Federal Court of Australia

Sands Contracting Pty Ltd v Cant [2021] FCA 638

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiffs’ appeal be allowed.

2. The defendants’ rejection of the plaintiffs’ proof of debt or claim dated 28 October 2020 in the liquidation of Foodcorp (Vic) Pty Ltd (ACN 074 563 385) be set aside.

3. The defendants or any replacement liquidator do admit the plaintiffs’ proof of debt or claim for $253,051.

4. Should either party seek its costs, the moving party is to file written submissions (not exceeding 3 pages) within 7 days of the date of this order, with the other party permitted a further 7 days from receipt of the moving party’s submissions to file any responsive submissions.

5. Any question of costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCKERRACHER J

INTRODUCTION

1 The plaintiffs (Sands) carry on a storage and delivery business. In or around December 2013, by oral agreement (the 2013 agreement), Sands contracted with Foodcorp (Vic) Pty Ltd (now in liquidation) (the Company) for the storage and delivery of ice cream products. In November 2019, the Company’s directors resolved to place the Company into administration and in January 2020, the Company passed into liquidation by reason of its failure to execute a deed of company arrangement: s 444B and s 446A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). This judgment concerns a long running dispute between Sands and the Company about the quantum of the debt owed to Sands pursuant to the 2013 agreement.

2 In separate proceedings to the present, Sands sought to replace the Liquidators of the Company on the grounds that, when acting as administrators, they had failed to act independently, had incorrectly valued Sands’ proof of debt at $1 and had failed to adequately investigate the claims of other creditors before admitting those proofs of debt in full (the Removal Proceedings). In Sands Contracting Pty Ltd v Foodcorp (VIC) Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1274 (Sands (No 1)), I declined to remove the Liquidators but held that a proper examination of Sands’ debt should have been undertaken. In Sands Contracting Pty Ltd v Foodcorp (VIC) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 1415, I ordered that the Liquidators ‘file and serve a report on the outcome of the adjudication of proofs of debt in the liquidation of the [the Company] within 21 days of completion of the process of adjudication’. Such a report has been provided. The report of the Liquidators as it relates to Sands’ claim is annexed to these reasons as Annexure A.

3 These reasons should be read together with the reasons in Sands (No 1) and Sands (No 2) which provide further detail to the factual background of the matters in issue. The same abbreviations are also used.

4 Sands claims that it is owed $253,051 from the Company under the 2013 agreement. Following adjudication, the Liquidators concluded that Sands’ debt should be allowed in the sum of $39,629.50. Shortly after the report of the adjudication was filed by the Liquidators in the Removal Proceedings, Sands commenced this proceeding against the Liquidators in which it appeals from the adjudication. It does so pursuant to reg 5.6.54(2) of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) and seeks the following orders:

1. [T]he [Liquidators’] rejection of [Sands’] proof of debt or claim dated 28 October 2020 in the liquidation of [the Company] be set aside.

2. The [Liquidators] admit [Sands’] proof of debt or claim for $253,051.

3. [Sands’] appeal be allowed.

4. The [Liquidators] pay [Sands’] costs of the application.

5 Somewhat unusually, shortly after this appeal proceeding was filed, Sands and the Liquidators resolved, in the Removal Proceedings, to provide consent orders to the Court terminating the Liquidators’ appointment to the Company. Accordingly, the defendants to this proceeding are in fact the former Liquidators of the Company and they do not wish to be heard on the issue of Sands’ adjudication appeal and intend to abide the decision of the Court. Accordingly and unusually, the hearing of Sands’ appeal proceeded unopposed.

6 The absence of a contradictor to this appeal (due to the Liquidators’ decision not to oppose it), has given rise to consideration of whether the former directors of the Company should have been given notice of the appeal on the basis that it is conceivable that their interests may be indirectly affected in the event that Sands is successful. Inquiries of Sands post-hearing revealed that Sands had not given notice to the directors of this proceeding, but that they considered such notice need not be given because the appeal concerned only the Liquidators’ adjudication of the claim. No response was received to a similar inquiry of the Liquidators.

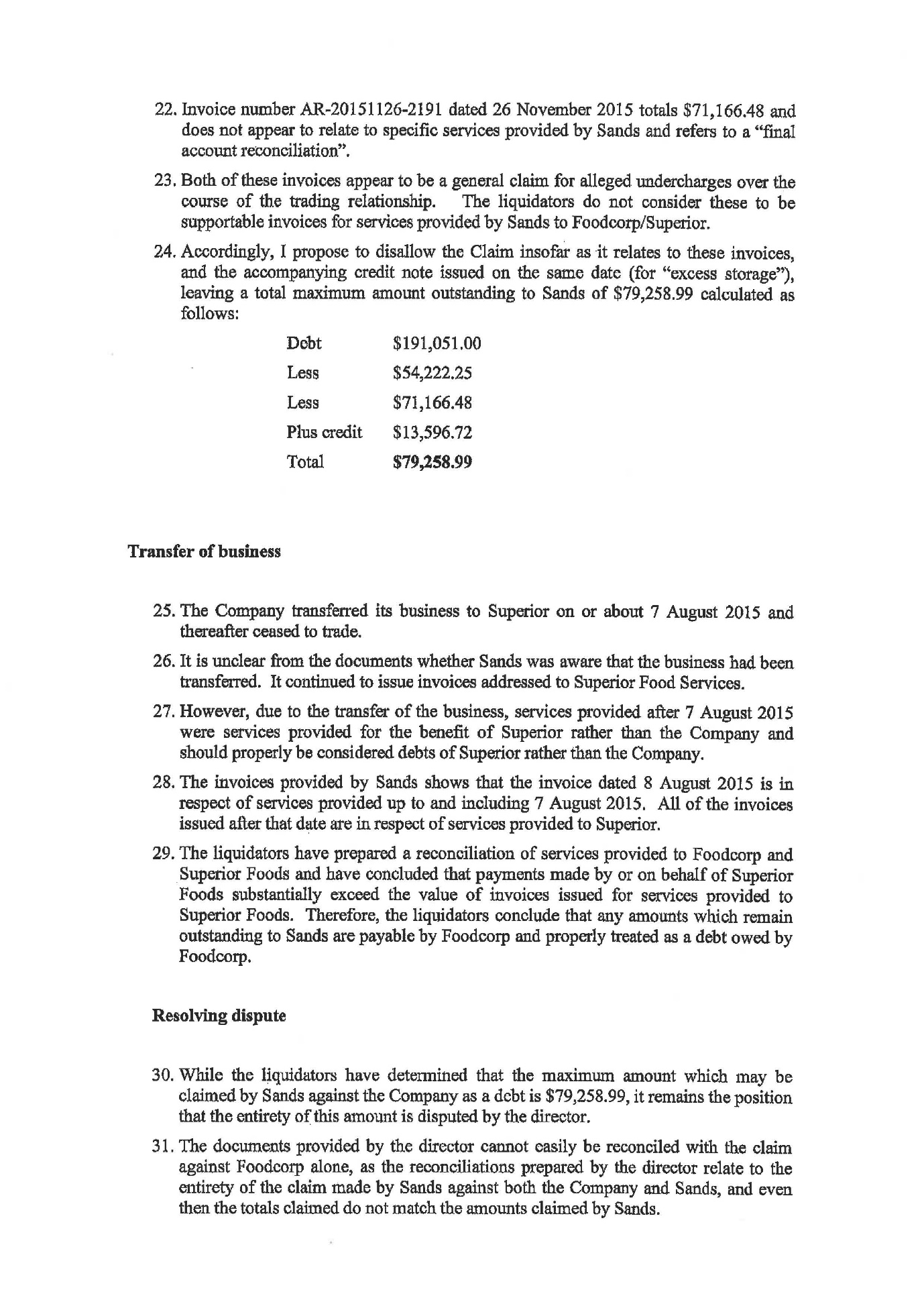

7 During the hearing of the appeal, counsel for Sands had indicated that any replacement liquidator that is appointed to the Company may examine two large dividends paid out by the Company’s directors in the years leading up to the liquidation. This is all entirely conjectural at this stage and was in response to my question as to what benefit Sands would receive in a successful appeal given the Company’s current lack of assets. In light of that response, careful consideration was given to the question of whether the directors should have been joined in the appeal or at least given notice of it (if the former Liquidators have not already done so). There is no evidence that the directors have been informed of this appeal.

8 Although there does not appear to be any statutory requirement that notice be given, r 14.1 of the Federal Court (Corporations) Rules 2000 (Cth) provides as follows:

14.1 Appeals against acts, omissions or decisions

(1) All appeals to the Court authorised by the Corporations Act must be commenced by an originating process, or interlocutory process, stating:

(a) the act, omission or decision complained of; and

(b) in the case of an appeal against a decision—whether the whole or part only and, if part only, which part of the decision is complained of; and

(c) the grounds on which the complaint is based.

(2) Unless the Corporations Act or the Corporations Regulations otherwise provide, the originating process, or interlocutory process, must be filed within:

(a) 21 days after the date of the act, omission or decision appealed against; or

(b) any further time allowed by the Court.

(3) The Court may extend the time for filing the originating process, or interlocutory process, either before or after the time for filing expires and whether or not the application for extension is made before the time expires.

(4) As soon as practicable after filing the originating process, or interlocutory process, and, in any case, at least 5 days before the date fixed for hearing, the person instituting the appeal must serve a copy of the originating process, or interlocutory process, and any supporting affidavit, on each person directly affected by the appeal.

(5) As soon as practicable after being served with a copy of the originating process, or interlocutory process, and any supporting affidavit, a person whose act, omission or decision is being appealed against must file an affidavit:

(a) stating the basis on which the act, omission or decision was done or made; and

(b) annexing or exhibiting a copy of all relevant documents that have not been put in evidence by the person instituting the appeal.

(Emphasis added.)

9 Although an appeal instituted under reg 5.6.54(2) of the Corporations Regulations clearly falls within the scope of the types of proceedings to which r 14.1 is directed (see for instance Re ION Limited (No 2) [2012] FCA 561 per Dodds-Streeton J at [13]-[23]), references to this rule in the authorities appear to deal almost exclusively with power to extend the time within which to bring proceedings under subs 14.1(2) and subs 14.1(3). Specific consideration does not appear to have yet been given to the operation of subs 14.1(4), and in particular the phrase ‘each person directly affected by the appeal.’ In my view, the former directors of the Company will not be directly affected by the outcome of this proceeding. They would have, at best, a contingent interest only to the extent that the quantum of proven liabilities in the Company’s liquidation may bear upon the actions a liquidator chooses to take. From both a practical and legal point of view however, if another liquidator were to seek to recover funds from the directors of the Company (on a basis that is not yet articulated with any precision) the directors would not be bound by a decision of the court in this appeal to which they have not been joined or of which (if it be the case) they have not had notice. The prospect of such events materialising are at this point, entirely speculative.

10 Appeals of this nature against the adjudications of liquidators are intended to be relatively simple affairs. Every creditor in a winding up could be indirectly affected by the outcome of such appeals but there is no suggestion they should all be joined or served, and it is difficult to see how the former directors of the Company could be more ‘directly affected’ than other creditors.

11 For these reasons, no steps were taken to compel Sands to give notice to the directors of this appeal.

EVIDENCE

12 In support of the relief sought, the fourth named plaintiff, Mr Anthony Jerome Sands has sworn an affidavit which is the only evidence before the Court.

13 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that this evidence establishes that Sands is owed the full amount of its claim against the Company and is therefore entitled to the substantive relief it seeks.

THE PRINCIPLES

14 In an appeal of this nature the party appealing against a liquidator’s decision to reject the proof of debt has the onus of showing the decision was wrong. It is a hearing de novo in which the creditor’s claim is to be determined by reference to the evidence before the Court when it considers whether or not to affirm the liquidator’s decision, even if this includes additional evidence to that which was before the liquidator. As was explained by Kunc J in Capocchiano v Young [2013] NSWSC 879 (at [46]-[47]):

46 The relevant legal principles are not in doubt. An appeal against the rejection of a proof of debt is a hearing de novo. The Court must take into account all relevant evidence, whether or not it was before the liquidator at the time the proof was rejected. The fundamental question is whether the claim sought to be proved is a true liability of the company enforceable against it according to law. Nevertheless, the claimant bears the onus to demonstrate that the liquidator was wrong in rejecting the proof. If that onus is not discharged, the Court will not overturn the liquidator’s decision. If the Court is unable to conclude either way whether the proof should be admitted, then the liquidator’s decision must stand.

47 The authorities for the principles summarised in the preceding paragraph are Tanning Research Laboratories Inc v O’Brien (1990) 169 CLR 332 at 338-341 (per Brennan and Dawson JJ); Re Kentwood Constructions Ltd [1960] 1 WLR 646 at 647-648; Westpac Banking Corporation v Totterdell (1998) 20 WAR 150 at 154 per Ipp J, Pidgeon and White JJ agreeing; Re Galaxy Media Pty Limited (recs and mgrs apptd) (in liq); Walker and Another (in their capacity as recs and mgrs of Galaxy Media Pty Ltd) v Andrew (as liq of Galaxy Media Pty Ltd) and others (2001) 39 ACSR 483; [2001] NSWSC 917 at [23]-[34].

THE LIQUIDATORS’ ADJUDICATION

15 As is apparent from Sands (No 1) the former directors of the Company dispute the debt claimed by Sands. They say that Sands has already been paid all that it is owed under the 2013 agreement. In 2016, Sands commenced proceedings in the District Court to recover debts said to be owed to it by the Company and Superior Foods (the fourth defendant in the Removal Proceedings and a creditor of the Company). The Liquidators were provided with the pleadings filed by Sands and the Company in the District Court action as well as other supporting documentation. Sands also points to the fact that during negotiations in late 2019, Mr Phillips (former director of the Company) offered to settle the District Court action for $205,000. This was a topic of much debate in the Removal Proceedings: see Sands (No 1) (at [58(d)], [63], [67]-[73] and [124]).

16 It is common ground that the plaintiffs rendered invoices totalling $1,245,161.57 and issued credit notes totalling $78,920.34. The Company paid the plaintiffs $913,190.20. Accordingly, Sands maintains that it is still owed $253,051.

17 As noted by the Liquidators, the Company admits that invoices totalling $1,245,161.57 were issued but dispute that they correctly reflect the amounts entitled to be charged by Sands for its services.

18 The areas of factual dispute between the parties were set out by the Liquidators in the adjudication as follows (see [13] of Annexure A):

On the basis of the pleadings, the basis upon which Sands was entitled to charge for goods is partly agreed and partly disputed:

(a) It is common ground that the plaintiffs would be paid $7.35 per tub, $5.95 per dry carton and $3.00 per inner (“the Agreed Rates”);

(b) The parties both contend that there was an agreed price per container but disagree on what the agreed rate was;

(c) Sands contends that the rates were payable to Sands upon receipt of the goods, but the Company contends that the rates were payable upon delivery to a customer;

(d) The parties are in dispute as to whether Sands was entitled to charge for various ancillary services such as transfer, transport and storage of excess stock (“the Additional Services”);

(e) In the statement of claim, Sands makes an alternative claim that if there was no agreement for a price for the Additional Services, then Sands is entitled to a reasonable amount for those Additional Services.

19 Two invoices issued by Sands at the end of the trading relationship in November 2015 for $54,222.25 and $71,166.48 did not appear to the Liquidators to relate to specific services and were wholly disputed by the Company (Additional Services invoices). A credit note to the Company for ‘excess storage’ was also issued by Sands for $13,596.72. These appear to be part of a final reconciliation by Sands at the end of the relationship.

20 The Liquidators also considered the following facts to be relevant to the adjudication:

(a) Sands had settled the balance of its claim against Superior Foods in the District Court action for $60,000 (Superior Foods settlement sum);

(b) over the course of the trading relationship, the payments made by the Company to Sands do not reflect the amounts shown in the invoices issued by Sands and it does not appear to the Liquidators that either party acted in a manner which would support an inference that their method of charging for services was accepted by a course of conduct or trading;

(c) both parties appeared to have been willing to continue that trading relationship notwithstanding that there appeared to have been disputes from the very beginning as to the rates Sands was entitled to charge for its services;

(d) on or about 7 August 2015, the Company transferred its business to Superior Foods and thereafter ceased to trade; and

(e) it is unclear from the documents whether Sands was aware that the business had been transferred.

21 The process adopted by the Liquidators in resolving these factual disputes in relation to Sands’ claim can be summarised as follows:

(a) they considered that the Superior Foods settlement sum of $60,000 paid by Superior Foods to settle the District Court action against it was in part fulfilment of Sands’ claim against the Company; and

(b) they considered that the Additional Services invoices and the credit note issued by Sands at the end of the trading relationship should be disallowed.

22 There appears to be a slight discrepancy in the maximum figure calculated to be owing to Sands by the Liquidators, though it is immaterial for present purposes: see [10]-[11] and [24] of Annexure A in which the maximum calculated to be owing to Sands (after deduction of the Superior Foods settlement sum) is variously recorded as $193,051, $191,051.03 and $191,051.00.

23 The final figure arrived at by the Liquidators, after deducting the Superior Foods settlement sum and the Additional Services invoices and credit note, was $79,258.99. In then considering how the factual disputes about the rates to be charged by Sands should be resolved, the Liquidators reasoned ‘that had the matter been considered by a court, that the Company would have been at least partly successful in arguing that the rates claimed by Sands should be reduced’. On this basis, the Liquidators applied a 50% discount to Sands’ claim and admitted its debt in the sum of $39,629.50.

LIQUIDATORS’ ALLEGED ERRORS

24 Sands contends:

(a) the Liquidators erred in not having regard to the without prejudice offers made by the Company: see Sands (No 1) (at [120]);

(b) the Liquidators erred in reducing the claim by the Superior Foods settlement sum of $60,000 on account of the settlement of Sands’ claim against Superior Foods in the District Court action; and

(c) the Liquidators erred in disallowing the Additional Services invoices dated 26 November 2015.

25 Sands reiterates that its statement of claim in the District Court action pleaded two related but separate claims against the Company and Superior Foods. Indeed, in its prayers for relief Sands claimed $253,051 against the Company and, separately, $26,016.98 against Superior Foods as well as interests and costs. It alternatively claimed $279,067.98 against both companies (the sum of the individual claims). Sands says its claim against Superior Foods was separate and distinct from the claim against the Company such that there was no proper basis for the Liquidators to deduct the Superior Foods settlement sum of $60,000 (inclusive of costs and interest) in the adjudication of its proof of debt against the Company.

26 Sands repeats the submissions made in Sands (No 1) about the Liquidators’ failure to adequately take into account the Company’s offer of $205,000 to settle the District Court action as against the Company. While it is not entirely clear how the making of such a without prejudice offer of compromise could be before the Court, I am not satisfied in any event that giving limited weight to such offers indicates error on the part of the Liquidators. Most people make offers to settle litigation for any number of reasons.

27 Sands accepts that the Liquidators were correct in finding that the Additional Services invoices were for undercharges over the course of the trading relationship. However Sands contends that the Liquidators erred in finding that the invoices do not relate to specific services provided. The shipping records are summarised in schedules A and B of the statement of claim in the District Court action, produced in evidence by Mr Sands. Schedule A records that Sands received:

(a) 101,908 cartons;

(b) 20,028 tubs;

(c) 11,597 inners; and

(d) 26 containers,

between December 2013 and December 2015 which entitled Sands to charge the Company $1,006,149.54. These contemporaneous business records are more likely than not to be correct in my view.

28 The two Additional Services invoices clearly sought to reconcile the goods received by Sands for the Company between these dates.

SANDS’ EVIDENCE ON THIS APPEAL

29 As Mr Sands’ evidence demonstrates, Sands’ proof of debt is based on the terms of the 2013 agreement which consisted of an oral agreement made between Mr Sands (as representative for Sands) and Mr Phillips (as representative for the Company) in or about December 2013. Mr Sands sets out his recollection of the relevant conversations with Mr Phillips. His affidavit also produces relevant documents including:

(a) Sands’ proof of debt or claim dated 28 October 2020;

(b) the Liquidators’ notice of rejection of proof of debt or claim dated 1 March 2021;

(c) Sands’ substituted statement of claim in the District Court Action dated 16 November 2018;

(d) the Company and Superior Foods’ defence dated 16 March 2018;

(e) internal emails between Sands employees;

(f) 136 tax invoices rendered by Sands to the Company over the course of the trading relationship; and

(g) a spreadsheet quantifying what Sands considered to be payable to it at the end of the trading relationship in November 2015.

30 Mr Sands’ evidence is that the agreement was that Sands would be paid by the Company when the goods were received by Sands (as ordered by the Company but held by Sands until needed by the Company). In my view this makes commercial sense.

31 In the District Court action, the Company admitted much of the terms of the 2013 agreement but disputed that:

(a) the verbal agreement was made in September 2013;

(b) he rate per container was $585 plus GST rather than $450 plus GST;

(c) the rates were payable upon receipt of the goods by Sands;

(d) the Company was required to pay:

(i) $145 plus GST per hour for the transportation of stock;

(ii) $87 plus GST per hour for any additional work; and

(iii) $7.50 plus GST for each pallet stored by Sands in excess of 150 pallets.

32 I am satisfied that the contemporaneous records demonstrate that Sands would charge the Company as follows:

(a) $7.35 plus GST per freezer carton;

(b) $7.35 plus GST per freezer tub;

(c) $5.25 plus GST per dry carton;

(d) $3.00 plus GST per unit;

(e) $585 plus GST per container;

(f) $7.85 plus GST per pallet in excess of 150;

(g) $145 plus GST per hour for the transportation of stock; and

(h) $87 plus GST per hour for receiving and labelling goods.

33 I am also satisfied that the records produced on affidavit by Mr Sands reveal that Sands would charge the Company upon receipt of the goods; and would also charge the Company for storage. Importantly, this was the manner in which the parties conducted their affairs without any demurrer or complaint from the Company. In the spreadsheet referred to above (at [29(g)]), the Company acknowledged that it was required to pay for:

(a) handling fees for dumping stock;

(b) handling fees for transferring stock;

(c) air freight collection;

(d) dumping charges; and

(e) unscheduled deliveries.

CONSIDERATION

34 I am satisfied that there is adequate proof to support the fact that the amount claimed by Sands is due in full. Although the Company raised challenges, I am satisfied that those challenges are adequately addressed by the additional evidence produced by Sands.

35 Two particular areas of concern addressed by the Liquidators and by the Company were whether or not Sands was entitled to claim in respect of ‘additional services’. It is clear, in my view, that Sands was so entitled and that this was indeed recognised in contemporaneous internal documents of the Company. The second query raised by the Liquidators related to the rate at which charges were to be raised – whether at the higher rate claimed by Sands or the lower rate claimed by the Company. The evidence reveals however that from inception, all invoices were rendered at the higher rate claimed by Sands and no objection was raised at any concurrent point. This strongly supports a conclusion that the rate Sands contended to be the contractual rate was in fact the correct rate.

36 Although the decision taken by the Liquidators effectively to reduce the claim by 50% does on its face appear to be a fair and reasonable compromise, the decision I am required to make on the plaintiffs’ present application to set aside that decision is to be, in effect, a hearing de novo in which the appellant is required to prove its case. I now have additional evidence and argument available to me which, in my view, casts real doubt on two of the key premises adopted by the Liquidators to reach the relevant compromise. In saying that I do not intend to be critical of the Liquidators who I consider carried out their task appropriately in the circumstances. Sands pressed the Liquidators to conduct an oral hearing. I do not consider it is reasonable for a liquidator to be expected to conduct an oral hearing in every case, even in this one where disputes were known to exist. In this case the moribund state of the financial affairs of the Company would mitigate against such an expense being incurred.

CONCLUSION

37 I consider that the plaintiffs have established that the Company is indebted to them in the sum of $253,051 and that therefore the appeal should succeed. The question of costs, if any, can be resolved on the papers. It follows that it will be ordered that:

(1) The plaintiffs’ appeal be allowed.

(2) The defendants’ rejection of the plaintiffs’ proof of debt or claim dated 28 October 2020 in the liquidation of Foodcorp (Vic) Pty Ltd (ACN 074 563 385) be set aside.

(3) The defendants or any replacement liquidator do admit the plaintiffs’ proof of debt or claim for $253,051.

(4) Should either party seek its costs, the moving party is to file written submissions (not to exceed 3 pages) within 7 days of the date of this order, with the other party permitted a further 7 days from receipt of the moving party’s submissions to file any responsive submissions (not to exceed 3 pages).

(5) Any question of costs be determined on the papers.

I certify that the preceding thirty-seven (37) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice McKerracher. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A