FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Prygodicz v Commonwealth of Australia (No 2) [2021] FCA 634

ORDERS

First Applicant ELYANE PORTER Second Applicant STEVEN FRITZE (and others named in the Schedule) Third Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Settlement Approval

1. The Respondent provides an undertaking to the Court in the form set out at Annexure A to these orders.

2. Upon the Respondent giving the undertaking in Annexure A to these orders, pursuant to ss 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act), the settlement of the proceeding upon the terms set out in the Deed of Settlement between the Applicants, the Respondent and Gordon Legal exhibited as “AG-1” to the Affidavit of Andrew Grech dated 22 April 2021 (Settlement Deed), together with the Settlement Distribution Scheme Implementation Plan in Annexure B to these orders (Implementation Plan), be approved subject to the following:

(a) the definition of Scheme Claimant, as contained in the Settlement Deed, is amended to mean “a Category 2 Group Member or an Eligible Category 3 Group Member for whom the Respondent has current bank account details or preferred payment destination at the date set out in or determined under the Implementation Plan”; and

(b) the Framework of Settlement Distribution Scheme at Annexure B to the Settlement Deed and the Implementation Plan (together “the Scheme”) are to be read together. To the extent of any inconsistency between the Framework of Settlement Distribution Scheme and the Implementation Plan (as amended in accordance with order 2 above), the Implementation Plan shall prevail over the Framework of Settlement Distribution Scheme.

3. Pursuant to ss 33V and 33ZF of the Act, the Court authorises the Applicants nunc pro tunc to enter into and give effect to the Settlement Deed and the Scheme for and on behalf of the group members.

4. Pursuant to s 33ZB of the Act the persons affected and bound by the settlement of the proceeding are the Applicants, the group members, and the Respondent.

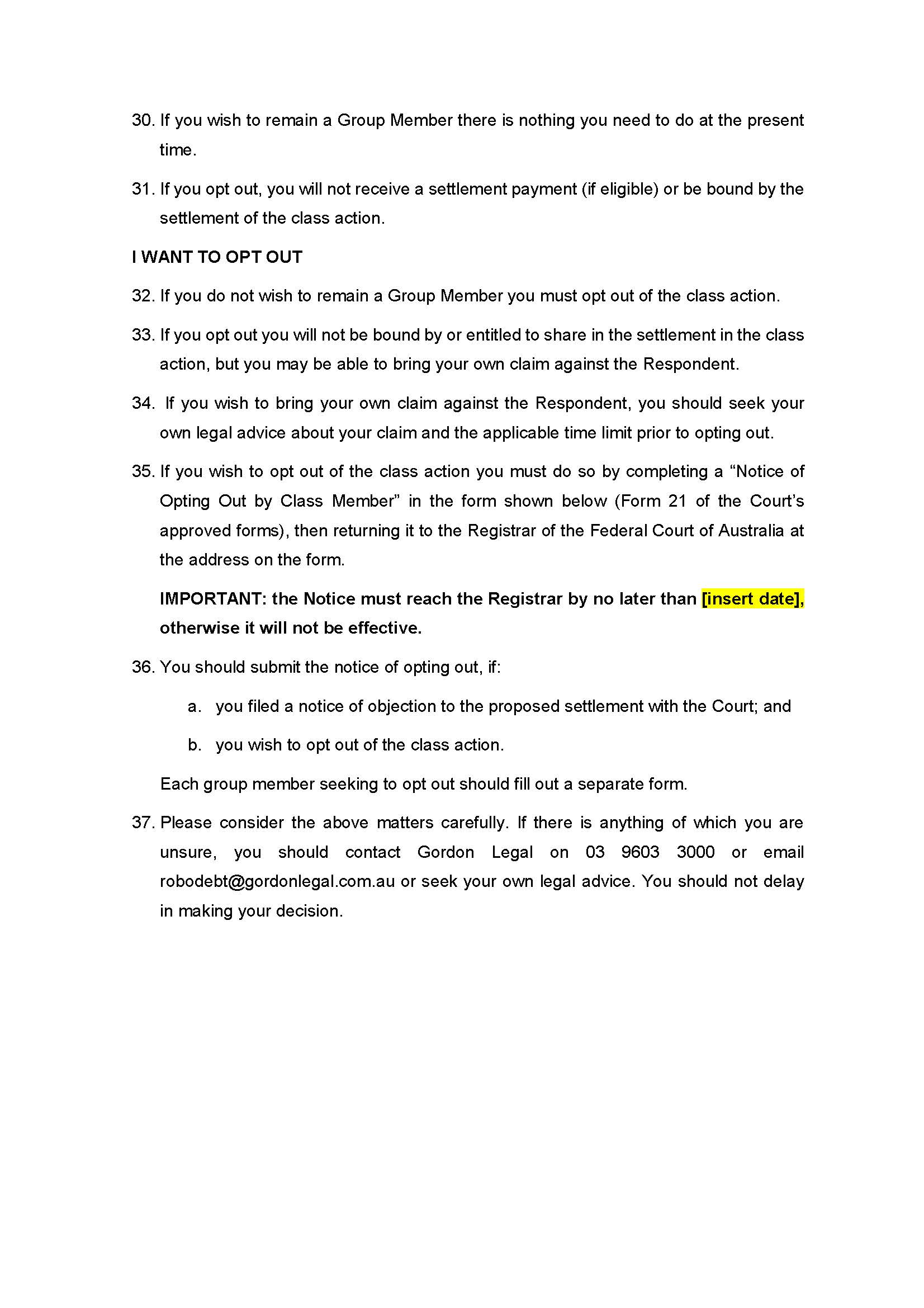

Opt Out for Objecting Group Members

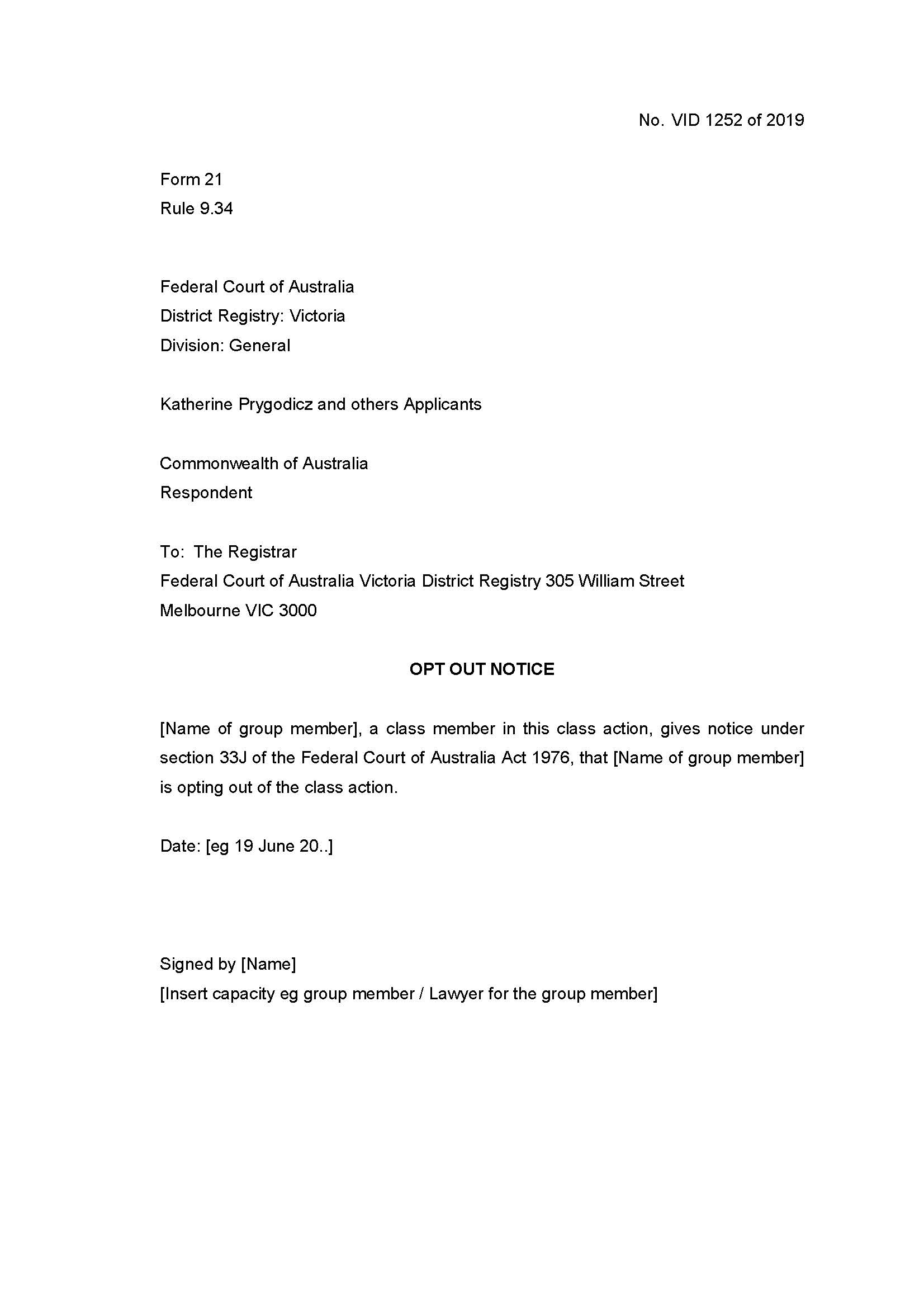

5. Pursuant to ss 33J and 33ZF of the Act, the date by which any group member, who pursuant to Order 17 of the Orders of 23 December 2020 filed a Notice of Objection with the Court on or before 4.00 pm on 5 May 2021 in respect of the proposed settlement of the proceeding (the Objecting Group Members), may opt out of the proceeding be extended to 4.00 pm AEST on 17 September 2021.

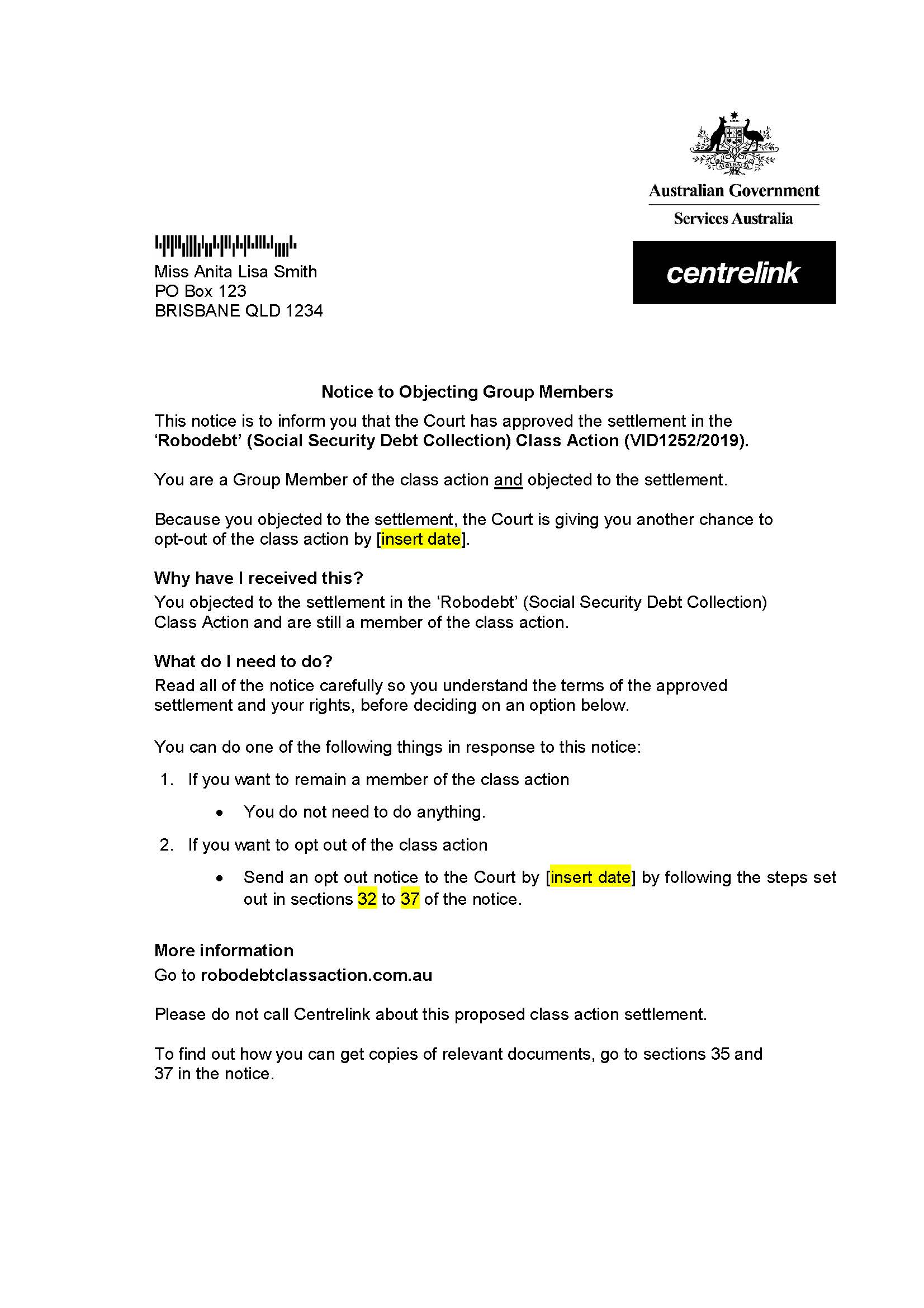

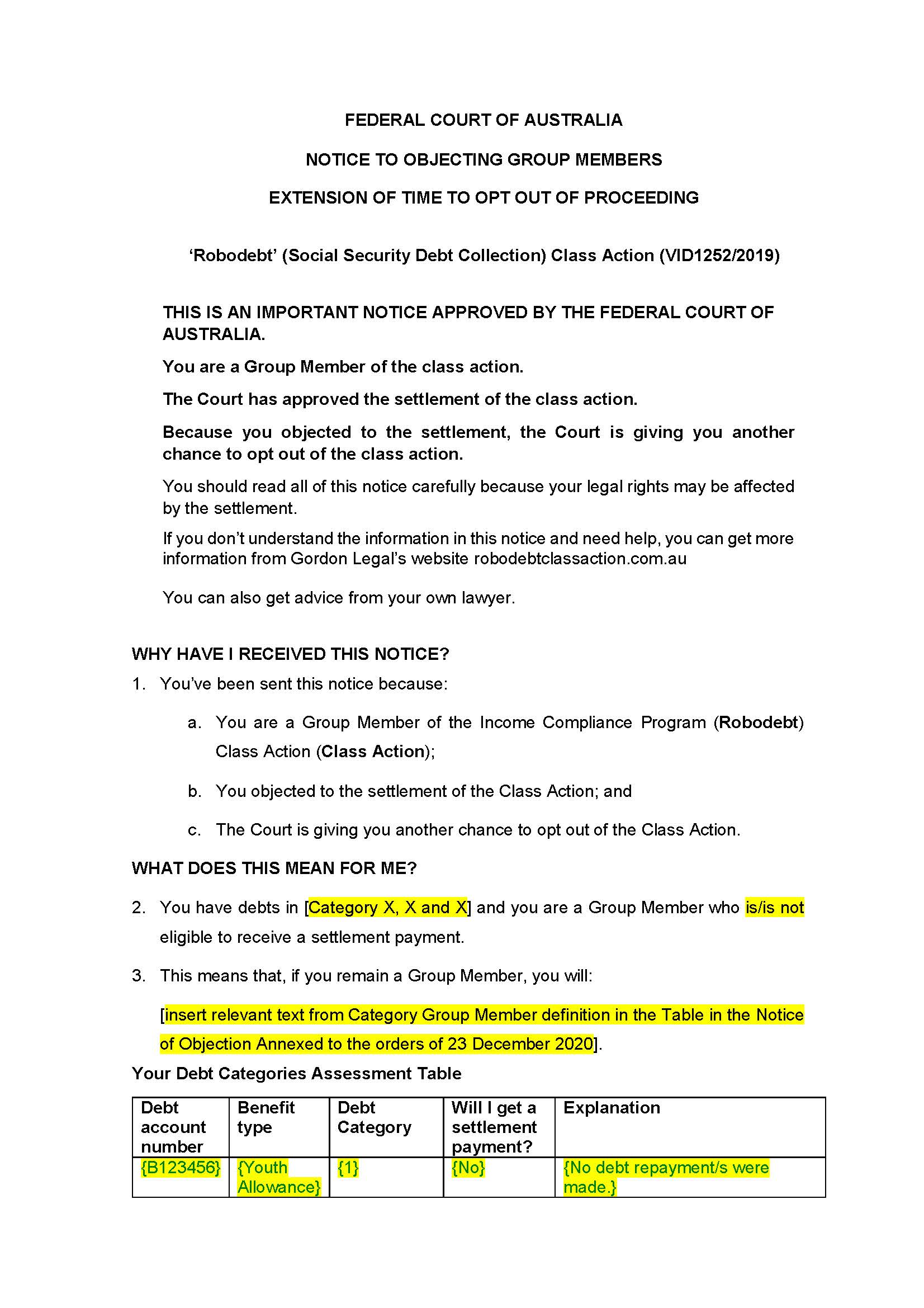

6. Pursuant to s 33Y(2) of the Act, the form and content of the notice set out in Annexure D (Further Opt Out Notice) is approved as that by which Objecting Group Members are to be given notice of their extended period to opt out of the proceeding.

7. Pursuant to s 33Y(3) of the Act, the Further Opt Out Notice is to be given to the Objecting Group Members by 6 August 2021 according to the following procedure:

(a) using its best endeavours the Respondent shall use its own resources to identify the names of all of the Objecting Group Members, the MyGov account details of those Objecting Group Members who have a MyGov account linked to Services Australia, and their last known contact details held by the Respondent including as identified on the Objecting Group Members’ Notice of Objection;

(b) where possible the Respondent shall cause the Further Opt Out Notice to be sent to each Objecting Group Member’s MyGov Account Inbox which is linked to Services Australia; and

(c) where an Objecting Group Member does not have a MyGov account Inbox linked to Services Australia the Respondent will use its best endeavours to send the Further Opt Out Notice by mail to the Objecting Group Member’s last known address.

8. The costs incurred by the Respondent of the procedure referred to in Order 7 above shall be borne by the Respondent, and otherwise the costs of each party of and incidental to the procedure set out in Order 7 above shall be costs in the cause. For the avoidance of doubt, reasonable work done in answering enquiries by class members and members of the public in relation to the Further Opt Out Notice and/or the proceeding generally is work incidental to Order 5 above.

9. The Further Opt Out Notice may be amended by the Applicants’ or Respondent’s solicitors before it is published in order to correct any website or email address or telephone number or other non-substantive error.

10. If the solicitors for any party receive, on or before 4.00 pm AEST on 17 September 2021, a notice purporting to be an opt out notice in response to the Further Opt Out Notice completed by any Objecting Group Member, the solicitors shall file the notice in the Victoria District Registry of the Court within three business days, and the notice shall be treated as an opt out notice received by the Court at the time it was received by the solicitors.

11. The Applicants’ solicitors and the Respondent’s solicitors have leave to inspect the Court file and copy any such opt out notices filed.

Declarations

12. The Court hereby makes the declarations in the form of Annexure C to these orders.

Costs of the proceeding to the date of settlement approval

13. Pursuant to ss 33V and 33ZF of the Act, so much of the Deduction Amount payable to Gordon Legal under the Settlement Deed as comprises legal costs pursuant to clause 2.8.4.a of the Settlement Deed in respect of conduct of the proceeding on behalf of the Applicants and group members be approved in the amount of $8,413,795.71.

Gordon Legal’s future costs for performing its functions under the Scheme

14. The reference to the Costs Referee pursuant to Order 11 of the orders made 23 December 2020 be amended to include the following:

(a) as soon as practicable the Costs Referee shall confer with Gordon Legal, and any other person the Costs Referee considers appropriate, and then determine the best method:

(i) to assess the reasonableness and proportionality of Gordon Legal’s costs for performing its functions under the Scheme on an ongoing basis, and for such costs to be considered for approval by the Court and paid at either monthly or two monthly intervals as the Costs Referee determines; and

(ii) to permit the Costs Referee to make an updated and more accurate estimate of Gordon Legal’s future reasonable and proportionate costs for performing its functions under the Scheme, intended to assist the Court to consider approval of a lump sum amount for future costs so that the distribution of settlement monies to the Scheme Claimants can proceed without material delay;

(b) the Costs Referee shall provide short reports to the Court providing her opinion as to the reasonableness and proportionality of the:

(i) costs in the invoices rendered by Gordon Legal for the firm’s ongoing work;

(ii) updated estimate of Gordon Legal’s future costs in a lump sum amount;

and the Court will decide whether to approve such costs on the papers; and

(c) the Costs Referee or Gordon Legal may seek urgent directions from the Court in relation to any issue which arises.

15. Following receipt and consideration of the Costs Referee’s reports as to Gordon Legal’s costs for performing its functions under the Scheme, pursuant to ss 33V and 33ZF of the Act:

(a) so much of the Deduction Amount payable to Gordon Legal under the Settlement Deed as comprises Gordon Legal’s costs pursuant to clause 2.8.4.b of the Settlement Deed in respect of conducting its functions under the Scheme, and in respect to the Costs Referee’s reasonable costs in performing her role and functions after the conclusion of the settlement approval hearing, will be approved and fixed by the Court; and

(b) so much of the Deduction Amount payable to Gordon Legal under the Settlement Deed as comprises legal costs pursuant to clause 2.8.4.a of the Settlement Deed in respect to the Contradictor’s reasonable costs in performing her role and functions after the conclusion of the settlement approval hearing, will be approved and fixed by the Court.

16. Within 7 days of the date of completion of Phase 3 of the Scheme (Assessment, Notification, and Distribution of Entitlements) Gordon Legal will file a confidential costs report with the Costs Referee and the Court for the purpose of reporting on the actual costs incurred in respect of it performing its functions under the Scheme.

Other orders

17. Pursuant to s 33ZF of the Act, the parties each have leave to apply to the Court for orders in respect of any issue arising in relation to the administration of the Settlement Deed or the Scheme.

18. All inter partes costs orders in the proceeding and in proceeding VID 648/2020 be vacated.

19. Upon the Court being informed by the Scheme Assurer that all distributions under the Scheme have been completed, the proceeding be dismissed with no further order as to costs.

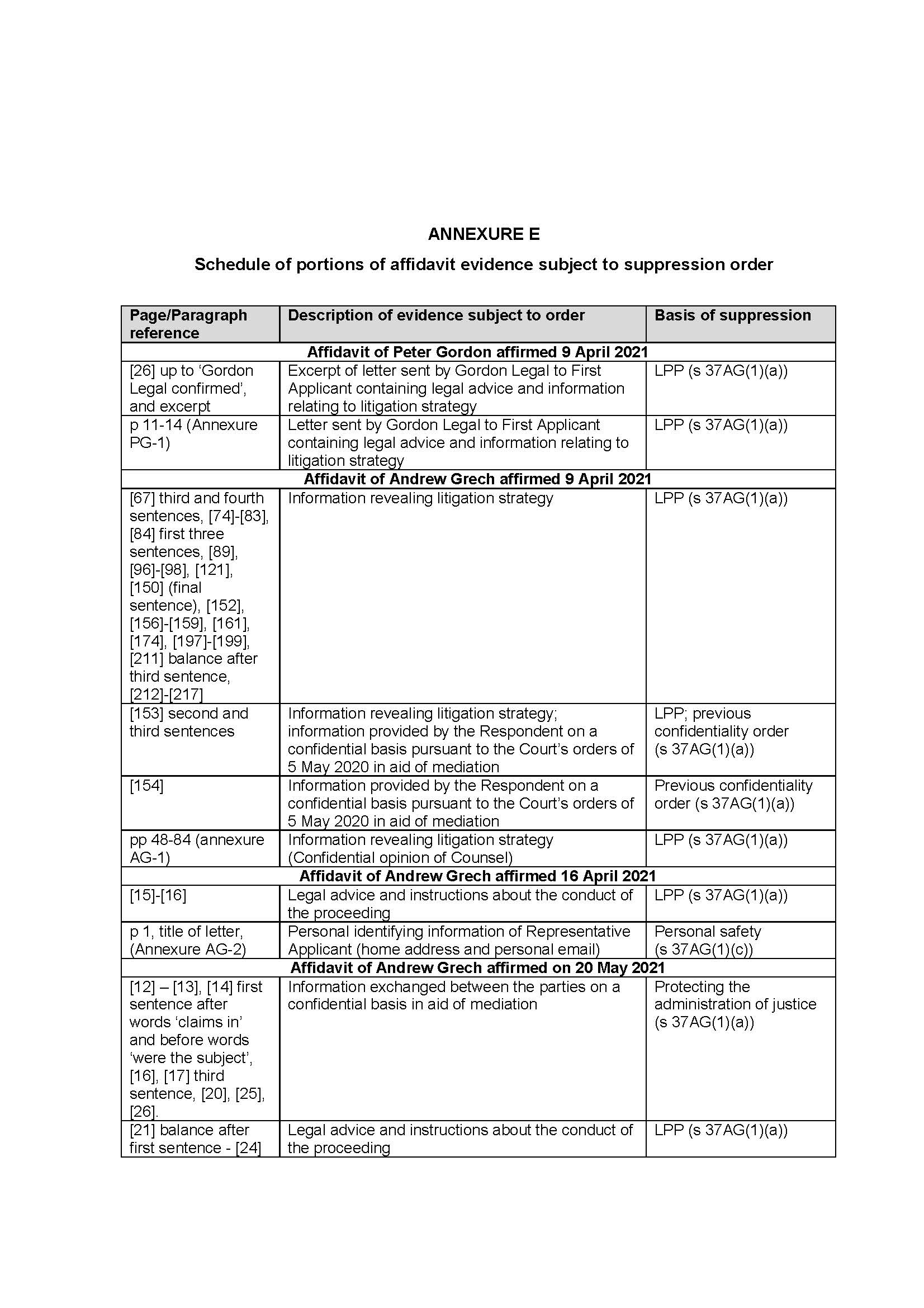

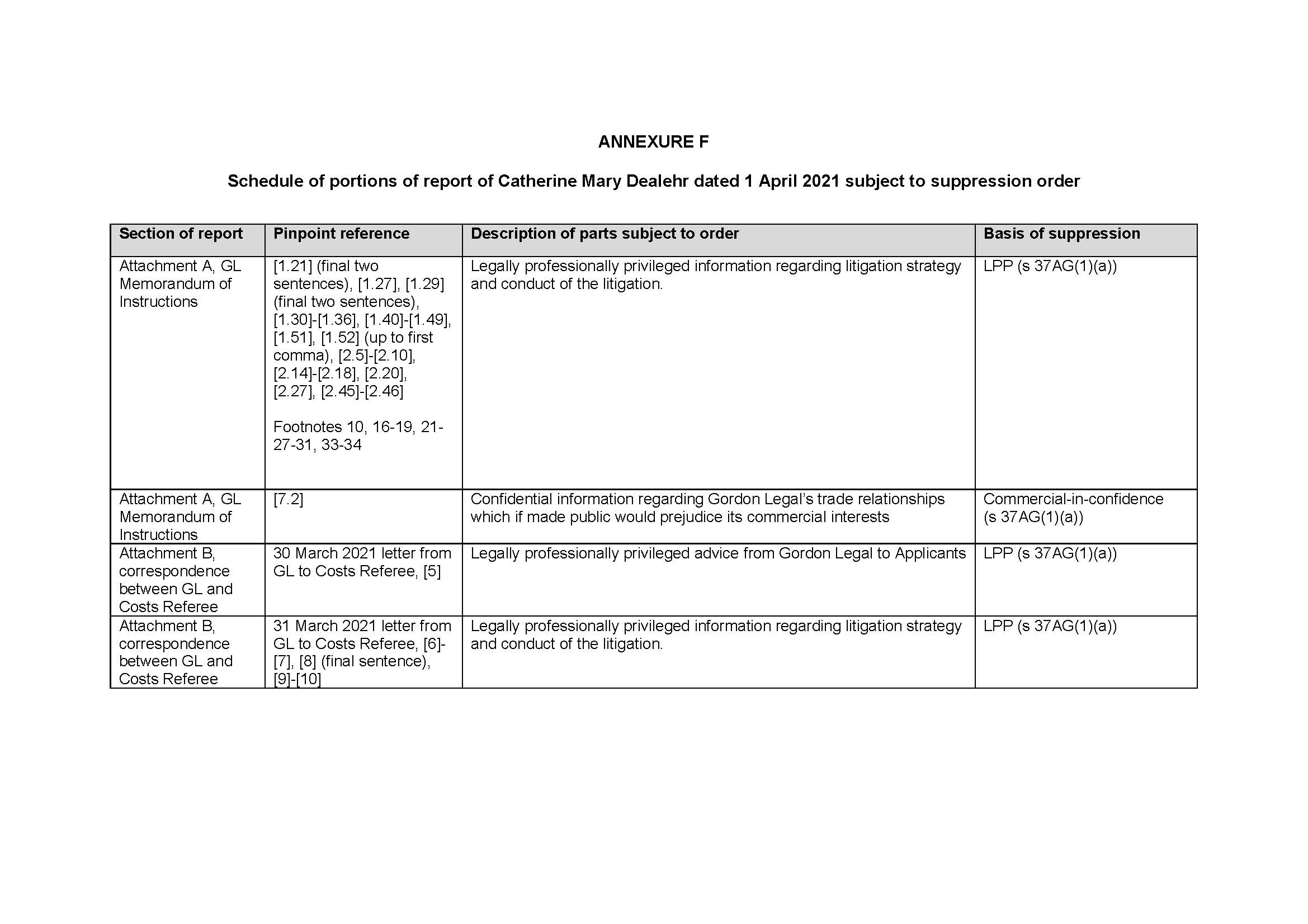

Confidentiality

20. Pursuant to s 37AF(1)(b) of the Act, on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, and until further order, the evidence identified in Annexures E and F to these orders not be published or disclosed without the prior leave of the Court to any person or entity other than the Applicants, their respective legal advisers, the Judge with the carriage of the matter from time to time and officers of the Court to whom it is necessary to disclose the evidence.

21. The parties have liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE A - RESPONDENT’S UNDERTAKING

The respondent undertakes to the Court that the intended operation and interpretation of clauses 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 of the Settlement Deed, when read together, is that:

(a) Group Members are precluded from objecting to or challenging a debt decision that was the subject of the proceeding if the nature of their objection or challenge is of the same nature as the claims made in the proceeding; however,

(b) Group Members are not precluded from enquiring about, objecting to or challenging (including by exercising their statutory rights of review) debt decisions which were the subject of the proceeding if the basis of their enquiry, objection or challenge is different in nature to the claims made in the proceedings.

ANNEXURE B

ANNEXURE C - DECLARATIONS

In respect of asserted overpayment debts raised against the applicants and group members, the Court declares that:

1. A decision that an applicant or group member owed the Commonwealth a debt under s 1223 of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth), because the person had obtained the benefit of a social security payment to which they were not entitled, was not validly made where all of the following apply:

(a) the rate of the social security payment for the applicant or group member was dependent upon the person’s ordinary income on a fortnightly basis;

(b) the Commonwealth based its decision on an assumption (Assumption) that the person’s ordinary income for a fortnight (relevant fortnight) was greater than the amount of ordinary income that the person had reported to the Commonwealth for the relevant fortnight;

(c) the Commonwealth relied solely on PAYG employment income data from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO data) to make the Assumption and did not have evidence that the person was likely to have earned employment income at a constant fortnightly rate during a period covered by the ATO data, or other evidence to support the Assumption; and

(d) the Assumption was based on an assessment of the person’s employment income for the relevant fortnight derived from averaging the ATO data, for a longer period that included the relevant fortnight, as if the person had earned income at a constant rate during that period.

ANNEXURE D

MURPHY J:

INTRODUCTION

1 In this application the applicants, Katherine Prygodicz, Elyane Porter, Steven Fritze, Felicity Button, Shannon Thiel and Devon Collins, seek court approval under s 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the FCA) of a proposed settlement of a class action they have brought against the respondent, the Commonwealth of Australia (the Commonwealth).

2 The class action arose out of the Commonwealth’s use of an automated debt-collection system between July 2015 and November 2019, intended to recover social security payments that had been overpaid, colloquially known as the “Robodebt system”. In summary, the system attempted to identify overpayments of social security benefits in a period under review (review period) through data matching. That was automatically conducted by:

(a) utilising PAYG income information of social security recipients kept by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO data) and evenly apportioning that income over fortnightly increments in the review period (in a process the parties called “income averaging”) to determine that person’s notional or assumed fortnightly income; and

(b) comparing the notional or assumed fortnightly income of the person with the actual fortnightly income information provided by the person (which was the basis upon which the level of social security payments had been assessed and paid to the person);

to determine whether the person had been overpaid social security benefits, and where that had occurred, to raise and recover that asserted debt.

3 The proceeding advances two broad claims against the Commonwealth:

(a) a restitutionary claim for unjust enrichment (principally monies had and received) alleging that the Commonwealth was unjustly enriched by its receipt or recovery of wrongly asserted debts from the applicants and group members; and

(b) a common law tort claim in negligence for damages for economic loss suffered by the applicants and group members as a result of the Commonwealth’s alleged breach of its duty of care in raising and recovering wrongly asserted debts, together with damages for “stress, anxiety and stigma” associated with the request or demand for, and threatened or actual, recovery of their asserted debts (distress damages).

4 In the course of the proceeding the Commonwealth admitted that it did not have a proper legal basis to raise, demand or recover asserted debts which were based on income averaging from ATO data. The evidence shows that the Commonwealth unlawfully asserted such debts, totalling at least $1.763 billion against approximately 433,000 Australians. Then, including through private debt collection agencies, the Commonwealth pursued people to repay these wrongly asserted debts, and recovered approximately $751 million from about 381,000 of them.

5 The proceeding has exposed a shameful chapter in the administration of the Commonwealth social security system and a massive failure of public administration. It should have been obvious to the senior public servants charged with overseeing the Robodebt system and to the responsible Minister at different points that many social security recipients do not earn a stable or constant income, and any employment they obtain may be casual, part-time, sessional, or intermittent and may not continue throughout the year. Where a social security recipient does not earn a constant fortnightly wage, does not earn income every fortnight, or only works for intermittent periods in a year, their notional or assumed fortnightly income based on income averaging is unlikely to be the same as their actual fortnightly income. It should have been plain that in such circumstances the automated Robodebt system may indicate an overpayment of social security benefits when that was not in fact the case. Yet, in the absence of further information from social security recipients, that is the basis upon which the automated Robodebt system raised and recovered debts for asserted overpayments of social security benefits.

6 It is, however, one thing for the applicants to be in a position to prove that the responsible Ministers and senior public servants should have known that income averaging based on ATO data was an unreliable basis upon which to raise and recover debts from social security recipients. It is quite another thing to be able to prove to the requisite standard that they actually knew that the operation of the Robodebt system was unlawful. There is little in the materials to indicate that the evidence rises to that level. I am reminded of the aphorism that, given a choice between a stuff-up (even a massive one) and a conspiracy, one should usually choose a stuff up.

7 It is fundamental that before the state asserts that its citizens have a legal obligation to pay a debt to it, and before it recovers those debts, the debts have a proper basis in law. The group of Australians who, from time to time, find themselves in need of support through the provision of social security benefits is broad and includes many who are marginalised or vulnerable and ill-equipped to properly understand or to challenge the basis of the asserted debts so as to protect their own legal rights. Having regard to that, and the profound asymmetry in resources, capacity and information that existed between them and the Commonwealth, it is self-evident that before the Commonwealth raised, demanded and recovered asserted social security debts, it ought to have ensured that it had a proper legal basis to do so. The proceeding revealed that the Commonwealth completely failed in fulfilling that obligation. Its failure was particularly acute given that many people who faced demands for repayment of unlawfully asserted debts could ill afford to repay those amounts.

8 In summary, the proposed settlement provides that the Commonwealth will, without admission of liability:

(a) consent to the Court making declarations (Declarations) which, in effect, provide that any decision by the Commonwealth:

(i) that an applicant or group member owed a debt under s 1223 of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth) (the SSA) because the person had obtained the benefit of a social security payment to which they were not entitled, where the Commonwealth relied solely on income averaging from ATO data; and

(ii) did not have other evidence that the person was likely to have earned employment income at a constant fortnightly rate during the period covered by the ATO income information;

was not validly made;

(b) not raise, demand or recover from any Category 1 Group Member or Category 2 Group Member (which categories I later explain) any invalid debt as described in the Declarations; and

(c) pay $112 million inclusive of legal costs (Settlement Sum), which after deduction of Court-approved legal costs (Distribution Sum), is to be distributed to Category 2 Group Members and Eligible Category 3 Group Members pursuant to a Court-approved Settlement Distribution Scheme (SDS).

9 The proposed settlement is on top of an earlier announced Commonwealth program under which it withdrew approximately $1.763 billion in debts based on income averaging from ATO data and promised to refund approximately $751 million it had received or recovered from social security recipients in relation to such debts (Commonwealth-recovered amounts).

10 The materials indicate that the Commonwealth maintained the Robodebt system in the face of approximately 29 decisions of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) up to 30 May 2017, which rejected income averaging based on ATO data as a basis for asserting a social security debt. Then, on 27 November 2019, in the “test case” of Amato v The Commonwealth of Australia (Federal Court VID611/2019), the Commonwealth consented to declarations to the effect that the debt in that case, raised based on income averaging from ATO data, was invalid. The financial hardship and distress caused to so many people could have been avoided had the Commonwealth paid heed to the AAT decisions, or if it disagreed with them appealed them to a court so the question as to the legality of raising debts based on income averaging from ATO data could be finally decided.

11 The result has been that, on top of the financial hardship, distress and anxiety caused to a great many vulnerable people and the costs to the public purse of a huge Commonwealth program to identify the debts to be withdrawn and to refund the Commonwealth-recovered amounts, the Commonwealth has now agreed to pay a further $112 million; to meet the substantial costs of the settlement distribution scheme to categorise eligible group members and to pay them a share of that settlement; and to meet its own significant legal costs. That has resulted in a huge waste of public money.

12 For the reasons I explain, in my view it is clear that the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable inter partes, that is, between the applicants and group members on the one hand, and the Commonwealth on the other. I was though troubled as to whether the proposed settlement was fair and reasonable inter se, that is, as between the different categories of group members.

13 That concern arises because, while the proposed settlement provides substantial financial benefits to Category 2 Group Members and Eligible Category 3 Group Members and some benefit to Category 1 Group Members, it provides no financial benefit to Ineligible Category 3 Group Members and Category 4 Group Members (Ineligible Group Members) who comprise approximately 202,000 of the about 648,000 group members. Yet Ineligible Group Members will also be bound by the release in the Settlement Deed and thus lose their rights (if any) to sue for the claims made in the proceeding or claims arising out of or related to the subject matter of the proceeding, without receiving any corresponding benefit.

14 Ultimately I concluded that it is appropriate to approve the proposed settlement, albeit with some changes to the settlement as initially proposed, including to allow the 680 group members who filed objections to approval of the proposed settlement an opportunity to opt out of the proceeding at this stage, if they wish to do so.

15 In a case such as the present, in which a large number of group members will be bound into the settlement but will receive no corresponding financial benefit, it is important that they understand why that result is appropriate. Out of a need to fully ventilate those reasons the judgment is longer than I would wish. However, for those who do not wish to trudge through the judgment in its entirety the salient reasons can be summarised as follows.

16 First, the Court had the benefit of a confidential joint counsels’ opinion dated 9 April 2021 provided by Bernard Quinn QC, Georgina Costello QC, Min Guo and Andrew Roe of counsel, who appeared for the applicants (Counsels’ Opinion). The provision of the opinion required counsel to frankly and candidly express their opinion as to the fairness and reasonableness of the proposed settlement, rather than advocating a position on behalf of their clients. Counsel recommended that the Court approve the proposed settlement. It is appropriate to give significant weight to the Counsels’ Opinion, and I have done so.

17 Second, the Court had the benefit of detailed submissions from Fiona Forsyth QC and Eugenia Levine of counsel (the Contradictor), appointed by the Court to represent group members’ interests. The Contradictor accepted that the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable as between the parties, describing it as “a very favourable outcome”.

18 The Contradictor however submitted that the proposed settlement is not fair and reasonable as between group members because Category 1 Group Members and Ineligible Group Members will receive no financial benefit under the proposed settlement but will be bound by the release. The Contradictor contended that the proposed settlement would only be fair and reasonable as between group members if Category 1 Group Members and Ineligible Group Members are permitted to opt out of the proceeding at this stage. I gave careful consideration to the Contradictor’s submissions, and I largely accepted them. I do not though accept that the proposed settlement will only be fair and reasonable as between all categories of group members unless Category 1 Group Members and Ineligible Group Members are given an opportunity to opt out of the proceeding at this stage.

19 In summary:

(a) Category 1 Group Members cannot in my view succeed in their unjust enrichment claims (or for negligently inflicted economic loss). No debts were recovered from them by the Commonwealth. Therefore they have suffered no economic loss and the Commonwealth has not been unjustly enriched at their expense. In those circumstances it is not unfair or unreasonable that they will not receive a share of the Distribution Sum;

(b) Category 2 Group Members and Eligible Category 3 Group Members have good prospects of success in their unjust enrichment claims, and it is fair and reasonable that they receive substantial financial benefits under the proposed settlement;

(c) Ineligible Group Members do not have debts that were raised based on income averaging from ATO data; instead largely being assessed from payslips, bank statements and other information they provided. For them to succeed in their unjust enrichment claims (and their negligence claims) they must establish that their debts were somehow “tainted” with illegality because the (accurate) income information upon which their debts were assessed (and then recovered) was provided in response to a notice generated by the Robodebt system or in response to a debt based on income averaging from ATO data which was previously raised. In my view their claims have weak prospects of success and are more likely than not to fail at trial. It is not unfair or unreasonable that they will receive no financial benefit under the settlement;

(d) the Contradictor submitted that, notwithstanding the weakness of Ineligible Group Members’ claims, they should be seen as having some value such that Ineligible Group Members should receive some share of the Distribution Sum. The evidence however shows that the applicants’ lawyers strived to obtain a measure of compensation for Ineligible Group Members, but the Commonwealth refused to meet that demand. The applicants’ lawyers having been unable to negotiate any financial benefit for Ineligible Group Members, the Contradictor’s contention that they should have received some benefit under the proposed settlement eludes the point. A negotiated settlement which gave them some benefit was not available and had their claims proceeded to trial it is likely that they would have failed. Given the risks that Ineligible Group Members’ claims faced I am not satisfied that the proposed settlement is not fair and reasonable as between them and the other categories of group members; and

(e) allowing any Category 1 Group Member or Ineligible Group Member who filed an objection to the proposed settlement to opt out should they so wish, including those who were late in filing their objection, operates to improve the fairness of the proposed settlement.

20 Third, I consider the negligence claims of the applicants and all categories of group member to be weak. I doubt that the applicants can establish the alleged duty of care. But the negligence claims are something of a distraction because even if (contrary to my view) the negligence claims are treated as likely to succeed at trial, they add little as they centrally concern the same losses as those claimed in the unjust enrichment claims. To the extent that they extend beyond the unjust enrichment claims by seeking distress damages and aggravated and exemplary damages those claims face significant uncertainty and are attended by considerable risk.

21 Fourth, because at the point of settlement the Commonwealth had already refunded $707.9 million of the Commonwealth-recovered amounts, and had promised to refund all such amounts, the potential quantum of the claims in the proceeding largely concerns the claims for interest on the Commonwealth-recovered amounts, or for the benefit the Commonwealth received by its use of the Commonwealth-recovered amounts (which the parties called “quasi-interest”). When regard is had to the different methods by which interest or quasi-interest might be assessed, and the risks those claims face, the proposed settlement of $112 million inclusive of costs is a very favourable one.

22 Fifth, prior to the settlement approval hearing 680 group members filed objections to settlement approval (objections) both within time and out of time. That comprises only about 0.1% of the approximately 648,000 group members, but it is not clear whether all of the objections were intended as such. Taking into account the objections that may not have been intended as such, it appears that less than 0.04% of group members filed objections.

23 One thing that stands out from the objections is the financial hardship, anxiety and distress, including suicidal ideation and in some cases suicide, that people say they have suffered through the Robodebt system, and that many say they felt shame and hurt at being wrongly branded “welfare cheats”. Some of the objections were heart-wrenching and one could not help but be touched by them. One bereaved mother told the Court that her son had committed suicide after the Commonwealth demanded payment of a social security debt which she says he did not owe, some group members spoke of contemplating suicide, and many spoke of suffering financial hardship and serious anxiety or stress. It is plain enough that many group members continue to feel a great deal of anguish, upset and anger at the way in which they or their loved ones were treated. Even so, for the reasons I explain, the objections do not justify refusing to approve the proposed settlement.

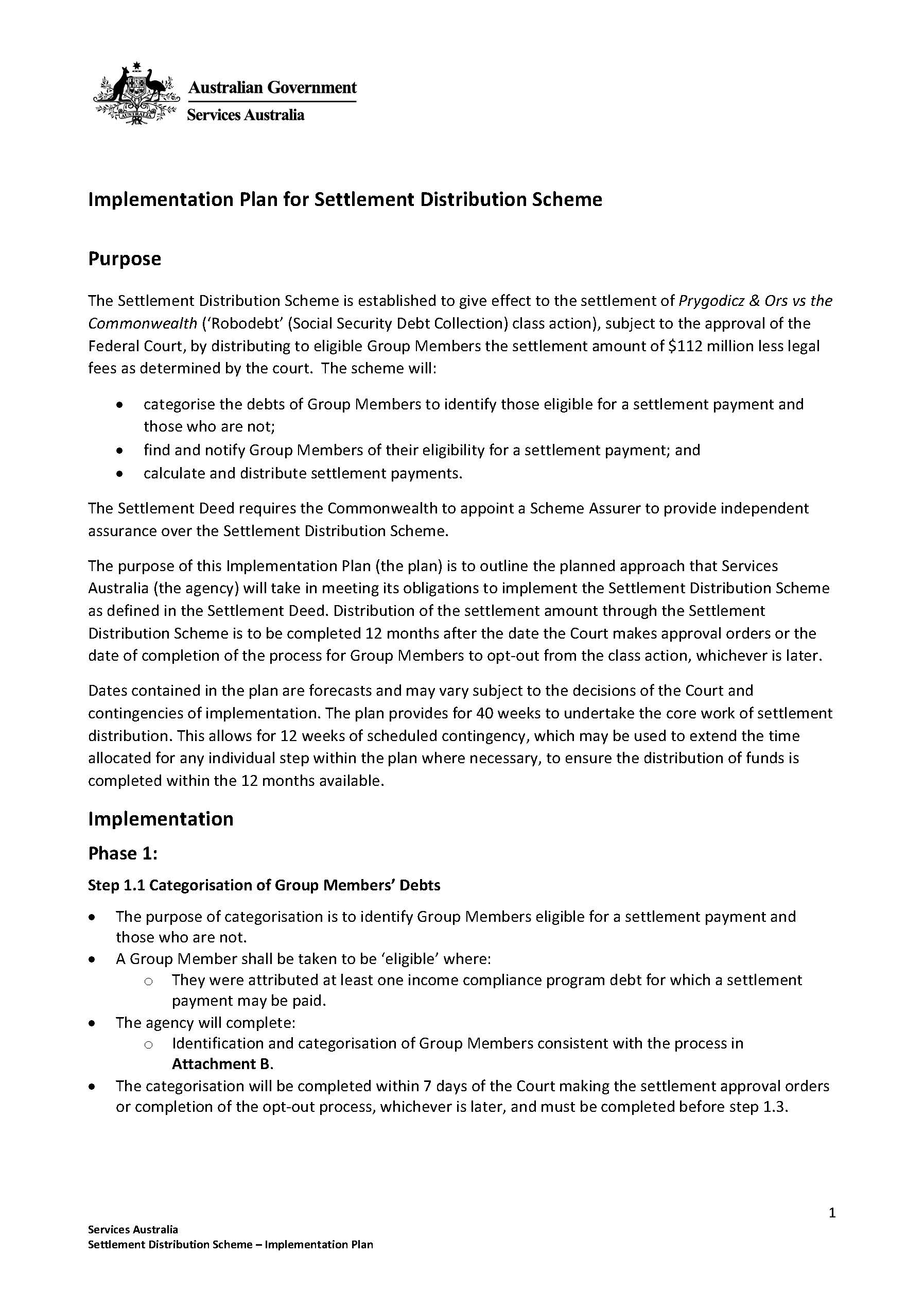

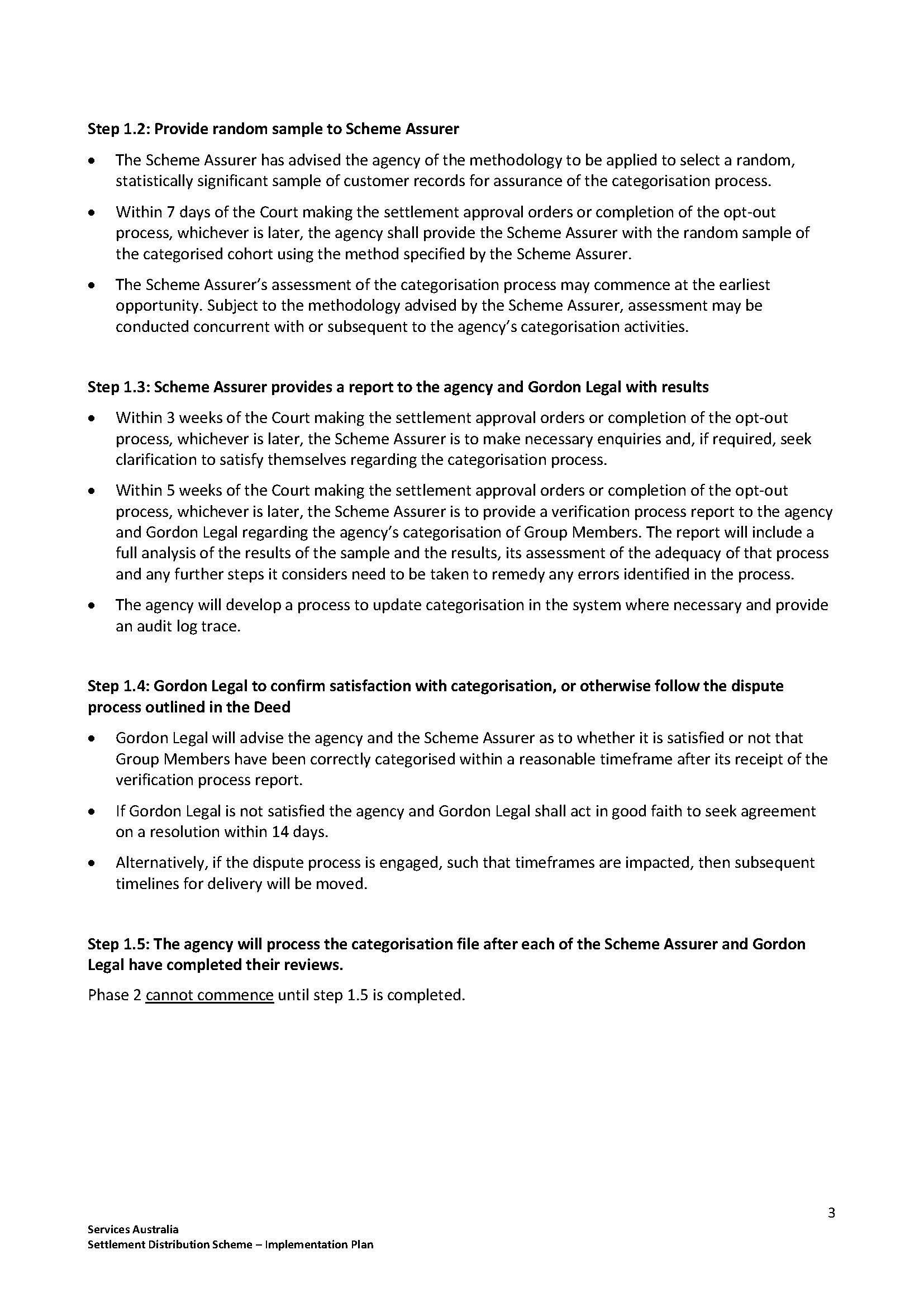

24 Sixth, with the discrete improvements and clarifications agreed between the Contradictor and the Commonwealth, I consider the system under the proposed SDS for categorising group members and distributing the Distribution Sum to Category 2 Group Members and Eligible Category 3 Group Members is fair and reasonable. It provides for the Commonwealth to categorise the group members into the categories under the Settlement Deed which categorisation must be independently verified by accounting firm KPMG (the Scheme Assurer) with Gordon Legal representing group members’ interests in relation to any dispute about categorisation. The calculation of each person’s entitlement is to be undertaken by the application of a simple interest formula based on the amount of any invalid debt recovered by the Commonwealth, and the length of time over which the Commonwealth had the use of the money. The Scheme Assurer has the obligation to independently verify the calculation of claimants’ entitlements and the Commonwealth’s payments of such entitlements. The costs of the Scheme Assurer are being paid separately by the Commonwealth and will not come out of the Settlement Sum.

25 Seventh, Gordon Legal conducted the case on a no-win no-fee basis, and provided an indemnity to the applicants against any adverse costs order against them if the case was unsuccessful. In my view the case could not have been brought without the firm doing so. I doubt that litigation funding would have been available for the case and it is unlikely the case could have been brought without the firm taking on those risks. That is to the firm’s credit.

26 I appointed an independent Costs Referee to inquire into and to report as to the reasonableness of Gordon Legal’s costs in the proceeding and in respect to its work under the SDS. I also appointed the Contradictor to represent group members’ interest in relation to the reasonableness of costs. The Costs Referee assessed the applicants’ reasonable legal costs of the proceeding at $8.4 million. Both the Contradictor and the Commonwealth submitted that it is appropriate to adopt that assessment, and neither the applicants nor Gordon Legal opposed adoption. It is appropriate to adopt that assessment. $8.4 million may seem like a huge or excessive amount for those uninitiated in relation to the legal costs incurred in large, complex class action litigation. But such a view would be uninformed having regard to the careful scrutiny given to the costs by the Costs Referee and the Contradictor and I am satisfied that amount is fair, reasonable and proportionate.

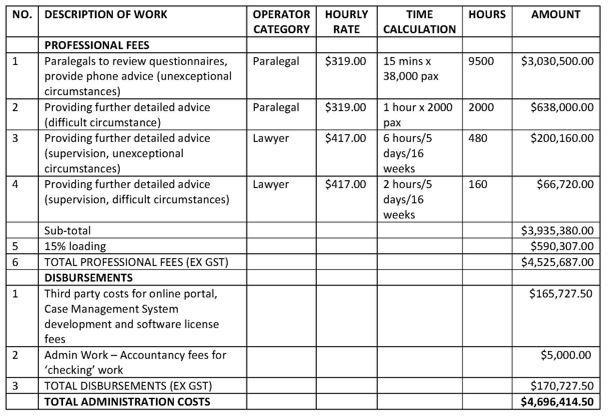

27 In relation to the costs likely to be incurred by Gordon Legal in the future in performing its functions under the SDS, I take a different view. On the basis of assumptions made by Gordon Legal to the effect that approximately 40,000 group members are likely to contact the firm and the time likely to be taken in dealing with their queries and concerns, the Costs Referee estimated that Gordon Legal’s reasonable costs for such future work would be approximately $4.22 million. On that basis the Contradictor submitted it was appropriate to now approve that lump sum amount.

28 In my view the assumptions upon which that estimate are based are inherently uncertain. At present one simply cannot know how many group members are likely to contact Gordon Legal. I accept that it is necessary to estimate and set aside an amount of costs before distributions can be made to group members, and the assessment cannot be delayed for too long or it will delay distribution of the settlement monies. However, I am not prepared to accept the estimate as sufficiently accurate at present. I have ordered the Costs Referee to confer with Gordon Legal and then to determine the best methods to assess the reasonableness and proportionality of Gordon Legal’s costs for performing that work on an ongoing basis and to have those costs paid monthly or two monthly, and to permit the Costs Referee to make an updated and more accurate estimate of the likely future costs:

29 Finally, for those perpetual critics of the Part IVA class action regime, the present case is one more example where the regime has provided real, practical access to justice. It has enabled approximately 394,000 people, many of whom are marginalised or vulnerable, to recover compensation from the Commonwealth in relation to conduct which it belatedly admitted was unlawful. The proposed settlement demonstrates, once again, that, when properly managed, our class action system works.

30 I thank the parties’ lawyers for the competent and capable way in which they conducted the case. Some of the legal issues in the case were complex and difficult, and the amount in dispute was large. The litigation was strenuously contested yet the solicitors and counsel for both sides conducted themselves appropriately and responsibly while strongly representing their clients’ interests. They did not get lost in the “fog of war” and were ultimately able to reach a settlement which is a credit to their efforts.

31 I also thank the parties and the Contradictor for the high quality of the evidence and written submissions filed in the settlement approval application, upon which I have directly drawn at some points.

THE EVIDENCE

32 The applicants relied upon the following material:

(a) the affidavits of Andrew Grech, a partner of Gordon Legal, affirmed 25 November 2020, 2 December 2020, 9 April 2021, 16 April 2021, 22 April 2021 and 29 April 2021 and 20 May 2021 (the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Grech Affidavits). The applicants claimed legal professional privilege and made claims of confidentiality in relation to parts of the Third, Fourth and Seventh Grech affidavits which I allowed after some reductions in those claims. The relevant annexures to those affidavits include:

(i) the Deed of Settlement between the parties (the Settlement Deed), and the execution pages of the counterparts signed by the parties on various dates between 20 and 30 November 2020;

(ii) the confidential Counsels’ Opinion;

(iii) the various conditional costs agreements signed by each of the representative applicants;

(iv) the supplementary report of Mr Dudman, the expert costs consultant engaged by Gordon Legal, dated 16 April 2021;

(v) the Framework of Settlement Distribution (SDS Framework); and

(b) the affidavit of Peter Gordon affirmed 9 April 2021.

The applicants filed short written submissions dated 9 April 2021, and made oral submissions at the approval hearing.

33 The Commonwealth relied upon the following materials:

(a) three affidavits of Emma Gill, a senior executive lawyer in the employ of the Australian Government Solicitor, the solicitors for the Commonwealth, affirmed on 20 April 2021, 30 April 2021 and 6 May 2021; and

(b) the affidavit of Robert McKellar, acting General Manager of Debt & Integrity Projects within Services Australia, affirmed on 5 May 2021 which, amongst other things, annexes the Implementation Plan for the Settlement Distribution (Implementation Plan). Together, the SDS Framework and the Implementation Plan comprise the “SDS”.

The Commonwealth filed written submissions in respect to the application for settlement approval dated 19 April 2021, the applicants’ reasonable legal costs dated 30 April 2021, and the Contradictor’s submissions dated 5 May 2021; and made oral submissions at the hearing.

34 The Contradictor filed written submissions dated 23 April 2021, and further submissions in respect to the applicant’s legal costs dated 30 April 2021, and made oral submissions at the hearing.

35 In relation to legal costs, the following materials were before the Court:

(a) the Costs Referee’s Report dated 1 April 2021, and the Costs Referee’s Second Report dated 26 April 2021; and

(b) the report of Mr Dudman dated 31 January 2021, the supplementary report dated 16 April 2021 and the further report dated 29 April 2021 (the First, Supplementary and Third Dudman Reports).

THE ROBODEBT SYSTEM

36 On about 1 July 2015, through Services Australia, the Commonwealth introduced the Robodebt system. Services Australia is the Executive Agency, created as a successor to the Department of Services Australia (formerly the Department of Human Services) (Department), responsible for administering social security payments under the SSA. At all relevant times the Department was responsible for the payment of social security payments under the SSA, doing so through Centrelink.

37 Under the SSA the amount of any benefit that social security recipients are entitled to receive is affected, amongst other things, by income tests set out in Chapter 3. From July 2010, the income tests were prescribed to be applied to a person’s income calculated on a fortnightly basis, and thus, where a person worked irregular hours or periods, the person’s entitlement to a social security benefit might vary from fortnight to fortnight. Social security recipients were required to report their income to Centrelink on a fortnightly basis so that the correct amount of the relevant social security benefit could be paid to them.

38 The Robodebt system was aimed at identifying and recovering overpayments of social security benefits from social security recipients and it was forecast to achieve very substantial recoveries of such overpayments for the Commonwealth. As I have said, the system attempted to identify overpayments of social security benefits in a review period through data matching, which was automatically conducted by:

(a) utilising the PAYG income information of social security recipients kept by the Australian Taxation Office and evenly apportioning that income over fortnightly increments in the review period (in a process the parties called “income averaging) to determine that person’s notional or assumed fortnightly income; and

(b) comparing the notional or assumed fortnightly income of the person with the actual fortnightly income information provided by the person (which was the basis upon which the level of social security payments had been assessed and paid to the person);

to determine whether the person had been overpaid social security benefits, and where that had occurred, to raise and recover that asserted debt.

39 Where the comparison indicated an overpayment of social security payments to a person during fortnightly periods in the review period, a letter was automatically sent to the person stating that the information received from the ATO was different to that which the person had told Centrelink, and telling the person that they were required to confirm or update their income information within a specified period, and if they did not do so the Commonwealth would rely on the ATO income information which might result in a debt that the person would have to pay.

40 If by the specified date the person had supplied no or insufficient further information, including payslips and bank statements, to explain the discrepancy, the Robodebt system made an assumption that the person’s previously reported income was incorrect and that the person had earned the amounts indicated in the ATO income information in equal fortnightly amounts during the relevant period of employment (the Fortnightly Income Assumption). The materials before the Court indicate that group members often experienced substantial difficulties in producing pay slips, statements by former employers and bank statements for review periods that sometimes related to periods that were some years earlier.

41 If the Robodebt system determined, based on the Fortnightly Income Assumption, that the person was entitled to a lesser amount of social security benefits for the review period, the system sent the person a letter stating that they owed a debt to the Commonwealth in the amount specified (Asserted Overpayment Debt), which was a notice for the purposes of s 1229(1) of the SSA. The letter advised the recipient of the availability of rights of administrative merits review pursuant to Parts 4 and 4A of the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 (Cth) (the SSAA).

42 If the asserted debt was not repaid by the person within the period specified the Commonwealth was able to require repayment of the amount by a variety of methods, including by garnishing tax returns, recovering monies from the person’s bank account or commencing legal proceedings against the person, and to impose an additional amount by way of a statutory penalty.

THE PROCEEDING

The class

43 The applicants commenced the class action on 19 November 2019. The group description in the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim filed 17 September 2020 (2FASOC) defines the represented class as all persons (group members):

(a) who at any time after 1 July 2010 received the benefit of one or more of the following social security payments from the Commonwealth: Newstart Allowance, Youth Allowance, Disability Support Pension, Austudy Allowance, Age Pension, Carer Payment, Parenting Payment, Partner Allowance, Sickness Allowance, Special Benefit, Widow A Allowance Payments and Widow B Allowance Payments (Social Security Payments); and

(b) in respect of whom the Commonwealth, at any time after 1 July 2015:

(i) generated correspondence or other notification referring to a difference between the income information obtained by Centrelink from the ATO and that used by Centrelink in assessing Social Security Payment entitlements and requesting, requiring or reminding the Social Security Payment recipient to check, confirm or update employment income information (Robodebt notification);

(ii) by or following the Robodebt notification, asserted an overpayment of one or more Social Security Payments recoverable by the Commonwealth as an Asserted Overpayment Debt; and

(iii) requested or demanded repayment of any Asserted Overpayment Debt or part thereof; and

(c) who:

(i) have paid, had paid on their behalf, or had recovered from them, any Asserted Overpayment Debt or part thereof; and/or

(ii) have not been informed by the Commonwealth that no recovery action will be pursued in respect of their Asserted Overpayment Debt.

The claims

44 I have previously set out the two broad claims made in the proceeding; (a) a restitutionary unjust enrichment claim; and (b) a claim in tort for negligently inflicted economic loss.

45 The Originating Application filed in November 2019 sought the following relief:

(a) declarations that:

(i) the Commonwealth does not have and has not had any statutory power to raise and recover or seek to recover any Robodebt raised debts or impose any penalty thereon;

(ii) the Commonwealth was unjustly enriched by receipt of each Commonwealth recovered amount and is liable to make restitution of each Commonwealth recovered amount to the applicants and group members;

(iii) the Commonwealth recovered amounts are moneys had and received by the Commonwealth to the use of the applicants and group members return of which they are entitled to;

(iv) the Commonwealth owed and owes a duty of care to the applicants and group members as alleged in the Statement of Claim; and

(v) the Commonwealth breached its duty of care to the applicants and group members in the manner alleged in the Statement of Claim.

(b) restitution of all of or the aggregate of Commonwealth recovered amounts and interest earned by the Commonwealth thereon;

(c) return of all of or the aggregate of Commonwealth recovered amounts as money had and received by the Commonwealth to the use of the applicants and group members;

(d) damages in negligence;

(e) interest pursuant to statute; and

(f) costs.

46 By an Amended Originating Application filed 1 July 2020 the applicants sought two further declarations, being that:

(a) the Commonwealth does not have and has not had any statutory power to use any income information provided by on behalf of an applicant or group member in response to a Robodebt notification to determine or assert an Asserted Overpayment Debt; and

(b) the Commonwealth acted unlawfully in:

(i) using calculations or other outputs of the Robodebt system to procure or compel the provision by any applicant or group member to the Commonwealth of income information and/or to generate or send to any applicant or group member any Robodebt notification;

(ii) determining and asserting against any applicant or group member any Asserted Overpayment Debt, or recalculation of it;

(iii) requesting or demanding repayment by any applicant or group member of any Asserted Overpayment Debt, or recalculation of it; and

(iv) recovering from any applicant or group member and retaining any Asserted Overpayment Debt, or recalculation of it.

47 In the 2FASOC, the pleading was amended to add claims for aggravated damages in respect of the negligence claims, and exemplary damages in respect of both the negligence claims and the unjust enrichment claims. The claims for aggravated and exemplary damages are founded in allegations that through identified Ministers of the Crown and senior public servants the Commonwealth had actual knowledge:

(a) of the vulnerabilities of some of the applicants and group members;

(b) that the automated system for identifying asserted overpayments and raising and recovering debts based on income averaging from ATO data led to the assertion of Asserted Overpayment Debts against the applicants and group members for amounts which may not have been, and in many cases were not, actually owed;

(c) that it had no statutory or other power to seek to recover such Asserted Overpayment Debts; and

(d) that it was acting unlawfully in asserting such debts.

The categories of group members

48 The initial Statement of Claim and the Amended Statement of Claim did not break the group members down into categories. Both the applicants and the Commonwealth said that it was not until about June 2020 that the parties came to understand that there were several different categories of group members within the class description.

49 On 1 July 2020, the applicants filed a Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASOC) which described four categories of group members (at paragraph 41A). Paragraph 41A of the Defence describes those four categories in different terms, but the differences are not material. To avoid confusion I use the categories as described in the Defence and the Settlement Deed.

50 “Category 1 Group Members” are those who have or had a debt that is alleged to be an Asserted Overpayment Debt that was determined wholly or partially based on apportioned ATO PAYG income information, but from whom the Commonwealth has not received or recovered any monies.

51 “Category 2 Group Members” are those who have or had a debt that is alleged to be an Asserted Overpayment Debt that was determined wholly or partially based on apportioned ATO PAYG income information, part or all of which has been received or recovered by the Commonwealth.

52 “Category 3 Group Members” are those who have or had a debt that is alleged to be an Asserted Overpayment Debt, part or all of which has been received or recovered by the Commonwealth, that was initially determined based on apportioned ATO PAYG income information, part or all of which was paid to or recovered by the Commonwealth, but which was later recalculated by the Commonwealth in the context of a subsequent review under s 126 of the SSAA based on information provided by or on behalf of the group member (such as payslips and/or bank statements) and not based on apportioned ATO PAYG income information.

53 A practical example of a Category 3 Group Member is a person who first received an Asserted Overpayment Debt determined based on income averaging from ATO data, and then provided income information which the Commonwealth used to assert a validly determined debt. The applicants alleged that the circumstance of the group member providing information which the Commonwealth then used against the group member “tainted” the subsequent debt with illegality, such that it is not recoverable by the Commonwealth, notwithstanding that the ultimate debt when viewed in isolation was lawfully raised.

54 Under the proposed settlement Category 3 Group Members are divided into two subcategories being: (a) Eligible Category 3 Group Members; and (b) Ineligible Category 3 Group Members. I later explain the basis for this sub-categorisation.

55 “Category 4 Group Members” are those who have or had a debt that is alleged to be an Asserted Overpayment Debt, all, part or none of which has been received or recovered by the Commonwealth, that was wholly determined based on information provided by or on behalf of the group member (such as payslips and/or bank statements) and not based on income averaging from ATO PAYG income information.

56 A practical example of a Category 4 Group Member is a person who first received a Robodebt notification and provided income information in response to the notification, which allowed the Commonwealth to validly determine a debt. The applicants alleged that the circumstance of the group member providing information which the Commonwealth then used against the group member “tainted” the subsequent debt with illegality.

Other relevant matters and steps

57 On 17 September 2019, Gordon Legal announced that it was investigating a class action against the Commonwealth in relation to the Robodebt system. On 19 November 2019 the firm commenced the proceeding.

58 On 27 November 2019, the Commonwealth consented to declarations in Amato which stated that the demand by the Commonwealth for payment of the alleged social security debt in that case was not validly made because the information before the decision-maker was not capable of satisfying the decision-maker that the debt was owed by the applicant to the Commonwealth within the scope of ss 1222A and 1223(1) of the SSA in the amount of the alleged debt. The alleged debt was a debt raised wholly or partially based on income averaging from ATO data.

59 In its Defence filed 14 February 2020, the Commonwealth did not contest that a social security recipient’s notional fortnightly income based on income averaging from ATO data did not provide a legal basis for the Commonwealth to assert that the person owed an Asserted Overpayment Debt to the Commonwealth. Even so, the Commonwealth denied that the applicants and group members had an entitlement to restitution from the Commonwealth on the basis of unjust enrichment or for compensatory damages in negligence.

60 Amongst other things, the Commonwealth asserted a “juristic reason” as a defence to the unjust enrichment claims, and contended that it permitted the Commonwealth to retain the Commonwealth-recovered amounts. The juristic reason alleged in relation to the first, third, fourth and fifth applicants and an unspecified number of group members was that those persons, in fact, had a debt payable to the Commonwealth pursuant to s 1223(1) of the SSA (even though the original basis upon which the debt was asserted was invalid, it being based on income averaging from ATO data).

61 In relation to the negligence claim, the Commonwealth denied the existence of the alleged duty of care.

62 On 1 July 2020, the applicants filed the FASOC by which the sixth applicant was joined to the proceeding. It set out four categories of group members and advanced different claims for the different categories. As I have said, the claims in respect of Category 3 Group Members and Category 4 Group Members do not rely on debts based on income averaging from ATO data.

63 On 29 May 2020, the Hon Stuart Robert MP, the Minister for Government Services, publicly announced that from July 2020 the Commonwealth would refund all repayments made on debts raised wholly or partially using income averaging of ATO income information and any interest charges and/or recovery fees paid on related debts (the 29 May 2020 Announcement).

64 On 1 July 2020, the Commonwealth publicly announced that:

(a) from 13 July 2020, it would write to people who were eligible for a refund in respect of a debt raised wholly or partially using income averaging of ATO income information and would start making refunds in respect of such debts from 27 July 2020; and

(b) debts raised using averaging of ATO income information, in respect of which no amount had been paid to the Commonwealth, would be reduced to zero,

(the 1 July 2020 Announcement). The evidence shows that shortly thereafter the Commonwealth then commenced to act upon those promises.

65 On 17 July 2020, the Commonwealth filed its Defence to the FASOC. It referred to the Minister’s public announcements on 29 May 2020 and 1 July 2020, and admitted that the existence of a debt in a particular amount could not be validly established for the purpose of s 1223(1) of the SSA where the decision that the person owed a debt in that amount depended, wholly or in part, on income averaging from ATO data, without other information capable of supporting a conclusion that the social security recipient received a consistent fortnightly income over the relevant period.

66 The Commonwealth continued to deny that it was required to make restitution for unjust enrichment. It continued to advance the “juristic reason” as to why it was entitled to retain any enrichment it had obtained by reason of its recovery of the Commonwealth-recovered amounts. It also continued to deny the existence of the alleged duty of care.

67 On 26 August 2020, the applicants sought to file the first proposed 2FASOC to include claims for aggravated damages in negligence, and for exemplary damages in respect of the claims for unjust enrichment and negligence. These additional claims were founded in allegations that the Commonwealth had actual knowledge that the Robodebt system of raising debts based on income averaging from ATO data led to the assertion of debts for amounts which may not have been and in many cases were not actually owed, knowledge that it had no statutory or other power to seek to recover such debts, and knowledge that it was acting unlawfully in asserting such debts. The proposed amendment was opposed by the Commonwealth. Following a hearing on 31 August 2020, leave was refused to file the first proposed 2FASOC because it did not adequately plead or particularise the serious allegations of knowledge of unlawfulness.

68 On 14 September 2020, the applicants served a second proposed 2FASOC which further pleaded and particularised the allegations that through identified Ministers and senior public servants the Commonwealth had actual knowledge that the Robodebt system was unlawful. The Commonwealth again opposed the amendment. Following a hearing on 16 September 2020 leave was granted for the amended pleading: Prygodicz v Commonwealth of Australia [2020] FCA 1454.

69 The Commonwealth unsuccessfully sought leave to appeal the decision to allow the 2FASOC: Commonwealth of Australia v Prygodicz [2020] FCA 1516 (Lee J). Although Justice Lee refused the application for leave to appeal, his Honour relevantly observed (at [14]-[15]:

The primary judge’s characterisation of the pleading of actual knowledge of illegality by the Commonwealth as “weak” might be seen as an example of his Honour’s characteristic polite understatement; it might be thought, albeit on an impressionistic basis, that aspects of the pleading suggest a real question arises as to whether there currently exists, within the knowledge of those acting for the applicants, a reasonable basis for some of the allegations made. One example will suffice.

The class action has been commenced on behalf of four categories of persons. Each of whom, following what is described as a Robodebt notification, received an assertion of overpayment of one or more Social Security Payments recoverable by the Commonwealth as a debt, and defined in the pleading as an “Asserted Overpayment Debt”. One category of the group members (and, apparently, the third applicant in respect of what is described as the Second Debt Period) had an Asserted Overpayment Debt that was neither wholly nor partly a Robodebt-raised debt at all, but simply had a debt determined by the Commonwealth based upon income information provided subsequent to a Robodebt notification. These are called the “Category 4 Group Members” in the pleading. In respect of these persons, even if there was not a relevant Robodebt-raised debt, it is nevertheless alleged that the Asserted Overpayment Debt was determined and based upon income information provided “in response to a Robodebt notification”: see 2FOSAC [sic] [1(b)(ii)], [41A(d)] and [45]. As I understand the pleading (and my understanding was not disputed by Senior Counsel for the applicants), it is said, even though there was no Robodebt-raised debt, given that a debt was raised in the circumstances pleaded, the Commonwealth was not only unlawfully alleging a debt, but that by virtue of [70A(k)], the Commonwealth actually knew it was acting unlawfully. Given the seriousness of the allegation and the novelty as to this aspect of the argument as to illegality, prima facie, this seems to me to be a most remarkable allegation to be made on the basis of the material identified.

(Emphasis in original.)

70 The case was listed for a two week trial to commence on 16 November 2020. On the first day of trial the parties reached the in-principle agreement which is now the subject of the settlement approval application. The parties’ agreement was subsequently recorded in the Settlement Deed.

The opt out notices

71 Pursuant to orders made 6 March 2020, by 25 May 2020 the Commonwealth was required to send group members an opt out notice in the form set out in Annexure B to those orders. The orders fixed 4:00 pm on 29 June 2020 as the time and date by which group members could opt out of the proceeding. I am satisfied on the evidence that group members were given notice of their right to opt out in accordance with the orders made on 6 March 2020.

72 The opt out notice informed group members as to the scope of the proceeding as follows:

The Applicants allege in the statement of claim in this proceeding that since 1 July 2015, Centrelink has sent to class members a notification (by mail, email, ‘myGov’ or the ‘Centrelink Express’ app) claiming that there was a difference between the income information obtained by Centrelink from the Australian Taxation Office and that used by Centrelink in assessing Centrelink payments, claiming that class members had been overpaid, and demanded that the claimed overpayment had to be paid back. Class members have received these demands and have paid, had paid on their behalf, or had recovered from them (by, for example, demands from debt collectors, or having had their tax returns garnished) amounts for these claimed overpayments.

The Applicants allege that Centrelink had no right to demand or recover any part of these overpayments, and that in doing so, the Commonwealth has been unjustly enriched, and has been negligent.

The Respondent to the class action is the Commonwealth of Australia, being the legal entity responsible for Centrelink. The Respondent admits that it has made demands and recovered parts of some overpayments, but says that in some cases, there was a valid basis known as a ‘juristic reason’ to recover the overpayments because the recipients were actually overpaid. The Applicants say that there is no such thing as a ‘juristic reason’ in Australian law. The Respondent denies that it was negligent as alleged by the Applicants.

The notice did not mention that the proceeding also sought damages for stress, anxiety and stigma associated with the request or demand for, and threatened or actual, recovery of their asserted debts.

73 The opt out notice expressly informed group members that if they did not opt out they would be bound by any outcome in the proceeding, including if the proceeding was not as successful as they wished. The notice said:

Class members are “bound” by the outcome in the class action, unless they have opted out of the proceeding. A binding result can happen in two ways being either a judgment following a trial, or a settlement at any time. If there is a judgment or a settlement of a class action class members will not be able pursue the same claims and may not be able to pursue similar or related claims against the Respondent in other legal proceedings. Class members should note that:

(a) in a judgment following trial, the Court will decide various factual and legal issues in respect of the claims made by the Applicants and class members. Unless those decisions are successfully appealed they bind the Applicants, class members and the Respondent. Importantly, if there are other proceedings between a class member and the Respondent, it may be that neither of them will be permitted to raise arguments in that proceeding which are inconsistent with a factual or legal issue decided in the class action.

(b) in a settlement of a class action, where the settlement provides for compensation to class members it may extinguish all rights to compensation which a class member might have against the Respondent which arise in any way out of the events or transactions which are the subject-matter of the class action.

If you consider that you have claims against the Respondent which are based on your individual circumstances or otherwise additional to the claims described in the class action, then it is important that you seek independent legal advice about the potential binding effects of the class action n before the deadline for opting out...

(Emphasis in original.)

74 In relation to the binding nature of any outcome in the proceeding, the opt out notice also said:

What will happen if you choose to remain a class member?

Unless you opt out, you will be bound by any settlement or judgment of class action. If the class action is successful you will be entitled to share in the benefit of any order, judgment or settlement in favour of the Applicants and class members, although you may have to satisfy certain conditions before your entitlement arises. If the action is unsuccessful or is not as successful as you might have wished, you will not be able pursue the same claims and may not be able to pursue related claims against the Respondent in other legal proceedings.

75 Subsequently, by orders made 17 August 2020, the Court varied its earlier opt out orders in respect of the following two groups: (a) persons who were not identified as group members by the Commonwealth as at 25 May 2020, but who the Commonwealth subsequently identified as such; and (b) the representatives of deceased estates of persons who were group members, where the Commonwealth held contact details for those representatives. Pursuant to the August orders, by 24 August 2020, the Commonwealth was required to send group members in those two groups an opt out notice in the form set out in Annexure A to those orders, being similar in form to the earlier notice. The orders fixed 4.00 pm on 14 September 2020 as the time and date by which such group members could opt out of the proceeding.

76 I am satisfied on the evidence that those group members were given notice of their right to opt out of the proceeding in accordance with the orders made 17 August 2020.

77 In my view the opt out notice informed group members in straightforward terms that if they did not opt out of the proceeding and the action was unsuccessful or not as successful as they might have wished, they would not be able pursue the same claims and may not be able to pursue related claims against the Commonwealth in other legal proceedings.

The Notice of Proposed Settlement

78 Pursuant to orders made 23 December 2020, by 25 January 2021 the Commonwealth was required to send a Notice of Proposed Settlement to group members (Notice of Proposed Settlement). I am satisfied on the evidence that the Notice of Proposed Settlement was sent to group members in accordance with the orders of 23 December 2020.

79 The Notice of Proposed Settlement informed group members as follows:

CATEGORIES OF GROUP MEMBERS AND WHAT THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT MEANS

10. If the proposed settlement is approved by the Court, you will not need to repay any ‘invalid debt’. The Court will declare debts to be invalid where:

a. the rate of the social security payment for the group member was dependent upon the person’s ordinary income on a fortnightly basis;

b. the Commonwealth based its decision on an assumption (Assumption) that the person’s ordinary income for a fortnight (relevant fortnight) was greater than the amount of ordinary income that the person had reported to the Commonwealth for the relevant fortnight;

c. the Commonwealth relied solely on PAYG employment income data from the ATO (ATO data) to make the Assumption and did not have evidence that the person was likely to have earned employment income at a constant fortnightly rate during a period covered by the ATO data, or other evidence to support the Assumption;

d. the Assumption was based on an assessment of the person’s employment income for the relevant fortnight derived from averaging the ATO data, for a longer period that included the relevant fortnight, as if the person had earned income at a constant rate during that period.

11. If the settlement is approved by the Court, $112 million will be made available to be paid to eligible group members, less an amount to be deducted for the Applicants’ reasonable legal costs (as approved by the Court) in bringing the proceeding and to pay Gordon Legal for performing its functions under the Settlement Distribution Scheme.

12. Under the proposed settlement, group members are in different categories. Not all categories of group members will receive a payment. A group member can be in more than one category if they had more than one debt. People who will receive a settlement payment are known as ‘eligible group members’. Further information about the categories and who will receive a settlement payment is in the Table at paragraph 15 below.

13. If you are an eligible group member, you may also have the amount you paid to Services Australia refunded (if it has not been refunded already) or no longer be required to pay the balance of your debt or both.

14. The amount eligible group members receive will depend on when they paid an amount towards an ATO income averaged debt and when that money was paid back to them.

15. This means that eligible group members who paid back more and were without their money for longer will receive a bigger settlement payment than those who paid back less and were without their money for a shorter time. The Table below explains how the proposed settlement will operate.

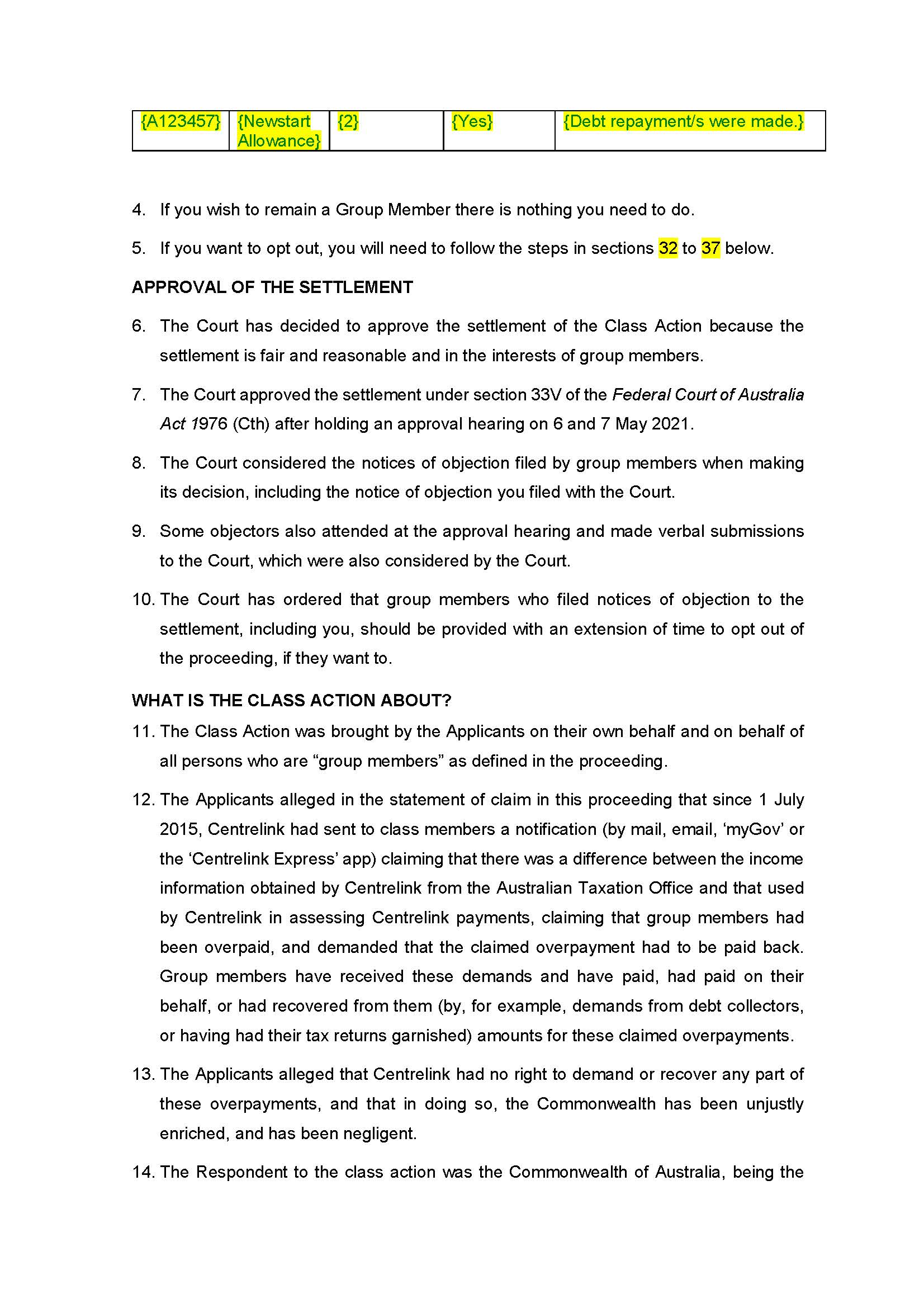

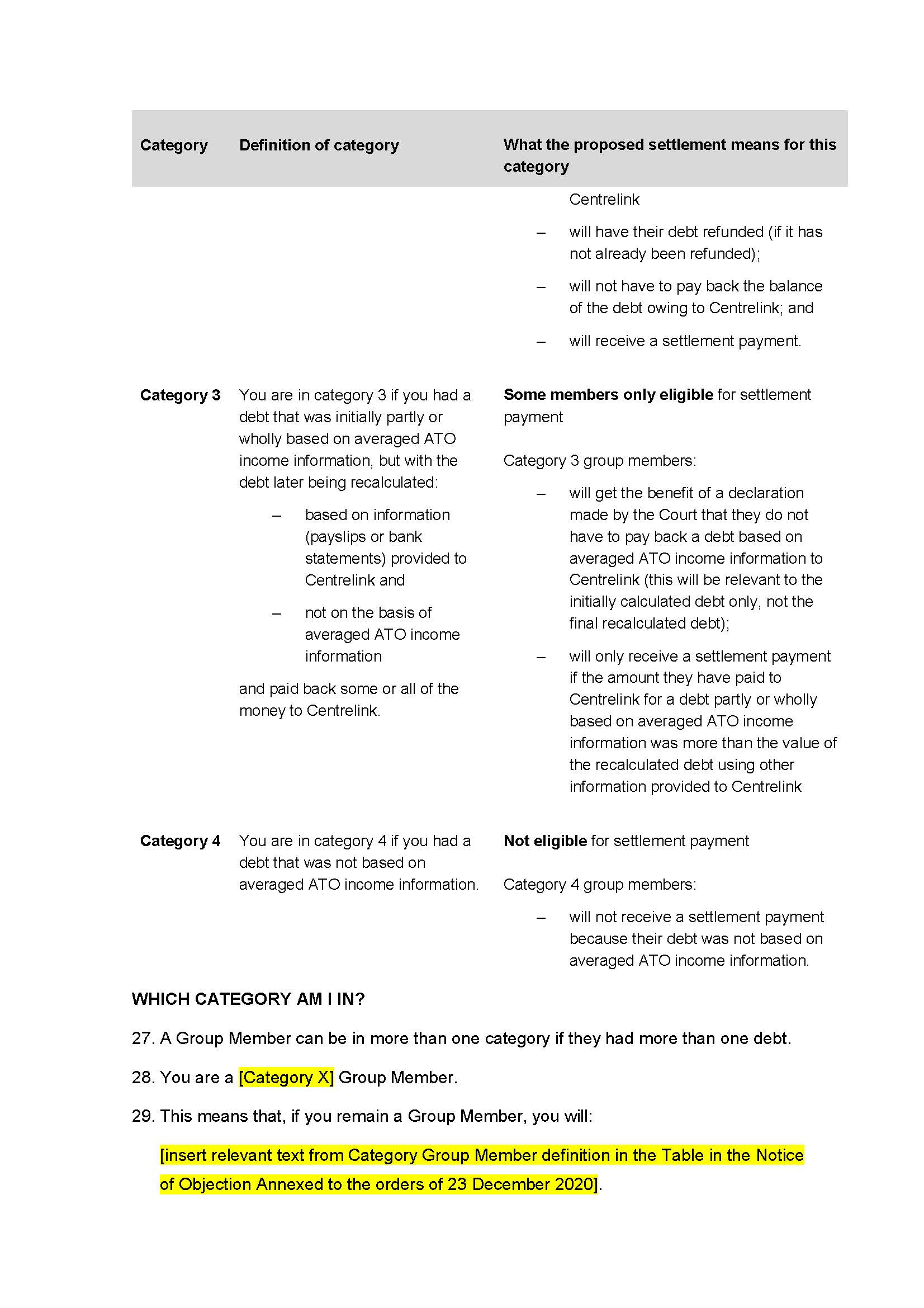

Category | Definition of category | What the proposed settlement means for this category |

Category 1 | You are in category 1 if you had a debt that was either partly or wholly based on averaged ATO income information, but did not pay any money to Centrelink in respect of the debt. | Not eligible for settlement payment Category 1 group members: - will get the benefit of a declaration made by the Court that they do not have to pay back a debt based on averaged ATO income information to Centrelink - will not have to pay back the debt based on averaged ATO income information to Centrelink; and - will not receive a settlement payment. |

Category 2 | You are in category 2 if you had a debt that was either partly or wholly based on averaged ATO income information, and you paid back some or all of the money to Centrelink. | Eligible for settlement payment Category 2 group members: - will get the benefit of a declaration made by the Court that they do not have to pay back a debt based on averaged ATO income information to Centrelink - will have their debt refunded (if it has not already been refunded); - will not have to pay back the balance of the debt owing to Centrelink; and - will receive a settlement payment. |

Category 3 | You are in category 3 if you had a debt that was initially partly or wholly based on averaged ATO income information, but with the debt later being recalculated: based on information (payslips or bank statements) provided to Centrelink and not on the basis of averaged ATO income information and paid back some or all of the money to Centrelink. | Some members only eligible for settlement payment Category 3 group members: - will get the benefit of a declaration made by the Court that they do not have to pay back a debt based on averaged ATO income information to Centrelink (this will be relevant to the initially calculated debt only, not the final recalculated debt); - will only receive a settlement payment if the amount they have paid to Centrelink for a debt partly or wholly based on averaged ATO income information was more than the value of the recalculated debt using other information provided to Centrelink |

Category 4 | You are in category 4 if you had a debt that was not based on averaged ATO income information. | Not eligible for settlement payment Category 4 group members: - will not receive a settlement payment because their debt was not based on averaged ATO income information. |

80 The Notice of Proposed Settlement also informed group members as follows:

36. An independent organisation will check that Services Australia correctly categorises group members and pays group members the right amount. Gordon Legal will also be told about how Services Australia has categorised group members and will have an opportunity to check that the categorisation is correct. If the Court approves the settlement, group members will be told if they are an eligible group member or not, and if they are an eligible group member, how payments will be calculated.

81 The Notice of Proposed Settlement set out the process by which the Court would decide whether to approve the proposed settlement. It also explained that the Court had appointed the Contradictor to represent the interests of group members, and had appointed the Costs Referee who was responsible for inquiring into and reporting on the reasonableness of the legal costs proposed to be deducted from the Settlement Sum.

82 In relation to the right of group members to object to the proposed settlement, the Notice of Proposed Settlement said the following:

IF YOU DON’T WANT TO OBJECT TO THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

25. There is nothing you need to do if you don’t want to object to the proposed settlement. If the settlement is approved, Services Australia will notify you about the category you are in, the amount of any payment you will get, and information about what to do if you don’t agree with your categorisation.

IF YOU WANT TO OBJECT TO THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

26. If you think you might want to object to the proposed settlement of the Class Action, you may want to get independent legal advice now (this can’t be from Gordon Legal).

27. If you want to ask the Court not to approve the settlement, you must send a completed copy of the attached Notice of Objection form by 5 March 2021 either:

a. by email to the Victoria registry of the Federal Court of Australia at the email address robodebt@fedcourt.gov.au; or

b. if you don’t have access to email, by post to the postal address;

Victoria Registry

Federal Court of Australia

Owen Dixon Commonwealth Law Courts Building 305 William Street

Melbourne VIC 3000

28. If you want to, you can file with the Court any written submissions, which further state the reasons why you object to approval of the proposed settlement, and any evidence upon which you may rely, by 19 March 2021. If you want to, you can also file further submissions after the Costs Referee’s report is available on 12 April 2021, doing so by 19 April 2021.

29. Written submissions and any evidence should be in approved Court forms. You might want to get an independent lawyer to help you fill these out.

30. You can attend (or send a representative to) the hearing 6 May 2021 when the Federal Court will consider whether to approve the settlement and you or your representative may make oral submissions in support of your objection. The hearing will take place at:

Federal Court of Australia

Owen Dixon Commonwealth Law Courts Building

305 William Street

Melbourne VIC 3000

31. Information about how to attend will be available on the Federal Court’s website, and may include options to attend online or by telephone.

83 The Notice of Proposed Settlement broadly informed group members of the effect of the release to be provided under the proposed settlement, as follows:

OTHER INFORMATION ABOUT THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

32. If the Court approves the proposed settlement, group members won’t be able to make the same legal claims made in this Class Action in new proceedings, unless the group member opted out of the Class Action.

84 In my view the Notice of Proposed Settlement gave group members timely notice of the salient elements of the proposed settlement, informed them that they had an opportunity to take steps to protect their own position by objecting to court approval if they wished to do so, and informed them that they would lose their rights (if any) to make the same legal claims if the settlement is approved. As I said previously, the opt out notice had earlier informed group members that if they did not opt out of the proceeding and the action was unsuccessful or not as successful as they might have wished, they would not be able pursue the same claims and may not be able to pursue related claims against the Commonwealth in other legal proceedings.

THE PRINCIPLES RELEVANT TO SETTLEMENT APPROVAL

85 The principles to be applied in a settlement approval application under s 33V of the FCA are well-established. The central question is whether the proposed settlement is a fair and reasonable compromise of the claims of the applicants and group members. That requires consideration of whether the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable, first, as between the applicants and group members and the respondent, and, second, as between the group members: Evans v Davantage Group Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 70 at [17] (Beach J); Blairgowrie Trading Ltd v Allco Finance Group Ltd (Recs & Mgrs Apptd) (In Liq) (No 3) [2017] FCA 330; (2017) 343 ALR 476 at [81] (Beach J). The Court assumes an onerous and protective role in relation to group members’ interests which is not unlike the role the Court assumes when approving settlements on behalf of infants: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Richards [2013] FCAFC 89 at [8] (Jacobson, Middleton and Gordon JJ); Kelly v Willmott Forests Ltd (in liquidation) (No 4) [2016] FCA 323; (2016) 335 ALR 439 at [62] (Murphy J); Blairgowrie at [81]-[85]; Caason Investments Pty Ltd v Cao (No 2) [2018] FCA 527 at [12] (Murphy J). The relevant principles were usefully summarised by Moshinsky J in Camilleri v The Trust Company (Nominees) Ltd [2015] FCA 1468 at [5].

86 In Botsman v Bolitho [2018] VSCA 278; (2018) 57 VR 68 at [203]-[208] (Tate, Whelan and Niall JJA) the Victorian Court of Appeal said:

[203] It is an essential starting point to identify the settlement and its terms. It is commonplace that a deed of settlement may address more than the settlement of the claims against the defendant and will also deal with the distribution of settlement money, including to a litigation funder. The structure of sub-ss 33V(1) and (2) suggests that such payments may be distributions of money that has been paid under a settlement to which the Court has given approval under s 33V(1). Those distributions are the subject of separate Court approval under s 33V(2).

[204] The question of fairness interposes itself at various levels. Most obviously, there will need to be consideration of the fairness of a proposed settlement sum.

[205] The Court is being asked to approve a compromise of litigation. Inevitably, that will require an assessment of whether the plaintiff is likely to succeed in the action, the measure of damages that a successful judgment would yield, the prospects of recovery, and the expenditure in costs, time and effort that would be required to bring the proceedings to a conclusion.

[206] That assessment does not involve a simple calculus but calls for matters of judgment based on imperfect knowledge and is influenced by the appetite for risk. It will be informed by the complexity and duration of the litigation and the stage at which the settlement occurs. It is important to acknowledge that it is the state of imperfect knowledge and the existence of risks that will have likely induced the settlement. It follows that those matters should be accorded a degree of prominence in any assessment of the reasonableness of the settlement.