Federal Court of Australia

Liberty Financial Pty Ltd v Jugovic [2021] FCA 607

ORDERS

LIBERTY FINANCIAL PTY LTD (ACN 077 248 983) Plaintiff | ||

AND: | First Defendant ORDE FINANCIAL PTY LTD (ACN 634 779 990) Second Defendant WINGATE GROUP HOLDINGS PTY LTD (ACN 128 511 035) Third Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

OTHER MATTERS:

Upon the plaintiff, by its counsel, undertaking to the Court and the defendants:

(a) to abide by any order the Court may make as to damages in case the Court should hereafter be of the opinion that the first, second or third defendant have sustained any by reason of these orders which the plaintiff ought to pay; and

(b) to pay the first defendant the same salary he earned with the plaintiff (as at the date of his resignation) until the final hearing of this proceeding or until further order of the Court.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The first defendant be restrained until the hearing and determination of this proceeding or until further order from being engaged with, employed by or otherwise involved in any capacity with the second defendant or the third defendant, except as required to defend this proceeding.

2. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 Liberty Financial Pty Ltd seeks to restrain a former employee, Mr Dragan Jugovic, the first defendant, from taking up employment with ORDE Financial Pty Ltd, the second defendant. Wingate Group Holdings Pty Ltd, the third defendant, is the ultimate holding company of ORDE.

2 Both Liberty and ORDE are finance companies, but are not authorised deposit taking institutions (ADIs). They are competitors, although at the moment any competition is more perceived than real given that Liberty is well established and ORDE, relative to Liberty, is a new entrant seeking to expand its market share.

3 Mr Jugovic held the position of Team Leader – Treasury with Liberty. Recently he has signed a contract to take up a position as Executive Director of Debt Capital Markets with ORDE.

4 In essence, Liberty seeks injunctive relief against Mr Jugovic taking up such a position. It has also sued ORDE and Wingate for the tort of inducing breach of contract, accessorial liability and the like in encouraging Mr Jugovic to take up his position with ORDE. For the moment I do not need to elaborate on these latter claims.

5 The present interlocutory application is focused upon Mr Jugovic and seeks to restrain him from taking up employment with ORDE until the hearing and determination of this matter or at least until his restraint period of 12 months elapses.

6 On 4 and 24 May 2021 I granted an injunction against Mr Jugovic imposing such a restraint in the interim pending the hearing and determination of the present application. The question is whether I should extend that injunction.

7 The relevant principles concerning injunction applications are not in doubt. As I said in Re Walden Cloud Group Pty Ltd (atf Walden Cloud Group Trust) (admins apptd) (2021) 149 ACSR 637 at [81] to [83]:

Now as in other contexts, on that latter aspect of the matter I have applied the two-pronged test of:

(a) whether Best Capital made out a prima facie case; and

(b) whether the balance of convenience favoured the grant of the injunction sought.

Let me first say something on the prima facie case limb. In relation to the test in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57; 229 ALR 457; [2006] HCA 46 (ABC v O’Neill) at [65] to [72] per Gummow and Hayne JJ and the prima facie case limb, it is necessary to show a sufficient likelihood of success to justify the grant of the injunction, with such sufficiency being dependent upon the nature of the right being asserted and the practical consequences that are likely to flow if an injunction was granted. The prima facie case formulation commanded majority support in ABC v O’Neill. It was expressly referred to by Gummow and Hayne JJ, supported by Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 618; [1968] ALR 469; further, Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreed with the exposition of the principles set out by Gummow and Hayne JJ. Further, many decisions of this Court have used the prima facie case language. Contrastingly, the serious question to be tried formulation had its genesis in earlier authority where the bar might be perceived to have been set too low as a consequence of the use of such phraseology. Earlier authority did not colour such a formulation with the flexibility and nuance that is now required.

As to the second limb, the balance of convenience looks at what the inconvenience, injury or injustice to the applicant would be if the injunction were refused and seeks to weigh that against the inconvenience, injury or injustice to the respondent if the injunction were granted. Only if the balance lies in favour of the applicant, that is, if the inconvenience, injury or injustice to the applicant if the injunction were refused outweighs the respondent’s prejudice, would an injunction be granted. Further, it is necessary to assess the balance of convenience in the context of considering the strength of the prima facie case (see Samsung Electronics Co Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 217 FCR 238; 286 ALR 257; [2011] FCAFC 156 at [67]). The stronger the prima facie case, the less strong the balance has to weigh in favour of the applicant. Putting it slightly differently, if the balance is more equally poised, but the applicant has a strong prima facie case, then the interaction between the two limbs may tip the balance in favour of granting an injunction. Further, under the second limb the interests of and potential prejudice caused to third parties by either granting or refusing the injunction may need to be taken into account.

8 Further, given that Liberty has also sought to invoke s 1324(4) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), I repeat what I said in Armstrong World Industries (Australia) Pty Ltd v Parma (2014) 101 ACSR 150 at [20] to [23]:

There are two bases asserted for the interlocutory injunction. First, there is the statutory basis under s 1324 of the Act, which provides for the statutory injunctive remedy applicable to an actual or threatened contravention of s 183(1) of the Act; there is express statutory power under s 1324(4) of the Act to grant what is described as an interim injunction which for practical purposes is equivalent to an interlocutory injunction. The second basis for the injunction sought is the standard equitable basis flowing from the alleged breach of the employment contract, enhanced by or reflected in the power under s 23 of the Federal Court Act 1976 (Cth).

The statutory test for the grant of an injunction under s 1324(4) is in form and partly in substance different to the equitable basis, which is discussed in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57; 229 ALR 457; [2006] HCA 46 (O’Neill) in the well-known passages from the reasons of Gummow and Hayne JJ at [65]–[72].

The jurisdiction that the court is exercising under s 1324(4) of the Act differs from the traditional equitable jurisdiction in at least one type of factor that should be taken into account. The additional factor that s 1324(4) of the Act considers is whether the injunction would have some utility, or would serve some purpose, within the contemplation of the Act such as preventing or ameliorating a threatened contravention of the Act. There is a discussion of the relevant additional dimension to the statutory provision in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mauer-Swisse Securities Ltd (2002) 42 ACSR 605; [2002] NSWSC 741 at [33]–[38] per Palmer J.

There are nice academic points as to the difference between the two bases. But such niceties matter not in this case. I have decided that an injunction ought to be granted, which can be supported in the traditional equitable jurisdiction by the principles illuminated in O’Neill. Further, and in any event, for the same reasons that those equitable principles can be invoked to justify the grant of an injunction, similar reasons would also justify the grant of an injunction under s 1324(4) of the Act in terms of the prima facie contravention of s 183(1), actual and threatened, which I consider to have been established on the material filed to date. I accept that the material is untested at this stage.

9 In summary, Liberty contends that there is a strong prima facie case that if Mr Jugovic commences his employment with ORDE that he will breach, inter-alia:

(a) cl 12 of his employment agreement with Liberty dated 3 October 2011 which, if valid, imposes restraints on his post-employment activities; and

(b) his contractual, equitable and statutory duties concerning Liberty’s confidential information, including under s 183(1) of the Corporations Act.

10 Liberty also says that the balance of convenience favours an injunction going and that damages are not an adequate remedy.

11 Contrastingly, the defendants deny or seek to diminish the force of any prima facie case.

12 In particular, they say that the restraint in Mr Jugovic’s employment agreement is unenforceable. They say that the non-compete clause is not limited to prohibiting Mr Jugovic from being engaged with a competing business. Rather, it operates to prohibit him from providing to any company whatsoever in Australia services which are the same as or similar to those which he provided to Liberty within the 12 months prior to the cessation of his employment. They say that the restraint purports to operate to prohibit Mr Jugovic from providing funding / treasury services to any business in Australia, whether or not that business has the capacity to affect Liberty. They say that such an anti-competitive restraint is unreasonable, goes beyond what is reasonably necessary to protect Liberty’s legitimate business interests, and is incapable of being cured via severance. Further, they say that the restraint is otherwise unnecessary to protect Liberty’s legitimate interests.

13 Further, they say that no breach of confidence has occurred and nor is any threatened.

14 Further, they say that the balance of convenience compels the denial of the injunction.

15 Liberty has filed various affidavits in support of its position including:

(a) two affidavits made by Liberty’s founder and executive director, Mr Sherman Ma;

(b) two affidavits made by Mr Peter Riedel, Liberty’s chief financial officer and company secretary; and

(c) various affidavits of its solicitor.

16 The defendants have filed four affidavits in support of their opposition:

(a) two affidavits made by Mr Jugovic; and

(b) two affidavits made by ORDE’s managing director, Mr Paul Wells.

17 I should also note that Liberty has filed an expert report of Professor Ullrich Ecker, a professor of psychology and a fellow of the Psychonomic Society, which apparently is the largest professional society for cognitive psychology researchers globally. He has given evidence concerning the question of memory for business-related information and its influence on decision making. Interesting subject matter, but material that I will leave for a later trial.

18 For the reasons that follow, I would grant the injunction sought, principally based upon the contractual restraint provision, which in my view is likely at trial to be held to be reasonable notwithstanding the defendants’ protestations to the contrary.

19 Let me now turn to some of the factual background which is disclosed in the evidence. But to be clear, I am not making any final findings. What I am setting out are the prima facie facts. But in this regard, given that my decision on the present application may practically amount to final relief, it has been necessary to evaluate the material more closely and to say more than is usual concerning the strength of Liberty’s prima facie case.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

20 It is convenient to discuss Liberty first.

Liberty

21 Liberty has established operations providing loans in the residential, commercial and self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF) finance markets. In Australia, the two main participants in these markets for lending are ADIs, which include Australian banks, building societies and credit unions, and non-ADIs, which include money market corporations, finance companies and non-bank lenders. Liberty is a non-ADI.

22 Most participants in the Australian financial services market are ADIs, which collectively hold a market share in terms of assets of approximately 95% in lending. Non-ADIs account for the remaining 5% market share.

23 The major difference between the two institutions is that ADIs are licensed to accept deposits from the public, whereas non-ADIs are not. As deposits represent the largest pool of capital and primary way in which ADIs obtain the necessary capital to fund their loans, Liberty, a non-ADI, has to rely on other sources of funding. These are predominantly securitisation and equity.

24 There were as at June 2020 129 non-ADI lenders with combined total assets of $250.8 billion. Liberty is one of the 129 with about $13 billion in assets. Liberty has about a 5% share in the non-ADI market for lending which is in itself about 5% of total lending. The highly specialised nature of non-bank specialty lending means that Liberty operates within a narrow segment of the broader financial services market, with the segment comprising non-bank lenders such as Liberty accounting for less than 5% of all housing loans.

25 Over the past 20 years, the narrowness of this segment has resulted in several barriers to entrants into this market. A key barrier to entry is the need to identify clients, that is, funding sources, with an appetite for specialty lending and being able to connect them with specialty borrowers, or match them to a pool of loans. This requires a significant investment in the development of a funding platform and in developing and maintaining underwriting capabilities that potential clients take comfort from. This level of investment has meant that the non-bank specialty market is comprised of only a handful of lenders that have forged businesses over a number of years. As a result, about four non-banks lenders account for about 75% of this segment. All of these lenders have been in operation for more than 10 years and raise funds by securitisation.

26 Barriers to entry have also meant that there have been multiple attempts by new entrants to establish a presence in the segment that have failed or stalled.

27 Liberty’s operating framework is made up of three integrated key components:

(a) distribution or loan origination;

(b) underwriting (or product offering); and

(c) funding.

28 In relation to distribution or loan origination, non-bank financial institutions typically source borrowers:

(a) by engaging directly with borrowers through sales employees and direct marketing;

(b) from professional referral networks such lawyers and accountants;

(c) from digital channels such as online comparison websites; and

(d) from third party introducers such as finance or mortgage brokers.

29 Liberty, a non-bank, does not have a branch network, that is, bricks and mortar stores, from which to source borrowers directly. It predominantly relies on independently-owned finance or mortgage brokers to source prospective borrowers. The team responsible for this task within Liberty is its distribution team.

30 In relation to the underwriting function, this comprises the activities undertaken between loan application and loan approval for the products that Liberty underwrites.

31 Banks generally lend to a conventional type of borrower. There are a variety of reasons why a borrower may be unable to obtain finance through a bank and Liberty’s specialty borrowers are quite varied. Whilst Liberty operates in 5% of the market for lending, it services borrowers which account for 95% of the variety of possible borrower attributes. So, Liberty’s borrowers might include persons with an imperfect credit rating, persons with short-term employment, high net worth individuals wanting to make an opportunistic investment, start-up businesses, or persons lacking historical tax returns.

32 The underwriting team is responsible for assessing loan applications for Liberty’s products by this higher-risk population of borrowers. The underwriting team is also responsible for loan approval, including approval as to loan terms, for example, security and loan length. The assessment function of underwriting mainly involves assessing the borrower. However, it also involves considering where the loan originated from, namely, via which mortgage broker, as that may also be an indication of the quality of a borrower; mortgage brokers may have different compliance track records, which would be relevant to the underwriter’s consideration of a loan application. In this way, the underwriting team is integrated with, and linked to, the distribution team.

33 To assess loan applications, Liberty uses its own approach to risk assessment. Over time, Liberty has continuously refined its risk assessment guidelines or modelling for its product offering, relying on prior learning about borrower characteristics and the boundaries for profitable and unprofitable lending for its products over different operating conditions.

34 Let me now say something about funding, which is dealt with as part of Liberty’s treasury function.

35 Liberty’s treasury team is located at its head office in Melbourne. At all material times, including to present day, it has had about five to six employees. Whilst position titles have changed slightly from time to time, the team is headed by a team leader or manager, who is responsible for the day-to-day management of the treasury function, and executives, who support the team leader / manager. Each executive reports directly to the team leader / manager who, in turn, reports to the chief financial officer, Mr Riedel. Mr Riedel reports to Liberty’s board.

36 The team’s role and its responsibilities have not changed in any material way since Liberty commenced operating in early 1997, except for its expansion. In summary, Liberty’s treasury team is and has been at all material times responsible for, inter-alia:

(a) securing funding for Liberty’s lending operations;

(b) establishing and renewing trusts to hold specialty assets against which debt securities can be sold to clients to raise funding;

(c) optimising the utilisation of trusts to maximise economic value while minimising risk;

(d) establishing, maintaining and developing relationships with wholesale investors and term trust clients, to ensure demand for notes and minimise the need for Liberty to invest its own capital in wholesale and term trusts;

(e) negotiating commercial terms with note holders for wholesale and term trusts;

(f) designing eligibility criteria and pool parameters for wholesale trusts;

(g) designing term trusts and managing subscriptions in them;

(h) executing the ongoing funding of Liberty’s portfolio of specialty assets thereby achieving Liberty’s capital and liquidity strategies;

(i) gaining and maintaining a detailed understanding of the operational processes and systems used by Liberty to originate, price, credit assess and service borrowers, so that Liberty’s receivables can, in effect, be sold to clients via debt securities; and

(j) establishing and maintaining the policies, procedures and systems necessary to perform the above tasks and the treasury function generally.

37 I will discuss securitisation, wholesale trusts and term trusts in more detail shortly. But for the moment let me return to the funding mechanisms.

38 Because Liberty is a non-ADI, attracting, securing and retaining non-deposit based funding is critical to Liberty’s business. Funding provides the capital that it uses to lend to borrowers. Non-bank funders like Liberty must constantly identify, secure and cultivate client relationships with niche sources of capital that will invest in debt instruments secured by specialty borrowers in a niche market for lending to such borrowers. Such clients include banks, managed investment schemes, which are regulated investment products, high net worth individuals who can invest in non-regulated investment products, insurers that invest premiums to generate returns to fund future liabilities, and institutional investors, which generally refers to superannuation fund managers, money managers, hedge funds and other such investment companies.

39 Liberty sources funding predominately from banks and institutional investors, which it describes as its clients; I will use that description in these reasons.

40 Funding is the responsibility of Liberty’s treasury team. Until recently, that team was headed by Mr Jugovic under the supervision of Mr Riedel.

41 Essentially, as a financial institution, Liberty makes money by, first, borrowing funds or by selling debt instruments to clients at a particular interest rate, then, second, lending those funds at a higher interest rate than Liberty borrowed, whilst, third, minimising arrears and losses experienced on the loans it makes. The margin represents, broadly, Liberty’s gross profit.

42 Without investments from clients, Liberty would not have any money to lend and would have no business. Liberty’s funding and lending capacity are therefore linked as are the teams responsible for them. This is because the treasury team needs to, in effect, attract clients to invest in a pool of loans. To do this, the treasury team needs to understand the unique underlying loan characteristics or attributes and performance of Liberty’s borrowers in order to solicit investor clients, each of whom have their own risk appetite and lending parameters. For that reason, clients have preferences for and want to know various details of the borrowers and the nature and terms of the loans Liberty provides to them. Potential clients assess the quality of a potential investment by reference to such matters.

43 Liberty predominantly arranges finance from clients using securitisation. Securitisation is the practice of pooling various types of loan receivables, that is, loans with borrowers and their related security such as mortgages and guarantees, and assigning interests in their related cash flows to third party investor clients as fixed income securities.

44 Due to the highly specialised nature of the business, serving a niche segment of borrowers and relying predominantly on one channel of distribution, the pool of potential sources of funding for Liberty and similar companies is relatively small. Liberty’s funding capability is a significant distinguishing feature of the organisation and has ensured the continued success and growth of the company. Further, knowledge relating to the details Liberty’s funding, especially its relationships with clients, would be of significant value to a competitor. Liberty’s funding capability has been obtained based on decades of continuous development and engagement, and cultivation of relationships.

45 Institutional investor clients have been a lot harder to identify and secure than bank clients. This is because such clients have a universe of securities which they might purchase, with long-term securities issued by a non-bank operating in a higher risk niche market, such as Liberty, being just one limited type of potential investment. Some of these relationships take years to cultivate and often involve bespoke arrangements.

46 Once established, funding relationships are and have been at all relevant times managed by Liberty’s treasury team, including Mr Jugovic. His role included managing the day-to-day aspects of the funding relationship and maintaining and developing relationships with clients. This has included responding to investment queries from clients about a potential opportunity to invest in Liberty’s debt securities. Questions asked by clients are driven by a variety of factors such as their risk appetite, investment mandate and particular outlook on general economic conditions, for example, the state of the residential property market. Clients have been more proactive in asking questions or seeking information from Liberty since the global financial crisis, applying their own proprietary investment processes and preferences in deciding whether to subscribe for securities rather than just relying on ratings provided by rating agencies. According to Liberty, answering client investment queries has been a key part of Mr Jugovic’s role since late 2010. It has given him insight into Liberty’s clients’ preferences and technical concerns, and their likelihood of investment.

47 According to the evidence before me, Mr Jugovic had weekly, if not daily, contact with certain clients once funding relationships were established.

48 Let me now say something more concerning securitisation, wholesale trusts and term trusts.

Securitisation

49 Liberty predominantly obtains the funds needed for its loans to borrowers using a process called securitisation. At a high level, securitisation is the procedure where an issuer designs a marketable financial instrument by merging or pooling financial assets into one group. The issuer then sells this group of packaged assets to investors.

50 Relevantly, at an organisational level at Liberty its distribution / loan origination, underwriting, risk management and servicing functions are provided by Liberty itself. And funds for approved loans are advanced by Liberty’s funding entity, Secure Funding Pty Ltd.

51 Liberty’s treasury function is responsible for securitisation. This involved pooling the loan receivables from borrower loans and packaging them into a trust which is, in effect, designed based on confidential knowledge of investor clients and their requirements in relation to various technical parameters such as borrower demographics, security location and profile. The trustees of Liberty’s securitisation trusts are related special purpose entities. They acquire and hold the financial assets of the trust, namely, the loan receivables and security.

52 Securitisation is done via wholesale, also referred to as warehouse, and term trusts. Investors in Liberty’s wholesale trusts are primarily banks (wholesale investors). Investors in Liberty’s term trusts are bank and institutional investor clients.

53 Since 2000, Liberty has been involved in the establishment of approximately 60 securitisation trusts.

Wholesale trusts

54 Loans sourced by Liberty are initially aggregated in a wholesale trust or trusts. Secure Funding obtains funding from wholesale investors via a wholesale facility pursuant to which funds are advanced by the investor to Liberty in exchange for a subscription of debt securities in the form of notes ultimately secured by the assets of the relevant trust. It is not uncommon for these notes to have a credit rating issued by a rating agency, based on the quality of the pool of underlying loans. Notes reflect terms that are specific to a wholesale investor for a wholesale trust.

55 Wholesale investors typically provide wholesale funding on terms of only 364 or 365 days, following which either the trustee has to repay the funds back to the wholesale investor, or the facility needs to be renewed. Because Liberty’s business has more than one wholesale trust, each with different terms including expiry dates, Liberty needs to constantly review the available limit of total wholesale funding and its utilisation of funding to assess the need to obtain alternative funding via term trust funding, otherwise it risks an event of default under a wholesale trust if the business is short on the necessary capital to repay a wholesale investor at loan maturity.

56 Typically, wholesale investors are only prepared to subscribe for up to a certain amount of securities and on terms that ensure they are senior ranking securities. Senior ranking means, in summary, that if the wholesale trust makes a loss, the senior security holder will take priority in terms of loss allocation thereby having less, if any, risk exposure. Other sources of capital are therefore required for the wholesale trust. These are provided by the issue of subordinated debt securities. For example, a trust containing $100 million of mortgages may issue a senior debt instrument totalling $80 million and a subordinate debt instrument of $20 million. Any losses experienced by the underlying trust are written off against the subordinate debt instrument first. Clients that invest in subordinate debt instruments are therefore important as without this source of funding Liberty would be constrained to using its own capital. They are also more difficult to find given the riskier nature of the security.

57 When Liberty first started it only had one wholesale trust. Today it has several.

58 The treasury team is solely responsible for the task of aggregating and allocating loan receivables to a wholesale trust or trusts. Often, there are multiple wholesale investors in a trust, whether senior or subordinate. When this happens, the treasury team has the complicated task of, in effect, designing the composition of loans in the trust, drawing on, inter-alia, Liberty’s prior dealings with and knowledge of investor appetites for risk in regards to the underlying trust assets, having regard to the eligibility criteria and pool parameters, and investor expectations in terms of willingness to invest, likely facility limits, pricing and return on investment. Cultivating clients for more risky subordinated debt instruments is important for financing the Liberty business.

59 The treasury team is also responsible for the prudent financial management of wholesale funding across several wholesale trusts at any one point in time.

60 Finally, the treasury team negotiates all commercial terms of the wholesale trust documentation with wholesale investors. When commercial terms are agreed, the team instructs external solicitors to prepare necessary documentation, without the involvement of in-house counsel.

61 Members of the treasury team are, and were at all relevant times, exposed to highly confidential and commercially sensitive and valuable information of Liberty in the work that they do relating to wholesale funding.

62 According to Mr Ma’s evidence, if known or otherwise available to ORDE, there is a likely risk that the information would provide a head start to new entrant ORDE, helping it to very quickly raise funding and establish its funding capability. Mr Ma considered the head start to be at least 18 months, but possibly longer to include learnings over the many years of Liberty’s business operations. This sort of head start would see ORDE be competitive with Liberty in a niche lending market, for a niche pool of potential client funders, particularly in the subordinated space, much sooner than it otherwise would have. This has the potential to damage Liberty.

63 As stated earlier, a key input into a funding platform is knowledge of clients interested in subordinated wholesale debt. The pool of available investors is narrow due to the risk, yet the need for subordinated securities is critical to the trustee’s ability to repay the wholesale facility. Liberty’s clients in this space are the responsibility of the treasury team and known to them.

64 A detailed understanding of client preferences and Liberty’s pool of borrowers is key to both securing funding and negotiating wholesale terms that are beneficial to Liberty.

65 The terms upon which Liberty obtains funding are confidential as between Liberty and its wholesale investors. Understanding the terms on which Liberty secures wholesale funding, coupled with an understanding of client preferences, would be of significant value to a competitor. Knowledge of such matters would assist a competitor in at least two ways.

66 First, it would provide the competitor with a significant head start, as it has taken Liberty a long time to determine what each wholesale investor is likely to accept and to structure its funding platform and arrangements accordingly.

67 Second, it would arm the competitor with the knowledge they need to undermine Liberty by presenting as a very real and immediate threat in terms of securing both funding and borrowers.

68 Take, for example, pool parameters, which limit the aggregate portfolio characteristics of the financial assets backing Liberty’s debt securities. They are, in effect, one of the key blueprints for funding. Pool parameter criteria might address geographical limits, employment limits, security types and arrears, for example. Different wholesale investors may and do insist upon different pool parameters.

69 Further, upon Liberty’s wholesale trust being wound up, the wholesale investor might choose to either not advance funds to Liberty again, to not advance as much funding, that is, allocating some to Liberty’s competitor, or to insist upon a change to the pool parameter which might not suit Liberty’s overall strategy in relation to its wholesale facilities.

70 Further, different wholesale investors may require different eligibility criteria. These are the pre-requisites that Liberty must comply with in order to use the wholesale investor’s funding. The types of criteria can include loan size limits, borrower credit history, serviceability and acceptable security. According to Mr Ma’s evidence, if known by a competitor, including ORDE, the competitor could use knowledge about the criteria to structure its own funding platform to make its securities more attractive to a wholesale investor, thereby potentially harming Liberty.

71 A competitor’s knowledge of terms such as Liberty’s profit margin, interest rate, unutilisation fees, stop funding events and facility end date, for example, could similarly provide it with a competitive advantage and cause harm to Liberty. The terms negotiated by Liberty with its wholesale investors are the result of years of engagement and negotiations.

72 Further, combined knowledge of the above terms would be particularly valuable to a competitor and potentially cause Liberty significant harm. The sum of the combined knowledge is in effect greater than the sum of its constituent parts.

73 The manner in which Liberty manages and managed its funding platform is the product of many years of experience including, importantly, learnings from mistakes over different operating conditions. According to Mr Ma’s evidence, Liberty’s methods of practice are confidential to Liberty and would be valuable to a competitor, especially a start-up like ORDE. ORDE will obtain a significant head start if it is able to replicate Liberty’s funding platform and methods of practice in this regard in a relatively short timeframe.

Term trusts

74 When the aggregate limit of available wholesale funding to Liberty is reached or nearing, Liberty assesses the need for creating a term trust or trusts. As term trusts are created, Secure Funding, as trustee of the wholesale trust/s, assigns selected receivables from a wholesale trust or trusts to the newly created term trust/s.

75 Term trusts are long term and based on the tenure of the underlying receivables.

76 The term trust issues debt securities in the form of notes to a limited population of institutional investors. As with wholesale trusts, the notes are secured against the receivables and associated revenue streams and provide investors with periodic returns. When notes are issued to institutional investors, funds are received from those investors by the trustee of the term trust. The trustee uses the funds to pay the wholesale trust for the assignment of loan receivables. The wholesale trust, in turn, uses those funds to repay the wholesale investors, both senior and subordinated investors.

77 Term securitisation is therefore an important part of Liberty’s funding platform because without the necessary funding to repay wholesale investors at maturity Liberty would need to find the capital to do so. Failure to do so would risk losing credibility with wholesale investors, some of whom could potentially suffer a loss, especially if subordinated. The use of Liberty’s capital in this way would mean that it would be constrained in its ongoing ability to grow.

78 Notes in a term trust are described in an information memorandum or offer circular document. Numerous classes of notes are issued by a term trust, each with different credit ratings which relates to the security ranking position of that class of note in the financing. Any losses experienced by the underlying loan receivables in the term trust will be charged off against lower-rated notes before higher-rated notes experience any losses. Investors with varying objectives will purchase notes with different risk profiles, credit ratings and offered interest rates. Whilst multiple investors can participate in a single class of notes, investors for junior or subordinate notes is constrained and limited because the investments are riskier. Therefore, the nature and terms of notes issued by a term trust will be designed with reference to the demand and risk appetite of various investors known to Liberty.

79 Liberty’s term trust documentation contains the commercial terms agreed as between Liberty and institutional investor clients. Internally, the register, supplementary terms notice and offering circular are, and have been at all relevant times, stored on Liberty’s secured network and accessible only to users within the treasury team at Liberty and its executive officers. Not even the in-house legal team has access to documents of this nature. The treasury team instructs Liberty’s external lawyers to draft documents like the supplementary terms notice. Liberty’s legal team is not involved in this process.

80 On occasion, third party entities involved in a securitisation, for example, advisers, may have access to term trust documentation, such as the register, for the purpose of helping Liberty with the notes issue. Information is provided to such entities on a confidential basis, routinely if not always under an express obligation of confidence. Also, as facilitators of a securitisation transaction, they will not be aware of the technical needs and requirements of specific clients in the manner that Liberty is aware.

81 As to the term trust documentation, one of the most confidential of the documentation relating to a term trust is the register. That records the outcome of the securitisation and contains, in summary, Liberty’s confidential client list and confidential terms relating to funding. The properties of the register record that it was created by Mr Jugovic on 16 September 2016.

82 Liberty’s treasury team is and has been at all relevant times responsible for sourcing client investors for term trusts based on prospective and established client relationships. It is also, and has been at all relevant times, responsible for monitoring wholesale funding and utilisation, and creating term trusts as required to ensure the continued financial stability of Liberty. This is a key part of their role.

83 Term trusts need to be attractive to potential investor clients. This involves a process of design, where the treasury team selects loan receivables suitable for inclusion in the term trust based on the team’s familiarity with potential clients, their investment preferences or conditions for funding and their appetite for risk. There are typically multiple classes of notes, each with their own margins and risk profiles. The design task requires the treasury team to understand the key parameters of the term securitisation, note quality and risk, and pricing, as well as which clients are likely to be attracted to investing in particular classes of notes, and therefore who to approach.

84 The register records the terms applying to notes in the term trust and composition of a term securitisation. It is generated by the treasury team and populated by that team as notes are subscribed for. It reflects the design process that the treasury team undertakes for each term securitisation.

85 The offering circular is the type of documentation generally distributed via a bank that contains the details of an offer for investment in a term trust. The treasury team is responsible for preparing it, in consultation with external lawyers. This document is typically generated after the event in that it is distributed after Liberty’s treasury team has worked out, first, where the demand for securities lies, second, who, of its clients, is likely to invest in the term trust, and, third, if so, the terms on which they will be willing to do so.

86 There are three key pieces of confidential information regarding Liberty’s dealings with clients to secure term trust funding. These are, first, the identity of term trust clients, second, the particular terms on which funding is secured from clients and, third, client investment preferences and risk appetites.

87 Clients of term trusts are not a matter of industry knowledge or experience. Rather, the identity of Liberty’s term trust clients is confidential information as between Liberty and the client. That information is critical to Liberty’s business because, as discussed above, if Liberty cannot attract a sufficient number of clients for term trusts, it has insufficient funding to enable the trustee to repay funding provided under wholesale trusts.

88 Identifying clients who will invest in term trusts is information that has been built up by Liberty over a number of years, at great expense and significant investment. According to Mr Ma’s evidence, if a competitor like ORDE had knowledge of Liberty’s clients, it would be able to very quickly become competitive with Liberty for funding from a very limited pool of funders. With funding, it could become competitive with Liberty very quickly for lending to borrowers in a niche market. The head start that ORDE would obtain in this regard would be at least 18 months.

89 Key terms applying to term securitisation are confidential as between Liberty and the client. For example, unlike its competitors, Liberty does not, and did not at all relevant times, disclose its margins to the public other than in relation to class A senior notes.

90 Liberty has, over its 24 years of trading, learned a lot about its clients, specifically their willingness to lend in a niche market and on what terms. Prior learnings are confidential to Liberty. Understanding client investment preferences and risk appetites in the context of term trusts would be of significant value to one of Liberty’s competitors especially a start-up like ORDE. That information is largely captured in documents such as the register. That document is highly confidential, as is the information contained within it. It is available internally only to a limited number of employees, being the treasury team, headed by Mr Riedel, and its executive officers. To put this in context, Liberty has a total of about 450 employees.

91 According to Liberty, if a competitor was armed with knowledge as to the identity and investment preferences of Liberty’s clients, it would put the competitor in a very good position to both take advantage of that information and harm Liberty.

ORDE

92 ORDE is a new entrant to the market as a non-bank specialist mortgage lender providing residential, commercial, SMSF and development loans. It was established in July 2019 by Mr Wells and Mr Ryan Harkness who each had long employment associations with another non-ADI specialty lender, La Trobe Financial.

93 Save for one important difference, ORDE operates with a similar structure to Liberty. It has a warehouse facility in place and is presently negotiating a second. Through Mr Wells and Mr Harkness, ORDE has established relationships with major lenders in the market, and with mezzanine financiers.

94 ORDE promotes itself as a specialty lender, targeting the specialty lending segment where Liberty is a leading participant.

95 Further, ORDE’s customer base and primary sales channel, with a significant emphasis on third-party networks such as mortgage brokers, is similar to that of Liberty. Like Liberty, ORDE has recruited a national sales team of business development managers to work with mortgage brokers.

96 Further, ORDE’s lending product range includes products that overlap and compete with Liberty’s range

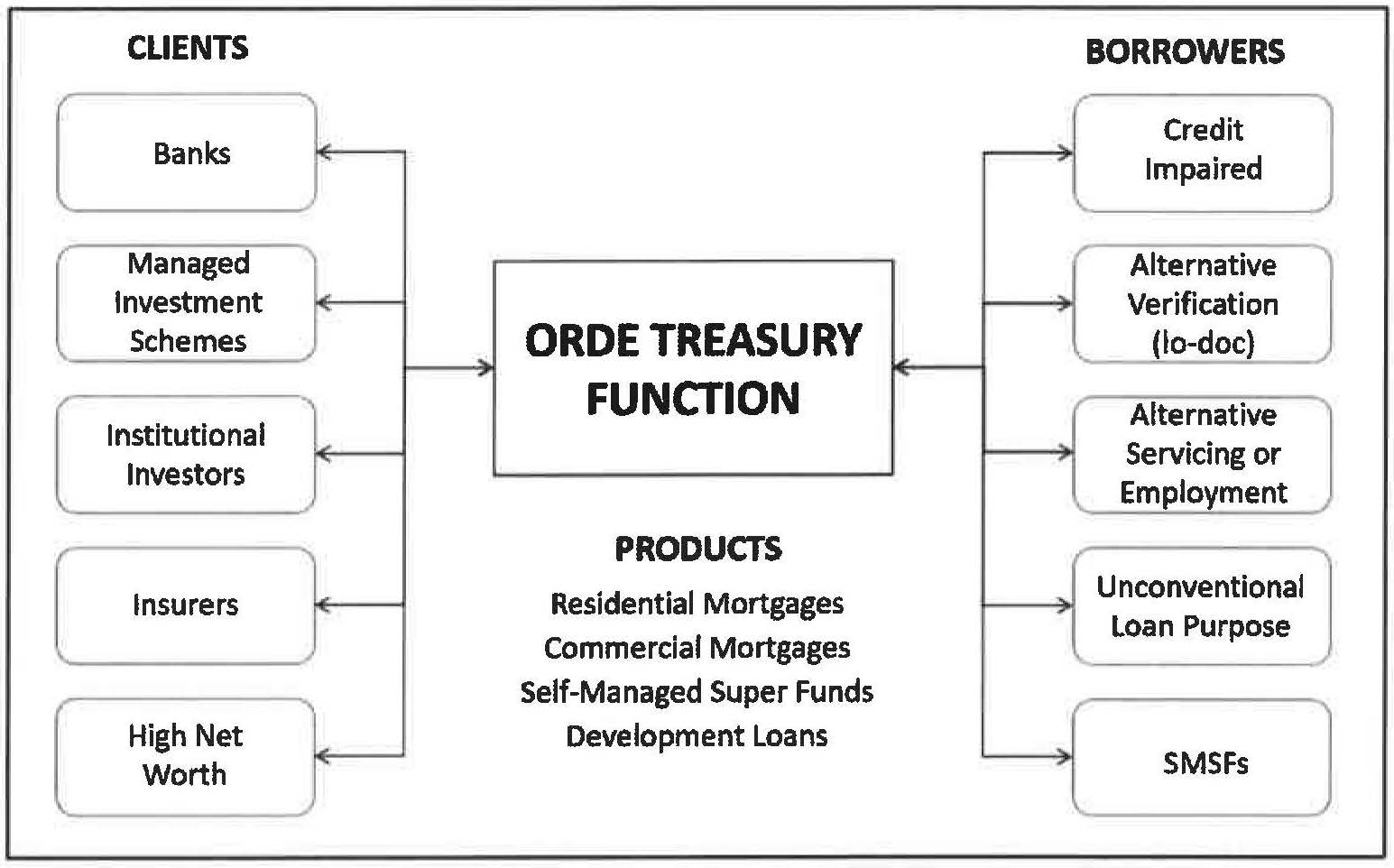

97 Now given the nature and diversity of the various specialty lending niches, ORDE’s treasury function needs to be and is skilled in identifying a range of prospective client funders to match the range of borrowers for specific products. Mr Ma prepared the following helpful diagram to explain the structure:

98 As a specialty lender, ORDE’s business is, like Liberty’s, fundamentally reliant on its ability to match clients that are willing to invest in borrowers fitting into one or more specialty niches, with borrowers in those niches.

99 ORDE’s customers are similar to Liberty’s, save that Liberty operates closer to the “prime” end of the market.

100 The key structural difference between ORDE and Liberty is that ORDE does not presently conduct any securitisation. That is because it has not been in operation long enough to establish a history which is capable of being assigned a credit rating by a rating agency. It will take a number of years for ORDE to be able to engage in securitisation of its mortgages.

101 ORDE’s business can broadly be broken down into two sides.

102 The first part of its business is lending. ORDE makes its revenue from lending money to its customers and being paid interest and other fees on such loans. Examples of the types of loans that ORDE offers its customers are:

(a) residential, typically being loans for the purposes of individuals or families buying property to live in, or for investment purposes or to refinance existing loans;

(b) commercial, typically being loans for the purposes of businesses buying new premises, refinancing existing loans or accessing liquidity for a variety of purposes;

(c) SMSF loans, being used to purchase residential and commercial investments; and

(d) development, typically being loans up to $10 million for the purposes of developing residential projects.

103 The other part of its business is funding. In order for ORDE to be able to make the types of loans just referred to, it needs to obtain finance. The funding side of the business concerns the avenues through which ORDE obtains such finance.

104 ORDE as a business has been relatively recently established and needs to accumulate operational lending history in order to optimise the terms of its funding. There are three points to note.

105 First, ORDE’s two managing directors have extended and primary backgrounds in funding with other leading specialist lenders prior to establishing ORDE.

106 Second, ORDE has now established funding and treasury operations and has various diverse funding relationships being progressively implemented.

107 Third, ORDE has primary determinants for all material improvements to funding terms in the near to medium term future, which are internal to lenders, being the demonstration and accumulation of performance history and profile over time of both ORDE’s lending operations and general organisational profile and asset pool/s, namely, loans. These determinants are predominantly driven by the credit / lending side of the business.

108 Any future incremental contribution through the funding side of the business such as securitisation will not become relevant to ORDE for at least two to three years. At that point in time, ORDE may be able to access diversified funding and may have much larger funding volume needs than in the near to medium term.

109 ORDE has been brought to market by two managing directors who have backgrounds founded on extensive warehouse funding experience. Their experience includes extensive preceding relationships across senior and mezzanine financiers of these businesses, experience with operation of funding and treasury platforms, particularly in relation to warehouses and technical knowledge and experience negotiating and setting up warehouse facility terms and funding arrangements.

110 ORDE’s treasury and funding functions have gained competency. This competency was required in order for:

(a) Wingate to invest in ORDE;

(b) ORDE to receive indicative term sheets or otherwise clear indicative support from six leading senior financiers prior to launching ORDE’s first warehouse;

(c) ORDE to secure and complete its first bank warehouse trust; and

(d) ORDE to progress its second bank warehouse to the point of pending completion.

111 During ORDE’s initial establishment, existing relationships with all leading senior financiers enabled ORDE to set up its warehouse funding.

112 ORDE now says before me that it does not need to establish any new relationships with financiers and has not employed Mr Jugovic for the purpose of establishing such relationships.

113 Similarly, ORDE secured early stage indicative support from mezzanine investors and broadened engagement with investors significantly in early 2021. As a result, ORDE now says that it has relationships with most leading mezzanine investors.

114 Further, as a result of this process ORDE has active engagements with a number of large mezzanine financiers and expects others to open engagement as ORDE builds its lending history. Apparently, mezzanine funding is in place for ORDE’s second warehouse facility and further mezzanine funding developments are expected once this is completed.

115 ORDE’s treasury and funding capabilities operate in conjunction with established lending operations. Whilst ORDE’s assets under management value is small compared to Liberty, it is in the hundreds of millions. As a result, ORDE has already established what it says are sophisticated operational treasury and funding capability, including all typical market processes for warehouse trust operations.

116 Let me say something further about funding.

117 Currently, ORDE obtains all finance through wholesale trust or warehouse arrangements which are said to be similar to Liberty’s wholesale trusts, and are comprised of funding from:

(a) senior financiers, which are the organisations who provide the majority of funding and carry less risk than the mezzanine financiers; and

(b) mezzanine financiers.

118 Now according to ORDE, one distinction between ORDE and Liberty is that ORDE does not presently have any term trusts. ORDE will not be able to obtain funding through such an avenue for at least two years.

119 It is said that ORDE will need at least two or three years of loan pool performance data, for example arrears, constant prepayment rate and loss performance, before a rating agency will assign required ratings opinions and before investors will be comfortable to invest.

120 In that context, ORDE says that its employment of Mr Jugovic will not give ORDE any advantage or head start in relation to setting up term trusts because his involvement or knowledge cannot reduce or change historical data requirements that mean that ORDE will wait for at least two or three years to access term trusts.

121 ORDE says that when it is ready to securitise, it will undertake this process working with commercial counterparties, in particular then existing senior and mezzanine financiers of ORDE warehouse trusts, as well as third party advisers including legal firms, an arranger, or other distribution partners, whose services will include meeting all of ORDE’s commercial information needs.

122 ORDE says that by the time it is ready to securitise, any information which Mr Jugovic holds about Liberty’s securitisation process will be years out of date and, accordingly, of no assistance to ORDE.

123 Further, it says that even if ORDE were able to establish a term trust today, the types of information which Mr Jugovic might know such as the identity of potential investors would be readily available to ORDE or to lead managers on the notes issue or other third party advisers who ORDE would engage as part of that securitisation.

124 Let me say something further about the warehouse facilities.

125 The majority of funding for a warehouse trust will be obtained pursuant to an arrangement with a large financial institution, whereby that institution agrees to provide senior funding to a warehouse trust. This is essentially a revolving facility secured against mortgages, where ORDE can draw down money as it is needed in order to fund loans provided to ORDE’s customers. In return for this, ORDE will pay an interest rate to the senior financier, as well as fees for not utilising the available warehouse facility limit.

126 Senior facilities represent typically 85 to 90% of the warehouse funding which is available to ORDE.

127 The identities of the main senior warehouse facility providers is common knowledge in the industry and there is nothing confidential about the identity of any of these facility providers. The most active providers include Commonwealth Bank of Australia, NAB, Westpac, Macquarie, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank and Bendigo Bank. Other banks, typically international, also provide facilities in lower volumes from time to time. ORDE says that these financiers’ preferences, appetite and processes in the provision and operation of warehouse facilities are in practice either common knowledge or available from the financiers in the ordinary course of developing funding relationships and able to be shaped to the respective lender’s strategy and demonstrated capabilities.

128 Mezzanine financiers are another category of financier of warehouse trusts. Mezzanine finance typically represents about 10 to 15% of ORDE’s funding.

129 Mezzanine funding is subordinate to senior funding in the sense that if the warehouse trust defaults on a financier payment obligation, the senior funding will be entitled to be paid first or in a priority framework, thus enjoying relative protection against any losses, and the mezzanine financer repayment will be paid second and will be more exposed to non-performance by the trust.

130 Now given that mezzanine financiers have higher risk than warehouse facility providers, the rates they charge for providing finance will be higher than warehouse facility providers.

131 ORDE asserts that the identities of the main mezzanine warehouse facility providers is common knowledge in the industry and there is nothing confidential about the identity of any of these facility providers.

132 Mezzanine warehouse investors also typically provide mezzanine funding to term trusts, where the pool of mezzanine investors is considerably broader, which ORDE says is also common knowledge or readily available.

MR JUGOVIC AND CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION

133 It is now necessary to say something more about Mr Jugovic and the question of confidential information.

134 The defendants sought to downplay Mr Jugovic’s role within Liberty. For that purpose my attention was drawn to Liberty’s prospectus issued on 26 November 2020 where there was a description of the senior management team. The defendants pointed out that this did not identify Mr Jugovic. But this point did not take the defendants far. That team included the chief financial officer, Mr Riedel. Mr Jugovic reported to Mr Riedel.

135 Mr Jugovic’s position description was in the following terms:

PD: Team Leader – Treasury

Department: Treasury (SU TRE)

Reporting to: Chief Financial Officer

1 POSITION OBJECTIVES

To ensure the timely execution of the company's funding and capital requirements within the framework of relevant covenant, policies and processes and to provide analytical support to senior management to assist with formulating and executing company funding and capital.

2 EXAMPLE DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

• Under the direction of the Chief Financial Officer manage the ongoing funding requirements of Liberty’s portfolio of assets with a view to achieving the Company’s capital and liquidity strategies.

• Monitor daily the liquidity and cashflows of Liberty accounts.

• Facilitate the ongoing operation of the Company through the timely review of surveillance reports, compliance with all allocated covenants, maintenance of sound relationships with all internal and external parties, and timely resolution of issues as and when they arise.

• Identify and resolve funding issues in a timely and competent manner under the direction of the Chief Financial Officer.

…

• Build a high performance Treasury team through proactive coordination of, but not limited to recruitment, team & individual development plans, budget & KPI adherence, staff training, regular team meetings & the development of strong external relationships.

136 Let me delve further into Mr Jugovic’s position with Liberty.

137 Mr Jugovic started with Liberty in January 2002 in the position of services officer within Liberty’s treasury team. He performed largely administrative duties and reported to Liberty’s then finance manager. In mid-2002, Mr Jugovic was transferred to the position of treasury officer where he commenced training in relation to the treasury team’s functions. In December 2009, Mr Jugovic was promoted to the position of senior analyst. In November 2010, Mr Jugovic was promoted to the role of team leader. Mr Jugovic’s most recent employment agreement for the position of Team Leader – Treasury was signed on 3 October 2011. He changed his title since, but his duties remained largely unchanged.

138 Since November 2010, Mr Jugovic has been responsible for overseeing the functions of the treasury team. For Mr Jugovic to be an effective treasury professional, that is, to secure funding from clients for Liberty’s debt instruments, he needed to understand and be able to explain key aspects of Liberty’s business.

139 Over the first ten years of Mr Jugovic’s employment, he became involved in working with Liberty’s clients on their day-to-day needs concerning funding arrangements and any renewals. By late 2010, he was heavily involved in these tasks, having overall responsibility for them. Mr Jugovic had relationships with Liberty’s clients and had frequent direct contact with them. During periods where the terms of securitisation were being negotiated between Liberty and its clients, Mr Jugovic had contact with relevant clients approximately weekly. For some clients, Mr Jugovic would typically be the first point of contact if they had a question regarding their investment.

140 By late 2010, Liberty relied very significantly on Mr Jugovic. He was responsible, under Mr Riedel’s guidance, for an important business division, the performance of which underpinned Liberty’s ability to write loans to borrowers. Mr Jugovic had simultaneously been involved in implementing Liberty’s funding models, its pricing structures, and risk profiles and, by this stage, had overall responsibility for Liberty’s funding platform. This necessarily entailed a reasonably high level of client contact and a detailed understanding of Liberty’s processes and its confidential information, being, in this context, particularly client identities, investment preferences and appetite.

141 Over the 12 months prior to Mr Jugovic’s resignation, Mr Jugovic had contact with a material number of Liberty’s clients. Mr Jugovic maintained relationships with clients, so as to obtain funding that enabled Liberty to lend to specialty borrowers. If Mr Jugovic performs services the same as or similar to those that he performed for Liberty for some other business, it would likely be for a business which competes with Liberty and for a business for which Liberty’s confidential and commercially sensitive information would be valuable. It is only non-ADI specialty lenders that operate as Liberty does, which require these services. There would be no role similar to Mr Jugovic’s role with Liberty in a non-competing business, or in a business where Liberty’s confidential information is not relevant or valuable. If Mr Jugovic were to perform a role within the treasury department of a commercial or investment bank, he would be performing different services to those that he had provided to Liberty. Whilst Mr Jugovic’s skills are more broadly transferable within the finance sector, the particular services he provided for Liberty were narrow and limited.

142 Let me say something further concerning confidential information.

143 Liberty’s treasury team is and has been exposed to highly confidential and commercially sensitive information of Liberty. At the date of entry into his employment agreement, Mr Jugovic had been working in the treasury team for about nine years and had been in a senior role, namely, team leader, for almost one year. He had therefore been exposed to Liberty’s confidential and commercially sensitive information relevant to the treasury function for a reasonably long period.

144 Such confidential information may broadly be described as client identities, client preferences in relation to investing in wholesale and term trusts, commercial terms for wholesale and term securitisation and the manner in which Liberty manages its funding platform including by way of its wholesale and term trusts.

145 Liberty’s evidence makes the point that there is value in that key information to competitors, including to a start-up like ORDE. All of that key information combines to enable the treasury team to do its core function, namely, to combine client funds in a manner that optimises the amount of funding available and the cost of funding. The cost of funding is critical in that lower costs may allow Liberty, for example, to out-compete rivals by offering borrowers products with a lower interest rate, or allow it to generate more revenue to be used for operating expenses or shareholder returns. A critical input into the cost of funding is margin, as issuers of debt securities are typically charged interest which is expressed as a function of the reference rate, for example, predominantly a one-month benchmark interest rate, plus a margin. Liberty aims to have the lowest margin. As the most experienced funder in this niche area, Liberty has more negotiating power than other non-banks. Further, potential investors in term trusts might agree to a lower margin in order to participate in certain securities. This is particularly important for the issue of subordinated debt securities where the potential client investor base is limited.

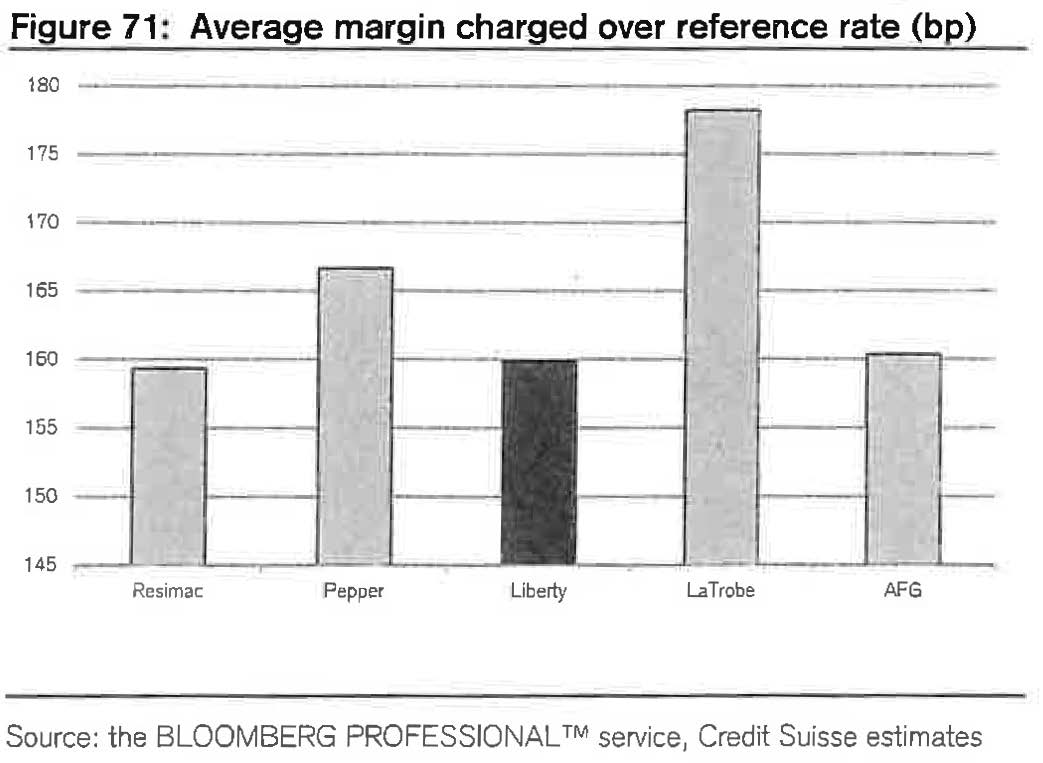

146 In evidence is an equity research report published by Credit Suisse on Liberty dated 9 February 2021. Figure 71 of that report shows a comparison between the average margin charged by Liberty to its clients versus other non-bank participants as estimated by the research analyst.

147 In that research report, Resimac and AFG Funding are non-banks who do not predominantly operate in Liberty’s specialty segment. As a result, they have lower margins, as their lending is mainly in a less risky sector. Contrastingly, Pepper, Liberty and La Trobe Financial do operate in Liberty’s specialty lending segment. Liberty’s lower margin means that it commands a material advantage relative to Pepper and La Trobe Financial.

148 Liberty makes the point that a new entrant like ORDE will have a significantly higher funding margin than those shown in the graph above and will do so for quite some time. Liberty makes the point that it took over 20 years to secure a relative margin advantage like that reflected above. It says that access to, or knowledge or use of, Liberty’s key commercially sensitive and confidential information would be valuable to ORDE as it will allow ORDE to gain a significant head start in accelerating its funding platform, thereby establishing itself as a threat to Liberty reasonably quickly.

149 On Liberty’s case, Mr Jugovic’s role as Executive Director of Debt Capital Markets at ORDE will necessarily require him to oversee and be responsible for ORDE’s entire treasury function. This will involve securing funding so as to meet ORDE’s needs and deliver its funding platform, as well as work aimed at continually improving that platform to make ORDE competitive in the market, including with Liberty. Mr Jugovic’s role will therefore be similar to, if not the same as, the role that he performed for Liberty. Whilst he may not be, although he initially might be, as involved in the day-to-day operational tasks involved in treasury, he will have overall responsibility for them and will be responsible to the board for establishing and continuingly improving its funding capability.

150 Liberty says that if Mr Jugovic commences employment with ORDE he will unavoidably and necessarily use or disclose, even if inadvertently, Liberty’s confidential information in performing his role. It will be impossible for him to perform his role in such a niche market for lending to specialty borrowers and in such a niche market for obtaining necessary funding, without him doing so. It is said that the risk of unauthorised use or disclosure of Liberty’s confidential information is real and unavoidable. It is said that it will not be possible for Mr Jugovic to establish a treasury function without drawing on his knowledge of Liberty’s confidential information such as the identity of potential clients and client preferences including as to the quality of underlying loan receivables. Further, it is said that information relating to Liberty’s pricing, eligibility criteria and pool parameters will necessarily inform how Mr Jugovic determines similar criteria to apply to ORDE’s securitisations. Further, it is said that information relating to Liberty’s pool parameters and strategy regarding usage of wholesale funding will inevitably influence the funding platform that he develops for ORDE. It is said that such information has enabled Liberty to operate through ebbs and flows, or even major crises, in the economy and would be attractive to ORDE.

151 Further, it is said that the employment of Mr Jugovic by ORDE will enable it to obtain a significant head start as it attempts to position itself as a viable investment alternative for some client funders and a real competitive threat to Liberty much faster than it would do so if it were to establish its treasury function without the confidential information held by Mr Jugovic. By employing Mr Jugovic, with its attendant real risk of unauthorised disclosure and use, Liberty says that ORDE will be able to circumvent years of learning and investment.

152 Further, Liberty says that if Mr Jugovic is permitted to work for ORDE, there is a real risk that Liberty will lose clients or that clients will reduce their business with Liberty. And it is said that if Liberty is ultimately successful in this proceeding, proving a loss of clients due to Mr Jugovic’s conduct in breach of any enforceable restraint will be difficult.

153 Now ORDE disputes these propositions.

154 Mr Wells gave evidence for ORDE that Mr Jugovic’s role at ORDE during the next 12 months will involve:

(a) responsibility for day-to-day treasury (cash movement) operations;

(b) operating ORDE’s completed warehousing arrangements, including managing and monitoring performance and compliance, building pool data sets, providing information and updates to financiers, managing portfolio allocations, utilisation and parameters;

(c) monitoring standard industry risk assessment models of trust pools;

(d) gathering public information on funding markets;

(e) management and completion of extensive generic warehouse trust facility documentation processes on behalf of ORDE;

(f) assisting Mr Wells to establish other significant funding operations relating to loan products not offered by Liberty and not funded through warehouses or term trusts, being product lines in which Liberty does not compete;

(g) participation in ORDE executive management committees covering core elements of the business (excluding the lending committee) reflecting both Mr Jugovic’s specific skills and also broad lending business acumen and skills; and

(h) learning detailed aspects of credit processes and operations and product characterisations.

155 It is said that these tasks relate only to established ORDE funding operations and to standard financing. It is said that ORDE will not involve Mr Jugovic in certain facility negotiations relating to either future warehousing agreements or existing warehouse extensions.

156 It is said that Mr Jugovic’s role will not involve the identification of new financiers or the development of the relationship with financiers with which ORDE does not already have developed relationships. It is said that such work has already been performed by Mr Harkness and Mr Wells, who hold the financier relationships.

157 It is said that Mr Harkness and Mr Wells are now in warehouse “scale-up” mode, in that they have established the required warehouse funding framework, and require Mr Jugovic to manage the operational aspects of this. It is said that they are well able and positioned to undertake the optimal negotiation of any new warehouses in the period to May 2022, but this is not what Mr Jugovic will be required to do.

158 It is said that Mr Jugovic will not be performing any work in relation to term securitisation in the next 12 months. Apparently, ORDE is still two or three years away from engaging in this type of funding and it is not possible to start this work within 12 months.

159 In summary, it is said that to the extent that Mr Jugovic has any information which may be considered confidential to Liberty, this cannot be used by ORDE to its advantage or to Liberty’s detriment.

160 First, ORDE already has an existing warehouse facility arrangement in place, and has agreed terms with a new financier. It is not seeking to take any market share of finance from Liberty.

161 Second, ORDE already has relationships in place with potential financiers. Mr Jugovic is not required to introduce ORDE to new financiers.

162 Third, the terms on which ORDE will be able to obtain finance are based on objective criteria. It is said that knowledge of Liberty’s specific terms cannot be used by ORDE to obtain better terms, as it simply won’t be able to meet the other criteria imposed by the relevant financier.

163 Fourth, Liberty has existing warehouse facilities with a number of financiers, which cannot be broken by Mr Jugovic, and financiers would not be influenced by Mr Jugovic to cease or reduce the amount of finance they provide to Liberty.

164 Now I should say at this point that I am not at all convinced about the defendants’ assertions and their evidence.

165 Evidence was given by Mr Wells of his understanding that Mr Jugovic’s role at Liberty did not involve any direct experience in, or detailed understanding of, the lending side of Liberty’s business. But evidence before me suggests that Mr Jugovic did have a detailed understanding of Liberty’s lending business as he needed to convey Liberty’s lending practices to its clients. Mr Jugovic had access to, and an understanding of, the interest rates offered to Liberty’s borrowers, the policies and approaches used to assess the credit risk of Liberty’s borrowers and the systems used by underwriters to assess the credit risk of Liberty’s borrowers. Further, Mr Jugovic was responsible for managing the on-site visits of clients in executing their loan file auditing procedures. And Mr Jugovic was responsible for providing and demonstrating the underwriting systems to clients to enable the completion of their auditing work.

166 Further, evidence was given by Mr Wells of his understanding that Mr Jugovic was not responsible for managing financier relationships. But the evidence suggests that Mr Jugovic was for many years the principal point of contact for most of Liberty’s senior funding clients.

167 Further, Mr Jugovic has also stated that he has not been involved in any discussions or negotiations about entering into new agreements following the expiry of Liberty’s current warehousing agreements. But this is disputed.

168 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that for new agreements, the key terms were generally agreed between Mr Riedel and his equivalent at the relevant financier. But again this is disputed. According to Mr Riedel, Mr Jugovic was, for many years responsible for managing the facilities and renegotiating terms to Liberty’s best advantage. He said that Mr Jugovic would recommend changes to him not the other way around.

169 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that financier parameters are dictated by the credit team within the relevant financier, and there is very little scope for Liberty or any other borrower to negotiate the terms. But again this is disputed. There is evidence before me to suggest that changes in parameters often occurred at each renewal and under Mr Jugovic’s management.

170 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that he was not involved in tailoring parameters at a day-to-day level. But according to Mr Riedel, Mr Jugovic was responsible for managing this day-to-day process.

171 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that certain costs of funding could be ascertained from publicly available information about what rates Liberty has generally agreed with its financiers. But according to Mr Riedel, publicised costs of funding relate to the aggregate costs of term and wholesale funding facilities. It is not possible to separate the costs of wholesale funding from such information.

172 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that securitisation clients are not kept confidential to Liberty. But Mr Riedel explained that whilst the identity of those clients is known to the advisers such as the joint lead managers of the notes, the identity of those clients has never been made public by Liberty and third party advisers are under strict confidentiality arrangements to ensure that the information that Liberty provides them is not disclosed to others.

173 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that his discussions with potential investors in the bonds are relatively limited. But according to Mr Riedel, Mr Jugovic had direct engagement with Liberty’s clients on each term securitisation.

174 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that the documentation for warehousing and securitisation facilities is prepared by external law firms and that he understands that the documents are basically industry standard, and are prepared regardless of the identities of the parties issuing the bond or entering into the warehouse facility. He stated further that because some bonds are publicly traded on the ASX, much of the documentation regarding securitisation is publicly available. But again according to Mr Riedel, there is no industry standard regarding the terms of warehouse facilities, and the terms negotiated between Liberty and its clients regarding warehouse facilities are not made public.

175 Now Mr Jugovic gave further evidence in an affidavit affirmed on 28 May 2021 seeking to contest some of these responses by Mr Riedel. But I cannot resolve such disputes in the present context. Suffice it to say that in my view, at the least, Liberty has a good prima facie case as to the likely risk of misuse of its confidential information, albeit subconsciously or inadvertently, if Mr Jugovic takes up his position with ORDE in the next 12 months.

176 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that to the extent that some financiers might have preferences about the mix of loans which would secure the relevant warehouse facility, that is a matter which is dictated by the financier. Mr Wells gave similar evidence. But according to Mr Ma, this is incorrect. It is not the case that the client dictates terms which are invariably met by Liberty. Liberty and the client negotiate the key terms of the relevant securitisation agreement, including but not limited to the pool parameters, eligibility criteria and the margins.

177 Further, Mr Jugovic stated that knowledge by him of the preferences of a financier does not give him any advantage. Further, Mr Wells said that in dealing with a client, it would be ORDE’s usual process to ask the client to disclose its preferences and to work with these, and accordingly there is no need for ORDE to use or know a client’s preferences vis-à-vis Liberty. But Mr Ma said that knowing the commercial terms to which a client has previously agreed to provide finance is valuable. This is the base from which any future negotiations commence. As Mr Ma explained, if you want to purchase a Mercedes, and you know the price that the dealer sold the same model to another person, and some of the other important features of the car, this sets the parameters of the future negotiations.

178 Further, although Mr Jugovic stated that the documentation for the wholesale and term trusts were industry standard, as Mr Ma explained, whilst it might be industry standard to have trusts, many of the terms are not standard; they are bespoke and unknown to Liberty’s competitors.

179 Again, the defendants have sought to counter this by further evidence. But these are all triable questions. I should also say that I have not set out all the evidence on this topic as much of it has been subject to confidentiality claims.

180 I am not able to resolve the assertions and counter-assertions. Suffice it to say that I have considered that there is a real risk that Mr Jugovic may inadvertently or subconsciously use Liberty’s confidential information if he takes up employment with ORDE in the next 12 months. But it is unnecessary for me to be more specific at this stage concerning the information. I am dealing with a threatened breach of confidence rather than a cause of action where there has been an actual breach. Further, I am not at all convinced that undertakings given by the defendants could address this problem. They would be difficult to police, particularly concerning subconscious or inadvertent misuse of confidential information.

181 In any event, I do not need to be more specific at this stage as in my view Liberty has made out a strong prima facie case in any event under the relevant restraint clause such as to now justify an injunction.

PRIMA FACIE CASE

182 Let me now turn to the prima facie case limb. But before turning to the various heads referable to considering the first limb, let me set out a little more of the chronology.

183 On 20 April 2021, Mr Jugovic gave Liberty two weeks’ notice of his termination under the employment agreement. That notice expired on 4 May 2021.