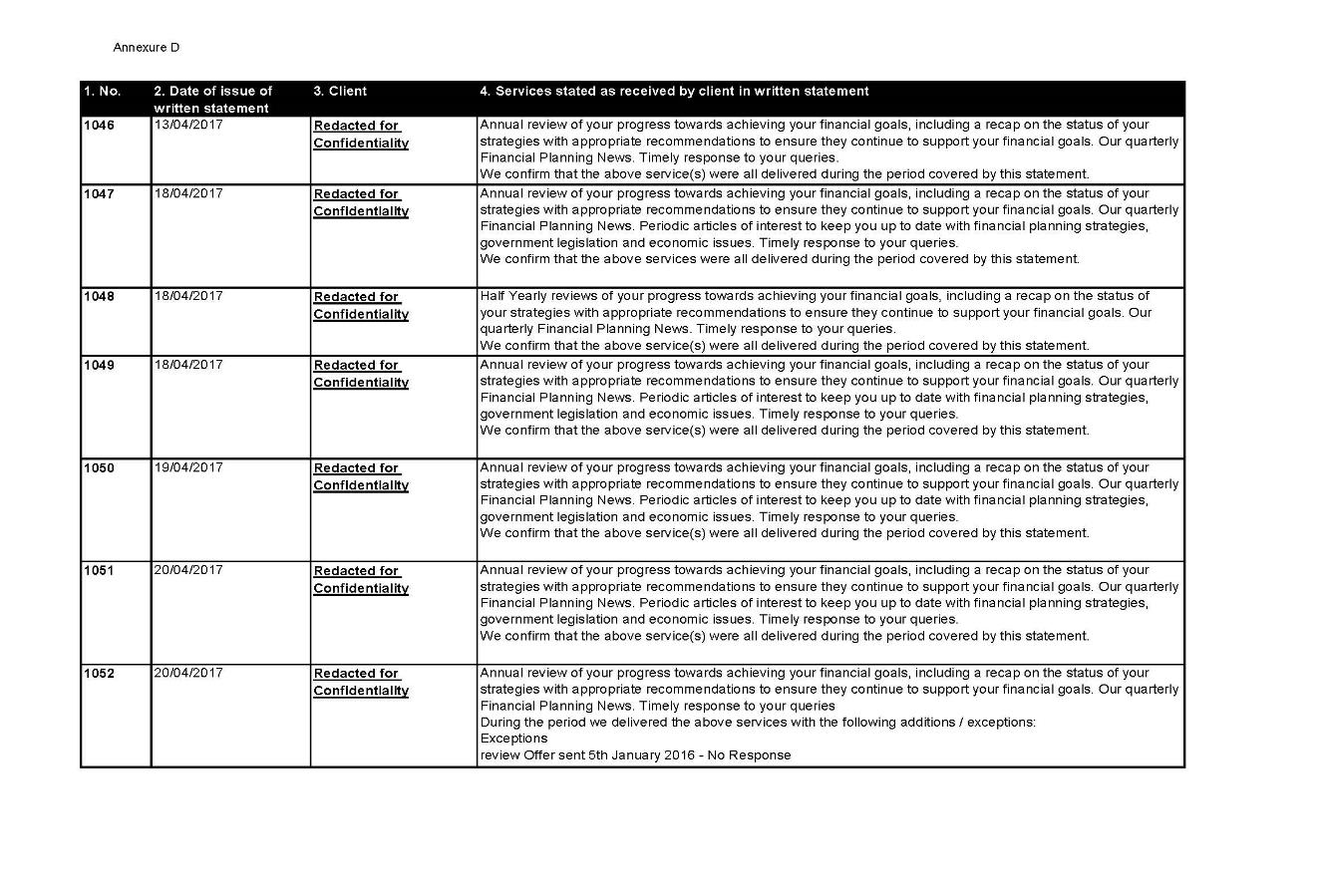

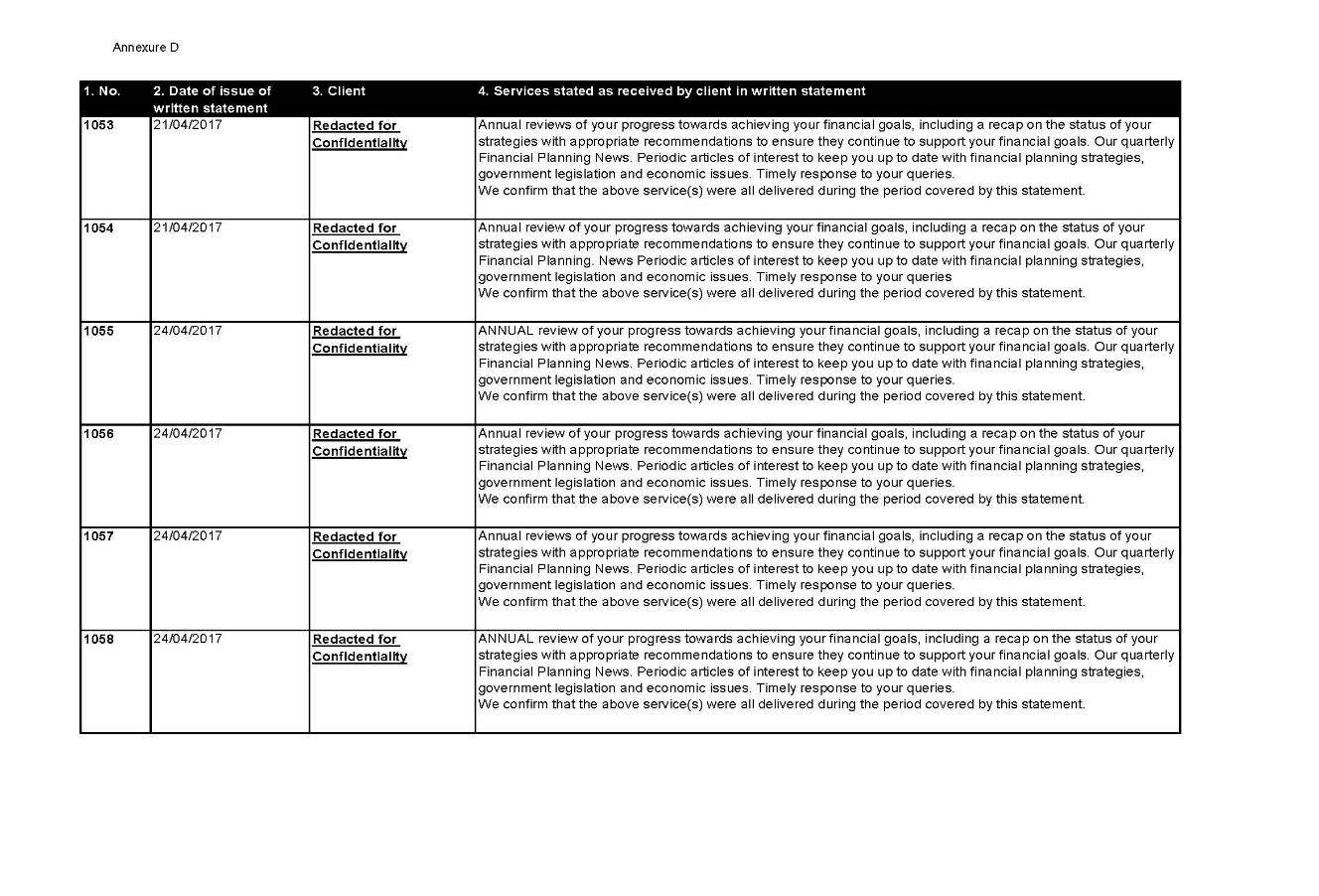

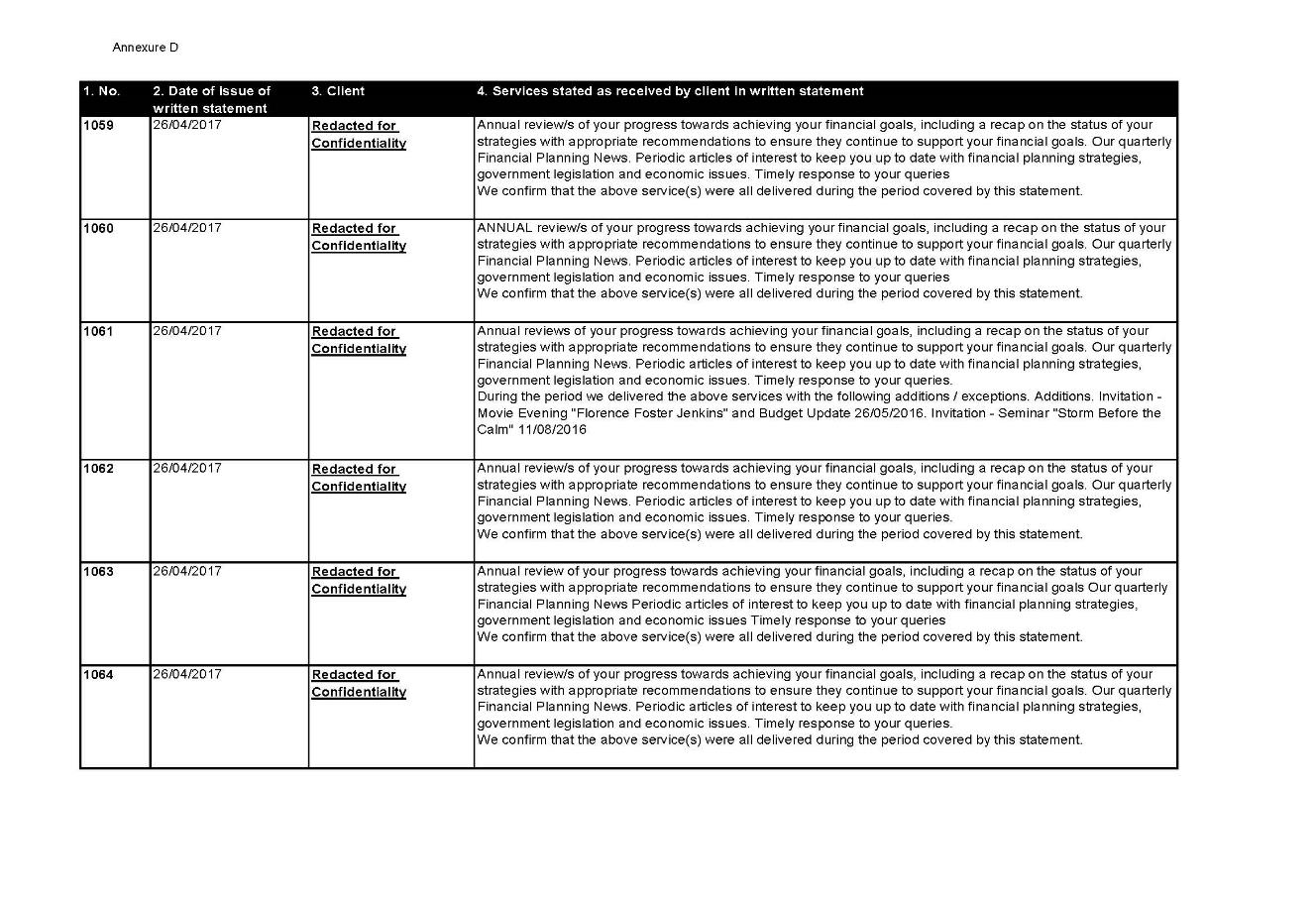

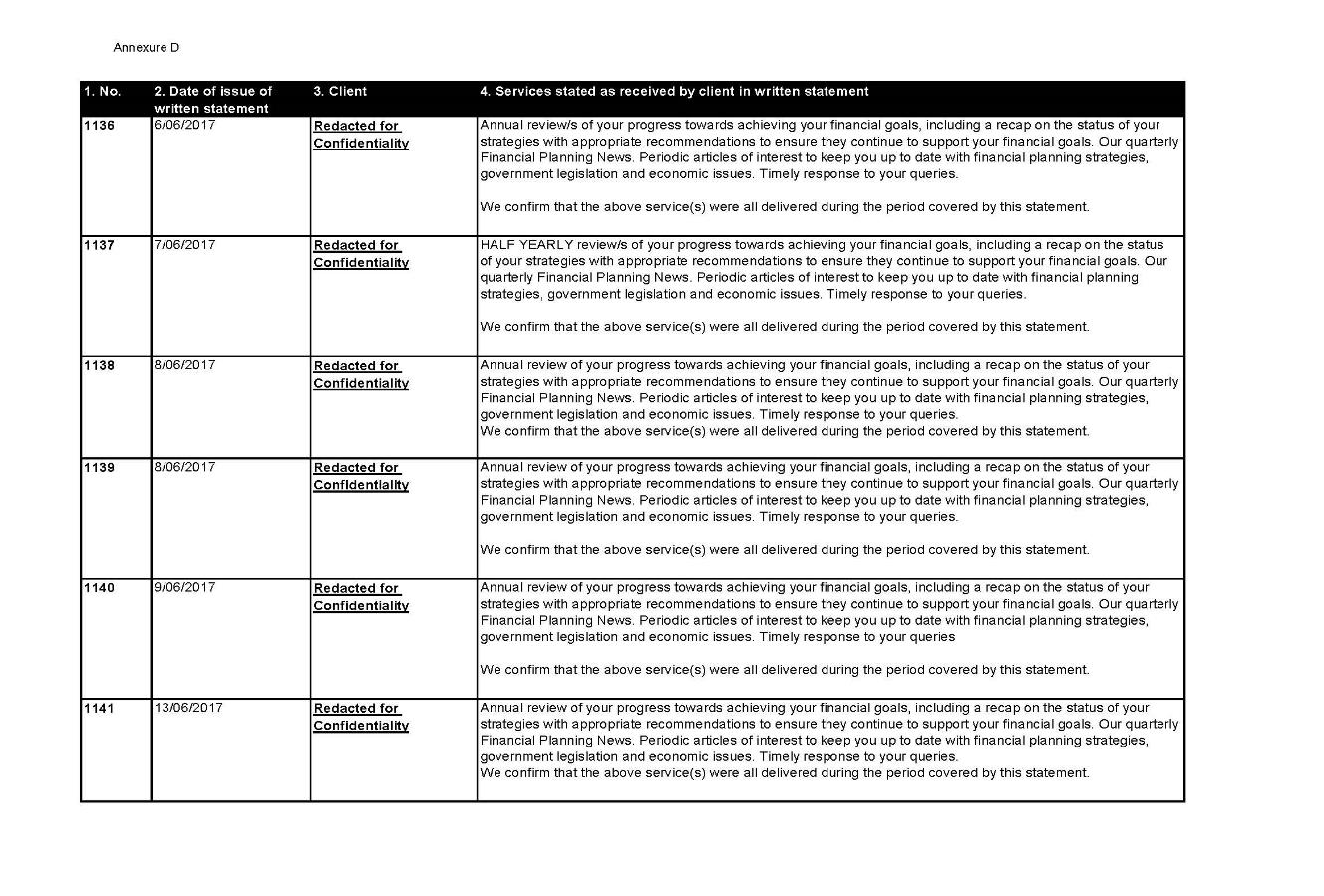

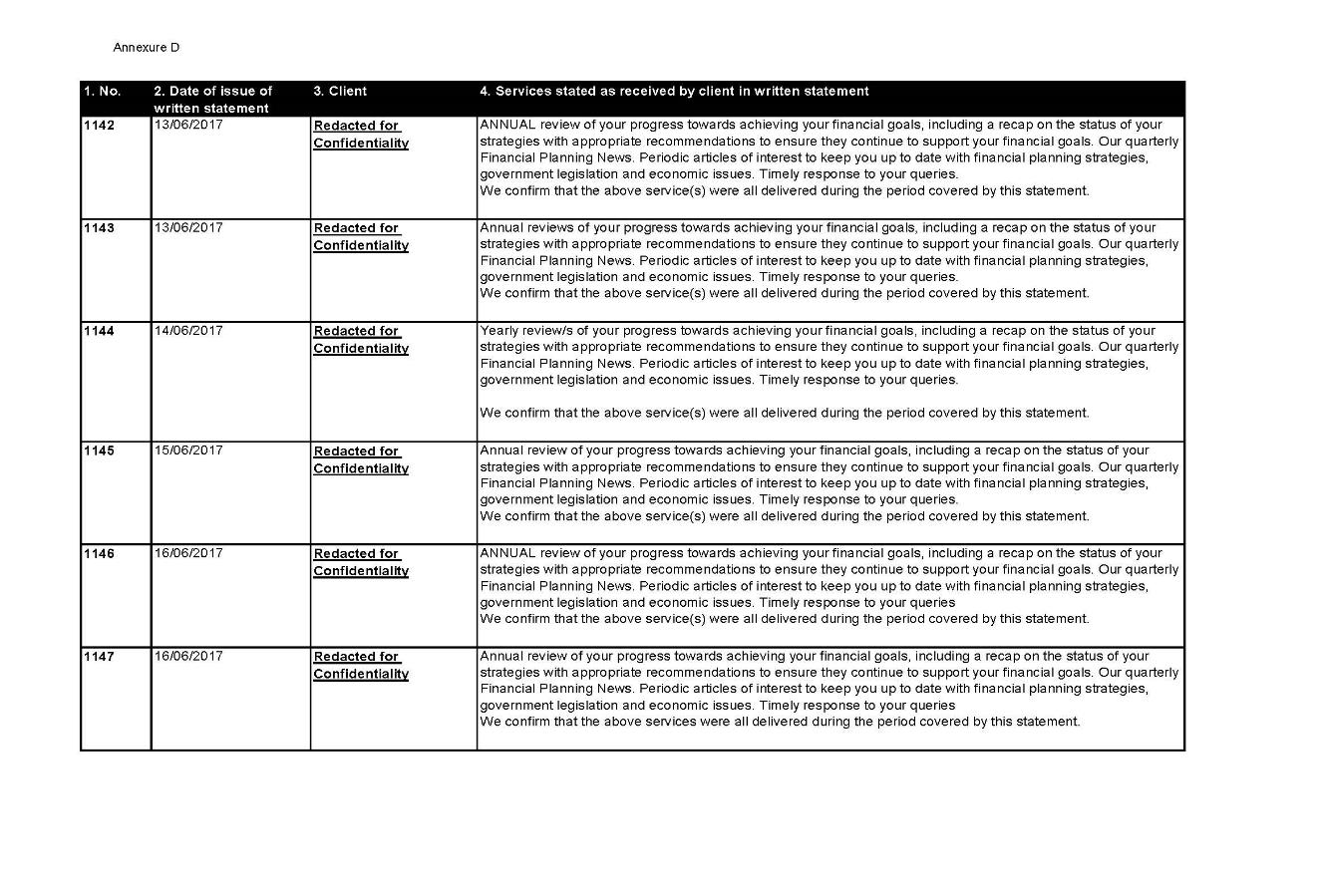

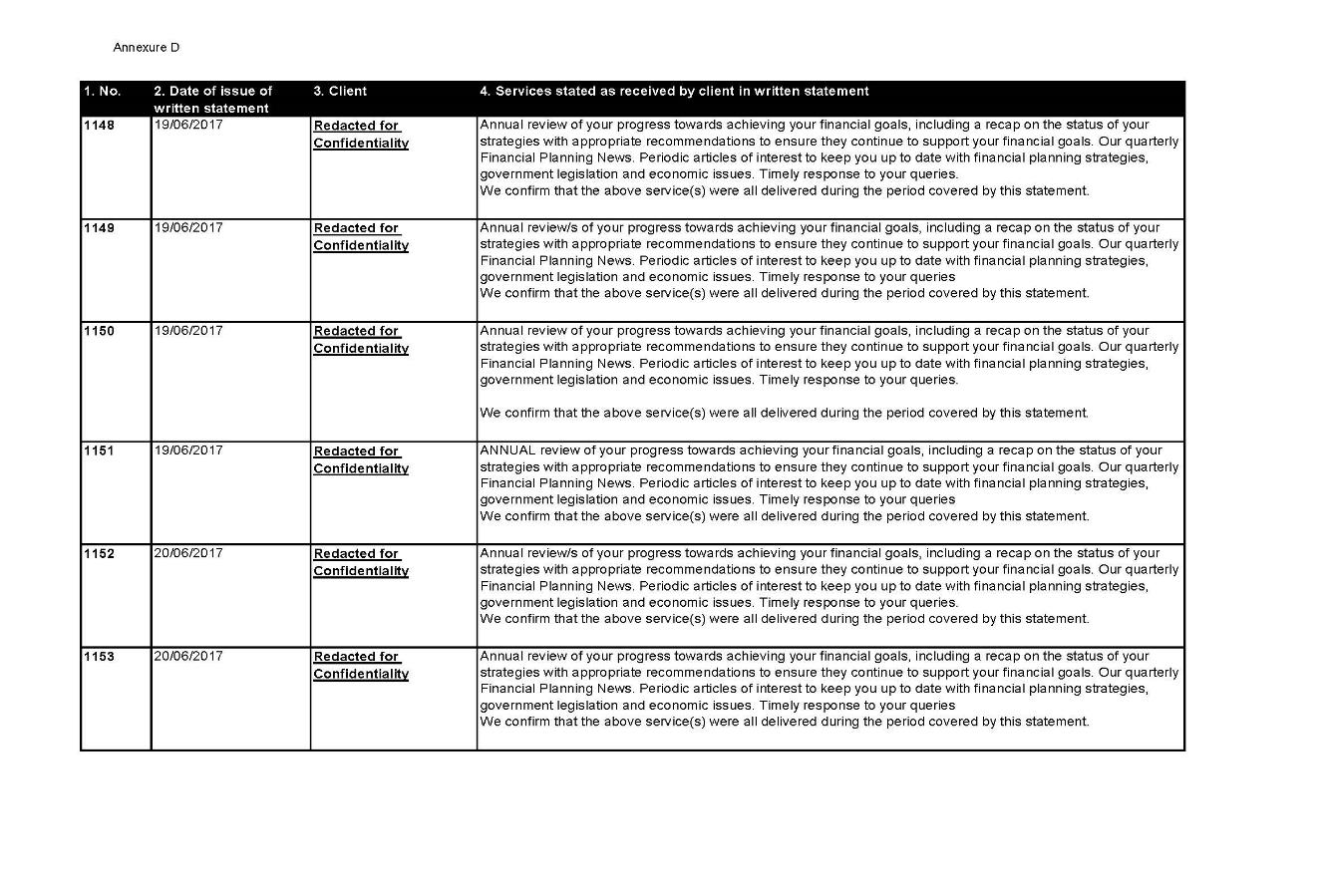

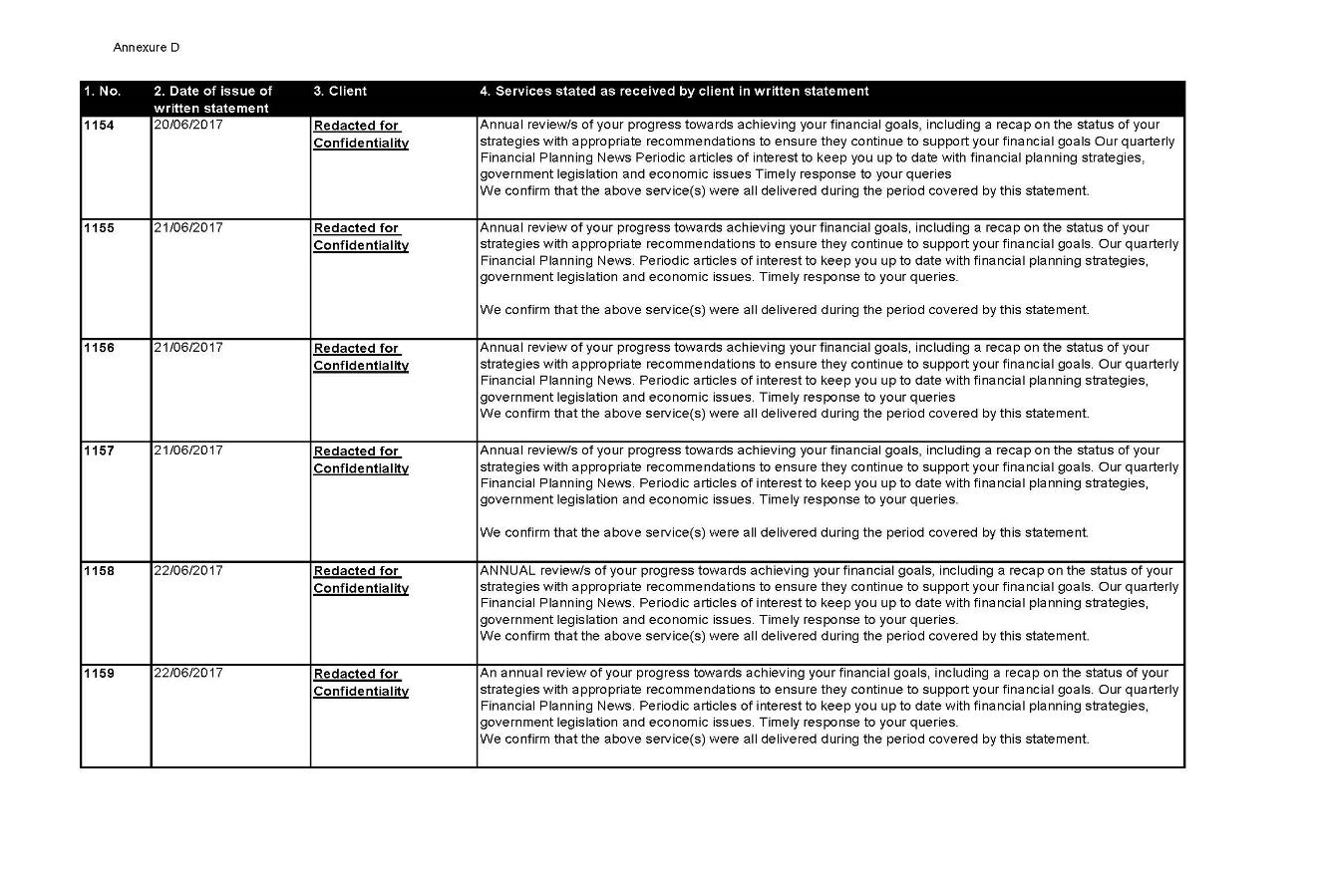

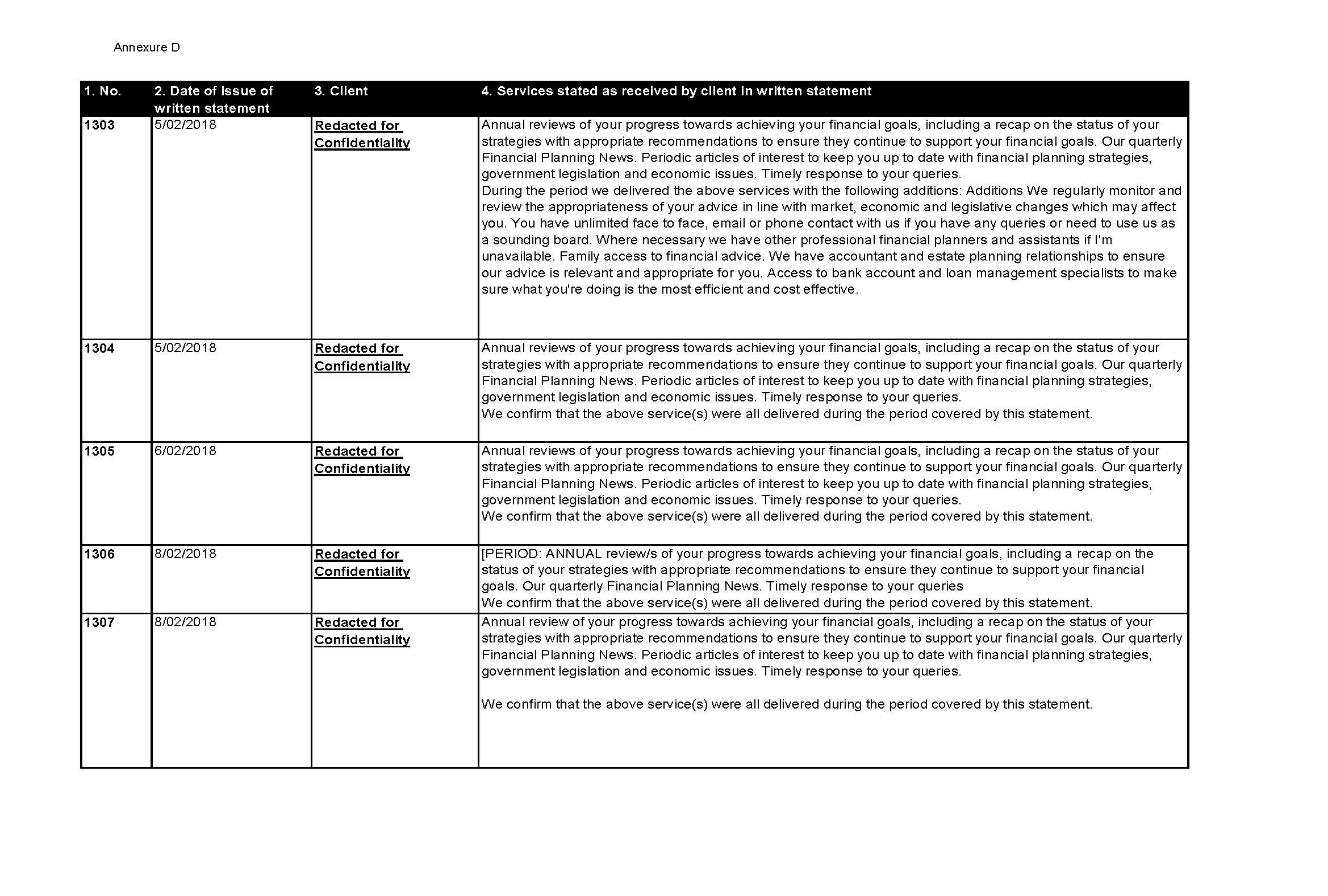

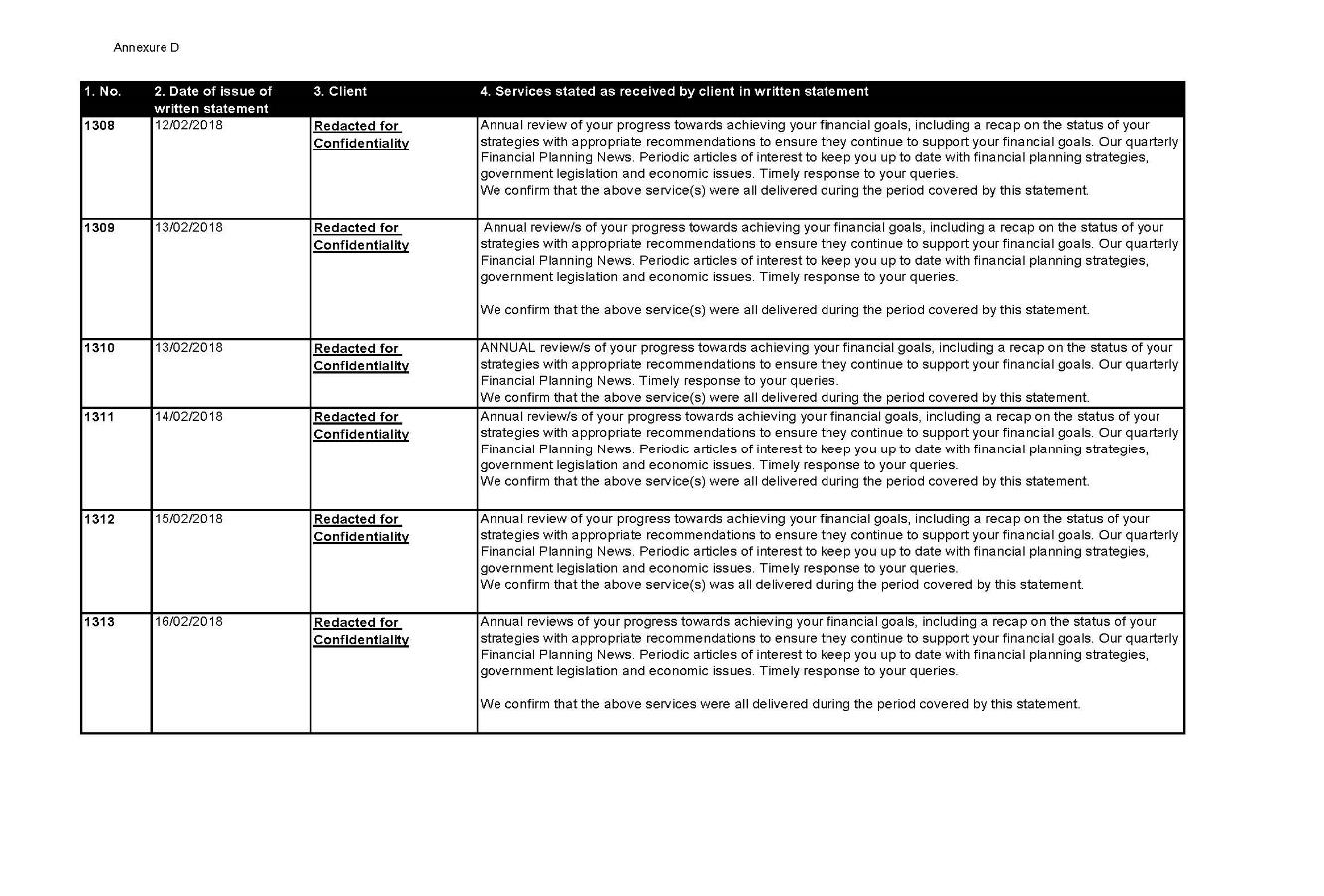

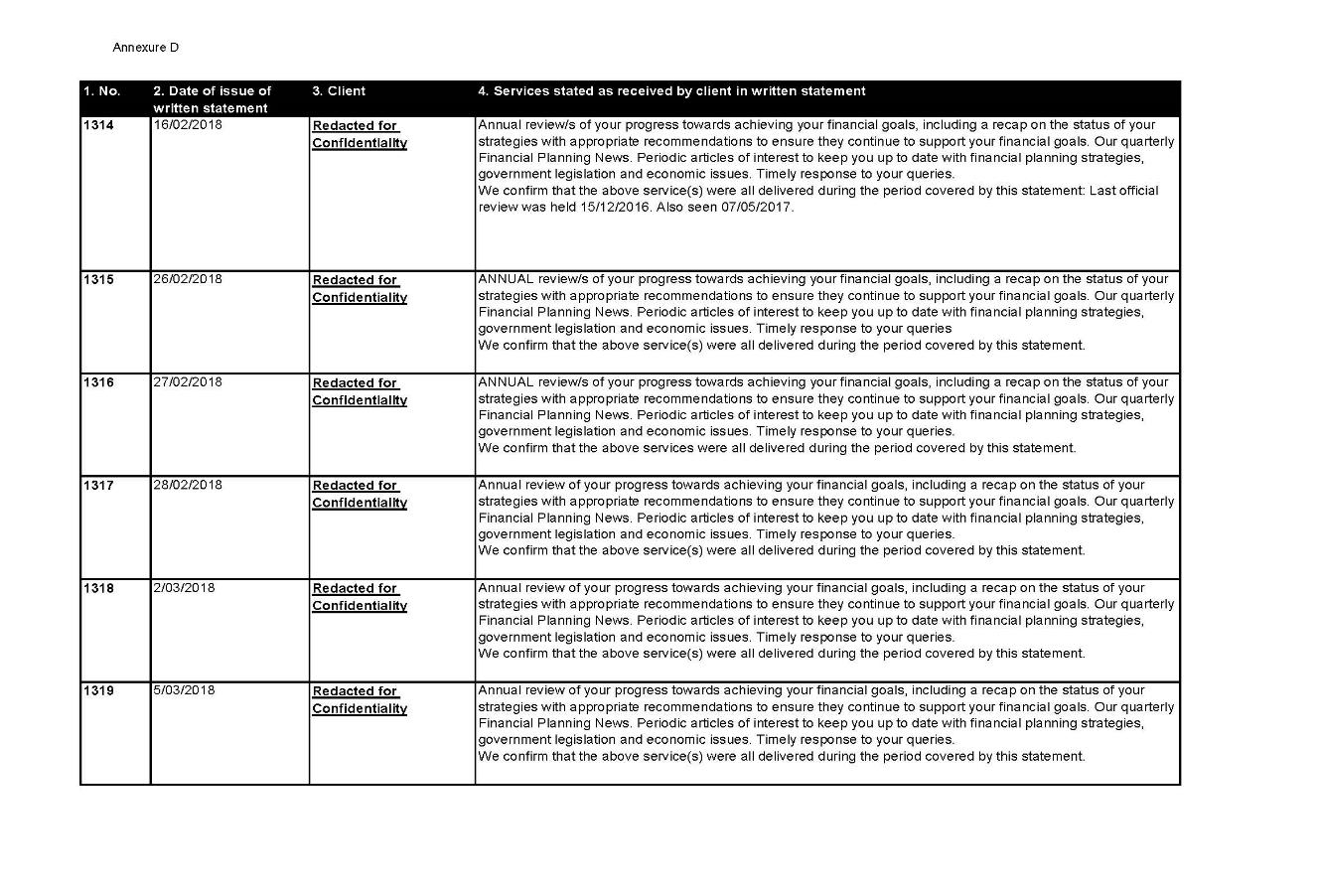

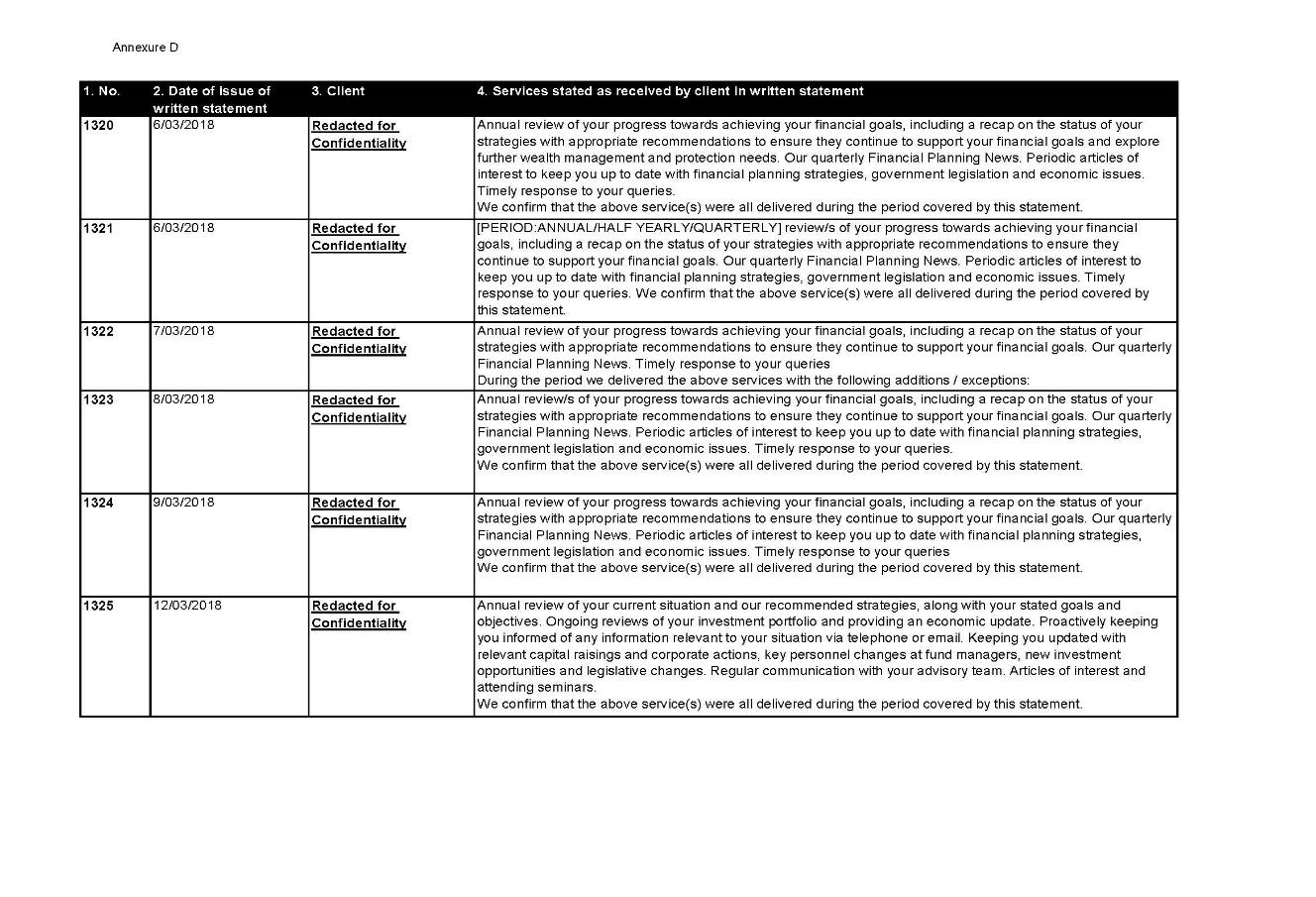

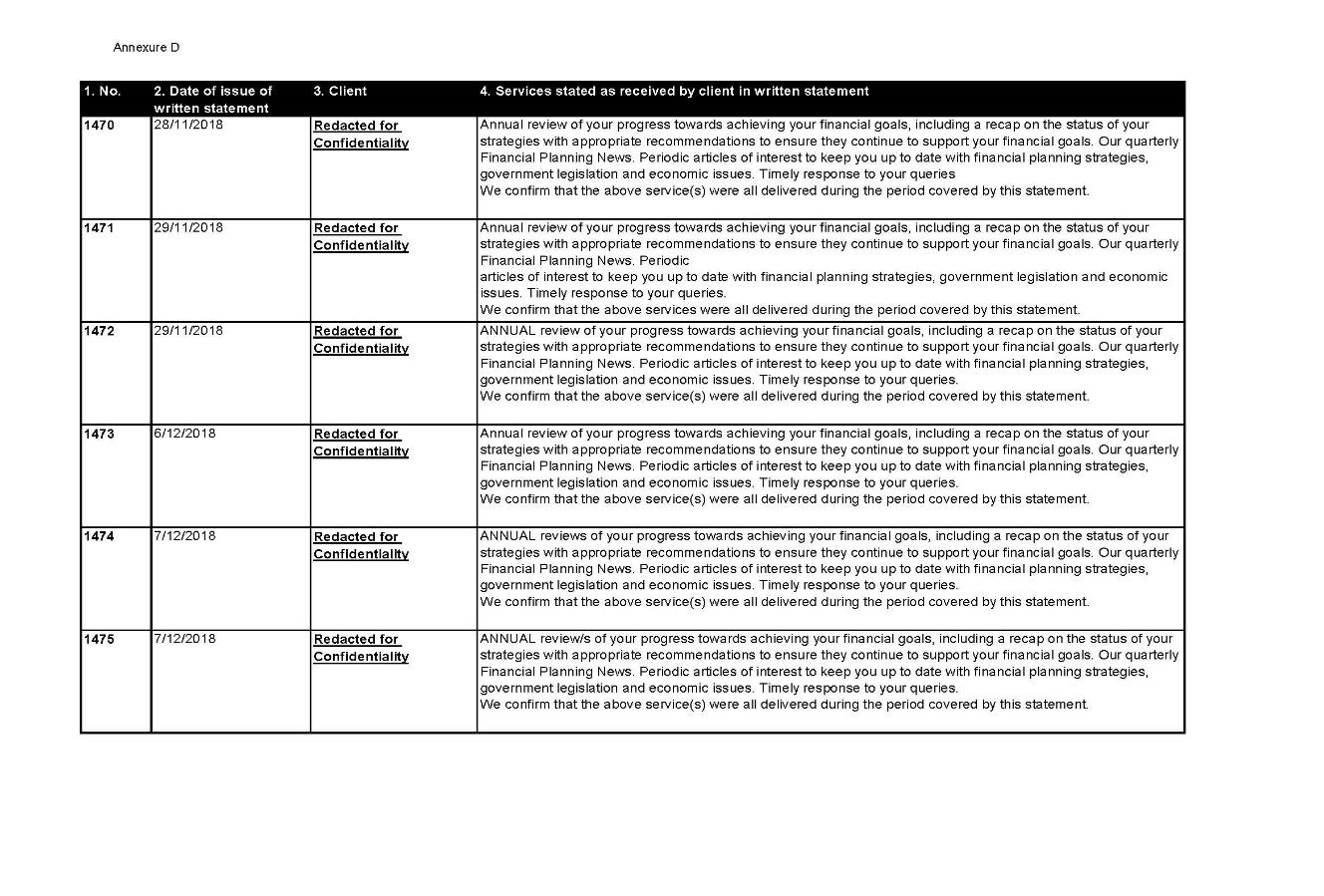

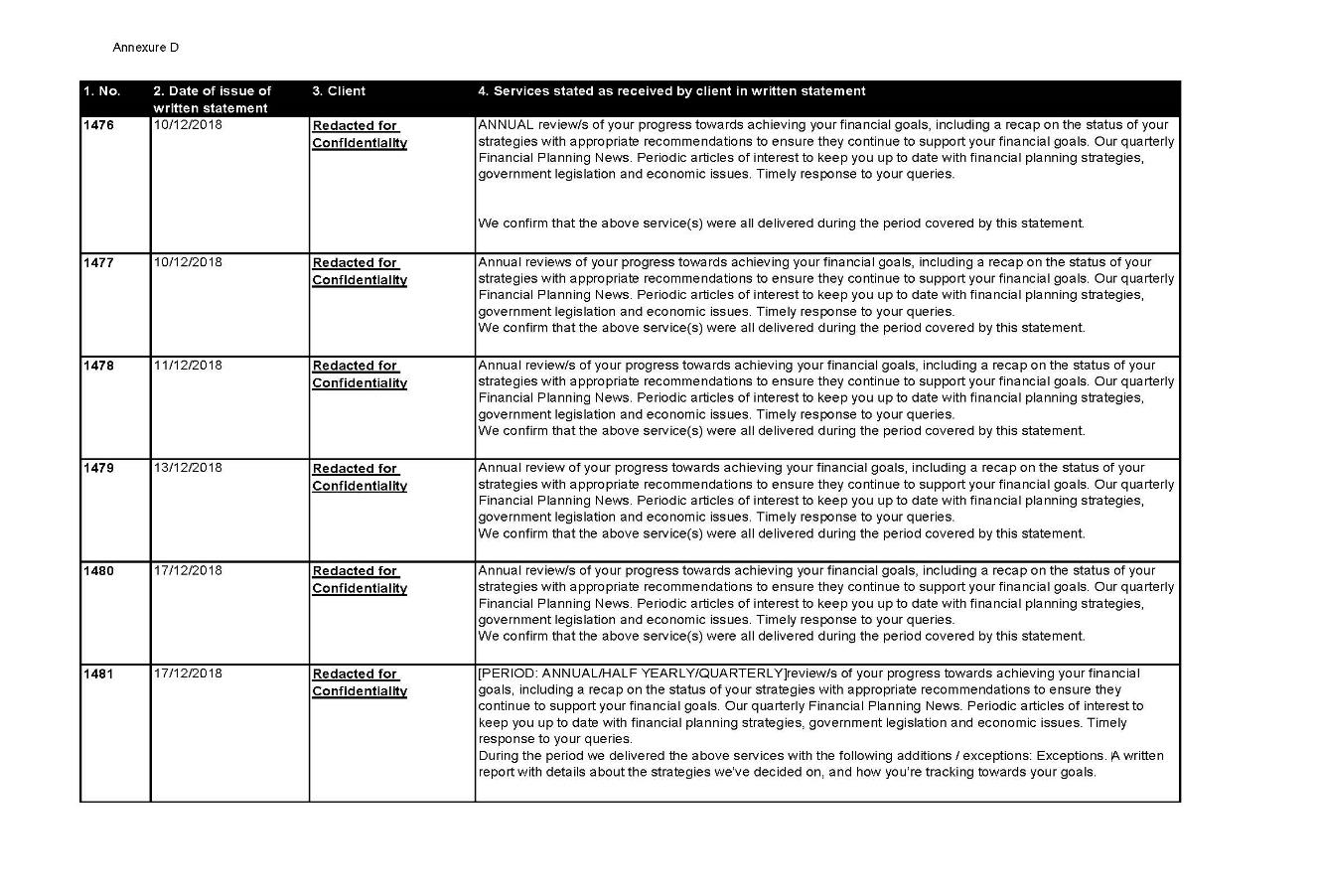

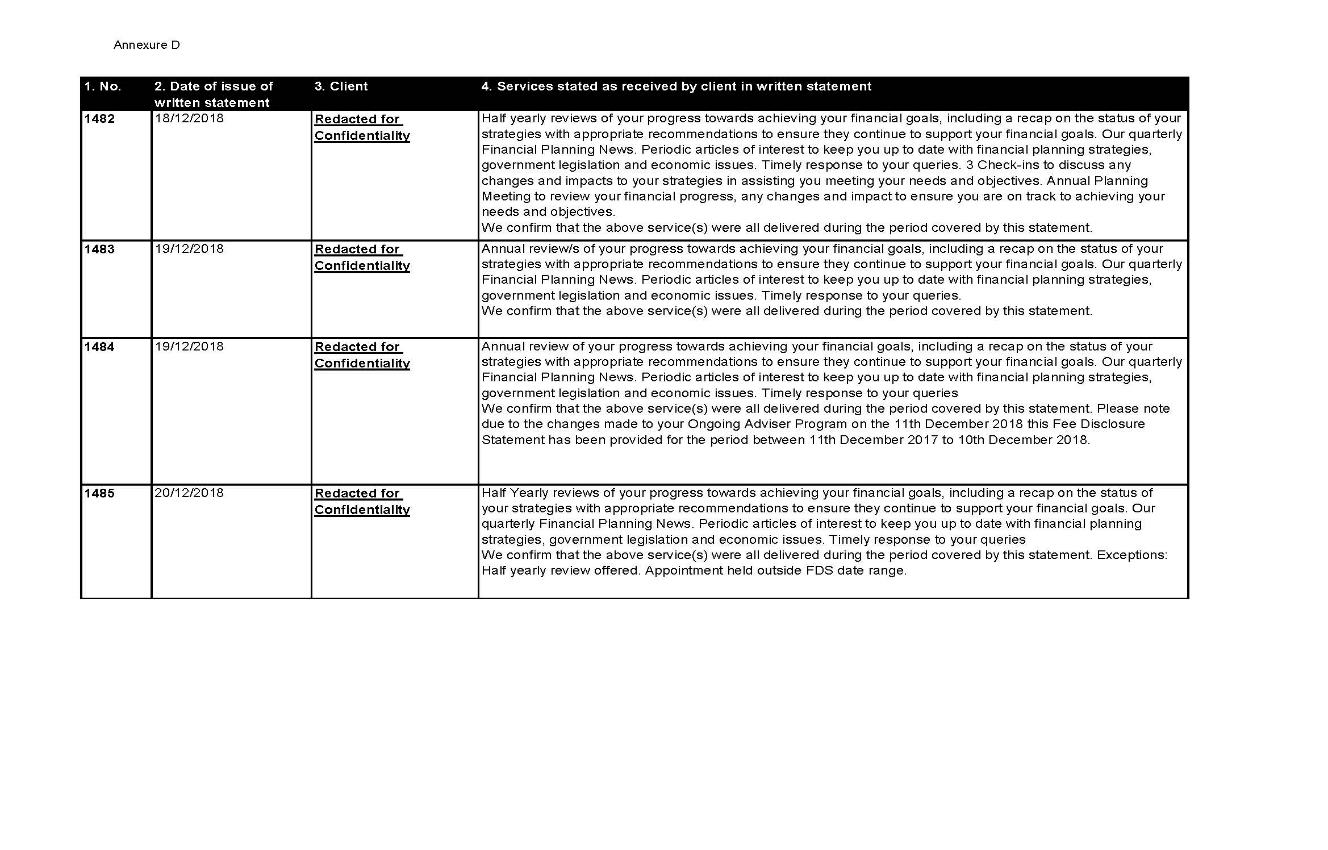

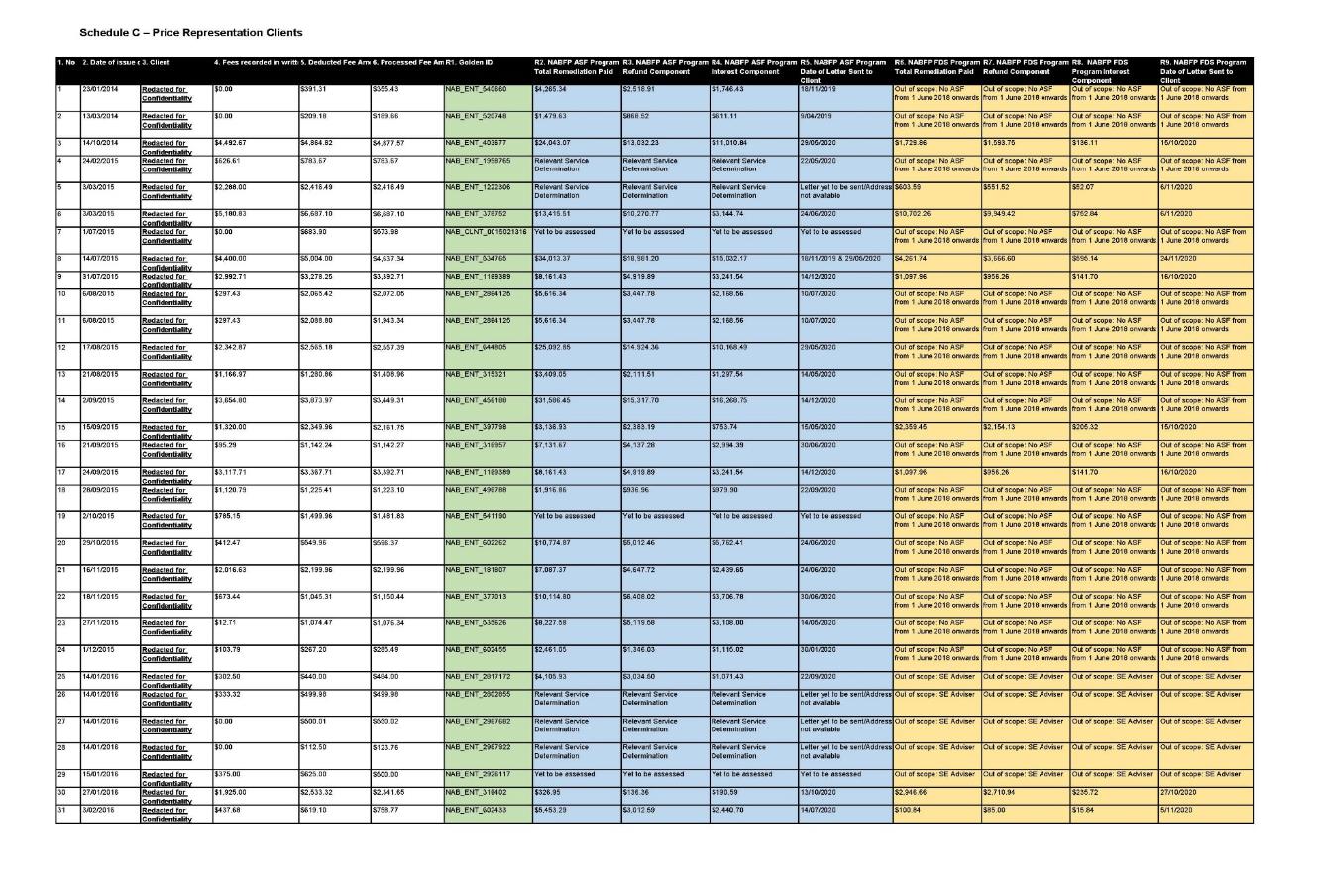

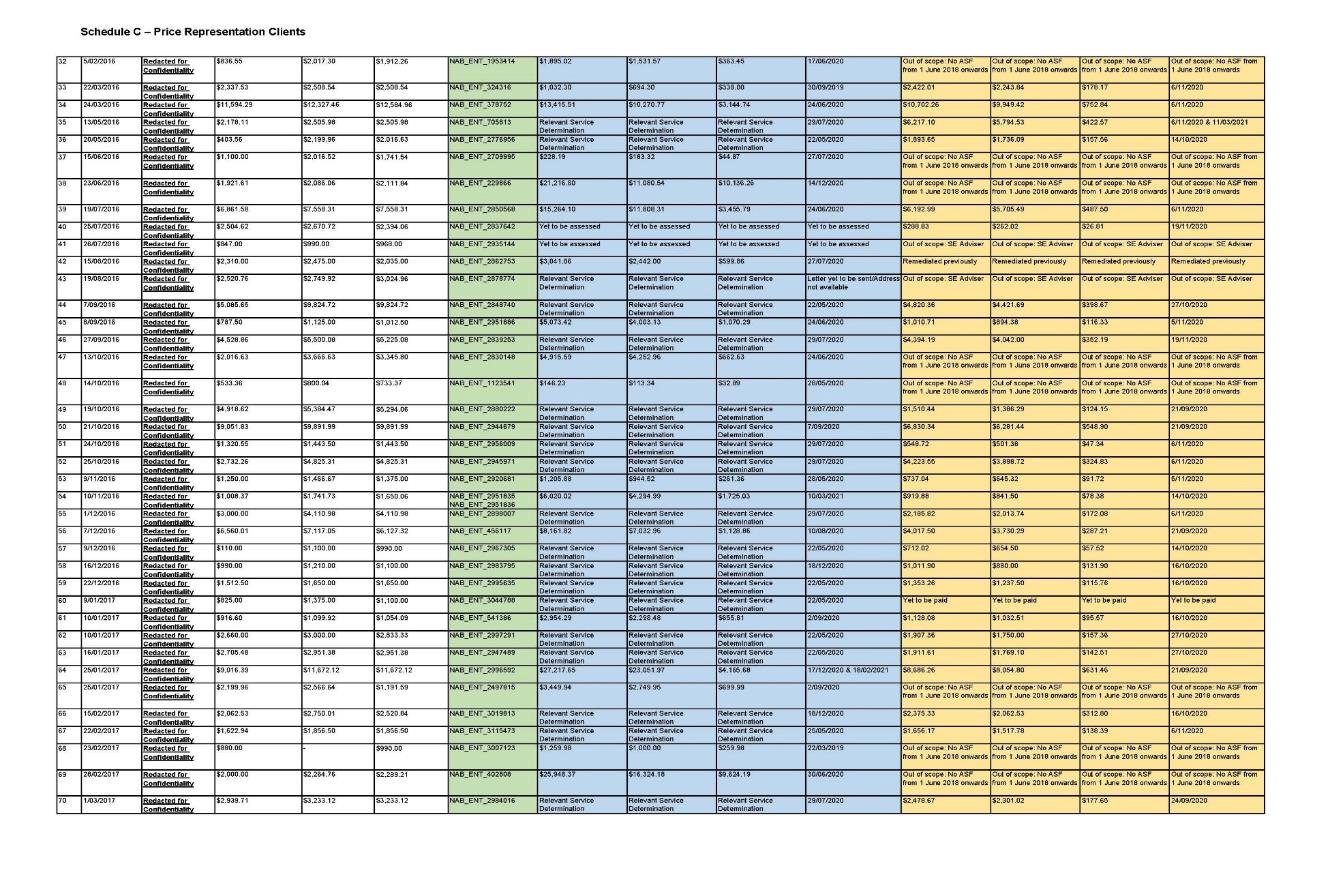

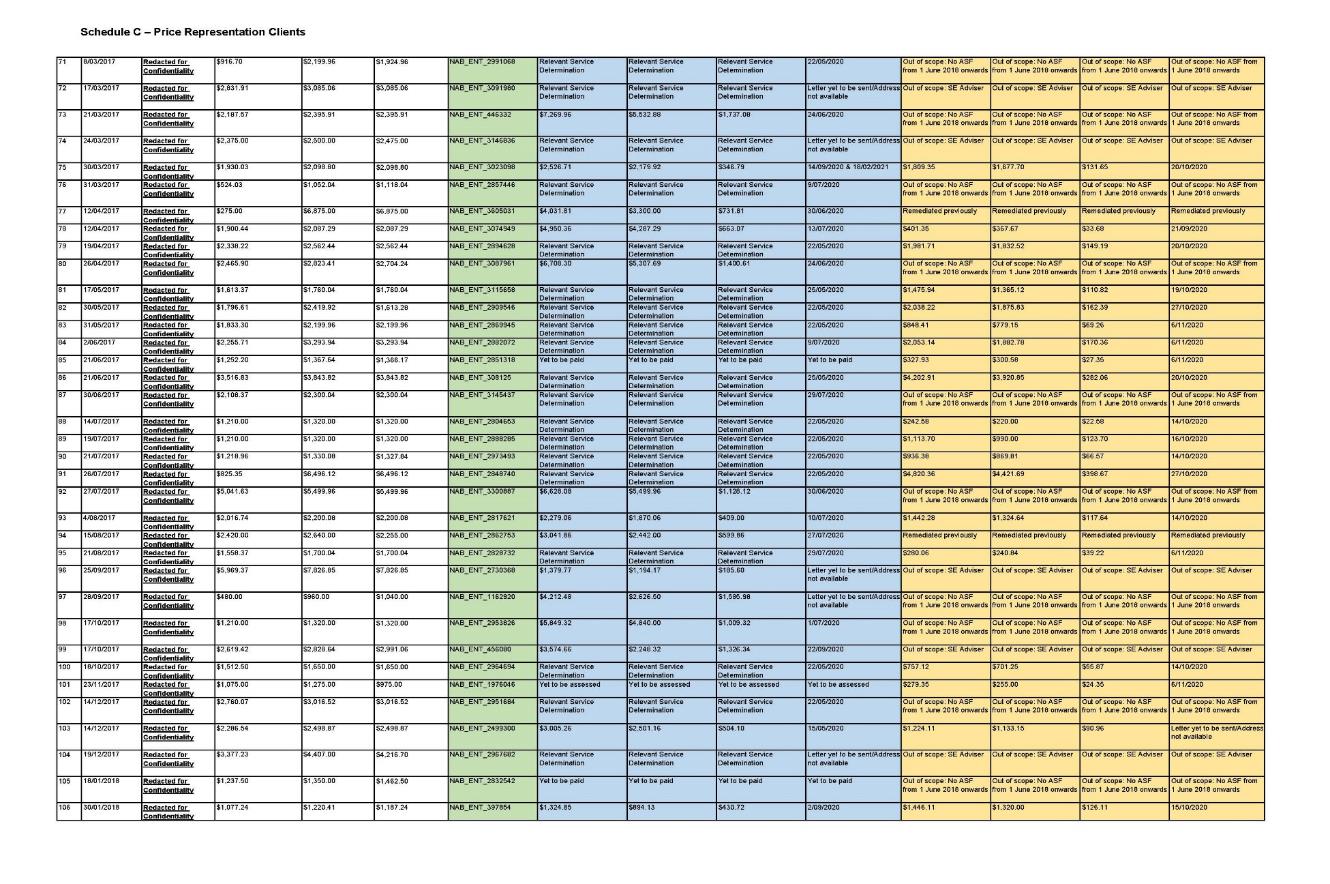

(a) it issued written statements to the clients listed in Schedules C and D to the agreed facts;

(b) each of these clients had entered into an ongoing service arrangement with NAB (or a representative of NAB) and NAB issued the written statements for the purpose of complying with its fee disclosure statement obligations under pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act; and

(c) the services to be provided to these clients pursuant to their ongoing service arrangement constituted “financial services” within the meaning of s 12BAB(1) of the ASIC Act and s 766A of the Corporations Act.

Price Representations

33 The relevant fee disclosure statements included the statement that:

Your Fee Disclosure Statement is a summary of the services we’ve provided to you and the fees you’ve paid for the delivery of these services in the last 12 months -

and, under the heading “Ongoing Fees” and subheading “Fees”, stated a fee amount, representing that the client, in the relevant statement period, had paid ongoing fees in the amount recorded.

34 The fee disclosure statements also included the statement that:

Fees shown are those we have processed during the period. Any unprocessed fees deducted from your account will be shown on your next statement -

or the statement that:

This statement shows fees we have actually received and processed during the period. Any fees deducted from your account that we have not yet received and processed will be shown in your next statement.

35 It is an agreed fact that the clients to whom the price representations were made had not paid ongoing fees in the amounts stated during the relevant statement period in the respective written statements and the price representations were thereby false and misleading.

Service representations

36 Each of the written statements referred to in Schedule D to the agreed facts contained a representation that the relevant client had received certain specified services, including a “review”, during the relevant statement period. In most instances, the service representations included words to the following effect:

Service Commitment

As part of your ongoing service agreement, we committed to providing you with the following:

• Annual review/s of your progress towards achieving your financial goals, including a recap on the status of your strategies with appropriate recommendations to ensure they continue to support your financial goals

• Our quarterly Financial Planning News

• Periodic articles of interest to keep you up to date with financial planning strategies, government legislation and economic issues

• Timely response to your queries

Service Delivery

We confirm that the above service(s) were all delivered during the period covered by this statement.

37 It is an agreed fact that by making the service representations, NAB represented to clients that services were of a particular quality within the meaning of s 12DB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, in that it represented that the services identified in the written statements had the “quality” of having been provided to the relevant clients during the relevant statement period, when the services had in fact not been provided during the relevant statement periods and therefore did not have that quality. It is also an agreed fact that those service representations were false and misleading.

38 Further, it is an agreed fact that insofar as the written statements stated that the client had received “appropriate recommendations” to ensure the strategies continued to support the client’s financial goals, NAB represented to the clients that the services had the “quality” and “standard” (within the meaning of s 12DB(1)(a)) of including recommendations appropriate for the stated purpose; and an agreed fact that clients to whom the service representations were made were not provided with the services the subject of the service representations in the relevant statement period and therefore did not receive appropriate recommendations in relation to such services; as such those service representations were false and misleading.

BASIS OF CONTRAVENTIONS OF SECTION 912A OF THE CORPORATIONS ACT

Section 912A(1)(a) – “efficiently, honestly and fairly”

39 NAB has admitted:

(a) the compliance deficiencies in its policies, procedures and systems in place during the relevant period;

(b) that it knew or ought to have known of the compliance deficiencies; and

(c) that as a result of its compliance deficiencies and its conduct in contravention of ss 962P, 962S, 12DA, 12DB and 1041H it did not do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFS licence were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly –

and it thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act during the relevant period.

40 The compliance deficiencies are identified in the joint submissions at [72]–[85] as follows:

Fee for Advice Standard

During the [relevant period], NAB had policies and procedures in place for the monitoring and oversight of the delivery of services under [ongoing service arrangements] and in relation to [fee disclosure statements]: Agreed Facts [145]. These included a set of standards on various topics which all financial advisers within NAB and the wider NAB group were required to follow (Licensee Standards). One of these standards was referred to as the “Fee for Advice” Standard (Fee for Advice Standard): Agreed Facts [145.2]…

At all relevant times, the Fee For Advice Standard specified requirements of the NAB Licensees in relation to financial advice fees, including in relation to [ongoing service arrangements] and [fee disclosure statements]. Amongst other provisions about [fee disclosure statements], the Fee for Advice Standard provided that, for the purpose of NAB providing a [fee disclosure statement], NAB’s representatives acting as advisers to clients must use NAB’s approved [fee disclosure statement] templates, which were electronic (FDS Templates): Agreed Facts [148.2].

At all relevant times, the FDS Templates contained fields that were populated with information entered and/or imported from NAB’s data systems.

From December 2013 to 1 February 2018, when it was amended, the Fee for Advice Standard contained a clause which stated:

Where actual fees or commission received cannot be readily obtained, (e.g. where product data does not break down revenue to an individual client level), a reasonable estimate must be included on the [fee disclosure statement]. For example, a percentage of the estimated average account balance over the 12 months.

From 1 February 2018, the above statement regarding use of estimated [fee disclosure statement] data was removed from the Fee For Advice Standard: Agreed Facts [150].

The Fee For Advice Standard did not adequately enable NAB to provide in every [fee disclosure statement] the information required. This was because:

a. the requirement for any amendment to the Default Service Statement to be made manually in the FDS Templates was not reliably or adequately controlled;

b. population of the Fee Field was reliant on a manual client mapping process that did not reliably record the fee amount in fact paid by the client during the respective statement period;

c. even where the client was properly mapped, the fees populated in the [fee disclosure statement] were based on amounts and dates recorded in NAB’s systems following processing by NAB of clients’ Ongoing Fees. However, the system data in relation to processed fees did not always accurately reflect the date on which clients were in fact charged by product issuers or third-parties. As a result this often caused the [fee disclosure statement] to record an amount of fees that did not accord with the requirement in s 962H(2)(a); and

d. the Fee for Advice Standard permitted an estimate of fees: Agreed Facts [151].

Advice Compliance Reviews and RWE Checkpoints

During the [relevant period], NAB had in place a procedure whereby a member of [NAB Financial Planning’s] Advice Compliance team reviewed a sample of client files of advisers to ensure adherence to Licensee Standards (Advice Compliance Reviews): Agreed Facts [145.3]. In September 2016, a document known as the Advice Compliance Policy Guide was introduced, which outlined the guiding principles and protocols for how Advice Compliance Reviews were to be conducted (Advice Compliance Policy Guide): Agreed Facts [145.4]. ..

During the [relevant period], NAB also had in place a procedure whereby supervisory oversight and thematic file checks were conducted by Regional Wealth Executives (RWEs) (or equivalent staff) on adviser files (RWE Checkpoints). The RWE Checkpoints were directed to be performed in accordance with RWE Checkpoint Guidelines … and the RWE Checkpoint File Review Checklist … as in force from time to time: Agreed Facts [145.5].

Between 1 July 2013 and May 2018 NAB had no documented policy or procedure mandating that [ongoing fee arrangement] files in particular be reviewed as part of:

a. Advice Compliance Reviews; or

b. Regional Wealth Executive Checkpoints.

This led to an inadequacy in NAB’s documented policies and procedures for reviewing adviser files.

Throughout the [relevant period], NAB’s policies and procedures to ensure compliance with its obligations in relation to [fee disclosure statements] and [ongoing fee arrangements] and the charging of Ongoing Fees should have expressly stipulated that:

a a given number of [ongoing fee arrangements] files be reviewed as part of the Advice Compliance Reviews and RWE Checkpoints; and

b. the accuracy of statements in [fee disclosure statements] as to the services provided to clients and the fees paid by clients in the relevant statement period be checked as part of such reviews.

XPLAN Monitoring and Supervision Procedures

From 2013, and throughout the [relevant period], [NAB Financial Planning] used software known as ‘XPLAN’ as its customer relationship management platform for clients under [ongoing fee arrangements]: Agreed Facts [51]. In relation to the XPLAN system:

a. As at 29 September 2016, the Control Assurance Summary delivered as part of NAB’s Control Transformation Program (see Agreed Facts at [73], [74], [76]) recorded that while XPLAN generated automatic triggers for issuing [fee disclosure statements], automatic triggers were not generated for all clients …: Agreed Facts [153.1].

b. Prior to about April 2017, there was no assessment criteria as part of the Advice Compliance Reviews which considered advisers’ use of XPLAN specifically. In about April 2017, new assessment criteria were introduced as part of the Advice Compliance Reviews that specifically considered: (a) whether advisers employed by [NAB Financial Planning] had maintained clients files in XPLAN including, where they had used XPLAN, whether documents were uploaded within the required timeframe of 1-3 days; and (b) where files had been maintained in XPLAN, whether they adhered to the file naming and format requirements ..: Agreed Facts [153.2].

c. Prior to about 2018, NAB’s systems for monitoring and supervision of the requirement to store electronic records in XPLAN did not always identify cases where: (a) [NAB Financial Planning] did not use XPLAN, or used XPLAN other than in accordance with the requirements in the Licensee Standards; and (b) advisers failed to issue [fee disclosure statements] as required … Based on reviews of certain advisers and self-reporting advisers, NAB estimated (in about September 2019) that in the period from 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018, no more than 86% of advisers were using XPLAN in accordance with the requirements in the Advice Compliance Policy Guide ..: Agreed Facts [153.3].

This led to an inadequacy in NAB’s documented policies and procedures for monitoring advisers’ use of XPLAN. To facilitate NAB’s compliance with its obligations in respect of [fee disclosure statements] and [ongoing fee arrangements] throughout the [relevant period], NAB should have established and maintained documented procedures or systems for ensuring that advisers properly used XPLAN to:

a. trigger reminders for [fee disclosure statement] generation; and

b. store electronic client records in a way that more readily enabled NAB to investigate and detect at an individual client level whether ongoing services and compliant [fee disclosure statements] had been provided (and therefore whether Ongoing Fees had been lawfully charged).

Policies to prevent segmentation

Between 1 July 2013 and at least February 2015, NAB did not have adequate policies, procedures or systems to ensure that clients were not incorrectly ‘segmented’ to NAB’s Direct Service Team without having their ongoing fees terminated, which would result in clients being charged Ongoing Fees without being provided any ongoing services. Once clients were ‘segmented’ into the Direct Service Team, they would no longer receive any [fee disclosure statements] and NAB did not consider them to be clients with advisers. Consequently, they would not be identified through NAB’s existing controls: Agreed Facts [154].

NAB should have established and maintained enhanced documented policies, procedures and systems to address such segmentation of clients.

Policies to ensure entitlement to charge fees

Throughout the [relevant period], NAB did not have adequate documented policies, procedures, and systems to identify whether [NAB Financial Planning] was entitled to charge clients Ongoing Fees in circumstances where as at 23 March 2018 (as identified in the PwC Report):

a. there were no clearly defined policies or procedures describing the circumstances under which the Licensee Support team determined whether to switch off fees for clients of departed advisers, or forward the client to another adviser;

b. the timeframes for switching off fees for clients of departed advisers were not clearly defined or effectively monitored; and

c. there were no documented controls to monitor the transfer and allocation of clients from departed advisers to other advisers and check and validate that clients had been mapped against the correct advisers.

41 The parties jointly submitted, and I accept their submission, that the nature and quality of the compliance deficiencies, and the fact that NAB knew or ought to have known of them, reflects the performance by NAB of its functions in a manner falling short of the standard of performance mandated by s 912A(1)(a). NAB’s conduct was inefficient and was also unfair, insofar as the inadequacy of its documented compliance policies may have impaired the prospect that clients would receive an accurate fee disclosure statement (and thus clients’ ability to make an informed decision as to the value provided by their ongoing fee arrangement) and reduced the likelihood that NAB would identify whether clients had received the services referred to in their ongoing fee arrangements. NAB’s conduct fell below the statutory norm reflected by the “efficiently, honestly and fairly” standard in s 912A(1)(a).

Section 912A(1)(b)

42 It has been a condition of NAB’s AFS licence at all relevant times that “[t]he licensee must establish and maintain compliance measures that ensure, as far as is reasonably practicable, that the licensee complies with the provisions of the financial services laws”. NAB has admitted that it failed to comply with that licence condition during the relevant period and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(b) of the Corporations Act. NAB has accepted that it did not establish and maintain documented policies, procedures and systems that were adequate to ensure, as far as reasonably practicable – that its fee disclosure statement obligations under ss 962G and 962S had been satisfied; that clients had been provided with services to which they were contractually entitled; and that it did not charge clients in contravention of s 962P. The parties jointly submitted that the Court should infer that the inadequacies could reasonably have been improved during the relevant period. I accept that submission.

Section 912A(1)(c)

43 A contravention by a financial services licensee of s 912A(1)(c) follows from a contravention of any other financial services law within the meaning of s 761A of the Corporations Act. NAB has admitted that, between 17 December 2013 and 31 December 2018, by its contraventions of ss 962P, 962S, 1041H of the Corporations Act and ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(a) and (g) of the ASIC Act, it failed to comply with the financial services laws and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

Section 912A(1)(ca)

44 ASIC alleged and NAB has admitted that by reason of its compliance deficiencies and its conduct in contravention of ss 962P, 962S and 1041H of the Corporations Act and ss 12DA and 12DB of the ASIC Act, NAB did not take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives complied with the financial services laws, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(ca) of the Corporations Act during the relevant period.

45 The parties jointly submitted, and I accept, that reasonable steps in this case within the meaning of s 912A(1)(ca) included establishing and maintaining documented policies, procedures and systems that were adequate to identify: whether review services are provided in accordance with ongoing fee arrangements; whether fee disclosure statements were provided to clients in the necessary timeframe with the requisite statutory content; and whether clients were being charged ongoing fees without authority. Although NAB established and maintained a number of documented policies, procedures and systems that were directed to identifying such matters, the steps taken by NAB were inadequate and fell below the standard of “reasonable steps” provided for in s 912A(1)(ca).

Section 912A(1)(e)

46 NAB has admitted that by reason of its compliance deficiencies and its conduct in contravention of ss 962P, 962S and 1041H of the Corporations Act and ss 12DA and 12DB of the ASIC Act, it did not maintain the competence to provide the review services pursuant to its ongoing service agreements and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(e) of the Corporations Act during the relevant period. The parties jointly submitted, and I accept, that competence to provide financial services in a financial planning context does not only extend to the qualitative standard of substantive advice provided, but also to competence to comply with statutory and contractual obligations applicable to the provision of financial advice. The admitted compliance deficiencies thus bore upon NAB’s competence to provide the review services, pursuant to its ongoing fee arrangements.

Section 912A(1)(f)

47 NAB has also admitted that by reason of its compliance deficiencies and its conduct in contravention of ss 962P, 962S and 1041H of the Corporations Act and ss 12DA and 12DB of the ASIC Act, it did not do all things necessary during the relevant period to ensure that its representatives were adequately trained and were competent, to provide financial services, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(f) of the Corporations Act. The parties jointly submitted, and I accept, that an aspect of providing adequate training to representatives and ensuring that they are competent to provide financial services includes training them to comply with statutory disclosure requirements applicable to the provision of relevant financial services. Although NAB did provide a number of training programs and materials to its representatives in relation to satisfying the fee disclosure obligations in div 3 of pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act (see agreed facts [123], [126], [145.9]), the nature and extent of such training, particularly when viewed against the facts giving rise to the admitted compliance deficiencies, did not satisfy what was required by s 912A(1)(f).

DECLARATORY RELIEF

48 I am satisfied on the basis of the agreed facts and NAB’s admissions that the declarations which the parties have agreed on are within the power of the Court to make.

49 Sections 962P and 962S of the Corporations Act are civil penalty provisions and by s 1317E of the Corporations Act, the Court must make a declaration of contravention of a civil penalty provision if it is satisfied that the person has contravened the provision. Accordingly, the declarations sought in respect of those contraventions will be made.

50 It is also appropriate to make the declarations sought in regard to the other contraventions, as making those declarations has the utility of identifying the nature and basis of the contravening conduct and making clear to other would-be contraveners that such conduct is unlawful: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68; [2017] FCAFC 113, 87 [93].

ORDER FOR THE APPOINTMENT OF AN INDEPENDENT EXPERT AND COMPLIANCE PROGRAM

51 The Court has the power under s 12GLA of the ASIC Act and s 1101B of the Corporations Act to make orders for the appointment of an independent expert to review, recommend and report on NAB’s compliance procedures and for the establishment of a compliance program incorporating the expert’s recommendation insofar as is reasonably practicable. NAB has agreed to those orders, notwithstanding that it does not currently enter into ongoing fee arrangements, but it is appropriate that the orders be made in case NAB decides to resume entering into ongoing fee arrangements.

PECUNIARY PENALTIES

52 Penalties may be imposed for the contraventions of ss 962P and 962S of the Corporations Act (s 1317G(1E) of the Corporations Act as in force at the time of the contraventions) and ss 12DB(1)(a) and (g) of the ASIC Act (which are also civil penalty provisions) (s 12BGBA of the ASIC Act as in force at the time of the contraventions) (collectively the civil penalty contraventions). NAB agreed that it is appropriate that pecuniary penalty orders be made pursuant to s 1317G(1E) of the Corporations Act and s 12GBA(1) of the ASIC Act, but the parties are not agreed on the amount of the penalty or on the relevance and significance of all facts to be considered in the determination of the appropriate penalty. ASIC has contended for a total penalty of $40 million in respect of all the civil penalty contraventions, whereas NAB has contended that an overall penalty in the order of $15 million would be appropriate and justified. Both parties made comprehensive submissions in support of their competing positions.

Overview of ASIC’s submissions

53 ASIC submitted that a total penalty of $40 million reflects the very serious nature of the conduct. In summary, ASIC submitted that the following matters, in particular, informed the appropriate amount of the penalties to be imposed.

54 First, both div 3 of pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act and s 12DB(1)(a) and (g) of the ASIC Act are provisions designed to protect consumers.

55 Second, the 2,285 civil penalty contraventions spanned over five years (between 17 December 2013 and 31 December 2018) and the conduct was not isolated but rather systemic in nature.

56 Third, the civil penalty contraventions directly impacted:

(a) 1,382 unique clients in total across all the contraventions;

(b) 1,195 clients who received false and misleading statements about the services received, fees paid, or both, in a document on which they could have been expected, and were entitled, to rely;

(c) those clients collectively paid $2,306,625.60 in fees, in circumstances where they were denied the opportunity to make an informed decision as to whether to cease paying ongoing fees; and

(d) 435 clients collectively paid $1,299,132.11 in ongoing fees, which NAB was prohibited from charging and were thus “kept out of money due which is to suffer real economic loss” (Paciocco v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Limited (2016) 258 CLR 525; [2016] HCA 28, 609 [263] (Keane J) and were, unless and until any later remediation, deprived of the benefit, including timely access to, their money, in many cases for extended periods of time.

57 Fourth, the root cause of the contraventions was NAB’s compliance deficiencies and its slow piecemeal and inadequate steps to address them. Under the terms of its AFS licences, NAB was obliged to establish and maintain compliance measures that ensured, as far as was reasonably practicable, that it complied with the provisions of the financial services law, including pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act. Instead, the compliance measures established and maintained by NAB were grossly deficient by reason of historical under investment in its operational risk and compliance framework.

58 Fifth, given NAB’s size and available resources (being the fifth largest listed company by market capitalisation in Australia) there can be no excuse for such historical under investment. It was submitted the decision making organs of NAB failed to ensure that proper systems were in place and the penalty imposed should not be so low as to provide an incentive for under investment in compliance by being merely the cost of doing business.

59 Sixth, there was deep knowledge within NAB:

(a) of the compliance deficiencies increasingly over 2013–2017, when NAB had identified prior to December 2013 that NAB Financial Planning advisors may have failed to issue fee disclosure statements within the time required by the Corporations Act;

(b) by NAB’s senior management by no later than 31 May 2018 and subsequently by NAB’s board by no later than September 2018 that there had been and continued to be systemic failures to deliver review services and timely and accurate fee disclosure statements to numerous yet unidentified clients, despite which NAB continued to charge ongoing fees and a target for rectification and remediation of those issues was not until 31 December 2020.

60 ASIC submitted that the knowledge of senior management is especially significant, because between 31 May 2018 and 4 February 2019, NAB continued charging ongoing fees to clients without ascertaining whether it was entitled to do so and over half of the prohibited charging contraventions include charges after 31 May 2018.

61 Seventh, by reason of the contraventions arising from systemic defects and NAB’s knowledge of them, the contraventions were not the result of negligence or carelessness.

62 Eighth, NAB’s conduct was not ethically sound. It was submitted that no bank should take from its customer unless it is entitled to do so and NAB has admitted that its conduct contravenes s 912A(1) of the Corporations Act by failing to ensure that financial services were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly.

63 Ninth, NAB has previously engaged in similar conduct.

64 These and other matters were elaborated in detail in the submissions, both orally and in writing.

Overview of NAB’s submissions

65 NAB, on the other hand, contended that an overall penalty in the order of $15 million would be appropriate and justified in respect of the civil penalty contraventions, comprising:

(a) approximately $5 million for the contraventions of s 962P of the Corporations Act;

(b) approximately $3 million for the contraventions of s 962S of the Corporations Act; and

(c) approximately $7 million for the contraventions of s 12DB of the ASIC Act.

66 NAB submitted that penalties of this magnitude would reflect the gravity of the contravening conduct and send a message that the contraventions of the penalty provisions are serious and unacceptable, achieving the twin objects of general and specific deterrence. It was submitted that such penalties, however, also fairly recognise that the contraventions fall at the lower end of the spectrum of seriousness and that there are significant mitigating factors.

67 NAB submitted that key considerations in support of its proposed penalty, which underscore why the $40 million figure is manifestly excessive, include the following:

(a) ASIC no longer asserts unconscionable conduct: the original claims made by ASIC included the claim that NAB engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 12CB of the ASIC Act, but as that claim has not been pressed, ASIC cannot bring to account assertions of systemic conduct advanced under its abandoned unconscionable conduct case to justify a higher than normal penalty for the contraventions;

(b) NAB’s s 912A admissions cannot be relied upon to justify a higher penalty: ASIC is not permitted to rely upon the facts giving rise to the s 912A admissions as an aggravating factor in assessing penalty in respect of the other contraventions;

(c) Statutory framework: the statutory framework does not justify a penalty higher than that proposed by NAB. The 2012 Explanatory Memorandum expressly recognised that fee disclosure obligation breaches are likely to be “relatively less serious” than, for example, a breach of the best interests duty. The 2012 Explanatory Memorandum also recognised that “disproportionate and unjust results” could arise if fee recipients were required to repay clients who had continued to receive services after automatic termination of ongoing fee arrangements and Parliament therefore confined the refund obligation to cases in which the fee recipient knowingly or recklessly contravened s 962P: s 1317GA. ASIC did not contend any knowing or reckless contravention by NAB of s 962P, yet proposed a single penalty some 30 times the fees actually charged by NAB. That outcome immediately suggested the excessiveness of ASIC’s position;

(d) Number of contraventions: the total number of contraventions (445 for s 962P, 225 for s 962S and 1,615 for s 12DB) is on a considerably smaller scale than the contravening conduct in comparable penalty decisions, in which the Court has imposed significantly lower penalties than are sought by ASIC. No inference can be drawn that additional contraventions may have occurred outside those pressed by ASIC;

(e) Profit resulting from contraventions: the total amount of fees charged by NAB contrary to s 962P was just under $1.3 million and the fees charged following contraventions of s 12DB total just over $2.3 million (including overlap with the s 962P charging). The $40 million penalty sought by ASIC is materially excessive in this context, especially so given that NAB has provided refund or remediation payments of almost $5 million to clients subject to the contraventions. The penalties that NAB seeks plainly ensure that it will not profit from its misconduct. They also have a deterrent effect and reinforce to industry the importance of compliance with the fee disclosure statement regime;

(f) Nature and circumstances of contraventions: ASIC’s submissions are premised on generalisations, which eschew examination of the facts relating to each of the contraventions. These do not all bear the same nature and quality. In many instances, the breaches can fairly be regarded as technical. The difference in the character of the different contraventions is consistent with them having arisen in a context where fee disclosure statements were prepared and issued by individual financial planners or client services officers, for individual clients, using electronic systems and manual processes susceptible to error;

(g) Contraventions were not deliberate: NAB communicated with ASIC about identified fee disclosure statement defects as they came to light and ASIC did not allege any dishonesty or concealment on NAB’s part. Nor did ASIC allege that the contraventions were deliberate or committed knowingly. Rather, ASIC relies on NAB’s awareness of certain compliance risks, however such awareness is not an aggravating factor for the purposes of penalty, given that NAB was taking steps to investigate and respond to that risk, the appreciation of which developed over time. Insofar as ASIC relies on NAB’s awareness of particular compliance deficiencies, it had not demonstrated sufficient connection between the systems issues identified and the subject contraventions. In relying on such matters, ASIC impermissibly brings the s 912A contraventions and the no longer pressed unconscionable conduct case into the penalty calculus;

(h) Response to FDS issues and compliance culture: NAB has undertaken a range of measures that show an appreciation of the seriousness of the contravening conduct and of NAB’s commitment to ongoing improvement in its compliance systems and processes. As a compliance risk was identified, NAB: provided breach report notifications to ASIC; sought to investigate the extent of the identified risk; implemented systems improvements for preparation and delivery of fee disclosure statements; conducted additional adviser training; and, in early 2019, ceased charging fees to a large cohort of clients, but continued to provide service (irrespective of whether or not they had received compliant fee disclosure statements). ASIC’s criticisms as to the speed of NAB’s response did not engage with the practical business setting in which the risks arose and were based on a selective presentation of the relevant chronology and information only available with hindsight;

(i) Impact on clients: NAB submitted that the evidence did not establish that the contravening conduct materially impacted clients, either at an individual level or as a whole. For some clients charged fees contrary to s 962P: (i) the fee amount in the fee disclosure statement, although wrong, was not materially inaccurate – for around 50% of clients this was within 10% of the fees actually paid in the statement period and the median difference was approximately $235; (ii) the fee disclosure statement incorrectly stated that services had been provided in the statement period, but the relevant service was provided after that period; (iii) the client elected not to continue with their arrangement with NAB, notwithstanding the defect in the disclosure. NAB submitted that these examples were at odds with the proposition that the fee disclosure statement errors necessarily led to a material inability on the part of clients to make informed decisions as to their advice arrangement. NAB further submitted that as to the overall client impact, the amount of fees collected without authority was $1.3 million, a significant portion of which has been refunded;

(j) Refund and remediation programs: NAB has administered a refund program under which it has returned a significant portion of fees paid by clients the subject of the contraventions. NAB submitted this was to its credit, given that: (i) NAB is not statutorily obliged to refund such fees (s 962F(3) of the Corporations Act ); (ii) ASIC has not sought a refund order under s 1317GA of the Corporations Act for NAB’s contraventions of s 962P, nor any other form of compensation order; and (iii) NAB has refunded fees paid by clients who continued to receive services. NAB has also undertaken extensive steps to identify and remediate any client who did not receive the services to which they were entitled under its “Adviser Service Fee remediation program”, using a methodology that ASIC was consulted on;

(k) Persons responsible for contraventions: NAB submitted that the contraventions were the direct result of the incorrect preparation and delivery fee disclosure by individual advisers and client services officers and did not flow from any decision by management around the extent or content of disclosures. It was submitted this is in marked difference to a number of other penalty decisions where the relevant contraventions arose from conduct that was directed, facilitated or condoned by senior management;

(l) Management knowledge of contraventions: almost all of the ss 962S and 12DB contraventions occurred before 31 May 2018, the date from which ASIC points to awareness on the part of NAB Financial Planning senior management of a risk that NAB had issued defective fee disclosure statements. As to the s 962P contraventions, there was no substance in ASIC’s contention that, from 31 May 2018, clients were charged in the face of knowledge by management that “there had been and continued to be a systemic failure … to deliver … timely and accurate [fee disclosure statements] to numerous yet unidentified clients”. As at that date, it was known that a very small group of clients had not received a compliant fee disclosure statement and that there was a risk of uncertain magnitude that other (unknown) clients might not have. Steps were subsequently taken by NAB, over 2018 and into 2019, to investigate and ascertain the extent of any such fee disclosure statement non-compliance. It was argued that those steps are objectively inconsistent with the earlier awareness of systemic failure that ASIC would have the Court infer;

(m) Cooperation: NAB has sought to work constructively with ASIC through the course of the investigation and proceedings. At an early stage in the proceeding, NAB admitted all s 962S contraventions that were ultimately pressed by ASIC and a significant number of the s 962P contraventions (including all allegations arising from non-compliance with s 962H(2)(d) of the Corporations Act). NAB also admitted to having made almost all the representations that underlie the s 12DB contraventions. NAB responded to various requests by ASIC for information leading up to and during the course of the proceeding and met with ASIC to seek to facilitate its response to such requests. It was submitted that in preparing and admitting to the agreed facts with ASIC, proposing and participating in a mediation of the proceeding and making additional admissions of liability at mediation, so as to resolve all issues of liability, NAB has demonstrated substantial cooperation. This has avoided the incurrence of additional costs and has conserved limited Court resources;

(n) Contrition: NAB read direct affidavit evidence of contrition and remorse at the hearing, in which an apology was delivered on behalf of NAB. NAB has also apologised publicly and to its clients for the conduct that gave rise to the civil penalty contraventions. NAB’s contrition was also said to be demonstrated by the significant amounts that it has refunded to date to clients the subject of the civil penalty contraventions – almost four times the amount of the fees charged contrary to s 962P;

(o) Minimal risk of repetition of the contravening conduct: it was submitted that considerations of specific deterrence carry diminished significance in this case, as NAB has undertaken extensive steps to improve its procedures around ensuring fee disclosure compliance and has since divested its financial planning business and is no longer entering into ongoing fee arrangements to which the fee disclosure statement regime in pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act applies. It was submitted that the subject contraventions thus cannot reasonably be expected to reoccur;

(p) NAB’s size and resources: it was submitted that the size and resources of a corporation cannot itself justify a higher penalty. NAB’s proposed penalty figure is more than 10 times the total amount of fees charged to clients without authority. Viewed in combination with the significant repayments NAB has already made to clients, such a penalty could not be regarded by NAB as “merely a cost of doing business”;

(q) Prior conduct of NAB: NAB has not previously been found to have contravened pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act, nor engaged in other statutory contraventions in respect of fee disclosure statements.

68 Each of these and other matters were elaborated by NAB in its submissions, orally and in writing.

Statutory maximum penalties

69 The maximum penalties for the contraventions in the relevant period were:

(a) $250,000 for ss 962P and 962S of the Corporations Act; and

(b) 10,000 penalty units for s 12DB of the ASIC Act, with a penalty unit varying from $170 to $210 across the relevant period, resulting in a maximum penalty of:

(i) $1.7 million between 28 December 2012 to 30 July 2015 (penalty unit value of $170);

(ii) $1.8 million between 31 July 2015 and 30 June 2017 (penalty unit value of $180); and

(iii) $2.1 million from 1 July 2017 onwards (penalty unit value of $210).

70 No penalty attaches to the s 912A contraventions or the s 1041H contraventions.

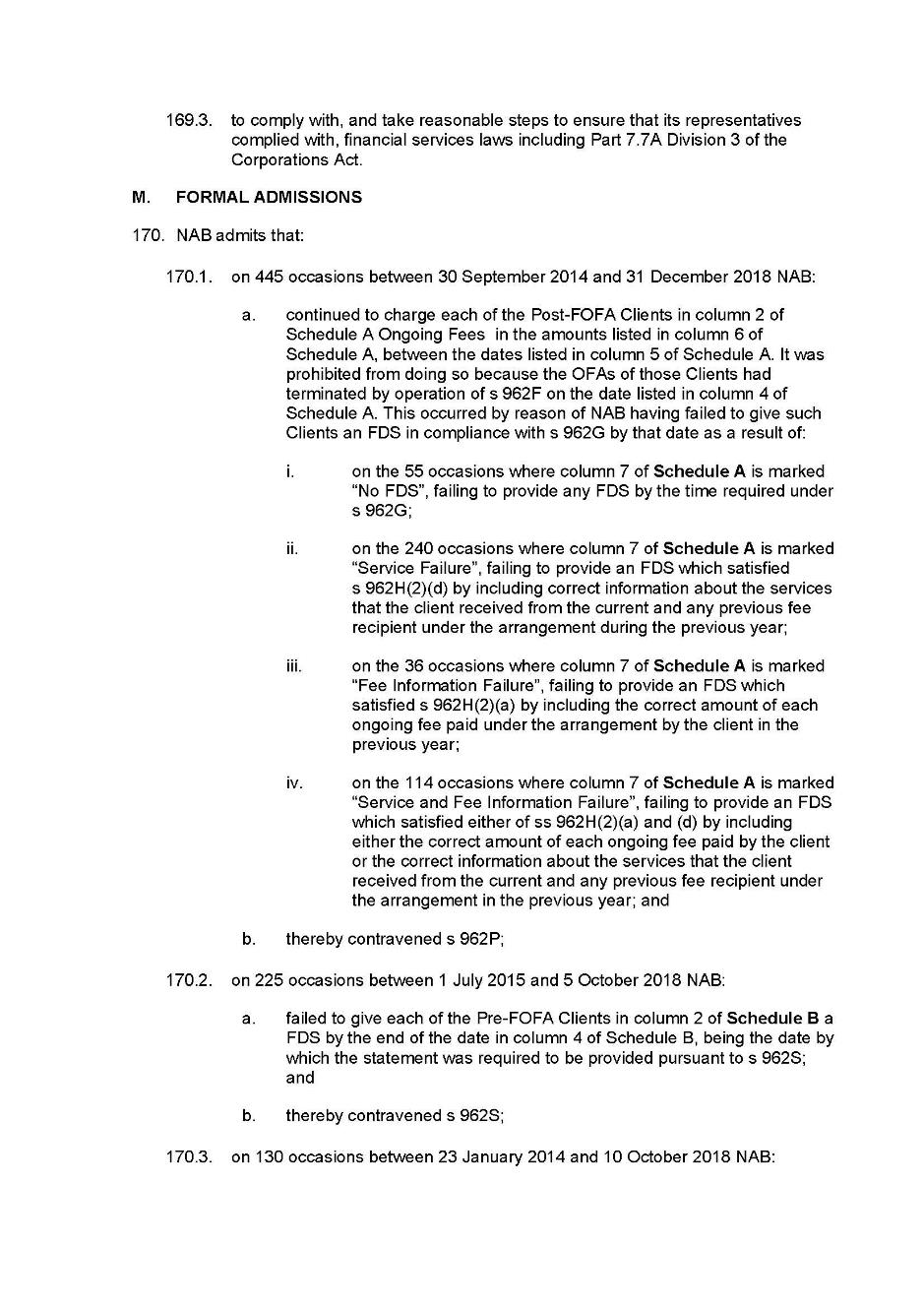

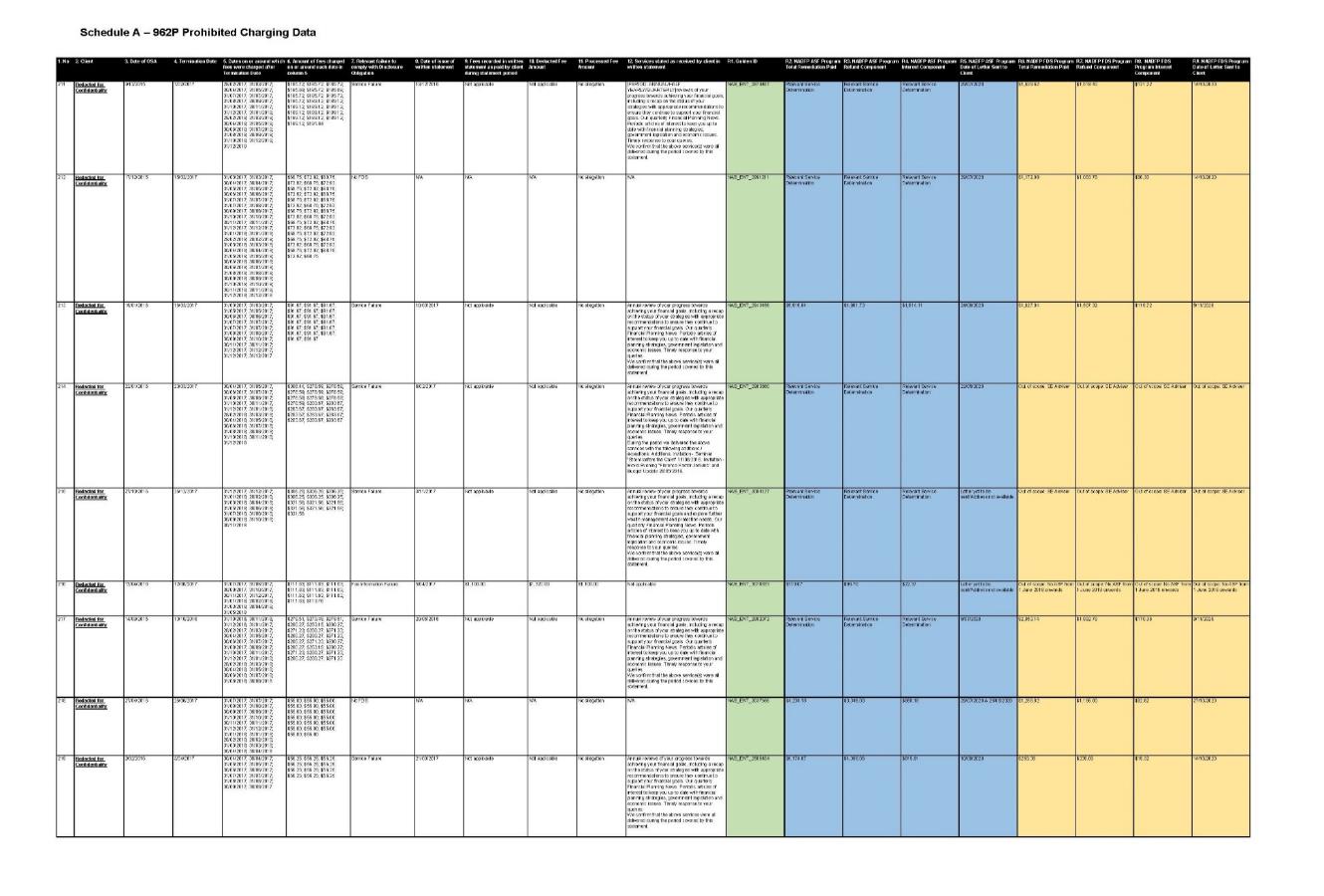

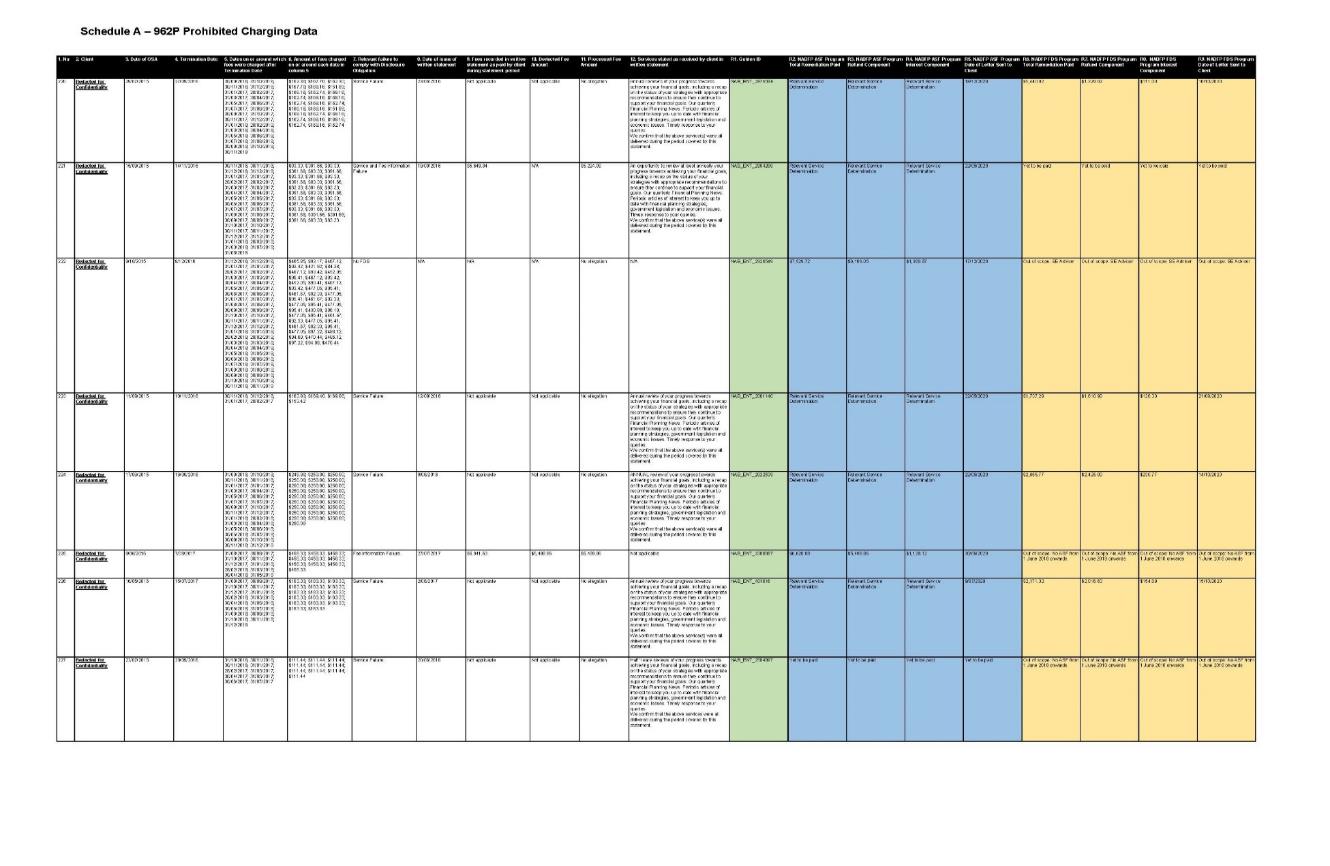

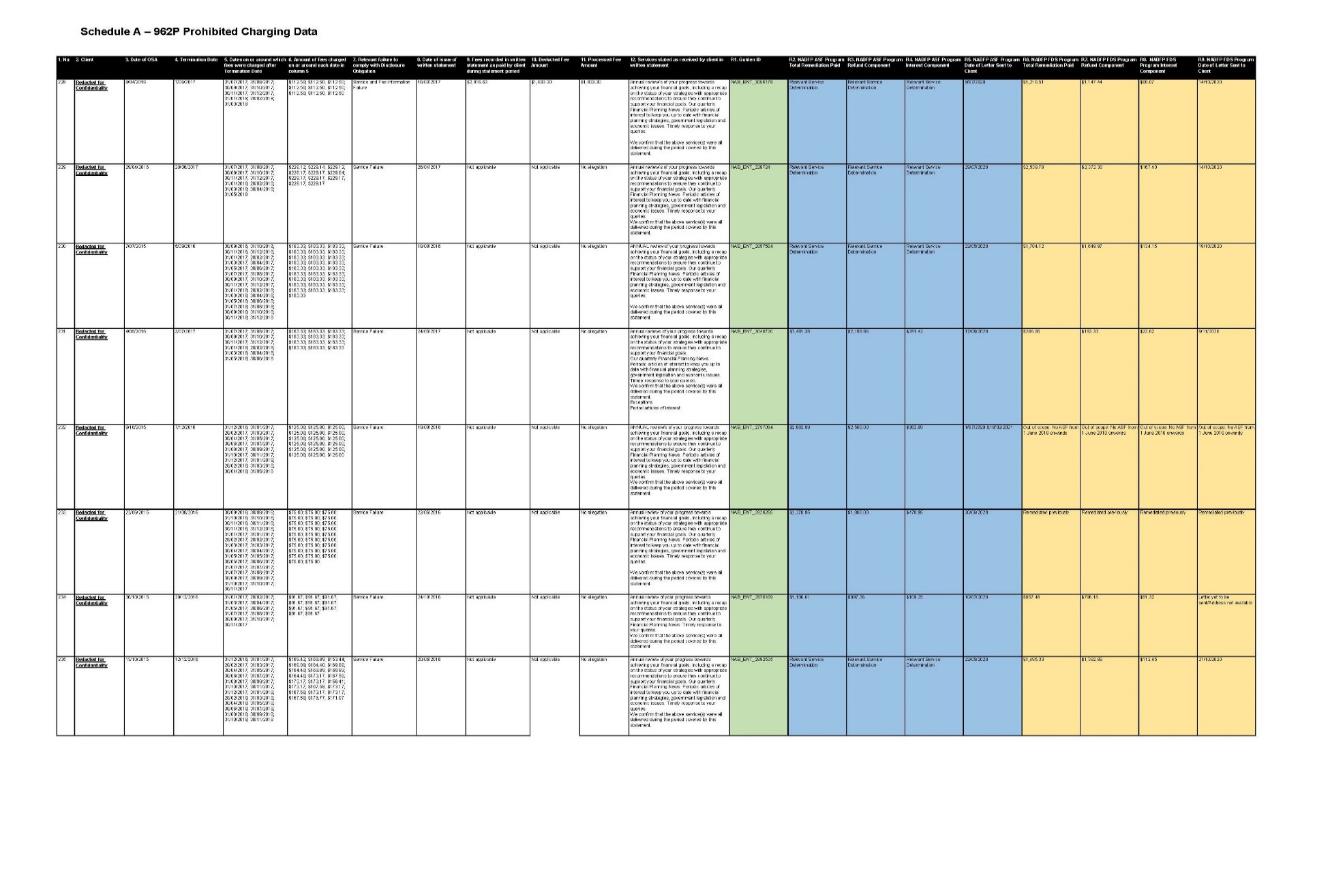

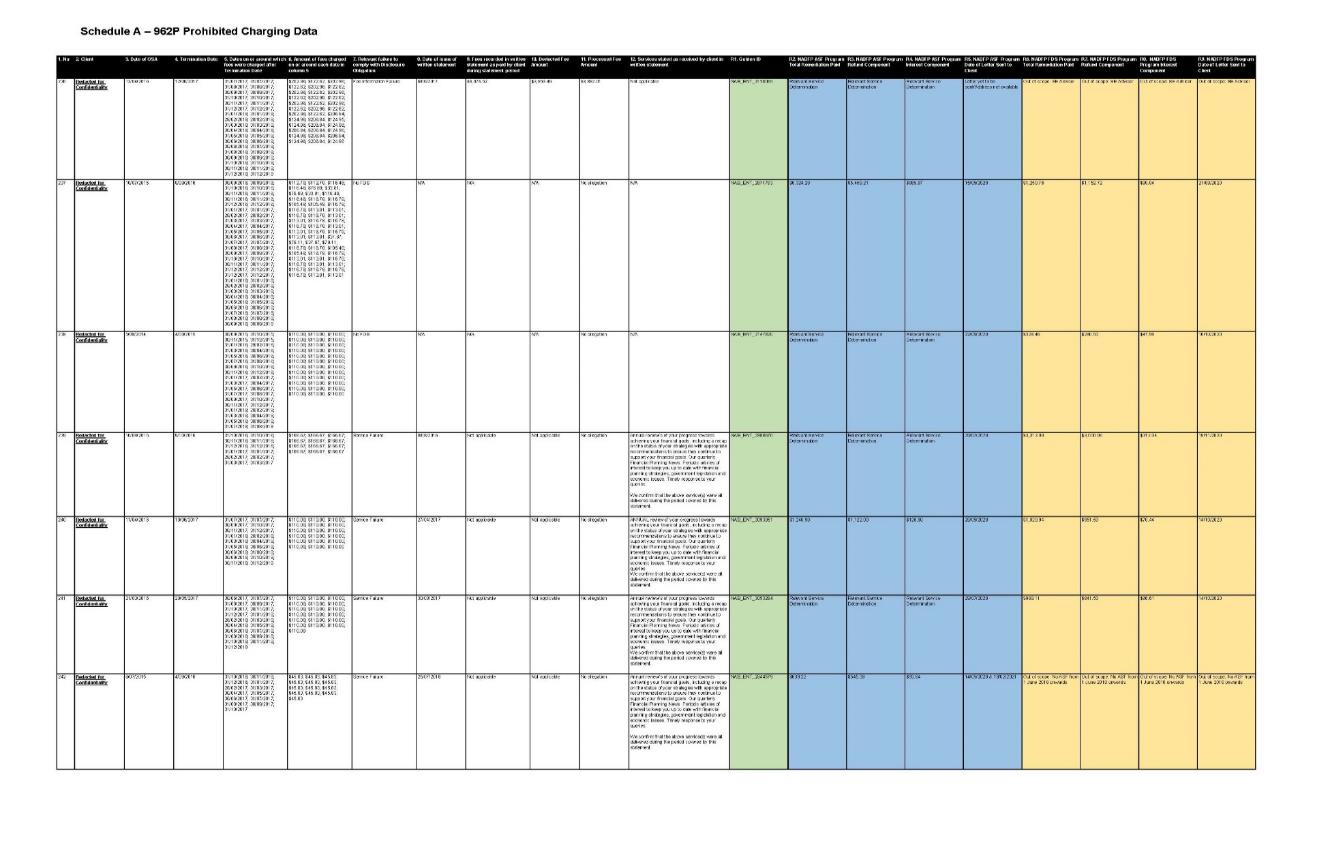

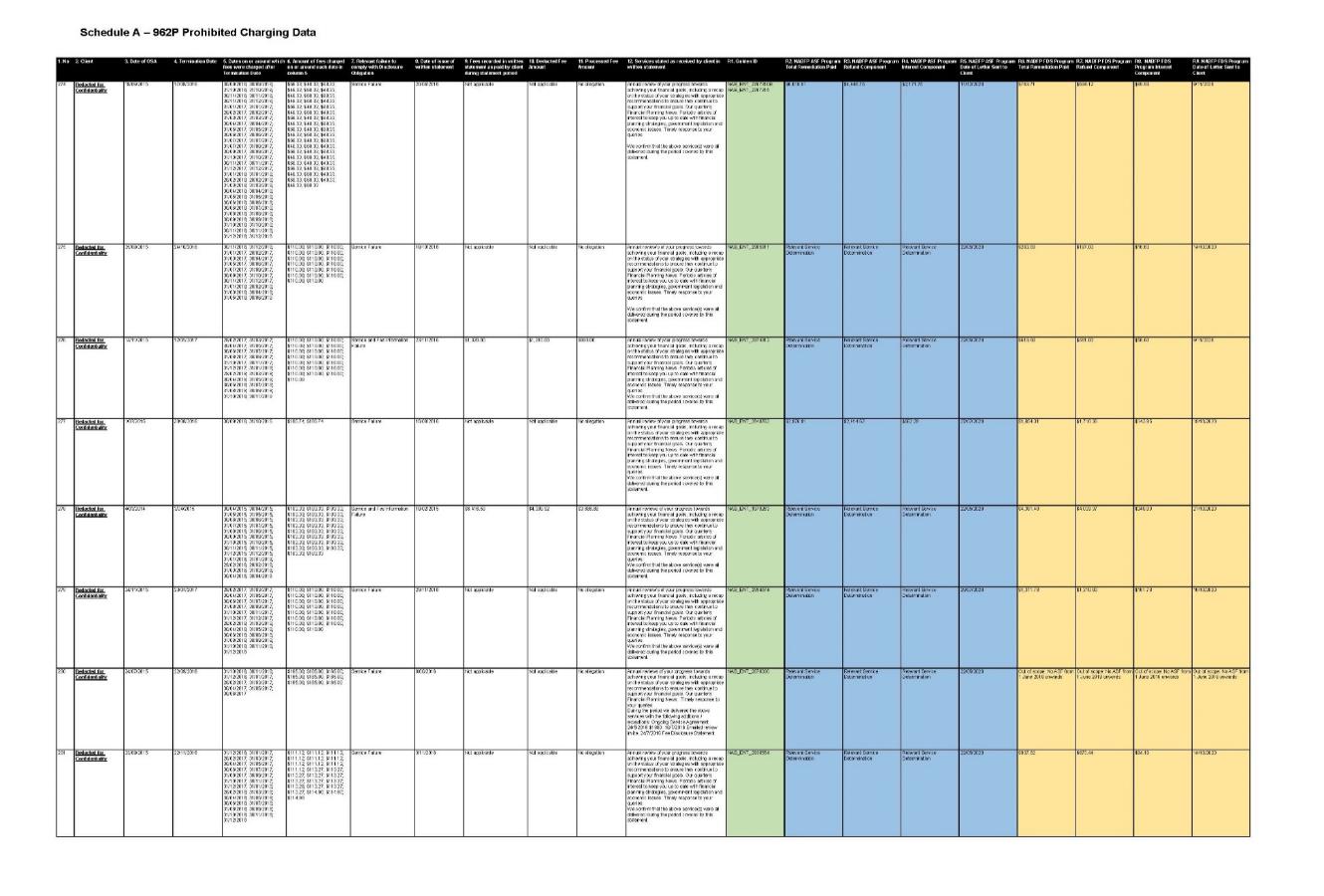

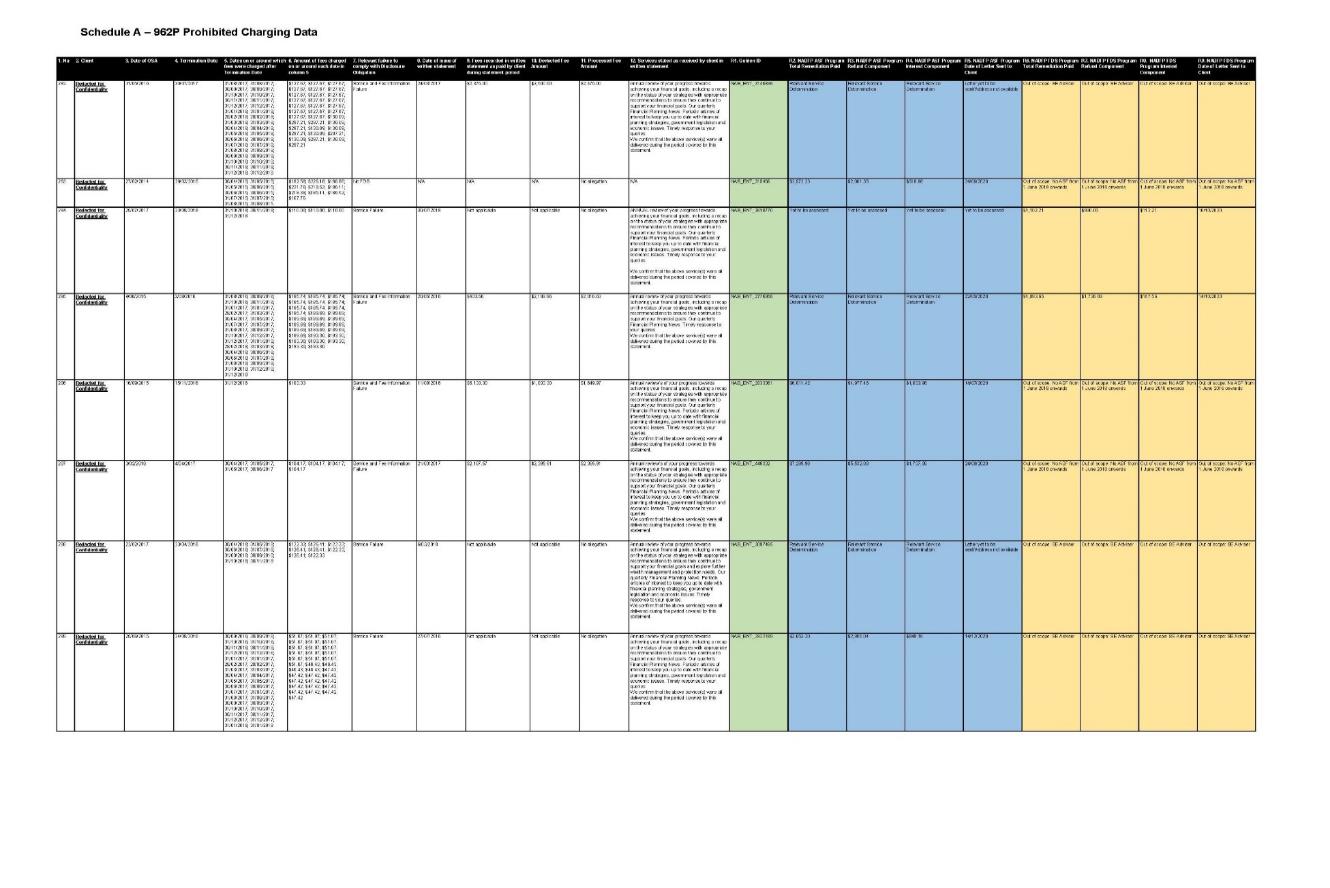

71 The total statutory maximum applicable to the admitted contraventions is set out in the table below:

Contravention | No. | Max per contr. | Theoretical cumulative max. |

Prohibited Charging: s 962P | 445 | $250,000 | $111.25M |

No Fee Disclosure Conduct: s 962S | 225 | $250,000 | $56.25M |

False or Misleading Representations: s 12DB | 1,485 (service) 130 (price) | $1.7–$2.1 m | $2,756m $246m |

Total | $3,169m |

Applicable principles

72 The purpose for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty is to act as a specific deterrent to the contravener and as a general deterrent to others who might be tempted to contravene the law: Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482; [2015] HCA 46 (Fair Work), 506 [55] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ, Gageler J agreeing at 511 [68], Keane J agreeing at 513 [79]). The specific and general deterrent effect of pecuniary penalties is achieved by putting a price on a contravention that is “sufficiently high” to deter repetition by both the contravener and would be contraveners: Fair Work, 506 [55]. The penalty must also be proportionate to it and should be no greater than is necessary to achieve the objective of specific and general deterrence. Notions of punishment or retribution are not engaged in the imposition of a penalty: Fair Work, 506 [55].

73 The fixing of the penalty involves the identification and balancing of all the factors relevant to the contravention and circumstances of the contravener. Factors that are usually relevant to consider include:

(a) the seriousness of the conduct and period over which it extended;

(b) the deliberateness of the conduct and whether the conduct was dishonest;

(c) the period of time over which the contraventions occurred;

(d) whether further contraventions are likely;

(e) whether the contravener cooperated with ASIC in relation to the contraventions;

(f) whether corrective measures have been taken by the contravener in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(g) whether the company has disgorged any profit or benefit received as a result of the contravention, or made reparation;

(h) the financial position of the contravener and its resources to pay a penalty in the sense that whilst the size of a corporation does not of itself justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed, it may be relevant in determining the size of the pecuniary penalty that would operate as an effective specific deterrent;

(i) the existence within the corporation of compliance systems, including provisions for and evidence of education and internal enforcement of such systems;

(j) the seniority of officers responsible for the contraventions;

(k) whether the directors of the corporation were aware of the relevant facts and, if not, what processes were in place at the time or put in place after the contravention to ensure the awareness of such facts in the future;

(l) the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties.

See Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (2016) 118 ACSR 124; [2016] FCA 1516, [87]-[88]; Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49 (Volkswagen), [150]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 3) (2018) 131 ACSR 585; [2018] FCA 1701, [49].

74 The list is not exhaustive nor a rigid catalogue or checklist of matters to be considered, however those factors may be taken to be relevant because they directly bear on the assessment of the penalty that is necessary to achieve general and specific deterrence: Volkswagen, [150]. In weighing and balancing the relevant factors, the Court must ensure that the penalty is just, bearing in mind the protective and deterrent purpose of a pecuniary penalty and the factors relevant to the contravention and the contravener: Fair Work, 523 [109].

75 Additionally, s 12GBA(2) of the ASIC Act (as in force at the relevant time) specifically directs the Court, in determining the appropriate penalty for the contraventions of s 12DB, to take into account the following matters (in addition to all other relevant matters): (i) the nature and extent of the act or omission; (ii) any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; (iii) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and (iv) whether the person has previously been found by a Court in proceedings under pt 2 div 2 sub-div D of the ASIC Act to have engaged in similar conduct.

76 In fixing a pecuniary penalty, the Court engages in an intuitive or instinctive synthesis of these matters: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 327 ALR 540; [2015] FCA 330, 543 [6]. The Court must weigh together all relevant factors rather than engage in a sequential mathematical process. It “is an inexact science, not subject to rigidity in approach but guided by well-accepted factors”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) (2020) 377 ALR 55; [2020] FCA 69 (ASIC v AMP (No 2)), 95 [159]. In the synthesis conducted, the appropriateness of a penalty must be assessed by reference to the civil penalty provision that has been contravened in light of its context and purpose and the objects of the relevant statute as a whole: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2020] FCA 790 at [78]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees Pty Ltd (2020) 147 ACSR 266; [2020] FCA 1306 (ASIC v MLC), 285–6 [117(6)]. The maximum penalty is “but one yardstick” to be applied: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25; [2016] FCAFC 181 (ACCC v Reckitt), 63 [155]. Penalties imposed in analogous cases are another yardstick, however, as the authorities caution, reference to other cases will offer limited assistance where the contraventions and facts are different: Flight Centre Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) (2018) 260 FCR 68; [2018] FCAFC 53, 86 [69].

77 Where the acts and omissions giving rise to different contraventions overlap, the Court should not penalise the contravener twice. Throughout the relevant period, s 12GBA(4) of the ASIC Act prohibited more than one pecuniary penalty being fixed under s 12GBA(1) in respect of the same conduct, if that conduct contravened two or more relevant provisions of the ASIC Act. This provision was repealed on 13 March 2019 and there is no equivalent provision in the Corporations Act, however, as held by Middleton J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Forex Capital Trading Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 570, [136], an analogous principle of avoiding “double punishment” for the same conduct still applies, whereby if the same act or omission is an element of two offences “it would be wrong to punish an offender twice for the commission of the elements that are common”. In the present case, there is an overlap between the conduct that gave rise to contraventions of s 12DB of the ASIC Act and s 962P of the Corporations Act, which ASIC acknowledged.

78 It is also appropriate to consider whether, and the extent to which, the contravening conduct can be regarded as the same course of conduct and penalised as one offence in relation to each category of contravention: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68; [2017] FCAFC 113, 99 [145]. The “totality” principle operates as a “final check” to ensure that the penalties to be imposed on a contravener, considered as a whole, are just and appropriate and that the total penalty for related offences does not exceed what is proper for the entirety of the contravening conduct: ASIC v MLC, 289 [131].

79 Finally, the Court has recognised the important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcomes in civil penalty proceedings, which encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and hence diminishes demand on the public resources constituted by both the Court and the regulator: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2021] FCA 423, [7], [29].

Consideration

80 NAB accepted that the contraventions were serious, however argued that the contraventions were not egregious and, on balance, were at the lower end of the spectrum of seriousness, given their nature and likely client impact. NAB made the following points:

(a) first, only about 5% of the 445 contraventions of s 962P arose in circumstances where no fee disclosure statement was given; around 95% of the contraventions arose in circumstances where the client was provided with a fee disclosure statement, but either the statement was not provided within the time prescribed by s 962G of the Corporations Act or it did not correctly set out the ongoing fees paid by the client and/or the services received (or entitled to be received) by the client during the statement period (s 926H);

(b) secondly, of the 150 fee disclosure statements provided to clients that did not accurately refer to the amount of fees clients paid in the relevant statement period, 78 (or 52%) involved discrepancies of 10% or less as between the annual fee amount included in the fee disclosure statement and the fee that ought to have been included. The median fee discrepancy for such fee disclosure statements was approximately $220;

(c) thirdly, many fee disclosure statements did not satisfy s 962H(2)(a) in circumstances where the amount stated in the fee disclosure statement was greater than the amount in fact deducted from the client’s account. It was submitted that a fee discrepancy of this kind may reasonably be expected to have led clients to be more, rather than less, circumspect about continuation of their advice arrangement (and thus cannot be assumed to have inhibited the objective of the fee disclosure statement provisions to facilitate the engagement of passive fee payers);

(d) fourthly, a number of fee disclosure statements did not satisfy s 962H(2)(a) only because they included the amount of fees that had been received and processed in NAB’s systems during the relevant statement period, instead of the amount that had been deducted by product issuers from the client’s account during that statement. The Court was taken to client 401 in Schedule A to the agreed facts, as an example where, at the time that the fee disclosure statement was generated, the client’s monthly payment of $110 had been deducted from the client’s account, but not yet processed in NAB’s systems and the fee disclosure statement recorded that the client had paid fees of $1,100 during the relevant statement period when in fact the fees paid were $1,210;

(e) fifthly, for a number of clients the fee disclosure statement was inaccurate because of a temporal misalignment between the period covered by the fee disclosure statement and when the service was provided. The following two examples were specifically mentioned:

(i) the first example was given of a client who had received financial planning advice from NAB Financial Planning in November 2015, including a written statement of advice dated 24 November 2015. The client subsequently entered into an ongoing fee arrangement with NAB on 7 December 2015 and pursuant to that arrangement, were entitled to receive an annual review of their financial position. On 15 November 2016, the client received an annual review and, on the same date, NAB Financial Planning issued a fee disclosure statement to the client. That fee disclosure statement is the subject of contraventions by NAB of s 962P of the Corporations Act and s 12DB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act in this proceeding, because it incorrectly stated that the annual review had been delivered “during the period covered by this statement”, referred to as 11 November 2015 to 10 November 2016, when the review was provided five days after the statement period; and