Federal Court of Australia

Campaigntrack Pty Ltd v Real Estate Tool Box Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 809

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to providing within 14 days agreed orders giving effect to these reasons for judgment and for the further case management of the proceedings.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THAWLEY J:

[1] | |

B THE FACTS | [6] |

B.1 The DreamDesk system and relevant terminology | [6] |

B.2 November 2014 to March 2015: Establishment of the DreamDesk venture | [13] |

B.3 March to August 2015: Biggin & Scott move to DreamDesk | [16] |

B.4 May 2016: Admission of infringement of Process 55’s intellectual property | [20] |

B.5 Late May to July 2016: Negotiations to purchase Process 55; sale of DreamDesk | [27] |

B.6 30 July to Mid-August 2016: Origins of Toolbox | [36] |

B.7 Mid to Late-August: Biggin & Scott consider software providers; sale of Process 55 | [70] |

B.8 26 August to Early September 2016: Early development of Toolbox | [75] |

B.9 5-7 September 2016: Variation of DreamDesk agreements; payment of purchase price | [82] |

B.10 Mid-September 2016: Ongoing development of Toolbox; relationship between Biggin & Scott and Campaigntrack deteriorates | [84] |

B.11 Campaigntrack and New Litho learn about Toolbox | [105] |

B.12 30 September to October 2016: Copying of files from DreamDesk system; preparation for DreamDesk being shut off | [119] |

B.13 November 2016 to May 2017: Modification of DreamDesk files | [152] |

B.14 June 2018: RETB ceases to trade; REDHQ takes its place | [162] |

B.15 Early 2019: Mr Semmens’ failure to provide information to the independent expert | [164] |

C COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT CLAIMS | [169] |

C.1 General principles | [169] |

C.1.1 Infringement | [169] |

C.1.2 Subsistence and originality | [176] |

C.1.3 The exclusive rights | [182] |

C.1.3.1 Reproduction | [183] |

C.1.3.2 Communication | [191] |

C.2 The works in suit and subsistence | [193] |

C.2.1 Source Code Works | [194] |

C.2.1.1 Source code works as a whole | [198] |

C.2.1.2 The three PHP files: EDMS PHP, Adhoc Edit PHP and Adhoc Edit 2 PHP | [199] |

C.2.2 Database Work and Table Works | [205] |

C.2.3 Menu Work | [224] |

C.2.4 PDF Works | [228] |

C.3 Ownership | [241] |

C.3.1 Source code as a whole | [241] |

C.3.2 Construction of clause 1.1 of the DreamDesk sale agreement | [243] |

C.3.3 The three PHP files: EDMS PHP, Adhoc Edit PHP and Adhoc Edit 2 PHP | [250] |

C.3.4 Database Work, Table Works and Menu Work | [253] |

C.3.5 PDF Works | [254] |

C.4 The alleged infringing work | [256] |

C.5 Infringement | [267] |

C.5.1 Primary and secondary infringement | [267] |

C.5.2 Campaigntrack’s submissions in respect of inferences | [272] |

C.5.3 Mr Semmens | [279] |

C.5.3.1 Primary acts of infringement | [280] |

C.5.3.2 Authorisation | [287] |

C5.4 Biggin & Scott, RETB, Mr Stoner and Ms Bartels | [291] |

C.5.4.1 Primary acts of infringement | [294] |

C.5.4.2 Authorisation by Biggin & Scott, RETB, Mr Stoner and Ms Bartels | [296] |

C.5.5 DDPL and Mr Meissner | [301] |

C.5.5.1 Primary acts of infringement | [302] |

C.5.5.2 Authorisation by DDPL and Mr Meissner | [304] |

D CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION CLAIMS | [307] |

E CONTRACT CLAIMS | [317] |

E.1 The “transfer term” and “assistance term” | [317] |

E.2 The “assignment term” and “transfer warranty” | [322] |

E.3 The “password term” | [323] |

E.4 The “non-modification term” | [328] |

E.5 The “non-access term” | [336] |

E.6 The “non-transfer term” | [341] |

E.7 The “licencing warranty” | [345] |

E.8 The “compliance term” | [348] |

F BREACH OF UNDERTAKINGS | [350] |

G CONCLUSION | [360] |

1 The applicant, Campaigntrack Pty Ltd, provides online marketing and sales services to the real estate industry using an online software system known as “Campaigntrack”. Campaigntrack brought these proceedings against the respondents, alleging, amongst other things, infringement of Campaigntrack’s copyright in the source code of the “DreamDesk” software system. DreamDesk was a cloud-based real estate marketing system originally created by the third respondent, Mr David Semmens, an experienced software developer. DreamDesk was in direct competition with Campaigntrack. Campaigntrack and New Litho Pty Ltd purchased the intellectual property rights in DreamDesk in order to shut down the software and persuade real estate agencies that were using DreamDesk to move to Campaigntrack’s system.

2 After DreamDesk was sold to Campaigntrack and New Litho, Mr Semmens created another real estate marketing software system called “Real Estate Tool Box” (Toolbox). Campaigntrack alleged that the Toolbox software reproduced parts of the source code of DreamDesk, thereby infringing Campaigntrack’s copyright.

3 Mr Semmens was represented when these proceedings were first commenced. However, during the course of the proceedings, and well before the commencement of the hearing, he continued unrepresented. The remaining respondents were represented by one legal team. The respondents other than Mr Semmens are referred to in these reasons collectively as the “represented respondents”:

(a) The first respondent, Real Estate Tool Box Pty Ltd (RETB), was incorporated approximately one month before the Toolbox software went “live”, and was the registrant of the domain name realestatetoolbox.com.au.

(b) The second respondent, Biggin & Scott Corporate Pty Ltd, was the franchisor of the “Biggin & Scott” group of real estate agencies operating in Victoria. Biggin & Scott used the DreamDesk software before the software was sold to Campaigntrack and New Litho. Biggin & Scott was also involved in the creation of Toolbox.

(c) The fourth respondent, Dream Desk Pty Ltd (DDPL), owned the intellectual property rights in the DreamDesk software before the software was sold to Campaigntrack and New Litho.

(d) The fifth respondent, Mr Jonathan Meissner, was the sole director and shareholder in DDPL and ran an advertising business, JGM Advertising Pty Ltd.

(e) The sixth respondent, Mr Paul Stoner, was the sole director of RETB and a director of Biggin & Scott.

(f) The seventh respondent, Ms Michelle Bartels (née Page), was the company secretary of RETB and a director of Biggin & Scott.

4 In addition to asserting infringement of copyright, Campaigntrack made claims for breach of contract against DDPL and Mr Meissner, breach of undertakings given to Campaigntrack by some of the represented respondents and, in equity, for breach of confidence. Campaigntrack’s claims have been made out against Mr Semmens to the extent indicated below. In particular, Campaigntrack’s claim for infringement of copyright has been accepted in most respects as against Mr Semmens. Campaigntrack’s various claims against the remaining respondents have not been made out.

5 It is necessary to set out the facts in some detail. Certain legal issues have been determined when addressing the facts given the relevance of these issues to the claims made and the defences to those claims.

B.1 The DreamDesk system and relevant terminology

6 Before setting out the relevant events in the order they occurred, it is useful to know something about the DreamDesk system. The DreamDesk system was comprised of two principal components relevant for present purposes:

(1) A “web application”: a software application provided to users over the internet, using a computer program or programs executed on a remote server to deliver functionality. The remote server of the DreamDesk system was a virtual server hosted by Amazon Web Services (AWS).

(2) A “relational database”: a database comprised of tables of data (or records) arranged in columns (or fields) and rows, which included means for “relating” or associating records within the database. The relational database was also stored on the remote server.

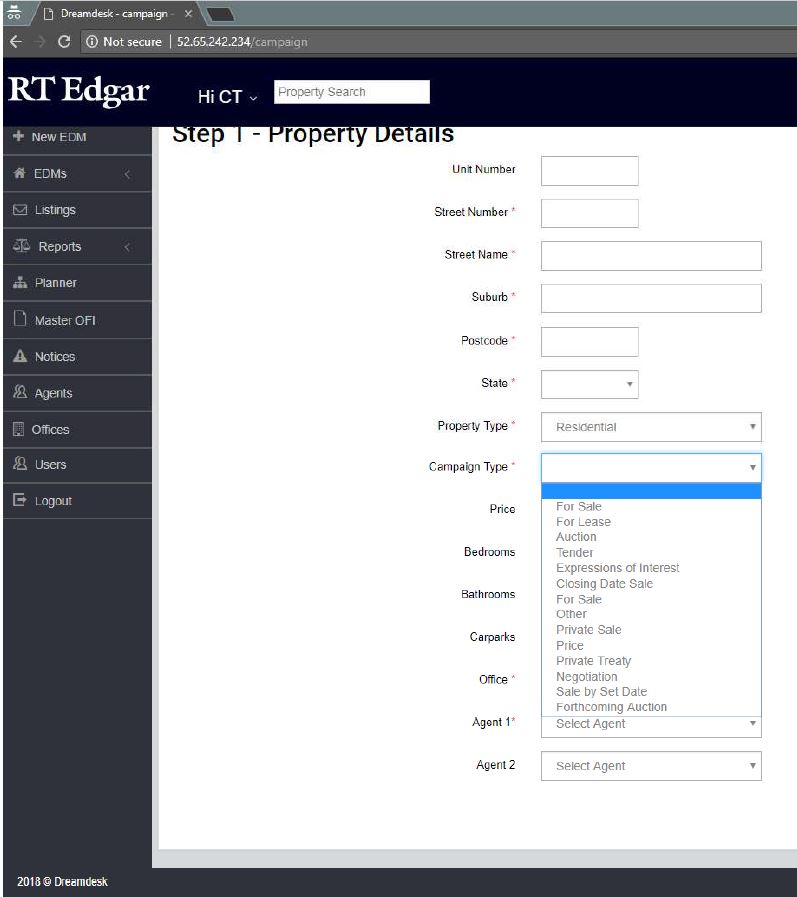

7 The DreamDesk web application allowed real estate agents to quote, manage, invoice and market real estate campaigns, generate print/online-ready PDF artwork and create email marketing.

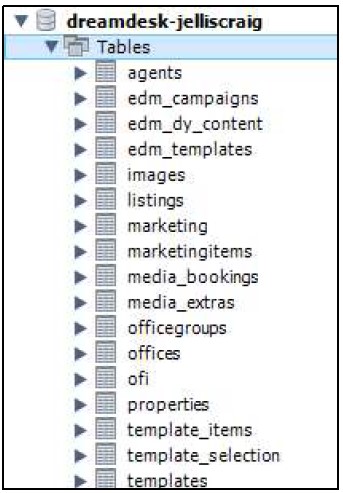

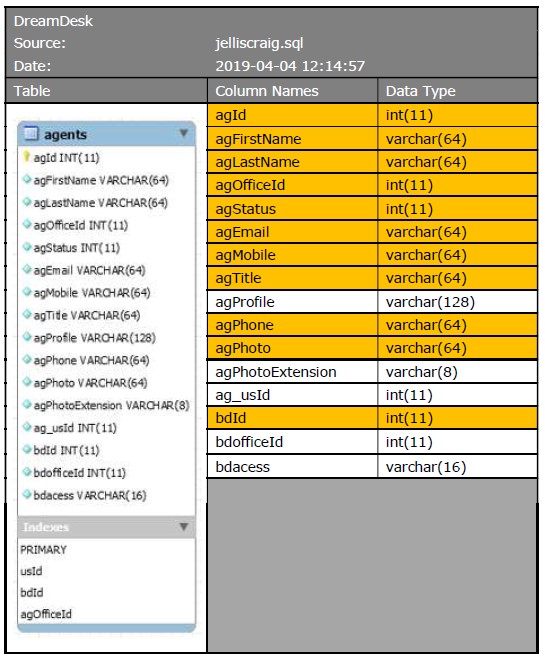

8 The DreamDesk relational database contained the tables of data used by the web application to deliver the functionality to which reference has just been made. Each database comprised a number of tables. Each DDPL client, including Biggin & Scott, had its own database. The DreamDesk relational database was replicated each time an installation was made for a client.

9 DDPL clients had access to the user-facing interface of the web application, sometimes inelegantly referred to as the “front end”. Clients did not have access to the underlying source code or to the structure of the relational database. The source code and the database, stored on the remote server, were protected by a password or key.

10 It is also useful to explain some terminology. “Git” is an open-source distributed version control system for source code. Git allows multiple software developers to work together on a software development project, while maintaining version control of the source code. Version control is maintained through a “Git repository”. Multiple software developers, working on the one project, might use a Git repository to coordinate their work in the following manner:

• the developer “clones” a copy of the Git repository on his or her local computer;

• the developer then makes changes to the source code on his or her local computer;

• the developer then “commits” the changes to the local copy of the Git repository;

• to share the committed changes, the developer “pushes (up)” the (modified) local copy of the Git repository to the “origin copy” of the Git repository hosted by a Git repository service. This push merges the developer’s “commits” with the origin copy;

• a developer may update his or her local copy of a Git repository by “pulling (down)” commits that have been made to the origin copy since the developer’s local copy was last made.

11 A Git repository contains the complete history of every change made in the development of the relevant source code or code base. In addition, information about the migration, creation and deletion of files as well as edits to contents of files is stored. Mr Semmens used Atlassian’s hosted Git repository offering, which is named “Bitbucket”. Bitbucket allows a developer to review the history of commits and the history of changes to each file.

12 In addition to its use as a verb, the word “commit” is also used as a noun, meaning the list of changes made to files and source code created, for example, when a developer commits their changes to their local copy of the Git repository. A “commit log” is a log summarising the history of commits. A commit log can be generated from the Git repository.

B.2 November 2014 to March 2015: Establishment of the DreamDesk venture

13 In November 2014, Mr Meissner met with Mr Semmens and his business partner, Mr Ewart. During the meeting, Mr Semmens and Mr Ewart proposed creating a new cloud-based real estate marketing system and sought investment by Mr Meissner to develop the system. Mr Meissner agreed to fund the venture (the DreamDesk venture).

14 On 11 March 2015, Mr Semmens, Mr Ewart and Mr Meissner agreed to form a company, DDPL, to pursue the DreamDesk venture. Mr Meissner was to be the sole director and shareholder. They also agreed that the shareholding would be divided 40%-40%-20% between Mr Semmens, Mr Ewart and Mr Meissner respectively, once Mr Meissner had recouped his initial investment. Because of subsequent events, that division of shares never eventuated.

15 DDPL was incorporated on 12 March 2015 with Mr Meissner as its sole director and shareholder. The domain name dreamdesk.com.au was transferred from Mr Semmens to DDPL five days later. Mr Semmens worked on the technical and software development of DreamDesk from about February 2015 and received ongoing payments for his work from DDPL. Campaigntrack characterised these payments as “salary”, whilst the represented respondents characterised Mr Semmens as being a “contractor” to DDPL. I do not accept that Mr Semmens was an employee of DDPL. He was an independent contractor. There was no suggestion that DDPL withheld tax from the payments made to Mr Semmens, which it would have had to have done if he were an employee. There was no suggestion that DDPL made contributions to superannuation which, likewise, would have been required if Mr Semmens were an employee. Mr Semmens issued invoices to DDPL in respect of his work as one would expect of a contractor. Whether or not Mr Semmens complied with relevant GST requirements is not determinative. The relationship between the parties, assessed objectively as a whole, is one of principal and contractor, not one of employer and employee. Although certain documents referred to Mr Semmens as being “employed” by DDPL, this reflects an ordinary use of language even if it is a use of language which might tend to be avoided by lawyers if trying to describe a relationship with precision. That was not the context.

B.3 March to August 2015: Biggin & Scott move to DreamDesk

16 At the beginning of 2015, Biggin & Scott was using the Campaigntrack software in its businesses. Biggin & Scott had used the Campaigntrack software between 2006 and 2009. It changed to a different advertising platform called “Advenda Pro” in 2009, and then returned to Campaigntrack in 2013 after it had been incorrectly informed that the company behind Advenda Pro was in perilous financial circumstances.

17 Between March and May 2015, Mr Stoner was approached by Mr Ewart. Mr Ewart suggested that Biggin & Scott should consider moving to DreamDesk. Agreement was ultimately reached for Biggin & Scott to move to the DreamDesk platform.

18 On 20 May 2015, an agreement entitled “Agreement between Biggin & Scott Corporate Pty Ltd and Dream Desk” (Biggin & Scott – DDPL Agreement) was signed by Mr Stoner (on behalf of Biggin & Scott) and by Mr Meissner (on behalf of DDPL). The agreement provided:

Biggin & Scott Corporate Pty Ltd agrees to become a client of Dream Desk under the understanding that at all times any templates or data relating to properties and staff put into Dream Desk remains the property of Biggin & Scott Corporate Pty Ltd and or the office that has built an advertisement.

Should Biggin & Scott decide at any stage to cease being a client (leave) Dream Desk all steps available to Dream Desk will be made available to Migrate Biggin & Scott’s templates and property related data to whatever system Biggin & Scott nominates.

Should Dream Desk for whatever reason chose to cease doing business with Biggin & Scott as a group, Migration of all templates and property related data [is] to [be] made available to whomever Biggin & Scott instructs.

Notice period for each company is a minimum of 3 months with all accounts being settled within 4 months from given date.

Biggin & Scott agrees [to] share ideas with Dream Desk that maybe [sic] onsold to other agents or groups under the understanding that they are always available to Biggin & Scott offices.

All price increases must be tabled and discussed 3 months prior to being implemented, Understanding that offices are working 3 months ahead.

19 Biggin & Scott went “live” with the DreamDesk platform on 17 August 2015.

B.4 May 2016: Admission of infringement of Process 55’s intellectual property

20 As described further below, on 26 May 2016, Mr Semmens stated that he had copied an earlier system, “Process 55”, when he developed the DreamDesk system. Process 55 was a web-based real estate marketing system. Mr Semmens was involved in the development of Process 55 during his employment with Digital Hive Pty Ltd from 2001 to 2006.

21 The Digital Hive business, including its intellectual property (which included Process 55), was sold in September 2013 by Digital Hive to The Digital Group Pty Ltd, a company founded by Mr Semmens and his brother-in-law, Mr Farrugia. Mr Semmens was a director of Digital Hive from 21 January 2005 to 7 April 2006. Mr Farrugia was also a director. Mr Stewart joined the venture after it as founded and became a director. Mr Farrugia and Mr Stewart held the view that Mr Semmens had stolen the intellectual property of Digital Group in the development of the DreamDesk system.

22 On 26 May 2016, Mr Semmens signed two documents, which both included the following:

I, David Semmens of [redacted address] state that:

(1) I am an officer of Dream Desk Pty Ltd which is a commercial competitor of The Digital Group Pty Ltd and Campaign Track.

(2) Whilst an officer of Dream Desk Pty Ltd, I have deliberately gained access to the private email accounts of Ashley Farrugia CEO The Digital Group and Gavan Stewart Exec Chairman of The Digital Group

(3) Whilst an officer of Dream Desk Pty Ltd, I have deliberately used confidential information and trade secrets and other intellectual property (including but not limited to the ‘Process 55’ system) being the property of TDG and Campaign Track so as to develop the business of Dream Desk Pty Ltd.

(4) Mr Martin Ewart, a person associated with Dream Desk Pty Ltd, is and was at all material times aware of the conduct I have engaged in as described above.

23 One version of the document also included an extra paragraph which stated:

I acknowledge that the actions admitted above prevent me from continuing any further employment with Dreamdesk Pty Ltd henceforth.

24 On 28 May 2016, Mr Semmens and Mr Ewart told Mr Meissner that they had been informed that the Digital Group’s intellectual property was being used in the DreamDesk software. Two days later, Mr Farrugia and Mr Stewart told Mr Meissner that they considered Mr Semmens had used Digital Group’s intellectual property in the development of DreamDesk without authorisation. Mr Farrugia told Mr Meissner that the intellectual property which was alleged to have been stolen related to the “PDF Distiller”, which Mr Meissner understood enabled the DreamDesk system to produce and edit PDF images, being the images used in real estate marketing campaigns by DreamDesk clients such as Biggin & Scott.

25 Understandably, Mr Meissner did not want to operate using intellectual property he or DDPL was not authorised or licensed to use. He decided either to negotiate to buy Process 55 or to sell DreamDesk.

26 Mr Meissner and Mr Farrugia discussed DDPL buying the intellectual property in the Process 55 system or a joint venture between DDPL and Digital Group. Those discussions were overtaken by Campaigntrack and New Litho’s negotiations with Digital Group, described next.

B.5 Late May to July 2016: Negotiations to purchase Process 55; sale of DreamDesk

27 In May and June 2016, Campaigntrack and New Litho had a number of discussions with Digital Group regarding the possible purchase of the intellectual property rights in the Process 55 system. These arose because Campaigntrack wished to purchase the rights in both Process 55 and DreamDesk in order to acquire control of the DreamDesk system, to shut it down and to attempt to persuade DDPL clients to move or return to Campaigntrack. It was ultimately agreed in principle that Campaigntrack and New Litho would purchase the intellectual property rights in Process 55 for $300,000.

28 Starting with a meeting on 15 June 2016, Mr Meissner and representatives from Campaigntrack and New Litho began to negotiate the sale of DreamDesk. The question whether DreamDesk’s clients had any rights in respect of data stored in the DreamDesk relational database was not raised at the meeting on 15 June 2016.

29 From early July 2016, Mr Meissner, Campaigntrack and New Litho negotiated the terms of the agreement for the sale of DreamDesk. It was eventually agreed that all intellectual property of DDPL relating to the operation of DreamDesk was to be sold to Campaigntrack for $50,000 and there was to be a separate incentive-based arrangement whereby payments would be made to Mr Meissner for securing DreamDesk clients to transition to Campaigntrack.

30 On 13 July 2016, Mr Meissner and DDPL’s solicitor had a conversation with Campaigntrack’s solicitor regarding a licence to use the intellectual property in the “Dashboard”. The “Dashboard” was a reference to the homepage or intranet page of the user-facing “front-end” of the DreamDesk system. This displayed key information to the user. Campaigntrack’s solicitor summarised the conversation in an email sent to Campaigntrack and New Litho (emphasis in original):

Dear All

I have just spoken to the other side in this matter.

They are happy with the issue of Process 55. Apart from the finer details, there appears to be one final issue. It involves the licence back of th[e] IP [intellectual property] to operate the ‘Dashboard’.

Apparently, Dream Desk want a licence to use the IP needed for the Dashboard so that they can develop it further and commercialise it. They want:

1. An exclusive and irrevocable licence for the Dashboard IP; and

2. For the Dashboard licence to not be conditional on RT [Edgar] and [Biggin & Scott] signing up. i.e. they want to be able to commercialise the Dashboard regardless of whether RT Edgar and B&S sign a deal to use CampaignTRACK.

Basically, they want to keep on trading as if the Dashboard was theirs. You would have to give consideration as to whether you would like to licence the Dashboard to third parties in the future but in any case, the licence will have to be on the basis that CT will also use the technology and provide the Dashboard to whoever wants it.

Has this been discussed, what are your thoughts?

31 Campaigntrack submitted that Mr Semmens’, Mr Meissner’s and DDPL’s intention to develop the Dashboard further, evidenced by this email, was later put into action by Mr Semmens’ development of the Toolbox system. Campaigntrack correctly observed that Mr Meissner occasionally referred to the DreamDesk system as a whole as “Dashboard” and that the Toolbox system, whilst under development, was sometimes referred to as “Dashboard” or “Dash”.

32 On 18 July 2016, Mr Meissner signed the following agreements:

(1) an agreement entitled “Agreement for the Sale of Assets” between, on the one hand, DDPL and him and, on the other, Campaigntrack and New Litho (the DreamDesk sale agreement); and

(2) a “Binding Heads of Agreement” between himself and Campaigntrack and New Litho.

33 The DreamDesk sale agreement provided for the sale of intellectual property associated with the operation of DreamDesk to Campaigntrack and New Litho. Clauses 1.1 to 1.4 of the DreamDesk sale agreement provided :

1. Sale of intellectual property and business assets

1.1. Dream Desk agrees that it will sell to Campaigntrack and New Litho (the “Purchasers”) the DreamDesk Platform and all intellectual property associated with the operation of the DreamDesk Business, including copyright (including any rights to source code), design, patents and trademarks and all rights to the business name of the DreamDesk Business and all domain names registered by Dream Desk, including dreamdesk.com.au (the [“]Intellectual Property”).

1.2. The parties acknowledge that the sale of the Intellectual Property does not include Process 55 as that is owned by Digital Group Pty Ltd. The sale does include any intellectual property that Dream Desk may have that is derived from Process 55 or that is separate but used in conjunction with Process 55 for the operation of the DreamDesk Business.

1.3. In consideration for the Purchasers purchase of the Intellectual Property the Purchasers will pay to Dream Desk an amount of $50,000.00 (the “Purchase Price”) within 7 days of the date that this agreement becomes binding under clause 5.

1.4. All rights, entitlement and interest in and title to the Intellectual Property will pass to the Purchasers on payment of the Purchase Price.

34 Clauses 2.1 and 2.3 of the DreamDesk sale agreement provided for DDPL to have a licence of the intellectual property for a limited period ending on 3 October 2016:

2. Licence of intellectual property

2.1. The Purchasers agree that on payment of the Purchase Price and the transfer of title to the Intellectual Property as anticipated by this agreement they will grant to Dream Desk an exclusive Australia wide licence to use the Intellectual Property for the restricted purpose of operating the DreamDesk Business and for the limited period commencing on the date the licence is given until 3 October 2016, unless extended by agreement between the Purchasers and Dream Desk (the “Transition Period”). The Purchasers agree that the licence period will be extended to 1 January 2017 if at least one client of Dream Desk known as RT Edgar and Biggin & Scott enter into agreements on or before 2 September 2016 with Campaigntrack or any entity associated with Campaigntrack for the use of the CampaignTRACK Platform.

…

2.3. In addition to the above, the parties agree that if either RT Edgar or Biggin & Scott enter into agreements on or before 2 September 2016 with Campaigntrack or any entity associated with Campaigntrack for the use of the CampaignTRACK Platform, the Purchasers will grant a limited, Australia wide licence to use the Intellectual Property for the restricted purpose of supplying the product currently provided by Dream Desk known as the Dashboard to clients of Dream Desk who are not engaged or associated with the real estate Industry on the following conditions:

2.3.1. The Intellectual Property licenced will be only that Intellectual Property that is required for the operation and supply of the Dashboard, including only that source code relating to the Dashboard. Dream Desk will have no licence to use, and no rights to any of the Intellectual Property that is not required for the operation and provision of the Dashboard.

2.3.2. The licence will commence on the expiry of the general licence under clause 2.1 on 1 January 2017.

2.3.3. If only one of RT Edgar or Biggin & Scott enters into the agreement contemplated by clause 2.3 the licence will be an exclusive licence for a period of five years from the date that such an agreement is entered into and any renewal of the licence will be on terms that it will be a non-exclusive licence. After the expiry of the exclusive licence period the Purchasers will be free to licence the same Intellectual Property to third parties. If both RT Edgar and Biggin & Scott enter into the agreements contemplated by clause 2.3 the licence will be an exclusive licence for a period of five years from the date that the first such agreement is entered into and any renewal of the licence will be on terms that it will be an exclusive licence.

2.3.4. The initial term of the licence will be five years. The licence will be renewed on the expiration of the initial term under the same terms if mutually agreed to by the parties. The licence renewal will not be unreasonably withheld by the Purchasers.

2.3.5. The licence granted to Dream Desk cannot be used for any existing client of Dream Desk unless agreed to by the Purchasers.

2.3.6. The licence will immediately terminate if the business structure or makeup of Dream Desk changes in a material way from the date of these Heads of Agreement or if Dream Desk breaches the terms of the licence.

2.3.7. The terms of the licence agreement will not restrict the Purchasers from supplying products and services of the same kind as the Dashboard using the same Intellectual Property that is licenced. The term ‘exclusive’ as referred to in this clause is to be taken to mean that the Purchasers will not grant the same licence to a third party but it does not restrict the Purchasers from exploiting any Intellectual Property in any way.

2.3.8. Dream Desk will not be permitted to transfer, assign, sub-licence or otherwise grant rights to third parties to the licenced Intellectual Property unless the Purchasers approve in writing.

35 On 26 July 2016, Ms Kylie Neal (a consultant to DDPL), gave a presentation via video conference to Campaigntrack staff members. Ms Neal’s presentation provided a comprehensive demonstration of the DreamDesk system. Mr Meissner also attended the presentation.

B.6 30 July to Mid-August 2016: Origins of Toolbox

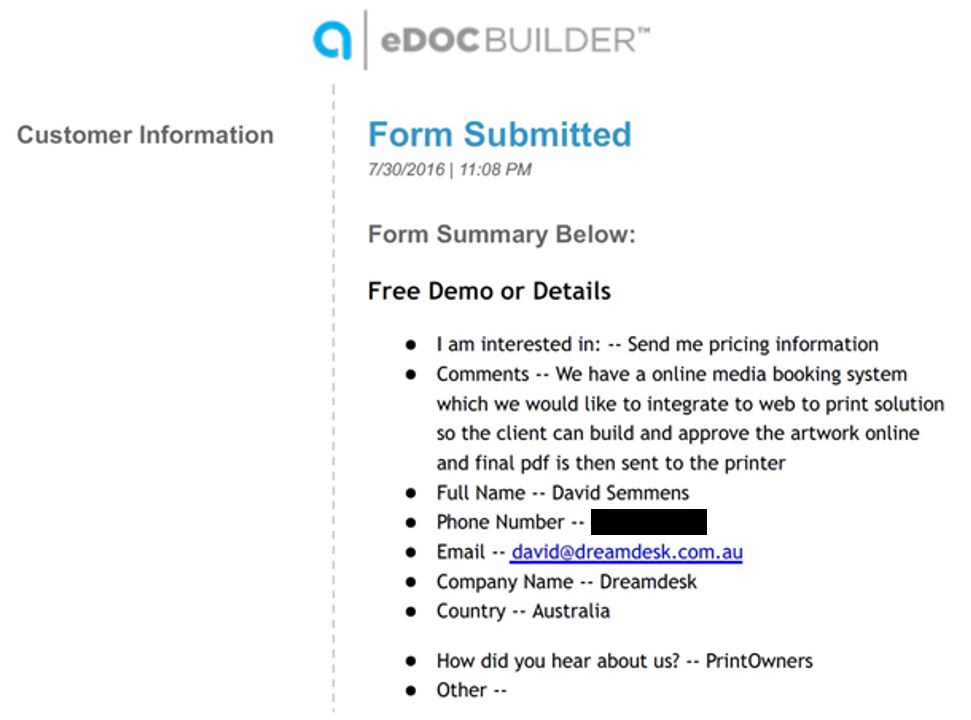

36 On 30 July 2016, Mr Semmens made an enquiry with the online software company, Aleyant Systems, LLC, which owned eDocBuilder, a web-based online design, personalisation and variable data publishing system that was designed to be integrated into web to print and other e-commerce systems. The online enquiry was in the following terms:

37 On 2 August 2016, Mr Semmens discussed his eDocBuilder enquiry with an Aleyant representative, Mr Jeffrey Protheroe, through an online demonstration/conference. I infer, including from events described later, that the point of the enquiry was to determine whether eDocBuilder might be used in a new system intended to have the same essential functionality as DreamDesk. As will become apparent, I also conclude that the new system (Toolbox) was developed by first copying substantial parts, probably the whole, of the source code of DreamDesk.

38 On 3 August 2016, Mr Semmens met with Mr Stoner at Biggin & Scott’s head office. Mr Semmens told Mr Stoner that he could create a system with similar functionality to DreamDesk and Campaigntrack and asked whether Mr Stoner would be interested in him developing the system. At the meeting, Mr Stoner (the CEO of Biggin & Scott) showed Mr Semmens a letter dated 3 August 2016, on Biggin & Scott letterhead. The letter, which had been written and signed by Mr Stoner, provided (errors in original):

David Semmens

You are instructed to build a web to print delivery system that does not breach any other companies IP or ownership, in particular Dream Desk or Campaign Track.

All products used should be off the shelf products owed by 3rd parties with a licence agreement or able to be used through open code or any other industry standard that classes the use as open (can not be claimed)

All fields should match industry standard so as to be delivered as per their specs and able to match our CRM’s in particular Box & Dice.

In simple terms we do not want any thing used that can be claimed as owned by the 2 companies above.

We are happy with E-DOC being used as the PDF delivery system as long as it can deliver our finished adds as per Biggin & Scott style guide. Please continue with the building of these templates.

With regards to property data that offices are loading into the Dream Desk system please arrange to migration scripts of this data to be loaded into the New E-doc templates to minimise as much disruption as possible.

We have an agreement in place with Jon Meisner regarding office and property data to which Jon assures me our clients and offices data is and always will be ours and is not part of his deal.

39 Mr Stoner had handwritten his and Mr Semmens’ name at the foot of the letter. Mr Stoner signed the letter above his name. Mr Semmens did not sign the letter. In cross-examination, Mr Semmens accepted that he discussed the letter with Mr Stoner. He could not recall whether he was provided with a signed copy of the letter during the meeting.

40 I infer from the terms of the letter, and the fact that Mr Semmens was looking into eDocBuilder, that the development of a new system (ultimately Toolbox) was already underway at the time Mr Stoner wrote the letter. It is also clear from the terms of the letter that Mr Stoner knew that it was proposed that the new system would use eDocBuilder.

41 Mr Stoner gave the following evidence in cross-examination:

So you say that this was the instruction that you gave Mr Semmens on 3 August 2016, to build a Web to Print delivery system that does not breach any other company’s IP or ownership, in particular, Dream Desk or Campaigntrack?---Yes.

And you say that you did that without knowledge of what I have taken you to in relation to Process 55?---Yes.

Other than what Mr Ewart said to you about a “problem”?---So on this date, I knew that Dream Desk was – had been, well, I’m not sure if it had been purchased or was being purchased.

You didn’t know or you did know?---I’m not sure. Well, I’m not sure if it had been purchased by then. But on that date, I knew that, who had bought it or was buying it and what the future looked like.

…

Why include “Breach any other company’s IP” if the only knowledge you had was that of the Dream Desk sale?---Well, that’s what their issue was, that they had breached Process 55’s IP.

Well, I think, the evidence you gave us, was you were only aware, very broadly, of what Mr Ewart had told you?---That’s in May, this is August.

So you – the evidence you give is that you became more familiar with the situation relating to Mr Semmens from May to August 2016. Is that correct?---Absolutely.

…

You knew there was a problem with Process 55 and the use of Process 55 by Dream Desk, did you not?----At that stage, yes. On 3 August.

…

You appreciated that there was real risk that Mr Semmens might infringe another company’s IP?---No. I would have to say, “No”. I trust David.

Well, why would you put in – you instructed to:

Build a Web to Print delivery system that does not breach any other company’s IP or ownership, in particular, Dream Desk or Campaigntrack.

?---Just to make it clear, I don’t want any crossovers with anything.

…

And the only basis for putting in an instruction, Mr Stoner, is that you were concerned about the possibility that he would use code belonging to Dream Desk or Campaigntrack? — It’s possible. But I don’t think that’s my meaning.

42 Campaigntrack submitted that “Mr Stoner knew there was a real risk that, in developing the new system, Mr Semmens might infringe the intellectual property rights of DDPL or Campaigntrack”. Campaigntrack also submitted that “Mr Stoner’s denials that he did not appreciate the risk of infringement, and that he was not seeking to address that risk by the instructions in [his letter], are simply not credible in light of his answers in cross-examination, and should be rejected”.

43 In the context of the events which had occurred, including the fact that – to Mr Stoner’s knowledge – Mr Semmens had admitted to using Process 55 in developing DreamDesk, it was hardly surprising that Mr Stoner would seek an assurance from Mr Semmens that he would not infringe the intellectual property rights of others in building a web to print delivery system. I am satisfied that Mr Stoner trusted Mr Semmens not to infringe the intellectual property rights of DDPL or Campaigntrack in developing the new system. I conclude that Mr Stoner did not want Mr Semmens to misuse intellectual property belonging to others in developing the new system.

44 Ms Bartels did not see the instruction letter. However, she was informed of the substance of it by Mr Stoner. Ms Bartels left it to Mr Semmens to determine the specifications of the new system. Campaigntrack referred to the following evidence given in Ms Bartels’ affidavit (Campaigntrack’s emphasis):

In August 2016, I was informed by Paul Stoner that he had been approached by David Semmens in relation to the development of a new online advertising system that did not have any software or information in it that it should not have … I trusted David enough that he would not make a mistake in terms of using material in the new system that should not be used.

45 Campaigntrack submitted that “[t]he deontic words — ‘should not have’, ‘mistake’ and ‘should not be used’ — show that Ms Bartels was aware that Mr Semmens had been accused of misusing the intellectual property in the Process 55 system, and that she was aware of the risk of infringement in the development of the new system” and that “[t]he word ‘enough’ shows that her trust in him was not unqualified; that she had some reservations about him”. I accept that Ms Bartels is likely to have known that Mr Semmens had admitted to using Process 55 in DreamDesk and that this had caused problems. I conclude that Ms Bartels did not want Mr Semmens to misuse intellectual property belonging to others in developing the new system.

46 As things stood at 3 August 2016, Mr Semmens had until 3 October 2016 to develop the new system. This was because the licence to use the DreamDesk system, granted by Campaigntrack to DDPL under the DreamDesk sale agreement, would end on 3 October 2016. Campaigntrack observed that the evidence suggested that the DreamDesk system was created over a period longer than 2 months, namely beginning in February 2015 and going live for Biggin & Scott on 17 August 2015.

47 On 5 August 2016, Mr Semmens received an email confirming the creation of an eDocBuilder account. Two similar versions of a welcome email from eDocBuilder were in evidence. The version of this email placed into evidence by Mr Semmens was in the following form:

From: “Aleyant Systems Support” <support@aleyant.com>

Subject: [140-1F367834-0A49] Welcome to eDocBuilder, JGM Advertising!

Date: 5 August, 2016 6:03:32 am GMT+8

To: david@jgmadvertising.com.au

Cc: jprotheroe@aleyant.com

Reply-To: “Aleyant Systems Support” <support@aleyant.com>

WELCOME!

Thank you for your order! Your account has been set up. Below you will find important information to access the system, and to take advantage of the services available to you. Please keep this email for future reference and share it with all staff that will be working in eDocBuilder!

The following is a summary of your order:

eDocBuilder Professional

----------------------------------------------------------------------

EDOCBUILDER ADMIN

----------------------------------------------------------------------

eDocBuilder Admin: http://creator-sg.edocbuilder.com

Your master login info:

User: ********

Password: *******

GETTING STARTED

…

48 Another version of this email was provided on 24 November 2016 by Mr Stoner to his solicitor, who provided a copy of the email to Campaigntrack’s solicitors. This version of the email indicated it was sent at the same time and included almost identical content to the email placed into evidence by Mr Semmens. The only difference was that Mr Semmens’ JGM Advertising email address was not in the “To” field, which instead included Mr Stoner’s Biggin & Scott email address. The User and Password fields were also different in that they referred to Mr Stoner’s Biggin & Scott email address, and the password “JlbMSTea”:

From: “Aleyant Systems Support” <support@aleyant.com>

Subject: [140-1F367834-0A49] Welcome to eDocBuilder, JGM Advertising!

Date: 5 August, 2016 6:03:32 am GMT+8

To: pstoner@bigginscott.com.au

Cc: jprotheroe@aleyant.com

Reply-To: “Aleyant Systems Support” <support@aleyant.com>

WELCOME!

Thank you for your order! Your account has been set up. Below you will find important information to access the system, and to take advantage of the services available to you. Please keep this email for future reference and share it with all staff that will be working in eDocBuilder!

The following is a summary of your order:

eDocBuilder Professional

----------------------------------------------------------------------

EDOCBUILDER ADMIN

----------------------------------------------------------------------

eDocBuilder Admin: http://creator-sg.edocbuilder.com

Your master login info:

User: pstoner@bigginscott.com.au

Password: JlbMSTea

GETTING STARTED

…

49 Campaigntrack also put into evidence a document printed from the Toolbox Git repository which indicated that the username and password for the template for eDocBuilder was “david@jgmadvertsing.com.au” and “JlbMSTea”.

50 Mr Stoner gave evidence that the reason for the two similar emails was that he wanted his own login to the eDocBuilder:

Is the evidence you give his Honour that this email was received by you from Aleyant system support, or was this email changed before you sent it on to Mr Maletic?---I think in memory of all this, the original one that I was sent was a login called “David” and I wanted my own login.

…

Well, was that you? Did you make that change?---No. I wanted – I remember with this very clearly I wanted to send Mr Maletic a login with my name on it, and my password - - -

…

MR GREEN: You can’t explain any reason why those details now appear in an email that has an identical time, can you?---As I said before, when David sent me the original one, I wanted my own.

So did you change the – did you change the details of the user and the password from the asterisked version?---I didn’t change anything.

Did you communicate with anyone asking for a change?---No.

…

… Because, as I said, the first one that I was sent had David who is the login. I called David straightway and said, “I need an email with me as the login and I need my own password, login and password.”

51 Campaigntrack submitted that the last statement “should be understood as an instruction by Mr Stoner to Mr Semmens to edit the [eDocBuilder] Welcome Email”, noting that Mr Stoner forwarded the edited email to Mr Maletic of Mills Oakley (who acted for Biggin & Scott) for the purpose of providing the document to an independent expert. The independent expert was engaged in November 2016 to determine whether there was any potential copying from the DreamDesk system. Campaigntrack submitted that the Court should find that Mr Stoner, Biggin & Scott and RETB wanted to convey a false impression that Mr Stoner and Biggin & Scott had registered to use eDocBuilder, independently of DreamDesk and JGM Advertising.

52 The first email set out at [47] above does not identify a username and password at all. It is unlikely this was the form of the email sent to Mr Semmens. The original email to Mr Semmens would have identified the username and password. I do not accept that the email as received by Mr Semmens was in the form identified at [47] above. I conclude that the original email referred to the username and password as “david@jgmadvertsing.com.au” and “JlbMSTea” respectively. It is possible that two emails (or more) were sent by Aleyant at precisely the same time to different email addresses providing different usernames and passwords. However, this was not Mr Stoner’s explanation or Mr Semmens’ explanation. On balance, I conclude that Mr Semmens changed the content of the email he had received from Aleyant.

53 I do not conclude that Mr Stoner instructed Mr Semmens to alter the 5 August 2016 email as such. However, the events do reflect adversely on Mr Stoner’s credibility. Mr Stoner did not give evidence that he was sent an email from Aleyant on 5 August 2016. There was no evidence to suggest that Mr Stoner considered he had been given his own username and password on or around 5 August 2016. No evidence or reason was given why Mr Stoner would want or require his own username and password. Mr Stoner gave evidence that he might have tried his (purported) login details once, but that he could not recall whether they worked. Mr Stoner denied that he provided the second version of the email to “hide Mr Semmens’ involvement in Real Estate Tool Box”. It is likely that Mr Stoner wanted his own login details to be created in order to provide those details to Campaigntrack’s solicitor so as not to provide them a document which indicated the involvement of Mr Semmens in the relevant events.

54 Mr Semmens most likely started to develop the Toolbox system on his local computer on about 9 August 2016. The first commit to the Toolbox Git repository (the Dashboard Vault1 Repository) was made by Mr Semmens on 26 August 2016. The time stamp of the files in the first commit showed that the first file was created on a local computer on 9 August 2016. Mr Semmens kept source code on his local computer whilst initially developing the code and used Bitbucket once he was to be assisted by other developers (Mr Gallagher and Mr Zhang) so they could share code between themselves.

55 It is likely that Mr Semmens started to develop the Toolbox system on his local computer at DreamDesk/JGM Advertising’s offices. The local computer on which initial development occurred has not been able to be located. In cross-examination, Mr Semmens said he discarded, overwrote or gave away old computers.

56 From 16 August 2016 to 19 September 2016, Mr Semmens ran a number of “migration scripts” in respect of the DreamDesk database. This was the subject of unchallenged evidence given by Mr Allen, a software developer who had previously been employed by Campaigntrack and who was engaged by Campaigntrack’s solicitors to provide technical assistance for the present proceedings. The migration scripts did not copy source code; they only copied data from one database to another database. The first migration script, run on 16 August 2016, was unsuccessful but, at least by 30 August 2016, some had been successfully run. The migration scripts copied database records from DreamDesk to a database at the domain “dash.vault1.net”. I infer that “dash.vault1.net” was the database for the Toolbox system. I draw that inference because: a login page to the Toolbox system was available when “dash.vault1.net” was entered into an internet browser; the Toolbox repository was named “Dashboard Vault1”; and “Dashboard” or “Dash” was the project name for the Toolbox system.

57 Migration scripts (not all of which were successful) were run in respect of the DreamDesk database for:

(1) Biggin & Scott: on 16 and 23 August and 2, 8, 12, 17 and 19 September 2016;

(2) RT Edgar: on 16 and 17 August 2016; and

(3) Jellis Craig: on 17 to 19 and 26 to 30 August 2016.

58 Mr Semmens accepted that he ran the migration scripts. In cross-examination, Mr Semmens stated that Mr Meissner had instructed him to “export the client’s data out” or give the client their data, but later clarified:

Was it Mr Meissner?---He would have just said give the client their data, I’m not sure. I don’t think he would have said synchronise their data.

59 Mr Semmens stated Ms Bartels may have told him to keep the client data up to date. He did not think any instruction was given to him by Mr Stoner in relation to client data.

60 I infer from the events which had occurred to this point, including the development of Toolbox and the running of the migration scripts, that Biggin & Scott was not intending to remain with Campaigntrack if at all possible, but was progressing its objective of setting up its own system.

61 It is important to appreciate, as Mr Semmens emphasised in submissions, that the running of migration scripts only transferred a client’s data from one database to another. The data so transferred was not the intellectual property of Campaigntrack.

62 Campaigntrack initially submitted that the running of the migration scripts “meant that there was a reproduction of the structure, the database structure, in the program itself” and that the running of the scripts necessarily copied the structure of the underlying database and contained the data structures. It was submitted that the “migration scripts are a way in which one can create the data structures through programmatic means, through running a program”. Campaigntrack submitted:

HIS HONOUR: So, but – and what does that mean, though? Doesn’t that mean – doesn’t running the migration scripts mean that you’re taking the data for Biggin & Scott? No.

MR GREEN: Yes, you’re copying the data structures.

HIS HONOUR: For Biggin & Scott’s - - -

MR GREEN: Well, you’re copying the databases.

…

HIS HONOUR: Are migration scripts always data?

MR GREEN: Migration scripts – the migration scripts always include the reproduction of the databases – the reproduction of the structure into which the migration – the data is then put.

63 Eventually, however, it became clear that the running of migration scripts does not necessarily involve a reproduction of the database structure. After asking what evidence supported these submissions and observing that the evidence the Court was then taken to did not appear to support the submissions, it became apparent that all that could be put was that the migration scripts showed that the databases into which the data was copied were structurally the same (or very similar). This might indicate that Mr Semmens modelled the Toolbox database structure from the DreamDesk database structure, but the running of the migration scripts was not a means by which the database structures themselves were copied.

64 Mr Semmens submitted, and I accept, that the migration scripts simply transferred the client’s data that the client owned. The running of the migration scripts did not, of itself, copy any intellectual property of Campaigntrack.

65 In cross-examination, Mr Semmens was asked about why he ran migration scripts in respect of Jellis Craig, when Jellis Craig was not involved in the Real Estate Tool Box venture:

And then you ran further migration scripts in respect of Jellis Craig on 17 and 19 August. Again, they were still with Dream Desk, weren’t they?---They were, yes.

And there was no basis for doing that on your - - -?---Yes.

- - - asserted basis that you were trying to move client data?---Yes, I can’t recall why I did Jellis Craig, there was actually no need to do Jellis Craig at all.

There was absolutely no need to do Jellis Craig?---No, no.

Except for the fact that you were building a replica system of Dream Desk, weren’t you?---Well, if you call Tool Box – I was building Tool Box, yes.

66 The applicant submitted that the inclusion of Jellis Craig in the migration scripts demonstrated that the respondents’ true objective was to maximise the prospects that existing DreamDesk clients would move to Toolbox after DreamDesk was shutdown.

67 In light of Mr Stoner’s instruction letter at [38] above, which stated “please arrange to migration scripts of this data to be loaded into the New E-doc templates to minimise as much disruption as possible”, I accept that Mr Stoner knew about the migration scripts in respect of Biggin & Scott data. It is likely that Ms Bartels also knew.

68 Mr Semmens gave evidence that he did not tell Ms Bartels or Mr Stoner that he ran the migration scripts on the RT Edgar and Jellis Craig data:

So, is the evidence you give now that you had conversations with each of Mr Meissner and Ms Stoner and possibly – sorry, Ms Bartels and possibly Mr Stoner about what should be done with the RT Edgar and Jellis Craig data. Is that right?---No. No, I wouldn’t have discussed RT Edgar and Jellis Craig data with them.

69 I accept that Mr Semmens copied the RT Edgar and Jellis Craig data in order to maximise the prospect of obtaining RT Edgar and Jellis Craig as clients of Toolbox should the opportunity later arise. I am not satisfied that Mr Stoner or Ms Bartels knew that Mr Semmens had run migration scripts to copy the data of RT Edgar or Jellis Craig.

B.7 Mid to Late-August: Biggin & Scott consider software providers; sale of Process 55

70 Mr Stoner gave evidence that, in about mid-August 2016, he decided that, if the Toolbox venture were to go ahead it should be done through “a separate and different company” to Biggin & Scott.

71 On about 18 August 2016, Ms Keys of Campaigntrack met with Ms Bartels to discuss whether Biggin & Scott would transition to Campaigntrack. Ms Keys gave an account of the conversation in which she stated she recalled Ms Bartels as having said that Biggin & Scott was “happy to agree terms with you but [we] just don’t want our business disturbed” in the context of stating that Biggin & Scott did not want DreamDesk shut down whilst they were entering spring, Biggin & Scott’s busiest time of the year. I accept that Ms Bartels sought to convey that Biggin & Scott were considering moving to Campaigntrack, whilst at the same time seeking to develop the new Toolbox system.

72 From 18 August 2016 until 6 September 2016, Biggin & Scott made enquiries with, and received offers from, other providers of online advertising systems, including Excel (Australasia) Pty Ltd and RealHub. Presentations were made to Biggin & Scott by both Excel (on 19 and 26 August 2016) and RealHub (on 5 September 2016). Mr Stoner gave evidence that these proposals were made in the course of Biggin & Scott exploring other options for online advertising systems. Campaigntrack submitted that Biggin & Scott’s interest in other systems was not a “bona fide interest”, but rather was done to: (a) obtain pricing information in order to price the Toolbox system competitively; and (b) feign interest in Campaigntrack so that Campaigntrack would keep the DreamDesk system operational. It is probable that there were a number of reasons for the enquiries. The likelihood is that Mr Stoner’s preference was that the new system would be operational by 3 October 2016 (when the “licence-back” granted by Campaigntrack to DDPL was due to end), but that – if it was not – another service provider might be required. The likelihood is that Mr Stoner’s least preferred option was to use Campaigntrack.

73 No doubt the enquiries with Excel and RealHub also provided pricing information and insights into the functionality of the Excel and RealHub software which might have been relevant and useful if the new system, Toolbox, was commercialised. I doubt that the enquiries were made with the object of “feigning interest in Campaigntrack”, although I accept that, at this time, Biggin & Scott conveyed to Campaigntrack that it was actively considering using Campaigntrack’s system when that was its least preferred option.

74 In August 2016, Digital Group, Campaigntrack, New Litho and their respective directors executed an agreement entitled “Agreement for the Sale of ‘Process 55’” (Process 55 sale agreement). From the date of completion of the agreement, being 25 August 2016, Campaigntrack and New Litho became owners of “the whole of Process 55”, including its source code and intellectual property rights.

B.8 26 August to Early September 2016: Early development of Toolbox

75 As noted earlier, the first commit to the Toolbox Git repository (the Dashboard Vault1 repository) was made by Mr Semmens on 26 August 2016. A total of eight commits to the Toolbox repository were made on this day. As also noted earlier, migration scripts for Jellis Craig were run on 26 August 2016.

76 On 1 September 2016, Ms Neal wrote an email (from “kylie@askthephantom.com.au”) to Ms Bartels, Ms Melissa Fato of RT Edgar and “accountservices9999@yahoo.com”, an email address being used by Mr Meissner. The email stated (emphasis in original, paragraph numbering added):

[1] Morning Ladies, (cc: Jon)

[2] This is my business email, best to use this for non-DD-related matters.

[3] Just some updates for you:

• [3.1] Jon has not received details of extension; he will forward when he does and advise CT to deal direct from here on in.

• [3.2] Reviewing Jon’s agreement, it appears the worst possible shutoff date is 3/10/16 - TBC by Jon’s solicitor.

• [3.3] It also appears that the extension to 1/1/17 is contingent upon ‘one of the DD clients known as RT Edgar or Biggin & Scott’ signing with CT. For me that’s pretty vague and could be a single office/entity. TBC by Jon’s solicitor.

• [3.4] Today I’m working on:

• [3.4.1] some alternate business continuity plans

• [3.4.2] reallocating resource from DD to work on new platform (which will mean minimising non-essential changes and putting them right into the new platform)

• [3.4.3] project plan for new platform

[3.5] The first hurdle is to register the business/domain - are we any closer from your perspective? What’s the next action on this?

[3.6] Call if you need me.

[3.7] K

[3.8] Kylie Neal

[3.9] M: [redacted mobile number]

77 RT Edgar’s involvement in Toolbox ceased a short time after this email.

78 I accept the submission advanced by Campaigntrack that it is likely that Mr Meissner was aware of the development of the Toolbox system by DDPL and JGM Advertising staff – see: [1] “(cc: Jon)”. Mr Meissner denied that he controlled the email address “accountservices9999@yahoo.com”. Whether or not Mr Meissner controlled the email address, I accept that he was using it at the relevant time.

79 Campaigntrack observed in submissions that Mr Meissner had agreed to use his “best endeavours” to persuade Biggin & Scott and RT Edgar to return to Campaigntrack’s system, as contemplated by cl 2.7 of the Binding Heads of Agreement. Campaigntrack submitted that the 1 September 2016 email showed that Mr Meissner (and Ms Neal, DDPL and JGM Advertising) were attempting to advance Biggin & Scott’s and RT Edgar’s interests in the Toolbox venture, by:

(1) seeking to extend the licence to use the DreamDesk system beyond the original 3 October 2016 deadline, so as to maximise the available time for development of the Toolbox system: at [3.1]-[3.3];

(2) actively developing a project plan for the Toolbox system: at [3.4.1], [3.4.3]; and

(3) allocating resources away from the development of the DreamDesk system to the development of the Toolbox system: at [3.4.2].

80 Campaigntrack also observed that, although the respondents appear to have created a detailed project plan for the development of the Toolbox system, none of the respondents put the Toolbox project plan into evidence or discovered any such plan.

81 Campaigntrack submitted that Ms Neal’s use of alternative email addresses (she did not use her DreamDesk email and she contacted Mr Meissner at the “acountservices9999” address) suggested that Mr Meissner, Ms Neal, DDPL and JGM Advertising “wished to act surreptitiously in their involvement in the development of the Toolbox system”. I accept that Ms Neal wanted to use different email addresses for work on the Toolbox system.

B.9 5-7 September 2016: Variation of DreamDesk agreements; payment of purchase price

82 The DreamDesk sale agreement and the Binding Heads of Agreement were varied on 5 September 2016, in respect to the mechanism for incentive-based arrangement for securing DreamDesk clients to transition to Campaigntrack.

83 On 6 or 7 September 2016, Campaigntrack and New Litho paid the purchase price of $50,000 under the DreamDesk sale agreement. On 7 September 2016, the CEO of New Litho, Mr Watts, sent an email to Mr Meissner and Ms Keys attaching the remittance advices for the payments to DDPL, and asking for the passwords that were to be provided as part of the handover of DreamDesk:

Jon,

Please find attached the remittances for the $50,000. $25000 from each party.

Now that payment is finalised, can you please instruct David Semmens to provide the following information to us via email as per clause 1.6:

1. Amazon webservices password

2. Administrator password to Dream Desk platform

3. Management passwords

4. Client logins for all clients

5. Any passwords for day to day operation of dream desk

6. Passwords and access details required for management and configuration of Dream Desk;

If you could CC me in on the request to David, I’m happy to chat with him if he has any questions. I’d like to sit down with him for a few hours and go through how the system is set up and managed as well.

Is Ewart out of the office?

B.10 Mid-September 2016: Ongoing development of Toolbox; relationship between Biggin & Scott and Campaigntrack deteriorates

84 On 8 September 2016, a number of emails were exchanged between Ms Neal and Ms Bartels (copied to Mr Semmens and Mr Stoner) regarding the media vendor integration (MVI) of data between the real estate agency’s customer relationship management system supplied by “Box+Dice” and the agency’s advertising system (eg DreamDesk or Toolbox). The emails refer to “the new system”, which I infer was a reference to the Toolbox system. The email chain included:

From: Kylie Neal [mailto:kylie@dreamdesk.com.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 September 2016 4:12 PM

To: Michelle Page <mpage@bigginscott.com.au>

Cc: David Semmens <david@dreamdesk.com.au>; Paul Stoner <pstoner@bigginscott.com.au>

Subject: Re: MVI (Box & Dice)

When offices have MVI turned on (in its current incarnation) OFIs [open for inspections] are entered into B+D and they sync to DD.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On Thursday, September 8, 2016, Michelle Page <mpage@bigginscott.com.au> wrote:

OK – is that being set up in the new system?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Kylie Neal [mailto:kylie@dreamdesk.com.au]

Sent: Thursday, 8 September 2016 4:19 PM

To: Michelle Page <mpage@bigginscott.com.au>

Cc: David Semmens <david@dreamdesk.com.au>; Paul Stoner <pstoner@bigginscott.com.au>

Subject: Re: MVI (Box & Dice)

Yes, but the first priority is to have offices able to place ads/orders. MVI is not guaranteed for day 1 but is a very early priority - Dave [I infer, Semmens] advises that it won’t be arduous to recreate, but the basics need to be available first. Happy to go through the plan/priorities if you wish.

85 On 9 September 2016, Mr Stoner sent an email to unnamed parties (although the recipients are likely to have included Mr Neil Pearson of Printco), with the subject line “structure”. Printco was a printing business that printed display boards for Biggin & Scott. It is likely that other recipients of the email were ABC (a display board company) and Mr Semmens. The email included (paragraph numbering added):

[1] Hi Guys

[2] Proposed structure for new co

[3] Name AGENT TOOL BOX Biggin & Scott Printco ABC To own 70% At a costs of $35,000 each

[4] David Seamans [sic] and partners 30% At a costs of $30,000

[5] I think we need to be open to JV’s with larger groups along the lines of white labelling the system on a 50/50 basis And also prepared to take on other investors should the need arise.

[6] We are currently sourcing a longer term for the platform 10 years at this stage so to be confirmed

[7] Where the team will sit is an issue as we cannot have one company being able to be see another’s pricing. We need to agree on this and quick. David may have a solution.

[8] Our objective is to get the system finished with Biggin & Scott using it by not later than October 3rd 2016 stage one As B&S are bringing in revenue this helps on a few levels but obviously part of start-up few is to help run the team until we pick up A few new clients.

[9] Biggin & Scott are happy for others to see how their work flow is happening.

[10] Reasoning behind Printco and ABC being partners is two fold Both have strong relationships with clients whilst at the same time can elevate some ongoing cost by introducing a system Which covers full web to print capabilities, Boards, brochures, stationary, papers, edm’s, intranet.

[11] First year each partner of the 70% must bring in at least the equivalent of what Biggin & Scott brings in production fee wise.

[12] Obviously if close not a problem but I think we need a taking the piss rule. Should this not happen under p[er]forming partner must offer shares back.

[13] Printco and ABC get full access of the system to offer to their clients obviously.

[14] Paul Stoner and Michelle page [Bartels] available to help get deals across the line should it be needed.

[15] If in agreement let’s get this set up with the rules as above and go for it.

[16] Dave will have a system presentation ready for us next week.

[17] Cheers Paul Stoner Chief Executive Officer

[Biggin & Scott signature block]

86 Campaigntrack emphasised the following matters about the email, which I accept as accurate:

(1) First, Mr Stoner was writing in his capacity as CEO of Biggin & Scott and as one of the prospective venturers: at [3], [17].

(2) Secondly, Biggin & Scott and its partners (Printco and ABC) were to take a controlling 70% interest in the venture, while Mr Semmens and his partners were to take a minority 30% interest: at [3]-[4].

(3) Thirdly, Mr Stoner’s and Biggin & Scott’s “objective” was to finish the Toolbox system and to have Biggin & Scott offices on the system by 3 October 2016 (at [8]), being the end-date of the “licence-back” to DDPL to use the DreamDesk system under the DreamDesk sale agreement.

(4) Fourthly, Mr Stoner, Ms Bartels and Biggin & Scott were taking an active role to ensure the success of the Toolbox venture by: bringing in production fee revenue from Biggin & Scott offices (at [8], [11]); sharing information about usage of the Toolbox system by Biggin & Scott offices (at [9]); and Mr Stoner and Ms Bartels being available to persuade customers to move to the Toolbox system: at [14].

87 On 12 to 13 September 2016, Mr Wentao Zhang and Mr David Gallagher made their first commits to the Toolbox Git repository. Mr Zhang is a software developer who was employed by Mr Meissner’s company, JGM Advertising, from 1 July 2016 to 6 October 2016. His “team leader” was Mr Gallagher, a DDPL consultant, who also worked on the development of the Toolbox system. Mr Zhang produced documents under subpoena. According to time sheets which he produced, by at least 8 September 2016, Mr Zhang was working on the development of the Toolbox System which was referred to as “Dashboard”. He continued working on the development of Toolbox until at least 3 February 2017. Whilst Mr Gallagher and Mr Zhang helped develop the software, Mr Semmens described himself as the “main developer” of the Toolbox system.

88 On 14 September 2016, Ms Bartels met with Ms Keys and Mr Dean of Campaigntrack in South Yarra. Ms Bartels showed Ms Keys and Mr Dean various functions and features of the DreamDesk system which she considered valuable, in particular the Electronic Data Management (EDM) function which was not a part of the Campaigntrack system. In her affidavit, Ms Bartels stated she did this “in the hope that [Campaigntrack] would keep [DreamDesk] alive for Biggin & Scott so we did not ultimately have to go down the track of launching a new system”. Ms Bartels asked Ms Keys not to shut down DreamDesk and stated that she recalled Ms Keys stating that Campaigntrack did not “want to interrupt your business but we will shut DreamDesk down”. I think it unlikely that, by this time, Ms Bartels did not want to launch the Toolbox system which was in the process of being developed.

89 According to Ms Keys, Ms Bartels said words to the following effect at the meeting:

Everything is pretty much set for Biggin and Scott to come back to Campaigntrack. The only issue is whether Campaigntrack could accommodate having an intranet feature? … I just need some time to go over the contract. I think that, at this point, it is just a matter of going through the contract and finalising the pricing. I also need reassurance that we keep the intranet page. … You have been great for not shutting [DreamDesk] down immediately.

90 I prefer Ms Keys account of the meeting. It is more likely in the context of the established surrounding circumstances.

91 RETB was incorporated on 15 September 2016. Mr Stoner became its sole director and 95% shareholder. Ms Bartels became its sole company secretary and 5% shareholder.

92 The Toolbox venture was operated by a trust (RETB Unit Trust), for which RETB was the corporate trustee. The RETB Unit Trust was established on 1 October 2016.

93 Mr Stoner confirmed that Mr Pearson or Printco made a $35,000 investment into the Toolbox venture. It is likely that Biggin & Scott and ABC also invested in the Toolbox venture.

94 By mid-September 2016, Campaigntrack had not yet received the passwords it needed to operate the DreamDesk software. Those had been requested on 7 September 2016 – see [83] above. Mr Meissner was on a cruise ship in Alaska from 6 to 19 September 2016 and Campaigntrack had difficulty getting in contact with him. On 16 September 2016, Ms Neal from DDPL sent the following email to Ms Keys regarding Mr Meissner’s whereabouts:

Hi Therese,

Just an update regarding Jon’s whereabouts.

Dave said that you are anxiously awaiting contact from Jon. He’s on a cruise ship in Alaska at the moment, and incommunicado.

He’ll be back on dry land Sunday/Monday [18/19 September 2016] if you email him I’m sure he will be in touch then.

If I can assist with anything in the meantime please let me know.

95 Mr Meissner gave evidence that before he left on his trip, he left Ms Neal and Mr Semmens in charge of turning the DreamDesk system off and giving it to Campaigntrack and negotiating the terms of any extension of the licence to use DreamDesk. Campaigntrack submitted that it should be inferred that Mr Meissner, Ms Neal and Mr Semmens deliberately delayed the handover process for two weeks, for the purpose of maximising the time to develop the Toolbox system and to seek to remove traces of the DreamDesk system from the Toolbox system.

96 Ms Neal’s email of 16 September 2016 to Ms Keys is odd. As noted earlier, on 1 September 2016, Ms Neal had sent an email saying she was “cc[-ing]: Jon” and the cc-ed email address was “accountservices9999@yahoo.com”. On 16 September 2016, Mr Meissner sent an email received by Mr Watts from the email address “accountservices9999@yahoo.com” saying he was sending the email from the account of “an Aussie resident of the US” whom he had met on the cruise and that it was not his email address. The email stated:

Sorry everyone

Since sept 6 I have been off the air ie phone and Internet wise

What they told me about ships was incorrect nothing works

I am back in Chicago on Monday and hopefully will be able to respond to any emails messages I have received

I am lucky to have met an Aussie resident of the US who has let me send this email on her account

Do not respond as it obviously is not my email address

Jon

97 I accept that Mr Meissner had difficulties being contacted whilst overseas. However, I conclude that Mr Meissner could have been contacted on 16 September 2016 by email.

98 On 21 September 2016, Mr Stoner emailed Ms Keys (Campaigntrack), copying Mr Meissner and Ms Bartels, stating that he was concerned that DreamDesk would be shut off (paragraph numbering added, typographical errors in original):

[1] Dear Therese [Keys], Tim [Dean] and Jon [Meissner]

[2] I am writing this email in the hope that we can all sort something out with regards to the Biggin & Scott group and the current situation we find our selves in after CT and Active pipe taking over or selling Dream Desk which as of today I am not [too] sure which it is.

[3] A conversation had on Monday of this week [19 September] with Tim and Therese has made me extremely nervous and concerned that either the system will be turned off or Dream Desk staff will be no longer after the 3rd of October 2016.

[4] I feel that I need to put forward my situation as simply a client using a system that has been taken over or in the process of being taken over.

[5] To date we have been happy to have conversations with respect to considering CT as our web to print solution but am extremely worried about the level of increased charges. Currently we are able to achieve through Dream Desk a level of production fees that we and our offices believe are fair for us and our suppliers, should we move forward with CT on current increases

$12 per page delivery fee for print of our ABODE magazine that does not currently exist

$15 per board order file delivery that does not currently exist

10% or $20 per print file delivery that does not currently exist

Which ever way I look at it the CT (campaign track) contract will increase our productions fees per property or across the board by 50-70% once the cost are passed on.

[6] During our meeting at RT EDGAR it was mentioned that you would handle this matter as good corporate citizens which as mentioned earlier in the week I have relied on.

[7] We also discussed the delicate timing being during our busiest time of the year which is extremely concerning to me. All rumours put forward to date are in accurate but again I ask you to understand how big a deal this is to have 34 offices change during the busiest time of the year-- this I am struggling with personally.

[8] When I consider the above increases it causes me a great deal of stress, as to position these cost with our offices would take time which we simply do not have and to say no results in Dream desk being turned off leaving Biggin & Scott with out a web to print system at the busiest time of the year with little to no warning or time to make other arrangements.

[9] At this stage we are very seriously considering going manual with suppliers help and a Mac operator in our office as we simply do not have the time or feel that we will be given time to work this out.

[10] I ask in good faith that we be given some normal or standard terms to exit Dream Desk maybe as per CT contract terms 90 days.

[11] In simple terms we are a customer of a system that has been bought by CT to close down to protect its position and I feel we need to be given some time. We are not your enemy just realestate agents using a system.

[12] As you will see above I have copied in our solicitors Mills Oakley whom are aware of the contracts and will be involved should Biggin & Scott fall victim to any thing that may damage our business through no fault of ours.

99 The applicant emphasised the following aspects of this communication:

(1) First, Mr Stoner was seeking to convey the impression that Campaigntrack was putting Biggin & Scott in a difficult position commercially and that, if Campaigntrack turned the system off on 3 October 2016, Biggin & Scott had little option but to “go manual”: at [7]-[9].

(2) Secondly, Mr Stoner did not refer to the 3-month contractual notice period under the Biggin & Scott – DDPL Agreement dated 20 May 2015: cf [10]. Instead, Mr Stoner sought to exit on Campaigntrack’s terms: at [10]. This was despite Mills Oakley, who were “aware of the contracts”, being copied to the email: at [12]. Mr Stoner’s failure to refer to the Biggin &Scott – DDPL Agreement was submitted to be inconsistent with the reliance in these proceedings by the represented respondents on that agreement as justifying the migration of the data from DreamDesk.

(3) Thirdly, Mr Stoner was seeking to convey the impression that he was a mere customer of the DreamDesk system, not a key venturer in the development of a competing system: at [11].

100 As to these matters:

(1) I accept that Mr Stoner sought to convey the impression contended and that this was not accurate because Mr Stoner considered that he would likely have available a competing system which, even if not fully functional, would be sufficiently operational to avoid “going manual”.

(2) I do not regard the failure to mention the Biggin & Scott – DDPL Agreement as significant. That agreement provided for a notice of period of 3 months if either party wished to bring the contractual arrangement between them to an end. It also provided that, if DDPL chose to cease to do business with Biggin & Scott as a group, migration of all templates and property related data was to be made available to whomever Biggin & Scott instructed. There was no express time limit with respect to migration of data. I do not regard it is as surprising that Mr Stoner did not rely on the term about 3 months’ notice with respect to use of the system as a whole, which is different to DDPL permitting migration of data.

(3) I accept that Mr Stoner’s communication did not convey that he was, together with others, developing a competing system and that his comments to Campaigntrack were intended to convey that his interests were more confined than they really were.

101 It was put to Mr Stoner that the purpose of his 21 September 2016 email was to “buy time” for Biggin & Scott until the Toolbox system became operational, a proposition which Mr Stoner denied:

… You were looking to build your own system and you were trying to buy time with Campaigntrack until you knew that the system was going to be operational?---Your opinion.

I’m putting that to you, Mr Stoner?---No.

102 Despite Mr Stoner’s evidence, it is probable that at least one of the purposes of the email was to “buy time” and it is likely that the time was being sought in order to further develop, or complete the development of, the Toolbox system.

103 Mr Meissner emailed Ms Keys and Mr Dean on 22 September 2016 stating:

I have been copied in on emails from Paul re our current predicament

Without making judgements or entering into discussions on the

Correctness of statements can I request the following

We would like an extension of 4 weeks to use the platform and would request you to indicate a fee payable now that RT Edgar is no longer using the platform and it would appear that CT has already had discussions with Jellis Craig in relation to ongoing services, which we at Dream Desk are unaware of

We initially agreed to $5000 per month when we were dealing with all clients

I await your response

Jon

104 Also on 22 September 2016, Mr Semmens provided Ms Keys with access to the cloud service on which the DreamDesk virtual server was stored. Mr Allen gave evidence that the migration scripts – which had last been run on 19 September 2016 – had been deleted from this virtual server, indicating that, at some time between 19 and 22 September 2016, Mr Semmens deleted the migration scripts from the DreamDesk system.

B.11 Campaigntrack and New Litho learn about Toolbox