Federal Court of Australia

Capic v Ford Motor Company of Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 715

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 112(b), the word “he” has been inserted between the words “line” and “gave”. | |

4 November 2021 | In the fourth sentence of paragraph 697, the full stop has been replaced with a question mark. |

4 November 2021 | In the third sentence of paragraph 739, “s 271(1)(a)” has been changed to “s 272(1)(a)”. |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | FORD MOTOR COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 004 116 223 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The direction of 29 July 2020 relating to the Applicant’s tender list be revoked to the extent it applies to the documents listed in Annexure A.

2. The matter stand over for further case management on 27 July 2021 at 9.30 am.

3. The parties not deliver written submissions in advance of the case management hearing.

AND THE COURT NOTES THAT:

1. The documents in Annexure A will be removed from the ‘Admitted Into Evidence’ section of the electronic Court Book.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure A

Document ID | Title | Date | |

1 | FOR.712.002.6164 | 6 Panel - Launch Judder 30-Nov-12 | 17/01/2013 |

2 | FOR.712.002.8367 | RE: DPS6 seals | 31/07/2013 |

3 | FOR.713.001.0347 | May 03,2012 B299 CMT | 2/05/2012 |

4 | FOR.729.004.7466 | RE: Ability to clean engine oil from the DPS6 clutches | 29/05/2015 |

5 | FOR.729.005.4035 | RE: DPS6 Clutch Cleaning | 21/10/2015 |

6 | FOR.729.005.4055 | RE: DPS6 Clutch Cleaning | 6/10/2015 |

7 | FOR.729.005.4064 | RE: DPS6 Clutch Cleaning | 7/10/2015 |

8 | FORD_DPS6-SAC_00053729 | 00.00-R-202_Functional_Attribute_Rating_of_Vehicles.doc | 22/05/2017 |

9 | FORD_DPS6-SAC_00053808 | 00.00-R-201_Vehicle_and_Attribute_Customer_Rating_System.doc | 22/05/2017 |

10 | VGS20034961 | RE: Dealer call Friday | 11/12/2010 |

11 | VGS20099409 | DPS6 Fiesta Shudder Take-off.pdf | 11/12/2012 |

12 | VGS20140955 | Proposed Solution to DPS6 Inertia and Thermal Issues | 30/04/2010 |

13 | VGS20141401 | ONE Ford PPT Template (Base Version) | 18/02/2013 |

14 | VGS20143863 | Fw At HPS Paper - Odell Review | 1/11/2011 |

15 | VGS20143864 | 2011 FWB Automatic Transmission - High Priority Study - M. Fields and S. Odell Follow-Ups - Key Follow-Up Items From Oct 27 2011 SAR Review | 27/10/2011 |

16 | VGS20143916 | Fw Note to Send out Under Joe's Signature | 4/11/2011 |

17 | VGS20143918 | 2011 FWB Automatic Transmission - High Priority Study - Key Follow-Up Items From Oct 27 2011 SAR Review | 27/10/2011 |

18 | VGS20150040 | Updated Agenda for the Engineering Governance Forum (EGF) - September 24th 2008 - Timing 08.30h AM - 9.30h AM US Time - 14.30h - 15.30h CET - Location PDC 1B-C73 / Merk18-MC4 / NetMeeting 19.171.147.108 | 24/09/2008 |

19 | VGS20151953 | 2013MY DPS6 Upgrade for 1.0L GTDI Unit PS/PSC - Executive Summary | 3/06/2009 |

20 | VGS20166367 | Transmission and Driveline PTTR Meeting Minutes - 7/31/09 | 5/08/2009 |

21 | VGS20166394 | DPS6 Clutch Torque Capacity | 7/08/2009 |

22 | VGS20168759 | DMF DPS6 NVH Assessment (Gear Rattle) Vehicle Test & CAE - Presenters H Jiang / G Pietron | 31/07/2009 |

23 | VGS20179358 | Engine Start Concerns Auto Trans Engagement Concerns Leaving Park And/or Check Engine Light with DTC P06B8 P0884-Built On or Before 8/17/2010 - TSB 10-19-6 | 24/12/2010 |

24 | VGS20185585 | DPS6 August 2007 Design Review Minutes Day 2 | 3/09/2007 |

25 | VGS20231997 | FW: Reviewing DPS6 Dry Clutch Durability and 1.0L GTDI w/Eli Avny | 4/04/2013 |

26 | VGS20231999 | DPS6 Application Assessment | 4/04/2013 |

27 | VGS20232207 | DPS6 Application Assessment | 4/04/2013 |

28 | VGS20254283 | Fw Cardanic-Damper Concept Issue Impacting Grattle | 8/12/2009 |

29 | VGS20343126 | DPS6 Design Review Minutes June 22 2007 | 26/06/2007 |

30 | VGS20345669 | Twin Dry PowerShift (DPS6) With 1.6L GTDI IR Status Review - Trans/Driveline Research & Advanced - August 2008 | 1/08/2008 |

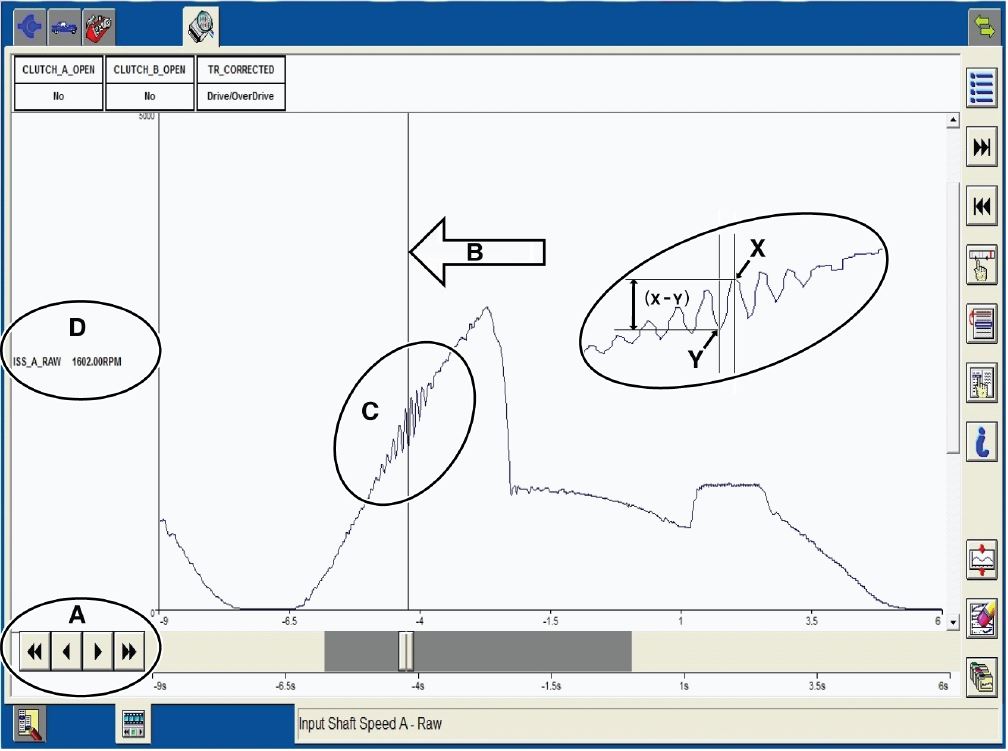

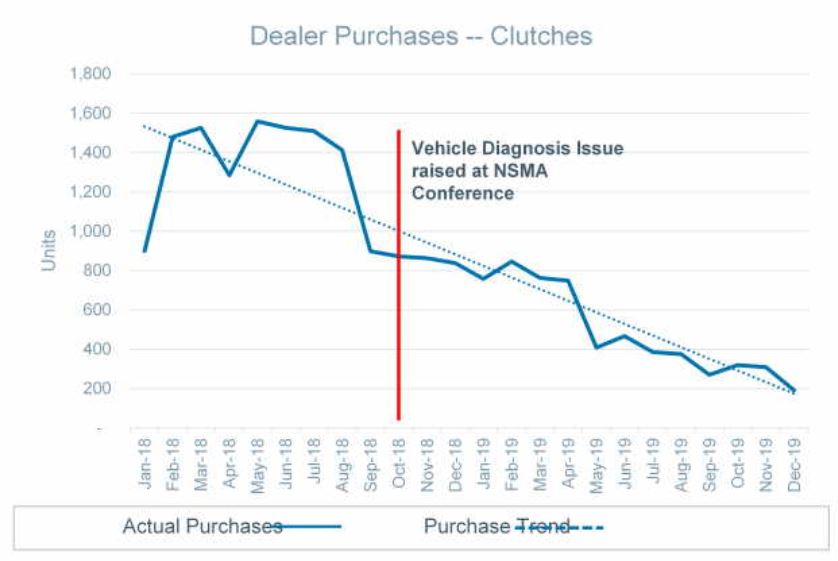

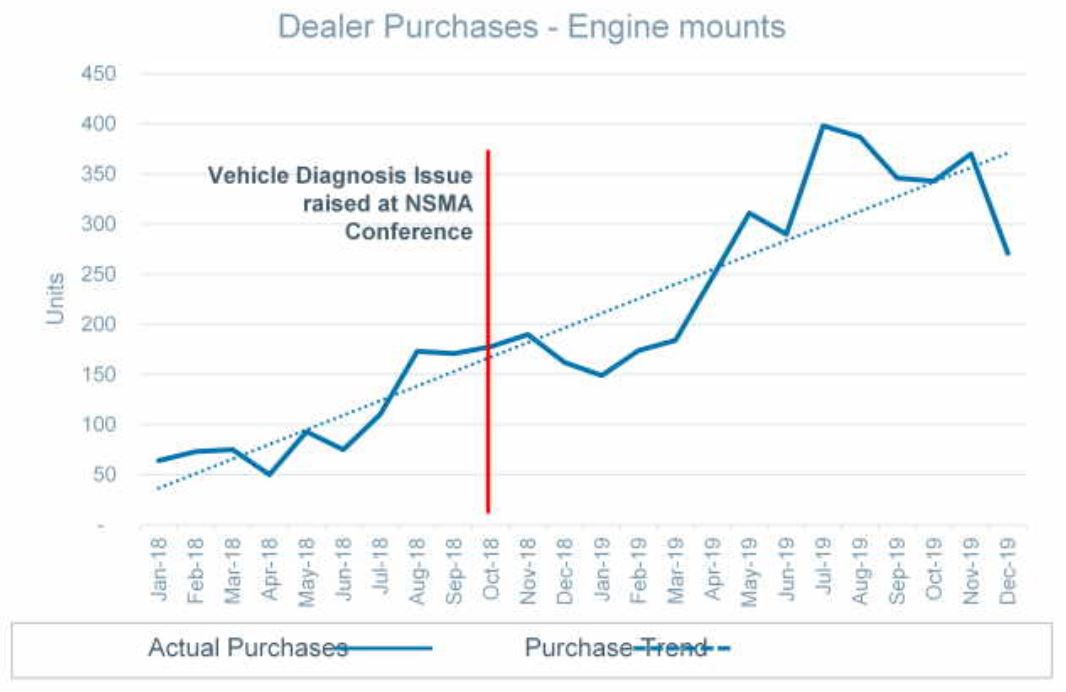

31 | VGS20387022 | FW: investigating abnormal noises vehicle 1 data | 15/08/2013 |

32 | VGS20415042 | RE: DPS6 Next Steps | 9/03/2014 |

33 | VGS20415048 | Talking Point MF March 11 rev1.docx | 9/03/2014 |

34 | VGS20419396 | Qs v4 - DPS6.docx | 7/03/2014 |

35 | VGS20481752 | TGW - Introduction into an Proposal - DPS6 Integrated Cooling System - Cascade Session Towards GTC/LuK Team - Mail 1 | 25/01/2013 |

36 | VGS20948373 | DPS6 Clutch Cooling Project | 5/10/2012 |

37 | VGS21239077 | 6DCT250 - Design Review - Ford and Getrag at LuK in Buehl | 28/09/2007 |

38 | VGS21274162 | October 6th 1 x1 w TKB/Steve Armstrong | 22/09/2011 |

39 | VGS21274195 | Getrag Group/GFT Briefing Paper for October 3rd Week Meetings with Armstrong and Hagenmeyer | 23/09/2011 |

40 | VGS21274196 | Getrag and GFT Relationship with Ford | 1/01/2012 |

41 | VGS21274198 | Getrag Briefing Paper | 1/01/2012 |

42 | VGS21274233 | Getrag Group/GFT Briefing Paper for October 3rd Week Meetings with Armstrong and Hagenmeyer | 27/09/2011 |

43 | VGS21276324 | Fw Roush Support for DPS6 | 7/12/2012 |

44 | VGS21276329 | DPS6 Dual Clutch Air Cooling Concept Project | 7/12/2012 |

45 | VGS21276340 | Roush Support for DPS6 | 12/12/2012 |

46 | VGS21277518 | PowerPoint Presentation | 31/01/2014 |

47 | VGS21293945 | SPD6 1.0L DMF - Initial Study - Update - 22-Mar-2012 | 22/03/2012 |

48 | VGS21343988 | Fw Slide About B8080 Implementation | 7/05/2010 |

49 | VGS21343990 | B8080 Implementation in B-Car | 7/05/2010 |

50 | VGS21354959 | Slide 1 | 19/11/2013 |

51 | VGS21355122 | FW: DPS6 Getrag Status Update | 20/03/2014 |

52 | VGS21513649 | Proposed Customer Hang Tag | 4/02/2013 |

53 | VGS21683733 | Thermal Mass to Forced Cooling Sensitivity Study Phase 1 | 28/02/2010 |

54 | VGS5-00129095 | RE: investigating abnormal noises vehicle 1 data | 18/08/2013 |

55 | VGS5-00170109 | RE: Meet with Ann Carter? | 18/11/2013 |

56 | VGS5-00170111 | DPS6 Warranty Negotiation Strategy.docx | 18/11/2013 |

57 | VGS5-00171150 | DPS6 Paper for SAR 10:30am | 27/01/2014 |

58 | VGS5-00171151 | DPS6 Cost Estimate 11-22-13 SR Submission v2 (01-27-14).pdf | 26/01/2014 |

59 | VGS5-00171156 | Getrag DPS6 Seal Leaks_1pager01262014vF2.docx | 26/01/2014 |

60 | VGS5-00188800 | Fw DPS6 Production Engrg Budgetary Estimate | 27/01/2013 |

61 | VGS7-0009634 | SREA C00867 Approved | 4/05/2015 |

62 | VGS7-0148130 | RE: Emailing: QCN Request Form V4 AE8Z-7048-A Seal leakers copy | 8/05/2013 |

63 | VGS7-0151656 | RE: Shudder Event | 22/02/2013 |

64 | FOR.700.005.0013 | 16X53-16131-Oct 21 extract AP only | 24/10/2016 |

65 | FOR.725.026.6816 | SSM Rear Seal Leaks_20087-2013-1750 | 27/08/2015 |

66 | FOR.725.026.6819 | Rear Main Seal and DPS6 Transmissions | 27/08/2015 |

67 | FORD_DPS6-SAC_00007042 | 10_22_15 DPS6 C12995785 all hands #23.ppt | 4/08/2016 |

68 | VGS20090227 | FW: DPS6 Clutch Cooling Project | 30/11/2012 |

69 | VGS20090292 | FW: Clutch Temp Testing | 30/11/2012 |

70 | VGS20109545 | C346 media drive feedback | 9/12/2010 |

71 | VGS20148606 | RE: TGW Improvement - Hardware Changes - Proposal | 5/04/2012 |

72 | VGS20169615 | Slide 1 | 2/10/2009 |

73 | VGS20190063 | Microsoft PowerPoint - Ford Focus TGW competitive analysis 7-21-2011 ver2.ppt | 26/07/2011 |

74 | VGS20956107 | FW: Ford Cardanic Clucth Application | 4/11/2012 |

75 | VGS21238832 | PS195 SDS Version 1.0.xls | 20/04/2006 |

76 | VGS20090230 | DPS6 Active Cooling Project CR Gateway & Project Status - Trans/Driveline Research & Advanced Engineering | 27/08/2010 |

77 | VGS20090260 | Active Cooling for Dry DCT Transmissions | 05/04/2012 |

78 | VGS20090281 | DPS6 Temperature and Torque Correlations | 04/10/2012 |

79 | VGS20204805 | Evolution and Outlook PowerShift DCT250 - Piero Aversa and Ernest DeVincent | 16/09/2010 |

PERRAM J:

1 The Applicant, Ms Capic, brings this suit on her own behalf and on behalf of the group whom she represents, against Ford Motor Company of Australia Pty Ltd (‘Ford Australia’). When referring to Ms Capic in her capacity as the group’s representative I will refer to her as the Applicant and when referring to her in her own capacity I will call her Ms Capic. I deal first with the position of Ms Capic and then of the group whom she represents.

2 On 24 December 2012 Ms Capic purchased a 2012 Ford Focus from Sterling Ford in Melbourne which had been imported into Australia by the Respondent. She claims that since its purchase her vehicle has displayed a number of mechanical difficulties which she says are associated with its transmission (a 6-speed dry dual clutch PowerShift transmission, known as the ‘DPS6’). These difficulties are alleged to include shuddering, sudden deceleration, grinding noises and difficulties with gear selection (but there are many others). As the case was run, Ms Capic said that the DPS6 had certain features which created a risk that the symptoms would occur and she says that those risks were all present at the time that she purchased the vehicle. She submits that the supply of a vehicle which is inherently subject to such risks of failure contravenes the guarantee of acceptable quality imposed by s 54 of the Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (‘the Act’).

3 For reasons I will later explain, there is no doubt that s 54 applies to the Respondent as the importer of the vehicle. ACL s 271(1) permits Ms Capic to sue the Respondent for breach of the guarantee of acceptable quality and to recover damages from it. Without expanding at this stage on what any of the following mechanical engineering jargon means, Ms Capic says that the DPS6 posed four risks related to components within it (‘the Component Deficiencies’). The components and their risks of failure were:

Input shaft seals which had a tendency to leak permitting lubricants from the gearbox side of the transmission to enter the part of the bell housing containing the otherwise dry clutch and drive plates and contaminate them;

Inadequate friction material on the faces of the clutch and drive plates (the friction material is also referred to as the ‘clutch lining’);

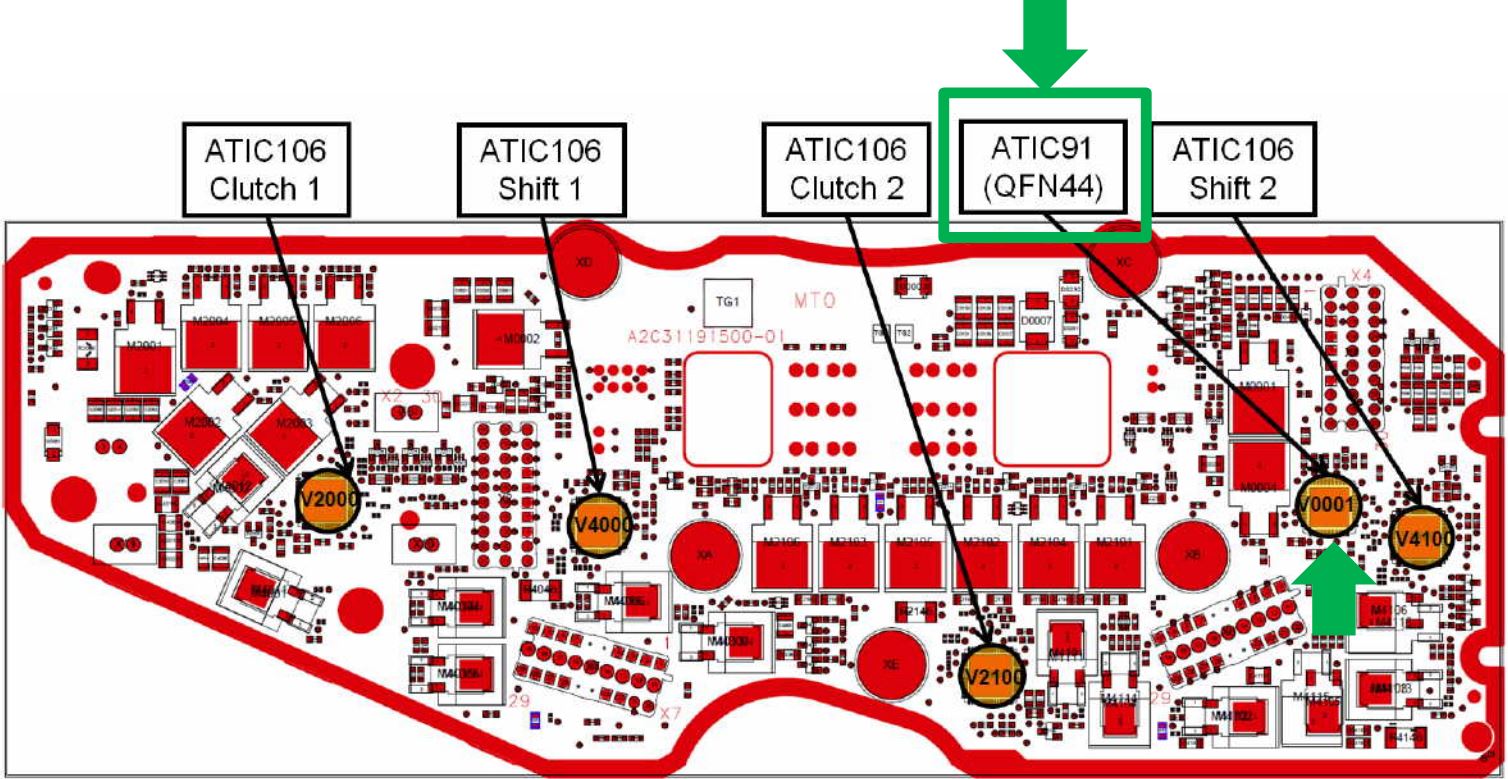

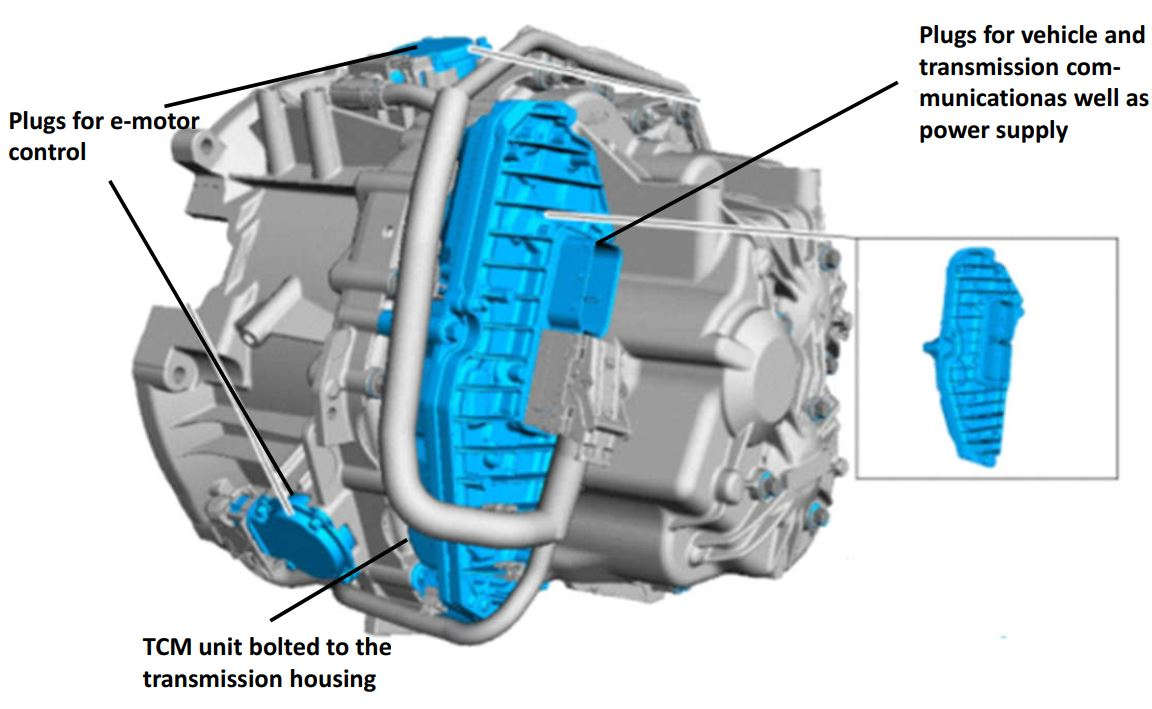

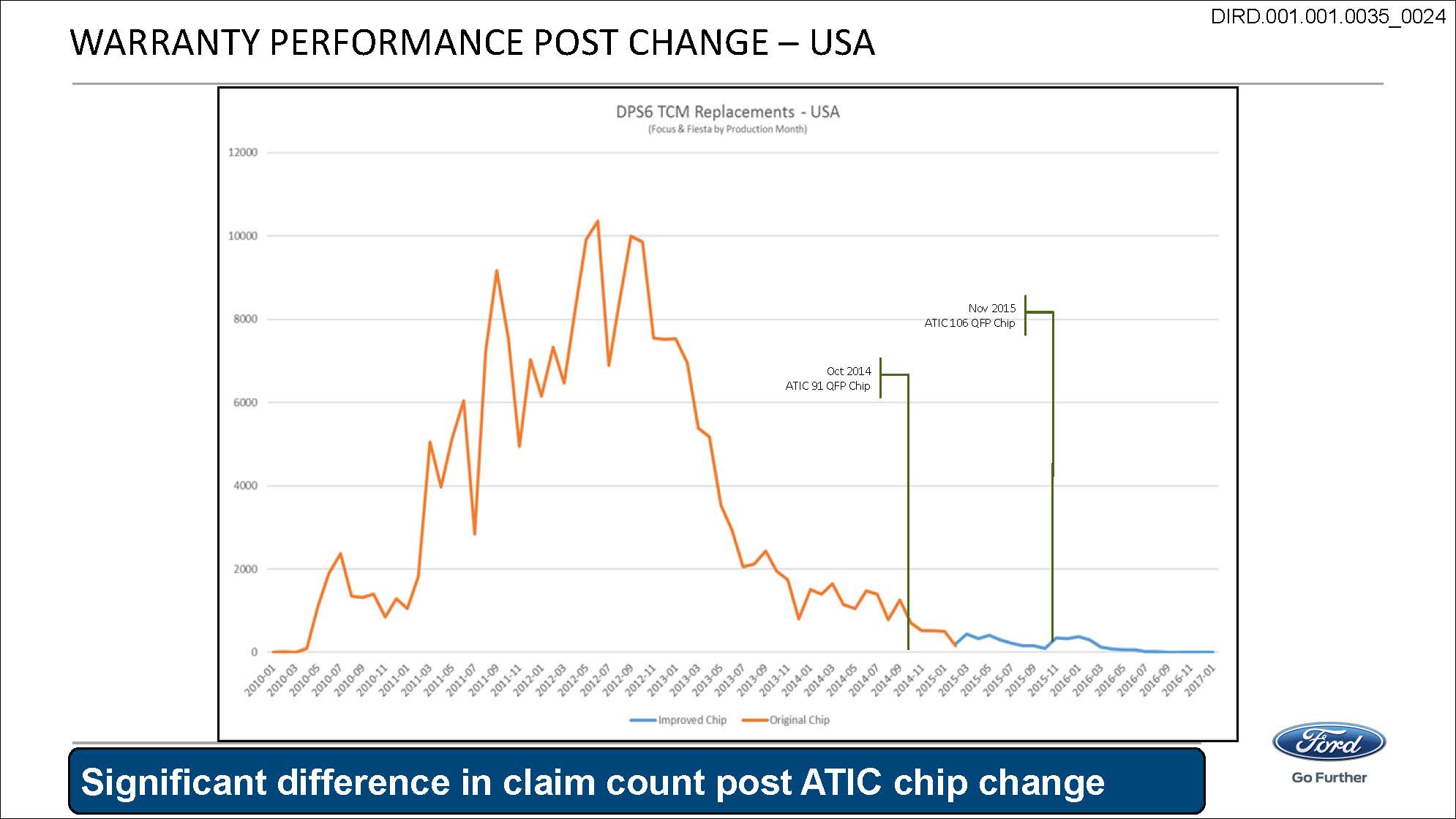

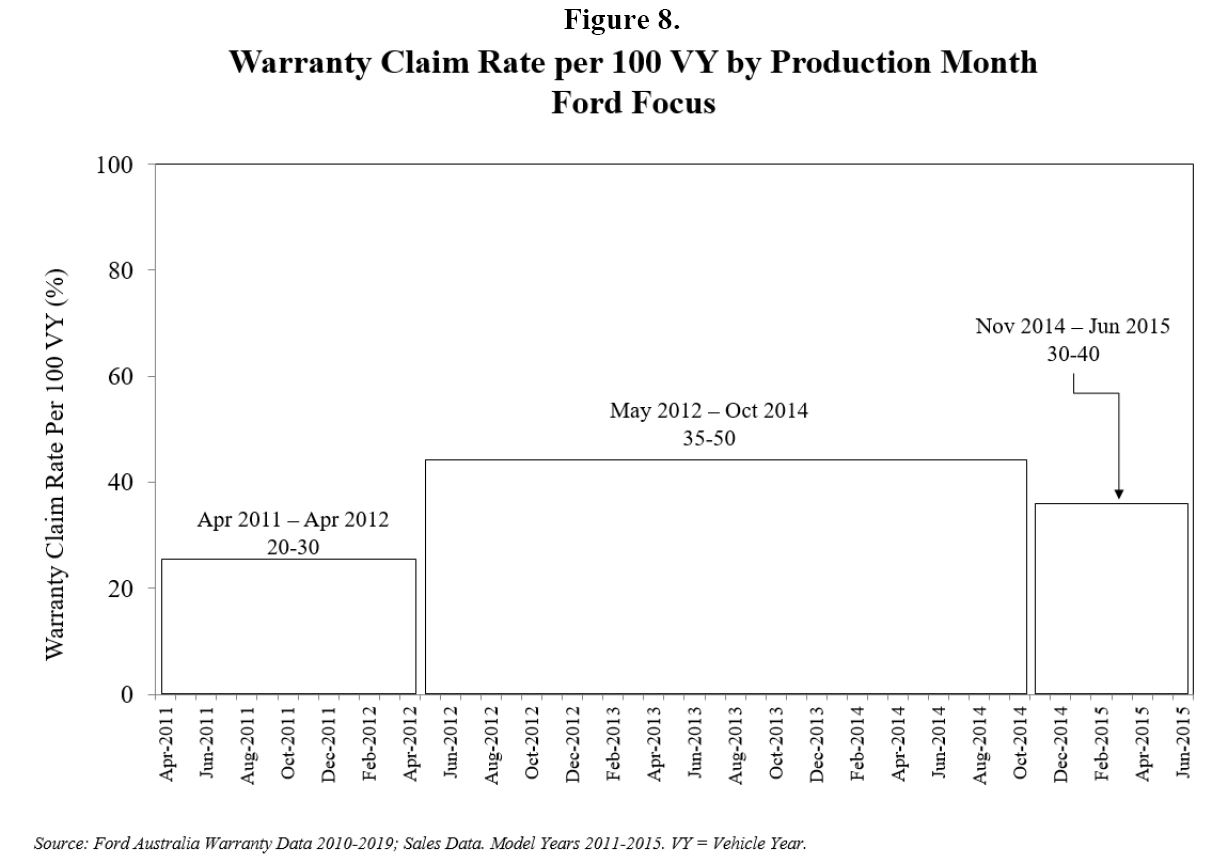

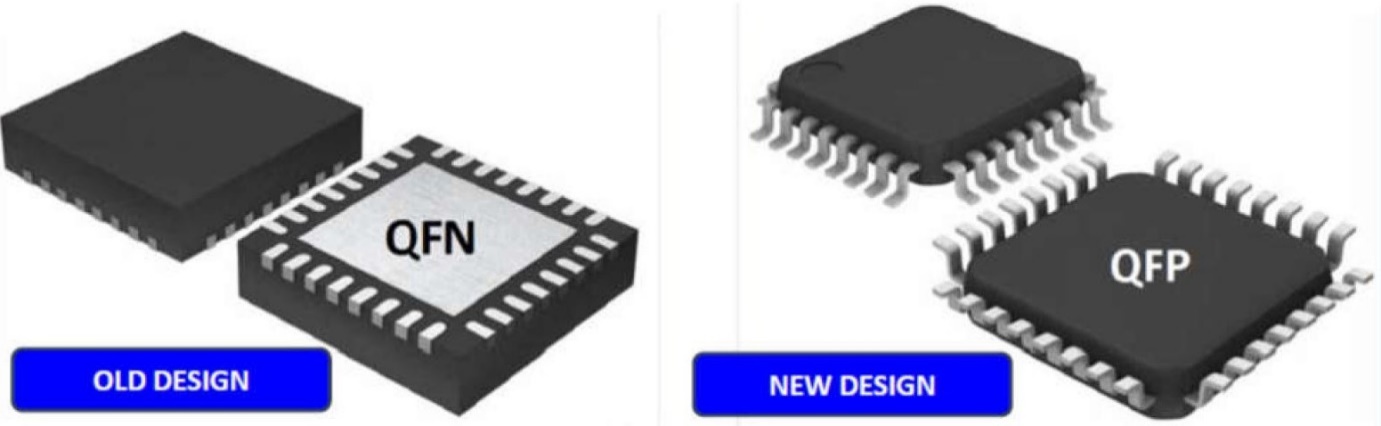

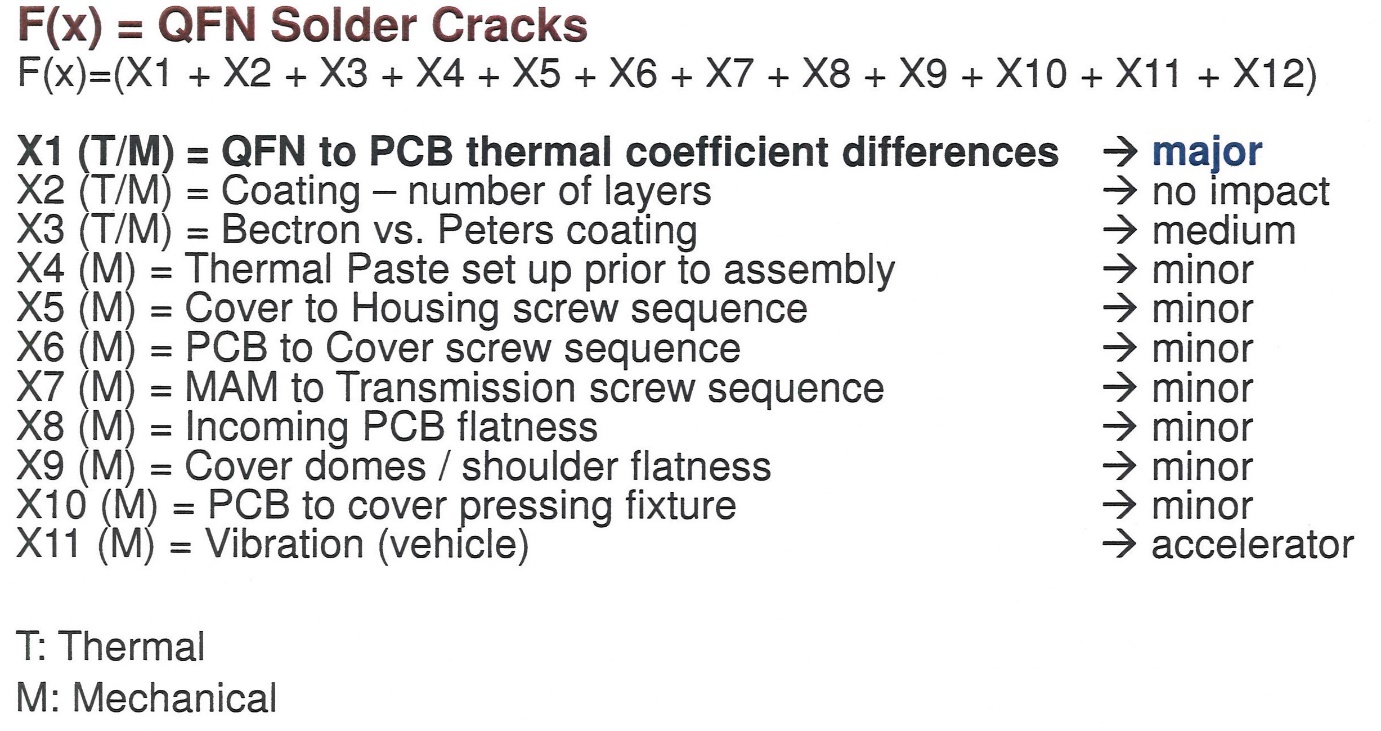

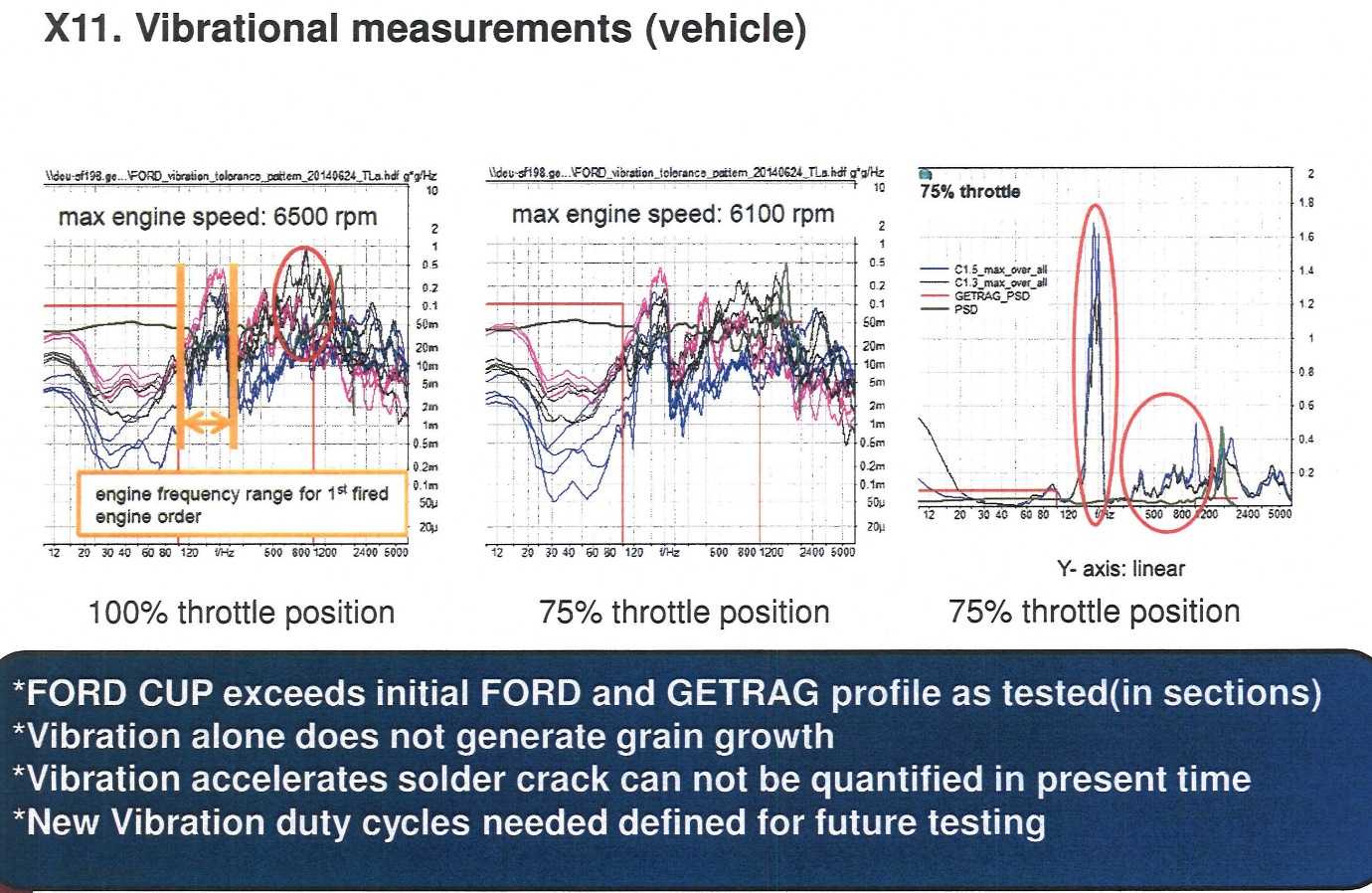

A transmission control module (‘TCM’) which contained a printed circuit board (‘PCB’) to which was affixed, amongst other things, two types of integrated circuits known as an ATIC 91 and an ATIC 106. These were affixed to the PCB by means of solder. Ms Capic says that the coefficients of thermal expansion of the PCB and the ATIC 91 and ATIC 106 chips were different and that repeated heating and cooling of the TCM (which is attached to the transmission assembly) created a risk of the solder cracking; and

A rear main oil seal which had a tendency to leak permitting lubricants to enter the bell housing from the engine side of the transmission and contaminate the clutch and drive plates.

4 Ms Capic submits that each of the first three risks eventuated in the case of her vehicle and gave rise to a range of symptoms including shudder. Her case, however, is not that her vehicle is not of acceptable quality because the risks materialised, it is rather that it was not of acceptable quality because it was supplied with these risks inherent in it. The full implications of running her case on the basis of risks were not always appreciated by either side.

5 I have concluded that she has established the existence of each of the risks set out above except the risk said to arise from the rear main oil seal. For each risk she has a separate cause of action under ACL s 271(1) entitling her to claim damages from the Respondent under s 272.

6 As it happens, I am also satisfied that in the case of her vehicle the three risks which I have accepted also manifested themselves and that after they did her vehicle displayed a troubling range of behaviours. Ms Capic took her vehicle for servicing on many occasions and complained about these problems. For a long time they were not fixed. However, in the case of the input shaft seals they were eventually replaced in a way which satisfies me that after the replacement the risk posed by them no longer existed.

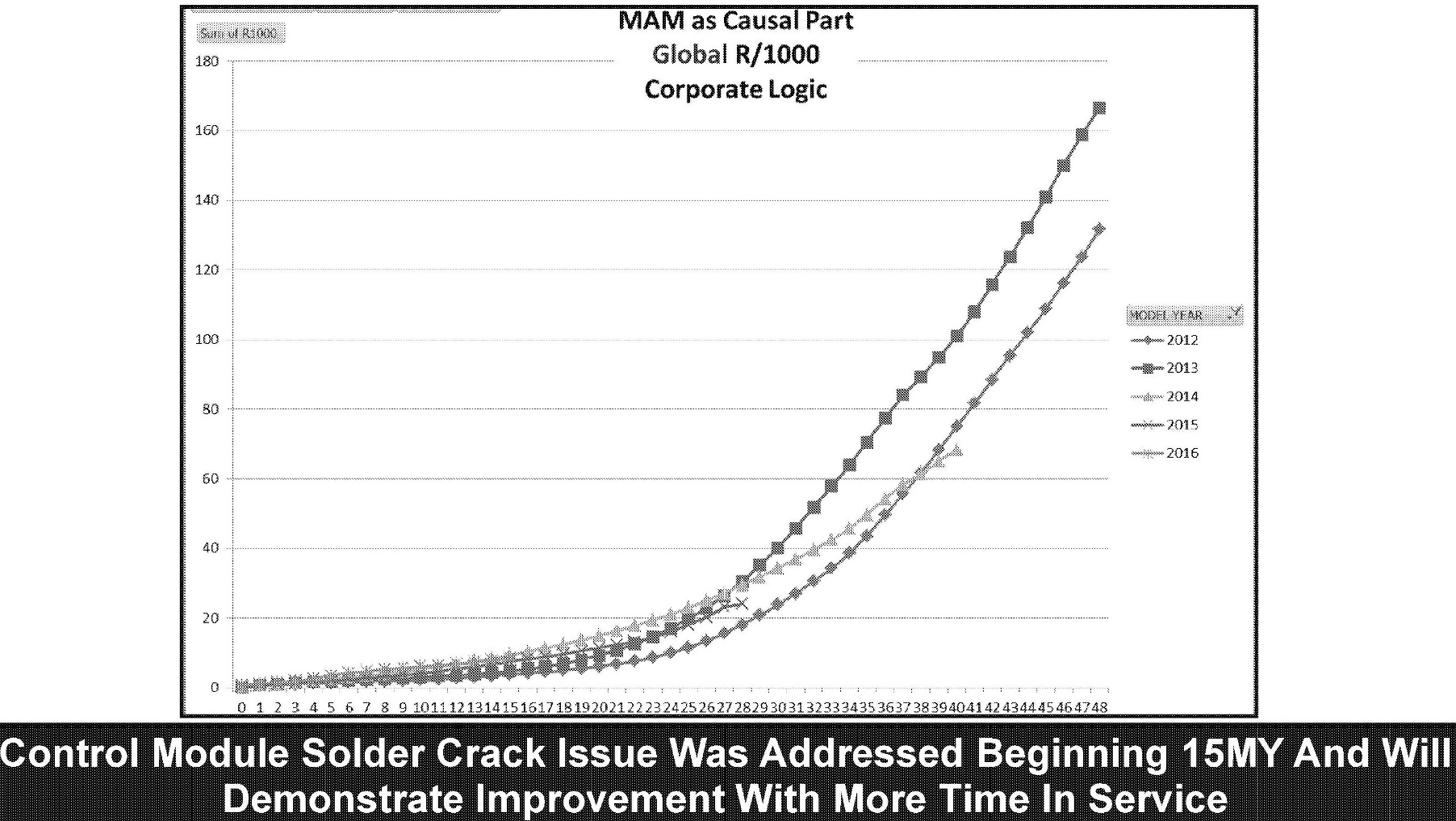

7 In the case of the TCM the issue is slightly more complex. There are two relevant events. The first involved the installation of a software update known as 15B22 which detected solder cracking before actual symptoms became perceptible to the driver. The second was the replacement of the old TCM with a new TCM with a revised ATIC 91 chip. It is only after this second event that I am satisfied that the relevant risk of TCM failure was removed in Ms Capic’s vehicle. I am not satisfied that she has demonstrated the existence of the problem with the original ATIC 106 chips.

8 In the case of the friction material I am not satisfied that the Respondent has satisfactorily resolved the problem.

9 These conclusions matter because the Respondent asserts that it is entitled to rely upon ACL s 271(6) in response to Ms Capic’s claim:

(6) If an affected person in relation to goods has, in accordance with an express warranty given or made by the manufacturer of the goods, required the manufacturer to remedy a failure to comply with a guarantee referred to in subsection (1), (3) or (5):

(a) by repairing the goods; or

(b) by replacing the goods with goods of an identical type;

then, despite that subsection, the affected person is not entitled to commence an action under that subsection to recover damages of a kind referred to in section 272(1)(a) unless the manufacturer has refused or failed to remedy the failure, or has failed to remedy the failure within a reasonable time.

10 The proper construction of this provision is very difficult and I will not touch upon it here. I will simply say that I accept that the risk inherent in the input shaft seals with which her vehicle was supplied was eliminated when they were replaced and that the risk posed by the TCM was eliminated when her vehicle received a new TCM with the revised ATIC 91 chip.

11 However, in both cases I do not accept that the Respondent did this within a reasonable time so that s 271(6) does not apply. Consequently, I am satisfied that Ms Capic is entitled to sue the Respondent for the reduction in value damage she has suffered as a result of the supply to her of a vehicle with the three inherent risks.

12 In addition to her case that the four components above were attended by a risk of failure Ms Capic also pursued a more general case that her vehicle was not of acceptable quality because it had a risk of certain symptoms (principally, but not only shudder) because of what were said to be two architectural features of the DPS6 (‘the Architectural Deficiencies’). These were:

Inadequate heat management; and

Inadequate damping of torsional vibrations.

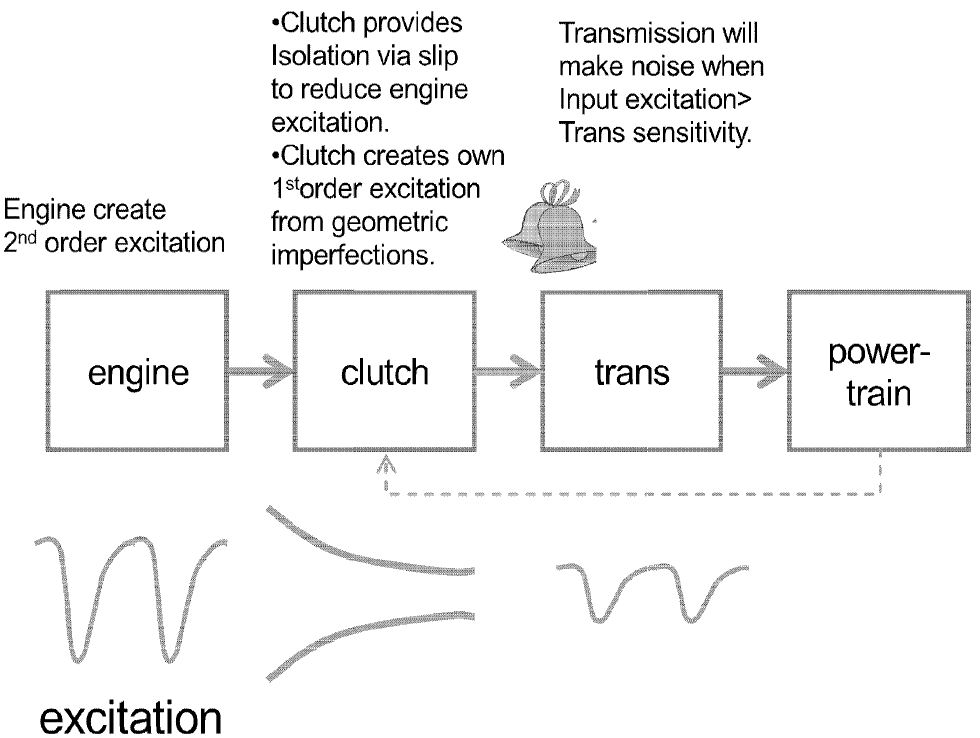

13 These problems were designated as ‘architectural’ because of a contention that they could not be cured without changes to the architecture of the DPS6 and that this in fact had not occurred. The Respondent denied the existence of either risk. I have concluded that the heat management case does not succeed. However, I have accepted that the manner in which the DPS6 damped torsional vibrations generated a risk that the gears in her vehicle would rattle and that the vehicle would display a slight shudder at low speeds. There was no dispute that there was a risk that these two symptoms could occur. Indeed, the Respondent submitted that they were both ‘normal operating characteristics’ of the DPS6. I have not accepted that the fact that gear rattling and a slight shudder at low speeds are described as normal operating characteristics has the consequence that they cannot constitute a breach of the guarantee of acceptable quality. I have concluded that the fact that Ms Capic’s vehicle was supplied with these two problems inherent in it has the consequence that it is not of acceptable quality for the purposes of s 271(1) and she has another cause of action against the Respondent in respect of them. Since the Respondent claims these features are normal operating characteristics it has not attempted to resolve them.

14 Ms Capic claims that she is entitled to reduction in value damages under s 272(1)(a). I have accepted that she is and that she is entitled to the sum of $6,820.91 together with interest up to judgment from 24 December 2012. Ms Capic also claims to be entitled to damages under s 272(1)(b) because, so it is argued, she paid too much GST and stamp duty on the purchase of the vehicle on the basis (as it has fallen out) that it was worth 30% less than the $22,736.36 she paid for it. For myself, there is an interesting and complex question not dealt with by the parties whether an award of these damages is conceptually coherent since Ms Capic is to be placed in the position she would have been if the vehicle had complied with the guarantee of acceptable quality. On one view, this has been done by awarding her $6,820.91 for reduction in value damages and there is then no sense in which GST and stamp duty represent losses, those being amounts Ms Capic always expected to pay in the bargained-for position to which she would have been restored. However, this was not a defence raised by the Respondent. In any event I have determined that even if it had been this issue would not have been a bar to Ms Capic recovering these sums. Of the actual defences raised by the Respondent to this claim for damages, I have not found any persuasive. I therefore award amounts for GST and stamp duty.

15 Ms Capic purchased the vehicle using a finance lease. She also claims to be entitled to damages for the fact that she was required to ‘borrow’ more than she should have. I have accepted this claim and rejected the Respondent’s defences to it. On each rental payment she paid GST and I have also concluded that she is entitled to an amount to reflect the fact that with lower lease payments she would have paid less GST on these.

16 Although Ms Capic made a claim for damages for inconvenience, distress and vexation in her pleadings she did not pursue it in her submissions and I make no award for it.

Liability

17 The DPS6 was fitted in 73,451 vehicles imported into Australia by the Respondent. I will call this cohort the ‘Affected Vehicles’. These vehicles consisted of the model lines of the Focus, Fiesta and EcoSport and the dates they were supplied new range from 22 September 2010 to 29 December 2017. The group consists principally of the persons who purchased these vehicles new together with subsequent second hand purchasers between 1 January 2011 and 29 November 2018. The Applicant estimated there are approximately 185,000 people in the group by reasoning that each car had been owned on average by 2.5 persons in this time.

18 The picture is much more complex in the case of the group than it is in the case of Ms Capic. The vehicles were manufactured by the Respondent’s parent, Ford Motor Company (‘Ford US’). As the problems with the DPS6 became apparent Ford US worked to resolve them. As a solution became available it was gradually implemented in vehicles which were already on the road. However, this was only done where the vehicles presented for service with a problem (except in the case of 15B22 which was installed when vehicles were brought in for regular servicing). This approach is known as a ‘fix on fail’ approach. Ford US also adjusted its manufacturing processes so that the fixes were applied in new vehicles. Turning to the particular problems advanced by the Applicant:

19 I am satisfied that the Affected Vehicles which were supplied with the original input shaft seals posed a risk of failure and that all of these vehicles were at the time of their supply not of acceptable quality.

20 Where the original input shaft seals have not been replaced no question under ACL s 271(6) arises and these group members have claims under s 271(1) for reduction in value damages under s 272(1)(a) and (if applicable) other reasonably foreseeable loss and damage under s 272(1)(b) .

21 Where the input shaft seals have been replaced with seals containing both the new FKM elastomer and a steel outer backing on the inner seal, I accept that each relevant group member ‘required’ the repair within the meaning of s 271(6). However, in these cases the issue of whether the repair was effected within a reasonable time was not the subject of the present trial. Both parties eschewed any attempt to prove whether group members’ vehicles had been repaired within a reasonable time by asserting that the other bore the burden of proving this matter. The effect of this impasse was that there is no evidence before the Court on the topic. Had either party attempted to prove this matter it would have been immediately apparent that it could not have been tried as a common issue since it turns on the individual position of each group member. For this reason the only conclusion is that the matter was not tried and could not have been tried as a common issue.

22 Consequently, it cannot presently be known whether these group members have claims for reduction in value damages although the prima facie position is that they may have claims for other reasonably foreseeable loss and damage under ACL s 272(1)(b). This conclusion about the present uncertainty as to the availability of reduction in value damages does not apply in those vehicles where an input shaft seal was replaced with one containing only the new FKM elastomer but not the new steel backing on the inner seal.

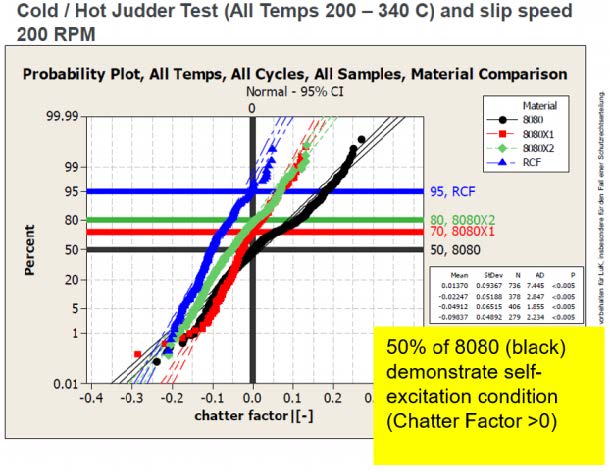

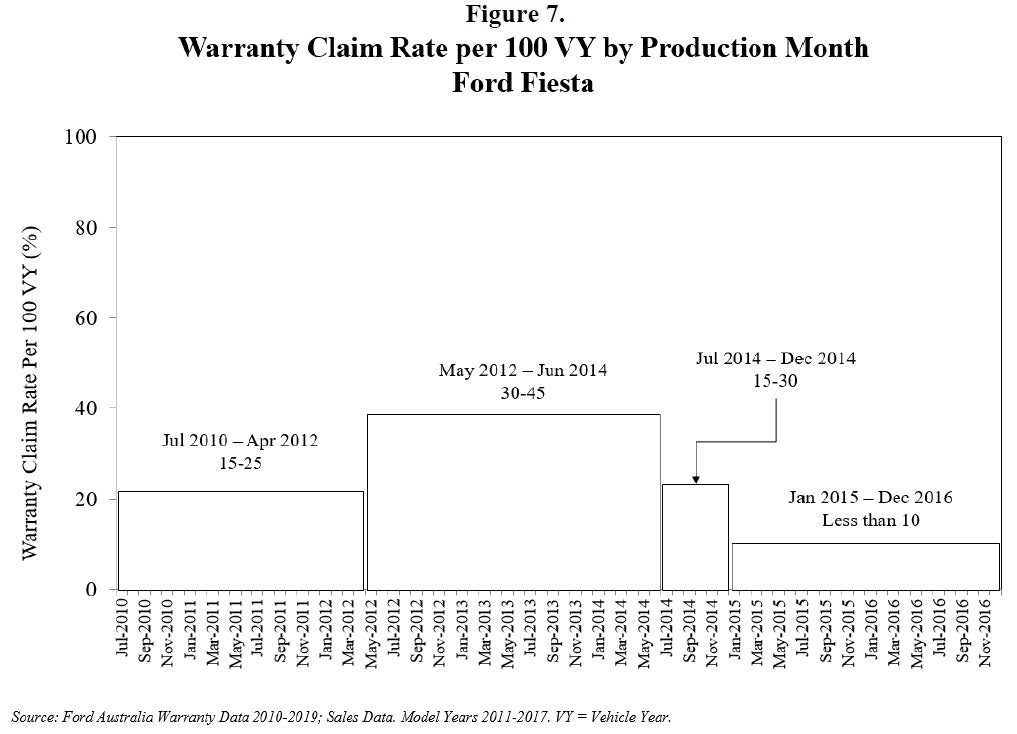

23 I am satisfied that each vehicle which was supplied with the original clutch lining material (known as B8080) suffered from a risk of developing symptoms such that it did not comply with the guarantee of acceptable quality.

24 Some of the Affected Vehicles supplied with this material have never had it replaced. I am satisfied that each such group member has a cause of action under s 271(1) for reduction in value damages under s 272(1)(a) and if applicable for other reasonably foreseeable loss or damage under s 272(1)(b).

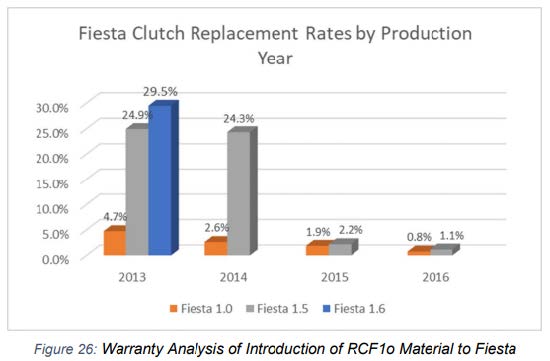

25 Some of the Affected Vehicles supplied with this material have since received replacement clutches using lining material known as RCF1o. I am satisfied that this replacement has removed the relevant risk of symptoms. The Respondent then seeks to rely on s 271(6) to defeat such a group member’s claim for reduction in value damages. I am satisfied that each such group member ‘required’ the Respondent to repair the vehicle, however, the issue of whether it did so within a reasonable time was not tried in the present trial. Its outcome will turn in each case on when the particular group member required the Respondent to repair the problem and when, in fact, the Respondent did so. Since that issue was not tried it is not presently known whether the Respondent has a defence to a claim for reduction in value damages under s 271(6) in the case of such a group member. This will not be known until the individual position of each group member is ascertained. However, as with the input shaft seals, s 271(6) does not affect a group member’s entitlement to seek compensation for reasonably foreseeable loss or damage other than reduction in value damages, ie under s 272(1)(b).

26 Some vehicles received a replacement clutch known as a half-hybrid B8040/B8080 clutch rather than an RCF1o clutch. I am not satisfied that the Respondent has proved that this half-hybrid clutch eliminated the risk. Consequently, no question under s 271(6) can arise. It follows that these group members do have claims for reduction in value damages as well as for other reasonably foreseeable loss and damage under s 272(1)(b).

27 Not all of the vehicles were supplied with B8080. Some were supplied with the half-hybrid B8040/B8080 clutch. I am not satisfied that the Applicant has demonstrated that this material posed the risks of failure she alleges and hence I am not satisfied that these group members have a claim for damages in respect of their clutch lining. It will be noted that I have already rejected the Respondent’s reliance on s 271(6) with respect to the half-hybrid clutch. In effect, both parties failed to prove anything useful about the half-hybrid clutch.

28 In the case of the vehicles which were supplied with RCF1o the group members do not have a claim in respect of the clutch lining.

29 The case based on the ATIC 106 chips fails on the facts. However, the case based on the original ATIC 91 chip is viable. Not all of the Affected Vehicles were supplied with a TCM containing an ATIC 91 chip attended by a risk of solder cracking. Affected Vehicles supplied with a TCM with the revised ATIC 91 chip were not in breach of the guarantee of acceptable quality for this reason and their owners do not have a claim under s 271(1) in respect of it.

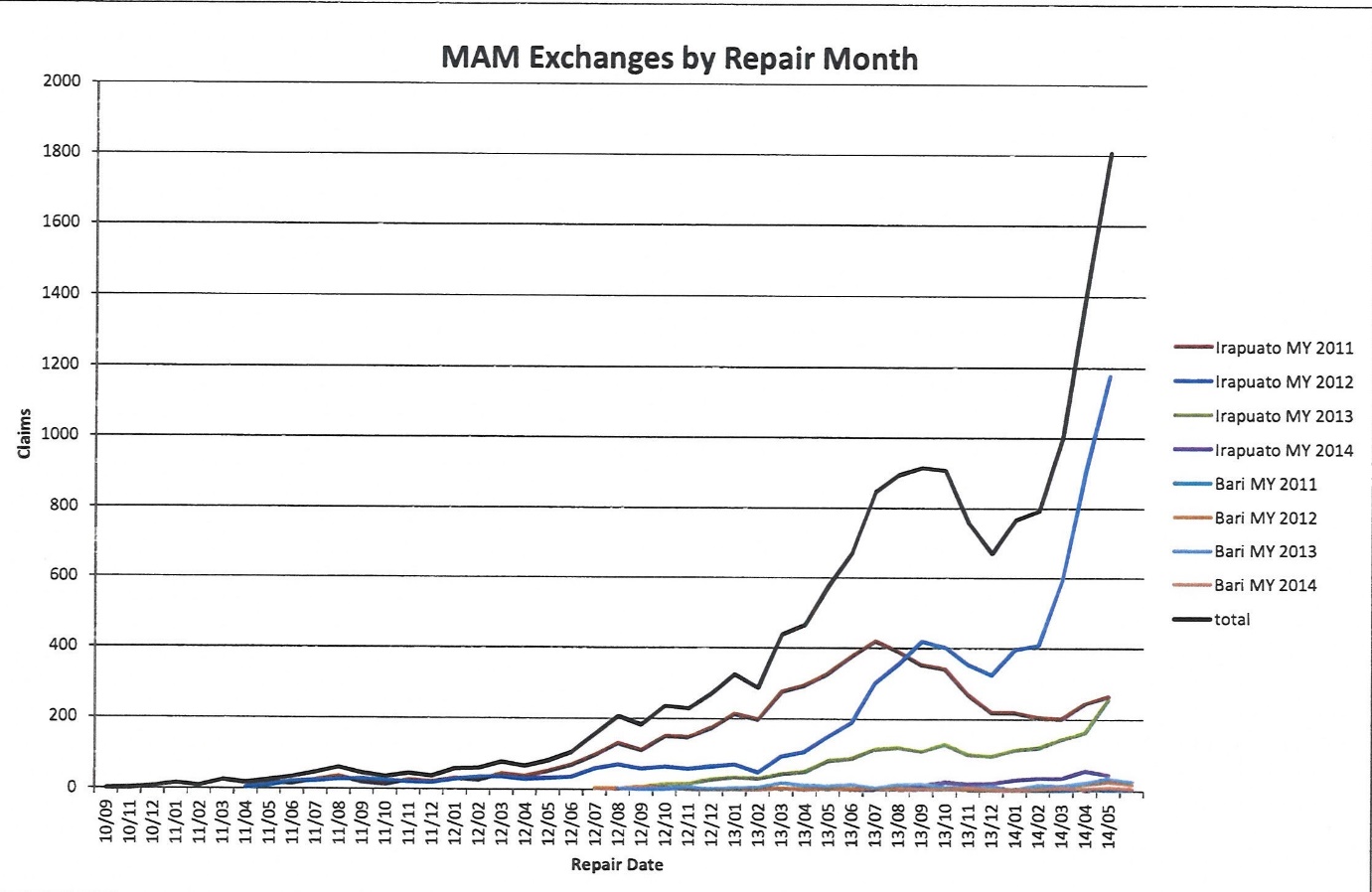

30 The vehicles supplied with TCMs containing the original ATIC 91 chip were not of acceptable quality at the time of their supply because of the risks they posed. The Respondent applied two fixes. First, each vehicle which was presented for service after 27 October 2015 received a software update known as 15B22. It did not address the physical problem of solder cracking but it detected that problem before the symptoms associated with it became perceptible to the driver and disabled the vehicle in a sufficiently confronting way, attended with warning lights and messages, that it may be accepted that a driver would take the vehicle in for service almost immediately and without fail. Secondly, once new TCMs with the revised ATIC 91 chip became available these were inserted into vehicles which showed symptoms of TCM failure or which had been brought in for service due to the operation of the warning system instituted by the 15B22 software update.

31 The first fix was effective in those vehicles into which it was installed where replacement TCMs with the revised ATIC 91 chip were available in service stock but not effective in those vehicles in which it was not installed or where it was installed without the corresponding availability in service of TCMs with the revised ATIC 91 chip. The second and third class of these have claims for reduction in value damages if their original TCM was not otherwise replaced. It is not known whether the first class have claims for reduction in value damages in respect of this issue because, while I accept that the installation was an effective repair for the purposes of s 271(6) where new TCMs were available as replacements in service, the issue of whether the repair took place within a reasonable time has not been tried nor has it been shown for each group member that replacement TCMs with the revised ATIC 91 chip were in fact available.

32 The replacement of the original TCM with a new TCM with the revised ATIC 91 chip was a successful repair and removed the risk posed by the original TCM. However, in the case of each such group member it is not presently known whether the replacement was effected within a reasonable time. It cannot presently be known whether these group members have claims for reduction in value damages.

33 The group members have not established that any of the Affected Vehicles had an inherent risk of failure due to the rear main oil seal. This claim fails.

34 The group members have not established that their vehicles had an inherent risk of failure because of the way in which heat was managed in the DPS6. This claim fails.

Rattling gears and slight shudder at low speeds

35 I am satisfied that all Affected Vehicles have a risk that they will develop these symptoms due to the manner in which the DPS6 damps torsional vibrations. I have concluded that the Affected Vehicles do not comply with the guarantee of acceptable quality because of this issue. The Respondent has not attempted to resolve this.

Damages

36 The group members sought damages on an aggregate basis under s 33Z(1)(f) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (‘FCA Act’). Such an award may only be made if the Court is satisfied that a reasonably accurate assessment can be made of the total amount to which group members will be entitled: s 33Z(3). Since it is not presently known which group members have which causes of action for reduction in value damages the question of whether there can be aggregation under this provision does not yet arise. The claim is therefore refused on the current state of the case. If and when the issue of whether the various repairs were effected within a reasonable time is resolved, this question may be revisited.

37 For reasons explained more fully in Section XIV, this conclusion is not disturbed by either of the following matters:

38 First, that all group members have causes of action in relation to the risks of rattling gears and a slight shudder at low speeds which I have concluded are caused by inadequate torsional damping. This was a comparatively minor issue when compared with the Applicant’s case on the Component Deficiencies. In any event, an award of aggregate damages cannot be made unless the Court can arrive at a reasonably accurate assessment of the total amount to which group members are entitled under the judgment: FCA Act s 33Z(3). This is not possible for reasons I have just outlined.

39 Secondly, that the group’s aggregate damages claim incorporated amounts for alleged excess finance and tax and repair time costs, comprising other reasonably foreseeable loss or damage under s 272(1)(b). While the entitlement to damages under that provision does not depend on the continued existence of a cause of action for reduction in value damages, nonetheless it is not possible to make a reasonably accurate assessment of group members’ total entitlement. In any event, as I explain in Section XIV, any assessment of excess finance and tax losses cannot be undertaken until the quantum of any entitlement to reduction in value damages is known. The result therefore is that there can yet be no award of aggregate damages.

40 Finally, before moving to the substantive issues in the case, it should be recorded that this trial was conducted during the Victorian lockdown in 2020 in circumstances of considerable hardship for both parties, their lawyers and those working within the Court. The entire 6 week trial was conducted by means of a virtual platform with not a single appearance in a court room by any person. This required a high degree of co-operation between the legal representatives for the parties. Whilst no doubt the trial was conducted with little quarter given by either side to the other, this formal hostility did not extend to facilitating the orderly conduct of the trial in the difficult circumstances of the pandemic. The Court records its thanks to the representatives of the parties for bringing the matter to trial in this fashion.

Section II: The Affected Vehicles

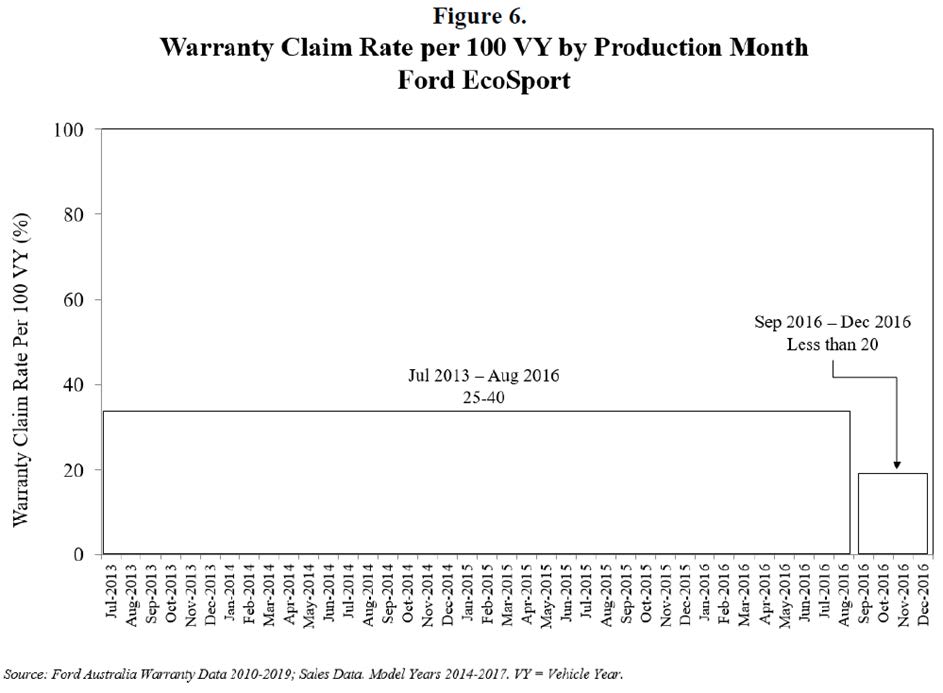

41 The Affected Vehicles consist of 73,451 separate vehicles manufactured by Ford US under the model lines Focus, Fiesta and EcoSport during the period between July 2010 and December 2016. Each of the vehicles was manufactured either in Rayong in Thailand, Saarlouis in Germany or Chennai in India. Each of the vehicles is equipped with the DPS6 transmission. Further, each of the vehicles was sold by the Respondent through Ford Australia dealerships to consumers in the Australian market.

42 Apart from the three model lines, the vehicles may relevantly be further sub-categorised by reference to their year of production and their engine size. In the case of production year, there can be a lag of up to one year between the time a vehicle is physically assembled at a Ford plant and the time at which it is eventually sold. Whilst sometimes the model year of a vehicle can be the same as the production year this is not inevitably so and for some vehicles the model year is the year following the production year. This is so, for example, in the case of the Affected Vehicles bearing a 2017 model year, as all were produced in 2016.

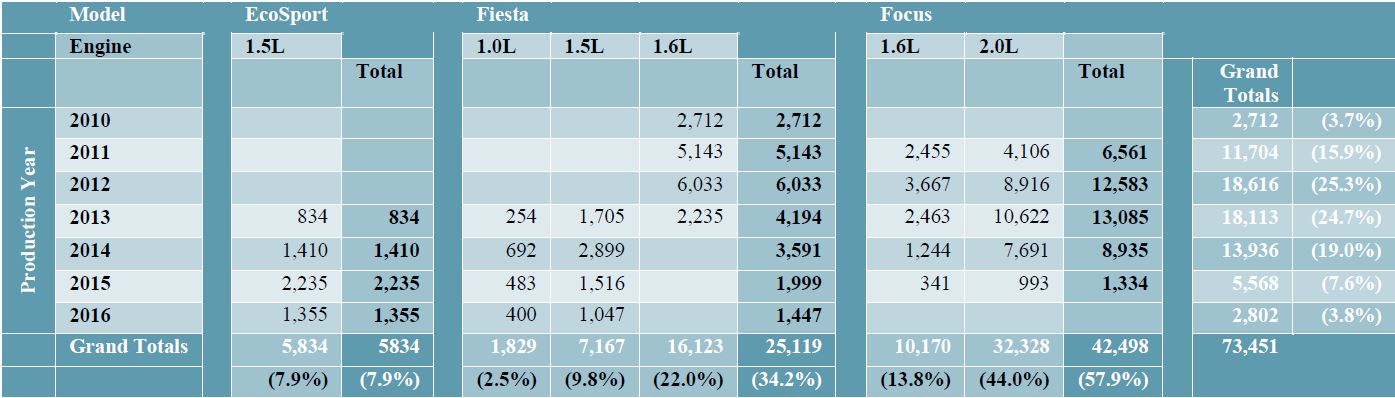

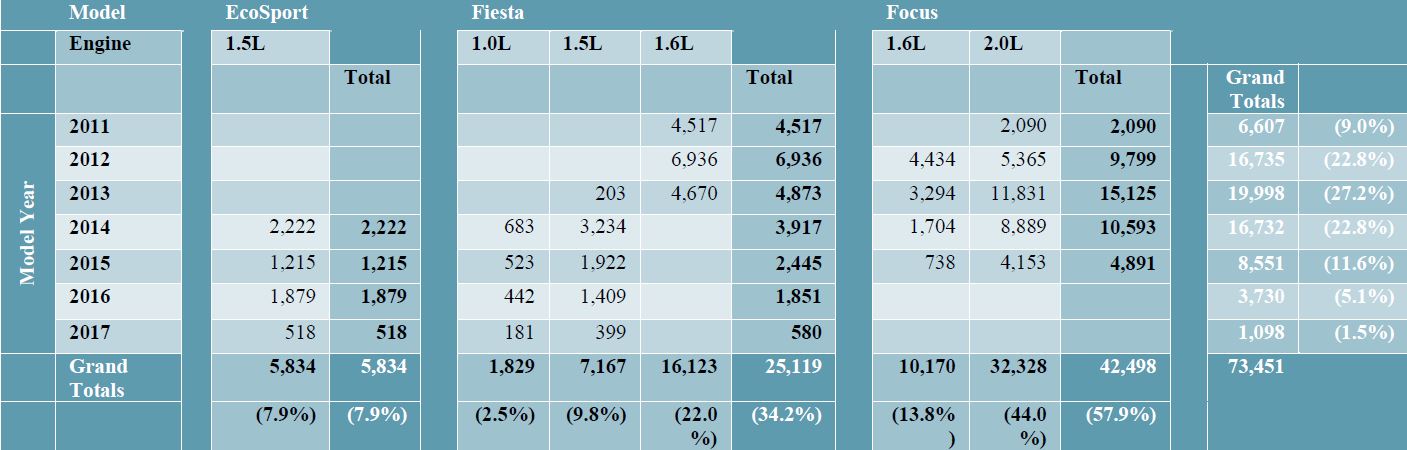

43 The Applicant’s submissions summarised the composition of the fleet of Affected Vehicles in Table 1 of her submissions which is based upon production year:

44 A table was also prepared by reference to model year (as opposed to production year):

45 The Respondent’s submissions contained a similar set of tables which very marginally differed. After judgment was reserved I queried the parties as to the discrepancy. On 6 August 2020, my Associate was informed by the parties that the Court should rely upon the tables in the Applicant’s submissions. The minor discrepancy related to the inclusion in the Respondent’s figures of some vehicles which had never been sold. For that reason, I will act on the basis of the tables I have just set out.

46 The Ford Focus constitutes the largest segment of the Affected Vehicles (57.9%) followed by the Fiesta (34.2%) and the EcoSport (7.9%). The small number of EcoSports involved is a reflection, in part, of the fact that it did not enter production until 2013. It will also be noted that there is a significant decline in the number of Affected Vehicles manufactured after 2014. Most of the Affected Vehicles (88.6%) were manufactured between 2010 and 2014 and 11.4% were manufactured in 2015 and 2016.

47 Next it is useful to note where these vehicles are located in the wider market for all vehicles. The Fiesta and EcoSport are what are known as B-segment vehicles whilst the Focus is a C-segment vehicle. Both B- and C-segment vehicles are designed to be lightweight, fuel efficient and relatively inexpensive to purchase and operate in comparison to larger and more expensive vehicles in the D-segment (eg the Audi A4) or the E-segment (eg the Mercedes-Benz E-class). C-segment vehicles are generally larger than B-segment vehicles. The Focus is larger than the Fiesta but similar in size to the EcoSport. B- and C-segment vehicles are typically equipped with smaller engines between 1.0 and 2.0 litres in size.

48 Although the tables above refer to engine size without discrimination between engine type, there is a debate between the parties about the role of ‘dual mass flywheels’. I need not explain what that debate is at this point (see Section X below) although it concerns the kind of flywheel connecting the crankshaft to the drive plate (I explain these terms below at Section IV).

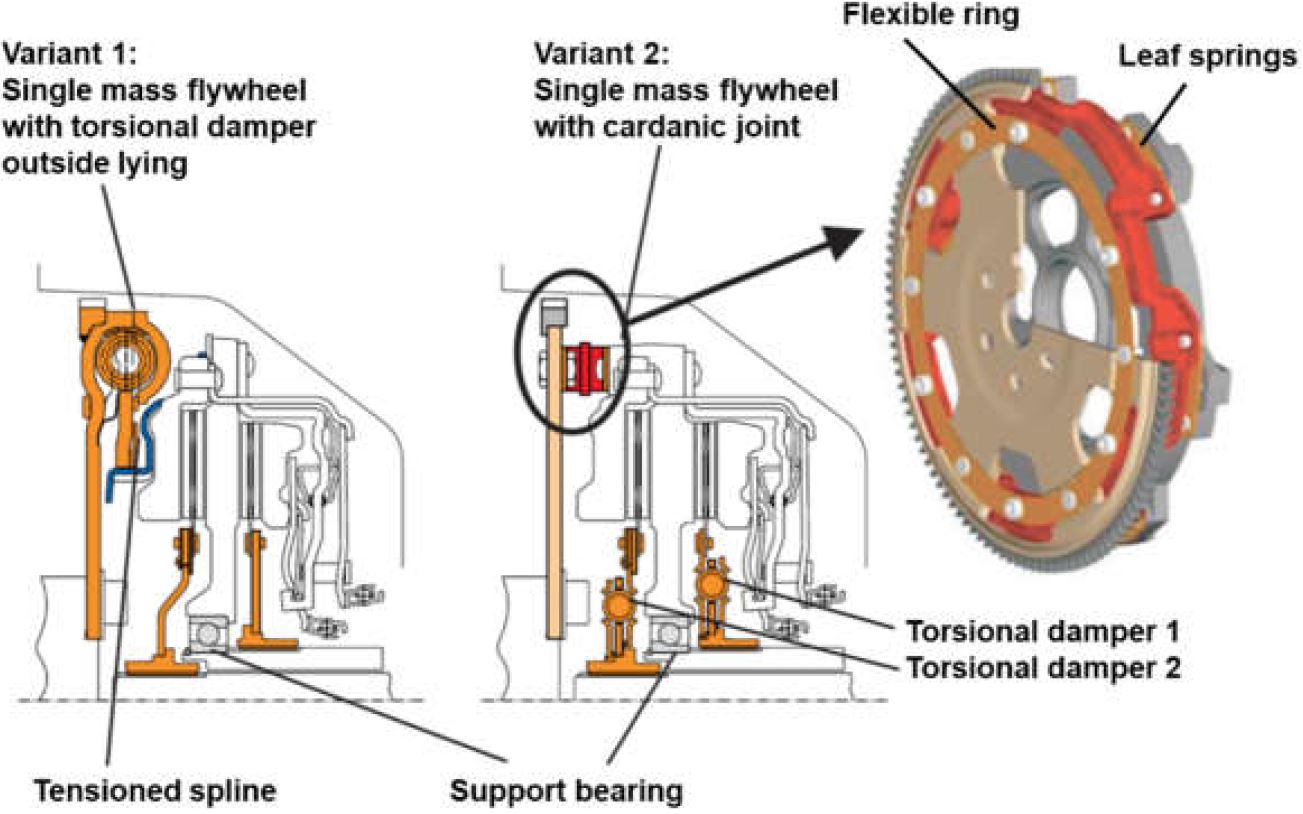

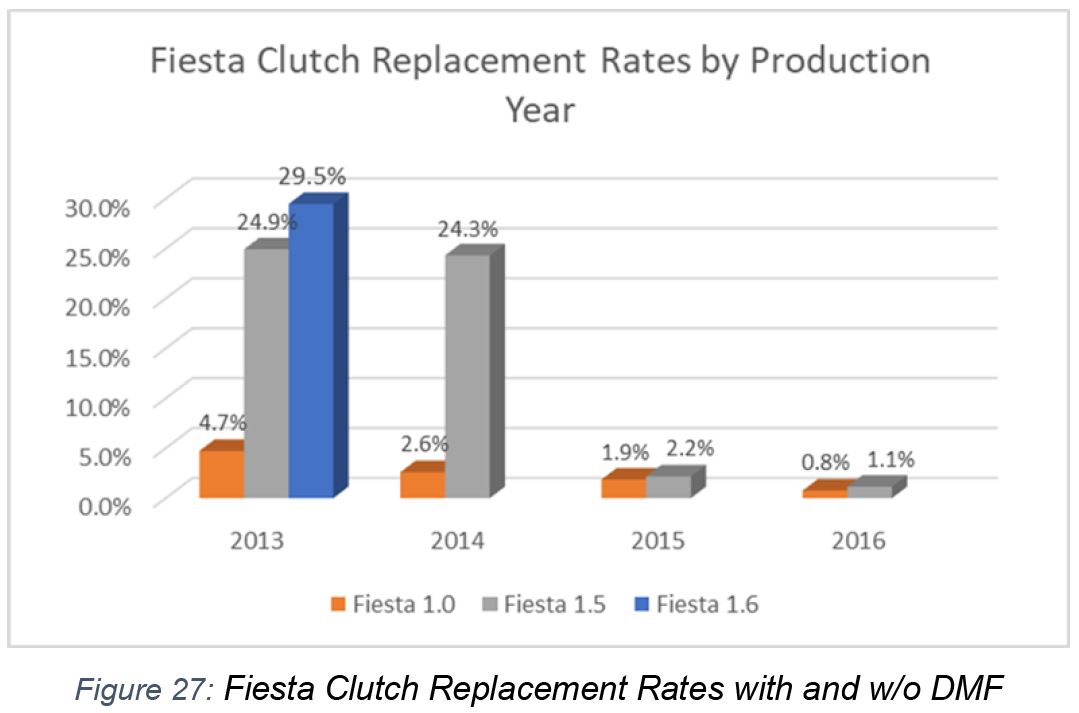

49 The flywheel debate does make it necessary, as a matter of background, to understand that, with the exception of the 1.0L Fiesta, all the Affected Vehicles have 4-cylinder engines. Each of these engines was equipped with a ‘single-mass flywheel’. The 1.0L Fiesta, on the other hand, was built with a turbocharged 3-cylinder engine (known as the ‘Fox’) equipped with a dual mass flywheel. I return to the large topic of dual mass flywheels and torsional vibrations below at Section X. It forms a significant part of the engineering debate between the parties.

50 Within model lines there were further distinctions which reflected differences in trim or additional functionality. In general, different levels of trim can range from the cosmetic (ie, leather seats instead of fabric) through to improvements in performance and comfort (ie, increased sound insulation and better powertrain mount tuning). For the Affected Vehicles, these different trims can be identified by each model line’s badge. The Affected Vehicles include the Fiesta in six different badges (CL, LX, ZETEC, Ambiente, Trend and Sport), the EcoSport in three (Ambiente, Trend and Titanium) and the Focus in four (Sport, Ambiente, Trend and Titanium/Sport). Nothing in this litigation turns on the differences between badges but since they often appear in the evidence it is useful to know what they mean.

51 I was not taken to any evidence directly on this matter, but in submissions the Applicant referred to there being 64,963 Affected Vehicles remaining from the 73,451 once the settled claims had been removed. In any event the total number of vehicles remaining in the class is not material at this stage.

Section III: Procedural Consequences of the Way the Case was Run

52 The Applicant’s case that the Affected Vehicles were not of acceptable quality is principally found at §6AB of the fourth further amended statement of claim (‘4FASOC’). It is a case alleging that the vehicles had a propensity towards certain identified misbehaviours. There was no issue in the case as to whether individual vehicles in the class actually exhibited the misbehaviours (although there was in Ms Capic’s individual case). This interpretation of §6AB reflected the parties’ understanding of it with which the Court had previously agreed: Capic v Ford Motor Company (No 3) [2017] FCA 771 at [16]. Any inquiry into the individual position of vehicles within the class would not have presented common issues suitable for determination in a class action trial. The Applicant did not therefore seek to prove the individual position of vehicles within the cohort. It is true that the Applicant did call 52 other group members to give evidence about their vehicles but she submitted their relevance was only to give anecdotal support for her case that the vehicles suffered from the propensities alleged and to exemplify the expectations of a reasonable consumer.

53 The case therefore is about the existence of propensities (or risks) of identified forms of vehicle misbehaviour. The method of proof selected by the Applicant was to seek to prove that the propensities or risks existed because of particular mechanical features of the DPS6. In an ordinary claim that goods are not of acceptable quality the question of why they are such is irrelevant. For example, if I buy a kettle and it does not work, it does not matter why it does not work. It is not of acceptable quality simply because it does not work. The applicant in such a case has no need to prove its design or componentry deficient, just that it does not work. However, where a case of unacceptable quality is pursued on the basis that the goods pose a risk of some kind, the qualities of the argument necessarily require an identification of some reason why the risk exists. Ordinarily, this will require some form of practical explanation of a problem in construction or design. For example, if an applicant wishes to prove that a kettle is defective because it has a 5% risk of exploding, it will usually be necessary to explain what it is about the kettle that gives rise to that risk. The only other alternative would be to rely on sufficiently robust empirical data to show that in fact 5% of the kettles did explode.

54 The manner in which the Applicant sought to prove the existence of the risks of the alleged misbehaviours was multi-faceted. She relied on:

the evidence of Dr Jürgen Greiner, a transmissions engineer;

the evidence of herself and 52 other members of the group as to the difficulties they had had with their own vehicles;

evidence derived from warranty claims and complaints data maintained by the Respondent;

documents produced by Ford US which were referred to by Dr Greiner in his reports; and

documents produced by Ford US which were not referred to by Dr Greiner in his reports.

55 For reasons I explain more fully in Section XVI the Applicant’s case was that the vehicles suffered from the risks of misbehaviour identified by Dr Greiner. This was not the way that §6AB of the 4FASOC was particularised but the Applicant later notified the Respondent that she would prove the existence of the deficiencies through Dr Greiner. By the time the matter came to trial, it was on this basis that it was conducted. The parties chose to make the correctness of Dr Greiner’s evidence the field of their dispute which they were at liberty to do.

56 Dr Greiner referred to a number of documents which had been created by Ford US and, in relation to these there is no doubt that the Respondent has been given an opportunity to meet the Applicant’s case. However, at the end of the trial the Applicant tendered a number of Ford US documents not referred to in Dr Greiner’s evidence without indicating at any time prior to her closing written submissions what their significance was. As I explain in Section XVI this is procedurally unfair and will not be permitted.

57 In relation to the 52 vehicle owners who were called, I explain in Section V as to why I do not think I can rely on their evidence to substantiate the existence of risks across the Affected Vehicles where the Applicant provided no evidence as to how these witnesses had been selected or what the statistical value of a sample of 52 vehicles from a cohort of 73,451 might be.

58 Consequently the case that the Respondent was required to meet on the existence of the alleged propensity of the vehicles to misbehave was the case consisting of:

Dr Greiner’s evidence including the Ford US documents referred to by him;

The Respondent’s warranty and complaints data and the evidence derived from that data.

59 It is then necessary to identify features of the DPS6 relevant to the Applicant’s case.

Section IV: The Nature and Relevant Features of the DPS6

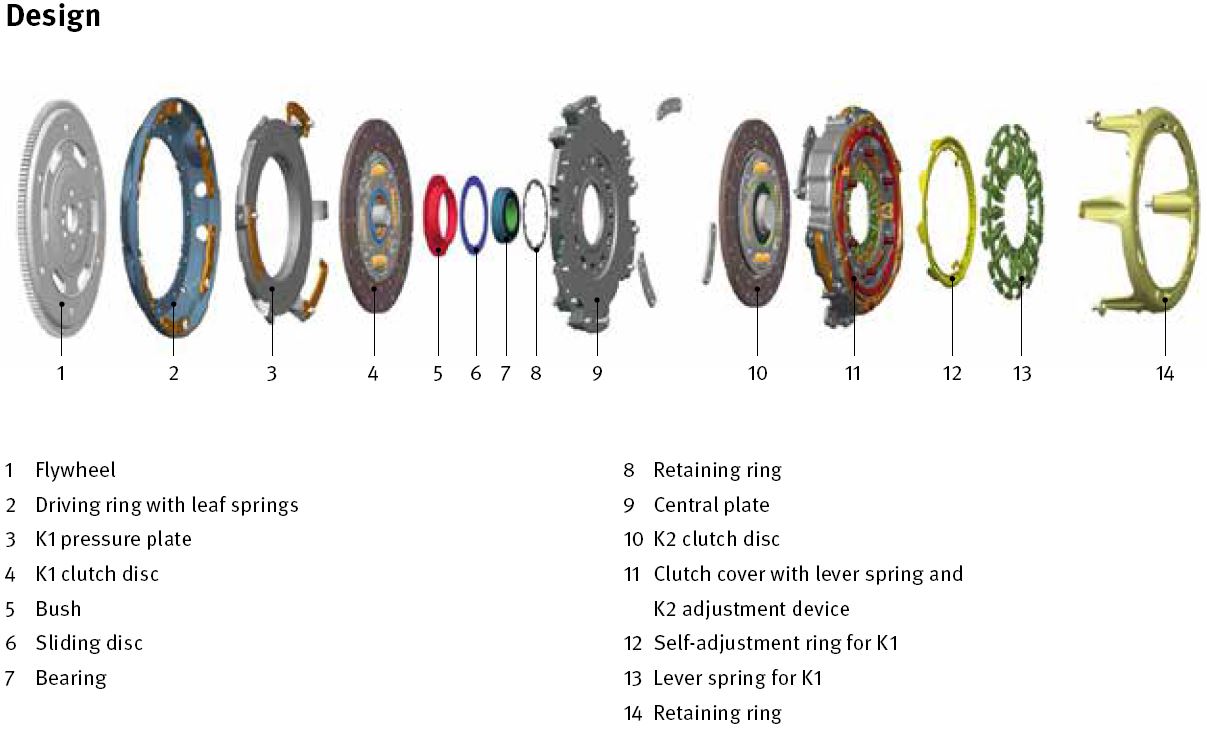

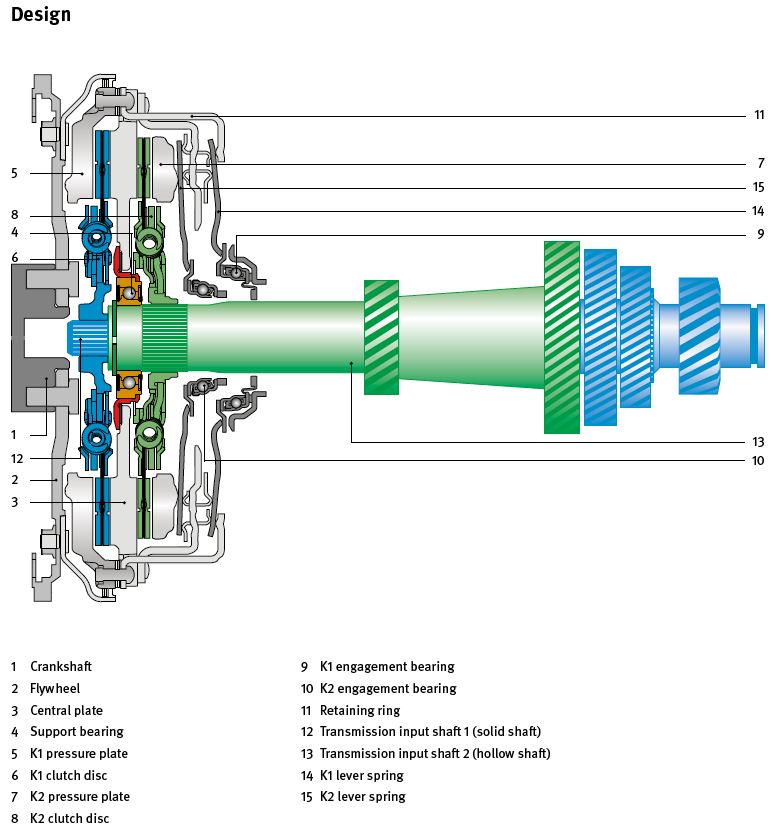

60 The DPS6 is a dry dual clutch transmission. A dual clutch transmission is a transmission with two clutches. In the DPS6 one clutch operates the odd numbered gears (‘clutch 1’) and the other the even numbered gears along with reverse (‘clutch 2’). This permits the transmission to have two gears selected at once. Clutch 1 is attached to an inner input shaft which is itself located within a hollow outer input shaft to which clutch 2 is attached. In both cases, the clutch plate sits between a pressure plate and a central drive plate. The pressure plates are controlled by actuators and squeeze the relevant clutch plate onto the drive plate. The drive plate is connected to the crankshaft (via a flywheel) and it is the crankshaft that takes power from the engine. The clutch plate is connected to the input shaft. When a gear is fully engaged, the drive plate and the clutch plate move at the same rotational speed and are pressed onto each other such that power flows from the crankshaft to the input shaft and from there through the transmission to the gears to drive the car. When the vehicle is moved from a standing position (‘launch’) or when a gear change is performed, the clutch plate and the drive plate move at different speeds until they are brought to the same speed in the same way as occurs in a manual transmission. This period of transition depends on the frictional qualities of the clutch lining or friction material which lines the relevant faces of the clutch plates, the pressure plates and the drive plate. This material is an important element in the operation of the transmission and its frictional qualities dictate the manner in which the transmission operates. Because there are two clutches in a dual clutch transmission there are four areas of frictional contact involved, one on each side of the drive plate and one between each clutch plate and its respective pressure plate. Below are two diagrams of the DPS6 architecture. By way of explanation, in the labels K1 refers to clutch 1 related components and K2 to clutch 2 related components, while the clutch plates are labelled ‘clutch disc’ and the drive plate is labelled ‘central plate’.

61 Because humans do not have three legs, it is generally not feasible for a dual clutch transmission to be operated by the driver. In the DPS6 the control of the two clutches is given over to a computer located on the transmission control module (‘TCM’). When the transmission is in one gear it works out what the next gear change will be and selects that gear whilst the relevant input shaft is not connected to the engine (via the drive plate–clutch plate system). The next change of gear therefore avoids any delay whilst the new gear is selected and correspondingly there is no need for an interruption in the delivery of power whilst the transmission is disengaged from the drive plate (as occurs in a manual when the clutch is disengaged in order to allow the driver to physically shift into the next gear with the gearstick). A change of gear in the DPS6 therefore only requires a switch of power between the input shafts, brought about by disengaging one clutch plate while simultaneously engaging the other clutch plate with the corresponding side of the drive plate.

62 With that brief discussion in mind, the following concepts are relevant to this litigation:

(a) Clutch lining. The surfaces of both sides of each clutch plate and the drive plate, along with the surfaces of the pressure plate that face the clutch plate are lined with the clutch lining material. The frictional qualities of the clutch lining are, as I have already said, central to the operation of the transmission. The TCM knows what these qualities are and they are factored into the procedures it uses for changing gears. Unpredictable variations in the frictional qualities of the clutch lining disrupt the process of gear shifts in ways which are themselves unpredictable. The frictional qualities of the clutch lining are also affected by heat, that is to say, some clutch lining materials behave differently (and unpredictably) the hotter the transmission is. This clutch lining is also referred to interchangeably in the evidence as clutch material or friction material.

(b) Clutch slip. When the clutch plate and the drive plate are fully engaged with each other they are pressed together in a state of static friction and rotate as one so that power passes from the engine through them to the gears and then on to the wheels. When they are being introduced to each other, on the other hand, they move at different speeds until they are brought to the same speed. The initial difference in their rotational speeds reflects the fact that after launch the drive plate will be rotating at a rotational speed related to the rotational speed of the crankshaft (with the influence of the flywheel in between) whereas the clutch plate will not be rotating at all. As they are gradually introduced to each other by increasing the pressure exerted on the clutch plate side (by a spring loaded pressure plate) the clutch plate begins to rotate sympathetically with the drive plate until, ultimately, it is rotating at the same speed. Whilst in the transition from not rotating at all (in a state of full disengagement before launch) to rotating at the same speed as the drive plate, the clutch is said to be in slip phase which reflects the fact that the plates are rotating at different speeds and therefore necessarily in a state of kinetic friction. Although this sounds complex, for persons who can drive a manual vehicle the ideas will be familiar. In particular, in a manual vehicle the slip phase corresponds to the skill involved in re-engaging the clutch by lifting your foot off the clutch pedal following a gear change. Clutch slip is used during gear changes but it may also be used as a form of braking. For example, the practice of ‘riding the clutch’ in a manual vehicle when on a slope so as to keep the vehicle stationary involves keeping the clutch in a constant state of clutch slip. This practice is generally regarded as unsound in a manual vehicle as it wears out the clutch lining and generates heat. One of the issues in this case concerns the programming of the TCM to use clutch slip as a method for damping torsional vibrations. This brings one to torsional vibrations:

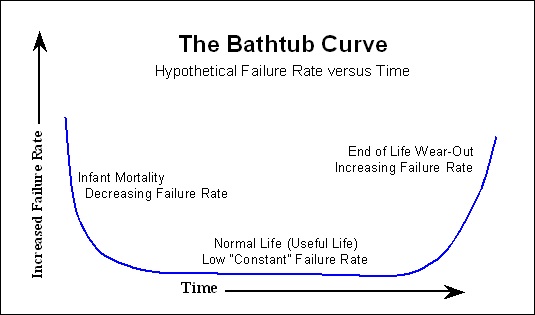

(c) Torsional vibrations. The pistons in an internal combustion engine are attached to the crankshaft. Because they fire at different times this means that the crankshaft accelerates as each piston fires and then begins to decelerate as the explosion finishes and continues to drop off until the next piston fires. Although it is usual to say that the crankshaft is rotating at a particular rate of revolutions per minute (rpm) this is in fact an incomplete description of what is occurring. In reality, the rotational speed of the crankshaft is not constant but oscillates at a high frequency related to the rate at which the pistons are firing. The intermittent nature of the piston firing also means that the turning force (or torque) output by the crankshaft also fluctuates. Torsional vibrations are a product of the fluctuations in both the speed and torque of the crankshaft. In an internal combustion engine they are a fact of life but can have negative consequences. For example, the presence of a vibrational oscillation in a vehicle may have unwelcome consequences if the frequency of the oscillation coincides with a harmonic frequency of any other component in the vehicle. When this occurs other components of the vehicle may begin to rattle. Consequently, at some point some effort must be made to damp the torsional vibrations produced by the engine. There are several ways of doing so. In the DPS6 the TCM was programmed to soak up the torsional vibrations by using clutch slip and also with the use of ‘torsional springs’ known as inner dampers which were located within the clutch plates. Other ways exist too, for example, by placing a flywheel on the crankshaft equipped with dampers. All of these solutions have strengths and weaknesses. A flywheel with torsional dampers will reduce torsional vibrations. But nothing is for free. Such a flywheel is heavy and can affect the vehicle’s fuel consumption. Further, the same phenomenon which soaks up the torsional vibrations also guarantees that more engine power is needed to drive the crankshaft. This corresponds with a reduced responsiveness in the vehicle to applications of power (and an overall reduction in power).

(d) The TCM. The TCM is a computer consisting of several integrated circuits soldered to a printed circuit board and is bolted onto the transmission housing (which is also referred to as the bell housing). As such it is exposed to the heat generated by the transmission. The temperature the DPS6 operates at depends, inter alia, on the amount of heat generated through the friction involved in clutch slip. This fluctuates with the manner and frequency of gear changes. A vehicle with a lot of gears will have more frequent gear changes and is likely to run hotter. The picture then is one of fluctuations in temperature. The integrated circuits and the printed circuit board expand and contract when heated and cooled. For the reasons just given, this occurs very frequently in a dual clutch transmission. If they expand and contract at different rates, this will expose the solder to mechanical strain and may cause cracking in the solder over time. Cracking in the solder in turn may cause electrical conductivity issues which may cause the TCM to behave erratically. This problem does not occur if the printed circuit board and the integrated circuits soldered to it have the same coefficient of thermal expansion, as the expansion and contraction would then occur at identical rates.

(e) Input shaft seals. The DPS6 is a dry dual clutch transmission. In general, dual clutch transmissions may be wet or dry. A wet transmission is one in which the clutch plates are bathed in a liquid. The purpose of the liquid is to remove heat from the transmission. A dry dual clutch assembly is one in which the clutch and drive plates are not so bathed but are instead cooled by the surrounding air in the bell housing, with the rotating clutch plates acting as fans. One advantage of a dry clutch is that it is lighter and the clutch plates experience less resistance when rotating (which improves fuel efficiency). A disadvantage is that air cooling is not as efficient as liquid cooling due to the higher heat capacity of liquids. In a dry clutch transmission the desired frictional properties of the clutch lining are premised on the clutch lining remaining dry. How is this achieved? The input shaft to which the clutch is connected is exposed in the gearbox to lubricants. It is important for the operation of the clutches that these lubricants do not find their way onto the surface of the clutch lining. The clutch plates and drive plate faces must therefore be sealed from the gearbox. This is achieved by means of seals. Relevantly there are two seals, both known as input shaft seals, which serve this purpose (one for the inner input shaft and one for the outer input shaft). If the input shaft seals fail then lubricants may find their way onto the clutch lining. The presence of fluid on the clutch lining affects the frictional qualities of the clutch lining and may cause the clutches to behave in unpredictable ways.

(f) Rear main oil seal. The problem just described exists on both sides of the transmission. Just as the clutch lining must be kept free of contamination from lubricants coming from the gearbox side so too must it be protected from oil contamination coming from the engine side. The purpose of the rear main oil seal is to provide that protection at the point where the crankshaft exits the engine and enters the transmission environment.

(g) Heat management. When a clutch is in its slip phase, the kinetic friction involved generates heat. Heat may affect the frictional qualities of the clutch lining. The clutch lining must be such as to perform predictably in the heat environment in which it finds itself. Where the clutch lining is not sufficient in a given temperature environment there are two possible solutions. Either the clutch lining material may be changed so that it can operate predictably in the actual heat environment of the transmission or additional cooling measures may be introduced into the transmission. For example, one might change to a wet clutch configuration or, perhaps, increase the air flow throughout the transmission by some means (like a fan).

(h) Wet clutch shudder. The term ‘shudder’ was used in a somewhat amorphous manner in this litigation to describe undesirable vehicle behaviour that is caused by a number of distinct problems. Wet clutch shudder is that subset of shudder which is the result of lubricating fluid contaminating the clutch lining and causing it to behave unpredictably.

(i) Dry clutch shudder. In distinction to wet clutch shudder, dry clutch shudder refers to that shudder emanating from the errant behaviour of clutch plates that have not been contaminated with fluid. Within this genus, ‘self-excited shudder’ is that which is linked to the inherent frictional properties of the clutch lining material, while ‘forced-excited shudder’ is the result of geometric variability in the clutch components.

Ms Capic

63 Ms Capic gave her evidence in chief by means of three affidavits dated 7 June 2018, 22 November 2019 and 5 May 2020. She was cross-examined on Thursday 18 June 2020 and Friday 19 June 2020 which were the 4th and 5th days of the trial. The cross-examination appears at T222-330.

64 The principal issue about her credit turned on some evidence she gave in relation to the financing of her vehicle. It is therefore necessary to understand that financing before that evidence can be assessed.

65 Ms Capic currently works for herself as a business consultant providing, inter alia, payroll management and bookkeeping services. At the time she gave her evidence she was 35 years old. On 24 December 2012 Ms Capic purchased a 2012 Ford Focus LW MKII Sport 2.0L from Sterling Ford who traded from Bundoora in Victoria. It was a 5 door hatchback and its colour was frozen white. In addition, Ms Capic also paid for tinted windows and some carpet mats. On top of these costs there were some on-road costs. The purchase costs for the vehicle were as follows:

Vehicle | $25,627.27 |

Carpet mats – 3pcs | $65.00 |

Window tint | $200.00 |

Discount: | -$2,890.91 |

Dealer delivery | $1,540.91 |

Total: | $24,542.27 |

GST: | $2,454.23 |

66 In addition there were the following on-road expenses:

Registration fee | $232.30 |

Compulsory third party | $464.20 |

Slimline Plate Fee | $92.00 |

Stamp Duty | $810.00 |

Total: | $1,598.50 |

67 Thus Ms Capic was required to pay the following amounts on the acquisition of the vehicle:

Car purchase costs | $24,542.27 |

GST | $2,454.23 |

On-road costs | $1,598.50 |

Total: | $28,595.00 |

68 On the same day, Ms Capic entered into a ‘novated finance lease’ with BMW Australia Finance Ltd (‘BMW Finance’) under which an amount of $27,930.27 was financed. A copy of the terms of this lease is not available but the evidence does include an amortisation schedule and it corroborates Ms Capic’s evidence that the lease was a novated finance lease. There was no direct evidence about this but I propose to assume that a novated finance lease is a hire purchase arrangement where an employer (a) agrees to meet the rental payments due under a hire purchase arrangement in relation to a motor vehicle provided to an employee; but (b) is not obliged to make the residual payment at the end. Ms Capic gave evidence that at the time of this first lease she was employed by IN-Fusion Management Pty Ltd and that it was a term of her employment agreement that she would be provided with a car. A copy of that agreement was not in evidence but Ms Capic says that she entered into a fresh employment contract with IN-Fusion Management Pty Ltd on 1 June 2014 in which there was a similar term. That agreement is available. One of its provisions is as follows:

In addition to your remuneration, you are also provided with a fully maintained motor vehicle which will operate under a personal novated lease. IN-Fusion Management will be responsible for meeting all lease payments on your behalf whilst you are an employee of the business and; be responsible for the costs associated with running and maintaining the vehicle accordingly, for example, Fuel, Registration, Insurance, Servicing, Tolls and Repairs.

69 In this case, one can discern from the amortisation schedule which was put in evidence that the lease had a four year term with monthly payments of $586.09 (including GST). There was a residual payment of $12,839.20 (including GST) due at the end of the fourth year on 24 December 2016. There is a gap of $664.73 between the total purchase price due to Sterling Ford of $28,595.00 and the amount provided by BMW Finance of $27,930.27. I am unable to account for this anomaly.

70 In August 2016 Ms Capic’s employer IN-Fusion Management Pty Ltd went into administration. In the period between 24 August 2016 and 25 October 2016 it appears to have continued to have been debited for the payments under the lease but on each occasion the payments were dishonoured. Ms Capic says, and I accept, that IN-Fusion (or perhaps what had been its business) was eventually purchased by a new entity, Interstate Enterprises Pty Ltd which traded as ‘Tecside Group’. Tecside employed Ms Capic under an employment contract dated 16 September 2016. It contained this term:

At the time of writing this offer, Tecside will continue with the current arrangements in relation to your novated lease. We will, however, reserve the right to incorporate the lease into your salary as a salary sacrifice arrangement. This will not impact your current net salary.

71 This was apt to pick up the former arrangement with IN-Fusion. A document entitled ‘BMW Group Financial Services – Transaction Inquiry’ printed on 17 September 2019 contains a complete history of the amounts due and payments made under the BMW Finance lease. It records that a single payment of $1765.77 was made on 14 December 2016 which was the amount by which the lease with BMW Finance had by then fallen into arrears. I infer that this payment was made by Tecside. This was, however, the only payment ever made by Tecside because on 24 December 2016 the BMW Finance lease expired under its own terms. Tecside’s obligations to Ms Capic were only to meet the rental payments and it was not obliged to, and did not, pay the residual amount then due. The residual was $12,839.20.

72 Ms Capic did not pay the residual either, at least not at that time. BMW Finance’s Transaction Inquiry document records that it corresponded with Ms Capic on 11 January 2017, 20 January 2017 and 28 February 2017 and I infer that is likely to have been in relation to her obligation to pay the residual.

73 One may infer that if unattended for a sufficiently long period of time it is possible that BMW Finance might have repossessed Ms Capic’s vehicle under the terms of the finance lease. In any event, by May 2017 it is clear that steps were underway designed to secure a new finance lease in the amount of the outstanding residual due under the BMW Finance lease. Ms Capic’s evidence in her affidavit of 7 June 2018 was that she thought that it was Tecside’s obligation to secure a new finance lease: §30. She says that on 22 March 2017 she signed an invoice for the sale of her vehicle. Whilst this is correct it is not an entirely complete statement. She was also the person to whom the vehicle on sale was to be supplied to. The sale price was for the amount of the residual payment of $12,839.20. Ms Capic is recorded therefore both as the vendor and as the person to whom the vehicle was to be delivered.

74 However, I am satisfied that no such transaction occurred on 22 March 2017. As I shortly explain, Ms Capic did not obtain finance until 29 May 2017 and I do not think Ms Capic could, or at least would, have paid out the first lease until the second lease was entered into. A more likely explanation for the date of this document is that it is a document which was, for some reason, thought necessary to facilitate the second lease.

75 That second lease was procured, and in fact probably advanced, by Ms Capic’s finance broker, Mr Crea. According to her evidence, he had been in touch with her and had impressed upon her the need quickly to refinance the amount due to BMW Finance. Under cross-examination she said that it was Mr Crea’s company Melbourne Finance Broking Pty Ltd which had refinanced the residual. Certainly the lease that began 29 May 2017 suggests that the lessor was Melbourne Finance Broking Pty Ltd as trustee for the Melbourne Finance Broking Unit Trust. Puzzlingly, however, subsequent demands for payment appear to have come from Macquarie Leasing Pty Ltd (‘Macquarie Leasing’) but it was not a party to the second finance lease. A letter from Macquarie Leasing dated 11 November 2019 seems to record a payment having been received on 30 May 2017. Furthermore, another letter from Macquarie Leasing dated 13 November 2019 appears to be, at first glance, a record that the first monthly payment of $368.18 had been made by Ms Capic to Macquarie Leasing on 29 May 2017. That might suggest that Macquarie Leasing has been the lessor on that day which is the same date as the lease with Melbourne Finance Broking. However, closer examination does not bear this out. The document is in fact merely an amortisation schedule and bears an annotation ‘This is not a payment history or statement of account and therefore does not reflect actual payment activity on your contract’. It would be unsafe to rely on this document to infer that Macquarie Leasing was first paid on 29 May 2017.

76 At T261.16 Ms Capic gave evidence that she thought, based on the documents, that Melbourne Finance Broking had paid out the first lease but that subsequently a new lease had been entered into. I do not think Ms Capic was purporting to give this evidence as an explicit exercise in recollection; rather, it was an attempt to explain why Melbourne Finance Broking appeared to have been the lessor on 29 May 2017.

77 There is clearly a missing piece in the evidence. There are only two available explanations. Either Melbourne Finance Broking novated the second lease to Macquarie Leasing or a fresh, third, lease was entered into with Macquarie Leasing which was used to refinance the second lease with Melbourne Finance Broking. Ms Capic’s reconstruction of events is consistent with the latter but I do not think her speculation is especially probative. As will be seen, it is not necessary to resolve this issue, although I would express a preference for the novation theory were it necessary – it seems more consistent with the absence of any evidence of a third lease. What is important, however, is that on either view, Melbourne Finance Broking was to be the lessor on 26 May 2017 and this means that it (and Mr Crea) were acting in that capacity on that day.

78 The second lease was a 3 year finance lease requiring the payment of 36 instalments of $386.18. Shortly after the second finance lease was executed (on 26 May 2017) Ms Capic was made redundant by Tecside. This occurred in June 2017. Tecside agreed however to continue to meet the lease payments under the second lease until 30 November 2017. I infer that it made no payments after that date. Consistently with the drawing of that inference, Macquarie Leasing wrote to Ms Capic on 29 January 2018 pointing out her account had fallen into arrears. This letter confirms that at least by then the lessor was no longer Melbourne Finance Broking although it does not explain how that came to be.

79 Ms Capic then began meeting the lease payments herself. The second (novated) or perhaps third (new) lease was due to expire on 29 May 2020 at which time she was bound to make a residual payment of $6,355.40. A few weeks before that day dawned, Ms Capic had already affirmed at §20(a) in her affidavit of 5 May 2020 that she felt financially trapped by her finance lease. She also said that between the date of that affidavit and 29 May 2020 (a period of only 24 days) she would shortly have to meet the residual payment and the then single remaining monthly instalment under the second (or perhaps third) lease. At trial she confirmed that she had in fact made these payments: T247.20.

80 It is then useful to turn to the credit attack which the Respondent launched across this somewhat dry ground. It submitted that Ms Capic had given evidence about her entry into the second finance lease which was not to her credit. The submission went this way: on 26 May 2017, her finance broker had sent her documents to be executed for the second lease and she had completed these. One of the documents was the lease itself which she signed. The document contained a section under which Ms Capic was asked to give a number of acknowledgements and warranties. Clause 3 was as follows:

Except for any defects disclosed in Item 4 of Schedule 1, the Goods are of merchantable quality and free from defect.

81 But no defect had been notified in the schedule. This was submitted to be surprising because Ms Capic had by then commenced this proceeding (on 17 May 2016) just over a year before. In the proceeding she already had alleged, at §19 of her original Statement of Claim, that her vehicle suffered from a number of identified problems and was not of acceptable quality within the meaning of ACL s 54. She found herself in the position therefore of having alleged in this class action that the vehicle was defective but having afterwards warranted to Melbourne Finance Broking that the vehicle was of merchantable quality and free from defect. This involves a potential inconsistency.

82 Ms Capic was extensively cross-examined about the inconsistency at T257-258 and her evidence was ultimately that she had in fact verbally told her broker, Mr Crea, about the defects. She was also criticised for not mentioning the fact that she had done so in any of her affidavits. Whilst I do not think Ms Capic is to be criticised for not mentioning the matter in her affidavits, I do not accept her evidence that she told Mr Crea of the problems with the vehicle for two reasons. First, Ms Capic had an incentive not to tell Mr Crea about the difficulties with the vehicle. Secondly, it seems doubtful had Mr Crea been informed of the problems with the vehicle as Ms Capic then perceived them that he would have extended the finance to her.

83 As to her failure to include her discussion with Mr Crea in any of her affidavits: I do not think this especially remarkable. Whether Ms Capic told Mr Crea about the vehicle’s problems does not relate to any issue in her case in chief. It was not raised in any of the Respondent’s evidence. It only finally became relevant once the Respondent decided to make a credit issue out of it during the cross-examination.

84 As to her motive not to tell Mr Crea about the problems with the vehicle: by 26 May 2017 Ms Capic was in need of finance. The residual under the BMW Finance lease had been due for many months and BMW Finance had written to her several times after the lease had expired. It is reasonable to infer that at some point BMW Finance would have looked to its rights. By 26 May 2017, Ms Capic had been in default for 5 months by not paying the residual. She may have been right that it was Tecside’s responsibility to organise another lease (I offer no view on that question) but, at the end of the day, if BMW Finance repossessed the vehicle after the non-payment of the residual, it was in a real sense, her problem. I think it fair to infer in that circumstance that she had a real motive to organise the second lease and that this need had become more pressing by 26 May 2017.

85 Furthermore, by May 2017 Ms Capic’s perception of her vehicle was negative. The car was serviced on 30 May 2017 very shortly after the date she signed the second lease. Her evidence in her affidavit of 7 June 2018 was that she had told the Ford dealer when it was serviced on that day that the vehicle was displaying the usual problems, ie shuddering, not enough power, vibration and an inability to take off. On this occasion the dealer replaced the clutch and input shaft seals. In her affidavit of 5 May 2020, she said at §20(b) that she could not in good conscience sell the car to another person. She had earlier stated this in her affidavit of 7 June 2018 at §153. Irrespective of the mechanical realities of Ms Capic’s vehicle, there seems little doubt that she was subjectively deeply dissatisfied with it. One does not, after all, start a class action on a whim. I infer that as at the time Ms Capic entered into the second lease on 26 May 2017, she thought her vehicle was something she could not in good conscience sell to another person. Although her evidence to that effect was only forthcoming in her 7 June 2018 affidavit, I do not think that at this point this was a revelation at which she had only recently arrived. It seems to me that it is likely to have been her view since at least the commencement of the class action.

86 Ms Capic found herself in the position on 26 May 2017 of needing the finance to avoid difficulties with BMW Finance but being the owner of a vehicle about which she had grave doubts. Revelation of the problems her vehicle presented to Mr Crea might well have led, in Ms Capic’s perception, to Melbourne Finance Broking refusing to refinance the residual. And, for the reasons I have already given, the situation by May 2017 was such that Ms Capic had been in default with BMW Finance for some months. These two factors gave Ms Capic incentives not to tell Mr Crea about the difficulties with the vehicle. I do not disregard the fact that Ms Capic denied that she had kept the matter from Mr Crea in order to ensure that the finance would be forthcoming, saying at T263.4 under cross-examination that she had not thought of that ‘until you [ie, the cross-examiner] just mentioned that now’. I accept that it is unlikely she set out deliberately to keep this from Mr Crea. A more likely scenario is that the two incentives lingered at the fringe of her conscious mind and merely edged her towards non-disclosure without her ever forming a complete thought that she would not disclose.

87 As to the unlikelihood of Mr Crea extending finance if informed of the problems with the vehicle: Ms Capic was seeking to refinance the residual under the BMW Finance lease. This was an amount of $12,839.20. Although some care should be exercised in assuming that this figure represented the depreciated value of Ms Capic’s vehicle by 26 May 2017 (the rates of depreciation set for tax purposes are usually higher than actual depreciation rates so as to encourage the replacement of equipment and hence economic growth) nevertheless it is a useful benchmark by which to gauge the value of the car even if only in a rough way. It is sufficient, for example, to conclude that for the amount being borrowed the loan to value ratio would have been reasonably high and hence the quality of the security was important. The revelation to Mr Crea that the vehicle was beset with the difficulties about which Ms Capic was complaining in 2017 would have affected the potential realisable value of the only security she was offering. It is difficult to see that it would have been in the interests of Mr Crea to extend the finance without knowing quite a bit more about what the difficulties were. Since Melbourne Finance Broking was the initial lender under the second lease this was not just a problem which could be waved through to some unfortunate third-party financier. Just as BMW Finance was Ms Capic’s real problem, so too it would have been Mr Crea’s real problem if he had lent against the vehicle’s capital value knowing, as on this hypothesis he would have, that it suffered from multiple problems and knowing, as he would have, that Ms Capic was in default under the BMW Finance lease. It is possible Mr Crea might have proceeded despite these problems, but it strikes me as unlikely.

88 These matters lead me to conclude that Ms Capic did not tell Mr Crea about the difficulties with her vehicle. Her evidence at trial that she did was therefore false.

89 It is difficult to think that this episode was to her credit although, in fairness to her, it is tolerably clear what happened. The fact that the defects had not been disclosed by her was a fact that she understandably felt embarrassed about and she was keen, I think, to come across – as she believes herself to be – as an honest person. The irony of the situation is that I do not think that her failure to disclose the defects in the financing documents reflected any deliberate dishonesty on her part. I accept that she most likely signed the lease without appreciating the significance of the warranty as many people would. In her efforts to appear honest on this issue regrettably Ms Capic was not telling the truth. The situation she found herself in during cross-examination was a difficult one and Mr Scerri QC’s cross-examination of her was searching and stern. It must have been a stressful occasion for her and this incident is, in some sense, unfortunate since it was unnecessary. The cross-examination persisted on the issue for several pages. Ultimately Ms Capic tried to say at T262.39-40 that she thought that the word ‘defect’ ‘meant something where it’s physically broken or, you know, can’t turn the car on or something along those lines….’. This answer did not strike me as very plausible. My impression was that by this stage of questioning Ms Capic was quite distressed and was, in some ways, flailing around.

90 I think I am bound to accept the Respondent’s submission that the cross-examination showed that Ms Capic, when presented with evidence which was not helpful to her case, would provide answers designed to advance her case. Ultimately the Respondent submitted that Ms Capic was ‘a generally honest although unreliable witness’. I accept this submission. Her evidence about what she told Mr Crea does not persuade me that Ms Capic is at the core of matters a dishonest person but it does persuade me that when pushed into a corner in the witness box her answers might not always be reliable.

91 There is also some reason to think that Ms Capic, at least in relation to the topic of her car about which she clearly feels strongly may, on occasion be carried along towards some overstatement. This is not an uncommon human trait and I think it reflects her passion for the cause rather than any underlying desire to deceive. A similar problem besets recreational fishers.

92 The Respondent instanced a number of examples of this. The first concerned Ms Capic’s account of an incident she experienced on 3 February 2016. She said that she had been driving on the Eastlink Freeway when her vehicle lost power and rapidly decelerated from 80 km/h to 20 km/h in ‘three to five seconds’. Under cross-examination she stated it was ‘a few seconds’ before clarifying that by this she meant approximately three to five seconds. The Respondent made two submissions about this evidence. The first was that it was implausible that the vehicle would have decelerated at such a rate. Ms Capic’s counsel submitted that there was no evidence to support such a proposition. I was initially attracted to that observation but upon reflection I have changed my mind about it. There is no doubt that an incident did occur on 3 February 2016 and, as I explain elsewhere, that the incident was most likely caused by the TCM solder issue. However, whilst there is evidence that the TCM solder issue sometimes resulted in sudden power losses there is no evidence that it resulted in powerful braking action. A reduction in speed from 80 km/h to 20 km/h in 3-5 seconds is not a circumstance which could result from a power loss but would appear to require the presence of braking action. Accepting that braking action in a car with gears and a clutch can be achieved by dropping gears there is no evidence that the TCM solder issue caused such a symptom and there is also no reason to think that it affected the braking system itself. I therefore do not think that it is possible that Ms Capic’s car decelerated on 3 February 2016 from 80 km/h to 20 km/h in 3-5 seconds as she initially affirmed in her affidavit.

93 I am fortified in that conclusion because it is Ms Capic’s own evidence that the vehicle lost power during the incident which shows that she was not trying to say that the vehicle suddenly decided to apply the brakes or to brake by unexpectedly shifting down gears. Put another way, I accept Ms Capic’s evidence that there was a power loss but I do not accept her initial evidence that this resulted in the rate of deceleration which she claimed.

94 There is therefore something in the Respondent’s submission that her evidence about this involved some exaggeration.