Federal Court of Australia

Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Qantas Airways Limited [2021] FCA 873

Table of Corrections | |

The reference to “ASOC [40.3A]” be amended to read “ASOC [44A]” |

ORDERS

TRANSPORT WORKERS' UNION OF AUSTRALIA Applicant | ||

AND: | QANTAS AIRWAYS LTD (ACN 009 661 901) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 July 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The claims for relief in terms of prayers 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8 of the amended originating application filed 31 December 2020 be dismissed.

2. The proceeding be adjourned to a case management hearing at 9:30am on 4 August 2021.

3. By 4pm on 3 August 2021, the parties provide to the Associate to Justice Lee agreed (or failing agreement, competing) short of minutes of order proposing a form a declaration to reflect these reasons and detailing the interlocutory steps necessary to ready the claims for relief identified in prayers 2A, 3 and 4 to be determined (to the extent all that relief continues to be sought).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[16] | |

[16] | |

[24] | |

[30] | |

[31] | |

[32] | |

[32] | |

[37] | |

[40] | |

[42] | |

[43] | |

[44] | |

The Scope of the Rule in Browne v Dunn and its Present Application | [49] |

C.6 Qantas’ Witnesses, their Role and their Credit Generally | [57] |

[59] | |

[70] | |

[77] | |

[80] | |

[87] | |

[93] | |

[94] | |

[96] | |

[113] | |

[148] | |

[161] | |

[190] | |

[203] | |

[203] | |

[206] | |

“Substantial and operative factor” and more on the “reverse onus” | [218] |

[240] | |

[241] | |

[253] | |

[259] | |

[260] | |

[282] | |

[306] | |

[311] |

LEE J:

a THE CASE IN GENERAL AND A PLEADING ISSUE

1 Despite some public statements to the contrary, this is not a test case about the industrial phenomenon of “outsourcing”; nor indeed is it a test case about anything at all.

2 Rather, this case resolves a fact specific controversy arising from a decision made late last year by Qantas Airways Limited (Qantas Airways) to outsource ground handling operations work at ten Australian airports to a number of third party ground handling companies (outsourcing decision). The outsourcing decision is the subject of challenge by the Transport Workers’ Union (Union), on behalf of a number of its members who are employed by Qantas Airways and Qantas Ground Services Pty Limited (QGS and together Qantas), being employees who previously provided those ground handling operations.

3 By the time of final submissions, the contention of the Union, in broad terms, was that Qantas embraced the approach of “never letting a good crisis go to waste”. The Union alleges that at the beginning of 2020, Qantas was antipathetic to the industrial influence of the Union. The COVID-19 pandemic, which struck at a time when the Union was unable to take protected industrial action, provided a vanishing window of opportunity for Qantas to rid itself of the influence of the Union and the exercise of workplace rights by its members by outsourcing a large number of jobs performed by its members. In this sense, the dark clouds that gathered in 2020 presented a glimmer of opportunity. The perceived financial benefits of outsourcing (which until the pandemic had not been pursued because of the risk of operational disruption), became for the first time feasible and Qantas, at the level of its group management committee (GMC), seized its perceived opportunity while it lasted. Alternatively, it is contended that if the GMC did not make or contribute to the relevant decision to outsource, various executives of Qantas perceived the benefits of outsourcing and either made, or materially contributed to, the decision for a prohibited reason.

4 The contention of Qantas is, as one might expect, quite different. By the beginning of 2020, there was no suggestion Qantas would transform its ground handling operations at the relevant ten ports (as reflected in the fact it had resolved to make the necessary and significant capital expenditure to allow that work to continue to be undertaken by employees). The pandemic had a devastating and wholly unprecedented impact upon Qantas’ operations and revenues. A recovery plan was fastened upon by Qantas, which was relevantly directed to the imperatives of reducing operating costs; increasing variability in its cost base, and minimising capital expenditure. Out of a range of remedial steps implemented to achieve these ends, the option of outsourcing of all remaining ground operations was assessed, was recommended, and was then adopted following a long process, because it fulfilled the imperatives of the recovery plan. Risks (including industrial risks) were necessarily considered in assessing this proposed course, along with other considerations, but no prohibited reason informed the outsourcing decision in whole or part.

5 It is inaccurate to say that this case is essentially about which of these narratives is made out on the evidence, but these characterisations represent, at a very high level, the “case theories” advanced by each party.

6 At first glance, it appears the case is a straightforward one. Given the pleaded controversy relates to one decision made by one man, it might be thought to turn simply upon whether the evidence given as to the outsourcing decision on 30 November 2020 by Mr Andrew David, the Chief Executive Officer, Qantas Domestic and International, should be accepted. I do find below that Mr David was the relevant decision maker and, for reasons that will become evident, my failure to reach a level of satisfaction in relation to one aspect of his evidence has turned out to be determinative. But notwithstanding this, the fact-finding task does have some degree of complexity. Mr David’s evidence is necessarily to be assessed contextually and, importantly, his actions were not made in a vacuum. His evidence as to the outsourcing decision cannot be assessed as though the final step in decision making can be divorced from what preceded it. The circumstances leading up to the impugned decision are contextually important, and are examined in considerable detail below.

7 Qantas, sensibly, did not suggest the outsourcing decision on 30 November 2020 could be placed in some sort of hermetically sealed box, but a controversy did emerge as to the reliance by the Union on dealings between the GMC and Mr David and those with whom he primarily worked in the Australian Airports business of Qantas. The dealings with the GMC in particular assumed an importance in the Union’s case, which would not have been evident from a review of the pleadings, and this has created a dispute as to the permissible scope of the Union’s case. Before going further, it is necessary to explain and resolve this dispute which, like most pleading disputes, is about procedural fairness.

8 In its final submissions of 30 April 2021 (UFS1), the Union asked the Court to find that on 5 August 2020 (see USF1 [7(b)], [88] and [117]), the GMC made “the practical decision” to proceed with a proposal for outsourcing being a proposal which “effectively resulted” in the outsourcing decision or, put another way, that “the reality of events” was that the outsourcing decision was made when the proposal to outsource was fastened upon by the GMC: UFS1 [7(a)], [56] and [59].

9 Qantas contends that this case is not open to be advanced. This submission should be accepted.

10 The case pleaded in the amended statement of claim filed on 31 December 2020 (ASOC) contends that there were two relevant decisions: the first was a decision to proceed with an outsourcing proposal, announced on 25 August 2020 (ASOC [15]–[18]); this decision was “for the purpose of initiating a process that would lead to the termination of the employment of the Affected Employees” (ASOC [18A]) (outsourcing proposal decision); the second was what was described as a “definite decision to outsource” (ASOC [29]–[30]) made on 30 November 2020, being what I have defined above (at [2]), as the “outsourcing decision”.

11 In its final submissions of 5 May 2020 (QFS1), Qantas accepted that during the course of the trial and up until final submissions, the Union’s case was that the outsourcing decision “was the culmination of a two-stage decision making process that went for some months”: QFS1 [26]. It further accepted the Union’s case to be that because the outsourcing proposal decision was a “precursor decision in that process”, the reasons for the earlier decision were relevant to understanding the real reasons for the subsequent “definite decision” (being the outsourcing decision made on 30 November 2020).

12 There is also no contest that the Union ran a case that Mr David was not the sole decision maker having regard to the involvement of other persons (most notably, the GMC) at earlier stages in the process. The nature and extent of the involvement of the other persons, particularly in the outsourcing proposal, was such as to have a “material effect” on the ultimate outsourcing decision. Such a case is consistent with the Union’s opening submissions of 8 April 2021 (UOS) (see [42.1]).

13 This summary by Qantas in QFS1 accords with my understanding of the way the case was conducted. In the absence of a successful application for amendment either prior to trial (when directly relevant documents were inspected), or during the course of the trial (when evidence of greater clarity might be alleged to have emerged), it would, or at least could, occasion an unfairness to Qantas to allow a case to be run by the Union which moves the focus away from the impugned outsourcing decision as pleaded, to an alleged earlier “practical decision” made by the GMC in August 2020. As I have already noted, the context and steps leading up to the outsourcing proposal decision are highly relevant, but only to the extent that they impact upon the subjective reasons for making the outsourcing decision in late November 2020. Qantas did not come to meet any other case, and considerations of fairness are particularly important in a civil penalty case.

14 This does not mean, of course, that the case that the GMC was “materially involved in the decision making process to outsource” is unable to be advanced. Although (for reasons I will explain), I do not accept the Union’s submissions as to the involvement of the GMC in the making of the outsourcing decision, it was accepted (at QFS1 [4(c)], [27]) that a case as to material involvement of the GMC in the outsourcing decision of 30 November 2020 was run.

15 Before coming to the principled approach to fact-finding and making relevant findings, it is noteworthy that the process of fact-finding in this case has several challenges, which are significant and should be identified at the outset.

16 Although this is an industrial case, as those experienced in commercial litigation are aware, in determining contested factual issues, what matters most is usually “the proper construction of such contemporaneous notes and documents as may exist, and the probabilities that can be derived from those notes and any other objective facts”: Mealey v Power [2015] NSWSC 1678 (at [4] per Pembroke J). As Leggatt J (as his Lordship then was) said in Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Limited [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) (at [22]):

… the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is, in my view, to place little if any reliance at all on witnesses’ recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known or probable facts.

17 Whether, as Full Court recently observed (in Liberty Mutual Insurance Company Australian Branch trading as Liberty Specialty Markets v Icon Co (NSW) Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 126 (at [239] per Allsop CJ, Besanko and Middleton JJ), this approach is best seen as a helpful working hypothesis rather than a form of rule or general practice of placing little reliance on recollections is not something that matters for present purposes. What presently matters is that, at least in part, such an approach has an unstated assumption: that is, that the contemporaneous notes and documents that do exist emerged as the extemporaneous and unvarnished product of the conduct of internal dealings or communications between the contesting parties. The confidence that can be placed in the narrative that emerges from the contemporaneous record is increased when the relevant documents can be seen as the unfiltered and sufficiently complete record of what people were thinking and doing in “real time”. In the present case, it is evident that Qantas always believed that any decision it made to outsource would be the subject of intense scrutiny by way of legal challenge. Unsurprisingly in these circumstances, it sought external industrial relations and legal advice. The process of obtaining specialist legal advice on matters directly relevant to the issues in this proceeding commenced at least by May 2020 (Ex P, item 80; T459.20–35) – almost six months before the outsourcing decision was made. To the extent that this advice was provided by lawyers, Qantas (as it is entitled to do), has claimed legal professional privilege over the content of the extensive communications in the period leading up to, and contemporaneous with, the outsourcing decision. This legal advice came from highly experienced industrial relations solicitors (and indeed, late in the process, by junior counsel subsequently briefed to appear in this proceeding).

18 By way of an example as to the extent of the very early involvement of lawyers, in June 2020 (immediately prior to the GMC discussing the risks associated with a full exit from in-house ground operations), a claim for legal professional privilege by Qantas is maintained over four copies of a draft of industrial relations advice proposed to be given by a long-standing external industrial relations consultant retained by Qantas (Ex P, Part 2, items 19, 20, 75–6, 81–4 and 88–9; Ex Q); at around the same time, a meeting, lasting a day, was apparently held between Mr Colin Hughes (the executive responsible for delivery of airport operations at Australia’s ten largest airports) and Herbert Smith Freehills (Freehills): Ex 1, 1812.

19 In these circumstances, unlike some other cases where decisions are impugned, it is unrealistic to assume uncritically that the decision making process adopted, and the documents relating to or recording the decision, materialised spontaneously through some sort of organic process or represent a sufficiently complete record of relevant communications. Even early on, there was an awareness that any business record created may end up being subject to subsequent critical scrutiny. This is not to say it is open on the evidence to find that documents were deliberately created or drafted so as to dissemble the true position, but it would be jejune to proceed on the basis that the documents can be assumed as representing a spontaneous and complete picture. Two examples illustrate this point. First, as will be detailed below, it emerged that negative advice, highlighting the industrial risks of a proposal for outsourcing, was given by Qantas’ external industrial relations adviser orally and this apparently valued adviser attended a number of relevant meetings of which there is no contemporaneous record of any of his oral representations. It might be thought a reflection of Qantas’ careful and circumspect approach, that even an early draft prepared by a long-standing industrial consultant as to risk, would be passed by external solicitors. Secondly, the final process of making the outsourcing decision occurred after at least some of the contemporaneous documents were apparently settled by lawyers. I hasten to stress that there is nothing wrong with any of this and no inference adverse to Qantas is open to drawn because it has claimed legal professional privilege over a large number of communications during the period with which this dispute is concerned. Nor, as I explain below, is it at all surprising that legal or industrial advice of the nature sought was obtained. But it does rather highlight the importance of a representation apparently intended to be made by “voice-over” (and hence not intended to be recorded in writing) (see, for example, below at [63]) or, to the extent they exist, any representation made in a document thought mistakenly to be protected from disclosure as being privileged. Without impugning the integrity of the authors of documents, it is naïve to ignore the reality that people often write or speak with greater candour if they consider their comment is going to be kept confidential.

20 Further, despite the vast array of material included in the court book (most of which was not received into evidence), it is noteworthy that some documents one might intuitively expect to exist, were not created.

21 Although category based discovery was initially proposed by the parties, an order was made for standard discovery: FCMH, 22 December 2020, T10.40–11.2; T13.19–14.39. A List of Documents and then an Amended List of Documents was filed, both verified by the Head of Industrial Relations at Qantas. Those lists do not contain any documents in Part 3 (which is to include discoverable documents that have been, but are no longer in the control of Qantas); hence it is possible to proceed on the basis that all directly relevant discoverable documents that were created are extant and have been listed (the non-privileged in Part 1 of the List, and the privileged in Part 2). With one important exception (which arose because handwritten notes of one employee on a typed document were scanned and sent by another employee by email), there are no documents recording oral communications, by way of file notes or handwritten notes.

22 It is also worth giving an example of some classes of documents, which do not exist. Mention has already been made of the GMC. The GMC is comprised of the leading executives within the business. It is described in two policy documents of Qantas and its website as an “executive decision making forum” (Ex D, E and J), and is said to set “the broad strategic goals and parameters for the entire Qantas Group” including, relevantly, developing the three year integrated recovery plan, and was the “forum for the most senior management of Qantas to meet and exchange information, and to consider and provide feedback on risks and opportunities arising from proposals currently being considered for implementation by any one of [the] senior managers”: see the affidavit of Mr David (at [8]–[9]). Although it was contended by Qantas, consistently with the affidavit evidence, that the responsibility and authority to develop, decide upon, and implement strategies and options relating to individual business units did not rest with the GMC, it is obvious that the GMC met very regularly during what was perceived to be a crisis for the company, and played a critical role in discussing the recovery of Qantas from the pandemic. Findings will be made about the role of the GMC below, but the preliminary point to be made is that during the period with which we are concerned, no minutes or notes were discovered as to any of its discussions. Nor are there any minutes or notes discovered of a GMC Sub-Committee or the Project Restart Steering Committee (Steering Committee) formed by the GMC which dealt with the implementation of the proposed outsourcing plan: see Ex 1, p 2674–9. It is unnecessary to make any findings as to why such documents were not created, indeed to do so would to be engage impermissibly in speculation. Closely prepared presentations and papers prepared in advance of meetings are available, but to the extent it is relevant to work out what actually happened at the GMC meetings, or GMC Sub-Committee or Steering Committee meetings (or indeed during almost all meetings between the witnesses discussing the outsourcing proposal), this task is not assisted by any contemporaneous record or note handwritten or typed in “real time” by a participant at those meetings.

23 Finally, as to the documentary record, there is also a class of documents which exist (or are likely to exist) recording contemporaneous communications which, somewhat surprisingly, have not been sought to be produced. Mr David gave evidence, in response to a question I asked following reference being made to texts, that he had not been asked by anyone “to look for your texts which might be relevant to these issues”: T751.31. Although it was clear that at critical times Mr David had been in SMS communication with in-house legal counsel (and possibly other persons called as witnesses), no attempt was made by the Union to procure any text material by way of subpoena or a call under s 36 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (EA) (and any such text documents as did exist were presumably not asked for by Qantas in compliance with its discovery obligations because they were not within its custody or control). Whatever the reasoning behind this forensic choice by the Union, it meant the Court did not have access to a class of informal communication produced at critical times, which apparently did exist (although how many of such communications did exist, between whom – other than between Mr David and in-house counsel – and how relevant these communications may have been, is entirely speculative).

24 This was a case where evidence in chief was given by affidavit. Consistently with the terms of the Employment and Industrial Relations Practice Note (E&IR-1) (at [9.1]), at the first case management hearing (FCMH), I raised with the parties my preference that evidence in chief in relation to controversial facts be led orally. In doing so, I had in mind both the terms of the Practice Note and the sort of considerations thoughtfully discussed by the Hon Justice A Emmett writing extra-judicially in his article, ‘Practical Litigation in the Federal Court of Australia: Affidavits’ (2000) 20 Australian Bar Review 28, where that very highly experienced judge observed (at 28):

Where an assessment of credit is required, a judge will have a much better prospect of assessing a witness who gives evidence in chief orally rather than being exposed to cross-examination immediately upon entering the witness box.

25 Qantas expressed a “strong preference” for affidavits (FCMH, T21.16) and senior counsel of the Union perceived some advantages in written evidence in chief, despite my indication (FCMH, T19.41–20.2) that:

I’m always conscious of what Lord Buckmaster said – and this is no [reflection on] any party, but it’s a famous quote that used to be repeated constantly by the Honourable T.E.F. Hughes AO QC, and that is that the truth comes out of affidavits like water from a leaky well, whereas people come along and tell their story in the witness box, there might be a better chance of the account being given in a more spontaneous way, and it may save a lot of money and cost and time.

26 This aphorism was one I had mentioned in Lloyd v Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 2177; (2019) 377 ALR 234 (at 269 [110]–[113]), where I also repeated the comment made by Lord Woolf MR contained in the Access to Justice Report, Final Report (HMSO), 1996 (at [55]) that:

Witness statements have ceased to be the authentic account of the lay witness; instead they have become an elaborate, costly branch of legal drafting.

27 In citing my observations in Lloyd v Belconnen with apparent approval in Queensland v Masson [2020] HCA 28; (2020) 94 ALJR 785, Nettle and Gordon JJ observed (at 810 [112]):

The oft unspoken reality that lay witness statements are liable to be workshopped, amended and settled by lawyers, the risk that lay and, therefore, understandably deferential witnesses do not quibble with many of the changes made by lawyers in the process – because the changes do not appear to many lay witnesses necessarily to alter the meaning of what they intended to convey – and the danger that, when such changes are later subjected to a curial analysis of the kind undertaken in this matter, they are found to be productive of a different meaning from that which the witness intended, means that the approach of basing decisions on the ipsissima verba of civil litigation lay witness statements is highly problematic. It is the oral evidence of the witness, and usually, therefore, the trial judge’s assessment of it, that is of paramount importance.

(Footnotes omitted).

28 These comments of their Honours have real resonance in this case.

29 It will be necessary to return to this topic below, but for the purposes of this introduction and explaining my approach to fact-finding, while having appropriate regard to the affidavits, in relation to matters of controversy, it is worth noting I have placed “paramount importance” on the contemporaneous documentary case (such as it is and subject to the important qualifications identified above) and my assessment of the oral evidence adduced during cross-examination and re-examination.

30 When it comes to assessing the oral evidence, speaking generally, it is noteworthy that at times it was obvious how chary some Qantas witnesses were of making any concession, however obvious that concession might be and how, sometimes non-responsively, they re-enforced what the witness perceived to be important points that: (a) no decision was made by anyone but Mr David on 30 November 2020; and (b) any recommendation or later decision to outsource was for reasons wholly unconnected to any proscribed reason. The witnesses, to my observation, were very well prepared and had obviously been taken carefully through all the materials (including, apparently, sometimes material that they had no involvement in preparing). I am not being critical of those preparing the witnesses in making this remark, who no doubt acted within appropriate professional constraints, but for whatever reason, there was a general wariness and lack of spontaneity of the oral evidence and this (like the other aspects of the evidence I have mentioned) has made fact-finding a somewhat more challenging exercise than in many cases when the oral evidence (assessed together with the documentary record) allows a tribunal of fact to feel a real sense of confidence that a complete and candid picture has emerged of what went on in “real time”.

B.4 Relevance of Challenges to Fact Finding

31 I have spent time focussing on these challenges to fact-finding by way of introduction because, as I remarked to the parties at the time of opening, this is, after all, a facts case. Who made the outsourcing decision and who materially contributed to it, are questions of fact. Whether the outsourcing decision was made or affected by a person holding a prohibited reason, although a subjective enquiry, is also a question of fact (remembering, as Bowen LJ famously said: “the state of a man’s mind is as much a fact as the state of his digestion”: Edgington v Fitzmaurice [1885] 29 Ch D 459 (at 483)).

C FACTUAL FINDINGS AND THE PRINCIPLED APPROACH

C.1 The Background and Non-Contentious Facts

32 There are several matters not in dispute, as is evident from a Statement of Agreed Facts, which became Exhibit A. There was also a large volume of affidavit evidence led by the Union (most of it irrelevant) that was not the subject of any challenge by Qantas. That evidence set out the long history of the relationship between the Union and Qantas.

33 To set the scene, it is useful to set out some background facts from Exhibit A, which I find for the purposes of the proceeding:

D.1. Impact of COVID-19 on Qantas’ operations

12. From January 2020, when the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic first entered Australia, and ongoing, the Commonwealth Government, the governments of various Australian States and Territories and various international governments (including the governments of those countries which comprise Qantas’ international passenger network), have implemented various measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the precise details of which have varied from time to time, many of which have dramatically curtailed the ability to engage in, or the demand for, passenger air travel, both domestic and international.

13. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the progressive impact of the matters described in paragraph 12 above, during the period from January 2020 and ongoing:

(a) Qantas and Jetstar progressively experienced an almost total reduction in travelling passengers (reflected in a reduction in bookings for future flights, an increase in cancellations of existing bookings and/or an increase in passengers not showing up for flights), and thereby passenger flights, on their respective international networks; and

(b) Qantas and Jetstar progressively experienced very significant reductions in travelling passengers (reflected in a reduction in bookings for future flights, an increase in cancellations of existing bookings and/or an increase in passengers not showing up for flights), and thereby passenger flights, on their respective domestic networks (including for regional, intrastate flights).

34 Exhibit A then outlined “Qantas’ immediate response to COVID-19” – detailing reductions in flight capacity and suspensions, the standing down of its employees and the “JobKeeper Scheme” – and continued:

20. On 5 May 2020, Qantas announced to the market that if current conditions persisted, the Qantas Group had sufficient liquidity until at least December 2021, on an average net cash outflow rate of $40 million per week on and from 30 June 2020.

D.3. Qantas’ recovery planning from COVID-19

21. On 25 June 2020, the Qantas Group announced a three-year recovery plan (Plan). The Plan involved three immediate priorities:

(a) ‘Rightsize’ the Group’s workforce, fleet and other costs according to demand projections, with the ability to scale up as flying returns;

(b) ‘Restructure’ to deliver ongoing cost savings and efficiencies across the Group’s operations in a changed market; and

(c) ‘Recapitalise’ through equity raising to strengthen the Group’s financial resilience for recovery and the opportunities it presents.

22. On 1 July 2020, Qantas and TWU representatives met in relation to voluntary redundancies.

23. On 27 July 2020, Qantas provided the TWU with information in relation to expressions of interest outcomes in anticipation of consultation meetings to occur the following day.

24. On 20 August 2020, the Qantas Group released its full year results for FY2020. Those results indicated, amongst other things:

(a) a $124 million underlying before tax profit for FY2020, which represented a 91% reduction compared to the prior financial year;

(b) a $2.7 billion statutory before tax loss;

(c) a $4 billion drop in revenue in the second half of FY2020, due to COVID-19 and associated border restrictions;

(d) the revenue of the Group fell by 82% in the fourth quarter of FY2020; and

(e) looking forward, the Group was anticipating a significant underlying loss in FY2021.

35 Exhibit A went on to outline a series of anodyne facts leading up to the outsourcing decision. But those uncontested facts form a component of a broader, disputed narrative, and I will recount them chronologically below.

36 While dealing with context, it must be stressed that the effect on commercial airlines of COVID-19 cannot be overstated, but need not be restated in any detail: see, for example, Qantas Airways Ltd v Australian Licensed Aircraft Engineers Association (No 3) [2020] FCA 1428; (2020) 299 IR 100 (at 118 [27]–[28] per Flick J). In Australia, there has been a drastic reduction in demand for air travel due to the closure of international and domestic borders, the requirement for international arrivals to undergo hotel quarantine and a reduction in the number of international arrivals permitted by the Federal, State and Territory Governments in response to new strains of the virus. Unsurprisingly, the extraordinary impact of Government measures taken in response to the pandemic on Qantas’ commercial viability is not disputed by the Union.

C.2 Further Unchallenged Background Evidence

37 As noted above, the Union’s evidence as to the relationship between the Union and Qantas, was not the subject of challenge by Qantas. For clarity, to the extent that the Union led evidence in relation to the in-house bid (IHB) process and the mechanics of its interactions with Qantas, although this evidence was again unchallenged, I address it in Section C.7 below (as, to the extent it has relevance, it conveniently fits within the narrative set out in that section).

38 To the extent that any of the pre-2020 evidence matters (and it is does not matter very much), the Union’s evidence in chief establishes that:

(1) in the late 1990s, Qantas began to use labour hire companies for, among other things, ground handling operations at some Australian airports, but the Union negotiated to maintain its members performing ground handling operations by submitting successful tenders on their behalf for their own jobs;

(2) in 2002, the Union received information indicating that Qantas intended to tender for work in entire areas, such as the baggage room at Melbourne Airport and the Union engaged in discussions with Qantas to attempt to minimise the use of labour hire companies;

(3) in 2003, Qantas agreed to the Union’s proposal that labour hire workers working side by side with Qantas employees would receive the same amount as the employees under the relevant enterprise agreement – this would act as a disincentive to Qantas to reduce employee numbers;

(4) in 2007, Qantas made decisions to outsource work at a number of Australian ports, including Hobart, Launceston and Coolangatta, the Union tendered unsuccessfully on behalf of its members for their jobs and negotiated redundancy packages for some members;

(5) in late 2007, Qantas announced its intention to put work out to tender by Union members at Adelaide Airport, and Union members took protected industrial action to protest that proposal – the matter was resolved through discussions between Qantas and the Union;

(6) prior to around 2008 to 2009, the Union and Qantas had a good working relationship;

(7) since that time, the relationship became more strained, as the Union conducted campaigns on issues relating to security of employment in Qantas and sought to limit the extent to which Qantas could contract out services provided by Qantas employees who are members of the Union;

(8) in 2008, Qantas announced it was forming a new company, QGS, to provide ground handling services as an internal labour hire provider. The Union opposed the introduction of QGS on the grounds that it threatened job security and was inconsistent with Qantas’ commitments made to the Union in bargaining for security of employment and contracting out functions; and

(9) in 2009, the Union campaigned against the establishment of QGS and undertook what was found by Moore J to be unprotected industrial action (Qantas Airways Ltd v Transport Workers’ Union of Australia [2011] FCA 470; (2011) 211 IR 1).

39 More relevantly, in recent times, both the Union and Qantas have been critical of each other and have taken opposing positions in law reform and regulatory matters. Further, by the beginning of 2020, after a number of instances of industrial action taken by Union members employed by Jetstar (a subsidiary of Qantas) in late 2019 and early 2020 (in relation to bargaining for a replacement enterprise agreement), the relationship had soured to the point where Mr Alan Joyce, Qantas’ Chief Executive Officer, considered the Union to be “militant”, and said so publicly in the media. Consistent with this description and the evidence generally, it is fair to describe the relationship between Qantas and the Union, by the time we get to the events the subject of these reasons, as being one which was not characterised by a high of degree of trust or mutual regard. Although the witnesses called by Qantas may not have been aware of the details of the points of difference between the Union and Qantas, I am satisfied that the members of the Australian Airports management team understood that the general relationship between Qantas and the Union by 2020 was antagonistic.

40 Before turning to the substance of the dispute, a few peripheral factual issues remain on the pleadings, which can be disposed of in a summary fashion given the lack of challenge to the Union’s evidence in chief.

41 First, it was disputed whether the employees affected by the outsourcing decision were in large part members of the Union. Secondly, it was disputed whether the employees affected by the outsourcing decision constituted the bulk of the Union’s members in Qantas’ airline business. Both of these matters were established beyond peradventure by the Union’s evidence in chief (and, for that matter, in numerous business records of Qantas). Thirdly, there was a dispute as to the impact of the outsourcing decision on the Union and its members. It is not in dispute that given the first and second disputed facts above, the effect of the outsourcing decision would be to remove the vast majority of Union members from Qantas’ business. For reasons that are unclear, it was disputed whether the Union’s industrial influence would be reduced in Qantas’ business. That disputed fact was the subject of evidence from the National Assistant Secretary of the Union (although this evidence was limited to evidence of the belief of the witness pursuant to s 136 of the EA). But despite this limitation on the use of this evidence, that opinion is consistent with the inherent likelihood of the diminished role of the Union following any outsourcing and the common ground that the only members likely to remain in Qantas’ business will be in the freight part of the business.

C.4 A Summary of the Nature of the Key Disputed Facts

42 In turning to the more substantive factual matters that were in dispute, as may already be evident, the factual dispute as to the outsourcing decision at trial had a number of components: first, a dispute as to the identity of the operative decision maker; secondly, if the decision maker was Mr David, the parties disagreed as to what persons may have had a “material effect” on the decision; and thirdly, what, in truth, was on the mind of all of those alleged to be materially involved in the decision and whether there were any proscribed reasons, in particular given Qantas’ then relationship with the Union and the unique state of affairs occasioned by the pandemic in 2020.

C.5 Principles of fact finding

43 Two matters of principle relating to fact-finding deserve attention because of the focus they received during final submissions: first, the operation of s 361 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FWA); and secondly, the proper scope of the so-called “rule” in Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R. 67.

44 During the course of its opening and submissions, the Union repeatedly stressed the central importance of what it called the “reverse onus”. At times, and particularly in parts of the UFS1, this submission seemed to be put in such a way as to suggest that Qantas bore the evidentiary and persuasive onus in relation to the proof of every fact in the case. No doubt inadvertently, this submission did not reflect the true operation of s 361 of the FWA.

45 There is no need in this case to spill more ink on the principled approach to determining the question of whether a person took certain action for a prohibited reason. With respect, the relevant principles were summarised usefully by Wigney J in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v De Martin & Gasparini Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 1046 (at [297]–[303]).

46 It is well established that the question of fact as to the reason or reasons for which adverse action was taken, must be answered in the light of all relevant facts and circumstances found and the inferences available from them. As the trier of fact, it is first necessary that I find the facts from the evidence admitted and from any inferences properly arising from that evidence (and inferences available to be drawn from the absence of any material). Findings as to the relevant facts and circumstances need to be made first, before then embarking upon the logically subsequent task of assessing those facts and determining the legal consequences of having found them.

47 As noted above, the reason or reasons for the outsourcing decision are to be determined on the balance of probabilities. To discharge its legal onus on the ultimate question to be determined, Qantas has adduced evidence as to the substantial and operative reasons for the outsourcing decision, directed at proving that those reasons were not the proscribed reasons alleged. Given the nature of that evidence in chief, if the evidence as to the reasons is accepted, Qantas’ onus is discharged and the case of the Union must fail. Importantly, however, and at the risk of repetition, Qantas is correct to stress that the determinative issue in respect of which Qantas bears the onus is to be assessed after the receipt and consideration of the evidence capable of bearing upon it.

48 The approach to making findings as to the intermediate or adjectival facts must not be misunderstood. With respect, the submissions of the Union and its focus on the “reverse onus”, tended to obscure the necessity for me to find facts in the orthodox way, as Qantas emphasises. Qantas also notes that part of this process of fact-finding is recognising that the graver the consequences of a particular finding, the stronger the evidence needs to be in order to conclude that any fact is established on the balance of probabilities. Although this is reflected in s 140(2) of the EA, and is undoubtedly correct, I would only add, given that Qantas placed emphasis on this being a civil penalty proceeding, that in considering the “gravity of the matters alleged”, the focus is upon the particular factual allegations in the case, not an examination of the cause of action or issues at a level of abstraction. This makes sense when one considers the focus on the gravity of the finding is linked to the notion that the Court takes into account the inherent unlikelihood of alleged conduct, and common law principles concerning weighing evidence: see Qantas Airways Limited v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; (2008) 167 FCR 537 (at 576 [137]–[138] per Branson J); Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 (at 361–2 per Dixon J).

The Scope of the Rule in Browne v Dunn and its Present Application

49 It might be thought trite to set out the true ambit of the rule deriving from such a famous case, but given its prominence in the final submissions of Qantas and the competing position of the parties, it is necessary that I do so. This can be done by gratefully adopting what Goldberg J said in White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (a firm) (1988) 156 ALR 169 (at 216–8) and by setting out the summary of the relevant principles by Vickery J in Amcor Ltd v Barnes [2012] VSC 434 (at [107]), where the following appears:

(a) The rule in Browne v Dunn is a rule of fairness which requires a party or a witness to be put on notice that a statement made by the witness may be used against the party or witness or to be put on notice that an adverse inference may be drawn against the witness or an adverse comment made about the witness in order that the witness may respond to that issue and give an explanation: Browne v Dunn [1894] 6 R 67 Lord Herschell LC (at 70), Lord Halsbury (at 76-7); Bulstrode v Trimble [1970] VR 840 at 849; Karidis v General Motors Holdens Pty Ltd [1971] SASR 422 at 425-6; Allied Pastoral Holdings Pty Ltd v FCT (1983) 44 ALR 607 at 623; White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (a firm) [1998] FCA 806; (1988) 156 ALR 169 at 216.

(b) The significance of the rule is that it requires notice to be given of a proposed attack on a witness or on the witness’ evidence where that attack is not otherwise apparent to the witness. The rule does not require that there be put to the witness every point upon which his or her evidence might be used against him or her or against the party who calls the witness: Browne v Dunn, Lord Herschell LC (at 70); White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (a firm) (1988) 156 ALR 169 at 217.

(c) Where, it is manifestly clear that the party or witness has had full notice beforehand that there is an intention to impeach the credibility of the story which he is telling, such as where notice has been so distinctly and unmistakably given, and the point upon which he is impeached, and is to be impeached, is so obvious, that it is not necessary to waste time in putting questions to him upon it, the rule may be dispensed with, where no unfairness will arise: Browne v Dunn, Lord Herschell LC (at 71); White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (a firm) (1988) 156 ALR 169 at 217.

(d) Notice of the relevant attack need not necessarily occur in cross-examination so long as it is otherwise clear that it will be made: Allied Pastoral Holdings Pty Ltd v FCT (1983) 44 ALR 607 per Hunt J (at 623); White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (a firm) (1988) 156 ALR 169 at 217-218.

(e) The necessary notice may be effected in pleadings, in an opening or in the manner in which the case is conducted: Seymour v Australian Broadcasting Commission [1977] 19 NSWLR 219 at 224-5, 236; Jagelman v FCT (1995) 31 ATR 467 at 472 -3; Raben Footwear Pty Ltd v Polygram Records Inc (1997) 145 ALR 1 at 15; White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (a firm) (1988) 156 ALR 169 at 218. To this list I would add notice given through witness statements or affidavits exchanged in advance of the trial.

(f) The rule has its foundation in the fair administration of justice: Browne v Dunn, Lord Halsbury (at 76-7).

50 At least at first glance, the Browne v Dunn criticisms of Qantas might have an understandable genesis. The cross-examination of each witness called by Qantas did follow a common pattern. In large part, the cross-examination involved a type of “page turning” exercise whereby the witness was asked to read a particular part of a business record (on occasions not prepared by the witness) and then the cross-examiner put propositions to the witness based upon a representation contained in the document: on occasions simply by asking the witness to confirm the existence of the representation. On more than one occasion, I indicated to the cross-examiner that such an approach may not be of optimal assistance (given I could read the documents myself) and, if propositions were to be put to a witness, they should be put directly: see, for example, T133.20–30.

51 Of course, as noted above, Mr David gave his reasons for the outsourcing decision, and Messrs Paul Jones, Colin Hughes and Paul Nicholas gave evidence as to their actual reasons for any involvement in the decision and each specifically denied that any part of their reasons included any of the proscribed reasons. Qantas contends that their “evidence as to those reasons was not directly the subject of cross-examination or any challenge in the course of their oral evidence”: QFS1 [3(e)–(f)]. It followed, Qantas submitted, that the evidence of the witnesses in this regard ought to be accepted.

52 The cross-examination was thorough and senior counsel for the Union displayed a mastery of the detail of the documents but, with no intended disrespect to the cross-examiner, although not milquetoast, it was not particularly direct nor forceful. Qantas asserts there was no suggestion put to any of these witnesses that their evidence given orally and in their affidavits as to their reasons was concocted, mistaken or unreliable: see, for example, QFS1 [46]. But it is important not to confuse different (and legitimate) styles of cross-examination with substance.

53 It must be accepted that as a general proposition unchallenged evidence which is not inherently incredible, ought to be accepted by the tribunal of fact (although such evidence can be rejected if it is contradicted by facts otherwise established by the evidence or particular circumstances point to its rejection): Precision Plastics Pty Limited v Demir (1975) 132 CLR 362 (at 370–1 per Gibbs J, with whom Stephen J agreed, and Murphy J generally agreed); Ashby v Slipper [2014] FCAFC 15; (2014) 219 FCR 322 (at 347 [77] per Mansfield and Gilmour JJ).

54 But this does not mean that the evidence given as to the absence of prohibited reasons is bound to be accepted in this case for two reasons: first, I still have to be satisfied the evidence is sufficiently cogent for it to be accepted on the balance of probabilities (a topic to which I will return in detail in Section E.2 below); and secondly, because, in any event, a fair review of the transcript does reveal that each of Mr David and Messrs Jones, Hughes and Nicholas, were sufficiently confronted with the proposition that despite the evidence as to their reasons or motivations they had given in chief, they were, in fact, motivated by the pleaded prohibited reasons. It suffices to set out in the below table some non-exhaustive examples of Mr David and Mr Jones being confronted with the prohibited reasons during their cross-examination:

Witness | Reference | Transcript Extract |

Mr David | T764.16–765.4 | MR GIBIAN: And to the extent that you made a decision about this, your reasons for doing so included the same reasons that you had in August for embarking upon the outsourcing proposal? --- Which were three commercial reasons, yes. Well, they included, didn’t they, that you knew that there were a large number of TWU members within the workforce of ground handling? ---That wasn’t what the decision was based on. And they included that you didn’t – you wished to avoid Qantas being in a position where it needed to bargain with and negotiate with the TWU in the future? --- That’s not the reason that we made the decision. That you wanted to avoid the legacy conditions within the QAL agreement and conditions within the QGS agreement? --- That’s not the reason we made the decision. You wished to access flexible EBAs that were available to third party providers? --- That’s not the reason we made the decision. That you wished to avoid the TWU and employees being in a position to exercise industrial power by taking protected industrial action in the future? --- That’s not the reason we made the decision. You wanted the employees to prevent – or you wanted to prevent employees disrupting services in the future by taking protected industrial action? --- That’s not the reason we made the decision. In answering all of those questions, you indicated that that was not the reason “we made the decision”. Who was that you were referring to as having made the decision? --- I made the decision. Well, why did you refer to “the reasons why we made the decision”, in answering each of those questions? --- Because it has been a long day and I would have used the word “we” instead of “I”. I don’t often use the word “I”. And could I just suggest to you that all of those answers were not truthful answers? --- Well, I can tell you they were truthful answers. Suggest that. I refute that. |

Mr Jones | T600.6–23 | MR GIBIAN: And the reasons that you had for endorsing the final outsourcing included the same reasons as you had as proposing that path in August and before, namely, that you knew – or you didn’t wish to have to negotiate with the TWU in the future? --- No. That you knew that there was a large number of members of the TWU within the ground handling workforce who would be influenced by recommendations or the positions adopted by the TWU? --- No. That you wished to – want the business to avoid the conditions under the QAL and QGS enterprise agreements? --- No. That you wished to avoid the TWU having – being able to exercise industrial power by its employees taking protected industrial action and bargaining in 2021? --- No. That you wanted to prevent the employees from disrupting services and interrupting services by bargaining and taking protected industrial action after the expiry of the enterprise agreement? --- No. They were not the reasons. |

T594.22–39 | MR GIBIAN: Now, in your involvement in recommending, as you had been doing for some months, that Qantas outsource the ground handling operations that it undertook in-house, at least part of the reasons for you making that recommendation is that you didn’t wish to have to negotiate or bargain with the TWU in the future? --- No. That you knew there was a high level of TWU membership and the TWUs position would be persuasive within the workforce? --- No. That you didn’t want employees to be in a – or the TWU to be in a position where it could have significant bargaining power in 2021 because the employees could take protected industrial action? --- No. And that you didn’t want Qantas to continue to have to pay their rates and afford the conditions of employment in the QAL and the QGS enterprise agreements? --- No. And that you knew if the outsourcing was pursued, Qantas would not need to bargain with ground handling employees or be subject to protected industrial action taken by those employees? --- No. |

55 The confrontation of each witness in this way was dismissed as “mere puttage” (to repeat a queer but pithy description used by Qantas). But the reality is that given the way the case was pleaded and opened, whatever else is unclear, one thing is pellucid: each witness called by Qantas had notice beforehand there was an intention on behalf of the Union to contend the outsourcing decision was not made by Mr David alone and that the decision was motivated by a prohibited reason or reasons. The content of the affidavits filed Qantas’ witnesses and the exchange of submissions before trial demonstrates this beyond sensible argument. Given the way this litigation was fought from the outset, it is artificial to contend that the witnesses did not understand the reasons they had given in chief for doing what they did in relation to the outsourcing decision were squarely in issue. Although, again without intended criticism of senior counsel for the Union, it is fair to remark that other cross-examiners may have impeached the testimony of the witnesses in a less unpresuming manner, I am satisfied that save in one respect, no relevant unfairness could be said to arise.

56 The qualification to this conclusion does not really matter (given what I have already said about the ambit of the case allowed to be advanced by the Union) but should be noted for completeness: I do not consider that any suggestion that the GMC, on around 5 August 2020, actually made the practical decision to proceed with the outsourcing proposal which “effectively resulted” in the outsourcing decision was sufficiently put to the witnesses who attended such a meeting or became aware of the meeting’s deliberations. Indeed, the cross-examination largely proceeded on the express basis no decision had been made until November, as had been pleaded.

C.6 Qantas’ Witnesses, their Role and their Credit Generally

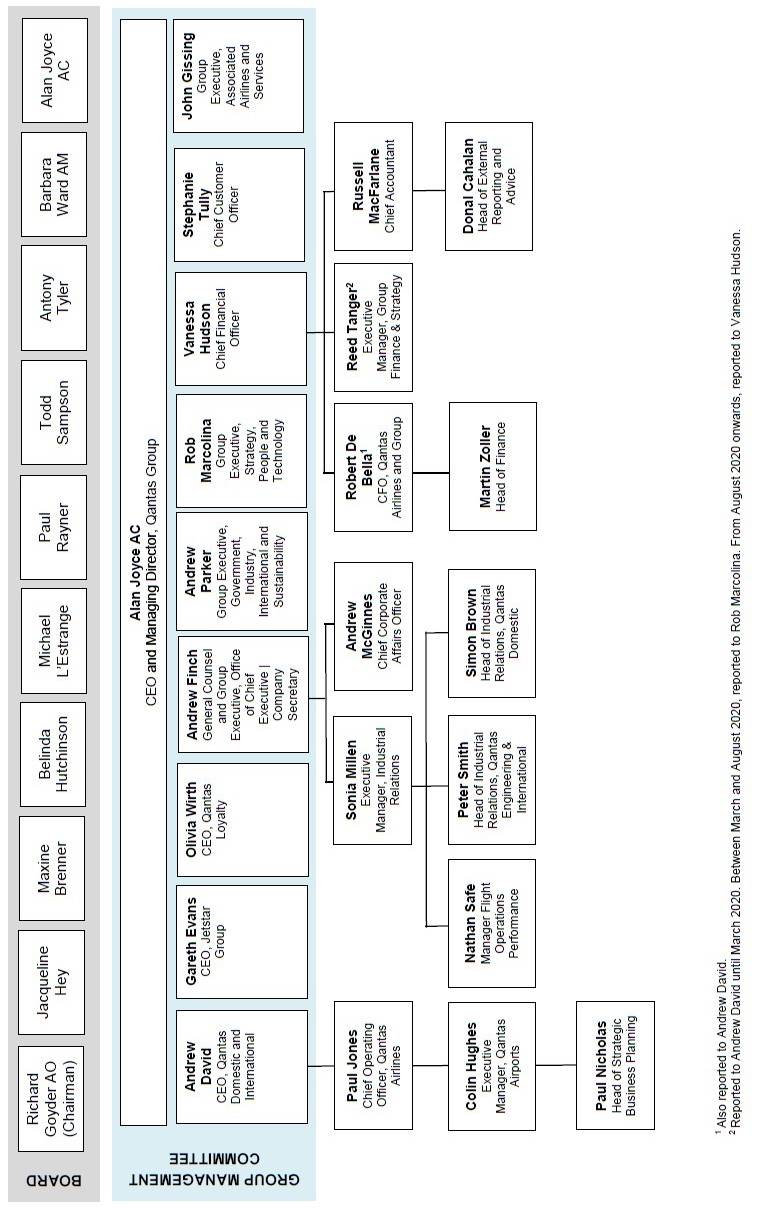

57 An organisational chart was helpfully prepared by Qantas, which set out the hierarchy within Qantas and the position in that hierarchy of its witnesses. That chart, which I accept is accurate, is set out below. Qantas’ witnesses called were (in order) Mr Hughes, Mr Finch, Mr Nicholas, Mr Jones and Mr David. I will deal with the witnesses in a somewhat different order, but what follows is a general description of their roles and how the witnesses related with one another.

58 I will also in this section make general observations as to the credit of these witnesses. In doing so, I am conscious that both parties have made very extensive submissions as to credit. I have considered these submissions, but it would add further to an already lengthy judgment to set them out in full, except where I consider them to be of especial importance. Further findings as to the individual conduct of the witnesses and, to the extent relevant, their state of mind, will be made when setting out the chronological narrative of what occurred in Section C.7 below

59 Mr Jones is no longer employed by Qantas, but is the former Chief Operating Officer of Qantas Airlines, and before taking on that position (in mid-2020), he was Executive Manager of Freight & Australian Airports. Mr Jones reported to Mr David, and Mr Hughes reported to him. Mr Jones was a member of the Qantas Airways Leadership Team (QALT), which comprised senior leaders across Qantas’ business and included Mr David. In April 2020, he instructed Mr Hughes to commence work to identify potential options to achieve financial targets in response to the pandemic. Mr Jones also attended a number of GMC meetings and made presentations at those meetings, which included options and recommendations for the business.

60 It is apparent that Mr Jones and Mr David worked closely together in their roles and there is no reason to doubt that they exchanged their views with one another in relation to matters they perceived to be important to the business of Qantas’ Australian Airports – it is more likely than not that they would have been candid with one another in relation to their views as to the options and recommendations for the business of Australian Airports discussed at GMC meetings.

61 Given that Mr Jones has now taken up a position with a competitor, one might have thought he may have been a witness who approached the giving of evidence without any of the conscious or subconscious inhibitions that sometimes exist when a witness considers that some aspect of their evidence may be adverse to the interests of their employer. Despite this, I regret to say that Mr Jones was an unimpressive witness. Although this was a view informed by several matters, it is appropriate to give a specific and important example of the unsatisfactory nature of his evidence. This concerned his handwritten annotations on a document prepared by Mr Nicholas: Ex 1, p 1178.

62 Mr Jones did not make any reference to this document in his evidence in chief and later gave evidence (at T602.26–603.2) that “I don’t have this document” and he assumed that Mr Hughes (who scanned it and sent the scanned document to Mr Nicholas) took the original of the document with him. The original of the annotated document was not tendered and it is unclear whether it exists, but a copy of the handwritten notes was discovered pursuant to the standard discovery order made (apparently because Mr Hughes happened to scan the handwritten notes made by Mr Jones and send the scanned annotated document to Mr Nicholas). Mr Hughes, who gave evidence before Mr Jones, had been cross-examined closely on the document (T118.31–119.45) and Mr Jones saw a copy of the document again for the first time when he had what he described as a “pre-discussion” shortly before he gave evidence and was being prepared for his cross-examination: T.602.38. Of course, I imply no criticism of the preparation of Mr Jones for cross-examination in the document being provided to him (notwithstanding he had not seen it since its creation nor given evidence in chief about it). But I mention the fact the document was drawn to his attention during the “pre-discussion”, because when it came to Mr Jones being cross-examined shortly thereafter, he would have thought about the document and its contents, presumably with an awareness that it was likely he would be cross-examined on his handwritten representations.

63 It suffices for present purposes to note that Mr Jones agreed that at around the time this document was created, discussions were taking place with Mr Nicholas and Mr Hughes and, from those discussions, he had understood that the combined view of Mr Hughes and Mr Nicholas was that the “above the wing” part of the workforce ought be retained (subject to a resizing exercise) and that the “below the wing” part of the workforce ought be tendered out: T.515–30. The annotated document was prepared during the course of the discussion leading up to the meeting of the GMC on 29 May 2020 where a presentation occurred entitled “People Recovery Plan: GMC Update” (being a meeting which Mr David and Mr Jones attended). Next to the handwritten notations was a reference to why options were different for “Customer vs Ground Ops”. Mr Jones accepted that notation read as follows:

Voice-over

> labour [sic] Gov lock in benefits

+ open EBA’s 2020 DEC?

64 Although regrettably lengthy, some extracts from the evidence (T516.14–526.15) as to this document illustrate the nature of the evidence he gave:

MR GIBIAN: You then made a hand notation in a box or two hand notations in boxes next to that typewritten text. The top box seems to me to read “voiceover”, and then there’s an arrow – underlined, and then there’s an arrow: “Labor government, lock in benefits”? --- Yes. I would agree that’s what that says.

Have I misread that or not? --- No. I think that is what that says.

What does “voiceover” mean? --- So I don’t recall, but it probably meant not for the presentation purposes being prepared. So I don’t recall the exact discussion at that time.

That is, you’re referring to information that you proposed to convey orally together with the – accompanying a presentation rather than including the written text of the presentation? --- So it’s speculative, because I don’t recall, but yes.

Right.

HIS HONOUR: Well, can you think of anything else that it could be a reference to – “voiceover” – than what you’ve assisted us with? --- I – I can’t.

Yes.

MR GIBIAN: Yes. And what you propose to deal with by way of an oral presentation reads, “Labor government, lock in benefits”. That’s what – you can read your writing, can you, and that’s what it says? --- Yes.

Is that a reference to a – the possibility that there would be a future Labor government, and you wished to lock in whatever cost-saving benefits you were able to obtain before that might happen?---It’s speculation as to what that means, because I don’t recall.

Well, you refer to the Labor government; do you see that? --- I do.

There was not at that time a Labor government – federally, at least; is that right? --- No. Just at the state level.

Only some states, obviously? --- Some, not all.

Would you understand that to be a reference to the federal government? --- Speculatively, yes, but I don’t recall.

And did you think – well - - -

HIS HONOUR: Sorry. You - - -? --- Yes. Yes, your Honour.

- - - keep on saying “speculative”. I don’t want you to speculate? --- Yes.

What I want you to do is to give your best truthful response to what is being put to you. If you’re not sure, say you’re not sure, by all means, but you’re the author of those words? --- Yes.

And I think what the cross-examiner is asking you to do is doing the best that you can to assist us with what you would have meant, given you’ve got the document in front of you, given you’ve got the words that you wrote less than a year ago – yes. Go on.

MR GIBIAN: Thank you, your Honour.

Would you accept that “Labor government” is a reference to a government at a federal level, and you would have differentiated if you were talking about particular state or territory governments? --- So I – I don’t – I genuinely don’t recall what this was – the discussion or context that I wrote those notes.

Well, the question I asked you is you accept that it’s – that can only be sensibly read as a reference to government at a federal level rather than government at a particular state or territory? --- I don’t recall the discussion at the time.

Qantas’ customer service and ground operations operate in each state or territory, do they not? --- They do.

… And what you were discussing here was the options for the customer service, above the wing and ground operations below the wing business of Qantas Airports generally, that is, the whole of those business units; correct? --- Correct.

That operate across all state and territories in Australia; correct? --- They do.

And it is the government at a federal level that would be relevant to all – the whole of that business; correct? --- Federal would be relevant to the whole of that business, yes.

And you would infer – you would accept that the natural inference from that is you were talking about government at a federal level; correct? --- Again, I – I don’t recall the conversation that occur.

…

MR GIBIAN: … And what you were referring to was locking in benefits, that is, obtaining whatever benefits you were referring to in a manner which was sustainable for Qantas in the event that Labor became elected at the federal level? --- So it – it may have meant that. It may have meant a number of things. It may have meant that – the concern that the benefits would not endure over time in an outsourced sense. So it has multiple possible meanings, the way I understand it.

All right. Firstly, I’ve apprehended correctly you say you cannot recall what you meant by writing, “voiceover – Labor government – lock in benefits”; is that right? --- Yes.

At all, that is, you have no recollection at all about what you meant by that? --- I don’t recall.

And the words alone, “Labor government – lock in benefits”, I suggest to you indicate what you were contemplating was that there would be a – in assessing the options, which option was superior, the need to lock in benefits in advance of a potential future Labor government was something that you were taking into account and wished to convey in the oral presentation to accompany the slides that you were preparing? --- So when I read that, sat here today, I think of two things: that’s one possible meaning, but another possible meaning is the concern that the benefits would not endure, post a Labor government.

Well, firstly, what you’ve written is “lock in benefits” – that is, not words that indicate the benefits would not persist, but expressing a desire to lock in those benefits? --- I don’t recall the conversation, nor the meaning of what’s written here.

Whichever way it is, you’ve expressed two – well, you say you’ve expressed two possible permutations or possible meanings.

HIS HONOUR: Sorry. Can I just understand what the second one is? I didn’t quite catch that. So one is locking in benefits now, on the basis of if there’s a future Labor government, they’re locked in. They can’t be changed. The second one, I didn’t quite understand. If you could just explain that one to me again? --- Yes, your Honour. So – and reading this, if a Labor government were to get in, understanding that there was a conversation around site rates, it might mean that the benefits of outsourcing would not endure - - -

…

MR GIBIAN: … In relation to the second construction that you proffered of these words, namely, that you may have been referring to a concern that the benefits of outsourcing would not persist, you raise that that may relate to a future Labor government enacting site rates provisions. Is that what you said? --- That’s one of the possibilities, reading this here today. Yes.

That is, your recollection is that – well, did you have a concern at that time that in the future, if a Labor government were elected then, at a federal level, they may enact laws requiring site rates to be afforded to labour hire and outsource staff? --- So I was aware of that as a possibility.

…

MR GIBIAN: … I’m just suggesting to you that you had a concern at that time that if in future Labor was elected at a federal level, they would enact laws that would constrain Qantas’ capacity to outsource staff or parts of its operations? --- No. I don’t believe that is what that was referring to.

Well, you refer to a – at least one of the permutations that you were raising as to these words to site rates provisions, and an apprehension that site rates provisions would or might be enacted in the future by a Labor government. Correct? --- Yes. You asked me what possibly this could mean. I gave you two examples of what it might possibly mean, but that doesn’t – I don’t recall the conversation.

…

MR GIBIAN: … In writing the words, “voiceover, Labor government lock in benefits”, what you… were communicating that you would convey to the group management committee, together with a presentation, was that it was desirable for Qantas to lock in benefits in advance of Labor being elected in the future? --- No.

And that the reason why it was desirable to lock in benefits in advance of Labor being elected at a federal level in the future was because you knew or you had a view it was possible Labor would enact constraints upon outsourcing of operations by employers, such as site rates provisions? --- No, that’s not what I understood at that time. I don’t recall the specific conversation around this, and I’ve provided multiple possible meanings as part of the questioning.

Well, you did say that you knew it was a possibility that Labor would enact site rates provisions if elected in the future? --- I’m aware of that possibility at this point in time, yes.

Yes. All right, and what I’m suggesting to you is your awareness of that possibility was what you were intending to convey to the group management committee as to one of the reasons as to why it was desirable to lock in benefits now? --- And I’m saying no, because one of the possible conversations from that is that the benefits would not endure in an outsource sense.

So one of the possibilities is – what I’m suggesting to you is one of the possibilities that you were raising was that you could lock in benefits now in advance of a law change that you apprehended may occur if Labor was elected. Correct? --- Well, I don’t recall the conversation.

Yes, but that’s one of the possibilities, correct? --- I understand that, yes.

Yes? --- Yes.

And another possibility that you have raised is you’re saying that if Labor is elected in the future, they may enact laws which would mean that the benefits of outsourcing would not persist. Is that what you’re saying the other possibility is? --- Well, there may be other possibilities beyond those two as well, because I don’t recall the conversation.

Well, you haven’t raised - - -

HIS HONOUR: What other possibilities could there be, other than those two possibilities that you’ve identified? --- It could have been around discussions at a state level. I don’t recall. So yes, on the balance of probability, which was, your Honour, your question to me, I thought it related to federal but there could have been other meanings in terms of the Labor government. That’s – they’re the three.

Anyway, your evidence - - -? --- Yes.

- - - on your affirmation is you have got no idea, at this stage – at this remove – from May last year, after being reminded of this document and reminded of your handwritten notes, what those handwritten notes mean. Is that what you say to me? --- I don’t recall.

…

MR GIBIAN: … In the box underneath those words, you’ve written, “plus open EBAs 2020, December”. I’ve read that correctly? --- Yes.

…

Open EBA is a reference, you understand, to a circumstance in which an enterprise agreement has passed its nominal expiry date? --- Yes.

And you understand the effect of an enterprise agreement passing – or one effect of an enterprise agreement passing its nominal expiry date is that the employees are able to bargain for a new enterprise agreement to replace it? --- Yes.

And as part of that bargaining process, are able to take protected industrial action in connection with that bargaining process? --- That’s one of the opportunities through an open EBA, yes.

And you were aware of that at that time? --- I would have been aware of that at that time, yes.

And the EBAs that were open at the end of – in December of 2020 – that is, past their nominal expiry date at the end of 2020 – included at least the Qantas Airways ground handling – TWU ground handling EBA. Correct? --- Yes.

And you were aware of that at that point in time? --- I would have been aware of that at that point in time. Yes.

So what you’re suggesting there would also be part of the voiceover that you would – oral presentation that you would make to the group management committee, together with the slide presentation – is that you would convey that a consideration in assessing the options for the above the wing and the below the wing was that the QAL EBA was open in December of – past its nominal expiry in December 2020? --- So I would have been aware that the EBAs were open then. I’m – again, because I don’t recall this conversation – I don’t know whether that was related to a voiceover or not. It’s a separate box. But yes, it was a part of the – in terms of awareness that I had in May that there were open EBAs at the end of December for this workforce. Yes.

And you made that notation because – leaving the voiceover to one side – that was a relevant matter in assisting which options were superior for the above the wing and the below the wing workforces? --- Well, it was a matter of fact at that time that the EBAs would be open. I’m not saying that that was – because I don’t recall the conversation, so I don’t recall the specifics of what in relation to the open EBAs was discussed.

What I’m suggesting to – well, you made this note. Correct? --- Yes, I made the note.

On a document which was discussing the key activities going forward in evaluating how the options are superior for resolving the current state, and why different outcomes for customer service and ground ops. Correct? --- As part of this document, yes.

Including – the discussions at that time with Mr Hughes and Mr Nicholas were to the effect that tendering out the below the wing was the preferred option, as opposed to rightsizing for the above the wing workforce. Correct? --- During this period of time, yes.

Yes, and I’m just suggesting to you that the only reason you would have written down “open EBAs, December 2020” is because the fact that the Qantas Airways ground handling EBA was past its nominal expiry date at the end of December 2020 was relevant in assessing the options, or which option was superior? --- No, it wasn’t in terms of “relevant to the options”, but it was very relevant to any future plans around transitioning business, operational risk, etcetera, which comes out in future documents.

That is, it was relevant in assessing the options in that once the EBA has passed its nominal expiry date, there was operational risk because the employees could take protected industrial action. Correct? --- There is a number of reasons why it was a much higher operational risk in 2021. That’s one aspect of why.

So one aspect that was relevant and that you noted to be considered, among two notes that you made, was that once the Qantas Airways EBA in particular was open after December 2020, there was operational risk because the employees could take protected industrial action? --- I can’t draw that conclusion that that was the conversation at this time, because I don’t recall it.

Yes, but you agree that that was a consideration that existed at the time, and was in your mind at that time in terms of assessing operational risk? --- So as documented as we go through timeline, operational risk was a factor in the implementation of the option that was needed for addressing the financial targets. Yes.

HIS HONOUR: Does that mean the answer to counsel’s question is yes? --- Do you mind asking the question again? Sorry.

Ask it again.

MR GIBIAN: Moving aside from the note, which you say you can’t remember why you wrote it, at that time, you knew that the Qantas Airways EBA was open at the end of 2020, and that as a result there was operational risk in 2021 because the employees could take protected industrial action. Correct? --- No, that’s not what I believe was in my mind at this period of time.

…

The next entry is to mark – in the notation of “Voiceover”, I think you’ve agreed that you wrote that because – and you can’t provide any other explanation, other than that you intended that to be part of the oral presentation to accompany a slide show, rather than as part of the written document itself? --- No, I don’t know whether that relates to a voiceover or not.

I’m sorry. Leaving aside whether the EBAs reference appears under “Voiceover”, you agreed that the reference to “voiceover, before the Labor government lock in benefits” was intended to convey – you couldn’t pick any other explanation for it other than that it conveyed you intended to make that comment orally, rather than included in a written presentation. Correct? --- I think that makes sense, yes.

And the reason why you would make that notation is because you didn’t want that content written down, it was something that you wished to communicate only in oral form? --- No, that doesn’t mean that I didn’t want it written down. It may be that it was not relevant to the core conversation that was occurring, and I certainly don’t recall a conversation on this topic at the time, or in the subsequent GMC meeting.

The only reason why you would make a note about the voiceover was that you intended that that matter not be recorded in the written presentation and only be dealt with in the oral presentation; correct? --- Yes.

Because you did not want that matter written down and recorded; correct? --- I don’t agree with the “because”. I don’t recall what the conversation was on the voiceover.

65 As the emphasised part of the extract makes clear, there was somewhat of a tension in the evidence given. The witness affirmed that he could not recall the discussion or what the notes meant. Despite this, Mr Jones accepted that it was a logical possibility that his notes recorded his view that benefits should be locked in “now in advance of a law change that [he] apprehended may occur if Labor was elected”. But despite that possibility existing, and notwithstanding his professed lack of recollection, he was intent in rejecting the notion that he held the view it was “possible Labor would enact constraints upon outsourcing of operations by employers, such as site rates provisions” and he was also able to give affirmative evidence that he did not believe at the time that he was concerned “that if in future Labor was elected at a federal level, they would enact laws that would constrain Qantas’ capacity to outsource staff or parts of its operations”.