FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Tregidga v Pasma Holdings Pty Limited [2021] FCA 721

ORDERS

First Applicant CATHERINE MARY JENKINS Second Applicant | ||

AND: | PASMA HOLDINGS PTY LIMITED ACN 093 774 559 TRADING AS PASMA ELECTRICAL Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants’ originating application filed on 11 October 2017 is dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs of the proceeding to be taxed failing agreement.

3. If any party wishes to seek a different order as to costs, then order 2 is vacated and the following orders will apply.

4. By close of business on 5 July 2021, that party is to prepare and submit to my chambers a set of submissions, limited to four pages, and any supporting affidavit material.

5. By close of business on 12 July 2021, the opposing party is to prepare and submit to my chambers a set of submissions in response, limited to four pages, and any supporting affidavit material.

6. The costs of the proceeding will then be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REEVES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 On the evening of 8 June 2016, the sailing motor yacht Miss Angel sustained extensive damage from a fire which started in her engine room. At that time, Miss Angel was slipped at the premises of BSE Cairns Slipways Pty Ltd (BSE) in Cairns, North Queensland. During the day of the fire, Mr Benjamin Tilton, an electrician employed by Pasma Holdings Pty Limited, the respondent, was undertaking work on Miss Angel’s electrical system.

2 In this proceeding, Mr Ross Tregidga and Ms Catharine Jenkins have claimed damages against Pasma alleging that the fire was caused by its breach of contract or its breach of a statutory guarantee and/or the negligence of Mr Tilton for which it is vicariously liable.

3 On 14 June 2019, the issue of liability in this proceeding was ordered to be dealt with first as a separate question. For the reasons that follow, I do not consider Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins have established, on the balance of probabilities, that Pasma is liable for the damage caused by the fire on board the Miss Angel. That is to say, I do not consider they have established that Mr Tilton’s negligence caused that fire. Their originating application must therefore be dismissed.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

4 In the second half of 2015, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins decided to establish a business sailing tourists from Cairns to the Great Barrier Reef. To that end, on 30 September 2015, they registered a company called Allure Cruises Pty Limited , of which they were the sole directors and shareholders. At the same time, the Trekins Family Trust was settled, of which they were the principal beneficiaries, and they caused Allure to be appointed as the trustee of that Trust with the intention that their tourism business would be operated by the Trust through Allure as its trustee.

5 In October 2015, Mr Tregidga travelled to Turkey to find a suitable vessel which could be brought into commercial survey in Australia. He eventually located, and decided to purchase, the Miss Angel. She had been built in Bodrum, Turkey in 2004 and was of traditional Turkish design. Consequently, Mr Tregidga was aware that she would require extensive works to bring her up to the requisite Australian commercial survey standard.

6 With that matter in mind, during October 2015, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins met in Cairns with Mr Russ Larkin and Mr Steven Larkin of Russ Larkin & Associates Pty Ltd. Steven Larkin is an Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) certified surveyor. He advised them on the works required to bring Miss Angel to the requisite standard mentioned above. Among other things, he advised that they would need to engage an AMSA certified electrical surveyor to attend to the upgrade to its electrical system. Steven Larkin told them he could not provide that certification himself because he was not AMSA certified for electrical surveys and he was not a licensed electrician.

7 On 23 October 2015, Allure entered into an agreement to purchase the Miss Angel. Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins loaned the monies to Allure necessary to complete that purchase. Those monies were transferred to Turkey in stages and the sale was eventually completed on 3 December 2015 when a bill of sale was executed transferring the Miss Angel to Allure. At about the same time, the vessel was insured with Pantaenius, a company specialising in maritime insurance.

8 Having completed the purchase, Mr Tregidga’s plan was for Miss Angel to set sail for Australia before Christmas 2015. However, he encountered two difficulties. The first was that, under Turkish law, the Miss Angel could not be removed from Turkey while it was owned by a foreign company unless Mr Tregidga produced certain documentation, which he was not able to do before the planned departure date. The second was that Miss Angel could not be imported into Australia as a commercial vessel unless she met the requisite AMSA survey standard and that could not be achieved without the extensive works mentioned above first being undertaken.

9 To comply with the former requirement, on 21 December 2015, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins caused Allure to execute a bill of sale to transfer the Miss Angel to them individually. As a consequence, the loan they had made to Allure to purchase the vessel was subsequently forgiven. As to the latter, following advice from an AMSA official that the Miss Angel could enter Australia as a recreational vessel, Mr Tregidga decided to register her in that category. Furthermore, to achieve that registration in sufficient time to allow Miss Angel to set sail from Turkey before Christmas 2015, he flew from Bodrum to the Turkish capital, Ankara, on 23 December 2015 and attended the Australian Embassy in that city where he obtained the necessary registration certificate for the vessel.

10 The Miss Angel departed Turkey to sail to Australia on 24 December 2015. A Turkish captain sailed the vessel from Turkey to the Maldives and, at the Maldives, he was replaced by Ms Anita Rak, who sailed the vessel for the remainder of its journey to Australia.

11 During February 2016, while the Miss Angel was in transit to Australia, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins met in Cairns with Mr Brian Keller of BSE to discuss the nature of the works that would need to be undertaken on the vessel and the timeframe required for those works. Mr Keller advised them that BSE could undertake the works on Miss Angel’s hull and propeller shaft, but he recommended other specialised contractors for other aspects of the works, including Pasma to undertake the electrical works.

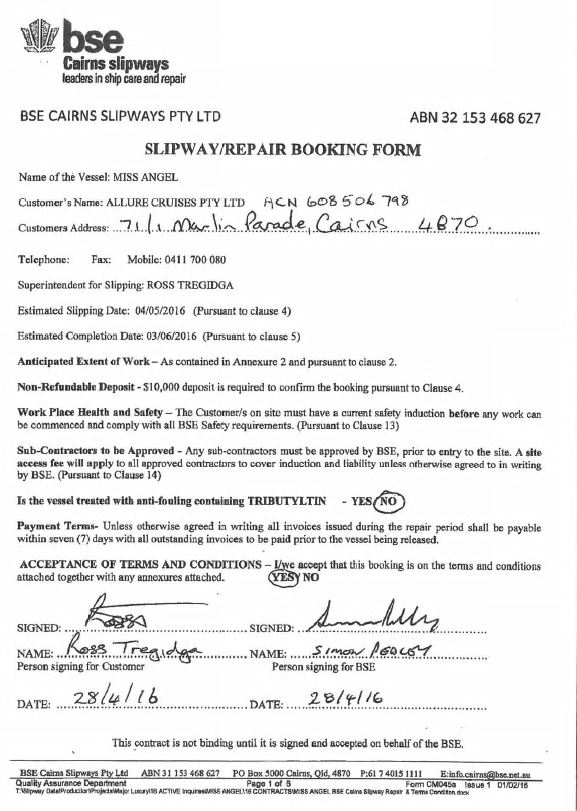

12 The Miss Angel arrived at Cairns on about 26 April 2016. After clearing customs, she was initially berthed at the Cairns Jetty. On or about 28 April 2016, Mr Tregidga met with Mr Keller and entered into a written agreement with BSE in the form of a “SLIPWAY/REPAIR BOOKING FORM” pursuant to which BSE was to undertake the works discussed during their February meeting above. On or about 3 May 2016, the vessel was moved to the BSE Shipyard, slipped and placed on a hard stand there. In that process, she was connected to 240 volt AC shore power by an employee of BSE.

13 In late May and early June 2016, there was a series of conversations which variously involved Ms Rak, Mr Tregidga, Mr Pasma and Mr Tilton concerning certain repairs to Miss Angel’s electrical system and the upgrade works necessary for her to attain commercial survey standard in Australia. At the conclusion of one of those discussions on or about 2 or 3 June 2016, Mr Tregidga entered into an oral agreement with Pasma to undertake the upgrade works mentioned above. Mr Tilton began to undertake those works on or about 2 or 3 June 2016 and continued on 7 and 8 June.

14 On the day of the fire, several people were present on the Miss Angel for various periods of time. First, Mr Tregidga attended the vessel between approximately 7.30 and 9.30 in the morning and between approximately 2.30 and 3.00 in the afternoon. Secondly, Ms Jenkins arrived at the vessel at approximately 10.00 or 11.00 in the morning and she left with Mr Tregidga at about 3.00 in the afternoon. Thirdly, during the day, a number of subcontractors were working on the hull of the vessel stripping and sanding it. Fourthly, Ms Rak, the captain, was on the vessel for most of the day. Finally, Mr Tilton was working on the vessel’s battery banks in the vessel’s engine room throughout the day. Ms Rak and he left the vessel together at about 4.15 pm.

15 At about 11.15 that night, Mr Keller contacted Mr Tregidga and advised him that smoke had been seen coming from the Miss Angel and she appeared to be on fire. Mr Tregidga attended the BSE shipyard immediately and observed firefighters attempting to control the fire. The fire lasted for about three to four hours before it was brought under control. As already mentioned, the Miss Angel suffered extensive damage as a result.

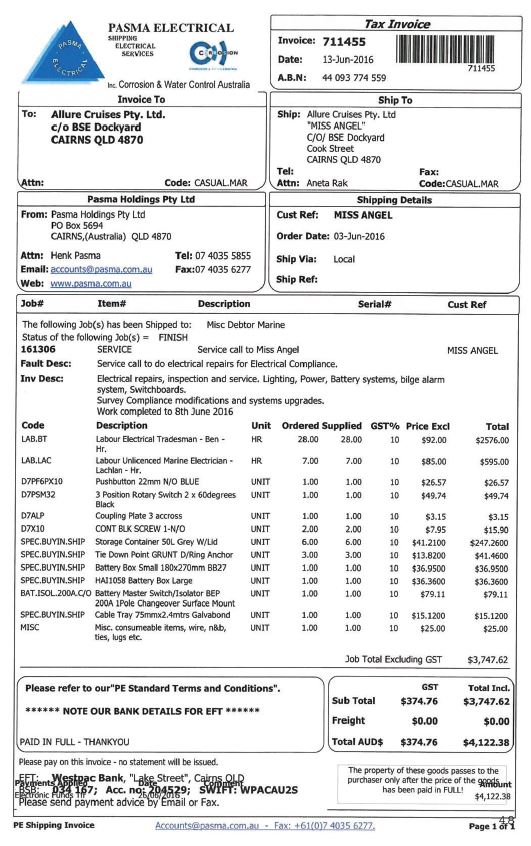

16 Five days after the fire, Mr Tregidga received a tax invoice dated 13 June 2016 from Pasma and addressed to Allure. It was in the sum of $4,122.38 and related to the works carried out on the Miss Angel to 8 June 2016. Ms Jenkins paid that invoice from her personal bank account on 26 June 2016.

THE ISSUES

17 Prior to closing submissions, counsel for the parties agreed that the following seven issues fell to be determined:

1. The ownership of the vessel – who was the owner of the Miss Angel at the time of the contract with Pasma and at the time of the fire?

2. The contracting parties – with whom did Pasma contract when it was engaged to undertake the work on the vessel?

3. The Australian Consumer Law issues:

(a) Are Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins “consumers” for the purposes of s 60 of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (the ACL)? and

(b) If so, are they entitled to pursue a claim against Pasma for breach of guarantee under s 60 of the ACL even if they are not a party to the contract with Pasma (see issue 2 above)?

4. The negligence issues:

(a) To whom is any duty of care in tort owed by Pasma? (This is linked to Issue 1)

(b) What is the scope of the duty of care owed by Pasma:

(i) in tort?

(ii) in contract?

(iii) pursuant to s 60 of the ACL?

(c) in particular, to what extent (if any) is the scope of Pasma’s duty of care in tort, contract or pursuant to the guarantee in s 60 of the ACL determined or affected by:

(i) the terms of the contract by which Pasma was engaged to work on the Vessel?

(ii) the terms of the contract between Allure and BSE?

(d) was there a breach of the duty of care by Mr Tilton/Pasma?

(e) was there a breach of that duty of care on the grounds of res ipsa loquitor?

5. The causation issues:

(a) what was the cause of the fire ?

(b) was it caused by Pasma’s alleged

(i) breach of its duty of care? and/or

(ii) breach of contract? and/or

(iii) breach of the s 60 ACL guarantee?

6. The proportionate liability issues:

(a) were any of the following concurrent wrongdoers?

(i) BSE;

(ii) the Master, Ms Rak;

(iii) Allure;

(iv) Mr Tregidga;

(v) Mr Steven Larkin;

(b) if so, should any liability of Pasma to Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins be reduced by the proportionate liability of any of the foregoing? and

(c) if so, by what amount (or amounts)?

7. The contributory negligence issues:

(a) is Mr Tregidga liable for contributory negligence?

(b) if so, should any liability of Pasma to Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins be reduced by Mr Tregidga’s contributory negligence? and if so, by what amount?

These issues will be dealt with in turn below. However, as will emerge later, it will not be necessary to deal with Issues 6 and 7.

1. THE OWNERSHIP ISSUE

The issue as pleaded

18 In their Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASC) (at [4A]), Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins alleged that, as at 8 June 2016, they were the owners of the Miss Angel. In the corresponding paragraph of its defence, Pasma denied that allegation and claimed that instead Allure was the owner.

The evidence

19 This issue essentially revolves around an email that Mr Tregidga sent to Pantaenius on 23 December 2015, shortly before the Miss Angel set sail for Australia, informing it of the change in ownership of the vessel and the circumstances in which that had occurred. That email relevantly stated:

Urgent

Please note that we have had to make the purchase of Miss Angel under our names due to requirements of Turkish authorities, as follows:

…

We have bought this for our company, Allure Cruises Pty Ltd. Miss Angel will revert to the Company ownership once we return to Australia. Cathy and I are the only Directors of Allure Cruises.

Will the current cover still suffice or will you need to reissue in our individual names? If so, can you please action urgently this morning and email to us as we are departing Turkey tomorrow and will not be contactable until after Boxing Day.

…

20 Pasma also relied upon a number of “contemporaneous documents”, including the agreement mentioned earlier that Allure entered into with BSE on 28 April 2016 to undertake works on the vessel and the invoice also mentioned earlier that Pasma submitted to Allure for the works it carried out on the vessel up to the time of the fire.

21 For their part, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins relied, among other things, on the accounting records in evidence which recorded that their loan to Allure of the funds necessary to purchase Miss Angel had been forgiven.

The contentions

22 Pasma contended that Mr Tregidga’s email evidenced a transfer by Allure “to it[s] directors on the basis of a promise to retransfer”. Further, it contended that the “contemporaneous documents” referred to above showed that all the dealings with the vessel after she arrived in Australia were conducted by Allure and it should therefore be inferred that the ownership of the vessel had been transferred from Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins to Allure prior to the fire. As well, in oral submissions, Pasma contended that the alleged promise arose in part from the serious context in which it was provided, namely by an insured to an insurer about the ownership of insured property. It also contended that this promise resulted in the grant to Allure of an equitable interest in the Miss Angel.

23 In their oral and written submissions, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins contended that the indication that Mr Tregidga gave to Pantaenius in his email of 23 December 2015 was not a contractually enforceable promise, nor a declaration of trust, but rather was a statement of future intentions with respect to the ownership of the Miss Angel which, by the time of the fire, had not come to fruition. Further, they pointed to the evidence that the Miss Angel remained at all times registered and insured in their names and that the loan they had made to Allure to purchase the vessel had been forgiven. As well, they contended that there was no evidence of any bill of sale or other document evidencing the transfer of the Miss Angel from them to Allure. As to Allure’s dealings with the Miss Angel after she arrived in Australia, they contended they were all consistent with the original intention that Allure should operate the tourism business as trustee of the Trust and were not indicative of any transfer of the vessel from them to Allure. Finally, even if Allure were the equitable owner of the vessel, they contended that they still retained the legal ownership and, as such, were still owed a duty of care such that they were entitled to sue in tort for any damage caused to it by another person’s negligent conduct.

Consideration and disposition

24 For the following reasons, I consider Pasma’s contentions with respect to this issue must be rejected. First, neither its context, nor its contents, permits Mr Tregidga’s email to Pantaenius of 23 December 2015 to be construed as a promise by him and Ms Jenkins to transfer ownership of the Miss Angel to Allure. Instead, that communication was, as Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins correctly contended, a statement of their future intentions concerning the ownership of the Miss Angel which was neither contractually binding on them, nor constituted a declaration of trust.

25 Secondly, there is simply no evidence which would support an inference being drawn that this statement of future intentions was acted on prior to the fire. No bill of sale or similar document that would ordinarily evidence the transfer of the ownership of a vessel such as the Miss Angel has been produced (see ss 36 and 37 of the Shipping Registration Act 1981 (Cth)). To the contrary, the Miss Angel remained registered and insured in the names of Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins and the loan Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins made to Allure to purchase the vessel was forgiven.

26 Finally, and relatedly, Allure’s dealings with the Miss Angel after it arrived in Australia do not provide that evidence. All those dealings were consistent with the original intention that Allure, as trustee of the Trust, should operate the tourism business. They say nothing about the ownership of the Miss Angel. For these reasons, the answer to the question posed in Issue 1 above is that Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins remained the legal and equitable owners of the Miss Angel as at the time of the contract with Pasma and at the time of the fire.

2. THE CONTRACTING PARTIES ISSUE

The issue as pleaded

27 In their FASC, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins alleged (at [9]) that they entered into the agreement with Pasma in the following circumstances:

On or before 3 June 2016, [Mr Tregidga] met in person with Mr Henk Pasma and Mr Benjamin Tilton of [Pasma] and entered into an oral contract for [Pasma] to examine, repair and refit the Vessel’s electrical systems to ensure that they complied with AS/NZS 3000 and NSCV.

28 In the corresponding paragraph of its defence, Pasma did not admit this allegation and instead pleaded that Allure entered into the agreement with it on or before 25 May 2016 in the following circumstances:

…

that, on or before 25 May 2016, [Mr Tregidga], acting on behalf of Allure, met in person with Mr Henk Pasma and entered into an oral contract between Allure and [Pasma] for [Pasma] to bring the Vessel’s electrical system up to standard to obtain certification required under the Marine Safety (Domestic Commercial Vessel) National Law Act 2012 (Cth) for the Vessel to operate in Queensland and certification in accordance with AS 3000 and NSCV.

29 Fortunately, in oral submissions, the following aspects of these two sets of allegations were accepted as common ground. First, that the agreement was oral. Secondly, that it was entered into by Mr Pasma on behalf of Pasma. Thirdly, that it was entered into in a conversation between Mr Pasma and Mr Tregidga. Fourthly, that its purpose was to ensure that the vessel complied with Australian Standard/New Zealand Standard (AS/NZS) 3000 and the National Standard for Commercial Vessels (NSCV), which set the relevant commercial survey standards. This issue is therefore confined to the question whether, when he had his conversation with Mr Pasma and entered into the agreement, Mr Tregidga did so on behalf of himself and Ms Jenkins, or on behalf of Allure.

The evidence

30 In his first outline of evidence, Mr Tregidga described the events leading up to and including the entry into the oral agreement with Pasma in the following terms:

49. I cannot recall the exact date but sometime before electrical works commenced, I met with Henk Pasma and Ben Tilton of Pasma Electrical.

50. About 7 or 10 days before the fire, Henk and Ben were at BSE for an unrelated matter and Brian, Commercial Manager at BSE, took the opportunity to bring them to the Vessel.

51. I explained to Henk and Ben that we needed the Vessel to be brought to survey, specifically ‘Class 1 D Certification’. Henk advised “don’t worry about it, we have undertaken the same work on many other boats, including up in Asia ” or words to that effect.

52. Henk and Ben represented to me that they knew what was required to bring the Vessel to survey so I instructed them to “get on with the work” or words to that effect. I had no knowledge of what was required so was led by Pasma Electrical and trusted their expertise.

53. Neither Henk nor Ben quoted me for the work to be performed and I did not enter a signed contract. Henk and Ben did advise me that they estimated at least three weeks worth of work which included a complete rewiring of the vessel. I trusted them to do what was necessary.

54. In terms of the billing address for works, I do not recall instructing Pasma to invoice Allure Cruises. It is possible that BSE provided Pasma with this instruction.

55. A copy of the electrical drawings (wiring plans) was provided to Ben …

56. I did not see Henk after that and I believe that all works were performed by Ben. I saw him on board the Vessel.

57. I recall catching up with Ben about one week into the job and asking how long it was likely to take. Ben advised me it would take another 2 or 3 weeks due to the amount of work, particularly the rewiring, which was time consuming. I offered to hire a tradesman to assist him with the pulling of wires but Ben replied “no, it’s okay, I’ve got it under control” or words to that effect.

58. Aside from that, I had no other communications with Ben. He did not report to me. I had no other communication with Henk, Ben or anyone from Pasma Electrical either.

(Italics in original)

31 In his second outline of evidence, Mr Tregidga returned to the same issue and added the following:

22. When engaging [Pasma] to complete electrical works on the Vessel, I did so in my personal capacity on behalf of the Partnership.

23. The Pasma’s engagement was completely oral and I did not sign any written agreement with them. During my conversations with Henk Pasma and my provision of oral instructions, I do not recall ever advising the Henk that I was contracting with Pasma on behalf of Allure Cruises. As far as I was concerned, the Pasma were dealing with me directly and was fully aware that Cathy and I were the owners of the Vessel.

24. On 13 June 2016 (i.e. five days after the fire), the Pasma issued an invoice for the electrical work performed pre-fire in the sum of $4,122.38 and addressed it to “Allure Cruises”. I do not know why the invoice was addressed to Allure Cruises save that the business address of Allure Cruises was a sensible place to send the invoice knowing that it would reach me.

25. I, on behalf of the Partnership, paid Pasma’s invoice soon after it was issued without hesitation.

(Errors and italics in original)

32 Mr Tregidga’s oral evidence on this aspect was to similar effect.

33 Ms Rak was not called to give evidence at the trial.

34 In his first outline of evidence, Mr Pasma described the events leading up to and including the entry into the oral agreement relating to the works to be undertaken on the Miss Angel in the following terms:

8. I was approached first approached by Brian [Keller] of BSE Cairns Slipways Pty Ltd (BSE) to determine whether we had availability to undertake electrical works on MV Miss Angel (the Vessel).

9. I received a telephone call from [Ms Rak] who I understood to be the captain of the Vessel to discuss undertaking works on the Vessel.

10. At the time of entering into initial discussions with [Ms Rak] to undertake works on the Vessel, I understood that the Vessel was slipped at the BSE Slipway located at 61-79 Cook Street, Portsmith in the State of Queensland (the BSE Slipway) and that BSE Cairns Slipways Pty Ltd (BSE) was undertaking works on the Vessel.

11. I was advised by Ross Tregida [sic Tregidga] to issue invoices for works undertaken by Pasma on the Vessel in the name of Allure Cruises Pty Ltd (Allure Cruises).

12. It was my understanding that the owners of the Vessel, who are the Applicants to these proceedings, required a Class 10 Electrical Certification as the owners of the Vessel intended to use the Vessel for commercial purposes.

13. During the works I [redacted] had little contact with [Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins] and relied on direction from the Captain, [Ms Rak]. I did not meet [Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins] in person until sometime after the project had commenced.

14. On or around 26 May 2016, I along with Benjamin Naho Tilton, met with the Captain of the Vessel [Ms Rak] at the BSE Slipway for the purpose of undertaking a visual inspection of the Vessel.

15. I undertook the visual inspection in the company of the Vessel’s Captain, Mr Tilton and one of my other apprentices, during which I noted and we discussed the various works that would be required on the Vessel. In addition, I took photographs of the Vessel …

…

24. On 13 June 2016 I caused an invoice to be issued to Allure Cruises (Invoice 711455) work undertaken on the vessel up to and inclusive of 8 June 2016 …

(Emphasis and errors in original)

35 In his second outline of evidence, Mr Pasma repeated much of this evidence, but he provided approximate dates when some of the events referred to occurred as follows:

4. In relation to work to be performed on the Vessel, I was first approached on or around 9 May 2016 by Brian Keller of BSE regarding whether Pasma had availability to give a quote to do electrical works to bring the Vessel into compliance. At that point in time Brian did not mention any specifics of the state of the Vessel.

5. Within a week from Brian calling me, Aneta Rak, The Vessel’s captain, called me by telephone to request I attend the Vessel to provide a certificate of compliance …

6. Within a week of speaking to the Vessel’s captain, on or about 25 May 2016, I attended the BSE shipyard where the Vessel was already slipped and on the hardstand and I entered the Vessel via the gangway where I was met by the Vessel’s captain. Ms Rak then gave me her business card …

7. When I arrived at the Vessel I entered by the gangway and observed that the Vessel was connected to shore power. Ms Rak told me that she was living on board. I observed that she had what appeared to be an office with a laptop set up in the lounge area and that the lights were on in all areas of the Vessel that I inspected.

8. On 26 May 2016, Ms Rak, Mr. Tilton and I met at the BSE Slipway to undertake a further visual inspection of the vessel.

9. At the inspection, Ms Rak told me of the feature lights she wanted to be installed on the mast of the Vessel. Ms Rak discussed with me aesthetic improvements only, such as the installation of “mood lighting”. I observed:

(a) That there were no identifiable issues which caused me to believe the electrical system posed a risk of injury to someone onboard the vessel;

(b) The current wiring was not compliant with Australia Standards, as the vessel was built overseas;

(c) There was no proper fire cladding in the engine room. I raised this specific issue with Ms Rak and said words to the effect that the fire cladding issue needed to be rectified and advice on what additions and changes would be required before we could undertake the electrical work in the engine room in particular, the accommodation, wheelhouse and galley areas. Structural changes would most likely be required in those areas of the Vessel.

…

11. On or about 2 June I gave a budget estimate of $30K with weekly updates and costings to Ross Tregidga, at a meeting with him on board the vessel. He advised me to issue invoices for works undertaken by Pasma to Allure Cruises Pty Ltd.

12. On or about 3 June, Ms Rak also advised me to issue invoices for works undertaken by Pasma to Allure Cruises Pty Ltd. Invoices of work were then addressed as required by those persons.

(Errors in original)

36 However, Mr Pasma clarified who it was he made the agreement with and changed when it was made at the conclusion of his oral evidence, as the following passages from the transcript demonstrate:

In this proceeding, the pleadings refer to you having – or your company having entered into an oral agreement to perform this work. And I just want to ask you about – firstly, if you go to your first outline, which is at page 77 of the court book. And you will see - - -?---Yes.

- - - from paragraphs 8 through to 22 you describe the dealings you had with, firstly, Mr Keller from BSE and then Ms Rak?---Yes.

In your second outline, you deal with the same issue from paragraph 7 through to –might be six. Five or six through to about 10. I’m telling you that to ask you this question: who did you make this oral agreement with?---With regards to the work on the vessel?

Yes?---Ms Rak.

And in those paragraphs, particularly in the paragraphs of your second statement, you seem to recount, I think, two or three meetings with Ms Rak?---Yes.

So in paragraph 6 you refer to one on 25 May. In paragraph 8 you refer to a meeting on 26 May, and you refer in paragraph 11 to giving a budget estimate to Mr Tregidga on 2 June?---I believe so, yes.

So when did you make this oral agreement?---When I was talking with Mr – Mr Tregidga at the time. He wanted some sort of indication on the possible costing.

… he wanted to know an approximate costing of … what I thought would be the extent of the works, from my experience.

So when did you make the oral agreement? You said you made it with Ms Rak. When did you make it?---It was with Ross Tregidga. Ms Rak asked me if I could have a think about a cost estimate, and it’s with Ross that I discussed that cost estimate.

So does that mean you made the oral agreement with Mr Tregidga?---That’s correct.

So the only reference – only mention of him is in - - -?---Sir, Ms Rak - - -

I’m sorry?---Sir, Ms Rak was available there as well.

So that must be – if you’re looking at your second outline that’s in paragraph 11?---Right.

You say:

On or about 2 June I gave an estimate –

etcetera?---Hang on. What page is that?

Page 83?---Yes. That’s correct.

So does that - - -?---Paragraph 11. Paragraph 11, is that what you’re referring to?

Yes. I’m asking you whether that’s the time when you made the oral agreement?---That’s correct, with Mr Tregidga.

On 2 June?---Yes.

Or about that time?---About – about that time.

(Italics in original)

37 Mr Tilton’s outlines of evidence did not include any information relevant to this issue.

38 Finally, there are two exhibits, the contents of which have a bearing on this issue. They are, first, the contract Mr Tregidga entered into in the name of Allure with BSE on 28 April 2016. As already mentioned, that contract took the form of a “SLIPWAY/REPAIR BOOKING FORM” (the Slipway Contract). Excluding the “STANDARD TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SLIPPING AND/OR REPAIR” (the Slipway Contract Terms) that were attached to it, that form was as follows:

39 Secondly, there is the tax invoice dated 13 June 2016 already mentioned above that Pasma submitted to Allure for its work on the vessel. That invoice was in the following form:

40 At the conclusion of his oral evidence, after Mr Pasma clarified and changed the position with respect to the oral agreement he made on or before 3 June 2016 (see at [36] above), he gave the following evidence about the “PE Standard Terms and Conditions” referred to in this invoice:

And one further area. When Mr Savage was taking you to various documents, he took you to the document at 1149 of the court book. That’s your standard terms and conditions?---That’s our standard terms and conditions. Yes.

So when you made this agreement on 2 June, were those terms and conditions discussed in any way?---They were not discussed, no. They were implied.

And, in particular, was there – if you look at page 1151, was there any discussion about who was responsible for the – I’m looking at clause 5.6. Who would be responsible for the safety and security of the vessel?--- ....

Was there any discussion about who would be responsible for the safety and security of the vessel?---There was no discussion, no.

Thank you?---The owner of the vessel is always responsible.

Well - - -?---In particular the captain.

41 Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins’ counsel then asked Mr Pasma some further questions concerning both matters as follows:

And when you had the conversation with Mr Tregidga, you had already been engaged to perform work on the vessel and were performing that work. That was the situation, wasn’t it?---That’s correct.

And the conversation with Mr Tregidga was in relation to the likely cost of that work and a request that you provide – I think you said a budget estimate, or – yes, a budget estimate is what you said in paragraph 11. That’s correct, isn’t it?---That’s correct.

And it was - the budget estimate that was being provided by you to Mr Tregidga was an estimate in relation to the work that was being performed under the engagement that you had concluded with Ms Rak, prior to 2 June. That’s the position, wasn’t it, Mr Pasma?---I believe so.

And when you spoke with Ms Rak on 26 May, or indeed at any time, I take it that you didn’t speak with her about the standard terms and conditions that his Honour has just taken you to, at page 1149 and following, at tab 52. That’s correct?---That’s correct.

And at no time did you provide those standard terms and conditions to Ms Rak, even before 8 June. That’s the position, is it not?---That’s correct. She was aware of our website, because she had visited us prior – after having had discussions with Mr Keller.

She was aware that you had a website, is that what your evidence was?---Yes.

But you don’t know to what extent that she had accessed, or had in fact accessed that website. That’s correct, is it not?---That’s correct.

And even if she had accessed that website after she had spoken with Mr Keller, and prior to speaking to you, at no point in time did you provide her with a copy of those terms and conditions, or refer them to her. That’s correct?---That’s correct.

And at no time did you provide a copy of those terms and conditions to Mr Tregidga, either before 2 June – is that correct?---That’s correct.

Or on 2 June, is that so?---That’s correct.

Or even after 2 June, before 8 June, is that correct?---That’s correct.

And indeed, would it be correct to say that at no time have you, or to your knowledge, your company, provided either Ms Rak or Mr Tregidga with a copy of those standard terms and conditions?---That’s right.

42 Finally, in her outline of evidence, Ms Jenkins said that, at the request of her husband, she paid Pasma’s invoice from her personal bank account on 26 June 2016.

The contentions

43 In their written submissions, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins contended that this question had to be determined by reference to who it was that the parties objectively intended to enter into the agreement. On that footing, they contended that, objectively assessed, they individually made the agreement with Pasma. In support of this contention, they pointed to the facts that they were the owners of the Miss Angel and that Ms Jenkins had paid Pasma’s invoice for the works from her personal bank account. With respect to Mr Pasma’s evidence that Mr Tregidga told him to issue the invoice to Allure, they contended that: that evidence was self-serving; that since, on Mr Pasma’s evidence, Mr Tregidga gave him the instruction concerned on or about 2 June 2016, that evidence conflicted with its pleaded case that the agreement was concluded on or before 25 May 2016 (see at [28] above); that, in circumstances where there was no evidence that Mr Pasma was aware of the existence of Allure, it was not possible to conclude that the objectively assessed contracting party was anyone other than the person to whom Mr Pasma was speaking, namely Mr Tregidga; and Mr Tregidga’s conduct in issuing that instruction must be assessed by reference to his evidence more broadly, which showed that he was a lay person who did not appreciate the legal significance of his request.

44 As already noted, Pasma contended that the agreement was made between it and Allure and it was made on the terms as to the work to be done and the price to be paid as reflected in the invoice it rendered to Allure on 13 June 2016. In support of this contention, it pointed to several other aspects of the factual background to the formation of the agreement, including: Mr Pasma’s evidence at [4]-[7] of his second outline of evidence concerning his dealings with Ms Rak (see at [35] above); the Slipway Contract that Allure had entered into one month earlier with BSE according to which Pasma was an approved contractor, pursuant to which Mr Tilton had attended a BSE induction and under which Allure had paid a contractor’s fee to BSE. It also pointed to Mr Tregidga’s evidence at [51]-[53] of his first outline of evidence (see at [30] above) and his oral evidence that he made the agreement with Mr Pasma on or before 2 June 2016.

Consideration and disposition

45 It is convenient to begin by noting two matters of principle that emerged as common ground in closing submissions. First, the identification of the parties to a contract requires an objective assessment of all the relevant surrounding circumstances. That principle was expressed by Allsop P and Handley AJA (Hodgson JA agreeing) in Air Tahiti Nui Pty Ltd v McKenzie (2009) 77 NSWLR 299; [2009] NSWCA 429 at [28]:

The identity of the contracting party is to be determined looking at the matter objectively, examining and construing any relevant documents in the factual matrix in which they were created and ascertaining between whom the parties objectively intended to contract.

46 To similar effect, in Lederberger v Mediterranean Olives Financial Pty Ltd (2012) 38 VR 509; [2012] VSCA 262 (Lederberger) at [19], the Victorian Court of Appeal (Nettle, Redlich JJA and Beach AJA) observed:

Identification of the parties to a contract must be in accordance with the objective theory of contract. That is the intention that a reasonable person, with the knowledge of the words and actions of the parties communicated to each other, and the knowledge that the parties had of the surrounding circumstances, would conclude that the parties had. The process of construction requires consideration of not only the text of the documents, but also the surrounding circumstances known to the parties and the purpose and object of the transaction. This, in turn, presupposes knowledge of the genesis of the transaction, the background, and the context in which the parties are operating.

(Footnotes omitted)

47 Secondly, at least in respect of a contract that is not wholly in writing (cf BH Australia Constructions Pty Ltd v Kapeller (2019) 100 NSWLR 367; [2019] NSWSC 1086 per Leeming JA), there is intermediate Court of Appeal authority that, in making the abovementioned objective assessment, regard may be had to post-contractual conduct (see Tomko v Palasty [2007] NSWCA 258 at [67]-[68] per Einstein J (Mason P agreeing) and Lederberger at [31]).

48 Turning then to the evidence, I consider the resolution of this issue rests with the contemporaneous documents to which Pasma has referred. Conversely, while I accept that Mr Tregidga and Mr Pasma were doing their best to give their honest recollections of the relevant events in May/June 2016, given that those events occurred about four and a half years before the trial of this matter, I do not consider those recollections are reliable. In particular, when the broader factual background to the dealings with Miss Angel in that period and the pertinent contemporaneous documents mentioned above are viewed objectively, I consider it becomes relatively clear that the contracting parties to the agreement were Allure and Pasma.

49 First, as the principles outlined above show, Mr Tregidga’s subjective perception (at [31(22)]-[31(23)] above) as to who the contracting party was is irrelevant. Secondly, I consider there is strength in Pasma’s contention that almost all the dealings with the Miss Angel after she arrived in Australia were conducted by Allure. Indeed, in cross-examination, Mr Tregidga was not able to point to, or produce, any invoices or similar documents that were not issued to Allure in this period. That pattern is, of course, consistent with Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins’ original intention already remarked on above that Allure should conduct the tourism business as trustee for the Trekins Family Trust.

50 Thirdly, I consider it is significant that, in his outlines of evidence, Mr Tregidga did not deny Mr Pasma’s claims above (at [34(11)] and [35(11)]) that Mr Tregidga had instructed him to issue the invoices to Allure. Instead, Mr Tregidga said that he did not recall advising Mr Pasma to do that (see [30(54)] and [31(23)]). This is to be compared with his similar evidence about the circumstances in which the first contemporaneous document of significance to this issue came into existence. That document is the Slipway Contract (at [38] above). In cross-examination, Mr Tregidga gave the following evidence about the circumstances in which that agreement was made:

And the person – this is a pro forma document from BSE, is it not?---I imagine it is, yes.

And the – this is the document that they gave to you for your consideration and signature?---Yes.

And the customer’s name is Allure Cruises Proprietary Limited?---Yes.

And you told them that. You told them that the customer’s name was Allure Cruises Proprietary Limited?---Sorry, I imagine we – as I said yesterday, there was times when it was referred to as Allure Cruises - - -

You just tell me the answer to my question, please. The question was: you told them that the customer name was Allure Cruises Proprietary Limited with that ACN number?---To be honest, I think they had actually prepared this before I came in and put it as Allure Cruises. And I accepted it as the time because as I said yesterday, we were working with the two areas.

And - - -?---To repeat, I believe this was a prepared document which they tabled for me which I then accepted and signed.

Yes. But you didn’t just accept it and signed, did you? Because you wrote on it in your hand. Because the handwriting on the document is yours, isn’t it?---That’s right. The ACN – I added the ACN to it.

That’s right?---Yes.

You wrote “ACN 608” so as to identify the company?---Yes.

And you wrote “71/1 Marlin Parade, Cairns” because that’s where you were residing at the time?---That’s right.

And more importantly, that’s the registered address of Allure Cruises Propriety Limited, isn’t it?---I can’t recall. It may well be, it may also be the registered address of the trustee, as well, of Trekins Trust.

51 I do not accept Mr Tregidga’s claim in these passages that BSE was the source of the information in that document concerning Allure. To the contrary, given the detailed nature of that information, I consider it was most likely to have originated from him. Accordingly, I think it is most likely that Mr Tregidga instructed BSE that Allure was to be the counterparty in that agreement. This is important because it demonstrates that Mr Tregidga’s recollection is unreliable with respect to the contracting party for an agreement that was entered into at about the same time and which involved the same general subject matter, namely the upgrading works to the Miss Angel necessary to achieve commercial survey standard.

52 Fourthly, there is the second contemporaneous document: the invoice that Pasma rendered to Allure on 13 June 2016 (see at [39] above). While that invoice does not contain the details of Allure mentioned above, it is addressed to that company at its business address. Given that Pasma’s first dealings with Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins were in May 2016 and that the business and commercial arrangements in relation to the use of Allure were matters at that time known to Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins, it is likely, in my view, that that information was provided to Pasma by one or both of them. On the other hand, I consider it is unlikely to have been provided by BSE, as Mr Tregidga faintly claimed in his evidence. Accordingly, I consider Mr Pasma’s evidence that Mr Tregidga instructed him to send the invoice to Allure is more likely to be accurate. Finally, I infer from Ms Rak’s absence as a witness that her evidence would not have assisted Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins on this issue (see discussion at [148] below).

53 For these reasons, on an objective assessment of all the relevant surrounding circumstances, I conclude that Allure Cruises Pty Ltd was the contracting party with Pasma. It follows that the answer to the question posed in Issue 2 above is: Allure Cruises Pty Ltd.

3. THE AUSTRALIAN CONSUMER LAW ISSUES

The issue as pleaded

54 Even if they were not the contracting party in the agreement with Pasma, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins claimed in the alternative that, as “consumers”, they were entitled to rely on the guarantee prescribed by s 60 of the ACL. They pleaded this issue at [12] and [28] of the FASC in the following terms:

12. Further and in the alternative, [Pasma] guaranteed that the Electrical Services would be rendered with due care and skill in accordance with sections 3 and 60 of the Australian Consumer Law.

…

28. As a result of the aforementioned breaches of the Contract, the guarantee pleaded in paragraph 12 above, and [Pasma’s] duty of care, [Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins] have suffered the following loss and damage totalling $1.1 million.

55 In its defence, Pasma did not admit the allegations in [12] of the FASC above and denied that Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins were entitled to the relief claimed in [28].

The relevant statutory provisions

56 Section 60 of the ACL provides:

If a person supplies, in trade or commerce, services to a consumer, there is a guarantee that the services will be rendered with due care and skill.

57 The right to pursue damages for a breach of the guarantee provided by s 60 is contained in s 267(4) of the ACL as follows:

The consumer may, by action against the supplier, recover damages for any loss or damage suffered by the consumer because of the failure to comply with the guarantee if it was reasonably foreseeable that the consumer would suffer such loss or damage as a result of such a failure.

58 The expression “consumer”, which is one of the qualifying criteria in s 60 above, is relevantly defined in s 3 of the ACL in the following terms:

3 Meaning of consumer

…

Acquiring services as a consumer

(3) A person is taken to have acquired particular services as a consumer if, and only if:

(a) the amount paid or payable for the services, as worked out under subsections (4) to (9), did not exceed:

(i) $40,000; or

(ii) if a greater amount is prescribed for the purposes of subsection (1)(a)—that greater amount; or

(b) the services were of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption.

…

Presumption that persons are consumers

(10) If it is alleged in any proceeding under this Schedule, or in any other proceeding in respect of a matter arising under this Schedule, that a person was a consumer in relation to particular goods or services, it is presumed, unless the contrary is established, that the person was a consumer in relation to those goods or services.

59 The expression “acquire”, which is pivotal to the above definition, is relevantly defined in s 2 of the ACL in the following terms:

2 Definitions

…

acquire includes:

…

(b) in relation to services—accept.

The contentions

60 Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins contended that there was no issue that Pasma provided the electrical services and that those services were supplied in trade or commerce. I interpose to note that, since Pasma did not contest these two contentions, I will assume they are not in issue. As well, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins contended that they were “consumers” for the purposes of s 60 of the ACL and they were entitled to claim damages under the guarantee in s 60 even if they were not a party to the agreement with Pasma. As to the former issue, they contended that their pleading of this issue, as set out above, activated the presumption in s 3(10) of the ACL such that Pasma bore the onus to establish that they were not consumers. In any event, they contended they fell within the definition of the expression “consumer” in s 3(3)(a)(i) of the ACL because the amount they actually paid Pasma for the services was $4,122.38, as evidenced by its invoice rendered on 13 June 2016. Further, they contended that the statutory guarantee in s 60 differs markedly from the equivalent provisions in the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) in that it may exist independently of any contractual relationship. Accordingly, since, as owners of the Miss Angel, they obtained the benefit of the works Pasma undertook on the vessel, they contended they were entitled to rely upon the guarantee provided by that provision, relying on the judgment of Campbell AJA in Alameddine v Glenworth Valley Horse Riding Pty Ltd (2015) 324 ALR 355; [2015] NSWCA 219 (Alameddine) at [77].

61 There was a number of reasons, so Pasma contended, why s 60 of the ACL did not avail Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins. First, it contended they were not parties to the agreement with it and s 60 of the ACL did not apply to third parties. In this respect, it contended that the judgment of Campbell AJA in Alameddine was obiter and should not be followed. Further, it contended that Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins could not rely on the presumption in s 3(10) of the ACL because they had not pleaded, with sufficient clarity, the “services” that were allegedly not rendered with due care and skill. In this respect, it claimed they were in no different a position to that of the plaintiff in Lets Go Adventures Pty Ltd v Barrett [2017] NSWCA 243 (Lets Go Adventures) at [4] per Basten and Gleeson JJA. In oral submissions, Pasma’s counsel clarified that he was not contending that Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins had not properly pleaded that they were “consumers”.

Consideration and disposition

62 For the following reasons, I reject Pasma’s main contentions on this issue and generally accept those of Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins. First, as the Full Court explained in Valve Corporation v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2017) 258 FCR 190; [2017] FCAFC 224 at [106]:

It is apparent on the face of Div 1 of Pt 3-2 [of the ACL] that it adopts the mechanism of providing that certain consumer guarantees apply to certain transactions, in contrast to the mechanism (adopted by the predecessor provisions) of implying terms into a contract. The consumer guarantee provisions are therefore capable of application whether or not there is a contract …

See also at [111].

It is to be noted that Division 1 of Part 3-2 of the ACL includes s 60. It follows that the fact Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins were not parties to the agreement with Pasma is not determinative of their claim under s 60.

63 Secondly, Pasma’s related contention that s 60 does not apply to third parties is inconsistent with the reasoning of Campbell AJA in Alameddine. That judgment was primarily concerned with the construction of ss 5M, 5L and 5N of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW). Macfarlan JA wrote the primary judgment and Simpson JA and Campbell AJA agreed. In that sense, Pasma is therefore correct in its contention that the observations of Campbell AJA at [75]-[77] are obiter. Indeed, so much is clear from his Honour’s qualifying comments at [75]. Nonetheless, I consider his Honour’s reasoning at [76]-[77] as follows is, with respect, compelling and I propose to apply it in this matter:

[76] The case was argued, both at first instance and on appeal, on the basis that the services relating to the quad biking activity that the respondents supplied to the appellant were supplied pursuant to a contract that had been entered on behalf of the appellant either by her mother (if the relevant contract arose from the telephone conversation) or by her sister (if the contract arose from the application form). The reasons of Macfarlan JA proceed in accordance with the basis upon which the case was argued.

[77] Often, a parent or sibling will not have authority to act as the agent for a child in entering a contract that binds the child. Indeed, there are many occasions when services are supplied to a consumer under a contract to which that consumer is not a party, that is a third party beneficiary contract. In particular, it commonly happens that a person enters a contract for services to be supplied in trade or commerce to a friend or member of the family of the contracting party, and that the person to whom the services are provided is a “consumer” within the meaning of s 3 of the Australian Consumer Law. As well, services can sometimes be supplied to a consumer in trade or commerce when they are not supplied pursuant to any contract at all –– for example, if a service provider gives a free trial of the services. Even in those circumstances, a “guarantee” can arise under s 60 or s 61 of the Australian Consumer Law. If such “guarantee” arises, then, subject to some limitations, s 267 of the Australian Consumer Law can entitle the consumer to take action if the guarantee is not complied with. That shows that the “guarantee” is not a contractual obligation, but rather a statutorily imposed obligation, concerning which s 267 provides a statutory remedy. Section 5N of the Civil Liberty Act and the provisions of the Australian Consumer Law that relate to the effect of contractual limitations on liability may well not operate in the same way when services are provided to a consumer pursuant to a contract to which that consumer is a party as they operate when services are provided to a consumer pursuant to a third party beneficiary contract.

64 In this matter, as owners of the Miss Angel, Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins were the beneficiaries of the works that Pasma carried out on that vessel under its agreement with Allure. As such, they were “consumers” of those services as defined in s 3 of the ACL and were therefore entitled to claim damages under s 267(4) of the ACL for any failure by Pasma to supply those services in accordance with the guarantee in s 60 of the ACL. This conclusion is reinforced, in my view, by the inclusive definition of the expression “acquire” in s 2 of the ACL and the breadth of the ordinary meaning of the word “accept” used in that definition.

65 Thirdly, I do not accept the third of Pasma’s contentions above that Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins have not pleaded the services concerned with sufficient clarity. Those services are defined in the FASC in the following terms:

9. On or before 3 June 2016, [Mr Tregidga] met in person with Mr Henk Pasma and Mr Benjamin Tilton of [Pasma] and entered into an oral contract for [Pasma] to examine, repair and refit the Vessel’s electrical systems to ensure that they complied with AS/NZS 3000 and NSCV.

10. The contractual scope of work included:

a. Inspection and survey of the existing electrical systems to identify defects;

b. Repair of all defects identified;

c. Electrical repairs, inspection and service.

d. Lighting, Power, Battery Systems, bilge alarm system, Switchboards

e. Survey compliance modifications and systems upgrades.

f. Ensuring that the Vessel’s electrical systems complied with AS300 [sic AS3000] and NSCV.

(Electrical Services).

(Emphasis in original)

The “Electrical Services” so defined are then identified as the services to which the guarantee in s 60 applied (at [12] of the FASC) (see at [54] above). Hence the services to which the s 60 guarantee applied are clearly pleaded.

66 This contention also requires consideration of the decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Lets Go Adventures at [4] upon which Pasma placed particular reliance. As in Alameddine, the observations in that paragraph are additional to the agreement of Basten and Gleeson JJA with the reasons and orders of Adamson JA (see at [1]). Those observations are therefore obiter. More importantly, when the comments in [4] are read in the context of the comments at [3]-[6], it becomes apparent that their Honours’ criticism of the “failure to identify the services with precision” relates, in particular, to the claim made in that matter under s 61 of the ACL that the services concerned were not fit for a particular purpose. It is therefore not difficult to see why the subject services needed to be pleaded with precision in that instance. However, I do not consider the same necessity applies to the more general claim under the guarantee in s 60. Pasma’s attempt to rely upon the comments in [4] of Lets Go Adventures is therefore misconceived.

67 Finally, and for completeness, because the amount that was actually paid for the works Pasma carried out on the Miss Angel was $4,122.38, as evidenced by Pasma’s invoice dated 13 June 2016 (see at [39] above), Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins fall squarely within the terms of s 3(a)(i) of the definition of “consumer” above (at [58]). In any event, since there is no challenge to the sufficiency of their pleading on this aspect of this issue, Pasma bore the onus to establish otherwise and it has not adduced any evidence directed to discharging that onus.

68 For these reasons, I consider the answers to the questions posed by Issue 3 above (at [17]) are:

(a) Yes; and

(b) Yes.

4. THE SCOPE OF DUTY ISSUES

Issue 4(a) – To whom was any duty of care in tort owed

69 As can be seen above (at [17]), this issue involves a number of sub-issues. Many of them have been affected by the conclusions reached on Issues 1 to 3 above. First, because of the conclusion reached with respect to Issue 1 above, that Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins were the owners of the Miss Angel at the time of the fire, the answer to the question posed by Issue 4(a) above (and [23] of the FASC) is: Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins.

Issue 4(b)(ii) – What is the scope of Pasma’s duty of care in contract?

70 Secondly, because of the conclusion reached with respect to Issue 2 above, that Allure was the party that contracted with Pasma, there was no contract between Pasma and Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins. Accordingly, the question posed by Issue 4(b)(ii) is, for present purposes, rendered redundant.

Issue 4(c)(i) – Is the scope of Pasma’s duty of care determined or affected by its contract with Allure?

71 The conclusion reached with respect to Issue 2 above also has an effect on the questions posed in Issue 4(c). That is so, with respect to Pasma’s agreement with Allure (Issue 4(c)(i)) because, while the terms of that agreement are binding as between Allure and Pasma, nothing has been advanced to show that they would bind third parties such as Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins. In any event, even if they were binding, there is no evidence that the terms and conditions upon which Pasma seeks to rely with respect to that issue, namely the “PE Standard Terms and Conditions” referred to in Pasma’s invoice dated 13 June 2016(see at [39] above), were ever incorporated as terms of that agreement. They were not mentioned in the discussion between Mr Tregidga and Mr Pasma when that oral agreement was made, they were not provided to Mr Tregidga, or Ms Rak, at any relevant time and nor were they, by some other means, incorporated as terms of it (see the questioning on this matter at [40]-[41] above).

72 This conclusion means that those terms neither determined the duty of care between Pasma and Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins, nor directly affected it. However, it is worth adding that the latter may have been a consideration if those terms were incorporated into that agreement because, as Windeyer J remarked in Voli v Inglewood Shire Council (1963) 110 CLR 74 at 85 with respect to the liability of an architect for injuries caused to third parties on the collapse of a building, while those terms could not operate:

… to discharge the architect from a duty of care to persons who are strangers to those contracts … Nevertheless his contract with the building owner is not an irrelevant circumstance. It determines what was the task upon which he entered. If, for example, it was to design a stage to bear only some specified weight, he would not be liable for the consequences of someone thereafter negligently permitting a greater weight to be put upon it.

Issue 4(c)(ii) – Is the scope of Pasma’s duty of care determined or affected by Allure’s contract with BSE?

73 Similar considerations are determinative of the question posed in Issue 4(c)(ii) (and at [19(b)(iv)] of Pasma’s defence). On that issue, Pasma contended that “its liability was excluded” because it was an approved subcontractor under the Slipway Contract between Allure and BSE (see at [38] above). The particular parts of that contract that it sought to rely upon were cll 9 and 14 of the attached Slipway Contract Terms as follows:

9, BSE’S LIABILITY

Subject to clause 8:-

BSE is not liable to the Client for any loss or damage (including consequential loss) to the Works or the Vessel while in the care or control of BSE or for the death or personal injury howsoever arising which is suffered or incurred by the Client arising out of:-

Any act or omission (whether negligent or otherwise) by BSE while undertaking the Works; or

Any breach of any contractual or other obligation imposed on BSE in respect of the works undertaken by BSE.

Any implied conditions, warranties and liabilities including liability for consequential loss and/or loss arising from negligence are hereby excluded.

If the Client is a “consumer” as defined under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (and/or any equivalent State legislation) (“the Act”) then:-

The Client’s rights under that Act are not excluded, restricted or modified; and

BSE’s liability for Work is limited to any of the following as determined by BSE:-

The replacement of the Works or the supply of equivalent Works and/or the repair of the Works; or

The payment of the cost of replacing the Works or acquiring equivalent Works or the payment of the cost of having the Works repaired; or

The supply of the services again; or

The payment of the cost of having the services supplied again.

Where components not manufactured by BSE are supplied, BSE:-

Will assign to the Client its rights under the warranty (if any) applicable to such components; and

Shall not be liable for any loss or damage arising from any deficiency or defect in such components except to the extent that the warranties were honoured by the original manufacturer.

…

14, SUBCONTRACTING

The Client acknowledges that BSE enters into this Agreement on its own behalf and on behalf of its servants, agents and subcontractors and warrants that no claim or allegation shall be made against any servant, agent or subcontractor of BSE which imposes or attempts to impose upon any of them any liability whatsoever in connection with the works whether or not arising out of negligence or a wilful act or omission on the part of any of them and if any such claim or allegation should nevertheless be made indemnifies BSE against the consequences thereof.

The Client shall save harmless and keep BSE indemnified against all claims or demands whatsoever by whomsoever made in excess of the liability of BSE under these conditions as to any loss, damage or injury howsoever caused whether or not by the negligence or wilful act or omission of BSE his servants, agents or subcontractors. Any sub-contractors must be approved by BSE, prior to entry to the site. A site access fee will apply to all approved contractors to cover induction and liability unless otherwise agreed to in writing by BSE.

(Emphasis in original)

74 Clause 8 of the Slipway Contract Terms, which is referred to at the beginning of cl 9, contains a series of warranties by BSE’s client or customer which are not presently relevant. Clause 1 of the Slipway Contract Terms below contains definitions of the expressions “BSE”, “Customer” and “Works” which appear throughout the two clauses above:

1, DEFINITIONS

In these terms and conditions the following words and phrases mean:-

“BSE” means BSE Cairns Slipways Pty Ltd and includes any employee of BSE or any subcontractor employed directly or indirectly by BSE.

…

“Customer” means and includes any entity whatsoever requesting the works to be carried out for the Customer by BSE and includes any employee, representative, or subcontractor representing the customer.

…

“Works” or “Work” means the Anticipated Extent of Work attached plus any agreed variations plus any Work Request List for works to be carried out by BSE including any goods or things associated with it.

While the expression “the Client” is not defined in cl 1, or elsewhere, in the present context it can only be taken to refer to Allure, which is described on the first page of the Slipway Contract as the “Customer” (see at [38] above).

75 It is therefore apparent that cl 9 above excludes BSE’s liability to its client or customer, in this instance, Allure. In this respect, it is important to emphasise that the expression “BSE” is defined in cl 1 to mean and include “or any subcontractor employed directly or indirectly by BSE”. Further, cl 14 above contains a warranty and indemnity by Allure as the client or customer of BSE that “no claim or allegation” will be made against, amongst others, any “subcontractor” of BSE. It follows that to gain the benefit of the exclusions of liability in either of these clauses of the Slipway Contract Terms, Pasma would need to bring itself within the expression “subcontractor” of BSE as that expression is used in both clauses. However, that construction is not open because, as discussed earlier, Pasma contracted directly with Allure on or about 2 or 3 June 2016, approximately five weeks after this Slipway Contract was entered into between BSE and Allure. Hence, from that point on, it became a “subcontractor representing the Customer”, namely Allure, within the terms of the definition of the expression “Customer” in cl 1 above.

76 This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the expression “Works” appearing in both the clauses above is defined in cl 1 of the Slipway Contract Terms to mean the “works to be carried out by BSE”. That expression could not therefore be construed to refer to the works carried out by Pasma for Allure. It follows that neither of these clauses applies to protect Pasma from liability for claims made by Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins. Put differently, as a non-party to Allure’s contract with BSE, Pasma cannot rely upon it to relieve it of the consequences of tortuous acts committed against third parties such as Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins (see Wilson v Darling Island Stevedoring and Lighterage Company Limited (1956) 95 CLR 43 at 67 per Fullagar J.

77 Accordingly, subject to the qualification below, the answers to the two questions posed by Issue 4(c) are:

(i) the terms of the contract between Pasma and Allure do not determine or affect the scope of Pasma’s duty of care to Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins;

(ii) the terms of the contact between Allure and BSE do not determine or affect the scope of Pasma’s duty of care to Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins.

78 The qualification mentioned above relates to the second aspect of these two questions: whether the scope of Pasma’s duty of care in tort was affected by the terms of either of those contracts. The reasons set out above explain why those terms neither determined, nor directly affected, that duty. However, in the circumstances of this matter, it should be noted that those terms may have some bearing on the question whether Pasma owed Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins a duty to take action to protect Miss Angel from injury or harm. That is so because, as will emerge later in these reasons, that question is partly determined by reference to the “salient features” of the relationship between Pasma and Mr Tregidga and Ms Jenkins and those terms may bear on those circumstances.

Issue 4(b)(iii) – What is the scope of Pasma’s duty of care pursuant to s 60 of the ACL?

79 Before turning to address the question posed by Issue 4(b)(i), it is convenient to deal with the other remaining question posed in Issue 4(b), namely the scope of Pasma’s duty of care pursuant to s 60 of the ACL (Issue 4(b)(iii)). For present purposes, that duty is concurrent and co-extensive with Pasma’s duty of care in tort (see the definition of “duty” in Sch 2 to the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld). That means that the answer to the question posed by Issue 4(b)(i) will apply equally to the question posed by this issue.

Issue 4(b)(i) – The scope of Pasma’s duty of care in tort – some relevant principles

80 Before considering the pleadings and evidence related to this issue, it is convenient to essay some of the relevant principles. A fitting starting point is the following observations of Mason J in the Council of the Shire of Wyong v Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40 at 47 where his Honour expressed the obligation of a person to respond to a risk of injury to another in the following terms:

In deciding whether there has been a breach of the duty of care the tribunal of fact must first ask itself whether a reasonable man in the defendant’s position would have foreseen that his conduct involved a risk of injury to the plaintiff or to a class of persons including the plaintiff. If the answer be in the affirmative, it is then for the tribunal of fact to determine what a reasonable man would do by way of response to the risk. The perception of the reasonable man’s response calls for a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the defendant may have. It is only when these matters are balanced out that the tribunal of fact can confidently assert what is the standard of response to be ascribed to the reasonable man placed in the defendant’s position.

(Emphasis added)

81 However, in the Council of the Shire of Sutherland v Heyman (1985) 157 CLR 424 (Heyman), Brennan J underscored the insufficiency of foreseeability of injury by itself to found a duty of care in tort in the following terms (at 477-479):

… The test of foreseeability of injury never has been applied as an exhaustive test for determining whether there is a prima facie duty to act to prevent injury caused by the acts of another or by circumstances for which the alleged wrongdoer is not responsible. Lord Diplock reminds us in Dorset Yacht:

“The branch of English law which deals with civil wrongs abounds with instances of acts and, more particularly, of omissions which give rise to no legal liability in the doer or omitter for loss or damage sustained by others as a consequence of the act or omission, however reasonably or probably that loss or damage might have been anticipated.”

A man on the beach is not legally bound to plunge into the sea when he can foresee that a swimmer might drown. In Jaensch v. Coffey Deane J. observed that “the common law has neither recognised fault in the conduct of the feasting Dives nor embraced the embarrassing moral perception that he who has failed to feed the man dying from hunger has truly killed him”.

If foreseeability of injury were the exhaustive criterion of a duty to act to prevent the occurrence of that injury, legal duty would be coterminous with moral obligation … The judgment of Lord Esher M.R. in Le Lievre v. Gould which Lord Atkin cites makes it clear that the general principle expresses a duty to take reasonable care to avoid doing what might cause injury to another, not a duty to act to prevent injury being done to another by that other, by a third person, or by circumstances for which nobody is responsible.

I can be liable only for an injury that I cause to my neighbour. If I do nothing to cause it, I am not liable for the injury he suffers except in those cases where I am under a duty to act to prevent the injury occurring. Indeed, he is not in law my neighbour unless he is foreseeably “affected” by my conduct. But he can be said to be “affected” by my omission to act to prevent injury being done to him only if I am bound to act and do not do so. He cannot be said to be affected by my omission to act if I am not under a duty to him to act. Lord Atkin’s “neighbour” test involves us in hopeless circularity if my duty depends on foreseeability of injury being caused to my neighbour by my omission and a person becomes my neighbour only if I am under a duty to act to prevent that injury to him. Foreseeability of an injury that another is likely to suffer is insufficient to place me under a duty to him to act to prevent that injury. Some broader foundation than mere foreseeability must appear before a common law duty to act arises. There must also be either the undertaking of some task which leads another to rely on its being performed, or the ownership, occupation or use of land or chattels to found the duty: cf Windeyer J. in Hargrave v. Goldman.

(Emphasis added; citations omitted)

82 Pertinent to this matter, his Honour then proceeded (at 479) to identify the circumstances in which a person may be required to act to prevent injury occurring to another as follows:

Thus a duty to act to prevent foreseeable injury to another may arise when a transaction – which may be no more than a single act – has been undertaken by the alleged wrongdoer and that transaction – or act – has created or increased the risk of that injury occurring. Such a case falls literally within Lord Atkin’s principle in Donoghue v. Stevenson. Where a person, whether a public authority or not, and whether acting in exercise of a statutory power or not, does something which creates or increases the risk of injury to another, he brings himself into such a relationship with the other that he is bound to do what is reasonable to prevent the occurrence of that injury unless statute excludes the duty. An omission to do what is reasonable in such a case is negligent whether or not the person who makes the omission is liable for any damage caused by the antecedent act which created or increased the risk of injury …

(Emphasis added; citation omitted)

See also Roads and Traffic Authority of New South Wales v Dederer (2007) 234 CLR 330; [2007] HCA 42 (Dederer) at [51] per Gummow J.

83 In this respect, it is also worth noting the judgment of Gleeson CJ in Woods v Multi-Support Holdings Pty Limited (2002) 208 CLR 460; [2002] HCA 9 at [41] where his Honour pointed to the relationship between the parties as a factor in determining whether a person may be obligated to provide protection or warning to another:

Where it is claimed that reasonableness requires one person to provide protection, or warning, to another, the relationship between the parties, and the context in which they entered into that relationship, may be significant. The relationship of control that exists between an employer and an employee, or of wardship that exists between a school authority and a pupil, may have practical consequences, as to what it is reasonable to expect by way of protection or warning, different from those which flow from the relationship between the proprietor of a sporting facility and an adult who voluntarily uses the facility for recreational purposes. I say “may”, because it is ultimately a question of factual judgment, to be made in the light of all the circumstances of a particular case.

(Emphasis added)

84 Gummow J made a similar point in Dederer in the context of a broader examination of the relevant principles, including the observations of Brennan J in Heyman set out above, and said (at [43]):

First, duties of care are not owed in the abstract. Rather, they are obligations of a particular scope, and that scope may be more or less expansive depending on the relationship in question. Secondly, whatever their scope, all duties of care are to be discharged by the exercise of reasonable care. They do not impose a more stringent or onerous burden.

As to the former, his Honour then went on to observe (at [44]):

Regarding the first point, a duty of care involves a particular and defined legal obligation arising out of a relationship between an ascertained defendant (or class of defendants) and an ascertained plaintiff (or class of plaintiffs).

(Emphasis added)

85 Gummow J then quoted the following observations of the Court (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Hayne and Callinan JJ) in Sullivan v Moody (2001) 207 CLR 562; [2001] HCA 59 at [50]:

Different classes of case give rise to different problems in determining the existence and nature or scope, of a duty of care. Sometimes the problems may be bound up with the harm suffered by the plaintiff, as, for example, where its direct cause is the criminal conduct of some third party. Sometimes they may arise because the defendant is the repository of a statutory power or discretion. Sometimes they may reflect the difficulty of confining the class of persons to whom a duty may be owed within reasonable limits. Sometimes they may concern the need to preserve the coherence of other legal principles, or of a statutory scheme which governs certain conduct or relationships. The relevant problem will then become the focus of attention in a judicial evaluation of the factors which tend for or against a conclusion, to be arrived at as a matter of principle.

(Emphasis added)

86 In Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd (2011) 243 CLR 361; [2011] HCA 11, French CJ and Gummow J made the same point where they said of the approach adopted by the trial judge in that matter (at [20]) that: