Federal Court of Australia

NSW Trains v Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union [2021] FCA 883

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN RAIL, TRAM AND BUS INDUSTRY UNION First Respondent PAUL DORNAN Second Respondent EDWARD DUNGER Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Amended Originating Application filed on 2 June 2021 is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FLICK J:

1 The Applicant in the present proceeding is NSW Trains. It is a corporation constituted under s 37(1) of the Transport Administration Act 1988 (NSW).

2 The First Respondent is the Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union (the “Union”), and is a registered organisation under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Fair Work Act”). It is entitled to represent the industrial interests of railway employees employed by NSW Trains, including train drivers and guards. The Second Respondent, Mr Paul Dornan, is employed as a driver by NSW Trains. The Third Respondent, Mr Edward Dunger, is employed as a guard by NSW Trains. Although they are named as individual Respondents, together they are representative of the drivers and guards employed by NSW Trains.

3 NSW Trains is in the course of introducing a new fleet of electric passenger trains, known as the Mariyung Fleet. Albeit not referred to in the evidence, the word “Mariyung” is drawn from the language of the Darug nation meaning “Emu”. The people of the Darug nation are the traditional custodians of what is now Sydney.

4 This new fleet of trains is planned to replace the existing fleet of trains, known as V-sets, OSCars and Tangaras. Before the Mariyung Fleet can be introduced it must receive accreditation pursuant to s 62 of the Rail Safety National Law (NSW), which is applied and modified as a law of New South Wales by the Rail Safety (Adoption of National Law) Act 2012 (NSW). Such accreditation has not as yet been obtained, although it is anticipated that NSW Trains will receive final accreditation sometime in July 2021. A Draft Revised Notice of Accreditation was issued on 30 June 2021 and was accepted by NSW Trains later on the same day, a date very proximate to the commencement of the present hearing. After the hearing of this matter the parties advised that a final Notice of Accreditation was issued on 29 July 2021. NSW Trains is now accredited to operate the Mariyung Fleet on the Sydney to Newcastle-Central Coast network. In future it is anticipated that accreditation will also be sought for the Sydney to Blue Mountains network and the Sydney to Wollongong network.

5 Train drivers and guards are covered by the NSW Trains Enterprise Agreement 2018 (the “2018 Agreement”). That Agreement contains a number of classifications for the employees of NSW Trains, including that of a driver and guard. But the Agreement does not go beyond those classifications to specify the class of trains being operated. The “nominal expiry date” of the Agreement has come and gone, that date being 1 May 2021.

6 Of present relevance is the fact that, after consultation between NSW Trains and the Union and its members, NSW Trains issued a publication on 28 November 2019 titled: Your Guide to the New Intercity Fleet. That was, as the Respondents would have it, a unilateral announcement on the part of NSW Trains as to how it was proposing to operate its Mariyung Fleet. Disputes followed. At least some of the issues which have arisen in respect to the new Fleet, it should be noted at the outset, have previously been the subject of a decision of the Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission on 2 March 2021: Re Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union v NSW Trains [2021] FWCFB 1113.

7 In very summary form, in issue is the ability of NSW Trains to give directions to its drivers and guards in respect to the Mariyung Fleet. NSW Trains contends that:

it can unilaterally give such directions to its drivers and guards,

because (inter alia),

any argument that the giving of such directions would constitute the making of “extra claims” – which is otherwise prohibited by cl 13.1(b) of the 2018 Agreement – is to be rejected.

In its submission, any such argument is to be rejected because:

the giving of the directions to its drivers and guards would not constitute an “extra claim” within the meaning of and for the purposes of cl 13.1(b).

NSW Trains contends in the alternative that:

the operation of cl 13 has come to an end.

NSW Trains further contends that, even if it is found that cl 13 continues to have legal force and that NSW Trains’ proposed directions to drivers and guards constitute “extra claims”:

cl 13.1(b) is invalid by reason of inconsistency with Part 2-4 of the Fair Work Act.

A number of subsidiary, but important, contentions are also in need of resolution.

8 Not surprisingly, the Respondents take a fundamentally different approach and (again in very summary form) contend that:

the directions proposed to be given by NSW Trains to its drivers and guards would constitute the making of an “extra claim” and that, in any event, that issue has been resolved by the decision of the Fair Work Commission;

cl 13.1(b) of the 2018 Agreement has not come to an end, notwithstanding the passage of the “nominal expiry date”; and

any declaratory relief should be refused for a variety of reasons.

9 In resolving these competing contentions it is necessary to set forth:

the background to the proceeding, including the process of accreditation being pursued by NSW Trains and the directions it proposes to give to its drivers and guards;

the form of declaratory relief sought; and

the centrally relevant terms of the 2018 Agreement.

It is thereafter necessary to resolve the questions as to whether:

cl 13.1(b) of the 2018 Agreement has in fact come to an end;

the directions proposed to be given by NSW Trains to its drivers and guards would constitute the making of an “extra claim”, together with the question as to whether, in that respect, NSW Trains is bound by the March 2021 decision of the Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission, and whether cl 13.1(b) is of “no legal effect” by reason of Part 2-4 of the Fair Work Act; and

any declaratory relief should be granted.

Each of these issues should be separately addressed.

10 These are the issues which emerged from the Amended Originating Application filed on 2 June 2021 pursuant to leave to amend then being granted. Leave to further amend was sought during the course of final submissions. The application to further amend was sought to be characterised by NSW Trains as a clarification of – and a narrowing of – the issues to be resolved. The application for leave to amend at such a late stage in the proceeding was opposed and leave was refused. The further amendments had the potential to recast the issues to be resolved and the potential to necessitate the calling of further evidence. A refusal of leave, on the other hand, did not occasion prejudice to NSW Trains as the issues it sought to have resolved, and indeed more, were already raised by the form of its June 2021 Amended Originating Application.

11 It may be noted at the outset, and by way of summary, that it has been concluded that NSW Trains has failed to make out any claim for declaratory relief. The proceeding should thus be dismissed.

THE BACKGROUND

12 The background to the present dispute is sufficiently addressed by an outline of:

the accreditation process being pursued by NSW Trains;

the relevant safety legislation applicable to the operations of NSW Trains;

the operational instructions proposed to be given by NSW Trains to its drivers and guards;

the contracts of employment of Mr Dornan and Mr Dunger;

the form of declaratory relief sought, that declaratory relief including declarations that the giving of those operational instructions would be “lawful and reasonable” directions; and

the terms of the 2018 Agreement and the well-accepted principles as to the manner in which enterprise agreements are to be construed.

The accreditation process

13 The accreditation process is addressed by Messrs Matthew Coates and Oliver Coovre. Mr Coates is the Director of Safety and Standards at Sydney Trains; Mr Coovre is the Senior Program Manager-Mariyung, at NSW Trains. Both prepared affidavits for the purposes of the present proceeding.

14 The process of accreditation, it would appear, has been long on-going.

15 Mr Coates states that the Office of the National Safety Regulator (the “Safety Regulator”) “is responsible for administering and enforcing the terms of the Rail Safety National Law as implemented in each State and Territory”. According to Mr Coates, the Safety Regulator “does not give a conclusive statement of what it considers to be or not be safe” but does require that it be “satisfied that the rail transport operator has effectively considered and addressed with appropriate controls the risks associated with its operations”. An accreditation once obtained may be varied on application. The Safety Regulator also undertakes “an ongoing process of assessment to ensure that the rail operator is complying with the terms of its” Safety Management System.

16 Mr Coovre states that a part of the accreditation regime requires NSW Trains to have a Safety Management System. Since 2016, NSW Trains has met regularly with the Safety Regulator “to discuss a wide variety of topics including the key changes for operations and management of safety risks, driver workload, CCTV assurance, zig zag tunnels, single person operations, management of software changes, the Applicant’s safety change management program and program updates generally”.

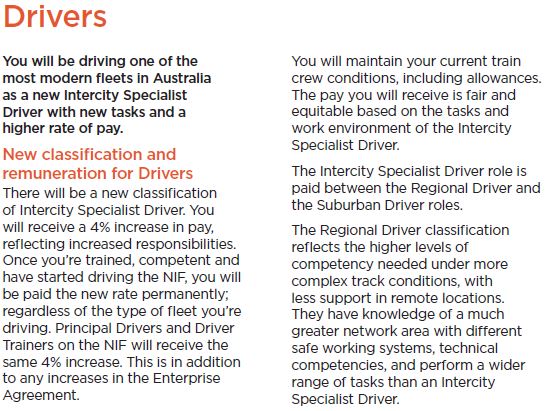

17 As at November 2019 when NSW Trains published its Guide to the New Intercity Fleet, the Guide provided in respect to drivers (in part) as follows:

The Guide went on to further provide:

It will be noted that, in respect to drivers, it was then being proposed that there would be a “new classification” but that drivers would retain their existing “crew conditions, including allowances.” In respect to guards, the Guide provided (again in part) as follows:

18 The Application for variation of accreditation was forwarded by NSW Trains to the Safety Regulator in November 2019. That Application foreshadowed the intention of NSW Trains to operate the new Mariyung Fleet on what it described as “the Central Coast and Newcastle, Blue Mountains and South Coast lines.” It is Mr Coovre who provides an update on the application to vary the existing accreditation. It was in May 2020 that a draft Safety Assurance Report was provided to the Safety Regulator. In December 2020 an updated final version of the Safety Assurance Report was provided. The Draft Revised Notice of Accreditation was issued on 30 June 2021. As advised in the covering email, the Safety Regulator proposed “one new restriction relating to the area in which Mariyung can operate passenger revenue services; and one new condition relating to the requirement for the Guard/Customer Service Guard to monitor PTI at station departure.” Notwithstanding the opportunity to make further “written submissions” in response to the draft within 28 days, it was later on the same day on 30 June 2021 that NSW Trains forwarded its response to the draft forwarded to them hours earlier. The response was that “NSW Trains agrees to the proposed amendments (namely one new restriction, one new condition and the cancellation of the existing restriction on automatic train protection) outlined in the draft notice of accreditation…”.

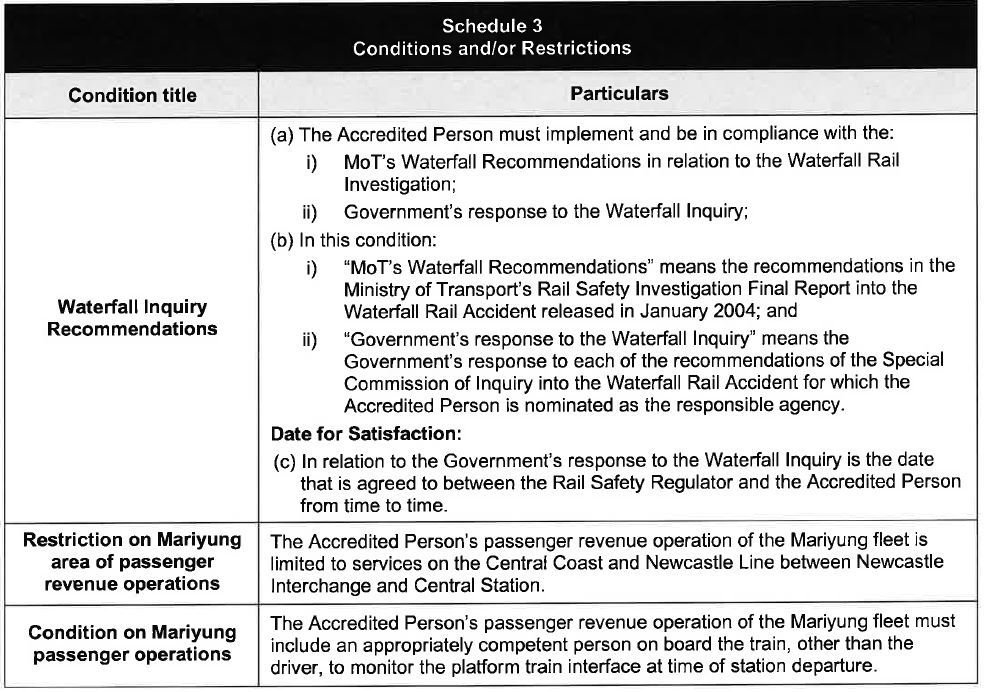

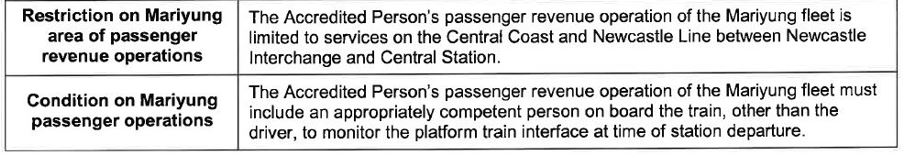

19 The final Notice of Accreditation, as issued on 29 July 2021, was substantially the same as that provided in the Draft. Schedule 3 to the final Notice provides as follows:

The implementation and compliance with the “Waterfall Inquiry Recommendations”, it will be noted, was a condition to which the existing accreditation and the proposed variation of accreditation is subject. Schedule 3 continued on to show the variation proposed in respect to the new accreditation and the “restriction” and the new “condition”, as follows:

The “appropriately competent person” referred to in the proposed new condition was accepted by NSW Trains as only capable of being a reference to a guard.

The legislative background – health and safety

20 The safety legislation of relevance to the operation of NSW Trains, and the duties of both NSW Trains as an employer and the duties of its employees, are to be relevantly found in:

the Rail Safety National Law (NSW) (the “Rail Safety Law”); and

the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW) (the “Work Health and Safety Act”).

It is necessary to provide a brief outline of some of the provisions in both Acts.

21 If reference is made initially to the Rail Safety Law, s 3 sets forth the “purpose, objects and guiding principles of Law”, the main purpose being “to provide for safe railway operations in Australia” (s 3(1)). The objects include the making of provision for a “national system of rail safety” and the carrying out of railway operations in a safe manner (s 3(2)). The objects also include making provision for “continuous improvement of the safe carrying out of railway operations” and promoting “public confidence in the safety of transport of persons or freight by rail”. It is s 12 which establishes the Safety Regulator and s 13 which sets forth its functions and objectives. The Safety Regulator must discharge of its functions in an independent manner free of Ministerial direction (s 14), and its functions include (s 13):

administering, auditing and reviewing the accreditation regime relating to rail safety;

working with rail transport operators, workers and others involved to improve rail safety nationally; and

monitoring, investigating and enforcing compliance with the Rail Safety Law.

It is also the Rail Safety Law which requires a “rail transport operator”, such as NSW Trains, to be accredited (s 62) and which provides for the procedure for gaining accreditation (s 64).

22 The Work Health and Safety Act finds its origins in a commitment in 2008 on the part of the Council of Australian Governments to the harmonisation of work health and safety throughout Australia. A national review developed a model work health and safety law. This model law has been implemented by the Commonwealth, the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania.

23 If reference is had to the provisions of the Work Health and Safety Act, NSW Trains accepts that it is a “person conducting a business or undertaking” within the meaning of and for the purposes of s 5 of that Act and, accordingly, that it is bound by the provisions of that Act. Its employed drivers and guards, it is further accepted, are “workers” for the purposes of s 7 of that Act. Part 2 of the Act sets out “Health and safety duties”. Section 17 provides for the management of risks as follows:

Management of risks

A duty imposed on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person:

(a) to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and

(b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

Section 19(1) places upon the “person conducting a business”, in this case NSW Trains, a “primary duty of care”, to ensure “so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety of …workers…” In commenting upon the phrase “reasonably practicable” in the identical Northern Territory model Act, Edelman J in Work Health Authority v Outback Ballooning Pty Ltd [2019] HCA 2, (2019) 266 CLR 428 (“Outback Ballooning”) at 493 observed:

[162] Although the requirement of reasonable practicability in s 19(2) is formulated in similar terms to a standard of care in the tort of negligence, it is a higher duty than the common law. An attempt to draw elements from the common law tort is “not … helpful”.

(footnotes omitted)

And, without limiting that expression of the duty imposed, s 19(3) provides instances of the duty, including to “ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable: (a) the provision and maintenance of a work environment without risks to health and safety; and (b) the provision and maintenance of safe plant and structures; and (c) the provision and maintenance of safe systems of work…” In commenting upon s 19(2), Edelman J in Outback Ballooning further observed (at 493 to 494):

[163] Section 19(2) is part of a strict liability duty to “ensure” a result. The offence is based upon risk, not outcome. Hence, no individual rights need be violated before the duty is breached. The duty is a general one concerned with regulating safety in the workplace. That general regulation is consistent with the 1972 recommendations of the committee chaired by Lord Robens ([United Kingdom, Safety and Health at Work: Report of the Committee 1970-72 (1972) Cmnd 5034, p 8 [30]]) to move away from a “haphazard mass of ill-assorted and intricate detail partly as a result of concentration upon one particular type of target”. The WHS Act, and s 19 in particular, thus follows the recommended model of imposing general duties, supported by regulations and codes of practice, requiring employers to participate in the making and monitoring of arrangements for health and safety in the workplace.

[164] As s 19(2) and other general duties in the WHS Act are designed to ensure safety, the s 19(2) duty is designed to be supplemented by regulations made by the Administrator under s 276. …

(some footnotes omitted)

In further commenting upon the Robens Report, Neave JA in R v Irvine [2009] VSCA 239, (2009) 25 VR 75 at 92 said:

[94] The Robens Report advocated greater reliance on self-regulation by employers and workers jointly, backed up by an effective inspectorate. It remarked that the lengthy process of investigating breaches, warnings, institution of criminal proceedings conviction and the ultimate fine was not a very effective way of preventing health and safety breaches and that criminal prosecutions should be reserved for breaches that were flagrant and wilful. …

[95] …The Robens Report emphasised the importance of employee involvement in improving work safety, but did not discuss whether employees should be held criminally liable for breach of occupational health and safety standards.

Further “duties” are imposed by ss 20 and 21 of the Work Health and Safety Act.

24 In addition to imposing duties on those “conducting a business”, the Act also imposes duties upon the “workers”’, employees such as train drivers and guards in the present case: s 28. Those duties include taking reasonable care for their own safety; taking reasonable care not to adversely affect the health and safety of other persons; and a duty to co-operate with any reasonable policy or procedure of the person conducting the business.

25 The Work Health and Safety Act also imposes upon those conducting a business a duty to consult with workers in respect to matters “relating to work health and safety”: s 47. The Act also provides for the election of a worker as a “health and safety representative” (s 50) and for the determination of “work groups” (s 51). Eligibility for a worker to be elected as a “health and safety representative” for a “work group” is dependent upon the worker being a member of that “work group”: s 60. Powers and functions are conferred by the Act upon a “health and safety representative”: s 68.

26 The Act also provides in Division 5 to Part 5 for the resolution of health and safety issues. Section 85 within Division 6 to Part 5 confers upon a health and safety representative a power to direct the cessation of unsafe work. Section 90 within Division 7 provides a health and safety representative the power to issue a “provisional improvement notice”.

The Operational Instructions

27 The Originating Application as initially filed sought a great number of declarations and did so by reference to a number of Annexures. As amended, the Amended Originating Application filed on 2 June 2021 confined the declaratory relief to 8 declarations and did so by reference to a single Annexure, the content of that Annexure being described as “the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet”.

28 The Amended Originating Application thus sought (by way of example) a declaration that by seeking to implement and implementing “the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet described in Annexure A, the Applicant will not thereby be making a claim falling within the description ‘no extra claims for any changes in remuneration or conditions of employment’ for the purposes of clause 13.1(b) of the Enterprise Agreement.”

29 There were initially a number of variations to Annexure A which NSW Trains prepared, being Annexures B to D. Annexure B involved giving the guard giving the driver an “all right” bell signal that the train is in a position to move. Annexure C contemplated there being a guard on-board during “empty car running”. Annexure D involved an adjusted procedure where “the guard will give the driver an ‘all right’ bell to signal that the guard is in position…” has observed the CCTV monitors to ensure customers have finished boarding and alighting and that “…it is safe to close the customer doors.”

30 It is nevertheless sufficient for present purposes, and given that the amendment effected the removal of the other Annexures, to address Annexure A to the Amended Originating Application, which provides as follows (without alteration):

ANNEXURE A

There is no change to the classification and pay rates in the NSW Trains Enterprise Agreement 2018 for the Applicant’s intercity drivers and guards.

The Mariyung fleet is operated in accordance with Operator Instruction Manual (OIM) that was consulted from 2019 to 2021 with the amendment that references to “Customer Service Guard” or “CSG” will be replaced by “Guard”.

The key features of platform activities during revenue service on the Mariyung fleet Is summarised below:

1. On approach to a platform (approximately 250 metres out from station) the CCTV in the guard’s cab automatically switches to external view to display the bodyside of the train on the platform side.

2. As the train approaches station, the guard may observe the platform using CCTV while velocity interlocking on crew cab door is active (i.e. crew cab door will not open while train is moving).

3. CCTV activates in the driver’s cab when the train is stopped and the passenger doors are ASDO-enabled. Train arrives at station (the front of train is positioned on the platform, the guard cab may be off the platform at some short platforms).

4. Driver releases/opens passenger doors.

5. During dwell time at the platform, CCTV showing the bodyside of the train on the platform is on for both driver and guard.

6. During dwell time, the guard may observe the customers boarding and alighting from the train. Where required, guards provide face-to-face customer service, including boarding assistance or perform other platform tasks.

7. During dwell time at platform, the driver may choose to observe the platform train interface (PTI) using CCTV.

8. After completing any required platform activities, the guard sits at the crew workstation and closes the crew cab door.

9. The driver prepares for departure by checking the signal in advance shows a proceed indication, it is time to depart, and that the guard has cut in the guard controls and closed the guard crew cab door.

10. The driver uses CCTV to monitor the platform, checking the customers have finished boarding and alighting and boarding assistance tasks have been completed. When the driver assesses it is safe to do so he or she closes customer doors.

11. Driver performs final PTI safety check using CCTV once all doors are closed and takes power.

12. Guard monitors CCTV and watches PTI until whole train is clear of platform. If a hazard is detected, the guard may apply the emergency brake using master controller or emergency brake tap, or give the driver the STOP IMMEDIATELY bell signal.

Other key operational features of the fleet are:

1. Mariyung train and track infrastructure configuration will remain as currently engineered.

2. Traction and velocity interlocking remain in place on crew cab doors.

3. CCTV to be used in to monitor customer boarding and alighting and for train dispatch.

4. There will be no guard onboard during empty car running (i.e. when the driver drives an empty train to or from a passenger platform and a stabling yard, between stabling yards and between other locations as required).

5. In-cab camera will be operational.

6. Customer Help Point calls go to the Network Services Coordination Centre (NSCC) in the first instance with the driver and guard playing key roles in the triaged response to the call.

7. Driver will undertake train preparation and stabling procedures.

Note

Nothing in this annexure is intended to apply or have the effect that any new train crew recruits into the role of guard will be employed with changed pay and conditions.

31 The affidavit of Mr Peters refers to this Annexure as containing a summary of the “key aspects of the Applicant’s preferred method of operation and [being] consistent with the tasks and duties” earlier described in his affidavit. However it be described, Annexure A is based upon the Mariyung Operator Instruction Manual (“Operator Manual”). It is that Manual which more fully sets forth the duties of train drivers and guards. Thus, for example, point 7 of Annexure A is based upon cl 3.6.3.1 of the Operator Manual. Part 3.6.2 of the Manual addresses the situation where a train is arriving at a platform. Part 3.6.3 addresses the situation when a train has arrived at the platform and is stationary. That Part relevantly provides as follows:

3.6.3 Train standing at a platform

While a train is standing at a platform, staff must perform the relevant:

• Driver tasks while train standing at a platform.

• CSG tasks while train is standing at a platform.

Where the dwell time exceeds the time required to carry out required platform activities, staff may take a short break or attend to personal tasks.

3.6.3.1 Driver tasks while standing at a platform

While the train is standing at the platform, Drivers must keep the master controller in MAX BRAKE and, if required, carry out the following activities:

• set the driver reminder appliance (DRA)

• release the passenger doors

• boarding assistance, if Station Staff and CSG are not available

• fault rectification

• train division and amalgamation

• termination checks.

3.6.3.2 CSG tasks while standing at a platform

Upon arrival at a platform, the CSG must check the platform for any customers requiring boarding assistance.

While the train is standing at the platform, CSGs carry out the following activities, as required:

• customer service

• boarding assistance, if Station Staff are not available

• fault rectification, under the direction of the Driver

• close open IEDR covers

• deal with lost property

• collect or distribute correspondence to Station Staff

• train division or amalgamation tasks

• termination checks.

32 Part 3.6.4 of that Manual sets forth in greater detail what is described as “Preparing train for departure”. Within that Part, cll 3.6.4.1 and 3.6.4.2 provide as follows:

3.6.4.1 Driver decision to depart

Before commencing the dispatch procedure, Drivers must check:

• that the signal ahead, if visible, shows a PROCEED indication

• that it is no more than 20 second until the scheduled departure time

• that the CSG, if required to carry out the CSG dispatch procedure, has cut in the CSG controls and closed the CBSD of the active CSG cab

• whether the driver reminder appliance (DRA) is set.

If the DRA is set, Drivers may carry out dispatch and proceed at caution. If any of the other conditions for departure are not met, the Driver must not commence the dispatch procedure.

3.6.4.2 CSG preparation for dispatch

If, while carrying out platform activities, the CSG observes any passenger behaviour or events that could prevent the train from being dispatched, they must communicate with the Driver that it is not safe for the train to depart.

When all platform activities are complete and it is safe for the train to depart, the CSG must:

• close the crew bodyside door (CBSD) in the active CSG cab

• sit at the crew workstation

• be ready to observe the CCTV monitor during train dispatch.

And point 11 of Annexure A has as its counterpart cl 3.7.2.1.1 of the Operator Manual which provides (in part) as follows:

3.7.2.1.1 Driver’s dispatch procedure for two-person operation

1. Prior to departure use CCTV to monitor the platform, checking that customers have finished boarding or alighting, and all boarding assistance tasks have been completed.

2. If a Station Staff handsignaller is present, check they are giving a RIGHT OF WAY handsignal.

3. When all customers are clear of the doors, press the DOORS CLOSE pushbutton and observe the CCTV monitor as the doors close.

4. Listen for the audible tone and check that the traction interlock (TI) light has extinguished, to confirm the doors are closed.

5. Complete a PTI safety check, systematically checking each external image on the crew workstation CCTV monitor, to ensure that:

a) nothing is caught in the doors

b) nobody is in contact with the train

c) Station Staff, if present, are not giving a STOP handsignal

d) the behaviour of people visible in CCTV images will not pose a risk when the train moves.

6. If concerned about the safety of customers on the platform or ahead of the train, you may choose to:

a) make an external PA announcement warning passengers before the train moves, or

b) tap the EXTEND tile on the CCTV monitor to keep it active following departure.

7. When it is safe to do so, move the train.

…

Point 12 of Annexure A has as its counterpart point 2 of cl 3.7.2.1.2 of the Operator Manual, which provides (in part) as follows:

3.7.2.1.2 CSG dispatch procedure

1. …

2. Watch the PTI on the CCTV monitor as the train departs, until the trailing car of the train has reached the departure end of the platform.

…

33 It may presently be noted that there are differences between Annexure A and the Operator Manual, including – and without being exhaustive – the following:

there is no reference in point 7 to Annexure A to the additional “tasks” which a train driver may be “required” to perform whilst a train is “standing at a platform” as referred to in cl 3.6.3.1 of the Operator Manual; and

there is no counterpart to the last three lines in cl 3.6.4.1 of the Operator Manual in Annexure A.

The contracts of employment

34 The Second and Third Respondents, being Mr Dornan employed as a train driver and Mr Dunger employed as a train guard, are said to be representative of the drivers and guards employed by NSW Trains.

35 Mr Dornan’s contract of employment is found in a letter dated 16 March 2007. That letter provides in relevant part as follows:

Your Role and Responsibilities

Your duties and responsibilities in the above position are set out in the attached Position Description.

Appointment to the Position

Your appointment will be dependent on successfully completing the training program and will not become formal until the statutory period for any reviews or appeals has elapsed and/or any reviews or appeals have been determined or withdrawn. You will receive written confirmation of the completion of this process.

…

Your conditions of employment will be in accordance with the relevant award and the RailCorp Enterprise Agreement, a copy of which can be obtained from your Human Resources department.

…

The reference to the RailCorp Enterprise Agreement, it was common ground, could now be taken as a reference to the 2018 Agreement. The “attached Position Description” to which the letter refers provides in relevant part as follows:

PRIMARY PURPOSE

• Drive trains safely and efficiently to destinations according to timetable and provide a transportation service to customers.

…

KEY ACCOUNTABILITIES

• …

• Perform all safeworking and operational procedures, either alone or in conjunction with the Guard where appropriate, that are necessary for safe and effective train operation and to meet safeworking requirements;

• …

CHALLENGES

Undergoing regular assessments and examinations in regard to Safeworking and Train Management;

• Constantly updating their knowledge of Safeworking procedures and Traction Manuals in a continually changing environment;

• Adapting readily to the driving requirements of a particular train, identifying whether it requires all or only some procedures to be performed;

• Mastering additional operational duties to ensure all aspects of train operation are conducted efficiently and safely;

• Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of new technology, and safety apparatus systems, so that they are used correctly and effectively;

• Working with the Guard to exchange information on either operational problems or customer service issues, such as a passenger urgently requiring medical attention; and,

• Where radios are in use, mastering the communications system in order to keep in touch with the Guard, Signallers and Network Control.

...

SELECTION CRITERIA

...

• Working knowledge of train management procedures, including train preparation and stabling and other requirements;

• Understanding of and ability to use new technology and systems, to carry out required procedures and activities effectively and efficiently;

• Problem solving and analysis skills for accurately and pro-actively identifying operational problems and determining the appropriate course of action;

• Well-developed interpersonal skills for effectively communicating with the Guard, Passengers, Network Control, Signal boxes, Defects, Rostering supervisor and other personnel as required;

• …

36 Mr Dunger’s contract of employment is found in a letter dated 13 October 2006 and provides in relevant part as follows:

Your Role and Responsibilities

Your duties and responsibilities in the above position are set out in the attached Position Description.

Appointment to the Position

Your appointment will be dependent upon successfully completing the training program and will not become formal until the statutory period for any reviews or appeals has elapsed and/or any reviews or appeals have been determined or withdrawn. You will receive written confirmation of the completion of this process.

…

Your conditions of employment will be in accordance with the relevant award and the Enterprise Agreement 2005, a copy of which can be obtained from your Human Resources department.

…

The “attached Position Description” to which this letter refers provides in relevant part as follows:

PRIMARY PURPOSE

• Provide effective, quality customer services to passengers travelling with NSW Trains to meet the information, safety and security needs of passengers and act as a deterrent to vandalism and fare evasion

• Perform various safeworking procedures, plus door operation, platform surveillance and fault management as required.

• Work in conjunction with the driver to ensure the safe operation of the train

KEY ACCOUNTABILITIES

• …

• Prepare and work the train in conjunction with the Train Driver to verify the operational safety of the train.

• Work in conjunction with the Train Driver in safe working and fault management of the train.

• Open the train doors when the train is standing at a platform so that passengers can safely alight or board the train.

• Visually check passengers alighting and boarding the train and make “Doors Closing, Please Stand Clear” announcements before closing the train doors and notifying the Train Driver that it is safe to leave the station.

• …

SELECTION CRITERIA

• …

• Understanding of and ability to use new technology and systems, particularly the communication system, to carry out required procedures and activities effectively and efficiently.

…

The Declaratory Relief sought

37 It is also desirable to set forth at the outset the terms in which declaratory relief is sought – it is the form of declaratory relief which (for example) identifies the claims made by NSW Trains in respect to clause 13.1(b) of the 2018 Agreement, and also its claims that the giving of directions to drivers and guards to work in accordance with the operational instructions would be “lawful and reasonable”.

38 The Amended Originating Application as filed on 2 June 2021 expresses the form in which declaratory relief is sought as follows:

1. A declaration that, upon the proper construction of clause 13.1(b) of the NSW Trains Enterprise Agreement 2018 (the Enterprise Agreement), by seeking to implement and implementing the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet described in Annexure A, the Applicant will not thereby be making a claim falling within the description “no extra claims for any changes in remuneration or conditions of employment” for the purposes of clause 13.1(b) of the Enterprise Agreement.

2. A declaration that, upon the proper construction of clause 13.1(b) of the Enterprise Agreement, by seeking to implement and implementing the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet described in Annexure A, the Applicant will not thereby be making a claim falling within the scope of clause 13.1(b) of the Enterprise Agreement, with the result that clauses 12.4 to 12.5 of the Enterprise Agreement are not engaged, and have no application.

3. A declaration that, upon the proper construction of clause 13.1(c) of the Enterprise Agreement, by seeking to implement and implementing the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet described in paragraph 30, the Applicant will not thereby impact upon the existing rates of pay and conditions of employment under the Enterprise Agreement of the train drivers and guards who will work on the Mariyung Fleet, including the Second Respondent and the Third Respondent, within the meaning of clause 13.1(c) of the Enterprise Agreement, with the result that clauses 12.4 to 12.5 of the Enterprise Agreement are not engaged, and have no application.

4. A declaration that:

(a) upon the accreditation by the Office of National Rail Safety Regulator of the Applicant in respect of the operation of the Mariyung Fleet in accordance with the operational features described in Annexure A, a direction by the Applicant to the Second Respondent to perform duties as a train driver on the Mariyung Fleet in accordance with those operational features is a lawful and reasonable direction, and the Second Respondent must follow that direction; and

(b) in the event that the Second Respondent fails or refuses to follow such a direction, the Second Respondent will have breached his contract of employment, and engaged in industrial action within the meaning of section 19(1)(b) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), unless one of the circumstances in section 19(2) applies.

5. A declaration that:

(a) upon the accreditation by the Office of National Rail Safety Regulator of the Applicant in respect of the operation of the Mariyung Fleet in accordance with the operational features described in Annexure A, a direction by the Applicant to the Third Respondent to perform duties as a guard on the Mariyung Fleet in accordance with those operational features is a lawful and reasonable direction, and the Third Respondent must follow that direction; and

(b) in the event that the Third Respondent fails or refuses to follow such a direction, the Third Respondent will have breached his contract of employment, and engaged in industrial action within the meaning of section 19(1)(b) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), unless one of the circumstances in section 19(2) applies.

6. In the alternative to orders 1, 2 and 3 above, a declaration that upon the proper construction of clause 13.1 of the Enterprise Agreement, by the Applicant making a claim seeking to implement and implementing the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet described in Annexure A is not a claim made within the “life” of the Enterprise Agreement, in that any such claim has been made by NSW Trains after the nominal expiry date of the Enterprise Agreement, and is not thereby prevented by clause 13.1 from implementing the operational features of the Mariyung Fleet set out in Annexure A.

7. In the alternative to order 6, clause 13.1 of the Enterprise Agreement is invalid and of no effect if and to the extent it purports to prevent or restrict the Applicant from making any new claims on or after the nominal expiry date specified in clause 6.1 (being 30 April 2021 or 1 May 2021), because it is contrary to, and seeks impermissibly to outflank, the statutory scheme of Part 2-4 Division 3 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) for the making of new claims by employers once an applicable enterprise agreement (such as the Enterprise Agreement) has passed its nominal expiry date.

8. A declaration that the whole of clause 12 of the Enterprise Agreement has no effect under section 253(1)(a) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) to the extent that it requires in principle agreement from the First Respondent or other relevant unions to implement changes described in clauses 12.1(a) and (b), because it is not a term about a permitted matter described in section 172(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

The 2018 Agreement & principles of interpretation

39 The 2018 Agreement is a lengthy document of some 86 pages and comprising some 128 clauses.

40 The Agreement was approved by the Fair Work Commission on 24 April 2018: NSW Trains [2018] FWCA 2319. Paragraph [10] of the Commission’s decision states that in “accordance with subsection 54(1) of the Act it will operate from 1 May 2018. The nominal expiry date of the Agreement as specified in clause 6.1 of the Agreement, is 1 May 2021.”

41 Some of the provisions which assume relevance to one or other of the submissions advanced in the present proceeding include the following.

42 The Objectives of the Agreement are thus expressed as follows:

2. OBJECTIVES OF THE PARTIES TO THIS AGREEMENT

2.1. The following are the objectives of this Agreement. They form a guide for the parties should there be a dispute relating to the interpretation of a clause or clauses within this Agreement.

2.2. To provide a mechanism for ongoing change, where required, in order for the Employer to meet its strategic objectives of a safe, reliable, efficient, financially responsible and customer focused service.

2.3. To recognise safety as a fundamental contributor to successful operations and to ensure that employment conditions and practices provide a framework within which the Employer can achieve a safe environment.

2.4. To commit to reform, continuous improvement and to promote a culture of continuous improvement, benchmarking and learning.

…

43 Consistent with the approval of the Agreement by the Commission in April 2018, cl 6 is in the following terms:

6. NOMINAL TERM OF THIS AGREEMENT

6.1. This Agreement will come into effect 7 days after the Agreement is approved by the Fair Work Commission and will remain in force for three years.

There is no other clause which addresses the duration of the Agreement as a whole.

44 Clause 7 of the 2018 Agreement addresses the Consultative Process envisaged by the Agreement and provides (in part) as follows:

…

7.2. Issues subject to consultation

Issues subject to consultation may include, but are not limited to the following:

(a) changes in the composition, operation, location or size of the workforce, or in the duties and skills required; the elimination or reduction of job opportunities;

(b) alterations to hours of work;

(c) the restructuring of jobs and the consequent need for retraining, training, transfer, or secondment of Employees to other work;

(d) changes to classification structures or position descriptions applying to a job or jobs; and

(e) changes to the operational structure of the Employer.

7.3. Consultative Arrangements

The Employer will consult with Employees when there is a proposed change that will impact upon the working arrangements of the Employees. Consultation shall be conducted in good faith with reasonable time for the Employees, Union(s) and their members to respond to the proposed changes.

When a change is proposed that will impact upon the working arrangements of Employees, the Employer will communicate the proposed change to the affected Employees and Employee Representatives.

7.4. Unresolved matters

Where matters cannot be resolved through the consultative process the dispute will be dealt with in accordance with the Dispute Settlement Procedure at Clause 8 of this Agreement.

45 Clause 8 addresses the “Dispute Resolution Procedure” envisaged by the Agreement and provides in relevant part as follows:

8. DISPUTE SETTLEMENT PROCEDURE (DSP)

8.1. The purpose of this procedure is to ensure that disputes are resolved as quickly and as close to the source of the issue as possible. This procedure requires that there is a resolution to disputes and that while the procedure is being followed, work continues normally.

8.2. This procedure shall apply to any dispute that arises about the following:

(a) matters pertaining to the relationship between the Employer and the Employees (including workload matters);

(b) matters pertaining to the relationship between the Employer and the Employee organisation(s), which also pertain to the Agreement and/or the relationship between the Employer and Employees;

(c) deductions from wages for any purpose authorised by an Employee who will be covered by the Agreement;

(d) the National Employment Standards; and

(e) the operation and application of this Agreement.

…

8.4. Any dispute between the Employer and Employee(s) or the Employee’s Representative shall be resolved according to the following steps:

STEP 1: Where a dispute arises it shall be raised in the first instance by the Employee(s) or their Union delegate directly with the local supervisor/manager. The local supervisor/manager shall provide a written response to the Employee(s) or their Union delegate concerning the dispute within 48 hours advising them of the action being taken. The status quo before the emergence of the dispute shall continue whilst the dispute settlement procedure is being followed. For this purpose “status quo” means the work procedures and practices in place immediately prior to the change that gave rise to the dispute.

…

STEP 4: If the dispute remains unresolved any party may refer the matter to the Fair Work Commission for conciliation. If conciliation does not resolve the dispute the matter shall be arbitrated by the Fair Work Commission provided that arbitration is limited to disputes that involve matters listed in sub-clause 8.2 of this procedure.

…

46 Clause 12 of that Agreement provides in relevant part as follows:

12. FACILITATION OF CHANGES TO THE TERMS OF THIS AGREEMENT

The parties acknowledge that continuous improvement, the acceptance of ongoing change and commitment to safety are fundamental to the success of NSW Trains. Associated with NSW Trains’ continuous improvement program and commitment to best practice, changes in technology, organisational structures and work practices will occur. The following provisions will facilitate such changes to the operation of the terms of this Agreement as specified in this clause following a ballot of affected Employees who will share the benefits of agreed changes.

12.1. Train Crew

(a) Notwithstanding the other terms of this Agreement, prior to the nominal expiry date of this Agreement, the Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union and the Employer may agree in principle to implement changes for Train Crew (as defined in clause 100) (Affected Employees) to the operation of:

(i) clause 24;

(ii) clauses 99 to 128 of Section 4 and Schedules 4A and 4B inclusive; and

(iii) the conditions of employment (as defined in clause 13.1(d)) contained within the Drivers Rostering and Working Arrangements (including the Overtime Bonus) (DRWA), Guards Rostering and Working Arrangements (GRWA), Stable Rostering Code and Drivers Depot Transfers and Roster Placement Policy / Procedure.

(b) The changes may include changes to working arrangements, conditions and payments and will be compensated for by the epayment of additional remuneration.

(c) The additional remuneration for changes cited in 12.1(a) may include:

(i) an aggregate payment in lieu of currently specified payments;

(ii) compensation for changes or variations to the operation of clauses and/or conditions of employment; and/or

(iii) Payment in recognition of employee related cost savings delivered by changes or variations to the operation of clauses and/or conditions of employment.

(d) Where agreement in principle is reached with any classification of Affected Employees, e.g. Drivers or Guards, clause 12.5 will apply. Any clause of this Agreement or in the DRWA, GRWA, Stable Rostering Code and/or Drivers Depot Transfer and Roster Placement Policy/Procedure the operation of which is changed in accordance with this sub-clause or for which a payment is made in accordance witrh this sub-clause will cease to apply to Affected Employees upon commencement of an Agreement approved in accordance with sub-clause 12.5. Any additional remuneration will be paid to Affected Employees in accordance with clauses 12.5(f) and (g).

…

47 Clause 13 of that Agreement provides in relevant part as follows:

13. NO EXTRA CLAIMS OTHER THAN IN ACCORDANCE WITH THIS AGREEMENT

13.1 This clause is subject to the right to a variation of this Agreement in accordance with Part 2-4 Division 7 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). This Agreement covers the field. During the life of this Agreement the parties:

(a) will continue to recognise the Employer’s managerial prerogative to propose and implement change in compliance with this Agreement;

(b) except in accordance with the terms of Clause 12, shall make no extra claims for any changes in remuneration or conditions of employment;

(c) agree that where any change proposed in Clause 12 above impacts upon Employees’ existing rates of pay and/or conditions of employment under this Agreement, then it will not only be implemented in accordance with the consultation and voting process included in Clause 12 of this Agreement.;

(d) for Train Crew it is recognised that “conditions of employment” includes current:

…

48 The manner in which such provisions of an enterprise agreement and other industrial instruments are to be construed is well-settled. Thus, in an oft-cited summary of principles, Madgwick J in Kucks v CSR Ltd (1996) 66 IR 182 at 184 observed:

Legal principles

It is trite that narrow or pedantic approaches to the interpretation of an award are misplaced. The search is for the meaning intended by the framer(s) of the document, bearing in mind that such framer(s) were likely of a practical bent of mind: they may well have been more concerned with expressing an intention in ways likely to have been understood in the context of the relevant industry and industrial relations environment than with legal niceties or jargon. Thus, for example, it is justifiable to read the award to give effect to its evident purposes, having regard to such context, despite mere inconsistencies or infelicities of expression which might tend to some other reading. And meanings which avoid inconvenience or injustice may reasonably be strained for. For reasons such as these, expressions which have been held in the case of other instruments to have been used to mean particular things may sensibly and properly be held to mean something else in the document at hand.

But the task remains one of interpreting a document produced by another or others. A court is not free to give effect to some anteriorly derived notion of what would be fair or just, regardless of what has been written into the award. Deciding what an existing award means is a process quite different from deciding, as an arbitral body does, what might fairly be put into an award. So, for example, ordinary or well-understood words are in general to be accorded their ordinary or usual meaning.

49 These observations were later cited with approval by Tracey J in Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Linfox Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 829, (2014) 318 ALR 54 at 58 (“TWU v Linfox”). His Honour there went on to further elaborate upon the principles of construing industrial instruments as follows (at 59):

[34] Guidance as to the construction of industrial instruments may also be obtained by reference to principles which courts apply to the construction of commercial contracts. Commercial contracts should, as Kirby J held in Pan Foods Company Importers & Distributors Pty Ltd v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (2000) 170 ALR 579; [2020] HCA 20 at [24] “be construed practically, so as to give effect to their presumed commercial purposes and so as not to defeat the achievement of such purposes by an excessively narrow and artificially restricted construction.” An interpretation which accords with business common sense will be preferred to one which does not: see Upper Hunter County District Council v Australian Chilling and Freezing Co Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 429 at 437.

In Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1009, (2016) 262 IR 176 at 189 to 190 (“BHP Coal Pty Ltd”) Logan J endorsed these principles and continued:

[32] There was no dispute between the parties as to the general principles applicable to the construction of industrial awards and agreements. In Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Linfox Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 318 ALR 54 (TWU v Linfox) at [29]-[41] Tracey J offered a comprehensive summary of those principles. I respectfully adopt that summary without separately reproducing it. It is a feature of the authorities discussed in that summary that it has been acknowledged that guidance as to the construction of industrial instruments may also be obtained by reference to principles which courts apply to the construction of commercial contracts.

[33] One such principle, and it is highlighted in the summary in TWU v Linfox, is that an interpretation which accords with business common sense will be preferred to one which does not: see Upper Hunter County District Council v Australian Chilling & Freezing Co Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 429 at 437. …

50 The provisions of an enterprise agreement are, moreover, to be construed by reference to the industrial context out of which they emerged and are not to be construed in a vacuum divorced from industrial realities: Workpac Pty Ltd v Skene [2018] FCAFC 131, (2018) 264 FCR 536. The Full Court there summarised the approach as follows (at 580):

[197] The starting point for interpretation of an enterprise agreement is the ordinary meaning of the words, read as a whole and in context: City of Wanneroo v Holmes (1989) 30 IR 362 (Holmes) at 378 (French J). The interpretation “turns on the language of the particular agreement, understood in the light of its industrial context and purpose”: Amcor Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2005) 222 CLR 241 (Amcor) at [2] (Gleeson CJ and McHugh J). The words are not to be interpreted in a vacuum divorced from industrial realities (Holmes at 378); rather, industrial agreements are made for various industries in the light of the customs and working conditions of each, and they are frequently couched in terms intelligible to the parties but without the careful attention to form and draftsmanship that one expects to find in an Act of Parliament (Holmes at 378-379, citing George A Bond & Company Ltd (in liq) v McKenzie [1929] AR (NSW) 498 at 503 (Street J)). To similar effect, it has been said that the framers of such documents were likely of a “practical bent of mind” and may well have been more concerned with expressing an intention in a way likely to be understood in the relevant industry rather than with legal niceties and jargon, so that a purposive approach to interpretation is appropriate and a narrow or pedantic approach is misplaced: see Kucks v CSR Ltd (1996) 66 IR 182 at 184 (Madgwick J); Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Woolworths SA Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 67 at [16] (Marshall, Tracey and Flick JJ); Amcor at [96] (Kirby J).

See also: National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2020] FCA 1709 at [124], (2020) 302 IR 272 at 322 to 323 per Thawley J.

THE 2018 AGREEMENT – SECTION 54 & THE NOMINAL EXPIRY DATE

51 If the provisions of the 2018 Agreement be presently left to one side, s 54 of the Fair Work Act addresses “when an enterprise agreement is in operation”. That section provides as follows:

When an enterprise agreement is in operation

(1) An enterprise agreement approved by the FWC operates from:

(a) 7 days after the agreement is approved; or

(b) if a later day is specified in the agreement – that later day.

(2) An enterprise agreement ceases to operate on the earlier of the following days:

(a) the day on which a termination of the agreement comes into operation under section 224 or 227;

(b) the day on which section 58 first has the effect that there is no employee to whom the agreement applies.

The continued “operation” of an enterprise agreement after the expiration of its “nominal expiry date” was not put in dispute. Nor could it be. Section 224, for example, expressly identifies those circumstances in which the “termination” of an enterprise agreement comes into operation, namely if termination is approved under s 223. So, too, does s 227 expressly identify as the date of termination the date upon which an enterprise agreement is terminated under s 226. Both ss 223 and 226 refer to the need for the Fair Work Commission to consider the views of employees. Section 223(c) thus refers to the Commission being “satisfied that there are no other reasonable grounds for believing that the employees have not agreed to the termination”. Section 226(b)(i) directs the Commission to a consideration as to whether “it is appropriate to terminate the agreement taking into account … the views of the employees…”

52 Section 54 should also be read together with s 52 of the Fair Work Act which provides (in relevant part) as follows:

When an enterprise agreement applies to an employer, employee or employee organisation

When an enterprise agreement applies to an employee, employer or organisation

(1) An enterprise agreement applies to an employee, employer or employee organisation if:

(a) the agreement is in operation; and

(b) the agreement covers the employee, employer or organisation; and

(c) no other provision of this Act provides, or has the effect, that the agreement does not apply to the employee, employer or organisation.

…

Read together, an enterprise agreement “applies to” an employee whilst it is “in operation”: National Tertiary Education Industry Union v Swinburne University of Technology [2014] FCA 606 at [18] per Mortimer J.

53 With reference to s 54 and the term “operates”, Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ in ALDI Foods Pty Limited v Shop Distributive and Allied Employees Association [2017] HCA 53, (2017) 262 CLR 593 at 605 (“ALDI Foods”) have observed:

[34] An enterprise agreement comes into operation in the sense of creating rights and obligations between an employer and employees in relation to the work performed under it only after it has been approved by the Commission. After that time the agreement applies to the employers and employees who are covered by it. …

54 But for any provision in the 2018 Agreement, s 54 thus provides that it continues to “operate”. Section 54(2) is unequivocal in its terms as to when an enterprise agreement “ceases” – namely upon the happening of one or other of the events specified in s 54(2)(a) or (b), and neither of those events has happened in the present case.

55 Notwithstanding the terms of s 54, NSW Trains places at the forefront of its submissions its contention that cl 13 of the 2018 Agreement has come to an end. If this be correct, it would thereafter be unnecessary to resolve NSW Trains’ other submissions that:

the directions proposed to be given to its drivers and guards would not constitute the making of an “extra claim”; or

cl 13.1 is invalid or void because of inconsistency with or repugnancy with Part 2-4 of the Fair Work Act.

56 No party has sought to approach the Commission with a view to terminating the 2018 Agreement. NSW Trains is (presumably) firm in its commitment that it may give its proposed directions to its drivers and guards free from (for example) the operation of cl 13.1(b) of the 2018 Agreement and hence there being no necessity on its part to terminate that Agreement; the Respondents being equally firm in their commitment that the 2018 Agreement continues to relevantly place constraints upon the unilateral power sought to be exercised by NSW Trains. Whatever be the reasons motivating the parties to the present dispute, no application has been made to the Commission to terminate the existing Agreement.

57 Contrary to the submission of NSW Trains, it has been concluded that cl 13.1 of the 2018 Agreement has not come to an end. It has been concluded that, in accordance with s 54, that that clause continues to “operate”.

The life of this agreement v the nominal expiry date?

58 If the focus is turned to the provisions of the 2018 Agreement, there are a number of clauses which direct attention to those points of time at which the Agreement itself or provisions within the Agreement come to an end, namely:

cl 6.1 which specifies that the Agreement “will remain in force for three years” from 7 days after it was approved by the Commission on 24 April 2018;

cl 12.1(a), 12.2 and 12.3 which refer to “prior to the nominal expiry date of this Agreement”; and

cl 13.1 which refers to “[d]uring the life of this Agreement”.

Clause 12 addresses what is referred to as “Facilitation of Changes to the Terms of this Agreement”; cl 13 addresses what is referred to as “No Extra Claims Other Than in Accordance with this Agreement”.

59 The use of two different phrases in clauses 12 and 13 would, at least initially, suggest that each phrase has a separate and discrete meaning.

60 Clause 13.1(b) of the 2018 Agreement provides (albeit in part) that “[d]uring the life of this Agreement the parties … except in accordance with Clause 12, shall make no extra claims for any changes in remuneration or conditions of employment”.

61 On its proper construction, it is concluded that the 2018 Agreement and cl 13.1(b) continue to “operate” by reason of s 54 of the Fair Work Act. It continues to create “rights and obligations between an employer and employees…”: cf. ALDI Foods [2017] HCA 53 at [34], (2017) 262 CLR at 605. Unlike cl 12, which defines the ambit of its operation to a period “prior to the nominal expiry date” of the Agreement, the use of the different phrase in cl 13 manifests an intention that that clause continues to “operate” so long as the Agreement itself continues to “operate”. The “life of the Agreement” is a period fixed – not by reference to the nominal expiry date – but by reference to the period during which the Agreement “operates”.

62 To be distinguished, by reason of the terms of the agreement there in issue, is the decision in Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Ltd v Marmara [2014] FCAFC 84, (2014) 222 FCR 152 at 171. By reference to the terms of the agreement there in issue, Jessup, Tracey and Perram JJ concluded:

[58] Here we note what is common ground, namely, that the expression “the end of this agreement” in clause 4 of the Agreement is to be understood in the sense “the nominal expiry date of this agreement”. When the clause is so understood, it is correct, as Toyota stressed, that the operation of the prohibition in clause 4 is co-terminous with the period during which industrial action could not be taken in support of claims for the acceptance of the proposals for variation made by Toyota on 11 and 15 November 2013. By a combination of ss 19(1)(d) and (3) and 417(1) and (2) of the FW Act, Toyota could not, in November 2013, have prevented its employees from performing work under their contracts of employment without terminating those contracts. Further, any suggestion of dismissing or otherwise disadvantaging those employees on account of their refusal to accede to the proposals would seem to be ruled out by the provisions of Div 3 of Pt 3-1 of the FW Act. …

63 The phrase “[d]uring the life of this Agreement” as employed in cl 13.1 of the 2018 Agreement is construed to mean something other than “prior to the nominal expiry date of this Agreement”. The latter phrase is, with respect, unambiguous in its terms – the Agreement itself expressly specifies the “nominal expiry date”. In contrast to a date set by reference to the “nominal expiry date”, the phrase “[d]uring the life of this Agreement” lacks the same degree of certainty. But such limited uncertainty as remains does not strip it of meaning. Albeit unspecified by date, the 2018 Agreement continues to operate until it is terminated. To that extent, at least, there is certainty as to the duration of cl 13.1.

64 The two phrases in cll 12 and 13 manifest an intent on the part of the drafter of the Agreement to identify two separate dates. The very juxtaposition of cll 12 and 13 in consecutive provisions in the 2018 Agreement and the incorporation of cl 12 into the text of cl 13.1(b) only serve to underline the conclusion that the two different expressions of time have different, and intentionally different, meanings – one being “prior to the nominal expiry date” and the other being “during the life of this agreement”.

65 Ritual incantation as to “industrial or commercial sense” or the “presumed intention of the bargaining representatives” when negotiating the 2018 Agreement take the argument, with respect, little further. In the absence of other considerations, there is no more compelling reason to presume that the “intention” of the parties was as asserted by NSW Trains rather than such “intention” as could be distilled from the fact that a different phrase is employed in cl 12 from that in cl 13. It is reference to the terms actually employed in cll 12 and 13 which provides the sounder reason for rejecting the submission of NSW Trains, rather than reference to an ill-defined “presumed” intention.

66 So, too, with assertions as to what would make “industrial or commercial sense”. But reference to the purpose sought to be achieved by a particular provision may assist in making some assessment as to what would make “industrial or commercial sense”: e.g., Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Hail Creek Coal Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 149. In departing from the assessment of the primary Judge as to what would make “industrial or commercial” sense, Jessup, Rangiah and White JJ there concluded:

[21] The primary Judge said that he was fortified in rejecting the construction promoted by the appellant “by reflecting upon whether that construction would make industrial or commercial sense”. After putting to one side, in effect, comparisons with other agreements in the mining industry proffered by the appellant, his Honour said that a construction of cl 13.7 that would give rise to an entitlement to take unlimited sick leave even a very limited time after the employee concerned had commenced his or her employment was not “a sensible industrial or commercial construction”. It escaped his Honour how, if such a construction were correct, a company director, faced with the responsibilities that fall on directors under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“the Corporations Act”), could ever make proper provision for sick leave contingencies in the relevant accounts. By contrast, if the entitlement were limited as proposed by the respondent, it was “readily possible to see how … prudent provision in corporate accounts could be made.”

Construing an industrial agreement in a manner which “accords with business common sense” is, it may be accepted, an established principle of construction: TWU v Linfox [2014] FCA 829 at [34], (2019) 318 ALR at 58 per Tracey J; BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1009 at [32] to [33], (2016) 262 IR at 189-190 per Logan J.

67 In the present context, just as cl 7.4 of the 2018 Agreement contemplates that there may be “unresolved matters” which may need to be resolved by means of the cl 8 “Dispute Resolution Procedure”, it is not inconsistent with “industrial and commercial sense” to conclude that “extra claims” may be such a matter that remains “unresolved”. If anything, the “presumed intention” of the parties and “business common sense” are both consistent with a conclusion that those negotiating the 2018 Agreement were familiar with s 54 of the Fair Work Act.

CLAUSE 13 – EXTRA CLAIMS & INVALIDITY

68 The conclusion that the 2018 Agreement continues to “operate” – including the continued operation of cl 13 – necessarily requires a resolution of NSW Trains’ other submissions that:

the decision of the Fair Work Commission is no impediment to this Court now granting appropriate declaratory relief; and

the directions proposed to be given to its drivers and guards would not constitute the making of an “extra claim”.

And, even if these submissions be rejected, NSW Trains further submits that:

cl 13.1 is in any event invalid.

69 In respect to these issues, it has been concluded that:

NSW Trains is bound by the March 2021 decision of the Full Bench of the Fair Work Commission, and cannot now seek to re-litigate either the question as to whether it would be making “extra claims” upon its drivers and guards, or the question as to whether cl 13 is inconsistent with Part 2-4 of the Fair Work Act.

Even if it were permitted to do so, it has been further concluded that:

its proposed directions to drivers and guards would be the making of an “extra claim”; and

cl 13 is not invalid by reason of Part 2-4 of the Fair Work Act.

The decisions of the Fair Work Commission

70 Prior to the publication in November 2019 by NSW Trains of its Guide to the New Intercity Fleet, there were meetings between NSW Trains and the Union with a view to resolving the question as to whether it could give the proposed direction to its drivers and guards. Agreement was not reached.

71 In January 2020 the Union thus filed with the Fair Work Commission an Application for the Commission to deal with a dispute in accordance with a dispute settlement procedure. That Application identified the “dispute” (in relevant part) as follows:

2. About the dispute

2.1 What is the dispute about?

…

1. The dispute relates to the imminent introduction by NSW Trains of a new fleet of trains, described as the New Intercity Fleet. These trains will operate on current routes.

2. As part of the rollout, NSW Trains is purporting to introduce changes which will have significant effects on staff employed in Driver Thereafter and Guard classifications under the NSW Trains Enterprise Agreement 2018 (the Agreement), discussed in detail below.

3. On 28 November 2019, NSW Trains distributed a booklet to its employees announcing these changes entitled “Your Guide to the New Intercity Fleet” (NIF Booklet). A copy of the NIF Booklet is annexed and marked ‘A’.

4. NSW Trains has not consulted, and does not propose to consult, with staff or the ARTBIU about these proposed changes.

Changes affecting Drivers

5. In respect of affected drivers, NSW Trains proposes to:

a. create a new classification of ‘Intercity Specialist Driver’, which does not currently exist in the Agreement,

b. ‘reclassify’ staff employed in the classification of Driver Thereafter in Schedule 4A of the Agreement as ‘Intercity Specialist Drivers’,

c. pay persons classified as ‘Intercity Specialist Drivers’ 4% above the wage rates prescribed for the Driver Thereafter classification, and

d. require ‘Intercity Specialist Drivers’ to perform a range of additional duties, including those usually performed by Guards or Customer Service Attendants such as providing boarding assistance.

6. In addition, there will be changes to the Transfer and Roster Placement Policy.

7. The ARTIBU contends that the proposed changes:

a. inadequately remunerate Drivers for the value of the work proposed to be performed; and

b. include inappropriate job duties leading to an unsafe working environment.

Changes affecting Guards

8. In respect of affected Guards, it appears that NSW Trains proposes to:

a. no longer employ any person in the Guard classification in the New Intercity Fleet, leading to a number of Guard positions being redundant;

b. create a new classification of ‘Customer Service Guard’, which does not currently exist in the Agreement, which will:

i. have a pay rate of 12% less than the Guard classification,

ii. remove access to the Guard Rostering and Working Arrangements and kilometerage entitlements under the Agreement, and

iii. incorporate duties usually performed by Customer Service Guards;

c. give displaced staff employed as Guards the option of:

i. retraining and redeploying into the Customer Service Guard position, with their current conditions grandfathered until the expiry of the Agreement; or

ii. accepting ‘voluntary’ redundancy.

9. The ARTIBU contends that the proposed changes:

a. inadequately remunerate Guards for the value of the work proposed to be performed; and

b. include inappropriate job duties leading to an unsafe working environment.

…

72 A Deputy President of the Commission resolved that “dispute” in August 2020: Re Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union v NSW Trains [2020] FWC 4359. An application was then made for permission to appeal from that decision to the Full Bench of the Commission. The Full Bench published its reasons for decision in March 2021: Re Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union v NSW Trains [2021] FWCFB 1113.

73 As stated by the Full Bench, the Deputy President sought to resolve three questions, namely:

1. Does Clause 12 of the NSW Trains Enterprise Agreement 2018 prevent NSW Trains from implementing its proposals in respect to the New InterCity Fleet, unless there is an in-principle agreement with the Union?

2. Is NSW Trains’ proposal an extra claim not permitted by Clause 13?

3. Have the provisions of the Consultation Clause (Clause 7), requiring arbitration as to the merits of the proposal, been completed?

The Full Bench concluded that “permission” to appeal should be granted. The grounds of appeal, as summarised by the Full Bench, asserted that the Deputy President erred in:

a) his interpretation of clauses 12, 13 and 7;

b) finding, as a matter of fact, that the Change was not contemplated by cl.12;

c) finding, as a matter of fact, that the Change was not an extra claim within the meaning of cl.13;

d) finding, as a matter of fact, that NSW Trains had met the consultation obligations under the Agreement;

e) finding that the Change could be introduced while matters remained in dispute which had not been resolved in accordance with the dispute resolution process; and

f) otherwise that NSW Trains could introduce the Change.

Grounds (a) to (c), (e) and (f) were upheld and the decision of the Deputy President was quashed.

74 In concluding that NSW Trains was seeking to make “extra claims” upon its drivers and guards and in concluding that no issue of “repugnancy” arose by reason of the consultation process provided for in cl 12 of the 2018 Agreement, the Full Bench reasoned as follows:

[14] The approach of the Deputy President was to consider Clause 13 through the lens of Clause 12 and what he understood to be a submission advanced by the Respondent that Clause 12.5 of the Agreement was repugnant to the variation of Agreement provisions in Part 2-4- Division 7 of the Act.

[15] As to the issue of repugnancy, we observe that before us there was no dispute between the parties that because Clause 13.1 is subject to the right to a variation of the Agreement in accordance with Part 2-4, Division 7 of the Act, no issue of repugnancy arises. We agree and to the extent he found otherwise, the Deputy President erred.

[16] As to Clause 13, we note the Full Court of the Federal Court in Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Ltd v Marmara & Ors [(2014) 222 FCR 152] (Marmara) accepted the proposition that a no extra claims clause is fundamental in the context of an Agreement, in that it delivers stability and predictability in the matter of the terms and conditions of employment ((2014) 222 FCR at 174). The statement within Clause 13.1 of the Agreement that it covers the field indicates it is the intention of the parties that the terms of the Agreement comprehensively outline the terms and conditions of employment for its duration, with changes in remuneration or conditions of employment only permitted through the variation process in the Act or Clause 12. The language is broad and does not limit changes to those that might be made to the text or terms of the agreement.