Federal Court of Australia

AGL Energy Limited v Greenpeace Australia Pacific Limited [2021] FCA 625

ORDERS

AGL ENERGY LIMITED ACN 115 061 375 Applicant | ||

AND: | GREENPEACE AUSTRALIA PACIFIC LIMITED ACN 002 643 852 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and, by 4.15pm on 9 June 2021, provide to my chambers proposed short minutes of order giving effect to the reasons published today, with any areas of disagreement between the parties identified in mark-up.

2. The proceedings be listed for a case management hearing at 9.30am on 10 June 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BURLEY J:

[1] | |

[8] | |

[8] | |

[11] | |

[23] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

3.2 Fair dealing for the purpose of parody or satire – s 41A | [31] |

[31] | |

[39] | |

[45] | |

[58] | |

[62] | |

3.3 Fair dealing for the purpose of criticism or review – s 41 | [87] |

[96] | |

[96] | |

[101] | |

[112] | |

[117] |

1 AGL Energy Ltd provides a range of gas, electricity and telecommunications services to customers in Australia. As part of its branding, AGL uses Australian registered trade mark no 1843098 (AGL logo), which is as follows:

2 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Ltd is a charity registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission and describes itself as an environmental campaigning organisation. Both it and AGL are well known in Australia.

3 On 5 May 2021 Greenpeace launched a campaign about AGL across a variety of media platforms using headlines such as “Still Australia’s Biggest Climate Polluter” and “Generating Pollution For Generations”. An example of an online banner used in the campaign is as follows:

In this example, it may be seen that the tagline “Australia’s Greatest Liability” appears in close proximity to the AGL logo. I refer to the combined logo and tagline as the modified AGL logo. Part of Greenpeace’s campaign drew attention to a detailed report commissioned by Greenpeace entitled “Coal-faced: Exposing AGL as Australia’s biggest climate polluter” (Exposing AGL report).

4 AGL does not seek to prevent Greenpeace from engaging in its campaign, but rather takes umbrage with the use by Greenpeace of its logo as part of that campaign. It contends that the modified AGL logo is substantially identical (but not deceptively similar) to the AGL logo and thus infringes AGL’s registered trade mark. AGL also claims that the modified AGL logo infringes copyright in the AGL logo. AGL seeks declarations of infringement, injunctions to restrain Greenpeace’s use of the modified AGL logo, and damages including additional damages in respect of the infringements.

5 Greenpeace does not dispute that AGL owns copyright in the AGL logo, or that it is validly registered as a trade mark. However, it denies infringing copyright on the basis that its use of the modified AGL logo amounts to fair dealing for the purpose of criticism or review or alternatively parody or satire within the terms of ss 41 or 41A of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). It denies trade mark infringement, broadly on the basis that it has not used the modified AGL logo as a trade mark in the sense required by s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) or otherwise used the AGL logo within the scope of its trade mark registration.

6 The proceedings were commenced urgently as a duty application on 7 May 2021 and, with the co-operation of the parties, were set down for an early final hearing on 2 June 2021. Orders have been made for questions of liability and entitlement to declaratory and injunctive relief and any additional damages to be heard separately and before questions going to quantum of any damages. At the hearing the parties agreed that the case could be determined by reference to nominated examples of the impugned Greenpeace use in, variously, online banner advertisements, street posters, photographs of placards, social media uses and a website. These uses are illustrated by separate categories in section 2.3 below and also in the annexure to these reasons.

7 For the reasons set out more fully below, I have concluded that AGL fails in its trade mark infringement claim. It also fails in respect of its copyright infringement claim in relation to all impugned uses with the exception of some of the social media posts and some photographs of placards. AGL also fails in respect of its claim for additional damages. The consequence is that injunctive relief will be granted in respect of the uses that infringe copyright but the proceedings will otherwise be dismissed.

8 In support of its claim AGL relies on affidavits affirmed on 6 May 2021 and 13 May 2021 by Anita Cade, the solicitor acting for AGL. Ms Cade exhibits instances of the impugned conduct of Greenpeace and attaches correspondence between the parties. It also relies on an affidavit affirmed by David Bland on 13 May 2021. Mr Bland is AGL’s General Manager, Customer Experience and Advocacy. He gives evidence about the AGL logo, consumer awareness of the logo and the AGL brand more broadly. Finally, it relies on an affidavit affirmed by Timothy Riches on 13 May 2021. Mr Riches is the Group Strategy Director of Principals Pty Ltd, which was the organisation responsible for creating the AGL logo. None of AGL’s witnesses were cross-examined.

9 Greenpeace relies on affidavits sworn by two of its employees. The first is affirmed by its Chief Executive Officer David Ritter on 25 May 2021. He gives evidence about the operations of Greenpeace, its mission and various campaigns that it has conducted over the years, the practice of “greenwashing”, his view of the environmental record and greenwashing conduct of AGL, the commissioning of the Exposing AGL report, and Greenpeace’s media campaign about AGL. The second is affirmed by Glenn Walker, Senior Campaigner leading Greenpeace’s AGL campaign. He gives evidence of the design brief and creative development process leading to the media campaign.

10 Mr Ritter and Mr Walker were cross-examined. I found them to be honest and credible witnesses.

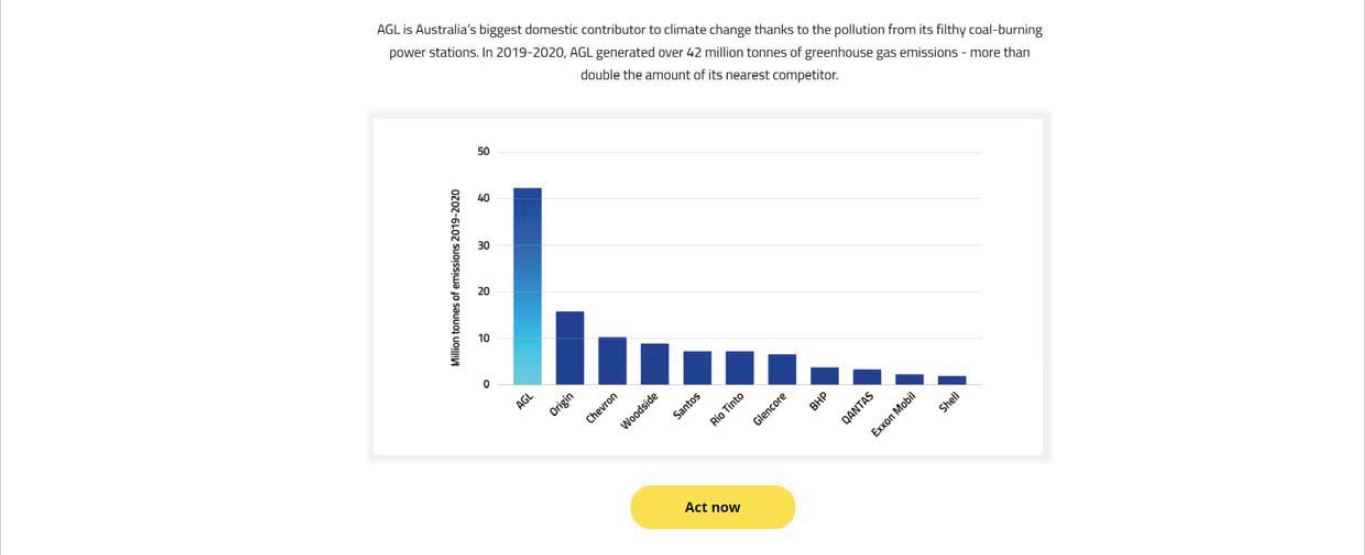

11 AGL is a significant producer of electricity in the Australian market. It uses a range of methods for generating that electricity, including three coal burning power stations, as well as gas, wind and solar power. In its 2020 Annual Report AGL refers to its vision for the long term future as electricity from renewable sources. It refers to its commitment to work towards the full closure of its coal-fired plants by 2050. It states that as “Australia’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, we have a particular responsibility to be transparent about the risks and opportunities that climate change poses to our business, the community and the economy more broadly”.

12 In late 2019 Greenpeace decided to launch a campaign targeting AGL for what Greenpeace considered to be AGL’s poor environmental practices. In broad terms, Greenpeace was concerned that the continued operation by AGL of its coal-burning power stations was harmful to Australia’s ability to reach net zero emissions in a time-frame consistent with the Paris Climate Goal. It was also concerned that AGL was burnishing its public image by engaging in “greenwashing” by falsely creating the impression in its promotional materials that it is doing more to protect the environment than it really is. For present purposes it is not necessary or appropriate to address the validity or otherwise of Greenpeace’s concerns. AGL, whilst contending that not all of the information concerning it in Greenpeace’s campaign is factually correct, does not seek to prevent Greenpeace from disseminating information or stifle public debate surrounding it. Nor does it object to the use of the initials “AGL” in the report or in the Greenpeace media campaign more generally.

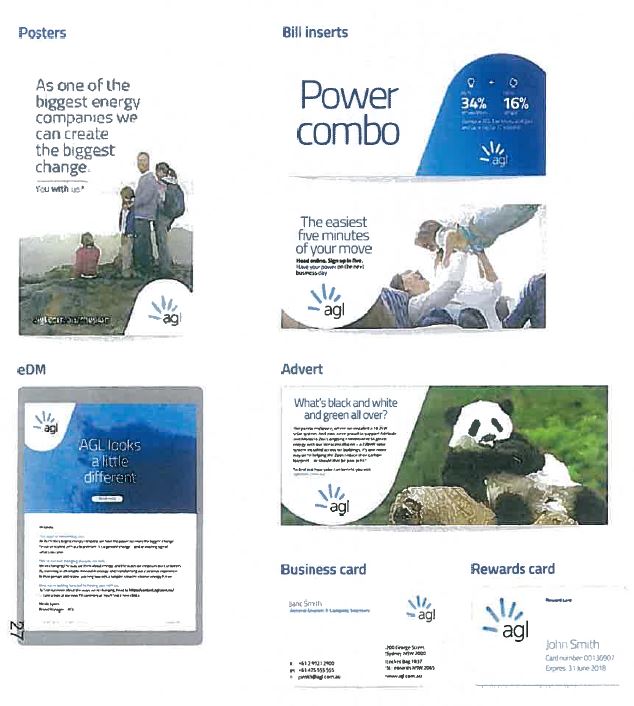

13 AGL uses the AGL logo as a central aspect of its marketing and “customer experience” strategy. Together with rigorously enforced brand guidelines, which provide identifiable “visual identity elements” used in its promotional materials, AGL uses the AGL logo to communicate its corporate message to consumers. An overview of aspects of these elements is depicted in AGL’s 2017 Brand Guidelines a sample of which is set out below:

14 The Brand Guidelines describe the visual identity elements as including the AGL logo, the colour palette, the typography, the curve, and the way that “hero” illustrations are used to support the message. Aspects of these components can be seen from the images above. The guidelines state that these elements consist of “a set of design elements that work together to create a distinctive look and feel, making the AGL brand instantly recognisable”.

15 Greenpeace’s concern about greenwashing arose in the context that it considered that AGL has successfully persuaded consumers in Australia that it is an environmentally responsible energy provider when Greenpeace did not consider this to be the case. It commissioned the Exposing AGL report in February 2021. The report is 44 pages long and is extensively footnoted to documents produced by AGL and other public sources, including government publications, privately written articles and news reports. The first page of the report makes plain that it is written for and authorised by Greenpeace. It includes a heading “Disclaimer” that illuminates the purpose of the document:

While this report does not suggest any illegal conduct on the part of any of the individuals or organisations named, it shows that AGL is currently using its position and power to slow the transition to a low carbon economy which is jeopardising both human and planetary health, and it presents alternative approaches that would allow AGL to transition from Australia’s biggest polluter to a green energy leader.

16 An Executive Summary commencing on page 5 raises concerns about AGL’s continued operation of its coal-burning power stations and concerns that AGL’s publicity material makes it seem like most of the energy and money that it generates comes from renewable power sources like wind, hydro and solar. The Executive Summary also states that AGL claims that it is “the biggest ASX-listed investor in renewable energy”, and the report suggests that the truth is otherwise, because of the continued operation of the power stations, one of which AGL intends to keep operating until 2048. This is said to be in contrast to the approach of AGL’s competitors in the energy market, which have taken steps to close their coal-burning power stations well before that date. The Executive Summary says that research shows that renewable energy and battery storage can secure the electricity grid more effectively than coal and gas, and provides Germany by way of example, where in 2020 renewables overtook electricity generation from coal, oil and gas, as it has in other countries. The Executive Summary concludes that “[a]s Australia’s biggest polluter, AGL can lead the way in this transition to a clear, sustainable future”. The Introduction to the report then states:

The aim of this report is to help AGL’s 120,000 shareholders, millions of customers, and the broader Australian public better understand the truth about the company, how it became Australia’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, and why it should retire all of its coal-burning power stations by 2030.

17 The Exposing AGL report formed a part of the Greenpeace media campaign in the sense that if the public facing aspects of the impugned conduct (to which I refer in more detail below) sufficiently attracted the attention of a reader, then they could locate it online through resources made available by Greenpeace, and read about the subject more. One of the impugned uses (a photograph of a school student holding up a placard) includes the AGL logo and appears on page 4 of the Exposing AGL report, opposite the Executive Summary.

18 According to Mr Ritter, the purpose of the campaign was to spark public debate about AGL’s activities and to review and criticise AGL’s greenwashing materials by pointing out the difference between those materials and AGL’s real environmental impact. The ultimate objective was said to be to persuade the company’s board and senior management to decide to retire AGL’s coal-burning power stations by 2030 and become a 100% renewable energy company. Insofar as the subjective intention of Greenpeace is relevant to these proceedings, I accept that evidence.

19 The creative aspect of the Greenpeace media campaign was developed under the supervision of Mr Walker. An external advertising agency called Monster Children Creative was briefed to pitch creative ideas. The brief explains to Monster that Greenpeace “uses peaceful protest and creative confrontation to expose global environmental problems, and promote solutions that are essential to a green and peaceful future”. It provides background to the AGL campaign, stating that “AGL is the worst domestic corporate villain in the country”, that its emissions are 236% more than the second-biggest polluter in Australia, and provides other statistics that are also set out in the Exposing AGL report. It says “We must compel Brett Redman [the AGL CEO] to either announce a new corporate strategy in line with our asks or stand down in favour of someone who will”.

20 In a passage emphasised by AGL in submissions, under the heading “Objective and Theory of Change” the brief states:

We will expose the underbelly of AGL’s business model, revealing their significant climate, environmental and health impacts and greenwashing. We’ll build on this to launch a full-scale brand “realignment” campaign, removing their social license and making their brand toxic. We’ll mobilise their customers and our supporters so they feel intense pressure to change, and we’ll engage and mobilise their staff so the pressure also builds rapidly from inside. We’ll also engage and mobilise key investors, so the C-Suite or Board read the writing on the wall about the urgency to change. Meanwhile, we’ll neutralise key opponents, to remove or reduce the barriers to coal closure. All of these interventions combined with specific persuasion from peers will win over the C-Suite or Board to announce a major new direction for the company and the early closure of their coal burning power stations.

(emphasis in original)

21 The brief requests the design of “a new campaign identity for the AGL campaign, primarily a ‘brand-jammed’ logo and tagline”. No idea would be “too wild”, and it was said that “the cheeky, innovative nature of your idea will be a big factor in our consideration”. The brief provides a number of examples of “creative brand-jamming” that Greenpeace has done in the past. One example was a brand-jamming of the Commonwealth Bank in an effort to stop the bank’s investment in coal. It undertook brand-jamming by doctoring the bank’s logo “into a trending CoalBank alternative”. Another campaign depicted in the brief was “Don’t Let Coke Choke Our Oceans”, designed to pressure Coca-Cola into addressing ocean plastic pollution. That campaign altered “Coke” to “Choke” in the distinctive red and white livery of Coca-Cola’s branding.

22 Monster produced several creative ideas before the final version was delivered. Mr Walker was tested in cross-examination as to the motivation of Greenpeace in using the AGL logo in the campaign:

Mr Hennessy SC: Why do you say it was important to use AGLs logo as opposed to – or in combination with AGLs name as opposed to AGLs name alone?

Mr Walker: Because parody is imitation and it made a funnier more effective creative from our perspective to use as much of their logo and, obviously, their creative look and feel to the advertisements as possible while still making it very clear that wasn’t an advertisement from AGL because it was saying something that you wouldn’t expect from AGL, and that’s what grabs people’s attention, the unexpected nature of a parody which is clearly labelled as by – presented by Greenpeace which we’re – Greenpeace is very well known for.

Mr Hennessy SC: But when it has suited Greenpeace in this campaign it has simply identified AGL by its name as distinct from the AGL – or separate from the AGL logo, hasn’t it?

Mr Walker: Sometimes we identify AGL by name but there are many parts of this campaign. In this particular instance, these – the use of AGLs logo into an amended logo and into the creative materials was part – was very deliberately part of what we call brand jamming or what others might refer to as parody.

23 The Greenpeace media campaign involves 7 elements, described as follows, each of which forms part of the impugned conduct for the purpose of the copyright infringement claim. The impugned conduct for the purpose of the trade mark infringement claim is confined to (a) and (b):

(a) Online banner advertisements, an example of which is set out in [3] above, and further images of which appear in the annexure to these reasons. In some versions this presents as a shifting image with the modified AGL logo including the words “Australia’s Greatest Liability” appearing first against the blue and white background, followed immediately by the words “still Australia’s Biggest Climate Polluter”, then “Act Now” and “Presented by Greenpeace” scrolling rapidly onto the screen in turn. I do not consider that there is a material difference in the message conveyed by the static image or the shifting image. In both versions, by clicking on the “ACT NOW” button the user is taken to a website at “www.australiasgreatestliability.com” which was referred to in the evidence as the parody website;

(b) Street posters erected in Sydney and Melbourne which use the image of an ominous orange, smog-filled sky located in an industrial setting on a wharf, with a young person in a mask and goggles walking a Labrador and fishing trawlers in the background. The modified AGL logo appears in the bottom left corner, above which are the words “Still Australia’s Biggest Climate Polluter”. In the bottom right corner are the words “Presented by Greenpeace”, and in the top right is a QR code which takes a user to the parody website. An example of a street poster is below:

(c) Mock up street posters, images of which were provided to media outlets via hypertext links from a press release. These have not been otherwise physically displayed. They use the modified AGL logo in the bottom left corner, while the Greenpeace logo appears in the bottom right. At the top of the poster is a tagline such as “Generating Pollution For Generations” or “Leaving A Mess For The Next Generation”, under which appears a QR code as follows:

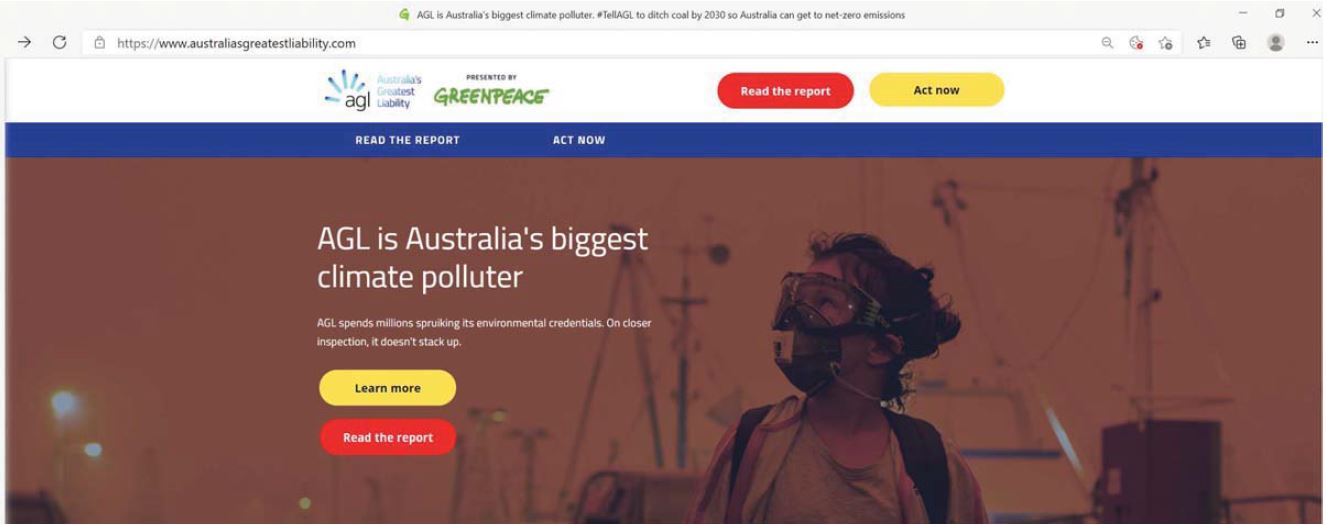

(d) The parody website, as depicted in the annexure to these reasons, includes on the landing page the modified AGL logo as part of the banner heading closely proximate to the words “presented by Greenpeace”, a large heading saying “AGL is Australia’s biggest climate polluter” and options for viewers to click through to the Exposing AGL report, join a campaign to “demand AGL rapidly close its coal-fired power stations” and to send an email to the CEO of AGL;

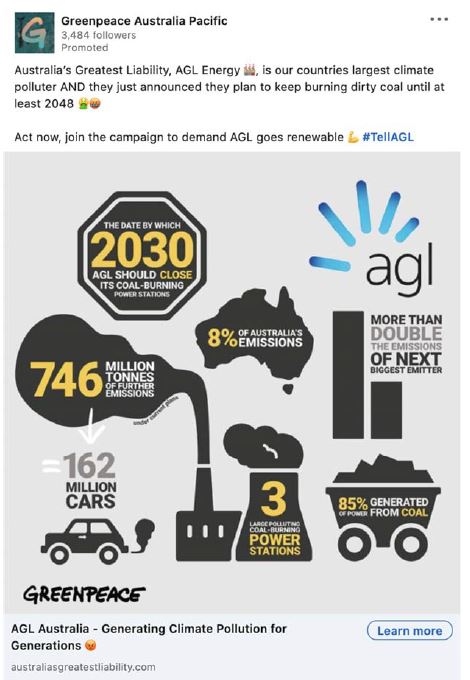

(e) Various social media posts, five representative examples of which are depicted in the annexure to these reasons. These were published on Greenpeace’ Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn accounts, and use the AGL logo (mostly unmodified) juxtaposed with images of pollution and visible headings such as “AGL Energy is Australia’s single largest climate polluter accounting for 8% of Australia’s entire domestic emissions” and “Tell AGL’s CEO to do the right thing and ditch coal for renewables!” as well as the Greenpeace logo;

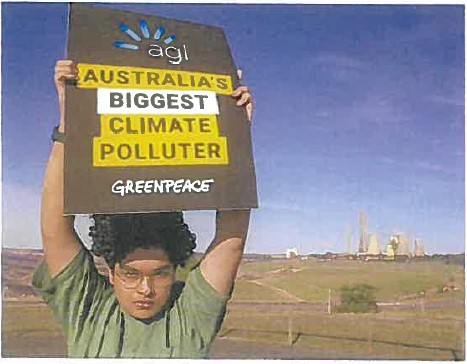

(f) A protest poster image at page 4 of the Exposing AGL report, which is situated opposite the Executive Summary:

; and

; and

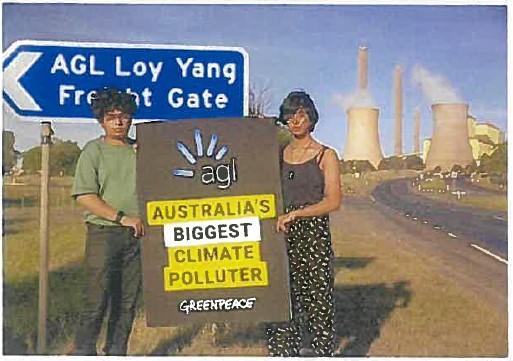

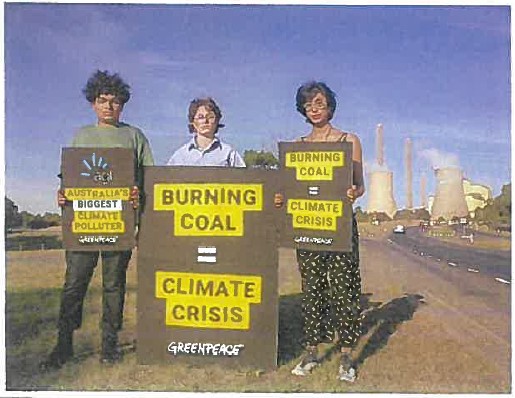

(g) Placards held by protestors, photographs of which are set out in the annexure. These are photos of school student protesters at AGL’s Loy Yang A power station in the La Trobe Valley taken by a photographer commissioned by Greenpeace. One photo was published in the Exposing AGL report. Further photos were made available online via a hyperlink in a press release issued by Greenpeace on 11 May 2021, which said “Images of the advertising creative and school strikers protesting ... available here”.

24 There is no dispute that, unless restrained, Greenpeace intends to continue in the conduct of its media campaign.

3.1 Introduction and relevant legislation

25 The copyright work in issue is the AGL logo. Greenpeace did not put in contest that it amounts to an “artistic work”. Mr Riches gives evidence that his creative agency delivered the AGL logo to AGL in about April 2017, although no evidence was read going to the creative process involved in its development. The AGL logo is a simple artistic work comprising three letters of the corporate name in a simple type font, accompanied by five radiating blue lines, shaded from lighter blue in the centre near the letters “AGL” to darker blue on the periphery.

26 The rights conferred by copyright protection include restraining the reproduction of a work in a material form: s 31(1) and s 36 of the Copyright Act. There is no dispute that the impugned uses by Greenpeace reproduce the entirety of the artistic work.

27 As noted, Greenpeace relies on the fair dealing defences under s 41 and s 41A of the Copyright Act.

28 Section 41 provides:

41 Fair dealing for purpose of criticism or review

A fair dealing with a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work, or with an adaptation of a literary, dramatic or musical work, does not constitute an infringement of the copyright in the work if it is for the purpose of criticism or review, whether of that work or of another work, and a sufficient acknowledgement of the work is made.

29 Section 41A provides:

41A Fair dealing for purpose of parody or satire

A fair dealing with a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work, or with an adaptation of a literary, dramatic or musical work, does not constitute an infringement of the copyright in the work if it is for the purpose of parody or satire.

30 In their submissions, the parties also referred to the fair dealing exception for the purposes of research or study. That defence is set out in s 40, which for present purposes relevantly provides:

40 Fair dealing for purpose of research or study

(1) A fair dealing with a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work, or with an adaptation of a literary, dramatic or musical work, for the purpose of research or study does not constitute an infringement of the copyright in the work.

...

(2) For the purposes of this Act, the matters to which regard shall be had, in determining whether a dealing with a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work or with an adaptation of a literary, dramatic or musical work, being a dealing by way of reproducing the whole or a part of the work or adaptation, constitutes a fair dealing with the work or adaptation for the purpose of research or study include:

(a) the purpose and character of the dealing;

(b) the nature of the work or adaptation;

(c) the possibility of obtaining the work or adaptation within a reasonable time at an ordinary commercial price;

(d) the effect of the dealing upon the potential market for, or value of, the work or adaptation; and

(e) in a case where part only of the work or adaptation is reproduced—the amount and substantiality of the part copied taken in relation to the whole work or adaptation.

…

3.2 Fair dealing for the purpose of parody or satire – s 41A

31 It is convenient to deal with the defence of parody or satire first. Section 41A was introduced into the Copyright Act by the Copyright Amendment Act 2006 (Cth). The then Attorney-General said of it (Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 19 October 2006, p 2 (Philip Ruddock, Attorney-General)):

A further exception promotes free speech and Australia’s fine tradition of satire by allowing our comedians and cartoonists to use copyright material for the purposes of parody or satire.

32 Senator Ellison said, when presenting the amendment in the Senate (Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 29 November 2006, p 111 (Senator Chris Ellison):

The government is also ensuring that Australia’s fine tradition of poking fun at itself and others will not be unnecessarily restricted by providing an exception for fair dealing for the purpose of satire and parody.

33 It is evident that underlying the introduction of s 41A was an intention to promote a degree of free speech and freedom to comment.

34 Earlier drafts of the legislation confined the exception to fair dealing for the purpose of parody alone. However, as the authors of Lahore Copyright and Designs (LexisNexis Butterworths, subscription service) observe at [41,085] (update 118):

US experience and literary criticism indicated the potential for considerable difficulty in distinguishing between permissible parody and impermissible satire. In addition, it was noted that the same rationales that justified protection for parodic activities also supported protection for satiric uses, namely, the value of free speech and criticism, the value of humour, the need for copyright laws to reflect Australian cultural traditions and the transformative rather than supersessive nature of such works.

(citations omitted)

35 The Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum to the Copyright Amendment Bill 2006 (Cth) stated that:

42. The amended parody and satire exceptions will apply where a person or organisation can demonstrate that the use for the purpose of parody or satire is a fair dealing.

43. These exceptions are consistent with the present structure of the Act which already contains fair dealing exceptions for criticism and review and reporting the news. Case law suggests that the use of copyright material for parody and satire is likely to overlap or be closely connected to uses for these other fair dealing purposes.

44. It is appropriate to require that a use for the purpose of parody and satire should be ‘fair’. Parody, by its nature, is likely to involve holding up a creator or performer to scorn or ridicule. Satire does not involve such direct comment on the original material but, in using material for a general point, should also not be unfair in its effects for the copyright owner.

36 Section 41A is an affirmative defence that must be established by Greenpeace. It contains two elements, first that there be a “fair dealing” with the artistic work, and secondly that such dealing be for the purpose of parody or satire.

37 In Pokémon Company International, Inc. v Redbubble Ltd [2017] FCA 1541; 351 ALR 676 Pagone J considered the application of s 41A and observed:

[69] … Difficult questions of characterisation arise where a work has been used in a modified form. To qualify for the protection the use must be both fair and for the purpose of parody or satire where parody or satire is not “used as a shield to avoid intellectual work in order to benefit from the notoriety of the parodied (or satirised) work”: see Productions Avanti Cine-video v Favreau (2012) 177 DLR (4th) 568 at 594 per Gendreau JA (Biron J concurring). In that case Rothman JA, agreeing with his colleagues, said at 575 that there was “an important line separating a parody of the dramatic work created by another writer or artist and the appropriation or use of that work solely to capitalize on to “cash in” on its originality and popularity”.

[70] It follows from these observations, and from the express terms of s 41A of the Copyright Act, that what must be shown for the protection to be relied upon is that the use made of the work was both fair and for the purpose of parody and satire, and not just that what was produced might in the eyes of some be a parody or satire. The relationship between a dealing as “fair” and the purpose as “parody” is apt to overlap, if not to be co-extensive, but the statutory protection in s 41A requires that there be established that the person dealing with the work did so for the purpose of parody … That some of the infringing works may be humorous, or even satirical or parodies, does not establish that the use was for [that] purpose where it may fairly be concluded that the purpose was not the parody or satire but the commercial exploitation of the original work in modified form.

38 For present purposes the defence in section 41A focusses attention on fair dealing with an artistic work for the purpose of parody or satire. The impugned work may be identical to or a material reproduction of the copyright work (both being forms of infringement to which the defence applies): provided that the dealing is adjudged to be “fair” and for the requisite purpose, the defence will be available.

3.2.2 The law relating to “parody or satire”

39 The words “parody” and “satire” are not defined in the Copyright Act. In her recent and thorough review of the law in Universal Music Publishing Pty Ltd v Palmer (No 2) [2021] FCA 434 at [289]-[294], Katzmann J referred to South African and United States authority concerning the meaning of “parody”. At [295] to [296] her Honour referred to the following obiter dicta remarks made by Conti J at [17] of TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd v Network Ten Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 108; 108 FCR 235 (Nine, Conti J), prior to the introduction of s 41A:

… the essence of parody is imitation … whereas satire is described [in the Macquarie Dictionary] as being a form of ironic, sarcastic, scornful, derisive or ridiculing criticism of vice, folly or abuses, but not by way of imitation or take off … parody … will not avoid copyright infringement since imitation is in the nature of copying, in contrast to satire which involves the drawing of a distinction between the satirist and the author, composer etc …

These remarks were made prior to the introduction of s 41A, in the context of an argument that a work of parody or satire would not amount to a substantial reproduction of a copyright work.

40 In Pokémon Company Pagone J at [68] quoted, and subsequently appeared to accept the definition of these terms supplied by Conti J, namely that the essence of parody is imitation whereas satire is a form of criticism without imitation or take-off.

41 The Macquarie Dictionary (5th ed, 2009, Sydney) definitions of each of the terms indicate that there can be an overlap between parody and satire. “Parody” is defined as “1. a humorous or satirical imitation of a serious piece of literature or writing … 5. to imitate (a composition, author, etc.) in such a way as to ridicule” (emphasis added) and “satire” as “the use of irony, sarcasm, ridicule, etc., in exposing, denouncing or deriding vice, folly, etc.” and “a literary composition...in which vices, abuses, follies, etc., are held up for scorn, derision or ridicule”. It is apparent that whereas parody may involve an element of imitation satire need not.

42 Translated to the present context, the use of an artistic work for the purpose of parody or satire may be one where the impugned work is used “to expose, denounce or deride vice”, often in the context of a humorous or ridiculous juxtaposition. Having regard to the second reading speeches, it would appear that the, or a, purpose of the introduction of the exception was to promote freedom of speech by permitting, in particular, the use of humour in the form of parody or satire.

43 It is necessary to consider the purpose of the impugned works objectively, having regard to the relevant work in question. As the Full Court said in TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd v Network Ten Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 146; 118 FCR 417 (Nine, FFC), albeit in the context of fair dealing for the purpose of criticism or review or reporting of the news in respect of subject-matter other than works (at [101] per Hely J, Sundberg J agreeing at [1], Finkelstein J agreeing at [17]):

Consistently with the decisions of the UK Court of Appeal earlier referred to, the “purpose” referred to in s 103A and s 103B is to be ascertained objectively, and it was neither necessary nor appropriate for officers of Ten or of Working Dog to give evidence that they had a sincere belief that he or she was criticising a work or an audio-visual item or reporting news.

44 In my view it is appropriate to consider the likely perception of the person who will be seeing the impugned work, who in the present case will be a member of the general public exposed to the online and other promotional materials used in Greenpeace’s media campaign. Such persons are likely to be familiar with AGL and also with Greenpeace.

3.2.3 The law relating to “fair dealing”

45 The amorphous concept of “fair dealing” has been part of common law doctrine in association with other defences to copyright infringement for many years. Lord Denning MR in Hubbard v Vosper [1972] 2 QB 84 at 94 said, in a passage cited with approval in Palmer at [301]:

It is impossible to define what is “fair dealing”. It must be a question of degree. You must consider first the number and extent of the quotations and extracts. Are they altogether too many and too long to be fair? Then you must consider the use made of them. If they are used as a basis for comment, criticism or review, that may be fair dealing. If they are used to convey the same information as the author, for a rival purpose, that may be unfair. Next, you must consider the proportions. To take long extracts and attach short comments may be unfair. But, short extracts and long comments may be fair. Other considerations may come to mind also. But, after all is said and done, it must be a matter of impression.

46 The learned authors of Copinger and Skone James on Copyright (18th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2021) at 9-47 say:

Fairness should be judged by the objective standard of whether a fair-minded and honest person would have dealt with the copyright work in the manner in which the defendant did, for the relevant purposes. Ultimately the decision must be a matter of impression.

(citations omitted)

47 It is apparent from the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum (see [35] above) that the established common law approach to “fairness” was intended to apply to s 41A, although with necessary adjustment having regard to the nature of the permitted acts. In this regard the observation at [44] of the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum is apposite, namely that “fairness” for the purpose of s 41A must take into account that parody, by its nature, is likely to involve holding up a creator or performer to scorn or ridicule, and although satire does not necessarily involve direct comment on the original material, using material for a general point should also not be “unfair in its effects for the copyright owner”.

48 In considering what may be unfair in the effects for the copyright owner in my view it is also appropriate to have regard to the right that is protected in the copyright, being a particular form of expression.

49 In IceTV Pty Limited v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited [2009] HCA 14; 239 CLR 458 at [28] the plurality (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ) observed the limited protection that copyright provides in the context of considering whether a substantial part of a compilation (a literary work) had been taken:

Copyright does not protect facts or information. Copyright protects the particular form of expression of the information, namely the words, figures and symbols in which the pieces of information are expressed, and the selection and arrangement of that information. That facts are not protected is a crucial part of the balancing of competing policy considerations in copyright legislation. The information/expression dichotomy, in copyright law, is rooted in considerations of social utility. Copyright, being an exception to the law's general abhorrence of monopolies, does not confer a monopoly on facts or information because to do so would impede the reading public's access to and use of facts and information. Copyright is not given to reward work distinct from the production of a particular form of expression.

(citations omitted)

50 Justices Gummow, Hayne and Heydon cautioned against looking to the “interest” which copyright protects, noting that “the more remote the level of abstraction of the ‘interest’, the greater the risk of protecting the ‘ideas’ of the author rather than their fixed expression” (at [160]). Their Honours found that Full Court of the Federal Court had erred by “treating the issue of substantiality as dominated by an ‘interest’ in the protection of Nine against perceived competition by Ice”: at [161].

51 What will be fair will depend on the nature of the work, the character of the impugned dealing, and the particular fair dealing purpose invoked. In Palmer at [301] Katzmann J considered that although s 41A does not specify factors which must be taken into account in assessing fairness, the non-exhaustive factors listed in s 40(2)(a)-(e) (set out in section 3.1 above) would have a bearing on the question of fairness for the purposes of s 41A. I respectfully agree with her Honour’s finding, while noting that in each case the relevance of those factors will vary according to the nature of the copyright work and that due allowance must be made for the fact that the s 40(2) factors bear on a different form of permitted purpose, namely research or study.

52 Her Honour also noted that two statements of authority concerning the defence of fair dealing for criticism and review in the United Kingdom are apposite when considering s 41A. First, at [310] her Honour referred to the following passage in Pro Sieben AG v Carlton UK Television Ltd [1999] 1 WLR 605 (Robert Walker LJ at 613, Henry and Nourse LLJ agreeing at 619):

It is a question of degree … or of fact and impression … The degree to which the challenged use competes with exploitation of copyright by the copyright owner is a very important consideration, but not the only consideration. The extent of the use is also relevant, but its relevance depends very much on the particular circumstances ... If the fair dealing is for the purpose of criticism that criticism may be strongly expressed and unbalanced without forfeiting the fair dealing defence …

53 Secondly, at [311] her Honour referred to the following statement of Henry LJ in Time Warner Entertainments Co. v Channel Four Television Corporation Plc. [1984] EMLR 1 at 14:

‘Fair dealing’ in its statutory context refers to the true purpose (that is, the good faith, the intention and the genuineness) of the critical work–is the programme incorporating the infringing material a genuine piece of criticism or review, or is it something else, such as an attempt to dress up the infringement of another’s copyright in the guise of criticism, and so profit unfairly from another’s work.

54 The factors set out in s 40(2) commence with “(a) the purpose and character of the dealing”. In Palmer Katzmann J noted at [307] that in the United States §107 of the US Copyright Act (17 USC) lists “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes” as a consideration in assessing whether there has been a “fair use” of copyright material. Her Honour noted that:

Souter J said in Campbell at 579 that the central purpose of the investigation is to see whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation or adds something new, with a further purpose or a different character, altering it with new expression, meaning or message. In other words, as his Honour put it, this factor is concerned with whether and to what extent the new work is “transformative”. He explained that “[a]lthough transformative use is not absolutely necessary for a finding of fair use … the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works”. The more transformative the new work, his Honour continued, the less significant other facts, such as commercialism, will be. He pointed out that “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value” because it can provide a social benefit “by shedding light on earlier work and, in the process, creating a new one”.

55 One must be cautious about applying the United States law in the present context, especially given, as noted above, that the United States fair use defence contains no reference to “satire”, and where the fair use doctrine forms part of a general limitation on the rights of owners of all copyright works: see Google LLC v Oracle America, Inc 593 U.S. ___ at 13. The central purpose to which Souter J referred in Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. 510 US 569 (1994) involves importing a requirement that the infringing work effect some “transformation”. In Oracle, the majority noted a precise replication of a work may fall within the fair use provision, providing as an instance an “artistic painting” that “replicates a copyrighted advertising logo to make a comment about consumerism” (at 24-25).

56 In Nine, Conti J the Court identified at [66] eight principles emerging from the authorities applicable to fair dealing for the purposes of criticism and review:

(i) Fair dealing involves questions of degree and impression; it is to be judged by the criterion of a fair minded and honest person, and is an abstract concept[;]

(ii) Fairness is to be judged objectively in relation to the relevant purpose, that is to say, the purpose of criticism or review or the purpose of reporting news; in short, it must be fair and genuine for the relevant purpose, because fair dealing truth of purpose;

(iii) Criticism and review are words of wide and indefinite scope which should be interpreted liberally; nevertheless criticism and review involve the passing of judgment criticism and review may be strongly expressed;

(iv) Criticism and review must be genuine and not a pretence for some other form of purpose, but if genuine, need not necessarily be balanced;

(v) An oblique or hidden motive may disqualify reliance upon criticism and review, particularly where the copyright infringer is a trade rival who uses the copyright subject matter for its own benefit, particularly in a dissembling way; “the path of criticism is a public way”’[;]

(vi) Criticism and review extends to thoughts underlying the expression of the copyright works or subject matter;

(vii) “News” is not restricted to current events; and

(viii) “News” may involve the use of humour though the distinction between news and entertainment may be difficult to determine in particular situations.

These considerations were repeated without criticism by the Full Court in its review on appeal: Nine, FFC at [98].Some of those may be considered of general application to the concept of “fair dealing” (being (i), (ii), (iv) and (v)) and others are apposite to the specific criticism or review defence then under consideration (being (iii), (iv) and (vi)-(viii)).

57 The Full Court noted that whilst the “purpose” is to be ascertained objectively, the intentions and motives of the user of the copyright material are “highly relevant” to the issues of fairness (Nine, FFC per Hely J at [97], [101]). The Full Court went on to consider the intent and purpose of the respondent, and noted at [104] that the fact that the respondent had dual purposes of (a) providing criticism and review and (b) entertaining to further its commercial interest in achieving ratings, did not preclude reliance on the defence, presumably because (b) was not unfair in the circumstances of that case having regard to (a).

58 In relation to purpose, Greenpeace submits that the impugned materials fall within the meaning of parody or satire. It submits that they reproduce the AGL logo in modified form only in order to juxtapose it with Greenpeace’s humorous reimagining of the acronym as “Australia’s Greatest Liability”, and with information about AGL’s real effect on the environment, so as to hold AGL up to scorn or ridicule. It submits that one would normally expect to see the AGL logo applied to material positively promoting AGL, and as such the deliberate dislocation in the impugned conduct is a parody because it applies the AGL logo to an unlikely subject. Further, the use of the modified AGL logo in the context of the whole of the campaign materials is satirical. The materials are, it submits, ironic, derisive criticism of AGL’s environmental vices, and the modified AGL logo is used for the purpose of making that satirical point.

59 Greenpeace submits that its dealing with the AGL logo was fair. It seeks to distinguish its conduct from the findings in Nine, Conti J at [70] and Palmer at [300] on the basis that Greenpeace has not sought commercially to exploit the AGL logo and has not attempted to “cash in” on its originality. It submits that each of the factors identified in Palmer at [302]-[312] favour a finding of fair use. In particular, it points to: the nature of the work being a simple corporate logo; the use being for the purpose of sparking public debate about the important issue of climate change; the fact that the genuine purpose of Greenpeace was for parody or satire (and not a pretence for an ulterior purpose); the fact that Greenpeace has not profited unfairly or at all from its use of the AGL logo; that there is no possibility that Greenpeace could have obtained a licence to use the AGL logo within a reasonable time at a commercial price; that Greenpeace’s use had no effect upon the potential market for the AGL logo; that the taking of the whole of the work was not unfair, in circumstances where the work is a small, homogenous work and Greenpeace could not have fulfilled its purpose of parody or satire by using only a part of it; that the AGL logo had been published and there was no impropriety in obtaining it; and that Greenpeace’s use was transformative insofar as it added something new to the AGL logo, giving it a different meaning and message.

60 AGL submits that the impugned conduct was not for a parodic or satirical purpose, but was for the purpose of disseminating information and pressuring AGL to announce a new direction for the company and the early closure of its coal-burning power stations. It submits that any vestige of parody or satire is a pretence for an ulterior purpose being to disseminate information and protest against AGL. In this regard AGL relies on the conclusion reached in Palmer at [351]. AGL also submits, based on the reasoning of the United States Supreme Court in Campbell at 580–81, cited in Palmer, that it is the dealing in the copyright works themselves that must be for the purpose of parody or satire, a proposition that they submit was accepted in Palmer at [353].

61 AGL also refers to the factors in s 40(2) of the Copyright Act bur submits that the impugned conduct is not fair. It emphasises that Greenpeace has used the entirety of the AGL logo, without any material changes, in circumstances “where there was no need for it to do so”. In particular, AGL submits that it has no objection to the use by Greenpeace of the initials representing its name, and that insofar as the purpose of Greenpeace was to criticise AGL it could have done so without using its logo. Instead, Greenpeace elected to use the AGL logo in its entirety and without alterations to get as close as possible to the AGL brand for the purpose of having deleterious effects on AGL and for the express purpose, set out in the brief to Monster, of making the AGL logo “toxic”. Such conduct, AGL submits, was opportunistic and sought to take advantage of the notoriety of the AGL logo and reputation.

Purpose

62 For the following reasons, in my view the impugned uses by Greenpeace fall within the meaning of “parody or satire” as those terms are contemplated within s 41A. Having regard to the overlap between those two concepts, it is unnecessary to distinguish between parody on the one hand and satire on the other.

63 The modified AGL logo is immediately juxtaposed by a play on the company’s initials “AGL” with the parodic or satirical words “Australia’s Greatest Liability”, accompanied by words decrying AGL’s environmental practices, such as “Still Australia’s Biggest Climate Polluter” or “Generating Pollution for Generations” or the like. The setting mimics elements used in AGL’s Brand Guidelines, thereby creating a “corporate look” about the Greenpeace images that also juxtaposes the AGL corporate branding style with an obviously non-corporate message, creating an incongruity that is striking to the viewer. The ridicule potent in the message is likely to be immediately perceived. It is stronger in the image of the young person with the goggles and mask, for example in the street posters. Many would see these uses of the modified AGL logo as darkly humorous, because the combined effect is ridiculous. AGL is exposed to ridicule by the use of its corporate imagery including by use of the modified AGL logo to convey a message that AGL would not wish to send. Furthermore, the words “Presented by Greenpeace” are positioned closely proximate to the modified AGL logo. Anyone reading the message would understand that the company held up for criticism as Australia’s Greatest Liability is not the author of the message. The viewer would understand that the message came from Greenpeace.

64 These findings reflect how I consider that objectively viewed, the content of each of the following impugned uses of the AGL logo is likely to be perceived by people who encounter it in:

(a) the online banner advertisements;

(b) the street posters; and

(c) the parody website.

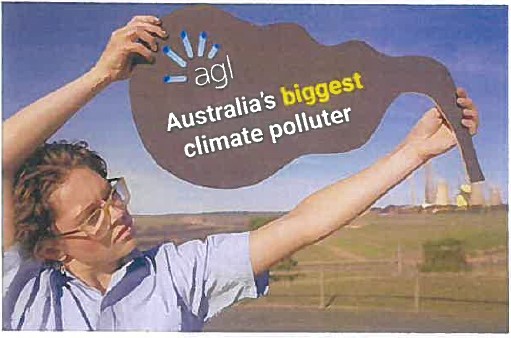

65 Turning to the other impugned uses, the protest poster image does not involve the tagline “Australia’s Greatest Liability”. It is a photograph of a school student holding up a poster bearing the AGL logo with the words “Australia’s Biggest Climate Polluter” and “Greenpeace”. It is a full page image located on page 4 of the Exposing AGL report opposite the Executive Summary. The photograph may be regarded as depicting a protest, but I cannot see any element of parody or satire, whether taken alone or in conjunction with its accompanying text. Similarly, I do not consider that the photographs of the placards identified as (a), (b) or (d) in the annexure to these reasons fall within the meaning of parody or satire; none have such a use of irony, sarcasm or ridicule that would meet the meaning of these terms. The image in (c), however, provides a humorous juxtaposition of the AGL logo in a black cloud, held above its Loy Yang A power station in a manner that suggests the cloud is emanating from the power station, and is, in my view, sufficiently parodic or satirical.

66 I now turn to the social media posts, examples of which are set out in the annexure. In my view the use of the AGL logo in the Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn posts in (a), (b) and (d) would not be perceived to have the characteristics or parody or satire. By contrast, the use in the Facebook and Twitter posts exemplified in (c) and (e) would, those each using the modified AGL logo in a context falling within my findings at [63] above.

67 The findings that follow in this section are directed to those uses that I have found were made for the purposes of parody or satire (which for convenience I refer to as the Greenpeace satirical uses).

68 I do not accept AGL’s submission that because Greenpeace seeks to bring about change by its media campaign, that must be considered to be its true purposes, thereby supplanting any other. It is not antithetical to the operation of the defence that an otherwise infringing work was created for more than one purpose. As the Full Court found in Nine, FFC (per Hely J, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ agreeing), the fair dealing defences are not so constrained that another purpose is not also permissible (at [104]):

Ten’s purpose in broadcasting its programme “The Panel” may have been, as Nine asserts, to entertain and to achieve ratings. If it does so by means of a programme involving or including criticism, review or reporting of news in which there is fair dealing with material in which copyright would otherwise subsist, then Ten is not disentitled from relying on the s 103A and s 103B defences by reason only of the commercial nature of its activities. Criticism may involve an element of humour, or “poking fun at” the object of the criticism. The fact that news coverage is interesting or even to some people entertaining, does not negate the fact that it could be news: Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1999) 48 IPR 333 at 340 pars [34] – [37]. News may be reported with humour and still fall within the ambit of s 103B.

69 The purpose of parody or satire is frequently to attract the attention of viewers and draw to their attention an object of criticism or ridicule. I reject the contention advanced by AGL that the satire or parody was supplanted by a disqualifying ulterior motive in the present case. The facts of the present case are a far cry from those in Palmer.

70 Nor do I accept that for the defence to apply, the parody or satire must be directed towards the artistic work itself. That was not the effect of the finding of Katzmann J at [353] of her reasons in Palmer. Section 41A directs attention to the dealing with the work. Her Honour found that the defence did not apply because it was the images in the videos to which the infringing song recording had been synchronised, not the dealing in the song in suit, that had been used to create any satire: at [352]-[353]. Her Honour commented that “[the infringing song] was not used to satirise anyone or anything, nor were the lyrics as varied” at [353].

71 Some of the sources to which I have referred in sections 3.2.1 and 3.2.2 above do suggest that there must be a link between the parodic or satirical work and either the original work or the creator or owner of the original work: see eg Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum at [44], Nine, Conti J at [17], Macquarie Dictionary definition of “parody”. If there is such a requirement, in the present case, the impugned works make plain the distinction between the satirist (Greenpeace) and the owner of the copyright work (AGL).

72 Moreover, the addition of the words “Australia’s Greatest Liability” as a tagline to the AGL logo does have some transformative effect, by “adding something new, with a further purpose or character”: American Geophysical Union v Texaco 60 F 3d 913 (2d Cir, 1994), cited in Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 984; 189 FCR 109 (Bennett J) at [142]); Oracle at 24.

Fair dealing

73 Having determined that the use of the modified AGL logo by Greenpeace has a parodic or satirical purpose as required by s 41A, it is now necessary to consider whether the dealing with the AGL Logo in the Greenpeace satirical uses amounts to a “fair dealing”. In my view it does. As a matter of structure it is convenient to assess the factors that I have identified in section 3.2.3 above by reference to those identified in s 40(2) of the Copyright Act. I address the Greenpeace satirical uses compendiously, although in making the findings below, I have considered each separately.

74 The purpose and character of the dealing by Greenpeace (s 40(2)(a)) is, as I have found, parodic or satirical, largely for the reasons set out at [63] above. I have accepted that Greenpeace’s intention was to draw public attention to, and to promote public debate about, what Greenpeace believes to be AGL’s “greenwashing” behaviour, by depicting AGL’s logo and trade livery against what Greenpeace perceives to be AGL’s “real” behaviour. The ultimate aim of Greenpeace’s media campaign was to promote change at a board level within AGL.

75 AGL’s submission that there was no need for Greenpeace to use the AGL logo and that it elected to do so to get as close as possible to the AGL brand and make it “toxic” is to be understood in the light of the nature of the s 41A defence and the nature of the work that has been reproduced. As I have noted at [80] above, copyright protects the owner’s interest in the artistic work, it does not provide a mechanism for protecting a copyright owner’s reputation. Indeed s 41A is a defence that specifically permits an infringement of copyright for the purpose of parody or satire. These are activities that intrinsically involve irony, sarcasm or ridicule to emphasise and promote criticism of the subject work, or its owner or creator’s conduct. Once it is established that the purpose of an alleged copyright infringement satisfies the definition of parody or satire, it can hardly be considered to not be “fair”, for that reason alone, to embark upon that conduct. It was no doubt for that reason that Pagone J in Pokémon Company observed at [70] that the relationship between a dealing as “fair” and the purpose as “parody” (or, I interpolate, “satire”), is apt to overlap, if not be co-extensive. However, as Pagone J went on to say, considerations of fairness will serve to elucidate whether or not the purpose was, truthfully, a commercial exploitation of the original work clothed in the dress of parody or satire.

76 The submission advanced by AGL that Greenpeace elected to use the AGL logo to make AGL’s brand toxic requires close attention. It is true that the briefing material provided to Monster by Greenpeace refers to the objective of “removing [AGL’s] social license and making their brand toxic”. This is colourful language, perhaps rhetorical hype of a type typically used in advertising and also environmental campaigning (which is no doubt tempted to pun on words like “toxic”), but in substance it does little more than indicating that it wanted Monster to develop a campaign that would assist Greenpeace in criticising AGL’s conduct and provoking debate.

77 There is, of course, a balance to be considered. Has Greenpeace crossed a line such that its dealing in the AGL logo is unfair to AGL? In my view it has not, when one has regard to the types of the Greenpeace satirical uses. Of particular note is the clear attribution of authorship (“by Greenpeace”). That attribution commands attention, because each of these uses immediately contrasts the AGL logo against a strongly negative “message”. No sensible reader can conclude other than that the impugned uses are statements emanating from Greenpeace about AGL. The reader will immediately deduce that AGL is the object of the message, not the author of it and that AGL does not endorse and is not the author of the modified AGL logo.

78 Nor, in my view, may it be said that Greenpeace has an ulterior motive, in the sense contemplated by the authorities. Although the ultimate purpose of the Greenpeace campaign is to bring about a change in AGL’s environmental conduct, the satirical message in the impugned materials has only the effect of drawing viewers into the debate about AGL’s environmental impact. As noted in Nine, FFC, more than one purpose is permissible in a dealing with copyright material.

79 Greenpeace also relies on its purpose as being one that is of public interest and of benefit to the community, namely to draw attention to important issues relevant to climate change . It relies on the decision in Aid/Watch Inc v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2010]) HCA 42; 241 CLR 539 at [47] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Bell JJ) in support of the proposition that the generation by lawful means of public debate (there concerning the efficiency of foreign aid directed to the relief of poverty) was a purpose beneficial to the community. I accept that the underlying purpose of Greenpeace was to use the modified AGL logo as part of its campaign to generate public debate concerning climate change. It was not for a commercial purpose. However, I do not consider that the factors going to consideration of “fair dealing” include a public interest component. It suffices to observe that one purpose of s 41A, apparent from the secondary materials including the second reading speeches and Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum, is to permit a degree of freedom of expression that that may otherwise be constrained by a copyright owner, so long as the dealing is fair.

80 In relation to the nature of the copyright work (s 40(2)(b)), here the artistic work protected by copyright is the AGL logo. The copyright protected lies in its existence as an original form of expression and is distinct from the rights that accrue by reason of any reputation that inures in its name or rights to AGL’s benefit by reason of the AGL logo being a registered trade mark. It is to be noted that the AGL logo is a simple, homogenous artistic work of two parts, the letters “AGL” and the five radiating lines. It is not readily susceptible of division into parts. Unlike other forms of work, any reproduction of the AGL logo in a material form is likely to involve the reproduction of the whole. Furthermore, it is not necessary to alter the work or effect a “transformation” of it in order for the impugned conduct to be either “fair” or for the purpose of parody or satire. In the particular circumstances of this case, I do not consider it to be decisive that the whole of the copyright work has been reproduced (s 40(2)(e)). In Fairfax, despite finding that the works in question were not protected by copyright at [50], Bennett J went on to consider whether, if they had been protected by copyright, the fair dealing exceptions could apply in circumstances where the whole of the work had been reproduced. Her Honour concluded that, having regard to the circumstances of that case, a finding of fair dealing was not precluded (at [141]-[143]).

81 I accept there is no realistic prospect that Greenpeace would obtain the work within a reasonable time at an ordinary commercial price (s 40(2)(c)). However, given the critical nature of most parodies and satires it is in my view intrinsically likely that it would be difficult to obtain the work within a reasonable time at an ordinary price. This consideration is perhaps more apposite to the defence of fair dealing for the purpose of research or study under s 40 than the present circumstances, where Greenpeace was manifestly holding up AGL for ridicule or scorn.

82 The effect of the dealing upon the potential market for or value of the work in question (s 40(2)(d)) is unlikely to be decisive in the present context given that most parody or satire can be expected to criticise, ridicule or deprecate. In that sense, some adverse effect may be expected. However, it is relevant to note that I accept that Greenpeace is not a commercial organisation and does not compete with AGL.

83 I reject the submission advanced by AGL that in reality Greenpeace was on a fund raising campaign and that the, or a, significant purpose of it was to attract attention to Greenpeace for the purpose of eliciting donations before the end of the financial year. Nor, in my view, can it be said that the dealing was for any other financial gain on the part of Greenpeace.

84 Furthermore, one looks at the objective effect, or likely effect of the use of the modified AGL logo, it is also significant to note that the work consists of little more than the letters “AGL”, which is of course immediately recognisable as the applicant’s corporate name. The Greenpeace media campaign is directed toward the corporate behaviour of AGL. Any damage caused to AGL by the campaign is caused by criticism of AGL as a corporate entity, on environmental grounds. It is not the use of the AGL logo in the campaign that causes damage, but rather the informational message that is communicated in the campaign, in particular by referring viewers to the Exposing AGL report about the corporate entity. AGL does not object to the use of the three letters of its name. The use of the artistic work adds to the parodic or satirical effect of the campaign overall, particularly when used in combination with other look-alike AGL corporate branding, but in my view it is not likely to otherwise be causative of harm to AGL. Rather it is the use of the letters AGL, not of themselves capable of being an artistic work, as part of the campaign that might cause harm, but again such harm would stem from the information supplied by Greenpeace, rather than the use of the letters.

85 In Palmer two further factors derived from a fact sheet issued in 2008 by the Attorney-General’s Department on s 41A (at [303]). One is whether or not the material is published. This derives from authority where a species of unfairness arises where the work in question has not previously been published. It is not presently applicable. The other is whether there was any impropriety in obtaining the material, which also does not arise.

86 Having regard to these considerations, in the context of the statements of principle set out above, my impression is that, although cutting and holding the conduct of AGL up to scorn or ridicule, a fair minded viewer of the Greenpeace satirical uses would conclude that they amount to a fair dealing with the AGL logo within s 41A of the Copyright Act.

3.3 Fair dealing for the purpose of criticism or review – s 41

87 Section 41 of the Copyright Act relevantly provides that fair dealing with an artistic work does not constitute an infringement of the copyright in the work if it is of the purpose of criticism or review, whether or that work or of another work, and a sufficient acknowledgment of the work is made. It is clear from the terms of the section that the defence can only be used where the criticism or review is of a work.

88 Section 10 defines “sufficient acknowledgement”, in relation to a work, as an acknowledgement identifying the work by its title or other description and, unless the work is anonymous or the author has previously agreed or directed that acknowledgement of his or her name is not to be made, also identifying the author.

89 Greenpeace contends that the impugned works were for the purpose of criticism or review. Having regard to the urgency of the proceedings, and also my findings in relation to the Greenpeace satirical uses, it is not necessary to address the applicability of this defence to that impugned conduct which I have found to benefit from the defence under s 41A. However, I have found that the s 41A defence is not applicable to:

(a) some of the social media materials;

(b) the protest poster; or

(c) some of the protest placards.

Accordingly, I now proceed to consider the defence advanced by Greenpeace pursuant to s 41 in respect of these remaining works only.

90 In Nine, Conti J the Court identified at [66] a number of relevant principles to have emerged from the authorities in relation to the criticism or review fair dealing defence, which are set out above at [55]. Those presently apposite are (iii), (iv), (v) and (vi).

91 In De Garis v Neville Jeffress Pidler Pty Ltd [1990] FCA 352; 37 FCR 99 at 107, Beaumont J adopted the following definitions of the terms “criticism” and “review”:

The Macquarie definition of “criticism” includes the following:

“1. The act or art of analysing and judging the quality of a literary or artistic work, etc: literary criticism. 2 the act of passing judgment as to the merits of something...4. a critical comment, article or essay; a critique.”

In my opinion, “criticism” in the context of s 41 is used in these senses. It has been held that criticism of any kind, and not only literary criticism, is within the provision: see Sillitoe’s case (supra), at 559.

The Macquarie definition of “review” includes the following:

“1. a critical article or report, as in a periodical, on some literary work, commonly some work of recent appearance; a critique...”

In my opinion, “review” is used in s 41 in this sense.

It would seem that the word “review” in the sense in which it is to be understood in s 41 is cognate with the work “criticism”. It may be said that one is the process and the other is the result of the critical application of mental faculties...

92 I now turn to consider the purpose of the remaining instances of impugned conduct, commencing with the examples of the social media posts set out in the annexure to these reasons. In my view, the Instagram post in (a) and Facebook post in (b) do not possess the character of critical comment or judgment of a work. Absent the use of the tagline “Australia’s Greatest Liability”, and taken, as they are, in the context of the words appearing in the images including “AGL Energy is Australia’s single largest climate polluter…”, the images that bear the AGL logo do not rise above the level of protest statements that are critical of AGL as a company, and would not be understood to represent criticism of review, whether of the AGL logo or any other work. The commentary accompanying the posts does not sufficiently qualify the image to influence this view.

93 The LinkedIn post in (d) of the annexure perhaps comes closer to amounting to criticism or review. The facts and figures relating to the conduct of AGL that is the subject of the criticism are clearly set out in that post together with language such as “More than DOUBLE the emissions OF NEXT biggest emitter”, which makes plain that the criticism is of the underlying conduct of AGL. However, contrary to the submission advanced by Greenpeace, it is not apparent from this post that it “was for the purpose of criticising or reviewing AGL’s greenwashing materials”, particularly because there is no reference to those materials in the post. Indeed, it is not apparent that it represents criticism of any work, whether the AGL logo or otherwise. I am not satisfied that Greenpeace has made out the defence in relation to this post.

94 The photographs of protesters holding placards identified as (a) to (d) of the annexure to these reasons also do not, in my view fall within the defence, substantially for the reasons identified in relation to the Instagram post in (a), although I have earlier found that the humorous juxtaposition in identified in the image in (c) falls within the defence under s 41A.

95 I finally turn to the protest poster image, which appears on page 4 of the Exposing AGL report, on the page facing the Executive Summary, which is on page 5. In submissions, Greenpeace points out that the Executive Summary refers directly to the conduct of AGL in promoting itself in its publicity materials as “green and environmentally responsible”, then states that “a deeper dive into AGL reveals the truth about the company” and further that “AGL is, in fact, Australia’s biggest domestic contributor to climate change”. It quotes statements made by AGL about its environmental practices, and provides a footnote to sources produced by AGL, including its website. The bibliography provided in the report also provides hyperlinks to the AGL website and other documents produced by AGL. Although perhaps closer, I am not satisfied that the purpose of the reproduction of the AGL logo on page 4, would be regarded by readers of the Exposing AGL report to be for the purpose of criticism or review. Whilst part of the text to which Greenpeace draws attention may satisfy that description, the accompanying image is not sufficiently connected to that text to do so.

96 Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act provides:

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

97 Section 120(1) provides:

A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

98 AGL contends that Greenpeace has infringed its trade mark in the AGL logo by its use of the modified AGL logo in the online banner advertisements and the street posters. It contends that the modified AGL logo is substantially identical with the AGL logo, and that Greenpeace’s use falls within the scope of AGL’s trade mark registration insofar as that registration is for the following registered services:

(a) in class 41, “education services relating to ... the environment” and “information and consultancy services relating to the aforementioned services” (educational services); and

(b) in class 42, “scientific and technological services and research and design relating thereto” and “industrial analysis and research services” (scientific services).

99 Greenpeace denies infringement. It submits that it has not used the modified AGL logo as a trade mark at all, that its use does not fall within the scope for the registered services, that the modified AGL logo is not substantially identical with the AGL logo trade mark, and that in any event Greenpeace is a charity and its use of the modified AGL logo does not amount to use in the course of trade.

100 For the reasons set out below in my view AGL has not established its case for trade mark infringement.

101 The first fundamental question is whether the conduct of Greenpeace in applying the modified AGL logo to the online banner advertisements and in the posters amounts to “use as a trade mark” within the meaning of that term in s 120(1), as elucidated by s 17. To paraphrase the language of Kitto J in Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; 109 CLR 407 at 425 (Dixon CJ, Taylor and Owen JJ agreeing), this involves consideration of whether, in the setting in which the modified AGL logo is presented, it would appear to consumers that the modified AGL logo possessed the character of a brand that Greenpeace was using in relation to the registered services so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between those services and Greenpeace (see also: Woolworths Ltd v BP plc [2006] FCAFC 132; 154 FCR 97 (Heerey, Allsop and Young JJ) at [77], and the cases there cited; Aristocrat Technologies Australia v Global Gaming [2016] FCAFC 22; 329 ALR 522 (Nicholas, Yates and Wigney JJ) at [114]-[116]).

102 In my view consumers perceiving the online banner advertisements or the street posters would answer this question in the negative. The use of the modified AGL logo is to identify that brand, and the company that it represents, as the subject of criticism. They would not perceive Greenpeace to be promoting or associating any goods or services by reference to that mark. Rather, it is the use of the modified AGL logo to refer in terms to AGL and the goods and services that AGL provides: see, for example, Irvings Yeast-Vite Ltd v Horsenail (1934) 51 RPC 110 at 115 (Lord Tomlin), cited in Shell Company at 426 (Kitto J).

103 The consequence is that AGL’s trade mark infringement case fails at the first hurdle.

104 Furthermore, it would also fail because AGL has not established that the use of the modified AGL logo is “in relation to” the registered services as required by s 120(1), even assuming (contrary to the conclusion that I have reached) that the use by Greenpeace of the AGL logo amounted to trade mark use.

105 AGL did not develop its submissions in this regard at any length. It asserts at a broad level of generality that the impugned online and poster uses fell within the registered services because a fundamental purpose of the Exposing AGL report, and the services provided by Greenpeace more broadly, is to provide “what [Greenpeace] considers to be facts and information about the environment to Australian consumers”. AGL bases this submission on the “Investigate” page of the Greenpeace website and the content of the Exposing AGL report. AGL also relies on registrations that Greenpeace has itself obtained for certain trade marks in the same classes as the registered services, apparently to suggest that Greenpeace does provide services.

106 It is necessary to focus on the impugned uses. Insofar as they promote the activities of Greenpeace, they do so in the context of a campaign to draw attention to, and criticise, the conduct of AGL. AGL draws attention to no evidence to support the contention that such conduct would fall within either of the classes of their trade mark registration.

107 A common sense approach must be taken to identifying the scope of a trade mark registration, having regard to the fact that the goods or services in respect of which a trade mark is registered provides the basis for the scope of the monopoly rights it confers.

108 If one considers the ordinary meaning of the words of the registration (an approach taken by the Full Court in MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd [1998] FCA 1616; 90 FCR 236 (Burchett, Sackville, Lehane JJ) at 242-243), the Macquarie Dictionary defines “education” as:

1.the act or process of educating; the imparting or acquisition of knowledge, skill etc.; systematic instruction or training. 2. the result produced by instruction, training, or study. 3. the field of study which deals with learners and learning, curriculum, the science or art of teaching, and related topics.

109 It is apparent that not every communication of information will amount to “education”. Nor does the provision of information about particular topics in the context of a media campaign naturally amount to the provision of “education services” or “information and consultancy services” relating to these things. None of the elements concerning the systematic imparting of instruction or the presence of a curriculum that one might expect to accompany the provision of education services and to fall within the definition of the provision of education services are present. Nor would I conclude, absent more, that what is offered by Greenpeace in the context of the impugned conduct should be understood to be in relation to “scientific and technological services” or “industrial and research services”. I am not satisfied that Greenpeace is using the trade mark (assuming for present purposes that it is a trade mark use at all) in relation to such services.

110 Finally, contrary to the submission advanced by AGL, I consider that the fact that Greenpeace has itself obtained trade mark registrations for its own name that include services in the same classes as the registered services, and which may to some degree overlap with the registered services, to be of little relevance. Registration does not equate to use, let alone use in the context of the impugned uses put forward by AGL.

111 Having formed these views, it is unnecessary for me to address the further arguments advanced on behalf of Greenpeace to conclude that the trade mark action must fail.