Federal Court of Australia

Taylor v Killer Queen, LLC (No 2) [2021] FCA 680

File number(s): | NSD 1774 of 2019 |

Judgment of: | CHEESEMAN J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – application for discovery of documents – objection to production of documents on the basis of legal advice privilege and litigation privilege – Alternatively object to production of documents on the basis of statutory privilege of patent and trade mark attorney advice privilege – whether the Respondents have waived privilege by either express or implied waiver – Held : all documents save for those over which waiver has been conceded are privileged by reason of advice or litigation privilege and / or trade mark attorney advice privilege |

Legislation: | Patents Act 1990 (Cth), s 200 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), s 229 |

Cases cited: | Archer Capital 4A Pty Ltd as trustee for the Archer Capital Trust 4A v Sage Group plc (No 2) [2013] FCA 1098 Cantor v Audi Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1391 Col Crawford Pty Ltd v Nissan Motor Co (Australia) Pty Ltd [2020] NSWSC 87 Commissioner of Australian Federal Police v Propend Finance Pty Ltd [1997] HCA 3; (1997) 188 CLR 501 Commissioner of Taxation v Rio Tinto Ltd [2006] FCAFC 86; (2006) 151 FCR 341 Council of the NSW Bar Association v Archer [2008] NSWCA 164; (2008) 72 NSWLR 236 DSE (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Intertan Inc [2003] FCA 384; (2003) 127 FCR 499 Eli Lily and Company v Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals (No 2) [2004] FCA 850; (2004) 137 FCR 573 Esso Australia Resources Limited v Commissioner of Taxation [1999] HCA 67; (1999) 201 CLR 49 Ferella v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy [2010] FCA 766; (2010) 188 FCR 68 Grant v Downs [1976] HCA 63; (1976) 135 CLR 674 GR Capital Group Pty Ltd v Xinfeng Australia International Investment Pty Ltd [2020] NSWCA 266 Hastie Group Ltd (in liq) v Moore [2016] NSWCA 305 Kennedy v Wallace [2004] FCAFC 337; (2004) 142 FCR 185 Kenquist Nominees Pty Ltd v Campbell (No 5) [2018] FCA 853 Macquarie Bank Limited v Arup Pty Limited [2016] FCAFC 117 Mann v Carnell [1999] HCA 66; (1999) 201 CLR 1 New South Wales v Betfair Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 160; (2009) 180 FCR 543 Osland v Secretary to the Department of Justice [2008] HCA 37; (2008) 234 CLR 275 Wheeler v Le Marchant [1881] 17 Ch D 675 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Trade Marks |

Number of paragraphs: | 59 |

Date of last submissions: | 7 May 2021 |

Date of hearing: | 11 May 2021 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | R Cobden SC with R Clark |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Silberstein & Associates |

Counsel for the Respondents: | M J Darke SC with E Bathurst |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Corrs Chambers Westgarth |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Applicant’s Interlocutory Application filed on 15 April 2021 is dismissed.

2. Subject to Order 3, the Applicant pay the Respondents’ costs of the Interlocutory Application filed 15 April 2021.

3. The parties are granted leave to apply for a different costs order to that in Order 2 by filing submissions (of no more than 3 pages) in support of the costs order they seek within 7 days of these orders, in which event any party opposing such different costs order is to file submissions (of no more than 3 pages) in support of such opposition within 7 days thereafter.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHEESEMAN J:

1 By interlocutory application filed on 15 April 2021 the Applicant and Cross-Respondent (Applicant) seeks orders that certain documents discovered by the Respondents and Cross-Claimants (Respondents) over which privilege is claimed be produced to the Applicant. The Applicant challenges the claims for privilege over the documents and contends that, if the documents are privileged, the Respondents have waived privilege. The Applicant asserts that privilege has been waived by express waiver or by implied, or issue, waiver.

2 The Respondents resist an order requiring them to produce the discovered documents on the basis that discovery of the documents would reveal communications which are subject to privilege in circumstances where privilege has not been waived. The Respondents rely on advice privilege and litigation privilege at common law and on the statutory privilege of patent and trade mark attorney advice privilege (TMAP).

3 The Applicant tendered a bundle of documents. The Respondents read the affidavit of their solicitor, Odette Gourley, sworn 23 April 2021 and tendered exhibit OMG-1, which was subject to orders in respect of confidentiality. An annexure to Ms Gourley’s affidavit was an affidavit of Mr Steven Jensen of 30 July 2020. Mr Jensen’s affidavit was tendered in evidence on the Interlocutory Application without prejudice to any objections that may be taken in the substantive proceedings.

4 The Respondents provided the Court with a confidential bundle of the documents which are the subject of the dispute. The parties agreed that the Court, constituted by a judge other than the docket judge, may inspect the documents for the purposes of determining the Interlocutory Application.

Background

The Substantive Proceedings

5 The Applicant, Ms Taylor, is a clothing designer who has traded clothing under the trade mark KATIE PERRY in Australia since about November 2006. She owns Australian Registered Trade Mark 1264761 for the word KATIE PERRY in class 25 for “clothes”, with the priority date of 29 September 2008 (the Applicant’s Mark).

6 The Second Respondent, Ms Hudson, is a recording artist/performer who, at some point before approximately 2007, adopted the name “Katy Perry” for the purposes of her professional musical career and associated commercial merchandise licensing activities. The date from which, and the extent to which, the Second Respondent has a reputation under her performing name in Australia is in issue. The First, Third and Fourth Respondents are United States companies associated with the Second Respondent’s interests.

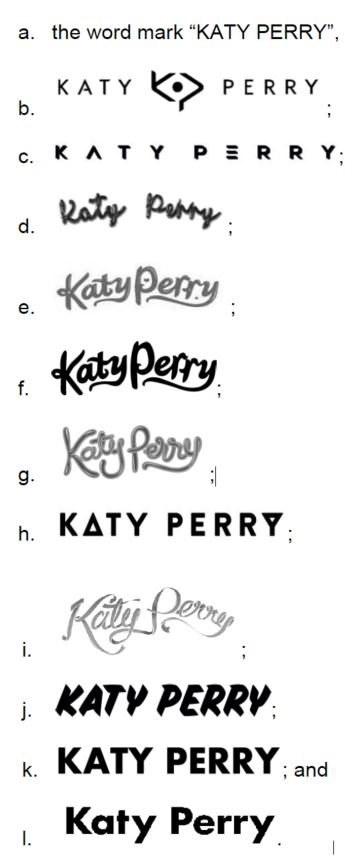

7 In broad terms, the Applicant sues the Second Respondent and the corporate respondents in proceedings commenced on 24 October 2019 for infringement of the Applicant’s Mark pursuant to ss 120(1) and (2) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Trade Marks Act). The Applicant seeks either an account of profits or damages together with additional damages pursuant to ss 126(1)(b) and 126(2) of the Trade Marks Act. The Applicant alleges that the Respondents have imported for sale, distributed, advertised, promoted, marketed for sale, supplied, sold and/or manufactured in Australia, or to people in Australia, clothes bearing the following marks:

Further and in the alternative the Applicant alleges that the Respondents acted with a common design to carry out those acts.

8 The Respondents raise various defences and also cross-claim for the removal of the Applicant’s Mark. In response to the whole claim the Respondents allege that the Applicant is disentitled to the relief she seeks by one or more of delay, laches, acquiescence and/or the Court’s discretion to refuse equitable relief on the basis that at all material times, the Respondents’ impugned use was undertaken with the Applicant’s knowledge, and in the period from 2009 onwards, with the Applicant’s encouragement.

9 The proceedings are listed for final hearing, on liability alone, before Justice Markovic commencing on 29 November 2021.

The 2009 Trade Mark dispute

10 The circumstances surrounding the registration of the Applicant’s Mark in 2009 are relevant to the privilege dispute. The documents the subject of the dispute date from this period, 8 May to 21 July 2009.

11 On 8 May 2009, prior to the Applicant’s Mark being registered but after the close of the legislative window within which third parties may oppose registration, an application for an extension of time to file a notice of opposition and a proposed notice of opposition to the mark were filed in the Second Respondent’s name supported by a statutory declaration of Paul Thompson, registered Australian patent and trade mark attorney, Fisher Adams Kelly (FAK). The Respondents concede that Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration expressly waived privilege over a limited number of documents, in whole or in part. The Applicant contends that Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration is an express waiver in respect of further documents over which the Respondents maintain their claim for privilege.

12 Following the lodgement of the Second Respondent’s extension of time application there were exchanges of correspondence between the Applicant or her legal representatives, on the one hand, and FAK and Holding Redlich (HR), Australian lawyers acting on behalf of the Second Respondent, on the other hand. In the course of that correspondence, in June 2009 in a YouTube video post, the Applicant communicated to the Second Respondent: “I wish you all the success but leave me to carry on my dream” and “I’m absolutely no threat whatsoever to you”. The parties exchanged but did not execute various draft settlement deeds regarding their dispute. In July 2009 in a blog post, the Applicant expressed a wish for a positive end to her dispute with the Second Respondent with a view to the Second Respondent visiting the Applicant’s studio in Australia. Ultimately, on 16 July 2009, the Second Respondent withdrew her extension of time application prior to it being heard. No settlement occurred. The Applicant’s Mark was registered on 21 July 2009.

13 In the interim on 26 June 2009, an Australian trade mark application was filed for KATY PERRY in various classes including apparel, naming the Second Respondent as the owner of the mark. Subsequently, the Applicant’s Mark was cited as a barrier to registration. The apparel class was removed from the Second Respondent’s application and her mark was registered: Australian Trade Mark No 1306481 (the Second Respondent’s Mark).

14 In May 2013, the Applicant was interviewed on radio in Sydney. The Respondents allege that in this interview the Applicant acknowledged that she was aware of the Second Respondent and that members of the public were confused as to an association between her and the Second Respondent and that this was commercially beneficial to her.

15 The Applicant commenced the substantive proceedings in October 2019.

The Privilege Dispute

Overview

16 The threshold issue is whether privilege subsists in the documents over which privilege is claimed. The Respondents have the onus on this issue: Grant v Downs [1976] HCA 63; (1976) 135 CLR 674 at 689. The dispute is concerned with pre-trial disclosure and inspection rather than the adducing of evidence and is to be determined according to common law principles rather than the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth): Esso Australia Resources Limited v Commissioner of Taxation [1999] HCA 67; (1999) 201 CLR 49 at 9 [17] – 13 [28] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ); at 23 [64] (McHugh J). Common law principles apply either directly because the communications relevantly involve Australian or foreign lawyers or by reason of s 229 of the Trade Marks Act and s 200 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Patents Act) (together, the Statutory Privilege Provisions) which, subject to their terms, extend common law privilege to communications which relevantly involve registered Australian patent / trade mark attorneys.

17 The second issue is whether such privilege, as existed, has been waived. The Applicant has the onus in establishing waiver: New South Wales v Betfair Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 160; (2009) 180 FCR 543 at 556 [54]; Archer Capital 4A Pty Ltd as trustee for the Archer Capital Trust 4A v Sage Group plc (No 2) [2013] FCA 1098 at [100]. The Applicant relies on allegations of express waiver and of implied, or issue, waiver.

Preliminary Issue as to Applicable Legislation

18 The Respondents rely on the common law as supplemented by the Statutory Privilege Provisions which substantially mirror each other. While the provisions have been subject to significant amendment over time, they have evolved in tandem so as to continue to substantially mirror each other. The effect of the Statutory Privilege Provisions is to create TMAP, a privilege which did not exist at common law. The privilege in relation to trade mark issues is conferred under both the Trade Marks Act and the Patents Act.

19 There was a divergence between the parties in relation to the version of the legislation which applied to the privilege claims the subject of the present application. The Applicant contended that the applicable legislation was that which was in force as at May to July 2009, the time at which the documents the subject of the privilege claims came into existence. The Respondents contended that the applicable legislation was that currently in force, the date at which the privilege was asserted and fell to be determined.

20 The Statutory Privilege Provisions have undergone significant amendment in the period between 2009 and 2021. Notwithstanding the difference in the parties’ positions as to the version of the Statutory Privilege Provisions which applies, neither party addressed this issue in a substantive way. That was likely because having regard to the particular documents in dispute the outcome was the same whichever version of the Statutory Privilege Provisions applied. That may be illustrated by one example. One of the significant amendments to the Statutory Privilege Provisions in the period was that directed to remedying the limitation in the scope of the statutory privilege so that it extended to foreign patent / trade mark attorneys and not only to their registered Australian counterparts: Eli Lily and Company v Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals (No 2) [2004] FCA 850; (2004) 137 FCR 573 at 575 [8]. In the present dispute, the Applicant expressly accepted that the communications over which privilege is claimed were sent by, or to, foreign or Australian legal practitioners and registered Australian trade mark attorneys. That concession was properly made having regard to Ms Gourley’s evidence and was borne out by my inspection of the documents in dispute.

21 Resolution of the present dispute did not turn on whether the statutory protection extended to foreign patent / trade mark attorneys. Neither party pointed to any different outcome in the present dispute which depended on the version of the Statutory Privilege Provisions which applied. Both accepted that the effect of the Statutory Privilege Provisions was to extend common law advice privilege to registered Australian patent / trade mark attorneys.

22 Insofar as the privilege claims in the present proceedings were based on litigation privilege, the relevant communications were those of either Australian or American lawyers. The assertion of the litigation privilege did not depend on the communications of the patent / trade mark attorneys being protected by litigation privilege. For this reason, it was not necessary to determine whether there was a difference as to whether the Statutory Privilege Provisions extended to protect communications in respect of anticipated or extant litigation by patent / trade mark attorneys depending on which version of the provisions applied. Further, in any event, common law legal professional privilege extends to advice sought from or given by foreign lawyers: Kennedy v Wallace [2004] FCAFC 337; (2004) 142 FCR 185 at 223 [211] and 223 [215] (Allsop J, as his Honour then was, with whom Black CJ and Emmett J agreed).

23 In these circumstances it is not necessary for the purpose of resolving the present dispute, or appropriate in the absence of submissions on the issue, to resolve the issue of which version of the Statutory Privilege Provisions is engaged.

Legal Principles

Principles relevant to establishing privilege

24 The relevant authorities as to the existence of privilege have been comprehensively reviewed in two fairly recent decisions of this Court: Cantor v Audi Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1391 at [56] - [74] (Bromwich J) and Kenquist Nominees Pty Ltd v Campbell (No 5) [2018] FCA 853 at [9] - [25] (Thawley J). I draw the following propositions relevant to the resolution of the present dispute from those decisions and the cases cited therein:

(a) Privilege is a substantial general principle or right reflecting a careful balance between competing public interests – namely the disclosure of all available and relevant information and the public interest in maintaining confidentiality in communications which assist and advance the administration of justice by encouraging and supporting the obtaining of legal advice and assistance;

(b) The test for achieving the requisite balance is to confine protection to confidential communications made for the dominant purpose of giving or obtaining (including preparation for obtaining) legal advice or the provision of legal services, including representation in court;

(c) The dominant purpose test can be difficult to apply when there are competing purposes. The “dominant” purpose is a prevailing or paramount purpose or one which predominates over other purposes;

(d) The purpose for which a communication is made is a question of fact to be determined objectively from the nature of the relevant communication, the content of the communication, the relevant commercial context and the relationships between the parties;

(e) Dominant purpose may be established by evidence and other material and circumstances showing such a description is justified. Proof of the various necessary characteristics of being in substance legal advice, confidential and having the requisite dominant purpose can be achieved in a variety of ways, depending on the case at hand. In discharging the onus, “focused and specific evidence” is usually needed. However, the nature and extent of the evidence needed to prove the existence of privilege is very much fact and circumstance dependent. For example, where communications take place with independent legal advisers, whether in Australia or elsewhere, it may be appropriate to assume, absent any contrary indications, that legitimate legal advice was being sought and provided;

(f) The relevant time for ascertaining purpose is when the communication was made. If the communication or a component of it was the provision of a copy document, it is the purpose of the creation of the copy which is relevant, ascertained at the time the copy was created. Privilege extends to a copy of a non-privileged document where the dominant purpose for bringing the copy into existence was to obtain legal advice;

(g) For legal advice privilege, a confidential communication with a legal adviser will not attract privilege unless it has the requisite purpose associated with obtaining or giving legal advice, although that concept is to be interpreted widely so as to include advice as to what a client should prudently or sensibly do in the legal context in which it arises, but not including advice that is purely commercial or public relations-related in nature;

(h) Where a lawyer has been retained for the purposes of providing legal advice in relation to a particular transaction, communications between the lawyer and client relating to the transaction will prima facie be privileged, notwithstanding they do not contain advice on matters of law; it is usually enough that they are directly related to the performance by the lawyer of his or her professional duty as legal adviser to the client. Particularly in the context of protracted or complex transactions, where information is passed between lawyer and client as part of a continuum aimed at keeping both informed so that advice may be sought and given as required, privilege may attach; and

(i) Privilege extends to documents from which the nature and content of a legally privileged communication might be inferred. Examples include: communications between various legal advisers of the client, draft pleadings, draft correspondence with the client, documents with a lawyer’s handwritten annotations and bills of costs. Privilege extends to internal documents or parts of documents of the client, or of the lawyer, reproducing or otherwise revealing communications which would be covered by privilege.

Email Chains

25 The majority of the documents in dispute comprise print outs of email chains. The lead email, the most recent in the chain, comprises the principal communication and is the document that has been discovered.

26 In Kenquist, Thawley J considered how the principle espoused in Commissioner of Australian Federal Police v Propend Finance Pty Ltd [1997] HCA 3; (1997) 188 CLR 501, as modified by the dominant purpose test in Esso, in relation to copy documents applies to email chains. His Honour stated at paragraphs [19] – [20] of his judgment:

[19] . . . The dominant purpose of making that lead communication is important to the analysis of the treatment of other emails in the chain. Often, the lead email forwards, or replies to, an email chain. Whilst the analysis turns each time on the particular document (a print out of the communication being the lead email and any chain), it is perhaps useful to make the following observations (disregarding for present purposes any question of waiver of privilege):

(1) If the communication being the lead email was not made for the dominant purpose of obtaining or giving legal advice, then it may nevertheless be appropriate to redact parts of the lead email or subsequent emails in the chain, or attachments to the lead email, if the content or nature of a privileged communication might be inferred from the document if it were left unredacted …

(2) If the dominant purpose of the communication being the lead email was the giving of legal advice by a retained lawyer, then it may be that the email chain will be privileged because the subsequent emails in the chain are to be regarded, in effect, as copies of documents furnished by the lawyer with the advice being the lead email. The lead email is a communication of legal advice, with the subsequent emails in the chain being components of that communication (in effect, copies of documents) provided by the lawyer for the dominant purpose of providing the legal advice (and perhaps also constituting copies of communications to the lawyer for the purpose of obtaining the advice). If the dominant purpose of the lawyer notionally making the copy of the email chain beneath the lead email was to provide the email chain to the client as part of the communication of legal advice, that email chain is privileged.

(3) If the dominant purpose of the communication being the lead email was the obtaining of legal advice from a retained lawyer, then the email chain may also be privileged because that email chain is, in effect, a copy of communications provided to the lawyer for the dominant purpose of obtaining legal advice. The forwarding of a chain of emails might constitute or be treated as “material prepared for submission to the legal adviser” or “components” of the privileged communication being the lead email: Propend at 571. So far as concerns the email chain forwarded with the lead email, the inquiry centres on the dominant purpose of the client in making what is, in effect, a copy of the email chain. It is at the point in time when the email chain is notionally copied (when it is notionally copied by forwarding or replying) that the question of dominant purpose must be analysed … . At that time, the whole chain is generally notionally copied (by forwarding or replying) as a component of the lead email, even though it may be that only particular emails in the chain were regarded as relevant or significant to the obtaining of advice. The dominant purpose of making the copy of the chain is often, if not generally, to put particular emails in the chain for submission to the lawyer. I did not exclude the possibility that it is appropriate in a particular case to treat the forwarding of an email chain as an act of copying each email in the chain individually, rather than a single act of copying the chain, such that one would need to analyse the dominant purpose of each act of copying. However, the circumstances were not such in the present case for such an approach to be taken.

[20] The third category above was considered in Kamasaee v Commonwealth (No 2) [2016] VSC 404 at [43]-[47]. Macaulay J held that ‘forwarding’ an antecedent chain of emails to a lawyer to obtain advice amounted to making a copy of the email chain for the dominant purpose of providing it to the lawyer for advice. It did not matter that the earlier emails themselves were non-privileged communications. See also Desane Properties Pty Ltd v New South Wales [2018] NSWSC 173 at [178]-[181], per Robb J; Cargill Australia Ltd v Viterra Malt Pty Ltd (No 8) [2018] VSC 193 at [33]-[36], per Macaulay J.

Principles relevant to Waiver

27 A person who would otherwise be entitled to the benefit of legal advice privilege may waive that privilege: Mann v Carnell [1999] HCA 66; (1999) 201 CLR 1 at 13 [28] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Callinan JJ). The present application concerns the common law principle of waiver, not with the application of s 122 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), which has the effect that privilege may be lost in circumstances that are not identical to the circumstances in which privilege may be lost under common law: Mann at 11 [23]; Osland v Secretary to the Department of Justice [2008] HCA 37; (2008) 234 CLR 275 at 299 [49] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Heydon and Keifel JJ).

28 Waiver occurs where the Court perceives some inconsistency between the conduct of the privilege holder and the maintenance of the confidentiality which the privilege is intended to protect: Mann at 13 [29]. This entails an evaluative decision based on a consideration of the whole of the circumstances of the particular case. The context and circumstances in which disclosure of legal advice is made may also be relevant to determining whether the requisite inconsistency arises. The circumstances may include the nature of the matter in respect of which legal advice was received, the evident purpose of such disclosure that is made and the legal and practical consequences of limited rather than complete disclosure. Each case will turn on its own facts and circumstances.: Osland at 296 - 297 [45] and 297 [46] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Heydon and Keifel JJ); Commissioner of Taxation v Rio Tinto Ltd [2006] FCAFC 86; (2006) 151 FCR 341 at 354 [45];

29 It is not sufficient that the content of the privileged communications could, as a reasonable possibility, be relevant and of assistance to the other party. It is the essence of legal professional privilege that, if maintainable, it entitles a party to withhold potentially relevant documents: GR Capital Group Pty Ltd v Xinfeng Australia International Investment Pty Ltd [2020] NSWCA 266 at [57(3)] (MacFarlan JA). The line between relevant to an issue and inconsistency in the context of waiver may be very fine and therefore one on which minds may differ: GR Capital at [57(5)] (MacFarlan JA).

30 While considerations of fairness may be informative, the test of inconsistency is not one of a general principle of fairness operating at large: Mann at 13 [28] - [29]. The subjective intention of the privilege holder is not determinative. Specific inconsistency is necessary to establish waiver and that inconsistency must be reasonably manifest: Cantor at [99]; Col Crawford Pty Ltd v Nissan Motor Co (Australia) Pty Ltd [2020] NSWSC 87 at [34]; Hastie Group Ltd (in liq) v Moore [2016] NSWCA 305 at [53] (Beazley P and MacFarlan JA).

31 Privilege may be waived where the privilege holder directly or indirectly puts the contents of an otherwise privileged communication in issue, makes an assertion (express or implied) which is either about the contents of the confidential communication or lays them open to scrutiny such that an inconsistency arises between the act and the maintenance of the confidence: Rio Tinto at 359 [61]; DSE (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Intertan Inc [2003] FCA 384; (2003) 127 FCR 499 at 519 [58] – 520 [61].

32 The relevant inconsistency may arise if the privilege holder makes assertions about their state of mind and there are confidential communications likely to have affected that state of mind or which are material to the formation of that state of mind: Col Crawford at [35]; Council of the NSW Bar Association v Archer [2008] NSWCA 164; (2008) 72 NSWLR 236 at 252 [48] (Hodgson JA). In Ferella v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy [2010] FCA 766; (2010) 188 FCR 68 at 81 [65] Yates J made the following remarks as to the test of inconsistency in the context of issue waiver:

... the question is not simply whether the holder of the privilege has put that person’s state of mind in issue but whether that person has directly or indirectly put the contents of the otherwise privileged communication in issue: see [Rio Tinto] at [65]. Indeed, even the fact that the holder of the privilege makes clear that the advice was relevant or contributed to a particular course of conduct would not be sufficient to waive the privilege unless, possibly, the contents of the legal advice (and not merely the fact of the advice) are specifically put in issue by relying on the contents of the advice to vindicate a claimed state of mind: [Rio Tinto] at [67].

This statement of principle was endorsed by the Full Federal Court as the “correct approach” to issue waiver in Macquarie Bank Limited v Arup Pty Limited [2016] FCAFC 117 at [28].

Documents in Dispute

33 Orders were made for discovery by category. The Respondents’ List of Documents was verified by Mr Jensen in accordance with orders of the Court. The documents the subject of the present dispute were discovered in category 6, which relevantly provided:

(a) created prior to 1 August 2009 in respect of, or referring to, any risks to the Second Respondent, or any related party of the Second Respondent, associated with the Applicant’s application for the Applicant’s Mark, or the registration of the Applicant’s Mark;

(b) associated with, or relating to, the decision by the Second Respondent to withdraw her application for an extension of time in which to file a notice of opposition to the Applicant’s application for the Applicant’s Mark; or

(c) associated with, or relating to, the decision by the Second Respondent to remove the Apparel Goods from the Second Respondent’s Application (as those terms are defined in the [Futher] Amended Statement of Claim).

34 As all the disputed documents fell within category 6, all of the documents were:

(1) created prior to 1 August 2009 in respect of, or referring to, any risks to the Second Respondent, associated with the Applicant’s application for the Applicant’s Mark, or the registration of the Applicant’s Mark; or

(2) associated with, or relating to, the decision by the Second Respondent to withdraw her extension of time application; or

(3) associated with, or relating to, the decision by the Second Respondent to remove the Apparel Goods classification from the Second Respondent’s Application for registration of a trade mark.

35 In Part 1 of the List of Documents, documents 99 to 104 were discovered pursuant to category 6 and were partially redacted (the Redacted Documents). Part 2 of the List of Documents identified a total of 31 documents, including the Redacted Documents, over which the Respondents claim privilege. During the course of the hearing, the Applicant withdrew its challenge to one document, the Respondents conceded that privilege had been waived in respect of one document and part of another document. Eliminating duplicates that left 27 documents in dispute.

36 All but two documents in dispute comprise print outs of chains of email correspondence, the remaining documents are letters and enclosed draft documents prepared by lawyers. The documents are individually listed in the Schedule to these reasons.

Consideration

37 On the basis of my consideration of the evidence, the parties’ submissions, and the documents the subject of the dispute, I am satisfied that the Respondents have established that the documents in dispute are privileged and that privilege has not been waived other than as has been conceded by the Respondents. My reasons for reaching those conclusions in relation to each of the documents are set out in the attached Schedule and should be read with the following general observations.

Existence of Privilege

38 Notwithstanding that the Respondents carry the onus on this issue, it is convenient to first address the Applicant’s contention that the Respondents could not claim privilege because the Second Respondent was not in a lawyer / client relationship with the relevant legal and trade mark advisers. The Applicant challenged the Respondents’ contention that the documents in issue, or some of them, were privileged on the basis that the Second Respondent was not a client at the relevant time and therefore the communications over which privilege is claimed did not arise in the confines of the requisite lawyer / client relationship. That submission was based on the Court drawing an inference that the Second Respondent was not aware of, and had not authorised, actions taken in her name in respect of the trade mark dispute in 2009.

39 The Applicant’s submission on this point is necessarily based only on part of the relevant contemporaneous communications. The Applicant only has access to that part of the document in category 6 that the Respondents have discovered on the basis of their acceptance that privilege over some parts of the document has been waived. Other parts of those documents have been redacted to preserve the claims for privilege which the Respondents maintain. Looking at the communications on which the Applicant relies in isolation and out of context there is some slight ambiguity which permits the Applicant to make the submission that the Second Respondent may not have been a client at the time the documents were created. However with the benefit of Mr Jensen’s affidavit as to the scope of his role in liaising on behalf of the Second Respondent with other service providers, including in respect of legal services, and his practice in keeping the Second Respondent informed of actions taken on her behalf, it is clear that Mr Jensen was acting as the Second Respondent’s agent in communicating with the various Australian and foreign lawyers and Australian registered trade mark attorneys: Wheeler v Le Marchant [1881] 17 Ch D 675 at 684. I am fortified in my conclusion in this regard by having read the whole of the communications in unredacted form and in context.

40 I am satisfied that the documents attract legal advice, TMAP or litigation privilege for the following reasons.

41 The documents in dispute all comprise confidential communications. The communications are relevantly between Australian or foreign lawyers and/or registered Australian patent / trade mark attorneys. I am satisfied that the documents in dispute were created for the dominant purpose of obtaining, or providing, legal advice or advice in relation to trade marks which is protected by the Statutory Privilege Provisions and/or for the dominant purpose of anticipated litigation.

42 The advice privilege and TMAP arose in the context of the application for registration of what became the Applicant’s Mark, the Second Respondent’s potential opposition to that application including the extension of time application and the application to register what became the Second Respondent’s Mark. To the extent that the communications concerned the potential for litigation in Australia in respect of the competing use of the names Katie Perry and Katy Perry the documents attract litigation privilege. Some of the disputed documents attract privilege on the basis of advice privilege, TMAP and litigation privilege.

43 The documents record communications involving one or more of the following:

(1) representatives of the Second Respondent’s agent, Direct Management Group (DMG), primarily Mr Jensen;

(2) representatives of Greenberg Traurig (GT), the US law firm acting for the Second Respondent on instructions from her agent, Mr Jensen of DMG;

(3) FAK, the Australian patent and trade mark attorney firm acting for the Second Respondent in relation to Australian trade mark matters, on instructions from GT and indirectly Mr Jensen; and/or

(4) HR, the Australian law firm acting for the Second Respondent on instructions from FAK, and on occasion on instructions from GT or Mr Jensen, DMG.

44 The evidence before me establishes, and it was conceded, that each of the personnel who repeatedly are party to the relevant communications were practising lawyers, in Australia or the United States of America, or registered Australian patent / trade mark attorneys.

45 Mr Jensen’s affidavit provides the following additional context to the communications over which privilege is claimed. Mr Jensen is a partner of DMG, a United States firm operating a talent management business in Los Angeles, California. Mr Jensen gives evidence in his affidavit about DMG’s role as talent manager of the Second Respondent since July 2004.

46 In May 2009, Mr Jensen became aware of the Applicant’s trade mark application when he was informed of it by GT. GT were authorised by Mr Jensen, as the Second Respondent’s agent, to send a cease and desist letter to the Applicant, and pursue action to stop her trade mark application proceeding to registration. Mr Jensen understood that GT instructed Australian lawyers to send the cease and desist letter. The cease and desist letter dated 21 May 2009 was in evidence. It was sent by FAK on behalf of the Second Respondent.

47 Subsequently, in June 2009, Mr Jensen was given more information about the Applicant by GT. In early June 2009, HR were retained with a view to potential legal proceedings in addition to the steps being taken in the trade mark application before the Trade Marks Office. Thereafter HR and FAK were both involved in the communications the subject of the dispute. It is clear that certain of the documents were prepared for the dominant purpose of lawyers providing professional legal services in relation to anticipated litigation against the Applicant for common law trade mark infringement or misleading or deceptive conduct. That such anticipated litigation was being explored is evident from the letter of demand sent to the Applicant on 21 May 2009 where it was alleged that the Applicant had contravened ss 52 and/or 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), and that the remedies available to the Second Respondent included an injunction, a claim for damages, an account of profits and “cost for any legal proceedings”. Also, in June 2009, Mr Jensen authorised GT to have FAK negotiate to seek to resolve the matter. Copies of the negotiations correspondence between the parties legal representatives in the period May to July 2009 were in evidence as a confidential exhibit with confidentiality orders in place until the substantive hearing. No party maintains any claim for without prejudice privilege over those communications.

48 In July 2009, Mr Jensen on behalf of the Second Respondent instructed GT, who in turn instructed FAK, to not appear at the hearing before the Trade Marks Office.

49 Subject to waiver, the Respondents have established that the relevant communications and documents the subject of the Interlocutory Application are privileged. In any event, parties agreed to the Court inspecting the documents for the purposes of determining the Interlocutory Application. That inspection confirms that subject to waiver the documents are privileged.

Express Waiver

50 The allegation of express waiver arises in the context of Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration and Mr Jensen’s affidavit. The Applicant contends that parts of Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration and Mr Jensen’s affidavit expressly waive privilege over some of the documents the subject of the present application. The Respondents accepted that Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration and Mr Jensen’s affidavit had waived privilege in respect of some of the discovered documents, namely the unredacted parts of the Redacted Documents but maintained privilege in respect of the redacted parts of the documents.

51 As noted above, during the hearing the Respondents made further concessions in relation to waiver in respect of document 6A and part of document 22. Based on my review of the balance of the documents in unredacted form I am satisfied that no other parts of the documents are subject to express waiver based on the contents of Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration and the parts of Mr Jensen’s affidavit that the Applicant relied on. The Applicant has not discharged her onus to establish waiver. The content of Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration and Mr Jensen’s affidavit do not directly or indirectly expose the content of confidential communications over which privilege is claimed.

Implied or Issue Waiver

52 The allegation of implied, or issue, waiver arises in the context of Mr Jensen’s affidavit and of the Respondents’ Amended Defence to the Further Amended Statement of Claim.

53 In addition to instances of express waiver, the Applicant contended that Mr Jensen’s affidavit also resulted in implied waiver. That contention was made on the basis that Mr Jensen had deposed to his state of mind in circumstances where it could be inferred that legal advice was relevant to, or considered by him, in forming the relevant state of mind. The difficulty for the Applicant on this issue was that the submission did not rise above an assertion that I should infer that legal advice received by Mr Jensen was relevant to his state of mind on various issues, or more generally that such legal advice was potentially relevant to matters put in issue by the Applicant in the proceedings (e.g. the claim for additional damages). Mr Jensen’s evidence goes no further than identifying that:

(i) he provided instructions to the US lawyers to send the cease and desist letter to the Applicant;

(ii) he received information from the US lawyers about the Applicant in June 2009;

(iii) he provided instructions to the US lawyers in June 2009 to have the Australian lawyers resolve the dispute with the Applicant on the basis of a mutually satisfactory co-existence agreement; and

(iv) he provided instructions not to pursue an extension of time for opposition to the Applicant’s Mark in mid-July 2009.

The Respondents accepted that they had waived privilege in respect of those four matters and have discovered communications relating to them. The Applicant did not demonstrate that Mr Jensen had put in issue legal advice to vindicate the states of mind to which he deposed in his affidavit other than in respect of the four matters identified in respect of which waiver was conceded: Ferella at 81 [65]; Arup at [28] citing Ferella at 81 [65].

54 The Applicant also seeks to establish waiver on the basis of paragraph 19 of the Amended Defence to the Further Amended Statement of Claim in which the Respondents plead:

In further answer to the claims for equitable relief in orders 1 to 6 of the Originating Application, the Respondents:

(a) say, in respect of any use by them of the name, brand and trade mark KATY PERRY that would otherwise amount to infringement of the Applicant’s Mark, until the commencement of these proceedings by the Applicant, such use has been undertaken:

(i) at all material times, without complaint by the Applicant and in circumstances such that the Applicant knew or ought to have known of any such use; and

(ii) in 2009 and subsequently, with the encouragement of the Applicant;

(b) say that they would suffer detriment if they were to be subject to equitable relief of the type claimed, with respect to the use of the name, brand and trade mark KATY PERRY;

(c) say further that, by reason of the matters pleaded in paragraphs 19 and 20 19(a) and 19(b) herein, the Applicant is thereby disentitled to equitable relief by one or more of delay, laches, acquiescence and/or the Court’s discretion to refuse equitable relief.

55 The marked up text in the extract above corrects a slip in paragraph 19 which was identified by the Respondents in their written submissions. The particulars to defence paragraph 19(a) include the following particulars of the Respondents’ allegation that any use by the Respondents of the name, brand and trade mark KATY PERRY that would otherwise amount to infringement of the Applicant’s Mark was undertaken with the “encouragement of the Applicant”:

C. In a YouTube video post in June 2009, the Applicant communicated to the Second Respondent: “I wish you all the success but leave me to carry on my dream” and “I’m absolutely no threat whatsoever to you”.

D. In a blog post in July 2009, the Applicant expressed a wish for a positive end to her dispute with the Second Respondent with a view to the Second Respondent visiting the Applicant’s studio in Australia.

E. In May 2013 in a radio interview with Tim Rosso on Radio Station 106.5 Sydney, the Applicant acknowledged that she was aware of the Second Respondent, that members of the public were confused as to an association between the Applicant and the Second Respondent and that this provided commercial benefits to the Applicant.

56 The Applicant contends that by this paragraph the Respondents were advancing a standalone defence of encouragement. That is not correct. Paragraphs 19(a) and (b) are allegations of fact pleaded in support of the defence in paragraph 19(c), that the Applicant is disentitled to equitable relief by reason of delay, laches, acquiescence and discretion to refuse relief of an equitable nature albeit sourced in statute. The factual allegations as to the Applicant’s knowledge and the Applicant’s conduct which is relied on as encouragement are particularised in support of the defences raised in paragraph 19(c).

57 In his affidavit, Mr Jensen says that he saw the YouTube video in late June 2009 and that he saw a 30 June 2009 blog post referring to and linking the video at the time. He does not give evidence that he or any of the Respondents were in fact encouraged as a result of the YouTube video or the other conduct of the Applicant that is particularised in paragraph 19 of the Amended Defence. The Respondents do not allege that they acted on the basis of the Applicant’s conduct which they characterise as acts of encouragement by the Applicant. The Respondents have not put their state of mind in issue. The Amended Defence affixes on the Applicant’s state of mind or knowledge and her conduct, not the state of mind of the Respondents or their agents. The Respondents’ pleading in paragraph 19 of the Amended Defence raises an issue about whether the Applicant acquiesced to the Respondents’ alleged infringing conduct as a result of her conduct which the Respondents seek to characterise in their Amended Defence as encouragement. The relevant delay or laches arises by reason of the Applicant’s awareness of the Respondents’ use of the KATY PERRY mark in relation to clothes for over almost ten years before commencing the proceedings and her “encouragement” in respect of that use as particularised in particulars C to E of paragraph 19(a) of the Amended Defence. Those particulars refer to a YouTube video post, a blog post and a radio interview conducted by the Applicant. The allegation at paragraph 19 of the Amended Defence essentially requires the Court to determine whether it would be inequitable to allow the Applicant to recover an account of profits or damages in circumstances where it is alleged that she knowingly stood by or encouraged the conduct of which she now complains.

Conclusion

58 For reasons outlined the Applicant’s Interlocutory Application is dismissed.

59 To the extent that the Respondents have not otherwise already done so they are to discover to the Applicant those documents in respect of which they conceded privilege had been waived in the course of the application and which are identified in the Schedule to these reasons. I do not expect it is necessary to make an order to this effect, the concession having been made, with respect, properly, in the course of argument.

I certify that the preceding fifty nine (59) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Cheeseman . |

Associate:

Schedule of Rulings in Respect of Each Disputed Document

Introduction

1 This Schedule identifies each of the documents in dispute by reference to the Respondents’ verified list of documents. The Respondents discovered the Redacted Documents in Parts 1 and 2 and therefore the Redacted Documents each have two identifying references. The date and description of each individual document has been taken from the Respondents’ list of documents. Where necessary, I have corrected or supplemented the document details provided in the Respondents’ list of documents. My ruling is given on each individual document. The ruling should be read with the substantive analysis in the reasons for judgment.

2 The following acronyms are used in this Schedule:

(1) DMG refers to Direct Management Group;

(2) GT refers to Greenberg Traurig;

(3) FAK refers to Fisher Adams Kelly; and

(4) HR refers to Holding Redlich.

3 The roles of each organisation and the personnel involved are set out in the reasons for judgment.

4 The Respondents’ claim for privilege is expressed in the same form for all of the documents in dispute: “legal advice (patent / trade mark attorney) privilege and / or litigation privilege”.

Individual documents

5 Part 1, Document No. 99 / Part 2, Document No. 15 – dated 5/6 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Partially redacted for privilege email chain dated 5/6 July 2009 between K Hudson, S Jensen and others in part requesting advice in relation to Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: The redacted portion of the email chain attracts common law advice privilege and TMAP for the reasons advanced by the Respondents in the document description. The redacted portion of the email is an email sent to Mr Burry (GT), one of the Second Respondent’s US lawyers, by Mr Jensen which seeks advice from and conveys instructions to the Second Respondent’s Australian lawyers.

6 Part 1, Document No. 100 / Part 2, Document No. 3 – dated 16/18 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Partially redacted for privilege emails 16 and 18 June 2009 between Kenneth Burry (GT) and Steven Jensen (DMG), Martin Kirkup (DMG), and Bradford Cobb (DMG) and others providing legal advice in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application with attachments not privileged.

Ruling: The redacted portions of the email chain attract common law advice privilege for the reasons advanced by the Respondents in the document description.

7 Part 1, Document No. 101 / Part 2, Document No. 9 – dated 24 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Partially redacted for privilege email dated 24 June 2009 from Paul Venus (HR) and Paul Thompson (FAK) providing legal advice in relation to Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email is from Paul Venus (HR) to Paul Thompson (FAK) providing legal advice in relation to the Applicant’s trade mark application. The redacted portion attracts common law advice privilege, noting that Mr Venus is an Australian lawyer retained by the Second Respondent through Mr Thompson, the registered Australian patent and trade mark attorney engaged by the Second Respondent.

8 Part 1, Document No. 102 / Part 2, Document No. 10 – dated 25 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Partially redacted for privilege email dated 25 June 2009 from Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Paul Thompson (FAK), and email in response dated 25 June 2009 in relation to negotiations concerning Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: The redacted portions of this email chain attract advice privilege and in part TMAP as well. The unredacted portion of the chain reveals that the lead email is an email from Mr Thompson, FAK to Mr Venus, HR.

9 Part 1, Document No. 103 / Part 2, Document No. 21 – dated 15 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Partially redacted for privilege email chain dated 15 July 2009 between Steven Jensen (DMG) and Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and others providing instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The redacted portions of the email chain attract privilege on the basis of advice privilege and litigation privilege for the reasons advanced by the Respondents in the document description. I note that the unredacted portions of the email chain were discovered by the Respondents on the basis that privilege in those portions has been expressly waived by paragraph [104] of Mr Jensen’s affidavit. Based on my inspection of the document I am satisfied that the redacted portions of the email chain address matters to which the express waiver does not extend.

10 Part 1, Document No. 104 / Part 2, Document No. 24 – dated 16 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Partially redacted for privilege email dated 16 July 2009 from Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Paul Venus (HR), Paul Thompson (FAK) and others seeking information in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application with attachments not privileged 16 Jul 2009.

Ruling: The redacted portion of the email chain attracts privilege on the basis of advice privilege and litigation privilege for the reasons advanced by the Respondents in the document description. I note that the unredacted portion of the email chain was discovered by the Respondents on the basis that privilege in that portion has been expressly waived by paragraph [104] of Mr Jensen’s affidavit. Based on my inspection of the document I am satisfied that the redacted portion of the email chain addresses matters to which the express waiver does not extend.

11 Part 2, Document 6A – dated 8 May 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 8 May 2009 from Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Paul Thompson (FAK) and another providing instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: Privilege waived. The Respondents conceded that privilege had been waived in respect of this email chain by express waiver as a result of Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration.

12 Part 2, Document 6B – dated 8 May 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Letter dated 8 May 2009 from Paul Thompson (FAK) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) providing legal advice and seeking instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: This letter attracts TMAP. Having inspected the document I am satisfied that it was written after Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration and that Mr Thompson’s statutory declaration does not waive privilege in respect of the matters subsequently communicated in this letter.

13 Part 2, Document 1 – dated 19 May 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 19 May 2009 from Grant Adams (FAK) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and others providing advice in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application, and email in response dated 20 May 2009.

Ruling: The document is an email chain. The lead email is in fact an email dated 20 May 2009 from Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Mr Adams (FAK) and others providing instructions in response to advice given by Mr Grant in relation to the Applicant’s trade mark application. The email chain attracts TMAP.

14 Part 2, Document 6C – dated 3 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 3 June 2009 between Paul Thompson (FAK) and Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) providing advice and seeking instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The email described as the concluding email is the lead email. It attracts privilege on the basis of TMAP.

15 Part 2, Document 6D – dated 6 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 6 June 2009 from Paul Thompson (FAK) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) providing advice and seeking instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The email attracts TMAP privilege.

16 Part 2, Document 2 – dated 11 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Letter dated 11 June 2009 from Paul Thompson (FAK) to Toby Boys (HR) and Paul Venus (HR) providing instructions concerning Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: This letter attracts TMAP and advice privilege.

17 Part 2, Document 6E - dated 12 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 12 June 2009 between Paul Venus (HR), Andrea Porter (FAK), Toby Boys (HR) and others providing legal advice and seeking instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The email described as the concluding email is the lead email of a chain which attaches three documents. The lead email is sent by Mr Venus (HR) to Ms Porter and Mr Boys (FAK), as agents for the Second Respondent, seeking instructions. The email chain and the attached documents attract both advice and litigation privilege.

18 Part 2, Document 4 - dated 17 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 17 June 2009 between Paul Venus (HR), Paul Thompson (FAK) and others providing legal advice and seeking instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email in this chain is from Mr Thompson (FAK) to Mr Venus (HR). The email chain is privileged on the basis of advice privilege, litigation privilege and TMAP.

19 Part 2, Document 6 - dated 18 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 18 June 2009 between Kenneth Burry (GT) and Steven Jensen (DMG) and others providing legal advice and receiving instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: This email chain attracts advice privilege. The lead email also attracts TMAP as it seeks instructions in relation to obtaining advice from an Australian patent and trade mark attorney in respect of the Applicant’s trade mark application.

20 Part 2, Document 7 - dated 18 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 18 June 2009 from Kenneth Burry (GT) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT), Paul Thompson (FAK) and others, and email in response dated 18 June 2009 providing legal advice and instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email in this chain is an email from Mr Thompson (FAK) to Mr Venus (HR) forwarding a chain of email for the purpose of Mr Thompson and Mr Venus liaising with Mr Burry (GT), the Second Respondent’s American lawyer. The email chain attracts advice privilege, litigation privilege and TMAP.

21 Part 2, Document 6F – dated 18 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 18 June 2009 between Paul Thompson, Paul Venus and others providing legal advice and instructions in relation to Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email is an email between Mr Thompson (FAK) and Mr Venus (HR). The email chain attracts advice privilege and litigation privilege.

22 Part 2, Document 8 – dated 18 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain dated 18 June 2009 between Kenneth Burry (GT) and Steven Jensen (DMG), Martin Kirkup (DMG), Bradford Cobb (DMG) and Paul Thompson (FAK) providing legal advice in relation to Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email is an email from Mr Burry (GT) to Mr Jensen (DMG) and others. It attracts advice privilege for the reason set out in the Respondents’ document description.

23 Part 2, Document 11 – dated 26 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 26 June 2009 from Paul Venus (HR) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and others in relation to negotiations concerning Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: This email attracts both advice privilege and litigation privilege.

24 Part 2, Document 12 – dated 30 June 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 30 June 2009 between Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT), Paul Venus (HR) and others being legal advice and instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email is from Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT), one of the Second Respondent’s American lawyers, to Mr Venus (HR), copied to Mr Thompson (FAK). The email attracts advice privilege and litigation privilege.

25 Part 2, Document 13 – dated 3 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 3 July 2009 from Toby Boys (HR) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and others providing legal advice and seeking instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: This email and its attachments attract advice privilege for the reasons advanced by the Respondents in the document description.

26 Part 2, Document 14 – dated 3 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 3 July 2009 from Steven Jensen (DMG) to Paul Thompson (FAK) requesting copies of legal correspondence and email dated 6 July 2009 from Paul Thompson (FAK) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) seeking instructions.

Ruling: The lead email is the email from Mr Thompson (FAK) to Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT) copied to Mr Boys (HR) dated 6 July 2009. The email attracts TMAP and advice privilege.

27 Part 2, Document 16 – dated 7 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 7 July 2009 between Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and Toby Boys (HR), Paul Thompson (FAK) and others providing information and legal advice in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email is from Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Mr Boys (HR) and Mr Thompson (FAK). It is copied to other lawyers at GT and HR and to Mr Jensen at DMG. The email provides instructions and contains legal advice. It attracts advice privilege and TMAP.

28 Part 2, Document 17 – dated 8 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 8 July 2009 between Steven Jensen (DMG) and Kenneth Burry (GT) and others providing instructions in relation to draft legal advice in relation to Ms Hudson’s trade mark rights.

Ruling: The lead email is from Mr Jensen (DMG) to Mr Burry (GT) providing instructions to Mr Burry in relation to a draft legal advice to the Second Respondent. It attracts advice privilege.

29 Part 2, Document 18 – dated 8 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 8 July 2009 from Kenneth Burry (GT) to Katy Perry and others including 4 attachments providing legal advice in relation to Ms Hudson’s trade mark rights.

Ruling: This email including the attachments attract advice privilege for the reasons advanced by the Respondents in the document description.

30 Part 2, Document 19 – dated 8 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 8 July 2009 between Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and Tanya Bunney (HR), Toby Boys (HR), Paul Thompson (FAK) and others seeking legal advice in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: This document comprises an email from Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Ms Bunney (HR), Mr Boys (HR) and Mr Thompson (FAK). It is copied to others at GT, HR and DMG. It attaches a redline version of a draft deed. The email and the attachment attract advice privilege and TMAP.

31 Part 2, Document 20 – dated 14 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 14 July 2009 from Paul Venus (HR) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and others providing legal advice in relation to Ms Howell and her trade mark application.

Ruling: This document comprises an email as described and its attachments, being a draft letter and draft agreement in respect of which instructions are sought. The document attracts advice privilege and litigation privilege.

32 Part 2, Document 22 – dated 15 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email dated 15 July 2009 from Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) to Steven Jensen (DMG) and Kenneth Burry (GT), and email in response dated 17 July 2009 providing information and legal advice in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: Waiver of part of the document with the balance privileged on the basis of advice privilege, litigation privilege and TMAP. The lead email is from Mr Jensen and others (DMG) to Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT), Mr Burry (GT), Mr Venus (HR), Mr Thompson (FAK). During the hearing the Respondents conceded that privilege had been waived in respect of part of document 22. The express waiver of part of document 22 was a result of paragraph [104] of Mr Jensen’s affidavit. The claim for privilege was therefore not pressed in relation to the following portions of the email chain:

“On Jul 15, 2009, at 3.53PM,

<[Ms Tenen-Aoki’s email address]>

Wrote:

Steve and Ken,

This is just to confirm that we are withdrawing from the hearing today.”

and

“Best regards,

Elise

[Ms Tenen-Aoki’s signature block]”

33 Part 2, Document 23 – dated 16 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain dated 16 July 2009 between Steven Jensen (DMG) and Kenneth Burry (GT) and others providing instructions and information in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email is an email from Mr Jensen (DMG) to Mr Burry (GT) copied to others at GT and DMG in which Mr Jensen provides instructions to Mr Burry. The email chain attracts advice privilege.

34 Part 2, Document 25 – dated 21 July 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Email chain concluding 21 July 2009 between Steven Jensen (DMG) and Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) and others providing instructions in relation to Ms Howell’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The lead email in this chain is from Mr Jensen (DMG) providing instructions to Ms Tenen-Aoki (GT) in relation to, inter alia, the application for what became the Second Respondent’s Mark. The email attracts advice privilege.

35 Part 2, Document 26 – dated 10 November 2009.

Respondents’ Document Description: Letter dated 10 November 2009 from Paul Thompson (FAK) to Elise Tenen-Aoki (GT) seeking instructions in relation to Ms Hudson’s trade mark application.

Ruling: The Applicant did not press for production of document 26 in Part 2, which was discovered in category 6(c).

NSD 1774 of 2019 | |

PURRFECT VENTURES, LLC | |

KATHERYN ELIZABETH HUDSON |