FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) [2021] FCA 956

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 13 august 2021 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. During the period from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015, Phoenix, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of certain online vocational education and training (VET) courses to consumers, engaged with respect to each consumer in conduct, being the Phoenix Marketing System (as defined by paragraph [73] of the Amended Statement of Claim), that was unconscionable, thereby separately contravening section 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), in respect of each consumer, in the circumstances set out below:

(a) the purpose of Phoenix, in marketing to consumers, eliciting enrolment applications from them, and enrolling them in online VET courses, was to maximise the number of consumers enrolled who received VET FEE-HELP, so as to maximise the revenue to Phoenix from the Commonwealth via the VET

FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme;

(b) Phoenix displayed a callous indifference as to whether the consumers it sought to and did enrol were within the target cohorts for the courses, satisfied the eligibility criteria for those courses, were suitable for the courses, whether the consumers had reasonable prospects of successfully completing the courses and whether the course delivery was adequately resourced;

(c) consumers to whom brokers and agents marketed the online VET courses were more likely to include vulnerable individuals as compared with other individuals within the Australian community;

(d) the tactics employed on behalf of Phoenix in soliciting enrolment applications were unfair and high pressure;

(e) the representations made on behalf of Phoenix by brokers and agents to consumers that:

(i) in order to receive a free laptop all the consumers needed to do was to sign up to an online VET course which was free; and

(ii) the online VET courses were free, or were free unless the consumer’s income was in an amount which they were unlikely to earn on completion of an online VET course, or at all;

were misleading; and

(f) completed enrolment forms were a necessary precursor to a consumer being enrolled in an online VET course or courses and exposed to a debt or likely debt where they were an Eligible Student or Purported Eligible Student.

2. During the period from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015, Phoenix, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of online VET courses to consumers, engaged with respect to each consumer in conduct, being the Phoenix Enrolment System (as defined by paragraph [86] of the Amended Statement of Claim), that was unconscionable, thereby separately contravening section 21 of the ACL in respect of each consumer, in the circumstances set out below:

(a) the purpose of Phoenix, in marketing to consumers, eliciting enrolment applications from them and enrolling them in online VET courses was to maximise the number of consumers enrolled who received VET FEE-HELP, so as to maximise the revenue to Phoenix from the Commonwealth via the VET

FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme;

(b) Phoenix displayed a callous indifference as to whether the consumers it sought to and did enrol were within the target cohorts for the courses, satisfied the eligibility criteria for those courses, were suitable for the courses, whether the consumers had reasonable prospects of successfully completing the online VET courses and whether the course delivery was adequately resourced;

(c) consumers to whom brokers and agents marketed the online VET courses were more likely to include vulnerable individuals as compared with other individuals within the Australian community;

(d) many consumers were exposed to incurring a debt or a likely debt even though the online VET courses were unsuitable to them or they were unsuitable to the online VET courses; and

(e) consumers were often deprived of the reasonable opportunity to withdraw from the online VET course before the census date for each unit of study had passed and therefore deprived of the opportunity to avoid incurring a debt or likely debt to Phoenix or the Commonwealth.

3. During the period from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015, Phoenix, by the conduct of its brokers and agents, in trade or commerce, in representing to Consumers A, B, C and D (as set out in the Amended Statement of Claim), in order to encourage them to enrol in its online VET courses that:

(a) if they enrolled in an online VET course, they would receive a free laptop; and

(b) the online VET courses were free or in the case of Consumer A, free until she earned a particular amount; and

(c) the consumer would not incur a debt by enrolling in one or more of the online VET courses;

engaged in conduct that was false or misleading or deceptive in contravention of each of sections 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

4. During the period from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015, Phoenix, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of online VET courses to Consumers A, B, C and D, engaged in conduct that was unconscionable, thereby contravening section 21 of the ACL, in the circumstances set out below:

(a) each of the consumers was a vulnerable person and in a weaker bargaining position than Phoenix;

(b) Phoenix enrolled each of the consumers in one or more online VET courses for which the consumer was not suited and for which she or he did not have the skills or work experience necessary to successfully complete;

(c) Phoenix, by the conduct of its brokers and agents, in trade or commerce, represented to each consumer, in order to encourage her or him to enrol in its online VET courses:

(i) that if the consumer enrolled in an online VET course, she or he would receive a free laptop; or

(ii) that the online VET courses were free or in the case of Consumer A, free until she earned a particular amount; and

(iii) that the consumer would not incur a debt by enrolling in one or more of the online VET courses;

thereby engaging in conduct that was false or misleading or deceptive in contravention of each of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

5. During the period from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015, CTI aided, abetted, counselled or procured Phoenix’s contraventions of s 21 of the ACL in connection with the Phoenix Marketing System (as defined by paragraph [73] of the Amended Statement of Claim), or was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in, or a party to those contraventions.

6. During the period from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015, CTI, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of online VET courses to consumers, engaged with respect to each consumer in conduct, being the Phoenix Enrolment System (as defined by paragraph [86] of the Amended Statement of Claim), that was unconscionable, thereby separately contravening s 21 of the ACL in respect of each consumer, in the circumstances set out below:

(a) the purpose of CTI, in marketing to consumers, eliciting enrolment applications from them and enrolling them in online VET courses was to maximise the number of consumers enrolled who received VET FEE-HELP, so as to maximise the revenue to Phoenix from the Commonwealth via the VET FEE-HELP Assistance Scheme;

(b) CTI displayed a callous indifference as to whether the consumers it sought to and did enrol were within the target cohorts for the courses, satisfied the eligibility criteria for those courses, were suitable for the courses, whether the consumers had reasonable prospects of successfully completing the online VET courses and whether the course delivery was adequately resourced;

(c) consumers to whom brokers and agents marketed the online VET courses were more likely to include vulnerable individuals as compared with other individuals within the Australian community;

(d) many consumers were exposed to incurring a debt or a likely debt even though the online VET courses were unsuitable to them or they were unsuitable to the online VET courses; and

(e) consumers were often deprived of the reasonable opportunity to withdraw from the online VET course before the census date for each unit of study had passed and therefore deprived of the opportunity to avoid incurring a debt to Phoenix or the Commonwealth.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

7. Subject to the following orders and to further order of the Court, pursuant to s 37AI of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and in order to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the reasons of Perry J in this proceeding delivered on 13 August 2021 (Reasons for Judgment) not be made available to or published to any person save for the following:

(a) Court staff and any other person assisting the Court;

(b) the applicants, commissioners, and staff of the first applicant, staff of the second applicant, and barristers and external solicitors retained by the applicants for the purposes of the proceeding;

(c) the liquidators of the respondents, and barristers and external solicitors retained by them for the purposes of the proceeding;

(d) the amicus curiae and solicitors instructing the amicus curiae for the purposes of the proceeding;

(e) the additional liquidators of the first respondent, and barristers and external solicitors retained by them for the purpose of performing their functions in relation to the first respondent;

(f) support staff of the persons listed in sub-paragraphs 7(b) to 7(e) above; and

(g) insofar as the relevant parts of the Reasons for Judgment refer to them, persons referred to in the judgment.

8. To the extent that the Reasons for Judgment refer to information which may be confidential to, or in respect of, a third party, if necessary an extract from the Reasons for Judgment containing that confidential information may be disclosed to the relevant third party for the purpose of obtaining instructions as to confidentiality.

9. No later than five (5) business days following delivery of the Reasons for Judgment, the applicants’ external legal advisors are to provide to the liquidators of the respondents a copy of the Reasons for Judgment which identifies any alleged confidential information. Such identification is to make clear:

(a) the person to whom the information may be confidential;

(b) the basis on which the information may be confidential; and

(c) the means by which or the manner in which the issue of confidentiality may be addressed.

10. No later than eight (8) business days following delivery of the Reasons for Judgment, the liquidators of the respondents are to respond to the copy of the Reasons for Judgment provided pursuant to order 9 above, outlining:

(a) their position in relation to the confidentiality issues identified by the applicants’ external legal advisors pursuant to order 9; and

(b) any additional confidentiality issues, identifying:

(i) the person to whom the information may be confidential;

(ii) the basis on which the information may be confidential; and

(iii) the means by which or the manner in which the issue of confidentiality may be addressed.

11. No later than ten (10) business days following delivery of the Reasons for Judgment, the external legal advisors for the Applicants and the liquidators are to jointly provide the Court with an agreed version of the Reasons for Judgment identifying any proposed redactions of allegedly confidential information and the basis for the proposed redaction of the confidential information or, in lieu of agreement, the external legal advisors for the Applicants and the liquidators are to separately provide the Court with versions of the Reasons for Judgment identifying any proposed redactions of allegedly confidential information and the basis for the proposed redactions of the allegedly confidential information.

12. Nothing in these orders prevents a person in sub-paragraphs 7(a) to 7(g) above reporting on the Reasons for Judgment in a manner that does not identify an individual referred to therein.

13. There be liberty to apply on short notice.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

14. The matter is listed for case management on Monday, 30 August 2021 at 4:30pm where, among other things, it is anticipated that a timetable will be set for the determination of any penalties and other relief sought by the applicants.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRY J:

[1] | |

[37] | |

[57] | |

[88] | |

[106] | |

[176] | |

[247] | |

8 EVIDENCE OF EX-EMPLOYEES AS TO ENROLMENT PRACTICES UNDERTAKEN FOR THE PHOENIX ONLINE COURSES | [287] |

[439] | |

[491] | |

11 ATTRIBUTION OF THE CONDUCT OF THE BROKERS AND AGENTS TO PHOENIX | [892] |

[965] | |

[1067] | |

[1175] | |

[1189] | |

[1247] | |

[1251] | |

[1279] | |

[1319] | |

APPENDIX 1: GLOSSARY | |

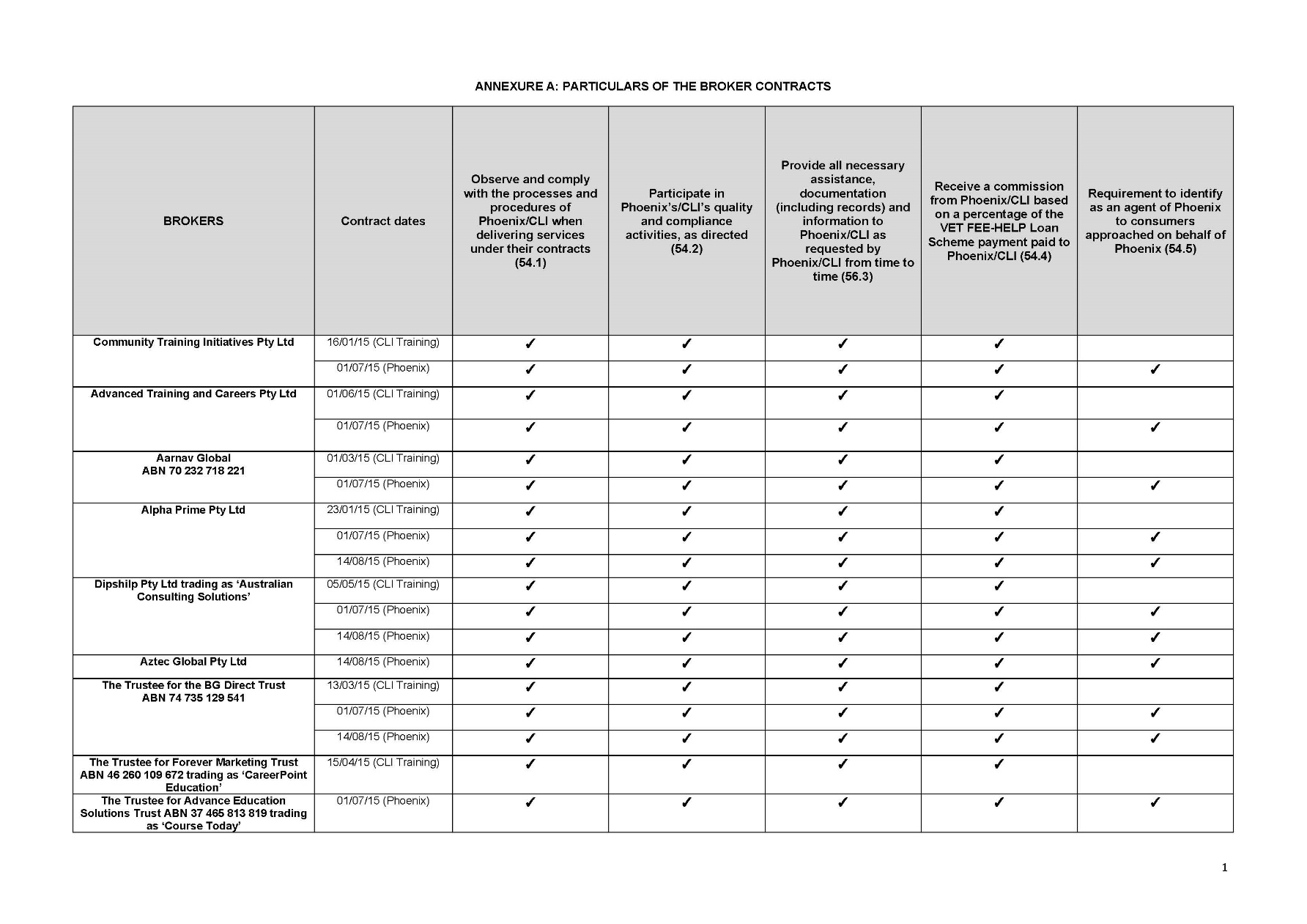

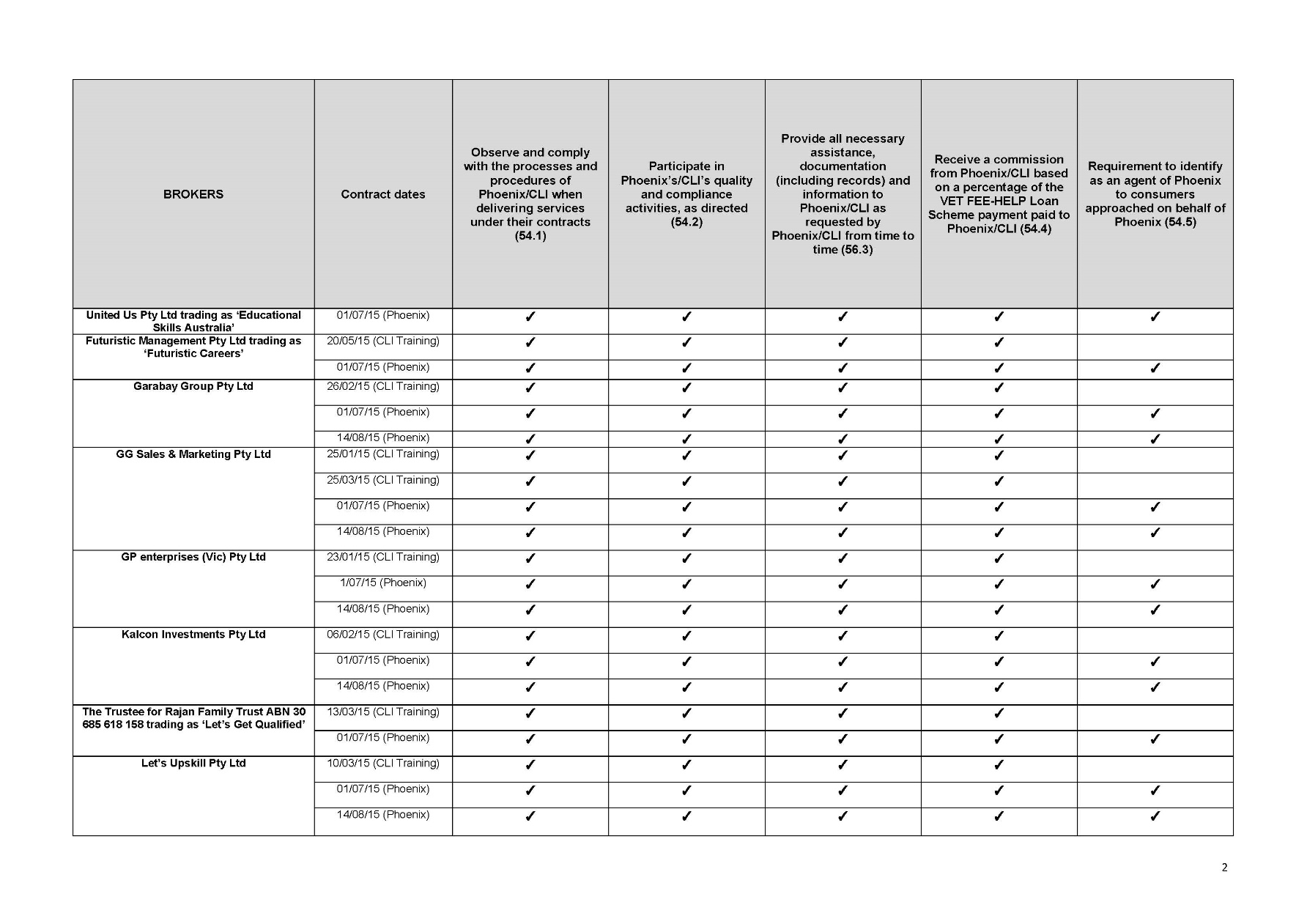

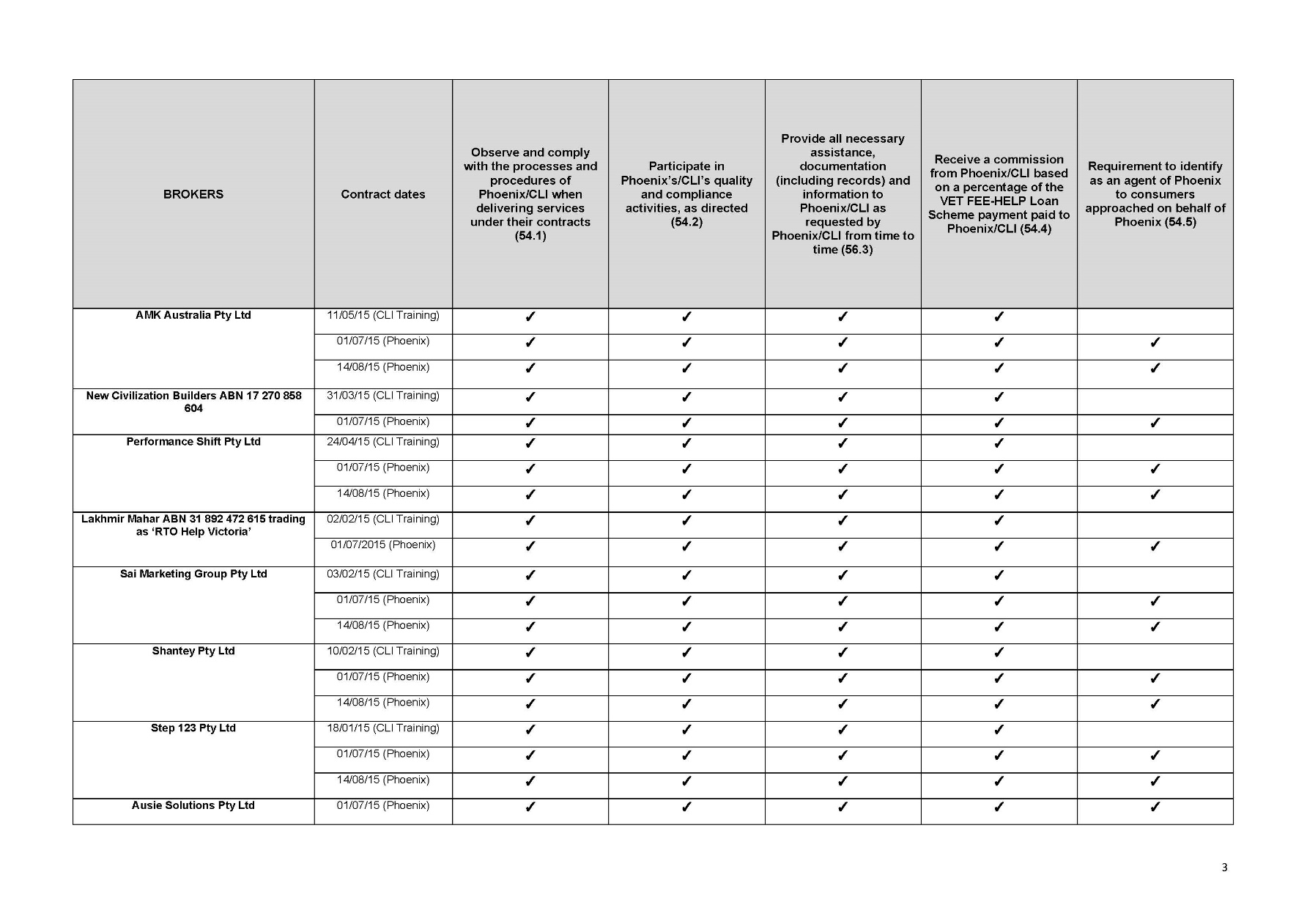

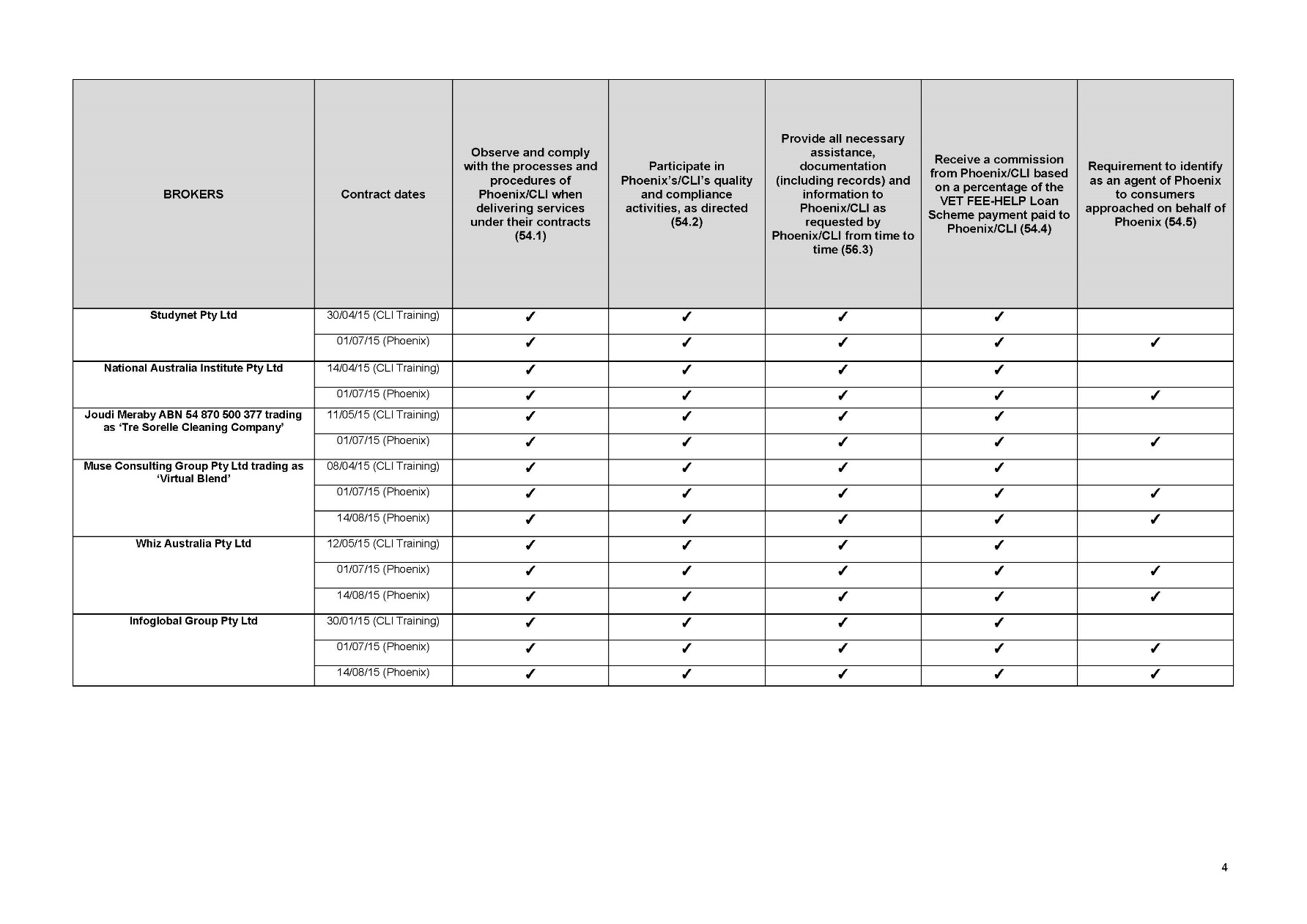

APPENDIX 2: LIST OF CONTRACTS ENTERED INTO BETWEEN CLI/PHOENIX AND BROKERS (ASOC, ANNEXURE A) | |

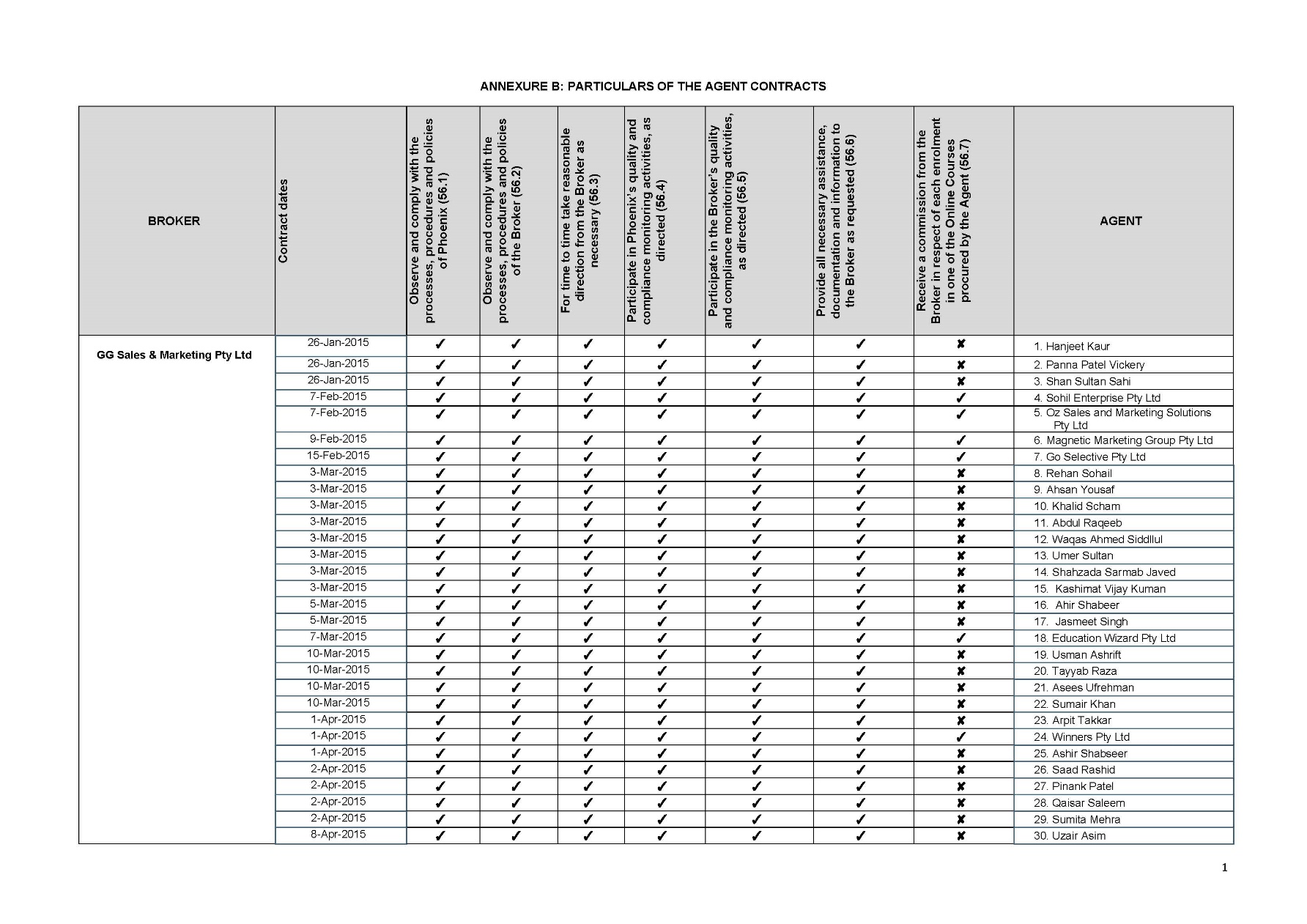

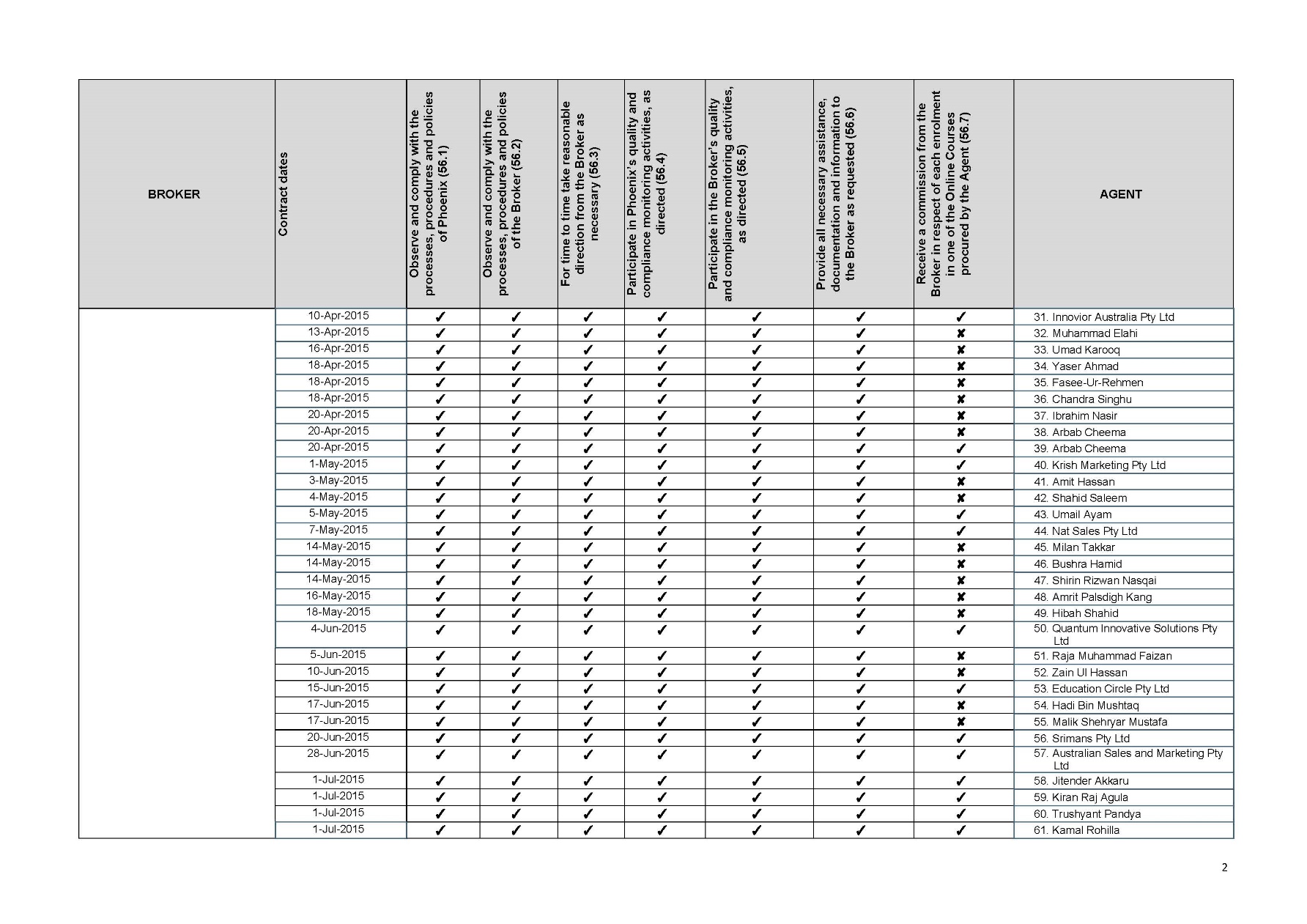

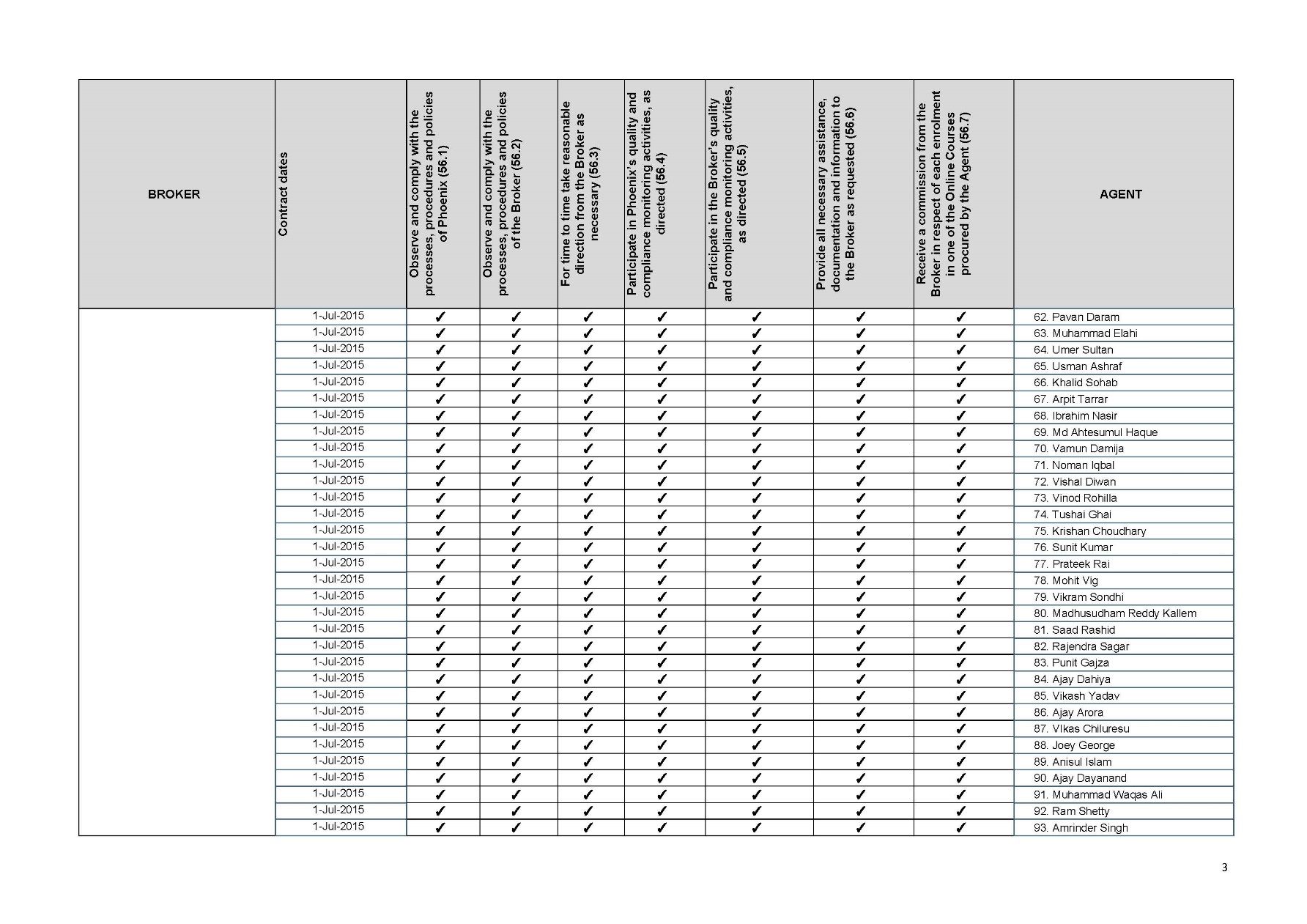

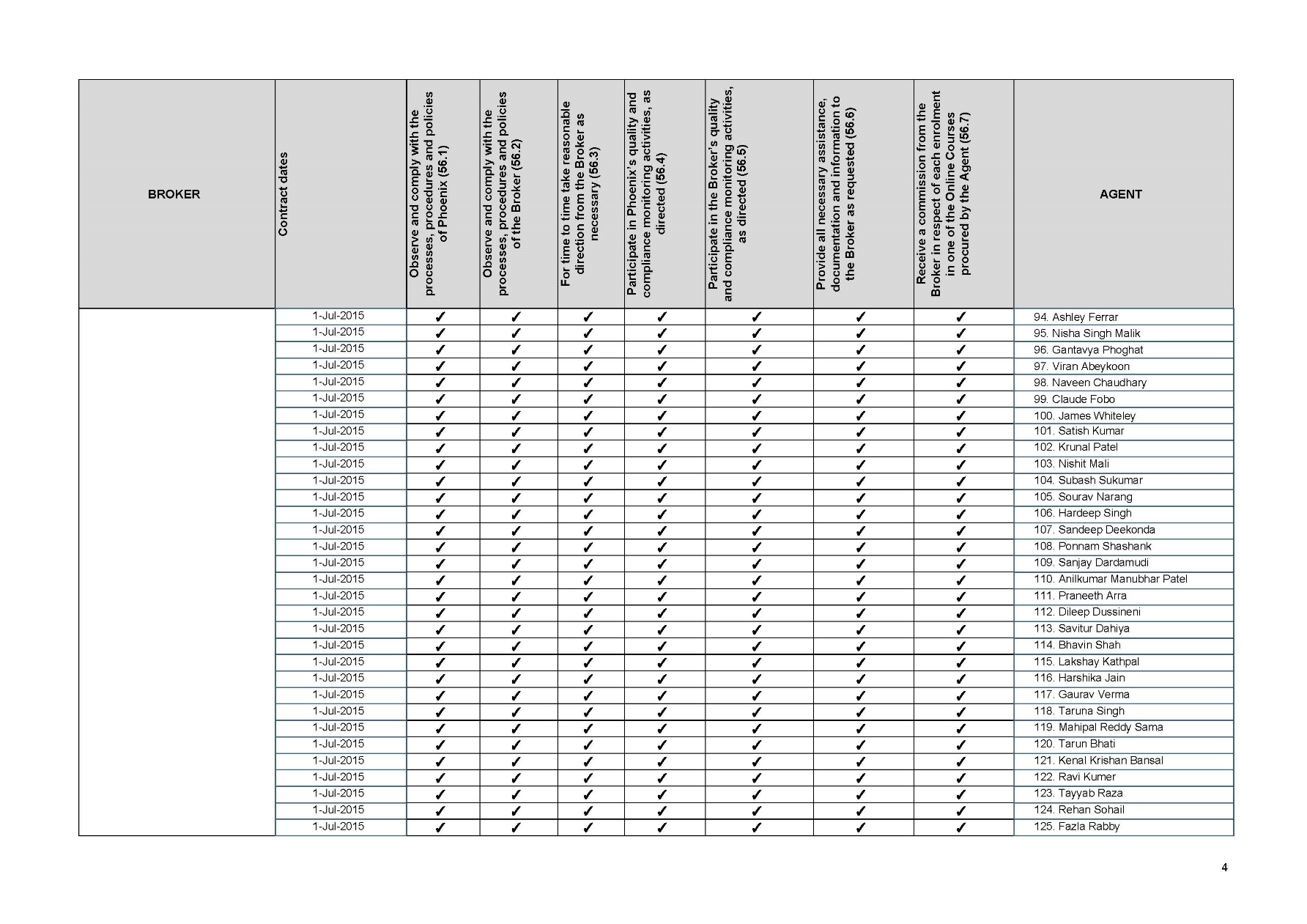

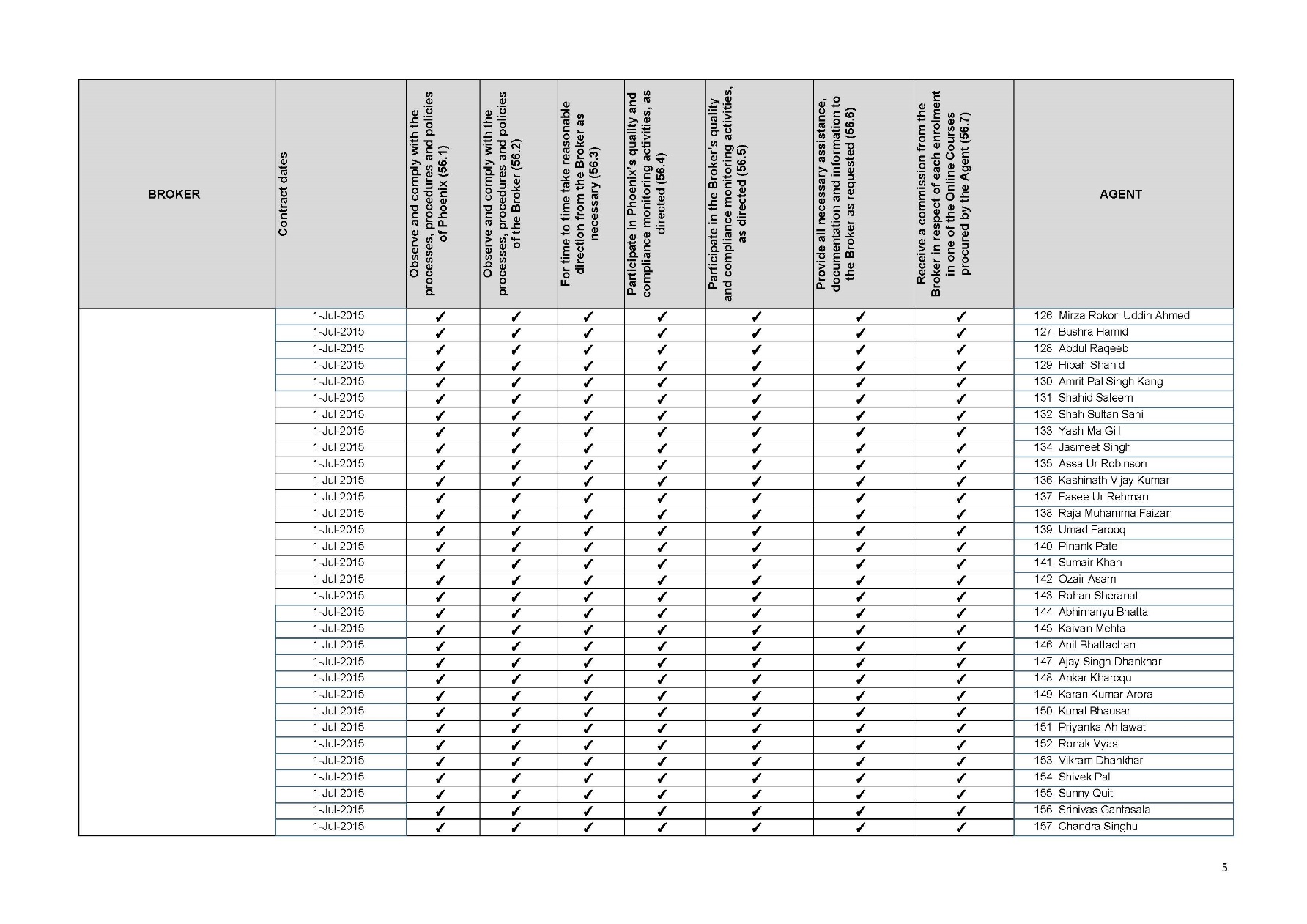

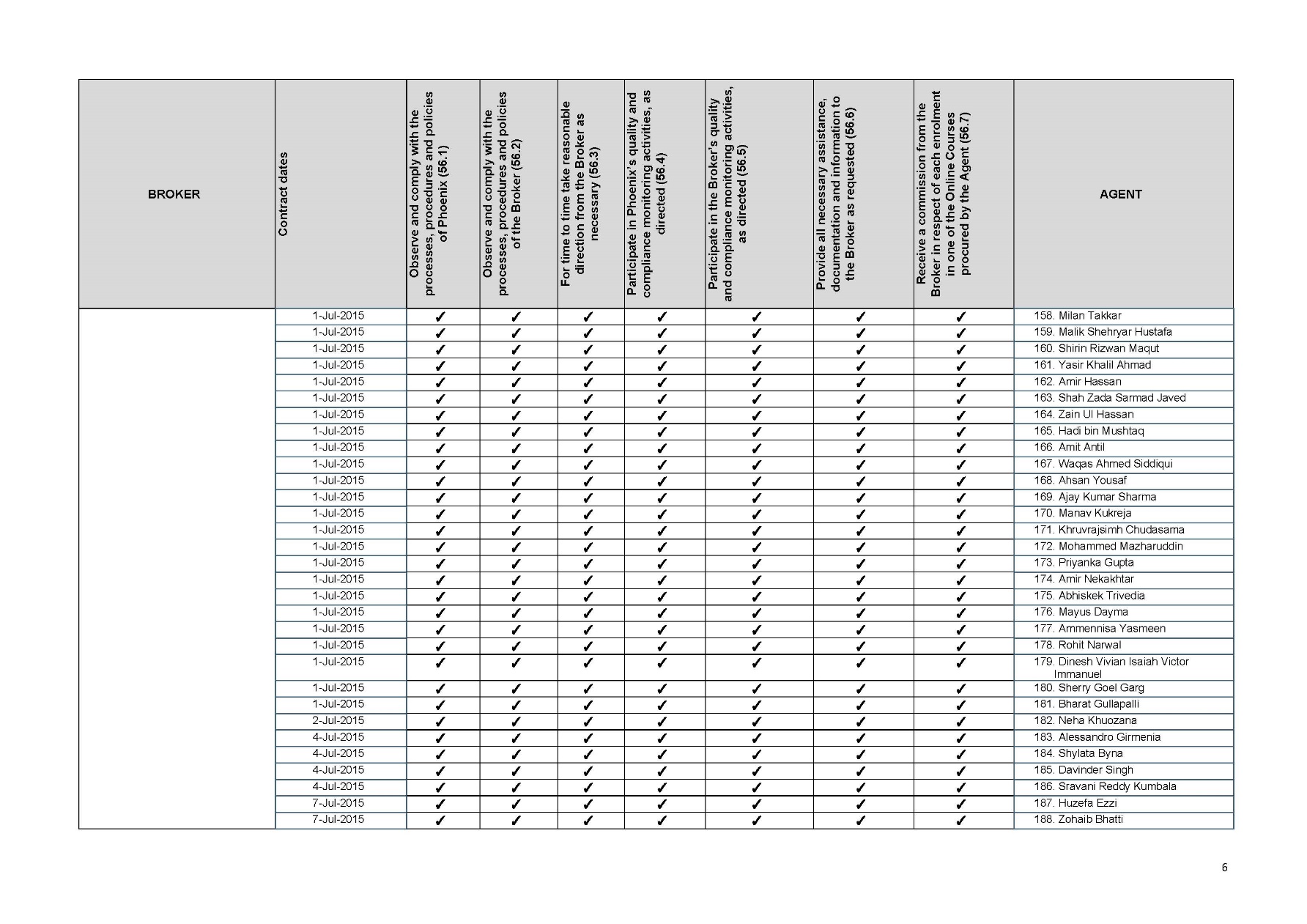

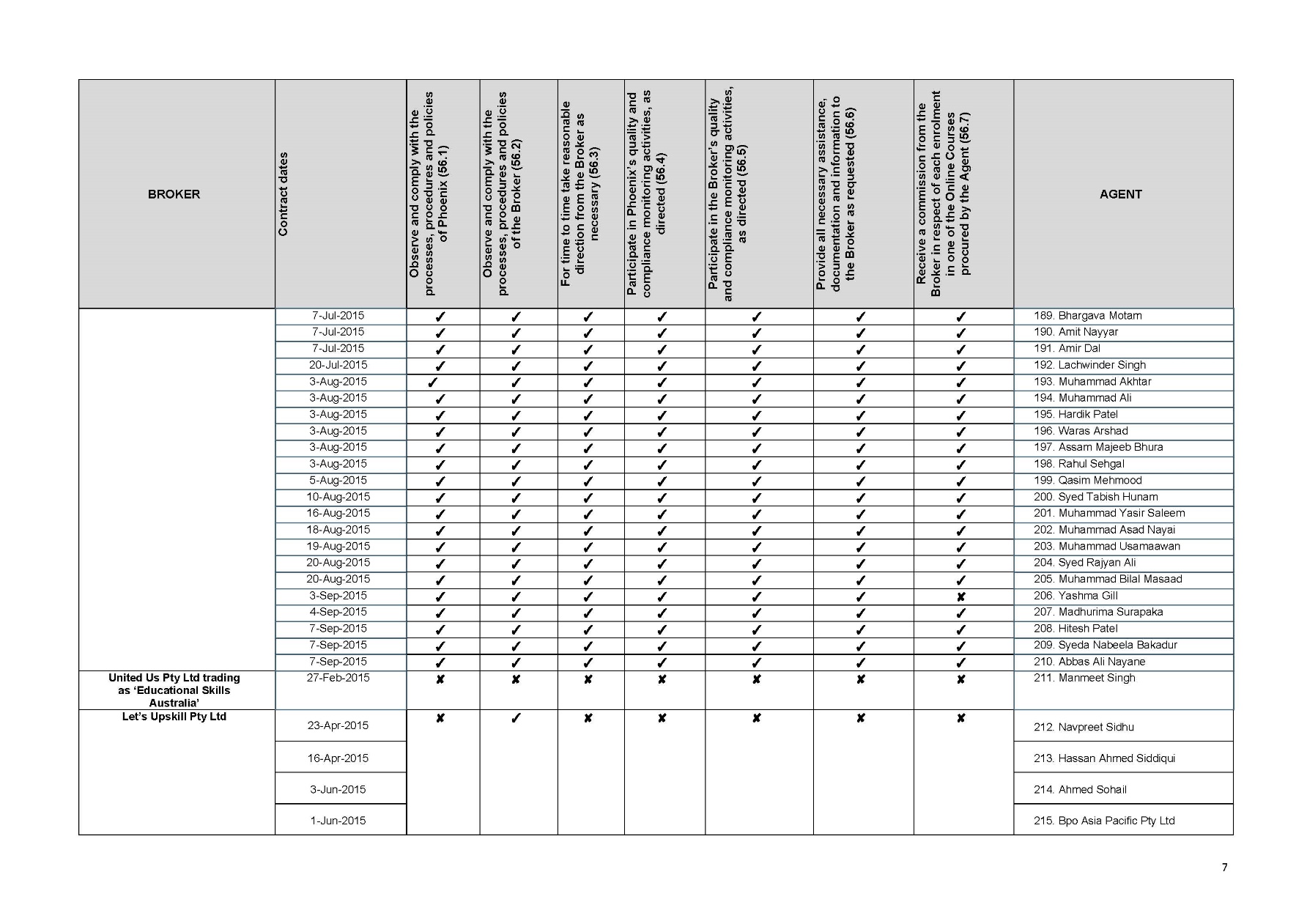

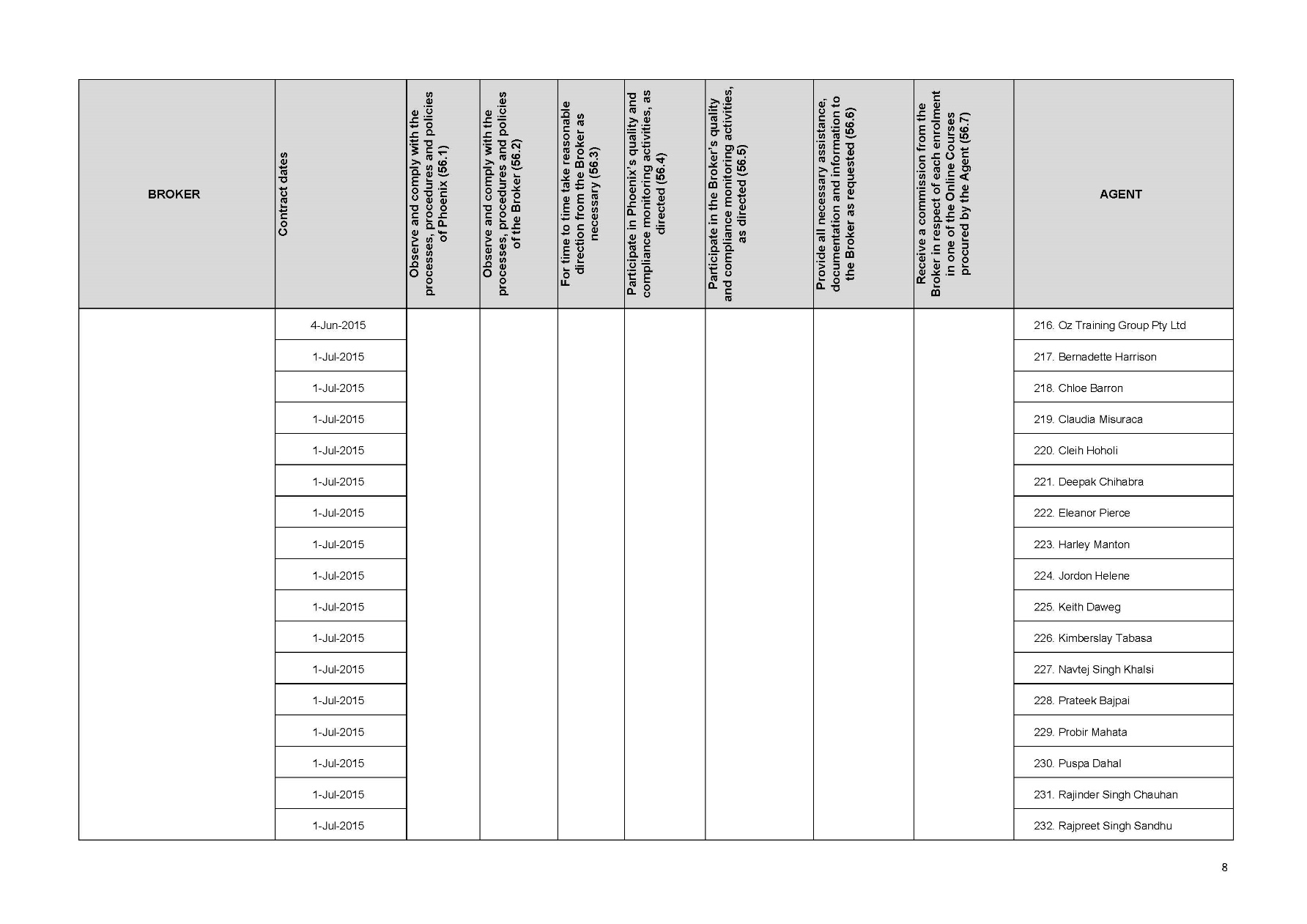

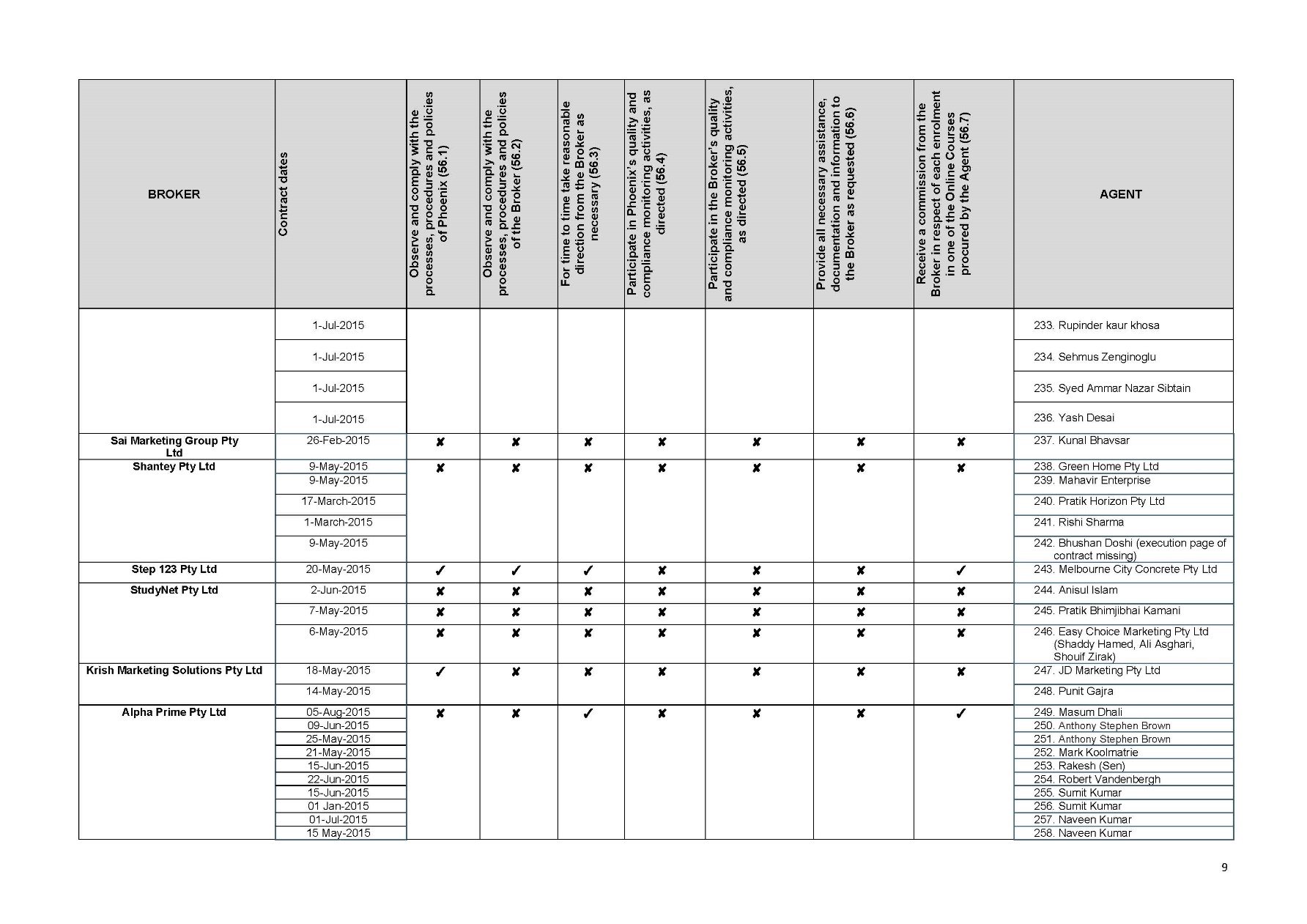

APPENDIX 3: LIST OF CONTRACTS ENTERED INTO BETWEEN BROKERS AND AGENTS (ASOC, ANNEXURE B) | |

APPENDIX 4: COMPREHENSIVE TABLE OF CONTENTS |

1 The applicants, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the ACCC) and the Commonwealth, seek declarations, pecuniary penalties, and orders for non-party redress pursuant to s 239 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA), against the respondents, Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (Phoenix) and Community Training Initiatives Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (CTI).

2 While the respondents were in administration, on 7 October 2016 I granted leave to the applicants under s 444E(3)(c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Corporations Act) to proceed against the respondents on the condition that the applicants do not seek to enforce any pecuniary penalties, any injunction pursuant to s 232(6)(a) of the ACL requiring monies to be refunded, and any costs order in their favour, without further leave of the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) [2016] FCA 1246; (2016) 116 ACSR 353 (Phoenix (No 1)). An appeal against that decision was dismissed on 29 September 2017 by the Full Court in Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2017] FCAFC 155.

3 In broad terms the applicants allege that from around 13 January 2015 until around 23 November 2015 (the relevant period), Phoenix and CTI engaged in conduct in connection with the supply of vocational education and training (VET) courses to consumers that was unconscionable in contravention of s 21 of the ACL. In particular, the applicants seek to establish a “system of conduct … whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged” (s 21(4)(b), ACL) that was, in all of the circumstances, unconscionable contrary to s 21(1) of the ACL. The applicants also seek to establish specific contraventions vis-à-vis four individual consumers, consumer witnesses A, B, C and D, as illustrations of the allegedly unconscionable systems in operation. It is further alleged that the respondents engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in marketing the online courses to the four consumer witnesses contrary to ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL on the basis that the actions of the Agents concerned are to be attributed to Phoenix under s 139B(2) of the CCA.

4 Initially, the respondents sought to defend the matter and filed a defence on 1 May 2019 (Defence).1 That defence responded to the statement of claim as originally filed on 5 March 2019 (SOC).2 Subsequently by leave granted on the first day of the trial (5 November 2019), the applicants filed and served an amended statement of claim (ASOC). Those amendments, as I later explain, were few in number and largely did not affect the case to which the defence had pleaded. Nonetheless, as no amended defence was filed to the ASOC, references have been included also to the SOC where admissions or other pleadings contained in the defence are relevant.

5 On 9 August 2019, the respondents filed a notice submitting to any order of the Court save as to costs on which they requested an opportunity to be heard. Nonetheless, as the applicants accept, s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act) applies, and consequently it remains necessary for them to prove their case on the balance of probabilities, having regard to the gravity of the matters alleged. As the applicants also accept, it is therefore incumbent upon them to establish the necessary elements of the statutory causes of action on the balance of probabilities by clear and cogent evidence, given the seriousness of the matters alleged and their potential to give rise to the imposition of pecuniary penalties: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2) [2017] FCA 709 (Get Qualified) at [8] (Beach J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cornerstone Investment Aust Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 4) [2018] FCA 1408 (Empower) at [5] (Gleeson J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2019] FCA 1982 (AIPE (No 3)) at [61] (Bromwich J). In discharging that onus, the applicants rely upon a voluminous body of evidence from a number of different sources. This included approximately 50 witnesses spanning expert witnesses, ex-employees, consumers, ACCC investigators, and other lay witnesses, extensive business records such as enrolment and student activity records and data, enrolment forms, complaints, records of complaint handling, policies, and internal correspondence. As such, the ACCC’s case was not only circumstantial but included important direct evidence of the internal workings of the respondents, as was the case also in AIPE (No 3) where similar allegations were upheld.

6 While acronyms and particular terms are defined during the course of these reasons, for convenience a glossary is also included at Appendix 1 to these reasons. A comprehensive table of contents has also been included in Appendix 4. For clarity, I note that each of the appendices (1 to 4 inclusive) comprise part of my reasons for judgment.

1.2 Summary of key aspects of this decision

7 Given the length of this decision and the scale of the evidence canvassed, it is helpful at the outset to provide a brief introduction to, and summary of, some of the key findings. This does not, of course, supplant my detailed reasons which follow and of its nature, involves a degree of repetition.

8 Phoenix was an approved VET provider with 378 enrolled students in face-to-face courses before it was purchased by the Australian Careers Network (ACN) Group in January 2015.

9 Following its acquisition, the key officers of Phoenix and CTI (and the parent company, ACN), Mr Ivan Robert Brown and Mr Harry Kochhar (also known as Harpreet Singh), acted swiftly to radically reorientate Phoenix’s operating model so as to offer for the first time, online diplomas nationally to many thousands of consumers under the banner of “myTime Learning”. Central to the respondents’ plans for rapid growth was the deployment of hundreds of Agents across the country through contracts with Brokers, who primarily employed high-pressure sales tactics, including the offer of inducements and the making of misrepresentations, so as to persuade thousands of consumers to sign up to Phoenix’s Online Courses largely through door-to-door sales. The consumers targeted included Indigenous Australians, people from non-English speaking backgrounds, with a disability, from regional and remote areas, from low socio-economic backgrounds and/or who were unemployed at the relevant time.

10 It is no coincidence that consumers from these target groups also fell within the demographic groups to which reforms to the Commonwealth’s VET FEE-HELP loan scheme were directed. These reforms had liberalised the scheme so as to make VET an end in itself as opposed to a pathway to higher education, in order to increase participation in VET by people from these demographic groups. As such, while in itself the targeting of consumers from these groups was not necessarily unconscionable, a not insignificant proportion of such consumers were likely to be vulnerable. Conscionable marketing and enrolment systems therefore needed to incorporate measures to mitigate the inherently higher risk that members of these demographic groups may be unsuitable for an online diploma, or require additional support in order to have a reasonable opportunity of successfully completing an online diploma.

11 Provided that a student was entitled to VET FEE-HELP assistance under cl 43 of Sch 1A of the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth) (the HES Act) (an Eligible Student), the fees for these courses were paid directly to the VET provider by the Commonwealth. In return, the Eligible Student would incur a debt to the Commonwealth via a loan scheme for the cost of the course, together with a loan fee. However, the debt would become repayable through the tax system by the students concerned once they began to earn more than a minimum amount. Safeguards existed under the scheme which the VET provider was required to observe in order to ensure that students were fully informed about their rights and liabilities under the VET FEE-HELP loan scheme before embarking upon a course and incurring the liability. This included ensuring that no liability for a debt to the Commonwealth would arise until the census date had passed. This key element of the scheme was intended to afford each student a “cooling off” period within which to ensure that she or he wished to pursue the unit of study or course and that it was suitable for them.

12 However, once the census date had passed, neither the student’s liability for the debt nor the making of payments to the VET provider depended upon the student actually embarking on the course in which they were enrolled. Furthermore, if approved by the Department of Education and Training (the Department or DET), VET FEE-HELP payments could be made to the VET provider in advance on the basis of the VET provider’s estimate of the amount of VET FEE-HELP to which it expected to be entitled during the calendar year. These features of the VET FEE-HELP scheme in particular rendered it ripe for ruthless exploitation by unscrupulous agents and brokers and VET providers, as Mr Brown candidly explained in a radio interview in April 2016. Hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue under the scheme were potentially available to a VET provider, without the provider actually affording any meaningful educational service to its “students”.

13 That is precisely what occurred in this case. The figures are telling.

(1) Between mid-January and mid-November 2015, at least 11,393 consumers were enrolled in 21,413 online courses with Phoenix, with most being enrolled in two diplomas concurrently despite each diploma involving a full-time study load.

(2) Phoenix was paid over $106 million by the Commonwealth under the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme in advance payments pursuant to cl 61(1) of Sch 1A to the HES Act, and claimed to be entitled to a further amount of approximately $250 million in payments from the Commonwealth.

(3) Only nine of the 11,393 enrolled consumers formally completed an online course with Phoenix. Indeed, only a very small number of the 11,393 enrolled consumers even attempted a unit of study of their courses, while some were unaware that they were enrolled at all and many remained enrolled even after requesting cancellation.

14 This was achieved first by the deployment without any effective training, monitoring or control, of a veritable army of at least 548 Agents engaged by the Brokers with whom the respondents contracted to market Phoenix’s Online Courses. The Brokers and Agents were highly incentivised by substantial commissions payable only after the census date to prey on vulnerable consumers likely to sign up unaware that an offer presented to them as a great deal to obtain a free laptop or other inducement, was in fact a very bad deal under which they would incur substantial debts. In particular, the Agents and Brokers (and respondents on whose behalf they acted) targeted vulnerable consumers whose general attributes meant they were less likely to understand their rights and obligations under the VET FEE-HELP scheme, to interrogate the misinformation they were given, and to resist the inducements offered to them for signing up. Far from reining in the unethical conduct of the Brokers and Agents or responding with a “root and branch” reappraisal of their operating model, among other things, the respondents actively sought and rewarded the submission of hundreds and even thousands of enrolment forms weekly by Brokers and increased the commission payable to the worst offending Broker.

15 Secondly, despite being aware from the outset of the risks (duly realised) of ineligible and unsuitable candidates applying for enrolment by deploying this marketing system, the respondents engaged in conduct which included enrolling consumers without verifying their eligibility or suitability for the course, their capacity to speak English, or even whether they intended to undertake the course. Directions were regularly given by Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar to bypass measures intended to protect against such risks, such as instructing staff not to undertake telephone verifications of enrolment applications, to overlook “red flags” when telephone verifications were in fact conducted, and not to check for suspicious patterns in enrolment forms indicating that they may have been forged. Moreover, a significant number of consumers were enrolled after the commencement date of their online course(s) without any extension to the relevant census date, or were enrolled on, shortly before, or after the census date so as to deprive consumers of the statutorily mandated “cooling off” period. Furthermore, staff who repeatedly raised concerns with Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar about these and other issues, including suspected Broker and Agent misconduct, and endeavoured to address them, were undermined, sidelined, bullied, subjected to verbal abuse, and directed to ignore the problems and to act against their conscience.

16 Not surprisingly, the flow of complaints by consumers and consumer advocates throughout the relevant period was unrelenting. Furthermore, as the respondents’ conduct increasingly came to the attention of the regulators, they sought to conceal what was truly occurring by, among other measures, statements of compliant policies which they knew were not in fact observed (“guff” as such statements were described in internal correspondence), the impersonation of student activity on Phoenix’s learning management system, and the backdating and falsification of student records on an industrial scale.

17 This conduct, together with other evidence, established that the focus of key officers of Phoenix and CTI was upon attaining the highest possible levels of enrolment so as to generate and retain revenue derived from VET FEE-HELP payments, rather than genuinely attempting to provide education and training to those ostensibly enrolled in online courses offered by Phoenix. As such, the respondents’ focus was upon presenting the appearance of compliance with precisely the kinds of measures required to protect and support consumers, but not upon implementing such measures in circumstances where to have done so would have undermined their business model and significantly impacted upon revenue. As Bromwich J found in AIPE (No 3) at [688], equally in this case it was both an accepted and anticipated part of the respondents’ business model that a very high proportion of students would pass the census date and incur a VET FEE-HELP debt in circumstances where it was predictable that they would never require training and support. This was a highly profitable outcome for the respondents who therefore were not required to, and did not, invest in the staff and resources which would have been required to train and support over 11,000 genuine students enrolled in over 21,000 full-time diplomas.

18 I have concluded that in all of the circumstances, the respondents engaged in a marketing system and an enrolment system which were separately “unconscionable” within the meaning of s 21 of the ACL. Both systems were informed by the desire to maximise profit over even modest levels of engagement by consumers with their courses, and by a callous indifference, among other things, to the suitability and eligibility of consumers to undertake the courses in which they enrolled. I also find that Phoenix has, by the conduct of its Brokers and Agents, engaged in conduct with respect to Consumers A, B, C, and D that was false or misleading or deceptive in breach of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL and in conduct that was unconscionable, thereby contravening s 21 of the ACL.

1.3 The applicants’ multipronged approach to proof of the alleged contraventions of the ACL

19 The applicants relied upon a number of different sources of evidence, accepting both that cogent evidence was required to prove the systems of unconscionable conduct and that that evidence must be representative of the systems across the whole cohort of consumers enrolled in Phoenix Online Courses (Applicants’ Closing Submissions dated 21 November 2019 (ACS) at [36]). The various strands of evidence relied upon may be summarised as follows:

(1) the evidence of eleven ex-employees of the respondents as to the development, emergence, and operation of the respondents’ marketing and enrolment systems and the callous indifference allegedly shown, among other things, towards consumers’ capacity to successfully complete the courses in which they were enrolled;

(2) the expert evidence of Ms Jana Scomazzon on VET online diploma courses including those offered by Phoenix (being an expert in evaluation and quality assurance of VET courses, and VET policy and product development and evaluation);

(3) the evidence of ACCC investigators;

(4) the contemporaneous documentary record (the chronological tender bundle (Exhibit A-1) (TB), the supplementary tender bundle (Exhibit A-4) (STB) and other documents in electronic form) including:

(a) internal correspondence involving key officers of the respondents, Mr Ivan Brown and Mr Harry Kochhar, said to demonstrate that the business model was “rotten to the core” to the knowledge of the senior officers of Phoenix;

(b) complaints from consumers and others on behalf of consumers and the respondents’ responses and approach to those complaints and the issues which they raised;

(c) contracts between CTI, Phoenix and Brokers, and contracts between Brokers and Agents; and

(d) investigations, inquiries and the audits by various State, Territory and Commonwealth regulators;

(5) the evidence of 24 individuals who were either approached by Agents on behalf of Phoenix in 2015 or subsequently assisted consumers who had been approached, including the four individual consumer witnesses the subject of specific alleged contraventions of the ACL said to illustrate the systems in operation;

(6) the formal audit of the reported enrolment data for 2015 and 2016 undertaken by McGrathNicol on 16 September 2016 at the behest of the Department in accordance with cl 26(2) of Sch 1A to the HES Act for the purposes of determining Phoenix’s entitlement to payments under the HES Act, including to consider the veracity of the enrolments that had been obtained (Forensic Audit of the Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) dated 16 September 2016) (the MGN Audit Report);3 and

(7) expert evidence analysing data and statistics from various datasets maintained by the Department, CTI and Phoenix, including as to course completion rates, the extent to which students’ suitability to undertake the Online Courses was assessed, problems with enrolment forms, and the lack of student engagement with the Phoenix Online Courses.

20 The data analysis is of particular significance in establishing the systemic nature of the impugned conduct. Notably in some instances, the data analysis covers the complete cohort of consumers enrolled with Phoenix, while in other cases statistically relevant representative samples selected at random are relied upon. This evidence (and the expertise of the expert witnesses to address the subjects on which they express their opinions) is dealt with later in these reasons.

21 The Court Book (CB), which was comprised of the pleadings and affidavit evidence of 47 witnesses, constituted 9 folders provided in hard copy and electronic format including the exhibits to those affidavits. In addition, the applicants relied upon a tender bundle (TB) and supplementary tender bundle (STB) which cumulatively comprised 29 folders and was also supplemented by documents and files in purely electronic form (such as, eg the electronic Supplementary Broker Tender Bundle (Exhibit A-5)). The tender bundle and supplementary tender bundle are accompanied by a lengthy separate Narrative Chronology providing a chronological analysis of the documentary tender, interspersed by witness accounts, together with a Detailed Chronology in table format and the applicants’ Dramatis Personae. The presentation of this voluminous body of material in readily workable, user-friendly format clearly involved a substantial, but necessary, amount of planning and work, and was of very great assistance to the Court.

1.4 The structure of these reasons

22 The following structure has been adopted in these reasons.

23 Chapter 2 of these reasons explains the respondents’ background and their relationship to the other companies in the ACN Group, as well as identifying the key officers within the respondents and the ACN Group of companies and their interests in the respondent entities.

24 Chapter 3 sets out the procedural history including the respondents’ initial defence of the proceeding, the appointment and role of amicus curiae, Dr Higgins SC, following the filing of a submitting appearance by the respondents, a preliminary issue of procedural fairness which ties in with certain aspects of the pleadings history, and suppression and non-publication orders made in the proceeding.

25 Chapter 4 gives an overview of the applicants’ pleaded case, key aspects of which are:

(1) the alleged Profit Maximising Purpose over the interests of customers;

(2) the alleged Callous Indifference to the suitability of customers for the Phoenix Online Courses or even whether they wished to undertake them;

(3) the Target Communities and their attributes; and

(4) the Phoenix Enrolment and Marketing systems which are said separately to be unconscionable systems within s 21 of the ACL or in the alternative, cumulatively to establish unconscionable conduct contrary to s 21.

26 Chapter 5 explains the principles by which it is determined whether Phoenix engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 21 of the ACL.

27 Chapter 6 explains the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme and the statutory obligations imposed upon VET providers by the HES Act, the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011 (Cth) (NVETR Act), and legislative instruments including, in particular, the VET Guidelines, the Registered Training Organisation (RTO) Standards, the VET Administrative Information for Providers, and the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) which governs the design and learning outcomes of VET accredited courses. It also identifies the inherent vulnerability of the scheme to exploitation by unscrupulous VET providers and Brokers and Agents, such as I find occurred in this case.

28 Chapter 7 deals with the Phoenix Online Courses. This chapter describes the learning outcomes specified for the diploma level courses and their target cohorts under the Training Package Qualification Rules published on the National Register of VET and the AQF. It also considers the mandatory admission requirements for enrolment under these statutory instruments and as specified by Phoenix.

29 The evidence of ex-employees of CTI as to recruitment and enrolment practices undertaken by the respondents are detailed in Chapter 8 of these reasons. In this chapter, I make findings based upon the evidence of the ex-employees on certain important themes, including as to:

(1) the different groups within CTI responsible for undertaking the various tasks involved in managing relationships with the Brokers and Agents engaged in recruiting potential students and in the enrolment process;

(2) the respondents’ lack of capacity to properly verify the extraordinary volume of enrolment applicants for the Online Courses submitted by Brokers and Agents, and instructions from key officers of the respondents, Mr Ivan Robert Brown and Mr Harry Kochhar, to the Data and Telephone Verification Teams to bypass the proper verification and assessment processes;

(3) the setting of weekly student enrolment targets of up to 1,000 to 5,000 students by Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar; and

(4) patterns in enrolment forms submitted by Brokers and Agents indicative of fraudulent behaviour by them and the responses by Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar when these concerns were drawn to their attention by ex-employees.

30 The evidence of former trainers and assessors is considered in Chapter 9. This evidence is striking in, among other things, establishing the extraordinarily high trainer-to-student ratios and the steps engaged in by the respondents to hide these ratios from the regulators.

31 Chapter 10 provides a comprehensive chronological account of the operations of Phoenix over the relevant period, included the nature and ever-escalating stream of complaints received by the respondents about unethical conduct by Brokers and Agents, the way in which the respondents responded to the complaints, the initial audit of Phoenix’s compliance initiated by the then CEO of Phoenix, Mr Bill Gale, and the actions of the regulators ending in the deregistration of Phoenix as a RTO including the audit by the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA).

32 Chapter 11 addresses the question of whether the conduct of the Brokers and Agents is to be attributed to Phoenix, including a discussion of the legal principles relevant to s 139B(2) of the CCA.

33 Chapter 12 considers the evidence of the 24 consumer witnesses including the alleged contraventions of the ACL with respect to Consumers A, B, C and D. In addition to the allegation that the respondents were in breach of s 21 of the ACL with respect to Consumers A to D, this chapter also considers whether Phoenix engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to ss 18 and 29 of the ACL in the case of these consumers and the legal principles governing that question.

34 Chapter 13 considers the data analysis evidence relied upon by the applicants in support of their systems unconscionability case. This Chapter addresses the expertise of the various expert witnesses addressing this topic, the methodologies which they adopted, and the source of their data, in the course of considering the following issues:

(1) the available data sets;

(2) the lack of successful course completion;

(3) the enrolment of students in multiple courses;

(4) the findings from the MGN Audit Report;

(5) the enrolment forms and how they were analysed;

(6) Pre-Training Review (PTR)/Language, Literacy and Numeracy (LLN) tests and discrepancies observed in the completion of these test indicative of fraudulent conduct;

(7) the results of analysing the enrolment forms;

(8) the absence of student engagement with the Phoenix Online Courses as revealed by FinPa, Phoenix’s online learning platform;

(9) the analysis of FinPa withdrawal notes and cancellation notes; and

(10) the analysis of telephone verification calls by CTI to consumers and the absence thereof.

35 The remaining chapters draw the evidence together to determine whether the applicants have established the various elements of their case that the respondents engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 21 of the ACL by reason of the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System (the systems unconscionability allegations), namely:

(1) the Profit Maximising Purpose (Chapter 14);

(2) the Callous Indifference (Chapter 15);

(3) the Target Communities and their Likely Attributes (Chapter 16);

(4) the Phoenix Marketing System (Chapter 17); and

(5) the Phoenix Enrolment System (Chapter 18).

36 My conclusions on the applicants’ systems unconscionability case are contained in Chapter 19.

2. THE RESPONDENTS AND RELATED COMPANIES

37 The first respondent, Phoenix, was established in 1998 and was then known as the Ikon Institute.4

38 On or about 16 February 2005, Phoenix was registered as a National VET Regulator (NVR) RTO under s 17 of the NVETR Act by the NVR, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA), and thereby became a RTO within the meaning of cl 1 of Sch 1 to the HES Act.5 It was approved as a VET provider under Div 3 of Sch 1A to the HES Act with effect from around 5 November 2009.6

39 ACN was incorporated on 17 March 2014.7 Phoenix was acquired by ACN on 12 January 2015 and remains a wholly-owned subsidiary of ACN.8 Following the acquisition, ACN derived its primary revenue from the operations of Phoenix.9 On 23 November 2015, ASQA notified Phoenix that it would be deregistered as a RTO.10

40 The second respondent, CTI, was also a wholly-owned subsidiary of ACN at all relevant times11 and was renamed VIA Network in October 2015, as advised in an email to all CTI staff on 16 October 2015.12 CTI operated as the marketing arm for the 11 RTOs owned and operated by ACN, including Phoenix.13 Over the relevant period, CTI managed relationships with Brokers and Agents and enrolments into Phoenix’s Online Courses on behalf of Phoenix via CTI’s Client Relationship Management Team (CRM Team), Data and Quality Team, Telephone Verification Tea, as well as the course trainers. That relationship was formalised in an agreement dated 1 July 2015 pursuant to which CTI agreed on a “non-exclusive basis” to:

(a) market or promote the RTO’s [Phoenix’s] VET courses of study;

(b) recruit persons to apply to enrol in the RTO’s VET courses of study;

(c) provide information and/or advice on the RTO’s VET courses of study;

(d) provide information and/or advice on the VET FEE-HELP scheme;

(e) accept an application to enrol from, or enrol, any person on the RTO’s behalf;

(f) refer a person to the RTO for the purposes of enrolling in a VET course of study or VET unit/s of study; and

(g) provide career counselling to a person on the RTO’s behalf.14

41 CTI and ACN operated out of an office located at Spotswood in Victoria.15

42 ACN, CTI, CLI Training Pty Ltd trading as CLI Training (CLI) and Phoenix went into administration on 21 March 2016 and became subject to a Deed of Company Arrangement on 4 May 2016.16

2.2 Key officers/controlling minds of Phoenix, CTI and the ACN Group

43 As the applicants contend, Mr Ivan Brown and Mr Harry Kochhar were controlling minds of CTI and Phoenix.

44 Mr Ivan Brown established the parent company, ACN, and a number of companies in the ACN Group, together with Mr Atkinson Prakash Charan.17 Mr Brown was the CEO and managing director of ACN at all relevant times,18 and had been appointed as a director and company secretary of ACN on 17 March 2014 when ACN was incorporated.19 Mr Charan sought to exit the Group through the sale of his shares in ACN via the public offering in November 2014 and, while he retained a 4.1% shareholding in ACN, it is not alleged that he had any ongoing role in any of the companies the subject of this litigation during the relevant period.20

45 Mr Brown was appointed as a director of Phoenix with Mr Stephen Williams when Phoenix was acquired, in place of Mr Martin Peake who ceased to hold office as the sole director of the company at the same time.21 Mr Brown was also the Chief Executive Officer of the “myTime Learning” division of Phoenix from August 2015 to 21 March 2016, being a separate division established in August 2015 and vested with responsibility for offering the Online Courses.22 In addition, Mr Brown was:

(1) a director of CTI from 7 September 2013, as well as the company secretary of CTI for the periods 7 September 2013 to 30 September 2014 and 4 September 2015 to 26 October 2015;23 and

(2) a director of CLI which was another of the suite of ACN’s wholly-owned subsidiaries and conducted marketing activities on behalf of Phoenix in respect of its Online Courses.24

46 Mr Brown’s expertise and experience in the VET sector is described in the 2015 ACN Annual Report as follows:

Mr Brown is the CEO and co-founder of Community Training Initiatives and has been instrumental to its growth and success. Mr Brown has had a substantial career working in the VET sector in executive management roles. He holds a Masters of Business Administration (Finance), Graduate Certificates in Management (Learning), Vocational Education and Training, Management and Human Resource Management and a Graduate Diploma in Community Sector Management. He is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Management.25

47 The other directors of CTI over the relevant period were Mr Stephen Ray Williams (from 30 September 2014), Mr David Keith Green (30 September 2014 to 4 September 2015) and Mr Wayne Norman Treeby (from 26 October 2015).26

48 In the case of ACN, the other members of the Board of Directors during the relevant period were:

(1) Mr Stephen Ray Williams (Chair) (from 27 August 2014);

(2) Mr Raymond Keith Griffiths (from 27 August 2014 to 16 October 2015);

(3) Mr Craig Graeme Chapman (from 27 August 2014);

(4) Ms Samantha Martin-Williams (from 27 August 2015 to 27 November 2015); and

(5) Mr Bruce MacKenzie (from 27 August 2014 to 19 January 2015).27

49 Mr David Green held the position of company secretary and Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of ACN.28

50 Mr Brown also had a significant interest in ACN throughout the relevant period.

51 First, the Prospectus issued by ACN dated 26 November 2014 advised that:

Importantly, your Chief Executive Officer, Ivan Brown, who is a co-founder of Community Training Initiatives and one of two major Existing Shareholders will continue to hold 23,267,974 Shares comprising 27.78% of the Company on completion of the Offer.29

52 Secondly, the 2015 ACN Annual Report disclosed that Mr Brown has “an indirect interest in 23,288,874 Shares (which are directly held by IBT Holdings Pty Limited as trustee for the IBT Holdings Family Trust, an entity controlled by Ivan Robert Brown) as well as an indirect interest in 8,700 Shares through Ivan Brown Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd.”30 Mr Brown was a director of IBT Holdings Pty Limited.31 A notation to the Directors’ Report contained in the ACN 2015 Annual Report at p. 24 records that “[t]he shares in ACN were issued to Mr Brown as part of the group reconstruction wherein Mr Brown received shares in ACN in exchange for his shares in entities that were rolled-up into the ACN Group as part of that transaction”. The share capital identified in the ACN company search dated 7 November 2019 is comprised of 74,895,834 ordinary shares with the amount paid being identified as $113,378,401.00.32

53 Mr Brown was based in CTI’s office in Spotswood in the western suburbs of Melbourne and had an office on the first floor next door to Mr Kochhar, who was also based in Spotswood.33 The close physical proximity of their offices is indicative of how closely Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar worked together, which is to be expected given their responsibility for day to day governance of the corporate group.

54 Mr Harry Kochhar (also known as Harpreet Singh)34 was the Chief Operating Officer (COO) of:

(1) ACN from September 2014 to December 2015;

(2) Phoenix from January 2015 to December 2015; and

(3) CTI from April 2014 to December 2015.35

55 Mr Kochhar’s experience and expertise, including in the VET sector, is described as follows in the 2015 ACN Annual Report:

Mr Kochhar has significant experience in RTOs, encompassing 10 years in senior management positons, including strategic management roles and operational management roles. Most recently, Mr Kochhar held the role of operations manager for Aegis Services Australia Limited, a global business process outsourcing company with over 55,000 employees.

Mr Kochhar has been involved in the application, implementation and stakeholder management of funded and fee for service programs. His experience includes defining and monitoring project budgets, identifying market needs and executing strategy to fulfil labour market needs.

Mr Kochhar has extensive practical training experience through his training roles with William Angliss Institute of TAFE, Holmes Institute, Sarina Russo Institute & Sarina Russo Schools, MCIE and Futurum Australia.36

56 Mr Kochhar resigned as COO from Via Network on 4 December 201537 but continued to work on a retainer as a consultant. 38 There is no evidence that Mr Kochhar had any shareholding in either of the respondents.

57 The applicants filed an originating application on 20 November 2015, together with an affidavit annexing a proposed draft concise statement. On 9 February 2016, the respondents filed a concise response. (The applicants’ concise statement was subsequently filed on 17 February 2016 after the commencement of amendments to the Court’s Commercial and Corporations Practice Note (C&C-1).)

3.2 The DOCA and leave to proceed

58 On 21 March 2016, the directors of the respondents, with other companies in the ACN Group, resolved to place the companies into voluntary administration. Under s 435C of the Corporations Act, the administration ended on 24 May 2016 when a Deed of Company Arrangement (DOCA) was executed by companies in the ACN Group, including the respondents. By force of s 444E of the Corporations Act, a person bound by the DOCA cannot proceed with a proceeding against the respondents until the DOCA terminates, save with leave of the Court and in accordance with such terms (if any) as the Court imposes.

59 By an interlocutory application dated 29 August 2016, the applicants sought orders pursuant to s 444E(3)(c) of the Corporations Act that leave be granted (to the extent that leave was required) to proceed against the respondents. The grant of leave was opposed by the respondents.

60 On 21 October 2016, I held in Phoenix (No 1) that leave to proceed should be granted to both applicants on condition that they did not seek to enforce any pecuniary penalties, any injunction pursuant to s 232(6)(a) of the ACL requiring monies to be refunded, or any costs order in their favour, without further leave of the Court. As earlier mentioned, an appeal against that decision was dismissed.

3.3 Amendments to the pleadings

61 On 8 December 2017, the applicants filed an amended originating application and amended concise statement which omitted some of the relief sought as a result of the grant of leave to the applicants to continue the proceeding against the respondents. Annexures A and B to the amended concise statement comprised particulars of the Profit Maximisation and Enrolment Conduct and particulars of the Agency Relationship between Brokers and the respondents respectively, such particulars having been requested by the respondents.

62 The parties thereafter embarked upon a protracted course of correspondence in which the respondents sought additional particulars. The additional particulars sought concerned, among other things, the issue of causation of loss or damage which forms part of the applicants’ cause of action pursuant to s 239.

63 The applicants subsequently applied for leave to file a proposed further amended originating application (FAOA) pursuant to r 8.21 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) and a proposed further amended concise statement pursuant to r 16.53 of the FCR. The application was taken to be an application to amend in terms of Annexures A and B respectively to the applicants’ written submissions filed on 22 June 2018, as amended by [4] of the applicants’ submissions in reply dated 20 July 2018. At the hearing of that application on 23 July 2018, I granted leave to the applicants to amend the amended originating application in terms of the FAOA, and to amend in part the further amended concise statement. I also set down a timetable permitting the parties to endeavour to reach agreement as to the remaining, more controversial proposed amendments.

64 On 11 September 2018, I made orders setting down a timetable for the hearing of an interlocutory application by the applicants for leave to file a proposed second further amended concise statement. On 9 October 2018, the parties advised the Court that, in light of the decision of the Full Court in Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2018] FCAFC 155; (2018) 362 ALR 66 (Unique (FCAFC)) delivered on 19 September 2018, the applicants intended to file an affidavit annexing a revised second further amended concise statement. The application was heard on 1 February 2019.

65 By an email to the Court dated 19 November 2018, the parties provided the Court with draft short minutes of order which provided for the filing of an affidavit annexing a proposed statement of claim. On 1 March 2019, the applicants’ solicitors advised by email that the respondents consented to the filing of a statement of claim and second further amended originating application (SFAOA) in the forms attached to that email. I made orders granting leave to the applicants to do so by 4 March 2019.

66 On 1 May 2019, the respondents filed a defence.

3.4 The respondents’ submitting notice and issues raised by the respondents’ counsel prior to withdrawing from the matter

67 At the case management hearing on 31 July 2019, (then) counsel for the respondents, Mr Brennan, referred to the affidavit of Mr George Georges affirmed on 30 July 2019, which was read for the purposes of the case management hearing, in which Mr Georges explained (at p. 76) that the respondents would shortly file a notice of termination of their solicitors’ retainer. That notice was filed on 13 August 2019.

68 Before withdrawing from the case, Mr Brennan drew a number of matters to the Court’s attention which he submitted may be of assistance to the Court.39 Mr Brennan first explained that while the applicants correctly characterised some of the respondents’ conduct as a “rort”, the difficult issues before the Court were whether the evidence established an unconscionable system and, if so, the extent of that system and the extent of the relief which might then be available under the ACL.

69 Mr Brennan then said that while he did not intend to make submissions, it may assist the Court to consider the following three matters:40

(1) First, Mr Brennan submitted that difficult factual issues arose in determining what inferences could properly be drawn about the conduct of all or some of the Brokers and Agents (and ultimately, the conduct of the respondents) from “evidence which focuses upon misconduct by small subsets of agents [or] of a small subset of brokers”.41 Mr Brennan also identified difficult factual issues relating to the impact of the alleged failure by the second respondent, by the deliberate choice of its management, to apply the student verification system to all enrolments.

(2) Secondly, Mr Brennan identified mixed issues of fact and law concerning the vulnerability of consumers, including the consumers in this proceeding, in light of recent High Court and Full Court authorities, and made remarks about the administration of vocational education policy. Mr Brennan explained that in so doing, he sought to give “colour” and context to the Court’s eventual consideration of the vulnerability of consumers.

(3) Finally, Mr Brennan referred to legal issues which may arise in applying s 239, ACL, which concerns orders to redress loss or damage suffered by non-party consumers. I note that by orders made on 31 July 2019, the question of liability in the proceeding is to be heard separately from the question of relief other than declaratory relief.

70 On 9 August 2019, the respondents filed a notice submitting to any order of the Court save as to costs.

3.5 The appointment of the amicus curiae

71 At the case management hearing on 14 August 2019, Ms Sharp SC, senior counsel for the applicants, submitted that the Court would be assisted by the appointment of amicus curiae as a contradictor on the legal issues surrounding systems unconscionability.42 By orders made on 28 August 2019, Dr Higgins SC was appointed as amicus curiae under r 1.32, FCR. The Court wishes to express its gratitude to Dr Higgins for her valuable assistance.

72 The amicus curiae was provided with a copy of the pleadings and the High Court’s decision in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kobelt [2019] HCA 18; (2019) 267 CLR 1 (Kobelt), as well as the transcript of the case management hearing on 31 July 2019 at which Mr Brennan made concluding remarks, as explained above.43

3.6 The grant of leave to amend the statement of claim

73 By an email to the Court dated 25 October 2019, the applicants provided the Court with an agenda for the case management hearing on 28 October 2019 which included an item, “Application re Amended Statement of Claim”. At that case management hearing, Ms Sharp SC, senior counsel for the applicants, explained that the applicants sought to amend the statement of claim “to correct errors and to bring the pleading into alignment with the evidence”, save for one significant amendment.44

74 That significant amendment was to designate Ms Nidhi Bagga as an additional controlling mind of the respondent companies as a result of the applicants’ further review of the documents, where previously only Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar had been identified as controlling minds.45 On the first day of the trial, however, the applicants ultimately did not press the application for leave to amend the ASOC in this respect.46

75 Leave otherwise to amend the statement of claim was granted on the first day of the trial. In reaching the view that the amendments were appropriately allowed, I took into account the fact that the amendments were not extensive, and did not alter the nature of the applicants’ case or seek any additional relief. Rather, they sought to supplement existing pleadings with additional factual details in line with the written submissions filed before the hearing, as well as omitting certain allegations that were no longer pressed.47 In particular, the amendments:

(1) identified the consumers to whom the Diploma of Community Services Work offered by Phoenix was directed and its course requirements with greater particularity;48

(2) identified a further face-to-face course offered by Phoenix prior to its acquisition by ACN;49 and

(3) added the allegation that Phoenix failed to withdraw a significant number of enrolled consumers who sought to cancel their enrolment and continued to claim VET FEE-HELP payments in respect of those consumers.50

3.7 A preliminary issue of procedural fairness

76 In the context of the discussion at the case management hearing on 28 October 2019 about the proposed amendments to the ASOC to include Ms Bagga as a controlling mind of the respondents, I raised an issue with the applicants’ counsel and the amicus curiae concerning procedural fairness to Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar (as well as, then, Ms Bagga), who were alleged by the applicants to be the controlling minds of the respondents and in respect of whom allegations of a most serious nature were made. Notwithstanding that these individuals are not parties to the proceeding, in circumstances where the respondent companies are subject to a DOCA and had filed a submitting notice, I was concerned to ensure that they were afforded procedural fairness and had the opportunity to be heard in a real and practical sense such that they could, if they so wished, apply to intervene in this proceeding.

77 On 4 November 2019, the amicus curiae and the applicants filed separate short submissions addressing this issue. Given that, as explained above, the applicants did not ultimately press the amendments to the statement of claim to include Ms Bagga as a controlling mind of the respondents, it is not necessary to consider the procedural fairness issue in relation to Ms Bagga. With respect to Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar, the applicants submitted:

It is commonplace – and almost inevitable in large documentary cases – that observations are made about non-parties to litigation (who are also sometimes not even called as witnesses) in judicial reasons …

(Applicants’ note concerning procedural fairness dated 4 November 2019 at [11], citing Ashby v Slipper [2014] FCAFC 15; (2014) 219 FCR 322 at [320] (Siopis J).)

78 The applicants contended that this proceeding has been properly constituted as to the parties, and that all parties interested or concerned in the relief claimed are before the Court.51 The applicants emphasised that Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar are not parties to the proceeding, will not be bound by any of the orders sought by the applicants, if granted, and that the respondents had not sought to adduce any evidence from Mr Brown or Mr Kochhar save for a statutory declaration relating to the veracity of student data.52

79 The applicants also submitted that when this proceeding was commenced in November 2015 and the respondent companies had not yet entered into administration, Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar were named in the concise statement. The applicants submitted that as senior management of the respondents, both individuals have been on notice of the allegations of their involvement in the conduct the subject of the proceeding since its commencement.53 I note that while the defence was filed after the respondents had entered into administration, the respondents filed their concise response prior to entering into administration. The evidence also establishes that while Mr Kochhar left the respondents’ employment in December 2015, he remained thereafter in a consulting capacity.

80 The amicus curiae also submitted that the present proceeding was properly constituted as to the parties. In addition, Dr Higgins SC addressed the issue of whether the relevant individuals have been accorded any, and an appropriate, opportunity to be heard. In her submission, on the available material, there was a basis to conclude that Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar have, at relevant times, been sufficiently on notice of the allegations against them to have received a real and practical opportunity to be heard had they sought to do so.54

81 I agree for the reasons given by Dr Higgins SC that Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar have been afforded procedural fairness, and the opportunity to be heard in a real and practical sense.

3.8 Suppression and non-publication orders under s 37AF, FCA Act

82 On 12 February 2016, while this proceeding was docketed to Yates J, his Honour made orders, by consent, relating to the anonymisation of the ex-employee witnesses. Order 1 of those orders provided that “[a]ny statement given by any Former Employee to the applicants or their legal representatives … be filed as … confidential”, and was followed by several other protective orders.

83 At the commencement of the trial, the applicants sought more extensive suppression and non-publication orders in order to ensure the confidentiality of personal information relating to consumers enrolled in Phoenix Online Courses and potential students, such as their names, addresses and dates of birth.55 The applicants handed up short minutes of order which provided for the following regime.

(1) Under proposed orders 1 to 3, order 1 of the orders made on 12 February 2016 would be vacated. In its place, until 29 November 2019, only parties to this proceeding, their experts and legal representatives, and the Court would be able to inspect the documents listed in Annexure A to the short minutes. Annexure A identified a large number of documents including, for example, the tender bundle and supplementary tender bundle, and a number of affidavits, exhibits and annexures in the Court Book.

(2) Proposed order 4 of the short minutes permitted the applicants, between 5 and 29 November 2019, to uplift and amend the tender bundle to remove documents which were not referred to in the course of the hearing or in written submissions. (The deadline was later extended to 3 December 2019 by orders made on 19 November 2019.)

(3) Under proposed order 5 of the short minutes, upon receipt of a non-party inspection request relating to any of the documents identified in Annexure A, the Registry was to notify the applicants’ solicitors of the request, and within 2 business days the applicants would advise the Registry of their position in relation to the access request. If the access request was opposed by the applicants, the applicants would file an interlocutory application and submissions within 5 business days of being notified of the request.

(4) Proposed order 6 required that any non-party intending to disclose “confidential student information” (which was given a detailed definition in notation 1 to the orders including, for example, name, signature, date of birth, address and tax file number) which had been referred to in open Court must notify the applicants’ solicitors of that intention. Orders 5 and 6 were to operate until 31 October 2020.

84 Section 37AF(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) relevantly empowers the Court, on grounds permitted by s 37AG, to restrict the publication or disclosure of information tending to reveal the identity of any person who is related to or otherwise associated with any party in a proceeding (s 37AF(1)(a)), or information that relates to a proceeding before the Court and comprises evidence or information about evidence (s 37AF(1)(b)(i)). Under s 37AF(2), the Court may make such orders as it thinks appropriate to give effect to an order made under s 37AF(1).

85 In light of the large volume of evidence containing confidential student information and the sensitivity of that information, particularly given the vulnerability of enrolled consumers and potential students, I was satisfied that these orders were necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice within the meaning of s 37AG(1)(a) of the FCA Act. I have taken into account that a primary objective of the administration of justice is to safeguard the public interest in open justice (s 37AE). However, as the Chief Justice explained in Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Egan [2018] FCA 1320, while the principle of open justice “involves justice being seen to be done … [o]pen justice is not an absolute concept, unbending in its form. It must on occasion be balanced with other considerations, including but not limited to considerations such as the avoidance of prejudice in the administration of justice or the protection of victims.”

86 Accordingly, I made orders in terms of the short minutes of order at the commencement of the trial on 5 November 2019. Annexure B to these orders comprised a one-page notice including an extract of order 6, and was placed on the door of the courtroom on each day of the trial. I have also substituted the names of consumers with pseudonyms, for the same reasons.

3.9 Evidence initially omitted from the Court Book

87 The Court Book was received into evidence in electronic form as Exhibit A-2.56 On 13 November 2019, Mr White, junior counsel for the applicants, explained that certain documents, being the curriculum vitae of Ms Scomazzon and other attachments, were not included in the filed version of the Court Book57 and handed up a hard copy volume entitled “Attachments to Annexure JS-1 to the affidavit of Jana Scomazzon affirmed 11 September 2019”. On 5 February 2020, in response to an enquiry by the Court, the applicants confirmed that this volume was intended to be admitted into evidence, and provided an electronic copy of these documents. On 6 February 2020, I made an order including that bundle of documents in evidence as part of the Court Book.

4. OVERVIEW OF THE APPLICANTS’ PLEADED CASE

4.1 The radical changes effected to Phoenix’s operations following its acquisition by ACN

88 In early 2015, ACN purchased Phoenix. By this time, CTI was a wholly-owned subsidiary of ACN. As the applicants allege, following the acquisition of Phoenix, there was a radical reorientation in Phoenix’s operating model. Prior to the acquisition Phoenix had offered only face-to-face classes for 300–400 students at any given point in time. Upon acquiring ACN, however, the respondents embarked upon recruiting many thousands of consumers Australia-wide to enrol in online courses in new subjects with Phoenix trading under the banner of “myTime Learning”. For each of these courses, Phoenix charged fees of $18,000 to $21,000.

4.2 Brokers and Agents marketing the Phoenix Online Courses

89 Phoenix and CTI marketed the Phoenix Online Courses by engaging third parties referred to by the applicants and in these reasons as Brokers. As the respondents admitted:

(1) between 16 January 2015 and 1 June 2015, CLI (another entity in the ACN Group of companies) entered into standard form contracts on behalf of Phoenix with at least 28 marketing entities which authorised those entities to act for or at the direction of CLI to recruit students into the Online Courses (the CLI Broker Contracts); and

(2) between 1 July 2015 and approximately 23 November 2015, Phoenix entered directly into standard form written contracts with at least 29 marketing entities, some but not all of whom had previously entered into CLI Broker Contracts, and these authorised those marketing entities to act for or at the direction of Phoenix to recruit students into the Online Courses (the Phoenix Broker Contracts).58

(Together, the CLI/Phoenix Broker Contracts.)

90 Annexure A to the ASOC (reproduced in Appendix 2 below) identifies the Brokers in question, the dates on which they entered into the contracts, and key terms of the contracts, with the agreements themselves being reproduced in the tender bundle. Every Broker negotiated its own commission with Phoenix and, while different, they were all substantial with the highest being 35%. As will become apparent, the existence and size of the commissions is one of the features relied upon by the applicants to establish the Profit Maximising Purpose.

91 The Brokers in turn entered into contracts with at least 548 entities and individuals (the Agents) to recruit consumers into the Online Courses (the Agent Contracts).59 Particulars of each agent contract are set out in Annexure B to the ASOC and reproduced in Appendix 3 to these reasons.

92 For reasons I later explain, I agree with the applicants’ submission that the Brokers and Agents were plainly agents of Phoenix such that their conduct is properly attributed to Phoenix pursuant to s 139B(2) of the CCA.60

4.3 Target Communities and Vulnerable Consumers

93 The applicants further allege that the marketing of the Phoenix Online Courses occurred in circumstances where Phoenix and CTI were aware of reforms to the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme introduced by the Commonwealth in late 2012 and early 2013 in order to increase the VET participation rates of Indigenous Australians, and people from non-English speaking backgrounds, with a disability, from regional and remote areas, from low socio-economic backgrounds, and/or not currently engaged in employment (the Target Communities).61 It is also alleged that Phoenix and CTI were aware that the consumers to whom the Brokers and Agents marketed the Online Courses were likely to include the Target Communities and that some members of those communities were likely to have low LLN results, low levels of formal education, and low levels of computer literacy (Vulnerable Consumers).62

4.4 The Profit Maximising Purpose and Callous Indifference

94 As earlier adverted to, an essential aspect of the applicants’ unconscionability case is that Phoenix and CTI were driven by a Profit Maximising Purpose which prioritised maximising the number of consumers enrolled in Phoenix Online Courses who received VET FEE-HELP, so as to maximise the revenue to Phoenix from the Commonwealth via the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme. In furtherance of that purpose, it is alleged that in eliciting enrolment from consumers and then enrolling them in the Online Courses, Phoenix and CTI were callously indifferent as to whether:

(a) the consumers were in the target cohorts of the online courses;

(b) the consumers satisfied the eligibility criteria for those courses;

(c) the online courses were suitable for the consumers and the consumers were suited to the courses, having regard to their formal education, previous work experience, and literacy, numeracy and computer skills;

(d) the consumers had reasonable prospects of successfully completing the online courses in respect of which they applied to be enrolled;

(e) the consumers meaningfully participated in the Online Courses, including any assessments;

(f) Phoenix had appropriate trainer to student ratios;

(g) there was a reasonable prospect that a consumer enrolled in an online course which required a work placement could secure a work placement; and

(h) Phoenix was capable of inspecting those work placement venues,

(the “Callous Indifference”).63

95 The applicants also allege that, when the level of complaints against Phoenix came to the attention of regulators including the ACCC, the respondents engaged in a desperate attempt to cover up their unconscionable conduct and to mislead the regulators, including by falsifying documents and dates, in order to maximise their profits from the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme.

96 In this regard, the applicants contend that there were two stages to a consumer enrolling in an online course. First, Brokers or Agents marketed the courses to consumers face-to-face and elicited a series of completed enrolment forms from the consumers, by which the consumers sought to be enrolled. At the second stage, the consumers were supposed to be vetted by CTI following which they would be enrolled if they successfully passed the vetting process. However, while that was the system in theory, among other difficulties little or no effort was in fact made at the vetting or verification stage to ascertain the suitability of consumers to undertake the Online Courses or to ensure that mandatory admissibility criteria were met.

97 On this basis, the applicants allege that two relevant systems were in play, which were unconscionable separately and cumulatively, namely the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System.

4.5 The Phoenix Marketing System

98 The applicants allege at SOC/ASOC [73] that there were eight essential features of the Phoenix Marketing System which consisted of Phoenix directly, and indirectly via CTI and CLI:

73.1 engaging Brokers and Agents to market its Online Courses to consumers as its agents, by way of unsolicited, “face[-]to[-]face” marketing;

73.2 engaging Brokers and Agents to obtain:

73.2.1 completed Online Course enrolment application forms;

73.2.2 completed Request for VET-FEE HELP Assistance forms [this was sometimes known as a Commonwealth Assistance Form or “CAF”];

73.2.3 completed LLN test sheets;

73.2.4 completed “Pre-training Review” (PTR) forms;

73.2.5 federal or State-issued ID and proof of citizenship or of permanent humanitarian residency status; and

73.2.6 completed Agreement to Tuition Fees forms,

(collectively, the Enrolment Forms);

73.3 engaging Brokers and Agents to represent to consumers that:

73.3.1 in order to receive a free laptop all the consumers needed to do was sign up to a Phoenix (or myTime) Online Course; or

73.3.2 the Online Courses were free, or free unless the consumer’s income was in an amount which they were unlikely to earn on complet[ion] of a course, or at all;

73.4 engaging Brokers and Agents to obtain, from the vast majority of applying consumers, completed Enrolment Forms applying to enrol in more than one Online Course, notwithstanding that each Online Course had an EFTSL [(equivalent full-time study load)] of 1.0;

73.5 providing financial incentives to the Brokers and Agents to maximise the number of completed Enrolment Forms for Online Courses; and

73.6 failing to:

73.6.1 train or adequately train the Brokers and Agents in their obligations under the ACL;

73.6.2 train or adequately train the Brokers and Agents in their obligations to comply with the RTOs Standards; and

73.6.3 instruct or require the Brokers and Agents to ascertain whether the consumer was suited to the Online Course and the Online Course to the consumer;

73.7 failing to ascertain whether the consumer was suited to the Online Course and the Online Course to the consumer;

73.8 Brokers or Agents often completing the LLN and PTR forms themselves, or coaching the consumers on how to complete these forms, when these forms were ostensibly designed to determine a consumer’s ability to undertake and interest in an Online Course

(collectively, the Phoenix Marketing System).

99 It is alleged at ASOC [74] that the Phoenix Marketing System was deployed on consumers in circumstances where:

74.1 Phoenix had the Profit Maximising Purpose and the Callous Indifference;

74.2 some consumers were likely to be Vulnerable Consumers;

74.3 notwithstanding the above, the tactics employed by the Brokers and Agents in soliciting enrolment applications were unfair and high pressure;