Federal Court of Australia

Kumova v Davison [2021] FCA 753

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

The parties are to bring in short minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons within fourteen days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FLICK J:

1 The Applicant, Mr Tolga Kumova, in the substantive proceeding seeks damages as against the Respondent, Mr Alan Davison.

2 Mr Kumova claims that he has been defamed by a series of statements made by Mr Davison on his “Twitter Account”. His Amended Statement of Claim relevantly sets forth six “matters complained of”, being publications on or about:

20 September 2019;

24 April 2020;

20 May 2020;

30 May 2020;

2 June 2020; and

27 June 2020.

In very summary form, Mr Davison denies that the natural and ordinary meaning of the statements made have the meanings complained of and raises a series of defences including justification and contextual truth.

3 Of present concern is a claim made by Mr Davison to protect the source of information communicated to him by a person, being a person described by Mr Davison in his affidavit as a “corporate advisor”. Mr Davison claims that he is entitled to invoke s 126K(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the “Evidence Act”). In very summary form, s 126K(1) is described as a “journalist privilege” and protects from disclosure the identity of an “informant” if the requirements of that sub-section have been met. Senior Counsel for Mr Kumova rejects the claim for “journalist privilege” and raises a number of “hurdles” in the path of Mr Davison, including submissions that for the purposes of that sub-section:

Mr Davison is not a “journalist”;

the material published by Mr Davison is not “news”;

Mr Davison’s “Twitter feed” is not a “news medium”; and

the “information” communicated to Mr Davison was not given pursuant to a “promise” not to disclose the identity of the “corporate advisor”, being a “promise” given before the information was in fact provided.

Not in issue in the present proceeding is any application that may be made pursuant to s 126K(2) of the Evidence Act.

4 The evidence relied upon by Mr Davison for the purposes of invoking the privilege, as opposed to such evidence as may ultimately be relied upon or admitted at any final hearing of the defamation proceeding, was to be found in his two affidavits – one being parts of an affidavit dated 27 November 2020 and the other being an affidavit dated 14 June 2021. The latter affidavit, it may presently be noted, was served on the Applicant the Friday before the Queen’s Birthday long weekend with the hearing commencing on the Wednesday following that weekend. The evidence relied upon by Mr Kumova was to be found in two affidavits of Ms Dunn, a partner of Gilbert + Tobin. The exhibits to those affidavits were also separately tendered together with what was referred to as the Court Book.

5 For the purposes of resolving the present application it is sufficient to conclude that Mr Davison on the facts of the present case has not discharged the onus upon him of proving that:

he is a “journalist”;

his “Twitter feed” is a “news medium”; or that

he had “promised” the person providing the information “not to disclose” his identity prior to the information being provided.

Expressly not resolved are far more broad ranging questions, including questions as to whether:

a “Twitter feed” may (in different circumstances) be a “news medium”; and

what is required to satisfy the requirement in the definition in s 126J of an “informant”, that information is to be given to a journalist “in the normal course of the journalist’s work”.

6 In reaching these conclusions it is prudent to initially:

set forth ss 126J and 126K of the Evidence Act; and

an outline of the “Twitter account” operated by Mr Davison and an outline of the material published on that account in his “Twitter feed”.

It is thereafter necessary to separately address the questions as to whether:

Mr Davison is a “journalist”;

the “Twitter account” as operated by Mr Davison is a “news medium”; and

the point of time at which any promise was made by Mr Davison to the “corporate advisor” not to disclose his identity.

Sections 126J and 126K – definitions & statutory counterparts

7 Section 126K, together with s 126J, constitute Division 1C of Part 3.10 of the Evidence Act. Part 3.10 deals with “Privileges” and Division 1C is addressed to “Journalist privilege”. The journalist privilege sections which now make up Division 1C were first inserted by way of amendment in April 2011. The provisions came into force on 13 April 2011.

8 These sections were modelled on the New Zealand Legislation, namely s 68 of the Evidence Act 2006 (NZ).

9 Section 126J of the Commonwealth Evidence Act provides as follows:

126J Definitions

(1) In this Division:

informant means a person who gives information to a journalist in the normal course of the journalist’s work in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium.

journalist means a person who is engaged and active in the publication of news and who may be given information by an informant in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium.

news medium means any medium for the dissemination to the public or a section of the public of news and observations on news.

10 Section 126K provides as follows:

126K Journalist privilege relating to identity of informant

(1) If a journalist has promised an informant not to disclose the informant’s identity, neither the journalist nor his or her employer is compellable to answer any question or produce any document that would disclose the identity of the informant or enable that identity to be ascertained.

(2) The court may, on the application of a party, order that subsection (1) is not to apply if it is satisfied that, having regard to the issues to be determined in that proceeding, the public interest in the disclosure of evidence of the identity of the informant outweighs:

(a) any likely adverse effect of the disclosure on the informant or any other person; and

(b) the public interest in the communication of facts and opinion to the public by the news media and, accordingly also, in the ability of the news media to access sources of facts.

(3) An order under subsection (2) may be made subject to such terms and conditions (if any) as the court thinks fit.

11 The definition of a “journalist” as provided for in s 126J, it may be noted, is different from that provided for in s 68(5) of the Evidence Act 2006 (NZ). The New Zealand definition is as follows:

journalist means a person who in the normal course of that person’s work may be given information by an informant in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium

Section 68(5) of the New Zealand Act also provides the following definition:

informant means a person who gives information to a journalist in the normal course of the journalist’s work in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium

The difference is that the New Zealand definition of “journalist” was changed in s 126J such that the Australian definition “means a person who is engaged and active in the publication of news.”

12 With reference to the Australian provision, it would appear from the explanation provided by the Attorney-General to the House of Representatives on 21 March 2011, on behalf of the minority government in support of the then Bill, that the provision was intended to “allow the court to take a case-by-case approach”. The explanation provided was as follows:

The bill was always intended to ensure adequate protection for journalists and their sources. The amendments passed in the Senate clarify these protections, and the government supports these amendments as the amendments fit within the objectives of the bill and are consistent with the Commonwealth Evidence Act 1995. The definitions in this bill are modelled on the New Zealand journalist shield provisions, as I have indicated. The definitions of ‘journalist’, ‘informant’ and ‘news media’ rely on their ordinary meanings and allow the court to take a case-by-case approach. These amendments clarify the concerns expressed as to whether the New Zealand based definitions are technology neutral and cover all engaged and active in the publication of news.

The explanation by the Member who introduced the Bill, the Honourable Andrew Wilkie, on the same day was somewhat different and referred to the objective of the privilege not extending to “the many thousands of people posting comments online”. That explanation was as follows:

The amendments broaden the definition of a journalist from the traditional, where someone works for a newspaper, radio, television station or newswire, to include those who work in what we call the new media – for example, those who blog, Tweet or who use Facebook or YouTube to publish news.

…

The simple fact is that technology is driving a seismic shift in the way news is delivered nowadays as well as how we consume news information. These amendments would allow the shield law to ride those leaps and bounds and remain contemporary. I would add, however, that the intent of this bill and these amendments is not to offer blanket protection to anybody and everybody out there making public comments – for instance, the many thousands of people posting comments online. Ultimately, the definition of a journalist as somebody who is engaged and active in the publication of news will direct the protection to those who genuinely deserve and require it. If uncertainty arises, the courts can be trusted to adjudicate. …

13 With reference to the Commonwealth provisions, but with particular reference to the common law “newspaper rule”, Rares J in Ashby v Commonwealth (No 2) [2012] FCA 766, (2012) 203 FCR 440 at 446 (“Ashby”) commented as follows:

[17] The amendments to the Act have created a statutory right of journalists, as defined in s 126G, to assert a privilege from disclosure of their sources which has greater force than the common law rule of practice known as the “newspaper rule”: McGuiness v Attorney-General (Vic) (1940) 63 CLR 73 particularly at 104-105 per Dixon J. In John Fairfax & Sons Ltd v Cojuangco (1988) 165 CLR 346 at 351-352 Mason CJ, Wilson, Deane, Toohey and Gaudron JJ described the precise area of operation of the newspaper rule as being “shrouded in uncertainty”. Their Honours explained (at 354-355) that the courts had refused to accord absolute protection on the confidentiality of a journalist’s source of information while at the same time imposing some restraints on the entitlement of litigants to compel disclosure of the identity of the source. They said:

In effect, the courts have acted according to the principle that disclosure of the source will not be required unless it is necessary in the interests of justice. So generally speaking, disclosure will not be compelled in an interlocutory stage of a defamation or related action and even at the trial the court will not compel disclosure unless it is necessary to do justice between the parties.

[18] Some of those concepts are repeated in s 126H. However, this provision replaced the common law uncertainty with a prima facie entitlement of the journalist to assert a privilege against disclosing his or her informant or source.

The reference in his Honour’s judgment to s 126G was a reference to the forerunner to what now appears as s 126J. The statutory amendment effected to the “newspaper rule” was also explained by Dixon J in Madafferi v The Age Company Ltd [2015] VSC 687 at [28] to [33] and [38] to [43], (2015) 50 VR 492 at 502-503 and 505 to 506.

14 Sections 126J and 126K of the Commonwealth Evidence Act also have as their counterparts like provisions in State legislation. In Victoria, their counterparts are also to be found in ss 126J and 126K of the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic). These provisions were inserted into that State’s legislation in 2012, and commenced in January 2013. In the Victorian legislation, s 126J is the definition section and provides as follows:

126J Definitions

(1) In this Division—

informant means a person who gives information to a journalist in the normal course of the journalist’s work in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium;

journalist means a person engaged in the profession or occupation of journalism in connection with the publication of information, comment, opinion or analysis in a news medium;

news medium means a medium for the dissemination to the public or a section of the public of news and observations on news.

(2) For the purpose of the definition of journalist, in determining if a person is engaged in the profession or occupation of journalism regard must be had to the following factors—

(a) whether a significant proportion of the person’s professional activity involves—

(i) the practice of collecting and preparing information having the characterof news or current affairs; or

(ii) commenting or providing opinion on or analysis of news or current affairs—

for dissemination in a news medium;

(b) whether information, having the character of news or current affairs, collected and prepared by the person is regularly published in a news medium;

(c) whether the person’s comments or opinion on or analysis of news or current affairs is regularly published in a news medium;

(d) whether, in respect of the publication of—

(i) any information collected or prepared by the person; or

(ii) any comment or opinion on or analysis of news or current affairs by the person—

the person or the publisher of the information, comment, opinion or analysis is accountable to comply (through a complaints process) with recognised journalistic or media professional standards or codes of practice.

15 The comparable New South Wales legislation, found in ss 126J and 126K of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) is a mixture of both – the exposition in s 126J of that State’s definition of “journalist” does not have any reference to a person being “active” in the publication of news but does refer to a person “engaged in the profession or occupation of journalism”.

16 Given even this divergence in definitions of terms fundamental to legislative attempts to codify “journalist privilege”, different judicial approaches can only be expected. So much may, perhaps, be inevitable – even if regrettable.

The @stockswami account, the information provided & other uses of the Twitter account

17 All of the six “matters complained of” in the present proceeding were published by Mr Davison on his “@stockswami account”, an account apparently known as a “Twitter account”. It is only the third matter, namely that published on 20 May 2020, which presently attracts the necessity to focus on ss 126J and 126K of the Commonwealth Evidence Act.

18 In resolving any submission as to whether Mr Davison is either a “journalist” or that his “Twitter feed” can be described as a “news medium”, it is necessary to briefly set forth how Mr Davison regarded this account; the manner in which the information was communicated to him by the “corporate advisor”; and the nature and character of what else can be found by those accessing the “Twitter feed”.

19 This account, however described, was started by Mr Davison in 2016. The “profile header” for the account initially described it as offering a:

Cynical and Cranky take on the ASX professional company manipulators, I mean operators, making a play on Retail. They can Block but they can’t stop the Swamo.

This description was varied on or about 12 January 2021 and thereafter provided that the Twitter account provided a:

Cyncial and Cranky take on the ASX professional company operators making a play on Retail.

They can Block but they can’t stop the Swamo.

Citizen Journalist.

20 Mr Davison maintains in his first affidavit that he has “always used the @stockswami account to present [his] honest opinions on shares and share promoters, and to present [his] research on shares and also on the people standing behind the online accounts promoting the shares.” He maintains that he has “always conduct[ed] substantial research before posting”, that research including recourse to:

statutory documents;

public announcements by listed companies;

searches of ASIC registers, including the historical companies registers;

media reports of market activity;

google searches;

searches of other public registers and databases; and

social media.

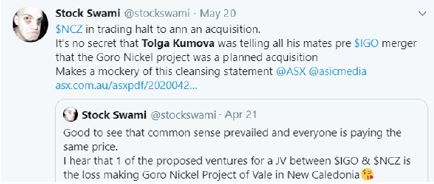

21 It was on this account that Mr Davison published the material going to the “third matter complained of” by Mr Kumova in his Amended Statement of Claim. The words complained of by Mr Kumova, and words which were said to be defamatory, were as follows:

This material was “uploaded” on Mr Davison’s “Twitter feed” on 20 May 2020. The Amended Statement of Claims pleads, and the Amended Defence accepts, that there were “approximately 6,808 followers” of this account.

22 The exchange between Mr Davison and the “corporate advisor” predating this “Tweet” on 20 May 2020 started with a series of exchanges on 15 April 2020 and was followed by a further series of exchanges on 17 and 18 April 2020. The content of the information being provided by the “corporate advisor” to Mr Davison in these exchanges could legitimately be characterised as commercially sensitive and “inside” information, and information presumably not then otherwise known in the market. If accurate, the information raises a real concern as to whether directors of a company had orchestrated a scheme whereby they could personally and impermissibly benefit from their knowledge of a deal which had been reached and not yet publicly disclosed, but “warehoused”. If accurate, the directors stood to gain by an increased value in stock.

23 Presently left to one side is more detailed consideration directed to whether a “promise” had been made by Mr Davison to not disclose the identity of the “corporate advisor” and when any such “promise” had been given.

24 Of present concern is an outline of what further information or material was available if regard was had to Mr Davison’s “Twitter feed”.

25 In addition to the information which formed the “third matter complained of”, it should thus be noted that Ms Dunn undertook what she described as “a non-exhaustive review of the Respondent’s Twitter Account”. She thereafter summarises that which she found to be also available on the “Twitter account”, being examples of what she describes as being:

unbalanced and non-factual tweets;

personal attacks;

tweets about Mr Davison’s personal life or stock trades;

offensive language;

a conversation with Jag Sanger, that conversation being directed to Mr Davison having been “ordered to give up [his] source for NCZ IGO scoop by Kumova’s party as they say I don’t qualify under Journalists [sic] privelege [sic]”;

a conversation directed to “TaxLossTrades”; and

a conversation with Timothy Clark.

Set forth under each of these examples are selections of the material found by Ms Dunn in support of the description she ascribes to each.

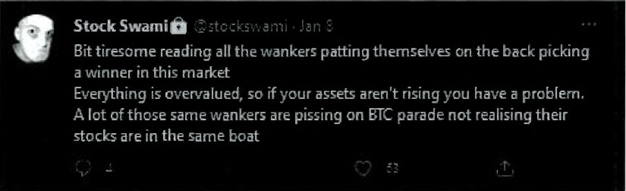

26 One of those entries which Ms Dunn described as “unbalanced and non-factual tweets” was one posted on 8 January 2020, which appeared as follows:

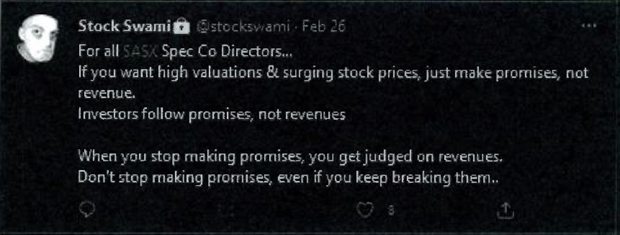

Another example is the following, namely one posted on 26 February 2021:

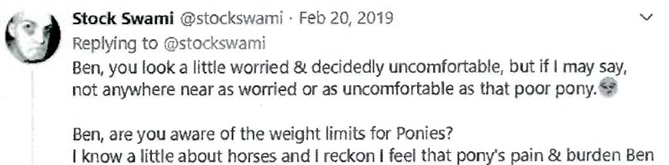

27 With reference to those examples of what Ms Dunn describes as “personal attacks” is the following dated 20 February 2019 and concerning Mr Kumova’s involvement in a polo tournament and was as follows:

A further exchange and one dated the following day was as follows:

Another example selected by Ms Dunn was an entry on 6 January 2021 with the following photograph of Mr Kumova’s car and was as follows:

Davison – A journalist?

28 It is with reference to this “Twitter account”, or on one view but part of that account, that the term “journalist” assumes central importance.

29 The definition of that term for the purposes of s 126K and “journalist privilege” remains a term defined for the purposes of the Division of the Evidence Act in which that privilege is addressed. And it is that Division of the Act which addresses the circumstances in which privilege may be claimed in respect to information given to a “journalist” by an “informant”. Hence the emphasis in the s 126J definition of a “journalist” who “may be given information” by an “informant”. Importantly, the definition in s 126J does not purport to otherwise define who may be a “journalist” who otherwise publishes “news”.

30 Within that statutory context, the definition of a “journalist” provided for in s 126J of the Evidence Act bears repetition. It provides as follows:

journalist means a person who is engaged and active in the publication of news and who may be given information by an informant in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium.

As this definition makes clear, the term “journalist” is to be read as a composite whole, including the further definitions of an “informant” and a “news medium”.

31 Although it is respectfully considered that there remains much uncertainty as to who falls within the common understanding of the term “journalist”, including the use of that term as further defined in ss 126J and 126K of the Evidence Act, it is nevertheless concluded that to be a “journalist” a person need not be:

formally engaged in a profession or business as a “journalist”;

nor

remunerated for the dissemination of that which is published.

Neither such requirement is for present purposes expressly specified in the definition; nor does any such requirement impliedly follow from the phrase “engaged and active in the publication of news”. Although that construction follows from the terms of the Australian legislation, it is also a conclusion supported by Slater v Blomfield [2014] NZHC 2221 at [73], [2014] 3 NZLR 835 at 852. Justice Asher there concluded:

[73] In my view the Commonwealth provision of “engaged and active in the publication of news” is more in line with the New Zealand definition “in the normal course of that person’s work”. On a plain meaning, like its Commonwealth counterpart, the New Zealand definition does not require remunerated work or engagement in a profession, although a lack of remuneration from the blog will be relevant to assessing “the normal course of work”. However, the phrase does require regular endeavour over a period of time.

It may be queried whether the legislative history to the Australian provisions may be called in aid in the interpretation and construction of ss 126J or 126K. But that matters not insofar as these two present conclusions are concerned.

32 Although the Commonwealth definition of “journalist” for the purposes of Division 1C of Part 3.10 of the Evidence Act is not as fulsome as (for example) its Victorian counterpart, it is nevertheless considered that that term in the Commonwealth legislation is to be construed not only by reference to the definition in s 126J and Division 1C of Part 3.10 of the Australian Evidence Act, but also by reference to at least some of those “factors” expressly set forth in s 126J(2) of the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic). To this extent, the Victorian legislation may be seen as doing nothing more than giving express content to what otherwise may be seen as necessarily to be implied or inferred from the common understanding of that term and the Commonwealth’s own use of the term “journalist”.

33 Whether, for the purposes of resolving the question as to whether a person is a “journalist” under the Commonwealth legislation, “regard must be had” to all those “factors” expressly identified in the Victorian legislation is a question which can presently be left to one side. It is sufficient for present purposes to conclude that “regard” may be had when determining whether Mr Davison is a “journalist” for the purposes of ss 126J and 126K of the Commonwealth Evidence Act to whether they are a person:

“engaged in the profession or occupation of journalism”;

engaged in “the practice of a person collecting and preparing information having the character of news”;

who “regularly publish[es] in a news medium”; and

who complies with “recognised journalistic or media professional standards or codes of practice”.

Having “regard” to professional standards or codes of practice would also inevitably involve “regard” being had to such further matters as to whether:

an account of events is sought to be presented in a fair and balanced manner, allowing always for the reality that a person conveying information may inevitably bring an individual and personal “bias” into the account being published; and

the motive or purpose of the person conveying the “news”, a purpose of belittling another would (for example) hardly be the hallmark of objectivity or fairness.

Irrespective of the terms of the Victorian legislation, such matters are matters which inform a decision as to whether someone is a “journalist”. The Commonwealth phrase “engaged and active” in the publication of news only, with respect, further reinforces a construction of the term “journalist” as not referring to someone who only and coincidentally publishes material which may otherwise be characterised as “news”, and does so in a manner which may on that one occasion comply with an aspiration of fairness and objectivity, and a person who publishes in a forum which contains so much other “non-news” material that the forum can in no real sense be described as a “news medium”.

34 Compliance – or non-compliance – with one or other of these “factors” may not necessarily dictate a conclusion one way or the other; but a consideration of these factors, it is concluded, at least helps to assist or inform any finding as to whether Mr Davison is a “journalist” as that term is commonly understood and as further defined in s 126J.

35 Whatever uncertainty there may be as to the term “journalist”, a submission placed at the forefront of those advanced on behalf of Mr Kumova is that Mr Davison could in no sense be described as a “journalist”. That submission is accepted.

36 Summarily rejected would be any contention that Mr Davison could bring himself within that term simply by his revamped profile to his twitter account in January 2021 describing himself as a “citizen journalist”. At best, this self-description could well be described – as with the defendant in Doe v Dowling [2019] NSWSC 1222 at [3] per Fagan J – as “loose”.

37 At the very heart of the conclusion that Mr Davison is not a “journalist”, however, are the accounts given by Mr Davison as to what he sought to achieve by publishing material on his Twitter account, starting with the “profile header” for that account stating that:

the Twitter account is a platform for providing a “Cynical and Cranky take on the ASX professional company manipulators”.

Totally consistent with that description is the admission in his Amended Defence that:

if “each” of the matters complained of in the Amended Statement of Claim were in fact defamatory, they were “published … as a means of defending and vindicating himself against tweets earlier published by the Applicant that attacked Davison”.

To this admission may be added, albeit to a lesser extent, the further admissions when the Amended Defence directs specific attention to “triviality” and s 33 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) that:

the “Twitter social media platform is notorious as a source of unreliable, unvetted and untrue information”; and

the “ordinary reasonable reader does not place reliance on tweets published by unverified, anonymous Twitter accounts”.

38 It is certainly not the hallmark of a “journalist”, as that term is normally understood, to publish – not “news” – but a “cynical and cranky take” on information and to publish material – not for the purpose of publishing “news” – but for the purpose of “defending and vindicating [oneself].”

39 The conclusion that Mr Davison was not acting as a “journalist” in publishing material on his “Twitter feed” is also to be founded, with respect, upon:

the entirety of the publications complained of in the present proceeding and not just one of them; and

the character and nature of such other material as may also be accessed on the “Twitter feed”.

It would be a conclusion which would not sit comfortably with either the facts of the present case, or the common understanding of a “journalist”, that Mr Davison could be found to be a “journalist”:

for one of the six “matters complained of” (namely the third matter) but not the remaining five; or

for the publication of an isolated exchange found amidst a “Twitter feed” containing much other diverse material of the kind described by Ms Dunn.

40 If this approach be erroneous, and if attention could be confined to Mr Davison’s conduct in publishing the third “matter complained of”, namely the 20 May 2020 material, then it must be accepted that on that occasion he came closer to falling within the normally understood meaning of the term “journalist” by:

considering the reliability of the source of the information, namely the reliability of the “corporate advisor”; and

attempting to verify the information.

The evidence as to Mr Davison satisfying himself of the reliability of the “corporate advisor” and his attempts to verify the information is set forth as follows in his first affidavit sworn on 27 November 2020, namely:

479. I considered my informant’s information to be reliable because:

(a) I had previously dealt with my informant and found him to be trustworthy;

(b) my informant was a highly experienced and senior capital markets participant;

(c) my informant’s information was detailed;

(d) my informant provided me, as part of those messages, with screenshots of what appeared to be Cannacord Genuity’s term sheet for the capital raise; and

(e) I was aware, from following Tolga’s Instagram feed, that Tolga had recently been in Cape Town, South Africa, for a mining conference, which was consistent with my informant’s statement that “Tolga was screaming about it in Capetown”.

480. I also had telephone conversations at this time with my informant in which he confirmed what he had told me in the messages.

481. Although I thought my informant was reliable, I am a sceptical person and I could not exclude the chance that my informant was feeding me a false rumour about a further capital raise at 15c in order to pump the share price, or had some other agenda.

482. I did not intend to publish what my informant had told me without seeking independent confirmation first.

483. On 17 April 2020, I told Johnny Shapiro of the AFR about the rumour I had heard regarding the Goro project and the 15c capital raise with IGO, and suggested he approach NCZ for comment.

484. On 19 April 2020, the AFR published an article under the headline “Independence may deploy war chest on zinc hopeful”.

For present purposes the evidence at paras [479] and [481] to [484] may be accepted. The evidence at para [480] warrants closer attention when consideration is to be given to what is conveyed by the phrase “at this time”.

41 Even if this alternative approach be warranted, however, there would nevertheless remain questions as to whether Mr Davison’s “Twitter feed” was a “news medium”, whether a “promise” had been given to the “corporate advisor” not to disclose his identity and when such a promise was given.

42 Each of these matters should be separately considered.

A news medium?

43 Another of the submissions advanced by Senior Counsel on behalf of Mr Kumova is that the “Twitter account” of Mr Davison was not a “news medium”. Again, that submission is also accepted.

44 In reaching this conclusion, reliance has been placed upon:

the conclusion that Mr Davison is not a “journalist”; and

the description of the account given by Mr Davison in the “header profile” to that account as initially provided and as revised in January 2021.

Reliance has also been placed upon:

the content of what other information is available on the Twitter account, other than information which could potentially be described as “news”.

Regard has also been had to:

the prospect that at least when publishing the “third matter complained of”, Mr Davison could possibly be described as having adhered to some of the hallmarks of a “journalist”.

But a “news medium”, it is respectfully concluded must remain a medium which is routinely or regularly used by journalists as a medium primarily, or at least substantially, for the publication of “news” as opposed to a medium which may from time to time be the source of “news”.

45 The conclusion that the Twitter account is not a “news medium” obviously overlaps with the former conclusion as to Mr Davison not being a “journalist”. But the two are separate components – as is made self-evident from the separate definitions of “journalist” and “news medium” in s 126J.

46 On the facts of the present case, and based in part upon:

Mr Davison’s own description of the purpose he sought to achieve through his Twitter account;

his own description of the account as being far from objective and the lack of any express statement on his part that a purpose he sought to pursue was that of disseminating “news”, however he may have described that term for his own purposes; and

the description provided by Ms Dunn as to the material otherwise found on the “Twitter account”, none of which could be described as “news”,

no conclusion is open, with respect, that the account (or his personal “Twitter feed”) can be described as a “news medium”.

A promise not to disclose identity?

47 A further submission advanced by Senior Counsel on behalf of Mr Kumova was that Mr Davison has not discharged the onus resting upon him to prove the requirements of s 126K(1).

48 Again it is worth repeating the terms of s 126K(1). That sub-section provides as follows:

If a journalist has promised an informant not to disclose the informant’s identity, neither the journalist nor his or her employer is compellable to answer any question or produce any document that would disclose the identity of the informant or enable that identity to be ascertained.

It is also worth repeating the terms of the definition of the term “informant” in s 126J, namely:

informant means a person who gives information to a journalist in the normal course of the journalist’s work in the expectation that the information may be published in a news medium

Section 126K(1), it will be noted, refers to a “promise” and s 126J refers to an “expectation”.

49 In resolving this further submission advanced on behalf of Mr Kumova, it has been concluded that:

the “promise” referred to must be a promise “anterior” to the provision of the information;

the “promise” must be a promise “not to disclose” the identity of a person who can be characterised as an “informant”;

the “promise” referred to must be an express “promise” in respect to the provision of identifiable information as opposed to any promise that may otherwise be inferred, or any promise that could be implied by reference to (for example) the character of the information being disclosed; and

on the evidence, Mr Davison has failed to discharge the onus of making out that any such promise was “anterior” to the provision of information – the evidence making good the proposition that there was a “promise” not to disclose the identity of the “corporate advisor” but, at best, being uncertain as to when that “promise” was first made.

50 As to the first two of these conclusions, reliance is placed upon the following observations of Rares J in Ashby which immediately follow the discussion of the purpose sought to be achieved by what was then s 126G and s 126H of the Evidence Act, now s 126J and s 126K, namely the following (at 446 to 447):

[19] How can the privilege be asserted? First, s 126G defines the informant as being the person who gives information to a journalist in the ordinary course of the journalist’s work in the expectation that that information may be published in a news medium. Secondly, the section defines the “journalist” as being the person who, in the practice of his or her profession, may be given information by an informant in the expectation that that information may be published in a news medium. Thus, the statutory definitions of “informant” and “journalist” in s 126G create a relationship that must exist between the particular information conveyed and the persons between whom it is communicated. The privilege in s 126H(1) relates to an anterior promise made by the journalist not to disclose the informant as the journalist’s source of that particular information: ie the journalist’s promise of confidentiality referred to in s 126H(1) is not to disclose the informant’s identity, or to enable that identity to be ascertained, in respect of that person as being the source of the particular information.

[20] If s 126H(1) were construed in the way in which Mr Lewis asserted, journalists would be able to resist producing, or disclosing to a court, any document or information provided by a person to whom they had once promised confidentiality that discloses the identity of the source or enables it to be ascertained, regardless of the connection between the promise and the particular information. This argument would extend the privilege to all instances where the journalist had spoken to, say, a politician on a confidential basis, or “off the record”, about a particular subject matter, even though they may talk together on a daily basis “on the record” about other matters.

[21] The section is not designed to produce such a result. Its purpose is to ensure that a person who provides particular information can do so knowing that his or her identity as its source can be protected by the journalist because he or she is not compellable to disclose that identity by force of s 126H(1). The privilege exists so that, ordinarily, the journalist cannot be compelled to disclose or identify his or her informant or source of particular information obtained for the purposes of the journalist’s work. That privilege is, however, subject to the court’s power created by s 126H(2), to override it in certain circumstances.

[22] The free flow of information is a vital ingredient in a democratic society such as that in which we live. The interests of justice are equally important and can override journalistic privilege if the conditions in s 126H(2) are established. Nonetheless, as the Court recognised in Cojuangco [(1988) 165 CLR 346] at 354:

The role of the media in collecting and disseminating information to the public does not give rise to a public interest which can be allowed to prevail over the public interest of a litigant in securing a trial of his action on the basis of the relevant and admissible evidence. No doubt the free flow of information is a vital ingredient in the investigative journalism which is such an important feature of our society. Information is more readily supplied to journalists when they undertake to preserve confidentiality in relation to their sources of information. It stands to reason that the free flow of information would be reinforced, to some extent at least, if the courts were to confer absolute protection on that confidentiality. But this would set such a high value on a free press and on freedom of information as to leave the individual without an effective remedy in respect of defamatory imputations published in the media.

(Emphasis added.)

The first of the conclusions seizes upon the observations of Rares J at para [19] as to the need for an “anterior promise”; the second of the conclusions is simply derived from the terms of s 126K(1); and the third seizes upon his Honour’s observations at para [20].

51 Some reservation may nevertheless be expressed as to any conclusion that there must necessarily be in all cases the extraction of a promise prior to the provision of any information at all. That reservation arises from:

the terms of s 126K(1), the sub-section being silent as to when any promise need be given;

the definition of the term “informant” and the reference in that definition to the “expectation” of the informant; and/or

the facts of a particular case.

As to the last consideration, in some cases in the course of a single communication (for example) the very content and subject matter of what is being conveyed may well attract an “expectation” on the part of the person conveying the information and the “journalist” receiving it, that all that is said is being conveyed in the “expectation” that the identity of a person will not be disclosed. It may matter not, in such cases, that the promise not to disclose the person’s identity comes mid-way through the exchange of information or even at the very end. A conclusion that the provision of all information has been conveyed pursuant to such a “promise” may well be sufficient to satisfy the terms of s 126K(1). It is, however, unnecessary to resolve the precise point of time during a conversation (or even a series of conversations within a confined timeframe) when a “promise” need be given. In the absence of any necessity to address such circumstances, deference is expressed to the view of Rares J in Ashby.

52 It is unnecessary to express a view because it has been concluded that, on the facts of the present case, it remains uncertain as to when any “promise” had been given to the “corporate advisor”, and uncertain as to the extent of the information that had been given without the “corporate advisor” either seeking assurance or having an “expectation” that his identity would not be disclosed. If any finding of fact were to be made it would be a finding that a great deal of information had been communicated without any “promise” being sought by the “corporate advisor” or given by Mr Davison.

53 The conclusion that Mr Davison has not discharged the onus of proof resting upon him of bringing himself within s 126K(1) is a matter of inference from the available evidence.

54 The evidence going to the point of time at which Mr Davison maintains he made a “promise” to the “corporate advisor” not to disclose his identity is largely to be found in both:

the chronological sequence in which messages were exchanged between Mr Davison and the “corporate advisor” on 15, 17 and 18 April 2020; and

his two affidavits.

55 Insofar as the chronological sequence of messages is concerned, the exchange of information between Mr Davison and the “corporate advisor” which led to the 20 May 2020 publication dated back to 15 April 2020 – as far as can now be determined by reference to such materials as can be found. Following an exchange of information starting at 6.14am on 15 April 2020, there then appears a series of intervening exchanges and then a message to Mr Davison which apparently was sent at 9.10am on the same day stating:

Oh wow. Game on. Do you take phone calls

There then follows a further exchange between Mr Davison and the person providing him with information on 17 and 18 April. But there is no further reference in those exchanges to any phone call having been made. There is no reference to any prior telephone conversation and no reference to any earlier exchanges of information even in respect to other communications between the “corporate advisor” and Mr Davison as to promises being made not to disclose the advisor’s identity.

56 Mr Davison further addresses the exchange between himself and the “corporate advisor” in his first affidavit sworn on 27 November 2020 as follows:

473. Between 15 April and 21 April 2020, I received a series of direct (i.e. private) messages on Twitter from a Twitter user I knew to be a corporate advisor with detailed knowledge of market activity in Australia and wide contacts.

474. I have promised my informant that I would not disclose his identity and I claim journalist’s privilege over his identity

…

After setting forth in the same affidavit the basis for his belief as to the reliability of the “corporate advisor”, Mr Davison states the time at which he had “conversations” with the “corporate advisor” as follows:

480. I also had telephone conversations at this time with my informant in which he confirmed what he had told me in the messages.

“This time” is presumably a reference to sometime “[b]etween 15 April and 21 April 2020”. In his second affidavit, being the affidavit filed outside of the time otherwise prescribed by the Court directions for the filing of evidence, and filed on the Friday preceding the hearing, Mr Davison returned to this exchange and proffered the following further evidence:

My promise to my informant

5. At par [480] of my first affidavit, I refer to telephone discussions with an informant around the time that informant sent me the Twitter direct messages referred to at par [473] of my first affidavit.

6. I recall that we had a telephone discussion to the following effect:

Informant: You can’t let anyone know that I gave you this material. You have to leave me out of this. I will be crucified if my name gets out.

Me: Don’t worry. I will leave you right out of it.

7. I had this conversation before 19 April 2020 and before I posted any tweet based on material or information given to me by this informant.

8. I consider myself bound to abide by my promise to my informant that I would not disclose his name.

By agreement between Counsel, there was no cross-examination of Mr Davison and agreement reached that no submission would be relied upon that any adverse inference should be drawn in reliance on Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 (“Jones v Dunkel”).

57 On behalf of Mr Davison reliance was obviously placed upon:

the nature of the information being communicated;

the reference to the “phone calls” in the exchange on 15 April 2020 and the sequence in which the messages were exchanged; and

the express statement in his second affidavit provided immediately before the hearing as to the conversation in which the promise was given having taken place “before 19 April 2020 and before [he] posted any tweet based on material or information given to [him] by this informant…”

If any analysis as to the facts is paused at this point, it may matter little that there was an agreement between Counsel to make no Jones v Dunkel submission. Any such submission would be one derived from the following observations of Kitto J in Jones v Dunkel at 308, namely:

…any inference favourable to the plaintiff for which there was ground in the evidence might be more confidently drawn when a person presumably able to put a true complexion on the facts relied on as the ground for the inference has not been called as a witness by the defendant and the evidence provides no sufficient explanation of his absence. …

The “inference” that could otherwise have been open to be made in submissions was that, in the absence of cross-examining Mr Davison, his evidence as to the timing as to when he made the promise should be accepted.

58 Irrespective of any agreement between Counsel, however, the “highest” Mr Davison’s evidence could reach was that a promise was given “before 19 April” – that leaving open the prospect that any promise was given at some point of time between 15 and 18 April 2020 and given only after information had been provided.

59 In resisting any conclusion that any promise was given “anterior” (cf. Ashby at [19]) to the receipt of information, Senior Counsel for Mr Kumova was thus content to rely upon the terms of Mr Davison’s own account as to the timing of that account – that account being that it was given:

…before 19 April 2020 and before [he] posted any tweet based on material of information given to [him] by this informant.

Even on this account, Mr Davison does not assert that he gave any promise before any information was provided. Any promise subsequently given, so it was submitted on behalf of Mr Kumova, came too late. If reference is made to the exchange of messages themselves, it is also abundantly clear that:

at least some of the information was communicated before any telephone conversation in which the promise was said to have been made – the message during which an inquiry was made as to “Do you take phone calls?” occurring apparently at 9.10am on 15 April 2020, with at least three exchanges occurring prior to that time, during which information was provided.

In further resisting any unqualified acceptance on Mr Davison’s account as to when the conversation took place, reliance was also placed on behalf of Mr Kumova upon the fact that:

the account given in the affidavit is lacking in any precision, such that the Court should be hesitant to accept it – there being no precision, so the submission ran, as to precisely when the telephone conversation occurred (other than “before 19 April”) in circumstances where it lay in the control of Mr Davison to corroborate the timing of that call by reference to telephone records; and

the affidavit in which the account was given was provided outside the time otherwise prescribed by previous Court directions, and at a point of time which precluded those on behalf of Mr Kumova from being put in a position to test the account by reference to (presumably) telephone records. The late provision of the affidavit upon such an important issue – an issue that prompted those on behalf of Mr Davison to file a late affidavit and expressly address a central matter of fact dividing the parties – and the onus placed upon him to make good the fact as to when the promise was given, was said to provide reason for caution.

There is, moreover, a tension between the two affidavits, that tension being:

in the earlier affidavit Mr Davison maintains that he “had telephone conversations at this time”, that time being presumably being a reference back to a period identified earlier in the affidavit as “ [b]etween 15 April and 21 April 2020” – whereas the latter affidavit refers (albeit as Mr Kumova would have it in terms lacking any detail and without explanation) to a time “before 19 April”; and

the earlier affidavit referring to “telephone conversations” whereas the affidavit served late, and specifically seeking to clarify what had earlier been deposed to, referring to a single conversation.

60 Given this evidence and these submissions, it is found that:

on any view of the evidence, at least some information was provided at a point of time prior to any promise being given by Mr Davison, namely prior to 9.10am on 15 April 2020.

It is further found as a fact that:

Mr Davison has not discharged the onus of proof resting upon him to make good his assertion that he made a promise to the “corporate advisor”, as stated in his later affidavit, “[b]efore 19 April 2020”.

Although caution needs to be exercised before making a finding of fact that has the effect of not accepting evidence – such as the present finding as to when a promise was given – and caution needs to be exercised in placing disproportionate weight upon differences and inconsistencies in evidence which may in other circumstances not assume much prominence, it is concluded that no finding of fact can be made that any promise was given “before 19 April” in circumstances where:

it is manifestly apparent that those advising Mr Davison recognised that a question of fact arose as to when any promise was made, which was not adequately addressed in an earlier affidavit, and sought to address that deficiency by the filing of a later affidavit,

and in circumstances where that later affidavit:

deposes in uncertain terms as to when the promise was given (the uncertainty being a question as to what point of time prior to 19 April 2020 the promise was made, even assuming that evidence was to be accepted) and there is a lack of certainty as to what was (for example) said by Mr Davison to the “corporate advisor” or what was said by that advisor to Mr Davison;

deposes to a date which was susceptible of being corroborated by reference to telephone records – as opposed to the date upon which messages were exchanged – but where such corroboration was not forthcoming; and

does not sit comfortably with the earlier affidavit, either as to time or whether there were several telephone conversations of relevance.

Even in the absence of cross-examination – and it is difficult to know what may have been the outcome of any cross-examination had it taken place – there may well have been difficulty in accepting Mr Davison’s account provided in his second affidavit as satisfying the requirements of s 126K(1).

61 Even if, contrary to the above conclusion and if a finding were to be made that a promise was given “before 19 April 2020”, difficulty would nevertheless still be confronted. Even if that evidence as to timing be accepted, the further difficulty confronting Mr Davison would be to identify with some acceptable degree of precision the information which had been conveyed to him on the basis of, or in the expectation of, identity not being disclosed. If greater attention is given to the content of the exchanges between the “corporate advisor” and Mr Davison, it emerges that:

the outline of the scheme whereby a “cap” was being placed on stock values and there have been already a “deal warehoused” was all information conveyed to Mr Davison on 15 April and prior to the question being posed “Do you take phone calls” later in the morning on the same day;

thereafter, and particularly on 17 April, greater detail as to the how the scheme was to work is disclosed with further information being given to Mr Davison on 18 April.

Accepting for present purposes that there was a conversation “before 19 April” during which a promise was given, any such conversation may well have taken place after the more extensive information was conveyed to Mr Davison on 17 April. And nothing is known as to whether any promise that was given “before 19 April” was given after any discussion as to what (if any) information that had previously been conveyed could be attributed to the “corporate advisor”.

62 The difficulty confronting Mr Davison, even accepting his evidence that there was a conversation “before 19 April”, is that there even then remains uncertainty as to whether the giving of a promise to protect the informant’s identity was a mere afterthought which neither the “corporate advisor” nor Mr Davison had previously considered was necessary. Even if a promise to protect identity need not necessarily be given “anterior” to the provision of information, the extraction or the giving of a promise cannot be a mere afterthought. And little is known as to the prior relationship between Mr Davison and the “corporate advisor” other than that Mr Davison had “previously dealt with” him and “had found him to be trustworthy”. Nothing is known, for example, as to whether the “corporate advisor” had previously provided other information on the basis of his identity not being disclosed or that there had long been in place a relationship which itself engendered some “expectation” that they had previously dealt with each other on the basis of confidentiality.

63 Whether the giving of a “promise” need be “anterior” to the giving of information or rather subsequently but necessarily as part of the course of the exchange of information, Mr Davison has failed to discharge the onus of proof resting upon him.

CONCLUSIONS

64 It has been concluded that Mr Davison cannot be characterised as a “journalist” within the common understanding of that term or that meaning as further employed in ss 126J and 126K of the Evidence Act. Although he may have complied with some of the standards normally expected of a “journalist” in one of the publications made via his “Twitter account”, his conduct in the use of the platform viewed in its entirety strips him of that characterisation. As put in oral submissions advanced on behalf of Mr Kumova, albeit now loosely and more generally expressed, Mr Davison “cannot be a journalist one day but not the next…”

65 Although it may be accepted that a “Twitter account” or “Twitter feed” may in some circumstances constitute a “news medium” for the purposes of s 126J(1), on the facts of the present case it has been further concluded that Mr Davison’s “Twitter account” cannot be so characterised. It has not been able to be concluded that his “Twitter account” can be so described in circumstances where its self-professed purpose is to make known “cynical and cranky opinions”, and where the account also publishes substantial amounts of material which can in no sense be described as “news”.

66 Nor has it been able to be concluded, on the balance of probabilities, that Mr Davison has discharged the onus upon him of bringing himself within the terms of s 126K(1). Even if it were to be accepted that a promise was at some stage made, the facts are equivocal as to whether that promise was made after or before the information was communicated.

67 These conclusions, it will be noted, depend very much upon the peculiar facts of the present proceeding. Those who drafted the legislative amendments to the Evidence Act clearly contemplating, as do the terms of the Act itself, that there remain many cases in which it will remain a task for judicial resolution to determine whether the privilege applies or not.

68 It may finally be noted that it was agreed at the conclusion of the hearing that the proceeding would benefit from a Court ordered mediation before a Registrar of this Court. An order to that effect should be made. So, too, should an order be made that the costs of the present proceeding follow the event.

THE ORDER OF THE COURT IS:

The parties are to bring in short minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons within fourteen days.

I certify that the preceding sixty-eight (68) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Flick. |

Associate: