Federal Court of Australia

Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCA 643

ORDERS

First Applicant E. R. SQUIBB & SONS, LLC Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The decision of the delegate of the Commissioner of Patents made on 16 September 2020 be set aside.

2. The application before the delegate for an extension of term of Australian patent no. 2011203119 on the basis of OPDIVO be granted.

3. The applicants within 7 days of the date of these orders file and serve submissions (limited to 3 pages) and minutes of proposed orders dealing with any consequential orders and on costs.

4. The Commissioner within 7 days of the receipt of such submissions and minutes file and serve responding submissions (limited to 3 pages) and minutes of proposed orders.

5. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The applicants, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd and E.R. Squibb & Sons, LLC, are the proprietors of Australian patent no. 2011203119 titled “Human monoclonal antibodies to programmed death 1 (PD-1) and methods for treating cancer using anti-PD-1 antibodies alone or in combination with other immunotherapeutics”.

2 The matter before me concerns the extension of the term of the patent. The applicants challenge a decision of a delegate of the Commissioner of Patents refusing an extension of term.

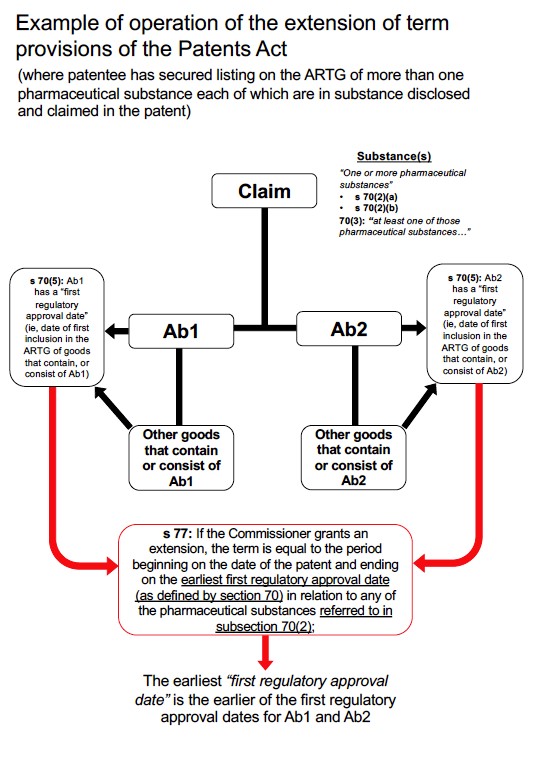

3 The extension of term regime set out in Part 3 of Chapter 6 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) operates where one or more pharmaceutical substances per se are in substance disclosed in the complete specification and fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification (s 70(2)(a)) or the same can be said in respect of a pharmaceutical substance produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology (s 70(2)(b)).

4 In short, the extension of term regime is restricted to new and inventive pharmaceutical substances; see the Explanatory Memorandum, Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Bill 1997 (Cth) (the 1997 EM) at 18, Boehringer Ingelheim International v Commissioner of Patents (2001) ¶AIPC 91–670 at [14] per Heerey J and Commissioner of Patents v AbbVie Biotechnology Ltd (2017) 253 FCR 436 at [57] per Besanko, Yates and Beach JJ.

5 The present extension of term regime was inserted into the Act by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 1998 (Cth) (the 1998 Amendment Act) because of an appreciation that pharmaceutical patentees might lose valuable time to exploit their invention because of the regulatory time involved in bringing a new pharmaceutical substance to market. But under the regime that was inserted to address that concern, that interest was balanced with the interests of generics and the public in having competition and generic substitution as soon as possible after patent expiry; see the 1997 EM at 2 to 6 and 9.

6 On 11 July 2016, the applicants applied to extend the term of the patent under s 70 of the Act. As the date of the patent is 2 May 2006 (s 77(1)(a)), its normal term expires on 2 May 2026. The term of the patent has not been previously extended.

7 The applicants made two applications for an extension of term. Let me deal with each in turn.

8 First, an extension was sought based on a pharmaceutical product marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb Australia Pty Ltd, a related entity of the second applicant, under the name OPDIVO (the OPDIVO application). The OPDIVO application was made under s 70(2)(a). If that foundation is justified, an extension of the patent to 11 January 2031 would be justified.

9 OPDIVO is a 10mg per mL concentrate solution for IV infusion which contains the active pharmaceutical ingredient nivolumab, water and a number of excipients. Nivolumab is a fully human anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody of the IgG4 isotype, produced in mammalian Chinese hamster ovary cells by recombinant DNA technology. It is a pharmaceutical substance per se which is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of at least claim 3.

10 OPDIVO is a good which was included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on 11 January 2016. Strictly there were two products known as OPDIVO with different concentration levels. Two ARTG certificates were issued to Bristol-Myers approving the supply of OPDIVO in Australia. Nivolumab is the first such pharmaceutical substance disclosed and claimed in the patent that is the subject of a good in respect of which the applicants or their related entities have obtained ARTG registration. There was no pre-Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) marketing approval given in relation to nivolumab or OPDIVO.

11 Second, the applicants have also applied to extend the term of the patent based on a pharmaceutical product marketed by a third party competitor of the applicants, Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Ltd, under the name KEYTRUDA (the KEYTRUDA application). This application sought to trigger an alternative basis for an extension. Further, the applicants have applied for an extension of time under s 223(2)(a) within which to file an application for an extension of the term of the patent based on KEYTRUDA.

12 The active pharmaceutical ingredient of KEYTRUDA is pembrolizumab. Pembrolizumab is a humanised anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody of the IgG4 isotype which is also produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells by recombinant DNA technology. Pembrolizumab is also a pharmaceutical substance per se in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and falling within the scope of at least claim 3.

13 KEYTRUDA is a good which was included in the ARTG on 16 April 2015. There is an ARTG public summary in the name of Merck Sharp approving the supply of KEYTRUDA in Australia. There was no pre-TGA marketing approval given in relation to pembrolizumab or KEYTRUDA.

14 The applicants’ preferred application is the OPDIVO application. If granted, it would entitle the applicants to a longer extension of term than if the KEYTRUDA application were to be granted. Moreover, the KEYTRUDA application has been made out of time and in any event requires an extension of time under s 223.

15 Accordingly, before the delegate the applicants first pressed for a ruling on the OPDIVO application. The KEYTRUDA application was put on the back-burner.

16 On 16 September 2020, the delegate held that the OPDIVO application did not comply with the statutory requirements, and that the OPDIVO application ought be refused pursuant to s 74(3). In essence, the delegate found that the OPDIVO application had not been made on the basis of the good on the ARTG with the first regulatory approval date, which good was KEYTRUDA, a good of the applicants’ competitor.

17 The delegate found that the good with the earliest regulatory approval date that contained or consisted of a pharmaceutical substance that fell within the scope of claim 3 of the patent, namely, pembrolizumab, was KEYTRUDA. As a result, the delegate found that the requirements in ss 70 and 71 were not satisfied concerning the OPDIVO application.

18 The applicants now seek to review that decision under s 5(1) of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) in essence asserting that the delegate made an error of law.

19 What is raised before me is essentially a question of construction.

20 The applicants contend that the requirements of ss 70(2), (3) and (4) may be satisfied by any one of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in ss 70(2)(a) and (b) which are disclosed and claimed in the patent. They also contend that any one or more pharmaceutical substances disclosed and claimed in the patent may be used for the purposes of calculating the time by which an application for an extension of term must be filed under s 71. They also contend that the ordinary meaning of s 77(1) is that the term of the extension is calculated by reference to the earliest first regulatory approval date of any pharmaceutical substance that is disclosed and claimed in the patent, being the substance that the patentee nominates in its application for an extension of term for the purposes of s 70(2).

21 Now if the applicants’ contentions are accepted, then the following consequences apply.

22 First, the first relevant inclusion of goods in the ARTG containing or consisting of the substance as required by ss 70(3) and (5) was the first inclusion of OPDIVO, which contained the pharmaceutical substance nivolumab.

23 Second, the OPDIVO application complied with s 71 because the application was made within 6 months of the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods, namely, OPDIVO, that contained or consisted of the pharmaceutical substance nivolumab, being one of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(3).

24 Third, pursuant to s 77 the term of the extension is the period beginning on the date of the patent being 2 May 2006 and ending on the “first regulatory approval date” being 11 January 2016, reduced by 5 years, being a period of 4 years, 8 months and 9 days. Accordingly, it is said that the term of the patent should be extended from 2 May 2026 to 11 January 2031.

25 Contrastingly, the Commissioner, who has sought to uphold the delegate’s decision, has disputed the applicants’ contentions on construction.

26 The Commissioner initially framed the question by saying that I need to decide whether, in circumstances where more than one pharmaceutical substance meets the description in s 70(2), the extension of term can be sought and effected by reference to the last-in-time substance to be the subject of a good registered on the ARTG, or whether the extension of term regime and the length of any extended term operates and is calculated by reference to the first-in-time date on which any of the substances were included in a good or goods included in the ARTG.

27 But as I would frame the question, it is whether an application for an extension must be filed within 6 months of the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods containing or consisting of any pharmaceutical substance falling with the claims of the patent:

(a) where the goods were those of the patentee (the applicants’ position); or

(b) irrespective of whether the goods were those of the patentee, that is, they could be the goods of a third party that had nothing to do with the patentee and, moreover, might be a competitor (the Commissioner’s position).

28 I should say now that apart from seeking to sell me a literal form of textualism, the Commissioner’s statutory construction has little to commend it. Indeed, the following questions would arise on the Commissioner’s construction. Is it suggested that a patentee would then need to strictly monitor the regulatory approvals for third party products? And how else could it ensure that its own or future extension application is not contaminated or stymied by the registration on the ARTG of a third party product earlier in time? And how could it tell if the third party product fell within the scope of the claim(s) of the patent or confidently work out whether it fell outside? That is not a simplistic desktop analysis based upon a superficial read of an ARTG public summary. And if the third party product fell within, what is the patentee to do? Is it compelled to file an extension based on the third party product? Indeed, should the patentee seek to amend the claims of the patent to define away the third party product thereby preserving its future right to extend based upon its own product?

29 Commercially, the Commissioner’s construction has little to commend it, and the statutory language does not compel it. I should also note that I was not blessed with any submissions concerning off-shore practices, but my limited research reveals that the applicants’ construction resonates harmoniously with the US practice concerning extensions of term (see 35 US Code §156). Of course though, I am construing domestic legislation.

30 For the following reasons, the applicants’ case and their construction of the relevant provisions should be upheld. Accordingly, the delegate’s decision should be set aside.

The patent

31 Before discussing the legal questions, it is useful to say something further about the patent.

32 The specification describes the invention as providing isolated monoclonal antibodies, particularly human monoclonal antibodies, that specifically bind to the protein known as programmed death 1 (PD-1) with high affinity. Nucleic acid molecules encoding the antibodies of the invention, expression vectors, host cells and methods for expressing the antibodies of the invention are also provided. Immunoconjugates, bispecific molecules and pharmaceutical compositions comprising the antibodies of the invention are also provided.

33 The invention also provides methods for detecting PD-1, as well as methods using anti-PD-1 antibodies for treating various diseases such as cancer and infectious diseases. The invention further provides methods for using a combination immunotherapy, such as the combination of anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies, to treat hyperproliferative disease such as cancer.

34 The specification says:

The present invention relates generally to immunotherapy in the treatment of human disease and reduction of adverse events related thereto. More specifically, the present invention relates to the use of anti-PD-1 antibodies and the use of combination immunotherapy, including the combination of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies, to treat cancer and/or to decrease the incidence or magnitude of adverse events related to treatment with such antibodies individually.

The protein·Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) is an inhibitory member of the CD28 family of receptors, that also includes CD28, CTLA-4, ICOS and BTLA. PD-1 is expressed on activated B cells, T cells, and myeloid cells. The initial members of the family, CD28 and ICOS, were discovered by functional effects on augmenting T cell proliferation following the addition of monoclonal antibodies. PD-1 was discovered through screening for differential expression in apo[p]totic cells. The other members of the family, CTLA-4 and BTLA were discovered through screening for differential expression in cytotoxic T lymphocytes and TH1 cells, respectively. CD28, ICOS·and CTLA-4 all have an unpaired cysteine residue allowing for homodimerization. In contrast, PD-1 is suggested to exist as a monomer, lacking the unpaired cysteine residue characteristic in other CD28 family members.

The PD-1 gene is a 55 kDa type I transmembrane protein that is part of the Ig gene superfamily. PD-1 contains a membrane proximal immunoreceptor tyrosine inhibitory motif (ITIM) and a membrane distal tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) … . Although structurally similar to CTLA-4, PD-1 lacks the MYPPPY motif that is critical for B7-1 and B7-2 binding. Two ligands for PD-1 have been identified, PD-L1 and PD-L2, that have been shown to downregulate T cell activation upon binding to PD-1. Both PD-L1 and PD-L2 are B7·homologs that bind to PD-1, but do not bind to other CD28 family members. One ligand for PD-1, PD-L1 is abundant in a variety of human cancers. The interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 results in a decrease in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, a decrease in T-cell receptor mediated proliferation, and immune evasion by the cancerous cells. Immune suppression can be reversed by inhibiting the local interaction of PD-1 with PD-L1, and the effect is additive when the interaction of PD-1 with PD-L2 is blocked as well.

PD-1 is an inhibitory member of the CD28 family expressed on activated B cells, T cells, and myeloid cells. PD-1 deficient animals develop various autoimmune phenotypes, including autoimmune cardiomyopathy and a lupus-like syndrome with arthritis and nephritis. Additionally, PD-1 has been found to play a role in autoimmune encephalomyelitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), type I diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis. In a murine B cell tumor line, the ITSM of PD-1 was shown to be essential to block BCR-mediated Ca2+-flux and tyrosine phosphorylation of downstream effector molecules.

Accordingly, agents that recognize PD-1, and methods of using such agents, are desired.

The present invention provides isolated monoclonal antibodies, in particular human monoclonal antibodies, that bind to PD-1 and that exhibit numerous desirable properties. These properties include, for example, high affinity binding to human PD-1, but lacking substantial cross-reactivity with either human CD28, CTLA-4 or ICOS. Still further, antibodies of the invention have been shown to modulate immune responses. Accordingly, another aspect of the invention pertains to methods of modulating immune responses using anti-PD-1 antibodies. In particular, the invention provides a method of inhibiting growth of tumor cells in vivo using anti-PD-1 antibodies.

(References to literature omitted.)

35 Relevantly to the present context, claim 3 is in the following form:

3. A monoclonal antibody, or an antigen-binding portion thereof, for use in treating a human subject which cross-competes for binding to human PD-1 with a reference antibody or reference antigen-binding portion thereof comprising:

a) a heavy chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 1; and a light chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 8;

b) a heavy chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 2; and a light chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 9;

c) a heavy chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set faith in SEQ ID NO: 3; and a light chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 10; or

d) a heavy chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 6; and a light chain variable region comprising amino acids having the sequence set forth in SEQ ID NO: 13; and

wherein the antibody, or antigen-binding portion thereof, binds to human PD-1 with a KD of 1x10-7 M or less , wherein the KD is measured by surface plasmon resonance (Biacore) analysis.

36 I should also note that the body of the specification contains the following definitions that assist with understanding some of the terms used in claim 3:

…

The term “antibody” as referred to herein includes whole antibodies and any antigen-binding fragment (i.e., “antigen-binding portion”) or single chains thereof. An “antibody” refers to a glycoprotein comprising at least two heavy (H) chains and two light (L) chains inter-connected by disulfide bonds, or an antigen-binding portion thereof. Each heavy chain is comprised of a heavy chain variable region (abbreviated herein as VH) and a heavy chain constant region. The heavy chain constant region is comprised of three domains, CH1, CH2 and CH3. Each light chain is comprised of a light chain variable region (abbreviated herein as VL) and a light chain constant region. The light chain constant region is comprised of one domain, CL. The VH and VL regions can be further subdivided into regions of hypervariability, termed complementarity determining regions (CDR), interspersed with regions that are more conserved, termed framework regions (FR). Each VH and VL is composed of three CDRs and four FRs, arranged from amino-terminus to carboxy-terminus in the following order: FR1, CDR1, FR2, CDR2, FR3, CDR3, FR4. The variable regions of the heavy and light chains contain a binding domain that interacts with an antigen. The constant regions of the antibodies may mediate the binding of the immunoglobulin to host tissues or factors, including various cells of the immune system (e.g., effector cells) and the first component (Clq) of the classical complement system.

The term “antigen-binding portion” of an antibody (or simply “antibody portion”), as used herein, refers to one or more fragments of an antibody that retain the ability to specifically bind to an antigen (e.g., PD-1). It has been shown that the antigen-binding function of an antibody can be performed by fragments of a full-length antibody.

…

An “isolated antibody”, as used herein, is intended to refer to an antibody that is substantially free of other antibodies having different antigenic specificities (e.g., an isolated antibody that specifically binds PD-1 is substantially free of antibodies that specifically bind antigens other than PD-1). An isolated antibody that specifically binds PD-1 may, however, have cross-reactivity to other antigens, such as PD-1 molecules from other species. Moreover, an isolated antibody may be substantially free of other cellular material and/or chemicals.

The terms “monoclonal antibody” or “monoclonal antibody composition” as used herein refer to a preparation of antibody molecules of single molecular composition. A monoclonal antibody composition displays a single binding specificity and affinity for a particular epitope.

The term “human antibody”, as used herein, is intended to include antibodies having variable regions in which both the framework and CDR regions are derived from human germline immunoglobulin sequences. Furthermore, if the antibody contains a constant region, the constant region also is derived from human germline immunoglobulin sequences. The human antibodies of the invention may include amino acid residues not encoded by human germline immunoglobulin sequences (e.g., mutations introduced by random or site-specific mutagenesis in vitro or by somatic mutation in vivo). However, the term “human antibody”, as used herein, is not intended to include antibodies in which CDR sequences derived from the germline of another mammalian species, such as a mouse, have been grafted onto human framework sequences.

The term “human monoclonal antibody” refers to antibodies displaying a single binding specificity which have variable regions in which both the framework and CDR regions are derived from human germline immunoglobulin sequence. In one embodiment, the human monoclonal antibodies are produced by a hybridoma which includes a B cell obtained from a transgenic nonhuman animal, e.g., a transgenic mouse, having a genome comprising a human heavy chain transgene and a light chain transgene fused to an immortalized cell.

…

As used herein, an antibody that “specifically binds to human PD-1” is intended to refer to an antibody that binds to human PD-1 with a KD of 1 x 10-7 M or less, more preferably 5 x 10-8 M or less, more preferably 1 x 10-8 M or less, more preferably 5 x 10-9 M or less.

The term “Kassoc” or “Ka”, as used herein, is intended to refer to the association rate of a particular antibody-antigen interaction, whereas the term “Kdis” or “Kd,” as used herein, is intended to refer to the dissociation rate of a particular antibody-antigen interaction. The term “KD”, as used herein, is intended to refer to the dissociation constant, which is obtained from the ratio of Kd to Ka (i.e,. Kd / Ka) and is expressed as a molar concentration (M). KD values for antibodies can be determined using methods well established in the art. A preferred method for determining the KD of an antibody is by using surface plasmon resonance, preferably using a biosensor system such as a Biacore system.

The extension of term regime

37 Section 70 currently provides:

(1) The patentee of a standard patent may apply to the Commissioner for an extension of the term of the patent if the requirements set out in subsections (2), (3) and (4) are satisfied.

(2) Either or both of the following conditions must be satisfied:

(a) one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

(b) one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

(3) Both of the following conditions must be satisfied in relation to at least one of those pharmaceutical substances:

(a) goods containing, or consisting of, the substance must be included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods;

(b) the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years.

(4) The term of the patent must not have been previously extended under this Part.

(5) For the purposes of this section, the first regulatory approval date, in relation to a pharmaceutical substance, is:

(a) if no pre-TGA marketing approval was given in relation to the substance—the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods of goods that contain, or consist of, the substance; or

(b) if pre-TGA marketing approval was given in relation to the substance—the date of the first approval.

(5A) …

(6) For the purposes of this section, pre-TGA marketing approval, in relation to a pharmaceutical substance, is an approval (however described) by a Minister, or a Secretary of a Department, to:

(a) market the substance, or a product containing the substance, in Australia; or

(b) import into Australia, for general marketing, the substance or a product containing the substance.

38 I note that “pharmaceutical substance” is defined in sch 1 as:

a substance (including a mixture or compound of substances) for therapeutic use whose application (or one of whose applications) involves:

(a) a chemical interaction, or physico-chemical interaction, with a human physiological system; or

(b) action on an infectious agent, or on a toxin or other poison, in a human body; but does not include a substance that is solely for use in in vitro diagnosis or in vitro testing.

39 The original form of s 70 was repealed by s 5 of the Patents (World Trade Organization Amendments) Act 1994 (Cth) Ch 6 Pt 3 Div 2. Section 70 was re-introduced by s 3 of the 1998 Amendment Act and commenced on 27 January 1999.

40 Pursuant to s 70(1), the patentee of a standard patent may apply for an extension of the term of the patent if the ss 70(2), (3) and (4) requirements have been satisfied.

41 Let me elaborate on these conditions.

42 First, s 70(2) provides that either or both of the following conditions must be satisfied:

(a) one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

(b) one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

43 Second, s 70(3) provides that the following conditions must be satisfied in relation to the pharmaceutical substance disclosed and claimed in the specification, namely, that:

(a) goods containing or consisting of the substance must have been included in the ARTG; and

(b) the period beginning on the date of the patent (s 65) and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years.

44 I have emphasised the definite article and will return to this later.

45 Third, s 70(4) provides that the term of the patent must not have been previously extended. That requirement is satisfied in the present case and I need say nothing further about it.

46 It is also important to note that s 70(5)(a) provides that if no pre-TGA marketing approval was given in relation to the substance, the first regulatory approval date in relation to a pharmaceutical substance is the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods that contain or consist of the substance. Again I have emphasised the definite article.

47 In terms of the form and timing of an extension application, s 71 provides:

(1) An application for an extension of the term of a standard patent must:

(a) be in the approved form; and

(b) be accompanied by such documents (if any) as are ascertained in accordance with the regulations; and

(c) be accompanied by such information (if any) as is ascertained in accordance with the regulations.

(2) An application for an extension of the term of a standard patent must be made during the term of the patent and within 6 months after the latest of the following dates:

(a) the date the patent was granted;

(b) the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods of goods that contain, or consist of, any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3), as worked out under subsection 70(5A) (if applicable);

(c) the date of commencement of this section.

48 So, as s 71(2) provides, an application for an extension of term must be made during the term of the patent and within 6 months after the latest of:

(a) the date the patent was granted;

(b) the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods that contain or consist of any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(3); and

(c) the date of commencement of s 71.

49 In the present context I need only concern myself with s 71(2)(b).

50 Section 74 deals with the acceptance or refusal of an extension application and provides:

(1) If a patentee of a standard patent makes an application for an extension of the term of the patent, the Commissioner must accept the application if the Commissioner is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that the requirements of sections 70 and 71 are satisfied in relation to the application.

…

(3) The Commissioner must refuse to accept the application if the Commissioner is not satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that the requirements of sections 70 and 71 are satisfied in relation to the application.

…

51 Finally, s 77, the calculation provision, provides:

(1) If the Commissioner grants an extension of the term of a standard patent, the term of the extension is equal to:

(a) the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the earliest first regulatory approval date (as defined by section 70) in relation to any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(2);

reduced (but not below zero) by:

(b) 5 years.

(2) However, the term of the extension cannot be longer than 5 years.

52 In essence then, if the Commissioner grants an extension of the term, the term of the extension is equal to the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the earliest first regulatory approval date (as defined by s 70) in relation to any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(2), reduced by 5 years but not such as to go below zero.

53 At this point I should also note two other matters concerning the legislative provisions.

54 First, at the time ss 70 and 71 were re-introduced by the 1998 Amendment Act, there was also introduced s 76A which provided:

In respect of each application for an extension approved by the Commissioner under section 76 in a financial year, the patent holder must lodge with the Secretary of the Department, before the end of the following financial year, a return setting out the following information:

(a) details of the amount and origin of any Commonwealth funds spent in the research and development of the drug which was the subject of the application; and

(b) the name of any body:

(i) with which the applicant has a contractual agreement; and

(ii) which is in receipt of Commonwealth funds; and

(c) the total amount spent on each type of research and development, including pre-clinical research and clinical trials, in respect of the drug which was the subject of the application.

55 Section 76A was introduced in the Senate as an amendment. But s 76A was later repealed by item 4, Pt 4 of Sch 1 to the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Productivity Commission Response Part 1 and Other Measures) Act 2018 (Cth).

56 Why am I mentioning s 76A? Implicitly it strongly supports the applicants’ construction arguments rather than those of the Commissioner. The reference to amounts spent on research and development clearly refer to the activities or investments of the patentee or under its authority, not a third party let alone a competitor. Is it seriously suggested that a patentee could obtain or provide such detail in relation to a competitor’s “drug” to use the term in s 76A? I think not. I will develop this point later.

57 Second, in February 2020 an object clause was added to the Act by item 1, Pt 1, Sch 1 of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Productivity Commission Response Part 2 and Other Measures) Act 2020 (Cth). The object provision, s 2A, provides:

The object of this Act is to provide a patent system in Australia that promotes economic wellbeing through technological innovation and the transfer and dissemination of technology. In doing so, the patent system balances over time the interests of producers, owners and users of technology and the public.

58 It is now convenient to note briefly the extrinsic material, although of course it is the statutory text construed in context that is the start and finish of the analysis.

59 The 1997 EM and the second reading speech to the Bill that became the 1998 Amendment Act, manifest the legislature’s recognition that due to the long development time and regulatory requirements involved in commercialising a new pharmaceutical substance, patentees of pharmaceutical products have considerably fewer years of patent protection within which to gain a return on their investment than patentees in other areas of technology. Accordingly, the manifest intention in introducing extension of term provisions directed to pharmaceutical substances was to provide an effective patent life, being the period after marketing approval was obtained, during which patentees were able to exploit their invention and to earn a return on their investment. This was to provide some form of commercial parity available to the proprietors of patents for inventions in other fields of technology. In essence, the purpose was to restore the time lost to patentees prior to gaining marketing approval to compensate the patentee for the additional time, expense and difficulty in developing and commercialising a new pharmaceutical substance.

60 As was explained in the second reading speech by the then Minister for Customs and Consumer Affairs (Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 26 November 1997, 11274 to 11275):

The development of a new drug is a long process. A new chemical entity, from which a pharmaceutical is derived, is patented early in the process. However, considerable research and testing is still required before the product can enter the market. This long development time, combined with the considerable regulatory process to register and market a new product, means that companies usually have considerably fewer years under patent in which to gain a return on their investment. This becomes significant to the industry as companies rely heavily on patents to generate the substantial cash flows necessary to finance the development of new drugs.

A country’s patent system is also an important factor in investment decisions. A strong patent system contributes significantly to a positive investment climate and sends a signal that Australia values an innovative pharmaceutical industry. The objective of this part of the bill is to provide an ‘effective patent life’ more in line with that available to pharmaceuticals inventions in other fields of technology. It will also create a patent regime for which is in line with our competitors.

An extension of up to five years will be available for a standard patent relating to a pharmaceutical substance that is the subject of first inclusion on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. The scheme will apply to all existing 20 year patents, as well as those patents granted after the commencement of the scheme. An extension is not however, automatic. Companies will need to apply within six months of the inclusion of the product on the ARTG or within six months of the date the patent is granted, which ever is the later. Transitional arrangements will be put in place to accommodate existing patents.

The new arrangements make provision for ‘spring-boarding’ activities. This allows manufacturers of generic drugs to undertake certain activities prior to the expiry of the patent solely for the purposes of meeting pre-marketing regulatory approval requirements. Companies will be permitted to spring-board any time after the extension has been granted.

61 There are various features to note about this speech.

62 First, there is reference to the proposed legislation providing an “effective patent life”. Presumably this is a reference to the effective time for the patentee to exploit its invention. One rhetorically asks how that could be so if “the product on the ARTG” triggering the start of the extension was not that of the patentee, but rather that of a stranger or indeed a competitor? That would not provide an “effective patent life” for the patentee at all.

63 Second, the reference to “the product” was clearly not that of a stranger let alone a competitor.

64 In the 1997 EM it was stated:

Extensions of up to five years on the standard 20 year term are available for pharmaceutical patents in the United States, the European Union and Japan in recognition of the exceptionally long development time and regulatory requirements involved in developing and commercialising a new drug. The aim is to provide an ‘effective patent life’, or period after marketing approval is obtained during which companies are earning a return on their investment, more in line with that available to inventions in other fields of technology.

…

The development of a new drug is a long process, estimated to average around 12 years, which requires a new chemical entity to be patented early in the process in order to secure its intellectual property rights. However, considerable research and testing is still required before the product can enter the market. As a consequence, patentees of new drugs usually have considerably fewer years under patent in which to maximise their return.

It is expensive to bring a drug to market, around US$380 million, and involves considerable risk. As such, research based pharmaceutical companies rely heavily on patents to generate the substantial cash flows needed to finance the development of new drugs from the discovery stage, through the pre-clinical and clinical development phases, to eventual marketing.

…

The objective of this proposal is to provide an ‘effective patent life’ – or period after marketing approval is obtained, during which companies are earning a return on their investment – more in line with that available to inventions in other fields of technology. It is also intended to provide a patent system which is competitive with other developed nations.

…

However for manufacturers and developers of patented drugs, the level of protection provided under the present patent system is less than that provided for other fields of technology, because of the longer time lost in developing and gaining marketing approval for new drugs. The industry thus gains a limited return on its investment and is restricted in its capacity to invest in the development of new products.

65 Again, there is a reference to the “effective patent life”.

66 I also note that the 1997 EM referred to the Industry Commission Report No. 51, The Pharmaceutical Industry of 3 May 1996 (the IC Report). Section 16.3 of the IC Report stated:

Patent term restoration refers to extending the patent term to ‘restore’ time lost in gaining marketing approval. Patent holders argue that, where a product must go through pre-marketing approval, the period during which they can exploit their statutory monopoly (the ‘effective patent life’) is reduced. The reduced patent life is too short to allow a satisfactory return on their investment in R&D.

67 There was also a reference to the EU and US practices concerning extensions of term. But there was no suggestion that there was contemplated to be any radical difference from, for example, the US position concerning “the product” being referred to, let alone that the regime could be affected by the product of a competitor.

68 Further, I note that the Government’s response to the IC Report (Final Government Response to the Industry Commission Report No. 51, The Pharmaceutical Industry (9 April 1997)) stated:

The Government will introduce a new extension of term scheme for pharmaceutical patents in recognition that the long development times and regulatory requirements for new pharmaceuticals significantly erode the time available under patent to exploit the invention. In line with the situation in the US, the EU and Japan, extensions of up to five years will be available for 20 year standard term patents for new pharmaceutical substances.

Where extensions are granted, third parties will be allowed to undertake activities solely for the purposes of meeting pre-marketing regulatory requirements without infringing the patents. This is in recognition of the legitimate interests of generic drug manufacturers in Australia.

69 Again, nothing in this material indicated that “the product” providing the trigger could be that of a stranger or even a competitor. Indeed, on this aspect there is simply nothing to indicate that it was intended that there be some radical departure from, inter-alia, the US practice on this aspect.

70 Now I accept that my brief excursion through the extrinsic material cannot drive the analysis. Rather it is the text of the provisions read in context which is the relevant inquiry. But context may be illuminated not just by other relevant provisions in the Act, but also by the legislative history and other extrinsic materials.

71 But as was said in Alphapharm Pty Limited v H Lundbeck A/S (2014) 254 CLR 247 at [42] by Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ:

The pre-existing law and the legislative history should not deflect the Court from its duty to resolve an issue of statutory construction, which is a text-based activity.

72 But as was also observed in Mondelez Australia Pty Ltd v Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union (2020) 381 ALR 601 by Gageler J, albeit in dissent in the result, at [66] and [67]:

The pronouncement of five members of the High Court in 2010 that “it is erroneous to look at extrinsic materials before exhausting the application of the ordinary rules of statutory construction” cannot be understood to have meant more than to stress that statements of legislative intention made in extrinsic materials do not “overcome the need to consider the text of a statute to ascertain its meaning”. The “modern approach to statutory interpretation”, which was well-established before the pronouncement and which has continued in practice afterwards, “(a) insists that the context be considered in the first instance, not merely at some later stage when ambiguity might be thought to arise, and (b) uses ‘context’ in its widest sense to include such things as the existing state of the law and the mischief which … one may discern the statute was intended to remedy”.

Applying the modern approach to statutory interpretation, consideration of context, including consideration of legislative history and extrinsic materials, “has utility if, and in so far as, it assists in fixing the meaning of the statutory text”. The quality and extent of the assistance extrinsic materials provide in fixing the meaning of statutory text is not uniform. The quality and extent of the assistance varies in practice in ways unable to be fully appreciated without regard to the provenance and conditions of creation of the extrinsic materials.

(Citations omitted.)

73 It is now appropriate to turn to the parties’ arguments.

A reasonable and commercial construction?

74 Let me begin with the applicants’ arguments and s 70.

75 The applicants submit that it is clear from the text of s 70 that the relevant requirements may be satisfied by any one of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in ss 70(2)(a) and (b) which are disclosed and claimed in the patent.

76 First, both ss 70(2)(a) and (b) recognise that there may be “one or more pharmaceutical substances” which are in substance disclosed in the complete specification and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims.

77 Second, s 70(3) requires that certain conditions be satisfied “in relation to at least one of those pharmaceutical substances”, that is, at least one or more pharmaceutical substances disclosed and claimed. By using the phrase “at least one”, s 70(3) recognises that the conditions in ss 70(3)(a) and (b) may be satisfied by one or more of the pharmaceutical substances that are disclosed and claimed. Provided the conditions of ss 70(3)(a) and (b) are met, s 70(3) does not otherwise impose any conditions or restrictions on which of the “at least one” pharmaceutical substances must be used to satisfy the requirements of s 70(3).

78 Third, ss 70(3)(a) and (b) require that “goods containing, or consisting of, the substance must be included in the [ARTG]” and that “the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years”. The use of the definite article “the” confines the operation of ss 70(3)(a) and (b) to the “at least one” pharmaceutical substance specified by the patentee as satisfying the pre-conditions set out in s 70.

79 The applicants say that this analysis is consistent with Bennett J’s approach in H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151 at [232], in which her Honour accepted that:

… s 70(2) operates to identify a candidate patent for extension, where the pharmaceutical substance per se is in substance disclosed and in substance within the scope of a claim. Once that patent and the substance are identified, the inquiry turns to s 70(3) and whether that pharmaceutical substance is contained in goods on the ARTG.

80 Fourth, the term “first regulatory approval date” is defined in s 70(5)(a) to mean “the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain, or consist of, the substance”. Again, it is said that the use of the definite article confines the operation of that definition to the “at least one” pharmaceutical substance forming the basis of the patentee’s application. So, properly understood, the relevant “first regulatory approval date” is that of the good containing the pharmaceutical substance specified in the application for the extension of term. And the period referred to in s 70(3)(b) must be calculated by reference to that approval date.

81 Fifth, s 70(4) requires that “the term of the patent must not have been previously extended under this Part”. The applicants say that this requirement reinforces the construction that any “one or more pharmaceutical substances” disclosed and claimed can be used as the basis for satisfying the requirements of s 70.

82 Accordingly, the applicants say that in the context of the OPDIVO application, the requirements of s 70 are satisfied by nivolumab. It is a pharmaceutical substance per se in substance disclosed in the complete specification and in substance falling within the scope of claim 3 (s 70(2)(a)). Goods containing nivolumab, namely OPDIVO, are included in the ARTG (s 70(3)(a)). The period beginning on the date of the patent (being 2 May 2006) and ending on the first regulatory approval date for OPDIVO (being 11 January 2016) is at least 5 years (s 70 (3)(b)). And the term of the patent has not been previously extended (s 70(4)).

83 Let me then move to the form and timing of the application and s 71.

84 The applicants say that any one or more pharmaceutical substances in substance disclosed and claimed in a patent may be used for the purposes of calculating the time by which an application for an extension of term must be filed under s 71.

85 Pursuant to s 71, an application for an extension of term must be in the approved form and accompanied by such documents and information as prescribed by the Patent Regulations 1991 (Cth). Regulation 6.8 provides:

(1) This regulation applies to an application under section 70 of the Act for an extension of the term of a standard patent for a pharmaceutical substance.

(2) For paragraph 71(1)(c) of the Act, the application must be accompanied by information showing that goods containing, or consisting of, the substance are currently included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods.

(3) The application must also be accompanied by information identifying the substance, as it occurs in those goods, in the same way (as far as possible) as the substance is identified in the complete specification of the patent.

86 Relevantly, reg 6.8(2) requires an application for an extension of term to be “accompanied by information showing that goods containing, or consisting of, the substance are currently included in the [ARTG]”. This means that an application must specify the substance the subject of the good currently included in the ARTG which is nominated for the purposes of satisfying the requirements of s 70. Further, the requirements of reg 6.8(3) implicitly talk to the patentee’s goods, not that of a competitor. But of course a subordinate instrument cannot drive the construction of the principal provision.

87 The applicants say that when the requirements of ss 70 and 71 are read together, there is a nice fit. The substance referred to in s 70 and used as the basis for the application for extension of term is the same substance as that used for the purposes of calculating the time by which an application must be filed.

88 Section 71(2) sets out the timing requirement for the making of an application under s 70. Relevantly, s 71(2)(b) provides that an application must be made within 6 months after “the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain, or consist of, any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3) …”.

89 Like s 70(3), s 71(2)(b) contemplates that the time by which an application for an extension of term must be made can be calculated by reference to “any of the pharmaceutical substances” disclosed and claimed in the patent.

90 The language of s 71(2)(b) substantially mirrors the definition of “first regulatory approval date” contained in s 70(5), save that it refers to “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)” rather than “the substance”. The applicants say that this is necessary as the substance specified by the patentee for the purposes of satisfying the requirements of s 70(3) can be any pharmaceutical substance that is in substance disclosed and claimed in the patent.

91 Further, s 71(2)(b) provides that an application for extension of term must be made, inter-alia, “within 6 months after … the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain, or consist of, any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)”. Even if the requirements of s 70 may have been satisfied at an earlier point in time in relation to another substance, an application for an extension of term can be made at a later point in time by another pharmaceutical substance satisfying the requirements of s 70. Section 70(4) provides that the term of a patent can only be extended once.

92 Finally, let me say something concerning the applicants’ submissions on s 77.

93 The term of an extension is calculated under s 77. It is calculated by determining the difference between the date of the patent and the earliest first regulatory approval date (as defined in s 70(5)) in relation to any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(2), and then subtracting 5 years, of course not going below zero. Where the calculation of the period is more than 5 years, the term of the extension is the maximum term of 5 years (s 77(2)).

94 Section 70(5)(a) defines “first regulatory approval date” in relation to a pharmaceutical substance as “the date of commencement of the first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain, or consist of, the substance”. For present purposes, the applicants say that nivolumab is “the substance”.

95 The applicants say that the language of s 77 is to be construed against the backdrop of the earlier provisions. They say that once an application for an extension of term has met the conditions for acceptance, the term of that extension must be calculated according to s 77. But the terms of s 77 do not prescribe the criteria for the grant of an extension in the first place. Of course I agree with that proposition.

96 The applicants say that the term of the extension is calculated by reference to the earliest first regulatory approval date of any pharmaceutical substance that is disclosed and claimed in the patent, being the substance that the patentee nominates in its application for extension of term for the purposes of s 70(2).

97 Now s 77 refers to “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(2)”. As with s 71(2)(b), the applicants say that the use of the word “any” means that s 77 does not impose any conditions or restrictions on which pharmaceutical substance may be used for the purposes of calculating the term of extension, save that it must be one of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(2). So on the applicants’ case it is the pharmaceutical substance specified by the patentee for the purposes of its application for an extension of term.

98 In summary, the applicants say that in accordance with s 77 and based on the regulatory approval date of OPDIVO, the term of the patent should be extended from 2 May 2026 to 11 January 2031.

A construction dictated by strict textualism?

99 Now as the Commissioner framed the matter, the Commissioner says that the applicants seek to limit the operation of ss 71 and 77 by reference to a particular substance nominated at the applicants’ election in the application form for an extension of time and to have ss 70, 71 and 77 operate only by reference to the date on which that substance was first included in the patentee’s goods included in the ARTG.

100 But contrastingly, the Commissioner submits that having regard to their plain meaning, the extension of term provisions are not so limited.

101 The Commissioner says that ss 71 and 77 operate by reference to considerations of the “first” and “earliest first” date on which goods containing “any” of the substances meeting the requirements of s 70(3) (in the case of s 71) or s 70(2) (in the case of s 77(1)(a)) were first included in the ARTG.

102 The Commissioner says that none of the provisions impose a requirement that there be any relationship between the patentee seeking the extension and the entity that holds the ARTG approval with respect to the “good” registered on the ARTG.

103 In essence, the Commissioner, like the delegate, considered the statutory scheme to be agnostic concerning any relationship between the patentee on the one hand, and the ARTG approval or the good on the other hand, a position that I might say I reject.

104 Let me say something about the Commissioner’s submissions concerning s 71(2)(b).

105 Now the words “first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain … any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)” are important.

106 As I have endeavoured to indicate, the applicants say that this is a reference only to the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods of the patentee containing one of the s 70(2) substances. And in cases where there is more than one s 70(2) substance, the substance referred to in s 71(2)(b) is that nominated by the patentee in its application for an extension of term.

107 But the Commissioner says that this puts the cart before the horse. The Commissioner says that s 71(2)(b) does not operate by reference to whichever substance an applicant for an extension of term choses to nominate in an application form, much less by reference to the patentee’s “good” or “goods”. Rather, s 71(2)(b) operates by reference to the “first inclusion” in the ARTG of goods that contain “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)”.

108 The Commissioner says that close attention must be paid to the words “any” and “substances referred to in subsection 70(3)”.

109 On its proper construction, the Commissioner says that the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(3) are all of the pharmaceutical substances the subject of s 70(2) and which meet the two further requirements set out in s 70(3).

110 The Commissioner then says that in practical terms, the result is as follows.

111 Take the first scenario where there were two substances, namely, substance A and substance B, the subject of s 70(2), but where only substance B met the further requirements in s 70(3). The Commissioner says that s 71(2)(b) would operate by reference to the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods containing substance B.

112 The Commissioner then posited a second scenario where there were two substances the subject of s 70(2), namely, substance C and substance D and where both met the further requirements of ss 70(3)(a) and (b). The Commissioner said that the phrase “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)” would pick up both of those substances. When the composite expression “first inclusion in the [ARTG] of goods that contain … any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)” is then pieced together, the Commissioner says that the result would be that s 71(2)(b) operates by reference to the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods containing either substance C or substance D.

113 Let me turn to the Commissioner’s submissions concerning s 77.

114 The Commissioner says that unlike s 71(2)(b), which cross-refers to “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)”, s 77 refers to “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(2)”.

115 In this context, the Commissioner then developed further the second scenario that I have just set out.

116 Let it be assumed that substance C is first contained in goods first included in the ARTG precisely 6 years after the date of the patent and that substance D is first contained in goods first included in the ARTG 6.5 years after the date of the patent. And let it be assumed that the patent has not been previously extended.

117 An application to extend the term of the patent would need to be made pursuant to s 71 within 6 months of the first inclusion of goods containing substance C on the ARTG. And if granted, the term of any extension would be calculated by reference to the regulatory approval date of goods containing substance C. This represents, in the language of s 77, “the earliest first regulatory approval date (as defined by section 70) in relation to any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(2)”. The extended term would be calculated as 1 year (6 years less 5 years).

118 The Commissioner then further modified the second scenario. Assume that substance C is contained in goods first included in the ARTG 4 years, instead of 6 years, after the date of the patent, but the timing in respect of substance D remained the same. The Commissioner said that the effect of s 71(2)(b) would be to permit an application to be made by the patentee within 6 months of the date that a good containing substance D was first included in the ARTG. But when it comes to calculating the extension of term, s 77(1)(a) would reduce the extended term to zero having regard to the timing of inclusion of goods containing substance C in the ARTG only 4 years after the date of the patent. I will return to this modified second scenario later.

119 Further, as to the applicants’ position that any third party products such as KEYTRUDA must be excluded from consideration when determining whether the conditions of ss 70, 71 and 77 are satisfied, the Commissioner says that this raises the frightful spectre of a need to rewrite the statutory provisions.

120 Further, the Commissioner says that the applicants neglect the precise wording of ss 71(2)(b) and 77 by their assertion that provided the conditions of ss 70(3)(a) and (b) are met, s 70(3) does not otherwise impose any conditions or restrictions on which of the “at least one” pharmaceutical substances must be used to satisfy the requirements of s 70(3), and accordingly, any of the substances that satisfies s 70(2) may be used for the purposes of calculating the time to file an application under s 71(2)(b).

121 First, it is said that this puts to one side the language in s 71(2)(b) of “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)” and the combined expression “first inclusion … of goods that contain … any of” such pharmaceutical substances. But the Commissioner says that this is the important point of distinction between s 71(2)(b) and s 70(5). It is said that the express terms of s 71 admit no limitation and election by the patentee in the way the applicants suggest.

122 Further, it is also said that the applicants’ contentions as to s 77 likewise gloss over the words in s 77 of “earliest first regulatory approval date (as defined by section 70) in relation to any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(2)”. The text of s 77 requires the definition of “earliest first regulatory approval date” in s 70(5) to be applied to all of the s 70(2) substances, not merely to only one of them, let alone just to the substance within the good that a patentee chooses to nominate in its application for an extension of term. If the latter were the case, then the word “earliest” would be otiose. Section 77 is expressly not confined to the substance or substances which meet the requirements of s 70(3); it is a reference to the “earliest first” regulatory approval date of any of the s 70(2) substances.

123 Second, as to s 71(2)(b) and the requirement to file the extension application within 6 months, the applicants assert that when read together with s 70, it is not inconsistent with the operation of the regime that the substance referred to in s 70, which is used as the basis for the application for the extension of term, is the same substance as that used for the purposes of calculating the time by which an application must be filed. But the Commissioner says that it is not by the patentee’s own whim which of the s 70(2) substances, or even which of the s 70(3) substances to the extent that there is any difference, is picked up by s 71(2)(b) as the basis for commencing the 6 month clock. Time starts to run for the purposes of s 71(2) according to the reference date specified in the text of s 71(2). Section 71(2) is explicit that time runs from the first inclusion in a good on the ARTG of “any” of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(3).

124 Third, the applicants say that the definite article in s 70(3)(a) and (b) comes under a chapeau that requires “at least one” of the s 70(2) substances to meet the conditions set out in s 70(3)(a) and (b). It is a test that might be met by more than one of the s 70(2) pharmaceutical substances. But the Commissioner says that the use of the definite article in both ss 70(3)(a) and (b) and in s 70(5) are simply identifying that each substance is to be tested against the limbs of (a) and (b). The result may be that more than one substance satisfies s 70(3).

125 Further, the Commissioner says that Bennett J’s comments in H Lundbeck at [232] were made in a context where only a single pharmaceutical substance, namely (+)–citalopram, was identified under s 70(2). Accordingly, her Honour’s use of the word “that” in the sentence “the inquiry turns to s 70(3) and whether that pharmaceutical substance is contained in goods on the ARTG”, does not provide support for the proposition that the regime operates by reference to the substance and goods specified in the patentee’s application and ignorant of whether that or some other s 70(2) substance has been previously included in some other goods earlier included in the ARTG. I agree and do not need to discuss this case further. The applicants have better points.

126 Fourth, the Commissioner says that the fact that s 70(4) prevents the extension of term regime being available to a patentee more than once does not assist the applicants. It reinforces that there may be more than one pharmaceutical substance which can trigger eligibility to make an extension of term application. But it does not mean that if a patentee fails to exercise within the time permitted by s 71 its right to apply for an extension of term referable to the first time a s 70(2) substance is contained in a good included in the ARTG, that the extension of term regime remains open to it.

127 Further, the Commissioner says that even if it is within the applicants’ discretion to nominate which of the “one or more” substances that satisfy s 70(2) is to be used to run through the s 70(3) hurdles or even to be used for the purposes of calculating application deadlines for the purposes of s 71(2), that does not alter the clear wording of s 77 that compels the calculation of the duration of the appropriate term of extension to be from the “earliest first” date of “any of the substances referred to in s 70(2)”.

128 Fifth, the Commissioner also prayed in aid the case law that the delegate relied upon.

129 Now the delegate principally relied upon the decision of Bennett J in Pfizer Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (No 2) (2006) 69 IPR 525 where her Honour was required to determine the meaning of “first inclusion in the ARTG” (in 70(5)) and the “earliest first regulatory approval date” (in s 77). Her Honour noted that s 70(5) recognises that there may be more than one inclusion in the ARTG, which is consistent with the structure of the ARTG, and found that the meaning of the expression “first inclusion in the [ARTG]” was on its face clear and unambiguous. Her Honour said at [32]:

When the reference to “first inclusion in the ARTG” is informed by an understanding of the nature of the ARTG, the first inclusion means the entry, first time, in a part of the ARTG. In the present case that is the first entry as listed goods.

130 Now the patentee in Pfizer contended that this construction was incorrect. The patentee said that the unifying notion of the phrase “first regulatory approval date” meant that the pertinent date must be the date that enables marketing in Australia. Now as her Honour perceived it, the patentee was seeking to read in an additional qualifier to the words of the definition, amending the “first regulatory approval date” to mean the first date that permits marketing in Australia. Her Honour rejected this, referring to s 77 which consistently includes a reference to the “earliest first regulatory approval date”. Her Honour concluded at [34] that:

Section 77 refers to the “earliest first regulatory approval date” (emphasis added). This recognises that the patent may cover more than one pharmaceutical substance and provides that the term of the extension is based on the earliest of the approval dates that apply to the patent.

131 The delegate applied her Honour’s reasoning at [34] and the reasoning of the delegate in G D Searle LLC (2008) 80 IPR 210, and considered that “[g]iven those paragraphs it is difficult to see how the present application on the basis of OPDIVO could succeed” (at [28]).

132 The Commissioner before me persisted in relying upon Pfizer. Further, the Commissioner says that Bennett J’s reasoning in Pfizer has been followed by several other APO decisions; see Re iCeutica Pty Ltd (2018) 146 IPR 342 at [28], G D Searle at [16] and [18] and Pfizer Italia S.r.l [2007] APO 2 at [24] and [27].

133 But I should say now that I agree with the applicants that Pfizer was a different case to the present because Bennett J was not asked to construe the meaning of the relevant provisions in the context of a patent that discloses more than one substance. I will return to Pfizer later. I should also say that I do not need to discuss these other cases in detail if Pfizer is not a secure foundation.

Analysis

134 The applicants’ construction of ss 70, 71 and 77 is the correct one.

135 The extension of term regime is beneficial and remedial. It is designed to compensate a patentee of a pharmaceutical substance for the loss in time before which it can exploit its invention. It is designed to remedy the mischief of a shortened period for an effective monopoly that has been caused by delays in obtaining regulatory approval. Accordingly, a liberal rather than a literal construction is to be preferred.

136 Let me begin with s 71(2)(b) where reference is made to the first inclusion in the ARTG of goods that contain or consist of “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)”.

137 If one looks at s 70(3), it refers to “the substance”. But “the substance” is that chosen from “at least one of those pharmaceutical substances”, that is, the “one or more pharmaceutical substances” referred to in ss 70(2)(a) or (b). So the word “any” in s 71(2)(b) and by reference back to s 70(3) just reflects that it is the one chosen which then becomes “the substance” under s 70(3). The one chosen is “the substance” under s 70(3) if it meets the condition(s) of s 70(2). And it is “the substance” under s 70(5)(a).

138 Clearly, provided the conditions of ss 70(3)(a) and (b) are satisfied, s 70(3) does not impose any additional conditions or restrictions on which of the “at least one of those pharmaceutical substances” may be used to satisfy the requirements of s 70(3). Further, s 70(3) is not free-standing in the sense that it is to be read with and in the context of s 70(2).

139 Further, s 71(2)(b) substantially mirrors s 70(5)(a) save that it refers to “any of the pharmaceutical substances referred to in subsection 70(3)” rather than “the substance”. But this is because the substance specified by the patentee to satisfy s 70(3) can be any pharmaceutical substance that is in substance disclosed and claimed in the patent.

140 Accordingly, it is for the patentee under s 71(2)(b) to stipulate the pharmaceutical substance. But of course in so stipulating, the requirements of s 70(3) read in the light of s 70(2) must be satisfied. But although the patentee has that freedom to stipulate, there are other broader constraints such as under s 70(4) and also under s 77(1)(a) concerning the calculation of the term which uses “the earliest first regulatory approval date” (my emphasis).

141 Now what I have just said fits nicely with s 77, which operates once an application for an extension of term meets the conditions for acceptance. Of course it is not dealing with the criteria for the grant of any extension.

142 Now the Commissioner has sought to finesse much from the fact that whilst s 71(2)(b) cross-refers to s 70(3), s 77(1)(a) cross-refers to s 70(2).

143 But s 71 is a timing provision. Understandably it refers back to s 70(3), which concerns timing requirements for a candidate pharmaceutical substance. Section 77 contains its own timing requirements expressly within s 77(1)(a). In any event, both ss 71 and 77 ultimately cross-refer back to the pharmaceutical substances referred to in s 70(2) in the light of the implicit cross-reference in s 70(3) back to s 70(2).

144 Further, the modified second scenario posited by the Commissioner, which I have set out at [118], demonstrates the inappropriateness of the construction for which the Commissioner contends. The Commissioner on the corollary of that construction identifies the circumstances in which different substances might be used for the purposes of s 71 and s 77, namely, where the substance with the earlier ARTG registration date did not satisfy the requirements of s 70(3)(b). But in the Commissioner’s modified second scenario, the term of the extension will always be reduced to zero by virtue of s 77, because goods comprising the earlier substance would have to have been included in the ARTG less than 5 years after the date of the patent, if they did not (by definition of this scenario) satisfy s 70(3)(b). The effect of the Commissioner’s construction is that the only circumstance in which a substance with a later-in-time ARTG registration might be used for the purposes of s 71 is one in which the extension application would not result in any extension of term. That construction leads to an absurd result.

145 But there are also other scenarios. Say the competitor’s product was approved at year 6, so 1 year after the 5 years in s 70(3)(b). Say the patentee’s product is approved at year 9 and is the subject of a s 71(2)(b) application. Now come to s 77. On the applicants’ construction the patentee gets a 4 year extension. On the Commissioner’s construction the patentee gets a 1 year extension. Further, a different application by the patentee would have needed to have been made under s 71(2)(b) within a different timeframe. Possible scenarios of disadvantage to the patentee can be multiplied.

146 Further, in my view, Pfizer does not assist the Commissioner. In Pfizer, Bennett J was not required to construe the meaning of s 77 in the context of a patent which in substance disclosed and claimed more than one pharmaceutical substance. The issue in Pfizer was whether the first inclusion in the ARTG was the date of listing for export only or the date of registration enabling Pfizer to market the substances in Australia. Pfizer contended that the relevant date was that of registration, not of any listing in the ARTG. Her Honour held that an inclusion in the ARTG, including an export only listing as listed goods, was an inclusion in the ARTG for the purposes of s 70. In doing so, her Honour rejected Pfizer’s submission that the relevant approval must be one which allows marketing in Australia, observing that inclusion in the ARTG as listed goods still permitted the patentee to exploit the patent and thus enabled a commercial return to the patentee. But that is a different case to the one before me. Now the Commissioner says that the fact that the skirmish in Pfizer centred on a construction of whether the “first inclusion in the ARTG” depends on a particular type of approval (or the absolute first inclusion) does not reduce the applicability of her Honour’s reasoning in the present context. But I disagree. The fact is that her Honour was not focused on what I have to consider. There is nothing in her Honour’s reasons, particularly at [21], [22] and [30] to [34] suggesting that she was doing anything other than talking about Pfizer’s goods at all times.

147 Further, the applicants’ construction is supported by the extrinsic materials relating to the introduction of Ch 6 Pt 3 of the Act that I have set out earlier.

148 Now in Alphapharm Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ said (at [60]):

The purposes of the extension of term scheme are to balance the competing interests of a patentee of a pharmaceutical substance whose exploitation of monopoly has been delayed (because of regulatory delay) and the public interest in the unrestricted use of the pharmaceutical invention (including by a competitor) after the expiration of the monopoly (that is, the term).

149 Further, Kiefel and Keane JJ (albeit in dissent) said (at [120]):

There is no doubting that the purpose behind s 70(1) is to benefit and encourage research and development. Other provisions of the 1990 Act, including those for advertisement of and opposition to applications for extension of the term of a pharmaceutical patent (156), recognise that there are interests, other than those of a patentee, which are affected by an extension. The Explanatory Memorandum for the 1989 Amendment Act said as much, in its statement as to the policy behind s 160(4A), when extension provisions for pharmaceutical patents were introduced. Against this background, the requirements of s 71(2), the strictness of which is reinforced by the effect of reg 22.11(4)(b), may be taken as intended to provide those other interested persons with a level of certainty as to whether an application for extension of the term of a patent is to be made by a patentee.

150 So I accept that the extension regime sought to balance a range of competing interests and purposes. The compensation of some time lost due to regulatory hurdles is a purpose of the regime. But it is not the sole purpose. Accordingly, ss 70(3), 71(2) and 77(2) reflect a balancing of purposes.

151 But even so accepting and even if I was to consider the later introduced object clause in s 2A, which I take to reflect the then existing goals of the patent system at the time of the introduction of s 2A, in any event the applicants’ construction is to be preferred. It reflects the mischief which the extension of term regime is intended to address. The evident purpose of the extension of term provisions is to provide the patentee with an effective patent life by restoring the time lost by the patentee prior to gaining market approval, thereby compensating the patentee for the additional time, expense and difficulty in commercialising its new product.